ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC

AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP

GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNAN

MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs S

CE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKIN

RM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFS

G UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION E

F ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs

CONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC G

ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP M

OVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANC

TO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESB

E ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMI

R EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP

IC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERN

AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SS

ANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BAN

M SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NC

KING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNIO

As NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AG

N ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOM

S DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MT

IC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERN

O SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM

ANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BAN

MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ES

KING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNIO

M ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EF

N ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMI

SM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP

IC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERN

CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA E

ANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BAN

WG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR C

KING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNIO

SRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP

N ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOM

EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NR

IC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERN

As SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS

ANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BAN

EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP E

KING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNIO

SAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MT

N ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOM

O SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM

IC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERN

MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF E

ANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BAN

SM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EF

KING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNIO

SM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP

N ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOM

CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA E

IC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERN

WG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR C

ANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BAN

SRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP

KING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNIO

SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs

N ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOM

NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS D

IC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERN

GS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO S

ANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BAN

CP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MI

KING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNIO

P MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM

N ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOM

ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM

IC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERN

EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CR

ANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BAN

D SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EW

KING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNIO

G NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSR

N ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOM

s AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP

IC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERN

EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NR

ANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BAN

As SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS

KING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNIO

EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP E

N ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOM

SAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MT

IC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERN

O SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM MIP MTO NRP CRD SSM SGP EIP MTO SCP ESAs EFSM EDP AMR CSRs AGS DGS EFSF ESM ESBR EBA EWG NCAs NRAs SRM

ANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE BANKING UNION ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE GOV

DIRECTORATE-GENERAL FOR INTERNAL POLICIES

ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE SUPPORT UNIT

I N -DEPTH A NALYSIS

Provided at the request of the

Economic and Monetary Affairs Committee

EN

ECON

IPOL

EGOV

Economic policy coordination in the euro area

under the European Semester

External authors: Klaus-Jürgen Gern

Nils Jannsen

Stefan Kooths

Kiel Institute for the World Economy

November 2015

IPOL

EGOV

DIRECTORATE-GENERAL FOR INTERNAL POLICIES

ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE SUPPORT UNIT

PE 542.678

IN-DEPTH ANALYSIS

Economic policy coordination in the euro area

under the European Semester

External authors: Klaus-Jürgen Gern

Nils Jannsen

Stefan Kooths

Kiel Institute for the World Economy

Provided in advance of the Economic Dialogue with

the President of the Eurogroup

in ECON

on 10 November 2015

Abstract

After three years of mixed operational experiences, the European Semester has been

streamlined and further reform has recently been suggested by the European Commission.

We outline the major modifications and evaluate to what extent this streamlining has

affected the nature of the 2015 country-specific recommendations. Any mechanism for

policy coordination depends crucially on the institutional framework that it is supposed to

operate in. Consequently, proposals for further improvement of the European Semester

must take the institutional environment into account. We therefore work out the

compatibility of different aspects of policy coordination with respect to the existing EU

architecture and discuss the proposals to modify this architecture put forward recently in

the Five Presidents Report. On this basis, we develop proposals for improving the

efficiency of the European Semester.

November 2015

ECON EN

PE 542.678 2

This paper was requested by the European Parliament's Economic and Monetary Affairs Committee.

AUTHORS

Klaus-Jürgen Gern, Kiel Institute for the World Economy

Nils Jannsen, Kiel Institute for the World Economy

Stefan Kooths, Kiel Institute for the World Economy

RESPONSIBLE ADMINISTRATOR

Jost Angerer

Economic Governance Support Unit

Directorate for Economic and Scientific Policies

Directorate-General for the Internal Policies of the Union

European Parliament

B-1047 Brussels

LANGUAGE VERSION

Original: EN

ABOUT THE EDITOR

Economic Governance Support Unit provides in-house and external expertise to support EP committees

and other parliamentary bodies in playing an effective role within the European Union framework for

coordination and surveillance of economic and fiscal policies.

E-mail: egov@ep.europa.eu

This document is also available on the Economic and Monetary Affairs Committee homepage at:

http://www.europarl.europa.eu/committees/en/ECON/home.html

Manuscript completed in November 2015

© European Union, 2015

DISCLAIMER

The opinions expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily

represent the official position of the European Parliament.

Reproduction and translation for non-commercial purposes are authorised, provided the source is

acknowledged and the publisher is given prior notice and sent a copy.

3 PE 542.678

CONTENTS

List of abbreviations ...................................................................................................................................... 4

List of figures ................................................................................................................................................. 4

Executive summary ....................................................................................................................................... 5

1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 7

2. The streamlined European Semester and the quest for ownership ......................................................... 8

3. The 2015 Country-specific Recommendations .................................................................................... 10

4. The institutional framework in which the european semester operates ................................................ 13

4.1 General aspects of economic policy coordination in the EMU ................................................... 13

4.2 The Five Presidents Report ......................................................................................................... 15

4.3 Directions for strengthening the institutional framework of the European Union...................... 17

5. How the European Semester can be made more efficient .................................................................... 19

5.1 Suggestions to improve the efficiency of the European Semester .............................................. 19

5.2 The proposals of the European Commission to improve the efficiency of the European

Semester from October 2015 – A first assessment ..................................................................... 21

6. Conclusions .......................................................................................................................................... 24

References .................................................................................................................................................... 26

5 PE 542.678

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

• After three years of mixed operational experience, the European Commission has implemented a

number of modifications to the European Semester in order to achieve a more consistent policy

agenda with respect to the main challenges, better implementation of recommendations, and a higher

level of ownership.

• Improved communication between the Commission and national authorities and stakeholders at the

national level, including parliaments, is an important tool to increase the level of ownership as insight

requires understanding and transparency supports acceptance. More transparency and updated

information on the process and status of implementation of country-specific recommendations would

increase peer-pressure and facilitate implementation of appropriate policies.

• The focus on a limited number of priority areas has successfully reduced the number of

recommendations. This comes, however, at the cost of dropping recommendations despite limited

progress in their implementation, which may give the wrong signals. In the future, balancing

continuity and variation in the focus of recommendations will be a challenge.

• The European Semester operates in a complex institutional environment that creates several trade-

offs for the implementation of intra-EMU policy coordination (subsidiarity vs. policy coordination,

soft vs. strict enforcement mechanisms, short-run vs. long-run requirements).

• The principle of subsidiarity, a key pillar of the European architecture introduced to make full use of

the advantages of diversity within the EU, suggests shifting competences to the lowest possible

government level. By its very nature, policy coordination works in the opposite direction. No

conflicts arise, however, if intra-EMU policy coordination addresses the well-functioning of the euro

area as a whole (common interest). Therefore, the Commission should identify areas that are

particularly relevant for the functioning of the EMU as a whole and communicate in the most

transparent way, whether specific recommendations address the common interest or the national

interest of a single Member State.

• While soft forms of coordination (such as peer reviewing, dialogue with national authorities, and

communication to the public) come at the cost of relatively weak implementation rates, stricter

enforcement mechanisms (rule-based approaches triggering automatic sanctions) are also problematic

as optimal rules, indicators, and thresholds vary across countries such that he resulting

recommendations would be notoriously sub-optimal.

• The need for operational policy coordination within the European Semester depends on the

institutional framework of the EMU, in particular with respect to the stability of the financial sector

and the fiscal soundness of the Member States. As long as the risk of negative cross-country spill-

overs emerging from these sources persists, the European Semester may have to address policy areas

(short- and medium-run) that will lose relevance once these destabilizing factors will be successfully

contained (long-run). The less the institutional framework reduces systemic risks that threaten the

proper functioning of the EMU as a whole or the more risk-sharing mechanisms (safety nets, EMU-

wide macroeconomic shock absorbers) are implemented, the more policy coordination and

surveillance is necessary. Prioritising the prevention of excessive risk-taking in the first place rather

than creating risk-sharing mechanisms would avoid this. Thus, the EMU should strive for becoming

the world’s most financially robust, market-oriented economic area.

• In an ideal institutional framework, the European Semester could focus on surveillance, peer

reviewing, and strengthening the capacities of national authorities to conduct structural reforms. The

existing soft enforcement mechanisms, such as peer-reviewing, dialogue with governments, and

communication to the public, should be further strengthened. Such a strategy would be consistent

PE 542.678 6

with the principle of subsidiarity and would be sufficient from a community perspective as

misconduct of policies in one country would not put at risk the functioning of EMU as a whole.

• In the currently prevailing institutional framework, the European Semester should also address the

prevention of systemic events that threaten the functioning of the EMU as a whole. The financial

sphere remains the most important source of negative cross-border spill-overs. Given the high costs

of financial crises, it is imperative to increase the implementation rate of appropriate

recommendations in the short to medium term. This calls for strict enforcement mechanisms that are

based on rules and automatic sanctions. In particular, debt sustainability could be increased by

applying the existing rules of the Stability and Growth Pact more rigorously.

• In principle, the MIP is an appropriate tool for the surveillance of financial stability from a

macroeconomic perspective. It should be unbundled from other areas, such as growth targets or

labour market performance. This would also strengthen the transparency of the European Semester as

a whole by reducing overlaps and multi-target instruments. The Scoreboard of the MIP should focus

more strictly on indicators that are relevant for financial stability from a macroeconomic perspective.

It should be complemented with economically more meaningful indicators in particular with

indicators that cover potential investment and capital stock distortions.

• The transparency of the European Semester could be strengthened by being more explicit on the

theoretical foundations on which recommendations are based. In particular, strong efforts should be

made to elaborate a coherent theoretical framework for those events that threaten the functioning of

the EMU as a whole. A common understanding is crucial for creating ownership for policy initiatives

that are supposed to address common interests shared by all Member States.

7 PE 542.678

1. INTRODUCTION

1

The European Semester is a regime for economic policy guidance and surveillance at EU level that

has been in operation since 2011. It was created in response to the failure to achieve the pivotal target

fixed in the Lisbon agenda of the year 2000, which aimed at making the European Union “the most

competitive and dynamic knowledge-based economy in the world” (European Council 2000). Important

goals to be reached by 2010 such as increasing the employment ratio to 70 percent, raising R&D

expenditures from 1.8 percent to 3 percent of GDP, or achieving average GDP growth of 3 percent were

missed by a large margin. Insufficiently consistent national economic policies and a lack of coordination

were identified as the key causes of the disappointing outcome.

The introduction of the European Semester was finally triggered by the European sovereign debt

crisis, which was seen as further evidence that more cooperation and surveillance was needed in

particular within the euro area. In order to fill the perceived gap and to raise the prospects for the

successful realization of the goals laid down in the follow-up long-term strategy “Europe 2020” (aiming

at smart, sustainable, and integrative growth), the European Semester was initiated. It is also instrumental

for macroeconomic surveillance as postulated in the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) and the

Macroeconomic Imbalances Procedure (MIP).

After three years of mixed operational experiences, the European Semester has been streamlined.

We outline the major modifications in chapter 2 and evaluate to what extent this streamlining has affected

the nature of the country-specific recommendations (chapter 3). Any mechanism for policy coordination

depends crucially on the institutional framework that it is supposed to operate in. Consequently, proposals

for further improving the European Semester must take this framework and emerging future

modifications thereof into account. In chapter 4, we therefore work out the compatibility of different

aspects of policy coordination with respect to the existing EU architecture and the far-reaching proposals

to modify this architecture put forward recently in the Five Presidents Report. Based on the results from

the preceding analysis, we develop proposals for improving the efficiency of the European Semester

(chapter 5).

While the European Semester applies to all EU Member States, this analysis focuses on the relevant

aspects for policy coordination within the European Monetary Union (EMU). As policy coordination

is a very broad concept, we use four categories for differentiation. Category 1 covers all forms of

information sharing among Member States (in particular, peer reviewing and best-practice exchange),

category 2 refers to those forms of policy coordination where a policy decision in country A is made

dependent ex ante on policy decisions in other countries (e.g., using fiscal space in country A to stimulate

economic activity in country B). Category 3 implies running similar polices in all Member States

(harmonization) and, finally, category 4 represents centralized policy-making at EMU level (shifting

competences from the national level to EMU institutions). We further distinguish between soft and strict

forms of policy coordination. While soft forms are of a non-binding nature and based on insight and

consensus finding, strict forms come with enforcement mechanisms that imply some type of legal

sanctions. Typically, policy coordination of category 1 draws heavily on soft forms of enforcement while

category 4 implies strict enforcement mechanisms. In categories 2 and 3 both forms of enforcement are

conceivable.

1

The authors thank Esther Ademmer, Niklas Drews, Jens Boysen-Hogrefe, and Ulrich Stolzenburg for highly appreciated

comments and discussions.

PE 542.678 8

2. THE STREAMLINED EUROPEAN SEMESTER AND THE QUEST FOR OWNERSHIP

The European Semester is the revolving annual cycle of economic budgetary coordination starting

from the Annual Growth Survey and culminating in country-specific recommendations to address

identified major challenges. The Annual Growth Survey (published in November/December of the

preceding year) in tandem with the Alert Mechanism Report of the MIP represent the starting point of the

European Semester. During the winter months, country reviews are compiled by the Commission

containing an analysis of macroeconomic backdrops and an in-depth analysis of country-specific cyclical

and structural problems for each Member State. In March, the European Council adopts guidelines for

directions of national policies before, in April, national governments present their policies for sound

public finances (in the stability programmes or convergence programmes, respectively) and outlines their

reforms and measures to make progress in the direction of the Europe 2020 goals (in the national reform

programmes). Usually in May or June, the Commission drafts country-specific recommendations

proposing economic policy measures for each Member State, depending on the country’s economic and

social performance in the previous year. The recommendations are based on the results of the country

reports and reflect the priorities set out in the Annual Growth Survey. They are adopted in July by the

European Council.

After three years of mixed operational experience, the European Semester has been significantly

streamlined. In 2015, the Commission has implemented a number of modifications in order to achieve a

more consistent policy agenda with respect to the main challenges, a better implementation of

recommendations, and a higher level of ownership. Implementation has been disappointing in recent

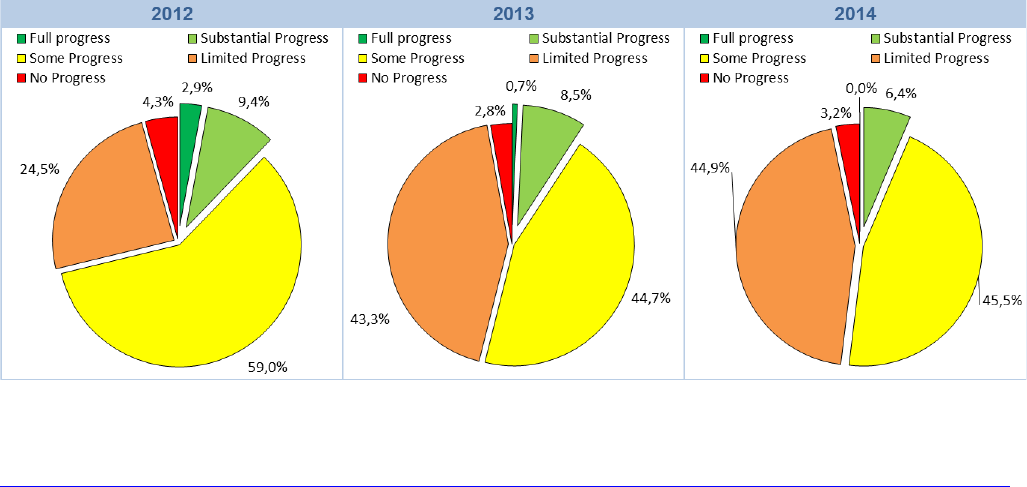

years. In 2012–2014, only around 10 percent of recommendations have been fully or substantially put

into legislation, meaning that Member States have adopted and implemented measures that are

appropriate or go a long way in addressing the country-specific recommendations. At the same time, the

share of recommendations which have been insufficiently addressed, where adoption or implementation

is at risk or no measures have been announced or adopted at all (limited or no progress in

implementation) has risen from 29 percent in 2012 to 46 percent in 2013 and 48 percent in 2014 (Figure

1).

Figure 1: Implementation of country-specific recommendations by EU Member States, 2012–2014

Source: European Parliament (2014, 2015a), 2012: own compilation of European Commission

assessments published in Commission Staff Documents available on the “Europe 2020” webpage

http://ec.europa.eu/europe2020/making-it-happen/country-specific-recommendations/2013/index_en.htm.

The streamlined European Semester includes focusing on the top priority areas in each Member

State, earlier publication of the country-specific and euro area analysis underpinning the

9 PE 542.678

recommendations (in January rather than in March/April), and a more intensive outreach at the

political level. Focusing on the key challenges as identified in the Annual Growth Survey implies a

smaller number of recommendations, which has been appreciated by national governments. A more

limited number of recommendations may lead to stronger compliance efforts as political capital is

limited. It may, however, be a problematic signal if recommendations that have been listed in one year

drop out of the list in the next year despite little or no effort to implement policies designed to improve

the situation, just because the focus in the Annual Growth Survey has shifted. With the streamlined

European Semester, the in-depth reviews prepared in the MIP context for countries that merit closer

monitoring are now integrated into the regular country reports. While this procedure may look

straightforward, it risks reducing the focus on key stability issues, which would be particularly dangerous

in terms of economic developments with community-wide implications.

Ownership creation for policy recommendations remains the most critical success factor. As

research related to IMF adjustment programmes suggests (Bird and Willett 2004, Dreher 2008, Khan and

Sharam 2001), the level of “ownership” (i.e., the insight into the reasonableness of reform proposals by

those in charge of implementing them) is the most critical element for the success of any structural reform

agenda. Thus, any modification of the European Semester should be primarily judged by the extent to

which it contributes to improving this condition sine qua non.

Involving national parliaments in the European Semester can help improve ownership and should

be strengthened. In the current procedure, national parliaments of Member States should participate in

the preparation of Stability and Convergence Programmes and National Reform Programmes in order to

increase transparency and ownership of the decisions taken, and the programmes should inform about

whether and how the parliaments were involved. A survey by the European Parliament (2015b) finds,

however, that only half of the 2015 programmes delivered the required information.

2

The Commission

should strengthen surveillance of this element of the European Semester and specify which form the

participation of the parliament at least should have. It should require Member States to report a schedule

for involvement of the parliament that should be publicly available.

Communication can play an important role for raising compliance with the country-specific

recommendations finally endorsed by the European Council. Improved communication between the

Commission and national authorities and stakeholders at the national level is an important tool to increase

the level of ownership as insight requires understanding and transparency supports acceptance. The early

presentation of an integrated country analysis facilitates more intense discussions with government

officials, political party representatives, social partners, non-governmental organizations as well as

academics and is intended to ultimately lead to a better understanding in the broad public.

More transparency and current information on the process and status of implementation of

country-specific recommendations would increase peer-pressure and facilitate implementation of

appropriate policies. Member countries should be required to submit an agenda outlining steps and

milestones on the way to implementation of measures addressing the country-specific recommendations,

which should be available to the public and could be monitored by Commission and/or European

parliament. Failure to address recommendations appropriately or achieve milestones should be explained

on a regular basis. The new format of country-specific recommendations with a smaller number of

recommendations is conducive to such an exercise.

2

Involvement of the national parliaments can take several forms: Information, discussion or approval. Stability/Convergence

Programmes and National Reform Programmes should explicitly state whether and in what form national parliaments have

been involved. Only 27 of the 54 of the 2015 vintage make the required reference.

PE 542.678 10

3. THE 2015 COUNTRY-SPECIFIC RECOMMENDATIONS

The 2015 European Semester focuses on investment, structural reforms, and fiscal responsibility. In

the streamlined European Semester, the country-specific recommendations are supposed to reflect the

focus of the Annual Growth Survey. The Commission identifies three priority areas for action in its 2015

Annual Growth Survey that mutually reinforce one another (“three pillar approach”): A coordinated

boost for investment with the establishment of the Investment Plan for Europe as a central element;

renewed commitment to structural reforms including administrative reforms to improve the business

climate; and pursuing fiscal responsibility, not only by keeping deficits and debt levels under control in

accordance with European rules, but also by improving the quality of public finance. As a consequence of

the concept of the streamlined European Semester, in its 2015 country-specific recommendations, the

Commission is to focus on recommendations addressing these challenges. In its presentation of the

country-specific recommendations, however, the Commission explicitly introduces a fourth area of focus,

namely improving employment policy and social protection, which in the Annual Growth Survey is

included under the label of structural reforms.

The three pillars of the Annual Growth Survey still cover a broad range of issues to be potentially

addressed in the country-specific recommendations. Concerning investment, there are a number of

relevant policy areas, including barriers to financing and launching of investment projects (credit

availability and capital market access, especially for small and medium-sized companies, administrative

red tape and corruption) and issues directly related to the implementation of the Investment Plan for

Europe.

3

Concerning structural reforms in product, service and labour markets, they can contribute to

productivity and investment and ultimately boost prosperity by fostering growth and employment.

Streamlining the public administration and judicial systems are instrumental for improving the business

climate and incentives for investment. Reforms geared at improving the functioning of the financial

sector could ease access to finance for investment without jeopardizing the necessary deleveraging in the

economy. Concerning fiscal policy, a key element is the continuation of fiscal consolidation, especially in

those countries that still have to go a long way to meeting the medium-term target of a structural general

government balance close to zero. However, against the backdrop of significant improvements in the

fiscal positions of most European countries in recent years and a declining number of countries in the

excessive deficit procedure, the Commission now sees the need to strike a balance between short-term

stabilization and long-term sustainability and advocates an increasingly flexible interpretation of the rules

of the Stability and Growth Pact (European Commission 2015). In addition, improving the structure of

revenues and expenditures remains a possibility for fiscal authorities to positively impact on growth.

The limited number of priority areas has successfully reduced the number of recommendations and

sharpened its focus. The total number of recommendations has been reduced from 165 in 2014 to 106 in

2015 (including 4 recommendations in each year for the euro area as a whole). The average number of

recommendations is now four, down from six in the previous year. At the same time, the individual

recommendation tends to have a stronger focus. In previous years, some recommendations were “mixed

bags” of issues, examples being the 2014 recommendation 6 for the Czech Republic (“accelerate reform

of regulated professions … and improve energy efficiency in the economy”) or Portugal (“improve

evaluation of the housing market … remove remaining restrictions in the professional services sector …

Eliminate payment delays by the public sector “). In 2015, recommendations are generally much more

targeted. In this respect, however, the approach was not uniform across all countries. While in some

cases, one complex recommendation that dealt with a diversity of fiscal issues (fiscal balance in general

and issues related to the tax system, the pension system and/or the health care system) was split into two

(e.g. France) or even three (Czech Republic) different recommendations, in other cases recommendations

on healthcare or pension reform were merged with a recommendation on the general fiscal stance

(Bulgaria).

3

Interestingly, only one recommendation explicitly features the Investment Plan for Europe.

11 PE 542.678

The nature of the country-specific recommendations has generally changed in the direction of

setting objectives rather than devising means. In 2015, the country-specific recommendations have not

only been reduced in number but also in terms of detail and complexity, albeit with some exceptions. The

recommendations are now generally much shorter, limited to one central aspect, and suggest general

objectives rather than specific measures to achieve it. This strategy is a two-edged sword. On the one

hand, ownership could rise by setting the goals at the European level (in close cooperation with national

representatives in the course of mutual debate during the European Semester) and leaving it to the

Member States to make the necessary commitments to concrete implementation measures. On the other

hand, a more general level of recommendations complicates monitoring and makes it easier for

governments to evade implementing appropriate action. There is also the problem that quantitative

variables tend to lose their relevance as soon as they are made a policy target (Goodhart’s law).

Dropping recommendations despite limited progress in their implementation may give the wrong

signals. In many cases, in fact in most of them, recommendations to take policy initiatives in areas that

are not in the current focus of the Annual Growth Survey have been eliminated, although their degree of

implementation has been less than substantial. Out of the 41 recommendations from the year 2014 that

did not make it in one form or another into the 2015 recommendations, only 2 had been implemented to a

substantial degree (completion of the ECB’s asset quality review in Croatia and reform of state owned

enterprises in Lithuania). Although the Commission stresses in its communication that this does not

indicate that those areas have lost importance, it may wrongly signal that reduced effort may be

acceptable. Policy areas that have been featured in previous years’ recommendations and that were

(almost completely) left out in this year’s edition include educational and environmental issues. Another

central strategy of the commission reflected in the recommendations in recent years was to advocate a

shift in taxation from direct taxes to indirect taxes and environmental taxes. Despite only moderate

implementation, this topic has almost disappeared this year.

The criteria for the selection of recommendations are unclear. Despite the communication of the

Commission explaining the new approach of focusing on specific areas (although still broadly defined),

questions with respect to the selection of the recommendations remain. A case in point is the treatment of

social policy and labour market issues. While in some countries recommendations related to labour

market policies (Ireland, Netherlands), youth unemployment strategies and social inclusion plans

(Luxembourg, Spain) or effectiveness of social transfer systems (Romania, Lithuania) have been dropped

although implementation has so far not been sufficient, in other countries similar recommendations have

been kept (Bulgaria, Portugal). Also, recommendations that could easily be related to the Commission’s

central policy directions have in a number of cases been eliminated despite only modest progress in

implementation, especially recommendations concerning administrative reforms, red tape, or tackling

corruption, fields in which action would be conducive to investment (Spain, France, Poland, Portugal,

Romania, Hungary, Malta). At the same time, in other countries these issues remain on the agenda

(Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Croatia, Italy, Latvia, Slovenia, and Slovakia).

Recommendations on the euro area level are mainly directed towards improvement of the

coordination framework and progress in deepening the economic and monetary integration. There

are four recommendations related to implementation of the broad guidelines for the economic policies of

the Member States whose currency is the euro. The recommendations include: (1) the use of peer pressure

to promote structural reforms and assessment of the delivery of reforms on a regular basis; (2)

coordination of fiscal policies to ensure an appropriate fiscal stance; (3) progress on the way to restoring a

healthy financial sector and towards a banking union; (4) suggestions for deepening of EMU and

improved governance in the euro area (based on the Five Presidents Report). Those recommendations that

relate to the institutional design of EMU (recommendations 3 and 4) and the execution of the European

Semester (1) seem appropriate, although progress and monitoring with regard to their implementation are

potentially complicated by the fact that it is not completely clear who is the addressee in each case

(Commission, Council, European Parliament, Member States). Recommendation 2, however, seems

problematic as it refers to a fiscal stance on the euro area level which, by coordination, should be brought

PE 542.678 12

in line with sustainability risks and cyclical conditions. The latter are, however, observed on the country

level and macroeconomic stability in the euro area would deteriorate rather than improve if the individual

countries’ fiscal stance would target European aggregates rather than national conditions.

Issues of particular relevance for the euro area level have lost importance. Especially those policy

areas that can be assumed to have the largest international spill-overs and therefore to make the strongest

case for cooperation at the EMU level are less visible in this year’s recommendations. The most

important of these areas would be the financial sector. While there is still a number of recommendations

left that deal with financial issues, the focus has shifted from reducing vulnerabilities to restoring normal

lending behaviour. Another set of policies with supranational importance would deal with environmental

issues, especially greenhouse gas emissions. These are almost completely missing in this year’s

recommendations. While the reduced presence of recommendations demanding action to safeguard

financial stability may be explained by the fact that the economies a few years after a financial crisis

generally do not show signs of froth in the financial sector, the absence of environmental issues suggests

a limited priority of the 2020 goal of environmental sustainability in times of subdued growth and high

unemployment.

Balancing continuity and variation in the focus of recommendations is challenging. On the one hand,

the focal areas of the Annual Growth Survey are, although not comprehensive, sufficiently general and

difficult to tackle that they can be expected to remain on the agenda for a number of years. On the other

hand, important policy areas have been moved out of the spotlight of the country-specific

recommendations this year and may need fresh attention in the coming years, or new priorities may arise.

It remains to be seen how the Commission is going to deal with the conflicting requirements of following

up on one strategy and catering for varying foci without increasing the number of recommendations

again.

13 PE 542.678

4. THE INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK IN WHICH THE EUROPEAN SEMESTER

OPERATES

The optimal design of the European Semester and its efficiency crucially depend on the institutional

framework of the EU and the EMU. In this Section, we discuss general aspects that are relevant for

economic policy coordination in the EMU (Section 4.1), comment on the Five Presidents Report that

aims to give a roadmap for completing the EMU (Section 4.2), and briefly outline an improved

institutional framework and its consequences for the European Semester (Section 4.3).

4.1 General aspects of economic policy coordination in the EMU

Economic policy coordination among EMU Member States should be clearly targeted to the

prevention of negative cross-border systemic spill-overs as it may otherwise conflict with the

principle of subsidiarity. The principle of subsidiarity, as laid down in Article 5 (3) of the EU Treaty, is

a fundamental pillar of the EU architecture. The key aspects of this principle (incentive structure,

availability of information, access to adequate instruments, democratic legitimacy) put strong emphasis

on shifting competences and responsibilities to the lowest possible governmental level, with the market

process (private coordination) marking the bottom end. Given the high importance of this principle, any

divergence from it should be explicitly justified by the common interest of all Member States. Systemic

external effects that harm the functioning of the monetary union affect this common interest and would

therefore be a case for regulating national policies at EMU level. These detrimental cross-border spill-

overs must not be confused with pecuniary “external” effects that simply reflect well-functioning

mechanisms of the single market. Economic performance losses due to badly designed policies in one

country would therefore have to be accepted as long as the consequences mainly affect the respective

member country and do not harm the stability of the union as a whole.

Subsidiarity implies diversity and thus sets limits for harmonization or centralization at EMU level

while simultaneously opening the field for intensive peer reviewing and best-practice exchange

within the European Semester. Diversity would be unnecessary if one-size-fits-all regulations existed

and if the best approach to policy-making was known or at least generally accepted as a consensus. So

far, this is not the case. Thus, allowing for diversity is a basic strategy that benefits all Member States. It

makes the community more robust as wrong regulations do not apply to all member countries

simultaneously and, even more importantly, it allows for trial-and-error search processes and evolutionary

improvements by mutual learning in a world of imperfect and decentral knowledge. The latter makes a

strong case for using the European Semester for intensive peer-reviewing and exchange of best-practice

experiences. Via learning, all Member States benefit from the experience made by their peers (both

positive and negative). This learning mechanism therefore depends crucially on diversity and the capacity

of testing new policies by pioneers. However, it should be kept in mind that the knowledge (and thus the

consensus) about what might be considered a “best practice” will remain limited. Plus, views on

mainstream paradigms typically change over time. Therefore, the economic governance within the EMU

must provide for mechanisms that allow for (gradual) paradigm shifts. This requires room for manoeuvre

for policy pioneers.

The notion of “competitiveness of countries” is conceptually flawed and may lead to misguided

policy recommendations. The concept of competitiveness is central in the European reform debate.

While competitiveness is a meaningful concept for companies, it is inappropriate when applied to

economic areas or countries (Krugman 1994, 1996). A company must exit the market when its costs

persistently exceed its revenues. Because a company in a competitive environment cannot reduce the

prices for its inputs (in particular, wages) it will either see its inputs move to competitors or become

insolvent right away. By contrast, within the economic system of a country, the price of domestic inputs

can adjust. As competition is a relative concept, the notion of “competitiveness” suggests that the

problems of one country are at least in part caused by the rest of the world. This view also invites to

overemphasize and misinterpret trade balances. International trade is not a zero-sum game but mutually

PE 542.678 14

beneficial for both parties. While competing firms operate on the same side of the market, trade between

countries includes both sides, sellers and buyers. Countries do not differ in terms of “competitiveness”

but in terms of “productivity” (including regulatory quality), which translates into different income levels.

Raising productivity is something to be done at home (or with the help of capital and knowledge imports),

but not via economic policy coordination of the category 2-type (i.e. a compensating policy response

abroad). With respect to unemployment, again, not the level of competitiveness is decisive but whether

wages are in line with productivity which is hardly a matter for international policy coordination.

4

The theoretical foundations for macroeconomic “imbalances” and “shocks” are insufficiently

specified, prone to confusing cause and effect, and too vague to shape the new economic governance

structure of the EMU. While the MIP was introduced to prevent macroeconomic imbalances from

destabilizing the euro area as a whole, it remains theoretically unclear what exactly should be regarded as

an imbalance and what the cause of such imbalances is supposed to be. So far, no satisfying clarification

has been reached,

5

and the economic reading of the scoreboard indicators is open to vast interpretations as

the debate on the twin-issue of “excessive current account balances” and “wage divergences” illustrates.

6

Similarly ambiguous is the notion of “macroeconomic shocks” that is central in the Five Presidents

Report. Most of what is typically classified as a shock is either the reversal of an unsustainable domestic

trend (including unsustainable policy stances) or the occurrence of an economically relevant event beyond

the reach of national policy makers. The first type of shocks does not simply occur but is deeply rooted in

unsustainable incentive structures, most of which can be summarized as a violation of the accountability

principle (i.e., the actual or perceived ability to shift risks to third parties resulting in excessive risk-

taking). Those shocks are not exogenous to the economic process (very often they build up over time –

like excessive debt financing – and materialize only when critical thresholds are reached). What then

shows up as a confidence crisis is the consequence of deficiencies in the regulatory framework.

7

The

second type of shocks (e.g., abrupt changes in external data like oil prices) can be either temporary or

permanent. Non-temporary shocks are structural changes to which the country must adapt anyway. The

idea of using the EMU as a macroeconomic insurance facility raises serious questions of mechanism

design (prevention of moral hazard, identification of shocks) making it unclear to what extent intra-EMU

policy coordination could help alleviate the consequences of such a shock for the EMU as a whole in an

intertemporal perspective. Temporary shocks are typically too short-lived to make the European Semester

a suitable mechanism to cope with them. To the extent that these shocks affect the national business cycle

in the short run, a country with sound public finances and access to capital markets has sufficient

domestic instruments available to dampen those destabilizing effects.

4

In a functional market framework, wages should respond to the situation in the very same labour market that they are set for,

and not with respect to the situation in foreign labour markets. If wages fall due to unemployment in one country (or in the

region of one country), this wage response creates a pecuniary “external” effect for the rest of the world, which is the very

essence of the market mechanism as it indicates varying scarcities via the price system. As the pressure for falling wages fades

away once full employment is re-established, there is no escalating downward spiral of wages in the EMU originating from

one Member State. Likewise, even in the case of a closed economy, a country would suffer from unemployment if its labour

market regime allowed wages to surpass the level of labour productivity.

5

EU Regulation 1176/2011 on the prevention and correction of macroeconomic imbalances defines an imbalance as “any

trend giving rise to macroeconomic developments which are adversely affecting, or have the potential adversely to affect, the

proper functioning of the economy of a Member State or of the economic and monetary union, or of the Union as a whole”.

This describes the symptom, not the cause.

6

While some economists look at trade flows from a labour market perspective (higher domestic wages translate into higher

domestic prices, causing higher imports and lower exports), other economists would stress the importance of capital flows that

shift purchasing power from one country to another, increasing nominal demand in the recipient country, which then translates

into higher prices and wages (not the other way around), triggering imports and dampening exports (and causing no “lack of

aggregate demand” in the recipient country). While the first view would recommend policy makers to intervene in the labour

market, the second view would stress potential distortions in the financial sector (like implicit guarantees) and – in the absence

of those – would not consider the free flow of capital (and thus current account balances) a problem at all.

7

E. g., the Greek debt crisis clearly did not come as an external shock to Greece. Given the unsustainable policy setup in the

country, a debt crisis would have occurred sooner or later.

15 PE 542.678

Economic convergence is not the prerequisite for but is supported by a well-functioning monetary

union within the single market. Fundamentally, a monetary union represents a group of countries that

agree on the same universal means of exchange (single currency). The usefulness of money to facilitate

the division of labour via indirect exchange does not depend on the relative income positions of the

money users. Therefore, a workable monetary union does not depend on similar or converging

productivity levels among participating countries; nor do productivity (and income) differentials require

compensating fiscal transfer mechanisms in order for the monetary union to operate smoothly. Both

market forces and the incentives for policy makers in less productive regions are sufficient to respond to

productivity differentials, provided they are reflected in price differentials to stimulate economic activity

and attract foreign direct investment. To the extent that productivity differentials are due to poorly

performing national policies (institutional framework), peer reviewing and exchange of views during the

European Semester (type-1 category of policy coordination) can play an important role for achieving

improvement. With regard to monetary policy, convergence in terms of the co-movement of the business

cycles (or the output gap) in all Member States would make policy making easier. However, this does not

refer to the convergence of productivity levels but to those of output gaps (deviation from normal

capacity utilization). While the former is envisaged within the European Semester (in particular with

respect to the 2020 goals), the latter hardly fits into this mechanism as business cycle synchronization via

policy coordination (type-2 category) would not only raise extremely difficult conceptual questions but

would also require a higher frequency of actions.

4.2 The Five Presidents Report

Next to specific proposals for the European Semester the Five Presidents Report provides a set of

broad institutional initiatives for economic, financial, fiscal, and political reforms of the EMU

framework with a strong emphasis on more policy coordination. While the proposals for the two-

stage European Semester (euro area analysis preceding country-specific recommendations) and for two

new types of institutions (system of Competitiveness Boards

8

and an advisory European Fiscal Board)

would directly affect the operation of the European Semester (in particular with respect to policy

coordination of the type-1 category), the broader institutional initiatives would affect the European

Semester indirectly (in particular by creating more EMU-wide macroeconomic mechanisms) or remain

very vague. The wording (“completing” and “deepening” the EMU or making it “genuine” or “fair”)

makes it difficult to identify the underlying theoretical concepts. While the report argues that more policy

coordination is needed for better economic, financial, fiscal and political performance, no reference is

made to the principle of subsidiarity or to other conceptual difficulties that a higher degree of policy

coordination may imply.

The European debt crisis revealed severely defective regulations in the financial system that call for

much stronger policy coordination. Financial stability is the key prerequisite for the smooth functioning

of the monetary union. It is hard to see any systemically relevant negative cross-border spill-over that is

not spread crucially via the financial system and the banking system in particular.

9

Therefore,

dysfunctional national financial regulations are the most important source of destabilisation of the

monetary union.

This is due to the debt-backed monetary system that puts the payment systems of the

euro area at risk whenever non-performing loans or other mal-investments by banks surpass critical

thresholds. A collapse of these systems would severely damage the real economy. Given the cross-border

interconnectedness of banks, the common interest is at stake, calling for strong euro area-wide policy

coordination of category type-3 or type-4. The regulatory response could follow two fundamental

approaches:

8

Formerly named Competitiveness Authorities.

9

Put another way: Once the financial system is robust, the scope for necessary further EMU-specific policy coordination may

become very narrow.

PE 542.678 16

• Approach 1

All participants in the financial system (in particular in the banking sector) become robust or

irrelevant enough to such an extent that the failure of one of them would not harm the whole

system as a whole (i.e. radically solving the “too-big-to-fail”-problem).

• Approach 2

Systemically relevant financial institutions may persist but the disturbances that the failure of

one of them may cause are absorbed by stronger safety nets and other “shock absorbers”.

The Five Presidents Report adopts an approach that is dominated by enhancing macro-

management and “shock absorption” at EMU level rather than making the need for “risk sharing”

(both public and private) less urgent. By strongly stressing the need for more “risk sharing” within the

EMU (both publicly and privately), the approach that the Five Presidents Report adopts clearly points at

the aforementioned second approach. Indeed, risk sharing is a suitable instrument to overcome the

national re-segmentation of financial markets that disintegrated the euro area and aggravated the financial

crisis. As long as implicit bail-out guarantees for systemically relevant financial institutions persist and as

long as they depend on the solvency of the sovereign (including bank-sovereign negative feedback loops),

there is no level playing field in the EMU banking market. To overcome this, the Five President Report

promotes several mechanisms for risk sharing (e.g. a common deposit insurance scheme and a “last-resort

financial safety net” as a common backstop to the Banking Union). However, these risk sharing

mechanisms are cures for symptoms, not the root causes. They create new room for moral hazard that

then has to be mitigated by even stronger supervision, the feasibility of which is extremely demanding if

not impossible.

10

The strong focus on macro-management is prone to treat aggregates as if they were

decision-making economic agents. But “the financial industry” or “the private sector” does not act.

Therefore, shifting risks to “the private sector” by compulsory risk sharing among all agents within the

private sector does not address the problem of excessive risk-taking of one agent at the expense of others

(unless one assumes that risks can be calculated in a sufficiently exact way by supervisors). While this

would shelter the tax payer from dysfunctional transfers to risk takers, other third-party private agents

would still be exposed to such risks (money users, credit clients of banks). The alternative approach

brings the risk that individual agents take and their individual accountability back in line with each other

(i.e. treating the root causes of the “shocks”). This would avoid severe incentive problems and the need

for EMU-wide safety nets for the financial sector as “shock absorbers”.

More joint liability at EMU level necessarily calls for stricter supervision and narrows the scope of

national policy-making. The more risk sharing and shock absorption mechanisms are implemented at the

EMU level, the more likely the impact of deficient national policies will also be compensated (i.e. shared

among all EMU Member States). To prevent these negative side-effects, stricter supervision would

become necessary, dampening the spirit of ownership when it comes to structural reform proposals within

the European Semester.

The proposal for a fiscal capacity on the EMU-level (euro area treasury) reflects the dominance of

macro-managing rather than curing structural problems. A fiscal capacity for the EMU would call

for an economic analysis of EMU-specific collective goods in the first place. While EU-wide public