October 2020

An Investigation into the

Insurability of Pandemic Risk

1

An Investigation into the Insurability of Pandemic Risk

Kai-Uwe Schanz, Deputy Managing Director and Head of Research & Foresight,

The Geneva Association

In collaboration with

Prof. Martin Eling, Chair for Insurance Management and Director,

Institute of Insurance Economics, University of St. Gallen

Prof. Hato Schmeiser, Chair for Risk Management and Insurance and Director,

Institute of Insurance Economics, University of St. Gallen

Prof. Alexander Braun, Vice Director, Institute of Insurance Economics,

University of St. Gallen

An Investigation into the

Insurability of Pandemic Risk

2

www.genevaassociation.org

The Geneva Association

The Geneva Association was created in 1973 and is the only global association of insurance companies; our

members are insurance and reinsurance Chief Executive Officers (CEOs). Based on rigorous research conducted in

collaboration with our members, academic institutions and multilateral organisations, our mission is to identify

and investigate key trends that are likely to shape or impact the insurance industry in the future, highlighting what

is at stake for the industry; develop recommendations for the industry and for policymakers; provide a platform to

our members, policymakers, academics, multilateral and non-governmental organisations to discuss these trends

and recommendations; reach out to global opinion leaders and influential organisations to highlight the positive

contributions of insurance to better understanding risks and to building resilient and prosperous economies and

societies, and thus a more sustainable world.

October 2020

An Investigation into the Insurability of Pandemic Risk

© The Geneva Association

Published by The Geneva Association—International Association for the Study of Insurance Economics, Zurich.

Photo credits:

Cover page—World Pictures and Sdecoret / Shutterstock.com

The Geneva Association—International Association for the Study of Insurance Economics

Talstrasse 70, CH-8001 Zurich

Email: [email protected] | Tel: +41 44 200 49 00 | Fax: +41 44 200 49 99

3

An Investigation into the Insurability of Pandemic Risk

Contents

Foreword 5

1. Executive summary 6

2. Quantifying the challenge: Global protection gaps in light of COVID-19 8

2.1. The notion of protection gaps 8

2.2. COVID-19: Assessing the shortfalls 9

2.2.1. The business interruption protection gap 9

2.2.2. The health protection gap 10

2.2.3. The mortality protection gap 15

3. Getting the basics right: The insurability of pandemic risk 16

3.1. The concept of insurability 16

3.2. The criteria of insurability 17

3.3. The limits to insuring pandemic risk: A comparative and holistic view 18

3.3.1. Pandemic business interruption risk 18

3.3.2. Pandemic life and health risk 21

3.3.3. Pandemic risk compared to other catastrophic risks 23

4. Conclusions 26

References 28

4

www.genevaassociation.org

Acknowledgements

The Geneva Association is very grateful to its Board members Oliver Bäte, CEO, Allianz, and

Brian Duperreault, CEO, AIG, for their personal guidance and support as co-sponsors of this

research.

Our special thanks go to all Geneva Association member company experts whose

comments have benefited this publication: Edward Barron (AIG), Paul DiPaola (AIG), Kean

Driscoll (AIG), Andreas Funke (Allianz), Gong Xinyu (PICC), Arne Holzhausen (Allianz), Kei

Kato (Tokio Marine), Christian Kraut (Munich Re), Roman Lechner (Swiss Re), Christiane

Meyer-Gruhl (Allianz Re), Cameron Murray (Lloyd’s of London), Guillaume Ominetti

(SCOR), Gisela Plassmann (ERGO), Olivier Poissonneau (AXA), Veronica Scotti (Swiss Re)

and Lutz Wilhelmy (Swiss Re).

We are also indebted to our academic partners and contributing authors Martin Eling, Hato

Schmeiser and Alexander Braun who co-shaped section 3 of this report.

We offer our deepest empathy to the countless people, communities and businesses

who have been impacted by COVID-19. At the time of publication of this report, in late

October 2020, there have been more than 40 million cases and 1 million deaths recorded

globally. Many countries are experiencing a second or third wave of the virus.

There is a great proliferation of information and views on COVID-19, and what we read,

unfortunately, is not always rooted in facts. The insurance space is no exception.

This first report in The Geneva Association’s research series on pandemics and insurance

sets out to explore – in objective terms – the capacities of insurers to absorb pandemic-

related costs.

Encouragingly, pandemics on the scale

of COVID-19 pose no fundamental

insurability challenges for health and

life insurers, allowing them to fully play

their protection and support role to

affected people and communities.

The picture is different for property

& casualty (P&C) losses. Even those

who anticipated the scenario of a

global pandemic did not fathom the nature and scale of government decisions taken

around the world to slow infections: wide-ranging shutdown measures that brought

economies to a standstill.

From an insurance perspective, this type of government response is neither predictable

nor modellable. That is one of the reasons why pandemic risk was not included in most

business interruption policies.

Our research findings are unambiguous: the property & casualty insurance industry,

which collects USD 1.6 trillion in premiums per year for all policies – and a mere USD 30

billion for business interruption risk – is not the right vehicle for shouldering the projected

global loss in GDP for 2020 of USD 4.5 trillion.

As a consequence, governments need to involve themselves in closing the pandemic

protection gap in P&C. And insurers still have a role to play. Our second pandemics

report will explore possible solutions: innovative, public-private efforts that recognise the

enormous magnitude and unique nature of pandemic risks.

Taken together, we hope these reports will help governments and insurers think about

and agree upon feasible, effective ways to work together to better protect society from

extreme risks, such as pandemics, going forward.

Jad Ariss

Managing Director

Foreword

5

An Investigation into the Insurability of Pandemic Risk

Health and life insurers can

fully play their protection

and support role to people

and communities affected

by COVID-19.

6

www.genevaassociation.org

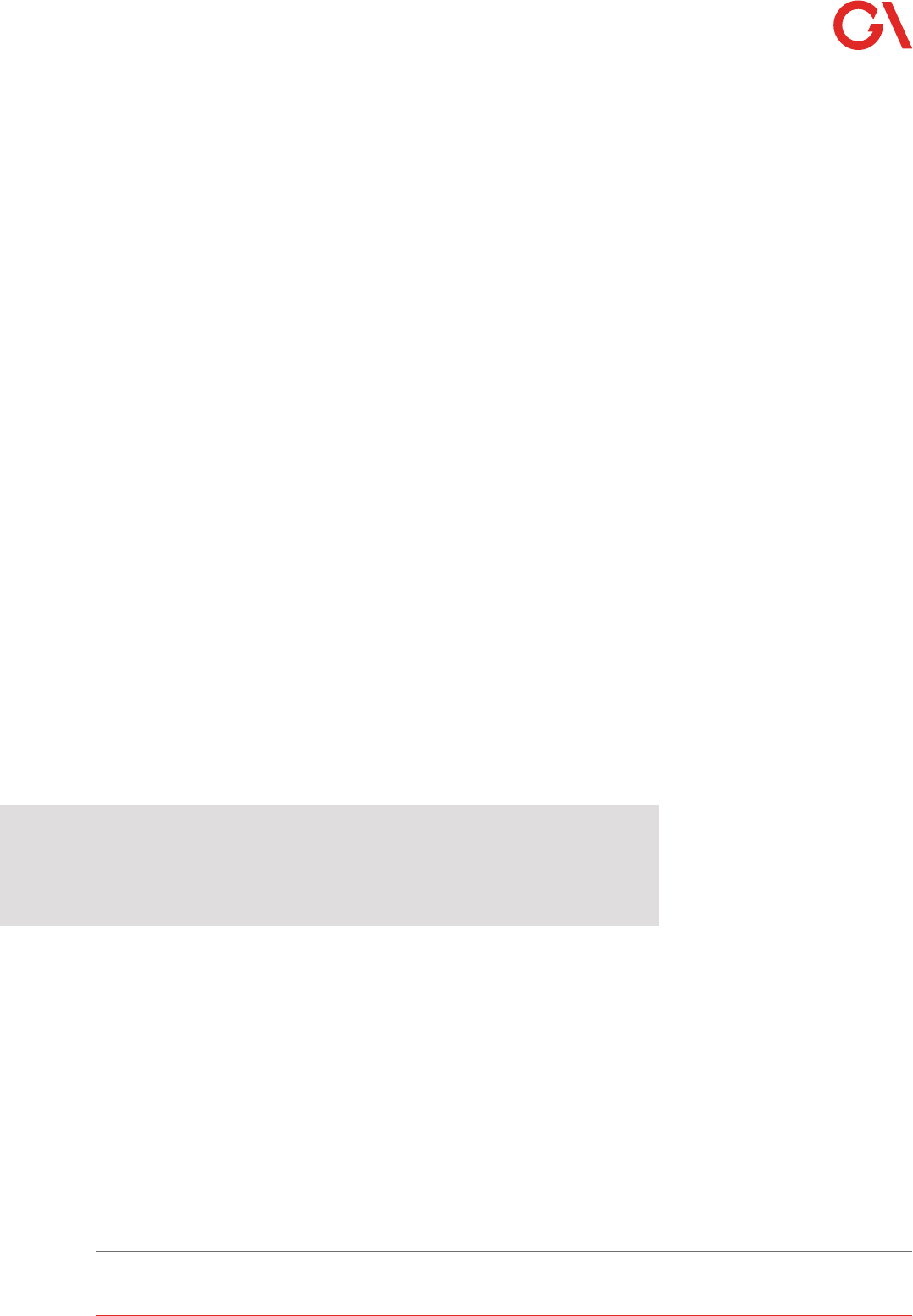

COVID-19 and the draconian shutdown measures adopted by many governments

to contain it have plunged the global economy into the deepest recession since the

Second World War. For the global insurance industry, too, the pandemic is a severe

loss event. Despite this massive strain, initially exacerbated by a steep decline in

capital markets, insurers worldwide promptly paid legitimate claims in all areas

where pandemic risk was intended to be covered; for example, under life, health

and event cancellation policies. In addition, also during the lockdowns, insurers

have continued to pay claims and benefits unrelated to the pandemic; for example,

in motor, liability and annuities insurance.

At the same time, COVID-19 has exposed massive protection gaps in the area

of business continuity risk. Less than 1% of the estimated USD 4.5 trillion global

pandemic-induced GDP loss for 2020 (source: The World Bank) will be covered by

business interruption insurance – a niche segment which generates annual premium

income of about USD 30 billion (less than 2% of the world’s property & casualty

insurance market), with cover generally intended for and triggered by physical

damage only.

The mismatch between economic losses and the risk-taking capacity of insurers

who offer business interruption cover, as well as past demand for pandemic

coverages, is staggering. With annual business interruption insurance premiums

of about USD 30 billion, insurers would have to collect premiums for 150 years

in order to absorb the estimated USD 4.5 trillion global output loss inflicted by

COVID-19 and its handling in 2020. Even the size of the entire global property &

casualty insurance industry (USD 1.6 trillion in premiums, according to McKinsey)

is eclipsed by the economic damage from the pandemic. In order to cover the total

cost, all property & casualty insurers worldwide would have to collect premiums

across all lines of business for almost three years, with no money left for covering

private homes and vehicles, injured workers and numerous liability exposures.

Therefore, property & casualty insurers have typically applied strict exclusions on

pandemic business continuity risk and never intended to cover it.

Insurers would have to collect business interruption

insurance premiums for 150 years in order to absorb

the estimated USD 4.5 trillion global output loss

inflicted by COVID-19 and its handling in 2020.

Existing protection gaps facing individuals and households in the areas of mortality

and healthcare risk have been much less highlighted by this pandemic due to

relatively moderate excess mortality and slightly reduced overall healthcare

expenditure.

The extent of correlation and aggregation of pandemic losses for businesses across

the globe has put the insurability of pandemic risk in the spotlight. It touches upon

1. Executive summary

7

An Investigation into the Insurability of Pandemic Risk

the pivotal question of whether pandemics are a type of

risk for which the insurance industry can play any kind of

role or if this is the type of risk where traditional insurance

products are not the solution.

It is not difficult to intuitively understand the limits to

insuring pandemic risk. The word ‘pandemic’ originates

in the ancient Greek (‘pan’ means all and ‘demos’ means

people). Pandemic-induced business continuity risk is

obviously unique given its potential to impact virtually all

policyholders simultaneously, over an extended period of

time. Applying the two most relevant customary criteria of

insurability to pandemic business interruption risk yields

the following conclusions:

First, losses are neither random nor independent. Even

though pandemics are naturally occurring phenomena,

policy decisions to lock entire economies are deliberate

and intentional. This means that expected loss amounts

and risk loadings cannot be set. There are also no historical

data for the policy responses witnessed during COVID-19.

Furthermore, the strong correlation among individual

risks renders efficient risk pooling and diversification

impossible.

Second, the maximum possible loss is not manageable

from the insurer’s solvency point of view. The

uncontrollable aggregation of losses could be ruinous to

the risk pool and, ultimately, to the insurance industry

as a whole. This in turn could lead to significantly further

financial stability risks across the wider economy.

The uncontrollable aggregation

of losses from pandemic business

interruption could be ruinous to the risk

pool and, ultimately, to the insurance

industry as a whole.

As opposed to business continuity, pandemic life and

health risks are generally non-systemic and privately

insurable. Excess mortality risk is modellable based on a

wealth of historical data. In addition, increased mortality

risk is (partially) offset by reduced longevity. For health

insurers, there is a ’natural’ limit to claims given the finite

capacity of healthcare systems and temporarily reduced

expenditure on non-pandemic-related procedures. Hence,

there are generally no exclusions for pandemics or other

common causes of extreme mortality and health events.

Having said this, life and health insurers’ resilience could

1 To be discussed in-depth in our forthcoming publication Public and private solutions to pandemic risk (November 2020).

be tested by future pathogens which may be more

aggressive and lethal than COVID-19.

In addition to distinguishing between uninsurable and

insurable parts of pandemic risk, it is important to

understand the differences between pandemic and other

catastrophic risks, first and foremost, in terms of the scope

for global diversification. Pandemics are, by definition,

not diversifiable as they occur on a very wide or even

global scale (as opposed to epidemics which are more

locally concentrated). Some other risks such as terrorism

or natural catastrophes are diversifiable on a global level

and routinely transferred via re/insurance or Alternative

Risk Transfer (ART) instruments. These disasters impact

a limited number of policyholders for a limited period of

time. As COVID-19 illustrates, economic losses caused

by extreme pandemics and their handling by public

authorities are neither locally nor globally independent.

Therefore, pandemic business continuity risks are

uninsurable.

Pandemics are, by definition, not

diversifiable as they occur on a very

wide or even global scale.

Having said this, insurers are aware of the need to address

this socio-economic challenge. The industry is prepared

to explore the scope for innovative solutions and public

sector-led efforts which acknowledge the enormous

magnitude and unique nature of this particular risk.

1

8

www.genevaassociation.org

2.1. The notion of protection gaps

For re/insurers there is significant uncertainty about the ultimate claims burden

from COVID-19. According to Swiss Re 2020, the mid-point of the range of current

publicly available estimates is around USD 55 billion for all lines of business. In any

case, the insured part will be dwarfed by the economic cost of the pandemic. For

2020, the World Bank currently expects a 5.2% contraction of the global economy

(World Bank 2020), amounting to more than USD 4.5 trillion in lost output.

The share of uninsured losses in total economic losses is generally referred to as the

protection gap. A more meaningful measure, however, is the notion of the insurance

protection gap, defined as the difference between the amount of insurance that

is economically beneficial for both insureds and insurers on the one hand and

the amount of coverage actually purchased or offered, on the other. This gap is

significantly smaller than the broader protection gap, for some of the following

reasons:

• Certain risks simply defy insurability, with pandemic risk being a case in point

(see section 3.3).

• A certain level of risk retention makes economic sense to incentivise risk

prevention measures and risk-conscious behaviors.

• Insurers implement deductibles to mitigate moral hazard, i.e. a tendency on the

part of the policyholder to behave more carelessly because they have insurance

cover. Deductibles translate into lower sums insured.

• Institutional factors, such as extensive social security benefits or government

post-disaster relief, reduce the need for individuals to take out private insurance

(The Geneva Association 2018).

In reality, however, the insurance protection gap is hard to measure and highly

subjective. Each insured individual or business assesses the economic benefits of

insurance differently. Similarly, on the supply side, insurance companies differ in their

view as to what is insurable and at what minimum price (Karten 1997). Therefore the

notion of the insurance protection gap is generally replaced by the wider, easier to

quantify but less meaningful overall protection gap measure which compares covered

losses with total economic losses.

In the following section, we explore protection gaps for the three areas of pandemic

risk discussed in this report – business interruption, health and mortality. The scope

and scale of such gaps is enormous. It entails businesses (especially small vulnerable

2. Quantifying the

challenge: Global

protection gaps in

light of the pandemic

9

An Investigation into the Insurability of Pandemic Risk

ones) defaulting within weeks, households suffering

financial stress from additional out-of-pocket healthcare

expenditure or, in extremis, impoverishment if the main

breadwinner dies from COVID-19.

Against this backdrop, it is important to understand

the limits to insurability presented by the various forms

of pandemic risk. This awareness is an indispensable

foundation for subsequent discussions on pandemic risk.

2

2.2. COVID-19: Assessing the shortfalls

In the following section we explore protection gaps in the

areas of business interruption (BI), mortality and health.

These risks were selected, first, because of their relevance

to both insurers and customers during COVID-19 and,

second, especially for mortality and health, because of the

availability of meaningful data.

2.2.1. The business interruption protection gap

In the context of COVID-19, the protection gap debate

focuses on the trillions of dollars of economic losses

arising from the impact of government-mandated

lockdown measures worldwide and the share of these

losses insurers could or should absorb.

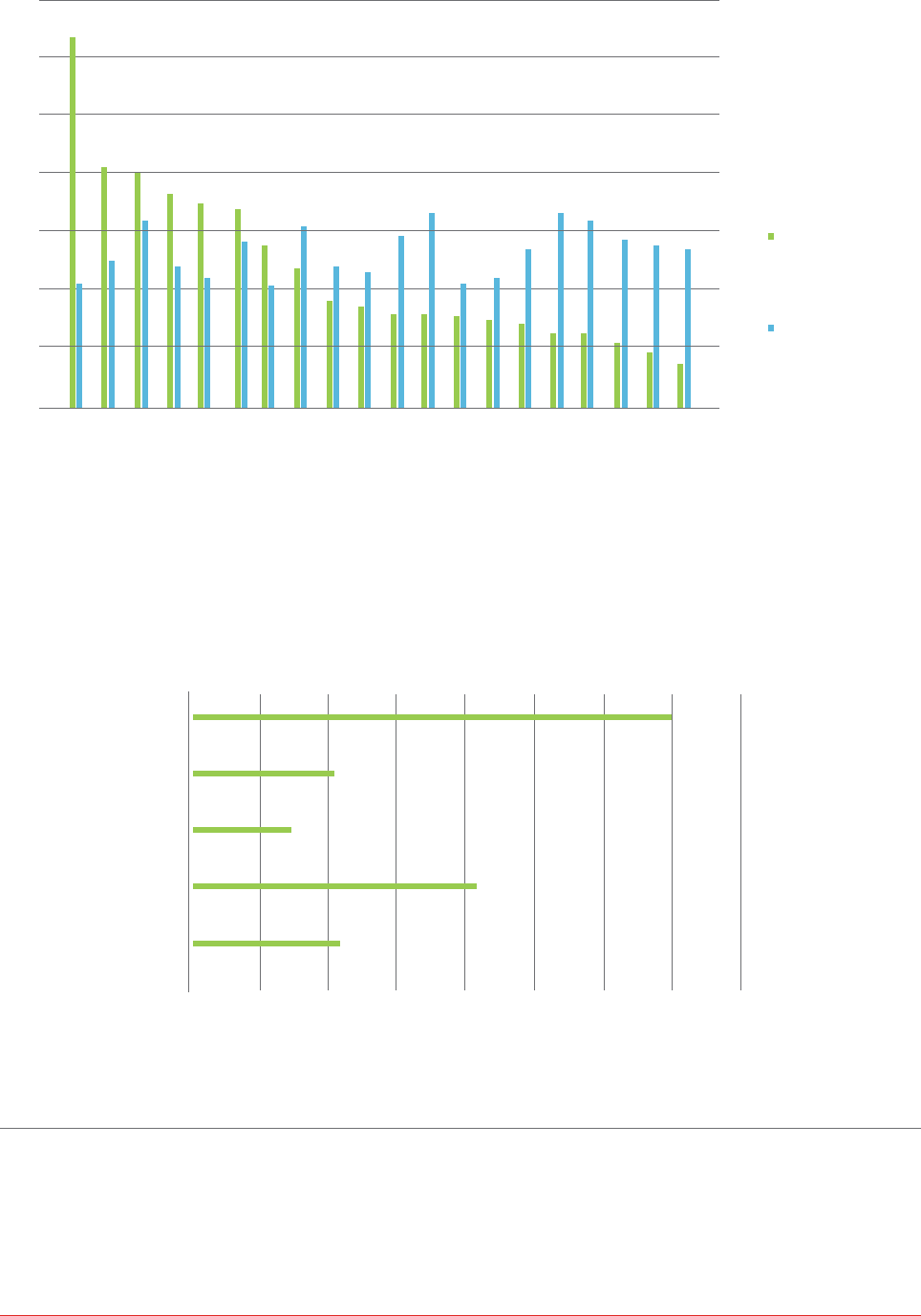

The relevant dimensions and proportions speak for

themselves: P&C insurers globally generate annual

premium income of about USD 1.6 trillion (McKinsey

2020). They would have to collect this amount of

premiums across all lines of business for almost three

years in order to cover the estimated USD 4.5 trillion

global loss in GDP (see Figure 1 for an illustration).

3

We estimate the aggregate capital base of the world’s

P&C insurance sector at a similar size of USD 1.6 trillion.

Therefore, in a global lockdown scenario, insurers’ entire

surplus would be exhausted after a few months. In light

of the probability of a major pandemic event (industry

experts put it at 30–40 years), and given the current levels

2 See section 3 of this report as well as The Geneva Association (2020).

3 Global output losses are obviously not a perfect proxy for business continuity losses. Government support measures have provided significant

relief to businesses.

4 For the U.S., The American Property Casualty Insurance Association (APCIA) estimates monthly lockdown-induced BI losses for smaller, and

arguably the most vulnerable, businesses with fewer than 100 employees at USD 255 billion to 431 billion (APCIA 2020). If fully insured, these

businesses’ losses alone would exhaust the U.S. P&C insurance industry’s entire capital in 2–3 months.

5 We estimate that 20–25% of global commercial property premiums of about USD 115 billion (source: Allianz Research, 2018 figure) reflect BI risk.

Note that this premium pot almost exclusively covers BI risks with an unequivocal physical damage trigger (e.g. a fire at a manufacturing plant).

6 Willis Towers Watson 2020 estimate insured BI losses (including event cancellations) in the U.S. at roughly USD 10–20 billion, including an

allowance to pay claims on policies where no coverage was intended, as triggered by litigation, regulation and/or legislation. The share of the U.S.

market in global commercial property premiums is about one third. Assuming a lower level of BI insurance penetration and legal uncertainty in

other parts of the world, global insured BI losses could come in at the estimated range of USD 20–40 billion.

7 Again, global output losses are not a perfect proxy for business continuity losses.

of industry capital (versus levels of exposure to pandemic

risk), this risk would impose a material solvency risk on

the sector and harm many other policyholders from other

lines of business, as well as create a potential financial

stability threat.

4

Only a tiny fraction (an estimated USD 25–30 billion

5

,

or less than 2%) of the world’s total P&C premium base

is linked to BI coverage. The lion’s share of the industry’s

premiums and capital backs private homes and vehicles,

injured workers and numerous liability exposures unrelated

to COVID-19 (Hartwig and Gordon 2020a).

Further assuming that global insured BI losses from the

pandemic could ultimately amount to USD 20–40 billion

for 2020,

6

insurance claims would cover less than 1% of

global COVID-19-induced GDP losses, translating into a

protection gap of more than 99% (based on the earlier

assumption of USD 4.5 trillion BI-related economic losses).

7

In other words, the global P&C insurance industry would

have to collect BI premiums for at least 150 years in order to

absorb the estimated global output loss from the pandemic

in 2020.

Effective private market insurance

coverage for BI losses would

necessitate rates which would likely

be unaffordable or unattractive for

commercial buyers.

Effective private market insurance coverage for BI losses

would require multiple times the current premium and

capital base of the P&C insurance industry and necessitate

rates which would likely be unaffordable or unattractive

for commercial buyers (see section 3.3). These supply-side

reasons for the private P&C insurance market’s decision

to limit exposure to pandemic risk are compounded by

demand-side barriers such as the underestimation by

10

www.genevaassociation.org

businesses and households of a pandemic’s probability

of occurrence,

8

the speed and/or extent to which a virus

spreads, the probability and/or duration of government-

imposed lockdown measures, or excessive optimism

about the ability of scientists to develop treatments and

vaccines. Demand can be further reduced by people’s

expectation that, if a truly disastrous pandemic event hits,

governments will be there to provide financial assistance

(Hartwig et al. 2020). This analysis suggests that the

overwhelming majority of pandemic BI risk will remain

uninsured by private insurers given the prohibitive amount

of premiums and capital required to offer credible and

secure insurance coverage (OECD 2020a).

In summary, in light of these supply- and demand-side

factors at work, the massive BI protection gap compares

8 PathogenRX, a BI pandemic risk product, was not widely purchased in the years preceding COVID 19; a clear indication of the demand-side

challenges highlighted above.

with a much smaller BI insurance protection gap as defined

as the difference between the amount of insurance that is

economically beneficial and feasible for both customers

and insurers, on the one hand, and the amount of coverage

actually purchased or offered, on the other.

2.2.2. The health protection gap

Even conceptually, the capture and quantification of the

healthcare funding gap is a challenging endeavour. To

a major extent, healthcare expenditure is discretionary

and depends on the quality of healthcare services. Public

healthcare services, for instance, are available in many

markets at affordable prices, but accessibility, long

average waiting times and quality are frequent issues.

Consumers seeking state-of-the-art or timely treatment

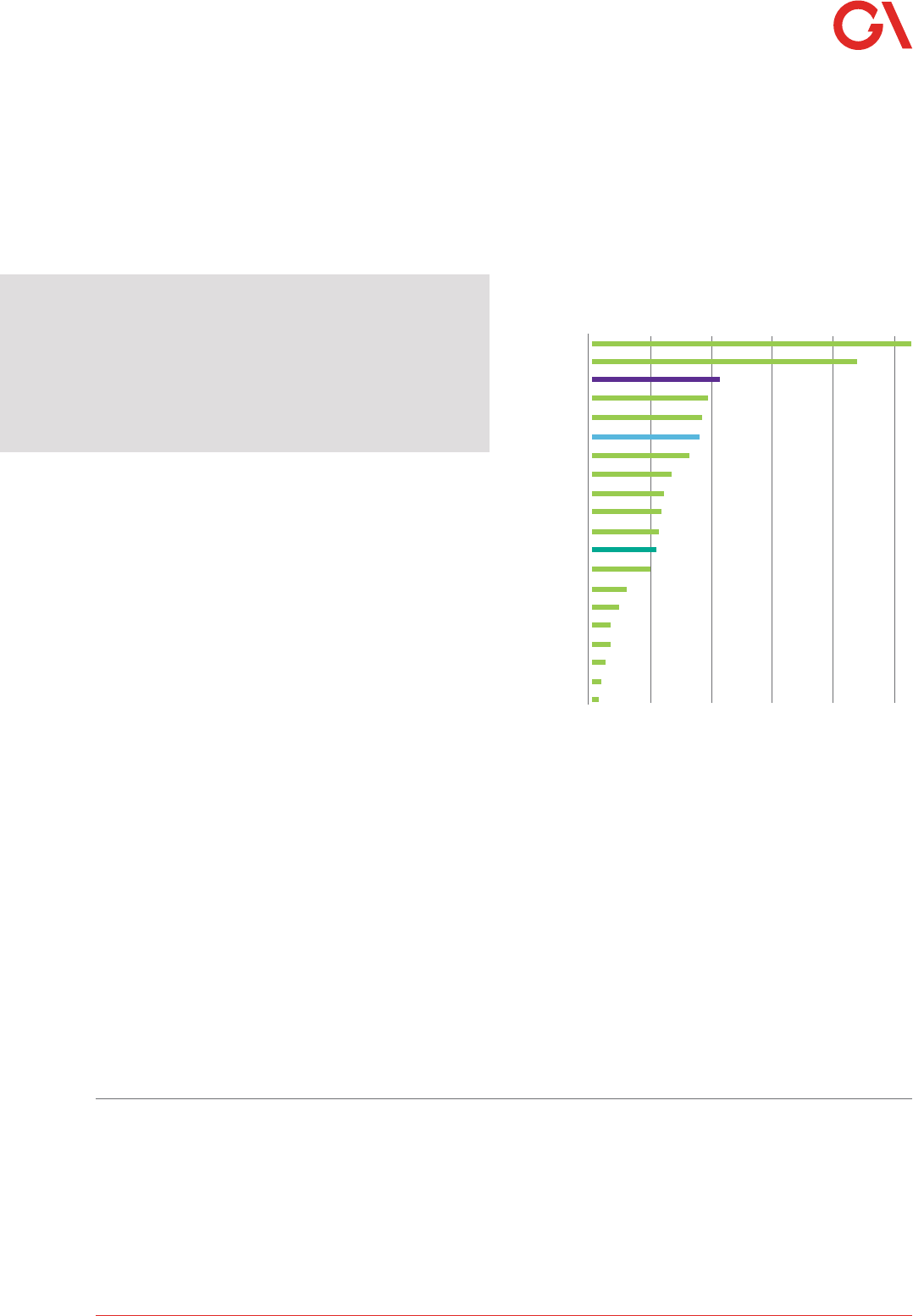

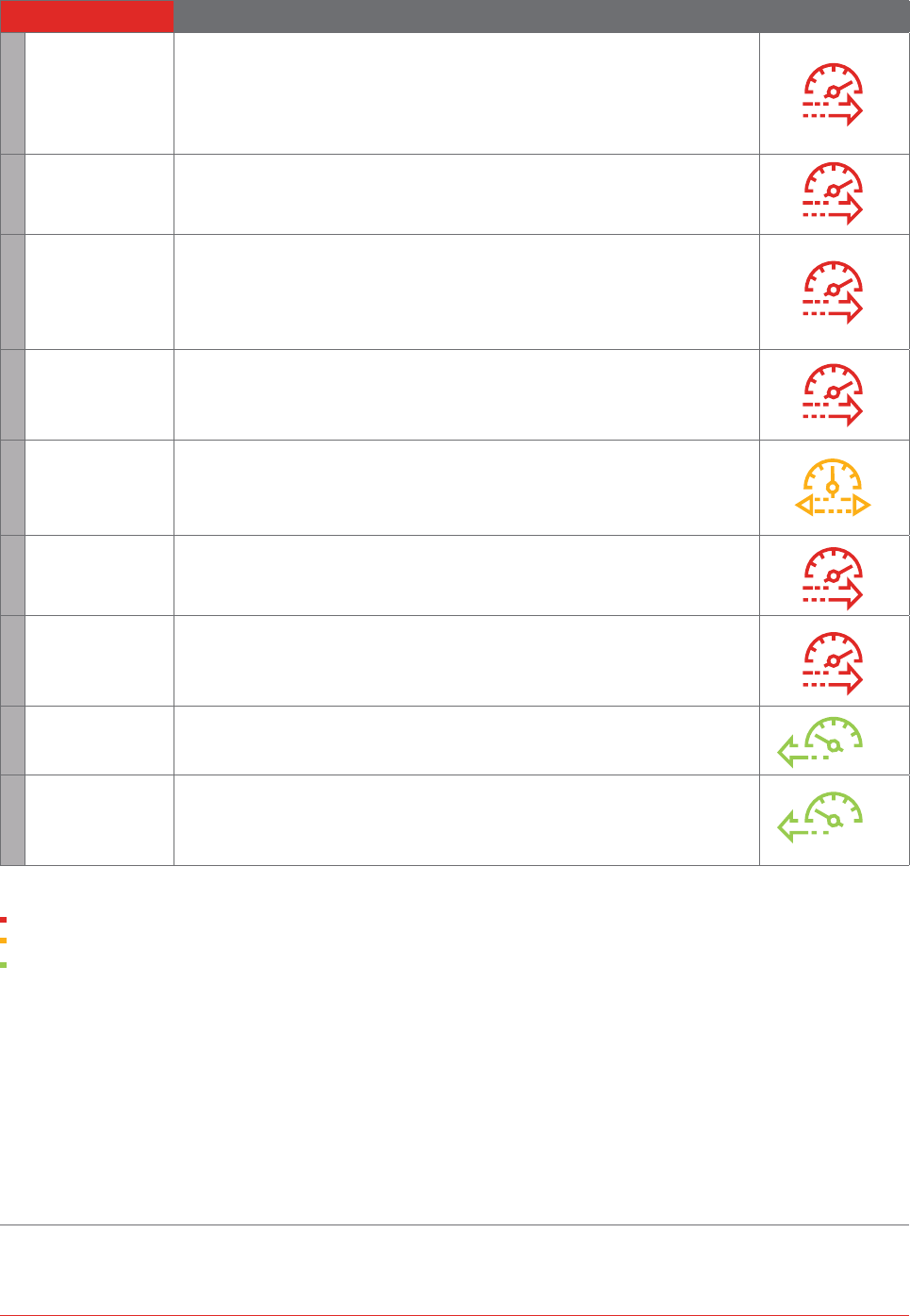

Figure 1: An illustration of the global pandemic BI protection gap

All figures are estimates.

Source: The Geneva Association (based on The World Bank 2020, McKinsey 2020a and contributions from Allianz Research)

$115 billion (USD)

Global commercial property

premium volume (2018)

up to $40 billion (USD)

Global insured pandemic

BI losses (2020)

up to $30 billion (USD)

Global BI premium volume

(2019)

$4.5 trillion (USD)

Global economic losses (2020)

$1.6 trillion (USD)

Global P&C insurance

premium volume (2019)

11

An Investigation into the Insurability of Pandemic Risk

usually face significantly higher costs. In addition, the

dynamics of socio-economic variables such as ageing

populations, volatile and difficult to predict government

policies (including subsidies and tax incentives) and cost

inflation as a result of medical advancements can have a

notable impact on the cost of necessary treatment (The

Geneva Association 2019).

Despite these challenges, various parameters have been

used to gauge the size of the health protection gap. One

common proxy is out-of-pocket spending (OOPS), i.e.

the part of national health expenditure that comes from

household savings. The focus here is on the share of OOPS

that is stressful to households – that results in the need

9 Other researchers have focused on catastrophic health expenditure or the risk of impoverishment from unexpectedly high medical expenses as a

key determinant of the health protection gap (see, for example, Wagstaff et al. 2018). Every year, about 100 million people are still being pushed

into extreme poverty (defined as living on less than USD 2per day) because they have to pay for health care. And over 900 million people, around

12% of the world’s population, spend at least 10% of their household budgets on health care (WHO 2019).

to reduce discretionary spending on food or education in

order to pay medical bills. OOPS, however, fails to take

into consideration cases of non-treatment or under-

treatment due to affordability and accessibility reasons.

9

Introducing the current context of the global pandemic,

Figure 2 compares the relevance of OOPS in the G20

countries with the estimated shares of the population

at increased risk of severe COVID-19 due to underlying

health conditions (reflecting primarily demographic and

lifestyle-related peculiarities). The figure illustrates those

countries’ populations’ vulnerability to financial stress or

even catastrophe as a result of COVID-19.

In 2019, credit insurers worldwide wrote around USD 15 billion in premiums (including surety). This corresponds to about

1% of the global premium pool in P&C insurance (excluding health). Despite its relatively small size, credit insurance is

of significant economic importance. Its total exposure amounts to around USD 3.3 trillion. That is, approximately 15% of

global merchandise trade is covered by credit insurance.

This raises two questions: How can such a small industry shoulder such a large exposure? And does the fact that about

85% of global trade is not insured suggest a huge ‘protection gap’?

On the first question, credit insurance differs from most other insurance lines in one key respect: it is based on a

dynamic relationship. Trade credit insurance policies are continually updated and cross-referenced over the course

of the policy period. While policyholders can constantly adjust their needs for credit limits, notably when increasing

business with existing clients or when approaching new prospects, the credit insurer monitors its customers' business

partners throughout the year to ascertain their continued creditworthiness. In case of doubt, individual coverage limits

are reduced. This flexibility allows credit insurers to keep pricing very moderate, with premiums as a percentage of total

exposure standing well below 1%. This has to be seen against the backdrop of the annual global corporate default rate

only having dropped below 1% in two years since the Global Financial Crisis – when it rose to over 5%.

On the second question, not every business relationship requires insurance, e.g. if the customer is a long-term trusted

business partner, a government, a blue chip company or a member of the same group (about two thirds of global trade

in goods are estimated to be intra-group deliveries). This also makes the real value of credit insurance clear: supporting

customers in their expansion by opening up new international markets and business relationships. Ultimately, credit

insurance is not only about indemnifying losses incurred from a default, but also providing businesses with the support

and expertise to improve their risk management. Credit insurers offer actionable economic knowledge, making them

information providers rather than pure risk carriers.

Having said this, credit insurers are not infallible. In extreme cases, individual limits may be withdrawn completely. This

happened in the Global Financial Crisis, accelerating the downward spiral because, in the worst case, transactions without

cover were not conducted at all. As a result of these experiences, many governments acted quickly in the COVID-19

crisis and, by means of state protection shields, enabled credit insurers to maintain their limits – for the benefit of their

customers and the economy at large.

Source: Allianz Research

Box 1: Protection gaps in trade credit insurance

12

www.genevaassociation.org

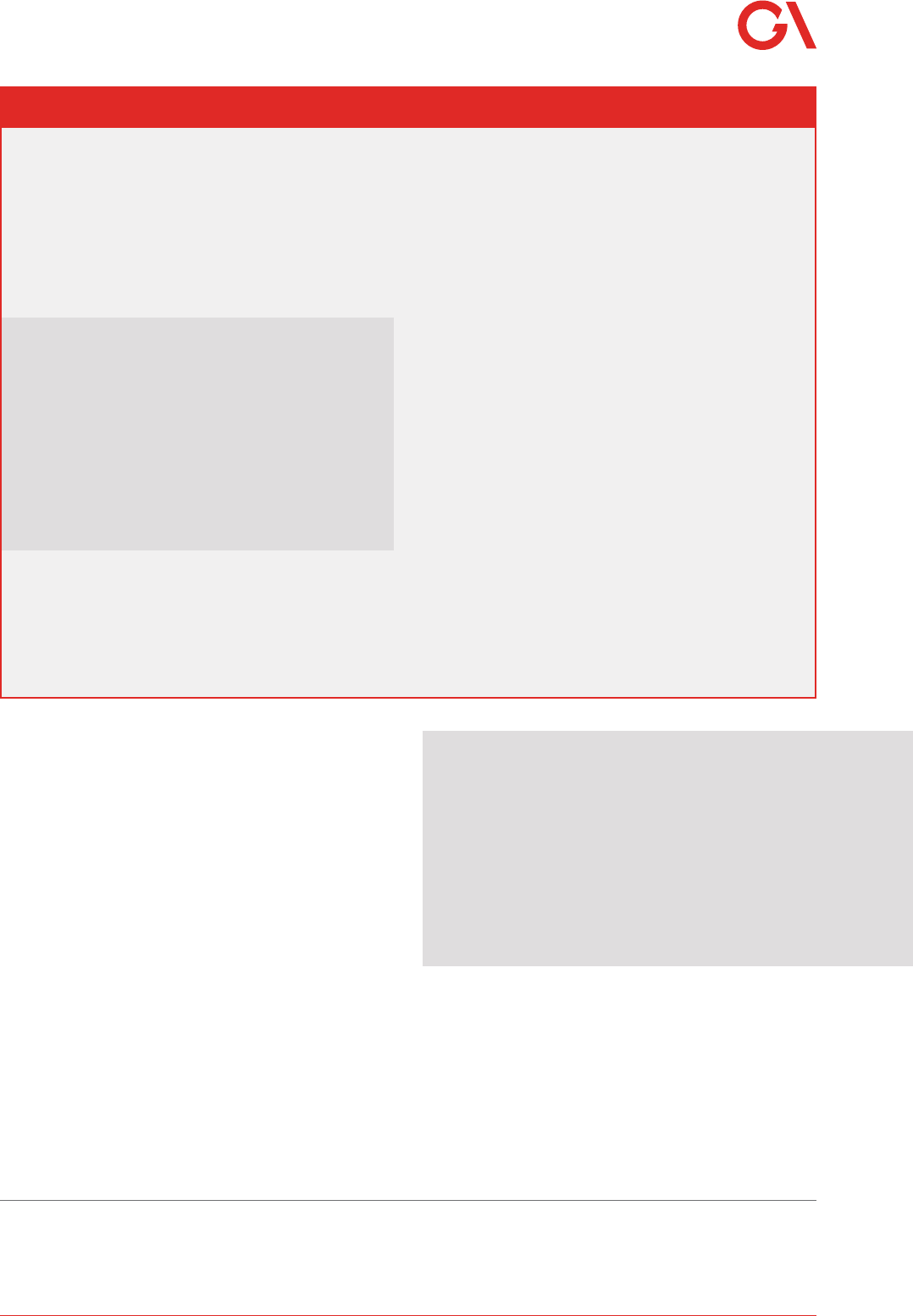

Figure 2: Out-of-pocket spending as a percentage of current health expenditure (2017) and estimated share of

population at increased risk of severe COVID-19 due to underlying health conditions

10

Source: The Geneva Association (based on WHO’s health expenditure database and Clarke et al. 2020)

10 In line with WHO standards, Clarke et al. (2020) define a severe case of COVID-19 as ‘a patient with severe acute respiratory illness’: 1) fever,

2) at least one sign/symptom of respiratory disease, e.g. cough, shortness of breath and 3) requiring hospitalisation. Conditions associated

with increased risk of severe COVID-19 include the following 11 categories: 1) cardiovascular disease, including cardiovascular disease caused

by hypertension; 2) chronic kidney disease, including chronic kidney disease caused by hypertension; 3) chronic respiratory disease; 4)

chronic liver disease; 5) diabetes; 6) cancers with direct immunosuppression; 7) cancers without direct immunosuppression, but with possible

immunosuppression caused by treatment; 8) HIV/AIDS; 9) tuberculosis (excluding latent infections); 10) chronic neurological disorders; and 11)

sickle cell disorders.

Out-of-pocket

spending as %

of current health

expenditure (2017)

Proportion of

population at

increased risk and

high risk of severe

COVID-19 (2020)

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

India

Mexico

Russian Federation

China

Indonesia

Republic of Korea

Brazil

Italy

Australia

Turkey

United Kingdom

European Union

Saudia Arabia*

Argentina

Canada

Japan

Germany

United States of America

France

South Africa

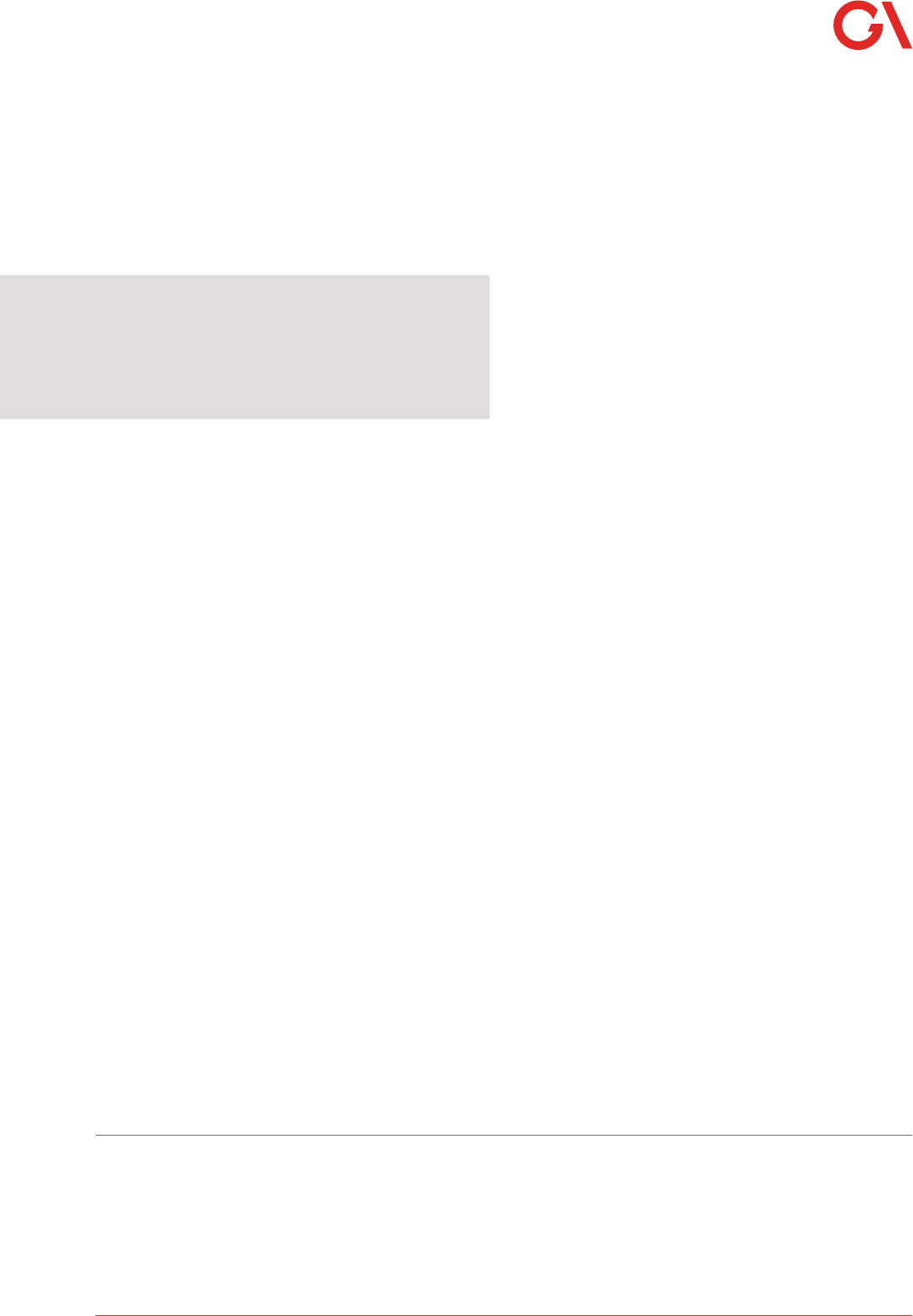

Figure 3: Regional health protection gaps (insurance premium equivalents as a share of GDP, in %)

Source: The Geneva Association (based on Swiss Re 2019)

Emerging Asia

Advanced Asia

Advanced Europe

Latin America and the Caribbean

U.S./Canada

10.60.2 0.80.40 1.61.2 1.4

13

An Investigation into the Insurability of Pandemic Risk

Figure 2 reveals, for example, that Indians’ massive

vulnerability to health protection gaps is somewhat

offset by a low level of increased risk of severe cases of

COVID-19. Russians look particularly vulnerable with an

OOPS share of 40% compounded by a 32% risk of severe

COVID-19. It is however important to note some of the

challenges inherent in analysing this type of data. While

the U.S. appears to be in a relatively strong position when

looking at OOPS, it is clear that other variables, such

as macro-economic conditions, can quickly lead to a

deterioration in healthcare (as discussed in Case Study 1).

Figure 3 offers a different perspective on the relevance

of health protection gaps in a number of major regions.

It is based on the premium equivalents of underlying

gaps in sums assured, or protection available from public

and private schemes versus protection needed, i.e. total

healthcare expenditure. The figures understate the true

extent of health protection gaps as they do not consider

the so-called 'treatment gap' (i.e. required healthcare

services not accessed because of a lack of availability or

affordability). The figures also require an estimation of

what level of OOPS on health is stressful for households,

which depends on a country’s development status. In

advanced economies, for example, a larger share of OOPS

is part of co-insurance and deductibles (Swiss Re 2019).

Premium-based health protection gaps as a share of

GDP are, as expected, most pronounced in emerging

11 COVID-19 has led to a sharp drop in spending on other conditions, with non-urgent care cancelled and patients avoiding hospitals and clinics.

However, EIU 2020 expect spending on non-coronavirus care to recover in 2021, also driven by the expected availability of effective vaccines and

treatments.

markets, especially in Asia. In advanced Europe, the gap

is smallest, at about one-fifth the level calculated for

emerging Asia (Figure 3). In absolute premium equivalents,

‘Emerging Asia’ and the U.S./Canada exhibit the largest

health protection gaps, at USD 278 billion and 95 billion,

respectively (Swiss Re 2019).

In general, closing these protection gaps through private-

sector insurance solutions looks much more realistic than

addressing pandemic BI risk, especially as pandemic health

risk is insurable, in principle (The Geneva Association 2019

and section 3.3.2 of this report).

From a macro perspective, COVID-19 is expected to

further exacerbate health protection gaps across the

globe. Even though healthcare spending globally is

forecast to fall in 2020 (EIU 2020),

11

the hit to national

incomes (as measured by Gross Domestic Product (GDP))

is almost certain to be significantly more severe. Therefore,

the share of healthcare expenditure in total GDP is

set to further increase in 2020. Assuming a constant

relationship between total healthcare expenditure and

OOPS, health protection gaps will become even more

acute, especially in emerging countries like India where

healthcare expenditure in 2020 is projected to increase by

5% (in local currency) but GDP is forecast to contract by

at least 3% (EIU 2020).

14

www.genevaassociation.org

12 In principle, while affordability could still be a challenge, a system that requires an employer to provide cover for a period after redundancy and/or

allows the individual to take over the cover in some form could help mitigate this.

Figure 4: Regional mortality protection gaps (insurance premium equivalents as a share of GDP)

Source: The Geneva Association (based on Swiss Re 2019)

Emerging Asia

Advanced Asia

Advanced Europe

Latin America and the Caribbean

U.S./Canada

0.50.30.1 0.40.20 0.6 0.7

Based on past hospitalisations for pneumonia and other respiratory illnesses, tens of millions of Americans could

face significant out-of-pocket medical expenses for COVID-19 hospitalisations, despite the fact that many insurers

have waived cost-sharing requirements. Researchers from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

analysed out-of-pocket costs for pneumonia and other respiratory illness hospitalisations from January 2016 through

August 2019 as a potential indicator of likely COVID-19 costs. The study found that these out-of-pocket costs

were particularly high for ‘consumer-directed health plans’ which account for about 60% of employer-sponsored

health insurance plans in the U.S. Those plans typically feature lower premiums but higher deductibles compared to

standard plans, and under their terms, insurers are not required to adhere to the cost-sharing waivers.

The study found that average OOPS for the 2016–2019 research period for these respiratory hospitalisations was

about USD 2,000 for patients with consumer-directed plans (Eisenberg et al. 2020). Another study estimates

average COVID-19-related OOPS across all employer-sponsored plans at more than USD 1,300 (Cox et al. 2020).

Those Americans who have lost or will lose employer-sponsored health insurance as a result of pandemic-related

unemployment will suffer even more financial stress,

12

with hospitalisation costs exceeding USD 20,000 for

pneumonia patients with complications and more than USD 80,000 for patients with the most serious respiratory

conditions that require ventilator support (Cox et al. 2020). More than 10 million people are estimated to lose

their employer-sponsored health insurance plans between April and December 2020 (Banthin et al. 2020).

This challenge comes on top of the well-documented fact that even before COVID-19, an estimated 87 million

U.S. adults (aged 19–64), or 45%, were inadequately insured for health (including those 23 million not insured at

all) [Collins et al. 2019].

Case Study 1: COVID-19-induced health protection gaps in the U.S.

15

An Investigation into the Insurability of Pandemic Risk

Having said this, there are COVID-19-related factors

which could actually mitigate health protection gaps. The

pandemic has catalysed the digital provision of health

services which could alleviate shortfalls associated with

access and affordability (APX/Porsche Consulting 2020).

In addition, heightened awareness of health risks and

the potential benefits of insurance could generally boost

demand for health insurance (McKinsey 2020b).

The accelerated provision of digital

health services catalysed by COVID-19

could actually mitigate health

protection gaps by addressing obstacles

to access and affordability.

2.2.3. The mortality protection gap

13

The mortality protection gap can be defined as the

difference between the amount needed to substitute

a household’s future income in the event of the main

breadwinner’s death, and the existing resources available

to repay outstanding debts and maintain the living

standards of surviving household members. Resources

available include the household’s existing financial assets,

benefits from life insurance policies and social security

payments. The mortality protection gap describes the

portion of the deceased’s regular income that cannot be

replaced by these existing resources (Swiss Re 2020b).

The pandemic is likely to have widened these gaps. Sharply

rising unemployment and eroding asset valuations reduce

available household resources, exacerbating the shortfalls.

Also, given the fiscal emergency in most countries,

the availability of social security payments is likely to

decrease.

Figure 4 offers an illustration of various regions’

vulnerability to the mortality protection gap, which is

measured in life insurance premium equivalents (Swiss Re

2019) as a share of GDP. It is most relevant in emerging

Asia, followed by Latin America and the Caribbean. It is

lowest in the U.S. and Canada.

14

For all regions, mortality

13 In addition to the heightened risk of premature death, life and health insurers are likely to be affected by longer-term changes to morbidity

patterns as a result of COVID-19.

14 Note, however, that the notional mortality protection gap in the U.S. amounts to a staggering USD 25 trillion, defined in absolute terms as the

difference between the amount needed to substitute a household’s future income in the event of the main breadwinner’s death and the existing

resources available to repay outstanding debts and maintain the living standards of surviving household members (Swiss Re 2018).

15 In absolute premium equivalents, mortality protection gaps amount to USD 129, 78 and 58 billion for Emerging Asia, Advanced Europe and the

U.S./Canada, respectively (Swiss Re 2019).

16 There are no recent comprehensive data capturing mortality protection gaps by country. Based on Swiss Re 2013, Peru’s mortality protection

gap (as defined above, i.e. in terms of the absolute notional shortfall) exceeds the country’s GDP by a factor of 2.3. The respective multiple for

Indonesia is 1.8. (Swiss Re 2020).

protection gaps are smaller than the respective shortfalls

in healthcare (see Figure 3).

15

As argued in section 3.3.2 of this report, COVID-19

pandemic mortality risk is insurable. Therefore, private-

sector insurance capital and expertise seem to be well

equipped to narrow such protection gaps.

Establishing the link to COVID-19, Figure 5 shows the level

of excess mortality for a number of countries, capturing

the period from March to mid-July 2020. Excess mortality

indicates the number of people who die from any cause

in a given region and period compared with the recent

historical average. Many Western countries, and a handful

of other nations and regions, publish such data regularly

(see FT 2020).

Figures 4 and 5 suggest that especially for Latin America,

massive regional mortality protection shortfalls are

significantly compounded by COVID-19 induced excess

deaths.

16

Figure 5: Excess mortality in % (March to mid-July 2020)

Source: FT 2020

Peru

Ecuador

Spain

Chile

UK

Italy

Belgium

France

Netherlands

Switzerland

Sweden

US

Brazil

Portugal

Austria

Denmark

Norway

Germany

Iceland

Sout Africa

7525 100500

16

www.genevaassociation.org

A pandemic creates mortality and morbidity risks that affect individuals. What affects

businesses and companies is primarily the handling of the pandemic by governments.

To prevent propagation, public authorities implement measures, such as lockdown

and stay-at-home orders, that restrict freedom of movement and the ability to work.

Such measures have major economic repercussions, simultaneously reducing supply

and contracting demand on a global scale and across a wide range of economic

sectors. This risk is the focus of the following sections.

For insurers to underwrite all of the economic losses

resulting from pandemic risk would impose a material

solvency risk on the industry and create a potential

threat to broader financial stability.

There is a broad consensus, including among governments and regulators, that it

would be ruinous for insurers to underwrite all of the economic losses resulting

from pandemic risk. As discussed in section 2.2.1., the mismatch between the

insurance sector’s current levels of capital, on the one hand, and the probability and

exposure levels of pandemic risk, on the other, would impose a material solvency

risk on the industry, as well as create a potential financial stability threat.

3.1. The concept of insurability

The insurability debate gained traction in the 1980s, based on this observation:

‘The insurance industry as a whole is increasingly confronted with risks where for

reasons of principle and capacity doubts arise as to whether they can and should

be covered. This increase of risks at the limits of insurability is due to growing

social and accumulation problems, advancing technology and concentration

of values, increased complexity and exposure of numerous risks’. (Berliner 1985).

These observations have to be seen in the context of the liability crisis in the

U.S. when, in response to the excesses of the U.S. tort system, some

re/insurers stopped insuring liability risks and the cost of cover in the U.S.

increased dramatically across all sectors as a result (Gollier 1997).

17

17 In March 1986, the front page of Time Magazine read, ‘Sorry, America. Your Insurance Has Been

Canceled’.

3. Getting the basics

right: The insurability

of pandemic risk

17

An Investigation into the Insurability of Pandemic Risk

In general, insurance markets tend to respond adversely to

major catastrophe events. Insurers may reevaluate their

estimates of the probability and severity of loss, restrict

the supply of capacity and raise the price of the (limited)

coverage they are willing to offer (Cummings 2006).

Such responses have been observed, for example, after

Hurricane Andrew in 1992, the Northridge Earthquake in

1994 and the World Trade Center terrorist attack.

18

Risks that can be insured need not be

‘legislated’; uninsurable risks, however,

have to be dealt with by nation states

(Stahel 2003).

After massive loss events in particular, uninsurability

implies that a prospective policyholder cannot buy the

coverage one reasonably needs to manage the adverse

consequences of damage resulting from an uncertain

occurrence. Specifically, this could mean three things.

First, the insurance product is not available. Second,

the insurance product is available, but the coverage

offered is insufficient. Third, the insurance product is

not affordable to certain groups because of its price

(Holsboer 1995).

Against this backdrop, the concept of insurability pivots

on ‘the ‘natural borderline’ between the market economy

and nation states: risks that can be insured need not be

‘legislated’; uninsurable risks, however, have to be dealt

with by nation states’ (Stahel 2003). This borderline

ultimately defines ‘the division of labour’ (Giarini 1995)

in risk taking between the private insurance sector and

the public sector.

3.2. The criteria of insurability

The insurability of risks is not an exact science. There

are no objective attributes which unambiguously

define a certain risk as ‘insurable’ or not. ‘Limits to

insurability cannot be defined, but only analysed’

(Berliner 1985). As a matter of fact, risks are insurable

if an insurer and an insurance buyer reach an

agreement about a specific insurance coverage and its

price, including a common understanding of what is

18 Given the vital role in the economy, major post-disaster fluctuations in the availability and price of coverage generally lead to pressure for

government intervention in insurance markets. This will be discussed in The Geneva Association (2020).

19 This is known as the ‘law of large numbers’, i.e. the larger the number of mutually independent risks in a risk pool, the lower the variance of losses

per risk (Bernstein 1996).

20 Moral hazard occurs when individuals or businesses have an incentive to increase their exposure to risk because they do not have to bear the full

costs of that behaviour, e.g. as a result of taking out insurance. Adverse selection describes a mechanism by which individuals or businesses choose

whether or not to buy insurance based on information not available to their insurer. See the seminal work by Arrow (1963).

insured and what not. From the insurer's perspective,

any decision to offer coverage also depends on

(partially) subjective elements such as the company’s

strategic objectives, risk assessment, risk aversion and

risk-taking capacity (determined by available equity

and reinsurance capacity) (Karten 1997).

From a more theoretical perspective, Berliner 1982, in a

seminal publication, introduced a simple, yet rigorous and

comprehensive set of criteria of insurability. This approach

still shapes the academic discourse on insurability and

continues to be frequently used by practitioners to analyse

insurance markets and products. For example, Berliner’s

set of criteria has been widely applied to climate insurance,

cyber insurance and microinsurance (Biener and Eling

2012; Biener et al. 2015; Charpentier 2018; Kunreuther and

Michel-Kerjan 2004). Ultimately, these criteria ‘can (…) be

interpreted as dimensions of insurability which have to be

gone through by the professional risk carrier individually

like a checklist when assessing the insurability of a risk’

(Berliner 1985). A risk is uninsurable for a professional

carrier if at least one criterion is not satisfied.

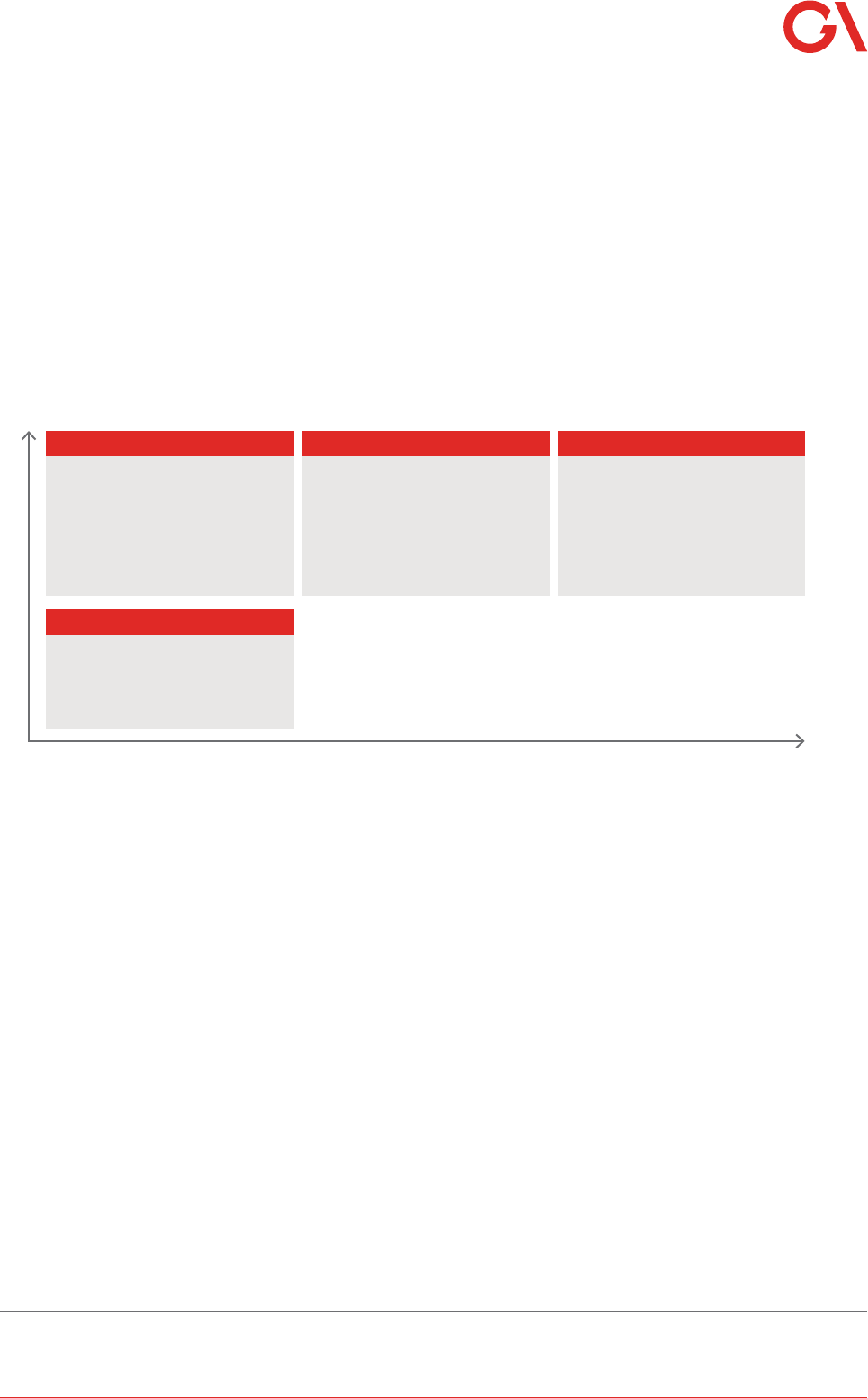

Berliner’s framework is three-pronged, consisting

of actuarial, market and societal conditions for

insurability. The first actuarial condition requires that

risks are random and independent (i.e. accidental and

unintentional in nature) so that loss probabilities are

reliably estimable within reasonable confidence limits.

Events that are highly correlated expose insurers to

systemic risk which cannot be diversified away through

risk selection and portfolio building. Second, maximum

possible losses per event must be manageable from

the insurer’s solvency point of view, i.e. they must not

be financially ruinous. Third, average loss amounts

per event must be moderate and, with a growing

number of mutually independent risks in the insurance

pool, converge towards expected losses, allowing for

acceptable and decreasing safety loadings.

19

Fourth,

actuarial insurability necessitates a sufficiently large

number of independent exposure units (policyholders)

and loss events per annum. The size of the risk pools

has to be adequate so that insurers can calculate

loss probabilities. Fifth, insurability from an actuarial

perspective requires the absence of severe information

asymmetries (i.e. moral hazard and adverse selection),

or, at least, the possibility to mitigate them through

contract design and underwriting, for example.

20

18

www.genevaassociation.org

Conditions for insurability include that

maximum possible losses per event

must be manageable from the insurer’s

solvency point of view. They must not

be financially ruinous.

In addition to the actuarial dimension, Berliner (1982)

establishes two market-related insurability criteria. First,

insurance premiums need to cover the insurer’s cost (e.g.

claims and operating expenses, cost of capital, etc.) and,

at the same time, must be affordable to the insured.

21 22

Second, cover limits imposed by the insurer must be

acceptable to the insured, i.e. not defeat the purpose of

buying insurance.

The third dimension of insurability is the societal one and

proposes two further criteria. First, coverage must be in

accordance with public policy and societal values (e.g.

not promote criminal behaviours) and, second, comply

with the legal and regulatory restrictions governing the

operation of insurance companies and the offering of

coverage.

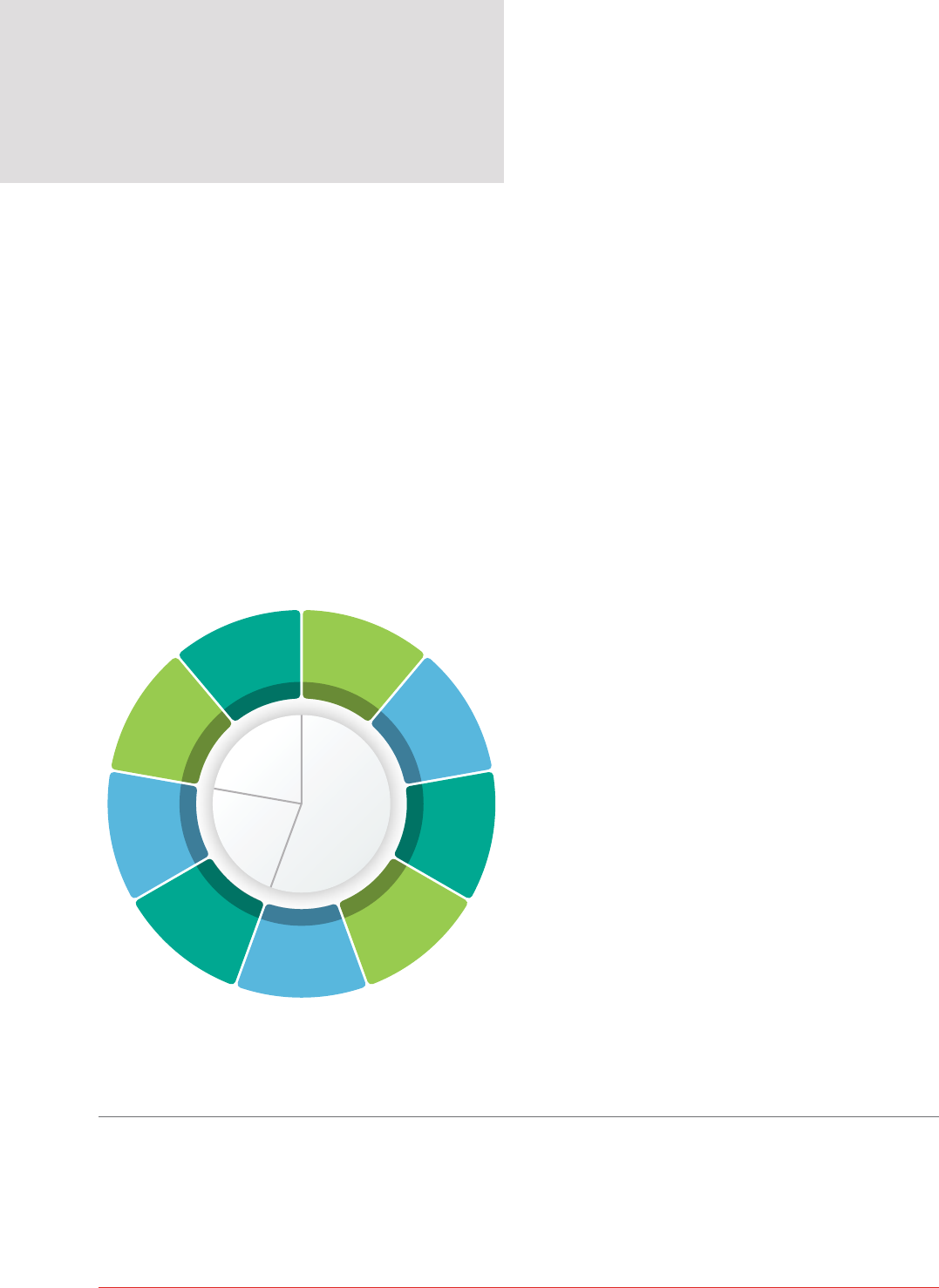

Figure 6: The fundamental criteria of insurability

Source: The Geneva Association (based on Berliner 1982)

21 If policyholders are risk averse, the pooling of risk makes them better off if transaction costs are low and the risks are not (fully) stochastically

dependent (Mossin 1968). In the case of stochastically dependent risks (such as pandemics) the benefits of pooling the small diversifiable risk part

may be offset by transaction costs associated with special pandemic risk schemes. This will be further explored in The Geneva Association (2020).

22 The risk loadings for pandemics are expected to be massive because of the large loss variance associated with individual events, the positive

correlation of the individual risk units in the pool and the negative correlation between pandemic risk and the insurer’s investment portfolio. These

factors are likely to translate into insurance rates where even very risk-averse policyholders would prefer to be not insured (Gründl and Schmeiser

2002). The cost of capital associated with pandemic risk will be further discussed in The Geneva Association (2020).

When exploring insurability, it is important to note

that the limits derived from Berliner’s criteria are not

set in stone. Progress in risk modelling driven by digital

technology, advanced analytics and the increased

availability of large amounts of data is a key to expanding

the boundaries of insurability. It enables insurers ‘to

more accurately quantify probabilities and underwrite

previously difficult-to-insure risks’ (Swiss Re 2017). This

will be further explored in The Geneva Association (2020).

3.3. Limits to insuring pandemic

risk – A comparative and holistic view

It is not difficult to intuitively understand the limits to

managing pandemic risk. The word ‘pandemic’ originates

in the ancient Greek (‘pan’ means all and ‘demos’ means

people). A pandemic outbreak spreads worldwide, or

at least across large regions. As witnessed during the

COVID-19 lockdown periods, pandemics have the

potential to paralyse entire countries and economies,

causing significant and simultaneous damage to virtually

all individuals and businesses. This enormous correlation

and aggregation of risks further highlights the enormous

challenges of insuring these.

3.3.1. Pandemic BI risk

Due to its systemic characteristics, the pandemics

insurability discussion pivots around commercial P&C

business and BI in particular. Pandemic-induced property

and business continuity risk is unique given its potential to

impact virtually all policyholders simultaneously, over an

extended period of time (OECD 2020a). The fundamental

mechanism of risk pooling and redistribution – spreading

the losses of the few among the many unaffected by

disaster – no longer works in the presence of systemic

risk where the destabilising effects of a pandemic ripple

through the entire economy. The simultaneous ‘losses of

the many’ cannot be diversified and mutualised across

risk pools (Van Hulle 2020; Hartwig and Gordon 2020a;

Richter and Wilson 2020).

No legal

restrictions for

coverage

Independent

and predictable

loss exposures

Manageable

maximum

possible loss

Coverage

consistent with

societal values

SOCIETAL

MARKET

ACTUARIAL

Moderate

average loss

per event

Acceptable

cover limits

Large number

of exposure

units

Acceptable

and affordable

premiums

No severe

information

asymmetries

19

An Investigation into the Insurability of Pandemic Risk

The fundamental mechanism of risk

pooling and redistribution – spreading

the losses of the few among the many

unaffected by disaster – does not work

with a systemic risk like a pandemic,

where the destabilising effects ripple

through the entire economy.

A second peculiar feature is the endogenous and political

nature of the risk which is almost entirely driven by

governments’ decisions taken before, during and after

the pandemic. Its economic severity may vary greatly

depending on:

23

• Level of preparedness of the country when the

pandemic occurs, notably in terms of availability of

masks and medical equipment (e.g. hand sanitiser,

ventilators etc.): The higher the level of preparedness,

the lower the need for implementing long lockdown

and stay-at-home orders across the board that are the

costliest in economic terms.

• Timing in terms of adopting and implementing

measures to contain the pandemic: The higher the

level of ‘denial’ from public authorities regarding the

actual risk posed by the pandemic at the onset, the

higher the ultimate economic cost to handle it.

• Decisions as to which businesses/sectors can continue

to operate, fully or partly, and which businesses/

sectors must be fully shut down.

• Timing in terms of relaxing lockdown measures: This

is to some extent a political decision; even more since

there is no clear, predictable time limit on a pandemic.

• Economic and fiscal measures adopted by

governments to dampen the economic impact of the

crisis on companies (e.g. furloughs, short-term hours,

reductions in social charges, etc.).

24

23 Special thanks to Guillaume Ominetti (SCOR SE) for contributing this thought.

24 If governments learn from this crisis and develop a ‘play book’ of responses for future pandemics, the scale of the economic loss could be

significantly reduced.

Hence there is a myriad of parameters that are driven,

or that can be changed or influenced, by governments’

actions and that will determine to a large extent the

magnitude of the economic burden of a pandemic crisis.

Covering this risk through private insurance would create

obvious moral hazard issues. Public authorities, which

decide the ways and means to handle the pandemic

and are accountable for the management of the crisis,

would ultimately not bear the full economic costs

of the decisions they take and could succumb to the

temptation to misuse private-sector capital.

A third distinguishing feature of pandemic risk is the

fact that it is very difficult to model and measure the

economic losses that are specifically linked to the

handling of a pandemic by public authorities.

Covering pandemic risk through private

insurance would create moral hazard

issues for public authorities, who would

ultimately not bear the full economic

costs of the decisions they take.

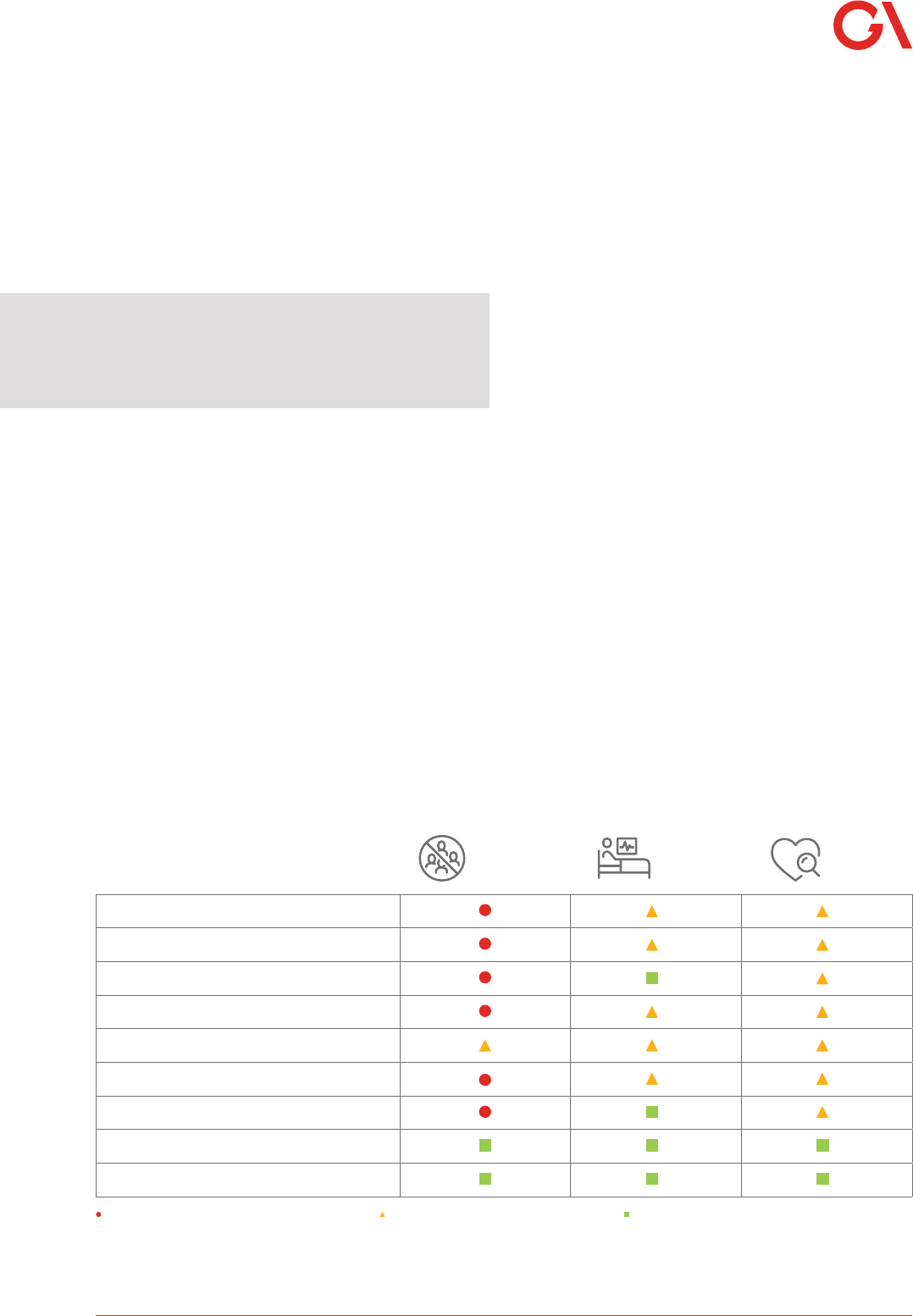

Table 1 comprehensively explores the insurability of

pandemic business continuity risk on the basis of Berliner’s

previously introduced criteria (see Figure 6).

20

www.genevaassociation.org

25 For example, changes in legislation which were unknown at the time of risk assessment and pricing or broader changes to the economic and social

environment such as the systematic increase in life expectancies.

Table 1: Criteria of insurability of pandemic business continuity risk

Highly problematic

Problematic

Less problematic

Source: The Geneva Association and University of St. Gallen, Institute of Insurance Economics

Insurability criteria Comments Assessment

1

Randomness and

independence

of loss occurrence

Losses are neither random nor independent

• Policy decisions to lock entire economies are deliberate and intentional. This means that

loss amounts and risk loadings cannot be set

• There are no historical data for the policy responses witnessed during COVID-19

• The strong interrelations among individual risks render efficient risk pooling impossible

2

Maximum possible

loss

The maximum possible loss is not manageable for the insurer

• The uncontrollable aggregation of losses could be ruinous to the risk pool

3

Average loss per

event (severity)

It is very difficult to keep the average loss amount per event at a moderate level

• The average loss for pandemic risk needs to be managed to an accepted level by

cover limits and exclusions, as adopted after previous pandemics

• In light of current political discussions and stakeholder expectations, the broader

acceptability of cover limits post COVID-19 is questionable

4

Exposure units

The number of independently exposed policyholders (exposure units) is too small

• As the economy as a whole is affected simultaneously by a pandemic, insurers

cannot build risk pools that are large enough and that diversify the losses. The law

of large numbers does not work

5

Information

asymmetries

Information asymmetries limit insurability

• Insurers are likely to face higher demand from exposed sectors (adverse selection)

and have to expect less risk-conscious behaviours (moral hazard)

• The mitigation potential (e.g. through contract wordings) is limited

6

Insurance premiums

Insurance premiums are not economically viable

• As pandemics threaten most, if not all, members of the risk pool at the same time,

the probability of loss (in addition to severity) is very high

7

Cover limits

Cover limits present challenges of complexity

• Non-physical trigger definitions create complexity (compared with clearly

describable property damage events) which can be problematic for both the

insurer and the insured

8

Public policy

Pandemic risk coverage should be in the public interest

• Issues could arise from certain government interventions (e.g. compulsory

insurance requirements)

9

Legal restrictions

Pandemic risk coverage should be compliant with existing legal and regulatory restrictions

• There might be a ‘risk of change’

25

or a ‘warlike’ scenario of the public sector

‘taking over’ and rewriting the rules that underpinned pricing and risk assessment

during ‘peace times’

21

An Investigation into the Insurability of Pandemic Risk

3.3.2. Pandemic life and health risk

This paper so far pivoted around P&C exposures

and business interruption in particular. Prior to the

unprecedented experience of wide-ranging lockdown

measures, the most obvious and probable source of

major insured pandemic losses was (term) life insurance

(individual and group policies) (CRO Forum 2007).

In contrast with P&C policies, there are generally no

exclusions for pandemics or other common causes for

extreme mortality events such as terrorist attacks or

natural disasters (NAIC 2020; Kraut and Richter 2015).

26 The reasoning for permanent life insurance which offers both death benefits and a savings portion is slightly more nuanced. It offers guaranteed,

not contingent, benefits, and as such the timing element to loss is more relevant than the contingency of loss. Considering the key issue is when

the loss will occur, not if it will occur, life insurers price in some level of volatility in the mortality and may also hold some extra capital for

pandemic stress scenarios.

Unlike the P&C exposures of

pandemic risk, such as business

interruption, life exposures, including

excess mortality, can be modelled.

There are therefore generally no

policy exclusions for pandemics and

other extreme mortality events.

The two main reasons behind the different treatment

of P&C and (term) life exposures by insurers is data

availability and the ability to model exposures.

26

For

life insurers, excess mortality (mortality above what

would normally be expected over a specific span of

time) associated with diseases is well-documented and

Politicians all over the world have compared COVID-19 to a warlike challenge. From an insurance perspective,

too, there are analogies between wars and pandemics. Both represent fundamentally cataclysmic, correlated and

incalculable risks which insurance as a risk transfer mechanism was never intended to cover. Both also come with

harsh restrictions and strong measures that are outside the scope of ordinary law and taken for national security

matters due to force majeure circumstances. These features, which explain why most insurance policies have a

war exclusion clause specifically excluding coverage for acts of war, would also justify that insurance contracts do

not cover economic losses arising from measures taken by public authorities to handle a pandemic.

Similar to a nation-wide economic lockdown due

to pandemic risk, there is no identifiable maximum

possible loss in a war scenario. It could cause a

catastrophic amount of damage that would be likely to

wipe out any insurance company liable to cover such

damages (Fitzsimmons 2004). Another parallel is that

exposures depend on mandatory government actions

which are impossible to model and to predict. As a

result, insurers are unable to calculate premiums for

both risks.

In summary, similar to pandemic business continuity

risk, war risk defies the criteria of insurability introduced before. Losses are neither random nor independent. A

maximum possible loss is impossible to establish. The average loss per event is very difficult to contain through

cover limits and exclusions. The law of large numbers does not work in the absence of a sufficient number of

independent exposure units. Insurance premiums covering the insurer’s cost of capital would be unattractive or

even unaffordable to customers.

Box 2: Analogies between pandemics and wars

Pandemics, like wars, represent

cataclysmic, correlated and

incalculable risks which insurance

contracts were not meant to cover;

not least because the insurance

premiums would be unattractive or

even unaffordable for customers.

22

www.genevaassociation.org

researched by epidemiologists around the world (CRO

Forum 2007).

27

For P&C insurers, however, modeling

pandemic risk is virtually impossible as it is driven as

much by subjective decisions of countless government

officials on national, regional or local levels as by

epidemiology (Hartwig and Gordon 2020b). In addition,

average mortality rates among life policyholders are

usually significantly lower than in the population as a

whole, mainly on the back of medical underwriting in

individual life insurance business (CRO Forum 2007).

Also, due to higher than expected mortality rates,

annuities may offer a natural hedge to the mortality

shock caused by a pandemic (Cox and Lin 2007; GCAE

2006), especially as many life insurers focus on annuities

rather than pure risk (term life) products and, as such,

tend to be more concerned about life expectancy

increases than sudden jumps in mortality.

28

29

27 The effects on group life business might be different as, in general, less underwriting has taken place and the state of health of the individuals in

the portfolio is less well known.

28 The full impact on life insurers may take time to develop. For example, increases in suicides tend to be correlated with extended higher levels of

unemployment.

29 It is important to emphasise that pandemic risk can be covered by life insurers offering broad, needs-based cover against hospitalisation costs or

death as the uncertainty in the pandemic element is small relative to the total coverage. However, this does not mean that they could necessarily

offer specific pandemic cover which might cause a number of elements in Table 2 to move from amber to red.

30 The impact of the Spanish flu on the insurance sector was limited due to the demographics of infections and deaths (Richter and Wilson 2020).

31 A 50% drop in surplus – presumably an existential threat to the industry – and maintaining all other assumptions of the severe pandemic scenario

would require a general population excess mortality of 13% or 4.3 million excess deaths (based on a U.S. population of 330 million in 2019). The

excess death toll from COVID-19 in the U.S. passed the threshold of 200,000 in September 2020.

32 Stracke and Heinen (2006) come to similar conclusions for the German insurance market.

The underwriting losses of life insurers

from COVID-19, while significant, are

expected to remain manageable.

Against this backdrop, the underwriting losses of life

insurers from COVID-19, while significant, are expected

to remain manageable. It is too early to estimate ultimate

losses but the standard pandemic scenario typically used by

insurers, regulators and industry observers may provide an

indication. Based on an excess death ratio of 1.5 per 1,000,

in the U.S., this would imply about 500,000 deaths (larger

than current official estimates of the potential death toll).

In such a scenario, underwriting losses would be about

USD 15 billion, or about 3% of pre-shock industry capital

(Kirti and Mu 2020). Having said this, life insurers’ exposure

could be significantly more severe in the case of a pandemic

involving a more lethal virus (see Box 3).

The Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918–19 is the most virulent on record, with an estimated global death toll of 25–50

million people, or 2–4% of the world’s population at that time (CRO Forum 2007). In the U.S., 675,000 excess deaths

from the flu were recorded between September 1918 and April 1919, corresponding to an excess mortality of 6.5‰

(Toole 2007).

Toole 2007 also analyzes the impact of a severe pandemic on the scale of the Spanish flu on today’s U.S. life insurance

industry. The scenario is based on 1.9 million excess deaths or an excess mortality of 6.5‰ for the general population

and 5‰ for the insured population.

30

It disregards, however, the potential mitigating impact of medical and other

interventions that were unavailable a hundred years ago. Under such an extreme scenario, the U.S. life insurance industry

would lose about 25% of its surplus.

31

Despite this massive hit, only a very small number of U.S. life insurers would face

an increased risk of insolvency. The industry as a whole could weather even a severe pandemic similar to the Spanish flu

(Toole 2007).

32

A wide range of circumstances must be taken into account when estimating the consequences of a disease outbreak

like the Spanish flu for today’s world: Medical care and technology have progressed dramatically, with the availability of

antibiotics, vaccines and anti-viral drugs. In addition, global surveillance and early-warning systems (e.g. by the WHO)

have been established. Furthermore, the socio-economic environment is markedly different from a hundred years ago,

with much improved hygiene conditions, nutrition and health status.

Risk factors to watch, however, include potential shortages in drugs, delays in data exchange among public authorities,

the increased prevalence of chronic diseases and the particular vulnerability of developing countries. Also, today’s degree

of urbanisation and global connectivity need to be taken into consideration (CRO Forum 2007).

Box 3: An extreme pandemic scenario on the scale of the Spanish flu

23

An Investigation into the Insurability of Pandemic Risk

For health insurers, too, pandemic risk poses no

fundamental insurability challenges. Some saturation

effects can be expected in the event of a large-scale

pandemic as healthcare provision capacities are limited,

e.g. a hospital bed can only be allocated once at any given

time (CRO Forum 2007; GCAE 2006). However, a virus

could cause more people to become chronically ill, with

negative consequences for health, long-term care and

occupational disability insurance.

Pandemic risk poses no fundamental

insurability challenges for health

insurers.

So far, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on private

health insurance has been relatively modest. In many

countries, for health insurance companies, the decline in

medical care for non-COVID conditions and routine or

elective procedures has more than offset the impact from

COVID-19 claims. However, as for life insurers, a more

severe pandemic could result in major insured losses,

with one estimate putting potential U.S. health insurance

losses at more than USD 30 billion (Dunks 2006).

In summary, pandemic life and health risks are privately

insurable in the context of COVID-19. Excess mortality

risk is modellable based on a wealth of historical data. In

addition, increased mortality risk is (partially) offset by

reduced longevity. For health insurers, there is a ‘natural’

limit to claims given the finite capacity of healthcare

systems and temporarily reduced expenditure for non-

pandemic-related procedures.

Based on the previous sections Table 2 offers a

comparative and illustrative summary assessment of

barriers to insurability of pandemic BI, mortality and

health risks.

As for pandemic BI risks, six of the nine insurability

criteria proposed by Berliner are deemed to present

insurmountable barriers to insurability and, as mentioned

before, a risk is uninsurable for professional risk carriers

if at least one criterion is not satisfied (Berliner 1985).

Most importantly, the almost perfect correlation and

uncontrollable accumulation of losses make the risk

uninsurable.

Barriers to insuring pandemic mortality risk, however, are

generally manageable and of relatively minor relevance,

such as the average loss size per event, the acceptability

and complexity of cover limits, the alignment with

public policy objectives and the compliance with existing

legal frameworks. For health insurers, too, barriers to

insurability appear to be surmountable, with no real

identifiable ‘game stopper’.

3.3.3. Pandemic risk compared to

other catastrophic risks

Table 3 compares the insurability of pandemics, wars,

nuclear accidents, cyber events, terrorist attacks and natural

catastrophes, outlining parallels and differences for these

types of low-frequency/high-severity risks.

Table 2: An illustrative summary assessment of obstacles to insuring pandemic risk

Prohibitively high barrier to insurability Manageable barrier to insurability Insignificant barrier to insurability

Source: The Geneva Association

Insurability criteria

Business

interruption

Mortality Health

Randomness/independence of loss occurrence

Maximum possible loss

Average loss per event

Number of exposure units

Information asymmetries

Insurance premiums

Cover limits

Public policy

Legal restrictions

24

www.genevaassociation.org

33 Projected economic losses from conceivable cyber viruses can be as massive as from natural viruses such COVID-19. In fact, while the economic

damage from lockdown measures was somewhat mitigated by digitally-enabled remote working, there would be no ‘safety net’ to fall back on in

the event of a wide-ranging IT outage.

34 One can argue that different forms of the handling of pandemic risk by public authorities introduce a ‘man-made’ component.

35 There are no fixed definitions of ‘extremely rare’ or ‘extremely severe’ events. Any assessment should reflect the relevant context. For the sake of

this paper, we consider an event as extremely rare if the return period is more than 25 years. We consider severity as extreme if the economic loss

is larger than 1% of GDP.

Table 3: A comparison of various types of extreme events

Source: University of St. Gallen, Institute of Insurance Economics

Type Pandemic War Nuclear Cyber

33

Terror NatCat

Examples

(loss amount)

COVID 19

(Economic loss

might be > 5% of

global GDP)

World War I

and II

(Economic loss

> 15% of global

GDP

Fukushima

(USD 214 billion

economic loss,

USD 36 billion

insured loss)

WannaCry

(USD 8 billion

economic loss,

insured loss

insignificant)

9/11

(economic loss

USD 80 billion,

USD 40 billion

insured loss)

Katrina

(USD 164 billion

economic loss,

USD 76 billion

insured loss)

Time horizon

Months

(potentially

longer)

Years Weeks

(potentially

longer)

Days/weeks Days Days

Risk origin

Natural (with

exceptions,

e.g. bio-logical

weapons)

34

Man-made Man-made Man-made

(with exceptions,

e.g. solar storm)

Man-made Natural

Frequency

35

Extremely rare

(SARS, COVID)