EU fiscal rules: reform considerations

This paper discusses the EU fiscal framework reform. It reviews the EU fiscal

governance history and reforms, and identifies key challenges. It then takes

stock of reform proposals made so far, and finally formulates a reform idea

that reconciles the post-pandemic macroeconomic context with existing

contributions by leading economists and institutions.

Olga Francová, ESM

Ermal Hitaj, ESM

John Goossen, ESM

Robert Kraemer, ESM

Andreja Lenarčič, International Monetary Fund (IMF)*

Georgios Palaiodimos, Bank of Greece*

October 2021

The authors would also like to thank Angela Capolongo, Alexander Raabe, Diana Žigraiová,

Gergely Hudecz, Giovanni Callegari, Luca Zavalloni, Markus Rodlauer, Matjaž Sušec, Niels

Hansen, and Nicola Giammarioli for helpful comments and support.

Disclaimer: The views expressed by the authors of this discussion paper do not necessarily represent those of the

ESM, the Bank of Greece, the IMF or their policies. The views presented are those of the authors and should not be

attributed to IMF staff, management, or Executive Board. No responsibility or liability is accepted by the ESM in

relation to the accuracy or completeness of the information, including any data sets, presented in this paper.

* Andreja Lenarčič and Georgios Palaiodimos contributed to this paper when employed at the ESM.

PDF

ISBN 978-92-95223-07-3

ISSN 2467-2025

doi: 10.2852/841074

DW-AC-21-003-EN-N

More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). Luxembourg: Publications

Office of the European Union, 2021

© European Stability Mechanism, 2021

All rights reserved. Any reproduction, publication and reprint in the form of a different publication, whether printed

or produced electronically, in whole or in part, is permitted only with the explicit written authorisation of the

European Stability Mechanism.

E U F I S C A L R U L E S : R E F O R M C O N S I D E R A T I O N S | 1

Table of contents

Executive summary 2

Introduction 3

1. Background: the current rules, and why change is needed 4

Rationale behind European Monetary Union fiscal rules 5

Adding flexibility: shortcomings and calls for change 7

The 2005 reform and output gap measure pitfalls 7

Reform in 2011 to strenghten institutions 8

2. After the pandemic crisis – calls for change 11

The macroeconomic context – a new normal? 12

Supporting the recovery comes at a cost – medium- to long-term risks 13

Advantages and limitations of current proposals 15

Can fiscal rules help boost investment? 19

3. Towards a new fiscal framework: a way forward 21

EU legal framework and constraints to the Stability and Growth Pact revisions 22

A new fiscal framework 24

4. Conclusions 31

References 33

Annex 1: 100% reference value proposal 38

Annex 2: Public debt developments: 1995–2022, projections for 2020–2022 39

Acronyms and abbreviations 40

2 | D I S C U S S I O N P A P E R S E R I E S | O c t o b e r 2 0 2 1

Executive summary

The pandemic changes the

macroeconomic context.

The pandemic crisis hit euro area economies hard, expanding

public debt to record highs. National government intervention

cushioned the downturn and mitigated social hardships, and EU

institutional support helped keep borrowing costs low. The

Stability and Growth Pact’s (SGP) general escape clause was

activated to help EU Member States adequately respond to the

crisis and stabilise their economies. Now, new economic reality

necessitates a fresh look at the European fiscal rules.

The EU fiscal framework

contributes to fiscal discipline.

The EU fiscal framework helped improve fiscal policymaking and

coordination because the euro area’s pre-pandemic aggregate

fiscal position was stronger than in other jurisdictions, although

it charted little progress on fiscal buffers during good times.

Successive reforms aimed at strengthening the fiscal framework

added complexity and made it more difficult to operate,

undermining compliance and credibility.

Reform without a treaty change

could accommodate the new

economic reality.

In this paper we suggest ways to simplify the rules to

acknowledge the new economic reality and higher debt-carrying

capacity, possibly without the need for any treaty change or

national parliament ratifications. Political support could help

resolve other legal constraints and support a shift to a new public

debt reference value.

For example, a two-pillar

approach centred on two limits:

3% fiscal deficit and

100% public debt.

In light of existing proposals, we formulate a two-pillar approach

that utilises a 3% fiscal deficit ceiling and a 100% general

government debt reference value that incorporates an

expenditure rule. Expenditure ceilings that track trend growth

would replace existing medium-term objectives expressed in

structural balance terms. A combination of a primary balance

and an expenditure rule would help anchor the pace of debt

reduction for countries with public debt above 100% gross

domestic product (GDP), and the 100% debt ratio would

converge at a pace of one twentieth per year – unless serious

economic circumstances or an investment gap justified

deviations. Breaching the 3% deficit limit or primary balance

target would trigger an excessive deficit procedure and, in

exceptional circumstances, allow recourse to a possible fiscal

stabilisation instrument that would offer additional breathing

room. Disbursements of EU funds under specific conditions could

further incentivise fiscal discipline. An alternative solution that

embraced the current debt reference value is possible, but

carries several shortcomings.

E U F I S C A L R U L E S : R E F O R M C O N S I D E R A T I O N S | 3

Introduction

Fiscal rules encourage discipline conducive to economic growth and macroeconomic stability,

but no universally applicable fiscal rules exist. There is no unique solution striking the right

balance between the need for debt sustainability and fiscal stabilisation. The changing economic

environment and policy challenges hinder designing rules that are at the same time simple,

flexible, and enforceable.

The SGP remained a good policy anchor for EU countries. The fiscal rules adopted in the 1990s

aimed to limit policy-makers’ discretion and encourage responsible policies across diverse

economies. Successive reforms introduced new elements addressing changes in Member

States’ preferences and economic realities.

The pandemic crisis radically changed the economic landscape, triggering temporary

suspension of the fiscal rules. The crisis brought higher debt-financed spending, with its

aftermath potentially further burdening public budgets. The monetary policy response to the

crisis kept interest rates low and debt-servicing burdens manageable, making higher deficit and

debt levels tolerable for the markets.

Post-pandemic fiscal rules should provide credible policy guidance. Well-designed and

transparent rules can boost fiscal performance and prevent policy missteps. In the medium-

term, revised rules can help phase out pandemic-related discretionary fiscal measures. In the

long-term, they can strengthen commitment to fiscal positions stablising public debt levels.

This paper examines avenues for EU fiscal rules reform. It takes stock of key proposals and

reviews them against SGP evolution within the current economic environment of high public

debt and low interest rates. The paper is structured as follows: Chapter 1 summarises the

history of the SGP, including its track record and changes. Chapter 2 identifies challenges

stemming from the current economic environment and examines reform options. Chapter 3

suggests a way forward to a revised set of fiscal rules, including legal, institutional, and

economic considerations. Chapter 4 concludes with an overview of main reform elements.

4 | D I S C U S S I O N P A P E R S E R I E S | O c t o b e r 2 0 2 1

1. Background: the current rules, and why change is needed

E U F I S C A L R U L E S : R E F O R M C O N S I D E R A T I O N S | 5

EU fiscal rules, peer pressure, market forces, and unyielding national frameworks and institutions

supported fiscal discipline by constraining government discretion. The SGP helped reduce overall

euro area debt faster than in peer jurisdictions, especially after the sovereign debt crisis.

Nevertheless, the fiscal discipline and sound public-finance track-record across the euro area

remains mixed. The need for improvement is underscored by a failure to prevent procyclical

effects due to the lack of fiscal consolidation in economic good times, mounting complexity,

measurement problems, and an expanding divide between low debt and high debt countries.

Rationale behind the Economic and Monetary Union fiscal rules

National fiscal policy was meant be the predominant macroeconomic stabilisation instrument

in the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU). When the single currency was created, concerns

prevailed about moral hazard and the possibility that fiscal risk sharing could lead to permanent

transfers. National fiscal policy and competitiveness-enhancing reforms – which can be difficult

and politically costly to implement – remained the main economic adjustment mechanisms. The

common EU budget provided limited solidarity transfers skewed towards less-developed

regions, targeting economic convergence.

Fiscal rules were needed to prevent negative spillovers, inflation risks stemming from

diverging fiscal positions, and potential overburdening of the European Central Bank (ECB).

Monetary union sustainability required the prevention of spillovers from unsound national fiscal

policies. The two reference values – 3% of GDP for the deficit and 60% of GDP for the public

debt, while political in character, reflected the prevailing economic reality with the 3% deficit

ceiling regarded as sufficient to stabilise the economy during downturns. Together with a

nominal growth of 5%, including inflation of 2%, it would stabilise debt at about 60% of GDP, not

far from the EMU average at the time (Boxes 2 and 3).

1

Meanwhile, fiscal rules enabled the ECB

to focus on its core mandate, maintaining price stability.

Rules anchored in the EU Treaty and the SGP enhanced trust in the single currency. In the run-

up to the common currency, implied risk sharing embedded in the project triggered concerns

about the sustainability of the monetary union and the ability of countries with weaker

fundamentals or traditionally lax fiscal policies to converge towards the euro area average.

Policymakers were aware that imprudent economic and fiscal policies, particularly in countries

with a long tradition of inflationary policies, could trigger inflationary pressures across the euro

area. The rules made the single currency politically acceptable despite some uncertainty around

the no-bail out clause.

The original rules aimed to accommodate countercyclical fiscal policy. The SGP’s preventive

arm obliged countries to improve their budget balance towards their medium-term objectives,

with the original rules specifying that each EU country should aim for a balanced budget on

average over the economic cycle. Accumulated fiscal buffers would ensure available fiscal space

in a recession, when a fiscal deficit could only reach a maximum of 3% of GDP. Violation of the

3% threshold would trigger corrective measures, and could eventually lead to the imposition

of sanctions.

2

Governments gravitated towards the 3% deficit despite it being intended as a ceiling, with

balanced budgets as the prescribed target. On average, the euro area deficit stood slightly

below 2% of GDP during 1999–2007, but countries were unable to use the unanticipated

revenue increases from 1999 onwards to rebuild their fiscal shock-absorption capacity. A similar

situation occurred in the mid-2000s. Caselli and Wingender (2018) show that the 3% deficit rule

1

Kamps, C., Leiner-Killinger, N. (2019), Taking stock of the functioning of the EU fiscal rules and options for reform, p. 13.

2

In addition, an escape clause allowed more significant deviations in case of a severe economic downturn, defined as drop in real

GDP of more than 2%. Lower drops were subject to further considerations. Source: Council Regulation No 1467/1997, Article 2.

6 | D I S C U S S I O N P A P E R S E R I E S | O c t o b e r 2 0 2 1

ceiling had not acted as an upper bound but rather as a target or a ‘magnet’. The number of

observations around the threshold increased, reducing the occurrence of both large government

deficits and surpluses.

3

Fiscal rules aimed to complement markets as a disciplining device, but had limited

effectiveness when faced with higher spending needs. Enforcement mechanisms based on peer

pressure, embedded in the original rules, failed when confronted with high French and German

fiscal deficits in 2002. Economic criticism and divergent views among EU Member States broke

the consensus on fiscal rules, and a 2004 European Court of Justice ruling

4

specified the margins

for EU institutions’ discretion. As economic imbalances expanded, market inertia compressed

sovereign bond yields. Abrupt market swings following the great financial crisis initiated a

sovereign debt crisis and the establishment of the EFSF and ESM to provide a safety net for

sovereigns (Box 1).

Box 1. Fiscal rules and the ESM framework

The EFSF/ESM and EU fiscal framework are economically and institutionally interlinked.

The EFSF and ESM were established at the height of the sovereign debt crisis to fend off severe

reprecussions of financial market pressure. The promise of stability support came with a

commitment to fiscal discipline. From an economic perspective, stability support mitigates

policy failures, including the lack of sufficient increases in fiscal buffers during economically

advantageous times. An efficient and effective EU fiscal and economic policy coordination

framework would, in principle, prevent any need for recourse to ESM financial assistance other

than in exceptional circumstances such as very large exogenous shocks and spillovers that might

affect ‘innocent bystanders’.

This reasoning is reflected in the legal connection between the application of the SGP and the

provision of ESM stability support. The Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance (TSCG,

penultimate recital)

5

underlines the importance of the ESM Treaty as a key element of the

strategy to strengthen EMU. It stipulates that granting assistance under ESM programmes is

conditional on the ratification of the TSCG and compliance with Article 3. Likewise, Recital 5 of

the current ESM Treaty states that granting ESM financial assistance is conditional on TSCG

ratification by the ESM Member concerned, and compliance with TSCG Article 3.

Respect for the fiscal rules explicitly governs access to ESM precautionary assistance. Under

the amended ESM Treaty, an ESM Member will need to respect the SGP’s quantitative fiscal

benchmarks to be eligible for the Precautionary Conditioned Credit Line.

6

A good track record of

fiscal discipline acts as a guarantee of responsible policies and conditions eligibility to financial

assistance programmes other than a full adjustment programme or the Enhanced Conditioned

Credit Line. Future changes in the EU fiscal rules might entail discrepancies between the new

fiscal framework and the recently agreed eligibility criteria for accessing the Precautionary

Conditioned Credit Line stated in the ESM Treaty Annex III and would have to be accommodated.

Finally, the interest earned by the European Commission on deposits lodged in accordance with

Article 5 and the fines collected in accordance with Articles 6 and 8 of the Regulation 1173/2011

3

Caselli, F., Wingender, P. (2018), Bunching at 3 Percent: The Maastricht Fiscal Criterion and Government Deficits.

4

Case C-27/04, Commission v Council, [2004] ECR I-6649.

5

Article 3 of the Treaty stipulating requirements on the national fiscal policies is often referred to as the fiscal compact.

6

To be eligible for the Precautionary Conditioned Credit Line the ESM Members will need to respect the quantitative fiscal

benchmarks. The ESM Member shall not be under excessive deficit procedure and needs to meet the three following benchmarks

in the two years preceding the request for precautionary financial assistance: a) a general government deficit not exceeding 3% of

GDP, b) a general government structural budget balance at or above the country-specific minimum benchmark, c) a debt benchmark

consisting of a general government debt-to-GDP ratio below 60% or a reduction in the differential with respect to 60% at an average

rate of one twentieth per year.

E U F I S C A L R U L E S : R E F O R M C O N S I D E R A T I O N S | 7

are assigned to the ESM.

Adding flexibility: shortcomings and calls for change

The 2005 reform and output gap measure pitfalls

Implementation of the SGP did not initially prevent procyclical fiscal policies, despite the

intended focus on stabilisation. In the early 2000s, strong growth led to a procyclical fiscal

expansion with no buffer accumulation. The debt reference value had no adequate operating

procedure. Consequently, the SGP lacked focus on debt sustainability. Setting the SGP around

nominal reference values attracted experts’ criticism for not sufficiently accommodating

countercyclical policies in downturns and insufficiently safeguarding debt sustainability and

investment.

7

Also, shifting economic circumstances and need to reflect the different member

states’ positions accelerated reform.

To establish a sounder economic basis for the SGP, reform in 2005 replaced nominal deficit

targets with structural balances and extended deadlines for correcting fiscal deficit. This

reform introduced a shift towards country-specific structural objectives, correcting for the effect

of business cycles to provide more granular fiscal policy guidance and reduce procyclicality.

Medium-term objectives referred to a cyclically adjusted budgetary position excluding one-off

or temporary measures. Deadline extensions prolonged the procedure and the horizon for

excessive deficit correction beyond one year, conditional on relevant factors. Political support

for the amended rules suggested new commitment to fiscal discipline.

However, the potential GDP and growth needed to compute structural balance are hard to

estimate and subject to substantial revisions.

8

Potential output could be underestimated

because standard measures cannot capture an increasing share of intangibles (Anderton et al.,

2020) or, conversely, overestimated by any failure to account correctly for capital stock

obsolescence, especially after large shocks or recessions. The output gap divergence estimated

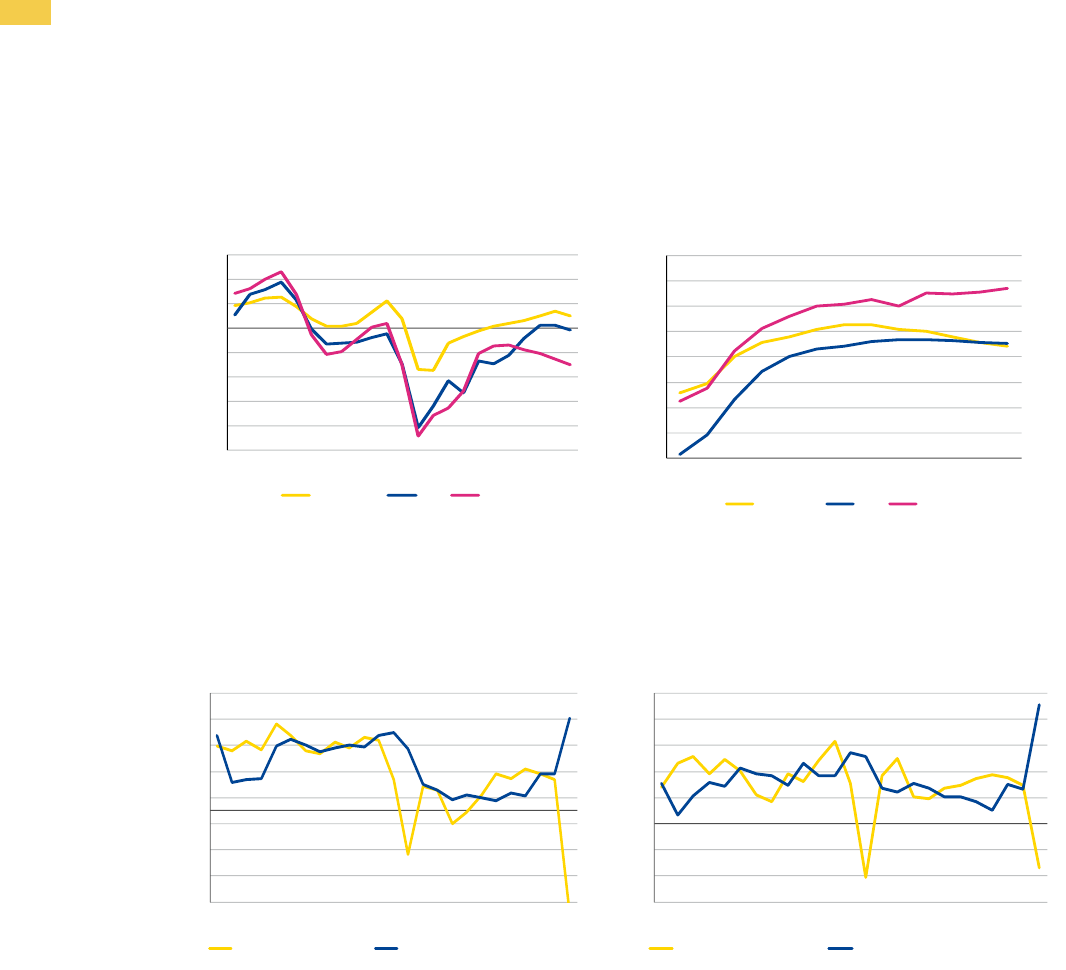

by international institutions reaffirms these persisting challenges (Figure 2).

As a result, the use of potential output to determine rule compliance was increasingly

questioned by the member states, especially after the global financial and sovereign debt

crises. Changes in output gap estimates can lead to significant differences in a country’s annual

structural-adjustment requirement because the country-specific medium-term objectives are

expressed in structural terms and its distance from the estimated potential plays a key role.

Frequent revisions of potential GDP and output gap undermined the credibility and

enforceability of fiscal rules based on cyclically adjusted variables.

9

Potential output estimates

after crises may have provided the analytical basis for procyclical adjustment pressures.

10

These

measurement issues reinforced scepticism about fiscal rules and eroded political consensus on

the output-gap based rules.

7

Buiter, W., Grafe, C. (2002), Patching up the Pact: Some suggestions for enhancing fiscal sustainability and macroeconomic stability

in an enlarged European Union. Blanchard, O., J., Giavazzi, F. (2004), Improving the SGP through a proper accounting of public

investment.

8

See Figure 1 illustrating this issue for Greece, which suffered from the turbulences of the sovereign debt crisis during this period.

9

Bilbiie, F. et al. (2020), Fiscal Policy in Europe: A Helicopter View.

10

Heimberger, O., Kapeller, J. (2017), The performativity of potential output: procyclicality and path dependency in coordinating

European fiscal policies.

8 | D I S C U S S I O N P A P E R S E R I E S | O c t o b e r 2 0 2 1

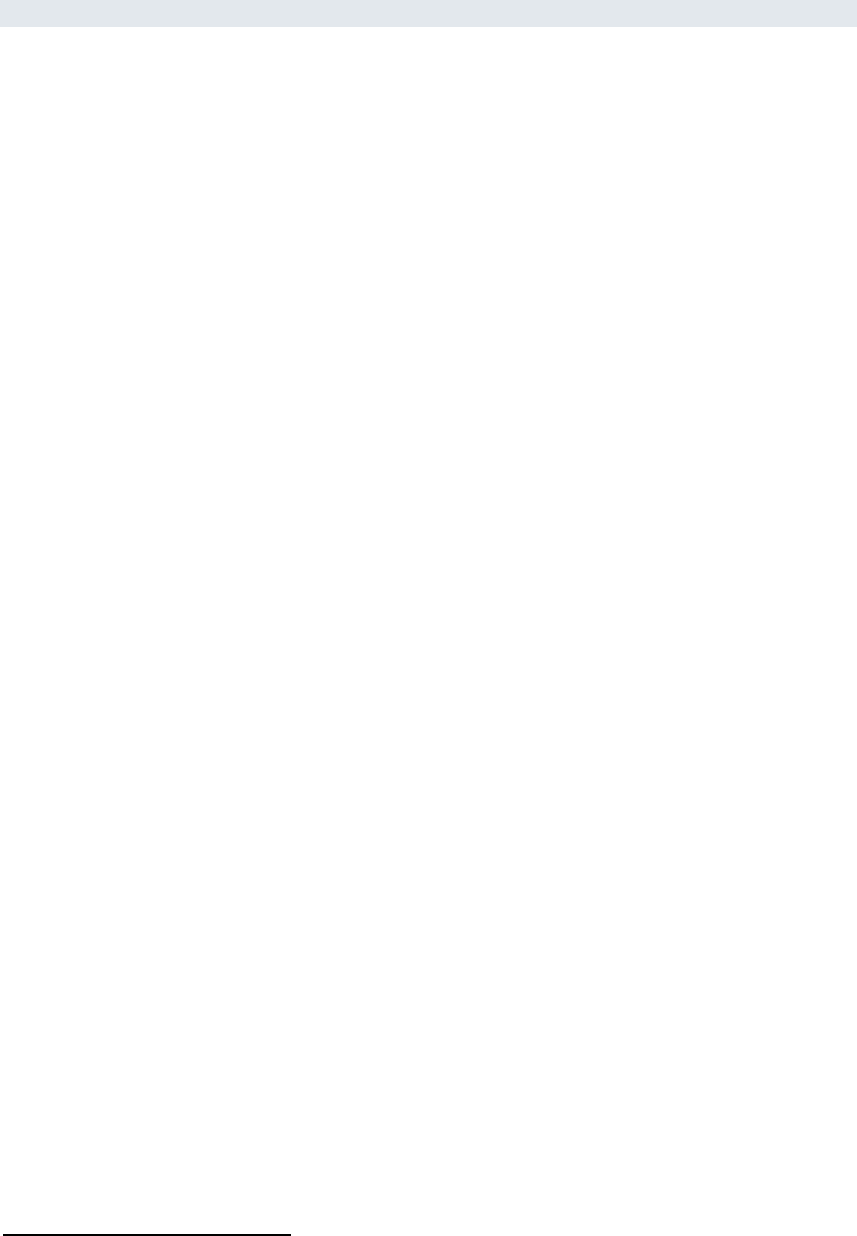

Figure 1

Potential growth projections for 2011 and 2012,

Greece

(in % of potential GDP)

Figure 2

Output gap estimates for the euro area

(in % of potential GDP)

Source: European Commission

Source: European Commission

Despite the new rules, stronger growth did not lead to lower deficits. The strong economic

performance of 2003–2007 was accompanied by fiscal deficits and increased expenditures.

The SGP reforms of 2005 did not have the expected impact on compliance.

11

The lack of national

fiscal buffers and supranational risk-sharing mechanisms exacerbated financial market stress

when the 2008 financial crisis hit Europe.

Reform in 2011 to strengthen institutions

Financial market turmoil and the ensuing economic crisis spurred the adoption of stricter rules

in 2011. Efforts to fend off financial market pressure during the sovereign debt crisis led to SGP

revision, new legislation, and sizeable financial assistance to countries in crisis. It also fostered

the creation of the European Financial Stabilisation Mechanism, EFSF, ESM and

intergovernmental treaties that reinforced commitments to fiscal discipline (Box 1). The

revamped rules aimed to ensure stricter enforcement of the SGP’s preventive and corrective

arms and introduce more automaticity. The European Commission proposed that country

recommendations could be overturned only by a qualified majority in the European Council,

strengthening the Commission’s powers and limiting the scope for political intervention by the

Council previously seen in 2002–2003.

The 2011 revisions made the SGP even more complex to interpret and apply. The changes

introduced an expenditure rule, first alongside the structural balance in the SGP preventive arm

and later also in the corrective arm. They also reinforced the debt criterion within the excessive

deficit procedure, and defined in detail applicable fines for non-compliance.

Enhanced macroeconomic surveillance and independent national fiscal councils aimed to

encourage fiscal discipline. Stronger national fiscal frameworks and an obligation to establish

independent fiscal institutions sought to ensure fiscal discipline at the national level.

The Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure screens both external and internal imbalances based

on a scoreboard of variables and potentially imposes financial sanctions on euro area member

states for persistent imbalances.

The European Commission’s enhanced authority came with an increasingly political role.

The Commission gained more power to assess and enforce the SGP, but this made assessments

more technically involved and subject to political considerations and judgement. In 2015, the

11

Eyraud, et al. (2017), Fiscal Politics in the euro area.

E U F I S C A L R U L E S : R E F O R M C O N S I D E R A T I O N S | 9

Commission introduced a matrix of requirements in the preventive arm that included a required

speed of adjustment towards the medium-term objectives for each member state, depending

on the size of the output gap and the debt level. In 2018, the margin of discretion applied. The

the SGP’s preventive arm allowed the Commission to deem a country compliant even if it had

violated adjustment requirements based on the medium-term objectives or expenditure

benchmark. Discussions on technicalities diverted attention from key policy issues.

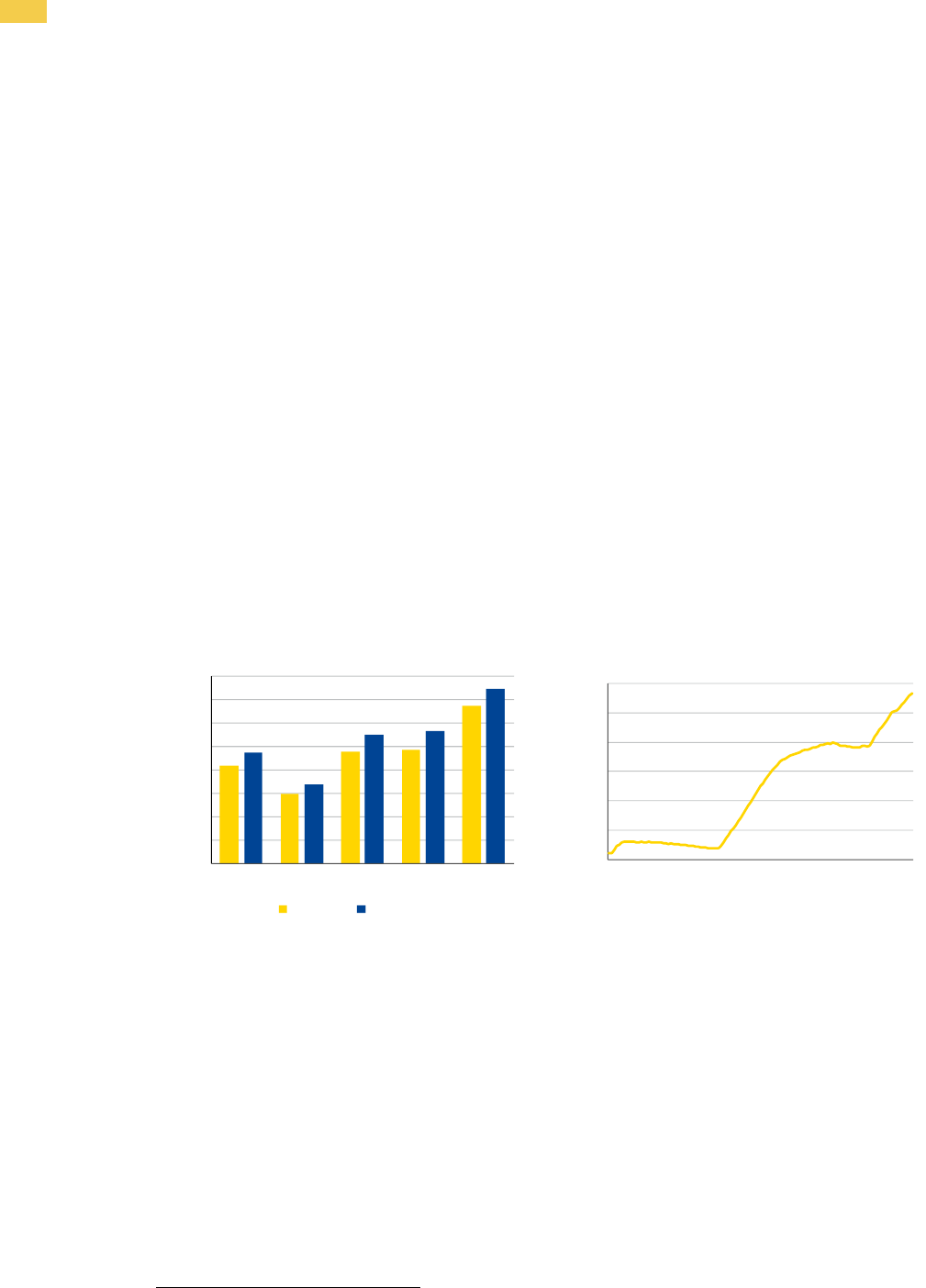

The market discipline channel – and European Commission surveillance – appeared stronger

after the crisis, although markets remained volatile. Markets appeared more prone to penalise

countries for non-compliance when called out by the European Commission (Figures 3 and 4).

Evidence suggests that higher debt and deficit levels can lead to higher risk premia.

12

The ECB’s

Outright Money Transactions commitment and, to a smaller extent, public sector purchase

programme did reduce risk premia, but financial markets penalised uncertainty on fiscal policy

choices perceived as risky by driving up yield spreads on bonds.

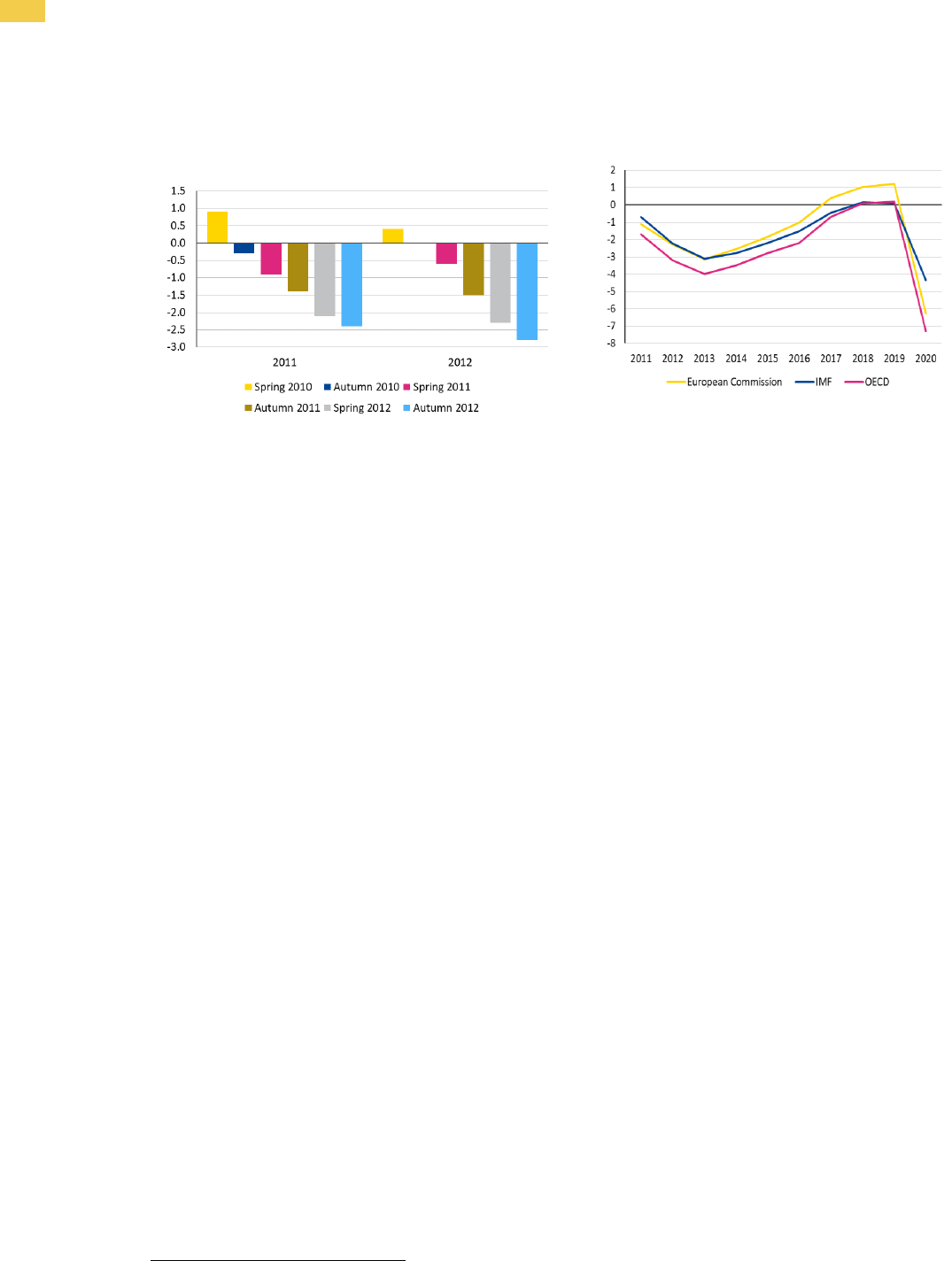

Figure 3

Market reaction during the 2016 discussions

between the Portuguese government and the

European Commission, PT 10-year spread to

Bund

(in basis points)

Figure 4

Market reaction during the 2018 discussions

between the Italian government and the

European Commission, IT 10-year spread to

Bund

(in basis points)

Source: Bloomberg

Source: Bloomberg

The SGP helped improve overall euro area fiscal position compared to peers, but

implementation and the resulting fiscal policy stayed procyclical. Fiscal rules helped the euro

area accumulate higher fiscal buffers than the UK and US, and reign in debt (Figures 5 and 6).

Despite being heterogeneous across countries, discretionary fiscal policy was procyclical 63%

of the time in 2011–2018, as opposed to 17% of the time in 1999–2010.

13

Lacking fiscal buffers

limited fiscal shock-absorption capacity. In the ensuing downturns, concerns about limited fiscal

options and endangered fiscal sustainability led to procyclical fiscal tightening (Figures 7 and 8).

The debt criterion has not always been respected. The debt criterion came into operation only

with the 2011 SGP reform and the introduction of the debt reduction, but even then it was

applied with several caveats. The signature of the intergovernmental TSCG did reinforce the

commitment to fiscal discipline, although no excessive deficit procedure has been activated on

12

Engen, E. M., Hubbard, R. G. (2004), Federal Government Debt and Interest Rates. Ardagna et al. (2007), Fiscal Discipline and the

Cost of Public Debt Service: Some Estimates for OECD Countries. Laubach, T. (2009), New Evidence on the Interest Rate Effects of

Budget Deficits and Debt.

13

European Fiscal Board (2019), Assessment of EU fiscal rules with a focus on the six and two-pack legislation, pp. 67-68.

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

400

450

Aug-15 Oct-15 Dec-15 Feb-16 Apr-16 Jun-16 Aug-16

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

Nov-17 May-18 Nov-18 May-19 Nov-19

10 | D I S C U S S I O N P A P E R S E R I E S | O c t o b e r 2 0 2 1

the basis of the debt rule to date.

Figure 5

Primary balance, general government for the

euro area and the UK, central government for

the US

(in % GDP)

Figure 6

Public debt in the euro area, UK, and US

(in % GDP)

Sources: US Treasury, Eurostat, Haver Analytics

Sources: US Treasury, Eurostat, Haver Analytics

Figure 7

Economic growth and current expenditure

growth, averages for ES, FR, and IT

(in % GDP)

Figure 8

Economic growth and current expenditure

growth, averages for AT, DE, and FI

(in % GDP)

Sources: European Commission, Ameco

Sources: European Commission, Ameco

-10

-8

-6

-4

-2

0

2

4

6

1997 2000 2003 2006 2009 2012 2015 2018

Euro area UK US

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

110

120

2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 2017 2019

Euro area UK US

-7

-5

-3

-1

1

3

5

7

9

1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 2016 2018 2020

Economic growth ES, FR, IT Expenditure growth rate ES, FR, IT

-6

-4

-2

0

2

4

6

8

10

1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 2016 2018 2020

Economic growth AT, DE, FI Expenditure growth rate AT, DE, FI

E U F I S C A L R U L E S : R E F O R M C O N S I D E R A T I O N S | 11

2. After the pandemic crisis – calls for change

12 | D I S C U S S I O N P A P E R S E R I E S | O c t o b e r 2 0 2 1

Taking stock of existing proposals for EU fiscal rules requires a review of existing economic

challenges. This chapter first assesses the current macroeconomic context and policymaking

debate, then reviews existing proposals for strengths and weaknesses. On that basis, it offers

insights on how to revisit the EU fiscal framework in the following chapter.

The macroeconomic context – a new normal?

The depth of the pandemic crisis has shifted the focus from limiting the downturn to fostering

a speedy, sustainable recovery. The pandemic triggered a severe economic downturn that

activated the escape clause within the SGP in March 2020, followed by rapid expansion of public

spending. The sustained focus on stabilising output contrasts with the euro area reaction to the

2012– 2014 sovereign crisis. The need for growth-supporting fiscal policies has become a new

paradigm in the economic policy debate.

Debt-financed spending is considered the appropriate response to the present crisis –

triggered by a global, exogenous shock – and markets seem to agree. An immediate firm fiscal

and monetary policy response emerged to counter the shock, leading to substantial increases in

already-high public debt levels (Figures 9, 10, and Annex 2) and the rapid expansion of central

bank balance sheets (Figure 10). The nature of the shock generated strong political support for

direct large-scale assistance to households and firms, which, alongside unprecedented central

bank support and ultra-low interest rates, largely muted market concerns about the jump in

debt levels.

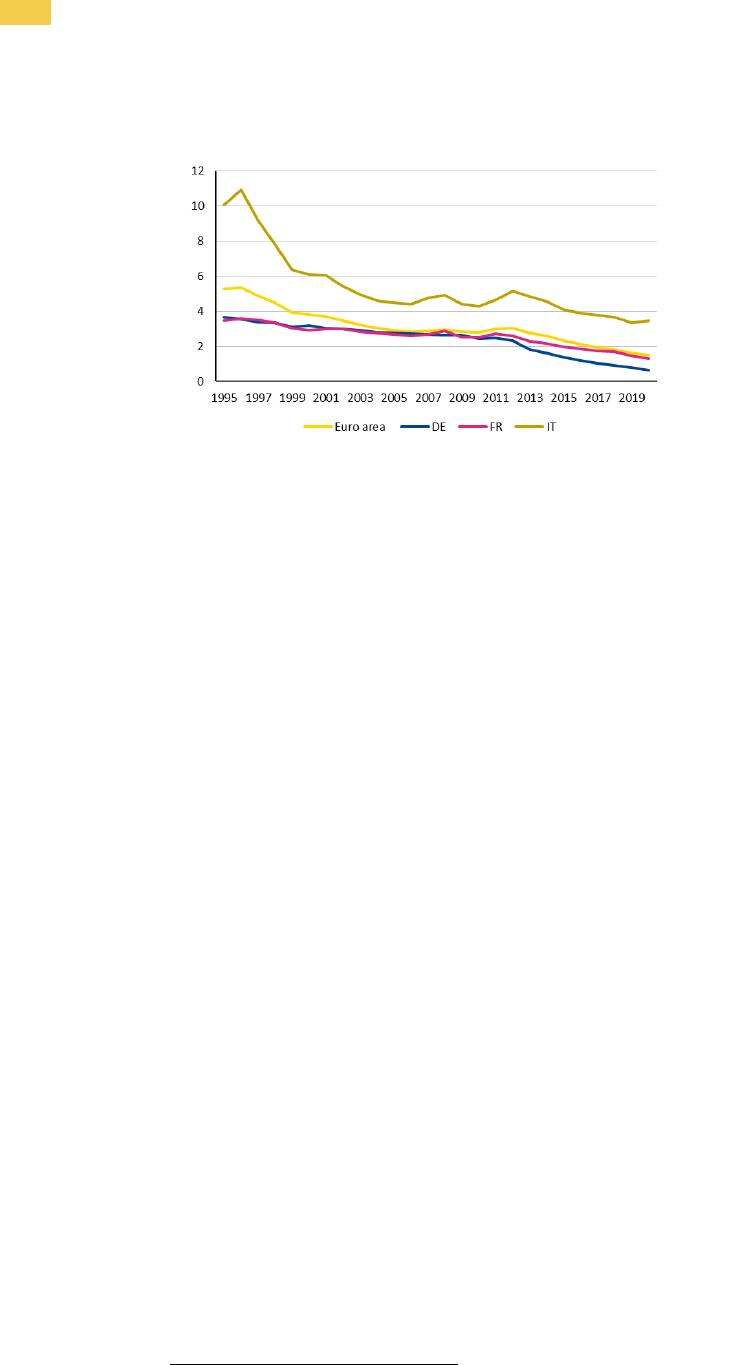

Figure 9

General gross government debt

(in % of GDP)

Source: Eurostat

Figure 10

Share of Eurosystem holdings of marketable

euro-denominated euro area government debt

(in % of total)

Note: Calculations are based on the assumption that 90% of PSPP

and PEPP are government debt. The denominator includes

marketable euro-denominated euro area central government

debt securities, but excludes official loans, dollar-denominated

debt and debt issued by government sub-sectors, agencies and

regions.

Sources: Haver, ECB

Economic divergence during the recovery from the pandemic crisis is a risk that could

challenge the ECB’s policy priorities. The ECB policy aim of maintaining price stability would be

tested if inflation threatened to exceed the target without a corresponding rebound in growth

and attendant crisis risks in some euro area member states. A substantial increase in key interest

rates and a tapering of central bank asset purchases could put pressure on the government

finances of some member states as growth and inflation expectations diverge, widening risk

premia. High government debt burdens in some countries may pressure the ECB to contain

interest rates and sovereign spreads

14

to ensure the operation of the transmission mechanism,

and safeguard fiscal sustainability and the cohesion of the monetary union.

14

Philip Lane made it clear in his inaugural blog that the ECB would “stand ready to do more ... if needed to ensure that the elevated

spreads that we see in response to the acceleration of the spreading of the coronavirus do not undermine transmission.”

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

Euro area DE ES FR IT

2019–Q4 2020–Q2

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021

E U F I S C A L R U L E S : R E F O R M C O N S I D E R A T I O N S | 13

The European pandemic crisis response alleviates pressure on governments but cannot

replace fiscal rules reform that would better handle high sovereign debt and recognise new

economic realities. Grants from the European Recovery and Resilience Facility create fiscal

space without burdening governments’ balance sheets. Still, rising indebtedness implies

governments will need to rollover increasing amounts of debt and finance newly issued debt.

Repeated failures of a rules-based system to reduce public debt imply a risk that the Eurosystem

and other central banks will be called upon to stabilise government bond markets in future times

of stress.

Supporting the recovery comes at a cost – medium- to long-term risks

The interest rate-growth (r-g) differential has steadily decreased, a trend accentuated by

accommodative monetary policy in recent years. This has made the intertemporal budget

constraint, the solvency condition for public debt sustainability, less binding, and shifted the

emphasis of the debt sustainability analysis from debt levels to rollover risks.

In the short- to medium-term r-g can be expected to remain negative. Accommodative ECB

policies have helped narrow spreads and contain interest rates (Figure 11). A positive short-term

outlook on growth can be justified, given the magnitude of the fall in GDP in 2020, and the

extensive monetary and fiscal stimulus employed to stem the economic consequences of the

Covid-19 pandemic.

Salient longer-term secular trends include lower long-run productivity and output growth,

shifting demographics, and safe asset shortages. These trends, which are likely to continue,

suggest that long-term interest rates will remain lower on average compared to the past.

Potential growth has been declining for decades in advanced economies. The decline can be

attributed to shrinking total factor productivity partly due to a lower rate of technology

diffusion, with the gap amplifying over time between labour productivity growth in firms

operating at the technology frontier and that of firms lagging behind.

15

Population ageing reduces investment and increases savings, and both cut the natural rate of

interest. The ratio of capital invested relative to workforce size increases as the population ages,

weakening the demand for capital. If the productivity of the older aged is lower than that of the

younger, then ageing can also dampen productivity growth and reduce investment

opportunities.

16

Rising life expectancy implies longer retirement periods, with escalating

incentives to save more, leading to higher savings rates. In turn, the increased savings raise

demand for safe assets, which leads to lower yields when combined with relatively

limited supply.

Lower interest rates, longer maturities, and a more robust European crisis prevention and

management framework have reduced rollover risks and raised debt levels that can be

sustainably serviced. The strengthened EU/euro area institutional framework – evidenced by

the swift and strong European response to the Covid-19 crisis and successful ECB action to

stabilise markets – have reduced debt servicing costs especially in some euro area countries

(Figure 11) and helped contain spreads even in times of crisis. As a result, market demand for

government debt remains high, and rollover risks are deemed to have declined substantially.

15

European Central Bank (2017), The slowdown in euro area productivity in a global context. OECD (2015), The future of productivity.

16

For comparison see Goodhart, Ch., Pradhan, M. (2020), The Great Demographic Reversal: Ageing Societies, Waning Inequality,

and an Inflation Revival.

14 | D I S C U S S I O N P A P E R S E R I E S | O c t o b e r 2 0 2 1

Figure 11

Interest expenditure: selected euro area countries, 1995–2019

(in % of GDP)

Source: Eurostat

However, r<g may not last. Scarring effects, lower-than-expected fiscal multipliers, insufficient

structural reforms, and low absorption of available funds might keep growth low. Also, due to

absorption capacity issues, suboptimal project planning and implementation, and an overall lack

of structural reforms, the Recovery and Resilience Facility may not lead to the expected lift in

potential growth. Furthermore, fiscal discipline and pressure for structural reforms could

weaken should easy funding conditions persist. This could lead to structural weakening and

lower growth in the long run.

Population ageing and rising healthcare costs may increase government spending faster than

revenue, leading to higher deficits with low interest rates. Rogoff (2019) claims that most social

security systems are debt-like in the sense that the government extracts money now with the

promise to repay with interest later.

17

For some countries, this ‘junior’ debt is relatively large

compared to the ‘senior’ market debt that sits atop it. Thus, hidden risks lurk within existing

government debt levels emanating from a shrinking labour force and a mounting

dependency rate.

An alternative school of thought suggests that global population ageing will lead to a trend

reversal, with savings rates falling, real wages increasing, and greater inflationary pressures.

An increase in ageing-related expenditures together with a structural weakening of the

dependency ratio is deemed inflationary. Inflation trends can be further exacerbated by labour

shortages and a rise in labour bargaining power relative to capital. Change in China’s economic

model from forced saving towards increased consumption could further amplify these trends.

18

Regardless of assumptions about future economic developments, limits exist as to how much

debt markets will sustain, and establishing thresholds is difficult. Empirically, reversals are

more likely to come with higher economic and social costs when debt is higher. Indeed, elevated

debt is associated with a greater likelihood of an exceptionally high interest rate to growth

differential in the future, and with higher interest rates in response to adverse shocks from weak

domestic growth and global volatility.

19

Fiscal support programmes initiated during the current crisis include public loan guarantee

programmes that establish contingent liabilities on government balance sheets. These could

become actual liabilities when grace periods end, especially if scarring effects materialise. The

17

Rogoff, K. (2019), Government Debt Is not a Free Lunch.

18

See e.g. Goodhart, Ch., Pradhan, M. (2020), The Great Demographic Reversal: Ageing Societies, Waning Inequality, and an Inflation

Revival.

19

Lian, et al. (2020), Public Debt and r - g at Risk.

E U F I S C A L R U L E S : R E F O R M C O N S I D E R A T I O N S | 15

sovereign-corporate nexus could emerge as a new euro area challenge, with uncertainty around

the true level of government debt created by these contingent liabilities reducing the markets’

debt tolerance. Till now corporate bankruptcies have been limited and risks seem contained.

Advantages and limitations of current proposals

Expenditure rules gained prominence before the pandemic and remain popular. Before the

pandemic, reform proposals from leading scholars and institutions

20

promoted expenditure

rules that would limit increases in adjusted current expenditure

21

to expected potential growth.

Some stipulated that spending growth reflects a given macroeconomic scenario and the size of

existing debt stock, given the main target was debt reduction.

Despite wide support for an expenditure rule with a debt anchor, the consequences of the

pandemic suggest existing proposals targeting debt reduction be revisited. Existing proposals

focus on different forms of expenditure rules with a debt anchor. The main differences relate to

operational rules, debt targets, benchmarks for expenditure growth, debt correction speed, and

the selected expenditure aggregate. The sharp debt increase after the pandemic calls for

revisiting the debt anchor and debt reduction pace proposed before 2020.

Box 2. Feasible debt reduction: raising the 60% reference value

In post-pandemic times, the new economic reality will challenge member states striving to

shrink debt through extended periods of high primary surpluses in line with the current debt

limit and reduction pace. Some countries have achieved a primary surplus of 3.5% of GDP and

above, and maintained it for up to five consecutive years. However, the post-pandemic debt

level is higher, widening the distance to the 60% reference value and the period in which

sovereigns would need to maintain high primary surpluses far beyond those maintained in the

past. Moreover, high primary surpluses achieved in the past accumulated from strong economic

growth at rates substantially above those that can be expected in the longer-term. Finally,

maintaining high primary surpluses for extended periods would work against the need for

investment in modernisation and a greening of European economies, so inhibiting growth.

At this juncture, requiring all euro area member states to converge to the current 60% debt-

to-GDP reference value appears unrealistic, and risks undermining fiscal framework credibility

(Figure 12). Keeping the 60% reference value and assuming a 20-year horizon to achieve it would

necessitate unrealistically high fiscal surpluses for several countries. For example, Portugal

would need a primary surplus of close to 2.5% of GDP on average for the next 20 years despite

a significant decline in debt service costs since the 1990s.

22

The required primary surplus would

be even higher for some other countries, which risks undermining the credibility of the EU fiscal

framework, thus impairing the market discipline channel and causing countries to adopt

inappropriately tight and unsustainable policies.

Where exactly to set the higher debt-to-GDP limit is partly a practical question, analogous to

the context for adopting the 60% limit several decades ago. The 3% deficit limit has proven a

good fiscal policy anchor, and general agreement suggests it has been effective and should be

kept. From there one can infer a debt limit of 100% of GDP, because a 3% deficit would stabilise

the debt-to-GDP ratio under the baseline macroeconomic outlook scenario (with real growth at

1% and inflation at 2%). In addition, a 100% reference value would be close to the current euro

20

See e.g. proposals by Andrle et al. (2015), Carnot (2014), Claeys et al. (2016), Bénassy-Quéré et al. (2018), Darvas et al., 2018,

Christofzik et al., 2018, and EFB (2018), EFB (2020).

21

Current expenditures are adjusted according to a narrowly set definition that excludes certain spending items.

22

This is an illustrative exercise, and the surplus quoted is different from that implied by the existing debt rule. Debt dynamics could

evidently vary over time and for example, require higher consolidation efforts, at the start with higher debt levels. Structural

measures of the primary surplus may lead to different outcomes, and possibly showing even higher adjustment needs.

16 | D I S C U S S I O N P A P E R S E R I E S | O c t o b e r 2 0 2 1

area average, as was the 60% limit when adopted.

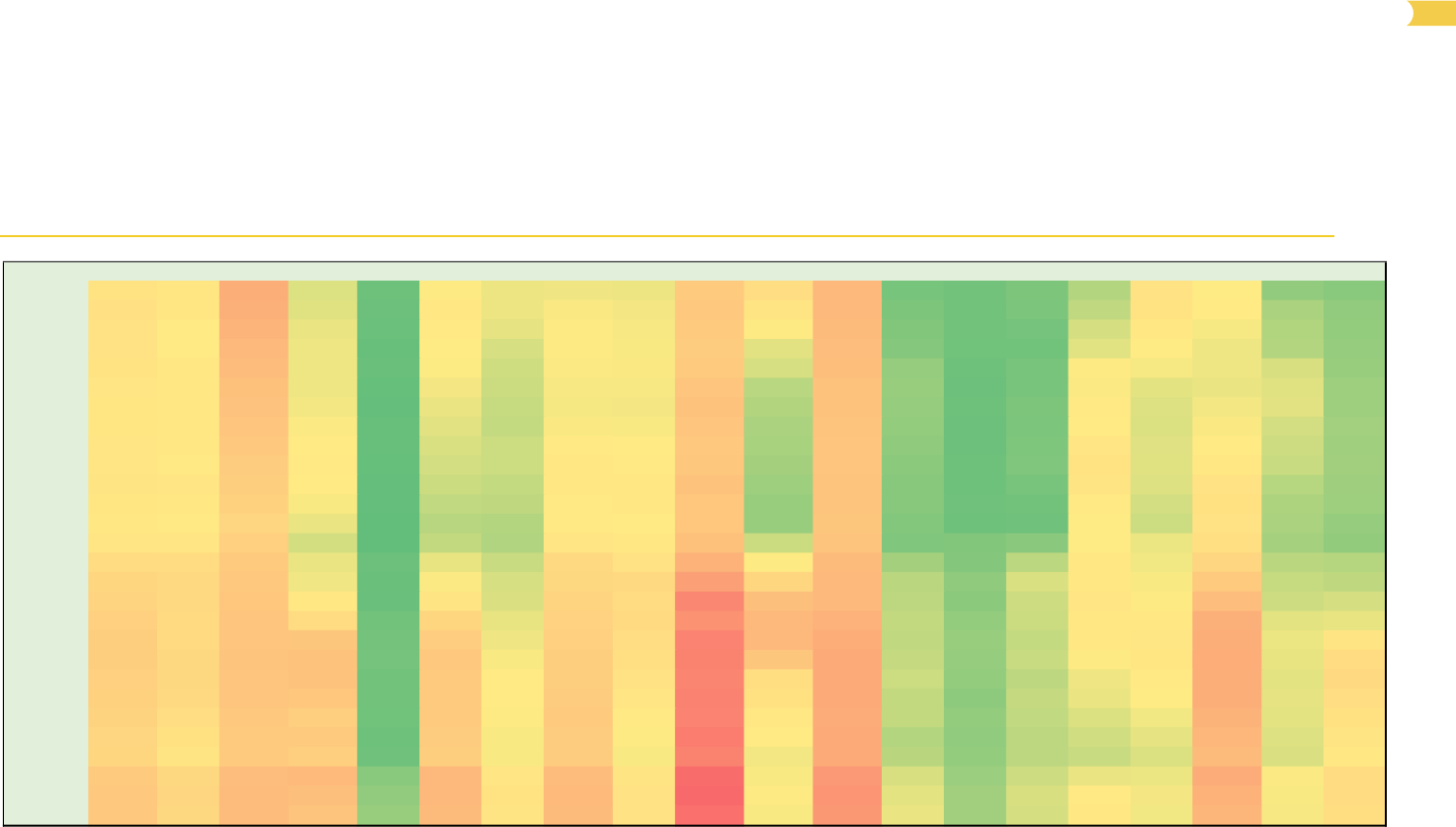

Figure 12

Primary balance (vertical axis) required to reduce debt ratio towards a selected anchor (horizontal axis)

(both axes in % of GDP)

Note: The assumptions on growth and implicit interest rates are based on the European Commission’s Debt Sustainability Monitor 2020. For PT, ES,

IE,and CY the starting level of debt is considered as of 2022 and the average implicit interest rate, inflation rate and real GDP growth are based on

2023-2031 period and extrapolated over the 20- and 30-year period. For EL, the initial debt level reflects the level projected for 2022 and the growth

and interest rates are averages for period 2023-2043 and 2023-2053 respectively. The computations are based on a number of simplifying

assumptions. The values were computed using the basic debt stabilising primary balance equation.

Sources: European Commission (2020) Debt Sustainability Monitor, Ameco, ESM calculations

The updated European Fiscal Board (EFB) recommendations (2020) suggest a country-specific

debt adjustment speed. The 2020 EFB report’s proposals included an expenditure ceiling rule,

a benchmark based on the trend growth of potential output, and a debt adjustment speed based

either on a matrix reflecting a fixed set of variables or on a case-by-case macroeconomic

scenario prepared by an independent assessor. These measures would translate into three-year

expenditure ceilings, which would encourage countercyclical fiscal policy, with its direction and

speed depending on both debt levels and macroeconomic conditions, so increasing debt in bad

times and reducing it in good times. The EFB 2020 proposal suggested the 60% debt-to-GDP

reference value should not necessarily be achieved within the 15 year maximum set in their

2018 proposal, and could be achieved at a different speed. It also considered a differentiated

debt target.

The EFB proposal does not fully address the risks of policy missteps on the revenue side and

the need to identify discretionary measures required to define an appropriate countercyclical

fiscal stance. Netting the expenditure aggregate of discretionary revenue measures requires

distinction between discretionary and nondiscretionary revenue changes and quantifying

individual measures.

23

The IMF and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and

Development (OECD) emphasise the risk of increased tax expenditures (i.e. advantageous tax

treatments), as countries relying on expenditure rules have experienced an increase in their

number.

24

Any expenditure ceiling aiming to reduce debt should assess the extent to which tax-

23

See e.g. EFB (2020), Annual Report 2020, p. 88-90. European Commission (2019), Vadamecum on the Stability and Growth Pact,

p.35.

24

OECD (2010), Tax expenditures in OECD countries.

-6%

-4%

-2%

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

60% 80% 100% 60% 80% 100% 60% 80% 100% 60% 80% 100% 60% 80% 100%

CY EL ES IE PT

In 20 years In 30 years Average 2010–2019

E U F I S C A L R U L E S : R E F O R M C O N S I D E R A T I O N S | 17

raising capacity supporting net expenditure growth is compatible with the required debt

reduction pace. Correspondingly, the assessment of revenue should guarantee that the revenue

contribution is at minimum not cancelling out the countercyclical fiscal policy stance.

A rule similar to the Swiss debt brake, which includes a tax dimension, would be constrained

by a limited EU authority. The Swiss debt brake requires that maximum expenditure must equal

revenue multiplied by the business cycle adjustment factor (k), which consists of the ratio of the

trend in real output to actual real output. Therefore, if k is greater than one, a (cyclical) deficit

is allowed, and if k is less than one, a (cyclical) budgetary surplus is required.

25

However, the rule

could necessitate revenue commitments, on which the EU has limited coordination powers.

In their 2018 analysis, the German Council of Economic Experts suggested a rule with the

structural balance as an intermediate target.

26

The paper combined a long-term debt limit with

an obligation to avoid structural deficits in the medium term, and an annual growth ceiling on

nominal expenditure. The debt-to-GDP limit remained 60%, and the discussed public debt

reduction pace was a symmetric one of one seventy-fifth or one fiftieth per year.

The German proposal makes strong points on governance. A limited number of exceptions and

escape clauses would simplify the framework. Together with improved enforcement and

monitoring, this would raise the political cost of non-compliance and strengthen the

fiscal framework.

Other researchers have suggested a country-specific debt adjustment pace.

27

The growth rate

of nominal public spending would be set at the sum of real potential growth and expected

inflation, minus a debt brake term taking into account any difference between the observed

debt-to-GDP ratio and the long-term target of e.g. 60% of GDP. The debt brake term would set

the speed at which a country converges towards its long-term debt target and should reflect

country-specific, five-year intermediate debt reduction objectives.

A more modest debt adjustment could help avoid unrealistic targets and increase credibility

in the current high-debt environment. Periodically updated country-tailored debt reduction

objectives would avoid unrealistic debt reduction efforts in high-debt countries.

Empirical evidence suggests benefits do flow from national expenditure rules. Manescu and

Bova (2020) analysed the performance of 14 national expenditure rules. Using the European

Commission’s fiscal rules database,

28

they concluded that such rules reduce spending

procyclicality and correlate to relatively higher compliance rates. Expenditure ceilings tend to

achieve better results than expenditure growth targets. A higher rate of compliance with

expenditure rules could reflect governments’ ability to exercise direct control

over expenditures.

29

However, a comparison with other rules highlights room for improvement. The research

highlights that budget balance rules contribute to countercyclical changes in overall and

investment spending, while expenditure rules exhibit a countercyclical impact on overall

spending and a procyclical impact on investment, making cuts during bad times more

politically palatable.

30

Revisions in medium-term potential growth projections could also dampen expenditure rules’

credibility. An important feature of expenditure rules is the anchor of a simple and not-

25

Geier, A. (2011), The Debt brake – the Swiss fiscal rule at the federal level.

26

Christofzik et al. (2018), Uniting European fiscal rules: How to strengthen the fiscal framework.

27

Darvas et al. (2018), European fiscal rules require a major overhaul.

28

Manescu, C. B., Bova, E. (2020), National Expenditure Rules in the EU: An Analysis of Effectiveness and Compliance.

29

Cordes et al. (2015), Expenditure Rules: Effective Tools for Sound Fiscal Policy?

30

Guerguil et al. (2016), Flexible Fiscal Rules and Countercyclical Fiscal Policy.

18 | D I S C U S S I O N P A P E R S E R I E S | O c t o b e r 2 0 2 1

frequently-revised variable. Numerous proposals use the medium-to-long term rate of potential

output growth, which should be relatively stable.

31

,

32

Conversely, Gros and Jahn (2020) argue

that revisions to medium-term potential growth tend to be similar in size to those of the output

gap used to compute medium-term objectives under the current framework.

33

An alternative proposal by Blanchard et al. (2021) would drop fiscal rules in favour of

standards accompanied by a stochastic debt sustainability analysis.

34

The proposal steered the

debate towards risks stemming from a potential rise in interest rates. Qualitative guidance

would give prominence to judgments on whether debt remains sustainable. Country-specific

assessments would use stochastic debt sustainability analysis to assess the probability of the

debt-stabilising primary balance exceeding the actual primary balance to indicate risks to debt

sustainability. These assessments could be led by national independent fiscal councils and/or

the European Commission. Disputes between member states and the European Commission

would preferably be adjudicated by an independent institution, such as the European Court of

Justice or a specialised chamber, rather than by the European Council.

Similarly, Martin et al. (2021) suggest debt sustainability analysis as a key instrument of the

revamped SGP to help avoid mechanical application of debt and deficit limits.

35

Every

government would have a country-specific numeric debt target to be achieved in five years. Its

pertinence would be evaluated at national level by an independent fiscal institution and

validated by the Ecofin, employing commonly agreed debt sustainability analysis methodology.

An agreed debt target would be broken down into five yearly spending targets. To respond to

any unexpected challenges, the European Commission could have the power to propose the use

of an exceptional circumstances instrument and recommend reorientation of the member

state’s budgetary policy.

Another strand of proposals suggests abandoning traditional deficit and debt sustainability

metrics in favour of debt stocks compared to the present value of GDP or interest rate flows

with GDP flows. Furman and Summers (2020) propose to shift away from traditional metrics in

favour of debt stock as a percentage of the present value of GDP, or real interest payments as a

share of GDP.

36

Hughes et al. (2019) suggest keeping the interest payments/revenue ratio

commonly used by rating agencies as an alternative metric. They argue that the long average

maturity of the UK government debt, roughly 14 years, means sharp falls or increases in

conventional interest rates take a number of years to work through the debt stock. This gives

governments time to gradually adjust fiscal policy settings to any new financing environment

and avoid breaching the limit.

37

The vision of Blanchard et al. is challenged in the short-run by the treaty change it requires. In

addition, the proposal raises operational questions. The Greek experience showed that even

debt sustainability analysis and its assumptions can lead to discord among the member states.

38

Also, the complexity in the underlying assessment increases the need for independent bodies to

provide the analysis. Lack of an appropriate operational setting would undermine the trust in

the rules. A proposal to allow the European Commission to prevent governments from adopting

national draft budgetary plans is legally not viable because the existing legal framework clearly

31

Christofzik et al. (2018), Uniting European fiscal rules: How to strengthen the fiscal framework. Darvas et al. (2018), European fiscal

rules require a major overhaul.

32

Clayes et al. (2016), Gros, D., Jahn, M. (2020), Benefits and drawbacks of an “expenditure rule”, as well as of a "golden rule in the

EU fiscal framework", pp. 20-23.

33

Gros, D., Jahn, M. (2020), Benefits and drawbacks of an “expenditure rule”, as well as of a "golden rule in the EU fiscal framework".

34

Blanchard et al. (2020), Redesigning the EU Fiscal Rules: From Rules to Standards.

35

Martin et al. (2021), Reforming the European Fiscal Framework.

36

Furman, J., Summers, L. (2020), A Reconsideration of Fiscal Policy in the Era of Low Interest Rates.

37

Hughes et al. (2019), Totally (net) Worth It: the next generation of UK fiscal rules.

38

Independent Evaluator (2020), Lessons from Financial Assistance to Greece – Independent Evaluation Report.

E U F I S C A L R U L E S : R E F O R M C O N S I D E R A T I O N S | 19

defines the powers of EU institutions in the area of fiscal policy coordination.

Giving up the deficit and debt metrics would be challenging. Decisions about debt maturity fall

under national competences and member states employ different structures to administer

government debt and rollover needs, which could prevent EU institutions from cross-country

comparisons and transparent and even-handed treatment. Any metrics beyond debt and deficits

might be too complex to explain to the wider public.

Can fiscal rules help boost investment?

After the global financial crisis, efforts to comply with fiscal rules might have discouraged

public investment. The financial crisis and ensuing market pressure led to cuts in government

investment expenditure in many advanced economies. The decrease in public investment was

significant, especially in countries subject to economic adjustment programmes such as Greece,

Ireland, and Portugal.

Post-pandemic, governments will have to address investment shortfalls and ensure additional

funding to meet targets set by key European initiatives and also to boost growth. Productive

investment enhances growth and reduces risks to medium-term debt sustainability.

The European Green Deal

39

sets ambitious goals in the commitment to a zero-carbon transition

and keeping pace with the digital revolution, while rebuilding Europe’s social cohesion will also

demand substantial investment efforts. The European Commission has projected that the

current 2030 climate and energy targets will necessitate €260 billion of extra investment each

year, about 1.5% of 2018 GDP. The European Investment Bank (EIB) estimated an overall

infrastructure investment gap of about €155 billion per year (about 1% of 2018 GDP) to attain

the goals the EU wishes to achieve by 2030, including ‘climate and energy’ and broadband

penetration. A similar gap of 1% of EU GDP exists in information and communications technology

compared to the US.

40

Introducing European fiscal rules that allow for higher investment remains a priority, but

needs to address related challenges. Resuming growth in the short-term and raising potential

growth rates over the medium-term calls for long-term investment. But, promoting investment

through fiscal rules must address concerns about transparency of a more complex framework.

Safeguarding investment through fiscal rules had mixed results. Decisions to facilitate public

investment by allowing for deviations from fiscal targets set at the EU level did not prevent

investment cuts during fiscal consolidation periods in the EU. Investment-friendly rules can lead

to excessive borrowing and weaken the link between fiscal targets and debt dynamics, fostering

potential risks to debt sustainability.

41

Creative accounting and the reclassification of

unproductive expenditures as investments to circumvent rules could challenge monitoring and

enforcement.

42

Recent research suggests investment-friendly rules can increase investment

expenditure without necessarily undermining fiscal discipline and public debt sustainability, but

only if investment efficiency is high.

43

A strong public investment and accounting framework mitigates risks from investment-

friendly rules or spending constraints in the short-term. Evidence suggests that improving the

governance of infrastructure investment can generate cost-savings and boost effectiveness.

44

To increase institutional capacity, the European Commission could conduct regular assessments,

issue reports and, potentially, also recommendations to improve public investment systems and

39

European Commission (2019), Communication from the Commission: The European Green Deal.

40

European Investment Bank (2019), EIB Investment Report 2019/2020 –Accelerating Europe’s Transformation.

41

For overview of obstacles to promoting investment through fiscal rules see EFB (2019), Annual Report 2019, p. 77.

42

Servén, L. (2007), Fiscal rules, public investment, and growth.

43

IMF (2014), Is It Time for an Infrastructure Push? The Macroeconomic Effects of Public Investment. Making Public Investment More

Efficient.

44

Schwartz et al. (2020), Well Spent: How Strong Infrastructure Governance Can End Waste in Public Investment.

20 | D I S C U S S I O N P A P E R S E R I E S | O c t o b e r 2 0 2 1

practices in member states, as proposed in the earlier suggestion to create the European

Investment Stabilisation Function. In the medium term, discussions on indicative investment

targets could be an alternative to explore.

A golden rule to protect productive public investment implying a separate capital account

remains attractive, but challenging. The EU division of powers implies that decisions on

expenditure composition are taken by the national governments, and removing investment

from reference values might alienate the targets from the numbers and reduce transparency.

Focusing on public sector net worth could boost investment in the medium term. Public sector

balance sheet accounting goes beyond the traditional debt and deficit approach and could

enable governments to take advantage of lower interest rates to borrow and invest in

modernising public infrastructure.

45

This approach accounts for the value of the assets created,

acquired, or sold using new statistical data on the public sector balance sheet, and it encourages

governments to generate assets with value exceeding the cost of financing. It could also guide

discussions about non-debt liabilities such as unfunded public sector pensions.

46

Country-specific solutions might require discretionary decisions. Building on existing

arrangements, member states could retain their discretion over decision-making about

conditions that would allow for a country-specific budgetary leeway to safeguard investment

spending. As with the old investment clause, member states might require respect for safety

margins to ensure the 3% of GDP deficit reference value

47

or respect for a reinforced investment

framework, with decisions possibly taken in accord with independent assessment guidelines.

45

See e.g. Hughes et al. (2019), Totally (net) Worth It: the next generation of UK fiscal rules.

Gaspar, V. (2019), Future of Fiscal Rules in the Euro Area.

46

Auerbach, A. (2019), The future of fiscal policy.

47

In spring 2014, the European Commission rejected a request by the Italian authorities’ to activate the investment clause because

they could not ensure the compliance with the debt rule.

E U F I S C A L R U L E S : R E F O R M C O N S I D E R A T I O N S | 21

3. Towards a new fiscal framework: a way forward

22 | D I S C U S S I O N P A P E R S E R I E S | O c t o b e r 2 0 2 1

The pandemic offers an opportunity to draw lessons from the past and improve the existing rules.

The member states could agree on a more credible framework after a transition period,

contingent on economic developments, political reality, and subject to legal constraints to SGP

revisions. Our ideas, articulated in this chapter, aim to balance sustainability and stabilisation in

the ‘new normal’, which includes growth challenges, lower interest rates, and a strong

interaction between fiscal and monetary policy. The proposal combines elements from the

existing framework and recent proposals, with an emphasis on simplicity and enforceability.

It also takes into account hurdles stemming from the EU legal framework and the transaction

costs of political decision-making.

We suggest a public debt anchor at 100% of GDP, an expenditure rule that would cap expenditure

growth by output trend growth, and a hard fiscal deficit limit at 3% of GDP. Member states with

debt above the 100% threshold would need to adopt a target expressed in terms of primary

balance consistent with a common predetermined debt reduction pace, complementing the

general expenditure rule. A new condition-based framework could provide additional

compliance incentives.

Any change to the future fiscal framework and its adoption timeline will depend on political,

legal, and economic factors, and should be carefully calibrated. The pandemic crisis required

the activation of the general escape clause, and the aftermath generated questions about the

duration of the clause and the relevance of existing rules. Key decisions on fiscal guidance for

2023 will be taken between March and May 2022, and the discussions on any new rules will be

shaped by both economic arguments and political considerations.

Taking decisions on fiscal guidance and potential reform of the fiscal framework matters for

market perceptions. Markets’ attention has shifted from the immediate crisis response to post-

2021 fiscal policy plans. As the pandemic crisis abates, markets will increasingly scrutinise EU

sustainability and national policy responses. Temporary fiscal support will have to be gradually

phased out to maintain sustainable debt levels.

The transition towards a new fiscal framework should ensure transparency of fiscal accounts,

and balance growth with fiscal sustainability concerns. The transition to a new set of rules

should depend on the pace of the recovery and incorporate clear guidance to ensure responsible

fiscal behaviour and minimise moral hazard.

EU legal framework and constraints to Stability and Growth Pact revision

The SGP is anchored in European and international law. Since the Maastricht Treaty, EU

primary law has acted as the backbone for fiscal policy coordination. Its provisions and the

annexed protocol stipulate key procedures and requirements that include the key reference

values of 3% for deficit-to-GDP and 60% for debt-to-GDP. The overall commitment to fiscal

discipline was further developed in a number of EU regulations and was reinforced by the 2012

TSCG signature in, an international treaty outside the EU legal framework.

The complex interaction between different rules is further specified in non-legislative

documents. In practice, two key documents – the Vade Mecum on the SGP and the Code of

Conduct – guide the European Commission and the member states when applying EU legislation.

E U F I S C A L R U L E S : R E F O R M C O N S I D E R A T I O N S | 23

The two reference values could be amended without a treaty change or national ratification.

The 3% and 60% criteria are defined in Article 126(2) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the

European Union (TFEU), and quantified in Protocol 12. The one twentieth rule is specified in

Regulation 1467/1997

48

, and codified in the TSCG. In our view, all of these could be amended by

an EU Regulation based on the TFEU Article 126(14). This would require unanimity in the

European Council, but would not be subject to national ratification.

49

Changes to the Treaty and

Protocol 12 can normally be made only through formal treaty revision, via the ‘ordinary’ or

‘simplified’ procedure.

50

The simplified procedure can be used to change the 3% and the 60%

thresholds in the Protocol 12.

51

However, TFEU Article 126 provides for a special legislative

procedure that allows amendments to the individual provisions of Protocol 12, upon

unanimous decision in the European Council and after consultation of the ECB and the

European Parliament.

52

The one twentieth debt reduction rule is laid down in both EU and international law, and

would likely be more difficult to change. Adjusting the one twentieth rule would require

amending Regulation 1467/1997,

53

but that is also laid down in the TSCG, together with the 60%

threshold. According to the TSCG,

54

when a country’s debt-to-GDP ratio exceeds 60%, it shall

reduce it at an average rate of one twentieth per year as a benchmark, as provided for in the

EU Regulation. The TSCG explicitly only applies to the extent that it is compatible (i.e. not

conflicting) with EU law. The relevant acts of secondary law do not entail a full harmonisation of

the rules on government debt, but rather define minimum requirements. As a result, EU

Member States remain free, in principle, to adhere to incremental, stricter rules that go beyond

their EU law obligations. Consequently, it is legally possible that they remain bound by the TSCG

as a matter of international law, even if the respective EU law requirements are amended.

55

This

might be remedied, depending on the precise issue, by a joint interpretative declaration, or by

the TSCG signatories mutually agreeing to a (temporary) suspension of the operation of certain

provisions of the TSCG pursuant to Article 57 of the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law

of Treaties.

The one twentieth debt reduction rule may best be adjusted by using a TSCG clause on

transposition into EU law to avoid changing the TSCG (including ratification). The TSCG includes

an obligation to incorporate its provisions into EU law within five years from its ratification.

56

Therefore, the EU could arguably adopt or amend a regulation, still on the basis of TFEU

Article 126(14), to incorporate the TSCG in secondary EU law. In the course of doing so, it may

even slightly alter its substance, subject to the general conditions and limits set out in the EU

Treaties. In this way, the one twentieth rule may arguably be amended without the need for

national ratification procedures.

48

Council Regulation (EC) No 1467/97 of 7 July 1997 on speeding up and clarifying the implementation of the excessive deficit

procedure, as amended by Council Regulation (EU) No 1177/2011 of 8 November 2011.

49

As regards Germany, using Article 126(14) TFEU is not listed in the Integrationsverantwortungsgesetz as a matter that requires

prior approval of the Bundestag. However, the possibility of the Federal Constitutional Court taking a different view cannot be ruled

out.

50

Article 48, EU Treaty on European Union.

51

The conditions for using the simplified procedure of 48(6), namely that the change does not create new competences for the

Union and pertains to Title III of the TFEU (Union policies), are met for changing the 3% and/or 60% thresholds.

52

Art. 126(14) TFEU provides that “[t]he Council shall, acting unanimously in accordance with a special legislative procedure and

after consulting the European Parliament and the European Central Bank, adopt the appropriate provisions which shall then replace

the said Protocol”. This is a lex specialis that allows the Council, within the parameters defined by Art. 126 and other Treaty

provisions, to adjust the reference values of the deficit and debt ratios.

53

Article 2(1a) of Council Regulation (EC) No 1467/1997 on speeding up and clarifying the implementation of the excessive deficit

procedure, as amended by Council Regulation (EU) No 1177/2011 of 8 November 2011.

54

Article 4, TSCG.

55

The introductory phrase of Article 3(1) TSCG makes clear that its stricter rules (notably the lower structural deficit limit of 0.5%)

apply “in addition and without prejudice to” EU law.

56

Article 16 TSCG expressly provides that, “within five years, at most […], the necessary steps shall be taken […] with the aim of

incorporating the substance of this Treaty into the legal framework of the European Union”.

24 | D I S C U S S I O N P A P E R S E R I E S | O c t o b e r 2 0 2 1

A new fiscal framework

Our proposal starts from a realisation that the original link between the deficit and debt

anchor is no longer valid. As discussed in Chapter 1, the 3% deficit limit was considered

adequate to stabilise the economy in response to shocks and, conditional on the 5% nominal

growth, to stabilise debt-to-GDP at 60%. The 60% debt ratio was close to the euro area average

at the time, and deemed serviceable under the prevailing macroeconomic situation.

Now, higher debt levels are serviceable, even though the expected nominal growth is lower.

Interest rates and the debt servicing burden – already on a steadily falling trend before the

pandemic – have been driven lower globally for an extended period of time and are likely to

remain below levels seen during the 1990s when the EU fiscal framework was derived.

The interest rate decline has raised the debt level that can be comfortably serviced, even though

steady state nominal growth for most euro area countries is now lower, estimated at about 3%.

In the foreseeable future with lower growth and a low interest rate environment, the 3%

deficit limit would be consistent with a debt anchor at 100% of GDP. The 100%-debt-to-GDP

reference value is consistent, at the steady state, with the 3% deficit limit and a 3% nominal

growth rate. In the present macroeconomic context of weak demand, restrained inflation

compared to the decades ago, and interest rates at the effective lower bound, public spending

remains a strong driver of growth, increasing the steady state debt level. Market appetite for

more public debt renders the 100% debt-to-GDP anchor acceptable. Given the present debt

levels, the 100% value is a more realistic target (Boxes 3–5), close to the current euro area

average, as was the 60% limit when adopted. Insisting on a 60% debt-to-GDP anchor would

either involve unrealistic reduction efforts over 20-year, or necessitate extending the

convergence horizon beyond that, essentially rendering the limit ineffective.

Box 3. The 3% reference value

The deficit reference value has been a reasonable and emprically backed anchor. The fiscal

deficit growth elasticity implied that a 1% decrease in output would lead to a 0.5% deficit

increase. With a deficit at about 1.5% of GDP in normal times, a 3% output gap – consistent with

a typical recession – would push deficit to 3% of GDP.

57

The 60% limit for debt-to-GDP reflected

the average value in the euro area, and was linked to the 3% deficit limit through the basic debt

accumulation equation.

58

In a steady state, a country’s debt-to-GDP ratio should converge to a

level that equals the deficit ratio divided by the nominal growth rate of GDP, at the time

expected to hover around 5%. The framework’s simplicity made political buy-in easier.

Experts and institutions supported the 3% deficit reference value and the medium-term target

of balanced or positive budget outturn. Buti et al. (1997) applied the envisaged framework to

the European fiscal and macroeconomic data over 1961–1996.

59

Their results emphasised a

need for a shift in member state policies towards accumulation of buffers in upswings. Such

fiscal buffers help countries restore a deficit swiftly to under the 3% ceiling in any cyclical

downturn. The OECD

60

and the IMF

61

confirmed that a structural deficit between 0.5 and 1.5%

GDP would provide sufficient space to allow automatic stabilisers to operate without breaching

57

Canzoneri, M. B., Diba, B. T. (2000), The SGP: Delicate balance or Albatross? In The Stability and Growth Pact – The Architecture of

Fiscal Policy in EMU eds. by Brunila et al. (2001).

58

b=d/y; b=debt-to-GDP, d=deficit-to-GDP, y=nominal growth. Morris, R., Ongena, H., Schuknecht, L. (2006), The Reform and

Implementation of the Stability and Growth Pact.

59

Buti et al. (1997), Budgetary Policies during Recessions – Retrospective Application of the Stability and Growth Pact to the Post-

War Period in the European Commission.

60

OECD (1997), Economic Outlook, 1997, p. 24.

61

IMF (1998), World Economic Outlook: October 1998, pp 131-136.