DRINK

DRIVING

A road safety manual for

decision-makers and practitioners

Drink driving: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners

A road safety manual for

decision-makers and practitioners

DRINK DRIVING

© International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies 2022. All rights reserved. This publication or any part thereof may

not be reproduced, distributed, published, modified, cited, copied, translated into other languages or adapted without prior written

permission from the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. All photos used in this document are copyright

of the IFRC unless otherwise indicated.

Module break photo source: Police MTTD, Accra.

Recommended citation:

Drink Driving: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners, second edition. Global Road Safety Partnership, International

Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, Geneva; 2022.

Design by Inis Communication

Preface v

Acknowledgements vii

Executive summary ix

Introduction 1

Why were these manuals developed? 1

Why were these manuals revised? 1

Safe System Approach 2

References 3

Module 1 Why must we address drink driving? 5

1.1 The context and magnitude of the drink driving problem worldwide 5

1.2 How is alcohol measured? 6

1.3 Effects of alcohol 7

1.4 Prevalence and economic impact 9

1.5 Risk factors for drink driving crash involvement 9

Module Summary 10

References Module 1 11

Module 2 Evidence-based interventions 15

2.1 Legislation 17

2.2 Licence Restrictions (Effective) 22

2.3 Offender Management 22

2.4 Public Education 24

2.5 Other effective legal measures 28

2.6 Engineering countermeasures 30

2.7 Post-crash response 30

Module Summary 31

References Module 2 32

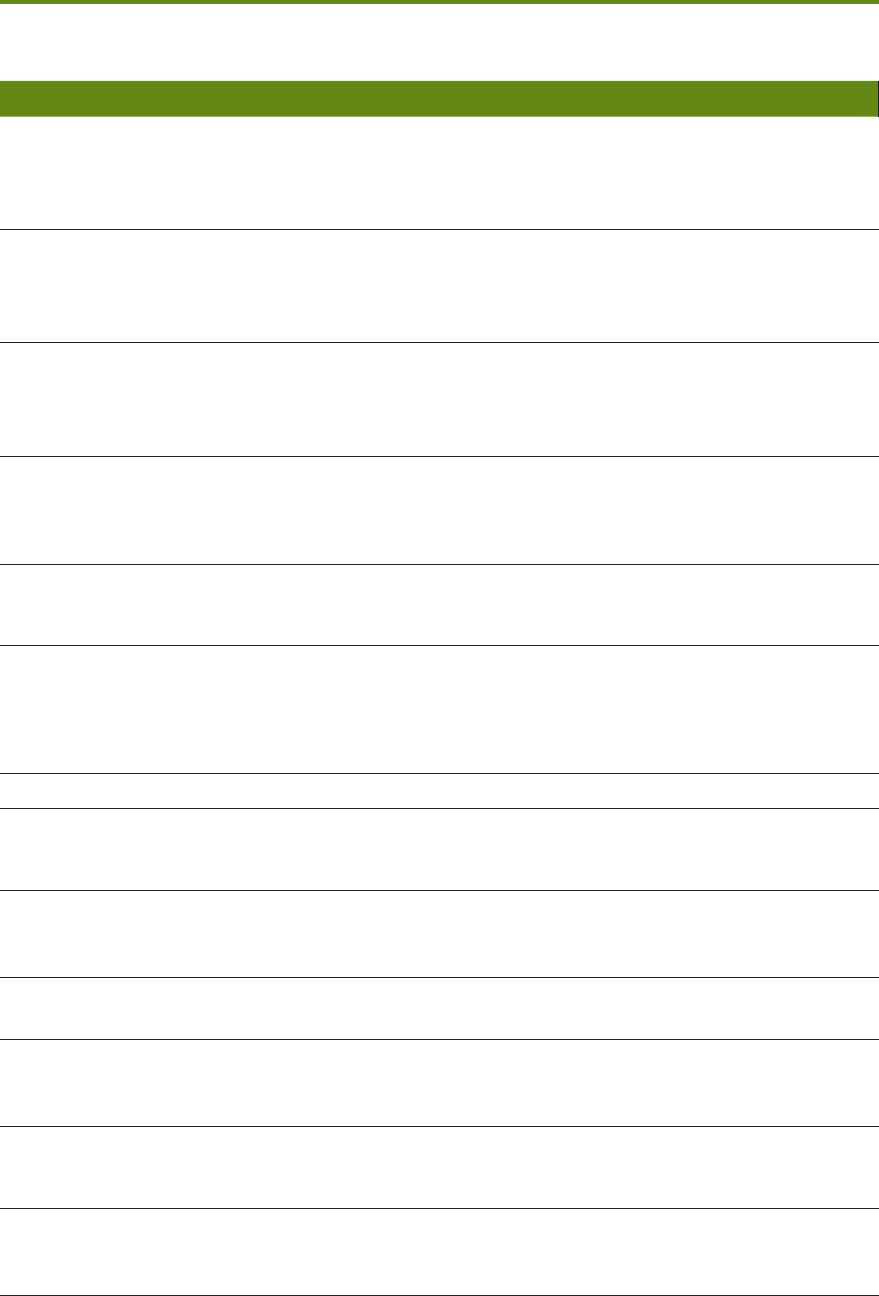

Contents

iii

Module 3 Enforcing drink driving laws 37

3.1 Enforcement methods 39

3.2 Safely intercepting vehicles 44

3.3 A dedicated alcohol intervention unit 47

3.4 Penalties for drink driving offences 47

Module Summary 48

References Module 3 49

Module 4 Implementing evidence-based drink driving

interventions 51

4.1 Cycle of improvement 51

4.2 Pathways to change 52

4.3 Assessing the situation 53

4.4 Opportunities and challenges in implementing drink driving interventions 60

4.5 How to evaluate progress and use results for improvement 63

Module Summary 65

References Module 4 66

Appendix A. Suggested wording for draft drink driving

legislation 69

Section 1: Who must undergo a breath screening test 69

Section 2: Adult drink driving 69

Section 3: Zero alcohol for under 20 / novice drivers 70

Section 4: Drink or drug driving causing injury or death 70

iv

Preface

Road traic injuries are a major public health problem and a leading cause of death and injury around the

world. Each year approximately 1.3 million people die and millions more are injured or disabled as a result

of road crashes, mostly in low- and middle-income countries. As well as creating enormous social costs

for individuals, families and communities, road traic injuries place a heavy burden on health services

and economies. The cost to countries, many of which already struggle with economic development,

may be as much as 5% of their gross national product. As motorization increases, preventing road

traic crashes and the injuries they inflict will become an increasing social and economic challenge,

particularly in low-and middle-income countries. If the present trend continues, road traic injuries will

increase dramatically in most parts of the world over the next two decades, with the greatest impact

falling on the most vulnerable citizens.

Appropriate and targeted action is urgently needed. The World report on road traic injury prevention,

launched jointly in 2004 by the World Health Organization and the World Bank, identified improvements

in road safety management and specific actions that have led to dramatic decreases in road traic

deaths and injuries in industrialized countries active in road safety. The use of seat-belts, helmets and

child restraints, the report showed, has saved thousands of lives. The introduction of speed limits, the

creation of safer infrastructure, the enforcement of limits on blood alcohol concentration while driving,

and improvements in vehicle safety are all interventions that have been tested and repeatedly shown

to be eective.

The international community must continue to take the lead to encourage good practice in road safety

management and the implementation of the interventions identified in the previous paragraph in

other countries, in ways that are culturally appropriate. To speed up such eorts, the United Nations

General Assembly has passed a number of resolutions urging that greater attention and resources be

directed towards the global road safety crisis. These resolutions stress the importance of international

collaboration in the field of road safety. These resolutions also reairm the United Nations’ commitment

to this issue, encouraging Member States to implement the recommendations of the World report on

road traic injury prevention and commending collaborative road safety initiatives so far. In particular,

they encourage Member States to focus on addressing key risk factors and to establish lead agencies

and coordination mechanisms for road safety. These were further encouraged through the Moscow

Declaration (2009), Brasilia Declaration (2015) and the Stockholm Declaration (2020).

Preface v

To contribute to the implementation of these resolutions, the World Health Organization, the Global

Road Safety Partnership, the FIA Foundation, and the World Bank have collaborated to produce a

series of manuals aimed at policy-makers and practitioners. This manual on drink driving is one of

them. Initially published in 2007, it has been updated to include new evidence and case studies. Each

manual provides guidance to countries wishing to improve road safety and to implement the specific

road safety interventions outlined in the World report on road traic injury prevention.

They propose simple, cost-eective solutions that can save many lives and reduce the shocking burden

of road traic crashes around the world. We encourage all to use these manuals.

Etienne Krug

Director

Department of Social

Determinants of Health

World Health Organization

David Cli

Chief Executive Oicer

Global Road Safety

Partnership

Saul Billingsley

Executive Director

FIA Foundation

Nicolas Peltier

Global Director for

Transport Sector

Infrastructure

Practice Group

The World Bank

vi Drink driving: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners

Acknowledgements

The World Health Organization (WHO) coordinated the production of this revised manual and

acknowledges, with thanks, all who contributed to its preparation. Particular thanks are due to the

people listed below.

Advisory Committee (1st edition): Saul Billingsley (FIA Foundation), Gayle Di Pietro (Global Road

Safety Partnership), Dipan Bose (World Bank).

Advisory Committee (2nd edition): Nhan Tran & Meleckidzedeck Khayesi (World Health

Organization), Margie Peden (The George Institute for Global Health), Dave Cli & Judy Fleiter (Global

Road Safety Partnership), Natalie Draisin (FIA Foundation), Alina Burlacu (World Bank).

Project coordinator (2nd edition): Meleckidzedeck Khayesi.

Writers (2nd edition): Judy Fleiter, Cristina Inclán-Valadez, Chika Sakashita, Dave Cli, Brett

Harman, Al Stewart, Margie Peden and Meleckidzedeck Khayesi.

Reviewers (2nd edition): Natalie Draisin, Barry Watson, Dante Rosado, and Marisela Ponce De

Leon Valdes.

Literature review (2nd edition): Martha Hijar, Cristina Inclán-Valadez.

Financial support: Financial support to update this manual was provided by Bloomberg

Philanthropies and the Global Road Safety Partnership.

Acknowledgements vii

viii Drink driving: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners

Executive summary

Alcohol plays a cultural and social role in many societies. However, the harmful eects of alcohol

that are experienced in many aspects of daily life are undeniable. In the context of improving road

safety outcomes, the need to manage harmful levels of alcohol use remains a paramount challenge.

Eective campaigns to reverse the level of community acceptance of drink driving behaviour, coupled

with sustained and well-resourced enforcement of strong anti-drink driving laws, has seen significant

reductions in alcohol-related road crashes in many jurisdictions. However, more must be done.

This manual provides advice and examples that, if implemented accordingly, will reduce the prevalence

of drink driving and associated road trauma. The manual is aimed at policy-makers and road safety

practitioners and draws on experience from countries that have succeeded in achieving and sustaining

reductions in alcohol-related road trauma. It includes recommendations for developing and implementing

drink driving legislation and advice on how to monitor and evaluate progress. A particular focus is the

design and implementation of interventions that include legislation, enforcement and public education/

advocacy measures. Importantly, these interventions must work in concert to achieve optimal results.

In developing the material for this manual, the writers have drawn on case studies from around the

world to illustrate examples of “good practice”. This 2nd edition of the manual was produced in 2022 to

reflect changes in road safety data, evidence and good practices, particularly evidence from low- and

middle-income countries. Strategies that work in one country may not necessarily transfer eectively

to another. The manual attempts to reflect a range of international experiences but does not oer

prescriptive solutions. Rather, it is hoped that the manual acts as a catalyst for local initiatives and actions

to improve road safety. It provides information and evidence that stakeholders can use to generate their

own solutions and develop advocacy and awareness-raising tools and legislation to reduce alcohol-

related road trauma.

Executive summary ix

Introduction

Why were these manuals developed?

The World Health Organization (WHO), the World Bank, the FIA Foundation and the Global Road

Safety Partnership (GRSP) produced a series of good practice manuals, following the publication of

the World report on road traic injury prevention in 2004, which provide guidance on implementation

of interventions to address specific risk factors in road safety. The topics covered in the initial series

of manuals are: helmets (2006), drinking and driving (2007), speed management (2008), seat-belts

and child restraints (2009), data systems (2010), pedestrian safety (2013), road safety legislation (2013),

powered two- and three-wheeler safety (2017) and bicyclist safety (2020). In addition, WHO produced

a road safety technical package, Save LIVES (2017), which presents evidence on 22 evidence-based

interventions related to speed management, leadership, infrastructure, vehicles, enforcement and post-

crash care. These documents are available in multiple languages on the World Health Organization

website at https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/publications/road_traic/en/.

Why were these manuals revised?

Since the series of manuals was first published, the scientific evidence base relating to various risk

factors and the eectiveness of interventions has continued expanding. Contemporary research has

refined our knowledge about specific risk factors, such as distracted driving, and vehicle impact speed

and risk of death for pedestrians. New issues and practices have arisen, such as a tropical helmet

standard and anti-lock braking system (ABS) for motorcycles. New and existing interventions have

been implemented and evaluated, with increasing application in low- and middle-income countries.

Research attention and policy response has also increasingly been applied to emerging road safety

issues including e-bikes, drugs other than alcohol, fleet safety, urban mobility, micro mobility options,

air and noise pollution, public transport, and technological advances.

As a result of these developments, the good practice manuals required revision so that they can continue

to be key references for road safety policy implementation and research. This is particularly important,

given the emphasis placed on road safety within the framework of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable

Development and because of the global impetus to reduce road deaths and injuries resulting from

the declaration of the two United Nations’ Decades of Action for Road Safety (2011–2020 and 2021–

2030). The manuals have been revised to reflect these developments as they continue to be valuable

resources providing evidence-based and cost-eective solutions to save lives and reduce injuries. An

extensive literature review has informed the revision and updating of all the manuals, and additional

information has been collated to allow more contemporary case studies to be showcased. In addition,

there was an identified need to broaden the topics covered in the manuals to include aspects such as

qualitative research methods, and participatory approaches to designing and evaluating interventions.

An emphasis on shifting traditional thinking away from blaming road users towards more contemporary

frameworks, such as the Safe System Approach is key in the revised manuals. An area requiring ongoing

consideration is decolonising knowledge and practice within the road safety field.

Introduction 1

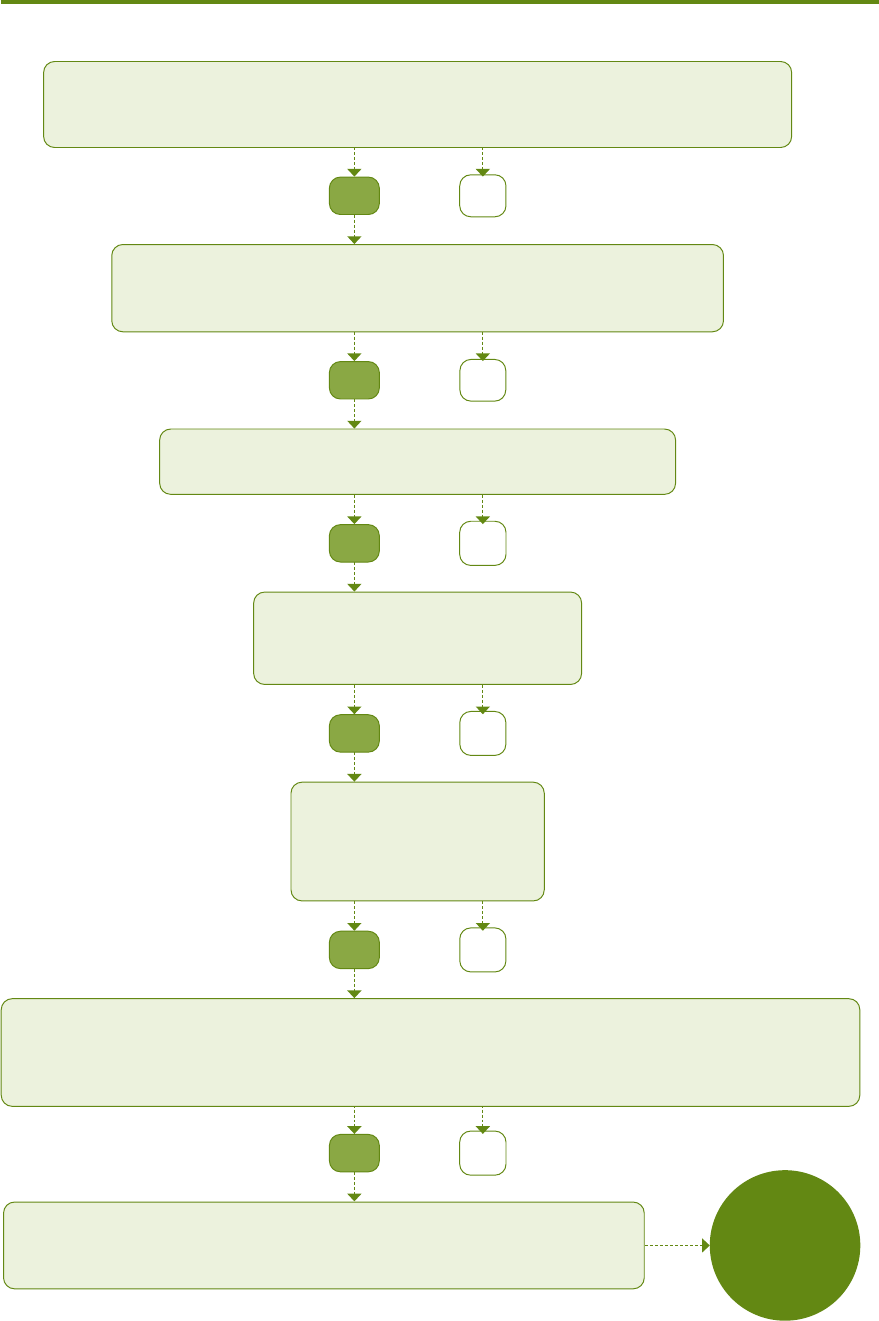

Safe System approach

The Safe System approach recognizes that road transport is a complex system and places safety at its

core (1). It also recognizes that humans, vehicles and the road infrastructure must interact in a way that

ensures a high level of safety (Figure 1). A Safe System, therefore:

anticipates and accommodates human errors;

incorporates road and vehicle designs that limit crash forces to levels that are within human tolerance

to prevent death or serious injury;

motivates those who design and maintain the roads, manufacture vehicles, and administer safety

programmes to share responsibility for safety with road users, so that when a crash occurs, remedies

are sought throughout the system, rather than solely blaming the driver or other road users;

pursues a commitment to proactive and continuous improvement of roads and vehicles so that the

entire system is made safe rather than just locations or situations where crashes last occurred; and

adheres to the underlying premise that the transport system should produce zero deaths or serious

injuries and that safety should not be compromised for the sake of other factors such as cost or the

desire for faster transport times (1).

Figure 1. Safe System approach

W

o

r

k

t

o

p

r

e

v

e

n

t

c

r

a

s

h

e

s

t

h

a

t

r

e

s

u

l

t

i

n

d

e

a

t

h

o

r

d

e

b

i

l

i

t

a

t

i

n

g

i

n

j

u

r

y

HUMAN

TOLERANCE

OF CRASH

IMPACTS

SAFE

SPEEDS

SAFE ROAD

USERS

SAFE

VEHICLES

I

n

n

o

v

a

t

i

o

n

D

a

t

a

a

n

a

l

y

s

i

s

,

r

e

s

e

a

r

c

h

a

n

d

e

v

a

l

u

a

t

i

o

n

R

o

a

d

r

u

l

e

s

a

n

d

e

n

f

o

r

c

e

m

e

n

t

L

i

c

e

n

s

i

n

g

a

n

d

r

e

g

i

s

t

r

a

t

i

o

n

E

d

u

c

a

t

i

o

n

a

n

d

i

n

f

o

r

m

a

t

i

o

n

M

o

n

i

t

o

r

i

n

g

,

m

a

n

a

g

e

m

e

n

t

a

n

d

c

o

o

r

d

i

n

a

t

i

o

n

SAFE ROADS

AND ROADSIDES

Source: (2)

2 Drink driving: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners

References

1.

Global Plan: Decade of Action for Road Safety 2021-2030. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization,

2021. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/documents/health-topics/road-traic-injuries/

global-plan-for-road-safety.pdf?sfvrsn=65cf34c8_33&download=true. Accessed 24 January 2022.

2. Department of Transport and Main Roads, Queensland Government, Australia. Safer roads, safer

Queensland: Queensland’s road safety strategy 2015–21. Department of Transport and Main Roads,

Queensland Government, Australia, 2015.

Introduction 3

1

Module 1

Why must we address drink

driving?

Alcohol has many functions in society and represents cultural, religious and symbolic meanings in most

countries. However, it is also a drug with many toxic eects and other dangers such as intoxication and

dependence. It is not the only substance that can impair driving performance. Impaired driving can result

from various things including alcohol consumption, use of licit and illicit drugs, and being unable to

function at optimal capacity because of fatigue. While all aspects of impaired driving deserve appropriate

attention, the focus of this manual is on drink driving. This module provides information on the global

problem and risks associated with drinking and driving. The information and recommendations in this

module can be useful in persuading political leaders and the public to support interventions that reduce

the prevalence of drink driving and associated harms.

1.1 The context and magnitude of the drink driving problem

worldwide

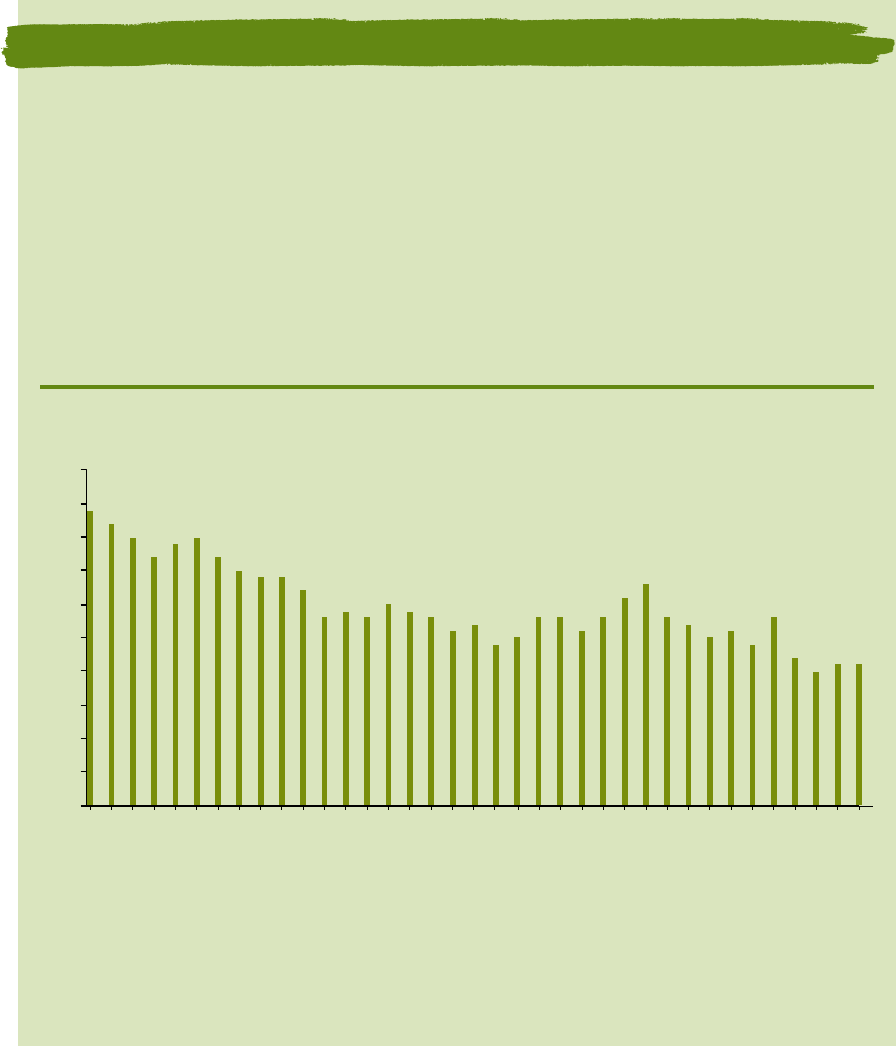

An extensive body of literature identifies that driving after drinking alcohol significantly increases the

risk of a crash and the severity of that crash, resulting in deaths and serious injuries. In its latest reports,

the WHO estimates that between 5% and 35% of global road deaths are alcohol related (1, 2). In most

high-income countries about 20% of fatally injured drivers have blood alcohol concentration (BAC)

levels above the legal limit (1). Studies in low- and middle-income countries have shown that between

33% and 69% of fatally injured drivers and between 8% and 29% of non-fatally injured drivers had

consumed alcohol before their crash (1). Figure 2 depicts the attribution of road traic deaths to alcohol

from a range of countries.

Module 1 Why must we address drink driving? 5

Figure 2. Attribution to road traffic deaths to alcohol [2013, 2014 data]

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

35%

Costa Rica

Canada

USA

New Zealand

Sweden

Russian Federation

Mexico

Cyprus

Australia

Thailand

Chile

UK (exludes NI)

Poland

R of Korea

R of Moldova

Peru

Germany

Ecuador

Romania

Ethiopia

India

Morocco

UR of Tanzania

Uganda

Denmark

% of annual RT fatalities attributed to alcohol.

Over the national legal limit

Note: Data on legislation and policies represent the country situation in 2014 while data on fatalities and vehicle registrations

are for 2013, or the most recent year for which these data were available. For method of estimation please refer to https://www.

who.int/data/gho/indicator-metadata-registry/imr-details/208.

Source: (3) with author’s elaboration.

1.2 How is alcohol measured?

Although it can be diicult to attribute a crash to a particular cause or causes, decisions about whether a

crash was alcohol-related are often based on how much, if any, alcohol was present in the bloodstream

or breath of the road users involved. To quantify the extent of the drink driving risk in a jurisdiction,

the most reliable measurement is the number of drivers fatally injured and found to have a

blood alcohol concentration (BAC) over the legal limit. The amount of alcohol contained within

the bloodstream or breath can be measured by testing a small sample of blood, urine, or through

analysis of exhaled breath. The results of a breath analysis may be expressed in terms of blood alcohol

concentration (BAC). For example:

mg/100ml:– milligrams of alcohol per 100 millilitres of blood

g/dl:– grams of alcohol per decilitre of blood.

The results of a breath analysis may also be expressed directly in terms of breath alcohol concentration

(BrAC) as below:

mg/L:– milligrams of alcohol per litre of breath

mcg/L:– micrograms of alcohol per litre of breath.

Table 1 shows the relationship between these various terms.

6 Drink driving: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners

Table 1. Relationship between various blood and breath alcohol concentration levels

BAC BrAC

mg/100ml g/dl mg/L mcg/L

20 0.02 0.10 100

50 0.05 0.24 240

80 0.08 0.38 380

Complete data showing the involvement of alcohol in all crashes are not always available. However, this

can be assisted by thorough investigation of crashes, the collection of evidence to identify risk factors,

and a system to analyse data and facilitate the development of road safety interventions.

Furthermore, the available data from dierent countries may not be comparable because of dierences

in the legal definitions of drink driving and in alcohol testing requirements for crash-involved drivers.

Despite these issues, data from various countries clearly demonstrate the major role that alcohol plays

in driver, passenger, and other road user deaths and serious injuries:

26%– 31% of non-fatally injured drivers in South Africa have BAC levels exceeding the country’s limit

of 0.05 g/100 ml (4);

in Thailand, nearly 44% of traic injury victims in public hospitals had BAC levels of 0.10g/100ml or

more (5);

in Colombia, 34% of driver fatalities and 23% of motorcycle fatalities are associated with speed and/

or alcohol (6);

in the United States of America, half a million people are injured and 17,000 killed every year in drink

driving-related traic crashes, and almost 40% of all youth road fatalities are directly related to alcohol

consumption (7);

in Sweden, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom, the proportion of fatally injured drivers with

excess alcohol levels is around 20%, although the legal limits in these countries dier considerably,

being 0.02 g/100 ml, 0.05 g/100 ml and 0.08 g/100 ml, respectively (8);

in Mexican municipalities, 19.5% of car occupant deaths due to road traic injuries were attributable

to alcohol consumption (9);

in Peru and the Dominican Republic, self-reported data from road users treated for road traic injuries

in emergency departments indicated that approximately 15% had consumed alcohol in the six hours

prior to their injury (10).

1.3 Effects of alcohol

The immediate eects of alcohol on the brain can be depressing or stimulating in nature, depending

on the quantity consumed, which causes degradation of driving performance directly related to BAC

levels. Alcohol results in impairment which increases the likelihood of a crash because it produces

poor judgement, increased reaction time, lower vigilance and decreased visual acuity. Physiologically,

alcohol also lowers blood pressure and depresses consciousness and respiration. It can take two to

three hours for the body to metabolise alcohol from one to two drinks, and up to 24 hours to process

the alcohol from eight to ten drinks.

Module 1 Why must we address drink driving? 7

A common issue in all jurisdictions is the lack of awareness of how much alcohol is required to adversely

impact a person’s coordination and concentration. As a result, some jurisdictions have used the concept

of a ‘standard drink’ to help inform the public about how much of what types of alcohol can reasonably

be expected to be consumed by a person before they reach the legal BAC limit. Importantly, it takes

very little alcohol to result in a person being over the legal limit. Because of this, the message

from all road safety partners needs to be clear – ‘don’t drink and drive’.

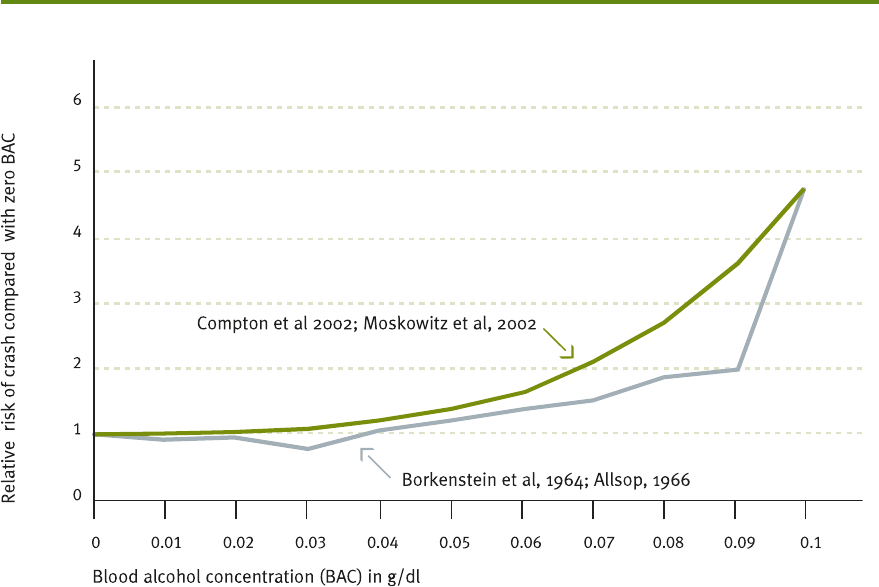

Alcohol can impair judgement and increase crash risk, even at relatively low BAC levels and the eects

become progressively worse as the BAC increases. In 1964, a case-control study was carried out in

Michigan in the United States, known as the Grand Rapids study (11). It showed that drivers who had

consumed alcohol had a much higher risk of involvement in crashes than those with a zero BAC, and

that this risk increased rapidly with increasing blood alcohol levels. These results were corroborated and

improved upon by studies over subsequent decades (12, 13, 14, 15). Many of these studies provided the

basis for setting legal blood alcohol limits and breath content limits in many countries around the world.

An extensive body of research demonstrates that the higher the blood alcohol level, the more rapidly

the risk of being involved in a casualty crash increases. The relative risk of crash involvement starts to

increase significantly at a BAC level of 0.04 g/dl (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Relationship between driver’s BAC and relative risk of involvement in a casualty crash

Source: (original sources 11, 14, 17, 18. Combined graphic source 16)

Due partly to its tendency to reduce inhibition, the consumption of alcohol is often associated with other

risk behaviours such as non-use of seat-belts or helmets, unsafe speed choice, and the use of other

drugs which can further impact upon driving performance (19). In addition, the presence of alcohol in

the body adversely aects the diagnosis, management, and treatment of and recovery from injuries

8 Drink driving: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners

because alcohol intoxication can complicate patient assessment and management (e.g., alcohol eects

can mimic head injury symptoms), and can exacerbate underlying medical conditions.

1.4 Prevalence and economic impact

Despite the well-known risks, drink driving remains prevalent around the world. A report from 32

countries indicated that the proportion of car drivers who report driving after drinking alcohol ranges

from 5% in Hungary to 34% in Portugal, from 4% in Japan to 24% in Australia, below 15% in Morocco and

Egypt to 32% in South Africa (20). Additionally, self-report data from road users treated for road traic

injuries in emergency departments in Peru and the Dominican Republic indicated that approximately

15% had consumed alcohol in the six hours prior to their injury (10). The estimated economic costs of

drinking and driving are also significant. In the United States, the total economic cost of motor vehicle

crashes in 2000 was estimated at US$ 230.6 billion, with drink driving-related crashes accounting for

US$51.1 billion, or 22% of all economic costs (7).

In the low- and middle-income country context, applying recent data on the incidence of drink driving

crashes to estimates of the total cost of road crashes in such countries (as outlined in the World report

on road traic injury prevention) established robust estimates (21). For example, in South Africa, applying

the estimate that alcohol is a factor in 31% of non-fatal crashes to the estimated hospital costs of US$

46.4 million attributed to road crashes, crashes involving drink driving cost the health system around

US$14 million. Using the same application in Thailand, where at least 30% of crashes are linked to alcohol

and the total cost of road crashes is estimated at $US3 billion (22), crashes involving drink driving cost

approximately $US 1 billion.

1.5 Risk factors for drink driving crash involvement

Drink driving oenders are commonly classified as first-time oenders or repeat oenders. Research

(largely from high-income countries) indicates that drink drivers are commonly characterised as (10, 23, 24):

male

18–44 years old

from a low socio-economic grouping

single or divorced

in a blue-collar occupation

of low education and limited literacy

of low self-esteem and

having started drinking at an early age (at age 14 or younger) (24).

Drink driving crashes commonly exhibit a number of characteristics:

Single vehicle crashes and high speed – drink driving crashes often involve high speed and a single

vehicle running o the road. Many of these crashes also result in the vehicle hitting a fixed roadside

object. In urban areas these can be signs or electricity poles, while in rural areas it is usually trees,

culverts, bridge ends and fence posts.

Module 1 Why must we address drink driving? 9

Night and/or weekend crashes – drink driving crashes occur more often at night (when more

alcohol is consumed) and generally on weekends or periods of high leisure activity.

Increased severity of injury – this is partly because once a crash and the injury-causing impact

has occurred, the existence of alcohol in the body of the injured works to limit the extent and level

of recovery from injury.

A study from India highlights the issue of severity of injuries: the National Institute of Mental Health

and Neurosciences, Bangalore [NIM-HANS] estimated that 21% of people who sustained brain injuries

during a crash were under the influence of alcohol (physician confirmed diagnosis) at the time, and

that 90% had consumed alcohol within three hours prior to the crash. (25)

Although much of the research on alcohol-related crashes has focused on car crashes, many of the

characteristics of alcohol-related motorcycle crashes are the same. A study in Thailand (26) indicated

that compared to non-drinking riders, drinking riders tended to crash at night, to have more non-

intersection crashes and more crashes on curves, were more likely to lose control, run o the road,

violate a red signal, be inattentive, and for rider error to be a contributing cause of the crash. Drinking

riders were five times more likely to be killed than non-drinking riders. It is also important to recognise

that alcohol consumption by drivers of four-wheelers puts pedestrians, cyclists, and riders of motorised

two- and three-wheelers at risk.

In parts of the world where the incidence of drink driving-related crashes is considered to be relatively

low (for example, where motorisation levels are low or where alcohol use is forbidden) countries should

be proactive in monitoring the situation so that it can be managed and prevented from escalating. The

magnitude of the drink driving problem, and its harmful consequences in terms of deaths and serious

injuries, highlights the critical need to invest in countermeasures to reduce this risky behaviour. Eective

interventions are presented in the next module.

Module Summary

Drink driving is a major road safety problem in many countries.

Even in quite modest amounts, alcohol impairs the functioning of several processes required for safe

road use, and drink driving can result in severe crashes involving deaths and serious injuries.

Alcohol consumption is associated with other risk behaviours such as non-use of seat-belts or helmets,

unsafe speed choice, and the use of other drugs which can further impact upon driving performance.

Research indicates that crashes involving drink driving and those who are more likely to drink and

drive display common characteristics, which may inform intervention targets.

10 Drink driving: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners

References Module 1

1.

Global status report on road safety 2018. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA

3.0 IGO.

2. Global status report on alcohol and health 2018. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. Licence: CC

BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO

3. World Health Organization. The global health observatory indicators. Attribution of road traic deaths to

alcohol %.https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators.Accessed20 December 2021.

4.

Parry CD, Pliiddemann A, Donson H, Sukhai A, Marais S, Lombard C. Cannabis and other drug use among

trauma patients in three South African cities, 1999–2001. South African Medical Journal. 2005;95(6).

5. Lapham SC et al. Use of audit for alcohol screening among emergency room patients in Thailand.

Substance Use and Misuse, 1999, 34:1881–1895.

6. Posada J, Ben-Michael E, Herman A. Death and injury from motor vehicle crashes in Colombia. Pan

American Journal of Public Health, 2000, 7:88–91.

7.

Traic safety facts 2000: alcohol. Washington DC, National Highway Traic Safety Administration (Report

DOT HS 809 3232001) cited in Drinking and Driving: a road safety manual for decision-makers and

practitioners. Geneva, Global Road Safety Partnership, 2007.

8.

Koornstra M et al. Sunflower: a comparative study of the development of road safety in Sweden, the United

Kingdom and the Netherlands. Leidschendam, Institute for Road Safety Research, 2002.

9.

Santoyo-Castillo, D., Perez-Nunez, R., Borges, G., & Hijar, M. (2018). Estimating the drink driving attributable

fraction of road traic deaths in Mexico. Addiction, 113(5), 828–835.

10. Cherpitel CJ, Witbrodt J, Ye Y, Monteiro MG, Málaga H, Báez J, Valdés MP. Road traic injuries and

substance use among emergency department patients in the Dominican Republic and Peru. Revista

panamericana de salud publica. 2021 Apr 30;45:e31.

11. Borkenstein RF, Crowther RF, Shumante RP, et al. The role of the drinking driver in traffic

accidents.Bloomington, IN: Department of Police Administration, Indiana University; 1964.

12. McLean AJ, Holubowycz OT. Alcohol and the risk of accident involvement. In: Goldberg L, ed. Alcohol,

drugs and traic safety. Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Alcohol, Drugs and Traic

Safety, Stockholm, 15–19 June 1980. Stockholm, Almqvist & Wiksell International, 1981:113–123.

13. Hurst PM, Harte D, Frith WJ. The Grand Rapids dip revisited. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 1994,

26:647–654.

14. Crompton RP et al. Crash risk of alcohol-impaired driving. In: Mayhew DR, Dussault C, eds. Proceedings

of the 16th International Conference on Alcohol, Drugs and Traic Safety, Montreal, 4–9 August 2002.

Montreal, Societe de l’assurance automobile du Quebec, 2002:39–44.

15. Keall MP, Frith W & Paterson TL, The influence of alcohol, age and number of passengers on the night-

time risk of driver fatal injury in New Zealand, Accident Analysis and Prevention, 2004, 36(1): 49–61.

16. Racioppi, Francesca, et al.Preventing road traic injury: a public health perspective for Europe. No.

EUR/04/5046197. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Oice for Europe, 2004:47. Data from Crompton et. al,

2002; Borkenstein et al, 1964; Allsop, 1966; and Mokovitz et al, 2002. https://www.euro.who.int/__data/

assets/pdf_file/0003/87564/E82659.pdf Accessed 21 January 2022.

17. Allsop, R. E. Alcohol and road accidents: a discussion of the Grand Rapids study. RRL Report No.6. 1966.

Module 1 Why must we address drink driving? 11

18.

Moskowitz H et al. Methodological issues in epidemiological studies of alcohol crash risk. In: Mayhew DR,

Dussault C, eds. Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Alcohol, Drugs and Traic Safety,

Montreal, August 2002. Quebec, Société de l'assurance automobile du Québec, 2002:45–50.

19. Marr JN. The interrelationship between the use of alcohol and other drugs: overview for drug court

practitioners. Washington DC, Oice of Justice Programs, American University, 1999. https://www.ojp.

gov/pdiles1/bja/178940.pdf Accessed 10 December 2021.

20. Achermann Stürmer, Y., Meesmann, U. & Berbatovci, H. (2019) Driving under the influence of alcohol and

drugs. ESRA2 Thematic report Nr. 5. ESRA project (E-Survey of Road users’ Attitudes). Bern, Switzerland:

Swiss Council for Accident Prevention.

21. Peden M et al., eds. World report on road traic injury prevention. Geneva, World Health Organization,

2004.

22. The Cost of Road Traic Accidents in Thailand. Accident Costing Report AC9. Asian Development Bank,

2005 cited in Drinking and Driving: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners. Geneva,

Global Road Safety Partnership, 2007.

23. Esser MB, Wadhwaniya S, Gupta S, Tetali S, Gururaj G, Stevens KAet al.Characteristics associated with

alcohol consumption among emergency department patients presenting with road traic injuries in

Hyderabad, India.Injury. 2016 Jan 1;47(1):160–165.

24. Hingson RW, Zha W. Age of drinking onset, alcohol use disorders, frequent heavy drinking, and

unintentionally injuring oneself and others after drinking. Pediatrics. 2009 Jun;123(6):1477–84.

25. World Health Organization. Alcohol and injury in emergency departments: summary of the report from

the WHO Collaborative Study on Alcohol and Injuries. World Health Organization; 2007.

26. Kasantikul V, Ouellet JV, Smith T, Sirathranont J, Panichabhongse V. The role of alcohol in Thailand

motorcycle crashes. Accid Anal Prev. 2005 Mar;37(2):357–66.

12 Drink driving: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners

Module 1 Why must we address drink driving? 13

2

Module 2

Evidence-based interventions

This module provides guidance on a range of interventions that can be included in drink driving

prevention programmes including laws, setting blood alcohol concentration (BAC) limits, enforcement

of these laws, public awareness and advocacy campaigns, and use of technology and rehabilitation

and treatment to help people separate drinking from driving.

Over recent decades, many countries have been successful in reducing the number of drink driving-

related crashes (for an example, see Box 1). While some adaptation may be required to suit dierent

contexts, experiences from countries that have succeeded in reducing drink driving-related deaths

and injuries (generally high-income countries) can be used to guide programmes in low- and middle-

income countries where alcohol plays a significant role in road crashes.

Module 2 Evidence-based interventions 15

Australia embarked on a sustained programme to tackle drink driving-related crashes from the mid-1970s

onwards. Substantial research information on the impairment eects of alcohol was collected, leading to

support for legislation setting out a maximum BAC level for drivers.

Following the adoption of legal BAC limits, large-scale police enforcement of these limits was undertaken

in the 1980s, through widespread and highly visible Random Breath Testing (RBT). This was supported

by a range of other interventions, including publicity, community announcements, community activity

programmes, and variations in licensing and distribution arrangements for alcohol (for a case study summary,

refer to this publication (1). There was also ongoing monitoring of performance involving blood tests on drivers

involved in crashes. Over this 30-year period, alcohol as a factor in crashes was almost halved in Australia

(see Figure 4), and community attitudes towards drink driving changed substantially, such that there is a

strong community view that the behaviour is socially irresponsible and unacceptable.

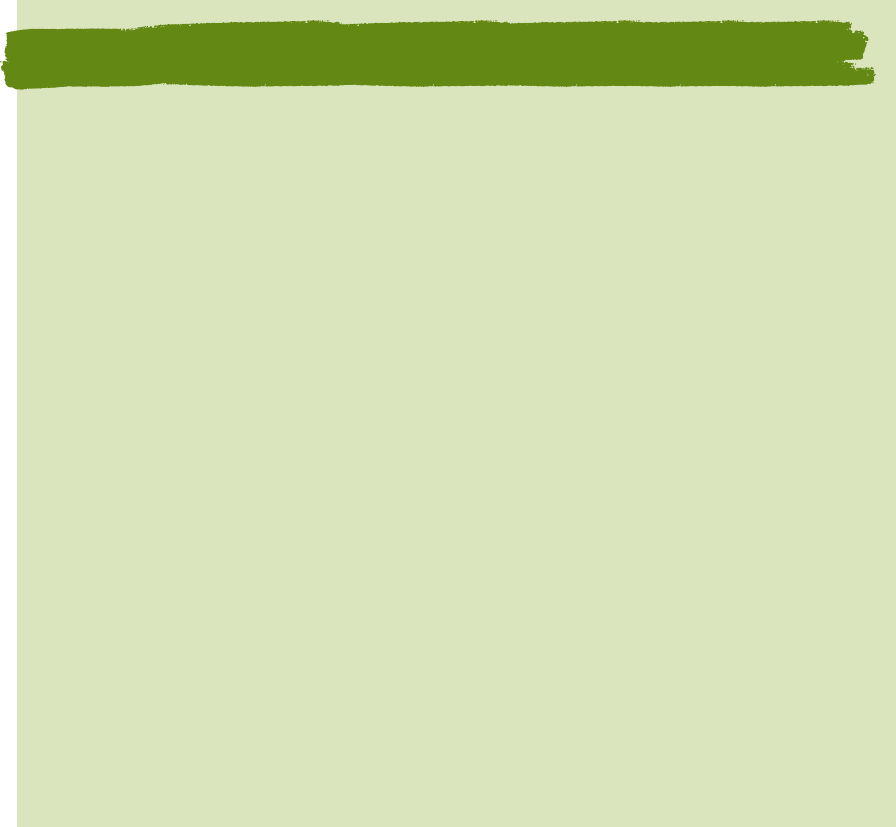

Figure 4. Percentage of drivers and riders killed with BAC of 0.05 or more in Australia:

1980-2017 (where BAC is known *)

44

42

40

37

39

40

37

35

34 34

32

28

29

28

30

29

28

26

27

24

25

28 28

26

28

31

33

28

27

25

26

24

28

22

20

21 21

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

35%

40%

45%

50%

1981 1984 1987 1990 1993 1996 1999 2002 2005 2008 2011 2014 2017

Year

*Excludes Victoria and Western Australia; excludes drivers with a special licence (Provisional, Learner, Heavy Vehicle)

that exceeded their special range limit but were below 0.05; some data cleaning applied to two jurisdictions.

Data sources: ATSB (undated). Alcohol and road fatalities. Monograph 5. Canberra: Australian Transport Safety

Bureau; BITRE. Data provided by Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport & Regional Economics. Canberra: Department of

Infrastructure & Transport. Source: (2)

Box 1. Changes in prevalence of and community attitudes towards drink driving – Australia

Success in addressing drink driving requires:

strong political commitment;

legislation that clearly defines illegal (for driving) BAC levels and a tiered suite of supporting penalties

for drink driving oences;

strong, well-publicised, highly visible and sustained enforcement through high visibility random or

compulsory breath testing (RBT/CBT) resulting in swiftly applied penalties when caught breaking

the law;

16 Drink driving: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners

targeted social marketing campaigns to change attitudes and behaviours – the public must:

– know why drink driving is both unsafe and anti-social;

– be aware that there are laws in place;

– perceive a high risk of being caught if they break the law; and

– know that if they are caught, there will be a heavy price to pay that cannot be avoided.

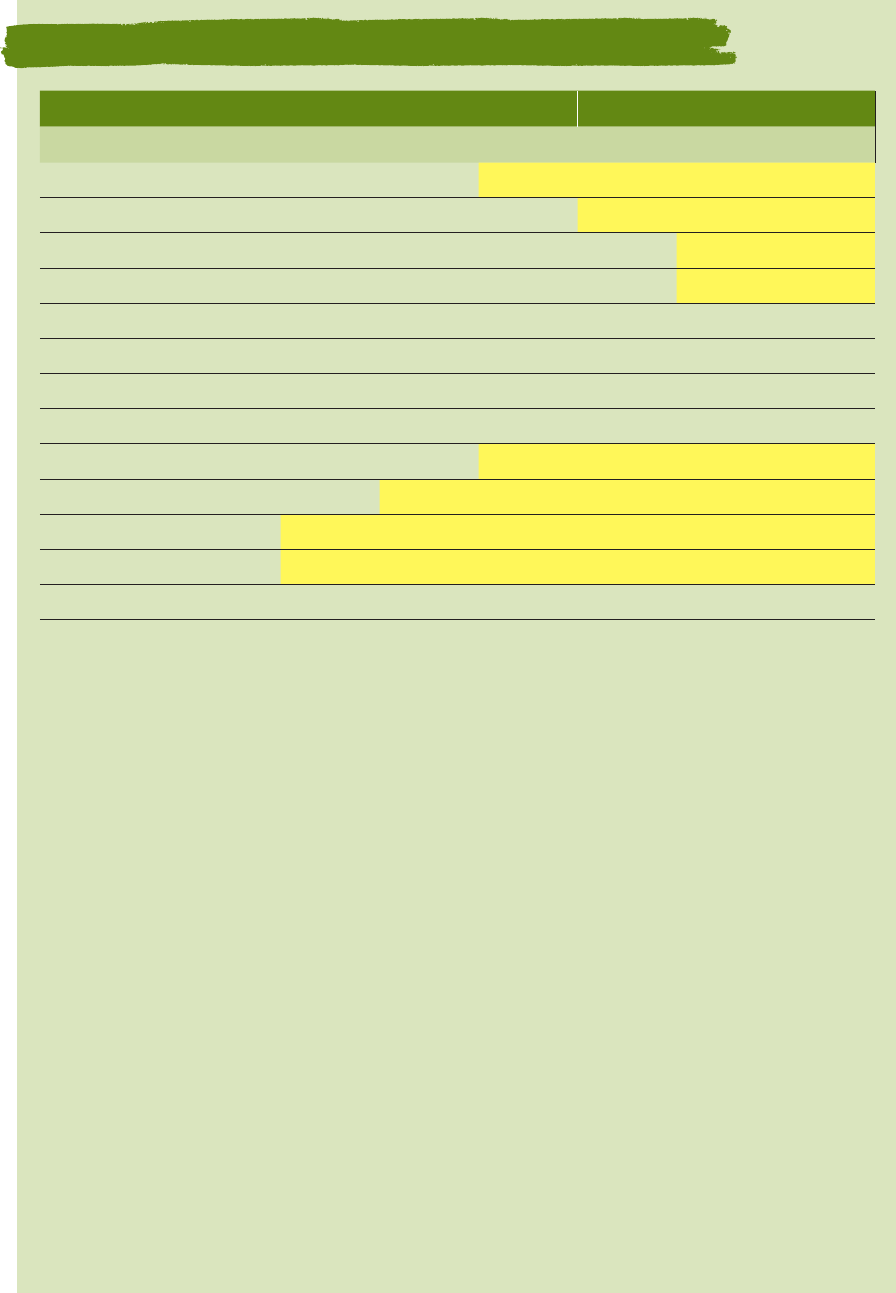

Table 2 provides an overview of existing interventions and a rating of their eectiveness: eective,

promising, insuicient evidence, and ineective. It is strongly recommended that programmes aimed at

reducing drink driving include “eective” or at least “promising” interventions.

Table 2. Evidence status of drink driving interventions

Interventions Eective Promising Insuicient

evidence

Ineective

Legislation (Section 2.1)

Setting BAC limits – e.g. BAC limit for the general

population not exceeding 0.05g/dl; BAC limits for other

driving groups (young/novice drivers, professional/

commercial drivers not exceeding 0.02g/dl).

Penalties that reflect the seriousness of oence (higher

penalties for higher BAC levels), and that are graduated

for recidivists

Enforcement of BAC levels (Section 2.1.2)

Random breath testing (preferred)

Sobriety checkpoints

Restrictions on young/inexperienced drivers: (Section 2.2)

Licensing restrictions – e.g. graduated driver licensing

(GDL), including lower/zero BAC for young drivers

Oender management: (Section 2.3)

Oender programmes

Alcohol ignition interlocks

Alcohol rehabilitation and/or treatment programmes

Public education: (Section 2.4)

Designated driver programmes

Public awareness campaigns (alone)

2.1 Legislation

Drink driving legislation that is evidence-driven, context relevant, consistently enforced, and well

understood by enforcement oicials and the public has been eective in saving lives in many

jurisdictions. The 2018 WHO Global Status Report on Road Safety (3) identified that only 45 countries

had drink driving laws that align with best practice. More information about best practice legislation

Module 2 Evidence-based interventions 17

is contained in various WHO documents, including this one: Strengthening road safety legislation: A

practice and resource manual for countries (4).

Various steps need to be taken when designing eective drink driving legislation. The first step in this

process is undertaking an assessment of relevant legislation already in place. If you identify that laws

need reforming, or that new laws are required, consider the following:

– address the absence of legislation and ensure that best practice recommendations are included;

– strengthen or complement an existing law using evidence and best practice recommendations;

–

provide greater legitimacy for the law and provide appropriate implementation and penalty mechanisms

so that laws can be eectively enforced and serve as a deterrent to drink driving.

It is important to remember that road safety is a dynamic field and that best practice continually

evolves. Therefore, countries must constantly review their legislation, revising and updating it to meet

the latest evidence (5). Consider the following elements when formulating or improving drink driving

laws or regulations.

The WHO requires that three minimum aspects are met to enable a country to be assessed as meeting

best practice drink driving legislative requirements:

1. presence of a national drink driving law

2. BAC limit for the general driving population not exceeding 0.05 g/dl and

3. BAC limit for young and novice drivers not exceeding 0.02 g/dl.

Appendix A contains sample wording to assist in drafting drink driving legislation.

Box 2 describes how the legislative situation in the state of Jalisco, Mexico evolved to help reduce drink

driving.

18 Drink driving: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners

In 2008, as part of the Bloomberg Philanthropies Global Road Safety Programme, a new road safety initiative

was piloted in four locations in Mexico, including the state of Jalisco. One focus of the initiative was to help

the government identify gaps in legislation relating to key risk factors and provide support to facilitate

improvements to these laws. To this end, a review of road safety laws in Jalisco identified the need to

strengthen the law on drink riving, including reducing the existing BAC limit, which was above recommended

best practice.

Strong relationships were established with dierent stakeholders, including federal and state authorities, local

legislators and civil society in order to advocate for legislative change. These eorts included: open forums

with civil society and media; expert meetings and informative sessions; and sessions with local authorities

and legislators from the main political parties.

After extensive consultation among local, national and international stakeholders, legislative recommendations

were drafted. In November 2010 the new state law, locally known as the “Ley Salvavidas” (“Lifeguard/life-

saving law”), was amended to incorporate these provisions, which included lowering the blood alcohol

concentration limit from 0.15 g/dl to 0.05 g/dl (in line with international best practice) and stier penalties

for transgressing this law. Continued monitoring of the law’s implementation resulted in findings that it was

not having the intended impact because of enforcement challenges. Notably the 2010 law specifically did not

provide for the establishment of random alcohol checkpoints, shown to be eective at reducing drink–driving.

Between 2010 and 2012, civil society and international road safety organizations engaged with policy-makers

to advocate for regulations that would allow for random breath testing, a process which culminated in 2013,

when the Jalisco state government adopted an amendment to the 2010 law that formally provided for the

establishment of random alcohol checkpoints and a protocol for their implementation. The occasion of

amending the law was also used to further increase penalties related to drink–driving.

The law amendment was accompanied by a hard-hitting social marketing campaign that supported

dissemination of the new regulations and penalties, and communicated the risk of drink driving (see https://

www.youtube.com/watch?v=boxRNvH5WEo&list=PL9S6xGsoqIBWAhPnNtIDoxP3OcRYqaQa0&index=30).

Alongside this legislative reform process and its dissemination, major capacity building eorts also took

place to train and support police in eectively running random alcohol checkpoints.

The eects of the initiative are being monitored. Short-term results have shown significant changes in the

proportion of alcohol-related deaths and collision rates in Jalisco following the implementation of the Global

Road Safety Programme.

Source: (3, 6)

Box 2. Reforming drink driving legislation in Jalisco, Mexico

2.1.1 BAC Limits (Effective)

Globally, legal BAC levels vary significantly. For instance, for the general driving population, BAC levels

range from 0.00 g/dl (e.g., Hungary, Paraguay) to 0.12 g/dl (e.g., Sao Tome and Principe). Specific details

of drink driving laws, BAC levels, enforcement, and the number of road traic deaths attributed to alcohol,

by country/area, can be found in Table A5 of the 2018 Global Status Report on Road Safety (3). The

table provides legal BAC levels for three driving groups: the General driving population, Young/Novice

drivers, and Professional/Commercial drivers.

In law enforcement investigations, BAC is estimated from breath alcohol concentration (BrAC) measured

with a machine commonly referred to as a breathalyser (note that dierent machines may have dierent

conversion factors applied to relate BrAC to BAC). Breath alcohol concentration (BrAC) is expressed

as the weight of alcohol, measured in grams, in 210 litres of breath, or, measured in milligrams, in

210 millilitres of breath. There is accurate correspondence between blood alcohol and breath alcohol

Module 2 Evidence-based interventions 19

levels (7). Because of the ease of administration, breath alcohol is more commonly measured in the

road safety context. As described in section 1.3, the presence of any amount of alcohol can impair

driving behaviour and there is a rapid, exponential increase in risk for BAC levels that exceed 0.05g/

dl. Therefore, international evidence and experience demonstrates a critical need to legislate lower

maximum BAC rates in order to reach, at least, the WHO recommended minimum requirements to limit

the harm caused by alcohol consumption and driving.

Screening for Alcohol – Breath testing at the roadside (Effective)

In general, there are two roadside breath testing approaches:

1.

Random breath testing (RBT) (recommended) – the statutory authority for an enforcement oicer to

stop a vehicle and test the driver at random, anywhere at any time, without the need to establish that

the driver committed another oence, nor that the driver showed any signs of impairment prior to

being stopped. This is primary enforcement of a drink driving law, is common in some European

countries, and throughout Australia and New Zealand, and is an eicient use of resources because

it allows for a greater number of drivers to be tested (high volume testing), per hour of enforcement

activity (as compared to a sobriety checkpoint), and if challenged, can be justified on civil and human

rights grounds, through a greater good, public interest argument. Note that RBT can be conducted

at a roadside checkpoint where every vehicle is stopped and every driver tested. However, if vehicle

volume through a checkpoint becomes such that it is no longer practical or safe for sta or road users

to stop every vehicle, the testing can be continued by stopping a random number of vehicles that

allows for overall volume of traic to be managed. This process ensures randomness and equity in

relation to who is stopped and tested. RBT can also be conducted away from a checkpoint operation,

where enforcement oicers can intercept a vehicle and test the driver.

2. Sobriety checkpoints – enforcement oicer is required to form a suspicion of alcohol impairment

before a driver can be intercepted and tested. This is also referred to as Selective breath testing

(SBT). This testing strategy, used in the United States of America, is generally less eicient because

of lower testing volumes for each hour of enforcement activity.

Overall, while both types of roadside breath testing approaches have shown positive road safety

impacts (8), RBT has produced superior results and is recognised as the more eicient way to allocate

enforcement resources and to deter drink driving, especially because it can expose every driver stopped

at the RBT site to a breath test (9, 10). Another approach to detect and apprehend drink drivers is to

conduct targeted enforcement based on intelligence. This can involve targeting vehicles as they depart

from known drinking venues (e.g., bars, nightclubs, restaurants). This approach may lead to detection

of some drink driving oenders but is less eective at creating a general deterrent eect (for the whole

driving population) because it is generally not highly visible, nor publicised (11).

2.1.3 Additional legislative considerations

Refusal to submit to a breath test: Legislation must address the consequences of a driver refusing

to submit to a breath test. In some jurisdictions, the penalty for failing to submit a breath sample

is equivalent to the penalty associated with the highest range drink driving oence. It is highly

recommended that the penalty for refusing to submit to a breath test are substantial and unavoidable.

An additional consideration is what mechanism/s can be used to dispute a test result.

20 Drink driving: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners

Requirement for mandatory alcohol testing for road crashes. This is an important strategy to help

determine crash causation as well as provide valuable information on level of intoxication of drivers,

passengers, and any other road users involved in a crash (e.g., pedestrians, cyclists) so that appropriate

intervention strategies can be developed.

Penalties: A range of penalties are used to deter drink driving, including monetary fines, demerit points,

licence suspension, licence loss, vehicle impoundment, and the requirement to fit and use an interlock

device for a specified time. It is critical that penalty severity reflects the severity of the oence. In other

words, it is important that riskier behaviours (i.e., driving with higher BAC levels, or repeat oending)

incur harsher penalties, to communicate the seriousness of the oence or reoending to the broader

community. It is also important to ensure that penalties for drink driving oences are appropriate

when compared to other traic oences. More severe penalties are often used for recidivist (repeat)

oenders. Additional information on the use of penalties to improve road safety can be found in the

guide produced by the Global Road Safety Partnership (GRSP) (A Guide to the Use of Penalties to

Improve Road Safety) (12).

Per se or impairment provisions: Consideration should be given to whether the legal framework of a

country is based on a per se law or an impairment law. ‘Per se’ is a Latin phrase meaning ‘by itself’. In

relation to drink driving, a per se law means that a person is breaking the law by having a BAC above

the legal limit, irrespective of whether there is any sign of impairment or any other evidence.

This issue is of particular importance for enforcement actions as well as to create a legislative system

that actively deters drink driving. Because of the wealth of evidence that shows increasing levels of

impairment with increasing BAC, it is common in many jurisdictions for graduated penalties to apply,

with penalties increasing in severity as driver BAC levels increase.

Identification of relevant enforcement agency: Specifically identifying the enforcement authority/

ies that will be responsible for enforcing the law, as well as their specific responsibilities, is necessary.

Restrict availability and aordability of alcohol: Approaches such as increasing taxes on alcohol,

regulation on point of sale, density of locations of sale, and minimum age for purchase and consumption

of alcohol can assist to reduce the level of harm created by alcohol consumption and drink driving (13).

Additionally, consideration should be given to making it an oence to sell or supply alcohol to an

intoxicated person. More details about these issues as well as topics such as national control of

production and sale of alcoholic beverages, restrictions on drinking in public, restrictions on alcohol

advertising, regulations on alcohol product placement and alcohol sales promotions, labelling, and

responsible beverage service training can be found in the Global status report on alcohol and health (14).

Testing and calibrating breath alcohol testing equipment considerations: It is recommended that

legislation covers: a) the approval of breath alcohol testing instruments for enforcement purposes,

resourcing mechanism necessary to procure relevant testing equipment and train relevant people how

to use and calibrate it, and b) testing and calibration protocols – to preserve evidence and mitigate risk

of litigation – this may include technical specifications for testing and calibrating devices and testing

facility protocols to ensure that all tests are administered properly and in a timely manner by fully

competent, trained personnel.

Employer provisions: It is recommended that legislation contains information that allows employers

to be held accountable for the safe operation of the work vehicle fleet, which could include monitoring

driver compliance with drink driving laws through workplace breath-testing and protocols. This might

include the necessity for vehicles to be fitted with interlock devices or random testing programmes.

Module 2 Evidence-based interventions 21

2.2 Licence Restrictions (Effective)

Novice drivers generally lack experience in regard to safe driving/riding skills when they enter the

licensing system. To help manage their exposure to risk, a range of programmes have been developed

and refined that consist of various restrictions which can ease over time, as more experience is gained.

These schemes are commonly known as Graduated Driver Licensing (GDL) or Graduated Licensing

Schemes (GLS) (15).

Specific components of GDL systems vary across jurisdictions. Common components include measures

such as: a reduced (or zero) BAC level (8), a minimum learner age and learner period, a minimum

supervised practice hours requirement, a minimum provisional period, peer passenger restrictions,

night driving restrictions, phone/other technology restrictions, and vehicle power restriction (16, 17).

The impact of various components on GDL systems have been examined. Significant reductions have

been found for the zero BAC component. For example, a 9–23% reduction in alcohol-related fatal

crashes among 15–19 year olds; a 4–17% reduction in fatal and injury crashes among 15–19 year olds,

and a 22% reduction in night-time single vehicle fatalities have been associated with zero BAC limits

that form part of GDL systems (for a comprehensive summary refer to (18).

2.3 Offender Management

Greater understanding of the factors that contribute to drink driving, together with access to in-vehicle

technology, has changed the way oenders (especially recidivists) are managed. Historically, penalties

for drink driving oences have commonly included jail sentences, monetary fines, demerit point

sanctions, and licence bans (suspension or revocation). However, a licence sanction (e.g. suspension)

does not necessarily mean that an oender will cease driving. Additionally, traditional types of penalties

did little to support oenders with alcohol dependence issues. As a result, countermeasures such as

interlocks, oender programmes, and rehabilitation/treatment programmes have been implemented

in various high-income countries in recent decades.

2.3.1 Offender programmes (Promising)

Programmes to educate and deter reoending dier considerably and can range from an education-

only programme to more tailored treatments that include components such as behaviour change

training, the use of case management to monitor progress, and referral to specialist help to deal with

alcohol dependency (see section 2.3.3 for more detail about alcohol rehabilitation programmes). Some

jurisdictions have programmes only for first oenders, others mandate programme completion for

all drink driving oenders; while some are only for oenders with mid- or high-range BAC threshold

oences or for recidivists. A summary of the wide range of oender programmes used across Australian

jurisdictions, for example, can be found in Table 8.1 of an Austroads publication from 2020 (19). Despite

the intuitive appeal of many of these programmes, robust evidence about which type of programme

oers greatest impact requires further research.

22 Drink driving: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners

2.3.2 Alcohol ignition interlocks (Effective)

An alcohol ignition interlock (also commonly known as an alcoholinterlock device oran alcolock) is an

electronic breath-testing device which prevents a vehicle from starting if alcohol (above a designated

threshold) is detected in the breath of the driver and then requires breath samples to be provided

randomly while the vehicle is being driven. An interlock device generally consists of two parts which:

1) measure breath alcohol concentration, and 2) immobilise the vehicle engine if a pre-programmed

BAC limit is exceeded. Interlocks have generally been used as a punitive, rather than a preventative

measure, and have aimed to reduce drink driving among two key groups: 1) repeat oenders, and

2) high-range BAC first time oenders. However, in Victoria, Australia, interlocks were introduced in

2018 as a mandatory penalty for anyone apprehended with a BAC level of 0.05 or higher, irrespective

of whether they were a first-time or repeat oender. An evaluation of the eectiveness of this sanction

in reducing oending and alcohol-related crashes was not available at the time of writing. In some

jurisdictions, interlocks are also used as a preventative measure in some occupational settings (e.g.,

heavy vehicle and bus fleets).

The interlock device can store data (e.g., number of attempts to start the vehicle and associated BAC

levels during such attempts, as well as attempts to tamper with the device) which can be used by

authorities to monitor compliance levels and rehabilitation outcomes. This kind of information is

particularly useful in jurisdictions where a violation-free period is needed in order for an oender to be

relicensed. Various additional features to help ensure integrity of a device while it is installed in a vehicle

are in use or in development and include: face recognition, biometric (fingerprint) recognition, real-time

reporting of violations, GPS tracking, and the use of PIN so that multiple users can use a single device.

Advances in technology continue to enhance capacity and functionality of interlock devices. For instance,

less obtrusive measurement mechanisms include passive options such as skin sensors, transdermal

perspiration measurements and alcohol ‘snier’ systems (sensors in a vehicle that measure alcohol in

the breath at a distance, rather than from a direct breath sample, also known as PAS – passive alcohol

sensor technology) that are integrated into the cabin of a vehicle and do not require a driver to provide

a direct sample of breath. More information about the various interlock capabilities and programmes

throughout Europe and Australasia can be found in a range of publications (20, 21). Additional information

about aspects of interlock programmes, including cost, installation, programme duration, and removal

requirements, can be found in Tables 2.1 and 2.2 of a 2015 Austroads publication (22).

Interlock evaluation research across many jurisdictions consistently demonstrates that the devices

are highly eective in reducing drink driving episodes (and re-arrest rates for alcohol-impaired

driving) while installed in the vehicle, but that this positive eect diminishes when the device is

removed (23, 24). Information is available on the use and eectiveness of interlocks in Europe (22), the

United States of America (25), and Australia (19). It is important to note that interlock programmes can

create financial hardship for some oenders because in some jurisdictions, oenders are responsible

for paying costs associated with installation and monitoring of interlock devices. A range of financial,

judicial and logistical issues should be explored and resolved by relevant authorities before launching

a new interlock programme.

2.3.3 Alcohol Rehabilitation Programmes (Effective)

As noted above, interlocks are eective at reducing drink driving while installed in a vehicle. The

return to oending, once the device is removed, indicates that for some people, problematic alcohol

Module 2 Evidence-based interventions 23

use is likely to play a large role in reoending and may not be addressed at all by the installation of

an interlock (26). As such, therapeutic (treatment) and educational rehabilitation programmes have

been implemented in some jurisdictions to address problematic alcohol use. These programmes vary

widely in content, length, cost, and quality, making evaluation diicult. Providers of these programmes

need to be accountable for delivery of their services and assessed by qualified agencies to ensure that

programmes are delivered to a high standard and are evidence-based.

They also vary in intent. For instance, some treatment or rehabilitation programmes focus specifically

on managing alcohol dependency and abuse, while others focus on separating drinking from driving. In

some jurisdictions, courts can impose alcohol treatment programmes as part of the sentencing process.

Medical consultations or alcohol assessments are undertaken in some jurisdictions, including Great

Britain, Sweden, Canada and New Zealand, to determine whether treatment for alcohol rehabilitation

is needed.

A summary of dierent types of rehabilitation programmes can be found in Tables 2.1 and 2.2 of a 2015

Austroads report (22) and examples from Europe can be found in the 2016 Best Practice guide (27).

Overall, eectiveness is diicult to assess because of the wide range of programmes and their aims.

However, the evidence indicates that a combination of education and treatment programmes can

reduce drink driving recidivism.

2.4 Public Education

2.4.1 Designated Driver programmes (Insufcient evidence)

These programmes generally aim to separate drinking and driving and change attitudes and societal

norms associated with drinking alcohol and driving by providing the opportunity for a sober person to

transport others who have consumed alcohol to a level that would mean they are not able to legally

drive. The programmes take many forms. For instance, some licensed premises oer courtesy vehicles to

return their patrons home; others invoke the desire for friends to look after each other when out drinking

in a group by deciding, in advance, that one person will remain sober and carry the responsibility of

transporting all others in the group safely home. Various incentives have been associated with these

kinds of programmes, including free entry to licensed venues or free non-alcoholic drinks for the

designated driver.

Generally, these programmes aim to reduce alcohol-related crashes by:

1. providing an alternative to driving under the influence of alcohol

2. promoting a non-drink driving norm, and

3. encouraging responsible travel planning (28)

Various names are associated with designated driver programmes that have been conducted in various

countries such as the Netherlands, Canada, Italy, the United States of America, France, Greece, Belgium,

and Australia, and include ‘Euro Bob’, ‘DES’, ‘Sober Bob’, and ‘The Skipper’. Evaluations have shown positive

changes, in some cases, in the proportion of people willing to use or actually using a designated driver,

though not necessarily an increase in people willing to be a designated driver. Overall, evaluation data

24 Drink driving: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners

is limited and inconclusive, with findings generally indicating no impact on drink driving rates or on

involvement in alcohol-related crashes (29, 30, 31, 32).

2.4.2 Public awareness campaigns (alone) (Ineffective)

A substantial body of evidence indicates that public education and awareness campaigns are important

tools to:

inform the community about the risks of unsafe road use

inform the community about road safety laws and the consequences (penalties) of not complying

with them,

promote the general deterrent eect of enforcement activities by informing the community that laws

are actively being enforced, and in doing so, raising the ‘perceived risk of being detected’ among the

community.

However, education, alone, is not eective in changing drink driving behaviour and must work in tandem

with eective enforcement of robust legislation to reduce the incidence of drink driving. As highlighted

in the Save LIVES Road Safety Technical Package published by WHO (5)

“Strong and sustained enforcement of road safety laws, accompanied by public education, has

positive eects on road user behaviour and thus has the potential to save millions of lives”.

Public awareness or social marketing/advocacy campaigns may require the services of a public relations,

advertising agency, or production company and a research agency, unless a government agency has

the expertise to provide these services. Overall control of the campaign should, however, stay with the

responsible government agency. It is important to specify the campaign objective/s from the outset so

that the campaign can be properly planned, conducted and monitored, and an appropriate evaluation

can be planned and implemented. Drink driving campaign objectives may include:

informing the public of new drink driving legislation, regulations, or penalties;

notifying the public about increased drink driving enforcement;

advising the public not to take the risk of drink driving, while highlighting a variety of dierent

consequences of doing so;

educating road users about the crash risk associated with consuming any alcohol;

quantifying the personal risks and legal consequences of driving while over the legal BAC limit;

warning people about social consequences of their drink driving to other (“innocent”) parties;

emphasising the risk of detection;

emphasising the social unacceptability of drink driving;

sharing personal stories related to adverse impacts of drink driving, while advocating for behavioural

change; and

warning drivers about the wide-ranging consequences of being detected and prosecuted for drink

driving.

Module 2 Evidence-based interventions 25

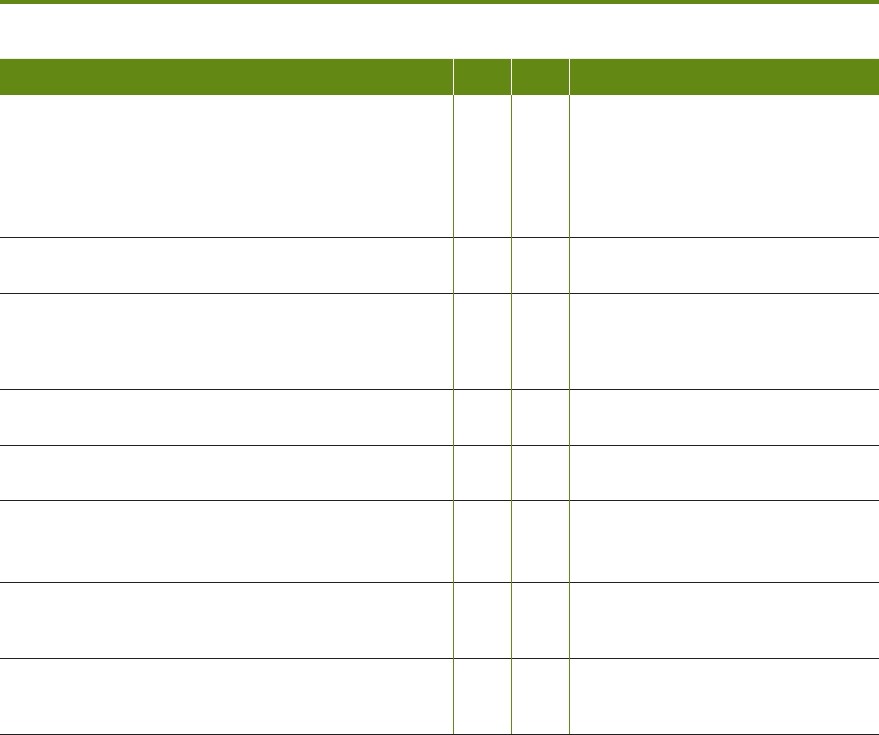

Figure 5 depicts a simplified version of the process that should be undertaken in developing a social

marketing/behaviour change campaign to reduce drinking and driving. No campaign will be eective

unless it identifies and develops appropriate, well-targeted messages. There is no easy formula for

determining the correct message, however there are some key steps that may assist in achieving this.

Working with skilled and experienced professionals is critical for campaign success. Market research

is used to determine peoples’ knowledge of legislation as well as the opinions, beliefs, fears, and

motivations of high-risk groups that are known to be involved in drink driving crashes.

A first step in this process is to identify the target groups involved and collect information from them that

is relevant for the campaign (diagnostic tone and message testing). On the basis of the information you

receive from testing with the target group, a range of messages and campaign materials are developed

to encourage a change in thinking and behaviour in relation to drinking and driving (e.g. don’t drink and

drive – your family is waiting for you at home). The draft campaign messages and materials should then

be tested with small groups who represent the target group before the final campaign message/s is

determined and the campaign is launched. It is important to consider and strategically chose relevant

channels (e.g., television, radio, social media) and times (e.g., immediately before public holidays) through

which the target audience can best be reached.

26 Drink driving: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners

Figure 5. Steps involved in a drinking and driving publicity campaign

Initiate agency meetings to ensure support

and understanding of publicity role

Conduct target group diagnostic research

to identify profile and motivations

Conduct communications testing research

to obtain likely eective messages

Publicity campaign agreed as component

of anti-drink driving programme

No

No

No

No

No

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Target group profile and behavioural

motivations are known

Eective communication messages are

known

Advertising agency contracted for

materials production

Good-quality, high-impact campaign

materials are available

Yes

Yes No

Commission

materials market

testing research

Eectiveness

of materials is

known

Initiate agency meetings to ensure

support and understanding of publicity

role

Most eective media mix for

communication is known

Commission media monitoring to

ensure media plan is delivered.

Commission communications

eectiveness research as

campaign is conducted

Commission advertising agency

to prepare media purchase plan in

accord with campaign budget

Run

Campaign

Module 2 Evidence-based interventions 27

Source: (33) with author elaboration.

Additional information about road safety public awareness programmes and social marketing campaigns

can be found in the 2016 manual produced by WHO– Road Safety Mass Media Campaigns: A Toolkit

and on the WHO website. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/road-safety-mass-media-campaigns-

a-toolkit (34)

2.5 Other effective legal measures

Licensing laws

The licensing laws of a country regulate the general availability and promotion of alcohol. A series of

measures can be employed to control criteria for granting licences for the sale of alcohol; places and

hours during which business may be conducted; the number of licensed premises within a local area,

the setting of a minimum drinking age, and restrictions relating to marketing of alcohol in the media

(e.g., restrictions on advertising alcohol products in prime time or in media accessible to children/

adolescents). Additional information on alcohol marketing regulation can be found in numerous

publications, including a special issue of the academic journal, Addiction, published in 2017 (35).

These laws, typically carried out by a “licensing board” (or similar entity), should require that stringent

requirements are met before a licence to sell alcohol is granted. Licensing laws aim to:

prevent crime and disorder;

maintain public safety;

prevent public nuisance;