FS

Monetary-fiscal

interaction

Achieving the right monetary-fiscal

policy mix in the euro area

Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit (EGOV)

Directorate-General for Internal Policies

PE 747.864 - September 2023

EN

IN-DEPTH ANALYSIS

Requested by the ECON committee

Monetary Dialogue Papers, September 2023

External authors:

Kerstin BERNOTH

Sara DIETZ

Rosa LASTRA

Marie RULLIÈRE

IPOL | Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit (EGOV)

2 PE 747.864

Monetary-fiscal interaction: achieving the right monetary-fiscal policy mix in the euro area

PE 747.864 3

Abstract

Achieving a balanced monetary-fiscal policy mix in the euro area

is crucial to ensure that monetary policy is able to fulfil its primary

price stability objective. This paper outlines, from an economic

and legal perspective, the interaction between monetary and

fiscal policy in light of the current monetary and fiscal stance and,

in particular, the “quasi-fiscal” effects of some unconventional

monetary policy measures. Since sustainable public finances are

a prerequisite for a price-stability-oriented single monetary

policy, the paper also analyses the EU economic governance

review proposals.

This document was provided by the Economic Governance and

EMU Scrutiny Unit at the request of the Committee on Economic

and Monetary Affairs (ECON) ahead of the Monetary Dialogue

with the ECB President on 25 September 2023.

Monetary-fiscal

interaction

Achieving the right monetary-fiscal

policy mix in the euro area

IPOL | Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit (EGOV)

4 PE 747.864

This document was requested by the European Parliament's Committee on Economic and Monetary

Affairs.

AUTHORS

Kerstin BERNOTH, DIW Berlin.

Sara DIETZ, Hengeler Mueller.

Rosa LASTRA, Queen Mary University of London.

Marie RULLIÈRE, DIW Berlin.

ADMINISTRATORS RESPONSIBLE

Drazen RAKIC

Giacomo LOI

Maja SABOL

EDITORIAL ASSISTANT

Adriana HECSER

LINGUISTIC VERSIONS

Original: EN

ABOUT THE EDITOR

The Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit provides in-house and external expertise to support

EP committees and other parliamentary bodies in shaping legislation and exercising democratic

scrutiny over EU internal policies.

To contact Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit or to subscribe to its newsletter please write

to:

Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit

European Parliament

B-1047 Brussels

E-mail: [email protected]

Manuscript completed in September 2023

© European Union, 2023

This document was prepared as part of a series on “Achieving the right fiscal-monetary mix (in the

context of the economic governance review)”, available on the internet at:

https://www.europarl.europa.eu/committees/en/econ/econ-policies/monetary-dialogue

DISCLAIMER AND COPYRIGHT

The opinions expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not

necessarily represent the official position of the European Parliament.

Reproduction and translation for non-commercial purposes are authorised, provided the source is

acknowledged and the European Parliament is given prior notice and sent a copy.

Monetary-fiscal interaction: achieving the right monetary-fiscal policy mix in the euro area

PE 747.864 5

CONTENTS

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS 6

LIST OF FIGURES 7

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 8

1. INTRODUCTION 9

2. THE JURISDICTIONAL DOMAIN OF MONETARY AND FISCAL POLICY 11

2.1. The price stability mandate of the ECB 11

2.2. Fiscal policies within the responsibility of the Member States 11

3. INTERACTIONS BETWEEN MONETARY AND FISCAL POLICY 13

3.1. Interdependencies and interaction of (conventional) monetary and fiscal policy 13

3.2. The current monetary and fiscal stance 14

4. ECB “QUASI-FISCAL” MEASURES 18

4.1. Legal analysis of ECB “quasi fiscal” measures 19

4.2. TPI and its role in preventing future fragmentation of sovereign bond markets 20

5. THE NEW EU ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE ARCHITECTURE 22

5.1. Legal foundations of the EU economic governance architecture 22

5.2. Proposal to reform the EU economic governance rules 23

6. IMPLICATIONS OF THE ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE REVIEW FOR MONETARY POLICY 25

7. CONCLUSION 27

REFERENCES 28

IPOL | Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit (EGOV)

6 PE 747.864

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

APP

Asset Purchase Programme

BIS

Bank for International Settlements

ECB

European Central Bank

ECJ

European Court of Justice

DSA

Debt Sustainability Analysis

ELA

Emergency Liquidity Assistance

EMU

Economic and Monetary Union

EP

European Parliament

ESCB

European System of Central Banks

EU

European Union

GDP

Gross Domestic Product

HICP

Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices

LOLR

Lender of Last Resort

MIP

Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure

OMT

Outright Monetary Transactions

PEPP

Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme

TLTRO

Targeted Longer-Term Refinancing Operations

TEU

Treaty on European Union

TFEU

Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union

TPI

Transmission Protection Instrument

TSCG

Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance in the Economic and Monetary

Union

USD

US Dollar

ZLB

Zero lower bound

Monetary-fiscal interaction: achieving the right monetary-fiscal policy mix in the euro area

PE 747.864 7

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1: Government benchmarks, 10-year, yield 15

Figure 2: General gross debt in % of GDP 16

Figure 3: Introduction of quantitative easing from 2014 by the European Central Bank 19

IPOL | Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit (EGOV)

8 PE 747.864

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

• While the jurisdictional domains of monetary and fiscal policy are separated – the former within

the exclusive competence of the European Union (with the European Central Bank (ECB) as the

institution entrusted with the conduct of the single monetary policy) and the latter within the

Member States' competences – monetary and fiscal policies are highly interdependent,

interacting in various ways.

• Though there have been tensions throughout the life of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU),

monetary and fiscal policies have been broadly aligned and mutually supportive at key

episodes in its history. This was also the case during the COVID-19 pandemic.

• However, with the return of inflation in 2021, there is renewed and high level of tension in

the monetary-fiscal policy mix. While monetary policy is tightening, discretionary fiscal support

in the euro area to counter rising energy costs has been substantial in 2022 and remains significant

in 2023. Some of these measures have had a direct dampening effect on energy prices (e.g. indirect

tax cuts or price caps). However, once they expire, inflation is likely to rise again, which could

hamper the ECB's disinflationary efforts.

• Some of the ECB interventions, especially large-scale asset purchase programmes, have

relevant fiscal implications. These “quasi-fiscal” monetary policy measures are characterised by

the fact they materially impact on the fiscal accounts and/or affect other aspects of fiscal policy

such as tax, spending or financing.

• “Quasi-fiscal” monetary policy measures are problematic from a legal point of view since

they partly over-stretch the mandate of the ECB. This could also be the case of the announced, but

not yet activated, new sovereign bond purchase programme, the Transmission Protection

Instrument (TPI).

• The proposal for a new EU economic governance framework aims to strengthen national

ownership of fiscal rules. This is an important step to ensure that public finances in the euro area

are sound and do not have to be indirectly addressed by monetary policy measures.

• While the current reform proposal addresses many of the shortcomings identified, too much

discretion remains in the interpretation of the rules by both the European Commission and the

Member States. This might lessen the fiscal discipline and fiscal homogeneity necessary for a

price-stability oriented monetary policy

.

• In the current inflationary environment, a reduction in fiscal stimulus or more targeted fiscal

support could reduce inflationary pressures. This could allow for a more gradual and moderate

tightening of monetary policy, thereby reducing financial stability and fragmentation risks and

making the use of the controversial TPI less necessary for the ECB.

• The ECB should only resort to “quasi-fiscal” monetary policy measures in exceptional cases,

such as when the interest rate level has reached the zero lower bound or when there are

divergences in government bond yields between Member States resulting from market

speculation that jeopardise a single monetary policy.

Monetary-fiscal interaction: achieving the right monetary-fiscal policy mix in the euro area

PE 747.864 9

1. INTRODUCTION

The Maastricht Treaty established a division of competences between monetary policy and fiscal policy,

with the former centralised and the latter decentralised. Notwithstanding the formal separation, the

Treaty envisaged some basic forms of coordination (positive integration) as well as some forms of

negative integration or prohibitions (with regard to monetary financing, excessive deficits, bail-out

policies and others).

1

Although there have been tensions throughout the life of the Economic and

Monetary Union (EMU), monetary and fiscal policies have been aligned during periods in its history.

This was the case during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, with the return of inflation in 2021, tension

in the monetary-fiscal policy mix reappeared. Monetary policy is tackling rising inflation (the primary

objective of the European Central Bank - ECB) by boldly raising interest rates to their highest level in 22

years and by phasing out the Asset Purchase Programme (APP). The ECB also announced a new bond

buying programme - the Transaction Protection Instrument (TPI) - which could be activated at any time

to counter unwarranted, disorderly bond market dynamics as we discussed in our earlier paper.

2

In

addition, there is the risk that sharply rising interest rates could trigger a systemic banking crisis, as the

recent turmoil in Switzerland and the US in the spring of 2023 vividly demonstrated.

Meanwhile, public debt levels in several euro area Member States remain very high. Debt reduction is

at the top of the agenda of euro area policymakers in order to create sufficient fiscal room for future

manoeuvring. However, the COVID-19 crisis, the energy price shock resulting from the war in Ukraine

and the rise in the cost of living have prompted euro area Member States to adopt supportive

discretionary fiscal measures.

3

Several member countries, such as France and Spain, have taken

measures that have had a direct dampening effect on energy price increases. However, once these

measures expire, inflation is likely to rise again in these countries, which could hamper the ECB's

disinflationary efforts.

The ECB cannot solve the current challenges and potential risks alone. Rather, in such an environment,

monetary and fiscal policy must work together in a coordinated manner.

4

The European Commission

is embarking on a reform of the economic governance framework in the EMU, including a more

country-specific approach within such a regime. The objectives of the proposals

5

are stronger national

ownership, simpler rules taking account of different fiscal challenges, facilitating reforms and

investments for EU priorities, and providing for effective enforcement.

6

This paper starts by briefly outlining the legal framework of EMU, which established the separation of

fiscal and monetary competences. Second, we examine the complex interaction between fiscal and

monetary policy in light of the current economic stance. Third, we discuss the “quasi-fiscal” implications

of the ECB's unconventional monetary policy measures, in particular its large-scale asset-purchase

programmes, also known as Quantitative Easing (QE). We go into more detail on their legal basis and

shed light on the Transaction Protection Instrument (TPI) announced in July 2022. Fourth, we consider

1

See Lastra (2015), pp. 293 ff.

2

See Bernoth et al. (2022).

3

For an overview, see Sgaravatti et al. (2021).

4

It should be noted that also financial supervision and macroprudential policy are important players to manage the challenges ahead.

But this is not subject of this paper.

5

These proposals would amend both (i) the preventive arm a new Stability and Growth Pact, (ii) the corrective arm to speed up and

clarify the implementation of the excessive deficit procedure and (iii) the Directive on the requirements for national budgetary

frameworks. See also footnote 6.

6

Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the effective coordination of economic policies and

multilateral budgetary surveillance and repealing Council Regulation (EC) No 1466/97, COM/2023/240 final (so called preventive arm

regulation); Proposal for a Council regulation amending Council Regulation (EC) No 1467/97 on speeding up and clarifying the

implementation of the excessive deficit procedure, COM/2023/241 final (so called corrective arm regulation); Proposal for a Council

directive amending Council Directive 2011/85/EU on requirements for budgetary frameworks of the Member states, COM/2023/242

final (so called budgetary frameworks directive).

IPOL | Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit (EGOV)

10 PE 747.864

the new proposals to reform the EU economic governance rules and their expected effect on monetary

policy. And finally we conclude.

Monetary-fiscal interaction: achieving the right monetary-fiscal policy mix in the euro area

PE 747.864 11

2. THE JURISDICTIONAL DOMAIN OF MONETARY AND FISCAL

POLICY

The legal framework of EMU, as laid out in the European Treaties (Treaty on European Union (TEU) and

Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU)), demarcates the mandate of the ECB and the

separation and different jurisdictional domains between monetary policy and fiscal policy.

2.1. The price stability mandate of the ECB

Monetary policy in the euro area is one and indivisible. It is governed by the Treaty framework, which

clearly establishes the primacy of price stability in the conduct of monetary policy.

7

As a contributory

task, the ECB should support financial stability.

8

Fiscal considerations within the broader scope of economic policies may not be targeted as such by

monetary policy, which ought to remain uninfluenced by the fiscal objectives of the individual Member

States. While fiscal policy is still decentralised, monetary policy is the exclusive competence of the ECB.

In order to protect the primacy of price stability in the conduct of monetary policy and to shield it from

political instruction (including fiscal policy considerations), the Treaty grants strong independence to

the ECB.

9

The Treaties remain silent on a definition or further explanation of what is meant by price stability. The

academic literature has discussed in-depth what was meant by the Treaty founders and resorted, inter

alia, to economic theory (of the time) and the Maastricht-criteria for accession to the euro area to

determine what precisely the term "price stability" entails. In this regard, price stability was interpreted

as aiming at an inflation of close to, but below 2% until 2021; in July 2021 the ECB amended this

interpretation as part of its monetary policy strategy review. On 8 July 2021, the ECB Governing Council

adopted a symmetric 2% inflation target over the medium term, thereby diverging from its previous

interpretation (ECB, 2021a).

2.2. Fiscal policies within the responsibility of the Member States

As stated above, while monetary policy is centralised at Union level and constitutes an exclusive

competence,

10

fiscal policies (as part of the economic policies) remain the competence of the Member

States. Hence, the jurisdictional domains of monetary and fiscal policy are separated in the Union legal

framework.

11

Thus, the monetary union and the ECB's monetary policy rests on, and interacts with,

heterogenous economies and fiscal policies of the 27 Member States.

TFEU provides for some coordination of economic policies and sets requirements regarding the fiscal

situation of the Member States to ensure a minimum level of economic convergence.

12

In practice,

however, the incompleteness of the EMU - also described as an asymmetry underlying the EMU with

centralised monetary policy at Union level and decentralised economic policy at Member State level -

7

Art. 127 (1) 1, 282 (2) TFEU and Article 2 of the Statute of the European System of Central Banks (ESCB Statute) lay out the ECB's primary

objective to maintain price stability. Only "[w]ithout prejudice to the objective of price stability, the ESCB shall support the general

economic policies in the Union with a view to contributing to the achievement of the objectives of the Union as laid down in Article 3 of

the Treaty on European Union" according to Art. 127 (1) 2 TFEU.

8

Art. 127 (5) TFEU.

9

Art. 130, 282 TFEU and other provisions.

10

Art. 3 (1) (c) TFEU.

11

See Lastra and Louis (2013), pp. 35 ff.

12

See in detail 5.1. of this paper and Lastra and Louis (2013), pp. 20 ff.

IPOL | Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit (EGOV)

12 PE 747.864

has been criticised as flawed since the beginning of the EMU.

13

The insufficient enforcement of the

existing ruleset is also the subject of considerable criticism.

14

13

See Hetges (2015), pp. 32 ff.; on the discussion see for example Seidel (2000), pp. 866 f.; Horn (2011), p. 1399; Siekmann (2013), marginal

notes 24 ff.; Lastra (2015), pp. 291 f.; Lastra and Louis (2013), pp. 4 ff.

14

See Degenhart (2013), pp. 88 ff.; Ohler (2019), pp. 13 ff.; Thiele (2013), pp. 3 ff. with further references; Konrad et al. (2010), pp. 143–171;

Antpöhler (2012), p. 355. In detail on the different forms of economic imbalances between Eurosystem members Smets (2012),

pp. 41 ff.; Lastra and Louis (2013), pp. 35 ff.

Monetary-fiscal interaction: achieving the right monetary-fiscal policy mix in the euro area

PE 747.864 13

3. INTERACTIONS BETWEEN MONETARY AND FISCAL POLICY

While monetary and fiscal policies reside in different jurisdictional domains, they are highly

interdependent, interacting with each other (see Chapter 3.1.). These interactions should be ideally

mutually supportive and in line with the respective goals and mandate of monetary and fiscal policy.

However, the current monetary and fiscal stance results into a complex monetary-fiscal policy mix (see

Chapter 3.2.).

3.1. Interdependencies and interaction of (conventional) monetary and

fiscal policy

Monetary and fiscal policies use different instruments to influence the economy and achieve their

objectives. Monetary policy instruments can be broadly divided into conventional and unconventional

instruments. In this section we will briefly discuss the interaction of conventional monetary policy

instruments with fiscal policy. In Chapter 4, we focus instead on unconventional monetary policy

instruments and their interaction with fiscal policy, which is why they are also referred to as “quasi-

fiscal policy measures”.

The main conventional monetary policy instrument is the steering of short-term interest rates. By

adjusting interest rates, central banks aim to influence borrowing costs spending and investment

decisions of households and firms, and, ultimately, the price level and inflation, the ECB's primary

objective.

Fiscal policy involves government decisions on taxation and government spending. Through these

instruments, governments influence the level of demand and supply in the economy and allocate

resources to different sectors with the aim to stabilise the business cycle and redistribute income and

wealth. the business cycle and redistribute income and wealth.

Since both monetary and fiscal policies affect the real economy, they inevitably interact. For example,

if the central bank adjusts interest rates to cool or stimulate the economy in order to achieve its price

stability objective, this will also have an impact on the government's debt servicing costs, thusly

affecting fiscal sustainability and the room for manoeuvring. Conversely, the level of government

borrowing affects the demand for credit and, hence, the level of interest rates, thus interacting with the

main instrument of monetary policy. Moreover, public investment and consumption affects aggregate

demand and, therefore, ultimately also the price level. In this way, monetary and fiscal policies can

support or disrupt each other in stabilising the economy and pursuing price stability.

In times of economic contraction and low inflation, coordination of monetary and fiscal policy is not

too difficult. Monetary policy could be accommodating by keeping interest rates low to avoid

burdening governments with high debt servicing costs. At the same time, governments could take

advantage of cheap financing and use fiscal stimulus measures, such as tax cuts and increased

government spending, to boost the economy.

15

However, it is more difficult to coordinate fiscal and monetary policy in times of economic contractions

when inflation is high, as is currently the case. An inflation-targeting central bank, as the ECB, must

tighten monetary policy by raising interest rates and phasing out asset purchase programmes. These

measures raise the cost of servicing government debt, thus discouraging the issuance of new

government debt. Moreover, government deficits increase as maturing debt has to be rolled over. At

the same time, government spending rises as automatic stabilisers operate. If the fiscal room for

15

Several studies show that the effectiveness of fiscal stimulus is also dependent on the monetary policy stance. For instance, the fiscal

multiplier turns out to be higher when monetary policy is accommodative or when interest rates have hit the zero lower bound (Klein

and Winkler, 2021).

IPOL | Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit (EGOV)

14 PE 747.864

manoeuvring is already constrained by high public debt levels, as it is the case in several euro area

Member States, governments may be prevented from further supporting monetary policy through the

use of expansionary fiscal measures. In case financial markets cast serious doubts on the solvency of

governments, governments may even resort to pro-cyclical fiscal policy by cutting government

spending, which would counteract an expansionary monetary policy. Thus, fiscal policy would be

constrained by monetary policy. The awareness that interest rate hikes worsen the debt sustainability

of governments could also lead central banks to be reluctant to raise interest rates further or to do so

by less than necessary - a situation referred to as “fiscal dominance”. In this case, monetary policy would

be constrained by fiscal policy.

When an economy is affected by an economic downturn or an inflation shock in only some sectors, as

was the case with the pandemic and during the current energy crisis, effective monetary and fiscal

policy coordination is particularly important. Monetary policy instruments can be viewed as relatively

blunt tools that affect the economy as a whole, including the general price level. In case of transitory

and sectoral shocks, fiscal policy is better suited to stimulate and support specific sectors and to

support the most affected households and firms (Woodford, 2022). In this case, monetary policy may

best support fiscal policy by keeping general inflation expectations low through a high degree of

credibility.

Thus, these examples illustrate the need for sound and solid public finances and sufficient fiscal room

to manoeuvre in order to ensure effective monetary and fiscal policy coordination and the use of

counter-cyclical fiscal measures as a stabilisation instrument. The EU legal framework does not provide

intensive ex-ante or ad-hoc coordination of monetary and fiscal decision making (see Dall’Orto et al.,

2020; Manzke, 2015). Rather, the Treaties only allow for limited coordination and cooperation (and the

forms of positive and negative integration mentioned in the introduction).

16

This inter-institutional

cooperation is based on rights of participation, rights to be consulted, and democratic accountability

duties

17

. In addition, the ECB has a consultative role.

18

These forms of coordination institutionalise the

exchange of information necessary to conduct monetary and fiscal policies based on a profound

understanding of each other (see e.g. Bodea and Huemer, 2010; Bini Smaghi and Casini, 2002; von

Hagen and Mundschenk, 2002; Beukers, 2013). The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) Annual

Report 2023 considers “the perennial but elusive search for consistency between fiscal and monetary

policy” and talks about the need for a “region of stability”: “the region that maps the constellation of

the two policies that foster sustainable macroeconomic and financial stability, keeping the inevitable

tensions between the policies manageable.”

3.2. The current monetary and fiscal stance

For more than a year and a half now, inflation in the euro area has been well above the ECB's inflation

target. Accordingly, monetary policy in the euro area has switched to a clear restrictive course. The

interest rates on the deposit facility, the main refinancing operations and on the marginal lending

facility have been gradually increased to 4.00%, 4.50% and 4.75% respectively, and quantitative

tightening has been initiated. Despite the current decline in headline inflation, the core inflation rate

remains stably too high and does not yet show any downward tendencies. Therefore, the ECB will

probably remain on a restrictive course for quite some time. There is the risk that sharply rising interest

rates could trigger a systemic banking crisis, as the turmoil in Switzerland and the US demonstrated in

the spring of 2023.

16

See No. 12 Resolution of the European Council of 13 December 1997 on economic policy coordination in stage 3 of EMU and on Treaty

Articles 109 and 109b of the EC Treaty, OJ C 35, 2.2.1998, pp. 1–4; see also ECB (2003), pp. 37 ff.; Beukers (2013), p. 1582.

17

Art. 284 TFEU.

18

Art. 282 (5), Art. 127 (4) TFEU and Art. 4 ESCB-Statute.

Monetary-fiscal interaction: achieving the right monetary-fiscal policy mix in the euro area

PE 747.864 15

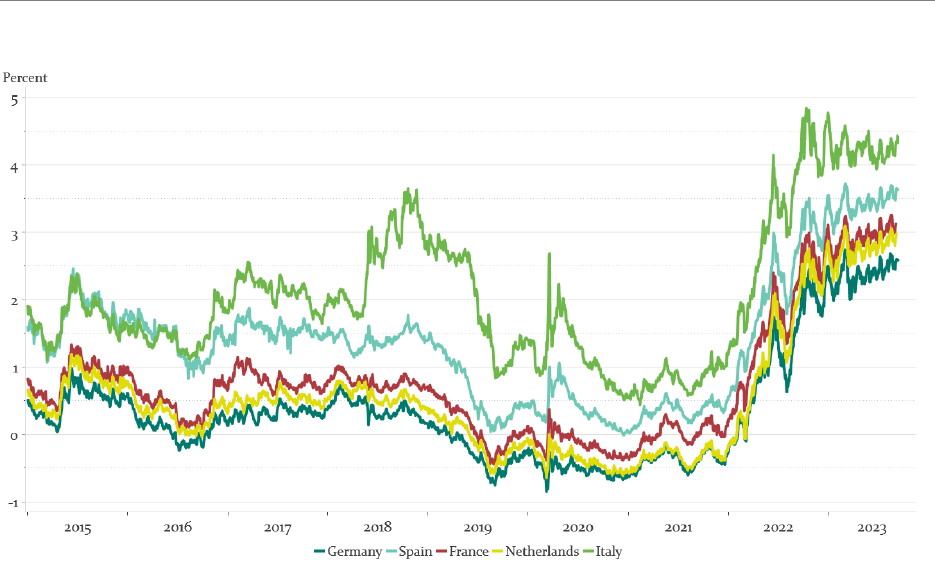

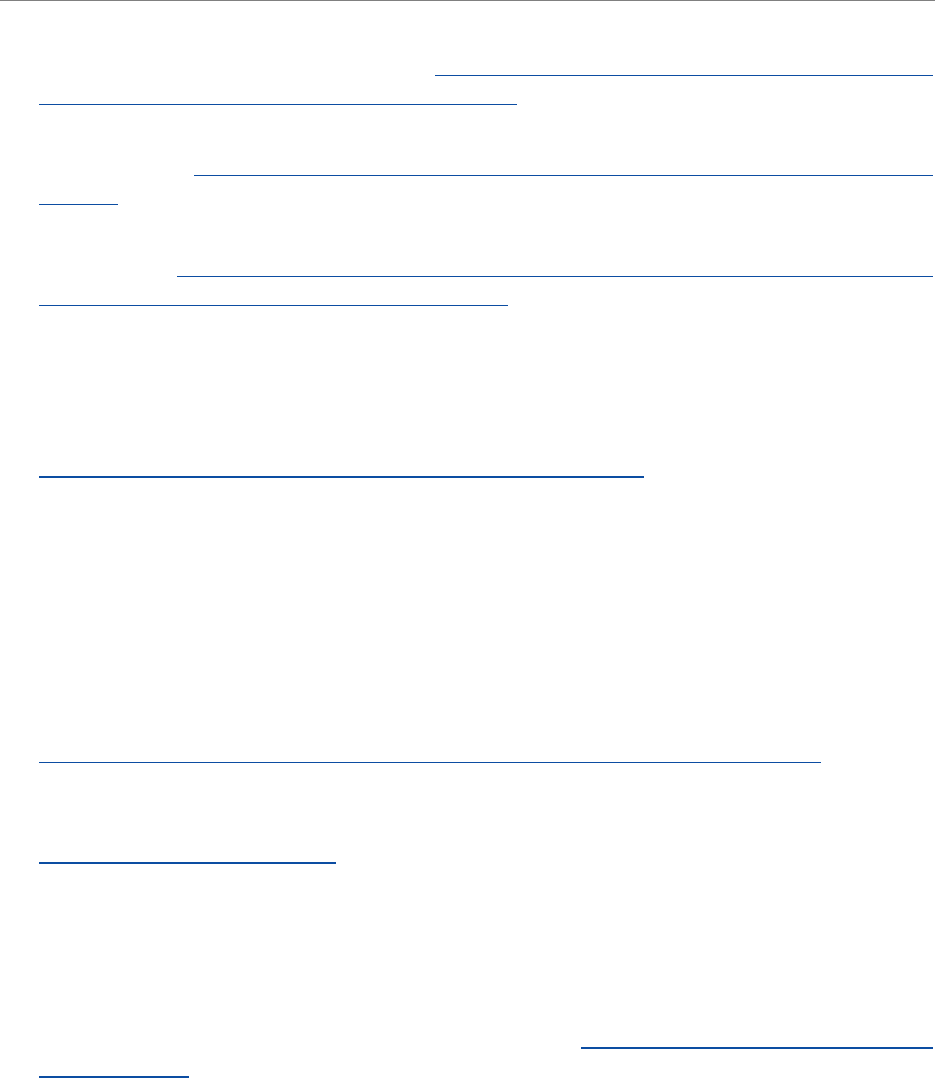

Figure 1: Government benchmarks, 10-year, yield

Source: Eurostat.

Note: Germany, France, Italy, Spain, Netherlands are represented as the largest economies in the euro area, as measured

by their 2021 GDP in US-dollars.

It is important to consider that this monetary tightening has very different regional effects, as interest

rates and risk premiums react differently due to the very heterogeneous public debt levels; they

typically rise more strongly and non-linearly in the highly indebted countries (Bernoth, 2012). Between

2020 and 2021, ten-year nominal government bond yields reached historic lows and were even

negative in the Netherlands and Germany. At the beginning of 2022, even before the ECB's first interest

rate hike in July 2022, yields in the main euro area economies rose sharply at the same time, reflecting

market expectations of ECB intervention (Figure 1). At the end of August 2023, bond yields in individual

countries ranged from 2.48% (Germany) to 4.13% (Italy), remaining relatively stable since the end of

2022. Although long-term government bond yield spreads widened slightly compared to Germany at

the beginning of 2022, risk premiums currently appear to have little impact on bond yields. This is

mainly due to the announcement of the TPI in July 2022. As a result of these rate hikes, the interest-

related costs of public debt servicing have risen since the sharp increase in the key interest rate.

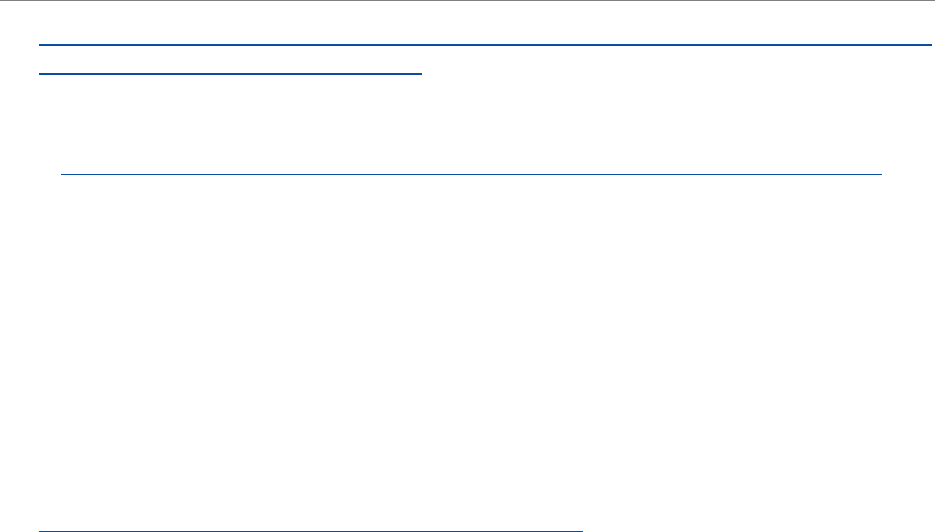

Moreover, the extraordinary fiscal measures implemented by governments to cushion the economic

effects of the COVID-19 crisis have led to a sharp increase in public deficits and a record level of

sovereign debt in most euro area Member States in 2020.

19

Thus, the public debt in the euro area

reached 97.2% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2020 before decreasing slightly to 91.5% in 2022.

While all euro area countries saw a rebound in their public debt in 2020, recent developments are

highlighting growing debt disparities within the euro area (Figure 2). Where Estonia's debt-to-GDP

ratio reached just 18.4% in 2022 (up by around 10 percentage points since 2019), Greece's now stands

at 171.3% (down by more than 9 percentage points since 2019). In total, in 2022, only eight countries

have public debt ratios below 60% and five countries have reduced their debt ratios compared with

2019 despite the significant economic impact of the COVID-19 crisis (Croatia, Cyprus, Greece, Ireland,

and Portugal). The Debt Sustainability Monitor 2022 (European Commission, 2023b), which gives an

19

Only Germany, Ireland, Latvia, Malta, Netherlands, Austria, and Slovenia did not reach an historic high in their debt-to-GDP ratio in 2020.

IPOL | Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit (EGOV)

16 PE 747.864

insight into fiscal sustainability risk encountered by EU Member States, estimated the fiscal risk to be

overall low in the short-term, before becoming high or medium for most countries in the medium- and

long-term. Especially in an environment of higher inflation, this situation poses the risk of “fiscal

dominance” emerging, compromising the ability of single monetary policy to adequately fulfil its

primary price stability objective.

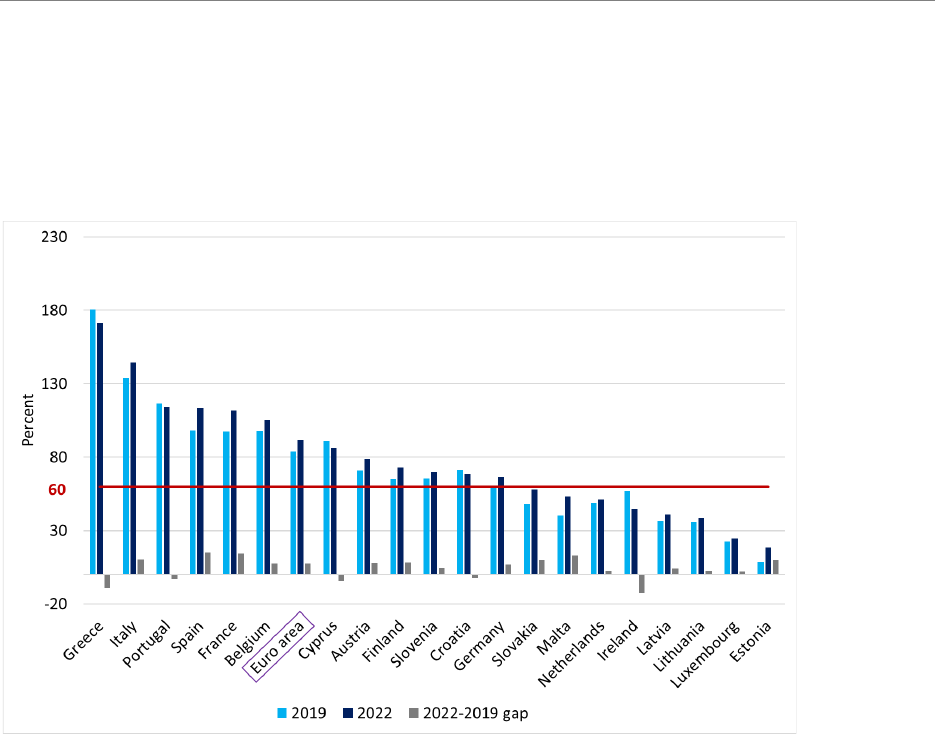

Figure 2: General gross debt in % of GDP

Source: Eurostat.

Note:

The horizontal line of 60% of GDP indicates the reference value for government debt as specified in the Maastricht

Treaty.

To strengthen the efficiency of tightening monetary policy and to avoid adding upward inflationary

pressures, the euro area fiscal stance has becoming more restrictive since 2023, although there are

significant disparities between countries, as highlighted in the Eurogroup statement of 13 July 2023,

on the fiscal stance for the euro area for 2024 (European Council, 2023). While the emergency fiscal

response measures adopted during the COVID-19 pandemic have already largely expired, falling

energy prices should allow euro area governments to progressively phase out the support measures

implemented to counteract the economic effects of the war in Ukraine (especially high energy costs,

supply chain disruptions).

The upcoming contractionary fiscal impulse in the euro area is warranted to ensure a gradual decline

in deficits and high public debt over time. Both remain well above their pre-pandemic levels, while

rising interest rates will – although only progressively – weigh on the cost of servicing public debts.

Thus, the fiscal strategy of Member States should restore fiscal buffers to secure debt sustainability.

At the same time, fiscal policy measures aimed at increasing economic growth over the medium term

by boosting the supply side of the economy are being implemented in most euro area countries. These

fiscal policies are supported in part by private and public funds but also through the NextGenerationEU

programme, via its core element: the Recovery and Resilience Facility. With this temporary instrument,

Monetary-fiscal interaction: achieving the right monetary-fiscal policy mix in the euro area

PE 747.864 17

the European Union is providing financial support to Member States to foster investments in ecological

and digital transformation over the 2021-2026 period.

20

The relation between fiscal policy and inflation is not straightforward. Indeed, the impact of fiscal

measures on inflation depends on various factors, notably the type and the size of the fiscal impulse

(change in government spending or tax rates, discretionary fiscal policies - targeted or not, side effect

on government deficit, demand- or supply-side measures), specific national features (level of debt,

position in the business cycle), the global economic and geopolitical context, and the monetary policy

stance.

21

Some of the temporary discretionary fiscal measures taken in the euro area at the beginning

of the war in Ukraine to cushion rising energy costs, such as indirect tax cuts or price caps, are estimated

to have contributed to reducing inflationary pressures in 2022 and 2023, although the effect is

mitigated by the discontinuation in 2022 of the subsidies to households and businesses intended to

counter the impact of the health crisis (Bankowski, 2023). However, these direct energy support

measures should increase inflation in 2024 and 2025 as most of them expire in 2023. In addition, direct

measures to support household income adopted by several euro area governments, such as public

sector wage rises, indexation of social benefits to inflation, and cash transfers, will weigh on inflation

with some delay as they are gradually transmitted to households' nominal disposable income and,

therefore, increase aggregate demand.

22

Although the implementation of the structural supply-side

reforms at the EU level has a stimulating effect on the economy by increasing public expenditure, the

overall impact on inflation in the euro area is likely to be limited in the medium term.

23

However, given

the complexity and size of the fiscal measures adopted, the ECB needs to closely monitor their impact

on inflation and take them into account in its decision-making.

20

See Bönke and al. (2023), pp. 296-297 for more details on the NextGenerationEU programme.

21

See Checherita-Westphal and al. (2023), pp. 15 ff.; See ECB (2021), box 6 entitled “Fiscal policy and inflation in the euro area: a VAR-

based analysis”; See IMF (2023), Chapter 2.

22

See ECB (2023), box 9 entitled “Update on euro area fiscal policy responses to the energy crisis and high inflation”.

23

See Bankowski (2022), pp. 33 ff.

IPOL | Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit (EGOV)

18 PE 747.864

4. ECB “QUASI-FISCAL” MEASURES

The interaction between monetary and fiscal policies is particularly relevant in the discussion of the

ECB's unconventional monetary policy measures, primarily the large-scale asset purchases also called

Quantitative Easing (QE) given their “quasi-fiscal” effects. A central bank activity can be considered to

have a “quasi-fiscal” component or effect if it has a significant impact on the government accounts

and/or affects other aspects of fiscal policy (taxes, spending, financing), either immediately or in the

future. This includes, for example, activities that result in financial losses for the central bank, which

ultimately must be borne by governments in the form of lower dividends or loss compensation. Central

bank activities can also impact fiscal policy if they affect the allocation of resources in the economy and

create distortions, or if they change the structure of government debt or the market for government

securities, thereby reducing the effectiveness of government debt management (Hooley et al., 2023).

During the Great Financial Crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic, the ECB applied a number of

unconventional monetary policy tools to address deflationary tendencies. This involved an

unprecedented expansion of central bank assets with quasi-fiscal characteristics:

• In 2010, the Securities Markets Programme (SMP), replaced by the Outright Monetary

Transactions (OMT) in 2012, was introduced to ease credit conditions by purchasing bonds on

the secondary market.

• The Targeted Longer-Term Refinancing Operations (TLTRO) announced in 2014 (TLTRO I), 2016

(TLRTO II) and 2019 (TLTRO III) provided banks with extended funding opportunities at

favourable conditions linked to the granting of loans to non-financial corporations and

households.

• Since October 2014, massive asset purchase programmes (APPs) have increased the size of the

ECB's balance sheet (Figure 2). In 2020, the ECB implemented another round of quantitative

easing with the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) to counter the effects of the

COVID-19 crisis.

24

On the whole, the unconventional measures were effective at stabilising financial and economic

conditions, easing financial market stress, and, thereby, also smoothing monetary policy transmission

(Cour-Thimann, 2013; Beckmann, 2020; BIS, 2019).

Combined with negative interest rates, large APPs

lowered both interest rates and the cost of borrowing, stimulated bank lending to businesses and

households, and encouraged consumption and economic activity (though the unintended effects of

APPs require further study). The real economy has also been supported through the exchange rate

channel, as currency depreciation induced by the expansion of the monetary base has improved the

competitiveness of businesses and fostered export recovery. In total, unconventional monetary

policies from 2014 boosted annual GDP growth in the euro area by 0.6 pp. and inflation by 0.4 pp., on

average, over the period 2015-2020 (Altavilla, 2021).

25

However, ECB unconventional monetary policy measures have increased financial risks on the

Eurosystem’s balance sheet (which has expanded significantly with QE), that may result in financial

losses for the ECB and the national central banks and, ultimately, the Member States’ governments and

taxpayers. Moreover, these monetary policy measures have relevant distributional effects which are

traditionally limited to, and characteristic of, fiscal policy (Dossche at al., 2021; Becker at al., 2015;

European Parliament, 2015).

Yet, the ECB has complete operational autonomy in the implementation

of unconventional monetary policies and there is no involvement of the fiscal authority in their design

24

See the European Central Bank website for more details on the different monetary policy instruments.

https://www.ecb.europa.eu/mopo/implement/html/index.en.html

25

See Beckmann and al. (2020), pp. 14-15, for an overview of the range of estimated effects of unconventional monetary policy on GDP

growth and inflation in the euro area from various studies.

Monetary-fiscal interaction: achieving the right monetary-fiscal policy mix in the euro area

PE 747.864 19

and implementation. Thus, in order to minimise these effects, unconventional monetary policy

instruments should only be used for limited periods of time.

Figure 3: Introduction of quantitative easing from 2014 by the European Central Bank

Source: European Central Bank.

Note:

The euro area government bond yield benchmarks are calculated on the basis of national bond yields weighted by

outstanding amounts of government debt in each maturity bucket.

4.1. Legal analysis of ECB “quasi fiscal” measures

From a legal point of view, “quasi-fiscal” monetary policy measures are problematic in terms of: (a)

competence, (b) principles underlaying the monetary policy legal framework, and (c) financial and

institutional independence.

First, monetary policy measures are characterised by their primary objective to maintain price stability.

However, the fiscal condition/state of Member States (economic and financial imbalances and

sovereign debt ratios) influence the transmission of monetary policy measures. This notwithstanding,

the ECB's price stability mandate does not provide the ECB with a competence to address disruptions

IPOL | Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit (EGOV)

20 PE 747.864

of monetary policy transmission that are rooted in the fiscal and economic situation of Member States

and which rest within their jurisdictional domain. While any economic and financial imbalances as well

as sovereign debt ratios inevitably affect monetary policy transmission, the ECB is not competent to

address any causes that directly or indirectly impede its price stability mandate. These causes partly

relate to issues that are firmly rooted in the fiscal and economic situations and within the competence

of the Member States. The ECB only has a secondary or contributory competence to support the

economic policies of the Member States, i.e. the ECB can only support the policies pursued by other

actors and institutions.

26

Second, while distributional effects of monetary policy measures are inherent to any policy measure,

for example, traditional interest rate policy, selective measures that directly privilege specific market

participants, certain Member States, or certain financial or non-financial institutions, are generally not

foreseen within the EU monetary policy framework. Such measures with highly distributional effects

are only allowed in very narrowly defined cases that rely on monetary reasons and not on economic,

social, or other preferences.

The EU monetary policy framework also rests on the principle that the ECB may only conduct monetary

policy operations with solvent counterparties and on the basis of adequate collateral. Even in crisis

situations, when national central banks act as lender of last resort (LOLR), it is a basic principle that they

can only lend money to credit institutions that are solvent, but experience liquidity problems and only

against sufficient collateral. These preconditions respond to two purposes: (i) to distinguish monetary

policy measures from fiscal measures, since it is the task and the competence of fiscal authorities to

inject capital into insolvent institutions, resulting in direct distribution of resources; and (ii) to safeguard

the ECB from incurring losses, which is important with regard to the ECB's financial and institutional

independence (see also Rogoff, 2021).

The third aspect to consider is that the independence of the ECB cannot be compromised by fiscal and

financial considerations. In a situation of so called “fiscal dominance” and/or “financial dominance”, the

ECB might depart from a monetary policy strategy that might be adequate in terms of price stability.

4.2. TPI and its role in preventing future fragmentation of sovereign

bond markets

In reaction to the fragmentation of the sovereign bond markets in the euro area, the ECB Governing

Council announced its new anti-fragmentation tool, named the Transmission Protection Instrument

(TPI) on 21 July 2022. The TPI aims to ease potential bond market fragmentation with secondary market

purchases of securities issued in jurisdictions experiencing a deterioration in financing conditions not

warranted by country-specific fundamentals. According to the press release, the TPI aims to support

the effective transmission of monetary policy in the case of "unwarranted, disorderly market dynamics

that pose a serious threat to the transmission of monetary policy across the euro area" by selective

sovereign bond purchases (ECB, 2022).

The TPI faces some legal and economic challenges with regard to its conformity with the ECB mandate

and its monetary policy competence, which we analysed in depth in a previous paper.

27

While the aim

of TPI – ensuring an “effective transmission of monetary policy” – is no doubt a necessary prerequisite

in the pursuit of a price stability-oriented monetary policy, this alone does not suffice to prove that the

measure falls within the ECB's price stability mandate. Currently, with surging inflation, the ECB is trying

to curb surging inflation by increasing interest rates. This puts a heightened burden of justification on

26

Art.127 (1) 2 TFEU states: “Without prejudice to the objective of price stability, the ESCB shall support the general economic policies in

the Union (…)”.

27

See in detail Bernoth et al. (2022).

Monetary-fiscal interaction: achieving the right monetary-fiscal policy mix in the euro area

PE 747.864 21

the ECB to explain how further asset purchases – an expansionary monetary policy – would fit within

the overall monetary policy stance of fighting inflation, should TPI be activated. It is only if market

failures are identified as the cause for the financial fragmentation of sovereign bond yield spreads that

the ECB allowed to take such selective and targeted measures to address these causes.

Fiscal support for highly-indebted Member States that struggle with higher, yet justified, risk premia is

not a task for the ECB and not within the monetary policy domain. It rather falls within the fiscal domain

and within the remit of the competence of the Member States according to the respective democratic

processes in place. Such a decision should be subject to political and public scrutiny. As the ECB stated

with regard to the TPI, the deterioration in financing conditions potentially hampering monetary policy

transmission, which TPI might be able to address, may "not [be] warranted by country-specific

fundamentals" (ECB, 2022). This is in line with the European Court of Justice (ECJ)'s ruling on OMT,

where it made clear that "the programme in question cannot be implemented in a way which would

bring about a harmonisation of the interest rates applied to the government bonds of the Member

States of the euro area regardless of the differences arising from their macroeconomic or budgetary

situation."

28

Moreover, activation of the TPI requires sound and sustainable budgetary and economic policies, as

stated in the eligibility criteria explained in the press release (ECB, 2022). However, as outlined also in

Bernoth et al. (2022), the institutional structure of the ECB is not well suited to assessing these criteria.

The monitoring of compliance with fiscal rules and the ultimate discretionary decision on whether a

Member State sufficiently fulfils the requirements of sound and sustainable fiscal and economic

policies may expose the ECB to political pressure and threaten its independence. The decision as to

whether the ECB should carry out such an assessment itself or whether this should be the responsibility

of external bodies (e.g. the European Stabilisation Mechanism and the International Monetary Fund)

therefore remains an important question to be clarified.

The ECB has not yet disclosed the method, benchmarks and criteria it will use to assess, whether bond

yield developments are “not warranted by country-specific fundamentals”. The provisions on how the

Governing Council will use the listed eligibility criteria as input to its decision-making process are very

non-specific and non-transparent and therefore allow for a certain degree of discretion.

The potential quasi-fiscal components of TPI and the corresponding legal challenges also become

apparent when considering the balance sheet implications. TPI interventions, if activated, would lead

to a further increase in the size of the Eurosystem's balance sheet if they are not sterilised by the sale of

other assets. If the Member State were not able to pay back its debt, the central bank would incur losses

on its balance sheet.

28

ECJ, Judgment of the Court of 16 June 2015, Case C-62/14, Gauweiler et al., ECLI:EU:C:2015:400, para. 113

IPOL | Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit (EGOV)

22 PE 747.864

5. THE NEW EU ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE ARCHITECTURE

Sustainable public finances are considered a prerequisite for a single monetary policy in the euro area

to be able to focus on its primary mandate of price stability, as well as for monetary and fiscal policy to

mutually support each other in their stabilisation function. An adequate governance structure in the

EU should create these conditions.

5.1. Legal foundations of the EU economic governance architecture

The EU economic governance framework, as laid out in the Treaties, provides a system of institutions

and procedures to coordinate economic policies of the Member States (see Art. 120f. TFEU) and aims

to monitor, prevent, and correct problematic economic trends that could weaken national economies

or negatively affect other EU countries. This framework has evolved over time, being and been refined

and reinforced.

29

The legal framework relies on the TFEU (Art. 120ff., 126 TFEU)

30

, the Stability and Growth Pact

31

(see

below), the European Semester (an annual cycle of economic, fiscal, employment and social policy

coordination) and the so-called six-pack and two-pack legislative reforms (additional secondary

legislation to strengthen the Stability and Growth Pact).

32

The European Commission monitors the

economic development in the euro area in order to detect potential problems and risks for economic

stability and competitiveness. To do this, it conducts regular assessments and forecasts, while also

producing an Annual Sustainable Growth Survey and the Alert Mechanism Report.

Prevention is a key pillar within EU economic governance as it aims to address economic problems

early on and prevent spill-over effects to other Member States. The Stability and Growth Pact (SGP)

plays an important role within the EU's prevention mechanism and requires the Member States to

pursue sound national fiscal policies by setting budgetary targets. The Macroeconomic Imbalance

Procedure (MIP), introduced in 2011 as part of the so called "six-pack" reform of the economic

governance, foresees, in the case of excessive imbalances in the economies of a Member State, that

said Member State is subject to enhanced monitoring and might even face sanctions. In addition, the

Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance (TSCG or the ‘fiscal compact’) sets standards for fiscal

policies by limiting the size of the structural deficit that a government may incur to 0.5% of GDP per

year and requires the establishment of automatic policies to correct significant transgressions.

33

Correction of economic imbalances and enforcement of the existing ruleset with the Excessive Deficit

Procedure (EDP) and the Excessive Imbalance Procedure (EIP) are a crucial part within the EU economic

governance framework.

34

Under EDP, if a national budget deficit exceeds 3% of GDP or if it fails to

reduce its excessive debts (i.e. is still above 60% of GDP), the Member State must commit to targets to

bring its excessive deficit or debt back down. The EU can also impose sanctions, such as fines that can

reach 0.2% of their GDP, if a Member State persistently fails to take adequate action.

Similarly, under the EIP of the EU’s MIP, a Member State experiencing excessive imbalances can be

required to submit Corrective Action Plans to address its situation and might likewise face fines if they

fail to sufficiently impose corrective measures.

29

See Lastra and Louis (2013), pp. 35 ff.

30

See Lastra (2015), pp. 293 ff.

31

See Lastra (2015), pp. 301 ff.; Lastra and Louis (2013), pp. 55 ff. with further references.

32

See Lastra and Louis (2013), pp. 66 ff., 144.

33

See Lastra and Louis (2013), pp. 144 ff.

34

See Lastra (2015), pp. 293, 298 ff., see also 231 ff.

Monetary-fiscal interaction: achieving the right monetary-fiscal policy mix in the euro area

PE 747.864 23

5.2. Proposal to reform the EU economic governance rules

The EU fiscal framework has been criticised for being too rigid on the one hand and for not promoting

sufficient convergence on the other, with the result that several EU Member States lack the fiscal

capacity to ensure effective coordination in times of economic downturn. In response to the

inadequacies and complexities of the current economic governance architecture, the Commission in

April this year presented its new package of proposals to reform the EU’s economic governance rules.

The proposed new economic governance architecture aims to strengthen public debt sustainability

while promoting progress towards a green, digital, inclusive and resilient economy and making the EU

more competitive.

35

The cornerstones of the proposal are stronger national ownership, simpler rules

taking into account different fiscal challenges, facilitating reforms and investments for EU common

priorities, and providing for effective enforcement.

The EU economic governance reform consists of three legislative proposals: (i) a proposal to create a

new regime for the SGP with regard to its preventive aspects (the so called preventive arm regulation)

36

,

(ii) a proposal to strengthen the corrective elements of the SGP (the so called corrective arm

regulation)

37

and (iii) amendments regarding the requirements for the budgetary frameworks of the

Member States.

38

In particular, the proposal on the preventive arm allows Member States to set their multi-annual net

expenditure path on the basis of reform and investment commitments that they would detail in their

medium-term fiscal-structural plan. For Member States whose government debt is above the 60% of

GDP reference value or whose government deficit is above the 3% of GDP reference value, the

Commission would propose “technical trajectory for net expenditure covering a minimum adjustment

period of 4 years of the national medium-term fiscal-structural plan, and its possible extension by a

maximum of 3 years […]”. as guidance for the multi-annual trajectory for net expenditure

39

with a view

of maintaining debt levels on a downward path. The extension of fiscal adjustment by a maximum of

3 years would allow for a more gradual adjustment path if countries undertake reforms and

investments commitments in line with EU priorities.

The proposal responds to the long-standing criticism that the current fiscal surveillance indicators are

based on numerical variables that are very difficult to measure in real time, in particular, the structural

balance and potential output variables. This has resulted in the fiscal policy being often pro-cyclical

when it should have been counter-cyclical according to the information available to policy makers in

real time (Bernoth, 2015). Steering on the expenditure side is more transparent and less susceptible to

manipulation (Anderson and Minarik, 2006). Moreover, focusing on a medium-term approach rather

than year-to-year monitoring gives governments more flexibility to respond to unforeseen events and

cyclical fluctuations in public expenditure.

35

Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the effective coordination of economic policies and

multilateral budgetary surveillance and repealing Council Regulation (EC) No 1466/97, COM/2023/240 final; Proposal for a Council

regulation amending Council Regulation (EC) No 1467/97 on speeding up and clarifying the implementation of the excessive deficit

procedure, COM/2023/241 final; proposal for a Council directive amending Council Directive 2011/85/EU on requirements for

budgetary frameworks of the Member states, COM/2023/242 final.

36

Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the effective coordination of economic policies and

multilateral budgetary surveillance and repealing Council Regulation (EC) No 1466/97, COM/2023/240 final (so called preventive arm

regulation).

37

Proposal for a Council regulation amending Council Regulation (EC) No 1467/97 on speeding up and clarifying the implementation of

the excessive deficit procedure, COM/2023/241 final (so called corrective arm regulation).

38

Proposal for a Council directive amending Council Directive 2011/85/EU on requirements for budgetary frameworks of the Member

states, COM/2023/242 final (so called budgetary frameworks directive).

39

Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the effective coordination of economic policies and

multilateral budgetary surveillance and repealing Council Regulation (EC) No 1466/97, COM/2023/240 final, Art. 5.

IPOL | Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit (EGOV)

24 PE 747.864

Moreover, the new proposal foresees that independent national financial institutions should be given

a stronger role in monitoring the implementation by Member States of their national medium-term

fiscal-structural plans.

40

The proposals allow Member States to have more control over the design of their medium-term plans,

but also foresee a more stringent enforcement regime to ensure Member States deliver on the

commitments undertaken in their medium-term fiscal-structural plans. The excessive deficit procedure

for breaches of the 60% of GDP reference value is strengthened. For a Member State facing substantial

public debt problems, the degree of debt challenge will be considered a relevant factor for the

initiation of an excessive deficit procedure upon departure from the agreed net expenditure path.

41

40

Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the effective coordination of economic policies and

multilateral budgetary surveillance and repealing Council Regulation (EC) No 1466/97, COM/2023/240 final, Art. 22.

41

Proposal for a Council regulation amending Council Regulation (EC) No 1467/97 on speeding up and clarifying the implementation of

the excessive deficit procedure, COM/2023/241 final (so called corrective arm regulation).

Monetary-fiscal interaction: achieving the right monetary-fiscal policy mix in the euro area

PE 747.864 25

6. IMPLICATIONS OF THE ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE REVIEW FOR

MONETARY POLICY

The economic governance review bears overall positive implications for the ECB's price-stability-

oriented monetary policy from an economic and legal perspective, as expressed in an official Opinion

by the ECB of 5 July 2023.

42

The proposed review establishes rules that monitor and restrict, where

necessary, fiscal deficits and helps to ensure that Member State's fiscal and economic situations can, at

least to a certain degree, converge, thus representing a precondition for a single monetary policy.

Likewise, it is important that national ownership of the framework, by setting national medium-term

fiscal structural plans, is strengthened to avoid situations where – due to a lack of fiscal capacity at the

Union level – the ECB might be de facto forced to address fiscal and economic imbalances in Member

States by means of monetary policy measures, which are outside of its mandate.

In general, rules that help delineate the responsibility of the ECB for ensuring price stability on the one

hand and the responsibility of the Member States for their fiscal and economic situation on the other

are essential for ensuring that monetary policy measures do not have “quasi-fiscal” effects of such a

scale and manner that they actually substitute fiscal measures. Therefore, the Governing Council's

decision to phase out unconventional monetary policy measures of a “quasi-fiscal” nature is welcome

and will help to reduce risks and increase transparency. It will protect the Eurosystem from interest rate

risks on large holdings of securities as policy normalises and will help reduce distortionary effects on

public and private sector assets. This will also reduce reputational risk for the ECB. However, it is worth

noting that the recent process of quantitative tightening has been very gradual and will continue for

several years to avoid market disruption. The ECB therefore faces a difficult trade-off.

This delineation and the avoidance of the wrong type of monetary-fiscal policy mix is not only

important to ensure that the ECB stays within its mandate, as laid down in Art. 127 TFEU, but also to

ensure that the ECB keeps its institutional and financial independence. Economic and fiscal measures

must be taken by the competent and democratically accountable institutions and actors, as they bear

an important social dimension. The existing forms of coordination between the ECB and economic and

fiscal policy makers are important to ensure an adequate level of information and better understanding

between both policy fields.

The current reform of the EU governance framework provides an opportunity to address the

shortcomings that have emerged over the past decades, leading to a situation where optimal

coordination of fiscal and monetary policies has been hampered. A well-functioning EU governance

framework that leads to effective fiscal consolidation and gradual debt reduction in the years ahead,

especially in the highly indebted countries, facilitates the ECB's monetary policy in several respects. In

the current high-inflation environment, a reduction in fiscal stimulus or fiscal support targeted at only

individual sectors in need reduces inflationary pressures (Beyer et al., 2023). This would allow for a more

gradual and moderate monetary tightening, thereby reducing financial stability risks posed by a rapid

and widespread increase in interest rates. Furthermore, fragmentation risks of European bond yields

(and spreads) would be mitigated, making the use of the controversial TPI less necessary for the ECB.

A closer look, however, shows that the current reform proposal, while eliminating many of the

identified shortcomings (see sub-chapter 4.2), still lacks transparency and leaves too much room for

discretion, which may once again open the door to clientelism and endless discussions. For instance,

the proposal says that “The national medium-term fiscal-structural plan shall ensure the fiscal

adjustment necessary to put or keep public debt on a plausibly downward path by the end of the

42

Opinion of the European Central Bank of 5 July 2023 on a proposal for economic governance reform in the Union (CON/2023/20), OJ C

290, 18.8.2023, pp. 17–25.

IPOL | Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit (EGOV)

26 PE 747.864

adjustment period at the latest, or remain at prudent levels, and to bring and maintain the government

deficit below the 3% of GDP reference value over the medium term “

43

How exactly is the "plausible

downward path" defined and how long is the "medium term"?

Moreover, the governments' medium-term fiscal-structural plans, and also the Commission's fiscal

trajectories, are based on medium-term projections of public debt. While the proposal says that the

Commission must disclose the underlying framework for these projections and its results, there is

always a degree of discretion in the assumptions underlying a projection model and its design. The

proposal states that "when Member States use assumptions in their medium-term fiscal-structural plan

that differ from the Commission’s standard medium-term debt projection framework, they should

explain and duly justify the differences in a transparent manner and based on sound economic

arguments. In particular, the debt projections at unchanged policy to be included in the plan should

be consistent and comparable with the Commission projections."

44

But no one can say with certainty

which model is the right one, and the question is why the Commission does not impose one from the

outset to avoid discussion.

In contrast to the previous governance structure, which was mainly based on negotiations between

Member States, the new proposal places more emphasis on negotiations between the European

Commission and each individual Member State. Whether this vertical structure will improve

compliance, however, is an open question. As Fuest (2023) argues, if countries do not want to comply

with the European Commission's requirements, it will be easy for them to argue, for example, that the

Commission is a technocratic institution with less democratic legitimacy than their national

parliaments.

There is still time to remedy these deficiencies in the coming months, and this should be used to put

EMU on a more stable position in the long term, able to exploit the synergistic effects between

monetary and fiscal policy.

43

See Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the effective coordination of economic policies and

multilateral budgetary surveillance and repealing Council Regulation (EC) No 1466/97, COM/2023/240 final, Art. 6 and 12.

44

Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the effective coordination of economic policies and

multilateral budgetary surveillance and repealing Council Regulation (EC) No 1466/97, COM/2023/240 final, p. 14.

Monetary-fiscal interaction: achieving the right monetary-fiscal policy mix in the euro area

PE 747.864 27

7. CONCLUSION

The EU Treaties establish a formal separation of competences between a centralised monetary policy

and decentralised fiscal policies. Despite their different jurisdictional domains, fiscal and monetary

policy are highly interdependent. While this close interaction has led to tensions in the past, monetary

and fiscal policy have been largely aligned and mutually supportive during the COVID-19 crisis.

Since 2021 with the return of inflation, tensions are again visible in the monetary-fiscal policy mix.

Indeed, while the ECB started tightening monetary policy in 2022, with the aim of bringing inflation

down to close to 2% in the medium term, most Member States have adopted supportive fiscal

measures designed to reduce the impact of rising energy costs on households and businesses. This

massive fiscal support is expected to lead to inflationary pressures over the next two years (Bankowski,

2023), partly as a result of the withdrawal of fiscal measures with direct dampening effect on energy

prices as indirect tax cuts, but also due to the lagged upward effect on inflation of household income

support measures. On the other hand, the “quasi-fiscal” monetary measures implemented by the ECB

in recent years, especially the large-scale asset purchase programmes, including the announced, but

not yet activated, TPI, have, by definition, a significant impact on the government accounts and/or

affect other aspects of fiscal policy (taxes, spending, financing), either directly or in the future. “Quasi-

fiscal” monetary policy measures are also problematic from a legal point of view since they partly over-

stretch the mandate of the ECB.

The Commission has presented a proposal to reform the EU economic governance framework. The

proposed new framework aims to ensure greater national ownership and simpler rules that account

for the different fiscal challenges, thereby facilitating reforms and investment for EU priorities. While

the proposal addresses many of shortcomings identified, too much discretion is still left to the

Commission and Members States in interpreting the rules.

In the coming years, it will be crucial to re-establish better coordination between monetary and fiscal

policy. This requires sound public finances to provide sufficient fiscal room for manoeuvring. Moreover,

the ECB should only resort to “quasi-fiscal” monetary policy measures in exceptional cases, such as

when the interest rate level has reached the zero lower bound or when there are divergences in

government bond yields between Member States resulting from market excesses that jeopardise a

single monetary policy. The current reduction in the balance sheet of the Eurosystem through the

gradual phasing out of the bond purchase programmes and the TLTROs is therefore to be welcomed.

IPOL | Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit (EGOV)

28 PE 747.864

REFERENCES

• Altavilla, C., Lemke, W., Linzert, T., Tapking, J. and von Landesberger, J. (2021). “Assessing the

efficacy, efficiency and potential side effects of the ECB’s monetary policy instruments”. Occasional

Paper Series No. 278. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpops/ecb.op278~a1ca90a789.en.pdf

• Anderson, B. and Minarik J.J. (2006). ”Design Choices for Fiscal Policy Rules”, OECD Journal on

Budgeting 5(4): 159-208. https://www.oecd.org/gov/budgeting/43479409.pdf

• Antpöhler, C. (2012). “Emergenz der europäischen Wirtschaftsregierung – Das Six Pack als Zeichen

supranationaler Leistungsfähigkeit“. Zeitschrift für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht,

Vol.72(2), pp.353–393.

• Bankowski, K., Bouabdallah, O., Domingues Semeano, J., Dorrucci, E., Freier, M., Jacquinot, P.,

Modery, W., Rodríguez-Vives, M., Valenta, V. and Zorell, N. (2022). “The economic impact of Next

Generation EU: a euro area perspective”. ECB Occasional Paper Series No. 279.

https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpops/ecb.op291~18b5f6e6a4.en.pdf

• Bankowski, K., Bouabdallah, O., Checherita-Westphal, C., Freier, M., Jacquinot P. and Muggenthaler,

P. (2023). „Fiscal Policy and high inflation”. ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 2 - Article.

https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/ecbu/eb202302.en.pdf

• Beckmann, J., Fiedler, S., Gern, K.-J., Kooths, S., Quast, J. and Wolters, M. (2020). “The ECB’s Asset

Purchase Programmes: Effectiveness, Risks, Alternatives”. Monetary Dialogue Papers.

https://www.europarl.europa.eu/cmsdata/211391/2_KIEL%20final.pdf

• Bernoth, K., Dietz, S., Ider, G. and Lastra, R. (2022). “The ECB’s Transmission Protection Instrument: a

legal & economic analysis”. Study for the Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs, Policy

Department for Economic, Scientific and Qualify of Life Policies, European Parliament, Luxemburg.

https://www.europarl.europa.eu/cmsdata/253891/QA-07-22-986-EN-N.pdf

• Bernoth, K., Hughes Hallett, A. and Lewis, J. (2015). “The cyclicality of automatic and discretionary

fiscal policy: What can real time data tell us?” Macroeconomic Dynamics, 2015, Volume 19(1), pp.

221-243.

• Bernoth, K., von Hagen, J. and Schuknecht, L. (2012). „Sovereign risk premia in the European

government bond market”. Journal of International Money and Finance, 2012, Volume 31(5), pp.

975-995.

• Beukers, T. (2013). “The new ECB and its relationship with the Eurozone Member States: between

central bank independence and central bank intervention”. Common Market Law Review, Vol.50(6),

pp.1579–1620.

• Beyer, R., Duttagupta, R., Fotiou, A., Honjo, K., Horton, M., Jakab, Z., Linde, J., Nguyen, V., Portillo, R.,

Suphaphiphat, N, and Zeng, L. (2023). “Shared Problem, Shared Solution: Benefits from Fiscal-

Monetary Interactions in the Euro Area”, IMF Working Paper WP/23/149.

https://ideas.repec.org/p/imf/imfwpa/2023-149.html

• Bini Smaghi and L., Casini, C. (2002). “Monetary and Fiscal Policy Co-operation: Institutions and

Procedures in EMU”. Journal of Common Market Studies, Vol.38(3), pp.375–391.

• Bank of International Settlements (2019). “Unconventional monetary policy tools: a cross-country

analysis”. Committee on the Global Financial System Papers No. 63.

https://www.bis.org/publ/cgfs63.pdf

Monetary-fiscal interaction: achieving the right monetary-fiscal policy mix in the euro area

PE 747.864 29

• BIS (2023). Bank for International Settlements Annual Economic Report 2023,

https://www.bis.org/publ/arpdf/ar2023e.pdf

• Bodea, C. and Huemer, S. (2010). “Dancing together at arm’s length? – the interaction of central

banks with governments in the G7”. ECB Occasional Paper Series No. 120.

https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpops/ecbocp120.pdf

• Bönke, T. and al. (2023). “DIW-Konjunkturprognose: Deutsche Wirtschaft kämpft sich aus der

Winterrezession“. DIW Wochenbericht No. 24.

https://www.diw.de/de/diw_01.c.875334.de/publikationen/wochenberichte/2023_24_2/diw-

konjunkturprognose__deutsche_wirtschaft_kaempft_sich_aus_der_winterrezession.html"

• Checherita-Westphal, C., Leiner-Killinger, N. and Schildmann, T. (2023). “Euro area inflation

differentials: the role of fiscal policies revisited”. Working Paper Series No. 2774.

https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecb.wp2774~aef6347c1e.en.pdf

• Clayes, G. and al. (2015). “ECB Quantitative Easing (QE): What are the Side Effects ?”. Monetary

Dialogue Papers.

https://www.europarl.europa.eu/cmsdata/105464/IPOL_IDA(2015)587287_EN.pdf

• Cour-Thimann, P. and Winkler, B. (2013). “The ECB’s non-standard monetary policy measures: the

role of institutional factors and financial structure”. ECB working paper Series No. 1528.

https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecbwp1528.pdf

• D. Bordo, M. and D. Levy, M. (2020). “Do enlarged fiscal deficits cause inflation: the historical record”.

NBER Working Paper No. 28195. https://www.nber.org/papers/w28195

• Dall’Orto Mas, R., Vonessen, B.,Fehlker, C. and Arnold, K. (2020). “The case for central bank

independence. A review of key issues in the international debate”. ECB Occasional Paper Series

No. 248. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpops/ecb.op248~28bebb193a.en.pdf

• Degenhart, C. (2013). “Missachtung rechtlicher Vorgaben bei der Umsetzung der Währungsunion“,

in: Möllers/Zeitler (Ed.), “ Europa als Rechtsgemeinschaft – Währungsunion und Schuldenkrise“,

Mohr Siebeck, pp.85–100.

• Dossche, M., Slačálek, J. and Wolswijk, G. (2021). “Monetary policy and inequality”. ECB Economic

Bulletin Series, Issue 2 – Article 1. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/ecbu/eb202102.en.pdf

• European Central Bank (2003). “The relationship between monetary policy and fiscal policies in the

euro area”. Monthly Bulletin February 2003.

https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/mobu/mb200302en.pdf

• European Central Bank (2021a). “ECB’s governing council approves its new monetary policy

strategy”. Press Release.

https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pr/date/2021/html/ecb.pr210708~dc78cc4b0d.en.html

• European Central Bank (2021b). “Monetary-fiscal policy interactions in the euro area”, box entitled

“Fiscal policy and inflation in the euro area: a VAR-based analysis”. Occasional Paper Series No. 273.

https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpops/ecb.op273~fae24ce432.en.pdf

• European Central Bank (2022). “The Transmission Protection Instrument”. Press release.

https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pr/date/2022/html/ecb.pr220721~973e6e7273.en.html

• European Central Bank (2023). “Economic, financial and monetary developments”. ECB Economic

Bulletin Series, Issue 2. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/ecbu/eb202302.en.pdf

IPOL | Economic Governance and EMU Scrutiny Unit (EGOV)

30 PE 747.864

• European Commission (2023a). “Economic Governance Review. Building an economic governance

framework fit for the challenges ahead”.

https://economy-finance.ec.europa.eu/economic-and-

fiscal-governance/economic-governance-review_en

• European Commission (2023b). “Debt Sustainability Monitor 2022”. European Economy Institutional

Paper 199.

https://economy-finance.ec.europa.eu/publications/debt-sustainability-monitor-

2022_en

• European Council (2023). “Eurogroup statement on the euro area fiscal stance for 2024”. Press

release.