Neurogenic Bowel:

What You

Should Know

A Guide for People

with Spinal Cord Injury

CLINICAL PRACTICE CONSUMER GUIDELINE: NEUROGENIC

BOWEL

SPINAL CORD MEDICINE

Administrative and financial support provided by Paralyzed Veterans of America

Consumer Guide

Panel Members

Steven A. Stiens, MD, MS

Chair, Consumer Guide Panel and

Member, Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine

Neurogenic Bowel Guideline Panel

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs

VA Puget Sound Healthcare System

Seattle, Washington

University of Washington

Department of Rehabilitation Medicine

Seattle, Washington

Carol Braunschweig, PhD

Member, Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine

Neurogenic Bowel Guideline Panel

University of Illinois of Chicago

Chicago, Illinois

John F. Cowell

Member, Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine

Neurogenic Bowel Guideline Panel

Paralyzed Veterans of America

Washington, D.C.

C. Mary Dingus, PhD

Member, Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine

Neurogenic Bowel Guideline Panel

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs

VA Puget Sound Healthcare System

Seattle, Washington

Mary Montufar, MS, RN

Member, American Association of Spinal Cord Injury

Nurses Bowel Guideline Panel

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs

VA Palo Alto Healthcare System

Palo Alto, California

Peggy Matthews Kirk, BSN, RN

Member, Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine

Neurogenic Bowel Guideline Panel

Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago

Chicago, Illinois

Consortium Member

Organizations

American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons

American Academy of Physical Medicine and

Rehabilitation

American Association of Neurological Surgeons

American Association of Spinal Cord Injury

Nurses

American Association of Spinal Cord Injury

Psychologists and Social Workers

American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine

American Occupational Therapy Association

American Paraplegia Society

American Physical Therapy Association

American Psychological Association

American Spinal Injury Association

Association of Academic Physiatrists

Association of Rehabilitation Nurses

Congress of Neurological Surgeons

Eastern Paralyzed Veterans Association

Insurance Rehabilitation Study Group

Paralyzed Veterans of America

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs

Who Should Read This Guide?

This Guide is for everyone who wants or needs to under-

stand how spinal cord injury (SCI) can affect and change

bowel* function. The clinical name for this condition is neuro-

genic bowel. It’s also for everyone who wants to learn about

ways to deal with these changes in bowel function. That

includes:

Adults with spinal cord injuries:

•People with a new SCI.

•People who’ve lived with SCI for years.

Caregivers:

•Family members.

• Friends.

•Personal care attendants.

Health-care professionals:

•Primary-care providers.

• Rehabilitation professionals.

• Other hospital staff.

This Guide is an educational tool. Feel free

to share it with your health-care professionals

when you discuss bowel management issues

with them and plans for actual changes. They

can also get a free copy of the full clini-

cal practice guideline, Neurogenic

Bowel Management in Adults with

Spinal Cord Injury, by calling

(888) 860-7244 or visiting the

Paralyzed Veterans of America

(PVA) web site at

http://www.pva.org.

A Guide for People with Spinal Cord Injury 1

*Words in italics are explained in the Glossary on page 41.

I

’m an avid sportsman and can’t get enough of the great

outdoors. Since my SCI, I’ve been experimenting with new

ways to do all the things I loved before my all-terrain vehicle

(ATV) accident. I spend all my free time camping, whitewater

rafting, kayaking, fishing, and hunting. I’ve got a T7

complete injury, so I needed some special adaptive

equipment to continue my outdoor interests.

The biggest problem I had after my injury wasn’t with

changes to my sporting equipment or other gear, but

in getting my body functions under control. I was

worried that I’d have a bowel accident while I was on

a camping or fishing trip, and that kept me from doing

the things I really enjoyed.

So I talked with my doctor, rehabilitation nurse, and

occupational therapist, and we developed a bowel program

that’s working well for me. Because I’m very physically active,

we changed the frequency of my bowel care. The occupational

therapist gave me some tips on positioning and

disposal. My doctor also linked me to a dietitian,

and we made some changes to my diet. It

worked. I’m in control of my situation and

that gives me confidence in other areas as

well.

I met a young woman I really care for.

We’ve been dating for a couple of months.

Last month she began asking some personal

questions about my injury, and I’m being really honest

with her. I gave her a copy of PVA’s Yes, You Can! book and

marked some important sections for her to read. The bowel

and bladder stuff is hard to talk about, but once she had read

the book, it was easier.

A proper

bowel program

promotes independence

and thereby improves

quality of life.

Cliff

Cliff

A Guide for People with Spinal Cord Injury 3

Contents

Why Is This Guide Important?........................................................................4

What Is the Bowel and Where Is It? ..............................................................5

How Does the Bowel Work? ..........................................................................6

How Does SCI Change the Way the Bowel Works? ........................................6

What Is a Bowel Program? ............................................................................8

What Is Bowel Care? ......................................................................................9

What Is Rectal Stimulation? ..........................................................................9

How Is Digital Rectal Stimulation Done?......................................................10

What Does My Health-Care Professional Need to Know? ............................11

How Do I Do Bowel Care?............................................................................14

Are There Other Ways to Improve a Bowel Movement? ..............................18

What Is a Bowel Care Record? ....................................................................19

Can I Be Independent in My Bowel Care? ....................................................20

Why Do I Need to Watch What I Eat and Drink?..........................................21

What Medications Are Used in Bowel Programs? ........................................26

Tips for Safe Bowel Care..............................................................................26

How Often Should My Bowel Program be Reviewed? ..................................28

What Should I Do if My Bowel Program Isn’t Working? ..............................29

Answers to Commonly Asked Questions ....................................................34

What Should I Know About Surgical Options? ............................................36

References and Resources............................................................................39

Glossary ......................................................................................................41

Food Record ................................................................................................46

Medical History............................................................................................48

Bowel Care Record ......................................................................................49

Tables and Figures

Figure 1. GI Tract ........................................................................................5

Figure 2. Colon and Anal Canal ..................................................................10

Figure 3. Digital Stimulation ....................................................................10

Figure 4. Placement of Suppository............................................................15

Figure 5. Colostomy/Ileostomy ..................................................................36

Table 1. How Much Fiber Is in Different Types of Food? ..........................23

Table 2. What You Can Do About Excessive Gas ......................................24

Table 3. Bowel Medications ......................................................................27

Table 4. Frequent Bowel Accidents: Possible Causes and Solutions..........31

Table 5. Common Bowel Problems: Solutions and Possible Causes..........32

4 NEUROGENIC BOWEL: What You Should Know

Why Is This Guide Important?

A spinal cord injury changes the way your body works and

how you will care for yourself. One important change that

may be difficult for many of us to talk about is how the bowel

functions.

Before an SCI, people don’t have to make special plans or

schedules for bowel movements. They can feel the need to use

a toilet, hold their bowels until the time is right, and then relax

and let stool pass out at the right place.

After an SCI, bowel movements require more time, thought,

and planning. People with SCI usually can’t feel when stool is

ready to come out, and they need help expelling the stool. As

people with SCI say, “The bowel rules.”

A well-designed bowel program can help you lead a healthi-

er and happier life after SCI. It can:

• Help prevent unplanned bowel movements (also called bowel

accidents, incontinence, or involuntaries).

• Help avoid physical problems such as constipation.

• Put you back in control of a bodily function that, if neglected,

can cause embarrassment.

• Improve your confidence in work and social situations.

This Guide will help you work with your family, caregivers,

and health-care professionals to create a bowel program that

fits your needs. After that, it’s up to you to stick with it.

Everyone’s body changes over time. Even if you’ve kept to a

regular bowel program for months or years, it may stop work-

ing for you as well as it once did. This Guide will tell

you what to do if that happens at any time in your life.

Talking About

Embarrassing Subjects

Most of us consider bathroom functions private and

personal. We’re not comfortable talking about them,

even with close family members or health-care pro-

fessionals. That’s one of the hardest changes

after SCI: talking about bowel functions—and

asking for help with them.

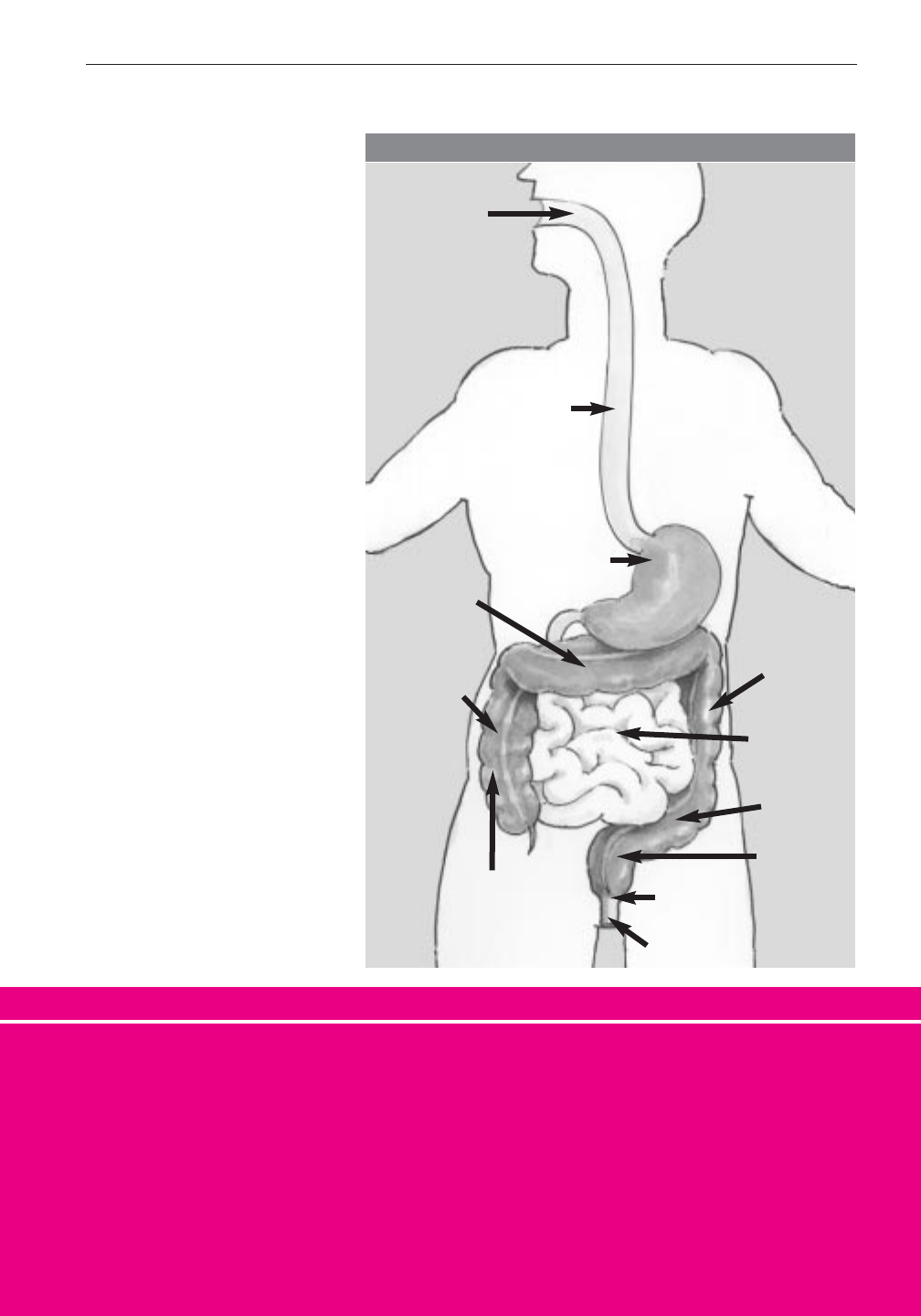

What Is the Bowel

and Where Is It?

Everything you eat

and drink travels from

your mouth through your

digestive system—also

called the gastrointesti-

nal tract or GI tract (see

Figure 1). The GI tract

includes the mouth,

esophagus, stomach,

small intestine, and

colon (also called the

large intestine) and ends

at the anus. The colon is

about 5 feet long and

forms a question mark

shape in the abdomen.

Together, the large and

small intestines are

called the bowel.

There’s no getting around it: Life is dif-

ferent now. Practice helps. The more you

talk about bowel issues, the easier it gets.

Remember that other people (except

health-care professionals) are likely to be

just as uncomfortable with bowel discus-

sions as you are at first.

Humor can be a good way to relieve

embarrassment. If you try to put other

people at ease, you’ll feel less embar-

rassed too.

A Guide for People with Spinal Cord Injury 5

Mouth

Esophagus

Stomach

FIGURE 1

Transverse

Colon

Descending

Colon

Small

Intestine

Ascending

Colon

Anus

Anal

Sphincter

Rectum

Sigmoid

Colon

Colon

(Large

Intestine)

How Does the Bowel Work?

The digestive process breaks down what you eat and drink

into nutrients your body uses and waste that you eliminate. A

wave-like action called peristalsis propels food through your GI

tract. The undigested food, waste your body doesn’t use, moves

into the colon from your small intestine. The colon takes the

moisture out of the waste and stores it. The waste follows the

question-mark shaped pathway of the colon: up the ascending

colon, across the transverse colon, down the descending colon

through the sigmoid colon, and into the rectum on its way out of

the body (see Figure 1, page 5).

People use many words to describe these wastes. Health-

care professionals call them bowel movements (BM), stool,

excrement, fecal matter, or feces. Your family and caregivers

may be more comfortable using terms like BM. (Liquid wastes

are eliminated as urine.)

How Does SCI Change the Way the Bowel Works?

Neurogenic bowel is a condition that affects the body’s

process for storing and eliminating solid wastes from food.

After SCI, the nervous system can’t control bowel functions the

way it did before.

For most people, the digestive process is controlled from

the brain by reflex and voluntary action. SCI interferes with

that process by blocking messages from parts of the digestive

system to and from the brain through the spinal cord. How it

interferes depends on where along the spinal cord the injury is.

Here’s what normally happens. The colon stores stool until

it’s propelled out as a bowel movement. When the stool is

6 NEUROGENIC BOWEL: What You Should Know

• Stick with a consistent schedule. That

means every day or every other day,

depending on your

needs.

• Find a convenient

time of day. That

means always in the

morning or always

in the evening—

whatever works for

you, but always the same time of day.

Tips for Following a Regular Bowel Care Routine

SMTWT F S

pushed into the rectum, it triggers a reflex action. This action

contracts the anal sphincter, keeping it closed so that stool

doesn’t slip out. Without SCI, people can feel stool in the rec-

tum and voluntarily contract the anal sphincter to hold in the

stool. They then find a toilet, relax the anal sphincter, and have

a bowel movement.

SCI can keep you from feeling stool in the rectum and from

controlling your anal sphincter. It can also affect peristalsis—

how stool moves through your colon.

Generally, two basic patterns of neurogenic bowel occur

after SCI, depending on which part of the spinal cord is injured.

Reflexic Bowel

This usually results from SCI at the cervical (neck) or tho-

racic (chest) level. This type of SCI interrupts messages

between the colon and the brain that are relayed by the spinal

cord. Below the injury, the spinal cord still coordinates bowel

reflexes. This means that although you don’t feel the need to

have a bowel movement, you still have reflex peristalsis. Stool

buildup in the rectum can trigger a reflex bowel movement

without warning. Between bowel movements, your anal sphinc-

ter will remain tight, and your colon will respond to digital

rectal stimulation and stimulant medications with reflex

peristalsis that pushes the stool out.

Areflexic Bowel

This results from SCI that damages the lower end of the

spinal cord (the lumbar or sacral level) or the nerve branches

that go out to the bowel. This means that you have reduced

peristalsis and reduced reflex control of your anal sphincter.

•Try to do bowel care after a meal or a

hot drink. That may help stimulate

your bowel to push stool out.

• Find a comfortable place and

positions.

•Privacy helps.

A Guide for People with Spinal Cord Injury 7

8 NEUROGENIC BOWEL: What You Should Know

Your bowel isn’t controlled by reflexes from the spinal cord. You

can’t feel the need to have a bowel movement, and your rectum

can’t easily empty stool by itself.

The location of your SCI also has a great deal to do with the

bowel program that will work best for you. (See pages 14-18 for

information about bowel care for reflexic and areflexic bowel.)

What Is a Bowel Program?

A bowel program is a total plan for regaining control of

bowel function after SCI. It deals with several aspects of your

life, including:

•Diet and fluids—what, how much, and when you eat and drink.

• Activity level—how active you are: for example, how often you

get a full range of motion of your joints, how many different

positions (sitting, standing, lying) you are in during the day and

for how long.

• Medications—what products you take for bowel care and for

other reasons. These include oral medications you take to

improve bowel function, rectal medications you use to stimulate

a bowel movement, and medications you take for other reasons

that affect bowel function.

• Bowel care—frequency and technique of scheduled, assisted

bowel movements.

A bowel program is designed to help you improve your

quality of life:

• Prevent or cut down on bowel accidents.

•Eliminate enough stool with each bowel care session at regular

and predictable times.

• Make bowel care go smoothly, allowing you to finish within a

reasonable time.

•Keep bowel-related health and other problems to a minimum.

You and your health-care professionals will work together to

design a bowel program that fits your needs.

A Guide for People with Spinal Cord Injury 9

What Is Bowel Care?

Bowel care is the term for assisted elimination of stool, and

it’s part of a bowel program. It begins with starting a bowel

movement. That’s usually done with digital rectal stimulation

and/or a stimulant medication. After the bowel movement

starts, intermittent digital rectal stimulation can also be used to

speed up defecation. (See page 18, “Are There Other Ways To

Improve a Bowel Movement?”)

What Is Rectal Stimulation?

It’s a way to turn on peristalsis in the colon, start a bowel

movement, and keep it going. Most people need to start bowel

care by stimulating the rectum to eliminate stool. There are

two main types of rectal stimulation:

• Mechanical stimulation. This method uses a finger or a

stimulant tool. It includes digital rectal stimulation and

manual evacuation.

•Stimulant medications. This method uses a suppository or

mini-enema (also called a liquid suppository).

Important:

If your SCI is at T6 or higher, stool in the rectum or any method

of rectal stimulation may cause autonomic dysreflexia. This is a

potentially life-threatening emergency medical condition! A

fast, major increase in your blood pressure is the most dangerous

sign of autonomic dysreflexia. Learn more about it and how to

prevent it. Read the guide called Autonomic Dysreflexia: What

You Should Know. For a free copy, call (888) 860-7244 or visit the

PVA web site at http://www.pva.org.

Important:

People with SCI need to stick with a regular schedule and tech-

nique of bowel care. You may have to revise your bowel pro-

gram over time, but keeping a regular schedule for doing

bowel care at a regular time is one of the best things you can

do for your health and well-being after SCI.

How Is Digital Rectal

Stimulation Done?

Insert a gloved, well-

lubricated finger gently

into the rectum. Direct the

stimulating finger toward

the belly button and follow

the anal canal (see Figures

2 and 3). When the finger

is inserted, digital rectal

stimulation can begin.

Move the stimulating finger

gently in a circular pattern,

keeping the finger in con-

tact with the rectal wall.

Digital rectal stimulation

usually takes 20 seconds

and should be done no

longer than 1 minute at a

time. Repeat the digital stimulation

every 5 to10 minutes until you have a

bowel movement. Sitting up or laying

on your left side may help stimulate a

bowel movement.

Digital stimulation relaxes and

opens the external anal sphincter (see

Figure 2), straightens the rectum, and

triggers peristalsis. From the time you start digital

stimulation, it should take only a few seconds to a few

minutes for stool to enter the rectum and come out.

Important:

At every stage of digital rectal stimulation, it’s important to

use plenty of lubricant and to be gentle. Pushing or rotating

the finger too roughly can irritate or tear the rectal lining

or anus and trigger autonomic dysreflexia. (For more

information about autonomic dysreflexia, see the glossary

and the guide called Autonomic Dysreflexia: What You

Should Know. For a free copy, call (888) 860-7244 or visit

the PVA web site at http://www.pva.org.)

10 NEUROGENIC BOWEL: What You Should Know

FIGURE 2

Colon

(Large

Intestine)

Sacrum

Rectal

Wall

Rectum

Anus

Internal Anal

Sphincter

Stomach

Transverse

Colon

Descending

Colon

Small

Intestine

Rectum

Sigmoid

Colon

Ascending

Colon

Anal

Sphincter

Anus

External Anal

Sphincter

FIGURE 3

Anal

Canal

A Guide for People with Spinal Cord Injury 11

What Does My Health-Care

Professional Need To Know?

No single bowel program is right for everyone. Every per-

son with SCI has a different diet, activity routine, need for med-

ication, and life schedule that regular bowel care has to fit. A

normal schedule for passing stool is whatever is usual for you.

That’s usually once a day or every other day. To find what

works best for you, tell your health-care professional about:

Any new problems with bowel function:

•Does your bowel care produce poor results, or no results?

• Do you have rectal bleeding?

• Does your bowel care routine take longer than before?

•Do you have a lot of gas or feel bloated?

Your medical history. In addition to information about

your SCI:

• Do you have, or have you had, diabetes?

• Do you have digestive problems, such as irritable bowel

syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, or colitis?

• Have you had any bowel surgery?

Medications you’re taking:

• What prescription products are you taking and for what?

• What nonprescription products, such as laxatives, are you

taking and how often do you take them?

Alcohol and other drugs:

• Do you drink alcoholic beverages? If so, what do you drink, how

much, and how often?

• Do you use, or have you ever used, any “street” drugs? If so,

which ones, how much, and how often?

• Do you use, or have you ever used, any alternative medicines? If

so, which ones, how much, and how often?

Important:

Alcohol and drugs can affect bowel function. If you use alco-

hol or drugs, your health-care professional needs to know, to

be able to design a bowel program that will work for you.

12 NEUROGENIC BOWEL: What You Should Know

The location of your SCI affects the

amount of control you have over your

bowel and determines which methods will

work best for you. Work with your health-

care professional to create a bowel pro-

gram that fits, for example:

•Work and home situations. These

help determine the best time and place

for bowel care. They also affect meals

and food preparation.

• Supplies and equipment. They need

to be affordable, available, and acces-

sible for you.

Your Bowel Program Is as Individual as You Are

A Guide for People with Spinal Cord Injury 13

•Bowel care. You need to be able to

perform the techniques yourself or

direct an attendant or other caregiver

on when and how you need help.

Discuss whether you need an assis-

tant with your health-care professional

and if so, how to tell the assistant

what to do.

• Insurance. Find out what your

insurance covers. If some products

aren’t reimbursed, advocate for

yourself—explain why the product

is needed. Involve your health-

care professional in any decisions

about what products you use.

Your bowel habits before the SCI:

•How often did you have bowel movements?

•At what time of day did you have bowel movements?

•Did you have recurring problems with constipation or diarrhea?

Your diet:

• How much do you drink every day and what do you drink?

• What sorts of food do you usually eat, how much, and how often?

• Do any foods affect your bowel movements?

• Do you have problems with dairy products (lactose intolerance)?

• Do spicy foods give you loose stool?

Your stool:

• Is it hard, soft, or diarrhea (liquid that takes the shape of any

container it goes in)?

• How much stool usually comes out during one of your bowel

movements? For example, if your stool were formed into a ball,

would it be a golf ball, a tennis ball, a softball, or, heaven

forbid...a basketball?

If you have a bowel program now, your health-care

professional will need to know:

• When and how often do you do bowel care?

• Which bowel care techniques do you use?

• How do you start a bowel movement?

—Digital stimulation?

—Stimulant medications (suppositories, mini-enemas)?

14 NEUROGENIC BOWEL: What You Should Know

• How long does it take for the stimulants to work?

•Have you changed what you eat or drink?

• Has your activity level changed?

• Have any of your medications changed (medications you take for

bowel care or anything else)?

• Are you having problems with any part of your bowel program?

How Do I Do Bowel Care?

If I Have a Reflexic Bowel

The goal of a reflexic bowel program is soft, formed stool

that can be passed easily with minimal rectal stimulation. The

bowel care routine usually starts with a stimulant medication or

with digital stimulation.

Getting ready and washing hands. Empty your blad-

der or move your urinary drainage equipment away

from the anal area. Whoever performs bowel care—you

or an attendant—should wash their hands thoroughly.

Setting up and positioning. Prepare for a bowel

movement by getting on or ready for a transfer to a

toilet or commode. If you’re sitting up, gravity helps

empty your rectum. When sitting, keep your feet on

the floor or on a footstool or on the footrest of your commode

chair, with your hips and knees flexed. If you need help with a

transfer, position yourself before bowel care. If you don’t sit

up, lie on your left side.

Important:

Bowel care needs to be done regularly to help prevent acci-

dents! If you’re having problems sticking with your pro-

gram, tell your health-care professional. Together, you

can help identify the problem by talking about your history of

bowel care, performing a physical examination, and taking

tests to explore why you’re having problems. Then, changes

can be made—one element at a time—that will help you fol-

low a regular routine. (See page 29, “What Should I Do if My

Bowel Program Isn’t Working?”)

STEP

R1

STEP

R2

A Guide for People with Spinal Cord Injury 15

Checking for stool. Check for stool by sliding a

gloved, well-lubricated finger into the rectum. Remove

any stool that would interfere with inserting a supposi-

tory or mini-enema (manual evacuation). Use one or

two gloved and lubricated fingers to break up or hook stool and

gently remove it from your rectum.

Inserting stimulant

medication. (If you

don’t use a supposito-

ry or mini-enema, go

directly to step R6.) To start a

bowel movement, insert a lubri-

cated suppository or squirt a

mini-enema high in your rec-

tum. (The suppository should

be coated with a water-soluble

lubricant.) Use a gloved and

lubricated finger or assistive

device. Place the medication

right next to the rectal wall (see

Figure 4).

STEP

R3

FIGURE 4

STEP

R4

Suppository

Sacrum

Rectal Wall

Rectum

Anus

Anal Canal

Internal Anal

Sphincter

External Anal

Sphincter

Belly Button

Waiting. Wait about 5 to 15 minutes for the stimulant to

work. If you pass gas or some stool, it’s a sign that the

stimulant is beginning to work.

Starting and repeating digital rectal stimulation.

Use digital rectal stimulation or other techniques. To

keep stool coming, repeat digital rectal stimulation every

5 to 10 minutes as needed, until all stool has passed.

(See page 10, “How Is Digital Rectal Stimulation Done?”)

Recognizing when bowel care is completed. To

make sure the rectum is empty, do a final check with a

lubricated and gloved finger or assistive device. You’ll

know that stool flow has stopped if:

— No stool has come out after two digital stimulations at

least 10 minutes apart.

— Mucus is coming out without stool.

— The rectum is completely closed around the stimulating

finger.

Cleaning up. Wash and dry the anal area.

If I Have an Areflexic Bowel

The goal of an areflexic bowel program is firm, formed stool

that: (1) can be passed manually with ease, and (2) doesn’t

pass accidentally between bowel care routines. Bowel care

doesn’t usually require chemical stimulants because the

response would be very sluggish.

Getting ready and washing hands. Empty your blad-

der or move your urinary drainage equipment away

from the anal area. Whoever performs bowel care—you

or an attendant—should wash their hands thoroughly.

16 NEUROGENIC BOWEL: What You Should Know

STEP

R8

STEP

R7

STEP

R6

STEP

R5

STEP

A1

A Guide for People with Spinal Cord Injury 17

Setting up and positioning. If possible, sit up. If

you’re sitting, gravity helps empty your rectum. When

sitting, keep your feet on the floor or on a footstool or

on the footrest of your commode chair, with your hips

and knees flexed. If you don’t sit up, lie on your left side.

Starting and repeating digital rectal simulation. Use

digital stimulation or other techniques. To keep stool

coming, repeat digital rectal stimulation every 5 to 10

minutes as needed, until all stool has passed. (See page 10,

“How Is Digital Rectal Stimulation Done?”)

Doing manual evacuation. Use one or two gloved and

well-lubricated fingers to break up stool, hook it, and

gently pull it out.

Use repeated Valsalva maneuvers. (See page 18.)

Use gentle Valsalva maneuvers to bring stool down

before and after each manual evacuation. Breathe in

and try to push air out, but block the air in your throat

to increase the pressure in your abdomen. Try to contract your

abdominal muscles as well. This technique can help you increase

pressure around the colon to push stool out. Repeat it for 30 sec-

onds at a time on and off as long as you need to expel all stool.

Bending and lifting. If you have good torso stability,

lift yourself as if doing a pressure release or do forward

and sideways bending with Valsalva maneuvers. This

helps change the position of the colon and expel stool.

Checking the rectum. To make sure the rectum is

empty, do a final check with a gloved and well-

lubricated finger. If stool is present, repeat Steps A4-7.

Cleaning up. When you are confident all stool has

passed, wash and dry the anal area.

STEP

A5

STEP

A4

STEP

A3

STEP

A2

STEP

A7

STEP

A8

STEP

A6

18 NEUROGENIC BOWEL: What You Should Know

Whether you have a reflexic or an areflexic bowel, you may be

able to rely on diet, fluids, and regular activity to give your stool a

healthy texture for bowel care. If these don’t work by themselves,

your health-care professional may suggest medications. (See

page 27, “What Medications Are Used in Bowel Programs?”)

Are There Other Ways to Improve a

Bowel Movement?

Once you have a regular bowel program that works, you and

your health-care professional may want to explore ways to sim-

plify it: doing bowel care less often, changing the stimulant you

use, or trying digital stimulation without a suppository or mini-

enema. Remember, before making any of these changes, discuss

them with your health-care professional.

Your health-care professionals may suggest a number of

assistive techniques or tips to improve your bowel care

results. The most common ones are:

•Positioning. Sitting upright in a cushioned commode chair or

padded toilet seat may help gravity to empty the lower bowel.

Placing your feet on footrests or footstools also gives you

support while you bear down (see Valsalva maneuver, below) to

push stool out.

• Abdominal massage. Rubbing or running a hand firmly over

the abdomen in a clockwise motion from the lower right across

the top and down the left helps move stool through the colon to

the rectum.

•Forward or sideways bending. For this, you need either a lap

safety belt if you’re using a commode chair or enough control of

your upper body to be able to return to a sitting position after you

bend forward or side to side at the waist. These maneuvers also

help move stool through the colon to the rectum.

• Push-ups. If you have strong upper arms, you can raise your

hips off the commode chair seat. Put yourself down in a slightly

different position to vary the pressure against your skin. Push-

ups also help move stool into the rectum.

•Valsalva maneuver. This technique works best for people with

areflexic bowel who have control over their abdominal muscles

and can help push stool out. Before doing Valsalva maneuvers,

A Guide for People with Spinal Cord Injury 19

check with your health-care professional, especially if you have a

history of heart problems. (See A5 on page 17 under “If I Have

an Areflexic Bowel.”)

• Gastrocolonic response or reflex. Eating a meal or drinking

warm liquids before bowel care may help some people with SCI

stimulate a bowel movement. Starting your bowel care within 30

minutes after you eat or drink may help it go faster and produce

more results.

What Is a Bowel Care Record?

A Bowel Care Record helps you and your health-care pro-

fessional see whether your bowel program is working. It’s

most helpful the first weeks after you leave the hospital, when-

ever you’re having problems, and a few weeks before your

annual checkup.

Use the Bowel Care Record at the back of this Guide. Every

time you do bowel care, write down:

• Date.

• Start time. The hour and minute you start stimulation or try to

start a bowel movement.

• Position. Left side lying, right side lying, sitting.

• Stimulation method. Stimulant medication, digital rectal

stimulation, or other technique you use to start a bowel movement.

• Assistive techniques. Methods used to promote bowel

emptying and the number of times used during bowel care, e.g.,

abdominal massage, bending, push-ups, Valsalva maneuver.

Important:

People with SCI need to stick with a regular schedule and

technique of bowel care. You may have to revise your bowel

program over time, but keeping a regular schedule for doing

bowel care at a regular time is one of the best things you can

do for your health and well-being after SCI.

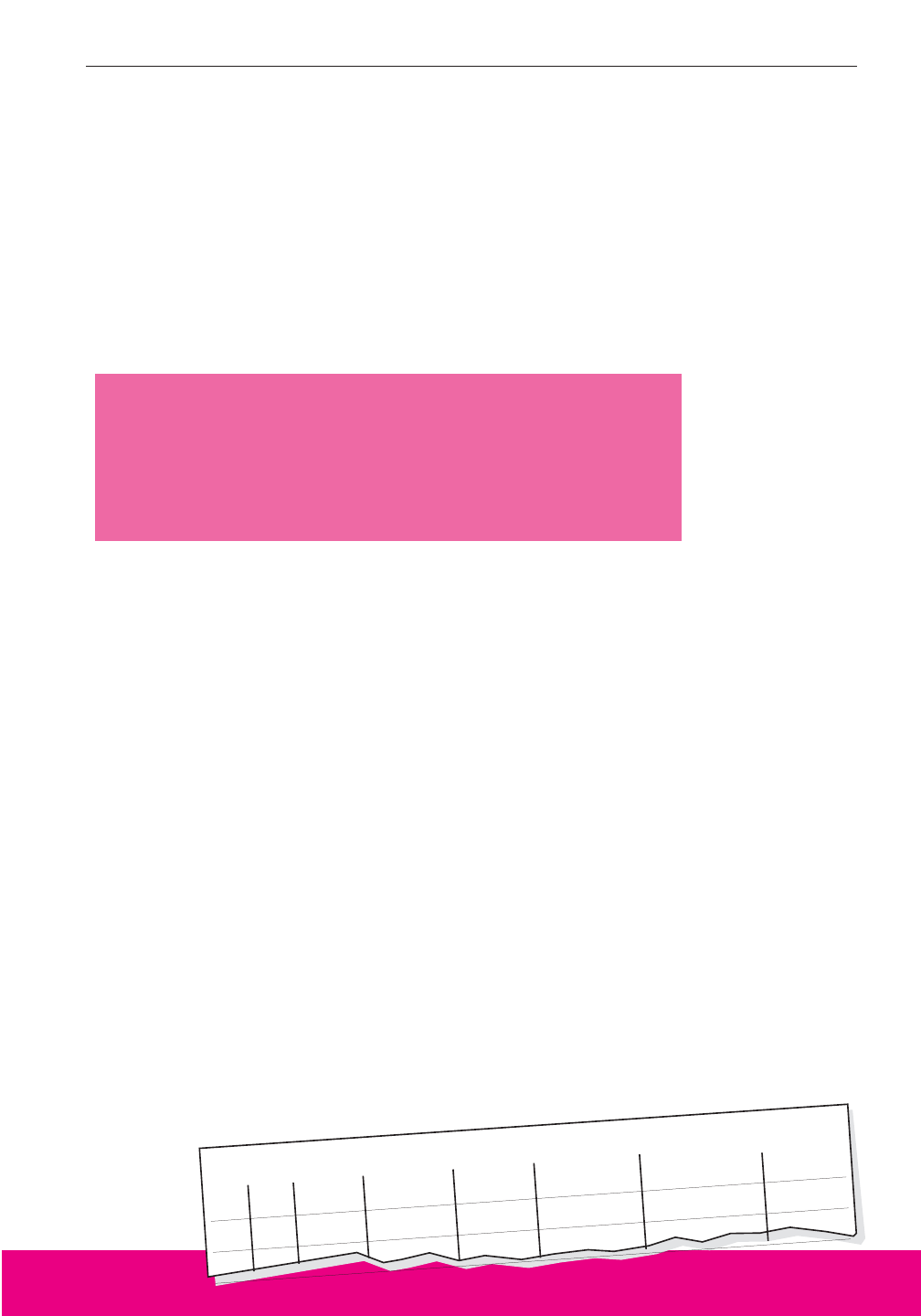

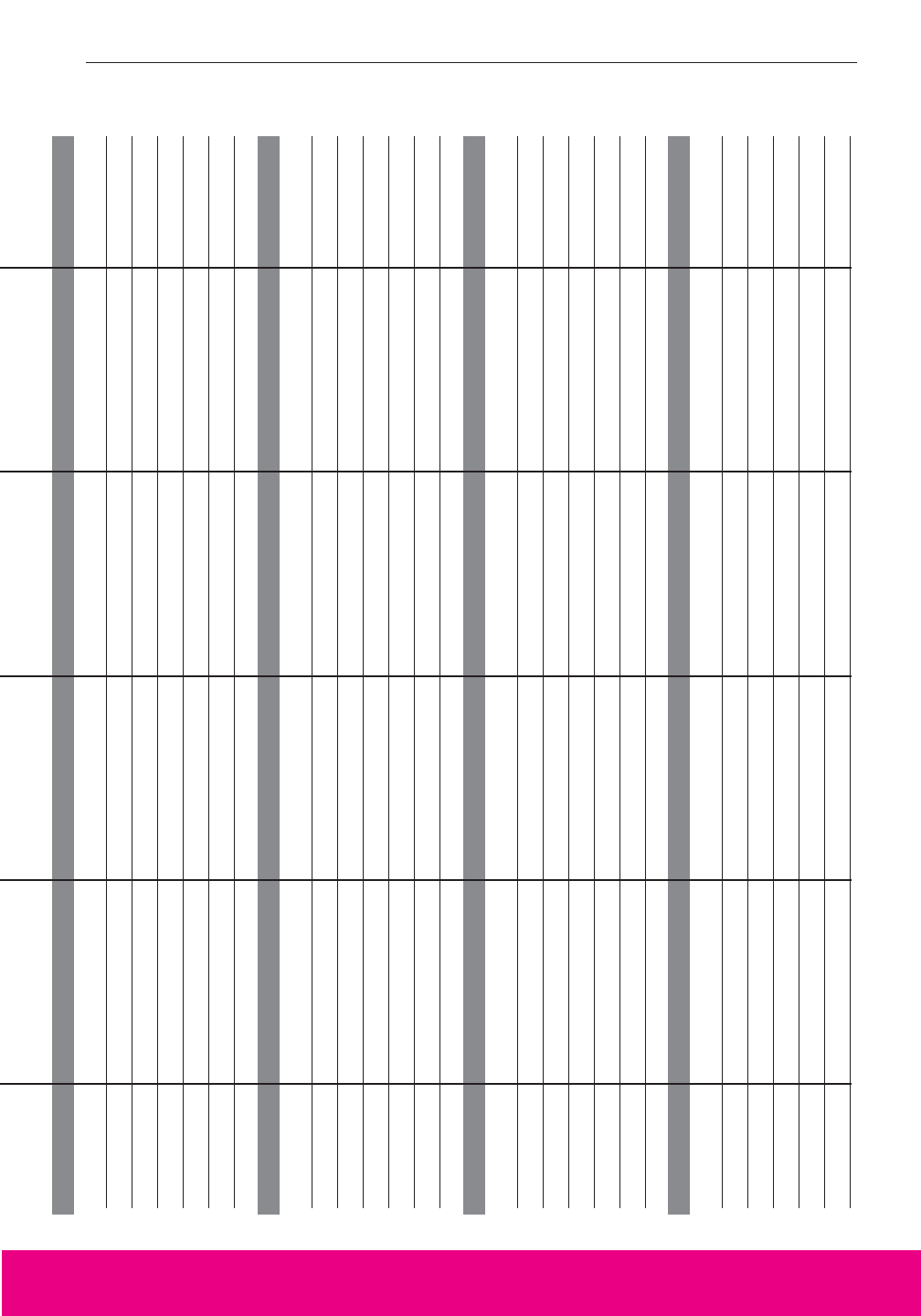

Bowel Care Record

Start Stim

ulation Assistive Tim

e of Results Stool Am

ount,

Date Tim

e Position M

ethod Techniques First/Last Consistency, Color Com

ments

20 NEUROGENIC BOWEL: What You Should Know

• Times of results. The time when the first stool begins to come

out of the anus and the time when the last stool comes out.

• Stool amount, consistency, and color. Amount: if stool were

formed into a ball—golfball, tennis ball, softball. Consistency:

hard, firm, soft, liquid. Color: especially anything unusual for

you.

• Comments. Problems such as any unplanned bowel

movements, abdominal cramps, pain, muscle spasms, pressure

ulcers, hemorrhoids, or bleeding.

If your bowel program is going well, there’s no need to keep

a Bowel Care Record.

Can I be Independent in My Bowel Care?

That depends on many factors: the level and completeness

of your SCI, your body type and general health, how strong you

are, and how much you want to be independent.

For complete independence, your arms and fingers need to

be strong enough to manage your clothes, get you into a bowel

care position, place stimulant medication, and do digital rectal

Important:

If you see any blood in your stool or any discoloration in your

stool, too dark or light, call your health-care professional right

away. It might indicate a medical problem. For example,

stool that’s dark, black, or tar-like could be a sign of bleeding

in the GI tract, like an ulcer. But be aware that iron sup-

plements will turn your stool black, and that’s not a

problem. (See page 29, “What Should I Do if My Bowel Pro-

gram Isn’t Working?”)

Alcohol and drugs can affect bowel

function and cause additional

problems for people with SCI.

• Alcohol. Alcohol, even beer,

can change your habits. It can

reduce your appetite, making it

hard to stick with the diet part

of your bowel program. It can

also cause problems in keep-

ing up with your bowel care schedule.

If you’re having trouble following your

bowel program because of alcohol

use, your health-care professional

needs to know, to be able to help.

• Drugs. Many street drugs,

as well as prescribed pills for

pain, cause constipation.

Because of that, many people

Alcohol and Drugs: What You Need To Know

R

X

stimulation. Most people with a thoracic, lumbar, or sacral SCI

are strong enough and have enough balance. Some people with

a cervical SCI at C6, C7, or C8 levels may not have enough fin-

ger strength or sitting balance to independently insert a suppos-

itory or mini-enema or do digital rectal stimulation. Special

devices like a digital stimulator and suppository inserter can

help with these activities.

Even if they can do bowel care themselves, some people

choose to have a caregiver do it. They find that it takes too

long, or it simply takes too much energy that they’d rather use

doing other things.

Whether or not you do your own bowel care, you still need

to manage your bowel program. That means watching what

you eat and drink, your activity level, your medications, and the

results of your bowel care routine. If you need assistance with

your bowel care, learn the process so that you can teach it to

caregivers and supervise your care. It’s your body and you are

the boss.

Why Do I Need to Watch What I Eat and Drink?

What you eat and drink can affect your bowel movements,

but everyone responds a bit differently to different foods. The

best way for you to learn how different foods affect you is to

keep a Food Record and Bowel Care Record. For about a

month, write down what you eat and drink each day and

describe your bowel movements. (See the Food Record and

Bowel Care Record at the back of this Guide.)

who use drugs end up overusing laxa-

tives—and that can cause more prob-

lems. If you use drugs and don’t tell

your health-care professional, there’s

a very good chance that the bowel

program you create together won’t

work. It’s also a good idea to discuss

any alternative medicines you use.

• Your bowel function is your responsi-

bility. It’s up to you to give your

health-care professionals the informa-

tion they need to help you rule your

bowel—not the other way around.

A Guide for People with Spinal Cord Injury 21

22 NEUROGENIC BOWEL: What You Should Know

Foods That Can Keep Stool Solid but Soft

Foods that have a lot of fiber can absorb liquids and help

make your stool solid but soft and easy to pass. High-fiber

foods are fresh fruits and vegetables, dried peas and beans, and

whole grain cereals and breads. It’s best to get the dietary fiber

you need from a variety of food sources. A starting goal of at

least 15 grams of fiber each day is recommended as part of a

healthy diet. An increase in fiber is recommended only if it is

necessary to produce a soft-formed stool. Table 1 gives a gen-

eral idea of how much fiber is in different types of food. It’s a

good idea to increase this amount gradually over a 6-week peri-

od to prevent a bloated feeling and too much gas.

If you can’t eat as much fiber as your health-care profession-

al suggests, you may want to try fiber supplements—natural

vegetable powders, like psyllium. You can get them at your

local drugstore and supermarket. If you take fiber supple-

ments, be sure to drink plenty of fluids. That means at

least 64 ounces a day. (Drinks with alcohol or caffeine don’t

count toward that total.) Remember, if you use fiber to vary the

consistency of your stool, you will have more total stool and

may need to do bowel care more often.

Foods That Can Cause Gas

Gas in the digestive tract may cause uncomfortable feelings

of fullness, bloating, and pain. If you’re having problems with

too much gas, you may want to cut back on or cut out foods

associated with gas. These include beans, broccoli, cabbage,

cauliflower, corn, cucumbers, onions, and turnips. (See Table

2. What You Can Do About Excessive Gas, page 24.) If your

Food Record shows that some of these foods cause problems

with gas, consider eliminating them from your diet.

Important:

Not everyone with SCI benefits from a high-fiber diet. You

need to recall how much fiber you usually had in your diet

before the SCI and how much you eat now. Talk with your

health-care professional about the amount of fiber in your diet

before and after your SCI.

A Guide for People with Spinal Cord Injury 23

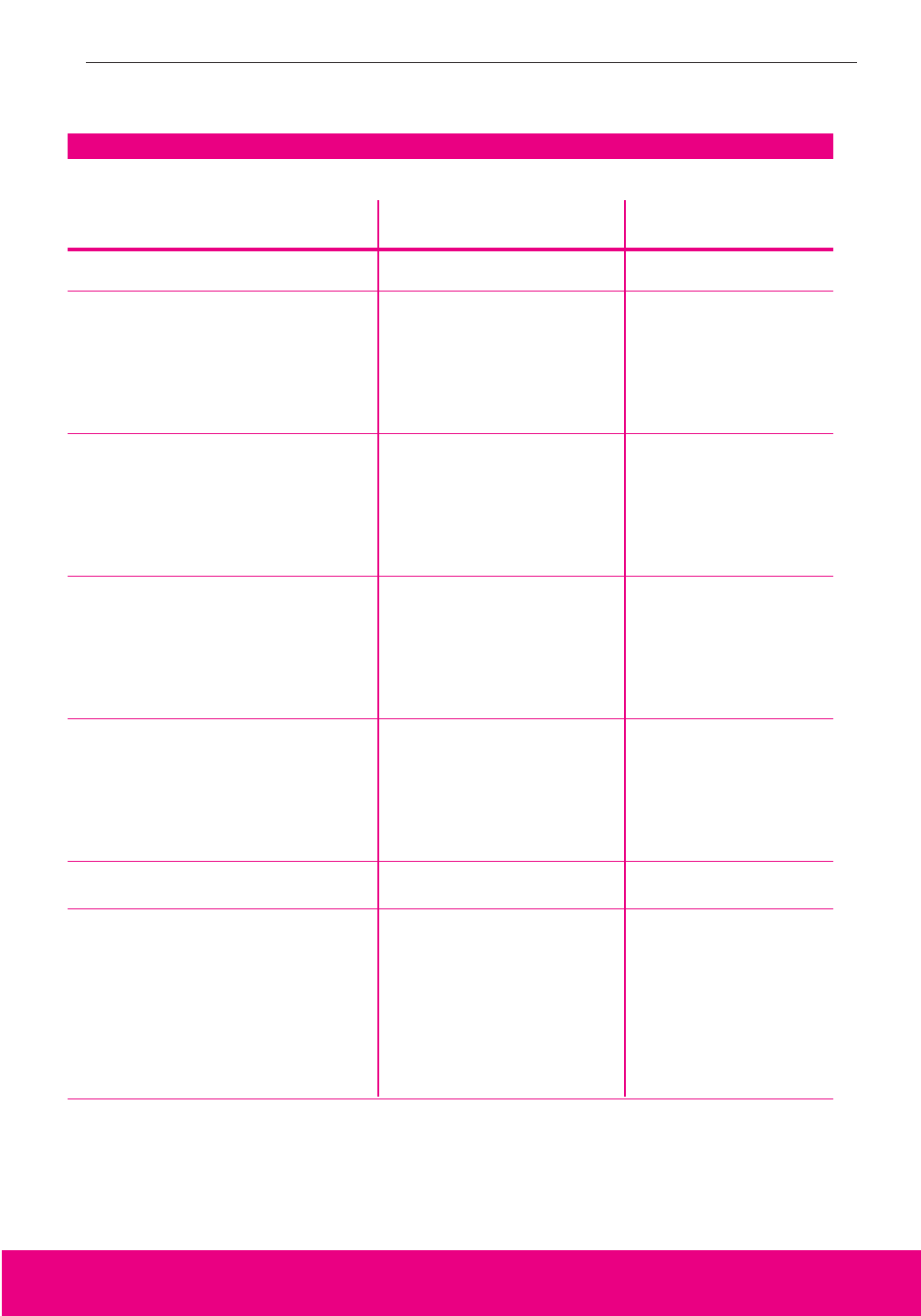

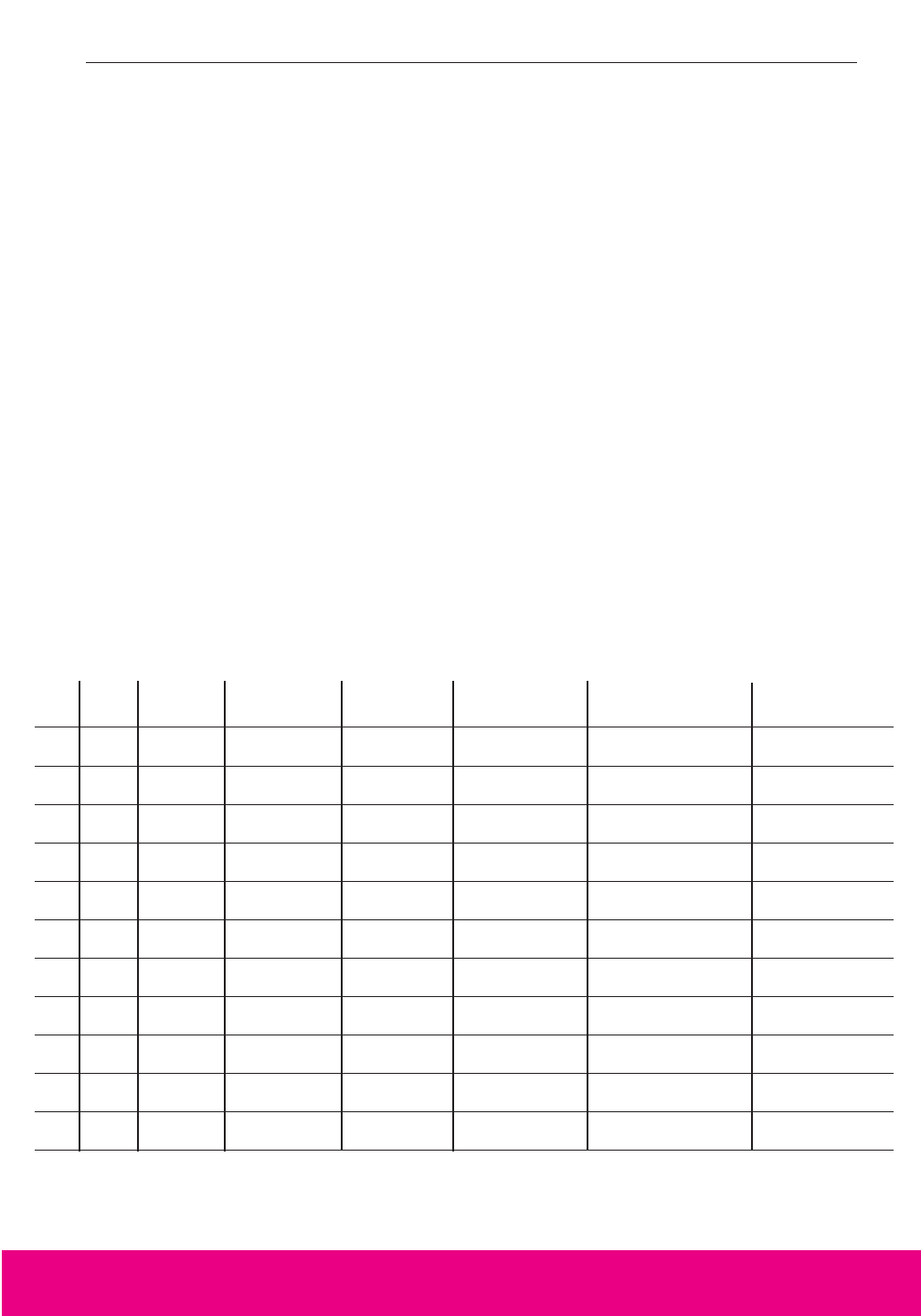

TABLE 1

How Much Fiber Is in Different Types of Food?

Grams of

Food Type Quantity Fiber/Serving

LEGUMES

Baked beans 1/2 cup 8.8

Dried peas, cooked 1/2 cup 4.7

Navy beans, cooked 1/2 cup 6.0

Lima beans, cooked 1/2 cup 4.5

CEREALS

Oatmeal 3/4 cup 1.6

Bran flakes 1/3 cup 8.5

Shredded wheat 2/3 cup 2.6

Raisin-bran type 3/4 cup 4.0

FRUIT

Apple (w/ skin) 1 medium 3.5

Banana 1 medium 2.4

Orange 1 medium 2.6

Prunes 3 3.0

BREADS

Whole wheat bread 1 slice 1.4

Pumpernickel bread 1 slice 1.0

Bagels 1 bagel 0.6

Bran muffins 1 muffin 2.5

MILK ANY AMOUNT 0.0

MEAT

Beef Any amount 0.0

Pork Any amount 0.0

Poultry Any amount 0.0

Lamb Any amount 0.0

Fish Any amount 0.0

Seafood Any amount 0.0

FATS ANY AMOUNT 0.0

Certain foods may cause gas, so substitutions may be necessary.

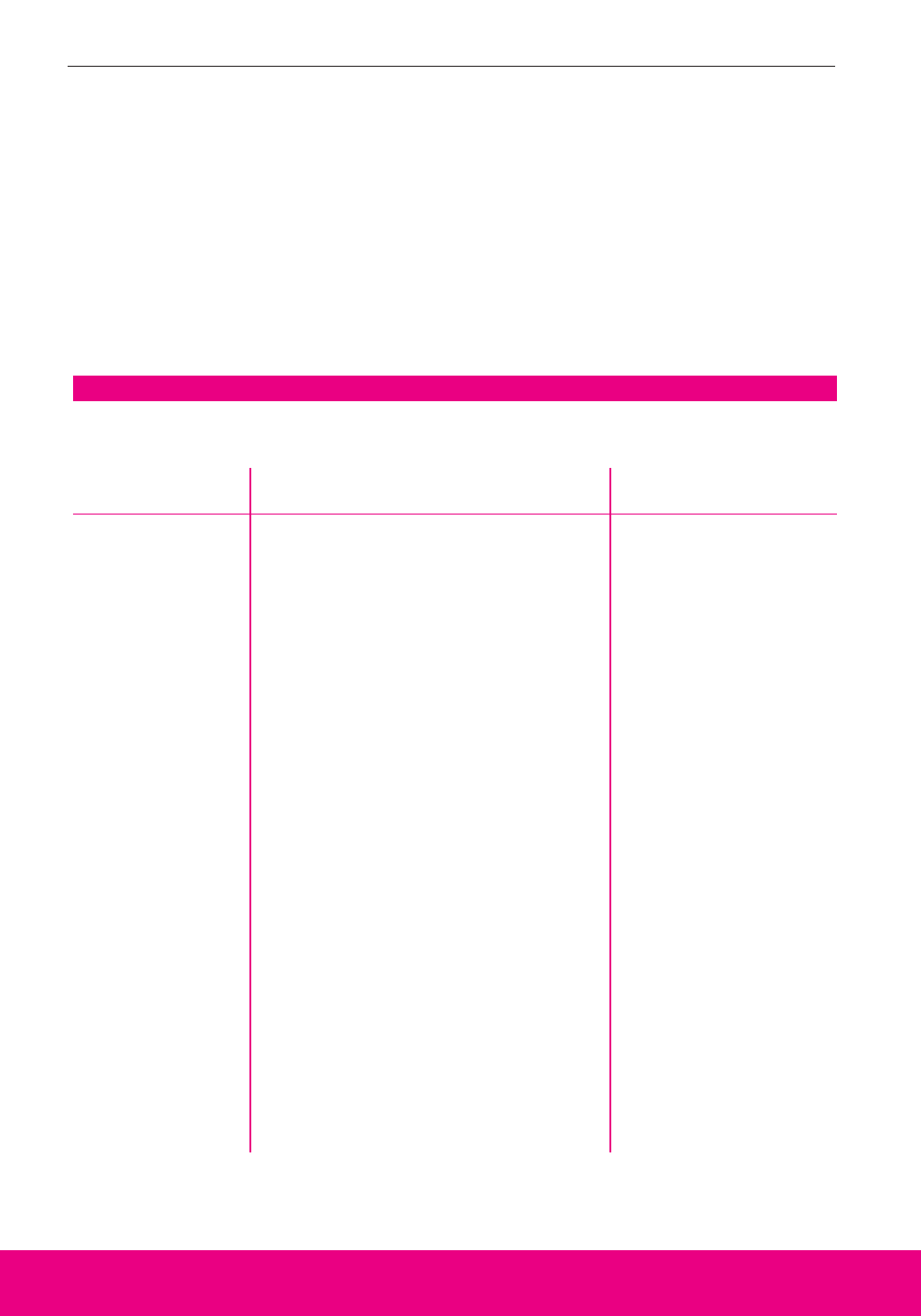

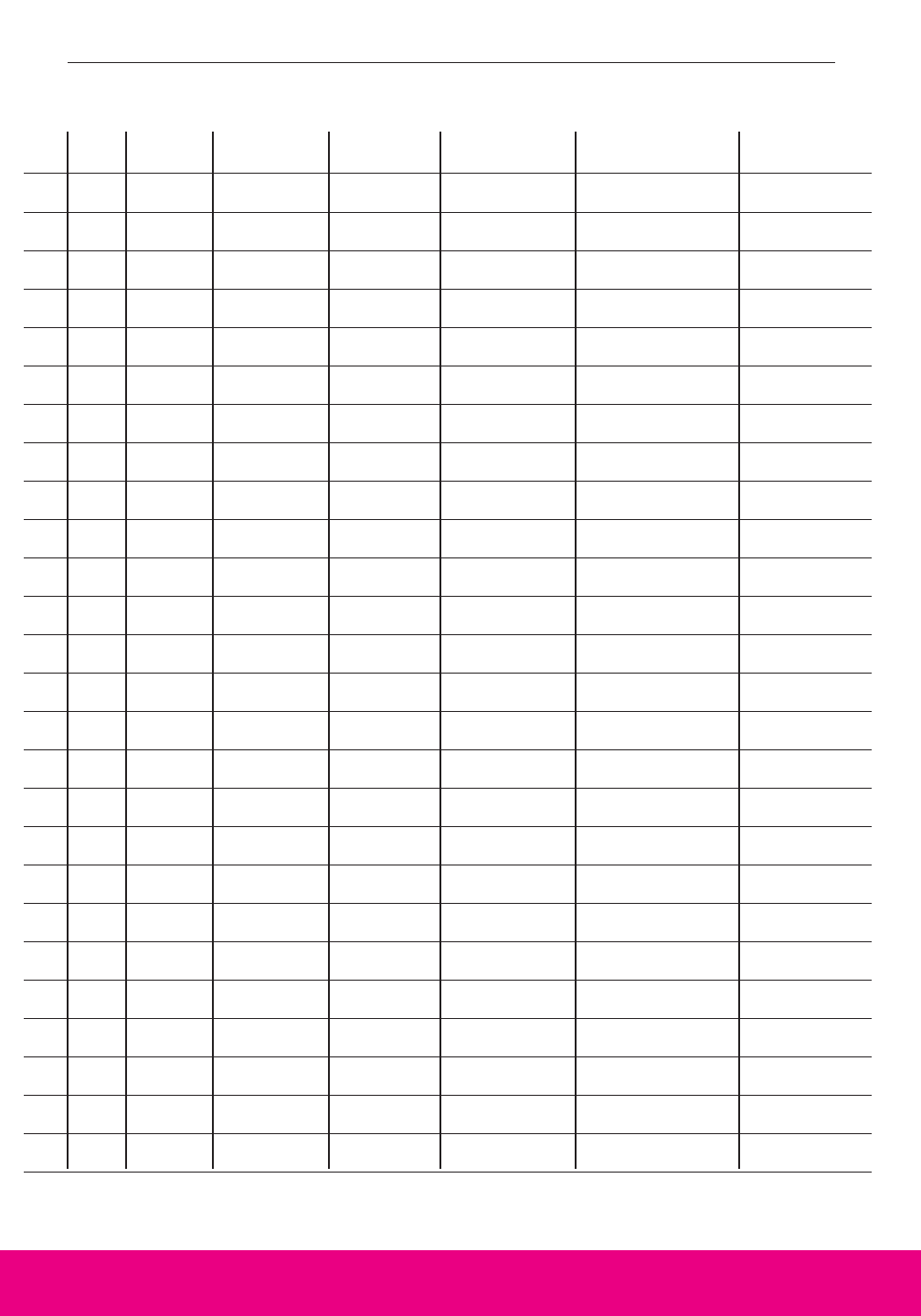

TABLE 2

What You Can Do About Excessive Gas

FOODS THAT

CAUSES SOLUTIONS CAN CAUSE GAS

Food

Constipation

Swallowing air while

you’re eating or

drinking

More bacterial

breakdown of bowel

contents than is

usual for you

Lactose

intolerance

Think about how you eat:

1. Eat your food slowly.

2. Chew with your mouth closed.

3. Try not to gulp your food.

4. Don’t talk with food in your mouth.

Experiment with foods that can cause gas:

1. Remove specific foods from your diet,

one at a time.

2. Do this for your favorite foods until

you’ve learned which, if any, cause you

to have gas.

3. Cut down on those foods.

Think about your surroundings:

1. Ceiling fans help remove odors.

2. Good ventilation, such as plenty of win-

dows or table-top fans, also helps.

3. Deodorant spray can mask the odor.

Release gas at appropriate times and

places:

1. Do digital rectal stimulation in the

morning or evening daily.

2. Do push-ups or lean to the side to

release gas when alone or before

meeting with people.

3. The bathroom is an appropriate place

to release gas.

Vegetables:

• Beans: kidney, lima,

and navy

• Broccoli

• Brussels sprouts

• Cabbage

• Cauliflower

• Corn

• Cucumbers

• Kohlrabi

• Leeks

• Lentils

• Onions

• Peas: split and

black-eyed

• Peppers

• Pimientos

• Radishes

• Rutabagas

• Sauerkraut

• Scallions

• Shallots

• Soybeans

•Turnips

Fruits:

• Apples (raw)

•Avocados

• Cantaloupe

• Melons: watermelon

and honeydew

Table 2 was adapted from Yes You Can! A Guide to Self-care for Persons with Spinal Cord Injury (Second

edition). Paralyzed Veterans of America, 1993.

24 NEUROGENIC BOWEL: What You Should Know

Foods That Can Cause Diarrhea

There are no foods that cause diarrhea in everyone. Some

people find fatty, spicy, or greasy foods seem to be related to diar-

rhea. Other people report that caffeine—found in coffee, tea,

cocoa, chocolate, many soft drinks—appears to cause diarrhea.

Diarrhea-causing bacteria can contaminate different foods as well.

If you have episodes of diarrhea, keep a Food Record of what you

eat and drink to help you identify what you’re sensitive to.

A Guide for People with Spinal Cord Injury 25

How Much Should I Drink Every Day?

You need to drink plenty of fluids every day to keep your

stool soft and to prevent constipation. Drinking enough is

especially important if you’re trying to eat more fiber. A good

guideline is 64 ounces every day (drinks with alcohol or caf-

feine don’t count). If you exercise a lot or the weather is hot,

drink more.

Some people may need to limit how much they drink because

of their bladder program. If that’s true for you, talk with your

health-care professional about a good daily fluid goal that will

work for both your bladder program and your bowel program.

Important:

If you enjoy drinks like coffee, tea, cocoa, or soft drinks, there’s

something you should know. All these drinks contain caffeine,

and caffeine is a diuretic. That means it may suck the fluid out

of your body. In fact, diuretics can cause you to lose even more

fluid than you drink. Caffeine is also a stimulant. For these

reasons, you may want to consider keeping caffeine drinks to a

minimum.

26 NEUROGENIC BOWEL: What You Should Know

What Medications Are Used in Bowel Programs?

Like the foods you eat, the medications you take can affect

your bowel activity. Some can help your body pass stool regular-

ly. Others can make regular bowel movements difficult. Table 3

lists the different types of bowel medications and examples of

each and describes what they do. For most people, the goal is to

have a successful bowel program without medications or with the

fewest medications possible.

Before taking any of the products in Table 3 regularly, dis-

cuss them with your health-care professional to learn how to

use them safely for the best results.

Tips for Safe Bowel Care

To prevent falls and pressure ulcers, follow these tips for the

safe use of equipment during bowel care. Don’t hesitate to ask

your health-care professional to show you how to use assistive

devices and stimulant medications correctly.

Toilets and Commode Chairs

•Use seats carefully to avoid skin problems. If you can,

consult an occupational therapist before you buy such

equipment.

• Make sure that seats and chairs are padded; seams shouldn’t

touch your skin.

• Don’t use a chair that has cracked or broken vinyl; it can hurt

your skin.

•Keep correct posture the whole time you’re on a toilet or

commode seat.

•Keep your weight evenly balanced over the seat.

•Do pressure releases every 15 minutes to prevent skin problems.

That means lifting yourself off the seat and shifting your position

to keep from putting pressure on the same skin area too long.

• Be careful not to forcibly separate your buttocks or squeeze

them together when you’re sitting.

• Check your skin after using your bowel care equipment. Report

any changes to your health-care professional.

A Guide for People with Spinal Cord Injury 27

TABLE 3

Bowel Medications

ORAL LAXATIVE MEDICATIONS

Stimulants

Increase the wave-like action of peristalsis to move stool through the bowel faster and

keep it soft.

• bisacodyl • castor oil

• cascara • senna

Osmotic laxatives

Increase stool bulk by pulling water into the colon. If you take these medications, you

need to drink extra fluids.

• lactulose • magnesium sulfate

•magnesium citrate • sodium biphosphate

• magnesium hydroxide • sodium phosphate

Bulk-forming laxatives

Add bulk to stool. If you take these natural vegetable fiber medications, you need to drink

extra fluids.

• hydrophilic muciloid • psyllium

• methylcellulose

Stool softeners

Help stool retain fluid, stay soft, and slide through the colon.

• docusate calcium (Doss) • docusate sodium

• docusate potassium • mineral oil

Prokinetic agents

Stimulate bowel peristalsis.

• cisapride • metoclopramide

RECTAL STIMULANTS

Suppositories

bisacodyl Increases colon activity by stimulating the nerves in the lining of the

rectum.

CO

2

Produces carbon dioxide gas in the rectum, which inflates the colon

and stimulates peristalsis.

glycerin Stimulates peristalsis in the colon and lubricates the rectum to help pass

stool.

Enemas

mineral oil Lubricates the intestine.

mini-enema Stimulates the rectal lining and softens stool.

28 NEUROGENIC BOWEL: What You Should Know

To prevent falls, be especially careful when you’re:

•Transferring to and from a toilet or commode chair.

• Doing forward or sideways bending.

• Bending to insert stimulant medication, do digital rectal

stimulation, or remove stool.

• Reaching for supplies.

Safety Straps

• Chest straps help people who have poor or no chest balance.

•Lap or waist straps help people who have spasms or tire easily.

Stimulant Medications

• Use plenty of water-based lubrication. Oil-based products, such

as petroleum jelly, can prevent stimulant medications from

working.

• Insert suppositories using lubrication, gently and correctly.

• Punch a hole in mini-enemas with a pin. Cutting them with a

knife creates a sharp edge that can slice or scrape your skin.

How Often Should My Bowel Program Be Reviewed?

Your bowel program should be reviewed at least once a year

to make sure that it’s working well for you. Your Bowel Care

Record is a key part of this review. Keep your completed Bowel

Care Records in a notebook, folder, or other handy place and

take them with you when you visit your health-care profession-

al. Ask your health-care professional how long you should

record your bowel care results.

If you use a commode chair or padded

toilet seat, avoid unpleasant surprises. It’s

a good idea to record the date you get

your equipment; cushions and pads tend

to wear out in about 18 months. Inspect all

your bathroom equipment every month:

• Check screws and other hardware for

loose or missing pieces.

• Lubricate axles to prevent rust.

• Check for cracks or splits in vinyl cov-

ering. If cracks develop, ask a mem-

ber of your rehabilitation team to

inspect the equipment to consider

replacement or repair.

Maintaining Bowel Care Equipment

A Guide for People with Spinal Cord Injury 29

What Should I Do if My Bowel Program

Isn’t Working?

If there is a problem, you have to get to the bottom of it

immediately. If you’re having bad reactions with your bowel

program, call and work with your health-care professional right

away. Bad reactions include:

•Fainting or loss of consciousness.

• Symptoms of autonomic dysreflexia, like a pounding headache

during bowel care. (For more information about autonomic

dysreflexia, see the glossary and the guide called Autonomic

Dysreflexia: What You Should Know. For a free copy, call

(888) 860-7244 or visit the PVA web site at http://www.pva.org.)

•Blood in your stool, on your rectum, or on your clothes.

• Any sudden change in the color of your stool—if it becomes

lighter, red, or black.

You may be able to take care of other problems yourself.

The most common bowel problems after SCI are:

• Repeated bowel accidents.

• Delayed results from bowel care.

Important:

If you’re having constipation or other bowel problems (see Table

4 on page 31, Frequent Bowel Accidents: Possible Causes and

Solutions), don’t wait for your annual bowel program review.

Call your health-care professional to discuss the problem and

what you can do about it.

• Check for water-logged or soggy cush-

ions or padded seats. Pushing on the

cushion or seat can squeeze out extra

water.

•Watch for worn-out cushions and

padded seats. If they stay flattened

after you get off, they’re probably

worn out.

• Replace worn, frayed safety straps and

broken buckles.

30 NEUROGENIC BOWEL: What You Should Know

• Prolonged bowel care (lasts more than 1 hour).

• Constipation.

• Inadequate or no stool results after two bowel care sessions.

• Diarrhea.

• Hemorrhoids.

•Too much gas or a bloated feeling.

Table 4 lists possible causes of and solutions to frequent

bowel accidents (more than once a week). Table 5 on pages

32-33 describes other problems, their possible causes, and

solutions. For many people with SCI, gas is a cause of embar-

rassment in public and private situations. Table 2 on page 24

provides information about excessive gas.

If you visit your health-care professional to discuss changing

your bowel program, bring your Bowel Care Record with you.

Be ready to discuss anything that might have changed in your

bowel program. Even one change in what you usually eat or

drink, for example, can affect how your program works for you.

Figuring out what’s changed and switching back to your previ-

ous habits may correct the problem.

If that doesn’t work, or if there’s a good reason for you not

to return to your previous routines, your health-care profession-

al will help you modify your bowel program. It’s important

for you to change only one of the following components

of your bowel program at a time:

• Diet.

• Fluids.

• Activity.

• Bowel care schedule.

•Position during bowel care.

• Rectal stimulant medications.

• Mechanical stimulation.

• Assistive techniques for bowel care.

• Oral medications.

With this approach, you can see which changes improve

your results.

A Guide for People with Spinal Cord Injury 31

Stools are too soft and If you are taking stool softeners, cut down on quantity

are oozing out. and/or frequency or stop taking them altogether.

Look at your diet to: (1) make sure you’re eating

enough high fiber foods, and (2) check for too many

foods that can soften stools (such as spicy or greasy

food).

You are eating more food Try doing your bowel care routine more often. For

than you did before. example, if your bowel care schedule is every other

day, you may need to do it every day.

Overuse of laxative medications If you are more active than you used to be or if you

to help food move through your are eating more fiber, you may not need bowel

stomach and bowel (peristalsis). medications anymore. Cut down on the number of

laxatives you take each day until you have:

(1) stopped having accidents, or (2) stopped taking

the laxatives.

Bowel care sessions are not Consider: (1) taking an oral laxative medication to

emptying your bowel well enough. help move food through your digestive system,

(2) using a stronger rectal stimulant and more fre-

quent digital stimulation, and (3) discussing the prob-

lem with your health-care professional.

Information in table 4 was adapted in part from Educational Guide for Individuals and Families Following

SCI. Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago, 1995.

TABLE 4

Frequent Bowel Accidents: Possible Causes and Solutions

NOTE: When changing your bowel program, change only ONE COMPONENT at a time, such as fre-

quency of bowel care, time of bowel care, or diet, so that each change can be fully evaluated.

POSSIBLE CAUSE SOLUTIONS

SCI may make it more difficult to spot

symptoms of colorectal cancer. That’s why

your health-care professional may want to

do tests for this condition, especially if

you’re 50 or older and have (1) a positive

test for unseen blood in the stool (fecal

occult blood test) or (2) a change in the

way your bowel works that doesn’t

improve after treatment.

Ask your doctor to help you follow cur-

rent recommendations about checking for

colorectal cancer. If you’re 40 or older, it’s

recommended that you have a rectal exam

and fecal occult blood test every year.

Other tests may include using a special

flexible scope to view the inside of the

colon.

Checking for Colorectal Cancer

32 NEUROGENIC BOWEL: What You Should Know

Delayed Results

Bowel movements start 1-6 hours after you begin

your bowel care.

Constipation or hard stools

Less than normal amounts of stool for at least 3 days

(and it’s usually hard); small or no bowel movements

for 24 hours or 2 or more bowel care routines. May

cause rectal bleeding that you can see as bright red

blood on your stool, toilet paper, or glove.

If you get constipated every few weeks, you may

need to change your bowel program.

IMPORTANT: If you are constipated and you have

(1) abdominal pain, (2) autonomic dysreflexia* that

doesn’t go away after stool is removed from your rec-

tum, or (3) sudden swelling in your abdomen, call

your health-care professional right away!

If you are not already doing digital stimulation, start; if

you are already doing it, try to do it more often.

If you can, sit up on the toilet or commode for bowel care

techniques.

Consider taking an oral laxative 6-8 hours before starting

bowel care (talk with your health-care professional first).

Try eating more fiber and drinking more liquids.

Consider using a strong rectal stimulant medication: (a) if

you are using a glycerin suppository, try a bisacodyl sup-

pository or enema, and (b) if you are using a bisacodyl

suppository, try a stimulant mini-enema, or a polyethyene

glycol-based bisacodyl suppository.

Do a rectal check.

—If you feel stool: (a) remove it gently with a gloved and well-

lubricated finger, using an anesthetic cream or jelly, and

(b) do your regular bowel care (suppository or mini-

enema).

—If you do not feel stool: (a) take a laxative or take more of

the one you’ve already taken, and (b) wait 6-8 hours and

do your regular bowel care (suppository or mini-enema).

Increase the frequency of your bowel care to daily until

normal volumes of stool results return.

If the above steps do not produce a bowel movement,

call your health-care professional. Suggestions may

include taking a product to add bulk to your stool or a

laxative at least 8 hours before you do your bowel care

routine.

Stool is too dry.

Stimulant is too weak or you’re not using enough.

Medications such as narcotics, iron, aluminum

hydroxide.

Not enough fiber in diet.

Inadequate rectal stimulation.

Performing bowel care in a lying position.

Digested food moving too slowly through the GI

tract.

Not following a regular bowel program.

Incomplete passing of stool.

Not enough fiber in diet.

Bed-rest or not much physical activity.

Medications such as narcotics, iron, aluminum

hydroxide.

TABLE 5

Common Bowel Problems: Solutions and Possible Causes

Note: When changing your bowel program, change only ONE COMPONENT at a time so that each change can be fully evaluated.

PROBLEMS SOLUTIONS POSSIBLE CAUSES

*Autonomic dysreflexia is a life-threatening condition. For more information, please refer to the consumer guide Autonomic Dysreflexia: What You Should Know, August 1997,

Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine. To order your free copy, call toll-free (888) 860-7244 or visit the PVA web site at http://www.pva.org.

A Guide for People with Spinal Cord Injury 33

POSSIBLE CAUSES

Not following a regular bowel program.

Incomplete passing of stool.

Not enough fiber in diet.

Bed-rest or not much physical activity.

Medications such as narcotics, iron, aluminum

hydroxide.

Spicy or greasy foods.

Drinks with caffeine (coffee, tea, cocoa, many

soft drinks).

Overuse of laxatives and bowel softeners.

Severe constipation or impaction.

Viral infection, flu, or intestinal infection.

Stress.

Antibiotics.

Persistence of hard stools.

Rectal straining.

Too vigorous digital stimulation or manual evacu-

ation. Suppositories, enemas, and digital stimu-

lation can irritate and worsen hemorrhoids.

Information in table 5 was adapted in part from Educational Guide for Individuals and Families Following SCI. Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago, 1995.

PROBLEMS

Fecal Impaction

See Constipation, but usually happens over a longer

period of time. You also may have small amounts of

liquid or watery stools.

Diarrhea

Loose watery stools, usually 3 or more times a day.

IMPORTANT: Call your health-care professional

right away if you have any of the following:

(1) abdominal pain, (2) dehydration (dry or chapped

mouth or lips, a lot less urine than usual, or dark urine

with a strong smell), or (3) diarrhea that lasts 3 or

more days.

Hemorrhoids

The first signs may be bright red blood on your

clothes, glove, or toilet paper after a bowel movement.

You may also see or feel bulging areas outside your

rectum.

IMPORTANT: Hemorrhoids are the most common

problem in bowel programs. You can help prevent

them by preventing constipation. Keep your stools

soft but formed.

SOLUTIONS

Start with the first step, and try others ONLY if previous steps

do not help:

Do a rectal check; if you feel stool, remove it gently with

a gloved and lubricated finger. Use an anesthetic cream

or jelly.

Drink 1 ounce of mineral oil to make the stool easier to

eliminate.

Take 1 or 2 tablets of senna or bisacodyl (bisacodyl is

stronger) to help move the stool down into your rectum.

Wait 6-8 hours and do your bowel care routine.

If the above steps do not produce a bowel movement, call

your health-care professional.

Stop taking any bowel medications. After the diarrhea

stops, you may start taking them again slowly.

Stay away from foods that can irritate your bowel (such

as spicy, fried, and greasy foods).

Eat foods that help make your stools hard (such as

yogurt with fruit, whole grain breads and cereals, rice,

and bananas).

Drink plenty of water, estimating what you are losing with

the loose stools and replacing it.

Make sure it is not a fecal impaction. If you do have an

impaction, your diarrhea may be very watery. If you are

taking antibiotics, try eating yogurt every day. If you have

diarrhea anyway, don’t stop taking the antibiotics but do

call your health-care professional.

After each bowel movement, use a cream or suppository

made for hemorrhoids as recommended by your health-

care professional.

If you have active hemorrhoids (bleeding, swelling, pain):

(a) try to avoid or minimize digital stimulation and manual

removal until the tissue heals, or (b) increase the amount

of stool softener or take them more often.

Use more lubricant.

Answers to Commonly Asked Questions

Q: What should I do if I have a bowel accident at school,

work, or a movie?

If you have an accident, don’t just sit there! If you can,

leave wherever you are and find a bathroom. Here are three

good reasons for you to deal promptly with the situation:

•Blocking stool flow can cause autonomic dysreflexia.

• Allowing your skin to be in contact with stool too long can cause

skin problems.

• Putting others at ease and calmly doing what you have to do can

help everyone get past the awkwardness. Accidents can be

touchy situations, not just for you but for other people.

A regular bowel program can help you take charge of your

bowel function and cut down on accidents. But accidents do

happen; be prepared. Many people keep a change of clothes

with them in a gym bag or overnight bag, just in case. The bag

might contain some toilet paper, moist wipes, exam gloves, a

diaper, clean underwear, loose-fitting pants, a water proof pad,

and a plastic bag for storage of soiled clothes. Some people use

disposable undergarments when they know they might be away

from a bathroom for a long time.

When you have to talk about bowel management, it may

help you and others if you are calm and matter of fact. As you

learn to live with SCI, it’ll become easier to discuss uncomfort-

able subjects like bowel functions and habits with your family

and friends, attendants, and health-care professionals.

34 NEUROGENIC BOWEL: What You Should Know

The best things you can do to prevent

bowel problems are to:

•Stick with your bowel program. If

you’re having trouble following any part

of your program, call your health-care

professional. Together, you should be

able to adapt your program to your life

demands, privacy needs, and

tolerance for various treatments.

• Pay attention to your body, your stool,

and your bowel care routine. You

know yourself best; you’ll be the first to

notice changes that may be important.

• If you need to change any aspect of

your bowel program, change only one

component at a time. And give

yourself plenty of time to decide if the

change has helped. A good rule is to

Preventing Bowel Problems

A Guide for People with Spinal Cord Injury 35

Q: What should I do if I pass a lot of gas? Passing gas in

public is embarrassing, especially if it smells.

Have a frank talk with your health-care professional. You

might be referred to a dietitian in case the gas and odor are

related to foods you’re eating. Think back to what you’d have

done before the SCI. Whatever you do, don’t try too hard to

hold in the gas. That can give you a stomachache or headache.

And remember: Passing gas means your digestive system is

working right. It was OK to pass gas before your SCI; it’s

still OK to pass gas now.

Passing gas and odor are just as embarrassing now as they

were before the SCI. With or without SCI, most people aren’t

comfortable with their bodily functions.

Some gas smells bad, and some gas doesn’t. Your gas will

probably smell bad after you eat food that’s high in protein,

such as meat, fish, or eggs. If you eat a vegetarian diet, your

gas probably won’t smell so bad, but you’ll have a lot of it.

Increasing the frequency of bowel care may reduce the amount

of stool you store in your colon to produce gas.

What did you do about gas odor before the SCI? Ventilation

is a good idea; fans and open windows help. Some people keep

room deodorizers or air fresheners in their office, home, and

bathroom.

allow 1 week or 3 to 5 bowel care

cycles before you make more

changes.

• If you’re having problems keeping a

healthy weight (you’re gaining or losing

too much), talk to your health-care

professional. Information about diet

and exercise and an evaluation may

be helpful.

• Get a checkup at least once a year.

Bring a completed copy of the Bowel

Care Record at the back of this Guide,

and review it with your health-care

professional.

These steps can’t prevent all bowel

problems related to SCI. If the tips in

Tables 2, 4, and 5 don’t help, talk with your

health-care professional.

36 NEUROGENIC BOWEL: What You Should Know

What Should I Know About

Surgical Options?

One common surgical procedure creates a new opening

(called a stoma) on the abdomen where stool can be pushed

into an attached, disposable bag. This surgery is called colosto-

my or ileostomy, depending on where the opening is made.

The choice between a colostomy or an ileostomy should depend

upon the results of studies examining how your stool moves

through your colon and consultations with your health-care pro-

fessionals. The site on your abdomen for the stoma placement

should maximize both your functional independence and your

body image (see Figure 5).

An important goal of this type of surgery is to improve your

quality of life by:

• Making you more independent in bowel care.

• Reducing the time and effort bowel care requires.

• Preventing bowel accidents.

People consider surgery for many reasons, including some

or all of the following:

• BM accidents or leaking of stool.

• Recurring pressure ulcers.

FIGURE 5

Stomach

Transverse

Colon

Colon

(Large

Intestine)

Descending

Colon

Small

Intestine

Ascending

Colon

Sigmoid

Colon

Rectum

Anal

Sphincter

Anus

Ileum

(~12” length)

Stoma—always

moist and red

A Guide for People with Spinal Cord Injury 37

•Persistent pelvic or rectal infections.

• Safety issues (transferring accidents).

• Skin problems from a toilet or commode seat.

• Bleeding hemorrhoids.

• Sweating.

• Nausea.

• Anorexia.

•Fatigue.

• Effects of aging.

• Abdominal pains.

•Too much time spent on bowel care.

Surgery is a serious matter. Before deciding if it’s the

right choice for you, you need to consider all other med-

ical therapies thoroughly. If they don’t work, discuss surgical

options with members of your rehabilitation team: your primary

care practitioner, psychologist, occupational therapist, rehabili-

tation nurse, family members, and other people who are impor-

tant in your life. Different team members can give you the

information you need to make your decision carefully. They can:

• Make sure you understand what the

surgery can—and can’t—do to make

you more independent.

• Discuss specific screening studies that

provide information for decision making.

• Predict how well the procedure will

work for you.

• Explain the risks you’ll face during

and after surgery.

38 NEUROGENIC BOWEL: What You Should Know

If you’re considering surgery, team members may suggest a

conference to discuss important issues. These include how to

take care of the opening, use of bags and other equipment, and

where on your abdomen the opening should be. Things you

need to consider in choosing a stoma site:

•Your preference (where you want it to be, and why).

•Your body image (how your clothes will fit and how you’ll feel

about the way you look).

• Independence in bowel care (how easy it is to reach and

care for).

This type of surgery is intended to produce permanent

changes in how the colon empties. It can be reversed, but only

in some circumstances. If you aren’t happy with the results,

you may be able to go back to your previous bowel care rou-

tine. Even though you can change your mind, reversing

the procedure requires more surgery. That’s why you

should ask as many questions as you need, to feel comfortable

with your choice before anything is done.

Even though surgery is seldom required, the decision should

include careful consideration of all alternatives. There are a

variety of surgical options available to improve management of

the neurogenic bowel. Evaluation of options should include

contact with a spinal cord center and, if possible, discussion of

the outcome with someone who has had the procedure.

References

Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine. Neurogenic Bowel Management in

Adults with Spinal Cord Injury. Washington, DC: Paralyzed Veterans of

America, 1998.

Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago. “Educational Guide for Individuals and

Families Following SCI.” Chicago: Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago, 1995.

Stiens, S.A., S. Biener-Bergman, and L.L. Goetz. Neurogenic bowel dysfunction

after spinal cord injury: Clinical evaluation and rehabilitation management. Arch

Phys Med Rehabil 78 (1997): S86–S102.

Resources

Autonomic Dysreflexia: What You Should Know. Consortium for Spinal Cord

Medicine. Washington, DC: Paralyzed Veterans of America, 1997. (Available by

calling (888) 860-7244 or visiting the PVA web site at http://www.pva.org.

“Bowel Management: A Fantastic Voyage!” In Take Control: A Multimedia

Guide to Spinal Cord Injury, Vol 3. University of Arkansas for Medical

Sciences, 1998. (CD ROM available by calling (800) 543-2119.)

“Bowel Management Program.” In Yes, You Can! A Guide to Self-Care for

Persons With Spinal Cord Injury, Second Edition, edited by Margaret C.

Hammond, Robert Umlauf, Brenda Matteson, and Sonya Perduta-Fulginiti.

Washington, DC: Paralyzed Veterans of America, 1993. (Available by calling

(888) 860-7244.)

Bowel Management Programs: A Manual of Ideas and Techniques, edited

by Raymond C. Cheever and Charle D. Elmer. RPT: Accent Press, 1975.

Constipation and Spinal Cord Injury: A Guide to Symptoms and Treatment.

D. Harari, J. Quinlan, and S.A. Stiens, Paralyzed Veterans of America: Washington

DC, 1996. (Available by calling (888) 860-7244.)

A Guide for People with Spinal Cord Injury 39

I

’m 24. Three years ago I had a spinal

cord injury at C6. They sent me home

from the hospital too fast. I didn’t have

time to learn much about bowel care and