FEES

THE PRICE OF

ENTRY

:

BANKING IN AMERICA

FEBRUARY 2023

AUTHOR

Sheida Elmi, Sohrab Kohli, and Bianca Lopez authored this report.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Aspen Institute Financial Security Program (Aspen FSP) would like to thank Sheida Elmi, Sohrab Kohli,

and Bianca Lopez for authoring this brief; as well as Genevieve Melford, Karen Andres, Kate Griffin, Rachel

Black, Joanna Smith Ramani, Noha Shaikh, Tim Shaw, and Elizabeth Vivirito for their assistance, comments,

and insights. Aspen FSP would also like to thank members of the National Unbanked Task Force for the

insights they contributed throughout the interview process: Felicia Lyles and Pearl Wicks at Hope Enterprise

Corporation; Sindy Marisol Benavides at the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC); Rico Frias at

NAFOA; Nicole Elam at the National Bankers Association (NBA); Cy Richardson at the National Urban League

(NUL); Dedrick Asante-Muhammad at the National Community Reinvestment Coalition (NCRC); Katherine Rios

at UnidosUS; and Patrice Willoughby and Keisha Deonarine at the National Association for the Advancement

of Colored People (NAACP). Additionally, Aspen FSP would like to thank the following professional experts for

sharing their perspectives: David Rothstein at the Cities for Financial Empowerment Fund (CFE Fund); Casey

Lozar at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis; Barbara L. Martinez at the Heartland Alliance; Ann Solomon

and Monica Copeland at Inclusiv; Silvia Rincon at the Latino Community Credit Union; Rocio Rodarte and Sean

Doocy at the Mission Asset Fund (MAF); Wole Coaxum at MoCaFi; Pete Upton at the Native CDFI Network;

Karen Edwards at the Oklahoma Native Assets Coalition (ONAC); Wesley Wright at Queens College; Leigh

Phillips at SaverLife; Terri Friedline at the University of Michigan School of Social Work; and Jud Murchie and

Nadia van de Walle at Wells Fargo.

This research is a product of Aspen FSP. The paper was developed with support from Wells Fargo. The

findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this report—as well as any errors—are Aspen FSP’s alone

and do not necessarily represent the views of its funders, National Unbanked Task Force members, or other

participants in our research process.

ABOUT THE ASPEN INSTITUTE FINANCIAL SECURITY PROGRAM

The Aspen Institute Financial Security Program’s (Aspen FSP) mission is to illuminate and solve the most

critical financial challenges facing American households and to make financial security for all a top

national priority. We aim for nothing less than a more inclusive economy with reduced wealth inequality

and shared prosperity. We believe that transformational change requires innovation, trust, leadership,

and entrepreneurial thinking. Aspen FSP galvanizes a diverse set of leaders across the public, private, and

nonprofit sectors to solve the most critical financial challenges. We do this through deep, deliberate private

and public dialogues and by elevating evidence-based research and solutions that will strengthen the

financial health and security of financially vulnerable Americans. To learn more, visit AspenFSP.org, join our

mailing list at http://bit.ly/fspnewsletter, and follow @AspenFSP on Twitter.

3Aspen Institute Financial Security Program

|

Executive Summary

The United States financial system is not

effectively serving everyone. A structurally

inclusive financial system provides all people

with the ability to access, utilize, and reap the

benefits of a full suite of financial services

that facilitate stability, resilience, and long-

term financial security.

1

Unfortunately, the U.S.

financial system currently fails to meet this

definition. In 2021, nearly 1 in 5 households

in the U.S.—approximately 24.6 million

households—were either entirely disconnected

from mainstream financial services or, despite

having an account with a bank or credit union,

still turned to costly alternatives to get the

financial services they needed.

2

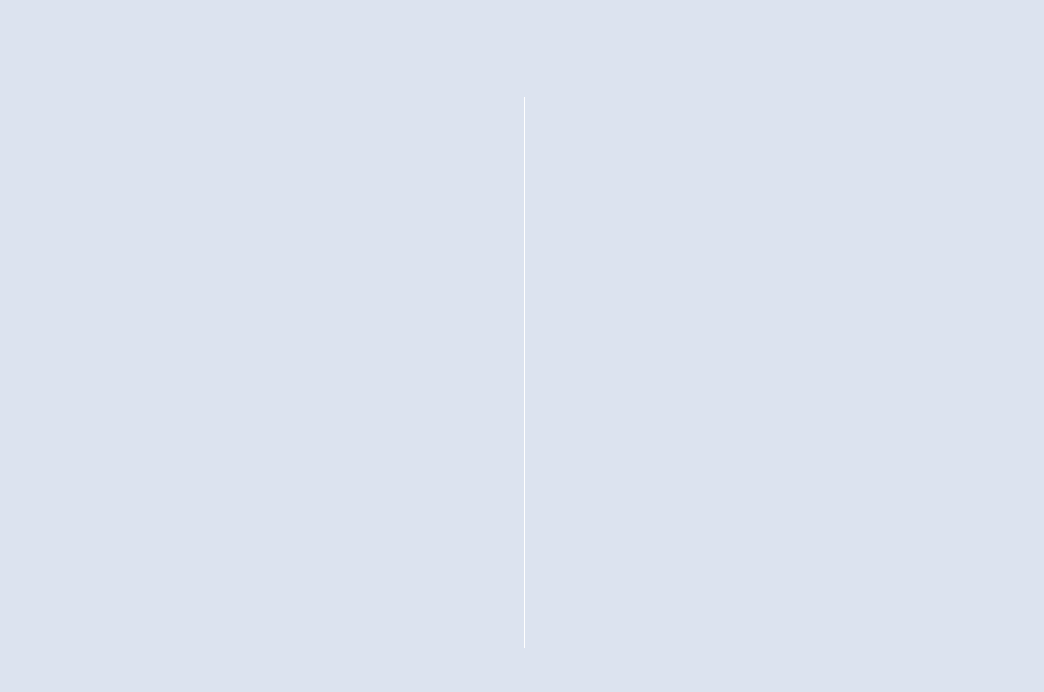

While 4.5 percent of all households in the

U.S.—approximately 5.9 million households—did

not have an account at a bank or credit union

in 2021, certain groups are unbanked at a

much higher rate. Black households, Hispanic

households, households with working-age

adults living with disabilities, households with

less education, and households with low income

WHAT’S IN THIS PAPER

A New Vision for Financial Inclusion................5

Why Financial Inclusion Matters ....................7

A Holistic Approach to Financial Inclusion .....9

State of Financial Inclusion: Consumer

Perspective ...................................................11

According to the Professional Experts:

Barriers and Opportunities .........................15

Opportunities for Further Research .............26

Conclusion ....................................................28

Endnotes ........................................................... 29

were among the groups even more unlikely

to own an account.

3

Historically, Indigenous

people have also faced significant barriers to

banking access.

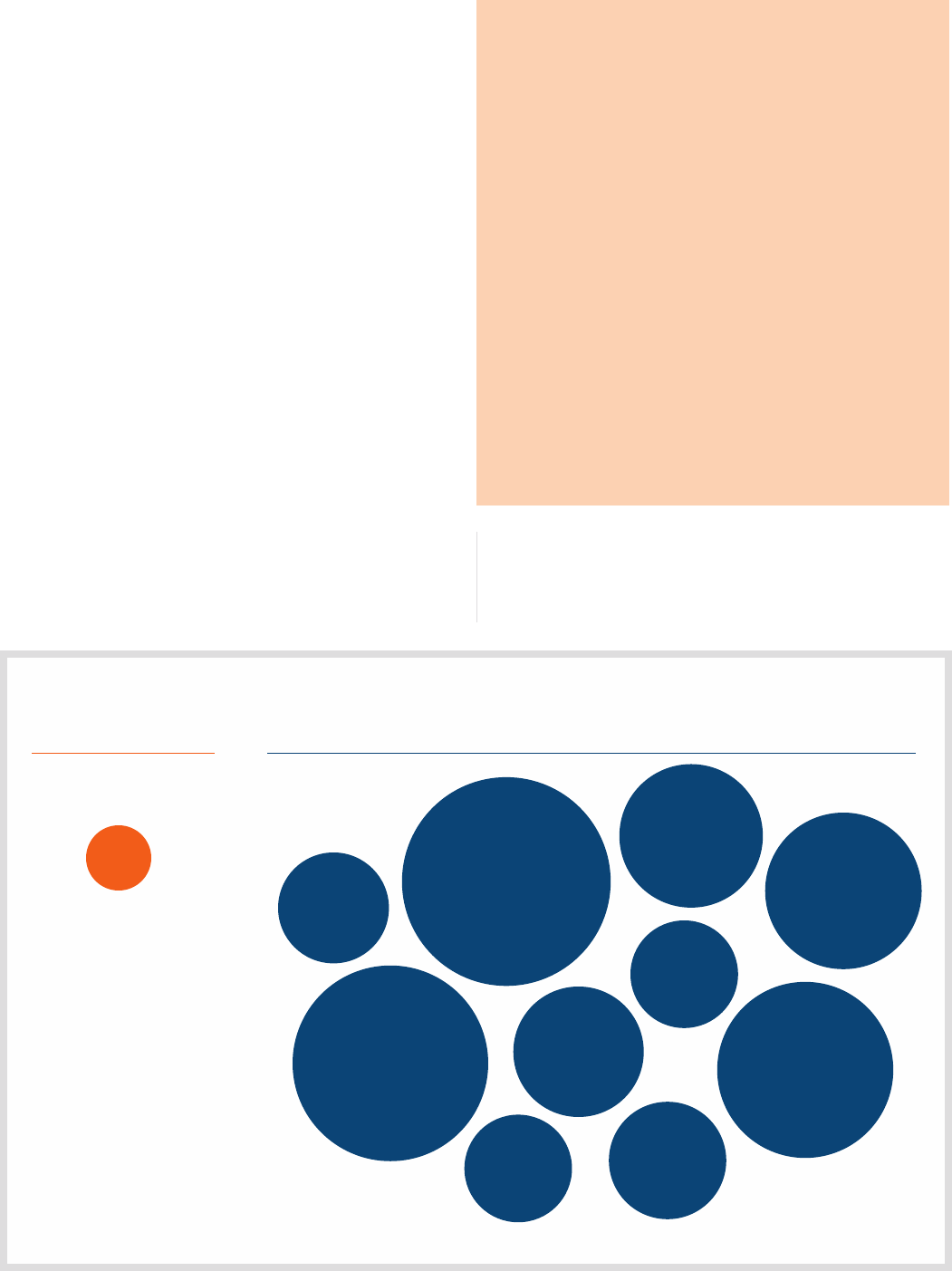

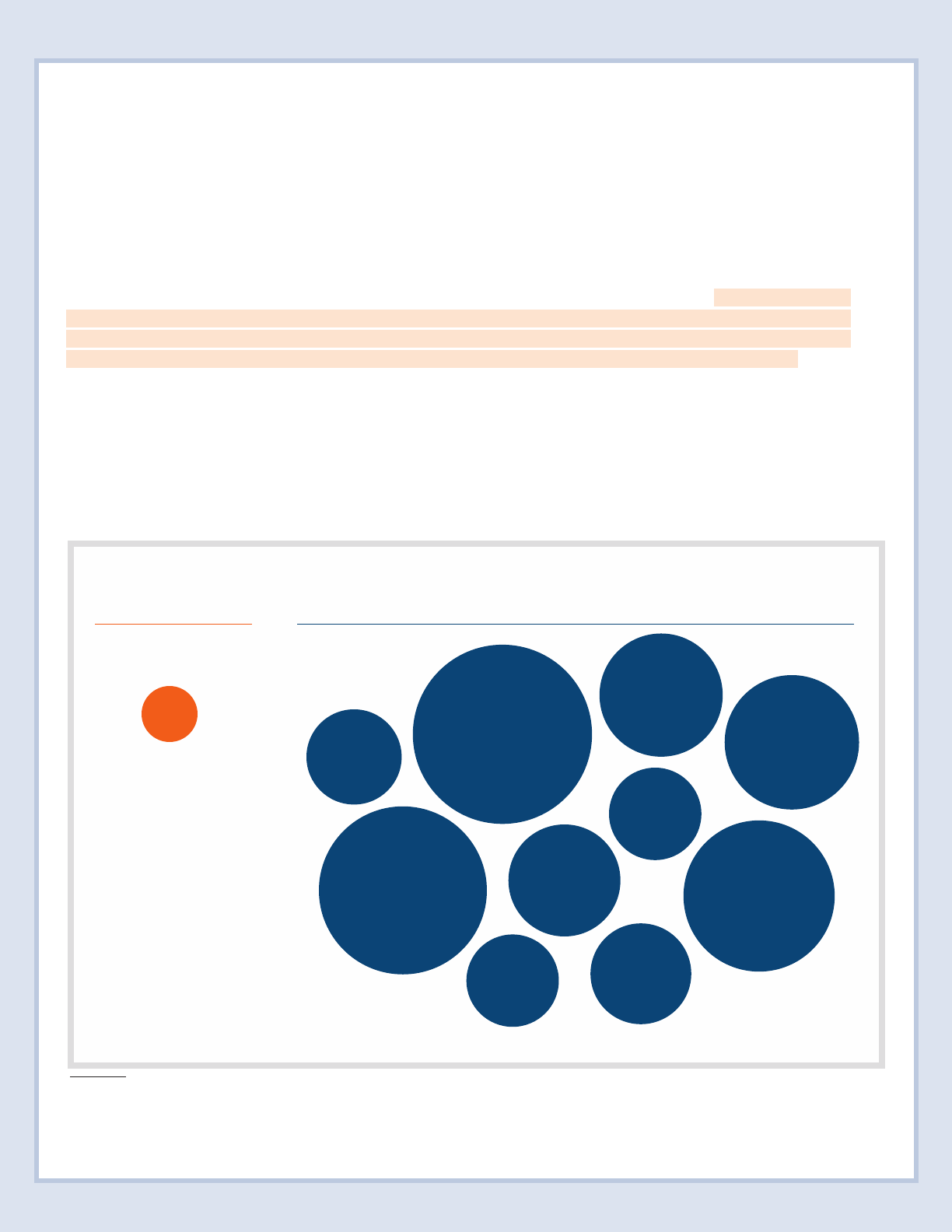

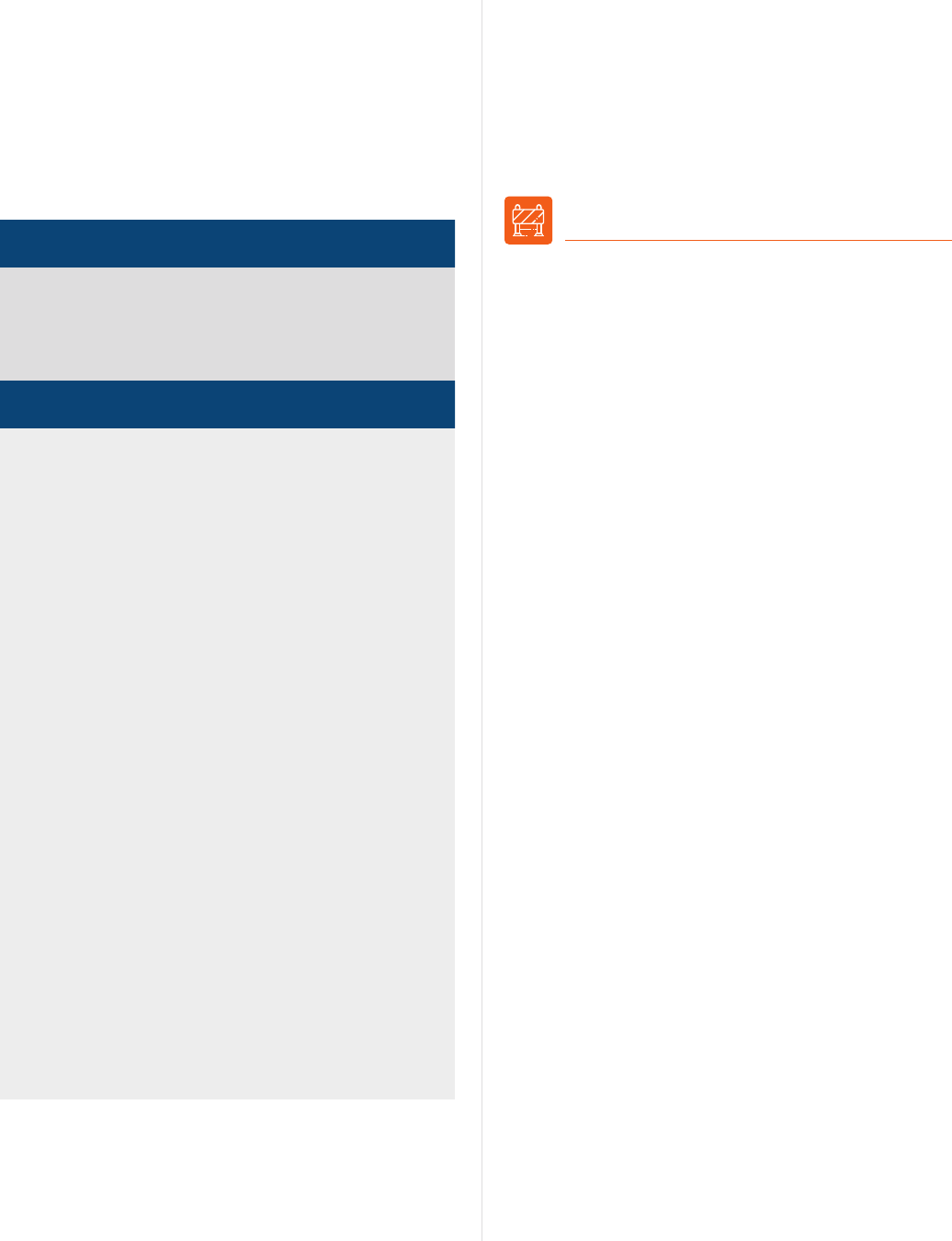

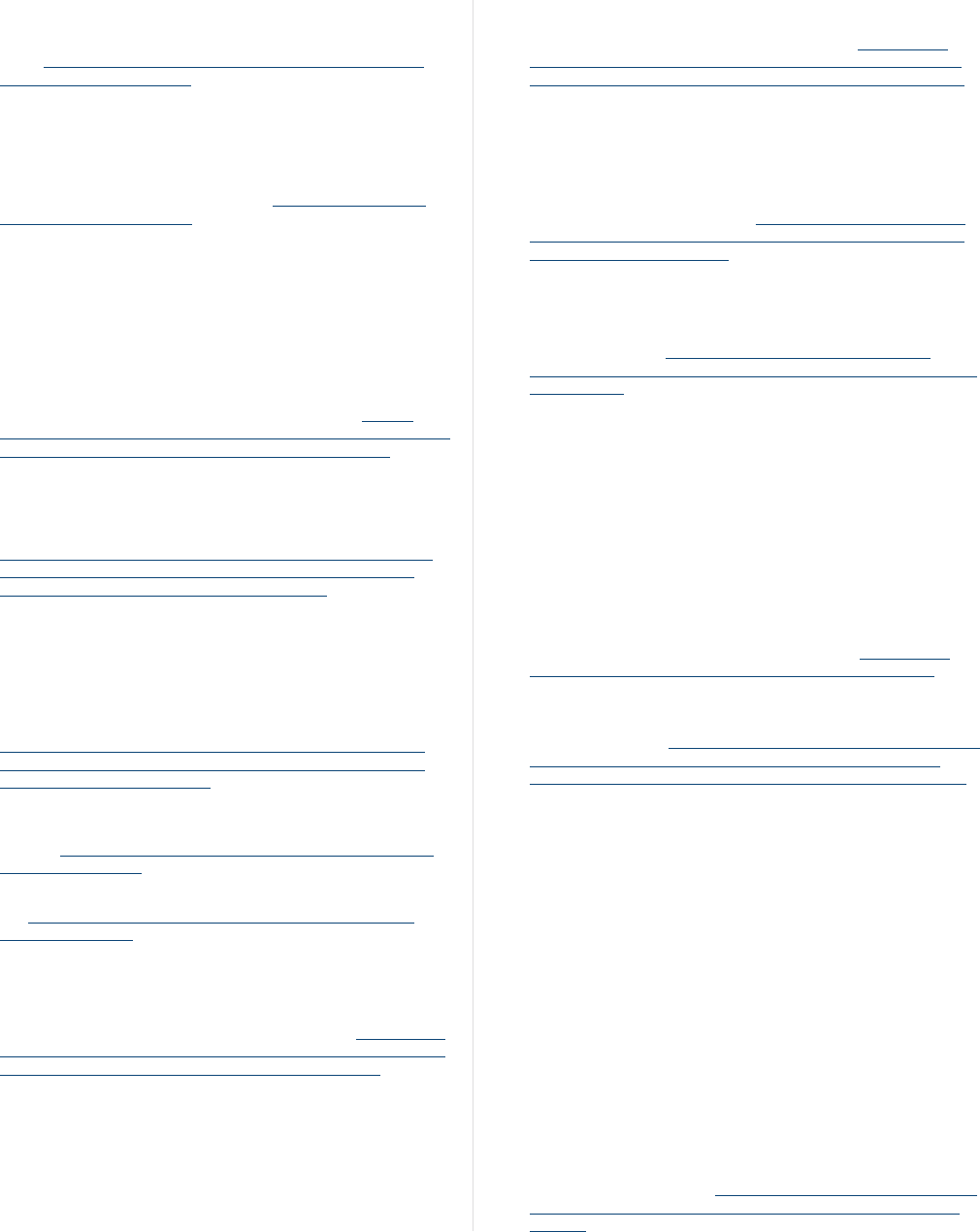

Source: Kutzbach, Mark, Joyce Northwood, and Jeffrey Weinstein. “2021 FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households.”

Households in the

U.S. in Aggregate

By Demographics

4.5%

Non-Home

Owner

9.4%

Living with

Disabilities,

Aged 25 to 64

14.8%

Hispanic

9.3%

Income

$15,000

to $30,000

9.2%

Foreign-Born,

Non-U.S. Citizen

11%

Black

11.3%

Unemployed

11.8%

No High School

Diploma

19.2%

Income

Less than $15,000

19.8%

Unmarried,

Female-

Householder

Family

9.2%

U.S. Households Do Not Have Equitable Access to Bank Accounts

Share of households without a bank or credit union account, by demographics

The Price of Entry: Banking in America

4Aspen Institute Financial Security Program

|

This report identifies how financial service

providers and practitioners interested in

improving financial inclusion are implementing

inclusive practices to counteract these barriers

and reach marginalized people and communities.

Product innovations, technological advances,

and participatory design have helped make

incremental progress toward ensuring

economically vulnerable people have access

to more and better financial services. On their

own, however, we believe these types of

institutional practices will be insufficient to

universally overcome these barriers. Further

research is required to understand how policies

and regulations are impacting the ability for

financial institutions (of all types) to scale these

inclusive practices, both positively and negatively.

Identifying systemic solutions is a critical next step

to sustainably and equitably connecting people to

critical financial systems.

The causes of financial exclusion are complex,

rooted in multiple places throughout our financial

system and the many other systems incorporated

within it and related to it. It will require coordinated

efforts between the public and private sectors to

ensure solutions are systems-wide, not only led by

individual institutions. That is why Aspen FSP has

joined with stakeholders from across the industry

and advocacy community to call for a National

Financial Inclusion Strategy, one that is co-

created by a mix of government representatives,

private sector actors, representatives of

underserved communities, and nonprofit leaders.

This comprehensive strategy will identify the

outcomes an inclusive financial system should

deliver for people in the United States, as well as

a prioritized set of actions this group can address

to affect key barriers to financial inclusion—the

kinds of barriers we highlight in this research.

While the next generation of financial

systems in the United States is currently being

developed through emerging technology and

innovative product development, a coordinated

national strategy can ensure it will also be

structurally inclusive.

To better understand the context and current state

of financial inclusion in the U.S. banking system,

the Aspen Institute Financial Security Program

(Aspen FSP) conducted research and detailed

interviews with more than 20 leaders from

advocacy and civil rights organizations, mission-

oriented financial service providers, and research

institutions. This report zeroes in on access to

basic banking as the price of entry to the current

U.S. financial system. Without basic banking

products, people are locked out of other related

systems, such as credit and financing, insurance,

and savings. This research reveals that despite

a spate of promising inclusive practices,

persistent barriers continue to undermine

financial inclusion at scale.

Barrier 1

Most mainstream banking products are not

currently designed to meet the functional money

management needs of economically vulnerable

consumers.

Barrier 2

Widespread market practices present significant

obstacles to banking access and utilization for

economically vulnerable consumers.

ACCESS BARRIERS

2.1: Regulatory requirements to verify customers’

ID and address can exclude some

consumers.

2.2: When consumer data shows past struggles

with financial products—whether correct or

not—on-ramps back into the system can be

difficult to find or navigate.

UTILIZATION BARRIERS

2.3: Digital access and comfort with technology

are essential to remote banking.

2.4: Branch hours and physical distances to bank

branches, particularly in rural areas, are

barriers to obtain in-person banking services.

2.5: Making cash deposits can be costly.

2.6: Some banks aren’t equipped with bank

tellers who have the cultural competency to

effectively interact with customers or who are

fluent in other languages.

2.7: Some major banks have consumer-friendly,

entry-level accounts and products; however,

interview participants reported a lack of

customer awareness of these accounts.

The Price of Entry: Banking in America

5Aspen Institute Financial Security Program

|

A New Vision for Financial Inclusion

Fifteen years after the Great Recession and

after decades of efforts to expand access to

foundational financial services in the United States,

the Aspen Institute Financial Security Program

(Aspen FSP) takes stock of how successfully

these efforts have removed the systemic barriers

to financial inclusion. Although banking access

gaps in the United States have narrowed over

time, in 2021, nearly 1 in 5 households in the

U.S.—approximately 24.6 million households—were

either entirely disconnected from mainstream

financial services or, despite having an account

with a bank or credit union, still turned to costly

alternatives to get the financial services they

needed.

4

Because of exclusionary practices and

policies embedded in our current financial

systems, millions of people—disproportionately

Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC),

those living in rural communities, and families

with lower incomes—continue to be left, or even

pushed, out of the systems that have provided

other consumers with safe and affordable tools

to manage money, invest in the future, and build

generational wealth.

To address this reality, the U.S. must intentionally

build the next generation of financial systems to

be structurally inclusive. A structurally inclusive

financial system provides all people with the

ability to access, utilize, and reap the benefits

of a full suite of financial services that facilitate

stability, resilience, and long-term financial

security.

5

Achieving this goal will require both

designing financial systems with historically

underserved consumers at the center as primary

users, and broadening the set of financial systems

traditionally considered in “financial inclusion”

conversations and initiatives. In addition to

basic transaction accounts, everyone in the U.S.

also needs short- and medium-term savings

tools, timely delivery of payments from work and

government, and access to fairly priced credit

with reasonable terms. We also need places to

effectively grow retirement savings and other

financial investments, and sufficient insurance to

protect from life’s inevitable ups and downs.

6

This

broader vision for financial inclusion would allow

everyone in the U.S. to leverage high-quality,

affordable financial services to best support their

financial security.

Building truly inclusive financial systems requires

action and coordination from a wide-ranging

coalition of stakeholders, including private sector

financial service providers, public-sector entities

(including financial services regulators and

government actors providing financial services),

nonprofit and social-sector organizations (e.g.,

community-based organizations, researchers,

advocates, and philanthropy), phone and internet

providers, and leaders from other sectors and

systems. For example, as finance has become

increasingly tech-enabled and digital, the

breadth of actors involved in providing financial

services has grown to encompass consumer

data companies, technology companies, their

regulators, and other actors in the digital economy.

7

Inclusive financial systems represent critical

infrastructure for the national economy, facilitating

commerce, economic growth, and financial stability

and security for all individuals, businesses, and

communities.

8

As such, a more inclusive system—a

fairer system—is a healthier financial system.

9

A structurally inclusive financial system

provides all people with the ability to

access, utilize, and reap the benefits

of a full suite of financial services that

facilitate stability, resilience, and long-

term financial security.

“

”

Inclusive financial systems represent

critical infrastructure for the national

economy, facilitating commerce,

economic growth, and financial

stability and security for all individuals,

businesses, and communities. As

such, a more inclusive system—a fairer

system—is a healthier financial system.

“

”

The Price of Entry: Banking in America

6Aspen Institute Financial Security Program

|

Wells Fargo’s National Unbanked

Task Force

Included in the set of professional expert

interviews were members of Wells Fargo’s

National Unbanked Task Force, a group of

leaders with perspectives on bringing more

people into the banking system–including

Black and African American, Hispanic and

Latinx, and Native American and Alaska Native

families. Representatives include leaders from

Hope Enterprise Corporation, LULAC (League

of United Latin American Citizens), NAACP

(National Association for the Advancement

of Colored People), NAFOA, NBA (National

Bankers Association), NCRC (National

Community Reinvestment Coalition), NCAI

(National Congress of American Indians),

National Urban League, and UnidosUS.

10

To better understand the history and current

state of financial inclusion in the U.S. banking

system, Aspen FSP conducted research and

detailed interviews with more than 20 leaders

from advocacy and civil rights organizations,

mission-oriented financial service providers,

and research institutions (see text box). While

we believe in the importance of expanding

our definition of financial inclusion beyond

access to basic transaction accounts, as you’ll

see in our research, this is a critical point of

entry to the U.S. financial system. Transaction

accounts are necessary to open and use most

other financial products—like a payment or

fintech app, investment account, or loan. We

focused our conversations with these experts

on access to and use of these transaction

accounts. This report summarizes insights from

these professional expert interviews and draws

from Aspen FSP’s years of work understanding

people’s lived financial experiences to analyze

the extent to which historically underserved

individuals have access to transaction accounts.

We highlight their perspectives on persistent

barriers to these essential products and, where

possible, present promising examples of the

ways institutions are working to address and

overcome these barriers. This report articulates

a vision for a more person-centered financial

system that ensures all people in our country

can access and use financial services to better

manage their money, overcome financial shocks,

and build generational wealth. We hope these

lessons can inform the efforts of leaders—in

financial services, technology, advocacy, civil

rights, and philanthropy, along with investors

and policymakers—as they shape the future of

the U.S. financial system.

The Price of Entry: Banking in America

7Aspen Institute Financial Security Program

|

Defining an Inclusive

Financial System

An inclusive financial system provides everyone the

ability to access, utilize, and reap the benefits of a

full suite of financial services that facilitate stability,

resilience, and long-term financial security. These

range from payments to short- term and long-term

savings vehicles, credit, investments, retirement

accounts, and insurance. This relies on a well-

functioning system of interrelated stakeholders—in

the public, private, and social sectors—providing

consumers with safe, affordable, and useful

financial products and services, protecting them

from bad actors, and providing educational

tools and resources consumers can use to make

informed financial choices.

Why Financial Inclusion Matters

An inclusive financial system provides the tools

and services people need to manage their money

in accordance with their financial goals. When

these tools and services are safe, affordable, and

allow people to advance their ability to save,

transact, and build assets, people are enabled to

invest in themselves and their communities.

11

An

inclusive financial system is foundational both to

personal financial security and the economic well-

being of our communities. However, the reality is

that today’s financial systems in the United States

do not yet equitably serve people in this way.

Promoting financial inclusion can directly impact

individuals and communities; it is also in our

long-term national interest. A 2019 analysis by

McKinsey estimated that the United States’ real

GDP could be 4 percent to 6 percent higher if

we created a more inclusive financial system to

remove racial and other systemic disparities.

12

Research from the International Monetary Fund

also shows a 2 to 3 percentage point GDP growth

difference over the long term between financially

inclusive countries and their less inclusive peers.

13

While our definition of an inclusive financial

system reflects the importance of a full range of

financial services, this report zeroes in on access to

basic banking as the price of entry to the current

U.S. financial system. Without basic banking

products, people are locked out of other related

systems, such as credit and financing, insurance,

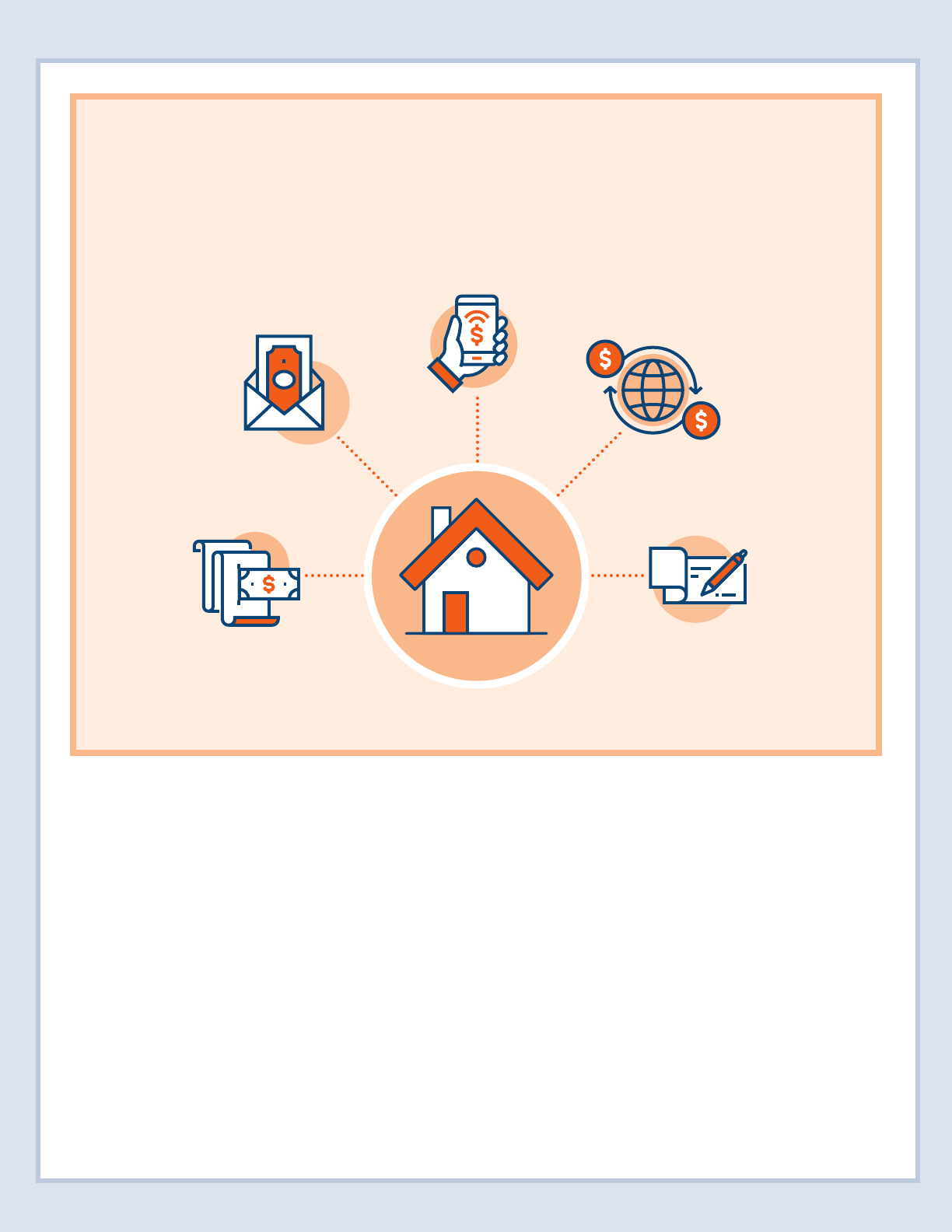

and savings. The costs and consequences of not

having a bank account include:

• Difficulty receiving and using earnings and

government payments;

• Limited access to the convenience brought by

innovative technology, including fintech and

digital payments;

• Higher cost to conduct transactions and access

credit;

• Higher risk of loss, theft, or damage when funds

are kept in cash;

• Inability to accumulate and grow savings with

interest; and

• Lack of access to longer-term wealth-

building opportunities, such as investing or

homeownership, and protective insurance.

Without a bank account, a person’s ability to make

efficient payments or access affordable credit and

financing may be severely limited. They might

miss out on the opportunity to start a business, or

they might not have the resources to bounce back

from a financial shock.

14

As one of the professional

expert interviewees, Terri Friedline, noted in a

prior publication: “Bank accounts are necessary

for full participation in the 21st century economy.

It is nearly impossible in today’s society to buy

groceries, pay the phone bill, rent a car, or apply

for a job or college without using a basic financial

product such as a bank or transaction account.

These activities pervade our everyday lives and they

are increasingly difficult to navigate without basic

financial products or services.”

15

Ensuring access

to banking and full economic participation are

essential components of financial inclusion.

... this report zeroes in on access to basic

banking as the price of entry to the current

U.S. financial system. Without basic

banking products, people are locked out

of other related systems, such as credit

and financing, insurance, and savings.

“

”

The Price of Entry: Banking in America

8Aspen Institute Financial Security Program

|

Public Benefits and Financial Inclusion

The design and delivery of our public benefits

have the potential to advance—or hinder—

financial inclusion. Financial systems are often

the intermediary facilitating public benefits

from governments to people. Inclusive

financial systems are necessary to ensure the

optimal performance of government benefit

programs and promote financial security for

recipients. Yet, barriers to access and fines

and fees can undermine the value of benefits.

According to the Federal Reserve Bank of St.

Louis, people who do not have bank accounts

spend between 2.5 percent and 3 percent of

a government benefits check to cash them.

16

The COVID-19 pandemic showed that

exclusionary financial systems can be even

more problematic in moments of crisis.

According to the Government Accountability

Office, non-filers (i.e., people who are not

required to file tax returns), first-time tax

filers, mixed immigrant status families,

people without access to bank accounts,

individuals with limited internet access, and

people experiencing homelessness were

among those likely to have trouble receiving

Economic Impact Payments (EIPs) and the

expanded Child Tax Credit (CTC) payments in

a timely manner.

17

Additionally, it is estimated

that EIP recipients paid $66 million in check

cashing fees.

18

Government programs can be designed

to promote inclusion, such as by making

delivery easy and seamless for the recipient

through the use of direct deposit, and

encouraging people to be connected to

the financial system.

19

New data from the

FDIC show that about 1 in 3 households that

recently opened a bank account said that

receiving a government benefit payment—

such as unemployment insurance or EIPs—

contributed to their decision to open an

account.

20

The Price of Entry: Banking in America

9Aspen Institute Financial Security Program

|

A Holistic Approach to Financial Inclusion

To date, banking inclusion efforts have

focused mainly on getting people access

to transaction accounts and credit and

financing, with less attention on whether or

how people use those accounts—or whether

those accounts better their financial lives.

The industry has also stopped short of

considering a more holistic definition of

financial inclusion—which includes other

critical financial products and systems,

such as insurance, short-term savings, and

investments. As a result, access gaps to

these other critical financial services remain

wide, and people across the U.S. continue to

struggle with many aspects of their finances.

And while access to a full suite of financial

products and services is a foundational step

to financial inclusion, access alone does not

meaningfully contribute to people’s financial

security, well-being, and health.

21

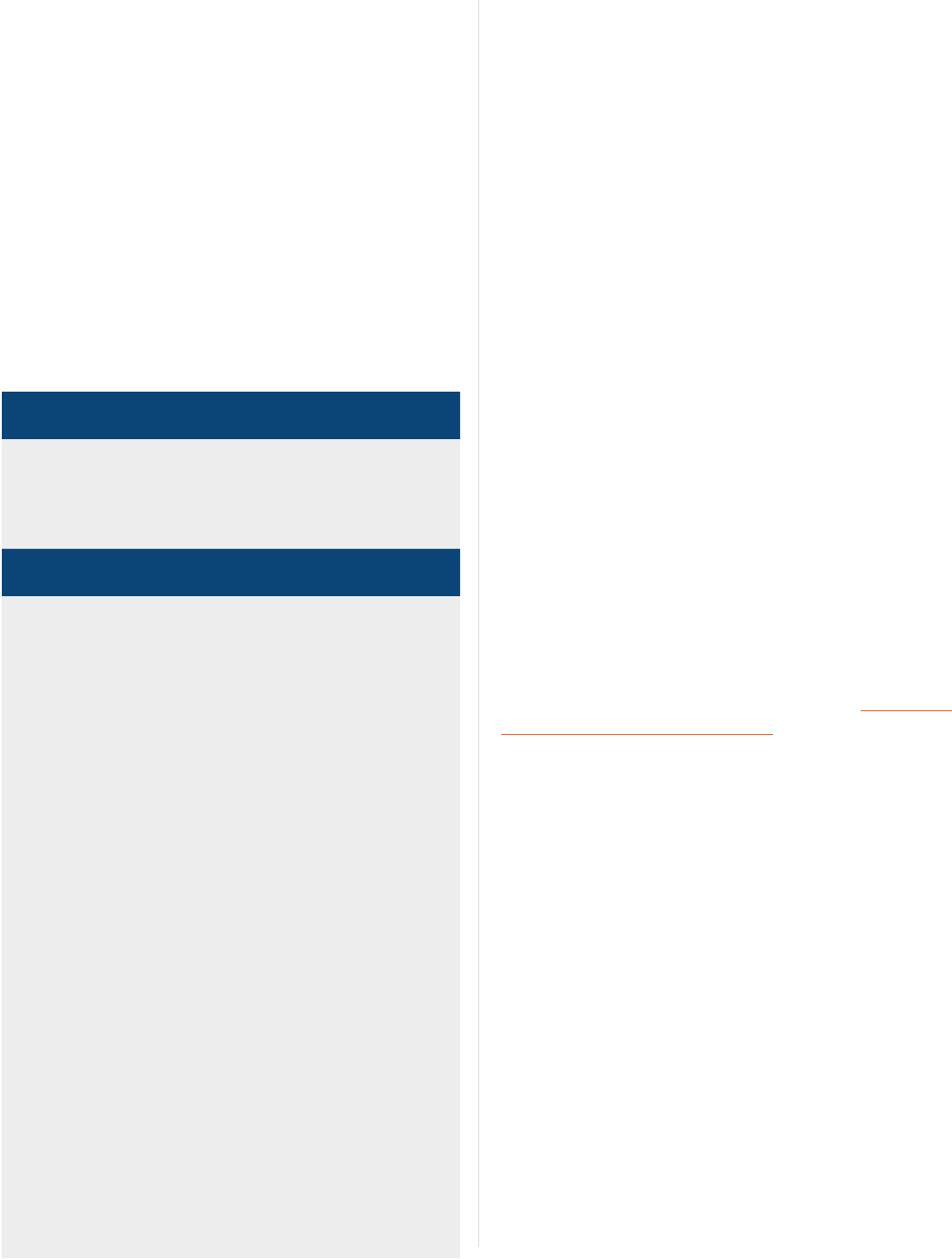

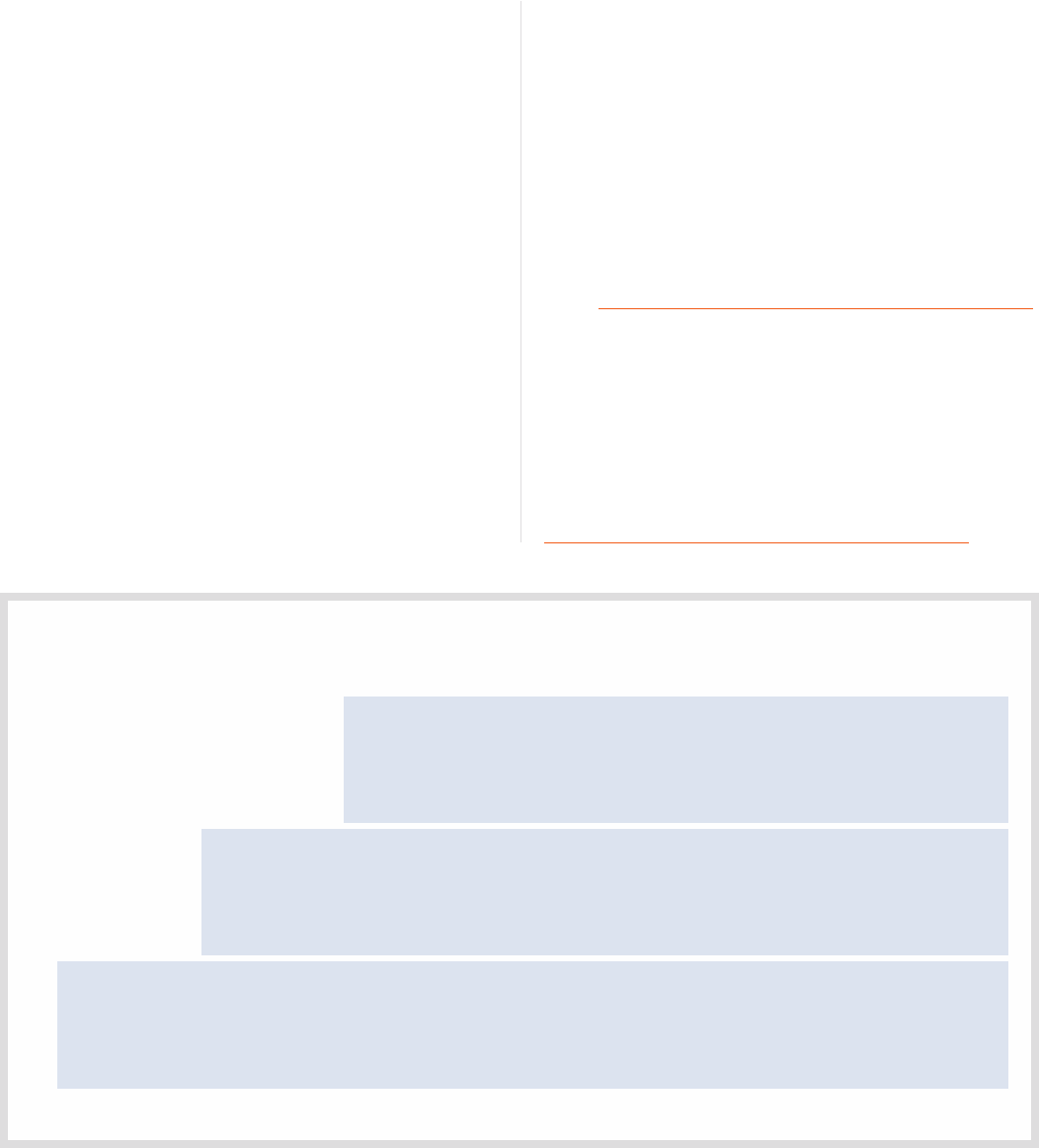

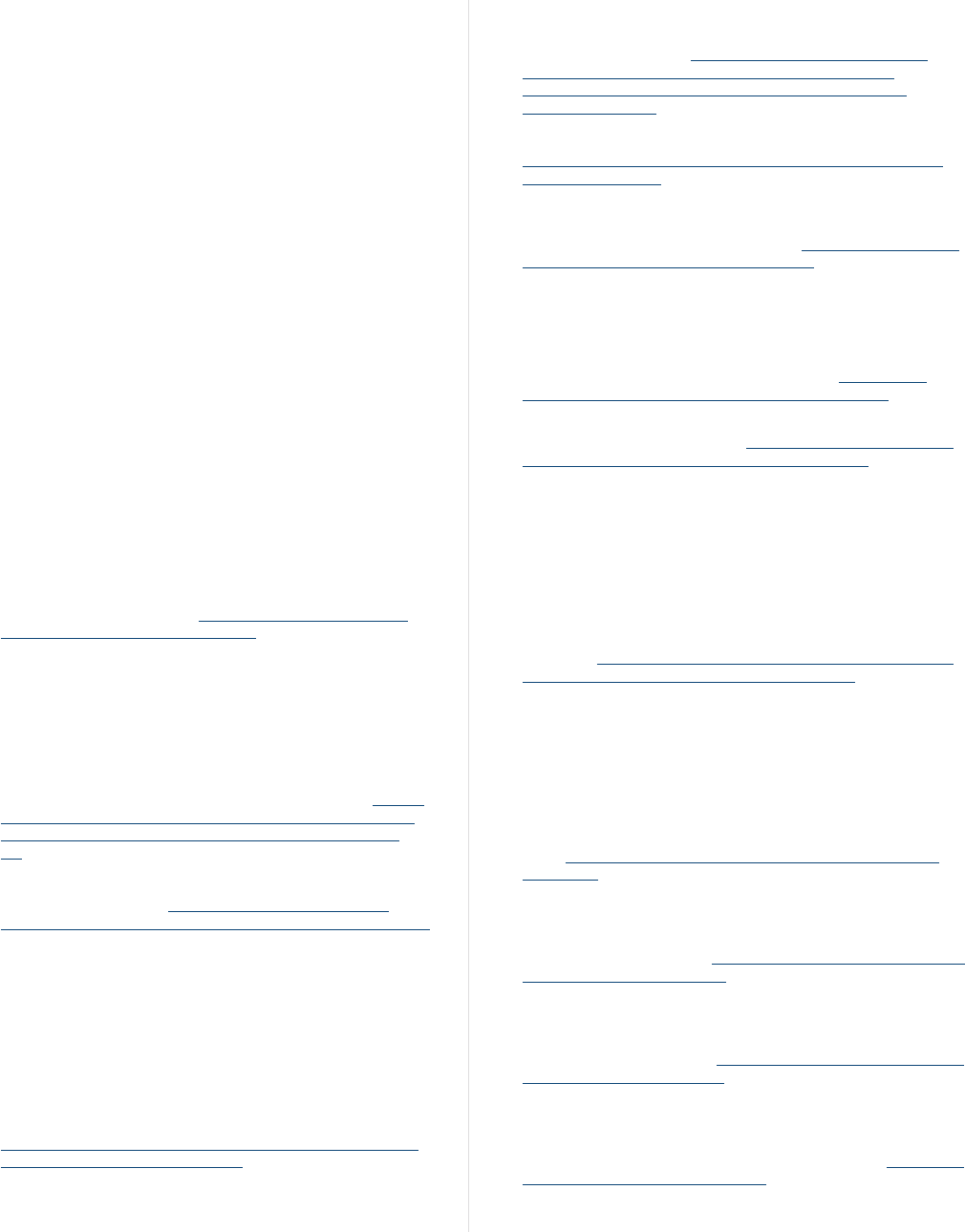

Three Conditions Must be Met for True Financial Inclusion

... while access to a full suite of financial

products and services is a foundational

step to financial inclusion, access alone

does not meaningfully contribute to

people’s financial security, well-being,

and health.

“

”

Inclusive financial products and services must be:

1. Accessible to everyone, including historically

excluded households;

2. Useful, performing the functions people

need, in a helpful way so individuals can utilize

and maintain these services; and

3. Beneficial, such that these systems facilitate

financial stability, security, and wealth building.

Beneficial

Useful

Accessible

3.

2.

1.

Inclusive financial products and

services must facilitate financial

stability, security, and wealth

building.

Inclusive financial products and services

must perform the functions people need, in

a helpful way so individuals can utilize and

maintain these services.

Inclusive financial products and services must

be accessible to everyone, including historically

excluded households.

The Price of Entry: Banking in America

10Aspen Institute Financial Security Program

|

Together, these three conditions allow people

to engage with, utilize, and reap the benefits

of high-quality, safe, and affordable financial

tools and services in ways that help them

build both short-term stability and long-term

financial security.

22

Defining the Terms Used to

Describe Race and Ethnicity in

this Report

In federal data, people indigenous to the

North American continent are referred to

as American Indian or Alaska Natives (AI/

AN), though Native Hawaiians are counted

as Pacific Islanders. In other research,

Native American is a frequently used

term, and throughout this report we use it

interchangeably with AI/AN. Similarly, we use

multiple terms to refer to Latinx people and

households. When citing statistics and official

government data, we conform to the source

data terminology (often “Hispanic” or “Latino”).

When discussing this demographic more

generally, we use the gender neutral “Latinx.”

As we laid out above, we believe financial

inclusion must be holistic, but currently, the

basic transaction account is the price of entry

into the U.S. financial system. In conducting

the research and interviews for this report, it

became increasingly clear that despite many

years of technological advances, product

innovation, and efforts to bring in more people,

millions of families still face financial exclusion.

These realities point to the need for solutions

to be more comprehensive in scope and to

address the systems that are hindering private

sector actors from delivering products that

better meet more consumers’ needs. Solving

for exclusion will require a systemic lens to

examine how leaders across the country

interested in improving inclusion can together

make changes that result in structurally inclusive

financial systems.

“Banking is a part of the journey,

not the destination.”

— Wole Coaxum, MoCaFi

The Price of Entry: Banking in America

11Aspen Institute Financial Security Program

|

State of Financial Inclusion: Consumer

Perspective

The U.S. banking system excludes millions of people

A structurally inclusive financial system provides all people with the ability to access, utilize, and

reap the benefits of a full suite of financial services that facilitate stability, resilience, and long-term

financial security. The U.S. financial system currently fails to meet this definition. In 2021, nearly

1 in 5 households in the U.S.—approximately 24.6 million households—were either entirely

disconnected from mainstream financial services or, despite having an account with a bank or

credit union, still turned to costly alternatives to get the financial services they needed.

23

Economically vulnerable households are more likely to be excluded

An estimated 4.5 percent of households in the U.S.—approximately 5.9 million households—did not have

an account at a bank or credit union in 2021.

24

Black households, Hispanic households, and households

with working-age adults living with disabilities, households with less education, and households with

low income were among the groups even more unlikely to own an account.

25

Historically, Indigenous

people have also faced significant barriers to banking access.

i

i In 2021, the FDIC found that 6.9 percent of American Indian or Alaska Native (AIAN) households were disconnected from bank accounts.

This is a sharp decline in the percentage of AIAN households from 2019 and 2017, when 16.3 percent and 18 percent, respectively, were

disconnected from accounts. This finding was also based on a limited sample size. Although we hope that these data mark a positive trend

for households being able to access bank accounts, future data will show whether this is a sustained, positive trend. As other data show,

many households transition in and out of bank ownership over time.

Source: Kutzbach, Mark, Joyce Northwood, and Jeffrey Weinstein. “2021 FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households.”

Households in the

U.S. in Aggregate

By Demographics

4.5%

Non-Home

Owner

9.4%

Living with

Disabilities,

Aged 25 to 64

14.8%

Hispanic

9.3%

Income

$15,000

to $30,000

9.2%

Foreign-Born,

Non-U.S. Citizen

11%

Black

11.3%

Unemployed

11.8%

No High School

Diploma

19.2%

Income

Less than $15,000

19.8%

Unmarried,

Female-

Householder

Family

9.2%

U.S. Households Do Not Have Equitable Access to Bank Accounts

Share of households without a bank or credit union account, by demographics

The Price of Entry: Banking in America

12Aspen Institute Financial Security Program

|

Avoiding a bank gives

more privacy

34%

Many mainstream financial institutions offer

banking products that are too expensive, too

risky, and out-of-reach for the most financially

vulnerable households

FDIC data reveal the reasons why people

say they do not have a bank account, the

most common of which include a lack of

sufficient funds to meet the minimum balance

requirements, privacy concerns, distrust of

banks, and high or unpredictable bank account

fees.

26

Research commissioned by the Cities

for Financial Empowerment Fund (CFE Fund)

revealed that safety and security concerns

about the potential for fraud, identity theft, and

aggressive fees also kept people—especially

Spanish speakers and rural residents—from

wanting a bank account.

27

Nearly half of those without bank accounts

in 2021 were previously banked, which

illustrates that households may transition in

and out of bank account ownership over time.

28

Source: Kutzbach, Mark, Joyce Northwood, and Jeffrey Weinstein. “2021 FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households.”

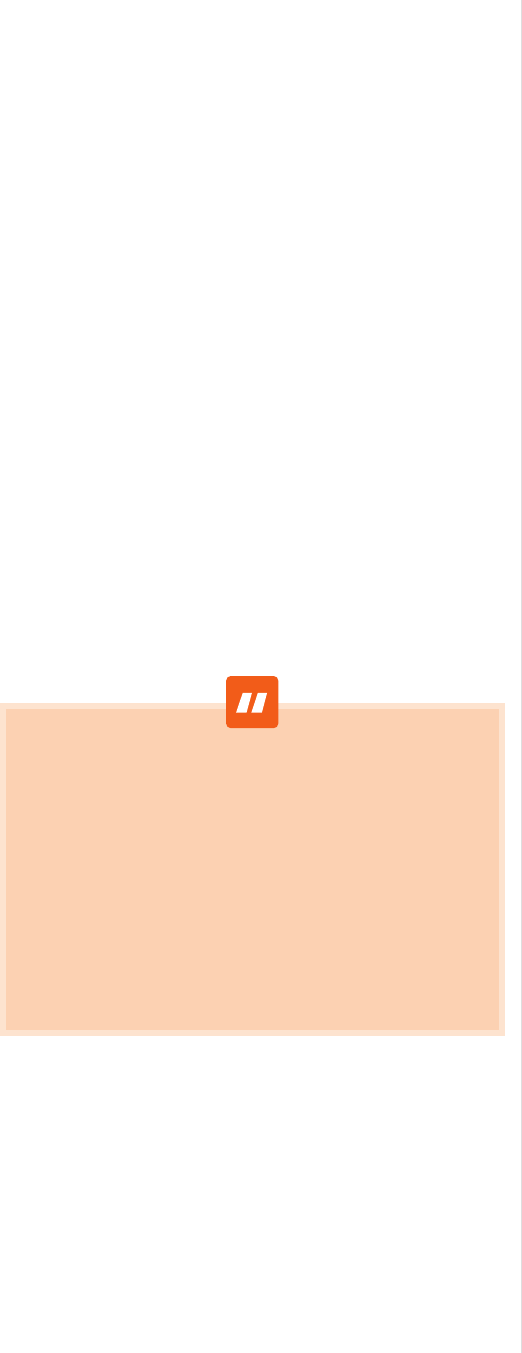

Affordability, Privacy Concerns, and Distrust Top

Why People Say The Don’t Have Bank Accounts

Reasons people say they don’t have a bank account

People that previously—but no longer—held

bank accounts cited not having enough money

to meet minimum balance requirements

and their distrust of banks as two of the

main reasons that they did not have a bank

account.

29

Similarly, the CFE Fund found that

the most common reasons individuals that

previously had bank accounts said they had

closed their accounts was because of fees—

including overdraft and minimum balance

fees—or the loss of direct deposit from work.

30

Nearly half of those without bank

accounts in 2021 were previously

banked, which illustrates that

households may transition in and out

of bank account ownership over time.

“

”

Don’t have enough money

to meet minimum balance

requirements

40%

Bank account fees are

too unpredictable

27%

Problems with past banking

or credit history

14%

Don’t have personal identification

required to open an account

12%

Bank locations are

inconvenient

15%

Bank account fees

are too high

30%

Don’t trust banks

33%

Banks do not offer

needed products and

services

19%

The Price of Entry: Banking in America

13Aspen Institute Financial Security Program

|

Many people with bank accounts still

operate outside of mainstream financial

systems to meet one or more of their money

management needs

In 2021, an estimated 14.1 percent of

households in the U.S., approximately 18.7

million households, had a bank account but also

used alternative financial services in the past 12

months—such as check cashing services, money

orders, international remittances, payday loans,

or auto title loans.

32

Some households are more

likely to have bank accounts but turn to alternative

services, including more than 1 in 4 American

Indian or Alaska Native households and foreign-

born, non-U.S. citizen households.

Demand for these alternative financial products

suggests that banks and credit unions are not

meeting these households’ needs for affordable

and effective ways to transact, make payments,

and send money; to get fast access to their own

funds; or to access short-term, relatively small-

dollar credit. The data also show that despite

some household segments having low instances

of being completely disconnected from bank

accounts, many continue to seek out alternative

services. For instance, despite fewer than 3 percent

of Asian households having no connection to a

bank account, more than 16 percent of Asian

households have accounts but continue to seek

out alternative financial services.

In 2019, households with bank accounts that

were not satisfied with their primary bank were

1.5 times more likely to use money orders, check

cashing, or bill payment services compared with

households with bank accounts that were satisfied

with their primary bank.

33

Mainstream financial services are significantly

more expensive for financially vulnerable

consumers than their more financially

secure peers

Having access to a bank account does not

guarantee that people are equally or well-served

by mainstream financial systems. In 2021, nearly

half of households with bank accounts reported

paying fees for their bank accounts, but these

fees were not evenly distributed.

31

Households with a Bank Account

Source: Elaine Golden, Hannah Gdalman, Meghan Greene, Necati

Celik. “FinHealth Spend Report 2022: What U.S. Households Spent on

Financial Services During COVID-19.”

Bank Account Fees Are Not Evenly

Distributed Among Households

TYPE OF FEE FOR THEIR

BANK ACCOUNT

PAID SOME

49%

AVERAGE

BANK

ACCOUNT

FEES

IN 2021

$182

Financially Vulnerable

Households Paid

$11

Financially Healthy

Households Paid

The Price of Entry: Banking in America

14Aspen Institute Financial Security Program

|

Source: Kutzbach, Mark, et al. “How America Banks: Household Use of Banking and Financial Services.”

Families Supplement Bank Offerings with Non-bank Transaction

Services to Meet Their Financial Needs

Use of non-bank transaction services by households not satisfied with their primary bank

34

International

Remittance

7.7%

Money Orders

16.5%

Person-to-Person

Payment Service

38.5%

Bill Payment Service

7.1%

Check Cashing

5%

Together, these data demonstrate that the current U.S.

banking system is not accessible, affordable, or useful to

all people, nor meeting all the financial services needs of

even those who do hold bank or credit union accounts.

The Price of Entry: Banking in America

15Aspen Institute Financial Security Program

|

In interviews conducted between February

and August 2022, more than 20 leaders from

advocacy and civil rights organizations, mission-

oriented financial service providers, and research

institutions shared their perspectives on the

drivers of financial exclusion, the strengths and

weaknesses of prior and current financial inclusion

efforts, and strategies for bridging gaps between

financially excluded individuals and communities

and financial systems in the U.S. Their perspectives

are based on their work with—and in service of—

historically excluded communities.

Across the interviews, professional experts

discussed the differential and harmful treatment

of economically vulnerable and BIPOC people

and communities, as well as the disinvestment

in, and wealth extraction from, many low-income

communities. As a result, many people do not

trust some or all financial institutions, and trust

continues to decline. Some of the professional

expert interviewees warned that trust may never

be won back with some individuals. For instance, a

profound deterioration of trust happened during

the 2008 recession, when many families lost their

homes, and with it, their wealth.

According to the Professional Experts:

Barriers and Opportunities

Moreover, other policies and practices serve as

mechanisms for further financial exclusion:

• Research examining fees for entry-level

checking accounts at primarily small and

community banks has shown that banks charge

higher fees to open and maintain accounts in

communities of color compared with white

neighborhoods and that the cost of banking

varies due to residential segregation.

37

• Past research has explored how discretion is

used to charge overdraft fees to people on

a case-by-case basis, meaning that a person

could have a different experience based on the

teller or branch manager that they interact with

on a particular day.

38

• Secret shopper studies have revealed that Black

and Hispanic customers applying for loans

receive different information from bankers than

white customers.

39

• For Native Americans, particularly those living

on tribal lands, resources and opportunities

for home ownership are limited. Data from

the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA)

indicate that only 0.6 percent of HMDA loans in

2015 went to Native American borrowers.

40

Unequal experiences with financial systems and

disparate costs further erode people’s trust of

these systems. Some potential customers may

decide not to apply for needed loans or to be

banked at all due to fear of disparate treatment

and discrimination, confusion around fees, and

worries about cost.

41

Distrust in the financial system is the starting

point for our analysis of the barriers to financial

inclusion, based on our summary of insights

learned in the professional expert interviews.

Here, we outline the barriers to financial

inclusion—which echo the consumer perspective

detailed in the previous section—and reflect on

the ways that the current financial system does

not align with people’s preferences, needs, and

financial realities. We also highlight inclusive

practices that address those barriers and provide

At the root of distrust is an extensive record of

discriminatory treatment and deep disparities

in banking and lending costs. Specific practices

and government policies that have contributed

to the history of financial exclusion in the United

States include: redlining, loan steering, racial

covenants, appraisal practices, and subprime

lending targeted at communities of color and

lower-income communities.

35

While some of

these exclusionary policies are no longer in

practice, their legacies persist, continuing to

produce negative impacts over generations.

36

“Everyone knows or is someone

that has had a bad experience.”

— Cy Richardson, National Urban League

The Price of Entry: Banking in America

16Aspen Institute Financial Security Program

|

It is notable, however, that people continue to

grapple with these structural barriers today

despite several institutions developing inclusive

practices that help address them. It will take

additional systems-level solutions that engage with

actors throughout the financial system to create

the inclusive system we hope to see.

Barrier #1

Most mainstream banking products

are not currently designed to meet

the functional money management

needs of economically vulnerable

consumers.

Even when people want and have the ability to

access certain financial systems, they may not find

products and services that are relevant to their

financial lives and goals. Products and services

may have design flaws that make participation

more difficult, risky, or not feasible for some. For

instance, transaction accounts with requirements

such as minimum balances, automatic monthly

contributions, or restrictions on the number of

withdrawals are not inclusive of marginalized

groups. This is especially true for households

without routinely positive cash flow, who may

have to transact more frequently or who have

less money that can be tied up in a minimum

balance.

42

These customers are also impacted by

the practice of banks typically holding deposited

funds for a period of time to prevent against fraud

or returned payments. If a person urgently needs

to cash a check at their bank, all of the funds may

not be immediately available for use, which leaves

their cash flow needs unmet.

Many mainstream financial products have been

designed for the needs of the mass market, and

typically meet the money management needs of

people with financial cushions and steady incomes.

However, people without routinely positive cash

flow may have different needs not currently met by

the available products and tools. As a result, they

may have to use these tools in suboptimal ways.

For example, while some customers may find the

liquidity offered by overdraft protection to be an

important tool to meet their short-term financial

needs, for many, the ensuing fees have harmed

their financial well-being.

opportunity to rebuild trust among potential

customers and communities. It is through the

ongoing use of inclusive practices at scale by

financial service providers that the industry

can begin to rebuild trust among members of

BIPOC and economically vulnerable people and

communities.

Barriers to Financial Inclusion

Barrier 1

Most mainstream banking products are not

currently designed to meet the functional money

management needs of economically vulnerable

consumers.

Barrier 2

Widespread market practices present significant

obstacles to banking access and utilization for

economically vulnerable consumers.

ACCESS BARRIERS

2.1: Regulatory requirements to verify customers’

ID and address can exclude some consumers.

2.2: When consumer data shows past struggles

with financial products—whether correct or

not—on-ramps back into the system can be

difficult to find or navigate.

UTILIZATION BARRIERS

2.3: Digital access and comfort with technology

are essential to remote banking.

2.4: Branch hours and physical distances to

bank branches, particularly in rural areas, are

barriers to obtain in-person banking services.

2.5: Making cash deposits can be costly.

2.6: Some banks aren’t equipped with bank

tellers who have the cultural competency to

effectively interact with customers or who

are fluent in other languages.

2.7: Some major banks have consumer-friendly,

entry-level accounts and products; however,

interview participants reported a lack of

customer awareness of these accounts.

It bears stating that none of the high-level barriers

described in this section were unknown even a

decade ago—they are some of the same issues

that led advocates and experts to begin concerted

efforts to connect people to bank accounts.

The Price of Entry: Banking in America

17Aspen Institute Financial Security Program

|

Inclusive Practice: Some financial service

providers are doing work to intentionally reach

marginalized people, and design products and

tools for their financial needs and realities. This

involves ensuring that programs reflect people’s

preferences and lived experiences and do not

create additional barriers to entry as a result of

their demographics or circumstances, such as

their working hours and the level and frequency

of their pay. Furthermore, some providers trying

to serve historically excluded people are directly

including their target customers in the design

process and aim to eventually co-create and

co-design products and services with them.

This design approach ideally leads to deeper

customer engagement with high-quality, safe,

and affordable products that build financial

well-being.

Inclusive Practice: To improve relationships

with the community being served and the

quality of offerings, some financial institutions

regularly conduct community listening

sessions to hear the goals and needs outlined

by community residents. In addition, these

financial institutions intentionally capture

customer feedback, incorporate those lessons

into their offerings, and communicate back

changes that are being made as a result

of what they heard. Many aspects of the

typical banking experience can be enhanced

to promote inclusion and to make all feel

welcome and dignified.

• Example: HOPE (Hope Enterprise

Corporation, Hope Credit Union, and

Hope Policy Institute) serves communities

across five states in the Deep South. Their

staff works with key anchor organizations

including historically Black colleges and

universities, churches, and municipalities to

help connect residents to needed services. In

addition, HOPE hosts community meetings to

receive real-time feedback and understand

the particular nuances, aspirations, and

needs in that community. The lessons from

these meetings inform product and service

offerings, and provide fodder for policy and

advocacy work.

“For too long, too many banks have profited

from those who can least afford to pay,

charging excessive fees that can trap

consumers in a debt cycle or force them to

leave the financial mainstream completely.

Your bank should contribute to your overall

financial stability and health, not strip wealth

from your account with excessive fees….

There is simply no reason for high-cost

overdraft fees to exist.”

— Leigh Phillips, president and CEO of

SaverLife and former chair of the CFPB

Consumer Advisory Board.

43

Interview participants emphasized that it is critical

that people feel as though they are the primary,

intended user of a given financial product or

service, not just a secondary or unwelcome user.

Rather than always having to jump over hurdles

to get what you need and possibly running into

rejection, Nicole Elam, President and CEO of

the National Bankers Association, summarized,

“a dignified financial system means I get

a ‘yes’ instead of a ‘no.’” This approach to

inclusion gives individuals choice, which offers

respect and builds trust.

“One of the bottom lines for us

is we want to make sure that

the people we serve, which are

particularly low-income immigrant

communities of color, feel like

they’re the primary users of the

financial system.”

— Rocio Rodarte, Mission Asset Fund

Without appropriate offerings that align with

a person’s circumstances and preferences, the

leaders we spoke with said their constituencies

feel as though these systems were not designed

for them and are less likely to engage with them

as a result. This is consistent with the data in

the prior section that show that despite having

bank accounts, households that are not satisfied

with their primary banks are more likely to

supplement their bank’s offerings with alternative

financial services.

44

The Price of Entry: Banking in America

18Aspen Institute Financial Security Program

|

address. Paired with the unique difficulties

associated with obtaining a government-

issued identification in the United States, these

requirements can be a barrier to individuals trying

to open an entry-level account without an ID, such

as a driver’s license or a passport, or for those

individuals without a permanent address. This has a

disproportionate impact upon specific populations

including: immigrants and refugees of all races,

people with very low incomes, people experiencing

homelessness, the formerly incarcerated,

communities of color, youth, and the elderly.

Identification Requirements

A primary challenge associated with obtaining a

U.S. government-issued ID is a person’s proximity

to an ID-issuing office. These offices typically have

limited business hours, with some open only two

days a week or fewer. For over 10 million adults

45

in

the United States, the closest state ID-issuing office

open more than two days a week is more than 10

miles away from their homes, requiring a vehicle

or other means to get there.

46

Moreover, the costs

associated with obtaining documentation to apply

for an ID can place a burden on households with

low income

47

or those with little wiggle room

between income and expenses.

Some financial service providers indicate that they

will accept alternative forms of identification, such

as Individual Taxpayer Identification Numbers

(ITINs)

48

, consular IDs, or non-US passports.

However, research has shown—and interview

participants echoed—–that these policies are not

always put into practice. Some financial institutions

have internal policies not to accept alternative

IDs and some only accommodate alternative IDs

alongside a U.S. government-issued ID. There are

also instances where an institution’s policies may

allow alternative IDs, but frontline staff may not be

aware of this option.

49

Identity verification is a barrier in communities

across the United States:

• Up to 25 percent of African American citizens of

voting age lack a government-issued photo ID.

50

• Several interview participants shared that

IDs issued by tribal governments may not be

recognized by bank tellers, leading to Native

Americans getting turned away from services

and resulting in unwelcoming and unpleasant

customer experiences.

Inclusive Practice: Some financial service

providers intentionally include target customers

in participatory design processes. This involves

ensuring that products reflect people’s needs,

preferences, and lived experiences and do not

create additional barriers to entry due to their

demographics or circumstances—such as their

working hours and the level and frequency of

their pay. Furthermore, some providers aim to

eventually co-create and co-design products and

services with target customers directly involved,

especially marginalized and historically excluded

people. This inclusive design approach ideally

leads to deeper customer engagement with high-

quality, safe, and affordable products that build

financial well-being.

Barrier #2

Widespread market practices

present significant obstacles to

banking access and utilization for

economically vulnerable consumers.

Individuals attempting to enter and participate in

the financial ecosystem in the U.S. must contend

with barriers to access (2.1-2.2) and utilization

(2.3-2.7).

ACCESS BARRIERS

In order to be inclusive, financial systems must first

be accessible to everyone, including historically

marginalized communities. Our research shows

that current market practices today create two

major barriers to entry into the financial system for

economically vulnerable consumers in the U.S.

2.1 Regulatory requirements to verify

customers’ ID and address can exclude

some consumers.

Without a U.S. government-issued ID or a

permanent address, it is much more difficult

to access banking and other financial services.

Financial institutions are required by law to

establish the identity of customers through Know

Your Customer (KYC), Anti-Money Laundering

(AML), and Combatting the Financing of Terrorism

compliance. As part of these regulations, potential

banking clients must prove their identity and

The Price of Entry: Banking in America

19Aspen Institute Financial Security Program

|

• Interview participants from Latinx-serving

organizations noted that identification

requirements can serve as a particular challenge

for young people in mixed-status households.

For instance, teens with undocumented parents

or guardians who lack a government-issued ID

may be unable to open a bank account until the

age of 18.

• The mismatch between the legal working age

51

and the legal banking age can also limit which

youth workers can access mainstream financial

services. As a result, working youth may rely on

high-cost or other alternative systems to cash

their paychecks, and may not transition out of

those services, even when they come of age.

52

• Traveling to a distant ID-issuing office can be a

particular challenge to the elderly, people living

with disabilities, and those in rural areas who do

not have a reliable form of transportation. For

example, people living in rural areas in Texas

may have to travel up to 170 miles just to reach

their nearest ID-issuing office.

53

ii The “+” recognizes non-straight, non-cisgender identities. For more information, see https://www.glaad.org/reference/terms and https://

www.hrc.org/resources/glossary-of-terms.

iii For the purposes of the Financial Health Pulse, LGBTQ+ refers to people who identify as nonbinary, gender-nonconforming, genderqueer,

transgender, homosexual, gay, lesbian, bisexual, pansexual, queer, asexual, or some other gender or sexual identity.

Financial Security and the LGBTQ+ Community

Previous research has found that lesbian, gay,

bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+)

ii

people worried more about their finances

and felt less prepared for retirement compared

with the general population, and that fewer

LGBTQ people owned basic banking products

or an employer-sponsored retirement account

than non-LGBTQ people.

54,55

Similarly, the

national Financial Health Pulse Survey found

fewer LGBTQ+

iii

individuals were financially

healthy compared with non-LGBTQ+ people.

LGBTQ+ individuals were also more likely to be

systematically excluded from needed economic

resources and experienced financial challenges

as a result.

56

These financial challenges include

the ability to pay for rent, food, and necessary

healthcare-related expenses.

57

Transgender and non-binary people can

face particular barriers to accessing financial

services due to many financial institutions not

recognizing people by their chosen name,

which may not match their legal name. This can

put their physical safety and security at risk, and

can make people feel unwelcomed. In a survey,

32 percent of respondents who presented an

ID that did not match their name or gender

reported verbal harassment, denial of services

or being asked to leave, or being assaulted or

attacked.

58

Legal name changes take time and

money, and young people may not be able to

go through the process until a certain age or in

some cases, without their parents’ permission.

Additional steps are needed to update gender

markers on formal identification such as

obtaining documentation from a healthcare

provider. Although a handful of banks allow

people to use their chosen name on their

credit or debit cards, they often must first use

their legal name to apply for an account. These

customers must also inform credit bureaus of

their chosen name, to ensure their credit profile

is not lost or severed, and that their credit

scores aren’t negatively impacted.

The Price of Entry: Banking in America

20Aspen Institute Financial Security Program

|

individuals regardless of immigration status,

have expanded the forms of ID they accept to

include matricula consular or other non-U.S.

government IDs, and do not require a Social

Security number to open an account. There are

128 Juntos Avanzamos credit unions, serving

9.7 million people in 28 states, Puerto Rico, and

Washington, D.C.

60

Inclusive Practice: Some cities and counties

are offering municipal IDs to better serve the

elderly, people experiencing homelessness,

foster youth and youth generally, undocumented

immigrants, and others who may struggle to get

and maintain a government-issued ID.

61

• Example: New York City provides residents

with free photo IDs (IDNYC), which can then

be used to open bank accounts.

62

New

York City is working with community-based

organizations to make IDNYC cards available to

all city residents, including individuals that are

undocumented, experiencing homelessness,

and others who may struggle to obtain a

government-issued ID.

Inclusive Practice: Banks, credit unions, and

other financial service providers can explore ways

to allow people to use their chosen names on

their bank accounts and credit and debit cards.

This action will increase inclusion for transgender

and non-binary people as well as immigrants and

others who may have changed or Westernized

their names.

• Example: In 2019, Mastercard began its “True

Name” initiative, which allows customers to use

their chosen name on their credit and debit

cards. Citi, BMO Harris Bank, and Republic

Bank have adopted True Name for several of

their products.

63

Inclusive Practice: Some banks, credit

unions, and other financial service providers

have found ways to serve individuals without

a permanent address, such as by using the

address of homeless shelters or working with

municipalities to obtain city addresses that can

be used as personal addresses. For example,

Latino Community Credit Union works with

potential members that do not have a way to

prove a permanent address, such as by having a

roommate sign a letter stating that the potential

member does indeed live with them.

Address Requirements

Financial institutions adhering to regulations must

include permanent address requirements as part

of customer identity verification. This requirement

presents a barrier for people with temporary

or seasonal employment, people experiencing

homelessness or unstable housing, and those

with a limited address history available or without

a permanent address—including survivors of

domestic violence and people that were formerly

incarcerated. Although interviewees suggested

that people experiencing homelessness may be

able to use the address of a homeless shelter or

certain municipal addresses, they also indicated

that there are some rules about how many

accounts can be opened under a single address,

which limits how many individuals can make use

of that option.

DM Traylor, a person currently experiencing

homeless, recounts her experience interacting

with the banking system, “For one thing, banks are

picky about the kind of address they’ll take. They

typically want a residential address and tend not

to take a P.O. box for certain things. You may have

no mailing address at all, or only a P.O. box, or you

may be relying upon an address with a homeless

services center. These last two may be rejected if

you try to update your address online.”

59

Inclusive Practice: Some financial service

providers are revisiting, and where possible

expanding, which forms of IDs they accept. Staff at

these institutions must then be adequately trained

to accept alternate forms of IDs such as IDs issued

by tribal governments, consular or embassy IDs,

and ITINs. Interviewees urged that there needs

to be consistency around bank ID acceptance

policies—so the same options are available to all

customers, regardless of location or which staff

member they’re engaging with—and individuals

should be made to feel welcome and comfortable

regardless of what form of ID they are using. One

interviewee encouraged financial institutions to

proactively work with their regulators on how to

balance their compliance obligations while being

inclusive in their business practices.

• Example: The Juntos Avanzamos (“Together

We Advance”) designation is given to credit

unions committed to serving Hispanic and

immigrant communities. In order to best meet

the needs of their customers, these credit

unions have bilingual staff and leadership, serve

The Price of Entry: Banking in America

21Aspen Institute Financial Security Program

|

Inclusive Practice: People with flawed

banking histories, debt, damaged credit, and

those flagged by ChexSystems or the Early

Warning System should have on-ramps back

into mainstream financial services, rather than

only being eligible for high-cost alternatives.

Some financial institutions offer second-chance

or entry-level accounts that do not incorporate

this kind of customer screening. Such accounts

usually have guardrails in place, such as no

overdraft protection, that make this kind of

screening irrelevant.

UTILIZATION BARRIERS

Current market practices present five

barriers that make it difficult for economically

vulnerable consumers in the United States to

use and maintain critical financial products

and services. These barriers to utilization can

deter engagement, undermine the customer

experience, and ultimately hold people back

from advancing their financial goals.

2.3 Digital access and comfort with

technology are essential to remote

banking.

While the increased digitization of financial

products and services may help connect some

people to financial systems, between 14.5 million

and 42 million people across the U.S. lack access

to broadband internet service.

69

Moreover, data

from the U.S. Census Bureau underscore that

even when internet connections are available,

service can be unaffordable, especially for

households with low income, rural households,

and households of color.

70

In 2021, the Pew

Research Center found that 15 percent of adults

in the U.S. had internet access at home via their

smartphone only, meaning that outside of their

phone, they did not have broadband service.

71

Professional experts from American Indian and

Alaska Native-serving organizations raised

these issues as persistent challenges for some

communities. Data from the U.S. Census Bureau

found that 67 percent of Native Americans have

an internet subscription, compared with 82

percent of those that do not identify as American

Indian or Alaska Native (AI/AN). Just over half

2.2 When consumer data shows past

struggles with financial products—

whether correct or not—on-ramps back

into the system can be difficult to find

or navigate.

ChexSystems and Early Warning Systems are

both consumer reporting agencies that collect

and report information on people’s checking

and savings account activity to other financial

institutions. Records of account closures and

inquiries stay in each agency’s files for at least

five years.

64

There are a variety of reasons that

people may have flawed banking histories,

including illness, divorce, surviving domestic

violence, struggles with addiction, serious mental

illness, previous incarceration or current or

previous homelessness.

65

Additionally, people

with volatile incomes or holding high or harmful

debt—student loan debt, state, local government,

and court fines and fees, and out-of-pocket

healthcare expenses and medical debt—are likely

to struggle with managing their cash flow and

finances, generally.

66

In a study, only 13 percent

of bank representatives indicated that their bank

offered second-chance accounts that charge

little to no fees for individuals with a negative

banking history—making it difficult for consumers

that need these accounts to find a way back into

banking.

67

The San Francisco Office of Financial

Empowerment (OFE) conducted an examination

of ChexSystems and found “systemic issues in

both ChexSystems’ design and implementation,

resulting in significant confusion and unfairness

and ultimately undue exclusion for low-income

consumers, and in particular Black consumers.”

According to the study, many individuals with

ChexSystems records aren’t aware of the record

or the reason behind the record and “it is

nearly impossible for a consumer to resolve a

ChexSystems record via a dispute.” Because banks

have discretion in how they report and categorize

account closures, this creates unequal treatment

and outcomes.

68

One interview participant even mentioned how

it is becoming common practice for fintech

neobanks to conduct additional customer

vetting that may include credit screening.

Credit checks can be a significant exclusionary

barrier for individuals with a damaged or

limited credit history.

The Price of Entry: Banking in America

22Aspen Institute Financial Security Program

|

of AI/AN people living on tribal lands own a

computer and have high-speed internet service.

72

Hispanic households, Black households, rural

households, older households, households

with less education, and households with less

income are also less likely to have broadband

internet at home.

73

In 2019, the FDIC found that

households that do not own a bank account are

less likely to have access to smartphones and

home internet access than their counterparts with

bank accounts, and the rates were lowest for rural

residents compared with urban and suburban

residents.

74, 75

Inclusive Practice: Funders and

philanthropists supporting financial inclusion

efforts can also strategically invest in promoting

digital access within communities. Moreover,

policymakers can support broadband

infrastructure investment and ensure the

affordability of broadband access.

76

• Example: In 2022, the Biden Administration

announced the Affordable Connectivity

Program which will provide a discount of

$30 a month from the internet bill of eligible

households. This will also include a one-time

discount of $100 toward purchasing a laptop,

desktop computer, or tablet.

77

2.4 Branch hours and physical

distances to bank branches,

particularly in rural areas, are barriers

to obtain in-person banking services.

Interview participants recognized that many of

the communities they serve still need brick-and-

mortar banks. For instance, in 2021, around a

quarter of households with incomes of $30,000

or less and households living outside of a

metropolitan area went to a physical branch

as their primary mode of accessing their bank

account.

78

Research prior to the pandemic

showed that people living in rural communities

were twice as likely to visit a bank branch than

their urban and suburban counterparts.

79

Despite the demand for in-person services,

7,500 brick-and-mortar bank branches in the

U.S. closed between 2017 and 2021, one-third

of which were in communities that are majority

people of color or residents with low- to

moderate-income.

80

A consequence of these bank closures in rural

areas is that customers are required to travel

further to reach a physical bank branch. In some

counties, people without access to a consistent

form of transportation could spend as many as

40 minutes in total just to get to and from their

nearest bank branch.

81

Additionally, people living

on tribal reservations may have to travel more

than 60 miles to visit the closest brick-and-mortar

bank or ATM.

82

A lack of access to reliable public transportation

was raised by multiple interview participants as a

barrier for historically excluded groups to be able

to fully utilize financial services. This is particularly

true for the elderly and for those living in rural

areas, who may struggle to reach branches, or for

whom branches are inaccessible.

In areas with limited brick-and-mortar bank

branches, such as in low-income communities,

there are often more alternative financial service

providers—like check cashers, payday loan

providers, and pawnshops—than mainstream

financial service offerings.

83

Many alternative

financial service providers make themselves

more accessible by setting up hours of operation

that extend beyond typical banking hours, which

typically overlap with people’s regular work

schedule.

84

However, these alternative financial

service providers can be expensive and employ

predatory practices.

85

Inclusive Practice: Some financial institutions

offer mobile banking units that bring banking

services to individuals that may not have an

easy-to-reach local branch, the ability to travel to

a branch, or the technology and skills needed to

access services from home.

• Example: Stepping Stones Community Federal

Credit Union, a Community Development

Financial Institution and Minority Depository

Institution in Wilmington, Delaware, utilizes

a van to reach their customers across

Wilmington. Customers can conduct their

day-to-day transactions, open accounts, and

be issued an instant ATM card.

86

Similarly,

the Bronx Financial Access Coalition and the

Lower East Side People’s Federal Credit Union

partnered together to launch the People’s

Mobile Branch Van in response to an increase

in bank closures during the pandemic.

87

The

People’s Mobile Branch Van is serving South

The Price of Entry: Banking in America

23Aspen Institute Financial Security Program

|

Bronx neighborhoods, where nearly 1 in 4

households do not have bank accounts.

88

Resources offered include checking and

savings accounts, credit-builder loans, help with

ITIN applications, and fee-free ATM use.

2.5 Making cash deposits can be costly.

Although there is a shift away from cash to digital

payments in the U.S.,

89

recent surveys show

that cash payments still account for about 20

percent of all payments.

90

People who do not

own bank accounts are far more likely to rely

on cash payments, using cash for 60 percent

of their payments in 2020, compared with 19

percent for individuals with bank accounts.

91

People who are primarily paid in cash, like many

undocumented workers, are particularly reliant

on cash payments.

Converting cash to digital payments can be

costly. For individuals trying to put cash into

a bank account or onto a prepaid card, they

may incur cash deposit fees or reload fees,

respectively. Only some providers offer these

services for free, and their locations and hours of

operation are often limited.

In addition to cost, interviewees emphasized that

it may be generally difficult for people to jump

from cash to digital payments. There can be an

element of distrust or discomfort for people who

are accustomed to seeing and handling their

cash. Interview participants also mentioned that

recent immigrants may be wary of participating

in formal financial systems after living through

inflation or political and social unrest in their

home countries. They might prefer transacting in

cash because they have experienced a banking

collapse or lost their savings, or come from a

country where affordable credit was unavailable

or uncommon.

Inclusive Practice: Financial service providers

are partnering with ATM networks and larger

banks to ensure that customers, especially