Learning English: Achievement and Proficiency (LEAP)

TARGETED

STRATEGIES TO

ACCELERATE SAE

PROFICIENCY

The Department for Education requests attribution as:

South Australian Department for Education | APRIL 2021

2 | Learning English: Achievement and Proficiency (LEAP) | STRATEGIES INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

This resource provides strategies to support students’

language development and progress through the LEAP

Levels. Teachers can use the strategies to intentionally

address students’ identified language needs, accelerate

their development of Standard Australian English

(SAE), and move them on in their level of ‘Learning

English: Achievement and Proficiency’ (LEAP).

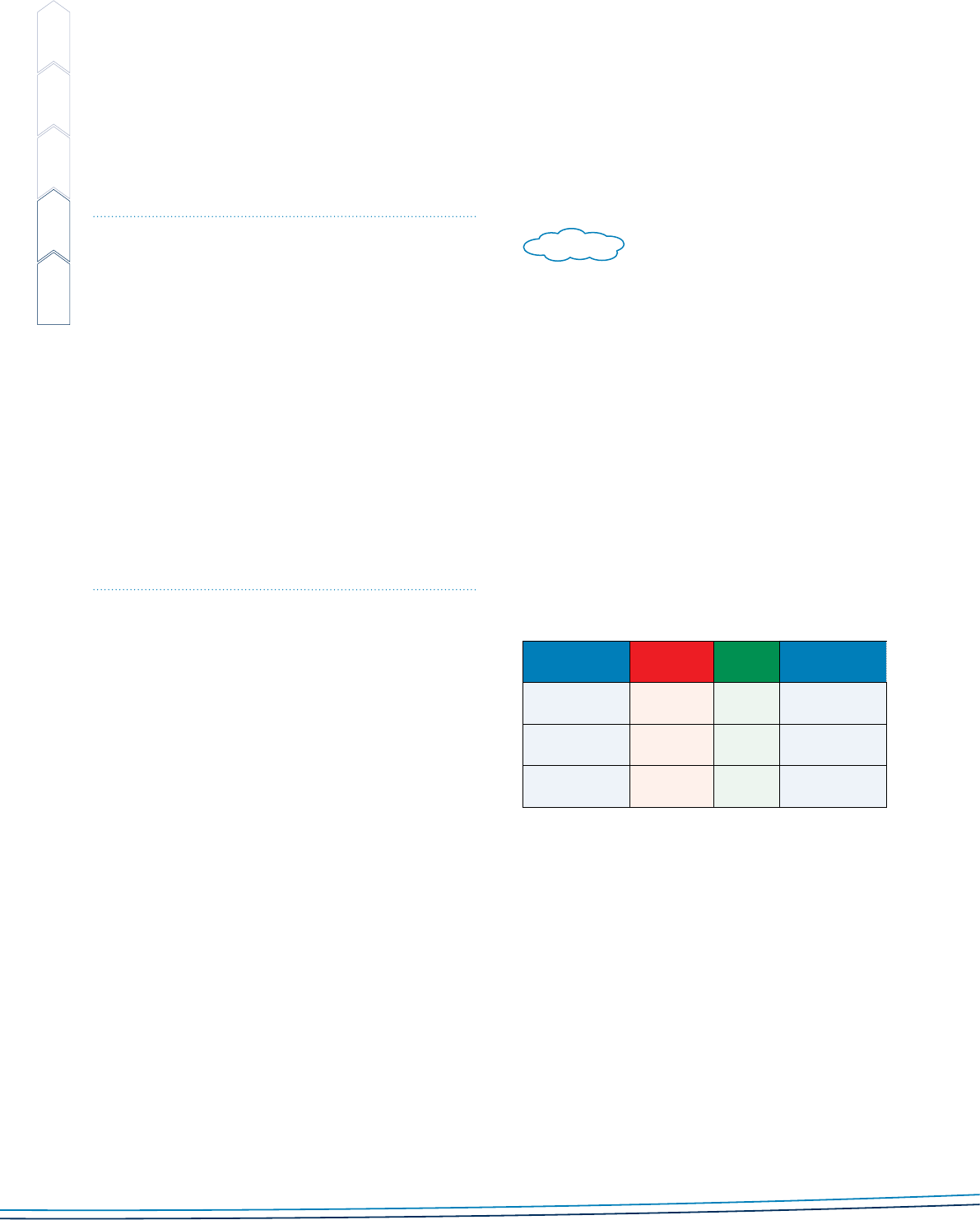

CONTENT ORGANISATION

Aspects of language

Strategies in this resource address the following key

aspects of language. Colour is used to indicate the

aspect being addressed as follows:

• cohesive devices (yellow)

• sentence structure (orange)

• verbs and verb groups (green)

• circumstances (blue)

• nouns and noun groups (maroon)

• evaluative language (purple).

An overview of content is provided at the beginning

of each aspect for quick identification of the learning

sequences. An introduction to each language aspect

describes its threads and explains associated forms

and functions with examples.

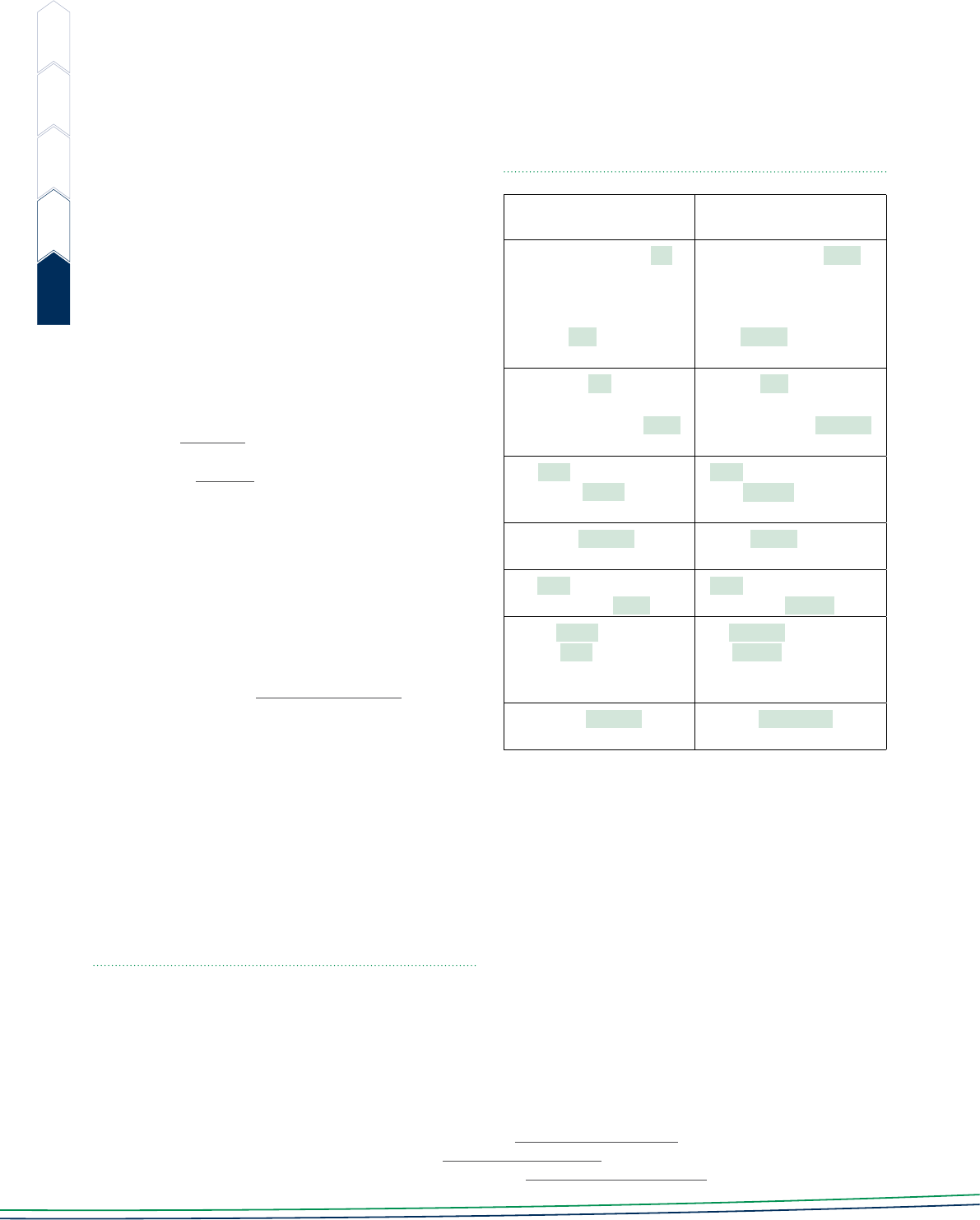

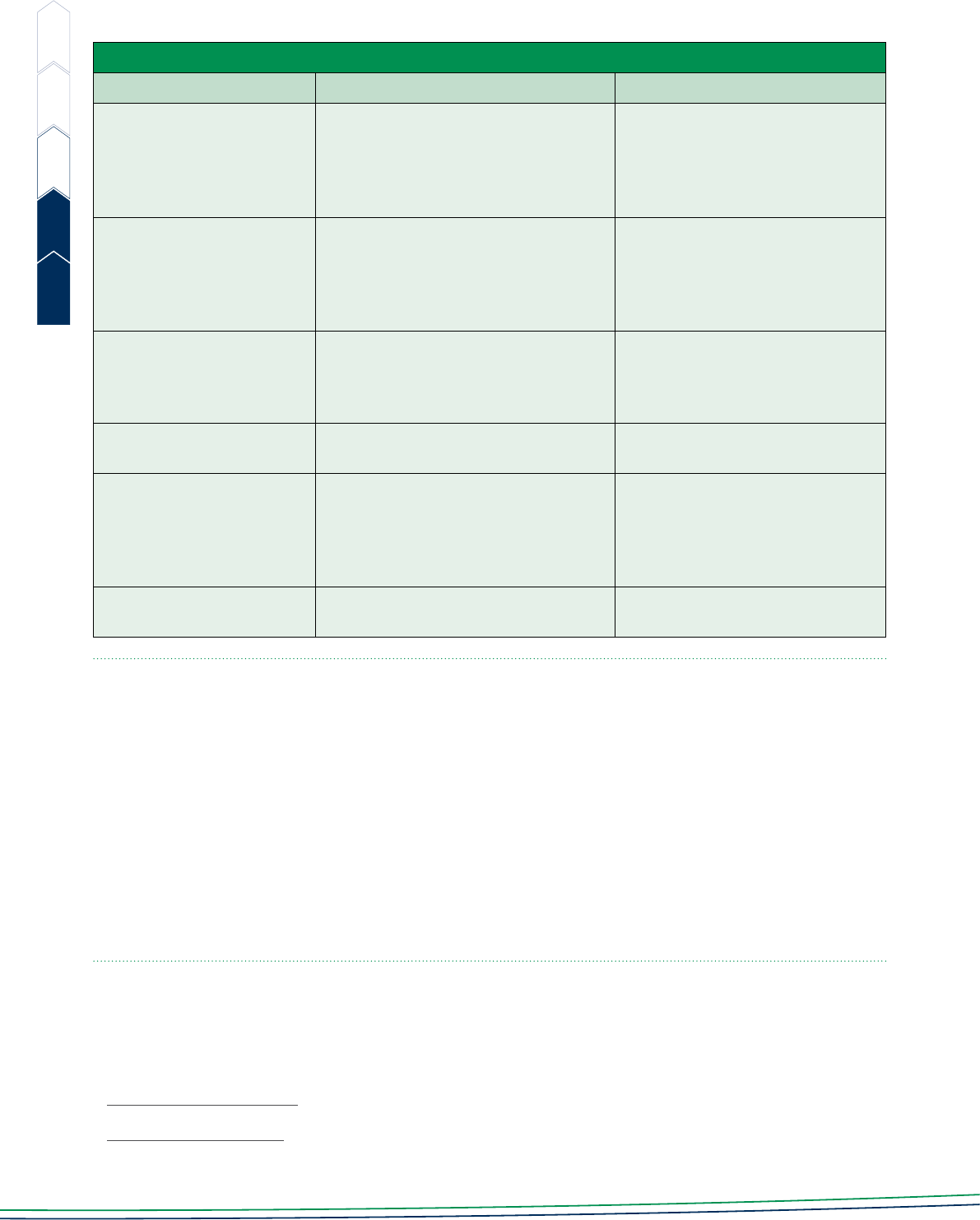

Participants, processes and

circumstances

Colour is also used to identify at the word level which

aspect of language is being demonstrated. At times,

this includes aspects that are not considered in the

levelling process.

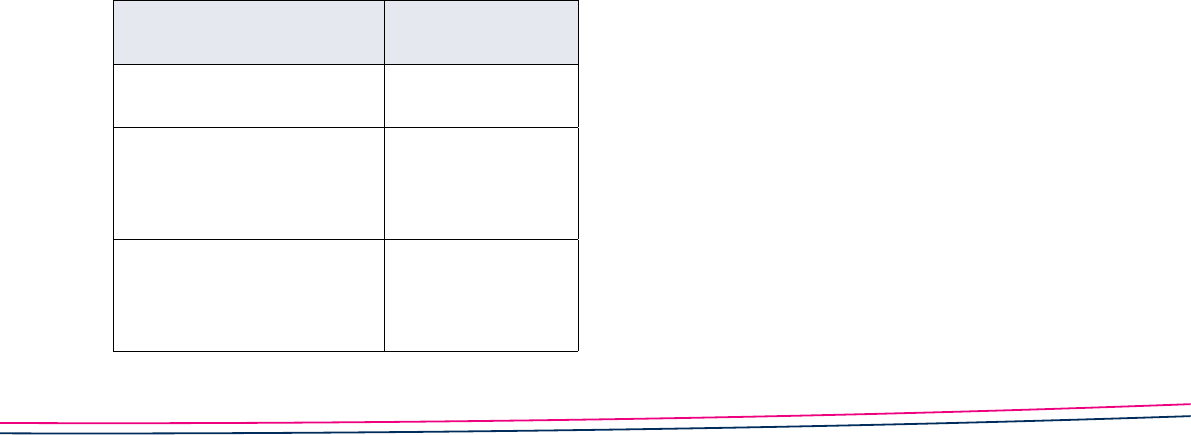

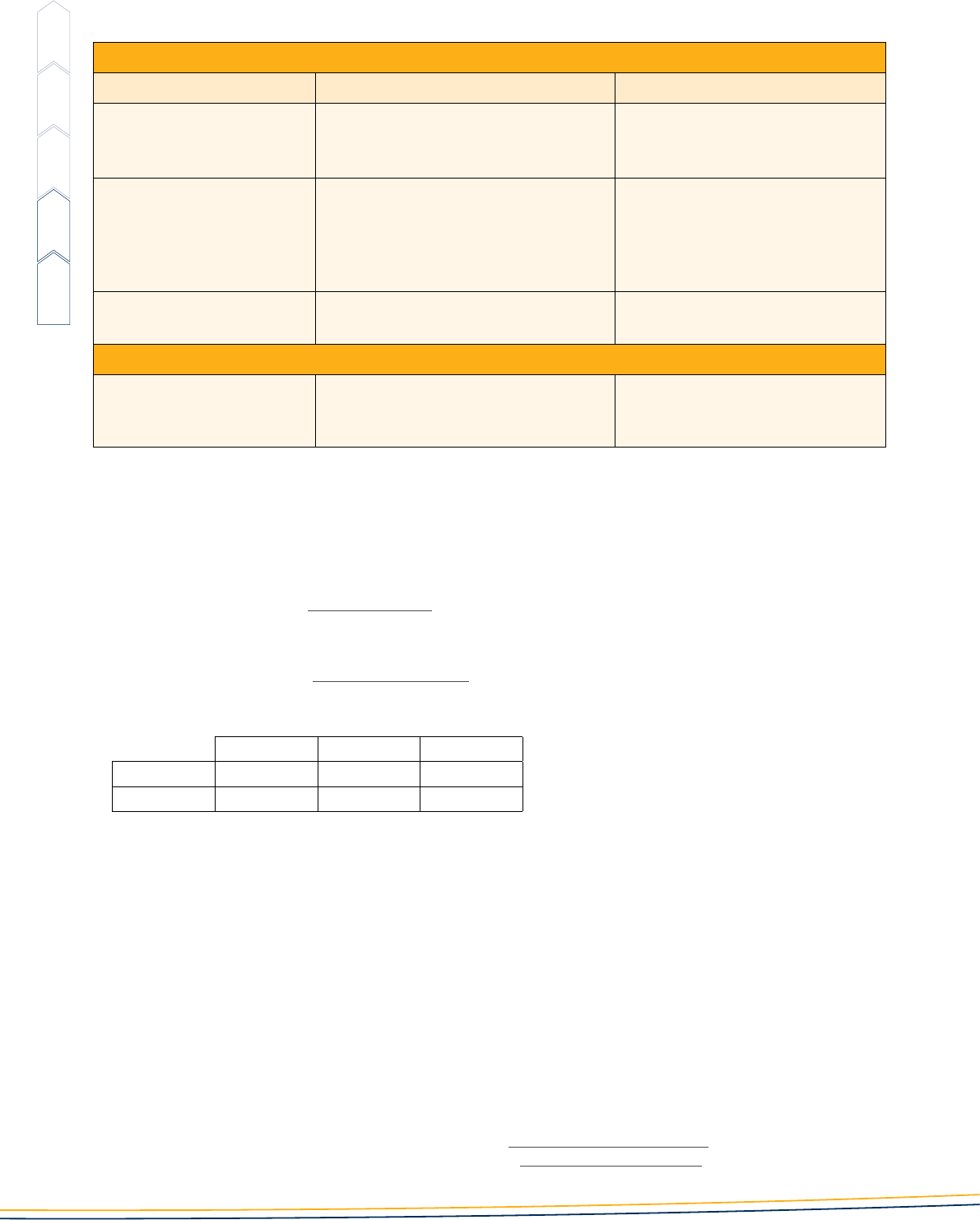

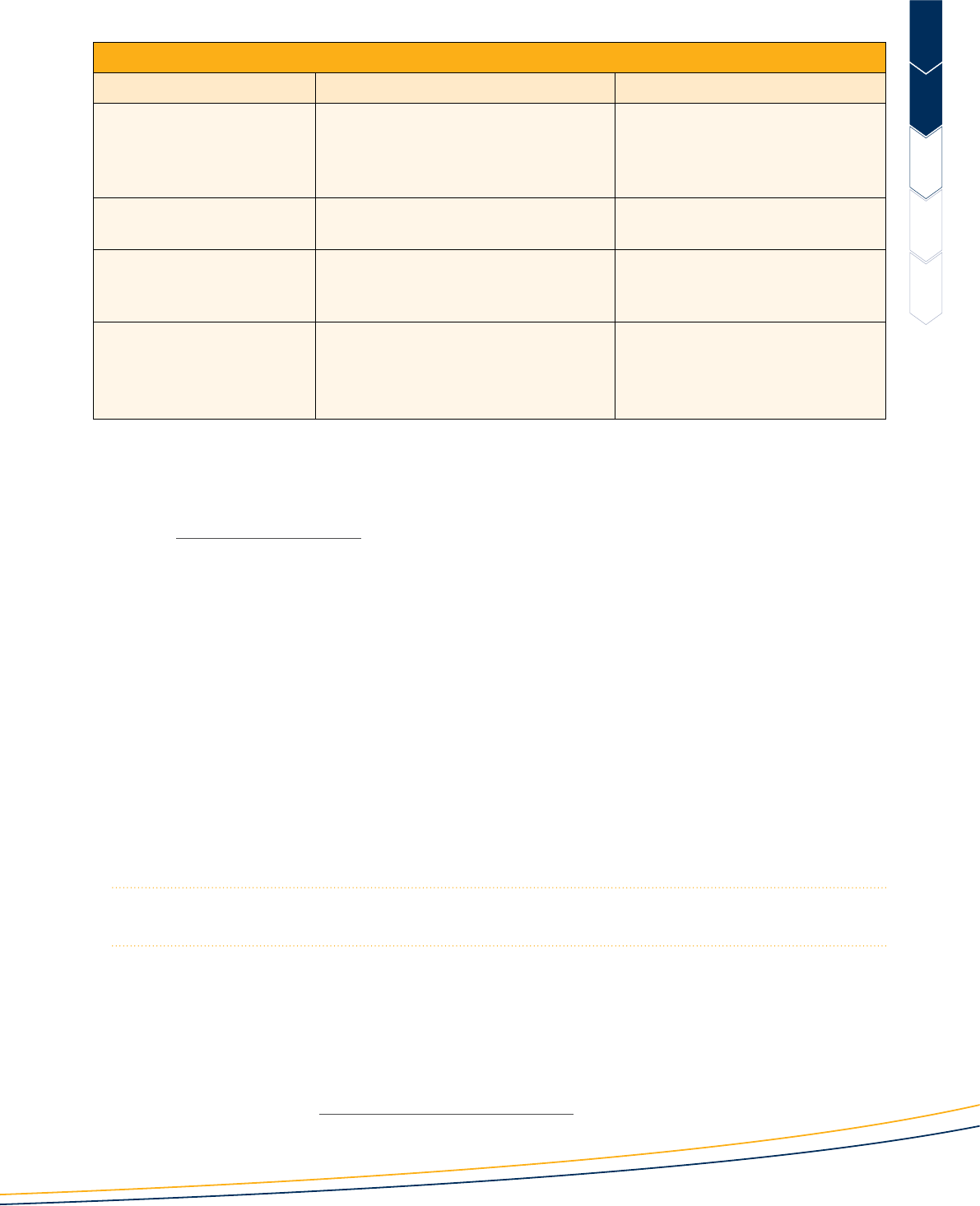

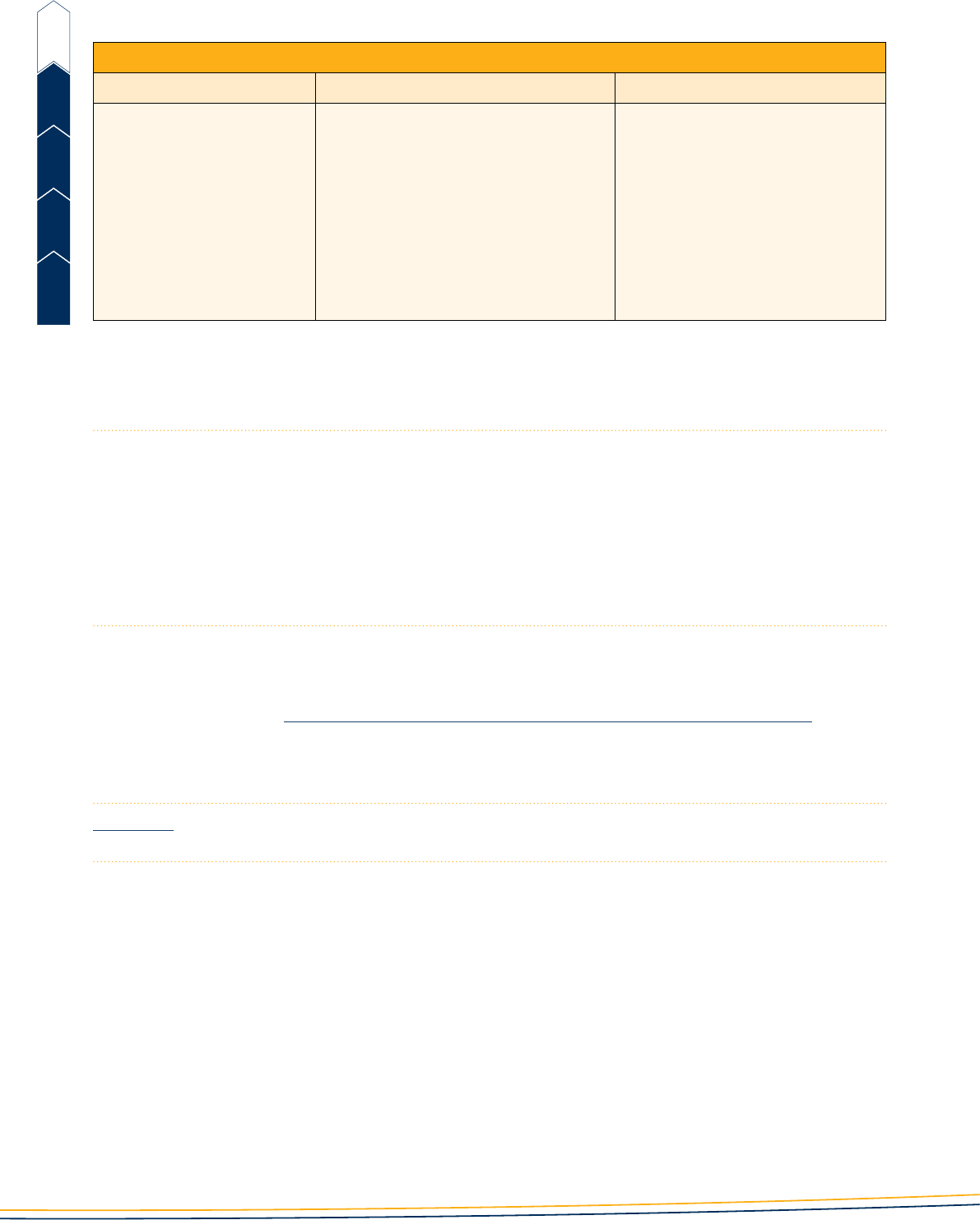

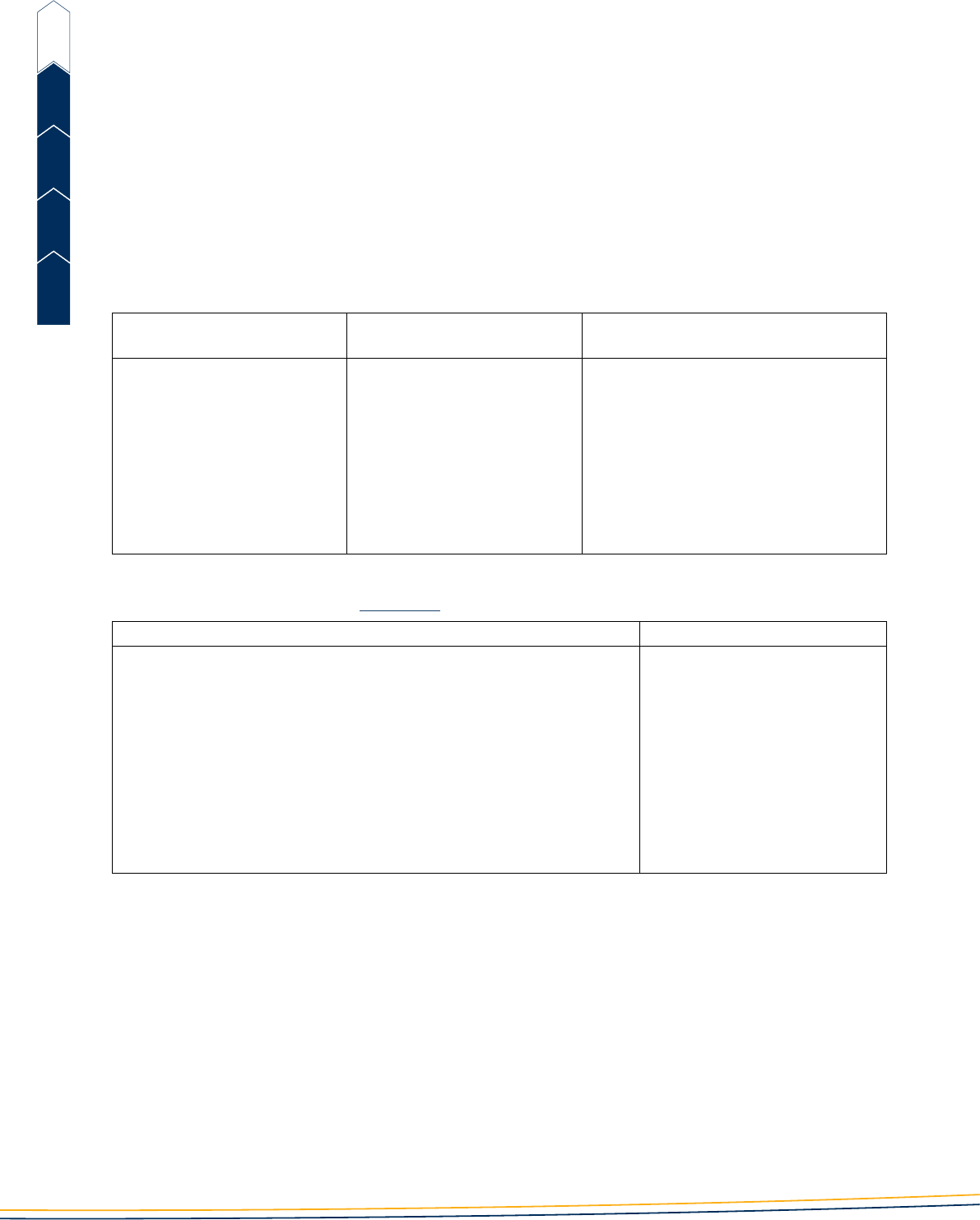

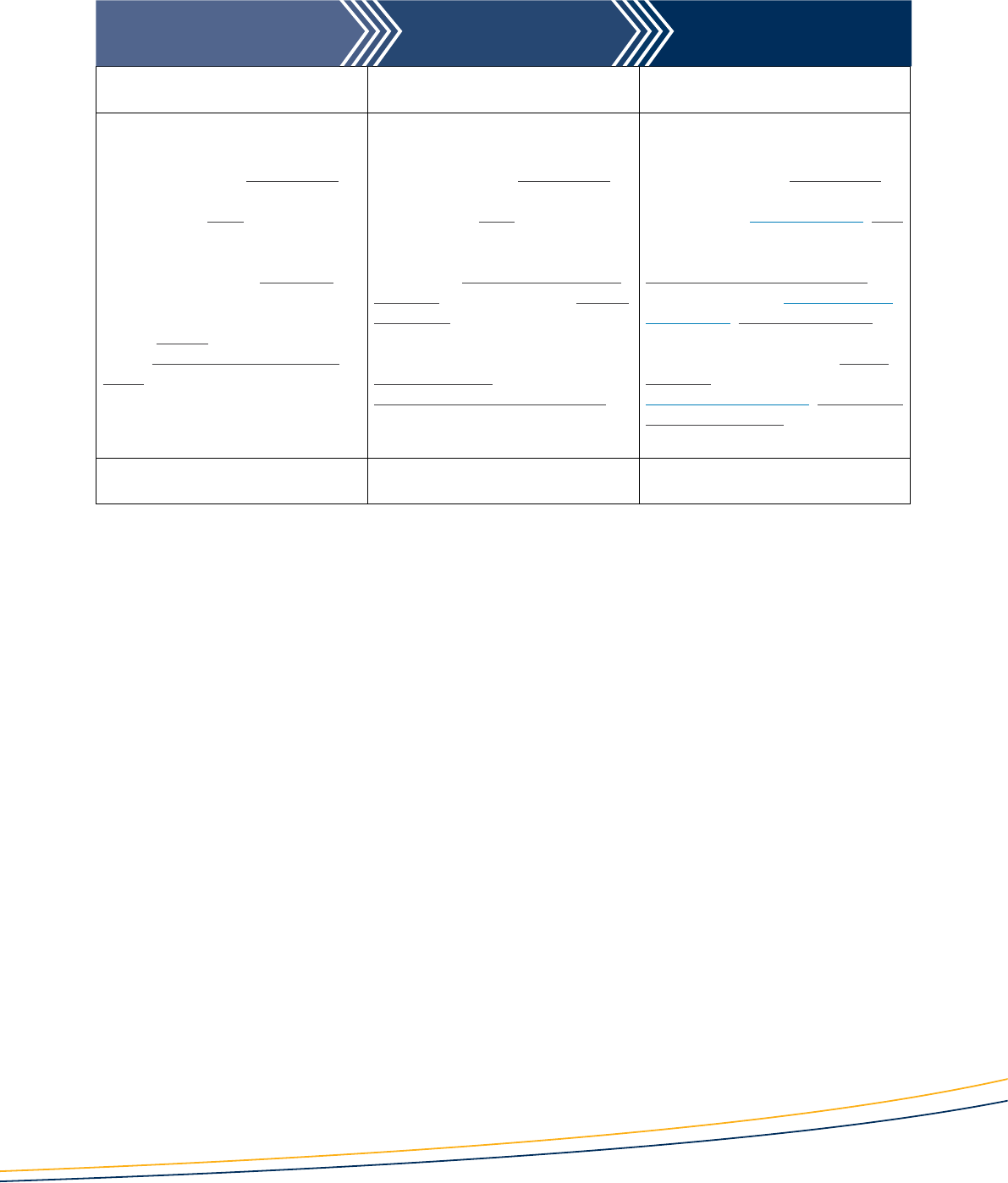

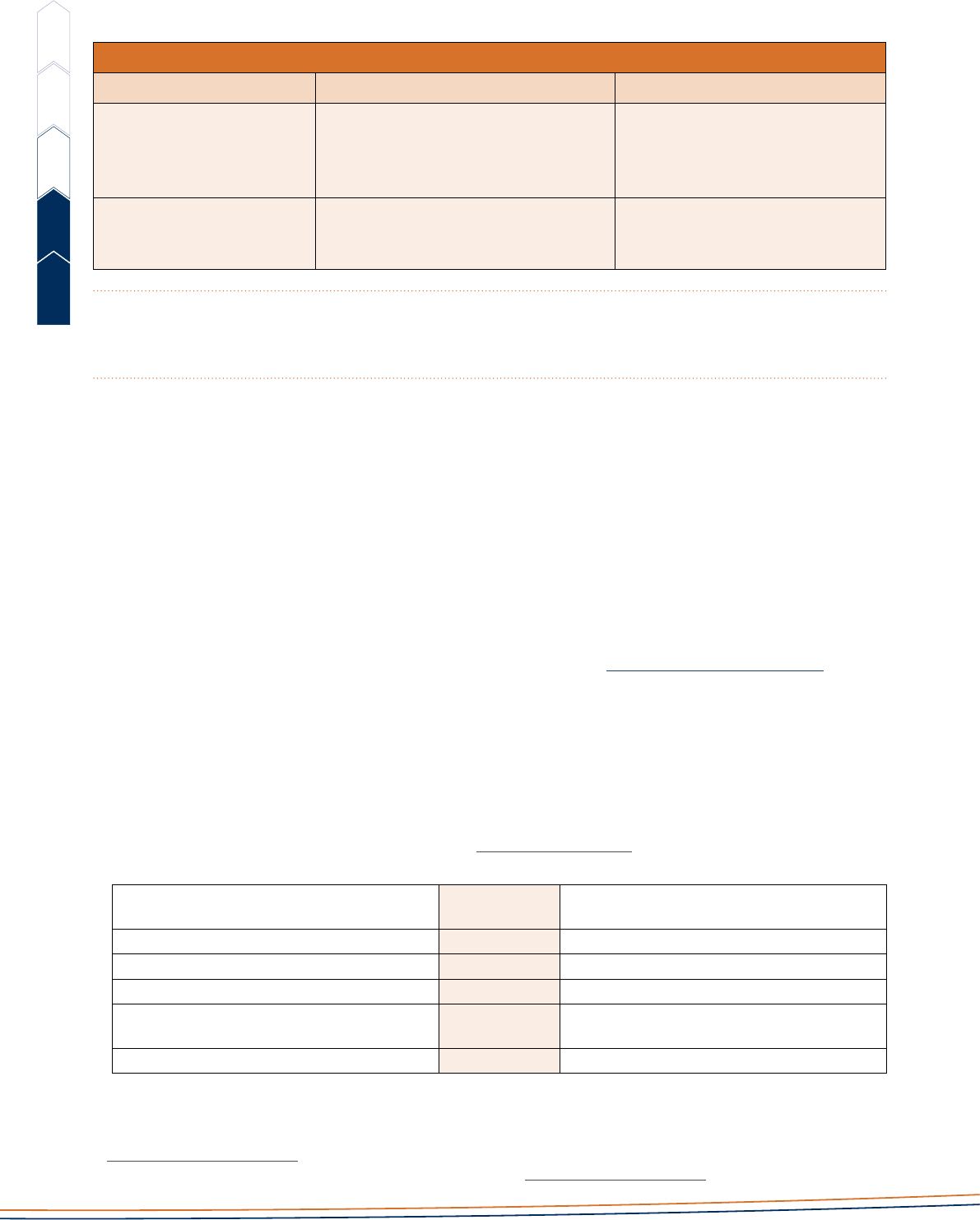

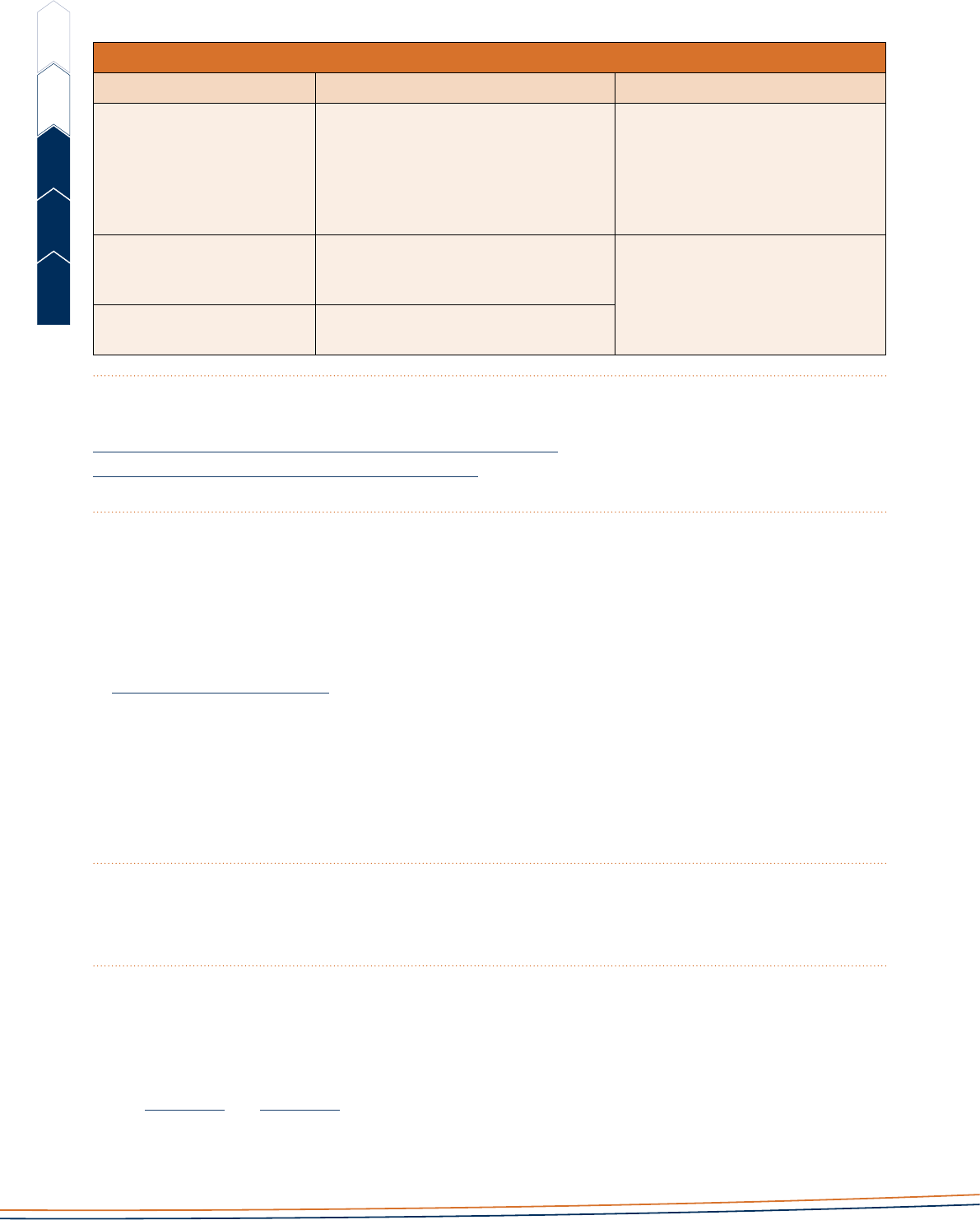

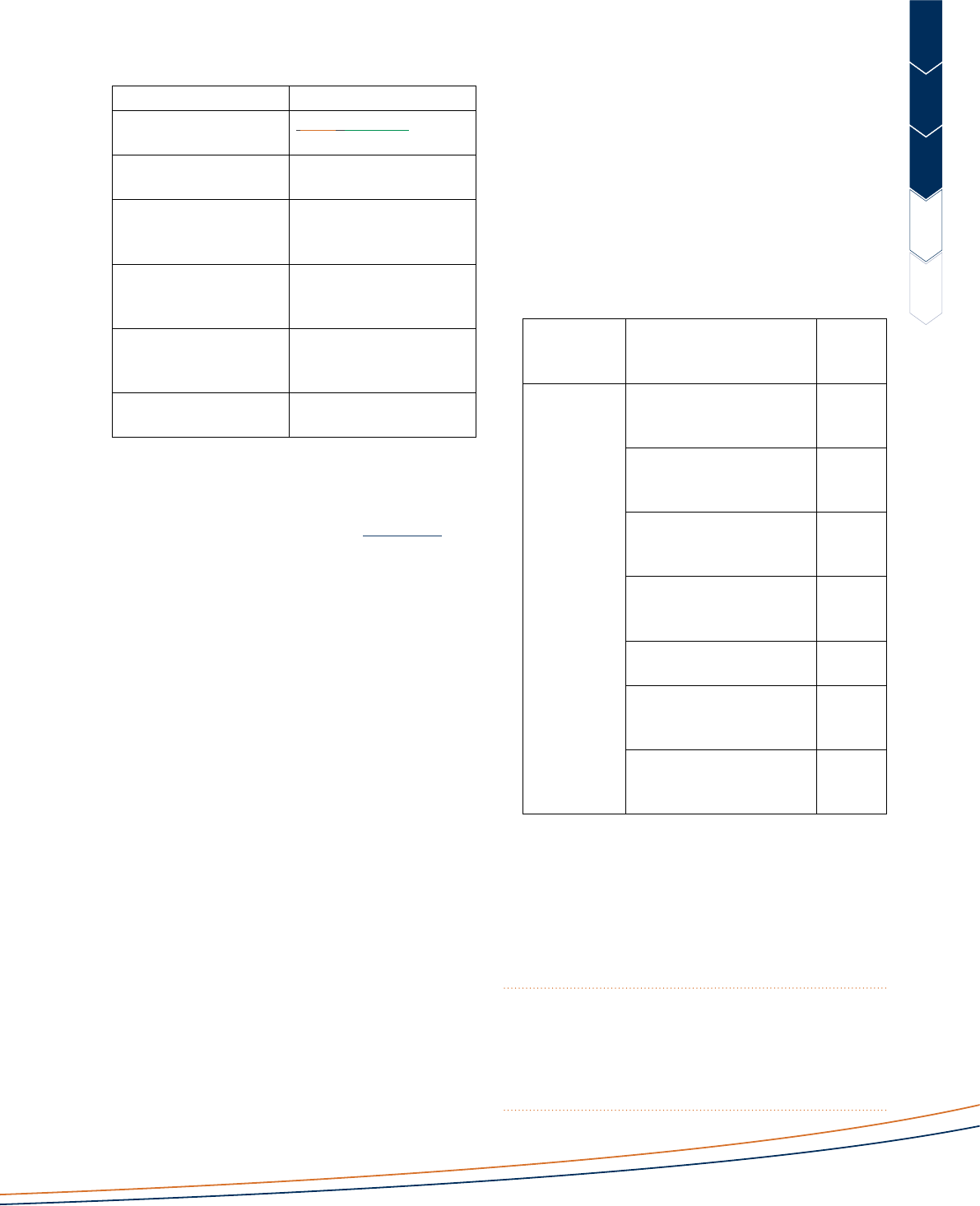

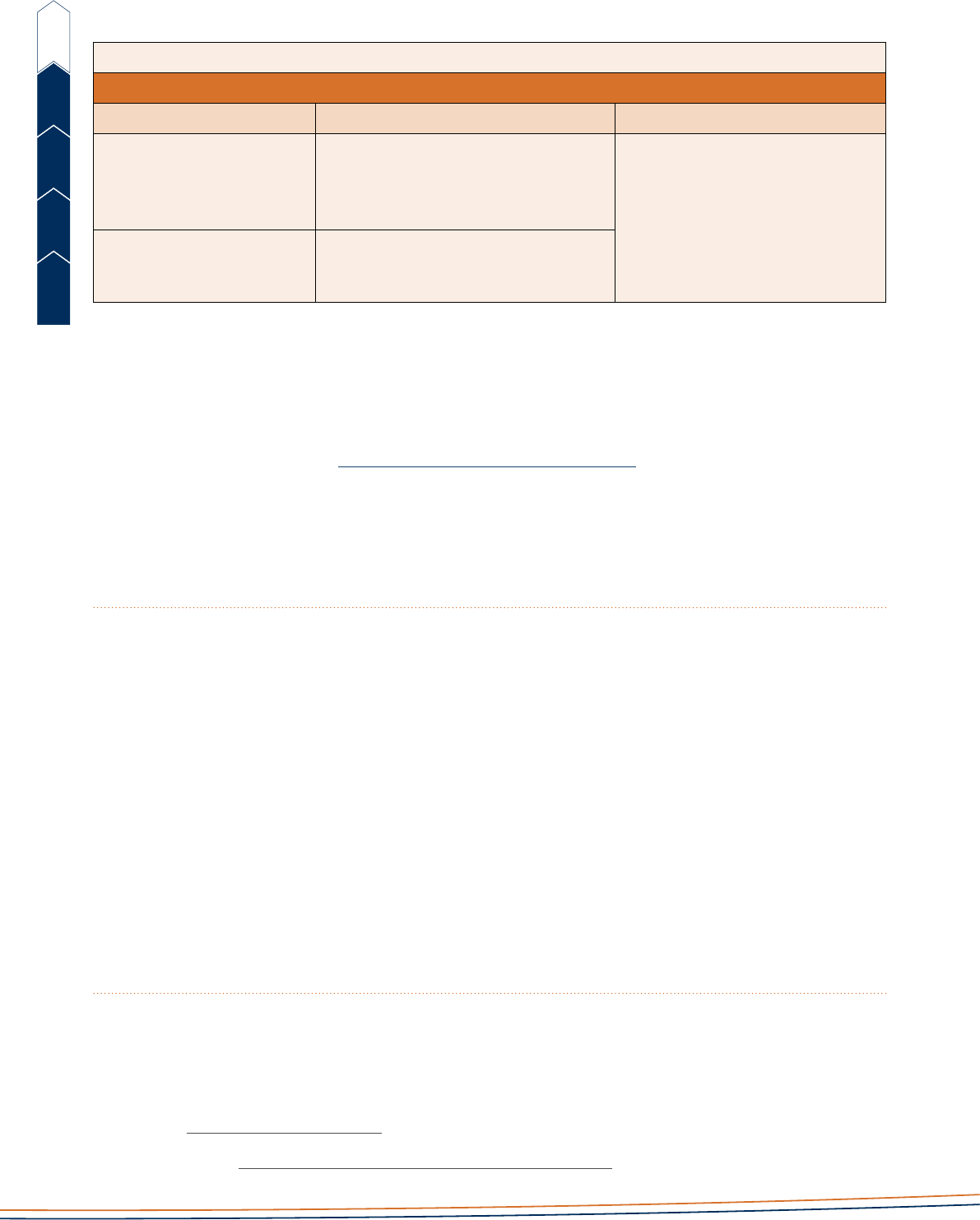

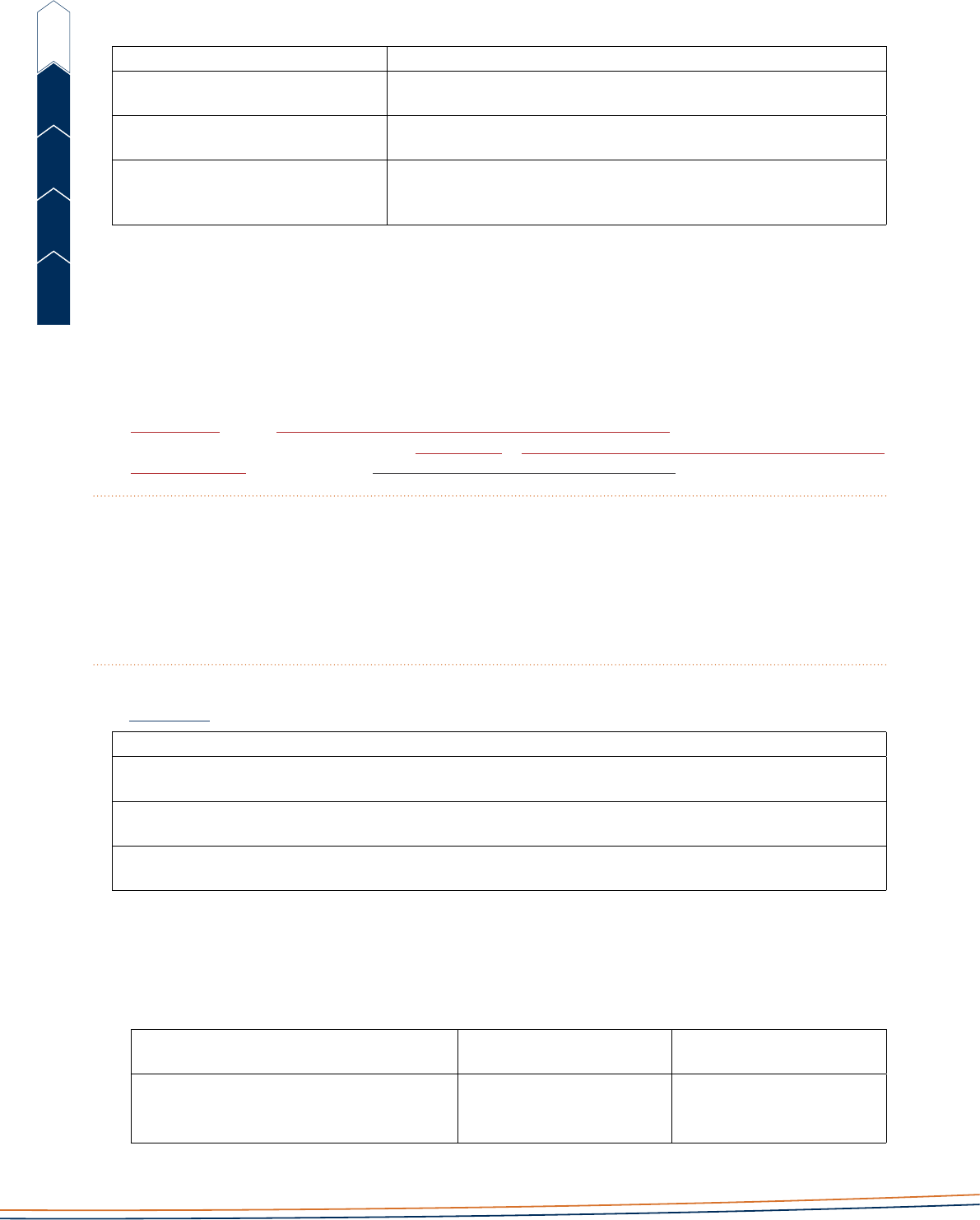

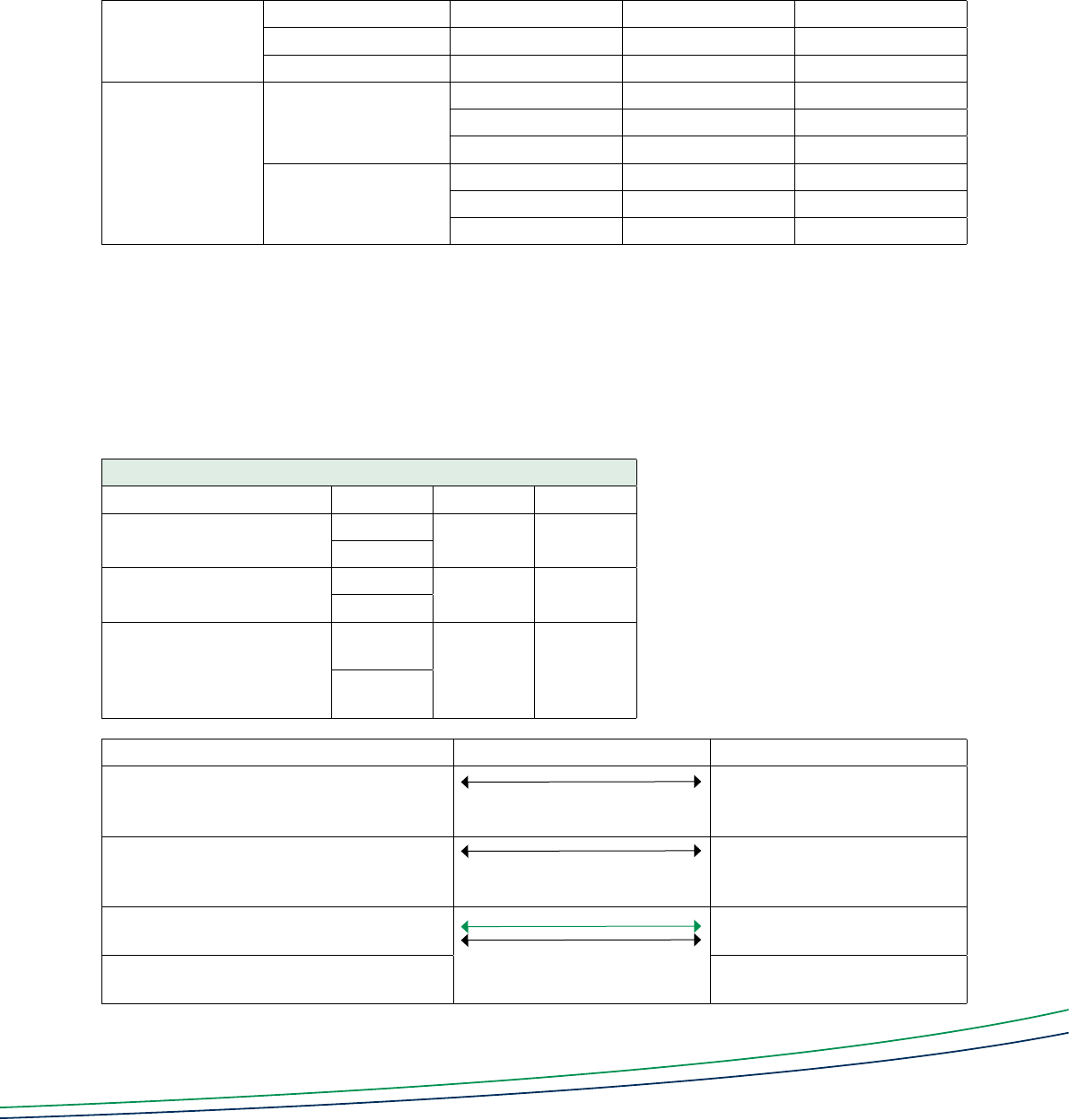

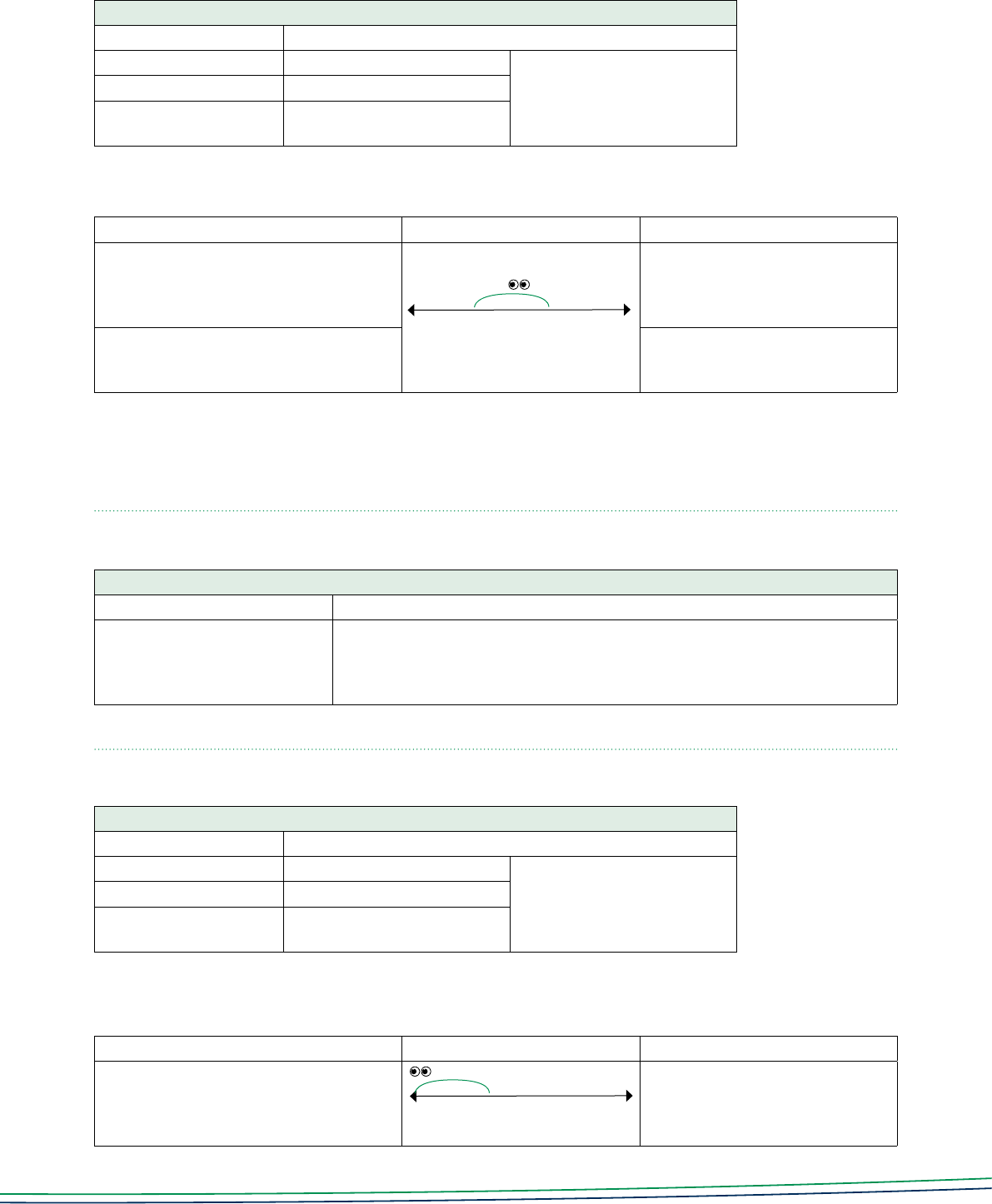

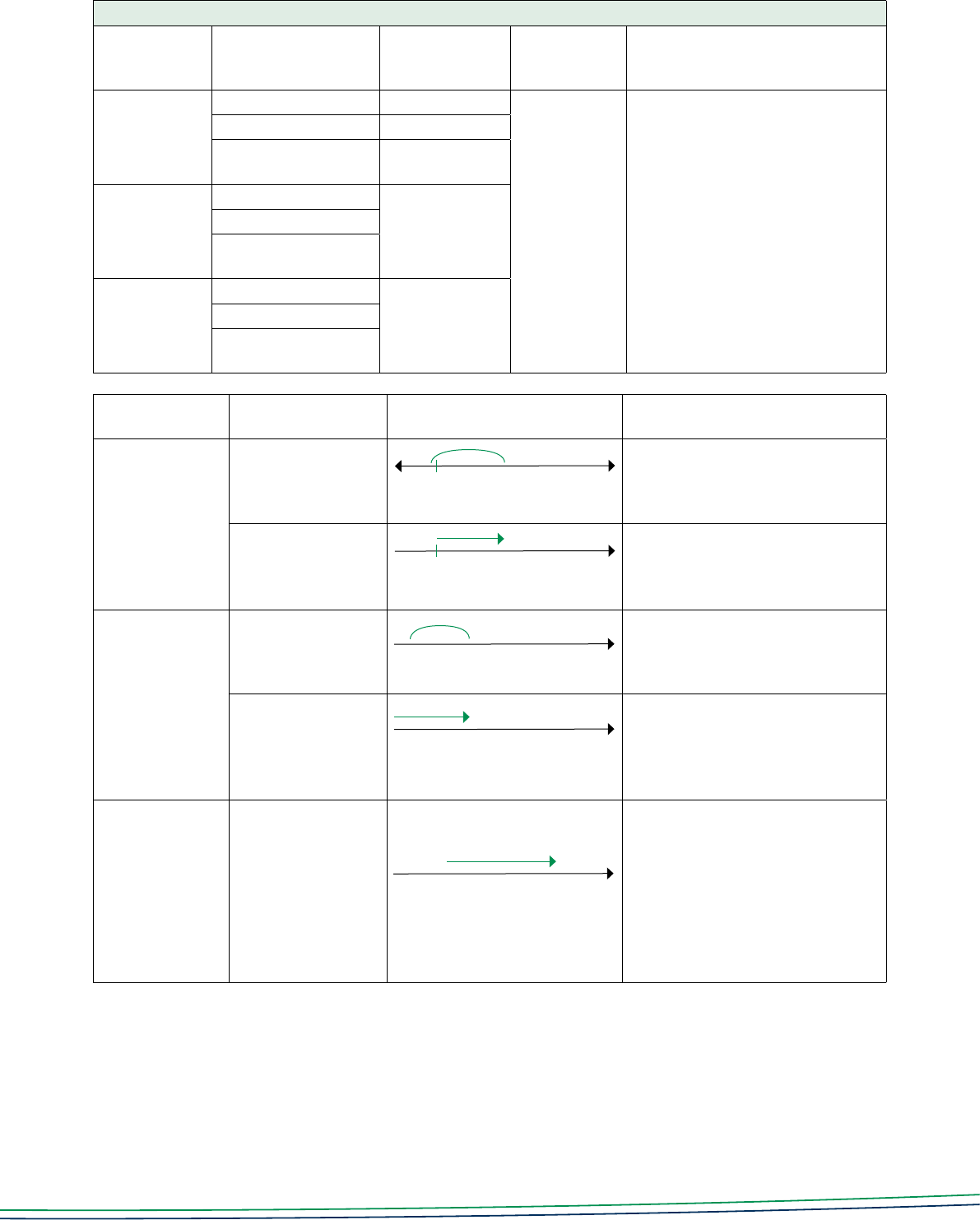

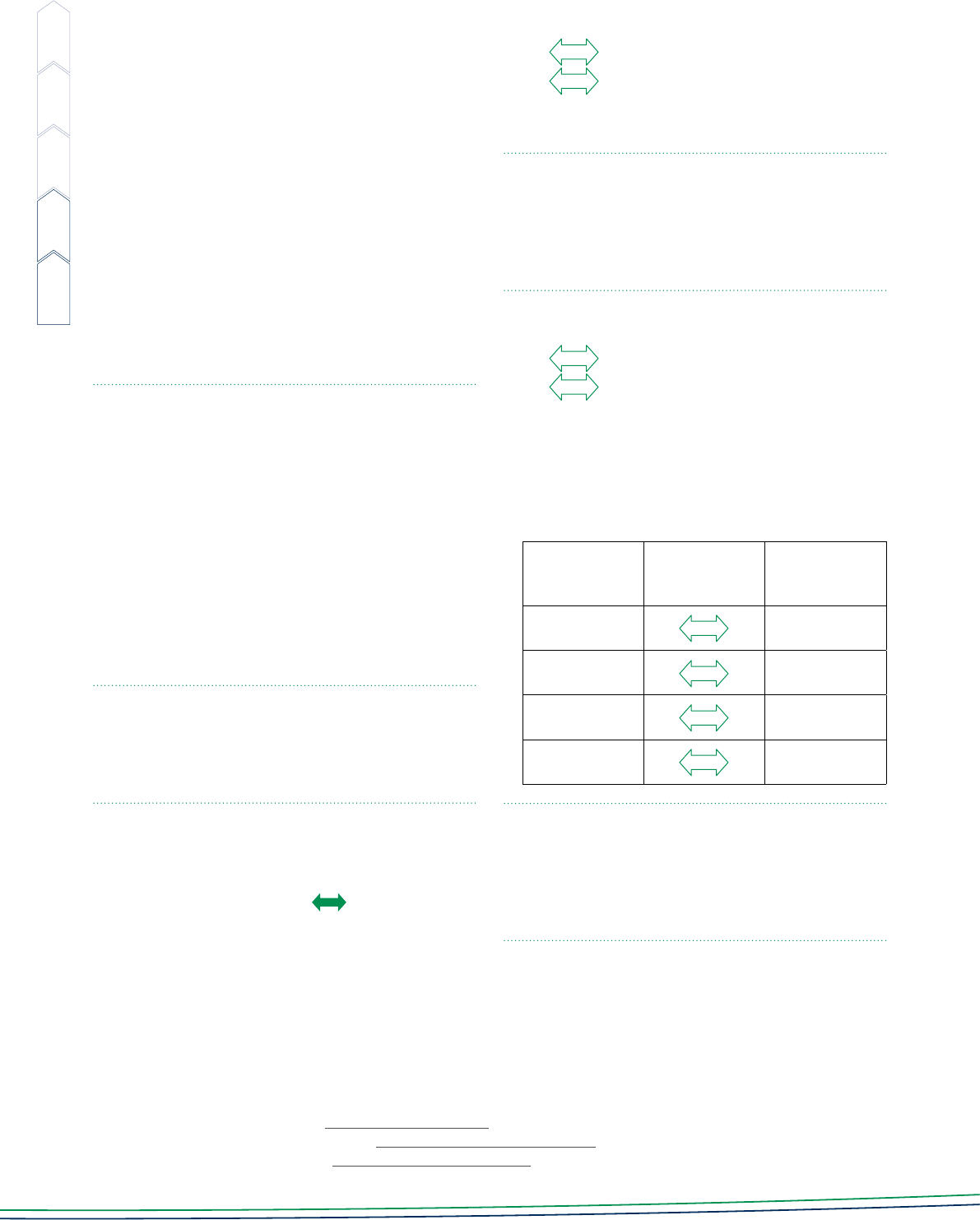

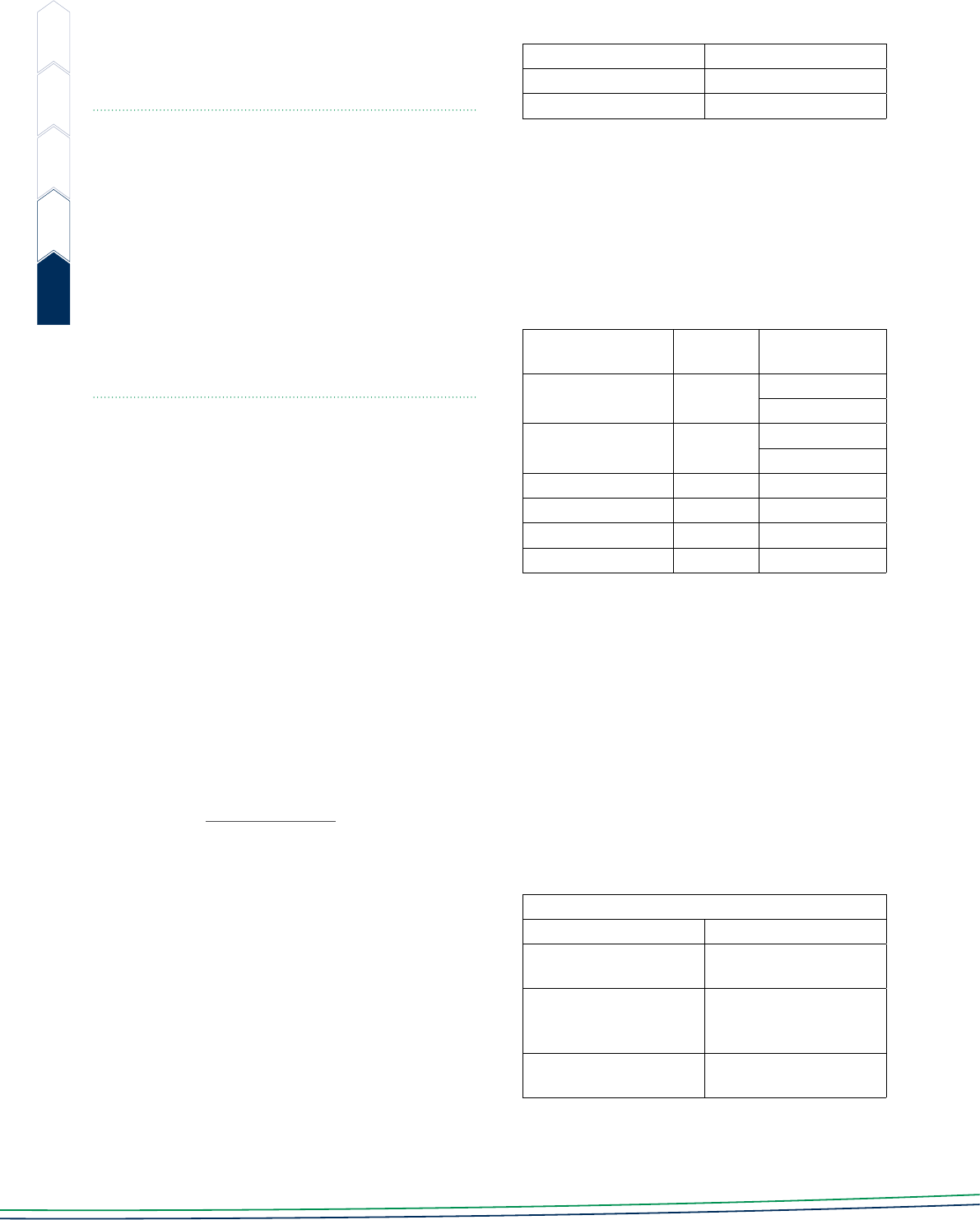

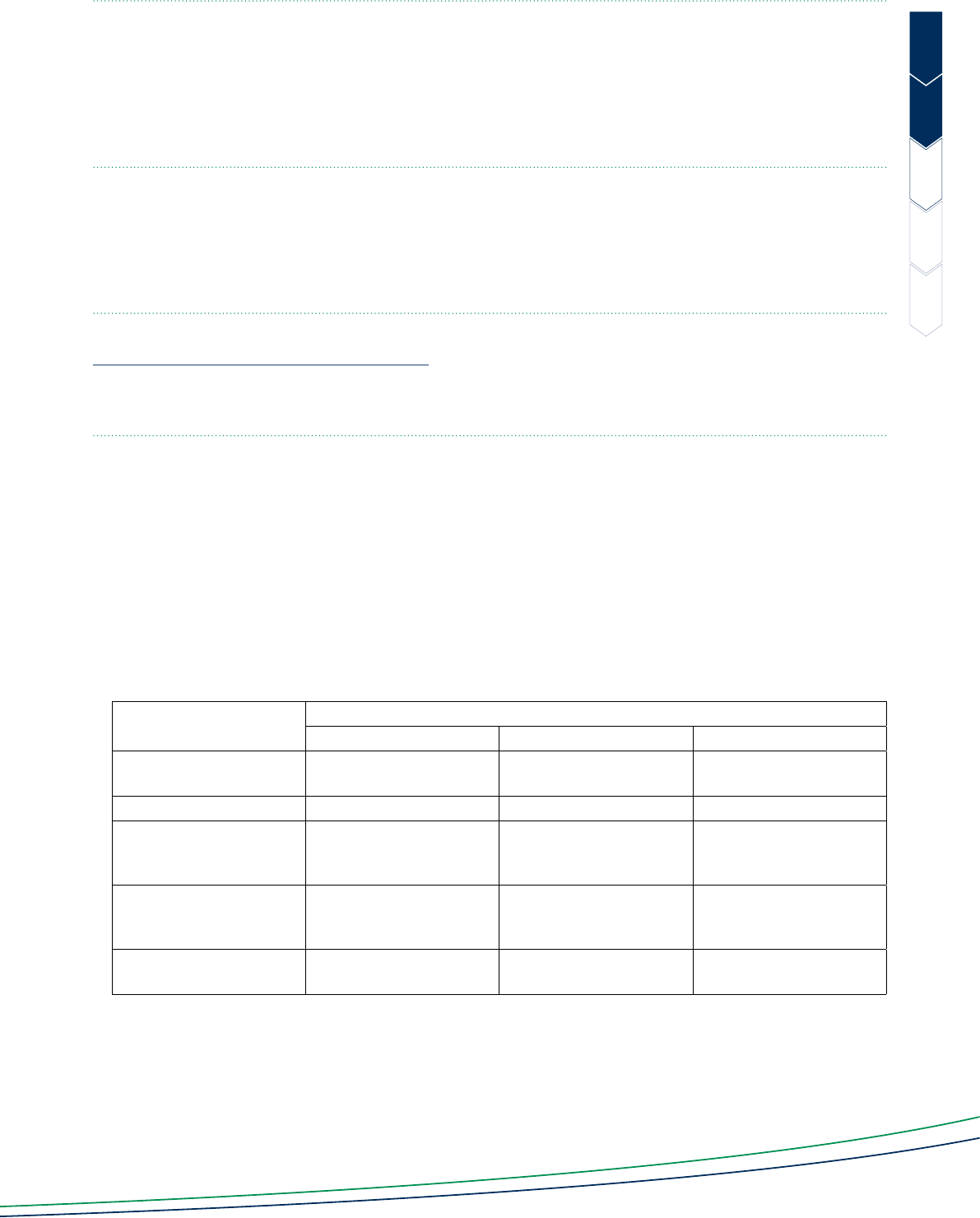

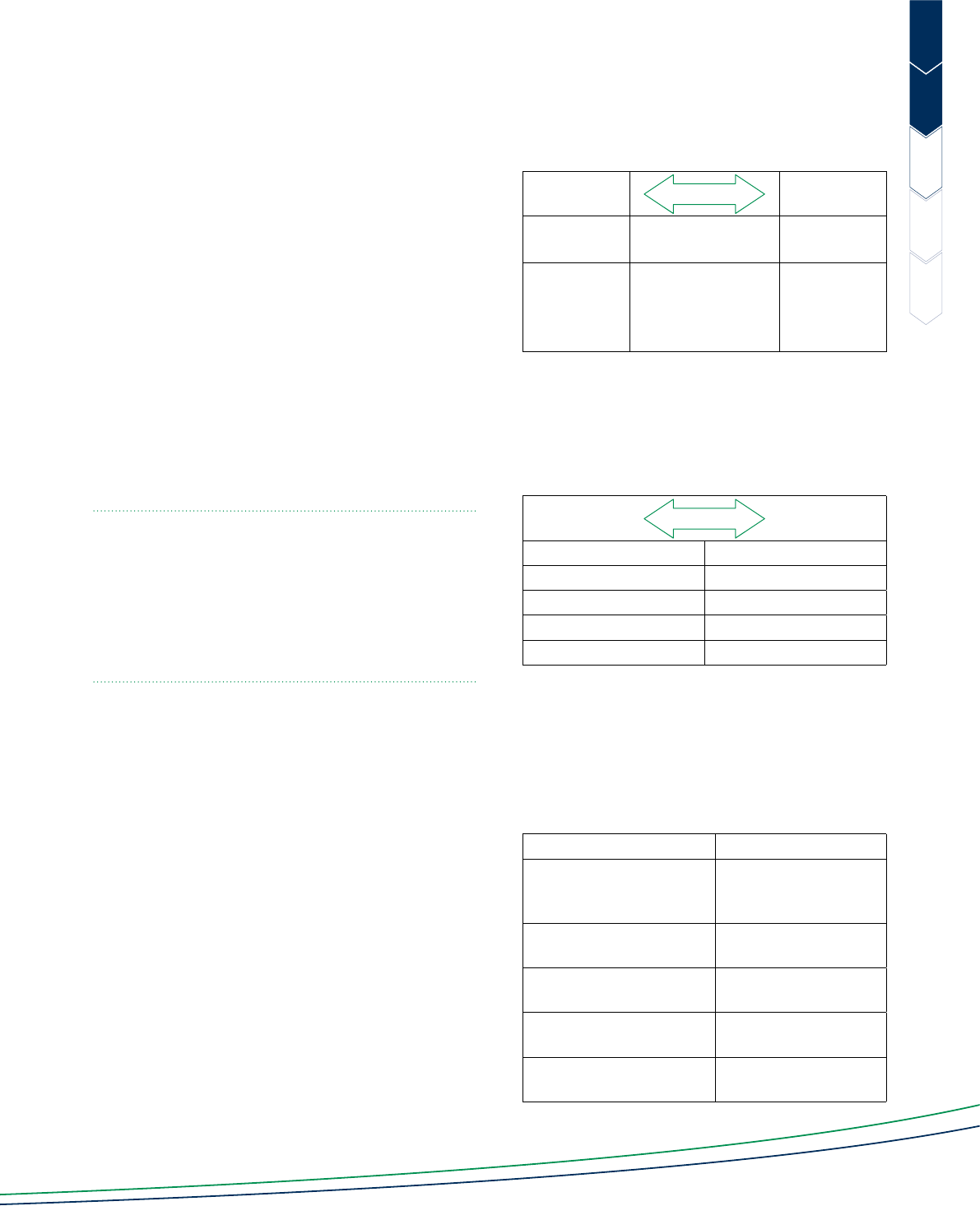

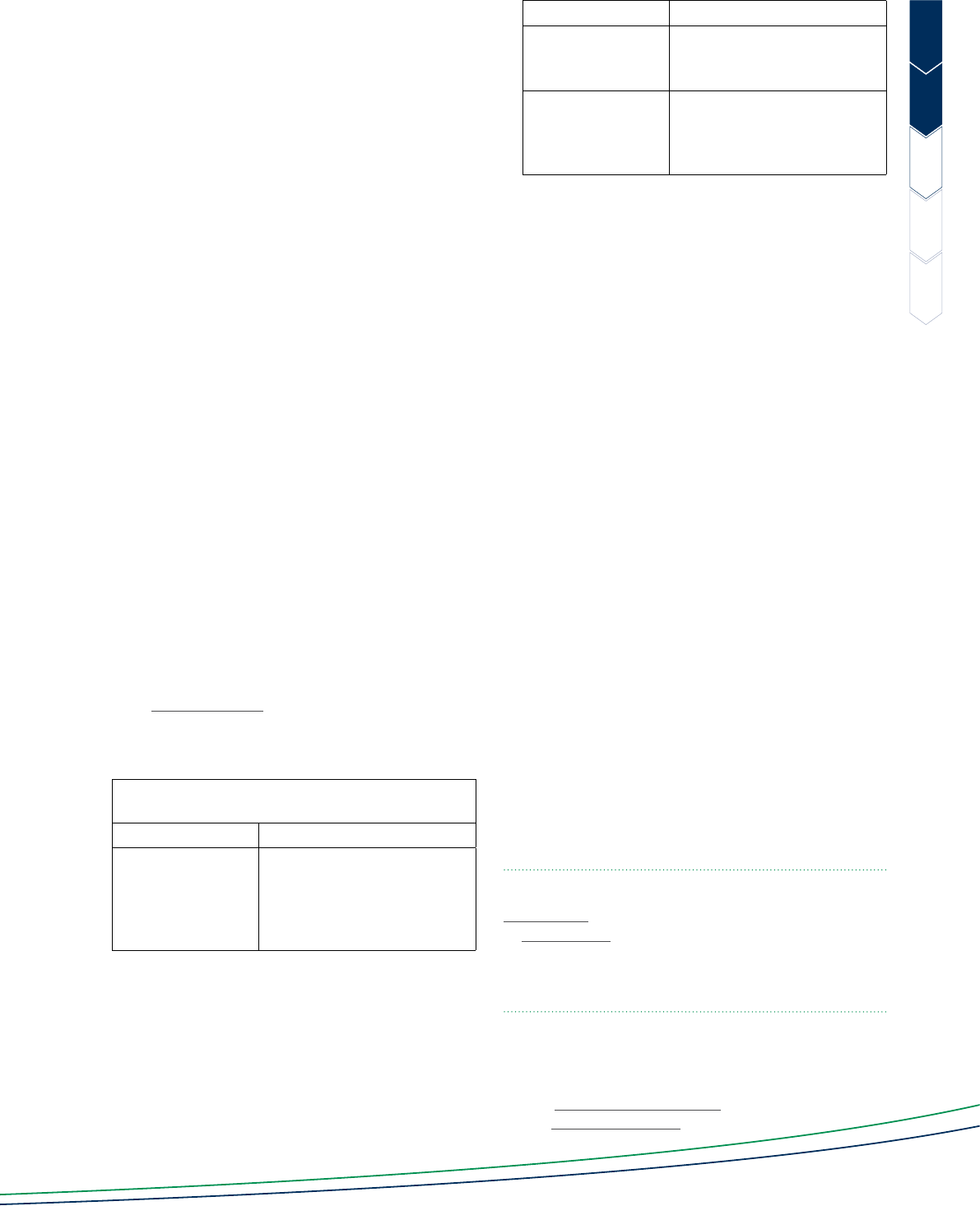

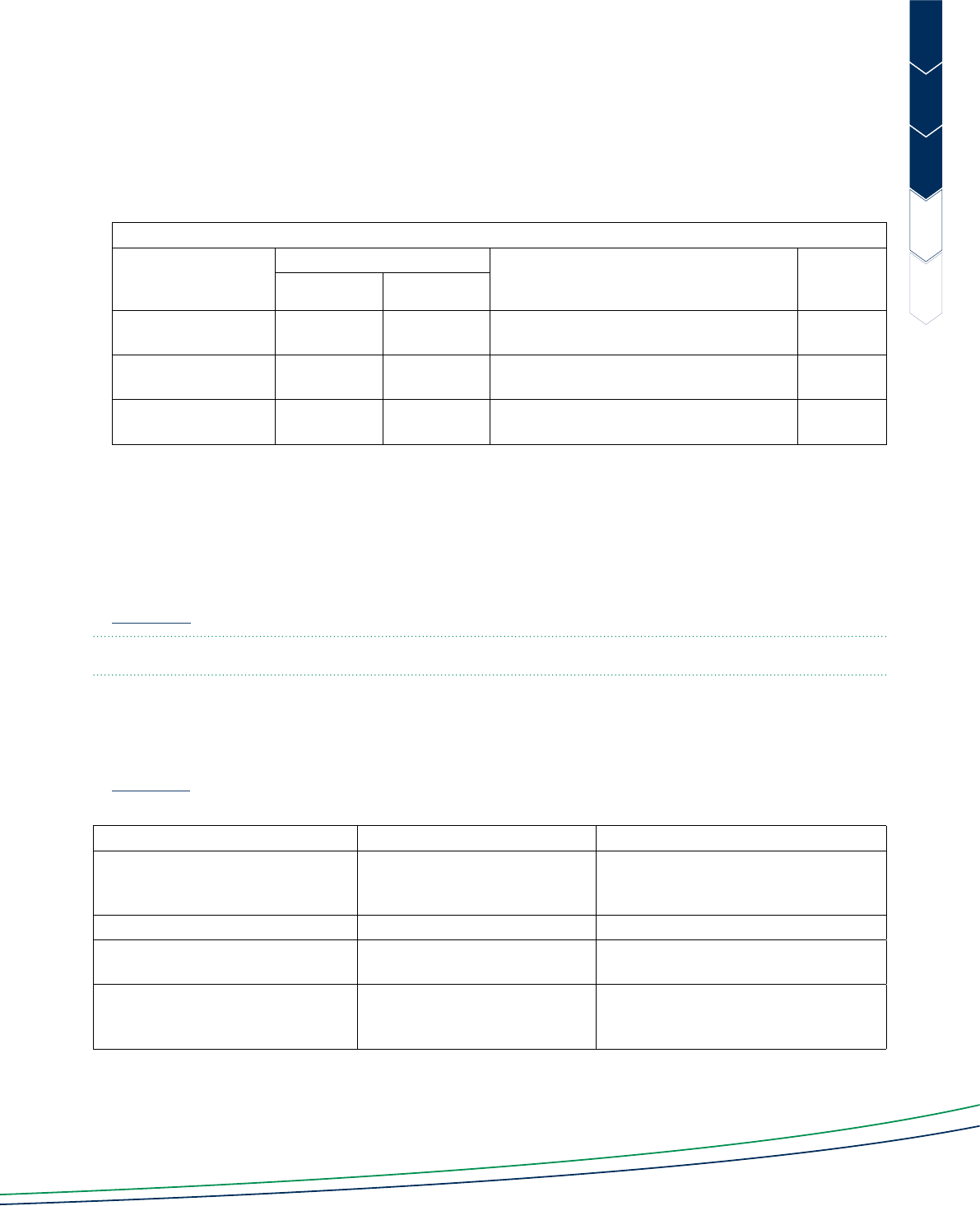

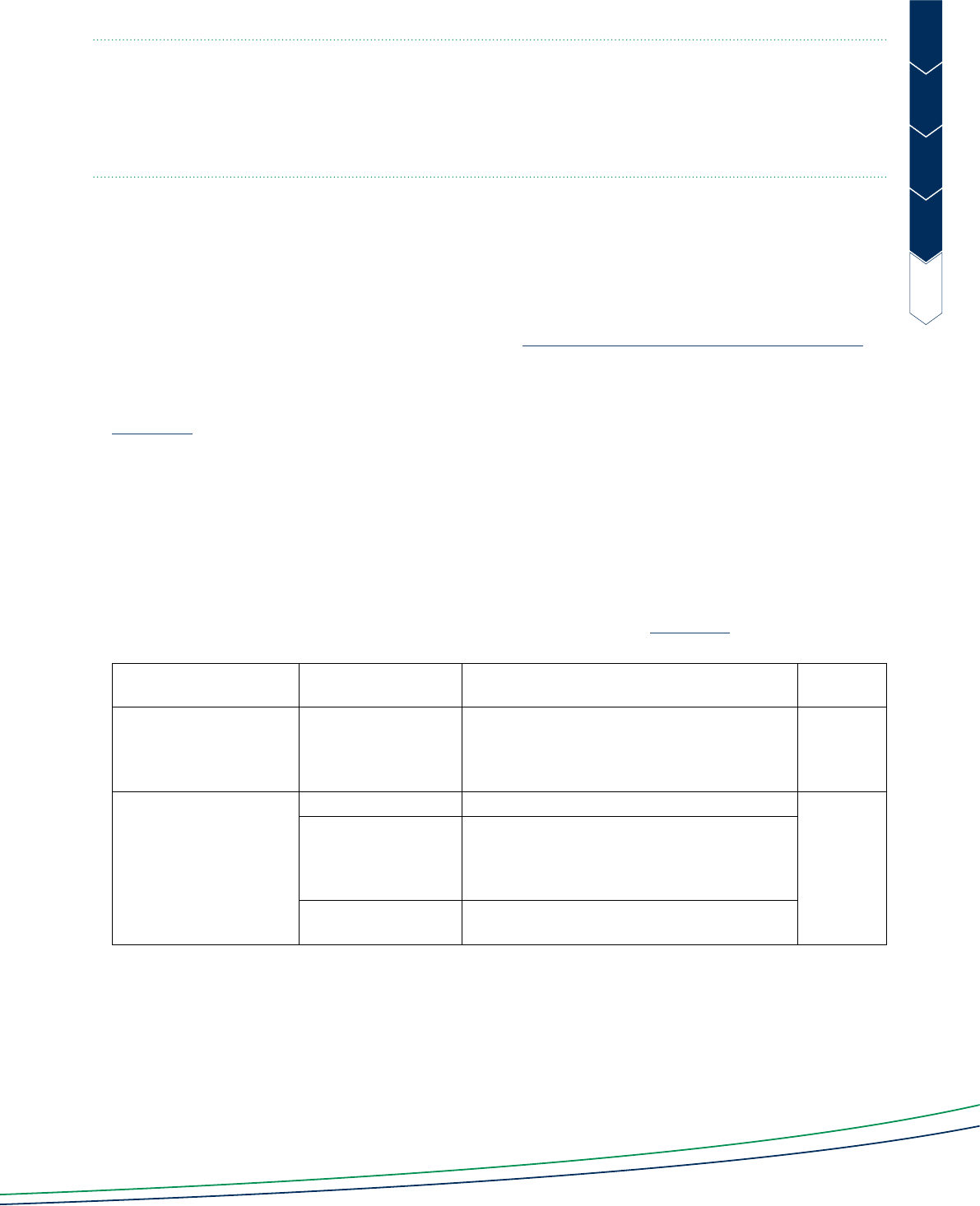

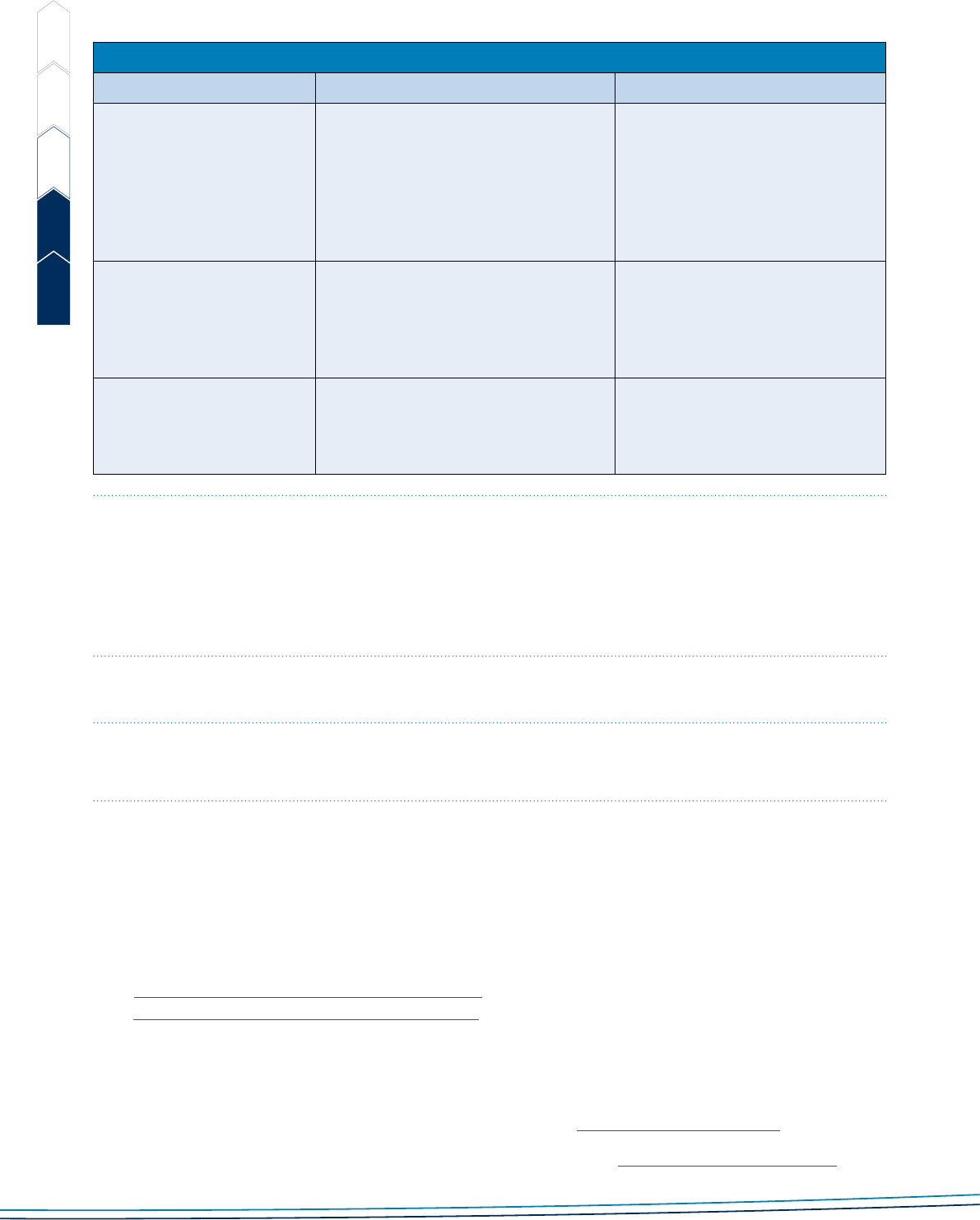

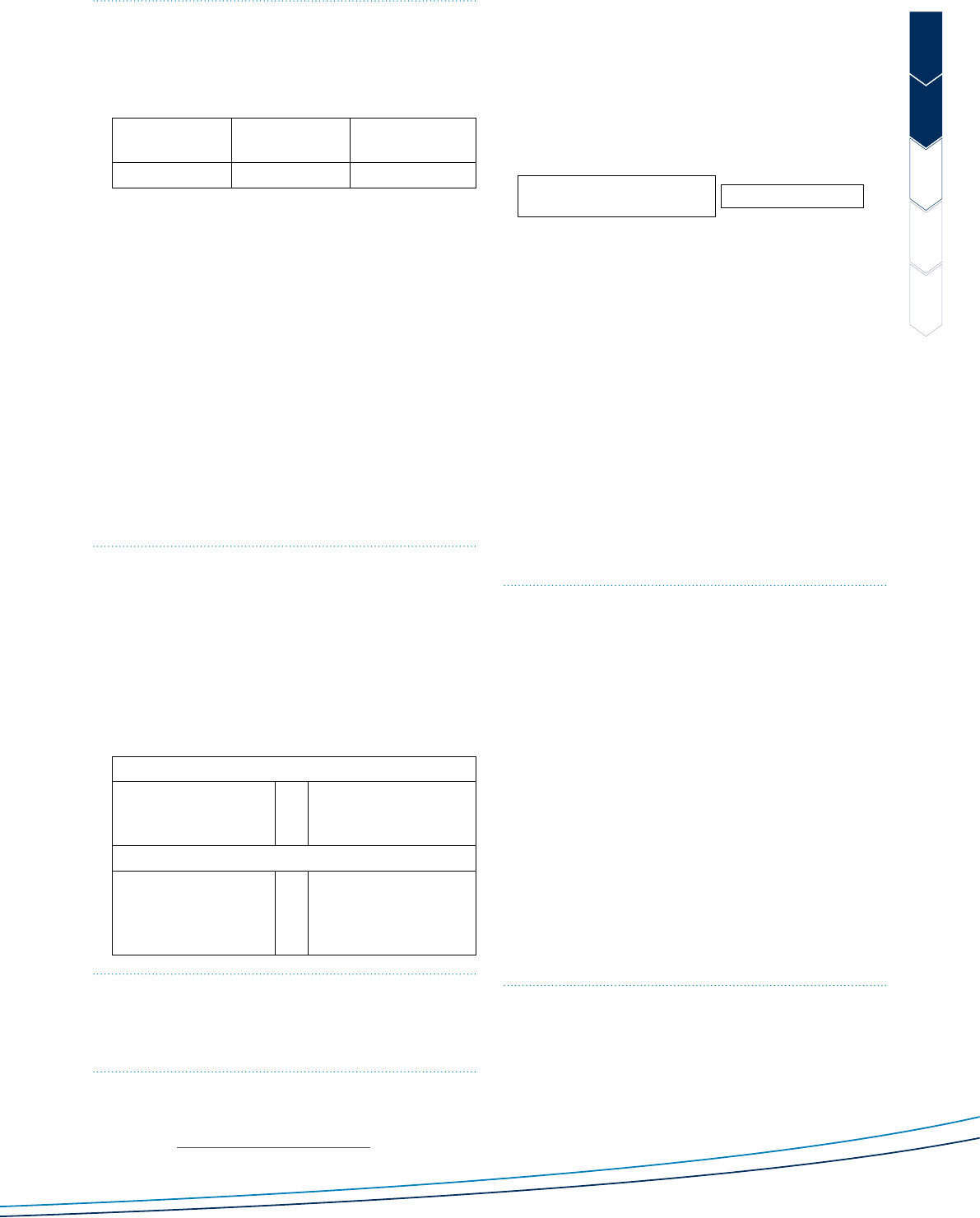

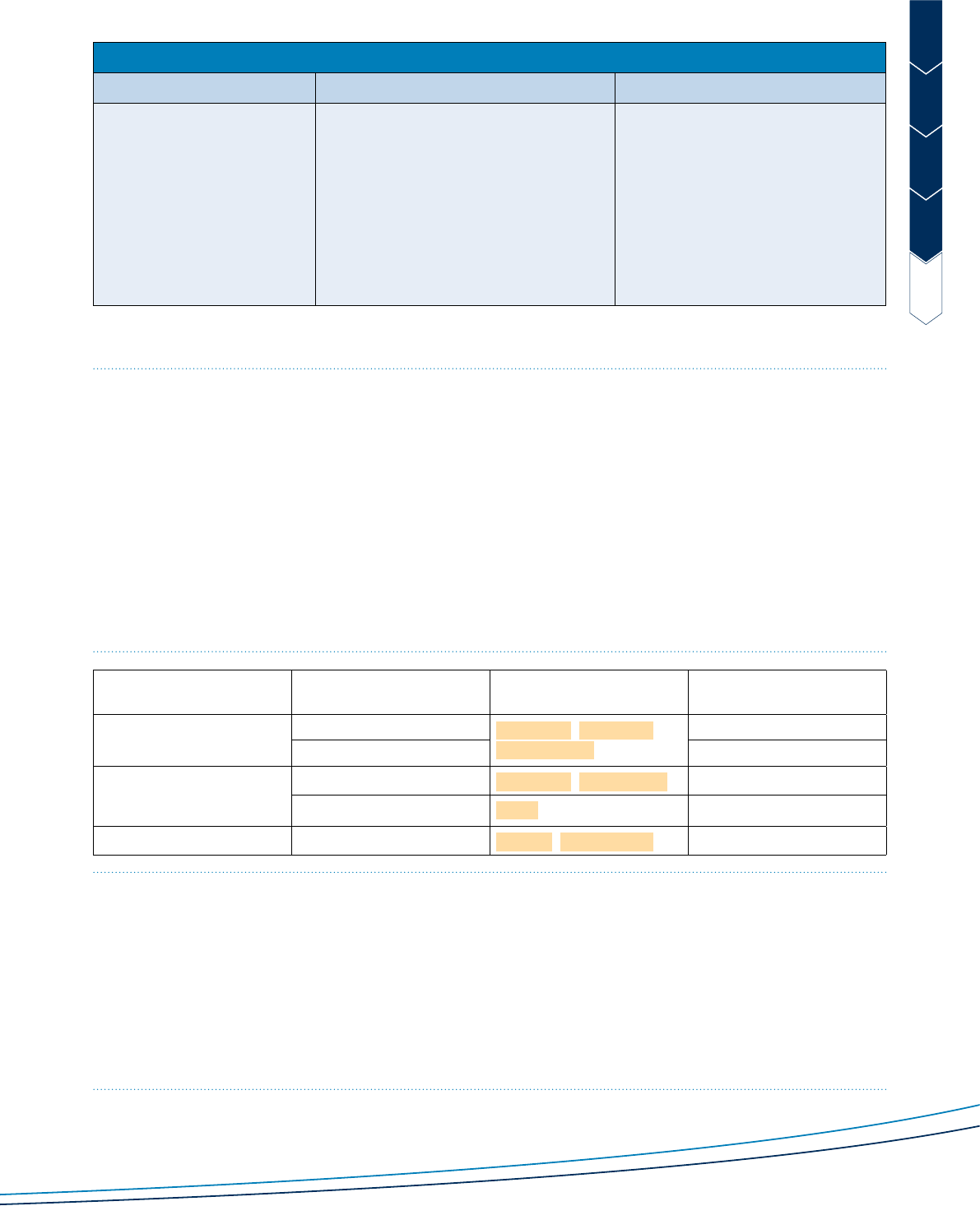

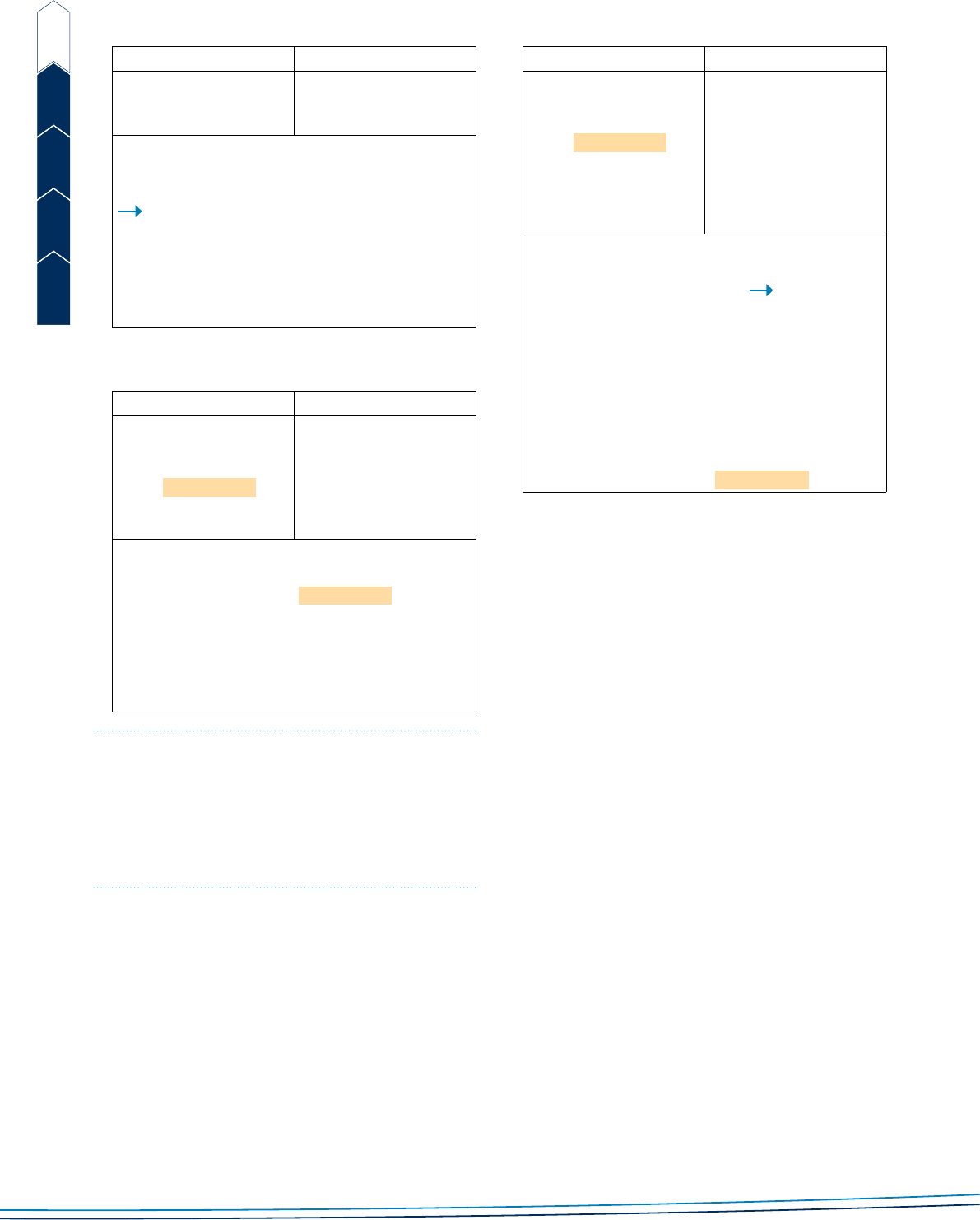

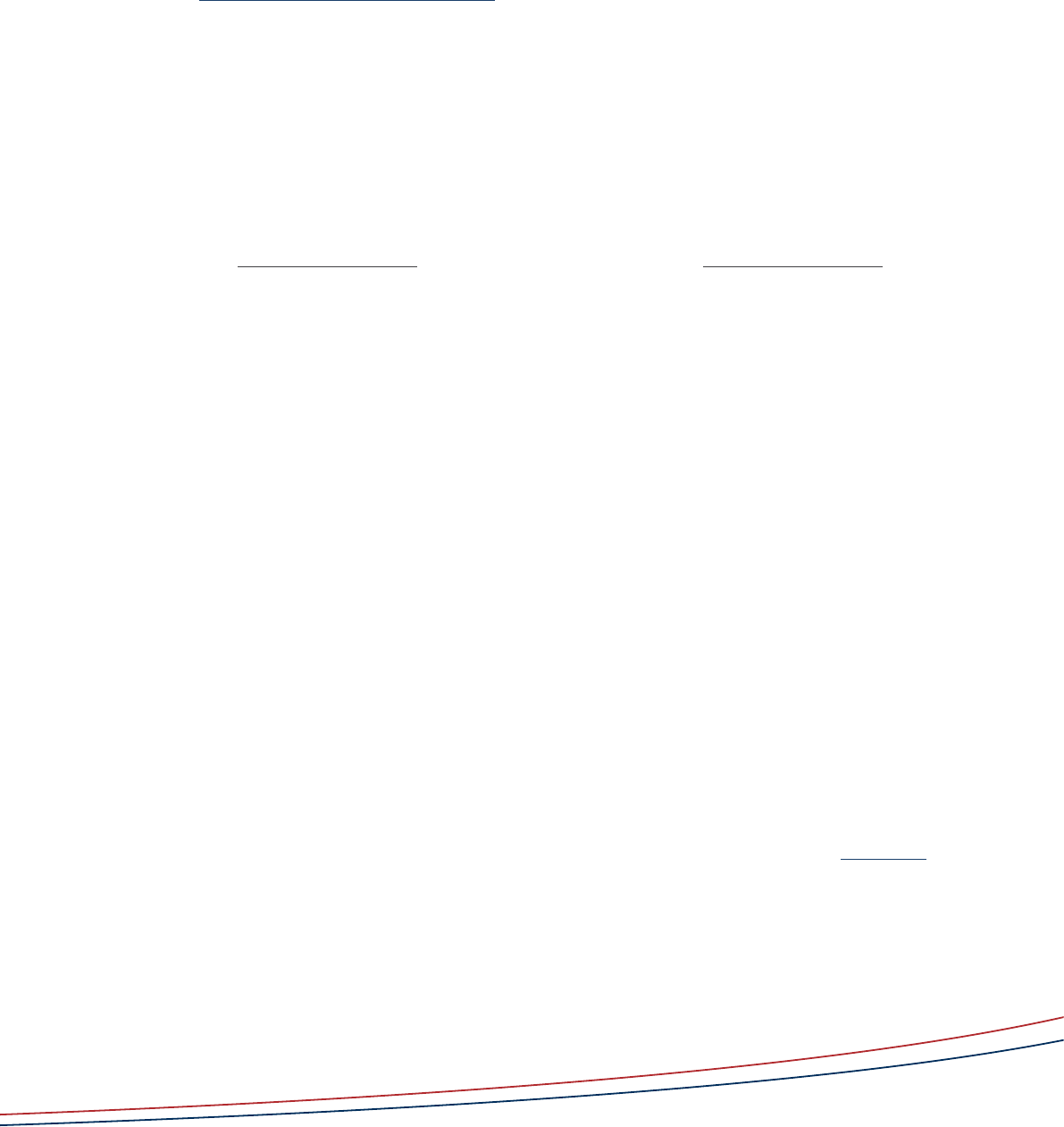

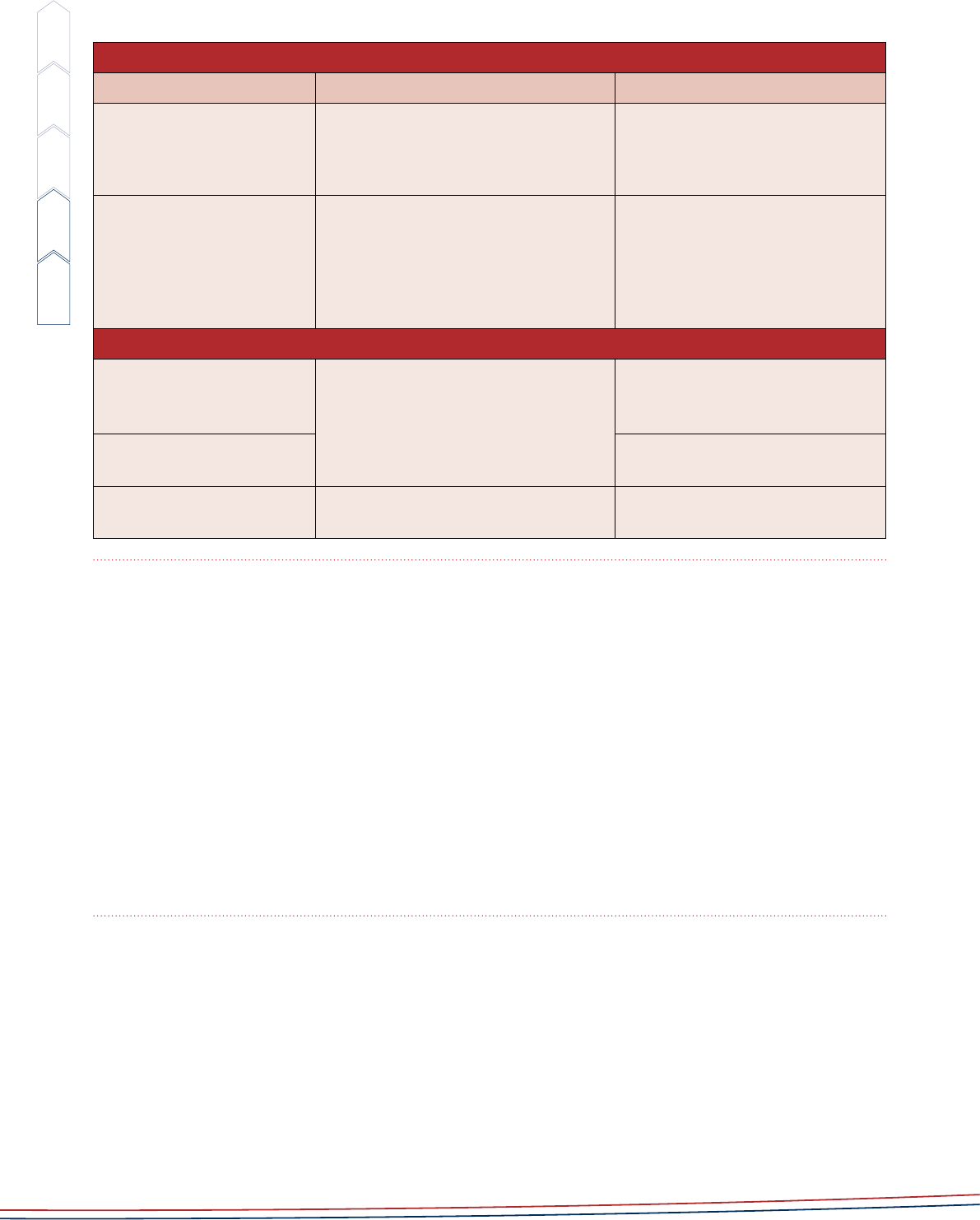

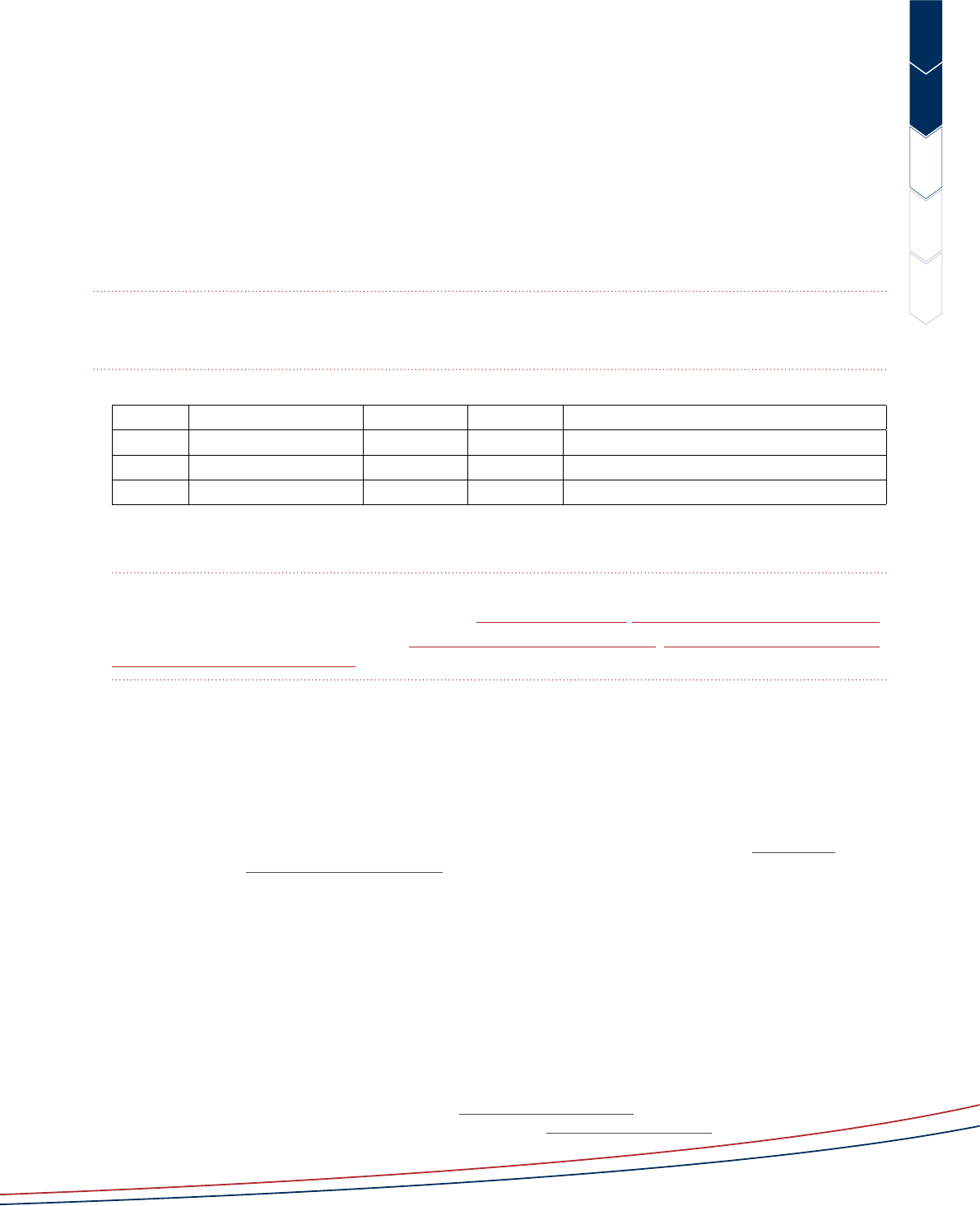

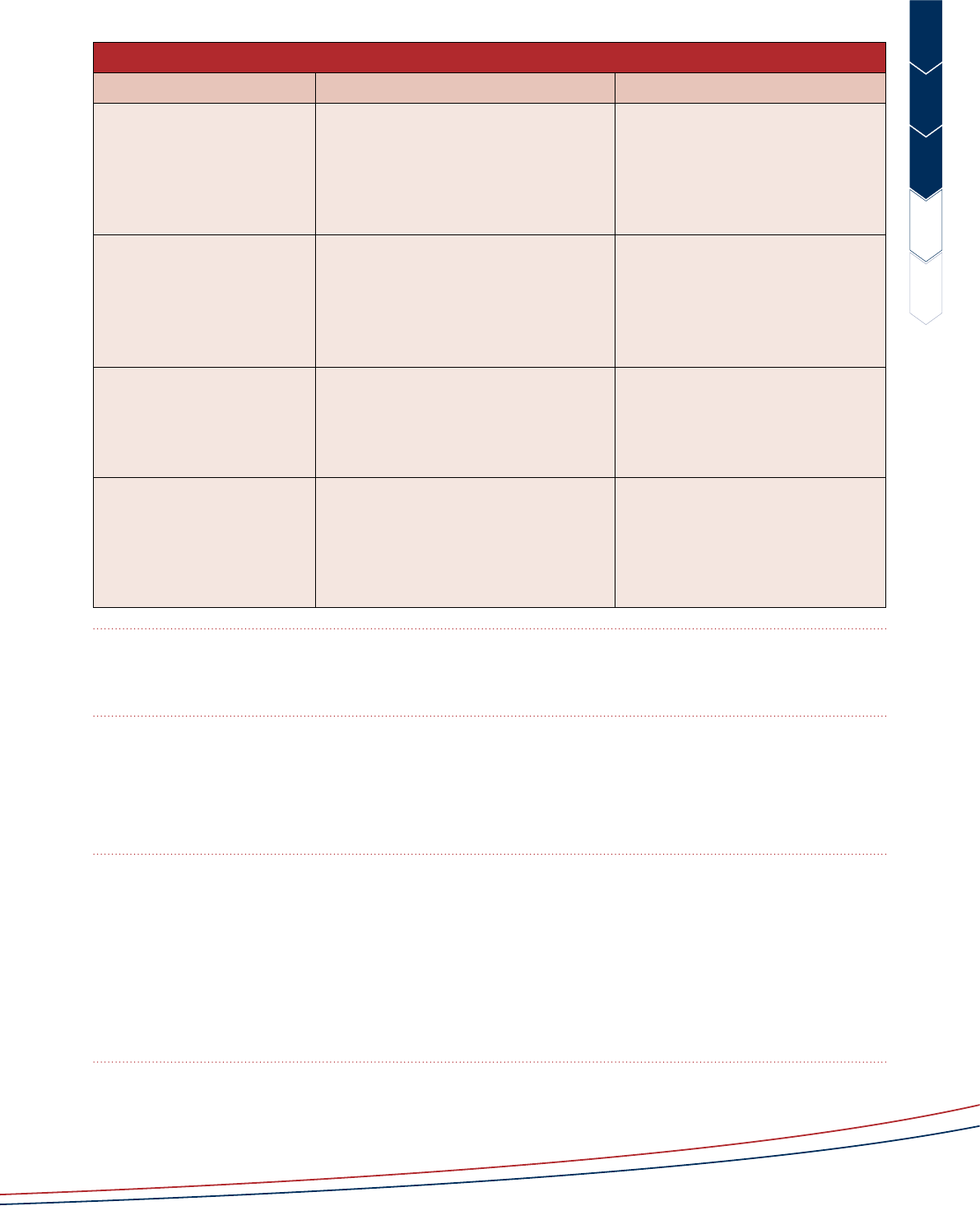

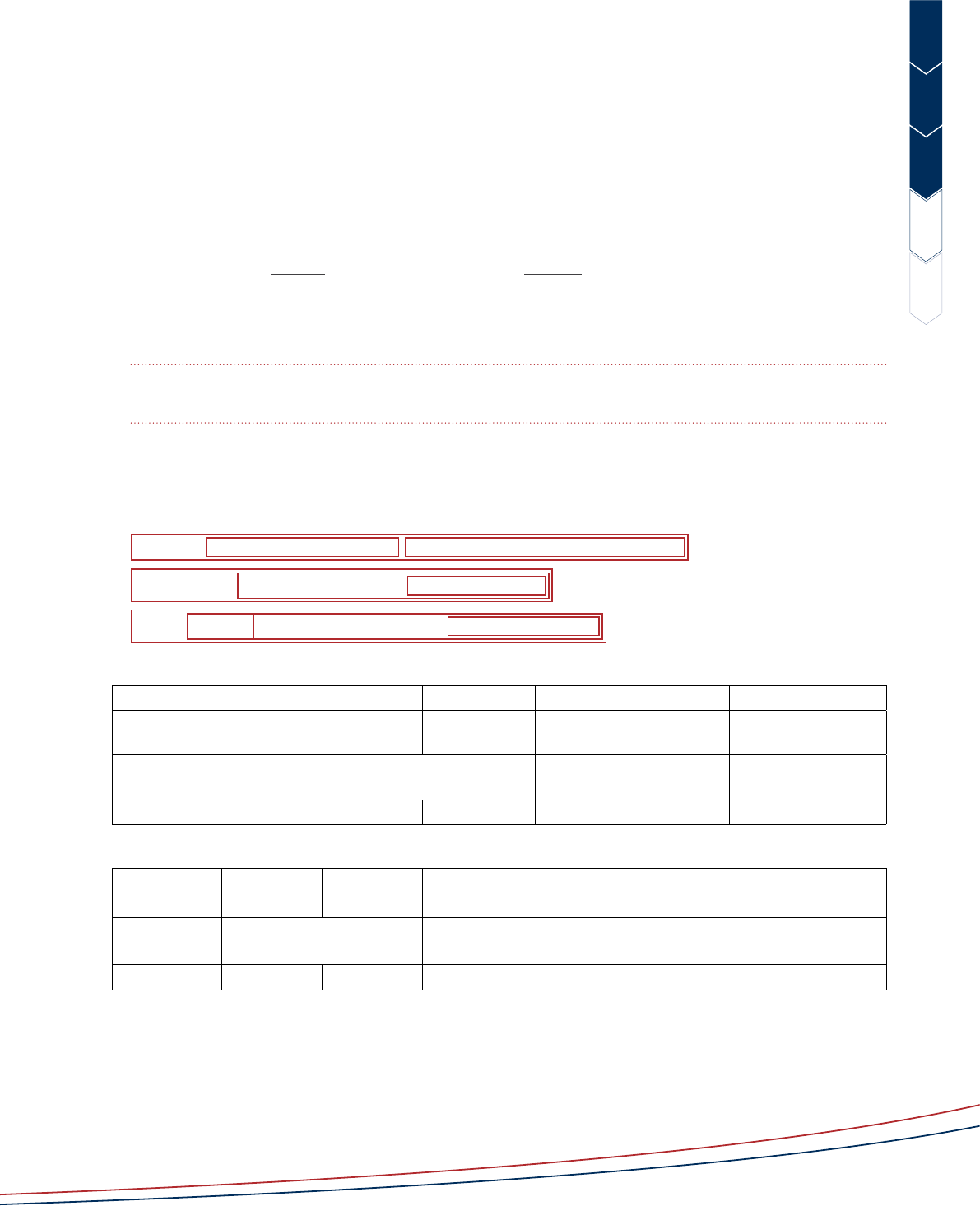

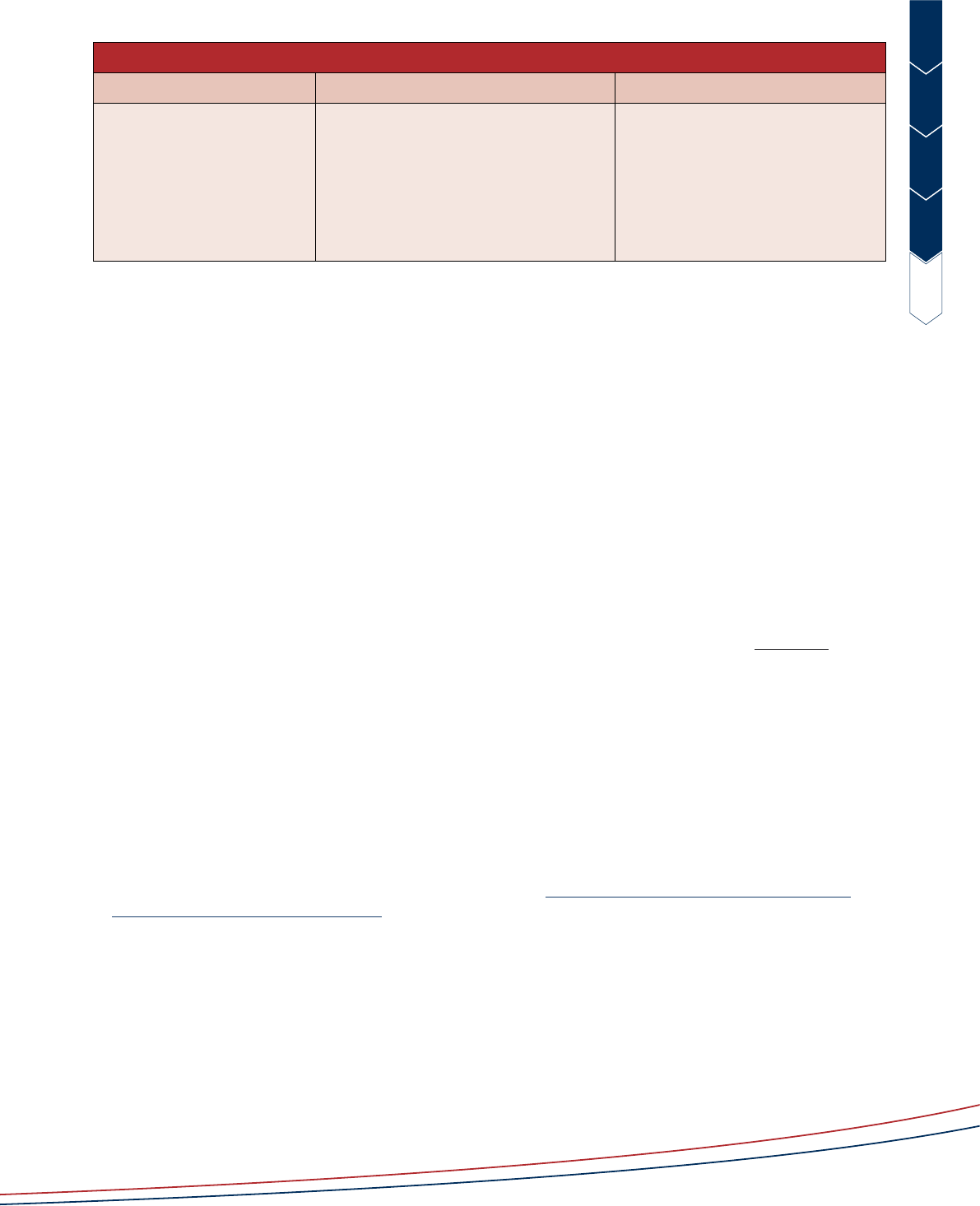

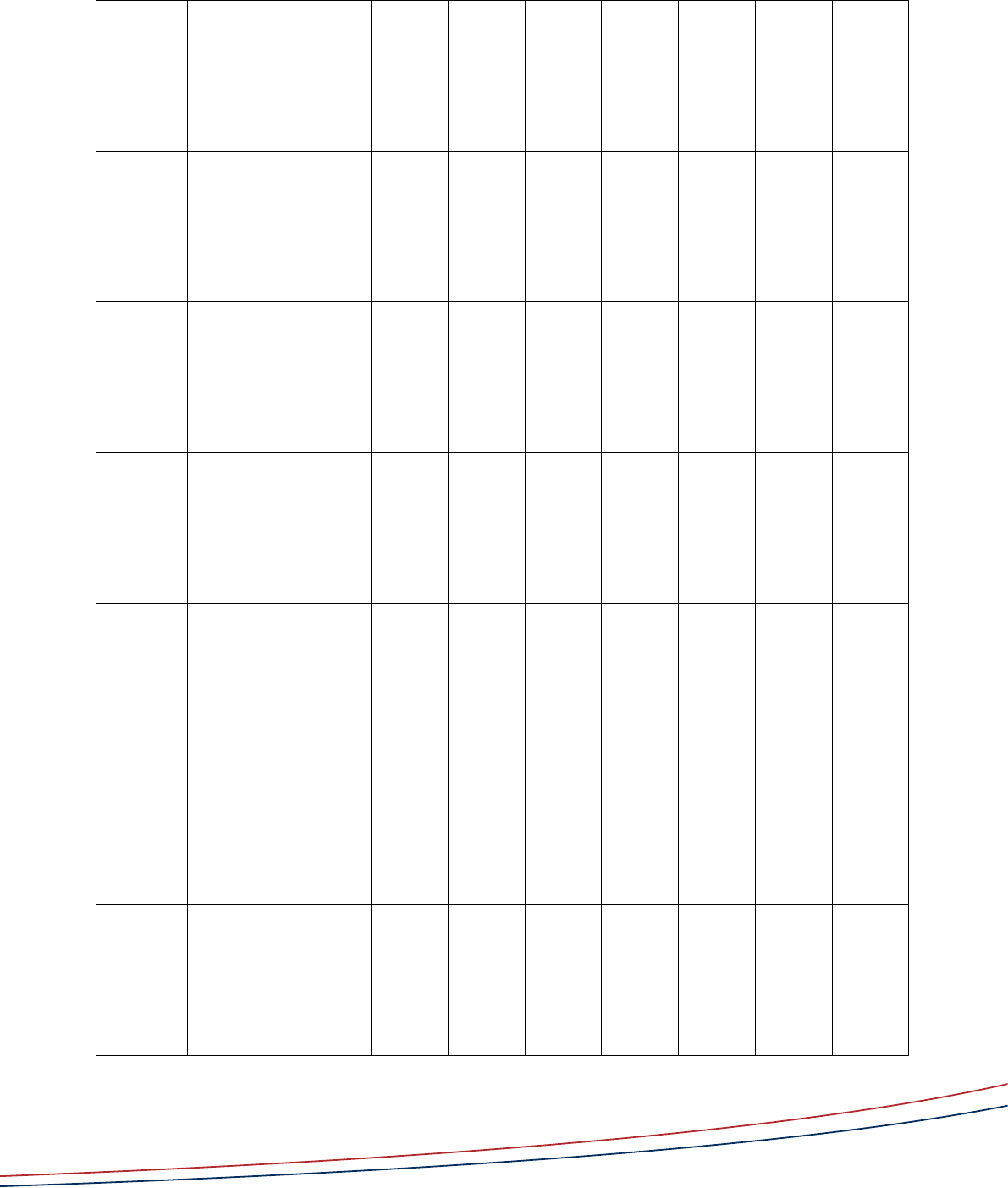

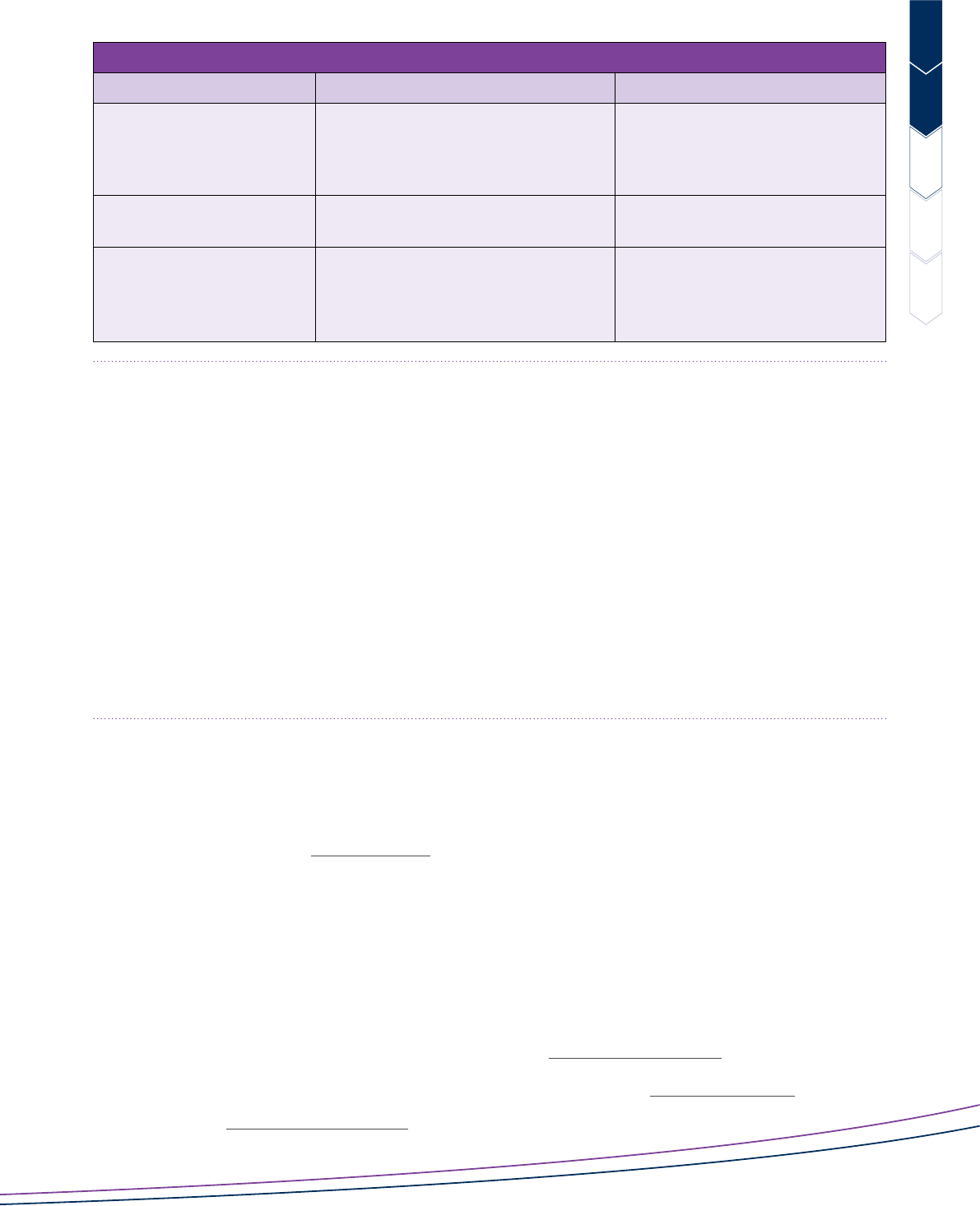

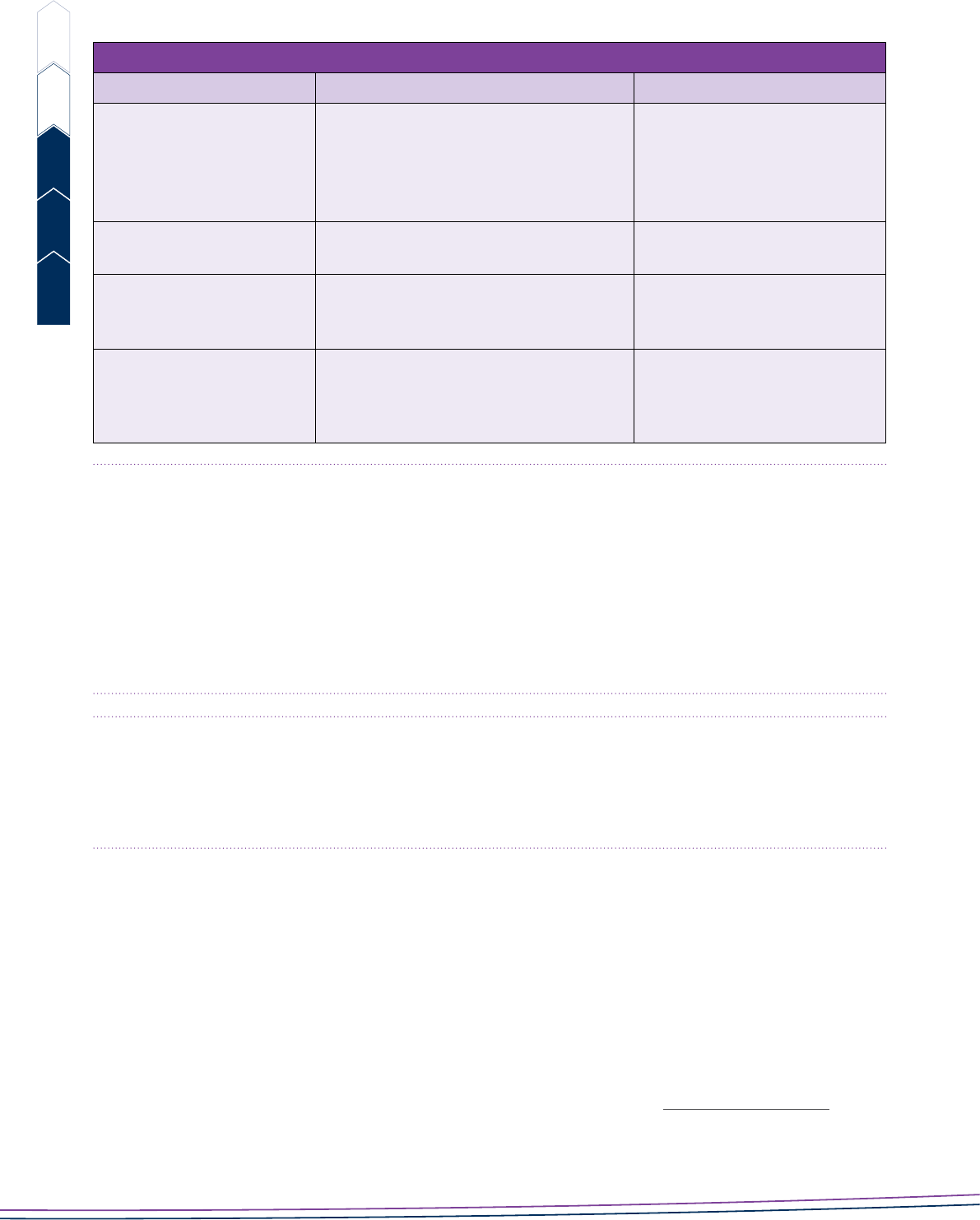

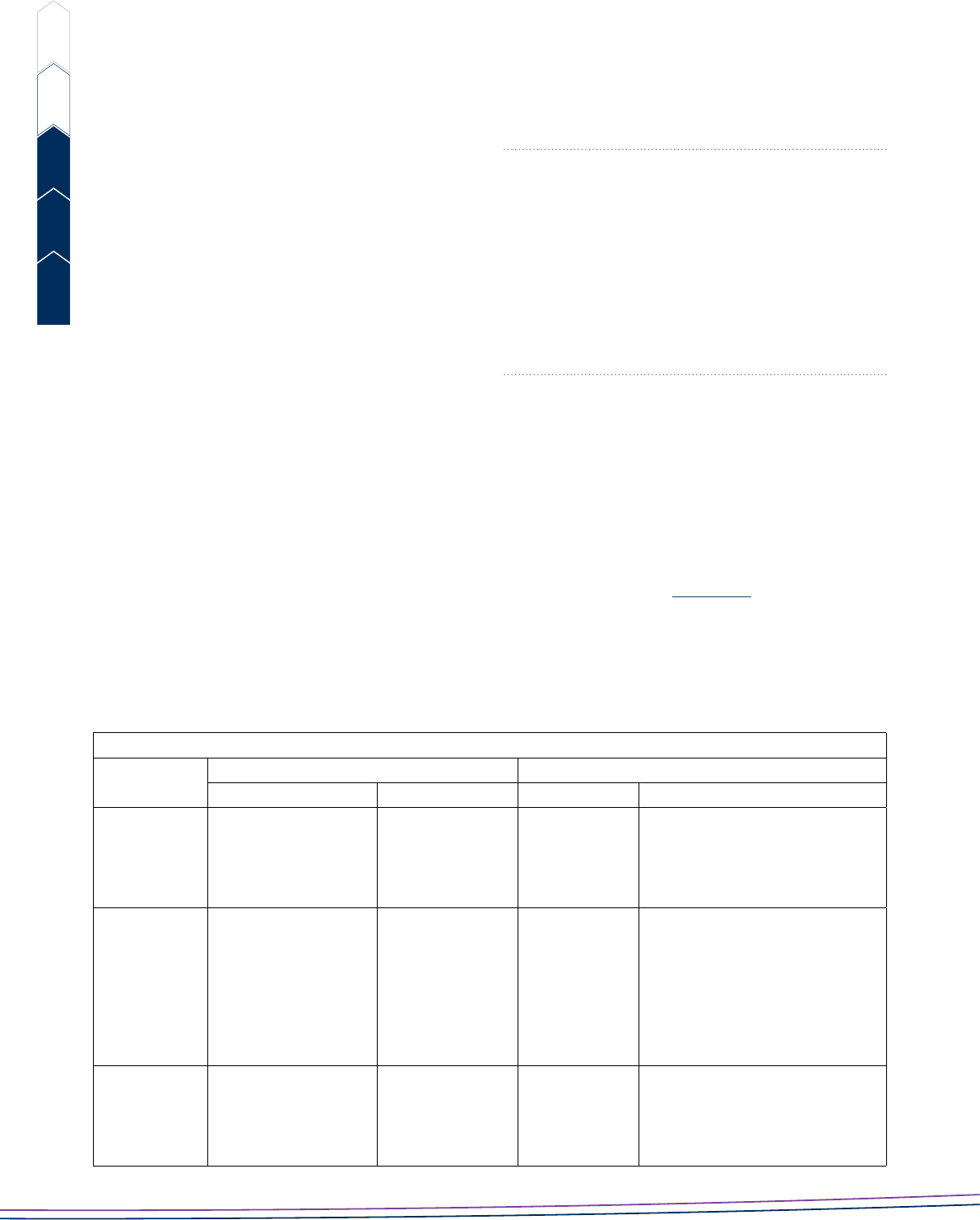

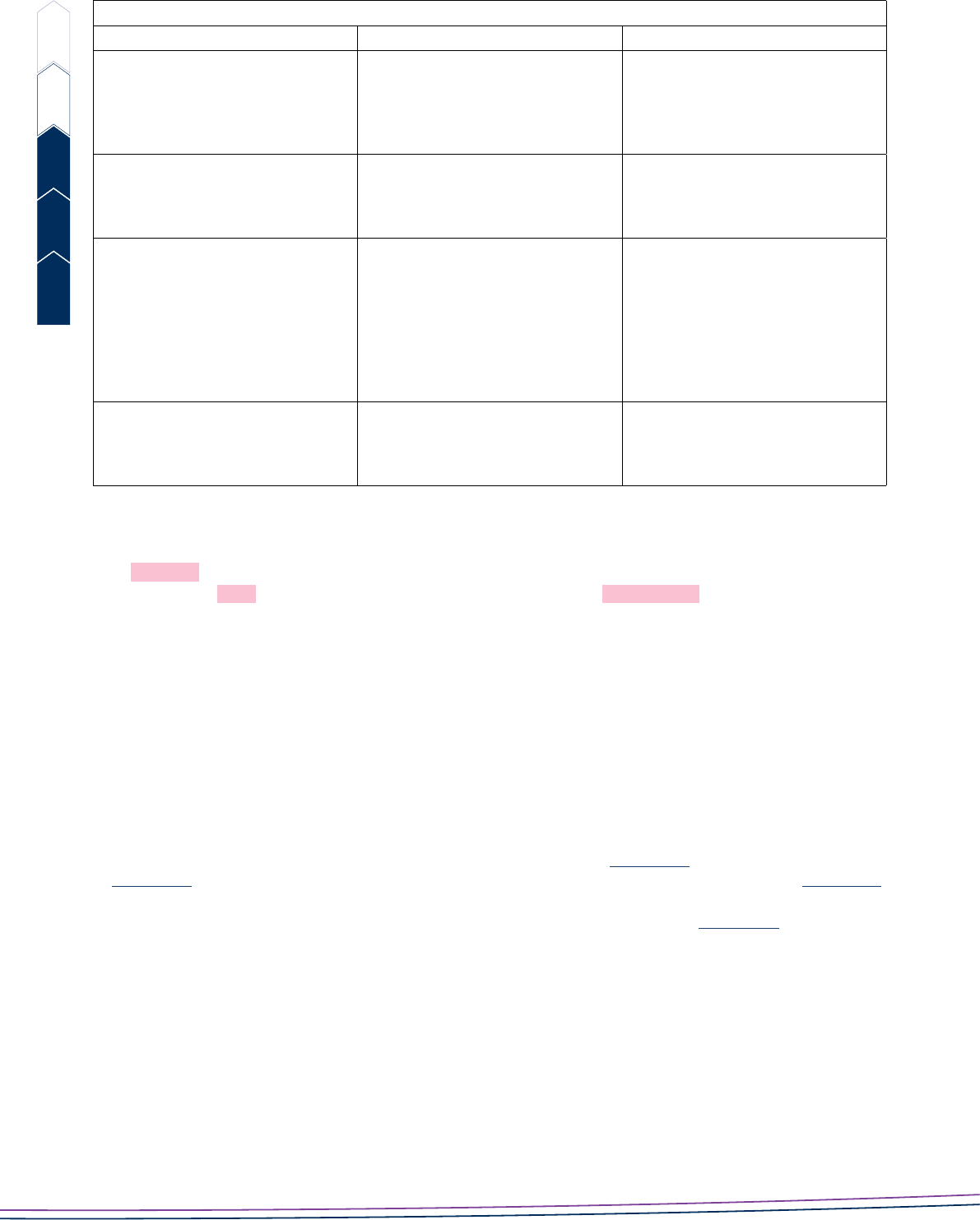

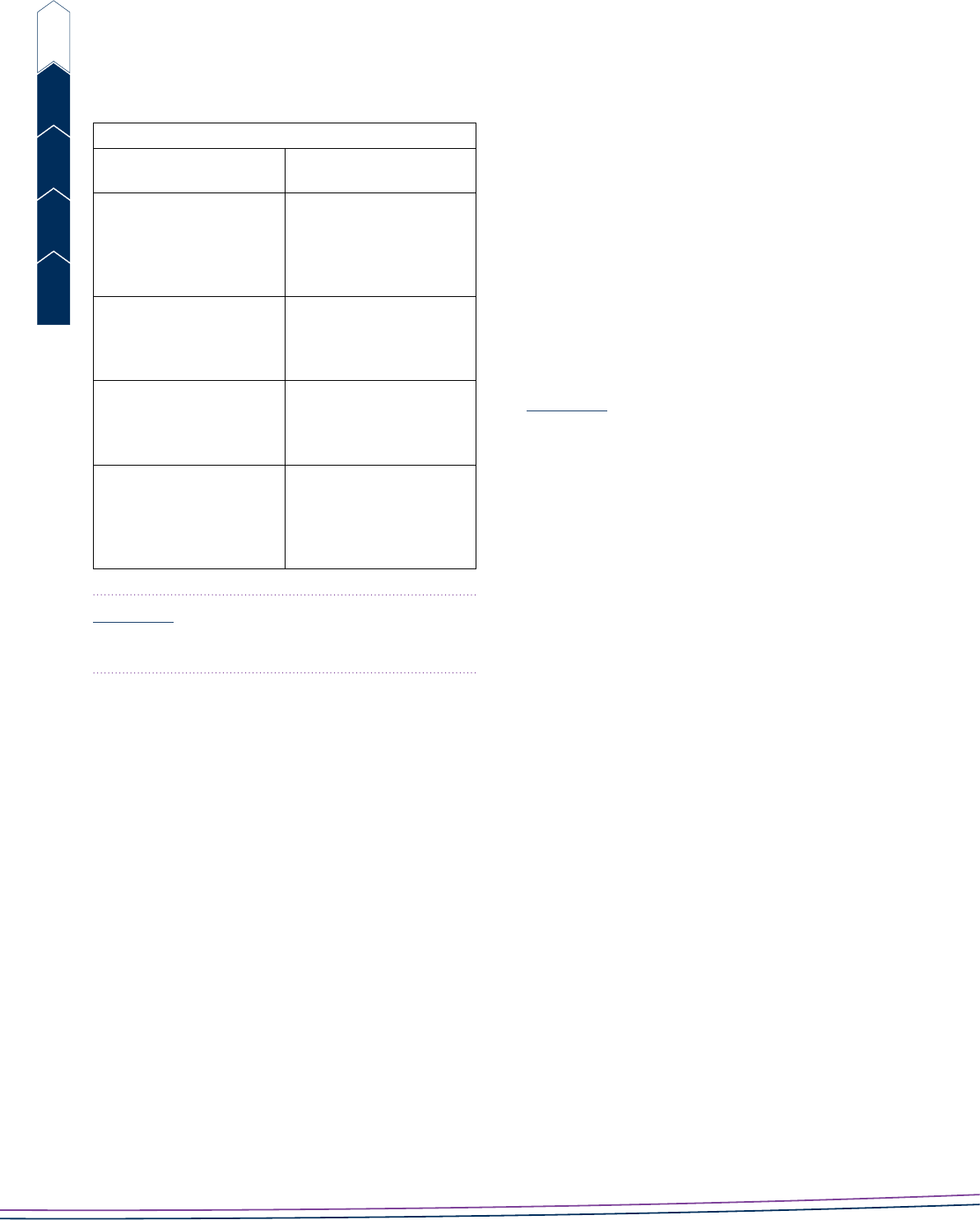

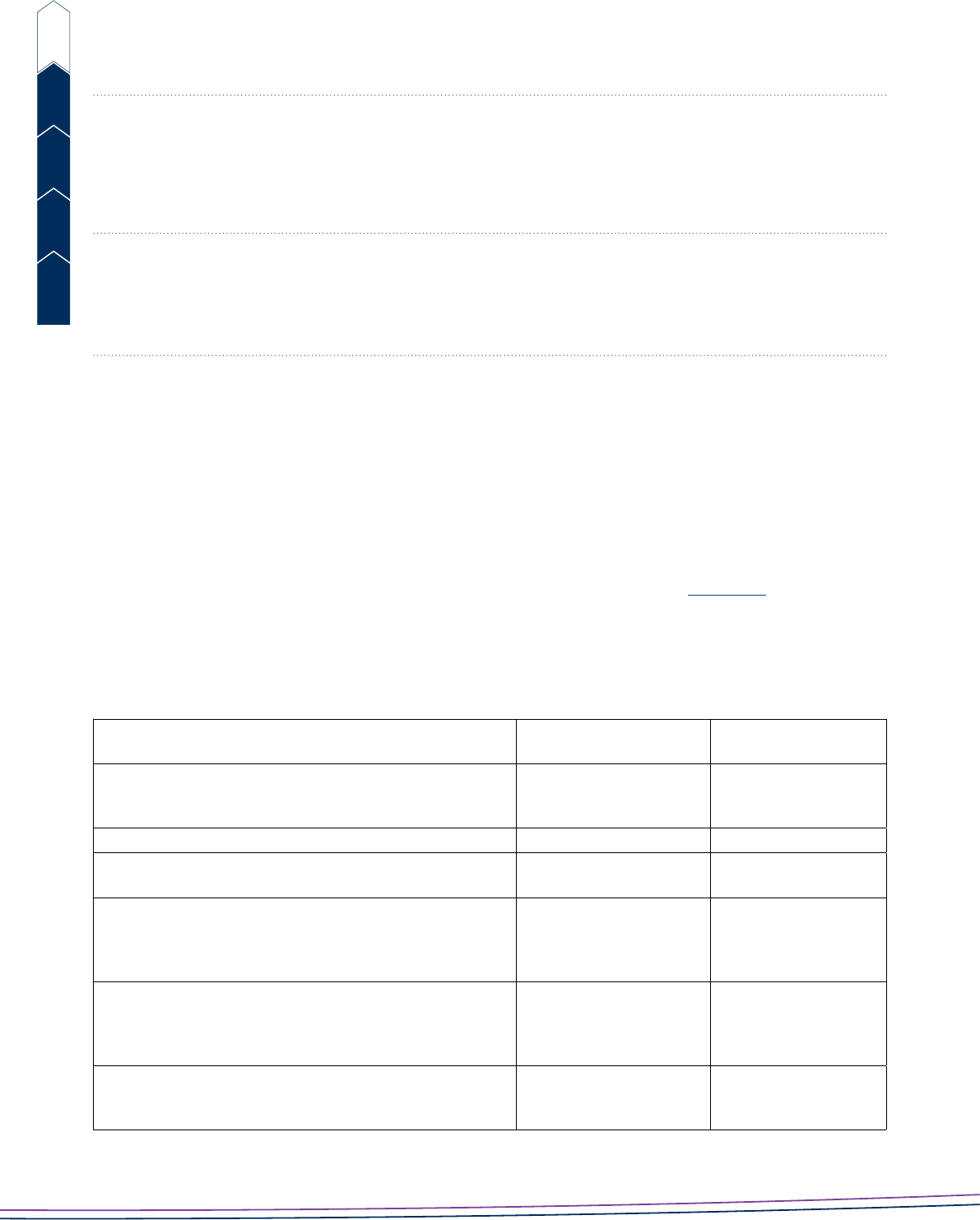

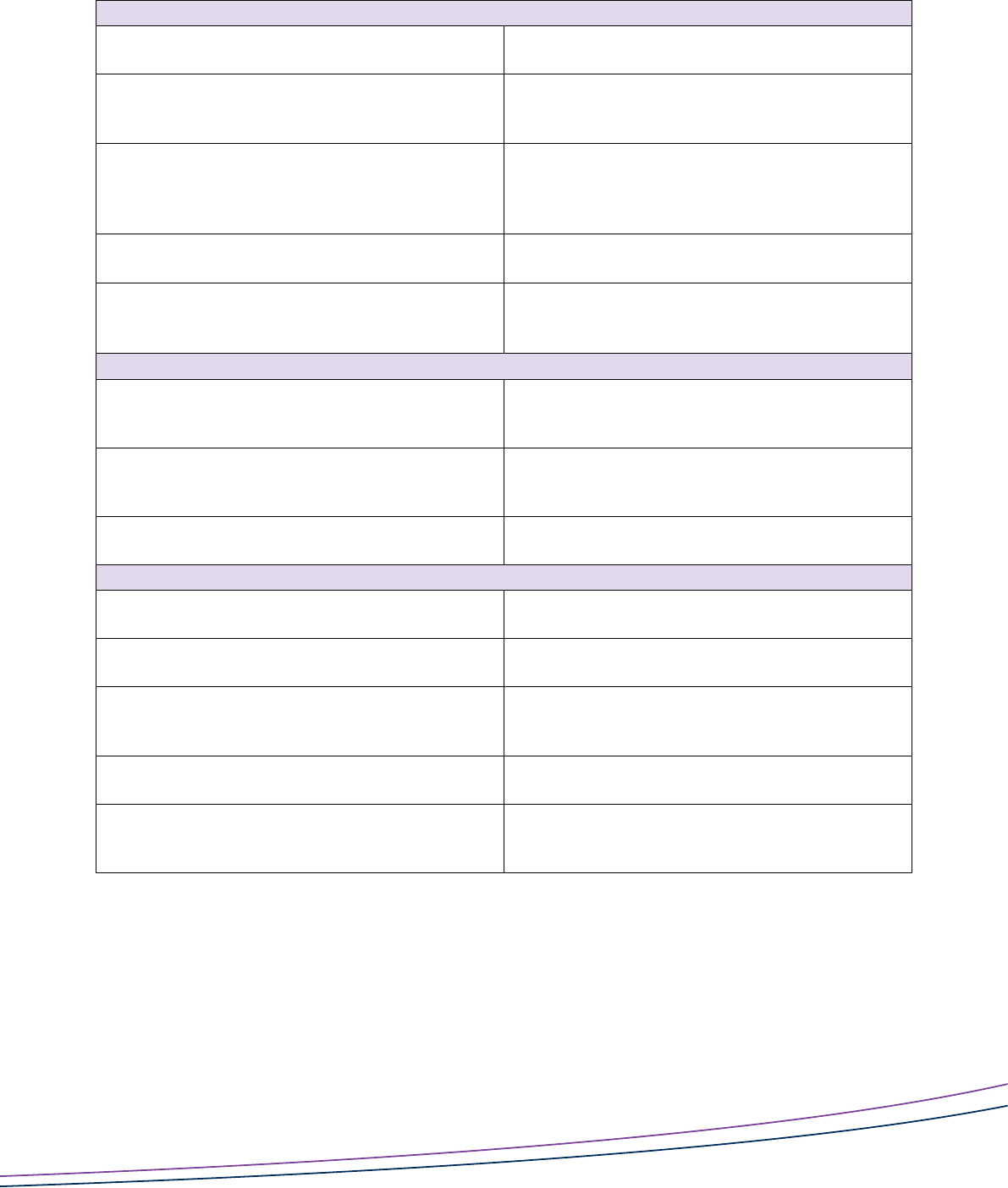

Targeted strategies to accelerate SAE proficiency,

particularly at sentence level grammar (sentence

structure), often involve explicitly teaching the 3

components of a clause:

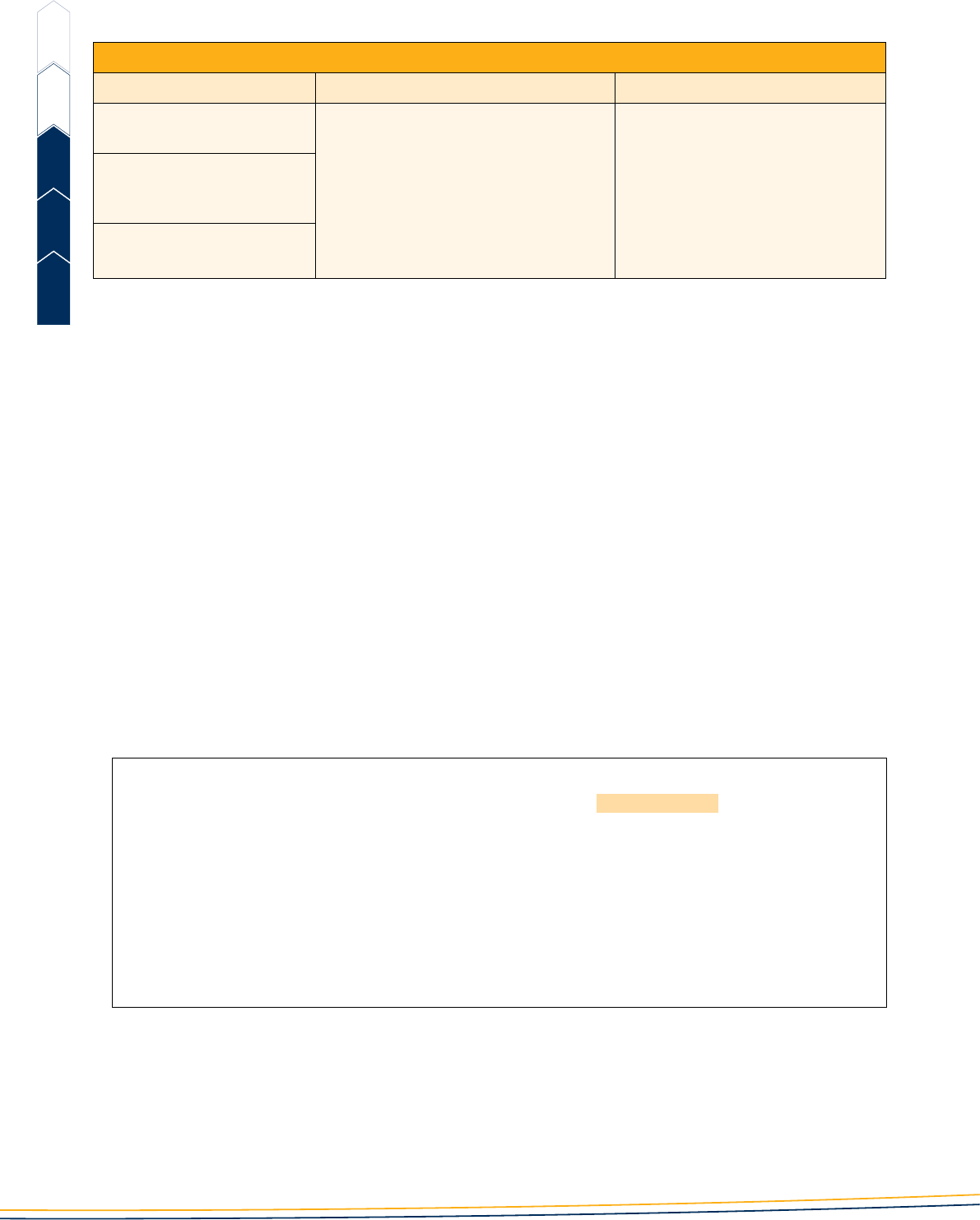

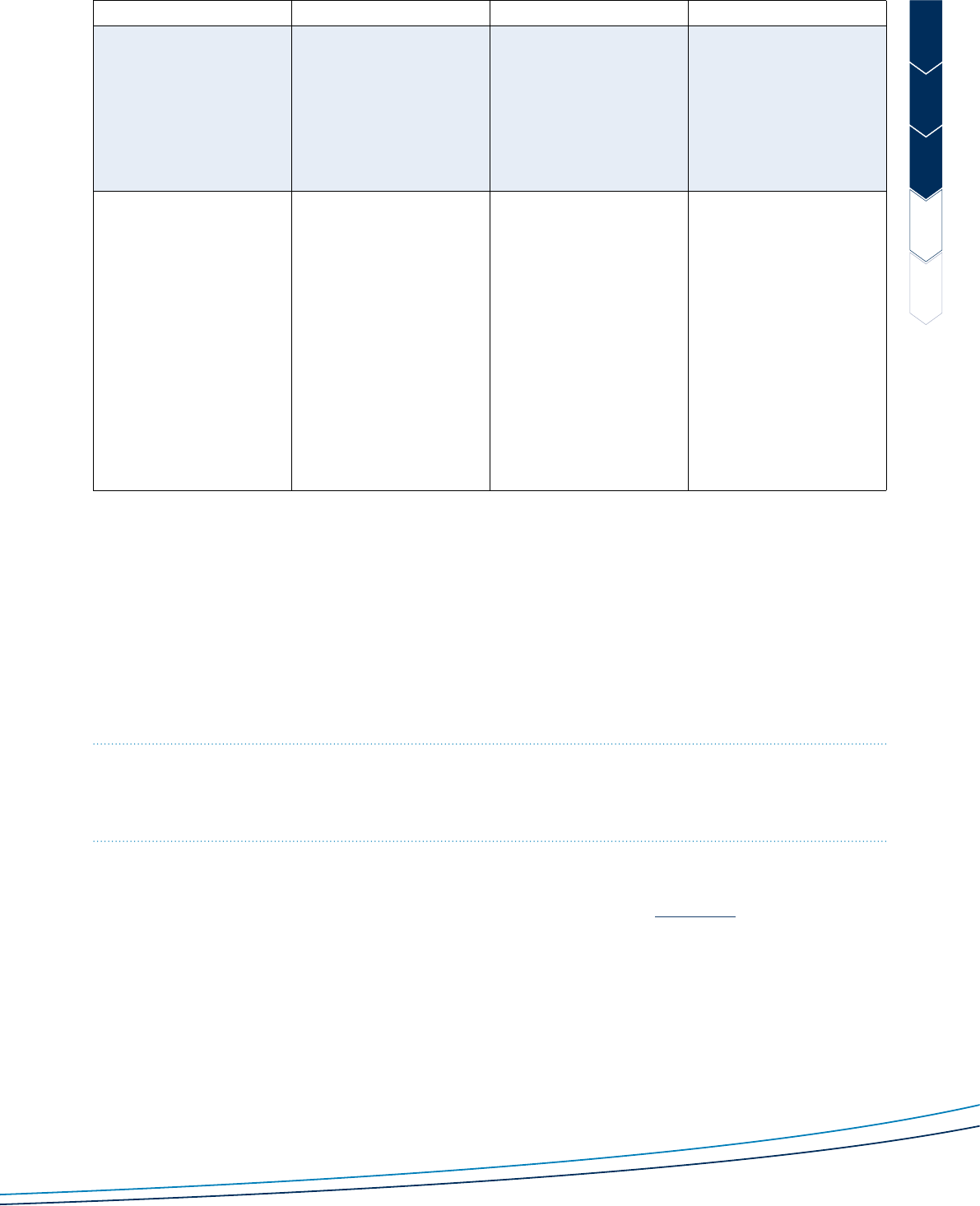

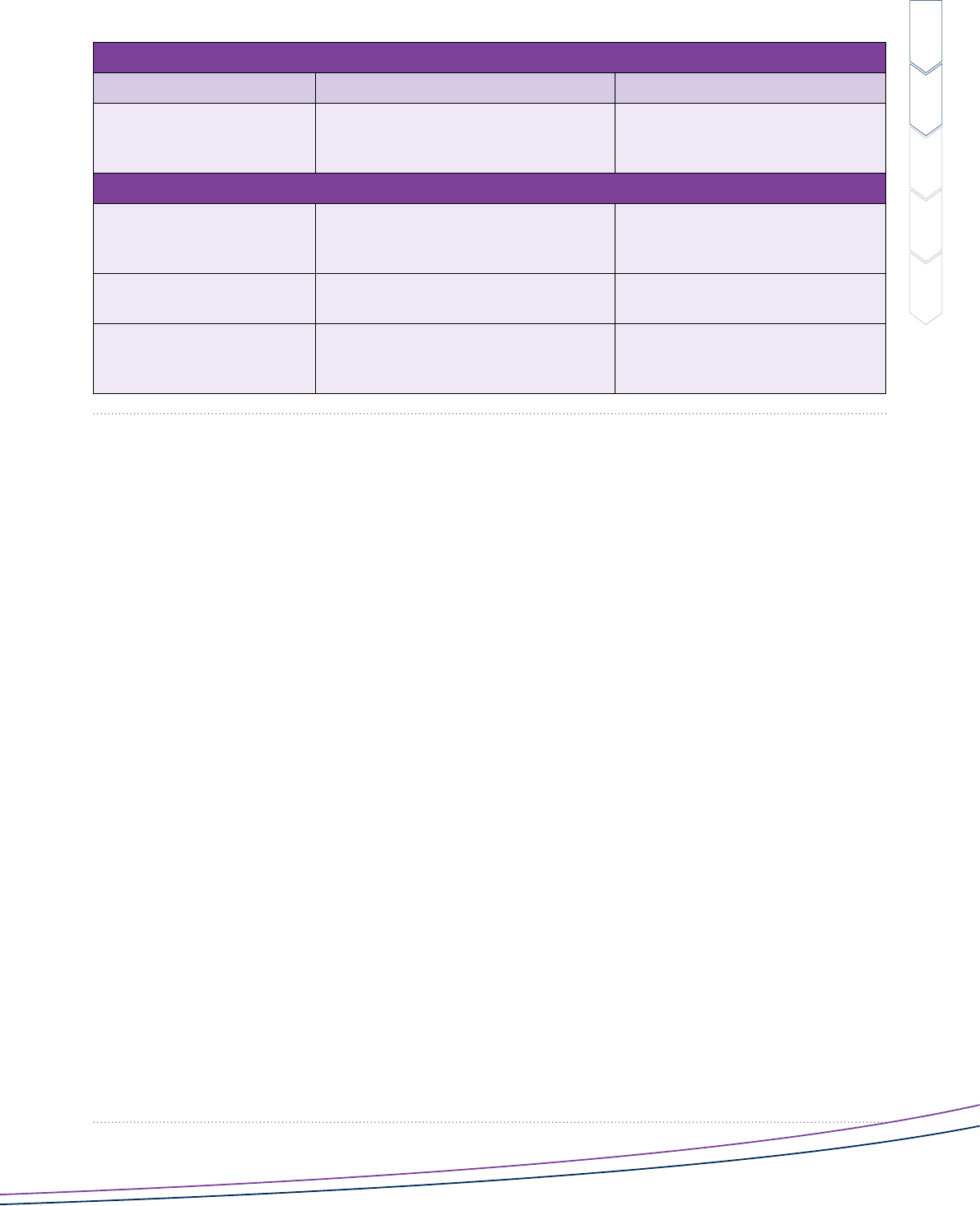

Functional components

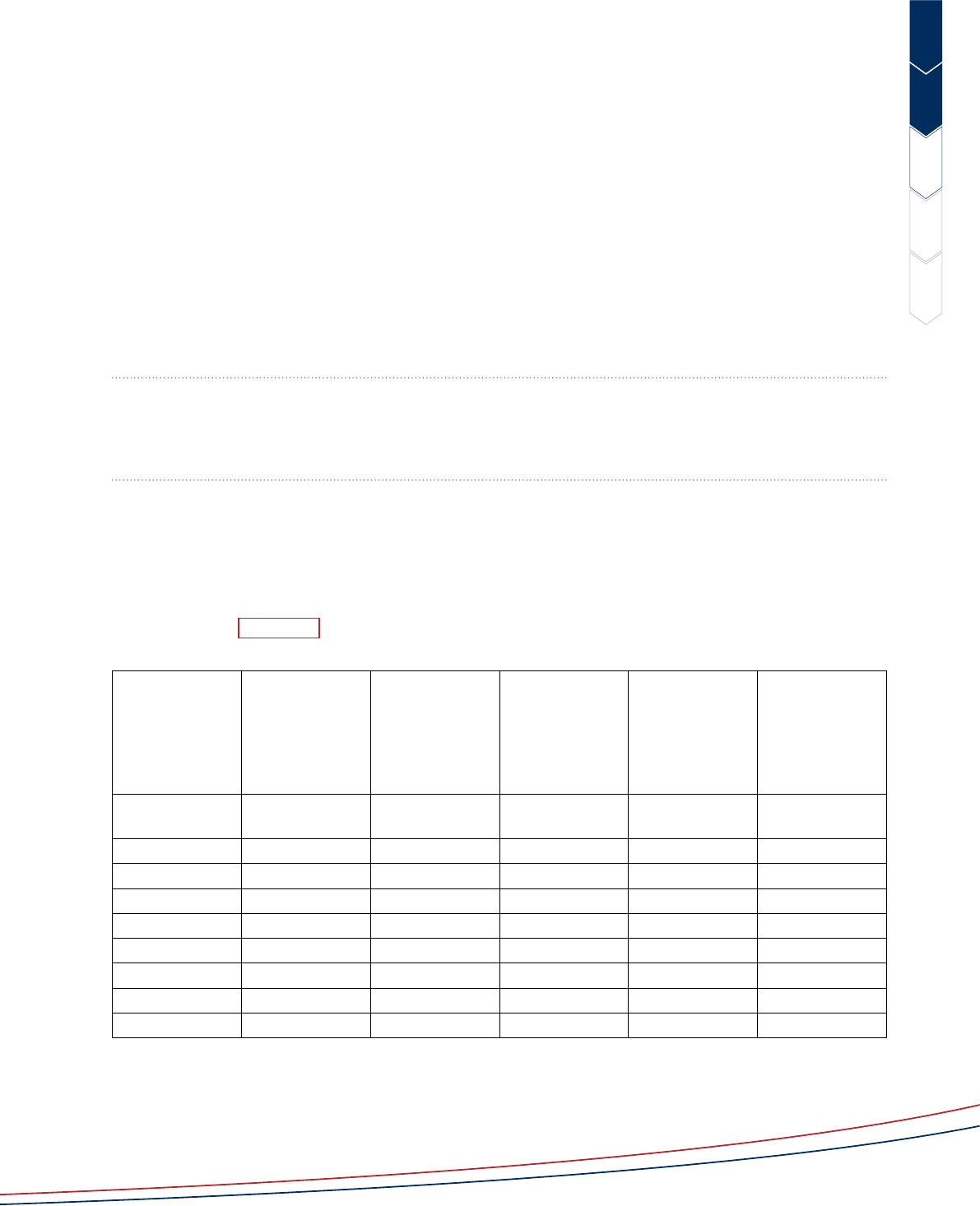

of a clause

Form typically

expressed by

a central process: what’s

going on?

a verb/verb group

one or more participants:

who or what is involved?

a noun/pronoun/

noun group or

adjective/adjective

group

(optional) extra details of the

circumstances surrounding

the process: when, where,

how, why did it happen?

an adverb/adverbial

group, prepositional

phrase or a noun

group

Two of the components of a clause also directly

correspond to 2 aspects of language, which are

included in the levelling process at the word and

word group level:

• verbs and verb groups (processes): here, the focus

is both on function (dierent types of processes)

and accuracy of grammatical form (eg tense).

The table also shows the typical 1:1 relationship

between form and function

• circumstances: here, the focus is on function,

what meaning is being added about the process

and the table shows that various forms can express

this function.

Participants are not identified as part of the levelling

process. Rather there is a focus on the form: nouns

and noun groups since the ability to build and

manipulate noun groups is key in developing academic

SAE. Maroon (not red) is used for nouns and noun

groups because they can be used to express either

participants or circumstances, as indicated in the table.

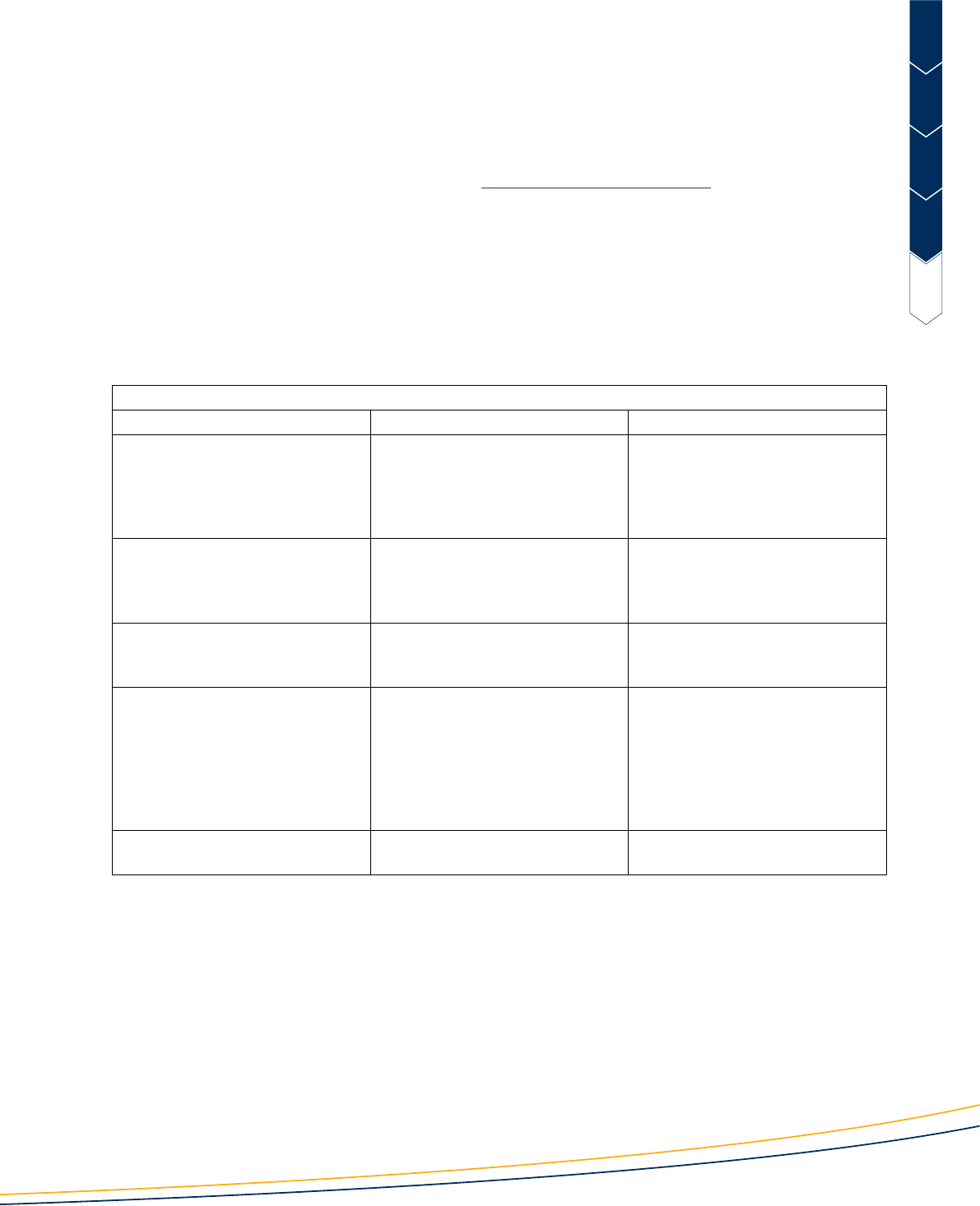

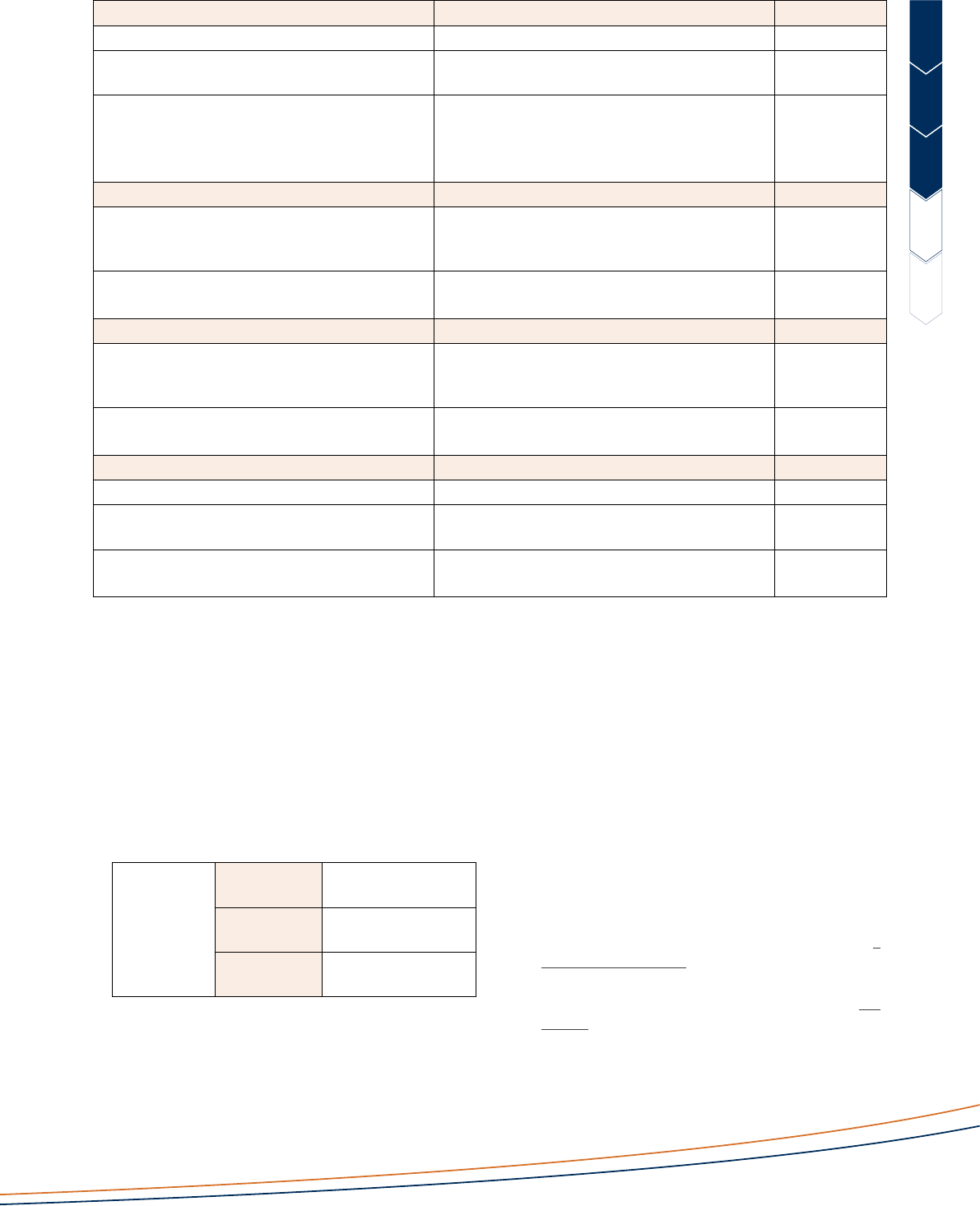

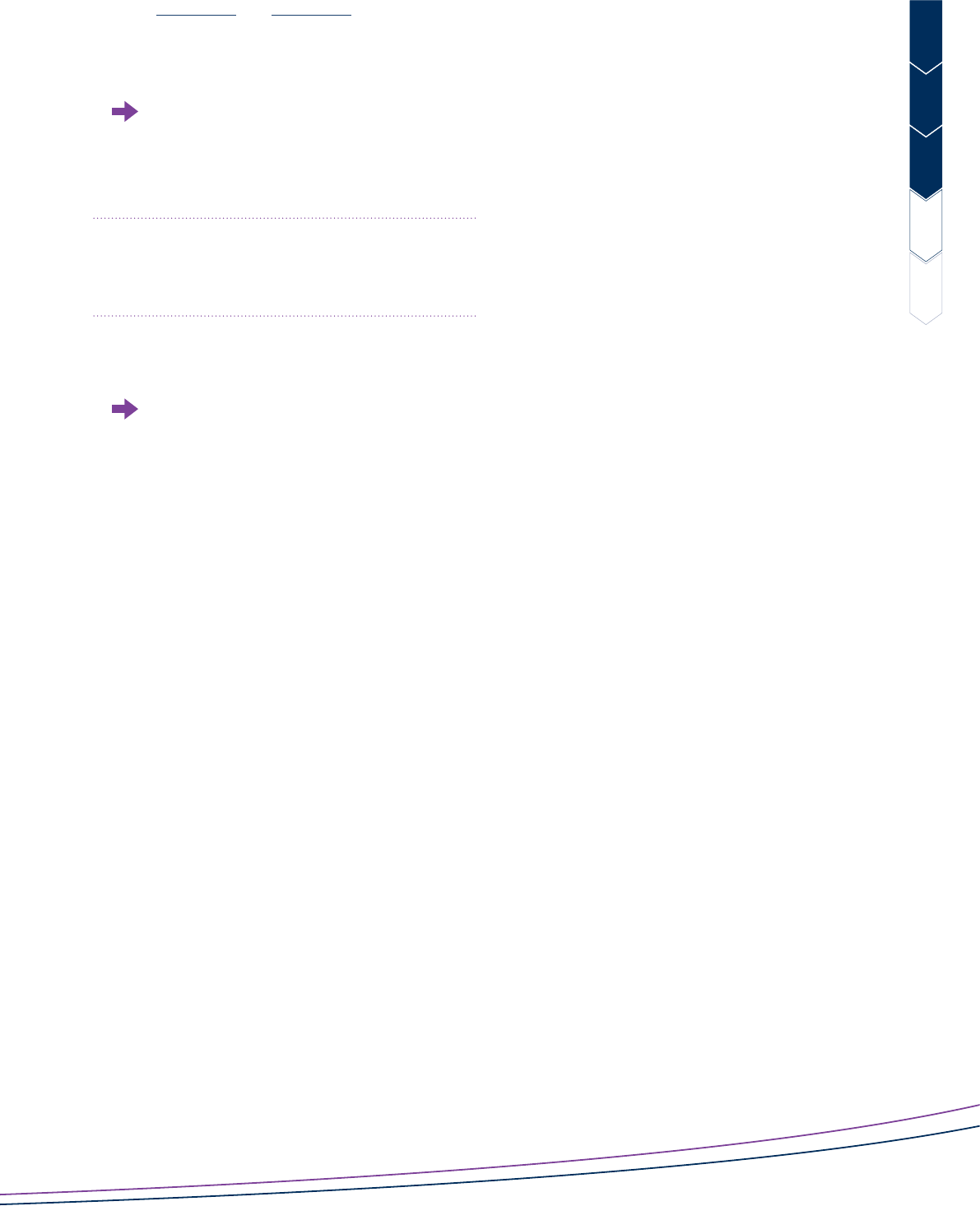

Proficiency bands

Following the introduction to the language element,

learning sequences with targeted strategies are

provided for 4 proficiency bands:

• LEAP Levels 1–4 and leaping to levels 5–6

• LEAP Levels 5–6 leaping to levels 7–9

• LEAP Levels 7–9 leaping to levels 10–12

• LEAP Levels 10–12 leaping to levels 13–14.

A chart, at the beginning of each band, provides: the

number and name of learning sequences, the language

in focus, and the genre/s used within each sequence.

HOW TO USE THIS

RESOURCE

1. Begin by assessing students to identify their

current LEAP Level and specific areas in need

of development.

2. Set tailored targets and learning goals.

3. Based on identified needs and learning goals,

go to the relevant aspect of language.

4. Use the overview of the content to identify where

the band matching your target level begins and

turn to that page.

5. Use the chart to identify a learning sequence that

addresses your language focus.

6. Follow the sequence or adapt for your context.

Strategies and texts may need to be adapted to

be age-appropriate for your students. Adaptations

may also be necessary to ensure they are supporting

the development of curriculum knowledge.

7. Refer to explanations in the introduction to the

selected aspect of language to build your knowledge

as required.

Learning English: Achievement and Proficiency (LEAP) | STRATEGIES INTRODUCTION | 3

HIGHIMPACT STRATEGIES

This resource supports the implementation of the

following high-impact strategies in Literacy and

Numeracy First

(DECD, 2018a):

• targeted dierentiated teaching

• clear learning intentions

• explicit teaching and

• ongoing feedback.

It particularly focuses on 2 literacy improvement

strategies:

• development of oral language for academic

purposes

• strengthening writing through meta-knowledge

of language.

Furthermore, it supports 2 high-impact strategies for

EALD students:

• translanguaging

1

: actively encouraging students to

draw on, make connections with, and use their first

language/s (L1s) or dialects to develop Standard

Australian English proficiency. Many learning

sequences use Unite for Literacy free digital

picture books, narrated in a variety of languages.

• multiple exposures: using multimodal resources

and providing students with multiple opportunities

to encounter, engage with, and elaborate on new

knowledge, language and skills.

Learning sequences are also informed by Myhill’s

(2018) LEAD principles for eective explicit teaching

of grammar/language:

• Link the grammar being introduced to how it

works in mentor texts.

• Explain the grammar through examples, not

lengthy explanations.

• Authentic texts used as models.

• Design-in high-quality discussion about grammar

and its eect.

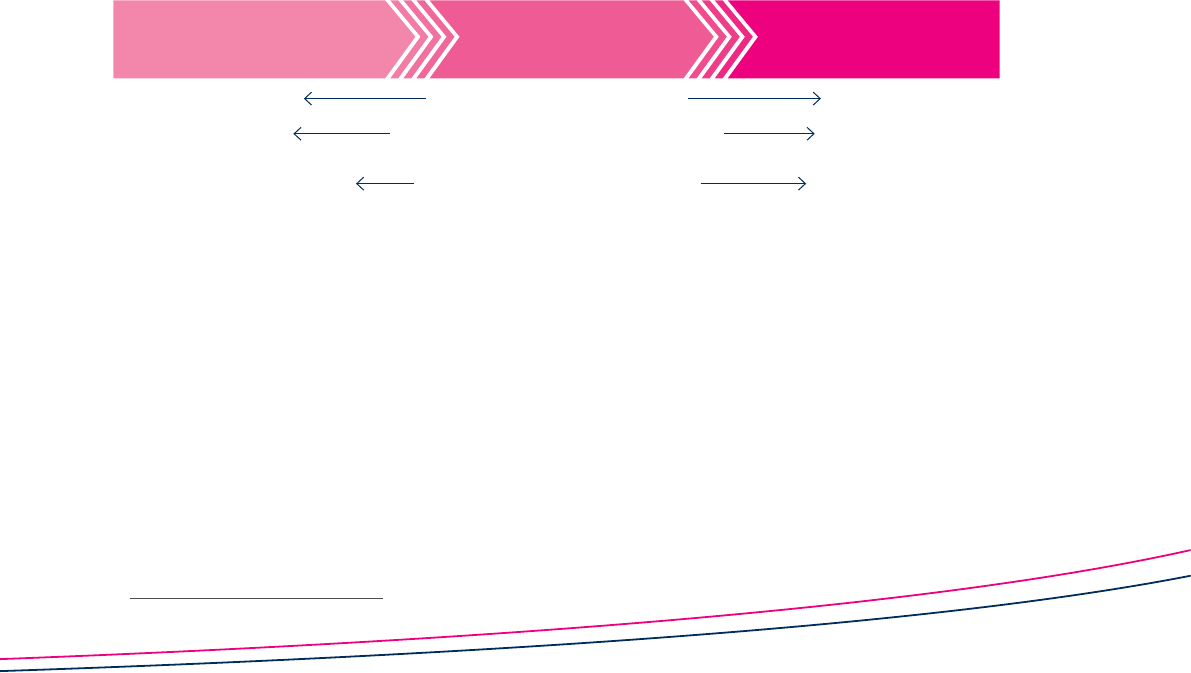

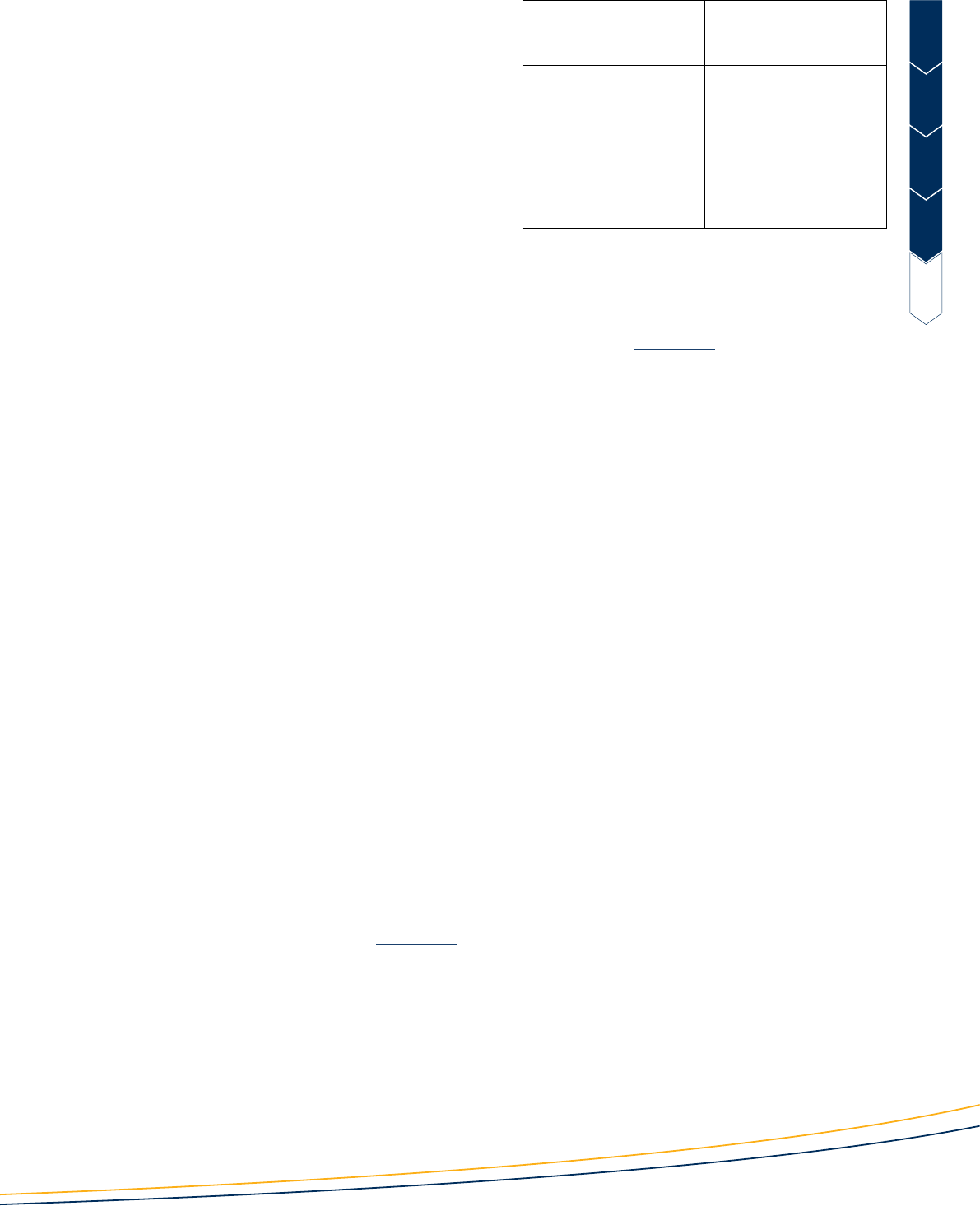

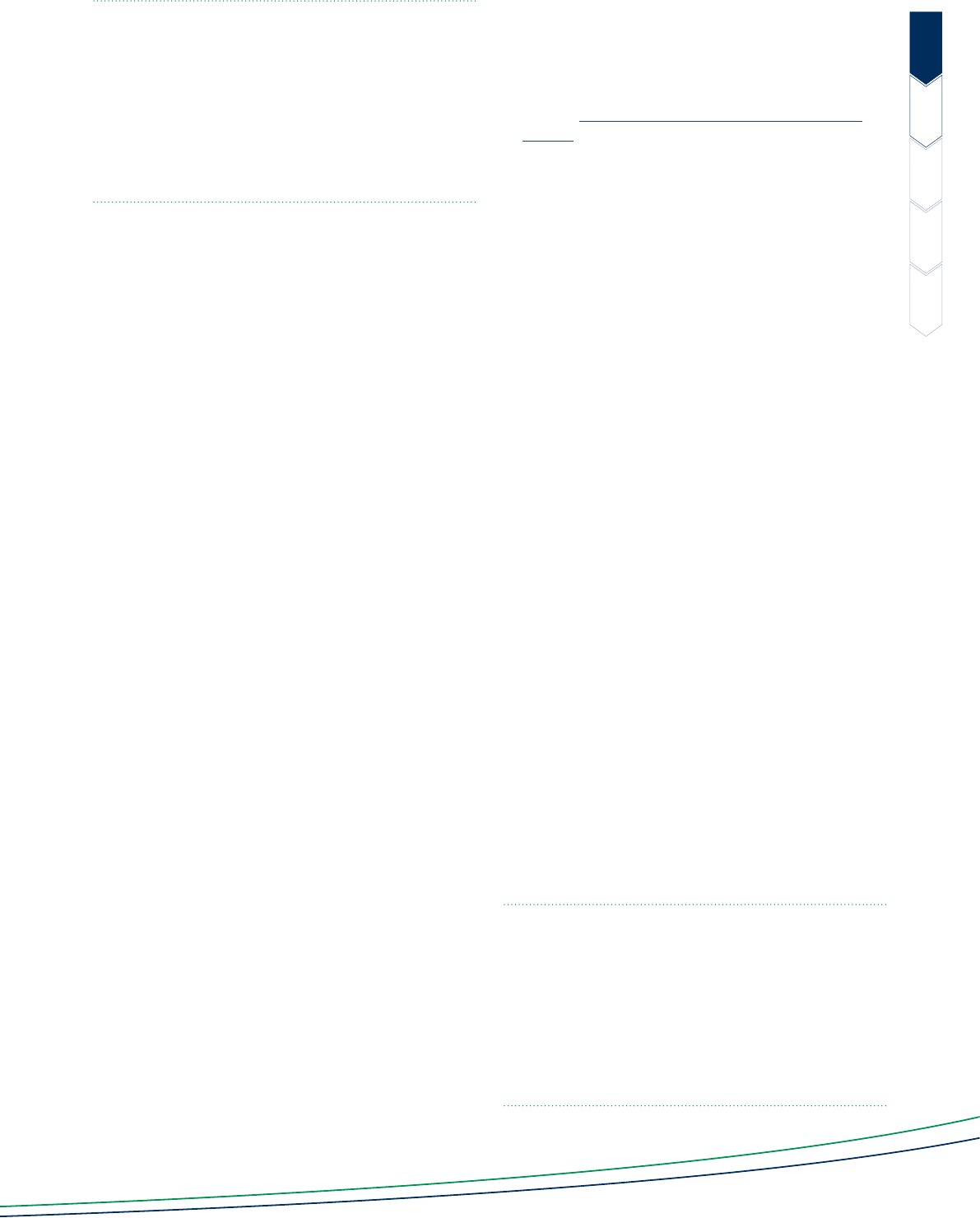

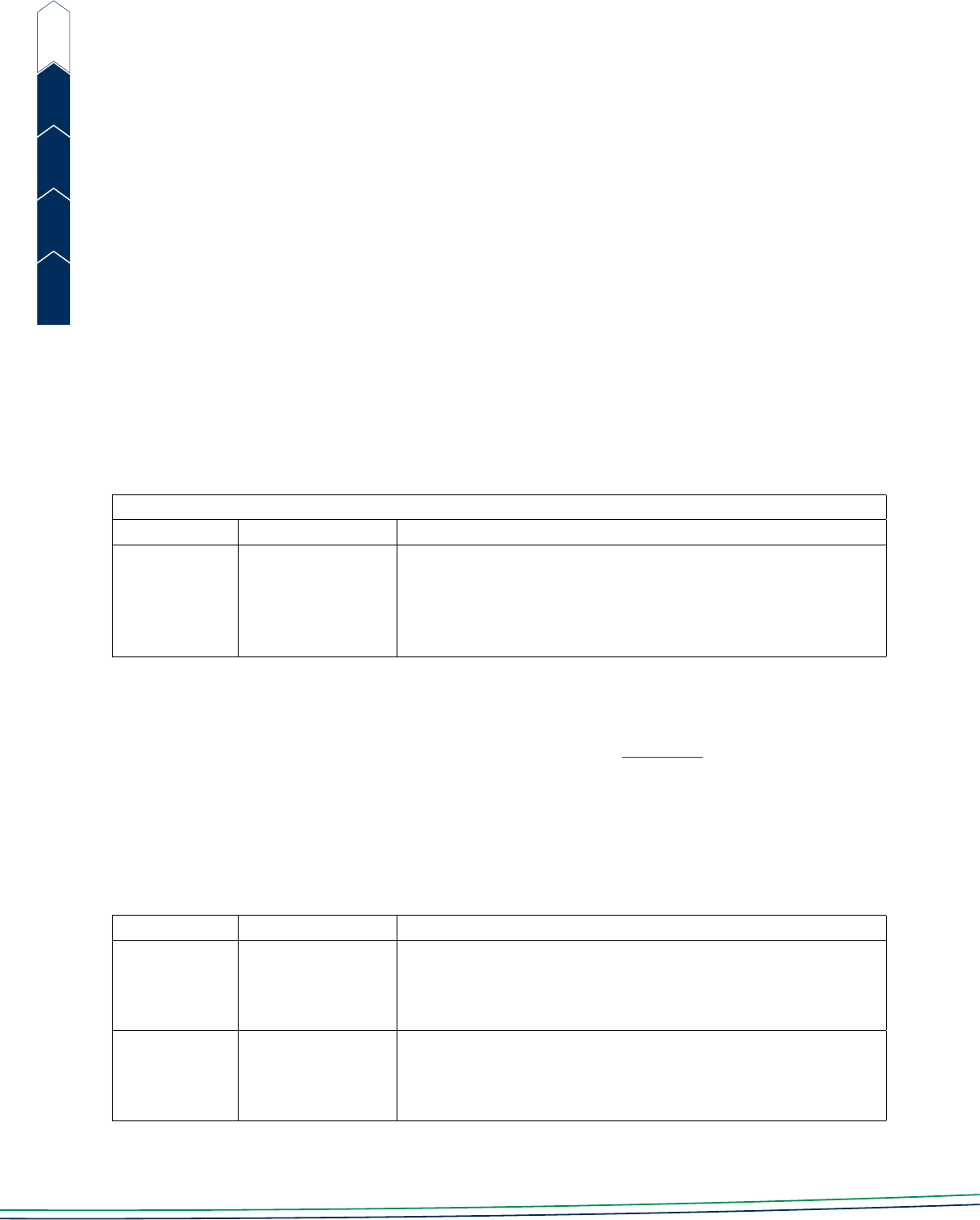

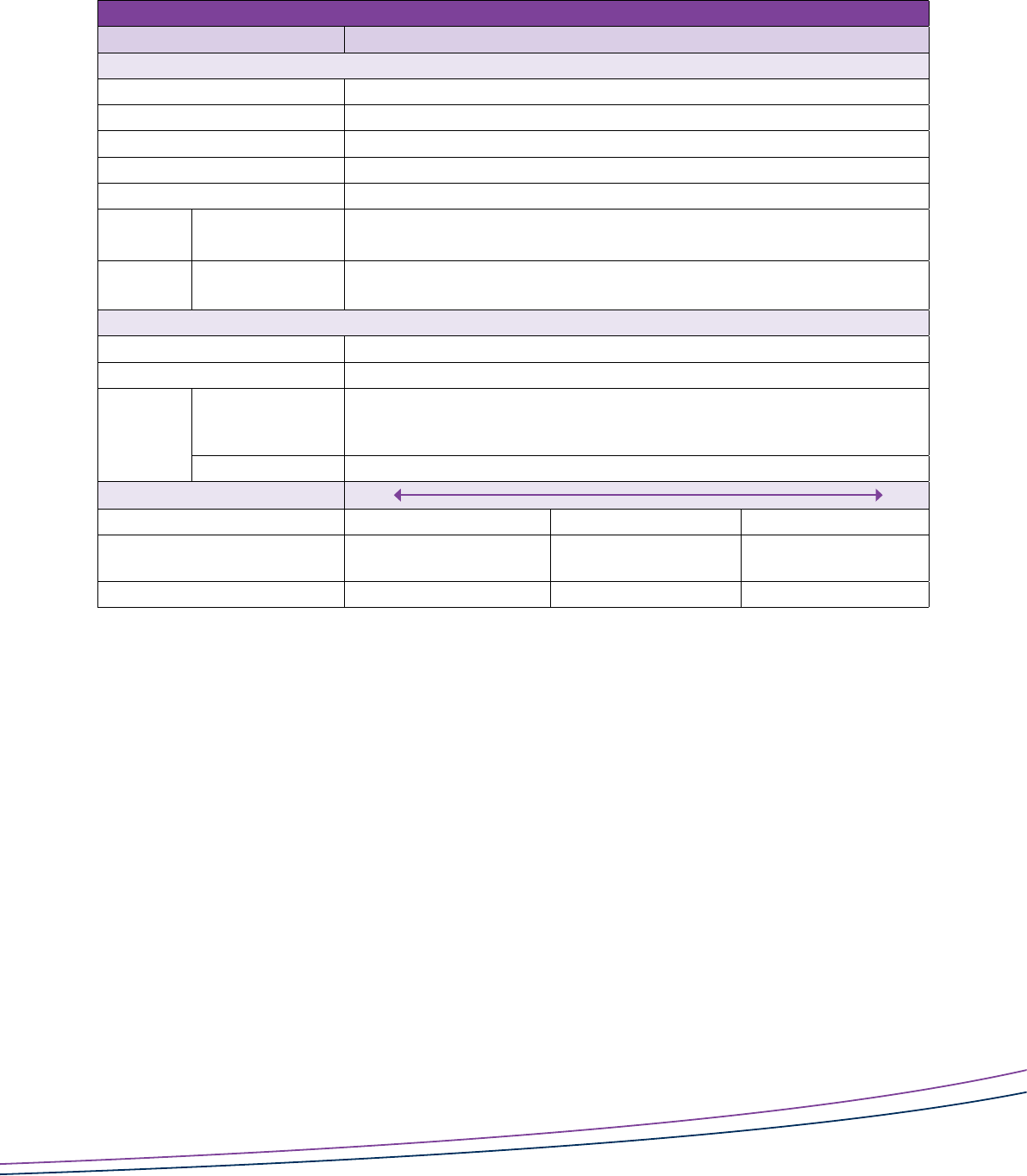

LANGUAGE AND CONTEXT PURPOSE, AUDIENCE

AND REGISTER

As students’ proficiency in SAE develops across the LEAP Levels, there is an increasing focus on the

development of academic language and the ability to operate successfully in a wider range of contexts

or registers. The register continuum is a valuable reference for discussing choices in texts and their

appropriateness and eectiveness for given contexts, including specific purposes and audiences.

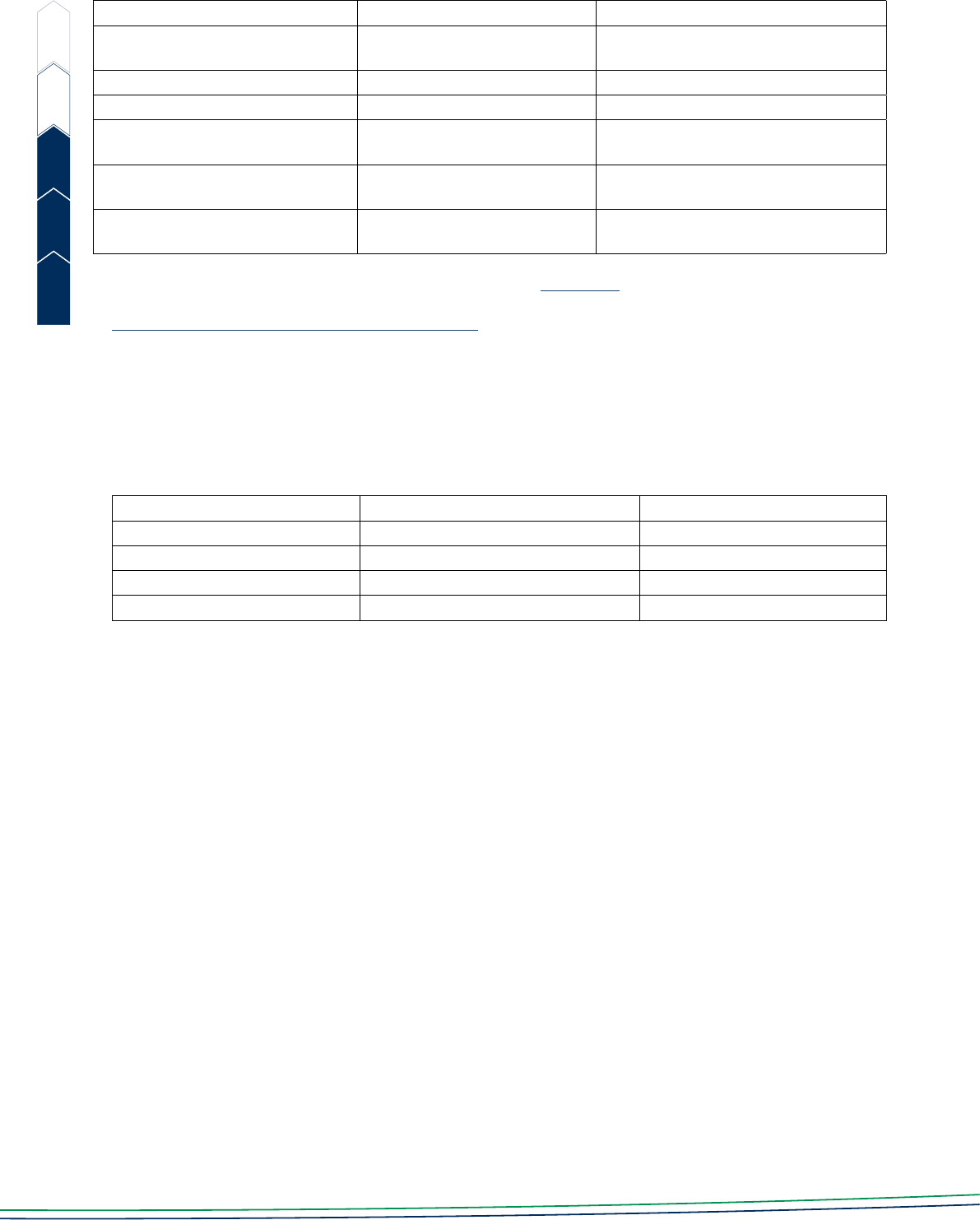

Register continuum

everyday, concrete What: field – subject matter technical, abstract

informal, personal Who: tenor – roles and relationships formal, impersonal

spoken, dialogic, specific,

‘here and now‘ context

How: mode of communication

written, monologic,

generalised context

Tier 1, 2 and 3 vocabulary

The development of EALD learners’ vocabulary across

the LEAP Levels can also be connected to the 3-tiered

system developed by Beck, McKeown & Kucan

(2013):

1. Tier 1 words are basic and high-frequency words

used in everyday conversation. While assumed to

be familiar to most students, EALD students will

often need this vocabulary explicitly taught as part

of building knowledge of the field.

2. Tier 2 words are those used by ‘at standard’ students

in academic contexts. They are words that can be

used across contexts to add clarity and/or precision.

These words appear more frequently in written texts

than in oral language. Whether a word is considered

to be Tier 2 or not will dier depending on the year

level. Given their importance in academic success

and transferability across topics and curriculum

areas, they warrant a great deal of attention.

1

For more on translanguaging, see ‘What is translanguaging?’, EAL Journal, available at

http://TLinSA.2.vu/translanguaging (accessed October 2020)

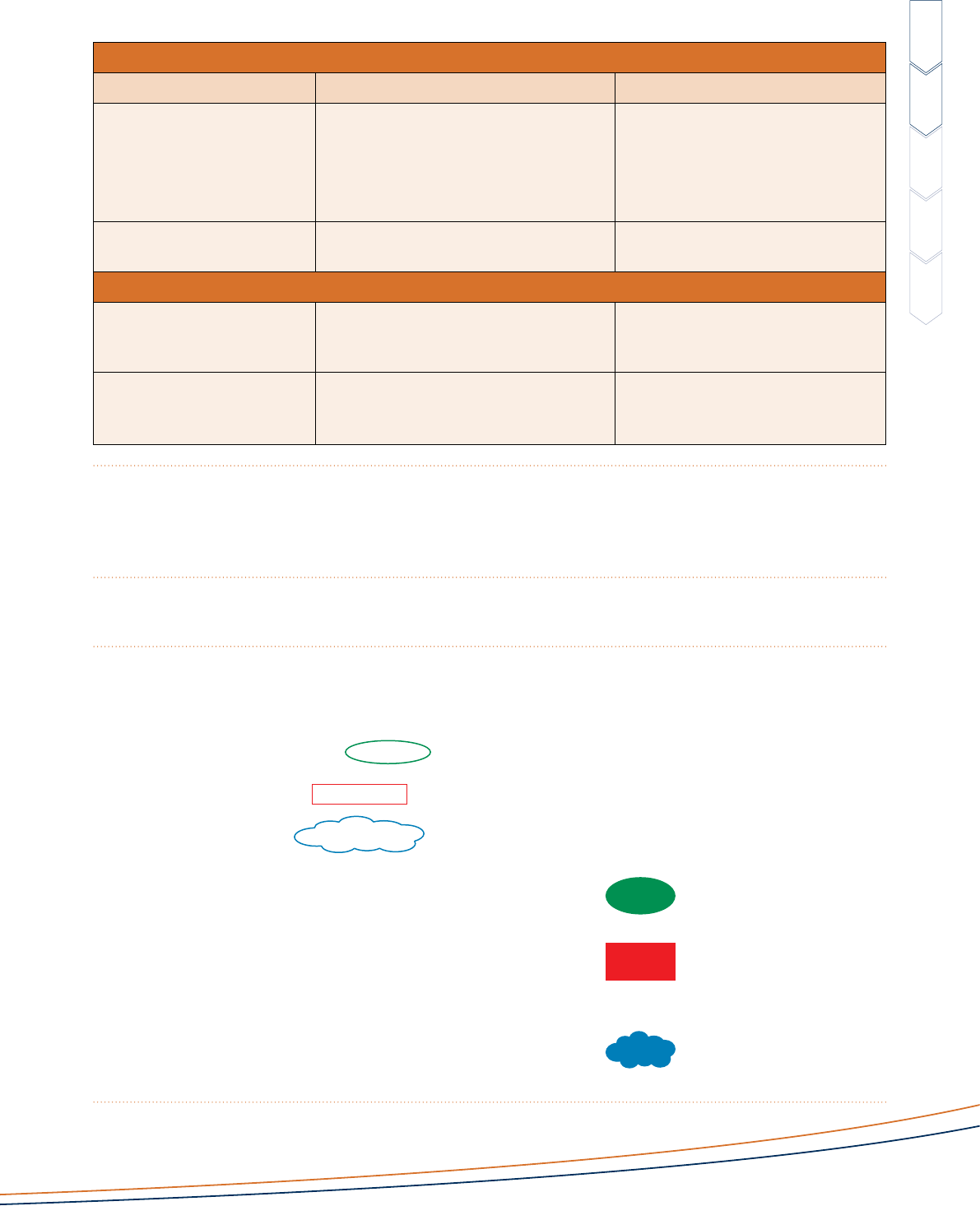

everyday, informal,

spoken

more specialised

and more formal

technical, abstract,

formal, written

4 | Learning English: Achievement and Proficiency (LEAP) | STRATEGIES INTRODUCTION

3. Tier 3 words are those that relate to specific fields

of knowledge. They have specialised meanings

according to the curriculum area and convey

technical, subject and topic-specific knowledge,

such as the sciences. These words need to be

taught in the context of the curriculum area tasks

specific to building content knowledge on a

particular topic.

See also the department’s Best Advice paper:

Vocabulary

(DECD, 2016).

2

CONTEXTUALISED

LEARNING

Explicitly teaching about language is best done where

language use occurs in authentic dialogue about a

curriculum topic. The starting point for planning then

is the identified target language in the context of

relevant curriculum learning. Key mentor and/or

model texts can then be identified or developed

to ensure that they provide important curriculum

content and the identified language features.

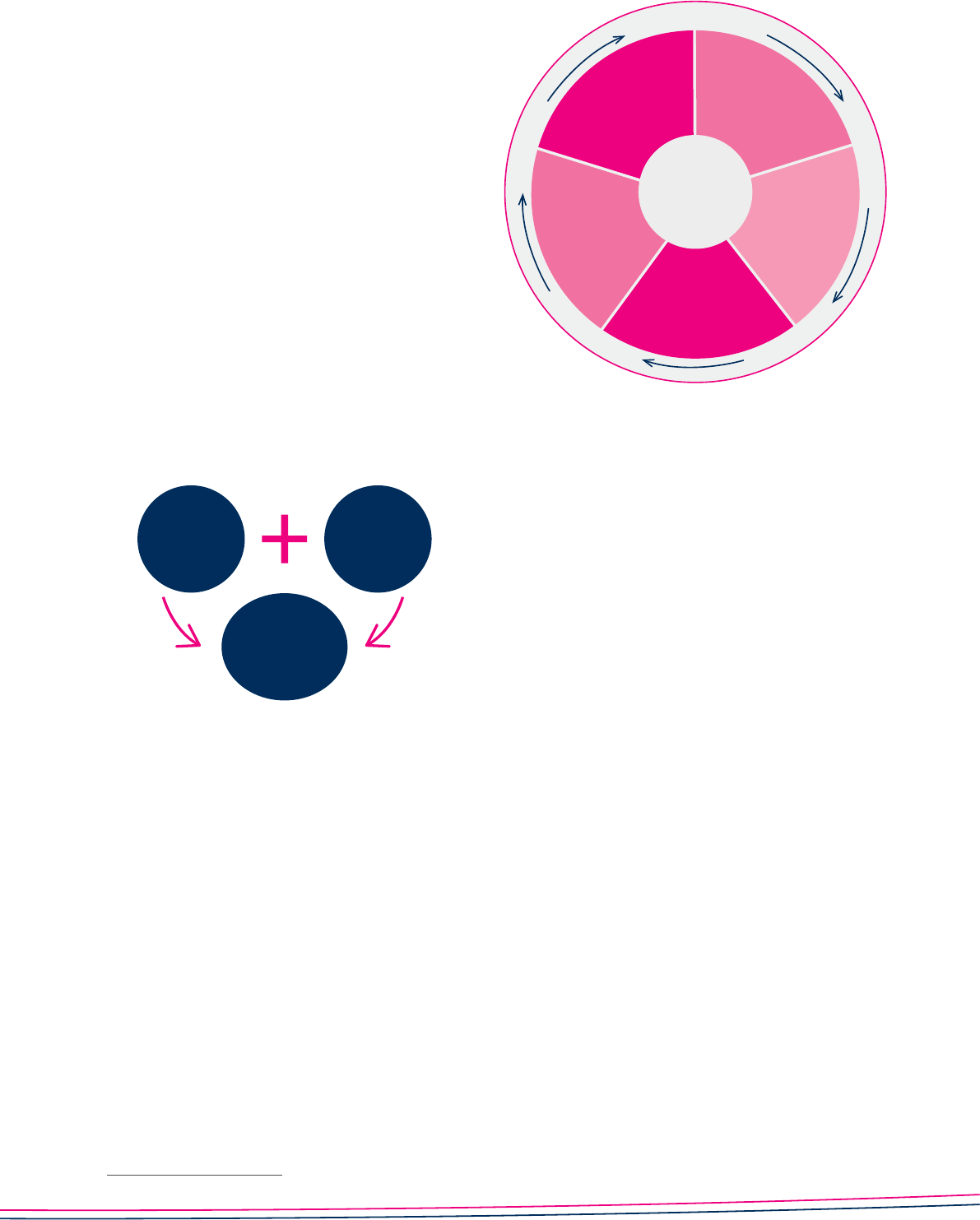

TEACHING AND

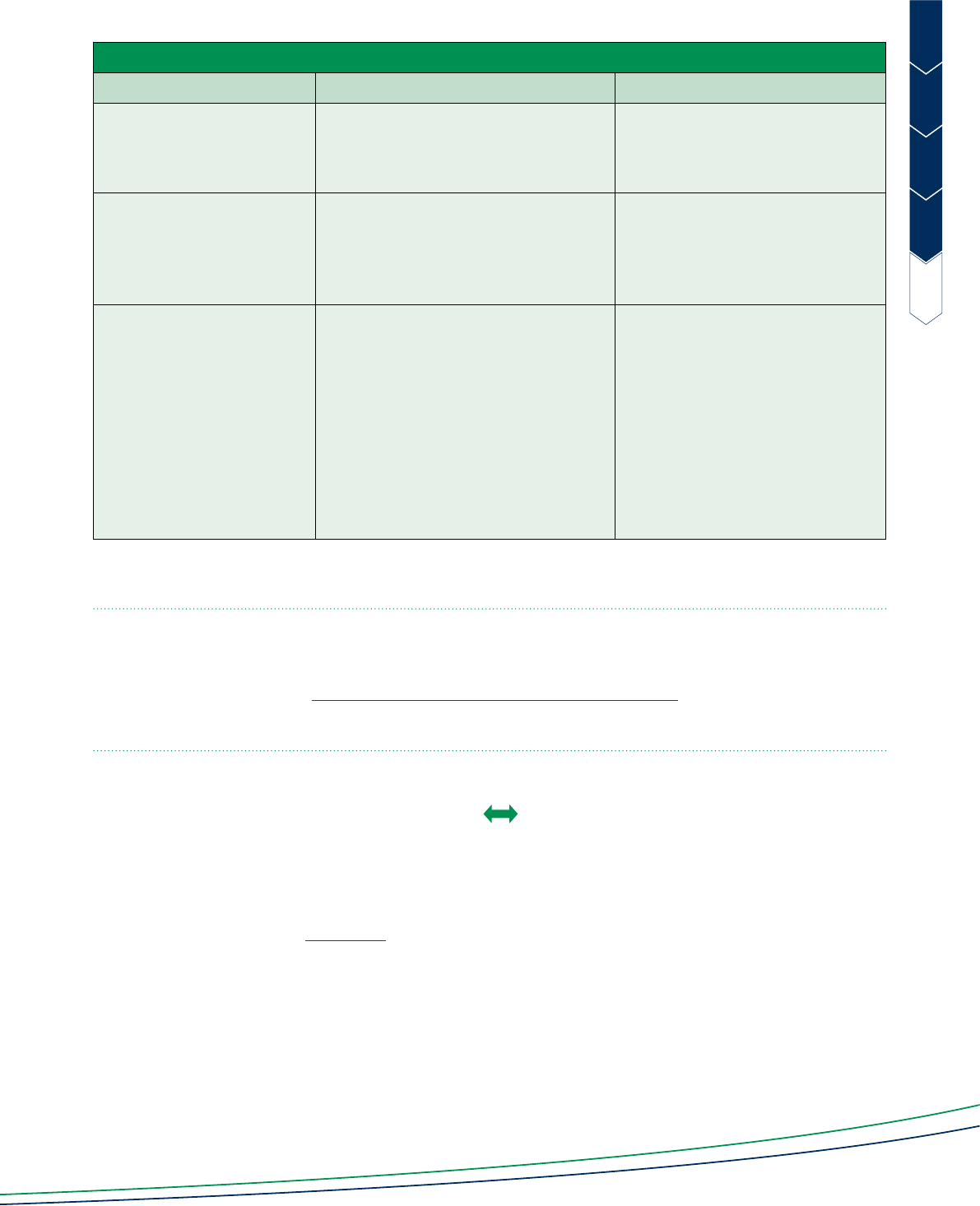

LEARNING CYCLE

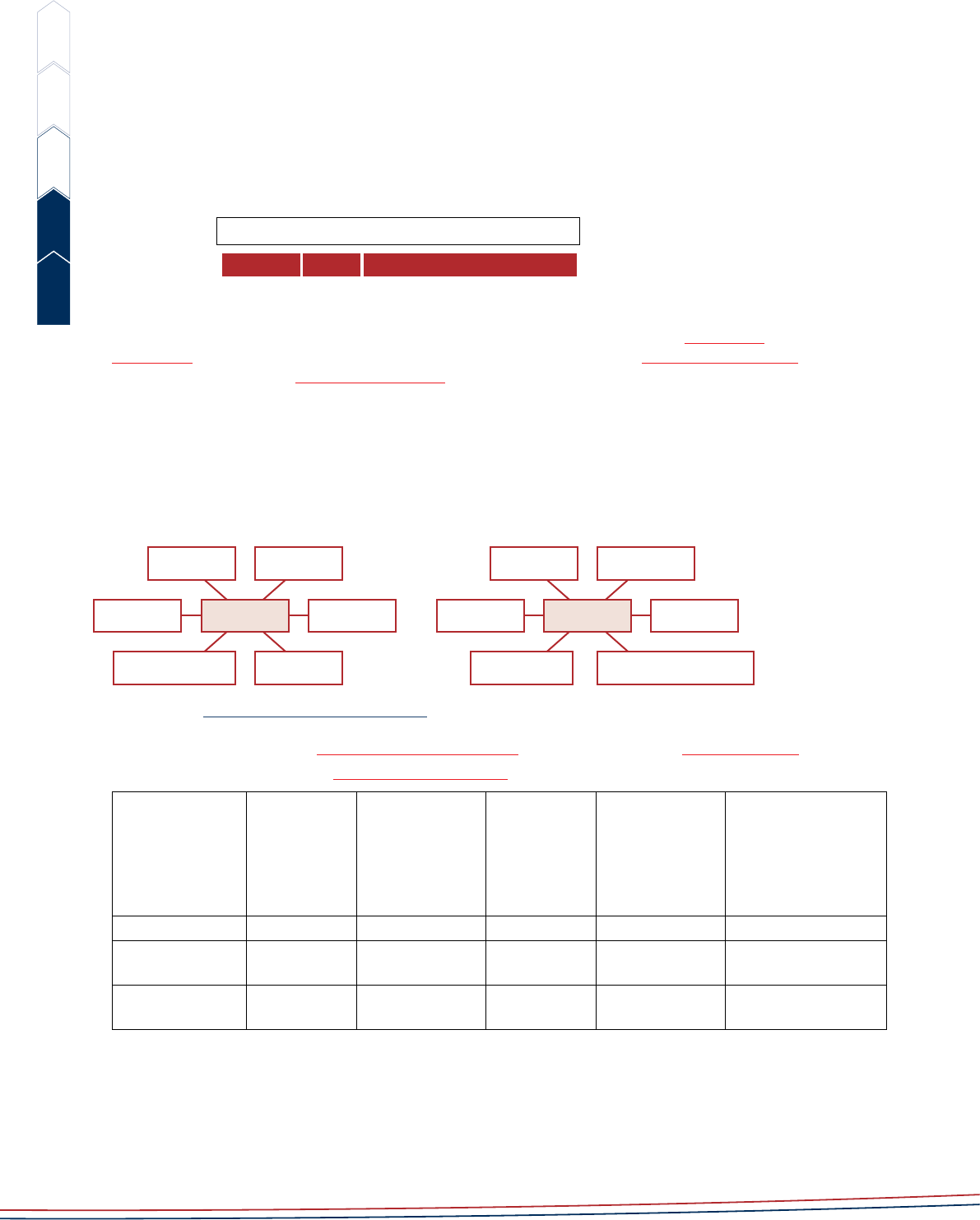

The learning sequences should be implemented

within an intentionally planned teaching and learning

cycle, enabling teachers to integrate oral language

(‘talking to learn’), reading and writing practices to

develop deep learning and understanding of genre.

This provides EALD students with time and multiple

exposures to new language, skills and knowledge.

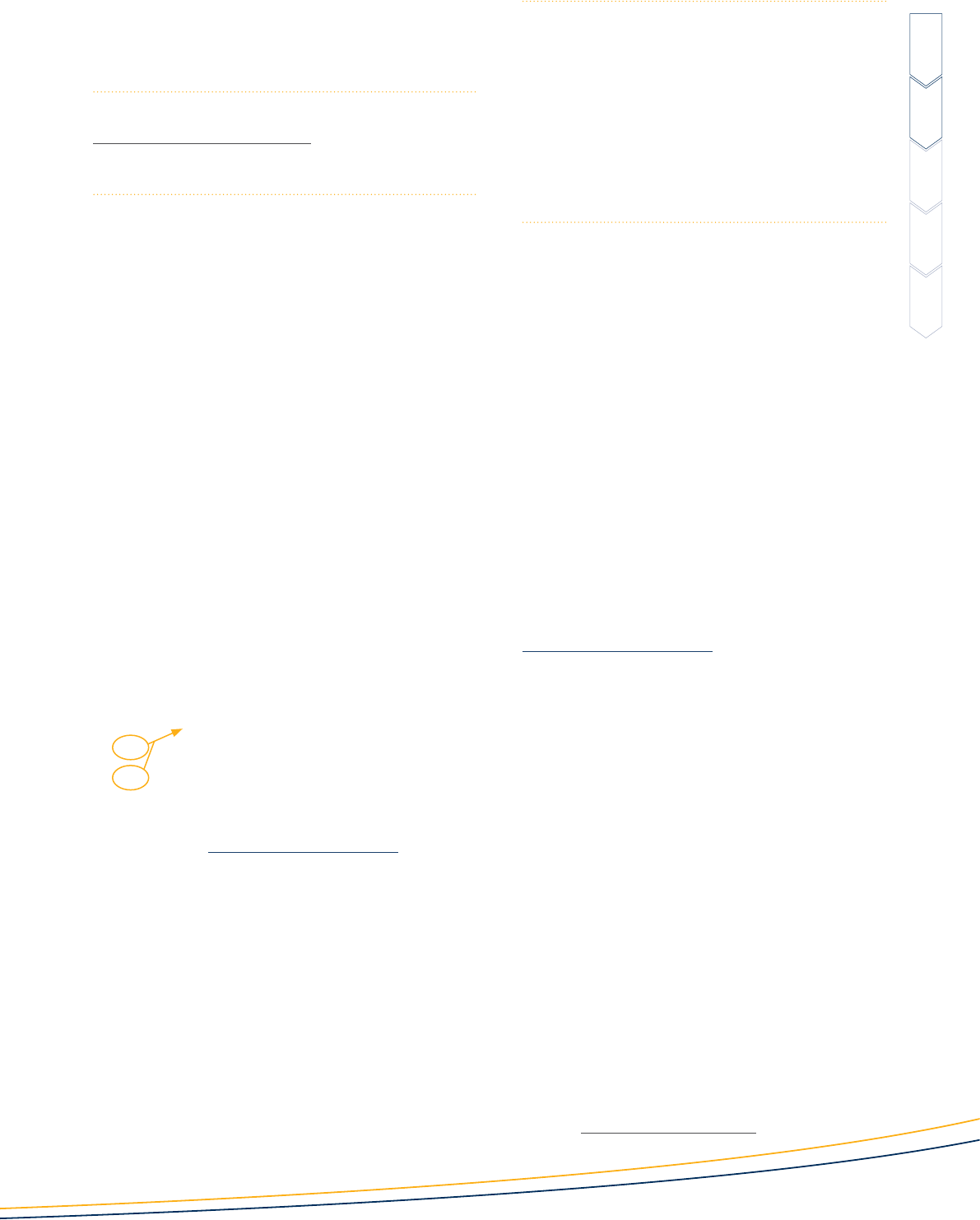

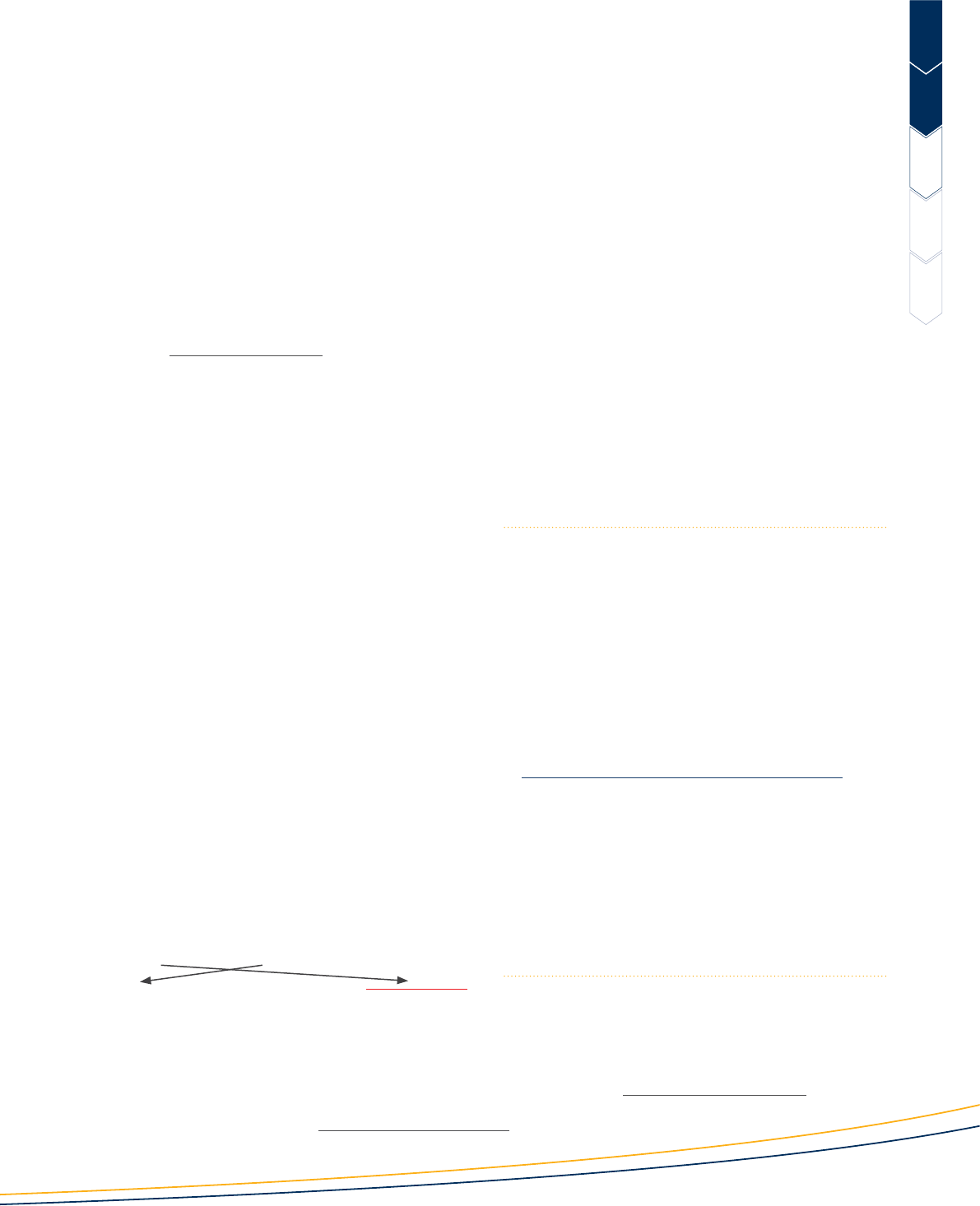

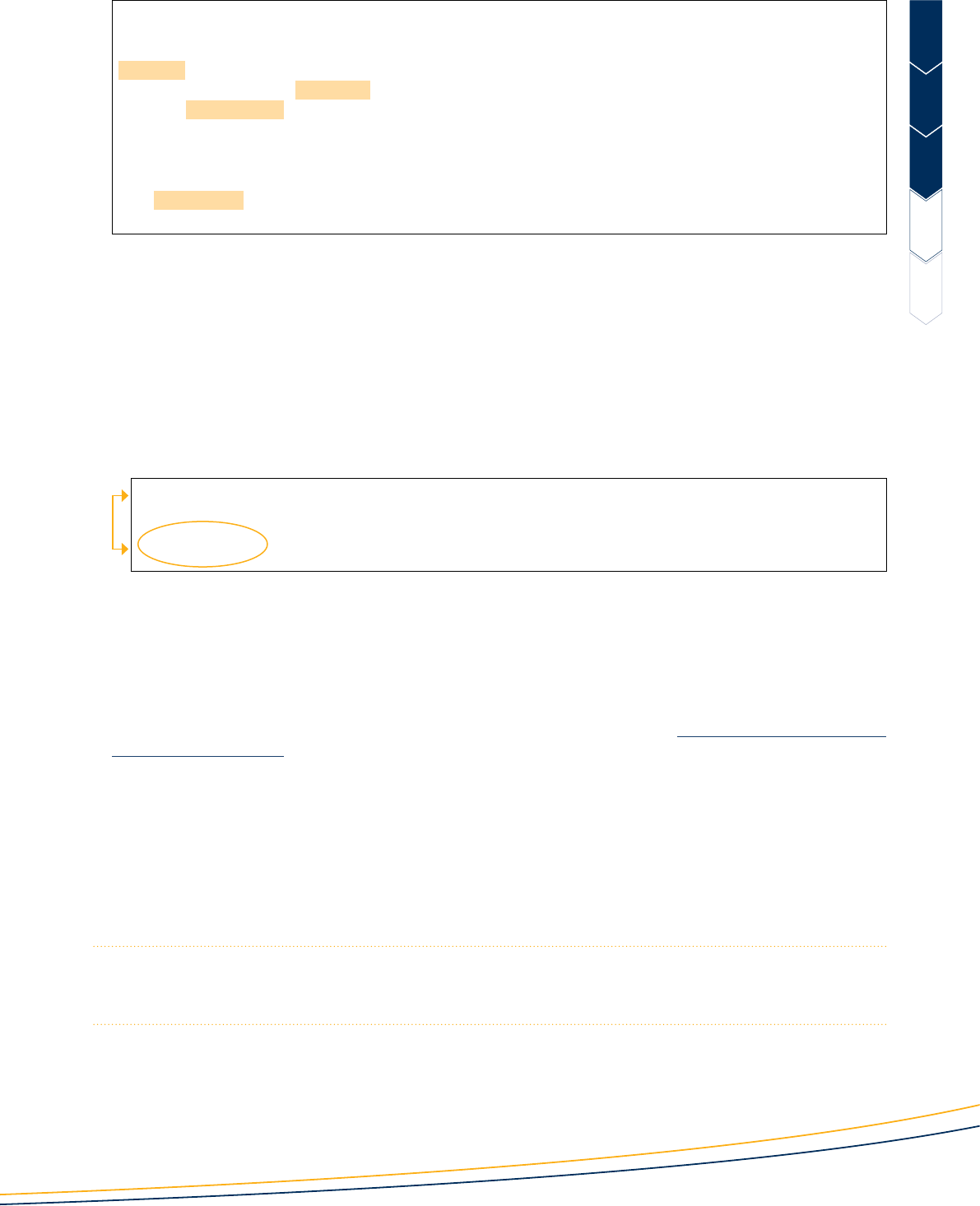

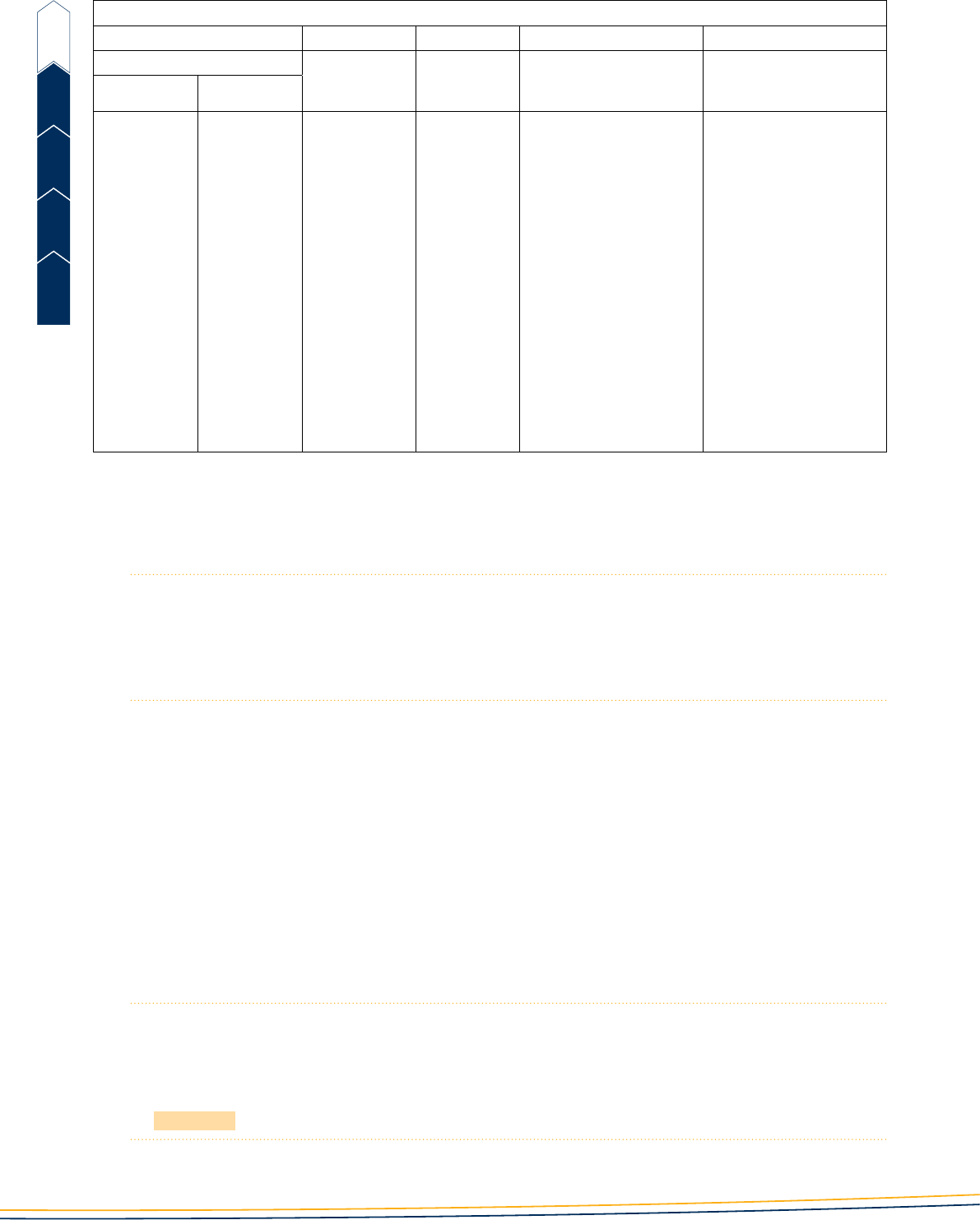

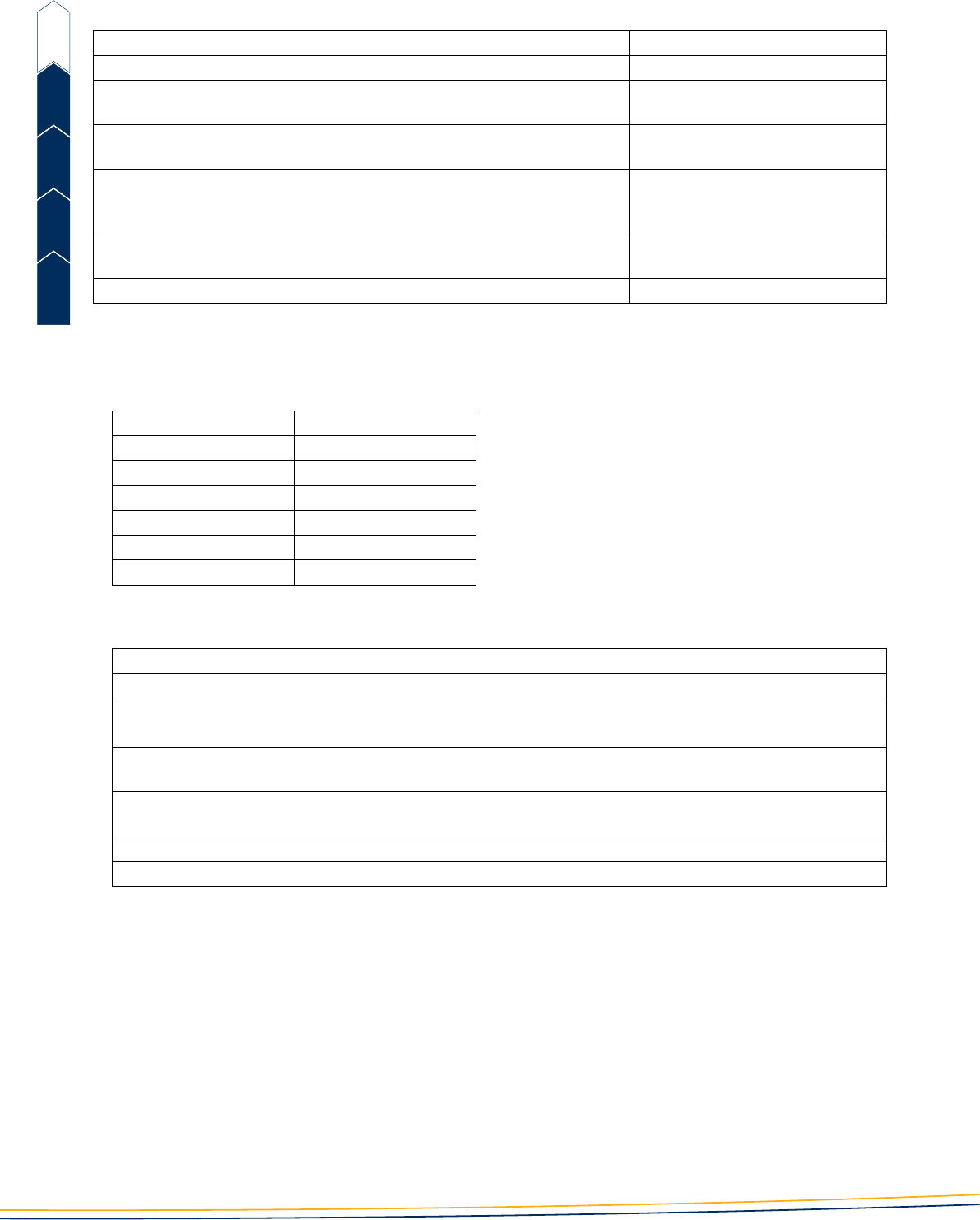

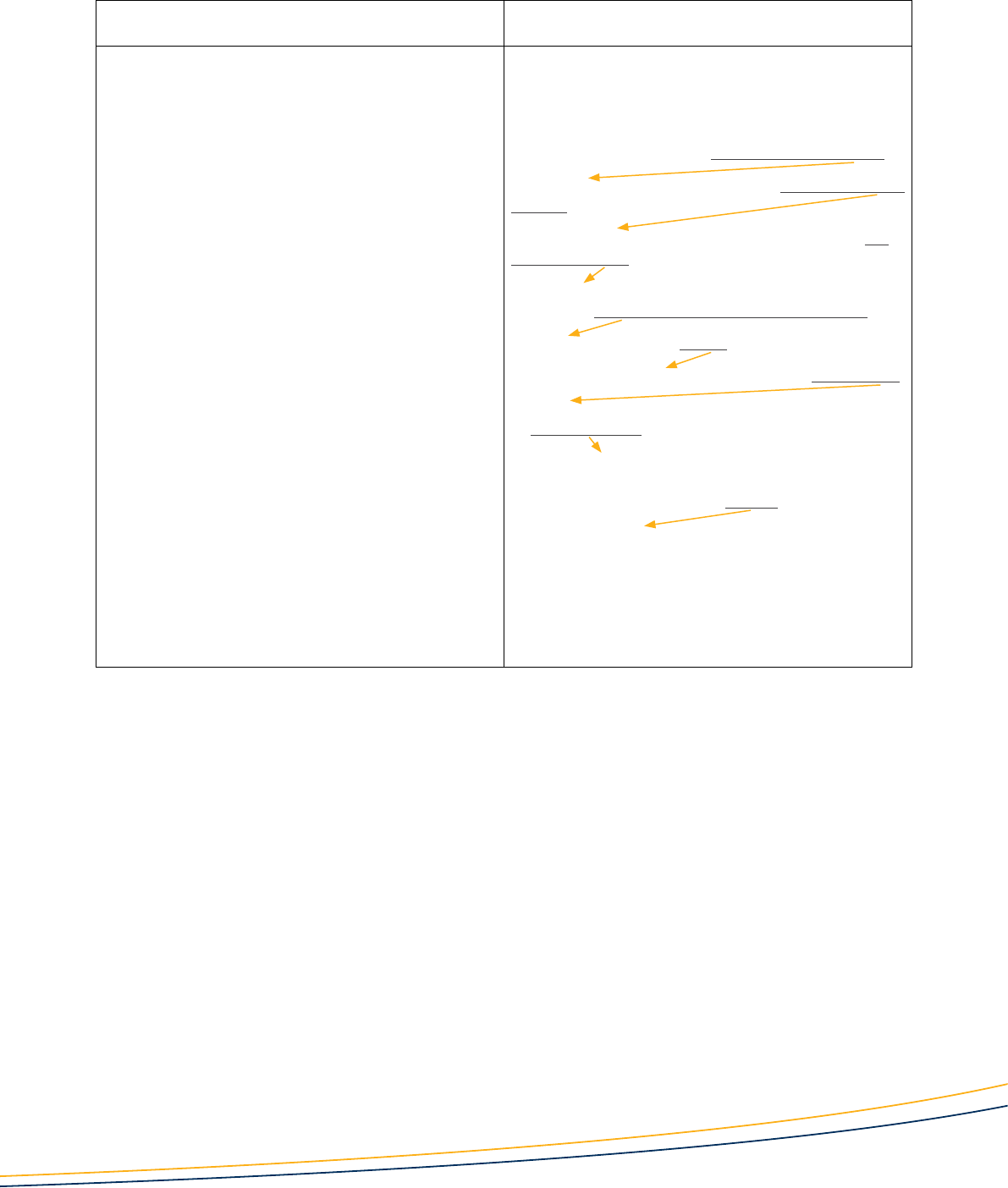

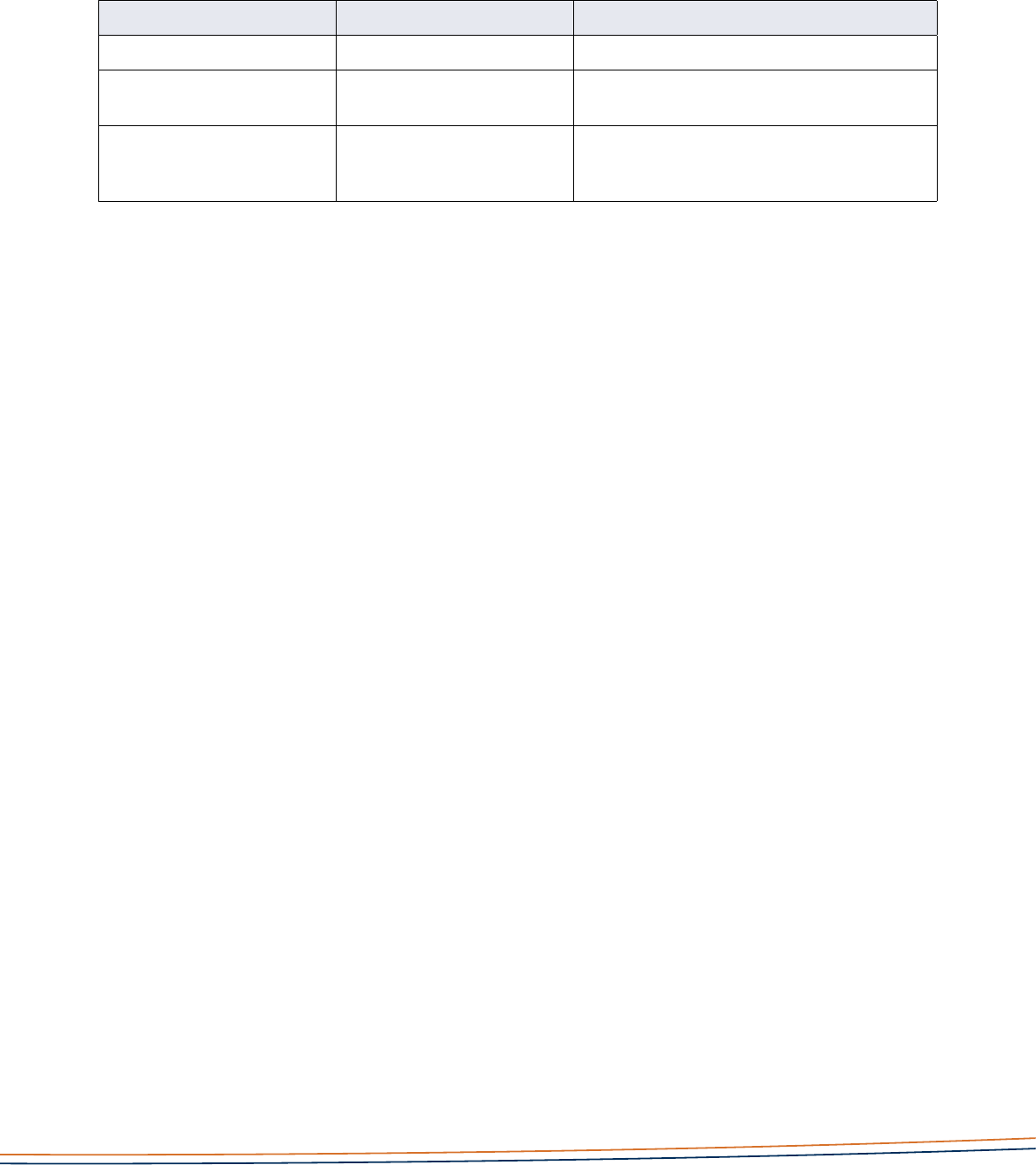

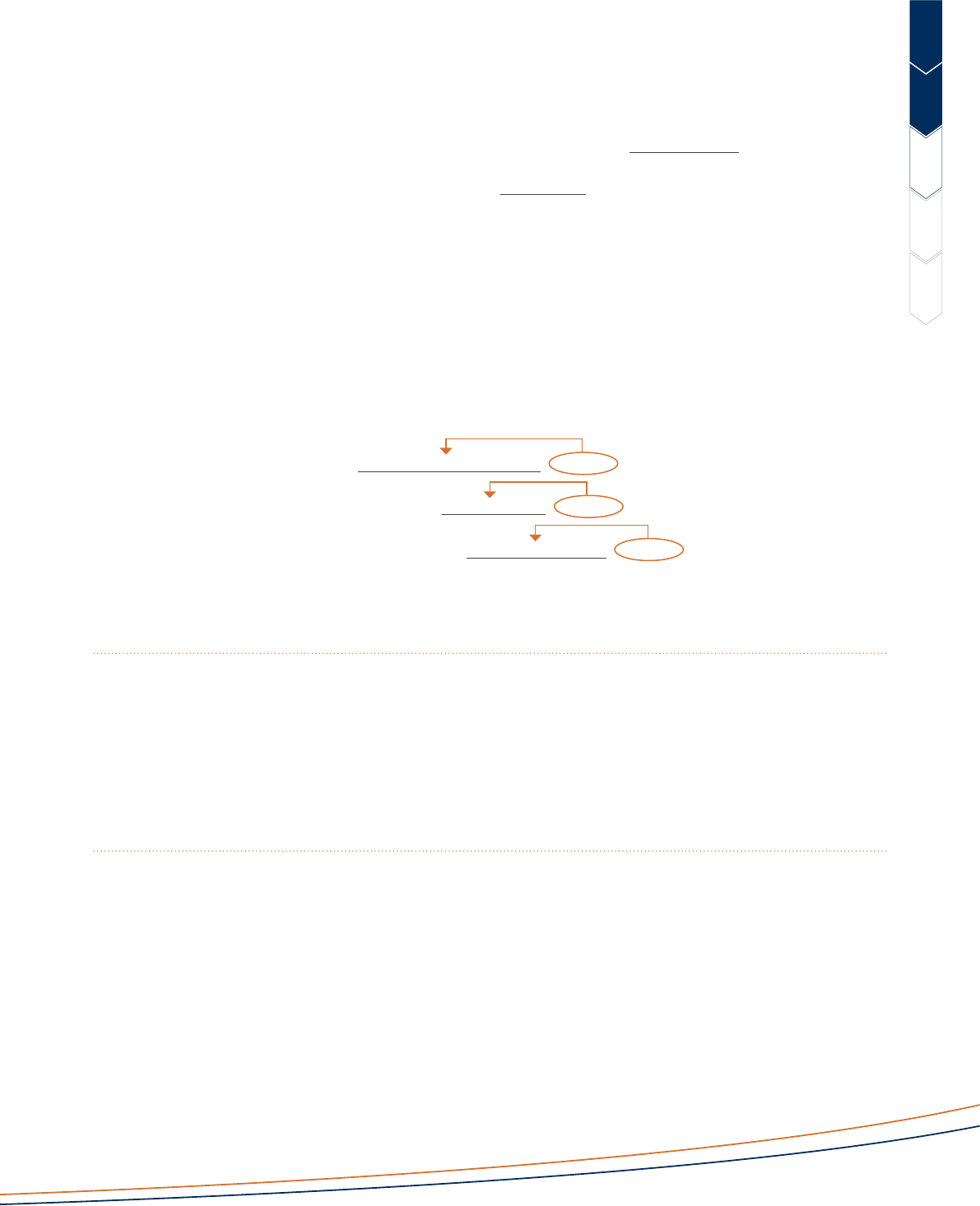

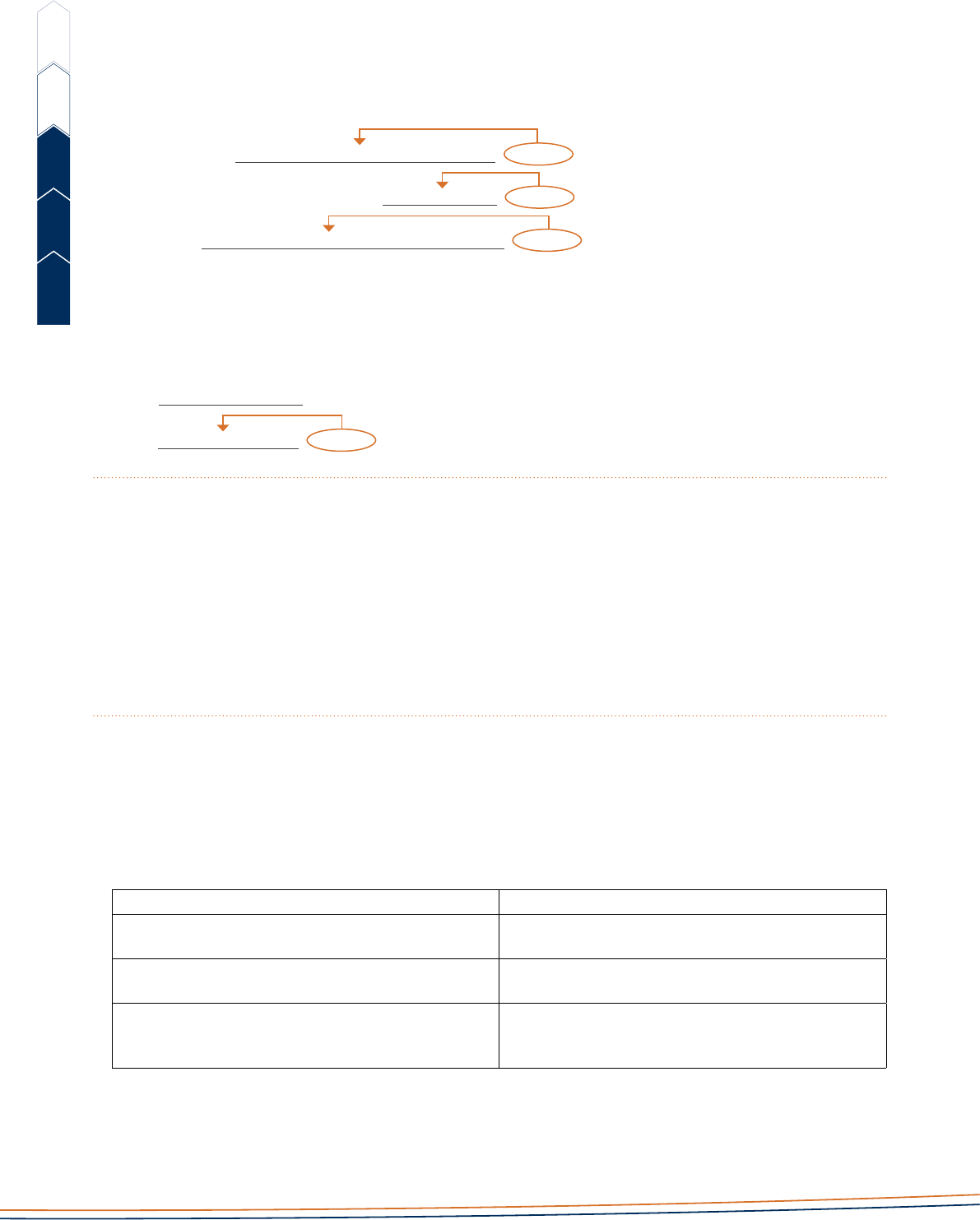

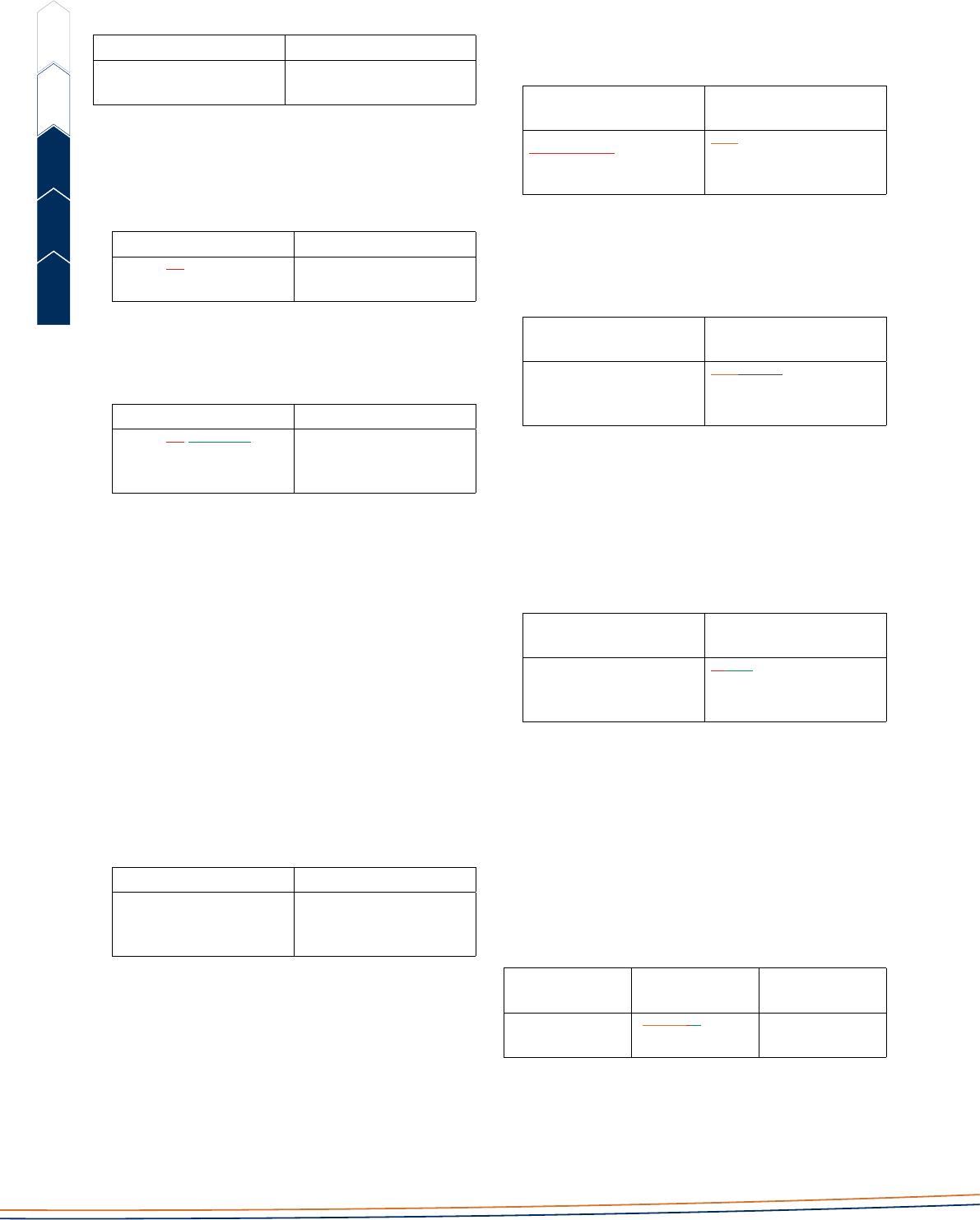

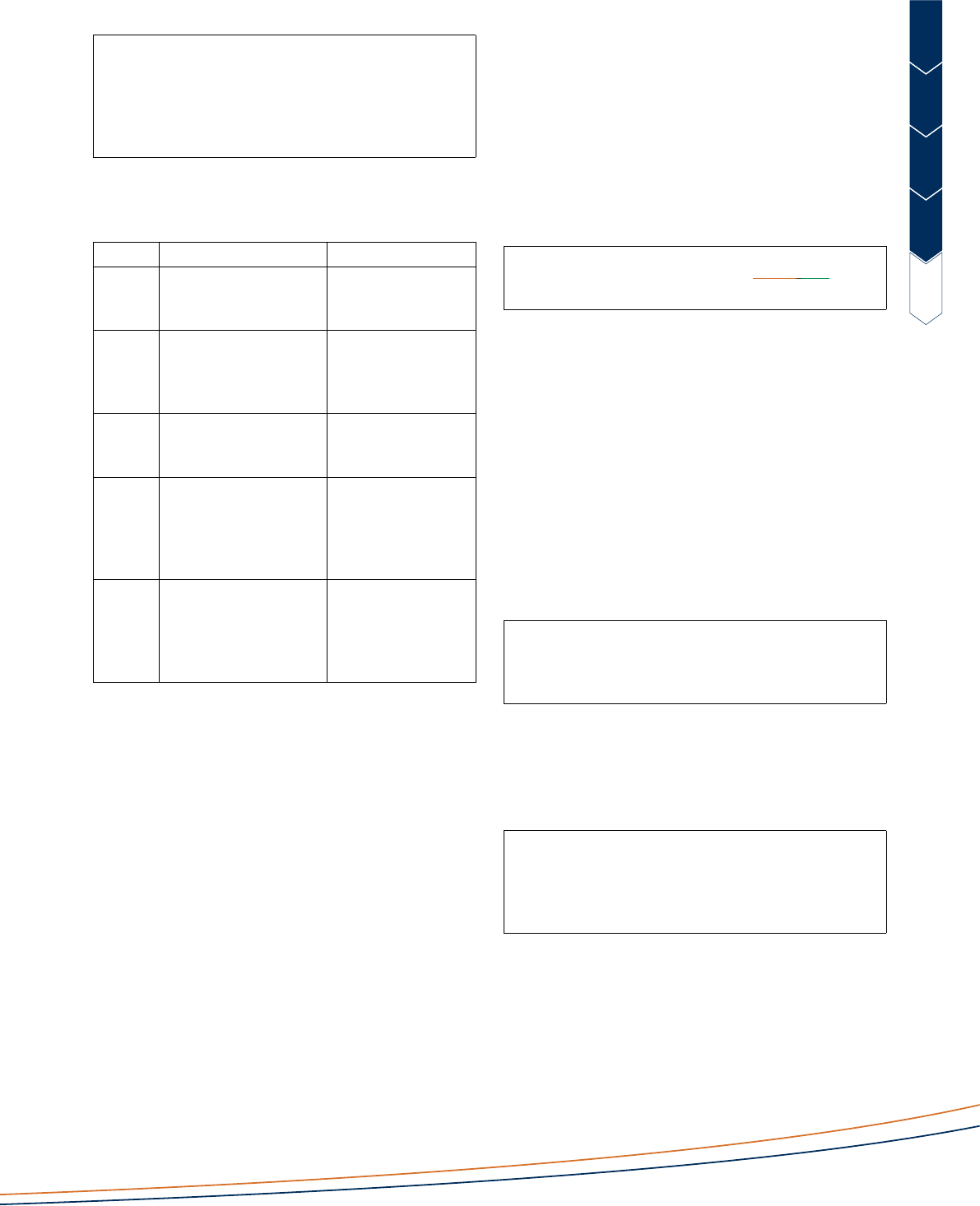

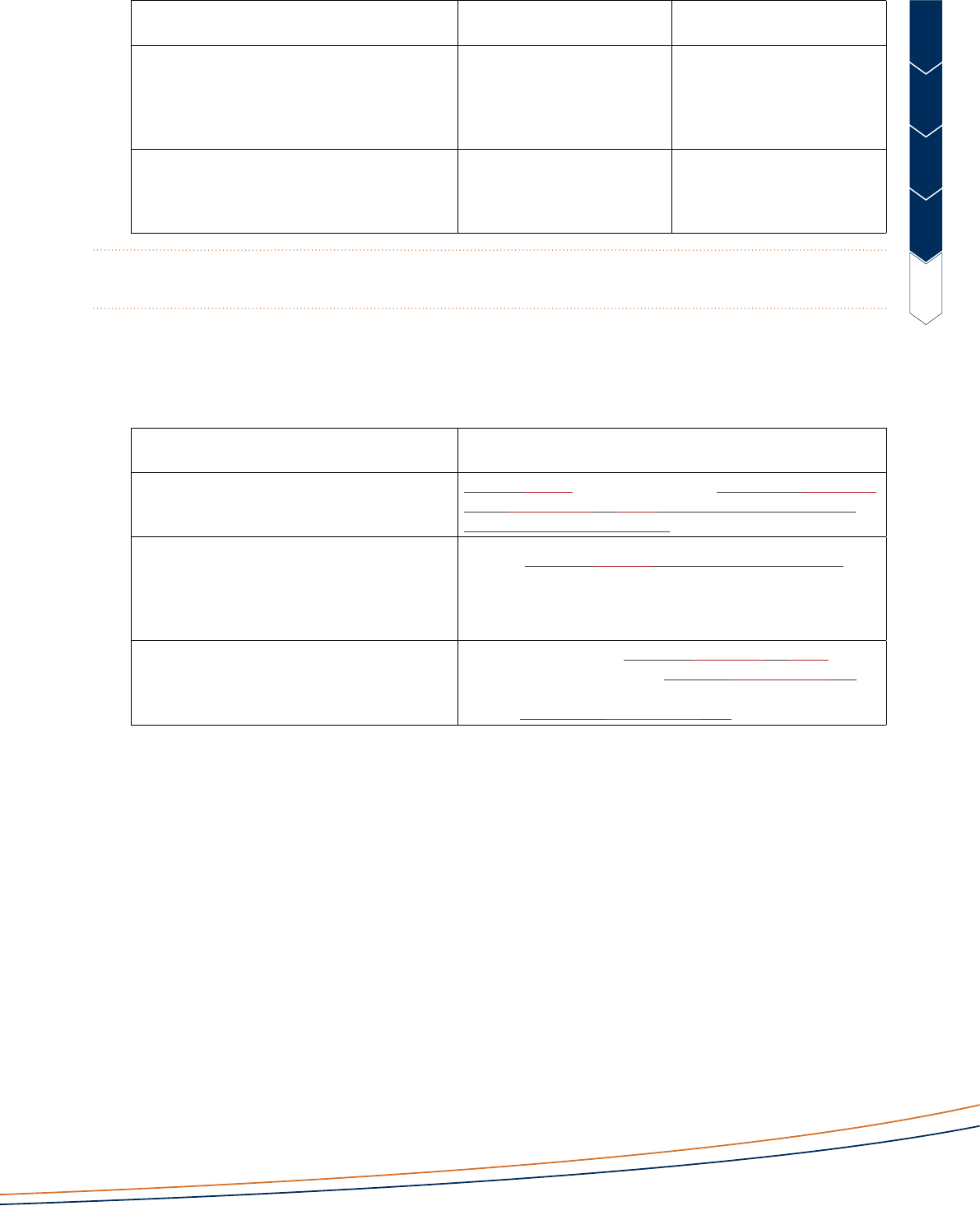

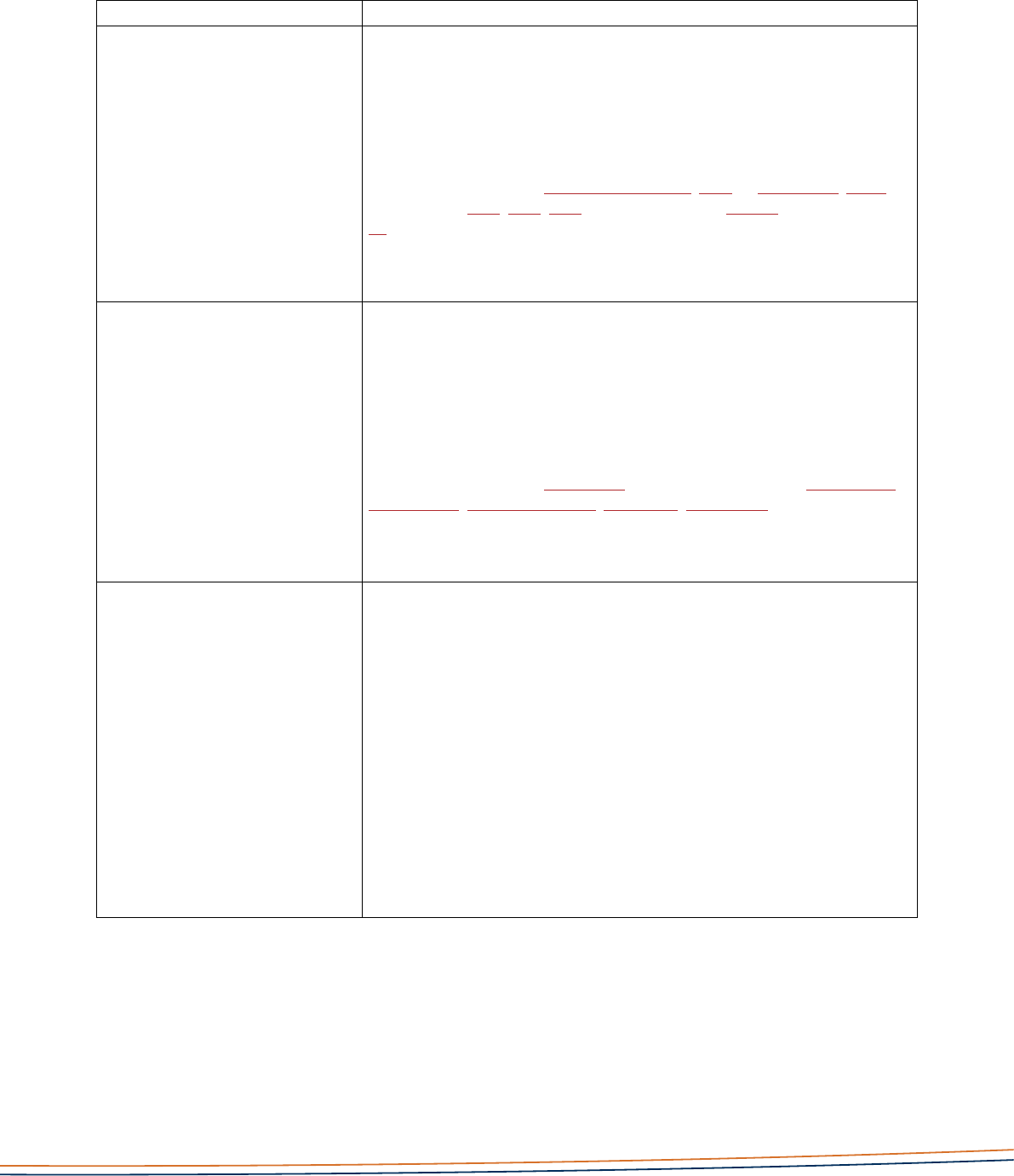

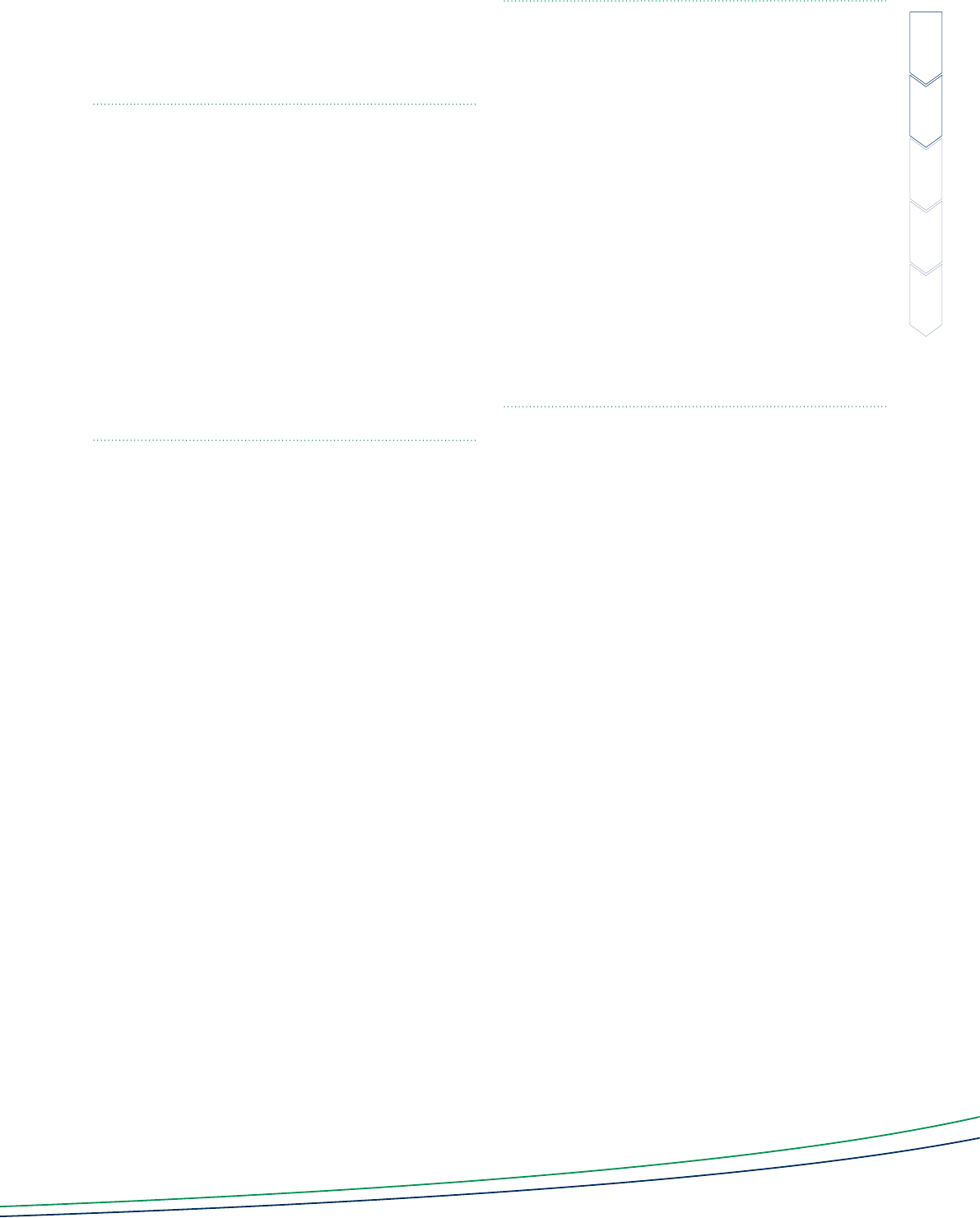

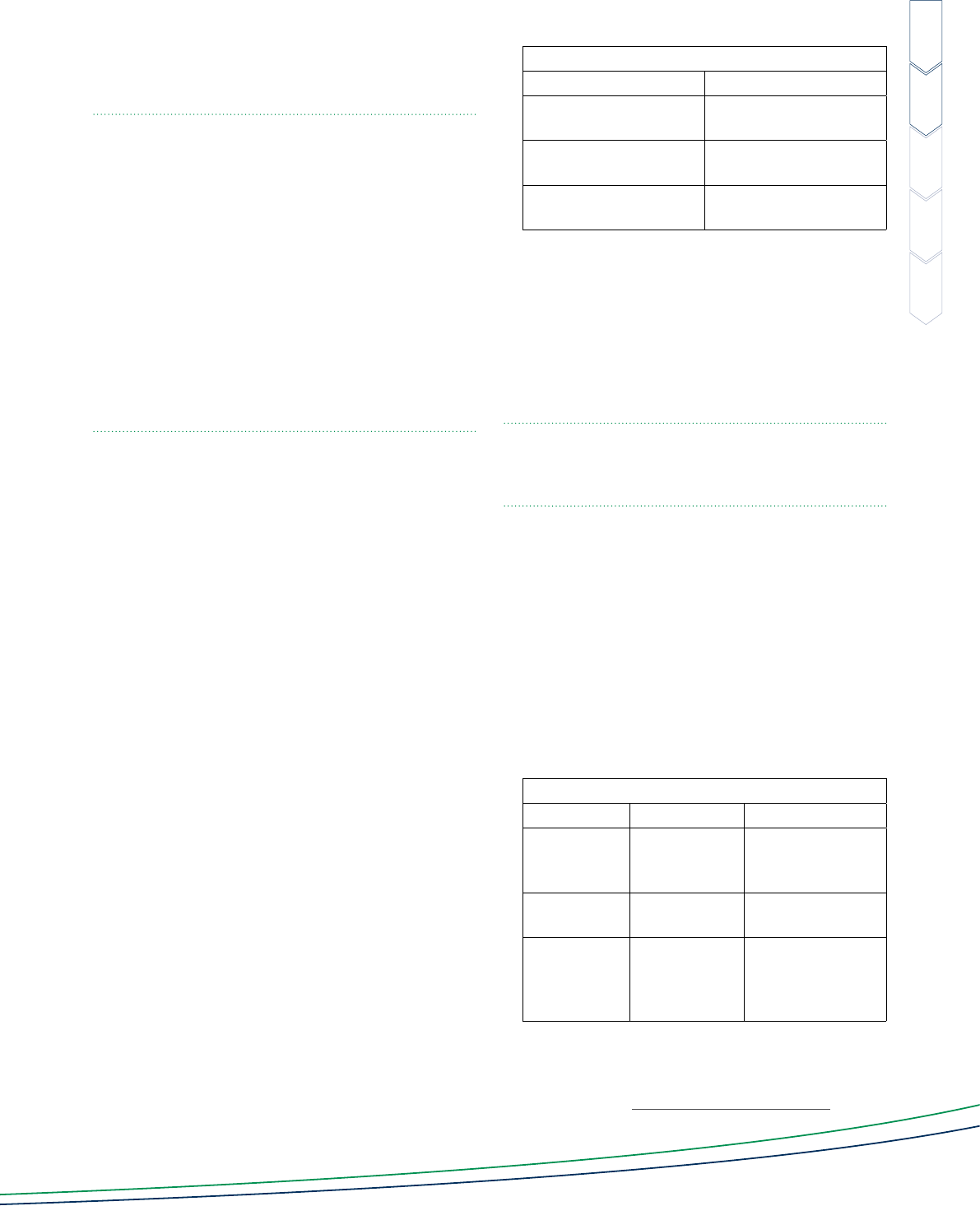

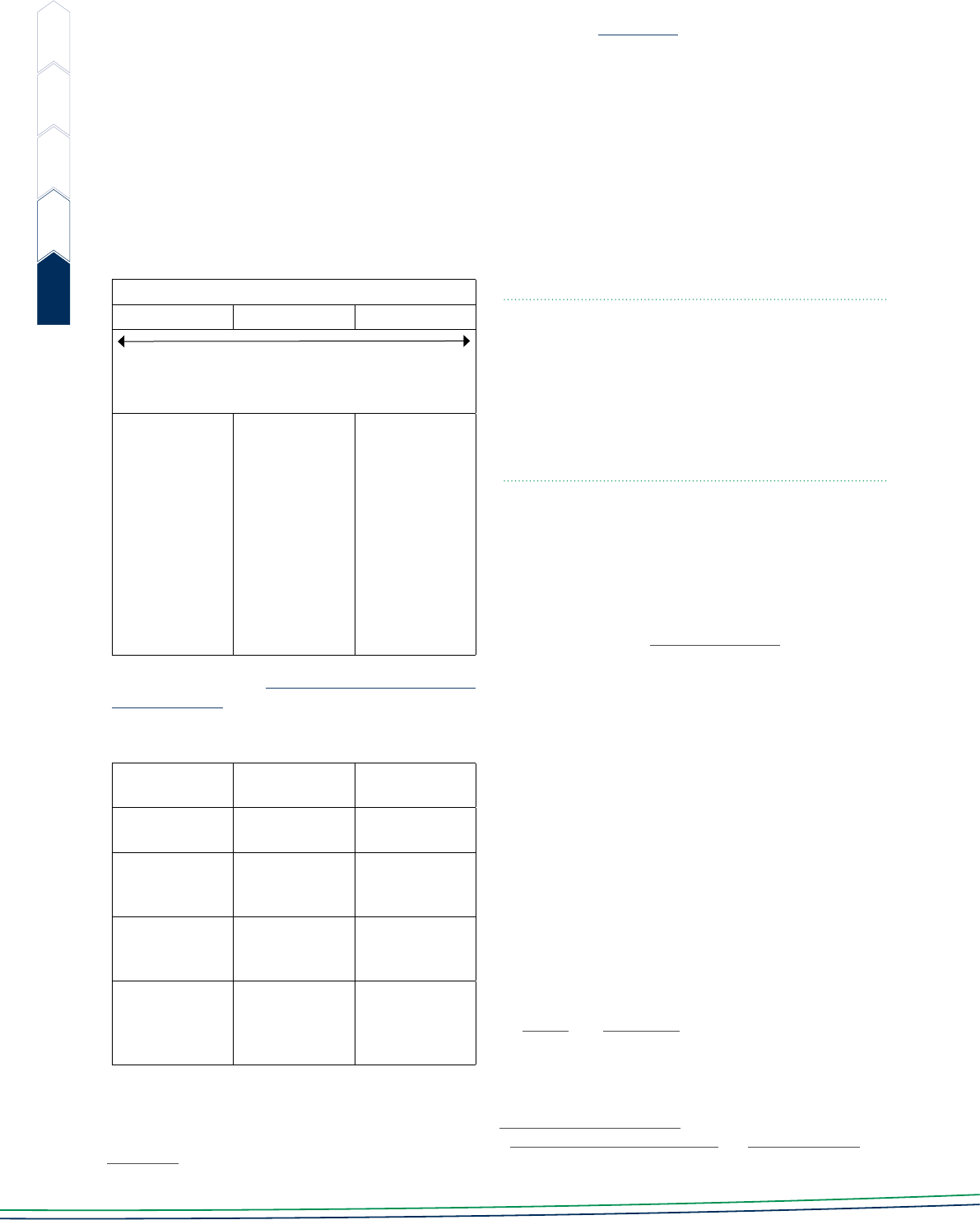

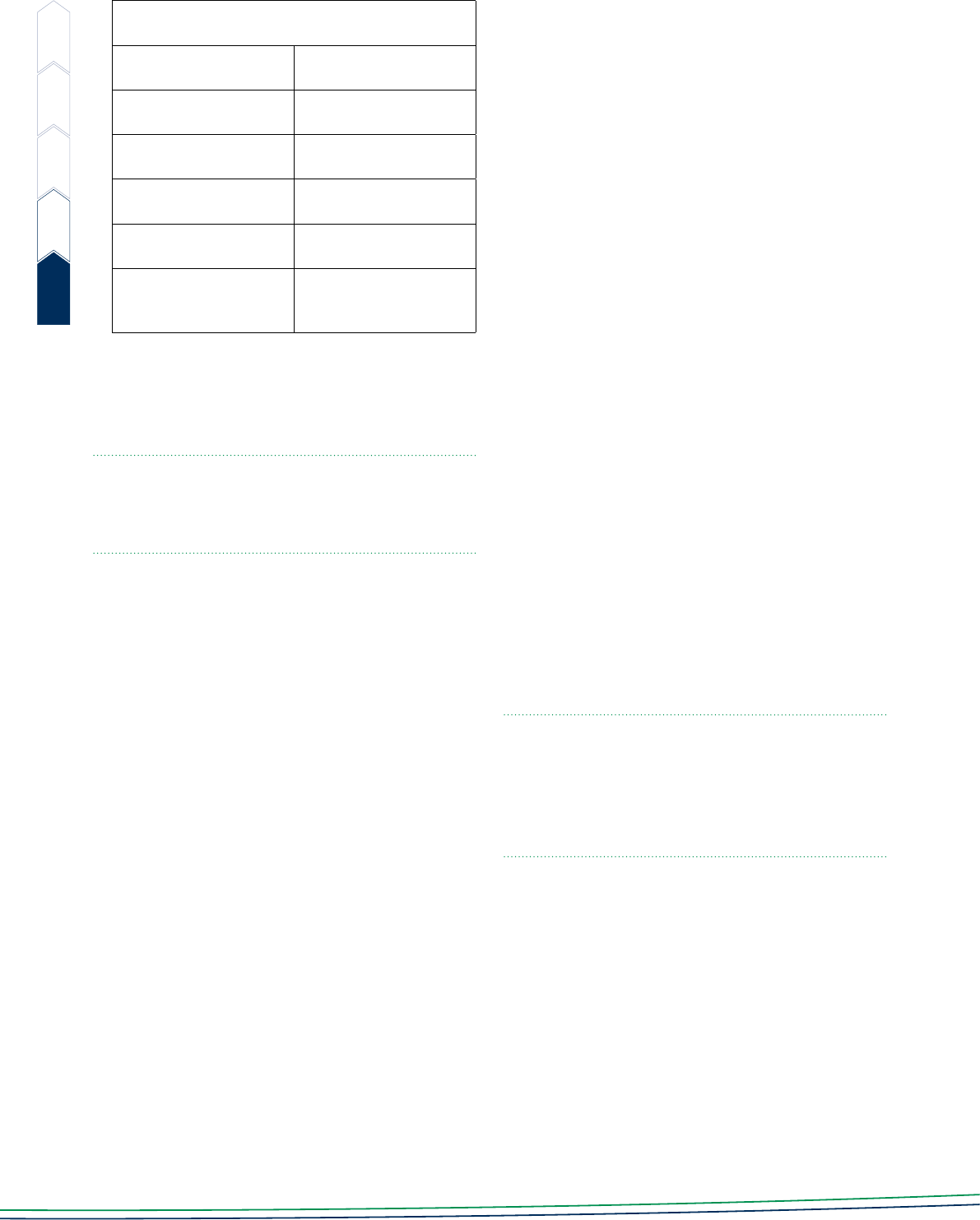

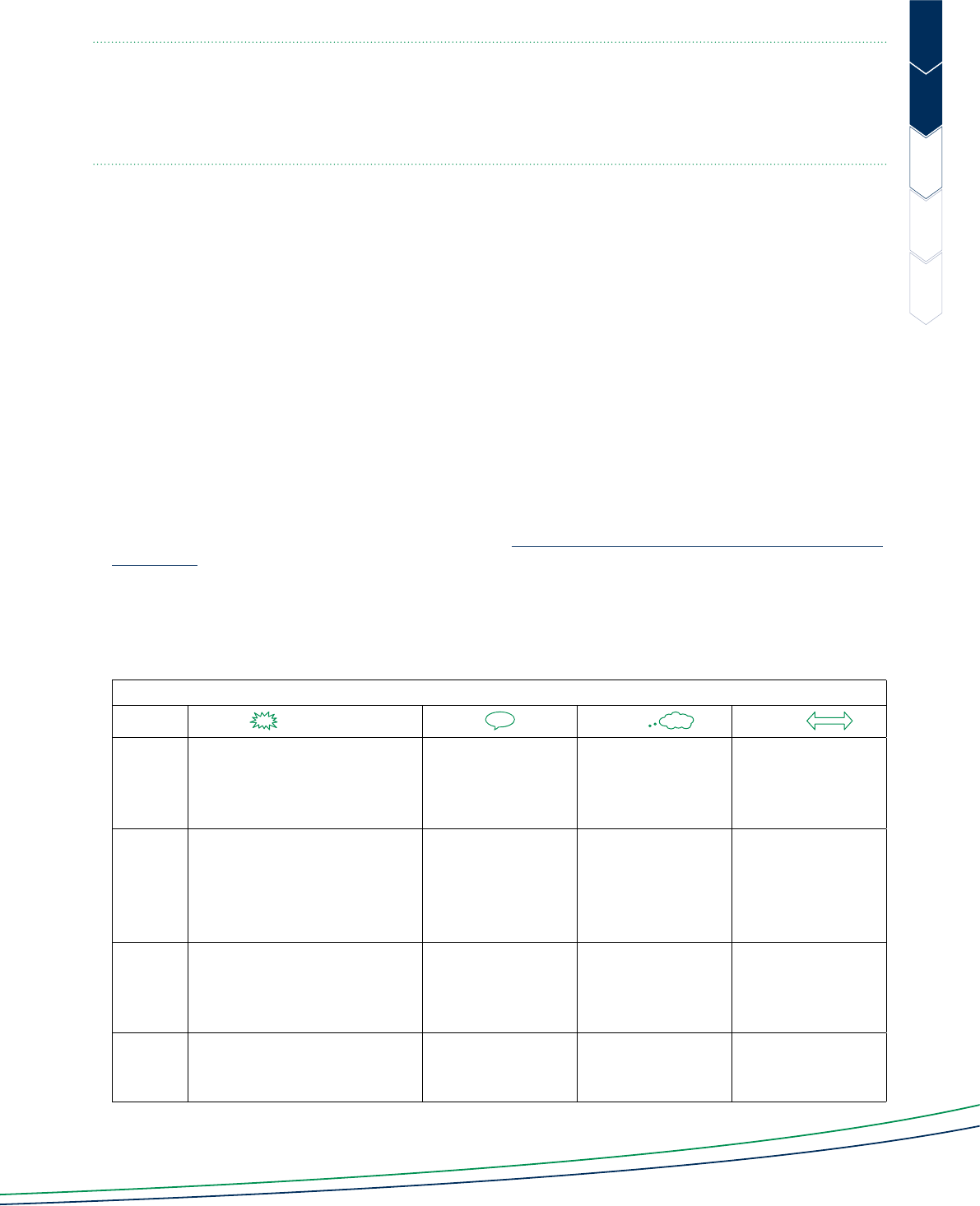

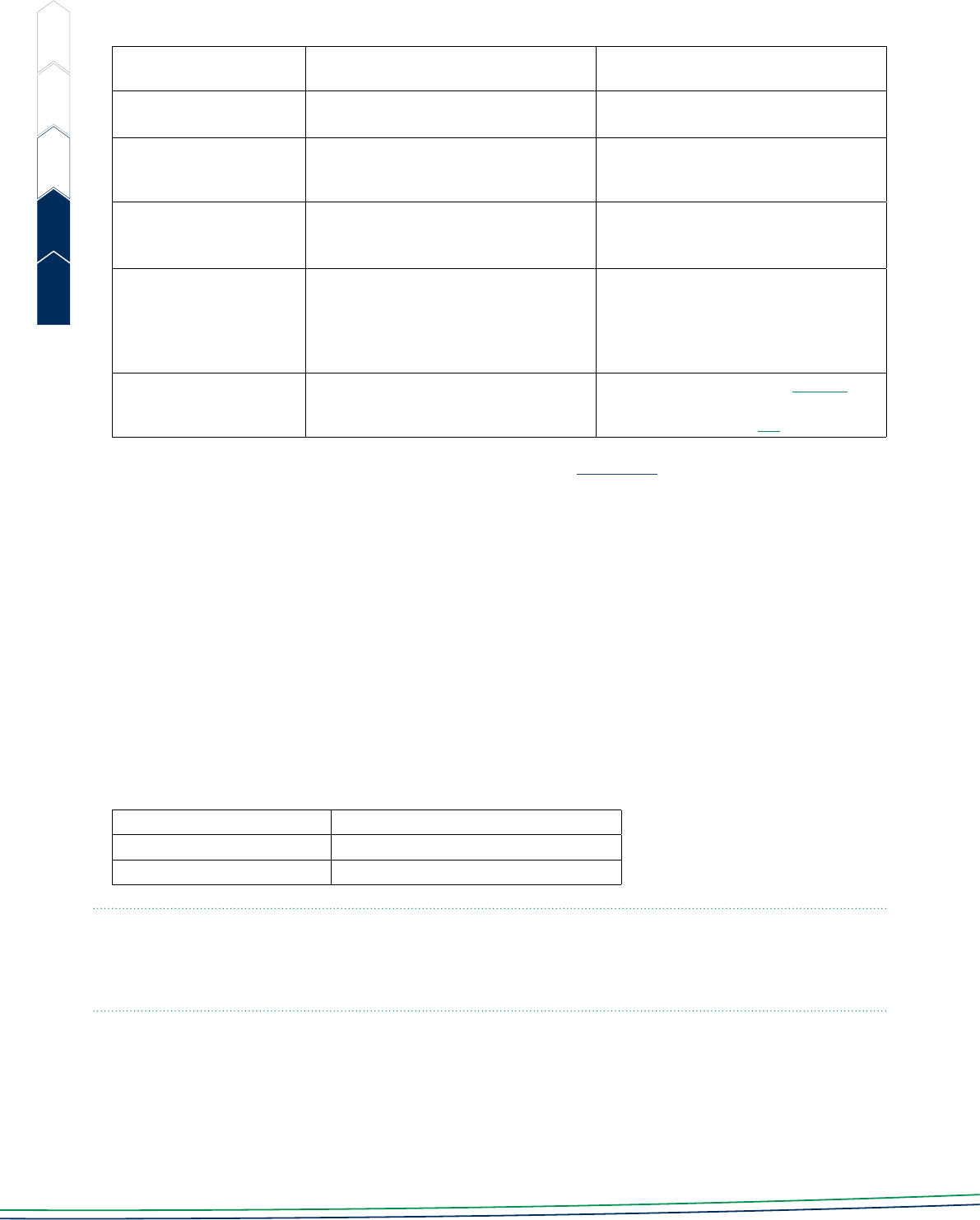

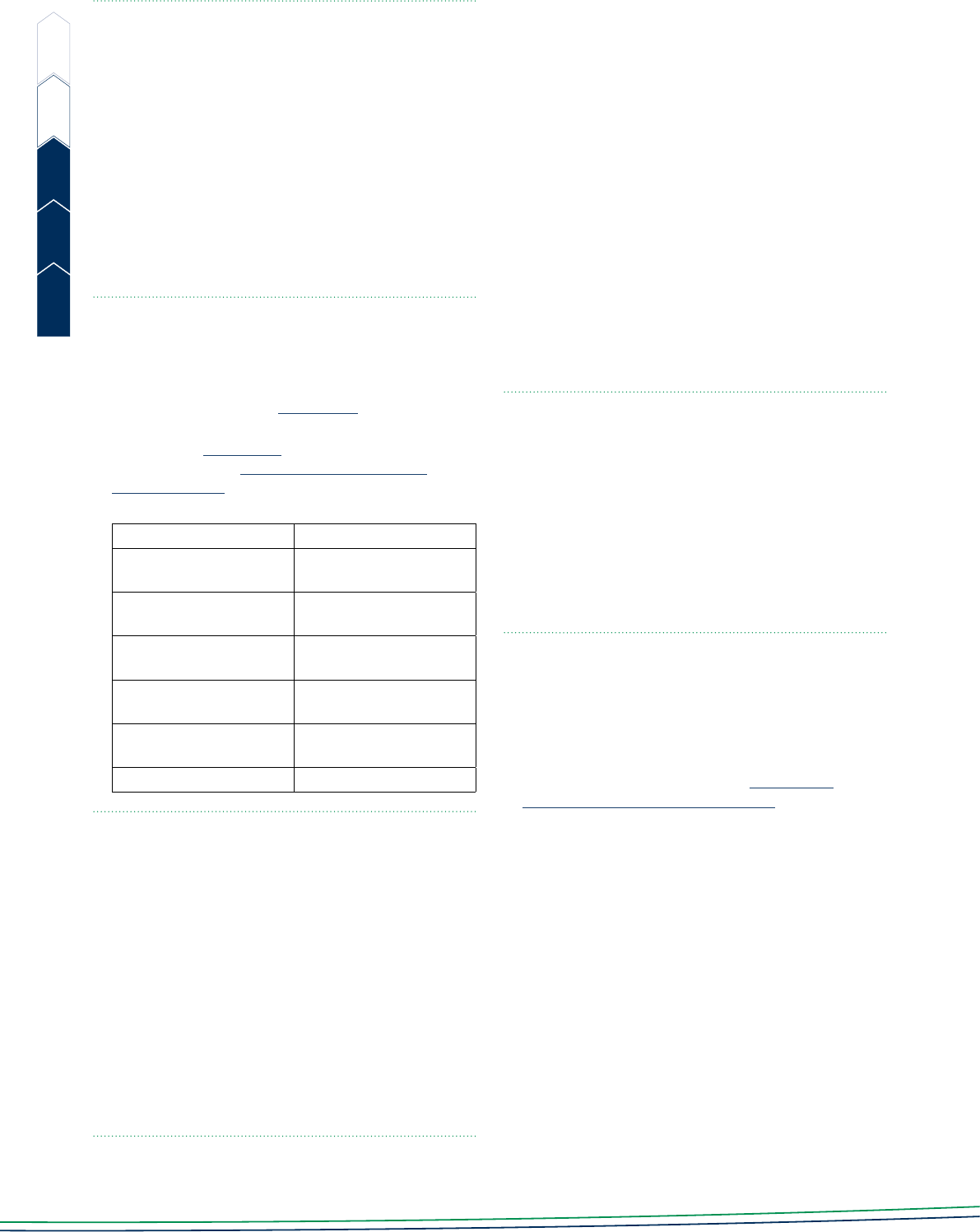

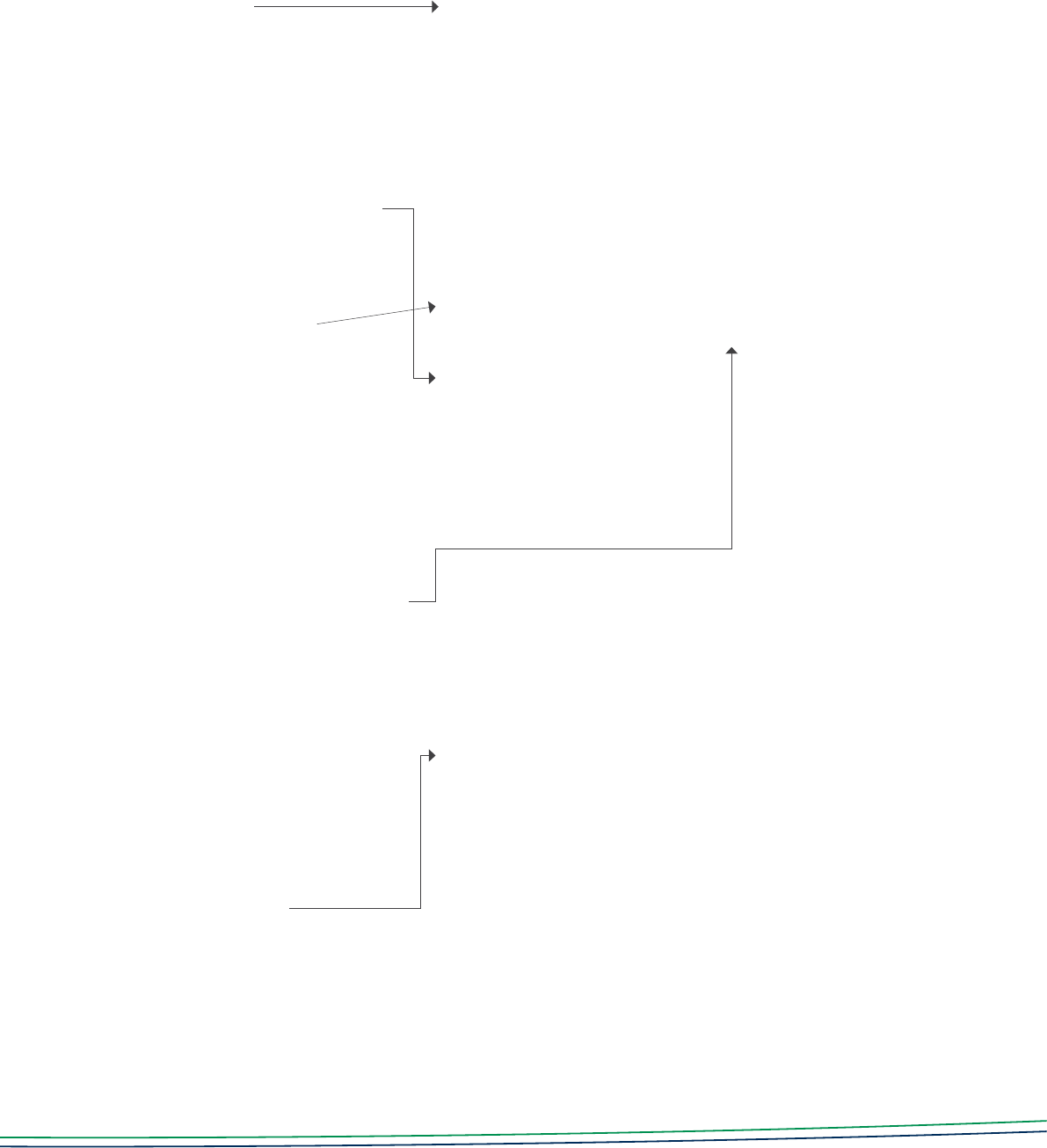

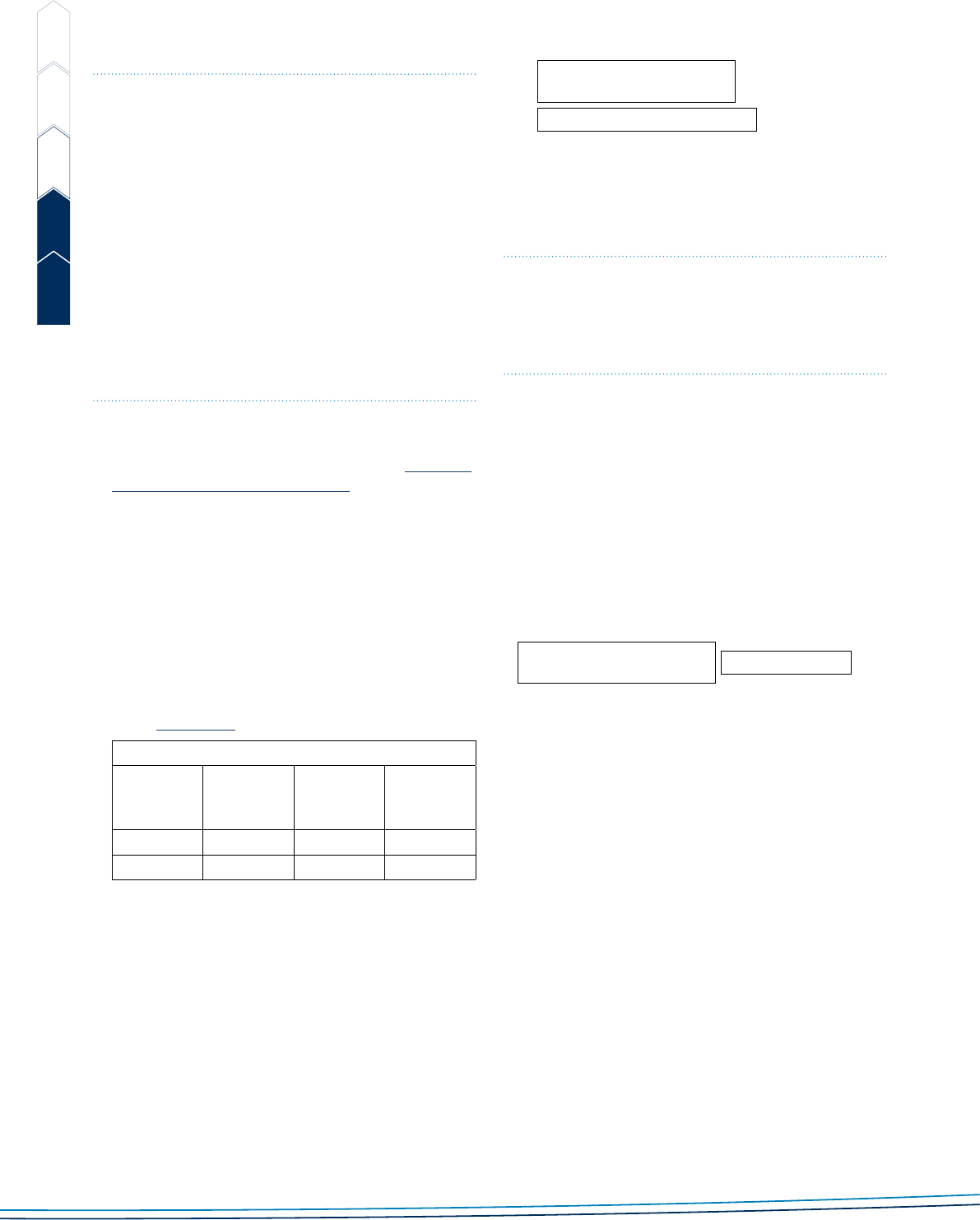

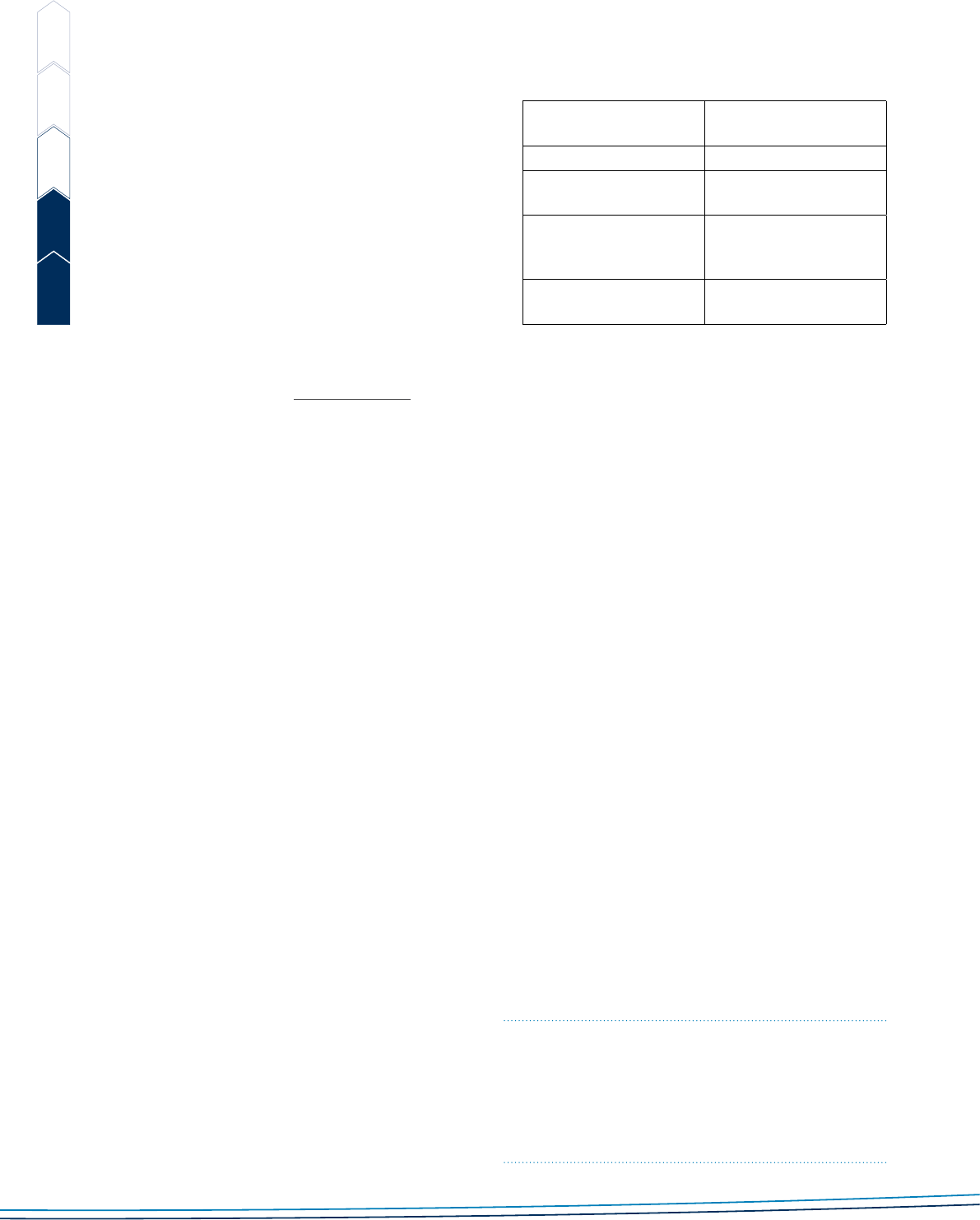

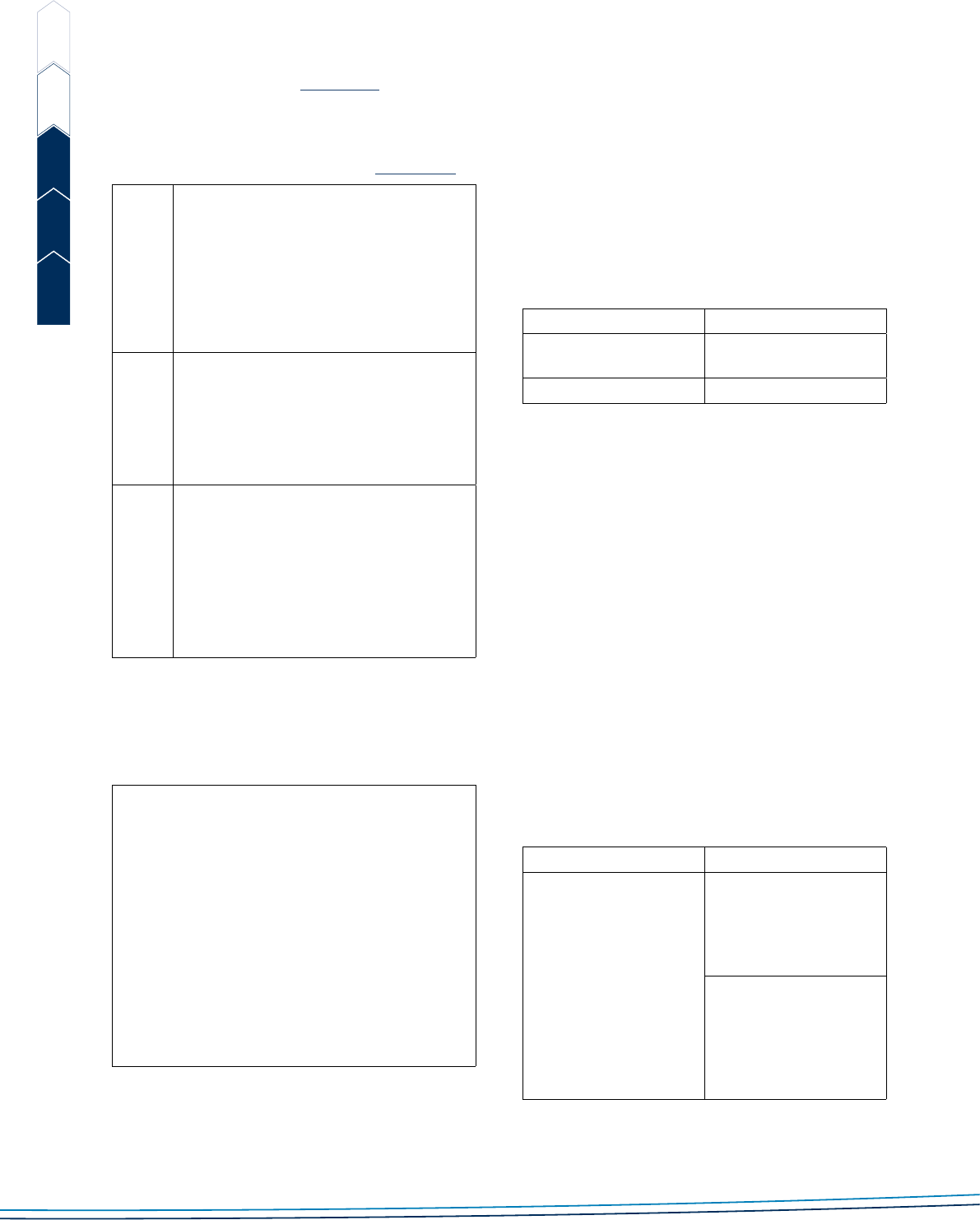

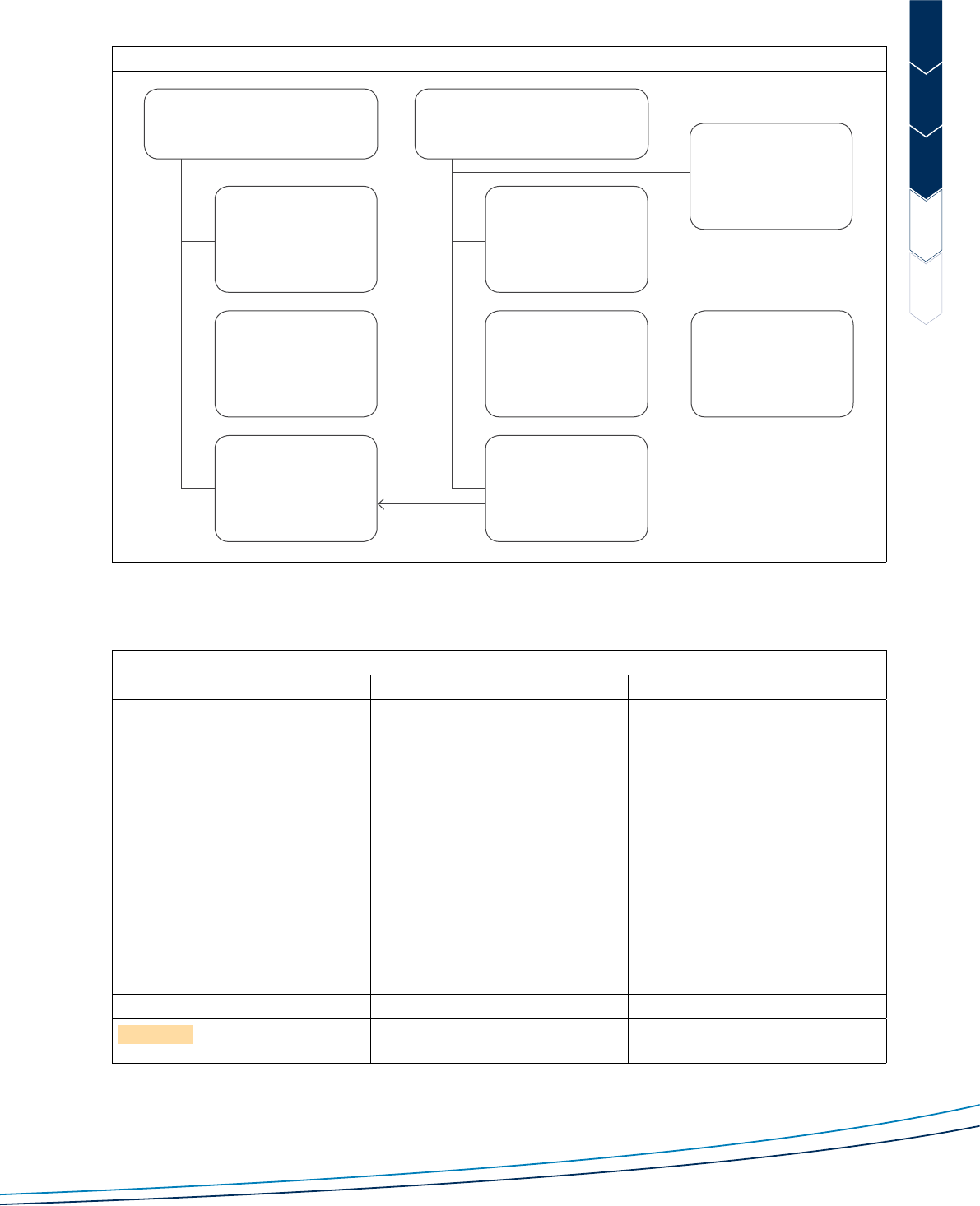

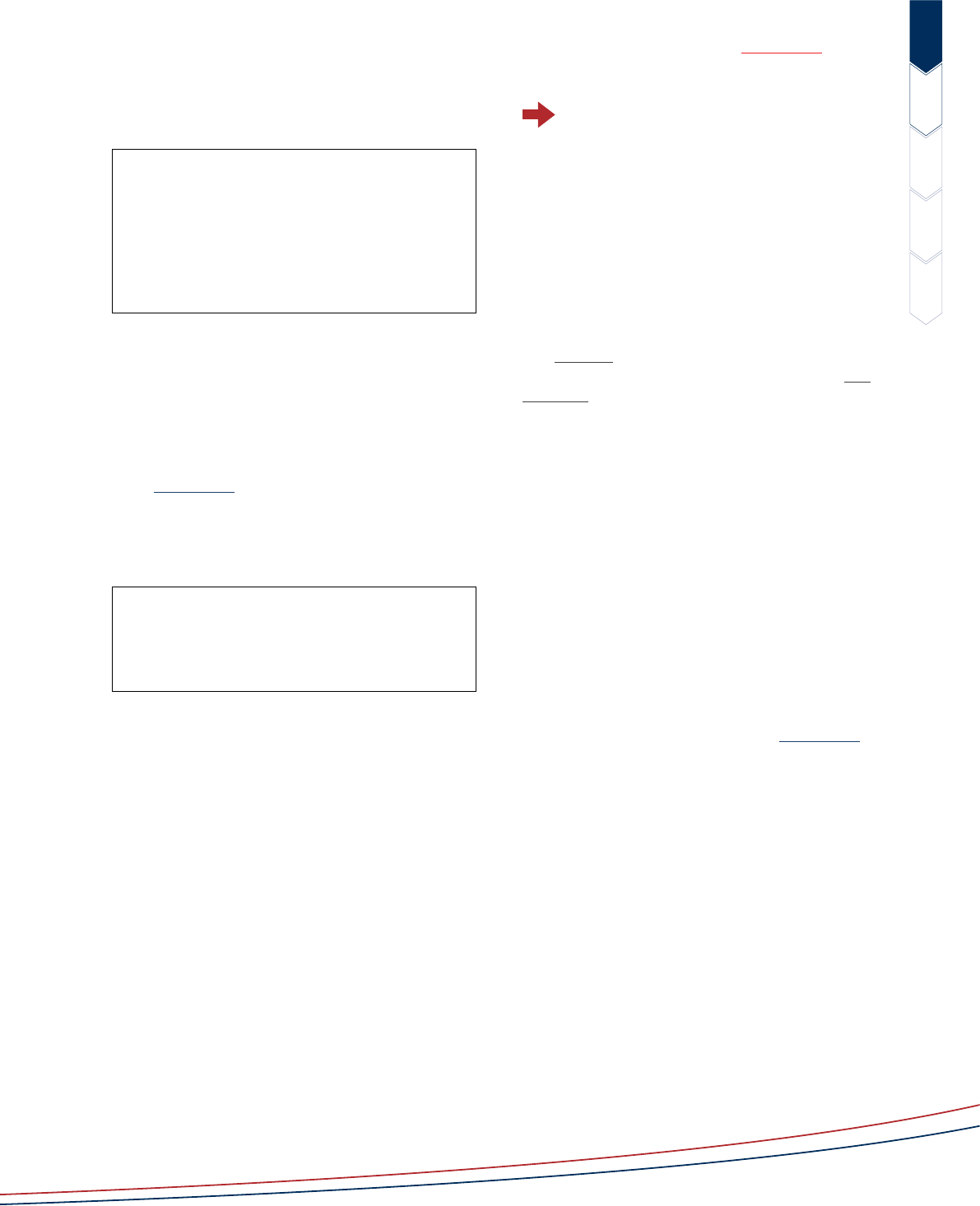

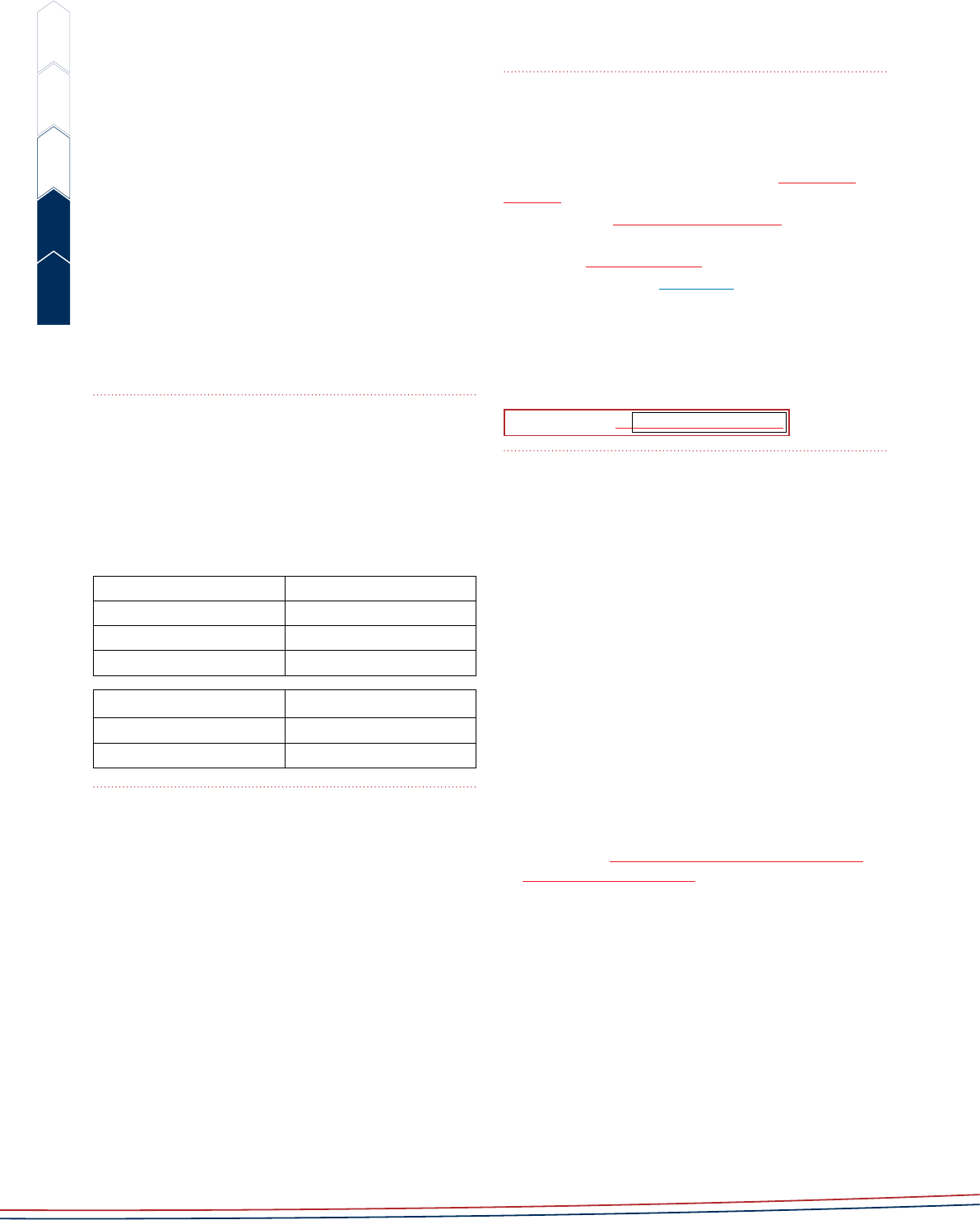

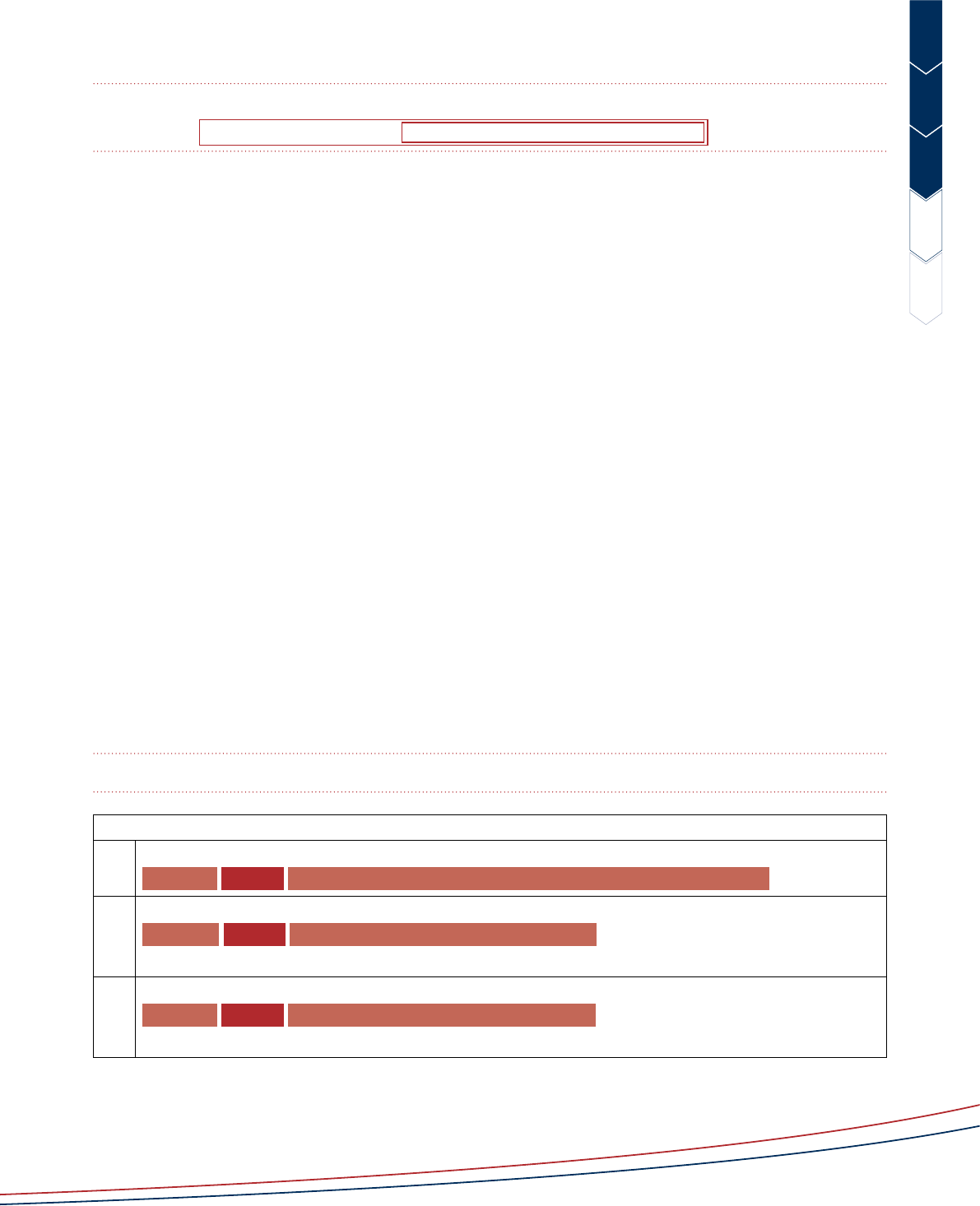

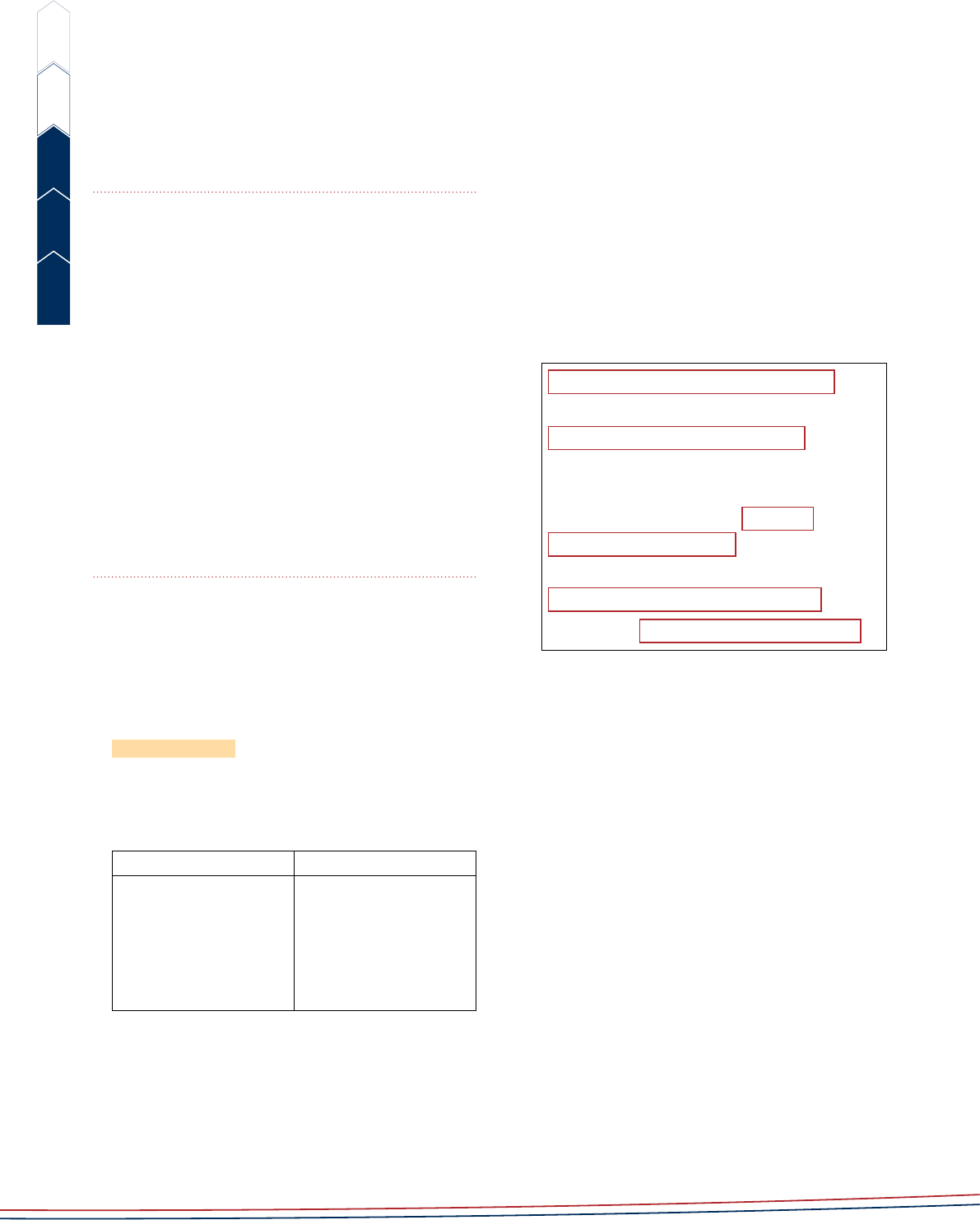

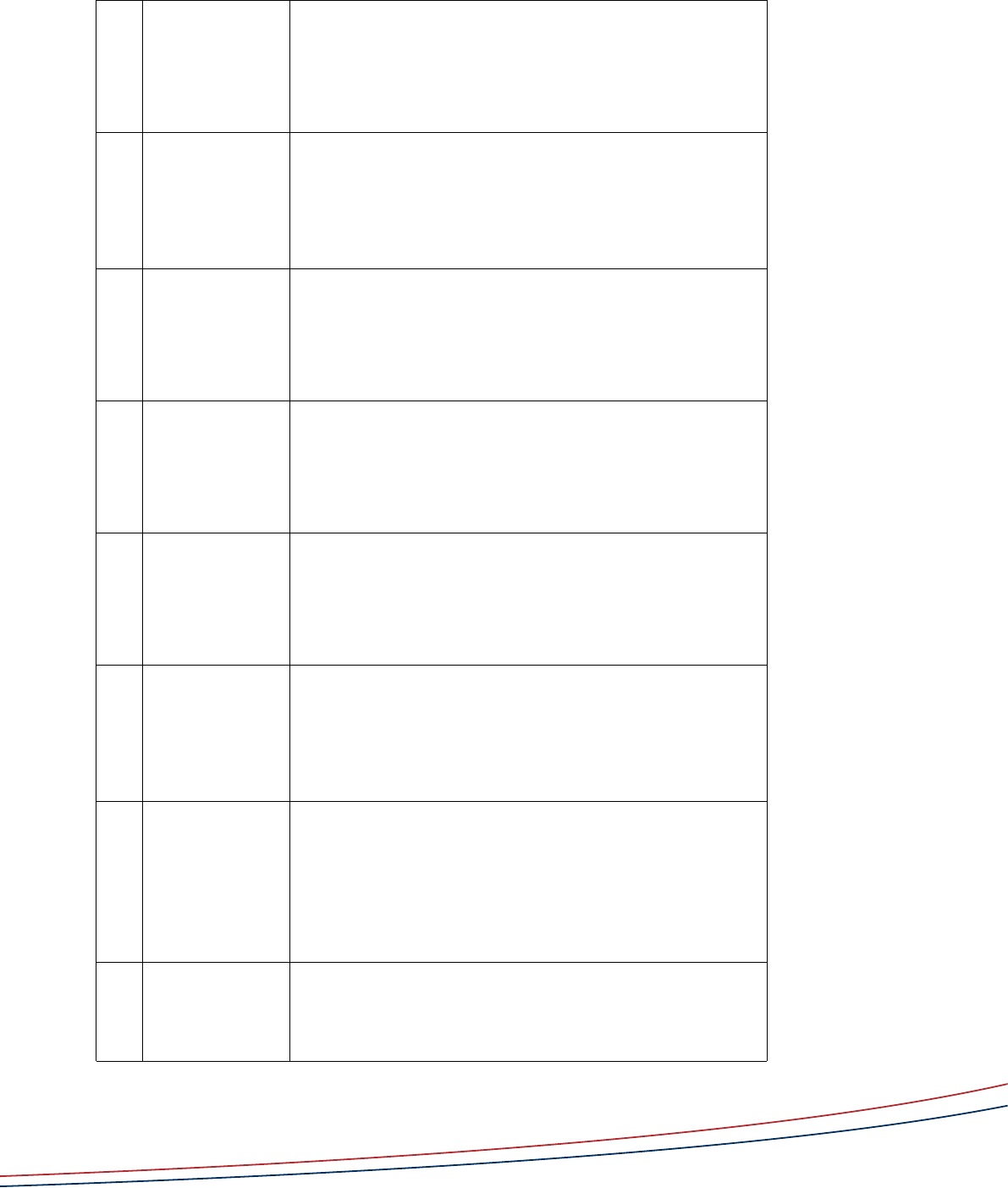

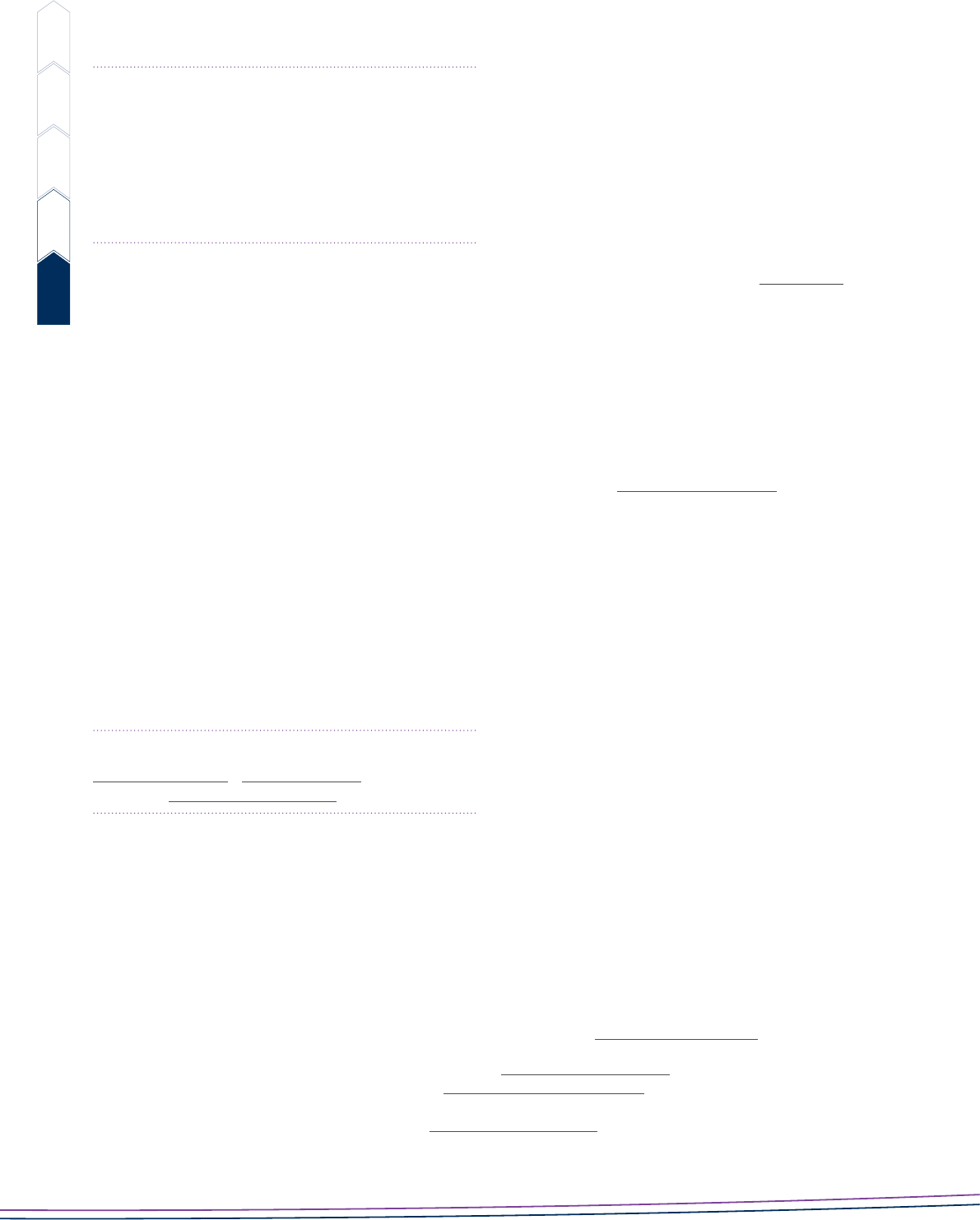

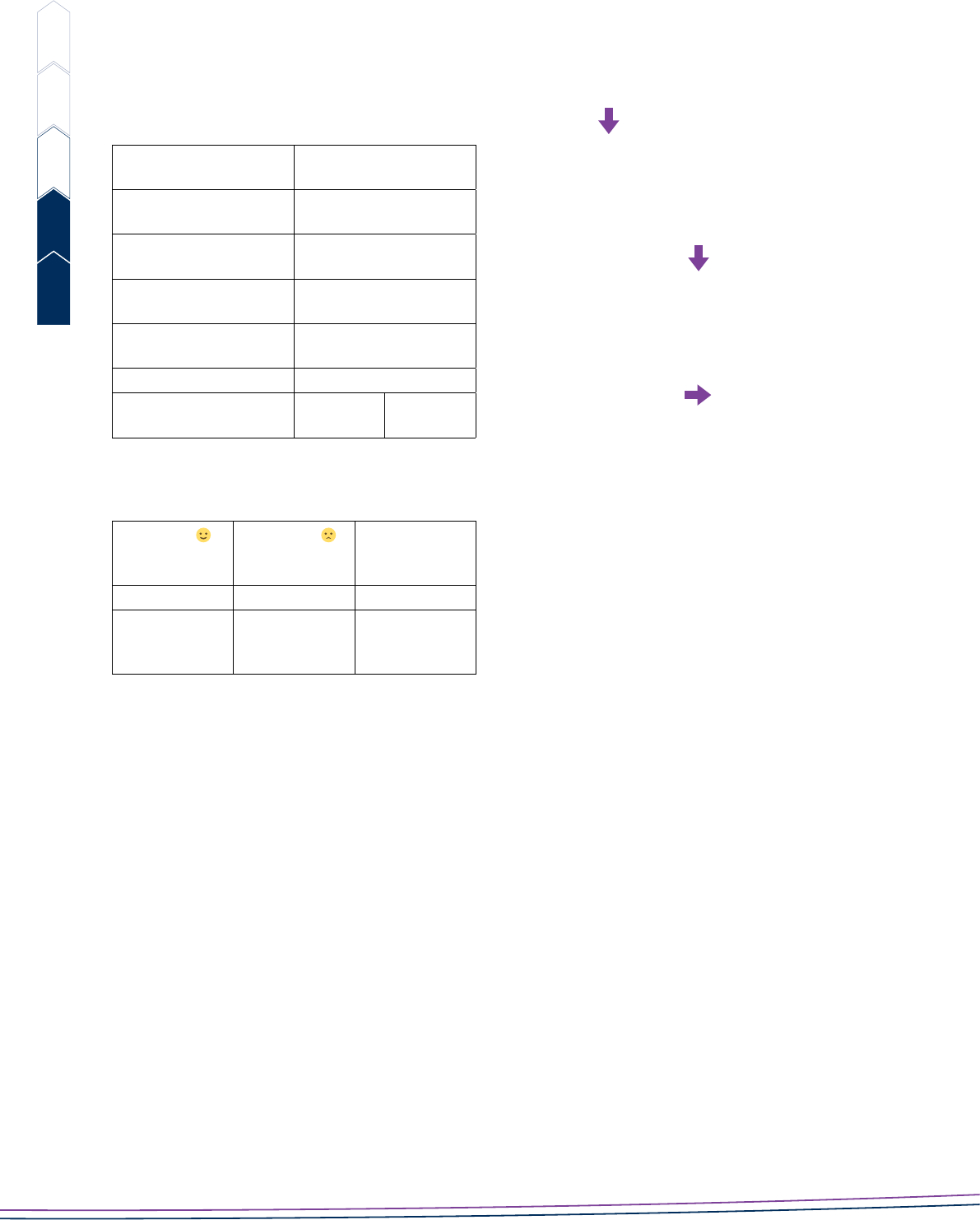

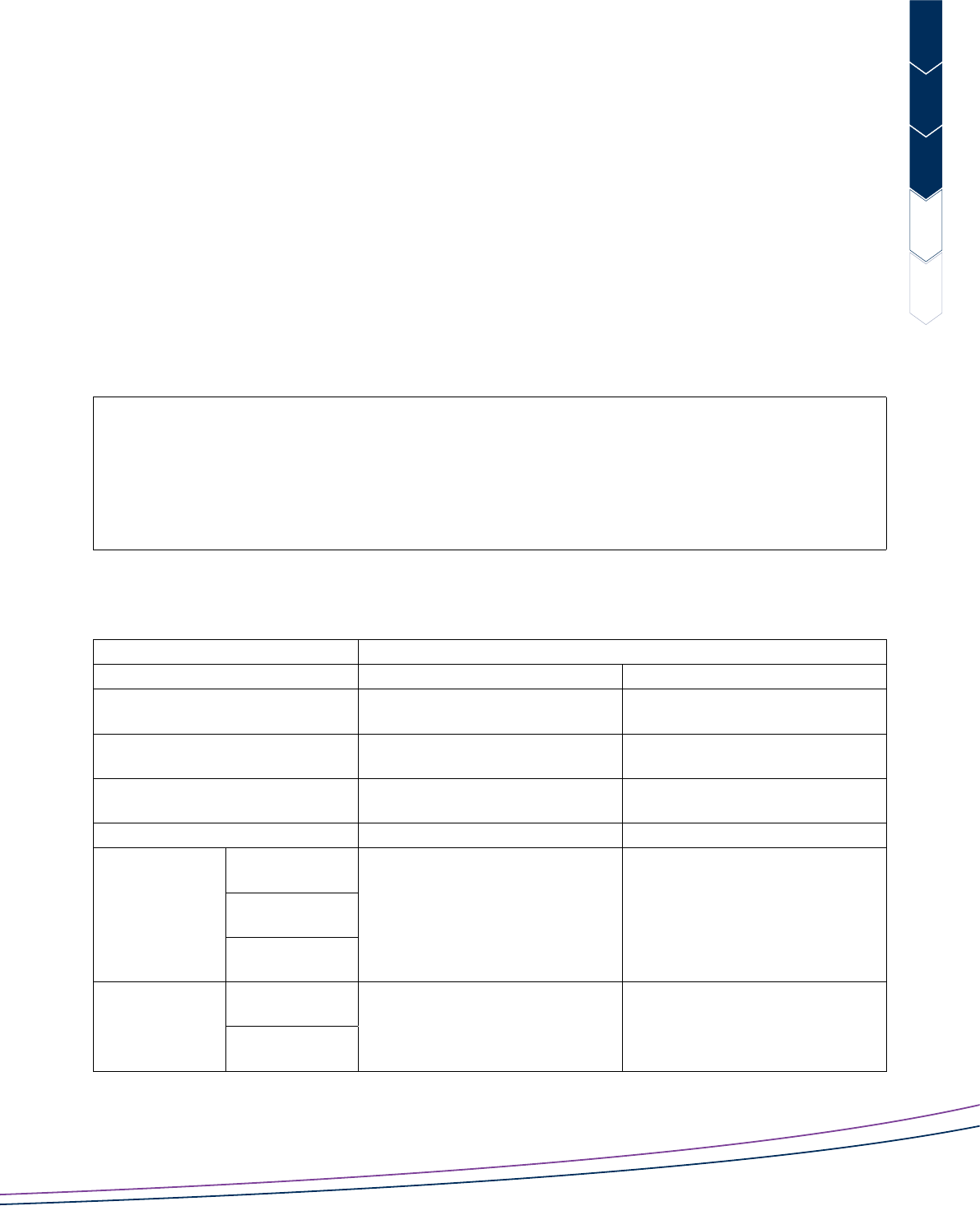

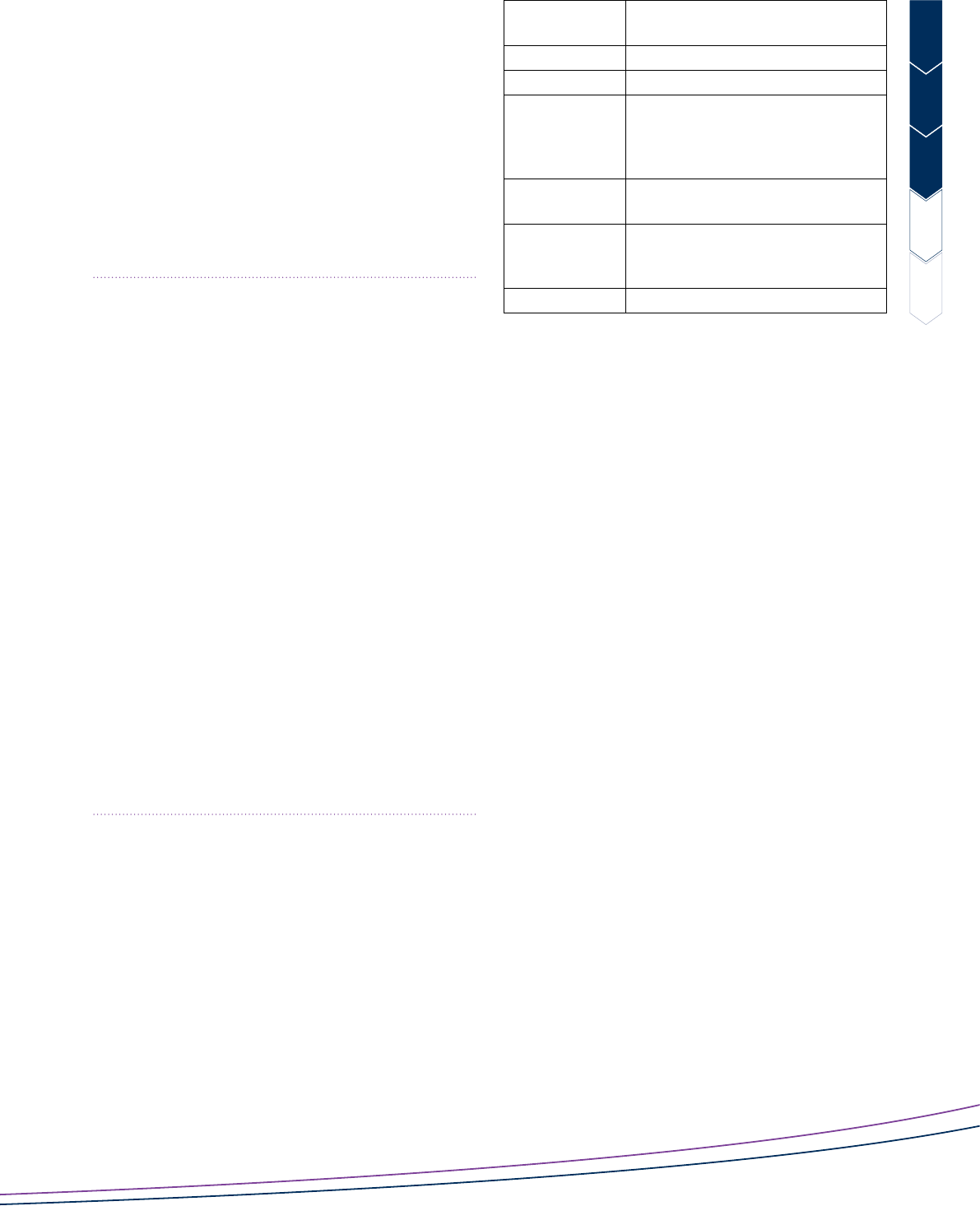

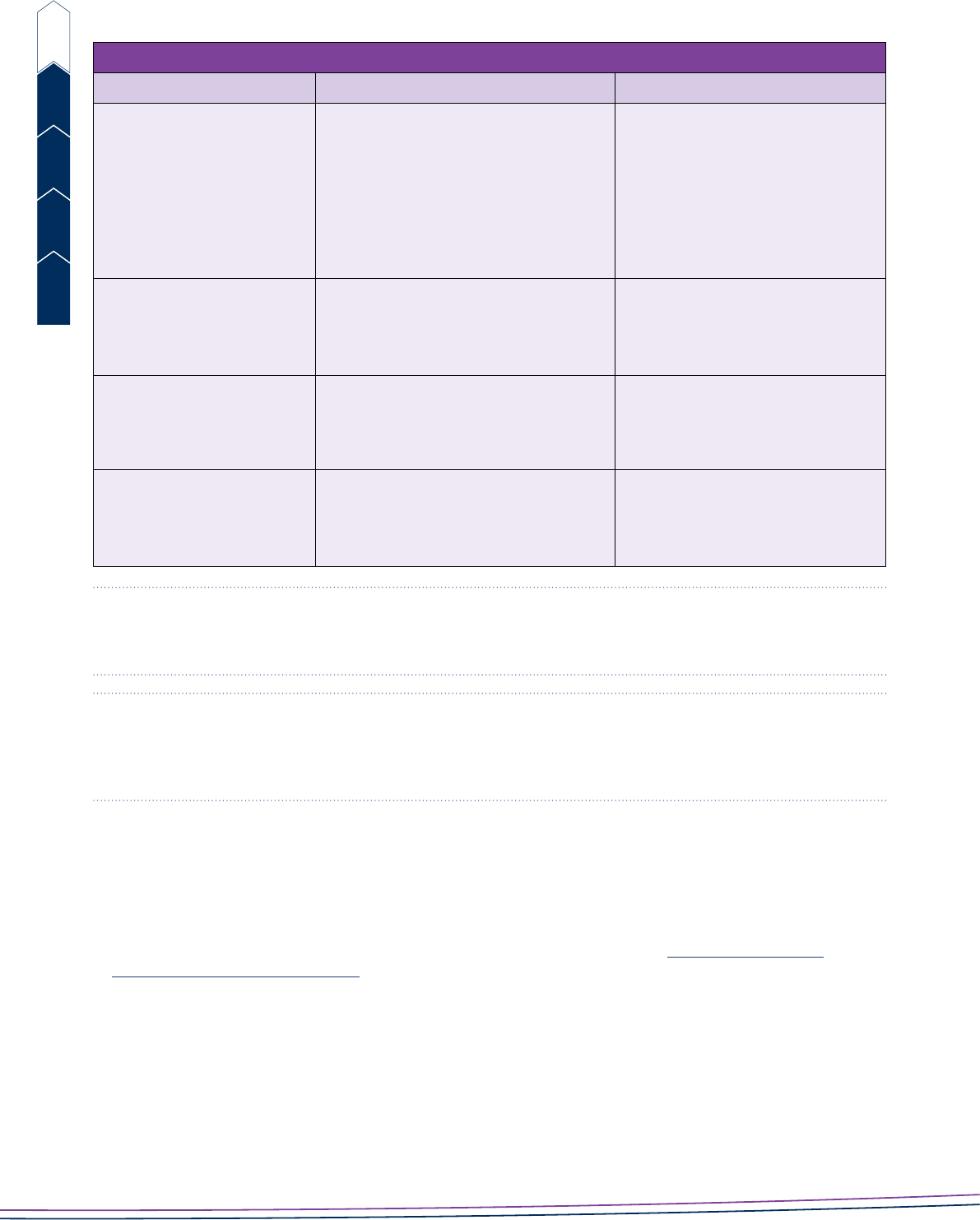

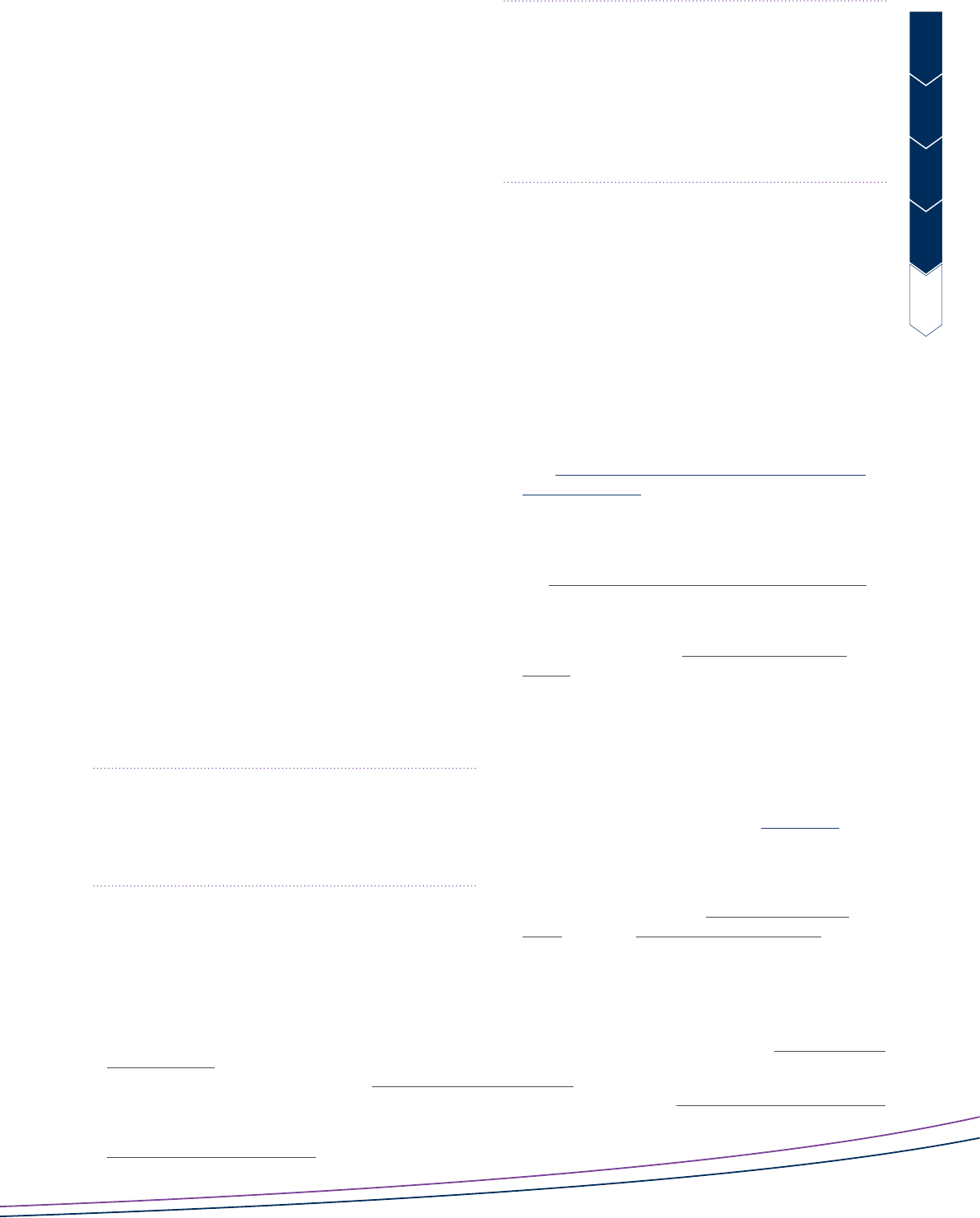

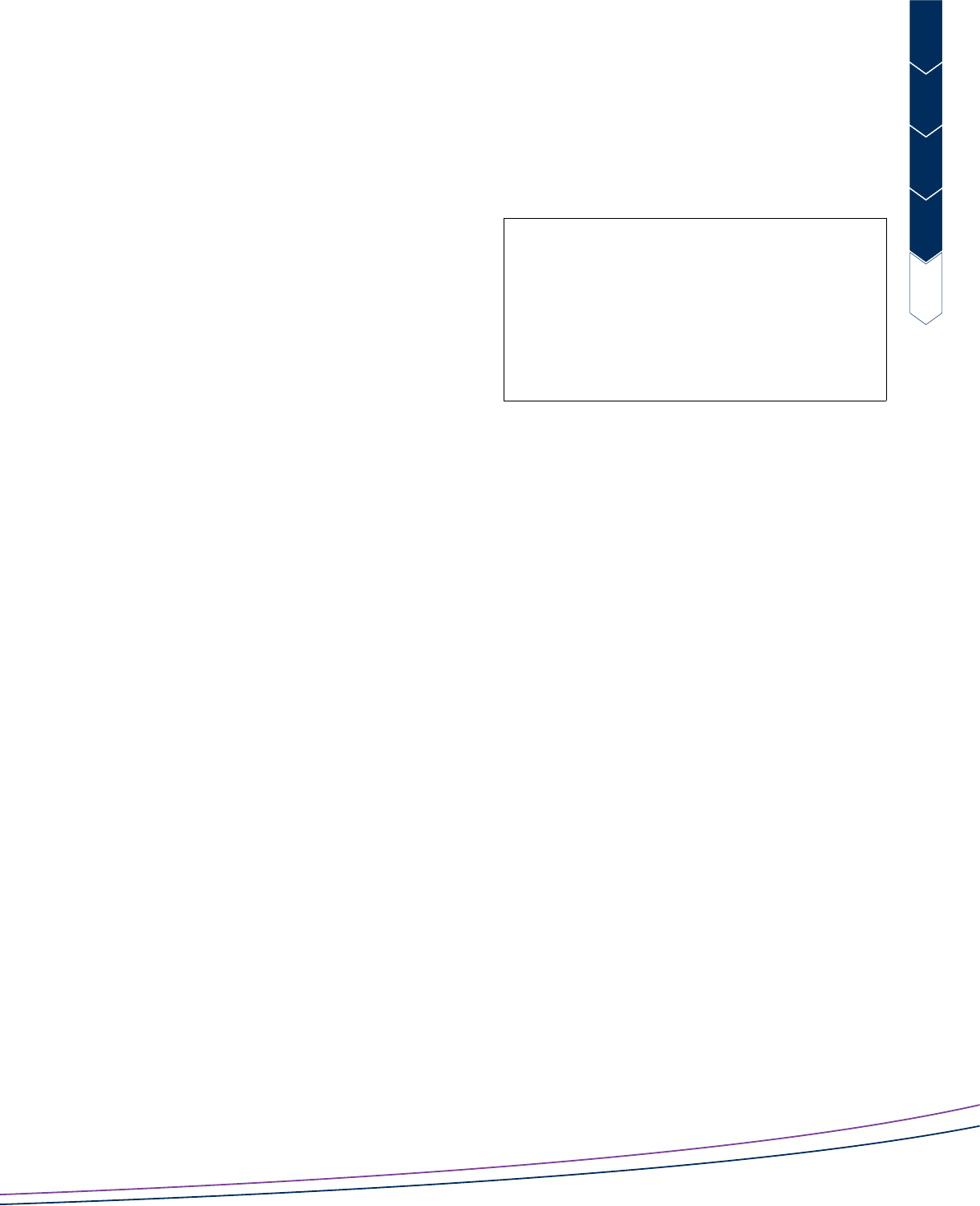

The diagram in the next column shows how the

teaching and learning cycle is situated in dialogic

processes, which lead to understanding about

content, text and language

(DECD, 2018b). Many of

the strategies here involve group and pair work

because ‘talk is a critically important tool in securing

meaningful learning about language’

(Myhill, Jones,

Watson & Lines, 2016:5).

Carefully sequenced learning is essential for students to

develop enough knowledge, skills and understanding

to transfer their learning:

The movement from surface learning—the facts,

concepts and principles associated with a topic

of study—to deep learning, which is the ability to

leverage knowledge across domains in increasingly

novel situations, requires careful planning.

(Fisher, Frey, Hattie & Thayre, 2017:18)

Building knowledge of the field

Developing content knowledge for specific learning

areas should include activating prior knowledge,

hands-on activities, exploratory learning – talk

accompanying action, learning to hear, and trying out

new vocabulary. This is also the time for engaging

learners’ interest in the topic: it is vital for engagement

and motivation for learning to be inclusive of students’

cultural experiences and welcome the use of home

languages in these initial discussions.

Supported reading

When learning to read is located in learning about

curriculum topics, there is a clear context and purpose

for reading which improves both engagement and

comprehension. It is a time to refer back to questions

about the learning topic and develop knowledge and

understanding in both the content and the language

required to access and utilise the content. Reading

procedures, such as shared reading, guided reading

and close reading, can focus on specific strategies

needed to comprehend learning area texts, for

example, the structure, language and key vocabulary

Supported

writing

Supported

reading

Learning

about the

genre

Independent

use of the

genre

Building

knowledge

of the field

Assessing

student

progress

T

A

L

K

I

N

G

T

O

L

E

A

R

N

Teaching and learning cycle

(Adapted from DECD, 2018b:13)

Identified

target

language

Curriculum

topic

Authentic

mentor and/or

model texts

2

http://TLinSA.2.vu/Big6vocab

Learning English: Achievement and Proficiency (LEAP) | STRATEGIES INTRODUCTION | 5

of an information text in science. Talking about

learning area texts and responding to reading

through writing journals and other daily activities

prepares students for composing their own writing

in the target genre.

The key point is that through talk and writing,

students are able to build a richer representation

of the content of the texts they read and deal with

the question that vexes every writer: How can I

find a way to say that so others will understand?

(Duke, Pearson, Strachan & Billman, 2011:78)

Learning about the genre

Ensure that students understand that genres have

particular purposes and are written with a specific

audience in mind. Wherever possible, connect

the target genre to outside of school examples,

so students understand they are learning to use

language ‘like a scientist’ or ‘like an historian’.

Provide multiple examples of the target genre and

support students to identify the generic features

they need to incorporate into their writing. Make the

target genre the focus of dialogue in the classroom,

so students can determine what they need to know

and learn to shape their content knowledge using the

target genre. Many of the language activities described

in this document will be situated in this part of the

teaching and learning cycle, as EALD learners in

particular will require repeated opportunities to learn

and practise new language structures.

Students learning English need to know how written

English diers from spoken English

(Gibbons, 2011).

By explicitly teaching language at word, sentence

and text level, you build each student’s repertoire

of language resources:

Showing learners the grammatical choices writers

make, and the grammatical choices they can make as

writers, can alter the way their writing communicates

and their understanding of the power of choice.

(Myhill, 2018)

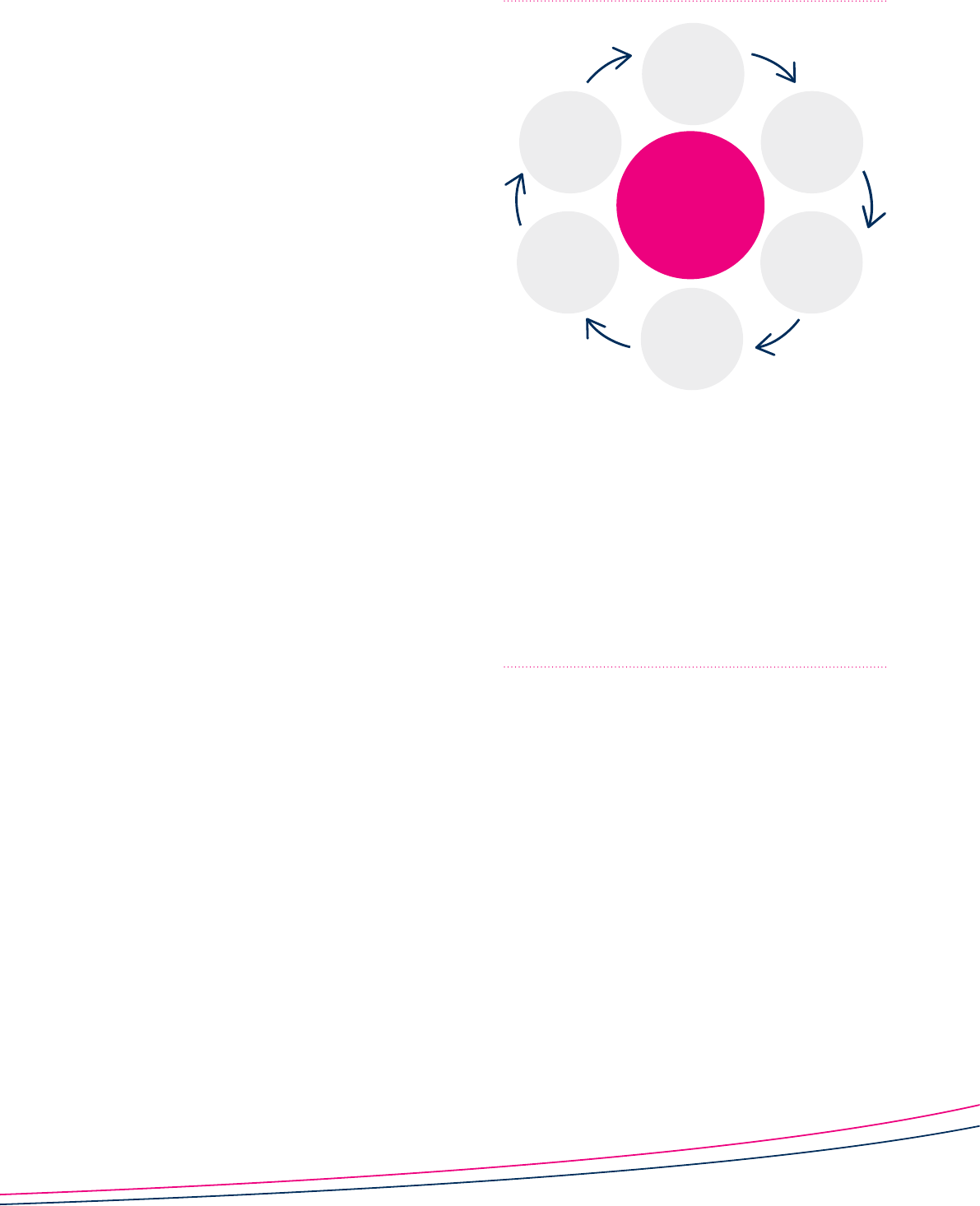

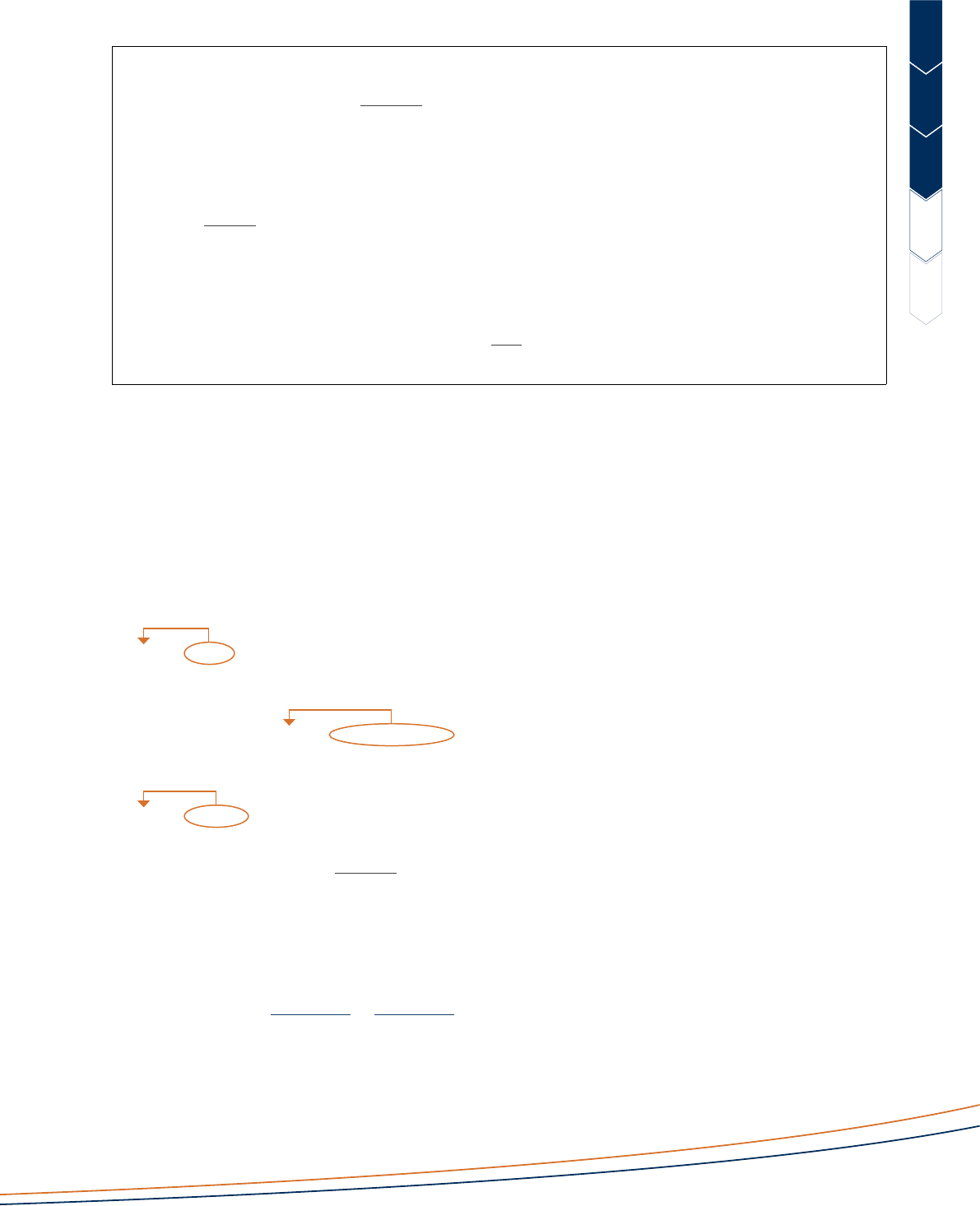

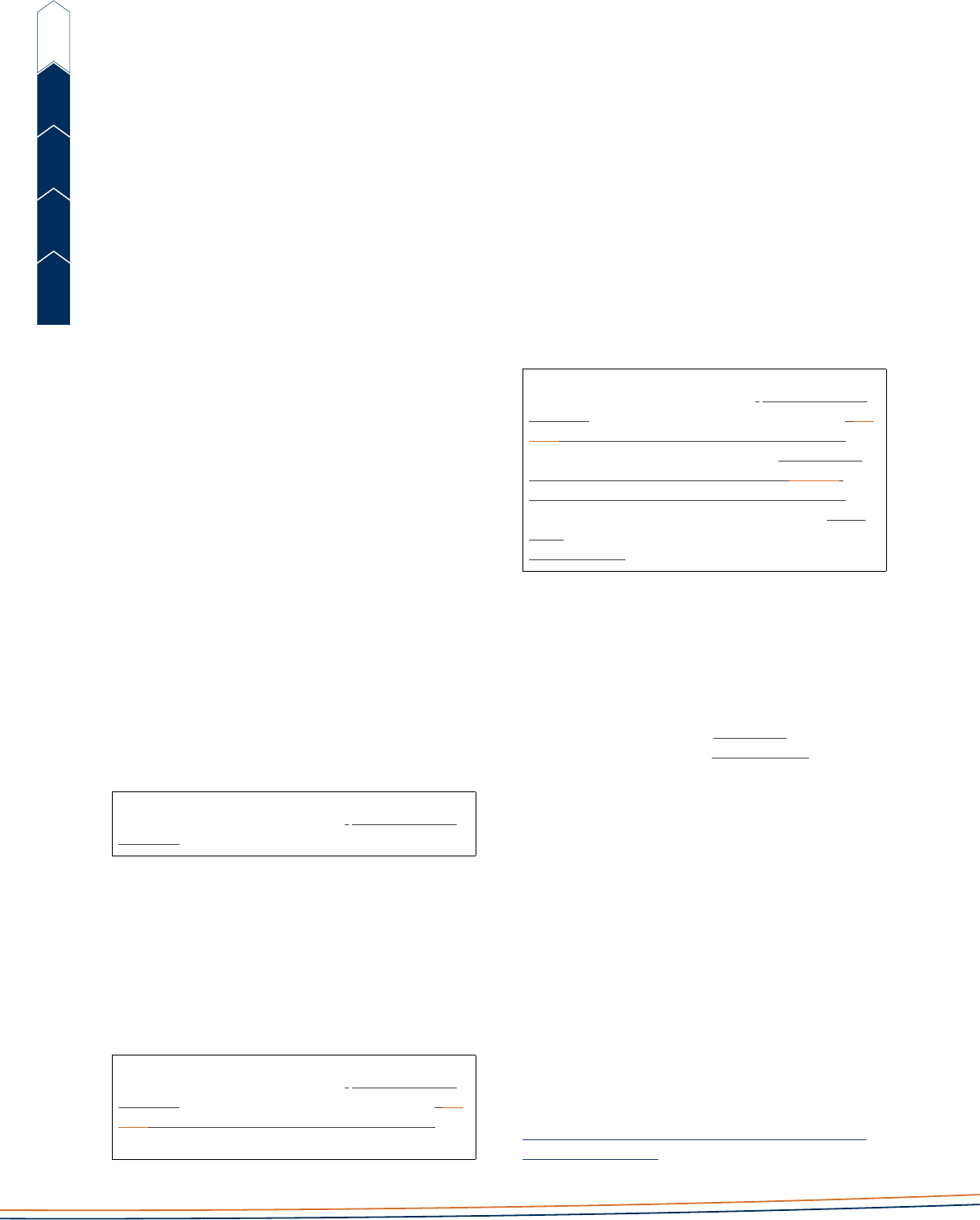

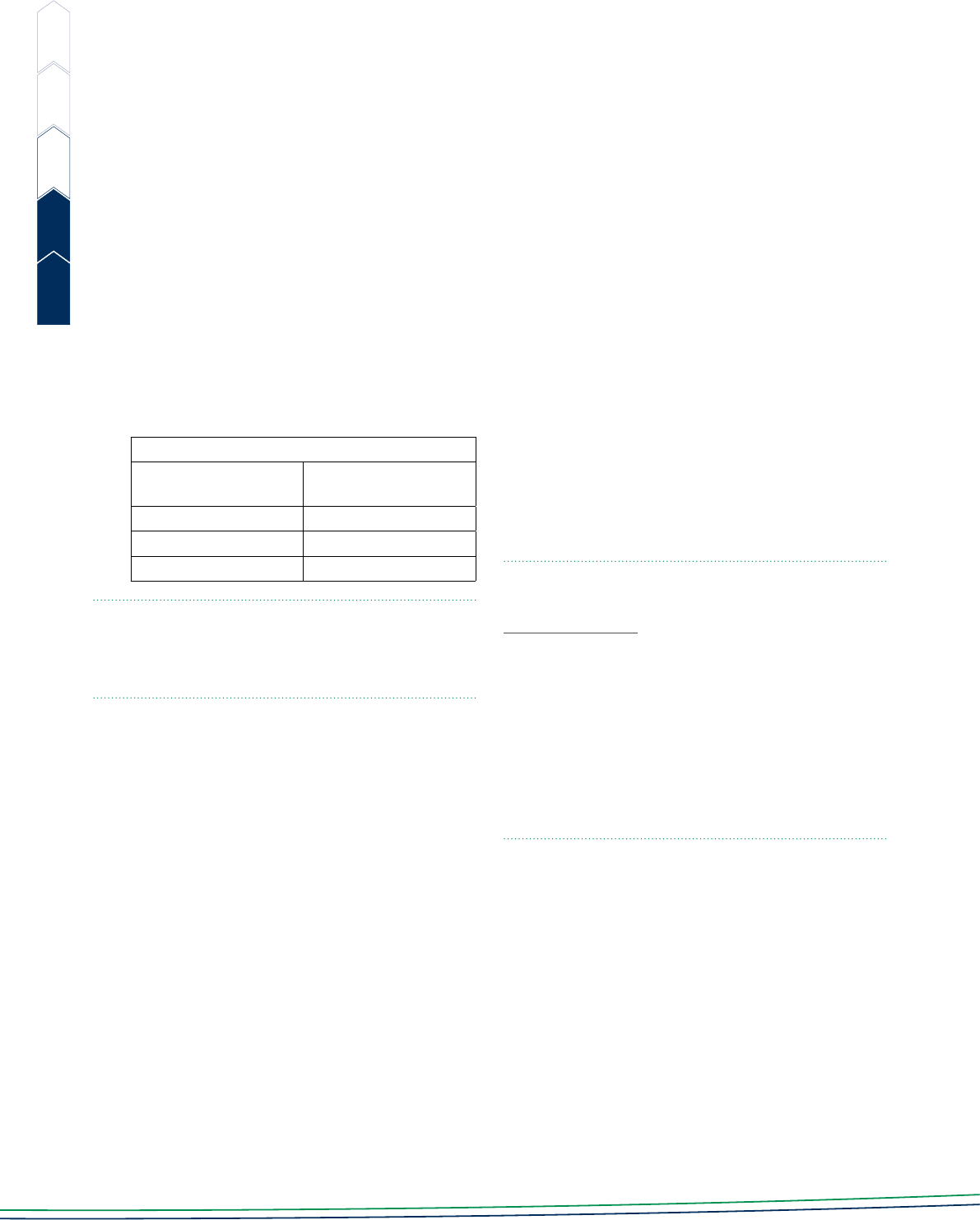

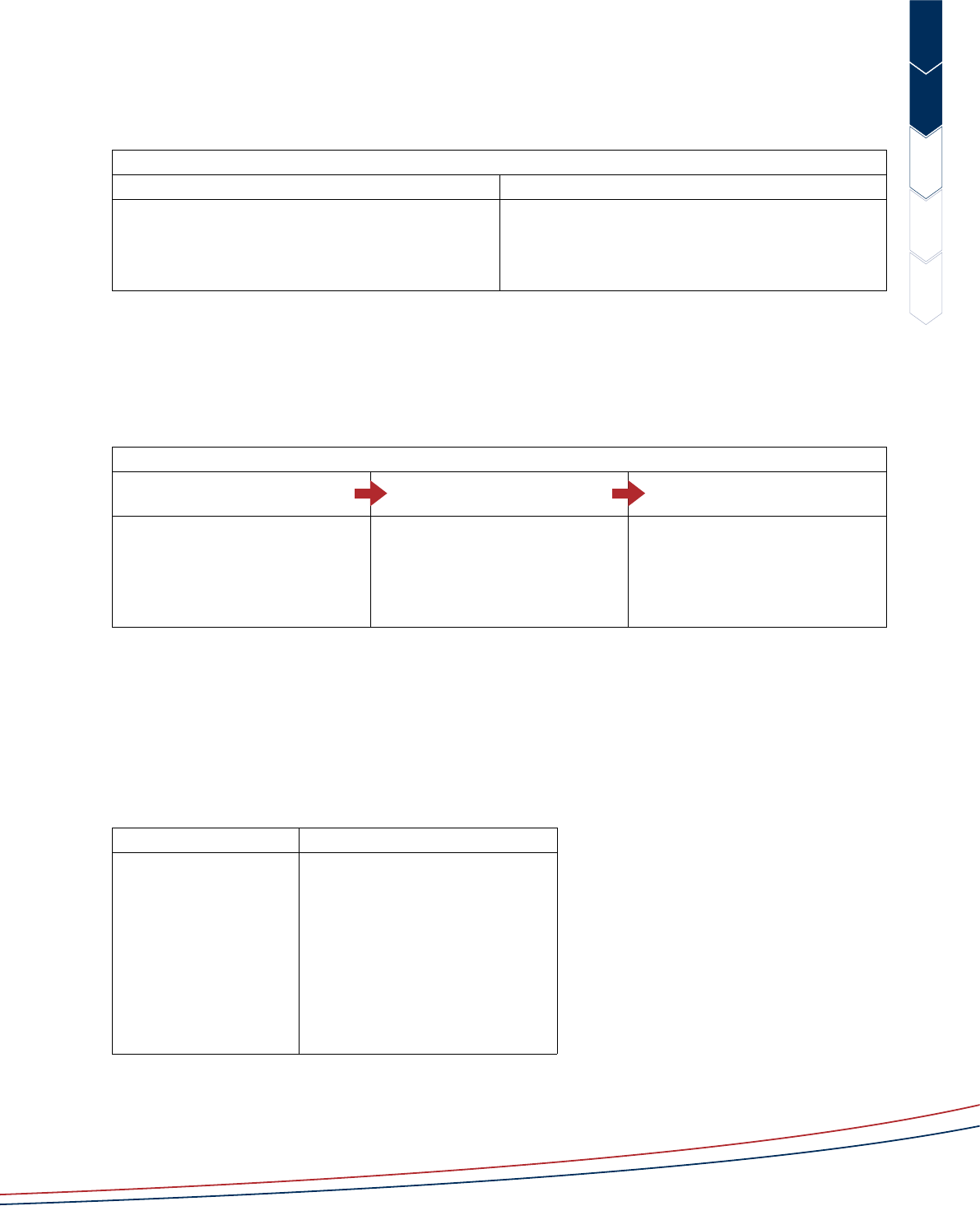

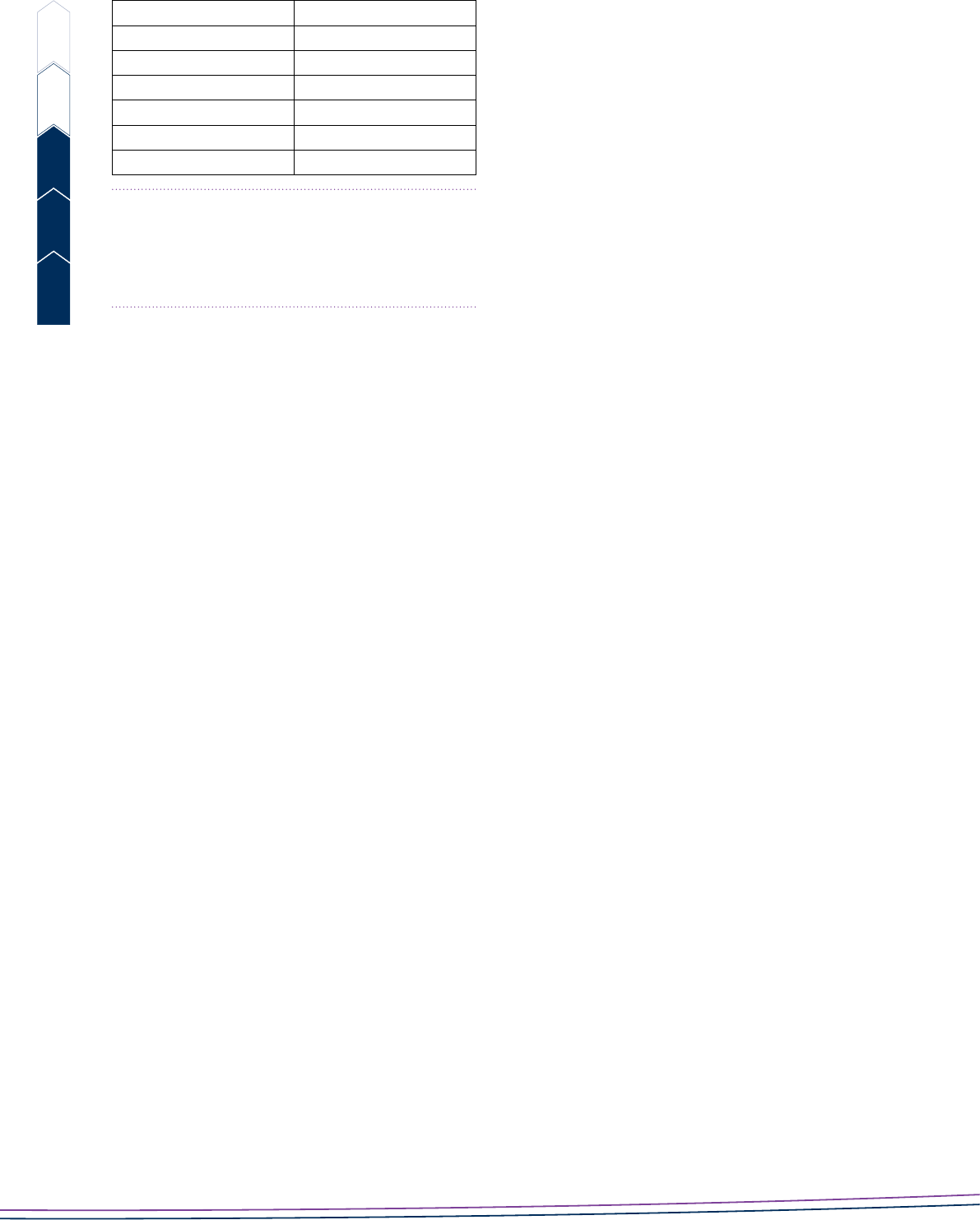

Supported writing

Support students to incorporate all they have learned

about content, genre and language into a new text

through joint construction, prior to students writing

independently. Time invested in this process is essential

if students are to move from ‘talk about content and

texts’ to the denser and highly structured language

required to purposefully write about content for an

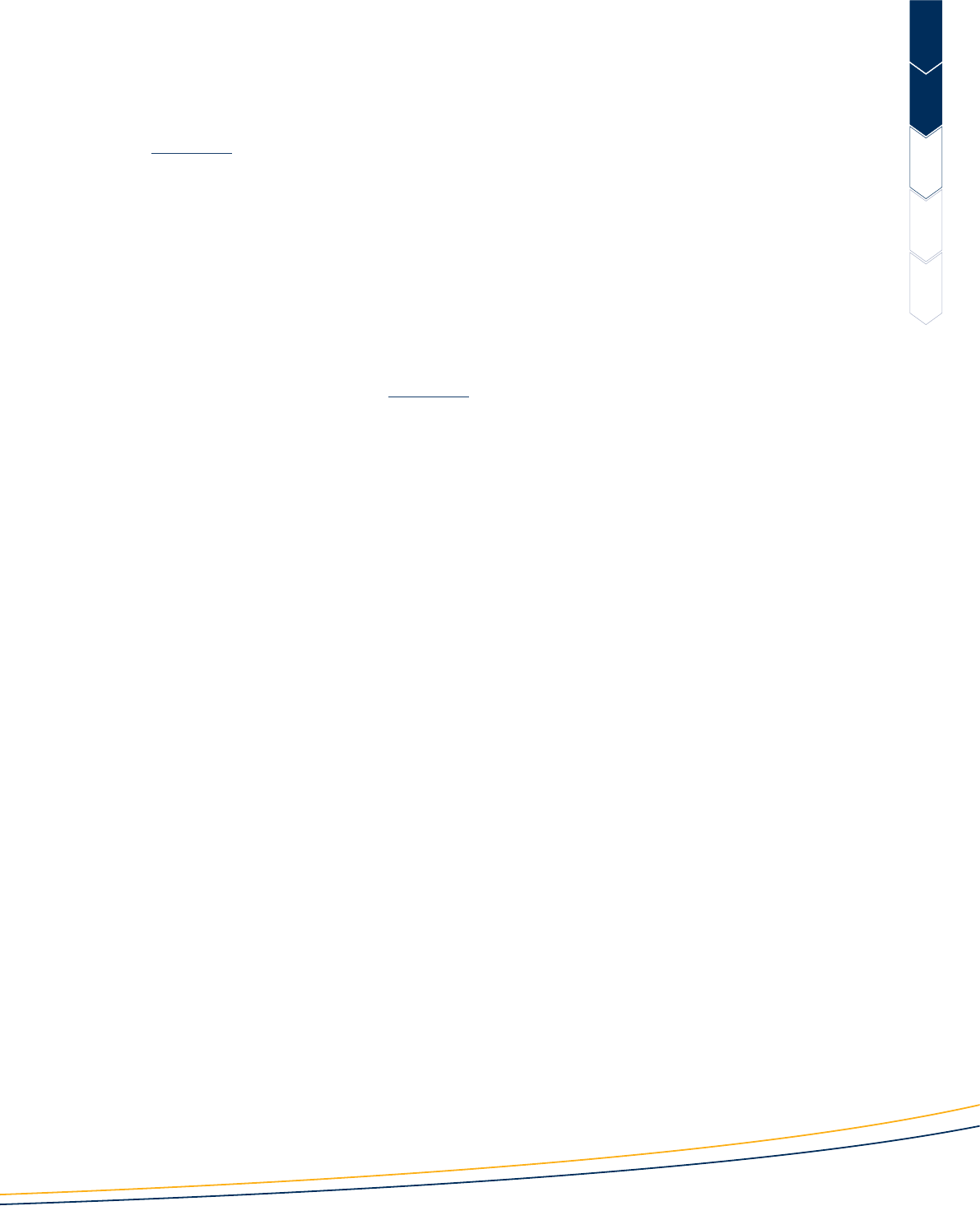

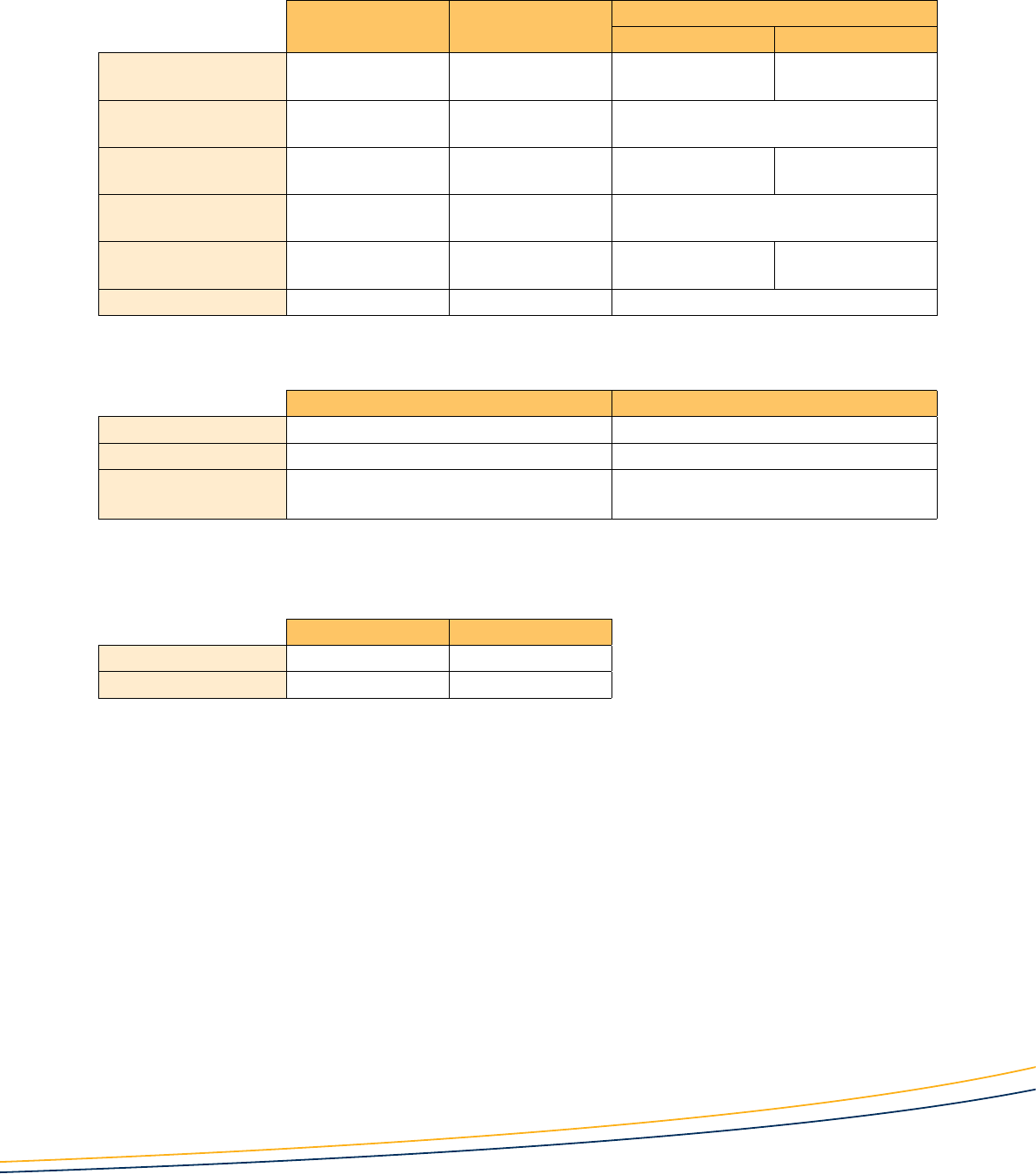

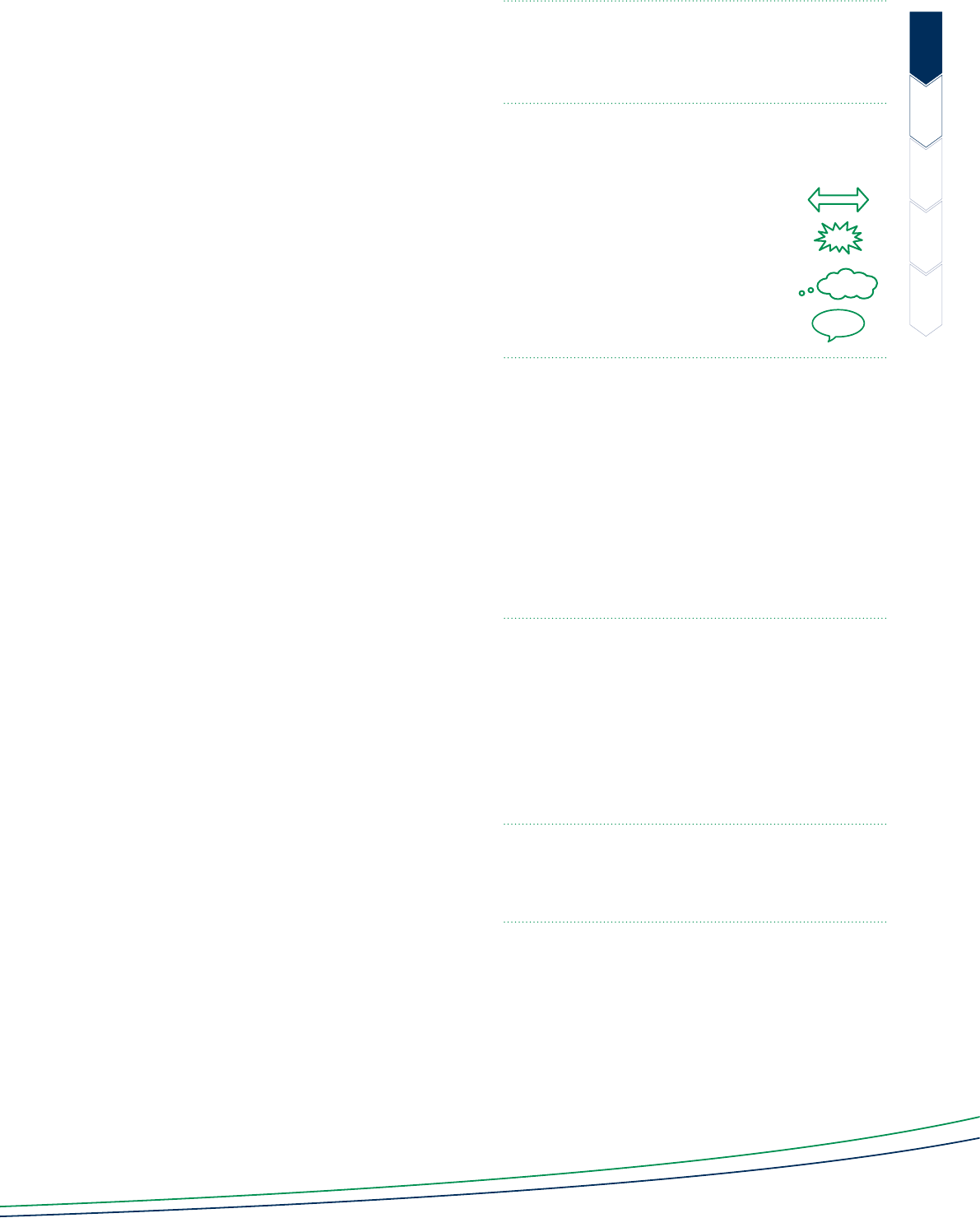

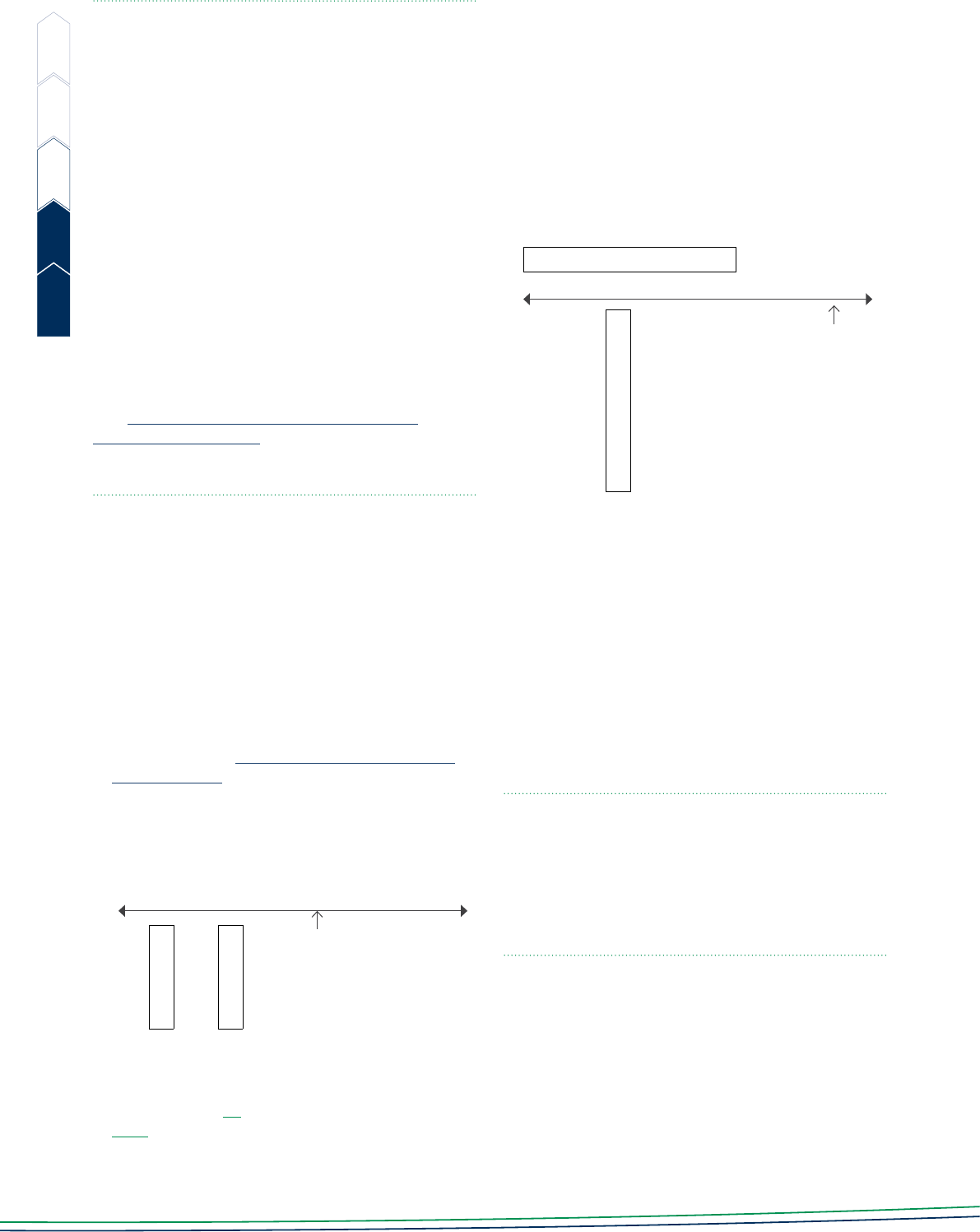

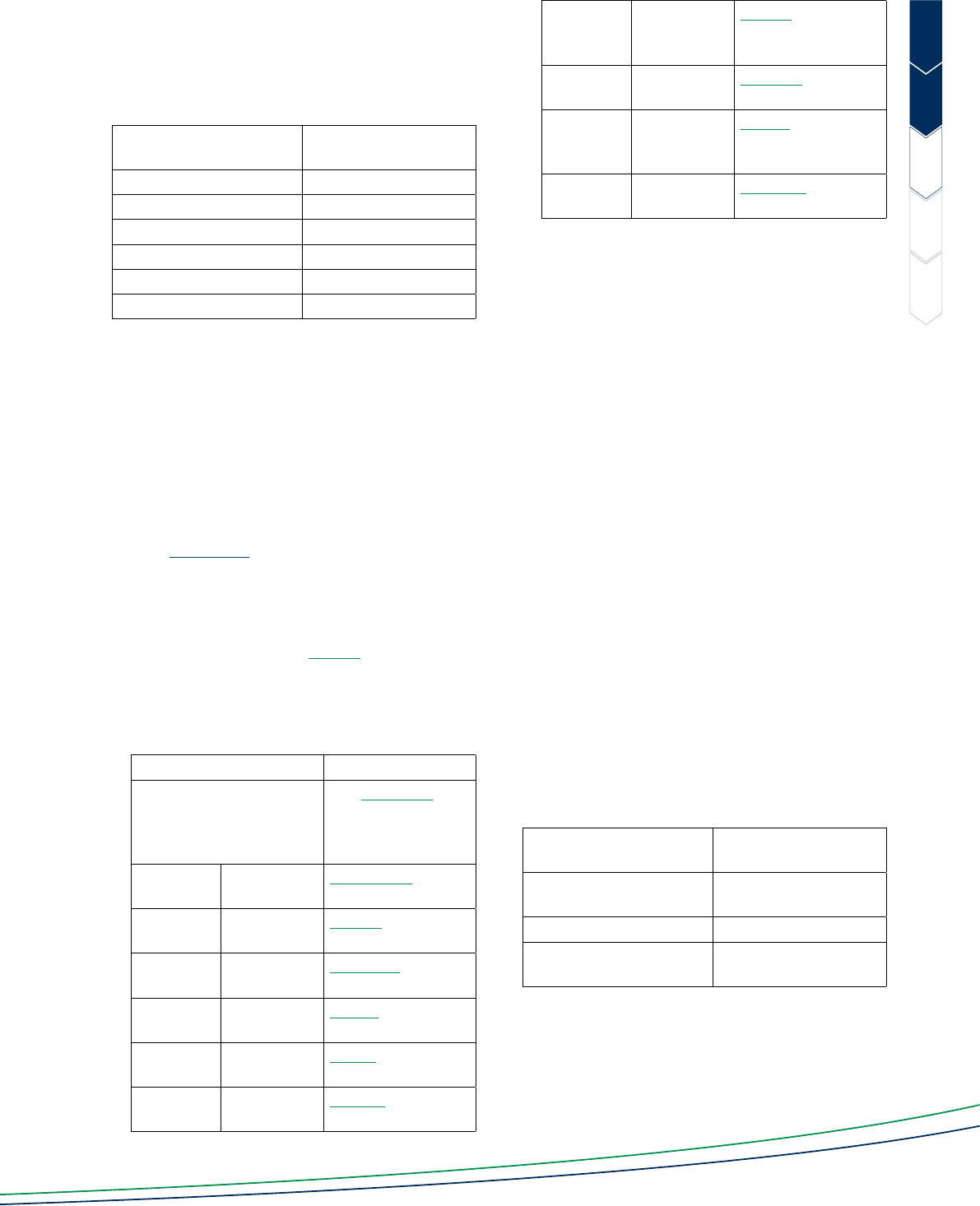

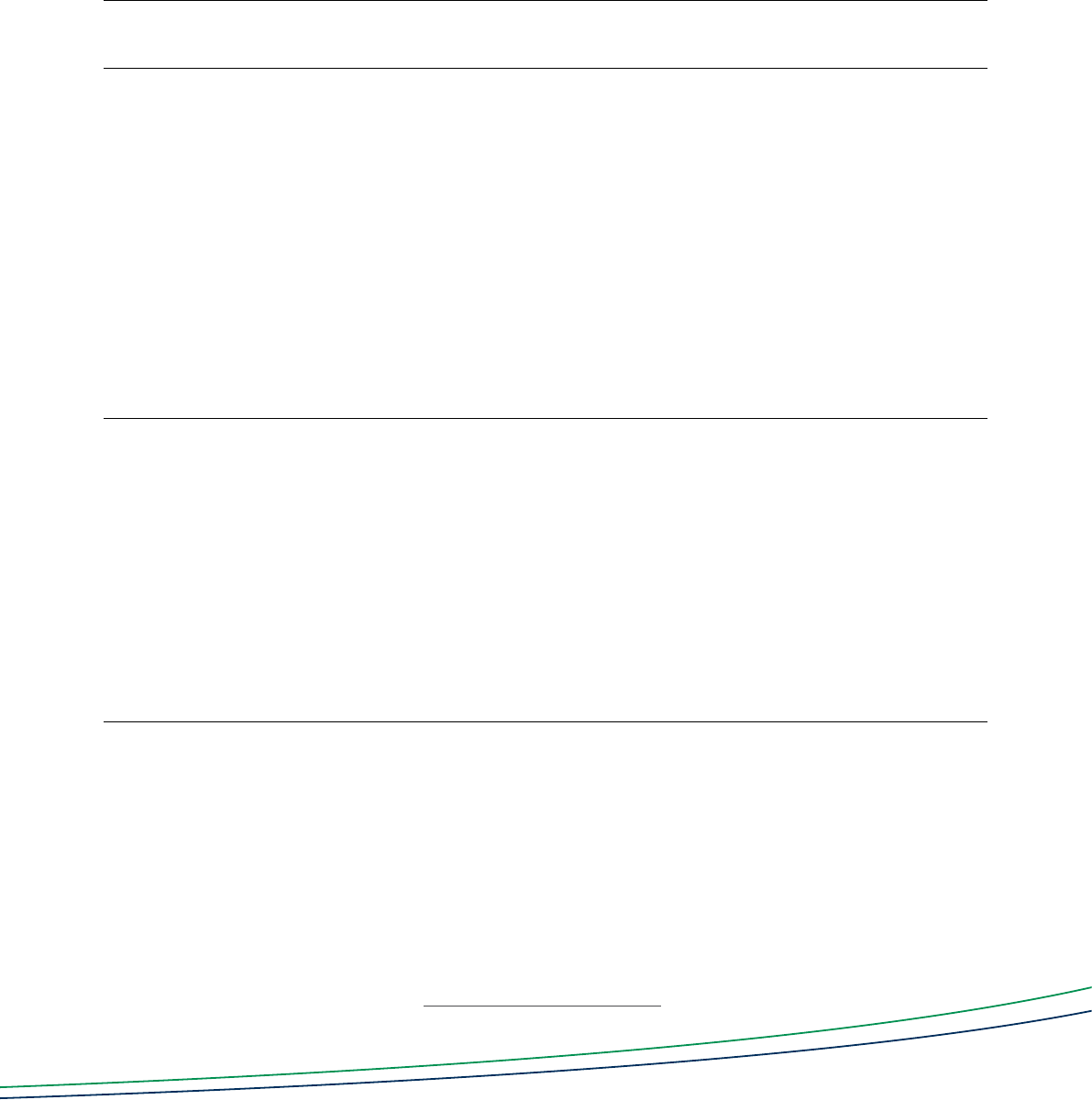

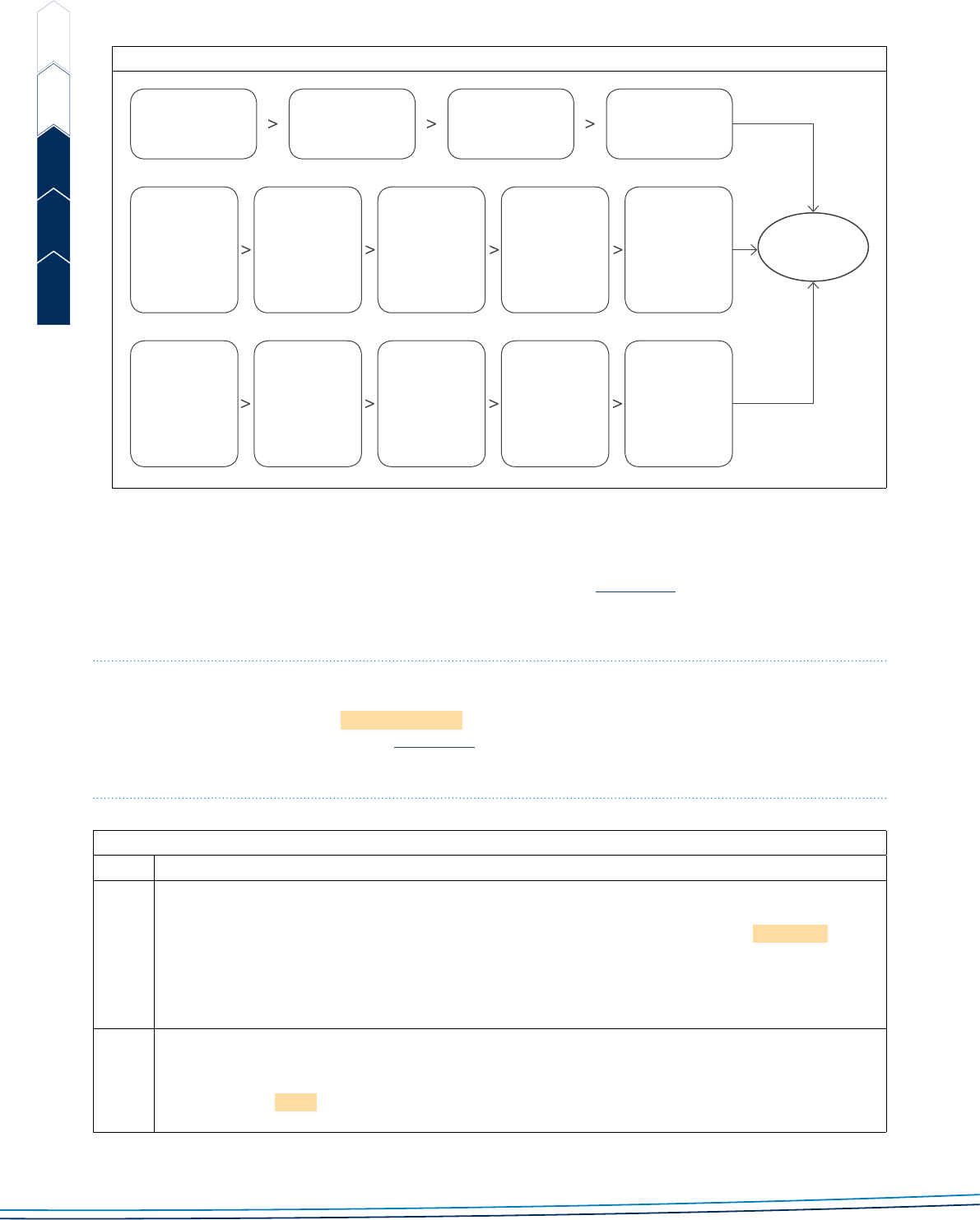

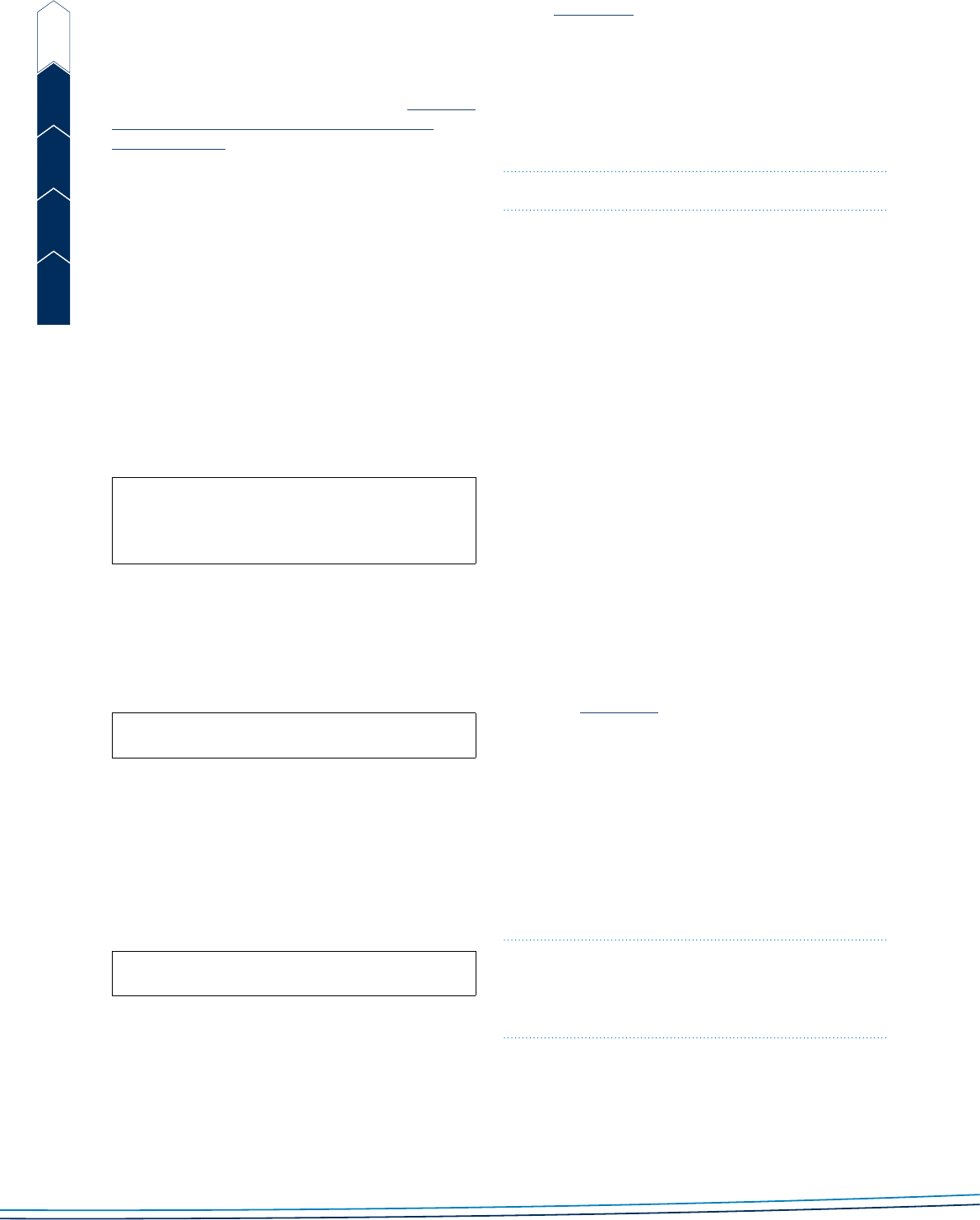

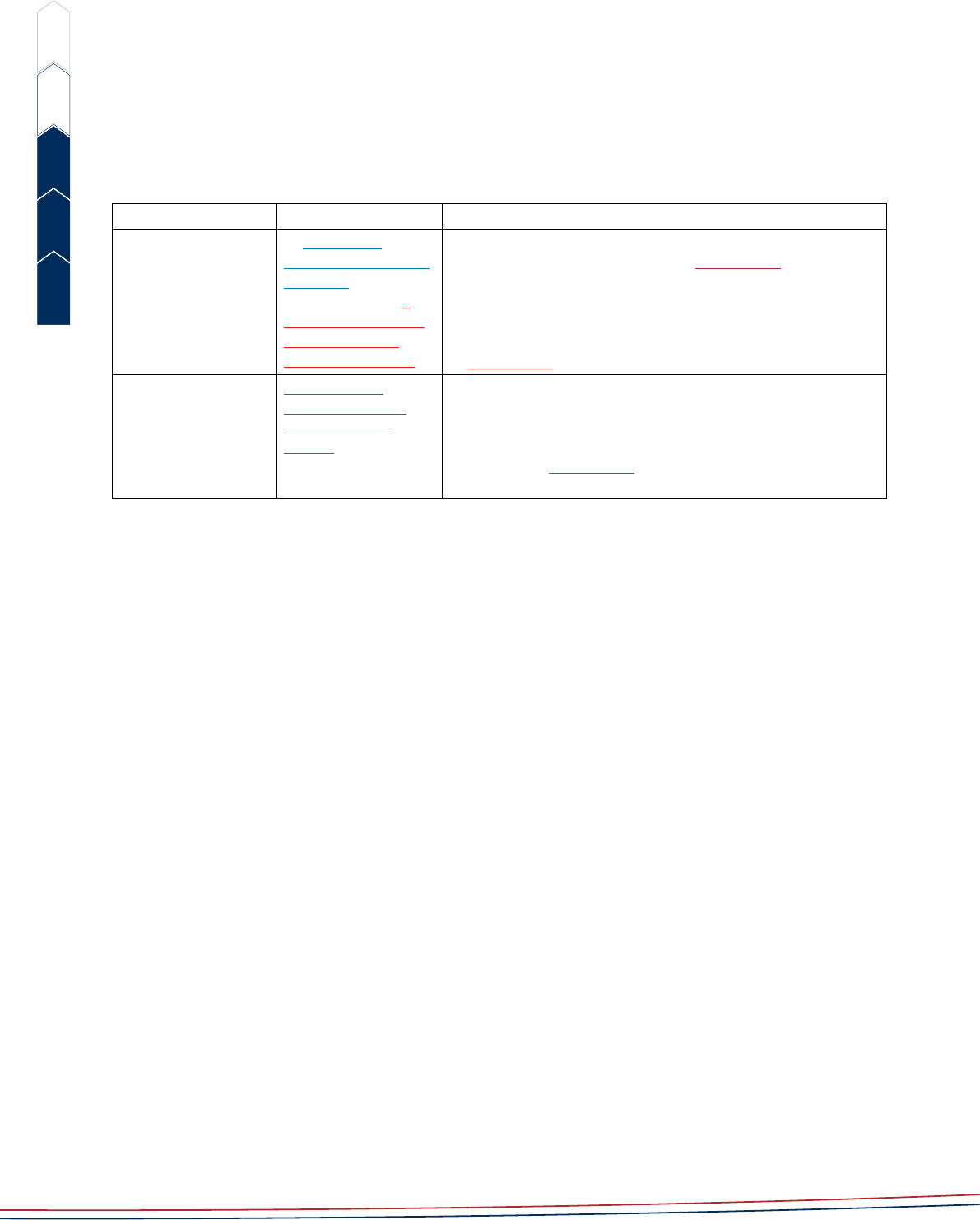

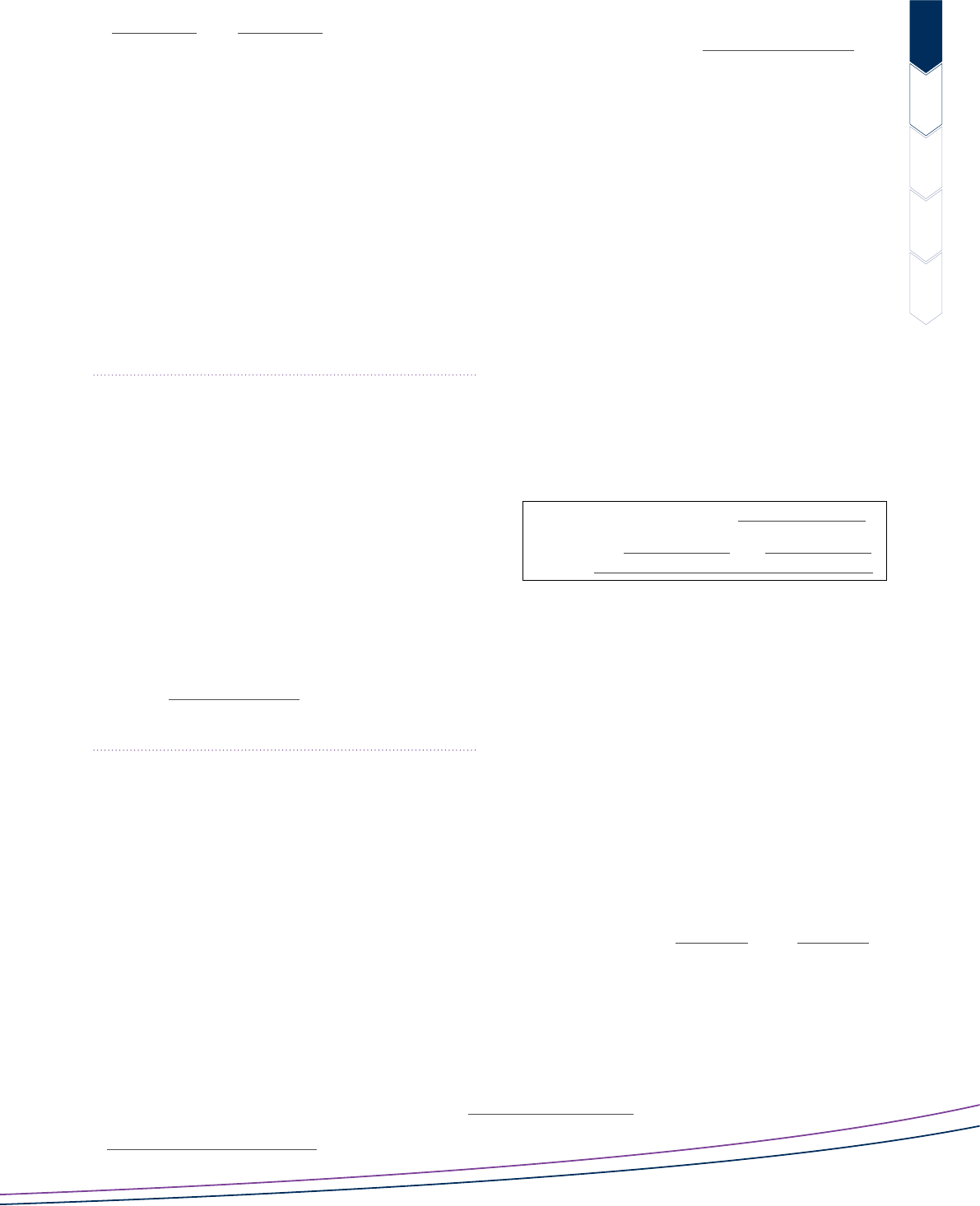

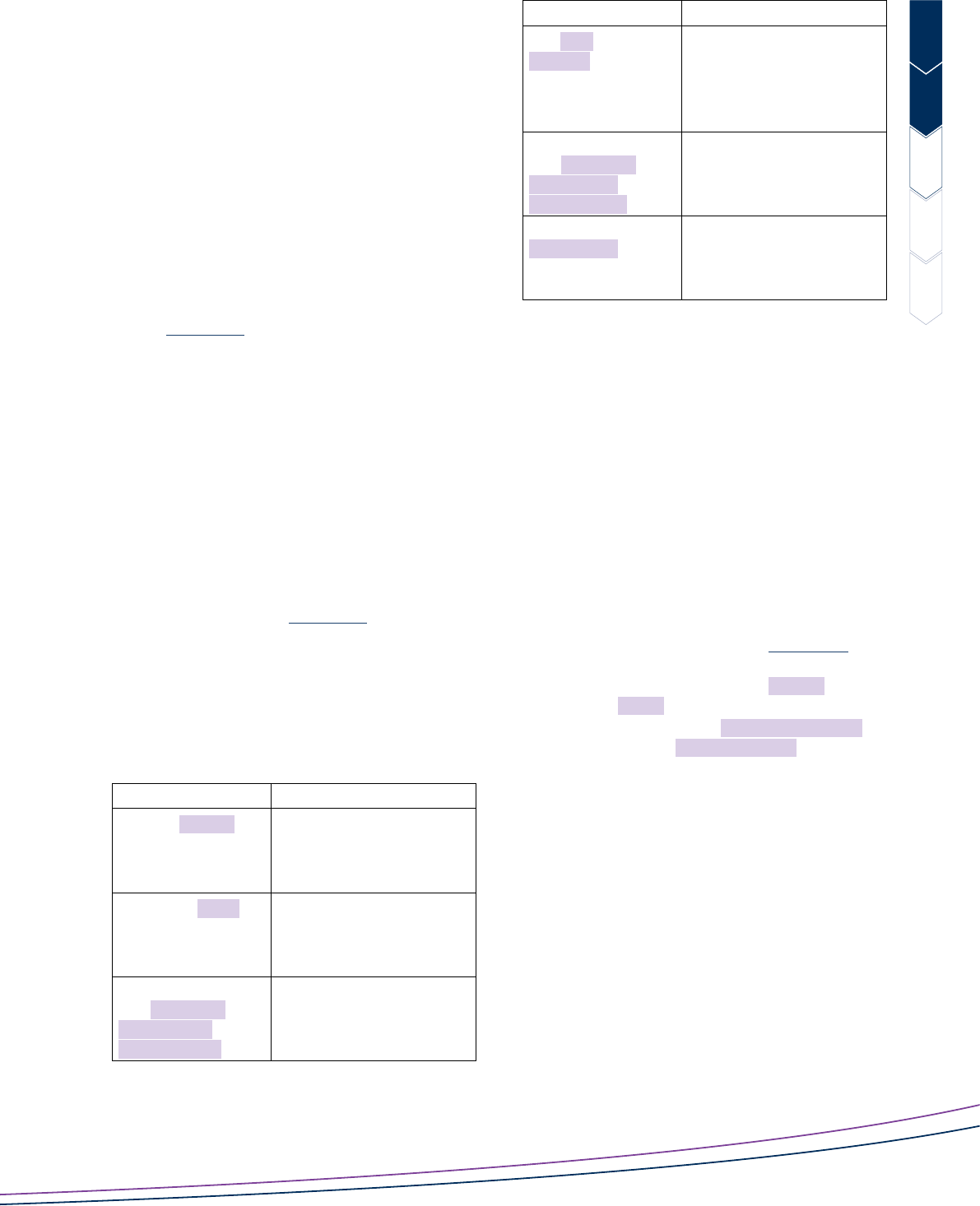

intended audience. The diagram in the next column

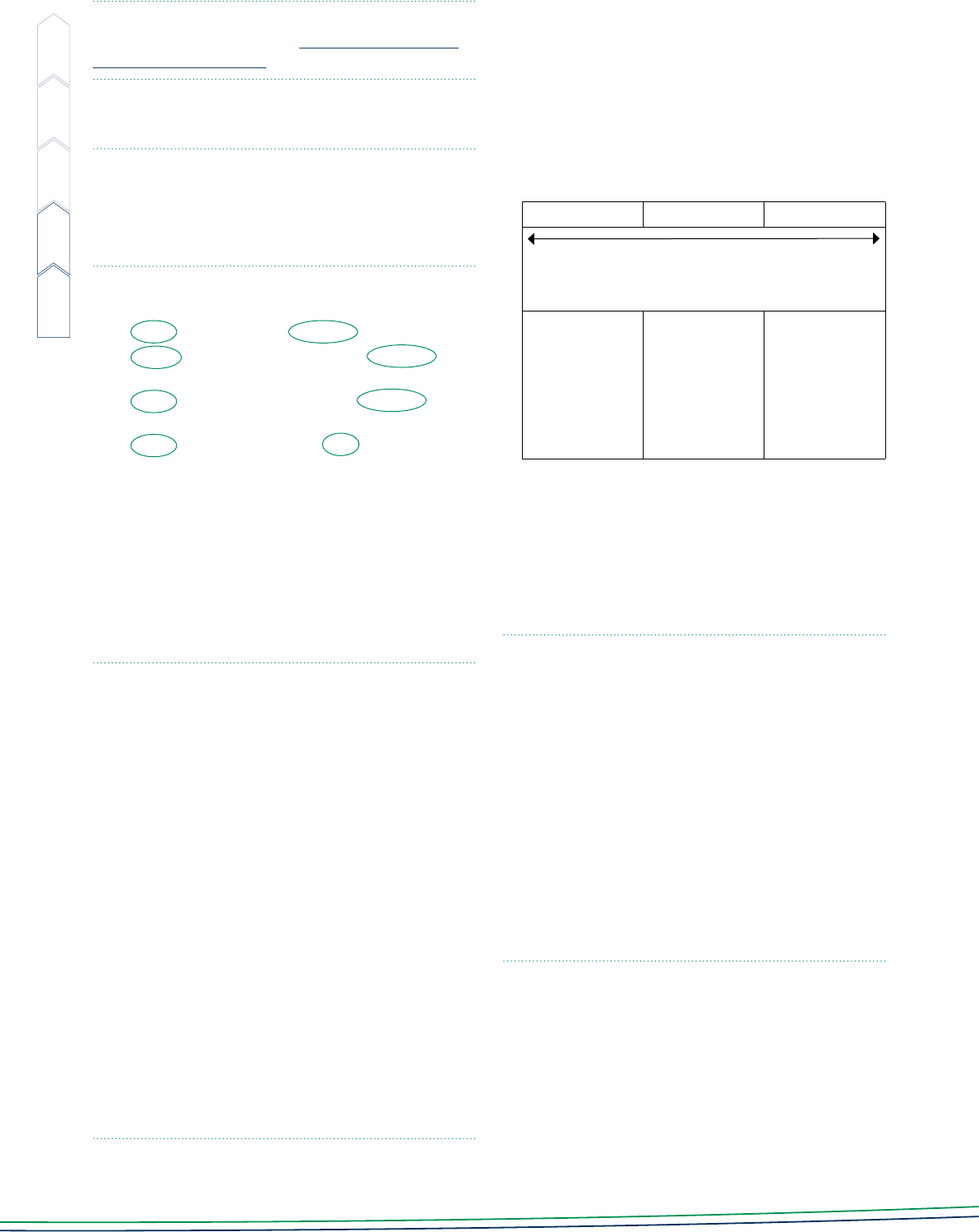

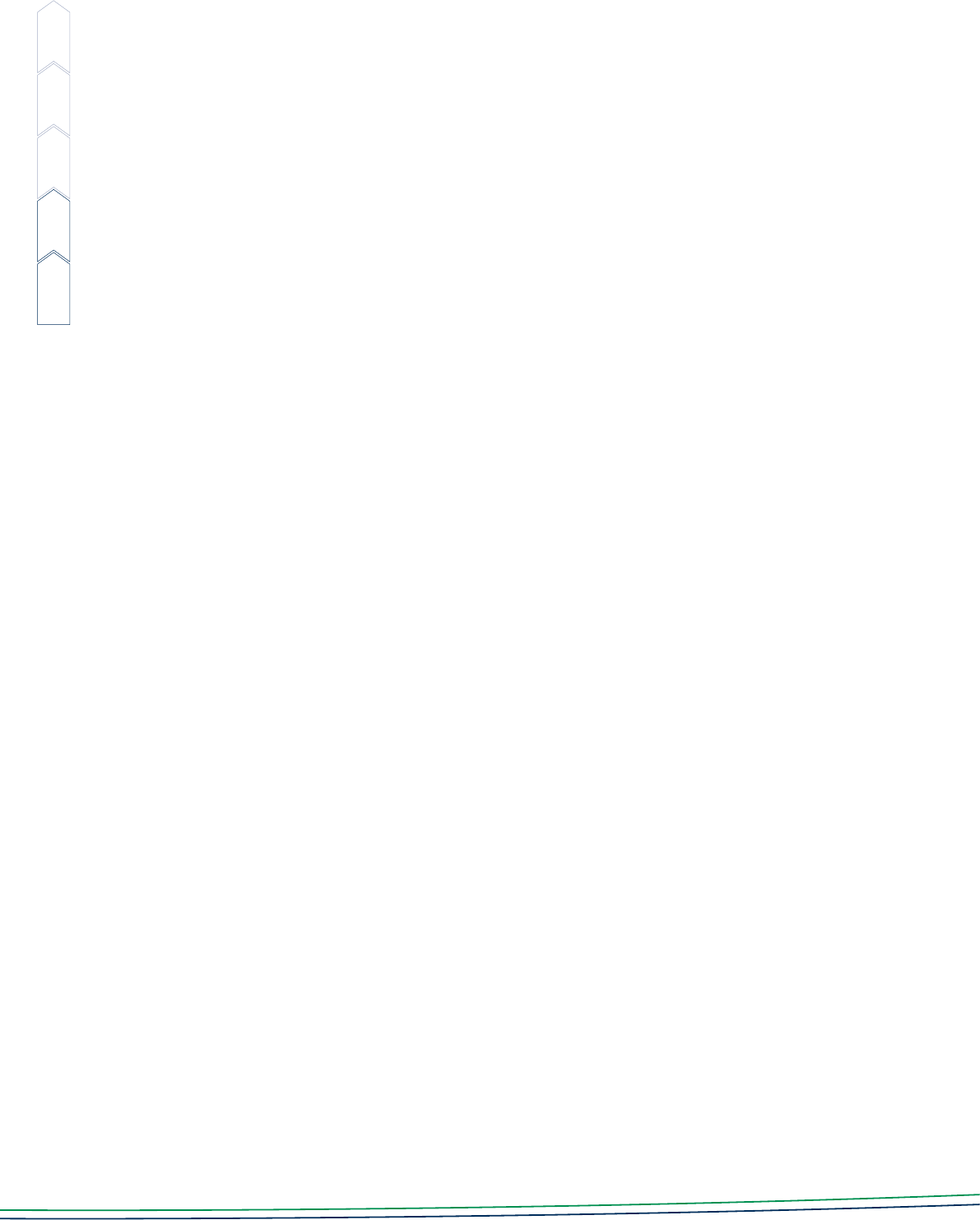

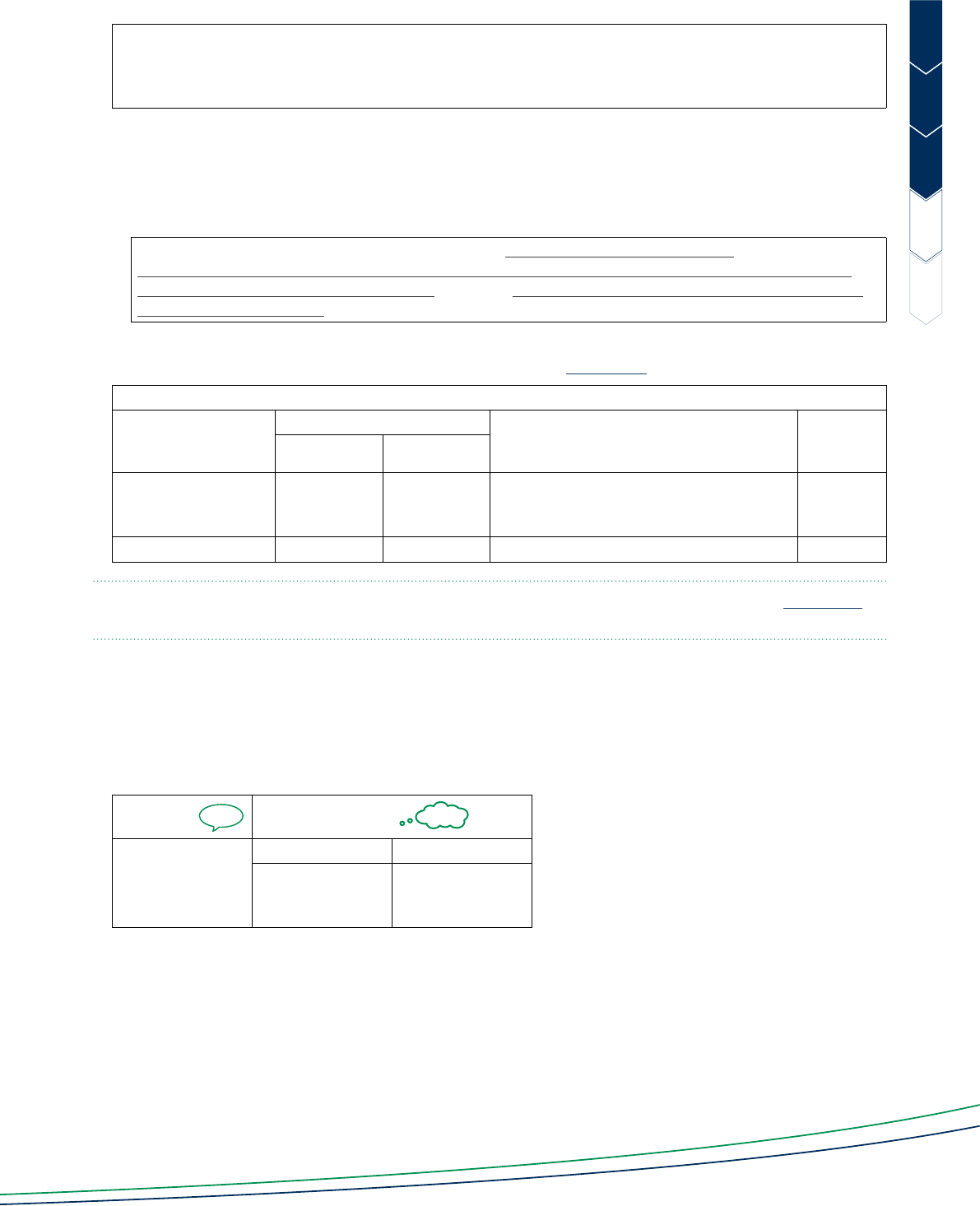

represents the process, which can occur over several

sessions, beginning with the teacher modelling

through ‘think aloud’

(Rossbridge & Rushton, 2014).

The joint construction process is highly interactive

and involves a gradual release of responsibility as

the teacher hands over the writing to the students:

The teacher’s role is to support the composition of

the text through the use of strategies which focus

the students’ attention on their language choices

when expressing their ideas. While the focus of

the joint construction is on composing a written

text, it is spoken language which is central to the

activity …

(Rossbridge & Rushton, 2014:4)

Independent use of the genre

As students prepare to write independently:

• jointly construct success criteria and annotate

examples of the target genre at dierent levels

so that students can have clear goals

• maintain high expectations for all students and

be available to support small groups who require

additional assistance

• incorporate opportunities for students to reflect

and evaluate the writing process so they can name

what they have learned and what they want to

improve on next time.

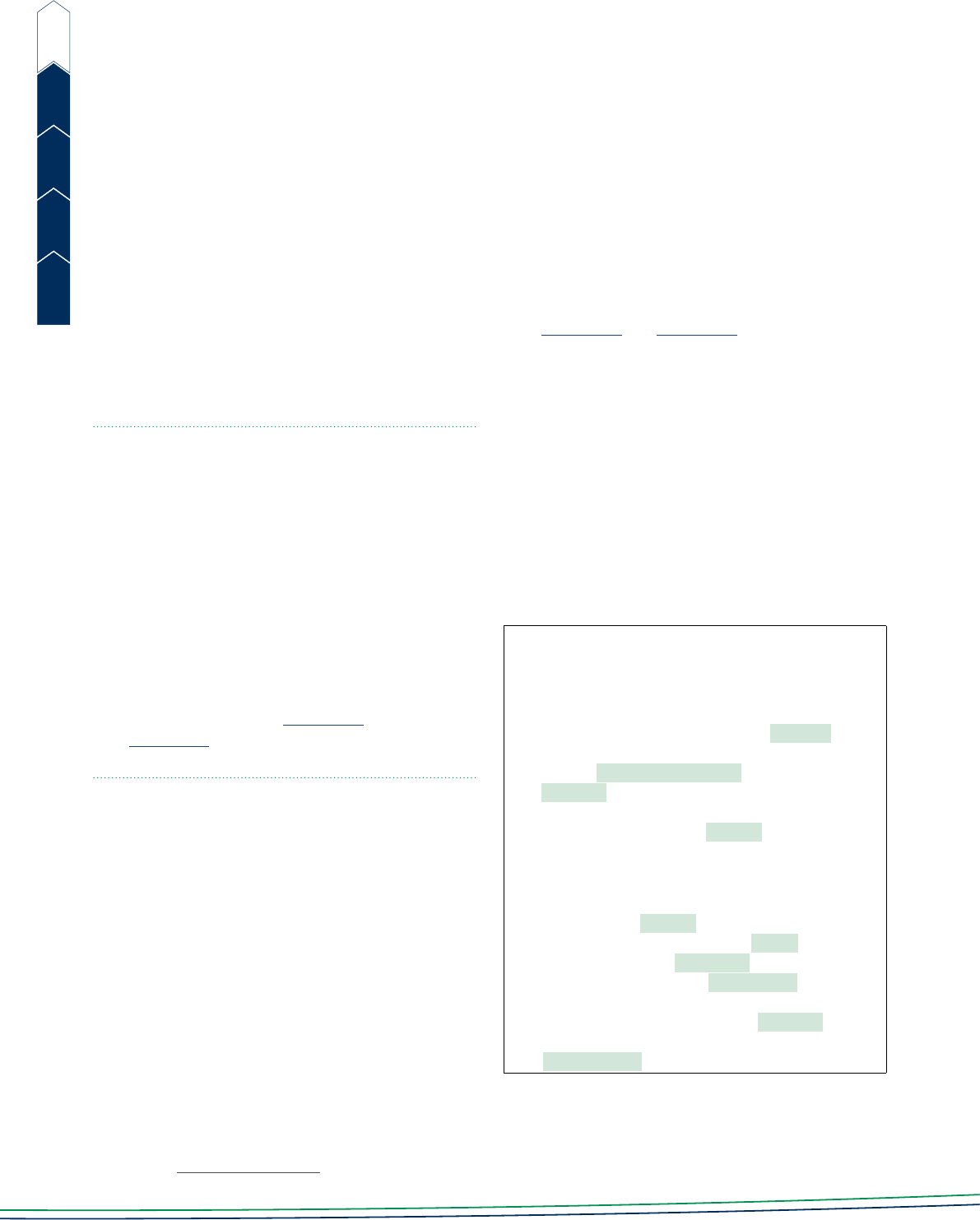

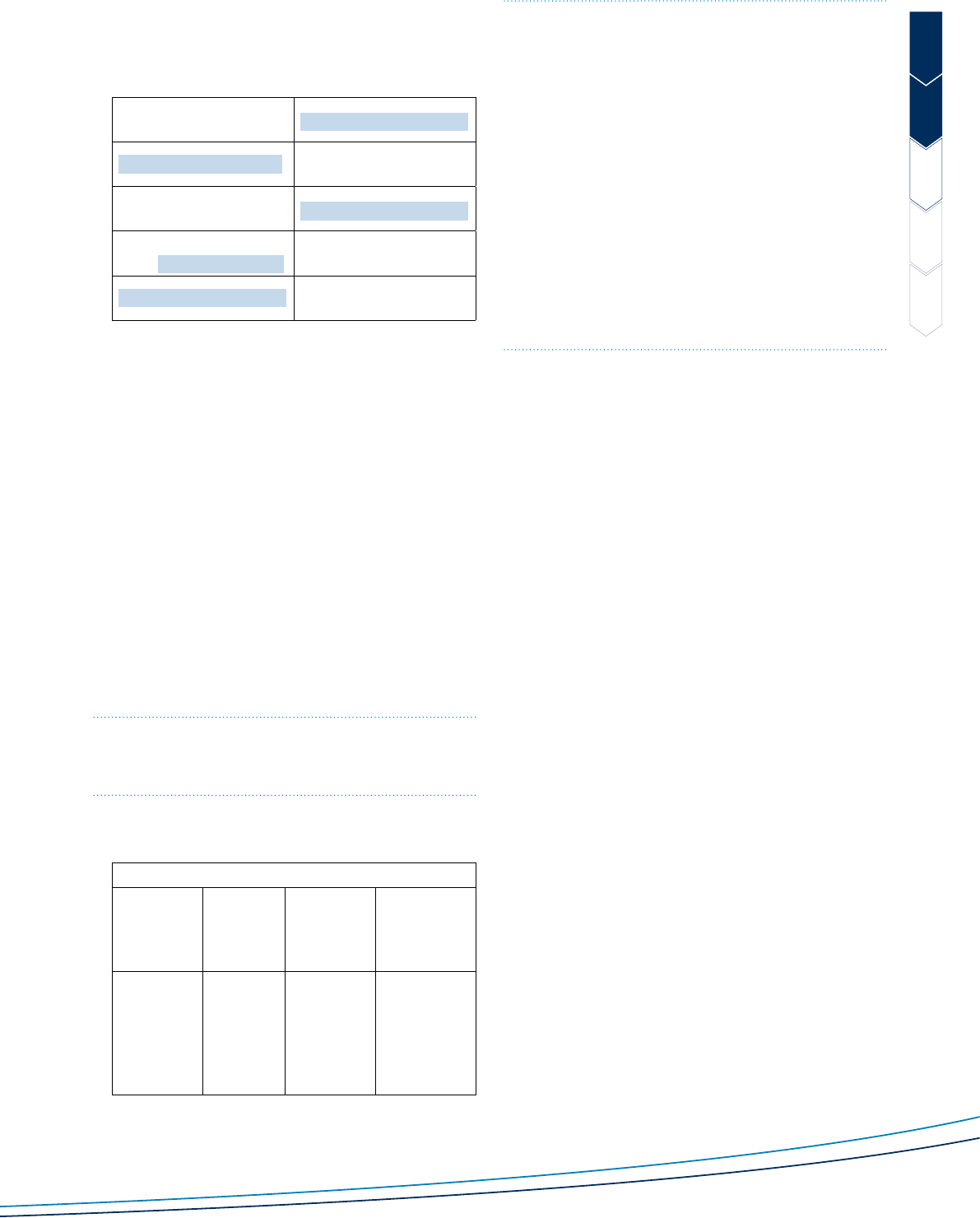

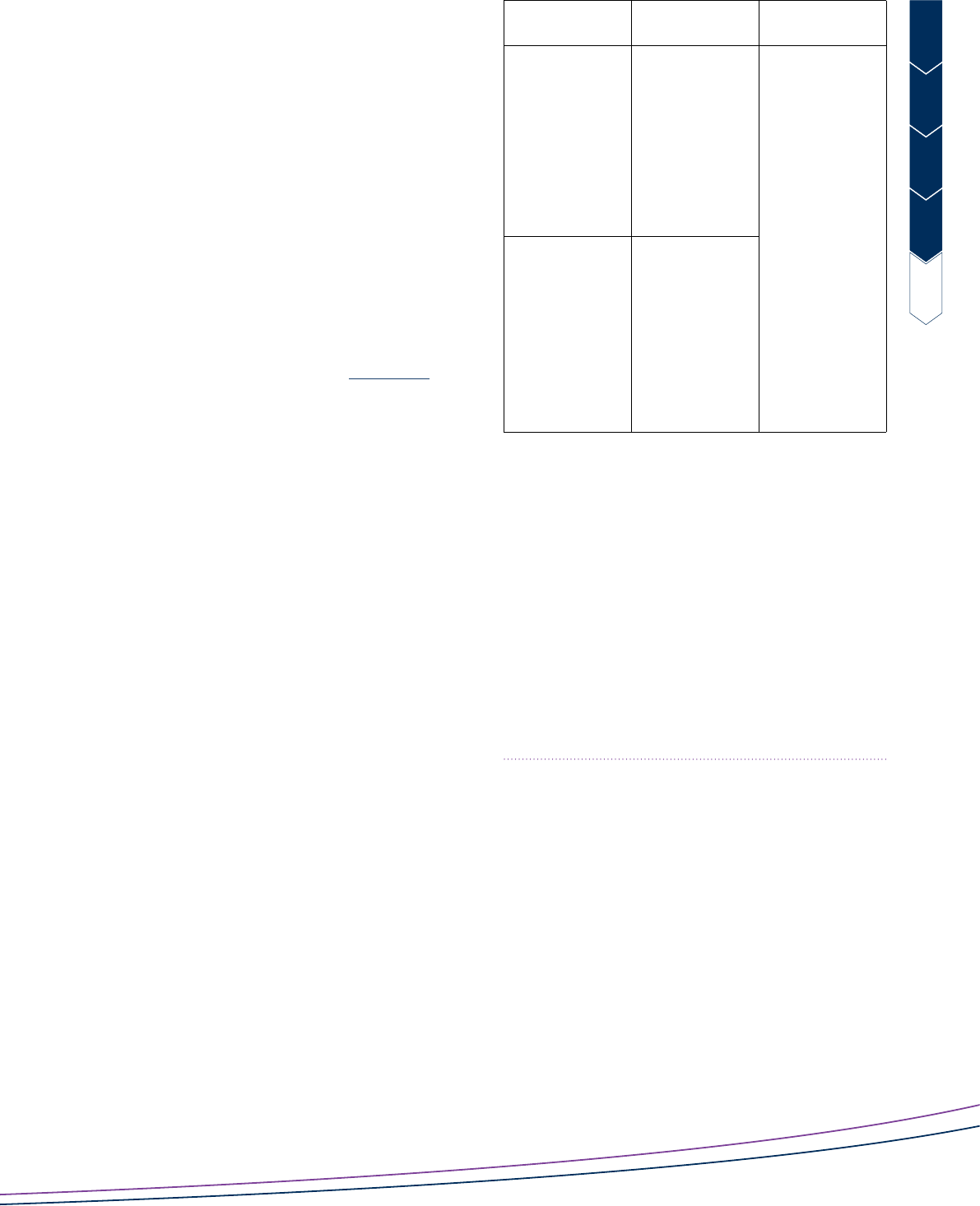

Student

composes

Teacher

‘thinks

aloud’

Student

questions

Teacher

paraphrases

Student

comments

Teacher

recasts

Joint

construction:

teacher and

students talk

about writing

and compose

together

Elements for supporting students in joint construction

(Adapted from DECD, 2018b:15)

The Department for Education requests attribution as:

South Australian Department for Education | APRIL 2021

Learning English: Achievement and Proficiency (LEAP)

TARGETED STRATEGIES TO ACCELERATE SAE PROFICIENCY

COHESIVE DEVICES

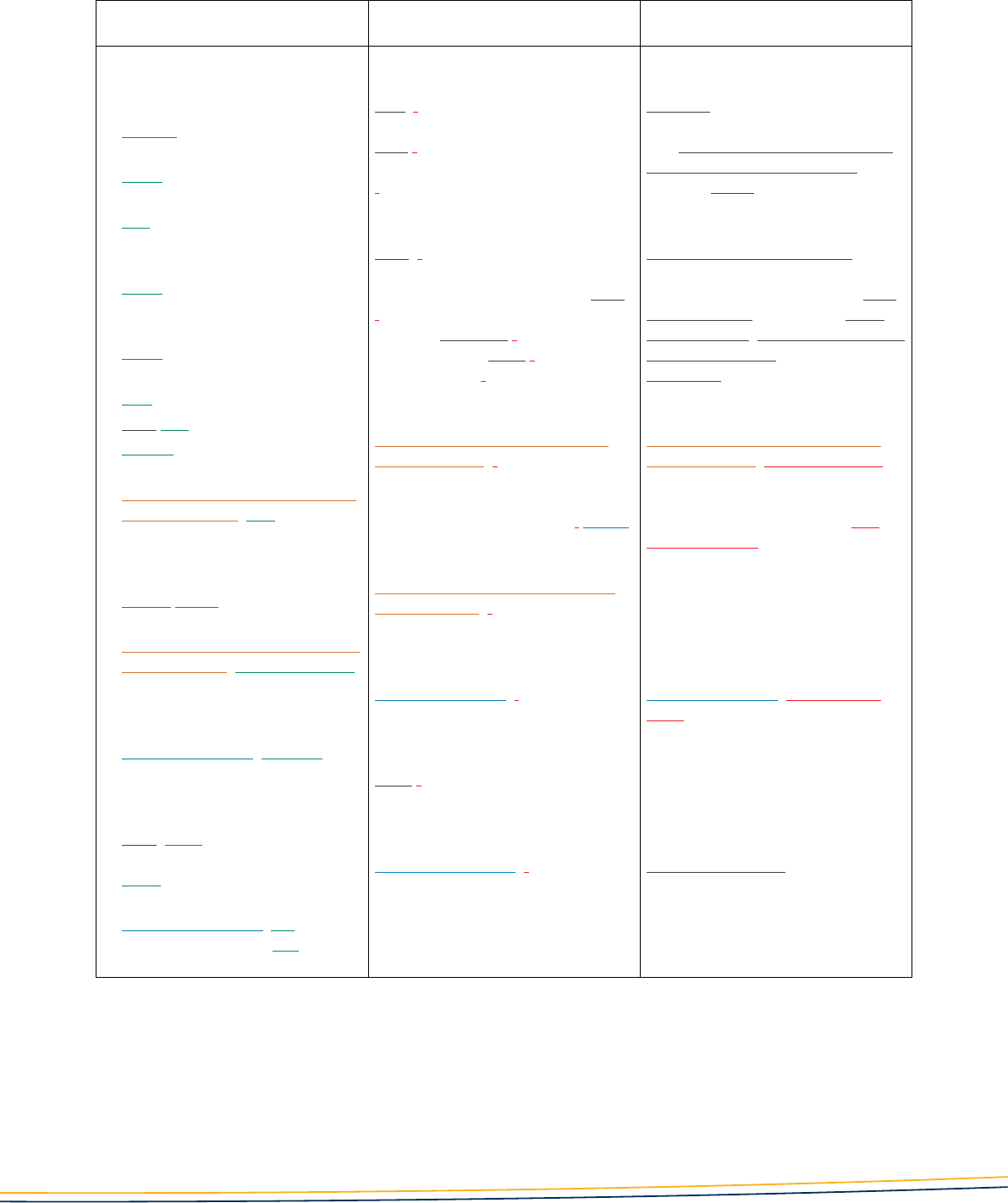

COHESIVE DEVICES: INTRODUCTION 2

Reference items 2

Text connectives 2

Orientations to the message 2

Sentence openers 2

Topic, circumstances and subordinate clauses 2

Passive voice 2

Nominalisation 3

LEVELS 1–4 AND LEAPING TO LEVELS 5–6 4

1. Pronouns referring to animals and things 4

2. Pronouns referring to people and things 5

Subject pronouns – who is doing the action? 5

Object pronouns – who/what actions are done to and possessive pronouns: whose is it? 5

3. Reference to point out which one 6

4. Text connectives to create sequence 6

LEVELS 5–6 LEAPING TO LEVELS 7–9 7

5. Sentence openers in procedures and protocols 7

6. Sentence openers in procedural recounts 8

7. Sentence openers in sequential explanations 9

Passive voice 9

Openers that link back to create flow 9

8. Text organisation in arguments 10

Whole text – structure 10

Paragraphs to group and develop ideas 11

LEVELS 7–9 LEAPING TO LEVELS 10–12 12

9. Text connectives when elaborating ideas 12

10. Sentence openers and text connectives for structure and orientation 14

11. Openers and connectives for cause and contingency 15

LEVELS 10–12 LEAPING TO LEVELS 13–14 16

12. Strategic orientations and text organisation 16

Text and paragraph openers as orientations 16

Text organisation and ecient orientation using nominalisation 17

Manipulation of text connectives 19

Orienting to angle, contingency and cause 19

Orientation to abstraction through passive voice and nominalisation 21

Resource 1: Pronoun chart 23

Resource 2: Changing sentence openers 24

Resource 3: Sentence openers to create flow 25

Resource 4: Animals should not be kept in zoos 26

Resource 5: Text connectives and logical relationships 27

Resource 6: The legacies of Ancient Rome for modern society 28

Resource 7: Moving from informal to formal language 29

Resource 8: Discussion/argument: Should children play computer games? 30

Resource 9: Register continuum 31

2 | Learning English: Achievement and Proficiency (LEAP) | STRATEGIES COHESIVE DEVICES

COHESIVE DEVICES: INTRODUCTION

Spoken and written texts that connect and flow well for a reader/listener utilise various cohesive devices, including:

• reference items: pronouns and demonstratives/pointers

• text connectives

• orientations to the message.

Reference items

This includes using an element of language to refer to something in a shared physical context (Pass it to him);

a shared cultural context (The queen is our longest serving monarch); or to another part of the text, such as

a word, word group or larger section of the text. These reference items connect or tie parts of a text together,

making it cohesive. The main elements considered here are pronouns and demonstratives.

Text connectives

These connect sentences and paragraphs and show the logical development of ideas across the text. They

function to:

• organise a text

• connect adjacent paragraphs and sentences in logical relationships (see Resource 5: Text connectives and

logical relationships for examples).

Orientations to the message

The opening of a text (a title and/or introduction), the opening of a stage/paragraph (sub-heading or topic

sentence) and the openings of sentences help orient a reader. They assist the reader to predict and follow the

development of ideas across the text. The connection between these openers at whole text level, at paragraph

level, and at sentence level (including clause level) is what makes a text flow and gives it coherence.

Sentence openers

Decisions about what is placed at the beginning of a sentence are determined by the topic, the genre and the

register of the text. As students gain control of language and an increasing range of genres and registers, they

begin to manipulate the elements of a sentence, adopting genre patterns, and consciously choosing how to

orient their audience to the message.

Topic, circumstances and subordinate clauses

Initially, sentence openers orient only to the topic or the action (in the case of a procedure). Then circumstances

and later subordinate clauses are brought to the front of the sentence to orient readers/listeners to details of

time and place and, later, to manner, condition, cause and contingency. These rearrangements of the sentence

do not require a change in grammar.

Passive voice

Passive voice and nominalisation also allow alternative orientations to the message. However, both require

changes to the grammar of the clause. In the passive voice, the clause is rearranged so that the ‘done to’

rather than the ‘doer’ of the action comes before the verb and so becomes the subject of the clause.

See the examples on page 3.

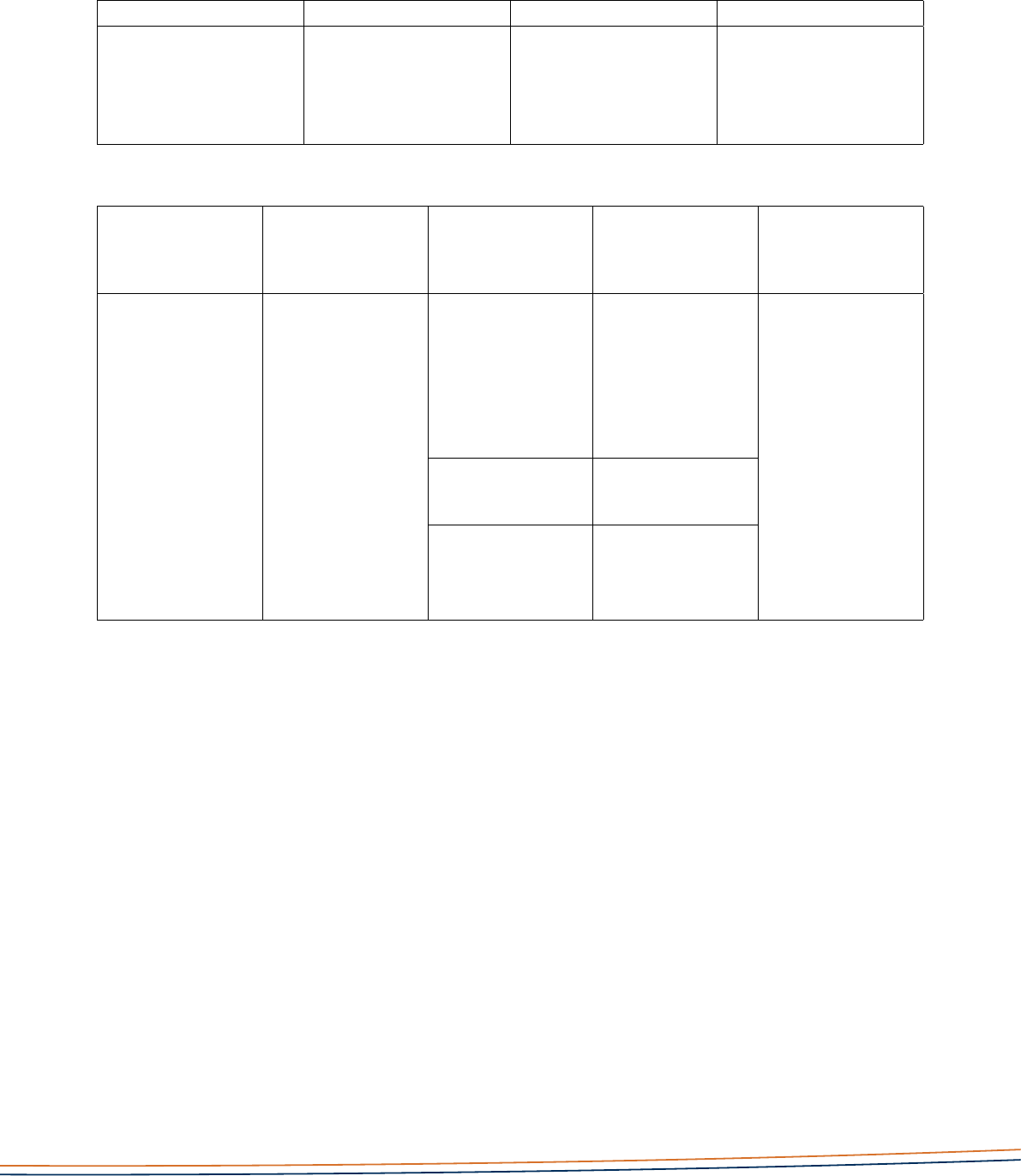

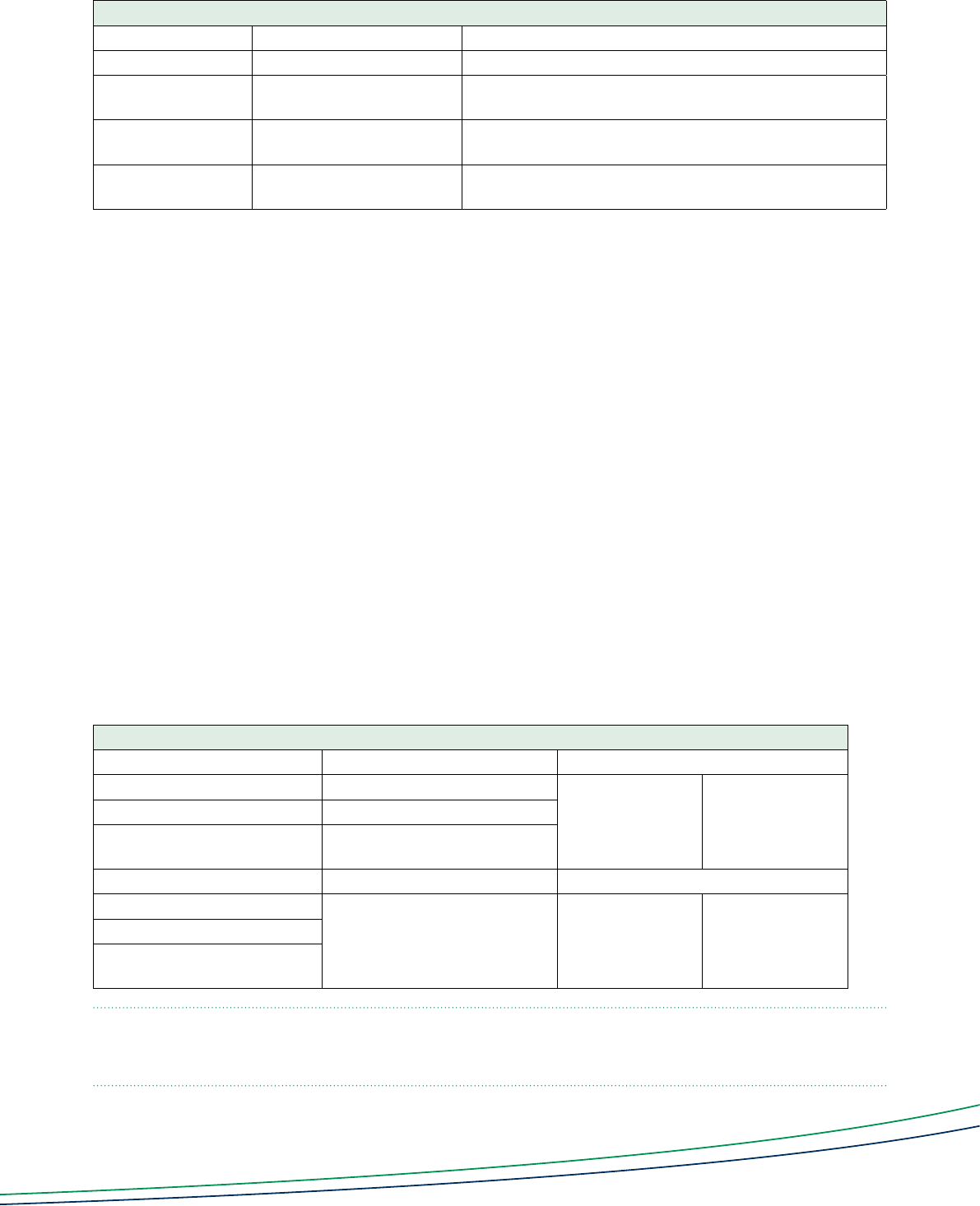

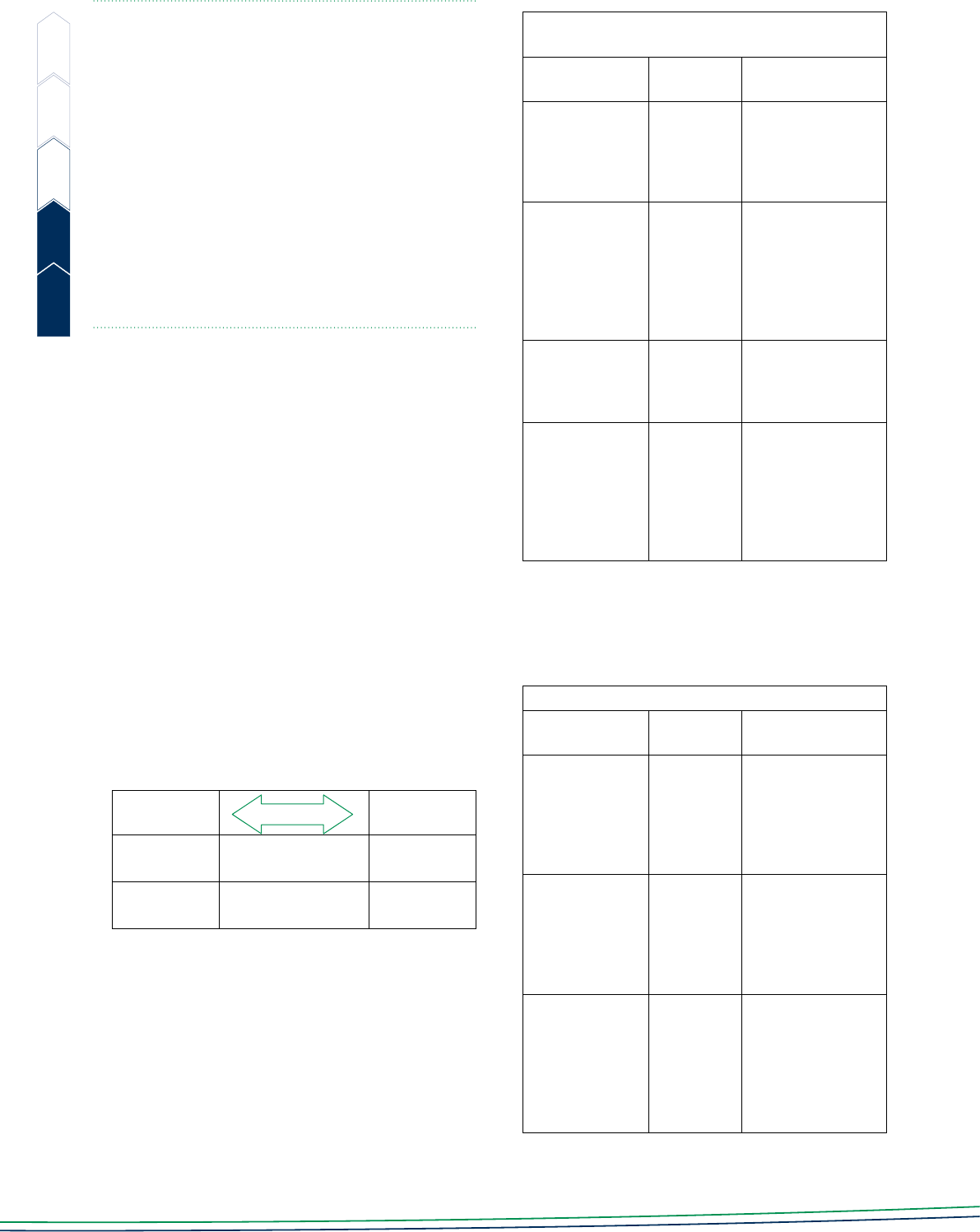

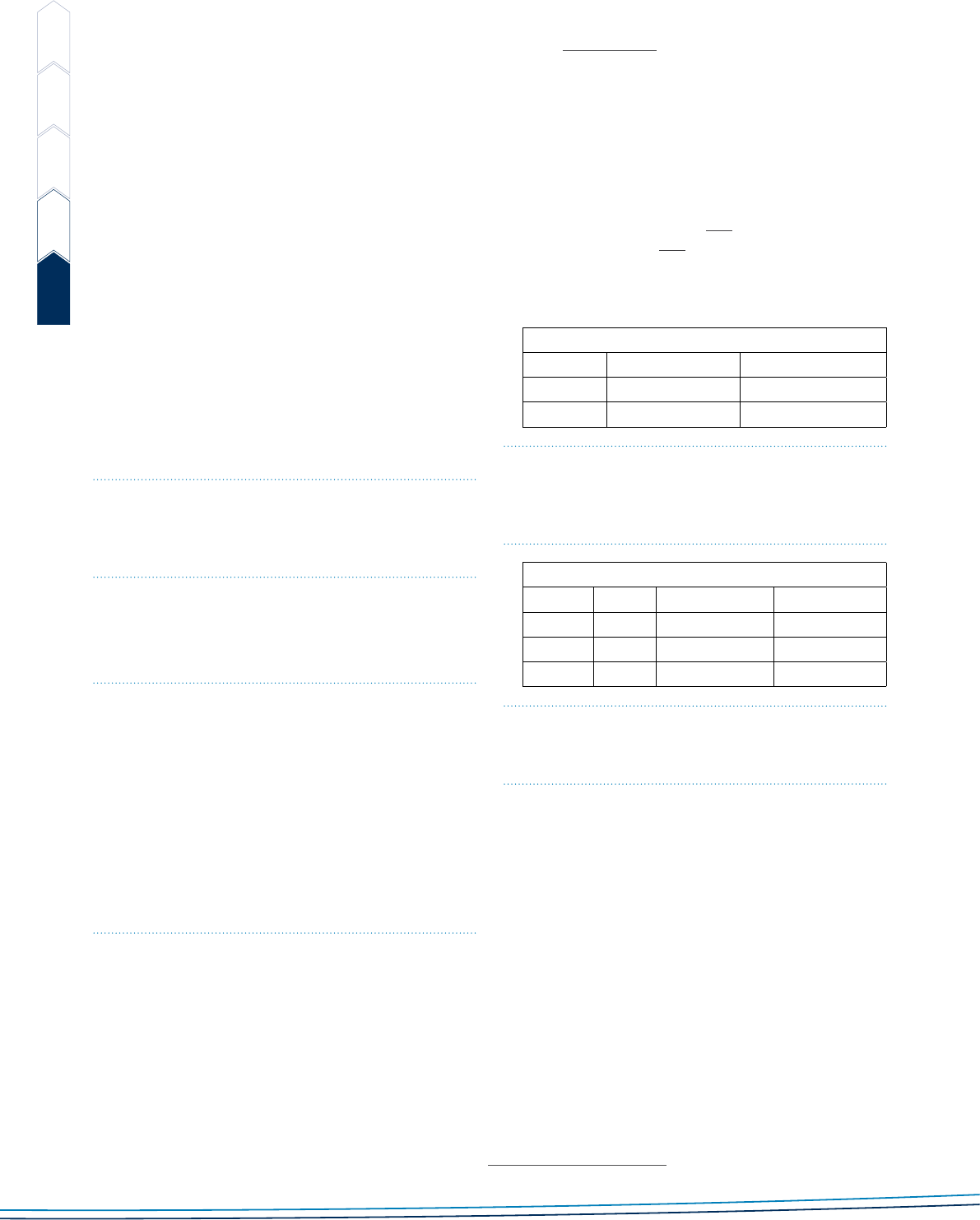

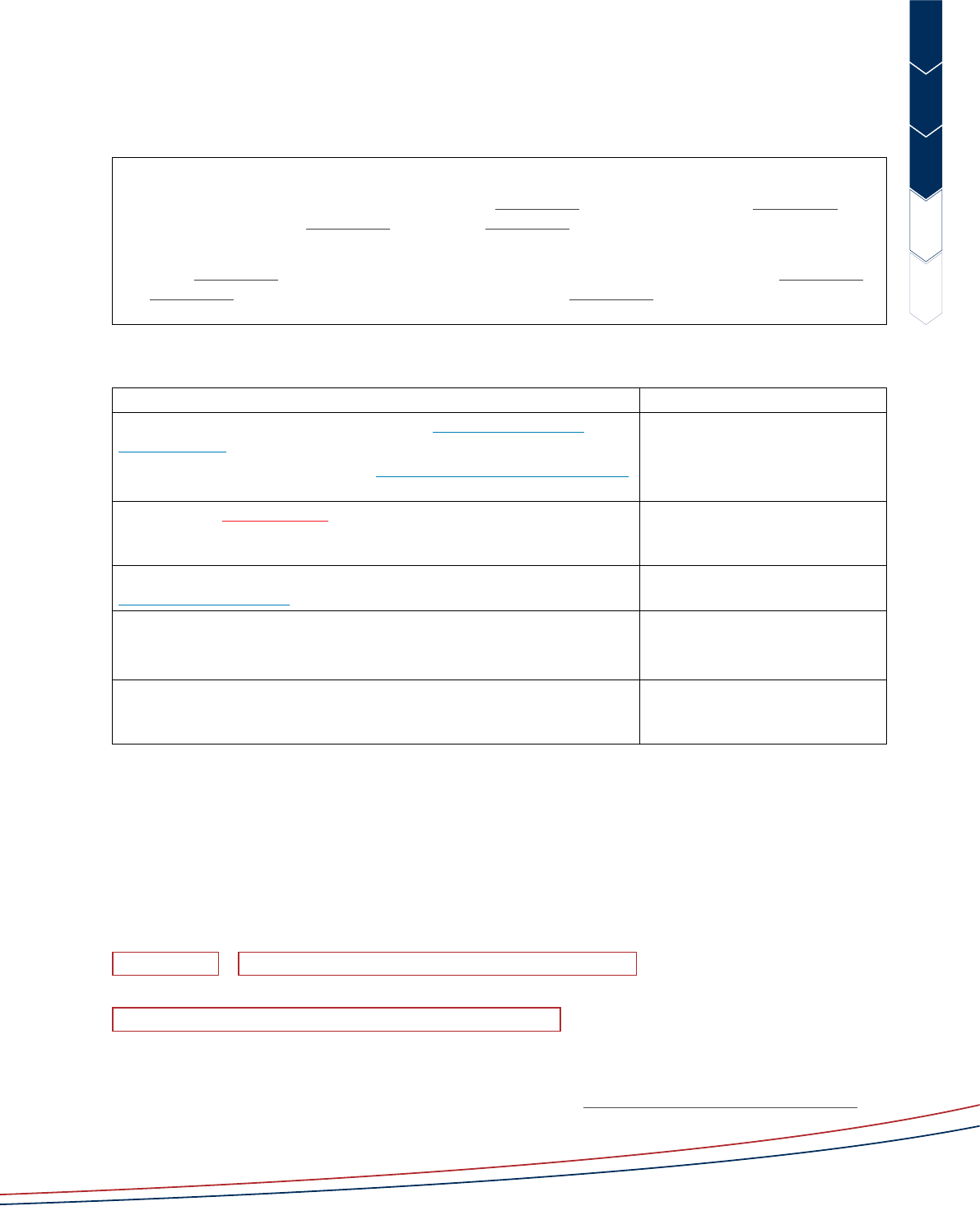

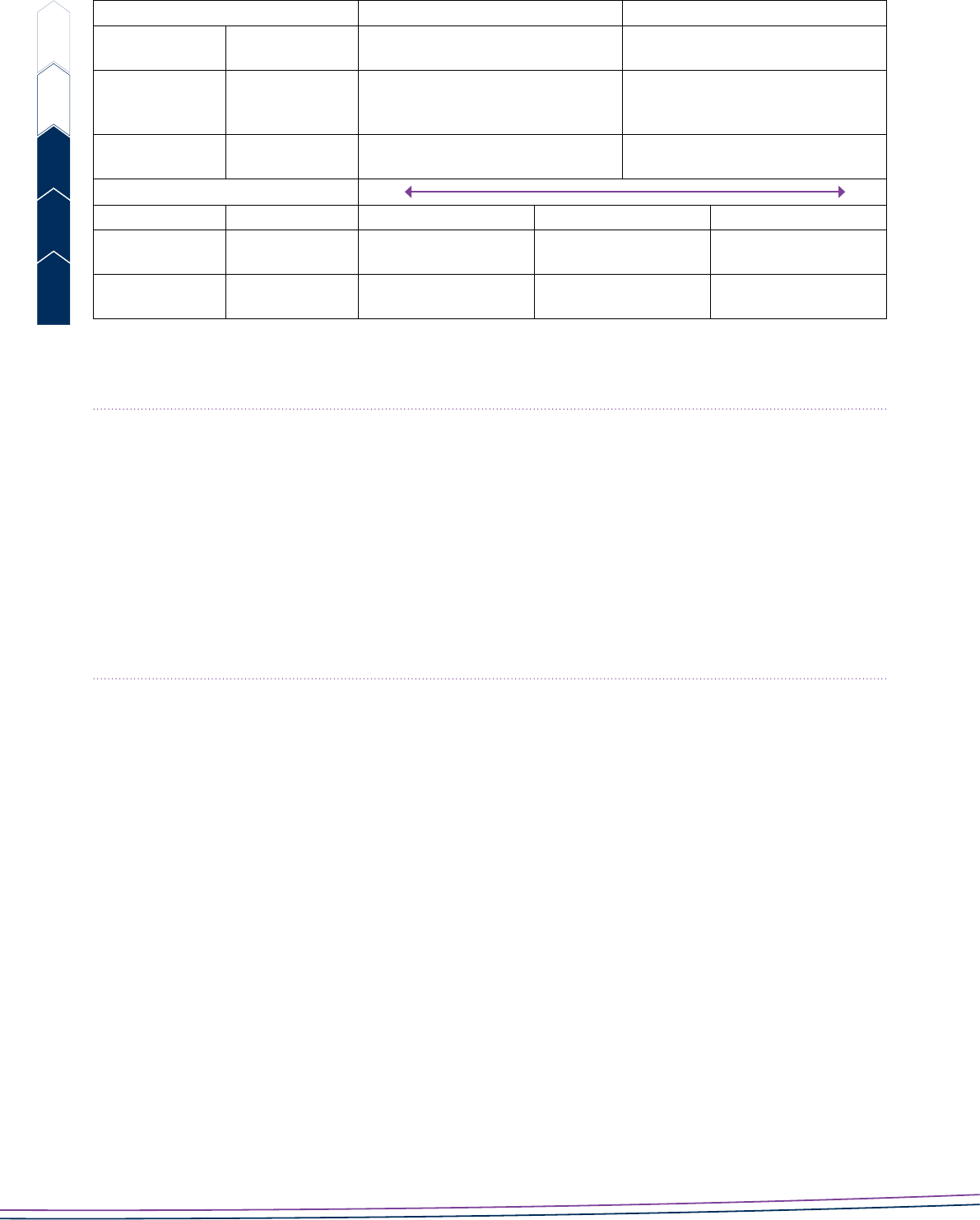

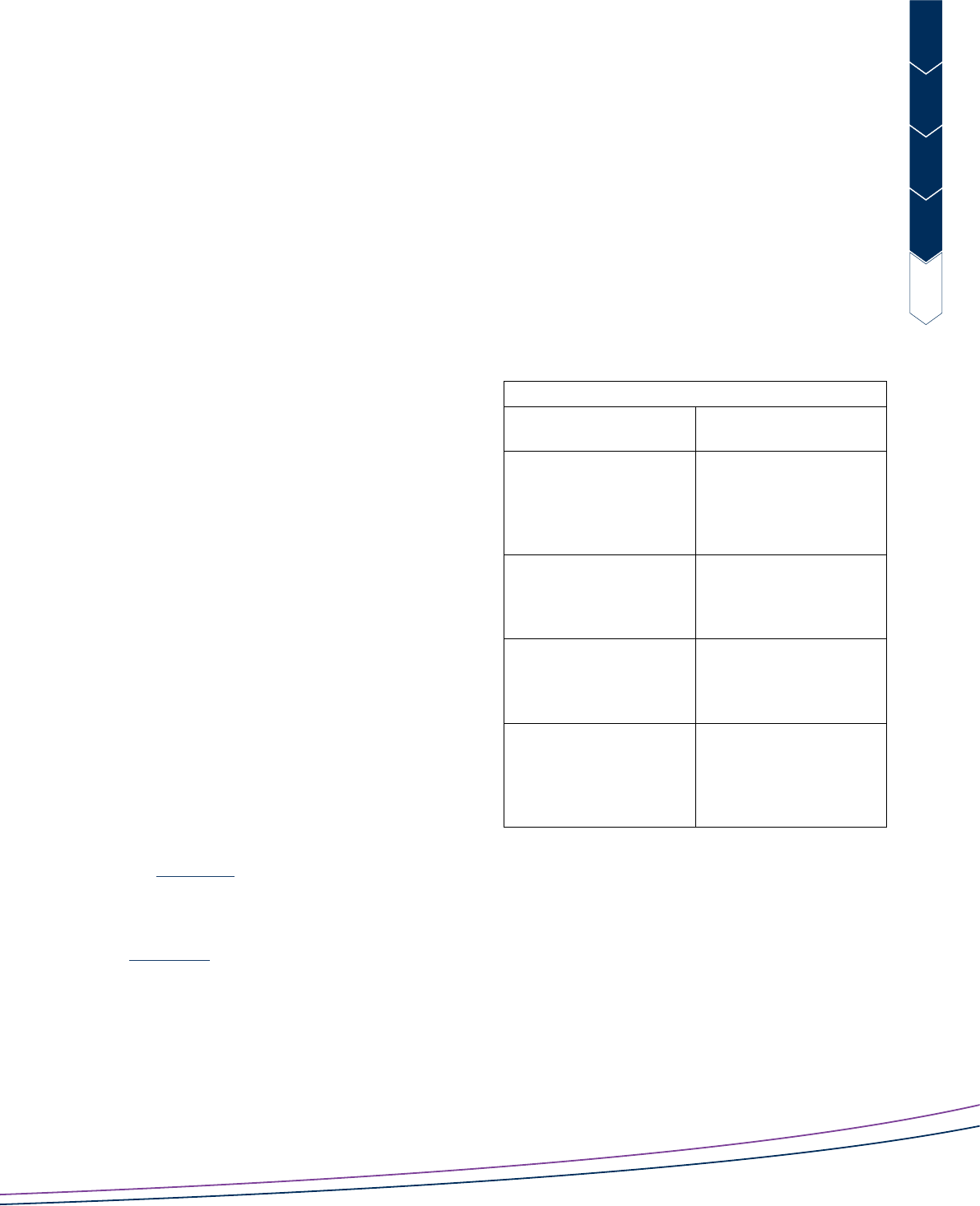

To form the passive voice with simple tenses:

• the person or thing that is ‘done to’ is brought to the front of the clause

• an auxiliary ‘to be’ verb is added to denote the tense (present, past or future)

• the -ed (en) participle form of the verb is used

• if the ‘doer’ is included, then ‘by’ is added to precede the ‘doer’.

Learning English: Achievement and Proficiency (LEAP) | STRATEGIES COHESIVE DEVICES | 3

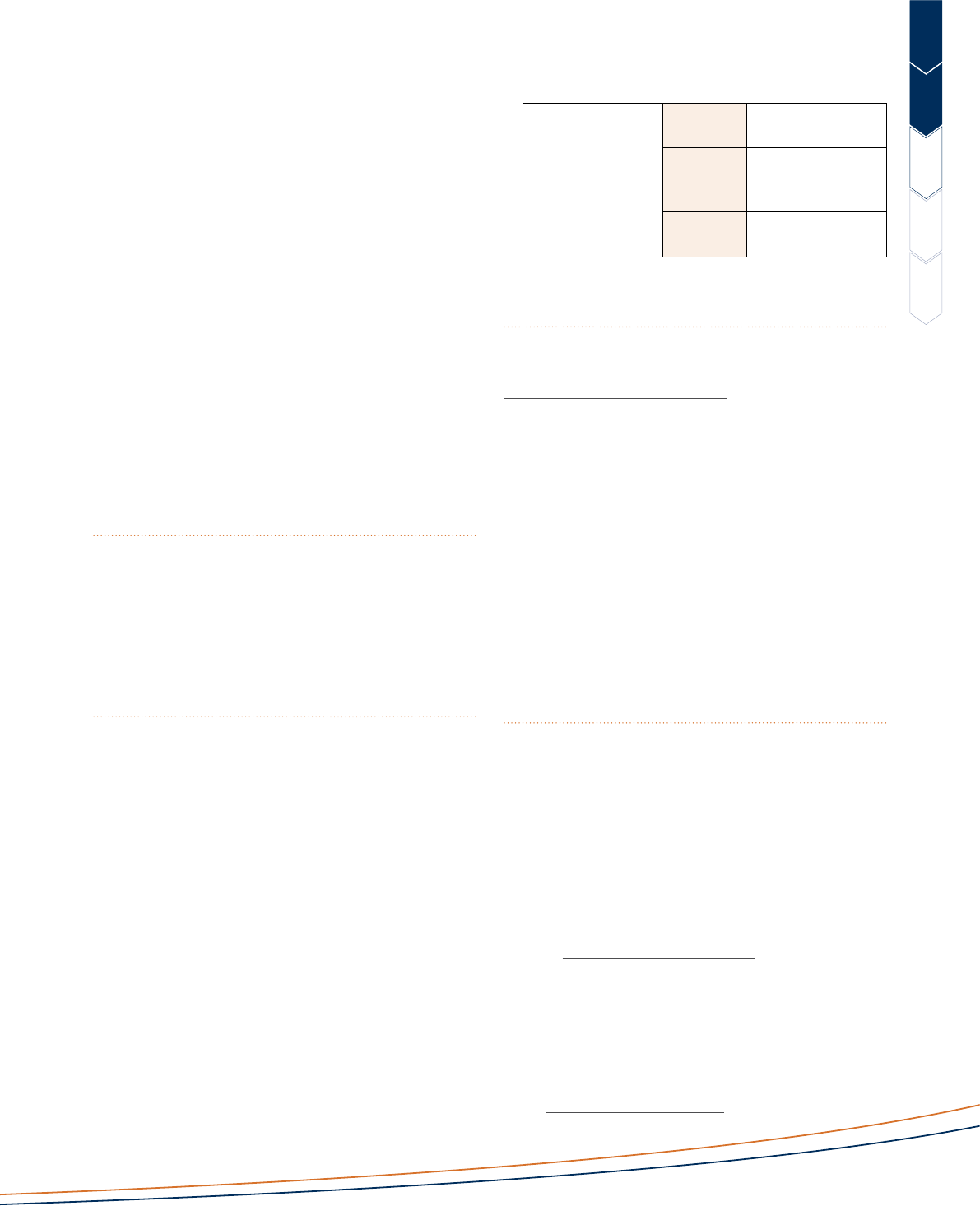

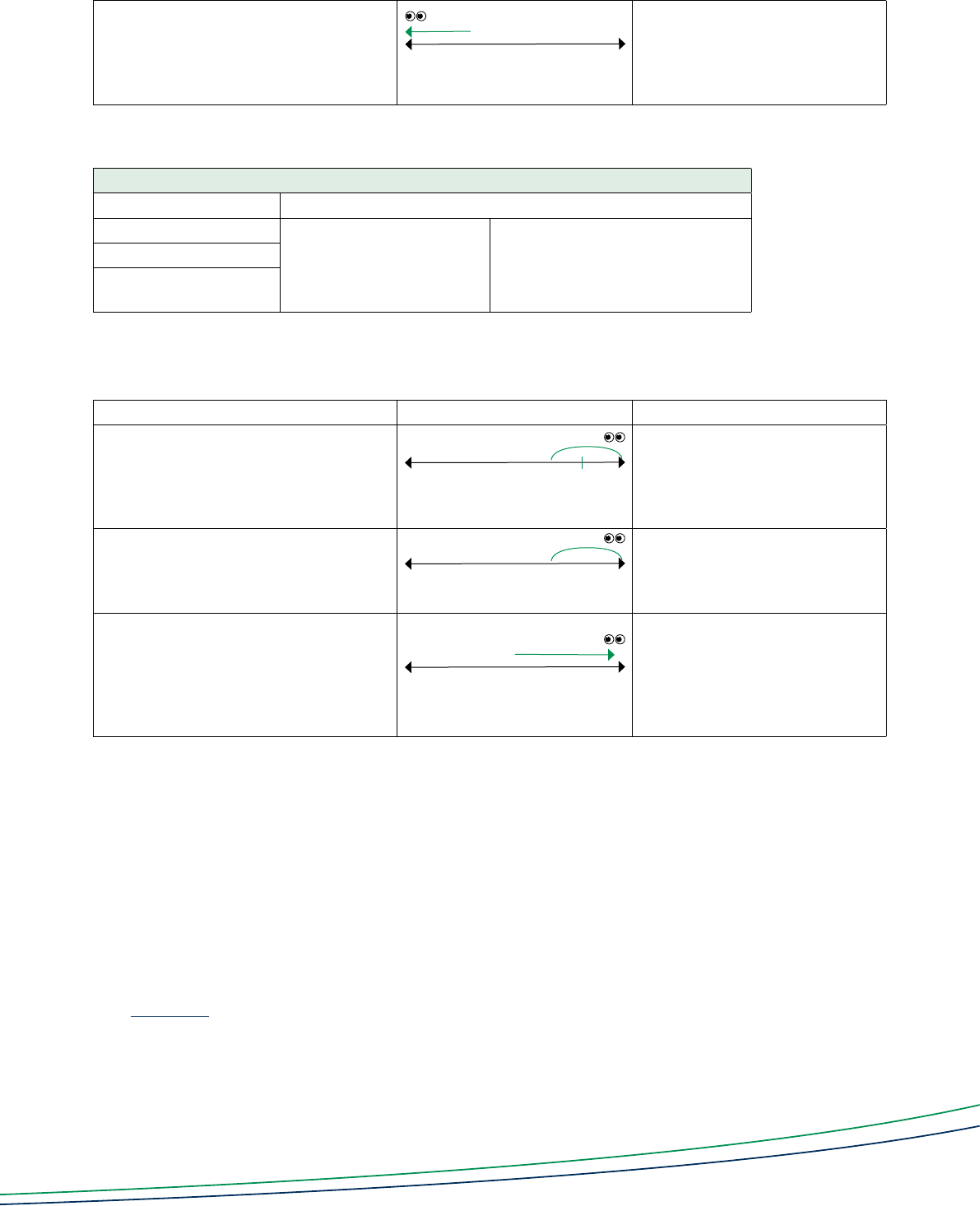

Present: Active Passive

My mother

takes

my brother

.

My brother

is taken

by

my mother

.

actor/doer verb done to done to verb ‘by’ actor/doer

Past: Active Passive

My mother

took

my brother

.

My brother

was taken

by

my mother

.

actor/doer verb done to done to verb ‘by’ actor/doer

Future: Active Passive

My mother

will take

my brother

.

My brother

will be taken

by

my mother

.

actor/doer verb done to done to verb ‘by’ actor/doer

To change the verb group to the passive voice for the continuous aspect:

• select auxiliary ‘to be’ according to the subject and tense: am, is, are, was or were, will be

• add the auxiliary being

• use the past participle, for example, taken.

For example: I am being taken by my mother; she was being taken by mother; they will be being taken

by my mother.

To change the verb group to the passive voice for the perfect aspect:

• select auxiliary ‘to have’ according to the subject and tense: have, has, had, will have

• add the auxiliary been

• use the past participle, for example, taken.

For example: I have been taken by my mother; he had been taken by my mother; they will have been taken

by my mother.

Nominalisation

Nominalisation allows a writer/speaker to move beyond orienting to people, concrete objects and circumstance

to orient to abstractions. It also allows an orientation to an action/event or a quality through a change in

grammatical form, eg from verb to noun or adjective to noun. This change in grammatical form then requires

subsequent grammatical changes to create a new sentence:

• Many fish died after the factory illegally dumped their chemicals and polluted the river.

> The death of many fish resulted from illegal dumping of chemicals that polluted the river.

> Water pollution resulting from illegal chemical dumping caused a marked increase in fish deaths.

• The story is neither credible nor believable.

> The credibility of the story has been called into question.

4 | Learning English: Achievement and Proficiency (LEAP) | STRATEGIES COHESIVE DEVICES

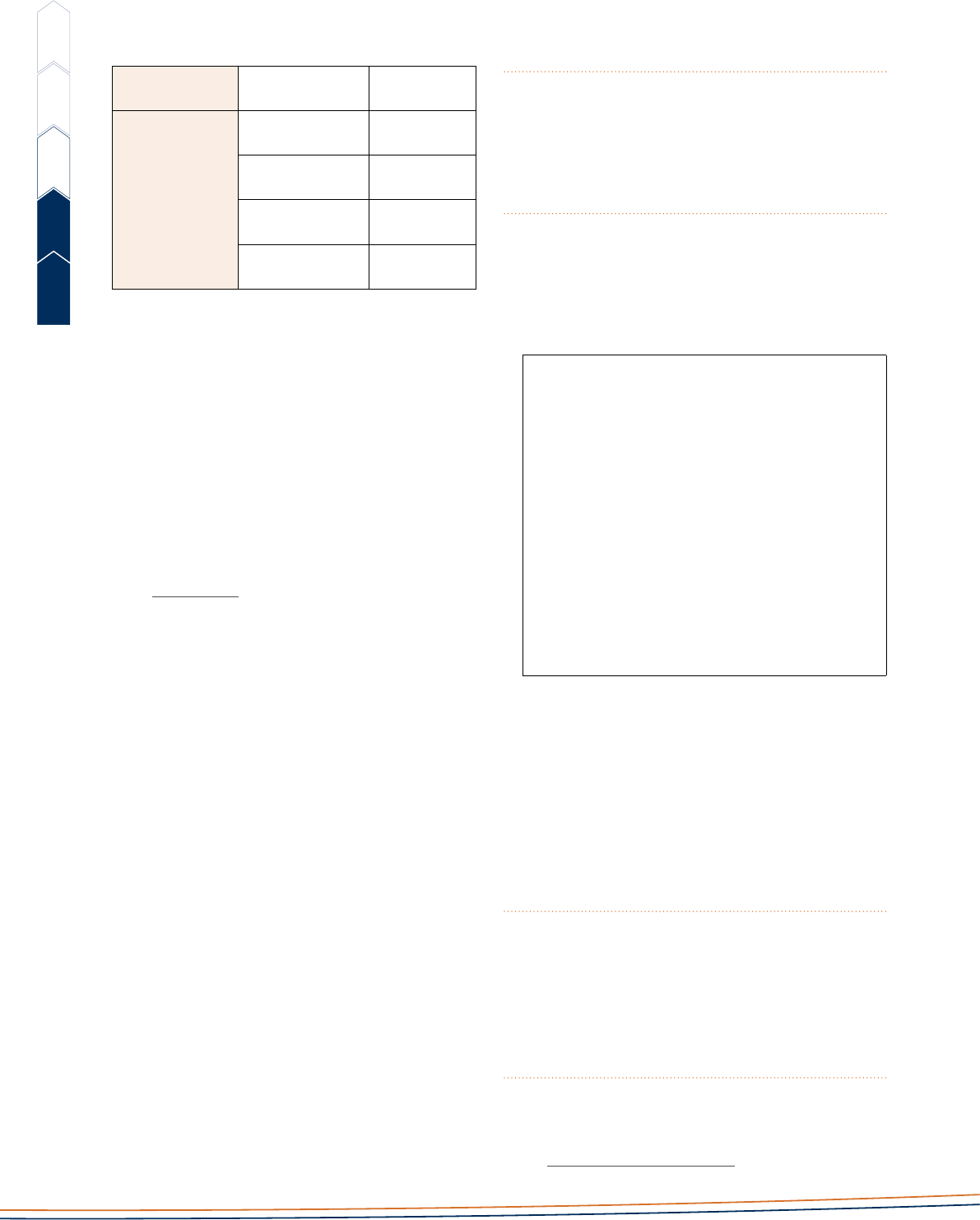

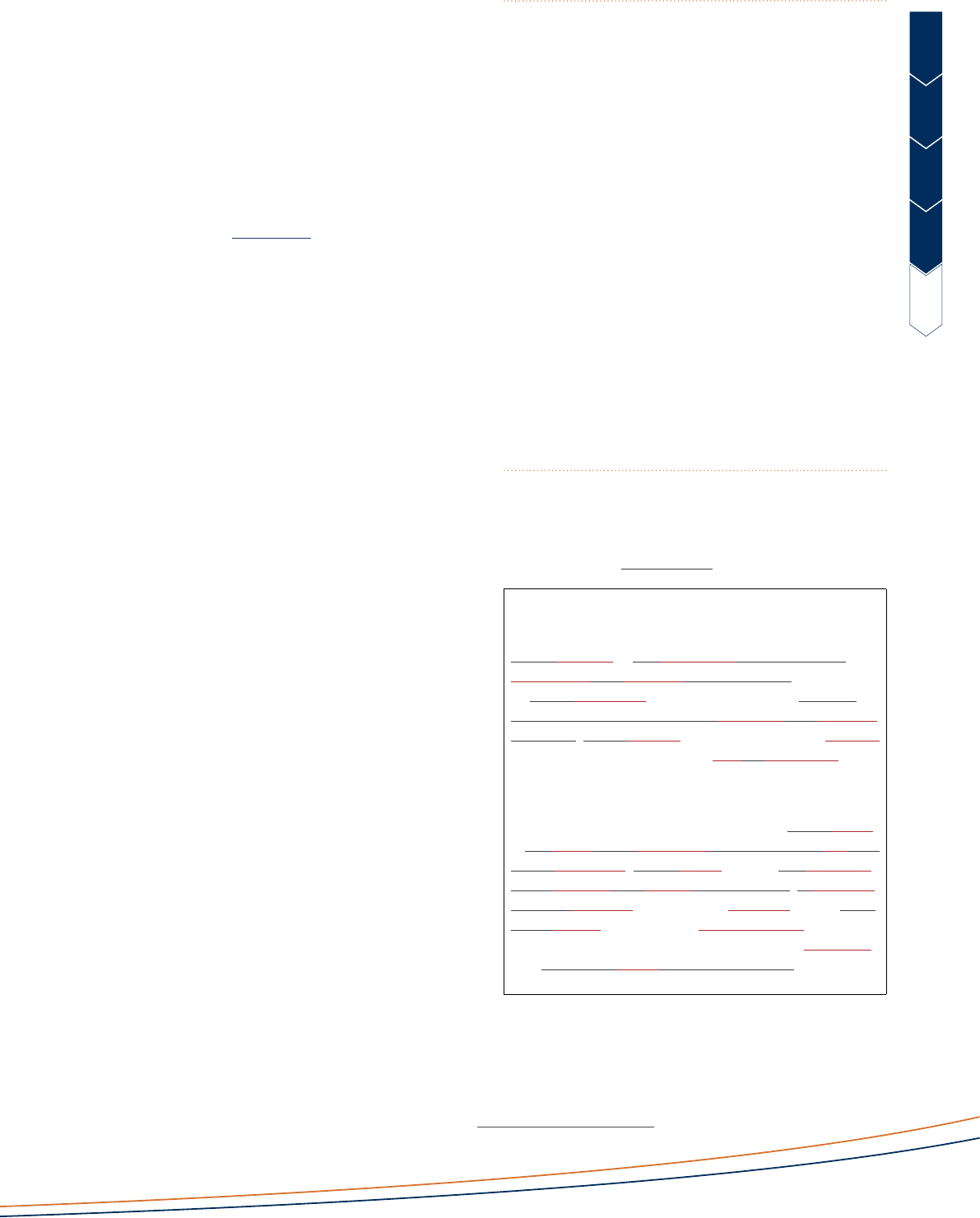

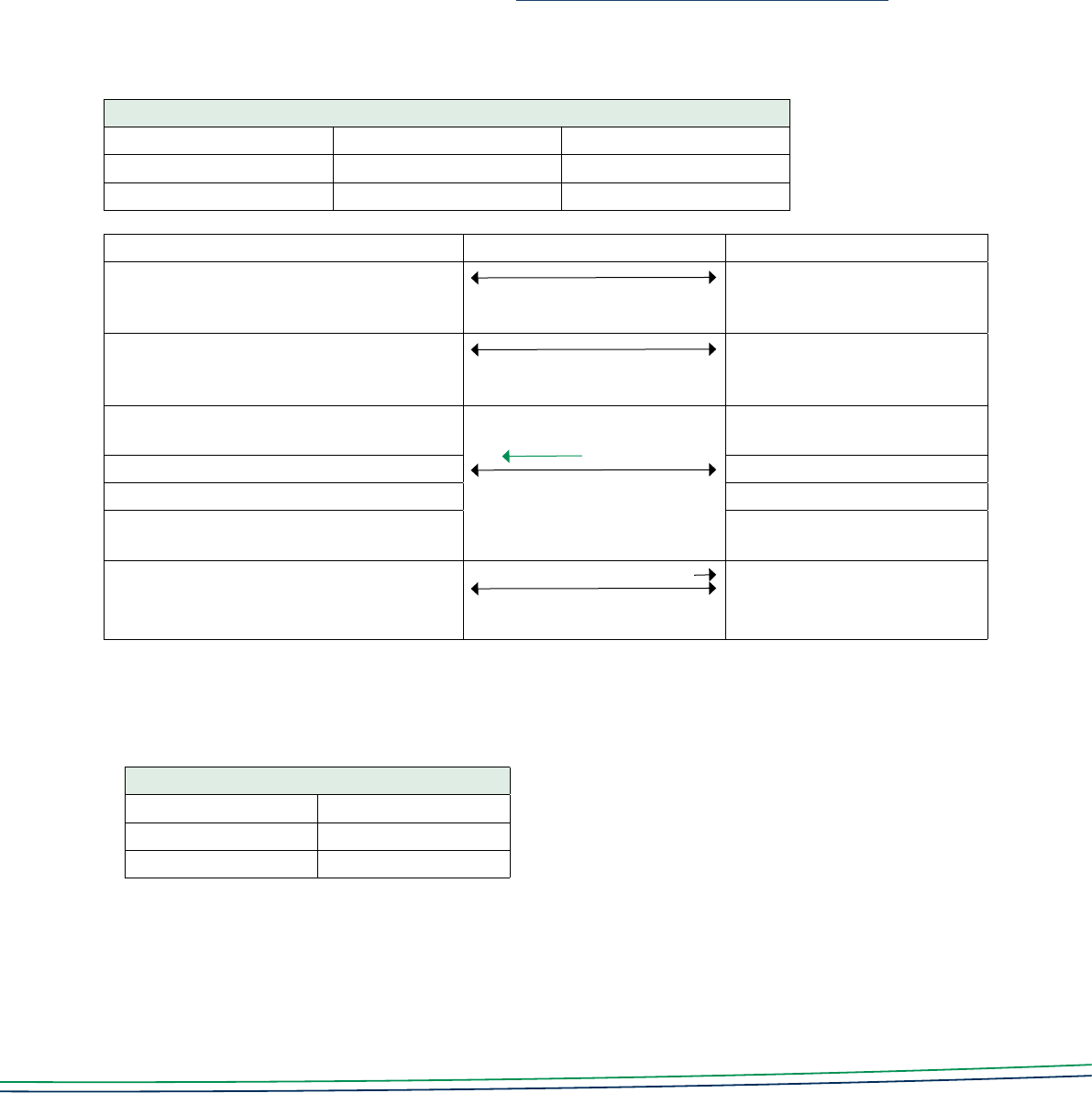

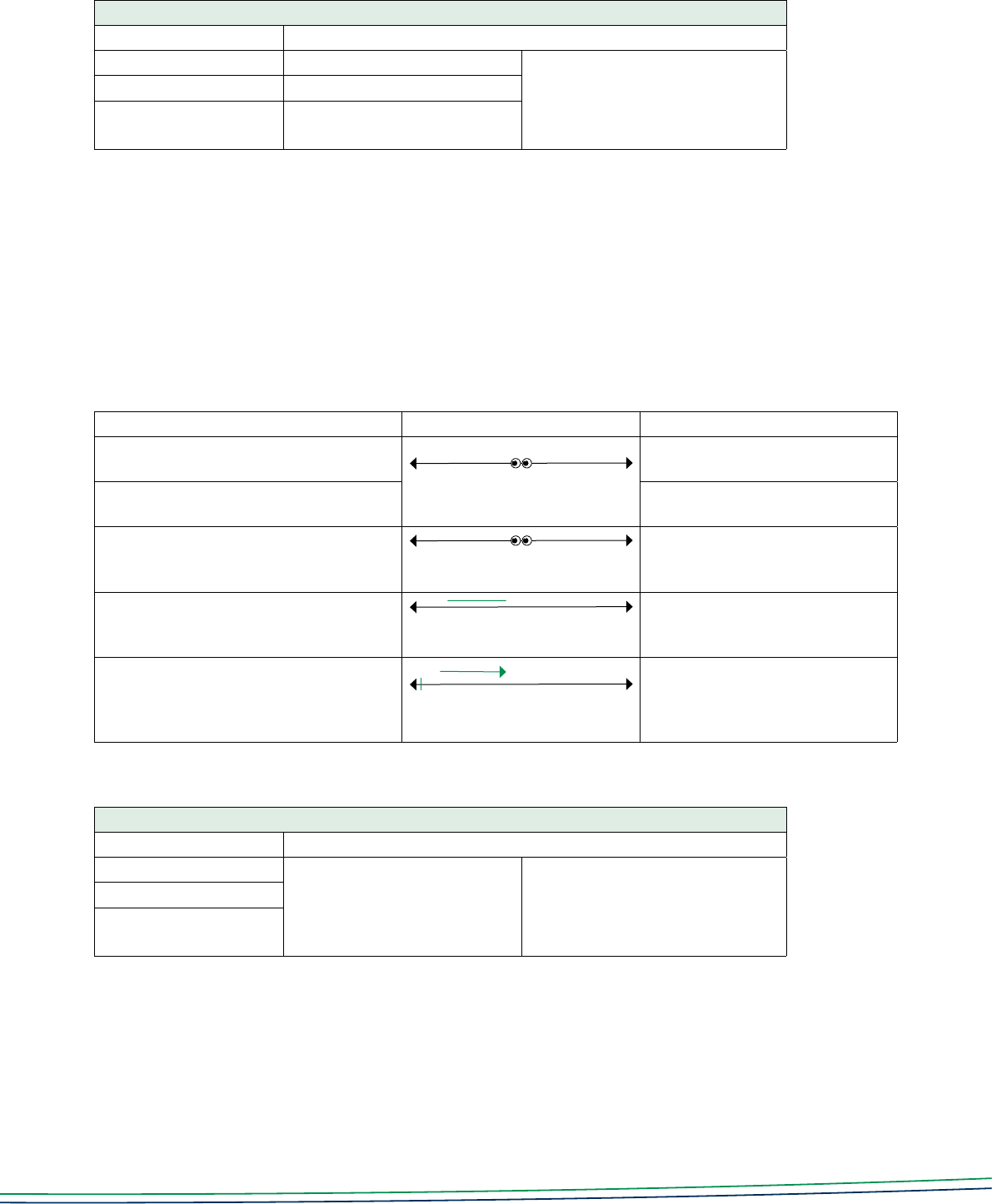

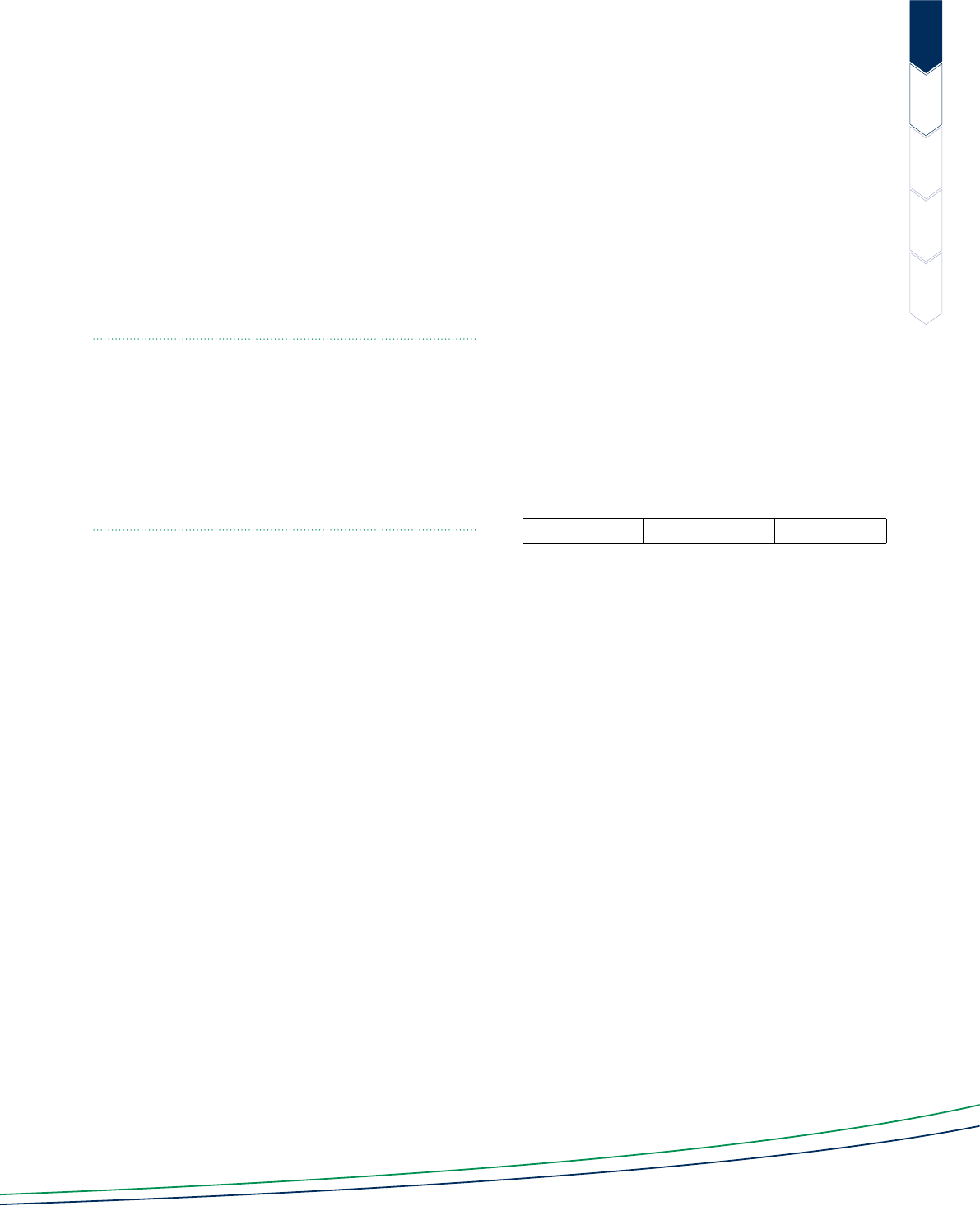

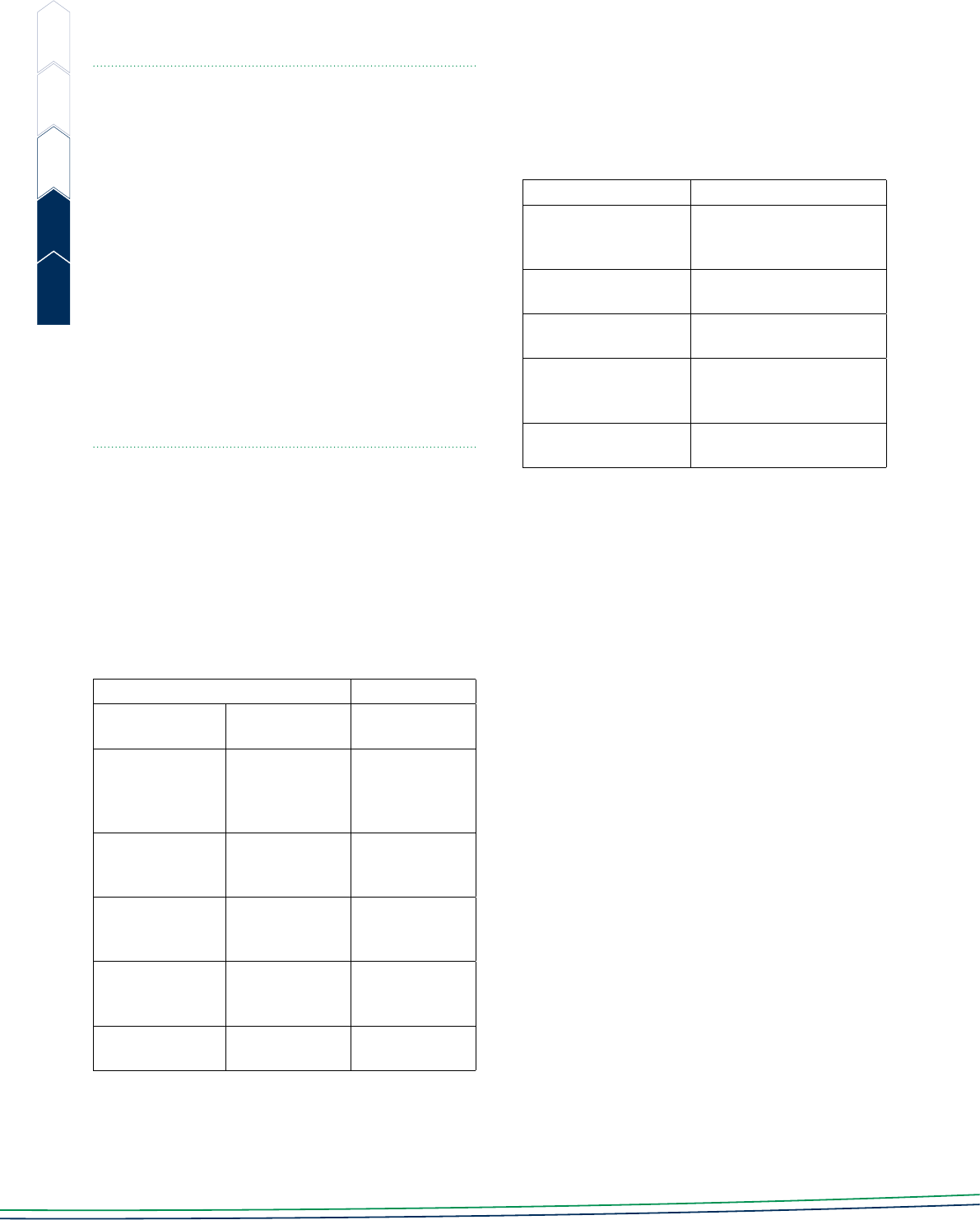

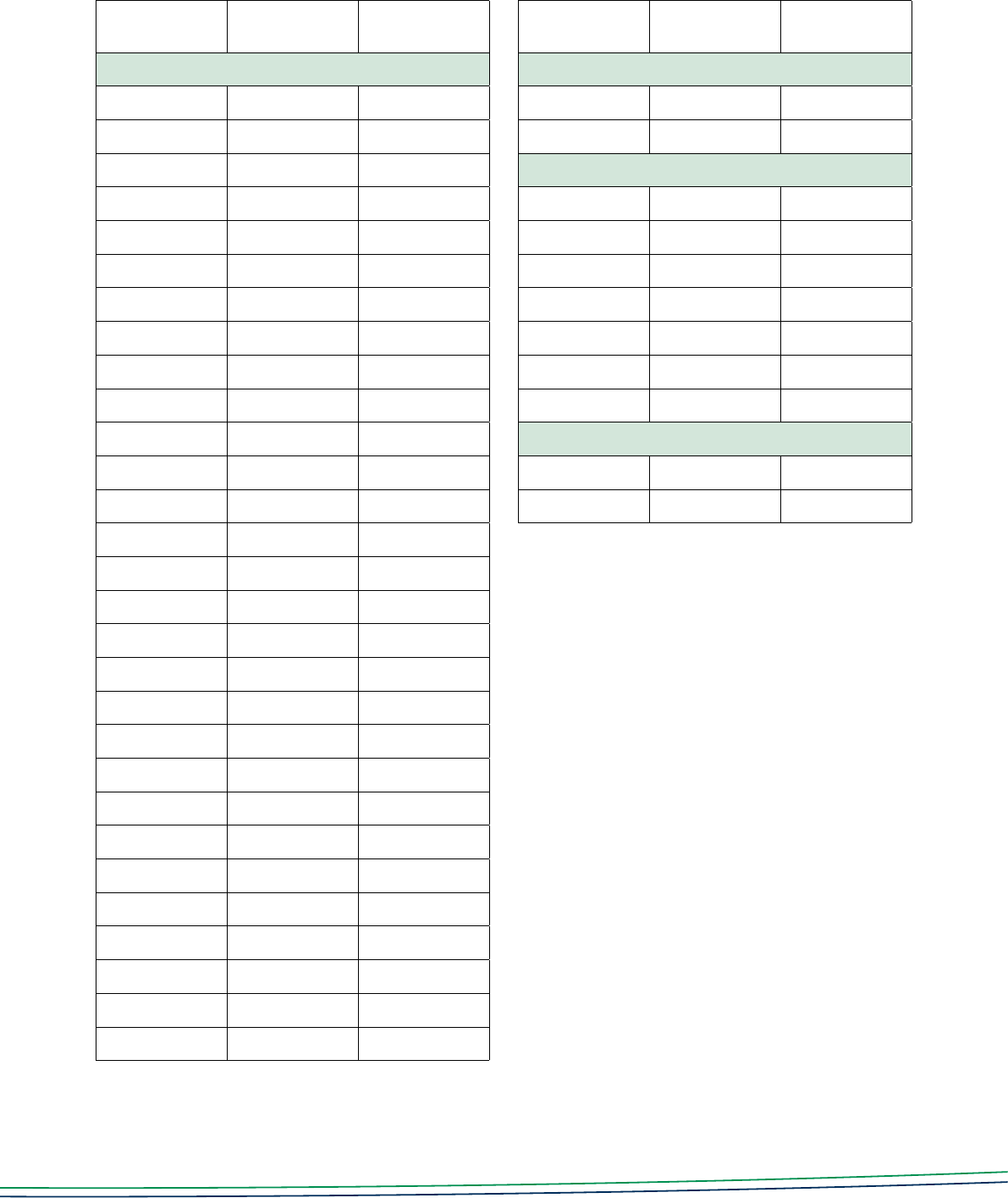

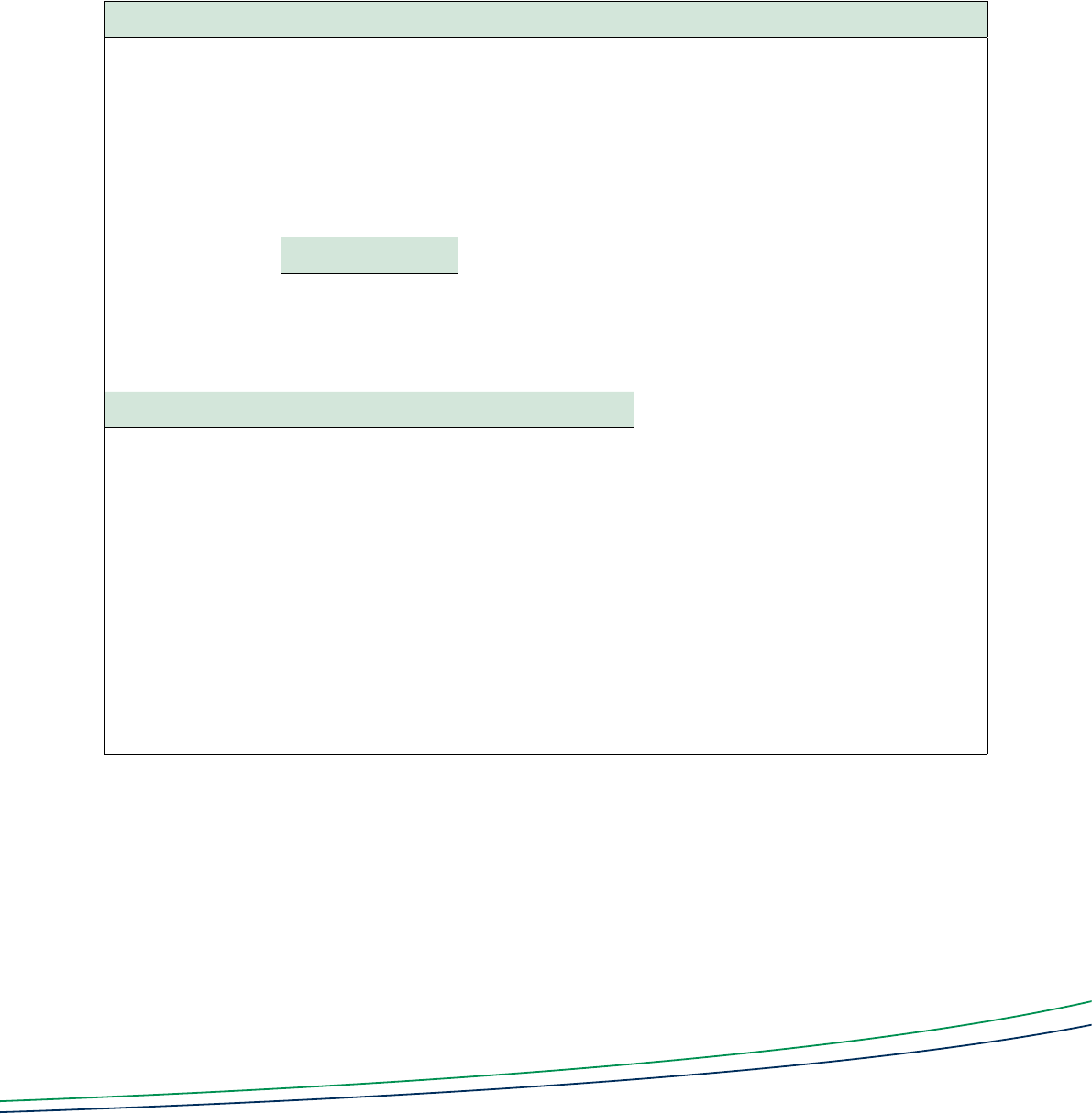

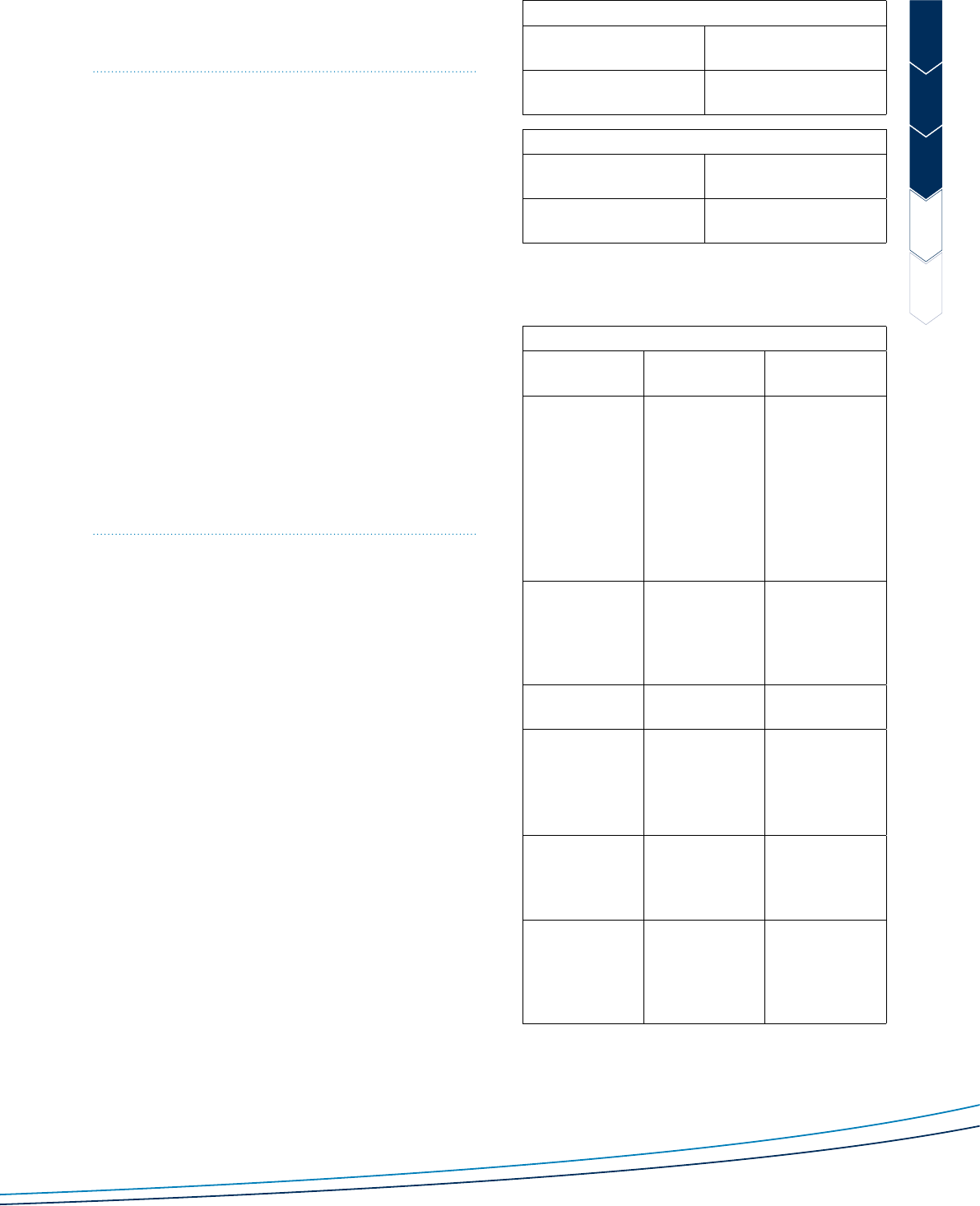

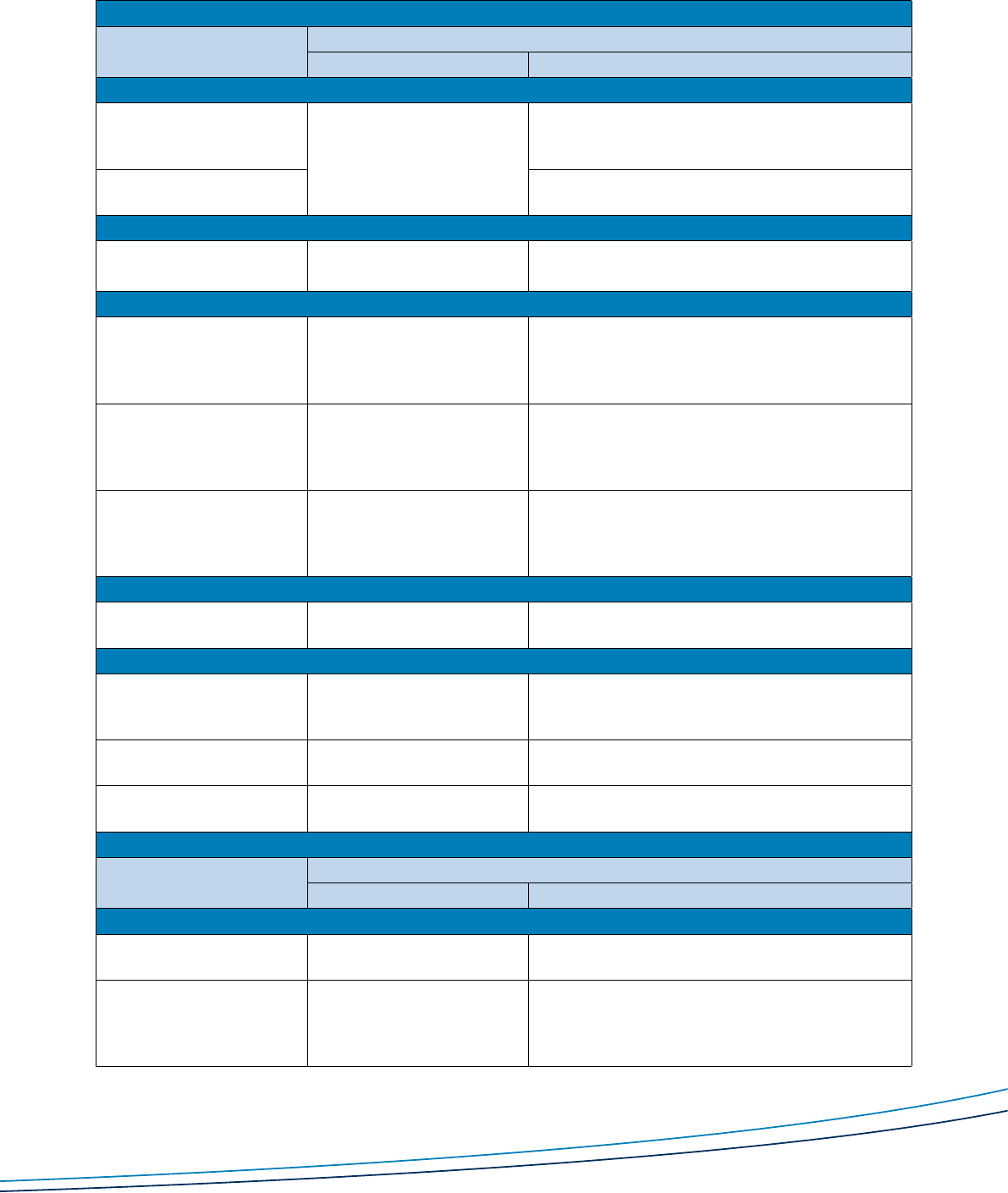

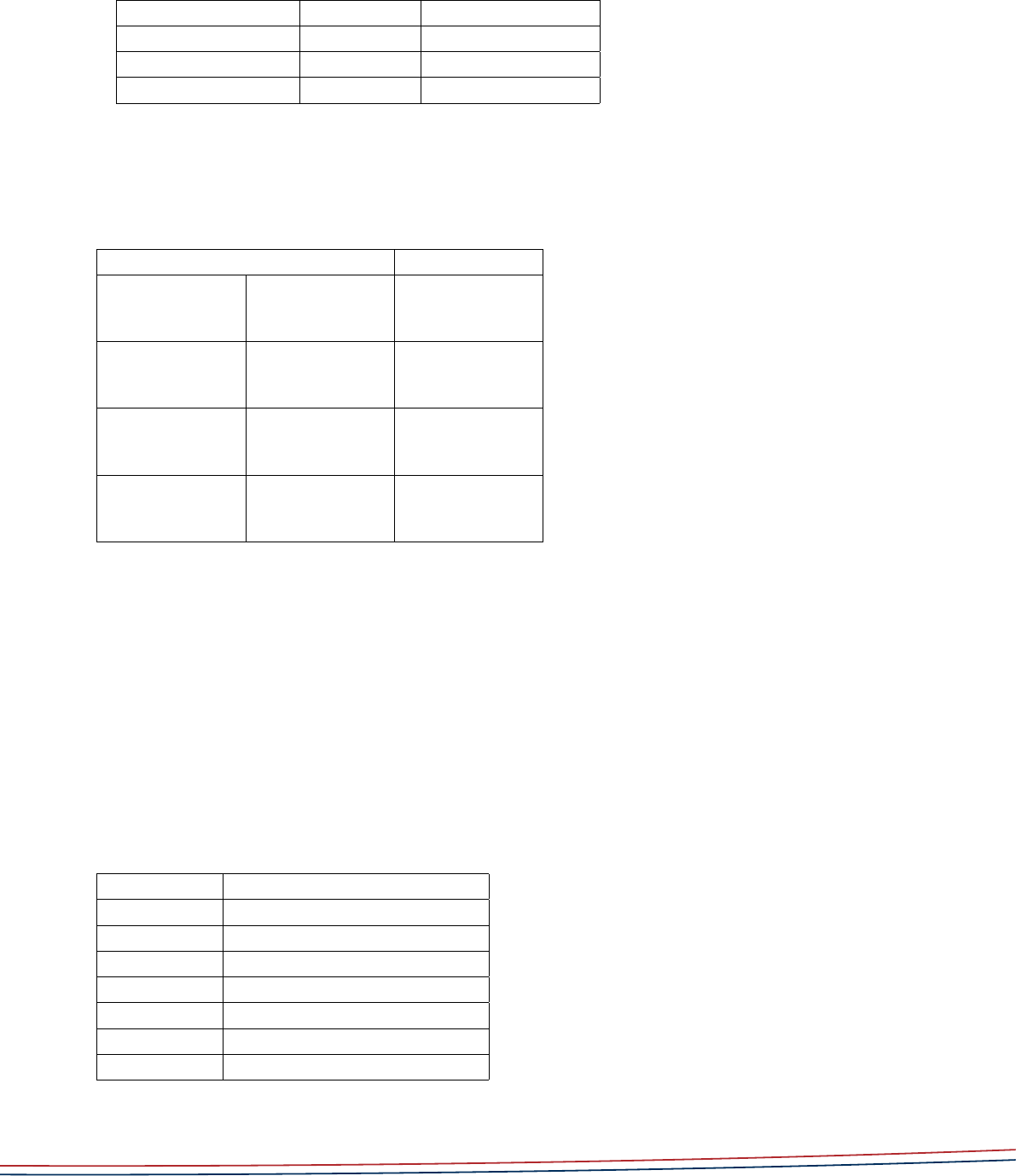

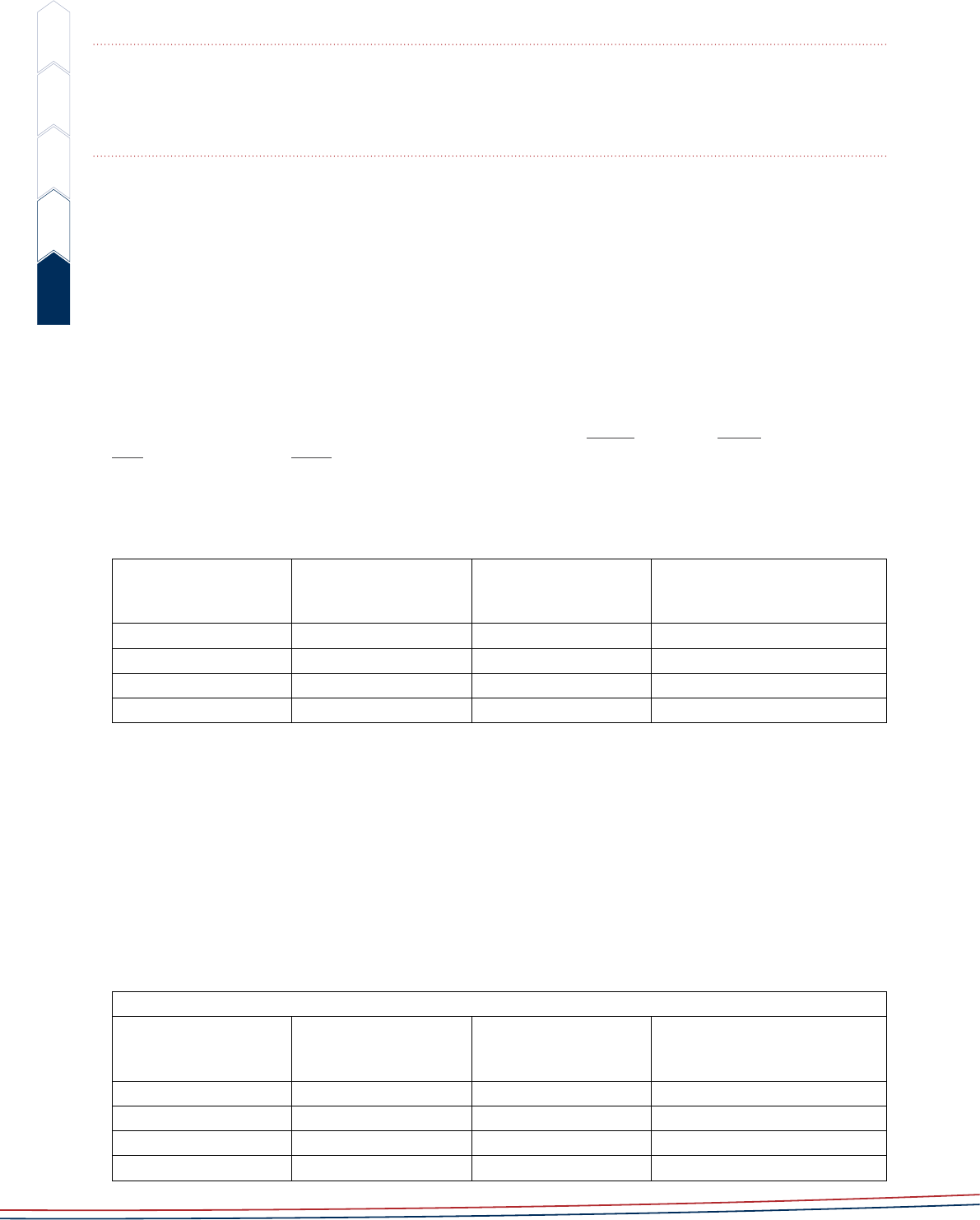

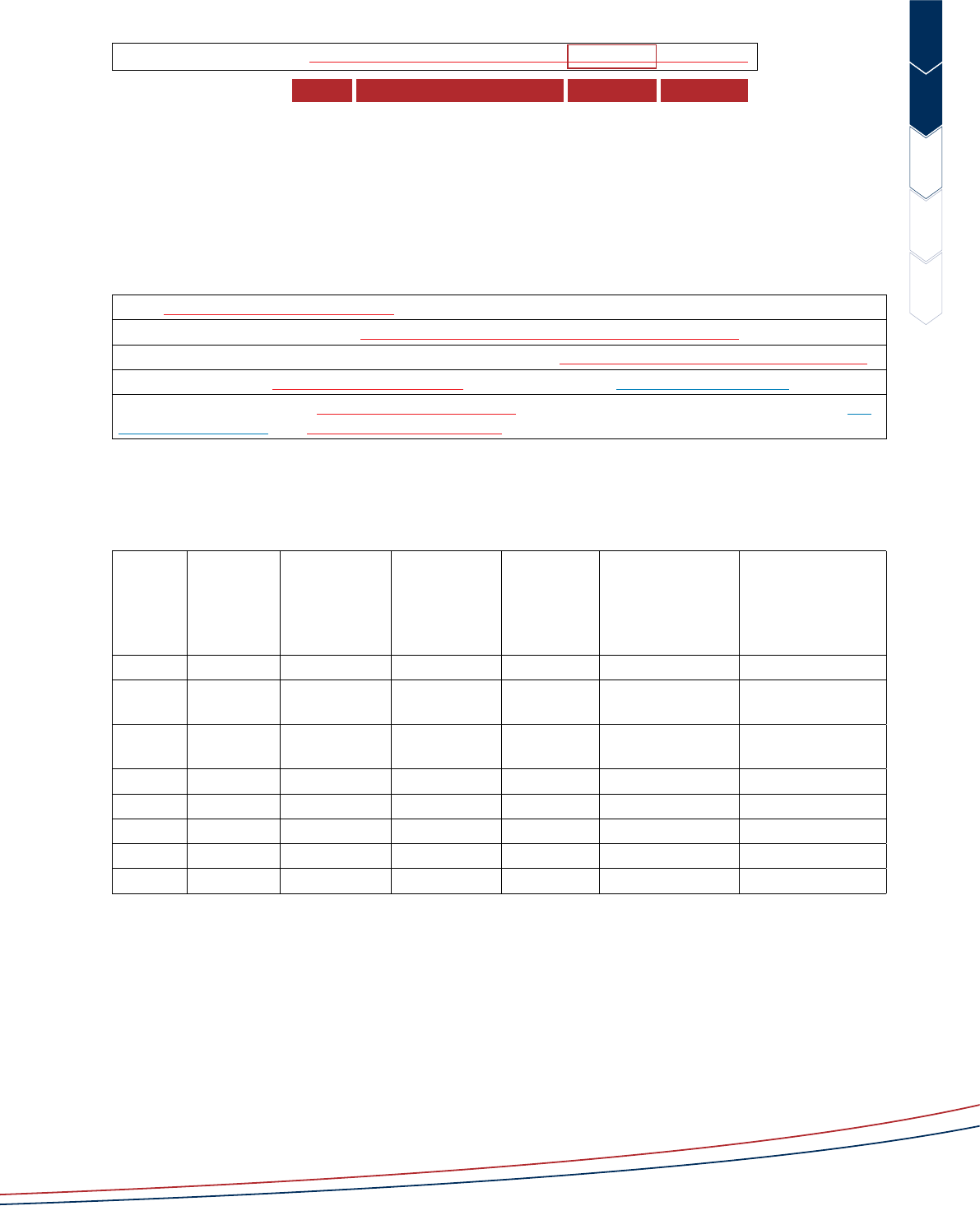

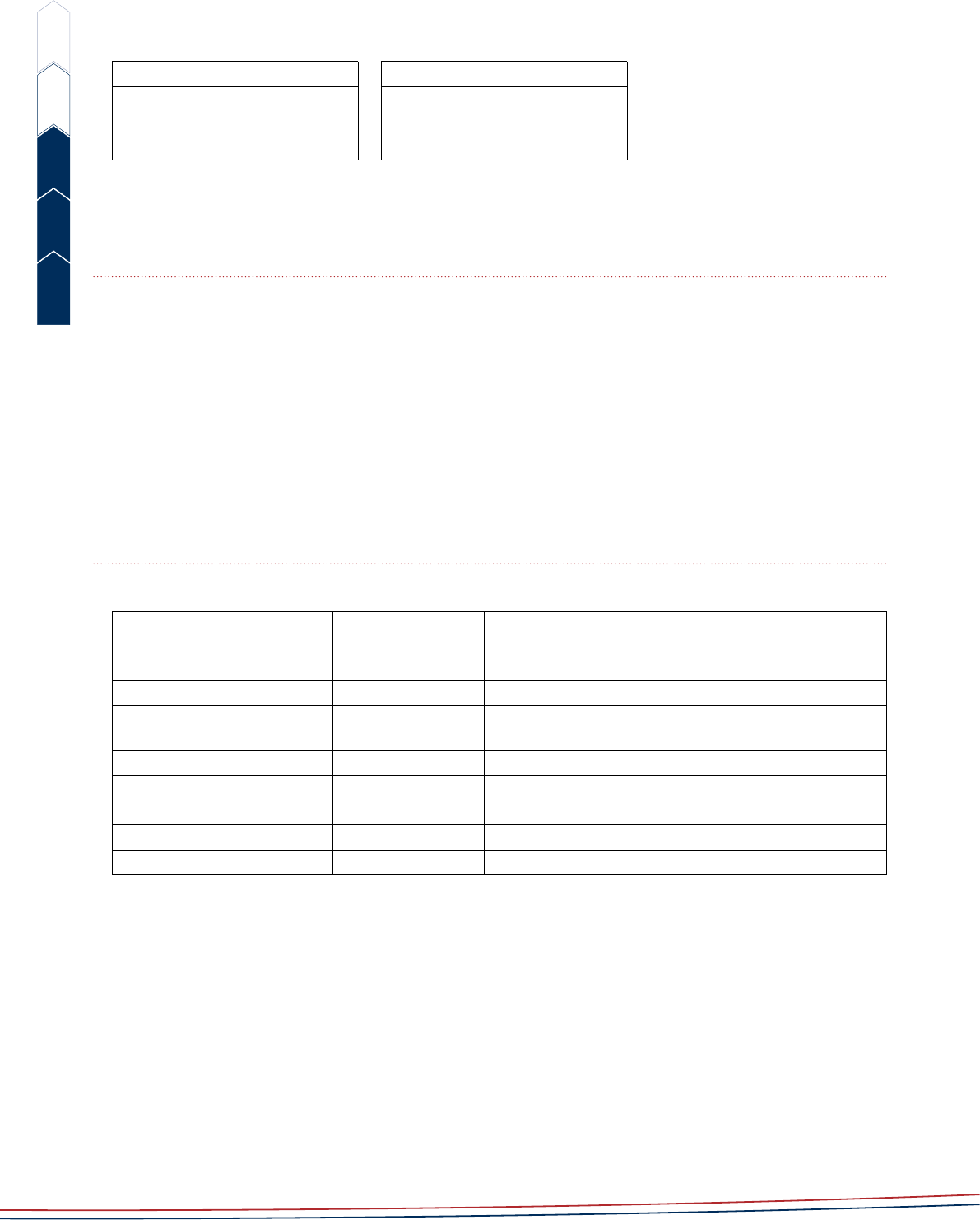

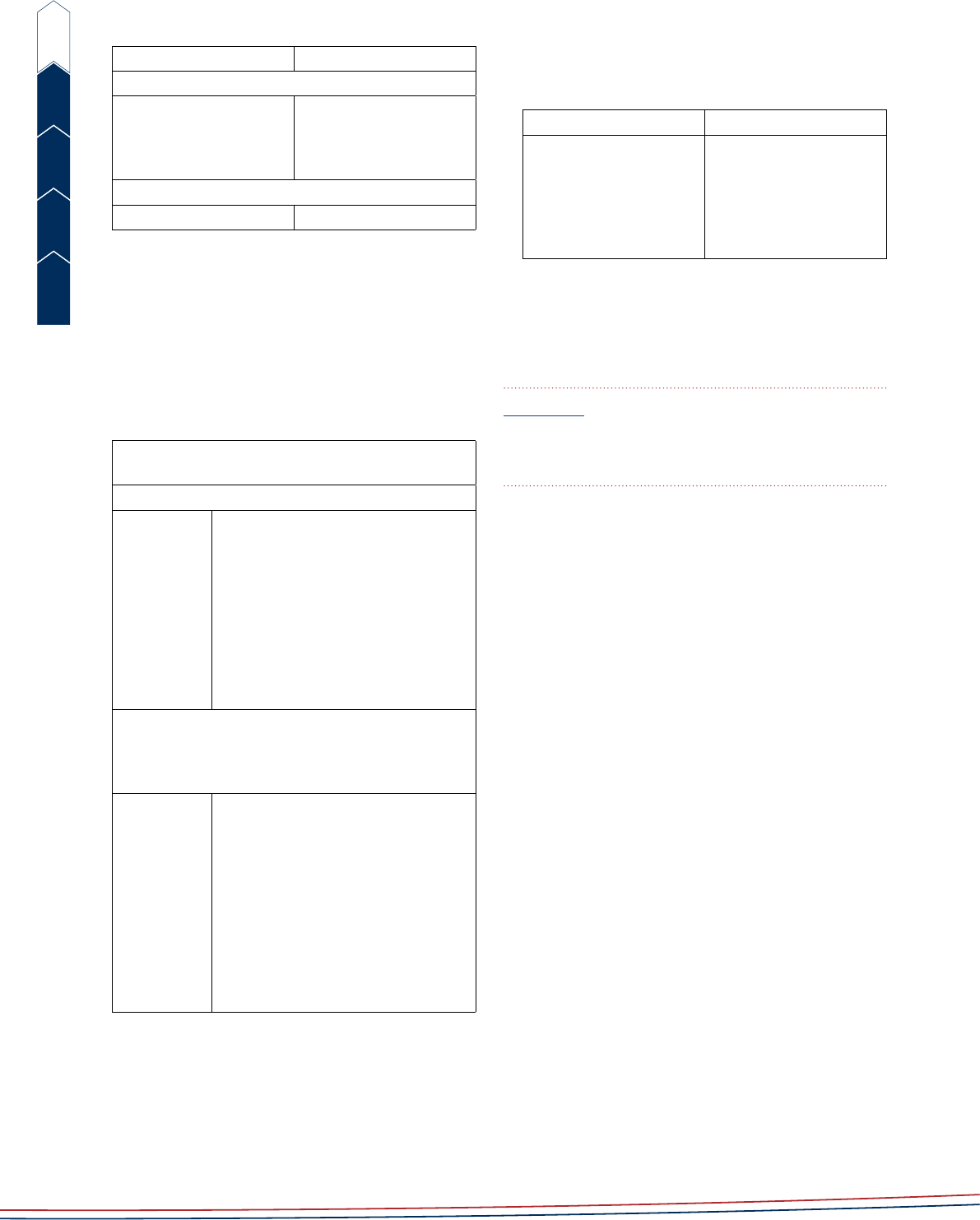

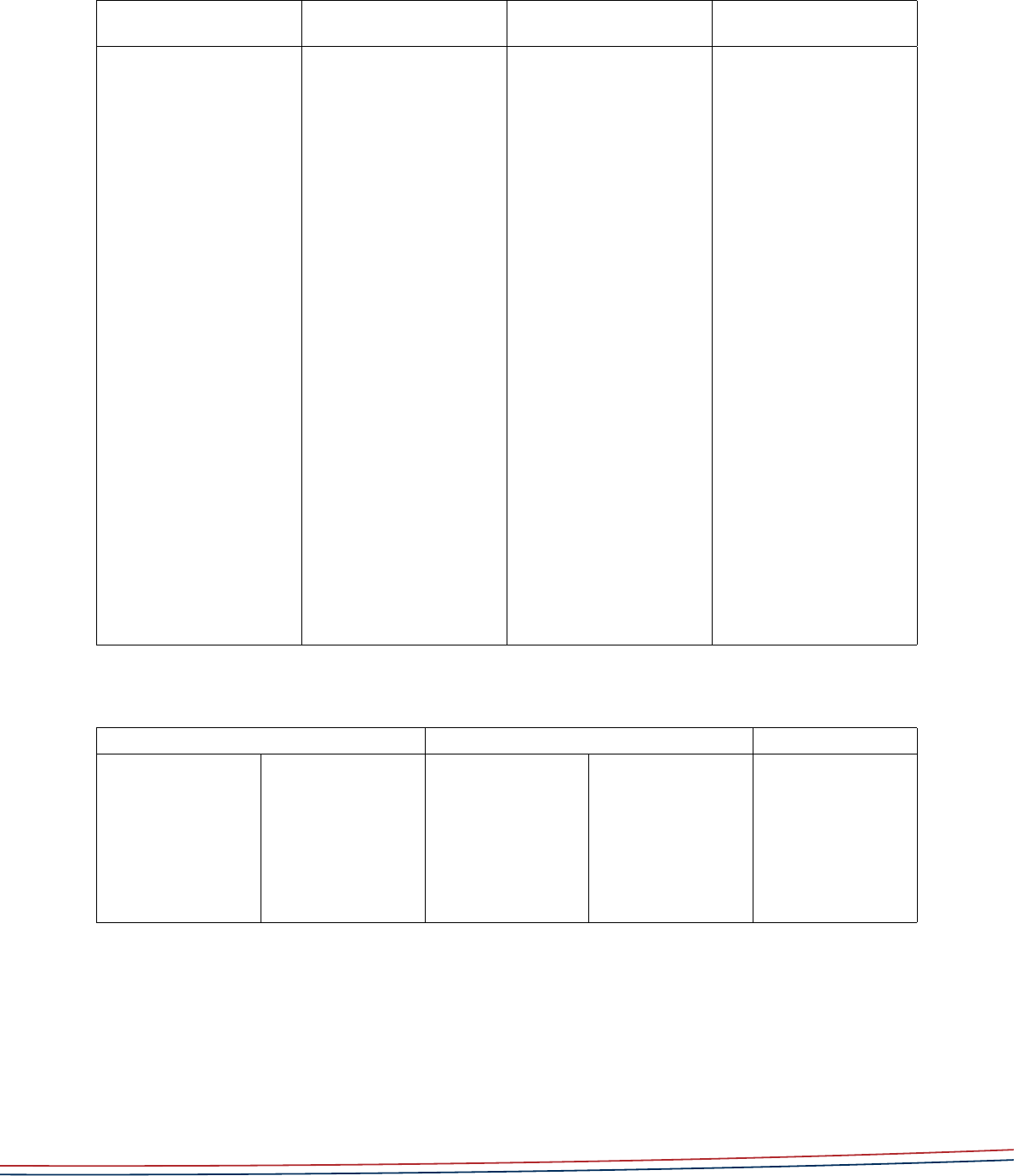

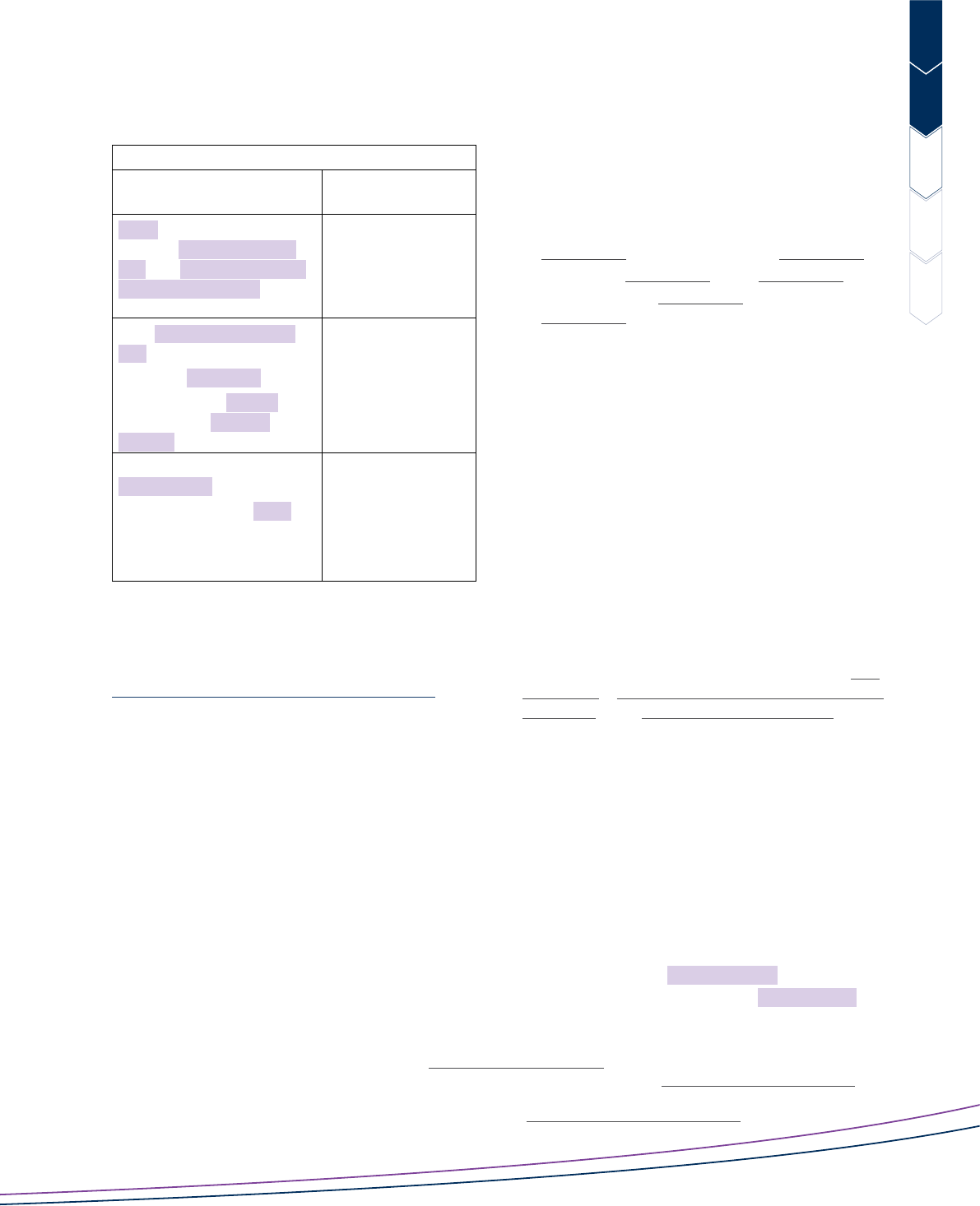

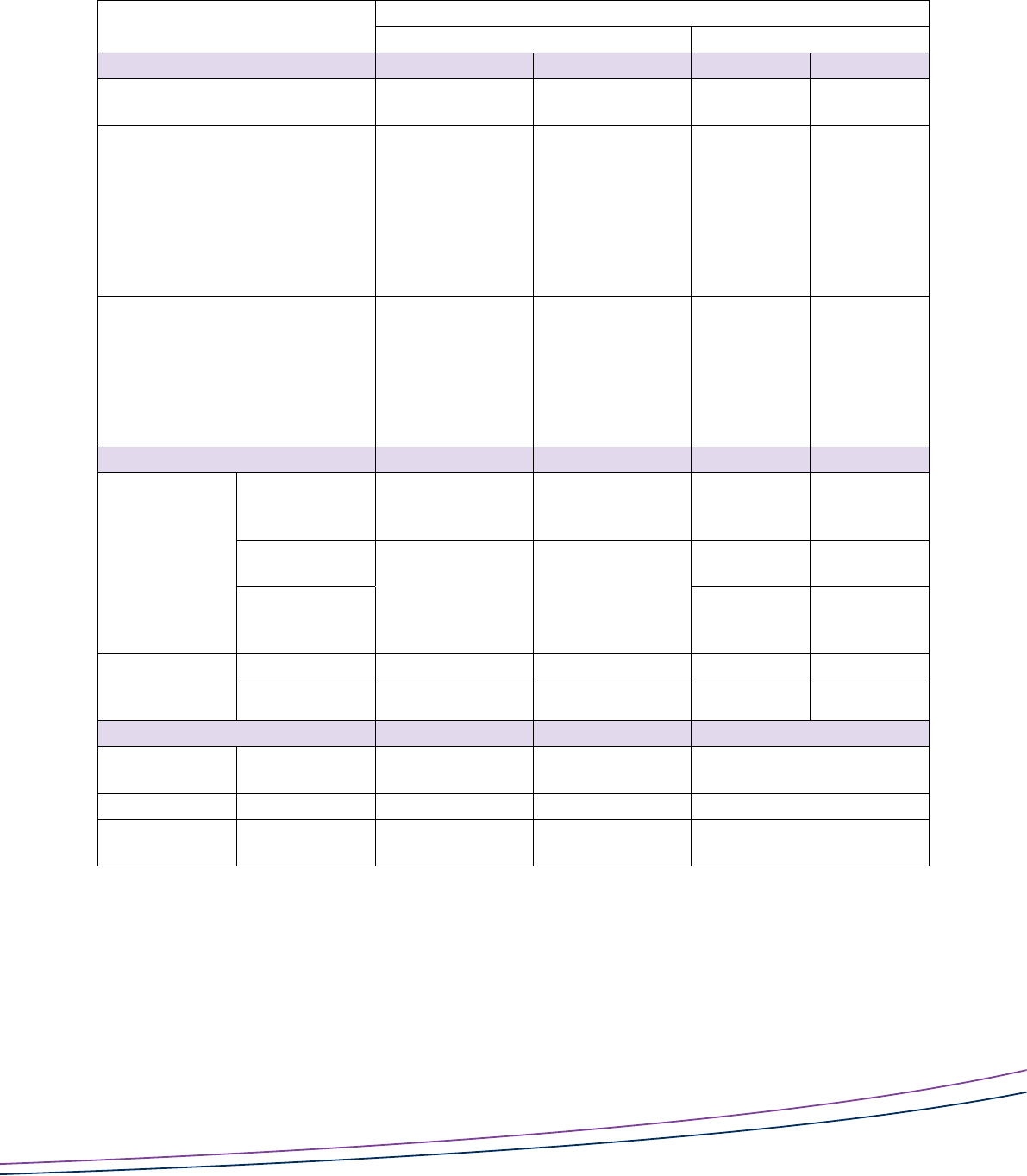

LEVELS

1–4

LEVELS

5–6

LEVELS

7–9

LEVELS

10–12

LEVELS

13–14

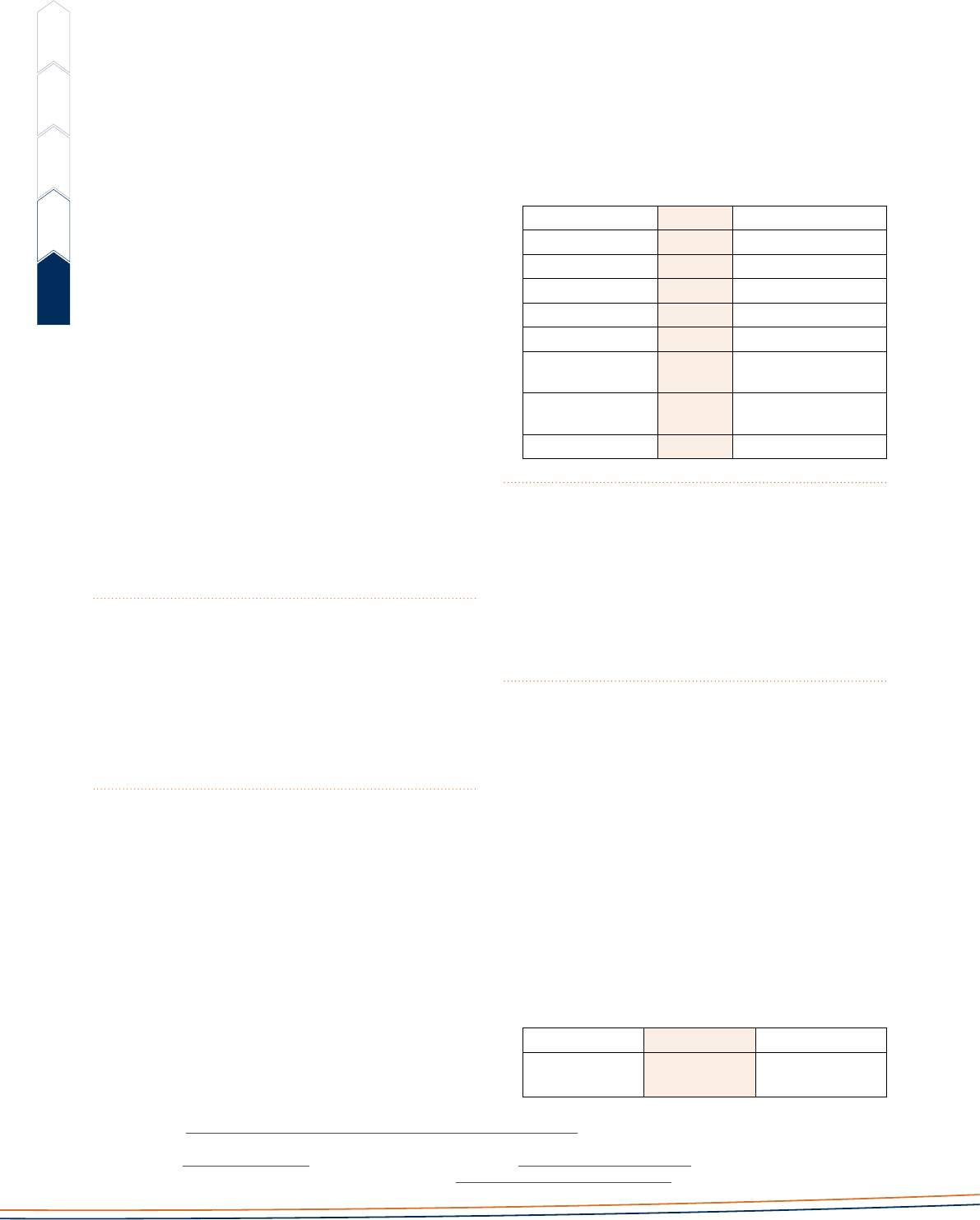

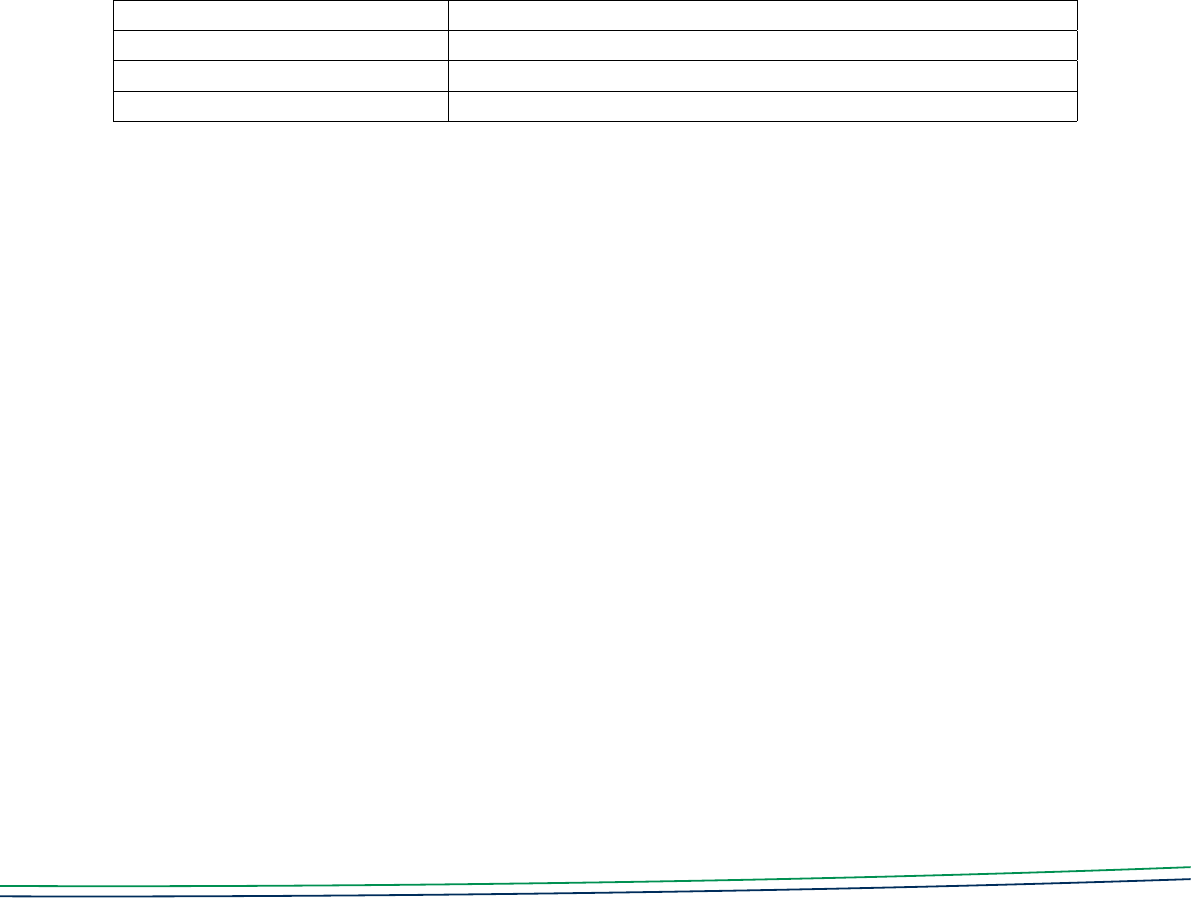

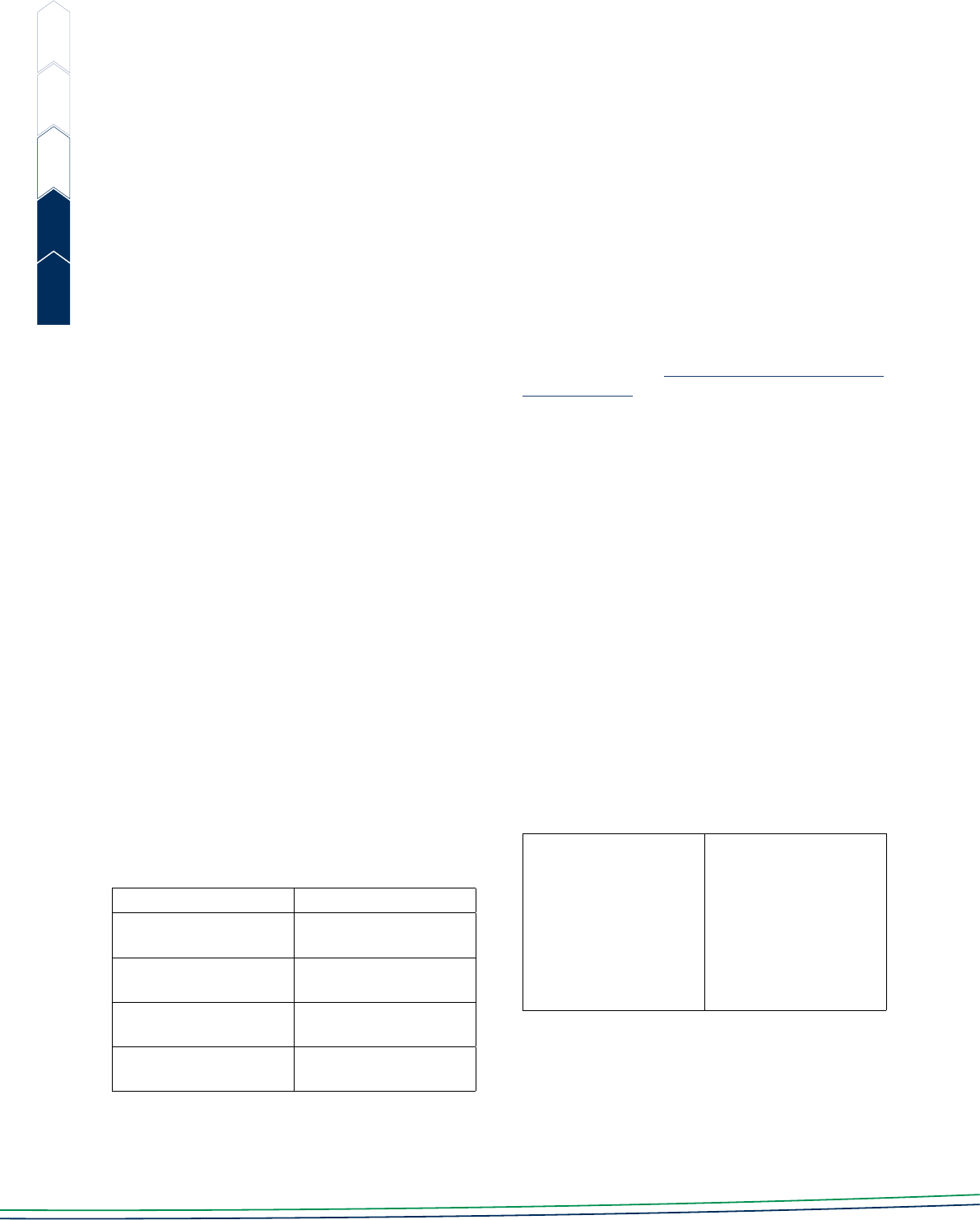

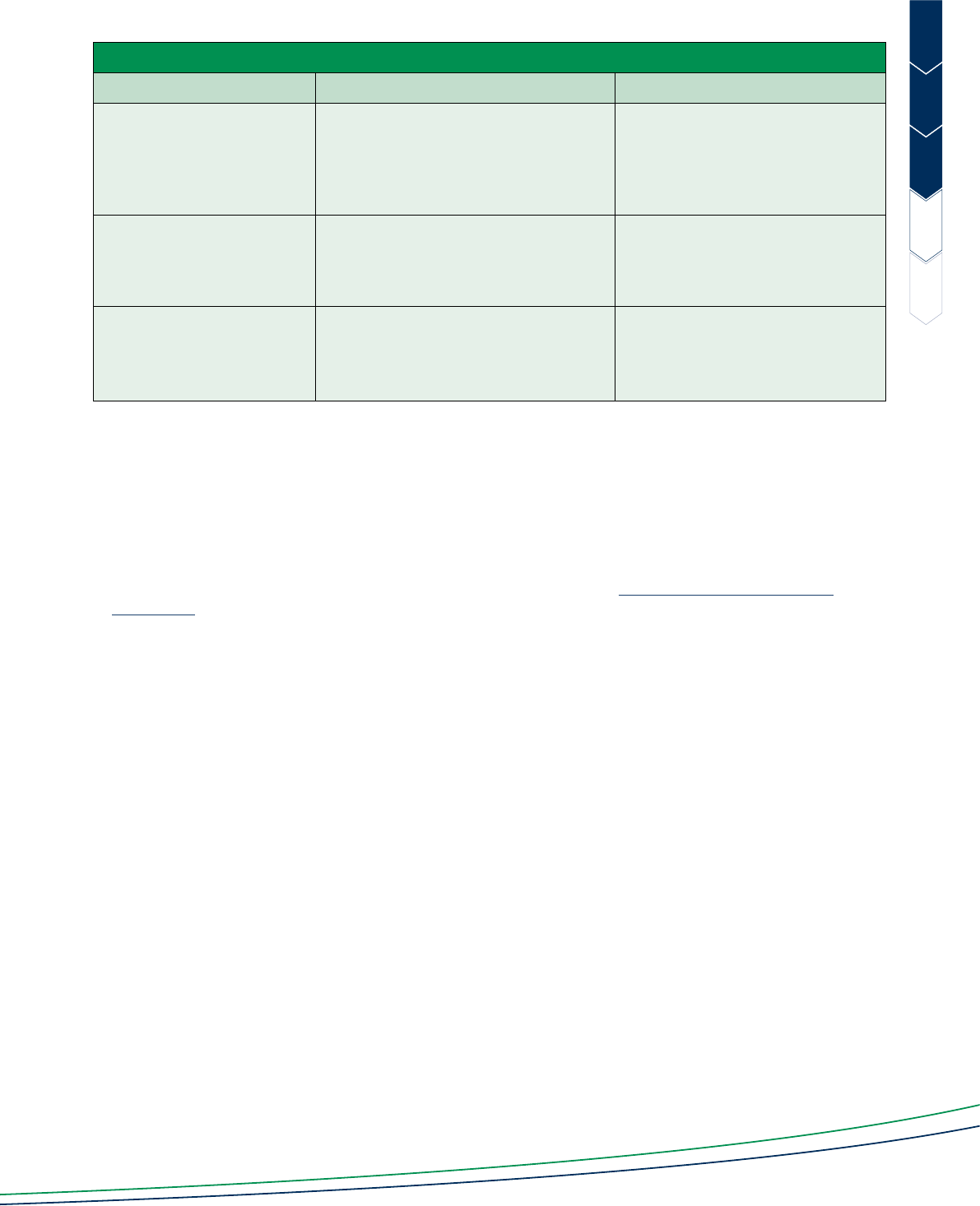

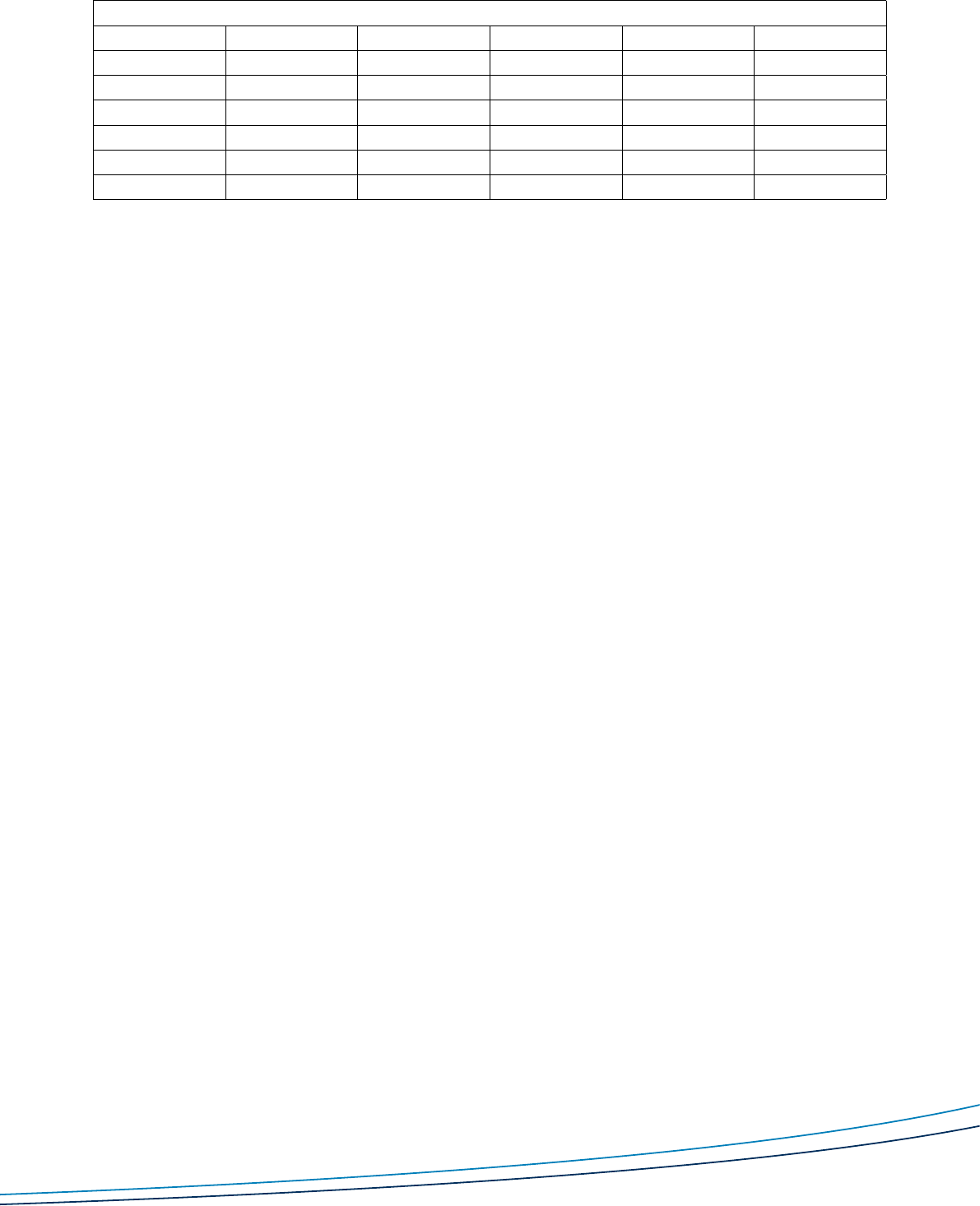

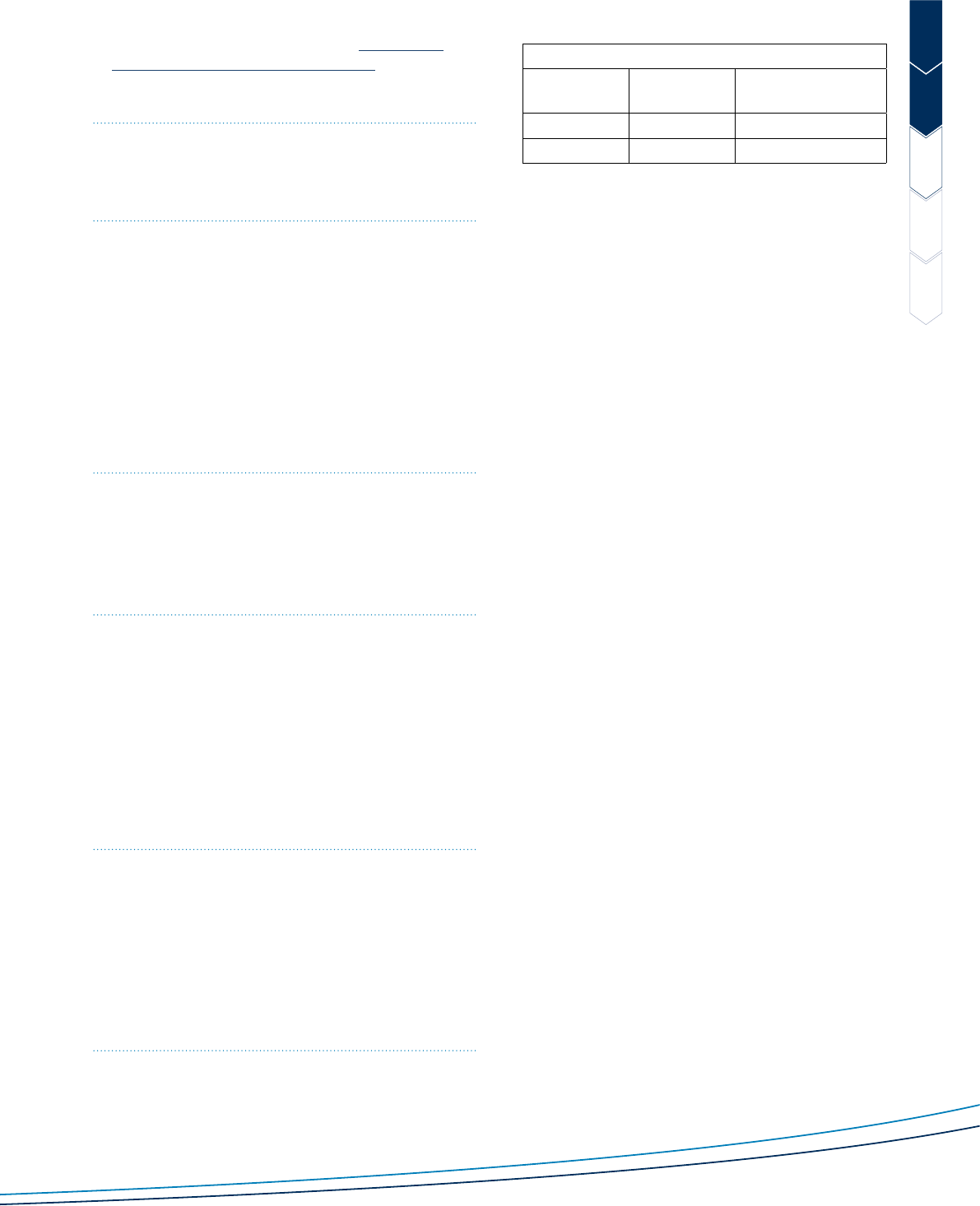

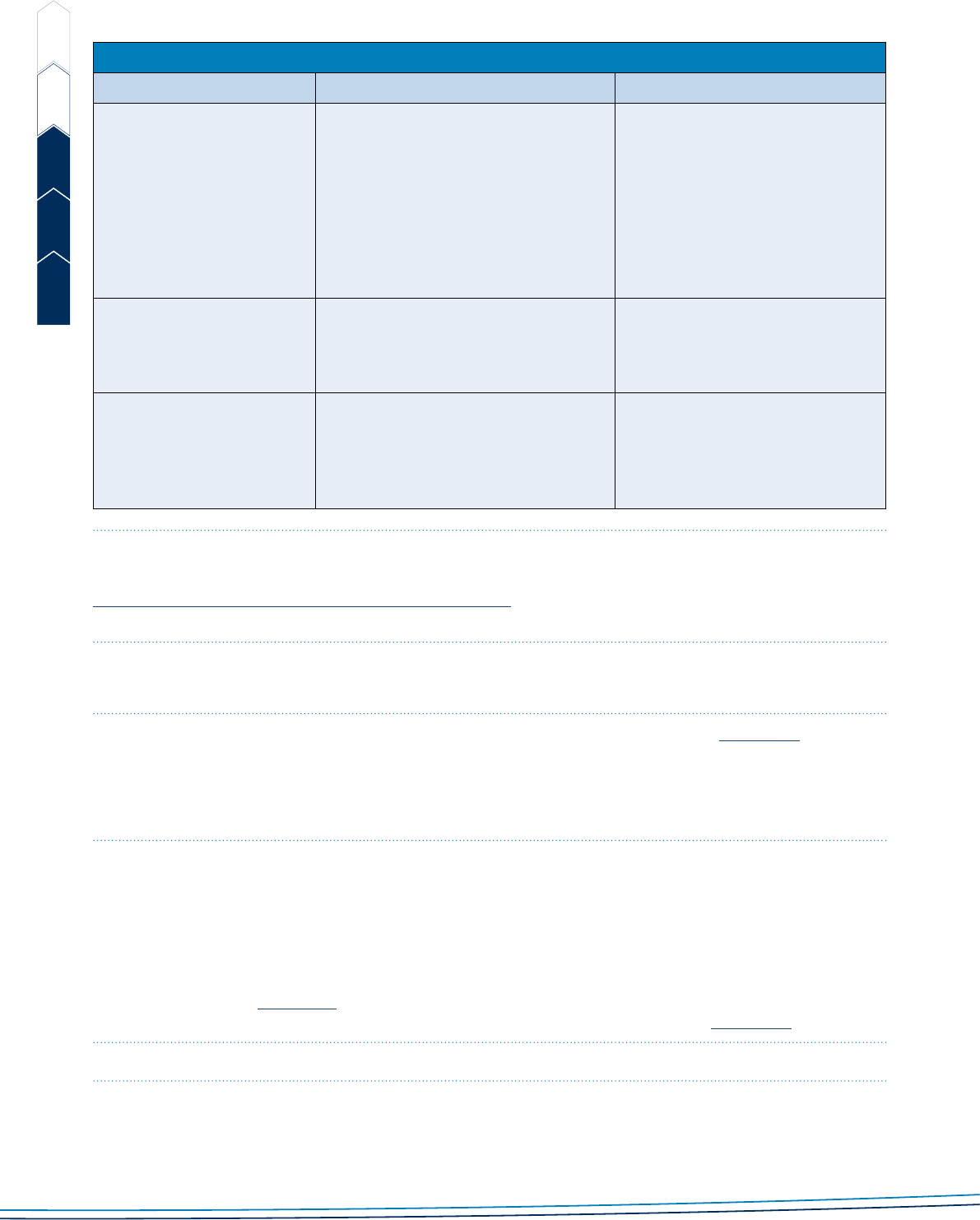

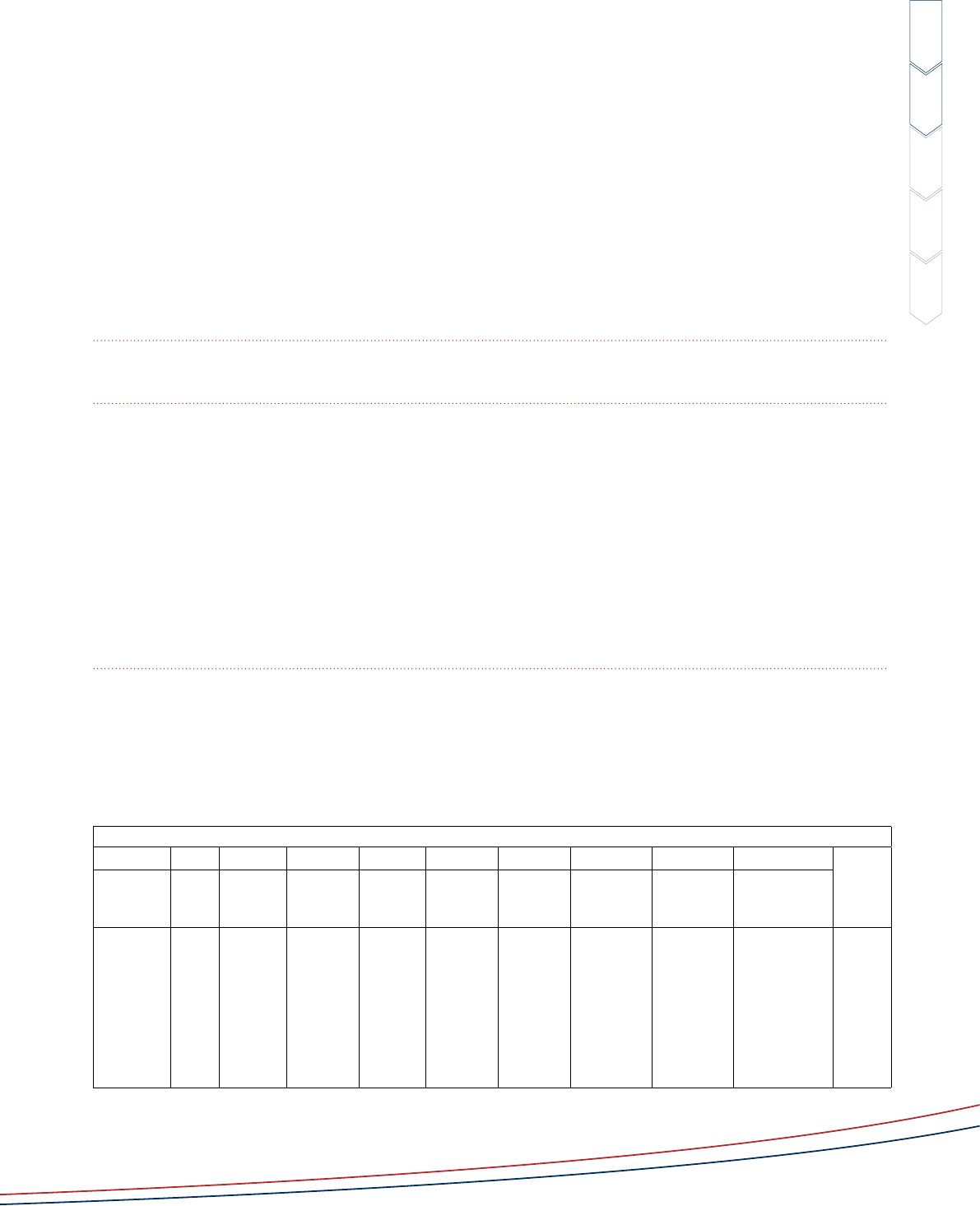

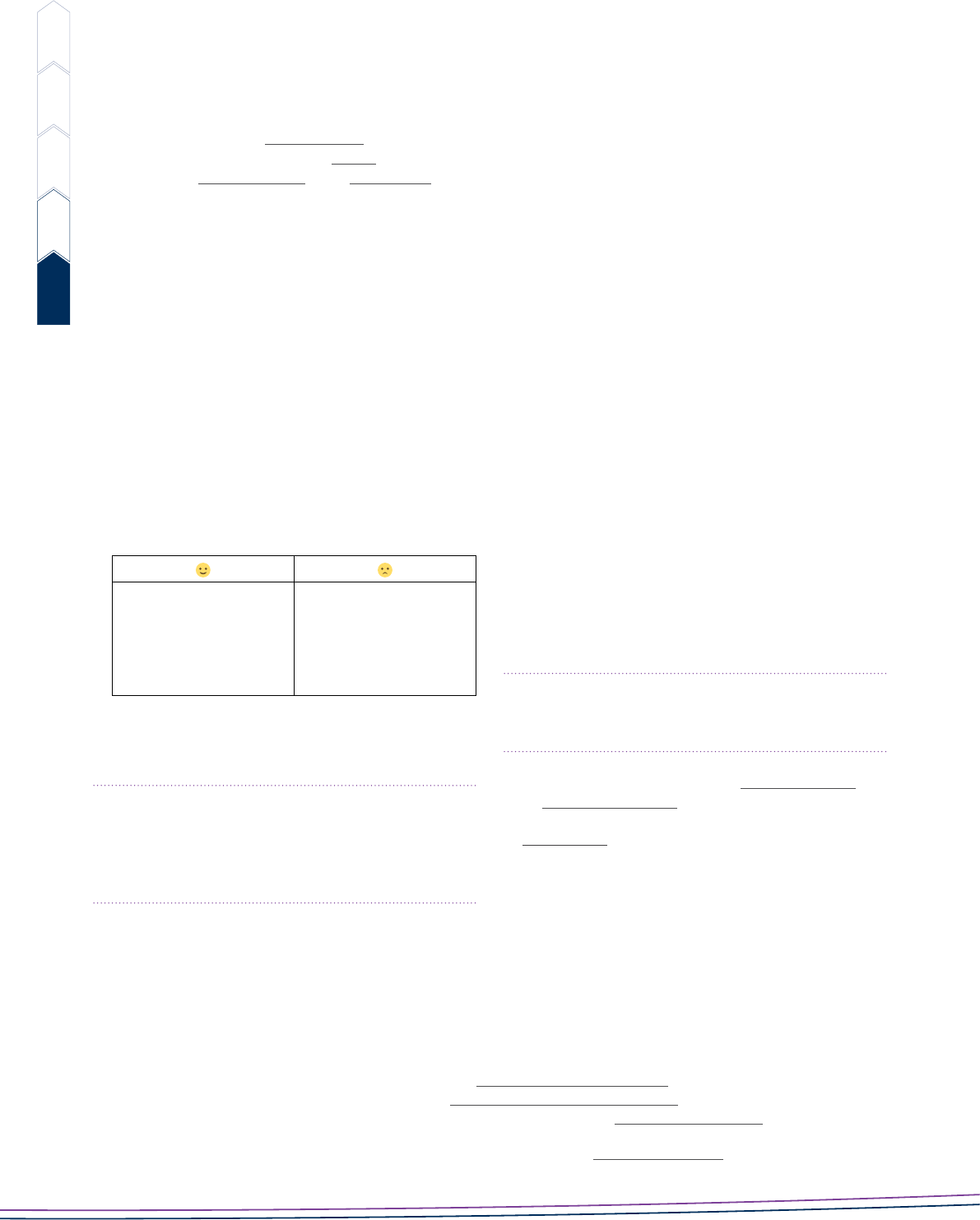

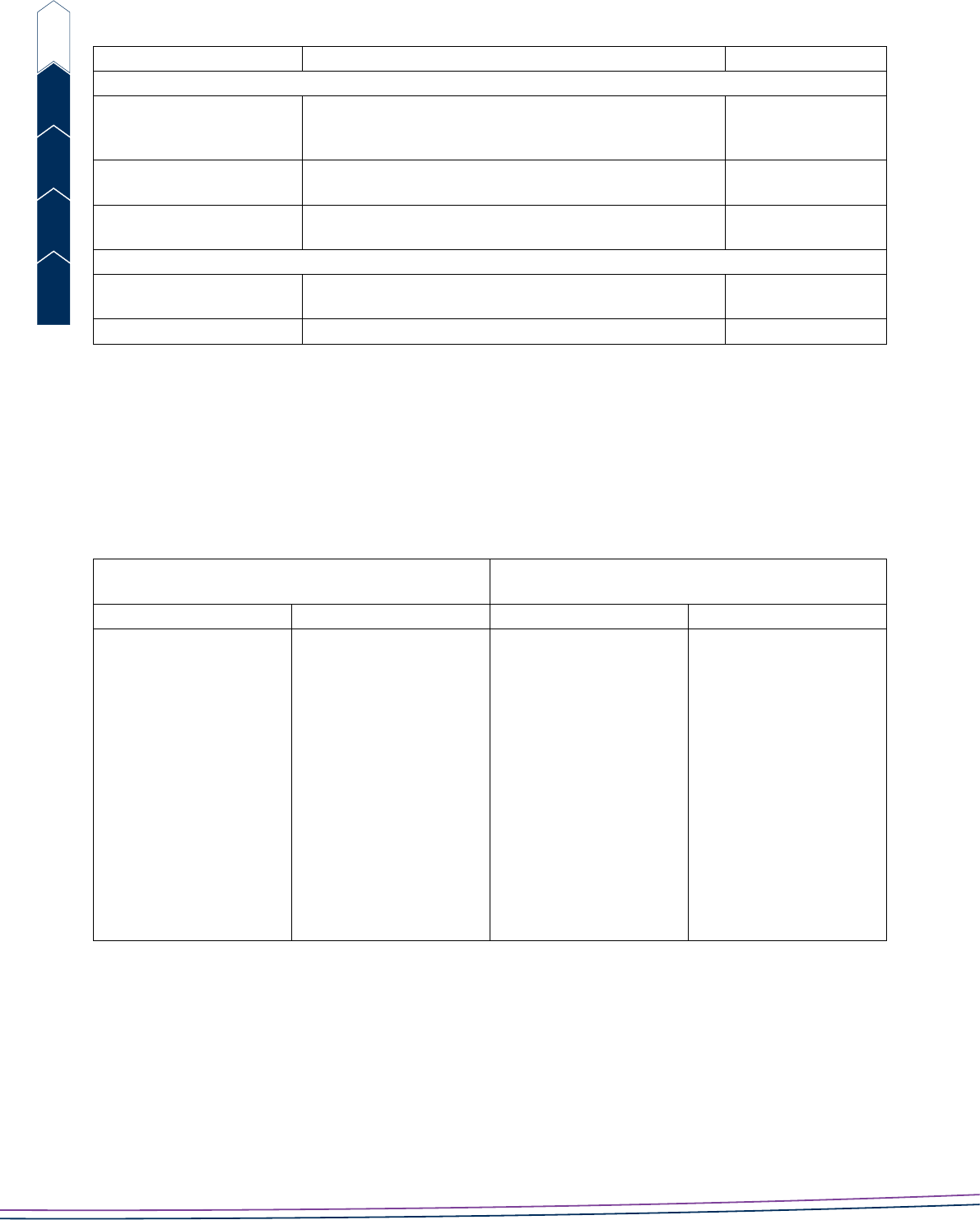

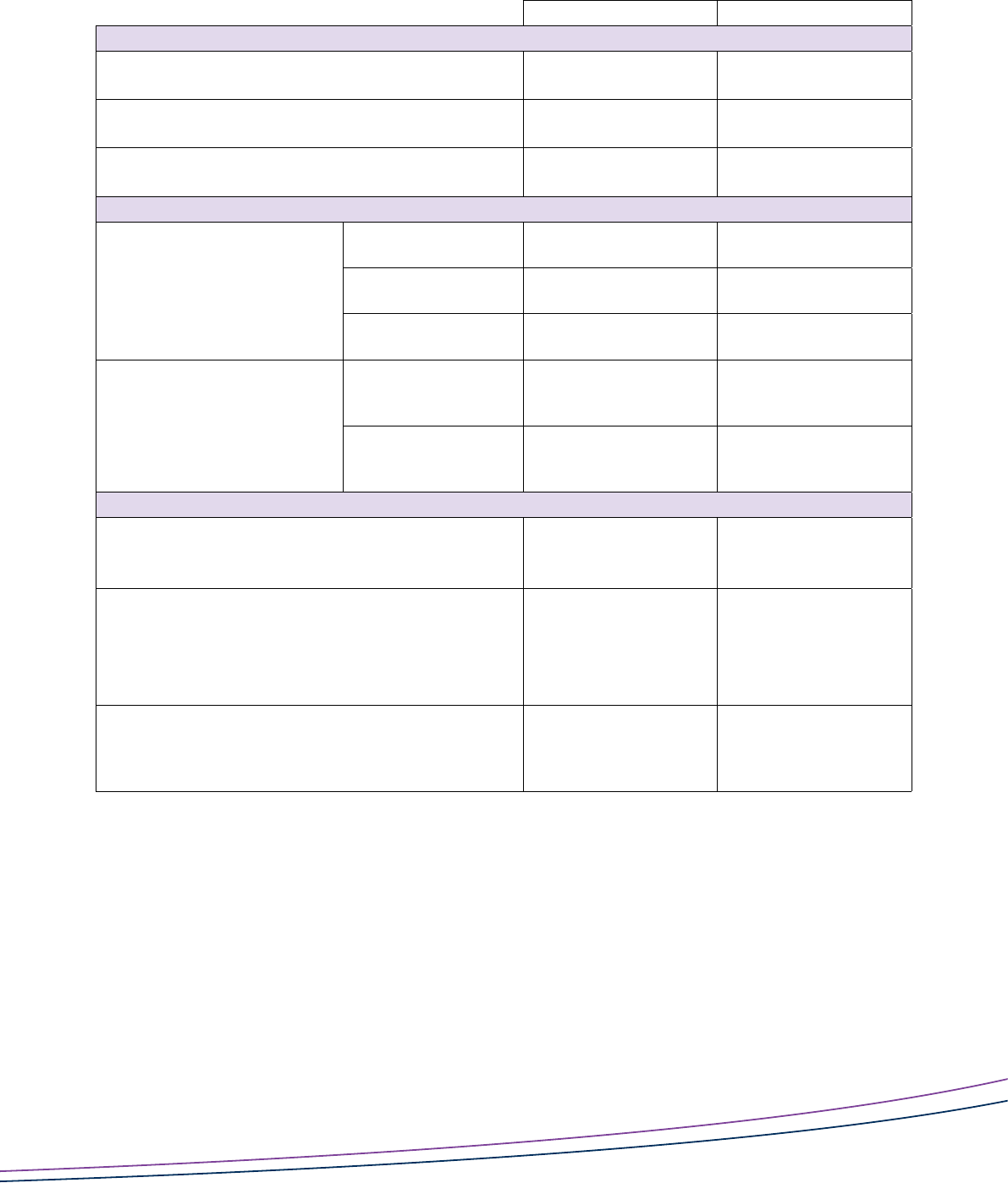

LEVELS 14 AND LEAPING TO LEVELS 56

LEVELS 1–4

Learning sequence Language in focus Genres

1. Pronouns referring

to animals and things

• subject pronouns: it, they

• object pronouns: it, them

• possessive pronouns: its, theirs

• descriptions and descriptive

reports

2. Pronouns referring

to people and things

• subject pronouns – who is doing the

action?

• object pronouns – who/what

actions are done to?

• possessive pronouns – whose is it?

• narratives (picture books, fables

and simple retells)

• personal recounts

3. Reference to point out

which one

• demonstratives and pointers: this,

that, these and those

• narratives

• oral interactions

LEAPING TO LEVELS 5–6

4. Text connectives to create

sequence

• simple text connectives and

circumstances of time

• personal recounts

• narratives (picture books, fables

and simple retells)

1. Pronouns referring to animals and things

Engage

• Introduce a topic, such as polar bears. Display pictures and ask students to describe features from the

pictures, beginning sentences with ‘Polar bears …’ or ‘A polar bear …’.

• Read a simple text, such as Polar Bears Rock!

1

, that continually repeats the noun group.

Explicitly teach: I do – we do – you do

• Repeat using a text, such as A Waddle of Penguins

2

, that begins each page with ‘Penguins’ and then refers

back to them using pronouns (they, their) or pointers (these birds).

• Display a chart such as the one below of pronouns that refer to things:

Subject Object Possessive

Singular: 1 it it its

Plural: 2+ they them their/theirs

• Explain that there are many dierent pronouns and that, to begin with, you will focus only on the subject

pronouns used at the beginning of sentences (before the verb).

• Point out the pronouns that begin sentences or appear before the verb (subject pronoun: it, they). Explain

that the author can refer to the topic without using its name all the time.

• Model circling the pronoun and linking it to the noun/noun group. Students repeat.

• Students match the correct pronoun card: ‘it’ and ‘they’ to pictures and/or nouns/noun groups, eg penguins

– they, a penguin – it.

• In pairs, students complete cloze activity on a familiar text, filling in deleted subject pronouns.

• Provide a text that continually repeats the topic and have students identify when to use a pronoun and

which pronoun to use.

1

McGuee P (2015) Polar Bears Rock!, Unite for Literacy, available at http://TLinSA.2.vu/McGuffee2015 (accessed October 2020)

2

McKay W (2019) A Waddle of Penguins, Unite for Literacy, available at http://TLinSA.2.vu/McKay2019 (accessed October 2020)

Learning English: Achievement and Proficiency (LEAP) | STRATEGIES COHESIVE DEVICES | 5

LEVELS

1–4

LEVELS

5–6

LEVELS

7–9

LEVELS

10–12

LEVELS

13–14

2. Pronouns referring

to people and things

Suggested model text

Goldilocks and the three bears

3

or any familiar story/

fable, including those from students’ first languages

(L1s).

Subject pronouns – who is doing

the action?

Engage

• Read a simple version of a familiar story, where

each page/segment begins with character’s name.

• Students sequence pictures of a familiar story.

Explicitly teach: I do – we do – you do

• Display the text and point out the first words on

each page/segment. Explain that the repetition

connects the parts of the story and tells the

reader they are going to hear more about these

characters.

• Students join in reading, chorusing the character

names, at the beginnings of each page/segment.

• Point out the pronouns at the beginning of

sentences (subject pronouns), explaining that these

refer to the characters without using their name

all the time. Ask students how this is done in L1.

• Model and then involve students in circling the

pronoun and drawing a line to the noun, eg:

One day Goldilocks was walking in the forest.

She

saw a house and knocked on the door.

She

went inside.

• Ask students if they have dierent words to refer

to males and females and/or singular or plurals

in L1. Display Resource 1: Pronoun chart. Point

out the many dierent pronouns to refer to people

and things. Explain that, to begin with, the focus

will be on subject pronouns used at the beginning

of sentences. Go through the chart with students

adding examples from L1.

Students can add L1 equivalents, where they

exist and/or make their own chart to show how

pronouns work to refer to people in their L1.

The dierence between ‘you and I’ or ‘you and

me’ is not formal/informal or correct/ incorrect.

It is whether it is subject or object, eg it is correct

to say, ‘You and I will be in trouble’ because it is

correct to say, ‘I will be in trouble.’ It is correct to

say, ‘That might happen to you and me’ because

it is correct to say, ‘That might happen to me.’

• Students match the correct pronoun cards

to pictures and/or names of the characters,

eg Goldilocks – she; The three bears – they;

Father – he.

• Read other texts with students, identifying

pronouns and to whom they refer.

• Students read a text to a partner and together

identify the pronouns and to whom they refer.

• Students complete a cloze activity on a familiar

story, filling in deleted subject pronouns.

Object pronouns – who/what

actions are done to and possessive

pronouns: whose is it?

Explicitly teach: I do – we do – you do

• Use the same text, and similar processes as above

to explore object and possessive pronouns in

Resource 1: Pronoun chart. For example:

> Who or what actions are done to? (object),

eg Goldilocks tried Baby Bear’s porridge and

she ate it all up. Baby Bear cried. Mother Bear

comforted him.

> Whose is it? (possessives) such as ‘my’ in my

porridge, my chair, my bed.

• Explore how these pronouns change when moving

from dialogue to narrator voice, eg She tried Mother

Bear’s porridge, but her porridge was too cold; She

tried Father Bear’s chair but his chair was too big.

Baby Bear looked at his chair. It was broken.

3

British Council (2015) ‘Goldilocks and the three bears’, Daily Motion, available at http://TLinSA.2.vu/Goldilocks

(accessed November 2020)

6 | Learning English: Achievement and Proficiency (LEAP) | STRATEGIES COHESIVE DEVICES

3. Reference to point out

which one

Engage

• Place a large bowl on a table near you and a medium

bowl further away.

• In pairs, students share which bowl they think is

Father Bear’s and which is Mother’s. Ask a student

to point to Father Bear’s bowl. Ask the student ‘This

bowl?’ Student repeats ‘This one’ and all students

repeat, ‘This bowl. This bowl is Father Bear’s bowl’.

Ask another student to point to Mother Bear’s

bowl, repeating the process, but this time using

‘That bowl’. Having students point to the bowl

introduces them to the function of the ‘pointer’

in the noun group.

Explicitly teach: I do – we do – you do

• Introduce a chart of demonstrative pronouns and

explain when they are used:

> for items in close proximity this (one), these

(more than one)

> for items at a distance that (one), those (more

than one).

• Students make up sentences using demonstrative

pronouns in spoken and written contexts.

• In pairs, students ask and answer questions like

‘Which toy(s) do you like best?’, eg I like this/that

one; I like these/those.

4. Text connectives to create

sequence

Engage

• Display a familiar narrative or a model recount that

begins with a focus on time.

• Underline the beginning of the first sentence,

pointing out that it doesn’t begin with the character/

person. Ask what it begins with, eliciting ‘time/when’.

• Discuss why an author would begin that way,

eg helps bring the reader into the story/recount,

lets them know when the events happened, and

prepares them for the type of text they will read.

• Provide a range of familiar stories/fables, online or

in books. Students identify and record the various

ways that narratives with a focus on time begin.

Create an anchor chart.

• Create another anchor chart of ways that recounts

begin with a focus on time. Compare the charts.

Explicitly teach: I do – we do – you do

• Provide a simple model text and underline the

beginnings of sentences that focus on time. Ask

students if they notice any patterns, eg sentences

start new paragraphs, a comma after the time

word/phrase.

• Discuss how this helps the reader to understand

the order and timing of events.

• Students resequence a cut-up model text and

discuss what helped them.

• Create a set of ‘time’ sentence starters, including

those that can open or start:

> a whole-text (Long ago; On the weekend)

> a new or next part of the text (The next day;

Then; Soon; Next; After lunch; Later).

• If appropriate to the learning goal, point out

that some of these are adverbial phrases giving

the circumstances of time and others are text

connectives, logically connecting and sequencing

the events in time.

• Model how to choose a ‘whole-text opener’ to

begin a recount or narrative and then a ‘new part’

opener to continue your story.

• Students use these for whole-class or small group

round-robin storytelling (retelling a familiar story,

recounting class events of the day), either orally

or as a joint construction of a written text.

LEVELS

1–4

LEVELS

5–6

LEVELS

7–9

LEVELS

10–12

LEVELS

13–14

Learning English: Achievement and Proficiency (LEAP) | STRATEGIES COHESIVE DEVICES | 7

LEVELS

1–4

LEVELS

5–6

LEVELS

7–9

LEVELS

10–12

LEVELS

13–14

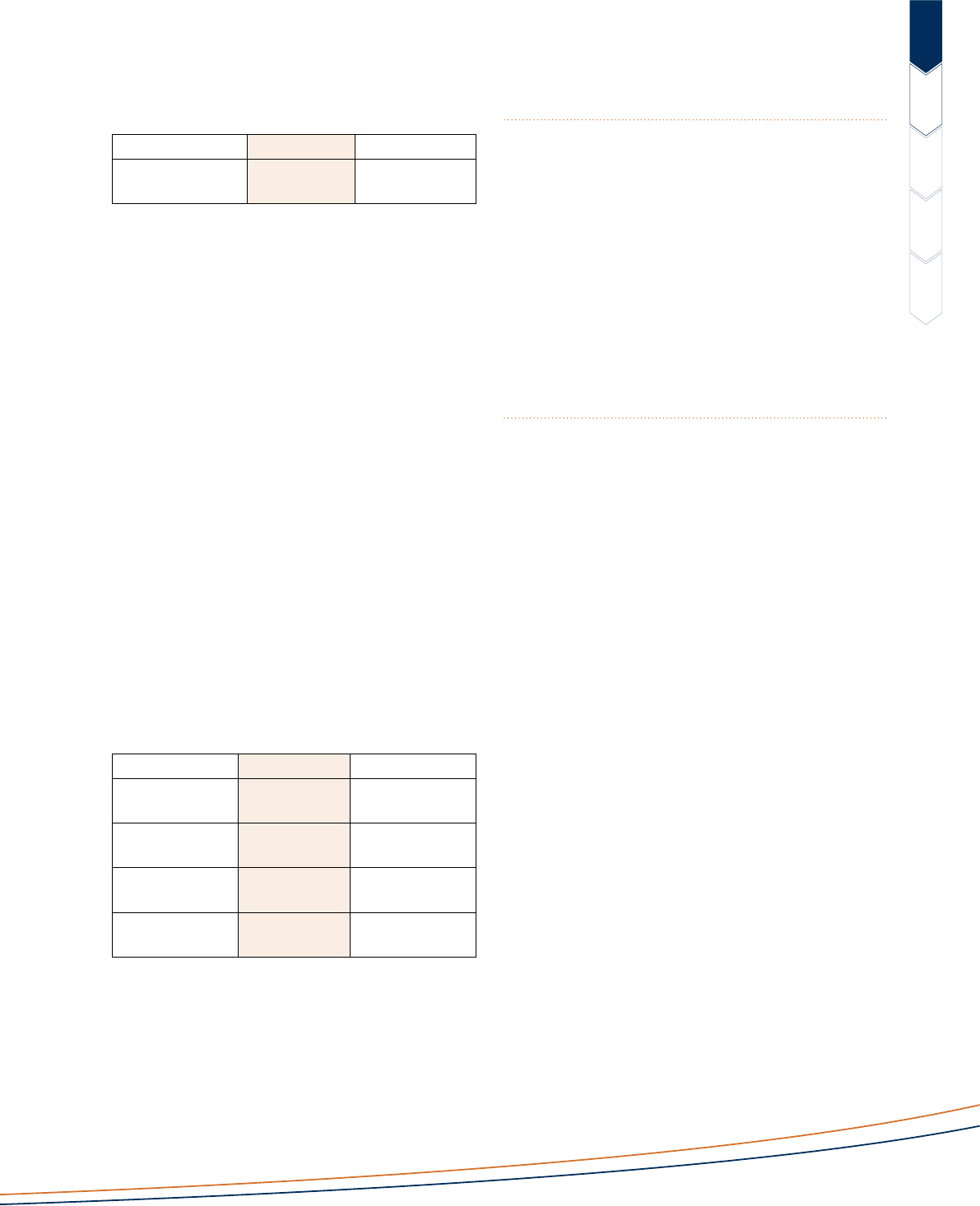

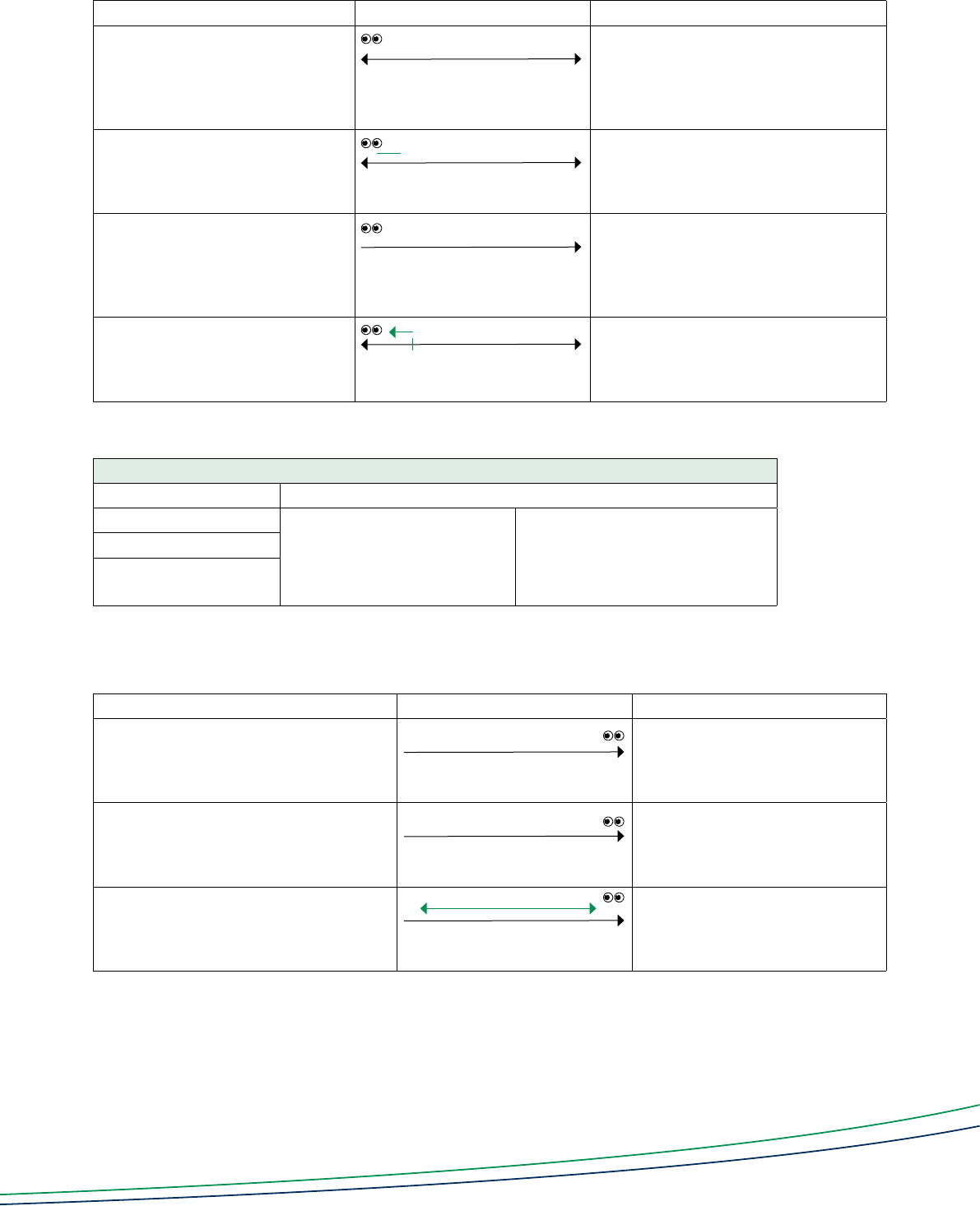

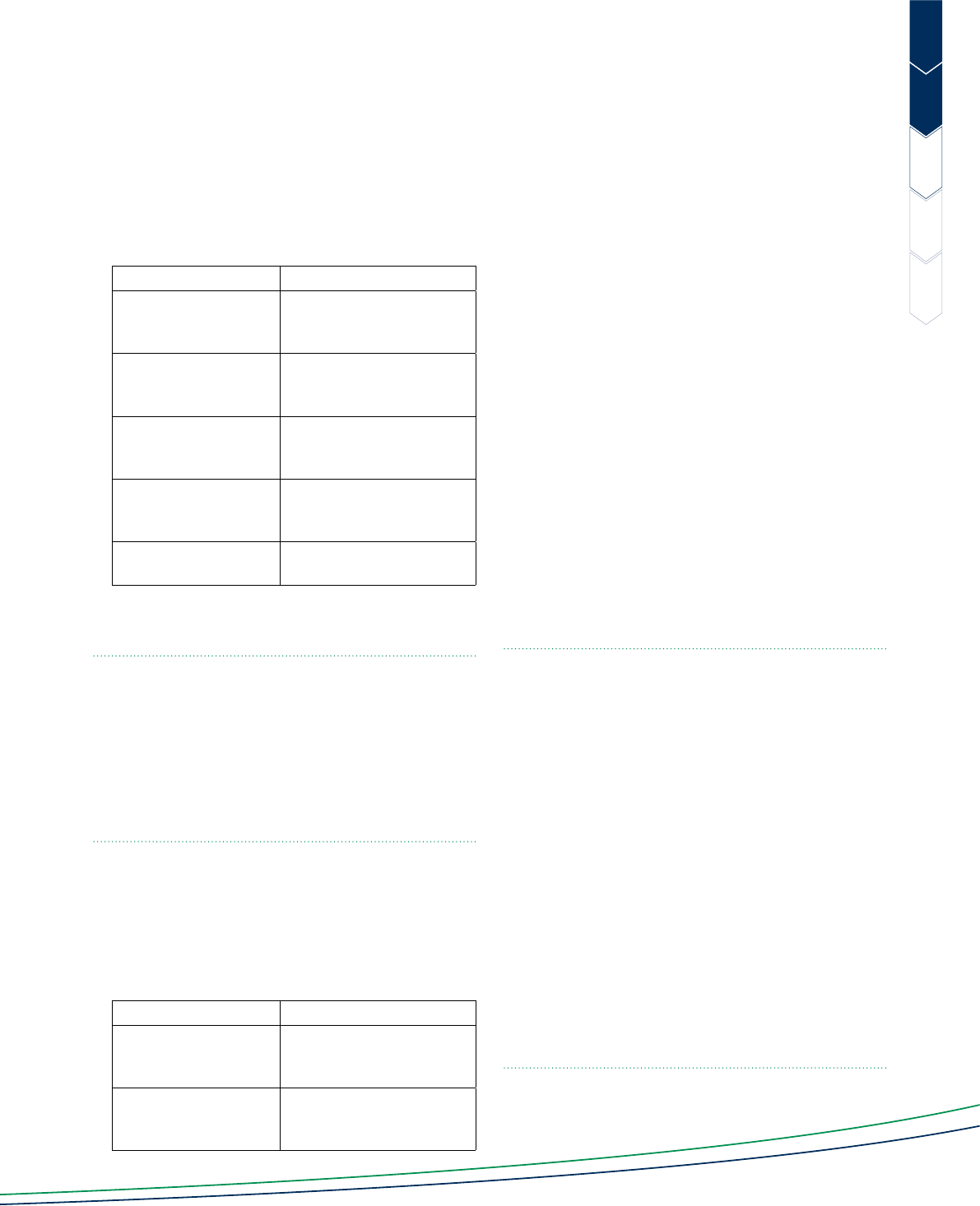

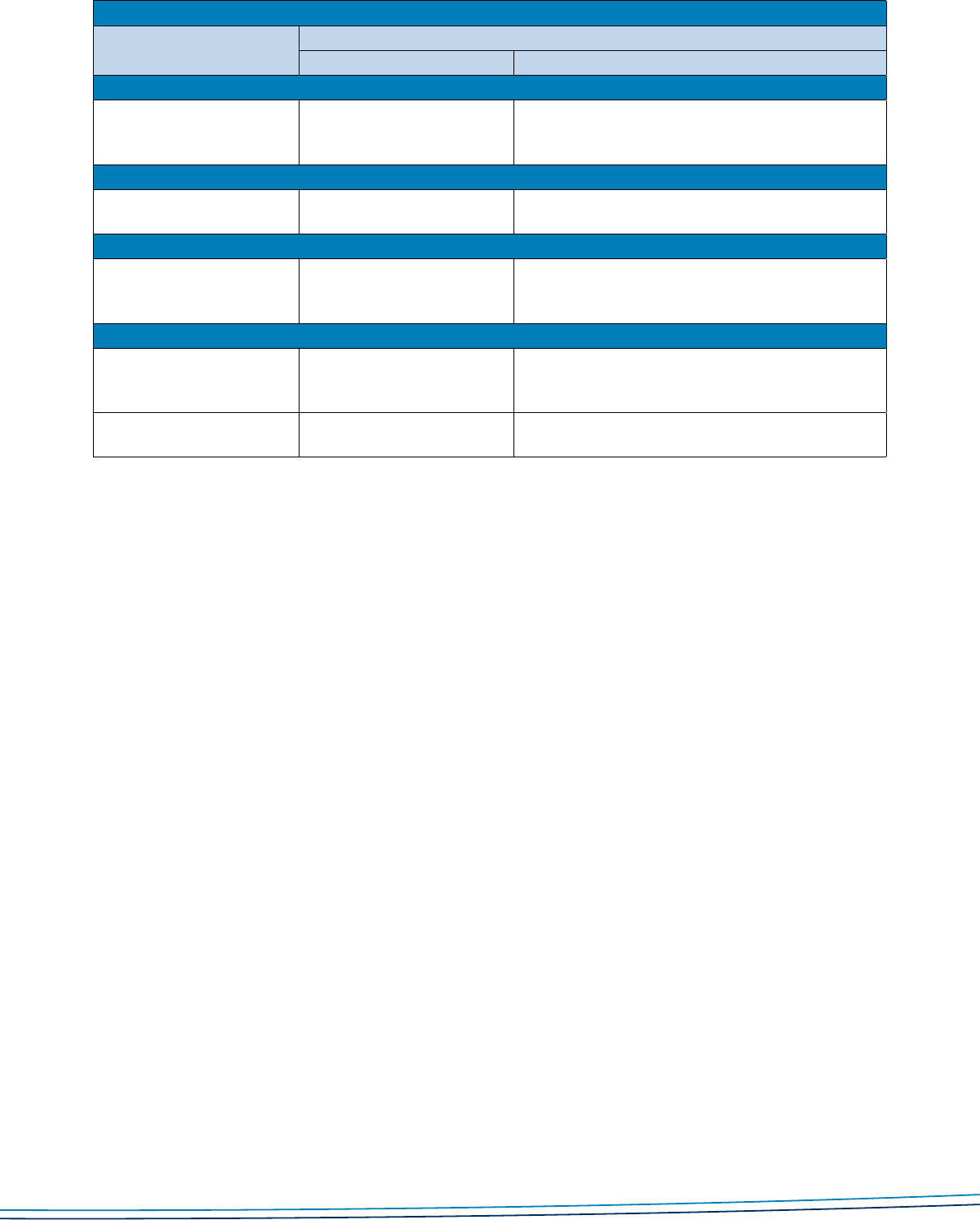

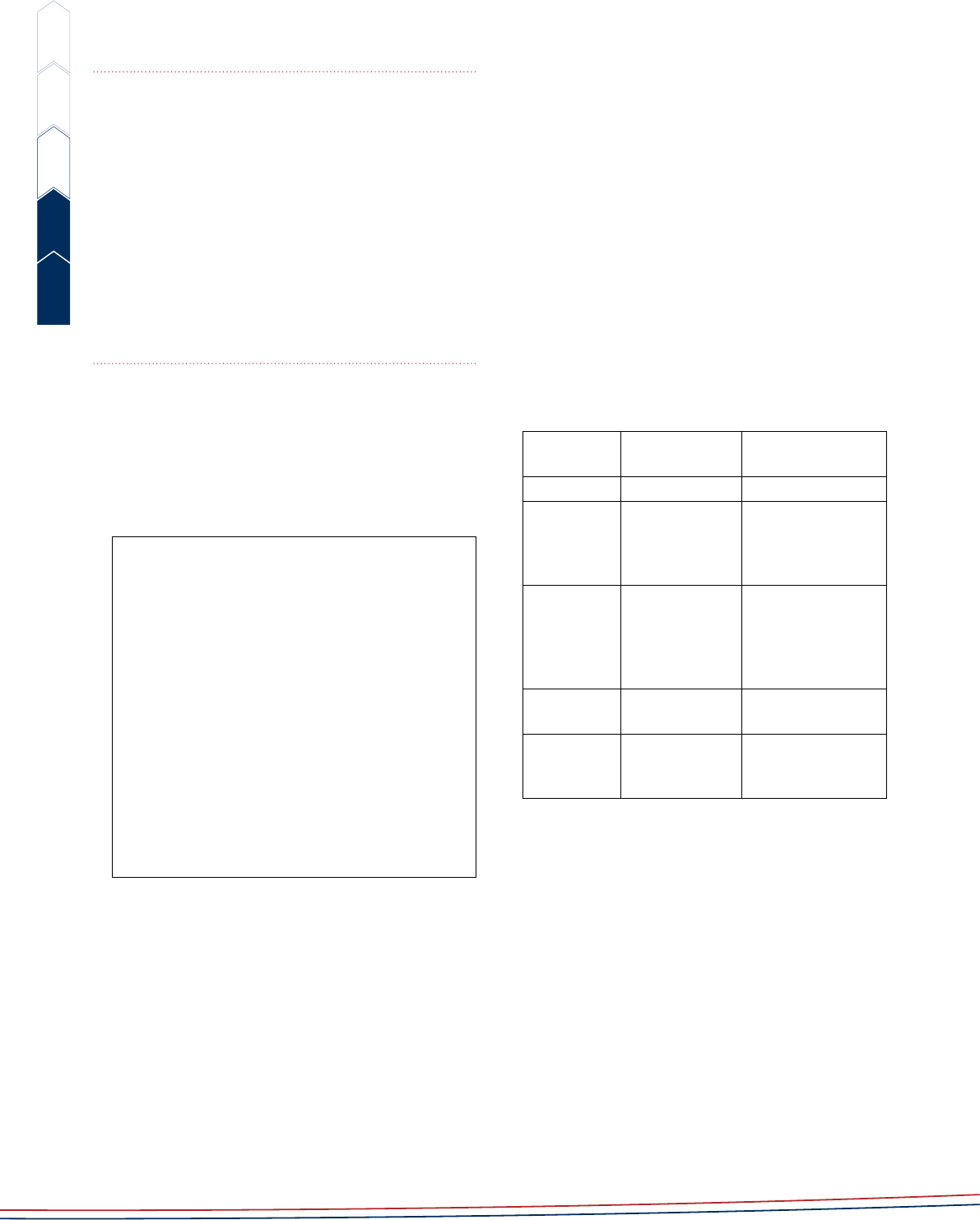

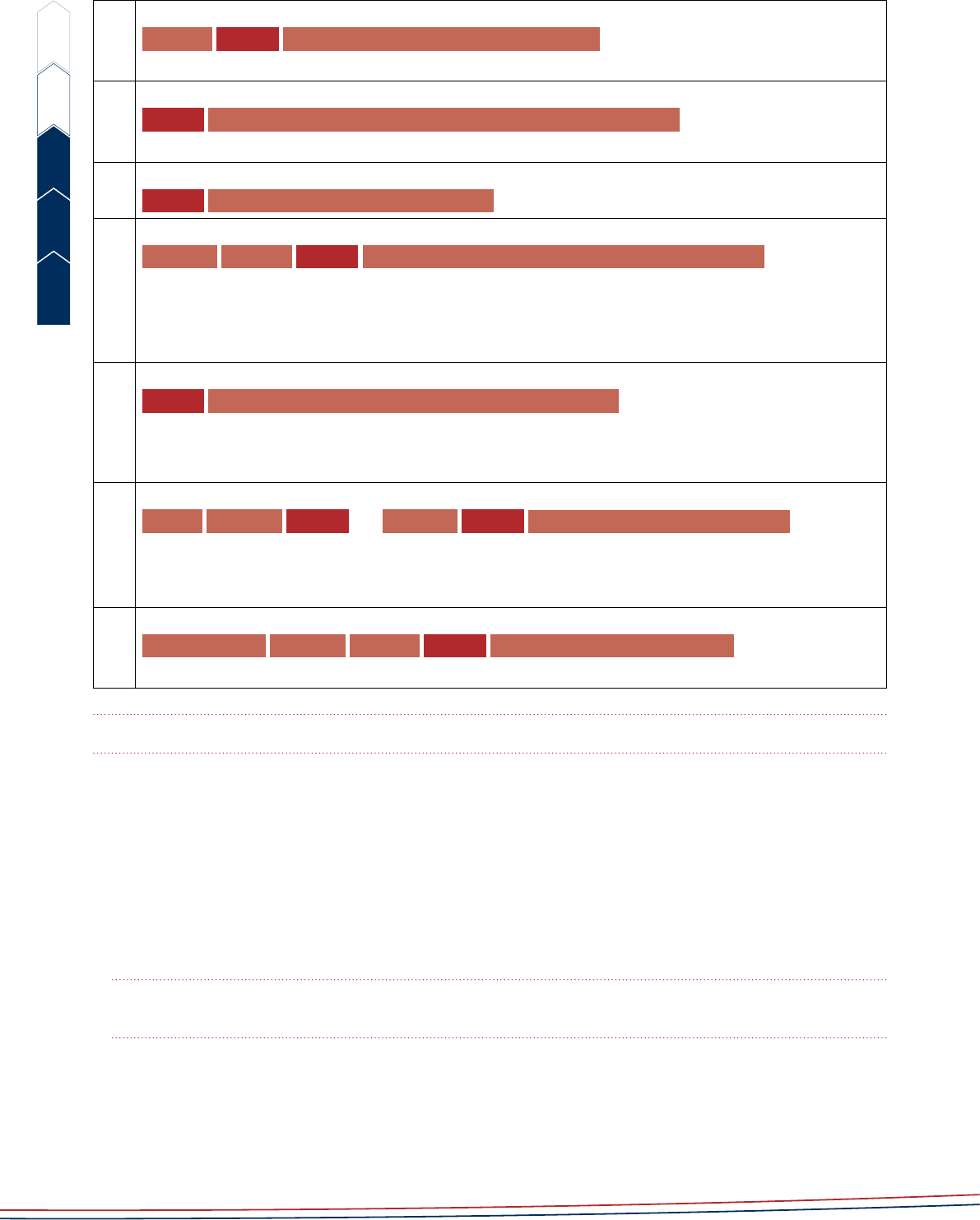

LEVELS 56 LEAPING TO LEVELS 79

LEVELS 5–6 LEAPING TO LEVELS 7–9

Learning sequence Language in focus Genres

5. Sentence openers in

procedures and protocols

• orienting to:

> circumstances and subordinate

clauses of time and condition

> circumstances of manner

• protocols and procedures

6. Sentence openers

in procedural recounts

• text connectives to sequence

• passive voice to remove doer

• procedural recounts

7. Sentence openers in

sequential explanations

• passive voice

• openers that link back to previous

sentence for flow

• sequential explanations

8. Text organisation

in arguments

• signposting for the reader:

> whole text openers

> paragraph openers

> text connectives

• expositions: arguments

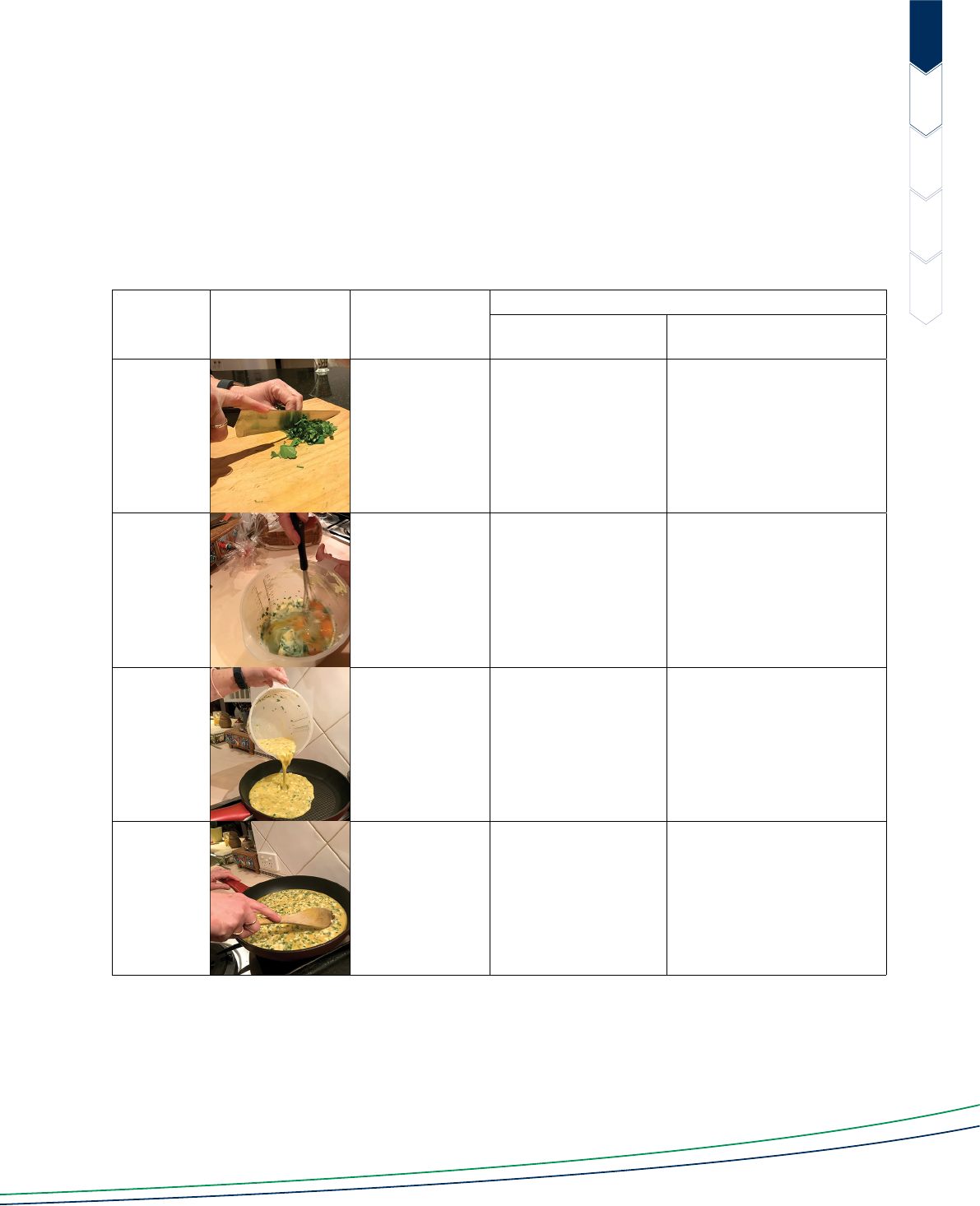

5. Sentence openers in procedures and protocols

Engage

• Refer to ‘Project 8: Procedure texts’

4

, one of many activities for multicultural classrooms.

• Provide a range of protocols (class rules, how to borrow a library book/play a game, emergency evacuation)

and procedures (recipes, art and craft activities, instructions for science experiment) in English and L1.

• Students identify what they have in common, eg they all tell you how to do something; may have pictures

and include lists, dot points or numbers to show sequence.

• Focusing on the English texts, draw out that instructions usually start with a verb (action process) and that

this is the grammar pattern used to give commands.

• Students compare this pattern to the pattern in L1 texts.

5

Explicitly teach: I do – we do – you do

• Highlight processes/verbs in green. (If students are familiar with the parts of the clause, analyse clauses for

participants, processes and circumstances as described in Sentence structure Levels 1–4.)

• Draw attention to places in the text where something other than a process is used to begin the sentence,

eg Gradually add the liquid ingredients.

• Discuss why the pattern might be changed, eg because it is important for success or safety that the step

is done at a particular time or in a particular manner.

There may also be places where, rather than giving a command, statements are made because some

information is needed about the step.

4

See Heugh et al (2019), available at http://TLinSA.2.vu/Project8ProcedureTexts (accessed November 2020).

5

See also Verbs and verb groups 3 ‘Action processes‘.

8 | Learning English: Achievement and Proficiency (LEAP) | STRATEGIES COHESIVE DEVICES

LEVELS

1–4

LEVELS

5–6

LEVELS

7–9

LEVELS

10–12

LEVELS

13–14

• Students rearrange the command and discuss the

changed eect and possible outcome, eg ‘Add

the liquid ingredients gradually’ – you might pour

them all in before you read ‘gradually’ and the

mixture could be lumpy.

• Create an anchor chart of alternative sentence

openers appropriate to the topic.

• Classify these as circumstances or subordinate

clauses and by the type of information they provide,

eg time: immediately – When the dough has risen;

manner – quickly; condition – If the mixture is

too sticky.

6. Sentence openers

in procedural recounts

Engage

• Explore the purpose of procedural recounts to record

how a process was carried out.

• Using a familiar procedure, provide a model of

a procedural recount, initially using active voice.

(See Resource 2: Changing sentence openers,

which provides an example of 3 texts about making

compost: a procedure and 2 procedural recounts,

one in active voice and the other in passive.)

• Students examine the dierences in the grammatical

choices between the original procedure and the

procedural recount. Colour-coding at least the

beginnings of sentences is helpful.

• Elicit 4 main changes:

> a doer (participant) has been added in front

of the verb

> commands have changed to statements

> the verb is in past tense since the action has

been done

6

> text connectives added to show the sequence

of actions and organise the text, replacing the

numbers used to sequence steps in the procedure.

• Students jointly or independently write a procedural

recount of a familiar procedure.

• Discuss how the patterns of a procedure and

a procedural recount match their genre purpose.

• In pairs, students examine the 2 procedural recounts

in Resource 2. Share observations and reflections

on choices, patterns and eects.

• Explore the purpose of procedural recounts in many

curriculum areas, eg to record how a process was

carried out so that a reader understands what was

done and can repeat the process. As such, the ‘doer’

of the actions is irrelevant and is usually omitted.

This happens, for example, in science experiments.

• Explain that we can remove the ‘doer’ from

a sentence by changing the grammar (using

passive voice).

Explicitly teach: I do – we do – you do

• Model making the changes to the beginning of a

class procedural recount, explaining and showing

visually the steps involved.

7

I added the liquid.

The liquid was added by me

.

• Students write 2 to 3 sentences on cards, rearrange

sentences and verbalise steps.

• In pairs or individually, students rewrite remaining

sections of the text.

• Students independently write a procedural recount

in passive voice and annotate/explain choices.

• Students underline, colour-code and annotate

(name the kinds of) sentence openers.

Sentence openers in commands and

statements

In statements, the opener includes everything before

the verb. In commands, the opener includes the verb

and anything that precedes it.

• Students write procedural recounts in active and/

or passive as relevant to the purpose and audience

for other procedures they have followed: as a class,

in small groups, pairs, or individually.

6

See Verbs and verb groups for more ideas about focusing on past tense.

7

See ‘Passive voice’ on pages 2–3 and the Glossary for more details about active and passive voice.

Learning English: Achievement and Proficiency (LEAP) | STRATEGIES COHESIVE DEVICES | 9

LEVELS

1–4

LEVELS

5–6

LEVELS

7–9

LEVELS

10–12

LEVELS

13–14

7. Sentence openers in

sequential explanations

Engage

• Watch, without audio, a video of a process being

studied, such as a YouTube clip on recycling glass.

8

• Ask students what they see happening and scribe

responses. Guide using:

> the simple past tense – what happened? People

put glass bottles and jars into a recycling bin.

Rubbish collectors picked them up, OR

> present continuous – what is happening?

Someone is putting glass in a recycling bin.

Rubbish collectors are picking it up.

• Provide a written explanation of the same process,

such as How glass is recycled.

9

• Students discuss dierences, first in small groups,

then whole-class sharing. During whole-class sharing:

> elicit that the written explanation uses simple

present tense to show that this is what always

happens

> contrast this to the tense used in student

responses to questions about the video.

• In the recycling guide, after the first step, it doesn’t

say who is taking the glass or doing other actions:

there are no people in the pictures or the text.

Discuss why the first doer is included, eg because

they want us to put our glass in a recycling bin.

Passive voice

Explicitly teach: I do – we do – you do

• Explain that in many schooling subjects, and in the

wider community, when a process is explained we

are usually more interested in what was done than

who did it. For example, if we want to learn how

glass is recycled or how milk gets from the cow

to our table, we don’t need to know that a truck

driver picks up the recycling or the milk. So, the

grammar patterns change to remove the doer and

focus on what is done: passive voice.

• Model making the changes to the beginning of the

scribed text, explaining and showing visually the

steps involved.

Consumers throw glass into a recycling bin.

Glass is thrown into a recycling bin by consumers

.

• In pairs, students write the next 2 to 3 sentences

and physically rearrange the sentence, verbalising

the steps they are taking.

• Students, in pairs or individually, rewrite remainder

of the text.

Openers that link back to create

flow

Engage

• Display models of a range of sequential explanations,

eg milk production, digestion, respiration, water

cycle, life cycle.

• Point out that many visuals in sequential explanations

are flowcharts and that these match the purpose:

explaining a series of steps to create or produce

something.

• Ask students how the visual texts accompanying a

range of explanations show the flow, eg numbered

steps, arrows connecting pictures, repetition of

things from one picture to the next.

• Explain that the language patterns of explanations

also create flow and sentence openers have an

important role in this.

Metaphors for flow

The metaphor of dominoes or of chaining could be

used – where the beginning of one sentence links

back to the end of the previous one so we see a

chain of events.

Flow in explanations

The flow in explanation texts is achieved by taking

the new information given at the end of one sentence

(or clause) and using it to begin the next sentence

(or clause).

In Resource 3: Sentence openers to create flow this

is mainly achieved by changing the noun group

(adding or deleting elements) to pick up previously

mentioned ideas, eg taken to a recycling centre –

At the centre, the glass is washed to remove any

labels and dirt – The clean glass.

On 2 occasions the noun group is part of a circumstance

of place: At the centre; At the bottle factory.

Subordinate clauses could also be used as openers to

create flow: Once the glass has been sorted …

8

For example, Recycle Devon (2010) The smashing story of recycling glass, available at http://TLinSA.2.vu/SmashGlass

(accessed November 2020).

9

‘How glass is recycled’, available at http://TLinSA.2.vu/RecycleGlass (accessed November 2020).

10 | Learning English: Achievement and Proficiency (LEAP) | STRATEGIES COHESIVE DEVICES

LEVELS

1–4

LEVELS

5–6

LEVELS

7–9

LEVELS

10–12

LEVELS

13–14

Explicitly teach: I do – we do – you do

• Provide students with jumbled sentences from

a model explanation that flows well, eg the text

in the right column of Resource 3 where sentence

openers create flow.

• Students reconstruct the text, discussing what

helped them to do so, underlining/circling and

drawing arrows to show the connection.

• Display Resource 3 and compare the flow of a text

written in active voice and one written in passive

voice. Discuss the patterns and their eects. Point

out that the passive voice allows us to focus on

the ‘glass’ in the beginning of each sentence and

to connect back to previous ideas and carrying

them forward to create flow.

• Use arrows to show the connection between the

last parts of one sentence and the beginning parts

of the next sentences.

• Create a cloze activity, deleting parts of the openers

that link back for students to complete, eg:

Next, the bottles and jars are taken by a truck

to the recycling centre.

At , bottle tops and lids are

removed before the glass is washed to remove

any labels and dirt.

The is then sorted into dierent

colours.

Once , it is crushed into small

pieces.

The are sent by truck to

a bottle factory.

At , the crushed glass is mixed

with some silica sand and then put into a big furnace,

where it melts and turns into a liquid.

Finally, the flows out of the

furnace.

• Provide students with an explanation written in active

voice, eg the left-hand column of Resource 3, and

model rewriting the first 1 to 2 steps of the process

in passive voice and to ensure good flow. Have

students continue the process in pairs.

• Students draw a flow chart of a familiar process

involving humans and write an explanation in the

passive voice, ensuring they maintain the pattern

of flow.

‘This’ as a sentence opener to refer back and carry

an idea forward could also be highlighted.

10

8. Text organisation

in arguments

Whole text – structure

Engage

Suggest a culturally inclusive metaphor to students,

eg an author takes a reader on a journey. Some texts,

like arguments, have:

• a text opener (introductory paragraph/s) that

provides a map showing us where we are headed,

the route we will take, and some places we will

stop along the way

• paragraph openers (text connective and/or topic

sentence) that are like signposts telling us where

we are on the map

• sentence openers (text connectives, circumstances

and subordinate clauses) to signal how we are

getting from one place to another or one idea

to another

• a final paragraph (conclusion) that tells us our

journey has finished: it is a brief reminder of the

places (ideas) we have visited and where we

are now.

Explicitly teach: I do – we do – you do

• Introduce the text structure of a 3 reason argument,

such as Resource 4: Animals should not be kept in

zoos, by reading the introduction of a model text

and using ‘think alouds’ to demonstrate how you

are taking note of the author’s signposts to set

yourself up for the journey.

• Then read just the first sentence of the first reason

(body) paragraph, modelling how you continue

to notice signposts and signals to follow the map.

• Read the first sentence of the second reason

paragraph and invite students to identify the

signposts and what they are telling you.

• Students read just the first sentence of the third

reason paragraph to a partner, identify the signposts

and discuss what they are telling the reader.

• Read the conclusion and model ‘think alouds’.

10

See Verbs and verb groups 13 ‘Relating processes: expanding choices‘ – ‘Grammatical changes when using a causal relating verb‘.

Learning English: Achievement and Proficiency (LEAP) | STRATEGIES COHESIVE DEVICES | 11

LEVELS

1–4

LEVELS

5–6

LEVELS

7–9

LEVELS

10–12

LEVELS

13–14

• Annotate the text to show how topic sentences

connect back to the ‘map’ provided in the

introductory paragraph: teach and use the meta-

language of ‘text opener: introduction’; ‘paragraph

opener: topic sentence’ and ‘sentence opener’. Make

the connection that each of these openers orients

the reader to the message at various levels of the

text. (Resource 4 uses colour to show connections

between the arguments introduced in the opening

paragraph, topic sentences and conclusion, as

well as underlining for text connectives or simple

alternatives that act as signposts.)

• Provide the same or a similarly organised argument,

cut into paragraphs. Students reconstruct it, noting

what helped them to do so.

Paragraphs to group and develop

ideas

• Provide sets of the 3 reason paragraphs (Resource 4)

as jumbled sentence strips (keep the topic sentences

coloured coded). In small groups, students match

sentences to appropriate topic sentence and order

sentences to create 3 paragraphs.

• Introduce a fork

11

as a visual metaphor that can

be used to understand the structure of a 3 reason

argument text at the whole text level and

paragraph level.

• Display a large fork image and write the position

statement on the handle and the 3 reasons on

the prongs.

• Use 3 smaller forks and write one of the reasons

on each handle and the elaborating ideas,

examples or evidence on the prongs.

• Students read another argument text and use one

large and 3 smaller forks to note-take (backward

plan/map) the arguments.

• In small groups, students use a large and smaller

forks to plan their own argument texts, oral or

written.

11

Adapted from Exley, Kirven & Mantei (2015:126–129).

12 | Learning English: Achievement and Proficiency (LEAP) | STRATEGIES COHESIVE DEVICES

LEVELS

1–4

LEVELS

5–6

LEVELS

7–9

LEVELS

10–12

LEVELS

13–14

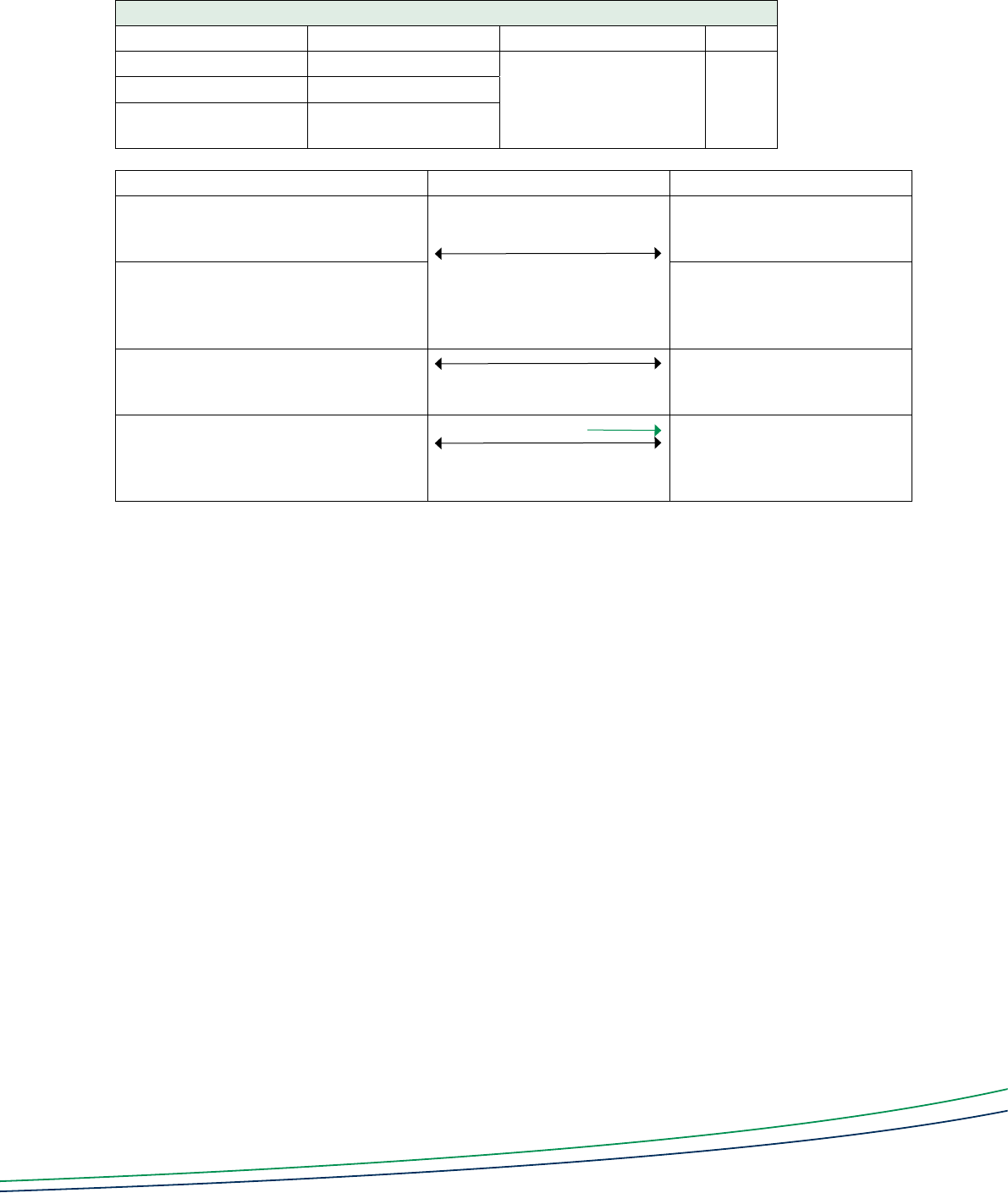

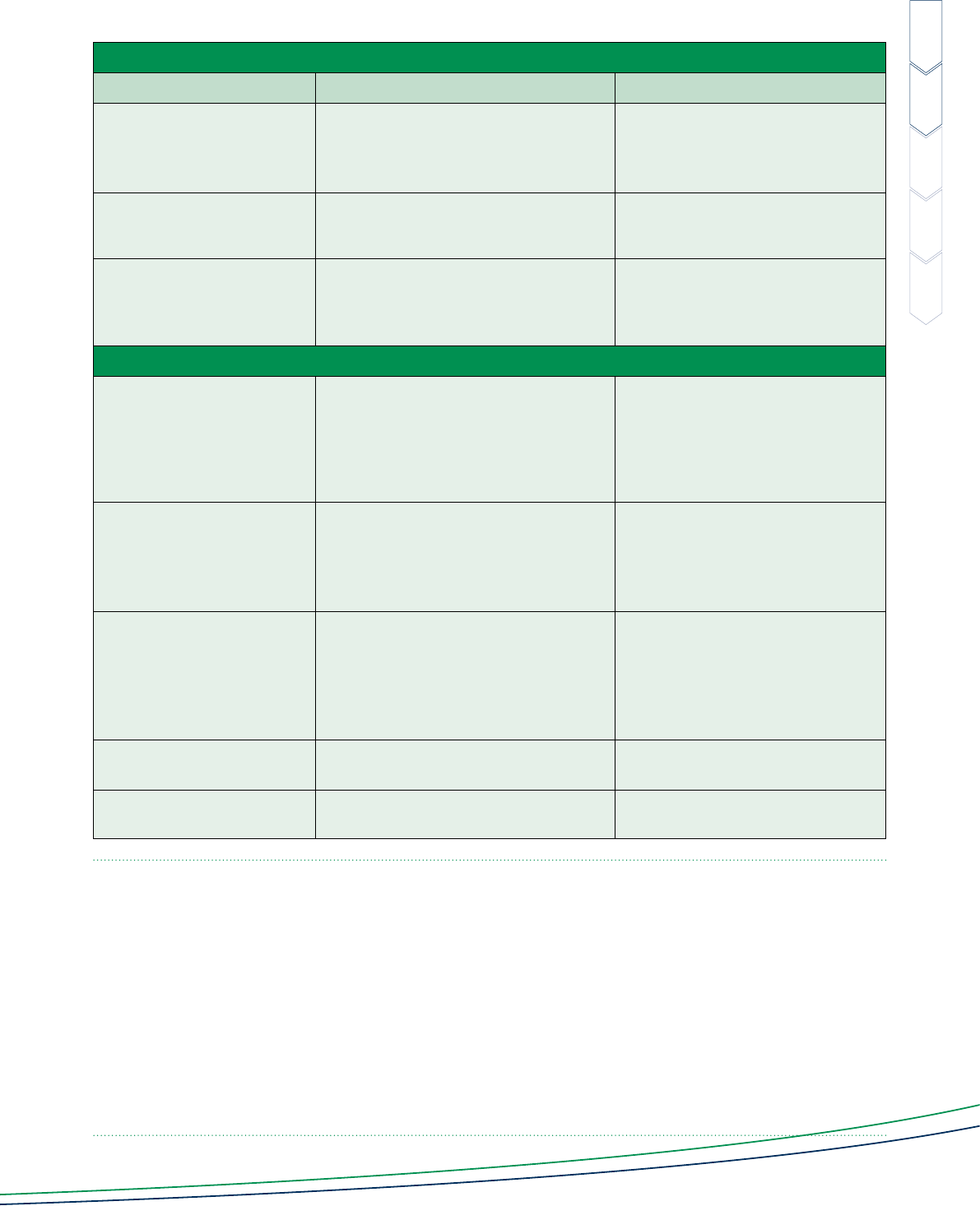

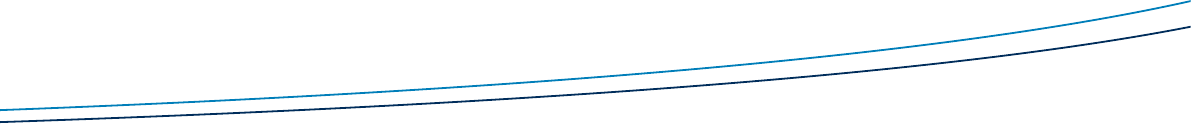

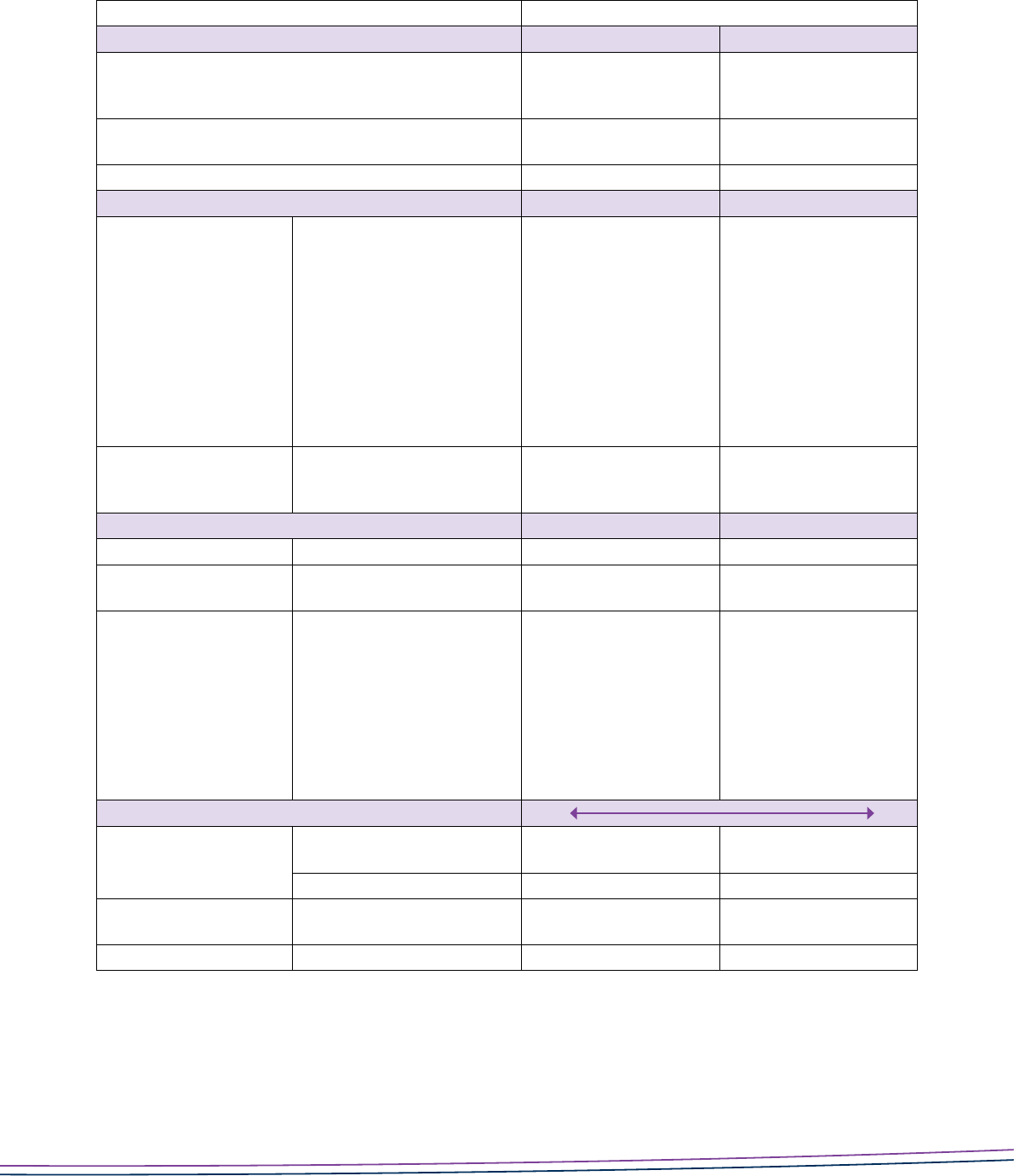

LEVELS 79 LEAPING TO LEVELS 1012

LEVELS 7–9 LEAPING TO LEVELS 10–12

Learning sequence Language in focus Genres

9. Text connectives when

elaborating ideas

• text connectives

• this, these, that and text connectives

for logical development of paragraphs

• ecient text structure using

nominalisation and orientations to

guide the reader

• orientation to cause and

contingency

• expositions: arguments,

discussions

• factorial and consequential

explanations

10. Sentence openers and

text connectives for structure

and orientation

11. Openers and connectives

for cause and contingency

9. Text connectives when elaborating ideas

In genres such as arguments, discussions, factorial and consequential explanations; body paragraphs tend to

begin with a point/topic sentence, followed by elaborating sentences (to expand, extend or give examples) and

may conclude with a sentence that links back to the topic or leads on to the next point. (This pattern is often

referred to as PEE/L or TEE/L.)

Revise

Discuss the various ways paragraphs develop an idea by elaborating on the main point/topic of the paragraph,

such as:

• expand (say the same thing in more detail)

• extend (give additional information)

• exemplify (give an example)

• explain (provide causes/eects).

Explicitly teach: I do – we do – you do

• Locate or write example paragraphs related to your topic of study.

• Model and jointly identify words in elaborating sentences that signal their functions and show the development

of ideas and their logical connection.

• Annotate as shown in the examples from 2 topics below:

Annotated examples of developing the topic sentence

Bold has been used for demonstrative this and yellow highlight for

text connectives

.

Explain/define

The Industrial Revolution was the period from about 1760 to sometime between 1820 and 1840.

(Topic/Point)

The term, ‘Industrial Revolution’, refers to the transition from earlier technology to new manufacturing

processes.

(Elaboration)

Expand/explain

An advantage of early technology in farming was that very little pollution was produced.

(Topic/Point)

This was because there were no fuel-powered machines to pollute the atmosphere since the power came

from the hard work of human’s animals.

(Elaboration)

Learning English: Achievement and Proficiency (LEAP) | STRATEGIES COHESIVE DEVICES | 13

Annotated examples of developing the topic sentence (continued)

Extend

However

, a disadvantage of this stage of farming development may have meant that not everyone was

employed.

(Topic sentence)

As a result

, some people may not have been able to feed and clothe themselves

properly.

Subsequently

, this may have led to more crime and more social problems.

(Elaboration extending

idea showing possible consequences)

Exemplify/give examples/evidence

One theory is that Aboriginal people came from Asia.

(Topic sentence) There is some evidence to support

this.

For example

, groups of people in Asia today who have physical resemblances to some Aboriginal

people and who may be part of the same original racial group.

(Elaboration)

• Read examples without cohesive devices and discuss the eect this has. Draw out their important role in

connecting ideas, creating flow and providing orientation for reader.

• Point out that referring back and forth in texts becomes more complex as texts become longer with more

complex ideas.

• Explain that pronouns and demonstratives (this/that/these) often refer to complex participants or large

segments of text.

• Deconstruct texts by circling demonstratives and connecting to relevant pieces of text. For example, in the

examples above, each ‘this’ is used to refer back to the whole idea contained in the previous sentence.

• Students annotate paragraphs from other texts classifying/explaining the various functions of the sentences

and the words used to signal this to the reader, such as the example below:

Canteens also have a trac lights method: green light foods are …, orange light foods are …, and red

light foods are …

This method

of food identification is …

• In pairs students match sentences to the appropriate topic sentences and then place sentences into order

for logical development of the ideas.

• Set up a cloze activity where the signal words have been removed. Students determine the logical connection

between the ideas and insert an appropriate signal.

• Create a set of ‘text connective’ cards. Students sort into various logical relations, eg showing cause-eect,

adding information, contrasting, clarifying or exemplifying, showing condition or concession. Turn this into

an anchor chart and add to it as students encounter more in texts they read. See Resource 5: Text connectives

and logical relationships.

• Create a series of statements related to a topic being studied. Pick and read a statement at random and model/

jointly construct (oral or written) selecting a text connective from the chart to begin an elaboration of the idea.

• Remind students to use the text connective chart in group discussions to help shift to academic language

in their dialogic talk and to hold each other accountable.

• Make the flow and logical development of ideas within paragraphs a key focus when providing feedback and

in peer and self-assessment.

• Students annotate own texts to highlight where they have used demonstratives or text connectives, justifying

their choices.

See learning sequence 8 ‘Text organisation in arguments‘, particularly the ‘fork’ metaphor on page 11. Elaborations

on the prongs could be ‘classified’ and text connectives placed on top of each prong to show how the point is

developed and how the elaborations are connected and flow.

LEVELS

1–4

LEVELS

5–6

LEVELS

7–9

LEVELS

10–12

LEVELS

13–14

14 | Learning English: Achievement and Proficiency (LEAP) | STRATEGIES COHESIVE DEVICES

LEVELS

1–4

LEVELS

5–6

LEVELS

7–9

LEVELS

10–12

LEVELS

13–14

10. Sentence openers and text

connectives for structure and

orientation

Links to other genres

The activities in this sequence could be adapted

to teaching the structure of:

• factorial explanations, eg factors contributed

to an event such as WW1 or a phenomenon such

as climate change or unemployment

• consequential explanations, eg consequences

of an event or phenomenon such as European

settlement of Australia, climate change, regular

exercise.

Engage

• View short videos about a topic of study such

as the pros and cons of playing competitive sport,

eg U14 FC Barcelona console their heartbroken

opponents

12

or The benefits of competitive sports

for kids

13

.

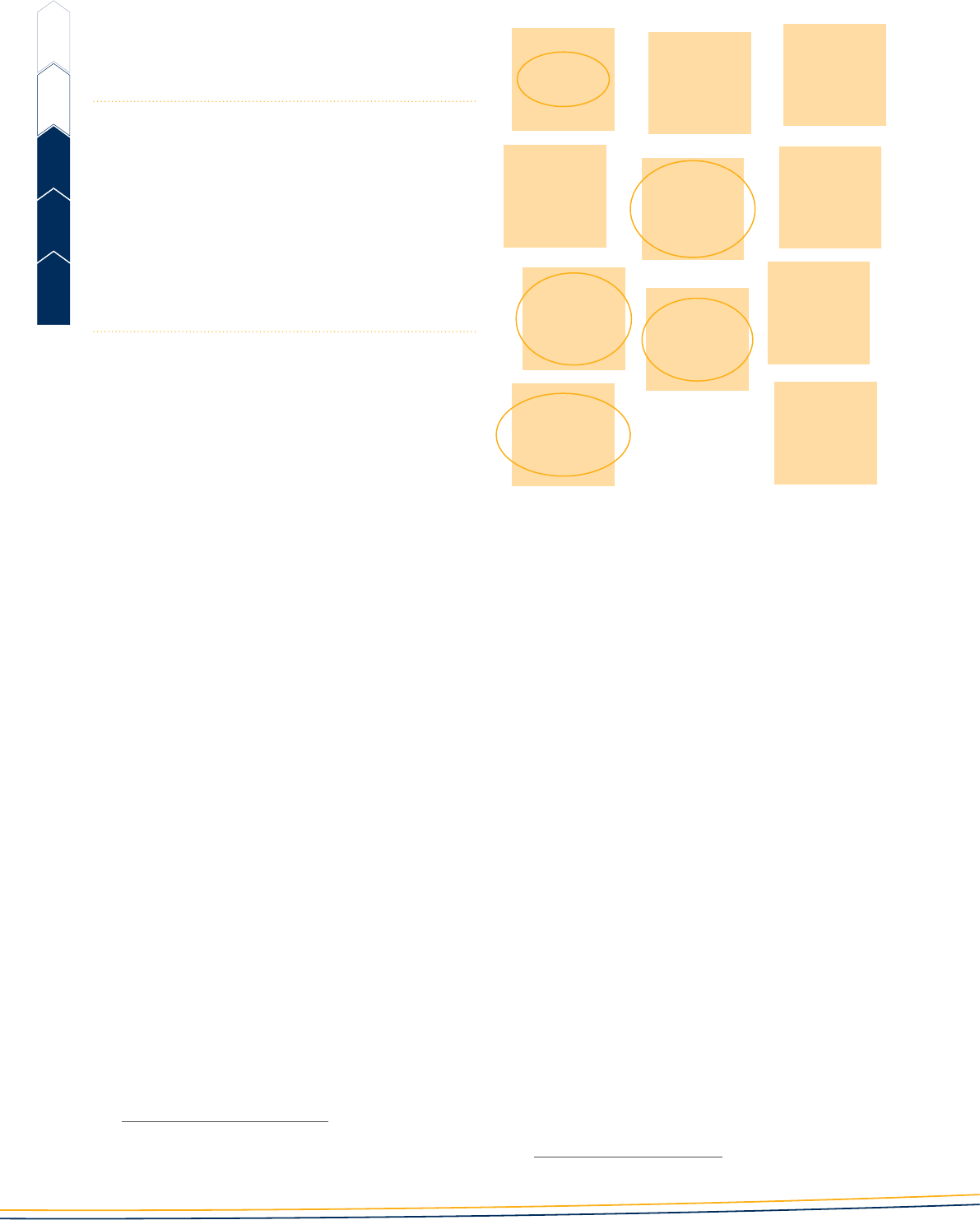

• Provide each student with 4 post-it-notes

(8 if generating ideas for and against).

• Watch the videos again. Drawing from the video

or their own experience/knowledge, students note

down 3 to 4 good things about the chosen topic

(a word or phrase for each idea on a separate

post-it-note). Add 3 to 4 bad things for a focus

on a discussion.

• If students are struggling to generate ideas, suggest

they consider other perspectives, eg What might a

parent say? A friend or sibling? A teacher or coach?

• Model grouping similar ideas, using a ‘familiar’

topic such as school uniform.

Benefits of school uniform

Saves

money

Don’t get

teased

Saves time

deciding

what to

wear

Need fewer

clothes for

school

Good

quality last

longer

Puts you

in the right

mind for

school

Public know

what school

you go to

No

competition:

who has the

best/most

clothes

Can

wear same

clothes for

several days

Promotes

sense of

belonging

Don’t

have to

keep up with

fashion

• In small groups, students share their ideas and

group those that are alike, aiming to end up with

3 to 5 groups of good things (and 3 to 5 groups

of bad things).

• Make explicit that each group of ideas will now

form the basis of a paragraph.

• Point out that in sorting ideas into groups, they

may have had 1 to 2 isolated post-it-notes that

they chose to discard. Alternatively, they may see

them as important and worthy of development.

• Explain that they now need a ‘heading’ word or

phrase for each group (likely an abstract noun or

nominalisation). For the school uniform example,

these could be: savings, cost, financial/economic

benefit.

Explicitly teach: I do – we do – you do

• Explain that we can use these headings words/

phrases to succinctly create:

> a text opener (introduction) that previews the

overarching ideas

> paragraph openers (topic sentences) that clearly

preview the paragraphs.

12

Good Play Guide (2018) ‘Are competitive sports doing more harm than good to children’s mental health?’, available

at http://TLinSA.2.vu/GoodPlayGuide (accessed October 2020). The video, U14 FC Barcelona console their heartbroken

opponents, is part way down the page.

13

Hawkins N (2014) The benefits of competitive sports for kids, available at http://TLinSA.2.vu/Hawkins2014 (accessed October 2020)

Learning English: Achievement and Proficiency (LEAP) | STRATEGIES COHESIVE DEVICES | 15

LEVELS

1–4

LEVELS

5–6

LEVELS

7–9

LEVELS

10–12

LEVELS

13–14

• Model/jointly construct an introduction and topic

sentences using headings words.

• List simple text connectives: Firstly, Secondly, Thirdly

and generate alternatives on an anchor chart.

• Using the headings and the anchor chart, groups

construct an introduction and topic sentences.

Example introduction and topic sentences

using ‘heading’ word/phrases

Recently there has been much discussion about

the compulsory wearing of school uniform. While

some argue for freedom of choice, there are many

good reasons for wearing school uniform. These

include time and cost savings, a sense of belonging

and an increased focus on learning.

One argument for school uniforms is cost saving.

In addition, school uniforms create a sense of

belonging and school pride.

A third benefit is a greater focus on learning.

11. Openers and connectives

for cause and contingency

Engage

• Display a model text related to the genre/topic

of study, eg Resource 6: The legacies of Ancient

Rome for modern society.

Resource 6 has been analysed and annotated to

show a variety of cohesive devices working across

the text, which could also be focused on as revision.

Revise text structure and orientations at the whole

text and paragraph level, using activities such

as those outlined in learning sequence 8 ‘Text

organisation in arguments‘.

• Display 3 versions of a paragraph from the model

text, eg Resource 7: Moving from informal to

formal language.

Point out that each paragraph begins with the same

topic sentence but that the elaborations are

expressed dierently. Students read and discuss

the dierences in eect of the 3 versions. Which do

they think is better/best and why? Which is more

spoken-written? Which flowed and developed the

ideas better? Which sounded more ‘expert’? Where

would the 3 versions be on the register continuum?

Explicitly teach: I do – we do – you do

• Model identifying and underlining sentence

openers (what precedes the verb) in the first few

elaborating sentences of version 1 in Resource 7.

• Jointly identify the sentence openers in the next

few elaborating sentences.

• In pairs, students continue identifying the sentence

openers in the remaining elaborating sentences

of version 1 and the elaborating sentences in

version 2 and 3.

• Discuss what this analysis shows and whether

it supports their original judgements.

• Using Resource 7, illustrate the main points:

> sentence openers shift from a focus on humans,

to one on abstractions, including cause and

contingency

> the ideas flow better in the third version since

it logically develops the explanation of the legacy

and its consequences: sentence openers typically

refer back to a previous idea and develop it

further, focusing on cause and contingency

> these shifts in language choices, shift the versions

toward the written-end of the continuum.

• Model and jointly construct taking notes on

a series of related events and asking questions:

> Why did this happen? What was the cause/

reason for this? What happened because

of this? What did it enable/allow/lead to?

> What conditions led to this? What was this

contingent on?

> What would have happened without this/

without these conditions?

• Model and jointly construct putting these ideas

into a paragraph with a focus on orienting to cause

and contingency.

• Provide groups with another spoken-like paragraph.

You could dierentiate by giving some groups a

paragraph without cause and contingency (harder)

and others a paragraph with cause and contingency

at the end of the clause (easier). Students rework it

to improve flow and shift up the register continuum.

Groups share and compare their reworked

paragraphs, explaining and justifying their changes.

• Students work in pairs to generate notes for a

paragraph, asking each other questions such as

those above, and then in pairs or individually write

the paragraph. Students share their paragraph with

another pair and discuss choices and suggested

improvements.

16 | Learning English: Achievement and Proficiency (LEAP) | STRATEGIES COHESIVE DEVICES

LEVELS 1012 LEAPING TO LEVELS 1314

LEVELS 10–12 LEAPING TO LEVELS 13–14

Learning sequence Language in focus Genres

12. Strategic orientations

and text organisation

• text and paragraph openers as

orientations

• text organisation and ecient

orientations using nominalisation

• manipulation of text connectives

and alternatives

• orientation to angle (perspective),

contingency and cause

• orientation to abstraction through

passive voice and nominalisation

• expositions: arguments,

discussions

• factorial and consequential

explanations

• reviews, evaluations

12. Strategic orientations and text organisation

Text and paragraph openers as orientations

Links to other genres and curriculum areas

The activities in this sequence could be adapted for use in most curriculum areas to teach the structure of:

• factorial explanations, eg factors contributed to an event, such as WW1 or a phenomenon such as climate

change or unemployment

• consequential explanations, eg consequences of an event or phenomenon, such as European settlement

of Australia, climate change, regular exercise

• evaluative texts, eg reviews/evaluations that evaluate features or components of a product, process,

performance, artwork or literary text.

Engage

• Provide students with only the introduction of a model text that uses text connectives and topic sentences

to structure the text, eg Resource 8: Discussion/argument: Should children play computer games?

• Read the introduction and then, in small groups, students use evidence to discuss:

> what genre it is

> what they expect it to contain and do.

Resource 8 has been analysed and annotated to show a variety of cohesive devices working across the text,

which could also be focused on as revision and/or taken up in sequences to follow.

Explicitly teach: I do – we do – you do

• Facilitate whole class sharing to confirm that, from reading only the introductory paragraph, they can predict

that the text:

> is a discussion genre, looking at 2 sides of an issue (signalled by words such as: debate, benefits and risks;

those who are against; whereas, those who are for)

> will elaborate on the benefits and concerns in a series of body (argument) paragraphs, before coming

to a conclusion (which side it falls on) and/or a recommendation

> in elaborating on the benefits: we expect to hear about leisure time with friends and the development

of skills and attributes; elaborating the risks: we expect to hear about the use of time and money and

exposure to violence.

LEVELS

1–4

LEVELS

5–6

LEVELS

7–9

LEVELS

10–12

LEVELS

13–14

Learning English: Achievement and Proficiency (LEAP) | STRATEGIES COHESIVE DEVICES | 17

• Provide the remainder of the text, cut into

paragraphs for students to reconstruct, using

language in the text to justify decisions, eg the order

in which the arguments were previewed and/or

text connectives or alternatives that structure the

text (Furthermore, On the other hand, Some of

the greatest positives, In support of the parents’

concerns).

• Students look for other words that signal the text

is a discussion and which side is being dealt with.

Text organisation and ecient

orientation using nominalisation

Engage

• Display a discussion topic pertaining to a curriculum

area for which you have already built students’

field knowledge, eg ‘Should mining be continued

in SA?’ The topic should consider various views,

eg environmental, economic, Aboriginal and local/

social perspectives.

• Each student is given 8 post-it-notes on which they

write words or phrases to represent 3 to 4 reasons

for and 3 to 4 reasons against, each reason on

a separate post-it-note. They should consider

various viewpoints, eg what others might argue.

• In small groups, students share ideas and group-

related ideas, to end up with 3 to 5 groups for

and 3 to 5 against. (If students need further help,

scaold using the arguments around school

uniform in 10. Sentence openers and text

connectives for structure and orientation.)

• For each group of ideas, students need to find

a ‘heading’ word or phrase that encapsulates

the point: this will likely be an abstract noun

or nominalisation.

Explicitly teach: I do, we do, you do

• Explain that we can use these headings words/

phrases to succinctly create:

> a text opener (introduction) that previews the

overarching ideas

> paragraph openers (topic sentences) that clearly

preview the paragraphs.

• Refer students to the introduction of Resource 8

and identify nominalisations used to preview the

arguments.

• Discuss the eects of previewing ideas in the

introduction using more ‘spoken-like’, denominalised

forms: it becomes long and rambling.

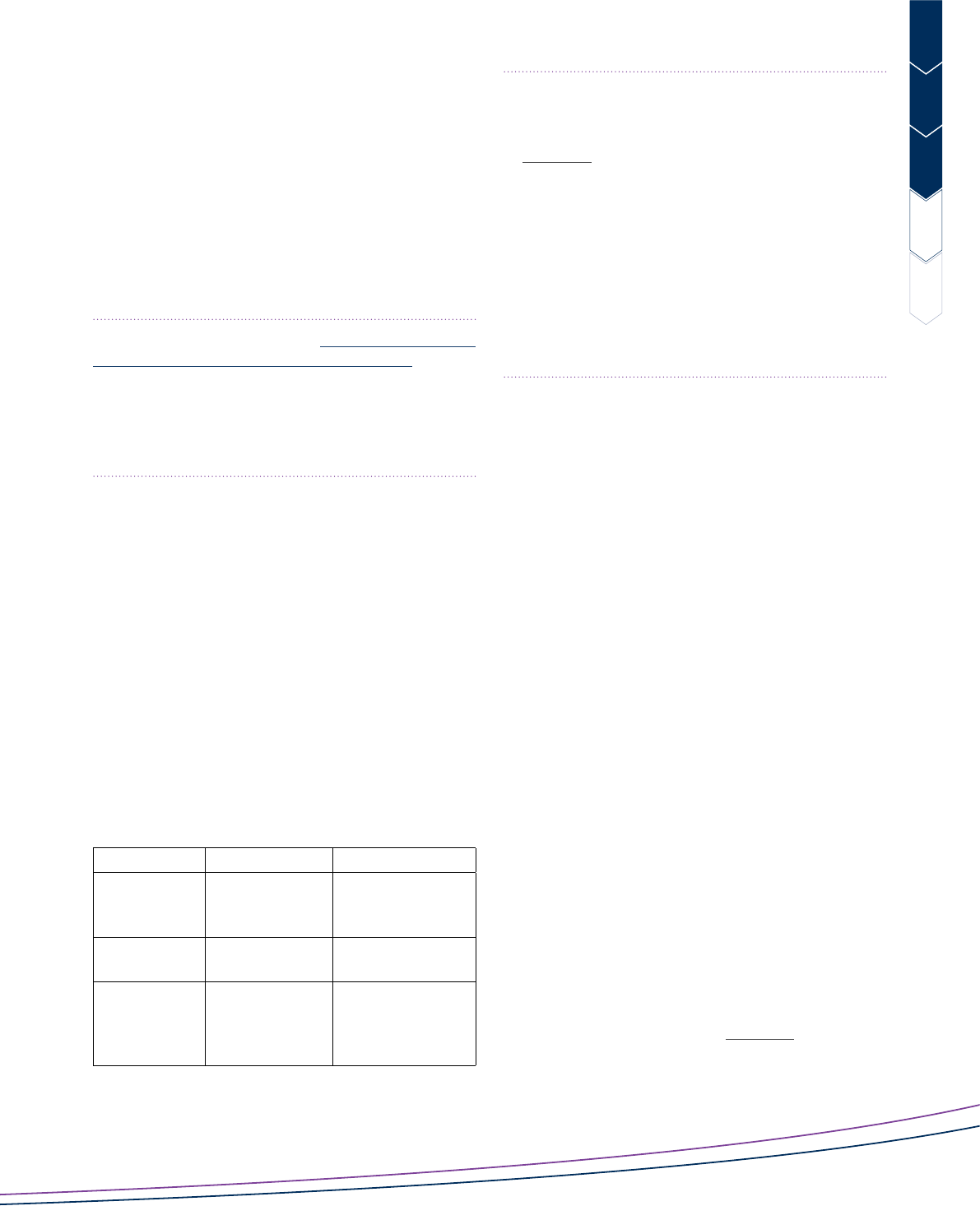

Without

nominalisations:

spoken-like

With nominalisations:

written-like

People worry that

players spend too

much time and money

playing the games and

that some of the games

are too violent and it’s

not good for players

to be exposed to that.

Against: concerns about

the use of time and

money and exposure

to violence.

• Model/jointly construct an introduction to the

discussion topic, using the encapsulating nouns/

phrases, eg social benefits, skill development,

exposure to violence, health problems.

• Students revisit Resource 8 and locate where the

previewed ideas from the introduction are taken

up in the following paragraphs, using arrows (or

colour-coding) to show connections.

• Paragraph 4 begins with a broader topic of ‘health

and habits’, which allows the author to deal with

the previewed issues of time, money and violence,

before extending the idea to physical health

problems in paragraph 5.

• Discuss why an author might do this: what is the

eect? eg avoids being too formulaic in taking up

previewed ideas; it is dicult to preview everything

in a discussion, especially if you are going to have

more than 2 arguments for each side.

• Point out that the text is well organised and

orients the reader well through the introduction

and paragraph openers using alternatives beyond

Firstly, Secondly, etc.

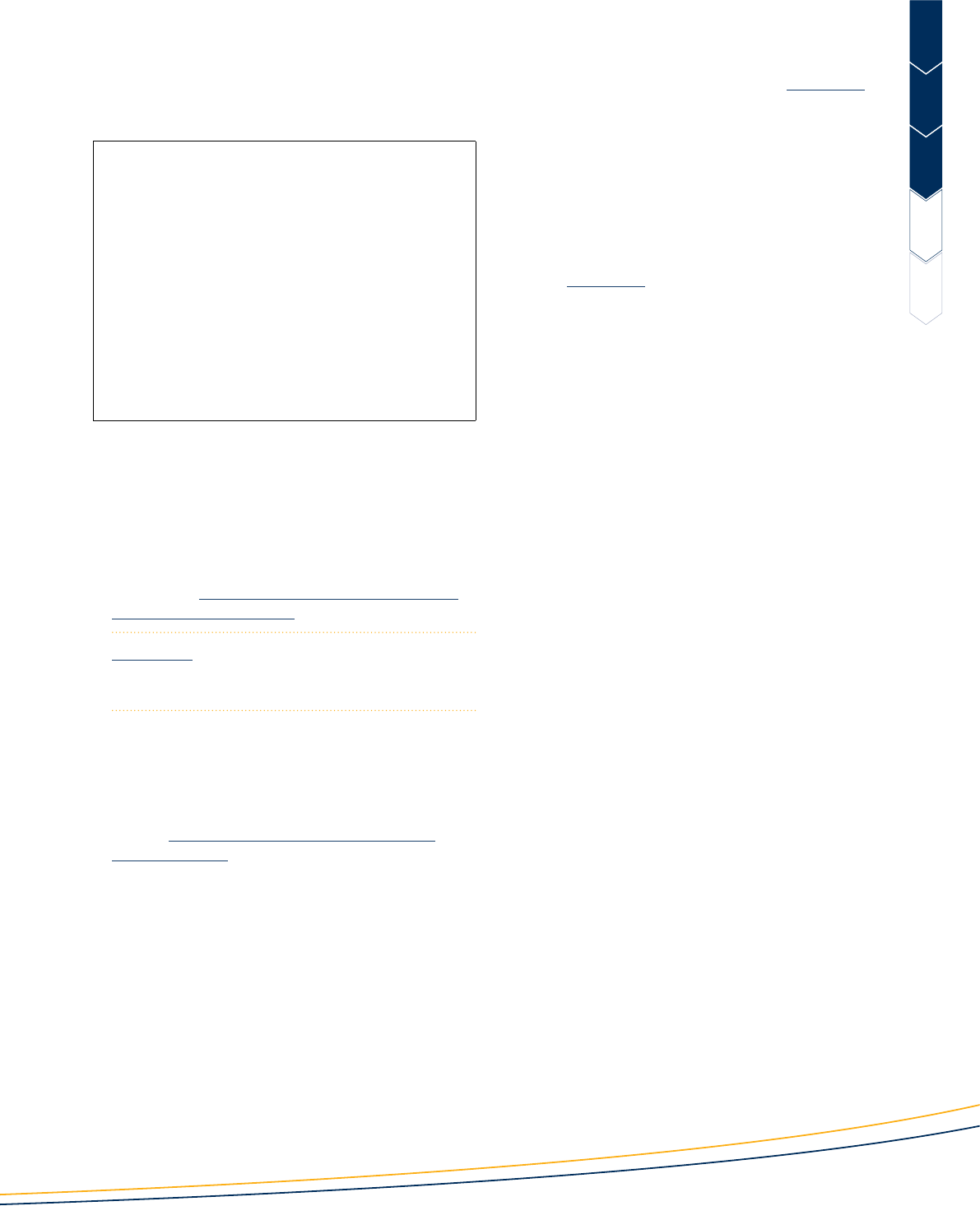

• Explain that we can use an understanding of the

noun group to create paragraph openers that

organise the text in this way. Display a blank

chart to create topic sentences for arguments/

discussions (see chart example on page 18).

LEVELS

1–4

LEVELS

5–6

LEVELS

7–9

LEVELS

10–12

LEVELS

13–14

18 | Learning English: Achievement and Proficiency (LEAP) | STRATEGIES COHESIVE DEVICES

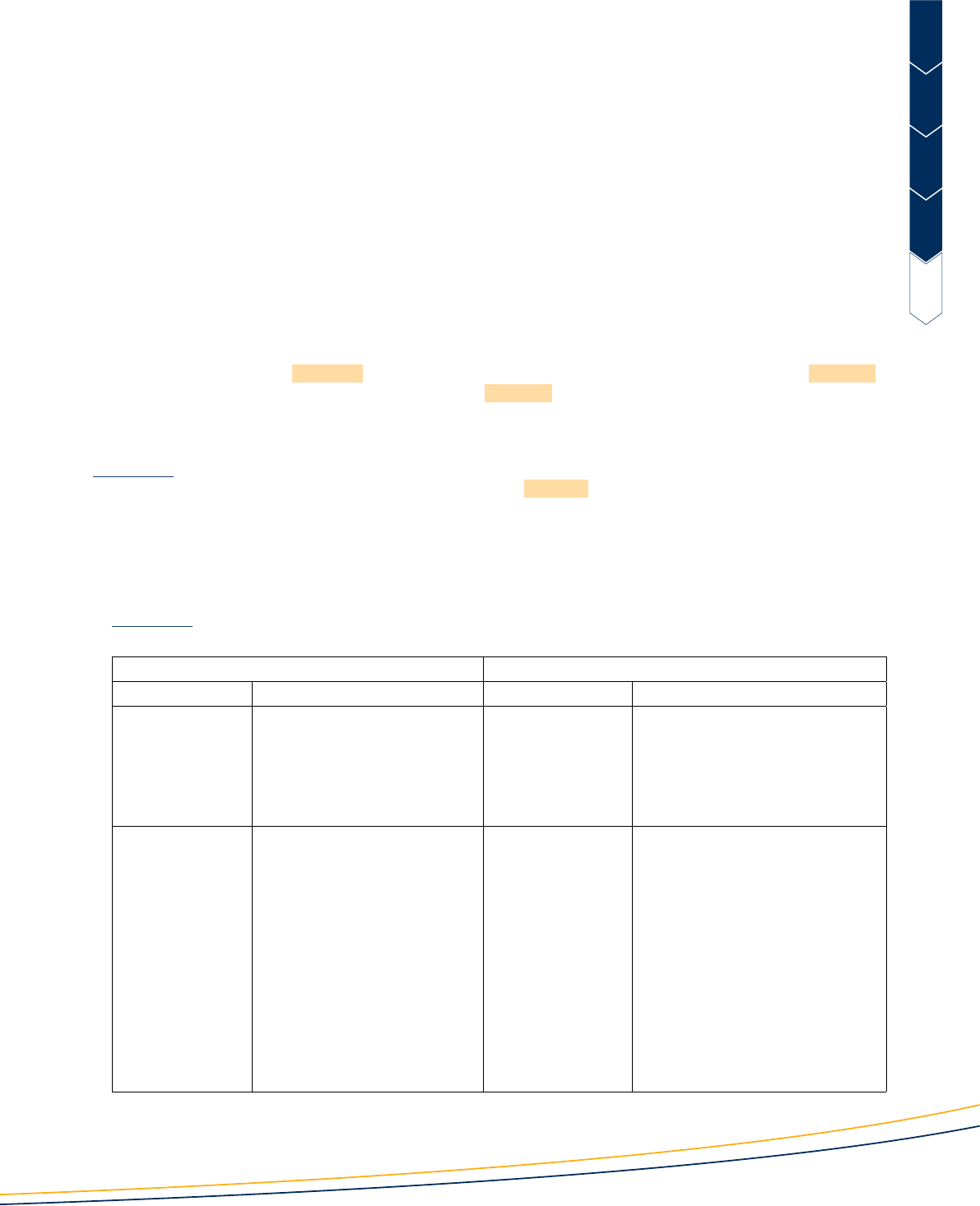

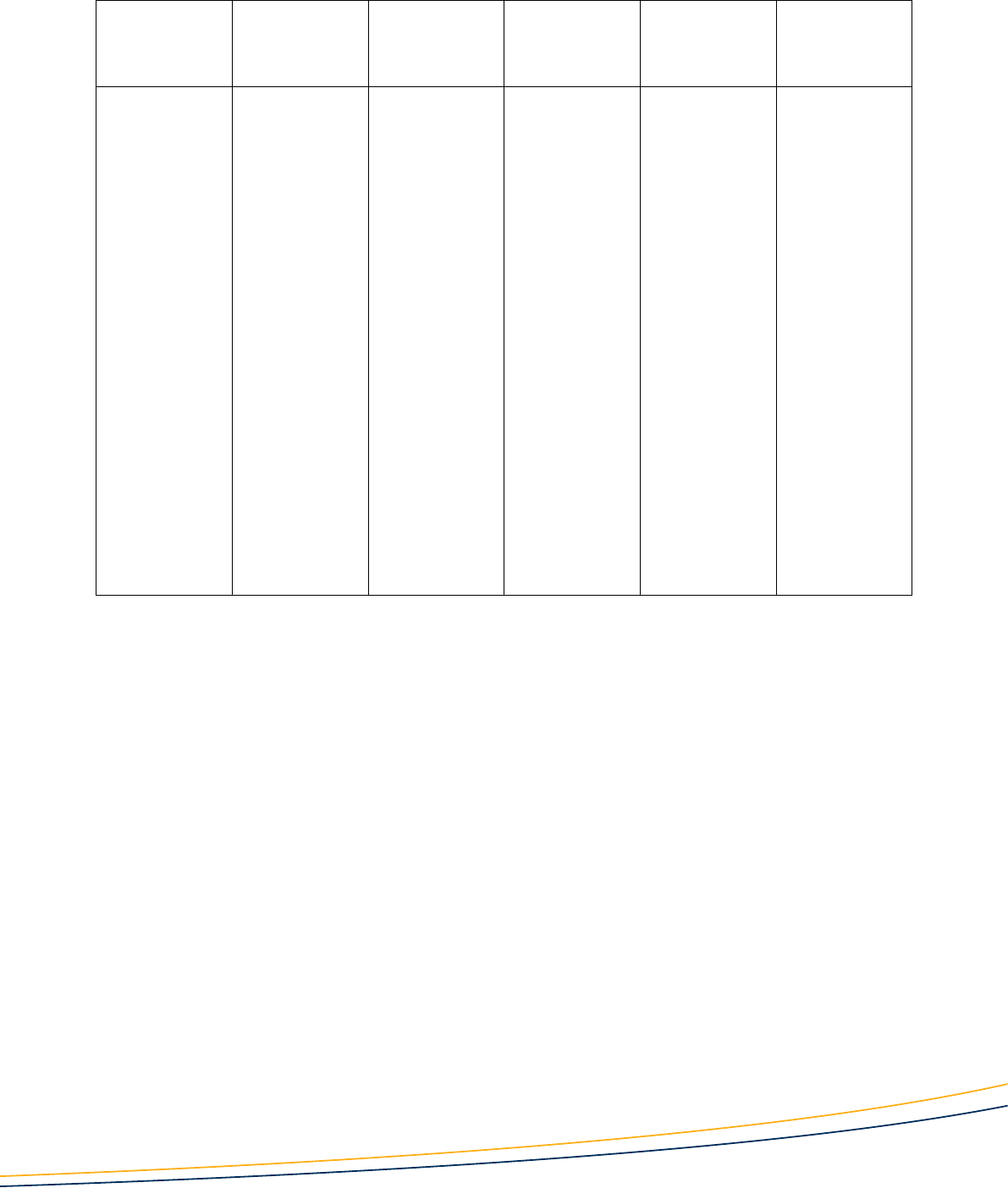

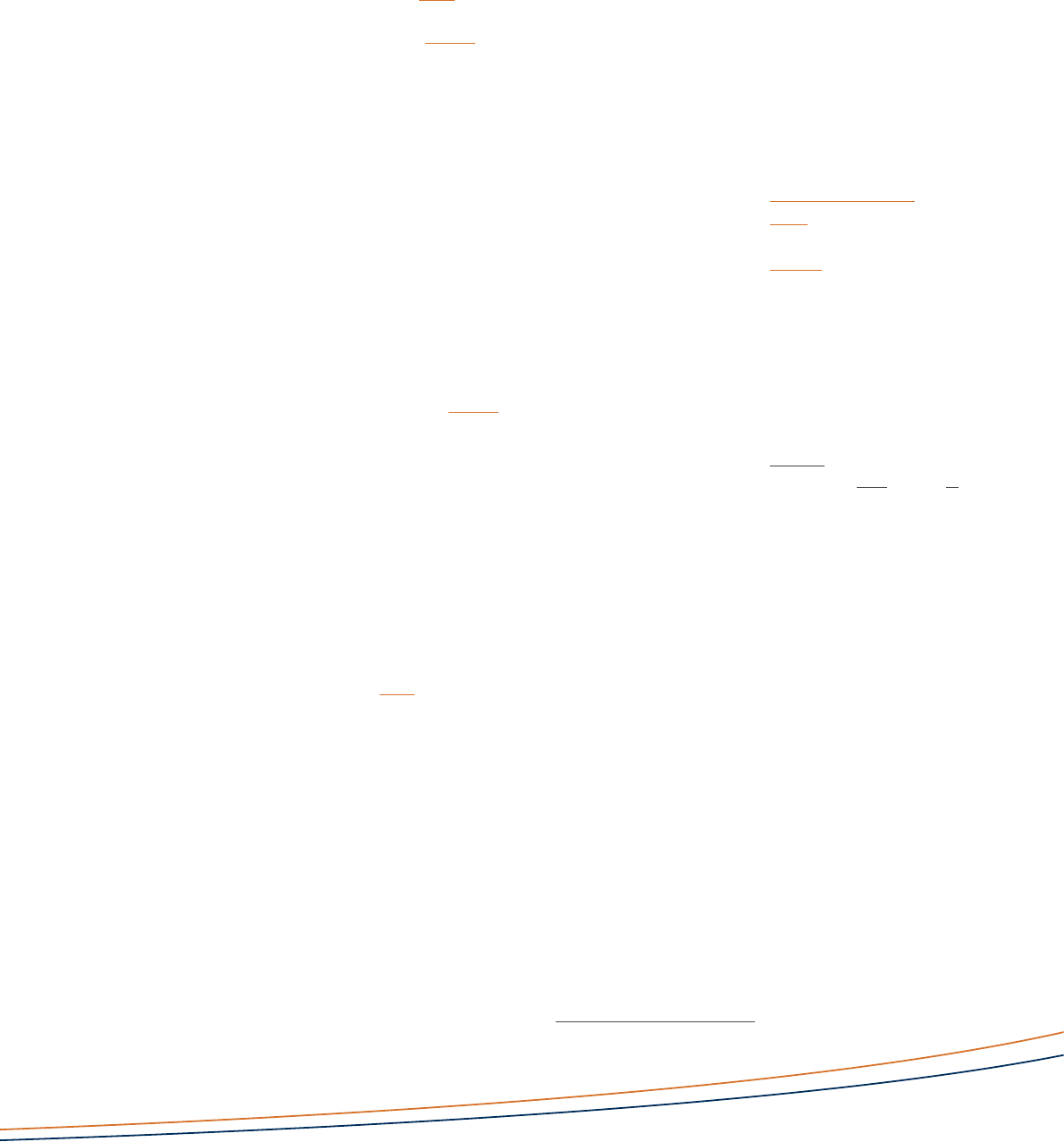

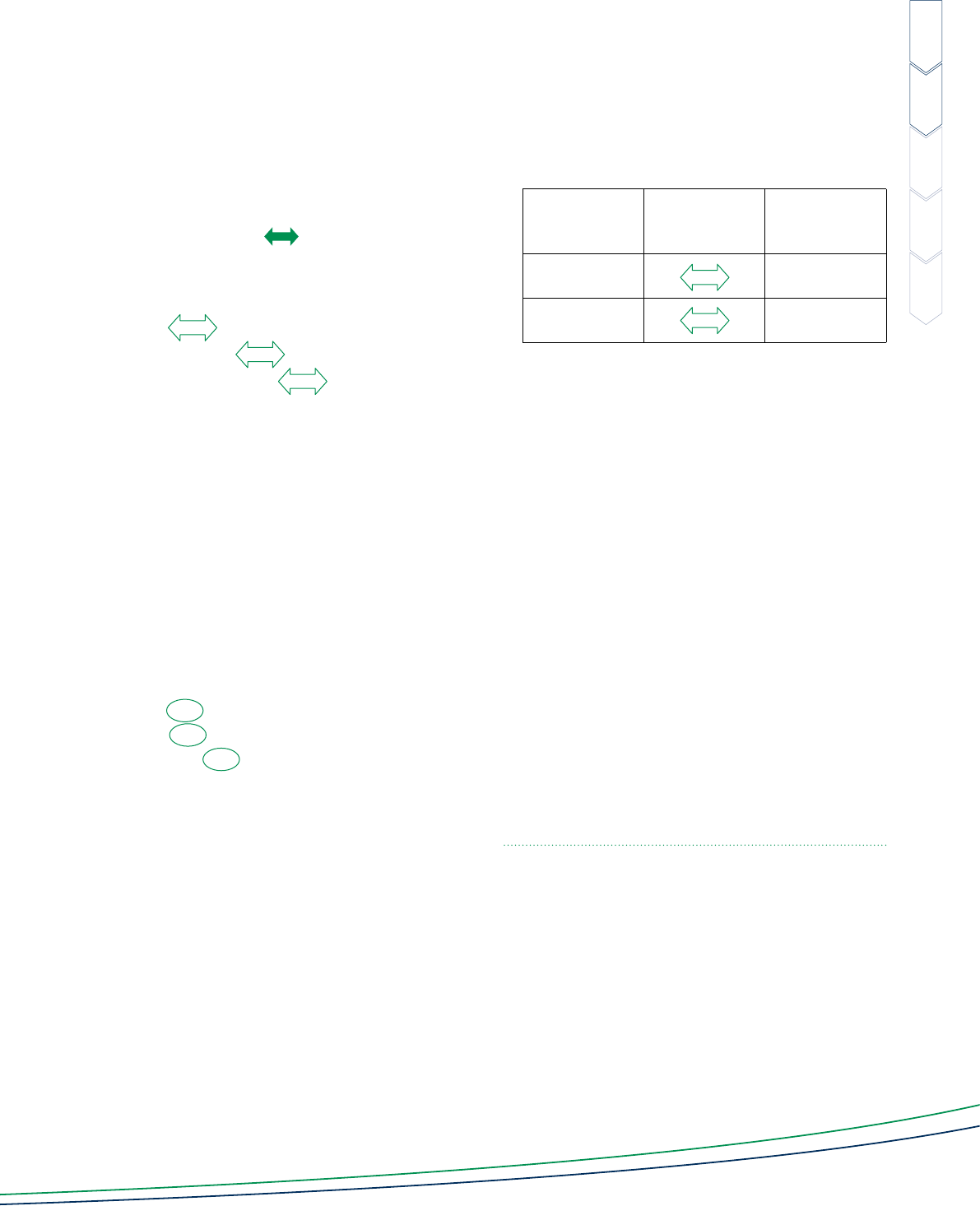

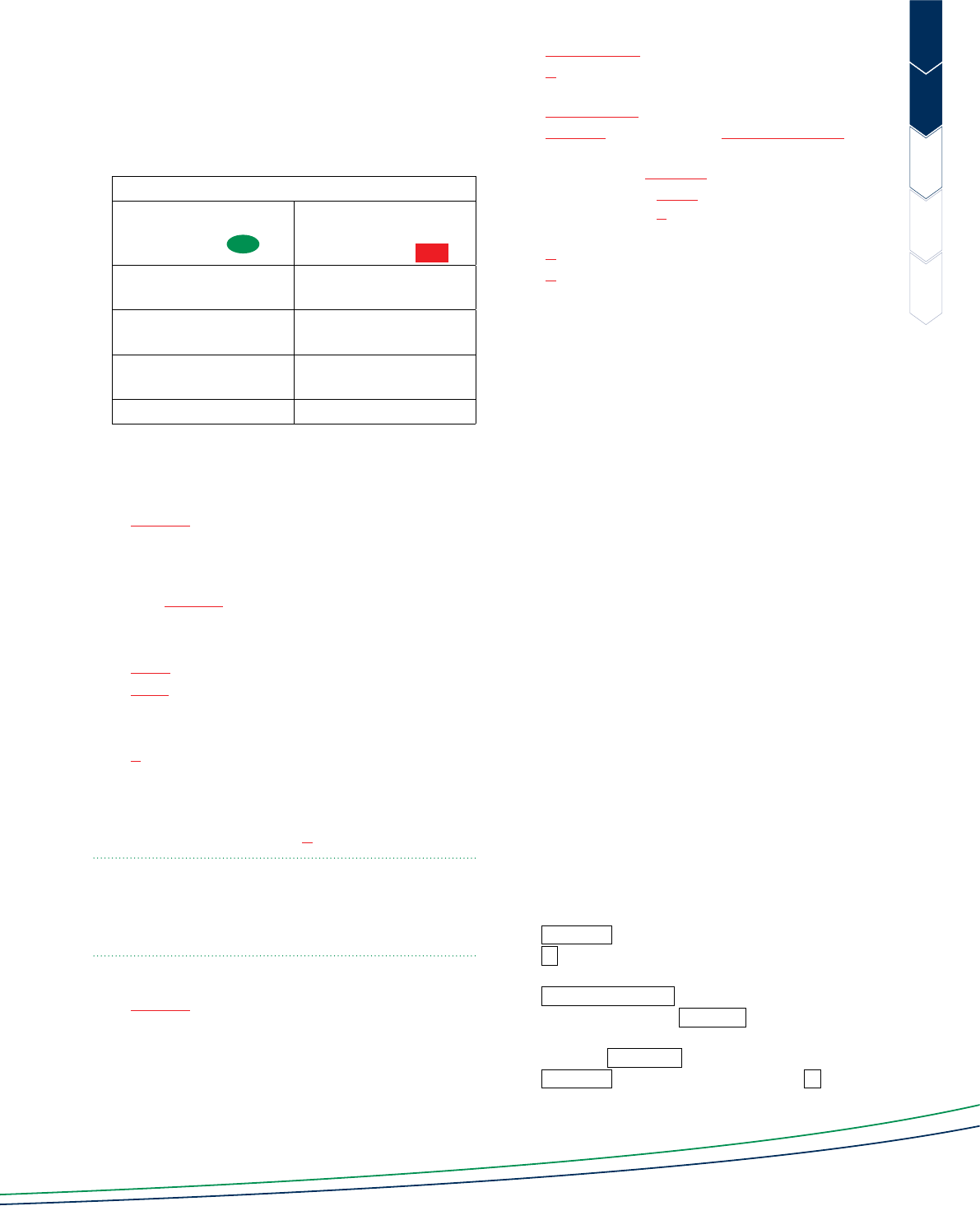

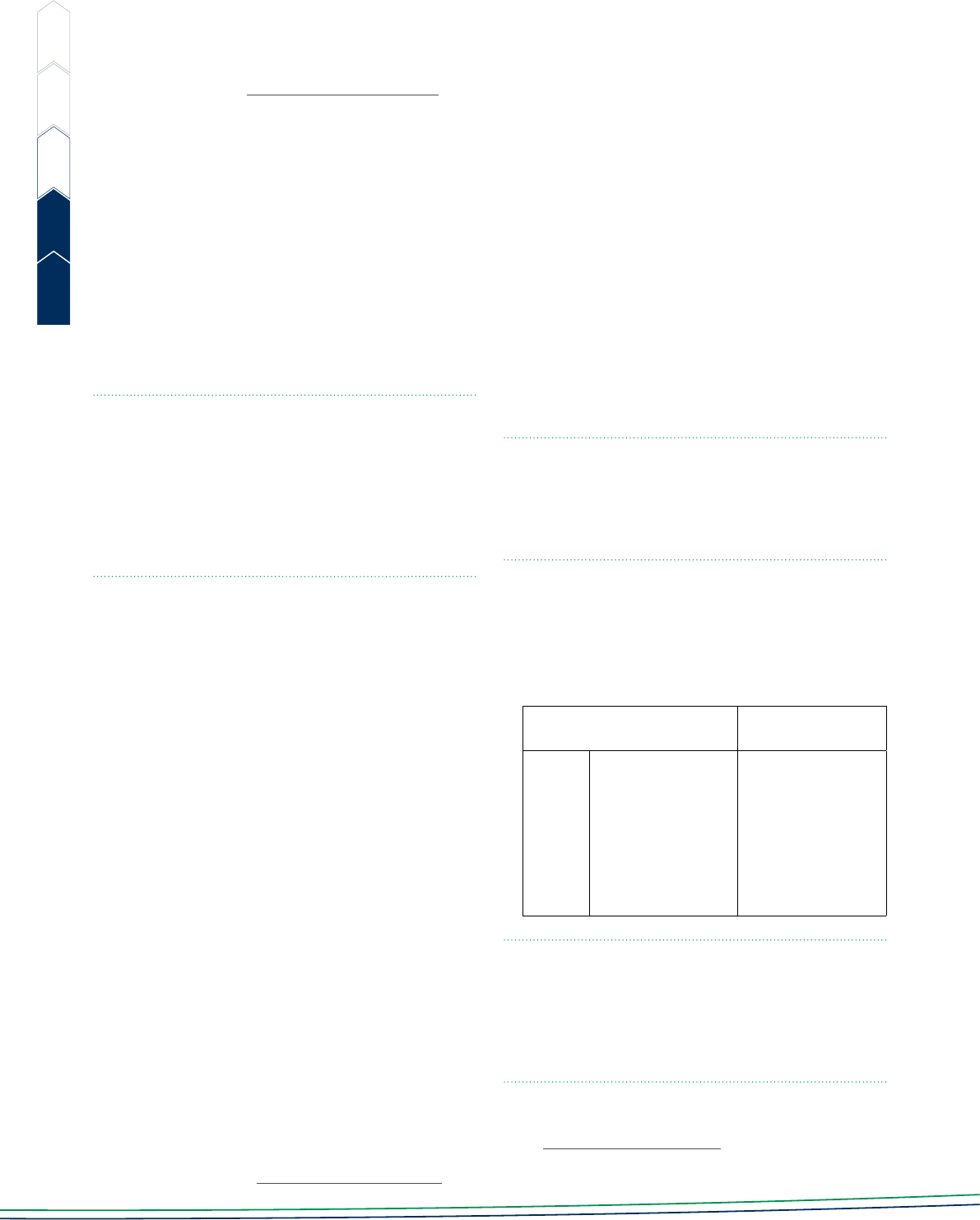

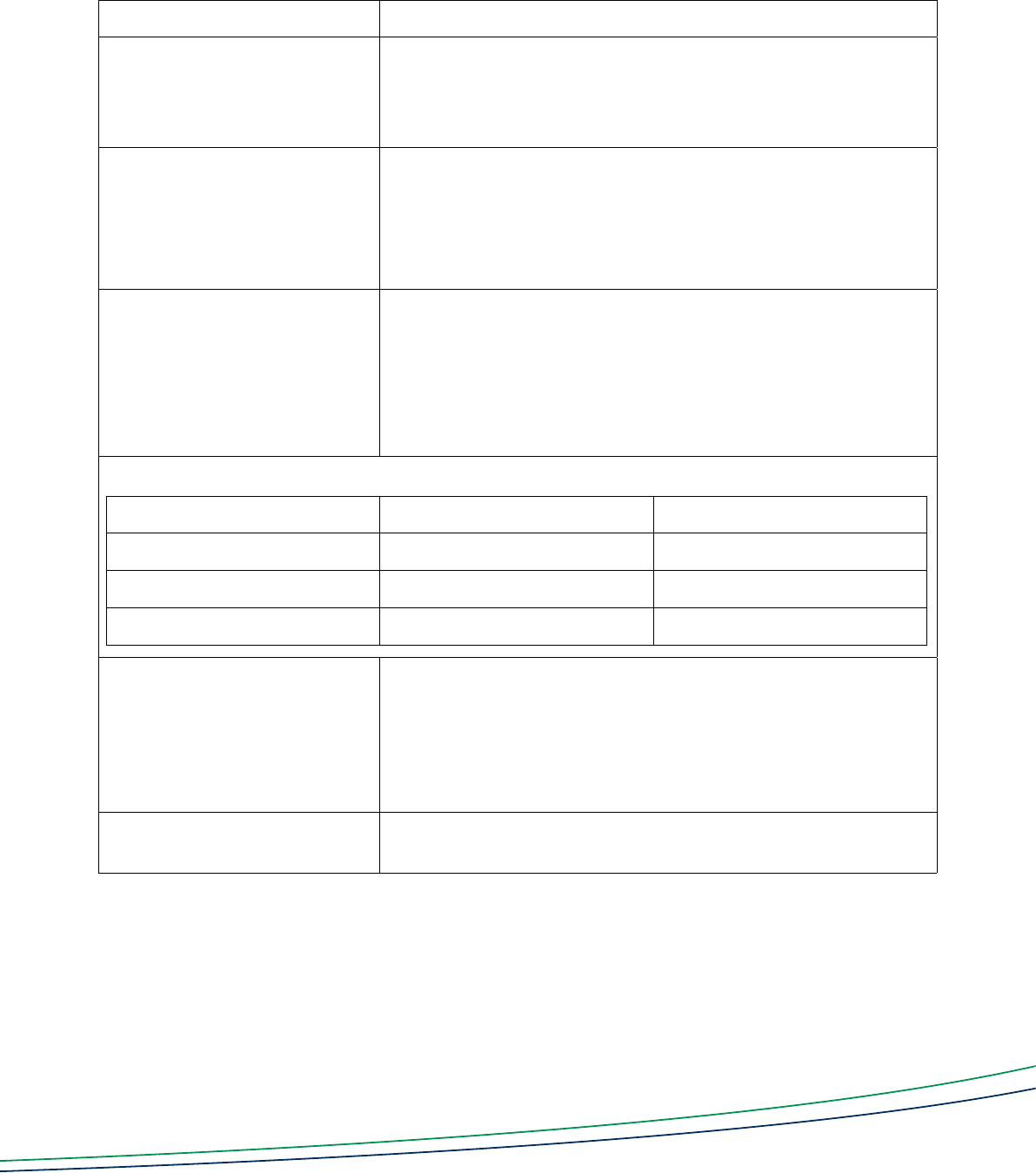

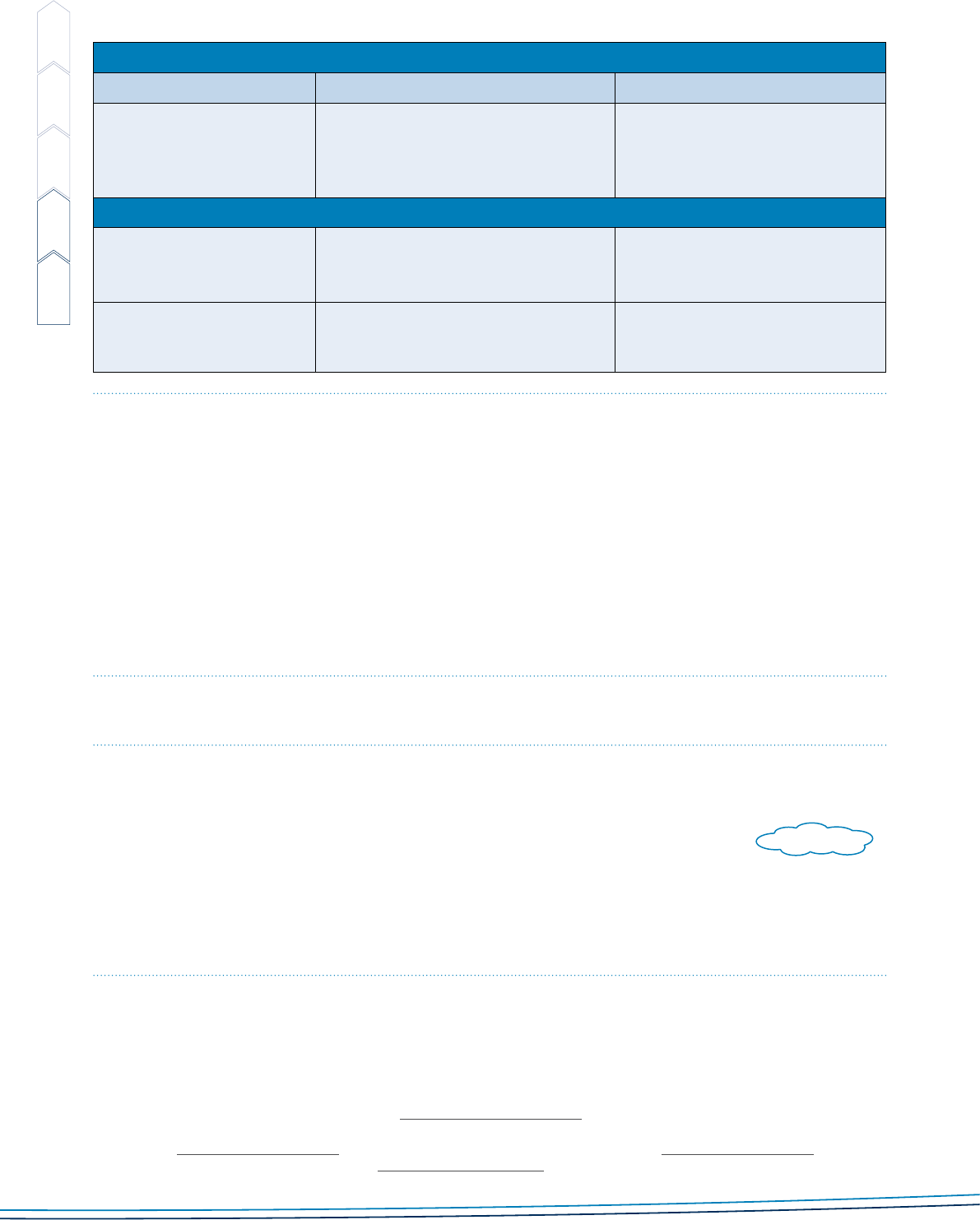

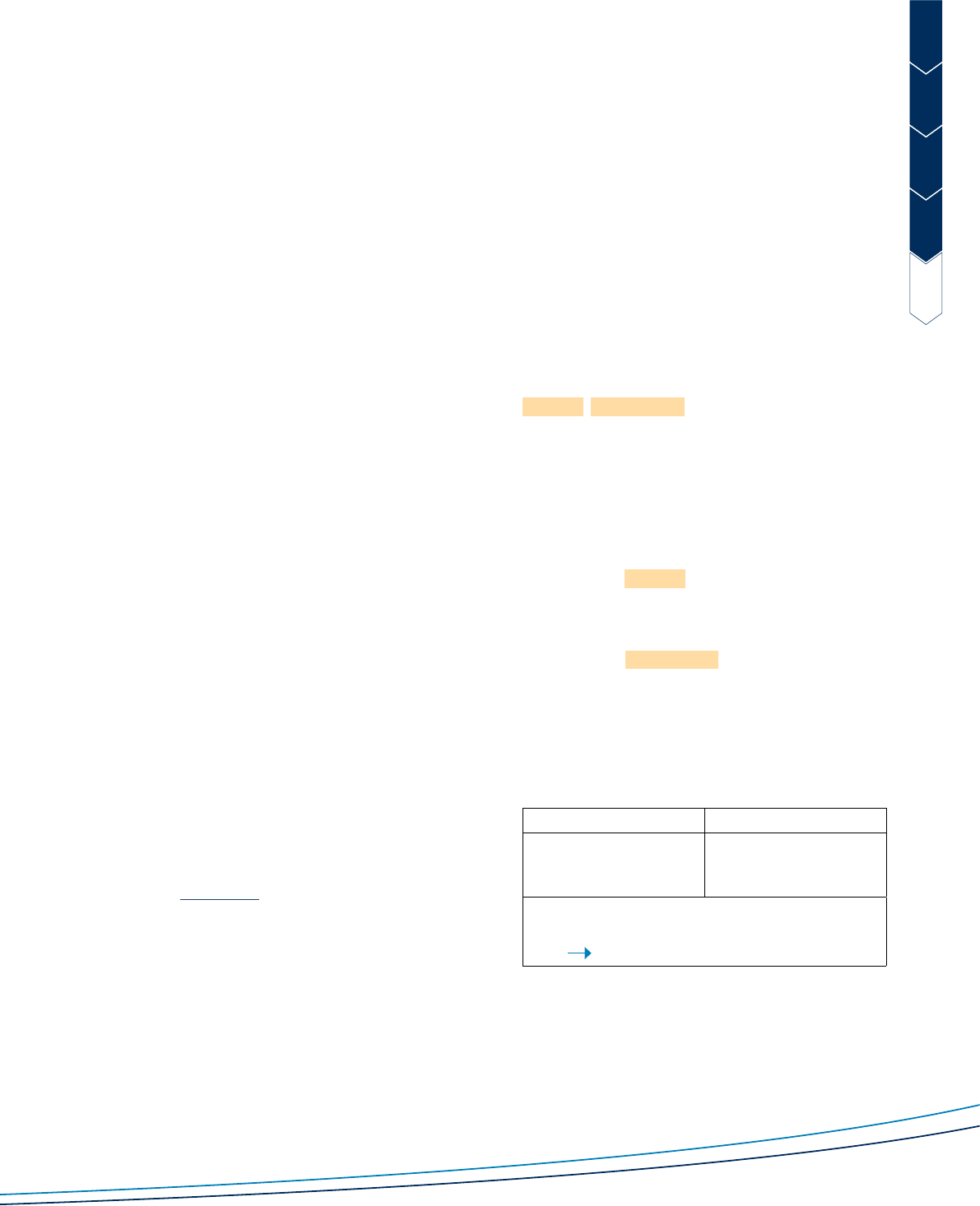

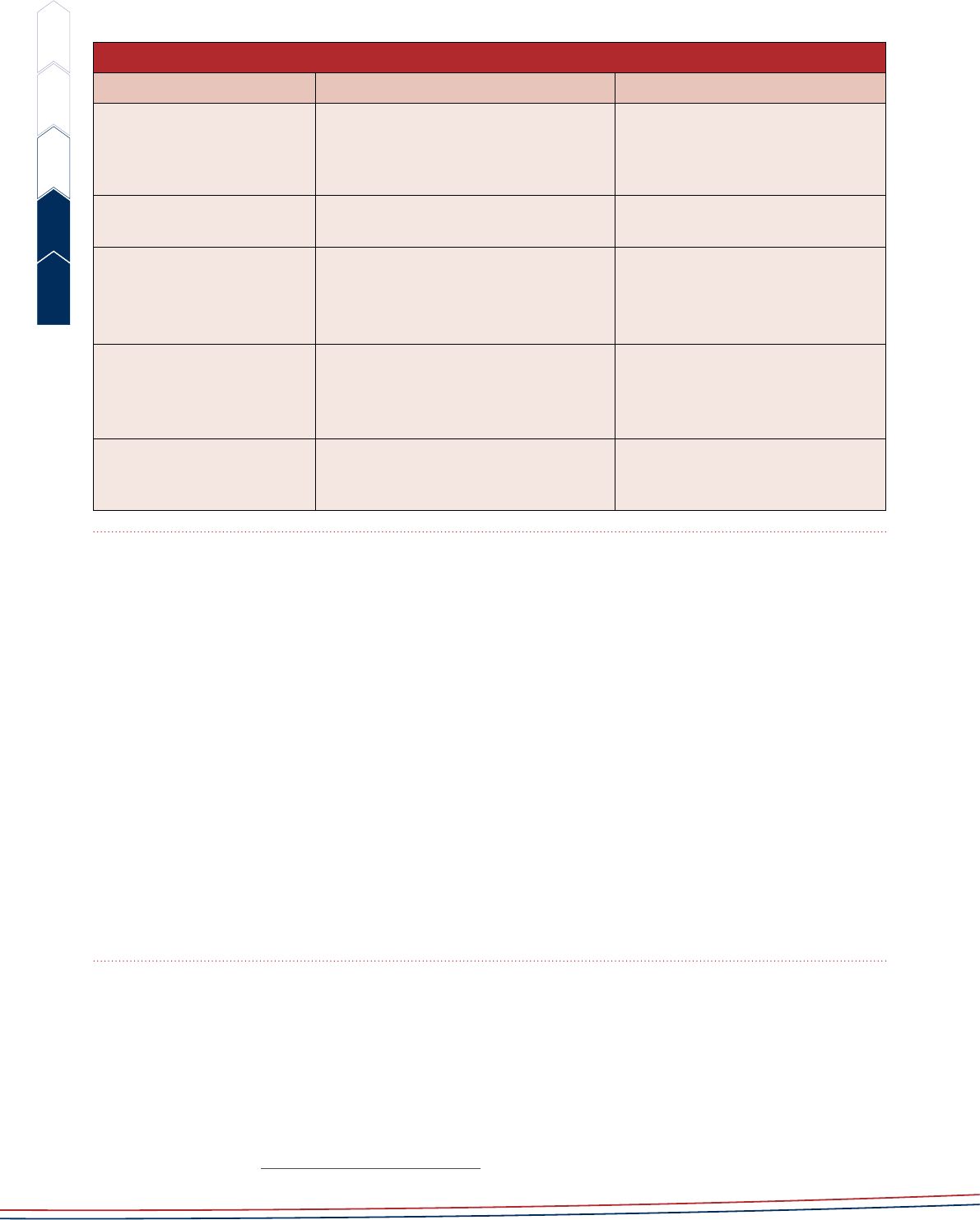

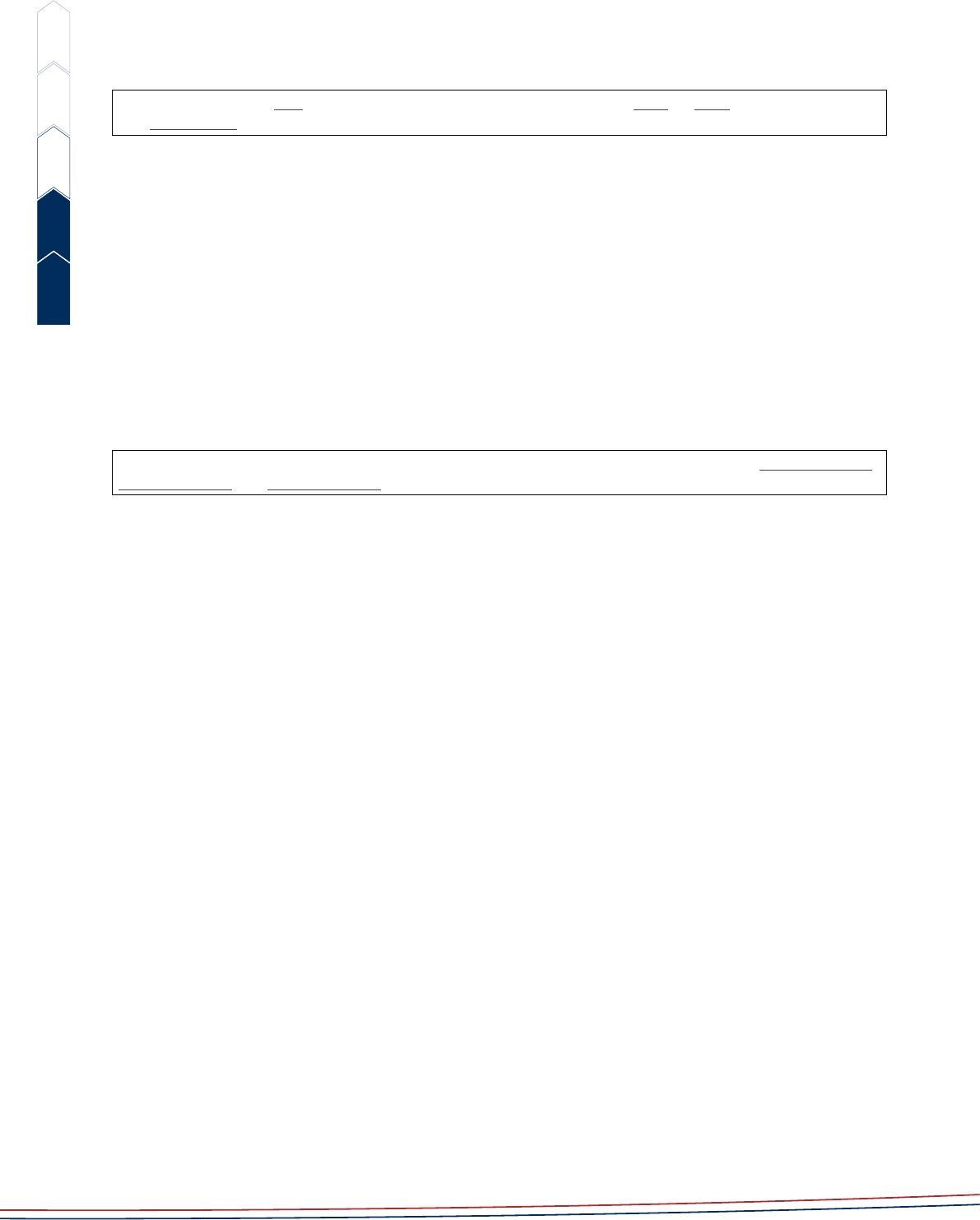

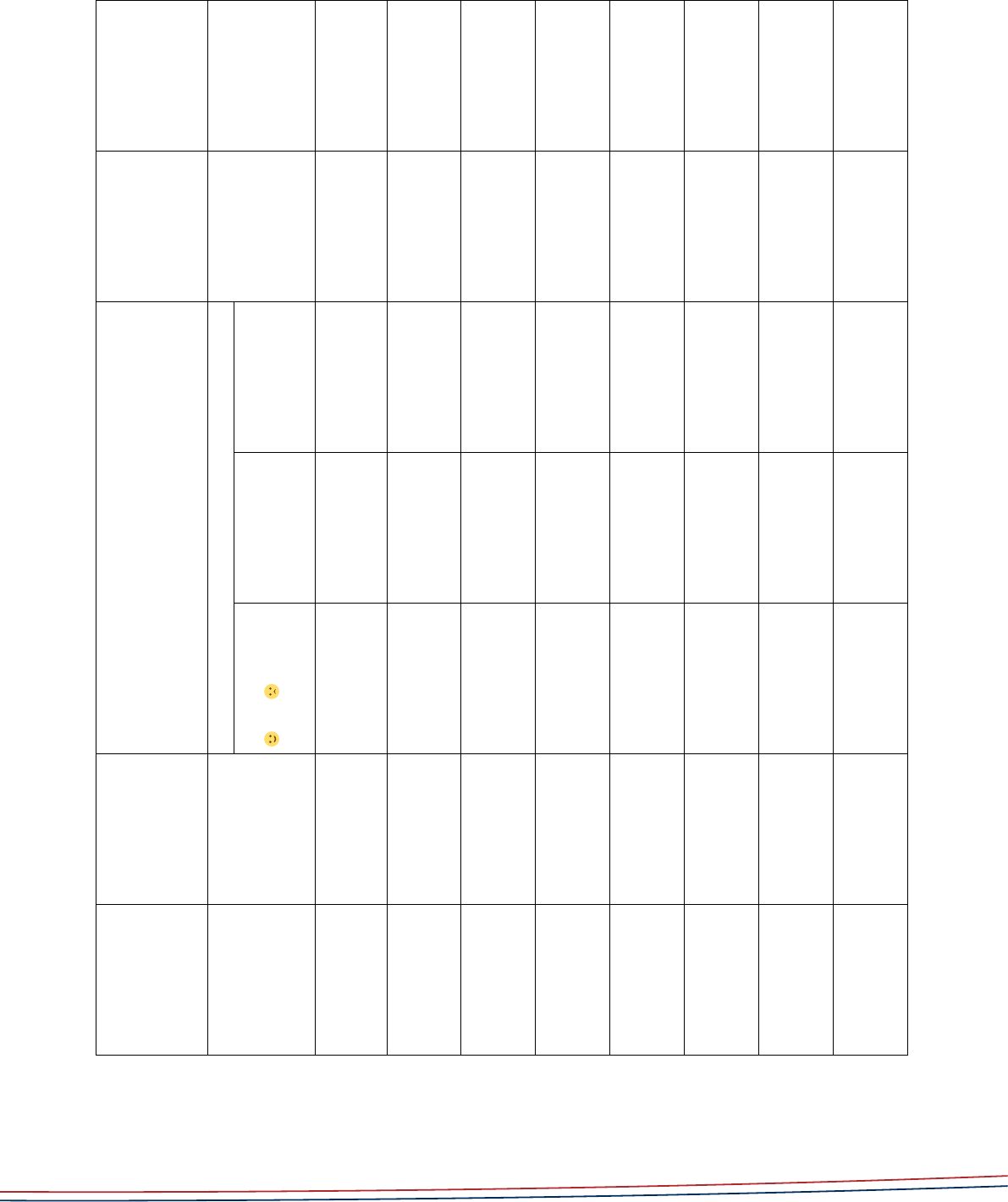

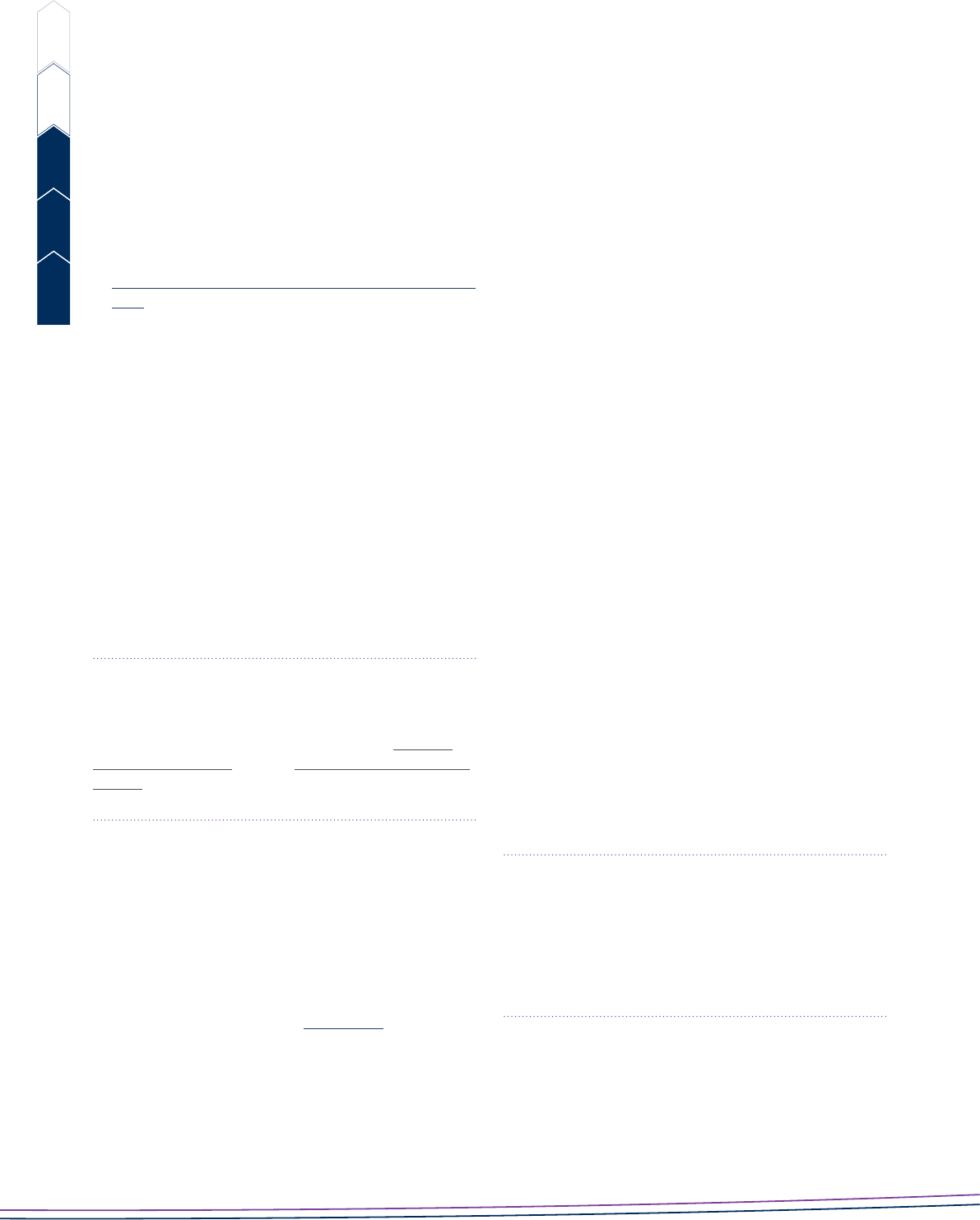

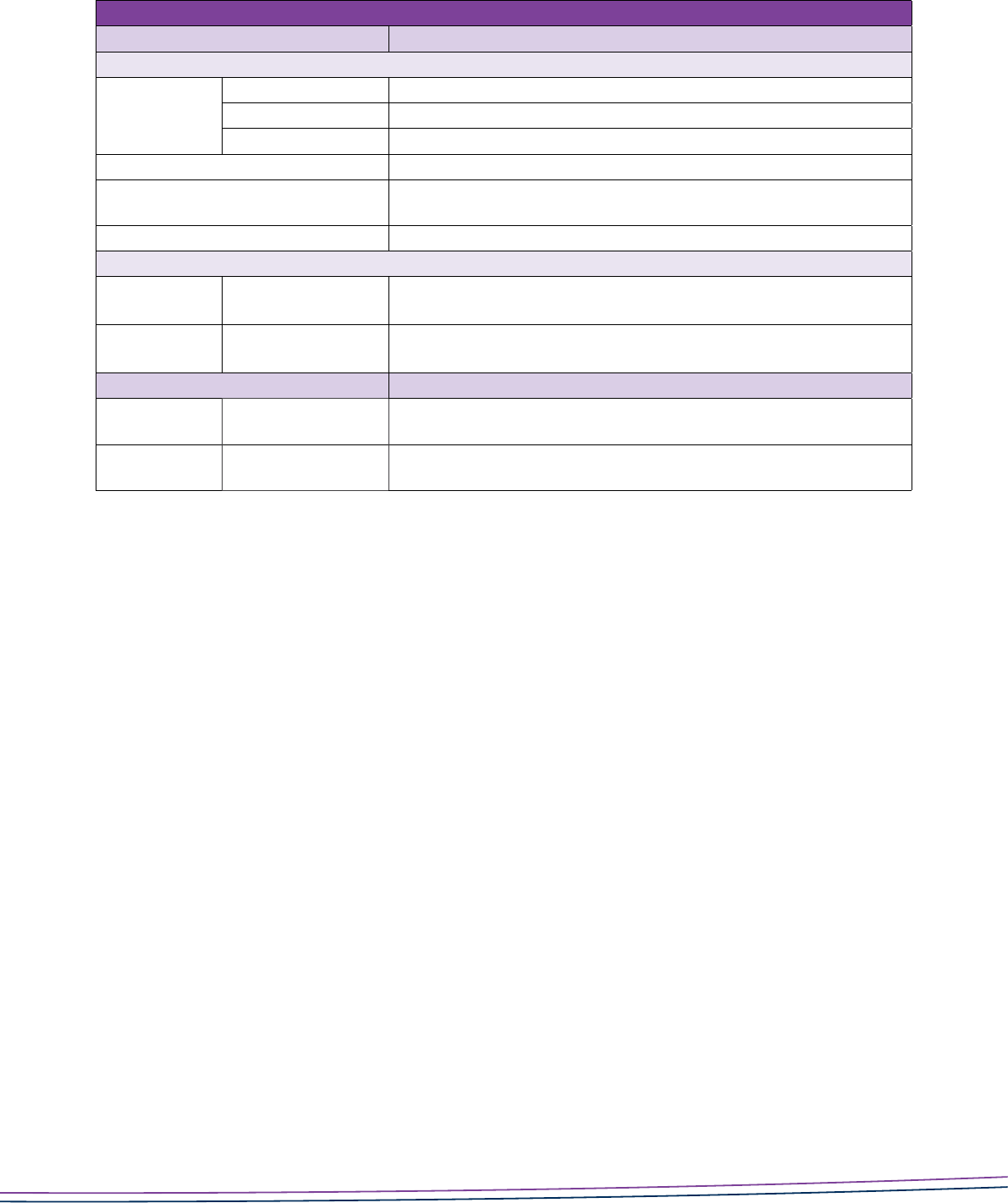

Using noun groups to build topic sentences

14

1 2 3 4 5

Sequences the paragraphs Describes the

importance/

value

Classifies

what kind/

type

The focus noun (thing)

– provides the angle

on the topic

Qualifier links to the

topic

Pointer Numerative

a

the

one (of the)

additional

another

subsequent

last, final

greatest

major

significant

critical

essential

crucial

physical

emotional

economic

good things – pros

advantage

benefit

gain

value

reason/argument (for)

positive outcome

bad things – cons

risk

problem

(negative) impact

argument (against)

disadvantage

cost

drawback

downside

• of playing computer

games

• aorded by gaming

• from being a player

• arising from playing

computer games

• resulting from

computer games

• Begin with column 4 to explain that:

> a discussion text is organised around the ‘good things’ and ‘bad things’ of each side. We talk about a topic

like this informally, but when we formally discuss it—orally or in writing—we need to shift from Tier 1

(everyday language) to Tier 2 (high-utility academic language used across topics and across disciplines),

often using abstract nouns. Generate words such as those in the focus noun column above.

Examples of Tier 2 abstract nouns used to organise how a topic is dealt with in other genres:

• cause: factor, reason, trigger, catalyst, impetus

• effect: result, outcome, impact, consequence

• part: element, feature, aspect, component

• technique: strategy, device.

• Work through columns 1 to 3 in sequence and then column 5 with students, pointing out the attributes

of each of the columns in relation to the abstract nouns that provide the angle on the topic.

> In front of this noun, we can indicate where we are in the sequence of arguments, using pointers and/or

numeratives (column 1). These are the sequencers. Invite examples suitable to the chosen topic.

> After the sequencer, we can describe the importance or ‘value’ (column 2). Add words to that column,

pointing out that some of these are more or less appropriate according to the topic and subject area.

Discuss which ones might not be appropriate for the context of your given focus genre/assessment task.

> For some contexts/topics we may be able to add a classifier (column 3). Add examples, stopping to reflect

on which ones might be appropriate for your topic.