A picture of the National Audit Office logo

SESSION 2022-23

24 MAY 2022

HC 243

REPORT

by the Comptroller

and Auditor General

Environmental compliance

and enforcement

Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs

The National Audit Office (NAO) scrutinises public spending

for Parliament and is independent of government and the civil

service. We help Parliament hold government to account and

weuse our insights to help people who manage and govern

public bodies improve public services.

The Comptroller and Auditor General (C&AG), Gareth Davies,

is an Officer of the House of Commons and leads the NAO.

Weaudit the financial accounts of departments and other

publicbodies. We also examine and report on the value for

money of how public money has been spent.

In 2020, the NAO’s work led to a positive financial impact

through reduced costs, improved service delivery, or other

benefits to citizens, of £926 million.

We are the UK’s

independent

public spending

watchdog.

We support Parliament

in holding government

toaccountand we

help improve public

services throughour

high-quality audits.

Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General

Ordered by the House of Commons

to be printed on 23 May 2022

This report has been prepared under Section 6 of the

National Audit Act 1983 for presentation to the House of

Commons in accordance with Section 9 of the Act

Gareth Davies

Comptroller and Auditor General

National Audit Office

17 May 2022

HC 243 | £10.00

Environmental compliance

and enforcement

Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs

The material featured in this document is subject to National Audit

Office (NAO) copyright. The material may be copied or reproduced

for non-commercial purposes only, namely reproduction for research,

private study or for limited internal circulation within an organisation

for the purpose of review.

Copying for non-commercial purposes is subject to the material

being accompanied by a sufficient acknowledgement, reproduced

accurately, and not being used in a misleading context. To reproduce

NAO copyright material for any other use, you must contact

[email protected]. Please tell us who you are, the organisation

you represent (if any) and how and why you wish to use our material.

Please include your full contact details: name, address, telephone

number and email.

Please note that the material featured in this document may not

be reproduced for commercial gain without the NAO’s express and

direct permission and that the NAO reserves its right to pursue

copyright infringement proceedings against individuals or companies

who reproduce material for commercial gain without our permission.

Links to external websites were valid at the time of publication of

this report. The National Audit Office isnot responsible for the future

validity of the links.

012143 05/22 NAO

© National Audit Office 2022

Contents

Aim of this briefing 4

Government’s overarching

environmental objectives andtargets 8

The main government bodies

responsible for environmental

complianceand enforcement 11

Environment Agency 13

Natural England 19

Office for Environmental Protection 21

How environmental compliance

ischanging 22

Case examples

Case example 1: Sites of special

scientific interest (SSSI) 24

Case example 2: Waste crime 29

Case example 3: Storm overflows 34

Appendix One

Our evidence base 39

If you are reading this document with a screen reader you may wish to use the bookmarks option to navigate through the parts. If

you require any of the graphics in another format, we can provide this on request. Please email us at www.nao.org.uk/contact-us

This report can be found on the

National Audit Office website at

www.nao.org.uk

If you need a version of this

report in an alternative format

for accessibility reasons, or

any of the figures in a different

format, contact the NAO at

For further information about the

National Audit Office please contact:

National Audit Office

Press Office

157–197 Buckingham Palace Road

Victoria

London

SW1W 9SP

020 7798 7400

www.nao.org.uk

@NAOorguk

4 Aim of this briefing Environmental compliance and enforcement

Aim of this briefing

Introduction

1 The purpose of this briefing is to support the Environmental Audit

Committee’s(the Committee’s) scrutiny of government’s environmental protection

work. It aims to provide the Committee with factual analysis as it considers the

impact of significant changes to environmental protection following EU Exit and

the Environment Act 2021, and concerns that have been raised about the work of

the regulators. Duringitsinquiries into water quality and biodiversity, issues arose

about the extentand effectiveness of government’s environmental compliance and

enforcement work including the response to reported breaches of environmental

standards andregulations.

1,2

2 The briefing gives a factual overview of the framework for environmental

compliance and enforcement in England, covering:

•

the definition of environmental compliance, its role in regulation and how it

relates to other concepts;

•

government’s overarching environmental objectives and targets and how they

are measured;

•

the roles and responsibilities of the main bodies responsible for environmental

compliance and enforcement;

•

what is known about the main bodies responsible for compliance and

enforcement, including performance, staffing and spend; and

•

recent changes for environmental compliance and enforcement.

3 It also includes case examples on compliance and enforcement issues

associated with waste crime, sites of special scientific interest and storm overflows.

1 HC Environmental Audit Committee, Water quality in rivers, Fourth Report of Session 2021-22, HC 74,

January2022, available at: https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/8460/documents/88412/default/

2 HC Environmental Audit Committee, Biodiversity in the UK: bloom or bust?, First Report of Session 2021-22,

HC136, June 2021, available at: https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/6498/documents/70656/default/

Environmental compliance and enforcement Aim of this briefing 5

Approach

4 This briefing summarises publicly available information and additional data we

requested from the Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (Defra), the

Environment Agency, Natural England and the Office for Environmental Protection.

5 It draws on our Principles of effective regulation framework (see Figure 2

on page 7) to highlight the importance of compliance and enforcement within

environmental regulation. We have used the principles as a framework for the

factualinformation we set out on government bodies and case examples, and to

draw out key issues.

3

6 The case examples are designed to illustrate the issues we cover using specific

areas of environmental protection in which there is strong public interest. They draw

on wider published National Audit Office (NAO) work on the environment and provide

specific demonstrations of the risks to environmental protection and the importance

of effective compliance and enforcement.

7 In order to help the Committee build on its previous findings, we have

highlighted issues arising within each section of the briefing. These are intended

as areas for further consideration by the Committee and can be used to support its

future inquiries.

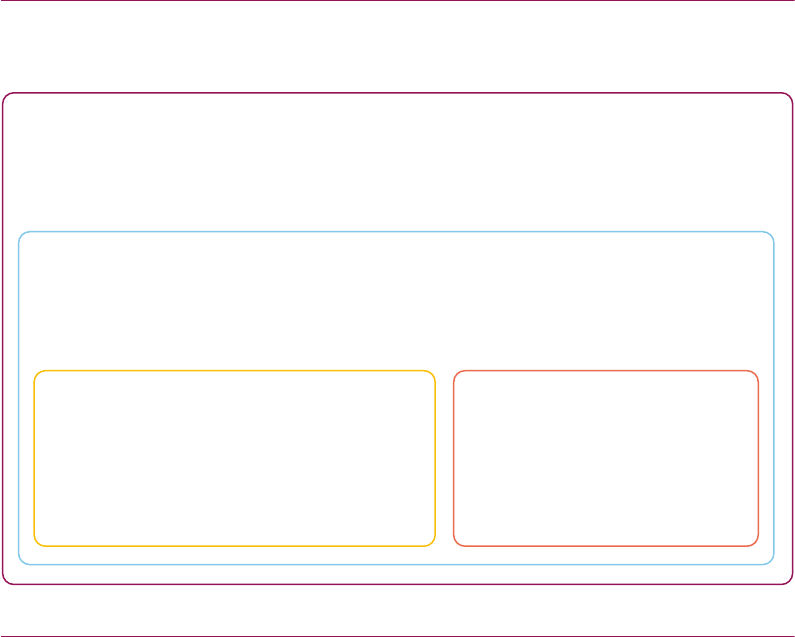

Definition of environmental compliance and enforcement

8 For the purpose of this briefing, we use environmental compliance to mean

action to encourage and require compliance with regulations, standards and permits,

whileenvironmental enforcement is the action against non-compliance or criminal

activity (Figure 1 overleaf).

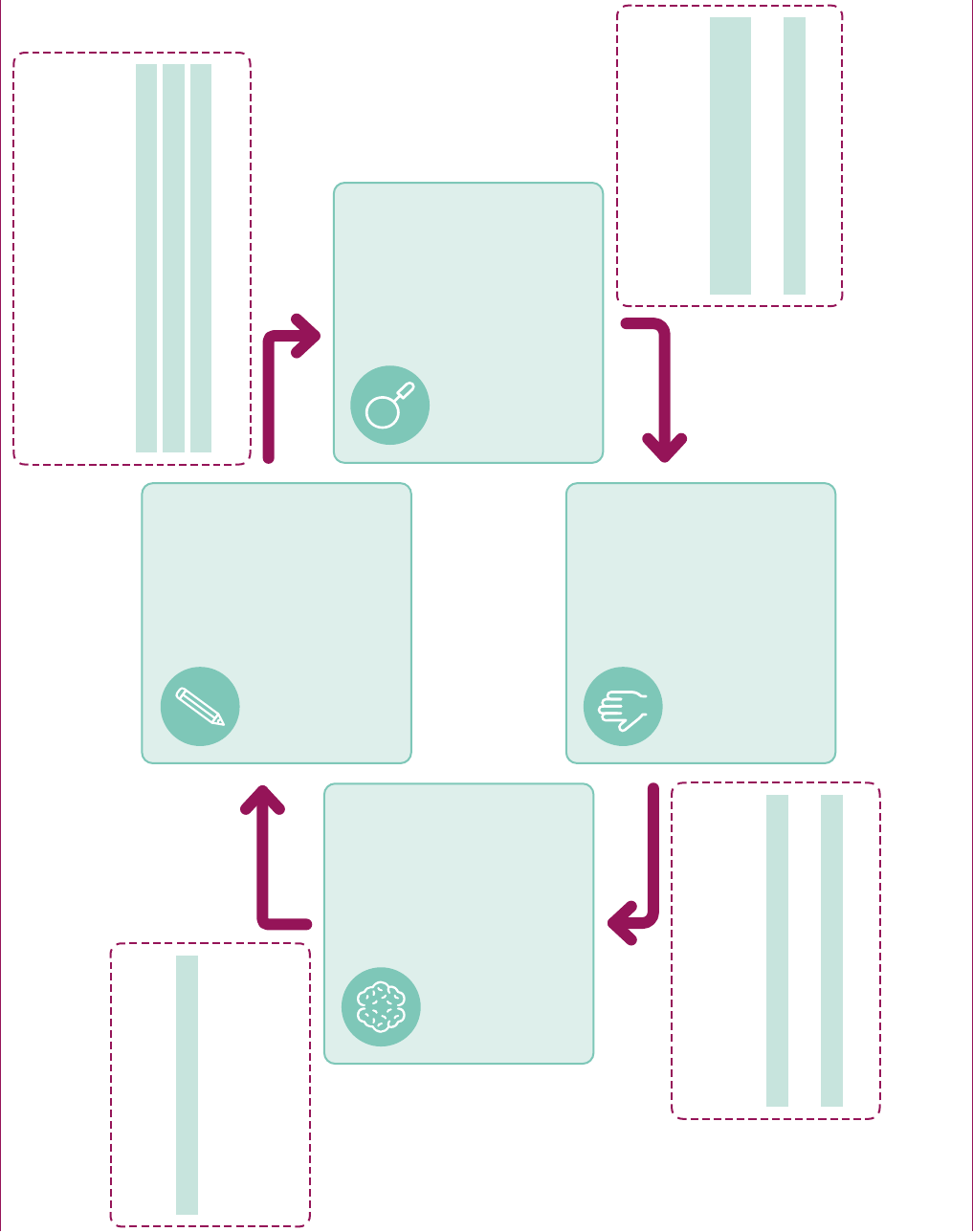

Principles of effective regulation

9 Compliance and enforcement activities are important parts of ensuring effective

regulation. Our Principles of effective regulation guide sets out the broad principles

of effective regulation, using a ‘learning cycle’ for assessing how well regulators and

policymakers are applying these principles (Figure 2 on page 7). Principles that are

central to effective compliance and enforcement include: monitoring service provider

compliance and incentives; ensuring capacity and capability; ensuring interventions

are proportionate, and measuring performance.

3 National Audit Office, Principles of effective regulation, May 2021.

6 Aim of this briefing Environmental compliance and enforcement

Environmental protection

In this briefing, we use the term environmental protection to mean maintaining or restoring natural

resources such as plants, animals, water, soil and the air. It encompasses government’s overall

approach to protecting the natural environment, includingdirect project delivery and setting up

environmental regulation systems.

Environmental regulation

Within this sits environmental regulation. Regulation is one tool government uses to achieve

its policy aims and is characterised by a set of rules and expected behaviours that people and

organisations should follow. It can include the issuing of permits, consents, licences, standards

and regulations.

Environmental compliance

Environmental compliance is a subset of

environmental regulation, which is action

to encourage and require compliance with

regulations, standards and permits. For example,

this could include monitoring, inspections,

guidance and support.

Environmental enforcement

Environmental enforcement is

action against the non-compliant

and potential criminals operating in

the market, which can include civil

penalties and prosecutions.

Source: National Audit Offi ce analysis of publicly available information

Figure 1

Defi nition of environmental protection, regulation, compliance and enforcement

Environmental compliance and enforcement Aim of this briefing 7

Analyse principles:

Using information and data

Embedding the citizenperspective

Monitoring service provider

compliance and incentives

Engaging with stakeholders

Ensuring capacity andcapability

Adopting a forward-looking approach

Design principles:

Defining the overall purpose ofregulation

Setting regulatory objectives

Ensuring accountability

Determining the degree of regulatoryindependence

Deciding on powers

Determining a funding model

Designing organisational structure andculture

Learn principles:

Establishing governance processes

Measuring performance

Evaluating impact andoutcomes

Engendering cooperation

andcoordination

Ensuring transparency

Intervene principles:

Developing a theory ofchange

Prioritising interventions

Drawing on a range of regulatorytools

Embedding consistency andpredictability

Ensuring interventions areproportionate

Being responsive

2. Analyse

These principles are to help

regulators and policymakers

analyse the market or issue being

regulated, and identify and assess

where problems are occurring

that may require intervention.

3. Intervene

Where regulators identify

problems, these principles are

to help them understand what

impact they might have, prioritise

actions, and consider how best

torespond.

1. Design

These principles are to help

translate the policy intent

and purpose of regulation

into the design of an overall

regulatoryframework.

4. Learn

These principles are to help

regulators and policymakers

maximise their effectiveness in

future by learning from experience

and working in a joined-up way

with other organisations.

Figure 2

Principles of effective regulation

Note

1

Highlighted principles are central to effective compliance and enforcement.

Source: National Audit Offi ce,

Principles of effective regulation, May 2021

8 Government’s overarching environmental objectives and targets Environmental compliance and enforcement

Government’s overarching

environmental objectives andtargets

10 Government wants this to be the first generation to leave the natural

environmentofEngland in a better state than it inherited and to help protect and

improve the global environment. In order to do so, it has committed to long term

cross-government goals (Figure 3).

How these are measured

11 An effective environmental performance framework is essential for government

to understand how it is performing against its objectives and to allow it to make

informed decisions.

12 Government collects and reports a wide range of environmental performance

metrics. These are a mixture of metrics used by government and stakeholders

to assess progress against domestic policy and to report against international

commitments. The four main sets of metrics cover reporting against:

•

Defra’s Outcome Indicator Framework;

4

•

the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals;

5

•

international conventions on climate change and biodiversity; and

•

the national Environmental Accounts, a set of supplementary accounts to the

UK’s National Accounts that measure the contribution of the environment to

society, and the impact of economic activity on the environment.

6

4 Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs, Outcome Indicator Framework for the 25 Year Environment Plan,

2021, available at: https://oifdata.defra.gov.uk/

5 There are 17 Sustainable Development Goals, adopted by all United Nations member states in 2015, covering

issues such as climate action, life on land and affordable and clean energy. The Sustainable Development Goals,

areavailable at: https://sdgs.un.org/goals

6 Office for National Statistics, Environmental Accounts, available at: www.ons.gov.uk/economy/environmentalaccounts

Environmental compliance and enforcement Government’s overarching environmental objectives and targets 9

Figure 3

Government’s overarching environmental objectives and targets

Source: National Audit Offi ce analysis of publicly available information

Environment Act

In 2021 the Environment Act set the overarching environmental legislation and required the government to set new long-term

legally binding environmental improvement targets in fourpriorityareas:

Net zero

In 2019, the government and the devolved administrations

committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions to

netzeroby2050.

Net zero strategy (2021)

In 2021 government also published its netzero strategy,

which sets out policies and proposals for decarbonising

allsectors of the UK economy by 2050.

COP26

The COP26 Glasgow Climate Pact in 2021 also saw

government pledge to fulfil its global role on climate

changethrough:

•

mitigation – reducing emissions;

•

adaptation – helping those already impacted by

climatechange;

•

finance – enabling countries to deliver on their

climategoals; and

•

collaboration – working together to deliver even

greateraction.

25 Year Environment Plan

The Environment Act requires the government to publish

an Environmental Improvement Plan(EIP). In January2018,

government published its 25 Year Environment Plan

(thePlan) which was adopted as the first EIP. The plan set

10overarching environmentalgoals:

•

Clean air

•

Thriving plants and wildlife

•

Enhancing biosecurity

•

Clean and plentiful water

•

Using resources more sustainably andefficiently

•

Minimising waste

•

A reduced risk from environmental hazards

•

Enhanced beauty, heritage and engagement

withenvironment

•

Mitigating and adapting to climatechange

•

Managing exposure to chemicals

Other strategies

Government has published strategies to set out its path to achieving its environmental objectives onspecific topics including:

•

Clean air strategy (2019)

•

Resources and waste strategy (2018)

BiodiversityAir quality Water

Resource efficiency

and waste reduction

10 Government’s overarching environmental objectives and targets Environmental compliance and enforcement

13 The Outcome Indicator Framework contains 66 indicators relating to the

10goals within the 25 Year Environment Plan. It pulls together information across

government and includes a number of compliance and enforcement-related

indicators, such as serious pollution incidents in water, extent and condition of

protected sites and waste crime, which we will discuss in the case examples below.

While the Framework is not in itself an official statistic, Defra states that it follows

theUK’s code of practice for statistics where possible in its production.

14 Defra publishes an annual progress report against the 25 Year Environment

Plan goals informed by the Outcome Indicator Framework and other evidence.

7

Thelatest report covering April 2020 to March 2021 assessed performance on one

third of 27 outcomes listed as “mostly desirable”, with 11 showing a “mixed picture”

and performance “mostly undesirable” on seven. The newly established Office for

Environmental Protection has responsibility for monitoring, critically assessing

and reporting on government’s progress in improving the natural environment

andpublished its first review of progress in May 2022.

7 HM Government, 25 Year Environment Plan Annual Progress Report, October 2021, available at: https://assets.

publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1032472/25yep-progress-

report-2021.pdf

Issues arising on environmental objectives

The Committee may wish to explore the following areas:

•

Defra’s oversight of the environmental compliance and enforcement work undertaken by public bodies

and whether it understands the implications of their performance on its 25 year aims.

•

How Defra defines and assesses performance against the 25 Year Environment Plan, using the

Outcome Indicator Framework and other evidence.

•

How Defra coordinates work across bodies which are working to shared goals.

Environmental compliance and enforcement The main government bodies responsible 11

The main government bodies

responsible for environmental

complianceand enforcement

15 Many areas of regulation involve one or more main regulators with specific

powers and duties to enforce or otherwise influence compliance with rules and

standards. These regulators can be at national and local level (Figure 4 overleaf).

Sometimes there is not a clear boundary between regulators’ remits, requiring them

to work closely together. Some public bodies that are not generally considered

regulators also deliver regulatory functions, such as local authorities.

16 The following pages give more information about the role, performance,

staffing, and spend on environmental compliance of the Environment Agency,

Natural England and Office for Environmental Protection.

12 The main government bodies responsible Environmental compliance and enforcement

Figure 4

The main environmental compliance and enforcement responsibilities

bypublic body

The Office for Environmental Protection holds government and public bodies to account for their

compliance with environmental law.

Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs has the overall policy responsibility for government’s

environmental goals. It relies on other organisations to monitor and enforce compliance with

environmental regulation and in some cases the environmental regulation itself is introduced and

overseen by other government departments.

Environment Agency is the environmental

regulator in England responsible for major

industry and waste, treatment of contaminated

land, water quality and resources, fisheries,

inland river, estuary and harbour navigations,

andconservationand ecology.

Natural England is the government’s adviser

on thenatural environment, it has regulatory

functionsand has the powers to enforce laws

that protect wildlife and the natural environment,

particularly protected sites and species.

Other environmental compliance and enforcement responsibilities by public body include:

•

Marine Management Organisation is responsible for licensing activities in the seas around

Englandto protect and enhance the marine environment.

•

Rural Payments Agency administers subsidies to farmers, traders and landowners to support

rural communities, as well as licensing the agri-food sector and regulating markets for dairy

andfarmproduce.

•

Health and Safety Executive is the regulator for work related health and safety, and is responsible

forregulating chemicals (including pesticides).

•

Forestry Commission is responsible for protecting, expanding and promoting the sustainable

management of woodlands, including licensing tree-felling.

•

Ofwat conducts the economic regulation of water and wastewater companies. Through the price

review process, it seeks to allow efficient funding for investment in environmental initiatives and

incentivises companies to deliver environmental improvements. It also takes regulatory action in

relation to breaches of its licence conditions and statutory obligations.

•

Local Authority Environmental Health and Trading Standards Services ensure compliance with a

range of environmental regulations in their local areas, for example on compliance with minimum

energy efficiency standards and single use plastic bag charging.

Source: National Audit Offi ce analysis of publicly available information

Environmental compliance and enforcement Environment Agency 13

Environment Agency

Role and reported overall performance on environmental compliance

17 The Environment Agency has compliance and enforcement responsibilities

fora range of sectors including agriculture, industry and waste management.

Thesecontribute to two of its three long term goals: “healthy air, land and water”;

and“green growth and a sustainable future”. These goals, and corresponding

five-yearaims, are set out in EA2025, which details the Environment Agency’s

priorities from 2020-25.

8

In its Regulating for people, the environment and growth

2020, the Environment Agency reported high (97% or more) rates of compliance

at industrial sites and in the energy efficiency and emissions trading schemes it

administers.

9

However it also reported that despite the progress made, the overall

quality of the environment is not where it, its partners, or society wants it to be

(Figure5 overleaf).

Compliance and enforcement activity

18 The Environment Agency records its compliance and enforcement activity

as outputs, which can be a range of activities, for example, issuing guidance,

sampling water quality, site audits and inspections, warning letters and prosecution

(Figure 6 on page 15). The overwhelming majority of these outputs have remained

compliancerelated. Between 2015 and 2021, most (81%) of the Environment

Agency’s compliance outputs related to its aim that ‘by 2025 rivers, lakes,

groundwater and coasts will have better water quality and will be better places

forpeople and wildlife’, and 10% to its aim that ‘by 2025 we will have cut waste

crime and helped develop a circular economy’.

19 The Environment Agency has published an enforcement and sanctions policy,

in which it commits to making sure its enforcement response is proportionate and

appropriate to each situation. It considers that interventions such as enforcement

notices and civil sanctions are often more effective than prosecution.

20 The Environment Agency told us the COVID-19 pandemic affected its

compliance and enforcement work in 2020 and in 2021 by restricting physical

inspections, requiring it to rely on other aspects of its regulatory approach such

asgathering intelligence, analysing data and remote audits.

8 Environment Agency, EA 2025, July 2020, available at: www.gov.uk/government/publications/environment-agency-

ea2025-creating-a-better-place

9 Environment Agency, Regulating for people, the environment and growth, 2020, October 2021, available at:

www.gov.uk/government/publications/regulating-for-people-the-environment-and-growth-2020

14 Environment Agency Environmental compliance and enforcement

Figure 5

Environment Agency’s reported performance on compliance and enforcement

activity that directly supports its ability to achieve its goals in 2020

Goal Five-year aims Environment Agency’s reporting of performance

in 2020

Healthy air,

land and water

By 2025 air will be

cleaner and healthier

Between 2010 and 2020 emissions of nitrogen oxides

from the 13,708 sites that the Environment Agency

regulates have decreased by 69%, sulphur oxides

by86% and small particulates by 47%.

Based on a five-year moving average, the permit

compliance rate at industrial sites has remained at

97%since 2013.

By 2025 rivers, lakes,

groundwater and

coasts will have better

water quality and will

be better places for

peopleandwildlife

In 2020, 86% of river water bodies had not reached

good ecological status.

The Environment Agency removed the risk of the

over-abstraction of more than 600 billion litres of water

from the environment, through changing, reviewing

andrevoking abstraction licences.

Green

growth and a

sustainable

future

By 2025 we will achieve

cleaner, greener

growth by supporting

businesses and

communities to make

good choices, through

our roles as a regulator,

adviser andoperator

Since 2010 emissions of greenhouse gases from the

13,708 sites that the Environment Agency regulates

under the Environmental Permitting Regulations have

decreased by 50%.

Since 2010 methane emissions from the sites it

regulatesunder the Environmental Permitting

Regulations have decreased by 45%.

The Environment Agency achieved 98% compliance in

the five major energy efficiency and emissions trading

schemes it administers. These cover more than 40%

ofthe UK’s carbon emissions from industry, business

andthe public sector.

By 2025 we will have

cut waste crime and

helped develop a

circulareconomy

The Environment Agency recognises there is progress

still to be made on waste crime, and this area of its work

is discussed in more detail in the case example section

ofthis briefing (see pages 29 to 34).

Note

1

This information is drawn from the Environment Agency’s latest report Regulating for people, the environment

andgrowth, 2020. The Environment Agency reported data for the 2020 calendar year, or for 2020-21 where

information was only available by fi nancial year.

Source: National Audit Offi ce analysis of Environment Agency documents

Environmental compliance and enforcement Environment Agency 15

Spend on compliance and enforcement

21 The Environment Agency uses fees and charges from permits and licence

holders to fund compliance activity. From April 2018 the Environment Agency

implemented a revised charging scheme following a review of its fees and charges,

which raised income for compliance activity and overheads to £338 million in

2020-21 from £294 million in 2015-16.

10

10 Fees and charges income funds Environment Agency overheads such as human resources and estate costs

aswellas compliance activity.

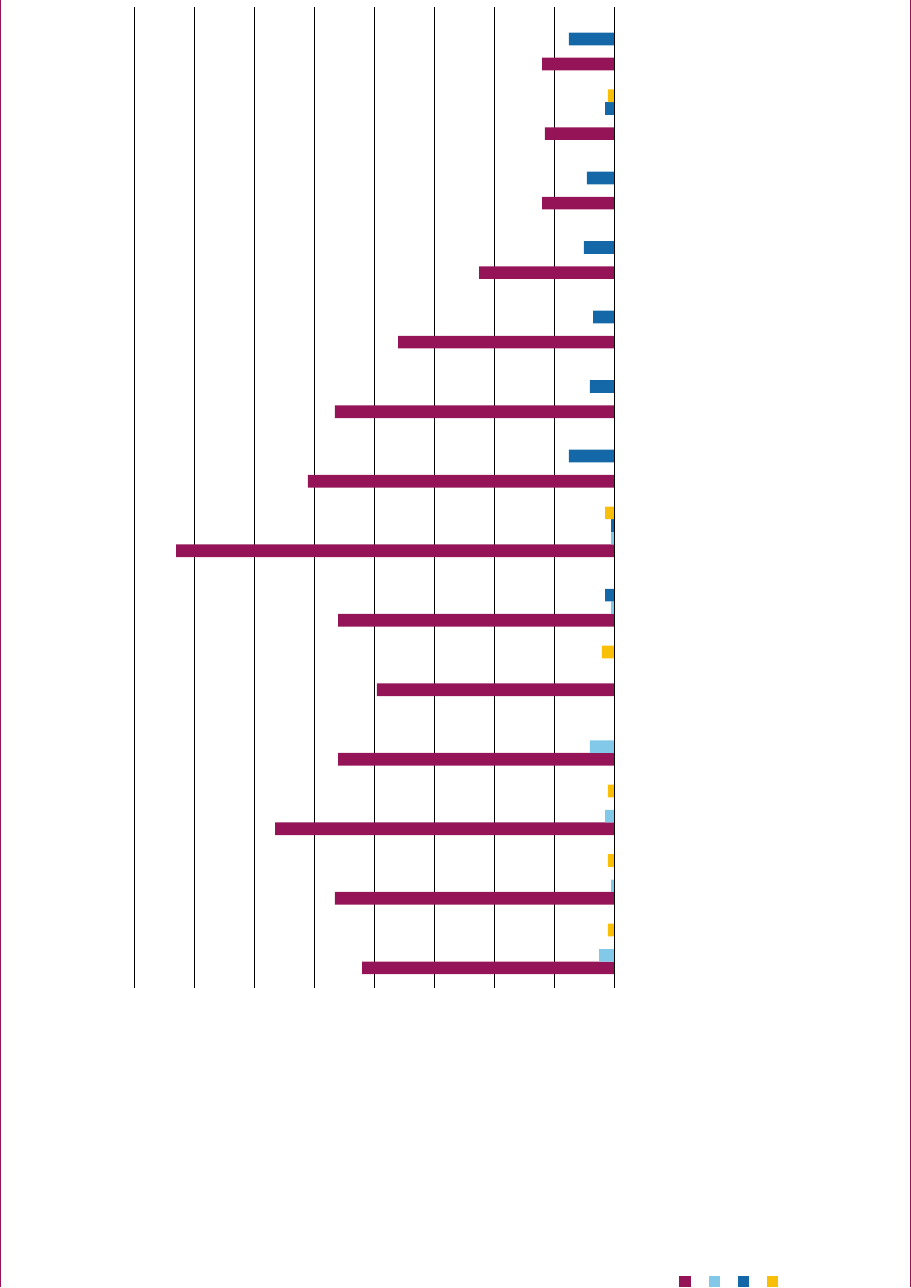

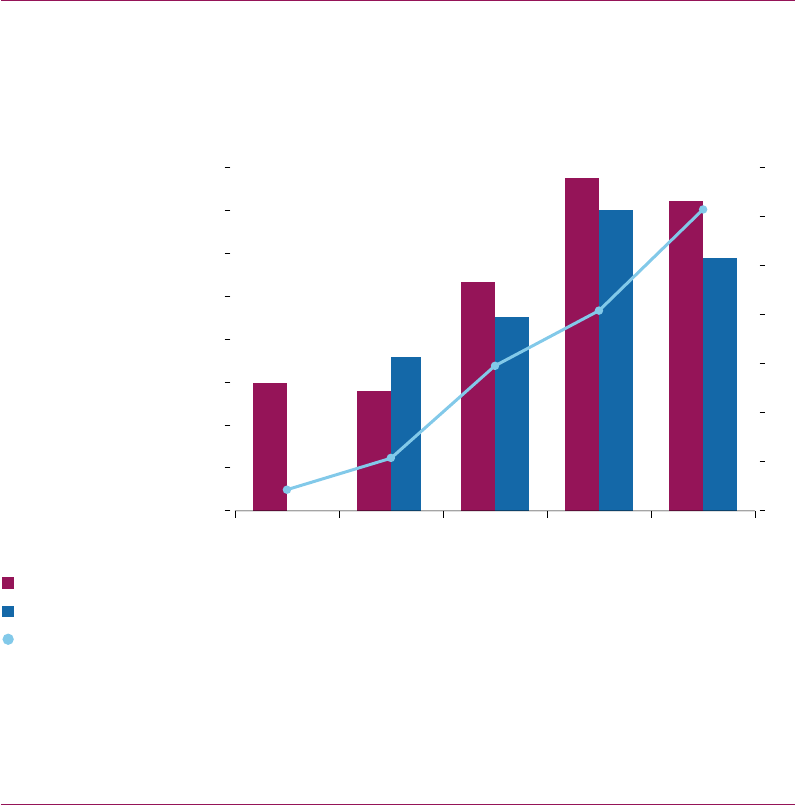

Figure 6

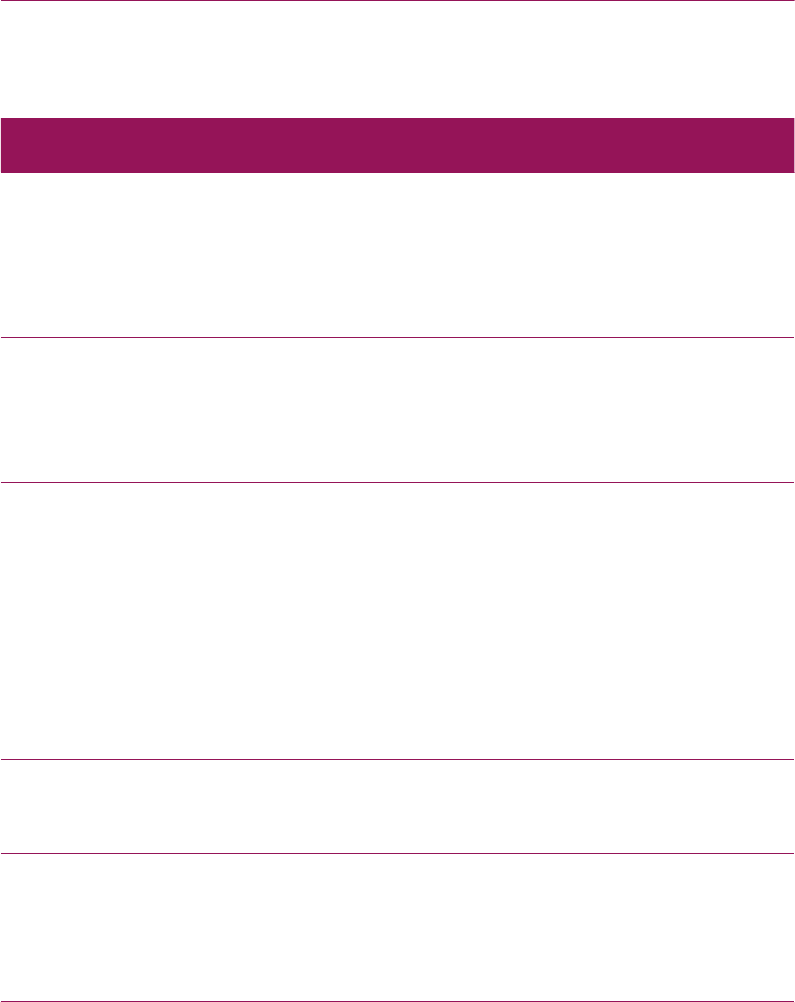

Environment Agency annual outputs between 2015 and 2021, by category

Number of outputs (000)

201520162017 2018 2019 2020 2021

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

Year

Note

1 Data are reported in calendar years.

Source: National Audit Office analysis of Environment Agency data

Compliance 166,339 156,361 154,950 148,876 161,589 78,132 117,460

Notices/letters 1,387 1,285 1,778 1,758 2,283 1,674 1,525

Enforcement 188 242 318 397 294 207 252

16 Environment Agency Environmental compliance and enforcement

22 Enforcement activities cannot be cross-subsidised from charges that

the Environment Agency makes for permits and licences. Instead, it allocates

resourcesto enforcement from its grant-in-aid funding for environmental protection.

This grant-in-aid funding fell by 80% between 2010-11 and 2020-21. Furthermore,

the amount of grant-in-aid that is ring-fenced for particular projects, including for

non-enforcement activity, has grown.

23 Between 2010-11 and 2020-21 the amount of grant-in-aid that the Environment

Agency allocated to generic enforcement activity fell from £11.6 million to £7 million.

This includes enforcement associated with the regulation of industrial facilities,

storm overflows and fisheries, as well as in response to serious pollution incidents.

Over the same period ringfenced funding for enforcement to tackle waste crime rose

to £10 million (Figure 7). From 2022-23, the Agency’s previously ring-fenced funding

for waste crime will be incorporated into its core funding.

Staffing for compliance and enforcement

24 The Environment Agency employed 2,711 full-time-equivalent (FTE) staff for

compliance activities in March 2022 and 294 on enforcement roles. On average, the

Environment Agency employs one member of enforcement staff to 10 compliance staff

(Figure 8 on page 18). The number of vacancies has fluctuated over the past six years,

with vacancies as a percentage of total compliance and enforcement staff reaching a

10% high in 2019, falling to 2% in 2021 and increasing again to 6% in 2022.

Issues arising on the Environment Agency

The Committee may wish to explore the following areas:

•

The amount of grant-in-aid allocated for enforcement and the rationale for this

•

How it has responded to its acknowledgement that its progress on the quality of the environment falls

short of expectations.

•

How it ensures its fees and charges income is reflective of the level of risk in its compliance work.

•

How Defra ensures the Environment Agency has the appropriate regulatorytools and funding to

provide effective environmental compliance and enforcement.

•

How its changing use of regulatory tools and approaches has impacted compliance and enforcement

with environmental regulation.

•

The Environment Agency and Defra’s understanding of the skills and staffing needed to deliver their

compliance and enforcement work, both now and inthe future.

Environmental compliance and enforcement Environment Agency 17

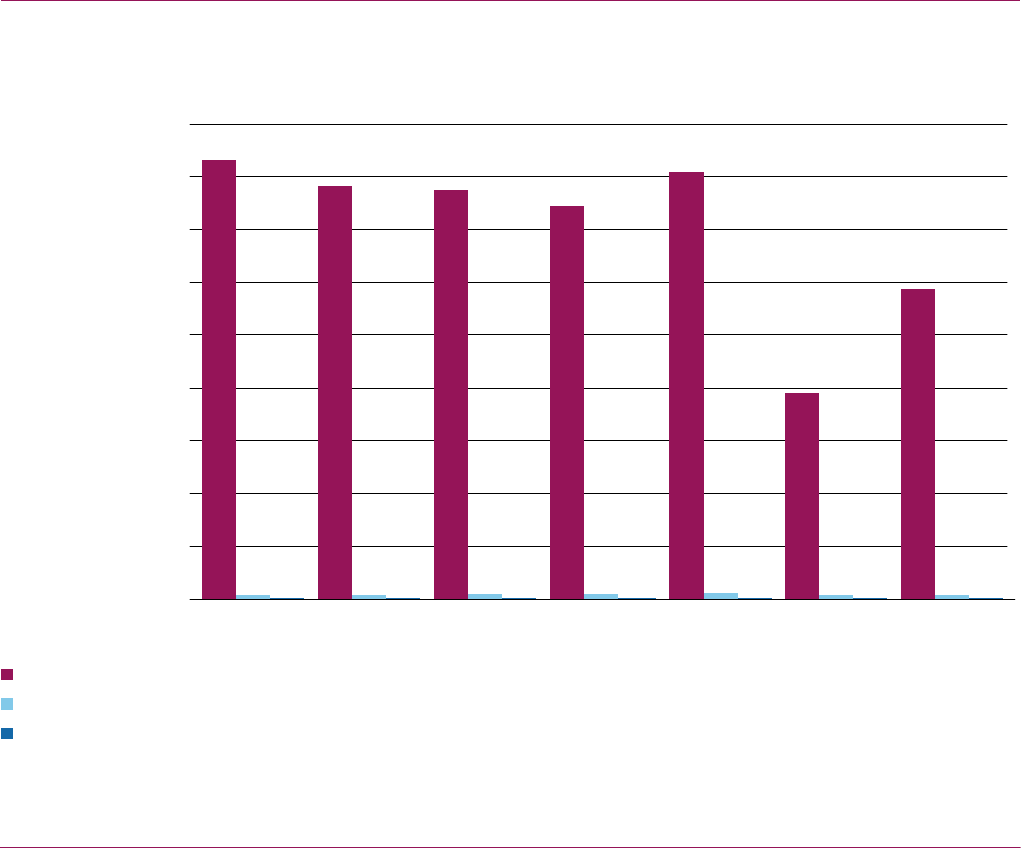

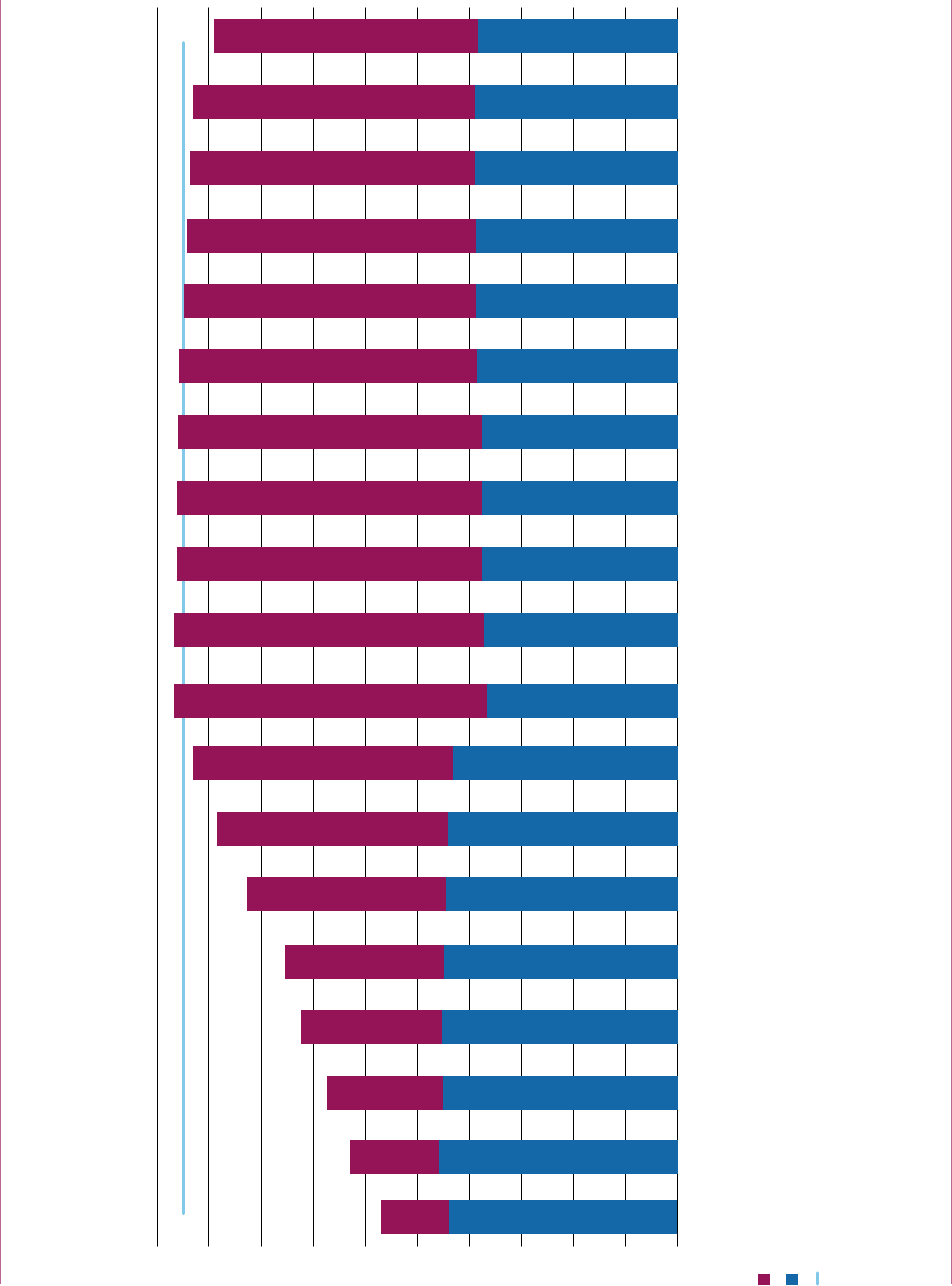

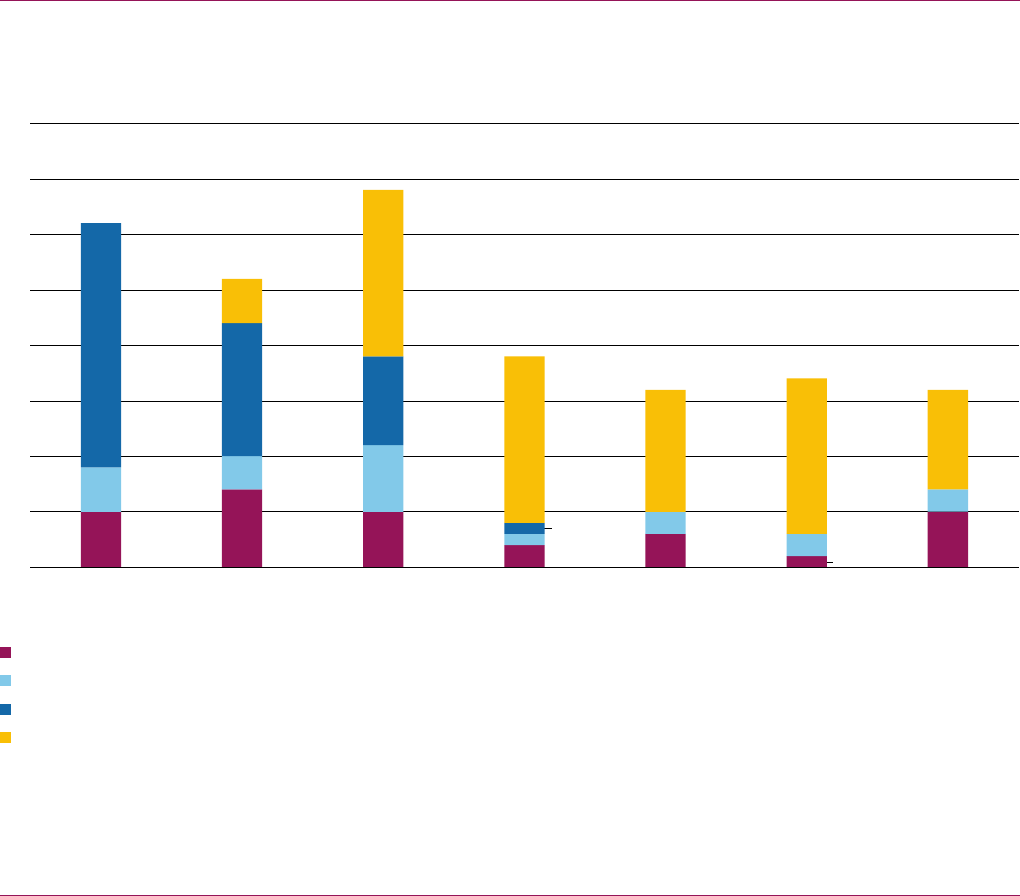

Figure

7

Gr

ant-in-aid funding to the Environment Agency for environmental protection, 2010-11 to 2020-21

Grant-in-aid (£m)

Notes

1 The Environment Agency has enforcement responsibilities for a range of sectors including agriculture, industry and waste management. This includes enforcement associated with

the regulation of industrial facilities, storm overflows and fisheries, as well as in response to serious pollution incidents and waste crime.

2 Figures are in nominal terms.

3 This grant-in-aid funding is for the Environment Agency’s environment and business Directorate. The Environment Agency also receives grant-in-aid associated with its flood and

coastal risk management.

Source: National Audit Office analysis of Environment Agency data

Financial year

Ring-fenced enforcement funding for waste crime

Generic enforcement funding (allocated from core grant-in-aid)

Other ring-fenced funding (non-enforcement)

Other grant-in-aid funding (not allocated for enforcement)

105.4

91.4

87.4

78.4

68.5

50.5

46.5

24.5

18.5

16.0 16.0

3.0

12.2

10.1

10.3

20.0

14.9

15.0

15.6

15.0

28.0

23.0

11.6

11.6

11.6

11.6

8.5

8.5

8.5

8.5

8.5

7.0

7.0

2.9

6.1

6.0

6.4

10.0

10.0

10.0

0.0

20.0

40.0

60.0

80.0

100.0

120.0

140.0

2010-11 2011-12 2012-13 2013-14 2014-15 2015-16 2016-17 2017-182018-19 2019-202020-21

1.7

3.0

0.8

18 Environment Agency Environmental compliance and enforcement

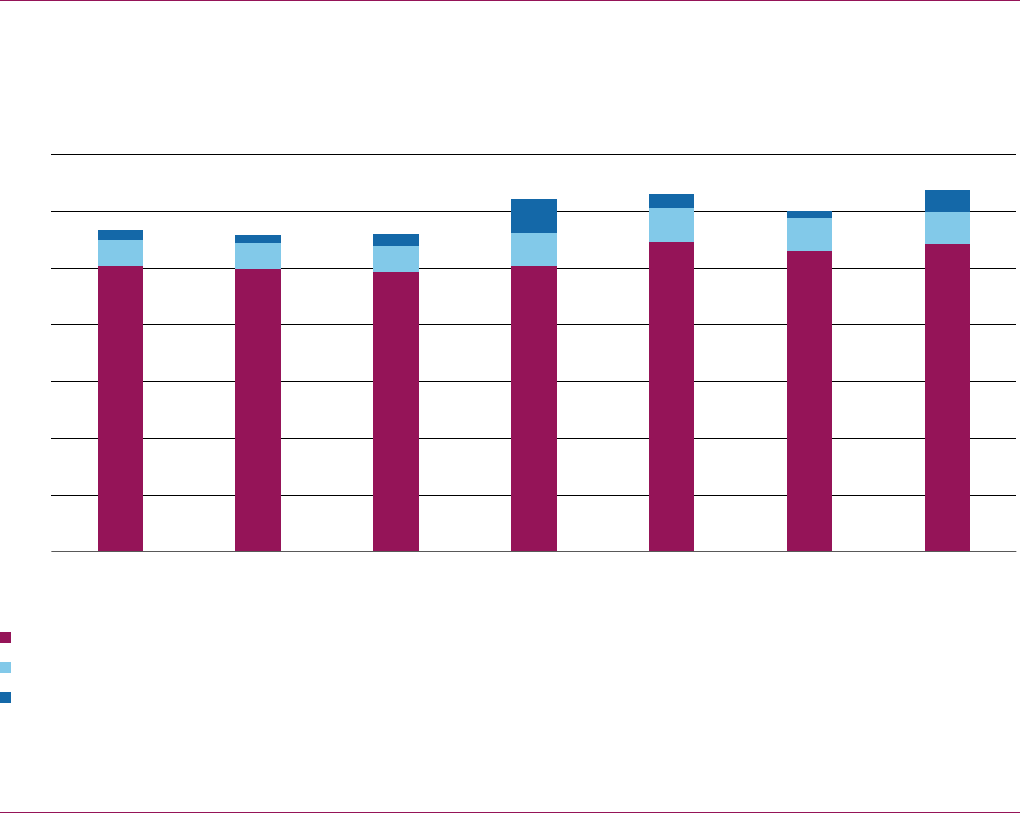

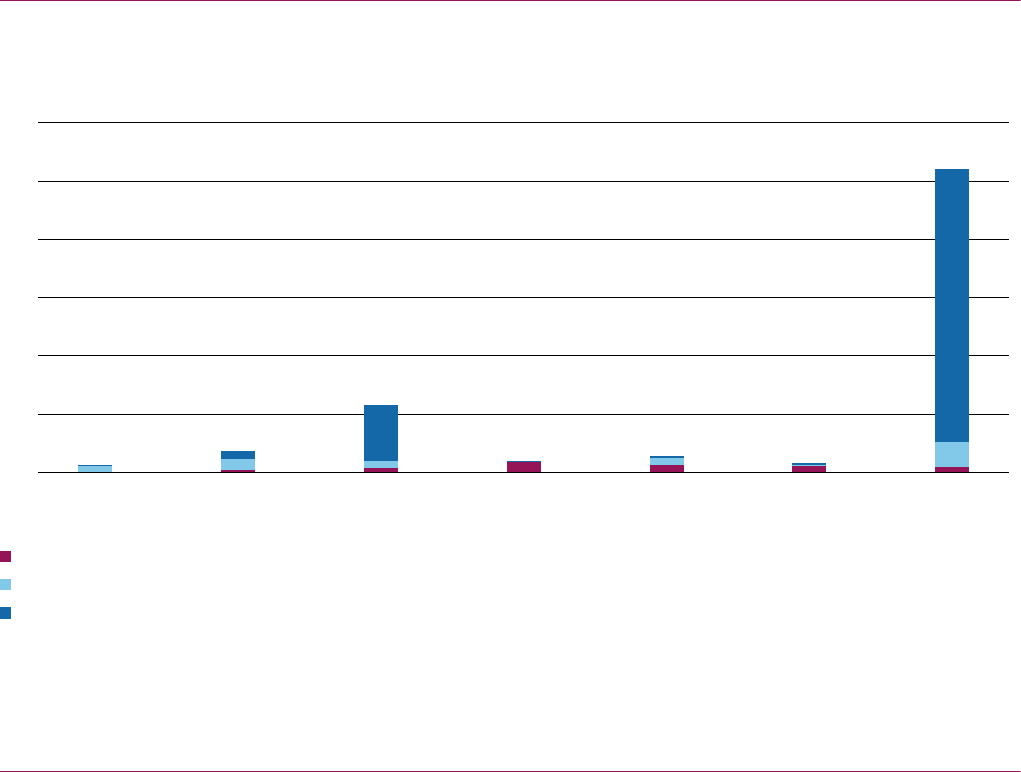

2,514

2,489

2,461

2,520

2,726

2,650

2,711

230

235

234

284

299

292

294

91

66

100

307

129

61

182

0

500

1,000

1,500

2,000

2,500

3,000

3,500

2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

Figure

8

En

vironment Agency compliance and enforcement activity full-time equivalent staffing profile,

20

16 to 2022

Number of full-time equiv

alent staff

Compliance

Enforcement

Vacancies

No

te

1

The numbers given are at 31 March for each year.

Source: National Audit Office analysis of Environment Agenc

y data

Environmental compliance and enforcement Natural England 19

Natural England

Role on environmental compliance

25 Natural England has compliance and enforcement responsibilities with

respectto sites of special scientific interest (see case example section of this

briefing), licensing of work that could affect wildlife and habitats, pesticide poisoning

to animals, complaints relating to weeds, and with respect to regulations relating

to environmental damage, heather and grass burning, and environmental impact

assessments of changes to rural land use.

Compliance and enforcement activity

26 Until 2017-18 Natural England produced an annual report on its enforcement

activity, that included data on complaints and queries it had received about breaches

of relevant regulations, as well as trends in the full range of enforcement action it had

taken including on investigations, enforcement notices and prosecutions. In 2020

Natural England published a register of enforcement action, but this only covers data

on civil sanctions, enforcement undertakings and prosecutions. The register was last

updated in September 2021 and includes data going back to 2007.

27 Natural England provided us with an update of the data included in itspreviously

published annual enforcement reports, which showed that in 2020-21 it:

•

found 276 breaches of species licences;

•

identified 184 poisoning activities under the Wildlife Incident Investigation

Scheme; and

in 2021 it:

•

undertook seven inspections and issued 15 enforcement notices with respect

toinjurious weeds; and

•

accepted two enforcement undertakings and carried out a prosecution against

the Environmental Impact Assessment (Agriculture) Regulations.

20 Natural England Environmental compliance and enforcement

Staffing and spend on compliance and enforcement

28 Over the past six years, the compliance and enforcement staffing profile at

Natural England has fluctuated as a result of funding changes and organisational

restructure. Natural England conducted a review of enforcement in 2017-18, which

found that 14 FTE was recorded against specific items of enforcement casework

across the organisation in the previous financial year. Following this review, it

formed a national enforcement and compliance team which comprised 22 FTE

staff in 2021-22. Natural England was unable to provide us with data on target

staffcomplement for this team over this period.

29 A wider group of staff at Natural England, beyond this core team, also spend

some of their time on compliance and enforcement activity such as monitoring,

inspections and issuing warning letters. Based on time-recording data, Natural

England estimates that total staff time for enforcement and compliance activities

such as monitoring, investigations, and issuing warning letters represented around

81 FTE staff in 2018-19, and grew to around 90 FTE staff in 2021-22. Natural

England estimates that an additional 217 FTE staff time was spent in 2021-22 on

wider regulatory activities such as issuing permits and licences, or dealing with

consents and assents for permitted activity. These are estimates of staff time and not

precise data, because Natural England’s time-recording codes do not consistently

differentiate between compliance and enforcement activity and other types of work.

Similarly, Natural England told us that it considers the increase in staff time reflects

an increase in the amount of grant-in-aid spent on compliance and enforcement

activity, but that it does not have sufficiently granular data to quantify this increase.

Issues arising on Natural England

The Committee may wish to explore the following areas:

•

How the organisation can be held accountable for its enforcement activity without publishing data on

its work and data on spend or staffing requirements.

•

Why it stopped publishing annual information on its enforcement activity (last published in2017-18).

•

How Defra ensures it provides the appropriate regulatory tools and funding to provide effective

environmental compliance and enforcement.

•

How its changing use of regulatory tools and approaches has impacted compliance and enforcement

with environmental regulation.

•

Natural England and Defra’s understanding of the skills and staffing needed to deliver their

compliance and enforcement work, both now and in the future.

Environmental compliance and enforcement Office for Environmental Protection 21

Office for Environmental Protection

Role and overall performance

30 The Office for Environmental Protection (OEP) is a new public body

establishedby the Environment Act 2021. It has a duty to identify and respond to

serious failures to comply with environmental law by public bodies. It has powers

toconduct investigations and commence legal proceedings when needed.

31 In its draft strategy, it outlines four strategic objectives, including

“improvedcompliance with environmental law”, and has committed to

developingaperformance measure framework in due course.

Funding

11

32 Funding for the OEP is provided through ringfenced allocation by Defra for

the current three-year Spending Review period. The budget is for £11.5 million in

2022-23, £7.25 million in 2023-2024; and £7.4 million to £7.7 million for the three

subsequent years, with the option for it to bid for more funds. These baseline

allocations will increase to allow for inflation. This does not include the Northern

Ireland contribution to the OEP’s budget which has not yet been confirmed.

Staffing

33 In its initial phase, the OEP expects to have between 50 and 60 staff across

arange of functions, including technical staff, a complaints and investigation

team,amonitoring team, an insights and analysis team and a legal team.

34 It plans to use multidisciplinary teams on its compliance and enforcement

work,driven by the nature of the issue.

11 The Office for Environmental Protection has not begun compliance and enforcement activity and therefore we were

unable to report on its spend.

22 How environmental compliance is changing Environmental compliance and enforcement

How environmental compliance

ischanging

35 There are a number of recent and proposed changes to the environmental

compliance landscape as a result of the UK’s exit from the European Union, the 2021

Environment Act, and wider developments.

36 A key change to environmental compliance and enforcement responsibilities

resulting from EU Exit is that the Rural Payments Agency will be responsible for

compliance inspections for the Sustainable Farming Incentive (SFI). This scheme

will pay farmers to undertake certain actions that will contribute to environmental

protection and enhancement. The SFI is part of government’s Environmental Land

Management Scheme which will become government’s primary mechanism for

distributing funding previously paid under the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy.

37 Following the Environment Act 2021, government has secured legislative

powers to introduce a number of major new environmental schemes and initiatives,

which will set new environmental requirements for particular organisations or

activities, and necessitate new responsibilities for monitoring, compliance and

enforcement against these requirements. In particular:

•

“biodiversity net gain”, will require developments such as house building to leave

the natural environment in a measurably better state than before work started

on the development.

12

Government issued a consultation on its proposed

arrangements for biodiversity net gain, which notes that planning authorities

will need sufficient capacity and expertise to enforce the biodiversity net gain

requirements, alongside the right powers, policy and guidance.

•

extended producer responsibility for packaging (EPRP) will require producers

to pay the full net costs of managing packaging which arises as waste in

households and is disposed of in street bins managed by local authorities,

which government estimates could involve total payments of around £1.7 billion

a year.

13

The Environment Agency will be the primary regulator for this scheme

in England, using its existing powers to monitor, audit and use civil and criminal

penalties to drive compliance and tackle non-compliance.

12 The Environment Act’s biodiversity net gain provisions involve: for development for which planning permission

is granted under the Town and Country Planning Act 1990, a new planning condition for net gain that must be

met before development may commence; and for Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects consented under

the Planning Act 2008, a new requirement to meet a biodiversity net gain objective. This will take effect after the

government has published a biodiversity gain statement, or statements, setting out the objective and how the

requirement is to be met, including transitional arrangements.

13 Not all of these payments are new costs, as packaging producers already pay towards the cost of recycling through

the Packaging Recycling Obligations.

Environmental compliance and enforcement How environmental compliance is changing 23

38 Other changes under consideration include:

•

the Competition and Markets Authority issued the Green Claims Code in

2021 to support businesses to ensure their environmental claims comply

with the law.

14

It committed to carry out a compliance review in 2022 and will

take appropriate action where there is evidence of breaches of consumer

protection l aw.

•

the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) will consult in summer 2022 on

proposals to implement the Sustainability Disclosure Requirements set out in

government’s Greening Finance: A Roadmap to Sustainable Investing policy

paper in October 2021.

15

The disclosures will require FCA-regulated firms to

adhere to common standards when classifying and labelling financial products

in order to hold firms to account for their sustainability claims.

•

Defra launched a consultation on the Nature Recovery Green Paper:

ProtectedSites and Species in March 2022. It looks specifically to address

existing licensing regimes and enforcement toolkits.

16

14 Competition and Markets Authority, Making environmental claims on goods and services, September 2021,

availableat: www.gov.uk/government/publications/green-claims-code-making-environmental-claims/environmental-

claims-on-goods-and-services

15 HM Treasury, Greening Finance: A Roadmap to Sustainable Investing, October 2021, available at: www.gov.uk/

government/publications/greening-finance-a-roadmap-to-sustainable-investing

16 Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs, Nature Recovery Green Paper: Protected Sites and Species,

March 2022, available at: https://consult.defra.gov.uk/nature-recovery-green-paper/nature-recovery-green-paper/

24 Case examples Environmental compliance and enforcement

Case examples

Case example 1: Sites of special scientific interest (SSSI)

Issues arising on SSSIs

The Committee may wish to explore the following areas:

•

Whether Natural England has sufficient assurance over the current condition of SSSIs, given it lacks

data on how regularly it has inspected each site.

•

Natural England’s approach to determining an appropriate level and balance of type of enforcement

action on SSSIs, and in particular why enforcement actions fell substantially between 2013-14 and

2020-21 (from 151 to 39).

•

Natural England’s rationale for increasing its staffing for monitoring of SSSIs between 2018-19 and

2021-22 (from 12 to 49 FTE), and how it assesses the effectiveness of this work.

•

Natural England’s plans to improve the condition of SSSIs, given that government did not meet its

2020 targets for their condition.

About sites of special scientific interest

39 An SSSI is an area of land notified by a conservation body as being of “special

scientific interest by reason of its flora, fauna, or geological or physiographical features”.

SSSIs are the most common statutory nature conservation designation in England.

There are more than 4,100 SSSIs in England, covering around 8% of the land area.

Significance for achieving government’s environmental objectives

40 In its 25 Year Environment Plan published in 2018, government committed to

protecting and enhancing England’s biodiversity on land, water and sea, including

restoring 75% of the protected land and freshwater SSSIs to favourable condition.

17

In 2011, Defra produced a strategy for England’s wildlife and ecosystem services with

the ambition of “better wildlife habitats with 90% of priority habitats in favourable

or recovering condition and at least 50% of SSSIs in favourable condition, while

maintaining at least 95% in favourable or recovering condition” by 2020.

18

17 HM Government, A Green Future: Our 25 Year Plan to Improve the Environment, January 2018, available at:

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/693158/25-

year-environment-plan.pdf

18 Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs, Biodiversity 2020: A strategy for England’s wildlife and

ecosystem services, August 2011, available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/

system/uploads/attachment_data/file/69446/pb13583-biodiversity-strategy-2020-111111.pdf

Environmental compliance and enforcement Case examples 25

Roles and responsibilities

41 Natural England is responsible for: designating SSSIs; consenting to activities

which may impact features of special interest; providing advice to SSSI owners

and managers; providing advice on the impacts of proposals which need other

permissions; assessing and monitoring the condition of SSSIs; investigating reports

of damage to sites; and assisting in the enforcement of legal measures to protect

sites and prosecute offenders.

The main environmental regulations and standards that apply

42 Owners and occupiers of SSSI-designated land must receive consent

fromNatural England before certain activities can be carried out on the land.

Theseactivities may be considered necessary for the long-term sustainable

management of the site. If the features of special interest on the SSSI are

deteriorating from neglect or poor management, Natural England can put a

management scheme in place. If the decline is a result of wilful or reckless damage

to the site, then it may take enforcement measures. If the owner fails to carry out the

work established in the management scheme, a management notice can be issued,

and if work is not carried out within two months of Natural England’s deadline, then

the owner is breaking the law and it is open to enforcement action.

Spending and staffing on enforcement and compliance for SSSIs

43 Natural England estimates that staff time on monitoring and enforcement of

SSSIs rose from around 12 FTE staff in 2018-19 to 49 FTE in 2021-22. This estimate

focuses on staff time for enforcement and compliance activities such as monitoring,

investigations, and issuing warning letters. It estimates that a total of 131 FTE staff

time was spent in 2021-22 on wider regulatory activities such as issuing permits and

licences, or dealing with consents and assents for permitted activity. It is not possible

to give a precise figure for staff time because Natural England’s time-recording

codes do not consistently differentiate between compliance and enforcement

activityand other types of work.

44 In 2021-22 Natural England received an additional £63 million funding from

Defra, some of which was used to re-establish a nationally co-ordinated programme

of SSSI monitoring and evaluation. It could not provide us with information on staff

and spend in this area over a longer time-period.

45 Natural England also pays external contractors to undertake monitoring work

on SSSIs, which increased from £205,000 in 2019-20 to £713,000 in 2021-22.

26 Case examples Environmental compliance and enforcement

Scale of compliance and enforcement activity

46 In October 2019, the UK statutory bodies agreed new common standards which

recognised that there has been a reduction in resources available for protected

area monitoring and removed a previous expectation that sites would be assessed

every six years. Natural England moved away from this six-year cycle in response to

a reduced capacity for monitoring and a shift to a more risk-based process. It was

unable to provide data on the extent of the shortfall against the six-year cycle.

47 Natural England told us that it has agreed memoranda of understanding with

a few organisations to support them in gathering their own data on the SSSIs they

own, which Natural England can then use to make a condition assessment. As part

of our 2020 Environmental sustainability overview of the Ministry of Defence, which

owns 3.5% of all British SSSIs, we found that it had been concerned about the

resource implications of carrying out detailed site condition surveys in the absence

of regular assessments by Natural England.

19

Natural England told us it is developing

a targeted long-term monitoring programme for its SSSIs and plans to work with the

Ministry of Defence and other major landowners to understand how this might best

be implemented on their land.

48 Natural England took enforcement action in response to 39 offences in

2020-21, a continued significant decline from the peak during the financial

year2013-14 (Figure 9).

49 The most common source of criminal activity on these sites from 2008 to 2021

has been due to vehicles, closely followed by construction and dumping.

Performance on improving the condition of SSSIs

50 Over the past five years, there has been very little change in the area of SSSIs

categorised as in favourable condition, from 38.5% in 2016 to 38.4% in 2021

(Figure 10 on page 28). This falls below the 50% target set out in government’s

Biodiversity 2020 strategy.

20

The overall proportion of SSSIs in favourable or

unfavourable recovering condition remained above the 95% target from 2011 to

2016 but has since fallen year-on-year to 91.4% in 2021.

19 National Audit Office, Environmental Sustainability Overview, May 2020.

20 See footnote 18.

Environmental compliance and enforcement Case examples 27

Warning Letter 84 93 113 92 79 92 146 102 93 72 45 24 23 24

Caution 5 1 3 8 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

Civil sanction (including EU) 0 0 0 0 0 3 1 15 8 7 10 9 3 15

Prosecution 2 2 2 0 4 0 3 0 0 0 0 0 2 0

Note

1

Warning letters, cautions, civil sanctions and prosecutions are increasingly severe enforcement actions and thus, an offence which receives a warning letter followed by a caution

orcivilsanction will be counted twice in this graph – once for each action.

Source: National Audit Offi ce analysis of Natural England data

Figure 9

Enforcement actions related to sites of special scientifi c interest (SSSIs), 2007-08 to 2020-21

Number of enforcement actions

Financial year

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

2007-082008-09 2009-102010-11 2011-122012-13 2013-142014-15 2015-162016-17 2017-182018-19 2019-202020-21

28 Case examples Environmental compliance and enforcement

Figure 10

Cumulative percentage of sites of special scientific interest (SSSIs) rated favourable or unfavourable (recovering)

by Natural England, 2003 to 2021

Percentage of SSSI (%)

No

te

1

Percentages do not sum to 100 as SSSIs are categorised into the following four conditions: favourable, unfavourable (recovering condition), unfavourable (no change) or

unfavourable (declining condition), and part destroyed or destroyed. Only favourable and unfavourable (recovering condition) categories contribute to the target.

Source: National Audit Office analysis of Natural England data

Unfavourable (recovering condition)

Favourable condition

Target (95%)

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021

Year

Environmental compliance and enforcement Case examples 29

Case example 2: Waste crime

Issues arising on waste crime

The Committee may wish to explore the following areas:

•

How the Environment Agency expects the lifting of the ringfenced enforcement budget will affect

performance on waste crime.

•

How the Environment Agency balances the type of enforcement actions used to tackle waste crime.

•

The Environment Agency’s understanding of its effectiveness in tackling serious criminality in

thewaste sector.

•

Whether government should improve its understanding of total spend on tackling waste crime

acrossdifferent organisations.

About waste crime

51 ‘Waste crime’ takes many forms, including fly-tipping, illegal dumping or

burningof waste; deliberate mis-description of waste; operation of illegal waste

management sites; and illegal waste export. The Environment Agency’s 2021

National Waste Crime Survey found that industry stakeholders perceived waste

crime to be widespread, with those from the waste industry estimating that 18%

ofall waste is illegally managed.

52 In the absence of an official estimate of the cost of waste crime to the English

economy, the Environment Agency, Defra and HM Treasury use an estimate made by

the Environmental Services Association (ESA), the trade body representing the UK’s

resource and waste management industry, of £924 million in 2018-19.

21

Significance for achieving government’s environmental objectives

53 In its 25-Year Environment Plan, published in 2018, government set the

ambition to eliminate waste crime and illegal waste sites within 25 years.

22

Thegovernment’s approach to waste crime over the short to medium term is

setoutin its Resources and waste strategy, published in December 2018.

23

21 Environmental Services Association, Counting the cost of UK waste crime, July 2021, available at:

www.eunomia.co.uk/reports-tools/counting-the-cost-of-uk-waste-crime

22 See footnote 17.

23 HM Government, Our waste, our resources: a strategy for England, December 2018, available at: https://assets.

publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/765914/resources-waste-

strategy-dec-2018.pdf

30 Case examples Environmental compliance and enforcement

Roles and responsibilities

54 Defra has policy responsibility for waste, including waste crime, within

government. The Environment Agency, an executive non-departmental public body

sponsored by Defra, is the principal body responsible for regulating the waste sector.

The Environment Agency is responsible for investigating certain types of waste

crime and taking action against the perpetrators, including illegal waste sites, illegal

dumping (the most serious fly-tipping incidents) and breaches of environmental

permits and exemptions. Responsibility for clearing waste ultimately sits with the

landowner or land manager. As we have previously reported, local authorities also

have powers and duties relating to fly tipping and deal with many smaller incidents.

HM Revenue & Customs has responsibility for pursuing the evasion of landfill tax.

The Environment Agency works with the police and other partners to investigate and

prosecute serious criminality in the waste sector with links to other types of crime.

The environmental regulations and standards that apply

55 One of the main regulations that applies to waste crime is the Environmental

Protection Act (1990), which created a duty of care for waste which applies to

anyone who imports, produces, carries, keeps, treats or disposes of controlled

waste. It requires them to take all reasonable steps to keep their waste safe,

including ensuring any third parties used are authorised to take it and are able

andlikely to deal with it or dispose of it lawfully and safely.

Resources and spending

56 Since 2011-12, the Agency’s core funding for environmental protection,

covering waste and other areas of work, has fallen, but over this period government

provided it with ring-fenced grants for tackling waste crime. The Agency’s total

funding allocated for enforcement and waste crime rose from around £12 million in

2010-11 to £17 million in 2018-19, (Figure11) remaining at this level in cash terms

through to 2021-22.

57 The Environment Agency can also draw on funding allocated to wider

enforcement for its work on waste crime, although it could not provide a breakdown

of how much was used for this purpose. Its wider funding allocated to enforcement

has declined over the same period (see Figure 7 on page 17).

58 From 2022-23, the Environment Agency’s previously ring-fenced funding for

waste crime will be incorporated into its core funding. The Environment Agency is

exploring options including the use of new powers in the Environment Act 2021 to

recharge for waste incidents and implementing charging schemes for upcoming

regulatory reforms which cover the cost of enforcement.

59 Defra does not collate total spending on tackling waste crime across the many

organisations involved, and most have experienced budget reductions since 2010-11.

Environmental compliance and enforcement Case examples 31

Figure

11

En

vironment Agency use of funding for enforcement and waste crime in England, 2010-11 to 2021-22

Grant-in-aid funding (£m)

No

tes

1

Ring-fenced waste crime funding includes a range of ring-fenced grants. For example, the Waste Enforcement Programme provided £23 million of funding over four years

(2016-17 to 2019-20) to tackle illegal waste sites, illegal exports and the mis-description of waste.

2

Figures are in nominal terms.

Source: National Audit Office analysis of Environment Agenc

y data

Environmental protection funding allocated to enforcement

Ring-fenced waste crime funding

13.0

11.6 11.6 11.6

8.5 8.5 8.5 8.5 8.5

7. 07.0 7. 0

0.8

2.9

1.7

3.0

6.1

6.0

6.4

10.0

10.0 10.0 10.0

0

2.0

4.0

6.0

8.0

10.0

12.0

14.0

16.0

18.0

20.0

2010-11 2011-12 2012-13 2013-14 2014-15 2015-16 2016-17 2017- 18 2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22

Financial year

32 Case examples Environmental compliance and enforcement

Scale of compliance and enforcement activity

60 The Environment Agency completed 11,987 investigations into waste crime

between 2014-15 and 2020-21, with most (64%) of these related to illegal waste

sites (Figure12).

61 The most common compliance and enforcement actions taken by the

Environment Agency in response to waste crime are issuing advice and guidance

and sending warning letters. In line with government policy for regulators to take a

risk-based and proportionate approach to enforcing compliance, the Environment

Agency’s policy is to give advice and guidance or issue a warning to bring an offender

into compliance where feasible, only moving to more formal sanctions, such as

cautions, and potentially criminal proceedings, in more serious cases or where informal

approaches have not worked. Over the period 2014-15 to 2020-21, the Environment

Agency issued advice and guidance in 52% of investigations into illegal waste sites

and in 53% of investigations into breaches of environmental permit conditions.

Sending warning letters was the second most common action for both types of crime.

The Environment Agency’s responses to major incidents of fly-tipping show the same

pattern. In contrast, it uses civil sanctions extensively in cases of producer responsibility

offences: between 2014-15 and 2020-21, it imposed civil sanctions in 57% of the 334

producer responsibility offence cases where it investigated and took action.

62 The number of prosecutions of companies and other organisations per year

has fallen from a peak of nearly 800 in 2007-08 to 17 in 2020-21 (Figure 13).

TheEnvironment Agency finds criminal prosecutions to be resource-intensive

and time-consuming, requiring high evidential standards. It therefore reserves

prosecution for cases of blatant criminality.

Figure 12

Environment Agency waste investigations closed between 2014-15 and

2020-21 andassociated actions, in England

Crime type Investigations

closed

Number of

resultant actions

Illegal waste sites 7,628 4,940

Environmental permit breaches 3,309 1,832

Illegal dumping (the most serious fly-tipping incidents) 665 187

Producer responsibility non-compliance 385 334

Total 11,987 7,293

Notes

1

Actions included in this count are: advice and guidance, warning letters, legal notices, fi xed penalty notices,

civilsanctions, cautions and prosecutions.

2

Some investigations may involve no relevant actions, and some may involve more than one action.

3

Environment Agency published data do not contain the number of incidents that led to an investigation.

Source: National Audit Offi ce analysis of Environment Agency Waste Investigations Report

Environmental compliance and enforcement Case examples 33

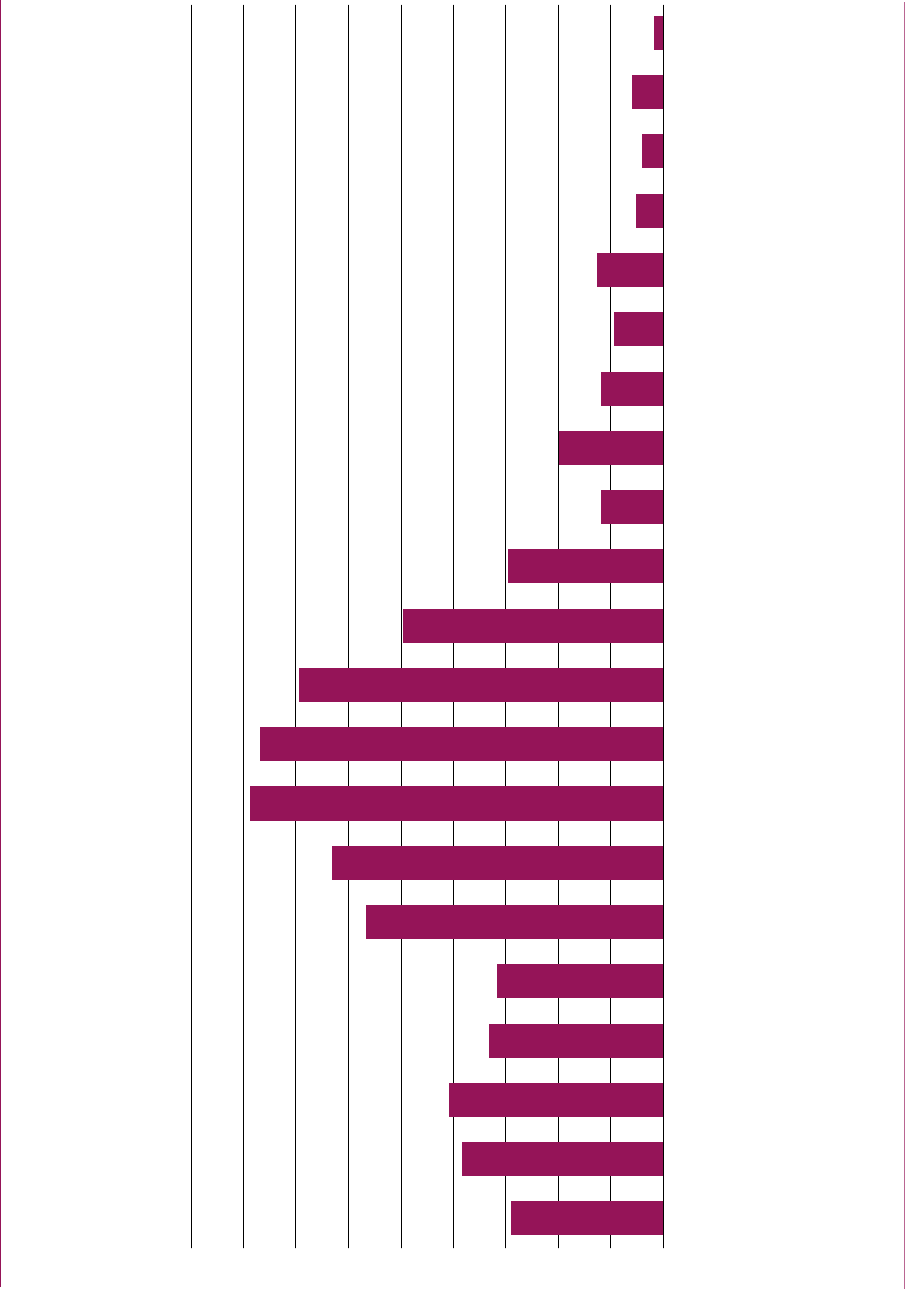

Figure 13

Number of prosecutions of companies and other organisations undertaken by the Environment Agency in England,

2000-01 to 2020-21

Number of prosecutions

The number of prosecutions per year has decreased significantly since 2007- 08

Notes

1 Prosecutions are assigned to financial years using the ‘date of action’ recorded.

2 Multiple charges against the same offender are counted individually.

Source: National Audit Office analysis of Environment Agency dataset: Environment Agency Prosecutions

2000-01

2001-02

2002-03

2003-04

2004-05

2005-06

2006-07

2007-08

2008-09

2009-10

2010-11

2011-12

2012-13

2013-14

2014-15

2015-16

2016-17

2017- 18

2018-19

2019-20

2020-21

290

383

408

332

317

567

630

787

768

693

495

295

119

198

118

94

126

52

41

60

17

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

700

800

900

Financial year

34 Case examples Environmental compliance and enforcement

63 The average fine associated with successful prosecutions has tended to rise

over the same period that the number of prosecutions has fallen, although the

smaller numbers involved leads to greater variability by year. The average of the

258fines in the five years to 2019-20 is £18,123, while the average of the 1,027

fines in the five years to 2014-15 was £4,996. Before 2016-17, the highest single fine

in the period was £100,000; from 2016-17 onwards, there have been individual fines

of several times this level.

64 For further information on government’s approach to waste crime, including

actions taken by local authorities and the Environment Agency, please refer to our

Investigation into government’s actions to combat waste crime in England.

24

Case example 3: Storm overflows

Issues arising on storm overfl ows

The Committee may wish to explore the following areas:

•

How the Environment Agency’s enforcement action will be impacted by climate change induced

changesto rainfall levels.

•

How the Environment Agency ensured monitors have been placed in appropriate locations.

•

How the Environment Agency balances the type of enforcement actions used to secure compliance.

About storm overflows

65 During heavy rainfall, the capacity of storm overflow pipes can be exceeded,

which means possible inundation of the sewerage system and/or sewage works

andthe potential to back up and flood people’s homes, roads and open spaces

unless it is allowed to spill elsewhere. Storm overflows were developed as overflow

valves to reduce the risk of sewage backing up during heavy rainfall.

Significance for achieving government’s environmental objectives

66 In its 25 Year Environment Plan, government committed to achieving clean and

plentiful water. Material spilling from storm overflows bypasses sewage treatment,

and can cause damage to the environment if concentrations of pollutantsare above

standards or objectives set down in legislation.

25

24 Comptroller and Auditor General, Investigation into government’s actions to combat waste crime in England,

Session 2021-22, HC 1149, National Audit Office, April 2022.

25 See footnote 17.

Environmental compliance and enforcement Case examples 35

The environmental regulations and standards that apply

67 Storm overflow permits for wastewater treatment works define the volume

of storm flow that should receive full treatment at a site. Only once an overflow

threshold is reached should flow be diverted to the environment, or at a sewage

treatment works into a storm tank of specified capacity. The contents of this tank

should then be sent for treatment once inflows reduce unless the ongoing inflow

exceeds its capacity. If that is the case, the contents of the tank are permitted to

bedischarged as a storm overflow. The capacity of these storm tanks and the

volume of overflow allowed to be discharged depends on the capacity of the sewer

or size of the treatment plant. In January 2021, the environment minister announced

thatmonitoring would be required for all storm overflows, adding requirements to

low- and non-amenity sites.

Roles and responsibilities

68 The Environment Agency is primarily responsible for maintaining and improving

the quality of fresh, marine, surface and underground waters in England, while policy

is set by Defra and Ofwat is responsible for the economic regulation of the privatised

water and sewerage industry.

Spending and staffing for compliance and enforcement activity on

stormoverflows

69 The Environment Agency did not receive any dedicated funding for

enforcement on storm overflows, prior to the 2021 Spending Review, in which it was

allocated £21 million for water company and agricultural enforcement for the period

2022-23 to 2024-25. From 2010-2011 to 2019-20, the core grant-in-aid from which

the Environment Agency’s enforcement work is funded reduced by 80%, from

£117million to £23 million (Figure 7 on page 17). The Environment Agency was not

able to provide a breakdown of enforcement activity spend or resource utilisation

specific to storm overflows.

The scale of compliance and enforcement activity

70 The Environment Agency told us that it is progressively rolling out new

technology to monitor spills from storm overflows and that this has substantially

increased its ability to secure compliance. The total number of overflows monitored

increased from 855 in 2016 to 12,286 in 2020. Figure 14 overleaf shows that

newly monitored overflows have spilled more on average than those that already

had monitors.

36 Case examples Environmental compliance and enforcement

71 Where the Environment Agency finds a water company has breached its legal

permit, including as a result of storm overflows, it can take enforcement action

such as prosecution. From 2016, the Environment Agency began to move more

towards pursuing enforcement undertakings from water companies (Figure15).

Anenforcement undertaking is a voluntary offer made by an offender to: put right

the effects of their offending; put right the impact on third parties; or to make

sure the offence cannot happen again. The Environment Agency states that it will

consider accepting an enforcement undertaking where it is not in the public interest

to prosecute; where the offer addresses the cause and effect of the offending; and/

or where the offer protects, restores or enhances England’s natural capital.

2016 2017 2018 2019 2020

14.9

0

855

14.0

17.9

2,145

26.7

22.6

5,906

38.8

35.1

8,160

36.1

29.5

12,286

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

Figure

14

Av

erage number of spills per overflow, comparing newly added monitors

each

year to existing, 2016 to 2020

Average number of spills

per overflow

Number of monitored

overflows (000)

Year

New

To tal monitored overflows

Existing

Note

1

We did not receive returns from the Environment Agency for all companies for 2016 and 2017. It confirmed

requirements for data provision in 2018, and all companies submitted returns in this format from 2018

onwards. Prior to this, five (2016) and six (2017) out of nine companies submitted returns in this format,

while some of the others submitted returns in different formats that were not comparable.

Source: National Audit Office analysis of Environment Agency data

Environmental compliance and enforcement Case examples 37

1

5

7

5

2

3

5

4

3

6

1

2

2

2

22

12

8

1

4

15

15

11

14

9

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021

Figure 15

Number

of enforcement actions against water companies by the Environment Agency, 2015 to 2021

Number of ac

tions

No

tes

1

We do not have the breakdown of formal cautions and enforcement undertakings which featured storm overflows.

2

Cases against a company sentenced in court on the same day count as one prosecution and if a prosecution has an appeal hearing it is

recorded here according to the date of the hearing, not the original prosecution date.

Source: National Audit Office analysis of Environment Agenc

y data

Year

Number of cases receiving formal caution

Number of enforcement undertakings

Number of prosecutions (storm overflow element)

Number of prosecutions (no storm overflow element)

72 Formal cautions moved from being the most common type of action used

in 2015 to none being applied between 2019 and 2021. In 2021, the number

of enforcement undertakings fell to nine, with an increase in the number of

prosecutions increasing to seven.

38 Case examples Environmental compliance and enforcement

73 Fines applied to water companies had been increasing up until 2017 and

then began to fall until 2020 (Figure 16). In 2017 the Environment Agency issued

a £18.75million fine to Thames Water and in 2021 a £90 million fine to Southern

Water, both relating to the illegal discharge of sewage, some of which was attributed

to storm overflows.

74 For more information on storm overflows, please refer to our publication

Understanding storm overflows: Exploratory analysis of Environment Agency data.

26

26 National Audit Office, Understanding storm overflows: Exploratory analysis of Environment Agency data,

September2021.

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021

Fines applied to

water companies (£m)

Year

Enforcement undertakings

Prosecution (nostorm overflowelement)

Figure 16

To

tal value of fines applied to water companies by the Environment Agency, 2015 to 2021

No

tes

1

Most of the fines from prosecutions in 2017 came from a case brought against Thames Water, totalling £18.75 million and in 2021 from a case

against Southern Water totalling £90 million. Both related to the illegal discharge of sewage, some of which is attributed to storm overflows.

2

Figures are in nominal terms.

Source: National Audit Office analysis of Environment Agenc

y data

Prosecution (storm overflow element)

Environmental compliance and enforcement Appendix One 39

Appendix One

Our evidence base

1 In compiling this work we drew on information and data from the Department

for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs, Environment Agency, Natural England and

Office for Environmental Protection.

2 We reviewed published documents and internal management information

relating to their role, spend, staffing, compliance and enforcement work, as well as

reported performance.

3 We also spoke to officials at each organisation to understand the policy

landscape within which it operates.

4 We conducted semi-structured interviews with the Local Government

Association and National Trading Standards to understand their roles within the

regulatory regime.

5 We did not conduct interviews with other public bodies, but did share extracts

with named bodies to check the factual accuracy of any references.