Working Paper Series

The impact of the ECB’s targeted

long-term refinancing operations

on banks’ lending policies:

the role of competition

Desislava C. Andreeva, Miguel García-Posada

Disclaimer: This paper should not be reported as representing the views of the European Central Bank

(ECB). The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the ECB.

No 2364 / January 2020

Abstract

We assess the impact of the Eurosystem’s Targeted Long-Term

Refinancing Operations (TLTROs) on

the lending policies of euro area banks. We first build a theoretical model in which banks compete in

the credit and deposit markets. We distinguish between direct and indirect effects. Direct effects

take place because bidding banks expand their loan supply due to the lower marginal costs implied

by the TLTROs. Indirect effects on non-bidders operate via changes in the competitive environment

in banks’ credit and deposit markets. We then test these predictions with a sample of 130 banks

from 13 countries focusing on the first TLTRO series. Regarding direct effects, we find an easing

impact on margins on loans to relatively safe borrowers, but no impact on credit standards.

Regarding indirect effects, there is a positive impact on the loan supply on non-bidders which

operates via an easing of credit standards.

JEL Classification: G21, E52, E58

Keywords: unconventional monetary policy; TLT

ROs; lending policies; competition

ECB Working Paper Series No 2364 / January 2020

1

Non-technical summary

The TLTROs are one of the non-standard monetary policy measures introduced by the ECB in the

course of the financial crisis to stimulate the supply of bank loans to the real economy. In these

operations banks could borrow money from the Eurosystem for up to four years at very attractive

interest rates. The maximum amount that could be borrowed was linked to a specific category of

bank loans (‘targeted’ or ‘eligible’ loans). These are bank loans to euro area households and non-

financial firms except for household mortgages. This link intends to ensure that the stimulus reaches

the real economy. This paper evaluates the impact of the TLTROs on the lending policies of euro area

banks, focusing on the first TLTRO series announced in June 2014.

Our analysis aims to capture both the direct impact of the measure on the lending policies of banks

which accessed the TLTROs and the indirect effects, as the remaining banks react to the change in

the behaviour of TLTRO bidders. Such indirect effects operate via changes in the competitive

environment in banks’ credit and funding markets. Their inclusion as object for analysis is a distinct

feature of this study.

The paper first presents a simple extension of the standard Monti-Klein model of bank competition.

For the sake of simplicity, the model features two banks. One of them is perceived to be risky and

thus faces higher funding costs. In the model only the risky bank bids in the TLTROs since thereby it

can lower its overall funding costs. The asymmetric recourse to the TLTROs allows us to study the

direct impact of the measure on the risky bank, which borrows from the central bank, and the

indirect impact on its competitor, the safe bank.

The model predicts a positive impact of the TLTROs on the bidding bank. The decline in its funding

costs allows it to expand its supply of loans. By contrast, the impact on the other bank is ex ante

ambiguous. On the one hand the risky bank is able to attract customers which in the absence of the

TLTROs the safe bank would have served, suggesting a negative impact. On the other hand, it also

indirectly lowers the funding costs of the safe bank, supporting its supply of bank loans. This indirect

effect arises as the risky bank demands less market funding, resulting in lower market funding costs

for the entire banking system, including the safe bank.

Our empirical analysis finds that the TLTROs had a positive impact on bank loan supply both directly

– on the bidders – and indirectly on their competitors. We find strong indirect effects of the TLTROs

on credit standards, but no significant impact on margins on safe loans. In the case of loans to

ECB Working Paper Series No 2364 / January 2020

2

enterprises, the impact is stro

nger for large firms. We also find some evidence that the TLTROs do

not lead to excessive risk taking, as TLTRO uptakes are negatively correlated with the probability of

narrowing margins on riskier loans. Regarding direct effects, the meas

ure affected mainly the

margins on loans to relatively safe borrowers. Moreover, the finding is mainly driven by adjustments

in the lending policy by banks which bid for larger amounts compared to those which borrowed less

from the TLTROs (i.e., the intensive margin of monetary policy pass-through) as opposed to

differences between bidders and non-bidd

ers (i.e., the extensive margin).

ECB Working Paper Series No 2364 / January 2020

3

1. Introduction

Since the 2008 global financial crisis, central banks around the world have undertaken nume

rous

unconventional monetary policies to prevent a credit crunch, stimulate aggregate demand and boost

inflation. In the euro area these included the provision of liquidity using fixed-rate full-allotment

tenders, a lengthening of the maturity of central bank credit operations, a wider set of eligible

collateral, large scale purchase programmes of public and private sector assets, negative interest

rates and forward guidance.

The goal of this paper is to assess the impact

of the Eurosystem’s Targeted Long-Term Refinancing

Operations (TLTROs) on the lending policies of euro area banks. The TLTROs are liquidity providing

central bank operations with maturity of up to four years. They were announced in June 2014 in a

context of slow economic growth, weak inflation outlook and subdued monetary and credit dynamics

in the euro area. Unlike their predecessors (VLTROs

4

), the TLTROs explicitly targeted lending to the

real economy and were designed to reduce the incentives to banks to use the liquidity for sovereign

debt purchases. Our analysis aims to capture both the direct impact of the measure on the lending

policies of banks which accessed the TLTROs and the indirect effects, as the remaining banks react

strategically to the change in the behaviour of TLTRO bidders. Such indirect effects operate via

changes in the competitive environment in banks’ credit and funding markets. Their inclusion as

object for analysis is a distinct feature of this study.

To guide our empirical research, we first present a simple extensi

on of the Monti-Klein model of

oligopolistic competition in the banking sector. For the sake of simplicity, we consider only two

banks, a safe and a risky bank, which compete à la Cournot in the loan and deposit markets. The

main departure from the standard model is the introduction of a funding impairment: one of the

banks is perceived to be risky, resulting in higher funding costs. Importantly, it also leads to an

asymmetric recourse to the TLTROs and allows us to study the direct impact of the measure on the

risky bank, which borrows from the central bank, and the indirect impact on its competitor, the safe

bank.

This asymmetric recourse arises as the TLT

ROs borrowing costs are assumed to be higher than the

deposit funding costs of the safe bank but attractive for its risky competitor. After the introduction of

4

Longer-term refinancing operations with a three year maturity implemented in December 2011 and February

2012. The abbreviations “VLTROs” stands for very long-term refinancing operations.

ECB Working Paper Series No 2364 / January 2020

4

the measure the

risky bank can fund part of its loan portfolio with the TLTROs rather than with more

costly deposits. The introduction of the TLTROs has both direct effects on the bidding bank (the risky

bank) and indirect effects on the non-bidder (the safe bank). Regarding direct effects, the funding

cost relief due to the TLTROs leads to an expansion of the loan supply by the risky bank. With respect

to indirect effects, we must differentiate between two opposite forces. On the one hand,

competition in the credit market becomes stronger. The TLTROs, by reducing the risky bank’s

marginal funding costs, allows it to compete more aggressively in the loan market. As banks compete

à la Cournot, loan quantities are strategic substitutes, implying that an expansion in the credit supply

of the risky bank leads to a contraction in the credit supply of the safe bank. On the other hand,

competition in the deposit market weakens because the risky bank substitutes some deposits with

TLTRO funding. The lower demand for deposits leads to lower deposit rates, which translate into

lower marginal costs also for the safe bank. Ceteris paribus, its loan supply expands. Hence, the

overall indirect impact of the TLTROs is a priori ambiguous and must be assessed empirically.

The empirical analysis meas

ures bank lending policies with credit standards (i.e., the internal

guidelines or loan approval criteria of a bank) and loan margins (i.e., the agreed spread over the

relevant reference rate), as reported by banks in the ECB’s Bank Lending Survey (BLS). Several papers

in the literature, such as Lown and Morgan (2006), and Ciccarelli et al. (2015), identify credit

standards as reported in lending surveys as proxies for credit supply. We use the confidential

answers by 130 banks from 13 euro area countries, matched with individual bank balance-sheet

information and proprietary data on banks’ participation in central bank credit operations. Our

empirical analysis of the causal impact of the TLTROs on bank lending policies focuses on the first

series of TLTROs introduced in June 2014, therefore when referring to TLTROs in general we have

TLTRO-I in mind. The identification strategy needs to address two major issues. First, banks

part

icipated in the TLTROs on a voluntary basis and thus selection into treatment is non-ra

ndom. To

obtain consistent estimates we construct an instrumental variable for the TLTRO uptake. The

proposed instrumental variable comes from the institutional setting of TLTRO-I, as in Benetton and

Fantino (2017). In particular, we exploit an allocation rule by the policy, according to which banks

could borrow an amount equivalent to 7% of their eligible loans outstanding on 30 April 2014.

Crucially, the stock of eligible loans was measured at a date prior to the announcement of the policy

(June 2014). The initial allowance constitutes an exogenous component of the TLTRO uptakes, as it is

based on exogenous parameters that are common across banks and on pre-determined bank balance

ECB Working Paper Series No 2364 / January 2020

5

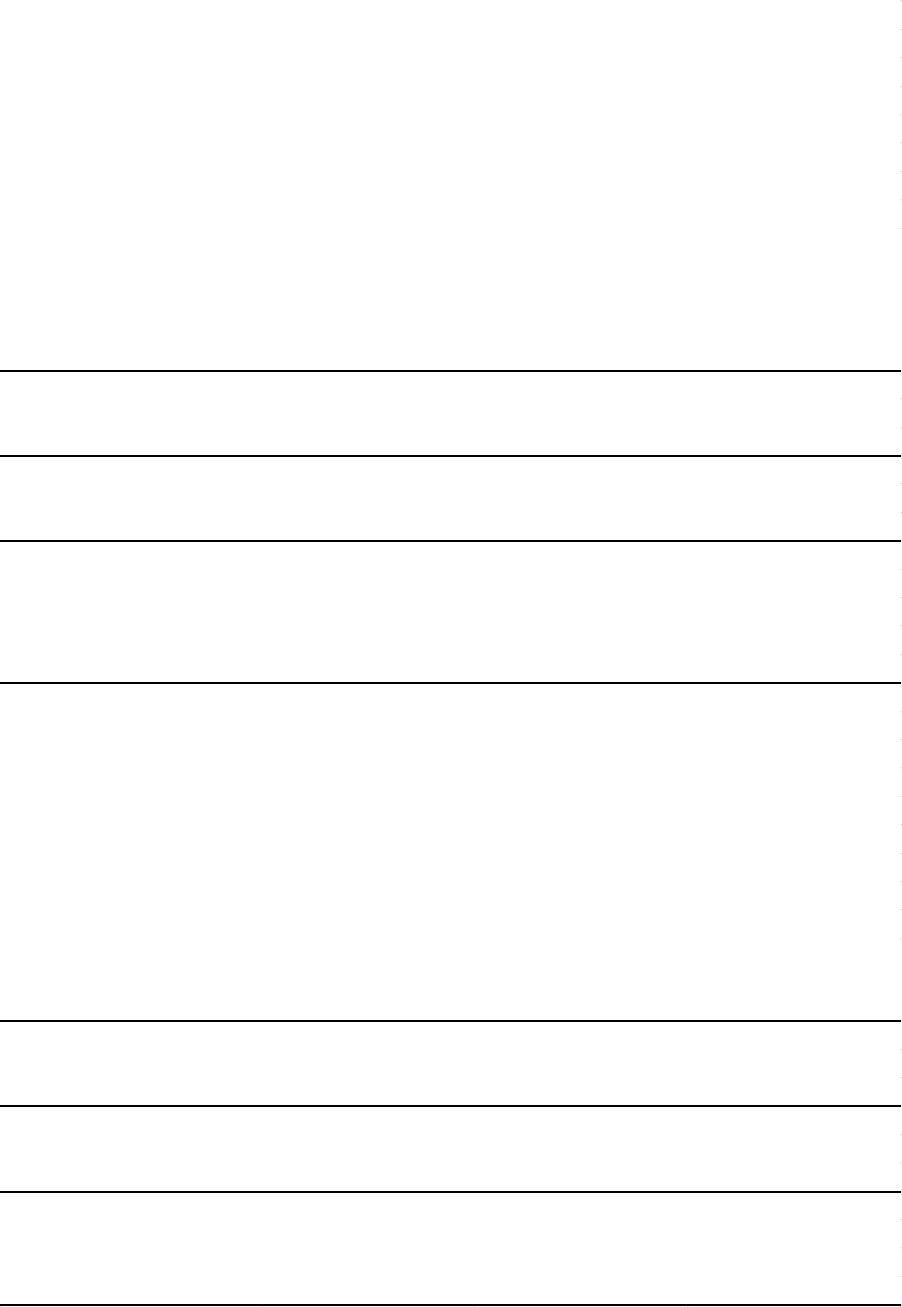

sheet characteristics. The relevance of our instrument is ensured by the fact that in the first two

TLTRO

s-I 80% of the participating banks in our sample borrowed at least 90% of their initial

allowance (Figure 1).

Second, credit supply must be disentangled from credit demand.

5

For instance, banks with high

TLTRO uptakes may face more dynamic demand conditions or deal with more creditworthy

borrowers, which may induce them to ease credit standards or narrow margins. To control for

demand factors, we include a large vector of control variables that measure the evolution of credit

demand by firms and households in the different segments of the credit market (e.g. loans to SMEs),

as well as the factors underlying those developments (e.g., consumer confidence), as reported by

banks in the BLS.

Our results suggest strong indirect effects of the TLTRO-

I on credit standards, but no significant

impact on margins on safe loans. In the case of loans to non-financial c

orporations, a standard

deviation increase in the TLTRO uptakes of a bank’s competitors leads to a 5.3 pp increase in the

probability that it eases overall credit standards. The impact on credit to large firms is even stronger,

resulting in an 8.8 pp increase in the probability of easing credit standards. In the case of loans to

households for house purchase, a standard deviation increase in the TLTRO uptakes of a bank’s

competitors implies an 8.8 pp increase in the probability that the bank eases its own credit

standards. These effects are concentrated in banks with low market share that face high competitive

pressures, suggesting that competition in the credit market plays a crucial role. By contrast, the

TLTRO uptakes of a bank’s competitors have no significant effect on margins on average loans in

either segment. We also find some evidence that the TLTROs did not lead to excessive risk taking, as

TLTRO uptakes are negatively correlated with the probability of narrowing margins on riskier loans.

All in all, the results suggest that the TLTROs generate positive funding externalities on non-bidders.

Regarding direct effects, the t

ransmission of monetary policy takes place mainly through the

adjustment of margins on loans to relatively safe borrowers. The effects are stronger in the

subsample of bidding banks (i.e., the intensive margin of monetary policy pass-through) than in the

5

While the BLS aims to distinguish between supply (measured by credit standards and loan margins) and

demand, note that some of the factors underlying the changes in credit standards and loan margins have a

demand component. According to the survey, credit standards and loan margins are determined by cost of

funds and balance sheet constraints, pressure from competition, bank’s risk tolerance and perception of risk.

The last factor comprises the sub-factors “general economic situation”, “industry or firm-specific situation” and

“risk related to the collateral demanded”.

ECB Working Paper Series No 2364 / January 2020

6

comparison between bidders and non-bid

ders (i.e., the extensive margin). In particular, for the

subsample of bidding banks, a standard deviation increase in a bank’s TLTRO uptake increases the

probability of narrowing margins on average loans to firms by 20 pp and raises the probability of

narrowing margins on average loans to households for house purchase by around 29pp. With respect

to the extensive margin, bidding banks are much more likely (62 pp) to narrow margins on average

loans than non-bidders in the case of housing loans, while there are no significant differences

between the two groups in the segment of corporate loans.

The rest of the paper is organised as follows. Section 2 reviews the most r

elevant literature on the

subject and discusses our key contributions. Section 3 describes the institutional background of the

TLTROs. Section 4 presents a simple theoretical model to guide our empirical analysis. Section 5

discusses the identification strategy in detail. Section 6 explains the data sources and the variables

employed in the empirical analyses. Section 7 comments on the main results. Section 8 explains

some robustness tests. Section 9 concludes.

2. Related Literature and contribution

Our

paper belo

ngs to the broad and by now mature literature on the effects of monetary policy on

bank credit supply, the so-called bank lending channel. It belongs to the set of empirical studies

focusing on the impact on unconventional monetary policies. The analysis is most closely related to

the branch of the literature analysing the impact of large scale liquidity injections via central bank

credit operations, as introduced for instance by the ECB and the Fed in the course of the financial

crisis.

6

Many of the papers using euro area data focus on the two longer-term refinancing operations

with a 3 year maturity (often labelled ‘VLTROs’ or ‘3yLTROs’) of 2011-2012, in which an

unprecedented overall amount of around one trillion euros were allotted to banks in the euro area.

6

Examples of injections of liquidity via central bank credit operations by the Eurosystem include the liquidity-

providing longer-term refinancing operations with a one year maturity announced in May 2009, the longer-

term refinancing operations with a 3 year maturity announced in December 2011 and the two series of TLTROs,

announced in June 2014 and in March 2016. The liquidity providing credit operations introduced by the Fed

include the Primary Dealer Credit Facility, the Term Auction Facility, Asset-Backed Commercial Paper Money

Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility, the Commercial Paper Funding Facility, and the Term Asset-Backed

Securities Loan Facility.

ECB Working Paper Series No 2364 / January 2020

7

As regards analyses usin

g aggregate data, Darracq-Paries and De Santis (2015) use information on

credit supply conditions from the ECB's Bank Lending Survey (BLS) to identify the credit supply shock

implied by the VLTROs in a panel-VAR for euro area countries. Their counterfactual experiments

point to a relevant increase in bank loans to non-financial corporations and a moderate narrowing of

lending rate spreads, together with a significant increase in the euro area real GDP. Casiraghi et al.

(2016) use bank-level data and the individual answers of the Italian banks to the BLS, together with

the Bank of Italy model of the Italian economy, to assess the effectiveness of the ECB's Securities

Markets Programme (SMP), the VLTROs and the Outright Monetary Operations (OMT). They find that

the VLTROs had a significant impact on credit supply, mainly through a sizeable reduction in the

interest rates paid by Italian banks in the interbank market. They also find that the overall impact of

the three policies on GDP growth, mainly via the credit channel, was a cumulative increase of 2.7 pp.

over the period 2012–2013.

A different appr

oach consists of exploiting very granular data coming from credit registers to identify

shifts in credit supply using the Khawja and Mian (2008) methodology. Andrade et al. (2015), in their

study of the French banking system, find that the VLTROs had a positive and sizeable impact on the

provision of credit to firms. The opportunity to replace outstanding short-term by longer-term

central bank funding (as banks rolled over their existing borrowings from the Eurosystem into the

VLTROs) enhanced this transmission. Similarly, Jasova et al. (2018), in their analysis of the Portuguese

case, show that the extension of bank debt maturity caused by the VLTROs had a positive and

sizeable impact on bank lending to the real economy thanks to the reduction in rollover risk. Garcia-

Posada and Marchetti (2016) find that the VLTROs had a positive moderate-sized effect on the supply

of bank credit to Spanish firms. The effect was greater for illiquid banks and it was driven by credit to

SMEs, as there was no impact on loans to large firms. Carpinelli and Crosignani (2017), for the case of

Italy, show that banks that experienced a wholesale market dry-up before the intervention reduced

their credit supply during the period of funding stress and restored their credit supply once the

central bank injected liquidity into the system, partly due to a regulatory change that expanded

eligible collateral.

7

While the above evidence suggests that the VLTROs were effective in preventing a credit crunch in

the euro

area, there is also ample evidence that banks used part of the liquidity to purchase high-

7

The Italian government offered banks the possibility to obtain a government guarantee on securities

otherwise ineligible as collateral against a fee.

ECB Working Paper Series No 2364 / January 2020

8

yield government bonds and engage in carry trade strategies (A

charya and Steffen (2015), Carpinelli

and Crosignani (2017), Crosignani et al (2017), Jasova et al. (2018)), which reinforced the sovereign-

bank nexus. Consistent with these findings, Van der Kwaak (2017) builds a DSGE model in which the

provision of central bank liquidity, for which commercial banks pledge collateral in the form of

government bonds, induces banks to shift from private credit to government bonds, and finds that

the cumulative effect on output is zero. Similarly, the model of Corbisiero (2018) shows that the

sovereign-bank nexus can impair a proper monetary transmission mechanism in the euro area,

because in times of high sovereign yields central bank liquidity injections can lead banks in stressed

countries to increase their domestic sovereign holdings, rather than channelling funds to the real

economy.

As a response to those criticisms, the TLTROs explicitly target lending to the real economy.

The

literature on the topic is still scarce. Balfoussia and Gibson (2016) analyse the potential impact of the

TLTROs on the real economic activity of the euro area within a VAR framework. Their results suggest

a significant impact of the TLTROs on economic growth via an easing of financial conditions.

Andreeva (2018) studies the impact of the TLTROs on bank lending rates and volumes in a difference-

in-differences framework. She finds that the TLTROs successfully boosted the supply of eligible bank

loans with limited spill-over effects on not targeted ones. Benetton and Fantino (2017) use the Italian

credit register to analyse the pass-through of the TLTROs to the cost of credit to Italian firms. As in

our paper, they use the initial borrowing allowance as an instrument for the endogenous take-up in

the TLTROs in a diff-in-diff framework. They find that banks participating in the TLTROs decrease

their rates by 20 basis points relative to non-participating banks. Crucially, the pass-through of the

TLTROs depends on the competition in local credit markets, as proxied by the Herfindahl-Hirschman

Index (HHI): a firm in a province with a standard deviation higher level of concentration experiences

almost no decrease in the rates as a result of the liquidity injection.

Our paper, while being

closely related to Benetton and Fantino (2017), possesses four important

distinct features. First, we analyse both the direct and the indirect channel of the transmission of the

TLTROs to the banking sector. Previous literature has focused on the direct channel (the direct

impact of a bank’s participation in the programme on its own credit supply) and has ignored the

indirect channel (the impact of the participation of a bank’s competitors on the bank’s credit supply

via changes in the competitive environment). Second, we analyse the impact of the TLTROs on both

bank credit standards and margins. Confidential survey data allows us to study lending standards, a

ECB Working Paper Series No 2364 / January 2020

9

variable that is not directly observed in credit registers.

8

A related analysis using banks’ individual

responses in the BLS to assess the impact of the APP and negative interest rates can be found in

Altavilla et al (2018a) and Arce et al (2018). Third, we analyse both loans to firms and households,

while previous literature has exclusively studied the former. Finally, we analyse the transmission of

unconventional monetary policy in 13 euro area countries, while the papers that rely on credit

registers only study the effect on a single country.

3. Institutional framework

On the 5th of June 2014, the ECB decided to support bank lending to the euro area nonfinancial

private

sector through a first set of Targeted Longer-Term Refinancing Operations (TLTRO I).

9

This

policy was implemented through eight auctions, one each quarter from September 2014 to June

2016, and participation was open to institutions that were eligible for the Eurosystem open market

operations. In addition, a second and third series of TLTROs (TLTRO-II and III) were announced on the

10

th

of March 2016

10

and 7

th

March 2019 respectively This paper focuses on the effect of TLTRO I on

banks’ lending policies, as measured via credit standards and margins.

All 8 TLTROs-I m

atured in September 2018, although early voluntary repayments could be done

starting 24 months after each TLTRO. The applicable interest rate was fixed over the life of each

operation at the rate on the Eurosystem’s main refinancing operations (MROs) prevailing at the time

of take-up, plus a fixed spread of 10 basis points in the case of the first two TLTROs-I. The spread was

abolished in the subsequent TLTRO-I operations.

The borrowing limits were differen

t for the first two operations in September and December 2014

(TLTROs against initial borrowing allowances/’stock TLTROs’) and the last six operations between

March 2015 and June 2016 (TLTROs against additional borrowing allowances/ ‘flow TLTROs’). In the

case of the stock TLTROs, banks’ borrowing could not exceed an amount equivalent to 7% of their

eligible loans outstanding on 30 April 2014. Eligible loans were loans to the euro area non-financial

8

This does not mean that the evolution of credit standards cannot be studied using hard data. See, for

instance, Rodano et al. (2017).

9

Press release: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pr/date/2014/html/pr140605_2.en.html

10

Press release: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pr/date/2016/html/pr160310_1.en.html

ECB Working Paper Series No 2364 / January 2020

10

private sector, excluding loans to households for house purchase.

11

In the case of the flow TLTROs,

the maximum amounts that could be borrowed depended on the evolution of banks’ net eligible

lending in excess of bank-specific benchmarks. More precisely, the additional borrowing allowance

was limited to three times the difference between the net lending since 30 April 2014 and the

benchmark at the time of each borrowing. The benchmark was computed as follows:

(i) for banks that exhibited positive eligible ne

t lending

12

in the twelve-month period to 30 April 2014:

the benchmark was always set at zero.

(ii) for banks that exhibited negative eligible net lending in the year to 30 April 2014, different

ben

chmarks applied. For the 12 months between 30 April 2014 and 30 April 2015, the average

monthly net lending of each in the year to 30 April 2014 was extrapolated. For the 12 months

between 30 April 2015 and 30 April 2016, the benchmark remained constant. Overall, its shape

resembled a kinked line.

Banks that borrowed in the TLTR

Os and failed to achieve their benchmarks as at 30 April 2016 were

required to pay back their borrowings in full in September 2016. Participation in the TLTRO-I was

massive. Euro area banks borrowed around 212 billion euros in the two initial TLTROs (September

and December 2014) and 220 billion euros in the six additional TLTROs (between March 2015 and

June 2016).

4. Theoretical framework

To illustrate the direct and indirect effects of the T

LTROs on banks’ credit supply we present a simple

version of the Monti-Klein model with oligopolistic competition. In particular, consider a banking

system with two banks, a safe bank S and a risky bank R, which compete à la Cournot. These banks

face a downward-sloping demand for loans and an upward-sloping supply for safe deposits . The

decision variables of bank = , are the quantity of loans

and the quantity of deposits

. For

simplicity we abstract from funding sources other than deposits and assets other than loans. De facto

our model captures by construction the most traditional form of banking and disregards banks’

capital market/trading/asset management activities. When choosing the optimal amounts of loans

each bank takes into account that a marginal increase in its supply of loans reduces equilibrium rates

11

The eligible loans also exclude loans securitised or otherwise transferred without derecognition from the

balance sheet.

12

Eligible net lending means gross lending in the form of eligible loans net of repayments of outstanding

amounts of eligible loans during a specific period.

ECB Working Paper Series No 2364 / January 2020

11

on loans, which in turn lowers the unit return on its own loan portfolio. The same logic applies to

the

ir demand for deposit funding.

For simplicity, let us assume that the inverse dem

and for loans

(

+

)

and the inverse supply of

deposits

(

+

)

are characterised by the following linear functions:

(

+

)

= (

+

) (1)

(

+

)

= + (

+

) (2)

In addition, the b

alance sheet identity needs to hold, which requires in our case that banks fund their

loan portfolios with deposits:

=

for = , (3)

The market clearing condition in the model economy requires that:

=

+

, where L* is the aggregate loan supply in the economy (4)

=

+

, where D* is the aggregate deposit funding (5)

=

(6)

Let us first consider the symmetric case in which bank S and bank R are identical. Bank

S’ profit

maximization problem is the following:

,

= (

(

+

)

)

(+ (

+

))

(7)

s.t.:

=

The solution of the above maximisation program, com

bined with

=

, yields bank S’s reaction

function to bank R’s loan supply decision

(

):

=

(8)

Since the maximisation problem is fully symmetric for bank R, its reaction function

(

)

is the

following:

=

(9)

ECB Working Paper Series No 2364 / January 2020

12

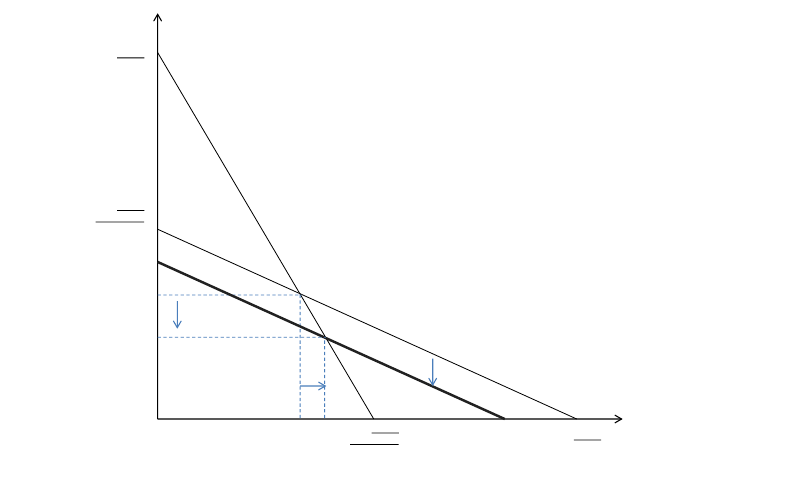

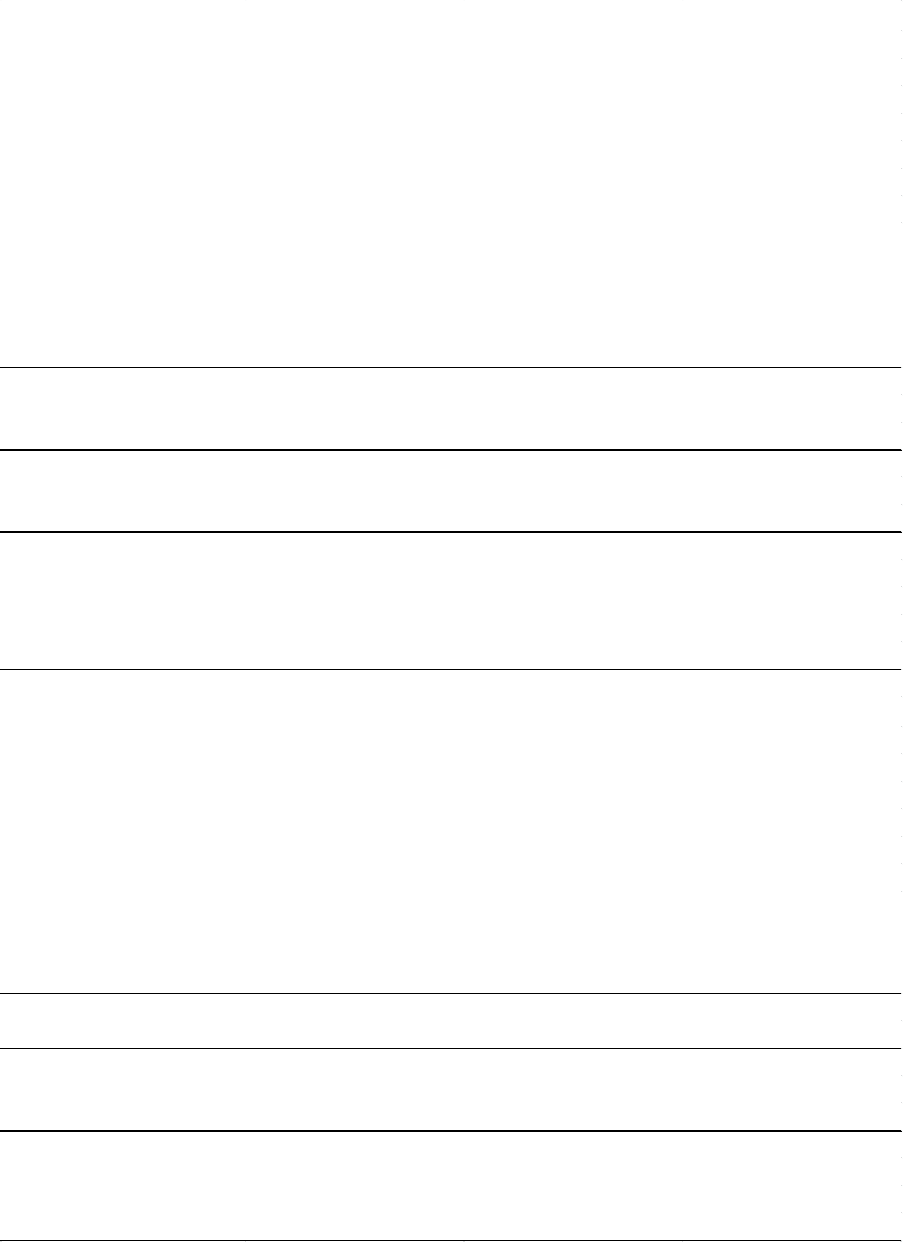

The standard rea

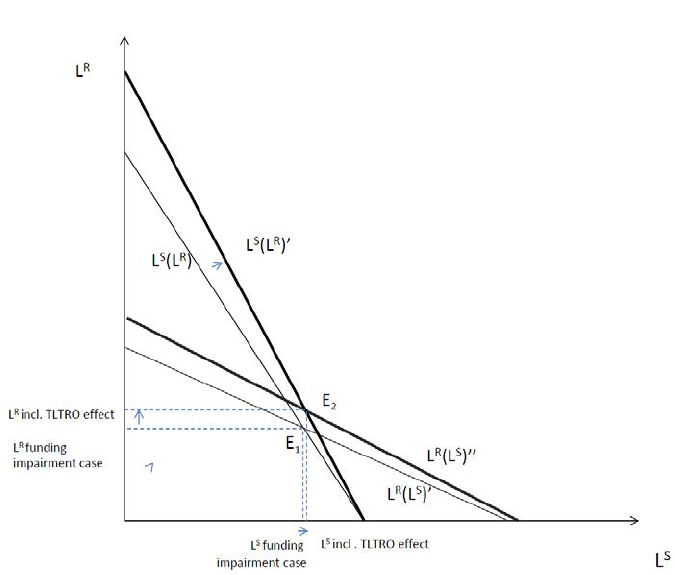

ction functions (8) and (9) are depicted by the thin lines in Chart 1. The intersection

of those lines represents the Nash equilibrium

in the symmetric case. Note that given the

oligopolistic setting, the overall quantity of loans and deposits in the economy will be lower

compared to perfect competition. By slightly reducing the quantity of loans and deposits banks S and

R can keep the rates on bank loans higher while those on deposits lower than under perfect

competition. This allows banks to extract some of the consumer surplus, a standard result in this type

of model.

Chart 1: Loan supply reaction functions in the symmetric case and in the presence of funding

impairments

We now turn to the

asymmetric case. We assume that bank S is perceived to be safe, while bank R is

perceived to be risky. As a result, depositors require an extra compensation of to fund bank R. The

premium reflects the perceived probability of default of that bank. Bank R’s profit maximization

problem is the following:

max

,

= (

(

+

)

)

(

1 +

)

(+ (

+

))

(10)

s.t.:

=

L

S

L

R

+

2

2

L

R

(L

S

)

L

S

(L

R

)

L

R

(L

S

)’

L

R

symmetric case

L

R

funding

impairment case

L

S

symmetric case

L

S

funding

impairment case

Δ

½ Δ

E

0

E

1

+

2

+

2

2

+

2

ECB Working Paper Series No 2364 / January 2020

13

The solution of the above maximisation program, co

mbined with the balance sheet identity for the

safe bank

=

, yields bank R’s reaction function to bank S’s loan supply decision

(

)

in the

case of a funding impairment:

=

(11)

The risk premium required by investors translates into higher marginal funding costs for bank R and

as result its overall supply of loans declines irrespective of the volume of loans provided by its

competitor S. This leads to a parallel downward shift in bank’s R reaction function, as depicted by the

thick line in Chart 1. The intersection between the new reaction function of bank R,

(

)

, and the

reaction function of bank S,

(

), represents the new Nash equilibrium

. The comparison of the

two equilibria

and

yields two main insights. First, the funding impairment of the risky bank

leads to a decline in its supply of bank loans. Second, overall credit supply is also lower, as the supply

of loans by the safe bank compensates for only half of the missing lending by its competitor (see

equation 8).

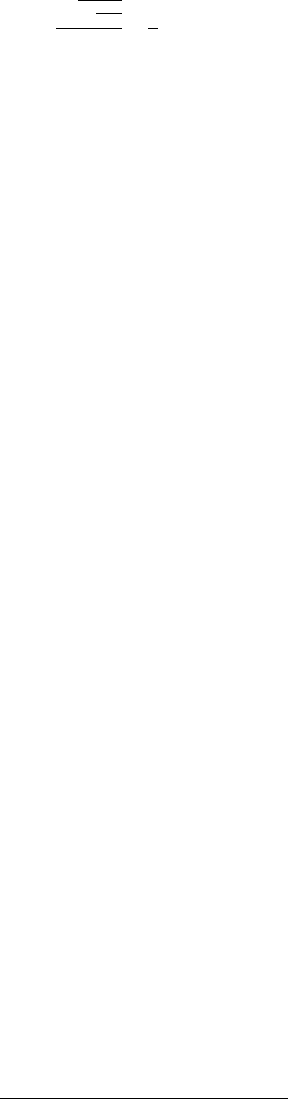

We now turn to the impact of TLTROs on the equilibrium in the loan market. We will show that the

introduction of the TLTROs affects the loan supply of both banks even if only one of them actually

bids in the operation, as the TLTROs have both direct and indirect effects. In particular, assume that

banks can fund up to a fraction of their loan portfolio with TLTROs at an exogenous interest rate .

We assume that the central banks sets equal to deposit rate paid by the safe bank. In addition, we

assume that bidding in the TLTRO entails additional, small fixed administrative costs.

13

In this set-up,

the safe bank will abstain from bidding since it does not benefit from a funding cost reduction and

avoids the administrative costs. By contrast, given the price attractiveness of the TLTRO funding, the

risky bank will exhaust its borrowing limit, so that =

. The balance sheet identity of the

risky bank includes now TLTROs in addition to deposit funding:

=

+ . The combination

of these two equations yields the new constraint,

(

1

)

=

, which indicates that the risky

bank only funds a proportion 1 of their loan portfolio with deposits. The new maximisation

problem of the risky bank is the following:

max

,

= (

(

+

)

)

(

1 +

)

+

(

+

)

(12)

13

These fixed administrative costs could be the reporting requirements and additional audit obligation that are

a pre-requisite for the access to the TLTROs.

ECB Working Paper Series No 2364 / January 2020

14

s.t.:

(

1

)

=

and =

.

The solution of the above maximisation program, combined with the balance sheet identity of the

safe bank

=

, yields bank R’s reaction function in the case of funding impairments after the

introduction of TLTROs

(

)

:

=

+

()

(

)

(13)

=

1

1

1 +

+

(

1

)

(

+

)

+

(1 )

1

1 +

+

(

1

)

(+

(

1

)

)

Finally, note that the maximisation problem of bank S remains unchanged after the introduction of

TLTRO. However, the shadow price of extending an additional unit of loans – in our case the marginal

costs of deposit funding – for the safe bank changes. Since the risky bank substitutes deposits with

TLTROs the competition in the deposit market weakens, providing a boost to the supply of loans by

bank S. Mechanically, this effect is taken into account by considering the new balance sheet identity

of the risky bank (

(

1

)

=

) when obtaining bank S’ loan supply reaction function. The new

reaction function of the safe bank is the following:

=

(

)

(14)

The comparison of equations (8) and (14) reveals that the safe bank’s loan supply is now less

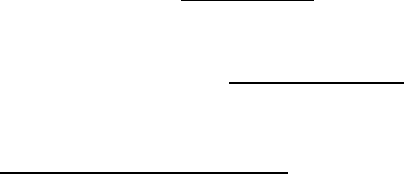

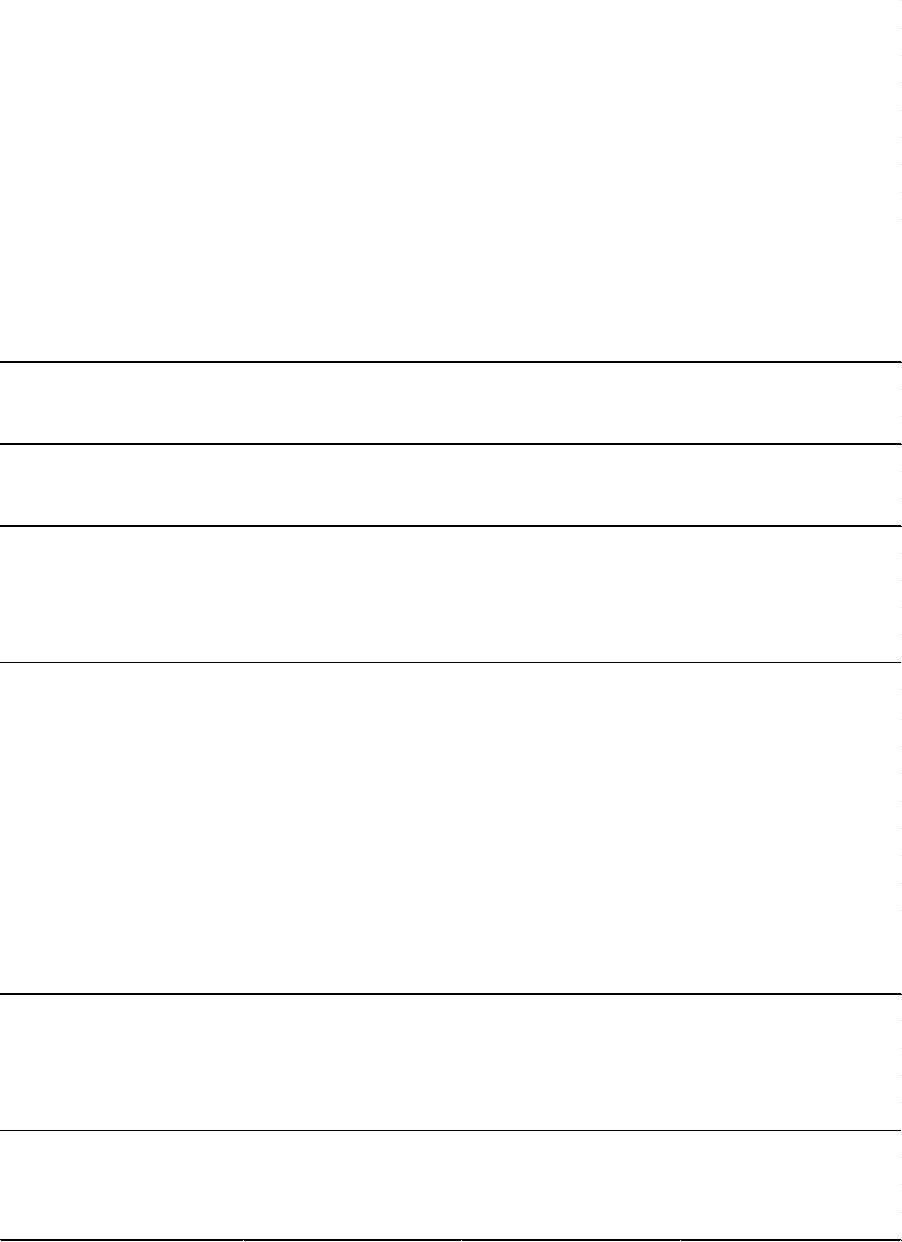

sensitive to changes in the supply of loans by the risky bank. This is illustrated in Chart 2, which

depicts the equilibria in the loan market before the introduction of the TLTROs (

) and following the

implementation of the TLTROs (

). The reaction functions of both banks shift. The reaction function

of the safe bank becomes steeper, while the intercept with the horizontal

axis remains

unchanged. In the case of the risky bank, both the slope and the intercept change, as the reaction

function steepens and shifts upwards: given that the risky bank receives a significant funding cost

relief due to the TLTROs, its supply of loans increases for any given value of loans granted by the safe

bank. The new Nash equilibrium in the illustration is

, which in the example features higher loan

supply by both banks. While lending by the risky bank always increases in equilibrium, for the safe

bank it very much depends on the exact parameter values, in particular on the shape of the loan

demand and deposit supply functions (a and c), the fraction of bank loans that can be funded with

TLTROs () and the exact TLTRO rate ().

ECB Working Paper Series No 2364 / January 2020

15

Chart 2: Loan supply reaction functions in the presence of funding impairments before and after the

introduction of a TLTRO

To put it differently, the impact on the loan supply by the safe bank is ambiguous because there are

two opp

osite effects. On the one hand, the TLTROs reduce the marginal costs of its competitor, the

risky bank, which expands its loan supply. Thereby the TLTROs promote stronger competition in the

credit market. Since the banks compete à la Cournot, loan quantities are strategic substitutes,

implying that an increase in the loan supply of the risky bank leads to a contraction in the loan supply

of the safe bank. On the other hand, the TLTROs lead to weaker competition in the deposit market by

the risky bank. As the risky bank substitutes deposits with TLTROs, competition in the deposit market

weakens, which in turn implies lower marginal funding costs for the safe bank, which boosts its loan

supply.

The upshot of the theoretical discussion is that the TLTROs may have important indirect effects on

the credit supply of non-participating banks, as measured empirically by credit standards and loan

margins. In particular, the TLTROs may have important funding externalities on non-bidding banks,

which are not necessarily restricted to retail funding. For instance, as the TLTROs allow participating

ECB Working Paper Series No 2364 / January 2020

16

banks to replace market-bas

ed bank funding with borrowing from the central bank, they can result in

a reduction in the supply of bank bonds in the economy. The scarcity of bank bond issuance should

translate into lower yields on bank bonds, including those issued by intermediaries not participating

in the TLTROs. In addition, the TLTROs may foster competition in the credit market by reducing the

marginal funding costs of participating banks, which allows them to expand their credit supply. Non-

participating banks may react by contracting their loan supply or by expanding their loan supply

depending on which effect dominates: a) the improved market position of competitors that borrow

from the TLTROs, which benefit from a direct funding costs reduction and are therefore able to (re-)

gain market shares at the expense of non-participants or (b) the indirect funding costs relief enjoyed

by bidders and non-bidders alike, which supports the supply of bank loans of both. Hence, the overall

impact of the TLTROs on non-participating banks is a priori ambiguous and must be assessed

empirically.

14

5. Identification strategy

Our

main goal is to estimate the impact of the TLTROs o

n banks’ lending policies, as measured by

bank credit standards and margins. There are two main channels. The first channel is direct: by

participating in the TLTROs, a bank may reduce its funding costs and improve its overall liquidity

position. This allows participating banks to relax credit standards, narrow margins and compete more

aggressively. The second channel is indirect and conceptually focuses on the strategic reactions of

banks – irrespective of whether they bid in the operations - to changes in the competitive pressure.

TLTROs may influence a bank’s lending policies through (i) the positive effect on the balance sheets

of its competitors, which increases the competition in the credit market, and (ii) the less tense

competition in important funding markets due to bidders’ recourse to long-term central bank

funding.

We construct two variables to measure those effects. The direct effect is captured with

bank TLTRO

, which is computed as the ratio between the uptake in the initial TLTROs (September

and December 2014) by bank i and its total assets.

15

The indirect effect is captured with

14

Note that demand for bank loans will increase as the lower funding costs of both bidders and non-bidders

results in lower rates charged on bank loans.

15

Using overall take-up instead of the take-up in only the first two TLTRO-I leads to overall very similar

empirical findings but leads to a weaker instrument, in terms of the first-stage regressions.

ECB Working Paper Series No 2364 / January 2020

17

country TLTRO

(

)

, which is the ratio between the sum of the initial TLTRO uptakes of all the other

banks in the country (i.e., excluding bank i) and the total assets of those banks. Formally:

bank TLTRO

=

(15)

country TLTRO

(

)

=

(16)

There are two main specifications. In the first one, we estimate the probability that lending policies

ease (i.e., eased credit standards or narrower margins, Y

= 1) as a function of bank TLTRO

,

country TLTRO

(

)

and a wide set of bank controls, demand controls and macro controls, plus time

dummies. Formally:

Y

= bank TLTRO

+ country TLTRO

(

)

+ X

+ W

+ X

+ d

+

+

(17)

where i is bank, c is c

ountry, t is quarter, Y

is the binary outcome variable (credit standards or

margins), X

is a vector of time-varying bank controls, W

is a vector of demand controls (which

also vary at the bank-quarter level), X

is a vector of time-varying macro controls, d

are time

fixed effects,

is a country-quarter error component and

is an individual error term. The main

coefficient of interest is , which captures the indirect effect of the TLTROs on lending policies.

The second specificatio

n is quite similar to (17), but focuses instead on the direct effect of the

TLTROs. To do so, we drop the variable country TLTRO

(

)

and the macro controls and saturate the

regression with country-time fixed effects (d

). Formally:

Y

= bank TLTRO

+ X

+ W

+ d

+

(18)

The main coefficient of interest is , whi

ch captures the direct effect of the TLTROs on lending

policies.

We estimate (17) and

(18) for the period 2014Q2-2017Q4. Hence, our empirical strategy implies a

comparison of changes in credit standards/margins between treated and non-treated banks (e.g.

high and low country TLTRO

(

)

) after the announcement of the TLTROs in June 2014.

16

We also

perform placebo tests to make sure that any potential differences in the outcome variable across the

16

Note that our dependent variables credit standards and, to a lower extent, loan margins, are quite sticky, i.e.,

they evolve very slowly over time. This means that we must also use the cross-section variation for

identification, which renders the inclusion of bank fixed effects not feasible.

ECB Working Paper Series No 2364 / January 2020

18

two groups of banks were not pres

ent already before the TLTROs and thus can be attributed to the

introduction of the measure.

Estimation of (17) and

(18) by OLS may lead to biased and inconsistent estimates due to selection

bias.

17

In particular, selection into treatment is non-random, as banks participated in the TLTROs on a

voluntary basis. In particular, the evaluation of the policy may be biased upwards if the banks that

borrowed (more) from the TLTRO had, on average, better lending opportunities. By contrast, the

estimates may be biased downwards if the banks that borrowed (more) from the TLTRO had greater

deleveraging needs.

In order to obtain consistent estimates of and w

e use two instrumental variables that come from

the institutional setting of the TLTROs, as in Benetton and Fantino (2017). In particular, as explained

in section 3, in the initial TLTROs-I (September and December 2014) banks could borrow an amount

equivalent to 7% of their eligible loans outstanding on 30 April 2014. Crucially, note that the stock of

eligible loans was measured at prior to the announcement of the policy (June 2014). This initial

allowance constitutes the exogenous component of the TLTRO uptakes, as it is based on exogenous

parameters that are common across banks and on pre-determined banks’ balance sheet

characteristics. By contrast, we disregard the amounts borrowed in the additional TLTROs (between

March 2015 and June 2016) because the additional borrowing allowances depended on the evolution

of banks’ eligible lending activities in excess of bank-specific benchmarks. Hence, both the additional

TLTRO uptakes and their borrowing allowances are clearly endogenous variables.

Therefore, we construct two instrumental variables, bank al

lowance

and country allowance

(

)

.

The first one is computed as the ratio between the initial borrowing allowance of bank i and its total

assets. The second one is constructed as the ratio between the sum of the initial allowance of all the

other banks in the country (i.e., excluding bank i) and the total assets of those banks. Formally:

bank allowance

=

(19)

country allowance

(

)

=

(20)

17

In addition to selection bias, the fact that one regressor, country TLTRO

(

)

, is the average of another,

bank TLTRO

, may complicate the interpretation of OLS estimates of equation (17). See Angrist and Pischke

(2009), pages 193-195, for an explanation.

ECB Working Paper Series No 2364 / January 2020

19

We then estimate (17) a

nd (18) by 2SLS.

18

Note that equation (17) includes the individual TLTRO

uptakes,

, although we are really only interested in the aggregate effect of TLTROs –the

effect of

(

)

- in that specification. The inclusion of

is motivated by

the fact that any instrument for

(

)

must be also correlated with

. By

including it in the regression (as a second endogenous variable) we avoid a violation of the exclusion

restriction.

19

Finally, an additional id

entification challenge is to disentangle shocks to credit supply from shocks to

credit demand, as those shocks are often correlated and what we observe are equilibrium outcomes.

For instance, banks with high TLTRO uptakes may face more dynamic demand conditions or deal with

more creditworthy borrowers, which may induce them to ease credit standards or narrow margins.

To control for demand factors, we include a large vector of control variables that measure the

evolution of credit demand by firms and households in different segments (e.g. loans to SMEs), as

well as the factors underlying those developments (e.g., consumer confidence) as reported by banks

in the BLS.

20

18

Notice that the estimation of (17) via OLS would entail in addition an omitted variables bias from the

correlation between country TLTRO

(

)

and other country-quarter effects embodied in the error component

. For instance, the country’s business cycle may affect the country’s level of TLTRO uptakes because it

determines banks’ lending opportunities and firms’ investment returns and it also affects credit standards and

margins, which are usually anticyclical. This may generate a spurious correlation between the two. While the

inclusion of time-varying macro controls (such as the industrial production index and the unemployment rate)

mitigates this problem, a more complete solution is the approach we follow, IV estimation. By contrast, the

estimation of (18) does not face this challenge, as the use of country-time fixed effects

eliminates this

source of variation.

19

See Acemoglu and Angrist (2000) for a similar identification strategy in the context of the social returns to

schooling and human capital externalities.

20

In the case of non-financial corporations, demand controls are dummy variables for changes (decrease,

unchanged, increase) in the demand of credit in the following segments: all firms, SMEs and large firms, short-

term loans and long-term loans, loans for fixed investment, loans for inventories, loans for mergers and

acquisitions and loans for debt refinancing/restructuring. In the case of housing loans, demand controls are

dummy variables for changes (decrease, unchanged, increase) in the demand of credit by households for house

purchase and changes in the demand due to housing market prospects, consumer confidence, the general level

of interest rates, debt refinancing and the regulatory and fiscal regime of housing markets.

ECB Working Paper Series No 2364 / January 2020

20

Regarding inference, standard errors are clustered at the bank level to allow

for potential

heteroscedasticity and serial correlation within groups in the error structure. Nevertheless, results

are very similar when clustering at a higher level of aggregation such as country.

21

6. Data and variables

The data employed in the baseline analyses come from four s

ources: the Individual Bank

Lending Survey (iBLS), the Individual Balance Sheet Items (IBSI), the Individual MFI Interest Rate

(IMIR) databases and proprietary information on banks’ participation in central bank credit

operations. The iBLS database contains confidential, non-anonymized replies to the ECB’s Bank

Lending Survey (BLS) for a subsample of banks participating in the BLS. The BLS is a quarterly survey

through which euro area banks are asked about developments in their respective credit markets

since 2003.

22

Currently the sample comprises more than 140 banks from 19 euro area countries and

covers around 60% of the amount outstanding of loans to the private non-financial sector in the euro

area. However, there are six countries that do not share the confidential, non-anonymized replies to

the BLS so they do not participate in iBLS (see Table 1 for a view of the distribution of observations

per country).

23

The BLS is specifically designed to distinguish between supply and demand conditions in the

euro area credit markets. Supply conditions are measured through credit standards (i.e., the internal

guidelines or loan approval criteria of a bank) and credit terms and conditions (loan margins, loan

size, loan maturity, etc).

24

The BLS also contains information on the evolution of credit demand by

21

While clustering at the country level may lead to standard errors that are biased downwards due to few

clusters (Bertrand et al. 2004), inference using wild cluster bootstrap, a solution developed by Cameron et al.

(2008), leads to qualitatively similar results.

22

For more detailed information about the survey see Köhler-Ulbrich, Hempell and Scopel (2016). Visit also

https://www.ecb.europa.eu/stats/ecb_surveys/ban

k_lending_survey/html/index.en.html.

23

Germany participates in the iBLS with a sub-sample of banks that have agreed to transmit their non-

anonymized replies to the ECB.

24

According to the BLS, credit standards are the internal guidelines or loan approval criteria of a bank. They are

established prior to the actual loan negotiation on the terms and conditions and the actual loan

approval/rejection decision. They define the types of loan a bank considers desirable and undesirable, the

designated sectoral or geographic priorities, the collateral deemed acceptable and unacceptable, etc. Credit

standards specify the required borrower characteristics (e.g., balance sheet conditions, income situation, age,

employment status) under which a loan can be obtained. On the other side, credit terms and conditions refer

to the conditions of a loan that a bank is willing to grant, i.e., to the terms and conditions of the individual loan

actually approved as laid down in the loan contract which was agreed between the bank and the borrower.

They generally consist of the agreed spread over the relevant reference rate, the size of the loan, the access

ECB Working Paper Series No 2364 / January 2020

21

firms and households and the factors underlying these developments. In addition, several ad hoc

que

stions have been added in the recent years to analyse the impact of the main non-standard

monetary policy measures introduced by the ECB, such as the negative deposit facility rate (DFR) or

the expanded asset purchase programme (APP), on several dimensions such as banks’ balance

sheets, credit standards and terms and conditions.

IBSI and IMIR contain balance-sheet and interest rate information of the 326 largest euro

area banks

,

25

which is individually transmitted on a monthly basis from the national central banks to

the ECB since July 2007. We have matched both datasets with the iBLS and information on banks’

participation in Eurosystem credit operations, among which importantly the TLTROs. We restrict the

sample to the period spanning from 2014Q2 (i.e., announcement of TLTRO-I) to 2017Q4

.

26

The

resulting sample contains 1,784 observations corresponding to an unbalanced panel of 130 banks

from 13 countries (see Table 1 for a view of the distribution of observations per country).

27

However,

the estimation sample will be generally smaller due to missing values.

The definitions of the variables used in this study are displayed in Table 2. The dependent

variables are changes in credit standards and margins in loans to enterprises and households for

house purchase, as reported in the BLS. In particular, the BLS asks banks on a quarterly basis about

the evolution of the credit standards applied to their new loans or credit lines to enterprises and

households, as well as the margins charged on them. Banks must answer whether they have

tightened credit standards, kept them basically unchanged or eased them over the past three

months.

28

Regarding margins (defined as the spread over a relevant market reference rate), the BLS

distinguishes between margins on average loans and margins on riskier loans. Banks must answer

conditions and other terms and conditions in the form of non-interest rate charges (i.e., fees), collateral or

guarantees which the respective borrower needs to provide (including compensating balances), loan covenants

and the agreed loan maturity.

25

55 monthly time series are required on the asset side, which include data on holdings of cash, loans, debt

securities, MMF shares/units, equity and non-MMF investment fund shares/units, non-financial assets and

remaining assets. On the liability side, the time series cover information on deposits, included and not included

in M3, issuance of debt securities, capital and reserves and remaining liabilities.

26

As most regressors are lagged one period, they are measured in the period spanning 2014Q1 to 2017Q2.

27

The level of consolidation of the banking group differs between BLS and IBSI. Consequently, we have 130

banks in IBSI but 112 banks in BLS, because sometimes the head of the group is the one that answers to the BLS

but we have unconsolidated balance sheets of the head and its subsidiaries in IBSI.

28

While the BLS differentiates between “tightened considerably” and “tightened somewhat” and between

“eased considerably” and “eased somewhat”, we aggregate these categories into “tightened” and “eased”, as

done in the regular BLS reports prepared by the ECB.

ECB Working Paper Series No 2364 / January 2020

22

whether they have tightened them (wid

er margins), kept them basically unchanged or eased

(narrower margins) over the past three months.

Descriptive statistics of the dependent variables can be found in Table 3

. They are dummy variables

that equal 1 in the case of easing and 0 otherwise. Credit standards are very stable over time. The

proportion of banks that report an easing of credit standards ranges between 5% and 7%, depending

on the segment. Margins on average loans ease more frequently, in about 25% of the observations,

while margins on riskier loans are narrowed less often (about 5%). Therefore, while banks adapt their

lending policies through the adjustment of both loan terms & conditions and credit standards, the

former seem to be more flexible instruments than the latter. Regarding bank-level controls, we proxy

bank size with the natural logarithm of the bank’s total assets (size). Leverage is defined as the ratio

of capital and reserves over total unweighted assets (capital ratio). Liquidity is measured with a

liquidity ratio, expressed as the sum of cash, holdings of government securities and Eurosystem

deposits over total assets (%). This variable may also capture the impact of the ECB’s expanded asset

purchase programme (APP) on banks’ balance sheets, which was announced in January 2015. We

also include a loan-to-deposit ratio, in logs.

29

The importance of deposits as a funding source is

captured with the deposit ratio, the ratio between the deposits by households and non-financial

corporations over total assets. Market share is the ratio between a bank's outstanding loans and the

total loans of the country's banking sector (%). We also control for the bank’s legal form (head

institution, national subsidiary, foreign subsidiary, foreign branch). Finally, we need to control for the

impact of negative interest rates on banks’ lending policies because both the TLTRO I and the

negative deposit facility rate (DFR) were announced in June 2014, as part of the ECB’s credit easing

package.

30

To do so we include the variable NDFR, a dummy variable that equals 1 if the bank

reported that the ECB’s negative DFR contributed to a decrease of the bank’s net interest income in

the past six months and 0 otherwise. This variable, which comes from Arce et al. (2018), is

constructed using an ad-hoc question in the BLS that is asked on a semi-annual basis.

31

We also

include a set of relevant macroeconomic controls: the 10-year sovereign bond, the industrial

production index, the unemployment rate, the consumer price index and the Herfindahl-Hirschman

Index.

29

To correct for right skewness and outliers.

30

The negative DFR was introduced on 11 June 2014, the TLTRO-I were announced on 5 June 2014.

31

The exact wording of the question is: “Given the ECB’s negative deposit facility rate, did this measure, either

directly or indirectly, contribute to a decrease / increase of your bank’s net interest income over the past six

months?”

ECB Working Paper Series No 2364 / January 2020

23

Table 4 displays descriptive statistics of the bank characteristics, including the key

re

gressors, the instrumental variables and the bank-level controls, as well as summary statistics of

the macro controls. Table 5 presents the means of the bank characteristics for banks that

participated in the TLTROs and banks that did not participate, together with the p-value associated

with a two-sample t-test of equality of means, at the quarter of announcement of TLTRO-I (2014Q2).

Out of the 116 banks in the sample at 2014Q2, 55 banks participated in the TLTRO.

32

The average

participating bank borrowed an amount equivalent to 1.7% of its total assets (mean of

bank TLTRO

), close to its borrowing limit, 2% (mean of bank allowance

). Regarding differences

between bidders and non-bidders, the average TLTRO uptake of a bank’s competitors (mean of

(

)

) is higher in the case of participating banks. This likely reflects that banks located

in countries under intense financial market scrutiny during the sovereign crisis episode participated

more widely and borrowed larger amounts. This is not surprising since the funding cost benefit of

accessing the TLTROs, instead of alternative funding, was on average higher for banks located in

those countries. To some extent it may also reflect that the recourse to the operations are strategic

complements: a bank is more likely to participate if its rivals borrow heavily in the operations. In

addition, TLTRO bidders are significantly larger than non-bidders, probably due to the fixed costs

associated with participation, and have a larger market share in the segment of loans to NFCs. With

respect to risk, there are no significant differences in terms of capital and non-performing loan ratios,

but bidders have higher CDS spreads than non-bidders, suggesting that they are perceived to be

riskier. However, this last result must be interpreted with caution, as we only have information on

CDS spreads for 83 banks. Participating banks also have a substantially higher share of liquid assets,

probably because some of those assets can be pledged as collateral in the TLTROs and the ECB’s main

refinancing operations. Bidders are also more likely to experience a decline in their net interest

income due to negative interest rates (NDFR=1) than non-bidders.

In our empirical exercises we also use controls for firms’ demand for credit. In particular, the

BLS asks banks about perceived changes in the demand for loans or credit lines to enterprises and

households. Banks must answer whether the demand for their loans has decreased, has remained

basically unchanged or has increased over the past three months.

33

In the case of loans to non-

32

Note that we have an unbalanced panel. Out of 130 banks in the whole sample (2014Q2-2017Q4), 60 of

them participated in the initial TLTROs.

33

As with the supply indicators, we merge “decreased considerably” and “decreased somewhat” into

“decreased” and “increased considerably” and “increased somewhat” into “increased”.

ECB Working Paper Series No 2364 / January 2020

24

financial corporations, we d

ifferentiate between demand for loans from SMEs and large firms and

also between short-term loans and long-term loans. We also distinguish the evolution of credit

demand according to the purpose of the loan (loans for fixed investment, for inventories and working

capital, for mergers and acquisitions and for debt refinancing). In the case of loans to households for

house purchase, we include dummy variables for changes in the demand of credit in that segment, as

well as changes in the demand due to the factors “housing market prospects” and “consumer

confidence”.

34

Table 6 presents descriptive statistics of these variables. The demand indicators are

also relatively stable, but they change more frequently than credit standards. In addition, demand is

more likely to increase than to decrease, as expected in a period of economic recovery.

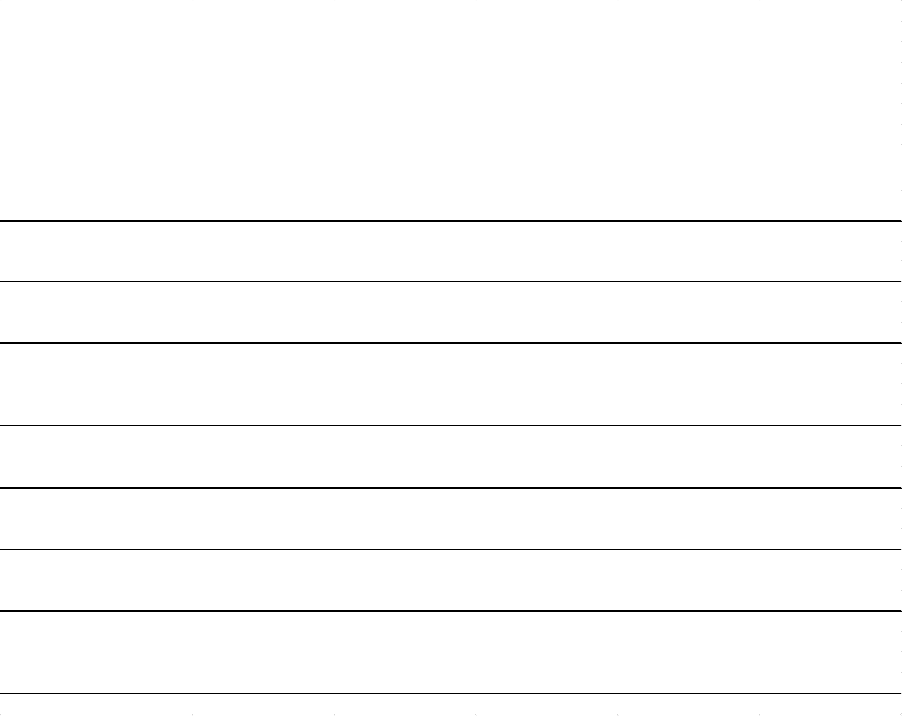

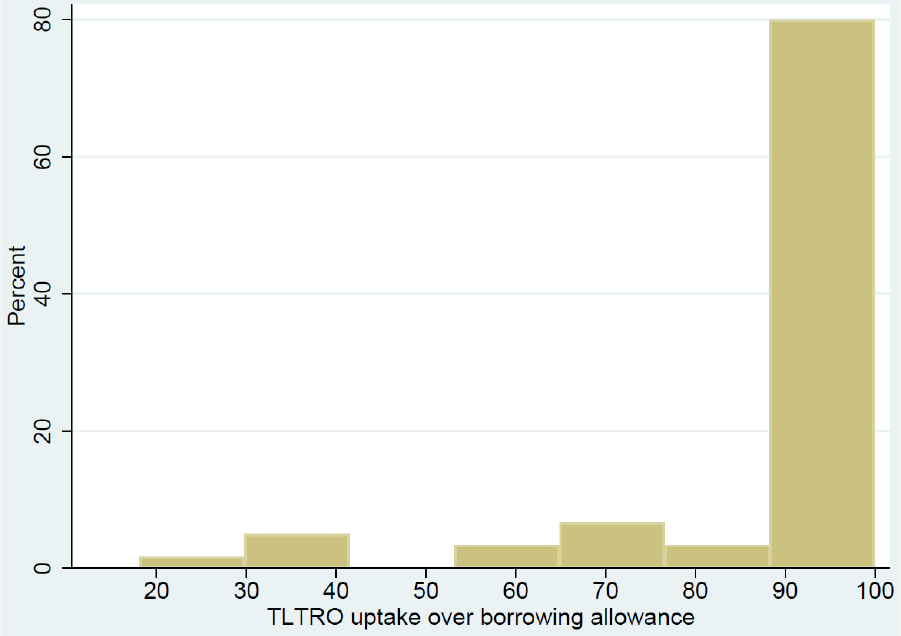

Descriptive analyses suggest a meaningful relationship between the dependent variables and

the key regressors. For the segment of loans to NFCs, Figure 2 displays the averages of the

dependent variables (i.e., the proportion of banks that eased credit standards/margins) for banks

with high/low values of

(

)

(above and below the median, respectively). According

to Figure 2, banks that belong to the high country TLTRO group are more likely to ease credit

standards and margins on average loans than banks that belong to the low country TLTRO. The

differences are sizeable and statistically significant.

35

For instance, the proportion of banks that

eased overall credit standards was 8% for the high country TLTRO group and only 3% for the low

country TLTRO group. By contrast, banks whose national competitors borrowed heavily in the TLTROs

(high country TLTRO group) were less likely to narrow margins on riskier loans than banks from the

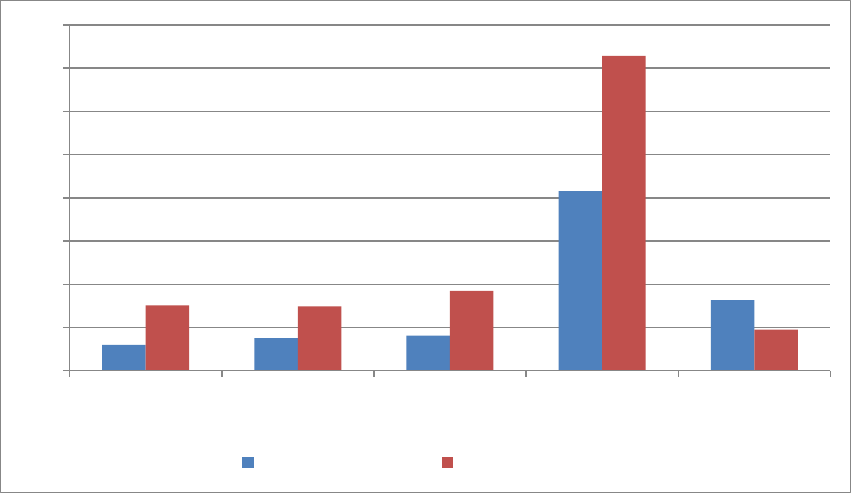

low country TLTRO group (5% and 8%, respectively). A similar analysis is displayed in Figure 3 for

banks with high/low values of bank TLTRO

(above and below the median).

36

According to Figure 3,

banks with high TLTRO uptakes were more likely to ease credit standards and margins on average

loans than banks with low uptakes. The differences are also statistically significant, although

somewhat smaller than in Figure 2. By contrast, the proportion of banks that narrowed margins on

riskier loans is very similar in both groups. All in all, the analysis of the two figures suggests

potentially meaningful links between TLTRO uptakes at the bank and country level and changes in

34

Similarly to the case of supply factors (e.g. competition), a demand factor may contribute to lower demand,

to keeping demand unchanged and to higher demand. We exclude other BLS demand factors (general level of

interest rates, debt refinancing/restructuring and regulatory and fiscal regime of housing markets) because

there are only available since 2015Q1 due a change in the questionnaire.

35

The statistical significance of those differences is assessed by performing two-sample tests on the equality of

proportions.

36

As the median of bank TLTRO

is 0, the two groups consist of participating and non-participating banks.

ECB Working Paper Series No 2364 / January 2020

25

banks’ lending policies. However, as these associations may be purely due to positive selection bias

(e.

g. banks with high TLTRO uptakes may have better lending opportunities) or confounding events

(e.g. those banks may have been more affected by the negative DFR that was introduced in parallel),

more formal analyses are required.

7. Empirical results

7.1 Baseline res

ults

Let us start with the segment of loans t

o NFCs. As a benchmark, Table 7a and Table 7b

display the estimation of (17) and (18) by OLS. Table 7a shows that there is a positive and significant

correlation between the TLTRO uptakes of a bank’s national competitors, as measured by

country TLTRO

(

)

, and the probability that the bank eases overall credit standards (column (1)),

credit standards to SMEs (column (2)) and credit standards to large firms (column (3)). This suggests a

significant indirect effect of the TLTROs on bank credit standards. By contrast, there is no significant

impact on bank margins (columns (4) and (5)). In addition, Table 7b shows no clear evidence of direct

effects, as a bank’s TLTRO uptake is not significantly correlated with the probability of easing credit

standards or lowering margins. The only exception is column (5), which displays a negative sign:

higher TLTRO uptakes are associated with a lower probability of narrowing margins on riskier loans.

This observation may indicate that the TLTROs did not lead to excessive risk taking by banks.

To make sure that our results are not biased by en

dogeneity we use the initial TLTRO-I

allowance (at bank and country level respectively) as instrument variables and estimate (17) and (18)

by 2SLS.

37

First we confirm that the instruments are not weak. Table 8 reports the first stage

regressions corresponding to (17) (columns (1) and (2)) and the first stage regression that

corresponds to (18) (column (3)). We observe positive and strong relationships between the

instruments and the endogenous variables. In particular, a 1 pp increase in a bank’s initial allowance

leads to a 0.49 pp increase in a bank’s TLTRO uptake (over total assets), and a 1 pp increase in a

country’s initial allowance leads to a 0.59 pp increase in a country’s total TLTRO uptake (over the

country’s total assets). In columns (1) and (2), the multivariate F-statistics developed by Sanderson

37

In a supplement to this paper we report estimates of (17) by probit and IV probit. Results are broadly similar.

ECB Working Paper Series No 2364 / January 2020

26

and Windmeijer (2016)

38

exceed Stock and Yogo (2005)’s critical values

39

and they are significantly

greater than 10, the rule of thumb suggested by Staiger and Stock (1997). The same is true for a

conventional first-stage F-statistic in column (3). Hence, we can conclude that our instruments are

not weak.

The 2SLS estimates, which are presented in Table 9,

are consistent with the previous OLS

results. Regarding indirect effects (Table 9a), country TLTRO

(

)

has a positive effect on overall

credit standards, credit standards for SMEs and credit standards for large firms (columns (1), (2) and

(3)). The effects are sizeable. For instance, a standard deviation increase in country TLTRO

(

)

leads

to a 5.3 pp increase in the probability that a bank eases overall credit standards and an 8.8 pp

increase in the probability of easing credit standards to large firms. By contrast, the TLTRO uptakes of

a bank’s competitors have no significant effect on margins on average loans (column (4)) and riskier

loans (column (5), coefficient only marginally significant). Finally, there is no clear evidence of direct

effects (Table 9b), as the coefficient on bank TLTRO

is insignificant in all specifications.

The analysis of loans to hous

eholds for house purchase is presented in Table 10 (OLS) and

Table 11 (2SLS). For the sake of brevity, let us focus on the IV estimates. With respect to indirect

effects (Table 11a), country TLTRO

(

)

has a positive effect on credit standards (column 1). In

particular, a standard deviation increase in the TLTRO uptakes of a bank’s competitors implies an 8.8

pp increase in the probability that the bank eases its own credit standards. Regarding direct effects

(Table 11b), there is no significant impact on credit standards (column 1). However, column (2)

reports a positive effect of bank TLTRO

on the probability of narrowing margins on average loans.

The effect is strong, as a standard deviation increase in a bank’s TLTRO uptake (relative to total

assets) implies a 15.8 pp increase in the probability of lowering margins on average loans.

7.2 Analysis of the direct effects of the TLTROs: the intensive vs. extensive margin

The evidence presented so far suggests that direct effects are weak, except in the case of

margins on loans for house purchase. However, notice that the regressor of interest,

,

38

For multiple endogenous variables, inspection of the individual first-stage F-statistics is not sufficient. To see

why, suppose there are two instruments for two endogenous variables and that the first instrument is strong

and predicts both endogenous variables well, while the second instrument is weak. The first-stage F-statistics in

each of the two first-stage equations are likely to be high, but the model is weakly identified, because one

instrument is not enough to capture two causal effects. See Angrist and Pischke (2009).

39

For a Wald test with maximal size of 10%.

ECB Working Paper Series No 2364 / January 2020

27

may hide some interesting heterogeneity. In particular, the variable takes the value 0 for about 50%

of the observations (banks that did not borrow in the TLTROs) and it is continuously distributed

between the values 0.1% and 5% for the other 50% of the observations (banks that borrowed in the

TLTROs). Hence, we may distinguish the direct effect of TLTROs on bank lending policies in the

extensive margin (participation vs. non-participation) and the intensive margin (amount of borrowed

funds, conditional on participation). For the analysis of the extensive margin, we estimate (18) but

replacing the variable

with the variable

, a dummy that equals 1 the

bank borrowed any amount in the initial TLTROs (September and December 2014). We treat

as endogenous and instrument it with bank allowance

. For the analysis of the

intensive margin, we estimate (18) for the subsample of banks that participated in the initial TLTROs.

The analysis for the segment of loans to NFCs is presented in Table 12. Table 12a examines

the intensive margin and Table 12b examines the extensive margin. According to Table 12a, there are

no substantial differences in the lending policies of participating and non-participating banks, as the

coefficient on

is always statistically insignificant. In other words, there is no

“participation effect”. By contrast, for the subsample of bidding banks (Table 12b), the coefficient on

is positive and significant in columns (3) and (4), indicating that high TLTRO uptakes

lead to a higher probability of easing credit standards on large firms and to a higher probability of

narrowing margins on average loans. The effects are strong: a standard deviation increase in a bank’s

TLTRO uptake increases the probability of easing credit standards on large firms by 12.4 pp and it

raises the probability of narrowing margins on average loans by 20 pp. This suggests that, for the

subsample of bidding banks, the reduction in funding costs caused by the TLTROs is transmitted

through easier lending policies to large firms and relatively safe borrowers.

The analysis for the segments of loans to households is presented in Table 13. Table 13a

examines the intensive margin and Table 13b examines the extensive margin. According to Table

13a, bidding banks are much more likely (62 pp) to narrow margins on average loans than non-

bidders, a strong “participation effect”. The effect on those margins also takes place in the intensive

margin (Table 13b): for the subsample of bidding banks, a standard deviation increase in a bank’s

TLTRO uptake raises the probability of narrowing margins on average loans by 28.6 pp. All in all, the

picture that emerges from Tables 9, 11, 12 and 13 is that there are substantial direct effects of

TLTROs on lending policies. The direct transmission of monetary policy takes place mainly through

the adjustment of margins on loans to relatively safe borrowers.

ECB Working Paper Series No 2364 / January 2020

28

7.3 Further analysis of indirect effects: the role of competition

The evidence presented so far suggests that the TLTROs have important indirect effects on

banks’ lending policies. Recall that, according to the above stylised model, large-scale recourse to the

TLTROs has two simultaneous effects: (i) it fosters intense competition in the credit market and (ii) it

eases pressures in funding markets. While for bidders (i.e., the risky bank) these two effects go in the

same direction,

40

for non-bidders (i.e., the safe bank) the effects are opposite. On the one hand their

relative competitive position vis-à-vis bidders worsens, ceteris paribus contracting the loan supply of

non-bidders. On the other hand, their access to market funding improves, supporting their supply of

loans. The empirical results presented so far suggest that the overall indirect effect is positive, i.e.