_____________________________________________________________________________

Combined Enforcement Policy

for

Clean Air Act Sections 112(r)(1),

112(r)(7), and 40 C.F.R. Part 68

June 2012

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

Office of Enforcement and Compliance Assurance

Office of Civil Enforcement

Waste and Chemical Enforcement Division

Table of Contents

Section 1: Introduction and Overview

Introduction ........................................................................................................................3

Overview of the Policy ........................................................................................................3

Section 2: Determining the Level of Enforcement Response

Administrative Compliance Orders/Notices of Noncompliance.…………………………4

Civil Administrative Penalty Orders....................................................................................5

Civil Judicial Referrals ........................................................................................................5

Criminal Sanctions...............................................................................................................6

Parallel Criminal and Civil Proceedings..............................................................................6

Section 3: Calculating Civil Penalties

Calculating the Penalty ........................................................................................................7

Economic Benefit of Noncompliance..................................................................................7

Gravity-Based Penalty .........................................................................................................9

Seriousness of the Violation(s)……………………………………………………9

Part 68 Violations . ..............................................................................................10

GDC Violations ………...……………………………………………………...12

Extent of Damages……………………………………………………………….14

Duration of Violation(s) …………...……………………………………………14

Size of Violator .....................................................................................................15

Modifying the Penalty........................................................................................................17

Degree of Culpability…………………………………………………………….17

Economic Impact of the Penalty (Ability to Pay) ……………………………….19

Offsetting Penalties Previously Paid to Federal, State, Tribal and

History of Violations……………………………………………………………..18

Good Faith ………………………………….…………………………….……..19

Local Governments or Citizen Groups for the Same Violations………………22

Special Circumstances/Extraordinary Adjustments……………………………...22

Documenting Penalty Settlement Amount……………………………………………….23

Apportioning the Penalty among Multiple Respondents…………………...……………23

Supplemental Environmental Projects…………………………………………...23

Settlement of Penalties…………………………………………………………………...22

Conclusion .........................................................................................................................23

Section 4: Appendices

Appendix A: Examples of Common Failures that Have Resulted in GDC Violations

Appendix B: Extent of Damages

Appendix C: Internet References for Policy Documents

Section 1: Introduction and Overview

I. Introduction

This policy addresses civil enforcement actions for violations of Clean Air Act (CAA) section

112(r)(1), 42 U.S.C. § 7412(r)(1), known as the General Duty Clause (GDC) and for violations

of section 112(r)(7) and its implementing regulations found at 40 C.F.R. Part 68. EPA is issuing

this policy to ensure that enforcement responses for these violations are consistent; that the

enforcement response is appropriate for the violations; and that parties will be deterred from

committing such violations in the future. This policy should be used to develop settlement

penalty amounts for civil judicial enforcement actions and for civil administrative cases.

This policy applies only to violations of EPA’s civil regulatory program. It does not apply to

enforcement pursuant to criminal provisions of laws or regulations that are enforced by EPA.

The procedures set out in this document are intended solely for the guidance of government

personnel. They are not intended and cannot be relied on to create rights, substantive or

procedural, enforceable by any party in litigation with the United States.

The Agency reserves the right to act at variance with the policy and to change it any time without

public notice. This policy is not binding on the Agency. Enforcement staff should continue to

make appropriate case-by-case enforcement judgments, guided by, but not restricted or limited

to, the policies contained in this document.

This policy is immediately effective and applicable, and it supersedes any enforcement response

or penalty guidance previously issued for CAA § 112(r).

II. Overview of the Policy

This Combined Enforcement Policy (CEP) is divided into four main sections. The first section is

“Introduction and Overview.” The second section, “Determining the Level of Enforcement

Response,” describes the Agency’s options for responding to violations of CAA § 112(r). The

third section, “Calculating Civil Penalties,” elaborates on EPA’s policies and procedures for

calculating civil penalties against persons who violate CAA § 112(r). The fourth section,

“Appendices,” contains examples of GDC violations, the extent of damages matrix, and a list of

references for policy documents.

3

Section 2: Determining the Level of Enforcement Response

Once the Agency finds that a CAA § 112(r) violation has occurred, it will need to determine the

appropriate level of enforcement response for the violation. EPA can respond with a range of

enforcement response options. These options include:

● Administrative Compliance Orders

● Notices of Noncompliance

● Civil Administrative Penalty Orders

● Civil Judicial Referrals

● Criminal Sanctions

An appropriate response will achieve a timely return to compliance and serve as a deterrent to

future non-compliance by eliminating any economic benefit received by the violator from its

noncompliance. The failure or refusal to comply with any requirement of section 112(r) (42

U.S.C. § 7412) is a prohibited act and civil penalties can be assessed to address each violation

pursuant to CAA § 113 (42 U.S.C. § 7413). In all but rare instances, EPA should seek penalties

to address noncompliance, either by initiating a civil administrative action or a civil judicial

referral. However, in limited circumstances, EPA may pursue a non-penalty action.

I. Administrative Compliance Orders/Notices of Noncompliance

A. Administrative Compliance Orders

An administrative compliance order (ACO), issued pursuant to CAA §§ 112(r)(9), 113(a)(3)(B)

or 303, is a formal action ordering compliance with the CAA. Regions should consider issuing

an ACO for violations that pose an immediate threat to human health and/or the environment or

in other circumstances when the Region concludes that it is important to obtain immediate

compliance. In such cases, the order should be clearly drafted to reserve the Agency’s right to

subsequently file a penalty action for those violations and to seek additional injunctive relief if

necessary. An ACO should cite the relevant statutory or regulatory requirements that the facility

is violating. Failure to comply with an ACO is a separate violation for which the Region should

seek penalties. In situations where immediate compliance may not be necessary, an order on

consent may be the appropriate response.

B. Notices of Noncompliance

On a case-by-case basis, EPA may determine that the issuance of a notice of noncompliance

(NON), rather than a civil administrative or judicial action is the most appropriate enforcement

response to a violation. Once the decision has been made to issue a NON, EPA should issue one

NON addressing all instances of noncompliance evident at that point in time.

4

Section 2: Determining the Level of Enforcement Response

If EPA should issue a NON (via Certified Mail, return receipt requested, or any other method

where delivery can be confirmed), the NON should require the violator to return to compliance

no more than thirty (30) days from the date of receipt (as evidenced by the signature and date on

the delivery confirmation) and describe the necessary steps taken to come into compliance.

Failure to correct any violation for which a NON is issued may be the basis for issuance of a

civil administrative complaint. EPA may issue one CAA § 112(r) NON to a facility in a three-

year period. The three-year time period begins the day after the date of the NON. If subsequent

violations of CAA § 112(r) occur in the three-year time period, EPA should take a penalty

action.

A NON may be issued to address violations in the following circumstances:

i. Where a first time violator’s violation has low probability of recurrence and low

potential for harm; or

ii. When a violator is in substantial compliance with the requirement as the specific

facts and circumstances support.

II. Civil Administrative Penalty Orders

A civil administrative penalty order is typically the appropriate response to violations of CAA §

112(r) and failure to comply with a notice of noncompliance. See Clean Air Act § 113(d).

III. Civil Judicial Referrals

Under CAA § 113(b), the EPA Administrator may refer civil judicial cases to the United States

Department of Justice (DOJ) for assessment and/or collection of the penalty in the appropriate

U.S. district court. EPA may also refer to DOJ an action for a permanent or temporary

injunction. EPA must refer to DOJ cases for which EPA is seeking a penalty greater than the cap

established in CAA § 113(d)(1) (which is adjusted regularly by the Civil Monetary Penalty

Inflation Adjustment Rule, see 40 C.F.R. Part 19), or for which the first alleged date of violation

occurred more than 12 months prior to initiation of the administrative action. EPA and DOJ may

jointly determine, however, to waive this requirement and address these cases administratively.

5

Section 2: Determining the Level of Enforcement Response

IV. Criminal Sanctions

This CEP does not address criminal violations of CAA § 112(r). If, however, the civil case team

has reason to believe that a violator knowingly violated any provision of CAA § 112(r), it should

promptly refer the matter to the Criminal Investigations Division (CID). Pursuant to 18 U.S.C. §

1001, it is a criminal violation to knowingly and willfully make a false or fraudulent statement in

any matter within EPA's jurisdiction. In addition, it may be considered a criminal violation to

knowingly or willfully falsify information provided to the Agency.

EPA may also refer to CID any negligent releases of listed hazardous air pollutants and

extremely hazardous substances. Pursuant to CAA § 113(c)(4), it is a criminal violation to

negligently release into the air any hazardous air pollutant listed pursuant to CAA § 112 or any

extremely hazardous substance listed pursuant to section 302(a)(2) of the Superfund

Amendments and Reauthorization Act of 1986 (42 U.S.C. § 11002(a)(2)) that is not listed in

CAA § 112 and negligently place another person in imminent danger of death or serious body

injury.

V. Parallel Criminal and Civil Proceedings

Although the majority of EPA’s enforcement actions are brought as either a civil action or a

criminal action, there are instances when it is appropriate to bring both a civil and a criminal

enforcement response. These include situations where the violations merit the deterrent and

retributive effects of criminal enforcement, yet a civil action is also necessary to obtain an

appropriate remedial result, and where the magnitude or range of the environmental violations

and the available sanctions make both criminal and civil enforcement appropriate.

Active consultation and cooperation between EPA’s civil and criminal programs, in conformance

with all legal requirements and with OECA’s Parallel Proceedings Policy (September 24, 2007),

1

is critical to the success of EPA’s overall enforcement program. The success of any parallel

proceeding depends upon coordinated decisions by the civil and criminal programs as to the

timing and scope of their activities. For example, it will often be important for the criminal

program to notify the civil enforcement program managers that an investigation is about to

become overt or known to the subject. Similarly, the civil program should notify the criminal

program when there are significant developments that might change the scope of the relief. In

every parallel proceeding, communication and coordination should be initiated at both the staff

and manager levels and should continue until resolution of all parallel matters.

1

See Appendix C: Parallel Proceedings Policy

6

Section 3: Calculating Civil Penalties

I. Calculating the Penalty

The factors relevant to setting an appropriate penalty appear in CAA § 113(e). These factors are:

the economic benefit of noncompliance; the seriousness of the violation; the duration of the

violation as established by any credible evidence; the size of the business; the violator's full

compliance history; good faith efforts to comply; the economic impact of the penalty on the

business; payment by the violator of penalties previously assessed for the same violation; and

other factors as justice may require. The purpose of this penalty policy is to ensure that: (1) civil

penalties are assessed in accordance with the CAA and in a fair and consistent manner; (2)

penalties are appropriate for the gravity of the violation; (3) economic incentives for non-

compliance are eliminated; (4) penalties are sufficient to deter persons from committing

violations; and, (5) compliance is expeditiously achieved and maintained.

Proposed penalties are comprised of two components: the amount equal to the economic benefit

of noncompliance and an amount reflective of the gravity of the violation. These components

should be calculated using the assumptions most protective of the environment. This policy also

allows for the upward or downward adjustment of the gravity component, depending on the

circumstances, as discussed below.

The proposed penalty amount is the result of the following formula:

Penalty = [Economic Benefit ] + [Gravity Component (i.e., seriousness of each violation)

+ Duration Component (of the violation with the longest duration) + Size of violator (both

duration and size are calculated only once)) ± Adjustment Factors]

2

II. Economic Benefit of Noncompliance

3

An entity that has violated CAA § 112(r) should not profit from its actions. The Agency’s Policy

on Civil Penalties (EPA General Enforcement Policy #GM – 21, February 16, 1984) requires

EPA to recover any significant economic benefit of noncompliance (EBN) that accrues to a

violator from noncompliance with the law. Economic benefit can result from a violator delaying

or avoiding compliance costs or when the violator achieves an illegal competitive advantage

through its noncompliance. A fundamental premise of the 1984 policy is that economic

incentives for noncompliance are to be eliminated. If, after a penalty is paid, a violator still

2

Note that the economic benefit plus the gravity component may not exceed the statutory maximum penalty on a per

violation basis.

3

See http://www.epa.gov/EPA-GENERAL/1999/June/Day-18/g15271.htm for a further discussion of the Calculation of the

Economic Benefit of Noncompliance in EPA's Civil Penalty Enforcement Cases.

7

Section 3: Calculating Civil Penalties

profits by violating the law, there is little incentive to comply. Therefore, the enforcement team

should always evaluate the economic benefit of noncompliance in calculating penalties.

4

A. Economic Benefit from Delayed Costs and Avoided Costs

Delayed costs are expenditures that have been deferred by the violator’s failure to comply with

the requirements. For example, an owner or operator who fails to implement necessary changes

to process instrumentation and equipment in a timely manner (e.g., installing monitoring systems

such as high temperature, pressure, level, and flow indicators and alarms) that are necessary to

safely operate the facility but ultimately makes the changes, has achieved an economic benefit by

delaying the costs associated with those changes.

Avoided costs are expenditures that will never be incurred. Using the example above, the cost of

installation is a delayed cost, while the cost of maintaining the equipment for a period when the

equipment should have been in use, is an avoided cost.

B. BEN Model

The primary purpose of the Agency’s computer BEN model is to calculate economic benefit for

settlement purposes. The model can perform a calculation of economic benefit from delayed or

avoided costs based on data inputs, including optional data items and standard values already

contained in the program. Enforcement personnel who have questions while running the model

can access the model’s help system. The help system contains information on how to use BEN,

how to understand the data needed, and how to understand the model’s outputs.

The economic benefit component should be calculated for the entire period for which there is

evidence of noncompliance (i.e., all time periods for which there is evidence to support the

conclusions that the respondent was violating the CAA and thereby gained an economic benefit).

Such evidence should be considered in the overall assessment of the penalty calculated for the

violations alleged or proven, up to the statutory maximum for those violations. In certain cases,

credible evidence may demonstrate that a respondent received an economic benefit for

noncompliance for a period longer than the period of the violations for which a penalty is sought.

4

See Economic Analysis in Support of the Final Rule on Risk Management Program Regulations for Chemical

Accident Release Prevention, as Required by Section 112(r) of the Clean Air Act (June 1996), Docket No. A-91-73,

for a detailed analysis of the costs of complying with CAA 112(r) requirements. See also Appendix B: Wage Rates

and Unit Cost Tables, Updated Based on 2006 BLS and OPM Wage Rates and Risk Management Planning

Handbook, 2

nd

Edition.

8

Section 3: Calculating Civil Penalties

In such cases, it may be appropriate to consider all of the economic benefit evidence in

determining the appropriate penalty for the violations for which the respondent is liable.

5

In most cases, the violator will have the funds gained through noncompliance available for its

continued use and/or competitive advantage until it pays the penalty. Therefore, for cases in

which economic benefit is calculated by using BEN or by a financial expert, the economic

benefit should be calculated through the anticipated date a consent agreement would be entered.

If the matter goes to hearing, this calculation should be based on a penalty payment date

corresponding with the relevant hearing date. It should be noted that the respondent will continue

to accrue additional economic benefits after the hearing date, until the assessed penalty is paid.

Note that economic benefit recapture may not exceed the statutory maximum penalty amount.

III. Gravity-Based Penalty

The statutory considerations relevant in determining the gravity component are the seriousness of

the violation, duration of the violation, size of the business, the violator's full compliance history,

good faith efforts to comply, the economic impact of the penalty on the business, and payment

by the violator of penalties previously assessed for the same violation. The seriousness of the

violation is incorporated into Tables I and II. The other statutory factors are discussed below.

CAA § 113(d) authorizes the Administrator to issue an administrative order assessing an

administrative penalty of not more than $25,000 per day for each violation of the CAA and

implementing regulations. Pursuant to section 4 of the Federal Civil Penalties Inflation

Adjustment Act of 1990, 28 U.S.C. § 2461 note, as amended by the Debt Collection

Improvement Act (DCIA) of 1996, 31 U.S.C. § 3701 note, EPA must make adjustments to civil

monetary penalties at least once every four years in order to account for inflation. As a result of

the DCIA, the Agency issued and periodically revises the Civil Monetary Penalty Inflation

Adjustment Rule, 40 C.F.R. Part 19.

A. Seriousness of the Violation(s)

The seriousness of a violation depends in part on the risk posed to the surrounding population

and the environment as a result of the violation. Risk is a function of the extent of the deviation

from the requirements, the likelihood of a release, and the sensitivity of the environment around

the facility. The extent of the deviation depends on the degree and nature of the violations of the

relevant requirements and their effect. The greater the extent of deviation, the more likely that

5

When considering the economic benefit of noncompliance that accrued to the respondent more than five years

prior to the filing of a complaint or a pre-filing Consent Agreement, the litigation team should consult with the

Waste and Chemical Enforcement Division.

9

Section 3: Calculating Civil Penalties

the owner or operator of the facility has compromised the safe operation of the facility and the

safe management of the chemicals. The sensitivity of the environment can be characterized by

considering the potential impact of the violation on the surrounding population and the

environment from a worst-case release at the facility. These factors will be more severe when the

community impacted by a violation is already overburdened by environmental pollution.

The GDC and the Part 68 regulations are two separate and distinct obligations imposed on

sources. This policy establishes two sets of tables for determining the seriousness of the violation

component, one for Part 68 violations and one for GDC violations. When EPA is alleging Part 68

violations, enforcement personnel should use Table I. When EPA is alleging GDC violations,

enforcement personnel should use Table II.

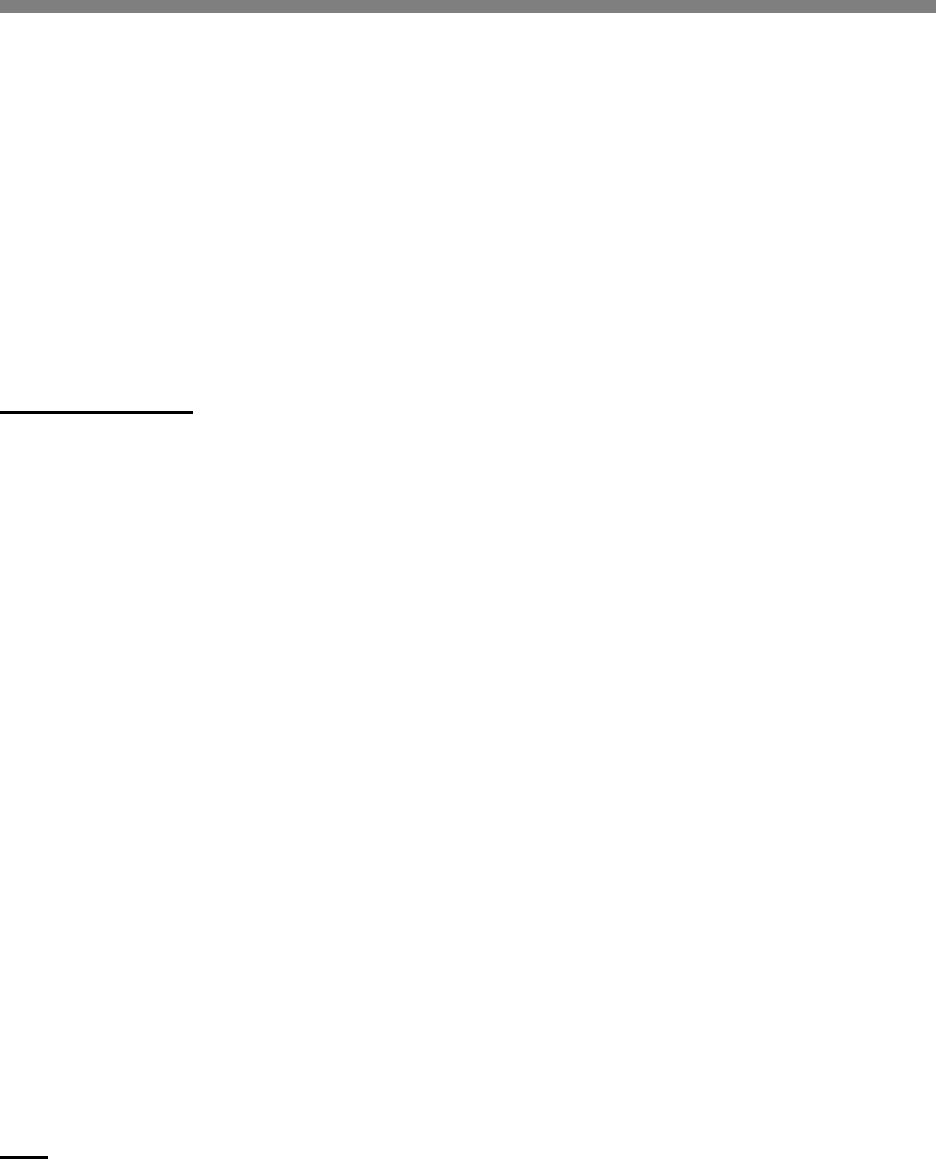

Part 68 Violations

In calculating the seriousness of the violation component of a penalty for Part 68 violations, first

determine the potential for harm resulting from each of the alleged Part 68 violations. The

potential for harm can be major, moderate, or minor.

To determine the potential for harm for a particular Part 68 requirement, use the following

guidelines:

Major: The violation has the potential to undermine, or has undermined, the ability of the

facility to prevent or respond to releases through the development and implementation of the Part

68 requirements.

Moderate: The violation has the potential to affect, or has had significant effect on, the ability of

the facility to prevent or respond to releases through the development and implementation of the

Part 68 requirements.

Minor: The violation has little potential to affect, or has had little effect on, the ability of the

facility to prevent or respond to releases through the development and implementation of the Part

68 requirements.

EPA personnel should consider the circumstances surrounding each violation to arrive at a

specific penalty within the range for a given cell in the matrices below. Some examples of

relevant factors are:

• Amount of regulated chemical present in a process;

• Toxicity of the regulated chemical;

• Whether emergency personnel, the community, and/or the environment, were potentially

or actually exposed to hazards that resulted from the violation;

10

Section 3: Calculating Civil Penalties

• The relative proximity of the surrounding population;

• The extent of community evacuation required or potentially required;

• The effect noncompliance has on the community's ability to plan for chemical

emergencies;

• Any potential or actual problems first responders and emergency managers encountered

because of the facility's violation;

• Number of processes at which the same violations occurred and,

• Prevention Program level.

Second, determine the extent of deviation from each of the Part 68 requirements for the

violations alleged. The extent of deviation can be major, moderate, or minor.

To determine the extent of deviation for a particular Part 68 requirement, use the following

guidelines:

Major: The violator deviates from the requirements of the regulations or statute to such an

extent that most (or important aspects) of the requirements are not met, resulting in substantial

noncompliance.

Moderate: The violator significantly deviates from the requirements of the regulations or statute

but some of the requirements are implemented as intended.

Minor: The violator deviates somewhat from the regulatory or statutory requirements but most

(or all important) aspects of the requirements are met.

These two determinations, the potential for harm and the extent of deviation, will lead to a cell

within one of the penalty matrices. Within that cell, choose an appropriate penalty figure from

the range given.

For those situations where a facility fails to submit a Risk Management Plan (RMP), the case

team should plead multiple violations of Part 68 in addition to the one failure to file a RMP (40

C.F.R. § 68.12), as long as the evidence supports the additional independent counts. For

example, if the Region has evidence of failure to perform an initial process hazard analysis on

covered processes (40 C.F.R. § 68.67) and failure to train an employee involved in operating a

covered process (40 C.F.R. § 68.71) then it should plead both violations. If a facility has not

submitted an RMP but has a chemical accident prevention program in place which satisfies the

specific Part 68 requirements, a single count for failing to file an RMP may be appropriate.

11

Section 3: Calculating Civil Penalties

Table I

The Part 68 Seriousness Matrix

Potential for Harm

Minor

Moderate

Major

Extent of Deviation

Major

Moderate

Minor

$37,500

$25,000

$30,000

$30,000

$20,000

$25,000

$10,000

$15,000

$20,000

$5,000

$10,000

$15,000

$1,000

$3,000

$5,000

$500

$1,000

$3,000

GDC Violations

In calculating the seriousness of the violation component of a penalty for GDC violations, first

determine the potential for harm resulting from each of the alleged GDC violations. The

potential for harm can be major, moderate, or minor.

To determine the potential for harm for each GDC violation, use the following guidelines:

Major: The violation has the potential to undermine, or has undermined, the ability of the

facility to prevent releases of any extremely hazardous substance(s) and/or to minimize the

consequences of any such releases.

Moderate: The violation has the potential to affect, or has had significant effect on, the ability of

the facility to prevent releases or threatened releases of extremely hazardous substances and/or to

minimize the consequences of any such releases.

Minor: The violation has little potential to affect, or has had little effect on, the ability of the

facility to prevent releases or threatened releases of extremely hazardous substances and/or to

minimize the consequences of any such releases.

EPA personnel should consider the circumstances surrounding the violation(s) to arrive at a

specific penalty within the range for a given cell.

12

Section 3: Calculating Civil Penalties

Table II

The GDC Seriousness Matrix

Potential for Harm

Minor

Moderate

Major

Extent of Deviation

Major

$25,000

$20,000

Moderate

$10,000

$5,000

Minor

$1,000

$500

$37,500

$30,000

$30,000

$25,000

$15,000

$20,000

$10,000

$15,000

$3,000

$5,000

$1,000

$3,000

Notes:

For a list of examples of common failures that have resulted in GDC violations see

Appendix A. This listing is not exhaustive and does not limit the case team from

identifying additional violations and proposing penalties for such violative acts.

In some situations, a facility will have both GDC and Part 68 violations. In most cases,

the case team should assess a gravity-based penalty for both the Part 68 and the GDC

violations.

6

Second, determine the extent of deviation from the requirements for each of the violations

alleged. The extent of deviation can be major, moderate, or minor.

To determine the extent of deviation for a particular GDC violation, use the following

guidelines:

Major: The violator deviates from the requirements of the statute to such an extent that most (or

important aspects) of the requirements are not met, resulting in substantial noncompliance.

Moderate: The violator significantly deviates from the requirements of the statute but some of

the requirements are implemented as intended.

Minor: The violator deviates somewhat from the statutory requirements but most (or all

important) aspects of the requirements are met.

6

In situations where a process may fluctuate between exceeding and falling below the RMP threshold, the case team

may choose to propose one gravity-based penalty for both GDC and RMP violations.

13

Section 3: Calculating Civil Penalties

These two determinations, the potential for harm and the extent of deviation, will lead to a cell

within one of the penalty matrices. Within that cell, choose an appropriate penalty figure from

the range given, using the guidance discussed below.

Pursuant to CAA § 112(r)(1), owners or operators have a general duty to: 1) identify hazards, 2)

design and maintain a safe facility, and 3) minimize consequences of accidental releases that do

occur. Therefore, when determining GDC penalties, the case team should consider each of the

three statutory obligations as an independent violation and calculate the penalty accordingly.

Each of the three specific statutory requirements may also implicate multiple violations.

Extent of Damages

The gravity component for both Part 68 and GDC violations already takes into account such

factors as the toxicity of the regulated chemical, the sensitivity of the environment, the length of

time the violation continues, and the degree to which the source has deviated from a requirement.

However, there may be cases where the actual damage caused by the violation is so severe that

the gravity component alone is not a sufficient deterrent, for example, in the case of a significant

release of a regulated chemical in a populated area.

Thus, in cases of a release, fire, explosion, or other significant event, after choosing an

appropriate number from Tables I or II, and, where the facts and circumstances warrant, go to the

Extent of Damages Matrix in Appendix B of this document to consider additional penalty

adjustments. The Extent of Damages multiplier should be applied to the gravity component

before adjusting the penalty for Duration of Violation, Size of Violator, and other

adjustments.

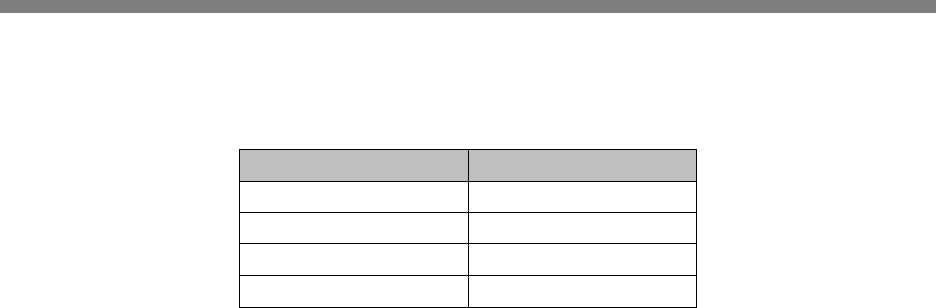

B. Duration of Violation(s)

The duration of a violation is based on the time period from the first day of violation for which

the Region has evidence through the last provable date of the violation, including those days

when the process may be under threshold except when six months have lapsed between days

when the facility had chemicals over threshold (note that stationary sources must delist their

facility within six months of no longer being subject to the Part 68 regulations). For example, if a

facility fails to submit an RMP, the first date of violation is the day the plan was due. The

violation continues until the day the facility submits the plan. Table III is used to determine the

duration component of a penalty.

Note: One-day violations should not have an added duration component.

14

Section 3: Calculating Civil Penalties

Table III

Duration of a Violation

Months

Penalty

0-12

$750/month

13-24

$1,500/month

25-36

$2,250/month

37 +

$3,000/month

For example, if a violation is found to have a duration of 30 months, the duration component

would be:

$9,000 ($750/month for the first 12 months) + $18,000 ($1,500/month for the second 12

months) + $13,500 ($2,250/month for the final 6 months) = $40,500

In cases where the duration of violation amount (as determined in Table III) exceeds the

seriousness of the violation component, EPA may, but need not, reduce the duration component

down to an amount equal to the seriousness component if the Region determines that the

duration component results in a penalty that is disproportionate for the violation. For example, if

the Region determines the seriousness component is $35,000 and the violation continued for 60

months, the duration component would be $126,000. Because the $126,000 duration component

is greater than the seriousness component of $35,000, the Region may choose to reduce the

duration component to no less than $35,000, so it equals the seriousness component.

C. Size of Violator

EPA should scale the penalty to the size of the violator. The size of the violator is based on the

company's net worth, or in the case of municipalities, the size of the service population. In the

case of a company with more than one facility, the size of the violator is determined based on the

entire company's net worth, not just the violating facility. With regard to parent and subsidiary

corporations, generally only the size of the current owner or operator subject to enforcement

should be considered. If the company's net worth cannot be determined, the size of the violator

may be based on gross revenues from all revenue sources during the prior calendar year. If the

revenue data for the previous year appears to be unrepresentative of the general performance of

the business or the income of the individual, an average of the gross revenues for the prior three

years may be used.

EPA should consider reducing the size of violator component if the initial penalty calculation

would lead to an inequitable result because the size of violator component is large and the rest of

the gravity component is comparatively small. Where the size of the violator figure (as

15

Section 3: Calculating Civil Penalties

determined in Table IV) represents more than 50% of the total gravity-based penalty (before

adjustments), EPA may, but need not, reduce the size of the violator figure to an amount equal to

the rest of the penalty without the size of violator component included. For example, EPA

calculates an initial penalty of $100,000, with $70,000 for size of violator and $30,000 for the

other penalty elements. Since the $70,000 size of violator component is more than 50% of the

$100,000 total penalty, the size of violator component may be reduced to $30,000 -- an amount

equal to the balance of the penalty ($30,000). With this reduction, the final resulting penalty will

be $60,000, and the size of violator component will be 50% of this amount. The size of violator

component is applied only once, regardless of the number of violations alleged.

Table IV

Size of Violator Component

Net Worth

Size Adjustment

Under $1,000,000

$0

$1,000,000 – $5,000,000

$10,000

$5,000,001 – $20,000,000

$20,000

$20,000,001 – $40,000,000

$35,000

$40,000,001 – $70,000,000

$50,000

$70,000,001 – $100,000,000

$70,000

Over $100,000,001

$70,000 + $25,000 for every

additional $30,000,000

Municipalities

Service Population

Size Adjustment

100 – 50,000

$0

50,001 – 100,000

$5,000

100,001 – 250,000

$10,000

250,001 – 500,000

$20,000

500,001 – 750,000

$30,000

750,001 – 1,000,000

$40,000

Over 1,000,000

$40,000 + $10,000 for every

additional 250,000

IV. Modifying the Penalty

This policy establishes adjustment factors to promote flexibility while maintaining national

consistency. In addition to the CAA statutory factors of: seriousness, duration, size of violator,

16

Section 3: Calculating Civil Penalties

history of noncompliance, good faith efforts to comply, and economic impact of the penalty

(ability to pay), this policy considers: degree of culpability, environmental damage, and other

factors. These adjustment factors apply only to the gravity component (which includes the

duration and size components) and not to the economic benefit component. In cases where the

gravity component is mitigated to reflect a violator's good faith efforts to comply, the violator

bears the burden of justifying any mitigation proposed. The gravity component may also be

aggravated by as much as 100% for degree of willfulness or negligence and history of

noncompliance. In addition, EPA may consider offsetting penalties previously assessed, special

circumstances/extraordinary adjustments, and quick settlement reductions. Finally, Supplemental

Environmental Projects (SEPs) may further reduce penalties and are considered only after the

above listed adjustments to the gravity-based penalty have been made.

In order to promote equity, the system for penalty assessment must have enough flexibility to

account for the unique facts of each case, yet must produce results consistent enough to ensure

that similarly-situated violators are treated similarly. The CEP allows for flexibility by

identifying the legitimate differences between cases and adjusting the gravity component in light

of those facts. The application of these adjustments to the gravity component prior to the

commencement of negotiation yields the initial minimum settlement amount. During the course

of a case, EPA may further adjust this figure based on new information to yield the adjusted

minimum settlement amount.

A. Degree of Culpability

This factor may be used to increase the gravity-based penalty. CAA is a strict liability statute for

civil actions, so that culpability is irrelevant to the determination of legal liability. However, this

does not render the violator’s culpability irrelevant in assessing an appropriate penalty. Knowing

violations generally reflect an increased culpability on the part of the violator. The culpability of

the violator should be reflected in the amount of the penalty, which may be adjusted upward by

up to 25% for this factor. In assessing the degree of culpability, all of the following points should

be considered:

● Amount of control the violator had over the events constituting the violation;

● Level of sophistication (knowledge) of the violator in dealing with compliance issues;

and

● Extent to which the violator knew, or should have known, of the legal requirement that

was violated.

B. History of Violations

Gravity-based penalties determined using the procedure provided in Part III of this section are

intended to apply to “first-time offenders.” The gravity-based penalty should be adjusted upward

17

Section 3: Calculating Civil Penalties

when EPA determines that a facility has had one or more prior CAA § 112(r) violations. Such

upward adjustment derives from the violator not having been sufficiently motivated to comply as

a result of the penalty assessed for the previous violation(s). In addition, it is appropriate to

penalize repeat offenders more severely than first time offenders because of the additional

enforcement resources required for the same violator. When determining whether an actionable

prior history of violation exists, the following criteria apply:

1. Prior Violations Must Have Resulted In an Enforcement Response: For purposes of this

section, a prior violation includes any act or omission for which an enforcement response has

occurred (e.g., notice of noncompliance, notice of violation, notice of determination, warning

letter, complaint, consent decree, consent agreement, or final order).

2. Prior Violations Must be Within Five Years: To be considered a compliance history for

the purposes of making an upward adjustment to the gravity-based penalty, the violation must

have occurred within five years of the present violation, regardless of whether a respondent

admitted to the prior violation.

3. Corporate Relationships: Generally, companies with multiple facilities are considered as

one entity when determining the history of violative conduct. The following criteria provide

more detail on analyzing corporate relationships:

o If a facility is part of a company with another facility with a prior

violation, EPA will consider each facility within the company to have the

same violative history.

o However, two companies held by the same parent corporation do not

necessarily affect each other’s history if they are in substantially different

lines of business, are substantially independent of one another in their

management, and are substantially independent in the functioning of their

Boards of Directors.

o EPA reserves the right to request, obtain, and review all underlying and

supporting financial documents that may clarify relationships between

entities to determine whether it is appropriate to consider prior history of

violation. If the violator fails to provide the necessary information, and the

information is not readily available through other sources, then EPA is

entitled to rely on the information it does have in its control or possession.

4. Amount of Adjustment:

a. One Prior Violation: The gravity-based penalty should be adjusted upward by 25% for

one prior violation;

18

Section 3: Calculating Civil Penalties

b. Two or More Prior Violations: The gravity-based penalty should be adjusted upward by

50% for two or more prior violations.

C. Good Faith

In cases where a settlement is negotiated prior to a hearing, after other factors have been applied

as appropriate, EPA may reduce the resulting adjusted proposed civil penalty up to a total of

30%. In addition to creating an incentive for cooperative behavior during the compliance

evaluation and enforcement process, this adjustment factor further reinforces the concept that

respondents face a significant risk of higher penalties in litigation than in settlement. The good

faith adjustment has two components:

EPA may reduce the adjusted proposed penalty up to 15% based on a respondent’s

cooperation throughout the entire compliance monitoring, case development, and

settlement process.

EPA may reduce the adjusted proposed penalty up to 15% for a respondent’s immediate

good faith efforts to comply with the violated regulation and the speed and completeness

with which it comes into compliance.

D. Economic Impact of the Penalty (Ability to Pay)

Absent proof to the contrary, EPA can establish a respondent’s ability to pay with circumstantial

evidence relating to a company’s size and annual revenue. Once this is done, the burden is on the

respondent to demonstrate an inability to pay all or a portion of the calculated civil penalty.

Under the Environmental Appeals Board ruling in In re: New Waterbury, LTD, 5 E.A.D. 529

(EAB 1994), in administrative enforcement actions for violations under statutes that specify

ability to pay (which is analogous to the economic impact of the penalty on the business) as a

factor to be considered in determining the penalty amount, EPA must prove it adequately

considered the appropriateness of the penalty in light of all of the statutory factors. Accordingly,

enforcement professionals should be prepared to demonstrate that they considered the

respondent’s ability to pay, as well as the other statutory penalty factors, and that their

recommended penalty is supported by their analysis of those factors. Thus, to determine the

appropriateness of the proposed penalty in relation to a person’s ability to pay, the case team

should review publicly-available information, such as Dun and Bradstreet reports, a company’s

filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission, other available financial reports, news

media reports about a company, or request information from the respondent before issuing the

complaint.

The Agency will notify the respondent of its right to have EPA consider its ability to pay in

determining the amount of the penalty. Any respondent may raise the issue of ability to

19

Section 3: Calculating Civil Penalties

pay/ability to continue in business in its answer to the complaint or during the course of

settlement negotiations. If a respondent raises inability to pay in its answer or in the course of

settlement negotiations, the Agency should ask the respondent to present appropriate

documentation, such as tax returns and financial statements. The respondent should provide

records that conform to generally accepted accounting principles and procedures at its expense.

EPA generally should request the following types of information:

● Last three to five years of tax returns;

● Balance sheets;

● Income statements;

● Statements of changes in financial position;

● Statement of operations;

● Information on business and corporate structure;

● Retained earnings statements;

● Loan applications, financing agreements, security arrangements;

● Annual and quarterly reports to shareholders and the SEC, including 10K reports;

● Assets and Liabilities Statement.

The violator’s ability to pay should be determined according to the Agency’s “Guidance on

Determining a Violator’s Ability to Pay a Civil Penalty,” December 16, 1986, codified as PT 2-1

in the General Enforcement Policy Compendium (previously codified as GM-56). There are

three relevant computer models used for determining the financial health of businesses,

individuals, and municipalities – ABEL, INDIPAY, and MUNIPAY. ABEL is used to calculate

inability to pay for corporations and partnerships, while INDIPAY can be used to calculate

inability to pay for individual taxpayers. For municipalities or other local governmental bodies,

enforcement personnel should use the MUNIPAY computer model. Enforcement personnel may

also consider obtaining the services of a financial analyst for assistance in determining a

violator’s ability to pay. Because these programs focus on a violator’s cash flow, there are other

sources of revenue that could be considered to determine if a firm is able to pay the full penalty.

20

Section 3: Calculating Civil Penalties

These include:

Certificates of deposit, money market funds, or other liquid assets;

Reduction in business expenses such as advertising, entertainment, or compensation of

corporate officers;

Sale or mortgage of non-liquid assets such as company cars, aircraft, or land;

Related entities (e.g., the violator is a wholly owned subsidiary of a Fortune 500

company).

A respondent may argue that it cannot afford to pay the proposed penalty even though the

penalty as adjusted does not exceed EPA’s assessment of its ability to pay. In such cases, EPA

may consider a delayed payment schedule calculated in accordance with Agency installment

payment guidance and regulations.

7

Finally, EPA will generally not collect a civil penalty that exceeds a violator’s ability to pay as

evidenced by a detailed tax, accounting, and financial analysis. However, it is important that the

regulated community not choose noncompliance as a way of aiding financially troubled

businesses. Therefore, EPA reserves the option, in appropriate circumstances, of seeking a

penalty that might exceed the respondent’s ability to pay, cause bankruptcy, or result in a

respondent’s inability to continue in business. Such circumstances may exist where the violations

are egregious and/or the violator refuses to pay the penalty. In such situations, the case file must

contain a written explanation, signed by the regional authority delegated to issue and settle

administrative penalty orders under CAA, which explains the reasons for exceeding the “ability

to pay” guidelines. To ensure full and consistent consideration of penalties that may cause

bankruptcy or closure of a business,the enforcement personnel should consult with the Waste and

Chemical Enforcement Division (WCED). In the event the violator is a small business, EPA

should refer to and apply all relevant factors given in the EPA Small Business Compliance

Policy.

E. Offsetting Penalties Paid to Federal, State, Tribal, and Local Governments or

Citizen Groups for the Same Violations

In assessing a penalty under the CAA § 113(e)(1), the court in a civil judicial action or the

Administrator in an administrative action must consider "payment by the violator of penalties

previously assessed for the same violation." While EPA need not automatically subtract any

7

See 40 C.F.R. § 13.18.

21

Section 3: Calculating Civil Penalties

penalty amount paid by a source to a federal, state, tribal, or local agency in an enforcement

action or to a citizen group in a citizen suit for the same violation that is the basis for EPA's

enforcement action, EPA may do so if circumstances suggest that it is appropriate. EPA should

consider primarily whether the remaining penalty is a sufficient deterrent.

F. Special Circumstances/Extraordinary Adjustments

A case may present other factors that the case team believes justify a further reduction of the

penalty.

8

For example, a case may have particular litigation strengths or weaknesses that have

not been adequately captured in other areas of this policy. If the facts of the case or the nature of

the violation(s) at issue reduce the strength of the Agency’s case, then an additional penalty

reduction may be appropriate. If after careful consideration the case team determines that an

additional reduction of the penalty is warranted, it should ensure the case file includes

substantive reasons why the extraordinary reduction of the civil penalty is appropriate, including:

(1) why the penalty derived from the CAA § 112(r) civil penalty matrices and gravity adjustment

is inequitable; (2) how all other methods for adjusting or revising the proposed penalty would not

adequately resolve the inequity; (3) the manner in which the adjustment of the penalty

effectuated the purposes of the Act; and (4) documentation of management concurrence in the

extraordinary reduction. Significant reductions for litigation risk must be approved by the

Director of the Waste and Chemical Enforcement Division. See Final Guidance and Procedures

for Nationally Significant Issues under EPCRA, CERCLA§ 103 and CAA § 112(r), March 9,

2012. EPA should still obtain a penalty sufficient to remove any economic incentive for violating

applicable CAA § 112(r) requirements.

G. Supplemental Environmental Projects

Supplemental Environmental Projects (SEPs) are environmentally beneficial projects that a

respondent agrees to undertake in settlement of an environmental enforcement action, but which

the respondent is not otherwise legally required to perform. Some percentage of the cost of the

SEP is considered as a factor in establishing the final penalty to be paid by the respondent. EPA

has broad discretion to settle cases with appropriate penalties. Evidence of a violator’s

commitment and ability to perform a SEP is a relevant factor for EPA to consider in establishing

an appropriate settlement penalty. While SEPs may not be appropriate in settlement of all cases,

they are an important part of EPA’s enforcement program. Whether to include a SEP as part of a

settlement of an enforcement action is within the sole discretion of EPA. EPA will ensure that

the inclusion of a SEP in settlement is consistent with “EPA Supplemental Environmental

Projects Policy,” effective May 1, 1998, or as revised.

8

See, Appendix C, TSCA Enforcement Policy and Guidance Documents, Memorandum, Documenting Penalty

Calculations and Justifications of EPA Enforcement Actions, James Strock, August 9, 1990.

22

Section 3: Calculating Civil Penalties

V. Settlement of Penalties

This policy should be used to calculate penalties sought in all Part 68 and GDC administrative

complaints or accepted in settlement of both administrative and civil judicial enforcement actions

brought after the date of the policy, regardless of the date of the violation.

VI. Documenting Penalty Settlement Amount

In order to ensure that EPA promotes consistency, it is essential that each case file contain a

complete description of how each penalty was calculated as required by the August 9, 1990,

Guidance on Documenting Penalty Calculations and Justification in EPA Enforcement Actions.

This description should cover how the preliminary deterrence amount was calculated and any

adjustments made to the preliminary deterrence amount. Furthermore, it should explain the facts

and reasons which support such adjustments.

VII. Apportioning the Penalty among Multiple Respondents

This policy is intended to yield a minimum settlement penalty figure for the case as a whole. In

many cases, there may be more than one respondent. In such cases, the case team should

generally take the position of seeking a sum for the case as a whole, which the respondents

allocate among themselves. Civil violations of the CAA are strict liability violations and the case

team generally should not discuss the relative fault of respondents or apportioning the penalty. In

some instances, however, apportionment of the penalty in a multi-respondent case may be

required if one party is willing to settle and other are not. In such cases, if certain portions of the

penalty are attributable to such party, that party should pay those amounts and a reasonable

portion of the amounts not directly assigned to any single party. If the case is settled as to one

respondent, a penalty not less than the balance of the settlement figure for the case as a whole

must be obtained from the remaining respondents.

VIII. Conclusion

Establishing fair, consistent, and sensible guidelines for addressing violations is central to the

credibility of EPA's enforcement of the CAA § 112(r) requirements and to the success of

achieving the goal of equitable treatment. This policy establishes several mechanisms to promote

consistency while retaining flexibility when determining significant violations of the regulations.

Also, the systematic methods for calculating both the economic benefit and gravity components

of the penalty should provide the consistency and flexibility to address any issue fairly (tailored

to the specific circumstances of the violation). Furthermore, this policy sets guidance on uniform

approaches for applying adjustment factors to arrive at an initial amount after negotiations have

begun.

23

Section 4: Appendices

Appendix A

Examples of Common Failures that Have Resulted in General Duty Clause Violations

(This listing is not exhaustive and does not limit the case team from identifying additional

violations and proposing penalties for such violative acts.)

Clean Air Act § 112(r)(1) states: The owners and operators of stationary sources producing,

processing, handling or storing such substances have a general duty in the same manner and

to the same extent as section 654 of title 29 to identify hazards which may result from such

releases using appropriate hazard assessment techniques, to design and maintain a safe

facility taking such steps as are necessary to prevent releases, and to minimize the

consequences of accidental releases which do occur.

FAILURES

To identify hazards:

Failure to identify chemical or process hazards which may result in accidental release or

explosion.

9

Failure to consider risk from adjacent processes, which may pose a threat to the process.

Failure to adequately consider safety considerations given the facility’s siting (e.g., when facility

is located in close proximity to residential neighborhoods, sensitive ecosystems, and/or to an

industrial park containing industries utilizing listed hazardous substances).

9

An important point of reference is the Legislative History for CAA § 112(r). This is Senate Report No. 101-228 in

which the Senate committee stated as follows: “Hazard assessments will be conducted in accordance with guidance

issued by the Administrator. That guidance may draw from recognized hazard evaluation techniques including

elements of any of the eleven different techniques described by the American Institute of Chemical Engineers

(AIChE) in the published report “Guidelines for Hazard Evaluation Procedures.” The applicability of various

techniques at specific facilities depends on the size and complexity of the facilities and the risks presented by the

processes and substances present.” Senate Report at pp. 3606-07. See also, GUIDANCE FOR

IMPLEMENTATION OF THE GENERAL DUTY CLAUSE CLEAN AIR ACT SECTION 112(r)(1) --

http://www.epa.gov/oem/docs/chem/gdcregionalguidance.pdf; “Review of Emergency Systems, Report to Congress,

section 305(b) SARA 1988 TD 811.5.r.263 1988 ; and “Guidelines for Hazard Evaluation Procedures, The Center

for Chemical Process Safety, American Institute of Chemical Engineers 1985, TP155.5g77 1985.

24

Section 4: Appendices

To design and maintain a safe facility taking such steps as are necessary to prevent

releases:

Failure to design and maintain a safe facility. In determining this factor, the case team should

consider the conditions at the facility, applicable design codes, federal and state regulations,

recognized industry practices and/or consensus standards.

10

Failure to provide for sufficient layers of protection. An additional layer of protection would

have prevented the release or explosion.

Failure to update design codes.

Failure to implement a quality control program to ensure that components and materials meet

design specifications and to construct the process equipment as designed.

10

Design failures include, but are not limited to failure to adhere to applicable design codes and/or industry

guidelines, including advisory standards. Examples include: API (American Petroleum Institute) standards; ASME

(American Society of Mechanical Engineers) standards; ANSI (American National Standards Institute) standards;

NFPA (National Fire Protection Association) guidelines; NACE (National Association of Corrosion Engineers)

standards; AIChE (American Institute of Chemical Engineers) guidelines; ISA (Instrument Society of America)

standards; International Fire Code.

Design failures also include failures to adhere to consensus standards which may also include manufacturer’s

procedures. An example of an industry consensus standard is a manufacturer’s product safety bulletin, the Material

Safety Data Sheet, or other publication which outlines safe handling and processing procedures for a specific

chemical or substance. Many of these publications discuss materials of construction, safety equipment, tank design,

and which API or ANSI standards to apply to the handling of that specific chemical or substance.

Other design failures include common sense design flaws or inadequate equipment such as failure to include

sufficient instrumentation to monitor temperature, pressure, flow, pH level, etc. Other design flaws include lack of

emergency shutdown systems, overflow controls, instrumentation interlocks and use of failsafe design. For

example, operators should typically design steam vent valves so that, if they fail, they will fail to a safe part of the

plant and not a part of plant where there is material in process. Instrumentation is vital for any process including

foods processing as well as industrial and petrochemicals. This is especially important in vessels and tank reactors

which handle polymers. Such chemicals have the potential for runaway reactions. It is important to have

automated systems to detect high levels of chemical vapors and alert the appropriate facility personnel/authorities

that a release may be occurring from a process. Such monitors and alarms should be placed in the appropriate

locations.

Maintenance failures would include failures to maintain tanks, piping, instrumentation, valves and fittings, such as

the isolation valves on tanks, or the steam shutoff valves and level switches and gauges. Such failures have

historically contributed to major catastrophic releases and/or explosions. For storage facilities, considerations must

be made for incompatible chemicals, spillage, tank/container integrity, appropriate secondary containment,

appropriate temperature conditions for storage, building code compliance, adequate aisle space for emergency

responders and forklifts, cut off storage, fire protection systems, etc.

25

Section 4: Appendices

Failure to provide for or to properly size pressure-relieving device on a tank or reactor subjected

to pressure.

Failure to train employees as to hazards which they may encounter; Failure to train chemical

plant operators how to safely respond to process or manufacturing upsets.

Failure of operators or employees to implement or follow operating instructions or company

rules.

To minimize the consequences of accidental releases which do occur:

Failure to develop an emergency plan that specifically addresses release scenarios developed

from the identification of hazards and historical information.

Failure to follow emergency plan or to coordinate with LEPC or local emergency management

agency.

Failure to monitor any shutdown of facility.

Failure to mitigate consequences of a releaseor an explosion. This may include the failure to

provide for or properly size an emergency scrubber, knock-out pot or other device or vessel to

contain vapors and expelled substances. This may also include failure to provide for

adequate water spray or deluge system, fire suppression or other minimization system.

Failure to provide for sufficient layers of protection. An additional layer of protection would

have prevented the release or explosion.

Failure to train employees as to hazards which they may encounter; failure to train chemical

plant operators how to safely respond to process or manufacturing upsets.

26

Section 4: Appendices

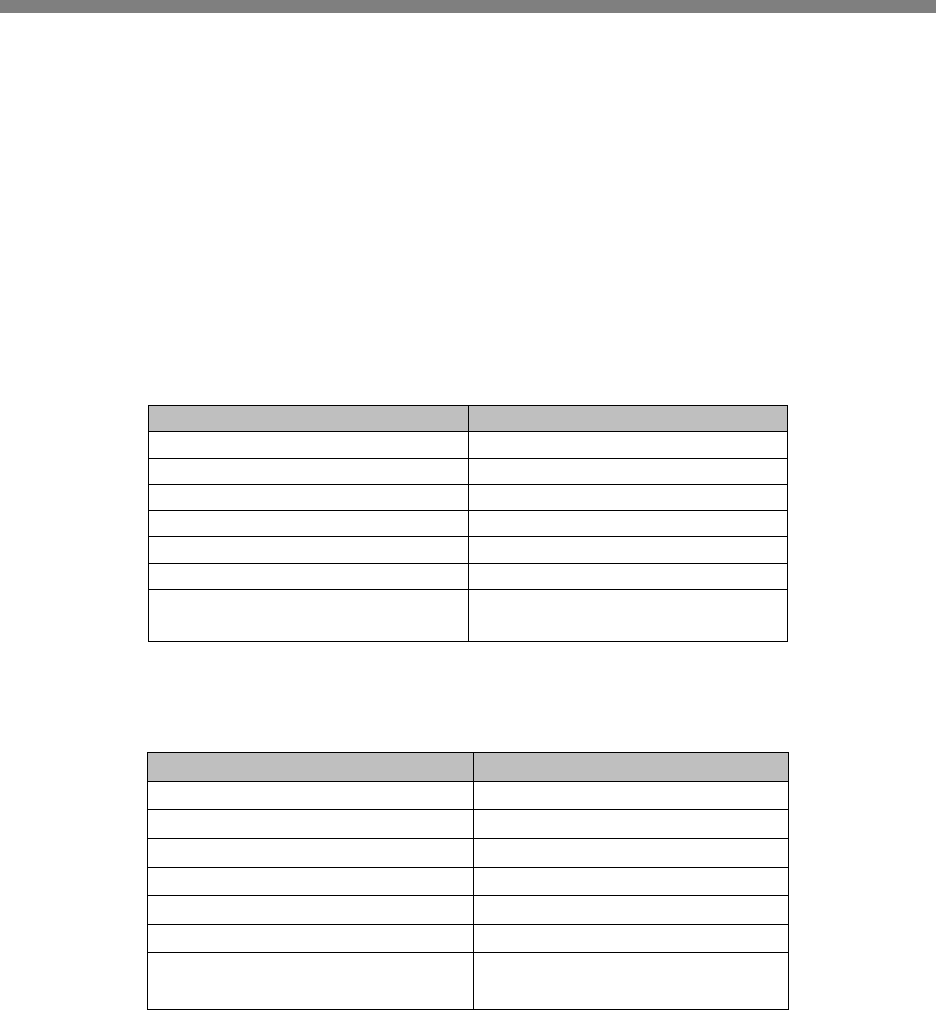

Appendix B

Extent of Damages

If consideration of Extent of Damages is applicable to the action, consider the following incident

consequences to determine which ones may apply to the facts. Each has a number of points

associated with it. After adding up the points, use the multiplying factor to increase the overall

baseline gravity component determined above. The Extent of Damages multiplier should be

applied to the gravity component before adjusting the penalty for Duration of Violation, Size of

Violator, and other adjustments.

Instructions: Depending on the facts and circumstances of the incident, for each chemical or for

the cumulative damage caused by the failures, circle the items that apply and are relative to the

incident. Add the points.

Total Points Multiplying Factor

1-10 1.1 to 2.0

11-20 2.1 to 3.0

21-30 3.1 to 4.0

31-40 4.1 to 5.0

41-50 5.1 to as necessary

Points Description of Incident Consequences

1 Explosion or fire only.

2 Explosion with offsite debris field.

3 Explosion with offsite debris and pressure shock wave.

Onsite and Offsite Release of Substances

Creation of Cloud or Plume.

1

2

3

4

5

Plume smaller than facility and remained onsite before dissipating.

Plume migrated off site then dissipated before reaching into populated area.

Plume large enough to migrate off site and reach into populated area or more

than 1 mile from facility.

Plume large enough to migrate off site and reach into populated area and

impact more than one county or more than 10 miles.

Plume large enough to migrate off site and reach into populated area and

impact more than one county or more than 50 to 100 miles.

27

Section 4: Appendices

Injury or Potential Injury to Human Health

1

2

3

4

Injuries or potential injuries to Human Health, undetermined amounts.

Injuries or potential injuries and/or chemical exposures with treatment by

EMT personnel.

Injuries or potential injuries and/or chemical exposures with hospital

admission.

Deaths or potential for deaths (include intensive care admissions) (multiply

for each).

Damage or Potential Damage to the Environment

1

2

2

3

Damage or potential damage to on-site flora/fauna.

Damage to off-site flora/fauna.

Destroyed or potentially destroyed flora/fauna.

Major environmental impact or threats of impact including: water runoff

from fire fighter water or water knockdown spray creating contaminated

creeks, lakes and ponds.

Damage or Potential Damage to the Facility

1

2

3

Damage or potential damage to facility, undetermined amounts.

Damages or potential damage to facility up to $750,000.

Damage or potential damage to facility greater than $750,000.

Damage or Potential Damage Offsite -- Public, Residential or Commercial

1

2

3

Damage or potential damage to offsite properties- undetermined amounts.

Damage or potential damage to offsite properties up to $750,000.

Damage or potential damage to offsite properties greater than $750,000.

Inconvenience to Public

1 Sheltering in place.

1

2

3

Evacuation of public for less than 4 hours.

Evacuation of public for more than 4 hours but less than 2 days.

Evacuation of public for 2 days or more.

1

2

More than 100 people evacuated or sheltered.

More than 500 people evacuated or sheltered.

28

Section 4: Appendices

3

4

5

More than 1,000 people evacuated or sheltered.

More than 10,000 people evacuated or sheltered.

More than 50,000 people evacuated or sheltered.

Interruption of Commerce

1 Closure of highways or roads; closure of businesses, undetermined amount of

time.

2

3

4

Closure of interstate highways; closure of businesses 1- 3 days.

Closure of ship channels; closure of businesses 3-5 days.

Closure of air space; closure of businesses more than 5 days.

Amount of Chemical or Substance Released

1 Amount of substance(s) released less than 1 pound but detected by

instruments.

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Amount of substance(s) released greater than 1 pound but less than or equal

to10 pounds.

Amount of substance(s) greater than 10 pounds but less than or equal to100

pounds.

Amount of substance(s) released greater than 100 pounds but less than or

equal to 1000 pounds.

Amount of substance(s) greater than 1000 pounds but less than or equal to

10,000 pounds.

Amount of substance(s) released greater than 10,000 pounds but less than or

equal to 100,000 pounds.

Amount of substance(s) greater than 100,000 pounds but less than or equal to

300,000 pounds.

Amount of substance(s) released greater than 300,000 pounds but less than or

equal to 1,000,000 pounds.

Amount of substance(s) greater than 1,000,000 pounds but less than or equal

to 10,000,000 pounds.

Amount of substance(s) released greater than 10,000,000 pounds.

Toxicity of Chemical/Substance:

IDLH = Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health concentrations.

1

2

3

4

5

If Toxicity of released substance(s) is IDLH 1000 ppm or more

If Toxicity of released substance(s) is IDLH 500 to 999 ppm

If Toxicity of released substance(s) is IDLH 400 to 499 ppm

If Toxicity of released substance(s) is IDLH 300 to 399 ppm

If Toxicity of released substance(s) is IDLH 200 to 299 ppm

29

5

Section 4: Appendices

6 If Toxicity of released substance(s) is IDLH 51 to 199 ppm

7 If Toxicity of released substance(s) is IDLH 11-50 ppm

8 If Toxicity of released substance(s) is IDLH 6-10 ppm

9 If Toxicity of released substance(s) is IDLH 1-5 ppm

10 If Toxicity of released substance(s) is IDLH less than 1 ppm

Other Factors

Carcinogen

Example list of substances and corresponding IDLH levels. Source NIOSH, 1997 Pocket Guide

to Chemical Hazards.

SUBSTANCE IDLH

PHOSGENE 2 PPM

BROMINE 3 PPM

CHLORINE 10 PPM

SULFURIC ACID MIST 15 PPM

ALLYL ALCOHOL 20 PPM

NITRIC ACID 25 PPM

HYDROFLOURIC ACID 30 PPM

HYDROGEN CYNANIDE 50 PPM

HYDROGEN SULFIDE 100 PPM

NITRO TOLUENE 200 PPM

NITRO BENZENE 200 PPM

AMMONIA 300 PPM

TOLUENE 500 PPM

BENZENE 500 PPM

30

Section 4: Appendices

Appendix C

Internet References for Policy Documents

Depending on the facts and circumstances of each case, the following policies should be consulted as appropriate:

Parallel Proceedings Policy:

http://www.epa.gov/compliance/resources/policies/enforcement/parallel-proceedings-policy-09-

24-07.pdf

Supplemental Environmental Projects:

http://cfpub.epa.gov/compliance/resources/policies/civil/seps/

Final Supplemental Environmental Projects Policy (1998):

http://www.epa.gov/compliance/resources/policies/civil/seps/fnlsup-hermn-mem.pdf

Incentives for Self-Policing: Discovery, Disclosure, Correction and Prevention of Violations (Audit Policy):

http://www.epa.gov/compliance/incentives/auditing/auditpolicy.html

Small Compliance Business Policy:

http://www.epa.gov/compliance/incentives/smallbusiness/index.html

Redelegation of Authority:

http://www.epa.gov/compliance/resources/policies/civil/rcra/hqregenfcases-mem.pdf

Documenting Penalty Calculations and Justifications of EPA Enforcement Actions, (Aug 1990):

http://www.epa.gov/compliance/resources/policies/civil/rcra/caljus-strock-mem.pdf

Amendments to Penalty Policies to Implement Penalty Inflation Rule 2008:

http://cfpub.epa.gov/compliance/resources/policies/civil/penalty/

Policy on Flexible State Enforcement Responses to Small Community Violations:

http://epa.gov/compliance/resources/policies/incentives/smallcommunity/scpolicy.pdf

Equal Access to Justice Act:

http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/html/uscode05/usc_sec_05_00000504----000-.html

Policy on Civil Penalties -- EPA General Enforcement Policy #GM-21:

http://www.epa.gov/compliance/resources/policies/civil/penalty/epapolicy-

civilpenalties021684.pdf

A Framework for Statute-Specific Approaches to Penalty Assessments: Implementing EPA's Policy on Civil

Penalties -- EPA General Enforcement Policy #GM - 22:

http://www.epa.gov/compliance/resources/policies/civil/penalty/penasm-civpen-mem.pdf

Enforcement Economic Models:

http://www.epa.gov/compliance/civil/econmodels/

31