Review of CBP’s

Major Cybersecurity Incident

during a 2019 Biometric Pilot

September 21, 2020

OIG-20-71

September 21, 2020

DHS OIG HIGHLIGHTS

Review of CBP’s Major Cybersecurity Incident

during a 2019 Biometric Pilot

September 21, 2020

Why We Did

This Review

In May 2019, a U.S.

Customs and Border

Protection (CBP)

subcontractor discovered it

had been the victim of a

cyber attack. Subsequently,

CBP data, including traveler

images from CBP’s facial

recognition pilot, appeared

on the dark web. We

conducted this review to

determine whether CBP

ensured adequate protection

of biometric data during the

2019 pilot.

What We

Recommend

We are making three

recommendations to aid CBP

with addressing the

vulnerabilities that caused

the 2019 data breach, and

mitigating the risk of similar

future incidents through

implementation of IT

security controls and best

practices recommendations.

F

or Further Information:

Contact our Office of Public Affairs at

(202) 981-6000, or email us at

DHS-OIG.OfficePublicA[email protected]

What We Found

CBP did not adequately safeguard sensitive data on an

unencrypted device used during its facial recognition

technology pilot (known as the Vehicle Face System).

A subcontractor working on this effort, Perceptics,

LLC, transferred copies of CBP’s biometric data, such

as traveler images, to its own company network. The

subcontractor obtained access to this data between

August 2018 and January 2019 without CBP’s

authorization or knowledge. Later in 2019, the

Department of Homeland Security experienced a

major privacy incident, as the subcontractor’s network

was subjected to a malicious cyber attack.

DHS requires subcontractors to protect personally

identifiable information (PII) from identity theft or

misuse. However, in this case, Perceptics staff

directly violated DHS security and privacy protocols

when they downloaded CBP’s sensitive PII from an

unencrypted device and stored it on their own

network. Given Perceptics’ ability to take possession

of CBP-owned sensitive data, CBP’s information

security practices during the pilot were inadequate

to prevent the subcontractor’s actions.

This data breach compromised approximately

184,000 traveler images from CBP’s facial

recognition pilot; at least 19 of the images were

posted to the dark web. This incident may damage

the public’s trust in the Government’s ability to

safeguard biometric data and may result in travelers’

reluctance to permit DHS to capture and use their

biometrics at U.S. ports of entry.

CBP Response

CBP concurred with all three recommendations.

www.oig.dhs.gov OIG-20-71

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Table of Contents

Background ………………………………………………………………………….. 1

Results of Review …………………………………………………………………... 5

Violation of DHS Security and Privacy Policies Resulted in the Breach of

CBP’s Biometric Data ……………………………………………………………… 6

Recommendations ………………………………………………………………… 15

Appendixes

Appendix A: Objective, Scope, and Methodology ………………………….. 18

Appendix B: CBP Comments to the Draft Report ………………………… 20

Appendix C: Recommendations from the Washington Dulles International

Airport and Unisys Lab Assessment Findings ..…………… 24

Appendix D: Report Distribution ..…………………………………………….. 26

Abbreviations

ACA Administrative Compliance Agreement

CBP U.S. Customs and Border Protection

IT Information Technology

OFO Office of Field Operations

OIG Office of Inspector General

PII Personally Identifiable Information

SPII Sensitive Personally Identifiable Information

TSA Transportation Security Administration

TVS Traveler Verification Service

TX Texas

USB Universal Serial Bus

VFS Vehicle Face System

www.oig.dhs.gov OIG-20-71

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Background

The Department of Homeland Security has primary responsibility for securing

U.S. borders from illegal activity and promoting lawful travel and trade. Within

DHS, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) is charged with keeping

terrorists and their weapons out of the United States while facilitating lawful

international travel and trade. CBP’s Office of Field Operations (OFO) is CBP’s

largest unit and is responsible for border security at United States ports of

entry. To carry out this mission, CBP personnel must be able to accurately

confirm the identities of arriving travelers and determine whether they pose

risks to the United States. For example, OFO personnel collect biometric

information, such as facial images, to verify in-scope

1

travelers’ entry to and

exit from the United States. Collecting biometric data also enables CBP

personnel to better document arrival and departure information on individuals

arriving at United States ports of entry.

DHS Components Rely on Biometric Data for Border Protection

The DHS Office of Biometric Identity Management maintains the Automated

Biometric Identification System, which contains the biometric data repository

of more than 250 million people and can process more than 300,000 biometric

transactions per day. It is the largest biometric repository in the Federal

Government, and DHS shares this repository with the Department of Justice

and the Department of Defense. At least five major DHS components use

biometric technologies to enforce Federal laws, support DHS and component

strategic goals, and to further mission operations. These components include

the Transportation Security Administration (TSA), United States Secret Service,

U.S. Immigrations and Customs Enforcement, U.S. Citizenship and

Immigration Services, and CBP.

CBP Biometric Entry-Exit Program

CBP is congressionally mandated to deploy a biometric entry/exit system to

record arrivals and departures to and from the United States.

2

Congress used

the FY 2016 Consolidated Appropriations Act (P.L. 113-114) to provide CBP with

up to $1 billion in funding over a 10-year period to develop a Biometric Entry-

1

Based on CBP’s Biometric Entry-Exit Program Concept of Operations, in-scope travelers

include all travelers, U.S. and non-U.S. citizens, between the ages of 14 and 79.

2

See 8 U.S.C. § 1365b; see also Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of

1996, Pub. L. No. 104-208, § 110(a) (1996); Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of

2004, Pub. L. No. 108-458, § 7208 (2004); Implementing Recommendations of the 9/11

Commission Act of 2007, Pub. L. No. 110-53, § 711(d)(1)(F) (2007); Consolidated and Further

Continuing Appropriations Act, 2013, Pub. L. No. 113-6, div. D, tit. III (2013) (appropriating

$232 million for DHS’s Office of Biometric Identity Management).

www.oig.dhs.gov 1 OIG-20-71

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Exit solution.

3

CBP’s Biometric Entry-Exit Program Management Office, within

OFO, is responsible for this effort. A long-term goal of the program is to

biometrically verify the identity of all travelers exiting the United States and

ensure that each traveler has physically departed the country at air, land, and

sea departure locations. The program also addresses longstanding

congressional mandates that the Department build an automated entry and

exit control system, and follow a 2017 Executive Order

4

to expedite its

implementation.

To date, CBP’s Biometric Entry-Exit Program Office has focused primarily on

air departures, starting with a pilot program at nine airports across the country

in 2017. According to component documentation, the facial recognition

technology piloted at these airports has enabled CBP to simplify and expedite

the entry-exit process for participating travelers. CBP’s biometric capability

relies on a cloud-based

5

facial recognition technology system known as the

Traveler Verification Service (TVS). The service provides real-time matching of

passenger photos against photos previously captured by CBP, other DHS

components, or the Department of State to verify the identity of the traveler

across the international border.

6

As of April 2019, CBP had processed 19,829

flights and 2.8 million travelers across 19 airports through its biometric

program.

CBP Use of Facial Recognition Technology at Land Border Crossings

CBP is currently expanding its TVS to provide the same biometric matching

capability for individuals departing the country by land. In 2018, CBP began a

pilot effort known as the Vehicle Face System (VFS) at the Anzalduas, Texas

(TX) Port of Entry. Among other goals, CBP intended for this VFS project to

test the ability to capture volunteer passenger facial images for biometric

matches “at speed” (under 20 mph) at the border for both entry and exit

(inbound and outbound) vehicle lanes, while also testing CBP’s use of TVS to

biometrically match captured images against a gallery of recent

3

Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016, Pub. L. No. 114-113, div. O, tit. IV, § 402(g) (2015)

4

Exec. Order No. 13,780, § 8; 82 Fed. Reg. 13,209, 13,216 (March 6, 2017)

5

Within the Federal Government, the cloud is often used to refer to a technology solution

provided by a vendor outside the Government. Cloud-based solutions allow for significant cost

effectiveness and can be quickly deployed, among other benefits.

6

TVS biometrically confirms traveler departure by using facial recognition technology.

Through TVS, CBP uses cloud-based information to create a gallery of photos on travelers on a

particular flight. The photos come from Government holdings, such as U.S. passport and visa

photos, photos in IDENT, etc. A photo captured by TVS is matched via algorithm against the

gallery to biometrically confirm a traveler’s identity. Based on the information returned by

TVS, CBP personnel will perform any needed enforcement actions.

www.oig.dhs.gov 2 OIG-20-71

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

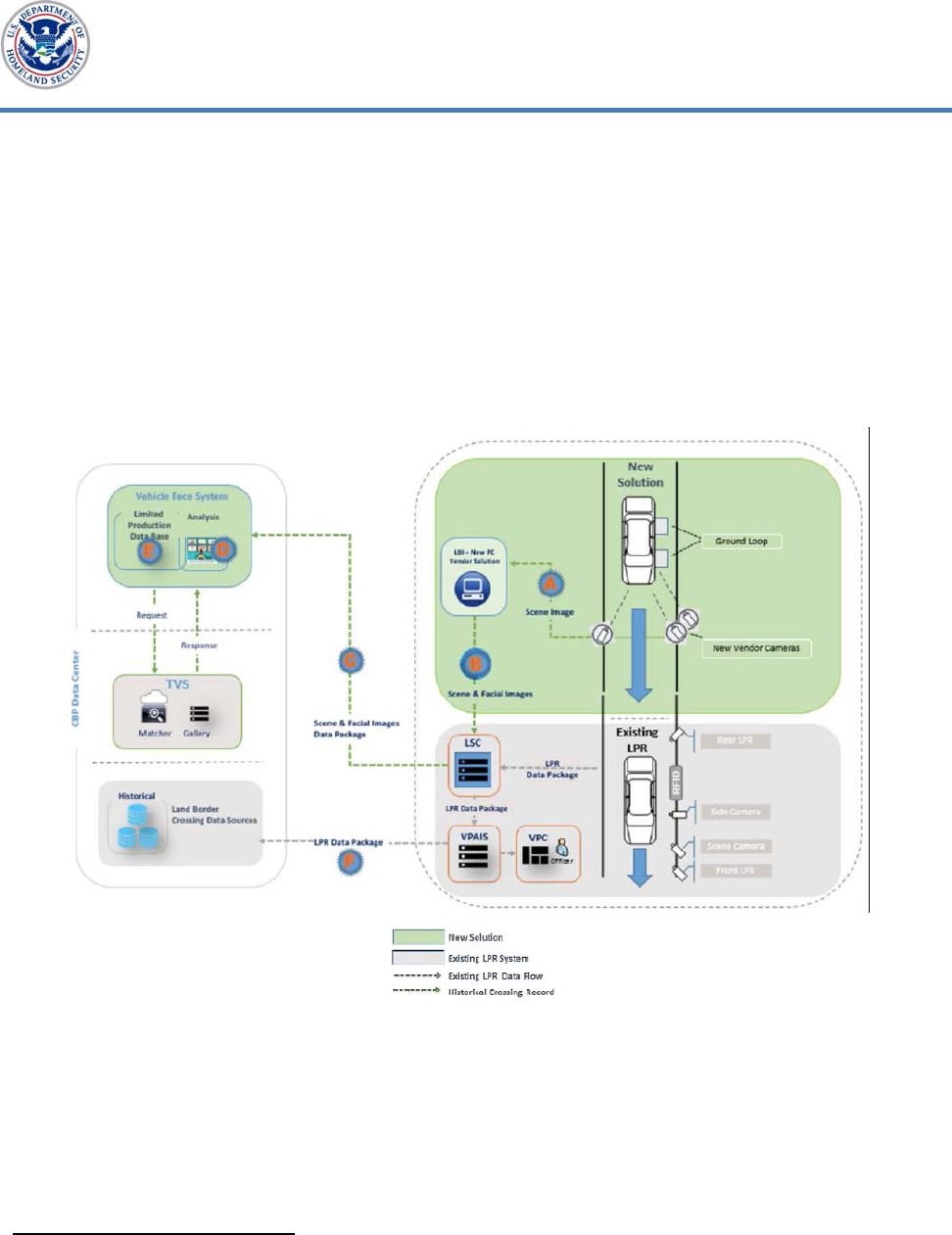

travelers. Figure 1 shows the transfer of vehicle occupant images to the VFS

database. During this process (starting top right), the vehicle occupant facial

images are captured on contractor-owned cameras and sent to a Lane Security

Controller. These images are then sent to a VFS database, which stores the

Lane Security Controller facial images packages for analysis and subsequent

processing. CBP’s network houses the VFS and stores additional information

relative to the images. The post-analysis includes evaluation of facial images

for photo quality and biometric matching accuracy. Through this evaluation,

CBP refines its approach to biometric matching.

Figure 1. Data Transfer from Image Capture to VFS Database

7

Source: CBP documentation provided to DHS Office of Inspector General (OIG)

CBP employed contractors to support the VFS capability pilot at the Anzalduas,

TX Port of Entry. CBP selected Unisys Corporation to design, develop, and

install a biometric entry-exit solution that would verify and confirm the arrival

and departures of passengers. In turn, Unisys Corporation hired Perceptics,

LLC,

8

as a subcontractor to install its proprietary facial image capture solution

7

In this graphic, CBP abbreviates the following terms for readability: Lane Security Controller

(LSC), License Plate Reader (LPR), Vehicle Primary Application and Integration Services (VPAIS),

Vehicle Primary Client (VPC), Radio Frequency Identification (RFID), and Land Border

Integration (LBI).

8

Perceptics performed technical work at air, land, and sea ports of entry on behalf of CBP.

www.oig.dhs.gov 3 OIG-20-71

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

and provide support for associated equipment. CBP relied on the images

captured from Perceptics’ facial image solution for testing and analysis

throughout the pilot. The information captured by the pilot was intended to

inform ongoing expansion of biometric verification for visitors entering and

exiting the country by vehicle.

9

Prior to the start of the VFS pilot, Perceptics

had already worked for CBP as a subcontractor providing License Plate Reader

technology at multiple U.S. Border Patrol checkpoints.

10

At the time of our

review in October 2019, CBP was continuing to test solutions across various

modes of transportation, including air entry and exit programs and seaport

pilots. Given the sensitive nature of biometric data and increased reliance on

biometric technologies, it was critical that CBP and its partners manage and

safeguard biometric data in compliance with DHS policies.

Protections for Biometric Data

DHS considers biometric information such as facial images to be sensitive

personally identifiable information (SPII).

11

The Department classifies certain

forms of information as SPII because if lost, compromised, or disclosed without

authorization, it could result in substantial harm, embarrassment,

inconvenience, or unfairness to an individual.

12

In 2017, the DHS Privacy

Office issued a policy

13

to classify biometric information as SPII and require

DHS employees, contractors, interns, and consultants to protect personally

identifiable information (PII) to prevent identity theft or other adverse

consequences, such as privacy incidents, compromise, or misuse of data.

According to the policy, all DHS staff and contractors must complete annual

training, including a mandatory online course on protecting personal

information. The policy also prohibits DHS employees from using any non-

Government-issued removable media (e.g., Universal Serial Bus (USB) drives),

connecting such devices to DHS equipment or networks, or storing sensitive

information on them.

9

The images were not used to verify identities or create border crossing records.

10

CBP uses license plate reader technology to assist in detecting, identifying, apprehending,

and removing individuals illegally entering the United States at and between ports of entry or

otherwise violating U.S. law. When a vehicle enters a primary inspection lane at a port of entry

or a Border Patrol Checkpoint, license plate readers capture vehicle license plate images. The

license plate numbers are used to conduct searches of law enforcement information linked to

that license plate.

11

SPII includes, but is not limited to, social security numbers, passport numbers, and

financial account numbers. SPII is more protected than other identifying information, such as

names and addresses.

12

Handbook for Safeguarding Sensitive PII, Privacy Policy Directive 047-01-007, Revision 3,

December 2017; and DHS 4300A Sensitive Systems Handbook, Version 12.0, November 2015

13

Handbook for Safeguarding Sensitive PII, Privacy Policy Directive 047-01-007, Revision 3,

December 2017

www.oig.dhs.gov 4 OIG-20-71

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

To protect and manage SPII, DHS has established detailed system security and

privacy protocols, known as the DHS 4300A Sensitive Systems Handbook.

14

The 4300A Handbook provides controls and best practices for personnel to

mitigate the risk of theft, loss, and mismanagement of biometric information,

as well as other system security information and protocols. It also contains a

compilation of guidance for implementing:

Management Controls, which focus on managing system information

security controls and system risk;

Operational Controls to improve the security of particular systems;

Technical Controls that provide automated protection from

unauthorized access or misuse, facilitate detection of security violations,

and support security requirements for applications and data; and

Privacy Controls to protect and ensure the proper handling of PII.

We previously reported on CBP’s efforts to develop and implement biometric

capabilities, including facial recognition technology, to track individuals at

ports of entry.

15

Our prior audit determined that biometric data collection

improved DHS’ ability to verify foreign visitor departures at U.S. airports. Since

our prior audit work, CBP continued to expand the Biometric Entry-Exit

program, including pilots at land ports of entry. We conducted this review to

determine whether CBP ensured adequate protection of biometric data during a

2019 pilot.

Results of Review

CBP did not adequately safeguard sensitive data on an unencrypted device used

during its facial recognition technology pilot (known as the Vehicle Face System).

A subcontractor working on this effort, Perceptics, LLC, transferred copies of

CBP’s biometric data, such as traveler images, to its own company network. The

subcontractor obtained access to this data between August 2018 and January

2019 without CBP’s authorization or knowledge. Later in 2019, DHS

experienced a major privacy incident, as the subcontractor’s network was

subjected to a malicious cyber attack.

DHS requires subcontractors to protect PII from identity theft or misuse.

However, in this case, Perceptics staff directly violated DHS security and

privacy protocols when they downloaded CBP’s sensitive PII from an

unencrypted device and stored it on their own network. Given Perceptics’

ability to take possession of CBP-owned sensitive data, CBP’s information

14

DHS 4300A Sensitive Systems Handbook, Version 12.0, November 2015

15

Progress Made, But CBP Faces Challenges Implementing a Biometric Capability to Track Air

Passengers Nationwide (OIG-18-80), September 21, 2018

www.oig.dhs.gov 5 OIG-20-71

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

security practices during the pilot were inadequate to prevent the

subcontractor’s actions.

This data breach compromised approximately 184,000 traveler images from

CBP’s facial recognition pilot; at least 19 of the images were posted to the dark

web. This incident may damage the public’s trust in the Government’s ability

to safeguard biometric data and may result in travelers’ reluctance to permit

DHS to capture and use their biometrics at U.S. ports of entry.

Violation of DHS Security and Privacy Policies Resulted in the

Breach of CBP’s Biometric Data

A CBP subcontractor providing facial recognition technology for the VFS pilot

transferred copies of biometric data, such as traveler images, to its own

company network. This subcontractor, Perceptics, obtained access to this data

without CBP’s authorization or knowledge. Perceptics’ staff directly violated at

least three DHS security and privacy protocols when they downloaded CBP SPII

data for their own use. CBP’s IT security controls were inadequate to prevent

these actions, which put traveler data at risk. The subcontractor’s network

was later the subject of a malicious cyber attack that compromised

approximately 184,000 traveler images from CBP’s facial recognition pilot.

After removing duplicate images, CBP reduced its estimate to 100,000

individual images, of which they discovered 19 were posted to the Dark Web.

This incident may ultimately result in damage to the public’s trust in

Government biometric programs.

Unauthorized Access and Improper Storage Made Pilot Data Vulnerable to

Exploitation

Perceptics gained unauthorized access to CBP’s data through a computer

system connected to cameras located at the test site in Anzalduas, TX. The

computer system contained images of vehicle drivers and passengers collected

during the pilot. Perceptics gained the access to CBP’s data by submitting

work order tickets through the CBP information technology (IT) help desk.

Perceptics did so on at least three occasions — August 31, 2018; November 2,

2018; and January 31, 2019 — to provide maintenance on cameras and other

related equipment. Once the tickets were approved by CBP and Unisys,

Perceptics personnel performed the requested system maintenance work at the

pilot site, but also used the access to download images from the system.

16

16

Perceptics requested and was approved by Unisys to perform the following work: adjusting

the ground loop sensitivity, replacing camera lenses, and switching cameras to monochrome at

CBP’s request.

www.oig.dhs.gov 6 OIG-20-71

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

None of the tickets authorized Perceptics to access or download images from

the equipment.

According to documentation from Unisys and CBP, Perceptics subsequently

admitted to Unisys that it had downloaded approximately 184,000

17

traveler

images from the equipment in conjunction with the work order tickets.

Perceptics personnel accomplished this using an unencrypted USB hard drive

that was eventually transported back to their corporate office in Knoxville,

Tennessee. This download set-up is depicted in figure 2. From there,

subcontractor personnel uploaded CBP’s images to a Perceptics server.

According to documentation from a Unisys investigation, Perceptics

downloaded images to improve performance.

18

CBP did not know of or

authorize the subcontractor’s removal of data and its subsequent storage on

the subcontractor’s network.

Figure 2. Perceptics’ Data Transfer Set-Up Using an Unencrypted Hard

Drive

Source: CBP data as provided to DHS OIG

Subcontractor Network Subsequently Hacked by an Outside Threat

Perceptics’ corporate network was subjected to a ransomware attack

19

at some

point prior to May 13, 2019. The attack compromised thousands of driver and

17

We were unable to independently validate the exact number of images on the graphics

processing unit during the time data was taken by Perceptics.

18

After learning about Perceptics’ actions, the prime contracting company, Unisys Corporation,

led an investigation, starting in May 2019.

19

A ransomware is a type of malicious software that infects a computer and restricts user

access to it until a ransom is paid to unlock it.

www.oig.dhs.gov 7 OIG-20-71

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

passenger images that CBP captured during the VFS pilot.

20

CBP determined

that more than 184,000 traveler facial image files, as well as 105,000 license

plate images from prior pilot work, were stored on the subcontractor’s network

at the time of the ransomware attack. In addition, the hacker stole an array of

contractual documents, program management documents, emails, system

configurations, schematics, and implementation documentation related to CBP

license plate reader programs.

CBP first learned of the data breach on May 24, 2019, and took prompt action

to notify the Department and mitigate risks from the incident.

21

On June 3,

2019, DHS officially declared the event a “Major Cybersecurity Incident” based

on the potential impact to the Department’s reputation and demonstrable harm

to public confidence.

22

As required by DHS Privacy Incident Handling

Guidance, CBP notified Congress within 7 days

23

and immediately stood up a

DHS Breach Response team.

24

The team coordinated a number of incident

response and mitigation activities between May 24, 2019, and October 8, 2019,

to eliminate the source of the breach, which included:

removing from service all equipment involved in the breach;

canceling Perceptics’ employee access to CBP information systems and

data; and

requiring its prime contractor, Unisys, terminate its contract with

Perceptics.

CBP initiated an investigation of Perceptics in May 2019. As part of the

investigation, CBP learned Perceptics had previously obtained more than

105,000 license plate images from prior pilots. These images were originally

obtained through a CBP-authorized process aimed at improving the License

Plate Reader program. Perceptics used that authorized process to acquire

20

Perceptics received a ransom note via an email from a hacker by the name of “Boris Bullet

Dodger” demanding 20 bitcoin within 72 hours. The ransom note stated that, without the

bitcoin, stolen data would be uploaded to the dark web. Perceptics did not pay the ransom and

the hacker uploaded more than 9,000 unique files to the dark web.

21

CBP officially reported this incident to the Department on May 24, 2019. CBP informed

several DHS offices or individuals including the Chief Information Security Officer, the Office of

the Inspector General, and the Enterprise Security Operations Center.

22

Following the incident, CBP Privacy conducted an assessment of the likelihood of substantial

harm, embarrassment, inconvenience, or unfairness to an individual based on the disclosure of

these images using the Office of Management and Budget breach notification guidance and

determined the information taken was of low risk. DHS’ Acting Chief Privacy Officer provided

this assessment to Congress.

23

CBP notified Congress of the major privacy incident on June 8, 2019.

24

The Breach Response Team included DHS’ Undersecretary for Management, Chief

Information Officer, Chief Information Security Officer, and Chief Security Officer, as well as

representatives from DHS Privacy, Partnership and Engagement, General Counsel, Public

Affairs, Legislative Affairs, and other relevant CBP offices.

www.oig.dhs.gov 8 OIG-20-71

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

images during both a 2008–2010 contract and a 2016 tactical pilot. However,

the images were stored on Perceptics’ servers for longer than the permitted 1

year.

CBP temporarily suspended Perceptics from participation in future Government

contracts, subcontracts, grants, loans, and other Federal assistance programs

in June 2019.

25

However, the suspension was lifted on September 26, 2019,

leaving Perceptics eligible to participate as a contractor in Federal procurement

processes. As a part of lifting the suspension, CBP and Perceptics entered into

an agreement in an effort to correct the risks identified in CBP’s investigation of

the data breach.

26

At the conclusion of our fieldwork, Perceptics was no longer

working with CBP as either a prime contractor or subcontractor.

Perceptics Violated DHS Requirements for Safeguarding PII

DHS maintains a number of requirements for contractor employee access to

sensitive information.

27

These requirements include passing a background

investigation and contractor training concerning the protection and disclosure

of sensitive information. Unisys records show that Perceptics employees did

complete all required training courses, including: IT Security Awareness and

Rules of Behavior Training, CBP Privacy at DHS: Protecting Personal

Information, CBP Annual Integrity Awareness Training, and Privileged User

Access Training. Additionally, all relevant clauses including DHS Special

Clauses and Homeland Security Acquisition Regulation clauses properly flowed

through the contract language from CBP to Unisys, and from Unisys to

Perceptics.

However, Perceptics failed to adhere to DHS requirements for protection of

privacy, including the need to protect sensitive information on the

Department’s IT systems from loss, misuse, modification, or unauthorized

access.

28

Perceptics also violated DHS rules related to the collection, storage,

use, and disposal of SPII by using an unencrypted hard drive to access and

download biometric images. The three DHS security and privacy requirements

that Perceptics violated are outlined in table 1.

25

Under federal law, suspension is an action that is taken in the public interest for the

Government’s protection and not for purposes of punishment. These actions were taken in

accordance with Federal Acquisition Regulation, 48 C.F.R. Subpart 9.4 (et seq.).

26

The agreement, known as an Administrative Compliance Agreement or ACA, is an agreement

between the Government and the contractor as an alternative to suspension or debarment, and

typically requires a contractor to accept responsibility for its conduct. An ACA also typically

requires a code of ethics, oversight, compliance, and employee training. A contractor’s failure

to comply with an ACA is cause for debarment.

27

DHS’ Handbook for Safeguarding Sensitive PII

28

DHS’ 4300A Sensitive Systems Handbook

www.oig.dhs.gov 9 OIG-20-71

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

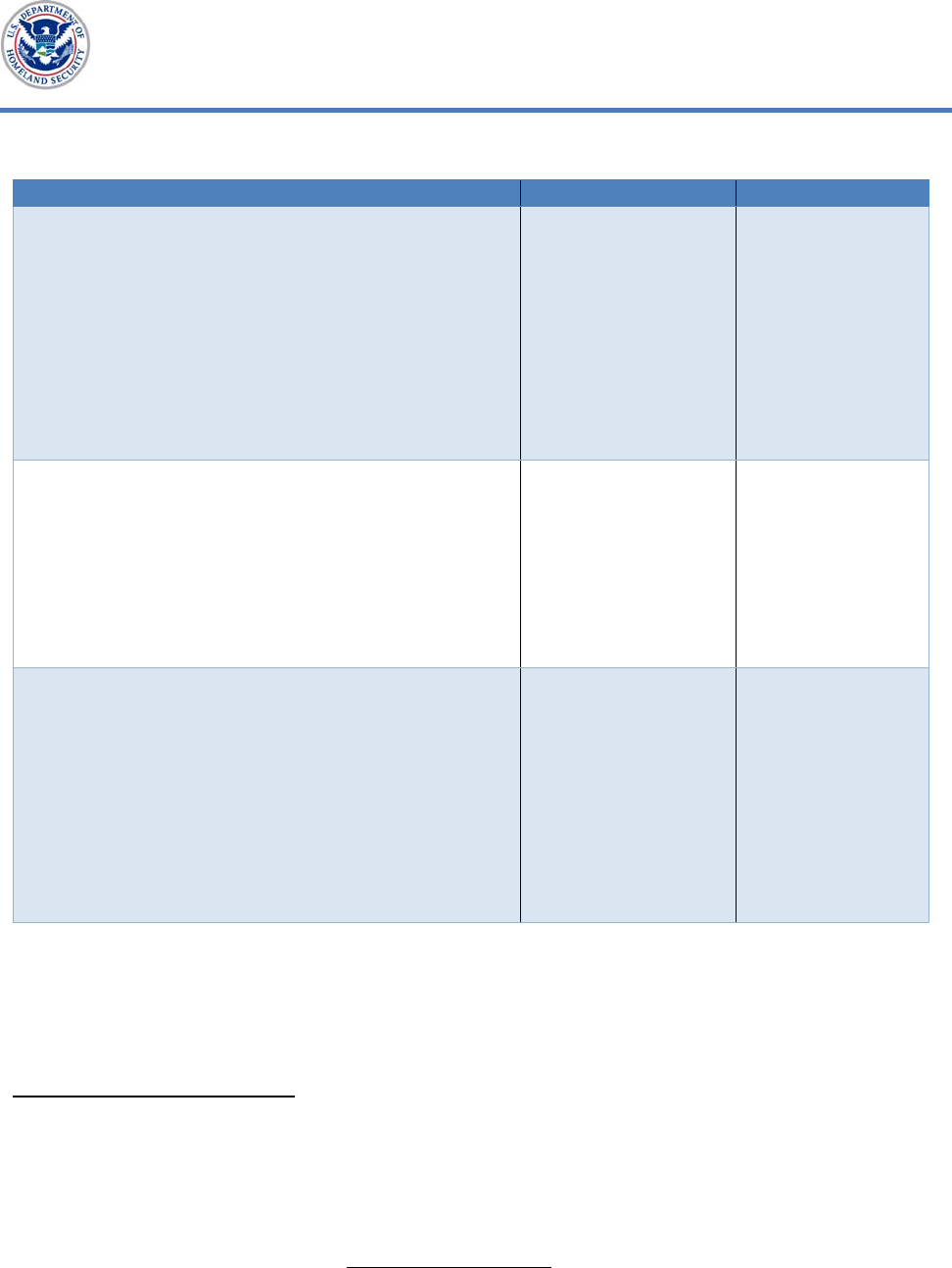

Table 1. DHS Security and Privacy Requirements Violated by Perceptics

Requirement Violation Source

1. Adherence to signed Rules of Behavior:

Contract staff with access to DHS computer

systems are required to take training on

security guidance and sign Rules of Behavior

agreements. These agreements are meant to

inform users of their responsibilities and

hold users accountable for their actions

while accessing or using DHS systems,

including the need to protect sensitive

information from loss, misuse, modification,

or unauthorized access.

At least one staff

member violated

the signed rules of

behavior by

downloading CBP’s

SPII and

transferring that

data to the

company’s network.

DHS’ Handbook

for Safeguarding

Sensitive PII and

the DHS 4300A

Sensitive Systems

Handbook

2. Protection of sensitive information by

limiting disclosures to official use only:

SPII may only be accessed, viewed, saved,

stored, or hosted on DHS-approved,

encrypted portable electronic devices, such

as laptops, tablets, and smartphones, as well

as encrypted Government-issued hard

drives.

A member of the

subcontract staff

used an

unencrypted USB

to access and

download CBP’s

SPII.

DHS Special

Clause -

Safeguarding of

Sensitive

Information (MAR

2015)

29

and DHS’

Handbook for

Safeguarding

Sensitive PII

3. Reporting: All known or suspected sensitive

information incidents shall be reported to

the Headquarters or Component Security

Operations Center within one hour of

discovery in accordance with 4300A

Sensitive Systems Handbook Incident

Response and Reporting requirements.

CBP found out

about the breach

from a news article

approximately 7

days after

Perceptics notified

Unisys.

Unisys and CBP

Contract,

30

DHS’ Handbook

for Safeguarding

Sensitive PII, and

DHS Special

Clause -

Safeguarding of

Sensitive

Information (MAR

2015)

31

Source: OIG-generated based on DHS data

First, we determined that Perceptics’ staff with network access did complete

necessary training and signed Rules of Behavior agreements. However, at least

29

The Clause explains that the Contractor shall not use or redistribute any sensitive

information processed, stored, and/or transmitted by the Contractor except as specified in the

contract.

30

Section 1.19, Sub-section (F) of the Unisys and CBP Contract, addresses DHS Special Clause

- Safeguarding of Sensitive Information (MAR 2015). Contract wording states: All known or

suspected sensitive information incidents shall be reported to the Headquarters or Component

Security Operations Center within one hour of discovery in accordance with 4300A Sensitive

Systems Handbook Incident Response and Reporting requirements.

31

Homeland Security Acquisition Regulation Class Deviation 15-01, Attachment 1:

Safeguarding of Sensitive Information (MAR 2015), Section C requires contractors to follow all

current versions of Government policies and guidance, which includes DHS 4300A.

www.oig.dhs.gov 10 OIG-20-71

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

one staff member directly violated the signed agreement by downloading CBP

SPII data and transferring it to the company’s own network.

Second, the data used for the CBP pilot was not appropriately protected in line

with DHS security requirements for protecting sensitive privacy information.

An open USB port allowed Perceptics’ staff to use an unencrypted hard drive to

gain access and download unencrypted biometric images (as previously shown

in figure 2). Even though the subcontractor provided the equipment, CBP is

ultimately responsible for securing its technology.

32

Third, Perceptics and Unisys both defied contractual obligations and DHS’

privacy and security requirements for immediately reporting privacy incidents.

Unisys chose not to inform CBP immediately of the data breach. CBP found

out about the data breach from a news article approximately 1 week after

Perceptics notified Unisys.

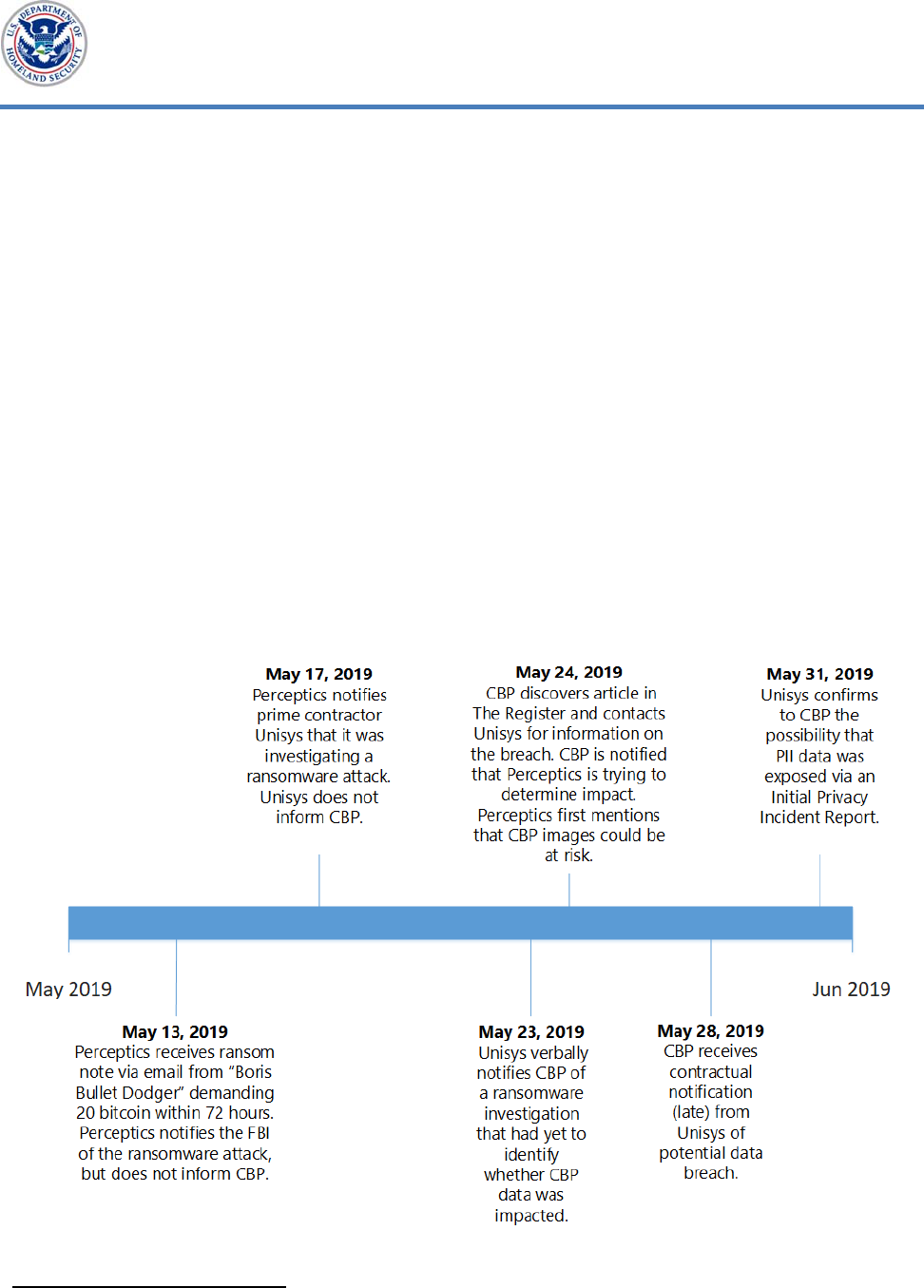

Figure 3 provides a timeline for the ransomware attack, including the

contractor’s delay in officially notifying CBP.

Figure 3. Timeline for the Ransomware Attack

Source: OIG-generated based on DHS data

32

DHS 4300A, Sensitive Systems Handbook

www.oig.dhs.gov 11 OIG-20-71

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

CBP Did Not Adequately Fulfill Its Responsibilities for IT Security

Although sufficient IT security controls are a requirement for all DHS

programs, CBP did not fully ensure protection of SPII during this technology

pilot. According to the DHS 4300A Handbook, components are responsible for

ensuring that contractors adhere to DHS information security standards and

guidelines.

33

The DHS 4300A Handbook also requires that CBP secure its

systems and technology. Additionally, DHS’ Handbook for Safeguarding

Sensitive PII states that DHS components are accountable for reviewing the

actual use of PII to demonstrate compliance with Department guidelines and

privacy protection requirements.

Perceptics was able to make unauthorized use of CBP’s biometric data, in part

because CBP did not implement all available IT security controls, including an

acknowledged best practice. Additional IT security controls in place during the

pilot could have prevented Perceptics from violating contract clauses and using

an unencrypted hard drive to access and download biometric images at the

pilot site. Following the data breach, CBP’s Chief Information Security Officer

acknowledged the equipment vulnerabilities at this pilot location in Anzalduas,

TX. Accordingly, CBP took swift action to prevent unauthorized access to, or

removal of, data. Specifically, CBP disabled all USB capabilities to help

prohibit further unauthorized access to pilot data. Additionally, approximately

4 months after the breach, CBP staff said they performed all needed software

updates to support encryption of equipment similar to that used for the pilot.

In response to the data breach, CBP took immediate steps to review possible IT

vulnerabilities at other locations with ongoing biometric pilot efforts. For

example, the CBP Chief Information Security Officer initiated a forensic

security assessment in 2019 of all existing cameras and biometric technologies

to ensure data was not being stored on any other endpoint devices. As of

November 8, 2019, CBP had completed onsite evaluations at five locations:

four major U.S. international airports participating in the Biometric Air-Exit

program, and a testing facility in Sterling, Virginia.

34

Three of the five locations

received more rigorous examinations, which revealed that no traveler

biometrics were stored on the devices.

35

Another assessment entailed

reviewing additional data protection and insider threat security controls that

could be incorporated to prevent similar breaches from occurring in the future.

33

DHS 4300A Sensitive Systems Handbook

34

Biometric Air-Exit program onsite evaluations occurred at Washington Dulles International

Airport, Chicago O'Hare International Airport, McCarran International Airport, and Seattle-

Tacoma International Airport.

35

CBP conducted a forensic analysis of the images and concluded that no traveler biometric

data was found.

www.oig.dhs.gov 12 OIG-20-71

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

As a result, CBP identified potential security vulnerabilities at four airports

conducting similar facial recognition pilots.

CBP ultimately made 10 mitigation recommendations and 3 policy

recommendations based on these assessments to protect against unauthorized

access to data from cameras and related equipment used for biometric

confirmation. One key recommendation was to ensure implementation of USB

device restrictions and to apply enhanced encryption methods. Appendix C

contains more information on CBP’s mitigation and policy recommendations.

To help mitigate future data breaches, CBP also sent a memo requiring all IT

contractors to sign statements guaranteeing compliance with contract terms

related to IT and data security. The memo asked contractors to provide

documents supporting compliance, and responses to a questionnaire entitled

“Baseline Security Requirements for Securing Sensitive Data.” As of October

11, 2019, CBP was in the process of collecting the signed attestations and

supporting documentation.

It should be noted that prior to the data breach, CBP conducted privacy

assessments in accordance with DHS requirements. The Biometric Entry-Exit

Program Office and the CBP Privacy Office worked together to create 56 privacy

products during the program’s development. These evaluations examined

privacy related aspects of program development and explained mitigation of

privacy concerns. Some of the documentation produced from these privacy

evaluations is also shared with the public on DHS’ website to provide

transparency on what information each system would collect and how that

data would be protected.

Data Breach Compromised Traveler Data and May Damage Public Trust

The malicious ransomware attack on Perceptics’ network directly and adversely

affected CBP, as well as the traveling public. CBP estimated that more than

184,000 traveler facial image files, as well as 105,000 license plate images were

stored on the subcontractor’s network at the time of the ransomware attack.

After removing duplicate images, CBP reduced its estimate to 100,000

individual images, of which they discovered 19 were posted to the dark web.

As facial recognition technology advances, facial images, like those in this data

breach, could be used in unauthorized ways to learn more information about

travelers whose biometrics are captured by the Department.

Additionally, this data breach may damage the public’s trust in the

Government’s use of biometric data. This data breach, and the subsequent

ransomware attack on Perceptics, became the subject of international news

coverage. Although the stolen images were not linked to other traveler PII, the

www.oig.dhs.gov 13 OIG-20-71

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Washington Post

36

and the New York Times

37

both released articles on June 10,

2019, about the cyber attack. Both articles highlighted that sensitive

information had been stolen and placed on the dark web. This concern could

create reluctance among the public to permit DHS to use photos in the future.

Likewise, members of Congress flagged the data breach as a concern. In June

of 2019, U.S. Senator Edward Markey called on DHS to halt its use of facial

recognition technology after CBP confirmed the data breach had exposed

images of travelers and their vehicles. Senator Markey stated the breach

“raises serious concerns about the Department of Homeland Security’s ability

to effectively safeguard the sensitive information it is collecting.” He also

stated, “Malicious actors’ thirst for information about U.S. identities is

unquenchable, and DHS must keep pace with emerging threats.”

38

Additionally, the Chairman of the House Committee on Homeland Security,

Representative Bennie Thompson, said, “We must ensure we are not expanding

the use of biometrics at the expense of the privacy of the American public.”

39

Congressional caution about the Department’s plans to use biometrics

predated this data breach. In December 2017 and May 2018, U.S. Senator

Mike Lee (R-Utah) called on DHS to halt the expansion of its biometric program

until it had safeguards in place.

40

Later, on June 22, 2018, Senator Lee and

Senator Markey released a joint statement about biometrics, calling for DHS to

complete the formal processes addressing privacy and security concerns before

further expanding the Biometric Entry-Exit program.

41

Conclusion

It is vital that CBP protect against unauthorized access to data from cameras

and related equipment used for biometric confirmation, especially when

entrusting third parties to manage its SPII. These measures are particularly

important as CBP is increasing its biometric data collection efforts at more and

more ports of entry. The consequences of this data breach, including the

damage to public perception, could pose a major threat to the Department’s

use of biometrics going forward to detect and prevent illegal entry into the

36

U.S. Customs and Border Protection says photos of travelers were taken in a data breach,

Washington Post, June 10, 2019

37

Border Agency’s Images of Travelers Stolen in Hack, New York Times, June 10, 2019

38

Ed Markey: Customs data breach ‘raises serious concerns’, Boston Herald, June 11, 2019

39

House Homeland Security Panel to hold hearings on DHS’s use of biometric information in

wake of CBP breach, The Hill, June 10, 2019

40

Ed Markey: Customs data breach ‘raises serious concerns’, Boston Herald, June 11, 2019

41

Senators Markey and Lee Release Statement on Facial Recognition Technology Use at Airports,

www.markey.senate.gov, June 22, 2018

www.oig.dhs.gov 14 OIG-20-71

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

United States, grant proper immigration benefits, facilitate legitimate travel and

trade, and enforce Federal laws.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1: We recommend CBP’s Assistant Commissioner for the

Office of Information and Technology implement all mitigation and policy

recommendations to resolve the 2019 data breach identified in CBP’s Security

Threat Assessments, including implementing USB device restrictions and

applying enhanced encryption methods.

Recommendation 2: We recommend the Deputy Executive Assistant

Commissioner, Office of Field Operations coordinate with the CBP Office of

Information and Technology to ensure that all additional security controls are

implemented on relevant devices at all existing Biometric Entry-Exit program

pilot locations.

Recommendation 3: We recommend the Deputy Executive Assistant

Commissioner, Office of Field Operations establish a plan for the Biometric

Entry-Exit Program to routinely assess third-party equipment supporting

biometric data collection to ensure partners’ compliance with Department

security and privacy standards.

OIG Analysis of CBP Comments

CBP provided formal written comments in response to a draft of this report.

We have included a copy of CBP’s response in its entirety in appendix B. We

also received technical comments from CBP and revised the report where

appropriate. CBP concurred with all three of our recommendations and

provided updates on the work it has completed in those areas since the

conclusion of our fieldwork.

In its response, CBP documented its commitment to protecting sensitive

information, including personally identifiable information stored on information

systems. CBP also outlined standard protection measures and contractor

requirements meant to protect data collected by the Department. Although

CBP maintains that it did what was required to protect the data associated

with its VFS pilot, the data was still removed without authorization. Our

recommendations are aimed at ensuring CBP’s data is no longer vulnerable in

order to limit the chances of future data breaches. A summary of CBP’s

response to our recommendations and our analysis follows.

www.oig.dhs.gov 15 OIG-20-71

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Further, CBP asserts that our draft report stated Perceptics admitted to

violating security policies in transferring the photos to its corporate servers.

We would like to clarify that even though our report notes that Perceptics

admitted to the prime contractor that it had downloaded traveler images in

conjunction with work order tickets, our report does not state that Perceptics

admitted to violating security policies.

A summary of CBP’s response to our recommendations and our analysis

follows.

Recommendation 1: We recommend CBP’s Assistant Commissioner for the

Office of Information and Technology implement all mitigation and policy

recommendations to resolve the 2019 data breach identified in CBP’s Security

Threat Assessments, including implementing USB device restrictions and

applying enhanced encryption methods.

Management Comments

CBP concurred and stated that between August 2019 and January 2020, CBP

completed work on the short- and long-term mitigation and policy

recommendations that CBP previously identified following the 2019 data

breach. This work included implementing device restrictions, security

enhancements, such as encryption, and penetration testing. CBP’s Office of

Information and Technology established periodic testing to help ensure

external storage device access is restricted. CBP requested that this

recommendation be considered resolved and closed, as implemented.

OIG Analysis

We appreciate CBP’s efforts thus far to implement all mitigation and policy

recommendations outlined in its 2019 Security Threat Assessments. Although

we consider these actions positive steps toward addressing this

recommendation, we suggest CBP continue its work to address these efforts

until all mitigation and policy recommendations are fully implemented. We

look forward to receiving status updates, along with documentary evidence, as

these controls are implemented. This recommendation remains open and

resolved.

Recommendation 2: We recommend the Deputy Executive Assistant

Commissioner, Office of Field Operations coordinate with the CBP Office of

Information and Technology to ensure that all additional security controls are

implemented on relevant devices at all existing Biometric Entry-Exit program

pilot locations.

www.oig.dhs.gov 16 OIG-20-71

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Management Comments

CBP concurred and stated that OFO and CBP’s Office of Information and

Technology have worked together to develop a plan to routinely assess third

party equipment supporting biometric data collection. These assessments are

aimed at ensuring third party compliance with the Department’s security and

privacy standards. The assessments may include interviews, security scans,

and penetration tests. CBP requested that this recommendation be considered

resolved and closed, as implemented.

OIG Analysis

We agree that a formal assessment plan is needed to ensure third parties are

not able to take advantage of Department data in the same manner again.

Until CBP addresses whether or how additional security controls are to be

implemented across relevant devices at all existing Biometric Entry-Exit

locations including land, air, and sea initiatives, this recommendation will

remain open and resolved.

Recommendation 3: We recommend the Deputy Executive Assistant

Commissioner, Office of Field Operations establish a plan for the Biometric

Entry-Exit Program to routinely assess third-party equipment supporting

biometric data collection to ensure partners’ compliance with Department

security and privacy standards.

Management Comments

CBP concurred with the recommendation. As stated in the response to

recommendation 2, OFO and CBP’s Office of Information and Technology

developed a plan for routine assessments of third-party equipment, including

interviews and security scans. CBP requested that this recommendation be

considered resolved and closed, as implemented.

OIG Analysis

We appreciate the work OFO and CBP’s Office of Information and Technology

put into the assessment plan. Creating the plan is a step toward better

securing Department data. Although CBP provided DHS OIG with a plan, the

plan did not appear to support the Biometric Entry-Exit Program specifically.

Until we receive supporting documentation outlining plans to address potential

vulnerabilities with equipment used to support the Biometric Entry-Exit

Program, this recommendation will remain open and resolved.

www.oig.dhs.gov 17 OIG-20-71

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Appendix A

Objective, Scope, and Methodology

The Department of Homeland Security Office of Inspector General was

established by the Homeland Security Act of 2002 (Public Law 107−296) by

amendment to the Inspector General Act of 1978. We conducted this review to

determine whether CBP ensured adequate protection of biometric data during

its 2019 pilot.

To conduct this review, we researched and used Federal, departmental, and

agency criteria related to Federal IT security requirements. We obtained and

reviewed published reports and other relevant documents, testimonial

transcripts, and media articles related to the Department’s management and

use of biometric data. Additionally, we reviewed Government Accountability

Office and DHS OIG reports to identify previous findings and recommendations

related to DHS’ use of biometrics.

We held more than 20 meetings and teleconferences with more than 100

individuals including DHS personnel and external stakeholders to learn about

the Department’s use and protection of biometric data, as well as the specific

biometric breach at Anzalduas, TX. At DHS Headquarters, we interviewed

representatives from the Office of the Chief Information Officer, the Privacy

Office, the Office of the Chief Technology Officer, the Office of Program

Accountability and Risk Management, and the Office of Strategy, Policy and

Plans.

At CBP headquarters, we interviewed officials from the Office of Field

Operations, the Office of the Chief Information Security Officer, the Office of

Information Technology, the Privacy Office, and Procurement Personnel. We

met with subject matter experts at the Office of Biometric Identity Management

and the TSA. Finally, we met with external stakeholders from Delta Airlines

and NEC Corporation.

In August 2019, we visited Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport in

Atlanta, Georgia, to observe CBP, TSA, and airline-run biometric pilot activities,

and to speak with staff about program successes and challenges. During this

visit, we observed operations of CBP’s Biometric Exit Program and its Global

Entry facial recognition pilot, TSA’s biometric identification verification pilot,

and Delta Airlines’ biometrics initiatives.

We requested and reviewed more than 250 documents and files from the

Department. We did not compile or review classified documents to conduct

this review. We also did not meet with or request information directly from the

www.oig.dhs.gov 18 OIG-20-71

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

contracting organizations, Unisys and Perceptics, LLC, mentioned in this

report.

We conducted this review between July and October 2019 under the authority

of the Inspector General Act of 1978, as amended, and according to the Quality

Standards for Inspections issued by the Council of the Inspectors General on

Integrity and Efficiency. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a

reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based upon our objectives.

www.oig.dhs.gov 19 OIG-20-71

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Appendix C

Recommendations from the Washington Dulles International

Airport and Unisys Lab Assessment Findings

Mitigation Recommendations

Short-term

Efforts

Install Digital Guardian agent on all workstations and camera images, and

apply USB encryption methods in accordance with FIPS 140-2.

Request documentation from Unisys evidencing that images are not being

stored locally.

Replace HTTP with HTTPS to ensure data is protected during network

transmission, and in accordance to FIPS 140-2.

Install and configure Symantec Endpoint Protection on all applicable devices.

Install Tanium agent on all applicable devices.

Install Splunk Forwarder on all applicable devices.

Long-term

Efforts

Implement USB restrictions to ensure USB devices are blocked (excluding

Human Interface Devices).

Perform detailed forensic analyses on onsite acquisition and/or production

vendor hard drives to verify the vendor’s claim that no images are being stored.

Document the provisioning and decommissioning processes for all devices.

Conduct a full live penetration test in the production environment after

business hours.

Policy Recommendations

Ensure that any time a new application is set for deployment inside CBP, the

Information System Security Officer for that department collaborates with the

Cyber Security Division to confirm that the necessary controls and

procedures are met before deployment.

www.oig.dhs.gov 24 OIG-20-71

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Policy Recommendations (continued)

Establish a team to adequately test security procedures and perform risk

assessments. Ideal goals would be:

Identify Functional Needs.

Identify Threats and Vulnerabilities.

Identify Security Needs.

Develop an implementation checklist.

Source: Compiled from CBP-provided information

www.oig.dhs.gov 25 OIG-20-71

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Appendix D

Report Distribution

Department of Homeland Security

Secretary

Deputy Secretary

Chief of Staff

Deputy Chiefs of Staff

General Counsel

Executive Secretary

Director, GAO/OIG Liaison Office

Under Secretary, Office of Strategy, Policy, and Plans

Assistant Secretary for Office of Public Affairs

Assistant Secretary for Office of Legislative Affairs

Deputy Under Secretary for Management, MGMT

Acting Commissioner, CBP

Administrator, TSA

Director, Office of Biometric Identity Management

Audit Liaison, MGMT

Audit Liaison, CBP

Audit Liaison, TSA

Audit Liaison, Office of Biometric Identity Management

Office of Management and Budget

Chief, Homeland Security Branch

DHS OIG Budget Examiner

Congress

Congressional Oversight and Appropriations Committees

www.oig.dhs.gov 26 OIG-20-71

Additional Information and Copies

To view this and any of our other reports, please visit our website at:

www.oig.dhs.gov.

For further information or questions, please contact Office of Inspector General

Public Affairs at: [email protected].

Follow us on Twitter at: @dhsoig.

OIG Hotline

To report fraud, waste, or abuse, visit our website at www.oig.dhs.gov and click

on the red "Hotline" tab. If you cannot access our website, call our hotline at

(800) 323-8603, fax our hotline at (202) 254-4297, or write to us at:

Department of Homeland Security

Office of Inspector General, Mail Stop 0305

Attention: Hotline

245 Murray Drive, SW

Washington, DC 20528-0305