The Global State

of Democracy 2022

Forging Social Contracts in a Time of Discontent

© 2022 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance

International IDEA publications are independent of specic national or political interests.

Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International

IDEA, its Board of Advisers or its Council members.

The maps presented in this publication do not imply on the part of the Institute any judgement

on the legal status of any territory or the endorsement of such boundaries, nor does the

placement or size of any country or territory reect the political view of the Institute. The

maps have been created for this publication in order to add clarity to the text.

References to the names of countries and regions in this publication do not represent the

ocial position of International IDEA with regard to the legal status or policy of the entities

mentioned.

Applications for permission to reproduce or translate all or any part of this publication should

be made to:

International IDEA

Strömsborg

SE–103 34 Stockholm

Sweden

Tel: +46 8 698 37 00

Email: [email protected]

Website: <http://www.idea.int>

International IDEA encourages dissemination of its work and will promptly respond to

requests for permission to reproduce or translate its publications.

Text editing: Kelley Friel

Cover design: Based on a template developed by Poet Farmer

Cover image: Created using Midjourney, published under the Creative commons

Noncommercial 4.0 Attribution International License (The “Asset License”),

<https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/legalcode>.

Infographic: Background Stories

Design and layout: Veranika Ardytskaya

ISBN: 978-91-7671-575-8 (Print)

ISBN: 978-91-7671-576-5 (PDF)

DOI: <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2022.56>https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2021.91>

THE GLOBAL STATE

OF DEMOCRACY 2022

Forging Social Contracts in a Time of Discontent

ii

The Global State of Democracy 2022

Forging Social Contracts in a Time of Discontent

Contents

Contents

Acronyms and abbreviations iii

Preface iv

Acknowledgements vi

Introduction vii

Chapter 1

Global trends 2

1.1. Global Patterns 6

Chapter 2

Regional trends 10

2.1. Africa and West Asia 10

2.2. Asia and the Pacic 18

2.3. Europe 24

2.4. The Americas 28

Chapter 3

Recommendations 35

3.1. Global recommendations 35

3.2. Regional recommendations 36

Chapter 4

Conclusion 39

Endnotes 40

About International IDEA 51

About the Global State of Democracy initiative 52

iii

International IDEA

2022

Acronyms and abbreviations

ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations

COPs Conferences of the Parties

EMB Electoral management body

GRECO Group of States Against Corruption

GSoD Indices Global State of Democracy Indices

IEBC Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (Kenya)

International IDEA International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance

LGBTQIA+ Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex and asexual

NUP National Unity Platform (Uganda)

SAIIA South African Institute of International Affairs

The Global State of Democracy 2022

Forging Social Contracts in a Time of Discontent

iv

Preface

The fourth edition of the Global State of Democracy

Report comes at a time when democracy is under both

literal and gurative assault around the world. The

steady drumbeat of such warnings—included in the

previous edition of this report, which was produced at

the height of the Covid-19 pandemic—always runs the

risk of becoming background noise, as today’s crisis

can quickly become tomorrow’s new normal. But the

dangers are real. Beyond the lingering pandemic, today’s

wars and a looming global recession, lies the challenge

of climate change and all it entails—severe weather

events, the necessary green transition and multi-fold

consequences for democratic governance.

Much has changed since International IDEA produced

its rst Global State of Democracy Report in 2017,

authored on the eve of Brexit and soon after the

election of Donald Trump. That report mixed cautious

optimism about the previous decades’ advances in

democracy with warnings about more recent ‘trendless

uctuations’—a stagnation of democracy, rather than

its erosion. It is a testament to how political shocks can

quickly reorient our thinking. This report will once again

take up the argument that it is democracy, rather than

21st century inventions such as electoral autocracy or

illiberal democracy—let alone the resurrection of 19th

century imperial revanchism and spheres of inuence—

that provides the necessary tools to solve today’s urgent

problems.

The recent series of global crises—including the Russian

invasion of Ukraine and conicts in Ethiopia, Myanmar,

Syria and Yemen, and their rippling effects—appear to

indicate the emergence of a new status quo, dened by

radical volatility and uncertainty, rather than a deviation

from previous historical trends.

Global opinion surveys show that this period has

coincided with declining public faith in the value of

democracy itself. This is immensely worrying for those

who care about the fate of democracy, but sadly not

surprising. The core of any social contract is that

citizens consent to be governed in return for certain

core goods provided by those who govern. Yet the ability

of democracies around the world to provide key public

goods to their citizens and to close the gap between

social expectations and institutional performance is

increasingly at risk. These troubling questions were

present well before democracies had to address the

grotesque inequities within and between countries

exposed by the pandemic, and the ination, shortages,

and threats of a global economic downturn that have

followed.

But contrary to what democratic pessimists may

suggest, authoritarian countries and alternative systems

of government have not outperformed their democratic

peers. Discontent at the neverending stream of Chinese

lockdowns and the tens of thousands of draft dodgers

eeing Russia for an uncertain existence in the South

Caucasus and Central Asia show that it is not just in

democracies where the social contract is in urgent need

of renewal.

Social contracts vary depending on the cultural and

historical context, but all democracies share certain

core commonalties, including respect for individual

civil and political rights, fair and competitive elections,

a reasonably equal exercise of power by the governed

over their government, and effective access to a set of

entitlements that make a dignied and meaningful life

possible. There is now a growing popular realization that

many of the world’s social contracts are no longer t for

purpose.

In some states governments and their people are

renegotiating these social contracts. For example,

the collective uprising against the failed Rajapaksa

government in Sri Lanka cut across previous ethnic and

socio-political cleavages. But it is not a straightforward

process, as the rejection of Chile’s new draft constitution

has demonstrated.

In places as varied as El Salvador, Hungary, Iran and

Myanmar, governing elites are attempting to forge new,

or reinvigorate old social contracts using various anti-

democratic means. Iran and Myanmar are authoritarian

regimes in search of self-preservation. Sometimes

we refer to countries like El Salvador and Hungary as

‘backsliding’, a term that should not always be taken

to mean a clean reversion to an earlier pre-democratic

era; it can also mark a move towards a novel form of

International IDEA

2022

v

Preface

anti-democratic politics. We are not moving forwards

and backwards along a single line of development,

but exploring diverse possible political outcomes as

autocracies and democracies contest our possible

futures.

Democracy has the best chance of forging social

contracts for the 21st century, which can meet the

challenges of the future, particularly the endishly dicult

task of protecting fundamental rights and the ecological

balances on which the future of those rights and human

life depends. Democracy must be reinvigorated—not

because it needs to prevail in a presumed new Cold

War era, but because it still offers the best chance of

preserving what is needed for (and valuable in) human

life. This is the true measure of success for democracies

and societies in this day and age.

We are proud to present this report as part of

International IDEA’s contribution to the global debate

on the fate and course of democracy. Much of the

report focuses on the core place that democracy has in

securing a sustainable and just future—and the fact that

such a future is not foreordained but must be earned.

In many places it is being earned in the hardest of

ways. There are those who are, right now, demanding

the rights and freedoms that democracy promises

at immense personal risk. The people of Ukraine are

resisting the brutal Russian invasion, women in Iran are

standing up to a 40-year theocratic dictatorship, and

the people of Myanmar refuse to accept a return to

military rule. They are proving beyond a doubt that self-

determination, freedom and democracy are universal

aspirations. Many of them are paying the ultimate price

for these aspirations. Many of them will have no other

grave but our memory. We owe it to them to remember

their struggles every day, to commit our steadfast

support to their cause, and to make our work worthy of

their sacrice.

Kevin Casas-Zamora

Secretary-General, International IDEA

vi

The Global State of Democracy 2022

Forging Social Contracts in a Time of Discontent

Acknowledgements

This report was conceptualized and written by the

Democracy Assessment team at International IDEA,

with inputs from the Regional Europe, Africa and West

Asia, Americas and Asia and the Pacic programmes.

It was produced under the supervision of Kevin Casas-

Zamora, Massimo Tommasoli and Seema Shah and

edited by Alistair Scrutton and Seema Shah. Alexander

Hudson and Emily Bloom produced all the graphs

in the report. Lisa Hagman oversaw the publication

production process. Many thanks to Katherine

Chapanionek, Sandor Adam Gorni, and Theodor Thisell

for their invaluable assistance with fact checking, line

editing and production of graphs.

Notwithstanding all the generous advice, help

and comments received from external partners,

International IDEA takes sole responsibility for the

content of this report.

International IDEA

2022

vii

Introduction

At the end of 2022, the world is trapped beneath

the weight of a multitude of old and new problems.

There are myriad causes of political and economic

instability, including the spiking prices of food

and energy, ballooning ination and an impending

recession. These phenomena are occurring in the

unstable context of continuing climate change,

long unresolved inequality, the Covid-19 pandemic,

declining standards of living

1

and the Russian war of

aggression in Ukraine. Long-held assumptions have

been shaken; post-truth narratives have jeopardized

the legitimacy of credible electoral processes; and

inter-state war—including the threat of nuclear

attacks—has resurfaced.

Worryingly, the number of people who believe that

democracy is the answer to these problems is

shrinking. The Global State of Democracy’s latest

ndings reveal a decline in and stagnation of

democracy around the world. A close look at the data

reveals that while many democracies have put in

place the laws and infrastructure required to support

democratic institutions, unequal access to those

institutions is a serious and continuing problem.

Democratic institutions are especially critical in times

of crisis and fear. They ensure open pathways for the

information and communication that citizens and

governments need to be able to act responsively and

effectively. To rebuild and revitalize these institutions

and to re-establish trust between people and their

governments, it is necessary to develop new and

innovative social contracts that better reect the

changing global environment and that meaningfully

prioritize equal access to the mechanisms of

participation.

BOX 1

What is a social contract?

Social contracts are implicit agreements about what

governments provide their people in exchange for public

legitimacy. They reect an understanding of how people

solve shared problems, manage risks and pool resources

to deliver public goods, as well as how their collective

institutions and norms operate.

2

The type of social contract

that underpinned so much of the post-Cold War expansion of

democracy is now under strain, and governments and their

people must renegotiate the terms of their relationships.

People’s needs have evolved; basic economic and social

security are still required, but new challenges have sparked a

demand for different types of guarantees from the state.

For instance, education, social welfare and professional

growth systems must adapt to new needs introduced by

changing ways of working, different kinds of employment,

and new technologies—and recognize the importance of

the care economy and multiple forms of inequality.

3

In an

interconnected global context,

4

social contracts must be

forward-looking to integrate protections against tomorrow’s

threats.

Renewed social contracts must also be grounded in equity.

It is no longer enough for the state to provide opportunities;

it must proactively design systems that facilitate access

to those opportunities in ways that put traditionally

marginalized groups at the centre while ensuring that there

are protections in place to mitigate the creation of newly

marginalized groups. New social contracts must establish

mechanisms that mitigate toxic polarization within societies

and mistrust between governments and their people by

providing the structures and institutions necessary to

develop and maintain shared citizenship.

New social contracts must address particular contexts

(see Box 1). In Asia and the Pacic, ethno-nationalist

parties are changing the face of what were once

considered to be some of the most diverse societies

in the world. Inequality—as seen through poverty,

access to services, violence, corruption and climate

change—cuts across these contexts and drives people’s

demands for change.

The Global State of Democracy 2022

Forging Social Contracts in a Time of Discontent

Introduction

viii

The Russian war of aggression in Ukraine has

shaken Europe, forcing the region to rethink security

considerations and deal with impending food and

energy crises. It has also raised important questions

about the very nature of European and western

democracy, which has exhibited troubling double

standards with regard to migration and the plight of

refugees. These questions are all the more important in

the context of the rise of parties that espouse nativist

and xenophobic beliefs.

In Africa, decades of state capture by illiberal ‘strong

men’ leaders

5

have resulted in serious democratic

decline. Some leaders are resorting to desperate efforts

to change constitutions and legal frameworks to help

them maintain power. A growing number of young

people are anxious for change and want leaders who are

more responsive to their unique concerns. The ongoing

war in Ethiopia, where there have been allegations of

ethnocide, has bloodied the promise of democratic

reform, which had been a hope as recently as 2019. In

West Asia, authoritarian rule remains the norm, although

social turmoil in places like Iran, Iraq and Lebanon may

be evidence of public demand for new and more open

societies as well as more accountable leadership.

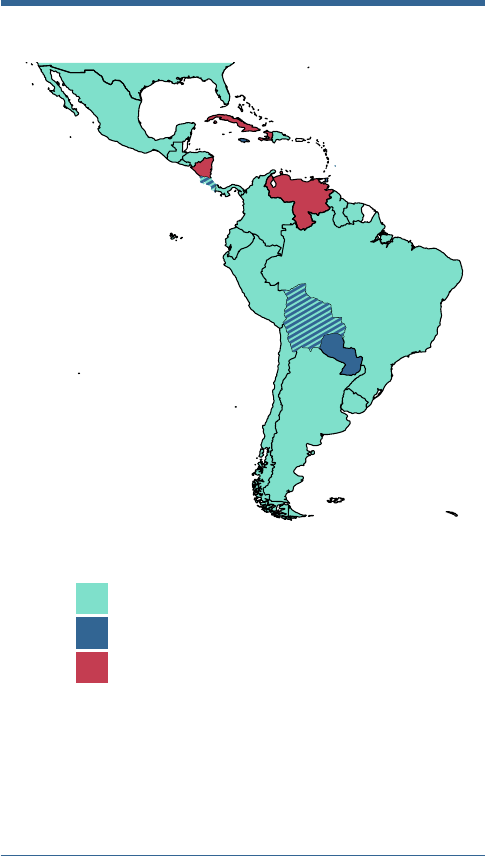

A diverse set of new challenges, including toxic

polarization and attacks on electoral management

bodies, is confronting the Americas; Haiti has

now joined Cuba, Nicaragua and Venezuela as an

authoritarian regime. Three out of seven backsliding

democracies are in this region, pointing to weakening

institutions even in longstanding democracies.

This report provides an overview of the global and

regional trends related to democracy and human rights,

along with examples of efforts to reinvigorate social

contracts around the world. It ends with a set of policy

recommendations designed to help policymakers

seeking to catalyse democratic reform.

1

International IDEA

2022

50%

0%

Countries moving

toward authoritarianism

Countries moving

toward democracy

1975 2021

1980 2021

1980 2021

The global context is rapidly changing, with pandemics,

wars and climate change creating new challenges for democracy.

New constitutions

Civic

education

Spaces for meaningful

youth participation

Stronger and updated

protection of freedom

of expression

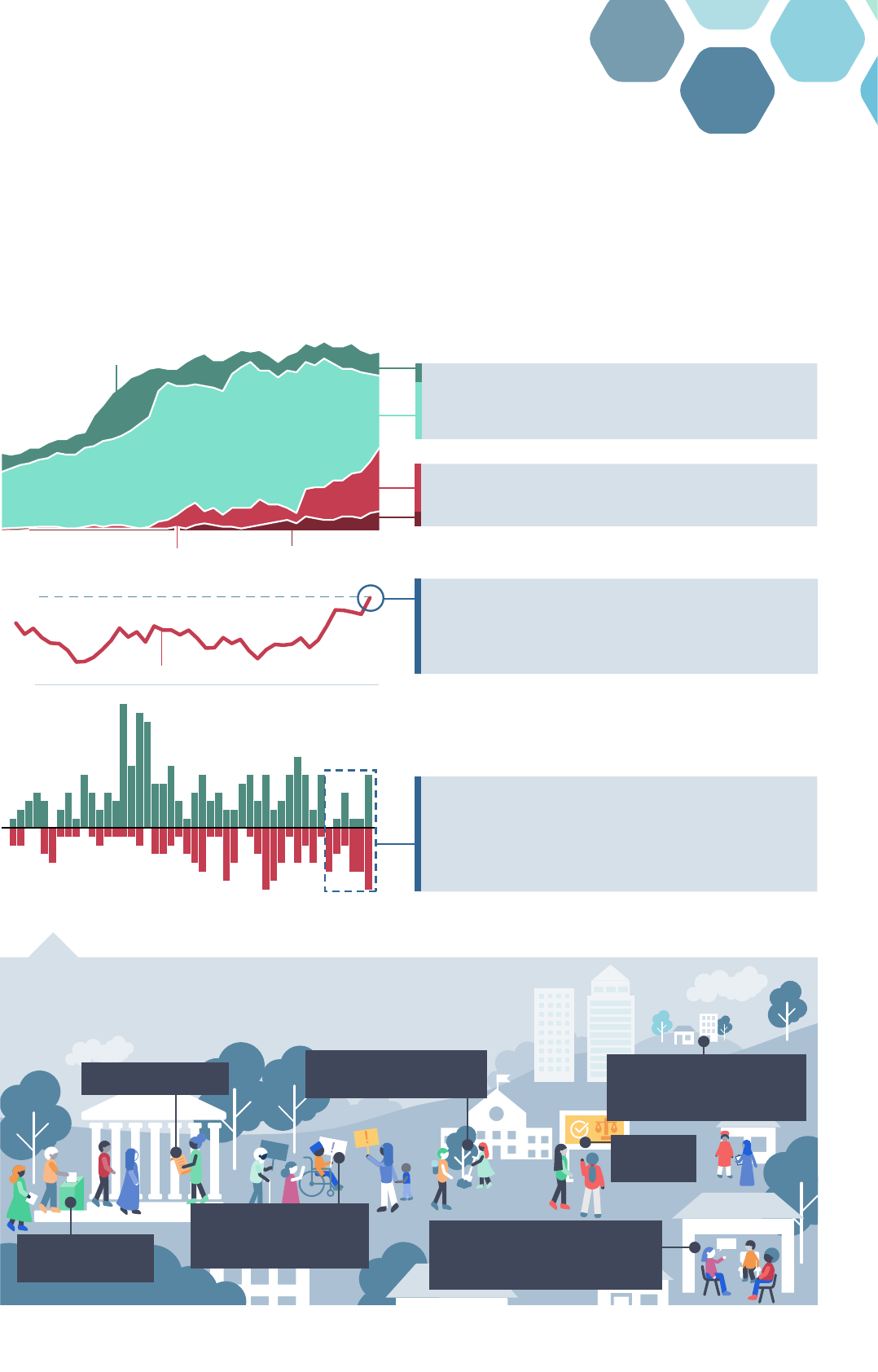

Over the past six years, the number of

countries moving toward

authoritarianism is more than double

the number moving toward democracy.

The number of democracies has

stagnated

and there has been a slow

uptake of institutional innovation.

Redesigning social contracts, with an emphasis on responsive

service delivery, can help realize democratic innovation.

THIS INCLUDES:

At the same time, half of the world’s

democracies

are in retreat.

Among non-democracies, 50% are

becoming significantly more repressive.

This amounts to 1 in 5 of all countries.

Electoral integrity

guarantees

Participatory mechanisms

that channel public demands

into new laws and policies

Regional input integrated

into national and local

laws and policies

Severely contracting democracy

Stable democracy

Expanding democracy

Moderately contracting democracy

Non-democracies becoming more repressive

Democracy in retreat, social contracts

under pressure

Chapter 1

Global trends

2

The Global State of Democracy 2022

Forging Social Contracts in a Time of Discontent

BOX 2

The Global State of Democracy measurement methodology

The Global State of Democracy Indices (GSoD Indices)

measure aspects of democracy and human rights that have

been central to International IDEA’s work for more than two

decades. While some primary data collection is conducted

within International IDEA, the majority of the input data for

the GSoD Indices are derived from 12 other publicly available

data sources, with a total of 116 input variables.

The indices are hierarchically organized. At the lowest level

are specic phenomena (such as Freedom of Expression or

Personal Integrity and Security) that we call subcomponents.

These are combined into measures of broader subattributes

(such as Civil Liberties or Clean Elections). Finally, the

subattribute indices are aggregated into our broadest

measures—the attributes of democracy. Each index is scaled

to range from 0 to 1; the boundaries are set by the best and

worst observed values across all country years. The GSoD

Indices do not include a singular value for democratic quality,

or any ranking of countries. Their primary utility is found in

the specic indices, which can be used to track progress over

time within countries, and to compare between them.

To group countries for analytical purposes, the GSoD

Indices also classify countries into three political regime

types—democracy, hybrid regime or authoritarian regime.

Democracies are dened as regimes that hold elections that

meet minimal standards of meaningfulness, competitiveness

and suffrage. Hybrid regimes perform at a mid-range level

or higher in Representative Government but do not meet this

electoral standard.

Within the category of democracies, the GSoD Indices also

include differentiations in overall performance to help group

countries for analytical purposes. These classications

are based on performance levels within the ve attributes

of democracy. For each attribute, we classify countries as

high (at least 0.7), mid-range (0.4 to 0.69), or low (0.39 and

below) performing based on their attribute values. Countries

that are high performing on all attributes are called ‘high-

performing democracies’; those that miss this high bar are

called ‘mid-range performing democracies’, and those that

are low performing on at least one attribute are called ‘low-

performing democracies’.

The GSoD Indices also take signicant changes over

time into account. Countries that are experiencing the

most severe declines in democratic quality are classied

as experiencing democratic backsliding. We assess

backsliding with particular reference to declines in Checks on

Government, Civil Liberties, and Clean Elections. Countries

that have declined by more than 0.1 on the average of

these three critical indicators are coded as experiencing

democratic backsliding.

Chapter 1

Global trends

Global democracy, already under increasing threat

over the last few years, approaches the end of 2022

with multiple tipping points on the horizon—a cost of

living crisis, an impending global recession, and recent

wars in places as diverse as Ukraine and Ethiopia.

Democracies are struggling to effectively bring balance

to environments marked by instability and anxiety, and

populists continue to gain ground around the world as

democratic innovation and growth stagnate or decline.

There are troubling patterns even in countries that are

doing relatively well, performing at middle to high levels

of democratic standards and not backsliding (Figure3).

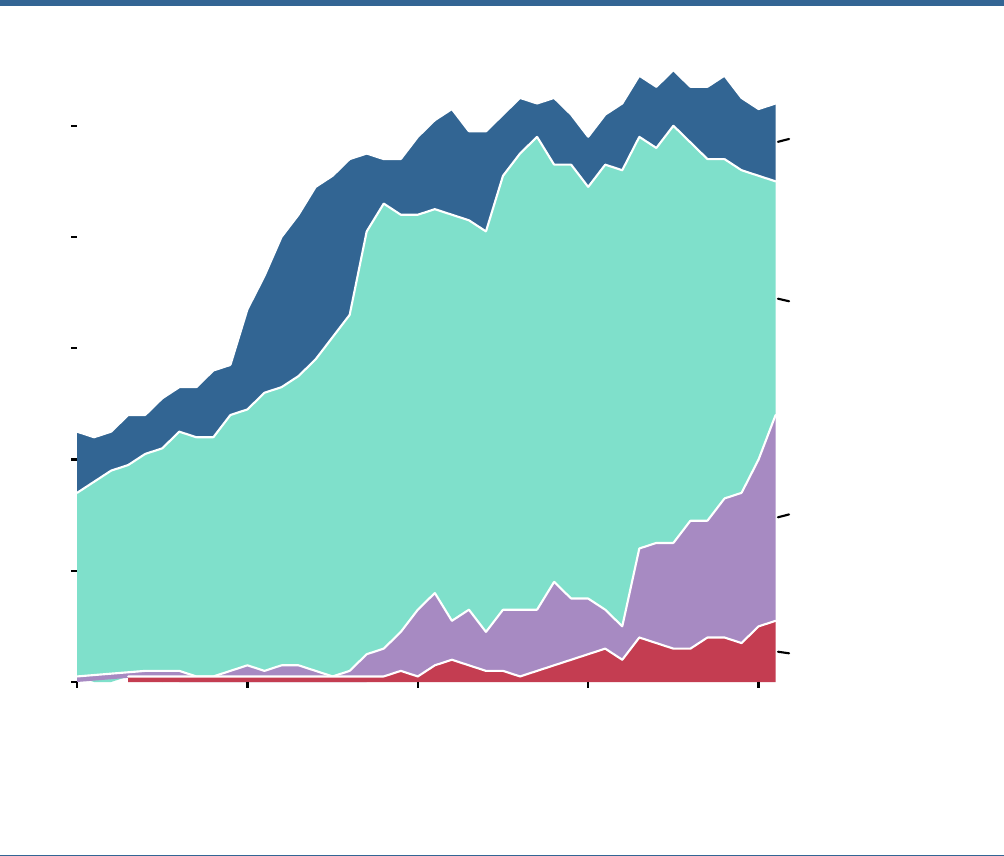

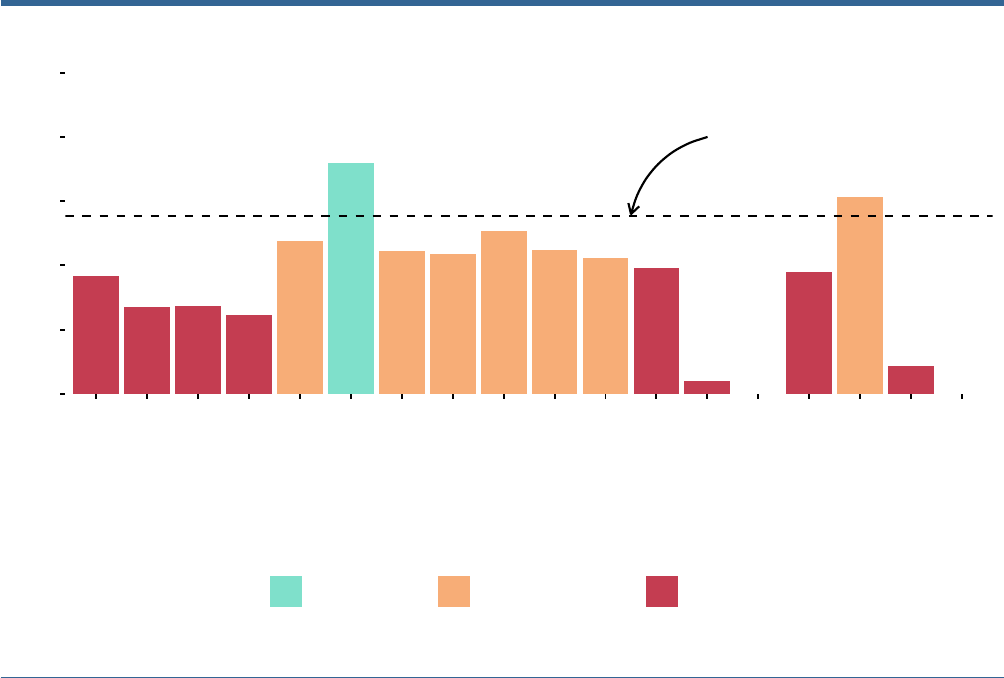

Over the last ve years, progress has stalled across

all four aggregated Global State of Democracy Indices

(GSoD Indices) attributes. In some cases, scores are the

same as they were in 1990.

The stagnation exists in parallel to democratic decline

elsewhere. The number of backsliding countries (seven)

remains at its peak, and the number of countries

moving towards authoritarianism is more than double

the number moving towards democracy. As of the end

2021, nearly one half of the 173 countries assessed by

International IDEA are experiencing declines in at least

one subattribute of democracy.

3

International IDEA

2022

Chapter 1

Global trends

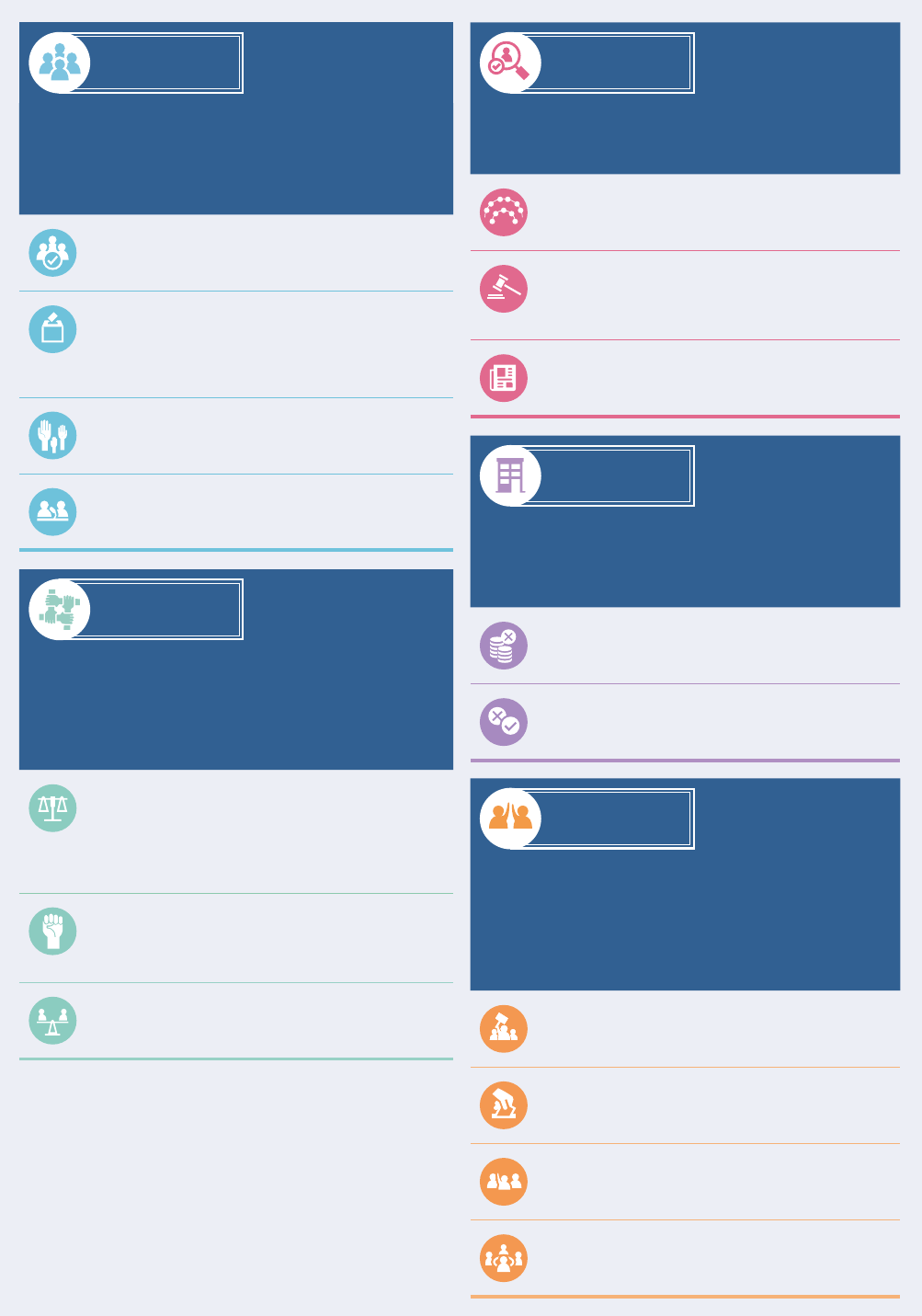

FIGURE 1

The Global State of Democracy framework

FIGURE 2

Regime classication

Democracy

Popular Control and

Political Equality

Representative

Government

Clean

Elections

Elected

Government

Access to

justice

Civil

Liberties

Social Rights

and Equality

Effective

Parliament

Judicial

Independence

Media

Integrity

Predictable

Enforcement

Civil Society

Participation

Electoral

Participation

Direct

Democracy

Local

Democracy

Absence of

Corruption

Inclusive

Suffrage

Free Political

Parties

Fundamental

Rights

Checks on

Government

Impartial

Administration

Africa Americas

Asia &

Pacific

Europe

Western

Asia

Participatory

Engagement

Fundamental

Rights

Representative

Government

Participatory

Engagement

Checks on

Government

Impartial

Administration

Attributes of democracy

Performance classified on each

attribute as high, mid-range or low

Democracy

Minimally

competitive

elections

Does not have minimally

competitive elections

At least mid-range score in

Representative Government

Hybrid

regime

Authoritarian

regime

Low score in

Representative

Government

Chapter 1

Global trends

4

The Global State of Democracy 2022

Forging Social Contracts in a Time of Discontent

Representative

Government

Representative Government covers the extent to

which access to political power is free and equal as

demonstrated by competitive, inclusive and regular

elections.

Elected Governmentdenotes the extent to which

national, representative government oces are lled

through elections.

Clean Electionsdenotes the extent to which elections

for national, representative political oce are free

from irregularities, such as aws and biases in the

voter registration and campaign processes, voter

intimidation and fraudulent counting.

Inclusive Suffragedenotes the extent to which adult

citizens have equal and universal passive and active

voting rights.

Free Political Partiesdenotes the extent to which

political parties are free to form and campaign for

political oce.

Fundamental Rights

Fundamental Rights captures the degree to which

civil liberties are respected, and whether people have

access to basic resources that enable their active

participation in the political process.

Access to Justicedenotes the extent to which the

legal system is fair (citizens are not subject to arbitrary

arrest or detention and have the right to be under the

jurisdiction of—and to seek redress from—competent,

independent and impartial tribunals without undue

delay).

Civil Libertiesdenotes the extent to which civil rights

and liberties are respected (citizens enjoy the freedoms

of expression, association, religion, movement, and

personal integrity and security).

Social Rights and Equality denotes the extent to which

basic welfare and political and social equality between

social groups and genders have been realized.

Checks on

Government

Checks on Government measures effective control of

executive power.

Effective Parliamentdenotes the extent to which

the legislature is capable of overseeing the

executive.

Judicial Independence denotes the extent to which

the courts are not subject to undue inuence from

the other branches of government, especially the

executive.

Media Integritydenotes the extent to which

the media landscape offers diverse and critical

coverage of political issues.

Impartial

Administration

Impartial Administration concerns how fairly and

predictably political decisions are implemented, and

therefore reects key aspects of the rule of law.

Absence of Corruptiondenotes the extent to which

the executive, and public administration more

broadly, does not abuse oce for personal gain.

Predictable Enforcementdenotes the extent to

which the executive and public ocials enforce

laws in a predictable manner.

Participatory

Engagement

Participatory Engagement measures people’s

political participation and societal engagement at

different levels. Because they capture different

phenomena, the subattributes of this aspect are not

aggregated into a single index.

Civil Society Participationdenotes the extent to

which organized, voluntary, self-generating and

autonomous social life is dense and vibrant.

Electoral Participationdenotes the extent to

which citizens vote in national legislative and (if

applicable) executive elections.

Direct Democracydenotes the extent to which

citizens can participate in direct popular decision-

making.

Local Democracydenotes the extent to which

citizens can participate in free elections for

inuential local governments.

5

International IDEA

2022

Chapter 1

Global trends

FIGURE 3

Expansion and contraction of democracies over time

Notes: This graph illustrates both the total number of democracies and their status. For 2021, it illustrates that there are a total of 104 democracies. Of those,

14are ‘expanding democracies’, meaning they have experienced positive and signicant changes in a net count of at least two subattributes (out of 16). Forty-two

more democracies are ‘stable’, meaning that the net counting of positive versus negative subattributes is zero or one. However, 37 democracies are classied as

‘moderately contracting’, meaning they have a net negative count of one or two subattributes. The democracies of greatest concern are the 11 that are classied

as ‘severely contracting’, which have a net negative of three subattributes or more.

Source: International IDEA, The Global State of Democracy Indices v. 6.1, 2022, <https://www.idea.int/gsod-indices>, accessed 24 October 2022.

Given these trends, increasing public frustration is

understandable. The number of protests around the

world more than doubled between 2017 and 2022,

sparked by a wide range of issues.

6

One of the most

striking examples has been in Sri Lanka, where

protesters took to the streets in mid-2022 to demand

accountability for the government’s debt default and

eventually forced the president’s ight and resignation

(see Box 7). While people’s ability and willingness to

publicly protest is a sign of functioning democracy, it

is also a warning. Governments’ failure to effectively

respond could damage the legitimacy of the democratic

model. The World Values Survey (which covers

77countries) demonstrates that less than half (47.4 per

cent) of all respondents believe democracy is important,

down from 52.4 per cent in 2017. This is a worrying

drop, especially since less than half believe that having

a democracy is ‘very good’.

7

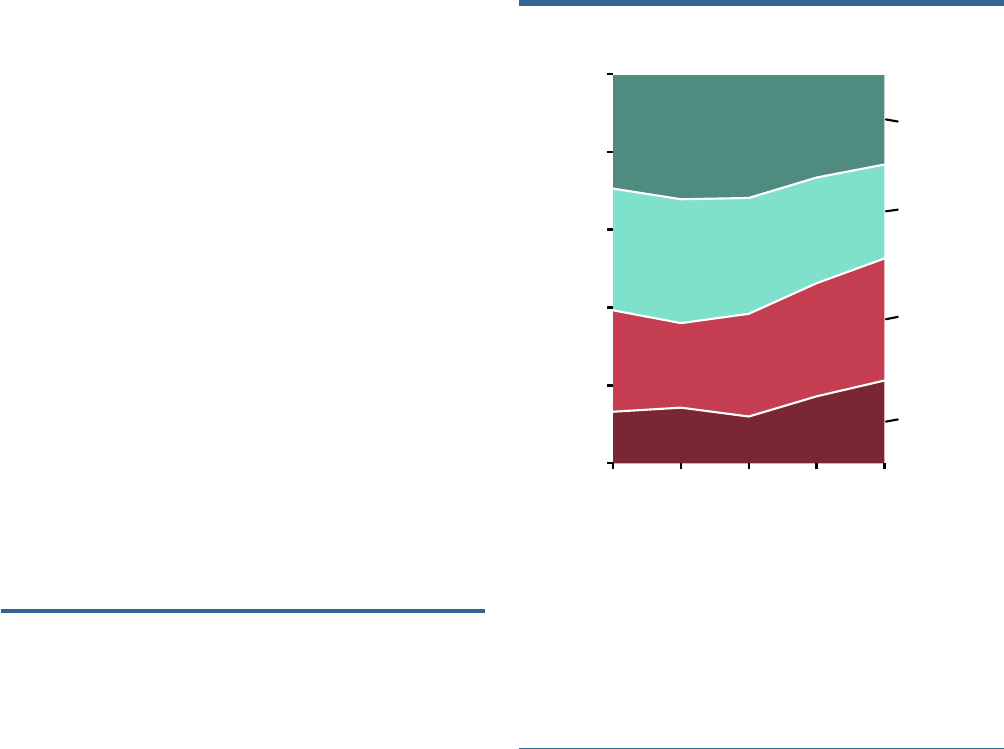

At the same time, condence in democratic government

is dropping. Survey data indicate that the proportion

of people who agree with the idea that having a strong

leader who does not have to bother with parliament

or elections has been consistently growing in recent

years. In 2009, the World Values Survey reported that

only 38per cent of respondents thought this idea was

fairly good or very good. In 2021, that gure had risen to

52per cent (Figure 4).

General declines and stagnation are not the only

problem, though. Russia’s war in Ukraine has catapulted

the idea of democracy into the international spotlight.

Chapter 1

Global trends

6

The Global State of Democracy 2022

Forging Social Contracts in a Time of Discontent

The war demonstrates just how threatening democratic

growth can be to authoritarian regimes, and it has

resurfaced the Cold War-era divide between a relatively

united democratic community and authoritarian

regimes.

8

The threat that democratization poses to

authoritarians also highlights how critical it is to ensure

that democracies have the internal and external support

they need to weather crises. This is one reason why

it is alarming to see many donor countries cut back

on development aid, which often includes democracy

assistance.

9

Non-western democracies’ relative unwillingness

to strongly condemn Russian President Vladimir

Putin reveals deep divisions. Some regimes view the

western outcry in support of democracy as somewhat

hypocritical, especially in light of multiple past instances

of western aggression.

10

Western calls for support

for democratic ideals also starkly contrast with racist

responses to refugee ows, and the clear difference

in attention to the plight of Ukraine compared to other

longstanding, deadly wars.

11

1.1. GLOBAL PATTERNS

The latest GSoD Indices data show that democracy

is in decline, compounding a decade marked by more

deterioration than democratization. First, between 2016

and 2021, the number of countries moving towards

authoritarianism was more than double the number

moving towards democracy (Figure 5). During that time,

27 countries experienced a downgrade in their regime

classication, while only 13 improved. The world also

lost two more democracies in 2021—Myanmar and

Tunisia. Moreover, 52 democracies are now eroding,

experiencing a statistically signicant decline on at least

one subattribute—compared to only 12 a decade ago.

FIGURE 4

Public opinion on autocratic leadership

Notes: The gure plots responses to the World Values Survey question:

‘Would you say that “having a strong leader who does not have to bother with

parliament and elections” is a very good, fairly good, fairly bad or very bad way

of governing this country?’

Source: R. Inglehart, C. Haerpfer, A. Moreno, C. Welzel, K. Kizilova, J. Diez-

Medrano, M. Lagos, P. Norris, E. Ponarin and B. Puranen (eds), World Values

Survey: All Rounds—Country-Pooled Datale Version 3.0, Madrid, Spain

and Vienna, Austria: JD Systems Institute and WVSA Secretariat, 2022,

<https:/www.doi.org/10.14281/18241.17>.

!"#$!!"

7

International IDEA

2022

Chapter 1

Global trends

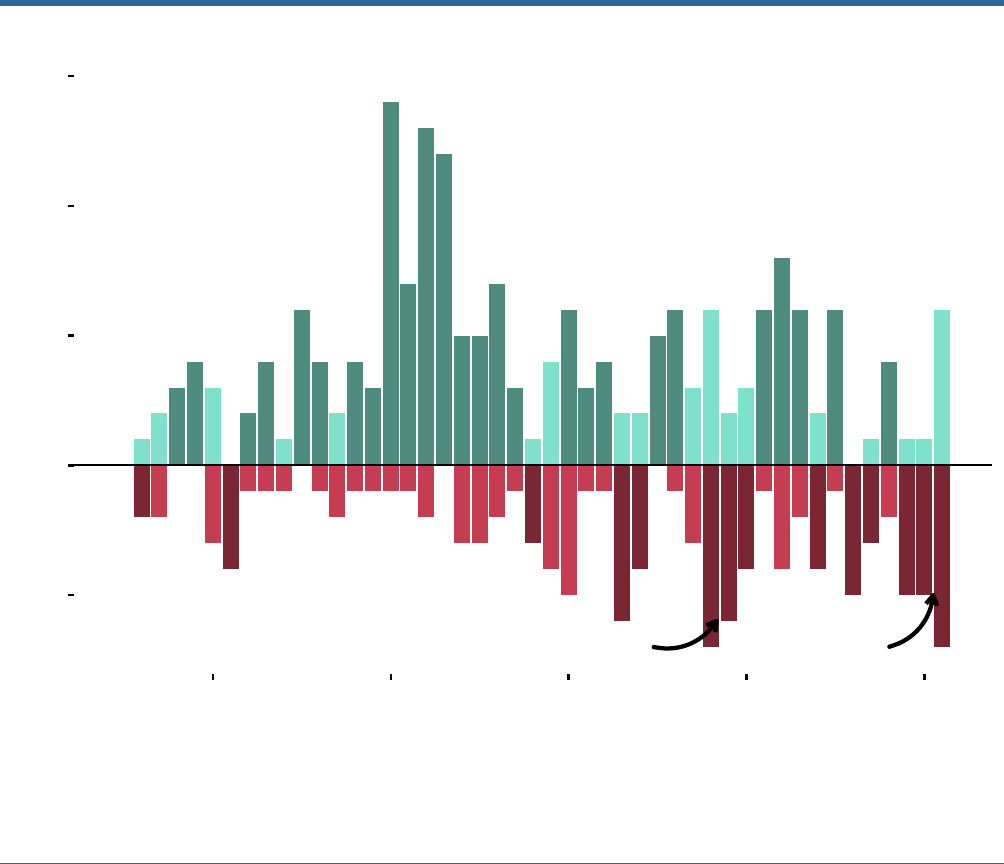

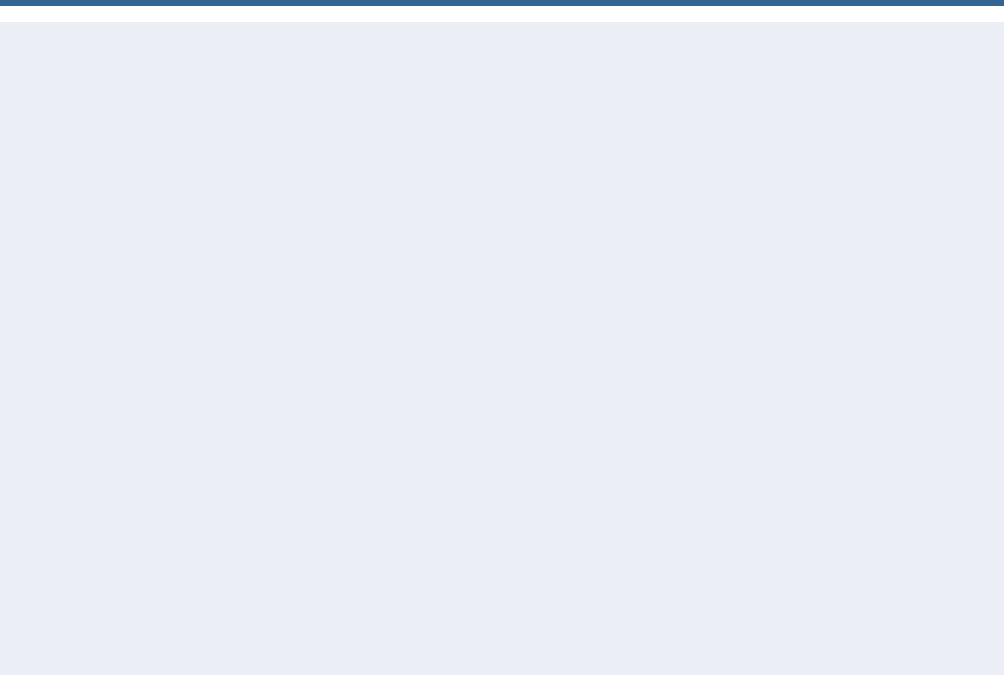

FIGURE 5

Net movements towards and away from democracy

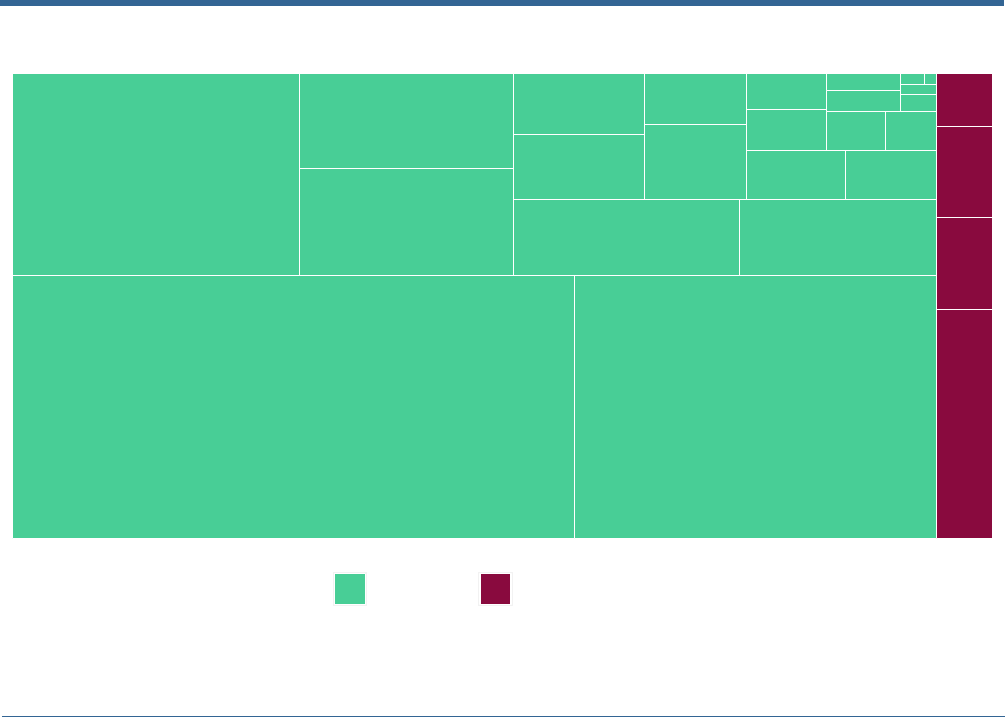

Notes: This bar graph shows the number of countries moving towards authoritarianism (from democracy to either a hybrid or authoritarian regime, or from a

hybrid to an authoritarian regime) in red or towards democracy (from either a hybrid or authoritarian regime to a democracy or from an authoritarian to a hybrid

regime) in green, by year since 1975. Years shown in dark green rather than pale green are those where the number of countries moving in a democratic direction

outnumbers those moving in an authoritarian direction. Years shown in dark red rather than pale red are those where the changes towards authoritarianism

outnumber the changes towards democracy.

Source: International IDEA, The Global State of Democracy Indices v. 6.1, 2022, <https://www.idea.int/gsod-indices>, accessed 24 October 2022.

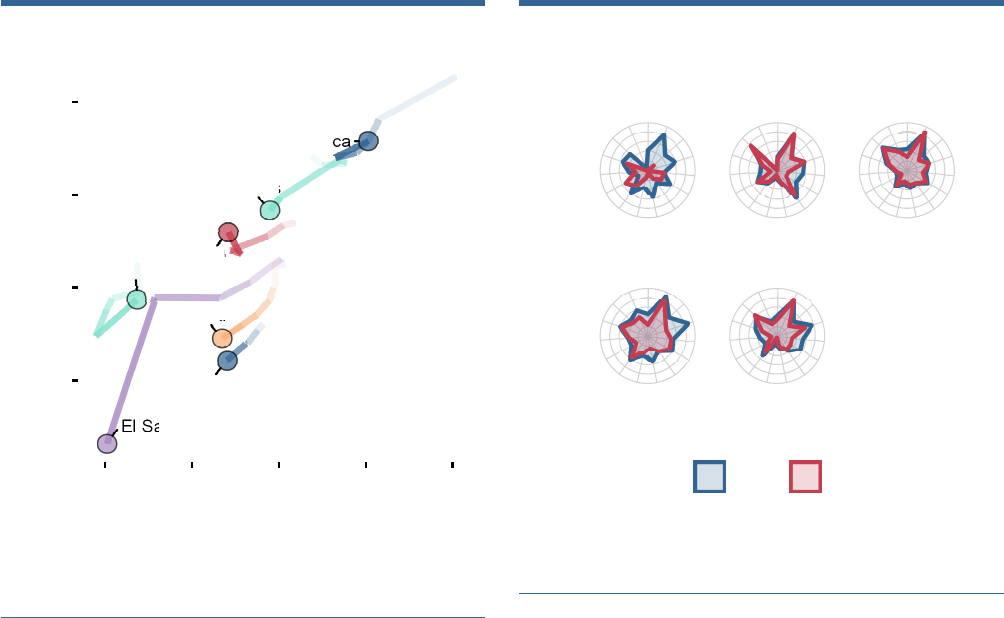

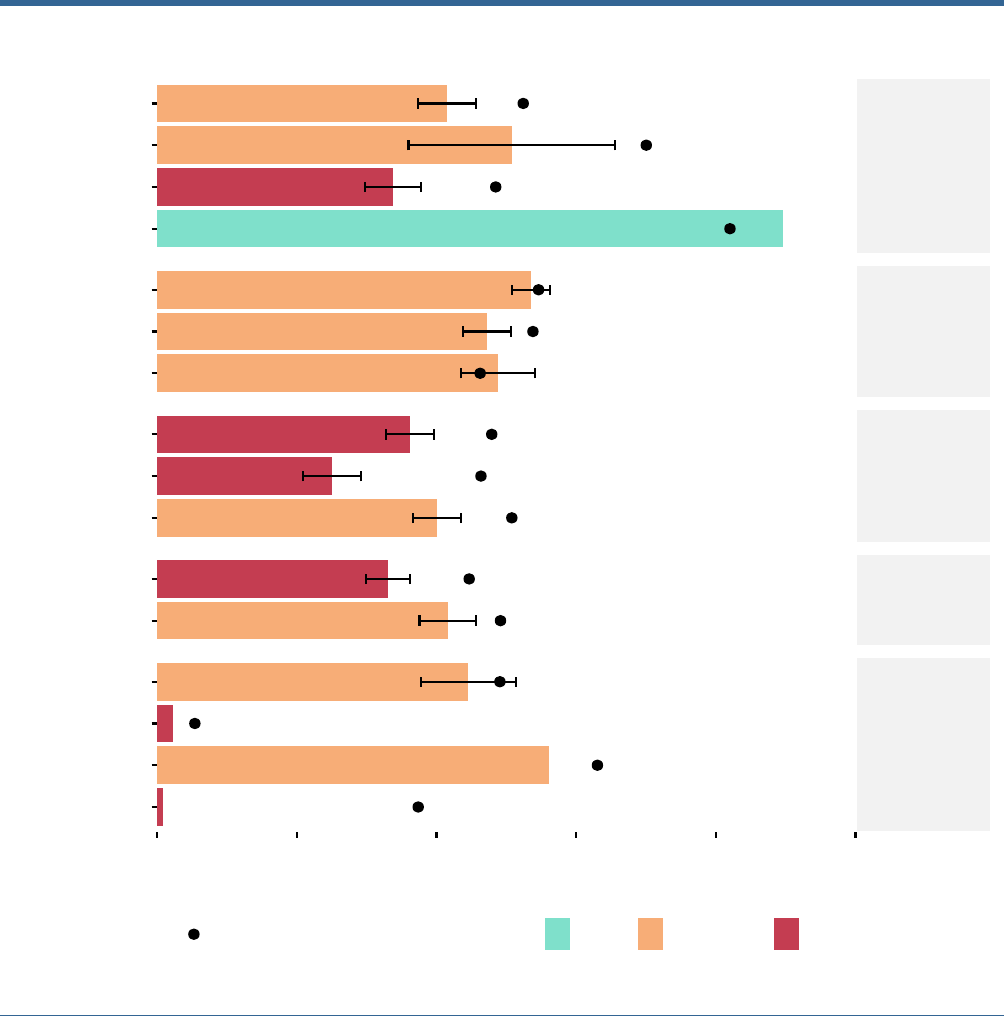

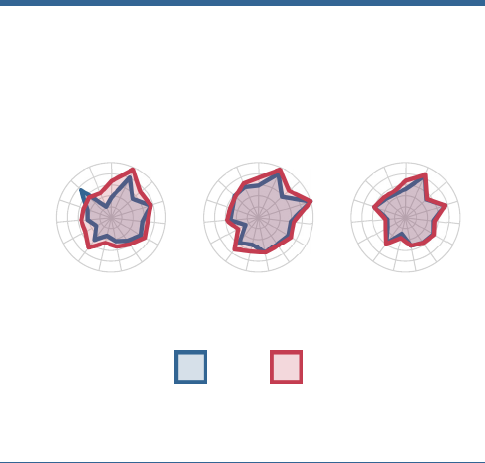

Second, backsliding, which refers to a more severe

and deliberate kind of democratic erosion, continues

to mar democracies’ trajectories; the latest data

show seven backsliding countries. Brazil, El Salvador,

Hungary and Poland are severely backsliding, and

India, Mauritius, and the United States are moderately

backsliding(Figure 6). This pattern, which reveals how

common it has become for elected leaders to use their

power to weaken democratic institutions from inside

the system, indicates the fragility of democracy and the

need to shore up institutions so they can withstand such

pressures, especially in times of crisis.

Chapter 1

Global trends

8

The Global State of Democracy 2022

Forging Social Contracts in a Time of Discontent

FIGURE 6

Trends over the past ve years in backsliding countries

!

"

! " #

$%&

$'()

Notes: Points at 2021 values and traces back to 2016.

Source: International IDEA, The Global State of Democracy Indices v. 6.1, 2022,

<https://www.idea.int/gsod-indices>, accessed 24 October 2022.

FIGURE 7

Declining performance among authoritarian regimes

Source: International IDEA, The Global State of Democracy Indices v. 6.1, 2022,

<https://www.idea.int/gsod-indices>, accessed 24 October 2022.

Third, authoritarianism continues to deepen. Almost

half (49.3 per cent) of all authoritarian regimes are

declining in at least one subattribute. Afghanistan,

Belarus, Cambodia, Comoros and Nicaragua have

experienced a broad decline across multiple GSoD

Indices subattributes (Figure 7). The Clean Elections

and Effective Parliament subattributes are the most

commonly impacted across these cases, suggesting

that even maintaining the façade of elections is

astruggle.

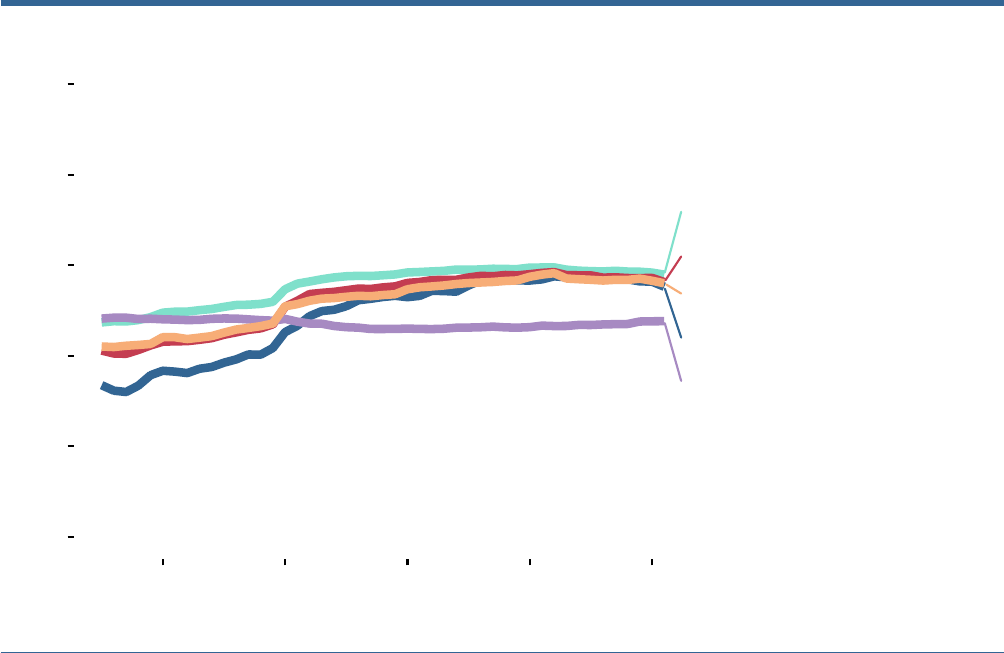

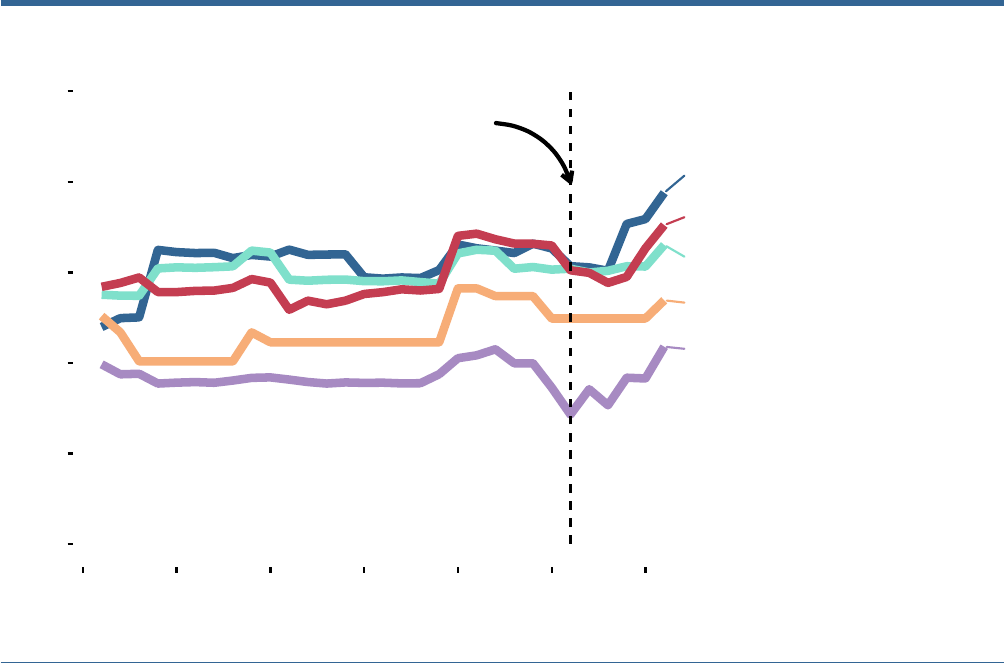

Fourth, democracy does not appear to be evolving in a

way that reects quickly changing needs and priorities.

There is little improvement even in democracies that

are performing at mid-range or high levels. The global

scores for Representative Government, Fundamental

Rights and Checks on Government are exactly the

same as they were in 2001, continuing at the same

mid-level range of performance (Figure 8). Impartial

Administration and Civil Society Participation have also

remained essentially static.

9

International IDEA

2022

Chapter 1

Global trends

FIGURE 8

World averages for attributes of democracy

!"#

$

%

%& %&& $ $% $$

Source: International IDEA, The Global State of Democracy Indices v. 6.1, 2022, <https://www.idea.int/gsod-indices>, accessed 24 October 2022.

The Covid-19 pandemic and Russia’s war in Ukraine

have highlighted the stark inequality between and within

countries, and the public are frustrated. Even countries

that are doing well, and even in the wake of crises,

democracies are not necessarily growing or developing

better or more broadly, or creating more innovative

institutions and mechanisms.

Chapter 2

Regional trends

10

The Global State of Democracy 2022

Forging Social Contracts in a Time of Discontent

Chapter 2

Regional trends

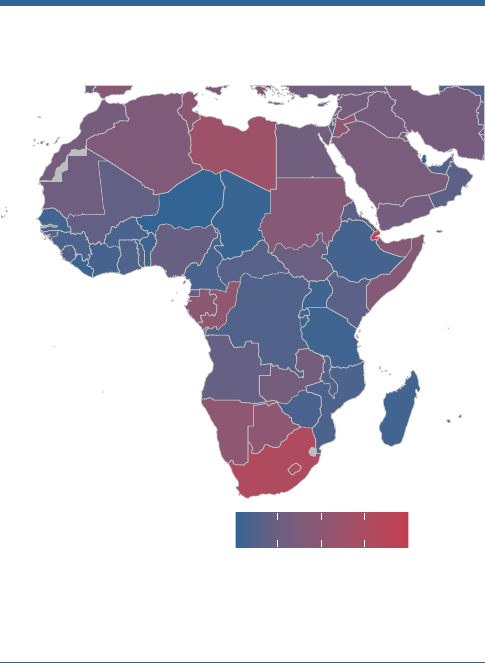

2.1. AFRICA AND WEST ASIA

Key ndings

• Despite myriad challenges, Africa remains resilient

in the face of instability. Countries including The

Gambia, Niger and Zambia continue to improve in

democratic quality. Overcoming a restricted civic

space, civic action in several countries has created

opportunities to renegotiate the social contract;

outcomes have varied by country.

• In West Asia, more than a decade after the Arab

Uprisings, protest movements continue to be

motivated by government failures in service delivery

and economic opportunities—key aspects of social

contracts. In response, disillusioned and excluded

youth have mobilized, and their demands for a seat

at the table highlight their political consciousness

and vital role as drivers of political change and better

governance.

• Some resource-rich authoritarian regimes that have

survived by distributing the economic benets of

hydrocarbon sales have come under scrutiny. There

is evidence that people want more accountability

and a reform of what have been limited obligations

to provide public goods and social welfare.

• Coups d’état and unconstitutional transfers of power

have transformed Burkina Faso, Chad, Guinea and

Mali into new frontiers of instability, but they are only

the most striking examples in a general picture of

declining regime performance across a number of

countries in sub-Saharan Africa.

2.1.1. Introduction

Africa and West Asia (also known as the Middle East)

is a key area of contestation between democratic

and autocratic approaches to politics. Legacies of

colonization remain politically and economically

relevant, as many national economies are built on the

extraction and export of raw materials—a dynamic

that has hampered political and economic progress.

12

Yet, the systems of governance that developed after

independence are being increasingly contested.

Systems of governance (and the social contracts

they enforce) vary widely across this diverse group of

countries. However, they can be broadly grouped into

two types, one dominant in sub-Saharan Africa and the

other dominant in North Africa and West Asia. In the

former, extractive institutions were developed in the

colonial period that concentrated political power and

material gains rst in foreign hands, and then among

a new local elite.

13

This political class then used the

distribution of some of these gains to cultivate support

for the legitimacy of the system. Such institutions have

tended to persist. This centralized relationship between

the provision of resources and the legitimacy of the

system of governance is often termed neopatrimonial.

14

A patrimonial social contract is not necessarily counter

to democracy, since reciprocity can be legitimate.

15

However, institutions in many states have developed in a

way that has limited accountability and maintained high

levels of inequality.

In recent years, several countries have experienced

opportunities to renegotiate these social contracts with

varied success. Large mobilizations questioning the

legitimacy and authority of governments have occurred

in 2021 and 2022 in Eswatini,

16

Ghana,

17

Libya

18

and

Sudan,

19

among other countries. The combination of

young populations, economic challenges and ethnically-

driven politics raises the stakes for changes in social

contracts.

Several countries in Africa have experienced major

changes in their democratic performance over the

past year—for good and for ill. The continent is key to

the future of the planet, as it is home to countries with

the fastest rates of population growth,

20

and many of

those most exposed to the effects of climate change.

21

It is also increasingly important geostrategically, as

various African countries supply rare-earth minerals, oil

and natural gas, and agricultural land that are coveted

by powerful states in other regions. The increasing

relevance of these resources, as well as the resurgence

Chapter 2

Regional trends

11

International IDEA

2022

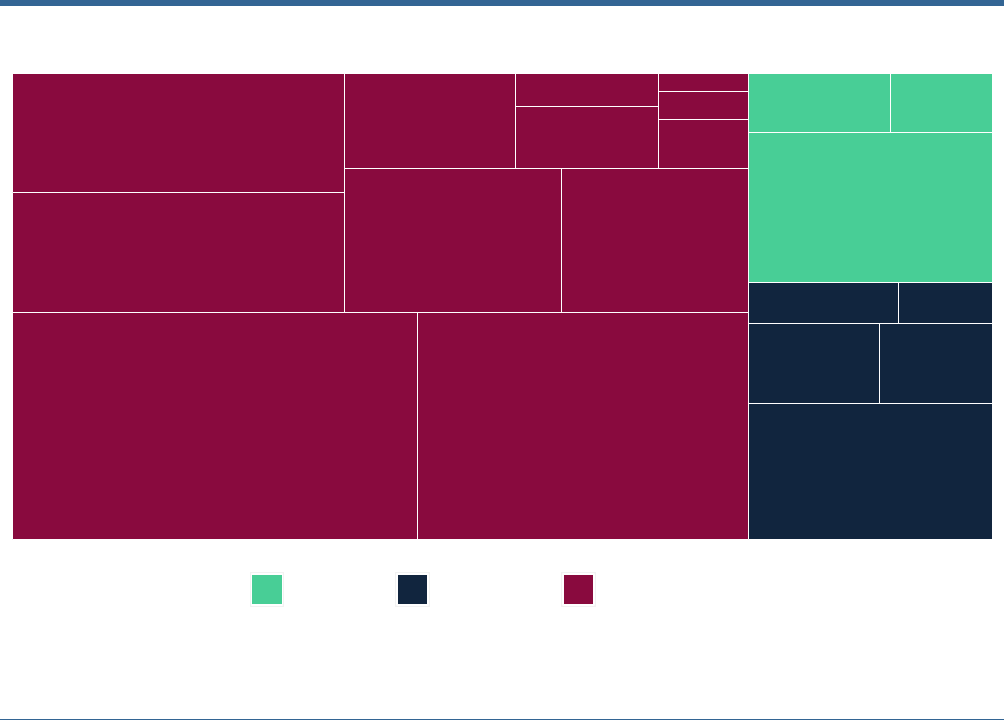

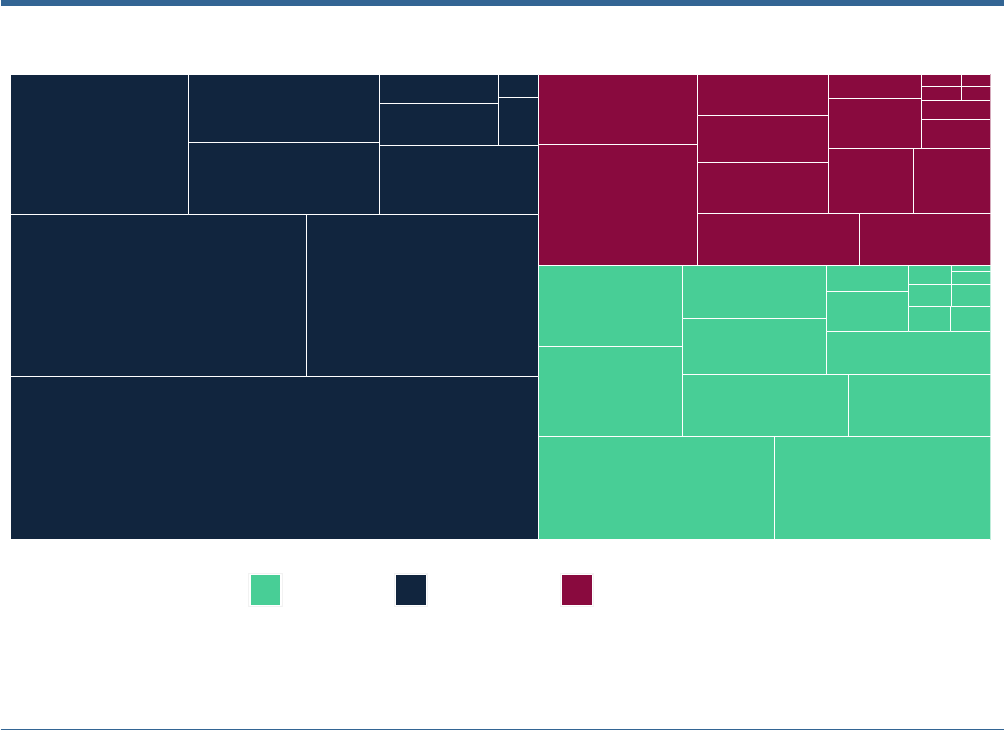

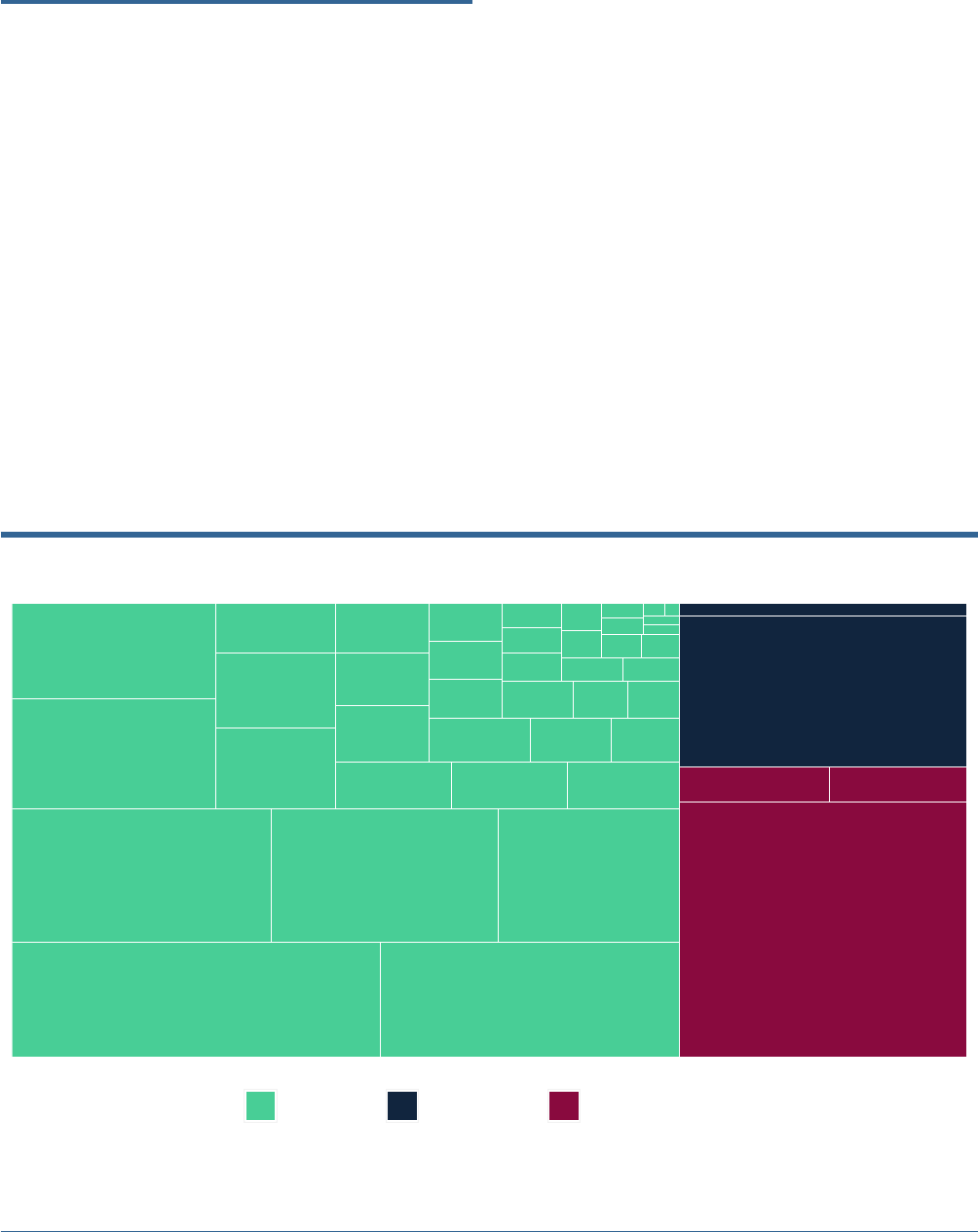

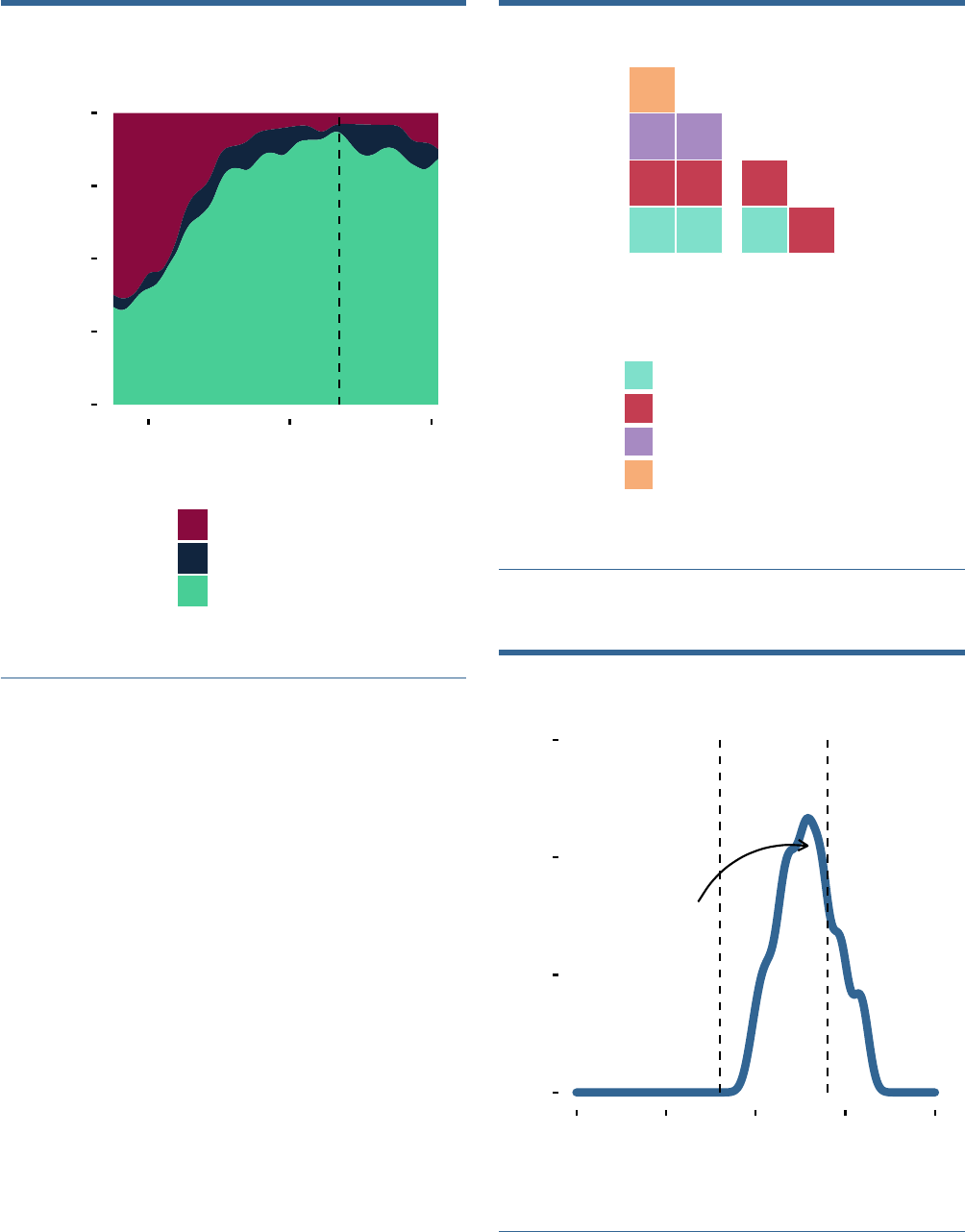

FIGURE 9

Population under regime types in North Africa and West Asia

!

"

#$

%

& ' $

Notes: The size of the box indicates population size.

Source: International IDEA, The Global State of Democracy Indices v. 6.1, 2022, <https://www.idea.int/gsod-indices>, accessed 24 October 2022.

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, World Population Prospects, Online Edition, 2022, <https://population.un.org/

wpp>, accessed 24 October 2022.

of coal exports in response to the global energy crisis,

22

may pose new challenges for democratic consolidation,

as external involvement in domestic politics may

increase alongside foreign economic interests.

Somewhat differently, social contracts across much

of North Africa and West Asia depend on a rentier

economy, in which the state is primarily funded through

the sale of raw materials (chiey hydrocarbons).

23

While

rent seeking may also characterize neopatrimonialism,

the extent to which rents from resource extraction

fund the state is a distinguishing feature between the

two models.

24

Rentier systems impede democratic

development because they undermine the reciprocal

relationships of rights and duties that enable

accountable governance. As long as the government

is able to provide sucient economic benets to the

people, rentier states can be relatively stable—even if

they are almost always authoritarian.

In West Asia, authoritarian leaders are still dominant a

decade after the Arab Uprisings, partly because of the

rentier model. Oil revenues have provided a substitute

for democracy in the oil-exporting countries in West

Asia, where rent distribution has secured the legitimacy

of authoritarian regimes. Some countries in the region—

such as Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia

and the United Arab Emirates—have never experienced

democracy and rely on their oil and gas assets and

geopolitical location to sustain their power.

2.1.2. Trends in West Asia and North Africa

West Asia and North Africa continues to be the

most authoritarian region in the world, with only

three democracies—Iraq, Israel,

25

and Lebanon. Five

countries are hybrid regimes (Jordan, Kuwait, Libya,

Morocco and Tunisia), and 12 countries (60 per cent)

are authoritarian. Several countries in the region have

experienced declines in political institutions and rights

protections since 2020, including Iran, Palestine,

Sudan and Tunisia. As of 2021 only 11 per cent of the

population of North Africa and West Asia were living

in a democracy, and 14 per cent were living in a hybrid

regime; the vast majority of people in the region (75 per

cent) were living in an authoritarian regime (Figure 9).

Chapter 2

Regional trends

12

The Global State of Democracy 2022

Forging Social Contracts in a Time of Discontent

FIGURE 10

Representative Government scores across West Asia and North Africa in 2021

!

"

#$%

&'

&'

())

*+

,

-$'

-$

.$!

/'+!

0+

1!2+!)

34+ (54+ &%4+

Source: International IDEA, The Global State of Democracy Indices v. 6.1, 2022, <https://www.idea.int/gsod-indices>, accessed 24 October 2022.

Two of the democracies, Lebanon and Iraq, remain

fragile and suffer persistently low (and declining)

performance. Amid these challenges to democratic

consolidation, attempts to reform the political system

through electoral means provide grounds for cautious

optimism. The parliamentary elections that took

place on 10 October 2021 (Iraq) and 15 May 2022

(Lebanon) were inuenced (and in the case of Iraq

directly triggered) by movements that were driven by

dissatisfaction with the quality of social justice, control

of corruption and public services. Although established

parties in both countries maintained their dominance,

the elections gave life to new movements that have

the potential to grow in future elections.

26

In Lebanon,

independent candidates opposed to the political

establishment also made breakthroughs.

27

In Iran, the legitimacy of the social contract seems

to be fading.

28

The 2022 protests were sparked by

the immediate issue of women’s rights, but they have

broadened in scope and highlight how demands for

change are manifested even in repressive contexts. The

case of the World Cup in Qatar highlights the international

linkages that arise in some repressive contexts, as

foreign workers who protested to demand their wages

were deported,

29

and the foreign football teams who will

participate in the tournament have struggled to nd an

effective approach to support the workers.

30

For a decade, Tunisia was the major success story

from the Arab Uprisings. The protests that led to the

overthrow of the Ben Ali regime’s 23-year reign in 2011

were driven by a widespread rejection of the social

contract. The 2014 Constitution created a new social

contract through an inclusive and participatory process,

enshrining several socio-economic rights, including the

right to decent working conditions and a fair wage. Yet

the economy continued to decline. In the midst of a

Covid-induced economic crisis and a loss of condence

in political parties,

31

President Saied suspended (and

then dissolved) the parliament and a signicant portion

of the Constitution in 2021 and 2022.

32

This effectively

suspended democracy in Tunisia; the GSoD Indices

reclassied it as a hybrid regime. A new constitution,

drafted in 2022 under Saied’s control and in violation

Chapter 2

Regional trends

13

International IDEA

2022

BOX 3

Renegotiating the social contract in Iraq

Democracy in Iraq has endured turbulent years. Anti-

government protests and political turmoil illustrate the

growing disconnect between citizens and public institutions.

A deteriorating economy caused by a fall in oil prices and the

effects of Covid-19 has increased public disillusionment.

34

Iraqis have grown increasingly tired of the state’s inability

to deliver services and development. As a result, Iraqis took

to the streets in October 2019. The cross-sectarian and

national uprisings, known as the Tishreen protest movement,

emphasized widespread discontent with ruling elites and

deep distrust in the state and its institutions.

35

The protests, driven by youth, called for the government to

step down and an end to the current consociational power-

sharing system, which they claim reduces representatives’

accountability.

36

Trust in the country’s political system is

among the lowest in the region, and corruption perceptions

are among the highest.

37

Iraq’s consociational system has

enabled the expansion of corruption and patronage networks

of the ruling ethno-sectarian parties.

38

A clientelist system

evolved based on sharing the country’s oil wealth, serving

elite interests at the expense of the citizens. With one of the

youngest populations in the world, where nearly 60 per cent

are under the age of 25, Iraq’s post-2003 patronage networks

have excluded an increasing proportion of the population.

The effects of the Tishreen movement still reverberate two

years later as the grievances remain, and young people

continue to be excluded from the decision-making process.

Reimagining a new social contract will be a long-term

process involving comprehensive political and economic

reform that includes genuine opportunities for the youth to

be heard and help improve the country’s situation. Short-term

responses can provide alternative venues to address some

of the protestors’ demands within the current government

structures. Two Baghdad-based think tanks provide cases

that suggest possible pathways for inclusive and resilient

social contracts.

The Al-Bayan Center for Planning and Studies supports youth

activism and mechanisms to channel social protest through

several initiatives to increase political awareness, engage

with civil society and create avenues for representation

to ensure their voices are heard by the political elite. A

dedicated series of skill development and entrepreneurial

training programmes provide better economic opportunities.

Al Bayan’s work promotes the political, social and economic

inclusion of youth in Iraq in an effort to restore hope and a

sense of belonging.

39

The Rewaq Baghdad Center is working towards creating

cultural and behavioural shifts in the political class, as well

as improving citizen–state relations in Iraq.

40

It works closely

with parliament to offer a wide range of knowledge products

and policy assistance to improve legislation. It launched

a mobile application ahead of the October 2021 elections,

designed to reinforce citizens’ participation in the decision-

making process and innovating democracy mechanisms.

41

The rst of its kind in the country, the online tool allowed

voters to engage in dialogue with candidates. Given young

people’s proclivity to use information and communications

technology tools and platforms, the application provided an

incentive for Iraqi youth to participate, beneting more than

100,000 users.

of the rules for constitutional amendment, signicantly

weakened the legislature and judiciary, concentrating

power in the presidency.

33

Tunisia’s December 2022

parliamentary election will be a key test of the degree

to which the new constitutional order can support

democracy.

2.1.3. Trends in sub-Saharan Africa

The situation in sub-Saharan Africa has been much

more dynamic (Figure 11). Free and fair elections

in Niger and Zambia have allowed both countries

to be reclassied as democracies. Zambia held a

credible general election in 2021 in which the defeated

presidential incumbent swiftly conceded.

42

Niger’s

transition has been more dicult. Its 2021 election

marked the country’s rst peaceful transition of power

as President Mahamadou Issoufou stepped down after

two ve-year terms and was replaced by Mohamed

Bazoum, who won the second round of the election.

However, opposition parties made allegations of fraud,

43

and a coup attempt was put down a few days before the

presidential inauguration.

44

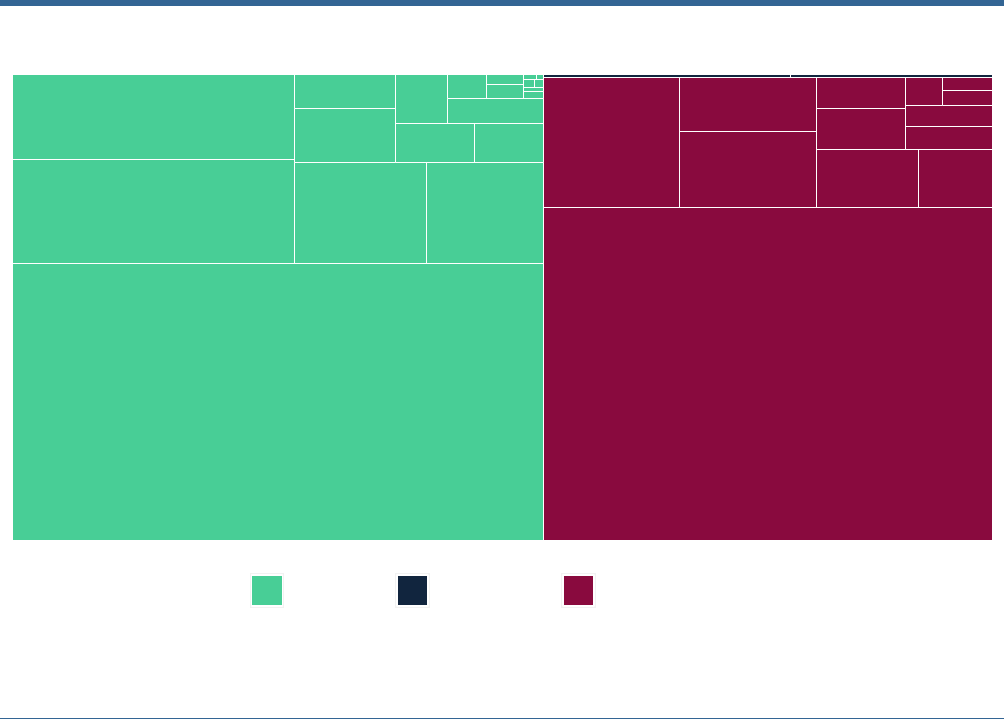

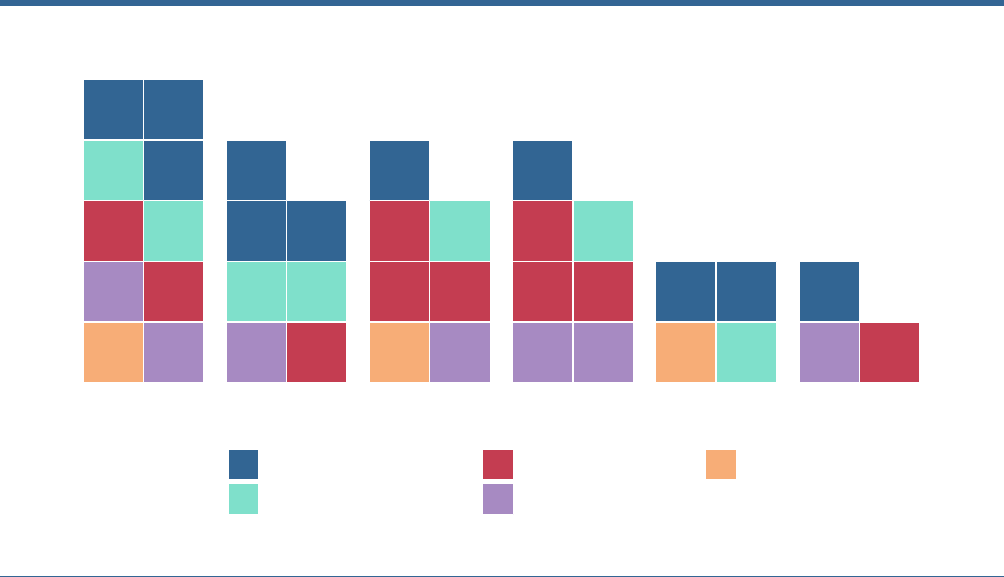

The share of the region’s population living under

democracy has declined over the last ve years. Asof

the end of 2021, only 27 per cent were living in a

democracy—equal to the share living in an authoritarian

regime. After the change in Nigeria from democracy to

hybrid (in 2019), the plurality of the region’s population

(45 per cent) now lives in a hybrid regime.

Chapter 2

Regional trends

14

The Global State of Democracy 2022

Forging Social Contracts in a Time of Discontent

FIGURE 11

Population under regime types in sub-Saharan Africa

!

"#

$!#

%&

&'

()*

$ +

Notes: The size of the box indicates population size.

Source: International IDEA, The Global State of Democracy Indices v. 6.1, 2022, <https://www.idea.int/gsod-indices>, accessed 24 October 2022.

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, World Population Prospects, Online Edition, 2022, <https://population.un.org/

wpp>, accessed 24 October 2022.

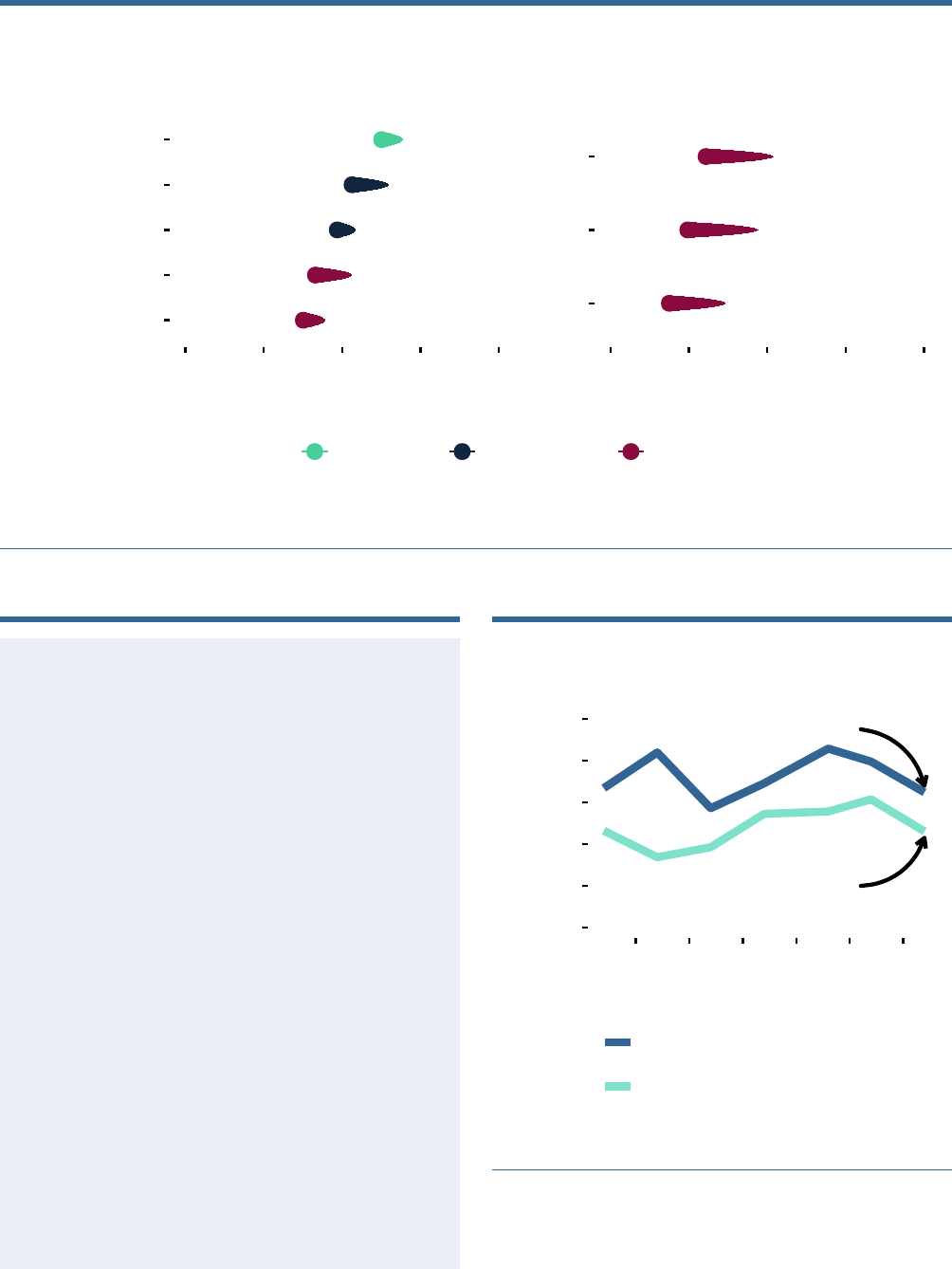

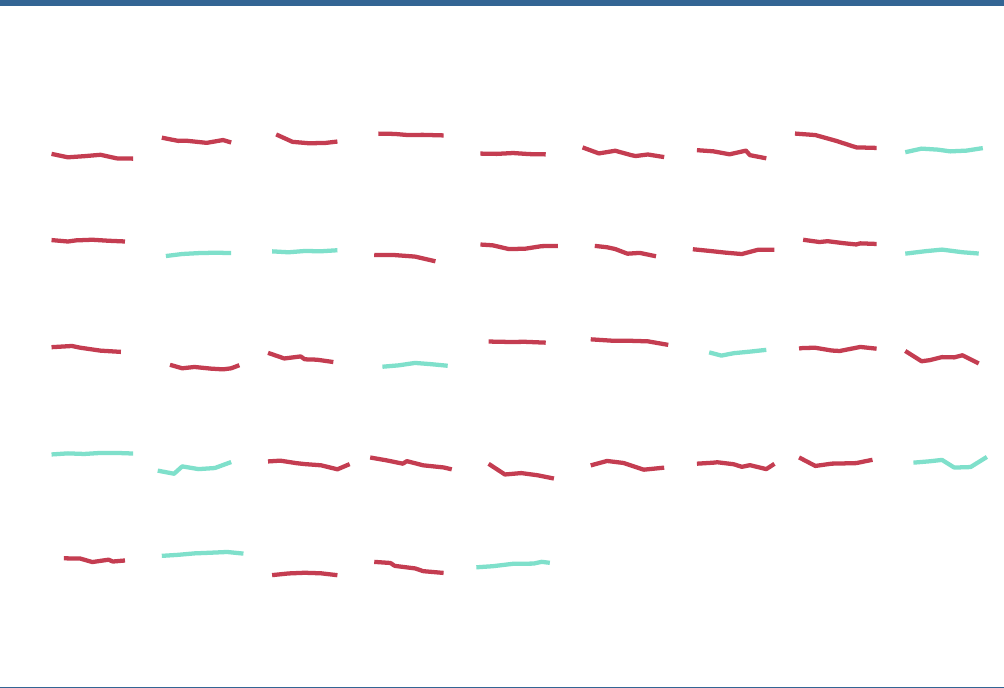

Three countries that stand out as having declined in

their performance have experienced coups d’état or

unconstitutional changes of government—Chad, Guinea

and Mali (Figure 12).

45

Benin, Central African Republic,

Comoros, Mauritius and Nigeria have demonstrated

broader declines in performance. Common themes in

countries in the region that are experiencing democratic

decline are the restriction of civic space

46

and the

manipulation of elections and term limits to serve

the interests of those with (ongoing or prospective)

presidential ambitions. The GSoD Indices show that

Civil Liberties have signicantly declined in eight African

countries over the last ve years.

The Gambia is the continent’s main success story over

the past ve years; it has dramatically improved its

democratic performance. Since Yahya Jammeh was

defeated in the 2016 presidential election, the country

has improved on almost every indicator measured by

the GSoD Indices. These advances reect the vision

of the country’s National Development Plan—a new

social contract for Gambians that aims to deliver

good governance, national reconciliation, improved

social cohesion and an inclusive economy.

47

Its

implementation has involved a transitional justice

process, security sector reform and a constitutional

review.

48

Kenya’s 2022 election is another success story

(see Box 4).

Chapter 2

Regional trends

15

International IDEA

2022

FIGURE 12

Change in average score across subattributes of democracy (2016–2021), selected countries in

sub-Saharan Africa

!"#$%

&' ('

Notes: Points denote current values; tails extend back to 2016.

Source: International IDEA, The Global State of Democracy Indices v. 6.1, 2022, <https://www.idea.int/gsod-indices>, accessed 24 October 2022.

BOX 4

Kenya’s 2022 election

The 2022 Kenyan election was broadly assessed

as credible and largely peaceful, and ethnicity was

less salient than in past years.

49

However, other

unresolved issues, both old and new, present an

ambiguous case for the country’s democratization

trajectory. The public fracturing of the Independent

Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC)

over the validity of the ocial result highlights the

diculty of achieving a fully independent electoral

process.

50

More broadly, the election was met

with widespread voter apathy (especially among

younger voters),

51

and turnout was only 64.8 per

cent (Figure 13).

52

However, the election moderately

increased women’s representation to 21 per cent

of the legislature, though this remains far below

the one-third target set by the Constitution.

53

It was

also lauded for increased transparency, due to the

use of a publicly accessible online results portal

and the IEBC’s memorandum of understanding with

media houses to announce the results from polling

stations. The successes of the 2022 election should

be celebrated, but much work remains to be done.

FIGURE 13

Voter turnout in Kenya (1992–2022), presidential

elections

Source: International IDEA, The Global State of Democracy Indices v. 6.1, 2022,

<https://www.idea.int/gsod-indices>, accessed 24 October 2022.

Chapter 2

Regional trends

16

The Global State of Democracy 2022

Forging Social Contracts in a Time of Discontent

BOX 5

BOX 6

Social contract renewal in Uganda

Uganda has one of Africa’s youngest populations yet one of its

oldest leaders. President Museveni has ruled for 36 years—his is

an increasingly authoritarian and sclerotic regime that is failing

to meet Ugandans’ growing democratic aspirations

58

and basic

socio-economic needs.

59

Yet the prospect that this aspiration–

reality gap will precipitate a renewal of the social contract is

currently remote, and is likely to remain so until Ugandans can

agree on a shared vision for the future. Such a convergence

requires pro-democracy activists to be able to effectively

counter the regime’s polarizing narrative, in which it presents

itself as the guarantor of stability and growth and its critics as

being in the service of foreign powers.

60

It is not for a lack of alternatives that this narrative has prevailed,

but rather the Museveni regime’s ability to limit Ugandans’

exposure to these accounts. Since the introduction of multiparty

elections in Uganda in 2005, opposition party voices have been

among the loudest calling for a new democratic dispensation.

Yet by starving such parties of funding, shutting them out of rural

areas, repressing their activists and restricting their access to

the media, the regime has ensured that their voices reach only a

fraction of their intended audience.

61

The 2021 general elections

were an inection point in this regard. The regime deployed

these tactics with an unprecedented level of violence, particularly

against the National Unity Platform (NUP) party; its governance

reform agenda and popular leader, the musician-turned-politician

Bobi Wine, had helped it galvanize Uganda’s urban youth.

62

In

response to this escalation, the NUP has sought to strengthen its

capacity to disseminate its message across the country through

the construction of a network of mobilization committees, known

as Kunga Committees.

63

The new committees’ ability to compete

with the deeply embedded structures of the Museveni regime and

to withstand its repression remains to be seen.

While generally less confrontational than the pro-democracy

opposition parties, Uganda’s civil society has historically been

a source of ideas and practices that challenge the country’s

authoritarian trajectory. The regime has increasingly come

to view them as a threat to its power. Using methods similar

tothose deployed against opposition parties, it has hollowed

out civil society’s democracy sector, forcing organizations

toclose or to engage in less overtly political work.

64

As demographic and economic factors push Ugandans into an

ever more conictual relationship with Museveni’s militarized

regime, the need for a responsive democratic social contract

has become urgent. However, those striving tobring it about

have been left muzzled and despondent.

South Africa’s young climate policymakers

As the demographic that will be hardest hit by continued

global warming, the world’s youth have the greatest stake in

the unfolding climate crisis.

65

Yet despite their widespread

advocacy on the issue, young people have largely been excluded

from climate policymaking.

66

In South Africa this is beginning to

change.

The most visible sign of this progress has been the recent

presence of ocial youth delegates among the country’s

delegations to the United Nations Climate Change Conferences

of the Parties (COPs).

67

Independent of the government, they are

mandated to represent the views of young South Africans at the

negotiations. The delegates are selected from a growing pool of

young climate activists with both a sophisticated understanding

of climate change and the skillset needed to effectively

participate in high-level policymaking. The South African Institute

of International Affairs (SAIIA) has cultivated a youth-run network

of organizations and activists that convenes to draft climate

policy documents which articulate its members’ perspectives and

priorities.

68

Stakeholders regard these documents as authoritative

representations of the youth voice and useful tools for shaping

climate policy. Young activists have also been involved in

formulating government climate policy: several worked on the

City of Johannesburg’s 2021 Climate Action Plan.

Youth participation in such policymaking and inuencing is a

marked departure from the situation in South Africa a decade

ago, when young voices were absent from climate policy spaces.

Desirée Kosciulek, the Head of Youth Programmes at SAIIA,

characterizes this progress as being youth driven but credits the

South African Government with being a responsive partner. She

notes its willingness to increase the number of ocial youth

delegates to the COP from one to three and to adapt policy

processes to meet the needs of young participants (e.g. scheduling

meetings outside of school hours and covering transport costs).

Having secured a seat at the table, the next challenge for

South Africa’s youth (and other stakeholders) is to ensure that

their participation in climate policy processes is meaningful.

For Kosciulek, the rst step will be to dene what meaningful

participation is, but she is clear that it is not one-off or tokenistic

engagement.

Chapter 2

Regional trends

17

International IDEA

2022

FIGURE 14

Unemployment rate among job-seeking youth (15–24)

in Africa and West Asia

Source: International Labour Organization, ILOSTAT database. Data as

of June2022, <https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.UEM.1524.ZS>,

accessed 15June 2022.

2.1.4. Conclusion

Across Africa and West Asia, social contracts are likely

to come under increasing strain in the short to medium

term as the broader effects of Russia’s invasion of

Ukraine drive food and energy costs up—though the

effects will vary between energy-exporting and -importing

countries. Many countries are also facing increasing

borrowing costs as a result of higher interest rates and

the strengthening of the US dollar. These challenges must

be addressed in a context of longstanding problems

with youth unemployment, poverty and inequality.

54

Generational change in politics could also play a role in

some African countries, as the already fragile legitimacy

of ageing autocrats will be further tested by demands

from a young population for better economic outcomes,

and more freedoms in politics and culture.

55

Longer-term dynamics that may disrupt these

rentier social contracts include continuing youth

unemployment (Figure 14) and the green energy

transition. The UN recently estimated that 33 million

jobs will need to be created across North Africa and

West Asia by 2030 to keep up with the growth in the

youth population.

56

Similar dynamics apply in Africa

more generally. The failure to deliver such jobs could

generate pressure for change. Looking further ahead,

decarbonization may threaten oil-exporting states’

ability to fund social programmes at current levels.

Several important elections are scheduled for 2023,

including a general election in Nigeria and a legislative

election in Benin. Both countries’ democratic

performance has declined since 2019, but they have an

opportunity to reverse that trend in 2023. Sierra Leone

will also hold elections for the president and parliament

next year, hoping to build on recent improvements

in democratic performance. While the situation in

Libya remains unpredictable, it is possible that a new

constitution will be drafted and national elections

organized in 2023.

Demand for democracy remains high in the region, but

satisfaction with democratic performance is low.

57

How

that gap is addressed will be determinative for many

countries in the next ve years.

Chapter 2

Regional trends

18

The Global State of Democracy 2022

Forging Social Contracts in a Time of Discontent

2.2. ASIA AND THE PACIFIC

Key ndings

• Democracy is receding in Asia and the Pacic,

while authoritarianism solidies. Only 54 per cent

of people in the region live in a democracy, and

almost 85 per cent of those live in one that is weak

or backsliding. Even high- and mid-performing

democracies, such as Australia, Japan and Taiwan

are suffering democratic erosion.

• Although erosion has taken place in all aspects of

democracy, the impact on Freedom of Expression and

Media Integrity is striking: 35 per cent of democracies

in the region exhibit erosion in at least one of them.

• Although highly diverse, common elements eroding

democracy are, inter alia, rising ethno-nationalism,

military intervention in political processes, patronage

politics and executive aggrandizement.

• This negative trend is tearing the social contract

apart in many countries, with a demand for increased

accountability and an overhaul of the political system

in countries as varied as Kazakhstan, Sri Lanka and

Thailand. The cases of Kazakhstan and Thailand

also highlight the popular discontent with some

fundamental characteristics of the political system

that were assumed to be immovable, such as the

role of the King in Thailand or the focus on economic

development over freedoms in Kazakhstan.

• The continuing effects of the pandemic and Russia’s

war on Ukraine have been particularly acute for

Central and South Asian countries, providing political

space for both democratic renewal and opportunistic

authoritarians.

2.2.1. Introduction

Democracy in Asia and the Pacic is receding. In

the last ve years, approximately 60 per cent of

the 35 countries in the region, including half of the

democracies, have suffered signicant decreases in

at least one subattribute. Although the most dramatic

examples of breakdown have been in Afghanistan

and Myanmar, even more longstanding and stable

democratic systems in India, Indonesia, the Philippines

and Taiwan are at risk.

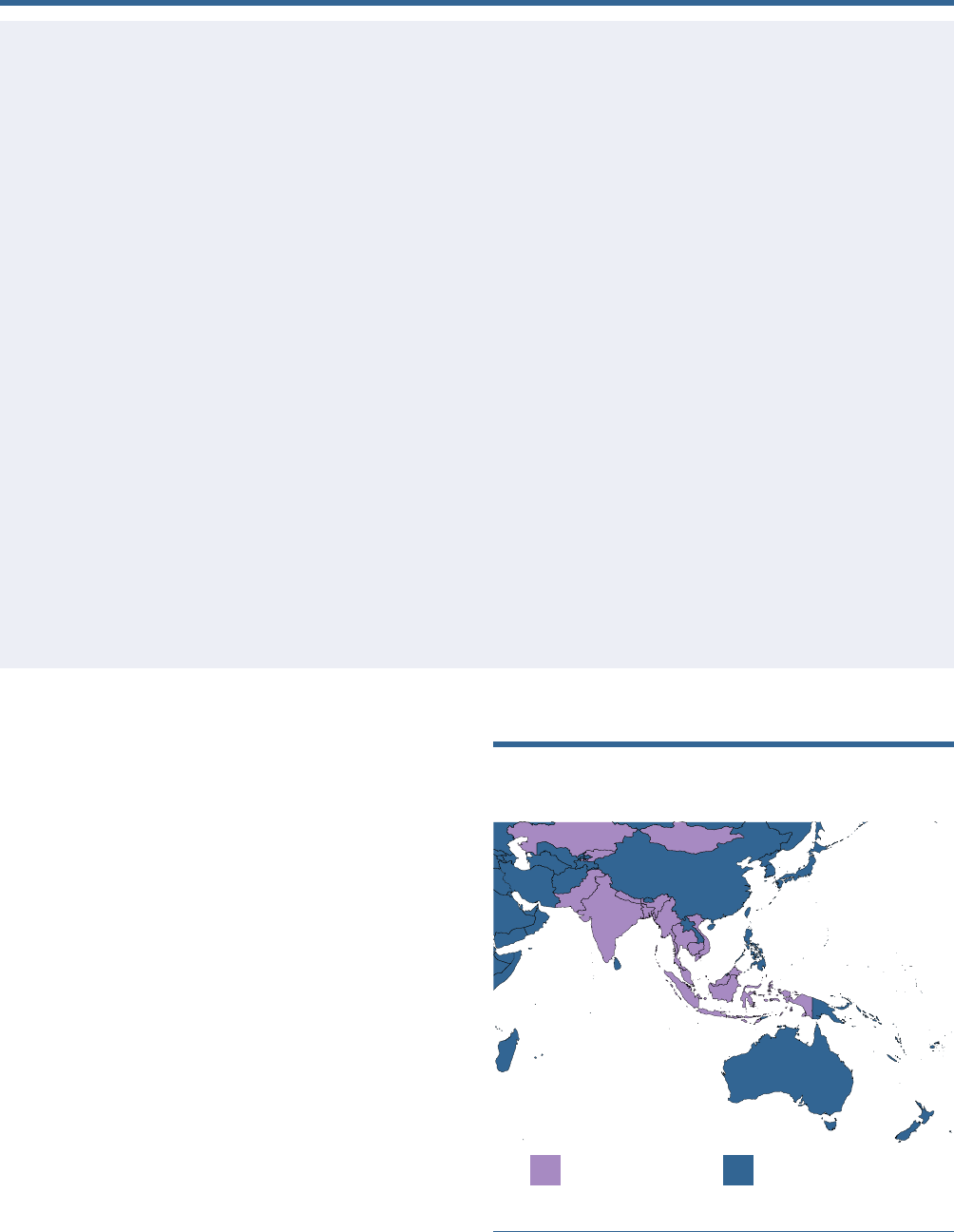

Nearly half of the region’s inhabitants live in an

authoritarian regime (72 per cent of those live in China)

(Figure 15). More than three-quarters (84 per cent) of

residents of a democracy in Asia and the Pacic live in

one that is weak or backsliding.

69

The erosion of democracy in the region is a product

of several factors, including the rise of exclusionary

ethno-nationalist movements fuelled by a mix of

real and politically manipulated social grievances,

armed and unarmed interventions by the military in

political processes, executive aggrandizement, stalled

democratic transitions and economic mismanagement

that has led to unsustainable debts and, in extreme

cases, nancial collapse. Countries’ democratic

trajectories are shaped by their postcolonial histories

as well as their neocolonial political and economic

relationships with regional hegemons. But these factors

should not be overstated: national elites have long

proved adept at using the legacy of colonialism to

deect criticism from their own mismanagement and

cronyism.

Additionally, foreign actors’ geopolitical interests are

impacting domestic politics. In Nepal, citizens protested

against the approval of a USD 500 million grant from a

US aid agency due to concerns that the grant conditions

unacceptably infringed upon national sovereignty.

70

In

Kazakhstan and Sri Lanka, foreign actors have assisted

incumbent leaders in various ways, angering citizens,

who demand accountability and responsiveness.

71

Chapter 2

Regional trends

19

International IDEA

2022

FIGURE 15

Population under regime types in Asia and the Pacic

! "#

"

$

%&

'## ( "

Notes: The size of the box indicates population size.

Source: International IDEA, The Global State of Democracy Indices v. 6.1, 2022, <https://www.idea.int/gsod-indices>, accessed 24 October 2022.

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, World Population Prospects, Online Edition, 2022, <https://population.un.org/

wpp>, accessed 24 October 2022.

2.2.2. Trends in the region

Social contracts are being tested, renegotiated and

disputed across the region, and subregional nuances are

fundamental to understanding these tensions. In South

Asia, where communal mistrust and competition have

in some cases been addressed through power sharing,

economic crises and the rise of illiberal forces have

contributed to the resurgence of ethno-nationalism.

Resulting violence against minority groups and

increased societal polarization highlight the pressures

exerted on the social contract.

72

The persistence of

pandemic-instigated disruption to migrant ows and

remittances on which South Asian economies heavily

depend adds to the economic anxieties that fuel ethno-

nationalism and remains an unsolved problem for the

region.

73

An active civil society and the strength of some

key institutions—such as the judiciary and electoral

management bodies (EMBs)—can act as bastions

of democracy. India’s active civil society have been

key in denouncing some states’ attempts to limit

religious freedoms. In Nepal, citizen and civil society

mobilizations demanding accountability, gender equality

and good governance remain a fundamental and

inuential political force.

74

The breakdown of democracy in Myanmar is the major

event in Southeast Asian democratic development.

Yet actors like the National Unity Government and the

Committee Representing the Union Parliament, which

are building new democratic institutions that reect

many longstanding concerns regarding minority rights

and equal access to public goods, demonstrate the will

to build a new social contract.

Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam remain rmly anchored

in authoritarianism with no visible signals of change.

Vietnam, like China and Singapore, has managed

to provide economic prosperity without granting

democratic rights, giving its communist regime a veneer

of public legitimacy. An economic crisis and possible

debt default in Laos have generated signs of popular

dissatisfaction with the government but have not

Chapter 2

Regional trends

20

The Global State of Democracy 2022

Forging Social Contracts in a Time of Discontent

manifested in the kind of organized protest in favour

of a responsive and accountable social contract seen

recently in Kazakhstan, Sri Lanka and elsewhere. As

Laos is politically and economically dominated by its

stable authoritarian neighbours, China and Vietnam, its

people may feel that democratic progress is currently

infeasible or too risky.

75

In the Philippines, an intensive disinformation campaign

supported the ascent of the son of Ferdinand Marcos,

known as Bongbong Marcos, to the presidency. Yet,

pro-democracy movements in Thailand and Malaysia

and the refusal to accept the military junta in Myanmar

demonstrate that democracy remains a core aspiration

for millions in Southeast Asia, even in the most

repressive circumstances. In Thailand, protesters

have demanded concrete policy changes, such as the

elimination of the military’s power to hand-pick senators

and select the prime minister, and the reversal of the

prohibition of some political parties. They have also

challenged the country’s political and economic elite

model of governance, including by questioning the role

of the monarchy for the rst time in decades. However,

the ghost of military dictatorships past is not always

easy to exorcise; in Indonesia and the Philippines,

the military’s signicant public role in the pandemic

response dashed hopes that the armed forces’ retreat

from the political sphere during recent periods of

democratization might be permanent.

76

East Asia remains stable and, apart from China,

predominantly democratic. During the last ve years,

democracy has expanded notably in South Korea

and remained stable in Japan and Taiwan. Mongolia

continues last year’s trend of declines across all

attributes except Representative Government. The rising

tensions in the Taiwan Strait and mainland China’s

suppression of democracy in Hong Kong and incursion

on Bhutanese sovereignty are clear examples of its

willingness to exert its inuence in the region.

77

Oceania continues to stand out for its strong democratic

performance, although declines in certain attributes,

largely due to expanded pandemic-related restrictions,

curb the region’s overall performance. It is particularly

vulnerable to climate change

78

and has been the site

of intense geopolitical competition between China,

Australia and the USA. Overall, the region has witnessed

a slight drop in its Impartial Administration score; New

Zealand and Papua New Guinea have experienced one-