United States

Department of

Agriculture

Rural Business–

Cooperative

Service

RBS Research

Report 194

Black Farmers in

America, 1865-2000

The Pursuit of Independent

Farming and the Role of

Cooperatives

Abstract

Black farmers in America have had a long and arduous struggle to own land and to

operate independently. For more than a century after the Civil War, deficient civil rights

and various economic and social barriers were applied to maintaining a system where

many blacks worked as farm operators with a limited and often total lack of opportunity

to achieve ownership and operating independence. Diminished civil rights also limited

collective action strategies, such as cooperatives and unions. Even so, various types

of cooperatives, including farmer associations, were organized in black farming com-

munities prior to the 1960s. During the 1960s, the civil rights movement brought a new

emphasis on cooperatives. Leaders and organizations adopted an explicit purpose

and role of black cooperatives in pursuing independent farming. Increasingly, new

technology and integrated contracting systems are diminishing independent decision-

making in the management of farms. As this trend expands, more cooperatives may

be motivated, with a determination similar to those serving black farmers, to pursue

proactive strategies for maintaining independent farming.

Acknowledgments

The idea of conducting this research was developed from reading an unpublished

manuscript by a co-worker, Beverly Rotan, which was based on several case studies

of black farmer cooperatives. Her research indicated that historical background was

essential to understanding many of the current conditions for black farmers and their

cooperatives. Discussions with Beverly and another co-worker, Edgar Lewis, were

indispensable in the effort to adequately understand the goals and practices of black

farmers and cooperatives. John Zippert of the Federation of Southern

Cooperatives/Land Assistance Fund provided background on some of the major devel-

opments of black farmer cooperatives during the 1960s and 1970s, as well as provid-

ing a substantial set of key documents. The historical component of this report relied to

a large extent on three excellent books by the Smithsonian Institution scholar, Pete

Daniel (see the References section). Furthermore, he reviewed an earlier version. His

suggestions were helpful for making several improvements in this report. A second

version was reviewed by Professor Robert Zabawa of Tuskegee University and

Spencer Wood, a doctoral candidate in sociology at the University of Wisconsin. They

offered several excellent critical observations and suggestions.

October 2002

Reprinted October 2003

Contents

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1

Black Farmers in the South, 1865-1932 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2

Independent Farming Initiatives, 1886-1932 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5

New Deal Agriculture . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8

The Civil Rights Movement and Cooperatives . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .10

Promoting Independent Farm Enterprise Through Cooperatives . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .13

Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .18

References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .19

Appendix Table 1- A Chronology, 1865-1965 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .22

Appendix Table 2- Number of farm operators and operating status, 1900-1959 . . . .23

Appendix Table 3- Farm operators in the U.S. by race, 1900-1997 . . . . . . . . . . . . . .24

i

Black Farmers in America, 1865-2000

The Pursuit of Independent Farming and the Role of

Cooperatives

Bruce J. Reynolds

Economist

Rural Business-Cooperative Service

Farming as a family-owned and independent

business has been an important part of the social and

economic development of the United States. But for

many black farmers it was more often than not a losing

struggle.

1

The end of slavery was followed by about

100 years of racial discrimination in the South that lim-

ited, although it did not entirely prevent, opportunities

for black farmers to acquire land.

Enforcement of civil rights in the 1950s-60s

removed many overt discriminatory barriers, although

by that time increased technology had significantly

reduced the demand for farmers in agricultural pro-

duction. Nevertheless, cooperatives, while having

some limited application in earlier decades, emerged

as a significant force for black farmers during the civil

rights movement. They assumed a major role in mar-

keting and purchasing and in improving opportunities

for black farmers to retain their ownership of land.

They essentially helped keep alive a traditional aspira-

tion for independent farming. This report reviews the

history of black farmers to explore the role of coopera-

tives in their pursuit of independent farming.

The term "independent farmer" is often used for

different purposes, ranging from description of a per-

sonality-type to justifications for farm policy. A gener-

al definition is an individual who makes farm-operat-

ing decisions that have variable risk and reward

outcomes. For independent farming to be successful,

risk/reward combinations must be competitive with

what is offered by alternative production systems that

diminish operating independence of farmers.

About 25 years ago, an independent farmer was

generally defined as having freedom to make decisions

with risk and reward consequences while functioning

in an interdependent market system (Breimyer, 116-17;

Lee, 40-43). While this definition is still valid, interde-

pendencies in the farm economy are increasing and

farm decision-making has become more coordinated

and restricted during the last 25 years (Wolf).

Definitional boundaries of farming independence

are left to farmers and agribusiness to negotiate with-

out major interference by government in determining

how risk and reward are shared. In general, public pol-

icy and agricultural research are focused on how to

increase aggregate income and to provide a farm safe-

ty net, but for the most part are neutral about the

extent of a farmer’s entrepreneurial independence.

2

1

1

The abolition of slavery did not end domineering systems of

command and control by some white planters over most black

farm operators. The undermining of opportunity for blacks to

develop independent farming, in many cases by the use of

peonage, existed well into the post-World War II era. (Daniel

1972).

2

U.S. agricultural policy in general has adhered slightly more to a

philosophy of "consumer sovereignty" in regard to not directly

promoting the operating independence of farmers, than for

example, French agricultural policy. For a comparison between

French and U.S. policies on the role of cooperatives with respect to

independent farming of grapes for wine production, see Knox. For

an institutional and policy comparison between the U.S. and

France regarding the relative importance of consumer sovereignty

and of human factors of production, i.e., independent farmers, see

Chen.

That leaves cooperatives, with their democratic

control of value-added businesses, as the major institu-

tional mechanism for sustaining independent farmers.

However, as applied in predominantly white farming

regions of the U.S., members’ operating independence

is assumed and the primary objective of cooperatives

is to maximize member earnings. By itself, indepen-

dent farming traditionally has been regarded as only

an implicit objective in these cooperatives.

3

For many white farmers, independent farming

has been an economically challenging vocation, but

unlike black farmers, they have not experienced social

and institutional barriers to owning and operating

farms. For many black farmers, there is a special incen-

tive to operate independently: to avoid both farming

under the controlling systems that many white

planters applied in the past, and the trade credit prac-

tices that led to foreclosure on land they owned

(Litwack, 137).

Since the civil rights movement, cooperatives

have played an important part in helping black farm-

ers to sustain or develop as independent operators. As

a public issue, the objectives have been civil rights and

fighting poverty, and not independent farming. In fact,

during President Lyndon Johnson’s "war on poverty,"

many of today’s black farmer cooperatives got their

start with financial assistance from the Federal

Government. But to black farmers and community

leaders, building and sustaining operating indepen-

dence is a concomitant objective and cooperatives have

a major role in achieving that end.

4

The experience of black farmers is directly con-

nected with major events in Afro-American and gener-

al U.S. history. For a quick reference on pertinent his-

torical developments, see a chronology of periods and

events for 1865-1965 in Appendix Table 1. The first sec-

tion of this report discusses farm-operating arrange-

ments that developed during Reconstruction and the

subsequent decades of progress for some, but worsen-

ing conditions for most black farmers with the rise of

the Jim Crow era in the 1890s. The second section

examines development of three strategies during the

period of 1880 to 1932 for establishing independent

farmers: cooperatives, farm settlement projects, and

farming self-sufficiency. The third section describes the

impact and legacy of the New Deal period, 1933-41, on

the prospects for black farmers. The fourth section

examines the influence of the civil rights movement on

the rise of black farmer cooperatives during the 1950-

60s and the role of the Federation of Southern

Cooperatives/Land Assistance Fund (FSC/LAF). The

last section discusses some of the challenges in using

cooperatives to sustain independent black farmers,

and how they are being met in rural black communi-

ties to accomplish value-added initiatives.

Black Farmers in the South, 1865-1932

Abolitionists worked to end slavery for several

decades before the Civil War, but most were uncon-

cerned about how former slaves would transition to

freedom in a capitalist society (Pease, 19 and 162).

When victory by the North was imminent, this issue

was immediately in the forefront. Its resolution

required answering a basic question: to what extent

should government provide for a transition to "free"

labor rather than support the desire of many freedmen

to be independent farmers?

There were isolated opportunities for former

slaves to acquire land. As early as 1862, Union gener-

als subdivided some plantations of Confederate lead-

ers for small farm settlements by former slaves. The

government sold confiscated land on St. Helena Island

and Port Royal, SC, in 1863 to a philanthropist-entre-

preneur who produced cotton by hiring freedmen and

arranged mortgage payment plans for those farmers to

gradually purchase the land (Pease, 139-41).

The first Freedmen’s Bureau Act in 1865 included

plans for 40-acre tracts to be sold on easy terms from

either abandoned plantations or to be developed on

unsettled lands. But by late 1865, President Andrew

Johnson terminated further initiatives by the Union

Army for small farm settlements. In 1866, a second

2

3

Joseph Knapp’s two-volume history of American agricultural

cooperatives, the most comprehensive to-date, describes how

farmers formed associations to improve their income. He attached

a different meaning to the term "independent farming" from the

way it is defined in this report. He viewed the late 19th century

commercialization of agriculture as eliminating farmer

independence. In his view, the decline of independent farming

created the need for cooperatives (Knapp 1969, 46). The stated

purposes of most cooperatives are synonymous with sustaining

the independence of farmers, but in following Knapp’s conception,

they are rarely ever described in such terms.

4

Even black political and government leaders emphasize economic

development and not operating independence. This emphasis,

which misses the desire of many black farmers, is described by

Jerry Pennick in the Federation of Southern Cooperatives/Land

Assistance Fund 25th Anniversary Report of 1992: "Of all the black

leaders, both locally and nationally, how many have provided us

with a real and viable plan for economic independence? Invariably

they say that in order for us to achieve economic independence,

we must have jobs. By jobs, they mean working for the established

employment producing industries, which are over 95 percent

white owned and controlled."

Freedmen’s Bureau Act was passed that lacked specific

terms and actions for implementing 40-acre settle-

ments (Shannon, 84).

Social scientists and economic historians have

considered the government’s reluctance to implement

a major land settlement program for the freedmen as a

lost opportunity for independent farming (Marshall

57; Higgs, 78-79). The extent to which land reform

would have required seizure and breakup of planta-

tions may have worked against adoption of such a pol-

icy. There were opportunities to provide small farms

on government-owned or unsettled lands. But a relat-

ed issue was what to do with large plantations and

how they would be farmed? By leaving the plantations

intact, a demand for farm-operating labor was created.

Despite early announcements of plans for land

settlement programs, the work of the Freedmen’s

Bureau focused instead on facilitating a transition from

slave to various types of farm operation or labor rela-

tionships. During a 4-year period, the Bureau mediat-

ed agricultural production contract negotiations

between planters and freedmen (Woodman 1984, 534-

35). In other words, national leaders decided that its

appropriate role was to help former slaves become

"free" in being able to offer labor and farm operating

services, while independent farming was left to indi-

viduals to pursue.

5

The demise of land distribution

plans did not eliminate opportunities for ownership

and independent farming, but its future depended on

the extent of economic mobility, or what was called

moving up the agricultural ladder. The Freedmen’s

Bureau sought to establish potential for mobility by

requiring fairness in the terms negotiated for farm pro-

duction.

The freedmen eschewed operating as wage-work-

ers out of concern that planters would establish a

"free" labor variant of the factories-in-the-field system

of slavery. They also wanted more connection to the

land with responsibility for raising crops such as cot-

ton on individually designated tracts. Furthermore, the

freedmen wanted separate family residences, in con-

trast to the centralized living quarters under slavery

(Ochiltree 357, 377). Each tenant or sharecropper fami-

ly had its own cabin and designated section of land.

The two general alternatives to wage labor were

tenancy arrangements under rental contracts and

sharecropping. The tenant contracts were often not a

fixed-rent type, but a specific share of either the har-

vest or of sales. In contrast to sharecroppers, tenants

supplied more farm production inputs in addition to

their labor. The distinction had originally meant that

tenants paid landowners for use of the land, including

debt payments, while sharecroppers received their

share, less debt payments, from landowners. Several

southern states passed laws during the late 19th centu-

ry that established the status of payment terms and

working relationships as subject to determination by

private negotiations between the landowner and ten-

ant worker, which resulted in negligible differences

between tenant and sharecropper (Edwards). Hence,

the alternative forms of contracting that are reported

in the Census of Agriculture for the South were in

many cases of actual practice equivalent to sharecrop-

ping in providing slight incentives to increase efforts

for more productivity and earnings, as observed in

later studies (Woofter, 10-11).

The Freedmen’s Bureau was not in a position to

uniformly establish fairness in farm contracting. Its

termination by 1869 may have been premature, but it

did help establish terms under which some planters

and black farm operators would develop effective

working relationships. The Bureau, in concert with pri-

vate organizations, also helped establish schools that

remained in operation throughout the Reconstruction

period (Vaughn, 9-23).

The presence of Federal troops also facilitated the

exercise of new freedoms by former slaves, especially

the establishment of their own churches. The churches

became a focal point of community development.

Some even assumed coordinating roles in education

and commerce.

Newspaper stories from Alabama in the 1870s

describe corn production and price agreement strate-

gies used by black farmers to withstand pressures to

sell cheaply. This coordination was accomplished

through the informal channels of church membership.

In fact, the value of church membership created suffi-

cient incentive and social cohesion to prevent free-rid-

ing behavior from unraveling group commitments.

These assertions of coordinated market power by black

farmers in the Reconstruction years, however, fueled

resentment among some elements of white society

(Curtin, 26 and 34).

The withdrawal of all Federal troops in 1877 sig-

naled a turn for the worse in making progress for inde-

pendent farming. The availability and quality of public

and private schools declined. In many rural areas,

there was no access to high school education for black

children (Litwack, 56-113). Concurrently, institutions

and arrangements for agricultural production in the

3

5

As noted in footnote 2, independent farming has seldom been a

direct concern of policy in U.S. history.

South evolved further away from incentive-based rela-

tionships to increasingly rely on more command and

control over farm laborers (Ochiltree, 367-68; Curtin,

35).

The extent of progress of black independent

farming does not admit easy generalizations for the

period of 1880-1920. Census data and other evidence is

mixed between progress in land ownership for some

and economic stagnation for most black farmers.

W.E.B. Du Bois estimated 19th century progress

in land ownership by black farmers: 3 million acres in

1875, 8 million in 1890, and 12 million in 1900

(Aptheker, 105). The Census of Agriculture shows a

steady increase in the number of farm operators own-

ing land in the South from 1880 to 1890 and again in

1900, but does not distinguish between white and non-

white owners until 1900. Census figures show 1920 as

the peak year in the number of nonwhite owners of

farmland in the South (Appendix Table 2). In terms of

acreage owned, the census shows 1910 as the peak

year for the South. More than 12.8 million acres were

fully and partly owned, respectively, by 175,290 and

43,177 nonwhite farmers.

6

Increases in land ownership after 1900 were part-

ly due to a significant rise in cotton prices that lasted

until the outbreak of World War I in 1914. The growth

in farmland acquisition by blacks during the late 19th

and early 20th centuries demonstrates a period of eco-

nomic mobility for about 25 percent of farm operators

(Appendix Table 2). In the early 20th century, there

were instances of black farmers having achieved the

status of landlords and becoming philanthropic com-

munity leaders (Grim, 412-14).

During the 19th century there were some oppor-

tunities to establish farms on unsettled lands, but over

the long run, most black farmers gained land through

their working relationships with white planters

(Higgs, 69, 130-31). Landowners profited by offering

tenant farm operators the incentive of having an

opportunity to buy certain tracts of land in exchange

for increased farming efficiency. Much of the land

black farmers own today is adjacent or relatively near

to farms owned by whites.

The increased land ownership and prosperity of

the first two decades of the 20th century, however,

were not shared by a large majority of black farm oper-

ators. Enactment of Jim Crow laws in the late 1890s

empowered landlords and planters to try to extract

more output from tenants and sharecroppers with less

compensation, rather than using incentives for self-

motivated work (Ochiltree, 367; Litwack, 127-29;

Alston, 267). Oppressive farm operating contracts were

easier to impose because the voting rights of blacks

were limited. Without the franchise, black tenants and

sharecroppers had no legal or political recourse. These

laws also facilitated tacit coordination by white land-

lords in applying stricter terms in agricultural con-

tracts.

The purchase of farm and household supplies

was financed by loans secured with crop liens from

merchants, which put many farm operators into a per-

sistent state of debt (Litwack, 136). In some southern

states, a peonage system developed from laws on

indebtedness that enabled planters to force some ten-

ants to remain as operators on their plantations

(Daniel 1972, 20). Cotton grown by tenants and share-

croppers was usually sold for them or credited to their

furnishing accounts. So, even when these growers

avoided peonage, they likely received lower returns

because they lacked the power to monitor marketing

transactions (Woodman 1982, 228; Litwack, 133).

The misery brought on by cotton crop liens was

not limited to blacks. During the antebellum period,

many southern whites had been small subsistence

farmers who did not grow cotton. They shifted to cot-

ton after the war, but many lost their farms because of

dependence on crop liens (Woofter, xxi; Woodman

1982, 229). Increasingly, landless whites became a large

part of the tenant and sharecropper workforce

(Appendix Table 2).

Census reports from 1900 to 1920 show an

increasing number of black tenant and sharecropper

families in the South. By 1920, there were 369,842 ten-

ants and 333,713 sharecroppers. Natural disasters and

agricultural price declines during the 1920s created

much economic distress. By the 1925 census, share-

croppers had become more numerous in the South

than rental tenants. By 1930, the number of southern

black sharecroppers peaked at 392,897. Between the

1920 and 1930 censuses, the number of white share-

croppers also increased; many of them may have fallen

from the ladder rungs of tenants and owner-operators

(Appendix Table 2).

While not all individuals succeed in farming in

any setting, the repressiveness of Jim Crow society sti-

4

6

The census only reported sharecroppers for classifications of white

and nonwhite farm operators. However, by confining the data to

southern states during this period, the count in the nonwhite

category is either identical or only slightly larger than the actual

enumeration of black farm operators. Although Texas and

Oklahoma were included as southern states in these census

reports, their sizable populations of Mexican-Americans were

included in the white category.

fled market incentives that enable economic mobility.

Economist Robert Higgs observed that many planters

were willing to trade off some potential earnings in

return for the social solidarity achieved by pursuing

white supremacist values (130). Many planters may

have also believed that it was advantageous to main-

tain a supply of low-paid farm workers by limiting

economic mobility for sharecroppers.

7

The erosion of opportunities for decision respon-

sibility and for education worked against black farm-

ers’ pursuit of independent farming. USDA studies

during the 1930s revealed that the production contract-

ing and furnishing system of previous decades created

dependency and ignorance about economic alterna-

tives (Woofter 142-43; Daniel 1985, 85-87). But

although opportunities and capabilities for operating

independence were systematically undermined, the

desire of tenants and sharecroppers to achieve the life

of an independent farmer was not extinguished.

Independent Farming

Initiatives, 1886-1932

Between 1886 and 1932, there were several types

of initiatives to promote more independent farming by

black tenants and sharecroppers. The most famous and

durable achievements were in agricultural education.

The Second Morrill Act of 1890 established state agri-

cultural colleges for black students. Booker T.

Washington (1856-1915) emerged as a leading public

figure in promoting education and farm improvement.

But three other initiatives of this period applied direct-

ly to development of independent farming: (1) organi-

zation of cooperatives for farmers and other communi-

ty services, (2) projects for land purchase and resale to

small farmers, and (3) farm diversification and self-

sufficiency. The first two directions proved to be

unsustainable, but they reemerged in later years as key

strategies for supporting the independence of black

farmers. The third initiative helped many farmers

avoid the continuous indebtedness and peonage that

often resulted from cotton sharecropping and crop lien

finance.

The Farmers Alliance of the 1880s and early 1890s

was a significant cooperative organizational move-

ment. The Alliance spread throughout the Plains states

and the South by regionally organizing into northern

and southern branches. Alliance cooperatives were

established in many communities. The movement also

attempted a centralized cooperative marketing

approach that had not existed with the earlier Grange

cooperatives. Opposition to the crop lien system was a

primary motivation for the Farmers’ Alliance, and its

leadership developed several innovative financial and

cooperative strategies (Knapp 1969, 57-67).

A faction within the Alliance tried to build a

cooperative society without segregation and racism,

but Alliance leaders were conflicted on the issue of

participation by black farmers. Black participation was

accomplished by establishing an organizationally seg-

regated branch of the movement, the Colored Farmers’

National Alliance and Cooperative Union (CFNACU)

in 1886 (Goodwyn, 278-85). A history of the association

claims that the CFNACU cooperative exchanges that

operated in several southern cities provided supplies

and loans to help members pay land mortgages.

8

But

the resources, size, and operations of these coopera-

tives have not been documented.

5

7

B. T. Washington, who preached that hard work would be

rewarded, observed how this was not always valid in practice. In

an article in the Country Gentleman magazine, he tried to point

out to planters the advantages from using incentives for gaining

more efficiency: "In one case I happen to remember a family that

had three or four strong persons at work every day that was

allowed to rent only about ten acres of land. When I asked the

owner of the plantation why he did not let this family have more

land he replied that the soil was so productive that if he allowed

them to rent more they would soon be making such a profit that

they would be able to buy land of their own and he would lose

them as renters. This is one way to make the Negro inefficient as a

laborer—attempting to discourage him instead of encouraging

him." (BTW, V12, 392).

8

The general superintendent of CFNACU was a white Baptist

minister, R.M. Humphrey, who had also served in the Confederate

Army. An historian, who is currently researching the CFNACU,

has studied the Alliance publications and a history written by

Humphrey (Ali).

The Alliance also tried to build organizational

bridges between farmers and laborers, with the latter

being represented by the Knights of Labor. The

Alliance was renamed the Farmers and Laborers

Union of America in 1890. Steps toward amalgamation

ended as farmer participation declined and attention

turned toward political actions in the formation of the

Populist Party. Ultimately, as one historian has pointed

out, unions were more relevant for sharecroppers than

cooperatives (Woodman 1982, 229-30). Nevertheless,

sharecropper and tenant unions can be regarded as a

stage in the pursuit of independent farming and, like

cooperatives, are forms of democratically governed

collective action.

CFNACU ordered a general cotton harvest strike

in 1891, although several of its local suballiances

opposed it. Black sharecroppers struck in a region of

Arkansas, and violent altercations ensued. This form

of activism increased divisiveness between CFNACU

and the Southern Alliance, which included some

planters who operated with sharecropping (Goodwyn,

292-94). The Alliance movement began to further

unravel when it effectively amalgamated with the

Populist Party. It dissolved after losses in the elections

of 1892 and 1896. But the Knights of Labor continued

to recruit sharecroppers and accomplished substantial

interracial organization (McMath, 126). Their work

may have influenced the specific unions of tenant

farmers that organized in the early 20th century.

In summary, the Alliance introduced the idea of

cooperatives to some black farmers in the South, and

may have contributed experience that was applied to

other types of associations in rural communities.

However, the Alliance’s political activism may also

have influenced many southern whites to move in the

direction of segregation and disenfranchisement with

the passage of Jim Crow laws in several states

throughout the 1890s (Goodwyn, 304-06).

A movement for black cooperatives, separate

from the Alliance, developed in East Texas. Robert

Lloyd Smith (1861-1942), a local school principal and

community leader, initiated it. His first step in the

direction of cooperatives was to establish a branch of

the Village Improvement Societies, a movement from

the northeastern United States. This movement was

dedicated to home and community improvement

efforts, but as Smith learned about the perpetual cycle

of debt caused by crop liens, he reorganized it as the

Farmers’ Improvement Society of Texas (FIST) in 1890

(Zabawa, 463-64).

FIST helped farm families develop more self-suf-

ficiency and strategies for operating on a cash basis. It

established local purchasing cooperatives that, while

separate from the Alliance, may have been influenced

by that movement’s promotion of cooperatives. Smith

was politically competitive with the Alliance support

of the Populist Party, which he defeated in the 1894

and 1896 elections to the Texas House of

Representatives by running on the Republican ticket.

FIST was a successful regional cooperative for

several years. Its membership grew from 1,800 in 1898

to 2,340 members by 1900, with 86 branches in Texas,

Oklahoma, and Arkansas. Its members owned 46,000

acres of farmland. FIST was also adaptive in its strate-

gy. While many members needed to operate on a cash

basis, others had credit needs for acquiring land or

developing their farms. To meet the needs of such

members, it established the Farmers’ Improvement

Bank in Waco, TX, in 1906. Even though it served

many low-resource farmers, FIST’s annual supply pur-

chasing volume was estimated at $50,000 in 1909.

Other projects and services included agricultural edu-

cation and facilities for applying best practices in pro-

ducing eggs, poultry, and swine (Texas State HA).

The success of FIST was partly due to achieving

critical mass by meeting a range of member needs.

Smith coupled the agricultural side of cooperation

with the Village Societies’ home and community

improvement work. The letterhead on FIST stationery

stated its purpose: "What We Are Fighting For: The

Abolition of the Credit System. Better Methods of

Farming. Cooperation. Proper Care of the Sick and

Dead. Improvement and Beautifying of our Homes"

6

(Washington, henceforth, BTW, V.5, 4). In other words,

its activities covered services from better living to dig-

nity in death.

In the early 20th century, many associations were

organized by black church leaders and provided a

range of community services for education, health

benefits, funerals, and credit services for buying land

and establishing homes. They often had religious

names, such as "Good Samaritans" or the "Order of

Moses." They operated with member dues and control

as in mutual insurance associations or shared-service

cooperatives (Ellison, 9-15).

Prior to the Depression, the largest type of self-

help association in terms of membership and financial

assets was often cooperatives for providing funeral

and burial services for predominantly black rural and

some urban residents. Members paid monthly assess-

ments and accumulated benefit certificates over time.

Many of these cooperatives were federated into orga-

nizations that covered fairly large geographic areas.

One of them had members in seven states. Some had

accumulated several million dollars in assets by 1931

(Ellison, 13).

The growth and formal structure of the funeral

cooperatives did not carry over to farmer coopera-

tives. Outside the Alliance experience and FIST, farmer

cooperatives were mostly of an informal and ad hoc

variety. Their informality reflected the limited com-

mercial opportunities and unequal market access

available to black farmers during the first half of the

20th century. A formal and countervailing-power type

of marketing cooperative of black farmers was not tol-

erated in the pre-civil rights era. Vocational agriculture

teachers and county agents often provided leadership

and management of informal cooperatives (Pitts, 21).

Their purposes were limited to making seasonal bulk

purchases of farm supplies, organizing street markets,

or handling occasional surpluses that farmers could

not sell or consume on their own.

The most direct strategies for the pursuit of inde-

pendent farming in the early 20th century were pro-

jects for coordinated land purchase and contiguous

settlements of small farmers.

By the late 19th century, a few prosperous black

communities emerged in the South and in other parts

of America (Grim). Booker T. Washington studied and

wrote about some of the most successful rural commu-

nities, pointing to them as examples of economic

uplift. Mound Bayou, MS, founded in 1887, became

famous for establishing black-owned businesses and

independent farms, and governance entirely by its

black residents (BTW, V9, 307-20).

B. T. Washington promoted land purchasing pro-

grams that influenced future rural development strate-

gists. He was a major public figure and widely

respected by political and business leaders such as

President Theodore Roosevelt and Andrew Carnegie.

He used his many connections to raise startup capital

for several settlement projects. His first project focused

on improvement for tenant housing. In the 1890s, the

Tuskegee Institute received a grant from a Boston phil-

anthropist to establish a revolving loan fund for home

improvements. This grant contributed to tenant well-

being, but the program always required new funding

because the economics of most tenant production con-

tracts did not generate sufficient earnings to capitalize

the program (Harlan, 213).

In future projects, Washington sought a kind of

hybrid plan for satisfying investor interests with a tar-

get rate of return and philanthropic interests by help-

ing black farmers establish independent farm enter-

prises. In the late 1890s, he and supporters debated

various alternatives for financing and managing a pro-

ject for land acquisition by small black farmers. The

experience of FIST in applying cooperative organiza-

tion prompted consideration of the idea of organizing

a "co-operative land association" with stock subscrip-

tions and application of a cooperative system for pro-

duction (Zabawa, 465-69). Yet, when this project was

implemented in 1901 as the Southern Improvement

Company (SIC), the cooperative dimension was left

out. Nevertheless, SIC intended to be a practical way

for black farmers to obtain ownership of land.

SIC was capitalized by a group of northern phil-

anthropist entrepreneurs and managed by a Tuskegee

graduate. A 4,000-acre tract of land was purchased

and subdivided. The business plan included housing

and small-acreage farms for purchase with relatively

low mortgage interest rates. Project revenue was gen-

erated primarily by cotton and cottonseed sales that

were exclusively handled by agents for SIC

(Anderson, 114). Historical research on SIC offers con-

flicting views about its success.

9

The project worked

well when cotton prices were high, but after condi-

tions worsened, individual farm holdings foreclosed

by 1919 (Zabawa, 467).

7

9

See Harlan; Zabawa and Warren for an appraisal of the SIC’s

positive impact, while Anderson, who used different archival

sources, argues that it became exploitative of the farmers.

Washington wrote in glowing words about the accomplishments

of the SIC in a magazine article in 1911, but died before farm

earnings plummeted and undermined the project (BTW, V10, 605-

06).

Washington initiated another land project in 1914

that was earmarked for Tuskegee graduates who

lacked family farm ownership. An 1,800-acre tract was

purchased by a group of investors, led by a Tuskegee

trustee. The Tuskegee Farm and Improvement

Company, also called Baldwin Farms, basically fol-

lowed the same operating procedures as SIC (BTW,

309-10). Unfortunately this project was started as the

cotton market entered a period of low prices and boll

weevil problems. A community of independent black

farmers sustained operations until 1949 (Zabawa, 467-

69).

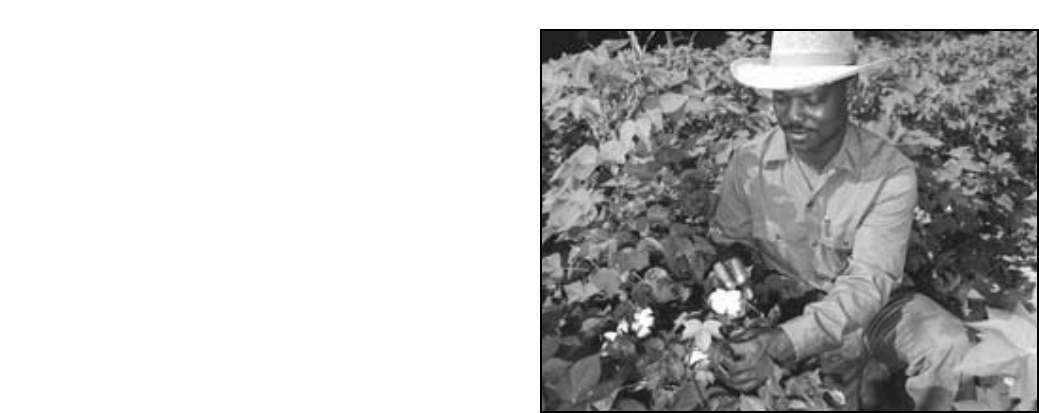

The most successful strategy for independent

farming in the early 20th century was crop diversifica-

tion to build self-sufficiency. Washington regarded this

as a way for black farmers to avoid the problems of

dependence on cotton and indebtedness from crop

liens. He influenced the development of the black

extension agent system and the content of what was

promoted to farmers. Much of this influence was car-

ried forward by Thomas M. Campbell, a student and

assistant to Washington at Tuskegee. Campbell was

the first farm extension agent to be appointed by

USDA, and over his career from 1906-53 he was the

predominant leader of the black extension agent ser-

vice (Jones).

In addition to crop diversification, information

on preserving farm-grown foods was disseminated by

agents as a way to develop self-sufficiency and insula-

tion from white commercial society. Black extension

agents initially focused their efforts on farmers who

owned enough land for independent operating, but

depending on the receptiveness of planters, they

increasingly promoted gardening by sharecroppers

(Zellar, 432- 438).

Washington knew about cooperatives but did not

embrace them as an appropriate strategy for black

farmers, at least under the prevailing economic condi-

tions and political power structure. Extension agents

coordinated occasional group purchasing or joint-sell-

ing efforts but did not systematically disseminate

knowledge for formal cooperative development.

During the years of the New Deal, Campbell

seized the opportunity to establish a cooperative at the

Tuskegee Institute to serve as a model of this method

of self-help (Jones, 53). Prior to the 1960s and apart

from a few New Deal programs, the Federal

Government offered negligible assistance and encour-

agement of cooperatives for black farmers.

Of the three directions for developing indepen-

dent farming, self-sufficiency with crop diversification

had a more immediate and lasting impact at the time

than cooperatives or coordinated land purchase initia-

tives. Increased self-sufficiency would help to reduce

dependency on cotton, but with the exception of

tobacco-growing regions, there were insufficient alter-

natives for involvement in and experience with a more

commercial type of farming. In any case, crop diversi-

fication away from cotton was gradual and not uni-

formly adopted. As late as 1964, the Census of

Agriculture reported that about half of the black

farmer population produced cotton.

The period of the 1920s and 1930s was a water-

shed for many tenant farmers and sharecroppers. A

combination of steadily increasing mechanization and

economic depression forced a major reduction in the

demand for farm labor in the South (Appendix Table

2). Natural disasters in the late 1920s and major com-

modity price declines increased the role of govern-

ment in the farm economy. In 1929, the Federal Farm

Board was established to sanction and direct market

intervention by farmer membership associations, pri-

marily nationwide or regional cooperatives.

The onset of the Depression in 1933 triggered an

expansion of the interventionist role of government in

agriculture through the administering of commodity

payment subsidies directly to individual farmers.

USDA policies abated a market process of land

turnover to would-be independent farmers by restrict-

ing the entry of new producers and reducing incen-

tives for many landowners to quit farming. In retro-

spect, the apolitical approach advocated by Booker T.

Washington was to prove especially disadvantageous

to black farm operators with the increased politiciza-

tion of agriculture that the New Deal inaugurated.

10

New Deal Agriculture

The New Deal was for the most part a bad deal

for black farmers. Under the Agricultural Adjustment

Act (AAA) of 1933, cotton was supported by restrict-

ing acreage and guaranteeing minimum prices. The

immediate impact of reduced cotton acreage was dis-

placement for many black and white tenants and

sharecroppers. There were also cases of landlords who

8

10

Washington tolerated a temporary acceptance of

disfranchisement that he believed would change in step with

economic progress of blacks (Harlan, viii ; Lutwack, 146-47).

Though tolerating disfranchisement and segregation, he took a

behind-the-scenes activist role in fighting debt peonage because

of its direct interference with economic opportunity (Daniel 1972,

67).

did not distribute the share of payments that belonged

to their tenants or sharecroppers (Woofter, 67; Fite,

141-2; Daniel 1985, 101-4). The New Deal also marked

a significant increase of government services, for

which distribution was controlled by politically con-

nected groups in rural communities. For much of the

South, this system resulted in diminished access to ser-

vices for many blacks which, as alleged in recent law-

suits against USDA, persisted into recent years

(Pigford).

Another unintended consequence of the AAA

was to raise entry barriers to farm ownership.

Numerous studies estimate that commodity price sup-

ports raise the price of farmland by as much as 15 to 20

percent as a national average (Floyd; Ryan). The com-

modity programs are tied to specific lands, which capi-

talizes the future value of the programs into the value

of the land.

Although farmland prices were depressed during

the 1930s, ownership was often not feasible for those,

like many blacks, who had diminished access to AAA

programs. Incentives for land purchases and expan-

sions of farm acreage were increased for those with

access to AAA programs. Census figures show that

between 1930 and 1935, white farm owners and tenant

operators increased farmland acres in the South by 12

percent, or more than 35 million acres. But farmland

acreage owned by nonwhite farmers declined by more

than 2.2 million acres, from 37.8 million to 35.6 million,

during the same period. White farmers with full own-

ership in the South increased by 13 percent or 139,646

between 1930 and 1935, and white part-owners

increased by 8 percent or 15,299. Nonwhite full-owners

of farmland increased by 6 percent or 9,617 between

1930 and 1935, but part-owners decreased by 13 per-

cent or 5,571. During the same 5-year span, white ten-

ants increased by 145,763, while nonwhite tenants

decreased by 45,049. These divergent changes may

have reflected differences in access to subsidies

(Appendix Table 2).

The increased entry by whites into farming

appears to have been at least partly policy induced

because it occurred during a period of acreage reduc-

tion for cotton and low commodity prices. The gains in

land values from commodity price supports accrued

once it became evident that these programs would per-

sist. For those who added to their land holdings dur-

ing the Depression, the benefits were gained once

acreage restrictions for cotton and other program crops

were eased or lifted. Future inducements to expand

farming acreage would especially jeopardize much of

the land owned by black farmers that was adjacent or

near white farms. The AAA programs and continued

supporting of prices in farm policy raised barriers to

land ownership for black farmers and limited their

opportunities to either stay in farming or achieve the

status of operating as independent farmers. Yet, farm

policy is only one of several institutional factors that

have worked against ownership of land by black farm-

ers, and these have been examined in various studies

and investigations (see Gilbert; and Associated Press).

New Deal policymakers did not neglect displaced

tenants and croppers. Subsistence relief and resettle-

ment programs were offered for these farm operators

and their families during the mid-1930s. Such pro-

grams functioned more as a holding action for the

unemployed than in addressing the economics of

excess labor supply in southern farming. But during

1935-41, the programs of the Resettlement Admin-

istration, followed by the Farm Security

Administration (FSA), were a substantial government

effort to help tenants become independent farmers and

to use cooperatives (Knapp 1973, 299-316; Baldwin,

193-211). Lending programs were established to enable

tenants to purchase farmland and machinery. By ana-

lyzing creditworthiness, these programs tried to target

those with the most capability to farm efficiently.

Displaced tenants and sharecroppers, who were

selected for participation in some of the resettlement

programs, were in effect offered an opportunity to

develop as independent farmers. In many cases newly

settled farms were in contiguous areas. Such commu-

nities provided a basis for establishing cooperatives,

which FSA actively promoted and operated. These

cooperatives included both traditional farm supply

purchasing and marketing, but also a range of shared

services. The latter included associations for joint own-

ership of farm machinery and breeding stock

9

(Baldwin, 203). These initiatives represented an aware-

ness of the needs of new entrants to farming, of oppor-

tunities for farm ownership, and of the potential role

of cooperatives in rural development, which had been

put aside during the initial years of launching the

AAA programs.

Many tenants lacked sufficient farming assets,

equipment, and skills to qualify for land purchase

loans, a problem that the FSA sought to address by

implementing two types of cooperatives — farm pro-

duction and land-lease. The former projects failed due

to insufficient property rights incentives (Knapp 1973,

316). But land-lease cooperatives used a more individ-

ual-based incentive system. These cooperatives

received loans for leasing entire plantations that were

subdivided into family farms for subleasing to mem-

bers. They also operated the plantation cotton gin and

other facilities on a cooperative basis, in addition to

farm supply purchasing. By 1940, there were 31 land-

lease cooperatives, with 949 black and 750 white farm

families (Knapp 1973, 313).

An alternative program involved lending for the

acquisition of large tracts of land and subdividing

them into individually owned family farms. It fol-

lowed a plan similar to the projects promoted by

Washington 30 years earlier, but this time with govern-

ment support. FSA implemented 10 or more black set-

tlements that were designed for family farm owner-

ship. The Tuskegee Institute assisted the Prairie Farms

in Macon County, AL, in developing a community

infrastructure. The Prairie Farms community included

a cooperative for purchasing and machinery sharing

and a K-12th grade school (Zabawa, 480-3). Prairie

Farms shut down in the 1950s.

FSA programs for farm ownership and coopera-

tive development were phased out after 1941 although

shared services, particularly farm machinery sharing

cooperatives, were actively supported during World

War II (Sharing). In fact, 32 farm machinery coopera-

tives were reported to be active in black communities

of North Carolina throughout the 1940s (Pitts, 35).

These programs likely contributed to the increase in

farm ownership in the South between 1940 and 1945

(Appendix Table 2). Knapp’s general assessment of the

FSA initiative toward cooperatives was that the gov-

ernment was too directly involved and idealism often

crowded out the practical experience needed for long-

term sustainability (Knapp 1973, 316).

Some of the cooperatives organized by these pro-

grams lasted for several years after 1941. A 1946 sur-

vey showed that only 16 percent of the 25,543 coopera-

tives organized under FSA programs had gone out of

business (Baldwin, 203). Many closed during 1950-59,

the 10-year span with the largest rural exodus in the

Nation’s history (Appendix Table 3). This period was

also the turning point from increasing to decreasing

numbers of cooperatives in the United States (Mather).

Yet the Mileston Farmers Cooperative that was estab-

lished in Tchula, MS, by the FSA programs continues

to serve its members today.

The establishment of cooperatives through gov-

ernment initiative in FSA programs contributed to

knowledge about how individuals can work together

in organizing agricultural purchasing and marketing.

The FSA programs also applied the ideas for land

acquisition and community planning that Washington

had promoted. The elapse of these programs in 1941

and the post-war exodus from farming (Appendix

Table 3) ended a phase of cooperative development,

but made room for more enduring and grass roots

approaches in the future.

The Civil Rights Movement

and Cooperatives

The civil rights movement emboldened many

black farmers to join cooperatives. It may have also

provoked more discrimination by white-owned busi-

nesses against black farmers in commercial dealings.

But, discrimination in some cases induced cooperative

formation. In a time of interracial tensions, bulk pur-

chasing of farm supplies or assembling member prod-

ucts for consolidated transactions enabled black farm-

ers to minimize the frequency of their individual

interactions with white merchants and product bro-

kers. Cases of this mechanism are documented, where

farmers’ access to supplies or markets were blocked

when they were known to be members of the National

Association for the Advancement of Colored People

(NAACP).

In 1956, black farmers in Clarendon County, NC,

organized the Clarendon County Improvement

Association to circumvent discrimination due to their

NAACP membership. It provided small loans, farm

supplies, and services. When area gins would not

accept cotton from black farmers, the cooperative

transported it to distant facilities for ginning (Daniel

2000, 247). Circumventing discrimination was also the

purpose of forming the Grand Marie Vegetable

Producers Cooperative, Inc., in Louisiana in 1965, after

brokers boycotted some growers for their civil rights

activities (Marshall, 51).

10

While cooperatives helped reduce members’

exposure to potential racial discrimination in commer-

cial dealings, the formation of associations elicited

antagonism and reprisals from racist business owners.

The Clarendon association lost access to credit from

local banks, but it was able to borrow from the

NAACP and also received funds from the United

Automobile Workers for purchasing farm machinery

(Daniel 2000, 247). One of the largest and most widely

publicized black cooperatives to emerge in the late

1960s was South West Alabama Farmers Cooperative

Association (SWAFCA). It encountered numerous boy-

cotts from local businesses and discriminatory actions

from politicians.

11

The civil rights movement had a direct influence

on cooperative formation by introducing the critical

element of leadership. Black farmers were receptive to

cooperatives, but getting organized was often difficult

because many potential members lacked the training

and resources. As in the past, county or university

extension agents provided the initiative and leadership

for informal or ad hoc cooperation, but many civil

rights leaders wanted to help develop cooperatives of

a formal and more visible type.

Many initiators of cooperative development were

religious leaders, continuing a tradition of churches

taking an active role in community building. For

example, the Rev. Francis X. Walter founded the

Freedom Quilting Bee cooperative in Alabama in the

early 1960s. Father A. J. McKnight organized the

Southern Consumers Cooperative (SCC) and several

credit unions during the 1960s-1970s (Marshall, 37-40).

Father McKnight also contributed significant

institutional development for black cooperatives with

the founding of the Southern Consumers Education

Foundation (SCEF) in 1961. His work drew attention

and support from the Cooperative League of the USA

(CLUSA), the Credit Union National Association

(CUNA), and other national organizations.

12

Along

with some foundations, they helped establish the

Southern Cooperative Development Program (SCDP)

in 1967. It offered cooperative education and technical

assistance to cooperatives and credit unions located

primarily in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama.

After two years in operation, SCDP realized a need to

focus assistance on a group of 25 associations, rather

than spreading its resources on new cooperative devel-

opment (Marshall, 42).

The Federation of Southern Cooperatives (FSC)

was also founded in 1967, organized by representa-

tives from 22 cooperatives across the South (Federation

1992, 7-9). Its director was Charles Prejean, who, like

Father McKnight, was involved with improving adult

literacy and realized the importance of concrete inter-

ests and tasks such as cooperative participation in

helping people develop their economy (Bethell, 4). FSC

had common purposes with SCDP but was more

encompassing in its plan of action. For a brief period

in the early 1970s, SCDP combined with the FSC as a

11

11

SWAFCA had been approved for an Office of Economic

Opportunity (OEO) grant, but in June 1967 Alabama Governor

Lurleen Wallace vetoed it. Sargent Schriver, the director of the

OEO, overrode the veto (Marshall 48; Bethell, 6).

12

Father McKnight was inducted into the Cooperative Hall of Fame

in 1987.

Table 1 —Federation of Southern Cooperatives membership, 1969

Agricultural Credit Unions Consumer Othera Total

States co-ops members co-ops members co-ops members co-ops members co-ops members

AL 2 1,825 6 2,784 3 230 3 2,789 14 7,398

MS 5 1,875 1 500 3 1,080 8 1,482 17 4,937

LA 3 290 4 1,833 -- -- 1 2,050 8 4,183

Otherb 14 1,992 5 801 9 1,720 13 578 41 5,091

Total 24 5,982 16 5,918 15 3,030 25 4,303 80 --

a

Other cooperatives include handicraft, small industry, and fishing.

b

Other states are Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Missouri, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West

Virginia.

lending unit for cooperatives. It was renamed the

Southern Cooperative Development Fund (SCDF) but

has operated separately since the mid-1970s.

FSC encompassed a comprehensive range of ser-

vices for rural community development, including

help for farmers to secure their ownership of land and

operating independence. The scope of FSC programs

for training, consulting, and research, as well as capital

for land and business project development, has

required financial assistance, including grants from

government and private foundations.

Founded by 22 cooperatives, FSC had 80 mem-

bers after only two years. By the mid-1970s, it had 130

cooperative members (Voorhis, 212). Table 1 is a con-

densed version of FSC membership data in 1969 as

published in a study by Marshall and Godwin. The

total membership is not reported because some mem-

bers belonged to more than one cooperative. The FSC

draws from 14 states, but over time Alabama and

Mississippi have consistently accounted for much of

its membership.

The challenges in promoting cooperatives for

black farmers were demonstrated by the experience of

SWAFCA. It was the largest cooperative in FSC’s ini-

tial membership. It was established in 1967 with 1,800

farm families. SWAFCA epitomized the spirit of the

civil rights movement in asserting freedom from dis-

crimination and pursuit of economic uplift for poor

families. Its initial membership grew out of discus-

sions among black cotton farmers who wanted to

diversify into vegetable crops but needed a marketing

outlet. A large-scale membership campaign was

included in voter registration drives and in the Selma-

to-Montgomery "March for Freedom" in 1965 (see

Appendix Table 1). Civil rights workers and organiza-

tions such as the National Sharecroppers Fund and

CLUSA participated in its formation (Marshall, 46).

SWAFCA achieved some marketing successes,

despite harassment from some white politicians and

business leaders. Although members were predomi-

nantly black, SWAFCA’s vegetable marketing pro-

grams attracted membership from some white farmers

(Voorhis, 96). Nevertheless, it encountered problems in

establishing durable cooperative programs. Marshall

and Godwin observed that its management was not up

to serving such a relatively large membership. They

noted, "… members had very limited understanding of

cooperative principles" (Marshall, 47-9). FSC worked

diligently to bolster management and cooperative edu-

cation deficiencies, but market access problems and

sustaining the involvement of SWAFCA’s large mem-

bership continually weakened the organization.

During the mid-1970s, SWAFCA attempted to

shift its focus from marketing vegetables to producing

gasohol. The late Albert Turner, who was a civil rights

leader and an experimental engineer, led this endeav-

or.

13

In the 1970s he developed a system for using corn,

vegetables, and organic residues supplied by members

for producing gasohol. He adapted a pickup truck to

run on gasohol and drove from Alabama to

Washington, DC, to promote his plans. His proposals

also included feed byproducts and methane from cat-

tle waste for generating electricity. These projects were

appealing to the membership, but were denied fund-

ing from government agencies.

14

By the mid-1980s,

SWAFCA terminated its operations. Some of its assets

were transferred to another farmer association.

The civil rights movement also reinvigorated

land purchasing for small farms, yet land retention

became a more urgent issue for independent black

farmers. During the late 1960s, churches and other

groups were independently making purchases of rela-

tively small tracts of land for self-sufficient farm settle-

ments. In other cases, a few cooperatives purchased

small tracts of land for market production by mem-

bers. Both FSC and SCDP assisted in those projects

(Marshall 59).

In the late 1960s, several Alabama tenant farmers

were evicted after they won a lawsuit for their share of

USDA price support payments. They formed the

Panola Land Buyers Association to combine their

efforts for finding and acquiring farmland. With finan-

cial assistance from several individuals and groups

throughout the U.S., Panola and FSC jointly purchased

a 1,164-acre tract of land near Epes, AL, in the mid-

1970s. Panola members built homes on part of it, while

FSC established a training center and demonstration

farm on the remaining part (Federation 1992, 25-26;

Bethell, 6-8).

The Emergency Land Fund (ELF) was organized

in 1971 to assist black farmers in Mississippi and

Alabama with problems they faced in retaining land.

By the 1970s, displacement of tenants was abating, but

land loss by black farmers continued. While assistance

for land purchasing was provided, ELF’s major thrust

was to provide legal, tax, and estate planning advice.

12

13

Albert Turner was the Alabama director of the Southern Christian

Leadership Conference (SCLC). He was a leader of voter

registration drives and confronted considerable danger in these

activities during the 1960s. He was chosen by the SCLC to lead the

mule train that carried Dr. Martin Luther King in the funeral

procession.

14

This information was provided by John Zippert of the FSC/LAF.

ELF established a grass-roots network of citizens,

called the County Contacts System, who were trained

in identifying farmers in their counties who were in

danger of having to sell their land. When owners were

notified of pending problems, ELF followed up with

legal and other technical assistance (Wood 21).

Over time, County Contacts personnel developed

a system that paralleled the county extension service

of land-grant universities. But the information they

provided was more relevant to the economic survival

of small farmers. During the 1960s, the USDA con-

trolled much of the content that moved through uni-

versity channels of extension, including the black

extension service. In one instance, an initiative for

training on cooperatives for black farmers was blocked

(Equal Opportunity, 47). By contrast, County Contacts

personnel covered not only information directly relat-

ed to managing land ownership and rights, but also on

marketing strategies to generate more economic value

from the land. ELF generated much of this information

from its demonstration farms and greenhouses (Wood,

22-23).

ELF received Federal funding in 1977 to establish

land cooperative associations. The land cooperatives

operated like credit unions as member savings institu-

tions but were designed to help farmers finance con-

tinued ownership of their lands in times of financial

pressure. ELF also spawned several other organiza-

tions with a similar mission of land retention. In 1985

the Federation of Southern Cooperatives and the ELF

combined to form the FSC/LAF (Land Assistance

Fund).

FSC/LAF’s educational programs and concern

for land ownership carry on the tradition of Booker T.

Washington. But in its commitment to cooperatives,

FSC/LAF is more reminiscent of Robert Lloyd Smith

and FIST. In contrast to earlier initiatives, the

FSC/LAF leadership recognized the indispensability

of civil rights to achieving the goals of prosperous and

independent farming. FSC/LAF brought farmers

together in cooperatives for a unified voice to influ-

ence development of more favorable, equal-access

public policies (Marshall, 3-4).

Melding civil rights with cooperative develop-

ment has led to some outside criticism and to periodic

disruptions in funding of FSC/LAF programs (Bethell;

Campbell). Even supporters of civil rights regarded

the multiplicity of objectives in cooperatives like

SWAFCA as impractical for cooperative business effec-

tiveness (News 1969). In retrospect, progress on civil

rights has turned out to be slower than was anticipat-

ed in the 1960s. Its incompleteness disadvantaged

many black farmers and cooperatives. But the cooper-

ative system established by FSC/LAF has contributed

to identifying and eliminating discriminatory prac-

tices.

15

Recent court decisions and USDA reforms have

the potential for creating a new chapter of more

progress for black farmers (Civil Rights, USDA). Ralph

Paige, the executive secretary of the FSC/LAF,

observed: "Black farmers and all other others who are

recipients of government services deserve nothing less

than justice at the hands of government officials.

Perhaps now some healing can begin and Black farm-

ers can work toward becoming an integral part of

American agriculture" (Zippert, 152). One of the

avenues for progress is to assist black farmers in

greater use of formal cooperative methods and proce-

dures. Some of the challenges for and progress by

black farmers in applying cooperative business prac-

tices and establishing value-added businesses are

reviewed in the next section.

Promoting Independent Farm Enterprise

Through Cooperatives

Marketing and purchasing practices of black

farmers for most of the 20th century have centered on

local dealings where trusting relationships were sup-

ported. During this time, black extension agents initi-

ated informal associations or ad hoc cooperatives for

seasonal activities such as harvesting, assembling

products, and bulk purchasing of farm supplies (Pitts,

21). The acceleration of cooperative development in

the 1960s witnessed many associations continuing the

informal approach of the pre-civil rights era while

some of the civil rights-inspired cooperatives emerged

with a more progressive market access and value-

added orientation. The former cooperatives are more

tied to historical experience, while the latter have been

building new organizational strategies to develop and

maintain independent farming.

FSC/LAF currently has about 75 cooperatives

and credit unions. The majority are predominantly

black rural cooperatives and credit unions in the

13

15

Legislation such as the Minority Rights Act in the 1990 Farm Bill

and the favorable ruling in the recent anti-discrimination case

against USDA are visible signs of the political and legal gains that

have been made. Several studies by the U.S. Commission on Civil

Rights have documented the discrimination and inadequacy of

USDA services to black farmers (Equal Opportunity in Farm

Programs; The Decline of Black Farming).

South. Some nonmember cooperatives and credit

unions work with FSC/LAF State associations or with

universities. Table 2 lists these organizations by type

and location in a few of the major states and for the

South in total.

Eleven of the 50 agricultural cooperatives report-

ed are not members of FSC/LAF. Some have devel-

oped with assistance from the Arkansas Economic

Corporation, an organization with similar objectives

and services as the SCDF and FSC/LAF. While these

50 cooperatives have a formal organizational structure

and status, there are an unreported or undocumented

number of informal or ad hoc cooperatives.

Recent survey-based research in the lower

Mississippi Delta region (Scott) and in Southeastern

States (Onunkwo) have shown that most black farmers

have had experience with cooperatives in the past and

are aware of their potential benefits. Much of this

experience, however, was confined to the informal

type of cooperatives (Scott).

16

Although most of these

associations are defunct, they had lasting influence on

the preferences black farmers express about what they

want from cooperatives.

Membership size of most cooperatives in the

southeastern states ranged between 15 to 20 farmers,

while membership size surveys for the Mississippi

Delta states revealed fewer than 30 members per coop-

erative on average. A preference for smaller and local

membership cooperatives was indicated among a sam-

ple of black farmers in South Carolina. They preferred

smaller membership cooperatives because of ease of

communications and in organizing meetings

(Onunkwo, 16).

Leadership has played a critical role in both

informal and formal types of black farmer coopera-

tives. In informal cooperatives, leadership provides the

cohesion and coordination that would otherwise be

established in part by written membership agree-

ments, bylaws, and business plans. Many of the infor-

mal cooperatives that depended on leadership from

black extension agents have disappeared. In recent

years, the black extension service has been merged into

the general agricultural extension system. Changes in

its program have reduced the extent of past outreach

to farmers (Scott).

Many of today’s extant cooperatives are held

together by strong leadership from one or just a few

members.

17

Of the informal type of cooperative, bulk

seed purchasing is the most common service to persist

over time. Member involvement in these associations,

while lacking the equity capital commitment of the

standard cooperative model, has been an in-kind type,

based on volunteers for carrying out services

(Onunkwo,18). But volunteerism cannot sustain most

cooperatives that seek improved market access and

value-added operations.

The experience of FSC/LAF staff and the recent

survey research have identified weaknesses in cooper-

ative education regarding transition to formal coopera-

tive organization and operations. The pre-civil rights

ad hoc cooperatives did not provide this type of educa-

tion and experience. Thus, many aspects of the human

and social capital that make farmer cooperatives work

did not have enough opportunity to fully develop in

many rural black communities in the South.

For most of the 20th century, many black farmers

sought to protect their independence and ownership of

land by diversifying away from cotton and relying on

local sales of fruits and vegetables to citizens in their

communities. One cooperative operates today with

help from fellow parishioners of a church. Parishioners

volunteer for harvesting and packing, as well as pro-

viding a large share of consumer purchases (Rotan). A

1996 farmer survey in south-central Alabama observed

a predominance of local selling of fruits, vegetables,

and livestock where other potential higher-value mar-

kets could be developed (Tackie, 50). A concern for

protecting independence can sometimes work against

long-run sustainability of independent farming if a

more commercialized and remunerative system of

14

Table 2—Black cooperatives and credit unions in the

South

Location Agricultural co-ops Credit Unions

a

Other co-ops

b

Total

AL 6 6 6 18

MS 11 3 3 17

GA 7 3 4 14

SC 11 0 3 14

Other

c

15 7 5 27

Total 50 19 21 90

a

Includes only black credit union members of FSC/LAF.

b

Other cooperatives include handicraft, small industry, fishing,

housing, and day-care.

c

Other states are Arkansas, Florida, Kentucky, Louisiana,

Missouri, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Texas.

16

The research report by Scott and Dagher is in a draft stage, so

references will just refer to Scott, without page numbers.

17

Edgar Lewis (USDA/RBS), who has worked with some of these

cooperatives over several years, offered this observation.

marketing does not develop.

Without better prospects, younger

generations of black farmers will

increasingly seek economic opportu-

nities outside farming.

Some cooperatives, particularly

many members of FSC/LAF, have

made progress in commercialization

and value-added operations. The

founders anticipated long-term

needs in both the areas of coopera-

tive education and in coordinating

local production. They have helped

member cooperatives introduce and

coordinate adoption of various veg-

etable crops to replace cotton.

Obtaining sufficient volume of a new

crop for a marketing program

involves extensive outreach. FSC/LAF’s training cen-

ter and demonstration farm in Epes, AL, is designed