Written Testimony of Patrice H. Kunesh

Director, Center for Indian Country Development,

Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis

United State Senate Committee on Indian Affairs

“Lending Opportunities: Opening the Door to Homeownership in Indian Country”

October 16, 2019

1

Introduction

Chairman Hoeven, Vice Chairman Udall, and members of the committee:

Native nations’ economies and populations are among the fastest growing in the United

States, yet the gap in homeownership rates between tribal lands and the rest of the country

remains unacceptably wide. Despite Native households’ steadily increasing credit scores and

strong preference for homeownership, a smaller share of Native households own homes today

than in 2000, and homeownership rates among American Indians are lower than the nation as a

whole.

1

Some of this gap is due to limited resources, but restricted access to credit and capital is

stifling the development of Indian Country housing stock. Administrative burdens, lack of access

to land title records and data, and inter-agency inefficiencies have reduced conventional lender

participation in trust land lending. In addition, federal programs geared toward mortgage lending

for Native people largely bypass reservations. Even when Native borrowers are able to secure a

home loan on the reservation, their mortgages are higher priced: nearly 2 percentage points

higher than for non-Native borrowers outside the reservation.

2

This testimony presents an analysis of these trends and proposes reasons for the

incongruity between homeownership rates and signs of other economic growth in Indian

Country. It also shares examples of tribal government institutions that are making

homeownership work on trust lands and of federal agencies pursuing innovative housing finance

efforts to meet the dire need for housing in Indian Country.

The Center for Indian Country Development (CICD) at the Federal Reserve Bank of

Minneapolis uses its expertise in economic research and community engagement to better

understand housing challenges and find solutions.

3

The CICD is the national economic research

initiative within the Federal Reserve System. Our research reveals a complex web of historical

and legal forces that make it unreasonably difficult to use much of tribal lands for the benefit of

Native people for mortgage lending and other economic development.

4

2

Native Americans and Housing

Today, 573 federally recognized Indian tribes

5

control about 60 million acres of land in

the United States. The vast majority of these tribal lands are held in trust

6

by the federal

government and are encompassed within American Indian reservations. Social and cultural

connections to Indian Country remain strong among the 5.2 million American Indian and Alaska

Native (AIAN) peoples.

7

This is a rapidly growing population.

8

About 60 percent of Native

people live on or near reservations (also referred to as tribal areas in the U.S. Census).

9

Options

for housing in tribal areas are extremely limited, and households confront a very different market

than the one found in non-tribal areas.

There is a drastic need to increase both the supply and quality of housing in tribal areas.

In 2017, HUD estimated that 68,000 housing units were needed to ease overcrowding and

replace substandard homes in tribal communities, and the units needed today likely have

increased. We believe this number underestimates the severity of overcrowding on reservations.

About 16 percent of reservation households are overcrowded,

10

compared to 2.2 percent of the

general population.

11

All told, severe overcrowding, poor quality housing stock, and a rapidly

growing population mean the real need for additional housing units is likely substantially higher

than the 2017 estimate. The precise level of need is difficult to gauge because some tribal-level

data generally is unavailable.

12

The social consequences of substandard and inadequate housing

are distressing. They include chronic disease and other health problems, as well as harmful

effects on childhood development.

13

Additional housing units are also required to meet the demands for homeownership in

Indian Country. About 75 percent of Native households in tribal areas report a strong desire to

own their home,

14

confirmed by survey findings from recent community needs assessments.

15

Tackling homeownership on trust land also would address fundamental issues that affect

the entire spectrum of economic development in Indian Country and unlock potential for

community benefits though investments on reservation lands. For example, creating private

homeownership opportunities in Indian Country relieves pressure on traditional housing

programs that largely administer a stock of subsidized rental properties. Quality, affordable

rental housing and repairs to existing owner-occupied and rental properties are necessary but not

sufficient for supporting continued economic growth in Indian Country.

3

Tribes have sovereign authority over their lands, but they do not have control over the

federal processes to put these lands to good and productive use. The Bureau of Indian Affairs at

the U.S. Department of the Interior (BIA) oversees the process for approving loans on trust

lands. The path to homeownership on trust land requires navigating this complex maze of intra-

and inter-agency steps and touch points. Fundamental reforms are needed to standardize the

mortgage review process and make it efficient and reliable for lenders and borrowers alike.

16

Overcoming decades of housing deficits and meeting the pressing demands for homeownership

across Indian Country require targeted investments across an array of new housing construction

and housing preservation. The key now is to align processes and policies, backed by a firm

commitment to accountability and transparency.

Enduring Benefits of Investing in Native Communities

A growing body of evidence shows the long term benefits of investing in Native

communities and the positive economic impact on tribal institutions.

17

The need is great and

Indian Country is poised to take advantage of these investments.

As a whole, the Native population is growing much faster than the national population,

increasing by almost 27 percent between 2000 and 2010, compared to an overall U.S. rate of

about 10 percent. While AIAN household income is still far behind other demographic groups,

Native people overall have realized a steady increase in real per capita income.

18

Social and

cultural connections to Indian Country remain strong, with a high percentage of tribal citizens,

about two thirds, living on or near reservations.

Indian Country is a distinctively important component of the national economy.

Collectively, tribes are the 13th largest employer in the United States. Tribal government gaming

and other reservation businesses employ more than 700,000 people and offer benefits and diverse

occupational opportunities. Tribal revenue delivers billions of dollars into local economies and

contribute significantly to their tax base.

Evidence suggests that tribal revenues positively influence reservation households. For

example, modest increases in income to tribal citizens tend to dramatically improve measures of

educational attainment, arrest rates, and civic engagement.

19

Other benefits from enhanced

income stabilization include decreased rates of smoking, alcohol consumption, and obesity.

4

Positively changing household incomes also improves economic opportunities in the long

run. The CICD’s recent assessment of Indian Country data from the Opportunity Atlas finds that

Native children growing up in tribal statistical areas show greater upward mobility for all

parental income levels.

20

This suggests that investing in reservation communities equates to

investments in our children, and offers the hope of healthy and productive lives.

21

To sustain continued growth and address intergenerational wealth gaps, these investments

must include housing. Stable, safe, and affordable homes not only support a healthier and more

educated workforce, but they allow community members to take and keep jobs, raise families,

and build a vibrant economy where businesses flourish and children thrive.

Federal Programs with Native American Mortgage Products

After centuries of disastrous federal policies that impoverished and decimated Native

communities, Congress in the 1960s began to enact legislation affirming tribal rights,

strengthening tribal autonomy, and establishing resources to build reservation economies. The

Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975 (Public Law 93-638)

authorized “Indian Tribes and Tribal Organizations to contract for the administration and

operation of certain Federal programs which provide services to Indian Tribes and their

members.”

22

Subsequently, many tribes moved to self-governance and assumed full

responsibility for the design and implementation of their programs without federal oversight.

In 1996, Congress moved to explicitly address the intersection of tribal sovereignty and

housing. The Native American Housing and Self-Determination Act (NAHASDA)

23

recognized

the rights of tribal self-governance and encouraged expansion of reservation housing options by

allowing NAHASDA-allocated funds to be leveraged for new home construction. To further

encourage homeownership opportunities, Congress enacted the Helping Expedite and Advance

Responsible Tribal Homeownership (HEARTH) Act of 2012.

24

The HEARTH Act was designed

specifically to enhance self-governance over tribal lands and promote the efficient leasing of

those lands for housing and business purposes. To exercise this authority, tribes must first adopt

leasing regulations and submit them for approval to the BIA. This review process has itself

become a bureaucratic hurdle to the development of trust lands. Currently, 26 tribal residential

leasing regulation applications are awaiting BIA approval; only three tribal leasing regulations

have been approved in FY19.

25

5

Several federal programs support mortgage lending to Native borrowers.

26

These include

the HUD Section 184 Home Loan Guarantee program (the Section 184 program), the Veterans

Affairs Native American Direct Loan program (VA NADL), and the Department of Agriculture

Rural Development Rural Housing Service 502 Direct Loan program (RHS 502). Collectively

these programs have billions of dollars in loan authority. Sadly, not much of these funds and

resources are reaching Indian Country, even when programs are designed specifically for AIAN

borrowers. To deploy this enormous capital opportunity in Indian Country, we must have a

normalized and complementary inter-agency lending process in Indian Country.

The HUD Section 184 program was established in 1992 with the specific mission of

facilitating homeownership and increasing access to capital in Native communities. HUD

describes the Section 184 as “synonymous with home ownership in Indian Country.”

27

The

Section 184 program has greatly expanded the supply of mortgage credit to Native borrowers by

mitigating private lender risks. It provides lenders with a 100 percent guarantee for mortgages to

Native borrowers, thus eliminating concerns related to the collateralization of trust land. In

addition, its utility for new construction as well as existing homes, low down payments, low

interest rates, and protection from predatory lending make the Section 184 program a very

popular funding option for Native borrowers.

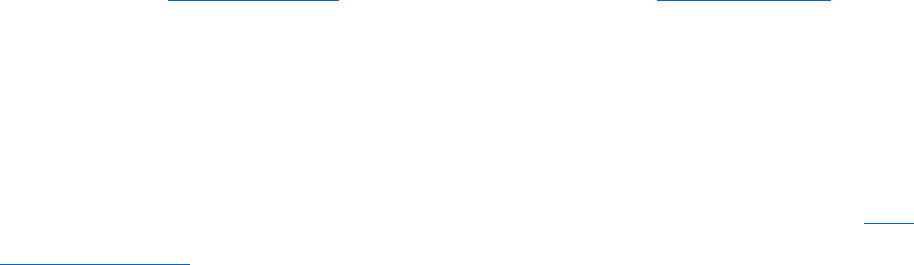

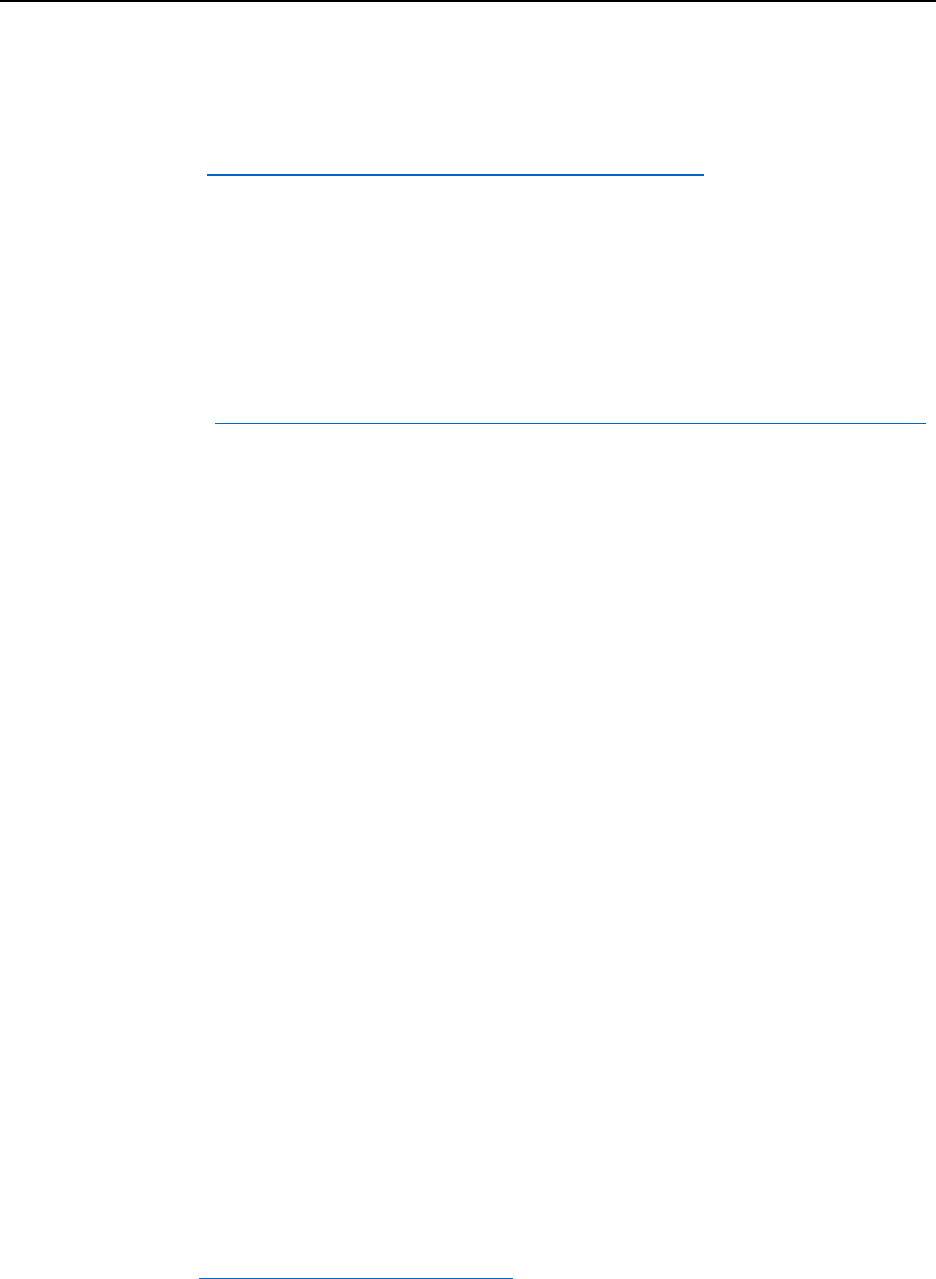

Figure 1 Number of HUD 184 Loans by Type of Land (1995-2018)

6

While the Section 184 program has expanded access to mortgage finance for Native

borrowers of all income levels, it has largely bypassed reservations. Only 7 percent of 184

program capital funded homes were on reservations in recent years, resulting in billions of

dollars of federally guaranteed funds supporting communities outside of Indian Country. See

Figure 1. Other federal programs that support mortgage lending on trust lands, the RHS 502 and

the VA NADL programs, also are woefully underutilized on trust lands.

The VA NADL program is meant to serve Native veterans on reservation lands.

28

The

program is similar to the VA standard home loan, offering favorable terms such as no down

payment requirement and low interest rates. Today, American Indians, Alaska Natives, and

Native Hawaiians serve in the military at one of the highest rates per capita of all population

groups: 133,000 veterans identify as Native. Currently, there is a potential NADL-eligible

population of 20,013 Native veterans who reside on trust land. However, between 2013 and

2015, the NADL program originated an average of 21 loans annually (the height of lending was

2003 with 120 loans and 2010 with 103 loans). It is noteworthy that most of these loans are made

in Hawaii and the Pacific Island territories. This disproportionate use of the program outside of

the lower 48 is possibly due to an established infrastructure in Hawaii for veteran benefits.

The RHS 502 program offers a path to homeownership for low- and very-low-income

families living in eligible rural areas, home to most of Indian Country. Rural Development’s

webpage notes, “Providing these affordable homeownership opportunities promotes prosperity,

which in turn creates thriving communities and improves the quality of life in rural areas.”

Rural Development invested more than $6.2 billion in Indian Country between 2001 and

2018.

29

About half of those funds, $3 billion, were invested through the Rural Housing and

Community Facilities programs for much-needed facilities such as community and senior

centers, hospitals and clinics, schools and food distribution centers. However, of the 6,575 loans

made through this program in 2014, only seven were to Native borrowers on tribal lands. As with

the other federal programs, we need to ensure that Rural Development programs and resources

are responsive to the current housing needs of tribes and tribal members on rural trust lands.

These powerful financial tools, established to help a most deserving population, are not

reaching Native borrowers on trust land. To address problems underlying this system failure, the

lending infrastructures in federal agencies that support the mortgage process must be normalized.

7

They must follow a standard streamlined process, similar to “one stop”-type

30

model mortgage

loan program, which can rely on a 30-day Title Status Report (TSR) turnaround from the BIA.

They also needs trusted lending partners and program supports to reach Native borrowers in

areas far from the lenders. Partnerships with Native Community Development Financial

Institutions (CDFIs) and tribal housing entities are also important to connect the funds with

institutions that understand the homeownership process in Indian Country. These partnerships

could transform Indian Country.

Experienced Native CDFIs and tribally owned financial institutions, such as banks and

credit unions,

31

provide much-needed credit building services and mortgage products to Native

borrowers. These Native CDFIs are perfect partners to connect Indian Country with federal home

loan programs, but their services are limited only by the amount of funding they have available.

For example, on the Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota, Lakota Funds, the first

Native CDFI, and Mazaska Owecaso Otipi Financial, offer affordable housing loans as well as

home buyer and financial education. In the summer of 2019, they and the Four Bands CDFI on

the Cheyenne River Sioux reservation were approved as re-lending intermediaries for the USDA

502 program. Loans to these Native CDFIs (33 years at 1%) will be used for housing on trust

land. While USDA has struggled to connect 502 money with Native homeowners on trust land,

Native CDFIs already have steady pipelines of mortgage-ready borrowers and the community

presence necessary for long-term relationships to ensure successful homeownership.

Then, there are state-based initiatives, such as the New Mexico Tribal Homeownership

Coalition and the South Dakota Native Homeownership Coalition. They, along with broader

associations that provide technical support and advocacy such as the National American Indian

Housing Council and CICD’s National Native Homeownership Coalition, support a systems

approach to shoring up the professional staff needed to plan, finance, and build homes in Indian

Country. These local and regional coalitions are establishing important networks to support a

well-functioning housing market, that includes contractors, inspectors, and appraisers.

8

Challenges to Mortgage Lending on Trust Lands

Making HUD 184 Work on Trust Lands

Despite the lack of any legal impediment to mortgage lending on trust lands, tribes and

Native people continue to be unduly hindered in using their lands for good and productive

purposes. Indeed, obstacles to effective use of trust lands for housing purposes remain severe and

troubling.

For example, the large majority of mortgages to Native borrowers under the Section 184

program are now on fee land.

32

This is due in large part to the rapid expansion of the program in

2004 to off-reservation areas following a lengthy period of little or no tribal implementation of

the program.

33

The number of Section184 mortgages made annually on trust land typically is in

the low hundreds and has shown no sustained growth since the early 2000s.

34

Because Section

184 loans have federal guarantees and present no risk to the lender, their limited use on trust land

reflects impediments other than borrowers’ creditworthiness or other financial characteristics.

While the BIA is making good efforts to streamline its mortgage process,

35

institutional

systems complicate the full utilization of the Section 184 and other federal mortgage programs

on trust lands. These include an elaborate review process, bureaucratic delays, and the

complexity of lending to low- and moderate-income borrowers. Holders of trust land must use a

leasehold interest as collateral, which requires the tribe to issue a leasehold interest to the

borrower, who then uses that interest as collateral. These transactions require two certified title

status reports (TSRs) from the BIA and various federal environmental reviews and appraisals,

which cumulatively result in a lengthy and involved process.

36

In a recent HUD-sponsored

survey of lenders, “mortgage lending on tribal trust land remains a time-consuming process that

reduces the appeal of lending on tribal trust land, even with the federal guarantee… Lenders

report that Section 184 Program loans can take up to 6 to 8 months to process and close; in some

cases, it can take even longer.”

37

(A chart illustrating the Bureau of Indian Affairs Mortgage

Package Business Process is attached.)

These transactions are recorded in the BIA’s Trust Assets and Accounting Management

System (TAAMS) to track and record title on trust lands. The TAAMS system, designed to

manage probate estates and payments of income from trust property, also includes property

9

maps. It was not designed to function as a national recording system for real estate transactions

on reservation lands. Nor is it publicly accessible like county property records. Moreover,

because different areas of the BIA manage different information in TAAMS, it can become

excessively difficult to issue the required real property records and TSR certifications. One

immediate way to address the bottleneck is to provide HUD and tribes access to TAAMS,

including certification for designated tribal individual users.

The continued difficulty of mortgage lending on trust land is suggested by both Figure 1

and the BIA mortgage package process (attached).

The High Price of Mortgage Financing for Native Americans

Access to affordable capital has been a constant challenge for aspiring Native American

homeowners. However, new CICD research shows that mortgage loans with Native Americans

as the primary borrower are also systematically more likely to be higher-priced.

38

Thus, even

when private capital manages to reach Native borrowers in Indian Country, they may pay an

unjustifiably high premium that greatly diminishes the possibility of accumulating equity and

building wealth.

Using public data from the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA),

39

the CICD study

examined first-lien home purchase loans with attention to “higher-priced loans.” The term

“higher-priced” is defined in the data set as loans that have a rate greater than or equal to 1.5

percentage points above the Average Prime Offer Rate (APOR), and the rate spread of loans

conditional on them being higher-priced, referring to the difference in percentage points from the

APOR for a given loan. We wanted to know the answer to two questions: (1) What proportion of

Native American loans are “higher-priced,” and (2) What is the rate spread of those loans?

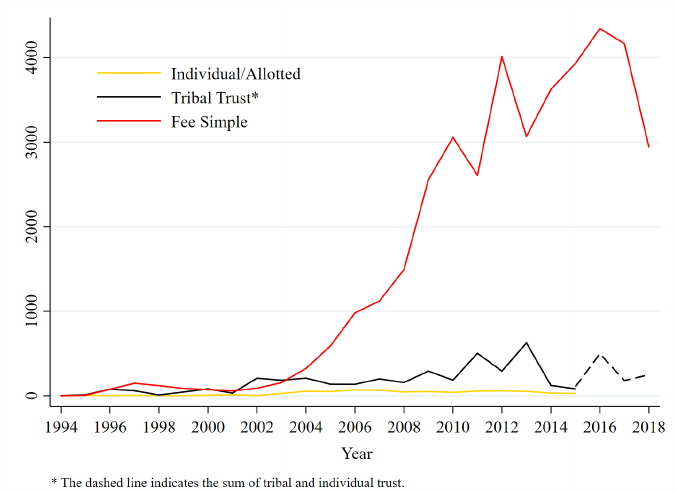

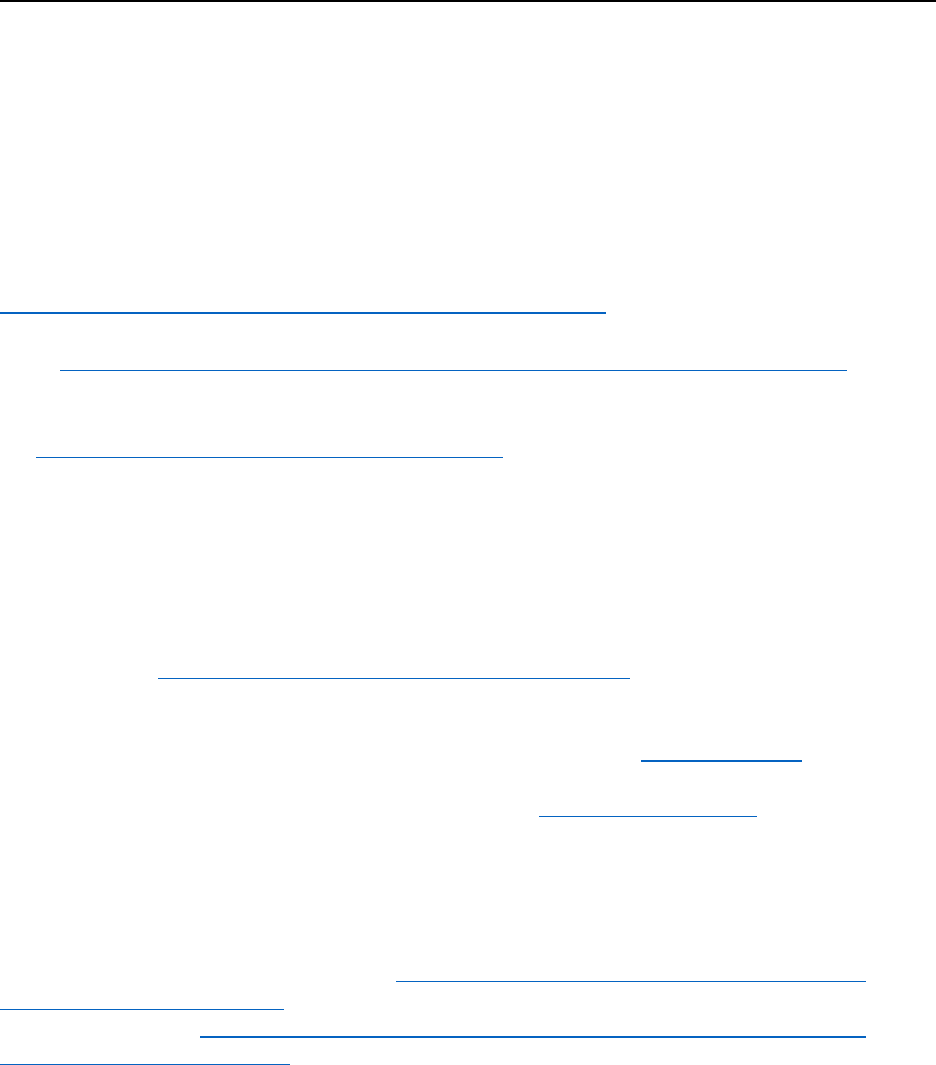

The CICD’s findings show that loans with Native Americans as the primary borrower

have an average interest rate nearly 2 percentage points above the average loan for non-Native

Americans. These higher-priced home loans are found predominately on reservation lands.

Around 30% of mortgages for Natives on-reservation were high-priced, compared to only 10%

for non-Natives near reservations (see Figure 2, Proportion of High-Priced Loans On and Near

Reservations). Native Americans burdened with high-cost mortgages had the highest average

rate spread of any group in the U.S. For Native Americans on reservations with high-priced

loans, the average spread in 2016 was 5 points above APOR. As an example, a Native American

10

on-reservation with a higher-priced loan buying an average-priced home in 2016 could pay

roughly $107,000 more in interest for a 30-year mortgage than a non-Native borrower off the

reservation.

Figure 2. Proportion of High-Priced Loans On and Near Reservations

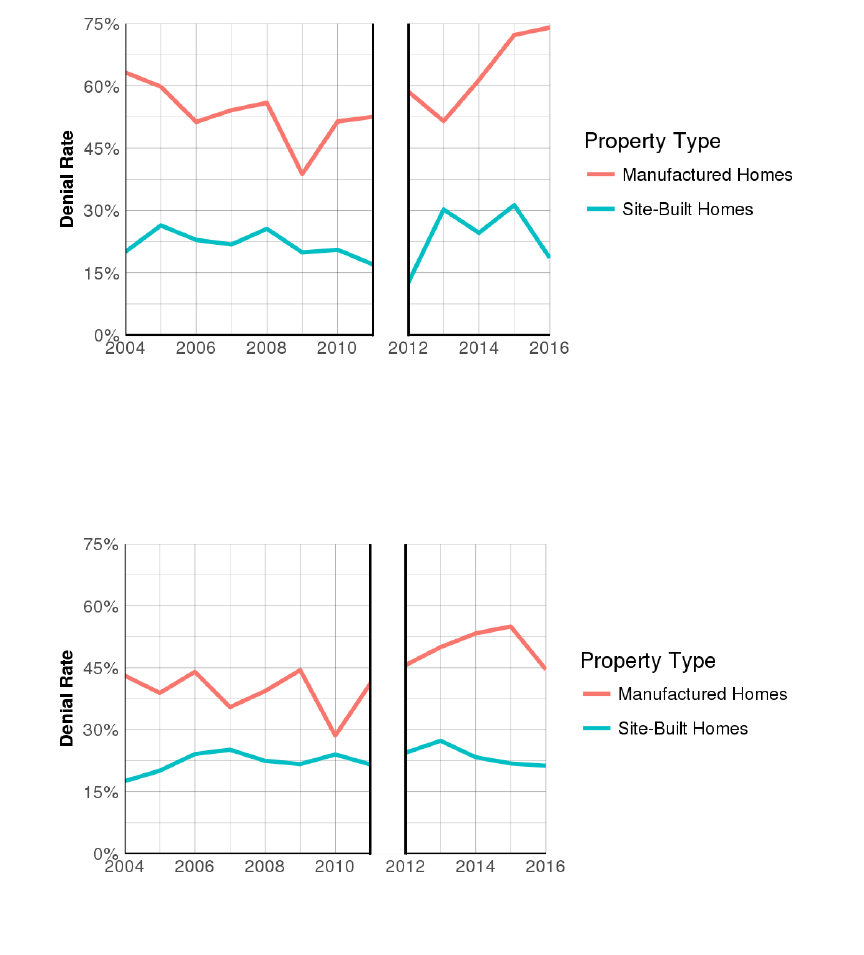

In the context of the high price of mortgage financing for Native Americans on trust land,

it must be noted that Native buyers tend toward manufactured housing – and loans for

manufactured housing often come with high-priced financing. The CICD analyzed HMDA data

from 2004 – 2016 and found that Native Americans were far more likely to apply for

manufactured housing loans across the U.S., but especially on reservations.

40

For example, in

2016, over 75% of home loan applications by Native borrowers on reservations were for

manufactured homes. By comparison, only 5.1% of all home loan applications in the U.S. for the

same year were for manufactured homes.

41

The data also showed that Native applicants had

much higher denial rates for manufactured-home loan applications than for site built homes. For

example, in 2015 – 2016, about 75 percent of applications for manufactured-home loans from

Native borrowers on the reservation were denied.

11

Figure 3. AIAN Loan-Denial Rates by Property Type and Tract Overlap Category

Census tracts with >90% reservation housing units

Census tracts with < 10% reservation housing units

The prevalence of manufactured housing on trust lands may derive from the difficulties

Native borrowers face in trying to finance site-built homes on their homelands. When purchasing

a manufactured home, buyers may finance their home as personal property, a chattel mortgage

similar to an auto loan, rather than as real property as in a typical mortgage. In so doing,

borrowers may circumvent some of the delays associated with building on trust land.

12

The simplicity of this financing, however, comes with a high price, may be subject to captive

financing, and may place additional risk on the borrower. The CICD study on high-priced

financing found that the prevalence of manufactured housing on reservation lands accounts for

25-35% of Native borrowers’ higher cost of financing. Another CICD study shows that 67% of

manufactured home loans to Native Americans were made by only two companies.

42

When

Native borrowers purchase a manufactured home as personal – rather than real – property, they

risk owning a less stable asset (the home alone) relative to traditional mortgage-holders, whose

property value is tied both to their home and the land underneath it. While manufactured housing

can offer less expensive construction and upfront costs, the higher interest rates, and denial rates

– along with the potential for captive financing – raise serious concerns about the current use of

manufactured housing in Indian Country.

43

Opening Doors to Homeownership in Indian Country through Tribal Self-Governance

Several tribes and tribal housing authorities have created successful homeownership

programs on trust lands by asserting self-governance over land leasing and titling processes.

They also have developed internal capacity to manage complex financing arrangements and

implement large-scale housing development. In doing so, they have demonstrated to their

communities and to the rest of Indian Country the powerful impact of making affordable credit

available to Native borrowers and creating an efficient lending process.

In the southwest, the San Felipe Pueblo of New Mexico built the Black Mesa View

subdivision in the heart of its community and created full service home building, housing

preservation, and related businesses that employ a wide range of workers and create

opportunities to develop a skilled tribal workforce.

44

Employment from construction projects

created a wide ripple effect as jobs were created over other sectors of the community, including

manufacturing, retail, and business services.

In Montana, the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Reservation

established a tribal land office that assumes much of the BIA’s lease processing and title work.

The Tribes’ housing program helps borrowers throughout the reservation become homebuyer

ready and complete the mortgage process efficiently, while building up a dedicated and skilled

tribal workforce in the process.

45

Meanwhile, tribally-owned Eagle Bank provides a ready source

13

of capital for mortgages at competitive interest rates. Overall, the Salish and Kootenai are

building a dynamic housing market that attracts a skilled and educated workforce.

On the high plains, the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribal Housing Authority has an ambitious

400-unit housing development project underway on tribal lands in Eagle Butte, South Dakota.

When completed, Badger Park will offer an array of design options and affordable price points,

mainly using factory-built construction. Financing for this impressive project is multi-layered

and complex. Designing and executing construction plans required years of careful work, starting

with a comprehensive community needs assessment.

46

Their patience and diligence paid off.

More than a dozen families moved into these homes last spring, and scores more will be

homeowners by the end of the year. The economic impact on the community emanating from

this housing development is exponential, with increased demand for local goods and services,

such as groceries and gas, and access to community amenities, such as schools and financial

services.

In the Midwest, the Ho-Chunk Nation of Wisconsin effectively implemented the

HEARTH Act and now provides land, leasing, title, and realty services within the boundaries of

its 15,000-acre reservation, comprised mostly of trust lands.

47

In addition, Bay Bank, owned by

the Oneida Nation in Wisconsin, supports a sizable HUD Section 184 mortgage portfolio for

Native borrowers across the northern Midwest region.

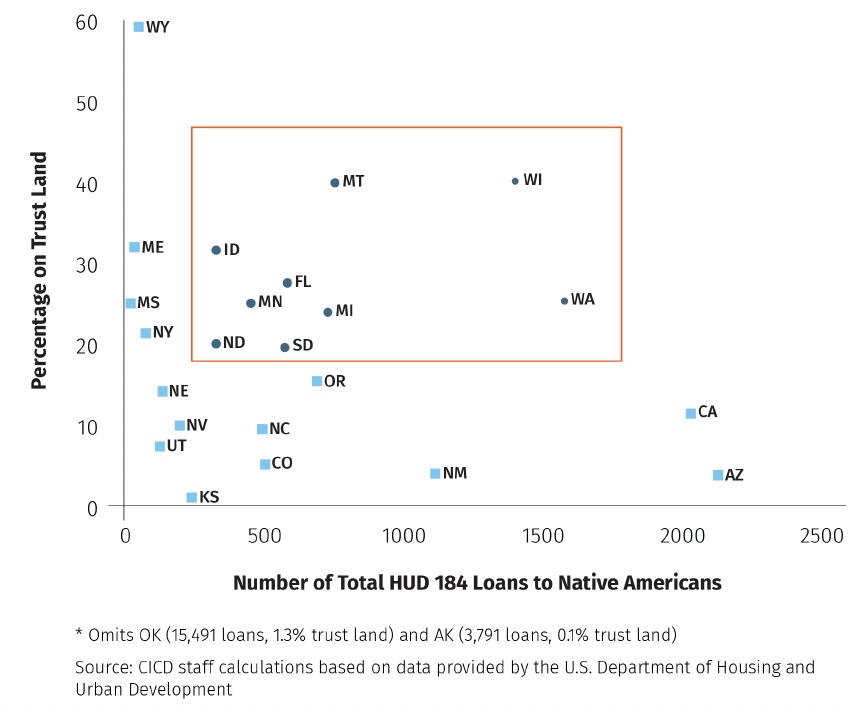

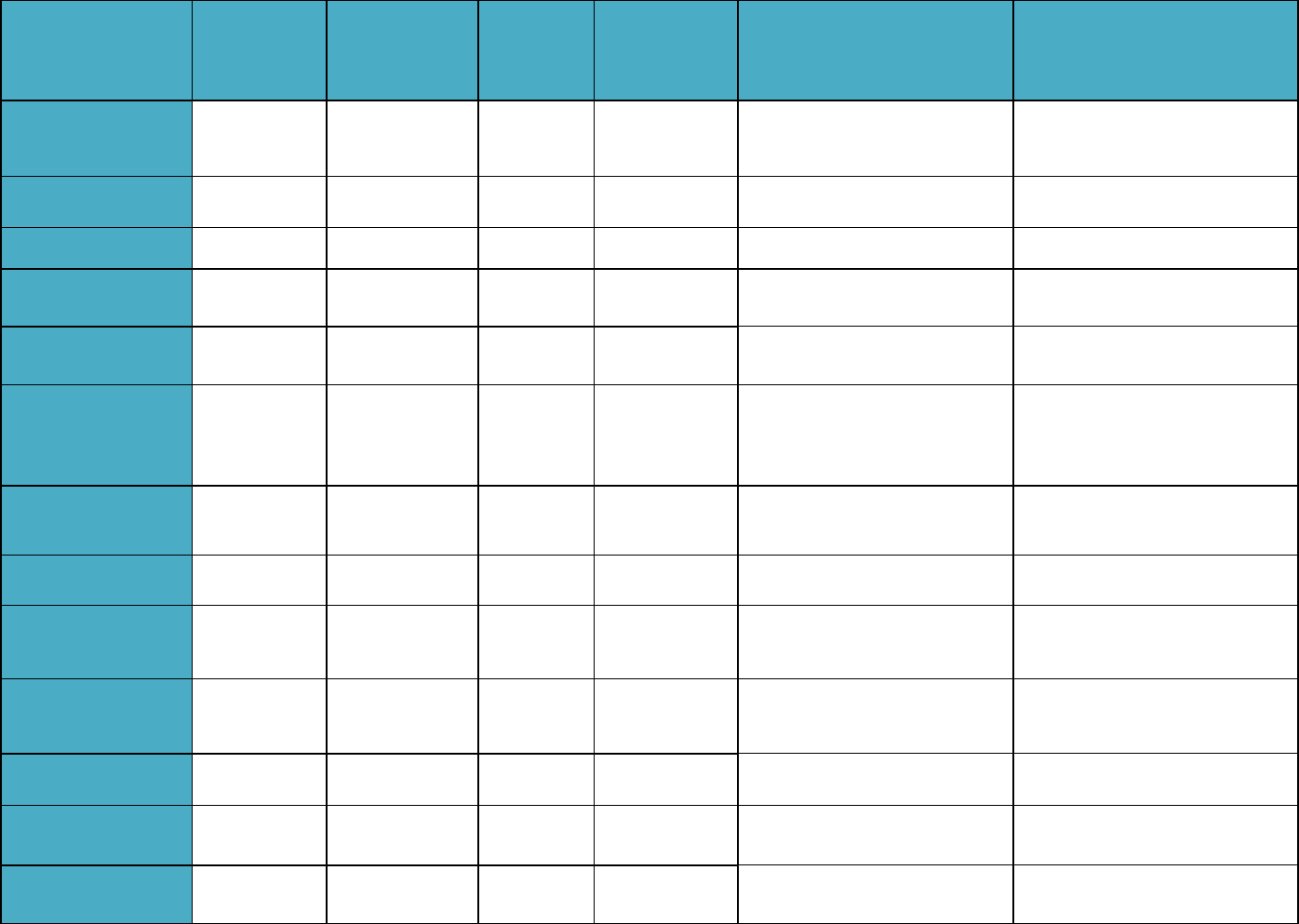

The success of these tribes and the achievements of several others is illustrated in Figure

4, which shows by state the total number of HUD Section 184 mortgages from 1995 to 2015, and

the percentage of those mortgages on trust land. Montana and Wisconsin are among the small

group of states that rank at least moderately high in both important metrics, demonstrating that

mortgage lending on trust land is viable if fully engaged with existing laws and programs.

14

Figure 4. States Where Tribes Are Making HUD 184 Loans Work on Trust Lands

What is strikingly important is that all of these projects are being accomplished under the

mantle of tribal self-determination and self-governance, producing models of success for all

tribes. Additional case studies are explored in the CICD’s Tribal Leaders Handbook on

Homeownership.

Policy Considerations

Bringing housing and homeownership opportunities to all of Indian Country requires

capacity, commitment, creativity, and collaboration. To do this, we need a multifaceted approach

to normalize lending on trust lands, leverage billions of dollars or federal funding, and generate

broad reservation-based economic development. Here are some suggestions:

15

1. Focus on trust land

CICD research has shown that most of the public resources for mortgage finance to Native

households are being utilized on fee simple lands. Lender surveys suggest that the additional

complexity of lending on trust land depresses the availability of credit and capital for home

loans. The barriers to building housing or otherwise leveraging opportunities on trust lands limit

Native people’s ability to live wherever they chose and to pursue meaningful economic

development strategies in their communities.

Addressing the issues with trust land homeownership will require coordination and

collaboration across the multiple federal agencies that assist Indian Country with

homeownership. In order to maintain this focus, better data practices are needed to identify and

map high-needs rural areas and persistent poverty counties, and overlay them with high Native

populations on or near trust land. The Department of the Interior should provide tribes with

current, accurate, and easily accessible information about their trust lands, along with data on

land ownership and encumbrances (including rights of way).

2. Modernize the lending process on trust land

Streamlined processes and reliable data are key components of a modern and efficient

lending system on trust lands. To better understand housing needs and determine whether these

programs are being put to good use in Indian Country, lenders and tribes both need access to data

on a timely basis and in a transparent manner. Requests for updated data often go unheeded, even

though the data are generally available and sharing is not burdensome. Furthermore, data

sharing, analysis, and reporting are critical to allocating scarce resources and holding federal

programs and private lenders accountable to constituents.

Additionally, the BIA lending system must be streamlined to meet the market demand from

Indian Country. This includes reform of the BIA title, lease, and land records processes to

conducting environmental reviews on trust lands. The importance of well-trained and responsive

BIA and tribal staff cannot be underestimated – they are essential to supporting an efficient

lending process in Indian Country.

48

But their apparent priorities do not seem congruent with the

pressing need for supporting more housing development. Many tribes, tribal housing authorities,

and other housing developers have yet to utilize the full potential of their programs for housing

16

development on trust land. Consequently, every year millions of federal funds fail to reach

Indian Country. Thus, modernizing the lending process requires a laser-focus on tribal self-

governance and land development tools such as the HEARTH Act and private sector financing.

3. Expand access to capital and credit in Indian Country: increase funding and

technical assistance for Native CDFIs

As conventional lenders retreat, Native CDFIs are emerging as critical sources of capital.

With local presences and professionals experienced in Indian Country, Native CDFIs are well-

positioned to service private mortgages, federal direct loans, and federal mortgage guarantees.

Native CDFIs also can be started with a much lower barrier to entry than banks and even credit

unions, and so are easier to access as vehicles for credit on reservations while also providing

essential services like small business loans and, in some cases, depository accounts.

In 2017, the CICD and the Minneapolis Fed’s Community Development Department, with

help from the Native CDFI Network and First Nations Oweesta Corporation, surveyed certified

Native CDFIs across the U.S. about their programs and funding. Findings from this study

suggest there are large unmet lending opportunities in the industry.

49

When asked about what

prevents their organization from providing programs and services, respondents overwhelmingly

cited limited financial resources as the leading factor. The estimated additional amount needed to

meet Native CDFI funding needs in 2017 was around $96 million. These additional funds would

be used primarily to expand existing services, but also to expand into new services or new

service areas (staff and capital). This includes technical assistance in becoming certified re-

lenders and sellers of mortgages to Fannie Mae.

Actions to support Native CDFIs with capital and technical support will be vital to expanding

homeownership in Indian Country.

4. Use innovative loan products.

Access to capital includes having funds to loan and also the ability to maintain liquidity. This

is even more critical for community lenders who provide services to high-need markets, such as

Indian Country. Federal agencies and lending institutions should explore a wide range of capital

and investment opportunities that support Native homeownership. The USDA Rural

Development pilot program in South Dakota using Native CDFIs as re-lenders of the Section 502

17

direct home loans on trust land demonstrates the capacity and opportunity for growth of the loan

program and the Native CDFI.

5. Support investment pools and secondary markets.

Indian Country also could benefit from innovative solutions that address lenders’ concerns

about risk and to shore up capital for investment needs. On the mortgage lending side, First

Nations Oweesta Corporation is becoming a national capital pool for Native CDFIs. Another

possibility is pooling leasehold mortgages as a way to offer investment-quality mortgage-backed

securities to a wide range of investors. On the risk side, the Sisseton Wahpeton Tribe in South

Dakota has established a risk mitigation pool to reduce the liquidation risk of mortgage lenders

operating on trust land, even as the Tribe supports to maintain heir homes and credit.

Access to secondary markets is essential to create liquidity and keep capital circulating for

more mortgage lending. Loan products such as Fannie Mae’s Native American Conventional

Lending Initiative single-family loan program provide an important mechanism for community

banks, credit unions, and Native CDFIs. It helps to deploy conforming conventional loans that

can be readily sold on the secondary market pursuant to a tri-party agreement between Fannie

Mae, the tribe, and the lender. This type of arrangement is a useful model for other lenders to

consider because it provides a structure that ensures efficiency of funding, suitable loan

servicing, and appropriate remedies, all of which support better systems for tribes.

Opening Doors to Homeownership in Indian Country

Indian Country’s growing population, positive economic growth, and increasing demand

for homeownership present a momentous opportunity for tribal communities, lenders, and the

United States. Innovative tribes and lenders are already finding a way to expand housing and

homeownership opportunities in Indian Country despite generations of economic deficits,

lagging infrastructure investments, and heavy bureaucratic burdens. They are re-establishing a

connection to the land and igniting the engines of economic self-sufficiency. Indeed, today’s

tribal leaders are framing their efforts with community-determined goals and designing new

paths forward to lift and support their people.

We need to recognize and support these efforts, and foster this forward momentum. This

means tackling the procedural barriers head on, ensuring access to capital at fair rates, and

18

creating more housing options on trust lands. Opening the door to homeownership also means

instilling hope for future generations of Native communities and families. This work – bringing

new resources and ideas into action in Indian Country – requires many hands. It can be done only

through partnerships, collaborations, and community commitments.

19

1

See Listokin, David et al., Mortgage Lending on Tribal Land: A Report from the Assessment of

American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian Housing Needs, U. S. Department of Housing and

Urban Development, December 2016 (hereafter Mortgage Lending on Tribal Land Report). “Actual”

homeownership here refers to non-rental status.

2

Feir, Donna. The Higher Price of Mortgage Financing for Native Americans, CICD Working

Paper 2019-06 (2019) (hereafter Higher Price Mortgage Financing for Native Americans).

3

See the Center for Indian Country Development website for research paper and research

resources, including the Tribal Leaders Handbook on Homeownership (2018) (hereafter TLHH).

The CICD published the TLHH as a comprehensive guide to the mortgage lending process in

Indian Country and a resource for addressing challenges to homeownership. It includes “best

practice” case studies illustrating how tribes overcame financial and institutional obstacles

through innovation and perseverance to create homeownership in their communities.

4

For a thorough discussion on the history of and contemporary issues facing mortgages on trust

land, see Davila, Christina, and Keith Wiley, Exploring the Challenges and Opportunities for

Mortgage Finance in Indian Country, Housing Assistance Council, Washington, D.C., 2018.

5

Federally recognized American Indian tribes and Alaska Native villages have a government-to-

government relationship with the United States and possess inherent rights of self-government

(i.e., tribal sovereignty). Because of this political relationship, the federal government has a

general trust obligation to promote the welfare of Native peoples by providing housing, health

care, and other services on reservations and tribal areas.

6

Trust lands are tribal lands held by the federal government in trust for the use and benefit of

tribes and Native people, most of which are located within reservations. Trust lands may not be

encumbered or conveyed without the consent of the federal government.

7

As used herein, the term Native people will be used interchangeably with the U.S. Census

category of American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN).

8

From 2000 to 2010, the growth rate for the total AIAN population in tribal areas was 12

percent. See Pindus, Nancy, G. Thomas Kingsley, Jennifer Biess, Diane Levy, Jasmine

Simington, and Christopher Hayes, Housing Needs of American Indians and Alaska Natives in

Tribal Areas: A Report from the Assessment of American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native

Hawaiian Housing Needs, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of

Policy Development and Research, January 2017 at 15-18 (hereafter HUD Tribal Area Study).

The U.S. Census Bureau forecasts continued growth rates for the AIAN population, projecting a

rise in the AIAN-alone population to about 4.2 million people by 2030. See Pettit, Kathryn L.S.,

G. Thomas Kingsley, Jennifer Biess, Kassie Bertumen, Nancy Pindus, Chris Narducci, Amos

Budde. Continuity and Change: Demographic, Socioeconomic, and Housing Condition of

American Indian and Alaska Natives. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development,

Office of Policy Development and Research, Jan. 2014, at 8.

9

HUD Tribal Area Study at 10. This report studied “tribal areas,” as used by the U.S. Census

Bureau, which generally includes Indian reservations and counties that encompass or surround

them.

10

For a more thorough discussion of the problems of overcrowdedness in Indian Country, see:

Overcrowded Housing and the Impacts on American Indians and Alaska Natives. Field Hearing

before the U.S. Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, S. Hrg. 115-404, August 25, 2018.

11

HUD Tribal Area Study, Exhibit ES.3, at XXI.

20

12

National data on Native communities is aggregated and reported as generalized observations,

lacking much contextual information at the tribal level. To better understand the needs and assets

of their communities, several American Indian tribes have undertaken tribe-specific community

assessments, including a more accurate reservation census count, the number of habitable

housing units, and a survey of housing needs.

13

Taylor, Lauren A., Housing and Health: An Overview of the Literature, Health Affairs Health

Policy Brief, Jun. 7, 2018.

14

HUD Tribal Area Study at 86.

15

(a) “Housing Needs and Homeownership Study,” Yankton Sioux Tribe and Big Water

Consulting, June 2019; (b) “Housing Needs and Homeownership Study,” Standing Rock

Community Development Corporation and Big Water Consulting, June 2019; (c) Case Study:

Housing Needs Study, Cheyenne River Housing Authority, Eagle Butte, South Dakota, TLHH at

48 (hereafter Housing Needs Case Study); (d) Model Housing Needs Assessments, TLHH

Appendix at 141.

16

Kunesh, Patrice H., Creating Sustainable Homelands through Homeownership on Trust Lands,

in “Meeting Native American Housing Needs,” Rural Voices, Housing Assistance Council,

Washington, D.C., Fall 2017.

17

(a) Akee, Randall K. Q., Katherine A. Spilde, Jonathan B. Taylor, The Indian Gaming

Regulatory Act and Its Effects on American Indian Economic Development, Journal of

Economic Perspectives 2015 v. 29, 185-208; (b) Akee, Randall K. Q., Maggie R. Jones, Sonya

R. Porter. Race Matters: Income Shares, Income Inequality, and Income Mobility for All U.S.

Races. Demography 2019 v. 56, 999-1021.

18

The modest increase was $9,650 in 1990 to $14,355 in 2018 (a 48 percent increase, compared

to a 9 percent increase for all Americans).

19

Akee, Randall K. Q., William E. Copeland, Gordon Keeler, Adrian Angold, E. Jane Costello.

Parents’ Incomes and Children’s Outcomes: A Quasi-Experiment Using Transfer Payments from

Casino Profits. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 2010 v. 2: 86–115.

20

Feir, Donna, The Landscape of Opportunity in Indian Country: A Discussion of Data from the

Opportunity Atlas. CICD Working Paper 2019-03 (2019).

21

Feir notes that this is exploratory research and the findings are nuanced depending on the

particular unit of observation (census tracts versus tribal statistical areas). This study seeks to

ascertain the experiences on census tracts covered by tribal statistical areas, which approximate

American Indian reservations.

22

Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975. Public Law 93-638. 88 Stat.

2203-2217, Jan. 4, 1975.

23

Native American Housing Assistance and Self-Determination Act of 1996. Public Law 104–

330. 110 Stat. 4016-4052, Oct. 26, 1996.

24

The HEARTH Act of 2012, Public Law 112-151, which creates a voluntary, alternative land

leasing process available to tribes, amended the Indian Long-Term Leasing Act of 1955, 25

U.S.C. Sec. 415 (July 30, 2012).

25

CICD staff conversation with Sharlene Round Face and David Moran, U.S. Department of the

Interior Bureau of Indian Affairs HEARTH Act Training, Sept. 4, 2019, Albuquerque, New

Mexico.

26

A list of Federal Mortgage Programs for Native Americans is attached.

27

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Section 184 Indian Home Loan

Guarantee Program. https://www.hud.gov/section184, accessed Oct. 9, 2019.

21

28

The NADL program, which began in 1992, focuses on assisting veterans who live on federal

reservation lands, Alaska Native villages, and Hawaiian Homelands. The NADL program differs

from the standard VA loan in a fundamental way – it is not a guarantee made by private lenders,

but a direct loan made by the VA. The NADL requires that tribes establish memoranda of

understanding (MOU) with the VA that delineate how the program operates and the

responsibilities of both the tribe and the federal government, including the process to

collateralize the loan on trust land.

29

See “Collaborating for Prosperity With American Indians and Alaska Natives Rural

Development Programs for Tribes, Tribal Families, Children, and Communities,” USDA Rural

Development Innovation Center (2018).

https://www.rd.usda.gov/files/508_RD_TribalReport_2019.pdf

30

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development and U.S. Department of the Treasury.

2000. One-Stop Mortgage Center Initiative in Indian Country: A Report to the President.

Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Treasury.

31

For a full list of Native American financial institutions and the scale and scope of their assets,

see Mapping Native American Financial Institutions, a dynamic map of Native owned banks,

credit unions, and community development institutions.

32

HUD Tribal Area Study at 86.

33

Mortgage Lending on Tribal Land at 10.

34

Analysis of data provided by HUD conducted by Center for Indian Country Development

staff.

35

For instance, the BIA recently released a mortgage handbook to delineate its review and

approval process. U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs, Division of Real

Estate Services, 52 IAM 4-H, Indian Affairs Mortgage Handbook, July 15, 2019.

36

Along with the leasehold (similar to owning a townhouse or condominium in which the land

and the dwelling unit are separate property interests), the Bureau of Indian Affairs must approve

a land survey and environmental review, and then issue a certified title status report on the

property (delineates the legal description and encumbrances on the property). The process for

obtaining a final TSR can be lengthy and involved. The HEARTH Act of 2012 creates an

alternative land leasing process that encourages tribes to make their own decisions about leasing

and leverage their lands for optimal development.

37

Mortgage Lending on Tribal Land at viii.

38

Higher Price Mortgage Financing for Native Americans.

39

Home Mortgage Disclosure Act of 1975, 29 U.S.C. §§ 2801–2811.

40

Todd, Richard M. and Kevin Johnson, Race, location, and manufactured-home loans on

American Indian reservations, CICD Blog, Dec. 4, 2018.

41

Todd, Richard M. Manufactured-Home Lending to American Indians in Indian Country

Remains Highly Concentrated, CICD Blog, Dec. 1, 2017 (hereafter Highly Concentrated

Lending).

42

Highly Concentrate Lending. Both of these two lenders are owned by Clayton Homes.

43

For a more comprehensive discussion of manufactured housing in Indian Country, see:

Manufactured Homes: An Affordable Ownership Option. Ch. 11, TLHH.

44

Case Study: Large-Scale Tribal Subdivision Black Mesa View, San Felipe Pueblo, New

Mexico. TLHH at 25.

45

Case Study: Homebuyer Readiness Program, Salish and Kootenai Housing Authority, Pablo,

Montana. TLHH at 57.

22

46

Housing Needs Case Study.

47

Case Study: HEARTH ACT Implementation, Ho-Chunk Nation Reality Division, Black River

Falls, Wisconsin. TLHH at 88.

48

Indian Programs: Interior Should Address Factors Hindering Tribal Administration of Federal

Programs. U.S. Government Accountability Office, January 2019.

49

Kokodoko, Michou, “Findings from the 2017 Native CDFI Survey: Industry Opportunities and

Limitations,” CICD Working Paper No. 2017-04, November 2017.

Inter Agency and Program Mortgage Package Business Process

BIA

REALTY

(Within 20 Days)

Lender

Borrower

Tribe

HUD/USDA/VA

BIA

LAND TITLES AND RECORDS OFFICE

(Within 30 Days)

Business Steps to Complete a Mortgage Package

Send Mortgage

Package

Review

Acknowledge

Receipt of Package to Sender

Include Date of Mortgage

documents Received, copy of the

Slip

Acceptable ?

Scan to TAAMS

Image Repository

Mail to

LTRO for Recording

And Request for TSR

LTRO

Review

Acceptable ?

Issue d TSR

* Send

to Realty by Email to

Print from TAAMS

Distribute d TSR

and Return Package to

Sender

Approved Package

With TSR

YES

YES

NO

Resolve and

Resubmit

Package

NO

FAX TSR to

other as

Requested

Review / Approve Mortgage

Documents with Lease

Verify Legal

Verify Survey/Plat

NEPA Compliance

Issue and of

Mortgage Approval

Correct BIA/Tribal

Land Area Code( LAC)

Tract Number

Original Mortgage Deed

of Trust with Legal

Survey / Plat

*Program c Rider

*Mortgage

Promissory Note

*Release of Mortgage

Recorded Lease Number

Consents

(*If applicable)

Record and Encode

Mortgage and

Associated

Documents

Notify Realty

document is

recorded.

Examine TSR

( Remove any

expired Documents)

Issue TSR

Examiner/Recorder

in receipt of mail

log

receive date into

log

Review Mortgage

and associated

Documents

Use Real Estate Contact Service Guide.

The guide contains three which allow the

user to locate the name, the and

obtain the address and main telephone number of a

Bureau of Indian (BIA) Real Estate Services

by Region or Agency. This will then allow the

user to secure the Land Area Code (LAC) for land

which is the subject of the mortgage package. All

mortgage packages must contain the correct Land Area

Code.

NOTE: If a leasehold mortgage approval is being

requested, the Guide will also provide to

assist the Borrower/Lender/ Agency in working directly

with the tribe for a mortgage approval (as in the case

with tribes that have leasing s approved

under the HEARTH Act.

IF THE REQUEST

IS INCOMPLETE,

THE PACKAGE IS

RETURNED TO

THE REQUESTOR

AND MUST BE

RE

SUBMITTED

TO BE

CONSIDERED

AGAIN.

IF THE

REQUEST IS

INCOMPLETE,

THE PACKAGE

IS RETURNED

TO THE

REQUESTOR

AND MUST BE

RE

SUBMITTED

TO BE

CONSIDERED

AGAIN.

Native American Mortgage Products

Details

USDA

Rural

Housing

502

Guarantee

USDA Rural

Housing

Service 502

Direct Loan

VA Native

American

Direct Loan

HUD Section

184 Indian

Home Loan

Fannie Mae

HomeReady

(Affordable Product)

Fannie Mae Conventional

(LTV 95-97%)

Income

Restrictions

115% of AMI 80% of AMI No No

No income limits in low-income census

tracts OR 100% of area median

income (AMI) for all other properties

No Income Limits

Max Loan

Amount None

Based on County

limits

Based on County

limits

Based on State and

County limits

$453,100 (1 Unit)

$679,650 High Cost Area (1 Unit)

$453,100 (1 Unit)

$679,650 High Cost Area (1 Unit)

Construction-to-Perm

Permitted

Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes

Rehab Yes Yes Yes Yes

Yes, in accordance with HomeStyle®

Renovation guidelines

Yes, in accordance with HomeStyle®

Renovation guidelines

Refinance

Subject to eligibility

Yes

Yes, including cash-

outs

See Refinance Information Above See Refinance Information Above

Manufactured

Housing

New w/permanent

foundation

New w/permanent

foundation; Approved

Dealer/Contractor

New on

permanent

foundation,

Approved Dealer

New/Existing

w/permanent

foundation

Yes: 1 Unit Principal Residence in

accordance with standard MH guidelines

Yes: 1 Unit Principal Residence

Second Homes acceptable at 90% LTV

(1 Unit)

Housing and Debt

Ratios

29/41

Very Low Income

29/41;

Low Income 33/41

41 41

Up to 50% with DU

®

Approve/Eligible

Recommendation

Up to 50% with DU

®

Approve/Eligible

Recommendation

Closing Costs

Financed

Yes Yes

No

Req. for Refi

Yes

Up to 105% CLTV if the subordinate lien

is a “Community Second”

Up to 105% CLTV if the subordinate lien is

a “Community Second”

Down

payment/Closing

Cost Assistance

Allowable Allowable

Allowable

Allowable

Yes; No minimum contribution from

borrower’s own funds (1 Unit)

Yes; No minimum contribution from

borrower’s own funds (1 Unit)

Foreclosure

Prevention

Intervention Intervention Intervention Intervention

As outlined in the executed

Memorandum of Understanding between

Fannie Mae and Tribe and Fannie Mae

Servicing Guide

As outlined in the executed Memorandum

of Understanding between Fannie Mae

and Tribe and Fannie Mae Servicing

Guide

Title

Insurance Required

Required

Required or BIA

approval and

Certified TSR

Bureau of Indian Affairs Approval and

Certified Title Status Report

Bureau of Indian Affairs Approval and

Certified Title Status Report

Legal

Documents

One Stop Docs or

Negotiated

One Stop Docs or

Negotiated

One Stop Docs

or

Negotiated

One Stop Docs or

Negotiated

One Stop Docs plus additional Fannie

Mae Agreements or Negotiated

One Stop Docs plus additional Fannie Mae

Agreements or Negotiated

Agreement

Documents

RHS/Tribe &

Investor

RHS/Tribe

MOU VA/Tribe

One Stop

Docs

As outlined in the executed

Memorandum of Understanding between

Fannie Mae and Tribe

As outlined in the executed Memorandum

of Understanding between Fannie Mae

and Tribe