Special Report

Sustainable water use in agriculture:

CAP funds more likely to promote greater rather

than more efficient water use

EN

20

21

20

2

Contents

Paragraph

Executive summary I-VII

Introduction

01-18

Water availability in the EU: current status and future scenarios 01-03

Agriculture needs water

04-06

The EU’s role in water quantity policy

07-18

Water Framework Directive 08-11

Common agricultural policy 12-18

Audit scope and approach 19-24

Observations

25-89

EU policy on sustainable water use involves derogations that

apply to agriculture

25-52

Member States have authorisation systems in place, and apply many

derogations 27-35

Member States have introduced incentivising pricing mechanisms, but cost

recovery is lower in agriculture than in other sectors 36-44

The Commission considers WFD implementation to be progressing slowly 45-52

CAP direct payments do not significantly encourage efficient

water use

53-68

CAP income support does not promote efficient water use or water

retention 55-57

The EU supports water-intensive crops in water-stressed areas through

voluntary coupled support 58-61

Cross-compliance covers illegal abstraction of water, but checks are

infrequent and penalties are low 62-68

3

Rural development funds and market measures do not

significantly promote sustainable water use

69-89

Rural development programmes are seldom used to improve water quantity 70-74

EU funding for irrigation projects has weak safeguards against unsustainable

water use 75-89

Conclusions and recommendations 90-98

Abbreviations

Glossary

Replies of the Commission

Timeline

Audit team

4

Executive summary

I Demographic growth, economic activity and climate change are increasing both

seasonal and perennial water scarcity in the EU. A substantial part of the territory is

already affected by water abstraction in excess of the available supplies, and current

trends indicate increasing water stress.

II Agriculture depends on water availability. Irrigation helps to shield farmers from

irregular rainfall, and to increase the viability, yield and quality of the crops, but is a

significant drain on water resources. While around 6 % of EU farmland was irrigated in

2016, the sector was responsible for 24 % of all water abstraction.

III In 2000, the Water Framework Directive (WFD) introduced the concept of water

quantity into EU policy-making. It established the ambitious target of “good”

quantitative status for all groundwater bodies by 2027 at the latest. This means that

water abstractions should not lower groundwater levels to the extent that it leads to a

deterioration, or non-achievement of good water status. For most Member States, the

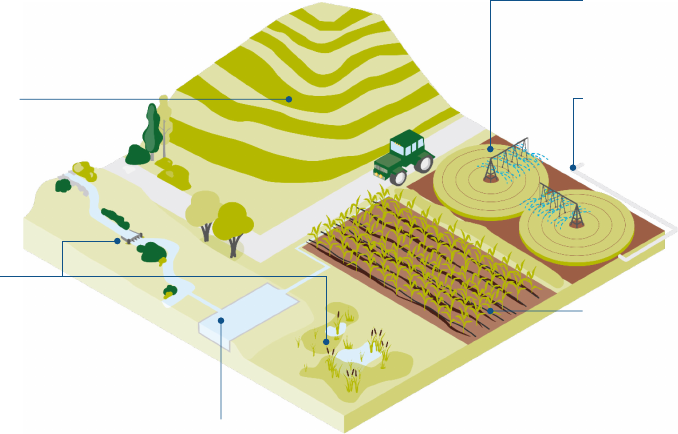

situation has improved, but in 2015, the quantitative status of around 9 % of

groundwater in the EU was “poor”. The Commission has assessed the WFD as being

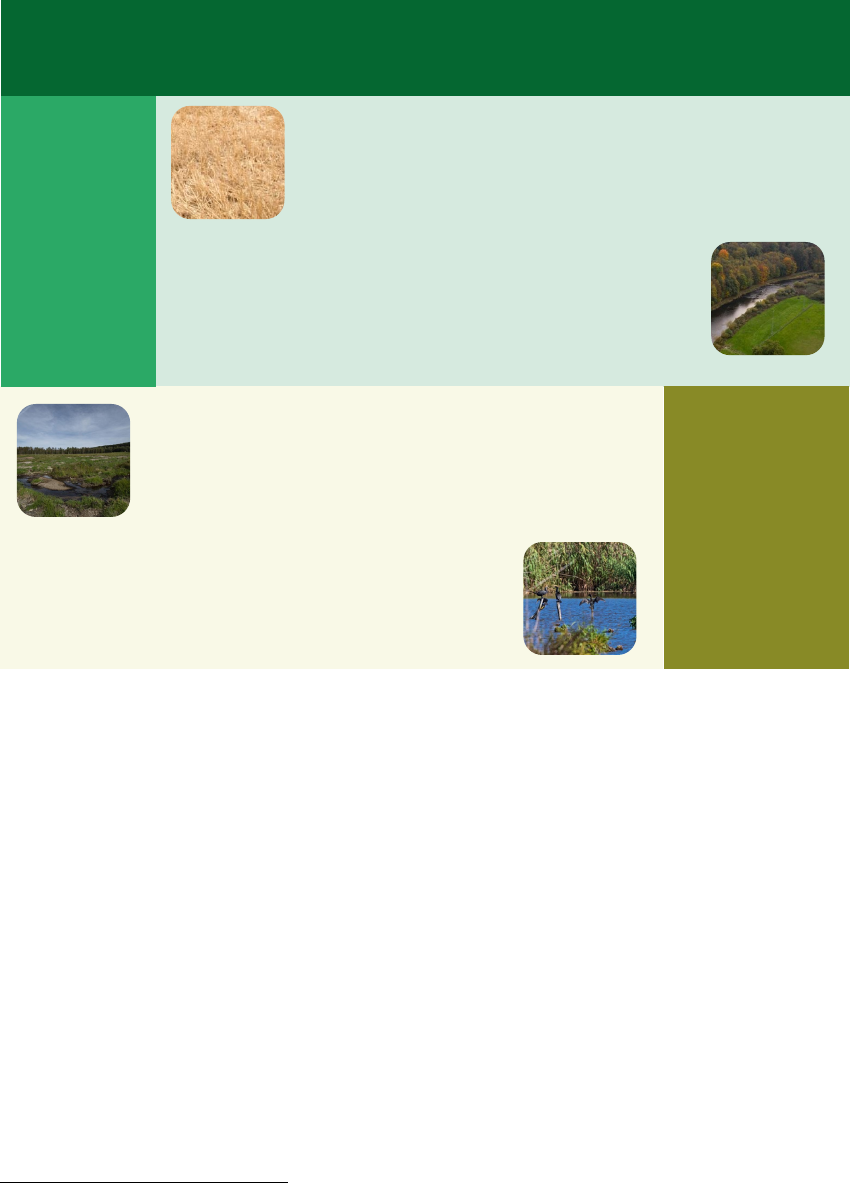

largely fit for purpose, but has noted significant delay in achieving targets.

IV The common agricultural policy (CAP) could incentivise sustainable agriculture in

the EU by linking payments to environmental standards. Sustainable agriculture in

terms of water use is embedded in the current CAP’s policy objectives and in the

proposals for the post-2020 CAP. The wide range of practices supported (including

support coupled to specific products, support for water retention measures or

investments in new irrigation) affect water use in agriculture in different ways.

V Our audit focused on the impact of agriculture on the quantitative status of water

bodies. We examined to what extent the WFD and the CAP promote the sustainable

use of water in agriculture.

VI We found that agricultural policies at both EU and Member State level were not

consistently aligned with EU water policy. Systems for authorising water abstraction

and water pricing mechanisms contain many exemptions for agricultural water use.

Few CAP schemes link payments to strong sustainable water use requirements. Cross-

compliance, a mechanism that may lead to (typically small) reductions in subsidy

payments if farmers are found to have breached certain requirements, discourages

5

unsustainable water use, but does not apply to all CAP support or to all farmers. The

CAP funds projects and practices expected to improve sustainable water use, such as

water retention measures, wastewater treatment equipment and projects improving

the efficiency of irrigation systems. However, these are less common than projects

likely to increase the pressure on water resources, such as new irrigation projects.

VII Based on our findings, we recommend that the Commission:

(1) ask Member States to justify water pricing levels and exemptions from the

requirement for water abstraction authorisations when putting the WFD into

practice in agriculture;

(2) link CAP payments to environmental standards on sustainable water use;

(3) ensure that EU-funded projects help achieve the WFD objectives.

6

Introduction

Water availability in the EU: current status and future scenarios

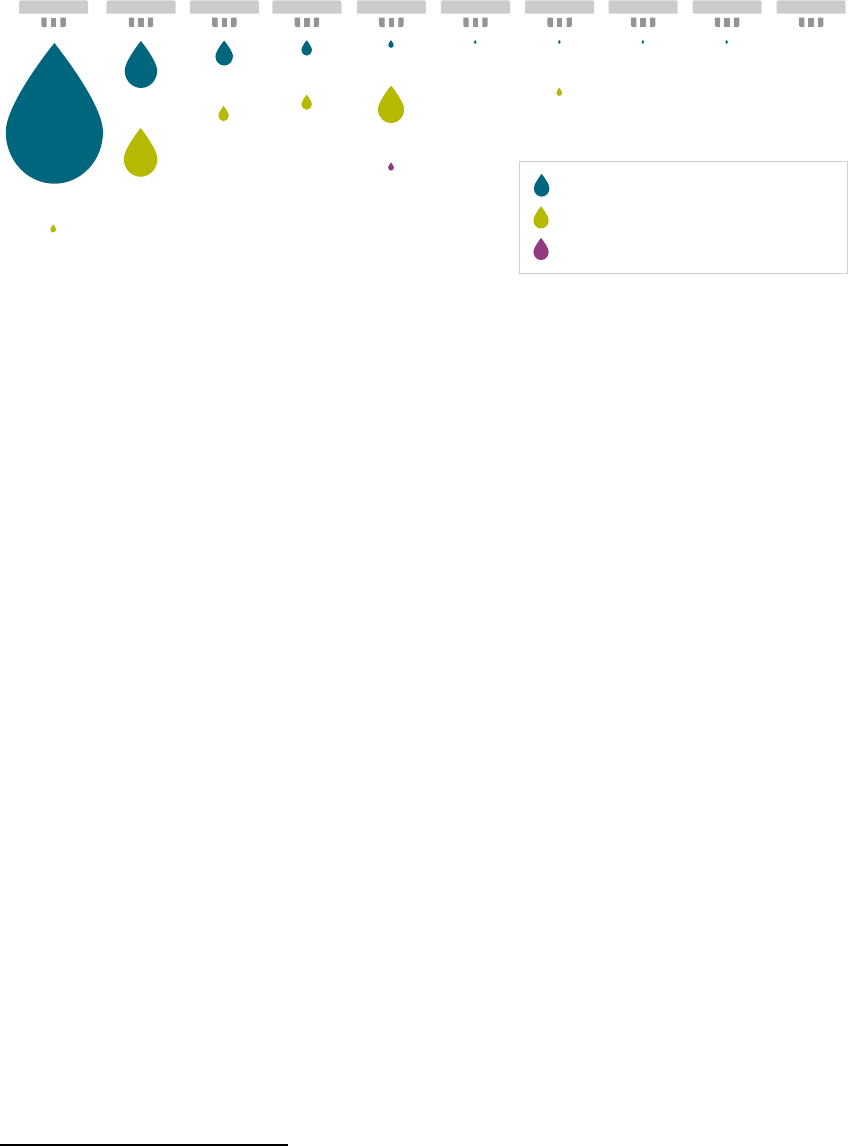

01 According to the World Bank, over the past 55 years, there has been an EU-wide

decrease of 17 % in renewable water resources per capita

1

. Though this is partly due to

population growth, pressure from economic activity and climate change is also

aggravating seasonal and yearlong water scarcity in parts of the EU.

02 Climate change, with higher average temperatures and more frequent, more

extreme weather events (including droughts), is making freshwater scarcer in the EU

2

.

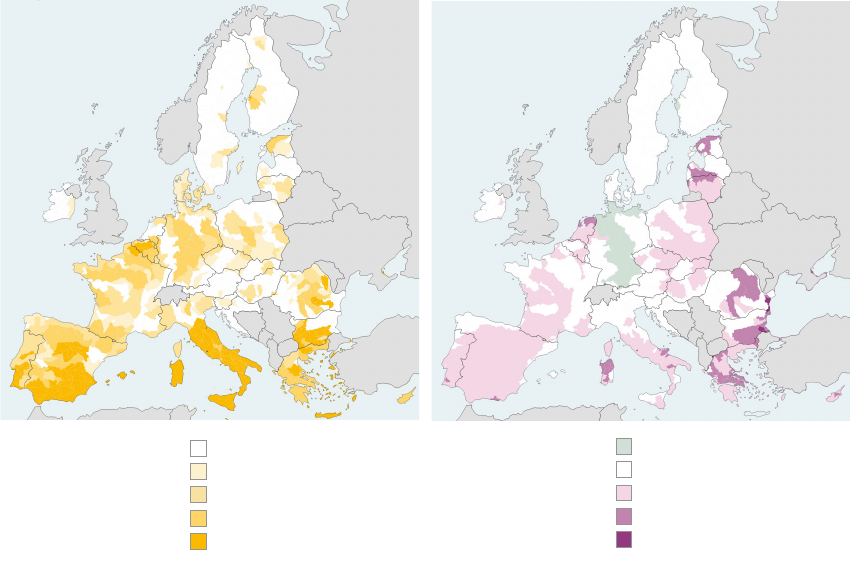

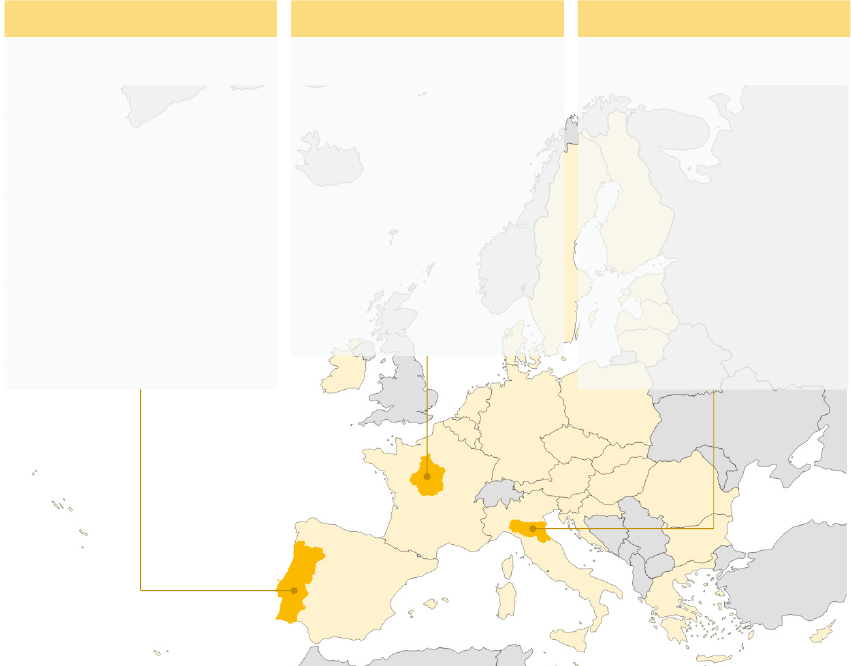

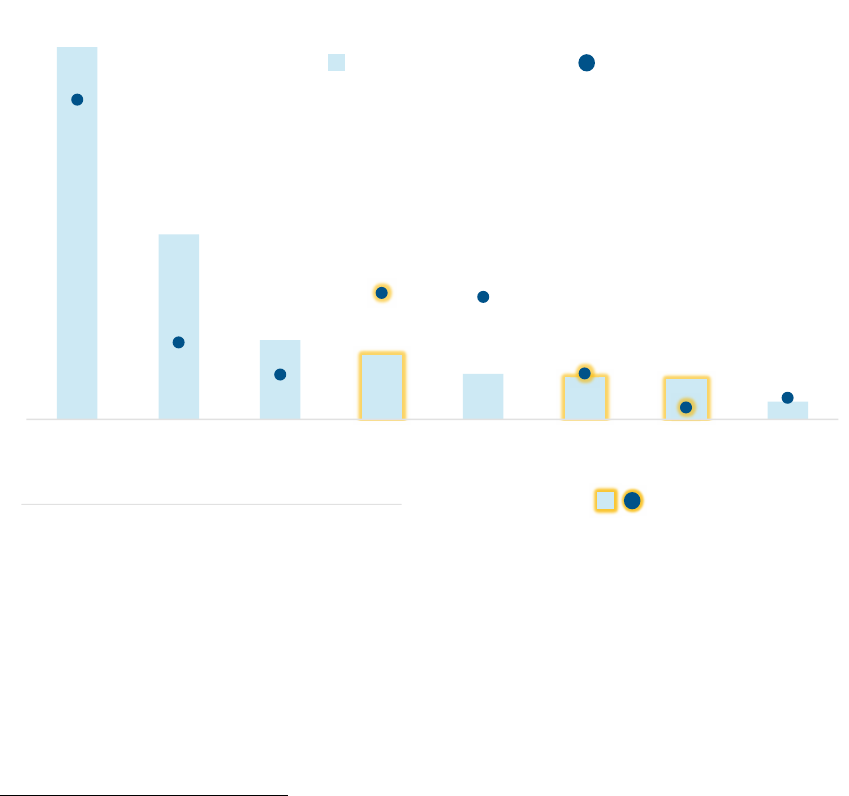

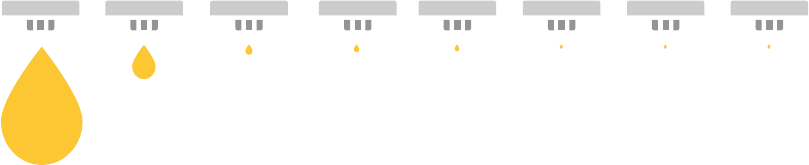

Forecasts indicate water stress is likely to increase in a significant portion of the EU by

2030 (Figure 1).

03 According to the Commission, “extreme droughts in western and central Europe

in 2018, 2019 and 2020 caused considerable damage. (…) With global warming at 3 °C,

droughts would happen twice as often and the absolute annual drought losses in

Europe would increase to €40 billion/year

3

.”

1

World Bank, Renewable internal freshwater resources per capita (cubic meters) - European

Union.

2

European Commission – JRC, “World Atlas of Desertification”, Change in aridity - shifts to

drier conditions.

3

Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the

European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: Forging a

climate-resilient Europe - the new EU Strategy on Adaptation to Climate Change

(COM(2021) 82 final).

7

Figure 1 – Water stress in the EU and future projections

© World Resources Institute – Aqueduct, accessed on 22/03/2021.

Agriculture needs water

04 Agricultural production depends on water availability. Irrigation offers multiple

benefits to farmers, such as increased crop viability, yield and quality. Irrigation water

comes from streams, rivers and lakes (surface water bodies), wells (groundwater

bodies), rainwater collection and reclaimed wastewater. Around 6 % of farmland in the

EU was irrigated in 2016. Drinking water for animals accounts for a small proportion of

agricultural water use.

05 Agriculture affects both water quality (e.g. through diffuse pollution from

fertilisers or pesticides) and water quantity. Low water flow, for example, decreases

the dilution of pollutants, thereby reducing water quality, and excessive water

abstraction in coastal areas can cause saltwater intrusion in the groundwater.

Water stress

baseline

(ratio of total water

withdrawals to available

renewable surface and

groundwater supplies)

Low (< 10 %)

Low-medium (10-20 %)

Medium-high (20-40 %)

High (40-80 %)

Very high (> 80 %)

Current situation

(baseline)

2030

Change from

baseline

(Variation in water stress

in a “business as usual”

scenario)

1.4x decrease or greater

Near normal

1.4x increase

2x increase

2.8x increase or greater

8

06 A recent report of the European Environment Agency (EEA)

4

indicates that

agriculture is responsible for 24 % of water abstraction in the EU: “the last 30 years

have seen some reduction in pressures, achieved thanks to efficiency gains in resource

use. Agricultural water use at the EU level has decreased by 28 % since 1990, while

nitrogen surplus has decreased by 10 % and nitrate concentration in rivers by 20 %

since 2000. However, further gains were modest in the 2010s and pressures continue

to remain at highly unsustainable levels.” In 2015, Member States reported to the

Commission the share of water bodies under significant pressure from agricultural

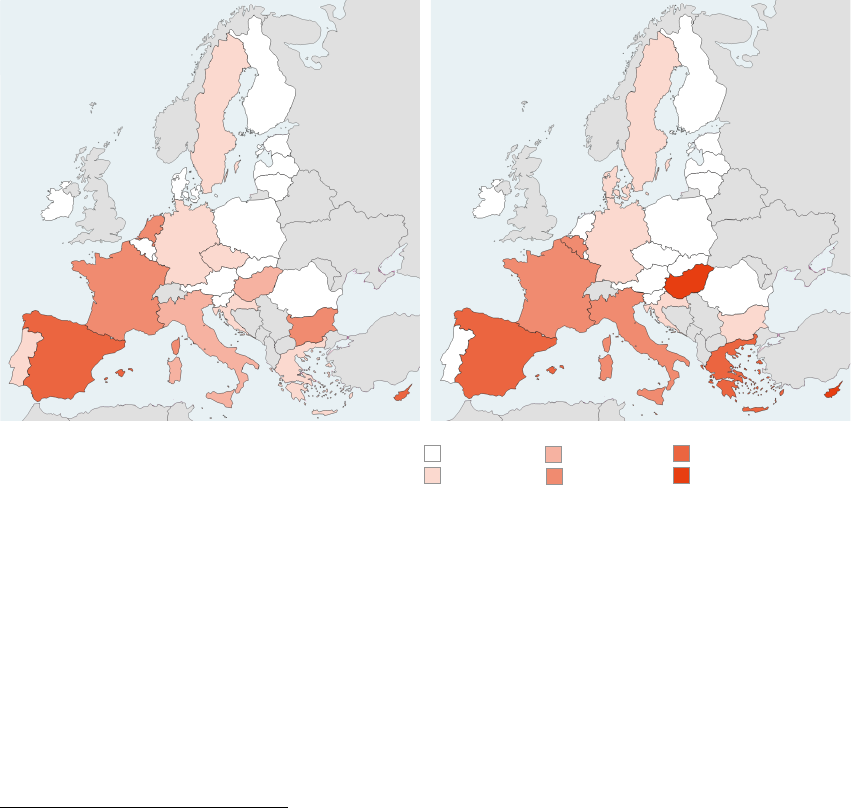

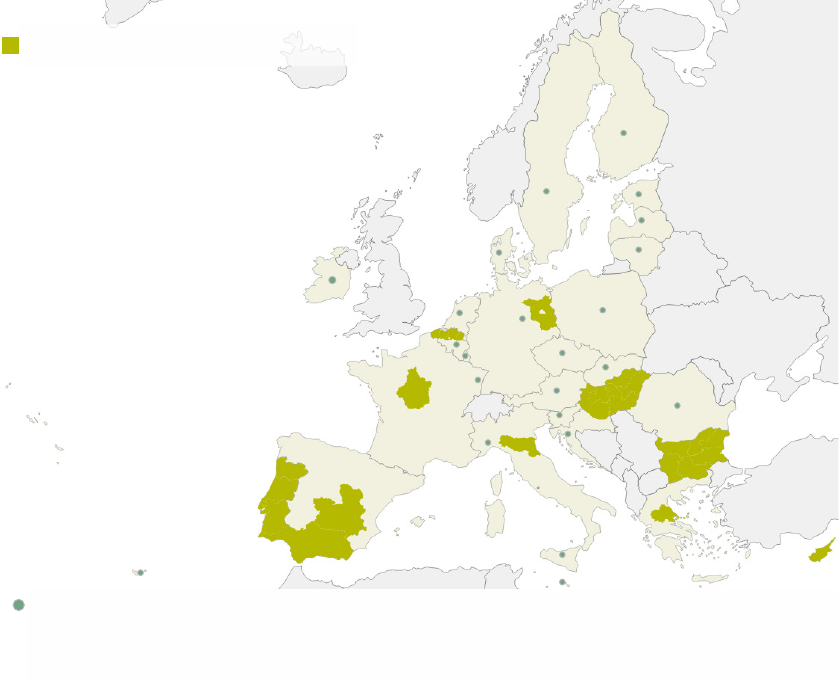

water abstraction (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 – Number of water bodies under significant pressure from

agricultural water abstraction

Source: ECA, based on EEA, 2018, ‘WISE Water Framework Directive (data viewer)’, European

Environment Agency.

4

European Environment Agency, “Water and agriculture: towards sustainable solutions”,

EEA Report No 17/2020.

Surface water Groundwater

0 %

1 – 5 %

5 – 10 %

10 – 20 %

20 – 40 %

> 40 %

Number of water bodies (%) under significant

pressure from agricultural abstraction

9

The EU’s role in water quantity policy

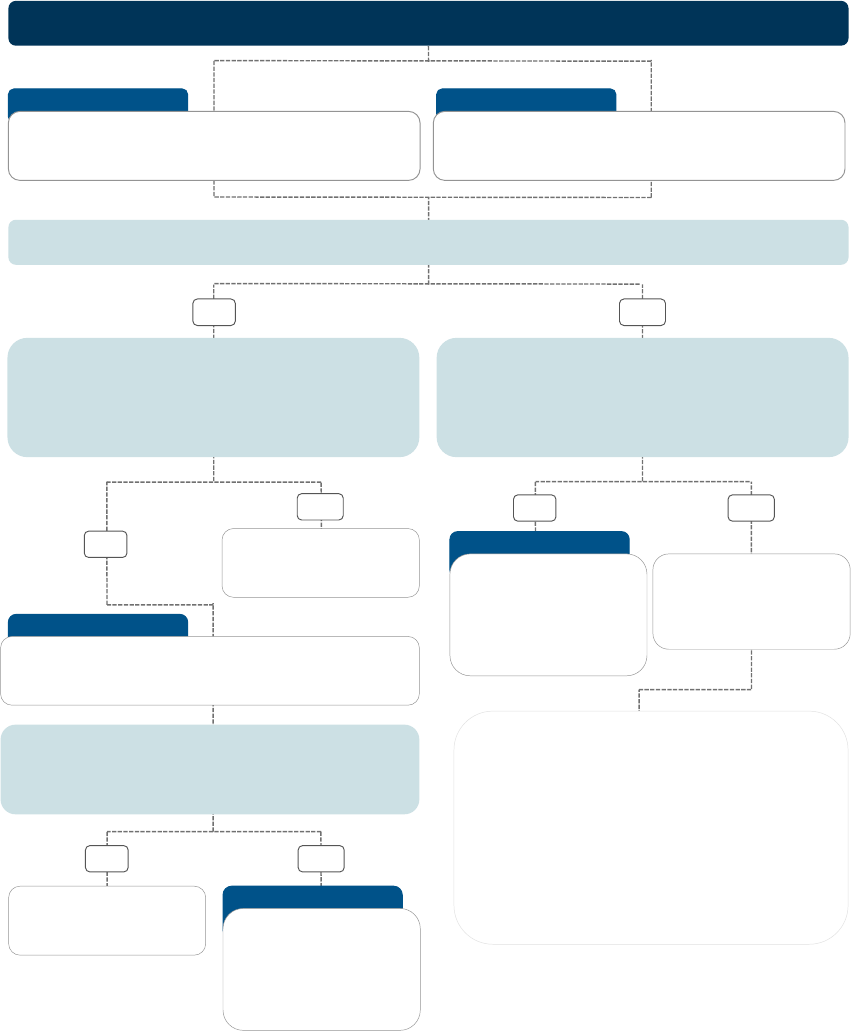

07 The main elements of the EU’s regulatory framework for water quantity and

agriculture are the Water Framework Directive

5

(WFD) and the common agricultural

policy (CAP). The main roles and responsibilities within the EU are outlined in Figure 3.

Figure 3 – Main roles and responsibilities (2014-2020)

Source: ECA.

5

Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2000

establishing a framework for Community action in the field of water policy (OJ L 327,

22.12.2000, pp. 1-73).

European Commission

Environment

(DG ENV)

Monitor

implementation of the

WFD

• Assess Member States’

RBMPs and produce

implementation reports

• Assess Member States’

compliance with the

WFD, particularly the

exemptions, measures

related to abstraction

controls and water

efficiency

Agriculture

(DG AGRI)

• Put in place the legal

framework for the CAP

• Ensure Member States

implement the CAP in

accordance with the

legal framework

• Approve RDPs and

monitor their

implementation

• Review the application

of cross-compliance

Design and oversee

implementation of the

CAP

Implement the CAP

Agriculture

(ministry of agriculture,

paying agencies,

managing authorities)

• Establish specific rules

for direct payments

• Draw up a national

framework and strategy

for operational

programmes in the fruit

and vegetable sector,

and support

programmes

in the wine

sector

• Prepare and implement

RDPs

• Detail and apply cross-

compliance

requirements

Environment

(e.g. competent

authorities for RBDs,

water authorities)

Implement the WFD

• Develop an RBMP for

each river basin district

within their territory

• Set up and operate a

water pricing system

• Set up and operate a

system to control water

abstraction

Member States

Task Force on Water and Agriculture

(DG AGRI, DG ENV, DG JRC, DG RTD and DG SANTE)

Coordinated initiative to work towards sustainable

water management

Acronyms: CAP – common agricultural policy; WFD

–

water framework directive; RDP – rural development programme; RBMP

– river basin management plan; RBD – river basin district

10

Water Framework Directive

08 The EU has had policies for improving water quality since 1991 (Urban Waste

Water Treatment and Nitrates directives). In 2000, the WFD introduced policies

relating also to water quantity. It promotes an ecosystem-based approach to managing

water, including principles such as water management at the scale of river basins,

public participation, and the need to consider the impact of human activities on water

resources.

09 Under the WFD, Member States must prepare river basin management plans

(RBMPs)

6

. These documents give details of monitoring, main pressures, objectives,

exemptions and measures for the next six-year period. Member States first submitted

plans to the Commission in 2009, and again in 2015. The Commission assesses

progress every three years

7

.

10 The WFD set a target of achieving good quantitative status for all groundwater

bodies by 2015, and by 2027 at the latest where justified exemptions apply. This

means that water abstractions should not lower groundwater levels to the extent that

it leads to a deterioration, or non-achievement of good water status. According to the

Commission’s latest implementation report

8

, in most Member States the situation

improved from 2009 to 2015, but the quantitative status of around 9 % of

groundwater bodies in the EU (by area) was still “poor” (Figure 4). The WFD addresses

quantitative aspects of surface water bodies in the definition of good ecological status,

namely the hydro-morphological elements (i.e. flow regime). Member States should

define objectives of "ecological flow" for each surface water body, which aim at

ensuring that there is sufficient water.

6

European Commission, Status of implementation of the WFD in the Member States.

7

Directive 2000/60/EC, Article 18.

8

European Commission, SWD(2019) 30 final, “European Overview - River Basin Management

Plans”.

11

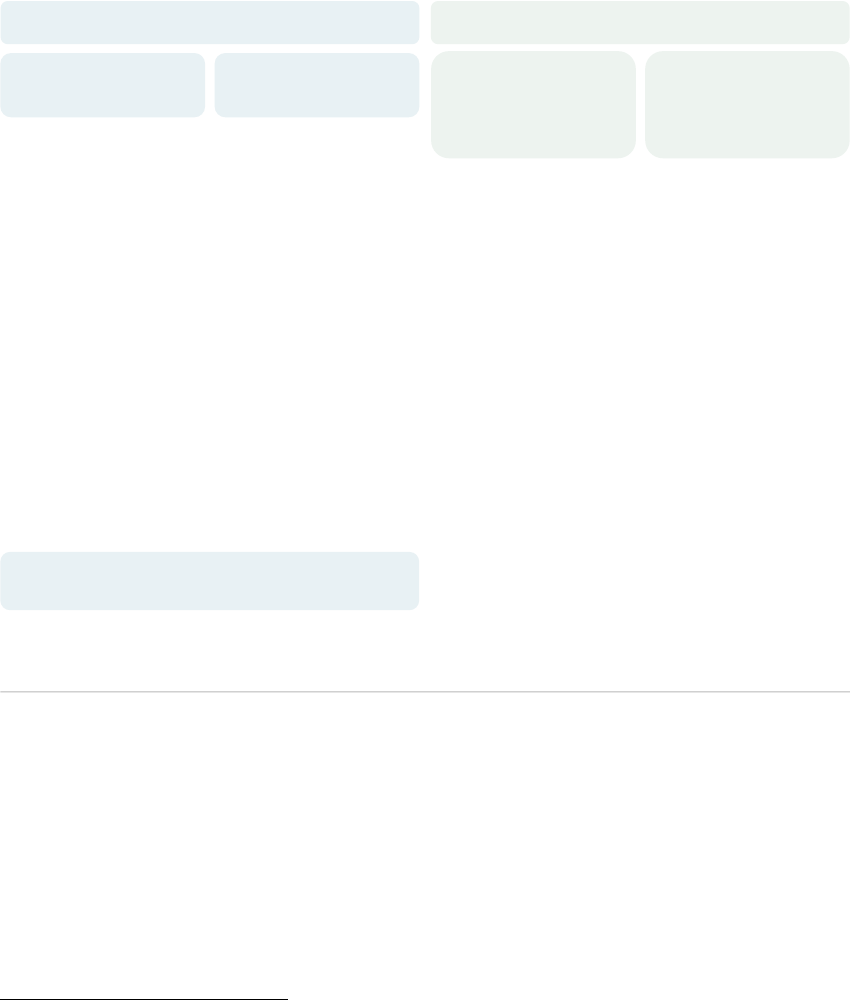

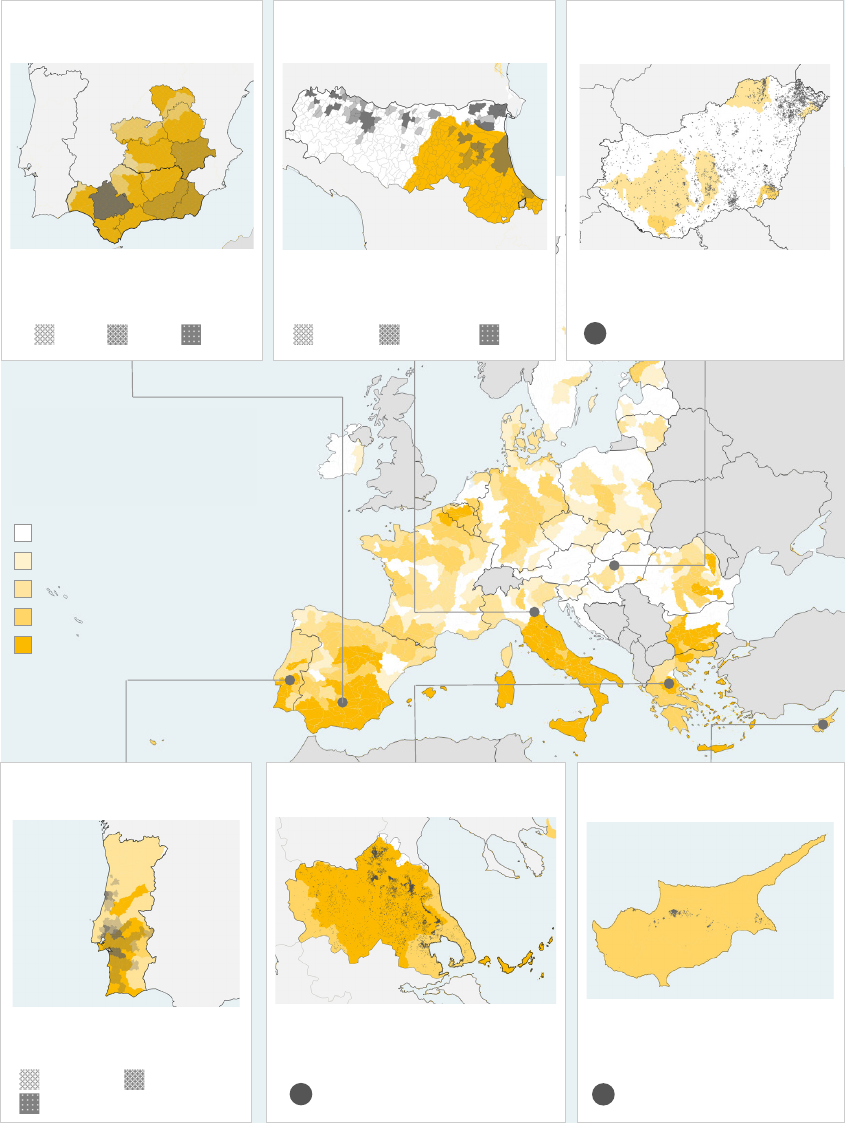

Figure 4 – Quantitative status of groundwater bodies

Source: ECA based on EEA, 2018, 'Groundwater quantitative and chemical status'.

11 In 2019, the Commission assessed the performance of the WFD between the end

of 2017 and mid-2019

9

. The overall conclusion of this assessment was that the WFD

was largely fit for purpose, although the Commission also noted: “the Directive’s

implementation has been significantly delayed (…). This is largely due to insufficient

funding, slow implementation and insufficient integration of environmental objectives

in sectoral policies.”

Common agricultural policy

12 Sustainably managing natural resources (including water) is one of the three

policy objectives for the 2014-2020 CAP

10

, alongside viable food production and

balanced territorial development. In 2018, the Commission published a proposal for

9

European Commission, EU Water Legislation - Fitness Check.

10

Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the

European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, "The CAP

towards 2020: Meeting the food, natural resources and territorial challenges of the future",

COM(2010) 0672 final.

0 %

25 %

50 %

75 %

100 %

Malta

Cyprus

Belgium

Hungary

Spain

France

Greece

Italy

Sweden

Czechia

Poland

Germany

Slovakia

Denmark

Portugal

Bulgaria

Estonia

Croatia

Finland

Ireland

Austria

Latvia

Lithuania

Luxembourg

Netherlands

Romania

Slovenia

Poor quantitative status by area (2015) Good quantitative status by area (2015)

Unknown quantitative status by area (2015) Poor quantitative status by area (2009)

12

the post-2020 CAP

11

. The nine specific objectives proposed include fostering

sustainable development and efficiently managing natural resources such as water, soil

and air.

13 The largest share of the CAP budget goes to direct payments (71 %)

12

. These

include:

o Decoupled income support such as the basic payment scheme (BPS), the single

area payment scheme (SAPS) and the greening payment, which together account

for 61 % of the CAP budget: €35.3 billion in 2019

13

.

o Voluntary coupled support (VCS), paid by area or by head of livestock. Member

States can use this optional direct payment scheme to support specific

agricultural sectors that are undergoing difficulties and are particularly important

for economic, social or environmental reasons. They allocated around

€4.24 billion to VCS in 2020

14

, with one quarter going to area-based support.

14 Producers of fruit and vegetables, wine and olive oil qualify for “common market

organisation” (CMO) support to help them adapt to market changes. CMO measures

include support for investments with a potential impact on water use.

15 The European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) supports EU rural

development policy through Member States’ rural development programmes (RDPs).

RDPs are drawn up on a national or regional basis and address EU priorities over a

seven-year period. They include support for agricultural practices and investments

with a potential impact on water use.

11

Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing rules

on support for strategic plans to be drawn up by Member States under the Common

agricultural policy (CAP Strategic Plans) and financed by the European Agricultural

Guarantee Fund (EAGF) and by the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development

(EAFRD), COM(2018)392 final.

12

European Commission, CAP Indicators - Financing the CAP.

13

European Commission, SWD(2020) 168 final.

14

European Commission, “Voluntary coupled support - Review by the Member States of their

support decisions applicable as from claim year 2020”.

13

16 Reusing treated wastewater is part of a circular economy. According to a 2015

study carried out for the Commission, around 1 100 million m³ of wastewater (some

0.4 % of annual EU freshwater abstractions) was being reused every year in the EU

15

.

The EU adopted a regulation on reusing wastewater for agricultural irrigation in May

2020

16

. It sets minimum requirements for water quality, monitoring, risk management

and transparency, and will apply from June 2023. According to the Commission’s

impact assessment

17

, the regulation will enable the reuse of “more than 50 % of the

total water volume theoretically available for irrigation from wastewater treatment

plants in the EU and avoid more than 5 % of direct abstraction from water bodies and

groundwater, resulting in a more than 5 % reduction in water stress overall”. The CAP

can finance water treatment infrastructure for the reuse of wastewater for irrigation.

17 Most direct payments, as well as some rural development and certain CMO

payments for the wine sector, are subject to a set of rules known as cross-compliance.

These comprise statutory management requirements (SMRs) from selected directives

and regulations on the environment, food safety, plant health, animal health and

welfare, and standards for good agricultural and environmental condition (GAEC),

which impose sustainable agricultural practices. CAP beneficiaries that are found not

to respect these rules as defined by national legislation may face a reduction in their

annual EU grant.

18 For example, GAEC 2 provides a mechanism to assess whether farmers

abstracting water for irrigation comply with the authorisation procedures in their

Member State. Between 2015 and 2018, 1.2 % of the CAP beneficiaries to which GAEC

2 applied were checked each year. These checks detected a low percentage of

infringements (1.5 %), most of which were penalised by a reduction of 3 % (Figure 5)

in the subsidy paid to the farmer concerned.

15

BIO by Deloitte (in collaboration with ICF and Cranfield University), “Optimising water reuse

in the EU – Final report prepared for the European Commission (DG ENV)”, Part I.

16

Regulation (EU) 2020/741 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 May 2020

on minimum requirements for water reuse (OJ L 177, 5.6.2020, pp. 32-55).

17

European Commission, SWD(2018) 249 final/2 - 2018/0169 (COD).

14

Figure 5 – GAEC 2 checks (average 2015-2018)

Source: ECA based on data received from the European Commission.

Percentage of farmers checked

(of those to which GAEC 2 applied)

Percentage of

infringements

Outcome of

infringement

1.2 %

1.5 %

Reduction (5 %)

25.4 %

Reduction (3 %)

67.9 %

Reduction (1 %)

4.6 %

Early warning

2.2 %

15

Audit scope and approach

19 This audit focuses on the impact of agriculture on the quantitative status of

water. As agriculture is both a major user of freshwater and one of the first sectors to

be impacted when water is scarce, we assessed to what extent EU policies, namely the

CAP and water policy, promote the sustainable use of water in agriculture.

20 The Council declared in 2016

18

that the EU’s water policy objectives should be

better reflected in other policy areas, such as food and agriculture. The European

Parliament has also called for better policy coordination. Water is the subject of UN

Sustainable Development Goal 6 (“water and sanitation for all”), whose targets relate

to water efficiency and integrated water management.

21 We examined to what extent:

o the WFD promotes sustainable water use in agriculture;

o CAP direct payment schemes take account of the WFD principles of sustainable

water use;

o CAP rural development and market measures have taken up the WFD principles

of sustainable water use.

22 The audit did not cover diffuse pollution of water due to agriculture (e.g. from

nitrates or pesticides). Previous ECA reports

19

have focused on this in more detail.

18

Sustainable Water Management Council Conclusions, 17 October 2016.

19

ECA special report 04/2014: “Integration of EU water policy objectives with the CAP: a

partial success”; ECA special report 23/2015: “Water quality in the Danube river basin:

progress in implementing the water framework directive but still some way to go”; ECA

special report 03/2016: “Combating eutrophication in the Baltic Sea: further and more

effective action needed”.

16

23 The audit ran from April to December 2020. We interviewed staff at the

Commission and Member State authorities and consulted other stakeholders in the

water and agricultural sectors. We examined:

o the Commission’s strategic documents, working documents, studies, evaluations,

guidance documents, statistics, water quantity implementation reports and

agricultural policies;

o rural development programmes, and national and regional rules and guidance on

cross-compliance, direct payment schemes, market and rural development

measures, as well as studies, research, analysis and statistics on penalties;

o river basin management plans, water abstraction rules and pricing policies;

o other relevant studies and reports, including those by the Organisation for

Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the European Environment

Agency (EEA).

24 Our audit covered the 2014-2020 CAP programming period. We performed

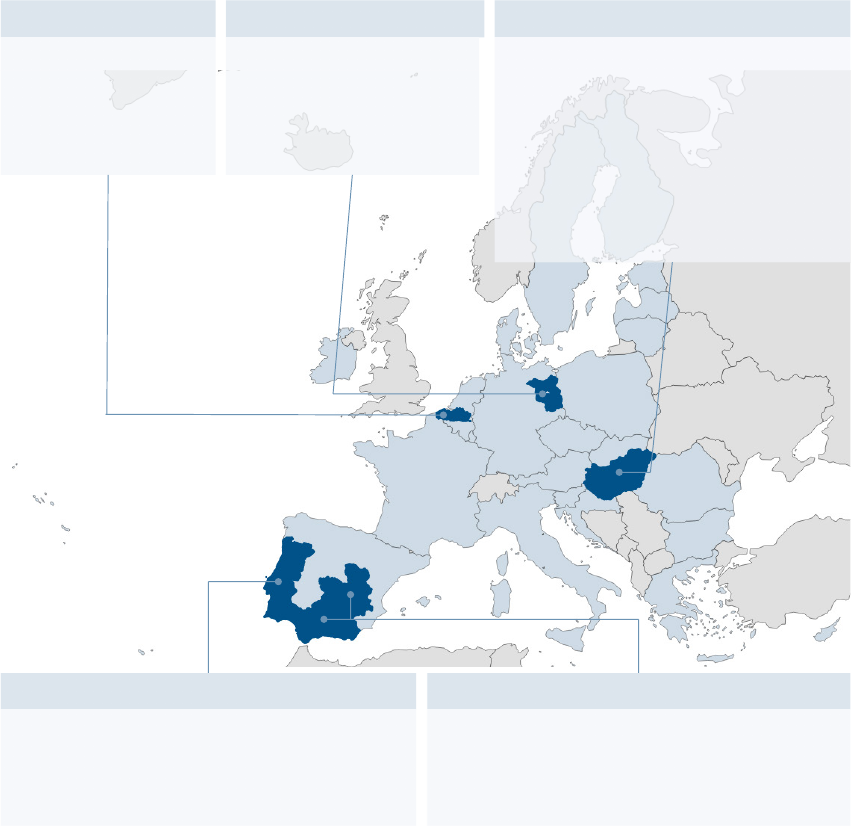

extended desk reviews for 11 Member States/regions (see Figure 6), seeking a

geographical balance between areas currently facing water scarcity and others where

this is likely to become an issue in the future. In six of the Member States, we focused

our work on one or two regions, as some Member States have regional RDPs and

water management measures are decided at river basin level. We also obtained

evidence for other Member States/regions from a desk review of 24 additional RDPs

and the audit work carried out for our annual report.

17

Figure 6 – Desk reviews

Source: ECA.

Extended desk review

Belgium (Flanders)

Bulgaria

Germany (Berlin-Brandenburg)

Greece (Thessaly)

Spain (Andalusia)

Spain (Castile-La Mancha)

France (Centre-Val de Loire)

Italy (Emilia-Romagna)

Cyprus

Hungary

Portugal (Mainland)

Desk review of RDPs:

Belgium (Wallonia), Czechia, Denmark, Germany (Saxony-Anhalt), Estonia, Ireland, Spain (Canaries), France (Alsace), Croatia, Italy (Sicily),

Italy (Liguria), Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta,

Netherlands

, Austria, Poland, Portugal (Madeira), Romania, Slovenia, Slovakia,

Finland, Sweden

18

Observations

EU policy on sustainable water use involves derogations that

apply to agriculture

25 The WFD provides safeguards against unsustainable water use. It requires

Member States, inter alia, to:

o operate a water abstraction authorisation system and register

20

;

o adopt water pricing policies that incentivise efficient water use and ensure

adequate cost recovery for water services from the various users (including

farmers)

21

.

26 We examined the extent to which Member States apply the above requirements

on water abstraction management, water pricing and cost recovery in the agricultural

sector, and how the Commission monitors their work.

Member States have authorisation systems in place, and apply many

derogations

27 The WFD requires Member States to keep a register of surface water and

groundwater abstractions and surface water storage (“impoundment”). Water users

must request prior authorisation to abstract or store water, but Member States may

choose to apply exemptions where abstraction or storage has no significant impact on

water status.

28 As part of water abstraction management, Member States are required to

identify and penalise any parties that use water without authorisation/notification or

fail to comply with water abstraction rules (e.g. as specifically authorised).

20

Directive 2000/60/EC, Article 11.3(e).

21

Directive 2000/60/EC, Article 9.

19

Prior authorisation systems

29 In eight of the 11 Member States/regions we covered in our audit, all water

abstraction points must be notified to the authorities. All of the Member

States/regions covered in our audit have a prior authorisation system for water

abstraction. When granting authorisations, Member State authorities take into

account the status of the water body concerned and specify the maximum annual (or

monthly) quantity that may be abstracted.

30 Member States apply numerous exemptions (see Figure 7). These can have a

significant impact on the quantitative status of the water bodies concerned. Where

there is also no mandatory metering, the authorities cannot monitor whether

abstraction remains below a significant level. This is the case for certain types of

abstractions in Belgium (Flanders), Bulgaria, Germany (Berlin-Brandenburg), Italy

(Emilia-Romagna), Cyprus and Portugal.

20

Figure 7 – Exemptions from authorisation for water abstraction

Source: ECA, based on data from the Member States, and Eurostat.

No authorisation needed

• Belgium (Flanders): surface

water from non-

navigable

waterways

• Bulgaria and Italy (Emilia-

Romagna): surface

water and

groundwater for

private/domestic

use

• Germany (Berlin

-Brandenburg

):

all surface water for landowners

and riparians and groundwater

for the household and in small

quantities for temporary

purposes

• Hungary: groundwater for

irrigation from wells less than 50

metres deep, subject from 2021

to certain restrictions and

requirements

No authorisation needed in exceptional

circumstances

• Greece: occasional water use in cases of

force majeure, emergency and/or

unforeseen need

• Hungary: temporary pumping stations

may be used, with certain limitations, to

obtain surface water for irrigation

during periods of ‘permanent water

scarcity’. Since 2017, permanent water

scarcity has been declared for several

months each year during spring or

summer

No authorisation needed

below a certain yearly

volume or abstraction

capacity

• Maximum thresholds vary

from 500 to 200 000

m³/year (see below)

No authorisation needed

for certain legacy

abstractions

• Cyprus

• Portugal

France

(groundwater

outside a water

stressed area – zone

de répartition des

eaux)

200 000 m

3

/year

Spain

(Andalusia / Castile-La

Mancha)

(groundwater if

body not declared

overexploited / at

risk)

7 000 m

3

/year

Germany

(Berlin-Brandenburg)

(groundwater for

farmyard use and

watering non-

farmyard animals)

5 000 m

3

/year

Belgium

(Flanders

)

(surface water

abstraction from

navigable

waterways)

500 m

3

/year

Cyprus

(maximum 5

m

3

/day)

1 825 m

3

/year

Average

household

consumption

(four persons)

Average amount

abstracted for

agriculture per

hectare of irrigated

land

Exemption ceilings for water abstraction authorisations

3 800

m3/year

175

m3/year

21

Systems for detecting illegal water use

31 Official recent data on illegal water abstraction in the EU is scarce. In 2015, the

OECD compiled estimates from a range of sources, such as 50 000 illegal boreholes in

Cyprus and over half a million unauthorised or illegal wells in Spain

22

. According to the

Worldwide Fund for Nature, the issue is especially acute in Castile-La Mancha and

Andalusia

23

. In Hungary, experts estimate unlicensed water use at nearly

100 million m³/year, or 12 % of registered abstractions

24

.

32 Ten of the Member States/regions we examined have a control system in place to

detect and penalise illegal water use. They carry out on-the-spot checks of registered

abstraction points based on an annual control plan, risk analysis and/or complaints.

The infringements detected in this way include unauthorised water use, unmetered

pumping, excessive pumping and various other breaches of the terms of authorisation.

Figure 8 shows the rate of infringements revealed by inspections of water abstraction

points.

Figure 8 – Infringements revealed by inspections of water abstraction

points for agriculture

Source: ECA.

22

OECD, “Drying Wells, Rising Stakes: Towards Sustainable Agricultural Groundwater Use”.

23

WWF, “Illegal water use in Spain: Causes, effects and solutions”.

24

Second river basin management plan of the Danube (2015), point 2, p. 10.

4.1 %

13.6 %

6.6 %

8.0 %

13.3 %

10.8 %

Belgium

(Flanders)

Bulgaria

Cyprus

Germany

(Brandenburg)

Greece

Spain

(Andalusia)

Spain

(Castile -

La Mancha)

France

(Centre

Val de Loire)

Hungary

Italy

(Emilia-

Romagna)

Portugal

(Mainland)

Not available

Not available

Not available

Not available

Belgium

(Flanders)

Bulgaria

Cyprus

Germany

(Berlin-

Brandenburg)

Greece

(Thessaly)

Spain

(Andalusia)

Spain

(Castile

-

La Mancha)

France*

(Centre-

Val de Loire)

Hungary

Italy

(Emilia-

Romagna)

Portugal

(Mainland)

* May include checks on water abstraction by other economic sectors

Not available

Infringement found

No infringement found

22

33 In addition to on-the-spot checks of registered water abstraction facilities, some

Member States have established or are developing other control mechanisms. These

include:

o satellite remote sensing (see Box 1);

o mandatory accreditation of drilling companies for new groundwater abstraction.

Drilling companies in Belgium (Flanders) must provide regular reports on drilling

operations and inform the authorities in advance of the start date to allow checks

during construction. Non-compliance may result in the suspension or withdrawal

of accreditation;

o regular checks on the correct functioning of flow meters for groundwater

abstraction facilities in Belgium (Flanders). Metered values are compared against

farm data and the annual declaration of groundwater extraction.

Box 1

Use of satellite images to detect illegal water use

Several research projects (DIANA, IPSTERS, WODA) have looked into the potential

of satellite images to detect unauthorised water abstraction. The results show that

it is feasible to:

— identify local or regional soil subsidence (vertical soil movements) with

millimetre accuracy using radar images (e.g. from Copernicus Sentinel 1),

which can indicate groundwater over-abstraction across a given area;

— identify irrigated areas, estimate abstracted volumes for irrigation and

improve water management policies and practices, especially in extreme

conditions such as drought, using optical remote sensing images (e.g. from

Copernicus Sentinel 2).

The projects encompassed pilot studies in Spain, Italy, Romania and Malta and

resulted in commercial platforms in Italy and Spain proposing services to water

use associations and farmers. The uptake of services depends not only on easy

access to comprehensive auxiliary data that is digital, geo-referenced and

validated, but also on the absence of legal barriers to using earth observation as a

detection method or metering device.

23

The La Mancha Oriental aquifer in Spain is a good example of a long-lasting

operational system of self-regulation. The local irrigation board monitors and

manages groundwater abstraction using satellite data in combination with flow

meters on the ground.

34 In some Member States, practical difficulties make the systems in place for

combating illegal water use less effective. Belgium (Flanders) and Bulgaria reported

that they were unable to deploy their respective systems as intended due to staff

shortages. In Cyprus, until October 2020, the authorities rarely imposed penalties or

sanctions, since those at fault had two months to comply and submit an amended

licence. Bulgaria and Hungary have repeatedly extended their deadlines for making

illegal abstractions compliant without a fine.

35 Regional authorities in the two Spanish regions we examined (Andalusia and

Castile-La Mancha) did not provide us with any information on whether or how they

detect and sanction illegal water use.

Member States have introduced incentivising pricing mechanisms, but

cost recovery is lower in agriculture than in other sectors

36 The WFD requires Member States to embrace the principle of cost recovery for

water services in accordance with the polluter pays principle. This means applying

incentivising pricing policies and ensuring that all categories of water users (industry,

households, agriculture, etc.) contribute adequately to cost recovery.

Incentivising pricing

37 Several Member States/regions have introduced pricing mechanisms that

incentivise efficient water use. Some of these mechanisms apply only to agriculture

and others to all water users. For example:

o Germany (Berlin-Brandenburg), Hungary and Portugal apply a water resource tax

based on the measured volume of use;

o Cyprus imposes a surcharge for every cubic metre of water used beyond the

authorised volume;

o Italy (Emilia-Romagna) is planning a system of variable water prices according to

the efficiency of the irrigation system;

24

o Bulgaria charges more for water used beyond a certain fixed volume for a given

crop;

o Belgium (Flanders) uses progressive pricing for certain types of groundwater (the

greater the volume abstracted, the higher the price).

38 Other Member States/regions have introduced price differentiation to

discourage/encourage the use of water from various sources. For example:

o prices are higher in areas where water is scarcer or under greater quantitative

pressure in Belgium (Flanders), France (Centre-Val de Loire), Hungary and

Portugal;

o groundwater is more expensive than surface water in Bulgaria, Germany (Berlin-

Brandenburg) and France (Centre-Val de Loire);

o fresh water is more expensive than recycled water in Cyprus.

39 Member States use a variety of methods to measure water used for agriculture

(see Figure 9). Volumetric pricing at an appropriate level can incentivise the shift to

water-efficient irrigation technologies and practices or to crops requiring less water.

Spain (Andalusia and Castile-La Mancha) bills most irrigation water on the basis of the

irrigated area, while in Italy (Emilia-Romagna) the charge for irrigation water usually

depends on pumping capacity.

Figure 9 – Billing methods: water for irrigation

Source: ECA.

Water is billed by

volume. The volume of

abstracted water is

measured by means of

a flow meter installed

at the abstraction point

(e.g. groundwater

well).

Volume

Farmers pay a price

per hectare,

regardless of their

actual water use. This

sometimes depends

on the crop grown.

Area

The water price

depends on the

maximum capacity of

the pumping

installation

(e.g. expressed in

kW/h or l/h).

Capacity

25

Lower water prices for agriculture

40 In eight of the 11 Member States/regions covered in our audit, water is

significantly cheaper if used for agriculture. Figure 10 compares some water

abstraction fees for agricultural use with the fees charged for use in other sectors.

Several Member States/regions apply specific derogations for irrigation water (see

Figure 11).

Figure 10 – Comparison of water abstraction fees by sector

Source: ECA, based on information provided by the Member States.

France (Centre-Val de Loire)

In the Loire-Bretagne river basin,

the fee for water abstraction for

irrigation (except gravity

irrigation) in water stressed

areas is set at 0.0213 €/m

3

. This

is:

•

2 times lower than for

drinking water supply

• 1.5 times lower than for

other

economic uses

•

6.7 times higher than for

industrial cooling

Italy (Emilia-Romagna)

Water abstraction fees for

irrigation are slightly below € 50

per module. This is:

• 308.5 times lower than for

industrial use

• 42.6 times lower than for

drinking water

• 9.8 times lower than for

aquaculture

One module is 100 liter per

second for drinking water and

aquaculture and 3 000 000 m³

for industrial use.

Portugal (Mainland)

The water abstraction

component of the water

resource tax has a basic unit

value for agriculture of 0.0032

€/m

3

. This is:

• 4.7 times lower than for

public water supply

• 4.4 times lower than for

other uses

• 1.2 times higher than for

thermoelectric energy

• 160 times higher than for

hydroelectric energy

26

Figure 11 – Price reductions applicable to irrigation water

Source: ECA based on information provided by the Member States.

41 Six of the Member States/regions do not require any payment for water

abstraction up to a certain volume. The pricing threshold varies. It is 500 m³/year in

Belgium (Flanders) and Hungary, 10 m³/day in Bulgaria, 7 000 m³/year in Spain

(Andalusia) and France (water-stressed areas), 10 000 m³/year in France (outside

water-stressed areas), and 16 600 m³/year in Portugal (private abstraction). In every

case it applies to all users, not only farmers.

Hungary

Tax exemption:

• 400 000 m

3

/year per water rights

licence

• 4 000 m

3

/ha/year for individual users

• 25 000 m

3

/ha/year for rice production

using surface water

Additional exemptions during persistent

water scarcity and COVID-19 pandemic.

Germany (Berlin-Brandenburg)

Tax exemption:

• surface water

abstraction for irrigation

(a significant proportion

of irrigation water)

Belgium (Flanders)

Tax exemption:

• 50 % of phreatic

groundwater for

irrigation (by

volume)

Portugal (Mainland)

90 % reduction:

• two out of five components of water resource

tax if the water is used for thermal regulation

of crops (e.g. water for flooding rice crops)

Spain (Andalusia and Castile-La Mancha)

No fee:

• groundwater or surface water for irrigation

when abstracted by farmers for their own use

(and not supplied by a consortium)

27

Cost recovery of water services

42 The WFD requires Member States to carry out an economic analysis of water use.

This calculation should help with assessing the extent to which the costs of water

services (e.g. water abstraction for irrigation) are paid by users (the cost recovery

principle). According to the EU guidance

25

, Member States should consider including

the following in the economic analysis:

(1) The financial costs of providing and administering water services:

o operating and maintenance costs (e.g. energy);

o capital costs (e.g. infrastructure depreciation);

o administrative costs (billing, administration and monitoring).

(2) The environmental and resource costs of water services:

o environmental damage due to abstraction, storage and impoundment;

o opportunity costs of alternative water uses (e.g. costs relating to groundwater

over-abstraction), as current and future users will suffer if water resources are

depleted.

43 In their economic analyses, several Member States/regions assess the

environmental costs by estimating the cost of the measures needed to achieve good

water status throughout a river basin district The authorities in Italy (Emilia-Romagna)

and Spain (Andalusia and Castile-La Mancha) consider resource costs relevant only if

they assess water to be scarce. The authorities of Bulgaria and Germany (Berlin-

Brandenburg) comment that there is still no common agreement on the methodology

for calculating environmental and resource costs.

25

European Commission, Common Implementation Strategy for the Water Framework

Directive, “Guidance document no. 1 Economics and the environment” and “Information

Sheet on Assessment of the Recovery of Costs for Water Services for the 2004 River Basin

Characterisation Report (Art 9)”.

28

44 Eight of the national and regional authorities of the Member States covered in

our audit considered that cost recovery for water services in agriculture is incomplete.

One element in this is that environmental and resource costs are not (yet) reflected in

water pricing. The Commission pointed out in its WFD fitness check (see paragraph 11)

that this represents a hidden cost to society and puts a strain on a potential source of

revenue for financing measures to implement the WFD.

The Commission considers WFD implementation to be progressing

slowly

45 The Commission is required to monitor how Member States implement the WFD.

To this end, it assesses the progress of implementation (see paragraph 09) every three

years, mainly relying on Member States’ reports, and publishes its own

implementation report. The most recent Commission report (February 2019) covered

the second round of RBMPs and contained an EU-wide overview and country-specific

assessments with recommendations.

Prior authorisation systems

46 A Commission staff working document

26

reported progress in the creation and

operation of prior authorisation systems, such as improvements in metering, water

abstraction controls, licenses and water abstraction datasets. However, as our

observations confirm (paragraphs 29-30), the staff working document concluded that

“more progress is needed especially in those Member States in which small

abstractions are exempted from controls and/or register, but water bodies are

suffering from significant water abstraction pressures and therefore do not achieve

good status”. The document concluded that there had been little progress in improving

status due to reducing abstraction pressures since the first round of RBMPs, but that

total water abstraction had decreased by around 7 % between 2002 and 2014.

26

European Commission, SWD(2019) 30 final.

29

Water pricing and cost recovery

47 In the 2014-2020 programming period, the Common Provisions Regulation

27

introduced a mechanism known as “ex-ante conditionality” for several EU funds,

including the rural development fund. If any ex-ante condition was not fulfilled by

30 June 2017, the Commission had the option of suspending interim payments to the

relevant RDP priority pending corrective action.

48 One such condition concerns the water sector. In practice, the financing of

irrigation investments programmed in focus area 5(a) “increasing efficiency in water

use by agriculture” depends on the Member State or region having a water pricing

policy that:

(a) provides adequate incentives for users to use water efficiently; and

(b) takes cost recovery for water services into account.

49 Overall, the Commission considers that the ex-ante conditionality mechanism

was an effective way of inducing Member States to upgrade their water pricing

policies

28

: “Steps were made in defining water services, calculating financial costs,

metering, performing economic analysis and assessing both environmental and

resource costs”. At the same time, the Commission acknowledges that cost recovery

for water services is incomplete in most Member States.

50 Despite the positive impact of the ex-ante conditionality for the water sector

during 2014-2020, the ex-ante conditionality mechanism did not appear in the

Commission’s proposal for the post-2020 CAP.

27

Regulation (EU) No 1303/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17

December 2013 laying down common provisions on the European Regional Development

Fund, the European Social Fund, the Cohesion Fund, the European Agricultural Fund for

Rural Development and the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund and laying down general

provisions on the European Regional Development Fund, the European Social Fund, the

Cohesion Fund and the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund and repealing Council

Regulation (EC) No 1083/2006 (OJ L 347, 20.12.2013, p. 320).

28

Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council on the

implementation of the Water Framework Directive (2000/60/EC) and the Floods Directive

(2007/60/EC), COM(2019) 95 final.

30

Compliance with the WFD

51 If the Commission considers that a Member State does not comply with the WFD

obligations, it can bring an infringement procedure against the Member State in the EU

Court of Justice. In case C-525/12

29

, the Court found that Member States are free to

determine the mix of policies and the funding that are needed to achieve the WFD

objectives. In accordance with its general policy on infringements, the Commission

now prioritises structural rather than individual cases of non-compliance.

52 The Commission recently decided to address specific points requiring attention in

letters to all Member States. Between September 2020 and April 2021, it sent letters

following up on its assessment of the information reported in the second round of

RBMPs. In those letters it identified apparent instances of non-compliance and asked

the Member States to justify those issues, rectify them or clarify how they had already

been addressed or would be addressed in the third round of RBMPs. In December

2020, the Commission sent another set of letters to all Member States in which it

specifically addressed their mechanisms for compliance assurance and penalties in the

field of abstraction and point source / diffuse pollution. The Member States were

asked to provide details of their domestic rules on water abstraction under

Article 11(3)(e) WFD.

CAP direct payments do not significantly encourage efficient

water use

53 According to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union,

“environmental protection requirements must be integrated into the definition and

implementation of the Union policies and activities, in particular with a view to

promoting sustainable development”. We therefore checked whether the EU’s water

policy objectives were reflected in the main CAP funding instruments.

54 Both decoupled (income support) and coupled (area-based) schemes assign aid

on the basis of the area farmed. We assessed whether:

(1) these support payments were conditional on sustainable water use; and

(2) they were an incentive or a disincentive to irrigate.

29

Judgement of the European Court of Justice of 11 September 2014 in Case C-525/12.

31

CAP income support does not promote efficient water use or water

retention

55 Payments under both the SAPS and the BPS are currently neutral on irrigation:

they neither provide an incentive to use water efficiently, nor to irrigate or use more

water. The SAPS payment rate per hectare is identical for all beneficiaries and crop

types within each of the ten Member States that apply the SAPS. The BPS payment

rate is set by the Member States and may vary between beneficiaries, partly

depending on their CAP payment history. In some Member States (e.g. Spain and

Greece) it may also vary by type of agricultural land. The ECA has previously reported

30

on the significant differences that persist in certain Member States, such as Spain.

56 Neither of these two direct payment schemes, nor the Greening Payment scheme

imposes obligations on farmers regarding sustainable water use. Greening may,

however, have indirect positive effects through the requirement for farmers to

preserve permanent grassland (which, unlike arable land, is not normally irrigated). It

also focuses on the conservation of terraces, other landscape features, and ecological

focus areas such as uncultivated buffer strips, all of which can increase natural water

retention. In practice, as we reported in 2017

31

, greening led to changes in farming

practices on only around 5 % of all EU farmland.

57 CAP support incentivises the drainage of fields rather than water retention. The

2014-2020 CAP makes drained peatlands eligible for income support, whereas

inspections sometimes consider farmed wet peatlands to be ineligible. Apart from

having a negative impact on groundwater reserves, draining peatland releases

greenhouse gases

32

. The European Parliament’s amendments to the Commission’s

post-2020 CAP proposal

33

take into account paludiculture (farming and forestry on wet

30

ECA special report 10/2018: “Basic Payment Scheme for farmers – operationally on track,

but limited impact on simplification, targeting and the convergence of aid levels”.

31

ECA special report 21/2017: “Greening: a more complex income support scheme, not yet

environmentally effective”.

32

Peatlands in the EU - position paper.

33

Amendments adopted by the European Parliament on 23 October 2020 on the proposal for

a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing rules on support for

strategic plans.

32

soils, predominantly peatlands) as an eligible agricultural activity for CAP income

support.

The EU supports water-intensive crops in water-stressed areas through

voluntary coupled support

58 VCS is used by all Member States except Germany to maintain or increase

production of certain crops from sectors in difficulties

34

. The EU restricts support to

specific sectors

35

, including water intensive crops such as rice, nuts, and fruit and

vegetables (see Figure 12).

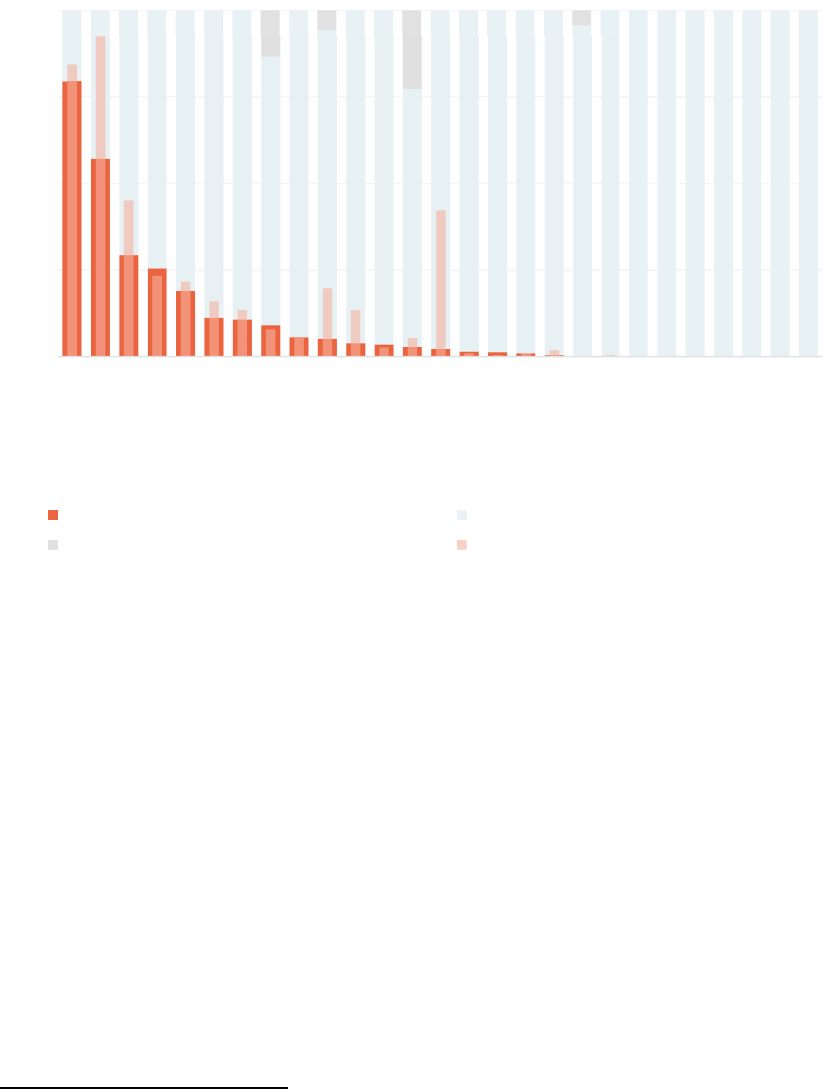

Figure 12 – Notified VCS measures for crops (2020)

Source: European Commission.

34

European Commission, “Voluntary coupled support - Review by the Member States of their

support decisions applicable as from claim year 2020”.

35

Regulation (EU) No 1307/2013, Article 52.2.

* Amounts budgeted by Member States for 2020,

not actual final payments

4 160

2 068

887

720

508

470

447

198

476

115

67

189

182

69

18

32

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

0

500

1000

1500

2000

2500

3000

3500

4000

4500

Protein crops Cereals Olive oil Fruit and

vegetables

Sugar beet Rice Nuts Other crops

Fixed number of hectares

(x 1 000)

Aid earmarked for 2020*

(million euros)

Water-intensive crops

33

59 The EU’s rules on VCS state that “any coupled support granted (…) shall be

consistent with other Union measures and policies”

36

, which should allow the

Commission to reject incompatible schemes. The Commission has not assessed the

impact of proposed measures on sustainable water use.

60 None of the Member States/regions we reviewed had introduced safeguards on

water use, such as restrictions on support in water-stressed areas or for parcels

without efficient irrigation systems.

61 Nine of the eleven Member States/regions covered in our audit use VCS for crops.

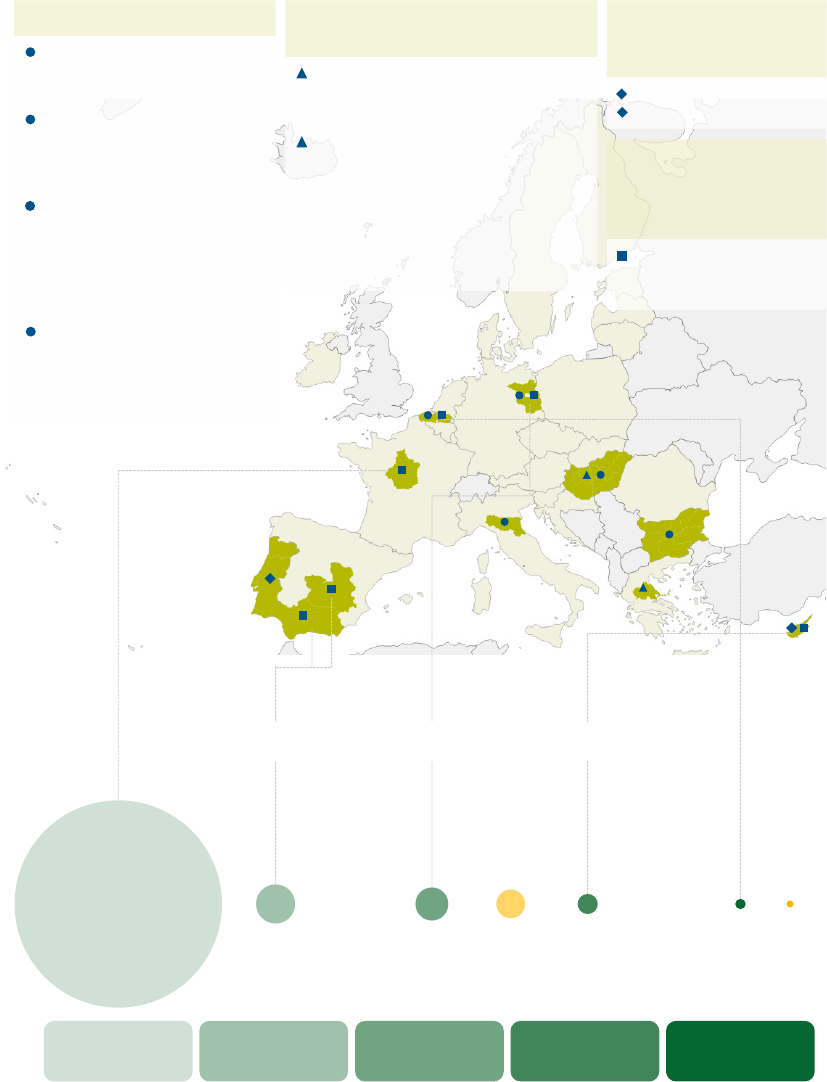

Eight support water-intensive crops without geographical restriction. As a result,

Member States use EU funds to support water-intensive crops in water-stressed areas.

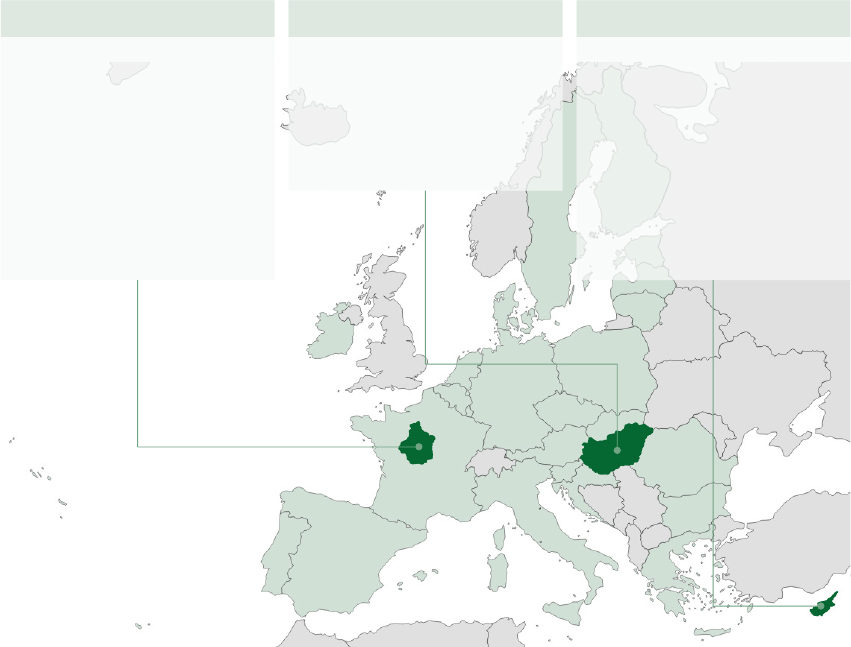

Figure 13 shows that six Member States use VCS for water-intensive crops in areas

with high or very high levels of water stress.

36

Regulation (EU) No 1307/2013, Article 52.8.

34

Figure 13 – VCS for water-intensive crops and areas under water stress

Source: ECA and World Resources Institute Aqueduct, accessed on 22/03/2021.

Low

(< 10 %)

Low-medium

(10-20 %)

Medium-high

(20-40 %)

High

(40-80 %)

Very high

(> 80 %)

Water stress baseline

(ratio of total water withdrawals

to available renewable surface

and groundwater supplies)

* VCS for water intensive crops only. Based on the analysis of data from several sources, we considered the following crops to

be water intensive: fruit and vegetables, rice, and nuts.

Disclaimer: due to differences in the source data, the maps are not comparable between countries.

VCS* claimed area (ha) by

municipality (2019)

Italy

(Emilia-Romagna)

1 – 100 100 - 200 > 200

Hungary

Agricultural parcels claiming

VCS* (2019)

Location of agricultural parcels

VCS* paid (million euro) by

province (2019)

Spain

(Andalusia and Castile

-La Mancha)

0-1 1-5 > 5

VCS* claimed area (ha) by

municipality (2019)

Portugal

(Mainland)

1 – 1 000 1 000-2 500

> 2 500

Agricultural parcels claiming VCS*

(2019)

Location of agricultural parcels

Greece

(Thessaly)

Agricultural parcels claiming

VCS* (2019)

Location of agricultural parcels

Cyprus

35

Cross-compliance covers illegal abstraction of water, but checks are

infrequent and penalties are low

62 Cross-compliance ties direct payments (and some other CAP payments) to certain

environmental obligations. One of the cross-compliance conditions (GAEC 2) covers

water abstraction authorisation procedures set by the Member States.

National/regional authorities check 1 % of specified groups of farmers who irrigate

their fields, and impose penalties (typically a 3 % reduction in their subsidy under BPS

or SAPS) for those who do not comply with national/regional water abstraction

authorisation procedures

63 In practice, arrangements have changed little since we reported on this in 2014

37

.

GAEC 2 is worded generically: “Where use of water for irrigation is subject to

authorisation, compliance with authorisation procedures”. The Commission did not ask

Member States to impose specific requirements, such as installing water meters and

reporting on water use. The GAEC will have no impact in Member States with weak

authorisation procedures. The fact that it does not apply to all CAP beneficiaries (e.g.

beneficiaries of the small farmers scheme, non-annual rural development payments or

CMO aid for the fruit and vegetable or olive sectors), and that Member States do not

carry out proper checks, further reduces its potential.

64 The Commission’s proposal for the post-2020 CAP continues with the concept of

cross-compliance (now re-named “conditionality”). It expands coverage to the small

farmers scheme, but simultaneously excludes beneficiaries of CMO wine payments.

65 Under the principle of subsidiarity, Member States are free to implement and

enforce the water authorisation obligation as they see fit. Ten of the Member

States/regions covered in our audit take a selective approach towards GAEC 2, often

omitting certain national or regional regulatory requirements for water abstraction in

their checks (Figure 14).

37

ECA special report 04/2014, “Integration of EU water policy objectives with the CAP: a

partial success”, paragraphs 38-48.

36

66 The only check common to all control systems we examined is on the need for

authorisation to abstract irrigation water. In most cases, inspections also include a

visual check of parcels to detect illegal abstraction or irrigation. This applies to Belgium

(Flanders), Germany (Berlin-Brandenburg), Spain (Andalusia and Castile-La Mancha),

Italy (Emilia-Romagna), Hungary and Portugal. Three of the eleven Member States and

regions check for the presence of meters - Belgium (Flanders), France (Centre-Val de

Loire), Cyprus. Ten of the 11 did not check the content of authorisations, such as

maximum abstraction volume and time of irrigation (all Member States/regions

covered in our audit except Belgium (Flanders)). A similar weakness is reported in the

evaluation support study on the impact of the CAP on water.

38

Figure 14 – GAEC 2 components checked in 11 Member States/regions

Source: ECA.

67 The cross-compliance control statistics which Member States report to the

Commission show significant differences both between countries and between

regions. In Spain, for example, the average non-compliance rate is significantly higher

for Castile-La Mancha than for Andalusia (Figure 15). In all the Member States/regions

for which we obtained data, the GAEC 2 non-compliance rate is lower than the rate for

other water abstraction checks as described in paragraph 32 (see Figure 15). There is a

significant risk that cross-compliance checks do not detect cases of illegal water

abstraction.

38

DG AGRI and EEIG Alliance Environnement, “Evaluation of the impact of the CAP on water.

Final report”.

Note: Each circle represents one

Member State/region

GAEC 2

Existence of authorisation

Presence of a water meter

Additional restrictions

(e.g. max abstraction volume, time of irrigation)

Requirement exists and is

checked

Requirement exists but no

indication that it is checked

Requirement does not exist

37

Figure 15 – Non-compliance rates revealed by GAEC2 checks and other

water abstraction checks in 11 Member States/regions

Source: ECA.

68 In 2013, the European Parliament and Council called on the Commission

39

to

monitor the Member States’ transposition of the WFD into national law, and its

implementation, and to present a proposal for including relevant parts of the WFD in

cross-compliance. The Commission did not make a proposal on including any parts of

the WFD in the 2014-2020 cross-compliance framework. However, the proposal for the

post-2020 CAP does explicitly refer to the WFD article on controls over water

abstraction

40

, making them a mandatory requirement (SMR1) under the new

conditionality rules. This introduces a clear link between the WFD and CAP payments

to farmers and could lend the article greater force.

39

Regulation (EU) No 1306/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of

17 December 2013 on the financing, management and monitoring of the common

agricultural policy (OJ L 347, 20.12.2013, pp. 549-607), Joint statement by the European

Parliament and the Council on cross-compliance.

40

Directive 2000/60/EC, Article 11.3(e).

0.4 %

4.1 %

13.6 %

6.4 %

6.6 %

0.4 %

3.5 %

8.0 %

6.5 %

22.3 %

1.6 %

13.3 %

0,0 %

10.8 %

0.6 %

1.0 %

Not available

Not available

Not available

Not available

Not available

Not available

Belgium

(Flanders)

Bulgaria

Cyprus

Germany

(Berlin-

Brandenburg)

Greece*

(Thessaly)

Spain

(Andalusia)

Spain

(Castile-

La Mancha)

France*

(Centre-

Val de Loire)

Hungary

Italy

(Emilia-

Romagna)

Portugal

(Mainland)

Infringements revealed by other

water abstraction checks

Infringements revealed by GAEC 2 checks

(average 2014 – 2018)

* Cross-compliance results are for the whole country, the results on other infringements for the region

Other water abstraction checks may include economic sectors other than agriculture

38

Rural development funds and market measures do not

significantly promote sustainable water use

69 Apart from direct payments, the CAP also funds farmers’ investments in fixed

assets and supports specific actions, such as a commitment to certain agricultural

practices. Some investments and actions have a positive impact on water use, while

others increase water use (see also Figure 16). Funding for farm advisory systems or

cooperation projects may also have an impact on water use, though indirectly.

Figure 16 – Agricultural practices and investments that affect water use

Source: ECA.

Rural development programmes are seldom used to improve water

quantity

70 Through rural development programmes national or regional authorities can

support:

(a) agricultural practices or green infrastructure with a positive effect on water

availability in agricultural soils (water retention measures);

(b) farmers for the additional costs and lost income stemming from implementing

WFD requirements;

(c) waste water treatment infrastructure for water reuse in irrigation.

Reuse of wastewater

for irrigation

Newly irrigated area

e.g. with sprinkler

irrigation

Switch to more efficient

irrigation systems

e.g. drip irrigation

Natural water

retention measures

e.g. strip cropping

along contours

Water reservoir

Small scale

water infrastructure

e.g. controllable weirs or

a wetland

39

We examined the extent to which these options are used.

71 Member States can use rural development funds to finance natural water

retention measures (see Figure 17). Five of the Member States/regions covered in our

audit take advantage of this opportunity:

o Belgium (Flanders), Spain (Andalusia), Hungary, Italy (Emilia-Romagna) and

Portugal have funded agri-environment-climate commitments

41

whose main

purpose is to conserve soil, build up organic matter and reduce erosion, thereby

helping to increase water retention.

o Belgium (Flanders) has financed one project concerning green infrastructure for

water retention

42

, and Hungary eight projects.

41

Regulation (EU) No 1305/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of

17 December 2013 on support for rural development by the European Agricultural Fund for

Rural Development (EAFRD) (OJ L 347, 20.12.2013, p. 487), Article 28.

42

Regulation (EU) No 1305/2013, Article 17.1(d).

40

Figure 17 – Natural water retention measures

Source: ECA, based on the EU catalogue of natural water retention measures.

72 Natural water retention measures may deliver multiple benefits, including

groundwater recharge, drought management and flood risk reduction, but their

effectiveness is limited if they are used in a small area

43

. Seven of the eleven Member

States/regions covered in our audit do not finance such measures through rural

development measures (see also Figure 18).

73 Member States can use rural development funds

44

to compensate farmers for

the additional costs and lost income resulting from requirements in a river basin

management plan. None of the Member States/regions covered in our audit used this

option.

43

EEA Report No 17/2020, p. 68.

44

Regulation (EU) No 1305/2013, Article 30.

Wetland restoration

Wetlands function as natural tubs or sponges,

storing water and slowly releasing it.

Re-naturalisation and stabilisation of river banks

Increases the potential for soil water retention,

since there is increased potential for infiltration to

the banks.

Water retention

measures at the

level of the

water body can

also increase

water availability

in surrounding

agricultural

areas.

Buffer strips and hedges

Due to their permanent vegetation, hedges and grass

buffer strips at the margin of fields or watercourses

offer good conditions for effective water infiltration and

slowing surface flow.

Conservation tillage

By leaving crop residue on the surface, conservation

tillage slows water movement and reduces soil erosion.

On

agricultural

soils, water

retention can

be improved

for example

through:

Natural water retention measures have the primary function of enhancing and/or restoring the

water retention capacity of aquifers, soils and ecosystems. This can be done in many ways.

41

74 National/regional authorities can include support for investments in

infrastructure for reusing wastewater for irrigation in their RDPs

45

. Five of the

Member States/regions we examined did not include the option in their RDPs. In three

Member States/regions it is included as part of a sub-measure but has not been used

to finance any projects. Two Member States have financed relevant projects (see

Box 2).

Box 2

Rural development funded investments in wastewater reuse

In Cyprus, rural development funds were used to finance one large project, which

involves building a 500 000 m³ water tank to store excess recycled water for use in

agriculture during the summer, as well as a 20 km primary and secondary distribution

network covering 1 700 hectares.

In Belgium (Flanders), rural development funds supported several projects for the

treatment of wastewater for irrigation or watering livestock. Two examples:

— water purification equipment at a tomato grower to disinfect the processed

water and remove pesticide residue;

— a purification plant to convert wastewater from a dairy processing company

into drinking water for cattle and liquid digestate from a dairy farm into

irrigation water.

EU funding for irrigation projects has weak safeguards against

unsustainable water use

75 Various forms of EU funding are available to finance irrigation projects. Member

States can use rural development funds for investments in physical assets, or CMO

support in certain sectors (fruit and vegetables, olives and olive oil, wine), to finance

the modernisation or first installation of irrigation equipment (e.g. on farms) or

infrastructure (e.g. networks).

76 We examined:

(1) the extent to which these funds are used to support irrigation projects;

45

Regulation (EU) No 1305/2013, Article 17.

42

(2) whether the Commission and Member States have defined safeguards against

unsustainable water use; and

(3) whether Member States have checked the respective requirements.

77 Modernising existing irrigation systems may increase water use efficiency, for

example by repairing leaking channels, covering open channels to reduce evaporation

or switching to more efficient irrigation systems. However, efficiency improvements do

not always result in overall water savings, since the saved water may be redirected to

other uses, such as more water-intensive crops or irrigation across a wider area. This is

known as the rebound effect

46

. In addition, in a phenomenon known as the

“hydrological paradox”, increased irrigation efficiency may reduce the return of

surface water to rivers, decreasing base flows that are beneficial to downstream users

and sensitive ecosystems

47

.

78 Installing new irrigation infrastructure that extends the irrigated area, is likely to

increase the pressure on freshwater resources unless the system uses rainwater or

recycled water. The Commission evaluation support study on the impact of the CAP on

water (see footnote 38) confirmed this risk: “to date, it is difficult to guarantee that

investments in irrigation are beneficial to water bodies, especially if the irrigated area

increases where water bodies are under stress.”

Rural development investment support

79 All but one of the Member States/regions we assessed use the rural development

funds to finance investments with an impact on water use (see Figure 18). New

irrigation installations and infrastructure are eligible in all ten of the Member

States/regions, and investments in abstraction infrastructure (e.g. wells) are eligible in

at least three. Half of the 24 RDPs in our additional sample allowed investment in new

irrigation infrastructure.

46

OECD (2016), Mitigating Droughts and Floods in Agriculture: Policy Lessons and

Approaches, OECD Studies on Water, OECD Publishing, Paris.

47

EEA Report No 17/2020.

43

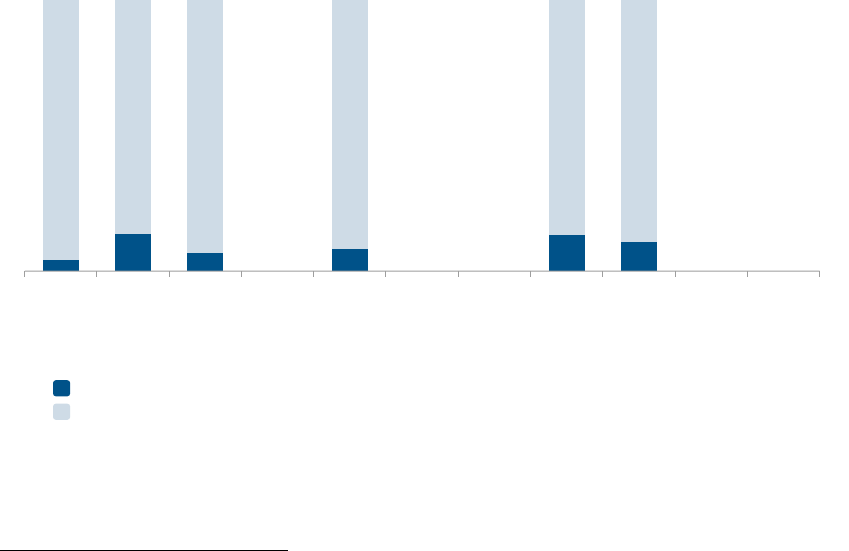

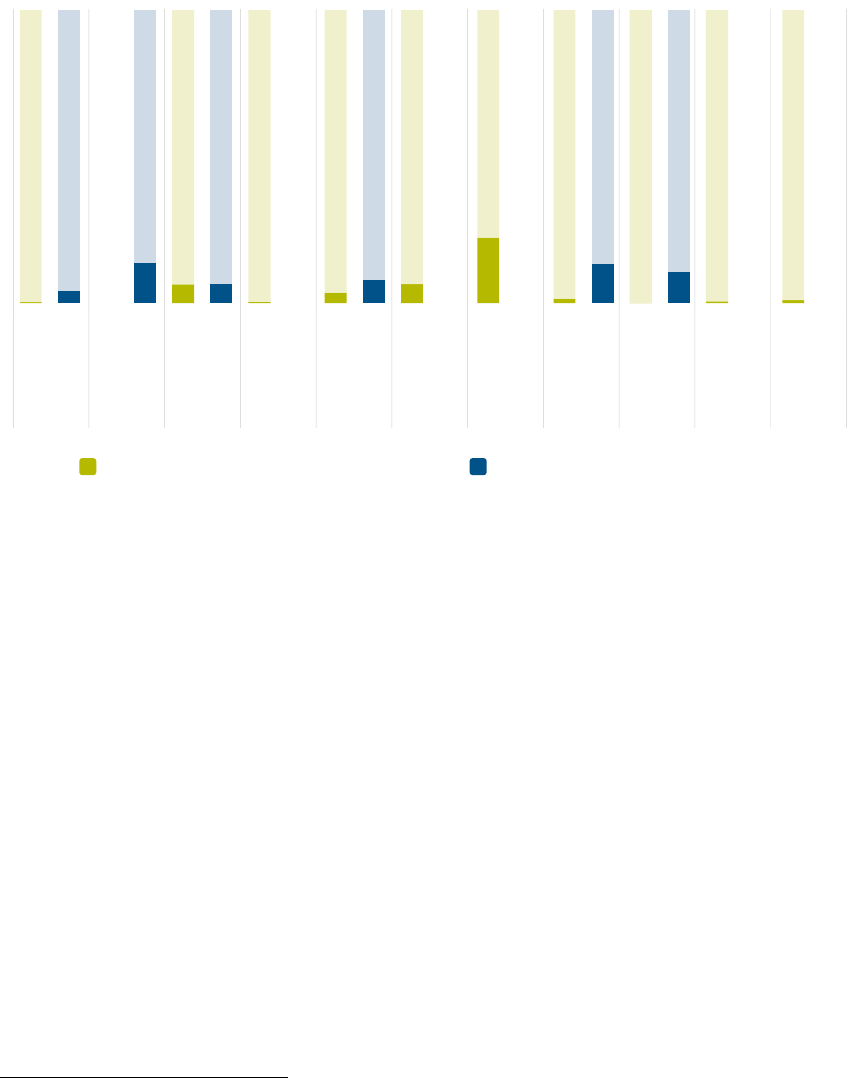

Figure 18 – EAFRD funding with an impact on water use in agriculture

(funds committed or paid in million euros) (2014-2020)

Source: ECA, based on data received from the Member States.

80 EAFRD support for investments in irrigation is subject to conditions set out in the

EU rules

48

(see Figure 19). Member States can also establish additional requirements.

For certain investments, three Member States/regions covered in our audit require

potential water savings beyond 5 %. For new irrigation infrastructure, five Member

States/regions require proof of title to the land and/or a valid water abstraction

authorisation.

48

Regulation (EU) No 1305/2013, Article 46.

402

122

83

65

20

5 3 2 2

Portugal

(Mainland)

Italy

(Emilia

-Romagna)

Greece

(Thessaly)

Spain

(Andalusia)

Hungary Cyprus

Belgium

(Flanders)

Germany

(Berlin-

Brandenburg)

Spain

(Castile-

La Mancha)

127

109

59

21

19

(a)

(e)

(d)

(b)

(a) all public support; (b) only partly corresponds to irrigated crops; (c) only partly corresponds to measures with an impact on

water use; (d) total expenditure declared for 2014-2020; (e) amount paid for claim year 2018; (f) only Natura2000 payments for

not draining and not irrigating grasslands.

Investment related to water use (measure 04)

Agri-environment-climate (measure 10)

20

(e)(f)

WFD and Natura 2000 payments (measure 12)

Bulgaria

55

(c)

44

Figure 19 – Conditions for irrigation projects under rural development

Source: ECA, based on Article 46 of Regulation 1305/2013.

81 Some of the requirements described in Figure 19 are not explained further in the

legal texts. For example, the WFD does not define what is meant by the quantitative

status of surface water bodies. The Member States therefore need to define what they

consider to be “less than good” status for quantitative reasons’ in the case of surface

water bodies. In eight of the Member States/regions we covered in our audit, it is

unclear how, and indeed whether, this is defined. The Commission has provided non-

Investments in irrigation

Does the investment increase the irrigated area?

Yes No

Yes No

No further conditions

apply

Does the investment affect a water body with

less than good status for quantitative reasons?

Eligibility requirement

Existence of a river basin management plan

Eligibility requirement

Water metering already in place or included in

the investment

Eligibility requirement

Eligibility requirement

Actual reduction in

water use of at least

50 % of the potential

water saving

Eligibility requirement

Environmental

analysis shows no

significant impact

from the investment

Does the investment only affect the energy

efficiency of existing installations, the creation

of a reservoir or the use of recycled

water?

Yes

No further conditions

apply

Does the investment affect a water body with

less than good status for quantitative reasons?

Potential (ex-ante) water savings of at least

5-25 % (percentage fixed by the Member State)

No

No Yes

Support not

permitted unless

derogations apply

Derogations:

• Investment is combined with improvements to

existing irrigations systems, potentially

delivering water savings of at least 5-25 %, and

an actual reduction of at least 50 % of the

potential, for the investment as a whole.

• Irrigation water comes from a reservoir

approved before 31 October 2013 and meeting

certain other conditions.

45

binding guidance on this issue

49

. Member States also interpret differently what is an

extension of irrigation area, as they may include areas that were irrigated in the recent

past as irrigated area. Some consider the “recent past” as up to five years ago, while

others interpreted it as going back to 2004.

82 As the EU rules allow for multiple possible interpretations and exemptions (see