Occasional Paper Series

The use of cash by households

in the euro area

Henk Esselink, Lola Hernández

Disclaimer: This paper should not be reported as representing the views of the European Central Bank

(ECB). The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the ECB

.

No 201 / November 2017

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 201 / November 2017

1

Contents

Abstract 3

Executive summary 4

1 Introduction 6

2 Research method and sample 9

2.1 Research scope and research population 9

2.2 Sample 9

2.3 Research method 12

Box 1 Payment diary surveys in Germany and the Netherlands 13

2.4 Recruitment of respondents and data collection 13

2.5 Translation of survey material 14

2.6 Weighting and adjustments 14

3 Validation 16

4 Cash usage in the euro area 18

4.1 Relative use of payment instruments 18

4.2 Average value of transactions 20

4.3 Average number of transactions per person per day 22

4.4 Payment behaviour by demographic characteristics 22

4.5 Use of payment instruments by value range 24

5 Use of payment instruments by market segment and for recurrent

payments 26

5.1 Market share of payment instruments by number of transactions 26

5.2 Market share of payment instruments by value of transactions 27

5.3 The use of cash for recurrent payments 28

6 Contactless payments in the euro area 30

7 Card ownership and card acceptance 32

7.1 Card ownership 32

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 201 / November 2017

2

7.2 Card acceptance 33

8 Amount of cash people carry 34

9 How people acquire cash 36

9.1 Cash withdrawal and replenishment by source 36

9.2 Regular income in cash 39

10 Cash as a store of value and use of high denomination banknotes 41

10.1 Cash as a store of value 41

10.2 Use of high denomination banknotes 43

11 Cash withdrawal habits and satisfaction with ATM services 46

11.1 Cash withdrawal habits by source 46

11.2 Satisfaction with ATM services 47

11.3 Satisfaction with ATM denominations 49

12 Payment preferences and other factors that influence consumers’

payment choices 52

12.1 Payment preferences 52

12.2 Factors that influence respondents’ choice of payment

instrument 54

13 Concluding remarks 56

References 57

Annex A Definition of payment instruments 59

Annex B Diary survey questionnaire: Study on the use of cash by

households 2016 61

Annex C Use of high denomination banknotes 67

Abbreviations 69

Acknowledgements 70

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 201 / November 2017

3

Abstract

Although euro banknotes and coins have been in circulation for fifteen years, not

much is known about the actual use of cash by households. This paper presents an

estimation of the number and value of cash transactions in all 19 euro area countries

in 2016, based on survey results. It presents an extensive description of how euro

area consumers pay at points of sale (POS). The aim of this study is to shed light on

consumers’ payment behaviour and in particular to improve the understanding of

consumers’ payment choices at POS, based on a large sample of countries.

Therefore, it provides central banks and relevant payment system stakeholders with

fundamental information for the development of their policies and strategic decisions

that can contribute to improving the efficiency of the cash cycle and the payment

system as a whole. Previous estimates of the value of cash usage by households in

the euro area date from 2008. Since then some central banks have carried out their

own research on cash usage. This paper is the first study to measure the transaction

demand for cash in the euro area. The results show that in 2016 around 79% of all

payments at POS were made with cash, 19% with cards and 2% with other payment

instruments. In terms of value, the market share of main payment instruments was

54% for cash, 39% for cards and 7% for other instruments. However, results show

substantial differences between euro area countries.

Keywords: payment behaviour, money demand, payment systems, cash, consumer

choice.

JEL codes: E41, E58, D12, D14.

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 201 / November 2017

4

Executive summary

The European Central Bank (ECB) has conducted a comprehensive study to analyse

the use of cash, cards and other payment instruments used at points of sale (POS)

by euro area consumers in 2016.

1

This paper presents the results of the study,

including an estimation of the number and value of payments made with cash and

cards by consumers in the euro area during the period under consideration. The

study also assesses the use of each payment instrument by consumers at the

country level. The methodology is first discussed, and the main findings of the study

are then reported.

The survey results show that in 2016 cash was the dominant payment instrument at

POS. In terms of number, 79% of all transactions were carried out using cash,

amounting to 54% of the total value of all payments. Cards were the second most

frequently used payment instrument at POS; 19% of all transactions were settled

using a payment card. In terms of value, this amounts to 39% of the total value paid

at POS.

The use of cash and cards differs according to country, place of purchase,

transaction value and consumers’ demographic characteristics. In terms of number

of transactions, cash was most used in the southern euro area countries, as well as

in Germany, Austria and Slovenia, where 80% or more of POS transactions were

conducted with cash. Cash was least used in the Netherlands, Estonia and Finland,

where its share in the number of transactions ranged between 45% and 54%. In

terms of value, the share of cash was highest in Greece, Cyprus and Malta (above

70%), while it was lowest in the Benelux countries, Estonia, France and Finland (at,

or below, 33%). When looking at the demographic characteristics of euro area

consumers, it can be concluded that men tend to use cash more often than women.

Furthermore, consumers aged 40 and over use more cash than younger age groups,

whereas cash usage appears to be relatively homogeneous across different levels of

education.

Overall, the results put the use of cash relative to non-cash payment methods by

consumers at POS into perspective, and indicate that the use of cash at POS is still

widespread in most euro area countries. This seems to challenge the perception that

cash is rapidly being replaced by cashless means of payment.

Indeed, as the results of this study show, when consumers are asked which means

of payment they prefer, a larger share report to prefer cards rather than cash –

despite the fact that they use cash more often. This contradiction may be explained

by the fact that nearly two-thirds of the transactions conducted at POS in 2016 were

1

By other payment instruments at POS we refer to the use of cheques, direct debit, credit transfers and

mobile payments, among others. We have grouped them into one category given their relatively small

market share compared with cash and cards. For a detailed definition of all payment instruments

considered in the study, see Annex A. The use of virtual currencies was not within the scope of this

study.

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 201 / November 2017

5

below €15. Moreover, two-thirds of all POS transactions took place in shops for

purchases of day-to-day items, as well as in restaurants, bars and cafés. On the

other hand, only 8% of all POS transactions were above €50, and only 14% were

made in shops for durable goods or in petrol stations.

When asked about their payment behaviour, people mostly seem to remember the

larger value payments which they make less regularly, and tend to forget how

frequently they make low-value payments on a daily basis.

Access to payment cards does not seem to fully explain differences in payment

behaviour, because on average access is high in all euro area countries. However,

there seems to be a relationship between card acceptance (i.e. the perceived

availability of card payment terminals) and cash usage. It can therefore be expected

that in countries and market sectors where card acceptance is still low, cash usage

may decrease once infrastructure for making card payments becomes more widely

available.

Although the share of contactless payments in many countries is still low, the survey

results suggest that the speed with which such payments have been embraced in

some countries may mean that once payment cards and POS terminals are enabled

with contactless technology on a wider scale, the share of contactless payments

could increase significantly. Since contactless payments are typically relatively low

value and 81% of all payments at POS are below €25, this could have a significant

impact on the use of cash for smaller value payments, especially given that

respondents who prefer cash and those who prefer cards both appear to place

importance on the transaction speed of their preferred means of payment.

The study confirms that cash is not only used as a means of payment, but also as a

store of value, with almost a quarter of consumers keeping some cash at home as a

precautionary reserve. It also shows that more people than often thought use high

denomination banknotes; almost 20% of respondents reported having a €200 or

€500 banknote in their possession in the year before the survey was carried out.

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 201 / November 2017

6

1 Introduction

Keeping abreast of the latest cash usage trends is essential for both the Eurosystem

and the relevant stakeholders of the payment system. National central banks are

responsible for the issuance of banknotes and often for the distribution of coins in

their respective countries. They require reliable statistics that allow them to compare

the development of cash usage in the different countries of the euro area.

Nevertheless, to date there have been no reliable statistics on the number and value

of cash transactions and there is limited information on the differences between euro

area countries regarding the use of cash compared with other means of payment.

With the increase in card payments and the rise of alternative payment methods, the

future of cash is under discussion and the relevance of cash in society is being

challenged.

However, without knowing exactly how people currently pay, these discussions have

no solid basis and result in speculation rather than fact-based findings. Often,

conclusions on payment behaviour in a certain country are drawn based on studies

available on other countries, without knowing whether people exhibit similar payment

behaviour in the country concerned. Moreover, data provided by certain retail chains

or associations of retailers may not give accurate information on payment behaviour

in general, as payment behaviour differs between market sectors. For example,

people may pay in different ways depending on whether their purchase is made at a

large supermarket chain or at a bakery.

Central banks have a strong interest in having accurate data on cash usage for

discussions on the role of cash in society, as well as for the development of their

policies and strategic decisions regarding the cash cycle and the efficiency of the

payment system as a whole. For example, the costs of cash and counterfeiting

statistics can be placed in perspective when the actual number of cash transactions

is known. Furthermore, for the development of certain policies it is important to

understand the determinants of cash usage, since this can be supply and/or demand

driven.

The latest estimates on cash usage in the euro area date from 2008, when the value

of cash transactions was estimated to amount to between €1,800 and €2,100 billion

(ECB 2011). This estimate was based on a household survey, payment statistics and

a company survey. The household survey involved 8,175 respondents from eight

euro area countries – Belgium, Germany, Spain, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the

Netherlands and Austria

2

– and was conducted between 18 September and

31 October 2008 by means of a questionnaire (i.e. no payment diary was used). The

ECB’s company survey on the use of cash was carried out in 2008 in the same

countries as the household survey (except Luxembourg) and surveyed a sample of

3,052 small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

2

These eight countries issued 92% of all banknotes in the euro area in 2008. See ECB (2011).

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 201 / November 2017

7

In order to better understand the current developments in cash usage, the

Eurosystem agreed in 2014 to conduct the survey on the use of cash by households

(SUCH) in all euro area countries, except in Germany and the Netherlands, where

the corresponding central banks have been carrying out similar payment diary

surveys since 2008 and 2007, respectively. The latest available survey results from

these countries are from 2014 for Germany and 2016 for the Netherlands. Even

though the methodology used in the SUCH survey is similar to the methodologies

used by the central banks of Germany and the Netherlands, the central banks in

those countries preferred to continue using their own methodology in order to avoid

deviating from their historical results. Nevertheless, to the extent possible, the results

of those countries have been integrated to present the results for the whole euro

area.

3

The ECB’s SUCH survey was conducted from October to November 2015 and

from January to July 2016. It involved 65,281 respondents who kept a diary to write

down all the payments and cash withdrawals or replenishments that they carried out

during the course of a single day. In the specific case of Cyprus and Malta,

respondents used three-day diaries. A total of 128,677 payments were reported. A

subset of 28,099 respondents was also invited to complete a questionnaire in order

to collect information on consumers’ access to payment instruments, their payment

behaviour and to analyse these results together with the reported transactions. The

total number of survey participants for the whole euro area, including Germany and

the Netherlands, was 92,080, reporting a total of 198,600 payments.

This paper reports on the main findings and conclusions of the SUCH survey. It

presents an extensive description of how euro area consumers pay at POS. The aim

of this study is to shed light on consumer payment behaviour in the euro area and in

particular to improve the understanding of cash payment economics based on a

large sample of households and countries. The paper is mainly descriptive in nature,

does not aim to analyse differences in payment behaviour in depth and suggests

opportunities for further research. It is hoped that, together with the unique

underlying data, it will lead to future research on the use of cash and cashless

means of payment.

The paper is organised as follows. Section 2 describes the research method and

sample used and Section 3 describes the validation of the survey results. Section 4

presents the findings related to the use of cash and other payment instruments in the

euro area. Specifically, it analyses the use of cash relative to other payment

instruments in terms of number and value of payments, by transaction amount, and

describes the impact of personal characteristics on consumers’ choice of payment

instrument. Section 5 analyses cash usage by market segment and the use of cash

for recurrent payments. Section 6 describes the use of contactless payments and

Section 7 presents the findings on card ownership and the acceptance of non-cash

instruments. Section 8 is dedicated to the amount of cash euro area consumers

carry in their wallet. Section 9 discusses how consumers obtain their cash and

Section 10 presents the results on the use of cash as a store of value and the use of

3

Each time the euro area results of 19 countries are presented it should be taken into account that the

results for Germany are from 2014 and that this country has a relatively high weight in the overall

results of the euro area. For a more detailed description of the German survey see Bundesbank (2015)

and for the Dutch survey see Jonker, Kosse and Hernandez (2012).

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 201 / November 2017

8

high denomination banknotes. Section 11 addresses consumers’ cash withdrawal

habits and their satisfaction with ATM services. Section 12 highlights consumers’

payment preferences and other factors which determine consumers’ payment

choice. Section 13 concludes.

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 201 / November 2017

9

2 Research method and sample

2.1 Research scope and research population

The purpose of this study is to analyse the number and value of cash payments

made in the euro area in 2016. In order to examine consumers’ payment behaviour

and the role played by cash, the study takes into account the use of cards and other

payment instruments commonly used at POS, including cheques, direct debits, credit

transfers and mobile payments. The study is limited to euro area residents aged 18

years and over and excludes payments made by consumers travelling outside of

their place of residence, as well as payments made by tourists, other non-residents

and payments between businesses. The study excludes payments carried out by

respondents who are below 18 years old in all countries except the Netherlands,

where payments by children from 12 years old were considered. The study includes

information on payments carried out at POS, as well as those carried out between

individuals, such as relatives and friends, charity donations or for home services

(e.g. babysitting) which are referred to as person-to-person payments here.

Recurrent payments (such as rent and utilities) are excluded from the study, unless

they were paid at a POS.

4

Internet payments (e.g. online shopping) were recorded in

the payment diaries but are excluded from the analysis, as the objective of the study

is to assess the attitudes towards and choice between cash and other payment

methods; cash is usually not accepted to pay for remote payments. For the same

reason, person-to-person payments were recorded, but not included in the results on

the share of cash and non-cash means of payment at POS.

5

It should be noted that

the remainder of this chapter mainly describes the research method and sample of

the survey on the use of cash by households carried out by the ECB in 17 euro area

countries and does not describe the methods used in the German and Dutch study.

2.2 Sample

The field work was carried out by Kantar Public (Brussels) in three waves from

October 2015 to July 2016. A total of 65,281 respondents participated in the diary

survey, reporting 128,677 transactions in the euro area, excluding Germany and the

Netherlands. The survey was carried out over eight months; 31% of interviews were

held in 2015 and 69% in 2016 (see Table 1). Over two-thirds of interviews were

carried out in October, November and February, which are considered to be fairly

average months with respect to POS payments made by consumers. The total

sample for the euro area – including data from Germany and the Netherlands – is of

92,080 respondents, reporting a total of 198,600 payments.

4

However, a question on recurrent payments was included in the survey questionnaire answered by a

subset of respondents.

5

With the recent developments in instant payment solutions, the choice to use alternative means of

payment rather than cash for person-to-person payments is expected to increase. Therefore, in future

research on these payments may be included in the results.

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 201 / November 2017

10

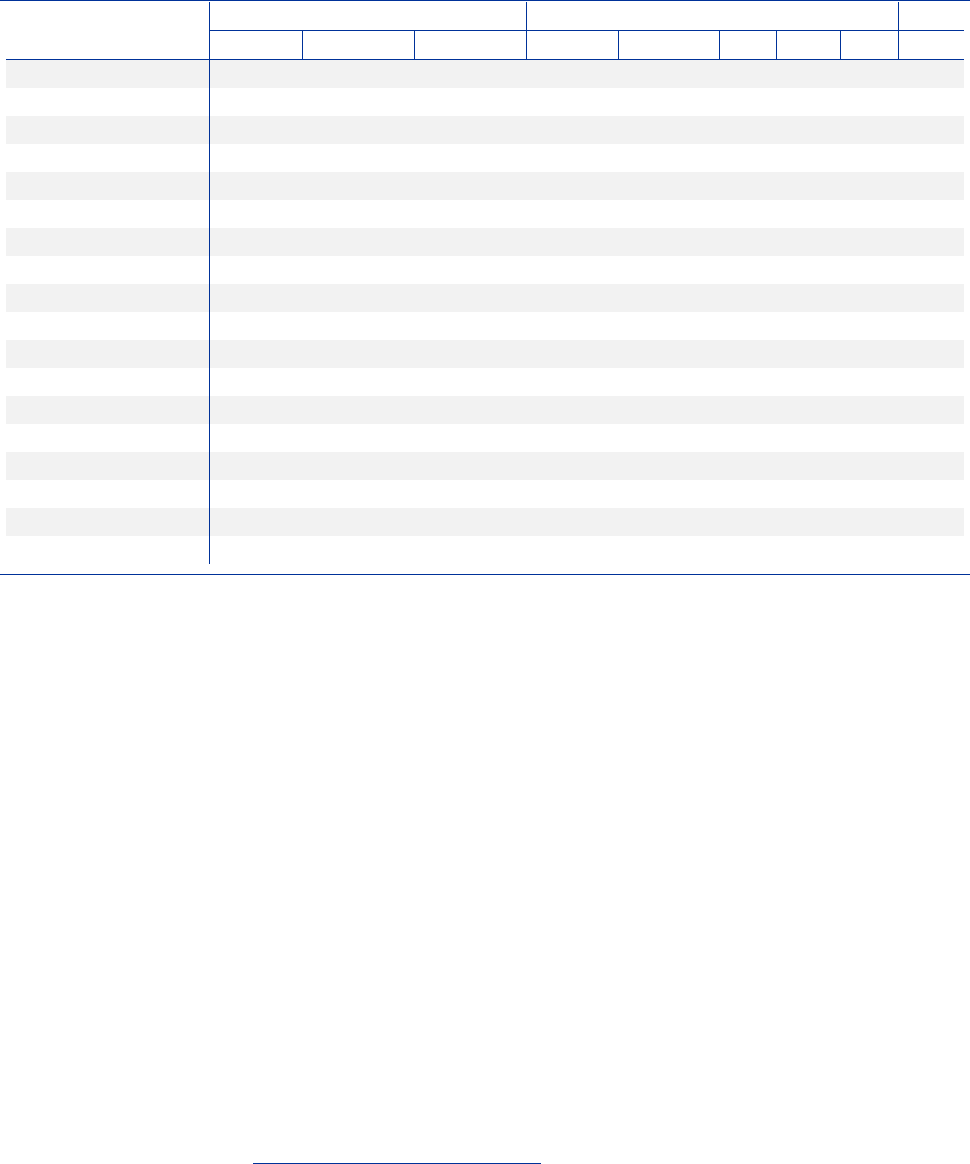

Table 1

Distribution of the sample, per month

Sources: ECB.

For practical reasons it was not possible to ensure an equal number of interviews in

all countries in each month. Furthermore, owing to the different dates of (public)

holidays in various countries and because the interviews were not held in all months

of the year, there could be some slight differences in the reported payment

behaviour. Moreover, as December was excluded (some interviews were held in the

first few days of December only in some countries), Christmas shopping was largely

excluded from the survey results. For this reason, the exclusion of the larger value

payments typically carried out in December may have an impact on the estimation of

the number and value of payments in the year of the survey.

To ensure the reliability and representativeness of the findings, Kantar Public drew a

sample of the population of each country from its internet panels, based on three

demographic characteristics: gender, age and region of residence. Purposive

sampling was used for the study. This is a non-random selection technique which

aims to achieve a sample that is representative of a defined target population.

6

The

quotas set in each country reflected the census-based population characteristics in

terms of gender, age and region of residence. The population figures used to set the

quotas came from the most up-to-date Eurostat (2011) data available at the time the

study was set up.

6

The most common purposive sampling ensures that a census-balanced sample is drawn to conform to

the overall population statistics. The basic idea is that if a sample is representative of a population for

which some characteristics are known, then the sample will also be representative of other survey

variables.

Country

Year 2015 Year 2016

October November December January February May June July Total

AT

2% 27% 3% - 41% 19% 6% 1% 100%

BE

2% 26% 0% - 39% 17% 12% 3% 100%

CY

33% 6% 0% - 61% 0% 0% 0% 100%

EE

3% 23% 7% - 38% 23% 6% 0% 100%

ES

2% 31% 0% - 41% 22% 4% 0% 100%

FI

3% 13% 8% 5% 39% 13% 19% 0% 100%

FR

2% 28% 0% - 38% 31% 1% 0% 100%

GR

2% 33% 0% - 45% 4% 6% 9% 100%

IE

2% 28% 0% - 37% 23% 5% 5% 100%

IT

2% 23% 6% - 42% 14% 7% 5% 100%

LT

3% 22% 8% - 38% 24% 5% 0% 100%

LU

4% 27% 0% - 44% 23% 3% 0% 100%

LV

4% 23% 7% - 38% 15% 2% 11% 100%

MT

21% 24% 0% - 55% 0% 0% 0% 100%

PT

2% 24% 5% - 42% 14% 13% 0% 100%

SI

3% 20% 9% - 37% 9% 6% 17% 100%

SK

3% 22% 5% - 39% 10% 5% 17% 100%

Sample euro area 17

3% 24% 4% 0% 40% 17% 7% 4% 100%

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 201 / November 2017

11

In addition to the internet panels, respondents aged 55 and over were interviewed by

telephone to compensate for the lower probability that those from this age group

would participate in online panels. Furthermore, it was considered that those over 55

without internet access would be less likely to adopt new means of payment than

those with internet access; they may thus have different payment behaviour from

those who have internet access. Given the unavailability of internet panels in Cyprus

and Malta, as well as the relatively low costs, all respondents in these countries were

interviewed face-to-face.

For the purpose of the telephone and face-to-face sample, the basic sample design

applied in the first stage was a multi-stage random (probability) one. As a second

step, respondents from the telephone sample were selected on the basis of age and

everyone under the age of 55 was excluded from this sample. Telephone

respondents who agreed to participate were called again to complete the diary. In

the case of the face-to-face sample, the recruitment process involved choosing

households at random. Quotas were used to make sure that a sufficient number of

respondents across gender, age and region of residence. An important feature of the

survey design was that the overall sample sizes could not be determined in advance

because the aim was to reach a certain number of recorded transactions per country,

even though the average number of transactions per person per day for each

country was unknown. Therefore, during the first wave of the study, a conservative

estimate of an average of 1.35 transactions per person per day and a specific target

for the total number of transactions was set for each country. The initial target was to

reach approximately 10,000 transactions in Belgium, Greece, Spain, France, Italy,

Austria, Portugal and Slovakia and Finland; approximately 7,500 transactions in

Estonia, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania and Slovenia; and approximately 5,000

transactions in Cyprus, Luxembourg and Malta. The results of the first wave showed

that the number of transactions per person per day was higher than initially

assumed. Therefore the sample sizes of the consecutive waves were recalculated

and resulted in fewer interviews. Given that payment behaviour differs according to

the day of the week, the interviews were distributed as evenly as possible over the

course of the week.

7

Education level categories were created based on the respondent’s age when

finishing full time education: still studying or no fulltime education, up to age 16 (low

level of education, equivalent to secondary education), between 16 and 20 years old

(medium level of education, equivalent to vocational education) and higher than 20

years old (high level of education, equivalent to university education).

7

The distribution of interviews by day of the week does not perfectly match the total number of each

days of the week in the month considered in the survey (e.g. an over-representation of Thursdays over

Saturdays). Therefore, it should be taken into consideration that this could have had an impact on the

estimation of POS payments carried out by households.

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 201 / November 2017

12

2.3 Research method

Respondents were asked to write down all the payments made during a single day in

all countries, except Cyprus and Malta, where three-day diary books were used.

Respondents were not informed who had authorised the survey, in order to avoid

influencing their behaviour. They were reminded to maintain the same behaviour as

usual and encouraged to participate in the survey regardless of whether they had

made any transactions. The choice of the duration of the diary survey is not unique

to this study; it was set to allow the collection of diary data from telephone interviews

and to minimise diary fatigue as described in Jonker and Kosse (2013). However, for

certain categories of payments, such as occasional high-value payments for

furniture, high-value electronics or cars, or for certain places of payment, such as

hotels, one-day diaries have some shortcomings, as these payments may be under-

recorded to some extent. These categories of payments and places of payment are

typically characterised by higher card use. Because of their low frequency, they have

limited influence on the number of payments, but may have some influence on the

average value of payments and the value of card payments.

The study was structured in two parts: the payment diary and a survey

questionnaire. All 65,281 respondents of the survey completed the payment diary,

while a subset of 28,099 respondents also completed the questionnaire.

8

The payment diary collected the relevant characteristics of all transactions, as well

as cash withdrawals carried out by respondents during one single day. The data

included information about the transaction value, the place of purchase (13 place

categories, e.g. shop for day-to-day items, shop for durable goods, online shop,

restaurants), the instrument of payment chosen (nine instrument categories)

9

, the

amount of cash carried at the beginning of the survey day and the perceived

acceptance of non-cash instruments in each place of purchase where a payment

was made in cash. Data on cash withdrawals included information on the source of

withdrawal (ATM, bank counter, cashback or other) and the value of withdrawals.

Moreover, the data included information on the demographic characteristics of each

diary respondent, such as gender, age and region of residence, along with

information on education level, occupation, household size, frequency of internet use

and family net income. The diary survey questions can be found in Annex B.

The survey questionnaire collected information on attitudes that may influence

respondents’ payment behaviour, such as payment preference, perceived

convenience of particular payment instruments, perceived payment and withdrawal

behaviour and information on consumers’ views on different cash policies. Moreover,

the questionnaire collected data on respondents’ access to non-cash payment

instruments, the use of cash for recurrent payments and information on the use of

cash as a store of value.

8

Results from all 19 euro area countries are based on the answers of 92,080 respondents who

participated in the diary survey and a subset of 32,907 respondents who completed the questionnaire.

9

The focus of this study is on the use of cash, cards (debit, credit or contactless) and other instruments

used at POS, including cheques, direct debits, credit transfers and mobile payments, among others.

For a detailed definition of each payment instrument, see Annex A.

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 201 / November 2017

13

Box 1

Payment diary surveys in Germany and the Netherlands

Payment diary surveys in Germany and the Netherlands have been carried out since 2008 and

2007, respectively. In both cases, the surveys consist of a diary and a questionnaire. In the case of

Germany, a seven-day diary was used. The latest diary survey was carried out between May and

July 2014 among 2,016 respondents who reported 19,823 transactions.

In the Netherlands, a one-day diary was used. The latest survey was conducted throughout 2016,

with an equal number of respondents per month. A total of 24,783 respondents participated in the

survey and reported 50,452 transactions.

2.4 Recruitment of respondents and data collection

For the ECB survey, a combination of web-based, telephone and face-to-face based

methods were used for recruiting respondents and for collecting the questionnaire

answers (see Table 2). The majority of the interviews were carried out online

(54,377). There were 8,996 interviews conducted by telephone and 1,908 via face-

to-face interviews. Table 2 presents the number of interviews conducted by month

and interview mode.

Online respondents were recruited to participate in the study two days before the

actual interview took place.

10

During first contact, when respondents were asked to

take part in the study, they were asked to record their payments for the following day,

keeping track of all their transactions. Once they had agreed to take part,

respondents were allowed a day in which to record all their transactions and were

called to collect the information the next day. For example, respondents who were

contacted on Monday were asked to record their transactions for Tuesday and were

then contacted to complete the interview on Wednesday. They were allowed a

48-hour window from the time the link was sent to them to complete the survey. For

the telephone and face-to-face

11

modes, the interview took place within two days of

the day on which the transactions were recorded. For example, respondents

contacted on Monday who recorded their transactions on Tuesday would be

interviewed on Wednesday or Thursday.

10

Online respondents were sent invitations by email, along with the instructions for pre-recruitment.

11

During the face-to-face interview, respondents were informed of the main objectives of the survey and

were read the pre-recruitment instructions. Once potential respondents had agreed to participate in the

study, they were given the printed three-day diary and asked to complete it each day. After the three-

day period, they were contacted by the research company by telephone, which recorded all

transactions.

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 201 / November 2017

14

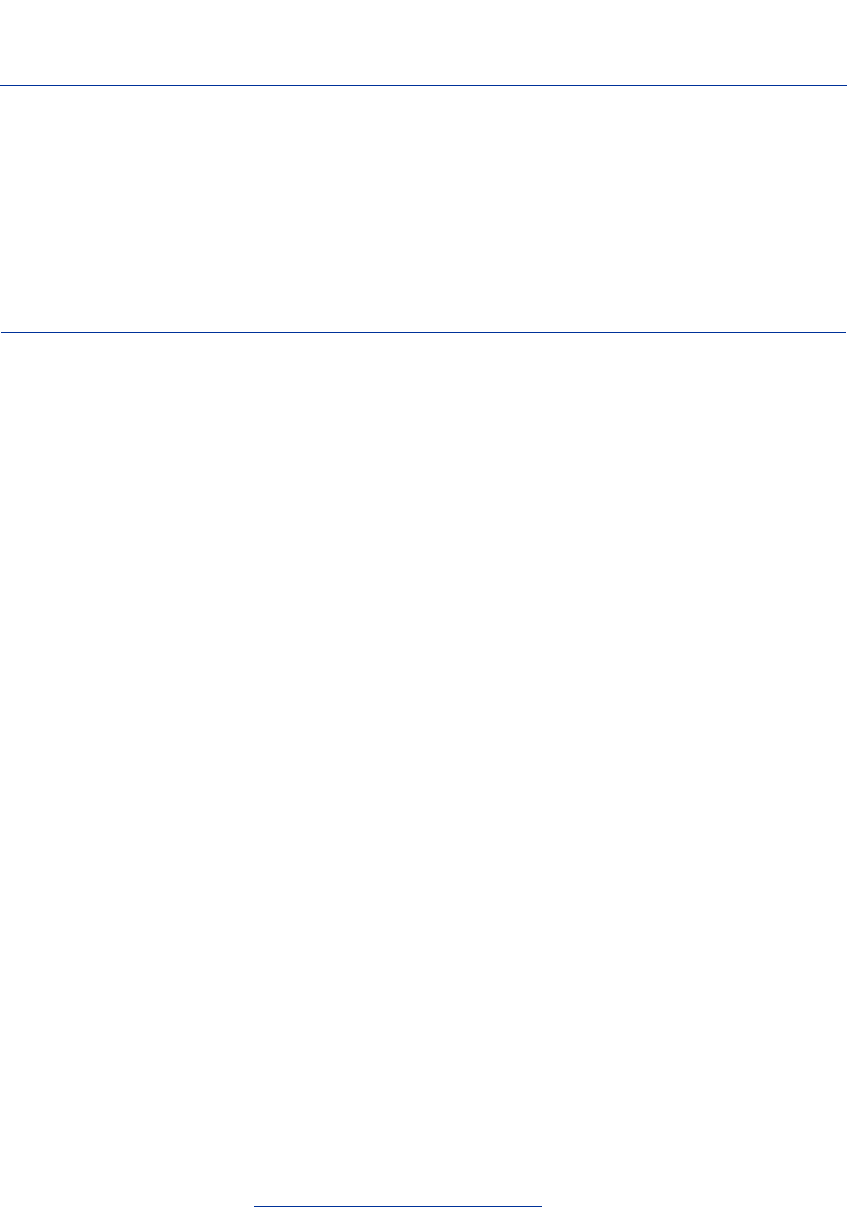

Table 2

Distribution of interviews by month and interview mode

Month Face-to-face Online Telephone Total

2015

October

518 0 1,669 2,187

November

278 15,543 0 15,821

December

0 2,532 0 2,532

2016

January

0 232 0 232

February

1,112 17,949 7,327 26,388

May

0 10,933 0 10,933

June

0 4,291 0 4,291

July

0 2,897 0 2,897

Source: ECB.

2.5 Translation of survey material

The translation of all survey material was a crucial aspect in the study. Kantar Public

was responsible for the whole translation process and used its own translation

department to deliver the required quality. Once ready, the translated material was

sent to the ECB, which sent it to its own translation department, as well as to a group

of national central bank experts who served as advisers during the whole process of

the study. An additional check of most translations was carried out by ECB staff from

the countries involved in the study. During the translation process, emphasis was put

on the use of terms that would be easily understood by the public. For example,

“debit card” could not always be translated literally, as in many countries another

term is used.

2.6 Weighting and adjustments

Given that the sample was not perfectly representative, sample weights were

needed to correct the sampling bias inherent to online panels and purposive

sampling.

12

The key variables used for the post-stratification adjustment were

gender, age and region of residence. A further factor used in the adjustment of

respondents aged 55 and over who were interviewed by telephone was the

frequency of internet usage. This was used as a fourth weighting variable, nested

12

All non-probability online panels have inherent and significant coverage errors, as even a relatively

large national panel of one million members would only have about 2% of adult internet users enrolled

at any given time (in France, for example). Another part of the bias comes from the fact that the

response rate of non-probability online panels is not accurately known. DiSogra and Callegaro (2009)

point out that there are currently no widely accepted metrics that can be used to accurately quantify or

otherwise characterise the non-response that occurs at the recruitment stage of non-probability online

panels. This is because the base (denominator) against which the number of people who joined the

panel (numerator) can be compared is often unknown.

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 201 / November 2017

15

under age. The external information source was the most recent Eurobarometer

survey containing the information available when the weighting targets were set.

The sample population was segmented into two groups:

• respondents aged 55 and over who were interviewed online and those in this

age cohort interviewed by telephone who said they used the internet frequently

(at least once a week);

• respondents aged 55 and over who are not frequent internet users (those who

use the internet two or three times a month, less often, or never and those with

no internet access).

The Eurobarometer survey shows that in all euro area countries, except in

Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Finland, people aged 55 and over use the internet

much less than those in the younger age cohorts. In Luxemburg, the Netherlands

and Finland, they have an internet use pattern similar to the younger age cohorts.

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 201 / November 2017

16

3 Validation

In order to check whether the results from the survey were reasonable, an extensive

validation of the data was carried out. For most countries, no alternative sources of

information that could be used to validate the survey results were available, such as

existing studies on retail payments or data from retail associations. The only country

with an available recent payment study was Portugal, which was carried out by the

Banco de Portugal. However, the scope of this study was different; it included not

only POS payments, but all payments made by individuals.

13

Furthermore, the

Oesterreichische Nationalbank (2017) carried out a study on payment behaviour by

households in 2015. The set-up was nearly the same as that of the SUCH, but

instead of one-day diaries, three-day diaries were used. The results of the

Oesterreichische Nationalbank study and the SUCH study appear to be very similar.

The only source available for all countries at the time of data validation was euro

area payment statistics

14

in the ECB’s Statistical Data Warehouse (SDW), with data

from 2015. Two main items of payment statistics were used from the SDW: i) the

value of cash withdrawals, in order to validate the estimated value of cash payments;

and ii) statistics on domestic card payments initiated at the POS,

15

in order to

validate the estimated number and value of card payments resulting from the survey.

The euro area payment statistics do not report domestic card payments split by debit

and credit card payments. For this reason, card payments have been validated as a

whole. The validation of the German survey results has been excluded, as they refer

to 2014 and have already been published.

When looking at the SDW data on cash withdrawals it should be considered that not

all cash withdrawals are used for payments. A proportion of withdrawn cash is used

by retailers as change and some cash is kept at home as a reserve. In addition,

some of the cash withdrawn leaves the country and is spent abroad when

consumers travel. The estimated value of cash payments resulting from the study

equals roughly 93% of cash withdrawals in the SDW.

16

Therefore, the estimated

value of cash payments from the survey is, in general, a good indication of the actual

use of cash at POS.

17

13

In September 2015 the Banco de Portugal published its study “Use of instruments of payment in

Portugal” based on one and three-day diary book data among respondents aged 18 to 74 years old, as

well as person-to-person payments and other non-POS payments. However, it should be noted that the

SUCH results include respondents aged 74 and over and focus on POS payments only.

14

These datasets are mainly collected on an annual basis according to Regulation ECB/2013/43

(regulation on payment statistics).

15

Using data on cards issued by resident payment service providers.

16

Excluding over-the-counter cash withdrawals from Luxemburg, Malta and Austria, which are not

available in the SDW, and excluding cashback at retailers, available in some countries.

17

The estimated value of cash usage for Ireland, Italy and Lithuania is higher than the value of cash

withdrawals reported in the SDW. Differences could be the result of variation in reporting

methodologies and data quality issues. Moreover, in all these countries cashback is offered at retailers.

In the case of Lithuania, the fieldwork of the SUCH coincided with the year of the adoption of the euro.

This brought changes in the reporting of statistics, as well as temporary changes in how consumers

use their money.

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 201 / November 2017

17

The validation of card payments shows that the survey results are, at euro area level

and for the majority of the euro area countries, roughly in line with card payment data

from the SDW. When comparing SDW data with the SUCH results, it should be

considered that the characteristics of card payment data from the SDW do not fully

match the characteristics of the survey data. The SDW includes card transactions

made by persons under 18 years old and businesses, while the SUCH data only

contain card payments from households and those aged 18 years and over.

Moreover, the survey was conducted during only a few months of the year, and

mostly excludes December. Since the number and value of transactions is higher in

this month than the yearly average, and higher value payments are more frequently

made by card, this may have led to an underestimation of the total value of card

payments by extrapolating the SUCH results to the whole year. In addition,

respondents may not have been able to distinguish between debit and credit cards

and certain special-purpose cards, such as public transport cards or canteen cards,

which are not recorded in the SDW as card payments. Furthermore, in some

countries, such as Greece and Italy, there are still a considerable number of people

below the age of 55 without internet access or who do not use the internet frequently.

Thus, internet panels used in these countries do not include this part of the

population. Since people with internet access are more likely to adopt new means of

payment more quickly, card use in these countries may be overestimated in the

SUCH results, to some extent. Finally, because of the introduction of capital controls

in Greece in 2015 and the introduction of the euro in Lithuania in that same year, it is

difficult to compare the relevant payment statistics data with the survey results.

However, it seems that these explanations do not fully explain the relatively large

differences between the SUCH results and the SDW data for some countries, in

particular for France, Italy, Slovakia and Finland in terms of the number of card

transactions, and for France, Ireland, Portugal and Finland in terms of the value of

card transactions. Chapter 4 describes the effect of using card data from the

payment statistics in the SDW instead of the survey results for these countries. As

shown, the resulting difference in the use of cash by applying the card data from the

SDW is limited for most countries, especially if the differences in data characteristics

between the SDW and the SUCH are taken into account. As an additional data

quality check, a margin of error for the estimated number and value of card

payments was calculated. Results showed that the estimated card payments from

the SUCH moved within a narrow margin of error. Considering that survey results

never provide a perfect representation of reality, and that the SDW may also have

shortcomings and limitations, it can be concluded that the SUCH results are

representative for the payment behaviour of euro area consumers of those aged 18

and over at the point of sale.

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 201 / November 2017

18

4 Cash usage in the euro area

4.1 Relative use of payment instruments

In 2016 euro area consumers made 163 billion payments by means of cash,

payment cards or other payment instruments, amounting to more than €2,968 billion

(see Table 3).

18

The large majority of these payments were made in shops for day-to-

day items, restaurants and petrol stations, as well as at street merchants and shops

for durable goods. These payments are referred to as POS and account for 96% of

all payments. The remaining 4% refers to payments between individuals, such as in-

home services and giving money to relatives, friends, churches or other charity

organisations.

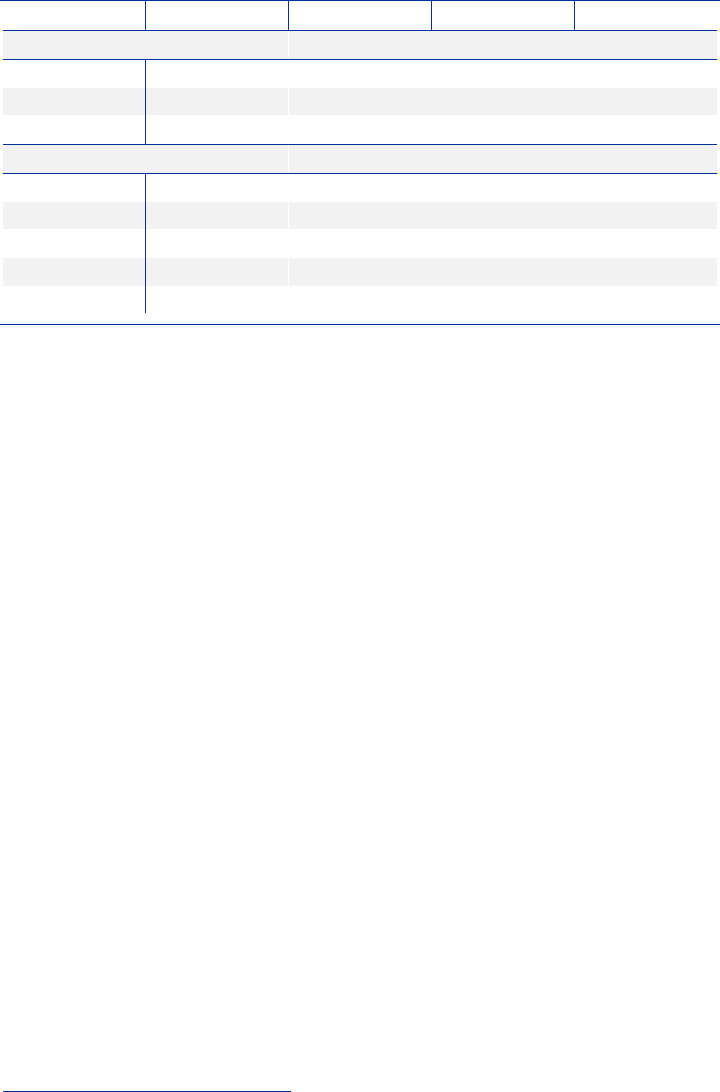

Table 3

Number and value of payments in the euro area in 2016

Payment instrument Number (billion transactions) Value (billion EUR) Average value

Cash

129 € 1,653 € 12.8

POS

124 € 1,530 € 12.4

P2P

6 € 123 € 21.1

Cards

30 € 1,110 € 36.9

Other

3 € 205 € 61.9

Total payments

163 € 2,968 € 18.2

POS

157 € 2,845 € 18.1

Source: ECB.

Notes: Online payments are not included in Table 3. Based on the diary survey results, the value of online payments in the euro area

in 2016 amounted to €144 billion. The latter estimation excludes German results, owing to a lack of data availability, as well as

standing orders for online recurrent payments, such as the monthly fee for an online music and entertainment service. The “Other”

category includes payment instruments, such as cheques, direct debits, credit transfers, mobile payments or other instruments used

by households at POS. Due to their low frequency of use, these instruments have been grouped in a single category.

To pay for their POS purchases, euro area consumers made 124 billion cash

payments, 30 billion card payments and 3 billion payments by means of other

instruments, such as cheques, direct debit, credit transfers and mobile payments.

Although cash was mainly used for low-value purchases, it was used four times

more often than debit or credit cards, bringing the total value of cash payments

above that of all card payments.

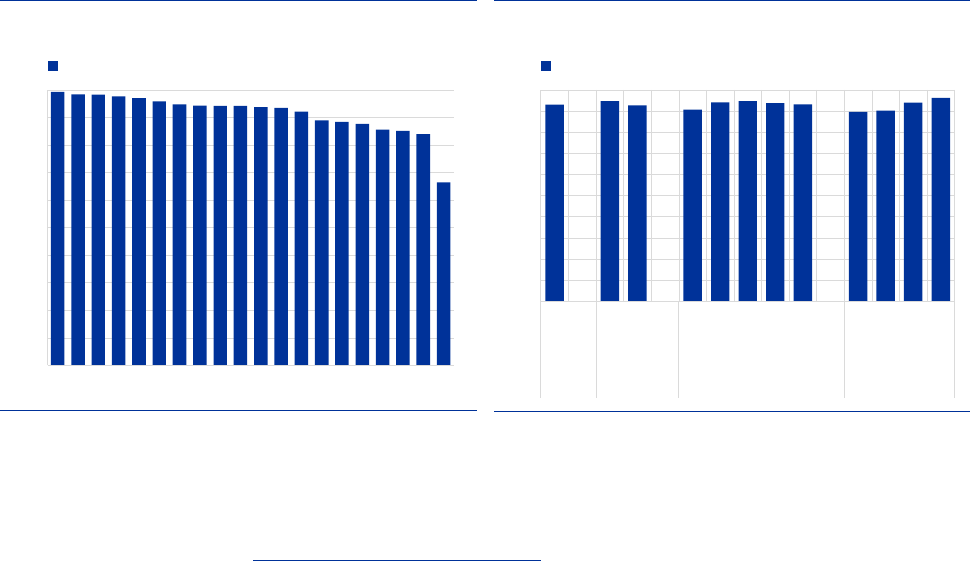

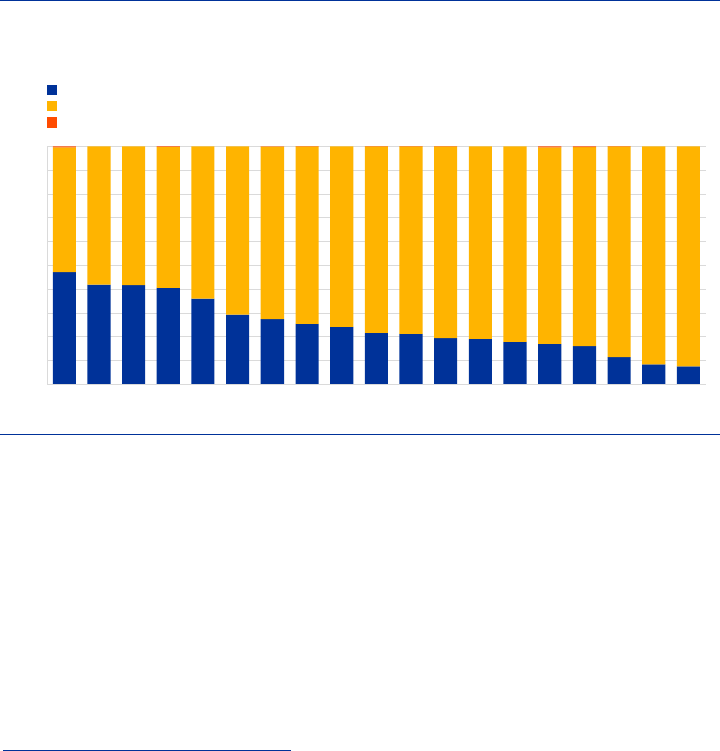

Survey results show that cash was dominant at the POS. In terms of number of

transactions, 78.8% of purchases at the POS were paid using cash, 19.1% using

cards and the remaining 2.1% was paid using various other payment instruments

(see Chart 1). In terms of value, cash payments accounted for 53.8% of all POS

payments, cards for 39% and other means of payment accounted for the remaining

7.2%.

18

Survey results extrapolated to a year for the total euro area population of 18 years and over (12 years

and over in the case of the Netherlands).

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 201 / November 2017

19

Chart 1

Market share of payment instruments at points of sale

Sources: ECB, Deutsche Bundesbank and De Nederlandsche Bank.

Notes: Euro area results, adjusted for country size.

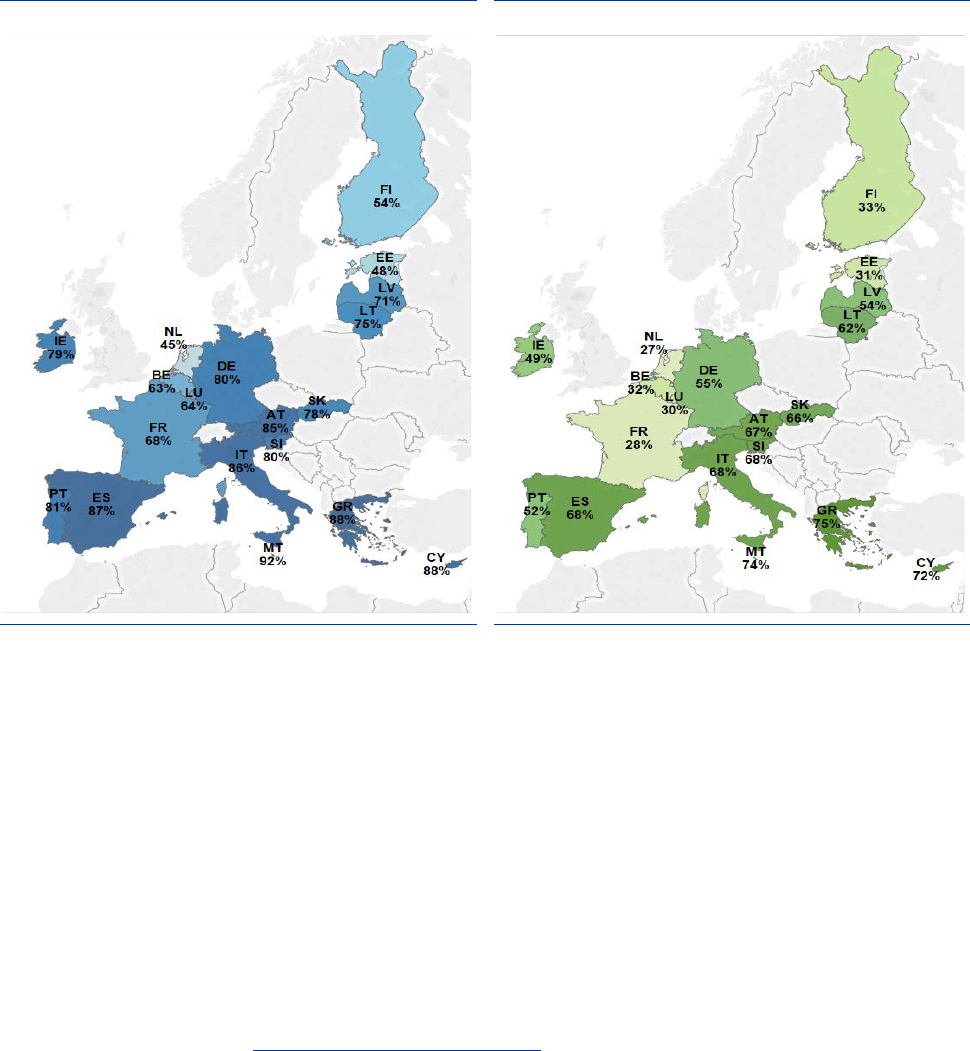

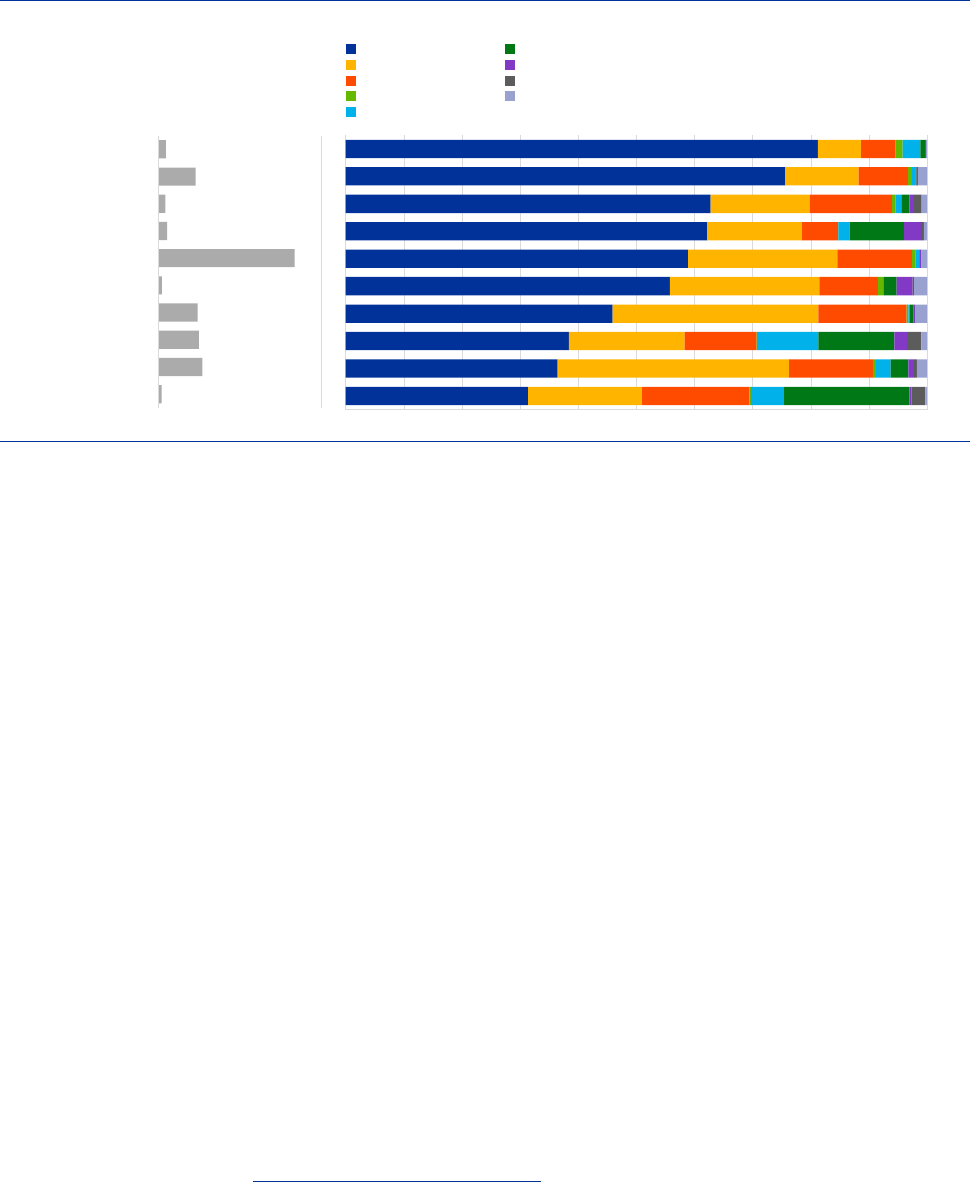

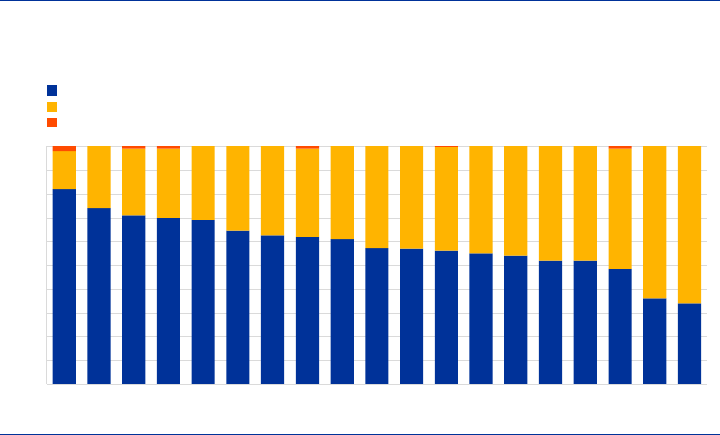

Comparing the use of cash per country, it can be concluded that cash was used

most in southern euro area countries, as well as in Germany,

19

Austria and Slovenia

(resulting in country shares of 80% or above for all POS transactions; see Chart 2).

The market share of cash was lower in Latvia, Lithuania, Slovakia and Ireland,

ranging from 71% to 79%. Belgium, Luxembourg and France follow with a cash

share ranging between 63% and 68%. The Netherlands, Estonia and Finland had

the lowest shares, ranging between 45% and 54% of all payments at POS.

20

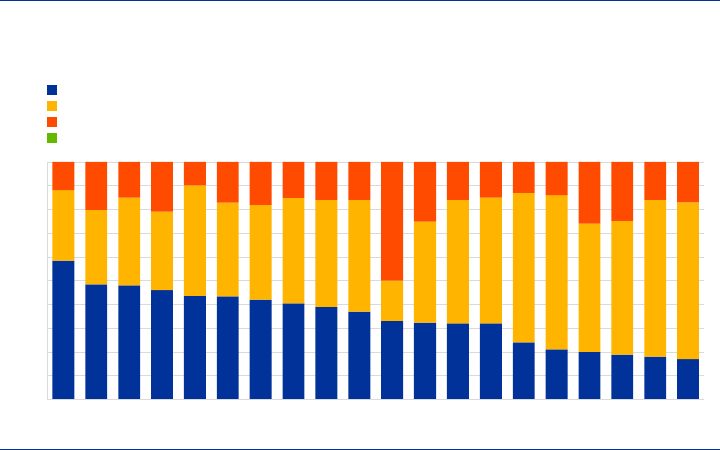

In terms of value of payments made at POS, in all countries the share of cash was

much lower than in terms of number of payments. In Cyprus, Malta and Greece the

share of cash in value of payments was the highest, ranging from 72% to 75%. In

Lithuania, Slovakia, Austria, Spain, Italy and Slovenia the share ranged from 62% to

68%. In Ireland, Portugal, Latvia and Germany the share of cash in value of

19

It should be noted that the results for Germany are included separately and are taken from the

Deutsche Bundesbank’s 2014 cash payment survey. Taking into account the trends in Germany, it can

be expected that the share of cash payments in Germany in 2016 was slightly lower than in 2014.

Consequently, given the high weight of Germany in the overall results for the euro area, the overall

share of cash in number and value in the euro area may be marginally lower in 2016. It should also be

noted that some of the figures published in this paper differ slightly from those published by the

Deutsche Bundesbank in 2014. This paper presents figures on the use of payment instruments at POS,

while the Deutsche Bundesbank’s report presents figures for all payments, including person-to-person

and internet payments. As a result and as presented in Charts 2 and 3, the share of cash usage in this

paper is 79.8% in terms of number and 54.6% in terms of value, while those published by the Deutsche

Bundesbank in 2014 are 79.1% and 53.2% in terms of number and value of payments, respectively.

20

As explained in Chapter 3, for some countries the survey results on card data deviate markedly from

the card statistics in the SDW. Using the card data from the SDW instead of the survey results (noting

all the caveats described in Chapter 3) would result in the following shares of cash payments in terms

of number of total payments at POS: France 63%, Italy 91%, Slovakia 86% and Finland 42%, while the

share of cash at POS for the euro area as a whole would remain at 79%.

53.8%

78.8%

39.0%

19.1%

7.2%

2.1%

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100%

Value

Number

cash

cards

other

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 201 / November 2017

20

payments was between 49% and 55%, while in the Benelux countries, France,

Estonia and Finland the share ranged from 27% to 33%.

21

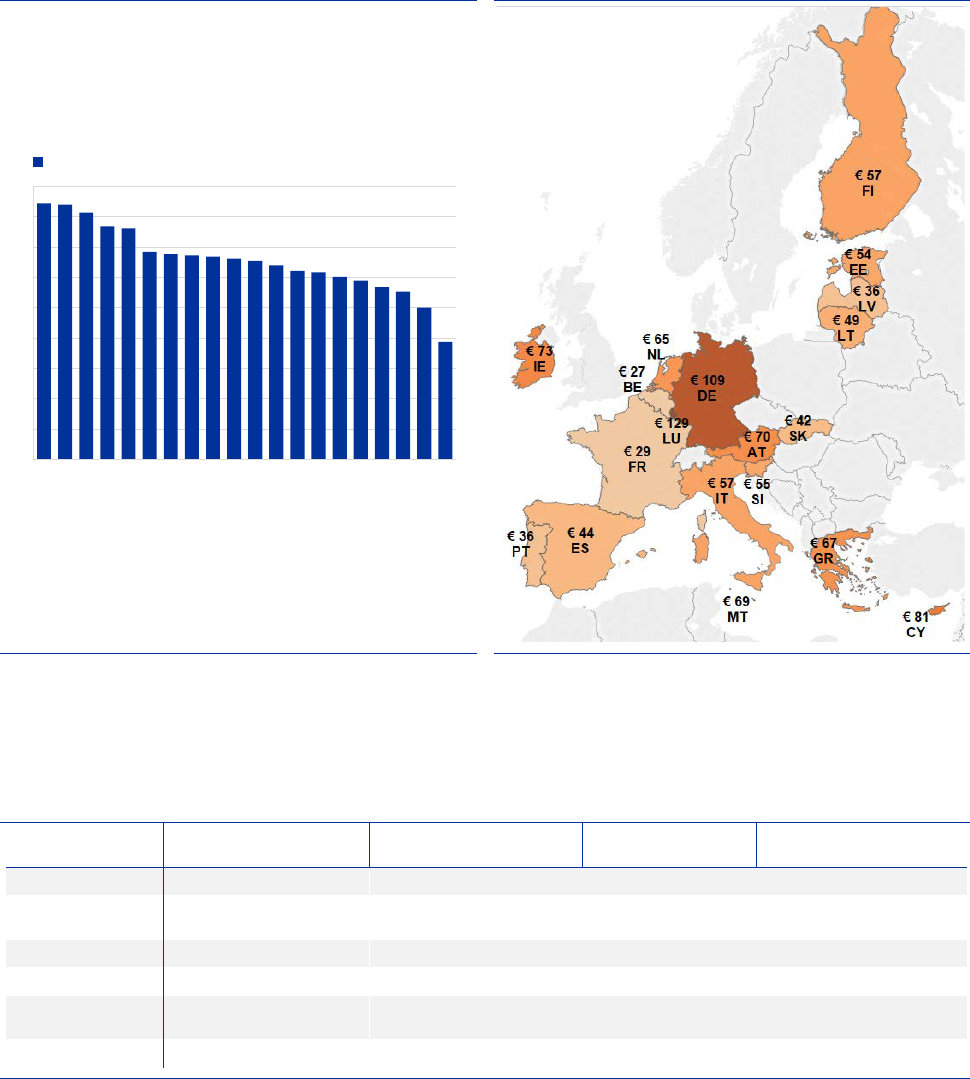

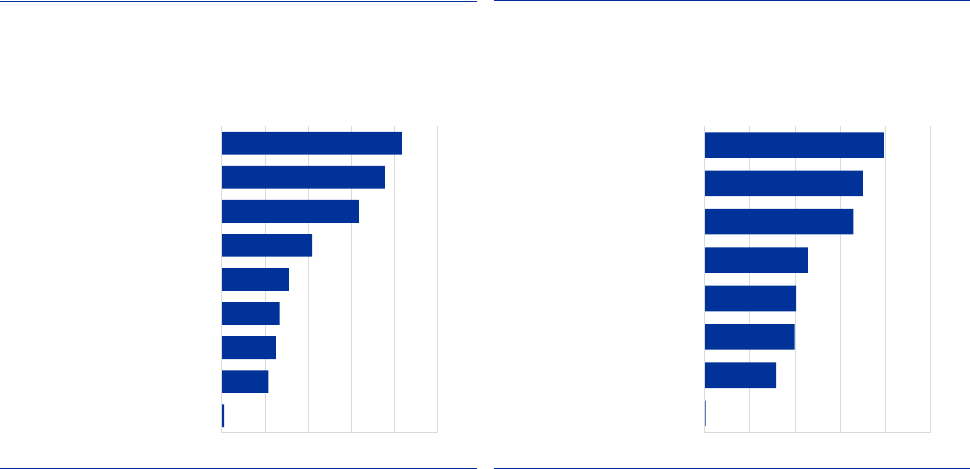

Chart 3

Share of cash transactions per country at points of sale

(value of transactions)

Sources: ECB, Deutsche Bundesbank and De Nederlandsche Bank.

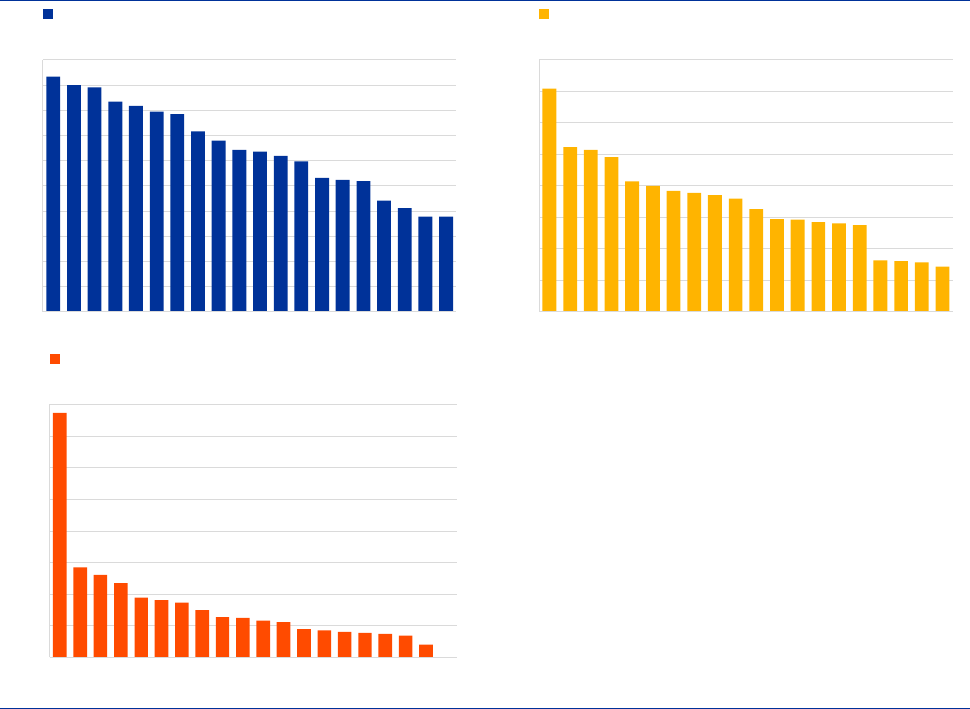

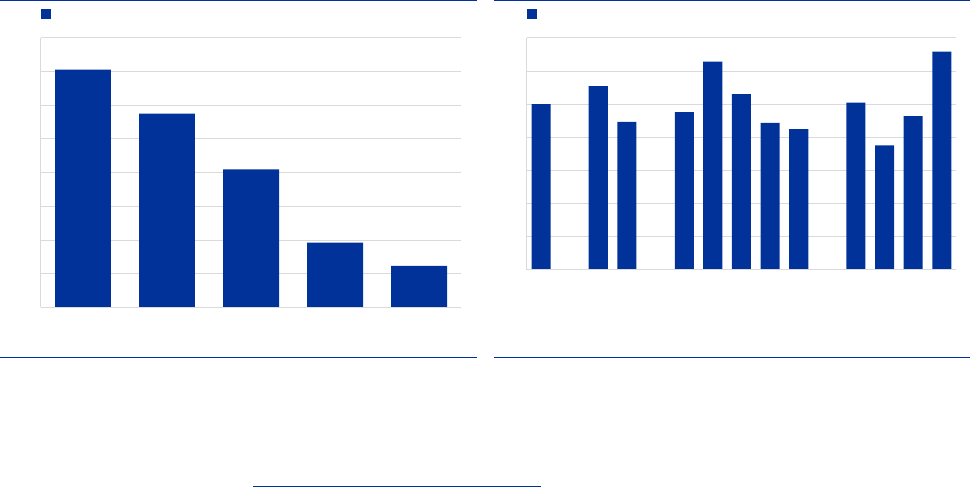

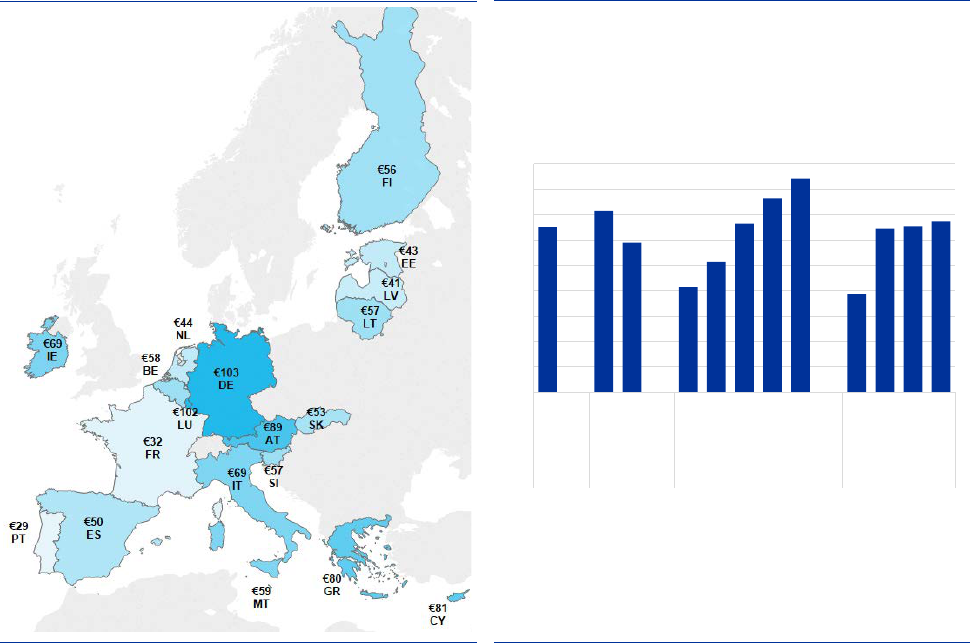

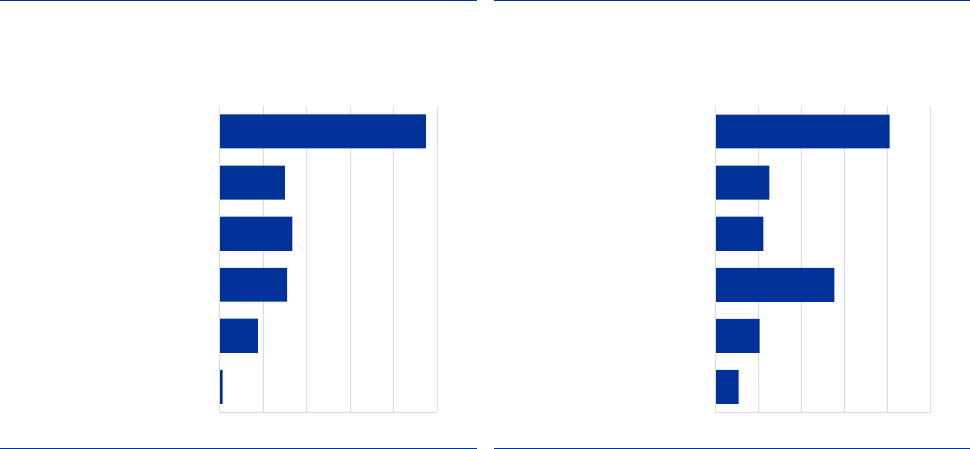

4.2 Average value of transactions

The different shares of cash in the total number and value of transactions at POS are

also reflected in the average value of a cash transaction to some extent. On average

in the euro area, the value of a cash transaction was €12.38. In terms of value of

transactions, the average value of a cash transaction was the highest in Cyprus,

Luxembourg and Austria where it ranged from €18.60 to €17.80 (see Chart 4a). This

suggests that consumers in these countries use cash not only to pay low amounts

but also relatively higher amounts. In contrast, the average cash transaction value

was the lowest (below €10) in Spain, Latvia, France and Portugal where it ranged

21

As described in Chapter 3, also in terms of value the survey results deviate markedly from the card

statistics in the SDW for some countries. Using the card data from the SDW instead of the survey

results (noting all the caveats described in Chapter 3) would result in the following shares of the value

of cash payments in total payments at POS: Ireland 41%, France 23%, Portugal 34% and Finland 23%.

Applying the whole euro area 2015 SDW card data instead of the SUCH results, the share of cash in

value of POS transactions would be 50%.

Chart 2

Share of cash transactions per country at points of sale

(number of transactions)

Sources: ECB, Deutsche Bundesbank and De Nederlandsche Bank.

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 201 / November 2017

21

between €8.80 and €7.50, indicating that in these countries cash is mainly used for

small payments.

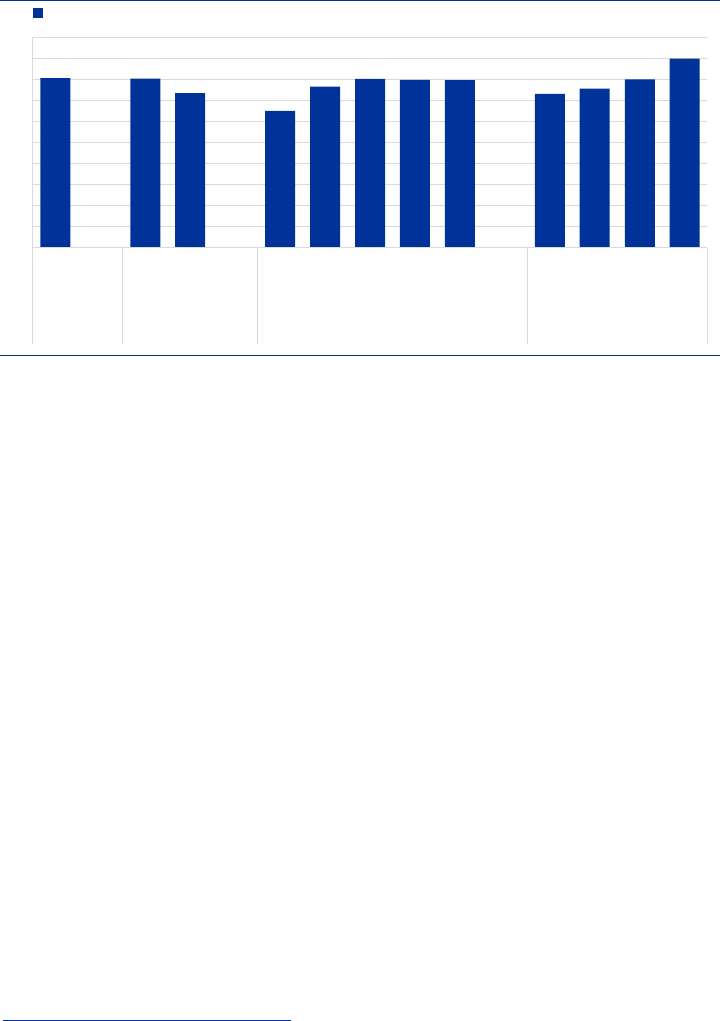

Chart 4

Average value of a transaction at points of sale

Sources: ECB, Deutsche Bundesbank and De Nederlandsche Bank.

Notes: The “other” category includes instruments such as cheques, direct debits and credit transfers.

The average card transaction value was the highest in Luxembourg, Malta and

Germany, where it ranged from €70.78 to €51.38 (see Chart 4b). In contrast, the

average card transaction value in the euro area was the lowest in Slovakia, Estonia

and Latvia where it ranged from €16.05 to €14.33, indicating that consumers in these

countries use cards for relatively low-value payments.

Diary results suggest that cheques or credit transfers and direct debits are commonly

used to pay for larger amounts, such as at hotels, certain service providers or at

public authority offices. The average transaction value of these kinds of payments

were therefore higher than those of cash and cards, the highest being in Ireland,

Cyprus and Luxembourg, where they ranged from €387 to €130 (see Chart 4c).

€ 0

€ 2

€ 4

€ 6

€ 8

€ 10

€ 12

€ 14

€ 16

€ 18

€ 20

CY LU AT DE IE GR MT SI IT NL FI euro

area

BE LT SK EE ES LV FR PT

average value cash

a) cash

€ 0

€ 10

€ 20

€ 30

€ 40

€ 50

€ 60

€ 70

€ 80

LU MT DE CY AT BE FR IT euro

area

GR IE PT ES FI NL SI LT SK EE LV

average value cards

b) cards

€ 0

€ 50

€ 100

€ 150

€ 200

€ 250

€ 300

€ 350

€ 400

IE CY LU MT AT EE GR DE FR euro

area

BE FI IT LT PT LV SK SI ES NL

average value other

c) other payment instrument

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 201 / November 2017

22

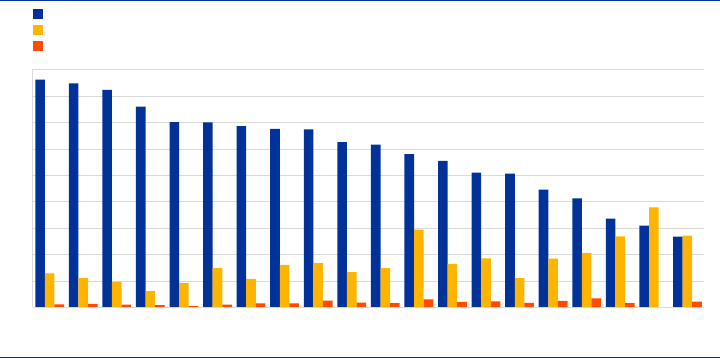

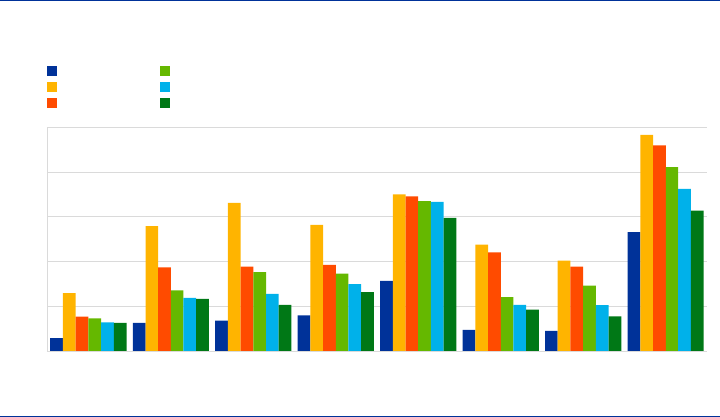

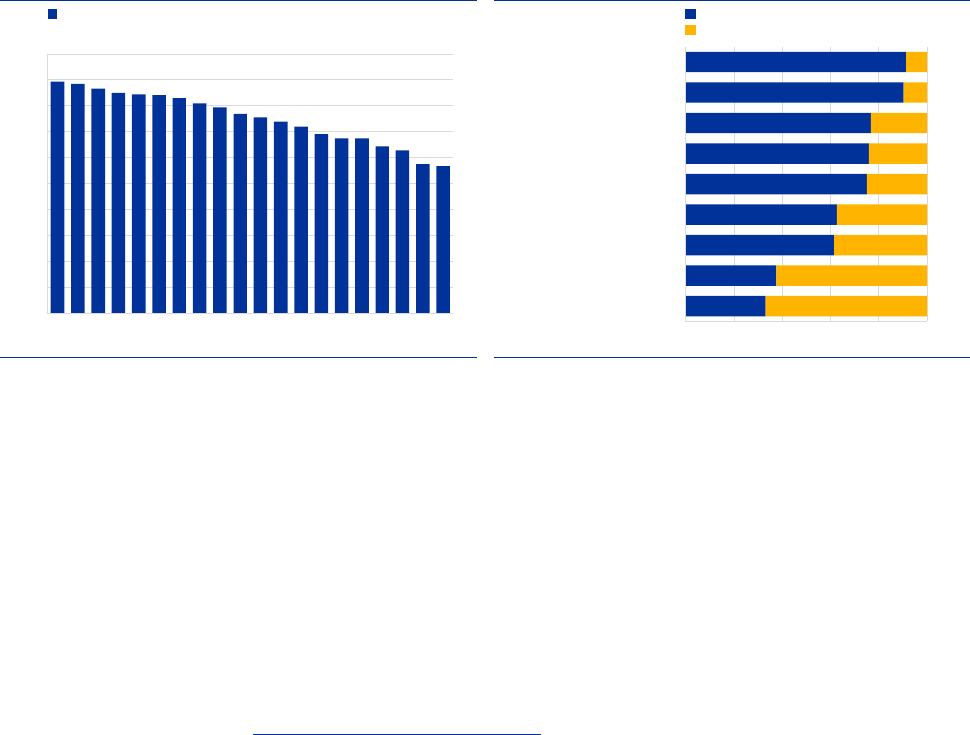

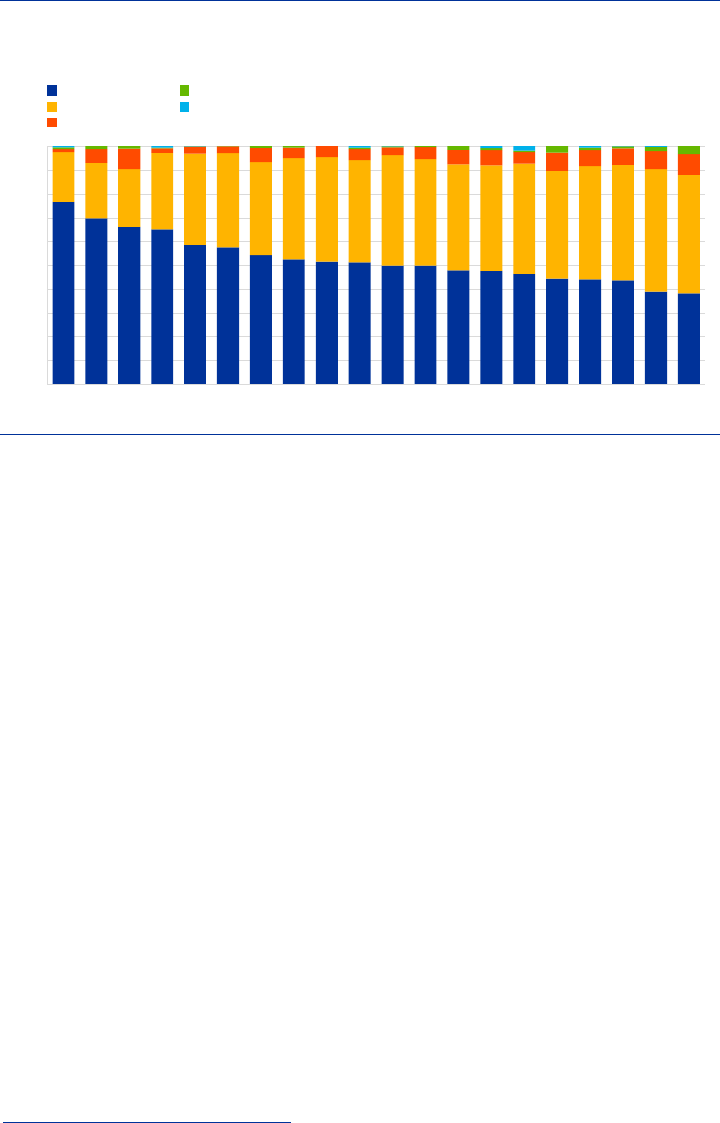

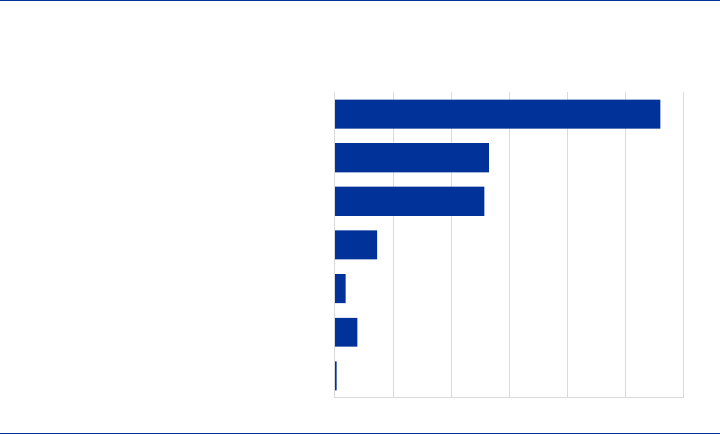

4.3 Average number of transactions per person per day

In 2016 euro area consumers made 1.6 payments per day on average, which equals

nearly 11 payments per week (see Chart 5). They used cash more frequently than

other payment instruments, making on average 1.2 cash payments per day, i.e.

almost nine per week. The second most frequently used payment methods were

payment cards, which consumers used on average 0.3 times per day, i.e. 2.1 times

per week. However, these are euro area averages, since payment behaviour varied

from country to country. Italy, Spain and Greece were the countries where

consumers made the highest number of cash payments per day, with 1.7

transactions per day, i.e. nearly 12 per week. On the other hand, consumers in the

Netherlands, Luxembourg, Finland and Estonia made the highest number of card

payments per person per day, with 0.8, 0.6 and 0.5 payments per day, respectively.

This is equal to 5.3, 4.1 and 3.8 payments per week, respectively.

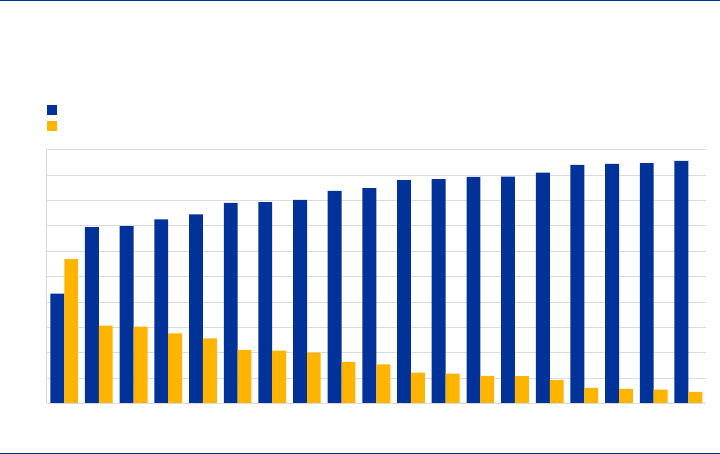

Chart 5

Average number of transactions per person per day, by instrument of payment

Source: Authors’ calculation based on ECB, Deutsche Bundesbank and De Nederlandsche Bank data.

In 2016 the Netherlands was the only euro area country where consumers used

payment cards more often than cash. They carried out 55% of all transactions using

a payment card, while in Estonia consumers carried out an equal number of

transactions by cash and card, on average.

4.4 Payment behaviour by demographic characteristics

Payment behaviour differs not only by country, but also from person to person. In line

with the literature on payments (see Whitesell, 1989; Boeschoten, 1998; Von

Kalckreuth et al. 2009, Stavins, 2011), the survey results show that consumer

characteristics, such as gender, age and level of education, appear to influence the

choice for a particular payment instrument at POS. Chart 6 shows that male

consumers aged between 40 and 64 and those with a high level of education carried

out a larger number of daily payments than their counterparts. On average, they

made between 1.6 and 1.8 payments each day at the POS using cash, cards or

1.7

1.7

1.6

1.5

1.4

1.4

1.4

1.3

1.3

1.3

1.2

1.2

1.1

1.0

1.0

0.9

0.8

0.7

0.6

0.5

0.3

0.2

0.2

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.2

0.3

0.3

0.3

0.3

0.6

0.3

0.4

0.2

0.4

0.4

0.5

0.8

0.5

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

1.2

1.4

1.6

1.8

IT ES GR MT CY PT AT IE SK SI euro

area

LU LT LV DE FR BE FI NL EE

cash

cards

other

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 201 / November 2017

23

other payment instruments, which corresponds to between 11 and 13 payments per

week. In contrast, the number of daily payments was lower among women, young

people and those who are still studying. These consumers made, on average,

between 1.3 and 1.6 payments each day, corresponding to between 9 and 10

payments per week.

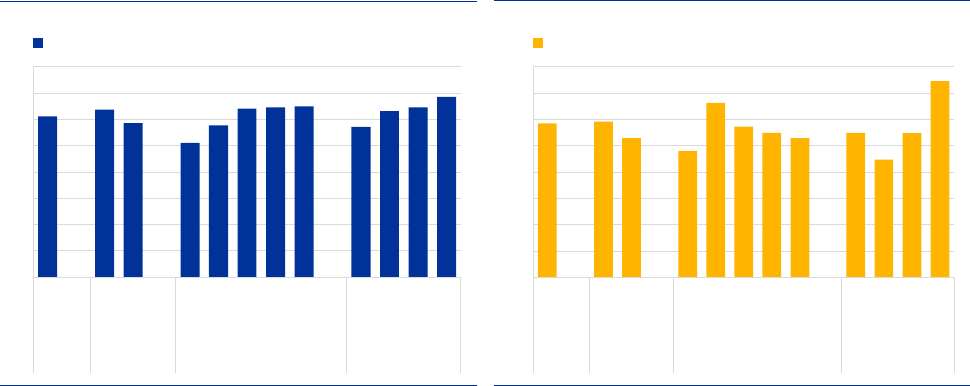

Chart 6

Average number of POS payments per person per day

Source: Authors’ calculation based on ECB, Deutsche Bundesbank and De Nederlandsche Bank.

A similar phenomenon can be observed when analysing the demographic

characteristics of cash users (see Chart 7). On average, euro area consumers made

1.2 cash payments per day, i.e. 8.4 per week. However, this varied by gender and

age. Men and consumers aged between 40 and 64 were more likely to use cash.

Younger consumers aged between 18 and 39 carried out fewer cash payments,

namely from 1.1 to 1.3 daily payments respectively. When looking at the results by

level of education, cash usage appears to be relatively homogenous among

consumers with a low, medium or high education level.

The use of payment cards also tends to be relatively homogenous among women

and men, as well as consumers aged over 25. However, results show that young

people (18 to 24 years old) and those with a low level of education used payment

cards the least (see Chart 8).

22

They made on average 0.24 and 0.22 card payments

per day respectively (i.e. around 1.6 per week), in contrast with the rest of the

population, which made on average 0.3 payments per person per day (i.e. around

2.1 per week).

22

It should be taken into account that young people (18-24 years old) carried out the lowest number of

payments per person per day, compared with the payment behaviour of consumers in older age groups

(see Chart 6).

1.6

1.6

1.5

1.3

1.5

1.6

1.6

1.6

1.5

1.5

1.6

1.8

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

1.2

1.4

1.6

1.8

2.0

male

female

18-24

25-39

40-54

55-64

65+

no educ /

still studying

low

medium

high

average gender age education

POS payments per person per day

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 201 / November 2017

24

Chart 8

Average number of card payments at POS

(per person per day)

Source: Authors’ calculation based on ECB, Deutsche Bundesbank and De

Nederlandsche Bank data.

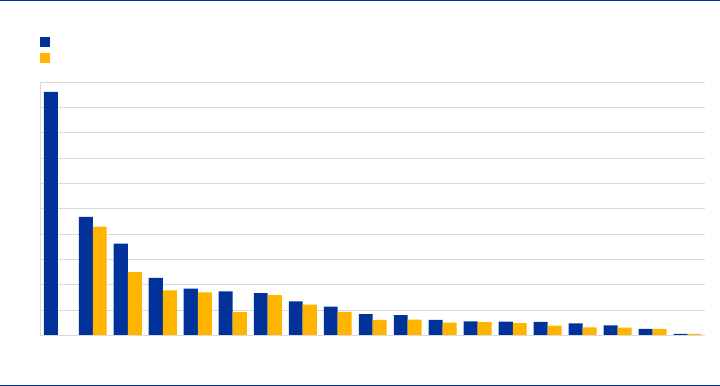

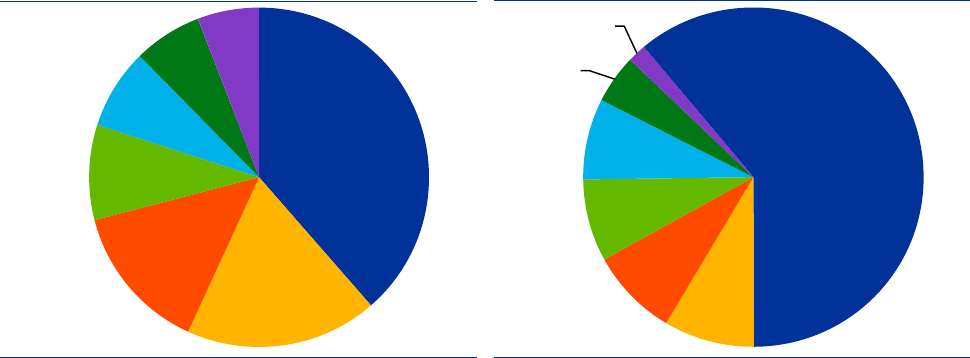

4.5 Use of payment instruments by value range

On a daily basis, consumers spent on average €18 every time they made a payment

at POS using cash, cards or other means instruments. Most POS payments carried

out by consumers involved lower transaction values; over a third of payments were

lower than €5, and 65% were lower than €15. Conversely, only two in over 100

payments were worth more than €100.

In line with the literature (see Whitesell, 1989; Boeschoten, 1998; Klee, 2008; Von

Kalckreuth et al., 2014 and Arango et. al 2017), consumers’ instrument of choice is

strongly influenced by the payment amount; cash is mainly used for low-value

payments while cards are used for larger-value payments. This is confirmed by the

survey results. Indeed, although absolute levels differed between countries, within

each country the average value of a cash transaction was lower than the average

value of a card transaction. Looking at the way consumers paid according to

payment instrument and amount, cash was the instrument of choice for purchases

under €45. These purchases accounted for 91% of all POS payments. Cards, on the

other hand, were the most frequently used payment instrument for purchases above

€45, which accounted for 9% of all POS payments. As can be expected, the higher

the amount to be paid at the POS, the more likely it is that a consumer pays by card

(see Chart 9).

0.29

0.30

0.26

0.24

0.33

0.29

0.27

0.26

0.27

0.22

0.27

0.37

0.00

0.05

0.10

0.15

0.20

0.25

0.30

0.35

0.40

male

female

18-24

25-39

40-54

55-64

65+

no educ /

still studying

low

medium

high

average gender age education

cards payments per person per day

Chart 7

Average number of cash payments at POS

(per person per day)

Source: Authors’ calculation based on ECB, Deutsche Bundesbank and De

Nederlandsche Bank data.

1.2

1.3

1.2

1.0

1.2

1.3

1.3

1.3

1.1

1.3

1.3

1.4

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

1.2

1.4

1.6

male

female

18-24

25-39

40-54

55-64

65+

no educ /

still studying

low

medium

high

average gender age education

cash payments per person per day

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 201 / November 2017

25

Chart 9

Use of payment instruments at POS, by value range

(number of transactions)

Sources: ECB, Deutsche Bundesbank and De Nederlandsche Bank.

Looking more closely at the payment amounts above €100, it is interesting to note

that the use of cash remained relatively high. Almost a third of POS transactions with

a value above €100 were paid with cash. However, it should be noted that the

number of payments above €100 was relatively small; only 2% of recorded payments

were above €100. For this reason, no reliable breakdown of the use of various

payment instruments for value ranges above €100 can be provided.

Although the share of cash payments above €100 was small, in terms of value they

amounted to 10% of the value of all cash payments at the POS in the euro area. The

share of cash payments above €100 in the total value of cash payments at the POS

was wide-ranging, from 3% in France or 5% in Belgium, to 21% in Ireland and

Slovenia or 26% in Greece.

32%

39%

44%

50%

51%

54%

57%

67%

71%

79%

86%

93%

35%

36%

31%

31%

30%

29%

26%

20%

17%

13%

8%

4%

21%

20%

20%

16%

16%

12%

13%

11%

9%

6%

4%

1%

4%

2%

4%

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100%

cash

debit card

credit card

contactless card

cheque

credit transfer

direct debit

internet

other

34%

19%

13%

8%

7%

3%

3%

2%

2%

1%

6%

2%

< €5

€5 to €9.99

€10 to €14.99

€15 to €19.99

€20 to €24.99

€25 to €29.99

€30 to €34.99

€35 to €39.99

€40 to €44.99

€45 to €49.99

€50 to €99.99

> €100

% from total POS

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 201 / November 2017

26

5 Use of payment instruments by market

segment and for recurrent payments

5.1 Market share of payment instruments by number of

transactions

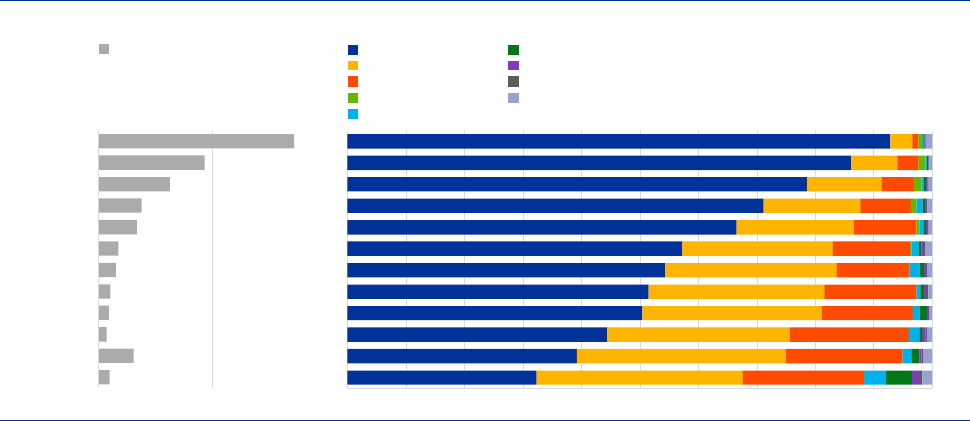

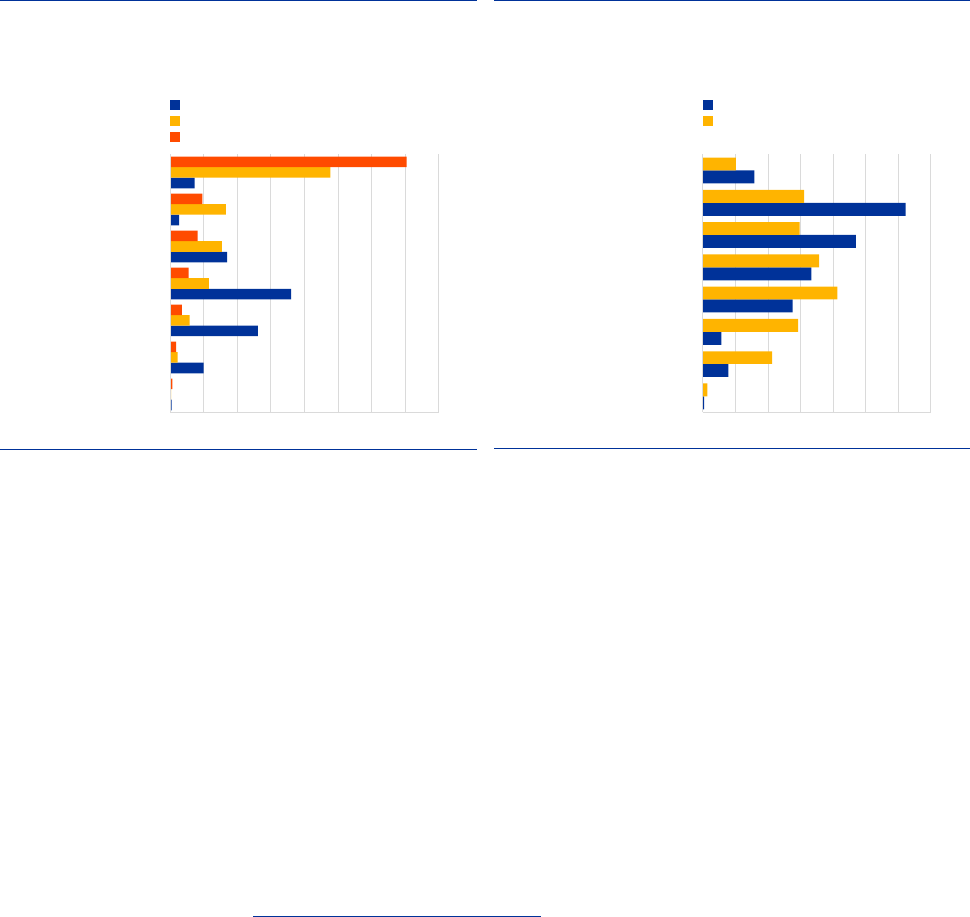

Although on average euro area consumers paid in 2016 for almost 79% of their

transactions using cash, this varied depending on the place of purchase. Cash was

the most dominant payment instrument in a large majority of POS. It held a market

share of payments of above 50% in all sectors, except in the accommodation sector

(hotels, guesthouses and camping sites), where payment cards and other non-cash

payment instruments were largely used. As shown in Chart 10, the share of cash

usage was the highest at (i) street or market vendors and in restaurants and bars

(both 90%), (ii) vending or ticketing machines (84%), (iii) in the entertainment and

recreation sector (83%), and (iv) in shops for day-to-day items, such as supermarket

or bakeries (80%). Cards were the second most frequently used payment instrument

after cash. From all sectors, cards were most frequently used in shops for durable

goods, petrol stations and in the accommodation sector where 41%, 38% and 37%

of all payments were made by card, respectively. It may be surprising that 60% of

payments in petrol stations were made in cash. However, it should be taken into

account that people also buy cigarettes, newspapers, flowers and snacks at petrol

stations, which are generally more-frequent, smaller-value payments.

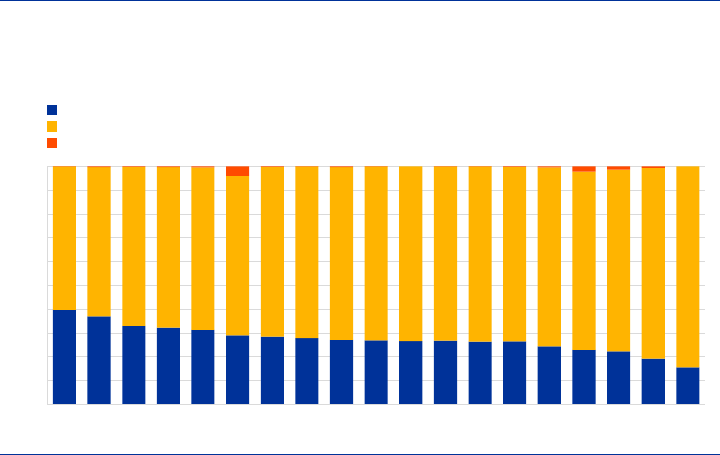

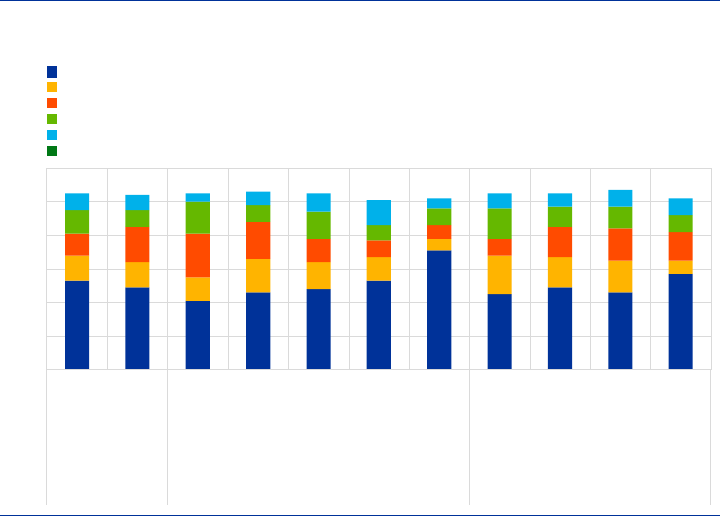

Chart 10

Market share of the main payment instruments

(number of transactions)

Sources: ECB, Deutsche Bundesbank and De Nederlandsche Bank.

Chart 10 also shows that by far most payments carried out by consumers at POS

were made in shops for day-to-day items (48%) and in restaurants, bars and cafés

0%

6%

8%

5%

1%

48%

2%

3%

21%

5%

hotel, guest house

or camping

in a shop for durable goods

(clothing, electronics, etc.)

petrol station

other POS

office of a

public authority

in a shop for day-to-day

items (supermarket, etc.)

arts, entertainment

& recreation

at a vending or

ticketing machine

restaurant, bar or cafe

street or market

(newspaper, florist, etc)

market share

45%

56%

60%

63%

69%

80%

83%

84%

90%

90%

18%

29%

26%

15%

15%

13%

8%

8%

5%

3%

14%

11%

11%

7%

6%

5%

4%

2%

3%

3%

4%

1%

7%

2%

3%

8%

4%

4%

3%1%

1%

6%

3%

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100%

cash

debit card

credit card

contactless

cheque

credit transfer

direct debit

internet

other

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 201 / November 2017

27

(21%). Furthermore, 8% of the number of payments was made at petrol stations and

6% in shops for durable goods. A total of 5% of all payments were made in “other”

places. This is typically in the services sector, such as hairdressing, dry cleaning and

plumbing services, the repair of cars and bicycles, or household and gardening

services.

The fact that payments for durable goods in shops and payments in petrol stations

made up only 14% of all POS payments compared with 69% in shops for day-to-day

items and restaurants and bars, may explain to some extent why cash is used more

than many people perceive it to be. Consumers are likely to remember how they pay

for less-frequent, higher-value payments than for frequent, lower-value payments

(see Jonker and Kosse, 2013). At the same time, it shows that if the infrastructure for

card payments in shops for day-to-day items and in bars, restaurants and cafés is

further built up, and contactless payments are facilitated, the share of cash usage in

terms of number and value of payments could decrease substantially. However, an

increase in card payments in sectors such as entertainment and recreation, hotels

and vending machines – which together accounted for 5% of all POS payments –

would have a limited impact on the total share of cash used at POS.

5.2 Market share of payment instruments by value of

transactions

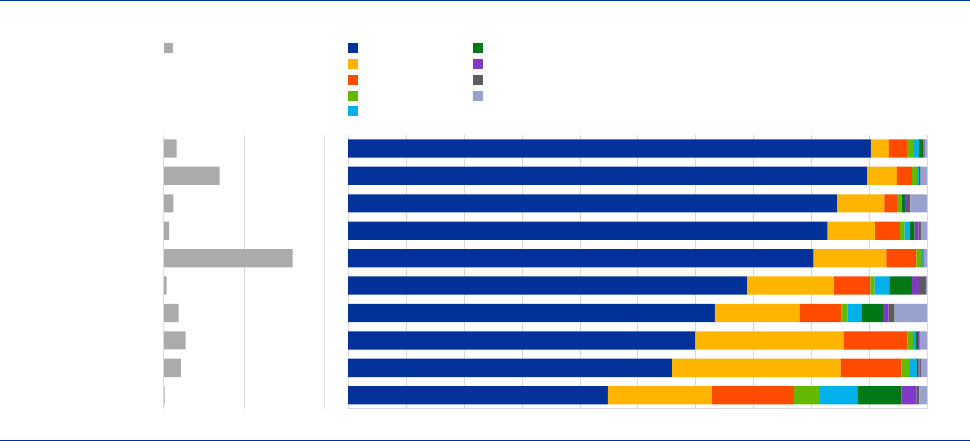

In 2016 the use of cash was not only dominant in the number of transactions, but

also in terms of value of payments, although to a lesser extent. The share of cash

was the highest at street or market vendors (81%) and in restaurants, bars and cafés

(76%; see Chart 11). Furthermore, cash payments accounted for 59% of the total

value paid at shops for day-to-day items. This is significant, given that 42% of the

turnover of all POS payments was concentrated in this sector. The share of cash in

terms of value was below 50% in four sectors, namely petrol stations, shops for

durable goods, the accommodation sector, as well as in the “other” sector, which

includes all services. In all these sectors, card payments were the most dominant

means of payment in value terms. The highest share of card payments was in shops

for durable goods, where 55% of the total turnover was paid using cards, followed by

petrol stations (51%), and the accommodation sector (38%). It is interesting to note

that credit transfers and cheques played a relatively important role in the

accommodation sector, the “other” sector (typically services) and at offices of public

authorities. As a credit transfer is a remote payment instrument, these transactions

are most likely understood to be transactions in which a respondent has agreed with

a payee at a POS (e.g. hotel or municipal administration) that the transaction could

be made by credit transfer.

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 201 / November 2017

28

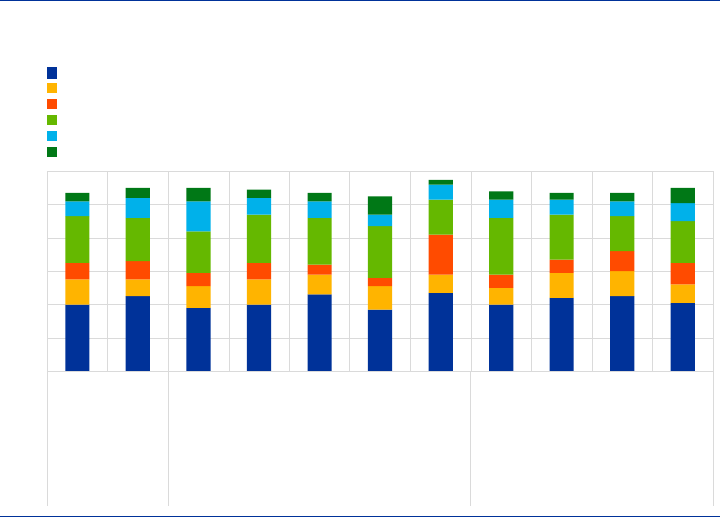

Chart 11

Market share of main payment instruments

(value of transactions)

Sources: ECB, Deutsche Bundesbank and De Nederlandsche Bank.

Examining the share of each market segment in the total turnover, it appears that –

similar to the number of payments – shops for day-to-day items dominate the

payments made at POS. On average, 42% of all turnover at POS in the euro area

was made in shops for day-to-day items. The market segments with the second

highest turnover were shops for durable goods, closely followed by petrol stations

and the “other” sector. Although the average value of a transaction at restaurants,

bars or cafés was lower than, for example, in shops for durable goods, given the

large number of transactions, this sector still held 11% of all turnover at POS in the

euro area. These results also highlight the economic importance of these sectors

and the relevance of various means of payment in these sectors.

5.3 The use of cash for recurrent payments

The “other” sector in Charts 10 and 11 includes, for some countries, payments made

at a POS, which in other countries would typically be made by remote payment

methods such as credit transfers or direct debits. These are mainly recurrent

payments, such as rent, utilities, telephone subscriptions and insurance, but also

payments for the home delivery of oil or gas, or medical services. As no breakdown

was required in the diary survey, respondents were asked in a separate

questionnaire whether they pay for any of these types of recurrent payments using

cash. As seen in Chart 12, in some countries it is not unusual to pay these recurrent

expenses in cash. On average, in the euro area (excluding Germany

23

) 6% of the

rent was said to be paid in cash, with 26% of all rent in Greece said to be paid in

23

It can be expected that since most recurrent payments in Germany are known to be made by direct

debit or credit transfer, the euro area average would be lower if the results from Germany were

included.

1%

13%

12%

12%

1%

42%

3%

2%

11%

2%

hotel, guest house

or camping

in a shop for durable

goods…

other

petrol station

at a vending or

ticketing machine

in a shop for day-to-day

items (supermarket, etc.)

office of a

public authority

arts, entertainment

& recreation

restaurant, bar or cafe

street or market

(newspaper, florist, etc)

31%

36%

38%

46%

56%

59%

62%

63%

76%

81%

20%

40%

20%

35%

26%

26%

16%

17%

13%

7%

18%

14%

12%

15%

10%

13%

6%

14%

8%

6%

6%

3%

11%

2%

3%

22%

3%

13%

9%

2%

3%

3%

2%

2%

2%

2%

2%

2%

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100%

cash

debit card

credit card

contactless card

cheque

credit transfer

direct debit

internet

other

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 201 / November 2017

29

cash, and around 15% in Slovakia and Malta. In addition, utility bills were frequently

paid in cash in several countries. For example, 56% of the respondents in Greece

and nearly 25% of those in Italy said they paid their electricity bill in cash. Also, 9% of

respondents indicated that they paid their taxes mainly in cash and 10% stated that

they paid their insurance mainly in cash. Furthermore, on average almost one out of

three respondents indicated that they paid their medical bills mainly in cash. Chart 12

also shows large differences in payment behaviour, since in many other countries

hardly any of these recurrent payments, or payments for medical services, were said

to be paid in cash. In general it can be concluded that in countries where the share

of cash in overall payments is high, recurrent payments are made more often in

cash.

Chart 12

Use of cash for recurrent payments (number of respondents)

Question: which of the following expenses do you mainly pay in cash?

(based on 30,871 respondents from the euro area)

Sources: ECB and De Nederlandsche Bank.

Notes: Label max1 to 5 indicate the top 5 countries holding the highest shares of responses per sector category.

6%

13%

14%

16%

31%

10%

9%

53%

GR

GR

MT

GR

CY

CY

CY

NL

SK

CY

CY

CY

GR

GR

GR

FI

MT

MT

GR

IT

MT

SI

LT

FR

LV

LT

PT

MT

SK

MT

SK

LU

CY

IT

LT

SI

LV

LT

IT

ES

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

rent or

mortgage

electricity

supply

gas or oil

supply

telephone line

or mobile

phone

medical

bills

insurance

policies

taxes none of

these

euro area

max1

max2

max3

max4

max5

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 201 / November 2017

30

6 Contactless payments in the euro area

In recent years contactless payments have become widely available in many euro

area countries, albeit at different paces, depending on the roll-out of contactless-

enabled cards and terminals. With contactless technology one can pay with a debit

card, credit card or a device (such as smart phone) by holding the card or device

within a few centimetres of a payment terminal enabled with near field

communication (NFC) technology. Normally no personal identification number (PIN)

is required for payments amounting up to €25, while for payments above that

threshold amount, a PIN code is needed.

24

For the purpose of this paper only those

contactless transactions have been considered for which no PIN is required. If

respondents indicated that they had paid amounts above €25 by means of

contactless payments, they were not considered as contactless payments, but as

“normal” card payments.

In 2016, approximately 1% of all payments at the POS consisted of contactless

payments amounting up to €25. Up to 35% of these payments were for amounts

lower than €5 and up to 65% of them for amounts lower than €10 (Chart 13). The

study results suggest that the adoption of contactless payments depends on gender,

age and level of education. Chart 14 presents the results on the use of contactless

payments by demographic groups, comparing each group to the average euro area