Misleading invoice fraud targeting the

owners of intellectual property rights

Crime situation in 2021

This Europol product is descriptive and oriented towards explaining the current crime situation providing an

overview of all relevant factors (OCGs, criminal markets, and geographical dimension).

AUTHORS

European Financial and

Economic Crime Centre

1

1

Key findings

2

Introduction

Aim of the report

3

Background

Intellectual property and Anti-Scam Network

Who? Profiling the most active scammers

How? Usual behavioural patterns of scammers

Shipping methods used

Pricing schemes

Combination of illicit/fictitious services with real IP services

To whom? Profiles of the scam targets and victims

4

Scamming impact

5 Anti-scam problems & vulnerabilities

When they receive the invoice, how do they react? Do they report it? To

whom?

When they pay, do they claim their money back (from the scammer or the

bank)? Why not?

The major stakeholders in the fight against scams

Who is acting now?

Who is not acting now (but could/should act)?

What are the needs for improving ongoing collaboration and potential

synergies?

Problems and deficiencies/areas for improvement:

What are the obstacles faced by stakeholders?

The way forward

2

6

Recommended anti-scam strategy

Strategic guidance for the major stakeholders in the fight against scams,

including concrete recommended actions

Legislators (EU & MS levels)

IP offices (EU & MS levels)

Law Enforcement Authorities

Business/User Associations/lawyers/professional representatives

Banks/Anti-money laundering regulated institutions

Annex 1: List of abbreviations

3

The misleading invoice scam, in the area of intellectual property rights (IPR) is

an old-fashioned but still very lucrative crime. Taking advantage of the by-design

transparency of related data, this scam deceives IPRs rights owners, a minimum

of a third of a million a year, during the trade mark, patent or design registration

process, wherever they are located.

IPR owners are being targeted by Legal Business Structures offering unnecessary

or fake services, such as registration for a private register or alleged IP watch

services which subsequently actually done. Some rogue Legal Business

Structures, also lure victims by requesting additional fees and presenting them

as part of the normal IP registration process or offering fake IPR renewal services

that directly affect the protection of the IP. Several rogue actors are also

currently expanding their scheme to domain name registration.

To achieve their goal, the Legal Business Structures mimic the activities of the

official IP offices, using names and logos that look and/or sound like genuine

offices

radar when defrauding their victims of hundreds or thousands of euros, knowing

investigate on a local or regional level.

The yearly turnover could be estimated to be millions of euros per attacker,

enabling them to build or rely upon a trustworthy supply chain of printing or

shipping Legal Business Structures and money laundering mechanisms. Added

to the cost affecting the IPR owners is the loss of trust that genuine IP offices

and IP professionals/lawyers may face, as a result of criminal schemes which can

affect the protection of IP itself.

In cooperation with the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO),

the Anti-Scam Network and the European Law Enforcement Authorities (LEAs),

Europol is supporting the initiatives and investigations of Member States and

third parties in tackling this scheme. Stakeholders still have a lot to do, such as

reinforcing the EU level and/or the national legal framework, strengthening the

implementation of the Know Your Customer (KYC)

1

procedure, developing

prevention campaigns and improving centralised data collection at a national

level to give this scheme the necessary attention to make Europe safer.

1

The Know Your Customer or Know Your Client guidelines in financial services require

professionals to make an effort to verify the identity, suitability, and risks involved in maintaining

a business relationship.

12/04/2022

The Hague

AP APATE

4

The aim of the report is to enhance awareness amongst the EU Member States

(MS) and participating stakeholders on the topic of acquisition fraud connected

with the national, European and international IPR registration processes and to

provide an assessment of the dynamics of the scam.

This report further intends to provide an overview in particular of the scope of

the invoice fraud, the modus operandi of the suspects and the impact of the

scams. Therefore, it may become a useful status report about this type of crime

for the attention of judicial authorities as well.

IP refers to creations of the mind everything from works of art to inventions,

computer programs to trade marks and other commercial signs

2

.

It covers a vast range of activities and plays an important role in both cultural

and economic life. Technological progress requires the development and

application of new inventions, while a vibrant culture will constantly seek new

ways to express itself. IP rights are also vital. Inventors, artists, scientists and

Legal Business Structures put a lot of time, money, energy and thought into

developing their innovations and creations. To encourage them to do that, they

need the chance to make a fair return on their investment. That means giving

them rights to protect their IP. Essentially, IPR such as design, patents and trade

marks can be treated the same as any other property right. They allow the

creators or owners of IP to benefit from their work or their investment in a

creation by giving them control over how their property is used. This protection

exists at national, European or international levels.

The IP protection process results in the public disclosure of information on the

IPR. IP offices have registers where these data are stored and can be freely

accessed by the public.

In 2019

3

, 22 million IPR were granted by national, European or international

fraudsters. Applicants for IP protection come from all over the world, including

for specific national protection.

Customers that have registered their IP with competent offices are contacted by

criminals trying to defraud them at various points in the IP protection period

2

3

The 2020 figures had not yet been published at the time of writing.

5

(during the application process, after the registration and before the protection

renewal processes). The fraudsters either impersonate the competent IP offices

or adopt company names that are homonyms, or names that look or sound like

legitimate, well-known offices, to deceive their victims. For example, by using a

standard letter or, in a recent phenomenon, email resembling those of

legitimate organisations, victims may be misled by a request for additional fees

service. This results in the distortion of the

decision-making process of the individuals or Legal Business Structures targeted

them to enter a transaction that they would not have undertaken otherwise.

The distortion of the decision-making process is even stronger when fraudsters

are using email addresses mimicking or typosquatting

4

a

email address. This new trend shows how agile and inventive the perpetrators

are.

If the main motivation of fraudsters for sending misleading invoices or

impersonating national or international offices is financial gain, data analysis

would allow for the consideration of the following possibilities:

- Misuse of the identity of EUIPO or of another official IP office purely for profit-

making purposes;

- Misuse of the identity of the EUIPO or another IP office in order to infringe on

the IP protection (competition, economic espionage etc.) or harm a company

- Misleading invoices related to an IP registration within a private register;

- Misleading invoices related to an IP watch service;

- Misleading invoices related to fake IP protection.

Based on the 2021 survey conducted by Europol

5

on the legal definition of the

scheme, and taking into consideration the Directive 2005/29/EC

6

, criminal

(swindle/fraud) and/or civil (misleading commercial practice) cases are built

against the various modi operandi described in this report. However, the survey

highlighted significant discrepancies in legal qualifications of these actions

among MS.

To tackle this scheme, the EUIPO, National Intellectual Property Offices (NO),

International Organisations administering IP rights (IO) and User Associations

(UA) have declared their readiness to further step up their joint efforts in the

pursuit of better and more efficient suppression of fraud with the creation of

the Anti-Scam Network in 2015. Since then EUIPO, acting as the entrusted

4

Typosquatting is a form of cybercrime that involves fraudsters registering domains with the

deliberately misspelled names of well-known websites. For example, fraudsters

could use an email address related to @euipos.europas.eu to try to pass as EUIPO, whose domain

name is @euipo.europa.eu.

5

The survey conducted by Europol with all Member States and Third Parties was dedicated to

retrieving legal assessment (civil or criminal) related to the various modi operandi seen in the

scheme.

6

Directive 2005/29/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 May 2005 concerning

unfair business-to-consumer commercial practices in the internal market and amending Council

Directive 84/450/EEC, Directives 97/7/EC, 98/27/EC and 2002/65/EC of the European Parliament

and of the Council and Regulation (EC) No 2006/2004 of the European Parliament and of the

6

secretariat of the Network, has been sharing information related to the involved

Legal Business Structures with Europol.

As the scheme utilises various modi operandi, it is difficult to draw a specific

profile of the acting Legal Business Structures. Aside from the impersonation of

genuine IP offices, the main actors involved in the scam are mainly Legal

Business Structures posing as genuine and legitimate businesses offering

services to IPR owners.

As in many scams, fraudsters hide behind company registration in several EU MS

and beyond, providing strawmen data to hide the ultimate beneficial owner of

the company.

Virtual seat facilities appear to be a phenomenon shared by the different actors

to deceive LEA.

It is not uncommon to identify a rogue company linked with addresses that are

different from the registration, the administrative address as mentioned on the

invoices or the fiscal address as linked with the bank account. Also, to support

their official standing, some Legal Business Structures mention addresses of the

official seat linked to the country or even the cities of IP offices, which are mainly

in Spain (EUIPO) or Switzerland (WIPO).

Over the years, however, a global correlation has been identified between the

registration country and the bank account nationality which has led to the

identification of three major clusters of Legal Business Structures involved in the

scheme.

Aside from impersonating a genuine IP office, these Legal Business Structures

deceive IPR owners by appearing official, mimicking the names and logos of IP

offices and using recognisable symbols to elicit a positive response.

When it comes to logos, the trend of using a globe or a round image to generate

the idea of a universal or worldwide company has been observed. According to

the dictionary of symbols

7

, round forms are synonymous with knowledge and

are associated with men, locations and places that celebrate or protect arts and

sciences. The round images are symbols of unity and alliance. When associated

with curved edges, the symbol shows movement and dynamism.

The use of stars might also be related to impersonating the EUIPO logo (the

EUIPO logo contains stars).

According to the dictionary of symbols, the star is a very complex cultural form

linked with various meanings such as vitality, energy, eternity or freedom. The

star is also associated with guidance as it prevents sailors and wanderers from

getting lost and brings them back to their loved ones. In this instance, the star is

also associated with protection. By fighting darkness, it is also associated with

truth and the link between God and humans.

The pentagram, a five branch star, is the most common representation of a star.

In many cultures and religions, the pentagram symbolises the accomplished

7

Jean Chevalier and Alain Gheerbrant, Dictionnaire des symboles, édition Robert Laffont, Paris,

2005.

7

man, in his physical and spiritual nature. The five elements associated with the

branches are earth, fire, water, air and the fifth element is the human spirit (at

the top).

Most of the logos used by the fraudsters are blue, which is known to be the most

appealing colour, probably because of marketing. Blue leads to feelings such as

sympathy, trust and harmony. It also refers to the collective notion of

appeasement. This reassuring hue is often favoured by Legal Business Structures

or organisations that want to forge a link with the public.

In 2020 and 2021, a dozen Legal Business Structures were using a very similar

logo made with yellow stars and blue lines, very similar to the EUIPO, WIPO or

the European Consumer Centre Network logo.

EUIPO logo WIPO logo ECC-Net logo

Below are some examples of logos used by Legal Business Structures involved in

the misleading invoice scam

8

:

8

Examples are extracted from the EUIPO dedicated webpage providing a searchable database of

misleading invoices as reported by users. See European Union Intellectual Property Office,

Misleading invoices, https://euipo.europa.eu/ohimportal/en/misleading-invoices

8

mainly used as in any IP office, as are the terms institute, register, registry,

office, service or agency. The idea is likely to get an official-sounding brand or

acronym that will sound familiar to the IPR owners.

The EUIPO dedicated webpage

9

provides a list of Legal Business Structures

considered active in the misleading invoices scam, such as:

- EAIP - European Agency Intellectual Property

- EIP - European Intellectual Property Institute

- EIPA - European Intellectual Property Agency

- EOIP - European Organization Intellectual Property

- EPT Agency - European Patent & Trade mark Agency

- European IP Register

- GOIP Intellectual Property

- IOIP - International Organisation Intellectual Property

- IPIO - Organization Intellectual Property

- IPOE - Intellectual Property Office Europe

- IPRO - Intellectual Property Registration Office

- IPRB - IP Register BENELUX - Intellectual Property Service

- IPTR - International Patent and Trade mark Register

- TM World - International Registration of Trade marks

- WOIP - World Organization Intellectual Property

- WPTA - World patent & Trade mark Agency

- WPTD - World Patent & Trade mark Database

- WTP - World Trade mark Publication

- WTPR - Trade marks & Patent Register

- WWT Worldwide Trade marks

To complete the scam, the rogue Legal Business Structures have to rely on

multiple stakeholders i.e. the bank, mailing and printing Legal Business

Structures, web design Legal Business Structures, software solutions creators

etc. However, based on Europol analysis, several actors took shares in Legal

Business Structures involved in these supporting activities.

Europol statistics indicate that Hungary, Poland and Spain were found to be the

main countries where bank accounts related to fake invoice scams were opened.

However, the rise of non-

preference to avoid European banks which may be seen to be more likely to

cooperate in a European Union framework.

9

European Union Intellectual Property Office, Misleading invoices,

https://euipo.europa.eu/ohimportal/en/misleading-invoices

9

Due to the COVID-19 situation, banks had to adapt to continue offering services

to their new and existing customers. This led to the development of online

registration for bank accounts, which may have aided the fraudsters.

The use of online banks or payment service providers is also considered a new

vulnerability and is monitored accordingly.

unsolicited and misleading invoices are

sent yearly. Such volume would require professional infrastructure and may

involve the service of printing and postal service Legal Business Structures. The

latter are necessary for mass-mailing fraud. The misleading invoice scheme

related to IPR owners showed that Dutch mailing Legal Business Structures and

German post offices were mainly used by the fraudsters.

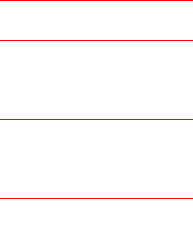

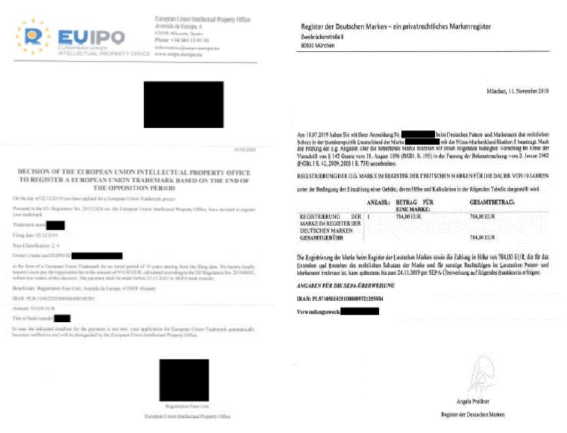

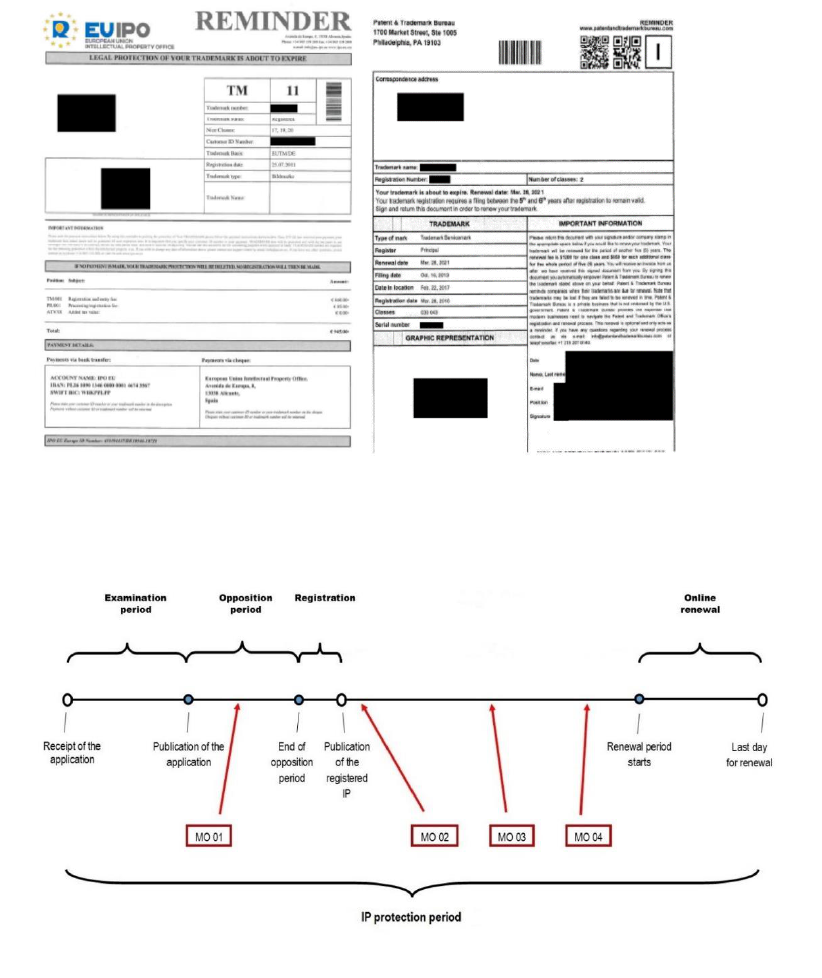

The scammers target the IPR owners during the entire IP protection process but

four main modi operandi have been identified so far:

- Targeting the IPR applicant between the publication of the IP applied for

and before the end of the opposition period (the fraudsters are

impersonating genuine IP offices) MO 01 (the following examples are

extracted from EUIPO’s webpage dedicated to misleading invoices

10

);

- Targeting the IPR owner in a short period just after the publication of

the registered IP to lure them into an unrequested service or additional

private registration MO 02 (the following examples are extracted from

EUIPO’s webpage dedicated to misleading invoices

11

);

10

European Union Intellectual Property Office, Misleading invoices,

https://euipo.europa.eu/ohimportal/en/misleading-invoices

11

European Union Intellectual Property Office, Misleading invoices,

https://euipo.europa.eu/ohimportal/en/misleading-invoices

10

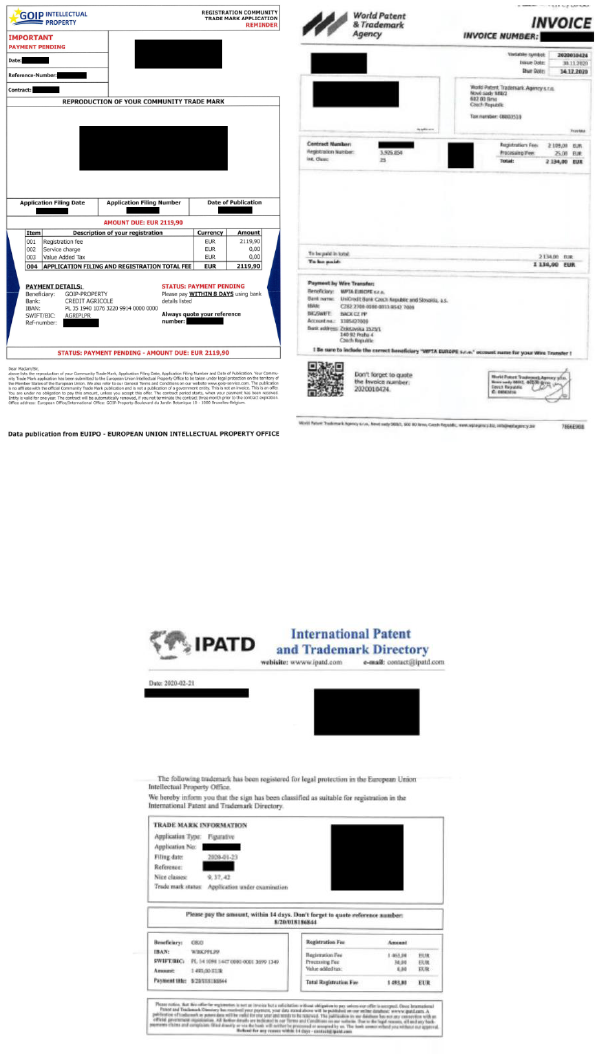

- Targeting the IPR owner several months after the publication of the

registered IP for additional fees by impersonating IP offices or by luring

them into unrequested service or additional private registration MO

03 (the following example is extracted from EUIPO’s webpage dedicated

to misleading invoices

12

);

- Targeting the IPR owner several months or, on some occasions, years

before the start of the official IPR renewal process to propose a renewal

application via a third party (a more expensive and sometimes not

effective contract) MO 04 (the following examples are extracted from

EUIPO’s webpage dedicated to misleading invoices

13

).

12

European Union Intellectual Property Office, Misleading invoices,

https://euipo.europa.eu/ohimportal/en/misleading-invoices

13

European Union Intellectual Property Office, Misleading invoices,

https://euipo.europa.eu/ohimportal/en/misleading-invoices

11

These four modi operandi rely on various tricks and biases so the IPR owner will

react positively.

Applying for IP registration is a multiphased and important process during which

applicants, and in particular direct filers acting without a representative, may

experience fear of not being able to protect their IP. Therefore, there are

significant consequences when fraudsters interfere with the application or

renewal process and send fake invoices or payment requests relating to the

registration or renewal of the IPR to the applicants or rights owners by

impersonating the IP office. This leads to the IPR applicant or owner, who was

expecting a positive answer from the IP office, becoming keener to pay the fees

and being less proactive in identifying that the received document was fake.

The fraudsters are mainly targeting the IPR applicant in the short period just

after the publication of the IP applied for, when the victim is still in the IP

12

registration process (MO 01). They will emphasise the urgency of the payment

(between 7 or 14 days) to pressure the victim and create fear of not protecting

the IP if the payment is not made. The use of bold or red font attached to words

used to show urgency or importance pressures the victim and creates a bias in

their will. Also the use of sentences including the form Please + verb is an

instructional or imperative way of writing, meaning that the fraudsters tell

people what to do and try and hide the instruction by using the word please.

The chosen words and the way the sentences are written have an impact on the

we perceive information.

This bias is optimised by the layout of a look-alike invoice template used by the

fraudsters, which goes beyond the simple use of a brand name that sounds

official.

Even if there is no specific layout for a uniform invoice, a genuine online invoice

generator lists compulsory information under the respective national law. Some

elements can be considered indicative of an invoice:

- The date of the invoice (date on which the invoice is issued),

- Invoice number (a unique number for each invoice and based on a

chronological and continuous

cannot be deleted. The numbering can be done by distinct series (for

example with a prefix per year) if the conditions of the exercise justify

it),

- The identity of the seller or service provider (company name, address of

the registered office, invoicing address if different),

- The identity of the buyer or customer (company name, address of the

customer, invoicing address if different and delivery address),

- Designation and statement of products and services rendered (nature,

brand, product references, materials supplied and delivered services),

- Quantity, rate and total amount to be paid excluding tax (excluding VAT)

and all taxes (including VAT), discounts and other possible rebates,

- The date or deadline for payment,

- Where applicable, bank details or additional elements, such as terms

and conditions.

If the document received by the IP applicant or owner follows the basic and

universally known invoice layout, there is a well-founded suspicion that the

sender is trying to mislead the victim by using these elements. The outcome

might be different if the Legal Business Structures receive a simple letter merely

proposing or offering a service.

The shipping method depends on the modi operandi. Several Legal Business

Structures are sending misleading invoices in regularly stamped envelopes

whereas others are using the service of a mailing company or services present

in the various EU MS such as in Germany and the Netherlands.

While the use of a contractual shipping company might be useful for

investigators to identify the supply chain, the use of regular mailboxes and post

offices leads to more difficult work for the LEA as it is not always possible to

identify the specific origin of the letter based on the postage stamp.

13

The scam relies on the openly accessible registration data provided by the IP

offices, as required by law. Therefore, depending on the modi operandi and the

targeted IP rights, the fraudsters, as any official national or international IP

office, adapt their fees to the protected IP (trade mark, design or patent) and

the number of classes in which the IP has to be protected.

While the official basic application fee for an individual EU trademark by

electronic means is 850

14

at EUIPO, the average fraudulent fees, requested by

fraudsters, are twice or three times as expensive as the genuine EUIPO fees. In

2021, the average fraudulent fee for private registration of an IP, for one class,

was 2 000.

Amounts greater than 2 000 are not uncommon in this type of fraud and have

been noted in previous years but in lower volume. However, no fees above

10 000 have been observed since 2015 when 1% of the invoices included such

an amount.

The difference in modi operandi leads to varied analysis when it comes to the

reality of service based on fees.

In the modi operandi of impersonating a regional, national or international IP

office, fraudsters will request either additional fees to complete the registration

or propose a renewal of registration but no service is actually fulfilled. They only

take advanta

When a company is acting as a hub or a proxy in the IP renewal process, the

analysis showed that in 40% of all cases the company actually renewed the IP

registration with the competent IP office.

When the fraudulent Legal Business Structures offered their services for private

registration, first checks showed that the latter hold actual databases full of IPR

potentially indicate that the service offer may be

genuine.

actual contracts between the IPR owners and the fraudulent company. As the

IPR register data is publicly accessible, it would be easy for the fraudsters to take

over the entire database, or a large part of it.

When the fraudulent Legal Business Structures are offering a monitoring service,

the first investigations demonstrated that no actual service was provided to the

IPR owners.

Moreover, it is likely that there is a cross-cutting fraud scheme based on the

publication of the trademark by EUIPO and WIPO.

For example, domain name cybersquatting

15

has been identified as a second

level threat impacting the IP owners who then have to battle to be able to

register a domain name with a desired top-level domain extension. In some

14

Plus 50 for a second class of goods and services and, plus 150 for each class of goods and

services exceeding two for an individual EU trade mark.

15

Cybersquatting is the practice of registering names, especially well-known company or brand

names, as internet domains in the hope of reselling them at a profit.

14

cases, when the domain name and its extension have already been registered

by fraudsters who are taking advantage of the public publication of the IP

related data, the IP owners have the option to launch a Uniform Domain-Name

Dispute-Resolution Policy (UDRP)

16

procedure or to buy back the domain name

from the fraudsters.

As acquisition fraud is targeting IPR owners either at a regional, national or

international level, there is no specific profile of the target, nor any mention of

any specific country affected more than another for any reason other than the

number of IPR owners from this country. As is visible in the EUIPO Statistics for

European Union Trade Marks evolution report, Germany has a leading position

in registering IP and therefore German Legal Business Structures/nationals were

the most targeted

17

.

Legal Business Structures targeting

specific countries (e.g. Switzerland) or expanding their scheme after having

targeted one country (for example, the EUIPO and WIPO misleading scam on

renewal fees was only targeting German IPR owners in early 2020, but the

scheme had expanded to other European countries e.g. Austria, France and

Italy).

Due to the lack of recent official statistics, the number of successful fraudulent

scams is hard to establish. In one of its articles published in 2018

18

, the World

Trademark Review website stated that the conversion rate (i.e. the percentage

of Legal Business Structures who actually paid the invoices) for an IP mailing

scam was 8%.

There is currently a survey under review amongst the Anti-Scam Network to be

sent to all IPR owners to gather information. This survey aims to identify

victims (such as external or in-house pre-authorised accountants, secretaries,

paralegals, CFOs, etc.) and common behaviour that led to payment (i.e.

shortcomings in or non-compliance with internal workflows, lack of consultation

payments, etc.).

For the IPR owners, public authorities and economic operators, to be able to

exercise the rights conferred on them and be informed about the existence of

prior rights belonging to third parties, all data published in the register, including

personal data, concerning the EU trade mark applications and registrations are

considered to be of public interest

19

- has,

however, the consequence that freely accessible data may be used by fraudsters

to target their victims.

16

The Uniform Domain-Name Dispute-Resolution Policy (UDRP) is a process established by the

Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) for the resolution of disputes

regarding the registration of internet domain names.

17

European Union Intellectual Property Office, EUIPO Statistics of European Union Trade Marks –

1996-01 to 2021-09 Evolution, 2021.

18

World Trademark Review, Tactics of a trademark scam: GloTrade offers clues on the strategy of

solicitation campaigns, 8 February 2018, https://www.worldtrade markreview.com/portfolio-

management/tactics-trade mark-scam-glotrade-offers-clues-strategy-solicitation

19

Article 111 of REGULATION (EU) 2017/1001 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE

COUNCIL of 14 June 2017 on the European Union trade mark.

15

There are some cases that suggest that IPR owners do not always expect that

their data is publicly available by law and are lured by Legal Business Structures

providing them with accurate information related to their IP protection process.

The urgency to pay the fees also triggers the targeted IPR owner with a short

timeframe to act. Sometimes this timeframe is even shortened by a voluntary

delay in the sending process so the target will receive the letter when the

deadline is no longer 8 days, but 2 or 3 days instead, based on postal delay or

invoice date.

Furthermore, the renewal of a registered IPR takes place ten years after (for

trademarks) or five years after (for designs) its first registration and then is

repeated at the same intervals. Legal Business Structures may not recall the

exact name of the competent IP office with which they are registered, so

variations may look legitimate to them.

In addition, many Legal Business Structures have a policy of not systematically

checking the authenticity of invoices below a certain threshold. Indeed, the

number of transactions they handle makes it more cost-efficient to assume the

risk than to employ a thorough checks policy that may require significant

investment in time and resources

20

.

According to WIPO statistics

21

, 22 million IPR were granted by regional, national

or international IP offices (industrial design, patent, trade mark and utility

model) around the world in 2019.

taken into account in the misleading invoice scheme, as the fraudsters seem to

be focusing their efforts on IP offices that maintain registers of larger territorial

scope. The scheme mostly targets trademark owners but design and patent

holders also receive a share of it.

Taking into account the number of average yearly applications with EUIPO and

WIPO, Europol considers that at least around 400 000 publications a year

22

are

being targeted by fraudsters. Therefore, small amounts of individual invoices

received per country have to be looked upon on a larger international scale, as

they could represent only a small part of a more global scheme.

In 2020, Europol received approximately nine hundred examples of misleading

or fake invoices. Regular discussions with representatives of IP law firms confirm

that many of the misleading invoices are detected as part of a scam and are

thrown away by the IPR applicants, without any reporting to law enforcement

or the Anti-Scam Network. However, due to the lack of reporting, measuring the

current number of misleading invoices actually paid by the IPR applicants is still

20

VIDT Datalink Awareness Team, Let’s get rid of fake invoices right now, 15 August 2019,

https://medium.com/@pim_vee/lets-get-rid-of-fake-invoices-right-now-f96381e700da

21

WIPO statistics database, https://www3.wipo.int/ipstats/index.htm

22

EUIPO published approximately 220 000 trade marks and 100 000 designs in 2020; WIPO and

its Madrid system published around 64 000 trade marks in 2020.

16

very challenging. In one of its articles published in 2018

23

related to a 2016 New

Zealand survey, the World Trademark Review stated that the conversion rate

(i.e. the percentage of Legal Business Structures who actually paid the invoices)

for an IP mailing scam was 8%.

With an average invoice fee of 2 000, the yearly net turnover made by one

actor sending misleading invoices can be assessed as up to 64 million, using the

2016 conversion rate suggested in the above-mentioned article.

As Europol has been able to identify forty different Legal Business Structures

involved in the misleading invoice scheme in 2020-2021, based on the above

assumption the yearly loss to the targeted applicants could reach 2.56 billion.

According to several analysts

24

, fraud ranging from 10 000 to 100 000 has a

direct impact on the finances of 56% of Small and Medium Enterprises which

could even lead to insolvency.

Based on the fact that several targeted Legal Business Structures have stated

that they have received several different misleading invoices, it is very likely that

the scheme has an actual negative economic impact on Legal Business

Structures.

Although money plays a very important part in the scheme, it is not the only

aspect to consider. The reputational damage this crime may cause to IP offices

has to be taken into consideration. Several IP owners are still wondering why

their personal data are available to the public despite the rules of the General

Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), although the IP offices merely comply with

their legal obligation when they make personal data entered in the register

accessible to the public. Some victims, who did not notice that the invoices were

not sent by EUIPO, complained to EUIPO regarding fees that they considered

lead them to reconsider their future relationship with the official IP agencies. It

may also discourage them from protecting their IPR or lead them to enter into

contracts with unofficial agencies which cannot legally grant IPR.

Despite warnings published on the official websites of the members of the Anti-

Scam Network, the number of reports received by EUIPO appear to be only a

fraction of the total quantity. It appears that only those Legal Business

Structures which successfully identified the scam and were willing to collaborate

ultimately shared their concerns with the relevant stakeholders.

23

World Trademark Review, Tactics of a trademark scam: GloTrade offers clues on the strategy of

solicitation campaigns, 8 February 2018, https://www.worldtrade markreview.com/portfolio-

management/tactics-trade mark-scam-glotrade-offers-clues-strategy-solicitation

24

Fraud survey 2019 by DFCG (French association of finance directors and controllers) partner of

Euler Hermes council.

17

In light of this, the two main obstacles are the ability to identify the scam and

then report it, or share it with the relevant stakeholders.

Also, as mentioned previously, the overall damage caused by fake invoice fraud

is difficult to determine in precise numbers, since many Legal Business

Structures unknowingly pay fake invoices, or do not want to make it publicly

known or report that they were defrauded. In addition, many Legal Business

Structures adopt a policy of not checking the authenticity of invoices below a

certain threshold. These Legal Business Structures are prepared to take the risk

of paying invoices that may turn out to be fake, rather than incurring the cost of

extensive invoice controls.

Another important vulnerability relies on the legal obligation that ties the IP

offices to make the details of their relationships with their customers publicly

available. The online availability of customer data on IPR applied for and

registered, the names and addresses of owners and representatives, and the

expiration date of the registration, creates a substantial vulnerability that is used

by the fraudsters to retrieve useful data for their scam.

Criminals specialised in invoice fraud exploit these vulnerabilities and are able

to gain profits from this criminal business.

Based on discussions with several law firms representatives, most of the Legal

Business Structures that spotted the scam did not pay the fees and threw away

the misleading invoice, with or without reporting it to EUIPO and the Anti-Scam

Network. However, the exchange of communication between IPR owners and

EUIPO (or the Anti-Scam Network member) mainly relies on the request for

IPR

owner nor their IP counsellor clearly spotted the scam.

document was not sent from official agencies offering private registration or IP

monitoring. In that case, they were willing to pay the requested fees to add

additional protection to their IP. After being informed of the scam, (no actual IP

monitoring or registration renewal was performed by the rogue company or the

registration into a private register was irrelevant) many Legal Business

Structures filed a complaint to their local LEA. However, some Legal Business

Structures simply decided not to bother the LEA with a complaint, having little

faith in stopping the scheme or simply blaming bad luck for being caught in a

scam.

IPR owners in the EU especially

when the scam is based on a proposal of service. Police agencies might be

reluctant to consider these facts as criminal, whereas it remains a question if the

IPR owner may be considered as a consumer, thereby relying on consumer

protection and able to share the information with consumer protection

agencies.

For example, in France, the General Directorate for Competition Policy,

Consumer Affairs and Fraud Control and its various Departmental Directorates

for the Protection of Populations receive complaints from business owners and

18

share awareness material and good practices related to misleading invoice

schemes.

When they become aware of the scam, the IPR owners either try to contact the

sender company itself to terminate the contract (and in some cases pay the

illegitimate 10% termination fees) or ask their bank to freeze the wire transfer

of money, informing them of the scam. In some cases, most likely because they

are aware of the scam or are suspicious about the abnormal financial activity,

several banks decide to stop the money transfer and/or re-credit it after the

destination bank account has been blocked or closed.

By mid-2021, Europol started witnessing new features in the fine print of

misleading invoices that could be assessed as counter-measures by the

fraudsters. They clearly mention that any attempt by the victims to contact their

bank will not be processed and/or will be refused by the bank as it cannot refund

any payments without the approval of the company (i.e. the fraudsters). Of

course, this has no legal value but it might discourage victims from claiming their

money back.

In other cases, some victims contacted the fraudsters and asked for the

termination or cancellation of the signed contract. The fraudsters agreed but

claimed that, as mentioned in the contract, a 10% penalty would have to be paid

to proceed with the request.

Since 2015, EUIPO, regional and national IP offices, international organisations

and several Users Associations have declared their readiness to voluntarily

cooperate by participating in a dedicated Anti-Scam Network. First through the

Spanish authorities, then directly with Europol thanks to a Service Level

Agreement, EUIPO has shared information and data related to the misleading

invoice scam from all around the world which was collected through the Anti-

Scam Network.

The data is collected, processed, analysed and disseminated to the competent

national authorities under

LEA agencies are engaged in the fight against the scheme if complaints are filed.

However, the lack of a centralised reporting platform appears to be an obstacle

in dealing with the scheme at a national level and makes it difficult to prioritise

this threat.

Currently, EUIPO, WIPO, some national IP offices such as the Czech agency and

User Associations such as MARQUES contribute considerably to the fight against

the scheme, by publishing awareness webpages and/or holding webinars.

19

es guidance, awareness materials and

a continuously updated searchable collection of misleading invoices

25

.

The United States Patent and Trade mark Office, Federal Trade Commission and

Law Enforcement Agencies such as the USPIS are very engaged in tackling the

scheme as well. In 2021, the US authorities caught two main actors involved in

an IP protection renewal scam.

When addressing the question of who is not acting, IPR owners are top of the

list. As in many scams, victims do not always report the crime. According to the

Scamadviser 2020 report, only 7% of all cases related to online scams are

reported. Based on the above-mentioned figures, misled victims are reporting

even less to the Anti-Scam Network or to Law Enforcement. This non-action can

sometimes be a result of IP owners considering that reporting is either a waste

of time or simply not operative.

IP specialised law

more active in the fight against this phenomenon. Prevention and awareness

material could be easily uploaded to their websites.

Considering the possible cross-cutting factor of this scheme (similar to the

registry scams of fake Legal Business Structures or domain name squatting

scams), additional stakeholders could be involved, such as the consumer

protection associations and authorities (at national and European level), and

especially the European Consumer Centre Network as their logo is inspiring at

least a dozen rogue actors involved in the scheme. Also, this network is hosting

the website www.europe-consommateurs.eu, on which awareness material on

fake professional registers can be found.

Banking associations, especially in the online bank community, could also be

more proactive in the KYC process and raise awareness amongst their customers

who are likely to be targeted by scammers.

Improving ongoing collaboration is always a need and a goal.

To do so, enlarging the Anti-Scam Network to include new members/observers

such as other organisations engaged in fighting scams or creating subgroups

within the Anti-Scam Network dedicated to specific aspects could be

considered.

The following problems and deficiencies could be improved in several ways

(non-exhaustive list):

25

European Union Intellectual Property Office, Misleading invoices,

https://euipo.europa.eu/ohimportal/en/misleading-invoices

20

- Raising awareness of, and providing training for, the IPR owners and

representatives and banking associations,

- Technically preventing fraudsters from retrieving actionable data easily,

- Developing information sharing among stakeholders,

- Identifying key LEA actors in each MS who will consider the scheme a

priority,

- Coordinating investigation at a European level,

- Providing precedent cases and arguments to the competent authorities

demonstrating that the scheme is criminal fraud,

- Involving consumer protection agencies to leverage investigations

where applicable,

- Recognising business identity theft as a criminal offence in all European

countries.

When there is a lack of reporting and prioritisation by LEA, users, lawyers and

members of the banking community will experience a deficit of awareness

material and training.

Reporting initiatives, either governmental, private or within a public-private

partnership, are not allowed to share their data due to the lack of official

cooperation mandate but also due to restrictions provided for in the privacy

legislation (i.e. GDPR).

As for IP offices, the limits of the national legal framework for the recognition of

their locus standi in criminal proceedings and the lack of criminal assessment by

LEA might be one of the top obstacles to overcome.

Several Member States

26

have developed web platforms where victims can

directly report or fill in a complaint related to a scam. However, some platforms

27

are mainly looking at online fraud which

is not the case for the current scam. There is a need therefore for the

centralisation of information in each MS in order to provide a better

understanding of the phenomenon.

The following investigations have been successful in the past:

2011 Belgian case (Open Source information)

On 29 April 2020, the Brussels Criminal Court convicted a Finnish citizen to four

years of imprisonment for being part of a large European scam network involved

in sending misleading invoices concerning trade mark renewals.

26

27

Légifrance, Arrêté du 26 juin 2020 portant création d'un traitement automatisé de données à

caractère personnel dénommé « traitement harmonisé des enquêtes et des signalements pour les

e-escroqueries » (THESEE), 1 July 2020,

https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/loda/id/JORFTEXT000042056637/

21

Back in 2011, the Benelux Association for Trade Mark and Design Law (BMM)

was informed that trade mark owners had received invoices from fictitious Legal

Business Structures with a Belgian address and a German PO box number. The

invoices reported to the trade mark owners that their trade mark was on the

verge of expiring and that these had to be renewed. The company logos of ECTO

S.A. and EPTO S.A. that were used on these invoices were more or less similar

to the logo of EUIPO which falsely gave the impression to the trade mark owner

that it concerned an official European organisation. For the renewal of one trade

mark, ECTO and EPTO charged fees of up to 3 750.

The payments for renewals were to be made to a Belgian bank account. The

amounts were subsequently transferred to bank accounts in Denmark and

Switzerland and even a bank account in Hong Kong. Based on the criminal file,

it was established that the criminal network involved in the scam generated a

turnover of over 1 million between 2010 and 2014 (the date of the

confirmation of the complaint). The investigations conducted by the bank also

showed that the criminal practices were maintained for years, utilising several

consecutive Legal Business Structures, names and logos, but always using the

same method of operation.

In a ruling of 20 December, 2017, the Court of Appeal in Stockholm (Svea

Hovrätt) sentenced twenty people for fraud for sending false invoices

concerning EU trade marks. The invoices appeared to be from the EU Intellectual

Property Agency, Office for Harmonization in the Internal Market (OHIM - now

EUIPO), and were sent to several hundred people in a number of countries. All

recipients had previously applied to OHIM for EU trade marks.

The main suspect was convicted of gross fraud in 355 individual cases and

received a penalty of 4 years and 8 months in jail. Another suspect was convicted

of assistance in gross fraud and sentenced to jail for 2 years and 9 months.

18 other people were also charged with gross fraud and assistance in gross

fraud, as these persons had allowed their bank accounts to be used in the fraud

activities and, in some cases, also sent the fraudulent invoices. Two of these

people were sentenced to prison.

The length of the prison sentences is high in the scale for gross fraud, justified

by the Court of Appeal, due to the aggravating circumstances, the large extent

of the fraud, the organized approach and the fact that the invoices appeared to

be from OHIM/EUIPO.

The IP offices may also consider filing a complaint that an attempt was made to

steal their identity or to damage their reputation through the use of a mimicked

name by the fraudsters.

22

Where applicable, a Uniform Domain-Name Dispute-Resolution Policy (UDRP)

28

could be initiated by national, regional or international IP agencies regarding

domain names used by the fraudulent Legal Business Structures to be able to

block the online aspect of the scam.

With a complaint about misuse of personal data, victims could express a

violation of their rights when the fraudulent Legal Business Structures retrieve

data from the IP office´s dataset and contact the customers without their

consent.

Once investigations are la -the-

considered. LEA can rely on a strong and very effective Financial Intelligence Unit

Network, which enables smooth cooperation.

Based on Article 2 of the Directive (EU) 2020/1828

29

, representative action for

t

possible as IPR owners are not considered consumers per se and the legal action

should not be used for professional purposes. No global action by any user

association could therefore be launched using the new protocol and procedure.

Finally, due to the EU-wide and worldwide aspect of the scheme, international

cooperation mechanisms should be used as soon as possible. Europol and its

European Financial and Economic Crime Centre are especially dedicated to this

scheme and should be approached from the beginning of the investigation to

provide support and guidance.

- Consider creating a criminal offence for business identity theft so IP

offices will be able to file a criminal complaint against such

impersonation.

28

The Uniform Domain-Name Dispute-Resolution Policy is a process established by the Internet

Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers for the resolution of disputes regarding the

registration of internet domain names.

29

Directive (EU) 2020/1828 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 November 2020

on representative actions for the protection of the collective interests of consumers.

23

- Similar to Directive (EU) 2020/1828 on representative actions for the

protection of the collective interests of consumers

30

, propose a legal

framework for representative actions by IPR owners associations.

- Assess the possibility of harmonising legislation on fraud, taking into

consideration the phenomenon of misleading invoices (mass invoice

fraud).

- Consider internal policies regarding the accessibility/timely availability

of contact data linked with IP, in line with the legal framework

applicable to the IP Office.

- Conduct a survey dedicated to assessing the global scope of the invoices

received, their payment and the actual existence of any of the services

offered by the senders of misleading invoices.

- Systematically file a complaint whenever EUIPO, WIPO or any national

IP office is impersonated in a fraud scheme.

- Consider sharing knowledge of the Anti-Scam Network with other

networks or agencies due to the ongoing commercial registration fraud

scheme.

- Develop an awareness campaign and update the existing training and

webinars.

- Whenever appropriate, initiate procedures with domain name

registrars, authoritative registries or engage in UDRP procedures against

Legal Business Structures.

- Encourage Police units to launch investigation in the area of misleading

invoice fraud.

- Strengthen international police cooperation in the area of misleading

invoice fraud.

- Support national awareness, in particular using EUIPO and Europol-

based material.

- Expand awareness to the Chambers of Commerce and Trade Registry

based on aspects of cross-cutting criminality.

- Improve knowledge transfer within the Anti-Scam Network.

- Develop an awareness campaign on this topic.

30

Directive (EU) 2020/1828 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 November 2020

on representative actions for the protection of the collective interests of consumers and

repealing Directive 2009/22/EC.

24

- Raise internal awareness in the use of misleading name in the bank

account opening process.

- Consider participation within the Anti-Scam network as observers.

- Develop an awareness campaign on this topic.

25

ECC-Net: European Consumer Centre Network

EUIPO: European Union Intellectual Property Office

GDPR: General Data Protection Regulation

IOs: International Organisations administering Intellectual Property Rights

IP: Intellectual Property

IPR: Intellectual Property Rights

IPR owner: unless otherwise indicated in the document, this term covers both

applicants and owners

KYC: Know Your Customer

NOs: National Intellectual Property Offices

OHIM: Office for Harmonization in the Internal Market

SMEs: Small and Medium Enterprises

UAs: User Associations

UDRP: Uniform Domain-Name Dispute-Resolution Policy

WIPO: World Intellectual Property Organization