1

FSIS Cooking Guideline for

Meat and Poultry Products

(Revised Appendix A)

December, 2021

Document ID: FSIS-GD-2021-14

This guideline provides information on the

Agency regulatory requirements

associated with safe production of ready-

to-eat (RTE) products with respect to the

destruction of Salmonella and other

pathogens. It applies to small and very

small meat and poultry official

establishments although all meat and

poultry establishments may apply the

recommendations in this guideline. It

relates to 9 CFR 318.17(a)(1), 9 CFR

318.23, 381.150(a)(1), and 9 CFR 417.

2

Table of Contents

Preface ............................................................................................................................ 4

Purpose of this Guideline .......................................................................................... 4

History of this Guideline and Reason for Reissuance ............................................... 5

Changes from the Previous Versions ....................................................................... 6

How to Effectively Use this Guideline ....................................................................... 8

Questions Regarding Topics in this Guideline .......................................................... 9

Background ................................................................................................................... 10

What is Lethality? ................................................................................................... 10

Products and Processes Covered by this Guideline ............................................... 10

Products and Processes Not Covered by this Guideline ........................................ 11

Biological Hazards of Concern During Cooking ...................................................... 13

General Considerations for Designing HACCP Systems to Achieve Lethality by Cooking

. ..................................................................................................................................... 18

Addressing Lethality in the HACCP System ........................................................... 18

Alternative Lethality ................................................................................................ 20

Monitoring, Calibration, and Recordkeeping ........................................................... 20

Corrective Actions under HACCP Cooking Deviations ........................................... 22

FSIS Critical Operating Parameters for Cooking ........................................................... 23

Come-Up-Time (CUT) ............................................................................................ 23

Relative Humidity .................................................................................................... 25

Table 1. Critical Operating Parameters for FSIS Humidity Options........................ 26

Relative Humidity Resources .................................................................................. 28

Situations when Humidity is Not Needed ................................................................ 31

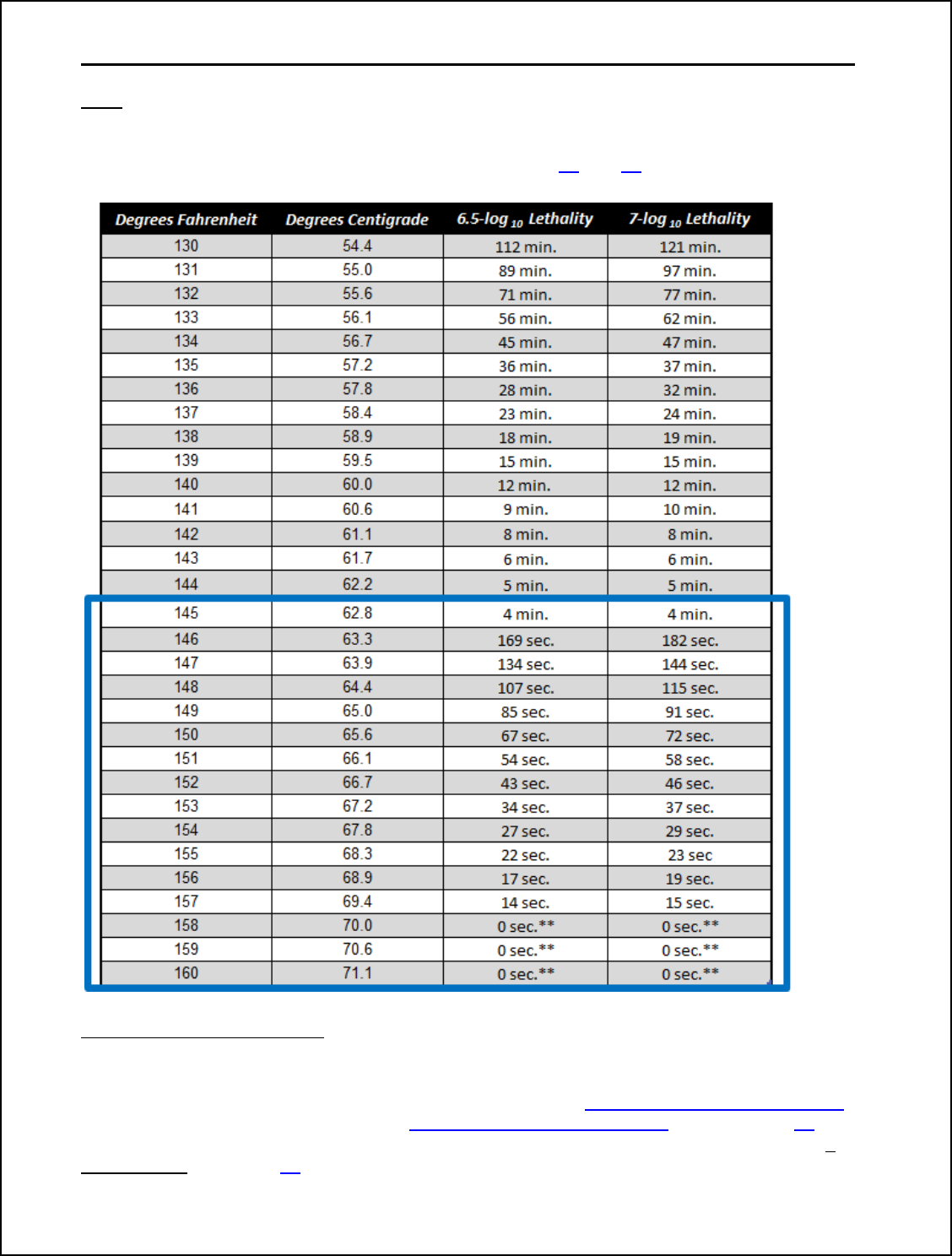

Endpoint Time-Temperature ................................................................................... 34

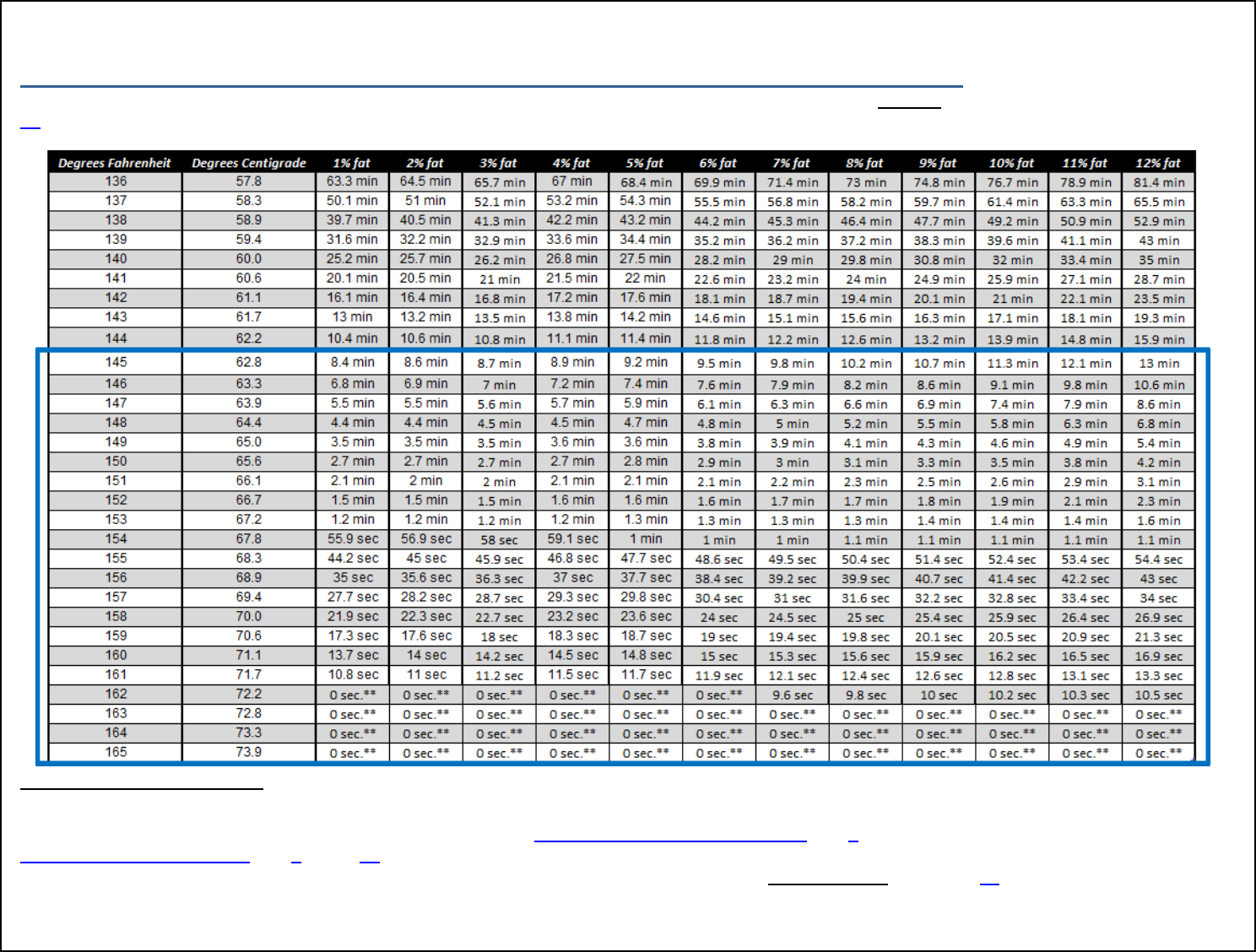

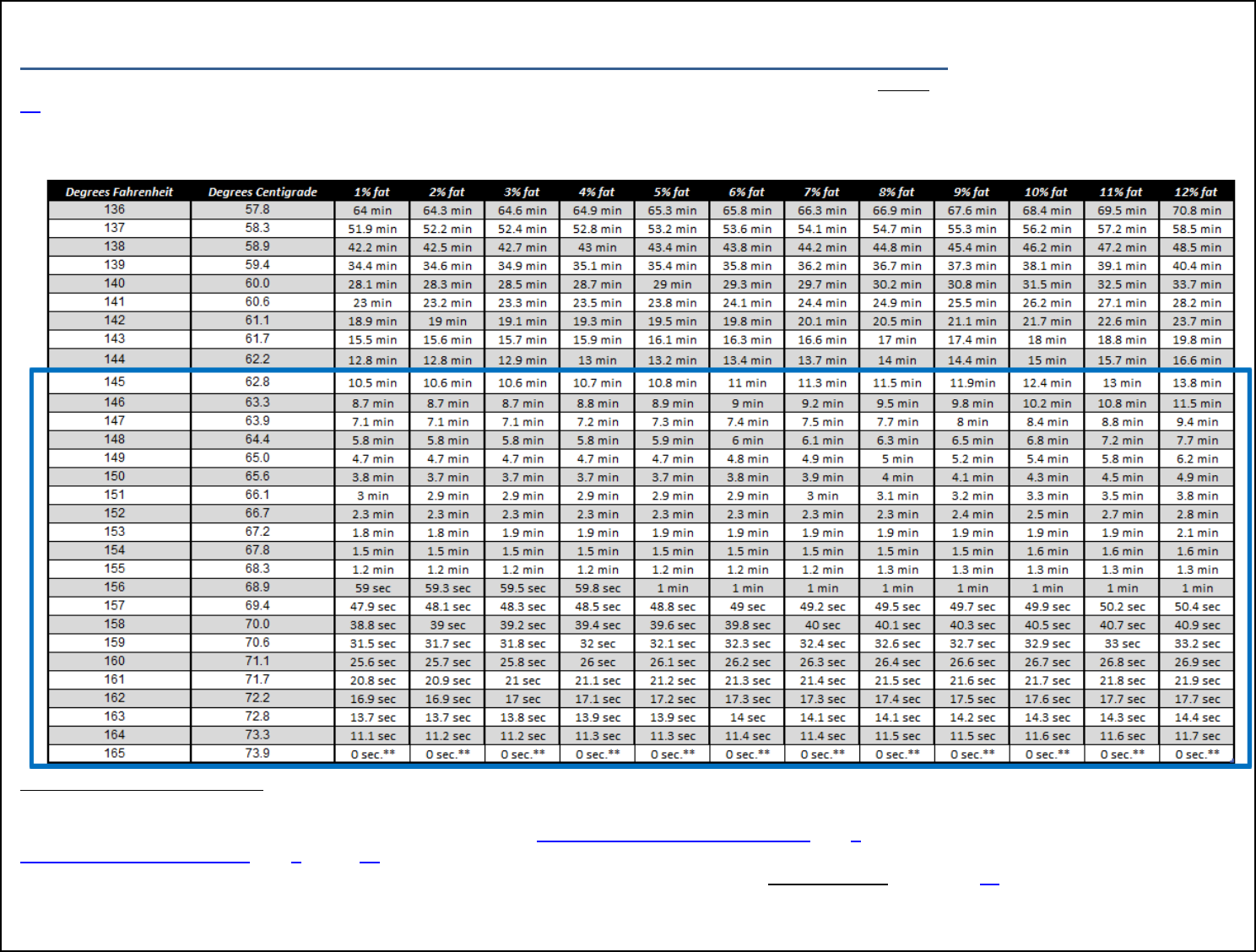

Table 2. Time-Temperature Combinations for Meat Products to Achieve Lethality

. .............................................................................................................................. 35

Additional Critical Operating Parameters for Poultry Products................................ 36

Table 3. Time-Temperature Combinations for Chicken Products to Achieve

Lethality .................................................................................................................. 37

Table 4. Time-Temperature Combinations for Turkey Products to Achieve Lethality

. .............................................................................................................................. 38

Resources for Customized and Alternative Support ...................................................... 40

Scientific Gaps Identified by FSIS .................................................................................. 41

Table 5. Scientific Gaps where Critical Operating Parameters From Older

Guidance May be Used .......................................................................................... 43

References .................................................................................................................... 49

Attachment A1. Customized Processes and Alternative Lethality Support ................... 55

3

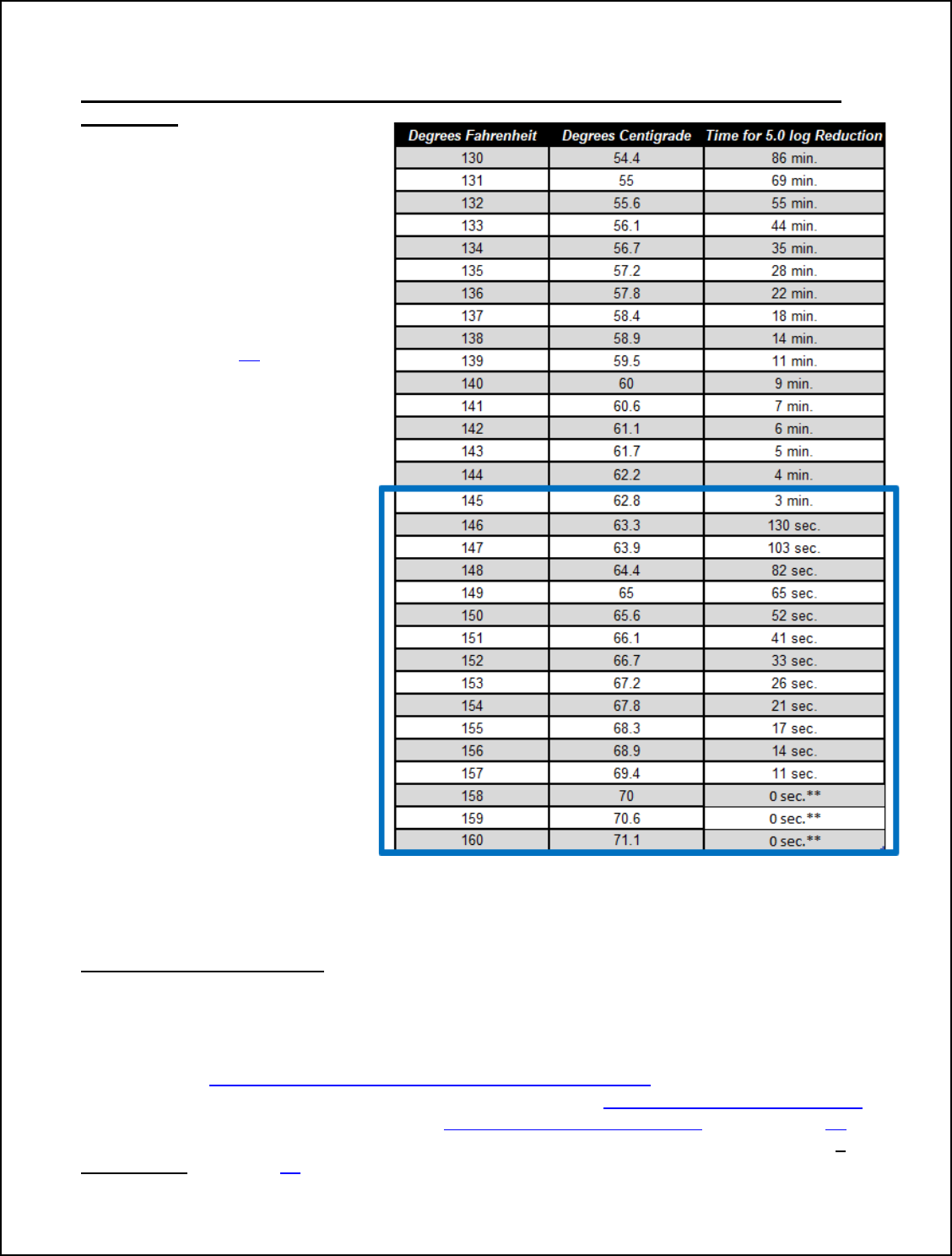

Supporting an Alternative Lethality Target (e.g., 5-Log) .......................................... 57

Table 6. Time-Temperature Combinations for Meat Products to Achieve a 5-Log

Reduction ............................................................................................................... 59

Predictive Microbial Modeling to Support CUT ....................................................... 62

Designing Challenge Studies for Cooking .............................................................. 63

Attachment A2. Cooking Deviations .............................................................................. 66

Corrective Actions to Perform When a Cooking Deviation Occurs ......................... 66

Type 1. Missed Endpoint Time-Temperature ......................................................... 67

Type 2. Insufficient Humidity During Cooking ........................................................ 69

Type 3. Long Heating CUT .................................................................................... 70

Predictive Microbial Modeling ................................................................................. 72

Product Testing ...................................................................................................... 77

Table 7. FSIS Recommendations for Product Sampling and Testing After Each

Type of Cooking Deviation to Determine Product Disposition ................................. 77

Disposition after Testing Results ............................................................................ 79

Attachment A3. When can Products be Labeled as Pasteurized? ................................ 81

Attachment A4. Sources of Salmonella Contamination in RTE Products and Best

Practices to Address It ................................................................................................... 82

Under-Processing ................................................................................................... 82

Cross-Contamination .............................................................................................. 82

Ingredients Added After the Lethality Treatment ..................................................... 84

Food Handlers ........................................................................................................ 86

Animals .................................................................................................................. 86

Attachment A5. RTE Salmonella Self-Assessment Tool ............................................... 87

Attachment A6. Cooking Country-Cured Hams ............................................................ 90

4

Preface

This is a revised version of the FSIS Cooking Guideline for Meat and Poultry Products

(Revised Appendix A). It has been updated in response to comments received on the

previous version and renamed. In addition, the guideline has been revised to include

recommendations from previous versions and new updates based on up-to-date

science. The guideline also includes changes to improve its readability.

This guideline represents FSIS’s current thinking on these topics. Establishments that

utilized previous versions of Appendix A as support should either:

• Update to this 2021 FSIS Cooking Guideline (Revised Appendix A) or

• Identify alternative support by December 14, 2022.

The information in this guideline is provided to assist meat and poultry establishments in

meeting the regulatory requirements. The contents of this document do not have the

force and effect of law and are not meant to bind the public in any way. This document

is intended only to provide clarity to industry regarding existing requirements under the

regulations. Under the regulations, meat and poultry establishments may choose to

implement different procedures than those outlined in this guideline, but they would

need to validate and support how those procedures are effective.

This guideline is focused on small and very small plants in support of the Small

Business Administration’s initiative to provide small businesses with compliance

assistance under the Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act (SBREFA).

However, all meat and poultry establishments may apply the recommendations in this

guideline. It is important that small and very small establishments have access to a full

range of scientific and technical support, and the assistance needed to establish safe

and effective Hazards Analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP) systems. Although

large plants can benefit from the information, focusing the guideline on the needs of

small and very small establishments provides them with assistance that may be

otherwise unavailable to them.

Purpose of this Guideline

This guideline contains information to assist meat and poultry establishments producing

products that undergo cooking in complying with the HACCP regulatory requirements in

9 CFR 417. This guideline includes information on:

• Biological hazards during cooking.

• Regulatory requirements associated with the safe production of cooked ready-to-

eat (RTE) products.

• Options establishments can use to achieve lethality of Salmonella and other

pathogens.

5

• Processes that do not have validated research available (referred to as “scientific

gaps”) and options establishments can use until research is available.

• Resources for alternative support.

• Recommendations for evaluating cooking deviations.

Establishments can always seek guidance from State university extension service

specialists and HACCP Coordinators on developing programs and plans not provided in

this guideline to comply with HACCP regulatory requirements.

History of this Guideline and Reason for Reissuance

In the 1970s and 1980s, FSIS included prescriptive time, temperature, and humidity

operating parameters in the regulations for cooked beef, roast beef, and cooked corned

beef (42 FR 44217; 47 FR 31854; 48 FR 24314) in response to several outbreaks

associated with these products and research performed to determine how to prepare

them safely. When the Pathogen Reduction/Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points

(PR/HACCP) final rule published in 1996, FSIS eliminated the prescriptive cooking

regulations and replaced them with performance standards requiring a 6.5-Log

reduction in Salmonella or alternative lethality for roast beef, cooked beef, and corned

beef, minimum internal temperature and holding times for fully cooked patties that

achieve a 5-Log reduction in Salmonella, and a 7-Log reduction in Salmonella or

alternative lethality for poultry products (9 CFR 318.17(a)(1), 9 CFR 318.23, 9 CFR

381.150(a)(1); see General Considerations for Designing HACCP Systems to Achieve

Lethality by Cooking, page 18. FSIS converted these former regulations to “Safe

Harbors” in an appendix to the final rule called Appendix A (64 FR 732).

Establishments have been using FSIS’s Appendix A, as published in 1999, as support

for cooking processes for many years. The original requirements and subsequent

guidance have been important to prevent human illness outbreaks and ensure the

production of safe food. See General Considerations for Designing HACCP Systems to

Achieve Lethality by Cooking, page 18 for more information on the current regulatory

requirements.

Over time, FSIS determined that some of its recommendations in the 1999 version of

Appendix A were vague, putting establishments at risk of producing unsafe products.

Additionally, some elements of the 1999 version of Appendix A were misunderstood or

overlooked, resulting in FSIS guidance being applied in ways that increased food safety

risks to consumers and potential risks to industry, including the risk of foodborne illness

outbreaks. FSIS also determined establishments were broadly applying the

recommendations for operating parameters in Appendix A beyond those meat and

poultry products it was originally designed to support.

To provide the needed updates and clarifications, FSIS issued revisions of both its

Cooking (Appendix A) and Stabilization (Appendix B) guidelines in 2017. The 2017

version of the guidelines took into account new and emerging technologies, processes,

and science. FSIS has updated this guideline in response to comments received on the

2017 version and has included additional options for cooking support based on updated

6

science and technology. The Agency is releasing this current 2021 version of the

FSIS Cooking Guideline for Meat and Poultry Products (Revised Appendix A) to

replace all previous versions.

Changes from the Previous Versions

This guideline dated December 14, 2021 is final. FSIS will update this guideline, as

necessary, should new information become available.

FSIS made the following changes to this guideline to reflect the comments received on

the previous version during the comment period and to include additional scientific

information.

For Appendix A, FSIS made changes to specify:

• The following products are not covered by the guideline (page 11): Fish of the

Order Siluriformes, pork rind pellets, rendered lard and tallow, dried products

processed under dry conditions, partially heat-treated NRTE products, and RTE

multi-hurdle products.

• The food safety significance of FSIS’s recommendations for relative humidity

(page 17).

• That relative humidity should be addressed for all cooked products (including

poultry) unless the establishment can support that humidity does not need to be

addressed. FSIS has not changed the relative humidity options (page 26) other

than re-emphasizing that they apply to all products.

• Additional resources for selecting a relative humidity option when following

FSIS’s cooking guidance (page 28).

• The situations when relative humidity does not need to be addressed including

by providing more information about situations considered to be direct heating

(page 31) (e.g., by clarifying that relative humidity does not need to be addressed

for meat patties cooked using FSIS’s time-temperature table for meat, if the

patties are cooked using direct heat (on page 31)). Previous guidance indicated

it did not need to be addressed for meat patties with the assumption all meat

patties are cooked using direct heat which is no longer the case.

• That natural casings become semipermeable during cooking, maintaining

moisture in the product, so that additional documentation to address relative

humidity is not needed (page 33).

• More detailed information for evaluating product safety following a heating

deviation (page 66). The revision also removes the recommendation for using

the ComBase model for Staphylococcus aureus growth (which was not validated)

7

because of the development and validation of the Danish Meat Research

Institute (DMRI) Staphtox model in 2018.

• Where gaps exist, recommendations from its older cooking guidance can be

used until research is completed (see, Table 5. Scientific Gaps where Critical

Operating Parameters From Older Guidance May be Used, page 43) for:

1. Products cooked for short times at high temperatures.

2. Products cooked using microwave cooking methods that are not

designed to control relative humidity.

3. Products cooked using cooking methods that are not designed to

control relative humidity.

4. Other processes that may inherently maintain relative humidity

around the meat and poultry filling but cannot follow one of the relative

humidity options.

5. Processes where the drying step comes before cooking under moist

conditions.

6. Products with long heating come-up-times (CUTs).

• That information is included about a listeriosis outbreak associated with a cooked

country-cured ham product and recommendations for establishments that cook a

similar product once (page 90).

For Appendix A, FSIS removed:

• Information about how establishments could remove poultry rolls from the

cooking medium before product has achieved the target endpoint temperature

and immediately apply another heating or processing method (64 FR 732).

Since FSIS has clarified that limiting heating CUT is a critical operating

parameter for applying any of FSIS cooking guidance (including these older

options), the parameter to “immediately fully cook” poultry rolls subject to multiple

heating mediums and processes has been removed.

• Specific recommendations for conducting a Salmonella baseline study on raw

source materials as support for using cooking critical operating parameters that

achieve a 5-Log reduction in Salmonella for meat products instead of a 6.5 or 7-

Log reduction. This information was removed since it was interpreted to apply to

all establishments when it was only intended for establishments that wanted to

support a lower level of pathogen reduction from cooking. In addition, FSIS is

not aware of any establishments that have pursued such baseline sampling.

In addition to these changes, the guidelines format was restructured to make it easier to

use as described in the next section. This list of changes is not comprehensive, so

8

establishments should read the section titled FSIS Critical Operating Parameters for

Cooking and other relevant sections as needed.

How to Effectively Use this Guideline

As explained above in the Changes from the Previous Versions, the guidelines format

was restructured to make it easier to use. Specifically, the guideline is organized to

include the following topics in the body of the guideline:

• Biological hazards during cooking.

• Regulatory requirements associated with the safe production of cooked ready-to-

eat (RTE) products.

• Options establishments can use to achieve lethality of Salmonella and other

pathogens.

• Processes that do not have validated research available (referred to as “scientific

gaps”) and options establishments can use until research is available.

Information included in the body of the guideline is intended as scientific support that

can be used alone by establishments to meet Element 1 of validation (9 CFR

417.4(a)(1)) and to support decisions in the hazard analysis (9 CFR 417.5(a)(1)).

The following topics are included in attachments to the guideline:

• Resources for alternative support and

• Recommendations for evaluating cooking deviations.

Information provided in the attachments is not sufficient to use as sole support and

additional documentation is needed. For example, Attachment A1. Customized

Processes and Alternative Lethality Support (page 55), contains descriptions or brief

summaries of available scientific articles. However, the summaries are not considered

adequate support on their own because they do not contain the details of each study.

For this reason, establishments must have the full copy of the article on-file as scientific

support for their HACCP System. The summaries are provided to help establishments

identify journal articles related to their process. Each establishment needs to determine

if the operating parameters of a particular study match the establishment’s process.

Establishments are not limited to using the scientific articles listed and summarized as

support. In addition, Attachment A2. Cooking Deviations (page 66), contains

recommendations for evaluating product safety in the event of a deviation but this

information is not considered adequate support on its own because establishments

should perform predictive microbial modeling and may conduct sampling and testing in

order to support product disposition. Other information included in attachments is

intended to be supplementary.

9

Questions Regarding Topics in this Guideline

If after reading this guideline you still have questions, FSIS recommends searching the

publicly posted Knowledge Articles (“Public Q&As”) in the askFSIS database. If after

searching the database, you still have questions, refer them to the Office of Policy and

Program Development through askFSIS and select HACCP Deviation & HACCP

Validation as the Inquiry Type or by telephone at 1-800-233-3935.

Documenting these questions helps FSIS improve and refine present and future

versions of the guideline and associated issuances.

10

FSIS Cooking Guideline for Meat and Poultry Products

(Revised Appendix A)

Background

What is Lethality?

Lethality treatments are processes used by

establishments to eliminate Salmonella and other

pathogens in RTE products. Lethality treatments achieve

a specific reduction in the number of Salmonella and other

pathogens in the product (i.e., an “X-Log10 colony forming

units per gram

1

(CFU/g)” reduction). The combination of

one or more lethality treatments must be sufficient to

eliminate or adequately reduce Salmonella and other

pathogens to undetectable levels and prevent the

production of toxins or toxic metabolites in the RTE

product (e.g., from Staphylococcus aureus).

Establishments may use a variety of different lethality

processes, such as:

• Cooking the product (covered in this guideline).

• Fermentation.

• Drying.

• Salt-curing.

• Other processes that make the product safe for

consumption.

Products and Processes Covered by this

Guideline

This guideline addresses lethality of pathogens (e.g.,

Salmonella) in meat and poultry products

2

by heat

treatment (cooking) including for products that are cooked

to lethality but classified under a not-ready-to-eat HACCP

plan.

NOTE: FSIS has provided additional information about

the safe production of meat and poultry jerky products in

1

In the rest of this document, Log

10

colony forming units per gram (Log

10

CFU/g) will be annotated simply

as “Log.” All notations of “Log” should be read as in the unit Log

10

CFU/g unless other information is

provided.

2

Throughout this document references to “meat and poultry products” may be considered inclusive of

meat by-products, meat food products, and poultry food products as defined in 9 CFR 301.2 and 9 CFR

381.1, unless otherwise stated (e.g., Products and Processes Not Covered by This Guidance).

KEY DEFINITIONS

A ready-to-eat (RTE)

product is defined as a

meat or poultry product

that is in a form that is

edible by the end

consumer without

additional preparation to

achieve food safety and

that may receive

additional preparation for

palatability, aesthetic, or

culinary purposes (9

CFR 430.1).

Lethality is the process

(or combination of

processes) that ensure a

specific, reduction in the

number of Salmonella and

other pathogens in the

product (i.e., an “x-Log”

reduction). Lethality

processes eliminate or

adequately reduce

Salmonella and other

pathogens and prevent the

formation of their toxins or

toxic metabolites,

facilitating the production

of a safe RTE food

product.

11

the FSIS Compliance Guideline for Meat and Poultry Jerky Produced by Small and Very

Small Establishments. The information for jerky production remains in a separate

guideline because of the complexities of the process, including drying procedures, and

to help address questions from small and very small processing establishments.

Products and Processes Not Covered by this Guideline

The recommendations in this guideline do not apply to the following specific products:

Fish of the Order Siluriformes (e.g., catfish)

FSIS cooking guidance was not validated for fish of the order Siluriformes. Therefore,

this guidance should not be used for fish.

Fish establishments may use the cooking guidance in Table A-3 of The Food and Drug

Administration’s (FDA’s) Fish and Fishery Products Hazards and Control Guidance as

support for the cooking step of fish products. The time-temperature recommendations

are designed to achieve a 6-Log reduction in Listeria monocytogenes (Lm).

Pork Rind Pellets

Establishments may cook pork skins in pork fat or oil for several hours rendering the fat

and reducing the skin into pellets. This intermediate product is then further processed

by frying to produce a finished product such as pork rinds, cracklins (cracklings), or

chicharrones. FSIS cooking guidance does not apply to the cooking or rendering of

pork skins into a pellet. Establishments may use the cooking requirements in 9 CFR

94.8(b)(4) as support for cooking pork skins into a pellet. Although these are Animal

Plant and Health Inspection Service (APHIS) requirements for imported pork skins from

countries where foot-and-mouth disease, African swine fever, classical swine fever, or

swine vesicular disease exist, these cooking requirements ensure at least a 6.5-Log

reduction of Salmonella (Juneja, et al., 2001a; Murphy et al., 2003; Murphy et al., 2004).

NOTE: FSIS cooking guidance may be used for cooking of pork skins for products other

than pork rind pellets (e.g., for use in pickled products) and for frying of pork rind pellets

into popped pork skins. Guidance for monitoring the cooking critical limit for these

products can be found in the Key Question on page 21.

Rendered Lard and Tallow

FSIS cooking guidance does not apply to the rendering of animal fats, such as lard and

tallow, which, due to the high fat content, generally need to reach higher temperatures

and longer dwell

3

times to achieve the same reductions in Salmonella (Ramirez-

Hernandez et al., 2018). However, based on the D values (time at a constant

temperature necessary to destroy 90% or 1-Log of the target organism) reported by

Ramirez-Hernandez et al. (2018), the cooking requirements for rendering in 9 CFR

315.1(a) are adequate to ensure an animal fat rendering process achieves at least 6.5-

3

“Dwell time” ref ers to the time a product is held at a specific temperature. Other commonly used terms

such as “hold time” or “rest time” may be considered synonymous for the purpose of this guideline.

12

Log reductions of Salmonella. Therefore establishments may

use 9 CFR 315.1 as support for a lard or rendering process,

provided the critical operational parameters (≥ 170°F for ≥ 30

minutes) are met throughout the product.

Dried Products Processed Under Dry Conditions

FSIS cooking guidance does not support lethality for a

process that relies on drying alone (e.g., biltong), nor does

this guidance support a process where the drying step comes

before a cooking step that does not apply humidity or does

not apply humidity during cooking at sufficient levels to

rehydrate the product surface (e.g., biltong or country-cured

ham that is cooked in an unsealed oven after drying). This

guidance also does not support lethality for a dried product

cooked under moist conditions several times after drying

(e.g., country-cured ham that is cooked in a sealed oven

several times after the hams have been salt-cured and dried).

Such dried products are typically considered intermediate

moisture foods (i.e., those foods that do not require

refrigeration to control pathogens). The water activity range

of foods considered intermediate moisture varies in the

literature. For example, FDA classifies intermediate moisture

foods as those with a water activity between 0.60 and 0.85

(FDA, 2018). However, some meat and poultry products may

have a water activity > 0.85 and still be considered

KEY DEFINITIONS

Stabilization is the

process of preventing or

limiting the growth of

spore-forming bacteria

capable of producing

toxins either in the

product or in the human

intestine after

consumption.

Stabilization processes

may include cooling, hot-

holding, or meeting and

maintaining a certain pH

or water activity level and

other processes, such as

drying and fermentation/

acidification that render

the product shelf-stable or

safe at room

temperatures.

“intermediate moisture” because of other factors such as pH and salt concentration

(Leistner, 1987). For example, country-cured ham has an average water activity of 0.88

but is considered shelf-stable due to the combination of water activity, high salt, and

nitrite (Mikel and Newman, 2003; Reynolds et al., 2001).

Establishments that apply these types of processes must identify other support for their

HACCP System (9 CFR 417.5(a)(1) and 9 CFR 417.4(a)(1)).

NOTE: This guidance includes critical operating parameters for cooking products which

are dried, then cooked under moist conditions. Scientific Gaps Identified by FSIS

describes critical operating parameters (page 47) and Attachment A6. Cooking

Country-Cured Hams includes additional tips, specific to country-cured hams (page

90).

Partially Heat-Treated NRTE Products

This guideline does not cover partially heat-treated products that are not ready-to-eat

(NRTE) and did not reach a validated lethality time-temperature combination (for

example: partially heat-treated bacon and hams). These products are addressed in the

FSIS Stabilization Guideline for Meat and Poultry Products because cumulative growth

of Clostridium perfringens and Clostridium botulinum are hazards of concern over the

course of partial cooking and cooling processes.

13

NOTE: As noted under the Products and Processes Covered by this Guideline, this

guideline may be used for products that are cooked to lethality but classified under a

Not RTE (NRTE) HACCP plan. For such products, please refer to the product

reclassification guidance in the Listeria Guideline, Attachment 1.2 on pages 22-23 and

Appendix 1.2 on pages 28-29 for guidance related to labeling, HACCP categorization,

and intended use.

RTE Multi-hurdle Products

This guidance does not address the safe production of products that rely on multiple

hurdles to achieve lethality and shelf-stability (e.g., fermented and dried sausage).

However, some regulatory information associated with such products is included in

General Considerations for Designing HACCP Systems to Achieve Lethality by

Cooking, page 18.

NOTE: Stabilization requirements and recommendations for cooling meat and poultry

products after heat treatment are described in the FSIS Stabilization Guideline for Meat

and Poultry Products.

Biological Hazards of Concern During Cooking

The following section is designed to complement FSIS’s Meat and Poultry Hazards and

Control Guide and to further assist establishments in conducting a hazard analysis for

cooked meat and poultry products as required by 9 CFR 417.2(a)(1) and for supporting

decisions in their hazard analysis as required by 9 CFR 417.5(a)(1).

The following hazard is present in raw products whose outgrowth during the

heating come-up time should be controlled:

• Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus)

The following are hazards present in raw products that the lethality treatment

should be designed to destroy:

• Salmonella

• Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia E. coli (STEC) (in beef)

• Campylobacter (in poultry)

• Lm

• Trichinae spiralis and Toxoplasma gondii (in pork, especially feral or non-

confinement raised swine)

NOTE: Although all of these hazards are a concern, Salmonella is considered an

indicator of lethality because the thermal destruction of Salmonella in cooked products

would indicate the destruction of most other pathogens (64 FR 732).

More details about S. aureus and Salmonella (an indicator of lethality) can be found on

the following page.

14

S. aureus

S. aureus is a bacterial pathogen that causes nausea, vomiting, and abdominal

cramping with or without diarrhea. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

(CDC) estimates over 240,000 illnesses annually in the U.S. are attributed to S. aureus

(Scallan et al., 2011). S. aureus causes illness when the bacteria grows to high levels

in food and one or more heat-stable enterotoxins are produced (Kadariya et al., 2014).

Various types of foods serve as the optimum vehicle for S. aureus. The pathogen has

been identified in meat products, such as fermented salami and brine-injected hams. In

the 1980s, S. aureus enterotoxin outbreaks were frequently attributed to hams.

Continued outbreaks at hotels, restaurants and institutions as documented in the

National Outbreak Reporting System (NORS)

4

highlight that S. aureus is still a concern

in hams particularly when prepared in these settings. For example, between 2013 to

2018, at least six S. aureus enterotoxin outbreaks at hotels, restaurants and institutions

were reported in NORS in which ham was the suspected food vehicle. S. aureus can

contaminate raw meat and poultry from the animal hide, skin, or tissue during slaughter.

After slaughter and cooking, RTE meat or poultry products can be contaminated with S.

aureus from handling by individuals carrying the organism. This pathogen is the main

food safety concern during long heating come-up-times (CUT) (that is the amount of

time product temperature is between 50 to 130°F while heating). S. aureus can be

present on the raw meat or poultry and grow to high enough levels to produce a toxin in

the food. Growth occurs from 45 to 118°F, but effectively begins at 60˚F, especially in

raw meats where the growth of other bacteria is inhibited by nitrite or salt. The critical

level for human illness is 5-Log or higher which allows enterotoxin production (Kadariya

et al., 2014). The toxin is not destroyed by the critical operating parameters described

in this cooking guideline.

FSIS recommends limiting the growth of S. aureus during processing to 2-Log or less.

Normal levels of S. aureus in raw meat are usually 2-Log (Doyle and Buchanan, 2013;

IFT, 2003; Waldroup, 1996). Limiting growth to 2-Log or less allows for a margin of

safety before S. aureus would produce toxins. Conditions that allow 3-Log growth are

considered a public health concern because they would result in a total of 5-Log S.

aureus in the product which is considered the minimum critical level for human illness

(Kadariya et al., 2014).

To limit S. aureus growth, some establishments formulate products with antimicrobials

such as phosphate or lactate. But the most common practice is to limit the amount of

time products spend in the temperature range where S. aureus grows the fastest (i.e.,

50 to 130°F). This guideline identifies CUT as a critical operating parameter to ensure

lethality by cooking when applying the time-temperature tables (see FSIS Critical

Operating Parameters for Cooking on page 23). FSIS is aware that establishments

preparing some products (e.g., ham or beef brisket) may not be able to follow FSIS’s

Come-Up-Time Option because of the thermodynamics of the heating process.

Therefore, FSIS identified long CUT as a Scientific Gap since support does not exist for

many common processes (page 48). This gap supports the use of any of FSIS’s

applicable time-temperature combinations (pages 35, 37, 38) and relative humidity,

4

https://www.cdc.gov/nors/index.html

15

KEY DEFINITIONS

Critical operating

parameters are those

parameters of an

intervention that must be

met for the intervention to

operate effectively and as

intended. Such

parameters include but

are not limited to time,

temperature, water

activity, concentration,

relative humidity, and type

of equipment (to the

extent that the use of

different equipment would

result in an inability to

achieve the critical

parameters of the study).

without considering CUT as a critical operating parameter until research can be

complete.

Salmonella

Salmonella is a bacterial pathogen that causes diarrhea and fever. Infection with

Salmonella may result in arthritis (Ajene et al., 2013). The CDC reports that

nontyphoidal Salmonella species (spp.) is one of the leading causes of foodborne

illness, with an estimated 1 million cases of foodborne Salmonella infection annually in

the U.S (Scallan et al., 2011). Salmonella spp. infections are the second leading cause

of foodborne illness in the United States. Meat and poultry outbreaks are frequently

associated with Salmonella spp.

Salmonella occurs naturally in raw animal products; however, Salmonella should not be

found in RTE meat and poultry products because these products have undergone a

lethality treatment. Also, RTE products are intended to be consumed without further

preparation for safety (i.e., cooking), and if pathogens are present, their consumption

may cause illness. FSIS considers all RTE meat and poultry products that are

contaminated with Salmonella, as well as Listeria

monocytogenes and STEC, to be adulterated under the Federal

Meat Inspection Act and Poultry Products Inspection Act (21

U.S.C. 601(m)(1)) and 453(g)(1)). Any detectable Salmonella or

other pathogens of concern adulterates RTE products (64 FR

732).

Salmonella as an Indicator of Lethality

Meat and poultry products may be contaminated with Salmonella

during the slaughter and dressing process and by cross-

contamination in the processing environment when insanitary

conditions are present. For cooked products, FSIS recommends

that establishments use Salmonella as an indicator of lethality

because the thermal destruction of Salmonella in cooked

products would indicate the destruction of most other pathogens

(64 FR 732). If the establishment’s scientific support

demonstrates that the lethality treatment achieves sufficient

reduction in Salmonella, it does not need to provide additional

support that adequate reduction of other pathogens such as

STEC, Campylobacter, Lm, Trichinae spiralis or Toxoplasma

gondii is achieved. As stated in the FSIS Compliance Guideline

HACCP Systems Validation, establishments should not use

pathogens other than Salmonella as indicators of lethality for

cooked products unless the alternate pathogen displays similar

or higher resistance to the lethality processes.

NOTE: While Salmonella is considered an indicator of lethality

for validation purposes, in the event of a deviation where the

establishment missed its time-temperature parameters or

applied insufficient relative humidity, FSIS recommends testing for other pathogens of

concern (e.g., E. coli O157:H7 and Lm) because the absence of Salmonella does not

16

assure the absence of other pathogens since the establishment was unable to follow

the critical operational parameters in its scientific support. In addition, depending on the

type of deviation, other pathogens may also be of concern (e.g., C. perfringens and C.

botulinum). For more information see Attachment A2. Cooking Deviations, page 66.

How to Control Salmonella

Establishments must ensure the target Log reduction of Salmonella and other

vegetative pathogens is achieved throughout the product. To ensure vegetative

pathogens, including Salmonella, are killed on the interior of the product, the endpoint

time-temperature combination the product achieves is a critical operating parameter.

Most often, the target temperatures used during cooking reported in scientific support

documents and this guideline are the internal temperatures that the product should

reach. FSIS has found that some establishments use the recommendations established

for internal product temperature to set critical limits for the oven temperature. However,

setting the oven temperature to the temperature identified in the FSIS time-temperature

tables is not appropriate because doing so does not ensure that the product will reach

the same target internal temperature.

In addition to the product temperature, the amount of time the product is held at this

temperature (also known as the dwell time) is also critical to ensuring that adequate

lethality is achieved. If the product is held at the target temperature for less time than

specified in the time-temperature tables in this guideline, then adequate lethality may

not be achieved.

To ensure a process achieves the target Log reductions of Salmonella on the surface of

the product, moisture during cooking is a critical factor. Moisture (e.g., relative humidity)

around a product during cooking promotes lethality on the product surface in two ways:

• Moist cooking reduces surface evaporation from the product during heating

(evaporative cooling). Producing products under conditions of high moisture

early in the cooking process reduces evaporative cooling allowing product

surfaces to reach higher temperatures resulting in a greater reduction in

microorganisms; and

• Moist cooking keeps the product surface (and any pathogens) wet which

prevents product drying. Product drying reduces the water activity and

concentrates solutes (e.g., sugar and salt). Research has demonstrated that

bacteria can become more heat tolerant as their moisture levels decrease, and

increased concentrations of solutes, especially salt, increase the heat resistance

of bacteria (Buege et al., (2006), Boles et al., (2004), and Sindelar et al., (2016)).

Therefore, drying of the product surface before pathogens are destroyed will

increase pathogen heat resistance and allow the pathogens to survive the

heating process.

By incorporating moisture (e.g., relative humidity) to minimize evaporation and the loss

of surface moisture from the product, the D values (time at a constant temperature

necessary to destroy 90% or 1-Log of the target organism) that are the basis for the

17

time-temperature combinations, will remain valid (Goepfert, 1970; Goodfellow and

Brown, 1978). If evaporation, drying, or an increase in solute concentration is likely to

occur, the times and temperatures in scientific studies and supporting documentation

are not likely to be sufficient to provide the required lethality.

How does Moisture Ensure Bacteria on the Surface are Killed During Cooking?

During cooking, achieving a high oven temperature and internal product temperature

alone are not enough to ensure the final product is free of harmful bacteria.

Establishments need to make sure that cooking is done in a moist environment to

ensure lethality. When relative humidity is low, oven air is dry, and a process called

evaporative cooling increases, which is something we do not want. Evaporative

cooling is the same thing that allows humans to keep cool by sweating. When you get

too hot, you produce sweat, and when that sweat evaporates, it cools you down.

Evaporation equals cooling.

When you get too

hot…

…you produce

sweat.

When that sweat

evaporates…

…it cools you down.

Just like on a person’s skin, evaporative cooling cools down the surface of meat and

poultry during cooking. Although the oven is hot, because the surface of the product is

cooling down, that moisture evaporation can actually prevent the surface of the product

from becoming hot enough to kill off harmful bacteria. We can reduce evaporative

cooling by keeping the humidity in the oven high. That way the moisture in the product

does not evaporate as quickly, keeping the meat’s surface moist and hot and resulting

in an adequate bacterial kill. Why

does this work?

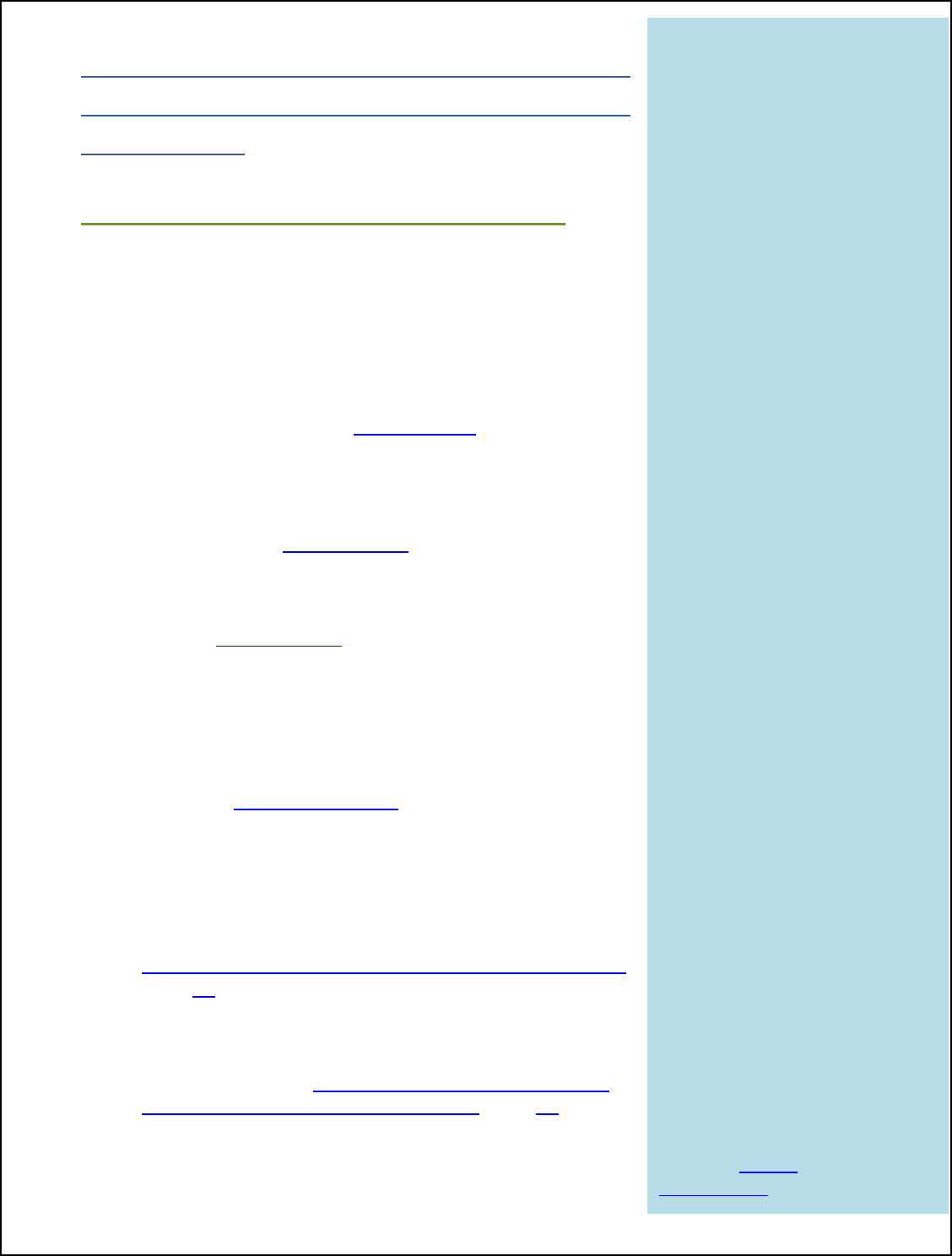

Imagine that you are in New

Mexico or Nevada where it is really

hot, but dry. If you’re outside,

you’re more likely to sweat and

that sweat will cool you down, so

you don’t feel as hot. Now imagine

you’re in Florida where it is not

only really hot, but also humid. If

you’re outside where it is humid,

your skin’s surface will stay sweaty

and hot, your sweat will not

Desert

Dry Heat

= Cooling Down

VS.

Tropical

More Humidity

= Less Cooling

evaporate, and you will not cool down. Since the air is already saturated, or full of

moisture (humid), there is less evaporation from your body and, therefore, less cooling.

The way humidity keeps you hot in Florida is the same way moisture keeps meat and

Evaporation

=

Cooling

18

poultry products hot, too.

19

General Considerations for Designing

HACCP Systems to Achieve Lethality

by Cooking

Addressing Lethality in the HACCP System

FSIS has established performance standards in the

regulations for specific ready-to-eat (RTE) products. The

performance standards for specific products set required

levels of Salmonella lethality during cooking as follows:

• Cooked poultry products must be processed to

achieve at least a 7-Log reduction of Salmonella or an

alternative lethality per 381.150(a)(1).

• Roast, cooked, and corned beef must be processed

to achieve at least a 6.5-Log reduction of Salmonella

or an alternative lethality (e.g., at least a 5-Log

reduction)) per 9 CFR 318.17.

• Cooked uncured meat patties must be processed to

meet or exceed the time-temperature combinations

listed in 9 CFR 318.23, which will achieve a 5-Log

reduction of Salmonella (and other pathogens

including STEC).

For products that are not subject to a performance standard,

FSIS recommends the following pathogen Log reductions

(i.e., targets) be achieved in order to support decisions in the

hazard analysis (9 CFR 417.5(a)(1)):

• For cooked meat products, FSIS recommends that

establishments achieve a target 6.5-Log or 5-Log

reduction of Salmonella in their process. To use a

target 5-Log reduction, establishments should provide

additional support for the safety of their process (see

Supporting an Alternative Lethality Target (e.g., 5-Log)

page 57).

• For shelf-stable meat products, FSIS recommends

that establishments achieve a target 5-Log reduction

of Salmonella (see How is Alternative 5-Log Lethality

Related to Risk of Foodborne Illness? page 57).

KEY DEFINITIONS

Performance standards

described in this guideline

are quantifiable pathogen

reduction levels or growth

limit requirements set by

FSIS for lethality and

stabilization of certain meat

and poultry products.

A Log reduction is a 90%

reduction of a pathogen.

For example, a 2-log

reduction is a 99%

reduction of a pathogen and

a 3-log reduction is a 99.9%

reduction of a pathogen in a

product.

Targets are quantifiable

pathogen reduction levels

or growth limits set by the

establishment to produce

safe products in the

absence of regulatory

performance standards.

An alternative lethality is a

treatment that achieves a

different (often lower) Log

reduction than what is

prescribed in the

regulations for certain

products, but still achieves

an equivalent probability

that no viable Salmonella

cells remain in the finished

product, nor other

pathogens and their toxins

or toxic metabolites. An

alternative lethality prevents

adulteration and must be

demonstrated to be

achieved throughout the

product (9 CFR

318.17(a)(1)).

20

An establishment should identify the performance standard or specific Log reduction

target its process is designed to achieve in its HACCP plan or supporting

documentation. If it does not, and FSIS cannot determine the pathogen reduction level

the process achieves, FSIS may determine the establishment lacks support for its

decisions related to Salmonella control (9 CFR 417.5(a)(1)). In addition, according to 9

CFR 417.2(c)(3), establishments must design their critical limits for Critical Control

Points (CCPs) to meet all applicable performance standards and targets.

NOTE: If an establishment uses the time-temperature tables provided in this guideline

or cooks beef patties according to 9 CFR 318.23, it does not need to indicate the

specific Log reduction that its process achieves. It would be sufficient for the

establishment to indicate that it uses time-temperature combinations from one of these

documents as these regulations were designed to achieve a 5-log reduction in

Salmonella and other pathogens including STEC.

Establishments are also required to validate that their HACCP system works as

intended to address these hazards (9 CFR 417.4(a)). For more information on

validation see the HACCP Systems Validation Guideline.

Key Question

Question: When a RTE meat food product is a mixture of meat and poultry such that the

product has a meat legend, and the establishment is following this cooking guideline, does the

RTE meat food product need to comply with the regulatory requirement found in 9 CFR

381.150(a)(1)?

Question: If a RTE meat food product has any amount of poultry in it, does it automatically

have to meet the poultry Log reduction in the FSIS Time-Temperature Tables?

Answer: Yes to both questions.

RTE meat or poultry food products consisting of any combination of meat and poultry must meet

the poultry lethality performance standard in 9 CFR 381.150(a)(1). Under the published final

rule "Performance Standards for the Production of Certain Meat and Poultry Products," cooked

product with any amount of poultry needs to meet the lethality requirements for the production of

fully cooked poultry products (9 CFR 381.150(a)(1)) which stipulate a 7-Log Salmonella

reduction or an alternative lethality that achieves an equivalent probability that no viable

Salmonella organisms remain in the finished product. This provision is based on the FSIS

national microbiological "baseline" survey of raw whole and ground meat and poultry products,

which found higher levels of Salmonella in poultry than in meat (USDA 1994, 1996a-f).

Consequently, FSIS established a higher lethality performance standard for RTE poultry

products than for meat (based on highest "worst case" levels).

21

Alternative Lethality

An alternative lethality is a treatment that achieves a different (often lower) Log

reduction than what is prescribed in the regulations but still achieves an equivalent

probability that no viable Salmonella cells remain in the finished product, as well as

ensures the reduction of other pathogens and their toxins or toxic metabolites (e.g.,

from S. aureus) necessary to prevent adulteration. Establishments may use alternative

lethality treatments to meet the performance standards (9 CFR 318.17(a)(1) and 9 CFR

381.150(a)(1)). When using an alternative lethality treatment (e.g., at least a 5-Log

reduction of Salmonella), the establishment must validate its HACCP system to ensure

that no viable Salmonella organisms (that is no organisms capable of causing human

illness) remain in the finished product. Risk assessments have demonstrated that

achieving a 5-Log reduction of Salmonella (instead of a 6.5-Log reduction) in cooked

meat and poultry products that are not shelf stable is less protective of public health

(Refer to text box: How is Alternative 5-Log Lethality Related to Risk of Foodborne

Illness? page 57). Therefore, to use these lower targets, the establishment must

provide additional support for its process as described in Attachment A1. Customized

Processes and Alternative Lethality Support: Supporting an Alternative Lethality Target

(e.g., 5-Log) on page 55. In contrast, risk assessments have shown that for shelf-stable

meat and poultry products, a 5-Log reduction of Salmonella (instead of a 6.5-Log or 7-

Log reduction) is sufficient. Therefore, no additional support is needed to use a 5-Log

reduction process in these shelf-stable products (9 CFR 417.5(a)(1) and 9 CFR

417.4(a)(1)).

Monitoring, Calibration, and Recordkeeping

The establishment’s cooking procedures should be designed to ensure all products in a

batch or lot achieve lethality, and the monitoring procedures should be designed to

detect a deviation when it occurs. To achieve these goals, establishments should

carefully consider the selection of the critical limit, as well as the design of their

monitoring procedures. Lessons learned from several recalls attributed, in part, to

insufficient monitoring procedures are shared on page 22.

Selection of the critical limit

Establishments producing cooked meat and poultry products should have sufficient

monitoring equipment, including recording devices, to assure that the time, temperature,

and relative humidity operating parameters of their processes are being met. With any

monitoring equipment, the establishment should take the normal variation of the

monitoring equipment into account when designing the critical limits. For example, if a

minimum internal temperature of 165°F is necessary to destroy pathogens in a product

and the thermometer has an accuracy of ± 1°F (plus or minus one degree), then the

critical limit should be set no lower than 166°F. The written reasoning and equipment

specification materials should be kept as part of the establishment’s supporting

documentation for its HACCP plan and the selection of its critical limit (9 CFR

417.5(a)(2)). All supporting documents and data from the recording devices must be

made available to FSIS employees upon request (9 CFR 417.5).

22

Selection of the monitoring procedures

Establishments are required to maintain documents supporting the selection of

monitoring procedures and associated monitoring frequencies (9 CFR 417.5(a)(2)). It is

important that establishments take into account variation within the cooking process

when developing monitoring procedures to ensure the procedures they develop can

identify any deviations.

In addition, to accurately measure the internal temperature of the meat or poultry

product, an establishment should understand the factors that can affect this

temperature. These factors include cold spots in the oven, as well as variations in oven

temperature during different seasons. Establishments should be aware that updated

smokehouses that contain alternating or rotating dampers that result in varying

breakpoints throughout the oven do reduce the temperature difference throughout the

oven, but they do not eliminate it. Although monitoring the internal product temperature

is strongly encouraged, an establishment can use the oven or smokehouse temperature

in place of the product temperature, provided that the establishment has a consistent

product and process and has sufficient data on file correlating the oven temperature

selected with the internal product temperature in the scientific support.

A disadvantage with monitoring oven temperature alone is that it may make supporting

product disposition after a cooking deviation more difficult. In many cases, FSIS

recommends using predictive microbial modeling programs to evaluate potential

hazards (see Attachment A2. Cooking Deviations on page 66). Microbial modeling

programs use product temperature to predict pathogen growth and potential Log

outgrowth or reductions achieved. Without product temperature records, the

establishment would need other support (e.g., product testing) to determine product

disposition.

Key Question:

Question: How does an establishment develop a monitoring procedure for measuring endpoint

temperature in meat or poultry products that are fried crispy such that a probe cannot be

inserted into the product to measure internal temperature (e.g., popped pork skins, and bacon

slices, pieces, or bits) because the product is too thin or hard or because the thin product cools

as soon as the product exits the cooking medium?

Answer: Depending on the product type, there are different recommendations. For example,

for a product such as bacon slices, it may be possible to cut a slice twice as thick as normal so

that the probe can be inserted. If this thicker piece reaches the lethality temperature, the thinner

pieces should as well. This procedure is also recommended for jerky. It is not recommended to

fold a piece of product over the thermometer, as this has been found to result in inaccurate

temperatures (Buege et al., 2006). For small products, such as bacon pieces or bits, it may be

possible to pile the pieces or bits around the thermometer for measurement. If none of these

procedures can be used, establishments may use other quantifiable measures such as a color

scale value that is correlated to crispiness or the number of pieces that pass as "fried until

crispy in all parts" based on a visual assessment as the critical limit for lethality for these

products due to the physical challenges in monitoring the internal temperature, and the lack of

outbreaks associated with them.

23

Lessons Learned from Undercooked Product Recalls

In 2016 and 2017, there were five recalls associated with under-cooked RTE poultry

products (RC-106-2016, RC-110-2016, RC-115-2016, RC-017-2017, and RC-037-

2017). For each of these recalls, FSIS determined that even though the establishments

had documentation showing the critical limit (either 160°F or 165°F) was met, there

were still pieces that may have entered commerce undercooked, indicating a loss of

process control and insufficient monitoring procedures to identify a process deviation.

Investigations revealed a variety of concerns related to monitoring procedures, including

taking temperatures from products not in the coldest spot, taking multiple product

temperatures, and averaging the results of multiple temperature measurements as

opposed to recording the lowest temperature.

Investigations also revealed a variety of contributing factors for inadequate cooking

including:

• Raw product was partially frozen.

• Belt speed was increased.

• Shorter dwell time and lower oven temperature than normal were used.

• Product was stacked during sous vide cooking, preventing full immersion of the

bags into the liquid cooking medium.

• Higher than normal product load overwhelmed the oven.

Each of these practices may have led to uneven or inadequate cooking. These findings

also highlight the importance of maintaining process control of critical operating factors,

such as oven temperature, product load, and belt-speed that affect the final product

temperature, dwell time, and relative humidity. The establishment is required to validate

that the entire HACCP system is operating as intended and to verify that it is producing

a safe and wholesome product on an ongoing basis.

Complete failure to document critical limit monitoring has also contributed to the recall of

cooked poultry products in the past due to a processing defect (RC-009-2017). Such a

failure highlights the importance of accurate records documenting the implementation of

the critical operating parameters to support the production of safe products.

Corrective Actions under HACCP Cooking Deviations

Cooking deviations occur when an establishment fails to meet its cooking CCP critical

limit or cooking humidity option. Common causes for cooking deviations include

product overlap, power failures, or breakdown of cooking equipment. The HACCP

regulations require establishments to take corrective actions in response to these

deviations, regardless of whether the cooking process is addressed through a CCP or

prerequisite program. Corrective actions include ensuring no product that is injurious to

health or otherwise adulterated because of the deviation enters commerce and

supporting product disposition decisions (9 CFR 417.3(a) and (b)).

24

When cooking is addressed through a CCP, establishments are required to determine

the cause of all cooking deviations, no matter how small (9 CFR 417.3(a)(1)), and

ensure measures are established to prevent recurrence (9 CFR 417.3(a)(3)). Continual

or repetitive process deviations from the critical limit demonstrate that the establishment

is unable to control its process.

When cooking is addressed through a prerequisite program, establishments are

required to reassess their HACCP system to determine whether the newly identified

deviation or unforeseen hazard should be addressed and incorporated into the HACCP

plan (9 CFR 417.3(b)(4)). Also, an establishment may not be able to continue to

support the decision in its hazard analysis that pathogens are not reasonably likely to

occur, if it has continual or repetitive deviations from its cooking prerequisite program (9

CFR 417.5(a)(1)). For more information on evaluating product disposition after a

cooking deviation see Corrective Actions to Perform When a Cooking Deviation Occurs

(page 66).

FSIS Critical Operating Parameters for Cooking

(Time-Temperature Tables)

Establishments that cook products to achieve lethality by applying the time-temperature

combinations from this guideline need to consider the critical operating parameters that

may affect pathogen Log reductions, specifically:

• Come-up-time (CUT),

• Relative Humidity, and

• Endpoint Time-Temperature.

Additionally, establishments cooking poultry products need to consider product species

composition and fat content if applying FSIS cooking lethality guidance in the tables on

pages 37 and 38. The FSIS Cooked Poultry Rolls Options (page 39) apply to all poultry

products regardless of poultry species or fat content. For information about why product

species should be considered when applying cooking lethality guidance on pages 37

and 38 and not when applying the FSIS Cooked Poultry Rolls Options see page 36.

Come-Up-Time (CUT)

When applying one of the time-temperature tables from this guideline, an establishment

must also consider the heating CUT to be a critical operating parameter unless the

establishment can provide a science-based rationale why heating CUT does not need to

be addressed. For example, products that are fermented and then cooked to lethality

may control S. aureus outgrowth by lowering the pH following the degree-hour concept

as recommended in the American Meat Institute’s Good Manufacturing Practices for

Fermented Dry & Semi-Dry Fermented Sausathge Products and therefore would not

address CUT.

FSIS has developed a CUT Option that establishments may use to support its process

control of S. aureus growth, specifically ≤ 2-Log that also

prevents enterotoxin formation:

Come-Up-Time Option: Total time product temperature is

between 50 and 130°F is 6 hours or less.

NOTE: This CUT Option is only for products that were cooked to

lethality (including those cooked to lethality but classified as

NRTE under a heat treated, not fully cooked, not shelf-stable

HACCP plan). Please refer to the FSIS Stabilization Guideline for

Meat and Poultry Products for the Agency’s recommendations

regarding CUT in partially cooked products that do not receive a

full lethality. Please also refer to the product reclassification

guidance in the Listeria Guideline, Attachment 1.2 on pages 22-

23 and Appendix 1.2 on pages 28-29.

FSIS is aware that establishments preparing some products (e.g.,

ham or beef brisket) may not be able to follow FSIS’s Come-Up-

Time Option above because of the thermodynamics of the

heating process. Therefore, FSIS identified long CUT as a

Scientific Gap since support does not exist for many common

processes (page 48). Additionally, alternative support for certain

long CUT processes have been included in Attachment A1.

Customized Processes and Alternative Lethality Support (page

55).

Temperatures referred to in FSIS’s Come-Up-Time Option above,

are internal temperatures. However, establishments may monitor

surface temperatures during CUT, if the establishment provides

support the product is intact and processed so pathogens have

not been introduced below the product surface. Non-intact

product temperatures should be taken internally at the center of

KEY DEFINITIONS

Come-up-time refers to

the

amount of time product

temperature is between 50-

130°F while heating.

Intact refers to products

where the interior remains

protected from pathogens

migrating below the

exterior/outside (such as

beef brisket or a picnic

shoulder that is not injected

or vacuum tumbled).

Non-Intact refers to

products where pathogens

may have been introduced

below the surface.

Examples include products

that have been

mechanically tenderized

(including those that have

been injected with

marinade or solution) or

vacuum tumbled.

the product (see Key Definitions panel to the right for an explanation of intact and non-

intact products). Establishments should also take temperatures at the center of the

product for products such as deboned and rolled hams where a portion of the product is

rolled or folded over and pathogens may be internalized.

NOTE: FSIS time-temp tables list internal endpoint temperatures during cooking. It is

not supportable to use surface temperature to address endpoint temperature. FSIS is

only making this recommendation for its CUT option.

24

Relative Humidity

FSIS time-temperature tables use relative humidity as a critical operating parameter to

ensure moist cooking and adequate surface lethality. An establishment that uses the

FSIS time-temperature tables to support its cooking process must address humidity,

unless it meets one of the criteria listed in Situations when Humidity is Not Needed

(page 31) or provides additional support for why

humidity would not be needed in its process to ensure

lethality on the product surface. FSIS has included

specific relative humidity options for use with the time-

temperature tables (page 26). Additional resources

for determining which relative humidity option to adopt

are included in Relative Humidity Resources (page

28).

NOTE: FSIS is aware that some establishments may

not be able to use FSIS’s humidity options because of

the nature of the cooking process. Examples include

products cooked for short times at high temperatures

(e.g., for meat balls or chicken tenders) or other

processes that do not allow the use of humidity (e.g.,

barbecue products cooked under dry heat including

those cooked in smokehouses or open pits). Please

refer to Scientific Gaps Identified by FSIS (page 41).

Selection of the proper relative humidity option

depends on the endpoint time-temperature. Products

cooked to endpoint time-temperatures of at least

145°F plus the dwell time, may apply any of the

relative humidity options in Table 1. Critical

Operating Parameters for FSIS Humidity Options.

25

Key Question

Question: An establishment cooks a brisket to full lethality but realizes the smoke

coloring is too light and wants to recook it to deepen the color. Can the establishment

apply a new 6 hour CUT for the second cook?

Answer: Yes. Once a product achieves a lethal time-temperature combination, the

allowed CUT is reset for the next cook. If the establishment chooses to recook the

product, it may apply a new 6 hour CUT limit (page 23). However, if the product did not

achieve a lethal time-temperature combination during the first cooking process, the CUT

does not start over. The establishment should support the total time product temperature

is between 50 and 130°F is 6 hours or less. Please review Attachment A2. Cooking

Deviations subsection Missed Time-Temperature Parameter (page 67) for additional

information.

KEY DEFINITIONS

Maintaining humidity means

keeping the humidity at the same

level throughout the cooking

process. If the humidity drops

during the cooking process, the

establishment will need to

provide additional support for the

safety of the product

A sealed oven is generally

defined as one in which the

smokehouse doors and oven

dampers are closed to prevent

moisture loss.

The cooking time includes the

time the product is placed in the

heated oven (including surface

preparation and color setting)

until the product reaches the

desired lethality time-

temperature combination (also

referred to as the “lethality

treatment”).

26

However, products cooked to an endpoint less than 145°F, should select Option 3 or 4

in Table 1. Critical Operating Parameters for FSIS Humidity Options depending on total

cooking time.

NOTE: To be most effective, humidity needs to be applied during the lethality

treatment, before drying. Using this guideline to support lethality processes in which

the drying step comes before the moist cooking step (e.g., country-cured ham)

creates a vulnerability in the establishment’s HACCP system. Establishments using

this guideline for these processes should read Attachment A6. Cooking Country-

Cured Hams (page 90) for recommendations to reduce this vulnerability, such as

measuring water activity after cooking to verify it increases and the product surface

was rehydrated during cooking.

To ensure that adequate humidity is attained, the establishment should monitor

the humidity throughout the lethality treatment. The process should be monitored

using wet and dry bulb thermometers (used to determine relative humidity) or a humidity

sensor. FSIS recommends that establishments monitor relative humidity for every lot or

batch of product produced.

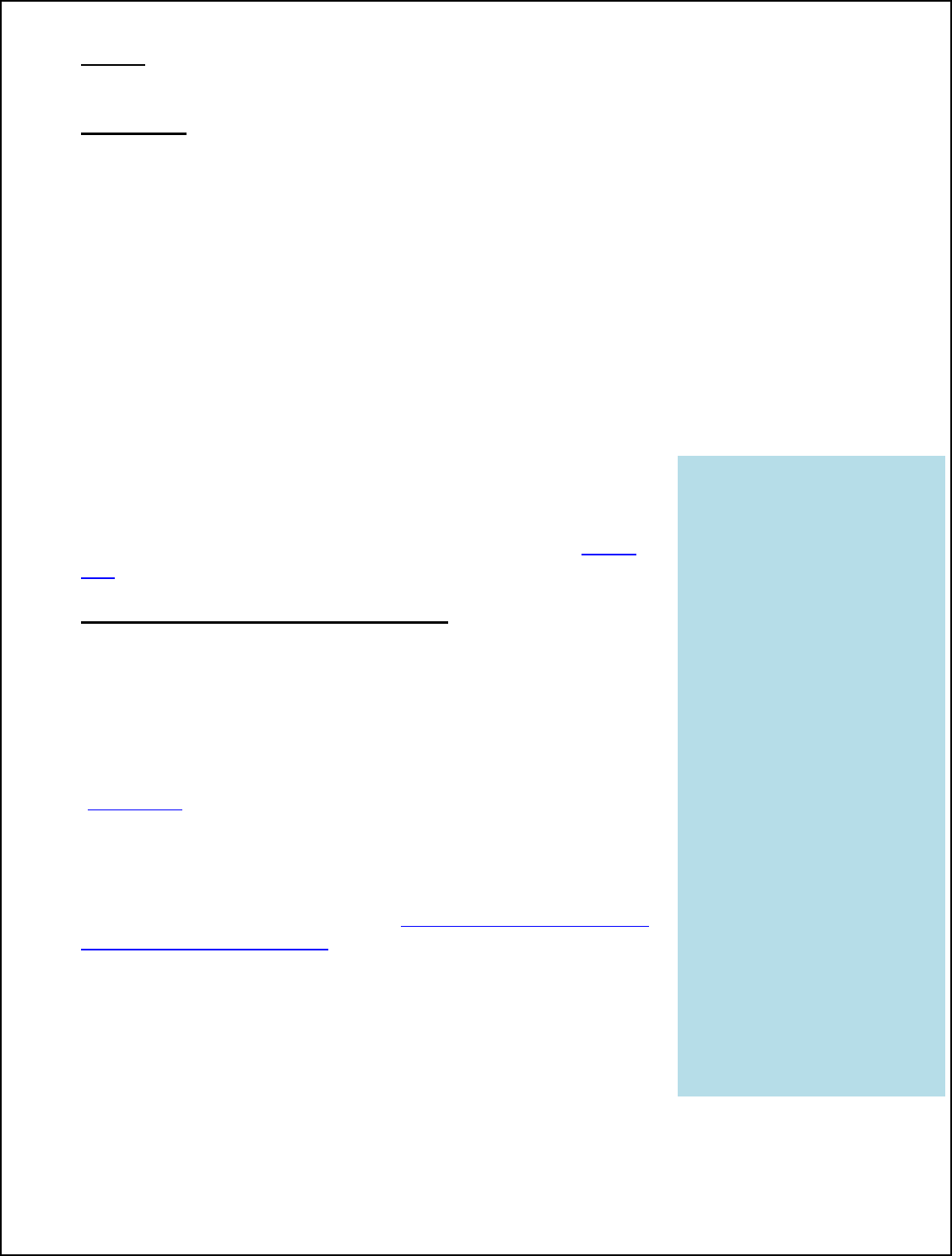

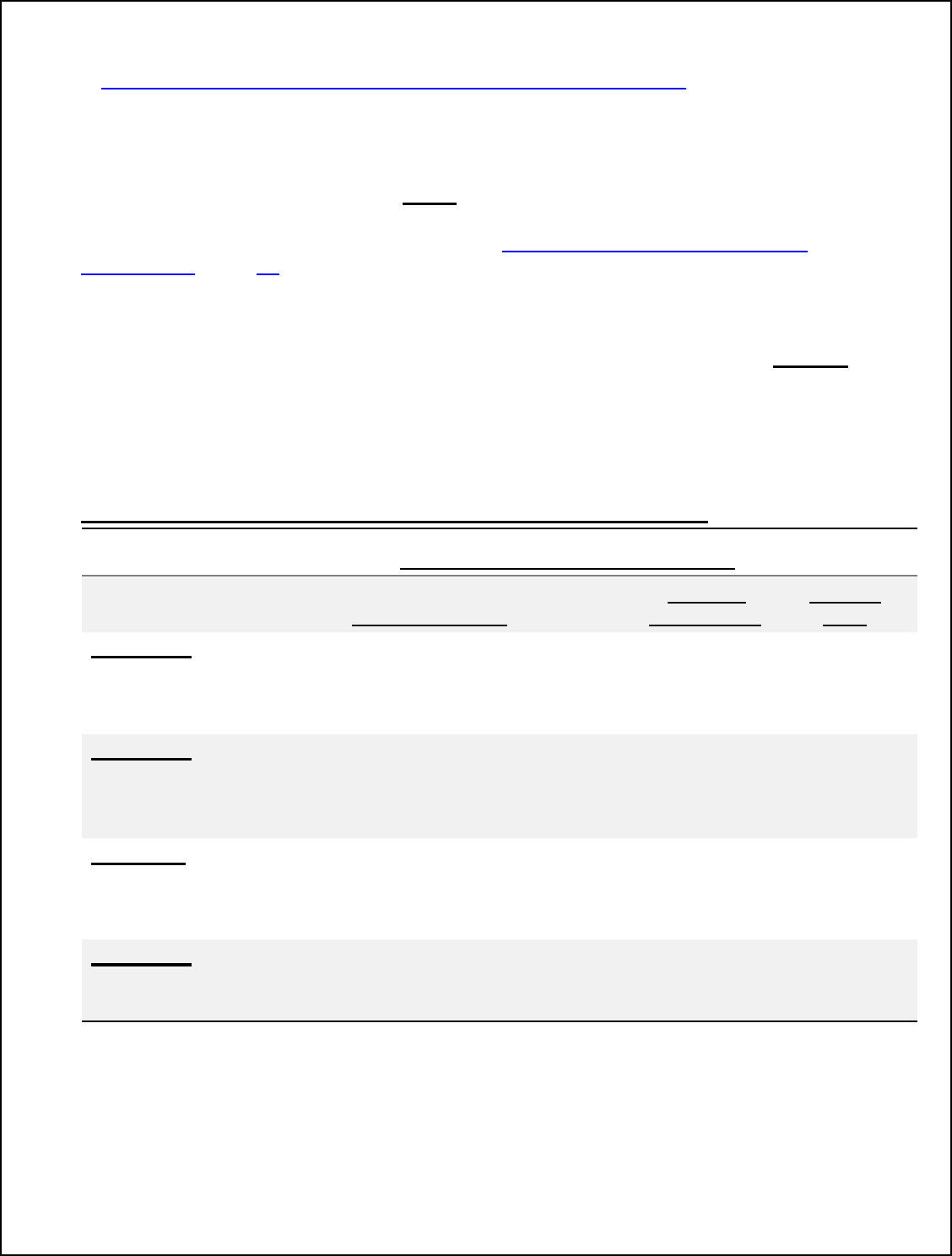

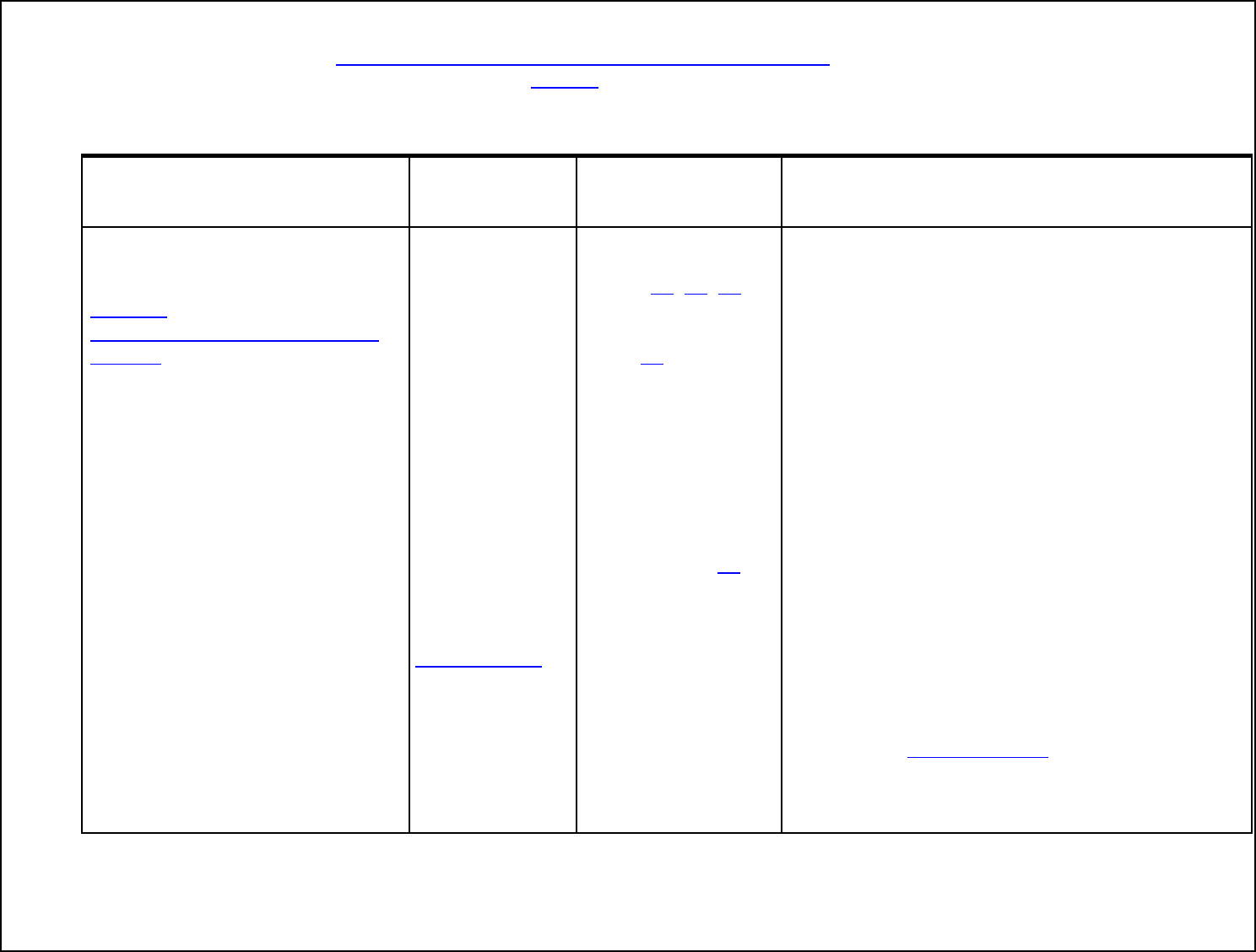

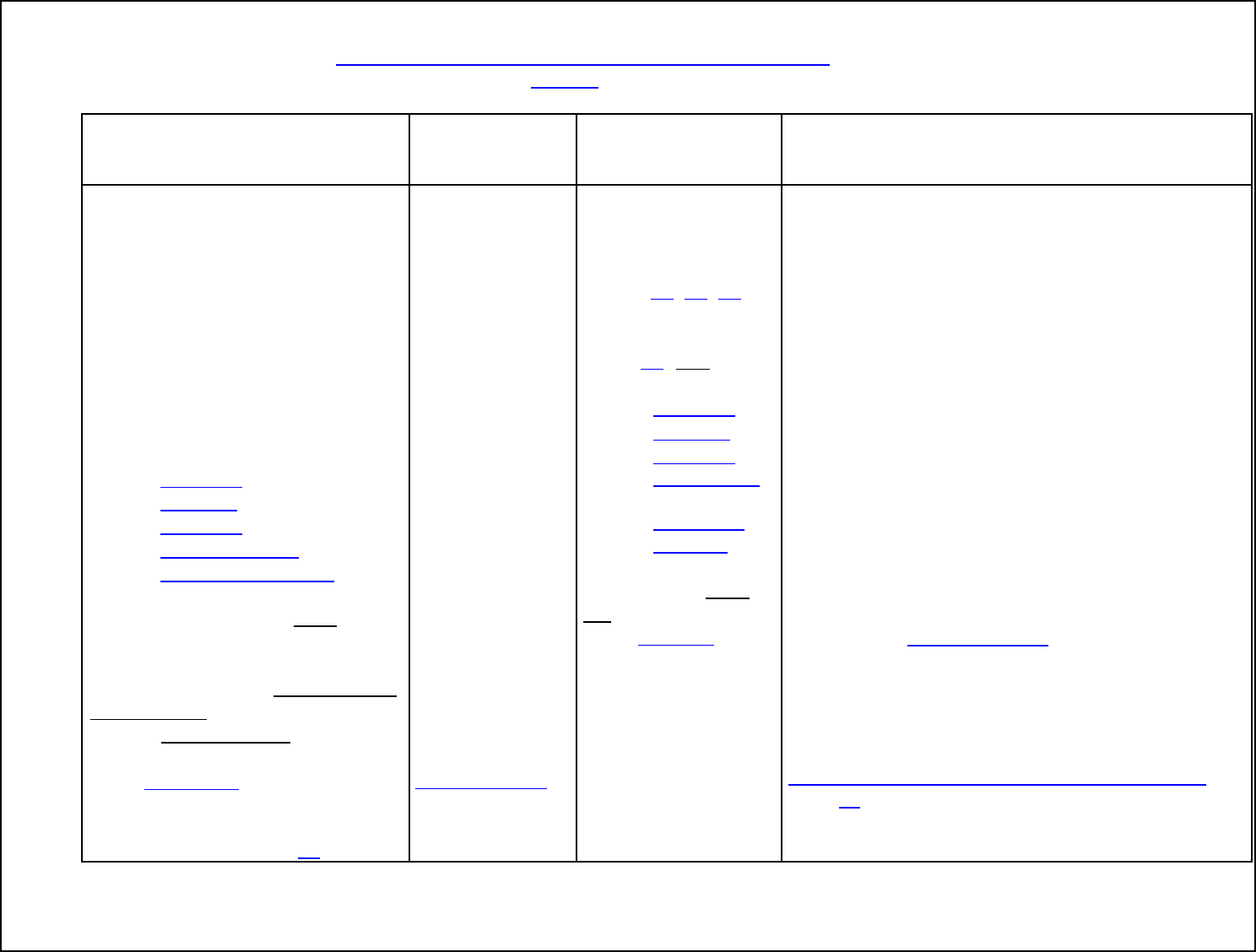

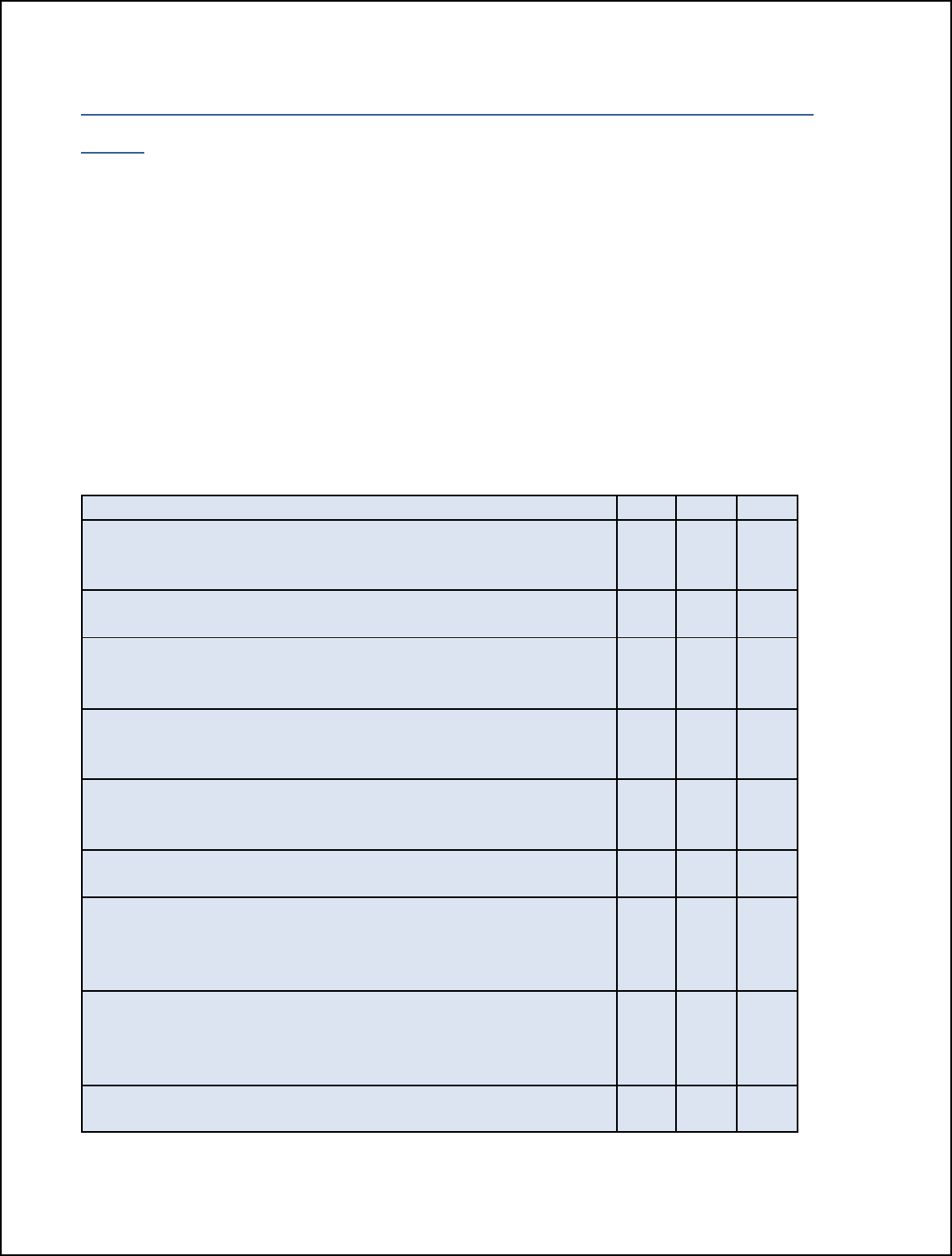

Table 1. Critical Operating Parameters for FSIS Humidity Options

CRITICAL OPERATING PARAMETERS

Relative Humidity

Endpoint

Temperature

Cooking

Time

OPTION 1:

The relative humidity of the oven is

maintained by continuously introducing

steam for 50 percent of the cooking time,

or 1 hour, whichever is longer.

≥145°F +

dwell time

≥1 hour

OPTION 2:

The relative humidity of the oven is

maintained by a sealed oven for at least

50 percent of the total cooking time, or 1

hour, whichever is longer.

≥145°F +

dwell time

≥1 hour

OPTION 3: The relative humidity of the oven is

maintained at 90 percent or above for at

least 25 percent of the total cooking time,

or 1 hour, whichever is longer.

Any ≥1 hour

OPTION 4:

The relative humidity of the oven is

maintained at 90 percent for the entire

cooking time.

Any

Any

27

Key Question

Question: To follow the sealed oven or steam injection options, must establishments

achieve a specific relative humidity?

Answer: No. Establishments do not need to achieve a specific relative humidity level in

the oven if they are following the steam injection or sealed oven options in this guideline

as their scientific support. Based on expert opinion, the 2014 FSIS Jerky Guideline

recommended that establishments producing jerky that monitor relative humidity try to

achieve a wet bulb temperature of at least 125-130°F for 1 hour or more along with a

corresponding dry bulb temperature needed to achieve at least 27-32% relative humidity

or more. However, the Jerky Guideline also noted, achieving a wet bulb temperature of at

least 125-130°F and at least 27-32% relative humidity for 1 hour or more is not adequate

on its own to support that the process is being implemented consistently with FSIS

Humidity Options. Rather, establishments should ensure that all critical operating

parameters described in this guidance are met. Relative Humidity Resources (page 28

contains specific guidance for how to implement Option 1 steam injection and Option 2

sealed oven in a validated HACCP system. In addition, establishments should not apply

the wet-bulb and relative humidity recommendations in the Jerky Guideline to other

products without additional support.

Current Support for FSIS Relative Humidity Options

Although the research cited as the basis of FSIS guidance dates as far back as 1978,

newer research by McMinn et al., (2018) supports that the time-temperature parameters in

FSIS’s cooking guidance achieves sufficient reductions of Salmonella. This research by

McMinn et al. (2018) was conducted with product cooked in vacuum-sealed bags

supporting the importance of cooking in a high moisture environment. While newer

research has not been conducted to validate the sealed oven and steam injection relative

humidity options, research does continue to support the importance of moisture during

cooking. For example, Mann and Brashears (2007), support the need for at least 30%

relative humidity during cooking of roast beef. Based on FSIS knowledge of

establishments’ processes through its verification activities, the Agency believes when the

oven is sealed, or steam is introduced, at least 30% relative humidity is maintained,

suggesting that these practical recommendations result in adequate relative humidity.

The Agency is also not aware of any establishments that have had Salmonella positives or

been associated with a salmonellosis outbreak when following FSIS temperature, time,

and relative humidity guidance while using effective monitoring procedures.

2

*Relative humidity (RH) is 90% or higher for at least 25% of the total cooking

time, or 1 hour, whichever is longest.

**RH is maintained for

50% of the cooking time, or 1 hour, whichever is

longest

For more information,

refer to FSIS Relative Humidity Options on page 25.—

wouldn’t it be good to put the information together?

Additionally,

the following information in the FSIS Jerky Guideline can be

useful when deciding which humidity option to adopt:

Instructions for making your own wet bulb (reprinted with

permission from the University of Wisconsin, page 49); and

An example of a time-temperature recorder chart to support the

option of continuously injecting steam (page 53).

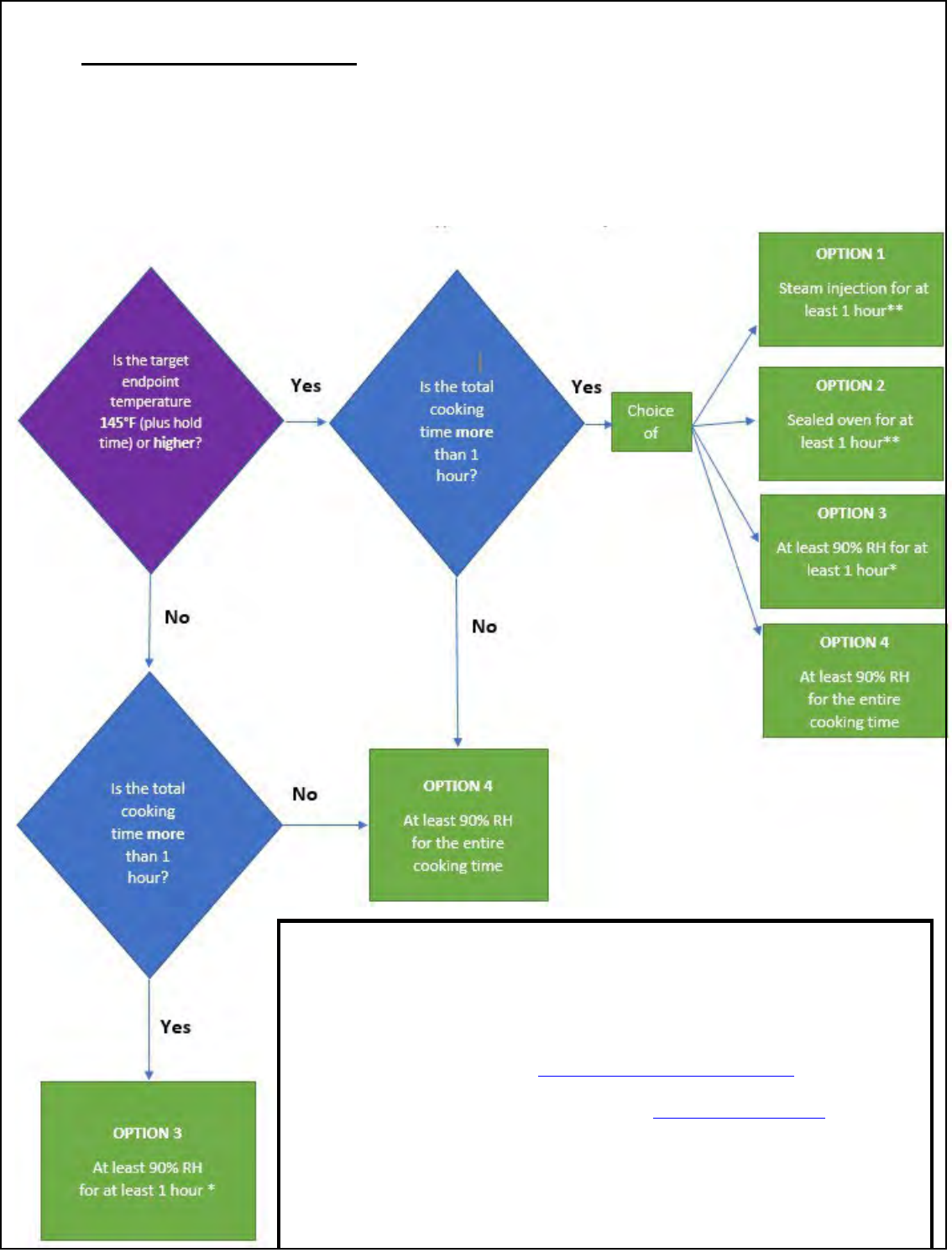

Relative Humidity Resources

The following flow chart contains specific guidance for how to choose a humidity option

and the resources on the next two pages are designed to help establishments

implement Option 1 steam injection and Option 2 sealed oven in a validated HACCP

system.

Flow Chart to Choose a Humidity Option