Dollars and Sense in Cook County

1

Title Page

DOLLARS AND

SENSE IN

COOK COUNTY

Examining the Impact of General

Order 18.8A on Felony Bond

Court Decisions, Pretrial Release,

and Crime

Don Stemen and David Olson

Loyola University Chicago

Dollars and Sense in Cook County

2

This research was supported by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation through the Safety

and Justice Challenge Research Consortium (Consortium). Launched in 2019, the Consortium advances

criminal justice research, grounded in the efforts and data of Safety and Justice Challenge sites, to

expand the field’s collective knowledge of how to safely reduce the overuse and misuse of jails and!racial

and ethnic disparities through fair and effective pretrial reforms. The Consortium is comprised of

research organizations who develop and are granted projects!under independent review by a panel!of

academic,!policy, and practice experts, including individuals with lived experience.!The Consortium is

managed by the CUNY Institute for State and Local Governance.

Dollars and Sense in Cook County

iii

Contents

INTRODUCTION

1

A

NOTE

ON

DATA

AND

METHODS

3

BOND COURT DECISIONS

5

PRETRIAL RELEASE

8

PRETRIAL RELEASE OUTCOMES

10

FAILURE

TO

APPEAR

10

NEW

CRIMINAL

ACTIVITY

10

NEW

VIOLENT

CRIMINAL

ACTIVITY

11

AGGREGATE LEVELS OF CRIME

12

CONCLUSION

13

APPENDICES

14

APPENDIX

A

–

DATA

AND

METHODS

14

APPENDIX

B

–

LOGISTIC

REGRESSION

RESULTS

18

NOTES

26

Dollars and Sense in Cook County

iv

Dollars and Sense in Cook County

1

DOLLARS AND

SENSE IN COOK

COUNTY

Examining the impact of General

Order 18.8A on felony bond court

decisions, pretrial release, and

crime

INTRODUCTION

ail reform efforts across the United States have

accelerated in recent years, driven by concerns about

the overuse of monetary bail, the potentially

disparate impact of pretrial detention on poor and minority

defendants, and the effects of bail decisions on local jail

populations. Proponents of bail reform advocate for

reducing or eliminating the use of monetary bail, arguing

that many defendants are held in jail pretrial solely because

they cannot afford to post bail. Opponents counter that

reducing the use of monetary bail or increasing the number

of people released pretrial could result in more defendants

failing to appear for court hearings (FTAs) or committing

crimes while on pretrial release.

Evaluations of recent bail reform efforts indicate that these

efforts have not been associated with increases in new

criminal activity. In 2017, for example, New Jersey

eliminated cash bail, resulting in a!drop!in the number of

pretrial detainees but no change in crime rates.

1

An

evaluation of New York City’s Supervised Release – which

allowed judges to release certain defendants under specific

supervisory conditions in lieu of monetary bail – found that

the program had no impact on FTAs or arrests for new

crimes among those released.

2

Similarly, in 2018, the

Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office created a

presumption of no cash bail for twenty-five non-violent

offenses; an evaluation of the policy found a 41% reduction

in the use of monetary bail and a 22% reduction in pretrial

detention, but no increase in FTAs or new criminal charges

for those released pretrial.

3

On September 17, 2017, the Chief Judge of the Circuit Court

of Cook County issued General Order 18.8A (GO18.8A) to

reform bail practices in Cook County.

4

GO18.8A established

a decision-making process for bond court judges. Under the

order, bond court judges were to first determine whether a

defendant should be released pretrial and, if not, hold the

defendant in jail. If the defendant could be released,

GO18.8A created a presumption of release without

monetary bail; however, if monetary bail was necessary, the

order stated that bail should be set at an amount affordable

for the defendant. In the end, GO18.8A established a

presumption of release without monetary bail for the large

majority of defendants in Cook County and encouraged the

use of lower bail amounts for those required to post

monetary bail. !

A debate has played out in the media regarding the link

between GO18.8A, the types of individuals released pretrial,

and the number and percent of individuals charged with a

new crime while on pretrial release. The debate centers

around an evaluation of GO18.8A conducted by the Office of

the Chief Judge (OCJ).

5

The OCJ’s evaluation found that the

number and percent of felony defendants released pretrial

increased after GO18.8A but that the percent of felony

defendants charged with a new crime while on pretrial

release was similar before and after GO18.8A.

Subsequent analyses by the media

6

and academics

7

suggested that the OCJ’s evaluation underestimated the

percent of defendants charged with a new crime after

GO18.8A. These subsequent analyses identified several

methodological problems with the OCJ’s evaluation that

could potentially influence the findings: a truncated follow-

up period for individuals released after GO18.8A, a failure to

account for seasonality in follow-up periods for individuals

released before and after GO18.8A, and a conservative

definition of violent offenses used to estimate rates of new

violent criminal activity of those released. These critiques

suggested that GO18.8A may have led to an increase in new

criminal activity of those released pretrial and contributed

directly to increases in crime in Chicago and Cook County.

These subsequent analyses, however, also suffer from

methodological problems similar to those in the OCJ’s

evaluation. By relying on the same public data collected and

distributed by the OCJ, these analyses were unable to

correct for the critiques made of the OCJ’s analyses –

namely a truncated follow-up period and a failure to

account for seasonality – without making assumptions

about, and estimations of, underlying recidivism rates of

those released.

8

More importantly, the analyses were

unable to verify or refute the OCJ’s analyses of bond court

decisions, release rates, or new criminal activity through the

independent analysis of defendant- and charge-level court

or jail data. As a result of these methodological

shortcomings and contradictory findings, the actual impact

of GO18.8A remains unclear. Missing from the discussion to

date, is a rigorous, objective, external assessment of the

impact of GO18.8A that can correct for these problems.

With data provided to the Institute for State and Local

Governance (ISLG) at the City University of New York,

Loyola University Chicago’s Center for Criminal Justice

Research, Policy, and Practice undertook an evaluation of

the impact of GO18.8A on four outcomes: bond court

decisions, pretrial release, pretrial release outcomes (FTAs,

new criminal activity, and new violent criminal activity), and

crime rates. This research was funded as part of the John D.

and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation’s Safety and Justice

Challenge Research Consortium.

B

Dollars and Sense in Cook County

2

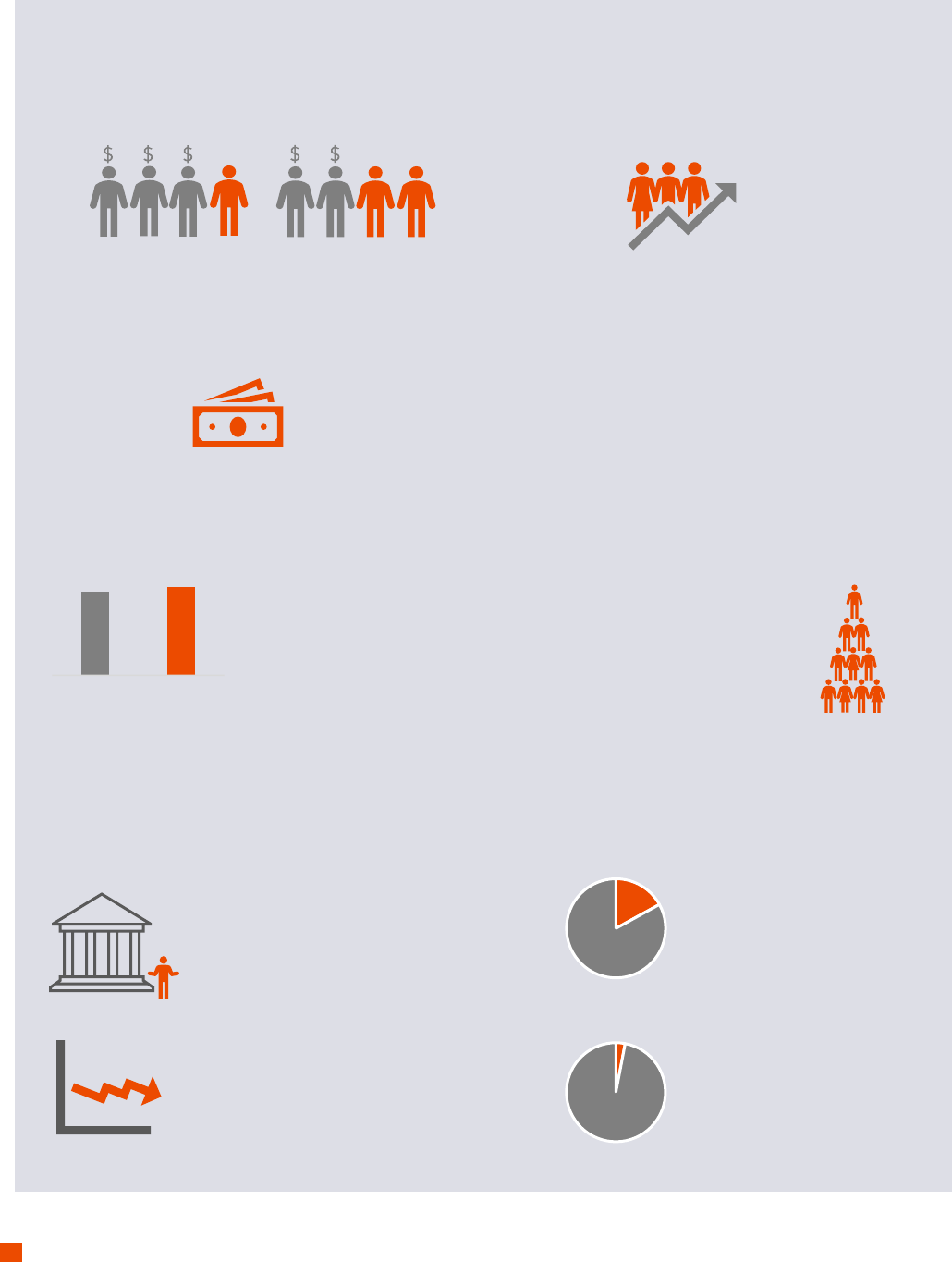

3,559 more defendants received an

I-Bond in the six months after GO18.8A

who would not have received one before

$31.4 million in bond costs were avoided by defendants

in the six months after GO18.8A due to increased use of I-Bonds

and lower D-Bond amounts

GO18.8A increased the use of I-Bonds and reduced the costs of bail for defendants

I-Bond

I-Bond

I-Bond

26%

of defendants received

an I-Bond before

GO18.8A

57%

of defendants received

an I-Bond after

GO18.8A

PRIMARY FINDINGS

77%

81%

Before

GO18.8A

After

GO18.8A

77% of defendants were

released pretrial before GO18.8A

81% of defendants were

released pretrial after GO18.8A

500 more defendants were

released in the six months after

GO18.8A than would have been if

release rates had remained unchanged

GO18.8A increased the percent and number of people released pretrial

17%

of defendants released

before and after GO18.8A had a

new criminal case filed while on

pretrial release

3%

of defendants released

before and after GO18.8A had a

new violent criminal case filed

while on pretrial release

17% of defendants released before GO18.8A

failed to appear for a court hearing

20% of defendants released after GO18.8A

failed to appear for a court hearing

There was no statistically significant change

in the amount of crime in Chicago in the

year after GO18.8A

GO18.8A had no effect on new criminal activity or crime

Dollars and Sense in Cook County

3

A NOTE ON DATA AND METHODS

This report details two sets of analyses: 1) an analysis of

bond court decisions, pretrial release, and pretrial release

outcomes for defendants charged with felonies in Cook

County and 2) an analysis of crime rates in Chicago. This

section briefly details the data and methods used in the

analyses. For a detailed description of data and analytic

methods see Appendix A.

Felony Bond Court Decisions and Pretrial Release

The analyses of felony bond court decisions, pretrial release,

and pretrial release outcomes relied on data for all cases

filed in the Circuit Court of Cook County between January 1,

2013 and April 30, 2019, all defendants screened using the

Public Safety Assessment (PSA)

9

between October 1, 2015

and April 30, 2019, and all individuals admitted to or

released from the Cook County jail between May 1, 2013

and May 2, 2019. These data provided information on

defendant demographics, charges, bond court decisions,

and jail bookings and releases.

The analyses examined two groups of defendants: a pre-

GO18.8A cohort consisting of all defendants with an initial

felony bond court hearing in the six months between

November 1, 2015 and April 30, 2016 and a post-GO18.8A

cohort consisting of all defendants with an initial felony

bond court hearing in the six months between November 1,

2017 and April 30, 2018. Overall, the analyses included

12,756 defendants in the pre-GO18.8A cohort and 11,372

defendants in the post-GO18.8A cohort. For each cohort, a

series of outcomes were tracked from the initial bond court

date until the case was disposed or for twelve months,

whichever came first. This follow-up period ensured the

same duration of at-risk periods for both pre- and post-

GO18.8A cohorts and accounted for potential seasonality

during time at risk.

The first outcome examined was the initial felony bond

court decision. All individuals arrested for a felony in Cook

County appear for a bond court hearing before a judge who

sets bail and determines the location and date of the next

court appearance. Bond court judges may impose four

different bond types:

• Individual recognizance bond (I-Bond) for which

defendants are released without having to post

monetary bail

• Deposit bond (D-Bond) for which defendants pay

10% of the bail amount in order to secure release

from jail

• Cash bond (C-Bond) for which defendants pay the

full value of the bail amount in order to secure

release from jail

• No bail in which defendants are denied bail and

ordered to remain in jail

Judges also may impose electronic monitoring (EM) as a

condition of release, which requires defendants to pay a fee

before being placed on EM. Based on these options, the

analyses categorized the bond decision into four possible

outcomes – I-Bond, EM, D/C-Bond, and No Bail – which was

used to categorize defendant/cases for subsequent

analyses.

The second outcome examined was release pretrial. If a

defendant spent any time outside of jail during the follow-

up period, they were considered released pretrial.

For defendants released pretrial, three additional outcomes

were examined: failure to appear (FTA), new criminal

activity, and new violent criminal activity. FTA was defined

as a defendant failing to appear for any court event in the

case during the follow-up period. New criminal activity was

defined as any new misdemeanor or felony case filed

General Order 18.8A - Procedures for Bail

Hearings and Pretrial Release

This order is intended to ensure no defendant is held in

custody prior to trial solely because the defendant cannot

afford to post bail, to ensure fairness and the elimination of

unjustifiable

!

delay in the administration of justice, to

facilitate the just determination of every criminal

proceeding, and to preserve the public welfare and secure

the fundamental human rights of individuals with interests

in criminal court cases,…

4. If the court determines that release on bail is not

appropriate, the court shall…make one or more of the

following findings and state the finding(s), together with

sufficient supporting facts, on the record in open court:

a. the defendant will not appear as required, and no

condition or combination of conditions of release can

reasonably

!

assure the defendant 's appearance in

court; or

b. the defendant poses a real and present threat to any

person or persons….

5. When setting bail, there shall be a presumption that any

conditions of release imposed shall be non-monetary in

nature, and

!

the court shall impose the least restrictive

conditions or combination of conditions necessary to

reasonably assure the

!

appearance of the defendant for

further court proceedings….

7. When the court determines that monetary bail is a

necessary condition of release, the court shall, in

substance, make the

!

following findings and state them,

together with sufficient supporting facts, on the record in

open court:

a. no other conditions of release, without monetary bail,

will reasonably assure the defendant 's appearance in court;

b. the amount of bail is not oppressive, is considerate of

the financial ability of the defendant, and the

defendant has

!

the present ability to pay the amount

necessary to secure his or her release on bail…

Dollars and Sense in Cook County

4

against the defendant within Cook County during the

follow-up period. New violent criminal activity was defined

as any new misdemeanor or felony case with a top charge

of a Person offense filed against the defendant within Cook

County during the follow-up period.

The examination of bond court decisions and pretrial

release outcomes relied on a series of multivariate

statistical models that isolated the influence of specific

defendant and case characteristics. Specifically, the

analyses used logistic regression models, which estimate

the effects of defendant and case factors on the odds of

specific outcomes (e.g., the odds of receiving an I-Bond or

the odds of having a new criminal case filed during the

follow-up period). The sections below summarize the most

important results of the logistic regression models. The full

results of all logistic regression models are presented in

Appendix B.

10

Following each logistic regression model, expected rates of

each outcome were estimated using predicted probabilities,

which represent the expected outcome for the average

defendant/case. The predicted probabilities are reported as

the percent of defendants with each outcome after

controlling for all defendant and case factors. For example,

calculating the predicted probability of receiving an I-Bond

provides an estimation of the percent of defendants who

would receive an I-Bond taking into account defendant

characteristics, offense types, and PSA scores that influence

the likelihood of receiving an I-Bond.

Crime Rates

The analyses of crime rates relied on data obtained from

the Chicago Police Department’s online public data portal. A

series of Bayesian Structural Time Series (BSTS) analyses

estimated the degree to which crime levels were different

than would have been expected between the pre- and post-

GO18.8A periods. For these analyses, historical data on the

number of violent and property crimes were used to model

expected crime rates using factors known to influence crime

and proxies for policing activity. Actual crime rates were

then compared to these expected crime rates to determine

whether crime rates fell within expected ranges.

Dollars and Sense in Cook County

5

BOND COURT DECISIONS

eneral Order 18.8A established a presumption of

release without monetary bail for the large majority

of defendants in Cook County. This presumption

implies an increased use of I-Bonds - individual

recognizance bonds for which defendants are released

without having to post monetary bail - after the

implementation of GO18.8A. Our analyses indicate that

GO18.8A was associated with an increase in the odds of

receiving an I-Bond.

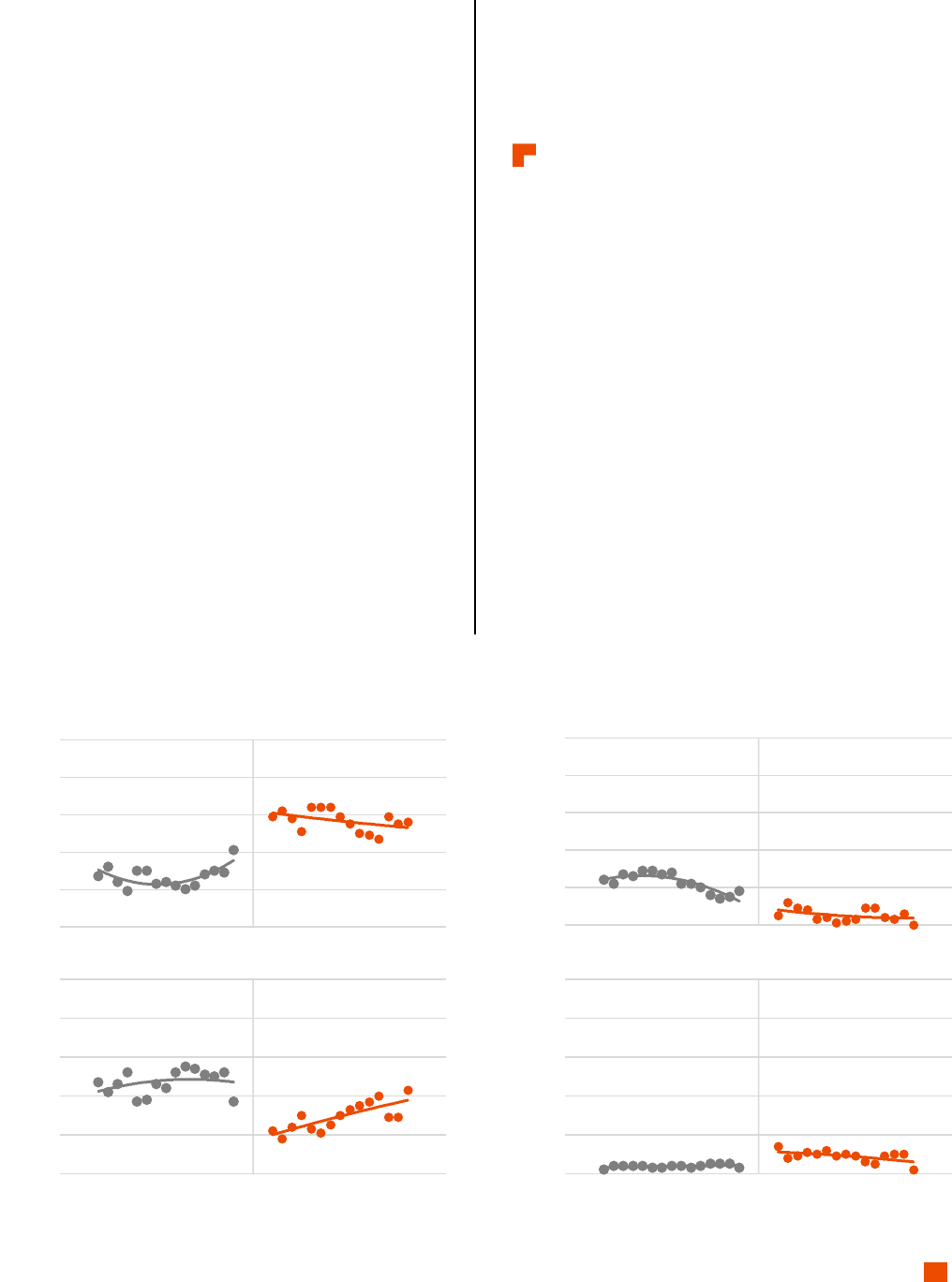

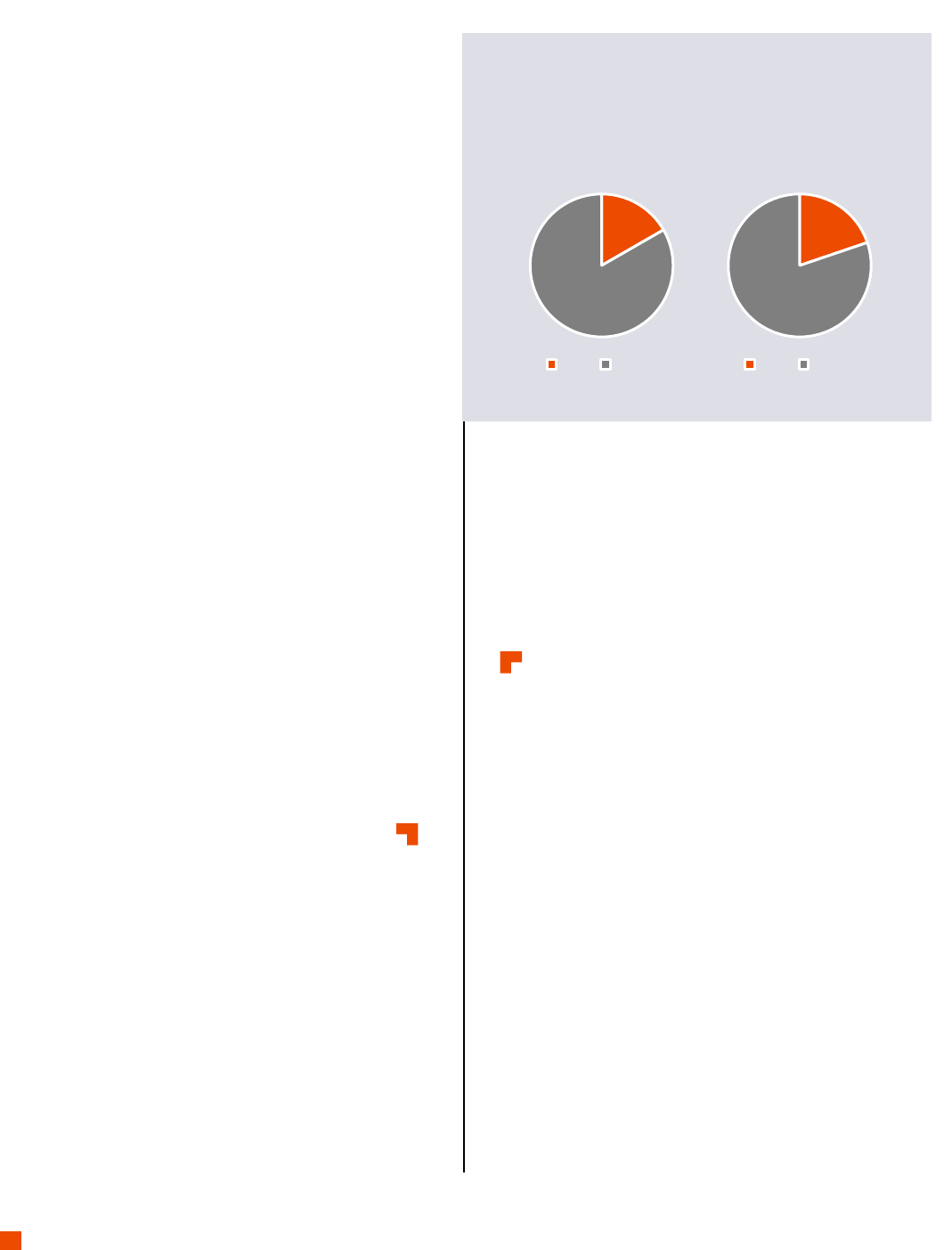

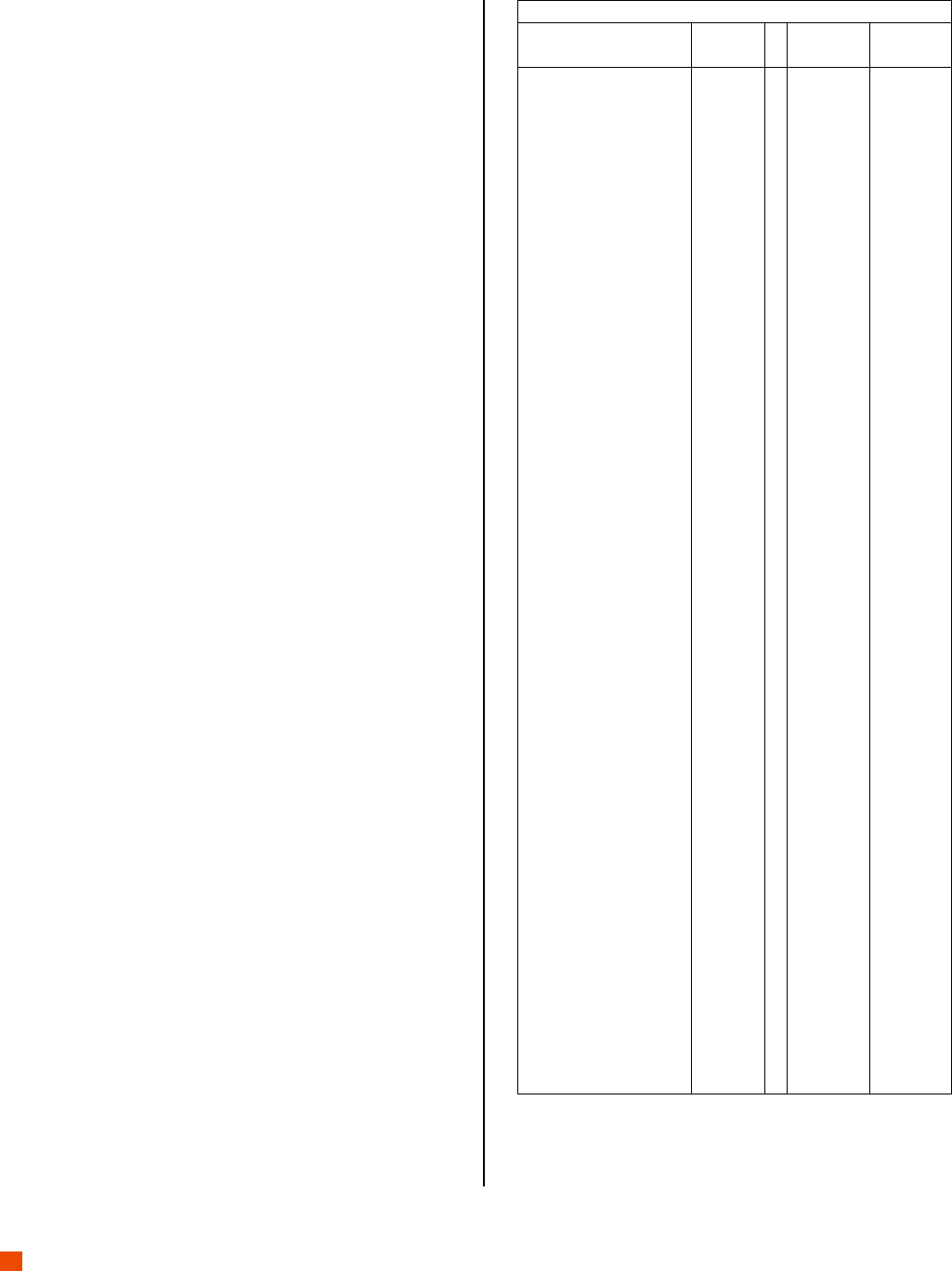

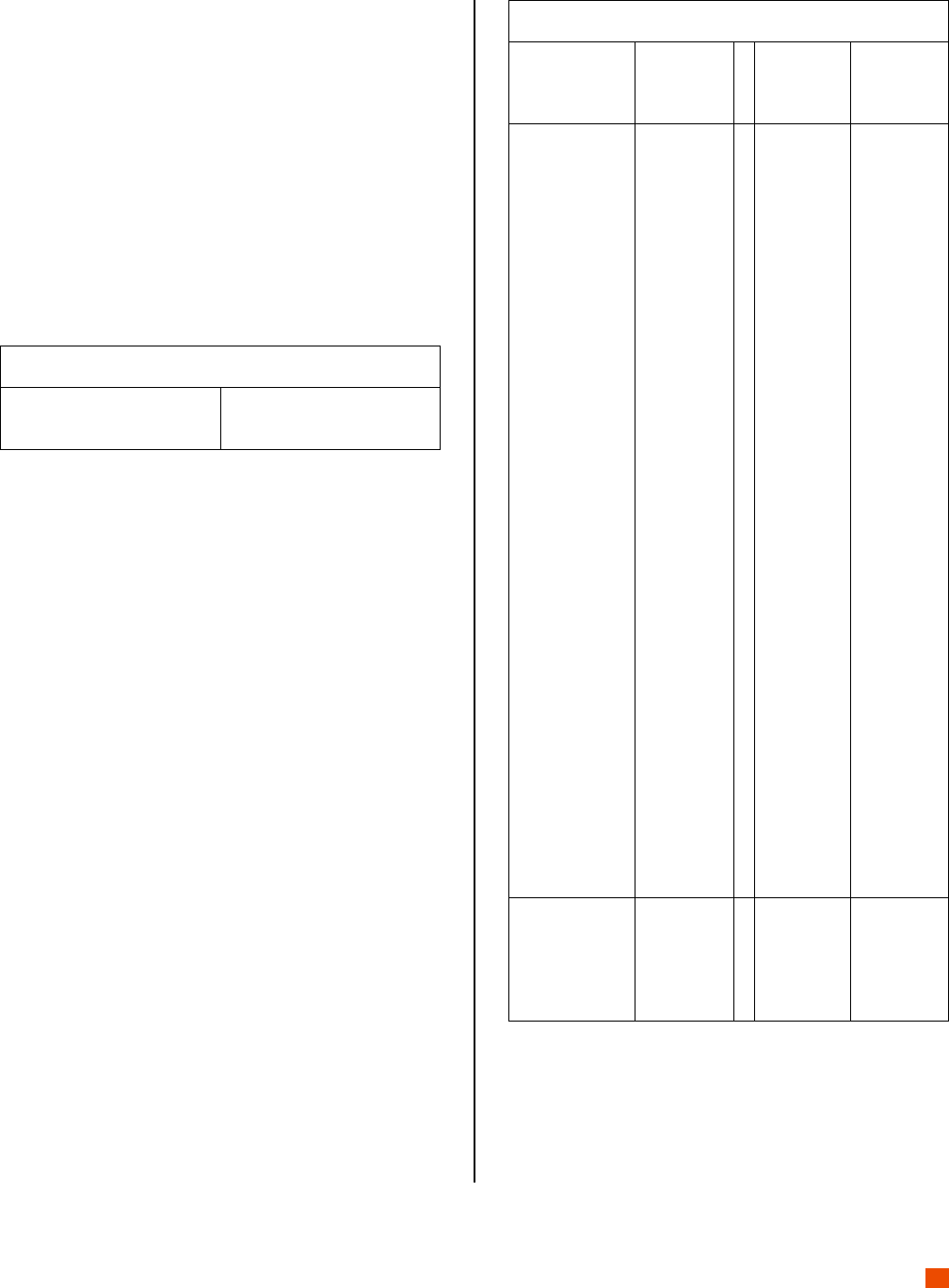

Figure 1 shows trends in bond court decisions before and

after GO18.8A. Each dot in the graphs represents a two-

week average of the percent of felony defendants receiving

an I-Bond, EM, D/C-Bond, and No Bail at their initial bond

court hearing.

11

As Figure 1 shows, bond court decisions

changed markedly after GO18.8A. Prior to GO18.8A, 20% to

40% of felony defendants received an I-Bond at their initial

bond court hearing. After GO18.8A, 50% to 60% received an

I-Bond. Figure 1 also shows that the use of I-Bonds

decreased slightly over time after GO18.8A. In November

2017 – immediately after implementation of GO18.8A – 59%

of felony defendants received an I-Bond; by April 2018, this

decreased to 55%.

There was a contrasting drop in the use of EM and D/C-

Bonds after GO18.8A. Prior to GO18.8A, 20% to 30% of

defendants received EM, decreasing to just less than 10%

after GO18.8A. Similarly, 40% to 60% of felony defendants

received a D/C-Bond before GO18.8A, dropping to 20% to

40% after GO18.8A. However, in contrast to I-Bonds, the

use of D/C-Bonds increased over time after GO18.8A, rising

from 22% in November 2017 to nearly 43% in April 2018.

Finally, the use of No Bail increased after GO18.8A, rising

from less than 4% of cases to roughly 8% of cases.

The percent of defendants

receiving an I-Bond increased

after GO18.8A.

While the descriptive statistics indicate an increase in the

use of I-Bonds after GO18.8A, this increase could be due to

differences in the types of defendants or cases appearing in

bond court before and after GO18.8A. In order to control for

such differences, a series of logistic regression models were

generated to examine the odds of a defendant receiving an

I-Bond. The analyses indicate that GO18.8A was associated

with a statistically significant increase in the odds of a

defendant receiving an I-Bond, after controlling for

defendant and case factors.

In addition to statistically isolating the effect of GO18.8A on

the likelihood of defendants receiving I-Bonds, the logistic

models also revealed that defendants were less likely to

receive an I-Bond when they were male, younger, charged

with a Person or Weapons offense, charged with a higher

G

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

Before GO18.8A After GO18.8A

D/C-Bond

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

EM

Figure 1.

Time trends in bond court outcomes

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

Before GO18.8A After GO18.8A

No Bail

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

I-Bond

Dollars and Sense in Cook County

6

felony class, or charged with more felony offenses, and

when they had a violation of probation or bail bond and

higher PSA scores. Defendant race was not associated with

the odds of receiving an I-Bond.

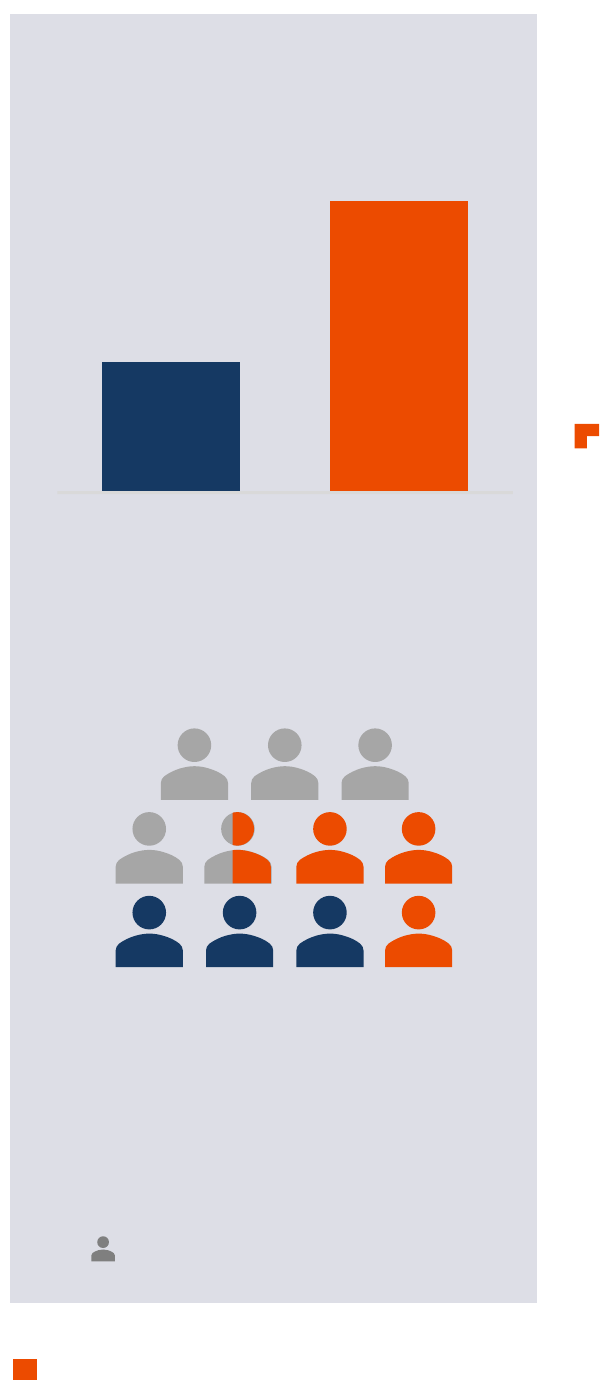

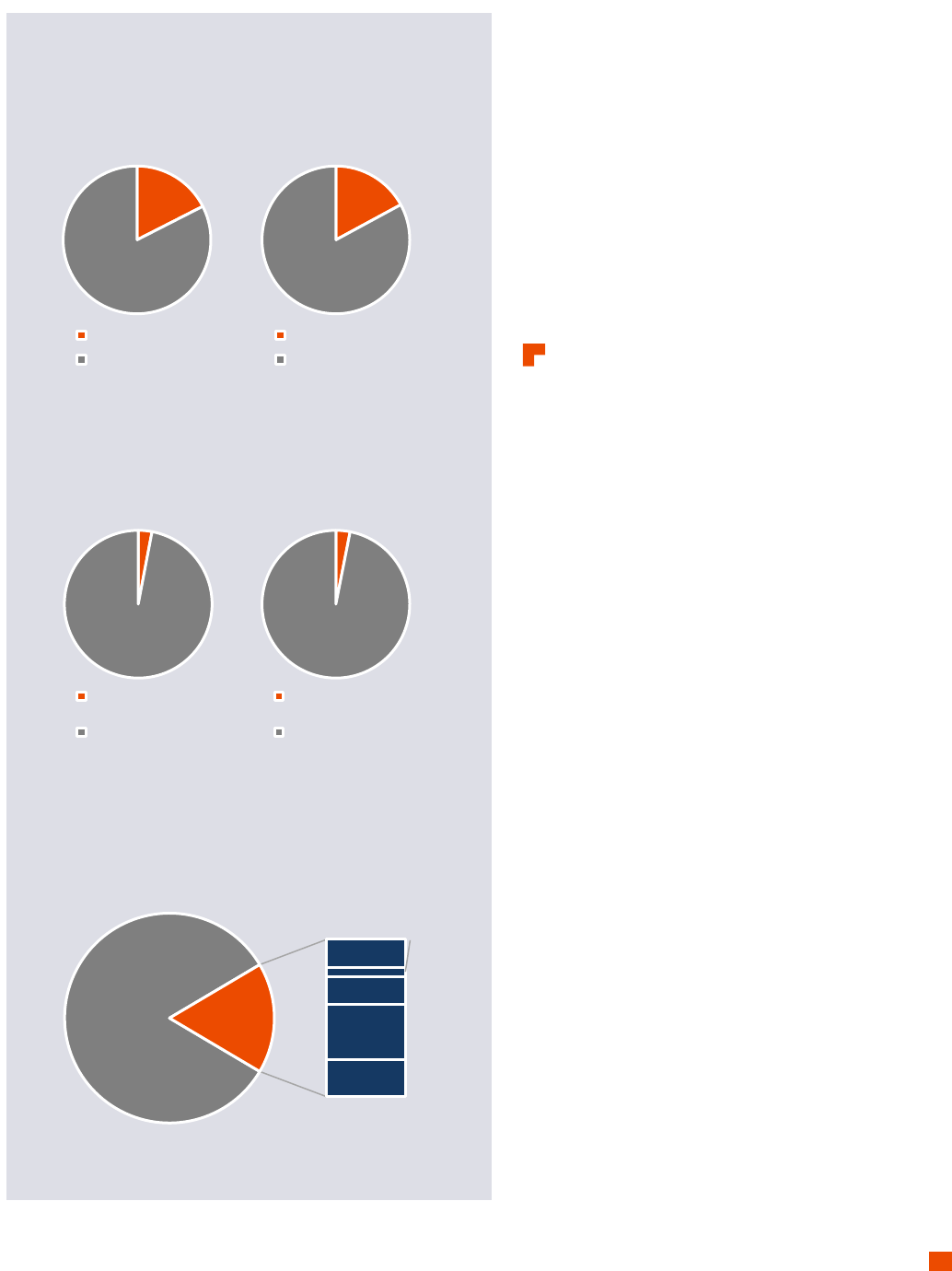

After controlling for defendant and case factors, roughly

26% of defendants were expected to receive an I-Bond

before GO18.8A compared to 57% after GO18.8A (Figure 2).

12

To put the increased use of I-Bonds into context, of the

11,372 defendants with an initial bond court hearing in the

six months after GO18.8A, just 2,900 would have received

an I-Bond if the pre-GO18.8A rates had continued (Figure 3).

However, the statistical model revealed that 6,459

defendants received an I-Bond after accounting for

defendant and case characteristics. Thus, 3,559 additional

defendants received an I-Bond in the six months after

GO18.8A than would have if pre-GO18.8A rates had

continued.

13

3,559 defendants - who would

have been required to post

monetary bond to secure

release before GO18.8A - did not

have to post any monetary

bond after GO18.8A

Although defendant race was not associated with the odds

of receiving an I-Bond before GO18.8A, the analyses

revealed that race was associated with receiving an I-Bond

after GO18.8A, with Black defendants more likely than

White defendants to receive an I-Bond after GO18.8A.

Controlling for other defendant and case factors, roughly

25% of Black defendants received an I-Bond before GO18.8A

compared to 26% of White defendants (Figure 4).

14

After

GO18.8A, 56% of Black defendants received an I-Bond

compared to 54% of White defendants.

15

This difference

was statistically significant.

To put this in context, of the 7,869 Black defendants with an

initial bond court hearing in the six months after GO18.8A,

just 1,952 would have received an I-Bond if the pre-GO18.8A

rates had continued. The statistical model revealed that

4,415 of these defendants received an I-Bond after

GO18.8A. Thus, 2,463 Black defendants received an I-Bond

after GO18.8A who would not have received an I-Bond

before GO18.8A. There was an increase in the likelihood of

receiving an I-Bond for White defendants as well; but, the

increase was not as great. Of the 2,578 White defendants

with an initial bond court hearing in the six months after

Figure 2.

Probability of receiving an I-Bond

before and after GO18.8A

25.5%

56.8%

Before GO18.8A After GO18.8A

Figure 3.

Number of additional people

receiving an I-Bond due to GO18.8A

11,372 defendants with an initial bond court hearing

in the six months after GO18.8A

• 2,900 defendants would have received an I-

Bond if the pre-GO18.8A rates had continued.

• 6,459 defendants received an I-Bond after

GO18.8A.

• 3,559

additional

defendants received an I-Bond

after GO18.8A than would have if pre-GO18.8A

rates had continued.

=1,000 defendants

Dollars and Sense in Cook County

7

GO18.8A, 673 would have received an I-Bond if the pre-

GO18.8A rates had continued and 1,382 received an I-Bond

after GO18.8A. Thus, 709 White defendants received an I-

Bond after GO18.8A who would not have received an I-Bond

before GO18.8A.

GO18.8A reduced the financial

burden on defendants by

$31.4 million in the six months

from November 1, 2017 to

April 20, 2018

GO18.8A also encouraged the use of lower bail amounts for

defendants required to post D-Bonds - deposit bonds for

which defendants pay 10% of the bail amount in order to

secure release from jail. In addition to the increased use of I-

Bonds after GO18.8A, there also was a reduction in the

average bond amounts individuals with a D-Bond had to

pay to secure pretrial release. Before GO18.8A, defendants

receiving a D-Bond were required to pay an average of

$9,316 to secure release; this decreased to an average of

just $3,824 after GO18.8A.

16

Thus, the financial burden on

individual defendants who received a D-Bond after GO18.8A

was reduced by $5,492. This means that the 3,256

defendants who received a D-Bond in the six months after

GO18.8A would have had to post a combined $30,332,896

to secure release if the pre-GO18.8A bond amounts had

continued. However, these defendants had to post just

$12,450,944 to secure release under the post-GO18.8A

amounts. Thus, the financial burden on these defendants

was reduced by $17,881,952 (Figure 5).

17

The financial burden on all defendants was reduced even

further. As noted above, 3,559 additional defendants

received an I-Bond in the six months after GO18.8A. If these

defendants had been required to post D-Bonds instead to

secure pretrial release, they would have posted an average

of $3,824 or a total of $13,609,616 in bond. Thus, GO18.8A

resulted in an additional reduction of roughly $13.6 million

($3,824 per individual) in bond to secure release.

Overall, GO18.8A saved defendants and their families a total

of $31.4 million in just the first six months after GO18.8A -

$17.8 million from reduced bond amounts for D-Bonds and

$13.6 million from the increased use of I-Bonds.

Figure 5.

Total bond savings for defendants with

I-Bonds and D-Bonds

$13.6 million saved by defendants

receiving I-Bonds instead of D-Bonds

$17.8 million saved by defendants

receiving lower D-Bond amounts

$31.4 million saved by all defendants

Figure 4.

Probability of receiving an I-Bond before and after GO18.8A and number of defendants

impacted, by race

2,463

709

Black defendants who received

an I-Bond after GO18.8A who

would not have received an I-

Bond before GO18.8A

White defendants who received

an I-Bond after GO18.8A who

would not have received an I-

Bond before GO18.8A

24.8%

56.1%

26.1%

53.6%

Before GO18.8A After GO18.8A

Black White

Dollars and Sense in Cook County

8

PRETRIAL RELEASE

lthough GO18.8A did not explicitly call for expanded

pretrial release, the increased use of I-Bonds and the

deceased bail amounts for D-Bonds may be expected

to lead to more defendants released pretrial. The analyses

presented here indicate that GO18.8A was associated with a

slight increase in the odds of pretrial release.

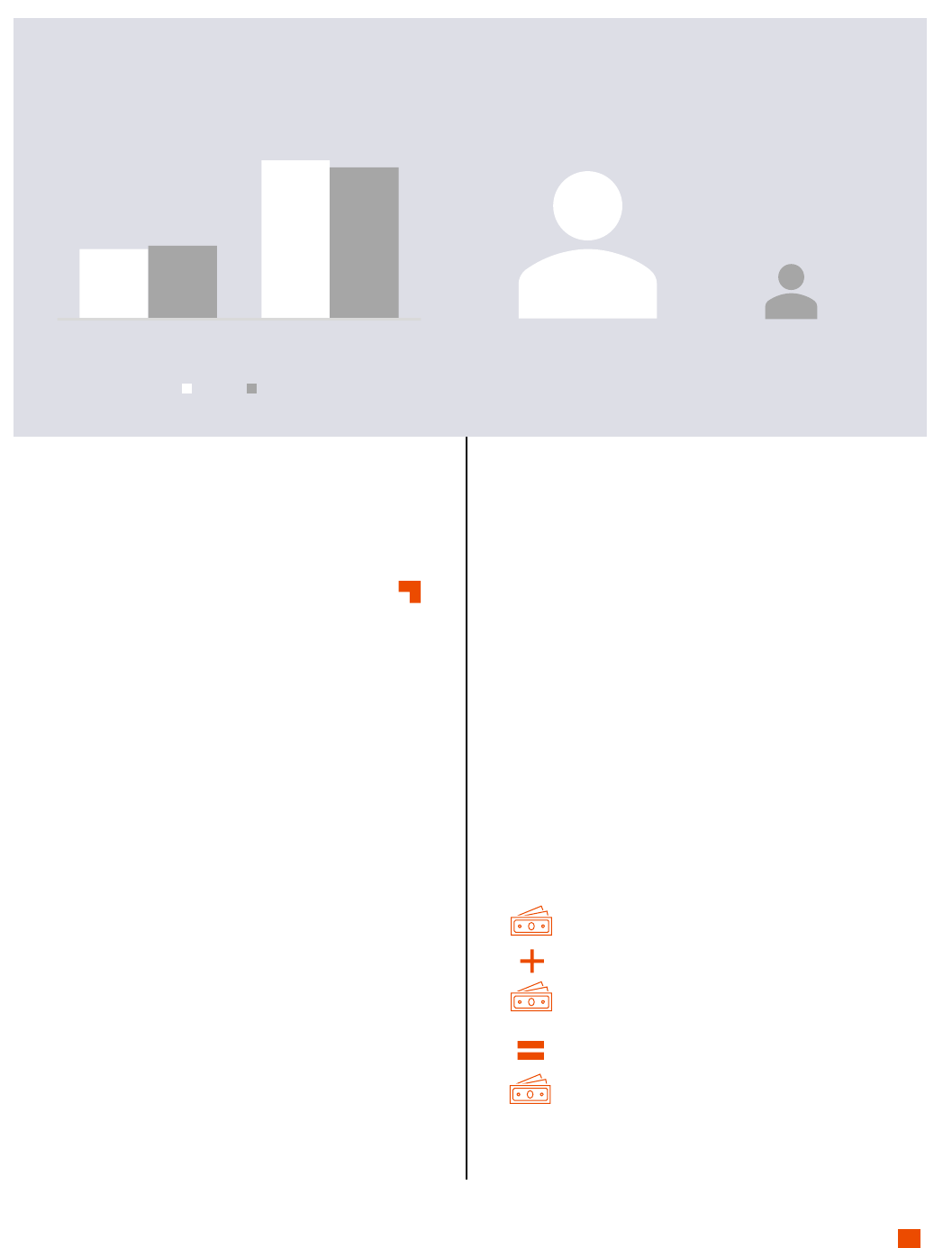

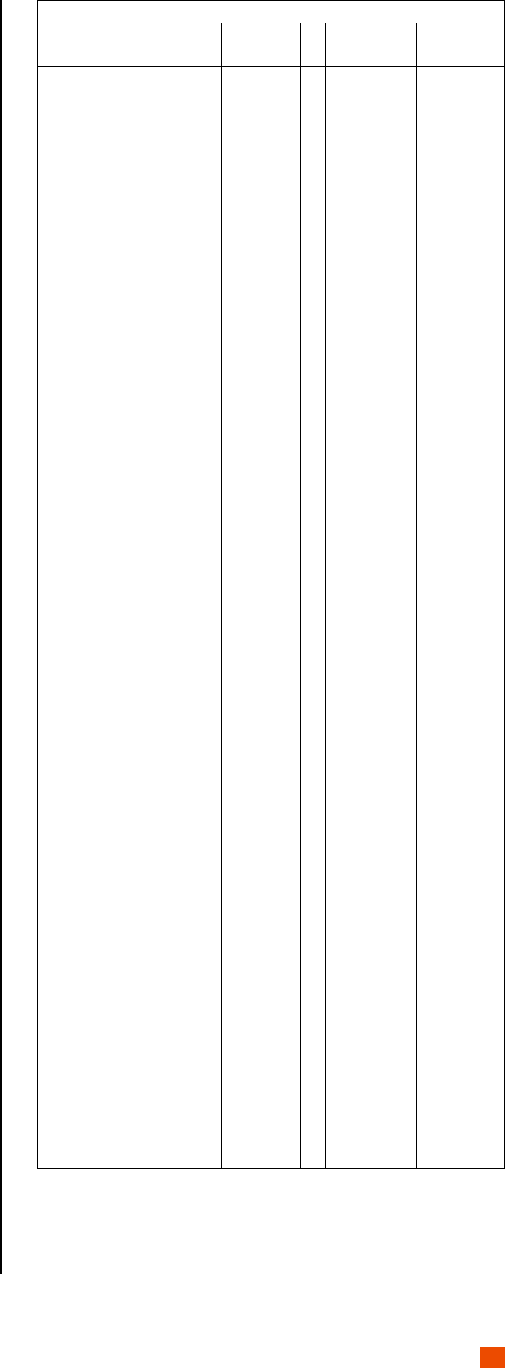

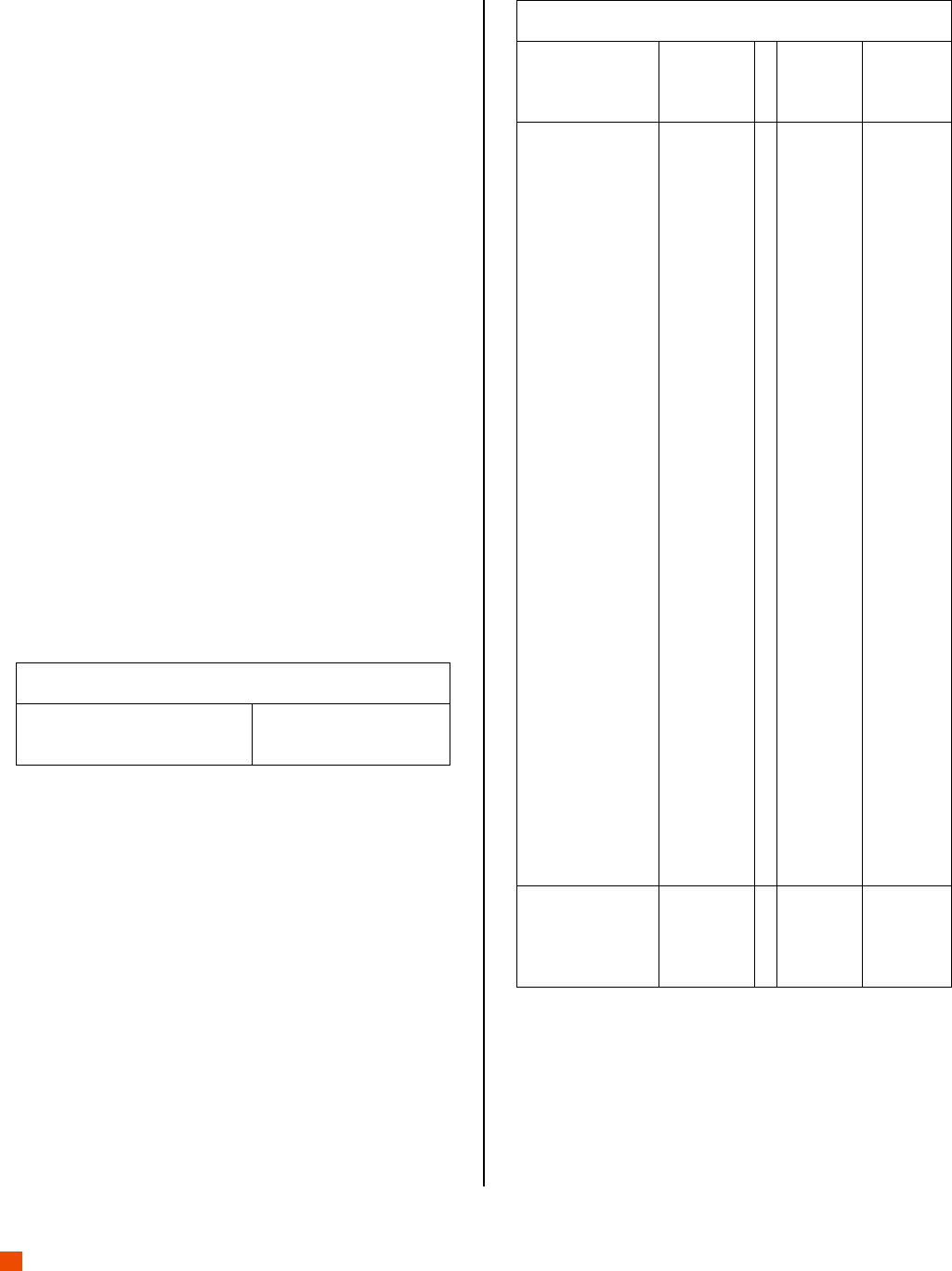

Figure 6 shows trends in pretrial release before and after

GO18.8A. Each dot in the graphs represents a two-week

average of the percent of felony defendants who were

released pretrial – meaning that they spent any time

outside of jail during the 12-month follow-up period. As

Figure 6 shows, the percent of defendants released pretrial

increased slightly for all bond types after GO18.8A, from

just

below

80% to just

above

80%. Trends were slightly

different for various bond types. The percent of defendants

released pretrial increased after GO18.8A for defendants

receiving D/C-Bonds, but decreased for defendants

receiving EM. And pretrial release rates remained stable for

defendants receiving I-Bonds.

Specifically, prior to GO18.8A, 60% to 70% of felony

defendants who received a D/C-Bonds at their initial bond

court hearing were released pretrial. After GO18.8A, 70% to

80% were released. In contrast, the percent of defendants

receiving EM who were released pretrial decreased from

75% to 80% before GO18.8A to 50% to 60% after GO18.8A;

in fact, Figure 6 shows that release rates for defendants

receiving EM also decreased slightly over time after

GO18.8A from 76% in November 2017 – immediately after

implementation of GO18.8A – to 50% by April 2018. Finally,

both before and after GO18.8A, almost all felony defendants

who received an I-Bond were released pretrial

(approximately 95%).

18

The percent of defendants

released pretrial increased

slightly after GO18.8A.

While the descriptive statistics indicate an increase in

pretrial release after GO18.8A, again, this increase could be

due to differences in the types of defendants or cases

appearing in bond court before and after GO18.8A. In order

to control for such differences, a series of logistic regression

models were generated to examine the odds of a defendant

being released pretrial; these estimates include all

defendants who appeared in bond court, regardless of the

bond type imposed. The analyses indicate that GO18.8A was

associated with a statistically significant increase in the

odds of a defendant being released pretrial, after controlling

for defendant and case factors.

While there was an overall increase in the likelihood of

release, the analyses also revealed that defendants were

less likely to be released when they were male, Black,

A

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

I-Bond

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

Before GO18.8A After GO18.8A

D/C-Bond

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

EM

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

Before GO18.8A After GO18.8A

All Bond Types

Figure 6.

Time trends in pretrial release

Dollars and Sense in Cook County

9

younger, charged with a Person offense, charged with a

higher felony class, charged with more felony offenses, or

they had higher PSA scores or received EM, a D/C-Bond, or

No Bail.

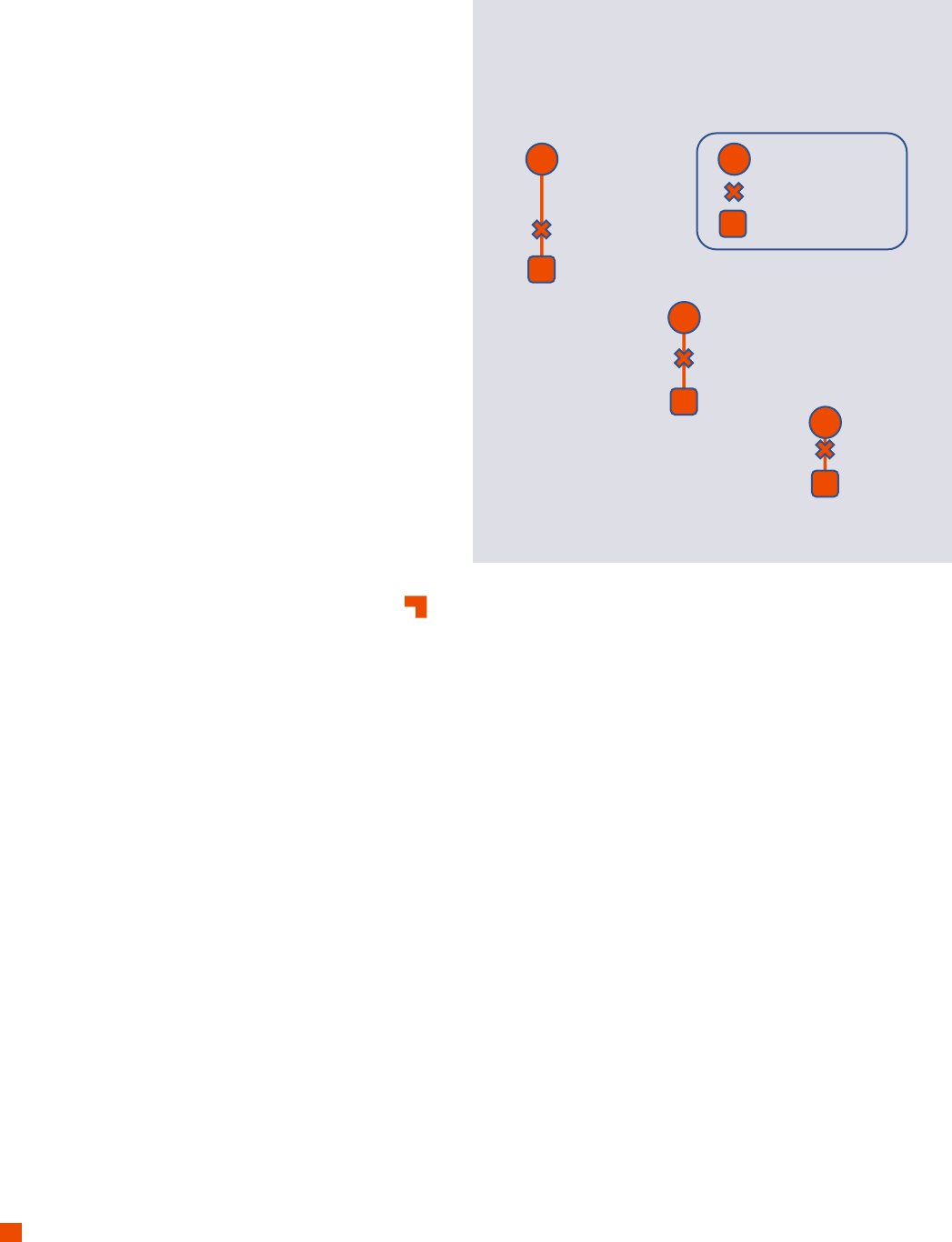

After controlling for defendant and case factors, roughly

77% of defendants were expected to be released before

GO18.8A compared to roughly 81% after GO18.8A (Figure 7).

To put this increased probability of pretrial release in

context, of the 11,372 defendants with an initial bond court

hearing in the six months after GO18.8A, 8,700 would have

been released if pre-GO18.8A rates had continued (Figure

8). However, the statistical models revealed that 9,200

defendants were released. Thus, just 500 additional

defendants were released in the six months from November

1, 2017 to April 30, 2018 as a result of GO18.8A who would

not have been released before GO18.8A.

19

Just 500 additional

defendants were released in

the six months after GO18.8A

than would have been if

release rates had remained

unchanged.

Overall, the increased use of I-Bonds and the reduction in

average bail amounts after GO18.8A did not dramatically

increase the percent or number of people released pretrial.

However, GO18.8A did change

how

people were released –

far fewer people were required to post monetary bond to

secure their release, resulting in individuals and their

families not having to post nearly $31.4 million in bond.

Figure 7.

Probability of pretrial release

before and after GO18.8A

76.5%

80.9%

Before GO18.8A After GO18.8A

Figure 8.

Number of additional people

released due to GO18.8A

11,372 defendants with an initial bond court hearing

in the six months after GO18.8A

• 8,700 defendants would have been released if

the pre-GO18.8A rates had continued.

•

9,200 defendants were released after GO18.8A.

• 500

additional

defendants were released after

GO18.8A than would have been if pre-GO18.8A

rates had continued.

=1,000 defendants

Dollars and Sense in Cook County

10

PRETRIAL RELEASE

OUTCOMES

eneral Order 18.8A decreased the use of monetary

bail and increased the percent and number of

defendants released pretrial. Critics contend that such

changes result in more defendants failing to appear for

court hearings (FTAs) and more defendants committing

crimes while on pretrial release. The following sections

examine the impact of GO18.8A on FTAs, new criminal

activity, and new violent criminal activity. For each of these

outcomes, a series of logistic regression models were

generated to examine the odds of defendants released

pretrial having each outcome. Our analyses indicate that

GO18.8A was associated with a slight increase in the odds

of an FTA but was not associated with the odds of new

criminal activity or new violent criminal activity.

FAILURE TO APPEAR

The analyses tracked defendants released pretrial to

determine if there was an FTA associated with any court

event in the case during the follow-up period (i.e., until the

case was disposed or for twelve months, whichever came

first). The analyses indicate that GO18.8A was associated

with a statistically significant increase in the odds of a

defendant having an FTA, after controlling for defendant

and case factors.

While there was an overall increase in the odds of an FTA,

the analyses also revealed that released defendants were

less likely to have an FTA when they were older, charged

with a Person or Weapons or Drug offense, charged with a

higher felony class, or received EM or a D/C-Bond.

Defendants were more likely to have an FTA when they had

higher PSA scores indicating higher risk of FTA or new

criminal conduct and spent more time on pretrial release.

GO18.8A was associated with

a slight increase in the odds of

an FTA.

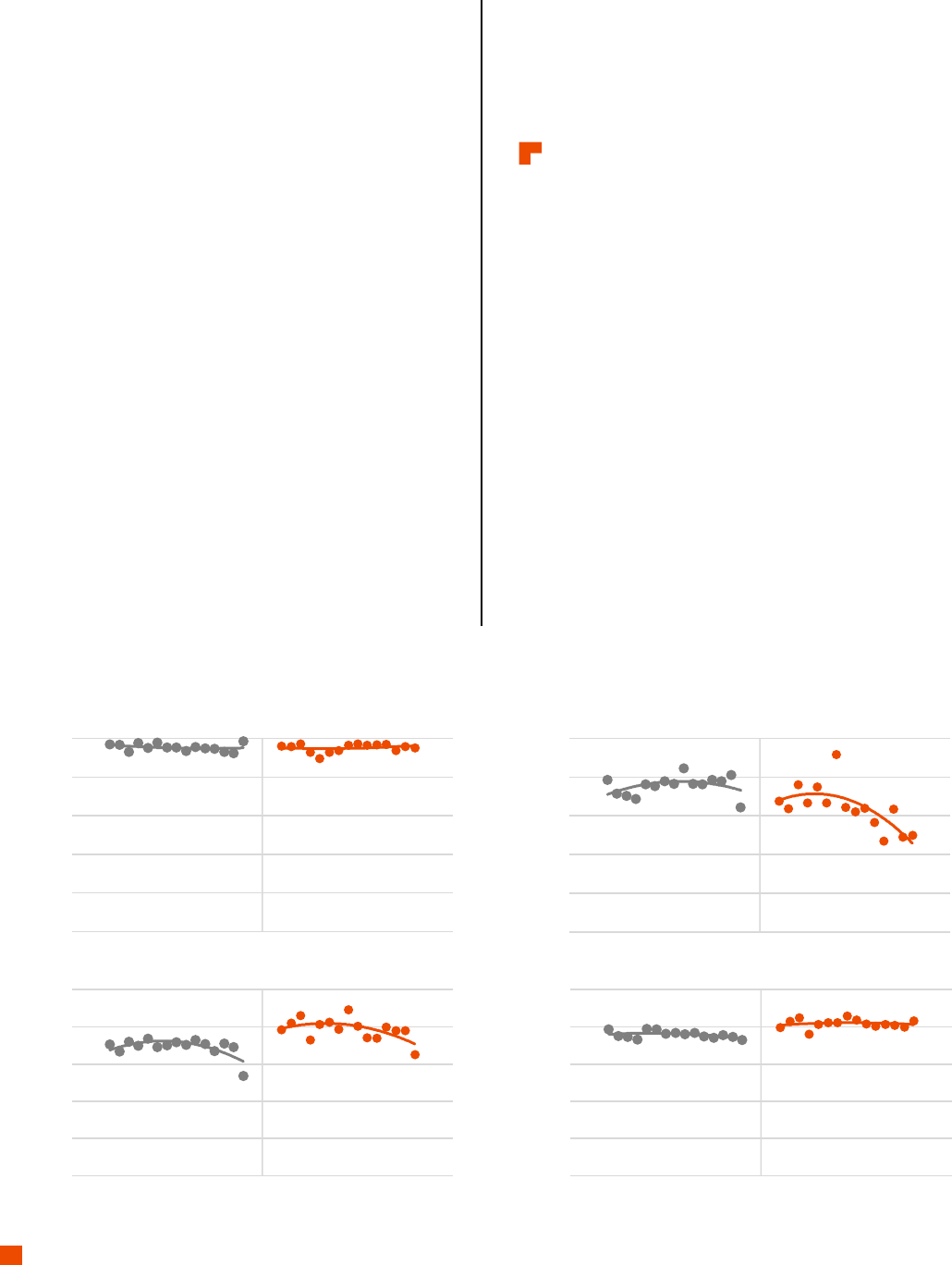

After controlling for defendant and case factors, 16.7% of

released defendants were expected to have an FTA before

GO18.8A compared to roughly 19.8% after GO18.8A (Figure

9). In other words, of the 9,200 defendants who were

released in the six months after GO18.8A, we would have

expected 1,536 to have an FTA if the pre-GO18.8A rates had

continued. However, the statistical model revealed that

1,822 defendants had an FTA after GO18.8A. Thus, just 286

additional defendants had an FTA in the six months from

November 1, 2017 to April 30, 2018 as a result of GO18.8A.

NEW CRIMINAL ACTIVITY

The analyses also tracked defendants released pretrial to

determine if they had any new misdemeanor or felony case

filed against them within Cook County during the follow-up

period. The analyses indicate that, after controlling for

defendant and case factors, there was no statistically

significant change in the odds of released defendants being

charged with new criminal activity after GO18.8A.

GO18.8A had no effect on

the odds of new criminal

activity of defendants

released pretrial.

The analyses did indicate that defendants were less likely to

have new criminal activity when they were female, White,

older, charged with a Person or Drug offense, or they spent

longer on pretrial release.

20

Defendants were more likely to

have new criminal activity when they were charged with a

higher felony class, had higher PSA scores indicating higher

risk of FTA or new criminal activity, had a violation of

probation/bail, or received EM. There were no differences in

the likelihood of new criminal activity between defendants

who received I-Bonds and defendants who received D/C-

Bonds.

After controlling for defendant and case factors, 17.5% of

released defendants were expected to have new criminal

activity before GO18.8A compared to 17.1% after GO18.8A

(Figure 10); this difference of 0.4 percentage points was not

G

16.7%

83.3%

Before GO18.8A

FTA No FTA

19.8%

80.2%

After GO18.8A

FTA No FTA

Figure 9.

Probability of FTA before and after

GO18.8A

Dollars and Sense in Cook County

11

statistically significant. Thus, most defendants released

pretrial were not charged with new criminal activity during

the follow-up period – 82% of released defendants before

GO18.8A and 83% of released defendants after GO18.8A.

NEW VIOLENT CRIMINAL ACTIVITY

The analyses also tracked released defendants to determine

if they had any new violent criminal activity – any new

felony or misdemeanor case with a top charge of a Person

offense filed against the defendant within Cook County

during the follow-up period. The analyses indicate that

there was no statistically significant change in the odds of

released defendants being charged with new violent

criminal activity.

GO18.8A had no effect on the

odds of new violent criminal

activity of defendants released

pretrial.

After controlling for defendant and case factors, just 3.0%

of released defendants were expected to have new criminal

activity before GO18.8A compared to 3.1% after GO18.8A

(Figure 11). Although this represents an increase of 0.1

percentage points, the difference is not statistically

significant. Put differently, of the defendants released

pretrial before and after GO18.8A, 97% were not charged

with a new violent offense while on pretrial release.

Defendants were less likely to have new violent criminal

activity when they were female, White, older, and charged

with a Drug offense. Defendants were more likely to have

new violent criminal activity when they were charged with

a Person offense, had a violation of probation/bail, or

received a D/C-Bond. No other defendant or case factors

were associated with the odds of new violent criminal

activity. While those originally charged with a Person

offense and released pretrial were more likely to have a

new violent offense, a relatively small percent had this

outcome. Specifically, just 6.0% of those originally charged

with a Person offense and released pretrial had a new

violent offense, compared to 2.8% of those originally

charged with other crimes.

Overall, just 6% of released defendants were charged with a

new Drug offense, 4% with a new Public Order offense, 3%

with a new Property offense, and 1% with a new Weapon

possession offense (Figure 12).

Figure 10.

Probability of new criminal activity

before and after GO18.8A

17.5%

82.5%

Before GO18.8A

New Crim. Act.

No New Crim. Act.

Figure 11.

Probability of new violent criminal

activity before and after GO18.8A

17.1%

82.9%

After GO18.8A

New Crim. Act.

No New Crim. Act.

3.0%

97.0%

Before GO18.8A

New Viol. Crim.

Act.

No New Viol. Crim.

Act.

3.1%

96.9%

After GO18.8A

New Viol. Crim.

Act.

No New Viol. Crim.

Act.

No New

Criminal

Activity 83%

Person 3%

Weapon 1%

Property 3%

Drugs 6%

Other 4%

New Criminal

Activity

17%

Figure 12.

New criminal activity before and

after GO18.8A, by offense type

Dollars and Sense in Cook County

12

AGGREGATE LEVELS OF

CRIME

s the preceding analyses indicate, GO18.8A was

associated with a slight increase in the likelihood that

defendants charged with a felony offense were

released pretrial, resulting in an estimated 500 additional

people released in the six months after GO18.8A. However,

there was no change in the likelihood that released

defendants were charged with new criminal offenses while

on pretrial release.

To gauge the degree to which there were changes in the

overall amount of crime in Chicago following GO18.8A, a

series of Bayesian Structural Time Series (BSTS) models

were generated to compare the number of Property Index

Crimes, Violent Index Crimes, and Violent Index Crimes with

a Gun reported to the Chicago Police Department before

and after GO18.8A.

21

These models created estimated

ranges of how many crimes would be expected in the 365

days after GO18.8A based on pre-GO18.8A crime patterns

and other factors that correlate with crime, but are

unaffected by GO18.8A.

22

Actual crime rates were then

compared to these estimates. In all of these models, the

number of crimes observed during the post-GO18.8A period

were not statistically different than the number of crimes

projected to occur.

23

There was no statistically

significant change in level of

crime in Chicago in the year

after GO18.8A.

As Figure 13 shows, the analyses estimated that between

77,407 and 107,316 Property Index Crimes would be

reported in Chicago in the 365 days following GO18.8A.

There were 88,085 actual Property Index Crimes reported

during this period. In other words, the number of Property

Index Crimes that occurred in Chicago in the year after

GO18.8A was within the range that would normally be

expected. To conclude that GO18.8A increased (or

decreased) crime, the number of crimes would have had to

be above (or below) the projected range. Similarly, the

number of Violent Index Crimes was projected to be

between 31,623 and 22,341 in the 365 days following

GO18.8A; there were 27,074 actual crimes reported. Finally,

the number of Violent Index Crimes with a Gun was

projected to be between 5,635 and 12,487, and there were

9,694 actual crimes reported. Again, all were within the

expected ranges.

A

Figure 13.

Projected and actual crime in

Chicago 365 days after GO18.8A

107,613

77,407

88,085

31.623

22,341

27,074

12,487

5,635

9,694

Property

Index

Projected High

Projected Low

Actual

Violent

Index

Violent Index

w/Gun

Dollars and Sense in Cook County

13

CONCLUSION

eneral Order 18.8A had two clear objectives – create a

presumption of release without monetary bail for the

large majority of felony defendants in Cook County

and consider defendants’ ability to pay monetary bail. The

analyses described here indicate that GO18.8A achieved its

intended objectives.

There was a significant increase in the use of I-Bonds, from

26% of defendants receiving I-Bonds before GO18.8A to 57%

receiving I-Bonds after GO18.8A. The impact of this shift

was dramatic – 3,559 additional people received an I-Bond

in the six months after GO18.8A than would have if these

rates had remained unchanged. The real impact of this

change – none of these defendants had to post monetary

bail to be released pretrial, saving these defendants and

their families $13.6 million in avoided bond costs.

GO18.8A also led to a dramatic change in bond amounts

imposed for defendants receiving D-Bonds. Average bond

amounts for defendants with D-Bonds decreased from

$9,316 before GO18.8A to $3,824 after GO18.8A. Again, the

real impact of this change – the 3,256 defendants who

received D-Bonds in the six months after GO18.8A saved

$17.8 million in bond costs needed to secure release.

Combined with the avoided bond costs associated with the

increased use of I-Bonds, GO18.8A saved defendants and

their families over $31.4 million in the six months after

GO18.8A. Although most money posted as bond is

eventually returned once the case is resolved, this is money

that defendants and their families do not have available to

them throughout the durtation of the case. In other words,

GO18.8A allowed defendants and their families to have

$31.4 million available to be used for rent, food, and medical

care while their case was being resolved.

Overall, the percent and number of individuals released

pretrial changed very little after GO18.8A. After controlling

for defendant and case characteristics, the percent of

defendants released pretrial increased from 77% before

GO18.8A to 81% after GO18.8A. Just 500 more people were

released in the six months after GO18.8A than would have

been released if these rates had remained unchanged.

Moreover, the risk assessment tool adopted as part of Cook

County’s bond court reforms appears to be providing judges

with additional insights to better inform bond court

decisions. Specifically, the analyses described here found

that the higher the risk level, the less likely the defendant

was to receive an I-Bond or to be released pretrial.

In the end, GO18.8A did not dramatically change the number

of people released pretrial. What did change was

how

people were released pretrial.

GO18.8A also had no impact on new criminal activity or new

violent criminal activity of those defendants released

pretrial. Overall, the probability of new criminal activity

remained at roughly 17% before and after GO18.8A.

Similarly, the probability of new violent criminal activity

remained constant at just 3% before and after GO18.8A.

And overall crimes rates in Chicago – including violent crime

rates – were not any higher than expected after the

implementation of GO18.8A.

Thus, GO18.8A increased the use of I-Bonds, decreased the

financial burden on defendants and their families, and

increased the percent and number of people released

pretrial – all without affecting new criminal activity of those

released or increasing crime.

Opponents of bail reform may continue to argue that

reducing the use of monetary bail and increasing the

number of people released pretrial will result in more

defendants committing more crimes while on pretrial

release. But that is not what happened following bail reform

in Cook County, consistent with experiences following bail

reform in New York,

24

New Jersey,

25

and Philadelphia.

26

Like

these other reform efforts, GO 18.8A demonstrates that it is

possible to decrease the use of monetary bail and decrease

pretrial detention – and lessen the financial, physical, and

psychological harms that come with pretrial detention –

without affecting criminal activity or crime rates.

Everyone wants safe communities. Releasing people on

their own recognizance does not make communities less

safe. Taking money away from people to secure their

release does not make communities safer – but it does

impose a significant burden on those individuals and their

families who are least able to afford it.

G

Dollars and Sense in Cook County

14

APPENDICES

APPENDIX A – DATA AND METHODS

Felony Bond Court Decisions and Pretrial Release

Data

The current study relied on three sets of data initially

provided to the Institute for State and Local Governance

(ISLG) as part of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur

Foundation’s Safety and Justice Challenge (SJC). These data

were provided to the Center for Criminal Justice Research,

Policy, and Practice under a grant from the SJC Research

Consortium to examine the impact of GO18.8A on bail

decisions, pretrial release outcomes, and crime in Cook

County.

The first set of data included all cases filed in the Circuit

Court of Cook County between January 1, 2013 and April 30,

2019 (court data).

27

These data were originally obtained

from the Clerk of the Circuit Court of Cook County, which

collects and maintains data on all criminal court cases filed

in Cook County. Though administrative data have limitations

(e.g. they are collected to track cases not to conduct

research, and data entry and terminology use may vary

over time), the court data provided rich detail on defendant

characteristics, bond court decisions, initial and final charge

information, dates and outcomes of all court events, final

charge dispositions, and sentences. Unique defendants

were identified using the Individual Record number (IR

Number); unique cases were identified using the court case

number (CR Number).

28

The combination of IR Number and

CR Number was used to identify unique defendant/case

combinations.

29

The court data included 714,327 unique

defendant/case combinations.

Court data were structured so that each court event

appeared as a separate row in the dataset. In other words,

the data were structured so that each row in the dataset

represented a unique court event for each defendant/case

combination, with a specific court event date for each event.

These court events included bond court, arraignment,

disposition, sentencing, and general hearings. For each

unique defendant/case combination, the analyses identified

the initial (earliest) bond court date. Initial analyses of the

data indicated that individual defendants were often

associated with multiple court cases that had bond court

hearings on the same date. The analyses treated separate

cases that involved the same defendant and the same bond

court hearing date as a single case, which reduced the total

number of defendant/cases to 711,947. Since the analyses

focused on initial bond court decisions, it also was

necessary to identify any defendant/case combinations that

overlapped in time in the dataset (e.g., if a defendant had an

initial bond court hearing in Case 1 and had a bond court

hearing in Case 2 before the disposition of Case 1); in such

instances, the bond court hearing in Case 1 was included as

the controlling case, which reduced the total number of

defendant/cases to 558,680.

Since cases often involve multiple charges, a procedure was

devised to categorize cases according to the “top charge” at

case filing. To determine the top charge at case filing, filed

charges were first ranked by offense severity according to

the state’s three-part misdemeanor and six-part felony

classification system. Filed charges were then classified into

five distinct offense types (person, weapons, property,

drugs, public order/other). The filed charge with the highest

offense severity in a case was designated as the initial top

charge for analysis purposes. When a case contained two

filed charges with the same offense severity but different

offense types, charges were ranked according to offense

type in the following way: person (most serious), weapons,

property, drugs, public order/other (least serious); when a

case contained two filed charges with the same offense

severity and the same offense type, charges were allowed

to randomly select as the top charge. For the analyses, only

defendant/cases with a felony as the top charge in the case

were included, which reduced the number of

defendant/cases to 203,003.

The second set of data included information for all felony

defendants screened using the Public Safety Assessment

(PSA, a pre-trial risk assessment instrument developed by

the Arnold Foundation) between October 1, 2015 and

December 9, 2019 (PSA data). These data were originally

collected by Cook County Adult Probation - Pretrial Services

Unit and obtained from the Office of the Chief Judge (OCJ).

The PSA data included information on defendant

characteristics, initial charge information, pretrial risk

assessment scores (risk of failure to appear, risk of new

criminal activity, and risk of new violent criminal activity

flag), initial bond court decisions, and bond court condition

recommendations. Unique defendants were identified using

the IR Number and unique cases were identified using CR

Number. As above, the combination of IR Number and CR

Number was used to identify unique defendant/case

combinations. The PSA data included 104,158 unique

defendant/case combinations.

Court data and PSA data were then merged using the CR

Numbers and IR Numbers to link the datasets. As noted in

the OCJ’s bond court report,

30

the PSA was implemented for

felony defendants on a pilot basis in Central Bond Court

beginning July 2015 and was implemented in Suburban

Districts for felony defendants in August 2016. As such, PSA

information was not available for 66.4% (134,854) of all

defendant/cases in the court data. The analyses accounted

for missing PSA data by including multiple models with and

without PSA information (see analytic strategy below).

Finally, the third set of data included information for all

defendants admitted to or released from the Cook County

jail between May 1, 2013 and May 2, 2019 (jail data). These

data were originally obtained from the Cook County

Sheriff’s office, which collects and maintains data on all

Dollars and Sense in Cook County

15

individuals admitted to and released from the Sheriff’s

custody. The jail data provided detail on defendant

characteristics, holding offenses, jail admission and release

dates, and reason for release (if released). Unique

defendants were identified using the Inmate Identification

Number (Inmate Number); unique bookings associated with

specific court cases were identified using the Jail Booking

Number (Booking Number). The jail data included 346,171

unique defendant/booking combinations.

Jail data were restructured so that each entry and exit from

the jail appeared as a separate row in the dataset. In other

words, the data were restructured so that each row in the

dataset represented a jail entry or jail exit for each

defendant/booking combination, with a specific jail entry

date or jail exit date. Many defendant/booking

combinations had multiple jail entries/exits if the defendant

was admitted to and released from jail custody multiple

times during the duration of a case. The jail data were then

merged with the combined court/PSA dataset.

The jail data also included IR Numbers for each unique

defendant and CR Numbers for each unique case. The

merged court/PSA/jail dataset was then sorted according

to IR Number, CR Number, and event date (i.e., court event

date, jail entry, jail exit date). This final merged dataset then

included events for each defendant/case combination in

chronological order.

The final merged dataset contained 5,084,471 rows of data,

representing every court event and jail entry/exit for unique

defendant/case combinations in which a top charge in the

initial bond court hearing involved a felony.

Sample

The purpose of the analyses was to examine changes in

bond court decisions, pretrial release, and pretrial release

outcomes before and after GO18.8A. Thus, a pre-GO18.8A

cohort of defendants was selected and compared to a post-

GO18.8A cohort. The current analyses included a pre-

GO18.8A cohort consisting of all defendants with an initial

felony bond court hearing in the six months between

November 1, 2015 and April 30, 2016 and a post-GO18.8A

cohort consisting of all defendants with an initial felony

bond court hearing in the six months between November 1,

2017 and April 30, 2018. Overall, the analyses included

12,859 defendants in the pre-GO18.8A cohort and 11,372

defendants in the post-GO18.8A cohort.

For each cohort, a series of outcomes was tracked from the

initial bond court date until the case was disposed or for

twelve months, whichever came first (follow-up period). A

critique of the initial OCJ report was a difference in follow-

up periods for the pre-GO18.8A and post-GO18.8A cohorts.

In order to ensure an equal follow-up period for the two

cohorts and a follow-up period that would allow sufficient

tracking of outcomes, it was necessary to restrict the

cohorts to a six-month window. Since court data included

court events only through April 30, 2019, it was necessary

to limit the post-GO18.8A cohort to cases only through April

30, 2018, which would allow a twelve month follow up for

the latest case. Also, to ensure that the post-GO18.8A

cohort began after the implementation of GO18.8A, the

cohort necessarily began on November 1, 2017. A similar

pre-GO18.8A cohort was chosen using the same start and

end dates (November 1, 2015 and April 30, 2016). The

follow-up periods ensured the same duration of at-risk

periods for both the pre- and post-GO18.8A cohorts,

accounted for potential seasonality during time at risk,

31

and

ensured that the two cohorts and follow-up periods did not

overlap in time.

Dependent variables

The analyses examined five dependent variables. The first

dependent variable, I-Bond, captured whether a defendant

received an I-Bond at the initial bond court hearing (1 = I-

Bond imposed; 0 = Other bond type imposed). The raw

court data included eight bond types: release on conditions

(ROC), I-Bond, electronic monitoring (EMI), C-Bond, D-Bond,

D-Bond with electronic monitoring (D-Bond/EMI), No Bail,

and Bond to Stand. These were combined in to four bond

types as follows: I-Bond (ROC, I-Bond), EM (EMI), D/C-Bond

(C-Bond, D-Bond, D-Bond/EMI) and No Bail (No Bail). Initial

bond court hearings with a bond type of Bond to Stand

(0.4% of cases) were dropped from the analyses. If a

defendant had multiple bond court hearings on the same

day for different cases, we used the most restrictive bond

court decision as the controlling decision and treated these

separate cases as a single case. In such instances, bond

court decisions were ranked from I-Bond (least restrictive)

to EM to D/C-Bond to No Bail (most restrictive). This initial

bond court decision was then used to categorize

defendant/case combinations for subsequent analyses. If a

defendant received a revised bond court decision later in a

case, the initial bond court decision was still used to

categorize the case.

32

For each defendant/case combination, the initial bond court

date was determined and an end date 12 months from the

initial bond court data was created; if the defendant/case

combination was disposed, the disposition date was also

included. These dates were used to calculate the follow-up

period for each defendant/case combination – from the

initial bond court data to the disposition date or to the end

date, whichever came first.

The second dependent variable, Released, captured

whether a defendant was released pretrial (1=Released

pretrial; 0=Not released pretrial). If a defendant spent any

time outside of jail during the follow-up period they were

considered released pretrial.

The third dependent variable, FTA, captured whether a

defendant had a failure to appear while on pretrial release

(1=Failure to Appear; 0=No Failure to Appear). FTA was

calculated only for defendants released pretrial. If a

defendant had any failure to appear flag during the follow-

up period, they were considered to have a failure to appear.

Dollars and Sense in Cook County

16

The fourth dependent variable, New Criminal Activity,

captured whether a released defendant had a new criminal

case filed in Cook County while on pretrial release (1=New

Criminal Activity; 0=No New Criminal Activity).

33

New

Criminal Activity was calculated only for defendants

released pretrial. If a defendant had any new case filed

during the follow-up period, they were considered to have

new criminal activity.

Finally, the fifth dependent variable, New Violent Criminal

Activity, captured whether a released defendant had a new

criminal case filed for a Person offense while on pretrial

release (1=New Violent Criminal Activity; 0=No New Violent

Criminal Activity). New Violent Criminal Activity was

calculated only for defendants released pretrial. If a

defendant had any new felony or misdemeanor case filed

during the follow-up period in which the most serious filed

charge was a Person offense, they were considered to have

new violent criminal activity.

34

Person offenses included

murder, kidnapping, criminal sexual abuse or assault,

assault, battery, domestic battery, reckless conduct,

robbery, vehicular hijacking, and violation of an order of

protection.

Case-level variables

Case-level variables in the present study included several

defendant, offense, and case processing characteristics.

Defendant characteristics were drawn from the court data

and included information on demographic attributes of

defendants. The analyses included a trichotomous variable

measuring defendant race/ethnicity (0=Defendant White

(reference), 1=Defendant Black, 3=Defendant

Hispanic/Other). The court data included one variable

capturing defendant race and ethnicity in the following

categories: American Indian and Alaskan Native,

Asian/Pacific Islander, Black Latino/Hispanic, Black non-

Latino/Hispanic, Other, Unknown/Missing, White

Latino/Hispanic, White non-Latino/Hispanic. These

categories were initially recoded into two variables

measuring race (White, Black, American Indian and Alaskan

Native, Asian/Pacific Islander, Other/Missing) and ethnicity

(Hispanic, Non-Hispanic). However, it was evident that

Hispanic ethnicity was not captured consistently in the

court data; just 1.7% of defendants in the pre-GO18.8A

cohort were Hispanic compared to 16.3% of defendants in

the post-GO18.8A cohort. Thus, in order to ensure the

inclusion of these defendants and the ability to examine the

effects of race and ethnicity, a single race/ethnicity variable

was created with Hispanic, American Indian, Alaskan Native,

and Asian/Pacific Islander defendants included in a third

race/ethnicity category. The analyses also included

defendant sex (0=Female (reference), 1=Male) and age (in

years). A variable capturing whether the defendant was in

violation of probation or bail bond was also included (0=No

Violation (reference); 1=Violation). A defendant was

determined to have a violation of probation if they had a

sentence of probation imposed within one year prior to the

initial felony bond court hearing date; a defendant was

determined to have a violation of bail bond if they had a

charge of violation of bail bond included in a prior case.

PSA scores measuring risk of FTA or New Criminal Activity

were coded as ordinal variables with three categories (1-2

(low risk) (reference), 3-4, and 5-6 (high risk)). A third

dichotomous PSA score measuring risk of New Violent

Criminal Activity was also included (0=No Risk, 1=Risk). PSA

scores were missing for 26.4% of the sample (35.5% of the

pre-GO18.8A sample and 16.0% of the post-GO18.8A

sample). In order to include PSA scores in the analyses,

missing values were recoded (Missing=99) to ensure the

cases were not dropped. Cook County Adult Probation and

the Office of the Chief Judge have found that over 90% of

felony defendants receive an assessment. The high missing

rate here is likely not due to Adult Probation - Pretrial

Services failing to meet assessment obligations; rather, it is

likely due to data quality issues and the study’s difficulty in

matching defendants across court and PSA datasets.

Offense characteristics included the number of filed charges

(continuous), number of filed felony charges (continuous),

and offense severity, which was coded as an ordinal

variable with seven categories (0=Unspecified Felony (least

serious) through 6=Murder (most serious)). The type of

offense was measured with a categorical variable

measuring the most serious offense in the defendant/case

combination (0=Property (reference), 1=Person, 2=Weapons,

3=Drugs, 4=Public Order/Other).

35

Lastly, one case processing variable was included: weeks at

risk (continuous), which measured the number of weeks a

defendant was released from jail during the follow-up

period. This was calculated only for defendants released

pretrial and included only the time that they were not

physically in the jail.

Analytical strategy

The impact of defendant, offense, and case characteristics

on case outcomes was analyzed using standard statistical

procedures to examine categorical data in multivariate

settings. Specifically, the baseline estimations relied on a

series of multivariate logistic regression models to estimate

the effect of these factors on the dependent variables listed

above. All models are estimated using Stata 14.

For each dependent variable, the analyses considered thee

models. The first model included the pre- and post-GO18.8A

cohorts with a control for the pre- and post-periods. This

allowed an estimation of the impact of GO18.8A on the odds

of the outcome (e.g., odds of I-Bond, Release, etc.),

controlling for defendant, offense, and case characteristics.

Two separate models were then run separately for each of

the pre- and post-GO18.8A cohorts; this was to examine

potential variation in the influence of defendant, offense,

and case characteristics during the two time periods.

Following each model, expected rates of each outcome

were estimated using predicted probabilities generated

using the Stata

margins

command. Predicted probabilities

Dollars and Sense in Cook County

17

represent the expected rate of a specific outcome after

controlling for all defendant and case factors.

Although results generated by the logistic regression

models are informative, these may be biased due to

differences in the pre- and post-GO18.8A cohorts. To

minimize this problem, propensity scores were used to

reconfigure the study sample to include similar offenders.

The creation of matched samples explicitly takes into

consideration that the variables differentiating each cohort

may not be independent of the variables associated with

case outcomes. These models report the average effect of

GO18.8A on the specific outcome.

Crime Rates

Data

The current study relied on data obtained from the Chicago

Police Department’s online public data portal. Data included

incident-level information on the number of Violent Index

Offenses, Property Index Offenses, and Violent Index

Offenses with a Gun. Counts of these offenses were

aggregated by day and week.

Control variables

Control variables in the present study included several

factors that correlate with crime, but are unaffected by

GO18.8A. For the day of each criminal incident, the following

information was included: whether the day was a weekend

day or a holiday, the average daily temperature, the level of

precipitation, the monthly unemployment rate, and the

number of drug arrests. Because unemployment rate data

was only available on a monthly basis, these monthly

unemployment rate measures were used for all days during

a particular month. Drug arrests were included as a proxy

variable to measure the degree to which police were

making arrests for “on-view” behaviors (i.e., an indicator of

how aggressively police were approaching enforcement).

Analytic strategy

To gauge the degree to which there were changes in the

overall amount of crime (Violent Index offenses, Property

Index Crimes, and Violent Index Crimes with a Gun) in

Chicago following GO18.8A, Bayesian Structural Time Series

(BSTS) models were used to develop a counterfactual

forecast of how many of these crimes would have been

expected in the 90 day- and 365 day-period following the

implementation of GO18.8A based on pre-GO18.8A crime

patterns and the control variables noted. These analyses

create a range of the expected number of crimes for each

crime type which are then compared to the actual number

of offenses reported to the Chicago Police Department in

each of these crime categories before and after GO18.8A.

A total of 16 multivariate models were developed and

tested. For each of the three types of crime examined,

models were developed examining daily crime counts as

well as weekly crime counts, and also to gauge 90 day-

impacts and 365 day-impacts of GO18.8A on crime. The pre-

GO18.8A period used to train the BSTS models covered

October 1, 2015 to August 31, 2017, while the post-period

covered October 1, 2017 to August 31, 2019. September

2017 was excluded as the reform was implemented during

that month.

Dollars and Sense in Cook County

18

APPENDIX B – LOGISTIC REGRESSION

RESULTS

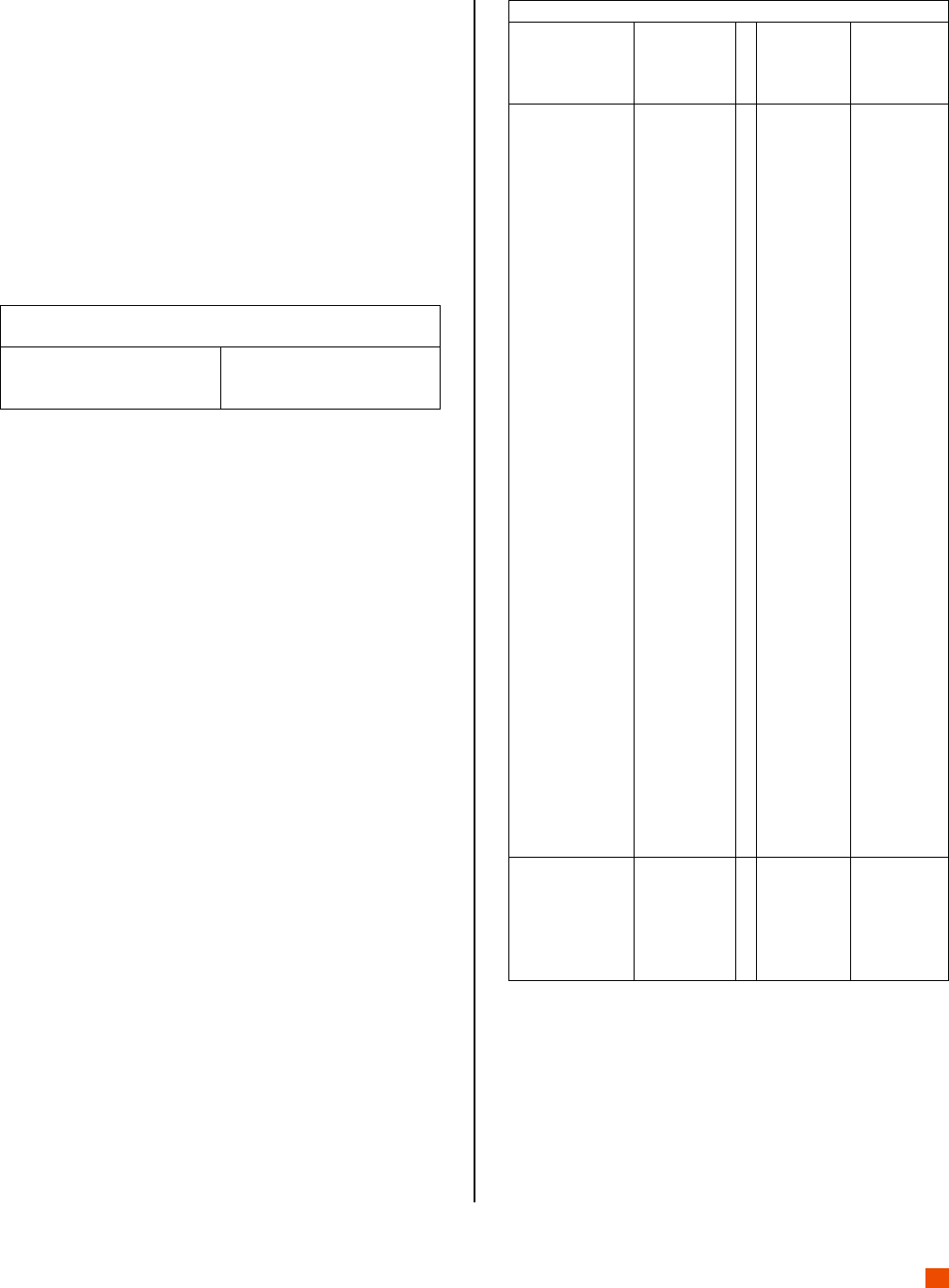

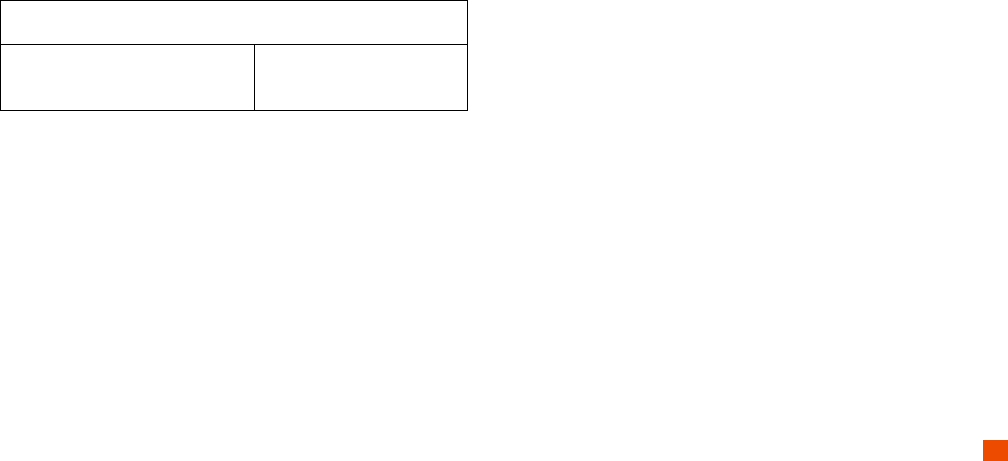

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics for the study sample are presented in

Tables B.1 and B.2. Table B.1 includes descriptive statistics

for the entire study sample and separately for the pre-

GO18.8A and post-GO18.8A cohorts; Table B.2 includes

descriptive statistics only for the defendants in the sample

who were released pretrial, and separately for those

released in the pre-GO18.8A and post-GO18.8A cohorts.

The first outcome variable, I-Bonds, showed significant

variation across the pre- and post-GO18.8A cohorts: overall,

39.9% of defendants in the sample received an I-Bond at the

initial bond court date, but the percent of defendants

receiving an I-Bond was significantly lower for the pre-

GO18.8A cohort than for the post-GO18.8A cohort (25.6% vs.

55.9%). There was also an increase in the second outcome

variable, the percent of defendants released pretrial;

overall, 78.3% of defendants in the sample were released

pretrial, with 75.7% of the pre-GO18.8A cohort released

pretrial compared to 81.3% of the post-GO18.8A cohort.

Table B.1 also shows that defendants in the overall sample

and in the pre- and post-GO18.8A cohorts tended to be

male and Black, with these percentages increasing slightly

in the post-GO18.8A cohort; roughly 30% of defendants

were 18-25 years old, but the largest proportion of

defendants were over 36 years old. There was a slight

increase in the percent of defendants in violation of

probation/bail bond, with 7.2% of defendants in the pre-

GO18.8A cohort in violation of probation/bail bond

compared to 11.8% of defendants in the post-GO18.8A

cohort. Defendants tended to be charged with unspecified,

Class 3, or Class 4 Felonies, and over 40% were charged

with Drug offenses. The percent of defendants charged with

Weapons offenses was lower in the pre-GO18.8A cohort

compared to the post-GO18.8A cohort (8.0% vs. 13.4%);

conversely, the percent of defendants charged with

Property offenses was higher in the pre-GO18.8A cohort

compared to the post-GO18.8A cohort (10.3% vs. 14.2%). The

majority of defendants (over 70%) in the overall sample and

in the pre- and post-GO18.8A were charged with a single

felony and over 40% were charged with a single offense.

Finally, the mean PSA scores – for FTAs, New Criminal

Activity, and New Violent Criminal Activity – remained

constant in the pre- and post-GO18.8A cohorts.

Table B.1. Descriptive Statistics for Initial Sample

Full

Sample

Pre-

GO18.8A

Post-

GO18.8A

Total Cases

36

24,056

12,756

11,300

I-Bond

39.9%

25.6%

55.9%

Released

78.3%

75.7%

81.3%

Female

14.4%

15.3%

13.4%

Male

85.6%

84.7%

86.6%

White

18.8%

20.2%

17.4%

Black

63.2%

61.7%

64.8%

Hispanic/Other

18.0%

18.1%

17.8%

18-25 years old

31.8%

32.3%

31.2%

26-35 years old

29.0%

28.3%

29.9%

36+ years old

39.2%

39.4%

38.8%

Viol. of Prob./Bail

9.3%

7.2%

11.8%

Unclassified Felony

11.5%

12.3%

10.6%

Class 4 Felony

45.7%

46.1%

45.6%

Class 3 Felony

13.9%

13.3%

14.8%

Class 2 Felony

11.7%

10.9%

12.7%

Class 1 Felony

6.5%

6.2%

6.9%

Class X Felony

9.9%

10.6%

8.8%

Murder

0.7%

0.6%

0.7%

Person Offense

11.1%

10.9%

11.3%

Weapon Offense

10.5%

8.0%

13.4%

Property Offense

17.5%

20.3%

14.2%

Drug Offense

42.9%

42.3%

43.5%

Other Offense

18.0%

18.4%

17.6%

1 Charge

43.2%

45.2%

41.0%

2 Charges

21.8%

20.9%

22.7%

3+ Charges

35.0%

33.9%

36.3%

1 Felony Charge

75.9%

77.8%

73.7%

2 Felony Charges

16.2%

15.5%

17.1%

3+ Felony Charges

7.9%

6.7%

9.2%

PSA FTA Score

(mean)

2.5

2.5

2.5

PSA New Crim. Act.

Score (mean)

2.9

2.9

2.9

PSA New Viol. Crim.

Act. Score (mean)

0.6

0.5

0.7

Missing PSA

26.3%

35.5%

16.0%

Dollars and Sense in Cook County

19

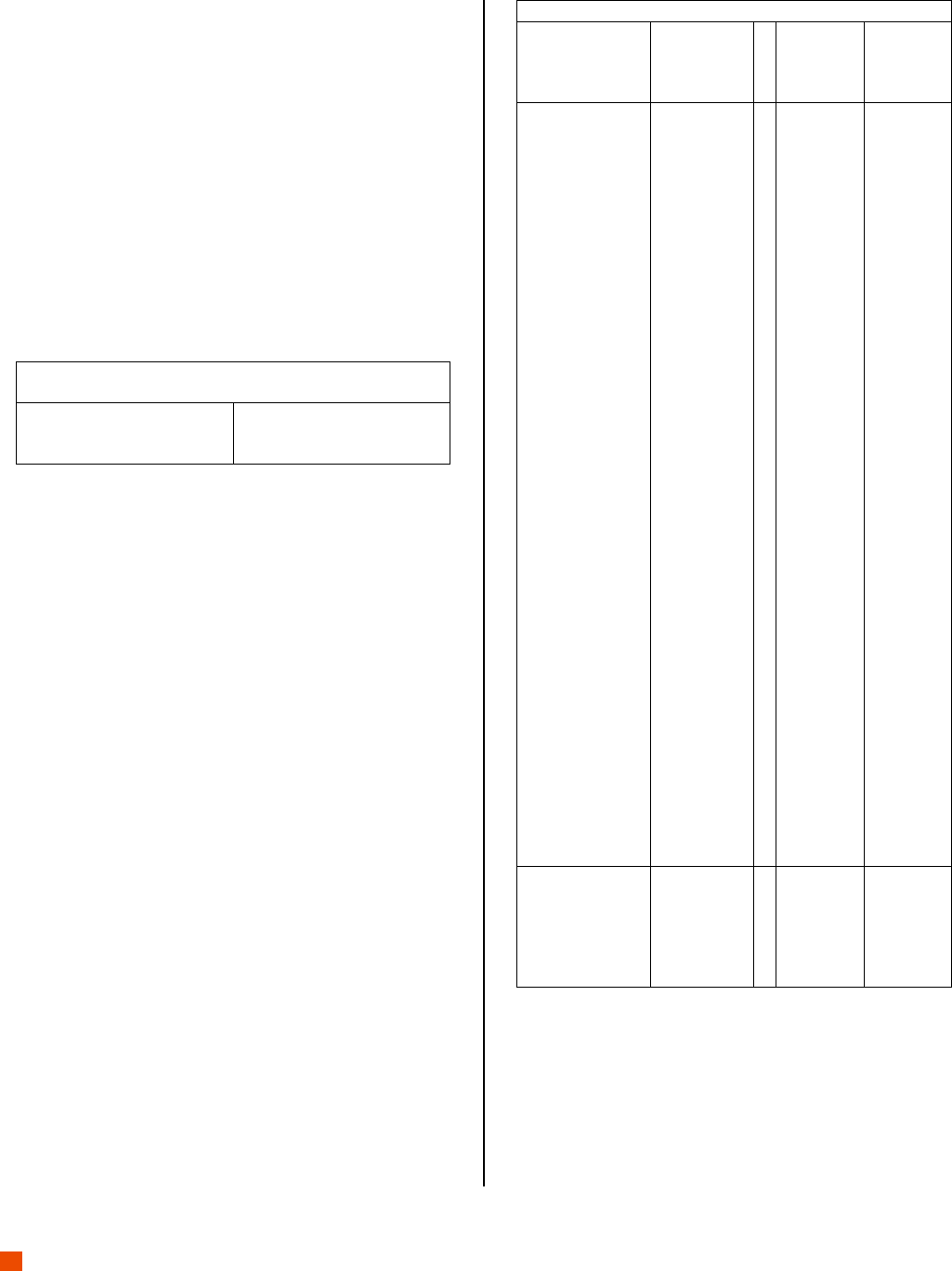

The remaining outcome variables – FTA, New Criminal

Activity, New Violent Criminal Activity – showed little

variation across the pre- and post-GO18.8A cohorts (Table

B.2). Overall, 18.3% of released defendants in the sample

had an FTA during the follow-up period, with the percent of

released defendants with an FTI slightly lower for the pre-

GO18.8A cohort than for the post-GO18.8A cohort (16.7% vs.

19.8%). There was also a slight increase in New Criminal

Activity; overall, 17.3% of released defendants in the sample

were charged with New Criminal Activity, with 16.7% of the

pre-GO18.8A cohort released pretrial compared to 17.8% of

the post-GO18.8A cohort. Finally, overall, 3.1% of released

defendants in the sample were charged with New Violent

Criminal Activity during the follow-up period, with the

percent of released defendants with New Violent Criminal

Activity slightly lower for the pre-GO18.8A cohort than for

the post-GO18.8A cohort (2.9% vs. 3.2%).

Table B.2 also shows that few differences in defendant and

case characteristics existed between the initial sample and

the released sample of defendants. The primary differences

involved charge factors. A slightly larger proportion of

released defendants were charged with Unspecified, Class

3, or Class 4 Felonies than the overall sample (74.9% vs.

70.1%). Similarly, a slightly higher proportion of released