GUIDING PRINCIPLES FOR

ENGAGING IN RESEARCH WITH NATIVE

AMERICAN COMMUNITIES

A Collaborative Effort By:

UNM Department of Psychiatry Center for Rural and Community Behavioral Health t Albuquerque Area Southwest Tribal Epidemiology Center

UNM’s Prevention Research Center

t New Mexico Tribal Strategic Prevention Framework Project

Nadine Tafoya and Associates t

Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation

Guiding_Principles_v1.indd 1Guiding_Principles_v1.indd 1 8/14/12 1:21 PM8/14/12 1:21 PM

2

Table of Contents

Introduction 3

Guiding Principles

Principle 1: Native Centered 5

Principle 2: Respect 6

Principle 3: Self-Refl ection and Cultural Humility 7

Principle 4: Authentic Relationships 8

Principle 5: Honor Community Time Frames 9

Principle 6: Build on Strengths 10

Principle 7: Co-learning and Ownership 11

Principle 8: Continual Dialogue 12

Principle 9: Transparency and Accountability 13

Principle 10: Integrity 14

Principle 11: Community Relevance 15

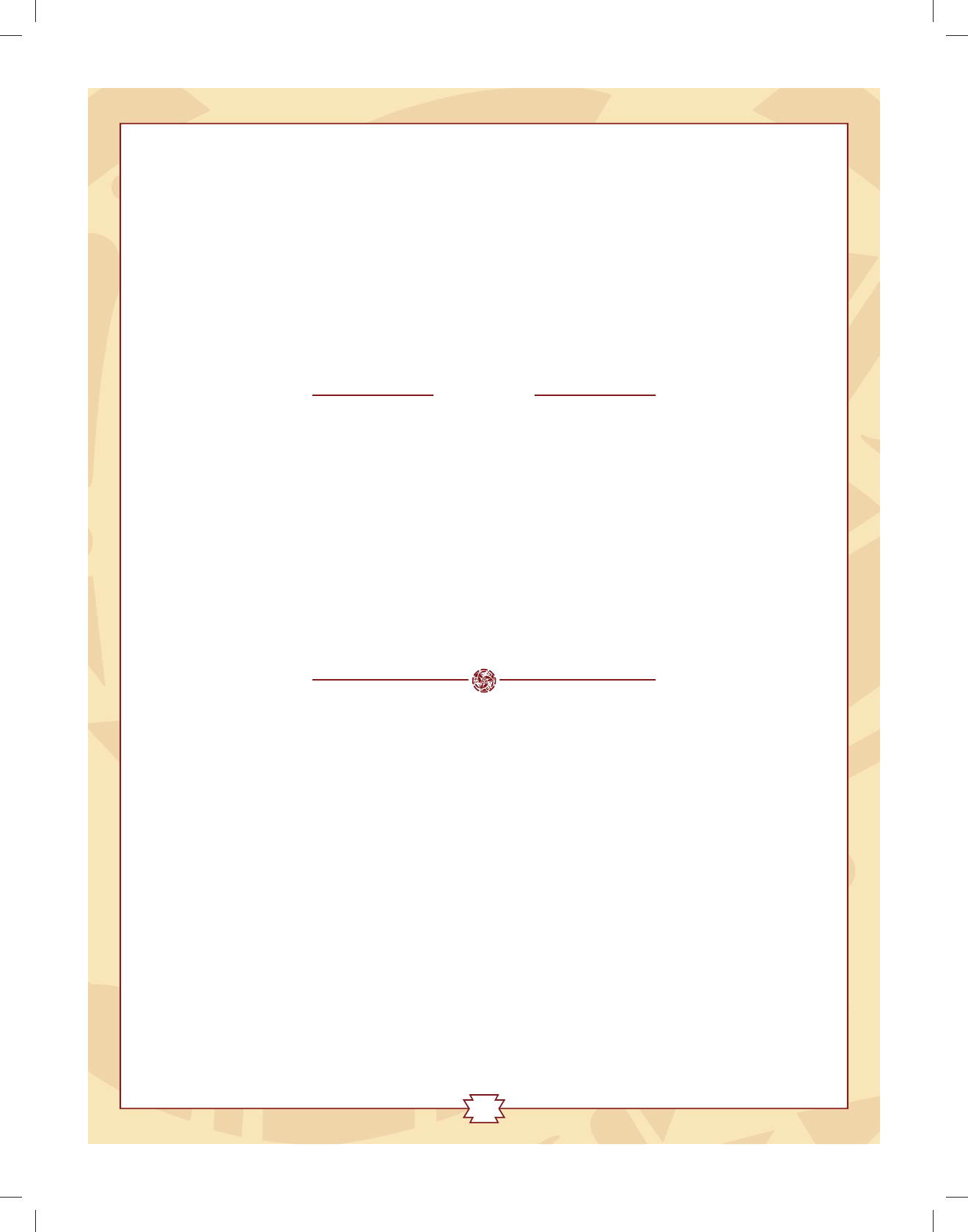

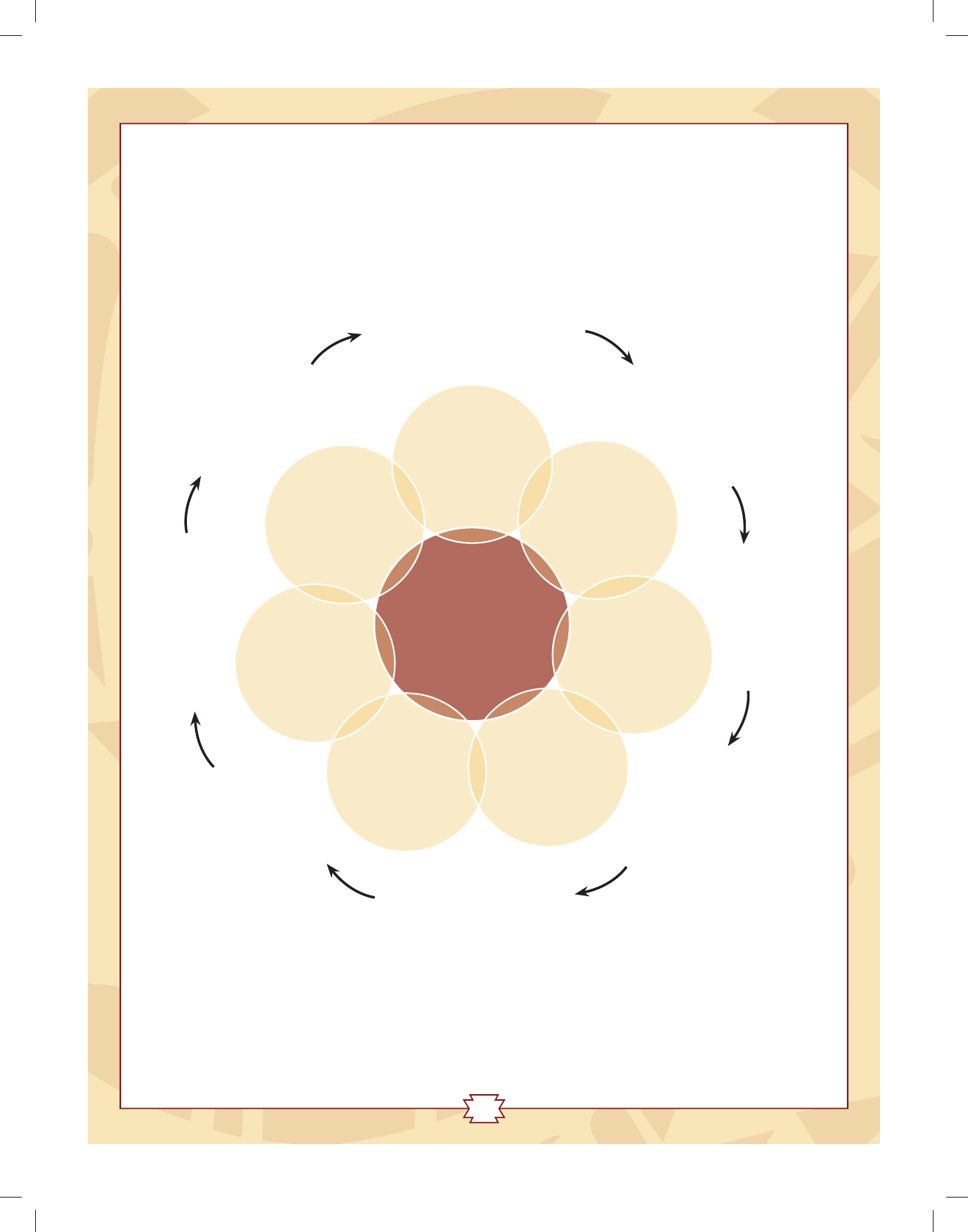

Guiding Principles Visual Reference 16

Resources 17

Suggested Citation: Straits, K.J.E., Bird, D.M., Tsinajinnie, E., Espinoza, J., Goodkind, J., Spencer, O.,

Tafoya, N., Willging, C. & the Guiding Principles Workgroup (2012). Guiding Principles for Engaging

in Research with Native American Communities, Version 1. UNM Center for Rural and Community

Behavioral Health & Albuquerque Area Southwest Tribal Epidemiology Center.

Guiding_Principles_v1.indd 2Guiding_Principles_v1.indd 2 8/14/12 1:21 PM8/14/12 1:21 PM

3

Introduction

This document is intended for use by researchers, both non-Native and Native,

working with Native American peoples and their respective communities.

In response to past injustices, research to promote individual, family, and community

health requires attention to issues of social justice and the distribution of resources.

Thus, engaging in research with Native American communities warrants a careful

review of principles that can help investigators to be more aware of Native-specifi c

issues (e.g. cultural values, diversity, appropriate protocols and approval processes),

and conscientious in their interactions with Native partners throughout the research

process. Until recent decades, Native American people have had little or no

representation in the research process.

This document was developed by a multi-ethnic group of researchers and community

consultants, including individuals who are also active tribal members, to:

1) provide written guidance when encountering challenges in research

relationships and processes;

2) elicit thoughtful discussion among researchers, and;

3) increase awareness of our responsibilities as investigators not only to the

individuals participating in research but also to the communities.

The reader should note that this document is limited in its ability to convey the

amount of time and effort it takes to get to a place of understanding and knowing

a community even before the research process begins. Additionally, research in

partnership with one Native American community does not necessarily translate

to processes or procedures needed in another community, thus highlighting the

uniqueness of each tribal nation. We intend for this to be a living document

1

that

can be adapted and refi ned as new approaches to research are developed and as

institutions and researchers confront diverse situations.

1

If you have a vignette arising from personal experience that illustrates the importance of one or all of the

principles, we request that you submit your vignette to Doreen Bird, MPH at [email protected] for

inclusion in future versions of this document. Please be sure to include your contact information.

Guiding_Principles_v1.indd 3Guiding_Principles_v1.indd 3 8/14/12 1:21 PM8/14/12 1:21 PM

4

Defi nitions

For the purposes of this document, the following defi nitions are used:

Culture: Culture and traditions vary greatly between Native American communities.

Native American individuals and communities also vary in adherence to their

cultures of origin and to Western cultural values and beliefs. For many Native

American people, spirituality and religion are generally perceived as an integral

aspect of culture. Spirituality also takes on many forms within Native American

communities, from use of traditional Indigenous practices to Christian beliefs.

Cultural humility

1

: A commitment and active engagement of continual self-

evaluation regarding the interaction and impact of one’s culture(s) on a given

situation or relationship so as to cultivate mutually benefi cial partnerships that

recognize and remedy any power imbalances.

Community: There is no single defi nition of community that applies to every

situation. This term can be co-defi ned with partners in the research process.

For example, a Native American community could refer to an entire tribe, smaller

groups within the tribe, an urban Indian community composed of individuals from

different tribes, or the larger Native American community within a city, state,

country, or the globe.

Native American: A member of any of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas.

We recognize that there are a number of other preferred terms. We also recognize

that there are native peoples outside of the United States, but for the purposes of this

document, we refer to Indigenous peoples of, or residing in, the United States when

we use the term Native American.

Non-Native: An individual who is not a member of the Indigenous peoples of the

Americas.We recognize the diverse histories of researchers of different races. We

have selected this general term to increase the applicability of this document to

researchers of all races/ethnicities not of Native American descent or heritage.

This encourages the reader to consider differences in historical experiences,

assumptions and stereotypes.

Tribal Sovereignty: “Sovereignty” is the authority of a state or nation to govern

itself. Tribal sovereignty in the United States of America provides federally

recognized Indigenous tribes the inherent authority for self-governance. However,

the federal government recognizes tribes as “domestic, dependent nations,” meaning

that they have local sovereignty, but not full sovereignty as other nations in the

world. Thus, many Native American communities in the USA are, or belong to

locally sovereign nations, and thus, have their own governance, laws, and leaders

that function independently.

1

This term was presented at the University of New Mexico Master of Public Health 2011 Community Based

Participatory Research Summer Institute, facilitated by Dr. Nina Wallerstein and Dr. Tassy Parker.

Dr. Parker discusses “cultural humility” to demonstrate the application of Indigenous knowledge and cultural

core value systems in health disparities research. The original article is included in the Resources section.

Guiding_Principles_v1.indd 4Guiding_Principles_v1.indd 4 8/14/12 1:21 PM8/14/12 1:21 PM

5

Guiding Principles

We offer 11 principles to guide research collaborations with Native American

communities. These principles are all of equal importance and are presented in

no particular order. Within the explanation provided for each principle, we offer

illustrative vignettes

2

and questions to elicit discussion. We have also summarized

how each of the principles may be utilized throughout the research process in a

visual diagram.

Principle 1: Native Centered

• Native centered means that Native American communities and people are the

driving force of the research.

• Native knowledge is at the heart of the research endeavor and Native American

people are the leaders and voice. “Nothing about us without us.”

• Research activity and action are centered on issues that are central to the Native

American community, not the research center, sponsoring institution, or agency.

Unite with Native American people to assist in achieving their visions and goals.

Questions To Facilitate Putting Principle Into Practice:

• Am I working to achieve my agenda or am I working with the community to

assist in visualizing, articulating, and developing their plan of action?

• Is my institution able and/or willing to give this Native American community the

time, resources, and expertise needed to meet their expectations?

Researchers invested many hours with a Native American community by attending

community programs, going to public events, and connecting with community

members in informal ways before they were invited by the leadership of that

community to assist with the writing of a grant for research purposes. Members

from the community, including family members, youth, service providers, elders,

and cultural leaders, participated in the initial planning meetings, as well as

subsequent meetings to provide continued guidance. Respecting the knowledge

that already existed in the community and listening to what the community wanted

allowed the researchers to integrate their ideas into the grant proposal. A community

member became the identifi ed Principle Investigator, and other community members

were also selected to fi ll key roles.

VIGNETTE

2

Most of the experiences drawn upon to develop the vignettes are centered in the Southwestern region

of the United States. We hope that other research centers can adapt vignettes to incorporate their specifi c

regional/tribal experiences.

Guiding_Principles_v1.indd 5Guiding_Principles_v1.indd 5 8/14/12 1:21 PM8/14/12 1:21 PM

6

Principle 2: Respect

• Treat all individuals and communities participating in research with respect.

Remember, it is an honor to work with Native American peoples in research.

• Purposefully seek understanding of the community and their reasons for

collaborating in research. This understanding will guide the researcher in showing

regard for the community.

• Respect and honor tribal sovereignty, cultural traditions, and diversity among and

within Native American communities.

• Be aware and respectful of existing community protocols. Many communities

have specifi c protocols of who to go to and how to go about garnering approvals

for all research activities.

Questions To Facilitate Putting Principle Into Practice:

• Am I aware of the protocols within a particular Native American community

for research projects? Am I aware of the protocols for convening and facilitating

meetings? To whom can I go and how else can I learn the protocols (e.g., calling

tribal community center to ask for guidance, talking with an elder or youth from

the community, knowledgeable colleague familiar with community, etc.)?

• Is the Native American community with whom I am working a sovereign nation?

Am I aware of and respecting the government structure, laws, and policies, as well

as specifi c procedures for engaging in research with this community? Am I aware

of where the Native community’s laws might converge or diverge from the laws

and policies of my institution, university, state, etc.?

A seasoned researcher attended a meeting in a new community to introduce a project

to local residents. One of the community members spoke up and said “We have been

researched to death” and “We never see anything come out of the research.” The

researcher realized the community members may be responding to past injustices

of researchers whose work ended up stigmatizing the community. The researcher

showed respect by taking the time to listen and validated their concerns by asking

“What is it that I can do differently?” One person responded, “Show your respect

by spending time in our community, being patient and listening when leaders speak,

attending our community events, and advocating for our tribe’s voice to be heard. Sit

back, listen, and be involved.”

VIGNETTE

Guiding_Principles_v1.indd 6Guiding_Principles_v1.indd 6 8/14/12 1:21 PM8/14/12 1:21 PM

7

Principle 3: Self-Refl ection and Cultural Humility

• Be mindful of one’s own cultural and class biases and how these biases can affect

researcher interactions in Native American communities and the research they

undertake.

• Strive to develop self-awareness and have a respectful and humble attitude

toward diverse points of view, which are shaped by the individual histories of each

community, as well as the distinct traditions that inform these perspectives.

• Engage in research with the understanding that Native American community

members have wisdom, knowledge, expertise, and experience that is relevant to

their community and to our efforts as investigators.

• An individual cannot master cultural competence for all Native American cultures

or tribes. Believing that one has attained “cultural competence” when working

with Native American communities can lead to reliance on faulty assumptions and

stereotypes, and undermine the research.

Questions To Facilitate Putting Principle Into Practice:

• Am I using my position, credentials, or power for this person/community?

• Am I continually mindful and actively refl ecting on myself for any assumptions I

may be making that infl uence the way I interact with others and conduct research?

• Am I recognizing the expertise of everyone in the community?

A Native American researcher was attending a meeting in her own community. A

non-Native community provider introduced her as “a resource from the University.”

The researcher then handed out program materials and business cards. The

community’s initial response was, “We are all resources, too!” One community

member pushed the researcher’s materials aside. The researcher suddenly realized

that, although unintentional, the introduction and the institutional authority implied

by the materials suggested to community members that the researcher considered

herself the expert in this situation. After a lot of thought and consulting with

colleagues, the researcher realized the importance of approaching projects with

humility and careful self-refl ection to ameliorate power imbalances.

VIGNETTE

Guiding_Principles_v1.indd 7Guiding_Principles_v1.indd 7 8/14/12 1:21 PM8/14/12 1:21 PM

8

Principle 4: Authentic Relationships

• Build relationships that are sincere, enduring, and based upon mutual trust

and respect. Genuine relationships are the cornerstone of mutually benefi cial

collaborations and equal partnerships.

• Relationship-based research will emerge and survive through challenges with

positive transformations on all sides of the partnership.

• Enter into partnerships with the community and community members with the

intention of building and sustaining a long-term commitment to the community.

Questions To Facilitate Putting Principle Into Practice:

• How am I demonstrating that I am fully present with this person/community?

• Am I an active participant in interactions and interpersonal moments that shows

my sincerity in assisting the community?

• Am I willing to commit to working through challenges that will inevitably rise,

to grow and learn within myself as I get to know the community, and develop

relationships that may extend beyond the life of the project.

A local provider was asked to assist a rural Native American community during

a crisis situation. He gave the community his full attention and was genuine in his

willingness to serve. He engaged with many community members and providers as

they dealt with the issues at hand. Once the crisis was over, the community reached

out to him to work on other projects that would benefi t their tribe. Again, he was

genuine and always willing to help. His partnership with the tribal community has

grown into developing more proposals and projects. His years working with the

tribe have led to authentic partnerships and lasting friendships. Community members

often consult with him over the phone, text message him and send him emails when

they want him to review something. The tribal members have grown fond of the

provider and continue to engage in research projects with him to this day.

VIGNETTE

Guiding_Principles_v1.indd 8Guiding_Principles_v1.indd 8 8/14/12 1:21 PM8/14/12 1:21 PM

9

Principle 5: Honor Community Time Frames

• Concepts of time differ among various cultures. Tribal community timelines may

be infl uenced by seasonal cycles, traditional events, and governmental functions.

As one Native community member phrased it, “spiritual time” is the ultimate

clock by which all events take place and goals or projects are accomplished.

• Research culture sometimes creates pressure to “get things done quickly” without

consideration for the communities’ timeframe. At other times, the research process

may move so slowly that Native community members question whether the

original purpose of the project will meet community needs in a timely fashion.

• Many Native people value time to process information. This time may be used to

refl ect on new concepts or translate the concepts into Native thought. Provide time

for moments of thoughtful silence.

Questions To Facilitate Putting Principle Into Practice:

• Is my time frame realistic for the research project in relation to the community’s

activity level and am I planning accordingly given the different concepts of time?

• What projects or activities occur annually to which my community partners will

need to attend?

• Am I taking time to refl ect on the information and how it translates into Native

thought? Am I giving the community time to translate into their own Native

worldview?

As a researcher was starting the planning process, she asked a local tribal community

member what to keep in mind during the yearlong project. The designated

community liaison stated that the tribal community had certain events (ceremony,

political, funerals, school activities, etc.) throughout the coming year. The liaison

recommended the researcher sit down with their local community contact to outline

the length of the project and to develop a timeline that encompasses both the

research and community events. During this conversation, the community contact

also reminded her that the research timeline and the community event timeline had

to complement each other in order to be respectful and move the research initiative

forward. The researcher made sure to keep her timeline fl exible and allow additional

time at the end for unexpected community events.

VIGNETTE

Guiding_Principles_v1.indd 9Guiding_Principles_v1.indd 9 8/14/12 1:21 PM8/14/12 1:21 PM

10

Principle 6: Build on Strengths

• Become aware of the strengths and particular abilities within Native communities;

explicitly recognize these aspects and build upon them. Focus on the community’s

culturally-protective strengths and other assets throughout all stages of research.

• The tone of written research is highly valuable for its ability to positively impact

the community by emphasizing resiliency factors and inspiring hope.

Questions To Facilitate Putting Principle Into Practice:

• Am I actively searching for positive qualities or strengths in the community?

• Am I coming from a positive or negative framework in how I perceive the

community?

A new researcher was excited to begin a project in a Native American community.

He came to the initial meeting with data and statistics from recent Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention, Department of Health and Indian Health Services

reports. He brought up concerns regarding the high rates of alcohol use, depression,

diabetes, and adverse childhood events among this population. He began by asking

the community partners to give their opinions and examples of why and how these

statistics are played out in their community. After the initial meeting was over, the

community partners were left with feelings of negativity and hopelessness. They

were not sure that they wanted to continue working with this particular researcher

because he pointed out all the bad things going on in their community. This might

have been avoided if the researcher balanced out his meeting by bringing forth some

positive qualities inherent in this community.

VIGNETTE

Guiding_Principles_v1.indd 10Guiding_Principles_v1.indd 10 8/14/12 1:21 PM8/14/12 1:21 PM

11

Principle 7: Co-Learning and Ownership

• Co-learning involves a reciprocal exchange of knowledge and ideas. Tribal

community partners bring their expertise across multiple areas, including a deep

understanding of their communities’ traditions, values, methods, and knowledge.

Researchers bring expertise in academic research methods and processes.

• Build community capacity. Consider what the Native American community would

like to learn and benefi t from the researchers just as the researcher gains important

knowledge from community members.

• Acknowledge that everyone has important contributions to make in research.

Community input is vital to fostering ownership and sustainability of the positive

project outcomes.

• Native communities have the right to ownership and control over their own data

and may choose to share or not choose to share ownership of the data.

Questions To Facilitate Putting Principle Into Practice:

• How am I helping to build capacity in the community through the research

process (e.g., using research funds for equipment retained by the community,

hiring community members, bringing tribal representatives to the research center,

providing trainings, etc.) and what am I learning from the community that

increases my own skills and capacity?

• Am I providing community members opportunities to contribute their knowledge

in meaningful ways? Am I prioritizing the use of existing programs and resources

in the community?

•

In what ways am I encouraging community members to take ownership of the

project to ensure sustainability?

In one collaboration between a Native community and a research center, community

members determined the degree to which their culture and traditions would be

included in the project. Both community members and researchers took different

sections of the grant to write, with all contributing equally to the fi nal product.

Research partners provided technical assistance whenever needed during the grant

writing process, facilitating the community’s capacity to write grants on their own

in the future. The community gained approval for the project by consulting with

the elders and tribal leaders. The researchers learned the approval process in the

community while the community members learned the approval process through the

institutional IRB. This process helped build capacity for the community and for the

researchers. It also instilled a sense of pride and ownership that carried the project

forward even after funding ended.

VIGNETTE

Guiding_Principles_v1.indd 11Guiding_Principles_v1.indd 11 8/14/12 1:21 PM8/14/12 1:21 PM

12

Principle 8: Continual Dialogue

• Ensure that communication about research is understandable, relevant and

accessible to the members of the community involved.

• Communication fl ows both ways. A continual and open dialogue may facilitate

co-learning, prevent misunderstandings, and address concerns before they become

problems.

• Be proactive in fi nding out the appropriate people and programs needed for

ongoing communication within each community and research project.

• Provide fi ndings back to community stakeholders on an on-going basis.

Questions To Facilitate Putting Principle Into Practice:

• Am I actively listening? Am I choosing not to talk in order to give community

members a chance to speak?

• Am I intentionally creating a relationship and atmosphere that allows my partners

to feel comfortable enough to bring up issues of concern?

• Am I communicating with the proper stakeholders of this community? Is there

a health board, tribal IRB, health director, tribal council or traditional leader with

whom I should be in contact? Am I updating the right people at the right time?

A researcher came before the tribal council:

Council – When was the last time you provided council with an update on this

project?

Researcher – I have not provided an update to council since the project was

approved by the Institutional Review Board two years ago last spring. I didn’t

know I was required to.

The council’s questioning caused the researcher to refl ect on her own expectations

for communication. She realized she needed to put more effort in aligning with

the community’s protocol for how information fl ows to and from the community/

researcher, in order for local decision-making to occur and project goals/

requirements to be met.

VIGNETTE

Guiding_Principles_v1.indd 12Guiding_Principles_v1.indd 12 8/14/12 1:21 PM8/14/12 1:21 PM

13

Principle 9: Transparency and Accountability

• Be open and clear about all activities and information throughout the research

process in order to build trust which may have been compromised by past negative

research endeavors in the community.

• Take responsibility for all actions and consequences of those actions when

engaging in research with communities.

Questions To Facilitate Putting Principle Into Practice:

• Have I clearly defi ned what my position as a researcher entails? Have I clearly

defi ned what my institution can and cannot provide? Should these expectations be

in writing?

• Am I being open about and taking responsibility for all research activities?

• Do we have a mutual understanding of each other’s expectations?

• Do I know whose approval is needed for different aspects of my project? Do I

know whom to work with in the community regarding consents, permissions, etc.?

A tribal leader came across information regarding her community while surfi ng

the web and was concerned at the way her community was portrayed. When asked

about this information, the researcher, who had posted the information, stated that

he had assumed the proper approvals had already been obtained and it was not his

fault that the information was put on the web. The researcher was caught off-guard

by the community member. He did not reveal that, despite being made aware of

the need to update tribal administration about new actions related to the research

project, he still neglected to inform them this information was being placed on the

web for fear that it would cause more discussion and delays than were necessary for

such a small detail. Although the information on the website of itself was not a huge

concern to the community and would have easily been approved if taken through

the appropriate protocols, the community lost some trust with this researcher for not

being open and for not taking the responsibility of remedying the situation.

VIGNETTE

Guiding_Principles_v1.indd 13Guiding_Principles_v1.indd 13 8/14/12 1:21 PM8/14/12 1:21 PM

14

Principle 10: Integrity

• Act with honesty and morality throughout every phase of research.

• Adhere to the existing ethical guidelines that are developed for and by Native

peoples and communities in addition to general ethical guidelines for researchers.

• Be vigilant about protecting Native American communities, as well as individuals,

from harm.

• Work to preserve and strengthen the wholeness of Native peoples and communities.

• Understand that the community’s rights take precedence over the researcher’s

pursuit of knowledge and personal career development. The community and any

member of the community has the right to say no to any part of or the entire

research project.

Questions To Facilitate Putting Principle Into Practice:

• How am I showing my integrity? What are the code of ethics to which I refer in

guiding my actions and decisions to ensure the morality of my research?

• Where is all the private/confi dential documentation being kept? How will all the

private/confi dential documentation be handed back to the community or destroyed

at the end? If destroyed, how will this be documented?

A tribal council required a researcher to make several changes to his submitted

presentation before they would give approval for the researcher to present at an

upcoming conference. One request required the researcher to delete a major fi nding

from his presentation. After much discussion, the researcher asked if there was any

way that the information could be presented in a more acceptable manner in order

to keep this central fi nding in the presentation. Ultimately, the researcher took out

this fi nding from the presentation. This researcher struggled with which guidelines

to adhere in order to maintain the integrity of his work, and decided that the reasons

for which this Native community had asked him to take out his fi ndings held greater

justice for this community than would be demonstrated in presenting the fi ndings.

VIGNETTE

Guiding_Principles_v1.indd 14Guiding_Principles_v1.indd 14 8/14/12 1:21 PM8/14/12 1:21 PM

15

Principle 11: Community Relevance

• Be mindful that historical experiences directly relate to Native communities’

present situations and impact the relevance of any research project.

• Develop research projects that have meaning and purpose within the Native

community’s way of being and knowing.

• Ensure that research fi ndings are useful and accessible to participating

communities by providing information that contributes to tribal-specifi c solutions,

greater well-being, and positive policy impact.

Questions To Facilitate Putting Principle Into Practice:

• How is this research going to help the community and/or individuals in addressing

the community’s identifi ed priorities (e.g., treatment/intervention, prevention,

jobs, training, and equipment)?

• Rather than going into the community and leaving once my research project

is complete, am I willing to follow up with research fi ndings that reveal barriers,

inequalities or other issues negatively impacting the community by providing

culturally relevant recommendations and engaging in socially responsive action at

a systemic level?

• How am I changing policies/behavior/norms in my current institution and the way

I engage in research with Native American communities, now that I know the

history of disrespect/abuse?

A researcher came before tribal leadership to present an HIV prevention project

that she wanted to begin at a school-based clinic on the reservation. She presented

information that supported counseling and testing as an HIV prevention strategy.

Leadership was skeptical of the need for such an intervention and questioned

whether it was the most productive use of the clinic’s limited resources. Leadership

said that the wellbeing of their youth was of utmost importance and they were open

to other project ideas that may better meet concerns such as substance abuse and teen

pregnancy, but they did not endorse the proposed project since HIV prevention was

not a priority. During the discussion of the project, members of council expressed

concern about the loss of their tribal language and the limited number of youth in the

community learning to speak the language. The researcher still hoped to offer her

expertise in children’s behavioral health, but also realized her previous proposal did

not take into account the community’s present concerns. Incorporating what she had

learned, a few months later the researcher presented a different project. This time the

project was a comprehensive substance abuse and risky sexual behavior prevention

project that focused on strengthening cultural identity. A major component of the

intervention was language preservation. Tribal leadership endorsed the project and

devoted tribal resources to support the program.

VIGNETTE

Guiding_Principles_v1.indd 15Guiding_Principles_v1.indd 15 8/14/12 1:21 PM8/14/12 1:21 PM

16

Guiding Principles for Engaging in Research

with Native American Communities

Native Centered

Respect

Integrity

Community

Relevance

Accountable &

Transparent

Continual

Dialogue

Build on

Strengths

Co-Learning

& Ownership

Self Reflection &

Cultural Humility

Honor Community

Time Frames

Authentic

Relationships

Build Community

Partnerships/Relationship

Identify a Project

& Tribal Approval

Apply for a Grant,

MOUs, Contract,

IRB, Approval

Study

Implementation

Final Reports and

Dissemination

Manuscript,

Publications,

Conference

Presentations

Feedback, Presentations,

Sustainability Plans

Data Analysis

and Findings

Guiding_Principles_v1.indd 16Guiding_Principles_v1.indd 16 8/14/12 1:21 PM8/14/12 1:21 PM

17

Resources

Fisher, P.A. & Ball, T.A. (2003). Tribal participatory research: Mechanisms of a

Collaborative Model, American Journal of Community Psychology, 32 (2/4), 207-216.

LaVeaux, D. & Christopher, S. (2009). Contextualizing CBPR: Key principles of

CBPR meet the Indigenous research context, Pimatisiwin, 7(1), 1-16.

Minkler, M. & Wallerstein, N. (2008). Community-Based Participatory Research for

Health From Process to Outcomes, 2nd Ed. Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA.

National Congress of American Indians Policy Research Center, Core Values: http://

www.ncaiprc.org/core-values

New Mexico Tribal Data Work Group. “Whose Data Is It?” and “Telling Our Story

With Data.” Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and New Mexico Behavioral Health

Collaborative. Electronic link: http://tribalspf.org/index.php?option=com_rokdownloa

ds&view=folder&Itemid=28

Northwest Portland Area Indian Health Board Epicenter, Conducting Research in

Indian Country: http://www.npaihb.org/epicenter/conducting_research_in_indian_

country/

Novins, D.K., Freeman, B., Jumper Thurman, P., Iron Cloud-Two Dogs, E., Allen,

J., LeMaster, P.L. & Deters, P.B. (2006). Principles for participatory research with

American Indian and Alaska Native communities: Lessons from the Circles of Care

initiative.

Tervalon, M. & Murray-Garcia, J. (1998). Cultural humility vs.cultural competence: a

critical distinction in defi ning physician training outcomes in multicultural education.

Journal of Healthcare for the Poor and Underserved, 9 (2), 117-125.

Wallerstein, N., & Duran, B. (2006). Using Community-Based Participatory Research

to Address Health Disparities. Health Promotion Practice, 7(3), 312-323.

Walters, K., Stately, A., Evans-Campbell, T., Simoni, J., Duran, B., Shultz, K., et al.

(2008). “Indigenist” Collaborative Research Efforts in Native American Communities,

146-173. In A. Stiffman (Ed.), The Nitty-Gritty of Managing Field Research: Oxford

University Press.

World Health Organization, Indigenous Peoples and Participatory Health Research:

http://www.who.int/ethics/indigenous_peoples/en/index6.html

Trainings and Presentation

Please contact: [email protected] or [email protected]

Guiding_Principles_v1.indd 17Guiding_Principles_v1.indd 17 8/14/12 1:21 PM8/14/12 1:21 PM

18

Special Thanks

We want to extend a special thanks to our partnering Native American communities and our more

experienced Native researchers who have been willing to teach us and help us learn from our

mistakes. They have also enriched our work by opening their communities to us, and by sharing

their strengths and knowledge. Without their collaboration in these research endeavors, we would

not have been able to develop the principles and vignettes we offer for other researchers. It is our

hope that you continue the progression towards social justice and having healthy, thriving tribal

communities.

Guiding Principles Workgroup

Marsha Azure (Turtle Mountain Chippewa), MSW, UNM Center for Rural and Community

Behavioral Health (CRCBH)

Doreen Bird (Kewa), MPH, UNM CRCBH

Judith Espinoza, MPH, Albuquerque Area Southwest Tribal Epidemiology Center (AASTEC)

Jessica Goodkind, PhD, University of New Mexico Prevention Research Center

Julie Griffi n Salvador, PhD, UNM CRCBH

Melina Salvador, MA, UNM CRCBH

Lindsay Smart, PhD, UNM CRCBH

Ophelia Spencer (Navajo), Tribal Survey Coordinator, AASTEC

Kee Straits (Quechua), PhD, UNM CRCBH

Nadine Tafoya (Mescalero Apache), MSW, LISW, Nadine Tafoya and Associates

Rachell Tenorio (Kewa), BSW, Native American Research Centers for Health (NARCH) Intern

Olivia Trujillo (Navajo), NARCH Intern

Eugene Tsinajinnie (Navajo), MPH, New Mexico Tribal Strategic Prevention Framework Project

Catie Willging, PhD, Behavioral Health Research Center of the Southwest

Acknowledgments

Steven Adelsheim, MD; Deborah Altschul, PhD; Utahna Belone (Navajo/Zuni/Oglala Sioux);

Robert Butler, MS; Roberto Chené, MA; Melanie Domenech Rodríguez, PhD; Cheryl Drapeau

(Zia); Kevin English, RPh, MPH; Francine Gachupin (Jemez), PhD, MPH; Brian Isakson, PhD;

Marianna Kennedy, MPA, MSW, MPH; Lindsay Lennertz, PsyD; Tassy Parker (Seneca), PhD;

Michele Suina (Cochiti); Greg Tafoya (Santa Clara), MPH; Esther Tenorio (San Felipe); Nina

Wallerstein, DrPH; and the New Mexico Center for the Advancement of Research, Engagement,

& Science on Health Disparities; and the many others from our institutions, research centers, and

Native American communities.

Guiding_Principles_v1.indd 18Guiding_Principles_v1.indd 18 8/14/12 1:21 PM8/14/12 1:21 PM