Achieving the right fiscal-

monetary mix (in the

context of the economic

governance review)

Compilation of papers

Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit (EGOV)

Directorate-General for Internal Policies

PE 747.830 - September 2023

EN

STUDY

Requested by the ECON committee

Monetary Dialogue Papers, September 2023

IPOL | Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit (EGOV)

2 PE 747.830

Achieving the right fiscal-monetary mix (in the context of the economic governance review)

PE 747.830 3

Monetary Dialogue September 2023

Abstract

Alignment of monetary and fiscal policies has proven to be

decisive for the euro area's ability to withstand successive crises

over the years. Today, the European Central Bank (ECB) continues

its fight against inflation by implementing a monetary policy

tightening unprecedented in pace and scale. At the same time,

after allowing for some deviations from regular budgetary rules

with the activation of the general escape clause in 2020, the EU is

set to reapply its fiscal rules fully from 2024. In addition, co-

legislators are currently discussing the proposed legislation by

the European Commission for the reform of the economic

governance framework. Five papers were prepared by the ECON

Committee’s Monetary Expert Panel, discussing the interaction

between monetary and fiscal policies in the euro area.

This document was provided by the Economic Governance and

EMU Scrutiny Unit at the request of the Committee on Economic

and Monetary Affairs (ECON) ahead of the Monetary Dialogue

with the ECB President on 25 September 2023.

Achieving the right fiscal-

monetary mix (in the

context of the economic

governance review)

Compilation of papers

IPOL | Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit (EGOV)

4 PE 747.830

This document was requested by the European Parliament's Committee on Economic and Monetary

Affairs.

AUTHOR(S)

The economic governance review and its impact on monetary-fiscal coordination

Zsolt DARVAS, Bruegel and Corvinus University of Budapest

Jeromin ZETTELMEYER, Bruegel and CEPR

Monetary-fiscal interaction: achieving the right monetary-fiscal policy mix in the euro area

Kerstin BERNOTH, DIW Berlin

Sara DIETZ, Hengeler Mueller

Rosa LASTRA, Queen Mary University of London

Marie RULLIÈRE, DIW Berlin

Big central banks and big public debts: The next challenges

Charles WYPLOSZ, The Graduate Institute, Geneva

An effective policy mix for the EU’s post-pandemic challenges

Paolo Canofari, Università Politecnica delle Marche, Ancona.

Giovanni Di Bartolomeo, Sapienza Università di Roma and University of Antwerp.

Marcello Messori, Luiss Guido Carli, Roma

Fiscal adjustment supports the fight against sticky inflation

Daniel GROS, Bocconi University, CEPS

Farzaneh SHAMSFAKHR, CEPS

ADMINISTRATOR RESPONSIBLE

Drazen RAKIC

Giacomo LOI

Maja SABOL

EDITORIAL ASSISTANT

Adriana HECSER

LINGUISTIC VERSIONS

Original: EN

ABOUT THE EDITOR

The Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit provides in-house and external expertise to support

EP committees and other parliamentary bodies in shaping legislation and exercising democratic

scrutiny over EU internal policies.

To contact Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit or to subscribe to its newsletter please write

to:

Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit

European Parliament

B-1047 Brussels

E-mail: [email protected]

Achieving the right fiscal-monetary mix (in the context of the economic governance review)

PE 747.830 5

Manuscript completed in September 2023

© European Union, 2023

DISCLAIMER AND COPYRIGHT

The opinions expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not

necessarily represent the official position of the European Parliament.

Reproduction and translation for non-commercial purposes are authorised, provided the source is

acknowledged and the European Parliament is given prior notice and sent a copy.

IPOL | Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit (EGOV)

6 PE 747.830

CONTENTS

THE ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE REVIEW AND ITS IMPACT ON MONETARY-FISCAL

COORDINATION 7

Zsolt DARVAS

Jeromin ZETTELMEYER

MONETARY-FISCAL INTERACTION: ACHIEVING THE RIGHT MONETARY-FISCAL POLICY MIX IN

THE EURO AREA 35

Kerstin BERNOTH

Sara DIETZ

Rosa LASTRA

Marie RULLIÈRE

BIG CENTRAL BANKS AND BIG PUBLIC DEBTS: THE NEXT CHALLENGES 65

Charles WYPLOSZ

AN EFFECTIVE POLICY MIX FOR THE EU’S POST-PANDEMIC CHALLENGES 91

Paolo CANOFARI

Giovanni Di BARTOLOMEO

Marcello MESSORI

FISCAL ADJUSTMENT SUPPORTS THE FIGHT AGAINST STICKY INFLATION 119

Daniel GROS

Farzaneh SHAMSFAKHR

Achieving the right fiscal-monetary mix (in the context of the economic governance review)

PE 747.830 7

The economic governance

review and its impact on

monetary-fiscal

coordination

Zsolt DARVAS

Jeromin ZETTELMEYER

External author:

Zsolt DARVAS

Jeromin ZETTELMEYER

IPOL | Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit (EGOV)

8 PE 747.830

Abstract

This paper analyses how the fiscal framework proposed by the

European Commission in April 2023 might affect the interplay

between fiscal and monetary policies, from three perspectives: its

impact on the medium-term fiscal stance in the euro area, its

design, and its implications for the ECB’s Transmission Protection

Instrument (TPI). It concludes with recommendations for

amending both the fiscal governance proposal and the TPI.

This document was provided by the Economic Governance and

EMU Scrutiny Unit at the request of the Committee on Economic

and Monetary Affairs (ECON) ahead of the Monetary Dialogue

with the ECB President on 25 September 2023.

Achieving the right fiscal-monetary mix (in the context of the economic governance review)

PE 747.830 9

CONTENTS

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS 10

LIST OF FIGURES 11

LIST OF TABLES 11

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 12

INTRODUCTION 13

IMPLICATIONS OF THE PROPOSED FISCAL GOVERNANCE FRAMEWORK FOR THE FISCAL

STANCE IN THE EU 15

DOES THE PROPOSED FRAMEWORK OPTIMALLY TRADE-OFF FISCAL SUSTAINABILITY AND

FLEXIBILITY? 21

REEXAMINING THE TRANSMISSION PROTECTION INSTRUMENT IN LIGHT OF THE

PROPOSED FRAMEWORK 25

4.1. Would the proposed framework complicate the application of the TPI? 26

4.2. Does the proposed framework offer an opportunity for improving the TPI? 27

CONCLUSION 30

REFERENCES 32

IPOL | Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit (EGOV)

10 PE 747.830

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

CFC

Central fiscal capacity

DSA

Data sustainability analysis

EC

European Commission

ECB

European Central Bank

EFB

European Fiscal Board

EGR

Economic governance review

ESCB

The European System of Central Banks

ESM

European Stability Mechanism

EU

European Union

GDP

Gross domestic product

IFIs

Independent fiscal institutions

MS

Member states of the European Union

MTO

Medium-term objective

NRRP

National recovery and resilience plan

OMT

Outright Monetary Transactions

TPI

Transmission protection instrument

QE

Quantitative easing

Achieving the right fiscal-monetary mix (in the context of the economic governance review)

PE 747.830 11

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1: IMF projections for the euro area, and adjusted growth projections corresponding to the

proposed new fiscal rules, 2022-2028 19

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1: Fiscal adjustment based on European Commission forecasts (2023-24), proposed framework

(2025-28), and current framework (2025-28) 18

IPOL | Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit (EGOV)

12 PE 747.830

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

• Fiscal and monetary policies interact through multiple channels and interfere with (or

support) each others’ objectives. The interplay between monetary and fiscal policy is hence

important for economic welfare. This paper analyses how the fiscal framework proposed by the

European Commission in April 2023 might affect this interplay, from three perspectives: (1) its

impact on the medium-term fiscal stance; (2) its capacity to reconcile debt sustainability and

flexibility; and (3) its implications for the European Central Bank (ECB)’s Transmission Protection

Instrument (TPI).

• The proposed framework would lead to substantial tightening in the medium term. In the

short term, tighter fiscal policy supports disinflation. But if the ECB’s inflation target is reached by

2025, as both ECB and International Monetary Fund expect, then continued fiscal consolidation

under the new fiscal framework might result in an overly tight fiscal stance, requiring the ECB to

offset it.

• The proposed new fiscal framework is broadly balanced between the objectives of ensuring

debt sustainability and preserving flexibility, but with room for improvement. We

recommend strengthening the requirement that seeks to prevent excessive ‘backloading’ of fiscal

adjustment, while the requirement that debt falls within the first four years of the application of

the framework should be removed or modified substantially, as should the minimum adjustment

requirement of 0.5% of GDP for countries with deficits above 3%. We also recommend a review of

the Commission’s debt sustainability analysis methodology, and a role for independent fiscal

councils in the process of activating the framework’s escape clauses.

• While the proposed fiscal framework would not complicate the activation of the

Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI) compared to the current framework, we

recommend amending one of its eligibility conditions. The ECB has delegated the assessment

of three of the four TPI eligibility conditions to the Council and the Commission. Since these

conditions will continue to be evaluated by the Council and the Commission under the proposed

framework, their application under the TPI does not change. One eligibility condition, however –

whether a country’s debt is sustainable – has not been delegated by the ECB. We argue that since

debt sustainability is a necessary condition for compliance with the proposed framework, this

condition is either redundant, or there should be a presumption that the ECB will follow the Council

and Commission when it decides on debt sustainability. This would not reduce the ECB’s

independence, since the decision on whether activation of the TPI is required remains at the

discretion of the ECB.

Achieving the right fiscal-monetary mix (in the context of the economic governance review)

PE 747.830 13

INTRODUCTION

*

Monetary and fiscal policy pursue different objectives. Monetary policy in the euro area has only one

primary mandate, price stability

1

. Fiscal policy, in contrast, has many objectives: provision and financing

of public goods, output stabilisation, redistribution, intergenerational equity and improvements in

economic allocation. Unlike monetary policy, which is centralised in the hands of the ECB, fiscal policy

in the euro area remains in the hands of national governments.

While they have different objectives, fiscal and monetary policies interact through multiple channels.

Monetary policy influences both inflation and real output, and thus fiscal revenues directly, and fiscal

expenditure indirectly. Monetary policy operates in part by influencing real interest rates, which impact

government borrowing cost. Fiscal policy influences the price level both through aggregate demand

and through its impact on the supply side (via labour supply and public investment, and potentially

muting the transmission of supply shocks, such as commodity price shock). It also influences measured

inflation through changes in excise and VAT tax rates. Finally, unsustainable fiscal policy can threaten

price stability, either through the dislocations induced by a debt crisis, or by leading to pressures for

debt monetisation to stave off the crisis. Such fiscal-monetary interactions were important

considerations in the creation of EU-wide fiscal rules before the euro was launched.

The potential to interfere with (or support) each others’ objectives implies that the interplay (“mix”)

between monetary and fiscal policies is important. Fiscal policy that gets in the way of monetary policy

objectives, and vice versa, can generate welfare costs. For example, if fiscal policy seeks to raise real

output above potential, it may raise inflation, forcing monetary policy to tighten. The result will not be

higher output, but rather higher real interest rates, which raise the cost of borrowing and reduce fiscal

space. Another example applies to a setting in which interest rates are close to their effective lower

bound and inflation is below the central bank’s target. In this case, reaching price stability without

compromising financial stability may require support from (expansionary) fiscal policy.

By influencing fiscal policy, the EU-level fiscal governance framework will have an influence on the

interplay between fiscal and monetary policies. The purpose of this paper is to analyse how the

framework proposed by European Commission in April 2023 (EC, 2023a,b) might affect this interplay.

We tackle this question from three angles.

First, by quantifying the potential impact of the framework on the fiscal stance in the next five years.

Inflation in the euro area is running high, and underlying inflation has proved to be persistent. A

frequently voiced view is that fiscal policy should be tighter in support of the disinflation process (see,

e.g., IMF, 2023). Fiscal policy is in fact projected to tighten this year, and next, before the proposed fiscal

framework would come into effect. The question is how the proposed framework might influence the

fiscal stance from 2025 onward if it were to become law next year.

Second, from a design perspective. We assume that fiscal policy makers are disciplined by elections,

but also subject to incentives that could result in overborrowing and in some cases in a bias toward

current spending. The purpose of fiscal frameworks is to ensure debt sustainability and ideally to

protect public investment, while otherwise providing flexibility to fiscal policy, allowing the fiscal

authorities to pursue their many objectives. Frameworks that achieve these objectives are also in the

*

The authors thank Marco Buti, Grégory Claeys, Maria Demertzis, Francesco Papadia, Lucio Pench, Lucrezia Reichlin, André Sapir, Armin

Steinbach, and Stavros Zenios for valuable comments, and Lennard Wleslau for preparing Figure 1.

1

The objectives of the European System of Central Banks (ESCB) are defined in the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union as: “the

primary objective of the ESCB shall be to maintain price stability. Without prejudice to the objective of price stability, it shall support the general

economic policies in the Union with a view to contributing to the achievement of the objectives of the Union as laid down in Article 3 of the Treaty

on European Union.”

IPOL | Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit (EGOV)

14 PE 747.830

interest of the central bank. Debt sustainability reduces the risk of fiscal dominance and disruptive

crises that threaten price stability

2

. Fiscal policy that is friendly to public investment and raises potential

output will lower inflation pressure for a given level of demand. Flexibility is important because it allows

the fiscal authorities to pursue their various objectives and to deploy policy in support of the central

bank’s price stability objective. We analyse the trade-off between debt sustainability and flexibility

under the proposed framework.

Third, from the perspective of a specific ECB instrument, the “transmission protection instrument” (TPI)

wascreated in July 2022 to maintain orderly debt market conditions in the face of sharply higher

interest rates. While the TPI is not the only ECB instrument at the intersection of monetary and fiscal

policy,

3

it is the only one whose eligibility criteria include compliance with the fiscal framework, as well

as debt sustainability. We answer the question whether the changes in the framework would have an

impact on the operation of the TPI, and whether the TPI should be modified to better “fit” the new

framework.

The remainder of this paper is structured in line with these three perspectives. Section 2 analyses the

implications of the proposed framework for the fiscal stance over the coming 5 years. Drawing on the

empirical findings of Section 2, Section 3 takes a view on the design of the proposed fiscal governance

framework from the perspective of the interplay between monetary and fiscal policy. Finally, Section 4

analyses the relationship between the proposed framework and the TPI. Section 5 concludes.

2

Fiscal dominance describes a situation in which large government debt and deficit prevent the central bank from controlling inflation. In

such a situation, a central bank interest rate increase to tame inflation might result in market pressure on government bond markets, and

the government might become insolvent without central bank financing.

3

Other instruments include Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) and all instruments that operate through bond purchases in secondary

markets (which are often called quantitative easing – QE).

Achieving the right fiscal-monetary mix (in the context of the economic governance review)

PE 747.830 15

IMPLICATIONS OF THE PROPOSED FISCAL GOVERNANCE

FRAMEWORK FOR THE FISCAL STANCE IN THE EU

The European Commission (EC)’s April 2023 proposal to replace the current EU fiscal framework

4

requires Member States (MS) to develop medium term fiscal-structural plans, following discussions

with the Commission, that meet two main requirements. Both must “hold in the absence of any further

budgetary measures over a period of 10 years” (EC, 2023a, Article 15) following the end of a 4-7-year

adjustment period:

(a) public debt as a share of GDP must be “put or kept on a plausibly downward path (…) or

stay at prudent levels”.

(b) the government deficit must be maintained or brought below the 3% of GDP reference

value.

5

Annex V of EC (2023a) defines debt that is “put or kept on a plausibly downward path (…) or stay at

prudent levels” as a debt path that slopes downward (or remains below 60% of GDP if it already meets

the 60% benchmark) both with sufficiently high probability for 5 years after the adjustment period, as

assessed by the stochastic debt sustainability analysis (DSA) of the Commission; and under the

deterministic stress scenarios described in the Commission’s 2022 Debt Sustainability Monitor (EC,

2023c).

In addition, the proposal commits the Commission to several additional conditions both in formulating

a “technical trajectory” that it must put forward as a basis for discussion with MS with debt or deficits

above the Treaty benchmarks of 60% and 3% of GDP, and in its assessment of MS medium-term fiscal-

structural plans. Specifically, it must check: ”whether the fiscal adjustment effort over the period of the

national medium-term fiscal-structural plan is at least proportional to the total effort over the entire

adjustment period” (no-backloading safeguard); “whether the public debt ratio at the end of the

planning horizon is below the public debt ratio in the year before the start of the technical trajectory”

(debt safeguard), “whether for the years that the Member State concernced is expected to have a deficit

above the 3% of GDP reference value, and the excess is not close and temporary”, the fiscal adjustment

is at least 0.5% of GDP (excessive deficit safeguard

6

), and whether “national net expenditure growth

remains below medium-term output growth, on average, as a rule over the horizon of the plan” (net

4

The proposal consists of two proposed regulations and one directive. The main reforms are contained in a “Proposal for a regulation of the

European Parliament and of the Council on the effective coordination of economic policies and multilateral budgetary surveillance and

repealing Council Regulation (EC) No 1466/97” (EC, 2023a

) which would replace the “preventive arm” of the current Stability and Growth Pact.

In addition, a “Proposal for a Council regulation amending Regulation (EC) No 1467/97 on speeding up and clarifying the implementation of

the excessive deficit procedure” (

EC, 2023b) would abolish the “1/20

th

rule” which required MS with debt above 60% of GDP to reduce their

debts by at least 1/20

th

of the difference between its debt ratio and 60% per year, and refocus the existing “debt-based excessive deficit

procedure” on departures from the fiscal path agreed with the Council under the regulation replacing the preventive arm. However, the

“deficit-based excessive deficit procedure” (EDP) would remain largely unchanged, requiring that “for the years when the general government

deficit is expected to exceed the reference value, the corrective net expenditure path shall be consistent with a minimum annual adjustment

of at least 0,5% of GDP as a benchmark.” Finally, a “Proposal for a Council directive amending Directive 2011/85/EU on requirements for

budgetary frameworks of the Member States” (

EC, 2023c) aims at strengthening national-level independent fiscal institutions and medium-

term budgetary frameworks.

5

See Articles 6, 12, and 15 as well as Annex I and V of EC (2023a).

6

We interpret “a minimum annual adjustment of at least 0,5% of GDP as a benchmark” wording of the draft regulation on the excessive deficit

procedure (EC 2023b

) as at least half percent adjustment. In our numerical calculations, we assume exactly half percent when otherwise

adjustment would be less than half percent. However, Pench (2023) argues that the adjustment requirement can be less than half percent,

because this safeguard, as well as the debt reduction safeguard, could be given a subordinated role relative to the sustainability criterion

when the Commission and the Council make an overall assessment of the medium-term plans.

IPOL | Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit (EGOV)

16 PE 747.830

expenditure growth safeguard, which we interpret as ruling out a decline in the structural primary

balance over the first four years of the adjustment period)

In Darvas, Welslau and Zettelmeyer (2023), we compute the fiscal adjustment implications of these

conditions for all MS with 2024 projected debts or deficits above the reference values (on the

assumption that the first adjustment year under the framework would be in 2025), based on a

replication of the Commission’s DSA methodology, using EC forecasts for growth, market-based

interest rate and inflation expectations, as well as some ancillary assumptions to enable us to apply the

safeguards.

7

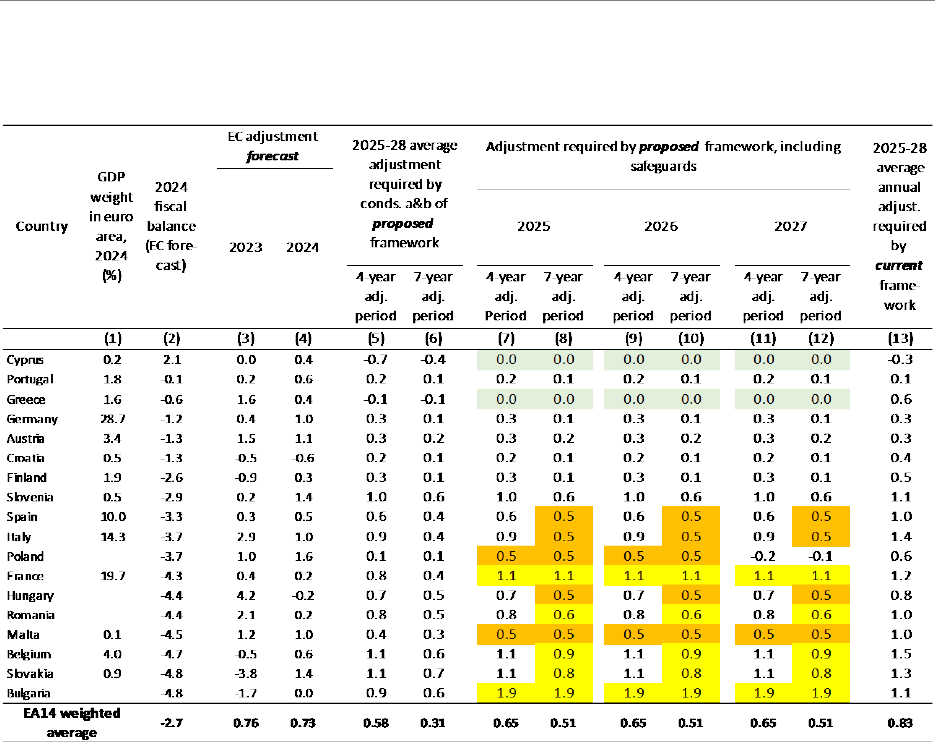

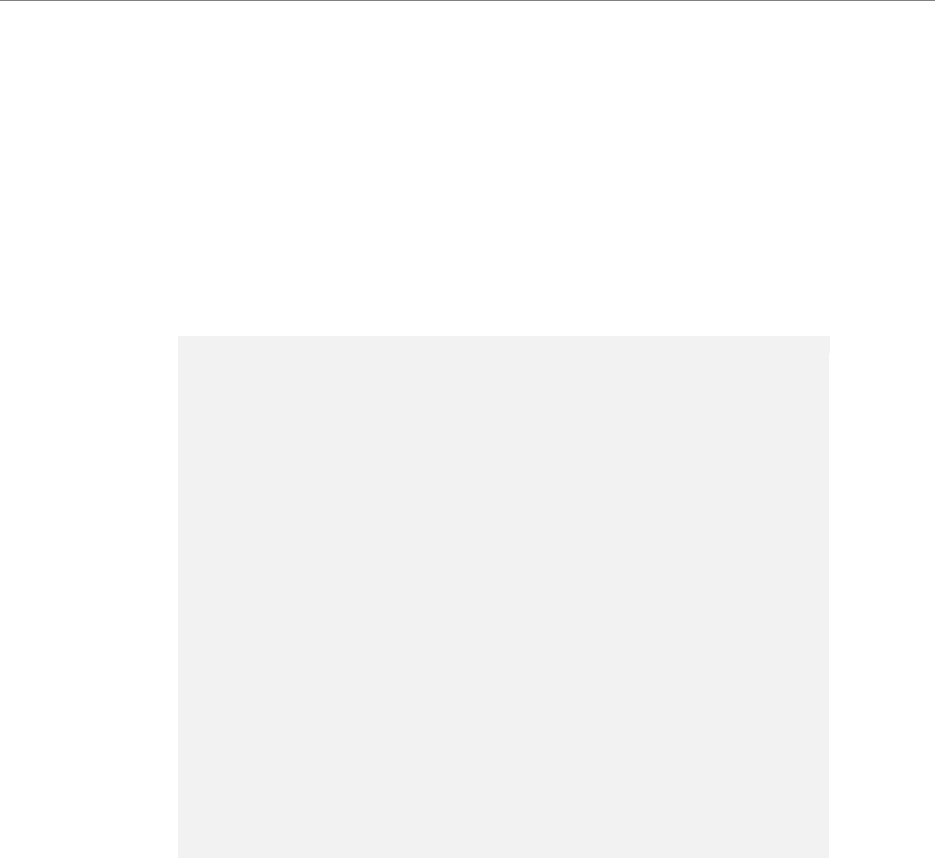

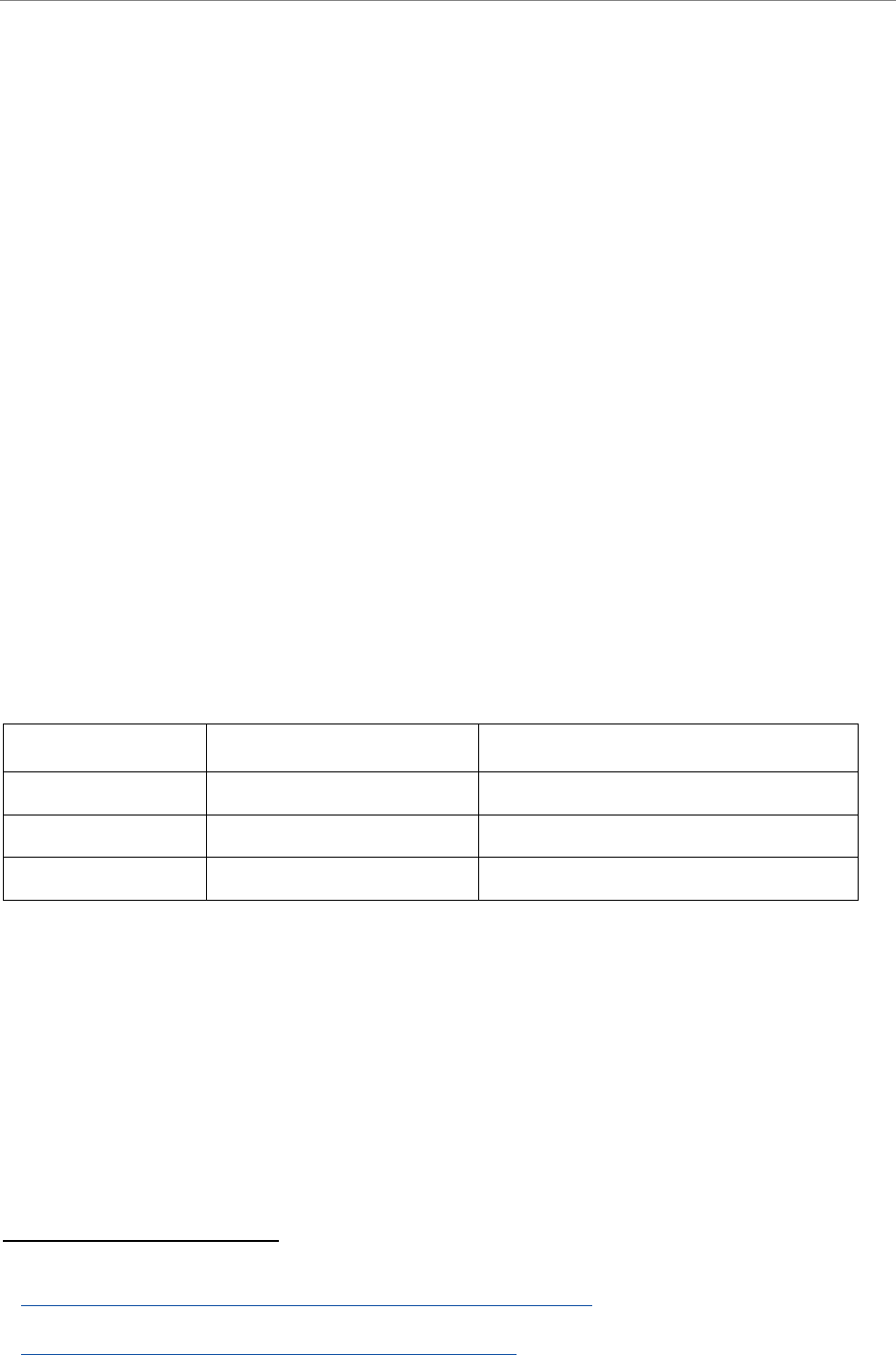

Table 1 summarises the main results. Positive numbers mean an increase in the structural primary

balance, i.e. a fiscal tightening, expressed in percent of GDP. Countries are listed in a declining order of

the fiscal balance forecast by the European Commission for 2024 (column 2). EC projections for fiscal

adjustment in 2023 and 2024 are shown in columns (3) and (4)

8

. These indicate that the Commission

expects sizeable fiscal consolidation in most EU countries, partly reflecting the withdrawal of COVID-19

and energy crisis support measures, albeit with exceptions (Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Finland, and

Slovakia). The GDP-weighted aggregate impact of this tightening for the euro area countries shown in

the table is close to 0.8% of GDP in 2023 and 0.7% in 2024 (see bottom row).

9

Columns (5)-(12) show the annual average fiscal adjustment that would be required for the 2025-27

period if the Commission’s proposed framework was enacted in 2024. This depends on the adjustment

period, which is normally four years, but could be extended to seven years for countries undertaking

growth-enhancing structural reforms, including in the context of National Recovery and Resilience

Plans (NRRPs).

10

The table is laid out in a way that makes it clear which of the requirements of the

framework are driving the results: Columns (5) and (6) show the average annual adjustment for 2025-

28 that would be required by conditions (a) and (b) of the proposed framework, that is, to (a) put or

keep debt on a sustainable downward path, and (b) to lower the deficit to less than 3% of GDP by the

end of the adjustment period and keep it there for at least 10 years. Columns (7) to (12) show the annual

adjustment, separately for the years 2025, 2026 and 2027, which the proposed framework would

require once the safeguards are additionally applied. The need to show each year separately comes

from the excessive deficit safeguard, which applies only in years in which the deficit is still above 3%

11

.

Countries and years for which this safeguard is binding are highlighted in orange, countries for which

the debt safeguard is binding in yellow, and countries for which the net expenditure growth safeguard

7

The main assumption is that the “planning horizon” referred to in the debt safeguard, which is not defined in the proposed regulation, is

four years. In addition, we assume that the total adjustment requirement over the 4-7-year adjustment horizon is broken down into equal

adjustment steps, in structural primary balance terms. This assumption implies that the net expenditure paths automatically satisfy the no-

backloading safeguard; indeed, they go further, as the no-backloading safeguard as currently drafted does not restrict backloading within

either the four-year adjustment period or the first four years and the last three years of the seven-year adjustment period. See Darvas, Welslau

and Zettelmeyer (2023) and Pench (2023) for a discussion.

8

The source is European Commission (2023d).

9

Including the remaining euro area countries in the average would somewhat reduce the impact in 2023, to 0.6% of GDP, mainly due to

projected fiscal easing in the Netherlands (-1.9%) and Luxembourg (-1.5%), but leave the 2024 impact unchanged.

10

The calculations underlying Table 1 use the same growth forecasts to compute fiscal adjustment under the four and seven year adjustment

periods. To the extent that the extension to seven years is determined by the strength of MS plans to raise growth, this could moderately bias

up the adjustment results for the seven-year period shown in the table. However, Article 13 of the draft regulation (EC 2023a)

says that “During

the lifetime of the Recovery and Resilience Facility (…) commitments included in the approved Recovery and Resilience Plan of the Member State

concerned can be taken into account for an extension of the adjustment period.” Given that NRRP investments and reforms qualify for the

extension, and Member States have difficulties even in implementing NRRPs, at least until the end of 2026, it is unlikely that countries would

propose new investments and reforms to obtain an extension. NRRP investments and reforms, however, are already incorporated into the

official growth projections on which the table is based.

11

In Table 1, this makes a difference only for Poland in 2027.

Achieving the right fiscal-monetary mix (in the context of the economic governance review)

PE 747.830 17

is binding in light green. Finally, column (13) shows the average annual adjustment that would be

required, in structural primary balance terms, if the current fiscal framework based on a “Medium Term

Objective” (MTO) were reapplied after 2024.

The main results are as follows.

1. The proposed framework would require continued fiscal adjustment from 2025 until the end of the

four-year planning horizon in 2028, from almost all MS (the only exceptions are Cyprus and Greece,

whose 2024 structural primary balances are projected to already be above the 2028 values

prescribed by the framework).

2. As indicated by the highlights (and by comparing columns (5)-(6) and columns (7)-(12)), the fiscal

adjustment requirements of the proposed frameworks are mostly driven by conditions (a) and (b)

above – that is, the debt sustainability requirement and the requirement that the deficit be reduced

to and remain below 3% of GDP by the end of the adjustment period. There are three exceptions:

o First, for a few countries with projected excessive deficits in 2024, the annual fiscal

adjustment prescribed by conditions (a) and (b) falls short of the 0.5% of GDP required by

the excessive deficit safeguard (Poland and Malta, and additionally Italy, Spain, Hungary

and Romania for the 7-year adjustment period which lowers the average annual

adjustment required by conditions (a) and (b)).

o Second, the debt safeguard is binding for two countries, France and Bulgaria, in both the

4-year and 7-year adjustment periods, and for three additional countries, Belgium, Romania

and Slovakia, in the 7-year adjustment period only. For France, the annual required

adjustment during 2024-28 goes up from 0.8% of GDP (4-year adjustment period) or 0.4%

of GDP (7-year adjustment period) to 1.1% of GDP. For Belgium, the increase is 0.3% of GDP

(7-year adjustment period only).

o Third, the net expenditure safeguard is binding for Greece and Cyprus. In the absence of

this safeguard, these countries would have been able to lower their structural primary

balances from their high projected levels in 2024 without running afoul of either conditions

(a) and (b) not any of the other safeguards.

3. While the proposed system prescribes a significant fiscal tightening, this is not as large as would be

required under the current fiscal rules, if these were to be reapplied from 2025 onward. A

comparison between column (13) and columns (7)-(12) shows that the fiscal adjustment

requirement under the proposed system would be at least 0.2% of GDP per year lower than under

the current system for Cyprus, Greece, Finland, Spain, Italy, Malta, Belgium, and Slovakia. For

Portugal, Germany, Austria, France and Slovenia, it does not make much of a difference (+/- 0.1%

of GDP). Only for Bulgaria would the proposed system require much higher fiscal adjustment than

the current one, on account of the debt safeguard. The difference comes mainly from the fact that

in the current system, higher debt raises the MTO via an ad-hoc formula, while fiscal adjustment

under the proposed system is based on a set of deterministic and stochastic debt projections (with

some ad hoc corrections via the safeguards, as discussed above).

IPOL | Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit (EGOV)

18 PE 747.830

Table 1: Fiscal adjustment based on European Commission forecasts (2023-24), proposed framework

(2025-28), and current framework (2025-28)

(in structural primary balance terms, expressed in percent of GDP)

Source: authors’ calculations based on Darvas, Welslau and Zettelmeyer (2023), economic growth projections from the European

Commission’s May 2023 forecast, and market-based interest rate and inflation forecasts.

Note: Countries and years for which excessive deficit safeguard is binding are highlighted orange, countries for which the debt safeguard is

binding are highlighted yellow, and countries for which the net expenditure safeguard is binding in light green.

The last line of the table shows the aggregate implications for the euro area fiscal stance, based on the

14 euro-area countries included (88% of the euro area in GDP terms). This implies that the consolidation

forecast by the Commission for 2023 and 2024 would continue during 2025-28, albeit at a slightly

slower pace. The Commission’s DSA and the need to reduce the deficit below 3% imply a tightening

between 0.58% and 0.31% of GDP per year, depending on whether countries are given 4 or 7 years

respectively to adjust (columns 5 and 6). The application of the safeguards bumps this adjustment up

by a notch, to 0.65% and 0.51% percent of GDP, mostly on account of the much higher adjustment for

France (columns 7-12).

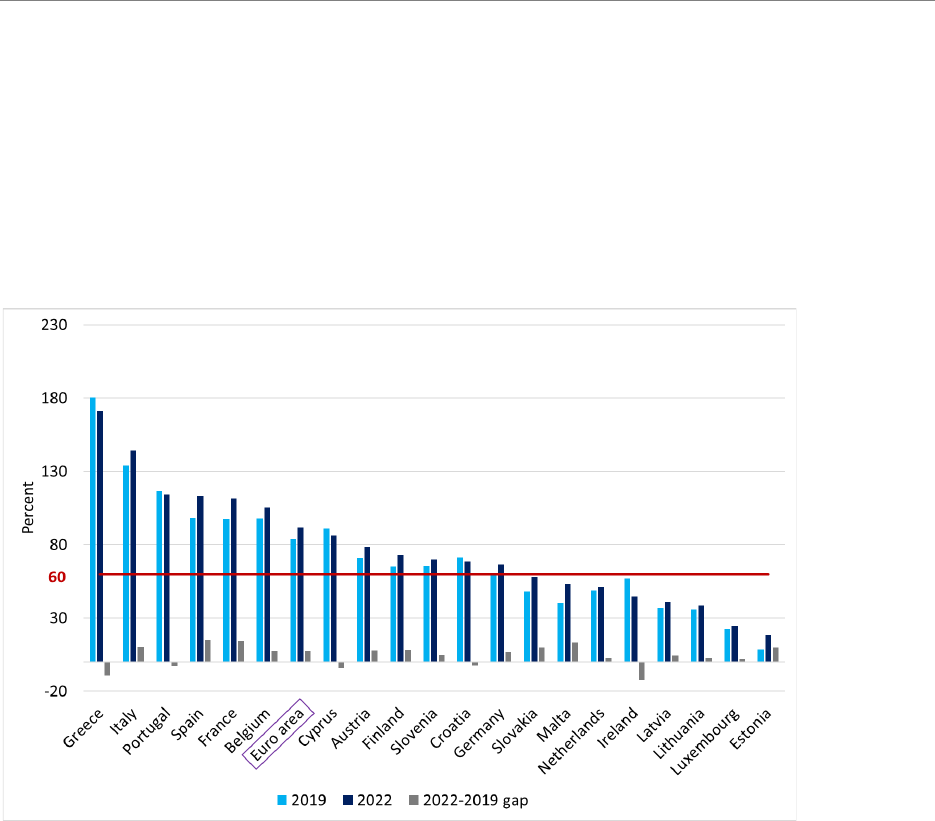

The question is whether this fiscal adjustment path would support the achievement of the ECB’s price

stability objective. Most private forecasts and all major official forecasts – by the ECB, the European

Commission, the IMF and the OECD – predict a return to the inflation target in the medium term.

However, these forecasts typically assume that the central bank will do whatever it takes to achieve its

inflation target and thus do not answer the question of whether fiscal policy could contribute either by

accelerating the process or lowering the output costs of disinflation. To take a stab at that question, it

is necessary to look at inflation forecasts together with forecasts for output and the fiscal stance.

The only institution that provides a set of consistent forecasts of these variables over the medium term

(until 2028) is the IMF in the World Economic Outlook. While these forecasts are somewhat dated (April

Achieving the right fiscal-monetary mix (in the context of the economic governance review)

PE 747.830 19

2023)

12

, it is worth asking what they imply if taken at face value. The IMF expects euro-area inflation to

return to very close to the 2% ECB target by 2025 and stay close to the target until the end of the

forecast horizon (Figure 1, Panel A). It also expects the euro area to avoid a recession; indeed, it projects

a recovery of growth by 2025. This said, there is high uncertainty around these projections, indicated

by the shaded confidence bands, which imply a recession probability of 25% in 2026.

13

Finally, as

regards fiscal adjustment, the IMF expects an adjustment similar to the European Commission in total

in 2023 and 2024, followed by much slower adjustment over the medium term, with the structural

primary balance gradually converging to zero after 2025. Panel A of Figure 1 also shows how fiscal

adjustment presented in Table 1 would differ from that projected by the IMF. Until 2025, the two fiscal

paths more or less coincide. After 2025, however, the fiscal path required by the proposed framework

is dramatically tighter (purple broken line).

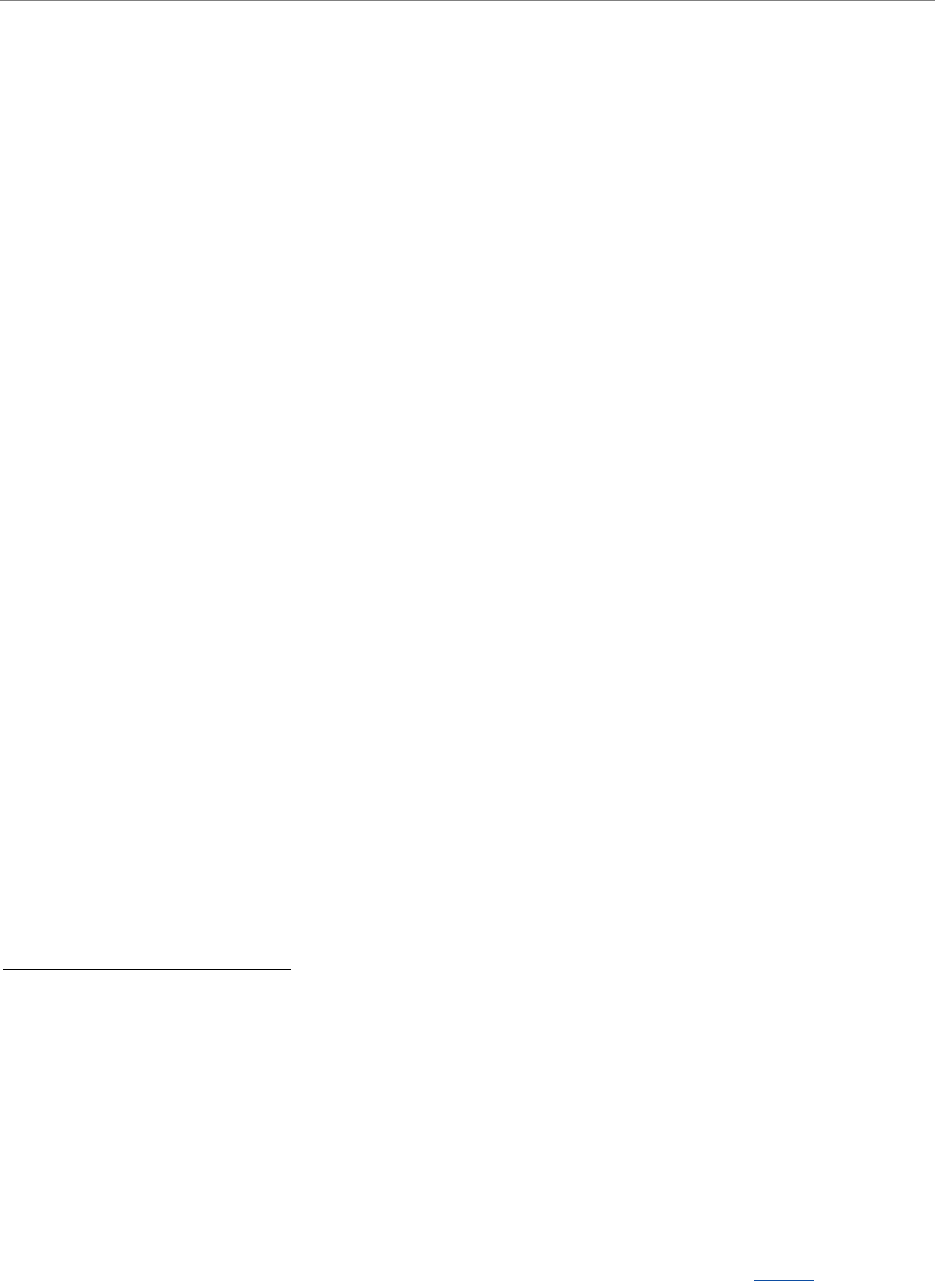

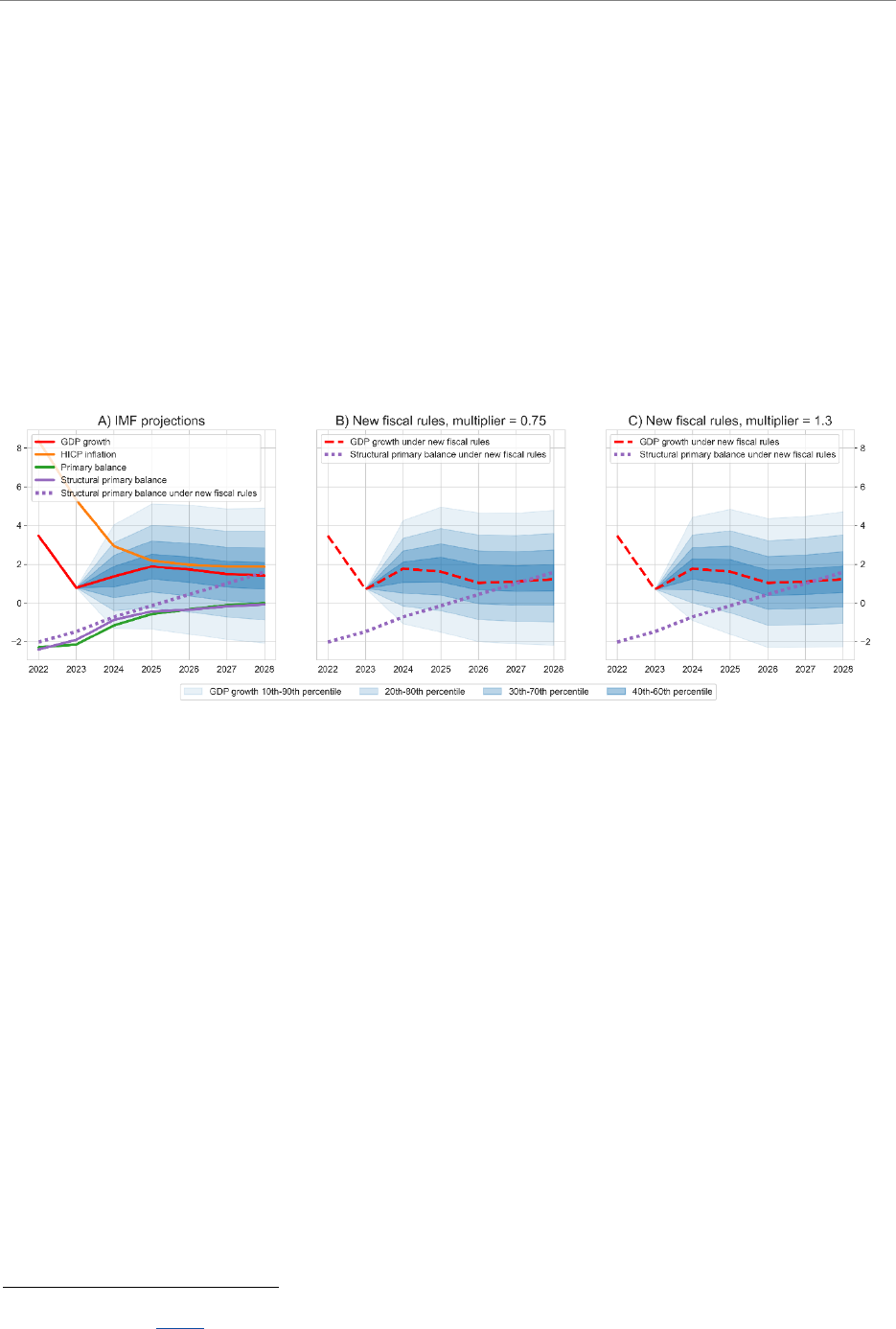

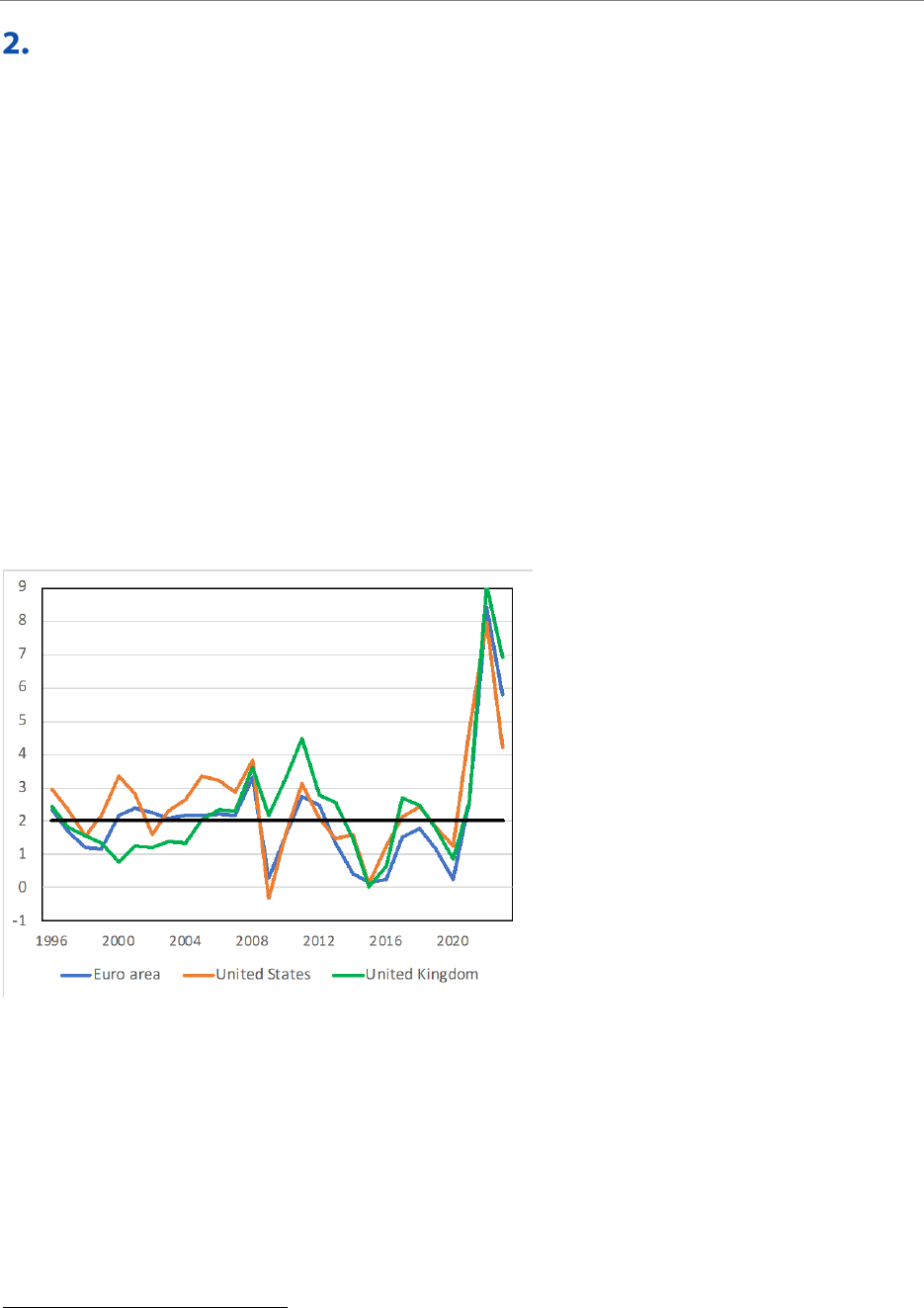

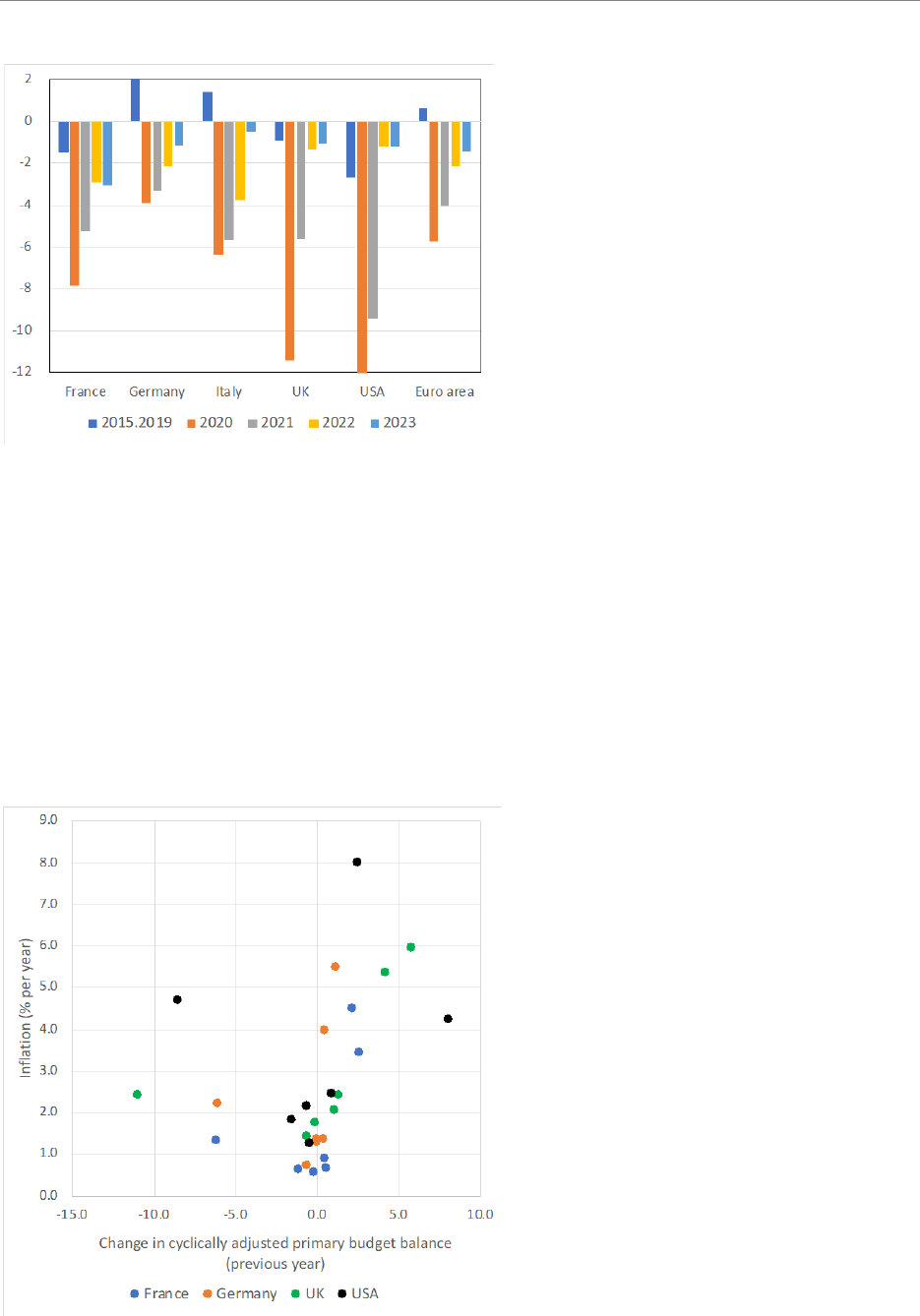

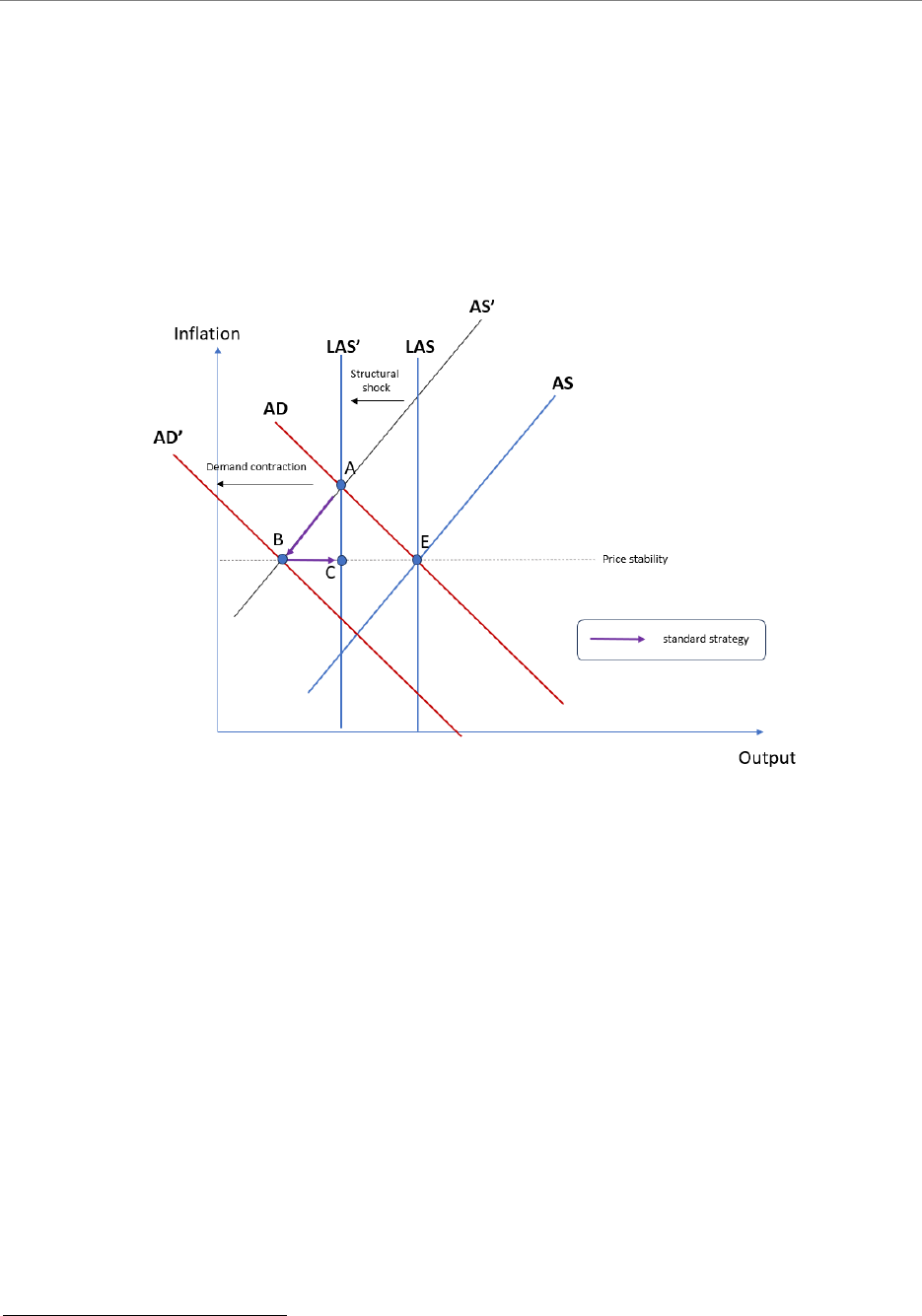

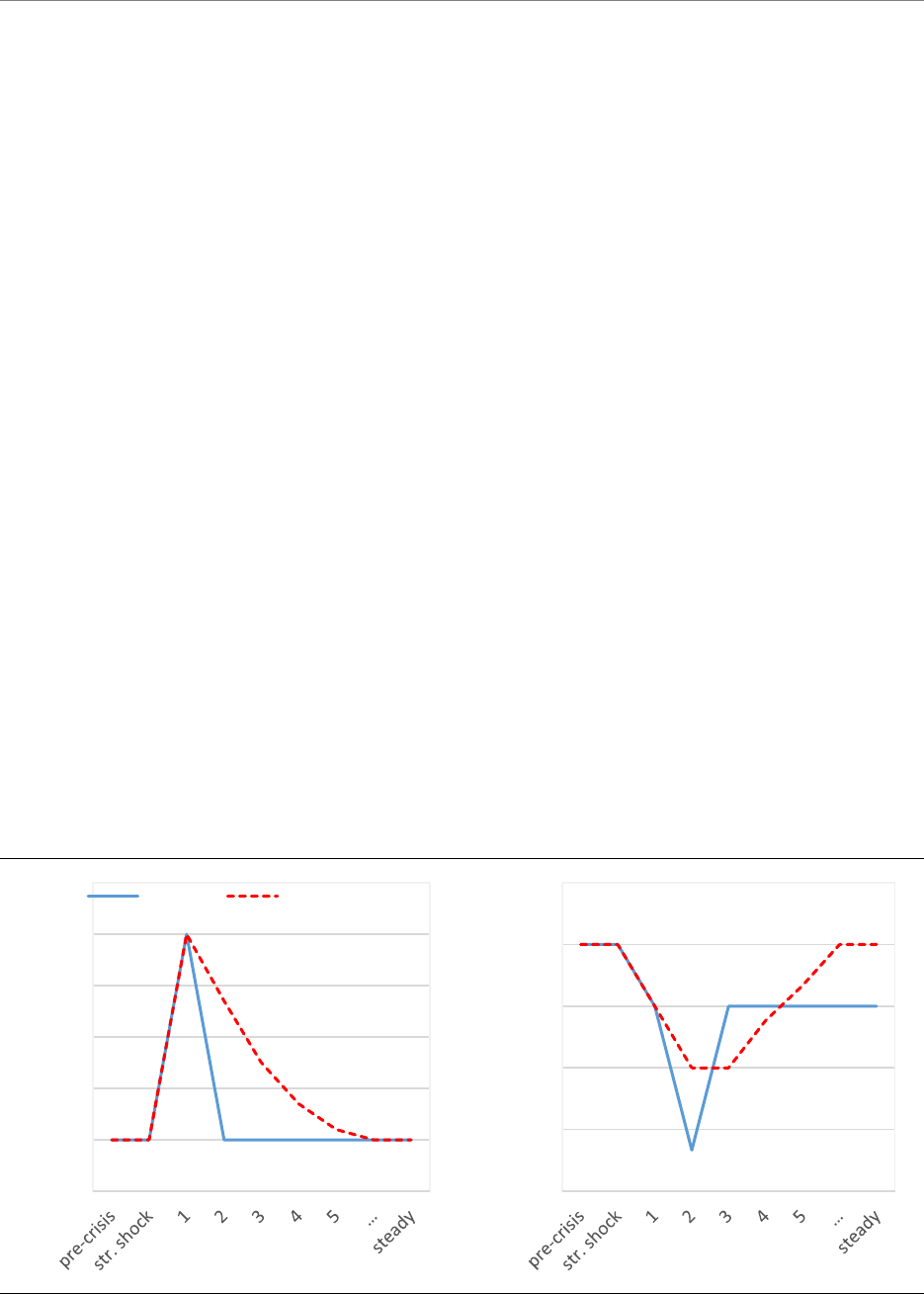

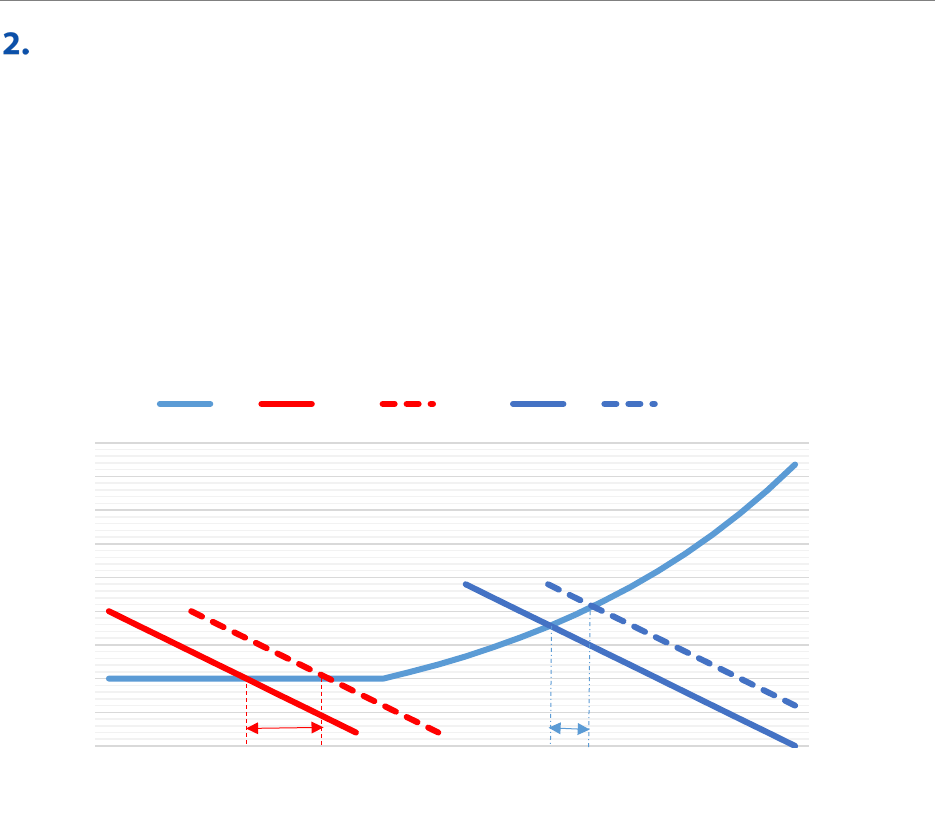

Figure 1: IMF projections for the euro area, and adjusted growth projections corresponding

to the proposed new fiscal rules, 2022-2028

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook database and Bruegel calculations.

Note: Structural primary balance is our calculation using IMF data on primary balance and output gap, and the average euro-area budget

balance semi-elasticity to the output gap from Table I.3 (p. 41) of Mourre, G. et al. (2019). We calculated the euro-area average elasticity as a

weighted average of the elasticities of euro-area countries. We did not exclude possible one-off expenditure and revenue items when

calculating the structural balance. “Structural primary balance under new fiscal rules” correspond to European Commission May 2023

forecast for 2022-2024 and our calculations for 2025-2028 by averaging the annual adjustment requirement under the 4-year and under the

7-year horizons (since some countries might opt for a 4-year plan, others for a 7-year plan). In Panels B and C, “GDP growth under new fiscal

rules” is our calculation by adjusting the IMF GDP growth projections with the impact of the difference between the changes in IMF

structural primary balance estimate and the change in our “Structural primary balance under new fiscal rules” estimate, assuming either the

0.75 fiscal multiplier parameter that the Commission uses (Panel B), or a fiscal multiplier of 1.3 (Panel C). In line with the Commission, it is

assumed that the impact of fiscal consolidation on the output gap gradually diminishes in three years. Percentiles are calculated by us

based on IMF historical forecast errors.

Panels B and C of Figure 1 show how GDP forecasts would be affected by faster fiscal consolidation

under the proposed new fiscal rules, using either the (relatively low) fiscal multiplier assumptions of

the European Commission (Panel B), or a somewhat larger fiscal multiplier (see table note). The

consequence would be a somewhat lower output path than that projected by the IMF. At the same

time, the probability of a recession in 2026 rises from 25% in panel A to 30% in panel B and 34% in

panel C. These probabilities are somewhat smaller than the recession probabilities presented in the

most recent ECB forecast, based on ECB growth forecast errors, which are in the order 40% by end-2025

(see ECB, 2023a, Chart 1).

We see two main takeaways in this analysis.

12

The IMF published an Update to its World Economic Outlook in July 2023, which, however, only provides forecasts for 2023 and 2024.

13

Confidence bands were calculated using historical IMF growth forecast errors.

IPOL | Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit (EGOV)

20 PE 747.830

First, by any measure – whether one believes the European Commission or the IMF’s forecasts – the

time where monetary policy and fiscal policy were pushing in opposite directions is over. Fiscal and

monetary policy are now moving in tandem and expected to do so until 2025, by when both the ECB

and the IMF expects that euro-area inflation will return close to the ECB’s 2% target.

Second, if fiscal balances evolve in line with the proposed economic governance reform, monetary and

fiscal policy may well drift apart again from in a few years from now, but in opposite directions

compared to where they were in 2022. If inflation indeed falls back close to 2% by 2025, the ECB will

stop tightening and might even cut interest rates (either in 2025, or perhaps even earlier), while fiscal

policy would continue on a tightening path for several years. This will imply a significant demand drag

on the euro area economy. To the extent that it translates into a drop of inflation below 2 %, monetary

policy will ease, thereby supporting output and avoiding a recession. But if the preceding monetary

and fiscal tightening has already created weaker economic conditions than predicted in the IMF’s

baseline scenario, a recession may ensue. Recent signs of economic weakening in the EU, with

downward revision to growth in both 2023 and 2024 in the European Commission’s September 2023

forecast (European Commission 2023e) relative to its May forecast European Commission 2023d),

suggest that this risk is growing.

Hence the answer to the question of whether the proposed framework would support price stability

objectives over the horizon of its first application is as follows. In the short run, it would not make much

of a difference. But over the medium term, there is a risk that it would induce a fiscal stance that is too

tight from a conjunctural perspective, and requires the monetary authority to offset it. Not surprisingly,

this risk depends on the length of the adjustment period: as the seven-year adjustment period would

spread out fiscal adjustment over more years, and the fiscal drag on growth over the first four years

would be substantially less.

14

14

In addition, the total required adjustment might be lower as a result of the growth-inducing reforms that are required to qualify for the

three year extension to the adjustment period. For the reasons explained in footnote 10, this effect is not considered in the Table 1 estimates.

Achieving the right fiscal-monetary mix (in the context of the economic governance review)

PE 747.830 21

DOES THE PROPOSED FRAMEWORK OPTIMALLY TRADE-OFF

FISCAL SUSTAINABILITY AND FLEXIBILITY?

As argued in the introduction, fiscal frameworks should seek to ensure debt sustainability while also

giving policy makers flexibility to pursue other objectives. This is both in the general public interest and

in the interest of monetary policy makers, who may require the help of fiscal policy makers in meeting

their price stability objective

15

.

Importantly, however, there can be a trade-off between the two objectives. This could arise from the

fact that fiscal authorities may have incentives to overspend, in light of short election horizons, or

perhaps in light of the fact that the electorate itself does not fully internalise the welfare of future

generations. In this case, ensuring debt sustainability may require restricting the flexibility of the fiscal

authority. This is the standard argument for fiscal rules (see, for example, Alesina and Tabellini, 1990).

For similar reasons, governments may prefer current spending to investment spending, since the latter

only partly benefits current voters. Fiscal rules could attempt to correct this bias.

A monetary union with sovereign fiscal policy at the level of Member States complicates this trade-off,

in two respects.

On the one hand, it strengthens the argument for rules that constrain overly expansionary fiscal

policies. Overborrowing by members of a monetary union has stronger negative externalities for other

members than across countries that are integrated only through trade and financial relationships. This

is true not only because financial linkages are tighter in a monetary union, but because a messy default

and/or exit from the currency area can threaten the credibility of the currency union as a whole (the

July 2015 crisis in Greece is a case in point). As a result, fiscal crises will lead to pressure for a bailout

through financial assistance, and possibly pressure for debt monetisation, endangering price stability

in all currency union member countries (Darvas et al, 2018, Bénassy-Quéré et al, 2018, Gourinchas et

al, 2023).

On the other hand, membership in a currency union also strengthens the possibility of a positive

externality associated with expansionary fiscal policy. The central bank may need help in increasing

aggregate demand, as was the case in the euro area between 2013 and 2020, but national policy

makers may not internalise the impact of fiscal policy on the euro area as a whole. As sovereign

countries cannot be forced to incur debt beyond the level that can be justified to national citizens, this

problem can only be solved through a central fiscal capacity (CFC), which can adjust the euro area fiscal

stance to the collectively optimal level.

From the perspective of monetary-fiscal coordination, one obvious problem of the proposed fiscal

framework is the lack of such a capacity. Leaving aside this problem, the question is whether the

framework ensures debt sustainability at minimum cost to restricting the possibility of expansionary

national fiscal policy when this is needed for price (and output) stability reasons. An important corollary

of this requirement is that the framework should not generate rules or incentives that induce

procyclical fiscal contractions in response to a negative output shock.

To answer the question, we need to briefly take stock of the design features that attempt to ensuring

debt sustainability on the one hand while preserving flexibility on the other.

15

For example, in her 27 July 2023 monetary policy statement, President Lagarde stressed: ” As the energy crisis fades, governments should roll

back the related support measures promptly and in a concerted manner. This is essential to avoid driving up medium-term inflationary pressures,

which would otherwise call for a stronger monetary policy response.”

https:/1/www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pressconf/shared/pdf/ecb.ds230727~9e147b657d.en.pdf

IPOL | Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit (EGOV)

22 PE 747.830

To ensure debt sustainability, the framework relies on a plethora of commitment devices:

• The main ex ante commitment device is the medium-term fiscal structural plan, which results

in a net expenditure path. This must satisfy not only criterion (a), the debt sustainability

criterion per se, but also criterion (b), the deficit criterion, which is conceptually irrelevant for

debt sustainability, but required by the treaty, and may be effective in disciplining policy

makers in practice (Caselli and Wingender, 2021). Furthermore, the European Commission is

supposed to assess whether the plan also meets three additional safeguards described above

— designed to prevent “backloading”, achieve debt reduction by the end of the planning

horizon, and require a minimum speed of adjustment of 0.5%of GDP per year for countries

whose deficits exceed 3% — and base its recommendation to the Council on this assessment.

• Ex post, the framework envisages four devices (lines of defense, so to speak) to make sure that

fiscal adjustment happens as planned. First, the agreed net expenditure path must be written

into law in every country, resulting in binding medium-term net expenditure ceilings. Second,

if the country violates these ceilings, it might be subject to a disciplining procedure (the “debt-

based” excessive deficit procedure). Third, even if the country does not violate the ceilings, it

could be subject to higher-than planned minimum adjustment if the conditions of the “deficit

based” EDP apply, namely, if its deficit exceeds 3% when its planned adjustment is less than

0.5% of GDP

16

. Even if the net expenditure path was designed to prevent this, this could happen

ex post as a result of a bad shock (lower nominal output or higher interest rates). And fourth,

fines for excessive deficit would be imposed at an earlier stage, and initially in smaller amounts,

than in the current system.

The framework also embodies three elements that seek to preserve flexibility, promote reforms and

investment, and avoid procyclical fiscal adjustment:

• First, the possibility to extend the adjustment period by three years for countries that put

forward growth-enhancing public investment and reforms. From the perspective of the ECB,

this is desirable because it raises equilibrium interest rates (“r*”), making it less likely that the

economy will return to a regime in which monetary policy is constrained by the zero lower

bound on interest rates.

• Second, the fact that the main commitment device is a net expenditure path, not a deficit path.

Net expenditures exclude items that the fiscal authorities cannot control, including interest

spending, as well as the cyclical drivers of the deficit (revenue and cyclical expenditure

categories such as unemployment benefits). In principle, this means that if the country is hit by

a bad shock, it should not be required to tighten;

• Finally, two “escape clauses”: a general escape clause in which the Council “may adopt a

recommendation allowing Member States to deviate from their net expenditure path, in the

event of a severe economic downturn in the euro area or the Union as a whole, provided it does

not endanger fiscal sustainability”, and a “country-specific escape clause”, where it may do the

same “where exceptional circumstances outside the control of the Member State lead to a

major impact on the public finances of the Member State concerned, provided it does not

endanger fiscal sustainability.”

The question is whether the benefits of the restrictions introduced for the sake of ensuring debt

sustainability justify the costs that they impose on flexibility, and vice versa for the devices that are

16

See footnote 6 about the ambiguity of whether the minimum half percent adjustment requirement is a hard constraint or not.

Achieving the right fiscal-monetary mix (in the context of the economic governance review)

PE 747.830 23

there to protect flexibility. Drawing on the analysis of Darvas, Welslau and Zettelmeyer (2023) and the

results of the last section, we answer this question as follows.

Aside from the lack of a CFC, the main elements of the proposed framework are sound: asking countries

to develop a medium-term fiscal-structural plans consistent with debt sustainability, creating

incentives for reform and public investment, requiring them to write the plan into national law in the

form of a net expenditure path; requiring corrective measures if the plan is violated; and letting

countries off the hook in the event of a major downturn that cannot be addressed through automatic

stabilisers alone.

17

We also see a rationale for a (properly designed) “no backloading safeguard” that

constrains the net expenditure path beyond what would be required by debt sustainability analysis

alone. The reason is that debt sustainability analysis alone may not put enough structure on the

adjustment path, giving a pass to adjustment proposals that are not time-consistent in light of the

political process. We therefore agree with imposing a no-backloading condition, which rules out net

expenditure paths that seek to leave most adjustments to the last minute.

Second, given its central role, there is a case for reviewing the European Commission’s DSA

methodology, in a way that involves Member States rather than just the Commission alone. While the

methodology is generally both reasonable and rigorous, there is scope for improving it with relatively

little effort (see Darvas, Welslau and Zettelmeyer 2023 for details)

18

. Furthermore, MS are unlikely to

comply with the implications of the methodology for fiscal adjustment unless they understand it and

agree with it. To make the review as objective as possible, we recommend the establishment of an

independent expert group to conduct the technical review, seeking the views of Commission staff,

Members States, the ECB, the ESM, and the European Fiscal Board (EFB), and submitting a report to the

Council recommending changes. This DSA review will take some time, while the economic governance

review (EGR) should be adopted in the next few months; otherwise, the existing fiscal rules will be

reinstated in 2024. We, therefore, recommend approving the EGR as soon as possible with a clause

requiring the revision of the DSA methodology before the end of 2024, making 2024 a transition year,

and launching the full implementation of the new fiscal framework from the beginning of 2025, based

on the new DSA methodology.

Third, there are several design flaws with the proposed safeguards which should be addressed before

the proposal goes into effect.

i. As currently drafted, the no-backloading safeguard is almost empty, in the sense that it would

not prevent the most common forms of backloading. This is because it requires that “the fiscal

adjustment effort over the period of the national medium-term fiscal-structural plan is at least

proportional to the total effort over the entire adjustment period.” If the “period of the plan” is

four years, this formulation would only ensure that the average adjustment in the last three

years of a seven-year adjustment is not smaller than the average adjustment in the first four

years, but not prevent backloading within the four-year adjustment period, nor within the first

four years and last three years of the seven-year adjustment period.

ii. Both the debt safeguard and the excessive deficit safeguard impose significant additional

restrictions on fiscal policy that cannot be justified with debt sustainability objectives

17

We have (separately) been arguing for this type of architecture for some time. See Claeys, Darvas and Leandro (2016), Bénassy-Quéré et al

(2018), Darvas, Martin and Ragot (2018), Blanchard, Leandro and Zettelmeyer (2021), Arnold et al (2022).

18

Technical issues are related to the maturity structure of debt; the interpolation of inflation; not differentiating between the GDP deflator

and harmonised index of consumer prices (HICP); using euro-area inflation expectations for Bulgaria, Czechia, Denmark, and Sweden;

disregarding the sensitivity of interest rates to alternative debt paths; assuming no uncertainty during the adjustment period in the

stochastic analysis; assuming normal distribution of shocks in the stochastic analysis; and a number of other simplifying assumptions. There

are a number of other assumptions as well, which are reasonable, but could be re-examined.

IPOL | Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit (EGOV)

24 PE 747.830

(particularly if the no-backoading safeguard is fixed). These are particularly apparent in the case

of the seven-year adjustment period. These safeguards prevent the countries to whom they

apply from benefitting from the extension of the adjustment period, namely, to lower the

annual adjustment requirement in exchange for growth enhancing reform or investment. By

doing that, they undermine the intended purpose of the extension of the adjustment period.

The effects can be large. For example, the application of the debt safeguard raises the annual

adjustment requirement for France from 0.8% of GDP with four-year adjustment, or 0.4% of

GDP with seven-year adjustment, to 1.1% of GDP. The impact of the debt safeguard on

Bulgaria’s adjustment requirement is even larger, which is ironic since Bulgaria has one of the

lowest debt ratios in the euro area. The excessive deficit safeguard has smaller effects, but they

apply to more countries. Both safeguards should be abolished or fundamentally redesigned.

19

If the reason for inserting the safeguards was the lack of trust in the DSA by some Member

States, then a better solution would be the joint review of the DSA methodology by the

Commission and the Member States and codification of the methodology in the Code of

Conduct of the Stability and Growth Pact, as recommended in Darvas, Welslau and Zettelmeyer

(2023).

20

iii. Consistent with abolishing or redesigning the excessive deficit safeguard, the deficit-based

excessive deficit procedure requires a redesign, because it can induce procyclical adjustment.

Member States that are in compliance with the net expenditure path agreed with the Council

should not be required to undertake a higher adjustment in the face of a shock that puts their

deficit above 3%, so long as the agreed path continues to satisfy the DSA-based requirements

(condition (a)).

Finally, we would have liked to see a greater role of independent fiscal institutions in the process of

activating the escape clauses. If this process becomes political, it could seriously undermine the

discipline that the framework is meant to impart. The participation of independent fiscal institutions

could reduce that risk.

Note that these proposals cut both ways. The recommendations to review the Commission’s DSA

methodology has nothing to do with shifting the weights that the proposal assigns to discipline and

flexibility in one direction or the other; rather, it is about making the framework more efficient in the

sense of increasing its capacity to predict unsustainable debt. Among our three recommendations on

safeguards, the first would make the framework tougher (at an acceptable cost to flexibility) while the

two others would make it more flexible (at acceptable costs to its disciplining function). Finally, the

recommendation on involving fiscal councils is again about increasing the efficiency and the credibility

of the new framework, at no or acceptable cost to flexibility and its disciplining function.

19

A fundamental redesign would mean (1) defining the safeguards so they do not block an extension of the adjustment period from

translating into lower adjustment requirements (for example, by changing the language such that the debt safeguard applies to the

adjustment period, not the “planning horizon”; (2) introducing an exception for EU-endorsed public investments into the safeguards. In

addition, the debt safeguard should not apply to countries with debt below 60% of GDP.

20

See also Blanchard and Zettelmeyer (2023)

Achieving the right fiscal-monetary mix (in the context of the economic governance review)

PE 747.830 25

REEXAMINING THE TRANSMISSION PROTECTION INSTRUMENT

IN LIGHT OF THE PROPOSED FRAMEWORK

In July 2022, the ECB Governing Council approved the Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI), which

allows Eurosystem secondary market purchases of securities issued in jurisdictions experiencing a

deterioration in financing conditions not warranted by country-specific fundamentals, provided

certain criteria are fulfilled. The declared aim of the new tool is to “ensure that the monetary policy

stance is transmitted smoothly across all euro area countries”, a precondition for the ECB to deliver on

its price stability mandate.

Stripped from ECB terminology, the objective of the TPI is to maintain orderly market conditions in

sovereign debt markets without undermining fiscal discipline and without giving rise to transfers from

the monetary authority (as might arise if the ECB were to purchase sovereign bonds of an insolvent

country). To achieve this, the July 2022 ECB decision set four criteria for the eligibility to the TPI, as

follows

21

:

(1) compliance with the EU fiscal framework: not being subject to an excessive deficit procedure (EDP),

or not being assessed as having failed to take effective action in response to an EU Council

recommendation under Article 126(7) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union

(TFEU);

(2) absence of severe macroeconomic imbalances: not being subject to an excessive imbalance

procedure (EIP) or not being assessed as having failed to take the recommended corrective action

related to a Council recommendation under Article 121(4) TFEU;

(3) fiscal sustainability: in ascertaining that the trajectory of public debt is sustainable, the Governing

Council will take into account, where available, the debt sustainability analyses by the European

Commission, the European Stability Mechanism, the International Monetary Fund and other

institutions, together with the ECB’s internal analysis;

(4) sound and sustainable macroeconomic policies: complying with the commitments submitted in the

recovery and resilience plans for the Recovery and Resilience Facility and with the European

Commission’s country-specific recommendations in the fiscal sphere under the European Semester.

These are necessary criteria for eligibility. When these criteria are fulfilled, the ECB will independently

decide whether to conduct TPI operations, by assessing whether “unwarranted, disorderly market

dynamics” arose, following a “comprehensive assessment of market and transmission indicators, an

evaluation of the eligibility criteria and a judgement that the activation of purchases under the TPI is

proportionate to the achievement of the ECB’s primary objective”.

All four eligibility criteria are related to the economic governance review. In this section, we focus on

the aspects most closely related to the reform of the fiscal framework, (1) and (3), and address two

questions. First, would the proposed framework pose any difficulties in applying the two conditions,

relative to the current framework? Second, does the proposed framework create opportunities for

improving the TPI? The answers are no, and yes, respectively.

21

Source: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pr/date/2022/html/ecb.pr220721~973e6e7273.en.html

IPOL | Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit (EGOV)

26 PE 747.830

4.1. Would the proposed framework complicate the application of the

TPI?

The short answer is no. Under the proposed framework, condition (1) will continue to be determined

by the Council as before, while condition (3) could be evaluated by the ECB exactly as before, as all the

debt sustainability analysis of the institutions named will continue to be available. Indeed, the DSA of

the Commission may be publicly available with greater frequency than under the status quo (when it

is published once a year), as it plays a critical role in the excessive deficit procedure (see below). Hence

checking (1) and (3) will be no harder, as a result of the proposed fiscal governance reform, than it was

before.

To see how the assessment of condition (1) would work in practice, is it nonetheless worth summarising

how the proposed regulation envisages the opening of an EDP, and whether there is clarity on the

interpretation of “effective action” once a country is under an EDP.

According the proposed “Council regulation amending Regulation (EC) No 1467/97 on speeding up

and clarifying the implementation of the excessive deficit procedure” (EC 2023b), two circumstances

could lead to the launch of an EDP:

• The deficit-based EDP remains unchanged from the current framework. An excessive deficit

exists if the deficit exceeds the 3% reference value, unless the deviation is small and temporary

or caused by exceptional circumstances beyond the control of the government.

• The debt-based EDP is revised. For countries with public debt ratios above 60% of GDP,

deviations from the Council-endorsed net expenditure path will be evaluated. Within this

group, a differentiation is made for countries with “substantial public debt challenges”

22

and

the remaining countries. For the former, a deviation from the agreed net expenditure path will

by default lead to the opening of an EDP, while for the latter, other factors will be considered

too.

The new debt-based EDP condition can be assessed only after some years the new framework will have

entered into force, so at the possible start of the new framework in 2024, only the conditions for a

deficit-based EDP will be assessed. Table 1 reports European Commission deficit forecast for 2024 and

shows that ten EU countries, of which six are members of the euro area, are expected to have more

than 3% budget deficit in 2024. Among the euro-area countries that suffered high spreads during the

euro crisis in the early 2010s, Italy and Spain are in this group and thus will likely enter an EDP in 2024.

Once in an EDP, a country would remain eligible for the TPI if it takes “effective action” in response to

the Council recommendation. Per Article 126(8) of the TFEU, it is for the Council to establish whether

effective action has been taken. Under the new framework, (Article 3, paragraph 4 of EC 2023b), the

Council would ask the MS to “implement a corrective net expenditure path” that meets the following

criteria.

• It meets condition (a), i.e. “puts the debt ratio on a plausibly downward path or keep it at a

prudent level” as defined by the regulation replacing the preventive arm;

• It ensures that the average annual fiscal adjustment effort in the first three years is at least as

high as the average annual fiscal effort of the total adjustment period.

22

As explained in the most recent debt sustainability monitor (EC 2023c, p. 11), these are countries which based on the Commission’s debt

sustainability methodology, are assessed as having high fiscal sustainability risks over the medium term. In 2022, this group included Belgium,

Greece, Spain, France, Croatia, Italy, Hungary, Portugal and Slovakia.

Achieving the right fiscal-monetary mix (in the context of the economic governance review)

PE 747.830 27

• “For the years when the general government deficit is expected to exceed the reference value,

the corrective net expenditure path shall be consistent with a minimum annual adjustment of

at least 0.5% of GDP as a benchmark.”

Hence, implementation of the requested corrective net expenditure path would constitute effective

action.

23

In addition, an amendment to Article 8 of the regulation (EC 2023b) lays out the conditions under which

the Council would “abrogate” (end) the EDP, namely “where budgetary forecasts as provided by the

Commission indicate that the deficit has been brought durably below the reference value and, where

the excessive deficit procedure was opened on the basis of the debt criterion, the Member State

concerned respected the corrective net expenditure path set by the Council (…) over the previous 2

years and is projected to continue to do so in the current year on the basis of the Commission forecast.”

Our reading of the proposed regulation is hence that it defines the conditions for compliance with the

EU fiscal framework at least as clearly as the regulation that it replaces. The Council will continue to

decide on the existence of an excessive deficit, and on whether countries in and EDP are taking effective

action. And the criteria for doing so are well described in the regulation, creating predictability.

4.2. Does the proposed framework offer an opportunity for improving

the TPI?

There is an important asymmetry between conditions (1) and (3). In condition (1) (as well as as

conditions (2) and (4)), the ECB delegates the assessment of whether the condition is satisfied to the

Council and the Commission. In condition (3), however, the decision whether a country’s debt is

sustainable is not delegated. While the ECB Governing Council “takes into account” the DSA of the

European Commission (as well as that of the European Stability Mechanism, the International Monetary

Fund and others) as well as the ECB’s internal analysis, it reserves the right to decide any way it wants.

The question is whether there may a case for removing this asymmetry, in either direction. If the ECB

Governing Council gives itself discretionary power to decide on debt sustainability, might it also make

sense to give itself discretionary power to in deciding whether the country’s fiscal policy is appropriate?

Conversely, if the ECB delegates the assessment of all criteria but (3) to Council and Commission, might

it also makes sense to delegate the assessment of debt sustainability?

To begin with the first question, the potential attraction of placing some decision-making power

related to condition (1) into the hands of the ECB is that this might undo some of the less useful, ridigity-

inducing features of the proposed system, such as counterproductive safeguards. In principle, the ECB

might take a narrower view of both the inappropriate fiscal behavior and “effective action” than the

Council, namely, one that is focused only on adherence to a net expenditure path consistent with debt

sustainability (criterion a) while disregarding minimum adjustment of 0.5% when this is inappropriate

in the eyes of the ECB.

The problem of this approach, of course is that it would be highly confrontational. Furthermore, the

ECB’s official opinion on the proposed framework (ECB, 2023b) takes a kinder view of the proposed

safeguards than we have taken in this paper. Hence, the idea that the ECB might use the enormous

power of the TPI to in effect fix some of the problems of the proposed framework is a pipe dream. We

conclude that condition (1) should remain as currently drafted.

23

That is, it is a sufficient condition for effective action. It may not be a necessary condition, if the Council considers the implementation to be

close enough to the requested corrective path. The proposed regulations do not provide any guidance in this respect.

IPOL | Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit (EGOV)

28 PE 747.830

Consider now the second question, on whether condition (3) should be aligned with the remaining

conditions in the sense that, rather than taking a discretionary decision on debt sustainability based on

various inputs, it defers to the DSA of the Council and Commission, as implemented under the

proposed framework.

As argued by Claeys and Demertzis (2022), this could be attractive for two reasons. First, the TPI

potentially involves fiscal transfers across euro-area countries. In the absence of a genuine fiscal union,

a decision with large potential fiscal consequences should involve considerable deference to the fiscal

representatives of euro-area Member States, like the Eurogroup (the euro-area finance ministers from

the ECOFIN Council). Second, piggybacking on the Council’s/Commission’s DSA would avoid noise that

could destabilise the debt markets. Markets would know that countries whose debt is found

sustainable by the Commission/Council, and meet the remaining conditions (all of which are

observable), will have access to the TPI. By contrast, under the current system, there will always be

doubt whether the ECB Governing Council ultimately agrees with the Commission’s/Council’s DSA or

not.

From the perspective of July 2022, it is understandable why the ECB did not go this route. First, there

was no mechanism for the Council/Eurogroup to assess the fiscal sustainability of Member States

(except when financial assistance is requested from the European Stability Mechanism, but this is not

a condition for the TPI). The Commission’s DSA analysis did not have a prominent role in the EU

governance framework, and the Commission DSA results were not endorsed by the Council. Second,

the Commission’s methodology was relatively obscure, and – while reasonable – embodied some

doubtful features (see Darvas, Welslau and Zettelmeyer 2023 for details).

In light of the economic governance legislative proposal, these arguments may no longer apply. First,

the status of the DSA methodology has in effect been upgraded: its results will be endorsed by the

Council. Furthermore, in Darvas, Welslau, and Zettelmeyer (2023) and the previous section, we

recommended that there should be a review and approval of the Commission’s DSA methodology

jointly by the Commission and all Member States and that the technicalities of the DSA methodology

should be codified in a document approved by Member States, possibly in the Code of Conduct of the

SGP. The ECB should be given a chance to comment and contribute to the review at the technical level.

Assuming the future fiscal framework encompasses debt sustainability as a necessary condition for

compliance with the fiscal framework and the DSA methodology is collectively reviewed, we would

therefore recommend a revision of the TPI conditions to give greater deference to the future, Council-

endorsed DSA. Specifically, we see two options, the first of which would take an incremental step, and

while second one would be more radical.

The incremental approach would be to change the language of condition 3 in a way that creates the

expectation that the ECB would normally defer to the Council/Commission DSA, without delegating

the debt sustainability decision entirely. For example, condition 3 could read (our addition to the

existing text is in bold):

fiscal sustainability: in ascertaining that the trajectory of public debt is sustainable, the Governing

Council will normally adopt the conclusions of the Council-endorsed debt sustainability

analysis conducted in the context of the implementation of the EU fiscal framework. In

addition, it may take into account, where available, the debt sustainability analyses by the

European Stability Mechanism, the International Monetary Fund and other institutions, together

with the ECB’s internal analysis.

The radical approach would be to either delete condition (3) altogether – since debt sustainability as

per the Council-endorsed DSA is automatically satisfied when a MS complies with the fiscal framework

Achieving the right fiscal-monetary mix (in the context of the economic governance review)

PE 747.830 29

– or maintain condition (3) but link the debt sustainability assessment fully to the Council/Commission

DSA.

The two approaches have different pros and cons.

• The main advantage of the radical approach compared to the incremental one is that it

excludes the possibility of market turmoil linked to the possibility that the Commission/Council

DSA might be rejected by the ECB.

• Against that, there may be a risk associated with the radical approach, namely the possibility

that the Commission/DSA might actually get it wrong.

It is important to emphasise that the independence of the ECB would not be compromised if it

delegates the DSA finding to Council and Commission, since the final decision to activate the TPI

remains entirely in the discretion of the ECB (this decision does not just depend on the four eligibility

conditions, but on the assessment of whether market conditions are justified by fundamentals and

whether the activation of the TPI is proportionate to the achievement of the ECB’s primary objective,

which the ECB does not delegate).

24

Moreover, if a government introduces fiscal measures

unfavourable to fiscal sustainability after the Council endorsed the national fiscal plan and thereby risks

a deviation from the agreed fiscal path, the ECB will continue to have full discretion in assessing

whether the increased interest rate spread of this country is in line with fundamentals or caused by

“unwarranted, disorderly market dynamics”.

For the same reason, the ECB would not be “stuck” if it were to find flaw with the DSA of the

Commission/Council. While formally deferring to the Council/Commission (i.e. calling debt sustainable

when the Council/Commission does), it could decide not to activate the TPI on the grounds that

secondary market spreads are sufficiently close to fundamentals. This would likely create less market

turmoil than to conclude that, contrary to the views of Commission and Council, the public debt of a

country is not sustainable.

24

Furthermore, there are several precedents for the delegation of eligibility criteria that address credit risk by the ECB. Under the OMT, the

ECB implicitly delegates the debt sustainability assessment to the European Stability Mechanism (ESM). Under its normal collateral framework,

it delegates to private rating agencies.

IPOL | Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit (EGOV)

30 PE 747.830

CONCLUSION

This paper analysed how the interplay between monetary and fiscal policy might be affected by the

proposed reform to the EU’s fiscal governance framework, and whether the TPI should be redrafted in

this light. We conclude as follows.

First, from the perspective of its main features, the proposed framework is mostly good news for

the fiscal-monetary policy mix in the euro area. With one notable exception – the lack of a central

fiscal capacity – the basic design elements of the framework are helpful to monetary policy. These

include its focus on debt sustainability; the use of a net expenditure rule to avoid procyclical

adjustment in response to shocks, allowing some flexibility on the timing of adjustment, creating

incentives for growth inducing reforms and investment, and two escape clauses that provide fiscal

policy makers with flexibility to react to large shocks.

Second, the new framework embodies several design features that imply that it is some way off

from striking the optimal compromise between debt sustainability and flexibility.

We propose five amendments:

• The first would strengthen the discipline of the proposal at acceptable cost to flexibility: review

the drafting of the “no-backloading safeguard” to make it more meaningful (that is, give it

more teeth).

• We also offer two amendments that would increase flexibility at acceptable cost to the

framework’s discipline (particularly if our proposal on the no-backloading condition is taken):