Universal Literacy

Year 2 Evaluation Summary Report

SY 2017–18

Submitted by

Research & Policy Support Group

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF CONTENTS ..............................................................................................................

................................................................................................................................

........................................................................................................................................

..........................................................................................................................

...........................................................................................

.........................................

................................................................

..........................................................................................................

................................................................................................................................

...............................................................................................................................

.....................................................................................................

.................................................................................

ii

Introduction 1

Reach 2

Implementation 3

Implementation: Coach Time Use 4

Implementation Perspectives: Teacher, Administrator, and Coach 5

Implementation Perspectives: Portraits of Practice 11

Early Indicators of Impact 12

Conclusion 14

References 17

APPENDIX A: Data Sources 19

APPENDIX B: GMRT – Technical Report 20

Introduction

The ultimate goal of the Universal Literacy initiative is to have all students reading on grade level by

the end of the second grade, by 2026. The initiative takes a research-based, capacity-building

approach by training educators to become Reading Coaches, who work with K–2 teachers

individually and in groups on how to effectively teach children to read.

Researchers from the New York City Department of Education’s Research & Policy Support Group

(RPSG) conduct evaluation activities for the initiative, working in partnership with the Early Literacy

team. In addition to the evaluation activities described in this report, RPSG researchers respond to

requests by policymakers for data and analytics; support the team in the development and

implementation of the Digital Daily Coaching Log; present to the Reading Coaches and staff on a

variety of research-related topics; and keep abreast of the empirical literature on literacy coaching.

In Year 1 (Y1), School Year (SY) 2016–17, RPSG collaborated with the Early Literacy team to collect

data to serve as a baseline for the initiative; provided formative findings to help inform program

implementation; and piloted instruments, data collection, and analysis.

The main purposes of the SY 2017–18 Year 2 (Y2) evaluation were to:

• Track metrics about the initiative’s reach;

• Learn about the initiative’s implementation, in order to:

○ Provide formative results that the program team can use to inform planning and

improvement;

○ Document successes and challenges related to implementation and sustainability;

and

• Analyze early impacts, including the extent to which the presence of a reading coach

influences the reading scores of Grade 2 students.

The Universal Literacy initiative (ULit) is informed by bodies of research

1

related to how children

learn to read and how teachers learn to teach children to read. Its organization and deployment

were influenced by research on literacy coaching and by past New York City Department of

Education (NYCDOE) coaching initiatives. The evaluation used these sources to develop research

1

See, for instance: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) (2000), National Research Council

(1998), Foorman, et al. (2016).

Universal Literacy Year 2 Summary Report | 1

questions and data collection protocols. The research questions described in Table 1 guided RPSG’s

work in Year 2.

Table 1. Year 2 Evaluation: Research Questions

Research Question

Data Sources

➊ What is the reach of Universal Literacy?

Program team data; DOE institutional

data; coach logs

➋ How is the initiative being implemented

in schools?

Group and individual interviews; site

visits/portraits of practice; surveys; coach

logs

➌ What is the impact of the Universal

Literacy initiative on student learning?

Gates-MacGinitie Reading Test (GMRT),

Level 2

Reading coaches must navigate complex school ecosystems in order to fulfill their mission of

providing job-embedded coaching to K–2 classroom teachers. They report to central district office

staff while working onsite in schools. They need to gain the trust of school-based educators.

Because they are not reading interventionists who work one-on-one with students, but rather

instructional coaches there to build the capacity of K–2 classroom teachers to teach students to

read, they need to clearly communicate the purposes and boundaries of their roles to school

building leaders and staff.

Reach

To answer the first research question, about the initiative’s reach, we used program data and DOE

institutional data.

In SY 2017–18, the Universal Literacy initiative scaled to 14 districts from its original four districts. It

conducted an intensive three-week summer training course on reading acquisition, instructional

coaching, and adult learning for them along with bi-monthly sessions during the school year for

new coaches; returning coaches attended a week-long summer session and monthly trainings to

deepen their knowledge about literacy coaching. Additionally, coaches received optional training

on curricular materials used in their schools, such as Fundations.

Universal Literacy Year 2 Summary Report | 2

The initiative recruited 150 Reading Coaches for SY 2017–18, who joined the 86 Reading Coaches

who began in SY 2016–17 for a total of 236 coaches.

2

In total, these coaches served 298 schools,

with 168 Reading Coaches serving one school and 68 Reading Coaches serving two schools. In all,

these schools served approximately 70,000 K–2 students. The average Economic Need Index

3

of

schools was 84.1%.

Based on coach log data, 3,343 K–2 teachers received individual coaching.

4

On average, coaches

spent a total of 287 class periods coaching individual teachers during the time frame the log was

active, with an average of just over 20 periods with each teacher and a range of 0 to 175 periods.

Coaches split their time fairly evenly coaching teachers of each grade, on average (37% of time with

K teachers, 34% with Grade 1 teachers, and 35% with Grade 2 teachers).

5

Implementation

To answer the question about the initiative’s implementation, we used program data as well as

data that RPSG collected via surveys, interviews, and site visits. A review of the empirical literature

and policy literature on reading acquisition, reading instruction, and instructional coaching

informed our approach.

6

2

Data taken from Spring 2018 coach roster; numbers fluctuated slightly throughout the year due to rolling hiring and

resignations. In SY 2017–18, ULit had 242 coach positions and 6 vacancies. A small number of large schools had two

Reading Coaches.

3

The Economic Need Index (ENI) estimates the percentage of students facing economic hardship. The metric includes

eligibility for public assistance from the NYC Human Resources Administration (HRA), temporary housing status, and

census tract data. The school’s Economic Need Index score is the average of its students’ Economic Need Values; The

highest possible ENI value is 100.

4

All data are from the period of December 2017 to June 2018, when the Digital Daily Coaching Log was active. Coaches

record their coaching activities for each period (approximately 45 minutes) that they are in a school. Digital Daily

Coaching Log. See footnote 8 below for more detail.

5

Teachers can be associated with multiple grades and coaches may work with two co-teachers in a single class period;

thus, percent of time use with different grades does not add up to 100.

6

See, for example: Coburn & Woulfin (2012), Deussen, Coskie, Robinson, & Autio (2007), Elish-Piper & L’Allier (2010, 2011),

L’Allier, Elish-Piper, & Bean (2010), Mangin & Dunsmore (2015), Matsumura, Sartoris, Bickel, & Garnier (2009), Phillips et al.

(2016), Scott, Cortina & Carlisle (2012), and Zigmond, et al. (2011).

Universal Literacy Year 2 Summary Report | 3

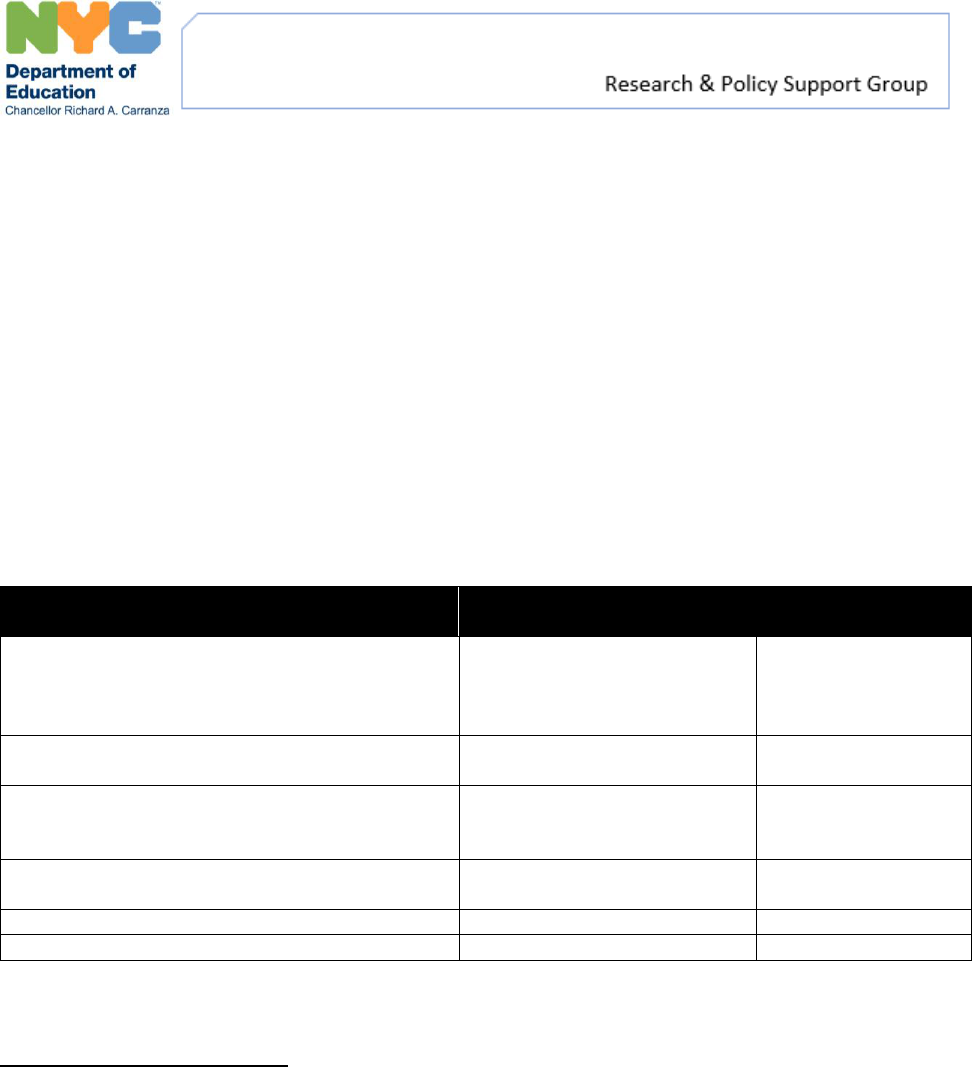

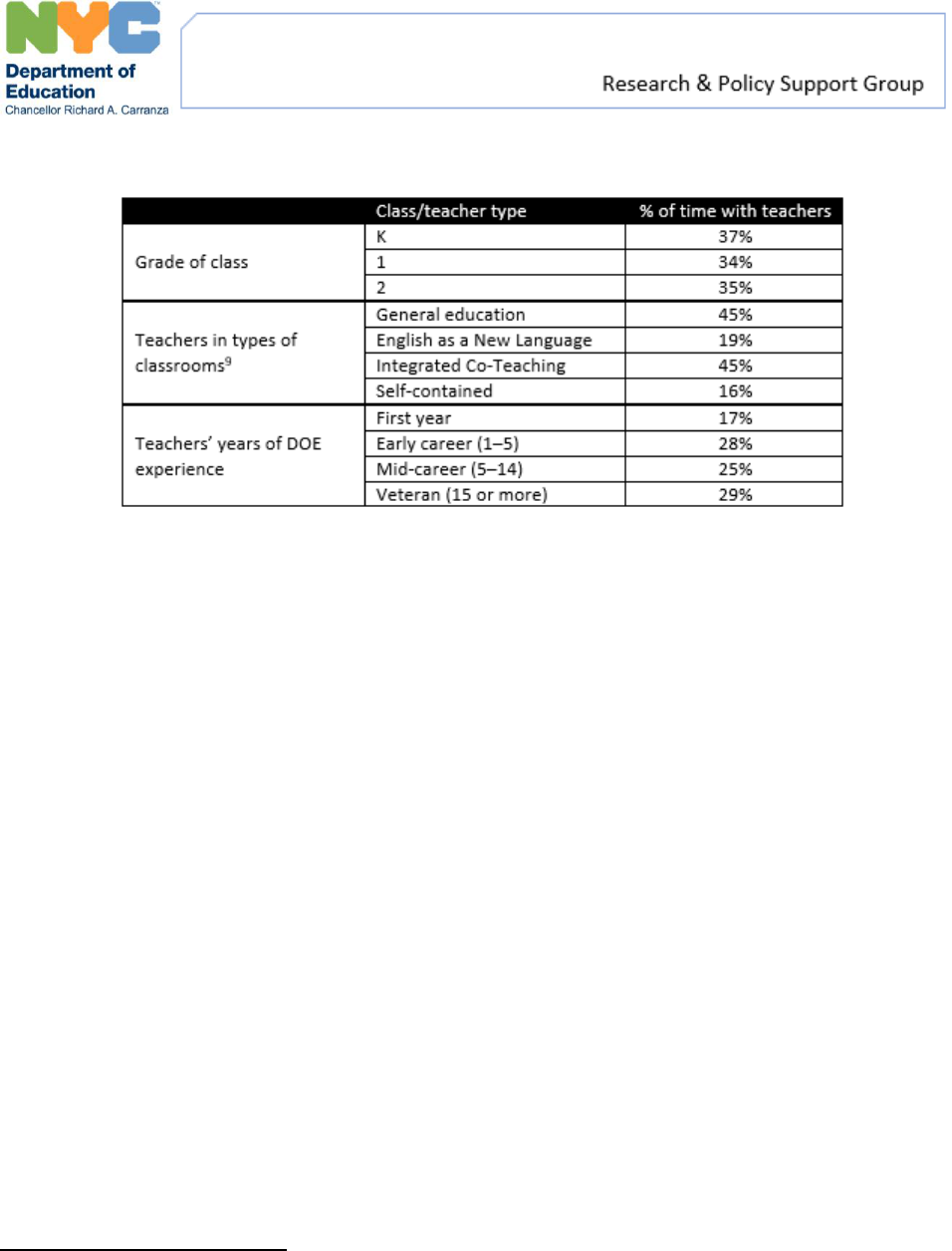

Implementation: Coach Time Use

An analysis of coach log data showed that coaches spent, on average, 42.4% of their work time in

schools with teachers.

7

This number includes time coaching individual teachers (34.1%), working

with groups of teachers such as in grade team meetings or peer observations (5.3%), and doing

formal professional learning sessions for educators (3.0%). See Table 2 for details. Table 3

describes how coaches spent their time in schools in SY 2017–18, disaggregated by class and

teacher types. The total number of periods coaches spent with individual teachers was fairly evenly

distributed across grades.

8

Coaches spent 59% of their time with teachers whose classrooms

contain students with disabilities (42% with teachers in integrated co-teaching (ICT) classrooms and

17% in self-contained classrooms). Comparatively, coaches spent the least amount of time with

brand-new teachers.

Table 2. Coach time use, averages for Dec. 2017 – Jun. 2018

Activity

Total Number of Periods

Percent of Total Time

(average)

Working with teachers 79,805

42.4%

Coaching individual teachers 64,169 34.1%

Coach

ing groups of teachers 10,030

5.3%

Pro

fessional learning sessions 5,606

3.0%

Planning (includes planning PD sessions, planning for

work with teachers, communications)

48,354

25.7%

Other (includes data analysis and assessment work;

work with Instructional Specialists, school literacy

consultants, and parents; and special ULit projects)

26,564

14.1%

Clinical application/practice

(Reading Rescue tutoring)

14,860

7.9%

Working with school leaders

12,876

6.9%

Time unrelated to coaching work

5,537

3.0%

7

Note that Reading Coaches are scheduled to work 7 hours and 30 minutes a day, excluding a 30-minute lunch break, as they

serve in a “teacher assigned” role; a typical teacher workday is 6 hours and 20 minutes, inclusive of a lunch period.

8

Reading coaches complete the Digital Daily Coaching Log for each day they work in a school. Reading coaches report how

they spent the majority of each period; although the length of a “period” and the number of periods varies slightly from school

to school, this approach provides a high-level look at how coaches spend their time. They reported a total of 64,194 periods

with individual teachers in the period December 2017 –June 2018. Coaches may spend time with more than one teacher in a

period. In addition, teachers can be associated with multiple classroom types; thus, percent of time use with different

classroom types does not add up to 100%.

Universal Literacy Year 2 Summary Report | 4

Table 3. Coach time, disaggregated by grade, class type, and years of DOE experience

Implementation Perspectives: Teacher, Administrator, and Coach

RPSG administered end-of-year surveys

9

for K–2 teachers, school building leaders, and Reading

Coaches. More details about the surveys and their response rates can be found in Appendix A.

Teachers

Over 90% of teacher respondents reported that their coach had worked w ith them during SY 2017–

18. Forty percent indicated t hat the coach worked with them “on an ongoing basis,” while 31% said

their coach worked with them in one or more coaching cycles and 16.8% reported t he coach

worked with them “from time to time.” Of the teacher respondents who worked with a coach, the

majority indicated that they incorporate more phonics, phonemic awareness, fluency, and

vocabulary instruction into their class as a result of working with the reading coach. See Table 4

below for details.

When asked how they would most like to work with their reading coach the following year, almost

half (47.2%) of teacher respondents indicated that they would like the reading coach to work with

them one-on-one. When asked about the areas in which they would like support in the future, a

similar number (48.3%) expressed a desire for support around working with struggling readers; the

second area that teachers would like support in is literacy content areas (39.8%).

9

Response rates were as follows: Reading Coaches, 86%; School Building Leaders, 39%; and Teachers, 25%.

Universal Literacy Year 2 Summary Report | 5

Table 4. Extent to which teachers say their teaching has changed as a result of working with their ULit coach

Not at all

To a small

extent

To a moderate

extent

To a great

extent

I incorporate more phonics and phonemic awareness

instruction in my class.

14.2%

13.5%

30.2%

42.0%

I incorporate more fluency instruction in my class.

15.0%

18.0%

30.9%

36.0%

I incorporate more vocabulary instruction in my class.

15.0%

18.5%

31.7%

34.7%

The ways I group students has changed.

18.2%

17.1%

32.8%

31.9%

The ways I assess students has changed.

16.5%

18.8%

33.1%

31.6%

School Building Leaders (SBL)

When asked how satisfied they were with the Universal Literacy initiative at their school on a scale

of 0–10, school building leaders expressed a variety of views, with a majority (59.0%) satisfied or

highly satisfied (e.g., chose 7–10 on the scale). Of SBL respondents, 18.8% were unsatisfied or

highly unsatisfied (chose 0–3 on the scale) and the rest (22.2%) in the middle (chose 4-6 on the

scale). Administrators whose schools were in the second year of the initiative reported much

higher satisfaction rates and lower overall dissatisfaction, with 69.2% of Cohort 1 administrators in

the “satisfied/highly satisfied” versus 52.6% for Cohort 2 administrators, leading us to speculate

that perhaps schools in their first year experience an adjustment period. Another hypothesis is that

because response rates for administrators were low, the ones who took the time to complete an

optional survey were disproportionately highly satisfied or highly dissatisfied.

The optional open-ended responses help to triangulate these responses. A number of school

building leaders wrote about the transformative work of the reading coach.

Having a Universal Literacy Coach in our building has helped us to support our K–2 teachers in a more

equitable way.

Our ULIT Coach has been an essential part of our literacy team. She has become an active participant in

the professional lives of our staff members. She has gained their professional trust and has created an

environment of support and mutual respect.

Teachers who were struggling in the area of instruction: Domain 3-Danielson Rubric are now effective and

highly effective in that domain. Teachers are willing to take the initiative and try new strategies.

A small number of school building leaders wrote about their negative experiences.

If the Universal Literacy Coach is not allowed to be flexible to adjust when administration truly needs

support, then the Universal Literacy Coach can't really be a member of the school community and thus a

disconnect … will limit the impact of this position.

Universal Literacy Year 2 Summary Report | 6

The most frequently cited implementation challenge, selected by just over a third of respondents

(36%), was that the coach was out of the building too often for professional learning. The next most

frequent challenge, selected by almost a quarter of respondents (24%), was that teachers in the

building were resistant to working with the reading coach. Some administrators felt that coaches

did not have sufficient time to work in the school (21%) or that they did not have enough

autonomy over the coach’s work (20%). About 30% of administrators reported no implementation

challenges.

Reading Coaches

Across survey items that asked coaches to share their perspectives on their work with teachers, the

majority of coaches believed they had helped teachers to a “moderate extent” or “great extent.”

The greatest challenge they named by far was teachers who were reluctant to working with the

coach. Because working with the coach is not mandatory, coaches need to gain the trust of

teachers in order to be invited in to their classrooms to work together.

Coaches were asked ab out their overall opinion of the Professional Learning Series (PLS) as well as

the extent to which the PLS helped them with specific k nowledge, skills, and coaching practices.

Coaches’ responses were generally positive, with Cohort 2 coaches providing much stronger

positive responses.

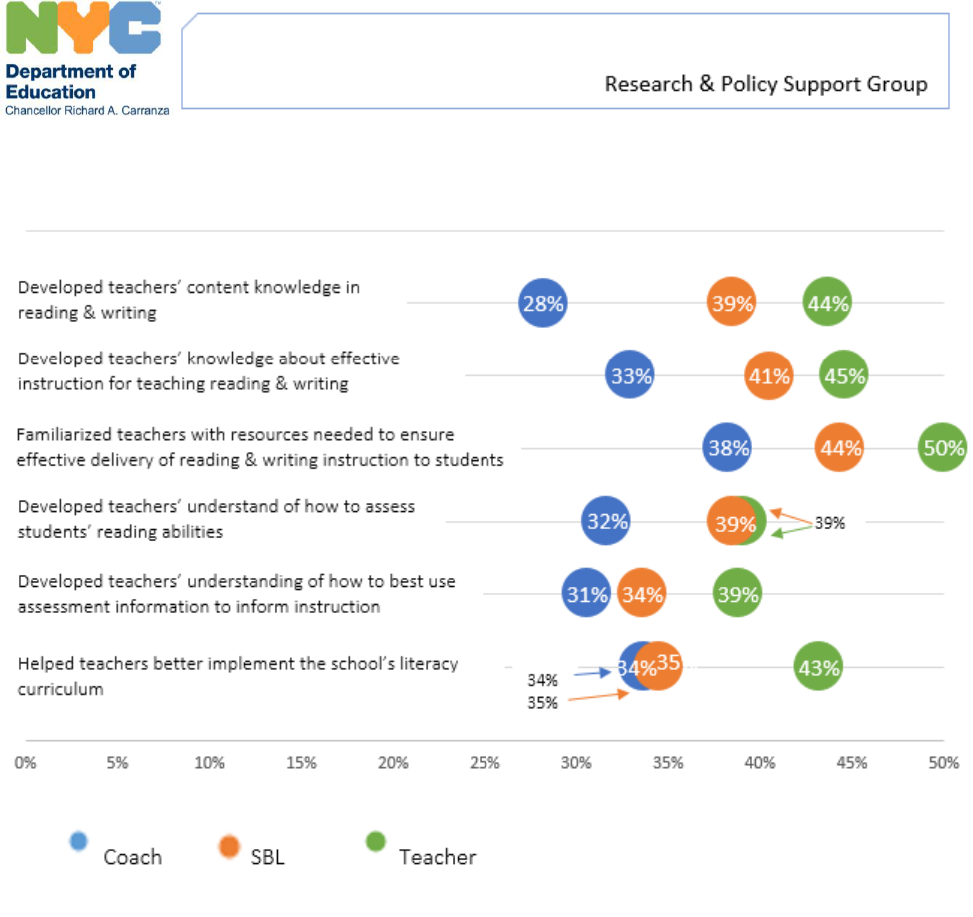

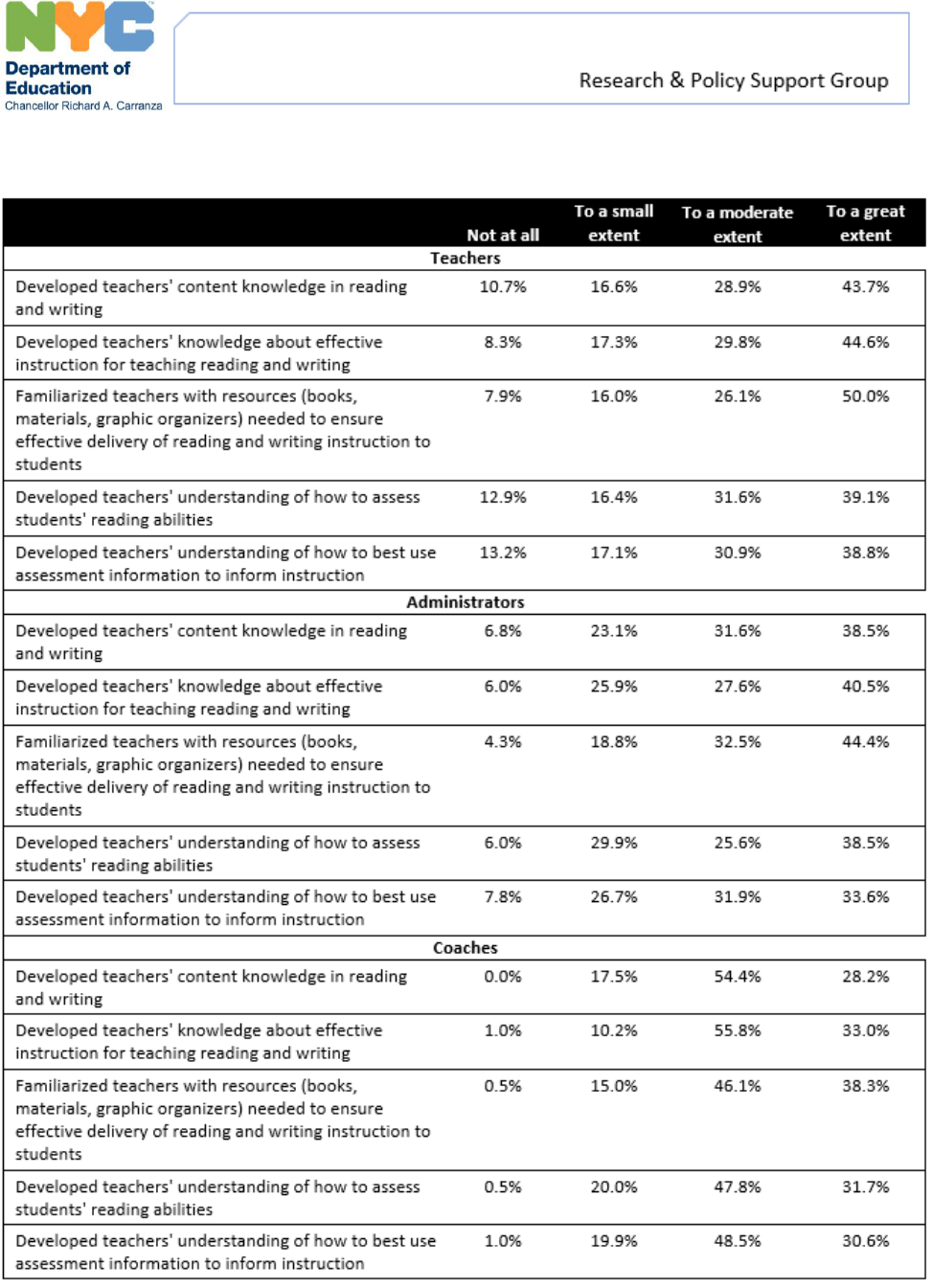

Comparative Responses from Teachers, Administrators, and Coaches

The survey asked respondents from all three groups—teachers, administrators, and coaches—their

perceptions about the extent to which the ULit Reading Coach helped K–2 teachers in a variety of

key areas: developing their content knowledge about reading and writing and instruction;

familiarizing them with resources for effective delivery of reading and writing instruction;

developing their understanding of reading assessments and how to use the data to inform

instruction; and supporting implementation of the school’s literacy curriculum. The majority of

respondents (two-thirds or more, on average) indicated that the ULit Reading Coach helped to a

moderate or great extent. Figure 1, below, shows the percent of respondents who felt the coach

helped “to a great extent” for each item. See Table 5 for details.

Universal Literacy Year 2 Summary Report | 7

Figure 1. Responses to item about how ULit Reading Coach helped teachers “to a great extent,” by respondent group

(Reading Coach, School Building Leader, Teacher)

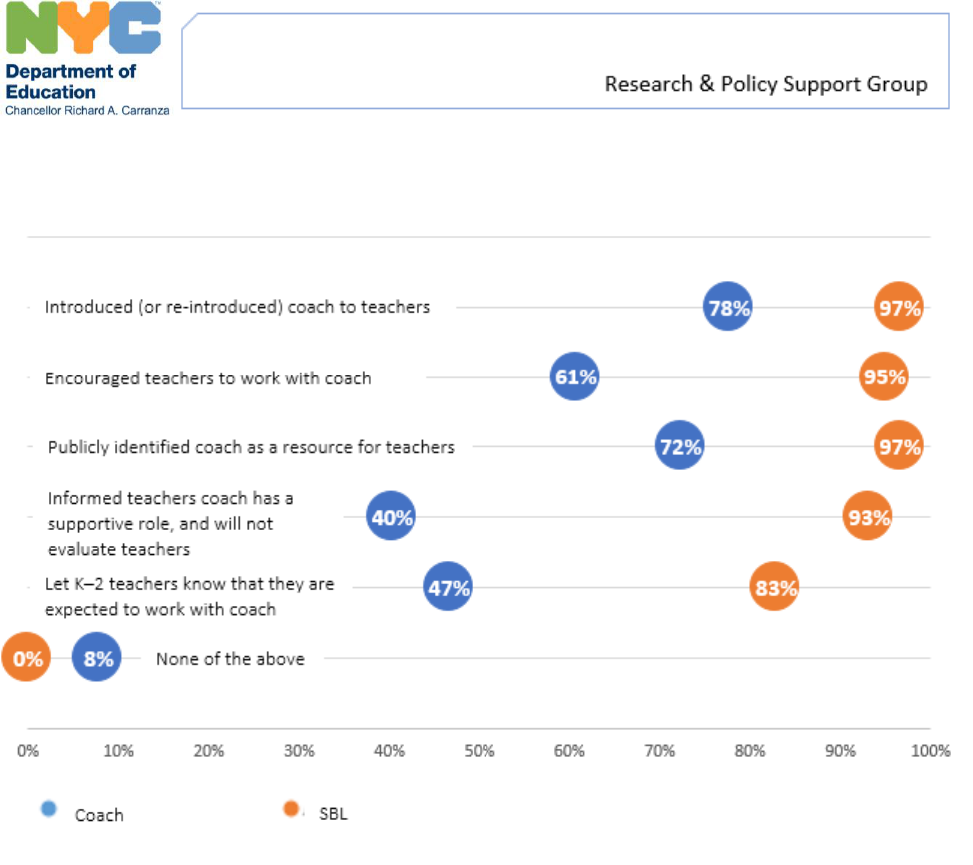

The survey asked c oaches and school building leaders about their perceptions of what

administrators did to support coaches. Survey results show gaps between coach and administrator

perceptions. Fo r example, 55% of administrator respondents reported speaking to their coaches

about their work with teachers on a weekly b asis, versus only 3 5% of coach respondents. Similarly,

17% of administrators reported n ever helping the reading coach deal with reluctant teachers,

versus 51% of coaches. A n important part of administrator support of coaches is setting the tone at

the beginning of the year. Figure 2 shows c oach versus SBL perceptions of what support actions

administrators took at the beginning of the school year.

Universal Literacy Year 2 Summary Report | 8

Figure 2. Responses to item, “At the beginning of the year, [administrator] did the following…,” by respondent group

(Reading Coach vs. School Building Leader/SBL)

Universal Literacy Year 2 Summary Report | 9

Table 5. Extent to which teachers, administrators, and coaches say ULit coaching helped in them/their school

Universal Literacy Year 2 Summary Report | 10

Implementation Perspectives: Portraits of Practice

In order to better understand the implementation of the coaching cycle, RPSG conducted

qualitative research to understand coach-teacher interactions in five Universal Literacy schools in a

case-study approach we call Portraits of Practice. The research team interviewed coaches,

teachers, and school building leaders, and closely observed coach interactions with one focal

teacher. Highlights of the “portraits of practice” findings included:

• Coaches believed that building relationships with teachers is essential for coaching to be

successful and consequently put efforts into forging those relationships.

• The focus of coaching cycles was highly dependent on the school’s literacy ecosystem as well as

coaches’ individual perspectives on coaching.

• There was more variation than consistency in terms of what constituted a coaching cycle.

○ Coaches articulated a need t o individualize their coaching for different teachers and "be

flexible" because teachers do not always p rogress as planned.

○ All coaches had routines for starting the cycle and working in the middle of the cycle (co-

planning, modeling, side-by-side coaching); most also collected student data at some point

during the cycle.

○ There was inconsistency around why and how a cycle ended.

• All coaches made purposeful coaching moves.

○ They actively engaged t eachers, using questioning strategies to elicit next steps and help

teachers name their own practices, and enacted a "think aloud" technique to help t eachers

understand lesson decision points in the moment.

○ Coaches were also skilled in altering initial plans for coaching sessions when n ecessary,

combining more than one coaching move.

• Attention to five essential components of effective reading instruction (“pillars”)—phonics,

phonemic awareness, vocabulary, fluency, and comprehension—was embedded in cycles as

opposed t o being the explicit focus of cycles; programs, curriculum, or strategies (e.g., guided

reading, Fundations) were frequently t he cycle focus and most coaches believe that teachers

were learning the components of reading acquisition while they are learning to teach those

programs, curricula, or strategies.

• Most c oaches worked in schools where other literacy coaches, staff developers, or consultants

were also working with teachers on literacy practices, curriculum, and/or content. Each school

engaged literacy partners differently.

Universal Literacy Year 2 Summary Report | 11

• All coaches participating in this study reported principals were supportive of the initiative and

their work; coaches had varying levels of autonomy regarding literacy decision-making in the

schools they support.

Early Indicators of Impact

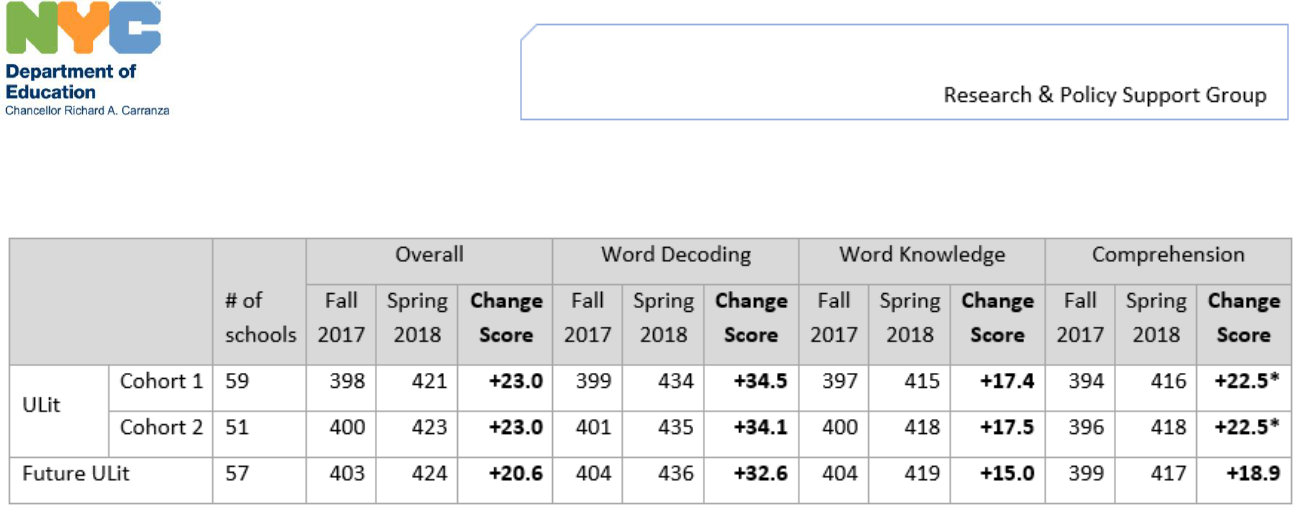

To answer research question 3, about the impact of the initiative, we used data collected by the

initiative on the Gates-MacGinitie Reading Test (GMRT), Level 2. Universal Literacy offered the

GMRT to second graders in a sample of schools in the original ULit districts (Cohort 1) and a

matched comparison sample of schools that joined the initiative in SY 2017–18 (Cohort 2), as well

as schools that joined the initiative in SY 2018–19 (future-ULit). Highlights of findings about early

indicators of impact include:

• Overall average GMRT scores, as well as scores on each of the subtests (word decoding, word

knowledge, and comprehension), of students at 110 schools with access to a Universal Literacy

coach grew more than those of their peers in the 57 future-ULit comparison schools. The

difference in change scores in the comprehension subsection was statistically significant.

• Students of teachers who received ULit coaching grew more than students of teachers who did

not. Moreover, the more coaching a teacher received, the more growth the students had, on

average. The difference between students whose teachers had more coaching and those who

did not was statistically significant.

These results are small but encouraging indicators of impact.

Given that sampling occurred on the school level, we looked at change scores across schools,

grouped by ULit cohort. Overall average scores, as well as scores on each of the subtests (word

decoding, word knowledge, and comprehension), grew sligh tly mo re at the 110 schools with access

to a Universal Literacy coach than at the 57 future-ULit comparison schools (which were slated t o

receive a ULit coach in SY 2018–19). The difference in change scores in the comprehension su btest

(22.5 for ULit schools versus 18.9 for future-ULit schools) was statistically significant. There was a

similar trend across the other subtests, but no statistically significant difference. Despite purposeful

sampling of comparison schools, school demographic c haracteristics varied slightly acros s sample

groups, because ULit prioritized giving coaching access to the districts most in need of early literacy

support (see Appendix B for more detail). In order to account for this variation, as well as any

changes that occurred between sampling and analysis, we controlled for ELL status, poverty,

students with disabilities, and ethnicity. Even with these controls, the greater growth of schools

with ULit coaching was statistically significant on the comprehension su btest. See Table 6, page 16

for details.

Universal Literacy Year 2 Summary Report | 12

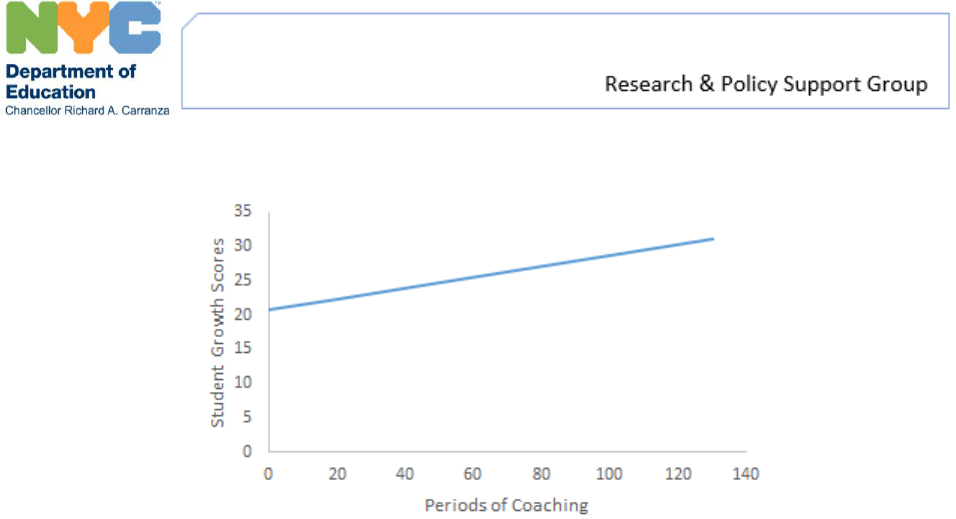

In addition to looking at the differences between schools in each cohort, we looked across all the

classrooms tested, to see if there was a relationship between the number of periods that teachers

were coached and their students’ achievement. When looking across these classrooms, students of

teachers who received coaching grew more than students of teachers who did not; the more

periods of coaching the teachers received, the more students’ scores grew, on average (p <

0.001). This relationship held true when looking across teachers

10

in all three cohorts, and when

looking at cohort 1 and 2 schools only. In order to account for the differences in classrooms and

teachers, we controlled for classroom type (ICT, self-contained, and ENL), student characteristics

(ELL status, disability status, poverty status, and ethnicity) and teacher characteristics (years of

experience). These findings persisted even when we included controls.

For each period of coaching, students had a 0.079 point higher Fall-Spring change score, on

average. An average student whose teacher received no coaching grew 20.8 points overall from

spring to fall administrations. Based on the relationship between periods coached and student

change scores on the GMRT, an average student whose teacher had 20 periods of coaching would

grow 22.37 points, roughly equivalent to half a month of instruction more than their peers whose

teachers had no coaching. 50 periods of coaching would equate to an extra month of growth

compared to their peers whose teachers had no coaching, while a student whose teacher received

130 periods of coaching would equate to two extra months of growth compared to their peers

whose teachers had no coaching. See Figure 3 below for an illustration of the linear relationship

between student growth scores and periods of teacher coaching.

For more information about our analytic methods, please see Appendix B.

10

The analysis included teachers who did not receive coaching, both those in schools that did not have a ULit Reading

Coach and those in ULit schools who did not receive coaching. The results were the same when we looked at the whole

sample and when we looked just at Cohort 1 and 2 schools.

Universal Literacy Year 2 Summary Report | 13

Figure 3. Illustration of relationship between average student growth scores and periods of teacher coaching

Conclusion

At the end of its second year, the overall evidence on the Universal Literacy initiative is largely

positive. It is meeting its objectives in terms of reach and it is showing positive early trends related

to impact.

That findings on the Universal Literacy initiative show early trends of improving student

achievement is noteworthy. A large body of empirical research in education points to multiple

factors that influence improvement, such as principal leadership, teacher quality, instructional

improvement approaches, and external support from district, state, and federal sources. This

research shows t hat improvement is incremental, occurs over years, and involves a complex

interplay of these components. A study on the Comprehensive School Reform Program

implementation and outcomes suggests, for example, that “implementation for at least three to

five years is typically the time necessary to see student achievement improve” (Aladjem et al.,

2006; Borman et al., 2003; Desimone, 2000; Zhang et al., 2006, as cited in Aladjem, et al., 2010,

p. 4).

In addition, there is a consensus in the research literature that elementary teachers enter the

profession lacking adequate preparation for effectively teaching students to read, and that

intensive support and learning is necessary for them to acquire the requisite knowledge (Moats,

1999, 2009; Snow, Griffin & Burns, 2007). By hiring and training a cadre of Reading Coaches and

deploying them to schools, the Universal Literacy initiative is building the capacity of the NYC

Department of Education to teach all children to read on grade level by the end of Grade 2. The

hundreds of educators who become ULit Reading Coaches not only apply their knowledge to

Universal Literacy Year 2 Summary Report | 14

supporting the educators they currently work with, but they will also take that knowledge to future

positions, whether as school building leaders, master teachers, or central office staff.

Finally, research shows t hat the role of principals is critical for instructional coaching to be

successful (Matsumura, Sartoris, Bickel & Garnier, 2009). Because the supervisory structure of ULit

has coaches reporting to the central office, ongoing efforts are needed t o communicate about and

support school building leaders’ understandings of reading acquisition and the role of the reading

coach.

Universal Literacy Year 2 Summary Report | 15

Table 6. GMRT Grade 2 scale scores, 2017–18

*Difference in change scores between ULit cohorts and the future-ULit cohort are statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Note: Cohort 1 are schools that received a Reading Coach in SY 2016–17; Cohort 2 are schools that received a Reading Coach in SY 2017–18; Future ULit are

schools slated to receive a Reading Coach in SY 2018–19.

Universal Literacy Year 2 Summary Report | 16

References

Aladjem, D. K., Birman, B. F., Orland, M., Harr-Robins, J., Heredia, A., Parrish, T. B., & Ruffini, S. J. (2010).

Achieving Dramatic School Improvement: An Exploratory Study. A Cross-Site Analysis from the Evaluation of

Comprehensive School Reform Program Implementation and Outcomes Study. Office of Planning, Evaluation

and Policy Development, US Department of Education. Retrieved from:

https://www2.ed.gov/rschstat/eval/other/dramatic-school-improvement/exploratory-study.pdf

Coburn, C. E., & Woulfin, S. L. (2012). Reading coaches and the relationship between policy and practice.

Reading Research Quarterly, 47(1), 5–30.

Deussen, T., Coskie, T., Robinson, L., & Autio, E; (2007); “Coach” can mean many things: five categories of

literacy coaches in Reading First (Issues & Answers Report, REL 2007–No. 005). Washington, DC: U.S.

Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and

Regional Assistance, Regional Educational Laboratory Northwest. Retrieved from

http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED497517.pdf

Elish-Piper, L., & L'Allier, S. K. (2010). Exploring the relationship between literacy coaching and student

reading achievement in grades K-1. Literacy Research and Instruction, 49(2), 162–174.

Foorman, B., Beyler, N., Borradaile, K., Coyne, M., Denton, C. A., Dimino, J., Furgeson, J., Hayes, L., Henke, J.,

Justice, L., Keating, B., Lewis, W., Sattar, S., Streke, A., Wagner, R., & Wissel, S. (2016). Foundational skills to

support reading for understanding in kindergarten through 3rd grade (NCEE 2016-4008). Washington, DC:

National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE), Institute of Education Sciences, U.S.

Department of Education. Retrieved from https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/PracticeGuide/21

Gibbons, L. K. & Cobb, P. (2017). Focusing on teacher learning opportunities to identify potentially productive

coaching activities. Journal of Teacher Education, 68(4), 411–425.

Heineke, S. (2013). Coaching discourse: Supporting teachers' professional learning. The Elementary School

Journal, 113(3), 409–433. DOI:10.1086/668767

L'Allier, S., Elish-Piper, L. and Bean, R. M. (2010), What matters for elementary literacy coaching? Guiding

principles for instructional improvement and student achievement. The Reading Teacher, 63(544–554).

doi: 10.1598/RT.63.7.2

Mangin, M. M., & Dunsmore, K. (2015). How the framing of instructional coaching as a lever for systemic or

individual reform influences the enactment of coaching. Educational Administration Quarterly, 51(2), 179–

213.

Matsumura, L. C., Sartoris, M., Bickel, D. D., & Garnier, H. E. (2009). Leadership for literacy coaching: The

principal’s role in launching a new coaching program. Educational Administration Quarterly, 45(5), 655–693.

Moats, L. C. (1999). Teaching reading is rocket science: What expert teachers of reading should know and be

able to do. (AFT Position Paper.) Washington, DC: American Federation of Teachers.

Moats, L. C. (2009). Knowledge foundations for teaching reading and spelling. Reading and Writing, 22(4),

379–399.

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). (2000). Report of the National Reading

Panel. Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading

and its implications for reading instruction: Reports of the subgroups (NIH Publication No. 00-4754).

Universal Literacy Year 2 Summary Report | 17

Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved from

https://www.nichd.nih.gov/sites/default/files/publications/pubs/nrp/Documents/report.pdf

National Research Council. (1998). Preventing Reading Difficulties in Young Children. Washington, DC: The

National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/6023.

Phillips, D., Nichols, W. D., Rupley, W. H., Paige, D., & Rasinski, T. V. (2016). Efficacy of professional

development: Extended use of focused coaching on guided reading instruction for teachers of grades one,

two, and three. International Research in Higher Education, 1(2). doi:10.5430/irhe.v1n2p12

Scott, S.E., Cortina, K.S., & Carlisle, J.F. (2012). Understanding coach-based professional development in

Reading First: How do coaches spend their time and how do teachers perceive coaches’ work? Literacy

Research and Instruction, 51(1), 68–85.

Snow, C., Griffin, P., & Burns, M. S. (Eds.). (2007). Knowledge to support the teaching of reading: Preparing

teachers for a changing world. John Wiley & Sons.

Zigmond, N., Bean, R., Kloo, A., & Brydon, M. (2011). Policy, research, and Reading First. In A. McGill-Franzen

& R.L. Allington (Eds.). Handbook of Reading Disability Research (pp. 464–476). New York: Routledge

Publishing.

Universal Literacy Year 2 Summary Report | 18

APPENDIX A: Data Sources

The evaluation used the following data sources:

• DOE institutional data – administrative data on district schools that contain grades K–2,

such as schools’ Economic N eed Index, ELA scores, school and student demographic

information, and numbers of students and teachers in K–2 classes.

• Program data – data collected b y the Universal Literacy initiative, including Digital Daily

Coach Log data and GMRT assessment data. The Digital Daily Coach Log data runs from

December 2017

– June 2018 and contains coaches’ self-reported responses about how they

spent their time in schools, measured b y how they spent the majority of each period in

school including which classrooms they worked in .

• Survey data – data from end-of-year online surveys sent to Reading Coaches, teachers, and

principals. Surveys focused on perceptions of the ULit initiative. Additionally, school

building leaders were asked about their desired communication channels and

communication quantity and their perceptions of coach responsibilities. Surveys w ere

anonymous and voluntary. Response rates for each group were:

○ Reading Coaches: 86% (206 out of 239 sent)—one-third of them Cohort 1 coaches

(72 out of 86 sent; 84% response rate) and two-thirds Cohort 2 (134 out of 150 sent;

89% response rate);

○ School building leaders: 39% (117 out of 303 sent); and

○ Teachers: 25% (1,026 out of 4,149 sent).

• Ethnographic data – data from site visits in SY 2017–18 to learn more about coach-teacher

dyads in five schools with Cohort 1 coaches. Sites were purposefully selected to be

representative of Cohort 1 district schools, with varied school sizes, ELL/SPED demographic

characteristics, and geographical locations in the Bronx and Brooklyn, and coaches who

planned their work with teachers in coaching cycles. Data collection activities included

observations, interviews, and artifact reviews.

Universal Literacy Year 2 Summary Report | 19

APPENDIX B: GMRT – Technical Report

This appendix provides technical information about the processing and analysis of Gates-MacGinitie Reading

Test (GMRT) data from the Universal Literacy (ULit) initiative.

ULit administered the GMRT in order to learn more about students’ reading abilities, since there are no city-

or state-wide reading tests administered in Grades K–2. Literacy leaders selected the GMRT Level 2 because

the assessment could be administered to an entire class at once, as opposed to each student individually.

School-based educators receive scores directly from the test vendor, Houghton-Mifflin Harcourt (HMH), via

an interactive online reporting system. The designated educator, usually the ULit Reading Coach or the

school’s testing coordinator, receives an email with login information that teachers can use to access their

students’ scores. Information from the GMRT about individual students can be used along with other

sources of information as the basis for organizing students into instructional groups, identifying students

who are ready for more advanced instruction, and selecting students for individual instruction. The

designated school-based educators also receive training in terms of implementing the GMRT and

interpreting the results and using them for instruction. Selected schools administer the GMRT in the fall and

spring of each year.

About the GMRT, Level 2

The Gates-MacGinitie Reading Tests are timed, norm-referenced assessments that measure reading

achievement from pre-reading to adult levels.

11

From Level 2 (corresponding to Grade 2) and above, the

tests are administered in group settings. The GMRT, Level 2 provides information about reading

achievement in three domains:

• Word Decoding — Student must accurately identify isolated words in grade word lists that

correspond to an illustration; “the test format and tested words measure primarily decoding skills

and word identification, rather than knowledge of word meanings” (MacGinitie, et al., 2002, p. 6).

• Comprehension — Student must read a passage of text and correctly answer relevant

comprehension questions, which in Level 2 are in the form of illustrations.

• Word Knowledge — Student must select an appropriate word based on given cues in a simple

illustration; vocabulary words are those GMRT authors judged as “likely to be known in speech and

print by Grade 2 students who possess good reading vocabularies” (MacGinitie, et al., 2002, p. 9).

The GMRT, Level 2 takes 75 minutes in total; students are given 20 minutes to complete the Word Decoding

and Word Knowledge subtests and 35 minutes for the Comprehension subtest. Universal Literacy

recommended that teachers administer the GMRT on three different days at their convenience, within a

two-week window. The GMRT, Level 2 comes in two parallel forms, S and T. Students received one version in

the fall and the other in the spring. Students mark their answers directly in the test booklet.

11

Source: GMRT test administration materials and https://usny.nysed.gov/rttt/teachers-leaders/assessments/docs/hmh-

gmrt-forms-c-and-g.pdf

Universal Literacy Year 2 Summary Report | 20

A designated person at the school shipped completed GMRT booklets to the vendor’s scoring center. HMH

machine-scored each box as it arrived and sent an email with information about how to access results to the

school’s designated GRMT coordinator, typically the ULit Reading Coach or school’s testing coordinator. The

DOE received a roll-up file with results after all test booklets were processed.

School Selection

School selection occurred in SY 2016–17, when schools were sampled from the original four districts.

Universal Literacy offered the GMRT to a random sample of schools in the original ULit districts (Cohort 1).

Each of those schools was then matched to a school that was slated to join the initiative in SY 2017–18

(Cohort 2), as well as a school that joined the initiative in SY 2018–19 (Future ULit). The matched schools

were offered the GMRT in advance of receiving coaching. The variables used for the matching included the

SY 2014–15 Grade 3 ELA proficiency rate; the trend in the Grade 3 ELA proficiency rate, 2013–2015; and a

neighborhood disadvantage index. A few schools were added in SY 2017–18 in order to ensure equal

representation among the three cohorts of ULit schools. Note: the selected schools are not representative of

schools across the city; ULit cohorts differ in terms of size, student demographics, and student achievement.

In addition, though the GMRT sample was created by matching schools, variation still exists between schools

across cohorts.

GMRT Scores

The GMRT reports student scores in a variety of ways, and in this report we use extended scale scores. In

previous reporting, we used grade equivalent scores. Scale scores refer to the continuous scale on which

GMRT results are measured, from Pre-Reading to Adult Reading. While grade equivalents are more easily

understandable, scale scores are more precise and are used for analyses. Scale scores on the GMRT capture

students’ reading ability on a linear scale that is useful for both comparison across grades and for analysis.

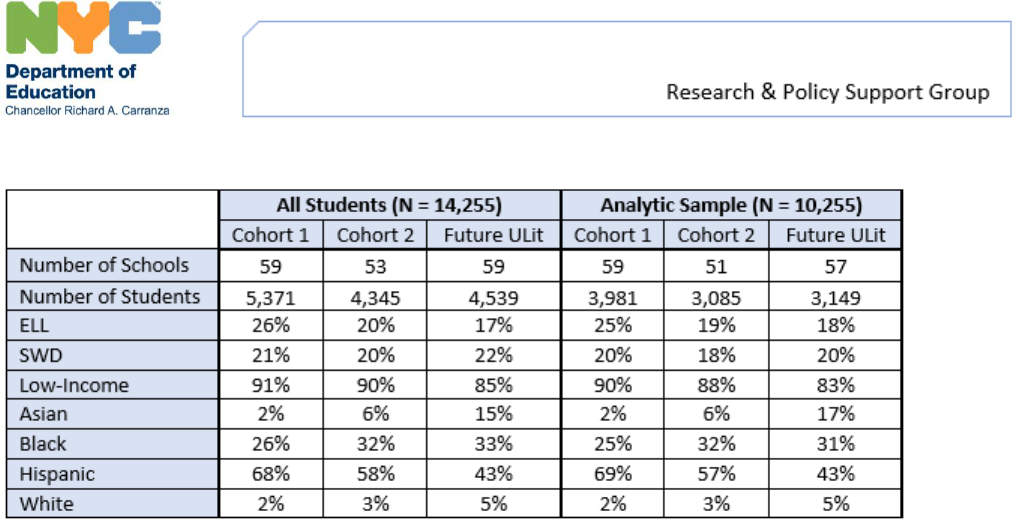

GMRT SY 2017–18 Administration

In SY 2017–18, 171 schools administered the GMRT to students in the Fall and Spring. A total of 14,255

Grade 2 students took the GMRT in SY 2017–18, defined as completing a minimum of one section. Of the

11,758 students completing both the Fall and Spring GMRT tests, 10,215 students attempted at least 90

percent of the items in both administrations. The analyses in this report use the growth scores of this latter

population, although results are similar when analyses are run with the former. Student characteristics were

similar for this analytic sample, when compared with the original universe of students (see Table below).

Universal Literacy Year 2 Summary Report | 21

Table B1. GMRT sample characteristics SY 2017–18 – All students vs. analytic sample

Multilevel Models

Our GMRT analyses rely primarily on multi-level models, which are used in many education studies. Multi-

level models account for the fact that the many students who took the GMRT are grouped together in a

smaller number of schools. We determined that this approach was appropriate because we did not sample

students randomly from across the city. Rather, ULit sampled schools from the initial cohort of Universal

Literacy and offered access to the GMRT to matched comparison schools across the city; Grade 2 students in

those comparison schools then took the GMRT. One effect of using these multi-level models is that the

results of schools with larger numbers of students do not outweigh those of other schools with smaller

numbers of students.

These multilevel models allowed us flexibility in controlling for student characteristics. We ran models

without controls, as well as models with student-level controls for poverty, ELL status, disability status, and

ethnicity. The outcome for these models was Fall-to-Spring Growth in GMRT scale scores, both overall and

for each of the three GMRT subtests. The predictor of interest was ULit cohort membership, whether a

school was in Year 1 of ULit, in Year 2 of ULit, or not yet part of ULit.

We ran teacher-level models in addition to the school-level models to learn more about the effect of

coaching. Using data from coach logs, we were able to determine how many periods of coaching each

teacher received. We used this variable as our predictor of interest in a multi-level model wherein students

were clustered by classroom teachers, instead of schools. Similar to the school-level models, we controlled

for student characteristics as well as teacher characteristics and classroom type.

References for Appendix B

MacGinitie, W. H., MacGinitie, R. K., Maria, K., Dreyer, L. G. (2002). Gates-MacGinitie Reading Tests

Technical Report – Forms S and T. Riverside Publishing, Rolling Meadows, IL.

Universal Literacy Year 2 Summary Report | 22

Acrobat Accessibility Report

Accessibility Report

Filename: ulit_y2evalsummaryreport_sy2017-18_final_ADA.pdf

Report created by: [Enter personal and organization information through the Preferences > Identity dialog.]

Organization:

Summary

The checker found no problems in this document.

Needs manual check: 2

Passed manually: 0

Failed manually: 0

Skipped: 1

Passed: 29

Failed: 0