DRAFT ISSUES PAPER

IMF ADVICE ON

FISCAL POLICY

MAY 3, 2024

I. INTRODUCTION

1. The IMF’s advice on fiscal policy has evolved with changing economic conditions

since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). The Fund’s membership has faced an increasing number

of challenges, which have required adapting the Fund’s fiscal advice. These challenges have

included a major global downturn following the extraordinary shock of the GFC; the potential

prospect of “secular stagnation” in advanced economies; risks of premature consolidation amid

the need to rebuild fiscal buffers after the GFC; a sharp increase in health spending and dramatic

global output contraction during the COVID-19 pandemic; a substantial increase in inflation and

in sovereign debt vulnerabilities in the post-pandemic period; and, more recently, increasing

geoeconomic fragmentation, amid rising geopolitical tensions and conflicts, and the accelerated

effects of climate change, which bring in turn a higher frequency of global supply shocks and

heightened uncertainty.

2. Fiscal policy is a central component of Fund’s advice. Fiscal policy is the subject of

central attention in bilateral and multilateral surveillance, as well as in the design of IMF-supported

programs. The 2012 Integrated Surveillance Decision (ISD) reaffirmed that fiscal policy, together

with exchange rate, monetary and financial sector policies, would “always be the subject of the

Fund’s bilateral surveillance with respect to each member” (IMF, 2012a). As specified in the ISD, in

addition to assessing whether a country’s policies help meet its domestic goals, the IMF also has to

consider their consequences and spillovers for other countries and for the international monetary

system. This issues paper proposes an evaluation on the IMF’s advice on FP provided mainly as

part of IMF’s surveillance. The IMF’s advice in the context of program arrangements will also be

considered to ensure broader coverage especially in the case of countries that have frequently

engaged with the Fund under a program during the evaluation period, and to assess the

consistency of multilateral with country-level advice in selected cases.

1

This evaluation will

complement the IEO’s recent assessments on other core Fund policies in the surveillance context,

namely, exchange rate (IEO, 2007; 2017a), financial sector policies (IEO, 2019a), and unconventional

monetary policies (IEO, 2019b).

3. Scope of the evaluation. The evaluation will assess the IMF’s advice on FP between

2008 and 2023 both at the multilateral level and by country income groupings in

advanced economies (AEs), emerging markets and middle-income economies (EMMIEs), and

low-income countries (LICs). It will assess the advice on FP to assist member countries with their

macroeconomic challenges, focusing both on cyclical aspects (e.g., fiscal stance, fiscal

adjustment, interactions of FP with other policies, and spillovers) and select structural aspects

1

During 2008–23 nearly 80 percent of the LICs had program arrangements with the Fund. In about one-quarter

of the LIC program cases, countries were under Fund arrangements for over 10 years during the period. The

evaluation will also draw from previous evaluations that assess selected aspects of FP in the program context,

including the evaluations of the emergency response to the pandemic (IEO, 2023a) and the ongoing exceptional

access programs (IEO, 2024 (forthcoming)). The last full evaluation dedicated to FP focused on IMF-supported

programs and was completed in 2003 (IEO, 2003), with an update in 2013 (IEO, 2013).

2

relevant to all country groupings (e.g., fiscal institutions, security-related spending amidst rising

conflicts).

2

While this evaluation will assess whether IMF advice appropriately flagged fiscal risks,

including of rising debt, an assessment of IMF advice on broader debt issues (e.g., debt

restructuring) and on specific policy areas (e.g., climate change or inequality), is deferred to

future evaluations (IEO, 2023b; 2024). The following sections elaborate on the evolution of and

rationale for changes in the Fund’s advice on FP over the 2008–23 period (Section II); a summary

of the existing views on Fund’s fiscal advice (Section III); and the objective, scope, and work plan

for the evaluation (Section IV).

II. CHANGES IN THE IMF’S FISCAL ADVICE SINCE THE GFC

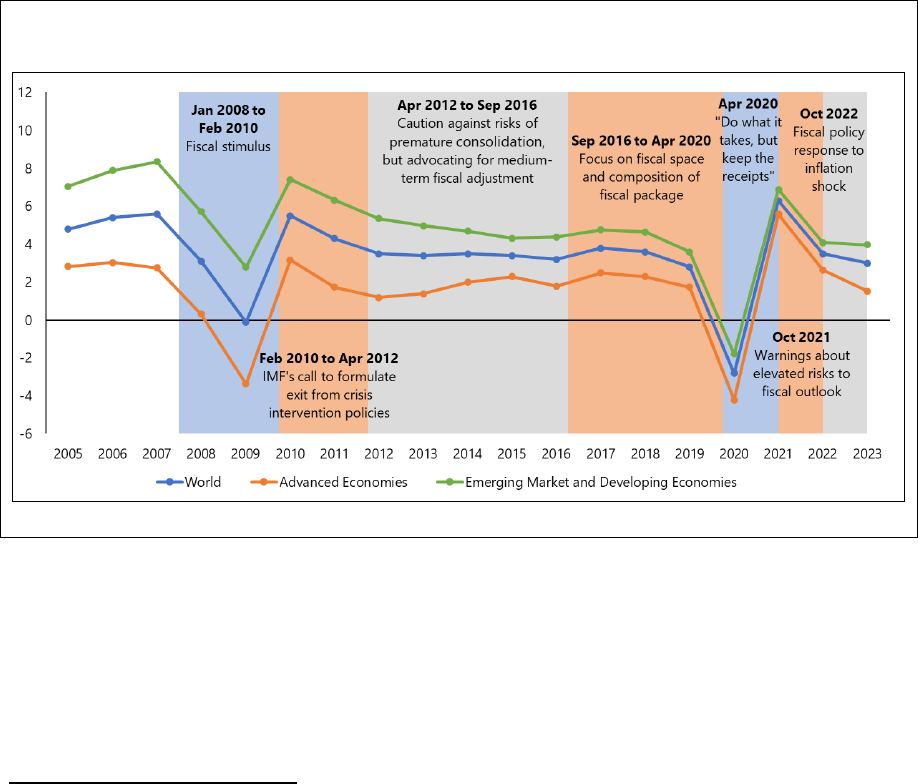

4. Evolution of Fund’s headline advice. IMF’s FP advice, as presented in flagship

publications such as the World Economic Outlook (WEO) and Fiscal Monitor (FM), policy papers,

and speeches, has evolved during the GFC and its aftermath in distinct phases (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Evolution of Fund’s Headline Advice

(GDP growth in percent)

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook.

5. Course corrections during and after the GFC. The IMF surprised observers in 2008, at

the onset of the GFC, moving from a long-standing “orthodox” approach of FP limited to

automatic stabilizers to an early endorsement of discretionary stimulus (Strauss-Khan, 2008;

IMF, 2008; Spilimbergo and others, 2008; Fiebiger and Lavoie, 2017). As the crisis wound down,

the IMF quickly moved to recommend that policymakers formulate and begin to implement exit

strategies, emphasizing that the appropriate timing, pace, and mode of exiting from crisis-related

2

The Fund’s fiscal advice is also a central component of its capacity development (CD) activities. This aspect will

not be covered in this evaluation, as CD activities were recently assessed by IEO (IEO, 2022a).

3

policies depended on the state of the economy and the health of the financial system (IMF, 2009).

The IMF also advocated adequate cross-country- coordination to mitigate risks to the global

recovery (IMF, 2010; Blanchard and Cottarelli, 2010). When consolidation began, and the recovery

weakened in 2011, the IMF’s advice started to caution against the risks of premature consolidation

in the short-term, while still advocating a credible medium-term adjustment (IMF, 2012b). The

Fund posited that the initial years of the GFC indicated that fiscal multipliers were significantly

higher than previously believed (IMF, 2012c; Blanchard and Leigh, 2013).

3

6. Secular Stagnation. In the mid-2010s, the IMF provided fiscal guidance amidst concerns

of “secular stagnation”, whereby demand in AEs could remain weak for an extended period

(Summers, 2013; Teulings and Baldwin, 2014). Recognizing the potential for prolonged low

growth and taking advantage of historically low borrowing costs, the IMF advocated for an

increase in public infrastructure investment to stimulate demand and support economic recovery

(IMF, 2014a). This stance was underpinned by the understanding that strategic investments in

infrastructure could yield significant macroeconomic benefits, including boosting productivity and

creating jobs, thereby countering the risks associated with secular stagnation.

7. Fiscal space and composition of fiscal packages post-GFC. Further elaborating on its

FP advice, the IMF also emphasized the importance of assessing fiscal space to ensure that such

investments were sustainable and did not compromise fiscal health. In 2016, the IMF introduced

an initial set of considerations for assessing fiscal space, offering a framework to evaluate a

country’s capacity to undertake fiscal expansion without endangering market access or fiscal

sustainability (IMF, 2016a; 2018a).

4

This approach highlighted the IMF’s commitment to tailoring

its advice to the specific circumstances of each member country, advocating for prudent fiscal

management while recognizing the critical role of public investment in driving economic growth

during times of uncertainty. The Fund’s recommendations also paid increasing attention to the

composition of fiscal packages, calling for measures that could reduce fiscal deficits in a growth

friendly manner (Gaspar, Obstfeld, and Sahay, 2016) and emphasized the need to manage fiscal

risks (IMF, 2016b). As global growth picked up starting in 2017, Fund’s advice shifted its attention

to the need of rebuilding fiscal buffers.

8. Advice during and after the COVID-19 pandemic

. At the onset of the pandemic the

IMF called for robust FP action alongside accountability (IEO, 2023a). The Fund quickly

formulated its policy advice in April 2020 as “do what it takes, but keep the receipts”

(IMF, 2020a, 2020b; Gaspar, Lam, and Raissi, 2020). The Fund encouraged significant fiscal

support, but also emphasized that spending needed to be targeted and temporary to avoid a

build-up of fiscal risks. The IMF adapted its advice cautiously as conditions evolved, gradually

3

Prior to the GFC, it was common to assume multipliers at around 0.5. However, evidence suggested that they may,

in fact, be greater than 1 for economies below potential (Blanchard and Leigh, 2013; Pescatori and others, 2011).

4

Fiscal space had long been an element of sound fiscal analysis. The term was initially coined to describe “room

in a government’s budget that allows it to provide resources for a desired purpose without jeopardizing the

sustainability of its financial position or the stability of the economy” (Heller, 2005).

4

shifting towards a less expansionary fiscal stance and stressing the need for revenue to keep up

with spending. In 2021, as global growth recovered, the October FM warned about elevated risks

to the fiscal outlook (IMF, 2021a). Later on, IMF’s advice to AEs called for targeting future shock

responses to the most vulnerable and putting fiscal houses in order, including via entitlement

reforms for several AEs with aging populations (Gopinath, 2023). IMF advice to emerging market

and developing economies emphasized options to rebuild depleted fiscal buffers, reduce the

footprint of state-owned enterprises, and strengthen fiscal frameworks.

9. Fiscal strategies amidst rising debt and new challenges post-pandemic. IMF’s advice

in 2022 focused on how to respond effectively to the sharpest increase in inflation in three

decades with “smart” FP in the form of fiscal restraint plus targeted transfers (Gaspar and

others, 2022; 2023). Amid tighter global credit conditions, some emerging markets’ spreads

widened significantly, and a large share of LICs faced high risk of debt distress. In this context, the

Fund supported efforts to address sovereign debt vulnerabilities, including through debt

restructuring (IMF, 2023). Fund’s advice focused also on other macro-fiscal challenges, including

protecting the most vulnerable, responding to inequality, supporting the green transition to a low

carbon economy, and addressing reemerging national industrial policies. Less attention was paid

in Fund’s advice to the need to accommodate security concerns despite global defense spending

reaching a record high in 2023 according to the International Institute of Strategic Studies (2024).

III. EXISTING VIEWS ON FUND’S FISCAL ADVICE

10. The Fund’s FP advice has been subject to different criticisms. Areas of criticism have

included: (i) questioning the recommendations of austerity policies both for the one-size-fits-all

nature approach of such policies and their social impacts repercussions (Blyth, 2013; Ortiz and

Cummins, 2019; Stuckler and Basu, 2013); (ii) concerns about the growth and unemployment

outcomes of fiscal consolidation advice and the size of fiscal multipliers (Przeworski and

Vreeland, 2010; Dreher, 2006; Van Waeyenberge and Bargawi, 2010); (iii) the disconnect between

the IMF’s advice in flagship reports and that reflected in the IMF’s country recommendations

(Setser, 2016; Sandbu, 2017; Oxfam, 2022).

11. Findings and lessons from internal reviews by IMF staff and evaluations by the IEO

have also found shortcomings on the FP advice:

• Fiscal anchors and targets. The IMF’s fiscal advice is sometimes presented without a

clear medium-term anchor (IMF, 2014b).

5

Providing clearer and more explicit

justifications for the path of fiscal adjustment would enhance the quality of the analysis,

5

The 2018 Interim Surveillance Review recognizes substantial progress in this respect, underpinned by greater

attention to fiscal anchors in the review process and the use of mandatory debt sustainability analyses to better

justify the fiscal advice (IMF, 2018b).

5

promote greater understanding of the risks faced, and facilitate mid-course corrections

(IEO, 2003; 2013).

• Integration of the policy mix. The role of FP within the policy mix is not always

considered in a sufficiently integrated way (IMF, 2014b; IEO, 2019b). Moreover,

surveillance reports generally cover fiscal-real linkages—such as the multiplier effects of

FP on growth—but rarely cover fiscal-financial, fiscal-monetary, and fiscal-BOP linkages

(IEO, 2011; 2014; 2019a and IMF, 2014b).

• Fiscal multipliers and cyclical considerations. The IMF’s underestimation of fiscal

multipliers’ impact during the Great Recession played a significant role in decelerating

recovery and unexpectedly exacerbated the rise in debt-GDP ratios in the short term

(IEO, 2014). Fiscal multipliers are rarely reported or discussed in IMF program and

bilateral surveillance documents (IEO, 2021). The IMF should explain fiscal multipliers

through the use of the structural fiscal balances and strengthen the analytical basis for

estimating them (IMF, 2014b).

6

• Fiscal forecasts. IMF forecasts on growth, fiscal balance, and debt tend to display a bias

toward optimism (IMF, 2018b; IEO, 2014; Flores and others, 2022), which is reinforced in

the case of large planned fiscal and external adjustments (IMF, 2018b; Ismail and

others, 2020).

• Guidance on expenditure measures. The Fund’s analysis and operational guidance on

spending tools should be deepened to provide more specific advice on the composition

of fiscal measures (IMF, 2014b).

• Social protection. Social protection is sometimes not thoroughly integrated and is

treated as a routine or formalistic part of the surveillance process (IEO, 2017b).

• Assessment of risks. Fund’s fiscal advice should be based on a more comprehensive

assessment of fiscal risks, including more attention to contingent liabilities, intersectoral

or intergovernmental risks, and long-term challenges (IMF, 2014b). Efforts in this area

have been undertaken in recent years (IMF, 2018b).

• Practical and political feasibility. Alternatives to first-best economic advice with

potential better chances of being implemented should be offered when preferred policy

advice is repeatedly rejected (IMF, 2014b; IEO, 2021).

6

The 2018 Interim Surveillance Review acknowledges that work on structural balances has advanced, including

research to improve the basis for estimates and the methodology for assessing potential output (IMF, 2018b).

Challenges remain, however, especially in LIDCs due to data and capacity constraints and large structural changes

that contribute to volatile estimates of potential output.

6

12. The IMF has acknowledged some of these criticisms and shortcomings and adapted

its approach to fiscal policy advice. This in turn has reflected a broader evolution of its

engagement with member countries, including: a recognition of the need to balance focus on

debt sustainability with longer-term growth and development objectives (Ostry, Loungani, and

Furceri, 2016; Sandbu, 2021); placing greater emphasis on protecting social spending

(Gaspar and others, 2019); considering country-specific circumstances more carefully

(Blanchard and Leigh, 2013); making its program conditionality more streamlined, focused, and

tailored to the varying needs of member countries (IMF, 2018c); adding considerations of

economic sustainability in its surveillance (IMF, 2021b); and engaging in broader consultations

with stakeholders (IMF, 2020c).

IV. OBJECTIVE, SCOPE, AND WORK PLAN OF THE EVALUATION

13. Objectives and Scope. The evaluation will review the rationale and evolution of the

Fund’s advice on key macro-fiscal issues. It will explore whether the IMF provided valuable

guidance to member countries on the appropriate stance of FP, composition of fiscal adjustment,

the likely efficacy of FP compared to other policy instruments, the role of FP within the policy

mix, and the broader repercussions associated with FP choices, including the long-term

implications and trade-offs for FP, and their international transmission channels and spillovers. It

will also assess whether the IMF’s advice on selected structural fiscal issues was effectively

integrated into its overall FP recommendations as well as the effectiveness of the IMF’s tools in

providing policy guidance, including on fiscal space availability. Importantly, FP advice in IMF

surveillance is typically distinct across country income groupings. This is to reflect different

contexts and circumstances, including constraints on available financing, political and

administrative limitations, and adaptation and development needs. Hence, the Fund’s advice on

FP is best examined within the context of each country grouping—AEs, EMMIEs, and LICs, which

will be reflected in specific background papers (see below).

14. Evaluation criteria and questions. The evaluation will assess Fund’s fiscal advice against

four main criteria:

• Relevance. This explores whether Fund’s advice was grounded in high-quality analysis

that allowed to identify key issues, trends, and risks facing the membership, and whether it

provided value-added in support of countries’ internal and external stability (IMF, 2021b).

For example, did multilateral and bilateral IMF advice adapt quickly to the changing

context, strengthen policy debates globally and within the country, respectively? Did it

identify major fiscal risks in a timely manner as well as possible spillovers? Were the

arguments and the analytical underpinnings of the policy advice clearly articulated? Were

the tools used for the analysis adequate?

• Consistency. This refers to the consistency between multilateral and bilateral

surveillance. For instance, was bilateral fiscal advice at the country-level consistent with

messages voiced in flagship publications, speeches, blogs, and management’s public

7

statements? Were any differences in the advice given justified by differences in the

circumstances facing each country?

• Evenhandedness. This explores issues such as: was similar advice provided in similar

circumstances? Were the insights from FP surveillance practical and sufficiently tailored

to country specificities, including security concerns or capacity constraints, or too broad-

brush for some countries or country groupings? Did the Fund’s recommendations

manage the trade-off between first best and second-best approaches equally well across

countries and country groupings, or did they pay insufficient attention to the political

economy considerations?

• Economic sustainability. This examines whether Fund’s advice promoted conditions

that, under realistic assumptions, would “support sustained, balanced and inclusive

economic growth without requiring large or disruptive adjustments to domestic or

balance of payments stability” (IMF, 2021b). For example, did IMF advice take into

consideration whether advocated policies could be sustained and lead to lasting change?

Did it sufficiently account for the potential long-run impact on growth, fiscal

sustainability, and critical social spending and green transition or adaptation needs?

15. Methodologies. The main sources of evidence will be: (i) analysis of bilateral surveillance

documents and program documents, when relevant; (ii) review of flagship publications as well as

research and policy papers, including through citation analysis and other tools; (iii) interviews of

IMF staff and Board members, staff at ministries of finance and fiscal institutions, as well as other

policymakers and stakeholders, including civil society, non-governmental organizations, and the

private sector; (iv) analysis of data on fiscal stance, fiscal stimulus, composition of adjustment,

and forecasts for each country grouping; (v) surveys of relevant stakeholders;

7

and (vi) analysis of

pertinent episodes of policy advice on representative samples of countries from all regions. The

evaluation will also take into account the findings and recommendations of other IEO

evaluations, when relevant, such as Fiscal Adjustments in IMF-Supported Programs (IEO, 2003);

Fiscal Adjustments in IMF-Supported Programs – Revisiting Past IEO Evaluation (IEO, 2013);

The IMF and the Crisis in Greece, Ireland, and Portugal (IEO, 2016); The IMF and Social Protection

(IEO, 2017b); The IMF and Fragile States (IEO, 2018); IMF Engagement with Small Developing States

(IEO, 2022b); and The IMF’s Emergency Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic (IEO, 2023a).

16. Background papers. The evaluation will include in principle five thematic background

papers (BPs) which will provide in-depth assessment on the following issues:

• The Fund’s advice to the AEs. This BP will address several key aspects, including

whether the multilateral surveillance products offered analysis and insights pertinent to

both the short-term and long-term challenges confronted by AEs; whether IMF’s bilateral

7

Relevant stakeholders may include, for example, key IMF counterparts at member countries’ finance ministries,

central banks, and revenue agencies or taxation authorities; all Executive Directors; and all IMF mission chiefs.

8

fiscal advice displayed enough candor, especially regarding the policies of major

economies that may have substantial spillover effects or create a build-up of fiscal risks,

notably those related to vulnerabilities in the financial sector and potential changes in the

interest-growth differential; and whether the advice paid sufficient attention at an early

stage to the need to build buffers for a future crisis or the attention to buffers only

emerged post-crisis. The BP will also explore examples of how Fund’s advice addressed

reemerging national industrial policies.

• Fund’s advice to EMMIEs

. This paper will investigate whether Fund’s advice to EMMIEs

kept pace with evolving policy challenges (e.g., spillovers from monetary policy in AEs,

food and energy price shocks) and policy space (e.g., monetary policy responses during

the COVID-19 crisis). It will also consider to what extent advice was tailored to the

country-specific circumstances and the political economy realities, and took into

adequate consideration policy trade-offs, financing constraints, implications for market

access, debt dynamics, and vulnerabilities within this country group. It will also explore

other aspects, such as whether multiplier assumptions and growth consequences of fiscal

adjustments were sufficiently discussed, whether buffers against risks were built in, the

perception of the Fund as a trusted advisor by the authorities, and the adequacy of the

advice on debt management in select cases. The paper will analyze relevant policy

episodes, striving to include also examples from Small Developing States (SDSs).

• Fund’s advice to LICs. The paper will explore whether in bilateral and multilateral

surveillance adequate resources were devoted to analyzing country specific FP issues for

LICs, including through country applications of tools (e.g., debt sustainability analysis)

and model-based toolkits (e.g., on debt-investment-growth nexus or food insecurity). It

will consider whether the advice on revenue mobilization and expenditure targeting was

well tailored to realities (e.g., large informal sectors, absence of targeting capability). It

will assess any progress in staffing country teams to address concerns related to country

knowledge and relationship continuity, and for the analysis of pressing country issues

(e.g., public financial management). The paper will aim to include relevant examples from

Fragile and Conflict-affected States (FCS).

• The consistency between the multilateral surveillance and country-level

recommendations. This BP will cover a number of issues, including whether the country-

specific advice issued by the IMF adequately reflected the broader factors influencing

fiscal policy assessments in its multilateral surveillance activities, and if it was sufficiently

tailored to the circumstances and characteristics of each country grouping. It will

investigate whether the global fiscal stance, as implied by the universal adoption of the

Fund’s country-specific advice, aligned with and supported its broader multilateral

recommendations.

9

• The policy advice on selected structural fiscal issues.

8

The first part of this paper will

focus on Fund’s advice on fiscal rules and institutions in AEs, EMMIEs, and LICs. It will

review the analytical work undertaken by the Fund and underpinning the policy advice, as

well as the country coverage and completeness of data collected for this purpose. It will

assess the specificity, tailoring, and thoroughness of advice on fiscal rules and institutions

in each country grouping. It will also explore whether IMF’s advice on fiscal rules and

institutions was effectively integrated into its overall FP recommendations. The second

part of the paper will focus on Fund’s advice on spending for security, including military

expenditure. It will evaluate how IMF’s recommendations managed the trade-off between

security spending vs. other spending priorities. The paper will include analysis of country

examples.

17. The evaluation is targeted for completion and discussion by the Executive Board in

the second half of 2025.

8

Structural fiscal issues examined by the Fund are vast and heterogeneous. They include fiscal frameworks and

fiscal rules, subsidy reforms, efficiency of public spending, tax reforms, fiscal federalism, debt management and

restructuring, pension and healthcare policies. The evaluation will only focus on selected topics.

10

REFERENCES

Blanchard O. and C. Cottarelli, 2010, “Ten Commandments for Fiscal Adjustment in Advanced

Economies,” IMF Blog, June 24. https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2010/06/24/ten-

commandments-for-fiscal-adjustment-in-advanced-economies.

Blanchard O. and D. Leigh, 2013, “Growth Forecast Errors and Fiscal Multipliers,” IMF Working

Paper No. 13/1 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

Blyth, Mark, 2013, “The Austerity Delusion,” Foreign Affairs, 2(92), pp. 41–56.

Dreher, Axel, 2006, “IMF and Economic Growth: The Effects of Programs, Loans and Compliance

with Conditionality,” World Development, 34(5), pp. 769–88.

Fiebiger, B. and Lavoie M., 2017, “The IMF and the New Fiscalism: was there a U-turn?”, European

Journal of Economics and Economic Policies, Volume 14 (2017): Issue 3 (Dec 2017)Flores,

J., D. Furceri, S. Kothari, and J. Ostry, 2022, “Worse Than You Think: Public Debt Forecast

Errors in Advanced and Developing Economies,” prepared for the Third Annual

Conference of the European Fiscal Board, February 26, 2021 (Brussels).

Gaspar, V., M. Obstfeld, and R. Sahay, 2016, “Macroeconomic Management When Policy Space is

Constrained: A comprehensive, Consistent, and Coordinated Approach to Economic

Policy,” IMF Staff Discussion Note 16/09, September (Washington: International Monetary

Fund).

Gaspar, V., and others, 2019, “Fiscal Policy and Development: Human, Social, and Physical

Investments for the SDGs,” Staff Discussion Note, March (Washington: International

Monetary Fund).

Gaspar V., M. Raissi, and R. Lam, 2020, “Fiscal Policies to Contain the Damage from COVID-19.”

https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2020/04/15/blog-fm-fiscal-policies-to-contain-

the-damage-from-covid-19.

Gaspar, V., R. Lam, P. Mauro, and R. Piazza, 2022, “Fiscal Policy Can Help People Rebound from

Cost-of-Living Crisis,” IMF blog, October 22.

Gaspar, V., C. E. Goncalves, P. Mauro, and M. Poplawski-Ribeiro, 2023, “Fiscal Policy Can Help

Tame Inflation and Protect the Most Vulnerable,” IMF blog, April 3.

Gopinath, G., 2023, “The Temptation to Finance All Spending Through Debt Must Be Resisted,”

Financial Times, October 27.

Heller, P., 2005, “Back to Basics—Fiscal Space: What It Is and How to Get It,” Finance and

Development, June, Volume 42, No. 2.

11

Independent Evaluation Office of the International Monetary Fund (IEO), 2003, Fiscal Adjustment

in IMF-Supported Programs (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

__________, 2007, IMF Exchange Rate Policy Advice (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

__________, 2011, IMF Performance in the Run-Up to the Financial and Economic Crisis: IMF

Surveillance in 2004–07 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

__________, 2013, Fiscal Adjustments in IMF-Supported Programs- Revisiting Past IEO Evaluation

(Washington: International Monetary Fund).

__________, 2014, IMF Response to the Financial and Economic Crisis: An IEO Assessment

(Washington: International Monetary Fund).

__________, 2016, The IMF and the Crisis in Greece, Ireland, and Portugal (Washington: International

Monetary Fund).

__________, 2017a, IMF Exchange Rate Policy Advice – Evaluation Update (Washington: International

Monetary Fund).

__________, 2017b, The IMF and Social Protection (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

__________, 2018, The IMF and Fragile States (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

__________, 2019a, IMF Financial Surveillance (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

__________, 2019b, IMF Advice on Unconventional Monetary Policies (Washington: International

Monetary Fund).

__________, 2021, Growth and Adjustment in IMF-Supported Programs (Washington: International

Monetary Fund).

__________, 2022a, The IMF and Capacity Development (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

__________2022b, IMF Engagement in Small Developing States (Washington: International

Monetary Fund).

__________, 2023a, IMF’s Emergency Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic (Washington:

International Monetary Fund).

__________, 2023b, Possible Topics for Future IEO Evaluations, 2024–25, States (Washington:

International Monetary Fund).

__________, 2024, Independent Evaluation Office—2024 Work Program (Washington: International

Monetary Fund).

12

__________, 2024, "The IMF’s Exceptional Access Policy" (forthcoming).

International Institute of Strategic Studies, 2024, “The Military Balance 2024 Spotlights an Era of

Global Insecurity,” The Military Balance 2024 spotlights an era of global insecurity

(iiss.org)

International Monetary Fund, 2007, “Decision on Bilateral Surveillance over Member’s Policies,”

Decision No. 13919-(07/51), June (Washington).

__________, 2008, “Transcript of a Press Briefing by Dominique Strauss-Kahn, IMF Managing

Director, John Lipsky, First Deputy Managing Director, Caroline Atkinson, Director of

External Relations,” November 15 (Washington).

__________, 2009, “Fiscal Implications of the Global Economic and Financial Crisis”, IMF Staff

Position Note, SPN/09/13, International Monetary Fund.

__________, 2010, “Exiting from Crisis Intervention Policies”, IMF Policy Paper; February 4

(Washington).

__________, 2012a, “Modernizing the Legal Framework for Surveillance—An Integrated

Surveillance Decision,” Decision No. 15203-(12/72), July (Washington).

__________, 2012b, “World Economic Outlook: Growth Resuming, Dangers Remain,” April

(Washington).

__________, 2012c, “Are We Underestimating Short-Term Fiscal Multipliers?", Box 1.1 in “World

Economic Outlook: Coping with High Debt and Sluggish Growth,” October, pp. 41-43

(Washington).

———, 2014a, “Is It Time for an Infrastructure Push? The Macroeconomic Effects of Public

Investment,” Chapter 3 in “World Economic Outlook: Legacies, Clouds, Uncertainties,”

October (Washington).

———, 2014b, “Triennial Surveillance Review – Review of Fiscal Policy Advice” (Washington).

__________, 2016a, “Assessing Fiscal Space—An Initial Consistent Set of Considerations,” IMF Staff

Paper, November (Washington).

__________. 2016b “Analyzing and Managing Fiscal Risks. Best Practices,” Fiscal Monitor, October

(Washington).

__________, 2018a, “Assessing Fiscal Space: An Update and Stocktaking,” June (Washington).

__________, 2018b, “Interim Surveillance Review” (Washington).

13

__________, 2018c, “Review of Program Design and Conditionality” (Washington).

__________,2020a, "Policies to Support People During the COVID-19 Pandemic" Fiscal Monitor,

April (Washington).

__________,2020b, "The Great Lockdown" World Economic Outlook, April (Washington).

__________,2020c, "Engagement with Civil Society Organizations – Factsheet (Washington).

__________, 2021a, “Fiscal Monitor: Strengthening the Credibility of Public Finances,” October

(Washington).

__________, 2021b, “2021 Comprehensive Surveillance Review—Overview Paper,” April

(Washington).

__________, 2023, “Coming Down to Earth: How to Tackle Soaring Public Debt,” Chapter 3 in

“World Economic Outlook: A Rocky Recovery,” April (Washington).

Ismail, Kareem, Roberto Perrelli, and Jessie Yang, 2020. “Optimism Boas in Growth Forecasts –

The Role of Planned Policy Adjustments,” IMF Policy Paper, November (Washington:

International Monetary Fund).

Ortiz, Isabel, and Matthew Cummins, 2019, “Austerity: The New Normal-A Renewed Washington

Consensus 2010-24,” Initiative for Policy Dialogue Working Paper (New York, Initiative for

Policy Dialogue).

Ostry, J. D., P. Loungani, and D. Furceri, 2016, "Neoliberalism: Oversold?" Finance & Development,

53(2) (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

Oxfam, 2022, “Behind the numbers: a dataset exploring key financing and fiscal policies in the

IMF’s COVID-19 loans.” https://www.oxfam.org/en/international-financial-

institutions/imf-covid-19-financing-and-fiscal-tracker.

Pescatori, Andrea, Daniel Leigh, Jaime Guajardo, and Pete Devries, 2011. "A New Action-Based

Dataset of Fiscal Consolidation," IMF Working Papers 2011/128, International Monetary

Fund.

Przeworski, Adam, and James R. Vreeland, 2010, “The Effect of IMF Programs on Economic

Growth,” Journal of Development Economics, 62(2), pp. 385–421.

Sandbu, Martin, 2017, “The IMF’s road to enlightenment”, September, The Financial Times.

https://www.ft.com/content/9d247d14-a4f6-11e7-b797-b61809486fe2.

__________, 2021, “A new Washington consensus is born”, April.

https://www.ft.com/content/3d8d2270-1533-4c88-a6e3-cf14456b353b.

14

Setser, Brad, 2016, “The IMF (Still) Cannot Quit Fiscal Consolidation…”

https://www.cfr.org/blog/imf-still-cannot-quit-fiscal-consolidation.

Spilimbergo, A., S. Symansky, O. Blanchard, and C. Cottarelli, “Fiscal Policy for the Crisis”, IMF

Staff Position Note, SPN/08/01, International Monetary Fund.

Strauss-Kahn, Dominique, 2008, “The Case for a Global Fiscal Boost,” Financial Times, January 30.

Stuckler, D., and S. Basu, 2013, The Body Economic: Why Austerity Kills,” Basic Books.

Summers, Lawrence H. 2013. “Remarks in honor of Stanley Fischer”, Fourteenth Jacques Polak

Annual Research Conference, November 7–8 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

Teulings, Coen, and Richard Baldwin, eds. 2014. “Secular Stagnation: Facts, Causes and Cures,”

VoxEU, August 15. http://www. voxeu.org/content/secular-stagnation-facts-causes-and-

cures.

Van Waeyenberge, Elisa, Hannah Bargawi, and Terry McKinley, 2010, “Standing in the Way of

Development? A Critical Survey of the IMF’s Crisis Response in Low Income Countries,”

TWN Global Economy Series No. 32, European Network on Debt and Development

(Eurodad) and Third World Network (TWN).