1

METHODS TO CALCULATE THE DIRECT

COSTS OF MEDICAL CARE FOR

PEDESTRIAN AND BICYCLIST INJURIES DUE

TO TRAFFIC COLLISIONS IN THE COUNTY

OF LOS ANGELES, 2014

PURPOSE OF THIS ANALYSIS

Motor vehicle traffic crashes (MVTCs) result in devastating health outcomes. However, the economic impacts

are also vast. In 2010, the economic costs of motor vehicle crashes totaled $242 billion for the United

States, with $23.4 billion related to medical costs.

1

Addressing the root causes of crashes requires

extensive investment and reallocation of government resources in infrastructure, communication, education,

and systems changes that involve multi-stakeholder collaboration. Local governments often lack information

about the extent of MVTCs and their associated costs, which makes decision making on important resource

investment tradeoffs challenging. To address this need in planning and practice, the Los Angeles County

Department of Public Health (DPH) calculated the minimum direct costs of medical care for pedestrian and

bicyclist motor vehicle traffic collision victims in Los Angeles County. A high-level summary of the approach

to the analysis follows. A more detailed version of this analysis can be found in the technical appendix on

page 4.

This document is an accompaniment to the brief: Porter K et al. Los Angeles County Department of Public

Health, Division of Chronic Disease and Injury Prevention, PLACE Program. Direct Costs of Medical Care for

Pedestrians and Bicyclists Hit by a Vehicle in Los Angeles County. Issue Brief. October 2018.

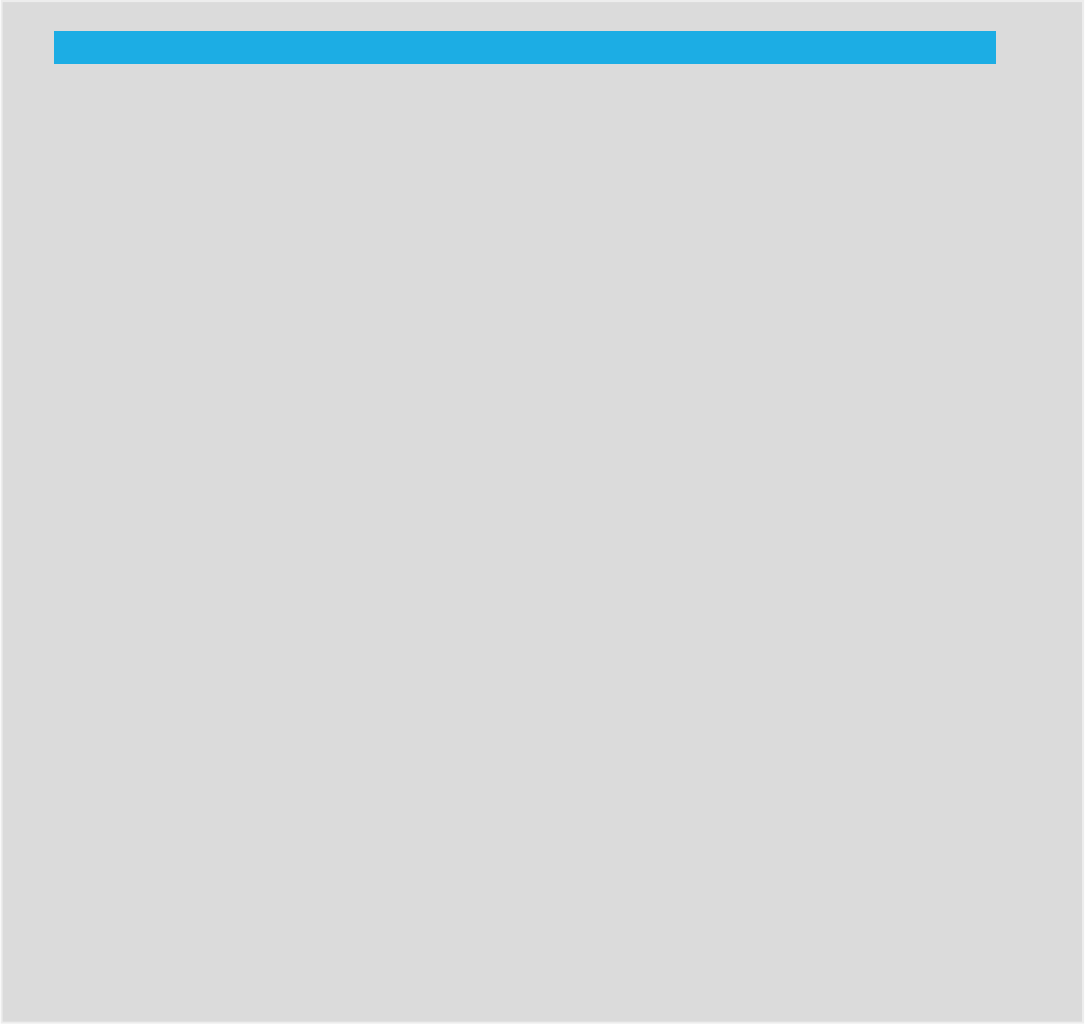

TYPES OF COLLISION COSTS

The overall costs of collisions come in many forms and accrue to both the individual and society at large.

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration summarizes economic costs into the categories of:

property damage; medical costs; emergency services; travel delay; administrative costs; legal costs; lost

earnings; lost household production; vocational rehabilitation; workplace costs; and pain and lost quality of

life.

2

These costs can be further categorized into direct and indirect costs. Direct costs are those that an

individual incurs due to a collision, whereas indirect costs do not directly relate to the collision itself but are

an eventual result of the collision, such as lost wages due to taking sick leave.

3

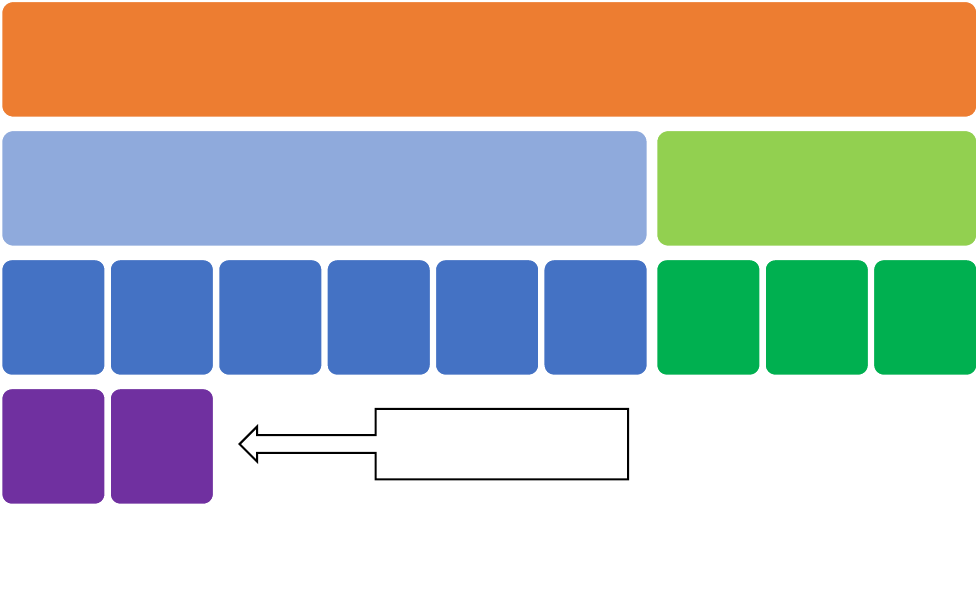

Figure 1 (next page)

visualizes the potential range of costs and highlights direct cost components included in our calculation of

medical costs.

2

FIGURE 1. Summary of Collision Costs

Although other agencies have produced estimates of the economic costs of crashes, their conceptual nature

can make it difficult for these values to be interpreted by the public. Although medical costs are just one of

many economic impacts of crashes, they are one of the most tangible costs that could be averted with

prevention.

Collision Costs

Direct Costs

Emergency

Response

Medical

Health

Services

Medical

Property

Damage

Travel Delay

& Pollution

Short-term

Productivity

Miscellaneous

Indirect Costs

Loss of

Productivity

Pain &

Suffering

Quality of

Life

Diagram modified from: Capital Region Intersection Safety Partnership (CRISP). Cost collision study: Report summary.

February 2010.

Portion of overall costs

included in this analysis

3

APPROACH

A high-level overview of the methodology used for this analysis is described below. The detailed

methodology can be found in the Technical Appendix on page 4. The calculations employed numerous

assumptions that are intended to approximate the minimum direct costs of medical care. They are

projections only.

Each cost component calculation (ambulance fees, hospital costs, and professional fees) is derived from a

different 2014 population of pedestrian and bicyclists who were motor vehicle traffic collision victims.

Data about all victims may not be available due to the complexity the response to a collision and how a

collision is reported or documented.

DPH modified an approach

2

developed by the University of

California, San Francisco:

1) Assign a cost for each

ambulance transport to a

medical facility

2) Convert inpatient hospital

charges to hospital cost

3) Assign a cost for each

emergency room service

provided to address injury

Direct costs of medical care were

calculated by summing costs

associated with transport by first

responders to a facility,

hospitalization, and treat-and-

release emergency department

visits.

Data was not available to calculate

emergency department costs for

patients treated-and-released or

professional fees for patients

admitted.

For more detailed information, visit:

http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/pl

ace/

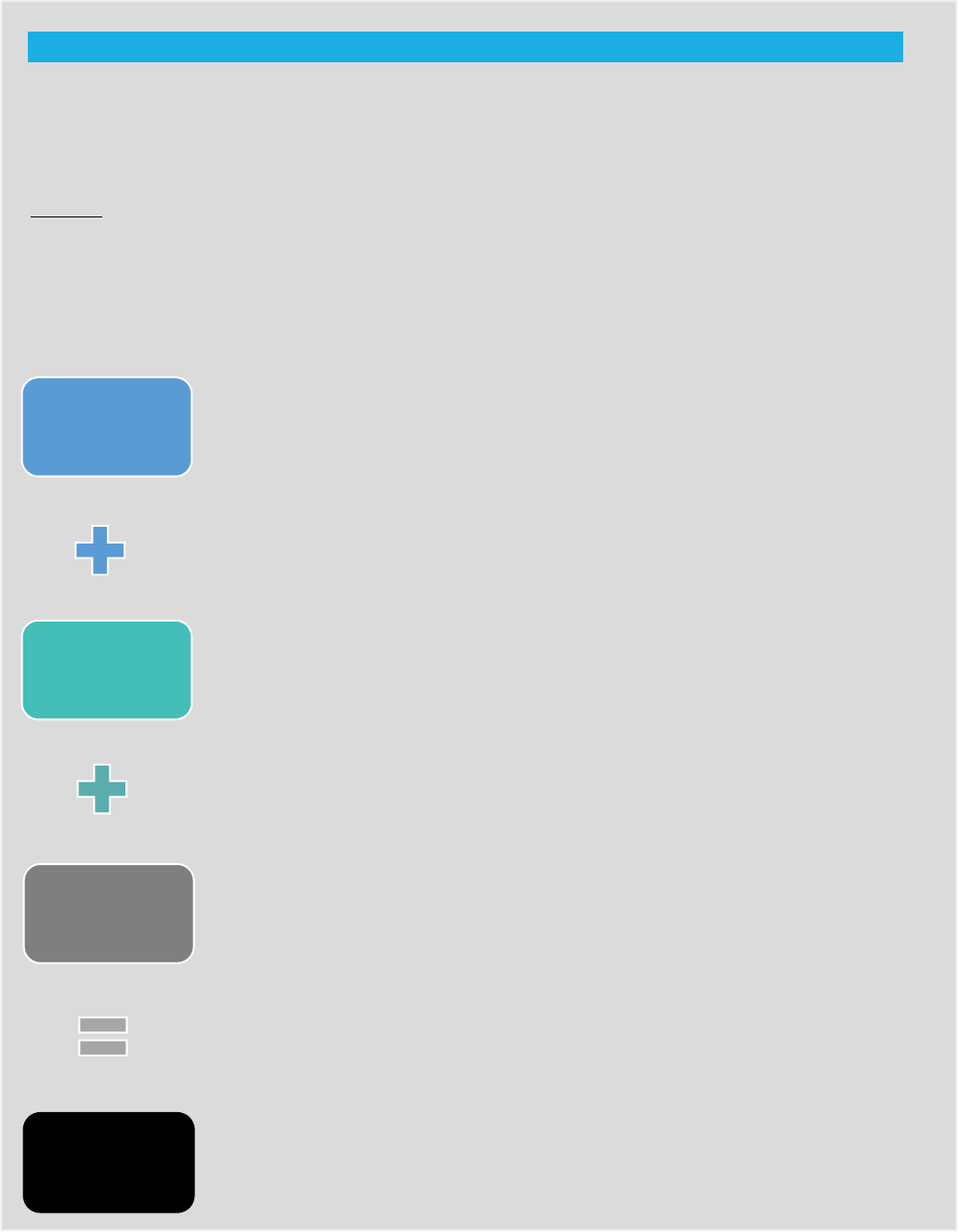

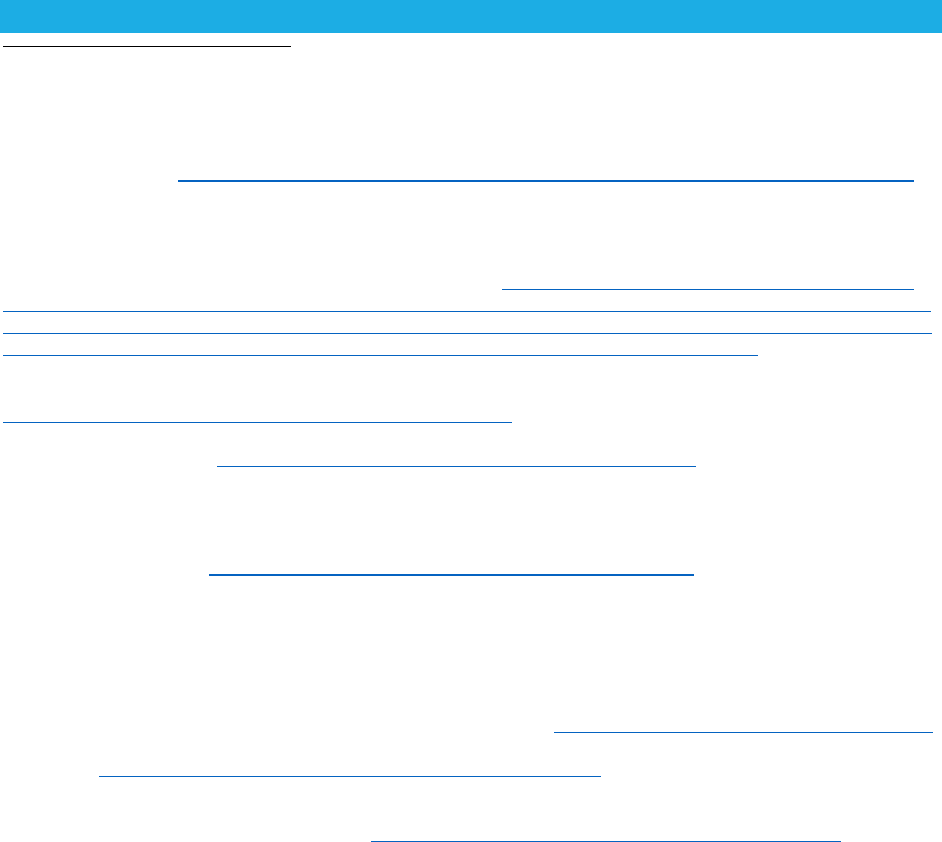

FIGURE 2: Basic Formula for Calculating Direct Costs

of

Medical Care

Ambulance fees are the allowable

maximum rates chargeable to the public

for transport by Emergency Medical

Responders to a hospital.

Hospital costs are expenses incurred by a

hospital in providing care during a

hospital stay, such as wages, utility costs,

and supplies, as opposed to the amount

the hospital charged a patient.

Professional fees are prices charged by

physicians and other healthcare providers

for services rendered during a treat-and-

release emergency department visit.

Direct costs include costs related to

emergency transport, inpatient services,

outpatient services.

Ambulance

Fees

Hospital

Costs

Professional

Fees

Direct Cost of

Medical

Care

4

Technical Appendix

In this appendix, we provide a more complete set of the details on the data and methods

we used to produce the estimates presented above. As mentioned, we made several assumptions to arrive

at our estimated minimum direct costs. However, other sets of assumptions and approaches could be used

that generate different findings. These calculations are intended to be suggestive and only describe our

approach. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 and ArcMap version 10.3.

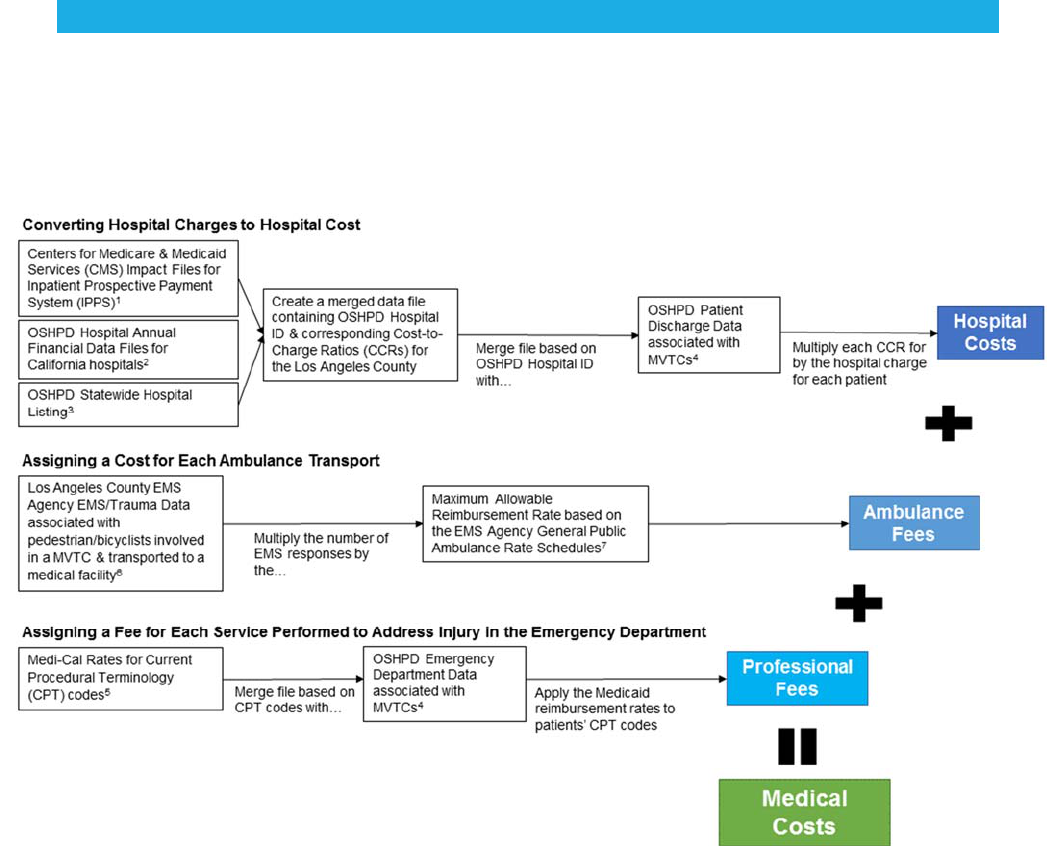

CALCULATING DIRECT COSTS OF MEDICAL CARE

The figure below is a visual representation of the overall process to calculate direct medical costs using a

modified University of California San Francisco Approach.

4

FIGURE 3. Process for Calculating Direct Medical Costs of Collisions Using a Modified University of

California San Francisco Approach

5

DATA SOURCES

We used:

Federal-level Cost-to-Charge Ratios (CCRs) from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

(CMS), where CCRs equals the total amount of money required to operate a hospital, divided by

the sum of the revenues from patient care and other operating revenues

5

;

State-level hospital data (financial

6

, hospital listing

7

, discharge and emergency department

8

) and

Medicaid reimbursement

9

and;

County-level Emergency Medical Services (EMS) and Trauma data

10

, and ambulance rate

schedules.

11

METHODS

Each cost component is derived from a different 2014 population of motor vehicle traffic crash (MVTC)

victims. These are described further below.

HOSPITALIZED AND EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT VICTIMS

DEFINING COLLISION VICTIMS

We used California's Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD) datasets for

California licensed local health departments to identify pedestrian and bicyclist collision victims treated in

a County medical facility. OSHPD patient discharge data was used to identify collision victims who were

admitted in the hospital. OSHPD Emergency Department (ED) data were used to identify victims who were

treated-and-released from the ED. A MVTC was defined as a hospital visit with a primary external cause

of injury code (E-code) of E810-E819 from the International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision.

Specific sub-categories of E-codes were selected to identify the injured party; for pedestrians (X.7) and

bicyclists (X.6).

IDENTIFYING INCIDENT LOCATION

Assumptions were made to identify where MVTC injuries occurred in the county versus the city of Los

Angeles. The OSHPD data for local public health departments cannot identify incident location because it

only contains geographic information on patient residence location and hospital location. As a proxy, we

used hospital location to assign incident location. The Los Angeles County hospital Geographic Information

Systems (GIS) shapefile

12

was used to map hospital locations and the county and city boundary shapefiles

were overlaid to assign boundary locations. We assumed that if the hospital was in the city of Los Angeles,

then the MVT injury occurred within the city. Likewise, we assumed that if the hospital was in the county then

the MVT injury occurred in the county.

6

AMBULANCE TRANSPORT VICTIMS

DEFINING COLLISION VICTIMS

A subset of the EMS/Trauma data from the Los Angeles County Department of Health Services EMS

Agency was used to identify victims who were transported to a medical facility from the incident (collision)

site. Our EMS dataset contains select indicators from the assessment of patient encounters with EMS

responders at the scene of an incident that is likely related to a MVTC and transported to a Los Angeles

County non-trauma center. Our Trauma dataset contains select information on patients involved in a MVTC

and transported to a Los Angeles County trauma center. Depending on the data source, collision victims

were identified in two ways:

1) For victims transported to a Los Angeles County trauma center (Trauma data), we selected (E-

codes) (E810 -E819) and subcategories occupants (X.0, X.1), motorcyclist (X.2, X.3), pedestrians

(X.7) and bicyclists (X.6) and other/unspecified (X.4, X.5, X.8, X.9) to identify those injured in a

MVTC.

2) For victims transported to a non-trauma center in Los Angeles County (EMS data), the identification

of MVTC-related incidents had to be estimated, because EMS data lacks E-codes.

We used the Trauma database to obtain the number and percent of collision victims for each mode of

travel (ex: occupant, motorcyclist, pedestrian, bicyclist, other/unspecified) that were transported to a

trauma center.

To estimate the number of pedestrian and collisions victims that were transported to a non-trauma center,

we used both the Trauma and EMS databases. Both the EMS and Trauma databases contain a variable

called the “Mechanism of Injury (MOI),” which describes the mechanism of the patients’ injury. This variable

has multiple field values, two which are associated with pedestrians/bicyclists/motorcyclists. They are: PB

(NOT thrown or run over at <20 MPH) and RT (Thrown or run over at >=20 MPH). Using the EMS and

trauma databases, we created two data subsets each containing only PB or RT field values.

To obtain the estimated number of pedestrian or bicyclist collision victims that were transported to a non-

trauma center and had a PB or RT field value, we applied the proportion of pedestrian or bicyclist

collision victims that had a PB or RT field value in the Trauma database to the number of patients with a PB

or RT field value that were transported to a non-trauma center.

To obtain the estimated number of pedestrian or bicyclist collision victims that were transported to a non-

trauma center without a PB or RT field value, we then applied that non-trauma value to the proportion of

the proportion of trauma center patients that were without a PB or RT field value.

Finally, to obtain a combined estimate of pedestrian and bicyclist collision victims that were transported to

trauma and non-trauma centers, we added the number of pedestrian and bicyclist collision victims in the

trauma database to the estimated number of pedestrian and bicyclist collision victims in the EMS database.

IDENTIFYING INCIDENT LOCATION

The EMS/Trauma datasets contain geographic data fields (ex: Global Positioning System (GPS)

coordinates, city, zip code) which, when data are available, provide information on incident location. For

collision victims with GPS data, we determined incident location based on county and city boundary GIS

shapefiles. In the absence of GPS coordinates, we assigned incident location based on city and zip code

combination, city alone, or zip code alone. Because political boundaries do not align with zip code

boundaries, we relied on the City of Los Angeles Housing Department’s map listing of zip codes

13

to assign

those incidents to the city of Los Angeles. Data without any geographic information were omitted, since

geography could not be determined.

7

CAVEATS

Data limitations necessitated the development of assumptions and approaches that may impact the

estimates, and our estimates are likely to be conservative. Challenges included:

Underestimation of hospital costs: Our hospital costs are based on hospital discharge data only,

and thus do not include hospital costs related to patients treated and released in the emergency

department.

Calculating ambulance fees: We used the most likely base ambulance fee for caring for a

pedestrian or bicyclist and applied this average fee to all incidents. However, special charges

such as an oxygen mask, bandages, cervical collar, mileage, etc., would be considered additional

fees and would be added to the ambulance fee. These special charges were not available by

incident.

Underestimation of professional fees: Our professional fee estimates are based on pricing rates

for Medicaid reimbursement for services rendered to outpatients in the emergency department,

and do not account for instances where the patient was hospitalized, has Medicare, or private

insurance. Reimbursement amounts vary widely across payers and both Medicaid and Medicare

set a much lower rate than private insurers for the same procedure

14

; in one example (treating a

broken leg), we found a difference of up to $584.00.

,15

Procedures not eligible for Medicaid

reimbursement were assigned a reimbursement of $0 by Medi-Cal, California’s Medicaid

program.

Estimation of MVTC victims transported by an ambulance to a non-trauma center: Information

on patients transported to non-trauma centers is in the EMS database. While the EMS data

contains geographic information related to an incident, it lacks identifying information on whether

the victim was involved in a MVTC versus some other incident. Our approach to estimating the

probable number of MVTC victims in the EMS data was to take the proportion of pedestrian and

bicyclist MVTC victims in the Trauma Data and apply this to the EMS data; this may have biased

the ambulance fee estimates.

Possible misclassification of victims injured in the county vs. city: We assumed that victims

were injured in the same general area as the medical facility they were transported to because

neither the hospital nor emergency department data (OSHPD) contained information on incident

location. Using the location of the treating facility as a proxy for the location of the incident may

have skewed the identification of victims injured in the county versus the city, and subsequently the

distribution of hospital costs and professional fees between the two regions.

Missing values: We imputed observations/values in the databases using corresponding county

and city costs averages when these missing values prevented the calculation of hospital costs and

professional fees.

Los Angeles County Department of Public Health

Division of Chronic Disease and Injury Prevention

Tony Kuo, MD, MSHS, Director

Jean Armbruster, MA, Director, PLACE Program

Chandini Singh, MA, Policy Analyst, PLACE Program

Kimberly Porter, PhD, MPH, Epidemiologist, PLACE Program

Isabelle Sternfeld, MSPH, Epidemiologist, IVPP

Los Angeles County Chief Executive Office

Ricardo Basurto-Davila, PhD, MSc

Suggested Citation:

Porter K, Singh C, Sternfeld I, Basurto-Davila R,

Armbruster J. Los Angeles County Department of Public

Health, Division of Chronic Disease and Injury Prevention,

PLACE Program. Methods to Calculate the Direct Costs

of Medical Care for Pedestrian and Bicyclist Injuries Due

to Traffic Collisions in the County of Los Angeles, 2014.

October 2018.

8

REFERENCES

1

Blincoe, L.J., Miller, T.R., Zaloshnja, E., & Lawrence, B.A. The economic and societal impact of motor vehicle crashes,

2010. (Revised) May 2015. (Report No. DOT HS 812 013). Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety

Administration.

2

Cambridge Systematics, Inc. Crashes vs. congestion – What’s the cost to society? November 2011. Retrieved

November 30, 2017. http://newsroom.aaa.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/2011_AAA_CrashvCongUpd.pdf

3

Churdar Law Firm. What is the difference between direct and indirect damages? [Accessed 23 January 2018].

4

Lopez, D.S., Sunjaya, D.B., Chan, S., Dobbins, S. & Dicker, R.A. Using trauma center data to identify missed bicycle

injuries and their associated costs. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 2012; 73(6):1602-1606.

5

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Impact Files for Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS)

2013-2014 [CCR Files]. [2013] Retrieved December 6, 2017. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-

Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Historical-Impact-Files-for-FY-1994-through-Present-Items/Impact-File-for-IPPS-

FY2013-Final-Rule.html. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteinpatientPPS/FY-

2014-IPPS-Final-Rule-Home-Page-Items/FY-2014-IPPS-Final-Rule-CMS-1599-F-Data-Files.html

6

Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD). Hospital Annual Financial Data Files for California

Hospitals 2013-2014. Retrieved December 17, 2017.

https://www.oshpd.ca.gov/HID/Hospital-Financial-Selected.asp

7

Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD). Statewide Hospital Listing as of Dec 2015.

Retrieved February 2016. http://www.oshpd.ca.gov/HID/Facility-Listing.html#Hospital

8

Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD) – (1) Emergency Department Data and (2) Patient

Discharge Data. 2013-2014. Data request to Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, Injury and Violence

Prevention Program

9

Medi-Cal Rates (Reimbursement Rates through the California Medicaid Program)

Most up-to-date rates at: https://files.medi-cal.ca.gov/pubsdoco/rates/rateshome.asp

Archived rates for years 2013-2014: Data request to California Department of Health Care Services, Fee-For-

Service Rate Development Division.

10

Los Angeles County Emergency Medical Services (EMS) & Trauma Data. 2013-2014. DatarequesttoCounty

DepartmentofLosAngelesDepartmentofHealthServices,EMSAgencyDataManagementDivision.

11

Los Angeles County EMS Agency General Public Ambulance Rate Schedules. 2013-2014. Data Request to Los

Angeles County Department of Health Services, EMS Ambulance Licensing.

12

Los Angeles County Hospitals (2011). Retrieved November 2016. https://egis3.lacounty.gov/eGIS/get-gis-data/

13

Los Angeles Housing Department (LAHD). Zip codes within the City of Los Angeles. (September 2007). Retrieved

May 2016. https://media.metro.net/about_us/pla/images/lazipcodes.pdf

14

Krause, T.M., Ukhanova, M. and Revere, F.L. Private carriers' physician payment rates compared with Medicare

and Medicaid. Texas Medicine. 2016; 112(6):e1.

15

FIND-A-CODE. Retrieved January 3, 2018. https://www.findacode.com/code.php?set=CPT&c=27750