MOODY’S ANALYTICS 1

GLOBAL FISCAL POLICY IN THE PANDEMIC

ANALYSIS

FEBRUARY 24, 2022

Prepared by

Bernard Yaros

Bernard.Y[email protected]

Assistant Director

Jesse Rogers

Assistant Director

Ross Cioffi

Ross.Cioffi@moodys.com

Economist

Mark Zandi

Chief Economist

Contact Us

Email

U.S./Canada

+1.866.275.3266

EMEA

+44.20.7772.5454 (London)

+420.224.222.929 (Prague)

Asia/Pacific

+852.3551.3077

All Others

+1.610.235.5299

Web

www.economy.com

www.moodysanalytics.com

Global Fiscal Policy in the Pandemic

Introduction

The U.S. and global economies have recovered surprisingly quickly

from the debilitating COVID-19 pandemic. Two years after the

pandemic first struck, much of the world has recovered the output

and employment lost during the severe recession suffered at the

start of the pandemic and is well on the way to returning to full

employment. This strong performance is due in significant part

to the vaccines and other therapies rapidly developed to fight the

virus, but also to the quick and massive global monetary and fiscal

policy response.

MOODY’S ANALYTICS 2

GLOBAL FISCAL POLICY IN THE PANDEMIC

Global Fiscal Policy in the Pandemic

T

he U.S. and global economies have recovered surprisingly quickly from the debilitating

COVID-19 pandemic. Two years after the pandemic first struck, much of the world has

recovered the output and employment lost during the severe recession suffered at the start

of the pandemic and is well on the way to returning to full employment. This strong performance

is due in significant part to the vaccines and other therapies rapidly developed to fight the virus,

but also to the quick and massive global monetary and fiscal policy response.

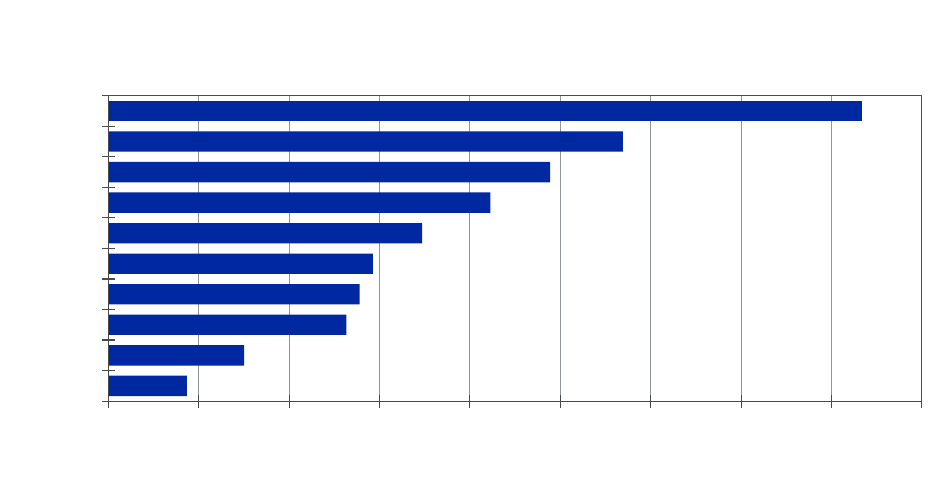

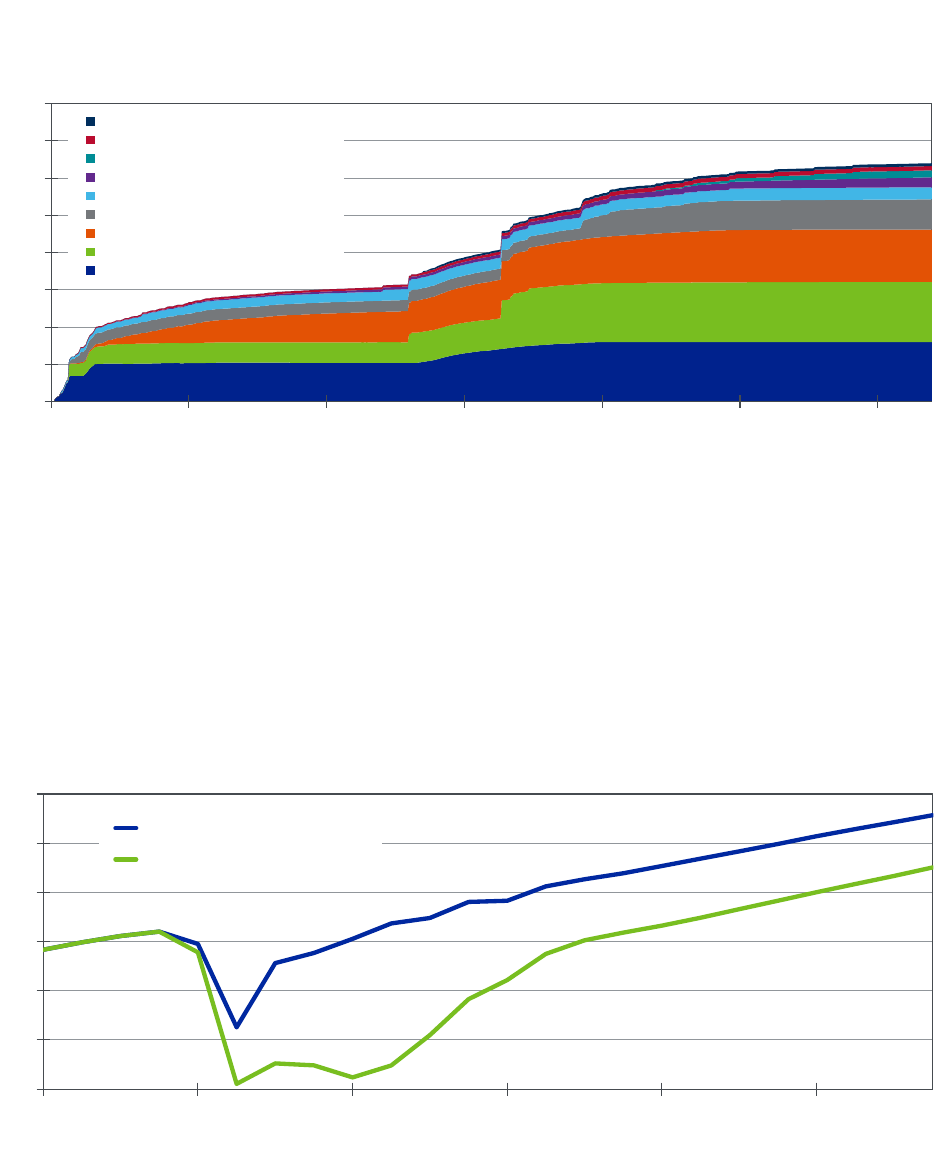

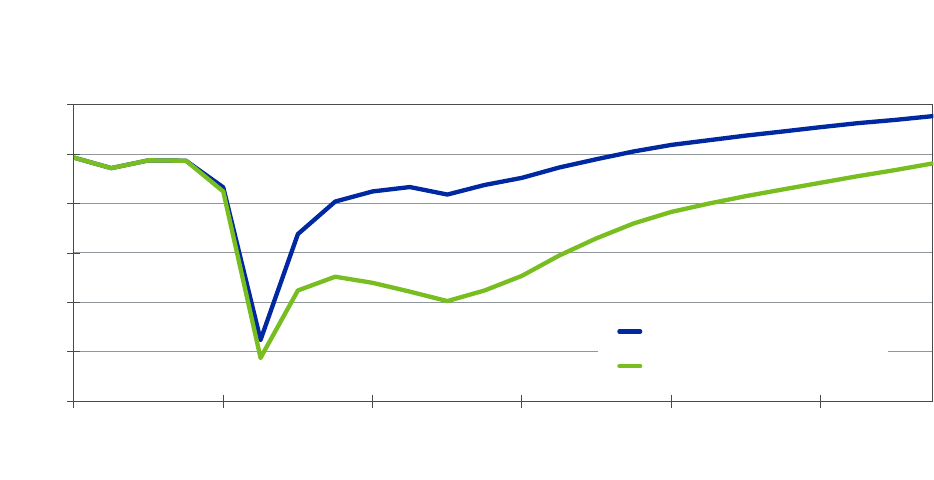

In this paper, we focus on the contribution of the global fiscal policy response to the pandemic. We

use the Moody’s Analytics Global Macroeconomic Model to construct a counterfactual scenario in

which governments in the world’s 10 largest economies—accounting for more than two-thirds of

global GDP—do not provide economic support to households and businesses during the pandemic

(see Chart 1). We compare this counterfactual scenario to our baseline, most likely, scenario, which

includes the macroeconomic impact of fiscal policies implemented by governments.

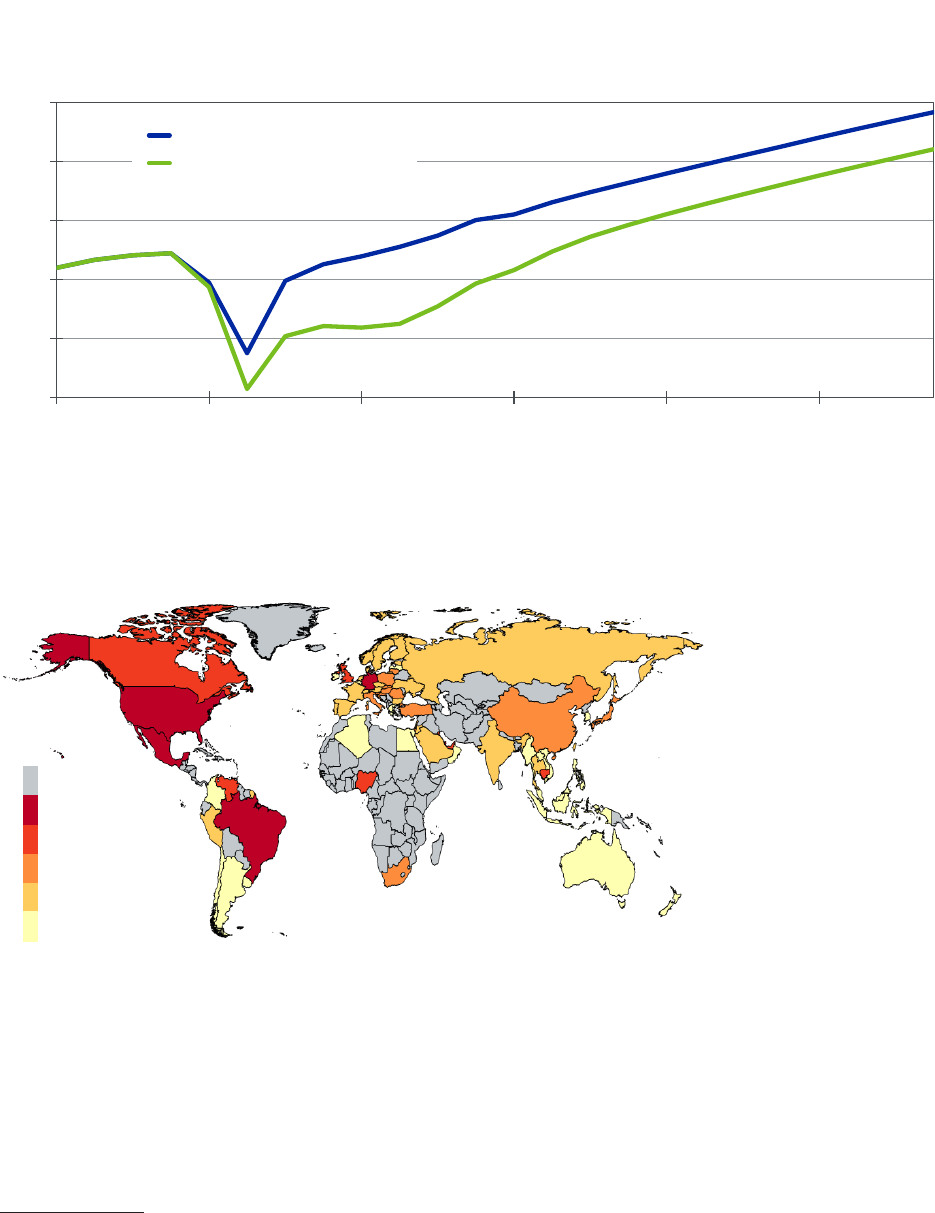

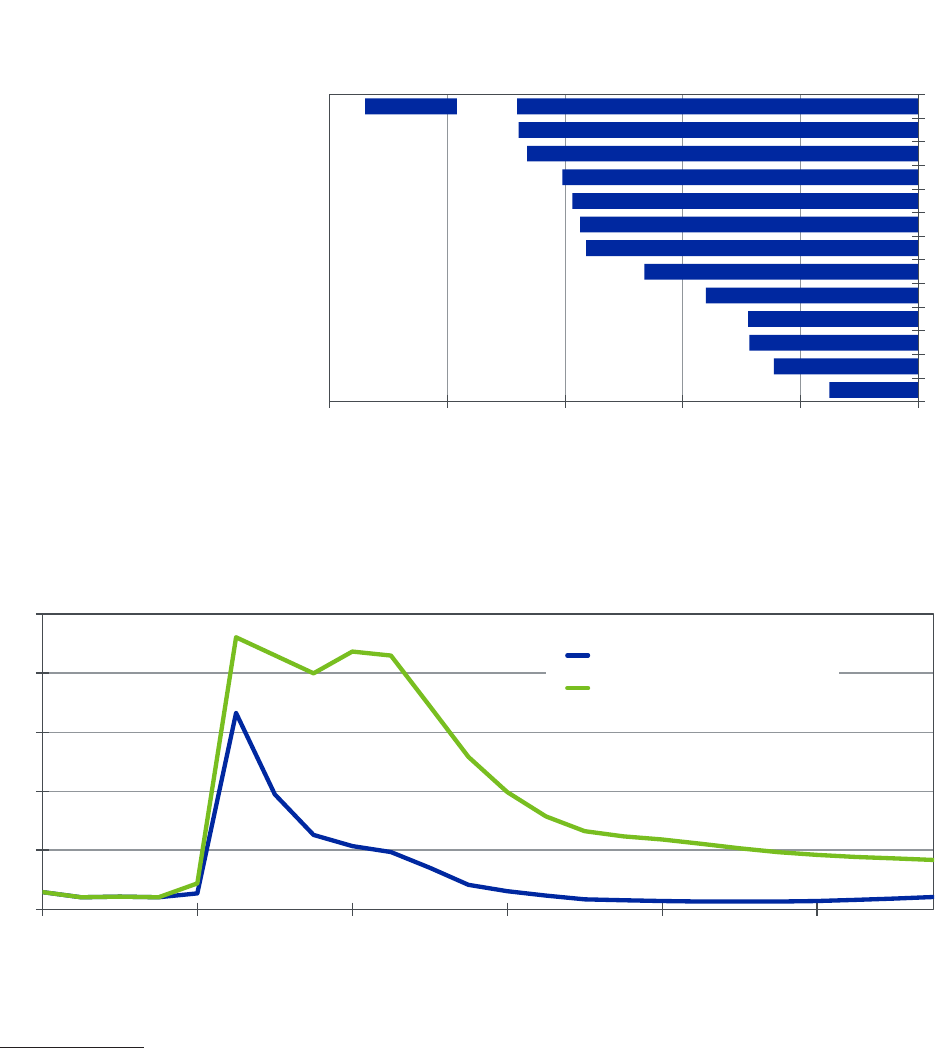

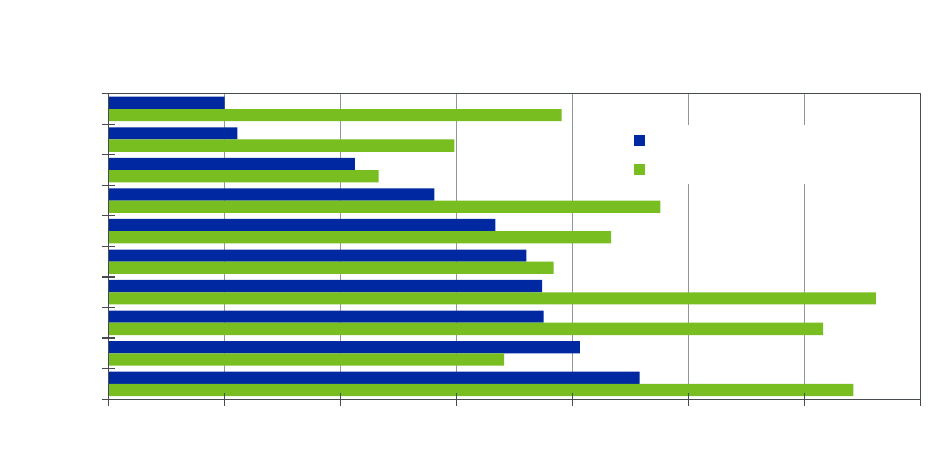

The macroeconomic consequences of governments failing to help their economies during the

pandemic would have been devastating. Global real GDP would have fallen twice as much in

2020, and while the economy would have begun to recover in 2021, growth would have been half

of what it actually was (see Chart 2). There would have been 40 million additional unemployed

Presentation Title, Date 1

0 3 6 9 12 15 18 21 24 27

U.S.

U.K.

Canada

Germany

Italy

Japan

France

Brazil

China

India

Chart 1: Governments Step Up

Source: Moody’s Analytics

Fiscal support during COVID-19 pandemic, % of 2019 GDP

MOODY’S ANALYTICS 3

GLOBAL FISCAL POLICY IN THE PANDEMIC

workers in 2021 and stubbornly high joblessness thereafter (see Chart 3). And the global economy

would forever be diminished, never fully recovering the output lost during the pandemic.

1

What if?

The counterfactual scenario we have constructed assumes national governments never imple-

mented the emergency discretionary fiscal measures they have actually put in place since the

pandemic hit at the start of 2020. This includes a wide range of policies that broadly encompass

1 This is known as hysteresis, which is a reduction in the economy’s potential due to a significant economic shock such as a pandemic. This occurs

because of the large number of business failures and bankruptcies, permanent job loss, credit problems, and reduced mobility of labor and capi-

tal. Once hysteresis sets in, it is difficult to reverse. Hysteresis effects are built into the Moody’s Analytics model of the global economy.

Presentation Title, Date 2

75

80

85

90

95

100

19 20 21 22 23 24

Baseline forecast

Counterfactual scenario

Chart 2: Deeper Fall, Weaker Recovery

Global real GDP, 2012$

tril, SAAR

Source: Moody’s Analytics

Presentation Title, Date 3

Chart 3: Severe Contractions Everywhere

Peak impact on real GDP, %

Source: Moody’s Analytics

N/A

<-10

-10 to <-7

-7 to <-5

-5 to <-3

-3 to <0

World avg=-7.4

MOODY’S ANALYTICS 4

GLOBAL FISCAL POLICY IN THE PANDEMIC

transfer payments to households and businesses, tax cuts, aid to subnational governments, and

public infrastructure and other direct spending.

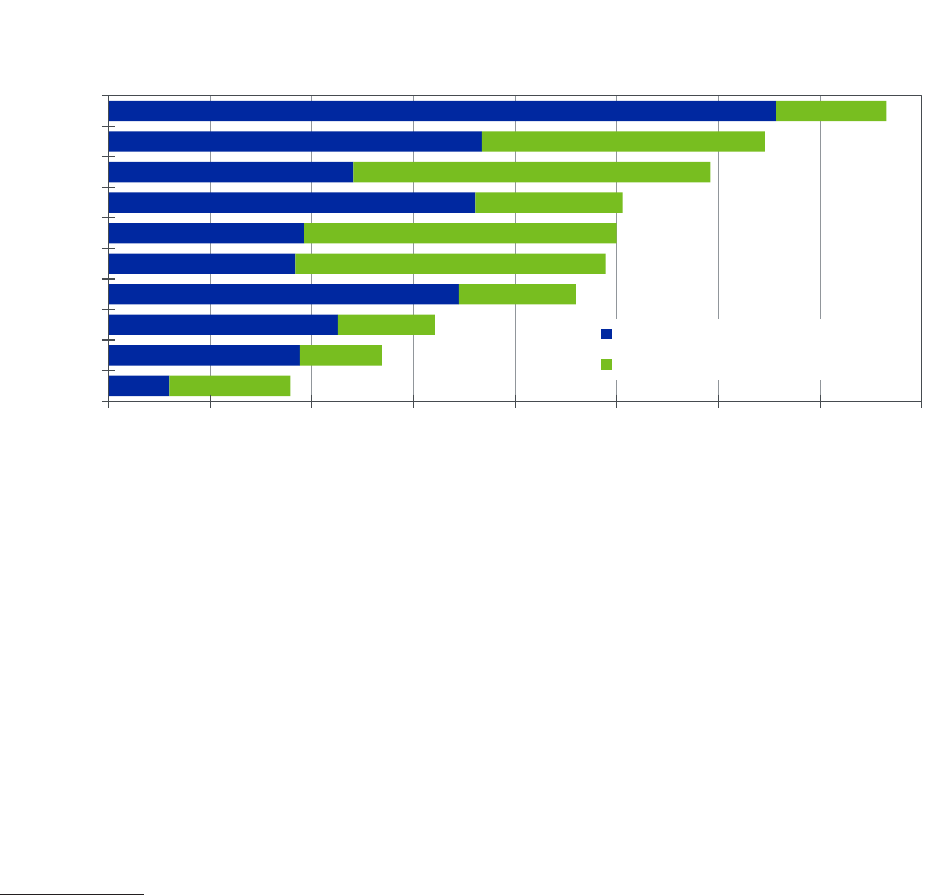

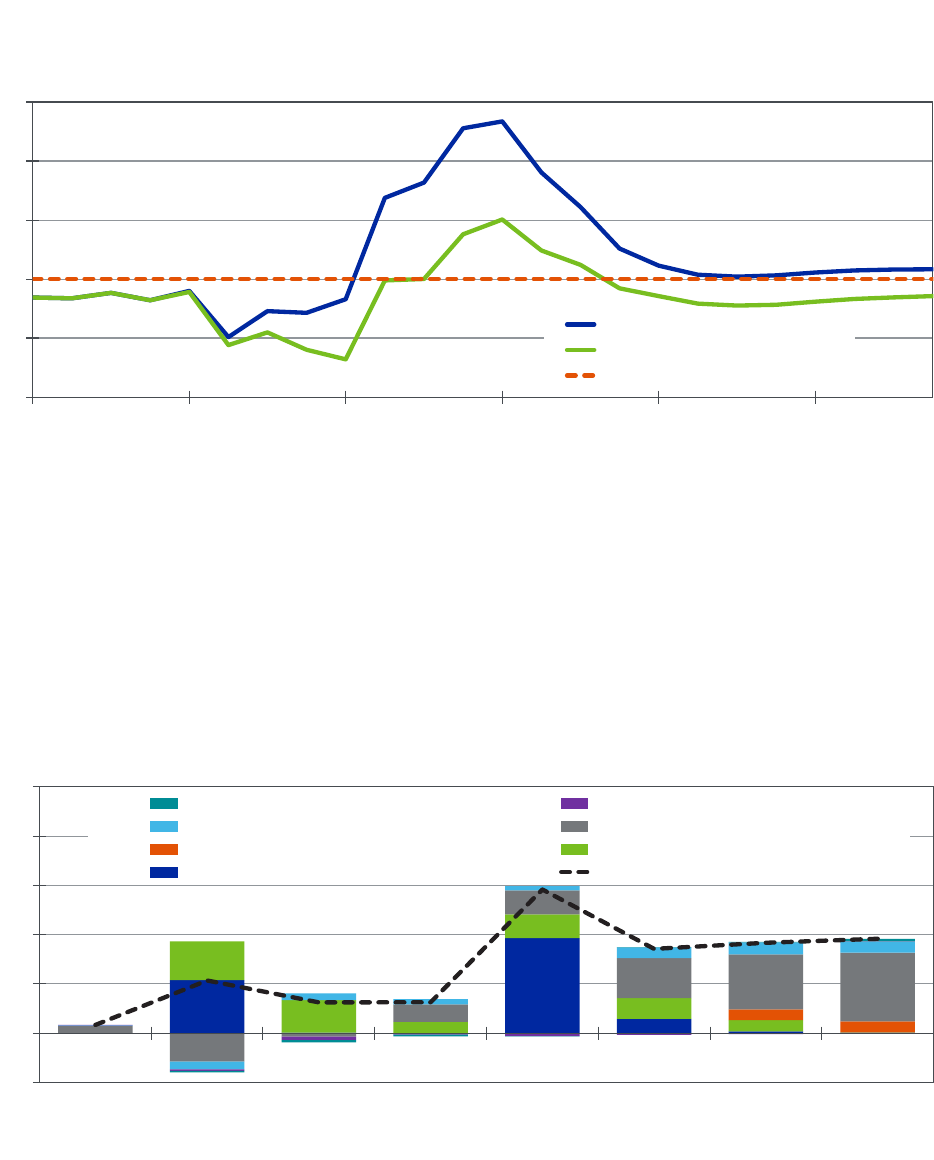

To quantify this counterfactual scenario, we have simulated the Moody’s Analytics Global Mac-

roeconomic Model.

2

The model links more than 70 countries through international trade, global

financial markets, exchange rates, consumer sentiment, and capital flows. The model is simulated

assuming an absence of fiscal support for each country by itself, and for all 10 countries at once.

By so doing, we are able to determine the spillover effects from one country’s policies on the rest

of the world. Nearly half the countries benefited more from fiscal support provided by other coun-

tries than they did from their own fiscal support (see Chart 4).

We make several simplifying assumptions in these simulations. First, we assume the course of the

pandemic and the development and rollout of vaccines proceeded as they did. Second, monetary

policy is determined endogenously in the model. That is, global central banks set interest rate and

balance sheet policies based on their reaction functions that account for the economy’s perfor-

mance, inflation, inflation expectations, and financial conditions.

3

Finally, we restrict the scope of

fiscal measures to include only those that explicitly address the fallout from the pandemic.

4

United States

No other nation responded more aggressively to the pandemic than the U.S. (see Table 1). In total,

the fiscal support was well over $5 trillion, equal to nearly 25% of GDP. This compares with less

2 This analysis is based on the February 2022 vintage of the Moody’s Analytics global macroeconomic forecasts.

3 A central bank’s reaction function is the estimated historical relationship between the bank’s monetary policy and the economic, financial and

other variables that monetary authorities use to set monetary policy.

4 Fiscal legislation that broadly seeks to invest in an economy’s long-run potential was excluded. Some examples are the Build Back Better agenda

in the U.S. and the Recovery and Resilience Facility in Europe. We even left out a handful of measures from pandemic-era legislation in Japan

that were not explicitly tied to the virus. Additionally, our analysis includes only fiscal measures that have a direct impact on budget deficits.

Liquidity supports, which were substantial in many countries, for example, were excluded.

Presentation Title, Date 4

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40

U.S.

Brazil

Canada

U.K.

Germany

China

Italy

Japan

France

India

Domestic fiscal support

External fiscal support

Chart 4: Fiscal Policy Knows No Borders

Source: Moody’s Analytics

Cumulative real GDP impact, % of GDP, 2020

-2024

MOODY’S ANALYTICS 5

GLOBAL FISCAL POLICY IN THE PANDEMIC

than 18% of GDP in the U.K., the country that provided the next most fiscal support, and the ap-

proximately 10% of GDP provided by all countries across the globe on average.

The unrivaled U.S. fiscal response was motivated in part by the nation’s meaningfully weaker

automatic fiscal stabilizers—tax and spending policies that automatically counteract declines in

economic activity without direct action by lawmakers—compared with those in other advanced

economies.

5

It was likely also motivated by lessons learned during the financial crisis a little over

a decade ago, when the policy response was slower in coming and much smaller, contributing to

what was a painfully slow economic recovery.

6

7

The U.S. economy’s rapid recovery was due to not just the scale of the fiscal support by fiscal pol-

icymakers but also how quickly they responded to the pandemic. The pandemic slammed the U.S.

in February 2020, the massive CARES Act was passed into law in late March, and no more than one

month later over $1 trillion in fiscal support was already disbursed to households and businesses.

5 N. Girouard and C. André (2005), “Measuring Cyclically-adjusted Budget Balances for OECD Countries,” OECD Economics Department

Working Papers, No. 434, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/measuring-cyclically-adjusted-budget-balanc-

es-for-oecd-countries_787626008442. M. Dolls, C. Fuest and A. Peichl (2012), “Automatic stabilizers and economic crisis: US vs. Europe,” Jour-

nal of Public Economics, Elsevier, Vol. 96(3), https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0047272711001642.

6 U.S. discretionary fiscal support during the financial crisis, including the Recovery Act that was passed into law in February 2009 and some mod-

est additional support, totaled less than 10% of U.S. GDP.

7 See “Blinder and Zandi: Policy Responses to Great Recession a Resounding Success,” white paper for Center on Budget and Policy Priorities,

October 2015.

Table 1: U.S. Fiscal Response to COVID-19

Legislation Actions $ bil

Coronavirus Preparedness and Response

Supplemental Appropriations Act

Funding for healthcare agencies and testing, funding for vaccine and other therapies across various

agencies, subsidized SME loans.

8.3

Families First Coronavirus Response Act Tax credits to rms for COVID-19-related paid sick leave and paid family medical leave; food assis-

tance via Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and Special Supplemental Nutrition Program

for Women, Infants, and Children; federal assistance for increased state unemployment insurance

benets; expand Medicare and Medicaid coverage to COVID-19 tests.

192.0

Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic

Security Act

Household cash transfers, federal assistance to expand state unemployment insurance benets,

grant-convertible loans to SMEs under the Paycheck Protection Program, grants to states and munic-

ipalities via $150 bil Coronavirus Relief Fund, student loan deferrals, expand Medicaid coverage to

telehealth services, various tax deferrals and credits.

1,756.0

Paycheck Protection Program and Health

Care Enhancement Act

Addition of $320 bil to Paycheck Protection Program, loans to smaller nancial institutions, grants

for hospitals, additional funding for states/municipalities for COVID-19 testing.

484.0

President Trump’s Executive Orders Extension of plus-up to federal unemployment insurance benets amounting to $300 per week, with

an additional $100 to be provided by states. Additional executive orders extend student loan deferral

for loans held by Department of Education, declare temporary payroll tax holiday, instruct govern-

ment agencies to assist renters and homeowners with eviction orders.

174.0

Coronavirus Response and Relief Supple-

mental Appropriations Act

Extension of unemployment insurance benets by $300 per week through March 14; second round of

stimulus checks; additional funds allocated for Paycheck Protection Program, virus-combat and vacci-

nation eorts, supplemental nutrition programs, emergency grants to entertainment venues, relief for

airline workers, increased federal spending on transportation.

915.0

American Rescue Plan Act Stimulus checks of up to $1,400, extends weekly unemployment insurance top-ups through the

beginning of September, additional provisions for renter and homeowner relief, increased outlays for

state and local governments, expansion of tax credits, nancial assistance to businesses and healthcare

providers.

1,821.0

U.S. total 5,350.3

Sources: CBO, CRFB, JCT, Moody’s Analytics

MOODY’S ANALYTICS 6

GLOBAL FISCAL POLICY IN THE PANDEMIC

There was a similar ramp-up in fiscal support in early 2021, largely via the American Rescue Plan,

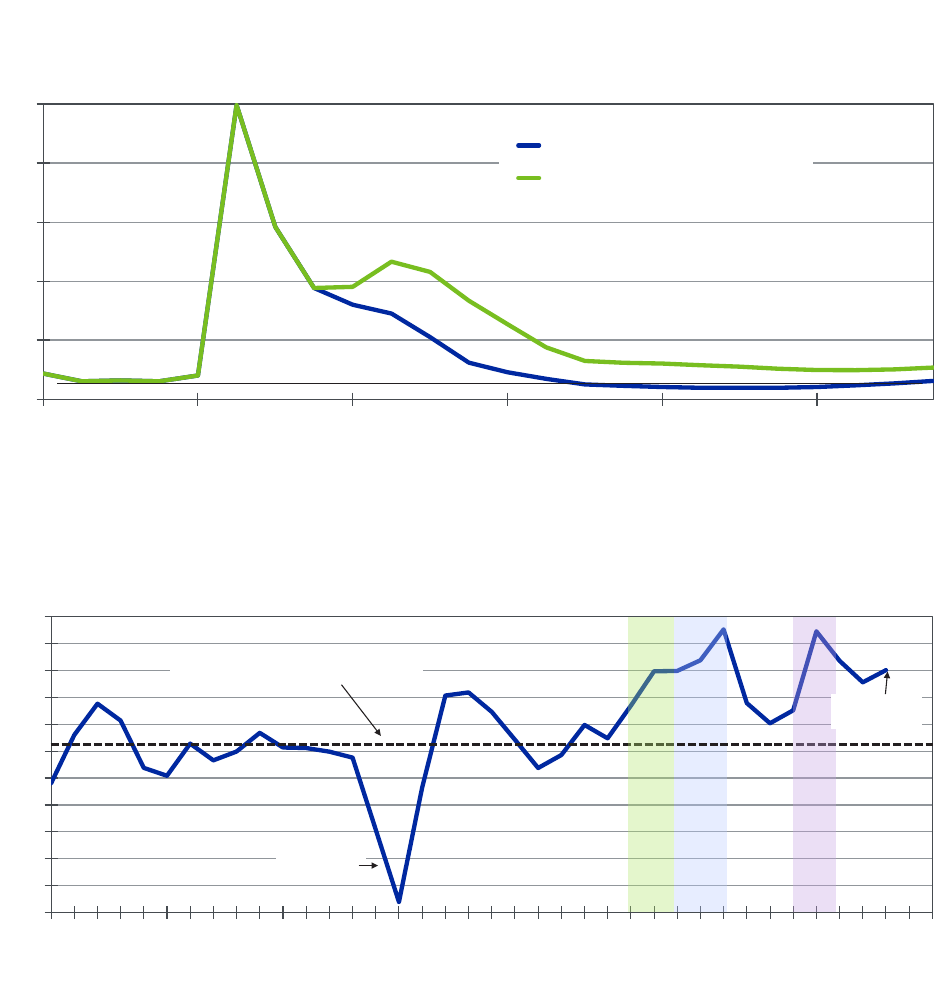

which was passed into law in March 2021 (see Chart 5).

In the counterfactual scenario where this fiscal support was not provided, real GDP falls by a stun-

ning 11% in calendar 2020, more than three times its actual decline. The economy would have also

succumbed to a double-dip recession in early 2021 (see Chart 6). A recovery begins in earnest in

the second half of 2021, but even then, the economy never fully returns to its pre-pandemic path,

as real GDP is permanently reduced.

The impact on the U.S. job market would have been equally grim. The economy is currently on track

to recoup all the jobs lost during the pandemic recession by late this year. Without government

Presentation Title, Date 5

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

4.0

Apr-20 Jul-20 Nov-20 Feb-21 Jun-21 Sep-21 Jan-22

Rental Assistance

Air Carrier Worker Support

Advanced Child Tax Credit

SNAP

Provider Relief Fund

Coronavirus Relief Fund

Enhanced UI

Stimulus Checks

Paycheck Protection Program

Sources: BEA, CRFB, HHS, SBA, U.S. Treasury, Moody’s Analytics

Chart 5: Rapid Ramp-Up in U.S. Support

Cumulative U.S. pandemic relief, $ tril

Presentation Title, Date 6

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

19 20 21 22 23 24

Baseline forecast

Counterfactual scenario

Chart 6: Double-Dip Recession in the U.S.

U.S. real GDP, 2012$ tril, SAAR

Sources: BEA, Moody’s Analytics

MOODY’S ANALYTICS 7

GLOBAL FISCAL POLICY IN THE PANDEMIC

support, this milestone would not have been achieved until summer 2026. Low-wage workers, who

have suffered most financially during the pandemic, would have been set back even further, since

they work in industries that have desperately needed government support during the pandemic.

This includes administrative and support services, healthcare, retail trade, and leisure and hospi-

tality (see Chart 7). The weaker job market means that unemployment remains stuck in the double

digits through 2021, declines only slowly thereafter, and ultimately never returns to its pre-pan-

demic full-employment unemployment rate (see Chart 8).

8

Moreover, with the economy operating

with high unemployment for an extended period, wage growth sharply slows to an all-time low.

9

8 We estimate the full-employment unemployment rate, or nonaccelerating inflation rate of unemployment, at 3.5%.

9 Wages as measured by the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Employment Cost Index.

Presentation Title, Date 7

Sources: BEA, BLS, Moody’s Analytics

-2.5 -2.0 -1.5 -1.0 -0.5 0.0

Admin. & support & waste srvcs

Healthcare

Construction

Retail trade

Manufacturing

Leisure & hospitality

Prof., scientific & technical srvcs

State & local government

Financial activities

Transportation & warehousing

Wholesale trade

Other services

Education

$48K

$56K

$69K

$38K

$74K

$109K

$58K

$59K

$86K

$54K

$50K

$28K

$108K

Note: Figures are avg industry wage in 2020. Avg for all industries was $66K.

Chart 7: Low-Wage Industries Most Hurt

U.S., jobs lost without government support, mil, 2021

Presentation Title, Date 8

3

6

9

12

15

18

19 20 21 22 23 24

Baseline forecast

Counterfactual scenario

Chart 8: Stubbornly High Unemployment

U.S. unemployment rate, %, SA

Sources: BLS, Moody’s Analytics

MOODY’S ANALYTICS 8

GLOBAL FISCAL POLICY IN THE PANDEMIC

In the counterfactual scenario, inflation picks up in early 2021 as the distribution of vaccines

prompts a reopening of the economy and a surge in consumer demand. However, it falls back be-

low the Federal Reserve’s inflation target by the second half of 2022. The Fed is not struggling with

uncomfortably high inflation as it is now. Rather, it contends with uncomfortably low inflation, as

in the decade after the financial crisis (see Chart 9).

Household finances have benefited enormously from government support. Thanks mostly to stim-

ulus checks, enhanced unemployment insurance, and rental and food assistance, personal incomes

declined only briefly at the very start of the pandemic (see Chart 10). If households had not re-

ceived this help, real disposable income would have plunged in 2020 and would not fully recover

until summer 2023.

Presentation Title, Date 9

0

1

2

3

4

5

19 20 21 22 23 24

Baseline forecast

Counterfactual scenario

Federal Reserve's target

Chart 9: Return of Too-Low Inflation

U.S. core PCE deflator, % change

yr ago

Sources: BEA, Moody’s Analytics

Presentation Title, Date 10

-1

0

1

2

3

4

5

20Q1 20Q2 20Q3 20Q4 21Q1 21Q2 21Q3 21Q4

Rental and interest income Dividend income

Proprietors' income Labor income

Advance Child Tax Credit Enhanced UI benefits

Stimulus checks Net effect

Sources: BEA, U.S. Treasury, Moody’s Analytics

Chart 10: Household Incomes Get Boost

U.S. personal income, $

tril, SAAR, change from 2019Q4

MOODY’S ANALYTICS 9

GLOBAL FISCAL POLICY IN THE PANDEMIC

Household wealth would also have been significantly diminished, as the Standard & Poor’s 500

stock price index would have plunged, cut in half peak to trough (see Chart 11). Consumers are

dour now despite the strong economic recovery, but confidence would be at an all-time low if fis-

cal policymakers had not stepped up.

American Rescue Plan

Arguably the most controversial of the U.S. fiscal support packages was the nearly $2 trillion

American Rescue Plan that became law in March 2021. The ARP has been criticized as being too

large, overstimulating an already fast-improving economy and significantly contributing to the

currently uncomfortably high inflation.

This perspective is not consistent with our results. Without the ARP, the U.S. economy would have

come close to suffering a double-digit recession in spring 2021. Based on a simulation of our mac-

ro model assuming no ARP, real GDP declines in the second quarter of 2021 and ekes out only a

small gain in the third (see Table 2). Because of the weakened economy, unemployment rises back

over 7% in summer 2021 and remains materially higher after that (see Chart 12).

10

The ARP is responsible for adding well over 4 million more jobs in 2021, and the economy is cur-

rently on track to recovering all the jobs lost in the pandemic by the second quarter of this year.

If there had been no ARP, it would have taken another year for the economy to recover all of

these jobs.

The ARP has contributed to the acceleration in inflation by supporting increased consumer de-

mand, but this occurred almost entirely in the first half of 2021 when higher inflation was not

considered a problem (see Chart 13). Indeed, at the time it was even viewed positively, as many

businesses were simply re-establishing the prices they had previously cut when the pandemic

10 Because of the much weaker economy, the Fed keeps the federal funds rate target at the zero lower bound and engages in quantitative easing

through the end of 2022.

Presentation Title, Date 11

1,500

2,000

2,500

3,000

3,500

4,000

4,500

5,000

19 20 21 22 23 24

Baseline forecast

Counterfactual scenario

Chart 11: Stock Prices Get Crushed

S&P 500 composite, 1941

-1943=10

Sources: S&P, Moody’s Analytics

MOODY’S ANALYTICS 10

GLOBAL FISCAL POLICY IN THE PANDEMIC

caused the economy to shut down. Moreover, inflation had been much too low for comfort since

the global financial crisis more than a decade earlier. The Federal Reserve and other global central

banks had been struggling to lift inflation back up to their targets.

Inflation only became uncomfortably high when the Delta wave of the pandemic hit in late sum-

mer last year. This inflation was a surprise, but so too was the Delta variant, as it came immediate-

ly on the heels of the vaccine rollout and widespread optimism that the pandemic was more-or-

less behind us.

Delta slammed consumer demand, as it prompted renewed self-quarantining and border restric-

tions, which by itself would moderate inflation, but it also severely disrupted supply. Global supply

Presentation Title, Date 13

Consumer price inflation, annualized % change

Chart 13: Don’t Blame ARP For High Inflation

Sources: BLS, Moody’s Analytics

-10

-8

-6

-4

-2

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

2019 2020 2021 2022

Pandemic

Recession

Federal Reserve Target

ARP

Omicron

Wave

Delta

Wave

Vaccine

Rollout

Presentation Title, Date 12

3

5

7

9

11

13

19 20 21 22 23 24

Baseline forecast

No American Rescue Plan

Chart 12: More Unemployment Without ARP

U.S. unemployment rate, %, SA

Sources: BLS, Moody’s Analytics

Full employment

MOODY’S ANALYTICS 11

GLOBAL FISCAL POLICY IN THE PANDEMIC

Table 2: The Macroeconomic Impact of the American Rescue Plan

Real GDP Nonfarm employment Unemployment rate Consumer price ination

Baseline

No American

Rescue Plan

Dierence Baseline No ARP Dierence Baseline No ARP Dierence Baseline No ARP Dierence

2012$ bil

Ann.

growth 2012$ bil

Ann.

growth 2012$ bil Mil

Change,

mil Mil

Change,

mil s % % Ppt

1982-

1984=100

Ann.

growth

1982-

1984=100

Ann.

growth %

2020Q1 18,952 (5.1) 18,952 (5.1) 0 151.9 0.308 151.9 0.308 0 3.8 3.8 0.0 258.5 1.0 258.5 1.0 0.0

2020Q2 17,258 (31.2) 17,258 (31.2) 0 133.8 (18.103) 133.8 (18.103) 0 13.0 13.0 0.0 256.5 (3.1) 256.5 (3.1) 0.0

2020Q3 18,561 33.8 18,561 33.8 0 140.5 6.688 140.5 6.688 0 8.8 8.8 0.0 259.4 4.7 259.4 4.7 0.0

2020Q4 18,768 4.5 18,768 4.5 0 142.5 1.998 142.5 1.998 0 6.8 6.8 0.0 261.0 2.4 261.0 2.4 -0.0

2021Q1 19,056 6.3 18,864 2.1 -191 143.7 1.262 142.7 0.219 -1,043 6.2 6.8 0.6 263.4 3.7 263.3 3.6 -0.0

2021Q2 19,368 6.7 18,828 (0.8) -540 145.2 1.453 142.1 (0.622) -3,118 5.9 7.7 1.8 268.8 8.4 268.5 8.0 -0.1

2021Q3 19,479 2.3 18,835 0.2 -644 146.9 1.695 142.8 0.714 -4,099 5.1 7.3 2.2 273.1 6.6 272.6 6.3 -0.2

2021Q4 19,806 6.9 19,185 7.7 -621 148.6 1.733 144.5 1.678 -4,154 4.2 6.3 2.1 278.6 8.2 277.8 8.0 -0.3

2022Q1 19,829 0.5 19,327 3.0 -503 150.4 1.757 146.8 2.302 -3,609 3.9 5.5 1.6 281.8 4.6 280.8 4.4 -0.3

2022Q2 20,123 6.1 19,757 9.2 -367 151.7 1.371 148.9 2.172 -2,808 3.7 4.8 1.1 284.1 3.3 282.9 3.0 -0.4

2022Q3 20,266 2.9 19,959 4.1 -308 152.6 0.842 150.2 1.231 -2,418 3.5 4.3 0.8 286.0 2.7 284.6 2.4 -0.5

2022Q4 20,390 2.5 20,082 2.5 -308 153.2 0.640 150.8 0.622 -2,436 3.4 4.2 0.8 287.7 2.5 286.2 2.2 -0.5

2023Q1 20,537 2.9 20,228 2.9 -309 153.8 0.607 151.3 0.526 -2,517 3.4 4.2 0.8 289.4 2.3 287.6 2.1 -0.6

2023Q2 20,685 2.9 20,379 3.0 -306 154.3 0.470 151.8 0.453 -2,534 3.4 4.1 0.8 290.9 2.2 289.1 2.0 -0.6

2023Q3 20,835 2.9 20,532 3.0 -303 154.7 0.383 152.2 0.413 -2,504 3.4 4.1 0.7 292.6 2.3 290.6 2.1 -0.7

2023Q4 20,984 2.9 20,688 3.1 -296 155.1 0.376 152.6 0.448 -2,431 3.4 4.0 0.6 294.2 2.3 292.0 2.1 -0.7

2024Q1 21,141 3.0 20,856 3.3 -285 155.4 0.326 153.1 0.441 -2,316 3.4 4.0 0.6 295.8 2.1 293.5 2.0 -0.8

2024Q2 21,288 2.8 21,015 3.1 -273 155.6 0.272 153.5 0.393 -2,195 3.5 4.0 0.5 297.5 2.3 295.0 2.1 -0.8

2024Q3 21,427 2.6 21,164 2.9 -263 155.9 0.229 153.8 0.339 -2,085 3.5 4.0 0.5 299.2 2.3 296.6 2.2 -0.9

2024Q4 21,569 2.7 21,312 2.8 -257 156.0 0.164 154.0 0.242 -2,008 3.6 4.1 0.5 300.9 2.3 298.3 2.2 -0.9

2025Q1 21,706 2.6 21,452 2.6 -254 156.2 0.115 154.2 0.161 -1,961 3.7 4.1 0.4 302.6 2.3 299.9 2.2 -0.9

2025Q2 21,834 2.4 21,582 2.4 -252 156.3 0.099 154.3 0.138 -1,922 3.8 4.2 0.4 304.4 2.3 301.6 2.2 -0.9

2025Q3 21,964 2.4 21,713 2.5 -250 156.4 0.102 154.5 0.143 -1,882 3.8 4.3 0.4 306.2 2.4 303.3 2.3 -0.9

2025Q4 22,098 2.5 21,851 2.6 -247 156.5 0.103 154.6 0.146 -1,839 3.9 4.3 0.4 307.9 2.4 305.0 2.3 -1.0

0

2020 18,385 (3.4) 18,385 (3.4) -0 142.1 (8.748) 142.1 (8.748) 0 8.1 8.1 0.0 258.8 1.2 258.8 1.2 0.0

2021 19,427 5.7 18,928 3.0 -499 146.1 3.950 143.0 0.846 -3,104 5.4 7.0 1.7 271.0 4.7 270.5 4.5 -0.2

2022 20,152 3.7 19,781 4.5 -371 152.0 5.877 149.2 6.163 -2,818 3.6 4.7 1.1 284.9 5.1 283.6 4.8 -0.4

2023 20,760 3.0 20,457 3.4 -303 154.5 2.489 152.0 2.810 -2,497 3.4 4.1 0.7 291.8 2.4 289.8 2.2 -0.7

2024 21,356 2.9 21,087 3.1 -270 155.7 1.276 153.6 1.622 -2,151 3.5 4.0 0.5 298.4 2.3 295.8 2.1 -0.8

2025 21,900 2.5 21,649 2.7 -251 156.3 0.571 154.4 0.821 -1,901 3.8 4.2 0.4 305.3 2.3 302.4 2.2 -0.9

Sources: BEA, BLS, Moody’s Analytics

MOODY’S ANALYTICS 12

GLOBAL FISCAL POLICY IN THE PANDEMIC

chains were badly scrambled, as this wave of the pandemic was especially hard on Southeast Asia,

which was lightly vaccinated at the time, and where most supply chains begin.

The job market was also roiled by the Delta wave, as some 8 million people told the Bureau of

Census’ Pulse Survey last September that they weren’t working because they were either sick, tak-

ing care of someone who was sick or fearful of getting sick. This is largely why so many open posi-

tions have gone unfilled, particularly for lower-wage jobs in industries where workers are in close

contact with their patrons, such as retailing, restaurants, healthcare and education and childcare

services. Wage growth has sharply accelerated, as employers struggled to keep their businesses

staffed, especially for these type of jobs. The Omicron wave further complicated efforts to get

workers back on the job, as in January at the peak of that wave, some 12 million people told Cen-

sus they weren’t working because of the virus.

Although the ARP was costly to U.S. taxpayers, without it, the ultimate cost to. them would have

been equally as large. Because of the weaker economy and automatic fiscal stabilizers, tax reve-

nues would have been lower and government outlays higher. By the end of this decade, the na-

tion’s debt burden would have been as large as it will end up being with the ARP (see Chart 14).

Canada and Mexico

Canada’s and Mexico’s economies have benefited enormously from the massive fiscal support

provided by the U.S. The Canadian and Mexican economies are closely linked to the U.S. economy

through trade, investment and immigration flows. These links are particularly important for the

North American vehicle industry, because autos dominate trade between the U.S. and the rest of

the continent. Without the fiscal support provided in the U.S., nearly 6 million fewer new vehicles

would have been sold in the U.S. in 2021, which, combined with an overall reduction in U.S. goods

consumption, would have slammed the Canadian and Mexican economies.

Presentation Title, Date 14

30

50

70

90

110

00 04 08 12 16 20 24 28

Baseline forecast

No American Rescue Plan

Chart 14: Debt Burdens As Heavy Without ARP

U.S. public debt outstanding, % of GDP, fiscal year

Sources: BEA, U.S. Treasury, Moody’s Analytics

MOODY’S ANALYTICS 13

GLOBAL FISCAL POLICY IN THE PANDEMIC

Presentation Title, Date 15

85

90

95

100

105

110

19 20 21 22 23 24

Baseline forecast

No U.S. fiscal support

Chart 15: Spillovers From U.S. Fiscal Policy

Real GDP, 2019Q4=100

Source: Moody’s Analytics

80

85

90

95

100

105

110

19 20 21 22 23 24

Baseline forecast

No U.S. fiscal support

Mexico

Canada

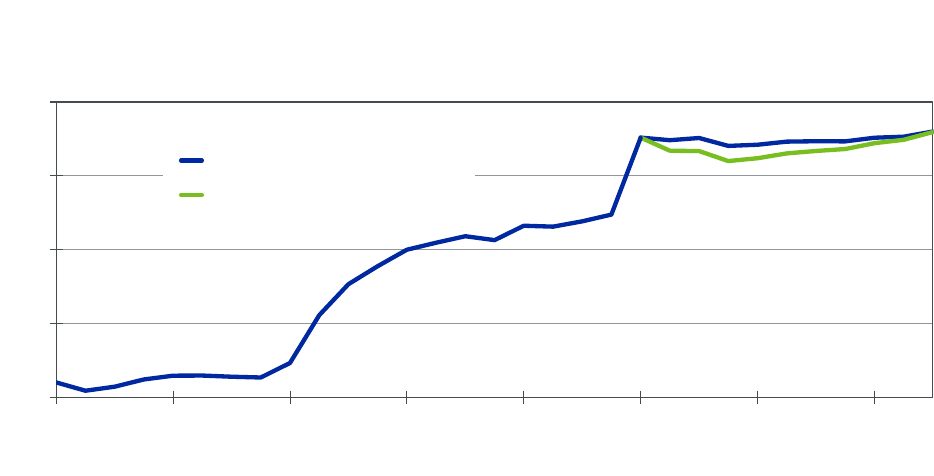

Without pandemic-related fiscal support in the U.S., real GDP in 2021 would have been 8% lower

in Mexico and 6% lower in Canada (see Chart 15).

Advanced economies

Governments in other advanced economies have also marshaled substantial fiscal support in re-

sponse to the pandemic (see Table 3). Job retention schemes have been an especially favored poli-

cy. These schemes helped cover the wages paid to workers who, instead of being laid off, were put

on furlough or had their hours cut. Germany, France, Italy and Japan already had short-time work

schemes but either increased eligibility or boosted the generosity of benefits, or did both. The pan-

demic spurred the U.K. government to stand up a new scheme, while Canadian policymakers intro-

duced a new wage subsidy covering a fixed percentage of wages regardless of hours not worked.

These job retention schemes not only maintained incomes and supported consumer demand but

also significantly limited the rise in unemployment. With the exception of Canada, jobless rates

increased meaningfully less in these advanced economies than in the U.S., where expanded unem-

ployment insurance benefits were the primary mechanism to support beleaguered workers.

11

Keeping more workers on payrolls also ensured fewer difficulties getting people back to work as

economies reopened, limiting disruptive labor shortages and the resulting wage and price pres-

sures. Though inflation has increased substantially in most advanced economies, this helps explain

why it has been less than in the U.S.

Advanced economies also did not hold back in buttressing household incomes via other social

safety net programs. Most notably, the Japanese government issued cash payments to residents

and an extra child allowance.

11 U.S. small businesses, those with 500 or fewer employees, did receive grants to maintain their payrolls through the Paycheck Protection Program.

MOODY’S ANALYTICS 14

GLOBAL FISCAL POLICY IN THE PANDEMIC

Table 3: Fiscal Response to COVID-19 in Other Advanced Economies

Euro Zone Provisions USD bil

Germany Supports for rms and workers (STW benets, grands, transfers, etc.) 283.5

Supports for public agencies and services 143.1

Tax cuts and deferrals 63.7

Public investment 15.9

Germany total 506.2

France Supports for rms and workers (STW benets, grands, transfers, etc.) 117.6

Public investment 87.2

Tax cuts and deferrals 30.1

France total 234.9

Italy Supports for rms and workers (STW benets, grants, transfers, etc.) 142.1

Tax cuts and deferrals 32.5

Public investment 24.6

Supports for public agencies and services 16.8

Italy total 216.0

Japan Provisions USD bil

Cash payment of ¥100K to Japanese residents and extra child allowance of ¥10K per child 138.5

Employment adjustment subsidies 97.4

Containment measures for COVID-19 51.7

Revitalization to cope with COVID-19 and other business supports 42.3

Support aected sectors in the form of discounts and vouchers 30.5

Supporting medical treatment providers 27.6

Measures to prevent the spread, build out medical treatment, and develop pharmaceuticals 23.1

Cash payments to SMEs and sole proprietors 21.2

Establishing rent support grant for SMEs 18.7

Additional payments to low-income single parent households 1.3

Deferred taxes and social security contributions and easing of property taxes for SMEs -0.0

Japan total 452.2

U.K. Provisions USD bil

Funding for National Health Service 207.9

Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme 101.7

Self-Employment Income Support Scheme 37.0

Additional transfers to devolved administrations 35.2

Direct grants to small businesses in most aected sectors 25.2

Property tax (business rate) holiday for rms in aected sectors 24.2

Expanded Universal Credit and Working Tax Credit Schemes 13.4

VAT reduced at 5% for hospitality, accommodation, and attractions until the end of Sep 2021, at 12.5% until Mar 2022 9.6

Temporary cut on stamp duty land tax until June 2021 6.6

Fuel Duty: one year freeze in 2021-22 5.6

Rent support by increasing the Local Housing Allowance 5.6

Public sector and social housing decarbonization and Green Homes Grant 5.3

Bring forward public infrastructure spending to FY2020/21 5.3

Boost of active labour market policies 3.8

Waiver of VAT and customs duties on critical medical imports 2.9

Support for culture, charities and sport 2.9

Funding to cover theNational Minimum Wagefor 25 hrs a wk for6 mos 2.7

Alcohol Duty: one year freeze in 2021-22 2.1

Deferral of VAT for 2020Q2 until June 21 2.0

Eat Out to Help Out 1.1

Deferral of income tax (self-assessment) of the self-employed until the end of January 2021 0.9

Extension the window for starting deferred payments through the VAT New Payment Scheme by up to 3 mos 0.6

Funding of 40,000 traineeships and 27,000 job coaches 0.6

Statutory Sick Pay Rebate Scheme 0.5

U.K. total 502.7

Canada Provisions USD bil

Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy 76.9

Canada Emergency Response Benet 64.0

Support to Health System 46.5

Canada Recovery Benets 17.7

Canada Emergency Business Account 11.2

Enhancements to Employment Insurance 7.9

Enhanced GST Credit 4.3

Canada Emergency Rent Subsidy and Lockdown Support 3.4

Other Measures to Support Vulnerable Canadians (Transfers) 2.9

Other Direct Support Measures 2.8

Canada Emergency Student Benet 2.3

Wage Top-Up for Essential Workers 2.3

Income Tax, Sales Tax, and Customs Duty Payment Deferrals 2.3

Other Support for Businesses (Direct Govt Outlays) 2.0

Other Support for Businesses (Transfers) 2.0

10% Temporary Wage Subsidy 1.9

One-Time Payment for Seniors Eligible for OAS and GIS 1.9

Canada Emergency Commercial Rent Assistance for Small Business 1.6

Enhanced Canada Child Benet 1.5

Regional Relief and Recovery Fund 1.1

Air Sector 1.0

Other Measures to Support Vulnerable Canadians (Direct Govt Outlays) 0.8

Support for Persons with Disabilities 0.7

Supporting Community Service Organizations 0.6

Support for Innovative Businesses 0.5

Support for Workers in the Live Events and Arts Sectors 0.2

Canada total 260.4

Sources: Bundesministerium der Finanzen, Department of Finance Canada, HM Treasury, IMF, Kantei, Ministère de l’Économie et des Finances, Ministero dell’economia e delle Finanze, Moody’s Analytics

MOODY’S ANALYTICS 15

GLOBAL FISCAL POLICY IN THE PANDEMIC

Some advanced economies were somewhat hampered by budget constraints in providing support.

Italy, for example, had less fiscal space for direct spending and therefore relied more heavily on

loan guarantees. The EU was able to work around budgetary constraints through joint stimulus

measures that were funded by mutualized debt obligations. Our analysis does not include the im-

pact of Europe’s Recovery and Resilience Facility, but these plans supported market confidence,

which in turn kept interest rates low and allowed countries to spend more than would have other-

wise been the case.

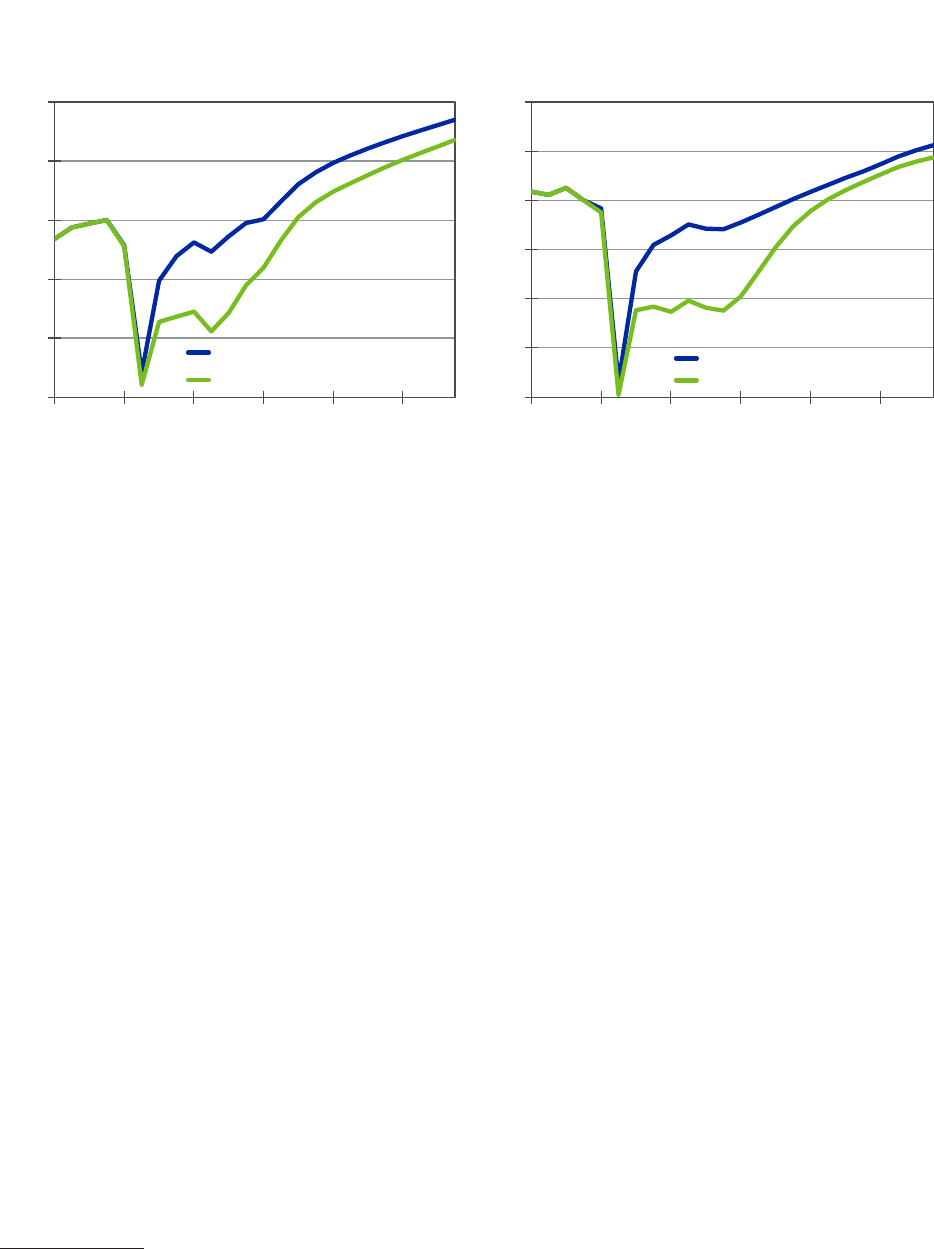

Advanced economies also benefited from fiscal support in other countries. In Europe, these spill-

over effects were most evident in Germany, where the country’s fiscal measures were not much

greater, as a share of GDP, than those in France and Italy. German exports, particularly of vehicles,

have been significantly buoyed by global demand that would have been substantially diminished

without the fiscal help provided around the world (see Chart 16).

The fiscal support has also helped Japan avoid a much more serious bout of deflation. Like the U.S.

dollar, the Japanese yen is a safe-haven currency that generally appreciates when global investors

are nervous. In the counterfactual scenario without government support, investors are substantial-

ly more skittish and thus flock to the yen, pushing up its value by over 10% on a trade-weighted

basis. This puts severe downward pressure on Japanese prices (see Chart 17).

Emerging markets

Emerging markets have been hit hard by successive waves of the virus, and a world without fiscal

stimulus would have been far less kind. Although the three largest emerging economies—China,

India and Brazil—traced different paths with respect to the magnitude and composition of fiscal

support, the consequences of not providing fiscal support are similarly clear: weaker economic re-

coveries, higher unemployment, and diminished long-run growth (see Table 4).

Presentation Title, Date 16

Chart 16: German Exports Are Crushed

Real German exports, 2015€

bil, SAAR

Sources:

Destatis, Moody’s Analytics

1,100

1,200

1,300

1,400

1,500

1,600

1,700

19 20 21 22 23 24

Baseline forecast

Counterfactual scenario

MOODY’S ANALYTICS 16

GLOBAL FISCAL POLICY IN THE PANDEMIC

Presentation Title, Date 17

-2.5

-2.0

-1.5

-1.0

-0.5

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

19 20 21 22 23 24

Baseline forecast

Counterfactual scenario

Japanese consumer price index, % change

yr ago

Sources: Japan Statistics Bureau, Moody’s Analytics

Chart 17: Deflation for Longer in Japan

Table 4: Fiscal Response to COVID-19 in Emerging Markets

China Provisions USD bil

Support for employment, incomes, reductions in taxes and fees for small businesses 299.7

Infrastructure spending 239.7

Exemptions from social insurance payments, reduction or exemption of value-added tax 74.9

Waiving of toll roads, reduction in commerical electricity taris 50.5

China total 664.8

India Provisions USD bil

Food aid and cooking gas 30.8

Fertilizer subsidy 10.8

Financial assistance for construction workers 4.3

Cash transfers to female heads of household 4.1

Increase in cash transfers for rural households 3.7

Infrastructure investment 3.4

Additional spending on public health 3.1

Travel and consumption vouchers 2.6

Subsidies for construction industry 2.4

Advance payments to farmers 2.4

Job support for rural economy 1.4

Supplemental health insurance for hospital workers exposed to COVID-19 1.3

Cash transfers to senior citizens 0.4

Payroll support program 0.3

Research and development funding for vaccine 0.1

India total 71.0

Brazil Provisions USD bil

Emergency family income 67.1

Aid for state and local governments 14.8

Additional spending on public health 13.0

Payroll support program 9.1

Vaccine procurement 4.6

Credits for machinery and equipment 0.9

Aid to tourism industry 0.7

Aid to energy sector 0.2

Expansion of Bolsa Familia 0.1

Brazil total 110.4

Sources: Government of India’s Ministry of Finance, National People’s Congress, Tesouro Nacional, Moody’s Analytics

MOODY’S ANALYTICS 17

GLOBAL FISCAL POLICY IN THE PANDEMIC

For China, the severe hit to global trade in the counterfactual scenario precipitates a double-dip

recession, with the economy contracting again in the first half of 2021. The subsequent economic

recovery is also materially slower. Global trade is a critical driver of China’s recovery, and with less

trade, the Chinese economy would have stumbled well into 2021.

Though Chinese officials spent less on direct fiscal support than they did during the global finan-

cial crisis, the timing and composition of spending were critical. Most of the support was delivered

in the third quarter of 2020, when the recovery in global trade was nascent. While a large share

of spending went toward infrastructure, almost half of the support was directed toward relief for

consumers and businesses in a departure from China’s traditional infrastructure-heavy playbook.

Without this boost, the economic recovery would have been cut short.

As in the rest of Latin America, the pandemic ripped through Brazil. But Brazil spent more on direct

fiscal support to its economy than almost any other emerging economy. Without this support,

public health and economic outcomes would have been substantially worse. The Brazilian econo-

my would have fallen back into recession in the first half of 2021 and would not have recouped its

pre-pandemic peak until the second half of 2024.

India’s economy benefits the least from fiscal support, since overall government spending was

limited. Even with the extension of cash transfer programs during the Delta wave of the pan-

demic, which hit India especially hard, cumulative spending in the past two years was just over

2% of GDP. Global fiscal support also played a role in India’s recovery, though to a lesser extent

than in China and Brazil. This is because India’s economy is less reliant on trade overall and global

fiscal policy was more effective at reviving trade in goods than in services, for which India has a

comparative advantage.

Conclusion

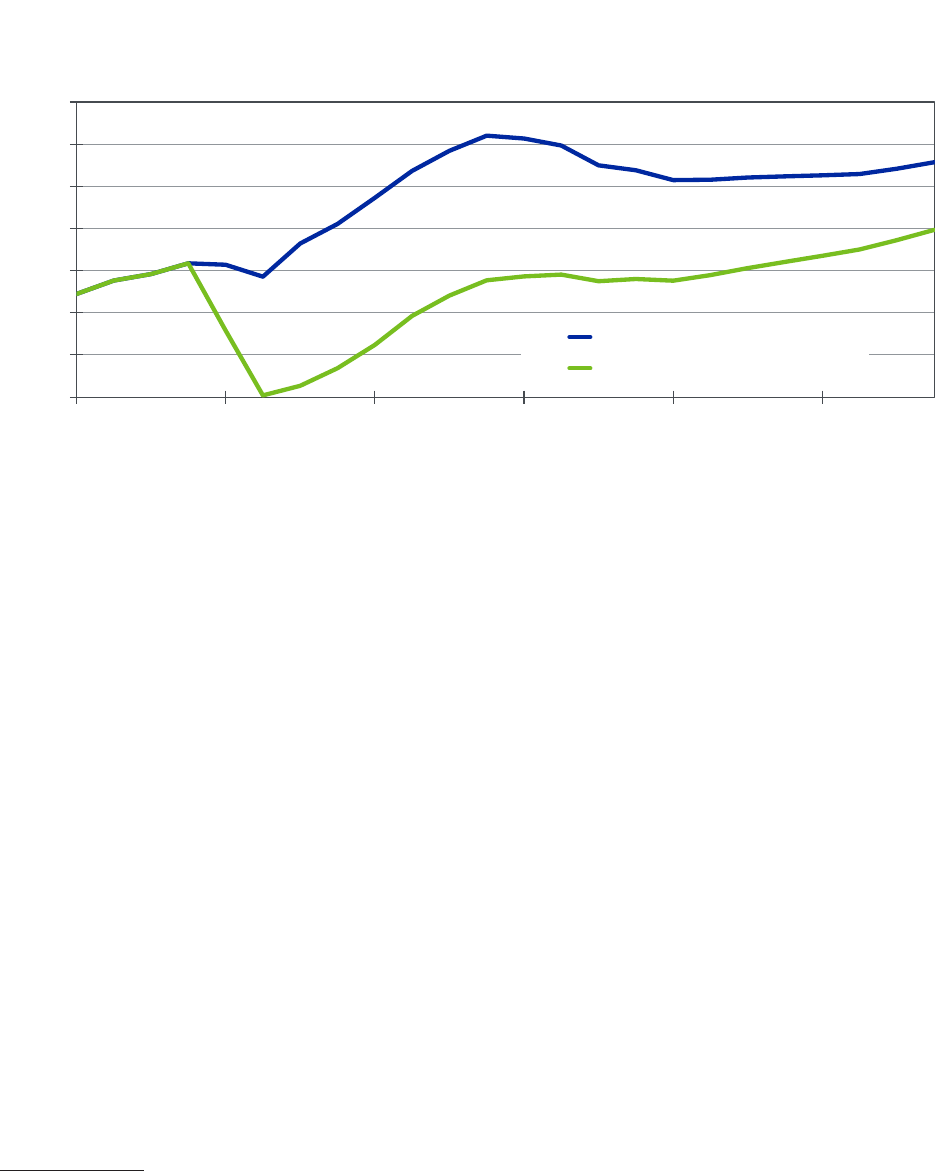

The massive global fiscal policy response to the pandemic deserves significant credit for limiting

the severity and length of the recession that occurred when the pandemic struck, and for the sub-

sequently strong global economic recovery (see Table 5).

There has been criticism of global policymakers for going overboard on the fiscal support, with crit-

ics pointing to recent concerns over high inflation and bigger government deficits and debt loads.

But as we show, even without the fiscal support, inflation would still be a worry. Not because in-

flation would have been too high, but too low—as it had been since the financial crisis. Many glob-

al central banks would have nervously watched as their economies flirted with or suffered outright

deflation in 2020. Though global inflation would have picked up in 2021 because of base effects of

prices being depressed a year earlier, its rebound would have been slower.

Further, the fiscal situation of most countries already would have been even worse if they had not

provided the fiscal support, as their much-weakened economies would have caused tax revenues

to plummet and government expenditures to automatically increase (see Chart 18). The case is the

same for the U.S., although it will take a bit longer for this to become clear.

MOODY’S ANALYTICS 18

GLOBAL FISCAL POLICY IN THE PANDEMIC

Thus, second-guessing the aggressive fiscal policy response of governments to the pandemic is

misplaced. Governments had no choice but to act quickly and massively. Perhaps some of the

specific policy steps taken during the crisis could have been better designed, at least in hindsight.

However, policymakers’ decisiveness in pushing forward with substantial government support has

been an economic game changer.

Presentation Title, Date 18

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35

Brazil

China

Germany

India

Italy

France

Canada

U.K.

U.S.

Japan

Baseline forecast

Counterfactual scenario

Chart 18: More Debt Was Unavoidable

Source: Moody’s Analytics

Debt-to-GDP ratio, ppt increase from 2019Q4 to 2021Q4

MOODY’S ANALYTICS 19

GLOBAL FISCAL POLICY IN THE PANDEMIC

Table 5: Macroeconomic Impact of Government Pandemic Aid in 10 Largest Economies

Real GDP, local currency, SAAR

World U.S. China Japan Germany U.K.

Baseline Counterfactual Baseline Counterfactual Baseline Counterfactual Baseline Counterfactual Baseline Counterfactual Baseline Counterfactual

2012USD

bil

Ann.

growth

2012USD

bil

Ann.

growth

2012USD

bil

Ann.

growth

2012USD

bil

Ann.

growth

2015CNY

bil

Ann.

growth

2015CNY

bil

Ann.

growth

2015JPY

bil

Ann.

growth

2015JPY

bil

Ann.

growth

2015EUR

bil

Ann.

growth

2015EUR

bil

Ann.

growth

2018GBP

bil

Ann.

growth

2018GBP

bil

Ann.

growth

2020Q1 84,775 (10.9) 84,389 (12.5) 18,952 (5.1) 18,780 (8.5) 81,671 (35.2) 81,262 (36.5) 545,000 1.2 544,736 1.0 3,194 (6.9) 3,170 (9.6) 2,201 (10.1) 2,196 (10.9)

2020Q2 78,792 (25.4) 75,759 (35.0) 17,258 (31.2) 16,106 (45.9) 91,388 56.8 85,874 24.7 501,140 (28.5) 494,290 (32.2) 2,874 (34.4) 2,775 (41.3) 1,773 (57.9) 1,641 (68.8)

2020Q3 84,916 34.9 80,228 25.8 18,561 33.8 16,521 10.7 94,553 14.6 90,564 23.7 526,742 22.1 505,644 9.5 3,134 41.4 2,842 10.0 2,084 91.1 1,898 78.9

2020Q4 86,328 6.8 81,089 4.4 18,768 4.5 16,482 (0.9) 96,869 10.2 92,496 8.8 538,909 9.6 510,521 3.9 3,158 3.0 2,753 (12.0) 2,116 6.1 1,943 9.7

2021Q1 86,996 3.1 80,952 (0.7) 19,056 6.3 16,239 (5.8) 97,028 0.7 91,971 (2.3) 535,012 (2.9) 502,474 (6.2) 3,099 (7.3) 2,788 5.1 2,089 (5.0) 1,916 (5.3)

2021Q2 87,791 3.7 81,267 1.6 19,368 6.7 16,481 6.1 98,160 4.7 91,597 (1.6) 537,631 2.0 502,912 0.3 3,161 8.3 2,942 24.0 2,202 23.6 1,997 18.0

2021Q3 88,747 4.4 82,750 7.5 19,479 2.3 17,096 15.8 98,721 2.3 92,376 3.4 532,778 (3.6) 501,821 (0.9) 3,215 7.0 3,008 9.2 2,226 4.3 2,033 7.5

2021Q4 90,070 6.1 84,687 9.7 19,806 6.9 17,829 18.3 100,178 6.0 94,105 7.7 541,302 6.6 515,120 11.0 3,191 (2.9) 3,002 (0.7) 2,236 1.8 2,077 8.9

2022Q1 90,540 2.1 85,826 5.5 19,829 0.5 18,217 9.0 101,442 5.1 95,710 7.0 540,490 (0.6) 518,252 2.5 3,196 0.5 3,024 2.9 2,258 4.0 2,128 10.2

2022Q2 91,568 4.6 87,403 7.6 20,123 6.1 18,748 12.2 102,834 5.6 97,454 7.5 545,895 4.1 526,654 6.6 3,241 5.8 3,081 7.8 2,277 3.5 2,166 7.4

2022Q3 92,428 3.8 88,650 5.8 20,266 2.9 19,027 6.1 104,332 6.0 99,096 6.9 550,808 3.6 533,739 5.5 3,280 4.9 3,137 7.5 2,294 2.9 2,194 5.2

2022Q4 93,219 3.5 89,649 4.6 20,390 2.5 19,181 3.3 105,875 6.0 100,634 6.4 555,215 3.2 539,903 4.7 3,307 3.3 3,178 5.3 2,307 2.4 2,218 4.5

2023Q1 94,006 3.4 90,558 4.1 20,537 2.9 19,324 3.0 107,373 5.8 102,171 6.2 557,807 1.9 543,915 3.0 3,338 3.7 3,217 5.0 2,318 1.9 2,237 3.5

2023Q2 94,779 3.3 91,414 3.8 20,685 2.9 19,483 3.3 108,852 5.6 103,650 5.9 559,226 1.0 546,409 1.8 3,360 2.7 3,245 3.5 2,329 1.8 2,253 2.8

2023Q3 95,534 3.2 92,239 3.7 20,835 2.9 19,659 3.7 110,327 5.5 105,140 5.9 560,615 1.0 548,672 1.7 3,381 2.5 3,270 3.1 2,338 1.6 2,265 2.2

2023Q4 96,285 3.2 93,042 3.5 20,984 2.9 19,829 3.5 111,774 5.3 106,616 5.7 561,961 1.0 550,864 1.6 3,401 2.4 3,293 2.8 2,346 1.5 2,275 1.8

2024Q1 97,047 3.2 93,835 3.5 21,141 3.0 20,003 3.6 113,303 5.6 108,141 5.8 563,275 0.9 552,693 1.3 3,421 2.3 3,314 2.6 2,358 2.0 2,287 2.3

2024Q2 97,789 3.1 94,593 3.3 21,288 2.8 20,169 3.4 114,803 5.4 109,614 5.6 564,556 0.9 553,690 0.7 3,438 2.1 3,333 2.3 2,369 1.8 2,298 1.9

2024Q3 98,504 3.0 95,328 3.1 21,427 2.6 20,332 3.3 116,231 5.1 111,039 5.3 565,804 0.9 554,301 0.4 3,454 1.9 3,351 2.1 2,378 1.6 2,308 1.7

2024Q4 99,202 2.9 96,059 3.1 21,569 2.7 20,506 3.5 117,618 4.9 112,437 5.1 567,020 0.9 555,056 0.5 3,468 1.7 3,367 1.9 2,386 1.3 2,316 1.4

2025Q1 99,881 2.8 96,794 3.1 21,706 2.6 20,683 3.5 118,990 4.7 113,852 5.1 568,204 0.8 556,008 0.7 3,480 1.4 3,381 1.7 2,392 1.1 2,323 1.2

2025Q2 100,545 2.7 97,522 3.0 21,834 2.4 20,853 3.3 120,352 4.7 115,241 5.0 569,350 0.8 557,197 0.9 3,491 1.2 3,395 1.6 2,400 1.3 2,331 1.5

2025Q3 101,206 2.7 98,249 3.0 21,964 2.4 21,022 3.3 121,708 4.6 116,610 4.8 570,457 0.8 558,520 1.0 3,501 1.2 3,408 1.6 2,408 1.3 2,340 1.5

2025Q4 101,875 2.7 98,985 3.0 22,098 2.5 21,198 3.4 123,063 4.5 117,942 4.6 571,528 0.8 559,832 0.9 3,511 1.1 3,421 1.6 2,417 1.5 2,350 1.8

2020 83,703 (3.5) 80,366 (7.4) 18,385 (3.4) 16,972 (10.8) 91,121 2.3 87,549 (1.7) 527,948 (4.5) 513,798 (7.1) 3,090 (4.9) 2,885 (11.2) 2,043 (9.4) 1,920 (14.9)

2021 88,401 5.6 82,414 2.5 19,427 5.7 16,911 (0.4) 98,522 8.1 92,512 5.7 536,681 1.7 505,582 (1.6) 3,167 2.5 2,935 1.7 2,188 7.1 2,006 4.5

2022 91,939 4.0 87,882 6.6 20,152 3.7 18,793 11.1 103,621 5.2 98,224 6.2 548,102 2.1 529,637 4.8 3,256 2.8 3,105 5.8 2,284 4.4 2,177 8.5

2023 95,151 3.5 91,813 4.5 20,760 3.0 19,574 4.2 109,582 5.8 104,394 6.3 559,902 2.2 547,465 3.4 3,370 3.5 3,256 4.9 2,333 2.1 2,257 3.7

2024 98,135 3.1 94,954 3.4 21,356 2.9 20,252 3.5 115,489 5.4 110,308 5.7 565,163 0.9 553,935 1.2 3,445 2.2 3,341 2.6 2,373 1.7 2,302 2.0

2025 100,877 2.8 97,888 3.1 21,900 2.5 20,939 3.4 121,028 4.8 115,911 5.1 569,885 0.8 557,889 0.7 3,496 1.5 3,401 1.8 2,404 1.3 2,336 1.5

Sources: National statistical agencies, Moody’s Analytics

MOODY’S ANALYTICS 20

GLOBAL FISCAL POLICY IN THE PANDEMIC

Table 5: Macroeconomic Impact of Government Pandemic Aid in 10 Largest Economies (Cont.)

Real GDP, local currency, SAAR

India France Italy Brazil Canada

Baseline Counterfactual Baseline Counterfactual Baseline Counterfactual Baseline Counterfactual Baseline Counterfactual

2011-

2012INR bil

Ann.

growth

2011-

2012INR bil

Ann.

growth

2015EUR

bil

Ann.

growth

2015EUR

bil

Ann.

growth

2015EUR

bil

Ann.

growth

2015EUR

bil

Ann.

growth

1995BRL

bil

Ann.

growth

1995BRL

bil

Ann.

growth

2012CAD

bil

Ann.

growth

2012CAD

bil

Ann.

growth

2020Q1 148,162 10.1 147,222 7.4 2,198 (20.9) 2,192 (21.8) 1,622 (21.4) 1,616 (22.5) 1,203 (8.8) 1,180 (15.3) 2,077 (8.4) 2,077 (8.4)

2020Q2 110,208 (69.4) 108,147 (70.9) 1,902 (44.0) 1,867 (47.3) 1,415 (42.0) 1,345 (52.0) 1,096 (31.0) 991 (50.3) 1,848 (37.4) 1,806 (42.9)

2020Q3 133,337 114.3 129,884 108.0 2,256 98.0 2,167 81.4 1,639 79.8 1,543 73.2 1,181 34.9 1,044 23.2 2,014 41.1 1,905 23.9

2020Q4 145,259 40.9 141,288 40.0 2,231 (4.3) 2,138 (5.1) 1,611 (6.6) 1,556 3.2 1,218 13.0 1,146 45.1 2,058 9.1 1,906 0.2

2021Q1 150,601 15.5 146,309 15.0 2,234 0.6 2,159 3.9 1,616 1.3 1,544 (2.9) 1,234 5.5 1,157 3.7 2,083 4.9 1,907 0.2

2021Q2 132,428 (40.2) 127,857 (41.7) 2,264 5.4 2,186 5.1 1,661 11.4 1,575 8.1 1,230 (1.4) 1,148 (3.0) 2,066 (3.2) 1,857 (10.1)

2021Q3 144,512 41.8 139,624 42.2 2,335 13.2 2,258 14.0 1,704 10.9 1,612 9.7 1,229 (0.4) 1,142 (2.0) 2,094 5.4 1,891 7.5

2021Q4 155,206 33.1 151,006 36.8 2,352 2.9 2,277 3.3 1,714 2.5 1,619 1.9 1,227 (0.5) 1,141 (0.3) 2,118 4.6 1,941 11.0

2022Q1 156,262 2.7 152,782 4.8 2,361 1.5 2,288 1.9 1,725 2.5 1,633 3.4 1,229 0.5 1,149 2.6 2,125 1.3 1,971 6.4

2022Q2 157,824 4.1 154,968 5.8 2,378 3.0 2,310 4.0 1,742 4.0 1,654 5.2 1,239 3.2 1,159 3.5 2,157 6.2 2,021 10.5

2022Q3 158,929 2.8 156,621 4.3 2,399 3.5 2,334 4.2 1,754 2.8 1,668 3.4 1,248 3.0 1,168 3.2 2,188 5.9 2,064 8.8

2022Q4 160,677 4.5 158,788 5.6 2,414 2.6 2,353 3.2 1,765 2.5 1,679 2.7 1,256 2.6 1,177 3.2 2,209 4.0 2,091 5.3

2023Q1 163,023 6.0 161,337 6.6 2,427 2.2 2,367 2.5 1,774 2.2 1,688 2.3 1,263 2.4 1,186 3.0 2,226 3.1 2,109 3.4

2023Q2 166,121 7.8 164,478 8.0 2,439 2.0 2,380 2.2 1,784 2.1 1,698 2.3 1,270 2.4 1,193 2.6 2,240 2.4 2,121 2.3

2023Q3 169,177 7.6 167,455 7.4 2,450 1.8 2,392 2.0 1,793 2.2 1,708 2.5 1,278 2.3 1,200 2.3 2,252 2.2 2,133 2.2

2023Q4 172,798 8.8 170,931 8.6 2,461 1.8 2,403 1.9 1,803 2.2 1,719 2.6 1,285 2.3 1,208 2.5 2,263 2.1 2,144 2.1

2024Q1 175,482 6.4 173,483 6.1 2,473 1.9 2,415 2.0 1,811 1.8 1,728 2.2 1,294 2.8 1,217 3.1 2,274 1.9 2,154 1.9

2024Q2 178,332 6.7 176,186 6.4 2,485 2.0 2,428 2.1 1,818 1.6 1,737 2.0 1,303 2.9 1,226 3.2 2,284 1.8 2,164 1.8

2024Q3 181,154 6.5 178,871 6.2 2,497 1.9 2,440 2.1 1,825 1.6 1,746 2.1 1,313 2.9 1,235 2.9 2,294 1.7 2,173 1.8

2024Q4 183,989 6.4 181,571 6.2 2,508 1.8 2,452 2.0 1,833 1.7 1,756 2.3 1,322 2.9 1,245 3.0 2,304 1.7 2,183 1.8

2025Q1 186,752 6.1 184,206 5.9 2,519 1.8 2,465 2.0 1,841 1.8 1,766 2.4 1,331 2.8 1,254 3.1 2,313 1.7 2,194 1.9

2025Q2 189,428 5.9 186,751 5.6 2,528 1.4 2,475 1.7 1,850 1.8 1,777 2.4 1,341 2.8 1,264 3.2 2,323 1.7 2,204 2.0

2025Q3 192,009 5.6 189,203 5.4 2,537 1.4 2,485 1.7 1,857 1.7 1,787 2.3 1,350 2.9 1,274 3.3 2,333 1.7 2,215 1.9

2025Q4 194,603 5.5 191,667 5.3 2,546 1.4 2,496 1.7 1,865 1.5 1,797 2.2 1,360 2.9 1,285 3.4 2,343 1.7 2,225 1.9

2020 134,242 (7.1) 131,636 (8.9) 2,147 (8.0) 2,091 (10.4) 1,572 (9.0) 1,515 (12.3) 1,174 (4.2) 1,090 (11.0) 1,999 (5.2) 1,923 (8.8)

2021 145,687 8.5 141,199 7.3 2,297 7.0 2,220 6.2 1,674 6.5 1,587 4.8 1,230 4.7 1,147 5.2 2,090 4.5 1,899 (1.3)

2022 158,423 8.7 155,790 10.3 2,388 4.0 2,321 4.6 1,746 4.3 1,658 4.5 1,243 1.0 1,163 1.4 2,170 3.8 2,037 7.3

2023 167,780 5.9 166,050 6.6 2,445 2.4 2,386 2.8 1,789 2.4 1,703 2.7 1,274 2.5 1,197 2.9 2,245 3.5 2,127 4.4

2024 179,739 7.1 177,528 6.9 2,491 1.9 2,434 2.0 1,822 1.9 1,742 2.3 1,308 2.7 1,231 2.8 2,289 1.9 2,168 2.0

2025 190,698 6.1 187,957 5.9 2,533 1.7 2,480 1.9 1,853 1.7 1,782 2.3 1,345 2.9 1,269 3.1 2,328 1.7 2,209 1.9

Sources: National statistical agencies, Moody’s Analytics

MOODY’S ANALYTICS 21

GLOBAL FISCAL POLICY IN THE PANDEMIC

Table 5: Macroeconomic Impact of Government Pandemic Aid in 10 Largest Economies (Cont.)

Employment, SA

World U.S. China Japan Germany U.K.

Baseline Counterfactual Baseline Counterfactual Baseline Counterfactual Baseline Counterfactual Baseline Counterfactual Baseline Counterfactual

Mil

Change,

mil Mil

Change,

mil Mil

Change,

mil Mil

Change,

mil Mil

Change,

mil Mil

Change,

mil Mil

Change,

mil Mil

Change,

mil Mil

Change,

mil Mil

Change,

mil Mil

Change,

mil Mil

Change,

mil

2020Q1 2,565.5 (9.104) 2,563.8 (10.807) 157.7 (0.838) 156.9 (1.666) 774.3 (0.307) 774.3 (0.316) 67.4 (0.110) 67.4 (0.123) 43.3 (0.051) 43.3 (0.075) 33.0 0.078 32.9 (0.038)

2020Q2 2,406.2 (159.277) 2,395.7 (168.045) 137.6 131.4 (25.460) 774.3 0.043 774.3 0.013 66.3 (1.057) 66.3 (1.103) 42.9 (0.372) 42.8 (0.483) 32.6 (0.407) 32.4 (0.521)

2020Q3 2,486.6 80.363 2,464.8 69.082 146.2 8.584 134.6 3.197 772.3 (2.077) 771.6 (2.657) 66.6 0.203 66.4 0.102 42.9 0.002 42.5 (0.333) 32.4 (0.255) 32.0 (0.384)

2020Q4 2,511.7 25.171 2,483.4 18.556 149.8 3.630 136.0 1.424 770.0 (2.252) 767.3 (4.313) 66.8 0.203 66.5 0.081 42.9 (0.037) 42.0 (0.500) 32.1 (0.201) 31.7 (0.316)

2021Q1 2,526.3 14.622 2,490.6 7.269 150.4 0.649 133.6 (2.402) 770.9 0.892 765.9 (1.463) 66.9 0.163 66.5 0.044 43.2 0.268 42.0 0.015 32.2 0.032 31.6 (0.074)

2021Q2 2,531.8 5.474 2,489.6 (0.995) 151.5 1.037 134.0 0.393 770.3 (0.578) 762.7 (3.121) 66.6 (0.353) 66.1 (0.453) 43.4 0.212 42.2 0.240 32.3 0.095 31.6 (0.020)

2021Q3 2,536.0 4.173 2,491.7 2.117 153.2 1.752 138.1 4.100 769.9 (0.430) 759.5 (3.266) 66.8 0.210 66.2 0.161 43.4 0.011 42.3 0.113 32.5 0.247 31.8 0.201

2021Q4 2,546.2 10.165 2,502.5 10.792 155.2 1.952 142.4 4.299 770.0 0.082 758.3 (1.177) 66.4 (0.370) 65.9 (0.362) 43.3 (0.058) 42.3 (0.010) 32.5 (0.055) 31.8 (0.030)

2022Q1 2,560.3 14.134 2,518.8 16.306 157.0 1.827 146.2 3.736 770.2 0.207 757.9 (0.436) 66.9 0.537 66.4 0.578 43.5 0.170 42.5 0.191 32.5 0.027 31.8 0.080

2022Q2 2,572.2 11.865 2,533.4 14.533 157.5 0.530 148.0 1.882 770.0 (0.160) 757.3 (0.584) 67.2 0.271 66.8 0.328 43.5 0.037 42.6 0.058 32.5 0.006 31.9 0.057

2022Q3 2,581.5 9.299 2,545.1 11.708 158.1 0.537 149.3 1.204 769.7 (0.319) 756.7 (0.571) 67.4 0.140 67.0 0.190 43.6 0.040 42.6 0.080 32.5 0.042 32.0 0.091

2022Q4 2,588.3 6.815 2,554.1 8.983 158.6 0.498 149.9 0.621 769.0 (0.660) 756.1 (0.642) 67.4 0.098 67.1 0.132 43.6 0.043 42.7 0.100 32.6 0.066 32.1 0.126

2023Q1 2,592.2 3.936 2,560.0 5.950 159.0 0.459 150.3 0.450 767.0 (2.016) 754.5 (1.606) 67.5 0.065 67.2 0.087 43.7 0.043 42.8 0.087 32.7 0.059 32.2 0.115

2023Q2 2,597.0 4.757 2,566.5 6.516 159.4 0.409 150.9 0.576 766.2 (0.823) 754.0 (0.433) 67.6 0.065 67.3 0.078 43.7 0.037 42.9 0.070 32.7 0.043 32.3 0.085

2023Q3 2,602.3 5.304 2,573.4 6.864 159.8 0.375 151.6 0.690 765.4 (0.795) 753.6 (0.382) 67.6 0.063 67.3 0.072 43.7 0.029 43.0 0.051 32.7 0.025 32.4 0.054

2023Q4 2,608.4 6.096 2,580.8 7.404 160.2 0.353 152.3 0.670 764.7 (0.736) 753.3 (0.304) 67.7 0.062 67.4 0.068 43.7 0.020 43.0 0.036 32.8 0.017 32.4 0.037

2024Q1 2,614.8 6.470 2,588.4 7.580 160.5 0.333 152.9 0.630 763.9 (0.720) 753.0 (0.293) 67.8 0.056 67.5 0.060 43.8 0.012 43.0 0.024 32.8 0.018 32.4 0.033

2024Q2 2,621.0 6.143 2,595.5 7.094 160.8 0.268 153.5 0.581 763.2 (0.793) 752.6 (0.418) 67.8 0.052 67.5 0.053 43.8 0.007 43.0 0.016 32.8 0.020 32.5 0.030

2024Q3 2,626.7 5.730 2,602.0 6.501 161.0 0.234 154.0 0.493 762.3 (0.829) 752.1 (0.490) 67.9 0.048 67.6 0.046 43.8 0.003 43.0 0.010 32.8 0.021 32.5 0.029

2024Q4 2,632.1 5.355 2,608.1 6.088 161.2 0.155 154.4 0.444 761.5 (0.848) 751.6 (0.532) 67.9 0.046 67.6 0.041 43.8 0.001 43.0 0.009 32.8 0.022 32.5 0.027

2025Q1 2,637.1 5.077 2,613.9 5.832 161.3 0.121 154.9 0.450 760.6 (0.860) 751.0 (0.561) 68.0 0.045 67.6 0.039 43.8 0.002 43.1 0.010 32.9 0.020 32.5 0.025

2025Q2 2,641.9 4.755 2,619.4 5.517 161.4 0.093 155.3 0.424 759.8 (0.860) 750.5 (0.573) 68.0 0.045 67.7 0.041 43.8 0.001 43.1 0.011 32.9 0.019 32.6 0.025

2025Q3 2,646.6 4.708 2,624.9 5.456 161.5 0.097 155.7 0.409 758.9 (0.842) 749.9 (0.571) 68.0 0.044 67.7 0.043 43.8 (0.001) 43.1 0.010 32.9 0.018 32.6 0.024

2025Q4 2,651.2 4.565 2,630.2 5.313 161.6 0.089 156.1 0.393 758.1 (0.823) 749.3 (0.566) 68.1 0.043 67.8 0.044 43.8 (0.004) 43.1 0.008 32.9 0.019 32.6 0.025

2020 2,492.5 (65.820) 2,476.9 (81.393) 147.8 (9.724) 139.7 (17.792) 772.7 (1.993) 771.9 (2.830) 66.8 (0.477) 66.6 (0.605) 43.0 (0.201) 42.6 (0.592) 32.5 (0.270) 32.2 (0.564)

2021 2,535.1 42.596 2,493.6 16.726 152.6 4.772 137.1 (2.681) 770.3 (2.452) 761.6 (10.291) 66.7 (0.099) 66.2 (0.470) 43.3 0.298 42.2 (0.413) 32.4 (0.167) 31.7 (0.556)

2022 2,575.5 40.466 2,537.8 44.209 157.8 5.217 148.3 11.278 769.7 (0.536) 757.0 (4.616) 67.2 0.574 66.8 0.647 43.6 0.244 42.6 0.408 32.5 0.175 32.0 0.273

2023 2,600.0 24.407 2,570.2 32.345 159.6 1.816 151.3 2.932 765.8 (3.909) 753.9 (3.110) 67.6 0.372 67.3 0.475 43.7 0.152 42.9 0.303 32.7 0.180 32.3 0.369

2024 2,623.6 23.694 2,598.5 28.287 160.9 1.245 153.7 2.415 762.7 (3.097) 752.4 (1.512) 67.8 0.225 67.5 0.240 43.8 0.057 43.0 0.113 32.8 0.085 32.5 0.153

2025 2,644.2 20.556 2,622.1 23.615 161.4 0.563 155.5 1.796 759.3 (3.380) 750.2 (2.167) 68.0 0.183 67.7 0.168 43.8 0.005 43.1 0.041 32.9 0.080 32.6 0.104

Sources: National statistical agencies, Moody’s Analytics

MOODY’S ANALYTICS 22

GLOBAL FISCAL POLICY IN THE PANDEMIC

Table 5: Macroeconomic Impact of Government Pandemic Aid in 10 Largest Economies (Cont.)

Employment, SA

India France Italy Brazil Canada

Baseline Counterfactual Baseline Counterfactual Baseline Counterfactual Baseline Counterfactual Baseline Counterfactual

Mil

Change,

mil Mil

Change,

mil Mil

Change,

mil Mil

Change,

mil Mil

Change,

mil Mil

Change,

mil Mil

Change,

mil Mil

Change,

mil Mil

Change,

mil Mil

Change,

mil

2020Q1 442.8 (1.736) 442.8 (1.736) 27.7 0.046 27.7 0.032 22.8 (0.165) 22.8 (0.229) 93.0 (0.859) 92.6 (1.321) 18.8 (0.251) 18.7 (0.313)

2020Q2 369.7 (73.164) 369.6 (73.231) 26.8 (0.925) 26.7 (0.983) 22.0 (0.785) 21.9 (0.865) 84.1 (8.960) 81.7 (10.930) 16.7 (2.127) 16.5 (2.243)

2020Q3 418.3 48.635 417.9 48.298 27.2 0.390 26.9 0.240 22.2 0.192 21.9 0.034 83.7 (0.417) 78.6 (3.070) 18.1 1.388 17.7 1.172

2020Q4 435.0 16.660 434.1 16.197 27.4 0.221 27.1 0.114 22.3 0.056 21.9 (0.073) 86.1 2.469 81.5 2.912 18.5 0.435 17.9 0.208

2021Q1 441.1 6.120 439.6 5.507 27.3 (0.106) 26.9 (0.136) 22.1 (0.191) 21.6 (0.293) 87.2 1.109 83.1 1.595 18.6 0.067 17.8 (0.104)

2021Q2 433.9 (7.164) 431.2 (8.390) 27.6 0.279 27.1 0.195 22.4 0.343 21.8 0.202 90.2 2.937 85.6 2.505 18.7 0.114 17.7 (0.030)

2021Q3 429.9 (4.057) 426.0 (5.192) 27.8 0.220 27.2 0.131 22.6 0.112 21.8 0.054 93.2 3.047 88.9 3.318 19.0 0.310 18.0 0.266

2021Q4 431.8 1.907 427.3 1.277 27.7 (0.081) 27.1 (0.095) 22.6 0.028 21.8 (0.034) 90.3 (2.896) 86.2 (2.678) 19.3 0.289 18.3 0.341

2022Q1 437.8 5.984 433.4 6.065 27.7 (0.039) 27.1 (0.029) 22.8 0.185 21.9 0.125 89.3 (1.038) 85.6 (0.622) 19.3 (0.009) 18.4 0.089

2022Q2 443.9 6.100 439.9 6.504 27.7 (0.002) 27.1 0.012 22.9 0.174 22.0 0.119 89.2 (0.130) 85.8 0.218 19.4 0.117 18.6 0.210

2022Q3 448.4 4.536 444.9 5.020 27.7 0.019 27.2 0.051 23.1 0.156 22.1 0.107 89.4 0.202 86.3 0.446 19.4 0.048 18.8 0.123

2022Q4 451.1 2.698 448.1 3.204 27.7 0.027 27.3 0.068 23.2 0.143 22.2 0.096 89.6 0.276 86.8 0.502 19.5 0.035 18.9 0.087

2023Q1 452.5 1.449 449.9 1.820 27.7 0.035 27.3 0.068 23.4 0.134 22.3 0.089 89.9 0.285 87.3 0.492 19.5 0.030 18.9 0.061

2023Q2 453.9 1.339 451.5 1.629 27.8 0.037 27.4 0.065 23.5 0.112 22.4 0.069 90.3 0.338 87.8 0.517 19.5 0.017 18.9 0.034

2023Q3 455.9 1.996 453.8 2.235 27.8 0.036 27.4 0.057 23.6 0.092 22.4 0.051 90.7 0.389 88.3 0.546 19.5 0.016 19.0 0.028

2023Q4 458.6 2.726 456.7 2.924 27.8 0.033 27.5 0.050 23.7 0.078 22.5 0.039 91.1 0.435 88.9 0.586 19.5 0.021 19.0 0.032

2024Q1 461.6 3.031 459.9 3.190 27.9 0.030 27.5 0.045 23.7 0.065 22.5 0.029 91.6 0.477 89.6 0.631 19.6 0.026 19.0 0.037

2024Q2 464.5 2.866 462.9 2.990 27.9 0.029 27.6 0.042 23.8 0.056 22.5 0.023 92.1 0.506 90.2 0.657 19.6 0.027 19.1 0.038

2024Q3 467.0 2.475 465.4 2.574 27.9 0.029 27.6 0.042 23.8 0.049 22.5 0.019 92.6 0.520 90.9 0.650 19.6 0.028 19.1 0.039

2024Q4 469.1 2.134 467.7 2.220 28.0 0.030 27.7 0.043 23.9 0.043 22.6 0.016 93.1 0.524 91.5 0.644 19.7 0.028 19.2 0.040

2025Q1 471.1 1.970 469.7 2.051 28.0 0.032 27.7 0.045 23.9 0.039 22.6 0.015 93.6 0.516 92.1 0.633 19.7 0.029 19.2 0.041

2025Q2 473.0 1.975 471.8 2.054 28.0 0.033 27.8 0.047 23.9 0.035 22.6 0.015 94.1 0.500 92.8 0.615 19.7 0.029 19.2 0.041

2025Q3 475.1 2.031 473.9 2.107 28.1 0.033 27.8 0.047 24.0 0.032 22.6 0.015 94.6 0.479 93.3 0.588 19.7 0.028 19.3 0.041

2025Q4 477.1 2.042 476.0 2.113 28.1 0.031 27.8 0.045 24.0 0.028 22.6 0.014 95.1 0.450 93.9 0.553 19.8 0.028 19.3 0.041

2020 416.4 (14.929) 416.1 (15.264) 27.3 (0.210) 27.1 (0.369) 22.3 (0.667) 22.1 (0.902) 86.7 (6.634) 83.6 (9.788) 18.0 (0.974) 17.7 (1.287)

2021 434.2 17.717 431.0 14.927 27.6 0.322 27.1 0.013 22.4 0.072 21.7 (0.377) 90.2 3.514 86.0 2.380 18.9 0.867 18.0 0.273

2022 445.3 11.113 441.5 10.518 27.7 0.095 27.2 0.067 23.0 0.593 22.1 0.343 89.4 (0.880) 86.1 0.167 19.4 0.512 18.7 0.711

2023 455.2 9.949 453.0 11.429 27.8 0.118 27.4 0.238 23.5 0.513 22.4 0.331 90.5 1.118 88.1 1.954 19.5 0.136 19.0 0.288

2024 465.5 10.328 464.0 10.992 27.9 0.126 27.6 0.190 23.8 0.274 22.5 0.131 92.3 1.854 90.5 2.451 19.6 0.096 19.1 0.142

2025 474.1 8.532 472.8 8.874 28.0 0.126 27.8 0.179 24.0 0.159 22.6 0.065 94.4 2.023 93.0 2.499 19.7 0.113 19.3 0.162

Sources: National statistical agencies, Moody’s Analytics

MOODY’S ANALYTICS 23

GLOBAL FISCAL POLICY IN THE PANDEMIC

Table 5: Macroeconomic Impact of Government Pandemic Aid in 10 Largest Economies (Cont.)

Unemployment rate, %, SA

World U.S. China Japan Germany U.K.

Baseline Counterfactual Baseline Counterfactual Baseline Counterfactual Baseline Counterfactual Baseline Counterfactual Baseline Counterfactual

2020Q1 6.2 6.3 3.8 4.3 3.6 3.6 2.4 2.5 5.0 5.0 4.0 4.3

2020Q2 9.3 9.7 13.0 16.8 3.7 3.7 2.7 2.8 6.1 6.4 4.1 4.8

2020Q3 8.0 8.8 8.8 15.9 4.0 4.2 3.0 3.2 6.3 7.2 4.8 5.8

2020Q4 7.5 8.5 6.8 15.0 4.3 4.7 3.0 3.4 6.2 8.0 5.2 6.6

2021Q1 7.1 8.4 6.2 16.1 4.1 4.9 2.8 3.4 6.0 8.4 4.9 6.6

2021Q2 7.3 8.8 5.9 15.9 4.0 5.2 2.9 3.6 5.9 8.3 4.7 6.7

2021Q3 7.3 8.8 5.1 13.3 4.0 5.5 2.8 3.6 5.5 7.8 4.3 6.4

2021Q4 7.1 8.6 4.2 10.7 4.0 5.6 2.7 3.5 5.3 7.5 4.2 6.3

2022Q1 6.9 8.2 3.9 9.0 3.9 5.6 2.8 3.5 5.1 7.2 4.5 6.4

2022Q2 6.7 7.9 3.7 7.7 3.9 5.6 2.7 3.3 5.1 7.2 4.6 6.4

2022Q3 6.5 7.7 3.5 7.0 3.9 5.6 2.7 3.2 5.0 7.1 4.6 6.2

2022Q4 6.5 7.6 3.4 6.7 4.0 5.6 2.6 3.1 5.0 6.9 4.5 6.0

2023Q1 6.5 7.5 3.4 6.5 4.0 5.6 2.6 3.1 5.0 6.8 4.4 5.8

2023Q2 6.5 7.4 3.4 6.3 4.0 5.5 2.5 3.0 5.0 6.7 4.4 5.6

2023Q3 6.5 7.4 3.4 6.1 4.0 5.5 2.5 3.0 5.0 6.7 4.4 5.5

2023Q4 6.5 7.3 3.4 5.9 4.0 5.4 2.5 2.9 4.9 6.6 4.5 5.5

2024Q1 6.4 7.2 3.4 5.8 4.0 5.4 2.4 2.9 4.9 6.6 4.5 5.5

2024Q2 6.4 7.2 3.5 5.6 4.0 5.3 2.4 2.9 4.9 6.5 4.5 5.5

2024Q3 6.4 7.1 3.5 5.6 4.0 5.3 2.4 2.8 4.9 6.5 4.5 5.5

2024Q4 6.4 7.1 3.6 5.5 4.0 5.2 2.4 2.8 4.9 6.5 4.5 5.5

2025Q1 6.4 7.0 3.7 5.4 4.0 5.2 2.3 2.8 4.9 6.5 4.5 5.5

2025Q2 6.3 7.0 3.8 5.3 4.0 5.2 2.3 2.8 5.0 6.5 4.5 5.4

2025Q3 6.3 7.0 3.8 5.2 4.0 5.1 2.3 2.7 5.0 6.5 4.6 5.4

2025Q4 6.3 6.9 3.9 5.1 4.0 5.1 2.2 2.7 5.0 6.4 4.6 5.4

2020 7.8 8.3 8.1 13.0 3.9 4.1 2.8 3.0 5.9 6.7 4.5 5.4

2021 7.2 8.6 5.4 14.0 4.0 5.3 2.8 3.5 5.7 8.0 4.5 6.5

2022 6.6 7.9 3.6 7.6 3.9 5.6 2.7 3.3 5.0 7.1 4.5 6.2

2023 6.5 7.4 3.4 6.2 4.0 5.5 2.5 3.0 5.0 6.7 4.4 5.6

2024 6.4 7.1 3.5 5.6 4.0 5.3 2.4 2.8 4.9 6.5 4.5 5.5

2025 6.3 7.0 3.8 5.2 4.0 5.1 2.3 2.7 5.0 6.5 4.5 5.4

Sources: National statistical agencies, Moody’s Analytics

MOODY’S ANALYTICS 24

GLOBAL FISCAL POLICY IN THE PANDEMIC

Table 5: Macroeconomic Impact of Government Pandemic Aid in 10 Largest Economies (Cont.)

Unemployment rate, %, SA

India France Italy Brazil Canada

Baseline Counterfactual Baseline Counterfactual Baseline Counterfactual Baseline Counterfactual Baseline Counterfactual

2020Q1 9.1 9.1 7.8 7.8 9.0 9.3 11.6 12.0 6.4 6.7

2020Q2 20.8 20.8 7.2 7.4 8.6 9.2 13.2 15.7 12.9 13.8

2020Q3 13.2 13.2 9.1 9.8 10.0 11.2 14.9 20.1 10.1 12.0

2020Q4 10.3 10.4 8.0 9.1 9.8 11.5 14.9 19.5 8.9 11.8

2021Q1 9.3 9.5 8.1 9.3 10.1 12.2 14.3 18.4 8.4 12.0

2021Q2 11.1 11.4 8.0 9.5 9.8 12.4 14.1 18.4 7.9 12.1

2021Q3 12.2 12.6 8.1 9.8 9.1 12.0 12.7 16.7 7.2 11.5

2021Q4 12.1 12.7 8.0 9.8 9.1 12.2 12.7 16.7 6.3 10.2

2022Q1 11.3 11.9 8.0 9.8 9.3 12.5 12.9 16.4 6.3 9.7

2022Q2 10.5 11.0 8.0 9.8 9.3 12.8 12.7 16.0 5.9 8.9

2022Q3 10.0 10.5 8.0 9.6 9.3 13.0 12.6 15.6 5.8 8.4

2022Q4 9.9 10.3 8.0 9.5 9.3 13.1 12.4 15.2 5.8 8.2

2023Q1 10.0 10.4 8.0 9.3 9.2 13.2 12.2 14.8 5.9 8.0

2023Q2 10.2 10.5 7.9 9.2 9.1 13.3 12.0 14.4 5.9 8.0

2023Q3 10.2 10.5 7.9 9.1 9.1 13.4 11.8 14.0 6.0 8.0

2023Q4 10.1 10.4 7.9 9.0 9.0 13.5 11.5 13.6 6.1 8.0

2024Q1 10.0 10.3 7.9 9.0 9.0 13.6 11.2 13.1 6.1 7.9

2024Q2 9.9 10.2 7.9 8.9 9.0 13.7 10.8 12.6 6.1 7.9

2024Q3 9.9 10.2 7.8 8.8 9.0 13.8 10.4 12.1 6.1 7.8

2024Q4 9.9 10.2 7.8 8.8 9.0 13.9 10.1 11.6 6.1 7.8

2025Q1 9.9 10.2 7.8 8.7 8.9 13.9 9.7 11.2 6.1 7.7

2025Q2 9.9 10.2 7.8 8.6 8.9 14.0 9.4 10.7 6.1 7.6

2025Q3 9.9 10.2 7.8 8.6 8.9 14.0 9.0 10.2 6.2 7.6

2025Q4 9.9 10.2 7.7 8.5 8.9 14.1 8.7 9.8 6.2 7.5

2020 13.4 13.4 8.0 8.6 9.3 10.3 13.6 16.8 9.6 11.1

2021 11.2 11.5 8.1 9.6 9.5 12.2 13.4 17.6 7.4 11.5

2022 10.4 10.9 8.0 9.7 9.3 12.8 12.6 15.8 6.0 8.8

2023 10.1 10.5 7.9 9.2 9.1 13.3 11.9 14.2 6.0 8.0

2024 9.9 10.2 7.8 8.9 9.0 13.7 10.6 12.4 6.1 7.8

2025 9.9 10.2 7.8 8.6 8.9 14.0 9.2 10.5 6.2 7.6

Sources: National statistical agencies, Moody’s Analytics

MOODY’S ANALYTICS 25

GLOBAL FISCAL POLICY IN THE PANDEMIC

Table 5: Macroeconomic Impact of Government Pandemic Aid in 10 Largest Economies (Cont.)

Consumer price index, SA

World U.S. China Japan Germany U.K.

Baseline Counterfactual Baseline Counterfactual Baseline Counterfactual Baseline Counterfactual Baseline Counterfactual Baseline Counterfactual

Index

Ann.

growth Index

Ann.

growth Index

Ann.

growth Index

Ann.

growth Index

Ann.

growth Index

Ann.

growth Index

Ann.

growth Index

Ann.

growth Index

Ann.

growth Index

Ann.

growth Index

Ann.

growth Index

Ann.

growth

2020Q1 133.3 3.0 133.3 2.9 258.5 1.0 258.4 0.9 112.2 3.5 112.2 3.4 100.4 0.1 100.4 0.1 106.0 (0.0) 106.0 0.0 108.8 2.1 108.6 1.4

2020Q2 133.2 (0.5) 133.0 (0.9) 256.5 (3.1) 255.8 (4.0) 111.2 (3.3) 111.1 (3.7) 100.1 (1.2) 100.1 (1.3) 105.8 (0.5) 105.6 (1.5) 108.5 (1.3) 108.2 (1.7)

2020Q3 134.4 3.7 133.0 0.0 259.4 4.7 255.7 (0.1) 111.8 1.9 110.1 (3.5) 100.0 (0.4) 99.8 (1.2) 105.7 (0.6) 104.6 (3.8) 108.9 1.5 107.8 (1.2)

2020Q4 135.4 3.1 132.9 (0.2) 261.0 2.4 255.4 (0.5) 111.2 (2.2) 107.9 (7.8) 99.5 (1.9) 98.9 (3.5) 105.9 1.0 103.9 (2.4) 108.9 0.3 107.5 (1.3)

2021Q1 137.2 5.4 133.7 2.4 263.4 3.7 256.3 1.4 112.1 3.3 107.2 (2.6) 99.9 1.5 98.8 (0.3) 107.2 4.9 104.5 2.1 109.4 1.9 107.8 1.0

2021Q2 139.2 5.8 134.9 3.6 268.8 8.4 260.3 6.4 112.5 1.5 106.3 (3.5) 99.3 (2.2) 97.9 (3.6) 108.2 3.7 105.2 2.9 110.6 4.4 108.8 4.1

2021Q3 141.1 5.7 136.5 4.8 273.1 6.6 263.8 5.5 112.7 0.8 105.9 (1.2) 99.8 1.8 98.1 0.8 109.8 6.3 106.8 6.1 111.9 4.5 110.2 4.9

2021Q4 143.6 7.4 138.8 6.9 278.6 8.2 268.6 7.4 113.1 1.5 106.0 0.2 100.0 1.1 98.2 0.4 111.3 5.4 108.1 5.0 114.3 8.9 112.6 9.0

2022Q1 145.6 5.6 140.6 5.3 281.8 4.6 271.3 4.1 113.8 2.6 106.5 2.0 100.3 1.2 98.4 0.6 112.6 4.8 109.4 4.7 115.7 5.1 114.0 5.1

2022Q2 147.1 4.2 142.0 4.2 284.1 3.3 273.6 3.4 114.7 2.9 107.4 3.3 100.5 0.8 98.4 0.3 113.4 2.7 110.1 2.6 118.2 8.9 116.4 9.0

2022Q3 148.3 3.4 143.3 3.5 286.0 2.7 275.4 2.7 115.5 2.9 108.6 4.5 100.7 0.8 98.5 0.3 114.0 2.4 110.6 2.2 119.4 4.1 117.6 4.1

2022Q4 149.5 3.1 144.4 3.2 287.7 2.5 276.9 2.3 116.4 3.1 109.9 5.0 100.9 0.8 98.6 0.4 114.4 1.1 110.9 0.9 120.3 3.3 118.5 3.3

2023Q1 150.6 3.0 145.5 3.1 289.4 2.3 278.3 2.0 117.4 3.5 111.3 5.1 101.1 0.6 98.6 0.2 114.9 1.7 111.3 1.4 121.0 2.2 119.2 2.2

2023Q2 151.7 2.9 146.6 2.9 290.9 2.2 279.6 1.8 118.5 3.7 112.7 5.0 101.2 0.6 98.7 0.1 115.1 1.0 111.4 0.6 121.7 2.2 119.8 2.2

2023Q3 152.8 3.0 147.6 2.9 292.6 2.3 280.8 1.8 119.6 3.8 113.9 4.5 101.4 0.6 98.7 0.1 115.4 1.0 111.6 0.5 122.2 1.9 120.4 1.9

2023Q4 153.9 2.9 148.6 2.8 294.2 2.3 282.0 1.8 120.7 3.7 115.1 4.1 101.5 0.5 98.7 0.1 115.7 1.1 111.7 0.5 122.8 1.9 121.0 1.8

2024Q1 155.0 2.9 149.6 2.8 295.8 2.1 283.3 1.8 121.7 3.5 116.1 3.8 101.6 0.5 98.7 0.1 116.1 1.2 111.9 0.7 123.4 2.0 121.5 1.9

2024Q2 156.1 3.0 150.6 2.7 297.5 2.3 284.5 1.8 122.7 3.3 117.1 3.4 101.8 0.5 98.7 0.1 116.5 1.4 112.1 0.8 124.0 2.0 122.1 1.8

2024Q3 157.2 2.9 151.6 2.6 299.2 2.3 285.7 1.8 123.7 3.3 118.0 3.2 101.9 0.6 98.8 0.0 116.9 1.5 112.4 0.9 124.7 2.1 122.7 1.9

2024Q4 158.4 2.9 152.5 2.5 300.9 2.3 287.0 1.8 124.7 3.2 119.0 3.1 102.1 0.6 98.8 (0.0) 117.4 1.6 112.6 1.0 125.3 2.1 123.2 1.9

2025Q1 159.5 2.9 153.5 2.5 302.6 2.3 288.3 1.8 125.7 3.2 119.9 3.0 102.2 0.6 98.7 (0.0) 117.9 1.7 112.9 1.0 126.0 2.1 123.8 1.9

2025Q2 160.6 2.9 154.4 2.5 304.4 2.3 289.7 1.9 126.6 3.1 120.7 3.0 102.3 0.6 98.7 (0.1) 118.4 1.8 113.2 1.1 126.6 2.1 124.4 1.8

2025Q3 161.8 2.9 155.4 2.5 306.2 2.4 291.1 2.0 127.6 3.1 121.6 3.0 102.5 0.6 98.7 (0.1) 119.0 1.9 113.6 1.2 127.3 2.1 124.9 1.8

2025Q4 162.9 2.8 156.4 2.5 307.9 2.4 292.6 2.1 128.6 3.0 122.5 2.9 102.6 0.6 98.7 (0.1) 119.5 1.9 113.9 1.2 127.9 2.0 125.5 1.8

2020 134.1 2.8 133.0 2.0 258.8 1.2 256.3 0.3 111.6 2.5 110.3 1.4 100.0 0.0 99.8 (0.2) 105.9 0.5 105.0 (0.3) 108.8 0.9 108.0 0.2

2021 140.3 4.6 136.0 2.2 271.0 4.7 262.3 2.3 112.6 0.9 106.4 (3.6) 99.8 (0.2) 98.3 (1.5) 109.1 3.1 106.2 1.1 111.6 2.6 109.8 1.7

2022 147.6 5.2 142.6 4.9 284.9 5.1 274.3 4.6 115.1 2.2 108.1 1.6 100.6 0.9 98.5 0.2 113.6 4.1 110.2 3.8 118.4 6.1 116.6 6.2

2023 152.2 3.1 147.1 3.2 291.8 2.4 280.2 2.1 119.0 3.4 113.2 4.8 101.3 0.7 98.7 0.2 115.3 1.5 111.5 1.2 121.9 3.0 120.1 3.0

2024 156.7 2.9 151.1 2.7 298.4 2.3 285.1 1.8 123.2 3.5 117.6 3.8 101.8 0.6 98.7 0.1 116.7 1.2 112.3 0.7 124.4 2.0 122.4 1.9

2025 161.2 2.9 154.9 2.5 305.3 2.3 290.5 1.9 127.1 3.2 121.2 3.1 102.4 0.6 98.7 (0.0) 118.7 1.7 113.4 1.0 126.9 2.1 124.6 1.8

Sources: National statistical agencies, Moody’s Analytics

MOODY’S ANALYTICS 26

GLOBAL FISCAL POLICY IN THE PANDEMIC

Table 5: Macroeconomic Impact of Government Pandemic Aid in 10 Largest Economies (Cont’d)

Consumer price index, SA

India France Italy Brazil Canada

Baseline Counterfactual Baseline Counterfactual Baseline Counterfactual Baseline Counterfactual Baseline Counterfactual

Index

Ann.

growth Index

Ann.

growth Index

Ann.

growth Index

Ann.

growth Index

Ann.

growth Index

Ann.

growth Index

Ann.

growth Index

Ann.

growth Index

Ann.

growth Index

Ann.

growth

2020Q1 150.0 6.3 149.1 3.9 104.8 0.7 104.9 0.7 103.0 (0.0) 103.0 0.0 5335.0 4.1 5335.5 4.1 137.0 0.2 137.1 0.4

2020Q2 152.2 6.0 150.5 3.9 104.5 (1.3) 104.3 (2.2) 102.8 (0.7) 102.6 (1.6) 5319.3 (1.2) 5323.2 (0.9) 136.0 (2.9) 136.2 (2.6)

2020Q3 154.5 6.2 152.3 4.8 104.8 1.1 103.5 (2.9) 102.5 (1.1) 101.7 (3.4) 5375.0 4.3 5300.1 (1.7) 136.9 2.7 136.6 1.1

2020Q4 157.0 6.8 153.4 3.0 104.7 (0.3) 102.7 (3.1) 102.8 1.3 101.2 (1.7) 5499.4 9.6 5326.0 2.0 138.0 3.2 137.1 1.6

2021Q1 157.7 1.7 152.4 (2.5) 105.6 3.3 103.0 1.2 103.5 2.6 101.0 (0.8) 5608.4 8.2 5381.8 4.3 139.0 3.0 137.8 2.2

2021Q2 160.7 7.8 153.6 3.3 105.9 1.3 103.0 (0.1) 103.9 1.7 100.7 (1.4) 5735.2 9.4 5483.3 7.8 140.4 4.2 139.0 3.4

2021Q3 162.3 4.3 155.0 3.5 106.7 3.1 103.6 2.5 104.7 3.0 100.9 1.0 5893.0 11.5 5602.5 9.0 142.3 5.5 140.4 4.0

2021Q4 164.6 5.7 156.8 4.9 107.6 3.2 104.4 3.2 106.5 6.8 102.3 5.7 6075.9 13.0 5744.1 10.5 144.4 5.8 141.8 4.1

2022Q1 167.4 7.0 159.2 6.2 109.0 5.3 105.8 5.4 107.6 4.2 103.2 3.4 6163.4 5.9 5801.4 4.0 145.7 3.6 142.4 1.7

2022Q2 169.9 6.1 161.3 5.3 109.6 2.4 106.5 2.6 108.1 1.9 103.5 1.2 6223.2 3.9 5844.1 3.0 146.6 2.7 142.6 0.5

2022Q3 172.0 5.0 163.0 4.5 110.0 1.4 106.9 1.4 108.3 0.9 103.6 0.2 6285.5 4.1 5892.0 3.3 147.5 2.4 142.7 0.5

2022Q4 173.9 4.5 164.7 4.1 110.1 0.5 107.0 0.4 108.3 0.1 103.4 (0.6) 6348.9 4.1 5938.3 3.2 148.3 2.2 143.0 0.6

2023Q1 175.8 4.5 166.4 4.2 110.6 1.6 107.3 1.3 108.7 1.1 103.5 0.3 6413.1 4.1 5984.7 3.2 149.1 2.1 143.3 0.9

2023Q2 177.7 4.5 168.2 4.2 110.8 0.8 107.4 0.5 108.8 0.5 103.4 (0.4) 6478.5 4.1 6032.5 3.2 149.9 2.0 143.6 1.0

2023Q3 179.5 4.0 169.7 3.8 111.1 1.0 107.6 0.4 108.9 0.6 103.3 (0.5) 6544.6 4.1 6079.4 3.1 150.6 2.0 144.0 1.1

2023Q4 181.3 4.1 171.3 3.7 111.4 1.1 107.7 0.5 109.2 0.8 103.2 (0.3) 6611.3 4.1 6126.4 3.1 151.5 2.3 144.5 1.4

2024Q1 183.2 4.3 172.9 3.9 111.7 1.3 107.9 0.7 109.4 1.0 103.1 (0.1) 6678.7 4.1 6174.9 3.2 152.4 2.4 145.1 1.6

2024Q2 185.2 4.4 174.7 4.1 112.2 1.6 108.1 0.8 109.7 1.2 103.1 0.0 6746.9 4.1 6223.4 3.2 153.3 2.4 145.6 1.5

2024Q3 187.2 4.5 176.4 4.1 112.6 1.7 108.4 0.9 110.1 1.4 103.2 0.2 6815.7 4.1 6273.2 3.2 154.2 2.4 146.2 1.5

2024Q4 188.9 3.7 177.9 3.3 113.2 1.9 108.7 1.1 110.6 1.6 103.3 0.3 6884.5 4.1 6323.7 3.3 155.2 2.5 146.7 1.6

2025Q1 190.7 3.7 179.3 3.2 113.7 2.0 109.0 1.2 111.0 1.7 103.4 0.4 6954.1 4.1 6375.0 3.3 156.1 2.4 147.3 1.5

2025Q2 192.4 3.7 180.7 3.2 114.3 2.0 109.3 1.3 111.5 1.8 103.5 0.6 7024.3 4.1 6427.9 3.4 157.0 2.4 147.9 1.5

2025Q3 194.1 3.7 182.1 3.1 114.9 2.1 109.7 1.4 112.1 1.9 103.7 0.7 7094.5 4.1 6482.1 3.4 158.0 2.4 148.4 1.6

2025Q4 195.9 3.6 183.5 3.1 115.5 2.1 110.1 1.4 112.6 2.0 103.9 0.8 7165.5 4.1 6538.4 3.5 158.9 2.4 149.0 1.6

2020 153.4 6.6 151.3 5.1 104.7 0.5 103.8 (0.4) 102.8 (0.1) 102.1 (0.8) 5382.2 3.2 5321.2 2.1 137.0 0.7 136.7 0.5

2021 161.3 5.2 154.5 2.1 106.5 1.7 103.5 (0.3) 104.7 1.8 101.2 (0.8) 5828.2 8.3 5552.9 4.4 141.5 3.3 139.7 2.2

2022 170.8 5.9 162.1 4.9 109.7 3.0 106.5 2.9 108.1 3.3 103.4 2.1 6255.3 7.3 5868.9 5.7 147.0 3.9 142.7 2.1

2023 178.6 4.6 168.9 4.2 111.0 1.2 107.5 0.9 108.9 0.7 103.3 (0.1) 6511.8 4.1 6055.7 3.2 150.3 2.2 143.8 0.8

2024 186.1 4.2 175.5 3.9 112.4 1.3 108.3 0.7 110.0 1.0 103.2 (0.1) 6781.5 4.1 6248.8 3.2 153.8 2.3 145.9 1.4

2025 193.3 3.8 181.4 3.4 114.6 1.9 109.5 1.2 111.8 1.7 103.6 0.4 7059.6 4.1 6455.8 3.3 157.5 2.4 148.1 1.5

Sources: National statistical agencies, Moody’s Analytics

MOODY’S ANALYTICS 27

GLOBAL FISCAL POLICY IN THE PANDEMIC

About the Authors