265

H

umans not only live incredibly social lives,

but they also live incredibly prosocial

lives. Biologists and social scientists have long

marveled at the human ability to join together in

efforts to produce public goods that could not be

achieved by any single person alone. The abil-

ity for humans to cooperate, that is, to engage

in behaviors that benefit others (sometimes

even at a cost to oneself), underlies some of the

most notable human accomplishments. Yet co-

operation can sometimes be very challenging

for individuals in a group (or between groups)

because some situations can contain a conflict

of interest, such that it is in each individual’s

immediate self-interest to free ride and take

advantage of others’ cooperation (i.e., social

dilemmas; De Dreu, 2010; Fehr, Fischbacher,

& Gächter, 2002; Van Lange, Rockenbach, &

Yamagishi, 2014).

For decades theorists and researchers have

attempted to understand why humans cooper-

ate in social dilemmas (Dawes, 1980; Komorita

& Parks, 1995; Pruitt & Kimmel, 1977; Van

Lange, Balliet, Parks, & Van Vugt, 2014). One

of the most long-standing traditions has been

from a biological perspective. According to

Darwinian theory of evolution, a species cannot

evolve to be cooperative unless there are sur-

vival and reproductive benefits from coopera-

tion, and cooperative traits must compete with

noncooperative alternatives, which can result in

potentially greater fitness benefits if social in-

teractions are modeled as a social dilemma (see

Rand & Nowak, 2013). This problem of coop-

eration has attracted some of the greatest minds

across a number of scientific disciplines in the

biological and social sciences.

Since the 1960s, many theories have been

proposed to explain why humans evolved to

cooperate. Hamilton (1964) formalized the idea

that cooperating with kin can increase the rep-

lication of one’s own genes by increasing the

chance of survival and reproduction of others

who share one’s genes (i.e., inclusive fitness).

This was followed by Trivers’s (1971) model

that people may cooperate with others from

whom they expect future cooperation (i.e., di-

rect reciprocity). With direct reciprocity, actors

receive (sometimes delayed) benefits directly

from the individual they helped. Several addi-

tional candidate models have been forwarded

in more recent years, including costly signaling

(Gintis, Smith, & Bowles, 2001), generalized

reciprocity (Pfeiffer, Rutte, Killingback, Ta-

borsky, & Bonhoeffer, 2005), and gene–culture

coevolution (Richerson et al., 2016).

CHAPTER 14

Indirect Reciprocity, Gossip,

and Reputation-Based Cooperation

Daniel Balliet

Junhui Wu

Paul A. M. Van Lange

VanLange_Book.indb 265VanLange_Book.indb 265 6/30/2020 11:17:37 AM6/30/2020 11:17:37 AM

266 I. PRINCIPLES IN THEORY

In this chapter, we draw attention to a model

of how humans evolved to cooperate (and also

avoid interactions with noncooperators)—rep-

utation-based indirect reciprocity—and this

model carries rich potential for understanding

some basic cognitive and motivational process-

es underlying social behavior. Indirect reciproc-

ity involves two events: (1) An actor extends a

benefit (or not) to a recipient and (2) a third party

obtains knowledge of the actor’s behavior and

decides to cooperate (or not) with the actor at

some point in the future (Alexander, 1987/2017;

Boyd & Richerson, 1989; Nowak & Sigmund,

1998b). An essential element for indirect reci-

procity to occur is that a third party directly

observes the interaction between the actor and

the recipient or learns about the actor’s behavior

through communication, such as gossip. Direct

and indirect reciprocity vary in how an actor

acquires benefits from his or her own coopera-

tion. Direct reciprocity occurs when the recipi-

ent of the benefit of a cooperative action returns

a benefit to the cooperative actor. Indirect reci-

procity, on the other hand, occurs when anyone,

except for the recipient of the benefit of a co-

operative action, delivers a benefit to the coop-

erative actor. Direct and indirect reciprocity can

also involve responding to others’ noncoopera-

tive actions by imposing either direct or indirect

costs on the noncooperative actor, respectively.

In this chapter, we focus on indirect reciprocity

and reputation-based cooperation. Indirect reci-

procity could be a unique evolutionary pathway

to human cooperation, although a few examples

suggest that indirect reciprocity can also occur

in other species, such as cleaner fish (Bshary

& Grutter, 2006) and song sparrows (Akçay,

Reed, Campbell, Templeton, & Beecher, 2010).

Regardless, the capacity for language has en-

abled humans to exploit this route to coopera-

tion in large groups of genetically unrelated

individuals (Dunbar, 2004).

Although much of the theoretical work on

indirect reciprocity emerged from the biologi-

cal sciences, the topic of indirect reciprocity

is now widely studied by a growing number of

scientists across numerous disciplines, includ-

ing behavioral economics and psychology. They

have studied (1) the influence of indirect reci-

procity on cooperation in the lab and field, (2)

environmental conditions that facilitate indirect

reciprocity, and (3) the proximate psychological

processes that underlie this human ability. Our

purpose in this chapter is to integrate biological,

economic, and psychological research on how

indirect reciprocity facilitates cooperation. In

doing so, we use models in evolutionary biolo-

gy to generate insights about how humans have

evolved to engage in reputation-based indirect

reciprocity and discuss ideas and research about

the proximate psychological mechanisms oper-

ating to make this form of cooperation possible.

Evolutionary Dynamics, Direct

Reciprocity, and Indirect Reciprocity

With the exception of species that reproduce

incredibly fast (e.g., fruit flies), we cannot ob-

serve how the process of evolution selects for

the adaptive design of a species. Because it can

be exceedingly difficult, or even impossible, to

study the process by which evolution shapes

organisms, scientists have resorted to creating

their own “organisms” (i.e., agents) in computer

programs. Agent-based modeling is an ap-

proach used to study how evolutionary dynam-

ics can select for certain behavioral strategies in

a population of agents. This method has become

incredibly popular over the last few decades and

has yielded several valuable insights about how

evolution could have shaped human social be-

havior (Nowak, 2006).

The models always begin with a population

of agents that have preprogrammed behavioral

strategies (e.g., always cooperate, always de-

fect, tit for tat, and win–stay, lose–shift), and

then these agents interact with each other over

a lifespan in a situation that contains specified

outcomes. The outcome is the number of off-

spring an agent produces in a lifetime, and off-

spring always have a higher chance to inherit

the behavioral strategy of their parents. In the

context of the study of cooperation, agents are

most often specified to interact in a prisoner’s

dilemma (PD; or some variant of the PD, see

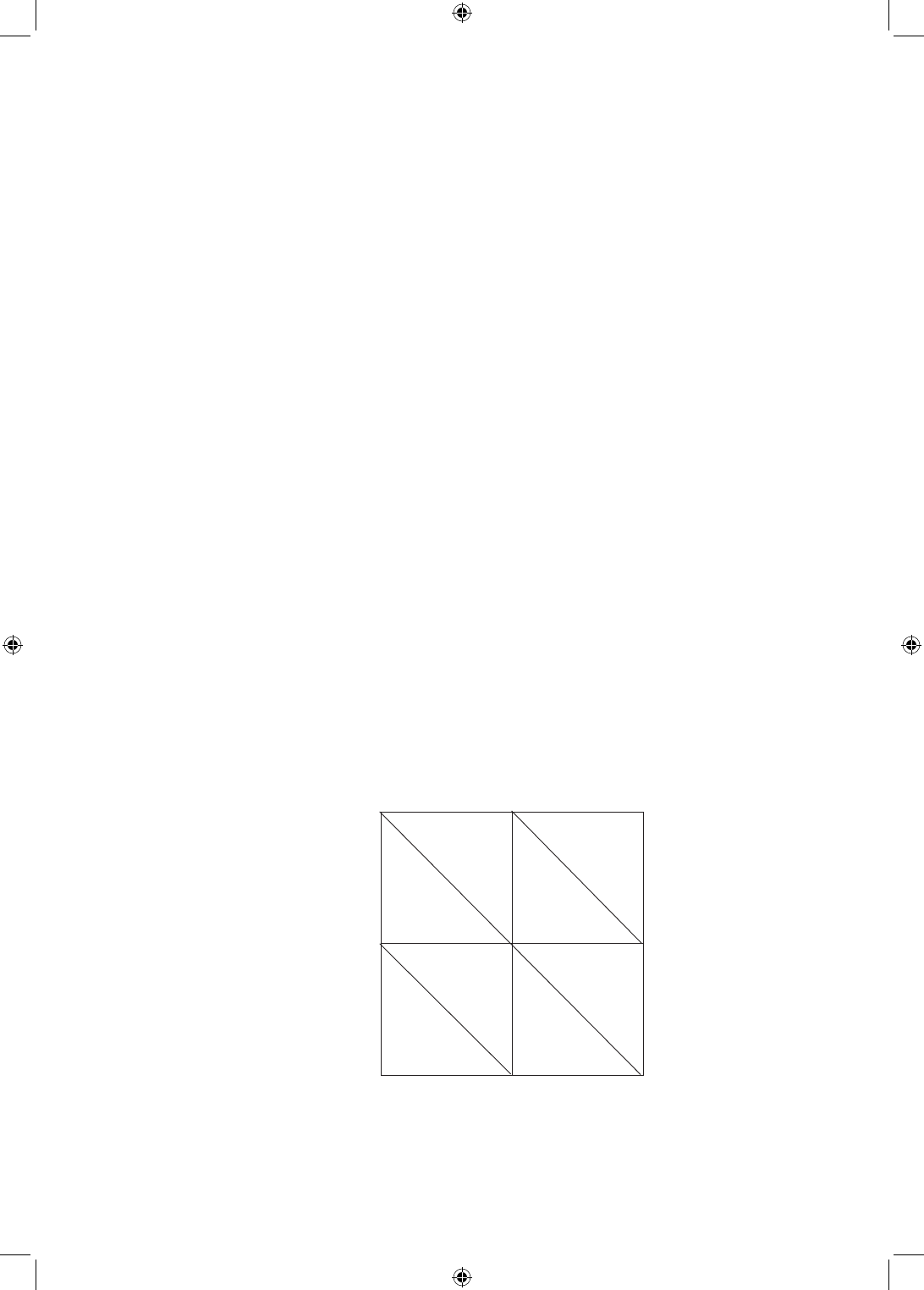

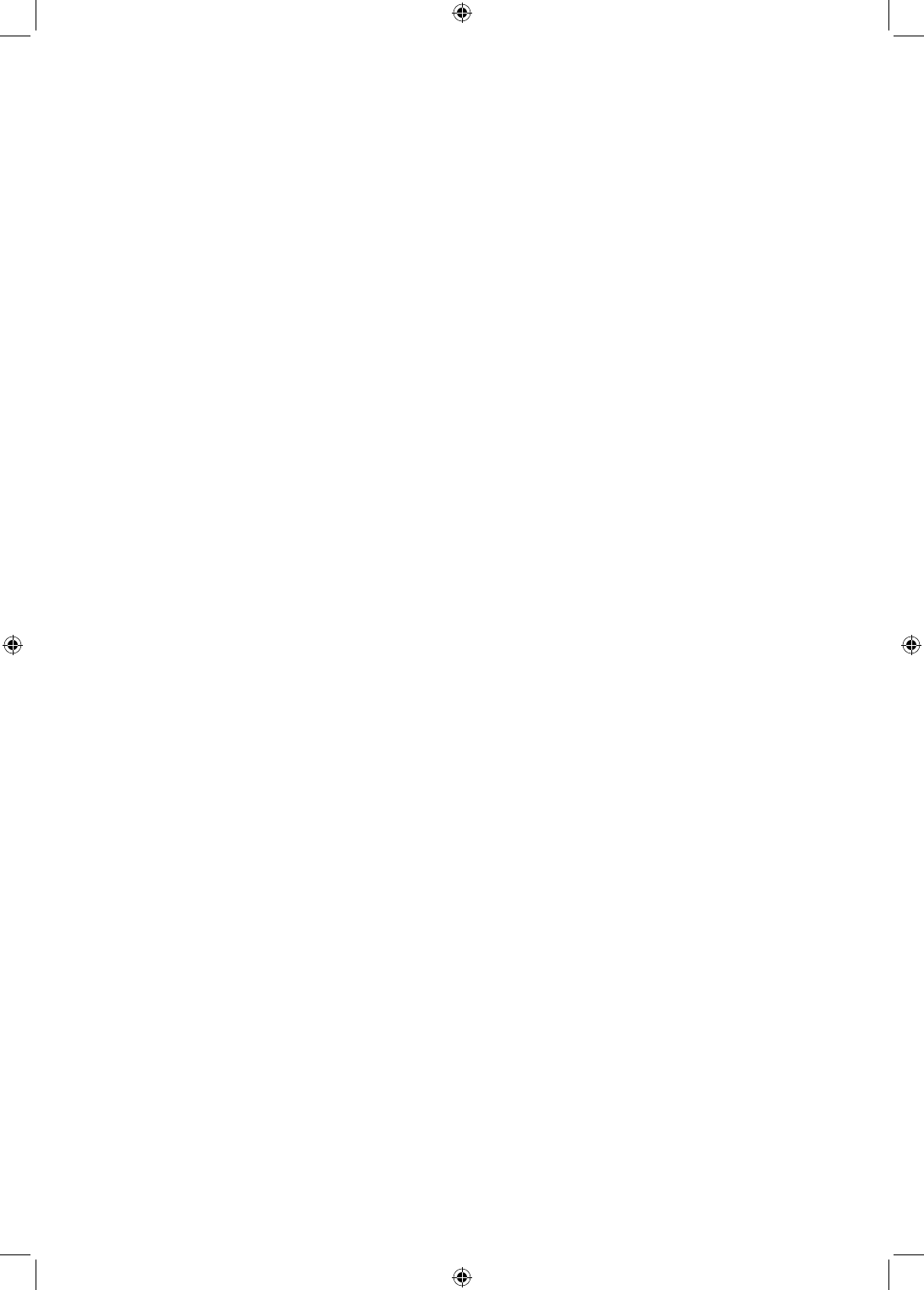

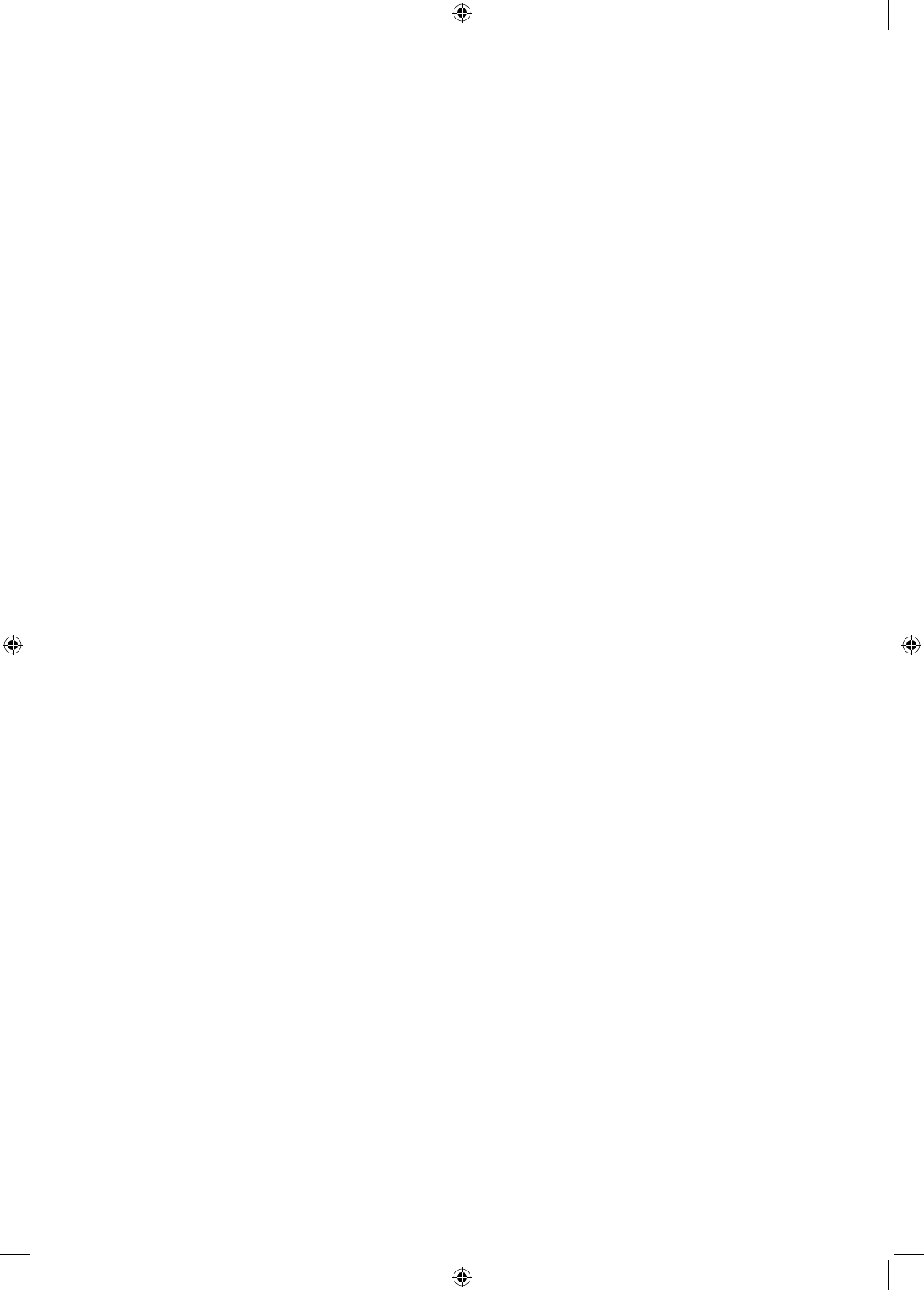

Figure 14.1). In the PD, each person can decide

to deliver a benefit (b) to the other at some cost

(c) to him- or herself. When the benefit to the

other is greater than the cost to oneself (b > c),

then both can obtain better outcomes if each

person decides to extend a benefit to the other.

However, in this type of situation, the best out-

VanLange_Book.indb 266VanLange_Book.indb 266 6/30/2020 11:17:37 AM6/30/2020 11:17:37 AM

14. Indirect Reciprocity, Gossip, and Reputation-Based Cooperation 267

come for each person can be obtained by not

paying the cost to deliver a benefit to the other,

and nonetheless receive a benefit delivered by

the partner. Thus, cooperation in the PD is mu-

tually beneficial, but it is always vulnerable to

exploitation and free riding by noncooperators.

A corpus of literature has formed around un-

derstanding the behavioral strategies that can

successfully maintain cooperation in a species

and are robust to invasion by noncooperators

(for reviews, see Nowak, 2006; Rand & Nowak,

2013; West, Griffin, & Gardner, 2007).

These models have generated support and

insights about behavioral strategies of direct

reciprocity in a population characterized by

repeated encounters. Early modeling work

demonstrated that the simple rule of tit for tat

(i.e., cooperate first, then follow one’s part-

ner’s previous behavior) outperformed many

other more complex strategies (Axelrod, 1984).

Subsequent modeling work discovered another

strategy that outcompeted tit for tat—win–stay,

lose–shift (i.e., cooperate only if both players

had the same behavior on the previous round;

Nowak & Sigmund, 1993). Yet these strategies

can make costly errors in environments where

people sometimes intend to cooperate but end

up defecting. In these environments, a more for-

giving tit-for-tat strategy (i.e., cooperates once

again after a partner defects, but then defects

after a partner’s second defection; tit for two

tats; Wu & Axelrod, 1995) is more successful.

Also, adding some generosity to the tit-for-tat

strategy can be effective in “noisy” environ-

ments in which it is not always certain that an

intended choice results in actual choice (Kol-

lock, 1993). Indeed, changing parameters of the

environment itself (e.g., the situation is noisy or

not) or the social environment (i.e., the strate-

gies followed by others) can affect which strat-

egy is most successful. Thus, modeling work

can benefit from attempting to make plausible

assumptions about the ancestral conditions in

which humans evolved to cooperate (Tooby &

Cosmides, 1996).

The modeling work reported here provides us

insights about how evolution may have shaped

certain strategies of cooperation that could ac-

quire direct benefits, and still prevent a popu-

lation from being invaded and exploited by

defectors. The models can be used to generate

hypotheses about different adaptions humans

could have developed to regulate their coop-

eration to acquire direct benefits (see Delton,

Krasnow, Cosmides, & Tooby, 2011), such as

cheater detection (Cosmides, Barrett, & Tooby,

Cooperate

Not Cooperate

Player B

Cooperate

Not Cooperate

Player A

b – c

b – c

b

– c

– c

b

0

0

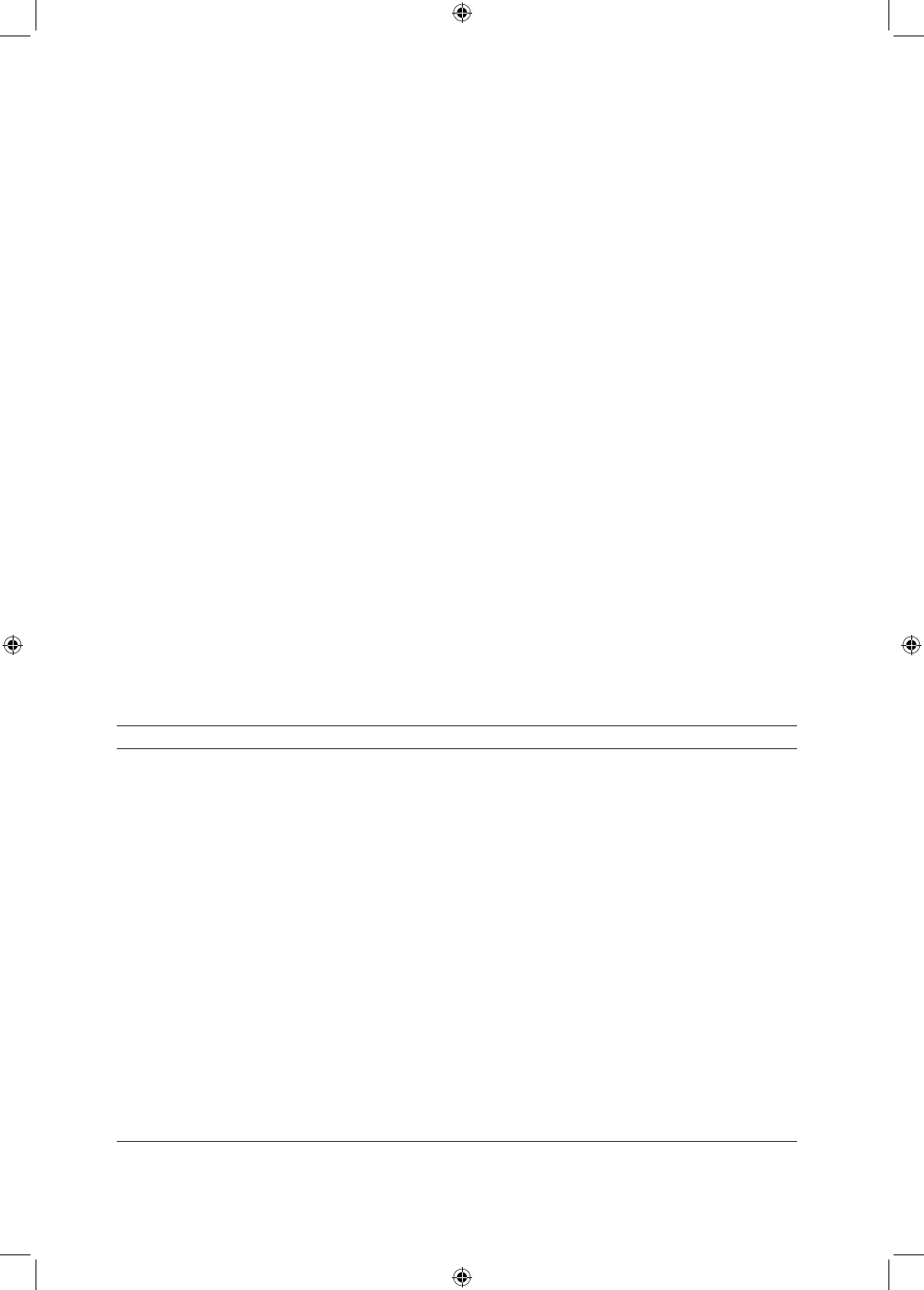

FIGURE 14.1. The interdependence structure of a prisoner’s dilemma. Cooperation means delivering

a benefit (b) to one’s partner at a cost (c) to oneself (b > c).

VanLange_Book.indb 267VanLange_Book.indb 267 6/30/2020 11:17:38 AM6/30/2020 11:17:38 AM

268 I. PRINCIPLES IN THEORY

2010), revenge and forgiveness (McCullough,

Kurzban, & Tabak, 2013), gratitude (Ma, Tun-

ney, & Ferguson, 2017), generosity (Van Lange,

Ouwerkerk, & Tazelaar, 2002), and inferences

about future interactions (Delton et al., 2011).

Similarly, agent-based models have also pro-

vided insights about how evolution may have

shaped the way humans engage in indirect reci-

procity and its role in the maintenance of large-

scale cooperation. Nowak and Sigmund (1998a,

1998b) found that indirect reciprocity can evolve

if agents have knowledge about how their part-

ners have behaved toward others in previous

interactions (i.e., image score), then condition

their behavior on their partners’ past behavior.

In this modeling work, in each round of inter-

actions between agents, agents were randomly

assigned to be a donor or a receiver. The donor

could decide to pay a small cost to provide the

receiver with a larger benefit. Each donor would

receive a positive point for each helping behav-

ior and a negative point for each failure to help.

Cooperation evolved when agents assigned as

donors conditioned their decisions to help based

on the recipients’ image score (i.e., only help if

the recipient has a positive image score). Since

this initial work, a number of models have fur-

ther examined how different environments and

decision rules can affect the evolution of coop-

eration via indirect reciprocity (e.g., Ohtsuki &

Iwasa, 2006).

The modeling research described here serves

two complementary goals. First, modeling be-

havioral strategies of indirect reciprocity can

help us understand how humans evolved to

cooperate. Second, the modeling work can be

used to develop and test hypotheses about how

evolution could have modified the design of an

organism to cooperate to acquire direct and in-

direct benefits. Modeling evolutionary dynam-

ics can be viewed as a way to develop theories

and generate new predictions that can be test-

ed using behavioral experiments—and this is

where the modeling becomes most relevant for

psychologists.

An initial step in testing predictions from an

agent-based model is conducting behavioral ex-

periments to observe whether human behavior

varies according to how the models predict (for

a list of predictions generated by specific agent-

based models of indirect reciprocity, see Table

14.1). For example, empirical researchers could

design lab experiments to examine whether the

possibility of punishing defectors, with the de-

cision to punish affecting one’s reputation, is

especially effective at promoting cooperation in

larger groups (e.g., groups of eight vs. groups of

four; dos Santos & Wedekind, 2015).

A further step would be unpacking the abili-

ties that could have evolved to promote these

types of behavior—and this is often an entirely

different enterprise in applying evolution to

understanding human behavior, often referred

to as an adaptationist approach or evolution-

ary psychology (Tooby & Cosmides, 1992).

The agent-based models provide insights about

the evolutionary success of certain behavioral

strategies, but the models are agnostic about

the actual psychological mechanisms that could

have evolved through the process of evolution

to promote such behaviors. Importantly, evolu-

tion does not select for organisms to engage in

a specific behavior. Instead, the outputs of the

evolutionary process are psychological mecha-

nisms that process input from the environment

and produce behavior. Interestingly, there has

been much more agent-based modeling work on

the role of indirect reciprocity on cooperation

compared to an adaptationist approach. Much

of what comes next is a discussion of the pos-

sible psychological mechanisms that could be

operating to enable indirect reciprocity to pro-

mote large-scale cooperation. Yet prior to dis-

cussing the proximate psychology of indirect

reciprocity, we take a moment to consider re-

cent work that has documented the phenomenon

that people actually engage in indirect reciproc-

ity in their daily lives and in controlled lab en-

vironments.

Indirect Reciprocity in the Field

Agent-based modeling of the evolution of in-

direct reciprocity suggests that humans could

have adaptations that regulate their cooperative

behavior in a way that is structured according

to indirect reciprocity. One of the first steps in a

program of research on this topic is to document

that humans in fact do behave in ways that look

like indirect reciprocity, and a number of recent

field studies give us insights in this matter.

VanLange_Book.indb 268VanLange_Book.indb 268 6/30/2020 11:17:38 AM6/30/2020 11:17:38 AM

14. Indirect Reciprocity, Gossip, and Reputation-Based Cooperation 269

TABLE 14.1. Examples of Testable Hypotheses about Human Behavior Derived

from Agent-Based Modeling on Indirect Reciprocity

Study Model description Hypotheses

dos Santos &

Wedekind (2015)

Computer simulations tested two

reputation systems (reputation

based on cooperative and

noncooperative actions and

reputation based on punitive and

nonpunitive actions) in a public

goods game involving groups of

unrelated individuals.

Compared to reputation systems based on

cooperation, reputation systems based on

punishment (1) are more likely to lead to the

evolution of cooperation in larger groups, (2)

more effectively sustains cooperation within

larger groups, and (3) are more robust to errors

in reputation assessment.

Leimar &

Hammerstein (2001)

Simulations tested how

cooperation evolves through two

indirect reciprocity strategies

(i.e., image scoring and standing

strategy).

(1) Image scoring strategies enhance

cooperation only when the cost of

cooperation is small.

(2) Standing strategy outperforms image

scoring even when there are errors in

perception.

Roberts (2008) Evolutionary simulations

compared indirect reciprocity

strategies (i.e., image scoring

and simple standing) with

direct reciprocity strategies in

large groups with less repeated

interactions and in small groups

with more repeated interactions.

(1) As probability of repeated interactions

increases, indirect reciprocity through image

scoring becomes less stable in promoting

cooperation than direct reciprocity by

experience scoring.

(2) Indirect reciprocity through standing

strategy is as stable as direct reciprocity in

promoting cooperation when individuals

have repeated interactions with few partners.

Sasaki, Okada, &

Nakai (2017)

An evolutionary analysis

compared a simple “staying” norm

with other prevailing social norms

that discriminate the good and the

bad.

Staying is most effective in establishing

cooperation than other social norms that rely

on constant monitoring and unconditional

assessment (i.e., scoring, simple-standing,

stern-judging, and shunning).

a

Giardini, Paolucci,

Villatoro, & Conte

(2014)

An agent-based simulation

assessed how cooperation rates

change when agents can punish

others or know others’ reputation

and then defect with free riders or

refuse to interact with them.

(1) Both punishment and reputation-based

partner selection are effective in maintaining

cooperation.

(2) Cooperation decreases when people defect

after learning about free riders’ reputations.

(3) A combination of punishment and

reputation-based partner selection leads to

higher cooperation rates.

Giardini & Vilone

(2016)

An agent-based model tested the

conditions under which gossip

and ostracism might enhance

cooperation in groups of different

sizes by addressing the effects

of quantity and quality of gossip,

network structure, and errors in

gossip transmission.

(1) Cooperation is more likely to thrive in

larger groups when the amount of gossip

exchanged is abundant.

(2) Inclusion errors (i.e., one’s negative

reputation is understood as positive) in

gossip transmission are more detrimental

to cooperation than exclusion errors (i.e.,

one’s positive reputation is understood as

negative).

a

Staying = the reputation of a person who gives help stays the same as in the last assessment if the recipient has a bad reputation;

scoring (or image scoring) = people lose reputations anytime they fail to help someone in need; simple standing (or standing strat-

egy) = reputation declines when one fails to help someone with a good reputation; stern judging = people lose reputations when they

help someone with a bad reputation or fail to help a person with a good reputation; shunning = people gain a good reputation only

when they help someone with a good reputation; otherwise they lose a good reputation.

VanLange_Book.indb 269VanLange_Book.indb 269 6/30/2020 11:17:38 AM6/30/2020 11:17:38 AM

270 I. PRINCIPLES IN THEORY

In a field study with 2,413 residents, re-

searchers collaborated with a utility company

to examine participation in a program to pre-

vent blackouts during high electricity demand

(Yoeli, Hoffman, Rand, & Nowak, 2013). They

found that participation rate was tripled when

residents’ identities were observable (vs. con-

cealed) on the sign-up sheet, and this positive

effect of observability was four times larger

than that of monetary reward. More important-

ly, observability had a larger effect for home-

owners (vs. temporary renters) and people liv-

ing in apartments (vs. houses), as they tend to

have longer-term relationships with neighbors.

In this study, we clearly see that people are more

cooperative when their behavior is observable,

and so can affect their reputation within their

social network.

Similarly, van Apeldoorn and Schram (2016)

examined indirect reciprocity in a field ex-

periment utilizing an online platform in which

people can ask and offer services to each other

for free. They created new member profiles that

vary in serving history (i.e., “serving” or “neu-

tral” profile), then sent out service requests to

worldwide members. People were more likely to

reward a service request from someone who had

previously offered services to others. Another

natural field experiment conducted in a hair

salon revealed that customers tended to offer

more tips to hairdressers who were collecting

donations to a charity, compared to doing noth-

ing (Khadjavi, 2016). These studies support the

idea that people are more cooperative with oth-

ers who have a cooperative reputation.

In fact, people are strongly influenced by in-

formation about others’ reputations, even more

so than information about their similarity with

others. Abrahao, Parigi, Gupta, and Cook (2017)

conducted a large-scale online experiment with

8,906 users of Airbnb playing an interpersonal

investment game. In this game, the users had

to make trust decisions toward potential receiv-

ers whose profiles varied in distance (i.e., the

extent to which the receiver matched the demo-

graphic attributes of participants across four

categories) and two reputation features (i.e.,

the average ratings and the number of reviews

on Airbnb). The users had 100 credits that they

could keep or invest in the receivers they chose.

Any amount invested was tripled and the re-

ceiver could then decide to return some amount

to users. The authors found that people tend

to trust receivers with a better reputation even

though they are dissimilar, and this was further

confirmed when analyzing real-world data of 1

million actual hospitality interactions among

users of Airbnb.

Taken together, these field studies show that

indirect reciprocity promotes cooperation in

contexts outside of the laboratory. Specifically,

this work documents that people are willing to

(1) behave in ways that maintain a positive and

cooperative reputation and (2) condition their

cooperation on their partners’ reputations.

Indirect Reciprocity in the Lab

Several experiments using economic games

as a paradigm to study cooperation have dem-

onstrated that people do engage in indirect

reciprocity. Wedekind and Milinski (2000)

conducted a behavioral experiment with a de-

sign similar to previous modeling work (i.e.,

Nowak & Sigmund, 1998b). In this study, par-

ticipants interacted with each other in several

rounds, and in each round they were selected to

interact with a different person as a donor or a

receiver. The donor decided whether to give 2

Swiss Francs to a receiver who would then earn

four Swiss Francs. In each round, participants

(assigned a pseudonym) could see the previous

decisions made by their partners. The study

revealed that people were more likely to give

money to another person who had given money

to others in the past.

Similar experiments have revealed that peo-

ple are more likely to help others who have a

positive reputation (Engelmann & Fischbacher,

2009; Seinen & Schram, 2006; Stanca, 2009).

When people can build a reputation in a group

based on their helping behavior, then groups

display higher levels of cooperation (Milinski,

Semmann, & Krambeck, 2002). Furthermore,

when people can gossip about each other during

interactions in a repeated public goods game

(i.e., a multiperson PD), then people become

more cooperative, compared to when gossip is

not allowed (Feinberg, Willer, & Schultz, 2014;

Wu, Balliet, & Van Lange, 2015).

Of course, people may strategically build

reputations to achieve higher earnings (e.g.,

VanLange_Book.indb 270VanLange_Book.indb 270 6/30/2020 11:17:38 AM6/30/2020 11:17:38 AM

14. Indirect Reciprocity, Gossip, and Reputation-Based Cooperation 271

only help others when being observed), and

economists have been interested in empirically

distinguishing such strategic behaviors aimed

at maximizing self-interest from a motivation

to extend benefits to others who have a coop-

erative reputation. To accomplish this, Engel-

mann and Fischbacher (2009) had participants

interact in an 80-trial helping game involving

a donor and a receiver. Participants were ran-

domly assigned to be a donor or a receiver in

each trial, and had a public or private score for

the first or last 40 trials (i.e., public scores dis-

played past behaviors to current partners, and

this information was not provided to current

partners in the private score condition). This

design allowed participants to interact with oth-

ers who had private or public scores. Important-

ly, they found that people with a private score

were still willing to help others with a higher

positive public score. Thus, participants with

a private score had no strategic incentives to

condition their cooperation toward people with

a cooperative reputation, so it is unlikely that

a motivation to maximize own outcomes was

directing these behaviors. The authors take this

as evidence that people have a social preference

to help others who have a helpful and coopera-

tive reputation.

Lab studies have also examined how effec-

tive and efficient indirect reciprocity can be at

promoting cooperation. This question becomes

especially relevant when one compares gossip

(i.e., reputation sharing) with another mecha-

nism that can support cooperation: the possi-

bility to punish others’ past behavior. A prior

study revealed that gossip is more effective and

efficient than punishment (Wu, Balliet, & Van

Lange, 2016a). Although punishment can be an

effective means to promoting cooperation, pun-

ishment is costly to enact and can result in re-

taliation. Gossip, on the other hand, may be less

costly to enact and involves less exposure to the

costs of retaliation. There can be reputational

costs in gossip, but this is not always true (Fein-

berg, Cheng, & Willer, 2012).

The agent-based models suggest that indirect

reciprocity is a possible route through which

evolutionary processes shape human coopera-

tion, and now we see that both lab and field

experiments have documented that people do

engage in indirect reciprocity. However, docu-

menting the existence, effectiveness, and effi-

ciency of indirect reciprocity does not provide

an explanation for this behavioral phenomenon.

Moreover, agent-based models and economic

models do not specify the cognitive and moti-

vational processes that produce behaviors in a

system of indirect reciprocity. Currently, there

is a need to develop theories about the proxi-

mate psychological mechanisms that could be

operating to produce these forms of behavior.

An Evolutionary

Psychology Approach

Agent-based models suggest that humans could

have evolved to cooperate in a system of indi-

rect reciprocity, so an evolutionary psychology

approach can be applied to hypothesize about

the proximate psychological mechanisms that

could have evolved to produce these behav-

iors. Evolutionary psychology aims to under-

stand how different cognitive and motivational

mechanisms of the human mind have evolved

to function and produce behavior. Prior to ap-

plying this perspective, we need to understand

a few key concepts (for several reviews, see

Confer et al., 2010; Cosmides & Tooby, 2013;

for comparisons of this perspective to other ap-

proaches in the social sciences, see Tooby &

Cosmides, 1992, 2015).

An evolutionary psychology approach is

an adaptationist research program, in that re-

searchers test hypotheses about some adaptive

designs of an organism that promote a function-

al output. An adaptation has four properties: (1)

It is a system of reliably developing properties

of a species, (2) it is incorporated into the design

of an organism, (3) it is coordinated with the

structure of the environment, and (4) it causes a

functional outcome (at least increases the prob-

ability of a functional outcome within the envi-

ronment that it evolved; see Tooby & Cosmides,

2015). Adaptations must solve a problem neces-

sary for the reproduction of an organism and can

be understood as the output of the evolutionary

process. Thus, an evolutionary psychology re-

search program is largely about understanding

the adaptations that underlie and explain vari-

ability in human behavior.

To understand any single adaptation, re-

searchers need to generate hypotheses about

VanLange_Book.indb 271VanLange_Book.indb 271 6/30/2020 11:17:38 AM6/30/2020 11:17:38 AM

272 I. PRINCIPLES IN THEORY

the environment of evolutionary adaptedness

(EEA). The EEA “for a given adaptation is the

statistical composite of the enduring selection

pressures or cause-and-effect relationships that

pushed the alleles underlying an adaptation

systematically upward in frequency until they

became species-typical or reached a frequency-

dependent equilibrium” (Tooby & Cosmides,

2015, p. 25). Each adaptation would have a cor-

responding specialized EEA with which the ad-

aptation is coordinated to promote a behavior

that enhanced survival and reproductive suc-

cess within those environmental conditions.

The EEA is not a specific time or place, but it

contains the reliably recurring environmental

challenges and opportunities that gave rise to

the adaptation. Thus, an evolutionary psychol-

ogy program of research generally tests hypoth-

eses about an adaptive psychological mecha-

nism that enables a specific behavior, and uses

knowledge and assumptions about the EEA

to generate hypotheses about how the adapta-

tion (i.e., proximate psychological mechanism)

might work to produce the behavior. Further-

more, this approach can be used to forward hy-

potheses about how an adaptation that evolved

to function for one purpose can be exapted and

applied to a different purpose (Andrews, Gan-

gestad, & Matthews, 2002; Buss, Haselton,

Shackelford, Bleske, & Wakefield, 1998). The

distinction between adaptations and exaptations

may be especially important in understanding

the emergence of indirect reciprocity, and how

the phylogenetically older psychological mech-

anisms that evolved for direct reciprocity could

be exapted to enable indirect reciprocity.

In the following sections, we break down a

system of indirect reciprocity into its most sim-

ple elements—three persons in a social network.

We discuss specific potential adaptive challeng-

es and opportunities in the EEA for each person

in this network and hypothesize about possible

adaptations that motivate fitness-enhancing be-

haviors to resolve those adaptive problems.

Emergence of Indirect Reciprocity

in the EEA

Humans lived in small hunter–gatherer groups

prior to the advent of agriculture, and it is

thought that many human adaptations for co-

operation have arisen from reliably recurring

opportunities and challenges before and dur-

ing this period. Research comparing humans

to chimps and bonobos suggests that a common

ancestor may have already possessed some key

adaptations for cooperation, such as for direct

reciprocity—to help others who are helpful to

you, and not help those who did not help you

(De Waal, 2008; Jaeggi, Stevens, & Van Schaik,

2010; Warneken & Tomasello, 2006). Adapta-

tions for direct reciprocity could have provided

the foundation for indirect reciprocity to emerge

in human societies.

Direct reciprocity can be an effective strat-

egy to maintain cooperation in small groups

in which people will interact with each other

in the future, can observe everyone’s behav-

ior, and share a history with each interaction

partner. However, direct reciprocity may face

difficulties in sustaining cooperation in larger

groups, or at least indirect reciprocity would

enable people to more effectively avoid costly

interactions with noncooperators (even during

the first encounter), and to capture even greater

benefits from cooperation by netting not only

direct but also indirect benefits in larger groups.

Furthermore, language was likely a key ability

that amplified the benefits of indirect reciproc-

ity. Language enabled people to communicate

their own social interaction experiences with

many others, and this information could be used

as an input to learn about others’ past behavior,

to update reputations, and to condition coop-

eration (Dunbar, 2004). Thus, as human groups

expanded in size, this increased the frequency

of people having valuable first-encounter in-

teractions and decreased the ability to directly

observe all possible interaction partners. These

changes in the social ecology, along with an

enhanced ability for language, were key con-

ditions that amplified the indirect benefits of

cooperation and paved the way for indirect reci-

procity, thereby enabling natural selection to

shape psychological mechanisms functionally

specialized for this structure of social interac-

tions.

How did indirect reciprocity become a major

force shaping human social behavior? One

critical action in a system of indirect reciproc-

ity involves one person cooperating or not with

another person, and this would have been oc-

VanLange_Book.indb 272VanLange_Book.indb 272 6/30/2020 11:17:38 AM6/30/2020 11:17:38 AM

14. Indirect Reciprocity, Gossip, and Reputation-Based Cooperation 273

curring deep into our ancestral past, and beyond

a common ancestor we share with the other

great apes. Therefore, it is possible that indirect

reciprocity takes hold when people learn about

others’ reputation and condition their behavior

toward others based on that reputation (as op-

posed to previous direct experience or benefits).

As mentioned earlier, humans likely had adap-

tations for direct reciprocity, and these preexist-

ing psychological mechanisms could have been

exapted to acquire input from others’ experi-

ences shared via language. Language enabled

people to communicate their experiences with

many others, and if people conditioned their co-

operation toward the actor based on this input,

then this enabled opportunities for people to

behave in ways to affect their reputations and

receive indirect benefits. This perspective pre-

dicts that at least some adaptations for direct

reciprocity, such as abilities for cheater detec-

tion and welfare tradeoffs (Cosmides, 1989;

Cosmides & Tooby, 1992; Sznycer, Delton,

Robertson, Cosmides, & Tooby, 2019), could

use language as input to condition cooperation

and partner selection.

Once humans were able to share informa-

tion with each other, then use that informa-

tion to condition their cooperation, this form

of structured interactions would have enabled

natural selection to operate on functionally

specialized abilities to (1) condition behavior

to acquire indirect benefits, (2) share informa-

tion to acquire direct benefits (since gossip has

value to interaction partners), and (3) evaluate

gossip and use it to select cooperative partners

and condition cooperation. An important line

of future research may consider understand-

ing what adaptations for direct reciprocity

have been exapted for indirect reciprocity and

which, if any, adaptations are unique to indi-

rect reciprocity. This line of research will need

to clearly delineate the different adaptive chal-

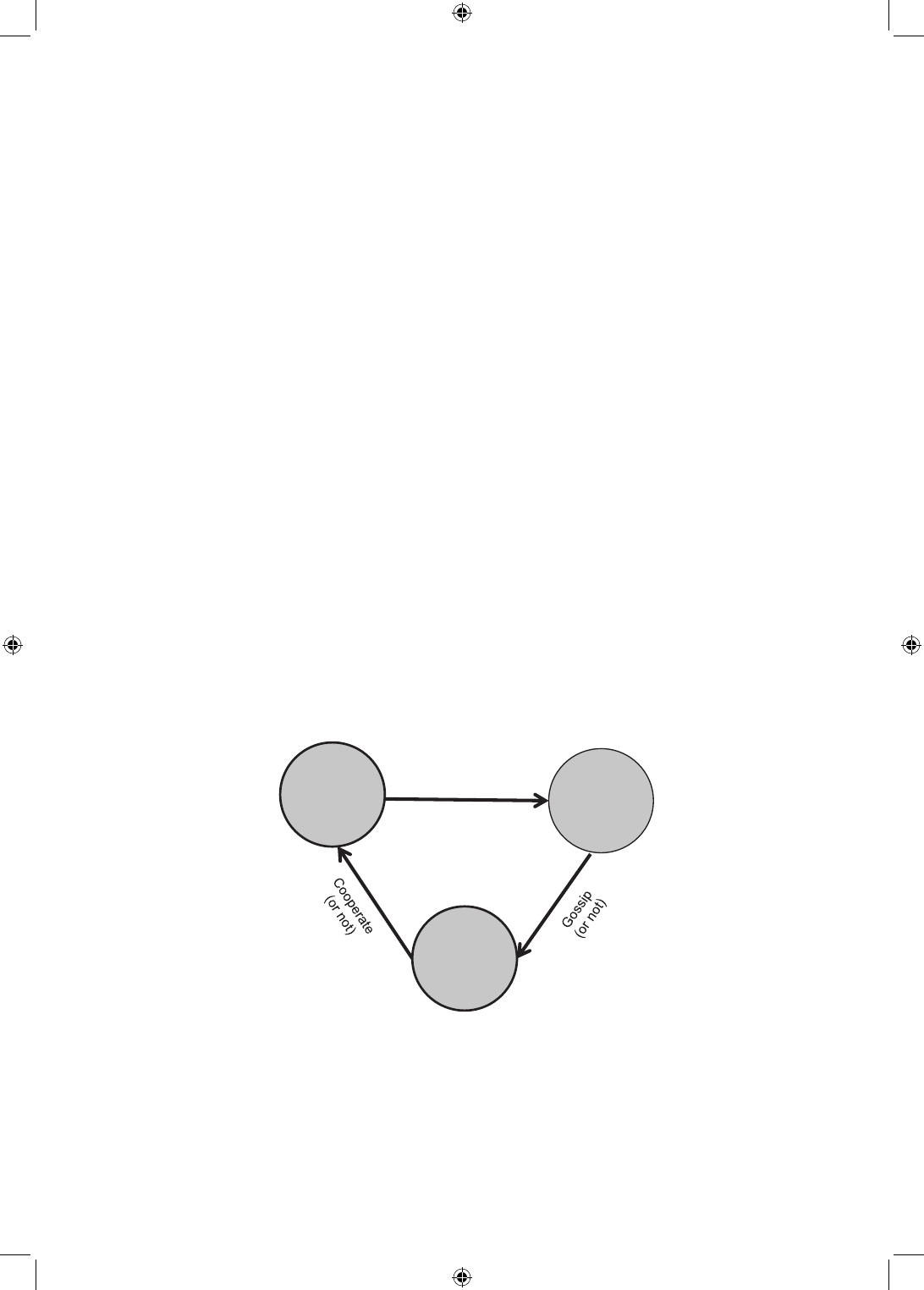

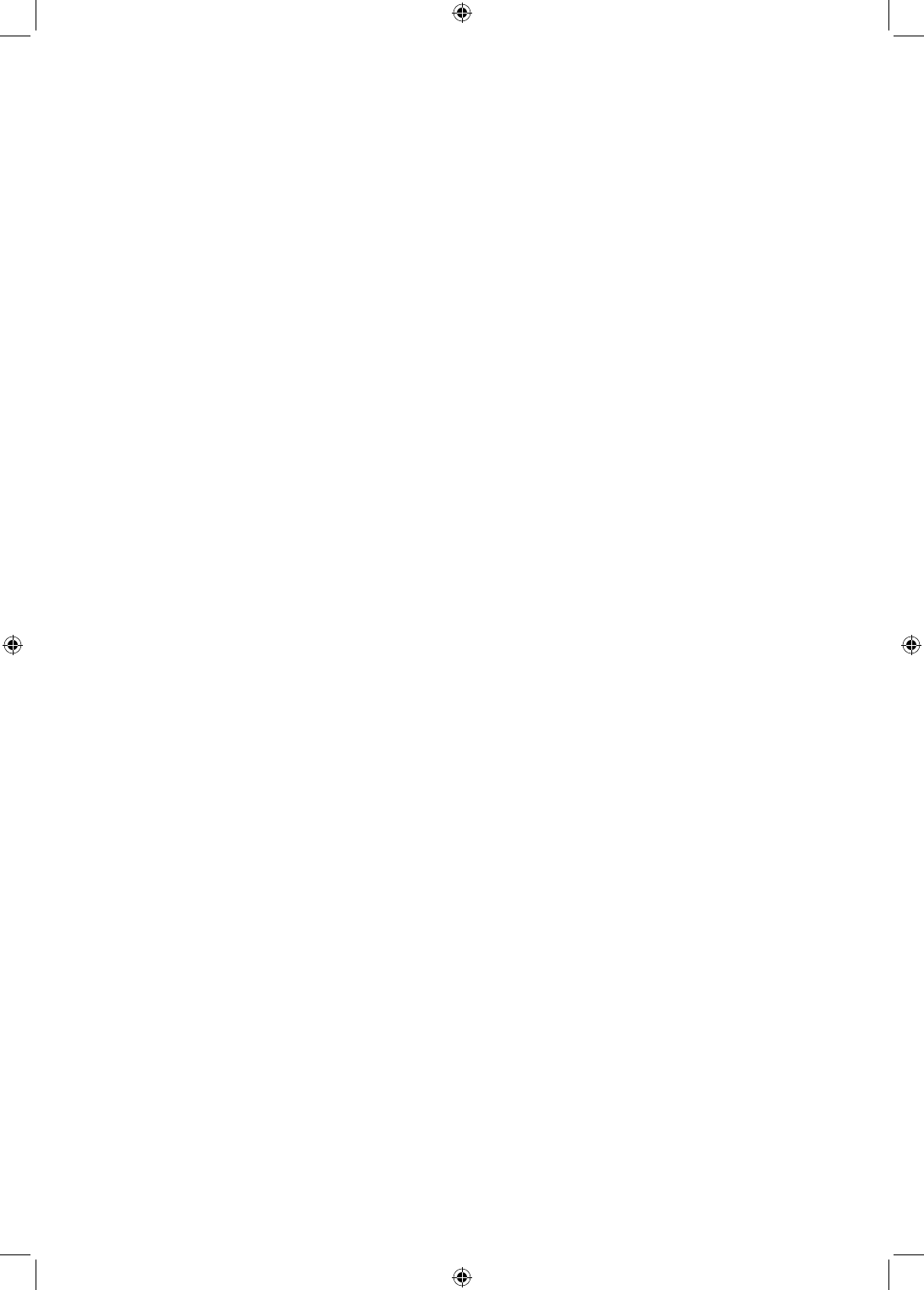

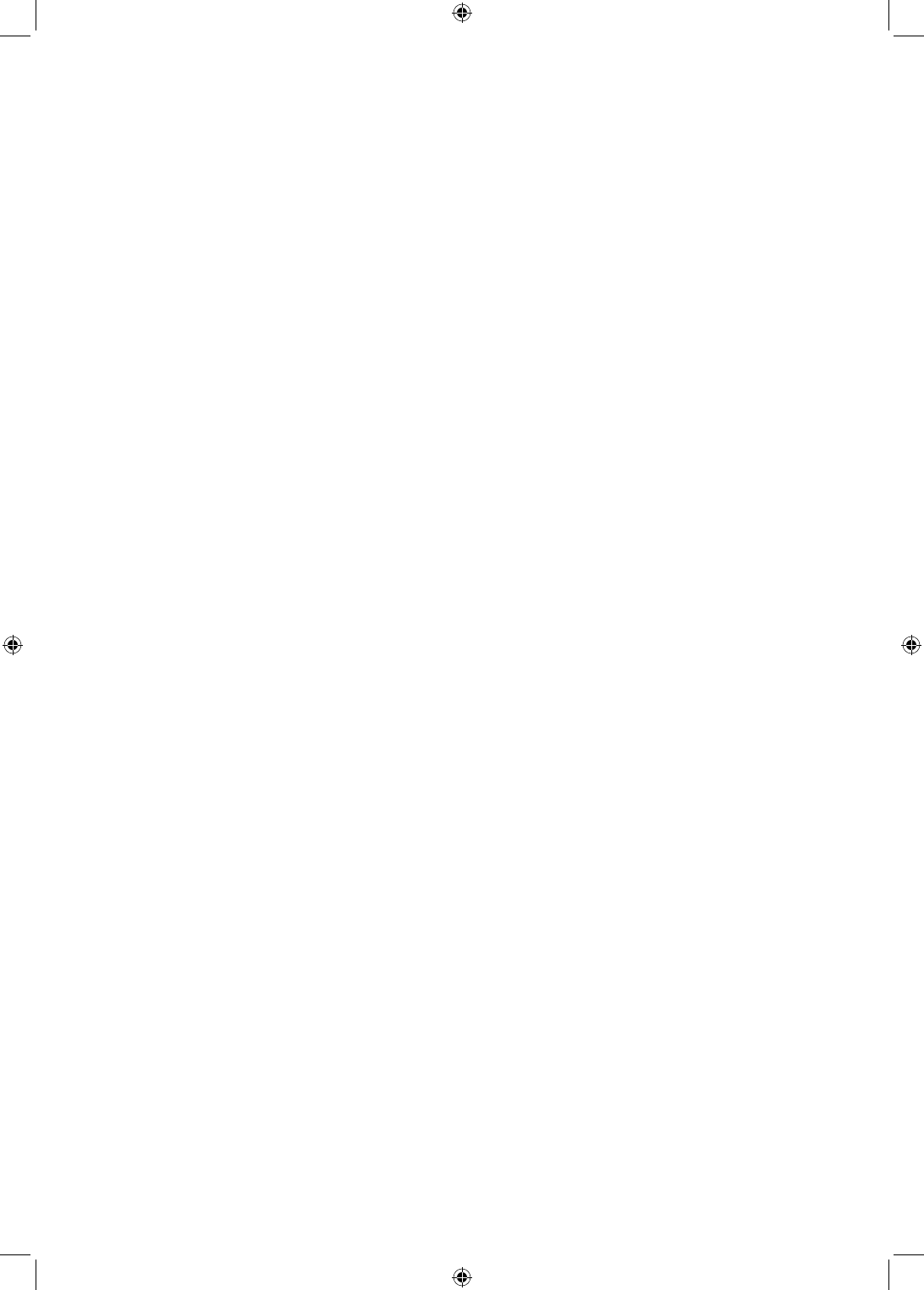

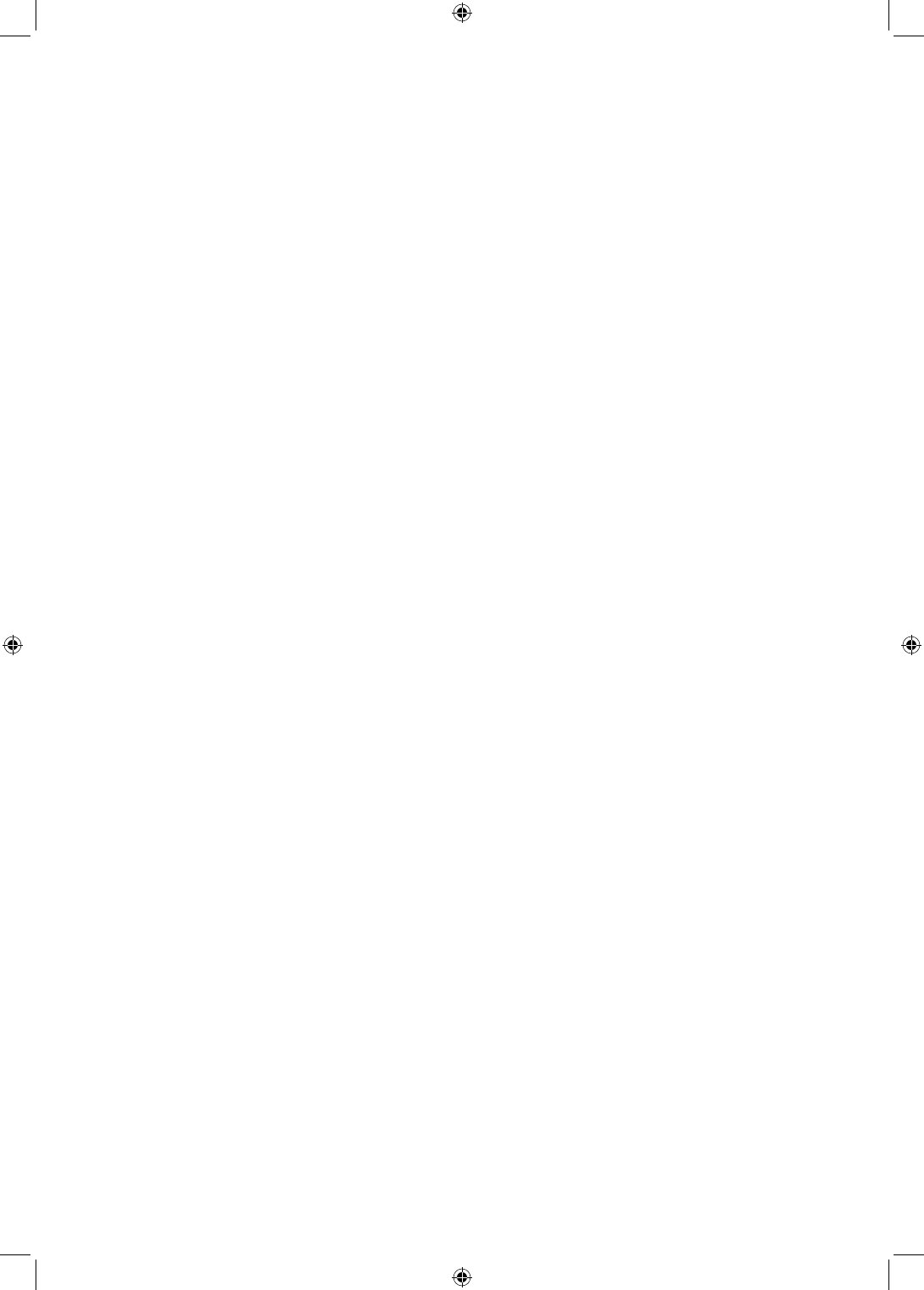

lenges of a system of indirect reciprocity. Fig-

ure 14.2 displays the essential components of

a system of indirect reciprocity and identifies

distinct adaptive challenges that can occur for

different persons within the network. Next, we

discuss the different adaptive problems, some

hypothesized solutions, and relevant research

on these topics.

FIGURE 14.2. Indirect reciprocity and adaptive problems faced by the actor, recipient, and third party.

Recipient

How to capture indirect benefits

How to impose indirect costs/benefits,

receive direct benefits via gossip

Update reputations of actors

Evaluate gossip veracity

Select cooperative partners

Condition cooperation on partner reputation

Cooperate

(or not)

Actor

Third

party

VanLange_Book.indb 273VanLange_Book.indb 273 6/30/2020 11:17:38 AM6/30/2020 11:17:38 AM

274 I. PRINCIPLES IN THEORY

Managing a Cooperative Reputation

(the Actor)

In a system of indirect reciprocity, cooperative

people can capture indirect benefits from others

and avoid ostracism in social interactions, and

this can offset the cost of cooperation. Thus,

conditioning cooperation in ways to acquire

these benefits and avoid these costs could be a

reliably recurring adaptive challenge. A gener-

alized learning system would have difficulty in

solving this problem because indirect benefits

can be incredibly challenging to anticipate, and

the rewards of one’s cooperative behavior can

occur a long distance in time from the actual co-

operative behaviors. In fact, to anticipate these

indirect benefits, people would need to under-

stand that the recipient would evaluate their

behavior positively, remember their behavior,

share that information with others—and espe-

cially others with whom the actor would meet

and interact in the future, that the recipients of

the gossip would use that information to form

an evaluation of the actor, that the recipients

of gossip would meet them in the future and

condition their behavior on that information,

and that the benefit received from that future

interaction would be larger than the cost of the

present cooperation. Previous research suggests

that people find this difficult to do, even when

they obtain very explicit information about how

their actions affect the recipient, that the recipi-

ent will communicate with a third person, and

that the third person has a chance to select them

as a partner (and to possibly reward them with

a larger benefit). For example, Wu, Balliet, and

Van Lange (2015b) conducted three studies in

which participants knew (or not) that a recipient

of their generous behavior could gossip about

their behavior to a third person, and that this

third person could use that information to con-

dition his or her own behavior toward them in a

future interaction. Although participants were

more cooperative when they knew their behav-

ior would be gossiped about, this increase in co-

operation was not explained by the participants’

expectation that the third person would be kind

to them in a future interaction. Perhaps the

problem of identifying opportunities to cooper-

ate to acquire indirect benefits is better solved

by a functionally specialized ability to use cues

in social interactions that would identify situa-

tions in which people could often acquire great-

er indirect benefits for their cooperation.

Social network structures can provide some

insights about situations that may result in

greater indirect benefits. Recent work has re-

vealed that several characteristics are reliably

recurring in social networks in large-scale

modern societies, as well in small-scale hunter–

gatherer societies (Apicella, Marlowe, Fowler,

& Christakis, 2012; Hamilton, Milne, Walker,

Burger, & Brown, 2007; Hill et al., 2011; Mc-

Glohon, Akoglu, & Faloutsos, 2011; Porter,

Mucha, Newman, & Warmbrand, 2005). Two

of these social network properties are that (1)

social networks are “small” and (2) some people

are better connected than others. Specifically,

in most social networks, it takes very few con-

nections to travel from one node to another, so

gossip and reputational information can easily

spread widely throughout a social network. Fur-

thermore, the number of network connections

any single individual has in a social network is

unevenly distributed, with some people having

more network connections than others. If these

properties of social networks did indeed covary

with the probability of actions translating into

indirect benefits, then it might be possible that

natural selection would favor an ability to con-

dition cooperation on the social network prop-

erties of an interaction partner (or any observer

of one’s behavior).

In order for this to be possible, there would

need to be cues that reliably covary across social

interactions that could be used to indicate which

situations are more likely to translate into indi-

rect benefits. Cues that a person is either con-

nected to one’s social network or that the person

is well connected within one’s social network

could both indicate opportunities for indirect

benefits (Wu et al., 2016c). Previous research

indicates that people extended greater coopera-

tion and generosity to a person who could com-

municate to a future interaction partner (Wu et

al., 2015), and that people were more generous

toward others who could communicate with a

greater number of their possible future interac-

tion partners (Wu et al., 2016c). Thus, initial

evidence provides support for the idea that cues

that covary with network properties may be

used to condition cooperation to acquire indi-

rect benefits. Similarly, Yamagishi, Jin, and Ki-

VanLange_Book.indb 274VanLange_Book.indb 274 6/30/2020 11:17:38 AM6/30/2020 11:17:38 AM

14. Indirect Reciprocity, Gossip, and Reputation-Based Cooperation 275

yonari (1999) suggested that people use group

membership as a cue of a shared social network,

and that cooperation with ingroup members is a

strategy to acquire indirect benefits.

Another possible cue for indirect benefits is

observability. Observers may select or avoid an

actor based on the observed behavior, and ob-

servers may also gossip about what they have

witnessed. Prior research indicates that reduc-

ing anonymity tends to increase cooperation

(Andreoni & Petrie, 2004; Wang et al., 2017),

and researchers have argued that this effect may

be due to reputational concerns (e.g., Sparks &

Barclay, 2013). Watching eyes, such as a pair

of eyes on a computer screen when people are

making decisions, have been found to enhance

generosity and cooperation (Haley & Fessler,

2005). Recent meta-analyses, however, have ei-

ther found no effect of eye cues (Northover, Ped-

ersen, Cohen, & Andrews, 2017) or discovered

only a few situations in which the effect may

be found. For example, eye cues only increase

the probability of giving but not the overall level

of generosity (Nettle et al., 2013), only increase

cooperation after brief exposure (Sparks & Bar-

clay, 2013), and the eyes need to be open and

attentive (Manesi, Van Lange, & Pollet, 2016).

Furthermore, it may be that observability af-

fects cooperation via a different process than

reputation. For example, the presence of others

may serve as a cue of being mutually dependent

on another person (Balliet, Tybur, & Van Lange,

2017). Observability is certainly a central issue

in indirect reciprocity that may have enabled a

simple form of indirect reciprocity prior to the

existence of language and sharing gossip about

others. Future research can attempt to better

understand how anonymity and observability

influence behaviors that are aimed at reputation

management, while controlling and accounting

for alternative explanations.

Two interrelated issues for future research on

reputation management are (1) how to manage

several dimensions of reputation and (2) how

the social ecology shapes the strategies people

use to manage their reputation. Modeling and

experimental research on cooperation has tend-

ed to focus on how people can form cooperative

reputations, but reputations can be multifaceted

and track many other traits and characteristics

of people (e.g., dominance, competence, and

mate value). Recent work in our lab had people

describe their daily-life events about which they

either shared or received gossip (Dores Cruz et

al., 2018). We found that the gossip people re-

ported in their daily lives covers a broad range

of personal characteristics that fall into the six

broad dimensions of personality (i.e., Honesty–

Humility, Emotionality, Extroversion, Agree-

ableness, Conscientiousness, Openness to Ex-

perience) and the major dimensions of social

perception (i.e., warmth, competence, domi-

nance, and morality). One adaptive challenge in

managing one’s reputation is to understand how

a behavior would be evaluated along each of

these dimensions, as well as what characteris-

tics would be of value to future interaction part-

ners. Moreover, little is understood about how

reputation management strategies vary across

social ecologies. One possibility is that varia-

tion across societies in the opportunity costs

of forming new relationships (Thomson et al.,

2018) relates to how much people will invest in

a cooperative reputation and which traits people

attempt to communicate to others.

Gossip and Reputation Sharing

(the Recipient)

People engage in actions that directly affect

others’ outcomes, and these actions can spark

recipient evaluations and behaviors in response

to these actions and outcomes—a topic that

has been widely studied as moral evaluations,

judgment, and behavior (e.g., Skowronski &

Carlston, 1987). From an evolutionary perspec-

tive, humans may have evolved strategies in

social interactions to increase the chance of fu-

ture benefits and reduce potential future costs.

These strategies would function to shape others’

behavior that can affect one’s outcomes. One

strategy is to directly reciprocate benefits and

costs. For example, when an individual is mis-

treated, he or she may experience anger, which

mobilizes direct confrontation that can function

to adjust the transgressors’ actions in future en-

counters (e.g., become more cooperative; Sell,

Tooby, & Cosmides, 2009). An alternative strat-

egy is to share information with others who will

confer benefits and impose costs on the actor.

For example, a person who is exploited in an in-

teraction can share this experience with a third

party, who then may decide against selecting

VanLange_Book.indb 275VanLange_Book.indb 275 6/30/2020 11:17:38 AM6/30/2020 11:17:38 AM

276 I. PRINCIPLES IN THEORY

the actor as a future cooperative partner. Here

we focus on the adaptive challenges of when

and how to share information about others’ be-

havior (e.g., gossip).

Human communication via language greatly

expands the human capacity to obtain knowl-

edge about others in their social networks.

People often talk about other people, and this

is pervasive across small- and large-scale soci-

eties (see Dunbar, 2004). Previous theory has

suggested that humans may use language stra-

tegically to communicate information about

others, and especially absent third parties. For

example, people who have been treated poorly

by another could directly aggress against that

person or impose harm on him or her, but this is

a strategy that is exposed to the costs of retali-

ation. Instead, people could share information

about that person’s past behavior with others

in the absence of the actor, and the recipients

of that information could then impose costs

on the actor (i.e., indirect aggression; Archer

& Coyne, 2005) or avoid the person in the fu-

ture. Humans may have a functionally special-

ized ability to share information about others in

ways that increase the likelihood that benefits

and costs occur to others because the behavior

could indirectly enhance an individual’s repro-

ductive fitness by further enhancing the fitness

of a cooperative ally or reducing the fitness of

a previously uncooperative exchange partner

(Molho, Tybur, Van Lange, & Balliet, 2020).

Talking about others, especially in their ab-

sence, is known as gossip. Unfortunately, gos-

sip has not received extensive research atten-

tion, perhaps because it has been widely viewed

as a trivial social behavior of little consequence.

Thus, when and how people gossip about others

is an understudied topic of research, and this is

unfortunate given that theory of indirect reci-

procity provides a functional account of gossip

in regulating social relationships and that peo-

ple around the world engage in this behavior.

Research over the past few decades has ap-

proached and defined gossip in many different

ways (for an overview of definitions, see Table

14.2). Common themes across these definitions

are that gossip involves communicating infor-

mation about an absent third party (or at least

the third party is not knowledgeable of the in-

formation exchanged). Other approaches have

emphasized that the communicated information

must contain some evaluative content (e.g., Fos-

ter, 2004) and that the communication must be

TABLE 14.2. Def initions of Gossip

Reference Definition of gossip

Dunbar (2004) “conversation about social and personal topics” (p. 109)

Feinberg, Cheng, & Willer (2012) “sharing of evaluative information about an absent third party” (p. 25)

Fine & Rosnow (1978) “a topical assertion about personal qualities or behavior, usually but not

necessarily formulated on the basis of hearsay, that is deemed trivial or

nonessential within the immediate social context” (p. 161)

Fonseca & Peters (2017) “the class of speech that transmits information about the behaviors and

attributes of third parties” (p. 254)

Foster (2004) “the exchange of personal information (positive or negative) in an

evaluative way (positive or negative) about absent third parties” (p. 83)

Hess & Hagen (2006) “personal conversations about reputation-relevant behavior” (p. 339)

Noon & Delbridge (1993) “the process of informally communicating value-laden information

about members of a social setting” (p. 25)

Piazza & Bering (2008) “the mechanism by which social information (derived from direct

experience) gets transmitted to absent third parties” (p. 172)

Wittek & Wielers (1998) “the provision of information by one person (ego) to another person

(alter) about an absent third person (tertius)” (p. 189)

VanLange_Book.indb 276VanLange_Book.indb 276 6/30/2020 11:17:38 AM6/30/2020 11:17:38 AM

14. Indirect Reciprocity, Gossip, and Reputation-Based Cooperation 277

informal (Noon & Delbridge, 1993). Yet previ-

ous theory of indirect reciprocity does not spec-

ify that the information communicated needs

to be evaluative; it could simply be factual, and

neither should it have to be informal. In fact,

formal evaluations, such as an employer giving

an evaluation of an employee, is an institution-

alization of gossip—organizations understand

the functional benefits of gossip in terms of

selecting and retaining cooperative allies. We

take the perspective that gossip is the sharing

of information about a third party who is not

knowledgeable about the information exchange.

Such gossip does not need to be evaluative; it

can be simply factual and can be either formal

or informal.

There are several adaptive problems of gos-

sip, such as when, how, and with whom to

gossip to impose costs or benefits on an actor.

First, people may gossip in ways that amplify

the benefits and costs to the actor. People may

strategically share gossip with others who will

have future interactions with the target of gos-

sip, and thus may be especially likely to share

gossip with ingroup members or people who are

connected to their social network. People may

share gossip in a way that communicates attri-

butes (e.g., competence, trustworthiness) of the

target that would make him or her especially

(un)desirable as a cooperation partner to others.

People could have an ability to understand when

to share facts versus evaluations, and when to

exaggerate certain evaluations of the target.

Second, people may use gossip as a resource

in exchange for other direct benefits from the

recipients of gossip. From the perspective of

indirect reciprocity, gossip can be a valuable

resource that enables others to select mutually

beneficial, cooperative allies and avoid costly

encounters with noncooperators. Thus, people

should be willing to reciprocate the benefits re-

ceived from gossip. Indeed, previous work has

indicated that exchanging gossip can enhance

trust, reciprocity, and social bonding (Peters,

Jetten, Radova, & Austin, 2017). Furthermore,

sharing highly negative gossip about others could

make the gossiper even more vulnerable and, in-

deed, people tend to share negative gossip only

when they trust the recipient (Ellwardt, Wittek,

& Wielers, 2012; Grosser, Lopez-Kidwell, & La-

bianca, 2010). An interesting possibility is that

sharing negative gossip could especially help to

further build trust and bonding between indi-

viduals.

Third, people may gossip in ways that reduce

the likelihood of exposure and retaliation from

the target of gossip. How would people avoid the

cost of retaliation for being exposed for gossip-

ing? People should be sensitive to the qualities

of the relationship between the recipient and the

target of gossip. In particular, people may be

less likely to share negative gossip about targets

who are genetically related to the recipient or

close to the recipient. Moreover, certain quali-

ties of the recipient may increase the chance of

detection, such as the person being well con-

nected within a social network, untrustworthy,

or highly dominant. In addition, certain quali-

ties of the target, such as how well connected

the target is in his or her social network, and his

or her prestige and standing within the group,

may also increase the chance of detection.

Reputation Updating, Partner Selection,

and Conditional Cooperation

(Third Party)

Previous modeling work has clearly displayed

that sharing information about others’ behavior

in a social network can promote the evolution

of cooperation, and we recognize at least three

adaptive problems for the recipients of gossip

(i.e., third parties): (1) how to update an actor’s

reputation based on new information, (2) how to

use reputation to select and avoid partners, and

(3) how to use others’ reputations to condition

their own cooperation.

Reputation has been discussed and defined in

many ways across different literatures (for some

prominent definitions, see Table 14.3). Across

these definitions, there are some key similari-

ties and differences. Reputation can be thought

to involve information that is shared about a

person among multiple people. The information

is usually about some attribute of the person,

and possibly a corresponding evaluation of that

attribute. Many scholars theorize that reputa-

tion exists at a collective level of analysis and

refers to a shared belief and evaluation of a per-

son (Anderson & Shirako, 2008; Emler, 1990).

However, most research also acknowledges that

an individual’s evaluation of another’s actions

can contribute to shaping that person’s reputa-

VanLange_Book.indb 277VanLange_Book.indb 277 6/30/2020 11:17:39 AM6/30/2020 11:17:39 AM

278 I. PRINCIPLES IN THEORY

tion in the mind of the individual, and if shared

with others, then the individual’s evaluation

contributes to the collectively shared evalua-

tion of that person. Reputation is meaningfully

tied to social status, prestige, and one’s standing

in a social group (Tedeschi & Melburg, 1984).

Indeed, future research can more clearly delin-

eate the uniqueness of reputation beyond these

existing constructs and situate reputation in the

nomological net of existing constructs in psy-

chology.

One adaptive problem is how to form a repu-

tation of the actor based on his or her actions

toward the recipient. The actor’s reputation

would ideally enable the third party to avoid

being exploited by a noncooperator and facili-

tate selecting cooperative partners for mutually

beneficial exchange. Initial models of indirect

reciprocity tested a simple rule of assessing

reputation called image scoring (Nowak & Sig-

mund, 1998b). To assess an image score, people

just kept track of whether someone was coop-

erative (+1) or noncooperative (–1) with others

in prior interactions, then cooperate with others

having a positive image score. However, this

reputation-updating strategy may be too simple

and actually punishes a person who defects (i.e.,

refuses to cooperate) with another person hav-

ing a negative image score. An additional strat-

egy that has been modeled in previous work is

called standing strategy (i.e., assigning a nega-

tive reputation only to someone who fails to

cooperate with a cooperator; see Yamamoto,

Okada, Uchida, & Sasaki, 2017). Although this

strategy places greater demands on memory to

update reputational scores, the standing strat-

egy does not impose punishment on people who

do not cooperate with others who have been un-

cooperative in the past, and thus can distinguish

between justified and unjustified noncoopera-

tors.

Some prior research has tested whether hu-

mans use image scoring or standing strategy to

update reputations. Milinski, Semmann, Bak-

ker, and Krambeck (2001) conducted an ex-

periment to observe how people behave toward

others who cooperate, or not, with a noncoop-

erative person. They found that participants

who did not cooperate with a noncooperative

person were defected on in subsequent inter-

actions. This was taken as evidence that the

people did not take into account the interaction

partner’s reputation but used a simpler updating

rule based on an actors’ behavior (cooperate or

not). In contrast, Bolton, Katok, and Ockenfels

(2005) found that while providing information

about a partner’s past behavior (i.e., image scor-

ing) increased cooperation, there was an even

higher increase in cooperation when partici-

pants were provided with second-order infor-

mation (i.e., the partner’s previous partner’s past

action), which suggests that standing strategy

exists. Thus, it is still uncertain whether people

follow a more complicated reputation-updating

rule like a standing strategy. It has been ar-

gued that image scoring is a simpler heuristic

that avoids the problem of recursive reasoning,

for example, that a person should know his or

her partner’s (say, person A) previous behavior

toward person B, person B’s previous actions

toward person C, person C’s actions toward

person D, person D’s actions toward person E,

and so on. If any single interaction is missing,

then a person cannot adequately use a standing

strategy to update the reputation of a partner,

so this could result in an image scoring heuris-

tic as a useful, though imperfect, shortcut. That

said, an evolved ability to update reputational

information may circumvent these problems by

only searching and using input from first-order

and second-order information, and not attempt

to secure all the information about the history

of interactions (which is likely an insurmount-

able computational problem). Future research

is necessary to better understand how humans

update reputations.

People may also spread false information

about others. There can be possible benefits to

an individual to manipulate gossip to derogate

competitors and enhance one’s relative stand-

ing in a social network (Barkow, 1992; Emler,

1990). Moreover, gossip can also contain er-

rors that occur during communication (Hess &

Hagen, 2006). In order for indirect reciprocity

to promote cooperation, people need to be able

to accurately assess others’ reputations. Thus,

one adaptive problem is assessing the verac-

ity of gossip. Hess and Hagen conducted sev-

eral experiments to test cues of gossip verac-

ity and found that people perceive gossip to be

more accurate (1) when they receive the same

information from multiple independent sources

VanLange_Book.indb 278VanLange_Book.indb 278 6/30/2020 11:17:39 AM6/30/2020 11:17:39 AM

14. Indirect Reciprocity, Gossip, and Reputation-Based Cooperation 279

and (2) when there is no detectable conflict or

competition between the gossiper and the target

of gossip. Thus, it seems that people use cues

that enable them to assess the accuracy of gos-

sip, and this could be an adaptation that enabled

more accurate updating of others’ reputations

and better selection of cooperative partners.

Innovative Directions for

Future Research

Social Learning, Reputation,

and Indirect Reciprocity

Societies and groups can have social norms of

cooperation, that is, a shared set of beliefs that

people should cooperate, and that noncoopera-

tion will result in negative evaluations, punish-

ment, and ostracism from group members (Fehr

& Fischbacher, 2004). Learning social norms

and the punishment of counternormative be-

havior may account for why people choose to

cooperate with others who are cooperative and

choose to defect with or ostracize noncoopera-

tors. From this perspective, people copy, mimic,

and learn the common (and successful) behav-

iors they observe from ingroup members (Hen-

rich & Boyd, 2001)—and can be biased to es-

pecially learn from prestigious group members

(Chudek, Heller, Birch, & Henrich, 2012). This

approach offers hypotheses about when people

will choose to cooperate, and the motivations

they have for cooperating, that differ from rep-

utation-based indirect reciprocity.

For example, when people are part of a

group that contains a majority of noncoopera-

tive members, a social norm perspective would

predict that people would learn to defect. How-

ever, what would happen in this situation when

a group member interacts with a newcomer to

the group who has a cooperative reputation? To

examine this issue, Romano and Balliet (2017)

assigned participants to a group in which other

group members were always noncooperative

or cooperative with a newcomer to the group.

They also manipulated whether the newcomer

was always cooperative or not in previous in-

teractions. A social norm learning approach

predicts that people should follow the majority

group member behavior, but this research found

that people condition their behavior on their

partner’s past (and expected future) behavior

(i.e., their partner’s reputation). Moreover, when

people did conform to their group members’ be-

havior (i.e., behaving as though conforming to

a social norm), they reported doing so because

they were concerned about their reputation in

the group. Thus, people were conforming to

group member behavior in order to avoid being

negatively evaluated by ingroup members.

These findings suggest that the psychological

mechanisms of indirect reciprocity may have

greater influence on decisions to cooperate than

the psychological mechanisms underlying the

TABLE 14.3. Def initions of Reputation

Reference Definition of reputation

Anderson & Shirako (2008) “the set of beliefs, perceptions, and evaluations a community forms about

one of its members” (p. 320)

Emler (1990) “that set of judgments a community makes about the personal qualities of

one of its members” (p. 171)

Milinski (2016) “the current standing the person has gained from previous investments or

refusal of investments in helping others” (p. 1)

Stiff & Van Vugt (2008) “socially shared information about a potential interaction partner” (p. 156)

Whitmeyer (2000) “an attribute attached to actors (or perhaps objects) that signals that they

are more or less likely to be desirable for some sort of interaction than those

without the attribute” (p. 189)

Wu, Balliet, & Van Lange

(2016b)

“a set of collective beliefs, perceptions, or evaluative judgments about

someone among members within a community” (p. 351)

VanLange_Book.indb 279VanLange_Book.indb 279 6/30/2020 11:17:39 AM6/30/2020 11:17:39 AM

280 I. PRINCIPLES IN THEORY

learning of social norms. Future research can

further test the contrasting predictions of theo-

ries about social norms and indirect reciprocity,

with a focus on distinguishing the psychologi-

cal mechanisms that are hypothesized to under-

lie each of these phenomena.

One line of inquiry can test to what extent

a general learning ability can account for how

people cooperate to acquire indirect benefits.

For example, humans could have a general

learning ability that identifies when their be-

havior can translate into good or bad reputa-

tional outcomes, and so indirect benefits and

costs. However, reputational consequences of

one’s current actions often occur in the distant

future, and this presents a challenge for leaning

about how one can adjust his or her behavior to

maintain a cooperative reputation. Instead, hu-

mans may have decision rules or heuristics that

help them solve exactly this problem. People

may use cues that are reliably associated with

indirect costs and benefits, then condition their

behavior on these cues. Future research can

contrast a reinforcement learning account of

reputation management, with an alternative ac-

count of functionally specialized decision rules

that rely on cues that can be associated with in-

direct benefits.

Indirect Reciprocity from

a Developmental Perspective

As we discussed earlier, humans may have

evolved abilities that enable reputation-based

indirect reciprocity, and this proposition has

inspired several researchers to examine when

these abilities emerge through development.

Field research making observations at a school

playground has documented that 5- to 6-year-

old children are more likely to receive help after

having previously helped another child (Kato-

Shimizu, Onishi, Kanazawa, & Hinobayashi,

2013). Such notable field observations present

immense challenges in ruling out alternative

interpretations, such as direct reciprocity and

the effects of the history of the relationships be-

tween the children.

However, lab research has also documented

that young children display indirect reciprocity.

Olson and Spelk (2008) presented 3½-year-olds

a puppet story with a protagonist who had to

decide how to divide resources among other

puppets. The participants learned that one of

the other puppets had previously helped other

puppets, while another puppet decided against

helping someone in the past. They found that

the children recommended that the protago-

nist give more to the puppet that had previ-

ously been helpful, compared to the puppet that

did not help previously, suggesting that chil-

dren at this age engage in indirect reciprocity.

Similarly, Kenward and Dahl (2011) found that

4½-year-olds, but not 3-year-olds, would decide

to give more resources to a puppet that had pre-

viously helped another puppet, compared to a

puppet that was a hindrance to another puppet.

Importantly, across both studies, children only

distributed resources as would be expected ac-

cording to indirect reciprocity when they were

forced to decide how to distribute unequal re-

sources (e.g., three cookies between two per-

sons). However, when they could divide the re-

sources equally (e.g., two cookies between two

persons), they preferred dividing the resources

equally between helpers and nonhelpers. Such

field and lab studies suggest that children at a

young age, and potentially even 3 years old, are

motivated to give more benefits to others whom

they observed to be helpful to others in previous

occasions.

Interestingly, the cognitive and motivational

mechanisms of indirect reciprocity may emerge

even earlier in development. Previous research

has found that even 10-month-old infants seem

to expect third parties to behave positively to-

ward someone who has behaved in an egalitar-

ian way in a previous interaction, compared to

someone who behaved unfairly (Meristo & Su-

rian, 2013). There is a need for future research

along these lines on the development of specific

cognitive and motivational abilities that under-

lie indirect reciprocity.

Do Reputations Transcend

Group Boundaries?

Social networks often contain clusters of indi-

viduals who have strong ties to each other, and

these clusters can be considered groups. Yam-

agishi and colleagues (1999) have claimed that

reputational benefits of cooperation may be

contained within groups. According to a bound-

VanLange_Book.indb 280VanLange_Book.indb 280 6/30/2020 11:17:39 AM6/30/2020 11:17:39 AM

14. Indirect Reciprocity, Gossip, and Reputation-Based Cooperation 281

ed generalized reciprocity perspective, groups

contain a system of reputation-based indirect

reciprocity, and humans have evolved a decision

heuristic to be more cooperative with ingroup

members than with outgroup members, in order

to enhance their cooperative reputation and to

avoid being ostracized from the group. Previ-

ous research using minimal group paradigm

has supported this claim through the observa-

tion that ingroup favoritism in cooperation only

occurs when people have common knowledge

of each other’s group membership (Balliet, Wu,

& De Dreu, 2014; Yamagishi et al., 1999). When

participants have unilateral knowledge of group

membership (i.e., participants knew their part-

ners’ group membership, but also learned that

their partners did not know their own group

membership), they could not gain reputational

benefits–costs from their behavior, and so they

did not discriminate in cooperation between

ingroup and outgroup members. A recent me-

ta-analysis of the literature on ingroup favorit-

ism indeed found that people only cooperated

more with ingroup than with outgroup mem-

bers when there was common knowledge, but

this ingroup favoritism completely disappeared

in the unilateral knowledge condition (Balliet

et al., 2014). This work is complemented by re-

search showing that 5-year-old children invest

in a positive reputation with ingroup, but not

outgroup, members (Engelmann, Over, Her-

rmann, & Tomasello, 2013).

Theory and research suggest that reputation-

al benefits of cooperation are contained within

groups, or at least that people have a reputa-

tion management strategy that is conditional on

group membership. However, research support-

ing this view has mostly relied on the common

knowledge paradigm to manipulate whether

actions can have reputational consequences.

Other research using different methodologies

has resulted in the conclusion that people care

about their reputation when interacting with

both ingroup and outgroup members (Romano,

Balliet, & Wu, 2017; Semmann, Krambeck,

& Milinski, 2005). Romano, Balliet, and Wu

(2017) conducted five studies in which they

manipulated both partner group membership

(using minimal and natural groups) and cues of

reputation (e.g., anonymity, gossip) via several

methods, and found that reputation promoted

cooperation during interactions with both in-

group and outgroup members. Additionally, a

large-scale study across 17 societies attempted

to replicate the previous work by Yamagishi and

colleagues (1999) testing how common/unilat-

eral knowledge affected ingroup favoritism in

cooperation (Romano, Balliet, Yamagishi, &

Liu, 2017). This study manipulated partner na-

tionality (own country vs. one of 16 other coun-

tries) and common (vs. unilateral) knowledge

of partner group membership, and found that