Conflict Resolution Activities for

Middle School Skill-Building

Contents

WHAT IS CRAMSS? ……………………………………………………………………… 4

TIPS FOR USING CRAMSS ………………………………………………………………. 5

BUILDING A SAFE ENVIRONMENT …………………………………………………….. 6

Ice Breaker And Relationship Builders

Class Agreements …………………………………………………………… 7

Chain Links ……………………………………………………………………. 8

Step Circle ……………………………………………………………………. 9

Mail Person …………………………………………………………………... 11

FriENN Diagram ……………………………………………………………... 12

Number Line ………………………………………………………………… 16

UNDERSTANDING CONFLICT ………………………………………………………..... 18

Constructive Response to Conflict

Conflict Response Ts ……………………………………………………….. 19

Constructive v. Destructive Responses ………………………………… 20

Conflict Response Cycle …………………………………………………. 21

Conflict Management Styles

Conflict Style Shuffle………………………………………………………... 25

Types of Conflict

Apple Arguments ………………………………………………………...… 28

Picture Types ………………………………………………………………... 31

Imbalance Challenges ………………………………………………….... 36

EMOTIONAL AWARENESS AND COMMUNICATION …………………………...…. 38

Vocabulary Building

Wear Your Emotions on Your Wall …………………………………... 39

Ang-o-Meters …………………………………………………………… 40

Mad Lips …………………………………………………………………. 42

Active Listening and Barriers

Classroom Complaint Line …………………………………………… 45

ReQuests …………………………………………………………………. 46

Listen“ing” ……………………………………………………………….. 47

Telephone………………………………………………………………... 48

I-Messaging

When, I Feel, I Need …………………………………………………… 50

You and I-Messages …………………………………………………… 52

I-Interpreter …………………………………………………...…………. 53

NEGOTIATION AND MEDIATION SKILLS ……………………………………………... 55

Negotiation Types and Skills

Cross the Line ……………………………………………………….…... 56

What’s Fair? ...................................................................................... 58

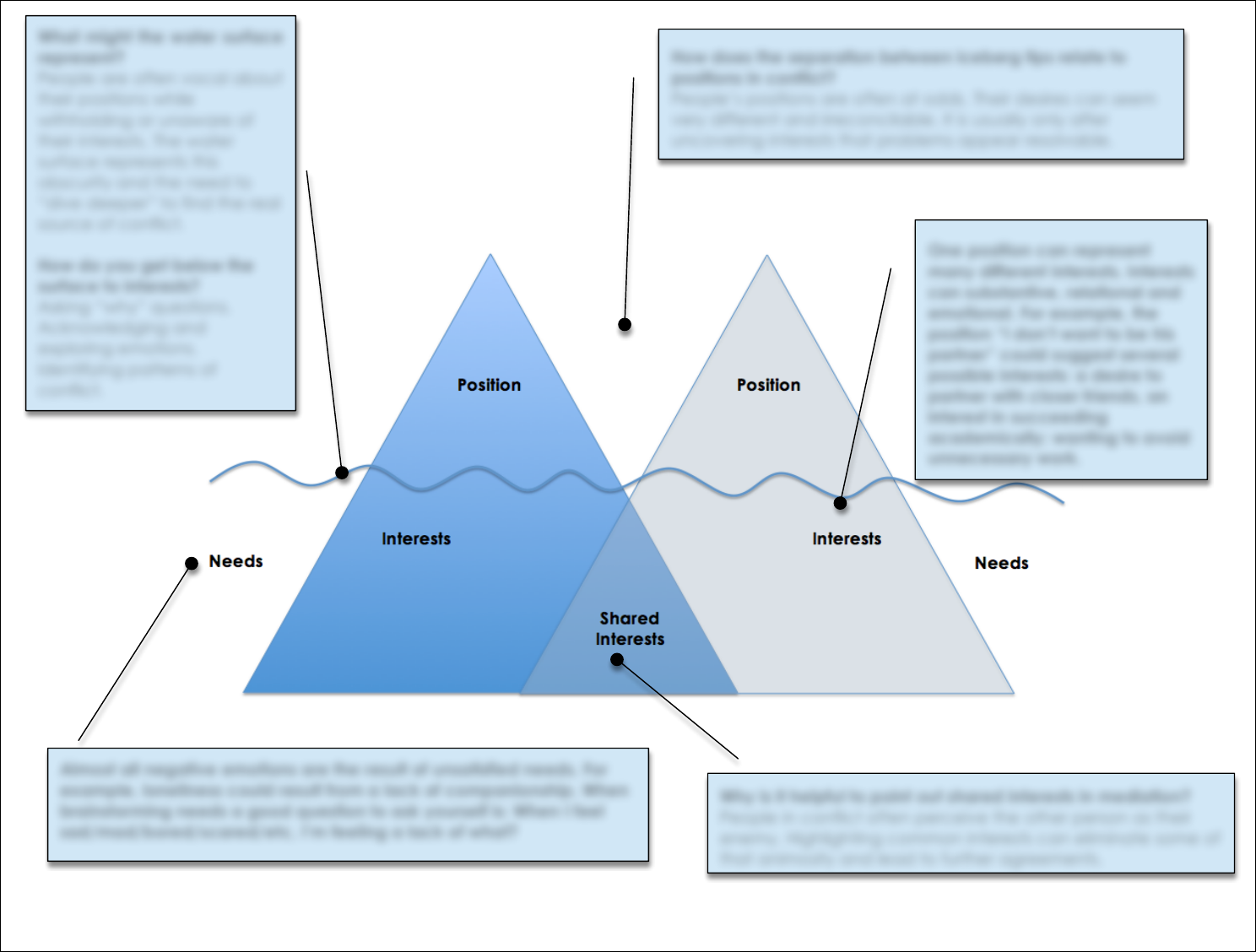

Positions, Interests and Needs

Mediator’s Iceberg …………………………………………………….. 60

From Positions to Interests ………………………………..…………… 63

The Pitchers ……………………………………………………………… 64

Paraphrasing and Reframing

Speed Dating ………………………………………………………….... 66

3 Framing ………………………………………………………………… 68

ReFRAMES ……………………………………………………………….. 70

Role-plays and Mediation Resources

Blue Streak ……………………………………………………………….. 73

Phone Games …………………………………………………………... 74

Rumor Amor ………………………………………………………..…… 75

Role-play Discussion Questions …………………………………….... 76

Role Player Prep Sheet …………………………..……………………. 77

Peer Mediator Cheat Sheet ……………………………….………… 78

What is CRAMMS?

Conflict Resolution Activities for Middle School Skill-Building (CRAMSS) is an

online repository of conflict resolution education exercises designed to

engage middle school students in the fun, collaborative learning of

appropriate conflict management and problem solving. Conflict resolution

education (CRE) programs strive to impart students with nonviolent conflict

resolution skills and opportunities for emotional growth and self-definition.

With these, students form safer learning environments and are better

prepared to peacefully enter a multicultural world. This repository is intended

to aid conflict educators in the achievement of these goals. While by no

means a standalone program, these activities align with and are meant to

supplement existing CRE curriculums.

Together, the complied activities cover four fundamental areas of conflict

education: Building a Safe Learning Environment, Understanding Conflict,

Emotional Awareness and Communication, and Mediation and Negotiation

Skills. They address a variety of competencies including: emotional

vocabulary building, empathy building, active listening, I-messaging,

stereotype checks, interest identification, reframing and paraphrasing.

Each activity contains a description of its intended learning objectives,

directions for running the activity, discussion questions for debrief and

reproducible handouts (when applicable). Their content is informed by both

the recurring concepts in prominent CRE programs nationwide and the

author’s own experience as a conflict educator. While their process design

conforms to fundamental principles of middle school pedagogy. Seeking to

stretch students’ bodies and minds in the meaningful exploration of conflict,

CRAMMS activities should integrate easily into CRE lesson plans.

Tips for Using CRAMSS

Voluntary Participation

All CRAMSS activities should be presented as voluntary. Students should

not feel obligated to share personal or potentially vulnerable information.

To reflect this voluntary nature, all CRAMSS directions are formulated as

requests: “Ask students to form a circle; Ask students to share; etc.”

Instructors are encouraged honor the entreating, rather than directive,

quality of these of activities. In this way, the exercises become joint

endeavors in the place of compulsory assignments.

Students should be given the option to observe the exercise or “pass” on

their turn. Observation need not be a passive action. Students who wish to

observe can provide valuable feedback to peers, and should be invited

to join activity debriefs and to offer their insights.

Brainstorms and Idea Gathering

During brainstorms, it is helpful to separate option generation from option

evaluation, an approach that (not coincidentally) is often found in

mediation and negation practices. This technique acknowledges all

student suggestions, giving them equal consideration (and a place on the

board) before ideas are evaluated in a structured, collaborative manner.

When appropriate, CRAMSS activities list option generation (in the form of

brainstorms) and option evaluation as separate, sequential steps to reflect

this approach.

Discussion and Debrief

Instructors are encouraged to foster discussions’ organic direction,

allowing students explore those questions most pertinent to them. CRAMSS

activities are meant to trigger curiosity, and debriefs offers students a

platform to voice theirs. The teacher’s role as a facilitator should be to

expand on, summarize and validate students’ interests. When facilitated

properly, post activity discussions will be mostly student driven.

During discussion, instructors should make space for, and validate, all

student contributions. Rather than distinguishing between right and wrong

responses, teachers are encouraged to help students recognize when

their statements are facts and when they are opinions.

Building a Safe Environment

Middle school is a transitional period for students. They find themselves with

greater autonomy, mobility and self-awareness along with many questions

surrounding how to manage these new responsibilities. Because of this, it is

crucial that middle school educators and educational materials work to

orient students with their learning environments, making them more

comfortable with each other and their teachers. Students learn, and

contribute to others’ learning, best when unencumbered by fear of ridicule

or being out performed. Physical, emotional and cognitive safety are all vital

to middle school classrooms, and especially in CRE classrooms where the

very subjects at hand are heightened emotions, altercations, biases,

difference of opinions and so on. A safe environment is widely

acknowledged as perquisite to effective learning, and is consistently

reiterated as the first step in the development of conflict resolution education

programs.

The activities in this section help build stronger relationships between

students, aiming to ameliorate the common discomfort of unfamiliarity. They

also support students’ in their natural process of identity formation and self-

definition, bringing to focus the life experiences and beliefs that make them

unique as well as those they share with others. These activities are fun, active

and powerful. Ideally, they will help create a safe, comfortable learning

space as students come to know each other as resources, cooperative

partners and friends.

Activities

Class Agreements

Chain Links

Step Circle

Mail Person

FriENN Diagram

Number Line

CLASS AGREEMENTS

Discussing conflict can be hard. It requires

trust, acceptance, respect and a

perception of safety. Most students know

they’re expected to treat one another

respectfully, but are not always sure, or

perhaps haven’t been asked to consider,

what respectful treatment looks like

specifically. Indeed, it changes context to

context, group to group and person to

person. Posting a list of jointly created

classroom agreements or guidelines can

help make this more explicit.

DIRECTIONS

1. Brainstorm with your class about behaviors that would make the classroom safe and most

conducive to learning. Brainstorm questions might include:

• When you’re sharing an idea, what would you like your classmates to do doing?

• What would you like your teachers to be doing?

• What can your peers do to show you respect?

• What requests do you have of your classmates while in our room?

2. Record a list of ideas on the board. Accept all ideas, initially.

3. Push for specificity. For instance, if students’ suggest, “Be respectful,” ask them what that

looks like.

4. Once everyone’s ideas are listed, ask the class if they can all agree to the proposed

guidelines. If there’s disagreement, ask why. Modify the list until it’s agreeable to all.

5. Have your students turn the list into a large poster.

6. Display the poster prominently in the room and refer to it when helpful.

ALTERNATIVELY

Ask your students to write down a time they remember feeling disrespected or unsafe in a

classroom. Ask what behaviors or rules might have prevented that occurrence. Use their

responses to spur your brainstorm.

OBJECTIVES

• Promote a sense of intellectual, emotional

and physical safety in the classroom.

• Gain students’ buy-in and promote

greater participation from all students.

• Smooth and enrich group discussions

throughout the course

CHAIN LINKS

Familiarity is an essential part of feeling safe in any

environment. In the classroom, your surroundings

are your classmates. When discussing conflicts or

other potentially polarizing subjects, it’s important

to feel comfortable with the people around you.

Many students in the class may know each other or be friends, but others may not. This activity is

an easy icebreaker that will help students become more familiar with one another and hopefully

feel safer in the classroom.

DIRECTIONS

1. Ask the class to stand in the middle of the room. Make enough space for everyone to

stand in a circle, but do not form one, yet.

2. Begin the activity by saying your name and a fact about yourself that’s important to you.

Then make a “link” by placing your hand on your hip and sticking out your elbow.

EX: I’m Avery and I am an older brother.

3. Then, someone from the class will link arms with you, someone who also identifies with the

stated fact. S/he will repeat that fact and add another one, making another “link” with

his/her opposite arm.

EX: I’m Allen and I’m also an older brother. I also belong to a sports team.

4. Repeat this process until everyone in the group has joined the chain. If someone names

a fact that nobody else shares, ask him or her to name a different fact. (Once a student

has joined the chain, they may not change places. Only students outside of the chain

may form a new link. Finding commonalities may become more difficult as the remaining

group dwindles.)

5. Once the whole class has joined the chain, ask the two people at either end of the chain

to find a commonality and link arms, creating a closed circle.

OBJECTIVES

• Students become better acquainted

and strengthen peer relationships.

STEP CIRCLE

Conflicts can be isolating, especially when

combined with the transitions and self-

consciousness of early adolescence. Often, middle

school students feel alone with their lot in life,

confident that others will not, or cannot,

understand their feelings, thoughts or situations. This

activity can help to penetrate that isolated

perception and make the classroom a more

comfortable place to discuss those issues like

emotion, biases and personal points-of-view that

are so essential to conflict education and resolution.

DIRECTIONS

1. Have the class stand in a large circle.

2. Inform the class that this is a completely silent activity, and ask them not to comment,

laugh, scoff or indicate during the exercise.

3. Instruct the students to listen to the following statements. Ask them to take one step into

the circle if they identify with the statement or feel it applies to their life. Ask them to

silently step in, pause for 2 seconds to observe and appreciate others, and then step

silently back into the outer circle.

• Encourage students to interpret the statements however they like, but ask

them not to question the statements or seek clarification.

• Emphasize that stepping in is always voluntary.

4. Read the I-statements aloud one at a time, pausing between each question for step-ins.

Use the statements provided and/or develop your own.

ALTERNATIVELY

If you feel comfortable, ask the circle to begin generating its own I-statements. Follow the same

process, only instead of reading, have students step in, one at a time, while making a personally

significant statement.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

• How did this activity make you feel? What did it make you think?

• What, if anything, surprised you during this activity?

• What did this activity make you realize about your classmates? What about yourself?

OBJECTIVES

• Students build positive classroom

relationships and learn to identify

with one another.

• Provide a safe, controlled space

for students to express their beliefs

and experiences.

STEP CIRCLE I-STATEMENTS

• I am an artist.

• I like to play sports.

• I am a good student.

• I am male.

• I am female.

• I am a girl.

• I am a boy.

• I identify strongly with one gender.

• I am an only child.

• I am the oldest child in my family.

• I am the youngest child in my family.

• I am a middle child.

• I live with both my parents in the

same home.

• I have divorced parents.

• I live with member(s) of my extended

family.

• I have never known my mother,

father or both.

• I have lost a family member.

• I feel responsible for my brothers and

sisters.

• I have very strict parents.

• I was born in the United States.

• I am American.

• English is not my first language.

• I am multi-lingual.

• I have family or friends living in

another country.

• I have travelled outside of the

country.

• I am or have been part of a majority.

• I am or have been part of a minority.

• I regularly see my culture

represented in the media.

• I often see my culture

misrepresented in the media.

• I learned or am learning about my

peoples’ culture, heritage and

customs in History or Social Studies.

• I believe I have at some point been

treated differently because of my

ethnicity.

• I have a disability.

• I think I will go to college.

• I am part of a wealthy family.

• I usually have access to the things I

need and want.

• I have lived in the same house my

whole life.

• I have moved around a lot.

• I and/or someone I know has been

arrested.

• I and/or someone I know has used

drugs.

• I have a friend or family member

with a metal illness.

• I have a friend or family member

with an addiction.

• I sleep as much as I need to most

nights.

• I eat as much as I need to most days.

• I sometimes feel depressed.

• I know someone who has attempted

suicide.

• I knew someone who completed

suicide.

• I have ended friendships.

• I have recently made a new friend.

• I would fight on behalf of a friend.

• I sometimes feel anxious and cannot

explain why.

• I have been bullied.

• I have bullied someone else.

• I or someone I know identifies as gay,

lesbian, bisexual or transgender.

• I expect a lot from myself.

• I am religious.

• I am popular.

• I am political.

MAIL PERSON

Many students in the class may already know

each other or be friends, and others may not.

Mail Person is a fun, physical activity gives

students an opportunity to share personal

information with one another and discover

commonalities between themselves. This activity is an easy way to build familiarity between

students and hopefully make all students feel more comfortable in the classroom. Use Mail

Person as an icebreaker or as a constructive way to burn energy.

DIRECTIONS

1. Arrange seats in a large circle. There should be one fewer chairs than people. Ask one

student to begin as the Mail Person and stand in the middle of the circle.

2. The Mail Person initiates the activity by saying, “I’m the Mail Person from (name any

place) and I have mail for everyone who (name something true of him or her),” This fact

could be a favorite food, a certain life experience, a belief, color of hair, etc.

EX: I’m the Mail Person from Brooklyn and I have mail for everyone who celebrates

Hanukkah.

3. All students in the circle for whom this fact is true should quickly get up and move to

another, not adjacent, seat. In the style of musical chairs, the student left without a seat

stays in the middle and becomes the new Mail Person.

4. Continue play until every student who wants a turn has had one.

ALTERNATIVELY

The race for a new chair is exciting and competitive. For more collaborative game play,

ask all students for whom the fact is true to stand in the middle of the circle and quickly

elect a new Mail Person together. Ask each group how they made their decision.

OBJECTIVES

• Students become better acquainted

and strengthen peer relationships.

FRIENN DIAGRAM

We all identify with parts of our personality and

cultures. You might identify as an artist or sister or

Native American or male. While we may feel an

especially strong connection to certain attributes,

we’re comprised of many. It’s important to

recognize that others hold different values and identify with different roles. These values may

seem foreign, but they’re worthy of acknowledgement and respect. This activity will help

students express their character, appreciate their uniqueness, and at the same time, consider

their commonalities.

DIRECTIONS

1. Pair students and ask them to complete the worksheet “FriENN Diagram.”

2. Ask students to generate their own interview questions or use the questions provided

below. Their questions and diagrams should reflect the personal qualities that are most

important to them.

3. Once completed, ask groups to share their diagrams with the class.

ALTERNATIVELY

• Ask each pair to partner with another group and compare their diagrams. What

connections do you share with the other group? Which connections are unique?

• Create new pairs! Ask students to create “FriENN Diagrams” with 2, 3, 4, or ALL of their

classmates.

• Ask students to form groups of three and complete the three set diagram.

OBJECTIVES

• Students appreciate their classmates’

character and cultures and

strengthen peer relationships

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

• Did you discover anything surprising about your partner? Any interesting similarities or

differences?

• Did any pair find NO shared qualities? Can you think of any now?

• Which do you think is more important: our similarities or our differences? Why?

FRIENN DIAGRAM INTERVIEW QUESTIONS

• What is your nationality?

• What is your favorite holiday?

• What is your favorite kind of food?

• How many siblings do you have?

• Are you a younger, older, middle or only child?

• Where are you from?

• Where are your parents from?

• What sports do you like to play?

• What is your favorite hobby?

• Are you religious?

• What kind of music do you like?

• Do you have a job?

• Do you come from a large or small family?

• What is your favorite animal?

• Do you have any pets?

• What is your favorite place you’ve ever been?

• Where do you want to go that you haven’t been?

• Do you have a girlfriend/boyfriend?

• What is your dream car?

• What is your favorite subject in school?

• At which subject do you think you’re best?

• What is your least favorite subject?

• Do you play any instruments?

• Do you act?

• Would you call yourself an artist?

• What languages do you speak?

• Where do you go with friends?

• Are you more talkative or quieter or somewhere in between?

• What is your favorite book, show or movie?

• How old are you?

• What do you want to study in college?

• What is your dream job?

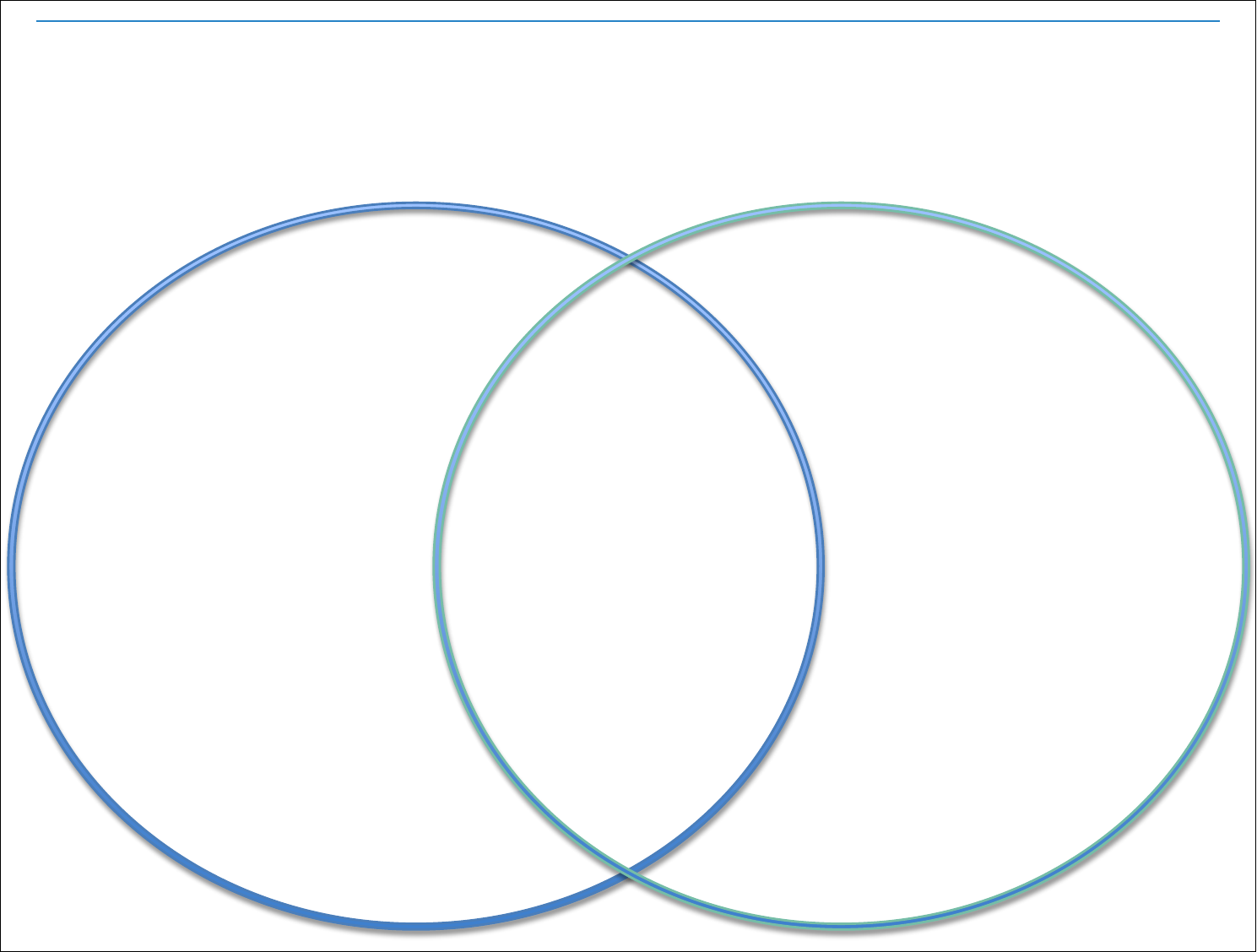

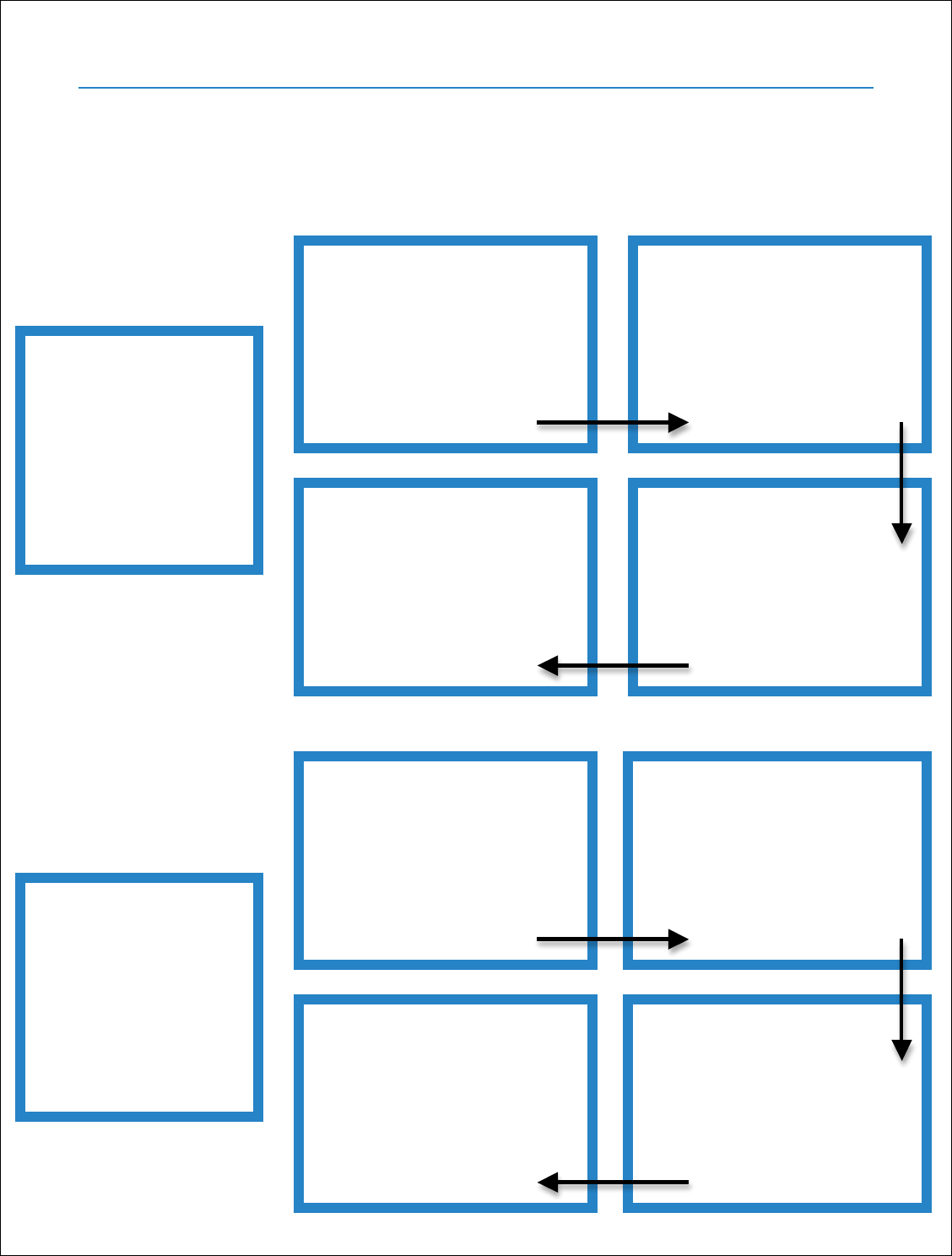

FRIENN DIAGRAM

DIRECTIONS: Take turns interviewing your partner about his/her personality and culture. Write one partner’s unique characteristics in left

circle and the other’s in the right. Write shared traits in the overlapping space. Be sure to cover the personal qualities that are most important to

you both! EX: My nationality is vey important to me. I’m Polish. What’s your nationality?

Name:

Name:

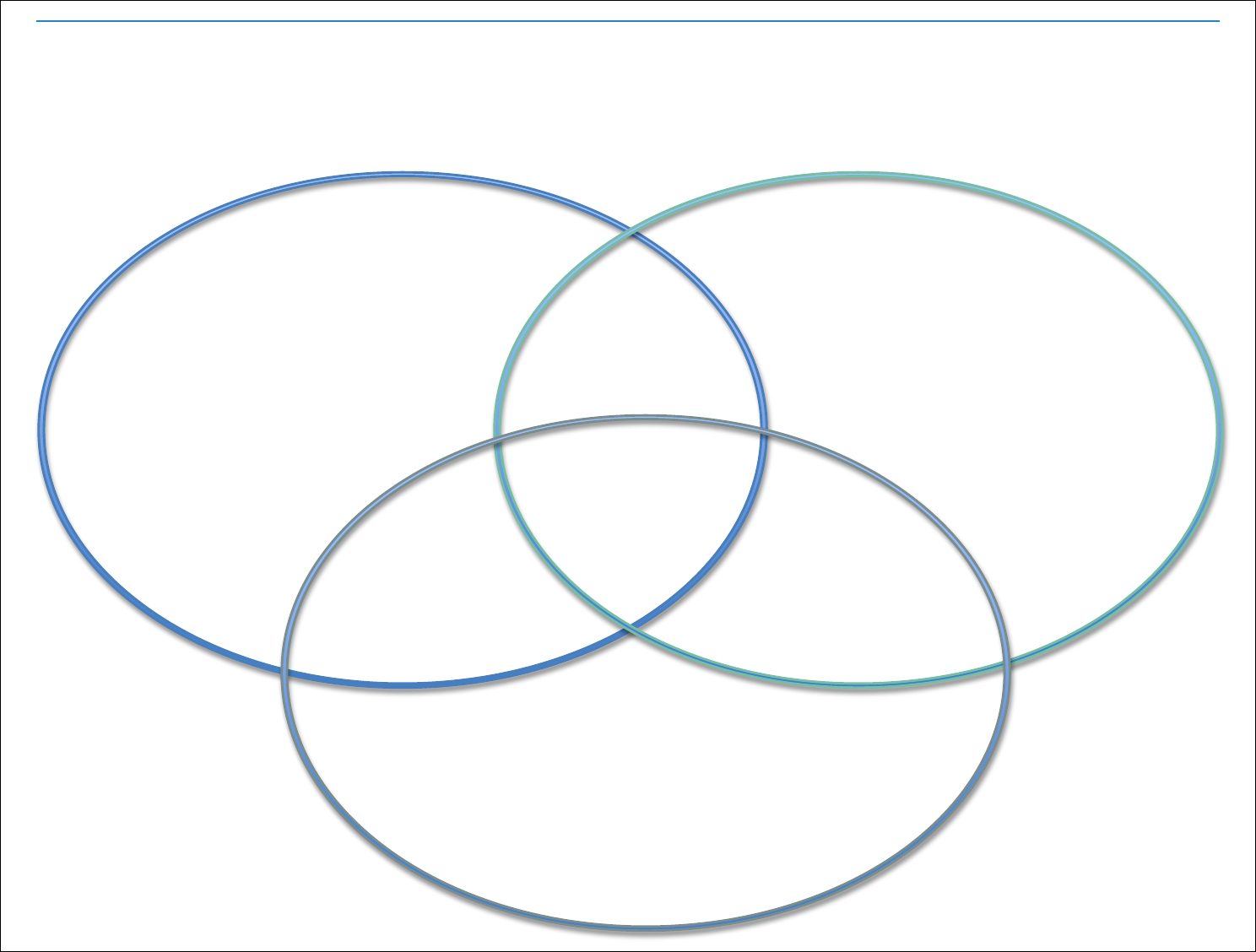

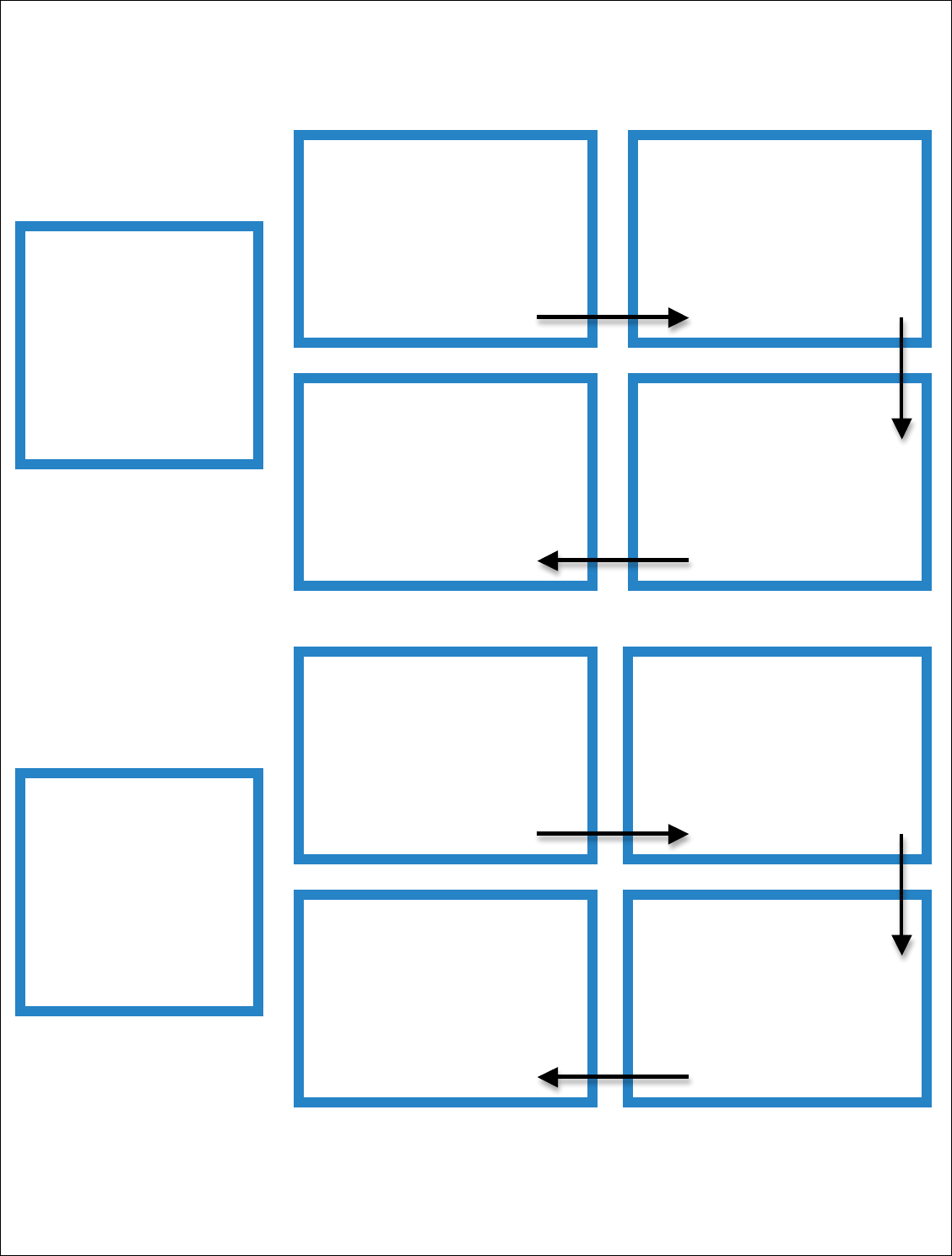

FRIENN DIAGRAM

DIRECTIONS: Take turns interviewing your partners about their personality and culture. Write one partner’s unique characteristics in left oval,

one partner’s in the right oval and one partner’s in the lower oval. Write shared traits in the overlapping spaces. Be sure to cover the personal

qualities that are most important to you all! EX: My nationality is vey important to me. I’m Polish. What are your nationalities?

Name:

Name:

Name:

NUMBER LINE

Difference of opinion is a common and exciting

part of life. We all have our own ideas and

opinions, but we’re not always given the chance

to describe those ideas or examine where they

came from or how they were developed. This

activity gives students the opportunity to express

their opinions both verbally and visually, as well

as listen to and consider other points of view. It

also helps illustrate that most issues are not black-

and-white, but rather a wide range of grey.

DIRECTIONS

1. Create a large number line across your

classroom wall by posting three signs, reading 0, 50 and 100.

2. Ask your students to stand along the line, in random order at first, and listen to the

statements you read.

3. Read prompts aloud to the class. Use the prompts provided or create your own.

4. After each statement, instruct your students to position themselves along the number line

according to how much they agree with the statement (0 being not at all). Ask them to

pick a specific number.

5. Call on individual students to explain which number they’re at and why.

6. Ask the other students to listen carefully, but not to talk or contradict the speakers during

their explanations.

7. Instead, if their minds change during a classmate’s explanation, ask students to respond

by moving silently along the number line.

8. When you see a student make a dramatic move, ask them to reflect on what their

classmate said that caused the shift.

ALTERNATIVELY

If the line feels too cluttered, have students go

up 2, 3 or 4 at a time, and give each group one

prompt.

Leave the number line up all year! Use it to poll

the class, or for structure when debate arise

between students.

Discussion Questions

• What new information did you learn

about these topics?

• Where do our opinions come from?

How are they shaped?

• If someone stands at a different spot

along the line, are they wrong?

• How does it feel listening to someone

with whom you disagree?

OBJECTIVES

• Students learn to articulate their

positions on social issues.

• Students learn to listen to differing

opinions considerately.

• Students understand that most issues

are not black-or-white, right-or-

wrong, but multidimensional and

nuanced.

NUMBER LINE PROMPTS

• Profanity should be allowed in schools.

• The drinking age should be lowered to 18.

• Marijuana should be legalized.

• Assisted suicide should be allowed.

• There are some things worth killing for.

• The President is doing a good job.

• Dogs are better pets than cats.

• Abortions should be legal in all states.

• Gay marriage should be legal in all states.

• Boys are better at sports than girls.

• Everyone should go to college.

• All problems can be solved with enough money.

• Religion is an important part of life.

• It is wrong to eat animals.

• There’s no better place to live than the United States.

• Videogames are an unhealthy influence.

• New technology almost always improves quality of life.

• Regular citizens should be allowed to carry guns.

• Fist fighting should only ever be a last resort.

• It’s important to have neat handwriting.

• Grades are an accurate measure of intelligence.

• Sometimes it is OK to lie.

• Sticks and stones really do hurt more than words.

• It’s good that we have nuclear weapons.

• Texting is preferable to talking on the phone.

• The type of clothes you wear matters.

• Men and women are fundamentally different.

• We should all be worried about climate change.

Understanding Conflict

Too often, conflicts carry a negative connotation in the minds of young

people. They are thought of as undesirable and primarily associated with

anger, sadness and violence. Conflict resolution education programs

adamantly stress the need to reverse this thinking. Students should

understand conflicts as having positive possibilities and as a necessary,

natural part of life. When handled appropriately, conflicts are opportunities

to make something better. They challenge us to learn, grow and create.

Unfortunately, negative perceptions of conflict pervade largely because of

the poor ways in which people choose to respond to it. It is important that

students understand that there are a variety of options when it comes to

handling conflict and that their reaction in conflict situations can greatly

influence the quality of outcome.

The activities in this section expose students to different types of conflicts and

conflict sources. They ask students to develop constructive approaches to

conflict resolution and consider how those approaches differ from

destructive ones. Students will also be exposed to traditional conflict

management styles and asked to think within these frameworks. Together,

these activities work to portray conflicts as potentially positive phenomenon,

because when viewed as such, conflicts become an opportunity for growth,

inspiring those with the appropriate skills to cooperate in their resolution.

Activities

Conflict Response Ts

Constructive v. Destructive Responses (handout)

Conflict Response Cycle

Conflict Style Shuffle

Apple Arguments

Picture Types

Imbalance Challenges

CONFLICT RESPONSES TS

We often think of conflicts as bad or unfortunate,

situations to be avoided if possible. Actually, in

most cases, conflicts are opportunities to make

something better. They challenge us to learn,

create and improve. That’s why textbooks call

them math “problems.” Conflicts get their bad

rap from the ways in which people choose to

respond to them. There are always multiple ways

to react in conflict situations, some destructive

and others constructive. This activity will help students understand that our responses help

determine whether conflicts lead to fall out or productive problem solving.

DIRECTIONS

1. Group students into teams of three.

2. Within their groups, ask students to come

up with a conflict. It can be imaginary or

a conflict from one of their lives.

3. Ask each group to create a T-chart for its

conflict, listing three constructive ways

one might respond to that conflict and

three destructive ways. Emphasize that

constructive ways likely lead to learning,

problem solving and better relationships,

while destructive ways will lead to

escalation and enmity.

4. Ask each group to share their conflict and

T-chart with the class.

5. For every constructive and destructive

response shared, ask a listening student

provide one possible consequence or

outcome.

OBJECTIVES

• Students understand that conflicts

are not necessarily negative.

• Students understand how their

reactions to conflict help shape its

course.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

• What is challenging about coming up with constructive response when you’re actually in

a conflict?

• Our T-charts list only constructive and destructive responses to conflict. Are all responses

either constructive or destructive, or might your response affect conflict in a different

way?

EXAMPLE

My brother always wears my

clothes.

Constructive Destructive

1. Ask if he knows

which clothes

belong to me. Offer

to mark my tags.

2. He seems to like

my shorts. Offer to

show him where I

bought them.

3. Explain that his

wearing my clothes

bothers me. See if he

has any solutions.

1. Yell at him or hit

him whenever I see

him in my clothes.

2. Wear his clothes

without asking,

since he’s in mine.

3. Keep all my

clothes dirty so he

won’t want to

wear them.

Name: Date:

CONSTRUCTIVE V. DESTRUCTIVE RESPONSES

DIRECTIONS:

Consider the conflicts below. Think about both a constructive and destructive way to

respond to each.

1. In years past, both the debate team and the Mathlete team received money from the

school for materials and to travel to competitions. This year, budget cuts have left less money

for student clubs, and the school will only be able to fund one of the teams. You’re on the

debate team and would hate to see it disappear. You also have many friends who are

Mathletes and know they value their club just as much as you value yours.

How could you respond to this conflict destructively? What consequences might result?

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

How could you respond to this conflict constructively? What consequences might result?

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

2. This year for Halloween you and two of your friends dressed up as The Three Amigos. You

wore sombreros and vests and spoke with a fake accent. During the day you learn that your

costume has offended some of your classmates. They feel that your dress and some of your

actions are disrespectful to their culture. You don’t mean any harm, but you’re really proud

of your costume and would like to continue wearing it.

How could you respond to this conflict destructively? What consequences might result?

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

How could you respond to this conflict constructively? What consequences might result?

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

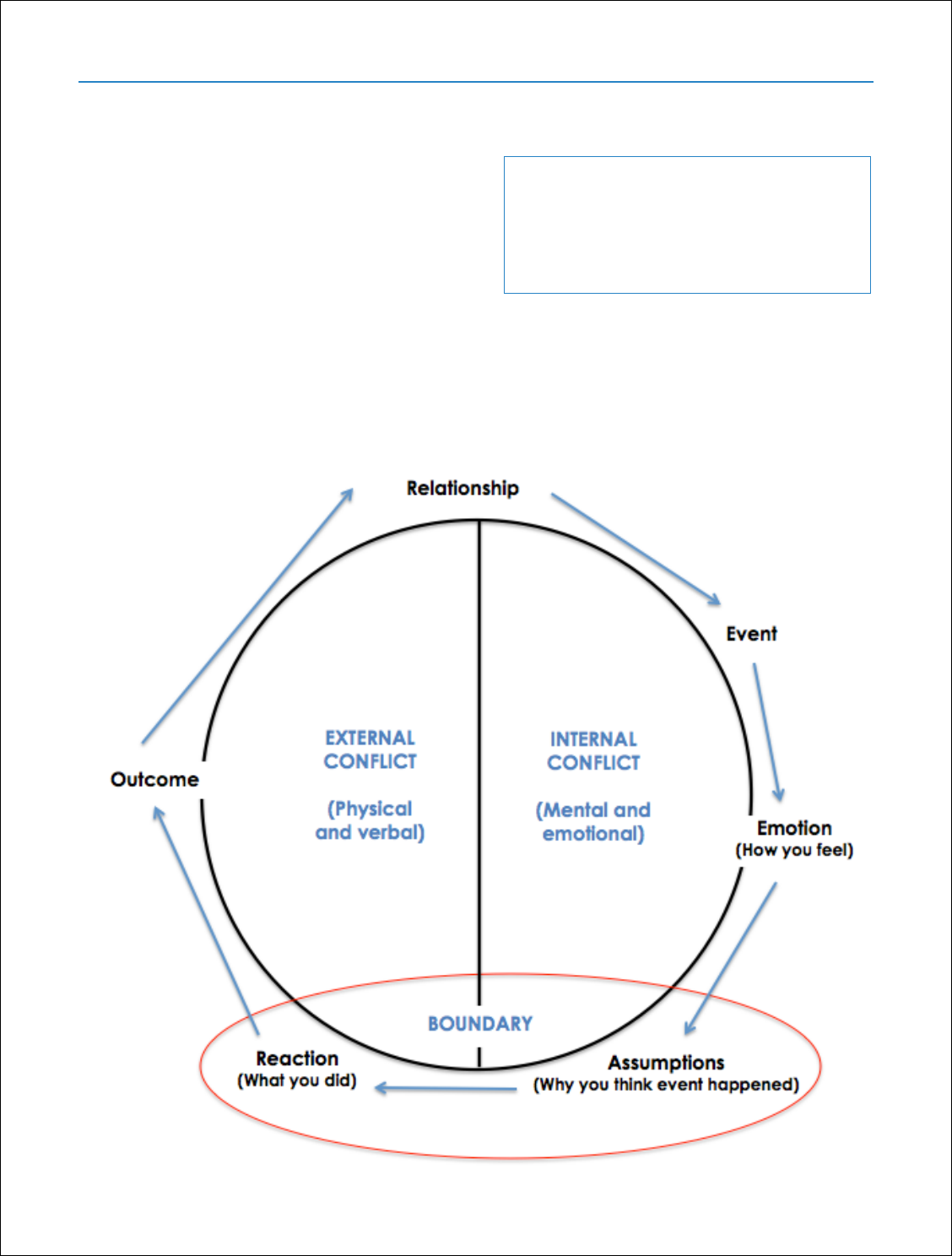

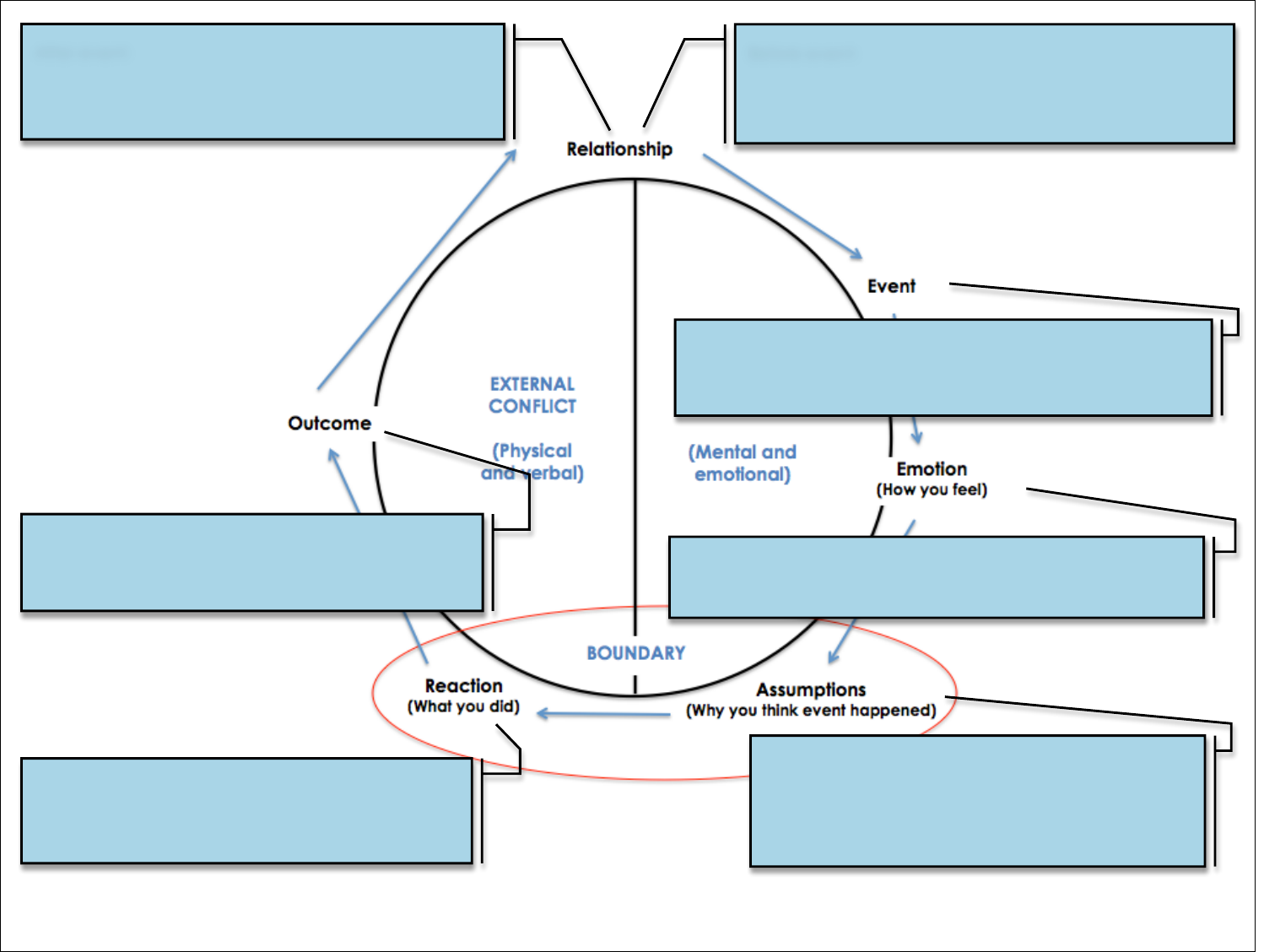

Conflict Cycle adapted from Hillsboro Mediation Program’s “The Anatomy of Conflict” (2014)

CONFLICT RESPONSE CYCLE

When confronted by things we perceive as

offensive or threatening, we react. For the most

part these reactions are fast and automatic. We

can respond so quickly that we sometimes end

up in conflict without realizing how it’s happened.

This exercise helps students understand the

mental process that fuels negative interactions,

and, hopefully, use that understanding to

respond more productively to upsetting stimuli.

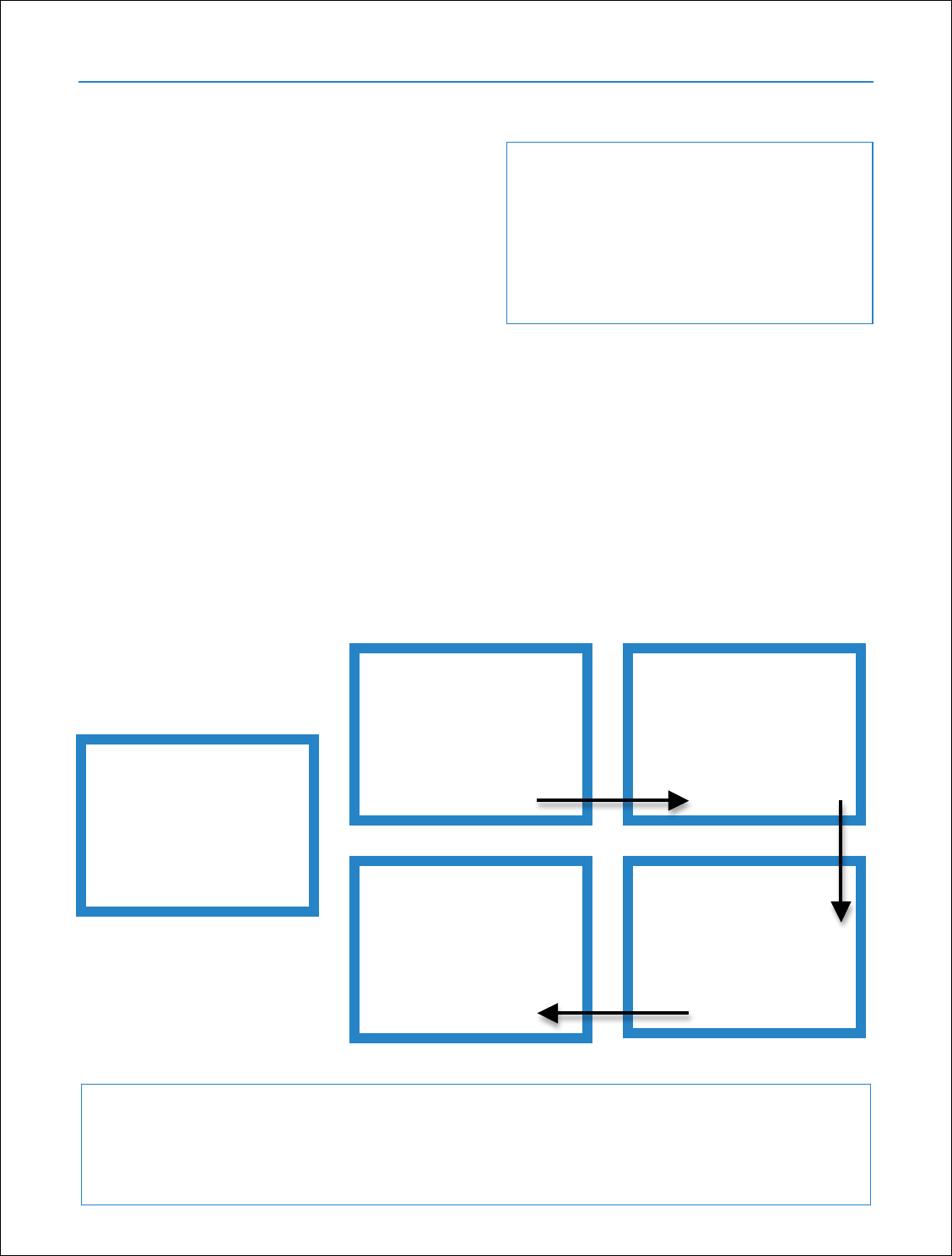

LECTURE TOPIC

Draw and explain the conflict cycle below.

OBJECTIVE

• Students understand their internal

responses to triggers and how they

influence external reactions.

Conflict Cycle adapted from Hillsboro Mediation Program’s “The Anatomy of Conflict” (2014)

Relationship: We each have unique relationships with the things around us that are shaped by

our previous interactions. We develop patterns of interaction with nearly everything, classes,

foods, groups, and events, however, in conflict we’re typically thinking about interactions

between individuals. Normal interaction is simply the way usually engage with a particular

person or thing.

EX: I see Jenna around, but we don’t really talk.

Event: An event is the trigger or action that is inconsistent with your normal relationship. In

conflict, these are negatively perceived interactions. Trigger events have the potential to

reshape relationships.

EX: Jenna pushed me in the hallway.

Emotional Response (internal): Your internal responses are the emotions roused by a trigger.

EX: hurt, scared, embarrassed, surprised, angry.

Assumptions (internal): At this stage you try to rationalize why the trigger event occurred. Often,

we have limited information about the situation, so we rely on intuitions and assumptions. Our

interpretation of an event can be very different from another’s.

EX: Jenna pushed me because she doesn’t like me; Jenna pushed me because she’s a mean

person.

Boundary: The boundary is actually a decision. It’s the decision, not always consciously made,

about how to act outwardly in response to the event, your emotions and assumptions.

EX: I’m going to push Jenna back; I’m going to just ignore it.

Reaction (external): The execution of the decision you made at the boundary. Your external

reaction has the potential to majorly improve the situation OR drive it further into conflict.

EX: Pushing Jenna.

Outcome: The impact your external reaction had on the situation or relationship. Whether the

outcome is positive or negative largely depends on how you choose to respond.

EX: You and Jenna get into a yelling match in the hallway; You ask Jenna why she pushed you

and it turns out she just wasn’t watching her step.

Relationship: As you return to the top of the

cycle, your notion of normal interaction has

changed, sometimes drastically. Your new

relationship can be much improved OR one in

which you’re more sensitive to future trigger

events and characterized by chronic conflict.

EX: Now I avoid Jenna when I see her.

The red oval is important! Here is where

you have control. You have the

opportunity to respond effectively and

resolve the problem OR to respond

impulsively and escalate the conflict.

When you’re in the oval, try to break

down the process. Check your

assumptions. Consider the likely

consequences of your reaction. It’s hard

to do, but immensely useful!

Conflict Cycle adapted from Hillsboro Mediation Program’s “The Anatomy of Conflict” (2014)

DIRECTIONS

1. Reconstruct the conflict response cycle in your classroom. Arrange six chairs in a loose

circle and assign each chair to a phase in the conflict cycle. Or, label six pieces of paper

and tape them to the ground.

2. In pairs, ask students to fill out the provided worksheet, detailing a conflict cycle from one

of their lives. If they’re uncomfortable sharing a personal story, ask them to invent one.

3. Ask each group to share their cycle. Ask one student to move his/her body from stage to

stage as his/her partner narrates the story.

4. Request that the rest of the class to watch silently. Remind them that sharing a personal

story requires trust and safety.

ALTERNATIVELY

If the full cycle seems too complicated at first, modify it. A simpler version of the cycle

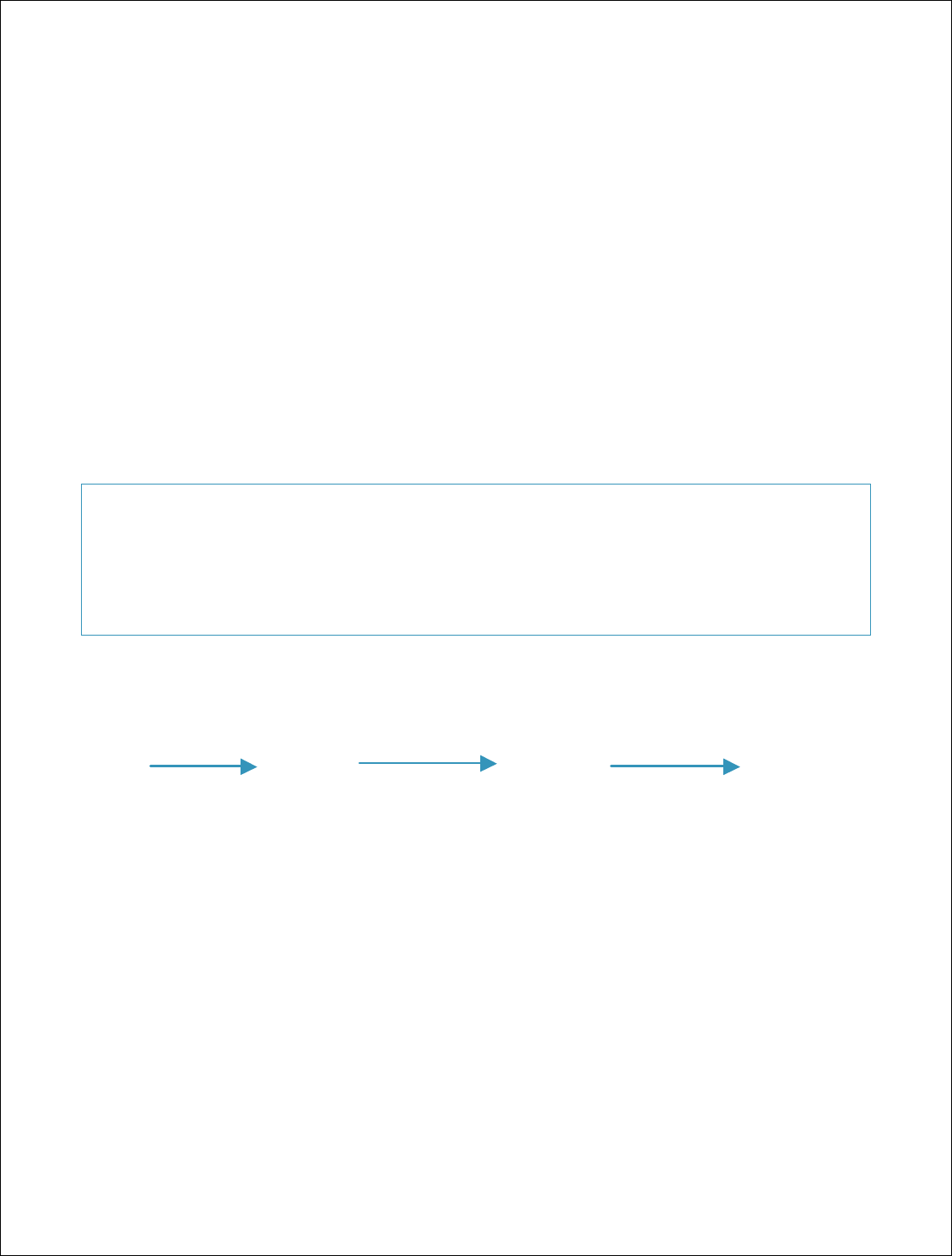

could look like this:

Event Emotion Reaction Outcome

Once students become comfortable with the concept, you can incorporate additional

phases like Assumptions and Relationship impact

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

• What do you think is the most important phase of the cycle and why?

• Why is it helpful to break down the cycle step-by-step?

• Are you currently in any conflicts with sensitive triggers? If so, how might you improve

that relationship?

Before event:

After event:

Internal

Conflict

CONFLICT STYLE SHUFFLE

There are a variety of ways to resolve a problem.

The way we approach a conflict depends on our

means, beliefs, the importance of the outcome

and the importance of our continued relationship

to those involved. There are five commonly

identified conflict management styles. We may

be prone to one, but the style we chose to adopt

usually depends on the situation. All styles have

an appropriate time and place.

CONFLICT MANAGEMENT STYLES

Competition – Competitors keep their “eye on the prize.” The emphasis is on winning, and if that

means others have to lose or a relationship is damaged, so be it. Competition is prevalent in our

society, from sports to business to war. Competition usually behooves the more powerful, but is

also the style of the determined and the strongly convicted. It is the style used when success is

important enough to risk defeat.

Avoidance – Sometimes a conflict just isn’t worth the trouble of getting involved, no matter the

outcome. Perhaps the issue doesn’t affect you much, or finding a solution would take time you

could better spend elsewhere. Occasionally problems just fizzle, but usually avoidance doesn’t

resolve conflicts. The problem will persist as is, and maybe that’s acceptable. Other times,

avoidance may allow the problem to escalate until another style is needed.

Accommodation – When relationships matter more than objectives, you may give up your

position to remain on good terms with others involved. If competition is “my way or the

highway,” accommodation is “Your way’s fine with me, friend.” Maybe you know that the other

person feels more strongly about the issue than you do. Or maybe you can’t stand the thought

of making an enemy. Accommodators appease the other parties, even if that means letting

them win.

Compromise – Splits and shares, in a compromise no party loses and no party really wins. Usually

a compromise involves some appeal to objective fairness like, 50/50, taking turns or “if we can’t

both have our way, neither of us will.” Compromises allow you to get part of what you want, and

usually don’t leave relationships any worse off. However, compromises can feel unsatisfying and

may replace a more creative, potentially win-win solution.

Collaboration – Collaborators place a premium on both their own goals and their relationship

with others involved in the conflict. Collaborators seek to create lasting, mutually acceptable

resolutions. Collaboration requires time and creativity, but usually results in win-win outcomes.

OBJECTIVES

• Students learn the 5 conflict

management styles.

• Students understand the benefits and

drawbacks of each style and that

circumstance determines a style’s

appropriateness.

Conflict styles from Thomas, K. (1976) “Conflict and conflict management”

Compromise

DIRECTIONS

1. Explain and discuss the conflict

management styles above.

2. Create 5 sections of the classroom, a

section for each conflict management

style. You might tape 5 signs on the walls

or form 5 desk islands.

3. Divide students evenly into each of the 5

Sections, creating 5 groups.

4. Read aloud one of the provided conflict

scenarios and give students 3-4 minutes to

consider these questions:

a. How might someone handle this problem using your section’s conflict

management style?

b. What might be the consequences of handling it this way?

5. Ask each group to share their answers.

6. Ask each group to rotate to the next section and repeat this process. Continue until

every group has responded from every section.

ALTERNATIVELY

• As you read aloud the conflict scenario, ask students to stand in the middle of the room.

After they’ve heard the scenario, ask students to move to the section with the style they

would adopt in that situation.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

• Which conflict management style do you think you identify with most? Why?

• Which conflict management style did you find it most difficult to adopt? Why?

• Do you think one style is always preferable to the others?

• In what kind of situation might it be best to compete? Avoid? Accommodate?

Importance of Relationship

Importance of Goal

Avoidance

Accommodation

Competition

Collaboration

CONFLICT SCENARIOS

• Your family just moved into a new house. There are three rooms available for you, your

brother and sister, but one is larger than the others and has a bigger closet. You sister has

the most clothes and insists she needs the room. Your brother thinks he should get the

room because he’s the oldest. You want the extra space for your drum set. It bothered

everyone when you practiced in the dining room. Your parents told you to work it out

amongst yourselves.

• This month, your school is engaging students in an anti-drug campaign. You and Eduardo

have been chosen to create a large banner to be hung in the school’s main hallway.

Eduardo wants to draw a series of student portraits, each with their own drug awareness

slogan. You don’t like drawing and would rather use the banner to explain the school’s

campaign in large block letters.

• Your best friend Jeremy has been flirting with the girl you like. It bothers you, but it’s not

particularly surprising. Jeremy flirts with just about every girl in school. However, as

Jeremy’s friend you know that the girl he really likes is Ashlynn. He’s had a crush on her for

years. You’re deciding how to handle the situation.

• You’ve recently become friends with Kelsey and sent her a friend request on Facebook.

You really like Kelsey in person, but online she’s a bit much. She likes and comments on

almost everything you post, and some of her comments are inappropriate. You’ve grown

very irritated and you’re worried that your parents and other friends will disapprove of

what they see on your profile.

• Every summer your work for your grandpa doing odd jobs around his farm. You enjoy the

work and really like having extra money for the school year. But this year, your grandpa

has also hired his neighbor’s son, Curtis, to help out. Slowly, Curtis is taking more and more

of your jobs. Some days you arrive and your grandpa has nothing for you to do! You

don’t know Curtis that well, but feel like you should have first pick of the jobs. You’re the

grandson, after all!

APPLE ARGUMENTS

Conflicts arise for all sorts of reason in every type

of situation. But when you think about it, these

reasons separate into a relatively small number of

conflict types. Different taxonomies exist, but

common categories include, data or

communication conflicts, opposed interests,

relationship conflicts, structural conflicts and

differing beliefs. Distilled even further, all conflicts

generally have one of two origins: resources and

values. These are the sources that drive conflict. They are intrinsically linked to human needs and

satisfaction. Understanding the cause of conflict is a great way to begin resolving it. This activity

will help students think about different types of conflict.

Resource conflicts involve contention over a limited commodity (land, money, time, materials,

labor). Resource conflicts are typically simpler to resolve and commonly settled using:

competition, division, sharing, and resource expanding.

Value conflicts involve clashes between personal beliefs and usually center around what’s right,

good or just. Value conflicts are more difficult to resolve because values are intricately tied to

individual and cultural identity. Value conflicts are commonly resolved using: education,

exposure, interest identification and compromise.

DIRECTIONS

1. Ask every student to provide an example of a conflict they’ve been in or heard of.

Record examples on the board. (Try to record approx. 20 examples. Individuals in smaller

classes may need to provide multiple examples).

2. As a class, ask students to group conflicts that are alike. Which conflicts seem to share

similar causes? How would they describe each category? What name would they name

each category? Record these categories.

3. Ask students to divide each conflict and conflict category into two super categories:

resource conflicts and value conflicts.

APPLE ARGUMENTS

1. Arrange seats in a large circle around a small table or desk. Put an apple on the table.

2. Cut and hand out an Apple Position to each student. If need be, two students can

share a position. Or, you can invent new ones! Ask students to keep their positions

secret, at first.

OBJECTIVES

• Students think about different types

of conflict origins.

• Students understand how

determining the origin of a conflict

helps inform approaches to

resolution.

3. Ask two students at a time to come to the table and read or describe their positions to

each other and the class.

4. For each pairing, ask the class to consider the following questions:

a. What type of conflict has formed, if any? (Which of the class’s conflict

categories would you place this problem in?) Is this a resource or value

conflict?

b. What needs are at stake in this conflict?

c. Can you think of a win-win solution to this problem?

EX: You want to eat the apple, but you only like the skin. You usually toss the rest.

You want to use the apple to make applesauce.

a. This is a conflict over resources.

b. Hunger. Validation. Creativity.

c. Peel the apple. One can eat the peel and the other can use the flesh for

applesauce.

5. Continue until all students who want a turn have gone.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

• Which conflicts seemed easier to resolve, resource conflicts or value conflicts?

• What would happen if you used the same resolution for all of these conflicts? Say, flip a

coin and winner gets the apple? Or, split the apple and give each person half?

• Did this activity help you think of any new conflict categories?

APPLE ARGUMENT POSITIONS

You want to eat the apple, but you only like the skin. You usually toss the rest.

You’re deathly allergic to apples. You cannot touch them or anything they’ve recently touched.

You believe apples are demonic. They should all be burned as soon as possible.

You’re certain this is the apple that was stolen from your lunchbox earlier, but cannot prove it.

You’re an apple farmer. You want the seeds to plant in your orchard.

You’re a hunger activist and think that using the apple or any purpose other than eating is

wrong.

You want to use the apple to make applesauce.

Apples are sacred in your religion. They must not be eaten or otherwise defaced.

You want to put the apple in a barrel and go bobbing for apples.

You hate apples. You don’t like the taste and you don’t like the texture. You’ll tell anyone who

asks.

You have Malusdomesticaphobia, the fear of apples, you can’t bare to see, be near or even

talk about apples.

You’ve just learned how to break an apple in half with your bare hands. You want to prove to

everyone that you can do it.

You want to cut the apple in half and use it to make painting prints.

In your culture, apples are believed to have incredible healing powers, but only if you eat the

whole thing, peel, seeds and stem.

You want to take pictures of the apple at various stages of decomposition for a science project.

PICTURE TYPES

We all make assumptions every day. Assumptions

and heuristics are necessary and allow us to act

reflexively, create routines and organize and

simplify our world. However, when relied on too

much assumptions can also cause mis-

understandings or lead to generalizations and

stereotypes. This activity helps students

understand the difference between observation

and inference, and become aware of

assumptions they may not realize they’ve made.

DIRECTIONS

1. Distribute a picture to each student.

Use the pictures provided, find your

own pictures online, or have your

students find their own pictures in

magazines, books or online. If using

the last option, ask students to find a

picture of an interesting person (or

people) they do not know.

2. Arrange seats into a circle. Have

your students sit with their picture.

3. In go-around fashion, have each

student show and describe their

picture. In this round, simply ask

“How would you describe the person

in your picture?” or “Tell us as much

as you can about your person.”

4. As they’re going around, take note

of any assumptions your students

make. These are any details that

cannot be definitively verified by the

picture. Listen for statements like,

“He’s nice/mean” or “She’s wealthy”

or “He’s a bad person.”

5. Break for discussion.

LECTURE TOPIC

The brain interprets and evaluates stimuli at

lightning speed; so fast it’s hard to realize

when we’re making assumptions. The

mnemonic ODIE v. ODIS breaks down the

cognitive process, and can help students

consciously avoid evaluative judgments.

Observe – the physical process of sensory

stimulation. Ex. Light hitting your eyes, Sound

hitting your ears.

Describe – turning the sensory data into

characteristics. Ex. Tall, pale, shiny, loud.

Interpret – using a composite of

characteristics to arrive at a named

category of being. Ex. Tall, older, at the front

of the room. “Ah! He must be a teacher.”

Evaluate or Suspend – when evaluating we

assign our existing values or biases to the

named thing. Ex. “He’s a teacher. He must

be mean.” To Suspend is to consciously

interrupt this evaluative process and allow

new sensory information to replace

assumptions.

Remember that these steps happen in our

brains almost simultaneously and can be

hard to distinguish.

Also, suspension does not mean our values

or judgments disappear. That’s impossible.

Rather, we’re reserving those judgments

until we have more specific information.

Discussion Questions

• Name specific assumptions you saw made.

Ask the student what led him/her to that

conclusion.

• What were other assumptions that you heard?

• Did you notice you were making an

assumption when, and if, you did?

OBJECTIVES

• Students learn the difference

between observed information and

inferred information.

• Students practice objective

description.

• Students identify and learn to

suspend stereotypes commonly

associated with groups of people.

Adapted from Intercultural Communication Institutes’ “D.I.E”

6. Go around a second time. This time, ask the students to practice ODIS and go through

only the Observe, Describe and Interpret phases with adding their personal evaluations.

7. Stop a student if you hear him/her making an assumption. Explain why it’s an assumption

and ask them how they could change their language to be purely observational.

8. Break for discussion.

Discussion Questions

• What felt different about the second go around?

• Why might it be helpful to suspend our assumptions, especially when in conflict?

• How might the people in these pictures be stereotyped?

• Why is it important to recognize the stereotypes that permeate our world?

IMBALANCE CHALLENGES

Conflicts rarely unfold on an equal playing field.

Power, one’s ability to influence the outcome, is

always a factor in conflict, and usually the

balance of power is tipped. One disputant may

have more smarts, more supporters, more money,

more conviction, more physical ability or more

verbal ability. Each is a form of power and there

are many more. A type of power can be more or

less useful depending on the situation. It is important to be aware of the power dynamics at play

in conflict (and normally hard not to be). This activity will allow students to experience and

appreciate different types of power and how they can influence conflict.

DIRECTIONS

1. Arrange seats in a large circle.

2. Two at a time, ask students to come into the middle of the circle to compete in an

“Imbalance Challenge.” Inform the class that in these challenges one student will be put

in a position of less power.

3. Ask students in the circle to think about the types of power and power imbalances they

see at play before them.

4. Continue challenges until every student who wants a turn has had one.

OBJECTIVES

• Students recognize different types of

power.

• Students understand how power

imbalances can affect conflicts and

competition.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

• What types of power imbalances did you see in these challenges?

• What did it feel like participating in a challenge with less power? With more?

• How do you think different types of power factor into real conflicts?

• Can you think of any real-world conflicts in which there is a large power imbalance?

• What can we do to add or detract to our own power? To others’ power?

IMBALANCE CHALLENGES

PHYSICAL POWER

• Two students will have a standing balance challenge. The student who stays balanced

longest, wins. However, one student must compete on one leg only.

• Two students will have a book balancing challenge. The student able to balance a book

on his/her hand longest wins. However, one student may use his/her palm while the other

must use only his/her index finger.

• (Blindfold required) Two students will have a writing challenge. The student who writes,

“balance” on the board first wins. However, one student must compete blindfolded.

POWER IN NUMBERS

• Two students will have a one-leg balancing challenge. The student who stays balanced

longest wins. However, one student may choose and use a teammate to help balance

(the teammate must not stand on one leg).

• (Requires a small rope) Two students will have a gentle tug-o-war challenge. The student

who pulls the other student across the circle wins. However, one student may choose a

teammate.

COMMUNICATIVE POWER

• Two students will have a story telling challenge. They must each tell a story about a time

they lost their balance. The student who finishes his/her story first wins. However, one

student may only speak in words that start with “B.”

• Two students will have a listening challenge. Ask students in the circle to randomly

whisper the word “balance.” The challengers must guess who whispered. The student

who guess right first wins. However, one student must play with his/her hands over his/her

ears.

RESOURCE POWER

• Two students will have an object balancing challenge. The student who balances his/her

object on end first wins. However, one student’s object will be a dry-erase marker and

the other’s object will be a pencil.

Emotional Awareness and

Communication

Almost universally, conflict resolution education curriculums underline how

important communication skills are to positive conflict management.

Miscommunication and lack of communication regularly contribute to the

formation and escalation of disputes. In order to effectively address and

solve their problems, students must be able to both: listen to understand and

speak to be understood. With this end in mind, CRAMSS provides activities

designed to improve students’ ability to identify and convey their desires in a

clear, unaggressive manner.

Activities in section cover three primary areas: emotional vocabulary

building, active listening and the use I-messages. Students must be able to

name their feelings in order to effectively communicate them. So CRAMSS

includes activities meant to expand students’ vocabulary of emotional words

and phrases. Listening activities explore common listening barriers and how

to overcome them as well as how true listening differs from simply hearing.

Finally, these activities help students make a habit of I-messaging, the

popular, non-accusatory means of self-expression. Although simple in theory,

they are difficult to recall in the moment. As they sharpen these skills, students

will become better equipped to express their needs, respond to others’ and

reach positive resolution in conflict.

Activities

Wear Your Emotions on

Your Wall

Ang-o-Meters

Mad Lips

Classroom Complaint

Line

ReQuests

Listen “ing”

Telephone

When, I Feel, I Need

You and I-Messages

I-Interpreter

WEAR YOUR EMOTIONS ON YOUR WALL

Generic feeling words are all too easy to overuse.

“Good” is a common favorite. How’re you

feeling? “Good.” How was your test? “Good.”

What’d you do today? “Good.” We all have go-

to emotion words like this. They’re easy and, after

a while, meaningless. Careful identification of

your mood and the ability to give words to others’

moods is essential to effective communication,

especially during conflict. This type of

communication requires a broad emotional vocabulary, the kind few of us – and certainly few

students – have or remember to use.

DIRECTIONS

1. Lead students in brainstorming as many emotion words as possible.

2. Get past the basics: mad, sad, happy etc. Challenge students to get 50 words. If that

comes easy, challenge them to get 75!

3. Open it up all ideas and acknowledge all suggestions. Accept slang and colloquial

terms. English or not, this is how students often express themselves.

4. Create a poster displaying all of the words, or have your students create it. If it helps, sort

the words into like categories. The four overarching emotional states are glad, sad, mad

and scared.

5. Display the poster prominently.

6. In the future, encourage students to be as specific as possible when describing their

emotions. Have them refer to the poster when necessary.

OBJECTIVES

• Students build their emotional

vocabulary.

• Students learn to articulate their

emotions more accurately.

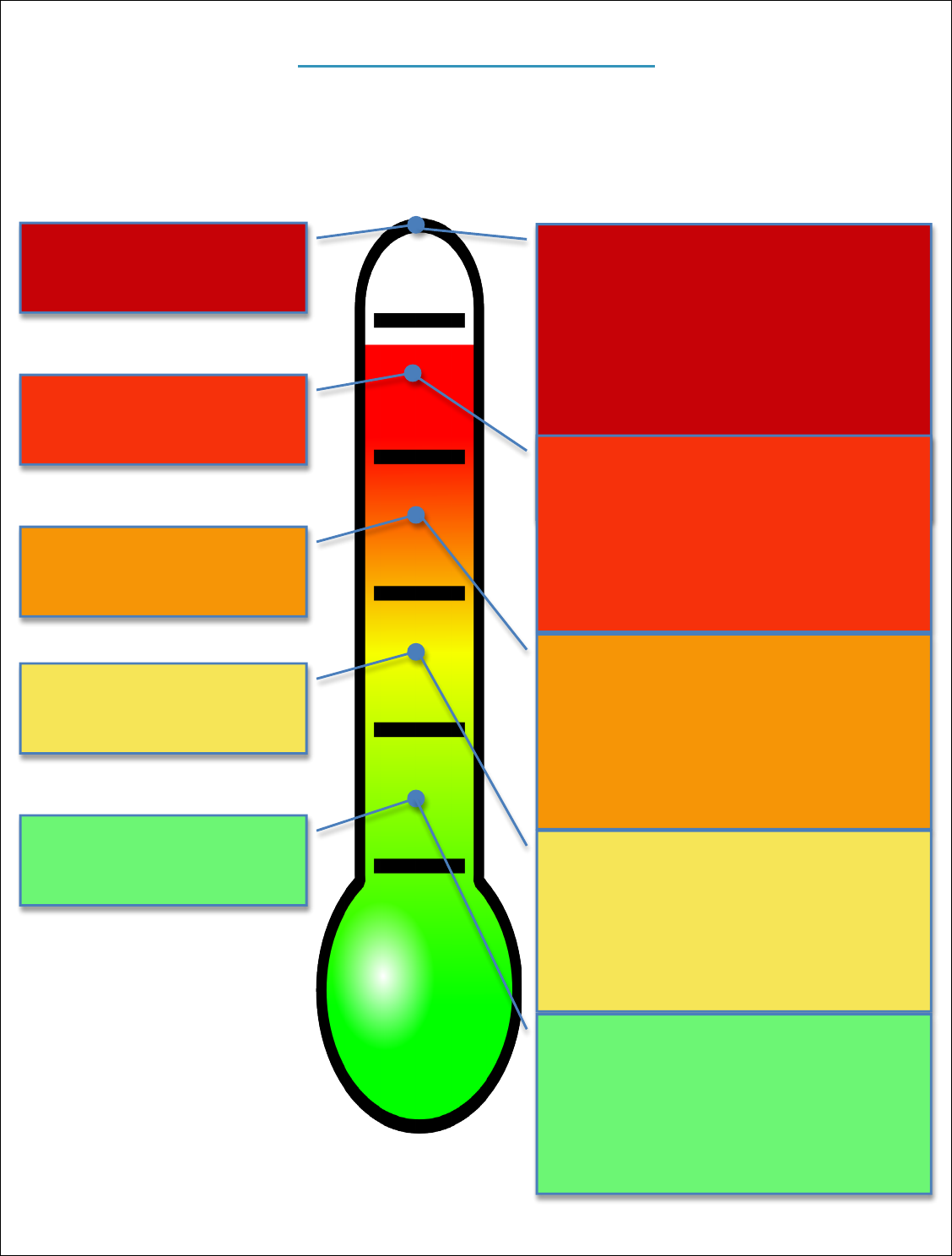

ANG-O-METERS

Anger is the emotion perhaps most commonly felt

when in conflict. And this is understandable. It’s

upsetting to be opposed; disagreement can be

maddening. Angry feelings escalate easily and

quickly, and can move from mildly annoyed to

furious before you know it. But anger often flares

more conflict than it solves. Anger impairs careful

decision-making and can lead to rash actions,

especially as you near your bursting point.

Examining your own escalation processes can

help you indentify your triggers and, hopefully,

interrupt cycles of growing anger.

DIRECTIONS

1. Ask students to complete the “My Ang-O-Meter” handout below.

2. In the left column students should chose five words or terms that describe increasingly

intense feelings of anger. In the right column students should supply a real-life example

for each word.

EX: In the dark orange boxes one may write: “When I’m this angry I call it boiling. That is

how I felt one time when my brother borrowed my skateboard and broke it.”

3. Once completed, encourage students to share their Ang-O-Meters with the class.

ALTERNATIVELY

• Ask students to complete the right column using different points of escalation from a

single example. For instance, in the green box: My brother borrowed my skateboard

without asking. In the yellow box: Then he broke it. In the light orange box: He didn’t

seem sorry about it, and so on.

• Ask students to think about what parts of the situation caused them to move up the

meter, and to consider what could have happened differently to deescalate their anger.

OBJECTIVES

• Students build their emotional

vocabulary, specifically concerning

expressions of anger.

• Students begin to understand how

anger escalates and how this process

might be checked.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

• What anger words did you use and what were your examples?

• When you’re angry, is it always clear how angry you are in the moment?

• Have you ever found yourself at the top of your Ang-O-Meter in response to something

you now realize was pretty minor? If so, why do you think that happened?

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

• In your example, how did you react at each level? What did you say? What did you

do?

• What could the other person have done to curb your anger? What could you have

done?

When I’m this

angry I call

it….

That is how I

felt one time

when…

My Ang-O-Meter

MAD LIPS

It’s believed that the majority of communication is

non-verbal. We rely on gestures, facial expressions

and tones to convey those subtle messages we

don’t speak aloud. But expressions are not always

as easy to understand as words. Non-verbal

communication is highly subject to our

interpretation, and the accuracy of those

interpretations is often undependable. This activity allows students to test their own empathic

intuitions. And helps illustrate the communicative limitations of non-verbal expression.

DIRECTIONS

1. Break students into pairs, A and B, and give each pair a copy of the exercise “Map Lips.”

2. Give one partner Sheet A and the other partner Sheet B. Ask partners not to share their

sheets with one another.

3. Ask partner A to read the first narrative aloud, pausing at each blank.

4. Ask partner B to follow along on his/her sheet. Where partner A’s sheet has blanks, partner

B’s sheet will have bolded emotion words.

5. When partner A gets to a blank, ask partner B to convey the corresponding emotion word

using only gestures and facial expressions.

6. Ask partner A to guess the emotion and fill in the blank in his/her narrative. Repeat this

throughout the narrative.

7. For the second narrative, ask partners A and B to reverse roles.

8. Once both narratives are filled in, ask partners to share their sheets.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

• How accurately were you able to read your partners expressions?

• Was it easy to express all of these feelings non-verbally? Do you have distinct expression

for each of these emotions?

• Compare your sheets. How much does the meaning of the narratives change from one

sheet to the other?

• What does this tell you about your non-verbal interpretations in everyday conversations?

OBJECTIVES

• Students appreciate the limitations of

non-verbal communication.

• Students test the accuracy of their

empathic intuitions.

MAD LIPS SHEET A

DIRECTIONS

Partner A will read Narrative One aloud, pausing at each underlined word. All of the underlined

words are emotion words. Instead of reading these words aloud, Partner A will try to convey

each word using facial expressions or gestures. Partner B will read Partner A’s expression, guess

the emotion, and fill in the corresponding blank. Reverse roles for Narrative Two.

NARRATIVE ONE

I had the worst time at school today. I was exhausted because I stayed up late finishing a

project for social studies. I overslept and got to school late, so I was already stressed when Mr.

Mann announced a pop quiz. It caught me by surprise. I don’t think I did well and that’s

frustrating. Then, in art class, I spilled water all over my painting! I was sad because that was

supposed to be my piece for the art show, but I’d be embarrassed to submit it now. Normally I

would talk to my friend Antonio about all this but he was absent. It always feels lonely when he’s

gone. All this to say, I’m happy you picked me up today, mom. When I saw your car I was so

relieved. I would’ve been overwhelmed on the bus.

NARRATIVE TWO

I’m usually so _______________ in Mrs. Knolls class. So I was _______________ today when she gave

us a fun assignment. We’re supposed to create a short skit about Greek mythology. I’m so

_______________! I don’t get _______________ performing in front of an audience like most people.

Maybe I’ll play an all-knowing oracle who foretells of betrayal and _______________. Or maybe I’ll

be an _______________ god from Olympus who _______________ the ungrateful citizens. No matter

the role, I feel _______________ I’ll steal the show. I just hope the class doesn’t get _______________.

Mythology can be tricky with all those long names. It’ll be up to me to make the characters

entertaining and keep the audience _______________.

MAD LIPS SHEET B

DIRECTIONS

Partner A will read Narrative One aloud, pausing at each underlined word. All of the underlined

words are emotion words. Instead of reading these words aloud, Partner A will try to convey

each word using facial expressions or gestures. Partner B will read Partner A’s expression, guess

the emotion, and fill in the corresponding blank. Reverse roles for Narrative Two.

NARRATIVE ONE

I had the worst time at school today. I was _______________ because I stayed up late finishing a

project for social studies. I overslept and got to school late, so I was already _______________

when Mr. Mann announced a pop quiz. It caught me by _______________. I don’t think I did well

and that’s _______________. Then, in art class, I spilled water all over my painting! I was

_______________ because that was supposed to be my piece for the art show, but I’d be

_______________ to submit it now. Normally I would talk to my friend Antonio about all this but he

was absent. It always feels _______________when he’s gone. All this to say, I’m _______________

you picked me up today, mom. When I saw your car I was so _______________. I would’ve been

just plain _______________ on the bus.

NARRATIVE TWO

I’m usually so bored in Mrs. Knolls class. So I was shocked today when she gave us a fun

assignment. We’re supposed to create a short skit about Greek mythology. I’m so excited! I

don’t get nervous performing in front of an audience like most people. Maybe I’ll play an all-

knowing oracle who foretells of betrayal and despair. Or maybe I’ll be an angry god from

Olympus who scares the ungrateful citizens. No matter the role, I feel confident I’ll steal the show.

I just hope the class doesn’t get confused. Mythology can be tricky with all those long names. It’ll

be up to me to make the characters entertaining and keep the audience pleased.

CLASSROOM COMPLAINT LINE

It’s said that behind every complaint is a request.

“I’m so tired of your lies!” can be interpreted as,

“Please tell me the truth” or perhaps simply, “Will

you stop lying?” It’s not always our first instinct to

hear the plea within complaining and potentially

rude comments. Ideally, we learn to translate our

own complaints and pose the request we’re

really trying to make. Short of this, it’s helpful to be

able to hear others’ appeals, even when they’re not stated as such. It’s not always best to

indulge whining, but reframing grumbles this way can smooth communication and help resolve

or even prevent disputes.

DIRECTIONS

1. Seats the class in a large circle.

2. Ask one student to volunteer as the “Classroom Complaint Line” and stand in the middle

of the circle.

3. In go around fashion, ask each student in the circle to make a complaint. Complaints

should be stated, “Ugh, I’m so…”

4. In response to each complaint, the student in the middle should mime an action that

placates the complaint, i.e. satisfy the request that he/she hears in the complaint. After a

brief charade, the student should say, “I heard you ask for… So I… Does that help?

EX: Ugh, I’m so hot!

(After pretending to open a window) I heard you ask for some cool air so I opened a

window. Does that help?

5. Let one student respond to 3-4 requests and then ask another volunteer to sevre as the

“Classroom Complaint Line.” Continue until all those who want a turn have had one.

OBJECTIVES

• Students understand that complaints

typically carry an implicit request.

• Students will practice interpreting

complaints as requests for a specific

action.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

• How might understating complaints as requests help in conflict situations?

• Can you think of an example from your own life when a request might have served you

better than a complaint?

• Do all complaints imply a request? Can you think of any that do not?

Name: Date:

REQUESTS

DIRECTIONS

Read the following complaints. How might you translate them into requests? Name two

ways that each request could be satisfied. Be creative!

1. Our cafeteria food is never any good.

The request: _________________________________________________________________________________

Two ways: ___________________________________________________________________________________

2. I’m so tired of reading about things that don’t apply at all to my life!

The request: _________________________________________________________________________________

Two ways: ___________________________________________________________________________________

3. I’m so over boyfriends like you. I can’t handle your mind games.

The request: _________________________________________________________________________________

Two ways: ___________________________________________________________________________________

4. It’s way too cold in here!

The request: _________________________________________________________________________________

Two ways: ___________________________________________________________________________________

5. I don’t have enough time to finish all this homework!

The request: _________________________________________________________________________________

Two ways: ___________________________________________________________________________________

6. Algebra is impossible!

The request: _________________________________________________________________________________

Two ways: ___________________________________________________________________________________

7. Ugh, Cindy always gets the lead roles in our productions!

The request: _________________________________________________________________________________

Two ways: ___________________________________________________________________________________

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

• Listeners, how was it different listening this time compared to last time?

• Speakers, did you feel like your partner was listening? How could you tell?

• We don’t really count “ing” words, but we do let things get in the way of our listening.

What are some things or thoughts that sometimes keep you from really listening, even

though you can hear the words? Do you have examples?

LISTEN “ING”

There’s a difference between hearing and

listening. Hearing is a physical process. For most

people it happens automatically. Listening is a

skill that involves hearing and also involves

meaning making, comprehension and

communication. Like most skills, listening takes

practice. There are many natural barriers to

effective listening like environmental distractions,

internal dialogues and personal agendas. This activity helps illustrate the difference between

hearing and listening, and helps students become aware of their own personal listening barriers.

DIRECTIONS

1. Pair students and have them sit facing each other. Ask them to pick one person to be the

speaker and the other to be the listener.

2. Instruct the speakers to describe their ideal family vacation (or any topic).

3. Without letting the speakers hear, ask the listeners to count the number of words ending in

“ing” that their partner says. This can be done by pulling all of the listeners aside or with

written instructions.

4. Ask the speaker to talk for 3-4 full minutes. Encourage them to be inventive and fill the

entire time.

5. Break for discussion.

6. Ask the speaker to describe one of their most vivid dreams (or any topic).

7. Ask the listeners to truly listen (perhaps tell them they’ll be asked to summarize the

speaker’s description afterward).

8. Ask the speaker to talk for 3-4 full minutes.

OBJECTIVES

• Students learn the difference

between hearing and listening.

• Students become familiar with

different types of listening barriers.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

• Listeners, how many “ing” words did you count?

• Listeners, how much of the speakers story do you recall? Were you able to concentrate

on both the story and the “ing” words?

• Speakers, did you feel like you were being listened to? How can you tell when someone’s

really listening?

TELEPHONE

This is the classic through-the-grape-vine game.

It’s fun! And, it illustrates perfectly the type of

misunderstandings and plain falsehoods that can

come of gossip and he-said, she-said tales.

Conflict often arises as a result of mis-

communications just like those in the game. The

skill – and this is much harder in practice – is

realizing when a real-life conversation might

actually be a game of Telephone.

DIRECTIONS

1. Arrange seats in a large circle.

2. Whisper a short narrative into the ear of the student sitting to your left. The narrative

should be no more than 2-3 sentences. Use the narratives provided for create your own.

3. Ask that student whisper the same sentences to the student to his or her left, and so on,

until the tale reaches the student on your right.