Overview Of State

ObligatiOnS relevant

tO DemOcratic

gOvernance anD

DemOcratic electiOnS

POlicy PaPer

Overview Of State

ObligatiOnS relevant

tO DemOcratic

gOvernance anD

DemOcratic electiOnS

04

intrODuctiOn 06

abOut thiS PaPer 07

table Of recOmmenDatiOnS –

DemOcratic gOvernance 08

table Of recOmmenDatiOnS –

DemOcratic electiOnS 12

05

06

Strengthening

internatiOnal law

tO SuPPOrt

DemOcratic gOvernance

anD genuine electiOnS

intrODuctiOn

International law contains a large number of obligations relevant

to democratic governance and democratic elections. International

human rights treaties guarantee key elements of democracy,

such as the respect of human rights, the rule of law, transparency

and accountability in public administration, and a free media.

The separation of powers, the independence of the judiciary,

and pluralistic system of political parties and organisations are

also part of international legal obligations. UN General Assembly

resolution 59/201 (2005)

1

and various other resolutions of the

General Assembly confirm these elements of a democracy.

International law also protects key principles of democratic

elections, including universal suffrage, the secrecy of the vote,

the right to vote and to be elected, the right to freely assemble

and associate, and the right to an election that is “genuine,” all of

which are enshrined in various human rights treaties.

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)

is the cornerstone of democratic governance and genuine

elections in international law. Article 25 of the ICCPR explicitly

grants the right to take part in the conduct of public affairs and

to equal suffrage. The ICCPR also guarantees other core elements

of a democracy and genuine elections, such as the freedoms of

association, assembly, and expression and the independence of

1 UN General Assembly, “Enhancing the role of regional, sub-regional and other

organisations,” (2005). With 172 States in favour, 15 abstentions, and no rejections,

resolution 59/201 marks a nearly global consensus on key elements of a democracy.

the judiciary. With 167 State parties from all regions of the world,

the ICCPR constitutes nearly global consensus on minimum

requirements for democratic governance and genuine elections.

Other human rights treaties contain similar or virtually identical

provisions, thereby complementing the ICCPR.

As developed by State practice or treaty bodies, these

obligations are often detailed and comprehensive. The United

Nations Human Rights Committee (HRC) and other treaty bodies

routinely interpret these previsions, thereby helping to further

develop consensus on the meaning of a relevant norm. Views on

individual petitions and General Comments of the HRC provide

an authoritative understanding of the obligations States have

undertaken to respect democratic governance and genuine

elections. While often surprisingly detailed and comprehensive,

ambiguities and gaps remain within this framework. International

law is often general in nature and does not cover all relevant

aspects of democratic governance and genuine elections. Many

of the shortcomings could be addressed through a new or revised

General Comment by the HRC on articles 21, 22, and 25 of the

ICCPR. Treaty amendments are generally not required to bridge

the gaps, although they would provide for the highest possible

degree of legal certainty.

07

abOut thiS PaPer

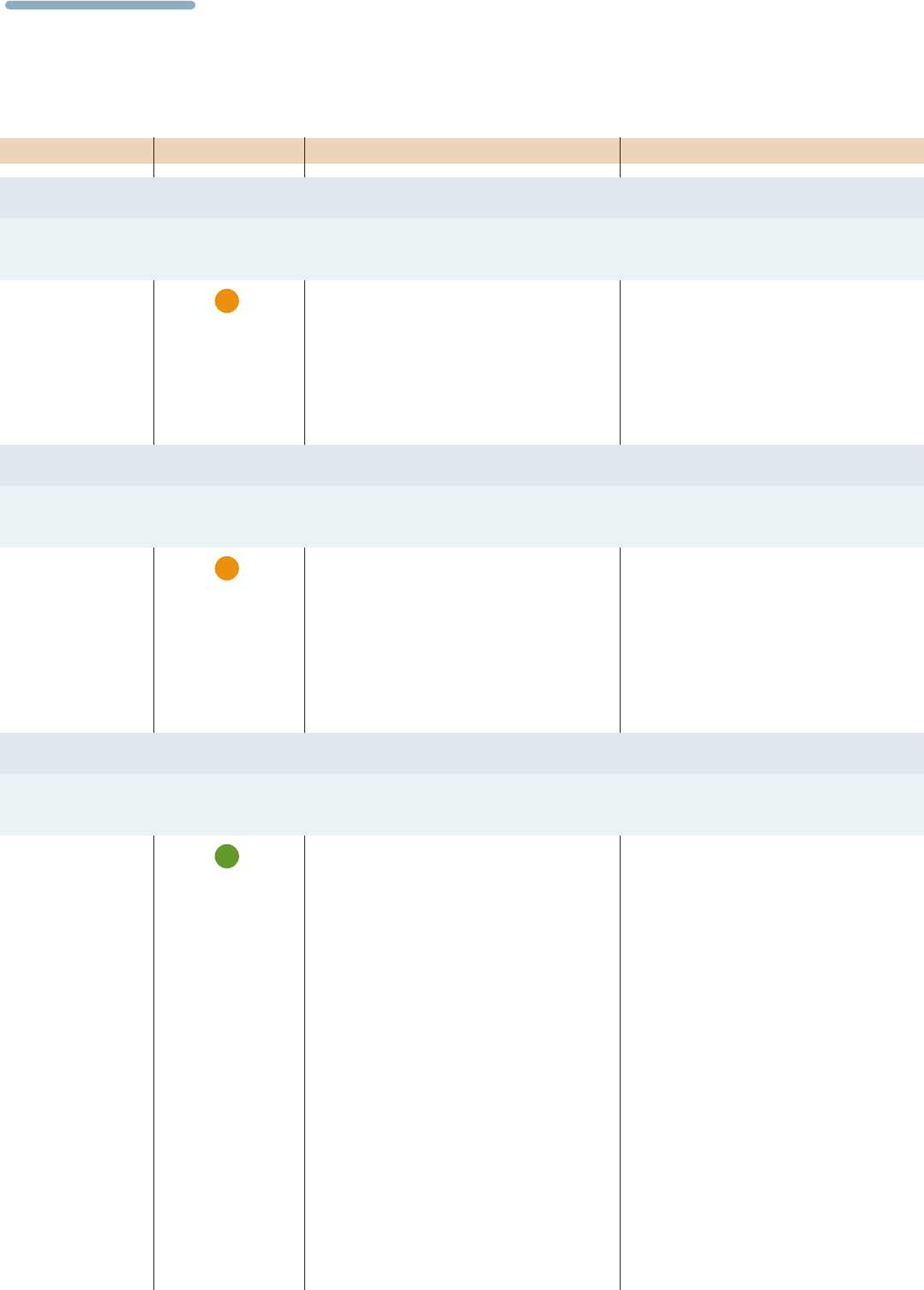

This paper gives an overview of the extent to which States are

obliged to organize themselves as a democracy and to hold

genuine elections. For easy access, the paper consists of a table

matrix. The table summarizes the relevant State obligations and

their content and meaning. The table also provides an overview

of the gaps and ambiguities in international law and provides

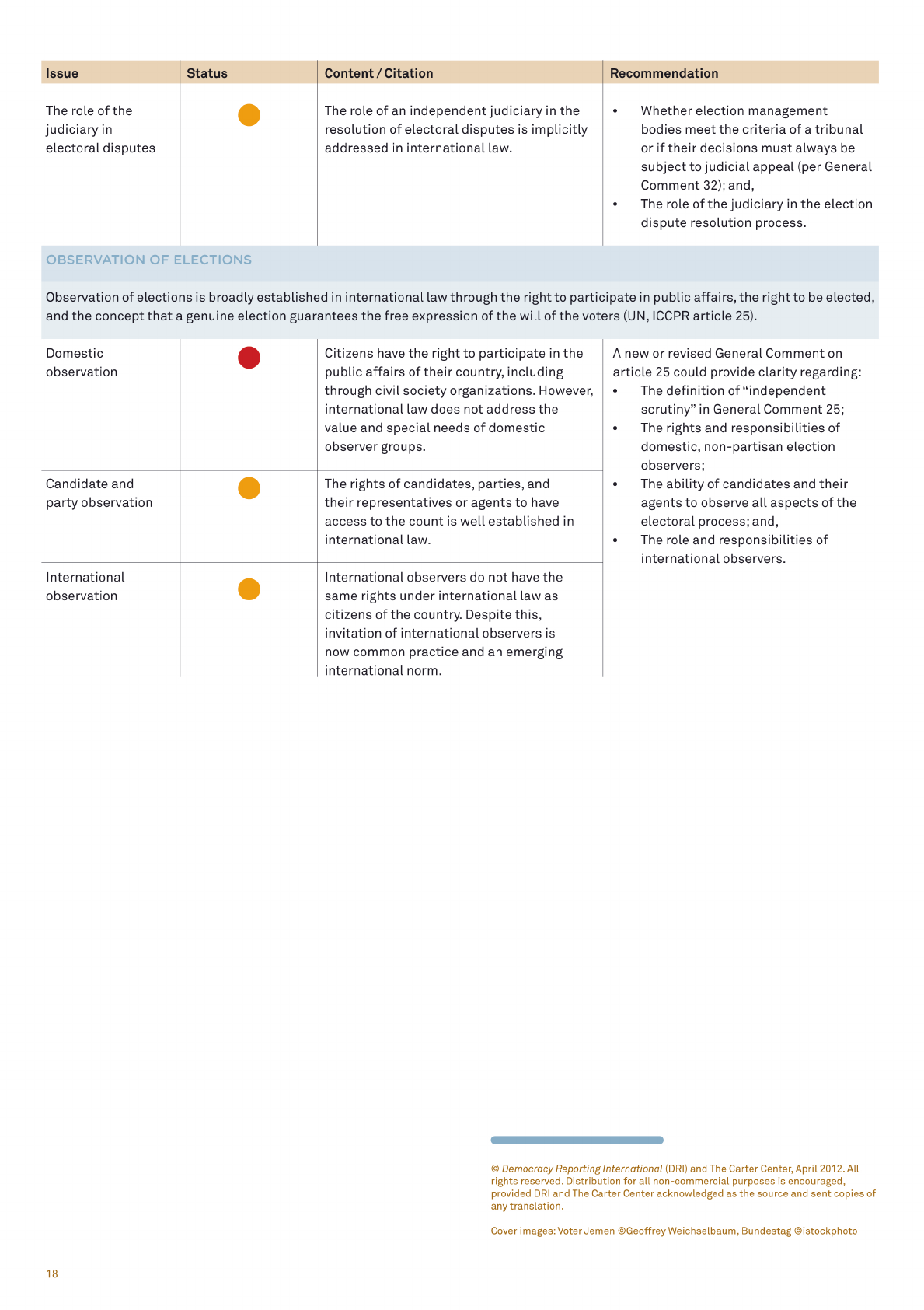

recommendations on how to address these shortcomings. Using

traffic light symbols, the table offers a summary evaluation on

whether international law largely, partially, or inadequately

covers a given issue.

This paper is a based on the study “Strengthening International

Law to Support Democratic Governance and Genuine Elections”.

This comprehensive study discusses State obligations under

international law relevant to democratic governance and genuine

elections in detail and can be downloaded at the websites of

Democracy Reporting International and The Carter Center.

Funding from the Federal Department of Foreign Affairs of

Switzerland, the Irish Aid Civil Society Fund, and the Bedford

Falls Foundation made this paper possible. DRI and The Carter

Center are appreciative of this support. The views expressed in

this report are those of the authors

2

and do not necessarily reflect

those of the donors. The report complements and expands upon a

DRI programme on democracy standards

3

and The Carter Center’s

on-going initiative on Democratic Election Standards.

4

2 This paper was written by Dr. Nils Meyer-Ohlendorf of Democracy Reporting

International and Avery Davis-Roberts of The Carter Center, who are also the authors

of the study “Strengthening International Law to Support Democratic Governance

and Genuine Elections”.

3 http://www.democracy-reporting.org/programmes/democracy-standards.html.

4 http://www.cartercenter.org/peace/democracy/des.html

08

Relationship

between the

executive and the

legislature

Issue Status

minimum rightS Of Parliament

Supervision of the

executive

Right to legislate

Procedural

autonomy

Budget autonomy

International law prohibits an overconcen-

tration of powers in the executive (ICCPR

articles 19, 25). According to the HRC,

cases of inadmissible over-concentration

of powers include:

Unaccountable decision-making; •

Legislative powers of unelected •

institutions or unfettered executive

powers of unelected bodies; and,

Powers of government bodies to issue •

laws, decrees, and decisions without

being subject to independent review.

The principle of no-overconcentration of

powers in the hand of the executive seems

largely unknown and should be subject

to awareness activities. A new General

Comment 25 could make this principle

explicit and could elaborate on the

principle in light of its decisions.

Content / Citation Recommendation

No explicit right to supervise the executive

exists in international law but it derives

from article 25 of the ICCPR: summon

government, conduct hearings, access

to information or criticize government in

public.

No explicit right to legislate exists in

international law but it derives from article

25 of the ICCPR. Article 25 of the ICCPR

forbids the full delegation of legislative

powers to government.

No explicit procedural autonomy exists in

international law but derives from article

25 of the ICCPR.

International law contains no explicit

guarantee of Parliament’s autonomy.

However, the right to adopt national

budgets is a key aspect of independent

parliaments. It is incompatible with article

25 if Parliament cannot survey and adopt

significant parts of the national budget.

Stakeholders should raise awareness for

the implicit rights to Parliament. A new

General Comment 25 should elaborate on

identified minimum parliamentary rights in

more detail.

Meaningful parliaments are a necessary precondition to render citizens’ right of political participation and suffrage effective, as granted

by article 25 of the ICCPR. For this reason a number of minimum rights derive from article 25. These minimum rights include—to differing

extents—the right to supervise the executive, the right to legislate, the right to procedural autonomy, the right to adopt the State budget,

and the immunities of parliamentarians.

table Of recOmmenDatiOnS –

DemOcratic gOvernance

Key:

Largely covered by international obligations:

Partially covered by international obligations:

Not or inadequately covered by international obligations:

SeParatiOn Of POwerS

The term “separation of powers” is not explicitly used in international human rights instruments; however, the HRC has recognized the

principle on various occasions.

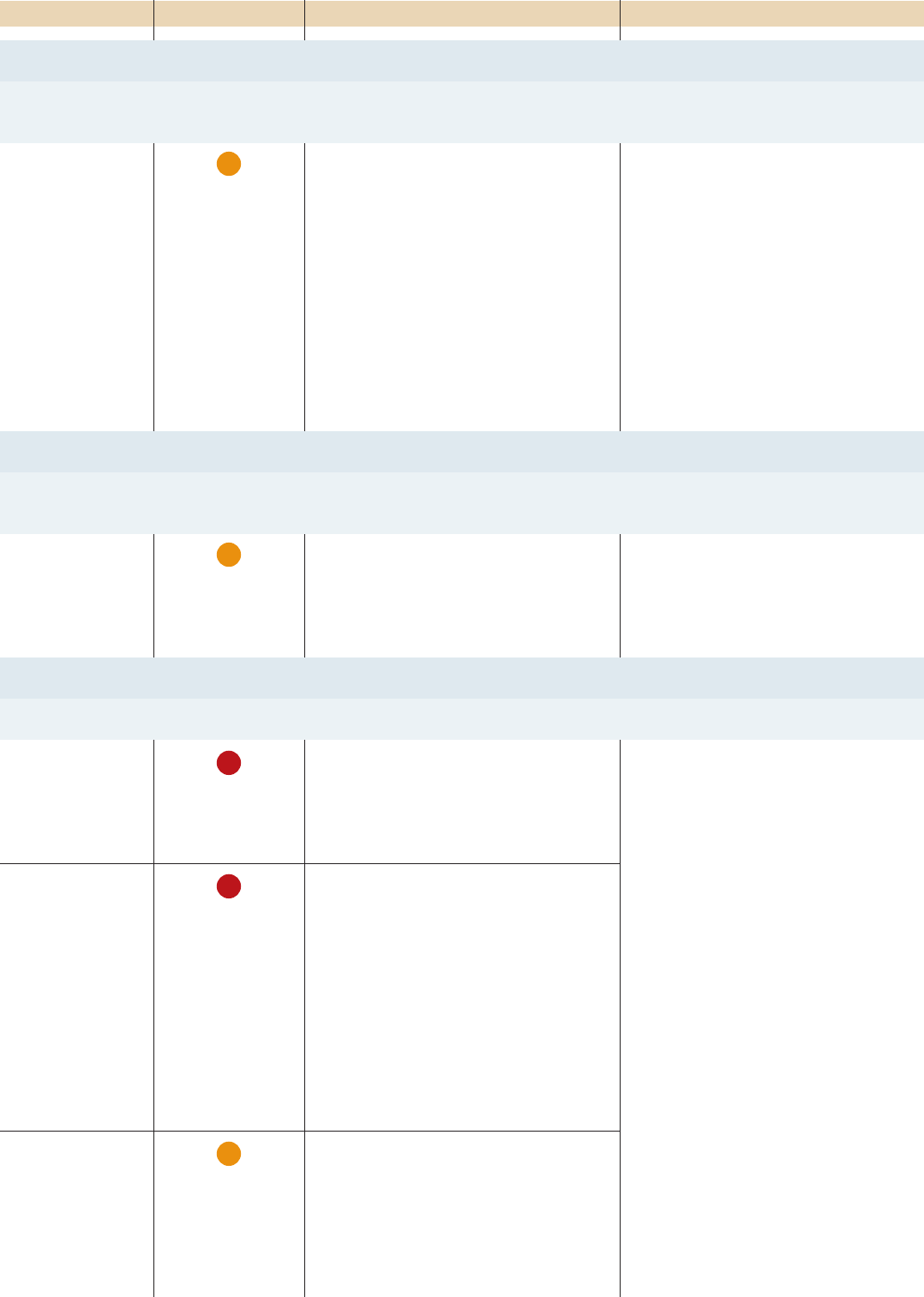

09

Immunities of

Parliamentarians

International law is silent on parliamentary

immunities. Parliamentary immunities can

only be derived from article 25 of the ICCPR

to a very limited extent in as far as they

are vital for ensuring the functioning of

parliament.

Issue Status Content / Citation Recommendation

inDePenDence Of the JuDiciary

cOnStitutiOn-making

State Of emergency

Tenure and

dismissal of judges

Interference

Validity of court

decisions

Process

Process

Requirements

International law forbids insecure tenure or

the dismissal of judges without reasoning

in law (ICCPR article 14).

International law forbids the ending of or

interference in proceedings by executive.

Non-judicial bodies may not adjudicate.

Court decisions are binding and may not be

changed by other branches of government.

According to the HRC, constitution-making

processes should be transparent and

inclusive. Other issues, such as broad

based consensus on a constitution or

qualified majority for adoption, are not

part of international law. International law

contains neither an obligation for States

to put a constitution to a referendum

nor a subjective right to demand direct

participation through referenda or

plebiscite.

A state of emergency must be officially

declared by constitutionally competent

body.

A state of emergency may only be declared

in extreme times that threaten the life of

the nation and its existence. It may not be

inconsistent with international law and

may not involve discrimination solely on

the ground of race, colour, sex, language,

religion, or social origin.

The legal framework set by international

law is adequate in principle.

New General Comment 25 should

make explicit that constitution-making

processes must be transparent and

inclusive.

Legal framework regulating a state of

emergency is detailed and comprehensive

but would benefit from clearer language

on the rights of Parliament during a state

of emergency. Revised General Comments

could clarify Parliament’s rights. Relevant

OSCE commitments could inform the

revision of General Comment 29.

Under international law, the relationship between the judiciary and the executive is largely determined by article 14 of the ICCPR and

similar provisions of regional human right treaties. Article 14 guarantees the right to a “fair and public trial by a competent, independent

and impartial tribunal established by law.”

According to article 25 of the ICCPR, citizens must have an effective opportunity to take part in the conduct of public affairs, which

includes constitution-making processes.

During a state of emergency democratic governance is diminished. The ICCPR and other international treaties provide a number of

detailed procedural and substantive legal rules on the state of emergency.

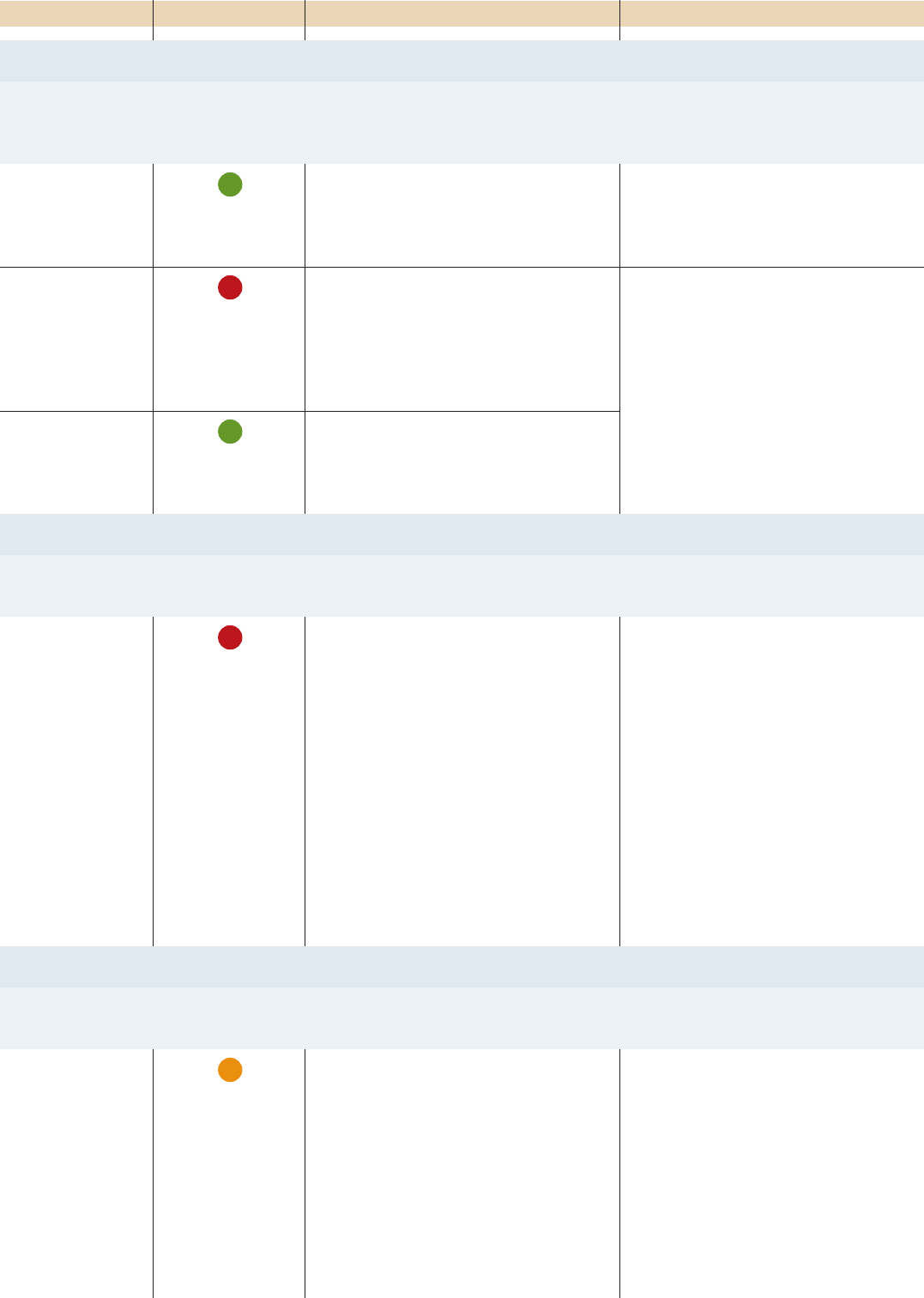

10

Duration and scope Emergency measures must be limited

to the extent strictly required by the

exigencies of the situation and meet

proportionality tests. The ICCPR regulates

only to a limited extent the dissolution of

Parliament during a state of emergency; it

should prohibit dissolution of parliament,

at least in general terms. General Comment

29 contains no geographic limitations

or accountability requirements, unlike

the OSCE, which adopted more detailed

commitments on the state of emergency.

Civilian supervision

Access to

information

Registration

Refusal of access

The HRC has developed the requirement of

“full and effective” civilian control over the

military. To ensure full and effective civilian

supervision, the mandate, composition,

command, and number of the armed forces

must be clearly defined in law.

The right to access to information held by

public bodies is enshrined in article 19 (2)

of the ICCPR and further specified by HRC

decisions.

Key aspects of political party registration

are implicitly regulated by international

law, including requirements for a

registration framework in law and a

prohibition on excessively restrictive

registration processes and requirements.

Public authorities should circumscribe

access to information narrowly but the

ICCPR contains no details on legitimate

grounds to refuse information. General

Comment 34 only requires States to

substantiate “any refusal to provide access

to information.”

There is only limited case law and no

explicit mention of civilian supervision

in relevant ICCPR case law. It would be

beneficial if a revised General Comment

25 could strengthen civilian supervision.

The principles of separation of power and

no-overconcentration of powers in the

hand of the executive could serve as key

benchmarks for elaborating on civilian

supervision (see above).

With the new General Comment 34, the

legal framework on transparency has

become more detailed and comprehensive

but it would still benefit from clearer

guidance on refusing access to information.

The Aarhus Convention on Access to

Information, Public Participation in

Decision-making and Access to Justice in

Environmental Matters could inform the

debate.

International law provides only a broad

framework for political party registration,

merely forbidding excessive restrictions

on registration. Although international

law is unlikely to regulate the details of

registration, the existing framework would

Issue Status Content / Citation Recommendation

civilian cOntrOl Of armeD fOrceS

tranSParency

POlitical PartieS

Implicitly deriving from article 25 of the ICCPR and principle of separation of powers, the security sector—as part of the executive—must

be supervised and controlled by elected authorities.

The principle of transparency, i.e. the right of access to government proceedings and information as well as information disseminated by

public authorities, is enshrined in several international treaties.

Article 22 of the ICCPR guarantees the right to freedom of association, which includes the right to establish and operate political parties.

According to article 22, freedom of association may only be restricted by law and in the “interests of national security or public safety,

public order (ordre public), the protection of public health or morals or the protection of the rights and freedoms of others.” Articles 20

of the UDHR, 11 of the ECHR, 10 of the ACHPR, and 16 of the ACHR also guarantee freedom of association. Treaty bodies have specified

detailed requirements on registration, operation, and banning of political parties.

11

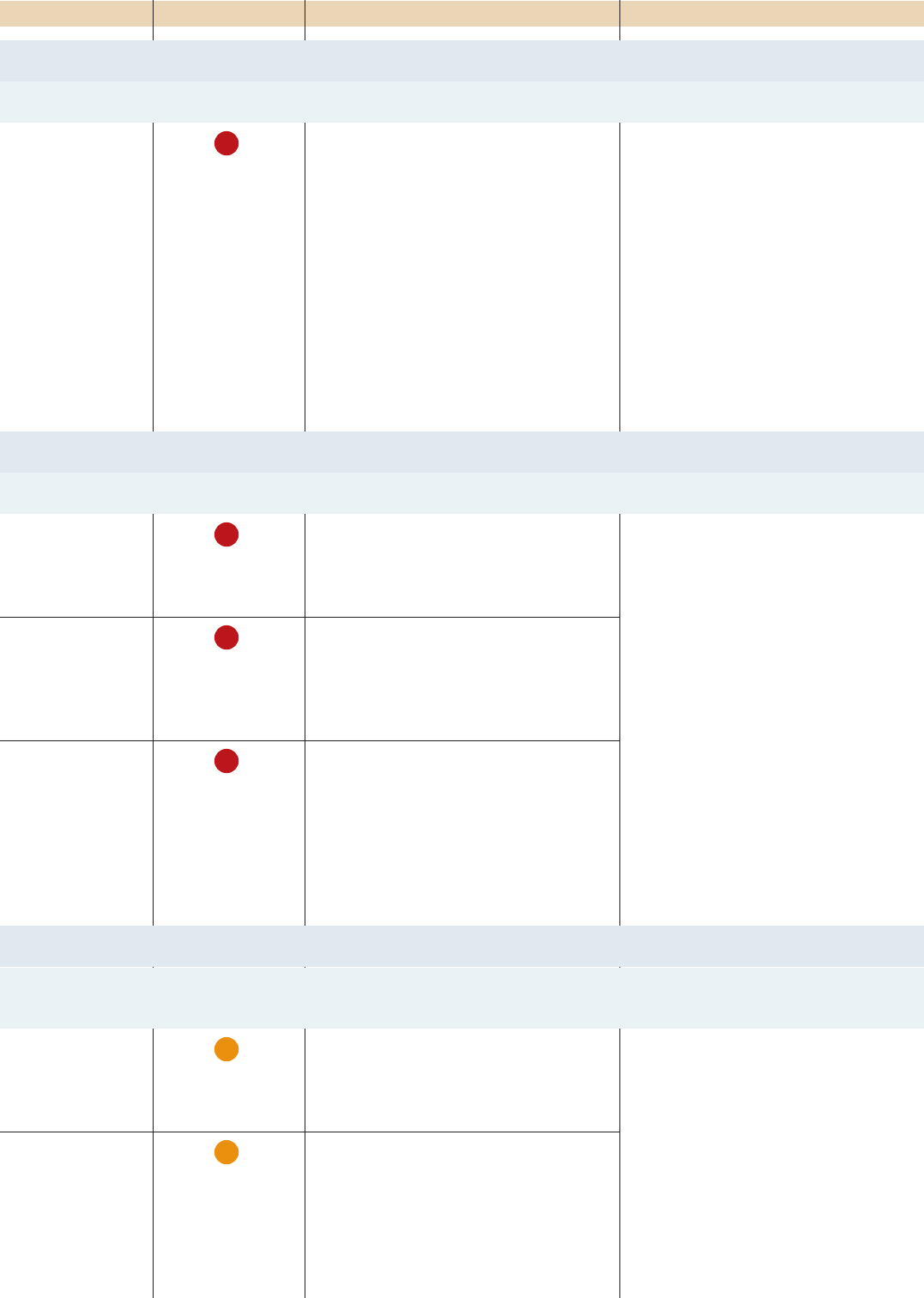

Discrimination and

harassment

Multiparty system

Ban of political

parties

Registration

Operations

Licensing and

accreditation

Overconcentration

of media

Independent and

unrestricted media

Inner party

democracy

The ICCPR requires State parties to treat

political parties on equal footing, for

example concerning access to media, and

forbids harassment of political parties

through, for example, detentions, fines, or

travel restrictions.

Today it is largely uncontested that the ICCPR

forbids one-party systems and requires

State parties to allow multiparty pluralism.

International law sets only general

and vague requirements, such as

proportionality, in regards to the banning of

political parties.

The HRC has criticized onerous registration

requirements for NGOs in addition to cases

of intimidation. There are no HRC decisions

on NGO cooperation with foreign partner

organizations, or on abusive taxing—

another practically relevant issue.

With a new General Comment on article

19 and extensive case law, the scope and

content of the freedom of media is well

established and elaborated in significant

detail.

Article 25 of the ICCPR requires State

parties to ensure internal party democracy

in general terms.

HRC decisions have developed criteria for

party registration only in general terms.

The legal framework to prevent

discrimination and harassment of political

parties is adequate in principle.

The framework on party-pluralism as

developed by the HRC and other bodies

constitute an adequate basis.

New General Comments on articles 21

and 22 could specify the requirements

regarding the banning of political parties

and issues of internal party democracy.

There is no General Comment on article

22, the ICCPR provision on the freedom of

association, which explains to some extent

why international law governing CSOs is

limited. A General Comment on article 22

could address this gap.

Protection of the freedom of media is well

established.

benefit from more detailed and illustrative

interpretation of articles 22 and 25, either

through a revised General Comment or

detailed decisions under the first protocol.

Issue Status Content / Citation Recommendation

civil SOciety OrganizatiOnS

meDia

Article 22 of the ICCPR protects the right of association, which includes the rights of citizens to register and operate civil society

organisations (CSOs). Treaty bodies have specified in general terms requirements on registration and operation of CSOs.

Article 19 (2) of the ICCPR protects the freedom of media, one of the cornerstones of a democratic society. The HRC has reinforced the

freedom of media and press in numerous cases and, most recently, in General Comment 34.

Internal political

self-determination

Article 1 of the ICCPR guarantees broad

autonomy within a State and participation

of people in the State’s political decision-

making process. Article 1 makes no

reference to democracy but is based on

elements of democracy.

As relevant HRC jurisprudence is thin,

a revised General Comment should

be considered. A new General Comment

should state that article 1 must be

interpreted in conjunction with the

political rights under the ICCPR.

right Of Self-DeterminatiOn

Article 1 of the ICCPR protects in general terms internal political self-determination.

12

Issue Status Content / Citation Recommendation

Definition of

“genuine elections”

Interval between

elections

Secret ballot

While genuine elections are required in

international law, there remains a lack of

clarity regarding the definition of the term

“genuine election.”

International law states that elections

should be held periodically and that the

interval between elections should not be

unduly long (General Comment 25).

There is little guidance regarding the

circumstances under which it is permissible

for elections to be postponed or cancelled.

The need for secrecy of the ballot is well

established in international law.

International law provides little guidance,

however, regarding possible measures

that can be taken to guarantee the secrecy

of the ballot, or the potential impact and

challenges of new election technologies on

the enjoyment of this right.

A new or revised General Comment on

article 25 could include:

Greater clarity regarding the definition •

of the term “genuine election;” and,

Clarity regarding whether the will •

of the people requires that the

candidates/s with the most votes win.

A new or revised General Comment on

article 25 could provide greater clarity on:

The permissible interval between •

elections;

The circumstances under which is •

permissible to postpone elections; and,

The circumstances under which •

elections should not be held.

A new or revised General Comment on

article 25 could include:

Greater detail regarding the measures •

States may take to protect secrecy of

the ballot; and,

The impact of new election •

technologies on the enjoyment

of secrecy of the ballot and other

fundamental rights and freedoms.

genuine electiOnS that guarantee the free exPreSSiOn Of the vOterS

PeriODic electiOnS

Secrecy Of the ballOt

Genuine elections that guarantee the free expression of the will of the voters are addressed in international law, specifically in UN, ICCPR

article 25 (b).

Periodic elections are addressed in international law emanating from the United Nations as well as regional bodies such as the Organization

of American States and the African Union.

The secrecy of the ballot is well established in international law (UN, ICCPR article 25 (b)).

table Of recOmmenDatiOnS –

DemOcratic electiOnS

13

Issue Status Content / Citation Recommendation

The right to vote

and to be elected

Restrictions on the

rights to vote and

to be elected

Independent

candidacy

Voter registration

Compulsory voting

Citizenship

The right to vote and to be elected is

included in the ICCPR, as well as regional

treaties. Additionally, reasonable and

unreasonable restrictions are addressed in

some detail in the ICCPR.

International law indicates what constitutes

a reasonable or unreasonable restriction

on the rights to vote and to be elected (HRC,

General Comment 25, para. 15).

The requirement that no one be compelled

to join a political association may require

that independent candidacy be permitted.

However, regional jurisprudence from the

Americas conflicts with this (HRC, General

Comment 25, para. 17; UDHR, article 20 (2)).

Voter registration is recognized in inter-

national law as a means of ensuring the

right to vote (HRC, General comment 25).

International law only implicitly addresses

the impact of voter registration procedures

on the enjoyment of article 25 rights.

Compulsory voting is not addressed in

international law.

Citizenship has historically been left to the

discretion of States. However, this is slowly

changing.

Citizens should enjoy electoral rights

regardless of race, colour, sex, language,

religion, political or other opinion, national

or social origin, property, birth or other

status, or sexual orientation (UN, ICCPR

articles 2 and 25).

Long-term residents may enjoy rights to

vote and to be elected, but this is left to

the discretion of the State (HRC, General

Comment 25, para. 3).

Internally Displaced People should be

granted full electoral rights (UN Guiding

Principles on Internal Displacement,

para. 22 (d); AU Convention for Internally

Displaced People, article 9).

The voting rights of refugees and asylum

seekers to vote in their country of origin are

unclear.

A new or revised General Comment on

article 25 could provide clarity regarding:

The rights and status of individuals •

with double citizenship;

The rights of long-term residents to •

participate in public affairs;

The rights of citizens outside of the •

boundaries of their country (including

refugees and asylum seekers) to vote

and to be elected;

The rights of military personal to vote •

and to be elected;

The impact of residency on the •

enjoyment of the rights to vote and to

be elected;

Compulsory voting; •

The impact of voter registration •

procedures on the enjoyment of article

25 rights; and,

The rights of independent candidates •

to contest elections.

the right tO vOte anD tO be electeD

The rights to vote and to be elected are protected by United Nations treaties such as the ICCPR, as well as regional treaties such as the

African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, the American Convention on Human Rights, and the Arab Charter on Human Rights.

14

Issue Status Content / Citation Recommendation

Boundary

delimitation

Electoral system

Stability of the

legal framework

Electoral calendar

Sanctions

Equal suffrage lies at the heart of the

boundary delimitation process. However,

international law is unclear regarding

the degree of deviation between districts

that is permissible. While not explicitly

addressed in international law, there

are a number of means by which States

can implement impartial boundary

delimitation.

Greater clarity could be provided on key

issues such as quotas and the requirement

of transparency in the means of converting

votes into mandates.

International law does not explicitly address

the need for a stable election law in the

months prior to the election (Exception:

ECOWAS, Protocol on Democracy and Good

Governance, article 2).

Elections occasionally place an extraordi-

nary time constraint on processes that are

essential to the fulfilment of rights—for

example, voter registration or electoral

dispute resolution processes. At other

times, there may be too much time allowed

for aspects of the process—for example,

protracted election dispute processes.

International law does not address the

need for a clear electoral calendar that

allows adequate time for all elements of

the process.

International law recognizes the need for

sanctions and penalties in the case of

violations of electoral and other human

rights. In addition, broader principles

established in General Comment 31

regarding the need for sanctions to be

proportionate, appropriate, and enforceable

also apply in the context of elections.

A new or revised General Comment on

article 25 could provide clarity regarding:

The impact of the process of boundary •

delimitation on the exercise of

electoral rights;

Reasonable and unreasonable devia- •

tions from equality between districts;

The frequency with which boundaries •

should be delimited; and,

The nature of the body responsible for •

boundary delimitation (e.g. whether

it should be independent from other

branches of government).

A new or revised General Comment on

article 25 could provide clarity regarding:

Transparency in the method for •

converting votes into mandates; and,

The use of quotas. •

A new or revised General Comment on

article 25 could provide clarity regarding:

The stability of the election law •

(recognizing that there may be

circumstances in which changes close

to election day are necessary); and,

The impact of the electoral calendar •

on the enjoyment of fundamental

rights and freedoms (and vice versa),

for example the need for clear and

predictable timelines for voter

registration, dispute resolution etc.

equal Suffrage

electOral SyStem

legal framewOrk fOr electiOnS

Equal suffrage is protected by international law and is critical to the voting process, as well as to boundary delimitation processes (UN,

ICCPR article 25(b)).

International law recognizes the need for an electoral system. All electoral systems are permissible as long as they uphold international

rights (HRC, General Comment 25, para. 21).

International law recognizes the need for a legal framework for the electoral process (HRC, General Comment 25, para. 19).

15

Issue Status Content / Citation Recommendation

Freedom of

assembly and

association

Party and

campaign finance

Election quiet

periods

Freedom of

movement

Campaign periods

The freedom of assembly and association

is addressed in international law. In

addition, the role of these freedoms on the

electoral process is addressed.

International law inadequately addresses

party and campaign finance.

Election quiet periods are permissible in

international law; however, there remains

a lack of clarity about their duration (HRC,

Kim Jong-Cheol v Republic of Korea).

Freedom of movement is guaranteed

by article 12 of the ICCPR. However, the

enjoyment of article 25 rights is dependent

on the fulfilment of this freedom.

Official campaign periods are a common

practice. However, it remains unclear

whether the benefits of such a campaign

period (i.e. for the regulation of campaign

finance) outweigh the potential restrictions

on rights and freedoms.

A General Comment on articles 21 and 22

of the ICCPR would be useful.

A new or revised General Comment on

article 25 could provide clarity regarding:

Access to information and the need for •

regular, public disclosure of campaign

contributions;

The relationship between campaign •

contribution caps and freedom of

expression;

The role of the State in providing •

public funds to support campaigns;

Eligibility to contribute to campaigns •

(for example, foreign or corporate

donations); and,

Access to state resources and •

prevention of their misuse.

A new or revised General Comment on article

25 could provide clarity regarding:

The question of equality versus equity •

vis-a-vis candidates’ access to the

media;

The regulation of free airtime for •

candidates;

Ensuring that citizens receive •

politically neutral information during

an election;

A new or revised General Comment on

article 25 could provide clarity regarding:

Whether official campaign periods are •

a permissible restriction of rights; and,

The clear link between freedom of •

movement and the enjoyment of

article 25 rights.

camPaigning

Party anD camPaign finance

the meDia anD electiOnS

Campaigning is recognized as a critical component of a genuine election. Campaigning as part of a genuine election process requires that

a number of related rights and freedoms be enjoyed, for example the freedoms of expression, association, assembly, and movement (UN,

ICCPR articles 12, 19, 21 and 22).

International law only briefly references the role of party and campaign finance in the electoral process (UN, CAC, article 7 (3); HRC,

General Comment 25, para. 19).

The role of a pluralistic and diverse media in promoting genuine elections is recognized in international law. Particularly relevant is freedom

of expression, protected in article 19 of the ICCPR and enshrined in regional treaties.

16

Issue Status Content / Citation Recommendation

The responsibilities of the media •

to provide electoral information to

citizens;

The permissible duration of election •

quiet periods; and,

The impact and challenges of new •

media on the electoral process.

Access to

the media by

candidates

The internet and

new media

Responsibilities of

the media during

elections

International law partially addresses

access to the media by candidates;

however, it remains unclear whether

that access should be equal or equitable

(HRC, General Comment 25, para 25;

AU Declaration of Principles Governing

Democratic Elections in Africa, article III a).

International law is beginning to address

the changes brought by the internet and

new media. However, this has yet to be

addressed explicitly in the context of the

electoral process.

International law could be strengthened

regarding the role of the media during

the electoral process, specifically the

responsibility of the media to provide

information regarding electoral processes.

Voter education

The EMB as

independent and

impartial bodies

Composition of the

EMB

The EMB and

necessary steps

Voter education is recognized in

international law as an important part

of the electoral process (HRC, General

Comment 25). However, there remains a

lack of clarity regarding the role of the

Election Management Bodies (EMB) in

providing voter education

In reference to the need for an independent

electoral authority, greater definition

regarding the term “independent” would

be helpful, e.g. whether independence

requires complete independence from

other branches of government.

International law does not address

the composition of the EMB or the

appointment of EMB members.

International law does not explicitly

address the need for an election

management body to take all steps

necessary in order to ensure the enjoyment

of article 25 rights.

A new or revised General Comment on

article 25 could provide clarity regarding:

Whether the EMB should bear primary •

responsibility for ensuring that

electors are informed of their rights.

A new or revised General Comment on

article 25 could provide clarity regarding:

The definition of “independent” in the •

context of the EMB;

The role and responsibilities of the •

EMB, particularly vis-à-vis other

organs of the State and specifically

with regard to the independence

of the EMB from other branches

of government (including financial

independence);

The responsibilities of the EMB in the •

administration of elections and the

fulfilment of rights; and,

The need for transparency and •

accountability in the functioning of the

EMB.

vOter eDucatiOn

electiOn management bODieS

International law recognises that voter education is necessary to ensure the enjoyment of electoral rights by an informed electorate (HRC,

General Comment 25, para. 11).

International law states that an independent electoral authority should be established to supervise electoral processes (HRC, General

Comment 25, para. 20).

17

Issue Status Content / Citation Recommendation

Voting procedures

Vote counting

procedures

Locus standi in

election disputes

Election

management

bodies as arbiters

of disputes

Accuracy of the

count

Publication of

detailed results

International law is largely silent on the

issue of voting procedures. This is likely

in large part due to the variety of practice

among States. However, election day

procedures greatly impact the enjoyment

of electoral rights.

International law does not address vote

counting procedures in any detail, most

likely because they vary widely across

countries.

International law does not explicitly

address the need for citizens to have

standing before a tribunal for violations of

electoral rights.

International law provides fairly detailed

general guidance on fair and impartial

hearings. When applied to elections, however,

international law is not explicit regarding

whether these principles mean that EMBs

should not serve as arbiters of election

disputes (a common practice) because this

may constitute a conflict of interest.

The need for an honest and accurate count

of the election results is only implicitly

addressed in international law in that

elections should reflect the will of the

people.

International law does not explicitly require

that polling station level election results

be publicly posted. Rather, a case can be

made that access to information, coupled

with the rights to vote, to be elected, and

to participate in public affairs, creates an

obligation on the State to provide such

information.

A new or revised General Comment on

article 25 could provide clarity regarding:

Necessary steps to ensure that the •

right to vote and to be elected can be

effectively enjoyed, such as ensuring

polling stations are open beyond

regular working hours; the provision of

enough, conveniently located voting

facilities; procedures that ensure

women and those with disabilities are

able to vote; and,

The impact of electronic voting tech- •

nologies on the enjoyment of article

25 rights.

A new or revised General Comment on

article 25 could provide clarity regarding:

A requirement of accuracy and •

honesty in the vote count so that

the will of the people might be

established; and,

An explicit reference to access to •

information in the context of the

vote counting process and results

tabulation, including the need to post

detailed polling station level results

immediately after the polls and to

publish all detailed and aggregated

results promptly.

A new or revised General Comment on

article 25 could provide clarity regarding:

The standing of key stakeholders to •

bring election related complaints;

The timeline for dispute resolution •

processes that de facto ensures that

citizens are granted effective and

expeditious remedies within the time

constraints imposed by the election

process;

vOting anD electiOn Day PrOceSSeS

vOte cOunting anD tabulatiOn

electOral DiSPute reSOlutiOn

Voting and election day processes are not well addressed in international law.

International law does not address vote counting and tabulation processes in great detail.

Dispute resolution processes are well established in international law through the rights to an effective remedy and the right to a fair and

impartial hearing (UN, ICCPR articles 2 and 14).

Democracy Reporting International is an independent not-for

profit organisation that promotes political participation of

citizens, accountability of state bodies and the development

of democratic institutions world-wide. Democracy Reporting

International analyses, reports and makes recommendations

to the public and policy makers on democratic governance.

A not-for-profit, nongovernmental organization, The Carter Center

has helped to improve life for people in more than 70 countries

by resolving conflicts; advancing democracy, human rights,

and economic opportunity; preventing diseases; improving

mental health care; and teaching farmers in developing nations

to increase crop production. The Carter Center was founded

in 1982 by former U.S. President Jimmy Carter and former First

Lady Rosalynn Carter, in partnership with Emory University,

to advance peace and health worldwide.

Democracy Reporting International

Schiffbauerdamm 15

10117 Berlin / Germany

T / +49 30 2787 73 00

F / +49 30 27 87 73 00-10

info@democracy-reporting.org

www.democracy-reporting.org

The Carter Center

453 Freedom Parkway

Atlanta, GA 30307 / USA

T / 404 420-5100

carterweb@emory.edu

www.cartercenter.org