1

1

Punishing Free-riders: Direct and Indirect Promotion of

Cooperation

Mizuho Shinada

a, b

& Toshio Yamagishi

a, *

a

Graduate School of Letters, Hokkaido University, N10 W7 Kita-ku, Sapporo, Japan

060-0810; and

b

Research Fellow of Japan Society for the Promotion of Science

*

To whom correspondence should be addressed.

Phone: +81-11-706-4157

Fax: +81-11-706-3066

E-mail: [email protected]

Running title: Direct and indirect effect of punishment

2

2

Abstract. Human cooperation in a large group of genetically unrelated people is an

evolutionary puzzle. Despite its costly nature, cooperative behaviour is commonly

found in all human societies, a fact that has interested researchers from a wide range of

disciplines including biology, economics, and psychology to name a few. Many

behavioural experiments have demonstrated that cooperation within a group can be

sustained when free riders are punished. We argue that punishment has both a direct and

an indirect effect in promoting cooperation. The direct effect of punishment alters the

consequences of cooperation and defection in such a way as to make a rational person

prefer cooperation. The indirect effect of punishment promotes cooperation among

conditional cooperators by providing the condition necessary for their cooperation —

i.e., the expectation that other members will also cooperate. Here we present data from

two one-shot, n-person Prisoner’s Dilemma games, demonstrating that the indirect

effect of punishment complements the direct effect to increase cooperation in the game.

Further, we show that the direct and indirect effects are robust across two forms of

punishment technology; either when the punishment is voluntarily provided by game

players themselves or when it is exogenously provided by the experimenter.

Key Words: Cooperation; Punishment; Expectation; Conditional cooperation; Prisoner’s

dilemma

3

3

1. Introduction

One of the most distinguishing features of human societies is large-scale

cooperation among non-kin. Examples of such cooperation include hunting and meat

sharing and collaborative childcare in hunter-gatherer societies, contributions to public

goods, such as an irrigation system in agriculturalist societies, and market exchanges in

industrialized societies. Cooperation produces mutually beneficial outcomes, and yet is

costly for the individual. Some cooperative behaviour can be understood by kin

selection (Hamilton, 1964) – helping others can enhance the benefactor’s inclusive

fitness when the beneficiary is a genetic relative – and direct reciprocity between those

who are willing to trade-off the roles of benefactor and beneficiary (Trivers, 1971).

These two mechanisms can account for much of the cooperative behavior observed

among the animals including humans, but are insufficient to explain costly cooperation

in sizeable human groups consisting of genetically unrelated individuals in the absence

of long-term relationships. While free-riding on a public good is expected from the kin-

based and reciprocal altruism under these circumstances, experimental studies have

shown nontrivial contributions in anonymously played one-shot games with genetically-

unrelated participants (Andreoni & Petrie, 2004; Issac & Walker, 1988; Marwell &

Ames, 1981; Orbell, Dawes, & Van de Kragt, 1988; Rapoport, 1987; Yamagishi, 1988).

One possible explanation for cooperation in human groups is the punishment of

free-riders. Experimental studies have consistently demonstrated that punishment

(monetary and symbolic alike) promotes cooperation (Fehr & Fischbacher, 2003; Fehr

& Gächter, 2002; Masclet, Noussair, Tucker, & Villeval, 2003). Not only do people

show a propensity to cooperate under the threat of punishment in experimental games,

they are also willing to absorb costs for administering punishment to free riders

(Anderson & Putterman, 2006; Casari & Plott, 2003; Price, Cosmides, & Tooby, 2002).

Given the power of punishment to promote cooperation, it is surprising to us that many

theorists have generally overlooked the reason for punishment’s efficacy. We speculate

that the paucity of effort to address this question is at least partly based on the fact that

the answer seems self-evident; administration of punishment transforms outcomes of

cooperation and defection such that cooperation is more profitable than free-riding. This

direct effect of punishment could be the sole factor in explaining cooperation if, and

only if, one assumes that humans are strictly self-regarding with no consideration for

4

4

the consequences to others. Olson (1965) clearly follows this logic when he wrote “…

rational, self-interested individuals will not act to achieve their common or group

interests” (p. 2) and “only a separate and selective incentive will stimulate a rational

individual in a latent group to act in a group-oriented way” (p. 51).

In this paper, we argue that the direct effect – transformation of incentives for

potential targets of punishment – alone is limited in its ability to explain the robust

effect of punishment. The limitation arises from the fact that punishment incurs a cost to

the punisher, whereas the benefit of punishment – public welfare generated by greater

cooperation – is shared equally by all members. Thus, the provision of punishment

involves a free-rider problem in itself; self-regarding individuals should not pay the cost

associated with imposing penalties on free-riders. This problem is called the second-

order public good dilemma (Oliver, 1980). Faced with this difficulty, some researchers

have argued that the cost of punishment becomes smaller in higher-order public good

dilemmas (e.g., punishment of non-punishers; punishment of those who don’t punish

non-punishers; etc.) than in the original public good dilemma (Boyd & Richerson, 1992;

Boyd, Gintis, Bowles, & Richerson, 2003; Henrich & Boyd, 2001; Henrich, 2004;

Sober & Wilson, 1998). Once the cost is reduced sufficiently for the provision of

punishment at a higher level, it should eventually stabilize cooperation in the original

public good dilemma.

We claim below that this cost-reduction argument can be augmented by an

efficiency-enhancement argument. In addition to the possibility that the cost associated

with providing punishment is smaller than that associated with providing the original

public good, we suggest that an indirect effect of punishment further enhances the

efficiency of punishment. There is a robust finding that an overwhelming majority of

players in the public goods game behave as conditional cooperators – individuals who

cooperate if (and only if) other members cooperate – rather than as unconditional

cooperators or unconditional defectors (Andreoni & Miller, 1993; Boehm, 1993;

Kurzban & Houser, 2005; Page & Putterman, 2005). Although players almost always

defect in response to defection in a public goods game, the majority of players choose to

cooperate when other players cooperate (Cho & Choi, 2000; Clark & Sefton, 2001;

Fischbacher, Gächter, & Fehr, 2001; Hayashi, Ostrom, Walker, & Yamagishi, 1999;

Kiyonari, Tanida, & Yamagishi, 2000; Watabe, Terai, Hayashi, & Yamagishi, 1996).

5

5

Moreover, numerous studies have demonstrated a relationship between the expectation

of cooperation and cooperative behaviour; the stronger the expectation that others will

cooperate, the more likely it is that a player will choose to cooperate him or herself

(Charness & Dufwenberg, 2006; Dawes, 1980; Pruitt & Kimmel, 1977). Conditional

cooperators seek mutually beneficial opportunities, but only when their effort is

unlikely to be exploited by free-riders. For them, the expectation that others will

cooperate is a necessary (though not sufficient) antecedent for a cooperative venture.

The threat of punishment for free-riding provides reassurance to conditional cooperators

that other group members will also cooperate. This reassurance that others will also

cooperate satisfies their condition for cooperation. Punishment promotes cooperation

among conditional cooperators through the reassurance it provides rather than by the

fear of being a target of penalization (the direct effect of punishment). We call this the

indirect effect of punishment.

Most experimental studies of punishment (e.g., Fehr & Gächter, 2002; Ostrom,

Walker, & Gardner, 1992: Yamagishi, 1986) do not appreciate the possibility that

indirect effect supplements the direct effect of punishment, and, instead, analyze the

combined effect (including both direct and indirect effects) of punishment for promoting

cooperation. The purpose of this study is to demonstrate the augmentative nature of the

indirect effect, such that the combined effect of punishment is greater than the level

expected from the direct effect alone. For this purpose, we compare the size of

punishment’s combined effect with the size of the direct effect alone. Specifically, we

design a one-shot, three-person PD game with three between-subjects conditions: the

no-punishment condition, the direct effect (of punishment) condition, and the combined

effect (of punishment) condition. We adopt a one-shot rather than repeated game design

often used in the study of punishment (Anderson & Putterman, 2006; Fehr & Gächter,

2002; Ostrom et al., 1992; Yamagishi, 1986). The reason for the use of a one-shot

instead of a repeated game is that measurement of the direct effect, in its pure form free

from the contaminating influences of indirect effects, is an indispensable part of this

study. In repeated games, those who are afraid of receiving a penalty (i.e., those who

experience the direct effect of punishment) and thus cooperate at a higher level may

unwittingly promote cooperation of the other players who are conditional cooperators.

The improved level of cooperation of the other players might, in turn, improve the

6

6

original players’ level of cooperation. That is, the direct effect of punishment in

repeated games can engender an indirect effect through the other players’ behavior, and

thus identifying the direct effect of punishment in its pure form is theoretically

impossible. This difficulty of identifying the direct effect can be avoided in one-shot

games in which changes in one player’s behavior are not reflected in other players’

behavior. On the other hand, whether or not punishment has an effect in the absence of

the actual experience of being punished has been debated, and no firm conclusions have

yet been reached (Eek, Loukopoulos, Fujii, & Gärling, 2002; Loukopoulos, Eek,

Gärling, & Fujii, 2006; Walker & Halloran, 2004). The current study thus aspires, first,

to provide evidence for the effect of punishment in the absence of the actual experience

of punishment, and, second, to sort out indirect and direct effects of punishment from

their combined effect.

We conducted two experiments, the major difference between the two residing in

the punishment mechanism. In the first study, punishment was provided exogenously.

That is, penalties were imposed by the experimenter, requiring no cost to be paid by

players themselves. In contrast, punishment in study two was endogenous, dispensed by

individual game players themselves who had to pay a cost for its provision. In both

experiments, each player of a three-person PD game first decided what portion of an

initial endowment they would contribute to benefit the other two players. Afterwards,

players faced the possibility of punishment for free-riding. In the direct effect condition,

the participant alone faced the possibility of punishment. Since no penalties were

administered to other players, they could free-ride with impunity. Thus, only the direct

effect of punishment could influence the participant’s decision to cooperate. In the

combined effect condition, all players were subject to punishment. Thus, in addition to

the direct effect of punishment for free-riding, participants could expect greater

cooperation (on average) from their fellow group members who also faced the

possibility of penalization. In the no-punishment condition, there was no penalty for

free riding. Thus, any difference in the sum contributed between the direct effect and

no-punishment conditions must be due to the direct effect of punishment alone. In this

sense, any additional contribution in the combined effect condition, over and above that

observed in the direct effect condition, can be regarded as evidence for the indirect

effect.

7

7

2. Study 1

2.1. Methods

A total of 157 freshmen (79 men and 78 women) at Hokkaido University in Japan

participated in this experiment for monetary rewards. They were recruited from a large

subject pool consisting of freshmen from various disciplines, and were randomly

assigned to one of three conditions (n = 52 in the no-punishment condition, 51 in the

direct effect condition, and 54 in the combined effect condition). Two of the participants

misunderstood the instructions and were removed from the analysis.

1

Participants were

assured that their contributions would remain anonymous to both the other participants

and to the experimenter with whom they met in person.

In all three conditions, participants played a one-shot, three-person PD game.

Participants were escorted to individual rooms without seeing or talking to other

participants. Each member of the three-person group was provided with an endowment

of 800 yen from the experimenter, and was asked to contribute some portion of that

endowment to the other group members. The actual amount was left up to each player.

Each player received the total amount contributed by the other two players. Thus, if

everybody contributed the full endowment of 800 yen, each player received 1,600 yen

(800 from each of the other players). Since each player decided on the sum to contribute

without knowing the value of the other contributions, contributing nothing was the most

profitable choice regardless of the amount other members decided to contribute. In the

event that all three players adopted this strategy of contributing nothing, each would

retain their original endowment of 800 yen. Thus, the monetary payoff for each

participant i in the no-punishment condition is given by

)1...(............................................................

∑

≠

+−=

ij

jii

gagy

π

where y is the endowment and a is the benefit generated by another member’s

cooperation (y = 800, and a = 1; note that the participant’s own contribution does not

generate any benefit to him or herself, as implied by j ≠ i).

8

8

Players in the no-punishment condition neither faced punishment nor were they

informed that punishment was even a possibility. Conversely, players in the remaining

two conditions were informed that they might be punished if they did not contribute the

entire sum of their endowment to the other group members. Furthermore, players in the

two punishment conditions were informed that there was an increasing probability of

punishment as the value of their contribution decreased; however, players were not told

of the specific probabilities

2

. We chose to implement a punishment mechanism with

incomplete information regarding the probability of being punished, since the exact

probability of punishment at various level of cooperation is hardly available in the real

world. Punishment was imposed exogenously by the experimenter, though this method

of administrating punishment was changed in the second study. While we used the term

“punishment” in the instructions of the first experiment, we omitted the term in the

second study. We discuss the implications of using (or not using) the term

“punishment” in the general discussion.

When a player was penalized, he or she lost half of the portion of the endowment

he or she kept at hand. Thus, the monetary payoff for each participant i when he or she

is punished is given by

)2..(............................................................2/)(

*

iii

gy −−=

π

π

The monetary payoff for the participant who was not punished is given by equation (1).

Participants in the direct effect condition were further told that only one of the

three participants would be subject to punishment, and that they had been randomly

chosen as the sole target of punishment. They were further instructed that the other

players would remain uninformed of this fact, having no knowledge about the

possibility of punishment. Since the participant alone was subject to punishment, and

the other members were not subject to punishment, only the direct effect was possible in

this condition. Players in the combined effect condition were told that all three members

of the group would face the possibility of punishment. In order to keep the threat of

receiving punishment constant across the two punishment conditions, players were told

that the probability of punishment would be determined independently for each player,

so that the likelihood of punishment was unaffected by the decisions made by other

players.

9

9

Three players assigned to the combined effect condition were grouped together to

constitute a single groups to play a public goods game. Other experimental groups

consisted of one player from the direct effect condition and two players from the no-

punishment condition. In order to maintain a balance in the number of players assigned

to each condition, one player in the no-punishment condition was sometimes paired

with more than one player in the direct effect condition when calculating their rewards.

3

After the experiment, all participants completed a post-experimental

questionnaire. Finally, they were informed of their game outcome—how much each of

the three members contributed, and whether or not they received a penalty (in the two

punishment conditions), and how much they earned. A secretary who knew nothing

about the experiment paid each participant individually and then discharged them. The

research protocol was approved by the ethics committee for the Department of

Behavioural Science at Hokkaido University.

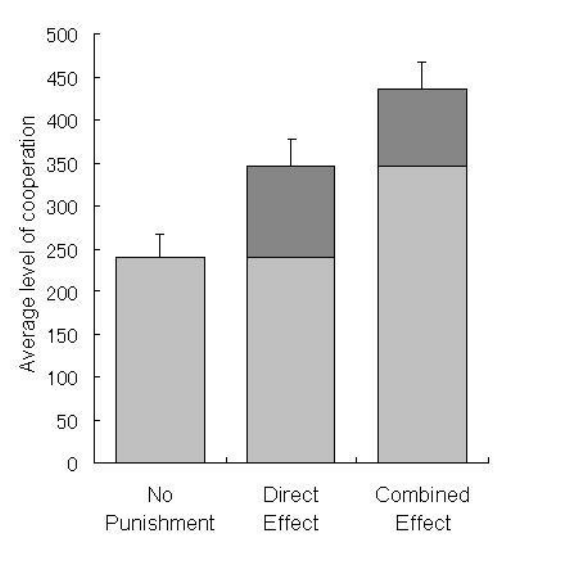

2.2. Results

Because there were no main or interaction effects involving player’s sex, the

following analyses used the combined data for men and women. The results of the first

study (Fig. 1) show that the base-rate level of cooperation (the portion of the initial

endowment contributed for other members) in the no-punishment condition was 239.81

yen (SD = 197.03), or about 30 percent of the endowment. Cooperation levels in the two

punishment conditions were higher than this base-rate level (345.60 yen, SD = 223.80,

in the direct effect condition, and 435.47 yen, SD = 231.17, in the combined effect

condition). We conducted a set of regression analyses for cooperation level using two

dummy variables; one for the presence of punishment (dummy 1; zero in the no-

punishment condition and one in the direct and the indirect effect conditions) and the

other for the presence of indirect effect (dummy 2; zero in the no-punishment and the

direct effect conditions and one in the indirect effect condition). Column 1 in Table 1

includes only dummy 1; the effect for the dummy variable represents the difference in

cooperation level between the no-punishment condition and the two punishment

conditions combined. The significant regression effect for this variable in Column 1

shows that punishment increased the cooperation level by 152.04 yen.

10

10

Table 1: The effects of anticipated punishment on cooperation in study one. Regression

analyses for contribution level on two dummy variables.

Variables (1) (2)

Dummy 1 152.04

(37.47)

P < .0001

105.79

(43.15)

P = .015

Dummy 2 . 89.87

(42.95)

P = .038

Constant 239.81

(30.54)

P < .0001

239.81

(30.21)

P < .0001

N 155 155

R

2

0.10 0.12

Standard errors in parentheses.

The second dummy was then added to the regression equation (Column 2) to

decompose the overall effect of punishment into two components: one for the direct

effect and one for the indirect effect: The contribution level in the no-punishment

condition is represented by the constant in Column 2, since both of the two dummies are

zero in this condition. The contribution level in the direct effect condition is the sum of

the constant and the regression coefficient for dummy 1 (that takes the value of one),

and thus the coefficient for dummy 1 represents the difference in cooperation between

the no-punishment condition and the direct effect condition. In Figure 1, this effect

corresponds to the dark portion of the bar for the direct effect condition. Similarly, the

coefficient for dummy 2 represents the difference in cooperation between the direct

effect condition and the indirect effect condition, corresponding to the bark portion of

the bar for the indirect effect condition. The two effects are similar in size, indicating

that the indirect effect was almost as strong as the direct effect. The interpretation of the

relative sizes of these two effects, however, has to be made with caution since effect

sizes depend on the parameters used in the experiment, including the cost and benefit

for cooperation and the cost and size of punishment.

11

11

Fig. 1: Direct and indirect effects of punishment in the first study. The left bar estimates

the base level of cooperation (sum of contribution) that occurs when free-riding is not punished.

The darker portion of the middle bar (105.79 yen) represents the direct effect of punishment –

cooperation over and above that observed in the no-punishment condition. The right bar

illustrates the combined effect of punishment (direct and indirect) on cooperation; the darker

portion (89.87 yen) represents the contribution level over and above that observed for the direct

effect of punishment (i.e., the indirect effect of punishment). Error bars represent standard error.

We expected that participants would cooperate more in the combined effect

condition than in the direct effect condition since the expectation that other members

would cooperate due to possible punishment would be higher in the former condition

than in the latter. We also argued that since there was no possibility that other members

would be punished in the no-punishment and direct effect conditions, participants’

expectations would not differ between the two. We measured participants’ expectations

in the post-experimental questionnaire by asking; “How much do you think the other

two contributed on average?” The average expectation was 400.57 yen (SD = 129.12) in

the combined effect condition, 329.00 yen (SD = 130.58) in the direct effect condition,

and 274.33 yen (SD = 157.81) in the no-punishment condition. A regression analysis

using a set of two dummy variables (see the analysis of contributions) indicated that

both the difference between the direct effect and the combined effect conditions (b =

12

12

71.57, t(152) = 2.60, p = .01) as well as the difference between the no-punishment and

the direct effect conditions (b = 54.67, t(152) = 1.97, p = .05) were significant. While

the former difference provides support for our argument, the unanticipated difference

between the no-punishment and the direct effect condition strongly suggests that at least

a substantial portion of the participant’s responses to the post-experimental questions

represents “projection” of their own behavior onto the other members. Participants in

the direct effect condition overestimated the other two members’ actual contribution

(329.00 vs. 239.81 yen) to match their own contribution (345.60 yen), at least in their

responses to post-experimental questions, whereas the estimations of those in the no-

punishment condition (274.33 vs. 239.81 yen) and in the combined effect condition

(400.57 vs. 435.47 yen) did not greatly differ from the actual levels of contribution. We

do not know if this overestimation by participants in the direct effect condition occurred

in the experiment and affected their decisions or emerged only in their responses to the

post-experimental question. However, even if it had affected their decision in the

experiment, it should have made their contribution higher rather than lower. The

“inflated” level of contribution in the direct effect condition beyond the effect caused by

the threat of punishment alone, if existing at all, should have worked against our

hypothesis concerning indirect effect. Thus, this result provided stronger support to our

conclusion about indirect effect.

3. Study 2

The results of the first study confirmed, first, that the threat of punishment can

enhance cooperation in a one-shot PD game. These results further provided evidence

that the indirect effect of punishment augments its direct effect. This finding, however,

has to be qualified in two important respects. First, the punishment was imposed

exogenously by the experimenter, rather than voluntarily administered by players

themselves. Second, administration of punishment required no cost from the players.

These two features of punishment in the first study are problematic for generalizing the

results beyond this particular enforcement mechanism. When players are required to pay

a personal cost to impose penalties, the likelihood of punishment of free-riding may be

less than that expected when the experimenter acts as requiter. The direct effect of

13

13

punishment may thus be reduced when the administration of punishment is costly.

Consequently, the expectation that other people will cooperate to avoid punishment may

also be reduced. As a result, the promotion of cooperation through the indirect effect

would be reduced

We conducted a second study to examine whether the indirect effect of

punishment observed in the first study would be replicated under a different

enforcement mechanism. In the second study, players decided how much personal cost

to bear in order to administer punishment to other players who fail to contribute. In

addition, we decided not to use the term “punishment” in the second study. Instead, we

choose to use the neutral word “reduce,” in order to avoid eliciting normative behaviour

associated with the term “punishment.”

The use of the endogenous punishment mechanism forced us to give up

measuring the pure direct effect of punishment as we did in Study 1. In the first

experiment, participants in the direct effect condition were informed that the other two

players were unaware of punishment at all. In Study 2 however, the other two players

were aware of the existence of punishment because they were able to deliver

punishment to the participant in the direct effect condition. Participants in the direct

condition in the second study thus face players who may be affected by indirect effect

of punishment, since other players face someone (the participant in the direct effect

condition) who can be punished. That is, participants in the direct effect condition in the

second study may be affected by the expectation of indirect effect that may enhance

other players’ cooperation—we may call this doubly indirect effect of punishment. We

decided to run the endogenous punishment mechanism despite the inability of

measuring purely direct effect mentioned above, since the merits of the new design

outweigh this potential problem. Furthermore, this doubly indirect effect of punishment

should work against our hypothesis concerning the operation of indirect effect, because

the test of indirect effect now involves cooperation in the combined effect and

“inflated” (due to the doubly indirect effect) level of cooperation in the direct effect

condition.

3.1. Methods

14

14

A total of 144 freshmen (72 men and 72 women) at Hokkaido University in

Japan participated in this experiment for monetary rewards. All participants played the

same one-shot, three-person PD game used in the first study. Each member of a three-

person group was asked to contribute some portion of their endowment of 800 yen for

other group members. Each of the other two players received the amount the player

contributed.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions (n = 48 in the no-

punishment condition, 48 in the direct effect condition, and 48 in the combined effect

condition). Three of the participants were removed from the analysis because their

responses to post-experimental questions made it clear that they failed to comprehend

the instructions.

4

The use of an endogenous punishment system forced us to use “extra”

participants to avoid deception. Participants in the direct effect condition were the only

potential targets of punishment in their group. The other two participants in their group

did not face the possibility of receiving punishment. They were informed that

punishment option existed in their group. Further, one of the two was given a chance to

punish another player (the participant in the direct effect condition). These features

disqualified them as players in the no-punishment condition. We did not use these

“extra” participants in our hypothesis testing, since they were not relevant to our

hypotheses.

Players in the no-punishment condition constituted a group in which no one

faced punishment. The monetary payoff for each participant in the no-punishment

condition is given by equation (1). Players in the remaining two conditions were

informed that they might be punished by other players. We introduced a system of

punishment in which one participant could be punished only by one other participant in

order to make punishment compatible across the two punishment conditions. If we

allowed both of the other two participants to punish the participant in the direct effect

condition, he or she would be subject to punishment by two individuals. In contrast, no

participant in the combined effect condition was the sole target of punishment by two

individuals simultaneously, since each of the other two participants had two potential

targets to choose from. As a result, participants in the direct effect condition faced twice

as strong punishment as those in the indirect effect condition. This problem was avoided

by restricting the number of potential punishers in the direct effect condition to one.

15

15

Remember that the group for the direct effect condition included the potential target of

punishment, D1, and two “extra” participants; one of the two, DE1, was given an

opportunity to punish D1, whereas the other, DE2, did not have such an opportunity.

Only the sole target of punishment in this group, D1, qualified for the direct effect

condition; the other two, “extra” participants were included in this group to avoid

deceiving the participants.

The monetary payoff for the player D1 in the direct effect condition is given by,

)3(......................................................................2

11

*

p

DD

−

=

π

π

where p is the amount of money that DE1 pays to punish D1. Player D1 in the

direct effect condition may be punished only by DE1. Since D1 did not have an

opportunity to punish another player, Eq1uation 3 does not include cost of punishment.

Participant C1 in the combined effect condition was a target of potential

punishment by C2, C2 by C3, and C3 by C1. Therefore, the monetary payoff for each

participant in the combined effect condition is given by,

)4....(............................................................2

*

ikjiii

pp −−=

π

π

where j i, i k, k j and pik is the amount of money that group member i

pay to punish group member k.

After all participants decided how much to contribute in the three-person PD

game, each participant in the combined effect condition (and the extra participants in the

direct effect condition) was informed of how much the target of his or her punishment

contributed. Then, they were given an opportunity to reduce the earnings of that

member. They were told that monetary costs were required to use the option; each yen

the participant paid reduced the target member’s earnings by two yen. The maximum

amount they could pay to reduce another’s earnings was 200 yen, the amount they were

paid before the experiment as a show-up fee (in addition to the endowment of 800 yen

they were given in the experiment). After deciding how much to pay to reduce the

earnings of that member, all participants completed a post-experimental questionnaire.

Finally, they were informed how much they earned in the PD game and, if they were

16

16

subjected to punishment, how much their earnings were reduced. Finally, participants

were paid their earnings individually, less the penalty, and dismissed.

3.2. Results

We found no main or interaction effects involving the sex of the participants and,

therefore, data was pooled across sexes for all subsequent analyses.

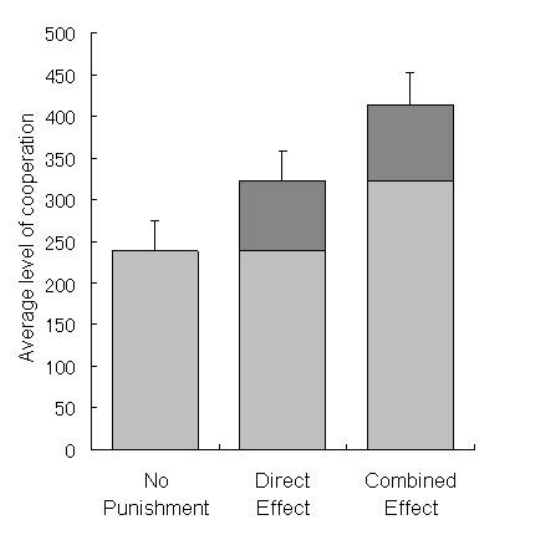

Cooperation. As shown in Fig. 2, the results of the second study largely

replicated those of the first study. On average, the contribution level was lowest (237.71

yen, SD = 264.56) in the no-punishment condition, highest (414.13 yen, SD = 256.13)

Fig. 2: Direct and indirect effects of punishment in the second study. The left bar

estimates the base level of cooperation (sum of contribution) that occurs when free-riding is not

punished. The darker portion of the middle bar (85.91 yen) represents the direct effect of

punishment – cooperation over and above that observed in the no-punishment condition. The

right bar illustrates the combined effect of punishment (direct and indirect) on cooperation; the

darker portion (90.73 yen) represents the contribution level over and above that observed for

the direct effect of punishment (i.e., the indirect effect of punishment). Error bars represent

standard error.

17

17

in the combined effect condition, and intermediate in the direct effect condition (323.62

yen, SD = 240.95). We used the same set of regression analyses used in Study 1 to

examine, first, whether punishment had a positive overall effect on cooperation and,

second, whether the predicted indirect effect manifested. Column 1 in Table 2 includes

only dummy 1. The significant effect for this dummy variable in Column 1 represents

the difference in cooperation level between the no-punishment condition and the two

punishment conditions combined. As was the case with exogenous punishment, the

results of Study 2 clearly show that endogenous punishment can increase cooperation

level even in a one-shot game. The dummy variable for the indirect effect was then

added to the regression equation (Column 2) to decompose the combined effect of

punishment into two components: the direct and indirect effects. In Column 2, either

dummy 1, representing the direct effect (the dark portion of the bar in Figure 2 for the

direct effect condition), or dummy 2, representing the indirect effect (the dark portion of

the bar for the indirect effect condition) reached the statistical significance at α = 0.05.

These results demonstrate, first, that punishment has a positive effect on contribution,

and second, that the positive effect of punishment can be decomposed into direct and

indirect effects of roughly equivalence sizes, although each of the effect was not as

strong as in the first study.

Table 2: The effects of anticipated punishment on cooperation in the second study.

Regression analysis contribution on two dummy variables.

Variables (1) (2)

Dummy 1 130.79

(45.48)

P = .005

85.91

(52.15)

P = .102

Dummy 2 . 90.73

(52.71)

P = .087

Constant 237.71

(36.94)

P < .0001

237.71

(36.68)

P < .0001

N 141 141

R

2

0.06 0.08

Standard errors in parentheses.

Expectations of other players’ contributions were also similar to the pattern

observed in the first study. We measured participants’ expectations using the same post-

18

18

experimental question used in the first study. The average expectation was 370.65 yen

(SD = 182.75) in the combined effect condition, 286.17 yen (SD = 172.17) in the direct

effect condition, and 236.04 yen (SD = 177.89) in the no-punishment condition. A

regression analysis using a set of two dummy variables (see the analysis of

contributions) indicated that the difference between the direct effect and the combined

effect conditions was significant (b = 84.48, t(138) = 2.29, p = .02), whereas the

difference between the no-punishment and the direct effect conditions (b = 50.13, t(138)

= 1.38, p = .17) was not significant.

Punishments delivered. Enforcement of punishment by participants was

relatively sparse, possibly because of the relatively high contribution levels of players

who were subjected to the threat of penalization, or perhaps because punishment was

costly. Only 26 % of the participants in the combined effect condition (12 of 46

participants) delivered some level of punishment. Those who punished spent an average

of 87.5 yen (SD = 62.25) to reduce another’s earnings. As in previous studies (Fehr &

Gächter, 2002; Falk, Fehr, & Fischbacher, 2005), punishment was more severe when

the target’s contribution level was less than the punisher’s. In this case, an average of

105.71 yen (SD=71.61) was spent on penalties to 39% of potential targets. When the

target of punishment contributed more than the punisher, an average of 62.00 yen

(SD=39.62) was spent on penalties to 18 % of potential targets5. The total cost of

punishment (i.e., the amount participants spent on punishment) was relatively small,

compared to the benefit of increased cooperation. On average, each participant

contributed 176.64 yen more in the combined effect condition than in the no-

punishment condition. This extra contribution generated a benefit of 176.64 × 2 =

353.28 yen for the other two members. That is, each participant generated a net benefit

of 176.64 yen (353.28 yen of total benefit for the cost of 176.64 yen), while spending an

average of 22.83 yen on punishment. Since punishment reduced the earnings of the

target by 45.66 yen, each participant in the combined effect condition was better off, on

average, than those in the no-punishment condition by 176.64 – 22.83 – 45.66 = 108.15

yen. In the direct effect condition, the participant’s average contribution level was

higher than that in the no-punishment condition by 85.91, thus producing an extra net

benefit of 85.91 yen. The matched extra participant spent an average of 22.34 yen for

punishment6. Thus, the overall benefit of punishment in the direct effect condition was

19

19

18.89 yen. Supplementing the direct effect with the indirect effect thus made the

administration of punishment much more cost effective.

Other findings. “Extra” participants (DE1 and DE2) were used to avoid the use

of deception. They did not face threat of punishment, and yet, they knew that one of the

three players would possibly face punishment. Thus, their contributions may possibly be

influenced by the indirect effect of punishment. On the other hand, they were also aware

that two of the three players were exempt from punishment. This would make the

indirect effect much weaker than the one observed in the combined effect condition in

which all three members faced possible punishment. Their responses to the post-

experimental question concerning the expectations of the other players’ contributions

suggest that their average expectations were higher than those in the no-punishment

condition (236.04 yen). One of the two “extra” participants, the one who was given a

chance to deliver punishment (DE1) expected that the other two would contribute an

average of 326.46 yen (SD=206.40), while the other “extra” participant (DE2), who was

neither punished nor given an opportunity for punishment, expected 313.89 yen

(SD=126.96). Despite these heightened expectations, their contributions were not larger

(270.00 yen, SD=294.39 for DE1; 198.33 yen, SD=232.49 for DE2) than in the no-

punishment condition (237.71 yen). There results indicate the lack of an indirect effect

among those participants. We discuss the implications of this finding in the discussion

section.

4. Discussion

The results of the two experiments support our argument that the direct effect of

punishment is augmented by an indirect effect to enhance cooperation. This is evident

in the fact that the level of cooperation in the combined effect condition was greater

than that observed in either the no-punishment condition or the direct effect punishment

condition.

As described earlier, the indirect effect of punishment has long been overlooked

despite its importance in solving the second-order dilemma. Eek and his associates are

among the few who recognized the importance of the indirect effect—which they called

the “spill-over effect”—of punishment (Eek et al., 2002; Loukopoulos et al., 2002).

20

20

They found evidence of an indirect effect of punishment, but the indirect effect was

observed in their study only when the direct effect of punishment exogenously imposed

by the experimenter was strong enough to make cooperation a more profitable choice

than free-riding (i.e., when the size of the imposed penalty exceeds the cost of

cooperation). In this case, participants in their experiments cooperated at a higher level

when one of the other members of a 5-person group was under the threat of such strong

punishment than when no penalties were administered. However, their studies failed to

demonstrate that the direct effect of weak punishment—i.e., not strong enough to make

cooperation a more profitable choice than free-riding—is augmented by an indirect

effect. The current study is the first to demonstrate that the direct effect of weak

punishment, which by itself is not strong enough to make self-regarding people

cooperate, is augmented by an indirect effect.

Our success in demonstrating an indirect effect of punishment when the penalty

was less than the cost of cooperation suggests that the symbolic or social nature of

punishment (Blau, 1964; Masclet et al., 2003; Noussair & Tucker, 2005) may play an

important role in producing indirect effects. In the Study 1, we explicitly used the term

“punishment,” whereas Eek and associates (Eek et al., 2002) expressed their penalty as

a “fee of 1000 SEK for [choosing non-cooperation]” (p. 809). When participants

encountered the term “punishment” in the instructions in our first study, they may have

taken note of the social implications of being a target of punishment, in addition to the

monetary cost imposed by the punishment itself. Recognition of the social implications

of punishment then may have made them more aware of social norms and obligations

for cooperation, and of the fact that others also operate under the normative pressure for

cooperation. This could in turn have strengthened the indirect effect of punishment.

This seems to be a reasonable account for the difference between our findings in the

first study and those reported by Eek and associates. However, we replicated the same

effects in the second study in which the term “punishment” was not used. The use of the

term “punishment,” thus, is not a necessary condition for the indirect effect of

punishment. On the other hand, there is a further possibility that the social implications

of punishment may have played an important role in enhancing the indirect effect. It is

possible that the inter-personal nature of endogenous punishment used in Study 2 made

the social nature of punishment—that is, the fact that punishment is something others

21

21

would want to enforce—salient to the participants. Whether or not the social aspects of

punishment are necessary for the indirect effect of “weak” punishment is an important

topic for future studies.

Another topic for future studies is the lack of indirect effects observed among

the “extra” participants in the second study. We used these participants mainly to avoid

the use of deception in the direct effect condition. That is, one of the two “extra”

participants, D

E1

, punished the “real” participant, D

1

, in the direct effect condition,

while he or she was not subject to punishment. Another “extra” participant, D

E2

, knew

that D

E1

could punish D

1

. In short, they knew that one of the other two players was

subject to punishment, and thus, would possible improve his or her cooperation level.

This might produce an indirect effect. On the other hand, the presence of another player

who was immune from punishment might have discouraged cooperation. Given the

finding by Kurzban, McCabe, Smith, & Wilson (2001), that conditional cooperators are

sensitive to the presence of non-cooperators, the presence of the immune player is likely

to prevent the indirect effect of punishment from taking place. Another possible

explanation for the lack of an indirect effect among these “extra” participants is that

indirect effect of punishment augments the weak direct effect of punishment, rather than

taking place by itself in the absence of a direct effect. That is, the nature of the indirect

effect is supplementary. Whether the indirect effect of punishment emerges by itself, or

requires the presence of a direct effect, is an important topic for future studies.

The indirect effect of punishment was suggested originally by Hobbes in the 17

th

Century (Hobbes, 1651). It is a popular misconception that Hobbes was an advocate of

the central authority forcing unwilling subjects to disarm (i.e., to use the direct effect of

punishment to force people to cooperate) (Kavka, 1983; Taylor, 1976; Yamagishi,

1992). Instead, his argument was focused more on the indirect effect of punishment; the

Leviathan (the central authority) playing the role of reducing fear of exploitation among

those who prefer Peace to War such that they can safely disarm themselves (i.e.,

cooperate) without fear of being exploited by those who don’t. The current study is the

first study to demonstrate experimentally the importance of the indirect effect as

implied by Hobbes’ view in Leviathan; punishment is a guarantor of Peace, not

(strictly) its enforcer. We have confirmed experimentally that the boost to cooperation

commonly observed in studies of punishment is better understood as a consequence of

22

22

two separate influences, one altering the payoffs associated with cooperation and

defection (the direct effect) and the other enhancing the expectation of cooperation by

others (the indirect effect).

The role of the indirect effect of punishment is argued to play a particularly

important role in the maintenance of common pool resources through voluntary

establishment of social institutions that monitor and sanction their members.

Researchers of resource management have alluded to the complementary nature of the

direct and indirect effects in field studies of common resources (Dietz, Ostrom, & Stern,

2003); while not ruling out the importance of the direct effect of punishment, they have

argued that “ruling by the sword” alone is insufficient to convince people to behave in a

mutually beneficial manner (Bewley, 1999; Gardner, Ostrom, & Walker, 1990; Ostrom

et al., 1992). This is because the key to a successful sanctioning system is the consent of

the people under its regulation (Hardin, 1968); voluntary acceptance assures that those

who are regulated want to cooperate, thereby enhancing the efficacy of punishment with

the indirect effect. We further suspect that factors such as ideology and shared beliefs

also play a positive role in raising expectations that others act cooperatively and,

consequently, accentuate the power of the indirect effect. The efficacy-enhancing role

of the indirect effect should be pronounced in social institutions perceived to be strong

and legitimate. While the direct effect depends more on the actual controlling power of

a social institution, the indirect effect depends more on the conviction that other

members believe in the legitimacy and efficacy of punishment. A sanctioning system

supported by a shared belief system should, thus, be more effective than the same

system dependent on the “sword” alone. An efficacious sanctioning system supported

by beliefs about its legitimacy would function well to induce people to comply,

transforming beliefs into reality; such a system could be self-sustaining (Aoki, 2001).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Paul Wehr and Mark Radford for their comments on earlier versions

of this manuscript, Mai Kasahara for her help in running the experiment, and our

colleagues at Hokkaido University for letting us recruit potential participants from their

23

23

classes. The research reported in this paper was supported by grants from The Japan

Society for the Promotion of Science.

FOOTNOTES

1

One participant in the combined effect condition thought that only one participant

faced the possibility of punishment, and another in the direct effect condition thought

that the other two members also faced the possibility of punishment.

2

We randomly administered punishment with a probability of 20 percent when a

participant in the combined effect condition failed to contribute their entire endowment

of 800 yen. No punishment was administered in the no punishment condition or in the

direct effect condition.

3

When, for example, four participants were involved in a session, two participants, N

1

and N

2

, were assigned to the no-punishment condition, and the other two, D

1

and D

2

, to

the direct effect condition. For calculating rewards for N

1

and N

2

, either D

1

or D

2

was

randomly selected as a member of their group. For either D

1

or D

2

, the other two

members were N

1

and N

2

. Each of the four participants was thus a part of a three-person

group.

4

Two participants in the combined effect condition believed that only one of the other

two participants faced the possibility of punishment, and one participant in the direct

effect condition believed that another member also faced the possibility of punishment.

5

While punishment of cooperators in this study seems to be rather high, punishment of

cooperators by defectors was also substantial, 34%, in Falk, Fehr, & Fischbacher’s

(2005) study.

24

24

REFERENCES

Aoki, M. (2001). Toward a comparative institutional analysis. Cambridge, Mass: MIT

Press.

Anderson, C. M., & Putterman, L. (2006). Do Non-strategic Sanctions Obey the Law of

Demand? The Demand for Punishment in the Voluntary Contribution

Mechanism. Games and Economic Behavior, 54, 1-24.

Andreoni, J., & Miller, J. H. (1993). Rational Cooperation in the Finitely Repeated

Prisoner's Dilemma: Experimental Evidence. The Economic Journal, 103, 570-

585.

Andreoni, J., & Petrie, R. (2004). Public goods experiments without confidentiality: a

glimpse into fund-raising. Journal of Public Economics, 88, 1605-1623.

Bewley, T. (1999). Why wages don’t fall in a recession. Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press.

Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and Power in Social Life. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Boehm, C. (1999). Hierarchy in the forest: The evolution of egalitarian behavior.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Boyd, R., & Richerson, P. J. (1992). Punishment allows the evolution of cooperation (or

anything else) in sizable groups. Ethology and Sociobiology, 13, 171-195.

Boyd, R., Gintis, H., Bowles, S., & Richerson, P. J. (2003). The Evolution of Altruistic

Punishment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United

States of America, 100, 3531-3535.

Casari, M., & Plott, C. R. (2003). Decentralized management of common property

resources: Experiments with a centuries-old institution. Journal of Economic

Behavior and Organization, 51, 217-247.

Charness, G., & Dufwenberg, M. (2006). Promises and partnership. Econometrica, 74,

1579-1601.

Cho, K., & Choi, B. (2000). A cross-Society Study of Trust and Reciprocity: Korea,

Japan, and the US. International Studies Review, 3, 31-43.

Clark, K., & Sefton, M. (2001). The sequential prisoner’s dilemma: Evidence on

reciprocation. The Economic Journal, 111, 51-68.

Dawes, R. M. (1980). Social dilemmas. Annual Review of Psychology, 31, 169-193.

Dietz, T., Ostrom, E., & Stern, P. C. (2003). The struggle to govern the commons.

Science, 302, 1907-1912.

25

25

Eek, D., Loukopoulos, P., Fujii, S., & Garling, T. (2002). Spill-over effects of

intermittent costs for defection in social dilemmas. European Journal of Social

Psychology, 32, 801-813.

Falk, A., Fehr, E., & Fischbacher, U. (2005). Driving forces of informal sanctions.

Econometrica, 73, 2017-2030.

Fehr, E., & Fischbacher, U. (2003). The nature of human altruism Proximate patterns

and evolutionary origins. Nature, 425, 785-791.

Fehr, E., & Gächter, S. (2002). Altruistic punishment in humans. Nature, 415, 137-140.

Fischbacher, U., Gächter, S., & Fehr, E. (2001). Are people conditionally cooperative?

Evidence from a public goods experiment. Economics Letters, 71, 397-404.

Gardner, R., Ostrom, E., & Walker, J. (1990). The nature of common-pool resource

problems. Rationality and Society, 2, 335-358.

Greif, A. (1994). Cultural beliefs and the organizational of society: A historical and

theoretical reflection on collectivist and individualist societies. The Journal of

Political Economy, 102, 912-950.

Hamilton, W. D. (1964). The genetical evolution of social behaviour I. Journal of

Theoretical Biology, 7, 1-52.

Hardin, G. (1968). The tragedy of the commons. Science, 162, 1243-1248.

Hayashi, N., Ostrom, E., Walker, J., & Yamagishi, T. (1999). Reciprocity, trust, and the

sense of control: A cross-societal study. Rationality and Society, 11, 27-46.

Henrich, J. (2004). Cultural Group Selection, Coevolutionary Processes and Large-scale

Cooperation. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 53, 3-35.

Henrich, J., & Boyd, R. (2001). Why people punish defectors: Weak conformist

transmission can stabilize costly enforcement of norms in cooperative dilemmas.

Journal of Theoretical Biology, 208, 79-89.

Hobbes, T. (1651). Leviathan. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press.

Issac, R. M., & Walker, J. M. (1988). Group size effects in public goods provision: The

voluntary contributions mechanism. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 103,

179-199.

Kavka, G. S. (1983). Hobbes's war all against all. Ethics, 93, 291-310.

Kiyonari, T., Tanida, S., & Yamagishi, T. (2000). Social exchange and reciprocity:

confusion or a heuristic? Evolution and Human Behavior, 21, 411-427.

Kurzban, R., & Houser, D. (2005). Experiments investigating cooperative types in

humans: A complement to evolutionary theory and simulations. Proceedings of

26

26

the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 102, 1803-

1807.

Kurzban, R., McCabe, K., Smith, V. L ., & Wilson, B. J. (2001). Incremental

commitment and reciprocity in a real time public goods game. Personality and

Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 1662-1673.

Loukopoulos, P., Eek, D., Garling, T., & Fujii, S. (2006). Palatable Punishment in Real-

World Social Dilemmas? Journal of Applied Psychology, 36, 1274-1279.

Marwell, G., & Ames, R. (1979). Experiments in the provision of public goods, I:

Resources, interest, group size and the free rider problem. American Journal of

Sociology, 84, 1335-1360.

Masclet, D., Noussair, C., Tucker, S., & Villeval, M. (2003). Monetary and

nonmonetary punishment in the voluntary contributions mechanism. American

Economic Review, 93, 366-380.

Noussair, C., & Tucker, S. (2005). Combining monetary and social sanctions to

promote cooperation. Economic Inquiry, 43, 649-660.

Oliver, P. (1980). Rewards and punishments as selective incentives for collective

action: Theoretical investigations. American journal of sociology, 85, 1356-1375.

Olson, M. (1965). The logic of collective action: Public goods and the theory of groups.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Orbell, J., Dawes, R. M., & Van de Kragt, A. (1988). Explaining discussion induced

cooperation. Journal of Personality and Social Pyschology, 54, 811-819.

Ostrom, E., Walker, J., & Gardner, R. (1992). Covenants with and without a sword:

Self-governance is possible. American Political Science Review, 86, 404-417.

Page, T., Putterman, L., & Unel, B. (2005). Voluntary association in public goods

experiments: Reciprocity, mimicry and efficiency. The Economic Journal, 115,

1032-1053.

Price, M. E., Cosmides, L., & Tooby, J. (2002). Punitive sentiment as an anti-free rider

psychological device. Evolution and Human Behavior, 23, 203-231.

Pruitt, D. G., & Kimmel, M. J. (1977). Twenty Years of Experimental Gaming:

Critique,Synthesis, and Suggestions for the Future. Annual Review of

Psychology, 28, 363-392.

Rapoport, A. (1987). Research paradigms and expected utility models for the provision

of public goods. Psychological Review, 94, 74-83.

Sober, E., & Wilson, D. S. (1998). Unto others: The evolution and psychology of

unselfish behavior. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

27

27

Taylor, M. (1976). Anarchy and cooperation. New York: Wiley.

Trivers, R. (1971). The evolution of reciprocal altruism. Quarterly Review of Biology,

46, 35-57.

Walker, J., & Halloran, M. A. (2004). Rewards and sanctions and the provision of

public goods in one-shot settings. Experimental Economics, 7, 235-247.

Watabe, M., Terai, S., Hayashi, N., & Yamagishi, T. (1996). Cooperation in the one-

shot prisoner's dilemma based on expectations of reciprocity. Japanese Journal

of Experimental Social Psychology, 36, 183-196.

Yamagishi, T. (1986). The provision of a sanctioning system as a public good. Journal

of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 110-116.

Yamagishi, T. (1988). Seriousness of social dilemmas and the provision of a

sanctioning system. Social Psychology Quarterly, 51, 32-42.

Yamagishi, T. (1992). Group size and the provision of a sanctioning system in a social

dilemma. In W. B. G. Liebrand, D. M. Messick & H. Wilke (Eds.), Social

dilemma: Theoretical issues and research findings (pp. 267-287). Oxford, UK:

Pergamon Press.