© 2015 International Monetary Fund

IMF Country Report No. 15/98

CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE:

NEW MEMBER STATES (NMS) POLICY FORUM, 2014

SELECTED ISSUES

This Selected Issues Paper on Central and Eastern Europe: New Member States (NMS)

Policy Forum, 2014 was prepared by a staff team of the International Monetary Fund. It is

based on the information available at the time it was completed on February 26, 2015.

Copies of this report are available to the public from

International Monetary Fund Publication Services

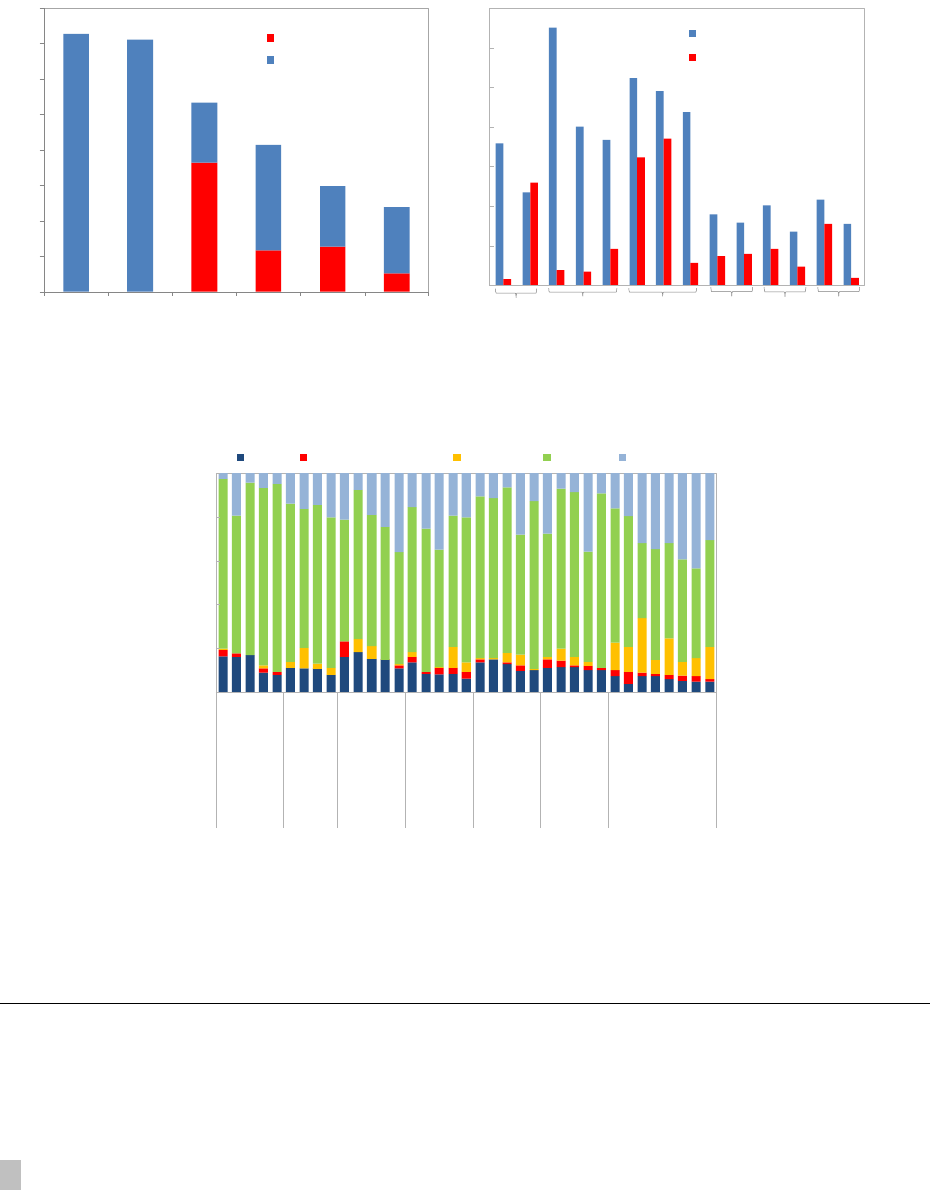

PO Box 92780 Washington, D.C. 20090

Telephone: (202) 623-7430 Fax: (202) 623-7201

E-mail: [email protected]

Web: http://www.imf.org

Price: $18.00 per printed copy

International Monetary Fund

Washington, D.C.

April 2015

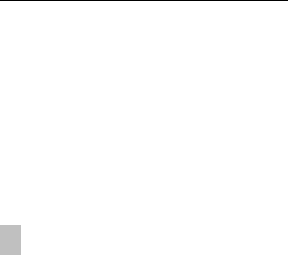

CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE:

NEW MEMBER STATES (NMS) POLICY FORUM, 2014

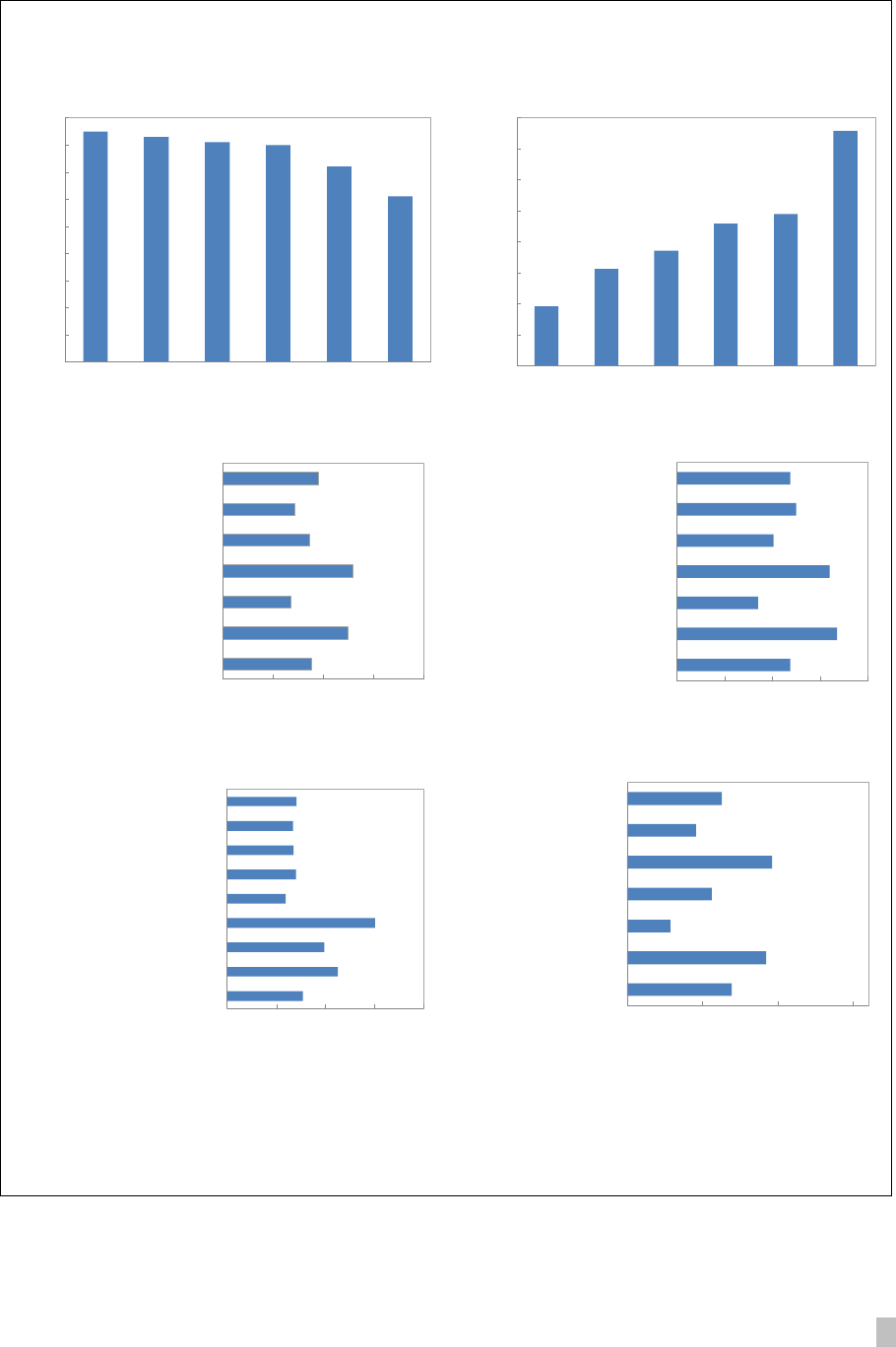

SELECTED ISSUES

Approved By

The European

Department

Prepared by: John Bluedorn, Greetje Everaert, Nan Geng,

Anna Ilyina, Plamen Iossifov, Jiri Podpiera, Jesmin Rahman,

John Ralyea, Ara Stepanyan, Yan Sun, Johannes Wiegand,

Jiae Yoo, Jessie Yang and Li Zeng. Min Song provided

research assistance.

EURO ADOPTION—MACROECONOMIC BENEFITS AND CHALLENGES _______________ 4

A. European Integration and Euro Adoption ______________________________________________ 5

B. Advantages from Adopting the Euro ___________________________________________________ 7

C. Advantages from Preserving Monetary Policy Autonomy and Exchange Rate

Flexibility ________________________________________________________________________________ 11

D. The Impact of Euro Adoption on Macroeconomic Policy Frameworks ________________ 15

E. Conclusions ___________________________________________________________________________18

BOXES

1. The 2004 IMF Study, and New Evidence on its Main Findings _________________________ 19

2. New Member States, Euro Adoption, and the Theory of Optimal Currency Areas _____ 20

3. Economic and Price Convergence in Emerging Europe ________________________________ 21

FIGURES

1. Euro Premium, 2001-13 ________________________________________________________________ 9

2. New Member States: Monetary Policy, 2003-07 _______________________________________ 14

3. New Member States: Monetary Policy, 2008-14 _______________________________________ 16

APPENDICES

I. Estimating the Euro Premium __________________________________________________________ 28

II. The Index of Monetary Conditions ____________________________________________________ 33

III. Model-Based Inflation Variance Decomposition ______________________________________ 34

REFERENCES ____________________________________________________________________________22

CONTENTS

February 26, 2015

CEE NEW MEMBER STATES POLICY FORUM

2 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

OPTING INTO THE BANKING UNION BEFORE EURO ADOPTION ____________________36

A. Why Did Europe Need a Banking Union? _____________________________________________ 37

- ________________________ 39

C. Banking Union Opt-In: Pros and Cons for Non-Euro EU Countries ____________________ 44

D. Conclusions ___________________________________________________________________________ 53

BOXES

1. Key Elements of the Euro Area Banking Union ________________________________________ 54

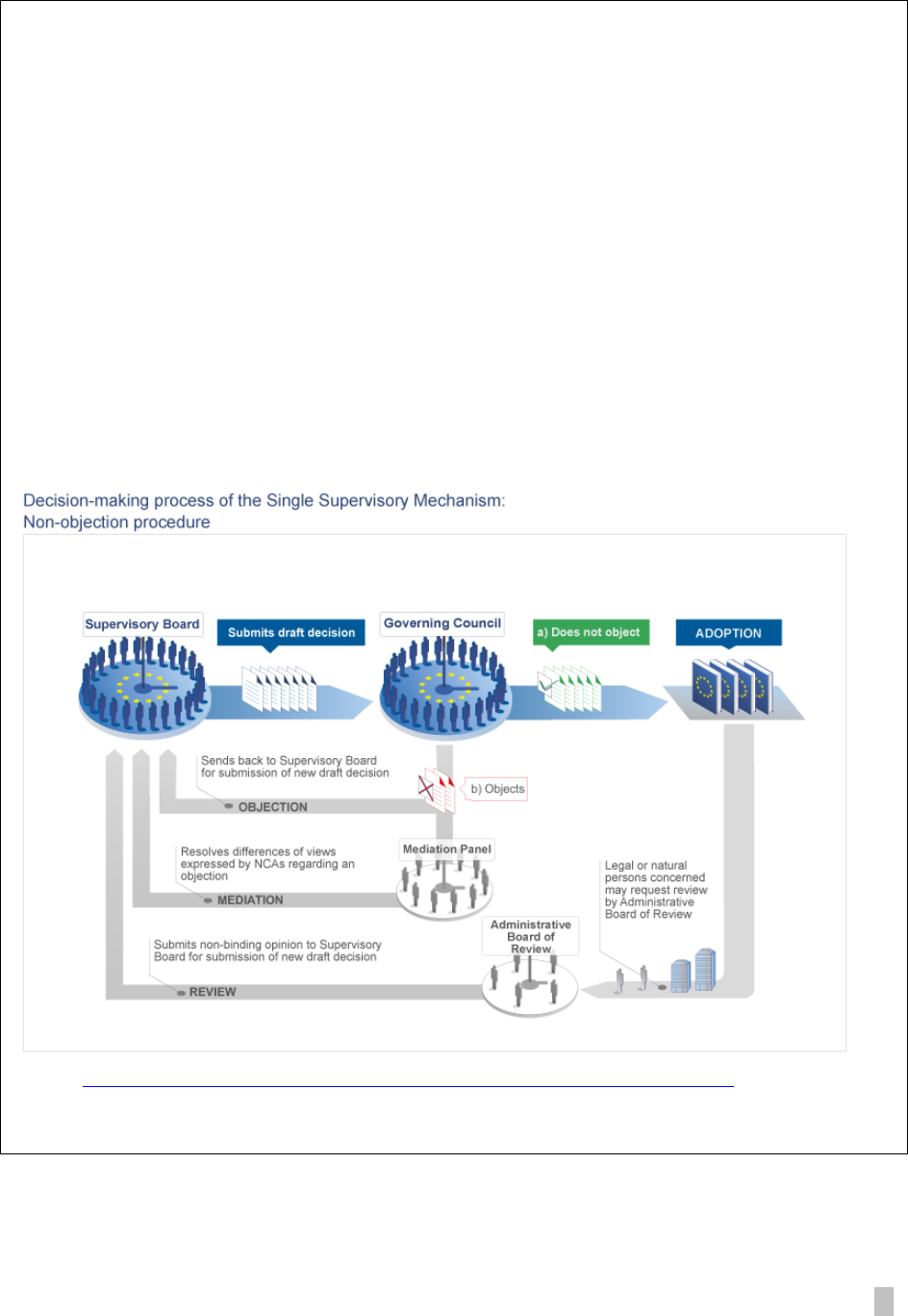

2. The SSM Modalities ___________________________________________________________________ 55

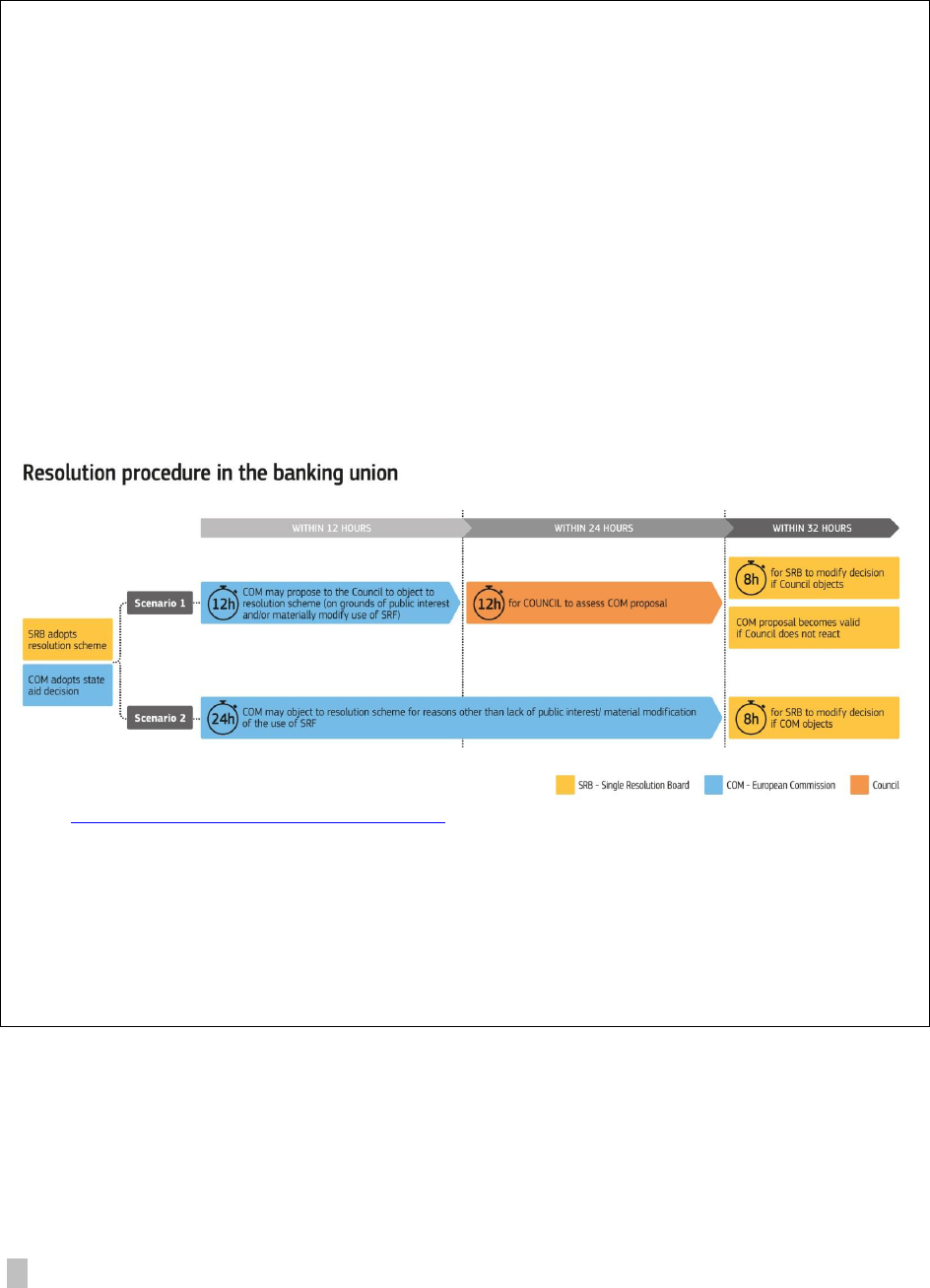

3. The SRM Modalities ___________________________________________________________________ 56

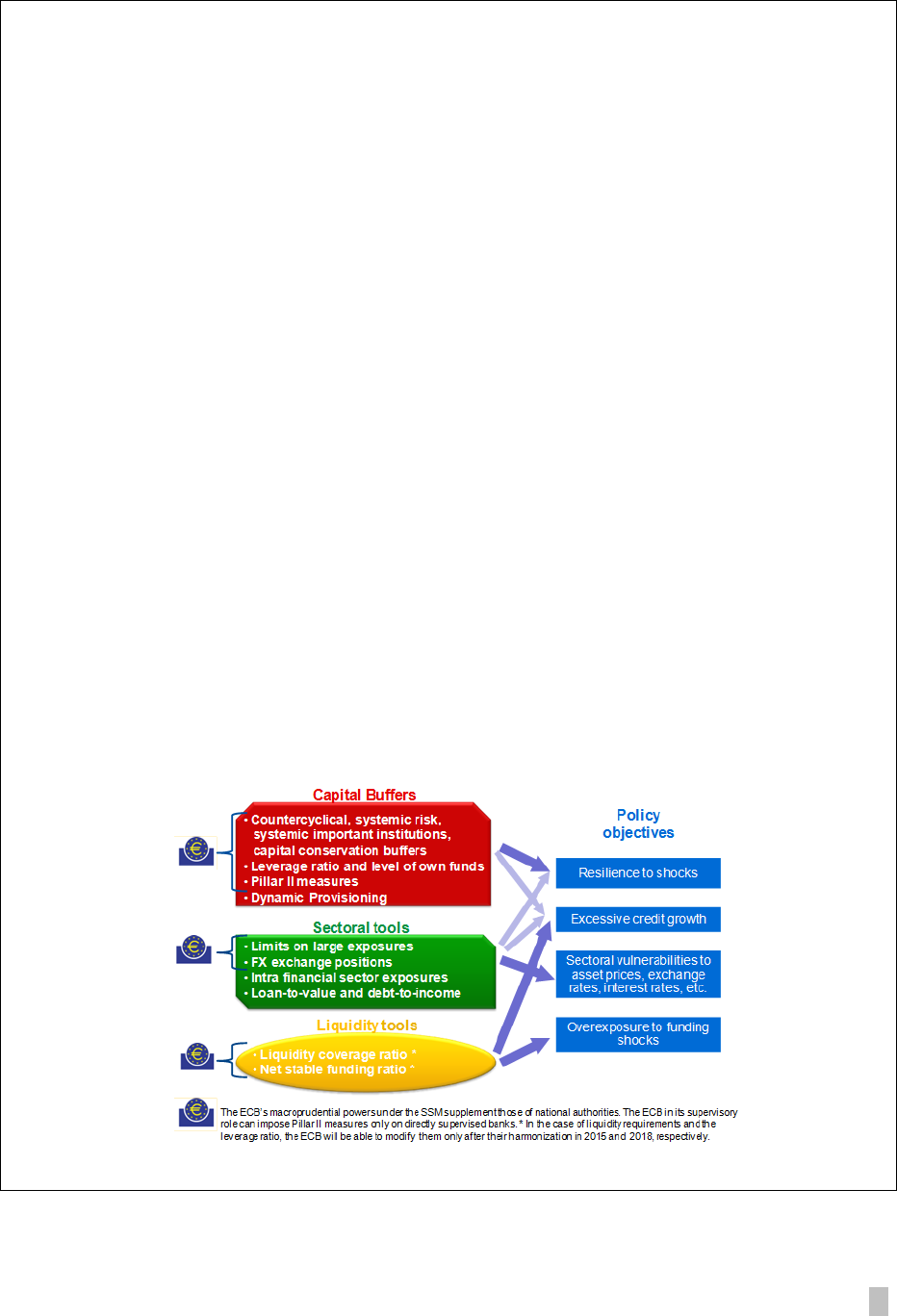

4. Macroprudential Policy Space for BU members _______________________________________ 57

5. Theoretical Considerations in Designing an Optiomal Banking Union _________________ 58

6. Cross-Country Differences in Policymakers Relative Preference for Promoting

Domestic Banks__________________________________________________________________________ 59

TABLE

1. Benefits and Costs of Joining Banking Union for Non-Euro Area Countries ___________ 47

APPENDIX

I. Largeset Banks in NMS-6 and their Ultimate Owners __________________________________ 60

REFERENCES ____________________________________________________________________________61

THE EU FISCAL FRAMEWORK AND PENSION REFORM _______________________________64

A. Public Pension Systems in New Member States: The Broad Picture ___________________ 65

B. Pillar II Pension Schemes: History, Rationale, Performance ____________________________ 68

C. The EU Fiscal Framework and Pillar II Reversals _______________________________________ 71

D. Conclusions ___________________________________________________________________________ 77

FIGURES

1. Selected European Countries: Key Demographic Data ________________________________ 65

2. Second Pension Pillars and National Savings __________________________________________ 70

3. Pillar II Pension Funds: Returns and Fees ______________________________________________ 72

4. Pillar II Pension Reversals _____________________________________________________________ 75

TABLES

1. Pension Spending Projections _________________________________________________________ 66

2. Net Present Value of Pension Deficits _________________________________________________ 67

3. Treatment of Net Cost of Systemic Pension Reforms in the EU Fiscal Framework (the

Stability and Growth Pact (SGP)) _________________________________________________________73

CEE NEW MEMBER STATES POLICY FORUM

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 3

APPENDICES

I. Pension Systems in NMS-6 and Recent Pension Reforms ______________________________ 81

II. Evolution of Pillar II Systems and Contribution Rates __________________________________ 84

REFERENCES ____________________________________________________________________________79

MAKING THE MOST OF THE EU SINGLE MARKET ____________________________________85

A. Introduction ___________________________________________________________________________ 86

B. Evolution of Exports to EU: Relative Success and its Determinants ____________________ 87

C. Export Quality in NMS-6: Room for Growth ___________________________________________ 93

D. Services Exports: Scope for Further Increase __________________________________________ 97

E. Policy Implications ____________________________________________________________________ 99

BOX

1. Czech Republic and Hungary: What can be learnt from Korea? _____________________ 101

FIGURES

1. NMS: Gross and Value Added Exports of Goods and Services _________________________ 87

2. Structural Factors: Relative Importance for Exports to the EU _________________________ 91

3. NMS-6: Contribution of Structural Factors to Relative Export Performance in the EU

Market ___________________________________________________________________________________ 92

4. NMS-6: Export Quality and Room for Improvement ___________________________________ 95

5. NMS-6: Services Exports and Services Directive ______________________________________ 98

TABLES

1. Determinants of Value-Added Exports of Goods and Services to EU: NMS-10,

200311 _________________________________________________________________________________ 90

2. RCA: Exports on Professional and Technical Services __________________________________ 99

ANNEX

Data Appendix and Robustness Check for Regression Analysis for Export Integration _ 102

REFERENCES __________________________________________________________________________ 103

CEE NEW MEMBER STATES POLICY FORUM

4 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

EURO ADOPTION—MACROECONOMIC BENEFITS

AND CHALLENGES

1

1

Prepared by Jiri Podpiera, Johannes Wiegand and Jiae Yoo. Jessie Yang provided excellent research

assistance. The authors are grateful to Csaba Balogh (Hungarian National Bank), Kalin Hrivstov (Bulgarian

National Bank), Paul Kutos (European Commission), Andrzej Raczko (Polish National Bank), and Vedran Sosic

(Croatian National Bank) who participated as discussants in the session on euro adoption at the New

Member States (NMS) Policy Forum in Warsaw on December 12, 2014, and to the NMS-6, EC and ECB

representatives who provided comments during bilateral discussions in November 2014. Ernesto Crivelli,

Anna Ilyina, Plamen Iossifov, Murad Omoev, Andrea Schächter, Michelle Shannon, (other) members of NMS-

6 country teams, and participants at an IMF seminar provided helpful discussions and comments.

2

NMS-6 includes Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Romania. NMS includes these

countries and NMS-EA consisting of Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovakia and Slovenia.

Summary

New Member States (NMS)

2

have considerable leeway over the timing of euro adoption. Even

though the NMS have committed to eventually joining the euro area in their accession treaties, key

steps to initiate adoptionsuch as harmonizing the legal framework with euro area standards, or

applying for ERM2 entryremain under sovereign control. Conversely, the euro area institutions have

substantial discretion in admitting countries to ERM2a pre-condition to euro adoption.

The NMS-6 maintain different monetary regimes. Bulgaria and Croatia have tied their currencies to

the euro, while the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Romania target inflation and allow exchange

rates to float.

The euro area crisis has reduced some attractions associated with joining the euro. While countries

credit risk, this premium has mostly vanished with the euro crisis. This said, euro adoption continues to

hold advantages for highly euroized economies.

For NMS that have maintained monetary autonomy, this has been helpful in containing macro-

economic imbalances, suggesting that, for them, ceding autonomy could be costly. Monetary

tightening and exchange rate appreciation helped contain credit booms in the mid-2000s. After the

outbreak of the 2008-09 financial crisis, monetary easing supported domestic demand. More recently, it

has helped offset imported disinflationary pressures.

The trade-offs associated with euro adoption present themselves differently for the NMS-6,

depending on their monetary regimes. For floaters, key issues are the extent to which monetary

autonomy can be replaced by instruments such as macro-prudential tools and fiscal policy, and the

scope for internal adjustment in the euro area. For peggers, the question is to what extent they can

continue to use macro-prudential and other regulatory tools after adopting the euro.

For many NMS-6, uncertainty about the euro area’s evolving institutional framework provides a

rationale to wait for final outcomes before taking an irreversible adoption decision.

CEE NEW MEMBER STATES POLICY FORUM

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 5

A. European Integration and Euro Adoption

1. Euro adoption forms the endpoint of monetary integration in the EU.

In their EU accession treaties, the NMS-6 committed to adopting the euro “once the

necessary conditions are fulfilled.

3

Parallel biannual reports by the European

Commission (EC) and the European Central Bank (ECB) assess the readiness of non-euro

area EU member states to join. In the latest reports from June 2014, no NMS-6 fulfills all

adoption criteria, hence, none is assessed as ready to join the euro at this stage.

4

The NMS-6 have considerable leeway over the timing of euro adoption. Especially

two adoption criteriaharmonization of the legal framework with euro area standards

and joining the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM2)require a sovereign

decision. At the same time, the euro area institutions have also substantial discretion in

the euro adoption process, especially as regards admitting countries to ERM2.

2. Since 2004—when the first Central and Eastern European countries joined the

EU—five NMS have adopted the euro: Slovenia, the Slovak Republic, and the Baltic

countries. While in the Baltics, euro adoption followed many years of unilateral hard pegs to

the euro, Slovenia and the Slovak Republic maintained monetary autonomy until shortly

before euro adoption. At the same time, new countries have joined the EU in the past

decadeBulgaria, Romania, Croatiaand now face the issue of euro adoption.

3. The NMS-6 that have not yet adopted the euro maintain fairly different

monetary regimes and strategies.

Bulgaria and Croatia have tied their currencies to the euro: the Bulgarian lev by means

of a currency board, the Croatian kuna in the form of a tightly managed quasi-peg. In

both countries, the exchange rate anchor was introduced in the mid-1990s to combat

hyper-inflation (in Croatia in the context of the dissolution of former Yugoslavia). Thus,

3

This distinguishes the NMS-6 from the United Kingdom or Denmark, both of which negotiated an opt-out.

Sweden did not negotiate an opt-out and is subject to the same assessment procedures as the NMS-6.

4

The criteria are fixed in the Treaty on European Union and defined as follows: 1/ Legal = includes the

statutes of the national central bank; 2/ Fiscal = a government budgetary position without a deficit and debt

level that are determined excessive; 3/ Price stability = a rate of inflation which is close to that of, at most,

the three best performing Member States in terms of price stability; 4/ Exchange rate stability = the

observance of the normal fluctuation margins provided for by the exchange-rate mechanism of the

European Monetary System, for at least two years, without devaluing against the euro; 5/ Interest rate

stability = observed over a period of one year before examination, a Member state has had an average

nominal long-term interest rate that does not exceed by more than 2ppt that of, at most, the three best-

performing Member States in terms of price stability.

CEE NEW MEMBER STATES POLICY FORUM

6 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

By contrast, central banks in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Romania target

inflation and, correspondingly, have in general allowed exchange rates to floata policy

targeting in 1997. In Hungary and Romania, central banks have at times carried out

significant interventions in foreign exchange markets, arguably to prevent the revaluation

of foreign currency denominated loans in case of excessive exchange rate volatility. As a

the Polish zloty is classified a

unconventional monetary policy at the zero interest bound. Until 2013, howeveri.e., in

the period covered by the empirical analysis of this paperthe Czech koruna was

4. This paper’s objective is to illustrate economic benefits and costs from euro

adoption by reviewing the main arguments and empirical evidence. The last time Fund

staff analyzed this issue systematically was in 2004 (published as Schadler et al, 2005; see

Box 1 for a summary of the main findings), in a study informed by the literature on optimal

currency areas (Box 2). This paper follows and builds on the conceptual framework of 2004,

by both reviewing new results from the literature and contributing analysis in areas less

covered by existing research. We also discuss issues that were less on the radar screen in

2004 but have since come to the forefront, especially in the wake of the global financial crisis.

5. Broadly speaking, the trade-off presents itself as follows:

On the positive sidei.e., in favor of euro adoptionthe 2004 study identified: (i) trade

generation that could translate into higher growth; and (ii) improved country risk

perception from deeper integration with the euro area that could, inter alia, lead to lower

funding cost.

EU Currency Exchange rate regime classification Earlier regimes

Accession (IMF, 2014)

Bulgaria 2007 Lev Hard peg - currency board Float until 1997. Currency board adopted in response to hyperinflation.

Croatia 2013 Kuna Soft peg - crawl-like arrangement Dinar until 1994, hyperinflation. Soft peg to deutsche mark until euro introduction.

Czech Republic 2004 Koruna Other managed arrangement Peg to dollar/currency basked until 1997. Inflation targeting; free float until 2013.

Hungary 2004 Forint Floating - inflation targeting Various pegs and crawling pegs until 2008 with increasingly wide bands (15% 2001-08).

Poland 2004 Złoty Free floating - inflation targeting Various pegs and crawling pegs until 2000.

Romania 2007 Leu Floating - inflation targeting Monetary based targeting with managed float until 2005. Abandoned amid high inflation.

Estonia 2004 Euro (since 2011) … Pegged to deutsche mark/euro (currency board).

Latvia 2004 Euro (since 2014) … Pegged to SDR 1994-2004, pegged to euro 2004-2014.

Lithuania 2004 Euro (since 2015) … Pegged to dollar 1994-2002, pegged to euro 2002-2014 (currency board).

Slovak Republic 2004 Euro (since 2009) … Float until 2004. Float with a 15% band during ERM II (2005-08), repeated parity adjustments.

Slovenia 2004 Euro (since 2007) … Float until 2004. Pegged to euro during ERM II 2004-06.

New Member States - Currency Arrangements

CEE NEW MEMBER STATES POLICY FORUM

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 7

On (i) there is a solid body of evidence now that trade generation has remained far below

original expectationssee Box 1and we do not delve into this issue further. As for

(ii) we reassess the impact of euro adoption on investor perception of country risk in the

light of the evidence of the past 10 years.

We also analyze a benefit of euro adoption not covered in the 2004 paper: the

elimination of currency mismatches resulting from the prevalence of foreign currency,

mainly euro

illustrated, currency mismatches can translate into large vulnerabilities in times of

financial strain.

As the main factor on the negative sidei.e., cautioning against rapid euro adoption

the 2004 study identified the loss of monetary autonomy; i.e., ceding the ability to adapt

hange rate as shock

absorber. We re-assess the value of monetary autonomy in light of the experience of the

past ten years that were characterized by far higher macro-economic volatility than

expected (Box 1).

Finally, we discuss how euro adoption changes

frameworks beyond monetary policy, and how recent euro area wide reforms in these

areasfiscal compact, banking union

6. Importantly, weighing the pros and cons of euro adoption is ultimately an issue

of preference that can differ between countries. Further, the decision on adoption clearly

goes beyond purely economic aspects and includes political economy and broader political

considerations. These are beyond the scope of this paper. As a result, we refrain from

recommendations on whether a country should adopt the euro or not, but instead focus on

key macro-economic tradeoffs.

7. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section B reviews key

economic advantages of euro adoption as sketched above, Section C the advantages from

maintaining monetary policy autonomy. Section D discusses the impact of euro adoption on

policy frameworks. Section E concludes.

B. Advantages from Adopting the Euro

8. As outlines above, this section analyzes two possible advantages of euro

adoption:

Improved country risk perception

institutional framework that may translate, inter alia, into lower funding costs, and

the elimination of currency mismatches between euros and domestic currencies.

CEE NEW MEMBER STATES POLICY FORUM

8 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Euro Area Membership and Country Risk Perception

9. Adopting the euro can reduce perceived risks through the elimination of exchange

rate risk and access to lender-of-last resort facilities in a global reserve currency. For

countries with weak institutions, euro adoption can also strengthen the credibility of the

monetary anchor.

5

Conversely, euro adoption may undermine a country risk perception,

especially when it reduces the ability to handle country-specific shocks (as discussed in

Section III).

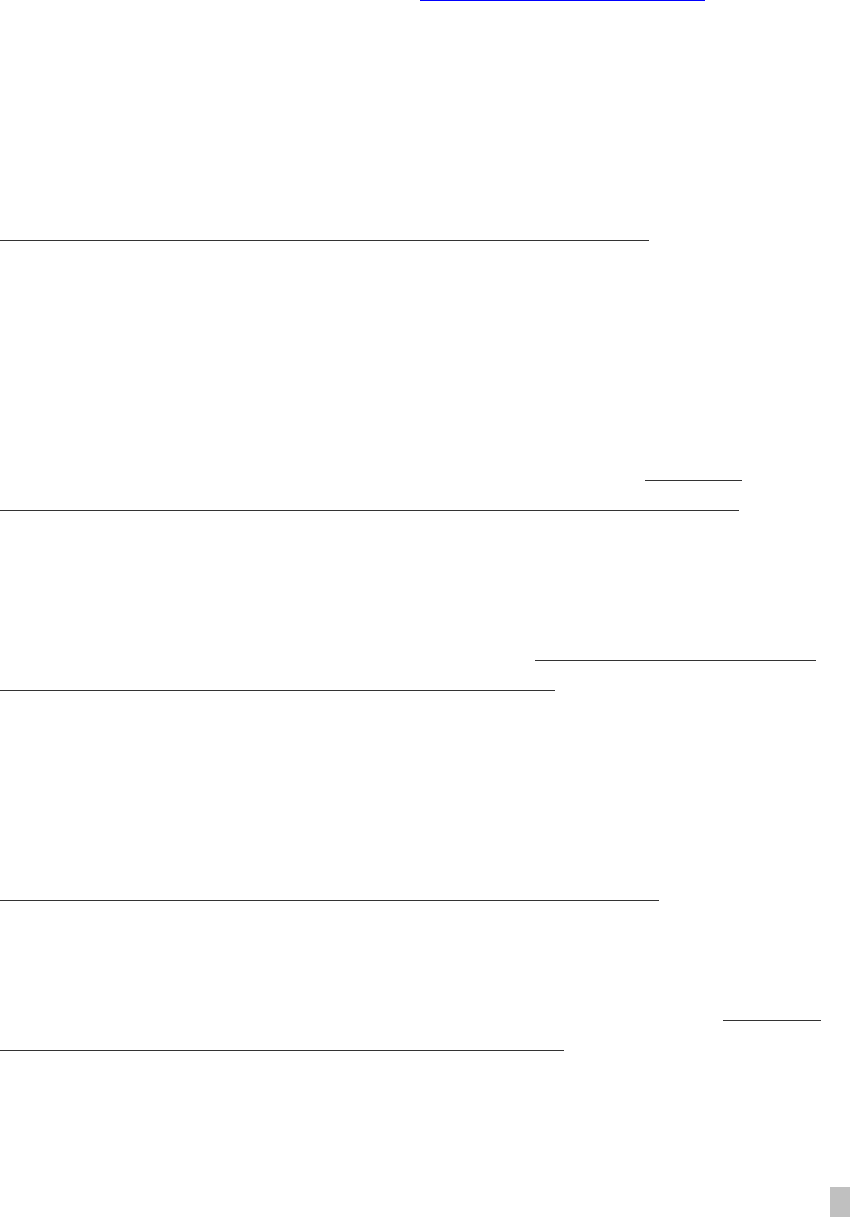

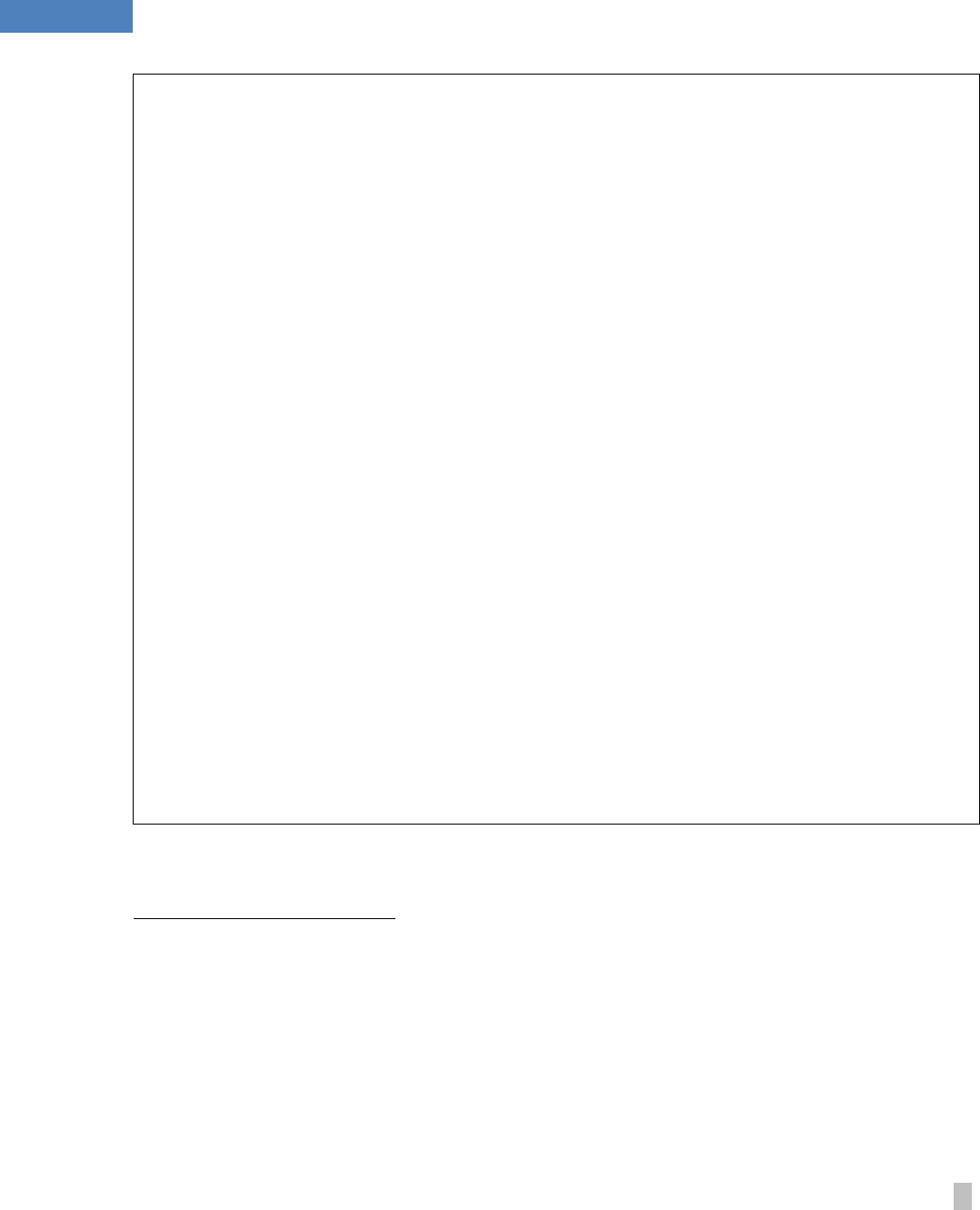

10. To analyze the effect of euro adoption on country risk perception, we estimate

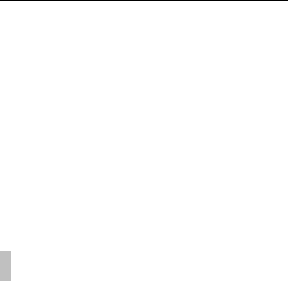

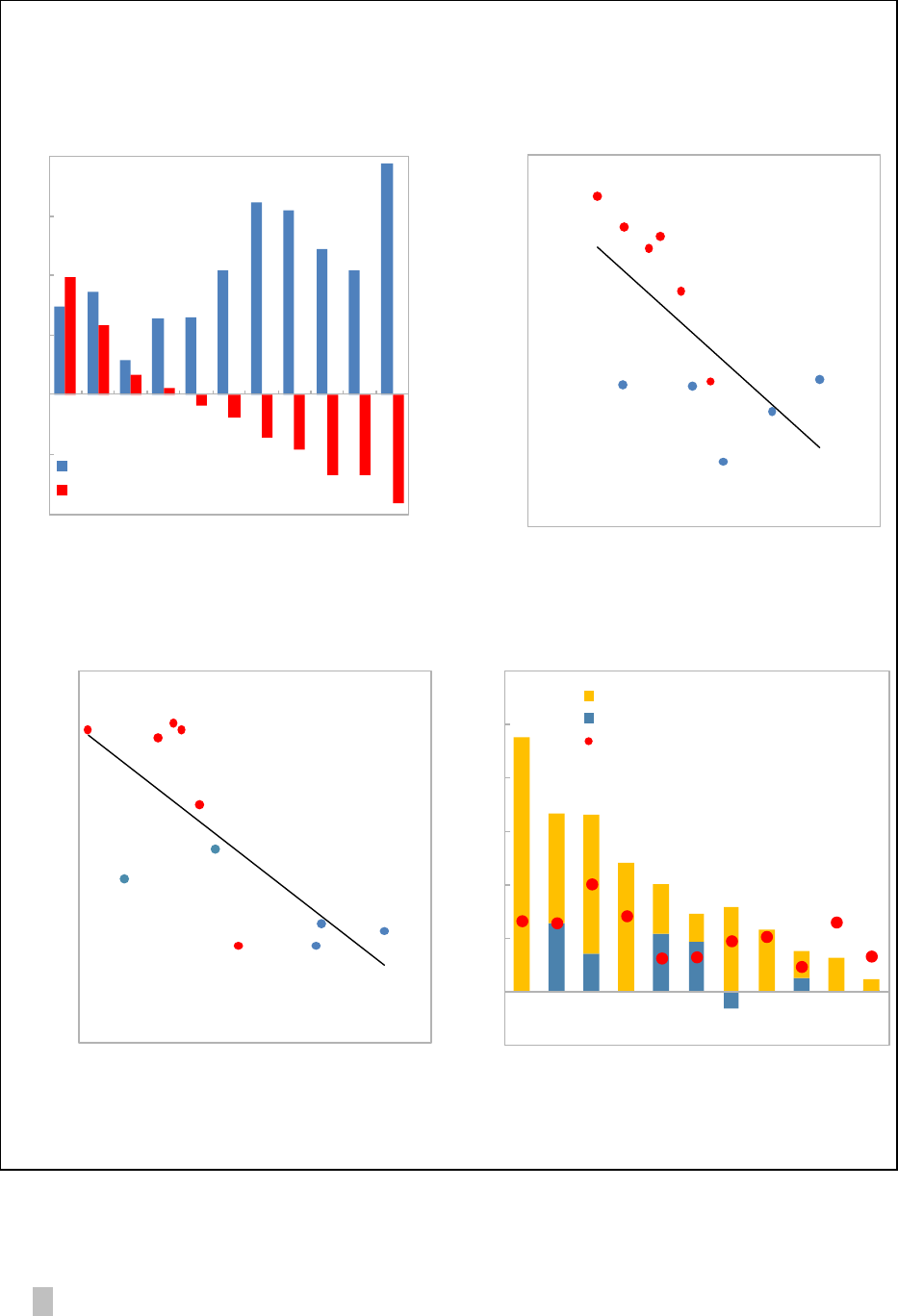

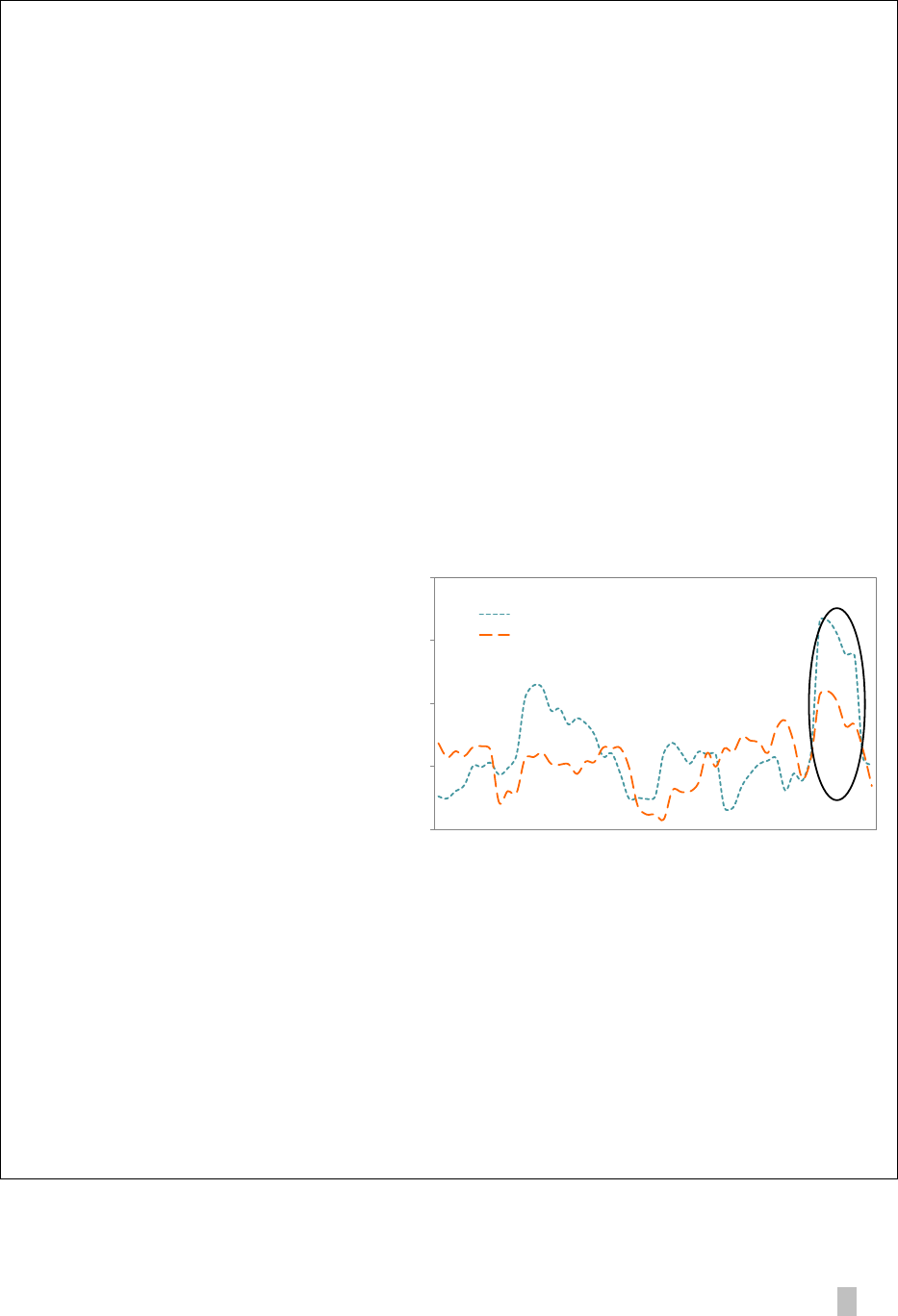

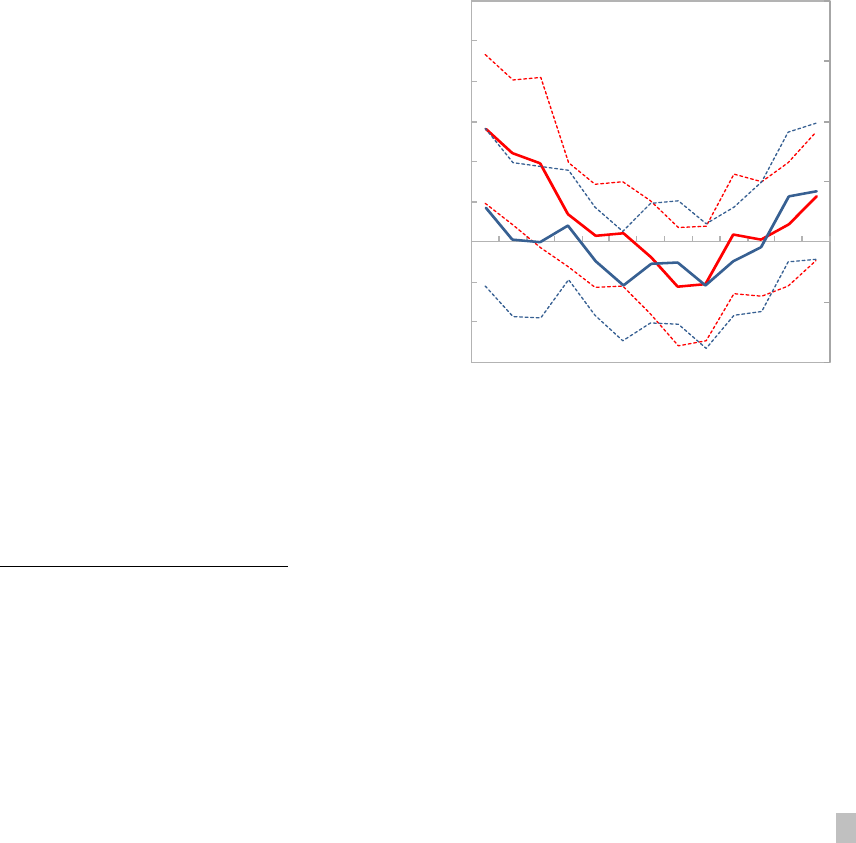

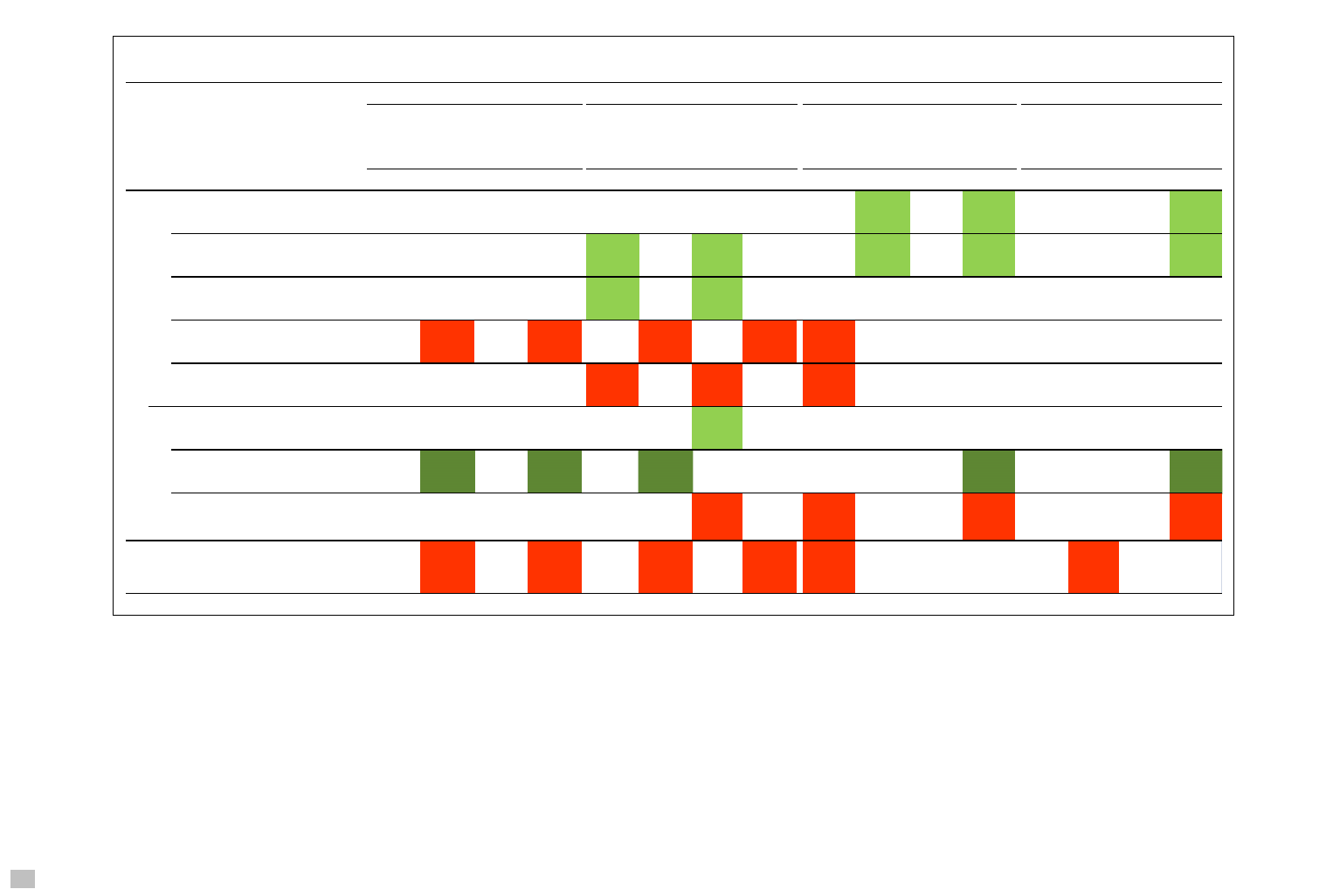

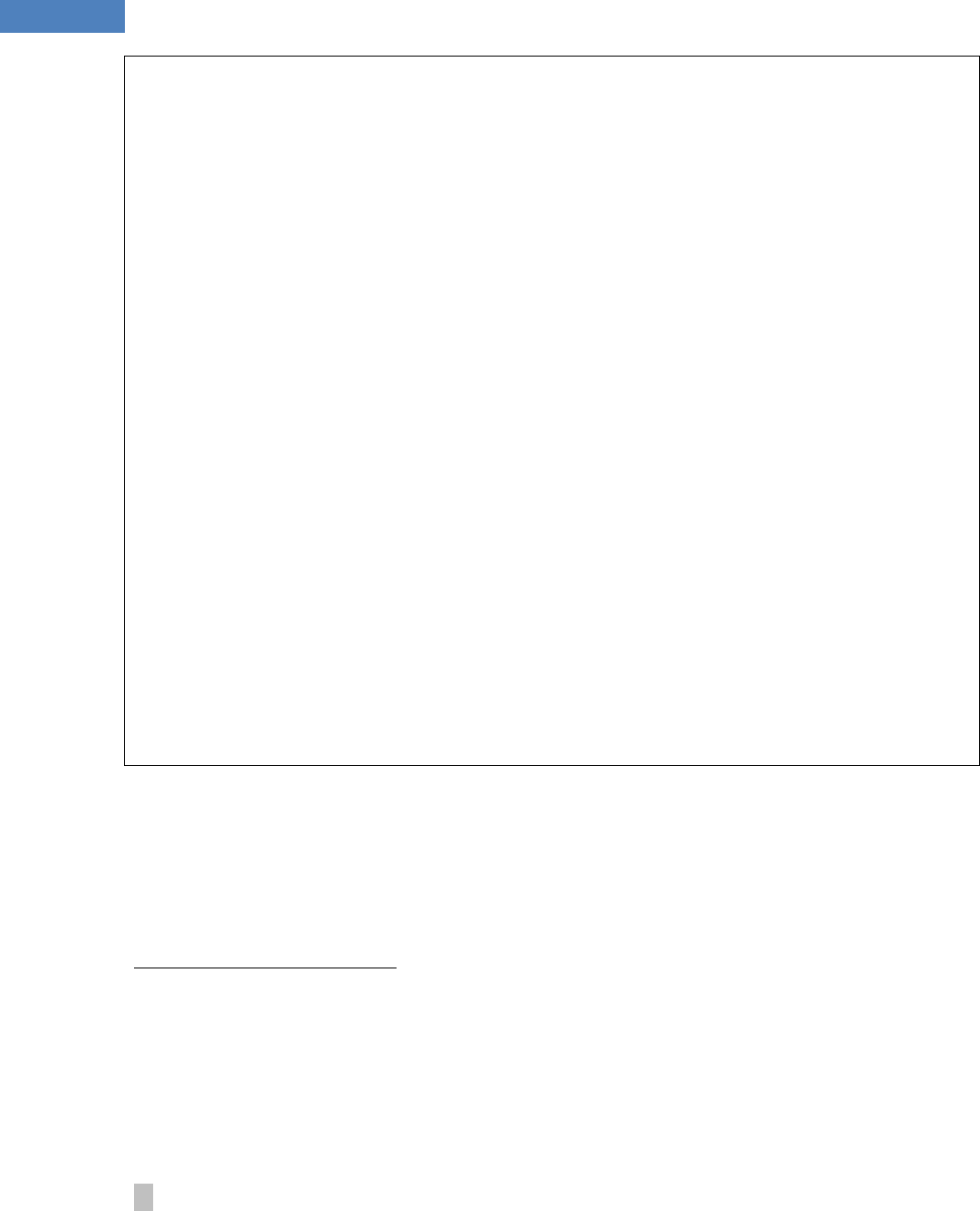

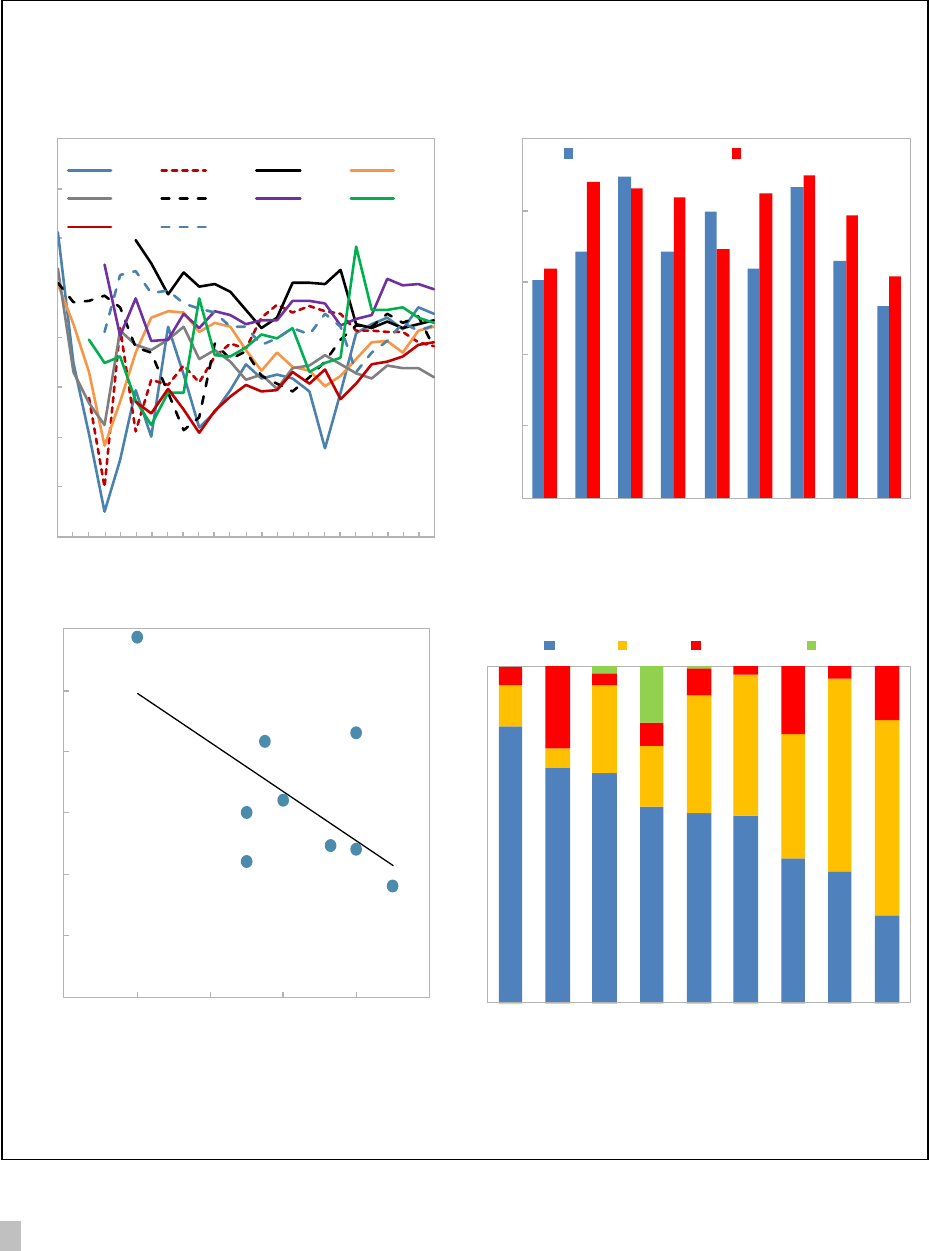

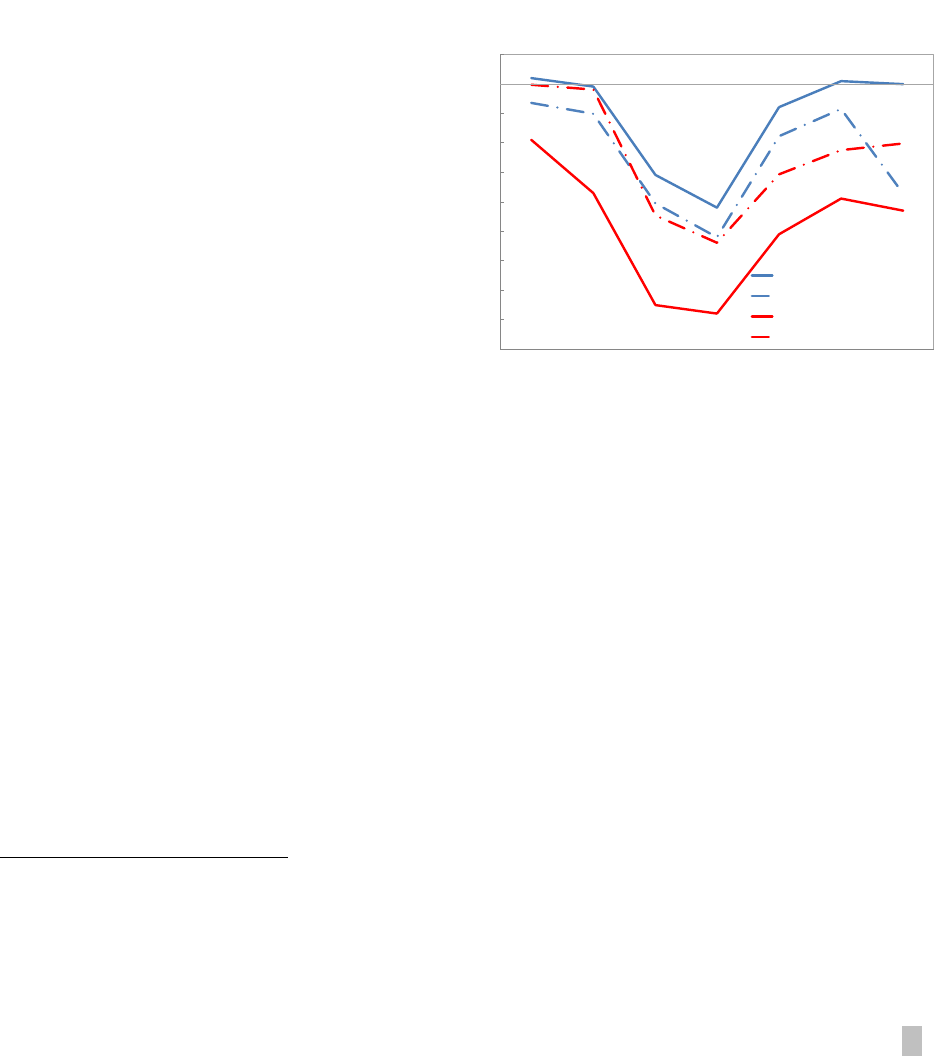

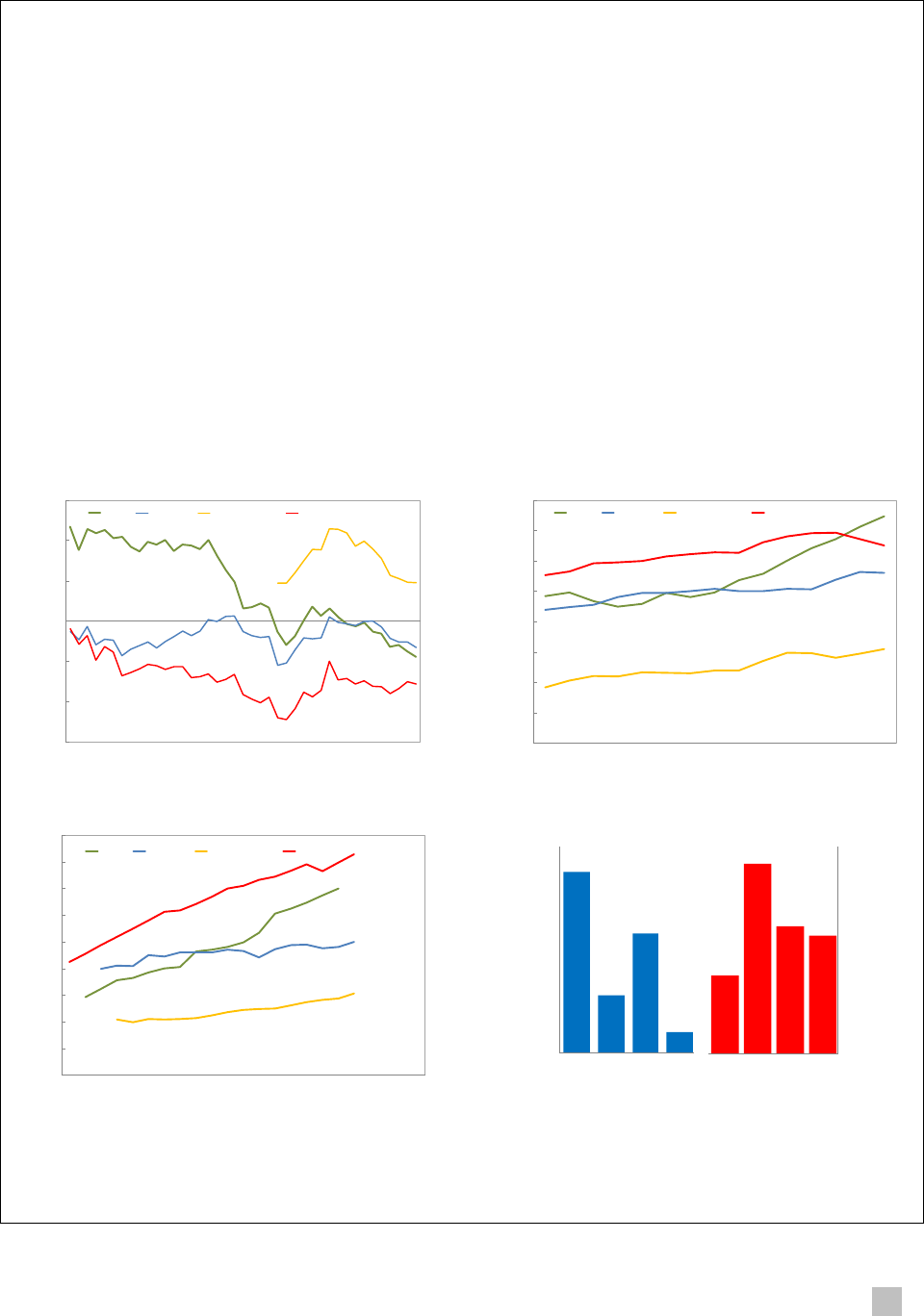

an econometric model (Figure 1).

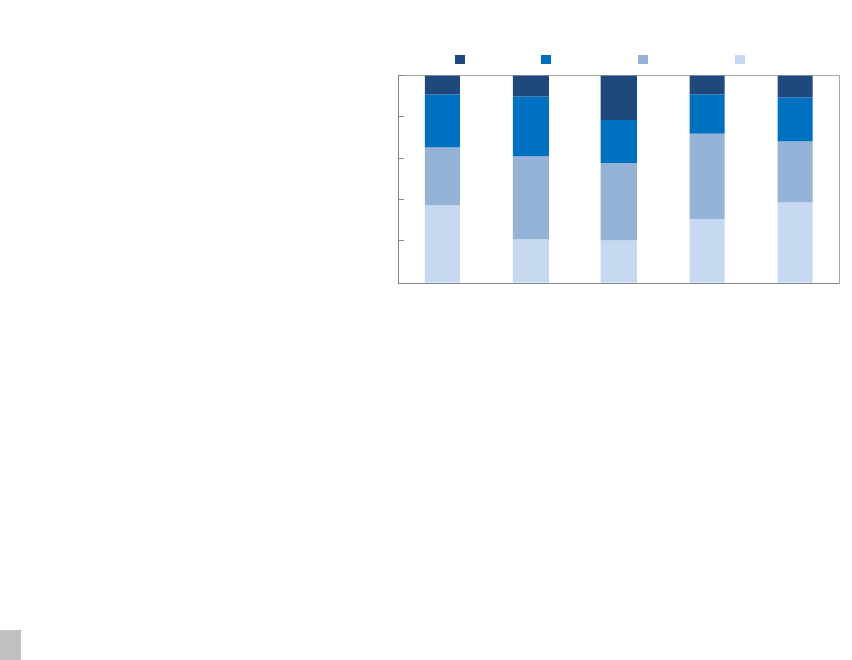

Country risk perception indices. We use two different indices: the Institutional

sovereign credit ratings (S&P). The IIR index is based on anonymous inputs from

economists and risk analysts at banks, money market funds, and securities firms.

directly measures investor attitudes toward country risk. The S&P rating is based on a

formal assessment methodology, complemented by judgment. It is used both for

regulatory purposes and to inform asset allocations of institutional investors, but has at

times been criticized for (alleged) biases (see e.g. Vernazza et al, 2014). The two indices

display similar patterns, and their relationship is broadly linear, with 45 points on the IIR

scale corresponding to one rating notch with S&P (Figure 1).

Analysis. We estimate the relationship between perceived credibility and country

characteristics for 34 countries during 200113. One characteristic is euro area

membership. A positive coefficient suggests that investors put a on

membership.

6

The premium is estimated for each year separately (see Appendix I).

Results. The reputational value of euro area membership has declined. Through most of

the 2000s, membership provided a substantial country risk premium of 1015 rating

points on the IIR scale, and of about two rating notches with S&P. This premium has

mostly vanishedentirely for the S&P index, and to a somewhat lesser degree for the IIR.

The timing of the declinestarting in 2010suggests that the euro area crisis triggered

a reassessment among investors of the relative benefits and drawbacks of euro

membership for country risk.

5

These advantages were clearly on the mind of the early euro adopters. For example, in 2003 the Slovenian

providing a more stable environment for the whole

economy”, and the adoption of the single currency will

represent the completion of the integration process”.

6

Strictly speaking, the premium measures the impact of euro membership on the perceived distance to

default.

CEE NEW MEMBER STATES POLICY FORUM

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 9

Figure 1. Euro Premium, 2001-13

Sources: EBRD; International Investor Ratings; Standard and Poors; and IMF Staff calculations.

-9

-6

-3

0

3

6

9

12

15

18

2001

2003

2005

2007

2009

2011

2013

International Investor Ratings Premium for Euro

Membership (Rating points)

-2

-1

0

1

2

3

4

2001

2003

2005

2007

2009

2011

2013

Standard and Poors Rating Premium for Euro

Membership (Rating notches)

y = -0.2258x + 21.957

R² = 0.9296

1

3

5

7

9

11

13

15

17

0 20 40 60 80 100

The S&P and IIR Credit Ratings

IIR Rating

S & P Rating (linearized)

50

55

60

65

70

75

80

85

90

95

2001

2003

2005

2007

2009

2011

2013

Euro area

EU, not euro

Outside EU

Evolution of Ratings per Country Group

IIR (lhs) S&P (rhs)

AAA

A

AA+

AA

AA-

A+

A-

BBB

BBB-

BBB+

CEE NEW MEMBER STATES POLICY FORUM

10 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

11. As a result, the NMS-6 today face a different situation than the early euro

adopters in the 2000s. While Slovenia or the Slovak Republicthat adopted the euro in

2007 and 2009, respectivelycould expect to benefit from a sizeable reputational boost

upon joining the euro, this benefit has vanished with the euro area crisis.

Eliminating Currency Mismatches

12. Beyond the impact of the euro on general risk perception, euro adoption can

benefit a country if it reduces specific vulnerabilities—notably foreign currency

mismatches. Such mismatches arise when households and corporations are indebted in

foreign currency (FX), while their assets and income streams are in domestic currency. In this

case, currency depreciation can trigger an upward revaluation of debt that can harm financial

stability and economic activity. While countries can self-insure against depreciation risk

through accumulation of FX reserves and regulations forcing financial institutions to hold

extra buffersthis is costly. FX indebtedness is widespread in Central and Eastern Europe,

oftenbut not alwaysintermediated by subsidiaries of banks located in the euro area (see,

e.g., Brown and de Haas 2012, or Rosenberg and Tirpak 2009). Among the NMS-6, balance

sheet euroizationproxied here by the share of bank loans to the private sector

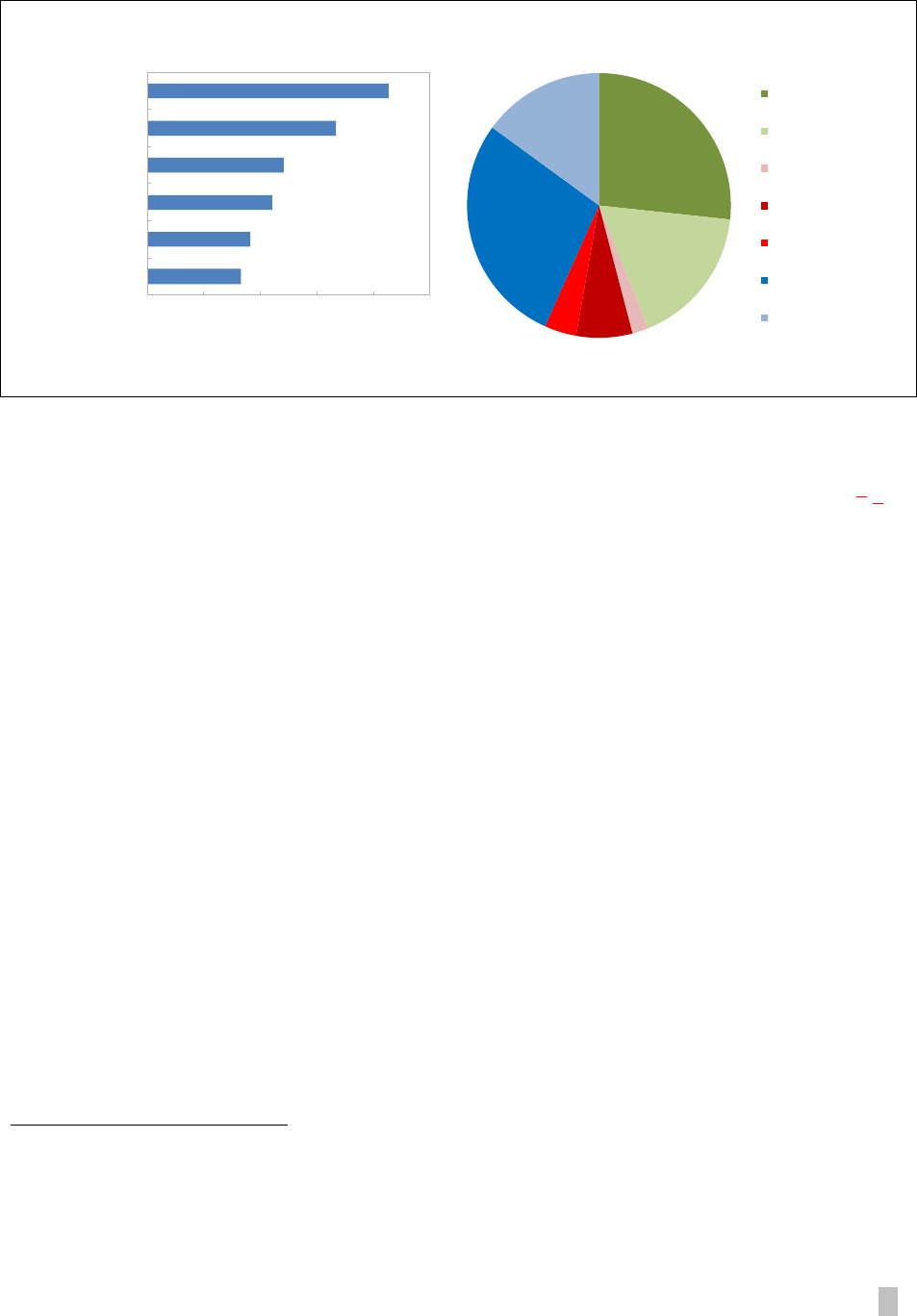

Investor Perception and Balance Sheet Euroization, 2006-14

Balance Sheet Euroization Euro Premium and Balance Sheet Euroization

(FX loans to the private sector as share in total) (Fixed effects, 2006-12)

Sources: EBRD; International Investor Ratings; Standard and Poors; and IMF Staff calculations.

0 20 40 60 80 100

HRV

ROU

BGR

HUN

POL

CZE

LTU

SVN

LVA

EST

SVK

2006

2010

2014 (Nov)

Balance Sheet Euroization

(FX loans to the private sector as share in total)

CZE

POL

HUN

ROU

BGR

LTU

HRV

LVA

R² = 0.390

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

-15 -10 -5 0 5 10

Credibility Premium and Balance Sheet

Euroization (Fixed effects, 2006-12)

Average premium (in IIR points)

FX loans to the private sector as share of total

CEE NEW MEMBER STATES POLICY FORUM

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 11

denominated in FX (see figure)is considerable in all economies except Poland and the

Czech Republic.

7

13. As most FX debt in the NMS is denominated in euro, euro adoption can

eliminate sizeable currency mismatches,

8

as it did in the Baltic states and in Slovenia upon

joining the euro (see figure). Similarly, euro adoption grants access to euro lender-of-last-

resort facilities for banks with a high share of euro denominated assets and, correspondingly,

high euro funding needs.

9

In contrast to the general euro premium discussed above, these

FX-specific benefits are disproportionately to the advantage of economies with a high share

of FX loans prior to euro adoption.

14. Our results suggest that for highly euroized economies, eliminating mismatches

through euro adoption is indeed beneficial. This is shown by correlating the country-

specific premiumcaptured by country dummieswith the share of FX bank loans. The

results show that for nearly fully euroized economies, euro adoption can eliminate a ratings

malus of more than 10 IIR points. Further statistical analysis points to a non-linear impact, i.e.,

the malus increases disproportionately with higher levels of euroization (see Appendix I).

15. In contrast to the general euro premium discussed above, FX-specific benefits

from euro adoption have not vanished. This provides an economic rationale why the Baltic

countriesall of them highly euroizedsought euro area membership in the early 2010s,

even though at the time the general euro premium was already waning.

C. Advantages from Preserving Monetary Policy Autonomy and

Exchange Rate Flexibility

16. We now turn to advantages from maintaining monetary autonomy, i.e., the

exchange rate to operate as a shock absorber. If successful, monetary policy autonomy helps

stabilize domestic demandespecially when economies are exposed to shockscontain

inflation volatility and credit developments. To assess the value of monetary autonomy for

the NMS, we look at three distinct episodes in the past 1012 years:

7

This proxy correlates closely with more comprehensive metrics of balance sheet euroization, such as the

currency mismatch index in Ranciere et al. (2010). Data requirements for these indices are larger than for FX

bank loans, however, which would have restricted our sample significantly.

8

In some economiesnotably Poland and Croatia a significant part of FX loans is denominated in Swiss

francs rather than euro (in Hungary, most CHF loans were converted into domestic currency, with a de-factor

conversion date of November 2014). Thus, some currency mismatch would remain even after euro adoption.

9

The value of ECB access became apparent during the financial crisis of 2008/09, when cross-border

currency markets became impaired. The problem was especially severe for banks with sizeable FX assets

and therefore high FX refinancing needsbut without a euro area based parent bank that could have

accessed ECB facilities on their behalf.

CEE NEW MEMBER STATES POLICY FORUM

12 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

economic convergence, i.e. the period of about 200307, when the NMS outgrew the

old EU member states (EU 15) by about three percentage points per year;

the financial crisis of 2008/09 and its aftermath that brought the convergence process

in most NMS to a halt; and

the most recent period of 2012–14

when the NMS were affected by

disinflationary pressures from global

commodity markets and the euro area.

For each episode, we map a standard

monetary conditions index

10

against domestic

demand volatility and related outcomes, such

as real credit growth and inflation, in (i) NMS

that have maintained monetary policy

autonomy and (ii) NMS that have used

external monetary anchorseither by

adopting the euro, or by tying their currencies

to the euro or other currencies/currency

baskets. While there is considerable

heterogeneity of outcomes within both

groupsreflecting

monetary policysome broad patterns emerge.

17. Importantly, this section is not about whether fixed or flexible exchange rates

are generally preferable. Many reasons that go beyond short-to medium-term demand

management as discussed here may call for one regime or the othere.g., in the case of a

fixed exchange rate regime, the need for a credible monetary anchor. What choice is

appropriate will typically depend on country-specific circumstances. A widespread finding in

the literature is that long-term growth and inflation outcomes tend to be broadly similar

under both regimes, while fluctuations tend to be larger with fixed exchange rates (see, e.g.

IMF, 2005 and 2013b).

Managing Convergence

18. In 2003–07, the NMS grew at an average annual real rate of about 6 percent,

3 percentage points faster than the old members of the European Union (EU 15). As a

10

The monetary conditions index is calculated as the weighted average of real interest rate and real

exchange rate, with weights representing the impact of each component on domestic demand (see

Appendix II).

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

BGR

HRV

CZE

HUN

POL

ROU

LTU

EST

LVA

SVK

SVN

GDP Per Capita in Purchasing Power Standard

(Percent of the euro area)

-4

-2

0

2

4

6

8

POL

CZE

HUN

SVN

SVK

Growth differential w/ Euro Area

Monetary Conditions differential w/ Euro Area

Growth and Monetary Conditions

(Percent; average 2003-07; peggers labeled red)

CEE NEW MEMBER STATES POLICY FORUM

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 13

result, the average income gap per capita (PPP) against the EU 15 fell by about 10 percent,

until convergence stalled with the outbreak of the global financial crisis.

19. Higher growth rates for an extended period require a tighter monetary policy

stance. Less wealthy countries have typically a smaller capital stock and therefore higher

returns of capital. This attracts capital inflows, boosts economic growth, and gradually

increases the capital share until economies converge. Unless the higher real return on capital

is matched by tighter monetary conditions, however, there is a risk that capital inflows trigger

credit and housing booms, inflation, and external imbalances (see Lipschitz et al., 2002).

11

As

countries with fixed exchange rate regimes tend to adopt the monetary policy stance of the

economy to which their currency is tied, there is a risk that during convergence, monetary

conditions are too loose. This risk increases with l income gap with the euro

area, and therefore with its potential for rapid growth.

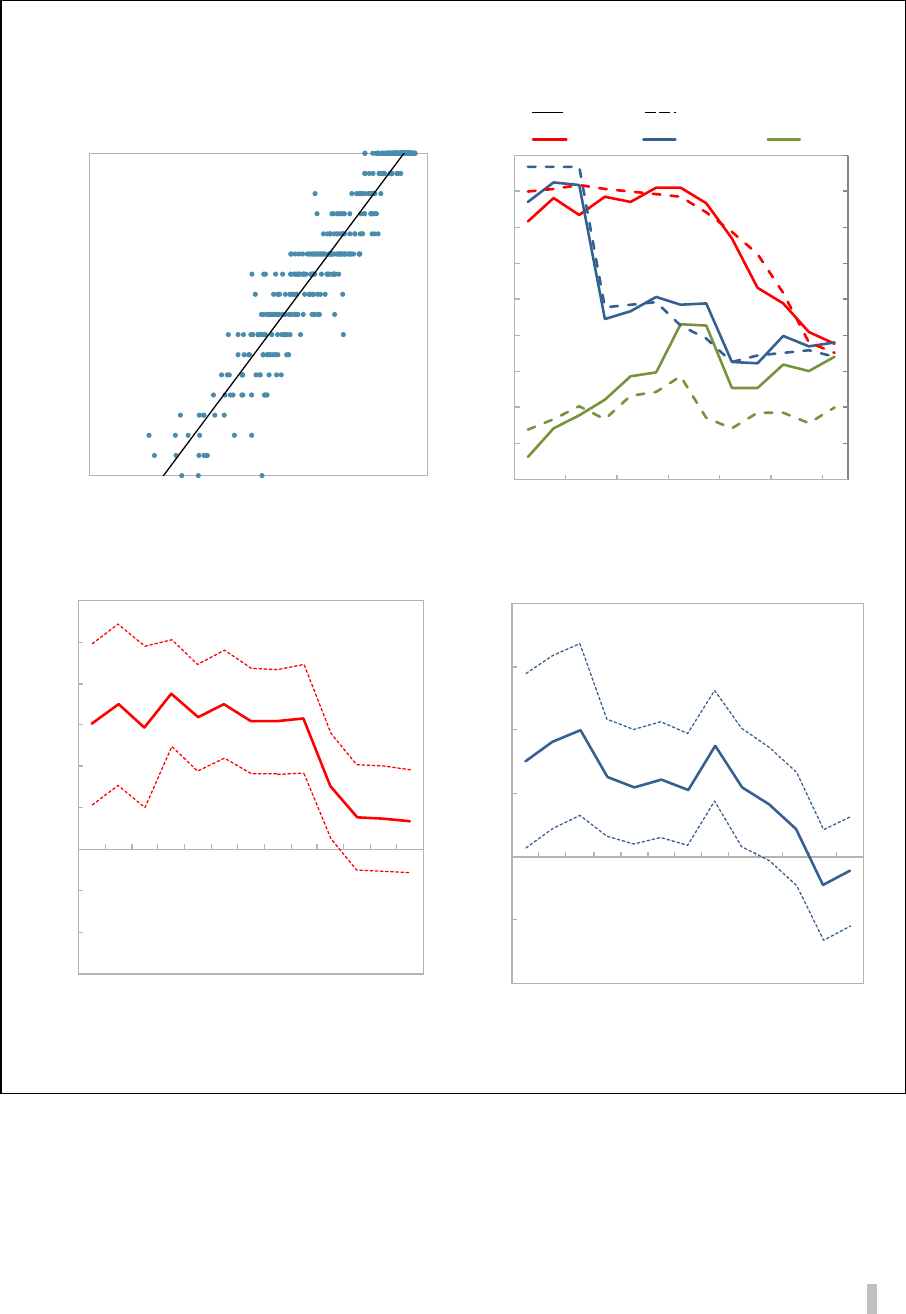

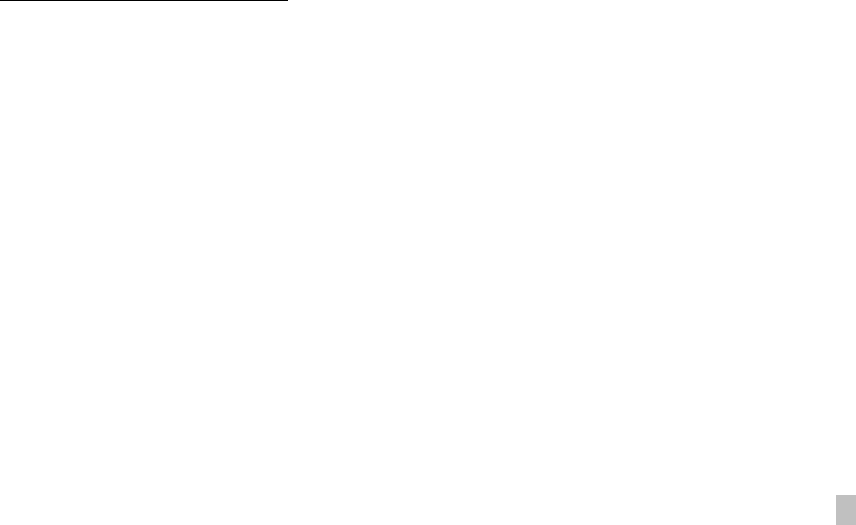

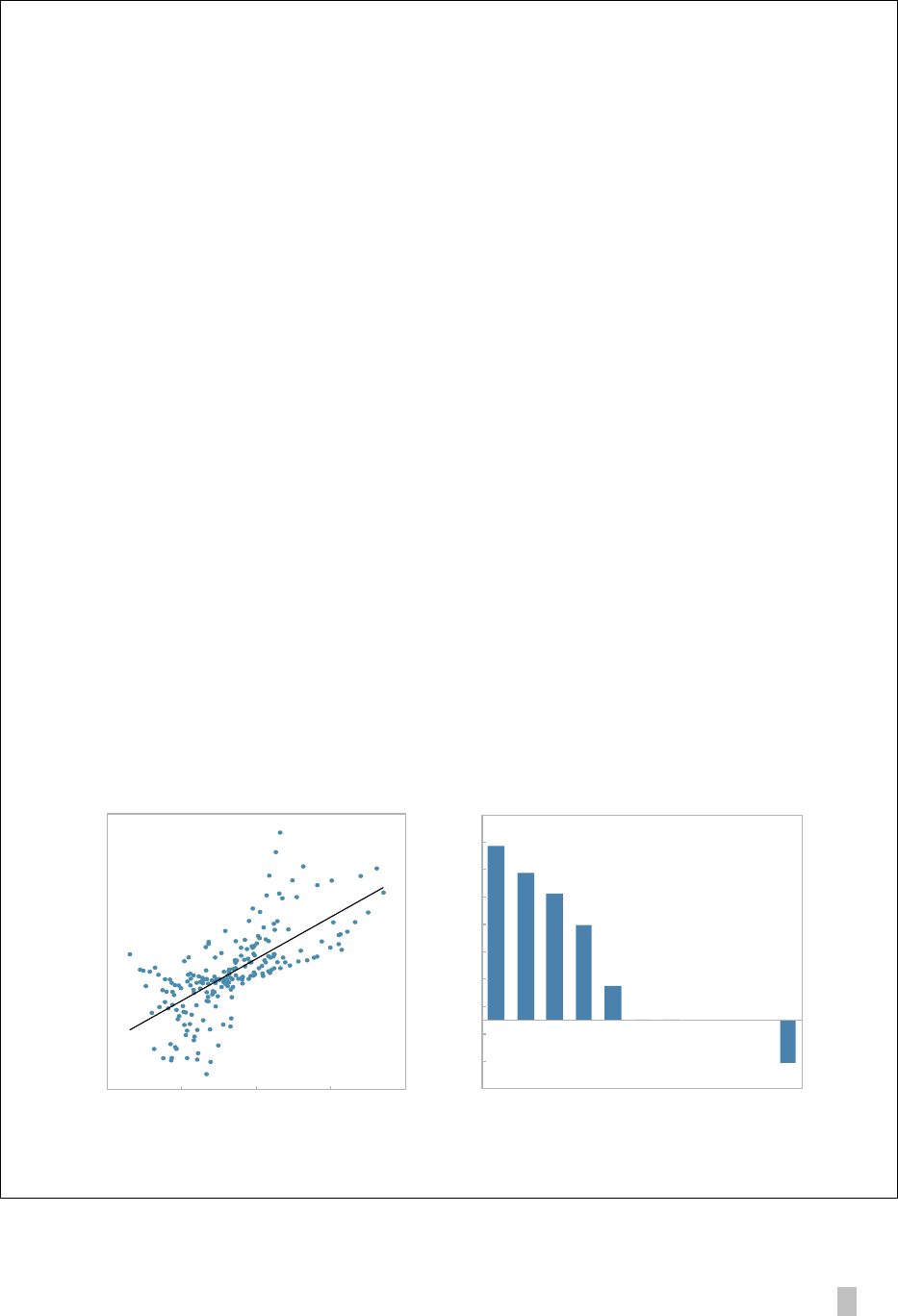

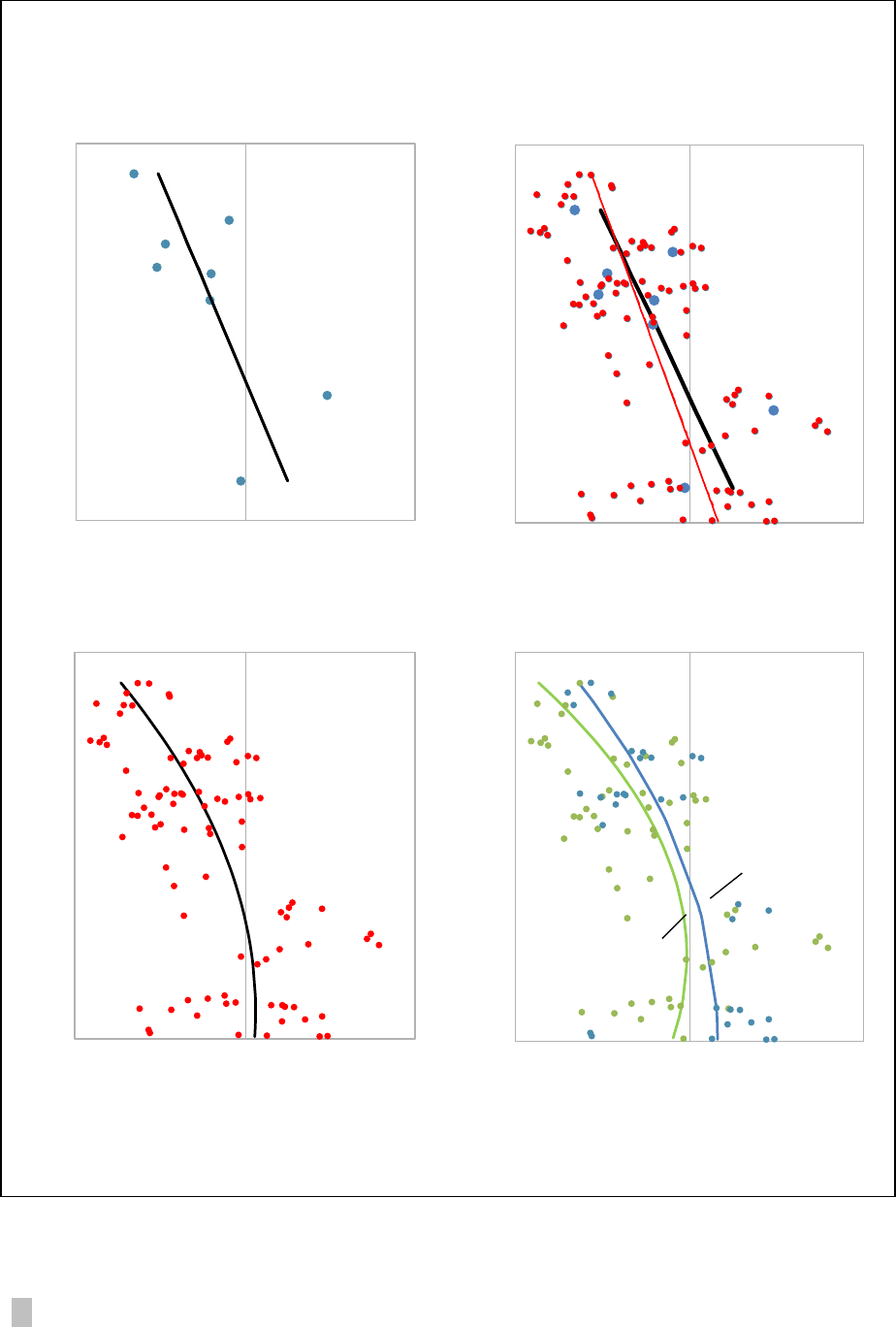

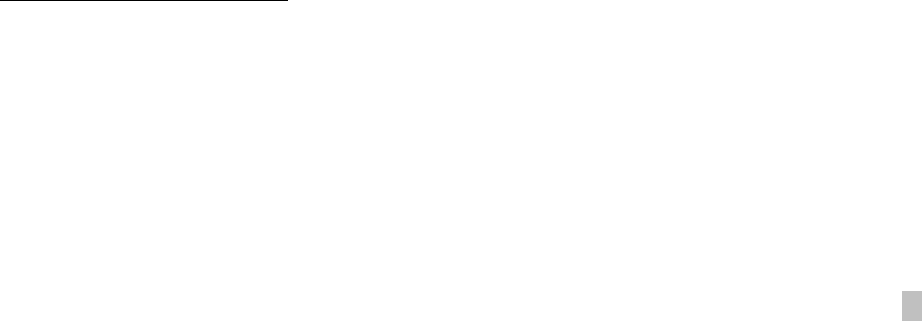

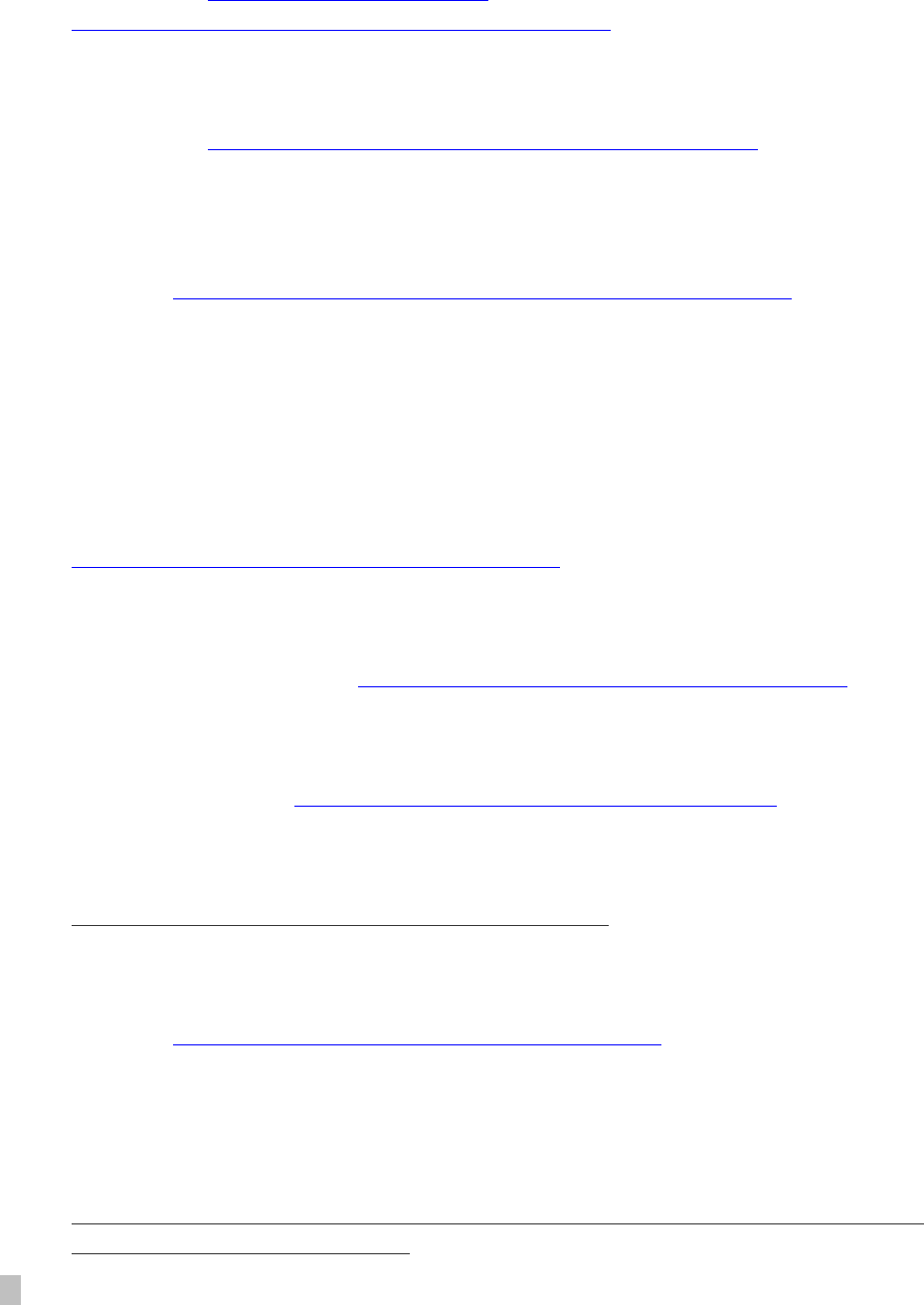

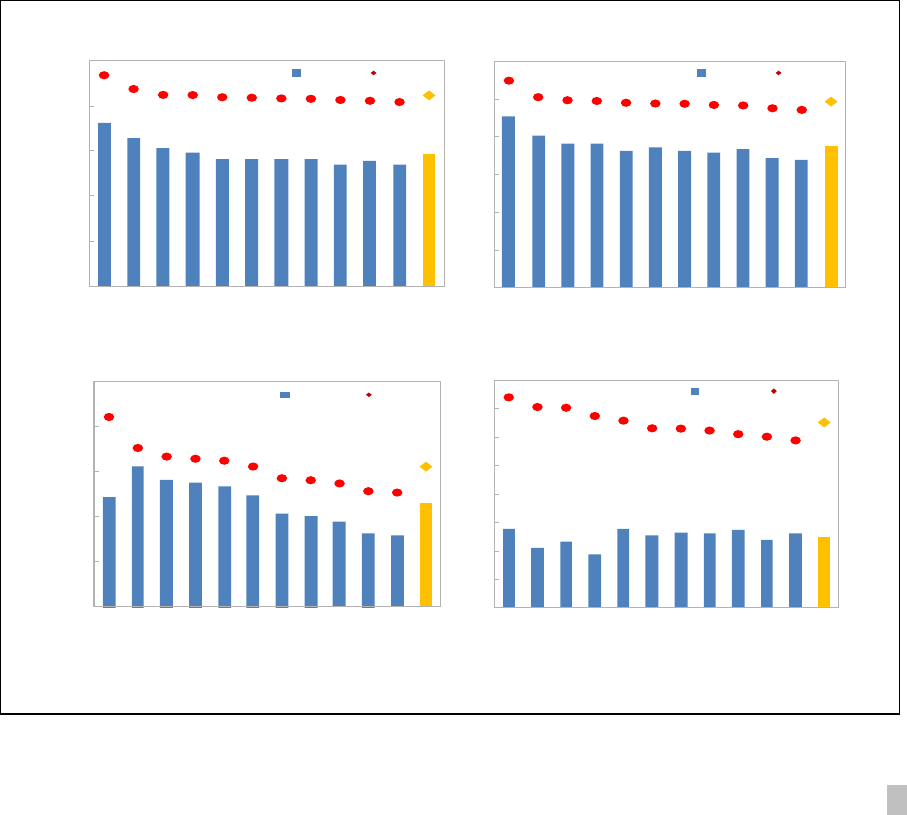

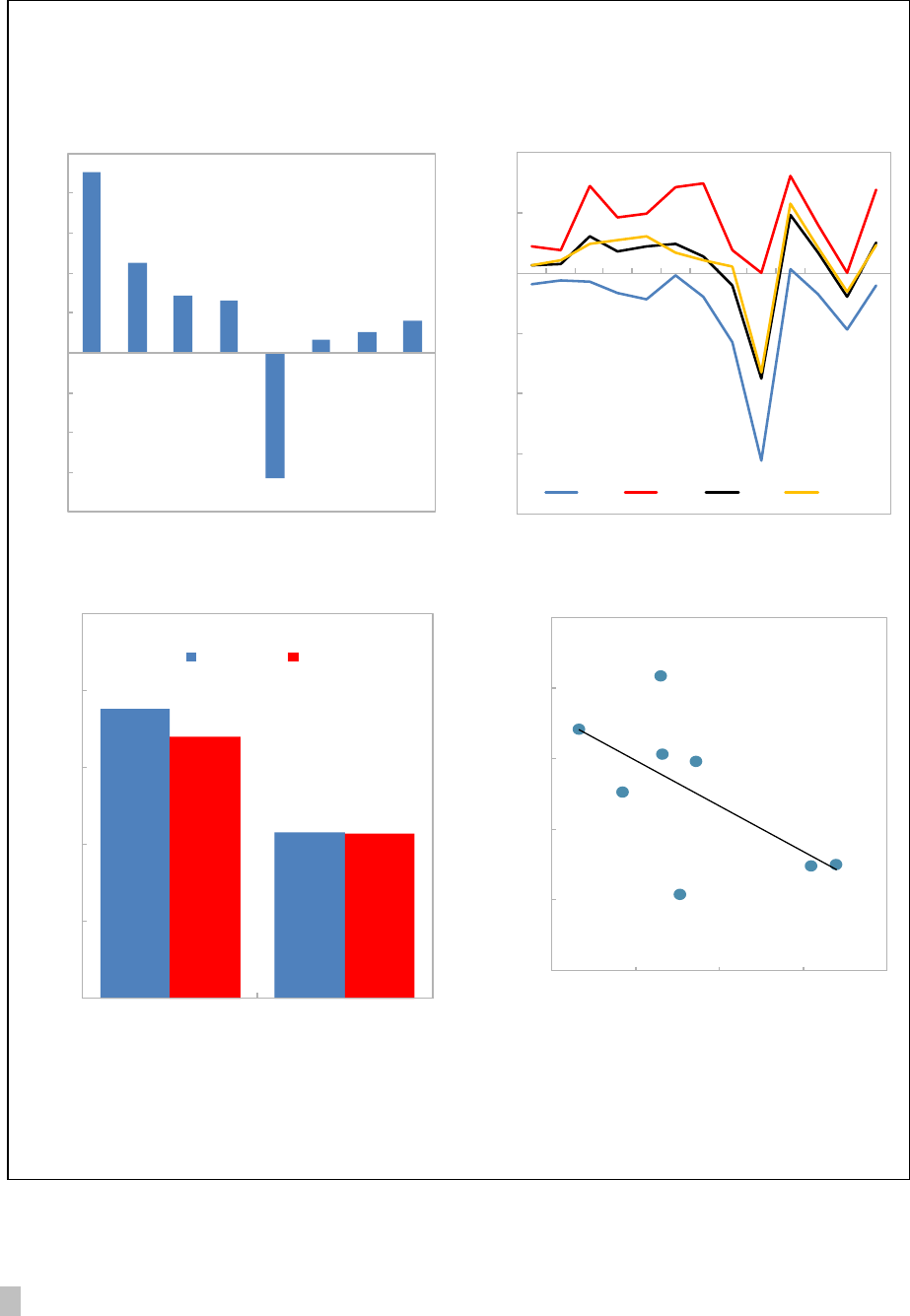

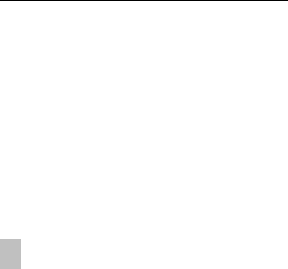

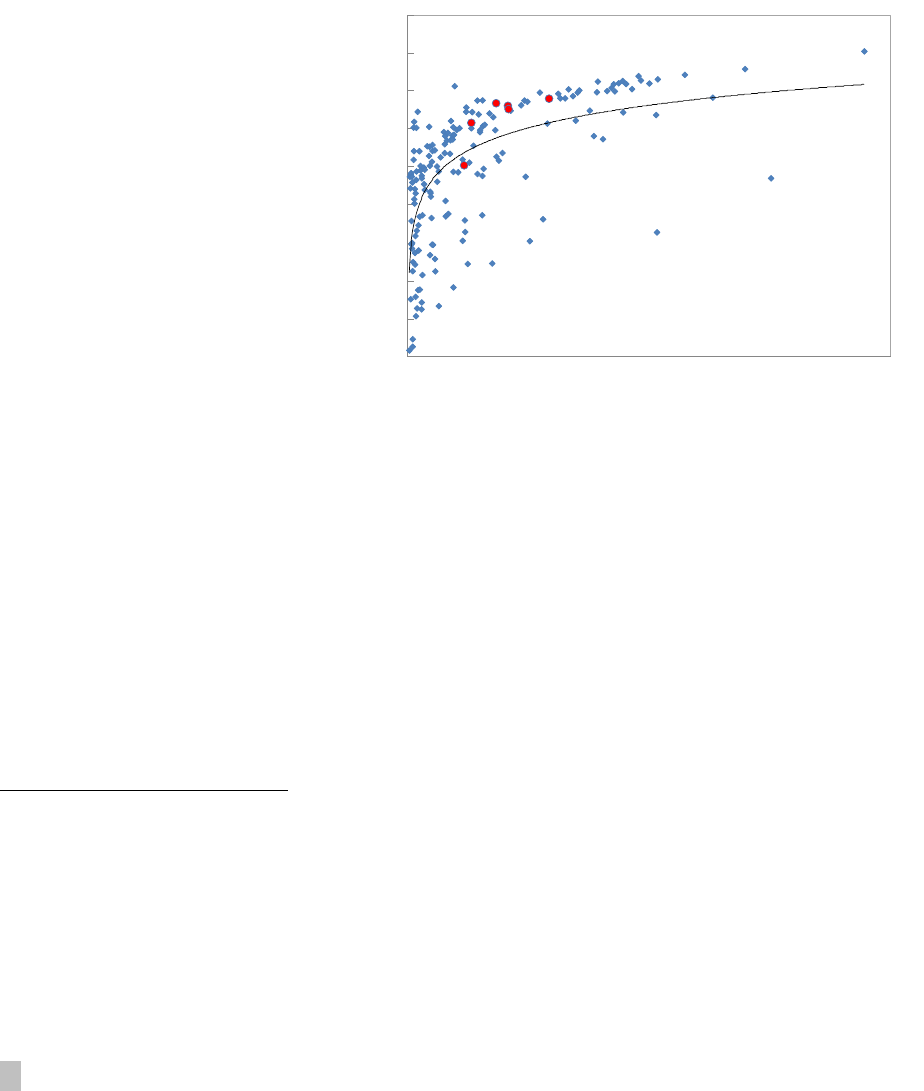

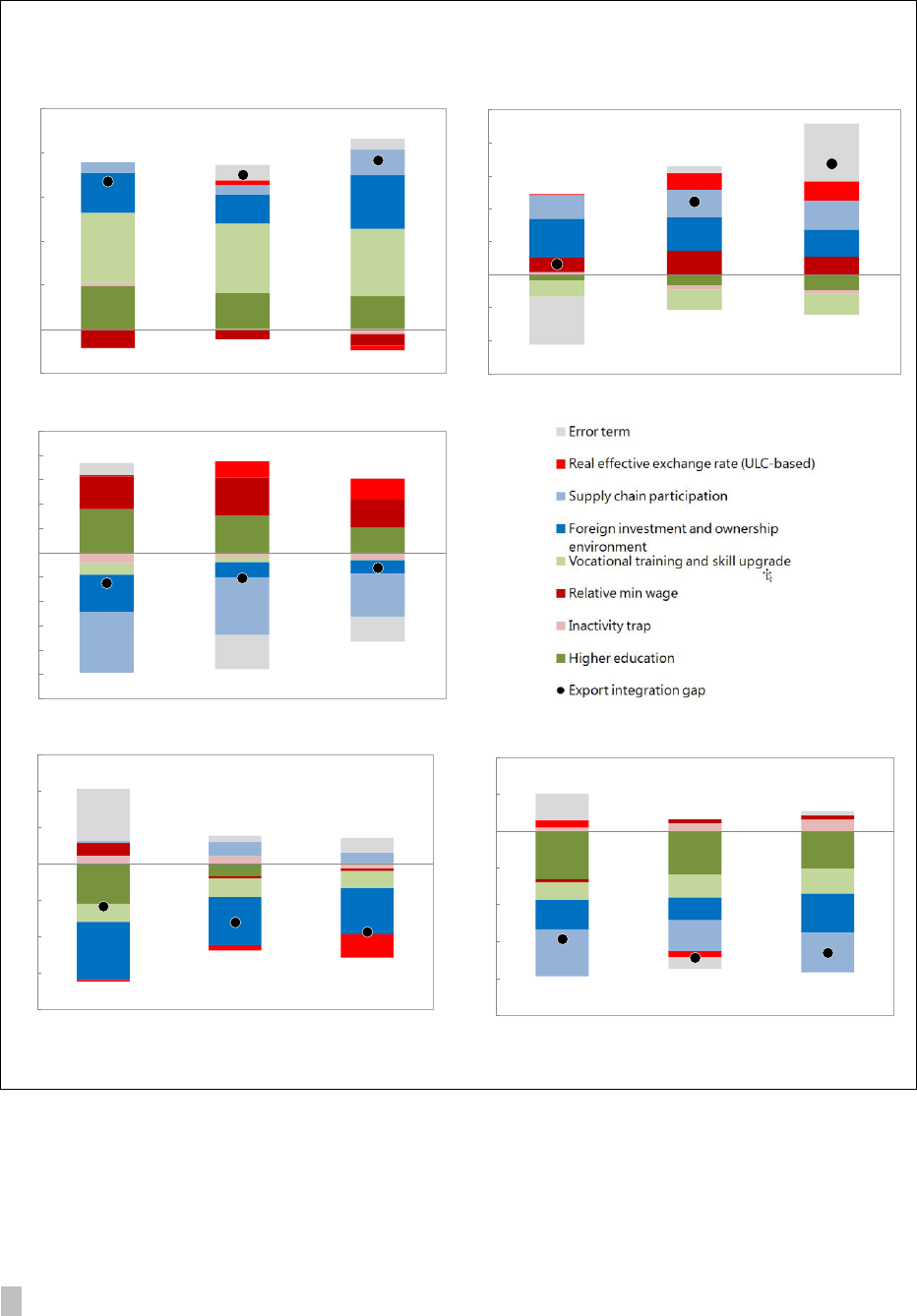

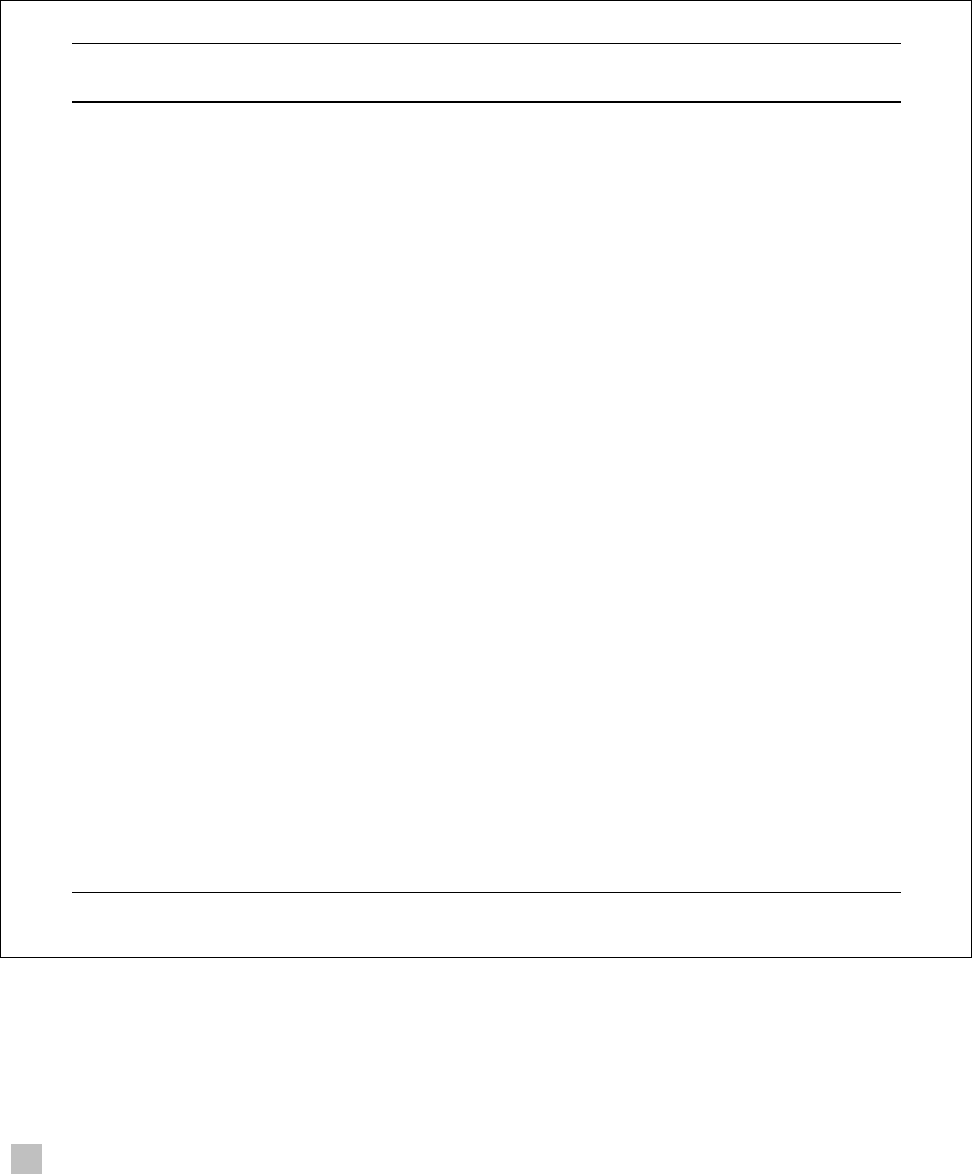

20. The data show a pattern of tighter monetary conditions for economies that

maintained monetary policy autonomy during convergence (Figure 3). This is especially

evident for the Czech Republic and Poland, both of which let their currencies float during this

period, and to a lesser degree for Hungary (that held the forint within a wide band against

the euro). Importantly, the tightening in monetary conditions was achieved mostly by means

of nominal exchange rate appreciation rather than higher central bank interest rates (Box 3).

21. By contrast, monetary conditions in countries with fixed exchange rates tended

to be, overall, fairly accommodative, often even more accommodative than in the euro

area. Correspondingly, such countries tended to experience stronger overshooting in

domestic demand, larger credit and asset booms, and higher and more volatile inflation (for

a detailed discussion, see Bakker and Gulde, 2010).

Managing Downturns

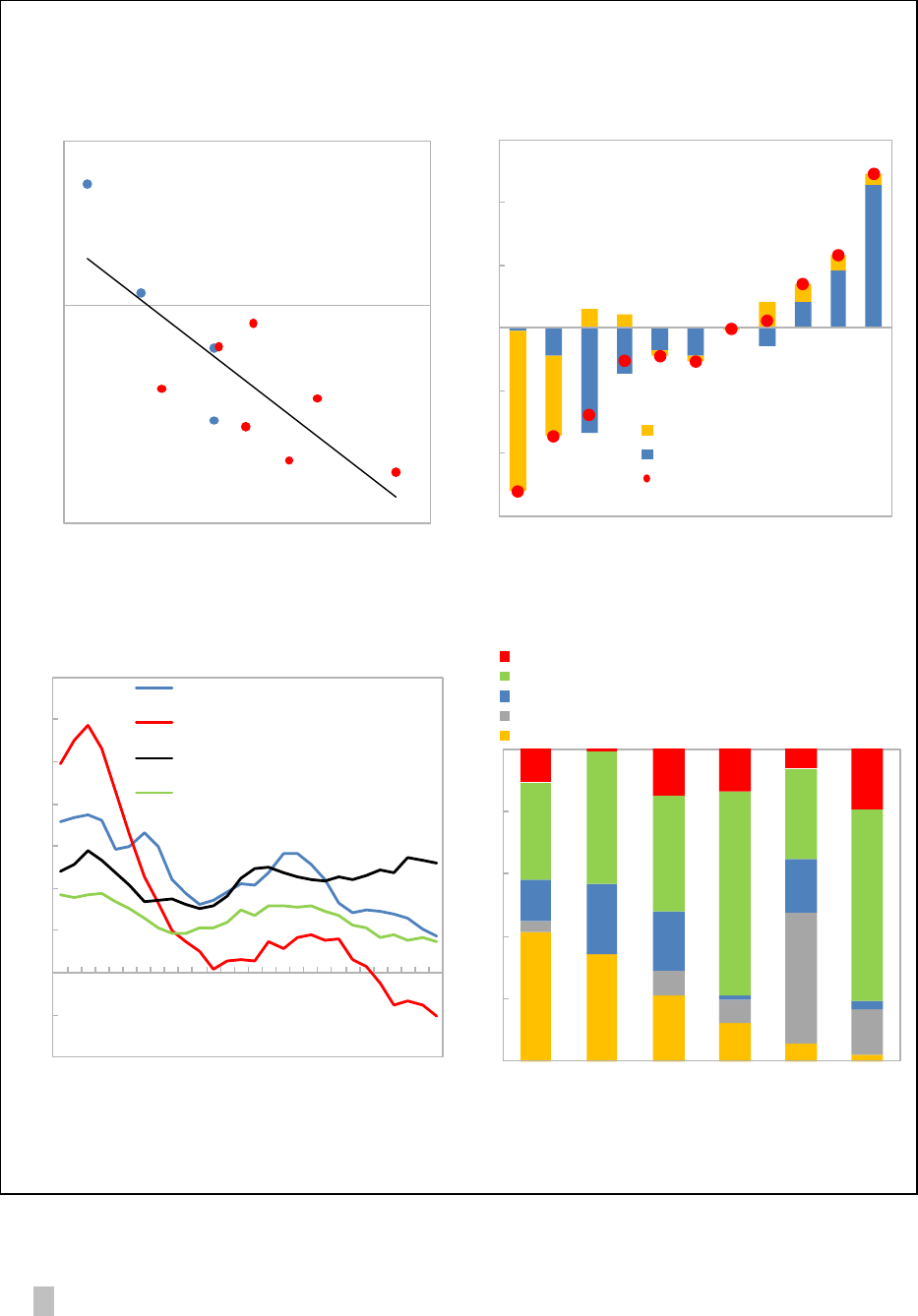

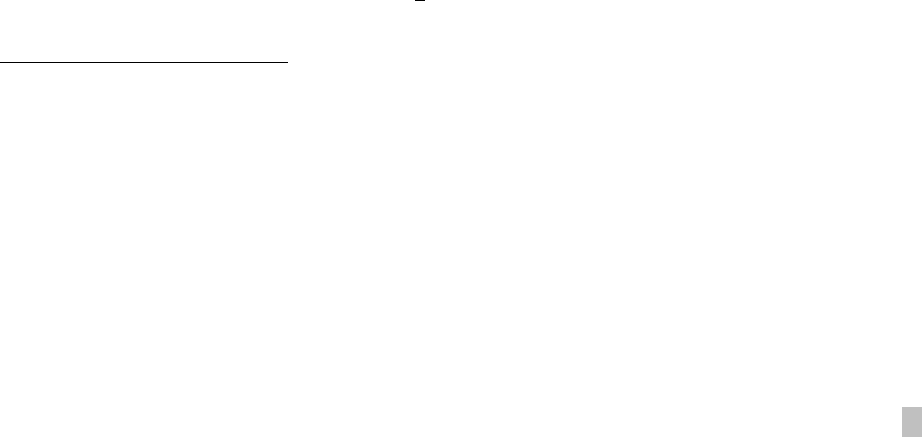

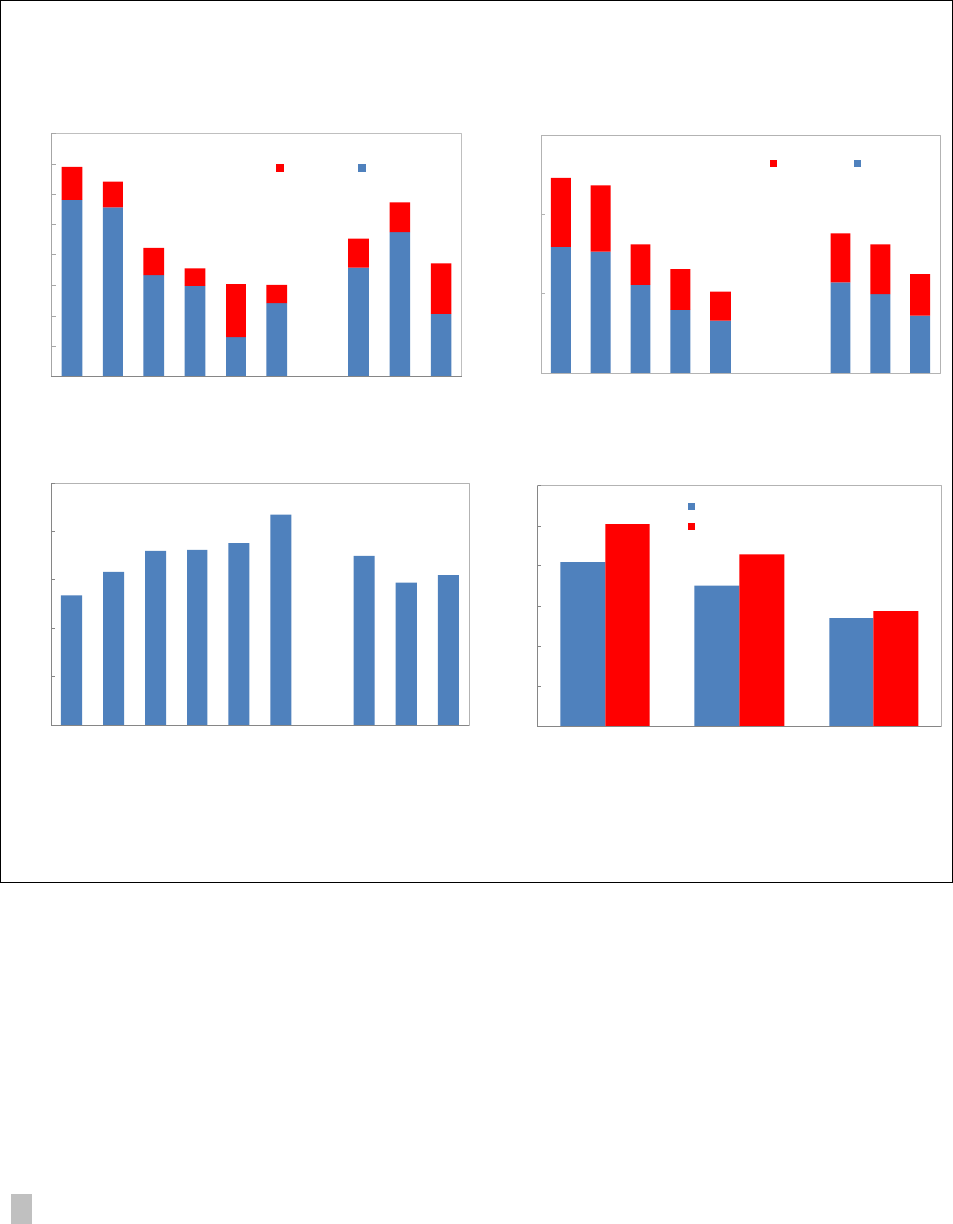

22. In the global financial crisis of 2008/09 and its aftermath, the NMS were hit by a

severe negative demand shock that stalled or even reversed convergence. Monetary

autonomy allowed central banks to respond by cutting policy rates andmore importantly

allow nominal exchange rates to depreciate and act as shock absorbers (Figure 4). Nominal

depreciations were especially large in Poland and Romania, where domestic demand held up

better than elsewhere.

12

By contrast, in countries with fixed exchange rates, monetary

11

This thought goes back as far as Wicksell (1898). It is also reflected in a simple Taylor rule that specifies the

cyclical behavior of policy rates around a neutral rate. Policy rates that are systematically above/below the

neutral rate will result in a monetary policy stance that is systematically too tight/too lose.

12

In Hungary, the scope for exchange rate depreciation was arguably constrained by the high share of

FX loans, see Bakker and Gulde (2010).

CEE NEW MEMBER STATES POLICY FORUM

14 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Figure 2. New Member States: Monetary Policy, 2003-07

Sources: Haver Analytics; and IMF Staff calculations.

POL

CZE

HUN

HRV

SVN

BGR

LTU

EST

SVK

ROU

LVA

y = -0.998x + 6.8999

R² = 0.4554

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

-6 -4 -2 0 2 4 6

Domestic Demand Growth and Monetary Conditions

(2003-07 average; percent; peggers labeled red)

Monetary conditions (+tighter)

Domestic demand growth

-2

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

SVK

CZE

POL

HUN

SVN

Inflation differential

Nominal exchange rate appreciation

Inflation volatility (std)

Real Exchange Rate Appreciation Against Euro

(Contributions in percentage points; average 2003-07)

LVA

ROU

BGR

EST

HRV

LTU

BGR

HRV

CZE

HUN

POL

ROU

SVK

SVN

LVA

LTU

EST

y = -4.1588x + 29.01

R² = 0.556

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

-3 -1 1 3 5

Real Credit Growth and Monetary Conditions

(Percent; average 2003-07; peggers labeled red)

Monetary conditions (+tighter)

Real credit growth

-4

-2

0

2

4

6

8

POL

CZE

HUN

SVN

SVK

Growth differential w/ Euro Area

Monetary Conditions differential w/ Euro Area

Growth and Monetary Conditions

(Percent; average 2003-07; peggers labeled red)

LVA

ROU

BGR

EST

HRV

LTU

CEE NEW MEMBER STATES POLICY FORUM

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 15

conditions tended to be tighter driven in part by the need to defend the exchange rate

arrangement.

13

As a consequence, the demand contraction in crisis tended to be larger, even

though there are exceptions.

14

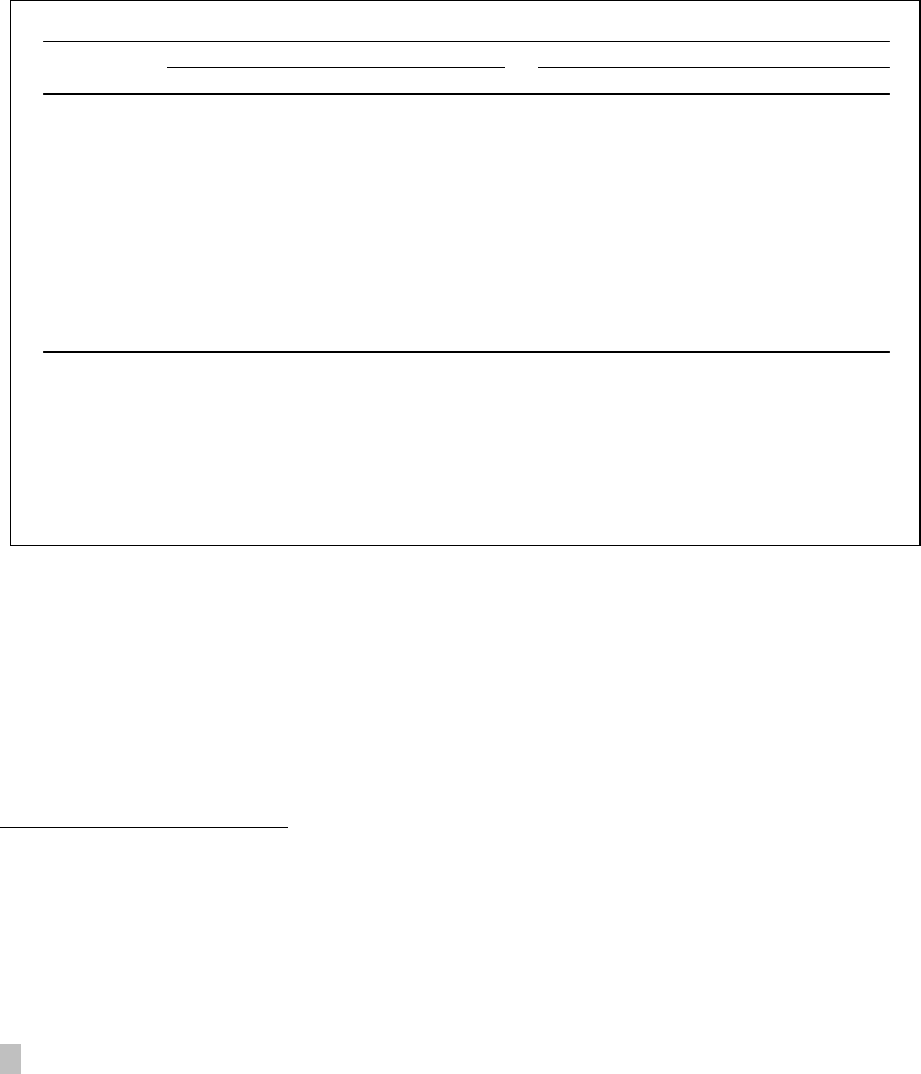

Offsetting Disinflationary Spillovers

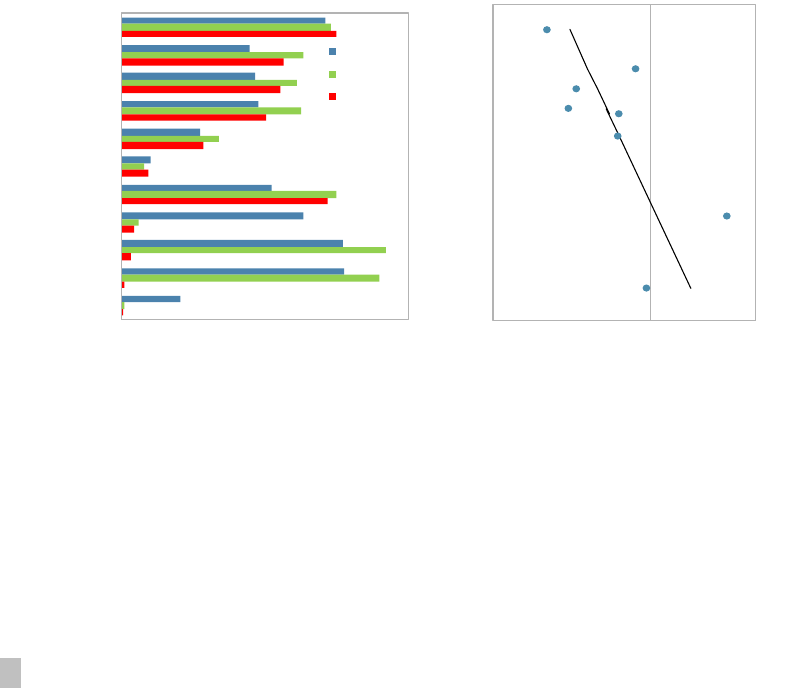

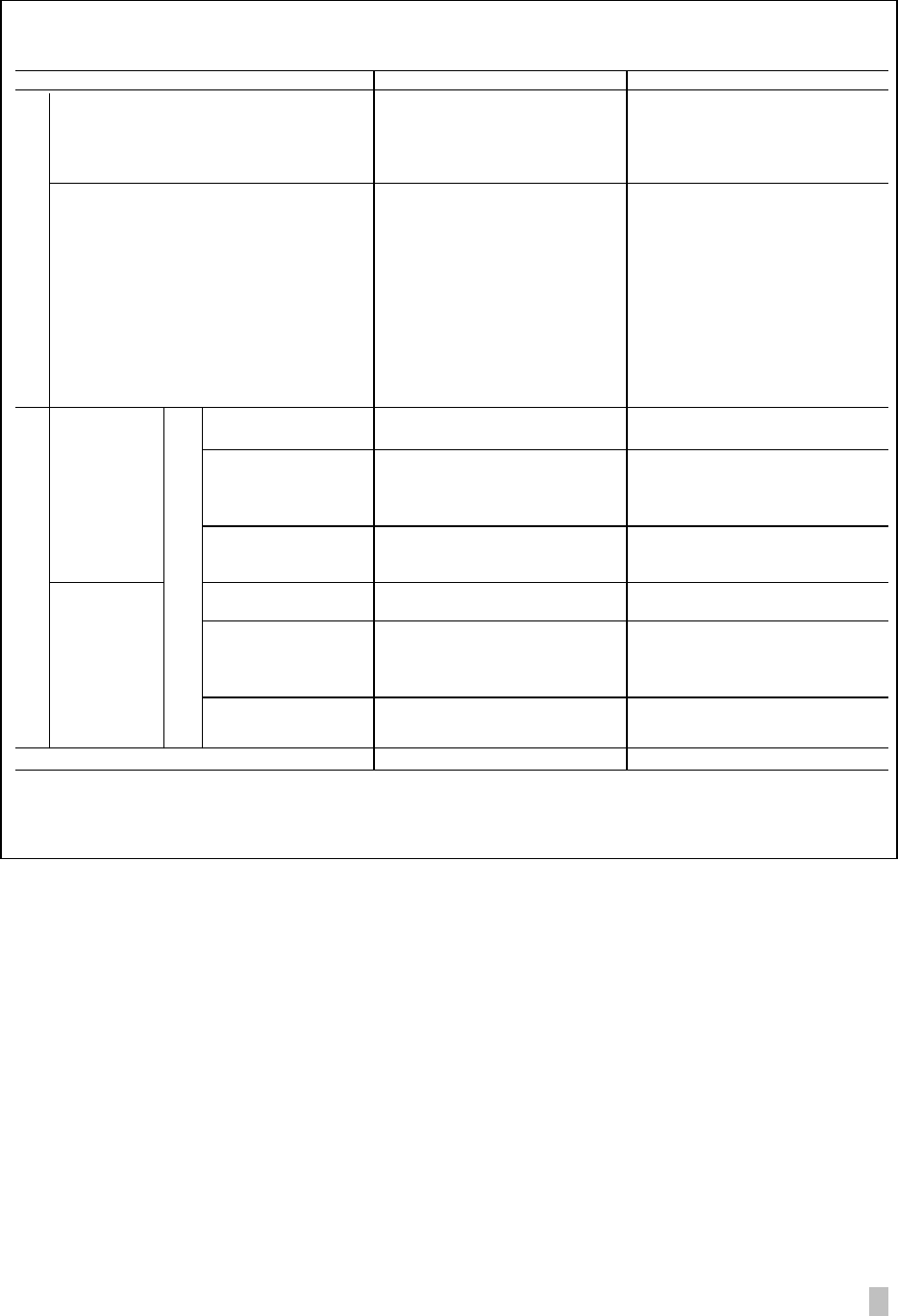

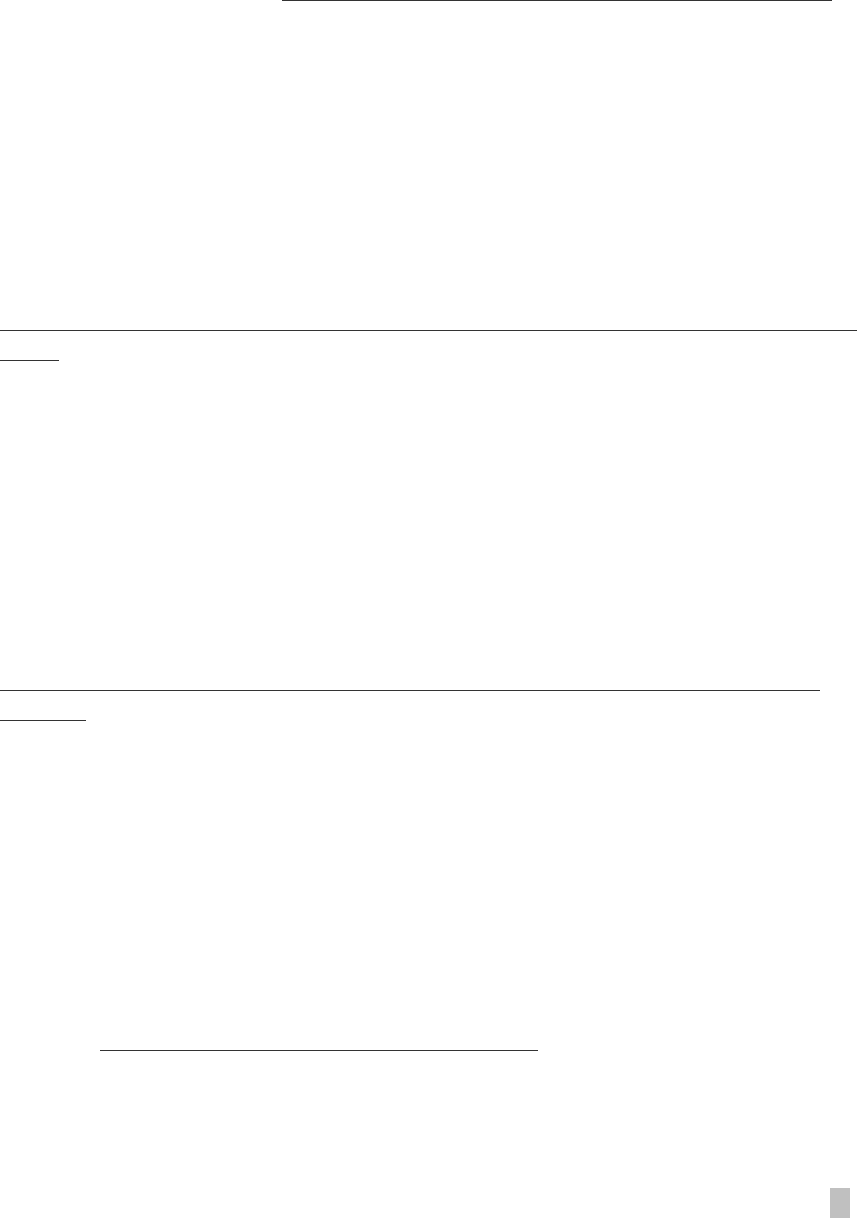

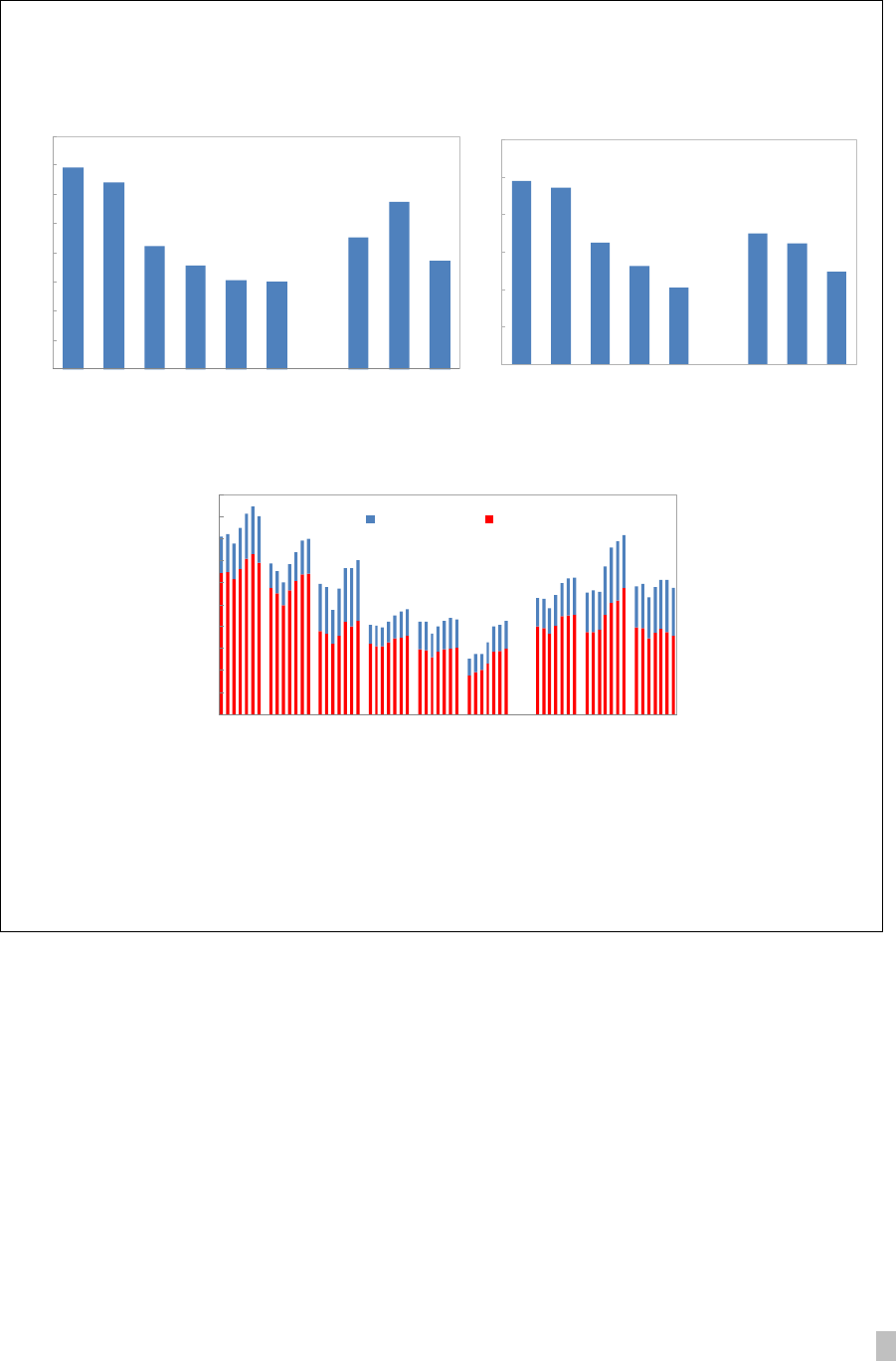

23. In recent years, the NMS have been affected by deflationary shocks from falling

global commodity prices and euro area disinflation. The impact on NMS has been

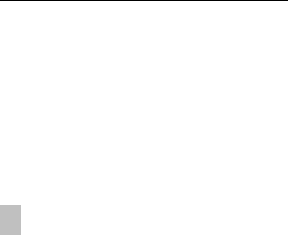

asymmetric: while in economies with flexible exchange rates, disinflation has mostly affected

headline inflation, in exchange rate pegging economies deflationary pressures have tended

to creep into core inflation.

15

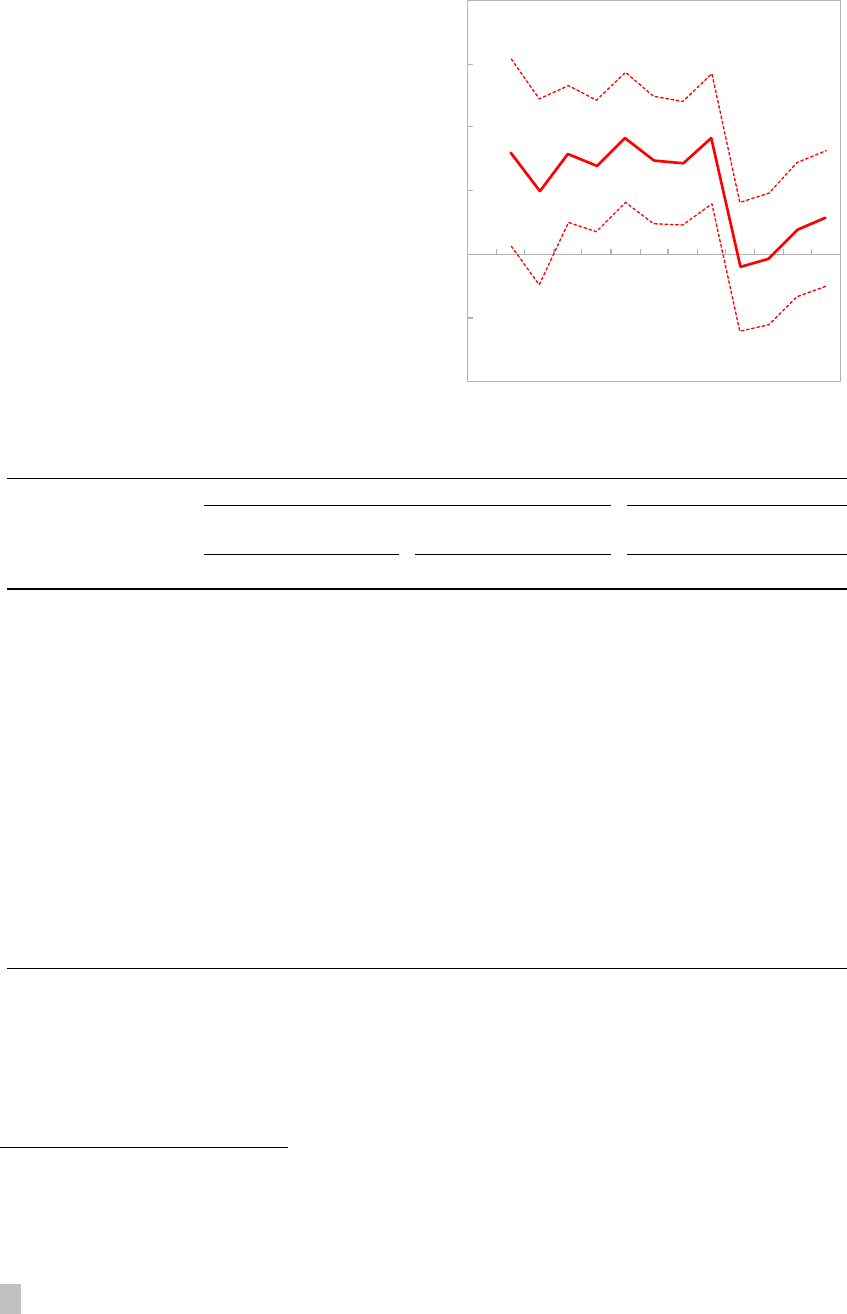

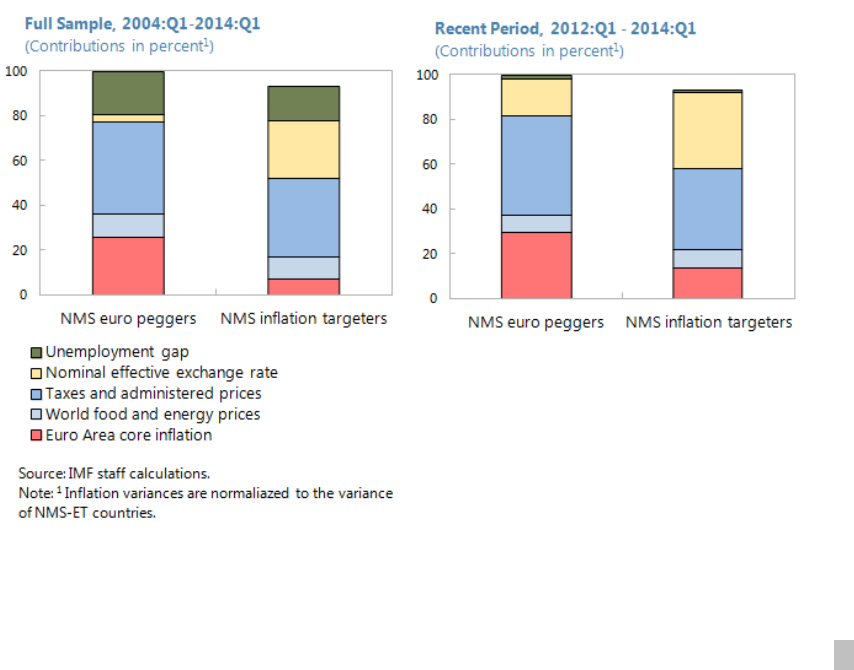

24. Econometric analysis suggests that the link between disinflation spillovers and

the exchange rate regime is systematic. Iossifov and Podpiera (2014) decompose headline

inflation in the NMS-6 into country-specific, global, and euro area factors using an open-

economy New Keynesian Phillips curve within 200414 panel data framework (see

Appendix III). The share of inflation variance explained by euro area developments is largest

in Bulgaria and Croatia, both of which have tied their currencies to the euro . By

contrast, inflation targeting central banks have thus far been able to largely offset the

deflationary impulse from the euro area with their monetary policy stance.

16

D. The Impact of Euro Adoption on Macroeconomic Policy

Frameworks

25. Euro adoption would change the NMS-6’s policy frameworks. Ceding monetary

autonomy is only onealthough the most importantcomponent. In addition, the stability

and growth pact foresees stricter enforcement mechanisms for euro area members

13

In this regard, there is an important difference between countries with currencies tied to the euro and

those already in the euro area (Slovak Republic and Slovenia), as the latter did not have to tighten monetary

policy in order to defend a peg.

14

Bulgaria, for example, had a relatively muted demand contraction, arguably reflecting in part the use of

fiscal buffers

15

This result holds even after controlling for the size of import exposure to the euro area.

16

The value of monetary autonomy is also being recognized by rating agencies, as the following quote from

Unlike in the Baltic countries, euro adoption would not immediately

lead us to raise the ratings on Poland. This is because the Baltics, unlike Poland, already had currency pegs to

the euro in place, which limited their monetary flexibility. Poland, on the other hand, has a flexible exchange

rate, and the current ratings clearly take into account its monetary flexibility and effective monetary

policymaking as a ratings strength. On the one hand, euro membership would give Poland access to a reserve

currency and the ability to issue debt in it, which would be positive for the ratings. On the other hand,

membership of a monetary union that has a monetary policy not necessarily geared toward the needs of

individual countries could be ratings-negative, especially if we saw a strong asynchrony between European

Central Bank (ECB) policies and a monetary policy stance needed for Poland's purposes.”

CEE NEW MEMBER STATES POLICY FORUM

16 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Figure 3. New Member States: Monetary Policy, 2008-14

Sources: Haver Analytics; and IMF Staff calculations.

0

20

40

60

80

100

HRV

BGR

CZE

HUN

POL

ROU

World food and energy prices, incl. taxes and admin. prices

Taxes and administered prices

Unemployment gap

Nominal effective exchange rate

Euro Area core inflation

Headline Inflation Variance Decomposition

(Contributions in percent; 2008-14)

LTU

BGR

HRV

SVK

SVN

EST

LVA

y = -0.4535x - 1.3689

R² = 0.6605

-4

-3

-2

-1

0

1

2

3

-6 -4 -2 0 2 4 6

Real Monetary Conditions and Domestic Demand Growth

(2008-14 average; percent; peggers labeled red)

Domestic demand growth

Monetary conditions (+tighter)

-6

-4

-2

0

2

4

6

LTU

BGR

HRV

SVK

SVN

EST

LVA

Real Effective Exchange Rate

Real Interest Rate

Monetary Conditions Index

Contributions to Monetary Conditions

(2008-14 average; percent; peggers labeled red)

POL

CZE

HUN

ROU

-2

-1

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

2008Q4

2010Q4

2012Q4

2014Q4

NMS-IT

NMS-ET

World core inflation (excl. NMS and

Euro Area)

Euro Area core inflation

Core Inflation

(y-o-y, percent)

CEE NEW MEMBER STATES POLICY FORUM

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 17

than for countries outside the euro area, and euro area members are obliged to join the

Banking Union, which comes with the transfer of most authority for micro-prudential

supervision and some aspects of macro-prudential policy to the ECB.

26. The challenge to adapt to the euro area policy framework presents itself

differently for countries with flexible and with fixed exchange rates.

17

For NMS-6 that let exchange rates float and target inflation, monetary policy

autonomy would have to be replaced with other instruments, such as counter-cyclical

fiscal policy, macro-prudential tools, and internal adjustment through wages.

For the NMS-6 that have pegged their currencies to the euro, an important issue is to

what extent they could use macro-prudential policies also within the euro areaas

Bulgaria and Croatia have been among the heaviest users of macro-prudential

instruments in Europe (see Lim et al., 2011, and , 2014).

18

27. At this juncture, key euro area reforms that will affect both fiscal and financial

sector governance are ongoing or have only just been completed. The final shape and

icy space in the euro

area, as well as the support they can expect from common euro area institutions in

combating economic and financial shocks.

28. Given the large uncertainty surrounding these reforms—regarding both their

final shape and how they will work in practice—there is a rationale to waiting for final

outcomes before taking an irreversible euro adoption decision. In an uncertain

environment, the option to wait until benefits and cost become clearer has value by itself.

The standard economic applicati

decisions (see McDonald and Siegel, 1986, or Dixit and Pindyck, 1994). However, the rationale

also applies to irreversible policy choices, such as euro adoption.

17

It is worth noting that in case the NMS-6 were to adopt the euro, this would not only affect the NMS-6

but also the existing euro area members. The NMS-6 would account for about 8 percent of

GDP (14 percent on a PPP basis), and a similar share of euro area consumption. In case convergence would

resume at the same pace as in the early 2000s, staff estimates that NMS-6 adoption could increase average

euro inflation by up to 0.3 percentage points, which would require a tighter monetary policy stance by the

ECB to preserve its current inflation target. This, in turn, would further diminish space for nominal adjustment

in case euro area members suffer asymmetric shocks.

18

The jury is still out on the effectiveness of these measures. A recent paper by Cerutti et al. (2015), for

example, finds some effectiveness of macro-prudential policies in managing credit cycles, but also severe

issues of avoidance through greater cross-border borrowing.

CEE NEW MEMBER STATES POLICY FORUM

18 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

E. Conclusions

29. The parameters of the euro adoption debate have shifted. While countries joining

the euro area in the 2000s could expect to benefit from a significant country risk premium,

this premium has mostly vanished with the euro crisis. When or whether it will return is

uncertain and will depend in part

institutional framework. At the same time, for countries with sizeable shares of foreign

currency loans, there are still important financial stability benefits from adopting the euro.

30. The NMS that have maintained exchange rate flexibility and monetary policy

autonomy have, in general, made good use of it. During convergence, nominal currency

appreciation supported more balanced growth and restrained credit and asset price booms.

In the crisis-induced downturn of 200809, depreciation and monetary loosening helped

stabilizing demand and, more recently, prevented external deflationary pressure from spilling

into domestic core inflation.

31. It is an open question whether the macroeconomic volatility of the past decade

will recur. If divergent growth patterns and volatility were to repeat, euro adoption would

constrain macro-policy options, especially for economies with large income gaps and a-

synchronized business cycles vis-à-vis the euro area. Thus, a large burden would be placed

on other policy instruments to safeguard balanced growth, notably counter-cyclical fiscal

policywhich, in turn, requires fiscal spaceand macro-prudential policies. Structural

reforms to boost growth potential and facilitate internal adjustment would also be key.

32. For countries that peg their currencies to the euro, the balance of the argument

is somewhat different, as they have already traded monetary autonomy and exchange rate

flexibility for benefitting from the euro as monetary anchor. Thus, for the most part, their

policy frameworks would not change materially upon adopting the euro. An important

remaining issue though is to what extent they could employ macro-prudential and other

regulatory instruments also within the euro area.

33. The scope for using fiscal policy and macro-prudential instruments is currently

being re-defined in the context of ongoing reforms of the European fiscal and financial

architecture. Depending on the final shape of these reforms, this may or may not constrain

policy space for euro area members. The uncertainty about the outcomes of these reform

effortsand the limited means of the NMS-6 to affect themprovides a rationale to wait for

and analyze final outcomes before taking an irreversible adoption decision.

CEE NEW MEMBER STATES POLICY FORUM

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 19

Box 1. The 2004 IMF Study, and New Evidence on its Main Findings

The 2004 IMF study “Adopting the Euro in Central Europe—Challenges of the Next Step in European

Integration” was cautiously optimistic about the net economic benefits of euro adoption.

As key factor in favor of euro adoption, the study singled out trade generation and, as a result, higher

growth. Based on estimates from the literature (e.g., Frankel and Rose, 1998 and Rose, 2000), staff

considered real GDP gains of 10 to 25 percent over 20 years plausible. Staff noted though that the

mechanism generating such large effects was not entirely clear, as the reduction in transaction cost and

the elimination of exchange rate uncertainty would explain only a minor portion. The study also

anticipated that adoption would reduce perceived credit risk which could, inter alia, reduce funding

costs for NMS in the euro.

As for possible risks from euro adoption, the study acknowledged that coping with asymmetric demand

shocks would become more difficult without an independent monetary policy. However, the study noted

that the NMS had experienced low growth volatility in the preceding years, suggesting that shocks may

be manageable also without monetary autonomyprovided countries had fiscal space for

countercyclical policies, and wages and prices were sufficiently flexible. Further, economic integration in

the wake of euro adoption was expected to lead to more synchronized business cycles. As another

potential risk from adopting the euro, the study identified large and volatile capital inflows and lending

booms, as well as higher inflation due to the Balassa/Samuelson effect. Again, fiscal space and wage

flexibility were seen as key to manage these phenomena, together with structural reforms to boost

competitiveness, and strong financial

supervision.

1

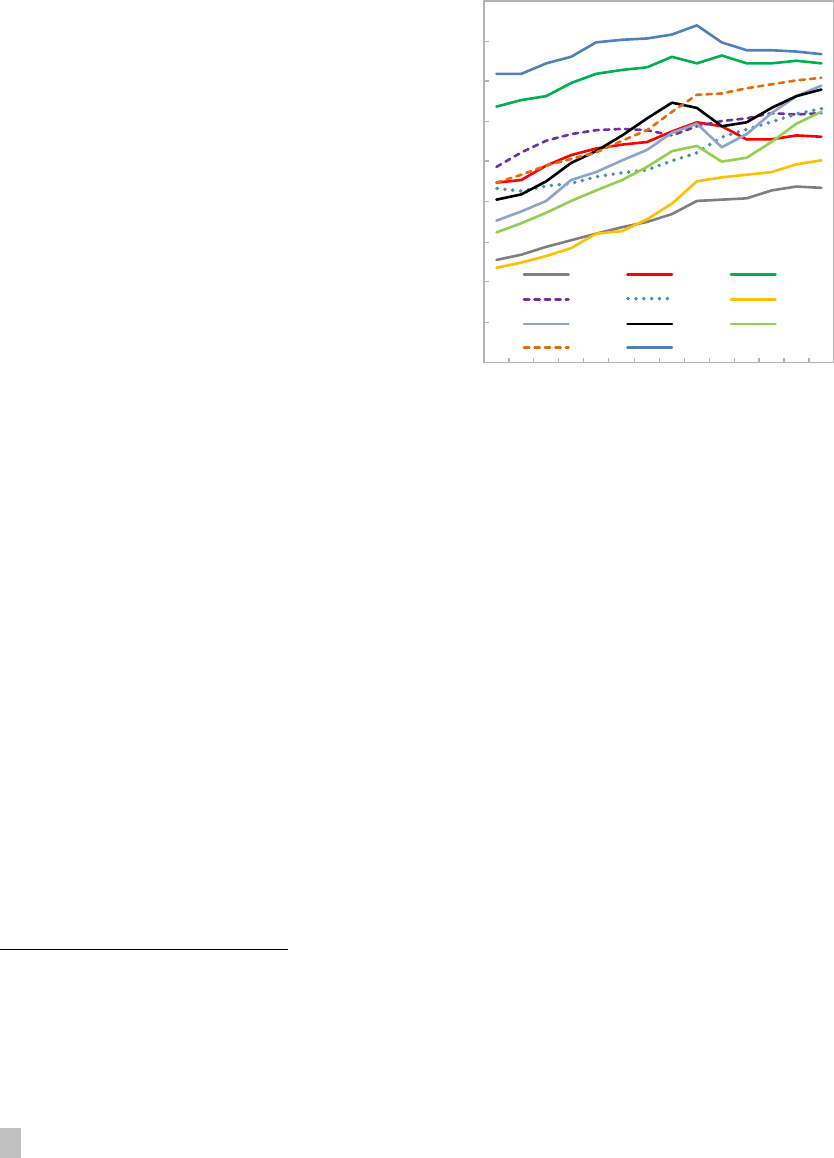

Subsequent developments confirmed

parts of the 2004 assessment, but in other

parts yielded new insights.

Risk spread compression happened as

anticipated in 2004, at least until the

warnings of excessive asset and credit

booms were well placed.

Recent estimates of trade and growth

effects are much smaller than assumed

at the time, however, and range from nil

(Havranek, 2010) to 2-3 percent of GDP

(Baldwin, 2006). Further, recent studies suggest that trade generation is more related to EU entry than to

euro adoption.

Demand volatility has been significantly larger than anticipated in 2004, especially in the wake of the

global financial crisis of 2008/09 and the ensuing euro crisis. Endogenous business cycle

synchronization with euro adoption has not materializedrather, there have been signs of divergence,

such as growing external imbalances (Gayer 2007; Holinski et al. (2012), Enders et al. 2013, Lehwald,

2013; and Degiannakis et al., 2014).

_____________________________

1/

The 2004 study also discussed ERM2-related strategies. The study recommended completing all necessary structural and fiscal

reforms prior to entry into the ERM2 to ensure a smooth transition. Countries with autonomous monetary regimesmostly

inflation targetingshould maintain these until ERM2 entry.

0

1

2

3

4

1963

1968

1973

1978

1983

1988

1993

1998

2003

2008

2013

Europe

Emerging Economies

Growth Volatility

(5-year rolling standard deviation of per-capital real GDP growth,)

CEE NEW MEMBER STATES POLICY FORUM

20 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Box 2. New Member States, Euro Adoption, and the Theory of Optimal Currency Areas

The academic literature on currency unions often casts the issue in terms of whether member

countries form an “optimum currency area, OCAMundell, 1961; McKinnon, 1963; and Kenen, 1969).

In principle, countries can benefit from a currency union through capital market integration, lower

terms-of-trade volatility and reduced exchange rate fluctuations. Countries with weaker institutions can

import monetary policy credibility (McKinnon, 2004; Tavlas, 1993).

There are also costs, mostly associated with forgoing exchange rate flexibility and monetary policy

autonomy for managing cyclical conditions. To minimize such costs, countries in currency unions would

best have synchronized business cycles and growth patterns, which is typically enhanced by intra-

industry trade (Frankel and Rose, 1998).

In currency unions with incomplete business cycle synchronization, flexible non-monetary

adjustment mechanism are needed: notably price and wage flexibility and cross-border labor mobility.

Risk sharing through integrated financial markets can also help, by diversifying income sources through

cross-country asset holdings (McKinnon, 2004; Mongelli, 2008).

Business cycle synchronization of NMS with the euro area is in general lower than within the euro

area, even though there are differences between countries (Fidrmuc and Korhonen, 2003; Artis et al.,

2004; Darvas and Szapáry, 2005; Van Arle et al. 2008). For Hungary, Poland, and the Czech Republic,

synchronization with the euro area is higher than for the other NMS; and also higher relative to Greece and

Portugal (Fidrmuc and Korhonen, 2006; Rinaldi-Larribe, 2013).

Wage flexibility in the NMS tends to be high while cross-border labor mobility has been increased

(Gruber, 2004; Dao et al. 2014), with substantial outward migration from some NMS in the wake of the

global financial crisis (OECD, 2013):

Wage flexibility. According to Gruber (2004) and Boeri and Garibaldi (2006) NMS tend to have lower

statutory minimum wages, union density rates and more decentralized wage bargaining structure than

the euro areaall pointing to wage flexibility.

Labor mobility. Outward migration in the post-crisis period of 2009-2011mostly was younger and

educated workers, typically finding employment abroad below their skill level (Anacka et al., 2011; Jauer

et al., 2014).

Cross-country risk sharing through financial market integration is low. While prior to the 2008/09

financial crisis, there was some evidence of increasing integration in equity and debt marketssuch as lower

interest rate dispersion and increasing effects of the euro area shocks on NMS equity markets (Cappiello et

al. 2006; Baltzer et al. 2008)these reversed in the wake of the crisis, with higher interest rate spreads

(Pungulescu, 2013) and funding market segmentation along national lines (van Rixtel and Gasperini, 2013).

In addition, cross-border asset holdings tend to be one-directional: euro area banks hold sizeable assets in

NMS, and also FDI and portfolio investment from euro area residents in NMS is much larger than vice versa.

As a result, domestic investment in the NMS is more sensitive to domestic saving than in EU15, and national

consumption is closely correlated with GDP (Pungulescu, 2013).

Overall, while there are significant structural differences and lack of integration with the euro area, for NMS

like the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Poland, this do not seem larger than heterogeneity within the euro

area itself.

CEE NEW MEMBER STATES POLICY FORUM

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 21

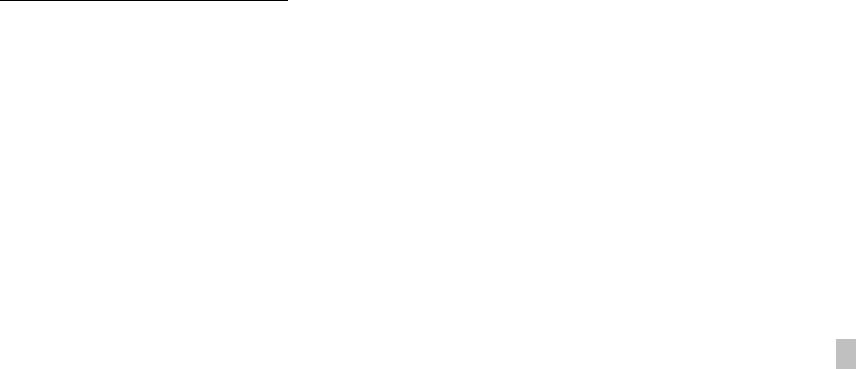

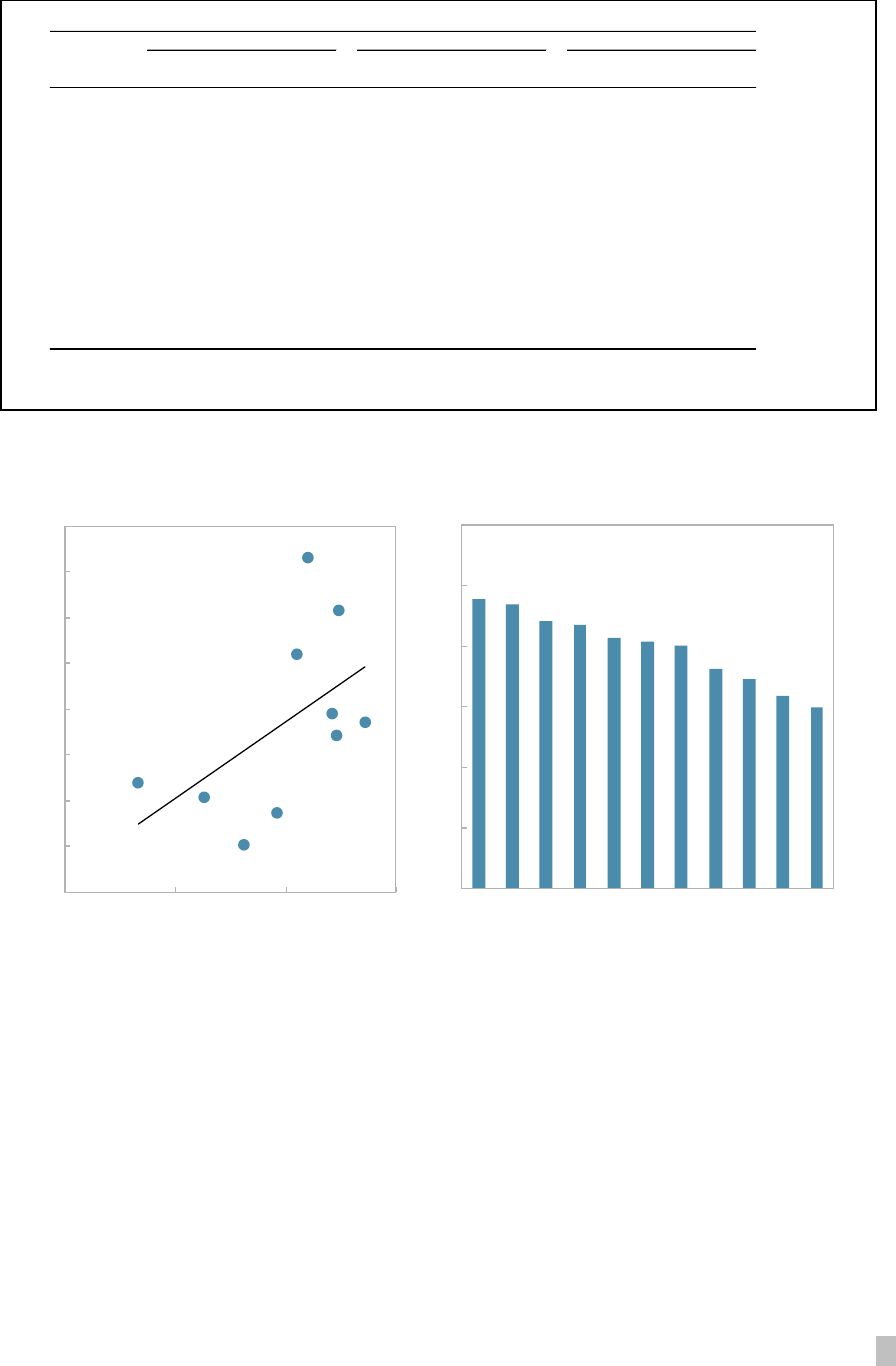

Box 3. Economic and Price Convergence in Emerging Europe

The political transformation in NMS in 1990s led to economic convergence through economic reforms,

including trade and price liberalization, privatization, and the adoption of the legal framework of advanced

Europe. Institutional change established the base for rapid growth, facilitated by external capital investment,

a supportive external financing environment, and an often skilled labor force and reasonable infrastructure.

As a result, productivity and income per capita increased by 20 percent relative to the Euro Area countries by

between 1995 and 2013 (see IMF, 2014).

Improvements in productivity go typically hand in hand with real exchange rate appreciation. There

are two, not mutually exclusive channels the Balassa-Samuelson and the Podpiera effect:

The Balassa-Samuelson effect reflects faster productivity growth for tradable than for non-tradable

goods during convergence. As the price for tradable goods is fixed in global goods markets, the price for

non-tradables has to rise. However, contrary to initial expectationsformed during early stages of

convergencethat such an effect could account for 1-2 percentage points of consumer price inflation per

year (Cipriani, 2000, Kovacs et al., 2002, and Mihaljek and Klau, 2003), more recent studies find much

smaller effects (Mihaljek and Klau, 2008).

The Podpiera effect is due to converging economies shifting production toward higher quality goods. As

quality improvements come with price increases and are typically underreported in domestic CPI indices,

these effects are reflected in real exchange rate appreciation. Cincibuch and Podpiera (2006) and

Fabrizio et al. (2007) document the rapid increase in prices in tradable sectors in NMS. Bruha and

Podpiera (2010 and 2011) devise and calibrate a model that explains the rapid (2-3 percent a year) CPI-

based real exchange rate appreciation during convergence. Sonora and Tica (2014) test jointly the

Balassa-Samuelson and Podpiera effects and find that the latter primarily explains the real exchange rate

appreciation in Emerging Europe.

Real exchange rate appreciation happened partly through nominal exchange rate appreciation in

countries with flexible exchange rate regimes. In exchange rate targeting countries, it happened solely

through higher inflation differentials (box charts and see figure on Investor Perception and Balance Sheet

Euroization).

y = 0.7597x + 0.2395

R² = 0.4716

0.8

0.9

1

1.1

1.2

1.3

0.85 0.95 1.05 1.15 1.25

Real and Nominal Convergence

(Indexes, 2005=1, 2003Q1-07Q4)

GDP growth differentials

Real exchange rate against euro

-5

-3

-1

1

3

5

7

9

11

13

15

SVK

CZE

POL

ROU

HRV

SVN

BGR

LVA

EST

LTU

HUN

Nominal Exchange Rate Against Euro

(Percentage change 2003Q1-07Q4)

Source: Haver and IMF Staff calculations.

CEE NEW MEMBER STATES POLICY FORUM

22 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

References

Anacka, Marta,

The 2011 SOPEMI Report.

Monte Carlo Evidence and an Review of

Economic Studies, Vol. 58/2, pp. 277-297.

CEPR Discussion Paper 4457.

Bakker, Bas B., and Anne-

IMF Working Paper No. 10/130. (Washington:

International Monetary Fund).

Working Paper 594, European Central

Bank, March.

Baltzer, Markus, Lorenzo Cappiello, Roberto A. De Santis and Simone Manganelli, 2008,

European Central Bank

Occasional Paper Series 81.

Boeri, Tito and Pietro Ga

Journal of Banking & Finance, Vol. 30, pp. 1393-1407.

Economic Policy, Vol. 27(69), pp. 57-98.

Economics of Transition, Vol. 18/3, pp. 599-628.

________________omic Convergence: The Role of Alternative

Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, Vol. 35/7,

pp. 1032-1044.

Integration of New Member States,European Central Bank Working Paper Series 683.

CEE NEW MEMBER STATES POLICY FORUM

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 23

Cerutti, Eugenio, Stijn Claessens and Luc Laeven, 2015,

Macroprudential Policies: New Evidence

-Samuelson: Real Appreciation in

Economics of Transition, Vol. 14/3, pp. 547-573.

-

prepared by the CEC5 National Banks for the Basle meeting on March 2002.

Dao, Mai, Davide Furceri and Prakash Loungani, Market Adjustments in

the United States IMF Working Paper No. 14/26.

larged EU:

CEPR Discussion Paper No. 5179.

EU: A Time-Scottish Journal of Political Economy, Vol 61(4),

pp. 348-370.

Dixit, Avinash K. and Robert S. Pindyck, 1994, Investment under Uncertainty, Princeton

University Press.

- Is

th

Dubrovnik

Economic Conference.

Enders, Zeno, Philip Jung and Gernot J. Müller

European Economic Review, Vol. 59, pp 189-211. European Commission,

2014, Convergence Report, ISSN 1725-3217.

Fabrizio, Stefania, Deniz Igan, and

IMF Working Paper No. 07/97.

Economic Systems, Vol. 27(3), pp. 313-334.

Fidrmuc, Jarko and -analysis of the business cycle correlation

Journal of Comparative Economics, Vol. 34(3),

pp. 518-537.

Frankel, Jeffrey A. and Andrew K. Rose, 1

Economic Journal, Vol. 108(449), pp. 1009-1025.

CEE NEW MEMBER STATES POLICY FORUM

24 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Freedman, C., 1994, The Use of Indicators and of the Monetary Conditions Index in Canada",

In: Balino, T. J. T. and Cottarelli, C. (eds.), Frameworks for Monetary Stability: Policy

Issues and Country Experiences, Chapter 18, pp. 458-476, International Monetary

Fund, Washington, D.C.

Journal of Monetary Economics, 44(2), October, pp. 195-222.

European Economy, Economics Paper 287.

Government of the Republic of Slovenia and Bank of Slovenia, 2003, The Euro is Coming,

OPOCE .

Focus 01/04, Osterreichische Nationalbank, pp. 96-121.

HavránekReview of World

Economics, June 2010, Vol 146(2), pp. 241-261.

the Role of

IMF Working Paper No.

14/17 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review,

January/February 2012, Vol 94(1), pp. 1-20.

Ilzetzki, Ethan, Car

Economics, mimeo.

International Monetary Fund

Chapter IV, World Economic Outlook, September, (Washington).

International Monetary Fund, 2013a, Annual Report on Exchange Arrangements and Exchange

Restrictions, (Washington).

International Monetary Fund

BaWorld Economic Outlook,

September (Washington).

CEE NEW MEMBER STATES POLICY FORUM

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 25

International Monetary Fund-Communist Europe and the

, (Washington).

-Euro Area EU Countries Importing Low

IMF Working Paper No. 14/191.

Adjustment Mechan

OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers No. 155.

Indicators: Methodology and Analytical IssWorld Bank Policy Research Working

Paper No. 5430.

In

R. Mundell and A. Swoboda eds, Monetary Problems of the International Economy,

The University of Chicago Press, pp. 41-60.

-Samuelson Effect in CEC5

on March 2002.

Synchronization? Evidence from

Empirica, Vol. 40 (4), pp. 655-684.

Lim, C., F. Columba, A. Costa, P. Kongsamut, A. Otani, M. Saiyid, T. Wetzel and X. Wu, 2011,

essons From

IMF Working Paper No. 11/238 (Washington: International

Monetary Fund).

Capital Flows to Transition

No. 02/11. (Washington:

International Monetary Fund).

Journal of International Money and Finance, Vol. 31/3,

pp. 657-672.

Matei, Iuliana and Angela Cheptea, 2012, "Sovereign Bond Spread Drivers in the EU Market in

the Aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis," in Essays in Honor of Jerry Hausman,

pp. 327-352.

CEE NEW MEMBER STATES POLICY FORUM

26 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Quarterly

Journal of Economics, Vol. 101 (4), pp. 707-727.

American Economic Review, Vol. 53,

pp. 717-724.

Journal of Common Market Studies, Vol. 42(4), pp. 689-715.

-Samuelson effect in Central Europe: A

BIS Working Paper 143.

______________________________-up and inflation in transition economies: the

Balassa-BIS Working Paper 270.

Economic Paper 302,

Directorate General Economic and Monetary Affairs (DG ECFIN), European

Commission.

American Economic Review,

Vol. 51, pp. 657665.

D

Publishing.

Emerging Markets Review, Vol. 17, pp. 106-124

ex of Currency

IMF Working Paper No. 10/263 (Washington:

International Monetary Fund).

Rinaldi-Larribe, Marie-

The European Journal of Comparative Economics,

Vol. 5(2), pp. 133-154.

Economic Policy, Vol. 15(30), pp. 733.

ign Currency Borrowing

Journal of Economics and Finance, vol. 59(3),

pp. 216-228.

CEE NEW MEMBER STATES POLICY FORUM

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 27

Schadler, Susan, Paulo Drummond, Louis Kuijs, Zuzana Murgasova, and Rachel van Elkan,

Adopting the Euro in Central Europe Challenges of the Next Step in

IMF Occasional Paper 234.

Slovakian National Bank, 2003, S

BIATEC, Volume XI, 10/2003.

d Samuelson (Re)Visit Eastern

Cogent Economics & Finance (2014-2).

The World

Economy, Vol. 16(6), pp. 663-685.

Working paper B18. Center for European Integration Studies, ZEI,

Bonn.

Van Arle, Bas, Marcus Kappler, Andreas Sachs, Atilim Seymen, and Klaus Weyerstrass, 2008,

European Economic Research (ZEW) and Institute for Advanced Study (HIS).

Van Rixtel, Adrian and Ga

BIS Working Papers 406.

21.

European Journal of

Political Economy, Vol. 27(1), pp. 36-43.

Wicksell, Knut, 1898/1936, Interest and Prices (Geldzins und Güterpreise), Sentry Press,

New York.

CEE NEW MEMBER STATES POLICY FORUM

28 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Appendix I. Estimating the Euro Premium

Euro Premium

The empirical analysis of the euro premium is based on panel data regression for

34 European countries with annual observations for the period 2001–2013. The time

period is mostly determined by data availability. We estimate the following equation:

, t=T

where

C is an expert assessment of country perception. We use two different measures, (i) the

a linearized

ings (S&P).

1

A possible alternative

measure would have been credit spreads as used, e.g., in Heinz and Sun (2014), Matei

and Cheptea (2012), Maltritz (2012), or von Hagen et al. (2011). The high volatility of

credit spreads, and the fact that spreads are affected by many other factors than

perceived credibilitysay, global liquidity conditions and/or cross-country spillovers

makes us select a metric that assesses investor perceptions directly.

X is a vector of country characteristics that may affect a coun

worthiness. X includes macro-variablessuch as fiscal and external balances, public debt,

per-capita-GDP, real GDP growth, the unemployment rate, inflation, the exchange rate

regime, national investment as share of GDP, and the c

position (NIIP)but also an indicator measuring institutional quality.

Most data are drawn from the IMF’s World Economic Outlook database. For

institutional quality, we use a simple average of the Kaufmann et al. (2010) governance

quality indices that is available, at this juncture, only for 200212. The exchange rate

regime is captured with a dummy variable for floating currencies (freely or managed)

drawn from Ilzetzki et al. (2011) until 2010 and extrapolated with IMF (2013a) for the

period thereafter. Public debt data is available for only about 90 percent of the

observations; we control for missing observations by including a corresponding dummy

variable.

1

For the IIR, respondents grade each country on a scale of zero to 100, with 100 representing the least

for the S&P index, the linearization assigns a value of 1 to an AAA rating, of 2 to AA+, and so on. We use the

foreign currency sovereign credit rating, but for the vast majority of countries, the local and foreign currency

ratings are identical.

CEE NEW MEMBER STATES POLICY FORUM

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 29

-2

-1

0

1

2

3

4

-9

-6

-3

0

3

6

9

12

15

18

2001

2003

2005

2007

2009

2011

2013

EU Membership Premium: IIR (red, lhs) and S&P (blue,

rhs) (Rating points)

-6

-3

0

3

6

9

12

2001

2003

2005

2007

2009

2011

2013

IIR Premium for Euro Area Membership: Arellano/Bond

GMM Dynamic Panel Estimator (Rating points)

is typically the expected outcome of variable for year t at the time when the WEO

fall forecast is produced. We experimented with leads and lags, but found that

concurrent values have the greatest explanatory power.

δ and θ are a country/time-dummies capturing unobserved, time invariant country-

specific factors/common unobserved time-specific factors, respectively. The time

dummies control for common macroeconomic and financial developments.

Euro is a dummy variable that takes on value 1 if country i was member of the euro

area in year t, and 0 otherwise (or technically speaking, we interact a general euro area

dummy with a time dummy). The

thus measure the impact of euro area membership

on country perception, holding country characteristics—both observed and

unobserved—constant. We allow γ to vary over time, to verify whether the value of euro

membership has changed. Similarly, EU is a dummy variable capturing EU membership.

Table A1 displays the regression results.

Euro and EU premia. While estimates

for the IIR index (column 1) and the S&P

indices (column 2) are in general similar,

the IIR tends to value euro area

membership higher than S&P

throughout. Further, the decline in the

premium in the wake of the euro crisis is

steeper for the S&P index than for the

IIR.

2

The premium for EU membership is

generally insignificant (see chart), except

for 2001/02, when EU membership

displays modest positive significance with

the IIR index.

3

Among controls, unemployment, and

government debt have the strongest impact on perceived credibility, followed by

inflation, growth, and the NIIP. Note that the IIP puts most weight on stock variables,

while for the S&P assessment flow variables also matter (budget deficit, current account

balance). Governance quality shows up as a strong determinant of credibility (column 3).

2

This is consistent with claims that rating agencies downgraded euro area countries excessively in crisis—

see, for example, Vernazza et al. (2014). The finding of a vanishing euro premium is consistent with the

results in Heinz and Sun (2014) for credit spreads.

3

The pattern in the early 2000s reflects arguably more an improvement in investor perception of non-EU

countries than a deterioration in the perception of EU member countries—see also Figure 1 in the main text.

CEE NEW MEMBER STATES POLICY FORUM

30 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

At the same time, its inclusion (or

omission) does not materially affect the

pattern of the euro premium over time.

To check for robustness we estimated

various other specifications, both by

including additional control variables—

such covariates capturing global

macro/liquidity conditions, e.g. the VIX

index—and by estimating dynamic

panels—notably the Arellano-Bond

(1991) GMM estimator. The basic

pattern—a steep decline in the euro area

premium from 2010—persists across all

specifications.

4

4

With Arellano-Bond, the estimated size of the euro premium is on average smaller by about one-third.

-2

-1

0

1

2

3

4

-9

-6

-3

0

3

6

9

12

15

18

2001

2003

2005

2007

2009

2011

2013

EU Membership Premium: IIR (red, lhs) and S&P (blue,

rhs) (Rating points)

-6

-3

0

3

6

9

12

2001

2003

2005

2007

2009

2011

2013

IIR Premium for Euro Area Membership: Arellano/Bond

GMM Dynamic Panel Estimator (Rating points)

(1) (2) (3)

Coeff. t-value Coeff. t-value Coeff. t-value

Controls

Per-capita GDP -1.8^(-5) -0.51 0.1^(-5) 0.58 -1.7^(-5) -0.39

Real growth 0.40 3.63*** 0.12 4.64*** 0.37 3.41***

Investment/GDP 0.13 1.36 0.04 1.74* 0.11 1.09

Unemployment rate -1.03 -9.56*** -0.31 -12.16*** -0.84 -7.13***

CPI inflation -0.26 -3.92*** -0.68 -5.88*** -0.20 -2.46**

Gen. gov. balance -0.10 -0.95 -0.07 -2.69*** -0.00 -0.01

Gen. gov. debt -0.17 -9.01*** -0.03 -6.62*** -0.14 -7.16***

External balance 0.06 0.82 0.04 2.42** 0.08 0.99

NIIP 0.03 5.15*** 0.01 4.10*** 0.02 3.60***

Floating (dummy) 0.16 0.14 -0.50 -1.82* 0.72 0.56

Governance quality … … … … 18.08 5.63***

Country fixed effects, time dummies, euro and EU membership dummies, dummy for missing gov.

debt observations (not reported)

Observations 442 442 374

Adjusted R

2

0.952 0.952 0.956

Significance of country FE F(33,359)= F(33,359)= F(33,292)=

37.63 (0.000) 45.30 (0.000) 22.10 (0.000)

1/

Linearized and inverted

Significance at the 1 (***), 5 (**), and 10 (*) percent level.

Table A1.Euro Premium - Panel Regressions

2001-2013

2002-2012

IIR Rating

S&P Rating

1/

IIR Rating

CEE NEW MEMBER STATES POLICY FORUM

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 31

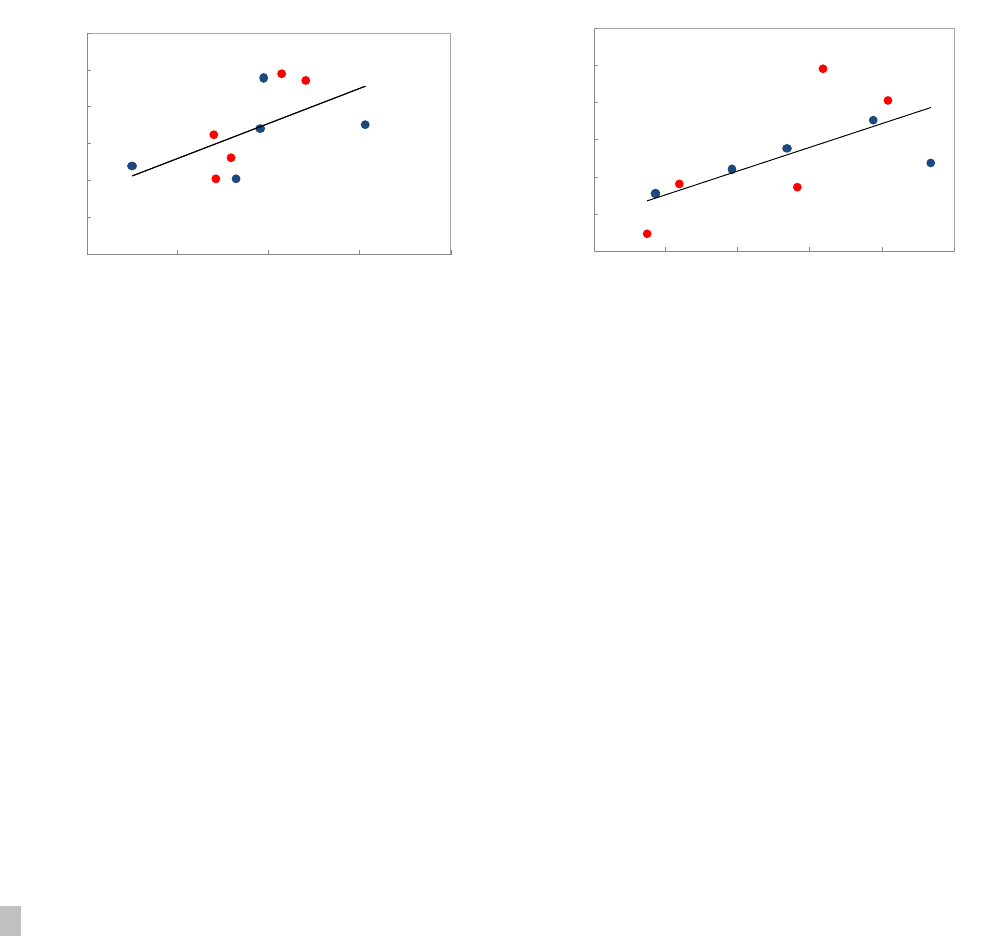

Euroization

The analysis of the impact of balance-sheet euroization on perceived credibility is

constrained by limited data availability. We have information for only 11 new EU members

states from 20062012 (in a few cases going back to 2004). This prevents including

euroization as a covariate into the regression equation above. As an alternative strategy, we

country fixed effects

and (ii)

residual credibility premium

with the share of FX loans in total private sector loans.

The estimated correlation (i) is unbiased as long as the share of FX loans is invariant over

time (which for most countries holds at least approximately), but the estimate is based on

very few observations. By adding a time dimension, (ii) greatly enlarges the sample (from i to

observations), but makes an orthogonality assumption about the relationship between

euroization and the other covariates included in the main regression equation above. This

assumption can, in general, not be assumed to hold, giving rise to potential estimation bias

in a priori unknown direction.

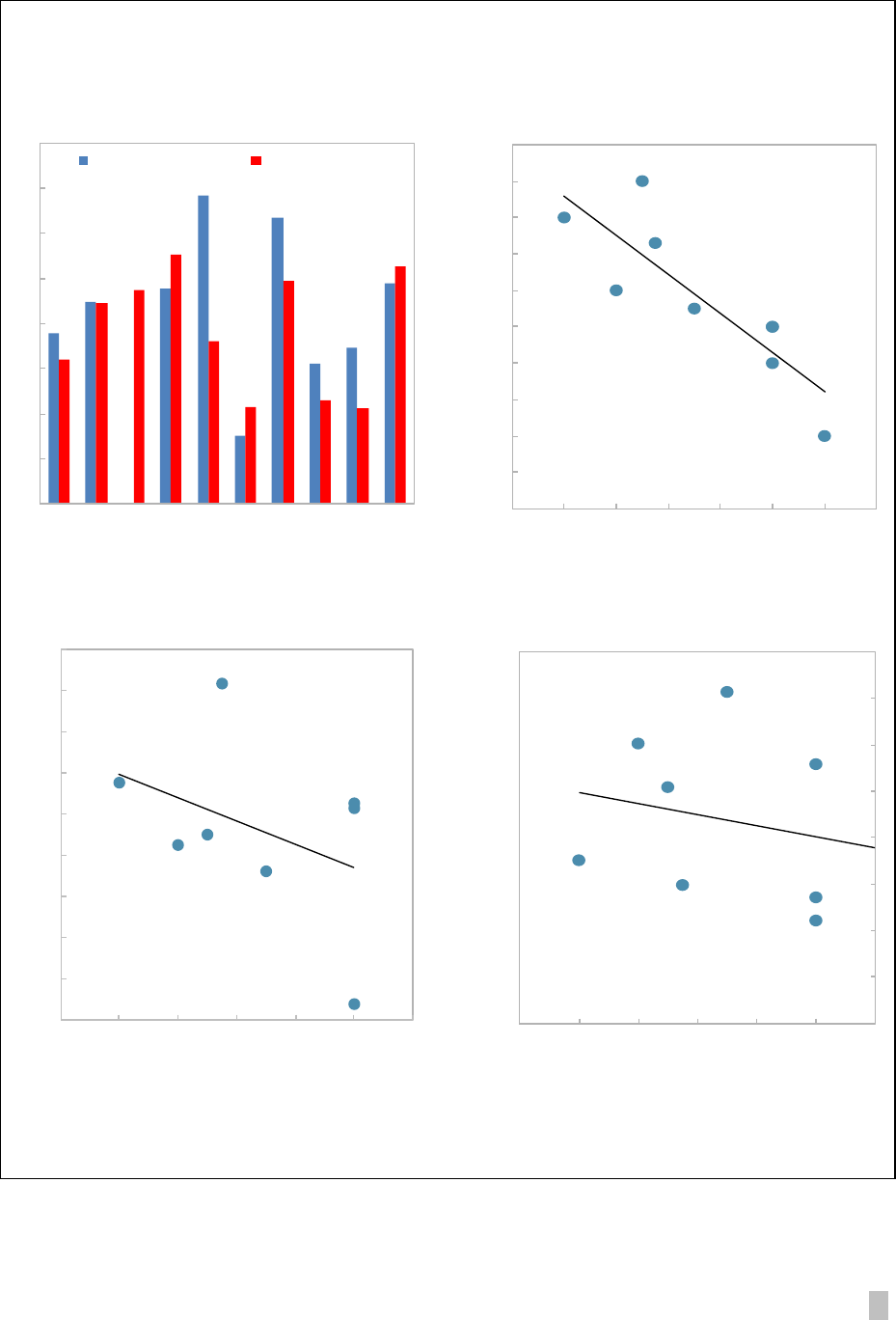

Figure A1 shows key results, using the

and

coming out of model (3).

5

While

correlation with euroization is marginally weaker for the residual credibility premium than for

fixed effects, the difference is so small that potential bias is unlikely to materially affect the

analysis. Further, the richer sample obtained from using the residual premium allows

extracting a non-linear relationship from the data: euroization becomes disproportionately

more detrimental for country perception the larger FX balance sheet mismatches are. This

relationship appears broadly stable over timethus, in contrast to the general euro

credibility premium, the FX-specific credibility premium has not vanished with the euro crisis.

5

Euroization correlates strongly with governance quality, thus inclusion of governance quality in X is

necessary lest to overstate the link between euroization and perceived credibility.

CEE NEW MEMBER STATES POLICY FORUM

32 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Figure A1. Ratings Premia and Euroization, Detailed Results

Source: IMF Staff calculations.

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

-15 -10 -5 0 5 10 15

Fixed Effects (blue/black) vs. Residual Premium (red)

(2006-12)

Residual premium (IIR points)

FX loans to the private sector as share of total

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

-15 -10 -5 0 5 10 15

FX loans to the private sector as share of total

Residual Premium: 2006-09 and 2010-12

2010-12

2006-09

Residual premium (IIR points)

CZE

POL

HUN

ROU

BGR

LTU

HRV

LVA

R² = 0.390

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

-15 -10 -5 0 5 10 15

Investor Perception and Balance Sheet Euroization

(Fixed effects, 2006-12)

Average premium (in IIR points)

FX loans to the private sector as share of total

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

-15 -10 -5 0 5 10 15

Residual Premium: Non-Linear Specification

(2006-12)

Residual premium (IIR points)