Analysis of Petroleum

Hydrocarbons in

Environmental Media

Total Petroleum Hydrocarbon Criteria Working Group Series

Volume 1

Analysis of Petroleum

Hydrocarbons in

Environmental Media

These organizations sponsored or contributed to the

completion of this technical document, prepared by

the TPH Criteria Working Group:

American Petroleum Institute

Association for the Environmental Health of Soils

Association of American Railroads

British Petroleum

Chevron Research and Technology Company

Exxon Biomedical Sciences, Inc.

Retec, Inc.

Shell Development Company

United States Air Force, Air Force Research Laboratory

University of Massachusetts

March 1998

Analysis of Petroleum

Hydrocarbons in

Environmental Media

Total Petroleum Hydrocarbon Criteria Working Group Series

Volume 1

SPONSORED BY:

Association of American Railroads

BP Oil Company

United States Air Force, Armstrong

Laboratory, Occupational Medicine

Division

EDITED BY:

Wade Weisman

Air Force Research Laboratory,

Operational Toxicology Branch

Amherst Scientific Publishers

150 Fearing Street

Amherst, Massachusetts 01002

© 1998 by Amherst Scientific Publishers. All rights reserved.

ISBN 1-884-940-14-5

The material contained in this document was obtained from independent and highly respected sources.

Every attempt has been made to ensure accurate, reliable information, however, the publisher cannot be

held responsible for the information or how the information is applied. Opinions expressed in this book are

those of the Total Petroleum Hydrocarbon Criteria Working Group and do not reflect those of the publisher.

This document was prepared by the Total Petroleum Hydrocarbon Criteria Working Group. Neither the

Working Group nor members of the Working Group:

a. Makes any warranty or representation, expressed or implied, with respect to the accuracy, com-

pleteness, or usefulness of the information contained in this report, or that the use of any appa-

ratus, method, or process disclosed in this report may not infringe privately owned rights; or

b. Assumes any liability with respect to the use of, or for damages resulting from the use of,

any information, apparatus, method, or process disclosed in this report.

This document may be reproduced only in its entirety for unlimited distribution. Every reasonable effort

has been made to give reliable data and information, but neither the TPH Criteria Working Group nor the

contributing individuals or their companies assume any responsibility for the validity of all materials or for

the consequences of their use or misuse.

A portion of the proceeds from the sale of this book will be donated to the Plant-a-Tree Program, a refor-

estation program managed by the U.S. Forest Service.

Printed in the United States of America

CONTENTS

PREFACE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ix

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . xi

1. PURPOSE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

2. INTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

3. OVERVIEW OF TPH . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

3.1 Risk Implications . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

4. UNDERSTANDING THE PETROLEUM ANALYTICAL PROCESS:

FROM SAMPLE COLLECTION TO MEASUREMENT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

4.1 Collection And Preservation Of Environmental Samples . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

4.2 Sample Extraction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7

Water Samples . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

Soil Samples . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

Free Phase Hydrocarbon Samples . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

4.3 Concentration of Sample Extract . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

4.4 Cleanup of Sample Extract . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

4.5 Measurement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

Total Petroleum Hydrocarbon (TPH) Measurement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

Petroleum Group Type Measurement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

Petroleum Constituent Measurement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

5. TOTAL PETROLEUM HYDROCARBON (TPH) MEASUREMENT:

DETAILED REVIEW OF SELECTED ANALYTICAL METHODS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

5.1 Gas Chromatography (GC) TPH Methods . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

Overview of the Technique . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

Example Methods . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

What Do GC Methods Measure? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

Interferences/Limitations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24

5.2 Infrared Spectroscopy (IR) TPH Methods . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

Overview of the Technique . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

Example Methods . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

v

What Do IR Methods Measure? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

Interferences/Limitations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

5.3 Gravimetric TPH Methods . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

Overview of the Technique . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

Example Methods . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

What Do Gravimetric Methods Measure? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

Interferences/Limitations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

5.4 Immunoassay TPH Methods . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

Overview of the Technique . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

Example Methods . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

What Do Immunoassay Methods Measure? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

Interferences/Limitations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

6. PETROLEUM GROUP TYPE MEASUREMENT: DETAILED REVIEW

OF SELECTED ANALYTICAL METHODS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

6.1 Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC) Group Type Methods . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

Overview of the Technique . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

Example Methods . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

What Do TLC Methods Measure? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

Interferences/Limitations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

6.2 Immunoassay Group Type Methods . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

Overview of the Technique . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

Example Methods . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

What Do Immunoassay Methods Measure? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

Interferences/Limitations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

7. INDIVIDUAL PETROLEUM CONSTITUENT MEASUREMENT:

DETAILED REVIEW OF SELECTED ANALYTICAL METHODS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

7.1 Gas Chromatography with Photoionization Detection

(GC/PID) Petroleum Constituent Methods . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41

Overview of Technique . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41

Example Methods . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41

What Do GC/PID Methods Measure? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41

Interferences/Limitations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41

7.2 Gas Chromatography With Flame Ionization Detection

(GC/FID) Petroleum Constituent Methods . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42

Overview of Technique . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42

vi

Example Methods . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42

What Do GC/FID Methods Measure? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43

Interferences/Limitations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43

7.3 High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) Petroleum

Constituent Methods . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43

Overview of Technique . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44

Example Methods . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44

What Do HPLC Methods Measure? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44

Interferences/Limitations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

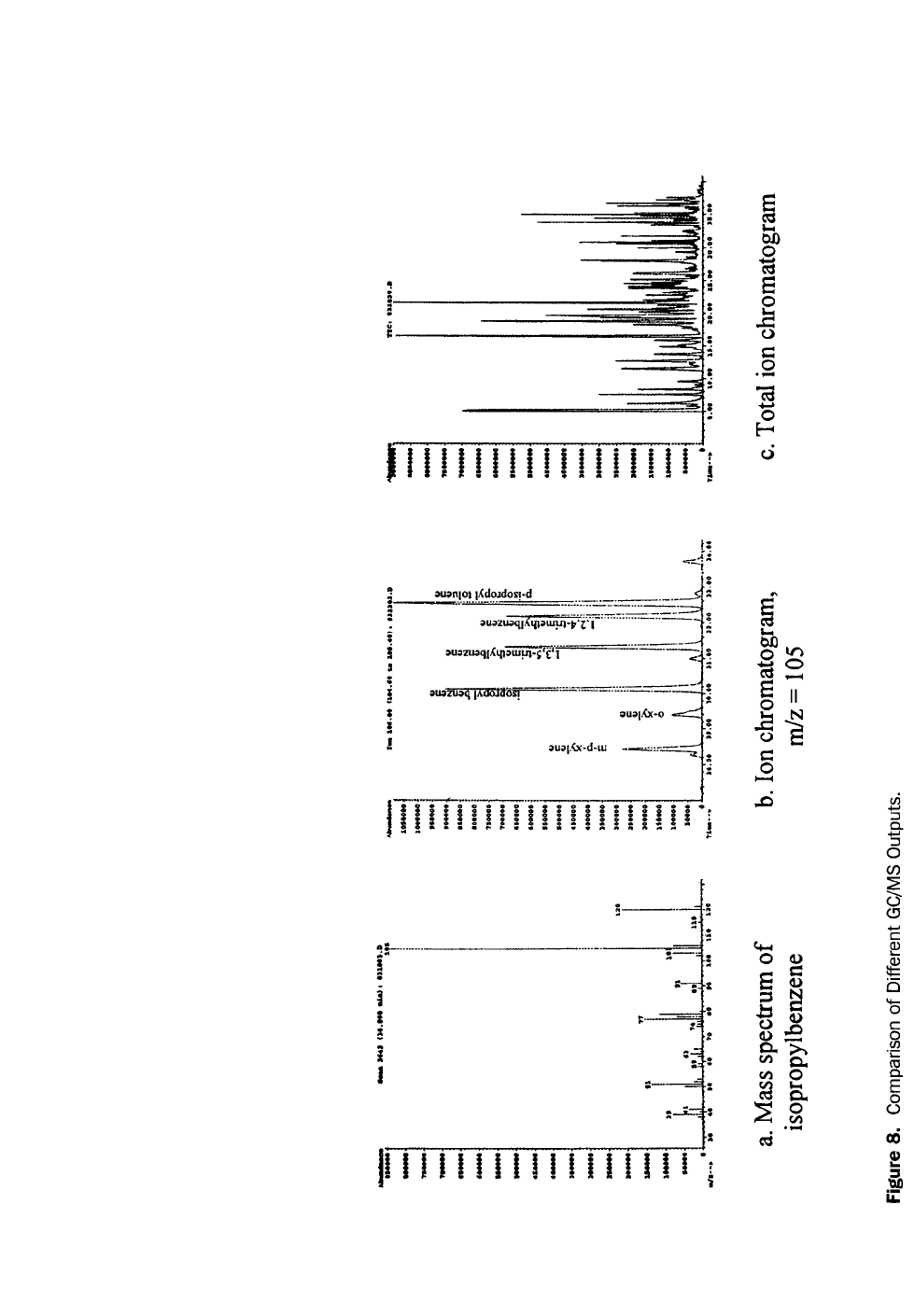

7.4 Gas Chromatography With Mass Spectrometry Detection

(GC/MS) Petroleum Constituent Methods . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

Overview of Technique . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

Example Methods . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47

What Do GC/MS Methods Measure? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47

Interferences/Limitations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47

8. EVOLVING METHODS FOR PETROLEUM HYDROCARBON FRACTIONS . . . . . . . . . 48

8.1 What Do Petroleum Fraction Methods Measure? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48

8.2 Why Use Petroleum Fraction Methods? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48

8.3 Examples Of Petroleum Fraction Methods . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49

TPHCWG Analytical Method . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49

Massachusetts EPH/VPH Method . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50

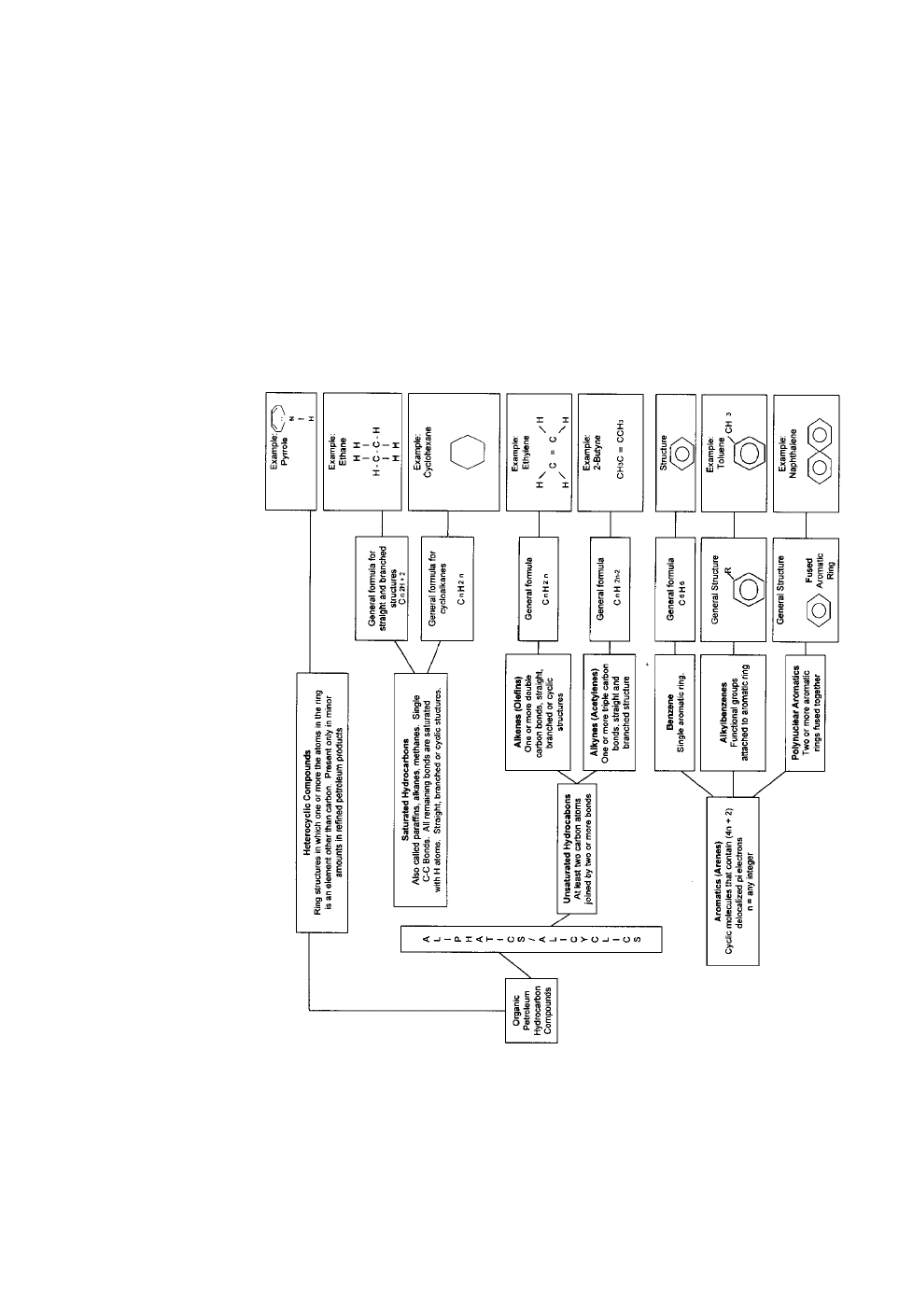

Appendix I - HYDROCARBON CHEMISTRY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51

Appendix II - CHARACTERIZATION OF PETROLEUM PRODUCTS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 59

Appendix II-A: PRODUCT COMPOSITION AND SPECIFICATION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61

Appendix II-B: ENVIRONMENTAL FATE OF PETROLEUM PRODUCTS:

WEATHERING AND TRANSPORT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70

Appendix III - Refinery Flow Diagrams . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 75

Appendix IV - Quick Reference of TPH Methods . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 81

EXPLANATION OF ACRONYMS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 87

GLOSSARY OF TERMS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 89

BIBLIOGRAPHY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 97

vii

PREFACE

This document is the first in a series from the Total Petroleum Hydrocarbon

Criteria Working Group (TPHCWG, or “Working Group”). The Working Group

convened in 1993 to address the large disparity among cleanup requirements

being used by states at sites contaminated with hydrocarbon materials such as fuels,

lubricating oils and crude oils. These requirements usually focus on total petrole-

um hydrocarbon (TPH), with numerical standards ranging from tens to tens of

thousands of milligrams of TPH per kilogram of soil. Recognizing that these stan-

dards are not based on a scientific assessment of human health risk, Working

Group members established the following goal for their effort:

To develop scientifically defensible information for establishing soil cleanup levels that

are protective of human health at petroleum contaminated sites.

The Working Group is guided by a steering committee consisting of representa-

tives from industry, government, and academia. Some of the active participants

among the more than 400 involved include the Gas Research Institute, several

major petroleum companies including Chevron, Exxon, British Petroleum and

Shell, the American Petroleum Institute, the Association of American Railroads,

several state governments (Washington, Texas, Colorado, Hawaii, Louisiana, New

Mexico, Massachusetts), the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the

Department of Defense, the University of Massachusetts, and private consulting

firms including EA Engineering, Science & Technology and Menzie-Cura &

Associates, Inc.

The Working Group compiled their data collection and analytical efforts into

five volumes:

Volume 1. Analysis of Petroleum Hydrocarbons in Environmental Media (this

volume) discusses and critiques analytical methods for quantifying

TPH, petroleum mixtures and individual petroleum constituents

in soil and water samples. It is designed to be a reference tool for

the nonchemist, describing what information analytical methods

can provide for risk assessment.

Volume 2. Composition of Petroleum Mixtures (in press) provides the best

available composition information for a variety of petroleum

products.

Volume 3. Selection of Representative Total Petroleum Hydrocarbon (TPH) Fractions

Based on Fate and Transport Considerations (1997, Amherst Scientific

Publishers) defines fractions of TPH expected to behave similarly

in the environment. Identification of these fractions simplifies

analysis of environmental samples, fate and transport modeling,

and risk assessment efforts at petroleum contaminated sites.

ix

Volume 4. Development of Fraction-Specific Reference Doses (RfDs) and Reference

Concentrations (RfCs) for Total Petroleum Hydrocarbons (TPH) (1997,

Amherst Scientific Publishers) provides the technical basis for the

development of TPH fraction-specific RfDs and RfCs for use in the

hazard assessment step of the Working Group’s risk-based

approach to establishing soil cleanup levels at petroleum contami-

nated sites.

Volume 5. Human Health Risk-Based Evaluation Of Petroleum Contaminated Sites:

Implementation Of The Working Group Approach.(in press). This docu-

ment integrates the findings of Volumes 1 through 4 into a risk-

based framework for development of cleanup goals at petroleum

contaminated sites. It includes descriptions of demonstration sites

where the Working Group approach has been used successfully.

Amherst Scientific Publishers will publish these volumes in 1997 and 1998. In

addition to these volumes, results of projects where use of the Working Group

approach has been demonstrated (demonstration sites) and a concise technical

summary document are now or will soon be available on the U.S. Air Force

Toxicology Division web site (http://voyager.wpafb.af.mil). At this web site,

Working Group publications may be downloaded from the “recent publications”

icon. Additional Working Group resources will be added to this web site as they

become available.

We hope you find these documents to be useful in your effort to evaluate and

determine acceptable risk-based cleanup criteria at petroleum contaminated sites.

Wade H. Weisman

Chairman, TPH Criteria Working Group

x

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The TPH Criteria Working Group would like to especially thank BP Oil for their

strong support of this effort through permitting the use of the “TPH in Soil Primer”,

developed by Elaine Schwerko for BP Oil, Environmental Technology Branch,

© September, 1993. The development and production of this document was sup-

ported, in part, through the financial contribution of the Association of American

Railroads (AAR). The continued support of TPH Working Group efforts by Dr.

Christopher Barkan of the Environmental and Hazardous Materials Research

Program of the AAR Research and Test Department is greatly appreciated.

Additionally, the following persons and organizations contributed significant

amounts of in-kind support toward the completion of this document:

Beth Albertson Friedman & Bruya, Inc.

John Fitzgerald Massachusetts Department of

Environmental Protection

Elizabeth A. Harvey, Chevron Research and Technology

John Fetzer

G. Cornell Long United States Air Force,

Armstrong Laboratory

Ileana Rhodes Shell Development Company

George Sawyer Mobil Oil Corporation

Wade Weisman Air Force Research Laboratory,

Operational Toxicology Branch

Donna J. Vorhees, Menzie-Cura & Associates, Inc.

Chris M. Long

xi

1. PURPOSE

The chemical composition of petroleum products is complex and may change over

time following release into the environment. These factors make it difficult to

select the most appropriate analytical methods for evaluating environmental

samples. The Total Petroleum Hydrocarbon Criteria Working Group (the

“Working Group”) prepared this volume to assist site managers, risk assessors, reg-

ulators and others who may not have expertise in analytical chemistry in under-

standing the complexities of petroleum hydrocarbon characterization. This

volume describes petroleum analytical methods and what they can and cannot tell

you about environmental media (e.g., soil, groundwater, and surface water) at

petroleum contaminated sites. The information provided in this volume will help

the reader to accurately interpret results from petroleum analytical methods. This

volume is not meant to be a comprehensive text on analytical methods and does

not recommend or mandate any particular method. The goal of the Working

Group is to provide the technical information needed by regulators, risk assessors,

and site managers to implement health risk-based decisions at petroleum contam-

inated sites.

2. INTRODUCTION

There are a significant number of petroleum hydrocarbon impacted sites across

the United States resulting from a wide range of past industrial, military, and petro-

leum production, and distribution practices. Difficulties in evaluating and remedi-

ating these sites arise from the complexity of the regulatory, scientific, and eco-

nomic issues regarding impacted soil and water. Most investigations involving

petroleum hydrocarbons are regulated by the states with different requirements in

methodologies, action levels, and cleanup criteria. The chemical composition of

petroleum products is complex and varied and changes over time and distance

when released to the environment. These factors make it difficult to select the most

appropriate analytical test methods for evaluating environmental samples and to

accurately interpret and use the data.

The Working Group developed this volume to provide summary information

about analytical techniques and methods for total petroleum hydrocarbons (TPH),

petroleum by chemical class and boiling point ranges, and individual petroleum

constituents. Newer fraction-based analytical approaches also are discussed.

Discussion centers on analytical methods for soil, sediment, and water because

most published methods measure TPH in these media. However, much of the dis-

cussion in this volume is relevant to other environmental media, such as air.

Analytical methods for media such as sediment and air are often modified versions

of established methods for soil and water.

This volume is organized into the following principal sections:

Section 3: Overview of TPH

This section provides an overview of the historical measurement and use of

TPH data.

1

Section 4: Understanding The Petroleum Analytical Process: From Sample Collection

To Measurement

This section provides a general overview of the analytical process characteris-

tics that are common to most methods for quantifying TPH, individual petro-

leum constituents, and petroleum fractions.

Section 5: Total Petroleum Hydrocarbon (TPH) Measurement: Detailed Review Of

Selected Analytical Methods

This section describes analytical methods for TPH that are based on four main

analytical techniques: gas chromatography, infrared spectrometry, gravimetry,

and immunoassay measurements.

Section 6: Petroleum Group Type Measurement: Detailed Review Of Selected

Analytical Methods

This section describes analytical methods for petroleum groups that are based

on two main analytical techniques: thin layer chromatography and immunoas-

say measurements. Petroleum groups include different categories of hydro-

carbons such as saturates, aromatics, and polars/resins.

Section 7: Individual Petroleum Constituent Measurement: Detailed Review of Selected

Analytical Methods

This section describes analytical methods for individual petroleum con-

stituents that are based on four main analytical techniques: gas chromatogra-

phy with photoionization detection, gas chromatography with flame ioniza-

tion detection, high performance liquid chromatography, and gas chro-

matography with mass spectrometry detection. Individual petroleum con-

stituents often include benzene, carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocar-

bons, and other compounds commonly associated with petroleum.

Section 8: Evolving Methods For Petroleum Hydrocarbon Fractions

This section provides an introduction to several newer analytical methods for

quantifying petroleum fractions rather than TPH, groups or individual con-

stituents. It explains why such methods are being developed for evaluating

human health risk at petroleum contaminated sites.

3. OVERVIEW OF TPH

This section presents a historical perspective on the use of TPH in evaluating petro-

leum contaminated sites. Technical terms used in this section are explained in

greater detail in subsequent sections. The use of TPH concentrations to establish

target cleanup levels for soil or water is a common approach implemented by regu-

latory agencies in the United States. Approximately 75% of the states use TPH-based

cleanup criteria. Because these values have become such key remediation criteria, it

is essential that everyone using TPH data - environmental coordinators, field per-

sonnel, and regulators - be knowledgeable about the various analytical methods. It is

important to know that minor method deviations may be found from state to state.

TPH is sometimes referred to as mineral oil, hydrocarbon oil, extractable hydro-

carbon, and oil and grease. There are many analytical techniques available that

measure TPH concentrations in the environment. No single method measures the

2

entire range of petroleum-derived hydrocarbons .Because the techniques vary in

the way hydrocarbons are extracted, cleaned up, and detected, they each measure

slightly different subsets of the petroleum-derived hydrocarbons present in a

sample. See Section 4. The definition of TPH depends on the analytical method

used because the TPH measurement is the total concentration of the hydrocarbons

extracted and measured by a particular method. The same sample analyzed by dif-

ferent TPH methods may produce different TPH values. For this reason, it is

important to know exactly how each determination is made. Interpretation of the

results depends on understanding the capabilities and limitations of the selected

method. If used indiscriminately, TPH data can be misleading and could lead to an

inaccurate assessment of risk.

There are several reasons why TPH data do not provide ideal information for

investigating sites and establishing target cleanup criteria. For example, use of the

term TPH suggests that the analytical method measures the combined concentra-

tion of all petroleum-derived hydrocarbons, thereby giving an accurate indication

of site contamination. But this is not always the case. Furthermore, target cleanup

levels based on TPH concentrations implicitly assume (1) the TPH result is an

accurate measurement of petroleum-derived hydrocarbon concentration, and (2)

the TPH result indicates the level of risk associated with the contamination. These

assumptions are not correct due to many factors including the nonspecificity of

some of the methods used and, the complex nature of petroleum hydrocarbons

and their interaction with the environment over time.

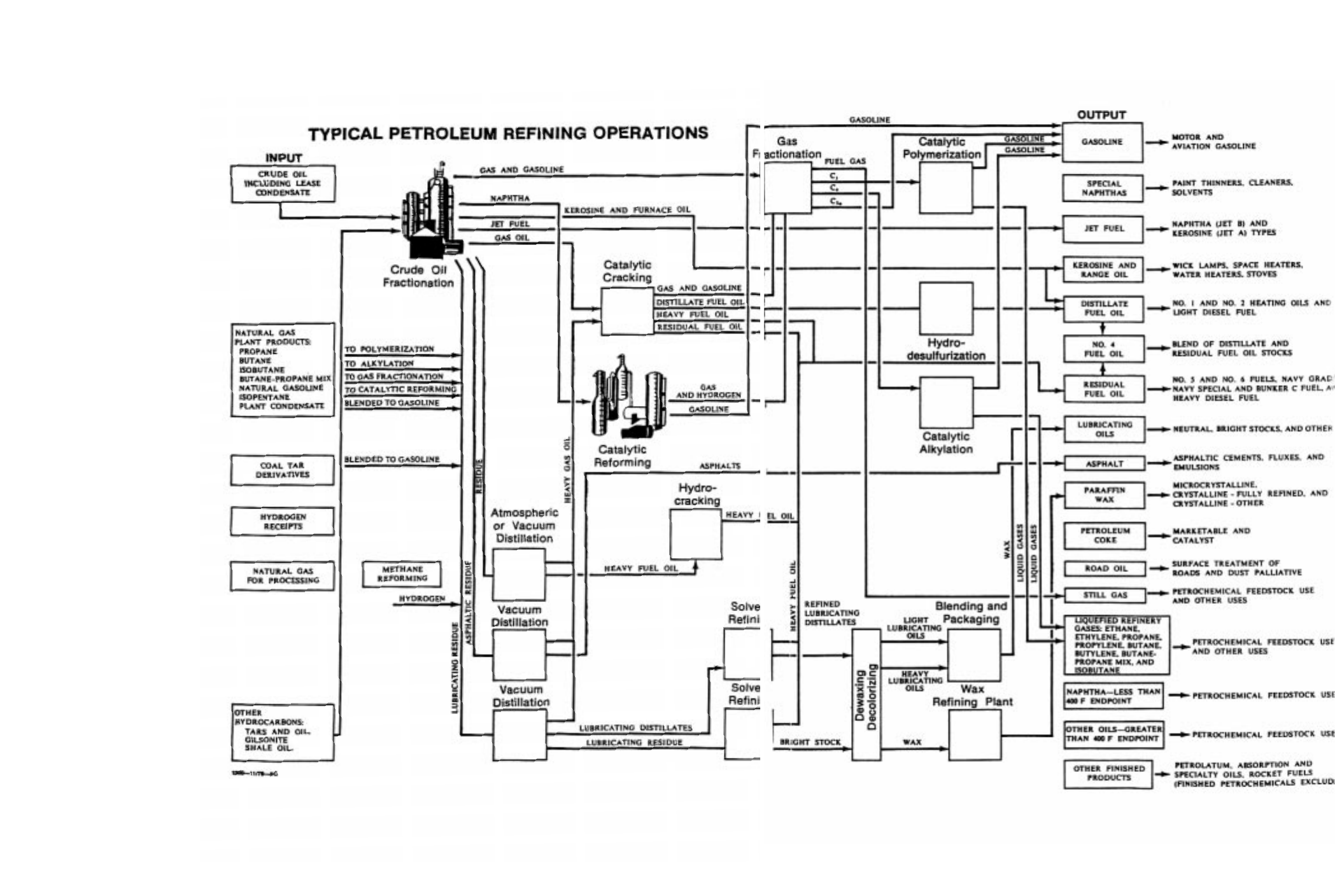

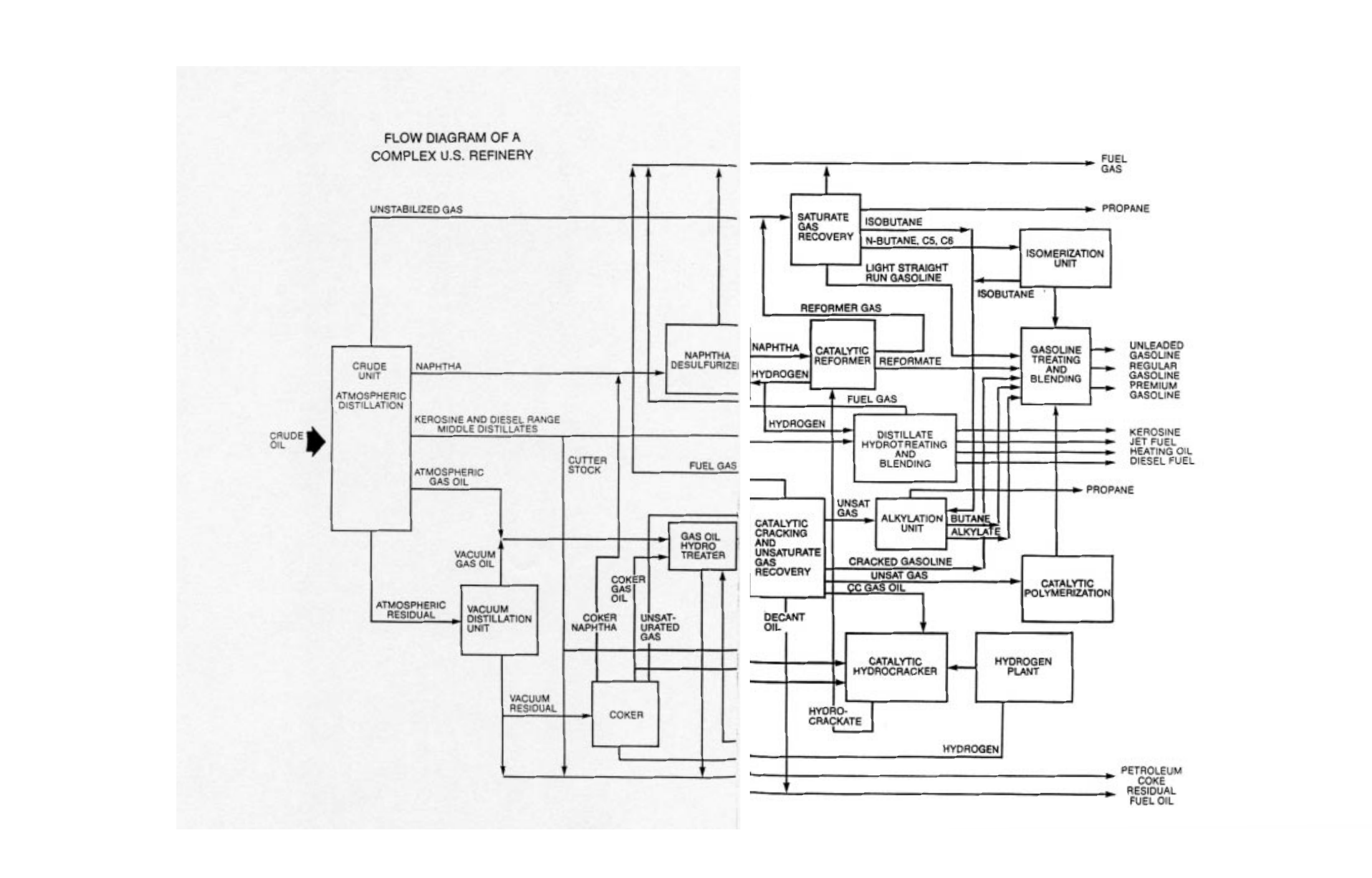

One significant difficulty in measuring TPH for different product types is the

fact that the boiling ranges and carbon number ranges of refined petroleum prod-

ucts often overlap. Refined petroleum products are primarily manufactured

through distillation processes that separate fractions from crude oil by their boiling

ranges. See Appendix III — Refinery Flow Diagrams. Manufacturing processes may

also increase the yield of low molecular weight fractions, reduce the concentration

of undesirable sulfur and nitrogen components, and incorporate performance

enhancing additives. Additionally, because it is impossible to identify all con-

stituents of a petroleum product, these constituents are often described by their

boiling point ranges. Because distillations are not capable of producing sharp dis-

tinctions in boiling point cutoffs, there is overlap between distillate fractions. The

boiling point ranges correlate to carbon number and the higher the carbon

number, the higher the boiling point. However, structure will also influence

boiling point. Branched and aromatic compounds of the same carbon number

differ in boiling point from their corresponding n-alkane analogs. For these

reasons, boiling point actually defines an approximate carbon range.

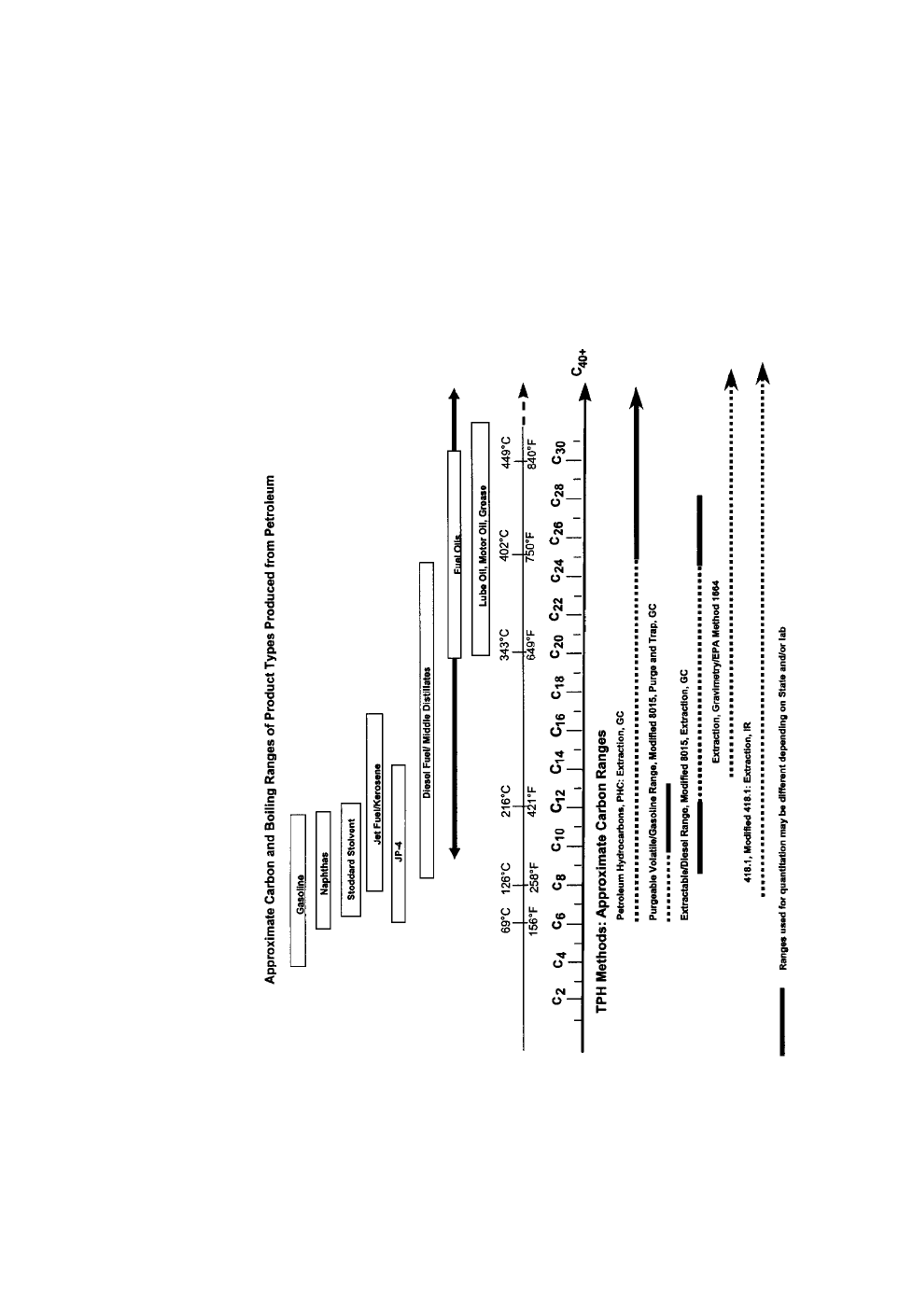

Figure 1 shows the relationship between boiling range and carbon number for

some common petroleum products. This figure clearly shows the overlap between

carbon ranges of different products as well as the overlap in corresponding ana-

lytical methods. For example, Figure 1 shows that an analytical method designed

for gasoline range organics may report some of the hydrocarbons present in diesel

fuel. The same is also true for analytical tests for diesel range organics that will

identify some of the hydrocarbons present in gasoline contaminated soils. A more

detailed discussion of boiling point and carbon number classification as well as a

discussion of petroleum product composition, specification, product additives, and

weathering is provided in Appendix II: Characterization of Petroleum Products.

3

4

Figure 1. Summary of Petroleum Product Types and TPH and TPH Analytical Methods with Respect to Approximate Carbon Number

and Boiling Point Ranges.

Ambiguous terminology associated with TPH methods presents additional diffi-

culty in interpreting results. Each method has its own designation. For example,

TRPH stands for total recoverable petroleum hydrocarbons, DRO stands for diesel

range organics, GRO stands for gasoline range organics, and TPH-G stands for

total petroleum hydrocarbons-gasoline. Frequently a method name that cites a

product - “gasoline” or “diesel” - only implies a carbon range. For example, TPH-G

does not necessarily imply that gasoline is present. These abbreviations may imply

different carbon ranges to different laboratories or states. TPH methods are not

optimized to identify product type. Even with improved, more detailed analytical

methods, identification of aged products may prove difficult.

There is a reason for the availability of a large number of TPH measurement

techniques. Because petroleum and petroleum-derived products are such complex

mixtures, there is no single “best” method for measuring all types of petroleum

contamination. As shown in Figure 1, some methods are appropriate for gasoline-

contaminated samples while others are designed for heavier hydrocarbon contam-

ination such as jet or diesel fuel. Some methods measure more compounds than

other methods because they employ more rigorous extraction techniques or more

efficient solvents. Other methods are subject to interferences from naturally occur-

ring materials such as animal and vegetable oils, peat moss, dried grass, or humic

material in topsoil, which may result in artificially high reported TPH concentra-

tions. Some methods use cleanup steps to minimize the effect of nonpetroleum

hydrocarbons, with variable success. Ultimately, methods are limited by the extrac-

tion and cleanup efficiency and measurement device detection limits.

The choice of a specific method should be based on compatibility with the par-

ticular type of hydrocarbon contamination to be measured. The choice may

depend upon state regulatory requirements for the type of hydrocarbon contami-

nation suspected to be present.

3.1 RISK IMPLICATIONS

TPH concentration data cannot be used to quantitatively estimate human health

risk. The same concentration of TPH may represent very different compositions

and very different risks to human health and the environment. For example, two

sites may have TPH measurements of 500 ppm but constituents at one site may

include carcinogenic compounds while these compounds may be absent at the

other site. The risk at a specific site will change with time as contaminants evapo-

rate, dissolve, biodegrade, and become sequestered. A valid correlation between

TPH and risk would have to be site- and time-specific, related to a single spill, and,

even then, the correlation might not be the same around the periphery of a plume

where the rate of compositional change accelerates.

Although the utility of TPH data for risk assessment is minimal, it is an inexpen-

sive tool that can be used for three purposes: (1) determining if there is a problem;

(2) assessing the severity of contamination; and (3) following the progress of a

remediation effort. If TPH data indicate that there may be significant contamina-

tion of environmental media, other data can be collected so that harm to human

health can be quantitatively assessed. These other data can include target analyte

concentration data and petroleum fraction concentration data obtained using new

fraction-based analytical methods developed by the Working Group and others.

5

4. UNDERSTANDING THE PETROLEUM ANALYTICAL PROCESS: FROM

SAMPLE COLLECTION TO MEASUREMENT

This volume focuses on three types of petroleum analytical methods:

• methods that measure a TPH concentration;

• methods that measure a petroleum group type concentration; and

• methods that measure individual petroleum constituent concentrations.

These three types of methods measure different petroleum hydrocarbons that

might be present in petroleum-contaminated environmental media. TPH methods

generate a single number that represents the combined concentration of all petro-

leum hydrocarbons in a sample, which are measurable by the particular method

(See discussion in Section 3 regarding limitations of TPH data). Petroleum group

type methods separate and quantify different categories of hydrocarbons (e.g., sat-

urates, aromatics, and polars/resins). The results of petroleum group type analyses

can be useful for product identification because different products (e.g., gasoline,

fuel oil no.2, and jet fuel) can have characteristic levels of various petroleum

groups (see Appendix II for a detailed characterization of petroleum products).

Individual constituent methods quantify concentrations of specific compounds

that might be present in petroleum-contaminated samples, such as benzene, ethyl-

benzene, toluene, and xylenes (BTEX), and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

(PAHs). Concentration data for individual petroleum constituents can be used to

evaluate human health risk, provided the necessary toxicity data are available.

Although these three method types measure different petroleum hydrocarbon

categories, there are several basic steps that are common to the analytical process-

es for all methods, no matter the method type or the environmental matrix. This

section will focus on these basic steps. Sections 5, 6 and 7 review analytical methods

that can provide the three different types of petroleum concentration data.

Most of the common analytical steps are related to the separation of analytes of

interest from a sample matrix prior to their measurement. In general, these steps are:

• Collection and preservation - requirements specific to environmental matrix

and analytes of interest

• Extraction - separates the analytes of interest from the sample matrix

• Concentration - enhances the ability to detect analytes of interest

• Cleanup - may be necessary to remove interfering compounds

• Measurement - quantifies the analytes.

Each step affects the final result, and a basic understanding of the steps is vital

to data interpretation.

6

4.1 COLLECTION AND PRESERVATION OF ENVIRONMENTAL SAMPLES

The ability to collect and preserve a sample that is representative of the site is a

critically important step. Obtaining representative environmental samples is

always a challenge due to the heterogeneity of different sample matrices.

Additional difficulties are encountered with petroleum hydrocarbons due to the

wide range in volatility, solubility, biodegradation, and adsorption potential of

individual constituents.

Most site investigations for assessment of petroleum hydrocarbon contamination

in the environment are regulated by the states. However, sample collection and

preservation recommendations follow U.S. EPA guidelines. A summary of the most

commonly used guidelines is included in Table 1. It should be noted that there

might be additional requirements in any given state. Before a sample is collected,

the particular state requirements must be investigated. Because of holding time

considerations, the laboratory must be selected and notified prior to the collection

of the samples.

4.2 SAMPLE EXTRACTION

For most analyses, it is necessary to separate the analytes of interest from the matrix

(i.e. soil, sediment, and water). Extraction of analytes can be performed using one

or more of the following methods:

• Extracting the analytes into a solvent

• Heating the sample (used in the analyses of volatile compounds)

• Purging the sample with an inert gas (used in the analyses of volatile compounds).

There are a variety of common sample extraction techniques. See Table 2.

Soxhlet, sonication, supercritical fluid, subcritical or accelerated solvent, and

purge and trap extraction have been promulgated by the U.S. EPA as soil extrac-

tion methods. Headspace is recommended as a screening method. Shaking/vor-

texing is presently not approved by EPA, but is quite adequate for the extraction of

petroleum hydrocarbons in most environmental samples.

For these extraction methods, the ability to extract petroleum hydrocarbons

from soil and water samples depends on the solvent and the sample matrix.

Surrogates (compounds of known identity and quantity) are frequently added to

monitor extraction efficiency. Environmental laboratories also generally perform

matrix spikes (addition of target analytes) to determine if analytes are retained by

the soil or water matrix.

Solvents have different extraction efficiencies. Extracting the same sample in the

same manner by two different solvents may result in different concentrations. The

choice of solvents is determined by many factors such as cost, spectral qualities,

method regulations, extraction efficiency, toxicity, and availability. Methylene chlo-

ride has been the solvent of choice for many semivolatile analyses due to its high

extraction efficiency, low cost, and specification by many state regulatory methods.

Chlorofluorocarbon solvents such as trichlorotrifluoroethane (Freon 113) have

been used in the past for oil and grease analyses because of their spectral qualities

(they do not absorb in the 2930 cm-1 infrared measurement wavelength) and low

7

8

TABLE 1. U.S. EPA-Recommended Sampling Protocols

Sample Container

a

Analytical Analytical Holding

Parameter Method(s) Media Volume Type Preservatives

c

Time

Trph

b

EPA 418.1 (IR); water 1 liter Glass jar with acid fix pH<2; extract in 7 days;

Gravimetric; Teflon lined cap cool to 4°C analyze in 40 days

GC/FID soil 125 mL Wide mouth glass cool to 4°C extract in 7 days;

Teflon lined cap analyze in 40 days

Volatile Petroleum various water 40 mL Glass vial with acid fix pH<2; 14 days

Hydrocarbons (VPH)

d

Teflon lined septum cool to 4°C

soil 40 mL Glass vial with cool to 4°C

e

14 days

Teflon lined septum

Extractable Petroleum various water 1 liter Glass jar with acid fix pH<2; extract in 7 days;

Hydrocarbons (EPH)

f

Teflon lined cap cool to 4°C analyze in 40 days

soil 60 mL Wide mouth glass cool to 4°C extract in 7 days;

Teflon lined cap analyze in 40 days

BTEX EPA 8240/8260

h

water 40 mL Glass vial with acid fix pH<2; 14 days

EPA 8020/8021

h

Teflon lined septum cool to 4°C

EPA 624

g

, EPA 602

g

soil 40 mL Glass vial with cool to 4°C

e

14 days

EPA 524

g

Teflon lined septum

PAHs EPA 8270

h

water 1 liter Glass jar with acid fix pH<2; extract in 7 days;

EPA 8310

h

Teflon lined cap cool to 4°C analyze in 40 days

EPA 8100

h

soil 60 mL Wide mouth glass cool to 4°C extract in 7 days;

Teflon lined cap analyze in 40 days

9

TABLE 1. (Continued)

a

Minimum sampling volume may vary depending on specific method.

b

Refers to extractable hydrocarbons only.

c

ACID FIXATION: use 1:1 HCL to adjust pH of aqueous samples to less than 2. Add approx. 500µl (2-4 drops) to 40 mL aqueous sample vials; 5

mL to 1 liter aqueous sample jars. Add acid to vials before collecting sample; use gloves and eye protection when sampling. Other preserva-

tives, such as sulfuric acid or sodium bisulfate may also be used for this purpose.

d

Generally C

5

through C

10±2

hydrocarbons detectable through purge and trap or headspace analyses; includes most “Gasoline Range Organics”

(GRO) methodologies.

e

Some states/methodologies require field preservation of soil samples in methanol. In such cases, methanol must be purge and trap grade; typi-

cally, add 20 mL methanol to vials prior to sample collection. Use gloves and eye protection when sampling. Shipping of methanol subject to

DOT regulation.

f

Generally C

9

through C

28±7

hydrocarbons detectable through a solvent extraction process; includes most “Diesel Range Organics” (DRO) method-

ologies.

g

40 CFR Part 136.

h

SW-846 methodology.

10

TABLE 2. Comparison of Common Extraction Techniques

Extraction US SW-846 Extraction Compounds

Method Method Number Matrix Extracted Purpose

Separatory funnel 3510 water semivolatile laboratory

nonvolatile

Continuous liquid-liquid 3520 water semivolatile laboratory

nonvolatile

Solid phase extraction 3535 water semivolatile laboratory/

nonvolatile screening

Purge and trap 5030, 5035 water, soil volatile laboratory/

field preservation

Headspace 3810, 5021 water, soil volatile screening/

laboratory

Shake and vortex

a

soil volatile screening/

semivolatile laboratory

nonvolatile

Soxhlet 3540, 3541 soil semivolatile laboratory

nonvolatile

Sonication 3550 soil semivolatile laboratory

nonvolatile

Supercritical fluid 3560, 3561 soil semivolatile laboratory

nonvolatile

Subcritical fluid 3545 soil semivolatile laboratory

nonvolatile

a

Not an EPA SW-846 approved method.

11

human toxicity. The EPA is phasing out use of chlorofluorocarbons, however, due

to their detrimental effects on stratospheric ozone. Tetrachloroethene and carbon

tetrachloride are possible replacements. Methanol is the most common solvent

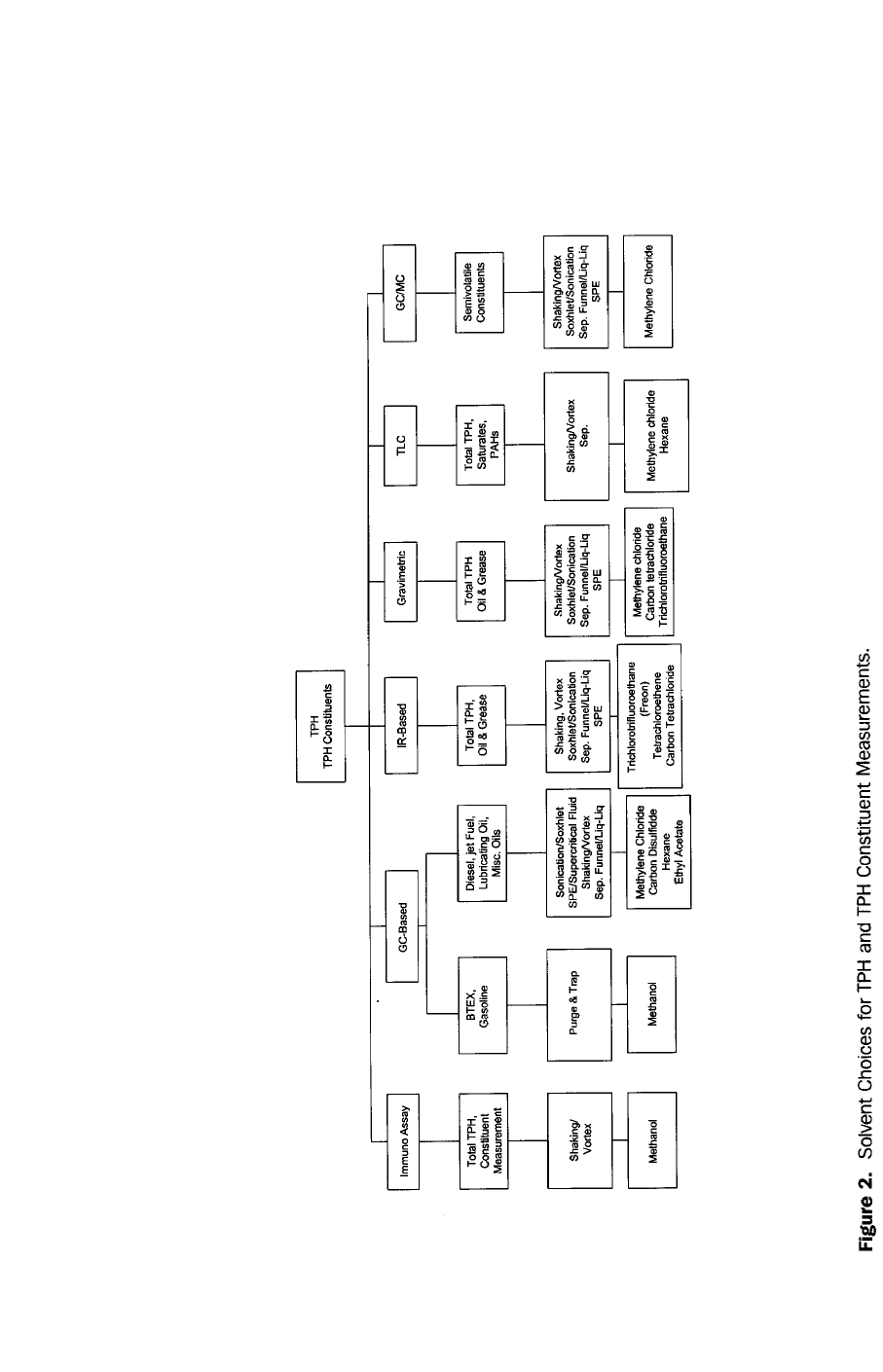

used to preserve and extract volatiles such as BTEX in soils. Figure 2 illustrates the

typical solvents used for different analyses.

Water Samples

Water extraction methods in common use include the following:

For Volatiles:

• Purge and trap

• Headspace

For Semivolatiles:

• Separatory funnel extraction

• Continuous liquid-liquid extraction

• Solid phase extraction.

Volatile compounds (gasoline, solvents) in water are generally separated from

their matrix by purging with an inert gas and trapping the compounds on a

sorbent (EPA 5030, purge and trap analysis). The sorbent is later heated to

release the volatile compounds, and a carrier gas sweeps the compounds into a

gas chromatograph.

Headspace analysis is recommended as a screening method by EPA (Methods

3810, and 5021), although it performs well in particular situations, especially field

analysis. In this method, the water sample is placed in a closed vessel with a head-

space and heated to drive volatiles into the gas phase. Addition of salts or acids may

enhance this process. In headspace analysis, instrument contamination is mini-

mized because only volatile compounds are introduced into the instrument.

Samples containing heavy oils and high analyte concentrations can severely conta-

minate purge and trap instrumentation.

The most commonly used water extraction method for semivolatiles is EPA

Method 3510, separatory funnel extraction. The sample is poured into a funnel-

shaped piece of glassware, solvent is added, and the mixture is shaken vigorously.

After layer separation, the extract (i.e., the solvent layer) is removed, filtered, dried

with a desiccant, and concentrated. Multiple extractions on the same sample may

increase overall recovery.

Another commonly used water extraction method for semivolatiles is EPA 3520,

continuous liquid-liquid extraction. Rather than shaking solvent with the water

sample, the solvent is continuously heated, nebulized (broken into small droplets),

and sprayed on top of the water. Liquid-liquid extraction is excellent for samples

containing emulsion-forming solids, but it is more time-consuming than separato-

ry funnel extractions.

Solid phase extraction (SPE, EPA Method 3535) also can be used for extraction

and concentration of semivolatile material. The technique involves passing the

water sample through a cartridge or disk containing an adsorbent such as silica or

12

alumina. The adsorbent is often coated with compounds that impart selectivity for

particular products or analytes such as PAHs. After extraction, the analytes are sep-

arated from the solid phase by elution with a small amount of organic solvent. A

variant of SPE involves dipping a sorbent-coated fiber into the water (solid phase

micro-extraction, or SPME). Adsorbed analytes are thermally desorbed directly

into a heated chromatographic injection port. SPE uses much less solvent and

glassware than separatory funnel and liquid-liquid extraction.

Soil Samples

Soil extraction methods in common use include the following:

For Volatiles:

• Purge and trap

• Headspace

For Semivolatiles:

• Shaking or vortexing (can also be used for volatiles)

• Soxhlet

• Sonication

• Supercritical fluid

• Subcritical fluid.

Volatile compounds (e.g., BTEX and gasoline) may be solvent-extracted from

soil. EPA Method 5035, purge and trap analysis, specifies a methanol extraction,

which is usually done by mechanical shaking of the soil with methanol. A portion

of the methanol extract is added to a purge vessel and diluted in reagent grade

water. The extract is then purged similar to a water sample.

Headspace analysis, (EPA Methods 3810 and 5021), also works well for analyzing

volatiles in soils. The soil is placed in a headspace vial and heated. Salts can be

added to more efficiently drive out the volatiles from the sample into the head-

space of the sample container. Similar to water headspace analysis, the soil head-

space technique is useful when heavy oils and high analyte concentrations are

present which can severely contaminate purge and trap instrumentation.

Detection limits are generally higher for headspace analysis than for purge and

trap analysis.

The simplest method to separate semivolatile compounds from soils is to shake

or vortex (vigorous mechanical stirring) soil with a solvent. Adding a desiccant to

the soil/solvent mixture can help to break up soil and increase the surface area.

The extract can be analyzed directly. Simple shaking is quick and easy, making it an

excellent field extraction technique. However, extraction efficiency may vary

depending on soil type.

Soxhlet extraction (EPA Method SW-846 3540) is a very efficient extraction

process which is commonly used for semivolatiles. Solvent is heated and refluxed

(recirculated) through the soil sample continuously for 16-24 hours or overnight.

This method generates a relatively large volume of extract that needs to be con-

centrated. Thus, it is more appropriate for semivolatiles than for volatiles.

13

Sonication extraction (EPA Method SW-846 3550) can also be used for semi-

volatiles, it involves the use of sound waves to enhance analyte transfer from sample

to solvent. Sonication is a faster technique than Soxhlet extraction, and it also can

require less solvent.

Supercritical fluid extraction (SFE), (EPA Methods 3540 for Total Recoverable

Petroleum Hydrocarbons and 3561 for PAHs), is applicable to the extraction of

semivolatiles. SFE involves heating and pressuring a mobile phase to supercritical

parameters (having properties of gas and liquid). The supercritical fluid is passed

through the soil sample, and the analytes are concentrated on a sorbent or trapped

cryogenically. The analytes are eluted with a solvent and analyzed with conven-

tional techniques. CO

2

is the most popular mobile phase.

Proposed EPA Method 3545, Accelerated Solvent Extraction, has extraction effi-

ciencies comparable to Soxhlet extractions. This method is sometimes referred to

as subcritical fluid extraction. Conventional solvents such as methylene chloride are

heated and pressurized, then passed through the soil sample (this technique also

works for sludges and sediments). Subcritical fluid extraction has the advantage of

requiring smaller solvent volumes than traditional solvent extraction techniques.

Free Phase Hydrocarbon Samples

In some releases of petroleum products to the environment where free phase

product is found, hydrocarbon material can be collected directly for characteriza-

tion. The ability to analyze free product greatly aids the determination of product

type and potential source. The samples may be diluted prior to analysis. EPA Method

SW-846 3580, waste dilution, gives some guidelines for proper dilution techniques.

4.3 CONCENTRATION OF SAMPLE EXTRACT

Extracts are generally filtered, dried with desiccant, and concentrated before analy-

sis. Concentration of the extract may allow for lower sample detection limits.

Frequently, sample extracts must be concentrated to obtain detection limits low

enough to meet regulatory action limits. Concentration may be achieved by:

For Volatiles:

• Sorbent trapping

• Cryogenic trapping

For Semivolatiles:

• Snyder column

• Kuderna Danish concentrator

• Nitrogen evaporation

• Vacuum.

The trapping step in a purge and trap analysis is essentially a concentration step.

Analytes are purged from the matrix into a gas stream and captured on a sorbent

trap. The analytes are released by heating the trap. Some laboratories use cryo-

genic trapping in place of sorbent trapping. A very cold material such as liquid

14

nitrogen surrounds a sample loop. As analytes are purged and swept through the

sample loop, they freeze in the sample loop. The analytes are released when the

trap is heated.

Snyder columns are designed to allow highly volatile solvents to escape while

retaining semivolatile analytes of interest. Snyder columns are generally fitted onto

the tops of flasks containing extracts. The column design permits solvent to escape

as the flask is heated. The analytes of interest condense from a gas to a liquid phase

and fall back down into the solvent reservoir. The Kuderna-Danish concentrator is

a Snyder column with a removable collection tube attached to the bottom. As

solvent is evaporated, the extract is collected in the collection tube.

As an alternative to a Snyder column, the sample extracts may be concentrated with

nitrogen evaporation by directing a slow stream of the gas over the extract surface at

room temperature, resulting in minor loss of volatiles. Placing the extract container

in warm water helps to speed the process, but then some loss of volatiles can occur.

Concentration by evaporating excess solvent with a vacuum is not very common

in environmental laboratories. Many semivolatile analytes are lost in the proce-

dure. Additionally, evaporating as a means of concentrating the sample cannot be

used if the goal is to detect volatile analytes.

4.4 CLEANUP OF SAMPLE EXTRACT

Cleanup steps can be an important component of infrared (IR)-based and gravi-

metric methods because these methods are very sensitive to nonpetroleum

hydrocarbon interferences. Cleanup steps are less commonly utilized for gas

chromatography (GC)-based methods because experienced GC analysts can rec-

ognize the presence of interfering compounds (e.g., animal- and vegetable-

derived hydrocarbons).

Cleanup steps are not always a part of the petroleum analytical process, but when

they are necessary, the goals of extract cleanup steps typically include one or more

of the following:

• Removal of nonpetroleum compounds

• Isolation of a particular petroleum fraction

• Concentration of analytes of interest.

The techniques employed to extract the analytes of interest can frequently

extract interfering compounds. Polar compounds such as animal and plant fats,

proteins, and small biological molecules may be improperly identified as petrole-

um constituents. Extract cleanup techniques can be used to remove them. In an

ideal situation, only interfering compounds are removed. In reality, some polar

petroleum constituents can also be removed.

Two techniques are used to clean petroleum extracts. In one technique, inter-

fering compounds are removed by passing the extract through a glass column

filled with sorbent. A second technique is to swirl the extract with loose sorbent,

then remove the sorbent by filtration.

Three of the EPA-promulgated cleanup techniques involve trapping the interfer-

ing compounds on a sorbent column. EPA SW-846 3611 is an alumina cleanup

designed to remove interfering compounds and to fractionate petroleum wastes

15

into aliphatic, aromatic and polar fractions. The fractions can be analyzed sepa-

rately or combined for a total TPH measurement. EPA SW-846 3630, silica gel

cleanup, is the most common cleanup technique used on extracts designated for

PAHs and phenol analyses. Variations of this technique are used to clean EPA

Method 418.1 extracts before IR analysis. EPA Method SW-846 3640, gel-permeation

cleanup, works on the principle of size exclusion. Large macromolecules such as

lipids, polymers, and proteins are removed from the sample extract. Extracts

obtained from soils with high biological activity may be cleaned by this method.

There are two noncolumn EPA-promulgated cleanup techniques. EPA SW-846

3650, acid-base partition can be used to separate the base/neutral and acid com-

ponents by adjusting pH. Very often, only one fraction contains the compounds of

interest. This technique is often used before alumina column cleanup to remove

the acid components. EPA Method SW-846 3660 is used for sulfur removal. This

technique uses copper, mercury, and tetrabutylammonium sulfite as desulfuriza-

tion compounds. Sulfur is a common interfering compound for petroleum hydro-

carbon analysis, particularly for sediments. Sulfur-containing compounds are very

common in heavy fuels and crudes and on refinery sites. Elemental sulfur is often

present in anaerobically biodegraded fuels. High levels of sulfur may be measured

as “TPH” by some techniques if the cleanup technique is not used.

Solid phase cartridges for sample cleanup are available from chromatography

suppliers. These cartridges are available in a wide variety of adsorbents with unique

chemical selectivities; however, they have limited capacity.

There can be several limitations to various cleanup steps. Reasons for decreased

effectiveness of cleanup procedures include:

• Sample loading may exceed the capacity of cleanup columns and cartridges.

• Nonpetroleum compounds may have chemical structures similar to petrole-

um compounds and may behave like a petroleum compound. These com-

pounds evade cleanup.

• The cleanup may not have been done properly (poor technique).

• Some analytes of interest may be removed.

• There may be cases in which no single cleanup technique removes all

interferences.

For example, Table 3 shows the results of serial silica gel cleanups of EPA Method

418.1 extracts of plant materials. These results illustrate the limited effectiveness of

multiple silica gel cleanups for the removal of biogenic hydrocarbon interferences.

4.5 MEASUREMENT

Once the sample preparation is complete, there are several approaches for detect-

ing and quantifying petroleum hydrocarbons:

• Total petroleum hydrocarbon (TPH) measurement

• Petroleum group type measurement

• Individual component measurement.

16

17

TABLE 3. Effect of Silica Gel on Removing Biogenic Hydrocarbon Interferences

from Vegetative Materials (Freon-113 Extracts)

a

TPH concentrations given in ppm (mg/kg)

Prior to Addition After First Addition After Second Addition After Third Addition

Vegetable Material of Silica Gel of Silica Gel of Silica Gel of Silica Gel

Fresh pine needles 16,000 1,700 1,400 —

Pine bark 2,400 380 370 —

Pine needle compost 1,200 70 67 —

Maple tree seeds 7,100 1,600 1,500 —

Oak leaves dried 18,000 4,800 4,600 —

Grass, dried 14,000 4,500 2,700 2,600

Gall nuts 9,700 4,500 1,300 1,200

a

Source: Data from “EPA Method 418-1 Total Recoverable Petroleum Hydrocarbons by IR”, Groundwater Analytical Bulletin,

(Buzzards Bay: Groundwater Analytical Inc. 1991).

Total Petroleum Hydrocarbon (TPH) Measurement

Total petroleum hydrocarbon (TPH) measurements are conducted to determine

the total amount of hydrocarbon present in the environment. There are a wide

variety of TPH methods. In practice, TPH is defined by the method used to

analyze it. Different methods often give different results because they are

designed to extract and measure slightly different subsets of petroleum hydrocar-

bons. No single method gives a precise and accurate measurement of TPH for all

types of contamination. The four most commonly used TPH testing methods

include gas chromatography (GC), infrared spectrometry (IR), gravimetric analy-

sis, and immunoassay.

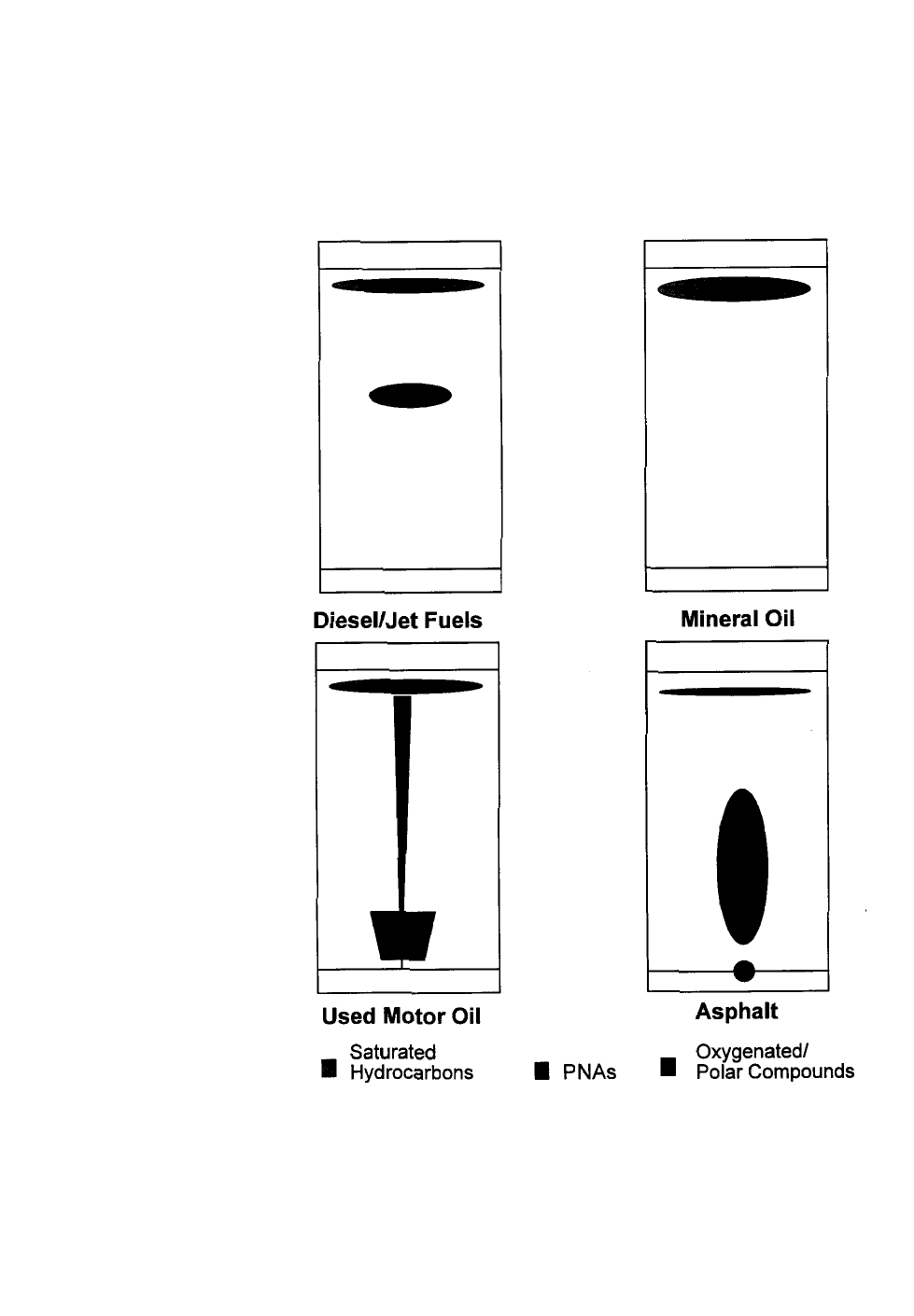

Petroleum Group Type Measurement

Petroleum group type measurements are conducted to determine amounts of

various petroleum compound classes (e.g., saturates, aromatics, and polars/resins)

present in a petroleum contaminated samples. Compound classes are discussed in

detail in Appendix I. This type of measurement is sometimes used to identify fuel

type or to track plumes. It may be particularly useful for heavier hydrocarbons such

as tar and asphalt. Group type test methods include multidimensional gas chro-

matography (not often used for environmental samples), high performance liquid

chromatography (HPLC), and thin layer chromatography (TLC).

Petroleum Constituent Measurement

Methods that analyze individual compounds (e.g., BTEX and PAHs) are generally

run to detect the presence of an additive or to provide concentration data needed

to estimate human health risk associated with individual compounds. Common

constituent measurement techniques include gas chromatography with second

column confirmation, gas chromatography with multiple selective detectors and

gas chromatography with mass spectrometry detection (GC/MS).

5. TOTAL PETROLEUM HYDROCARBON (TPH) MEASUREMENT:

DETAILED REVIEW OF SELECTED ANALYTICAL METHODS

A TPH method generates a single number quantifying the amount of petroleum

that is measured by the specified technique. The most popular TPH methods are

based on gas chromatographic (GC), infrared (IR), or gravimetric analytical tech-

niques. GC-based methods are currently the preferred laboratory methods for

TPH measurement because they detect a broad range of hydrocarbons, they

provide both sensitivity and selectivity, and they can be used for TPH identification

as well as quantification. IR-based methods have been widely used in the past for

TPH measurement because they are simple, quick and inexpensive. However, their

use is currently decreasing due to the worldwide ban on Freon production

(needed for sample extraction and measurement), the nonspecificity of these

methods, and their inability to provide any information on TPH identification and

potential risk. Gravimetric-based methods are also simple, quick, and inexpensive,

18

but they suffer from the same limitations as IR-based methods. Gravimetric-based

methods may be useful for very oily sludges and wastewaters, which will present

analytical difficulties for other more sensitive methods. Immunoassay TPH

methods are gaining popularity for field testing because they offer a simple, quick

technique for in-situ TPH quantification.

The following four sections provide detailed descriptions of these TPH methods.

Each section provides an overview of the analytical technique, example methods,

the purpose of the method (i.e., what it is intended to measure), and key interfer-

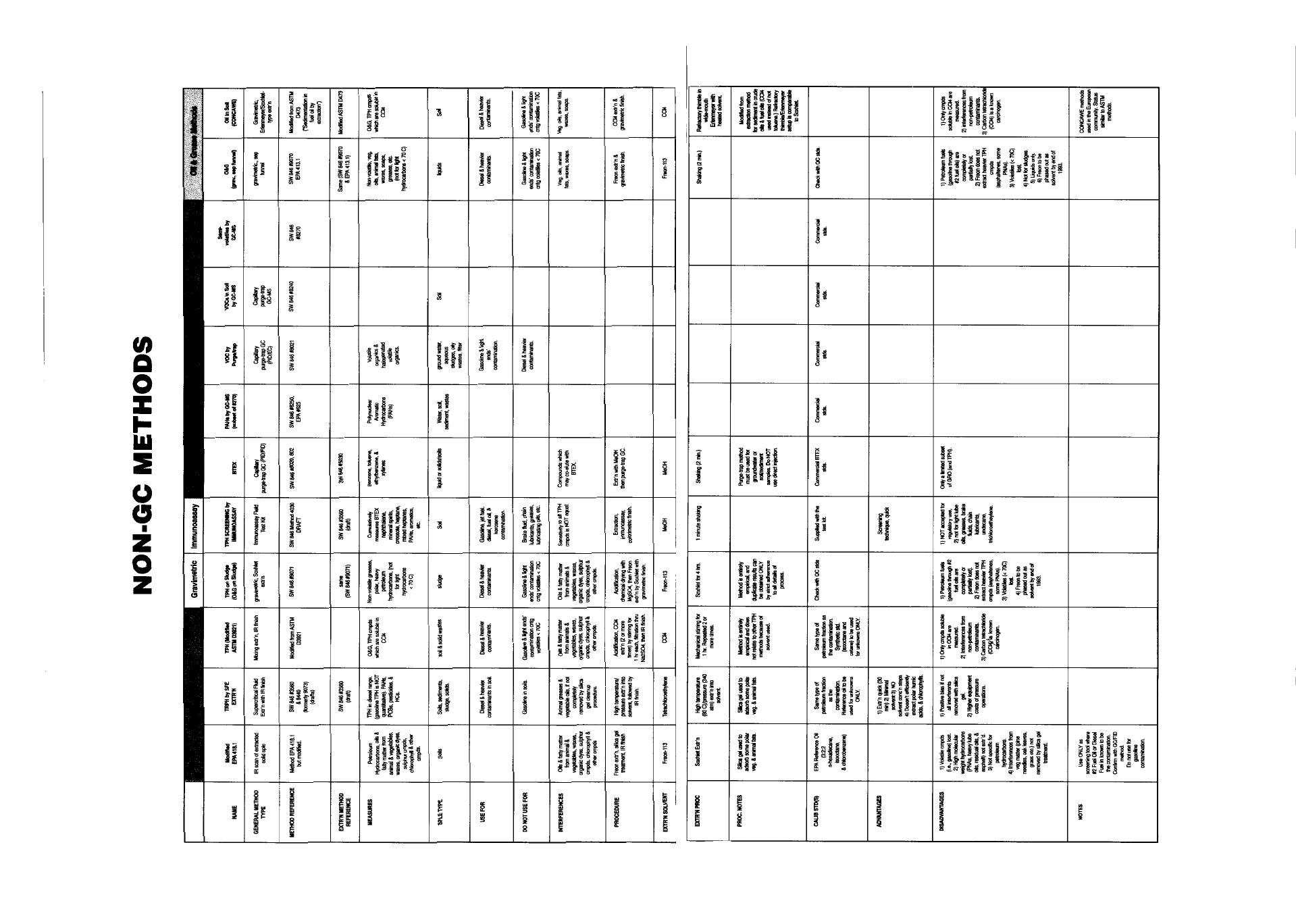

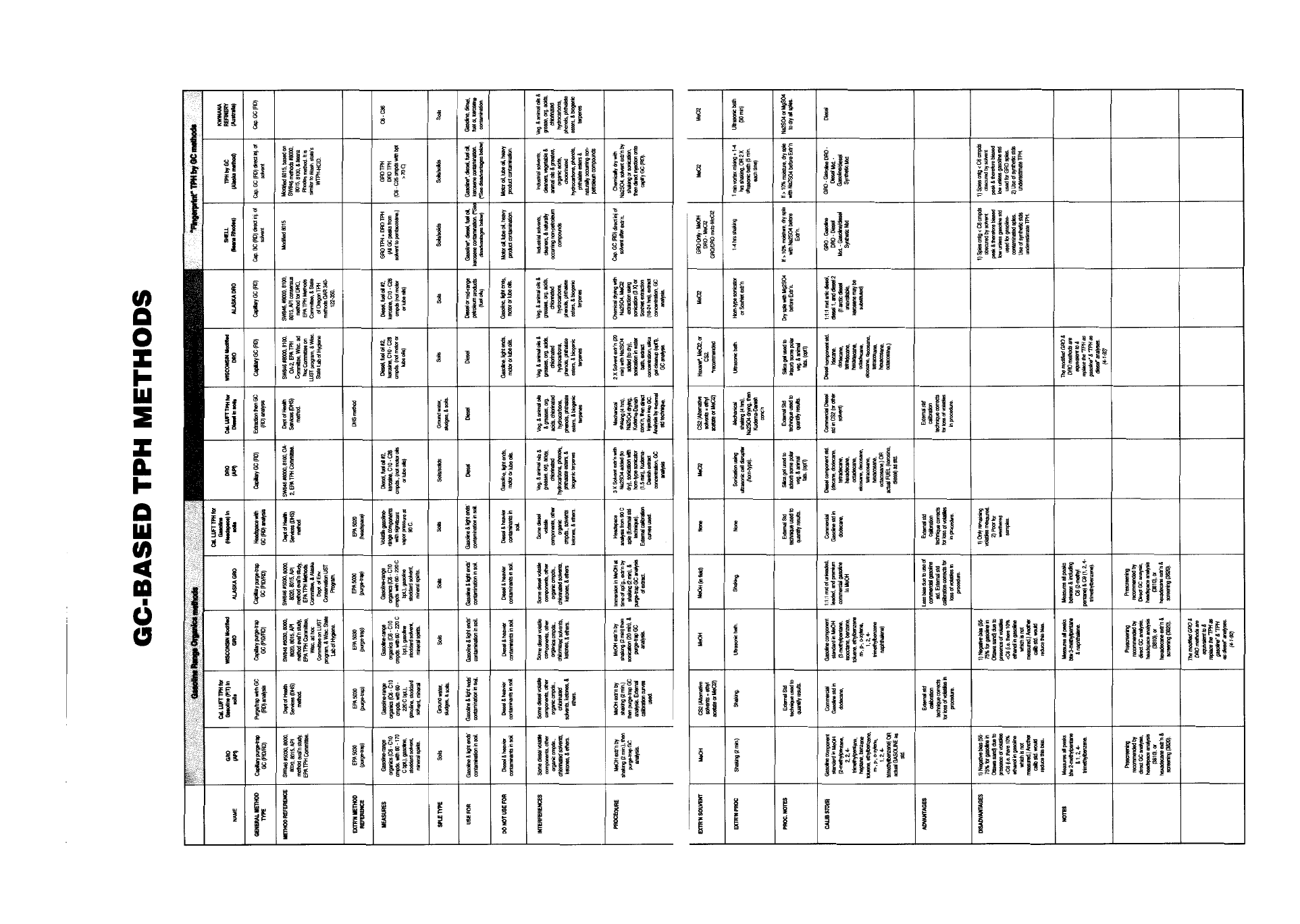

ences/limitations. Table 4 briefly summarizes this information for each TPH ana-

lytical method for quick reference. Appendix IV includes tables that provide more

detailed information about published GC-based and non-GC TPH methods. These

tables provide method-specific information for EPA and state methods, including

recommendations for method use, common interferences, procedural notes,

advantages, and disadvantages.

5.1 GAS CHROMATOGRAPHY (GC) TPH METHODS

For GC-based methods, TPH is defined as anything extractable by a solvent or

purge gas and detectable by gas chromatography/flame ionization detection

(GC/FID) within a specified carbon range. The primary advantage of GC-based

methods is that they provide information about the type of petroleum in the

sample in addition to measuring the amount. Identification of product type(s) is

not always straightforward, however, and requires an experienced analyst of petro-

leum products. Detection limits are method- and matrix-dependent and can be as

low as 0.5 mg/L in water or 10 mg/kg in soil.

Overview of the Technique

Gas chromatography is a technique that separates mixtures. “A mixture of chemi-

cals is separated into its individual components as the sample travels through a

column in the gas chromatograph. Separation is achieved by a combination of

factors including boiling point, polarity, and affinity differences among the differ-

ent components in the sample. The time a compound spends on a specific column

is called the retention time and it is reproducible. The retention time is character-

istic of a compound under given experimental parameters and specified column.

As the separated components elute from the column, they are detected” (Swallow

et al., 1988). The detector signal is proportional to the amount of compound

present.

Chromatographic columns are commonly used to determine TPH compounds

approximately in the order of their boiling points. Compounds are detected with

a flame ionization detector, which responds to virtually all compounds that can

burn. The sum of all responses within a specified range is equated to a hydrocar-

bon concentration by reference to standards of known concentration.

Two techniques are most commonly used to get the samples into the column.

• Purge and trap systems purge components out of water or water/methanol by

bubbling gas through the liquid. The components are concentrated on a very

short intermediate column or “trap,” which is heated to drive them onto the

19

20

TABLE 4. General Summary of Analytical Methods for TPH Measurement

Typical Typical

Method Type/ Products Carbon Published

Method Name Environmental Media Detected Ranges Detected Methods

GC-Based TPH methods primarily laboratory but also primarily gasolines, diesel fuel, normally between C6 and EPA Method 8015B,

field applications- can be and fuel oil #2 - can be C25 or C36 (can be modified state-modified 8015

adapted for all media modified for heavier hydro- for higher carbon numbers) methods

carbon mixtures (e.g., lubricating

oils, heavy fuel oils)

IR-Based TPH methods laboratory and field screening primarily diesel and fuel oils most hydrocarbons with EPA Method 418.1

- most appropriate for water exception of volatile and

and soil very high hydrocarbons

Gravimetric TPH methods laboratory - most appropriate most appropriate for heavier anything that is extractable EPA Method 9071;

for wastewaters, sludges, petroleum products (e.g., crude (with exception of volatiles EPA proposed Method

and sediment oils, lubricating oils, etc.) which are lost) 1664

Immunoassay TPH field screening - most various products (but yields aromatic hydrocarbons EPA Method 4030

methods appropriate for soil and water only screening numbers) (e.g., BTEX, PAHs)

21

TABLE 4.

Detector Approximate Key Interferences/

Type Detection Limits Advantages Limitations

GC/FID can be as low as 0.5 mg/L can detect broad range of normally cannot detect

in water, 10 mg/kg in soil hydrocarbon compounds; simple compounds below C6;

and sensitive; can provide infor- may not detect polar

mation (e.g., a chromatogram) for hydrocarbons (e.g.,

product identification alcohols, ethers, etc.);

chlorinated solvents

may be quantified as TPH

IR spectrometer 1 mg/L in water; technique is simple, quick, Freon is now banned;

10 mg/kg in soil and inexpensive lack of specificity; low

sensitivity; high loss of

volatiles; poor extraction

of high molecular weight

hydrocarbons; prone to

interferences; provides

quantitation only

Gravimetric balance 5 to 10 mg/L in water; technique is simple, quick, Freon is banned,

50 mg/kg in soil and inexpensive although other solvents

are available; lack of

specificity; low sensitivity;

high loss of volatiles;

prone to interferences;

provides quantitation only

Portable test kit 200 to 500 ug/L in water; technique is simple, quick, low sensitivity; can

10 to 500 mg/kg in soil inexpensive, and can be done detect interferences; pri-

in the field marily only measure

aromatics; low accuracy

and precision; should

only be used as screening

measurement; provides

quantitation only

analytical column where they are separated. Hydrocarbons from C

5

through

about C

12

can be analyzed using this technique. Purge and trap sample intro-

duction is used for light products such as gasoline and condensate.

• Direct injection involves taking the hydrocarbon, diluted hydrocarbon, or

an extract of hydrocarbon into a syringe and injecting it into the gas chro-

matograph. This technique can be used for any type of hydrocarbon, but it

is most frequently used for distillates, lube oils and crude oils.

Headspace sample introduction can be used for the determination of light

hydrocarbons, and it is most often used for field screening.

Example Methods

Prior to 1997, EPA SW-846 Methods 8015 and 8015A were often quoted as the

source of GC-based TPH methods, commonly referred to as “Modified 8015.”

However, the original 8015 methods were titled “Nonhalogenated Volatile

Organics” and were designed to measure a short target list of chemical solvents

rather than petroleum hydrocarbons. Because there was no universal method for

petroleum hydrocarbons, each state specified its own version. The recent Update

III of EPA SW-846, 3rd Ed. includes a new Method 8015B titled “Nonhalogenated

Volatile Organics Using GC/FID”, with guidance for the analysis of gasoline and

diesel range organics. Whether the new method will replace the many techniques

currently in use is uncertain. The current individual methods differ in procedure,

compounds detected, extraction techniques and extraction solvents used. Some

methods may include a cleanup step to remove biogenic (bacterial or vegetation-

derived) material while others do not. The methods have in common a boiling

point-type column and a flame ionization detector.

Some regulatory agencies specify two GC-based TPH methods. Selection of a

method depends on the type of hydrocarbon suspected to be in the sample:

• If gasoline is suspected to be the sole contaminant, the TPH method will use

purge/trap sample introduction. Many of these methods are referred to as volatile

range organics - TPHV, TPH-G, or GRO - gasoline range organics. Typically, gaso-

line or a synthetic mixture will be used to prepare calibration standards.

• If heavier petroleum fractions (diesel, middle distillates, motor oil) are the

contaminants, the analysis will use direct injection and hotter oven tempera-

tures. Many of these methods are referred to as extractable range organics,

TPH-D or DRO - diesel range organics. Typically, diesel fuel #2 or a synthet-

ic mixture will be used to prepare calibration standards. Jet fuel or lube oil

may be used when appropriate.

• Mixtures or unknown contamination may require both volatile range and

extractable range analyses. Alternately, a single injection can be used to

analyze the whole sample, but the extraction method must not use a solvent

evaporation step. Reporting limits for a single injection method are approx-

imately 20 mg/L.

22

What Do GC Methods Measure?

A GC/FID will detect any hydrocarbons that elute from the column and burn. The

analog signal from the detector is called a chromatogram. GC/FID methods specify

a certain portion of the chromatogram (a “window” or carbon number range) for

quantification. The carbon number range will approximate that of the fuel of inter-

est - gasoline, diesel, or heavier hydrocarbon. The carbon number range specified

for each fuel may differ from state to state. Volatile compounds that elute before the

solvent peak (usually those < C

6

) are typically not measured.

GC-based methods can be broadly used for different kinds of petroleum releas-

es but are most appropriate for detecting nonpolar hydrocarbons with carbon

numbers between C

6

and C

25

or C

36

.

Many lube oils contain molecules with more than 40 carbon atoms. Crude oils

may contain molecules with 100 carbons or more. These heavy hydrocarbons are

outside the detection range of the more common GC-based TPH methods, but spe-

cialized gas chromatographs are capable of analyzing such heavy molecules.

Accurate quantification depends on adjusting the chromatograph to reach as high

a carbon number as possible, then running a calibration standard with the same

carbon range as the sample. The lab must also check for mass discrimination, a ten-

dency for heavy molecular weight hydrocarbons to be retained in the injection

port. Labs should be notified if a sample is suspected to be heavy oil, or to contain

a mixture of light and heavy oils, so that they can use the appropriate GC method.

Gravimetric or IR methods are often preferred for very heavy samples. They can

even be used as a check on GC/FID results if it is suspected that heavy molecular

weight hydrocarbons are present but are not being detected. Laboratories should

flag data if heavy material is observed in the chromatogram, even if this material

cannot be quantified.

Calibration standards vary. Most methods specify a gasoline calibration standard

for volatile range TPH and a diesel fuel #2 standard for extractable range TPH.

Some methods use synthetic mixtures for calibration. Because most methods are

written for gasoline or diesel fuel, TPH methods may have to be adjusted to

measure contamination by heavier hydrocarbons - lubricating oils, heavy fuel oils,

or crude. Such adjustments may entail use of a more aggressive solvent, a wider GC

“window” - up to C

36

or more - and a different calibration standard that more

closely resembles the “heavier” contamination.

GC-based methods can be modified and fine-tuned so that they are suitable for

measurement of specific petroleum products or group types. Examples of modified

GC-based methods include GRO, DRO, and TPHV methods. These modified

methods can be particularly useful when there is information on the source of cont-

amination, but method results should be interpreted with the clear understanding

that a modified method was used for detection of a specific carbon range. It is essen-

tial that the user understand what hydrocarbons a GC-based method can and cannot

detect and how results are quantified. For example, BTEX is a subset of TPHV. If

benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and the three xylene isomers are present in a

sample, they will be quantified along with the other TPHV components. The TPHV

measurement typically is greater than the sum of the BTEX measurements. Gasoline

should not be quantified by adding the TPHV and BTEX quantities together.

23

Interpretation of GC-based TPH data can be complicated and the analytical

method should always be considered when interpreting concentration data. A

volatile range TPH analysis may be very useful for quantifying TPH at a gasoline

release site, but a volatile range TPH analysis will not detect the presence of lube

oil. In addition, a modified GC-based method which has been specifically selected

for detection of gasoline-range organics at a gasoline-contaminated site may also

detect hydrocarbons from other petroleum releases because fuel carbon ranges

frequently overlap (See discussion in Section 3). Gasoline is found primarily in the

volatile range. Diesel fuel falls primarily in an extractable range. Jet fuel overlaps

both the volatile and semivolatile ranges. However, the detection of different kinds

of petroleum does not necessarily indicate that there have been multiple releases

at a site. Analyses of spilled waste oil will frequently detect the presence of gasoline,

and sometimes diesel. This does not necessarily indicate multiple spills. All waste

oils contain some fuel. As much as 10% of used motor oil can consist of gasoline

(Owen and Coley, 1990). The fuel gets into the oil as combustion chamber gases

blowing past the piston rings - a more pronounced problem in high mileage

engines with worn rings. Liquid fuel will also seep past rings under cold start and

warm-up conditions (Rhodes et al., 1994).

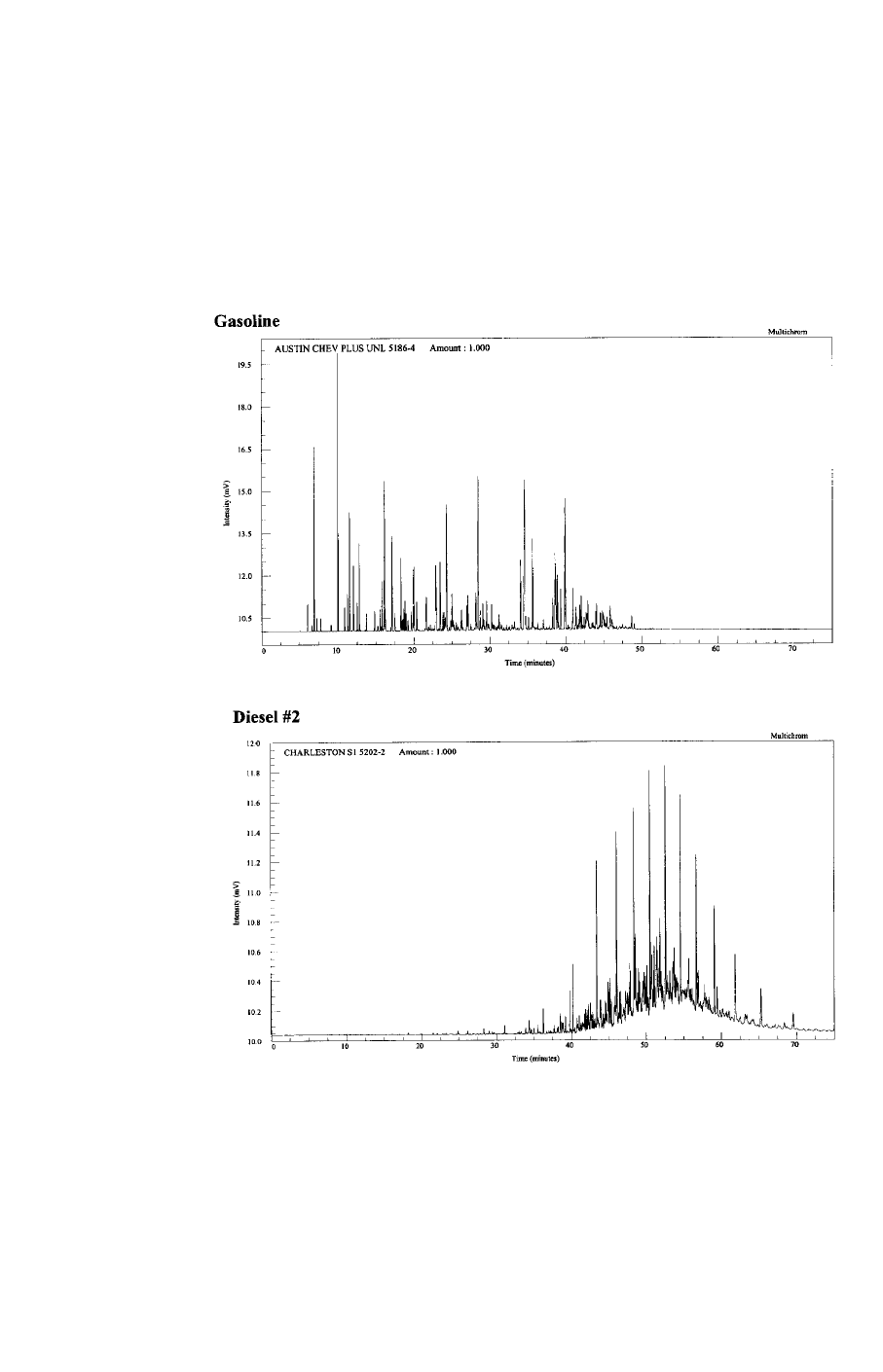

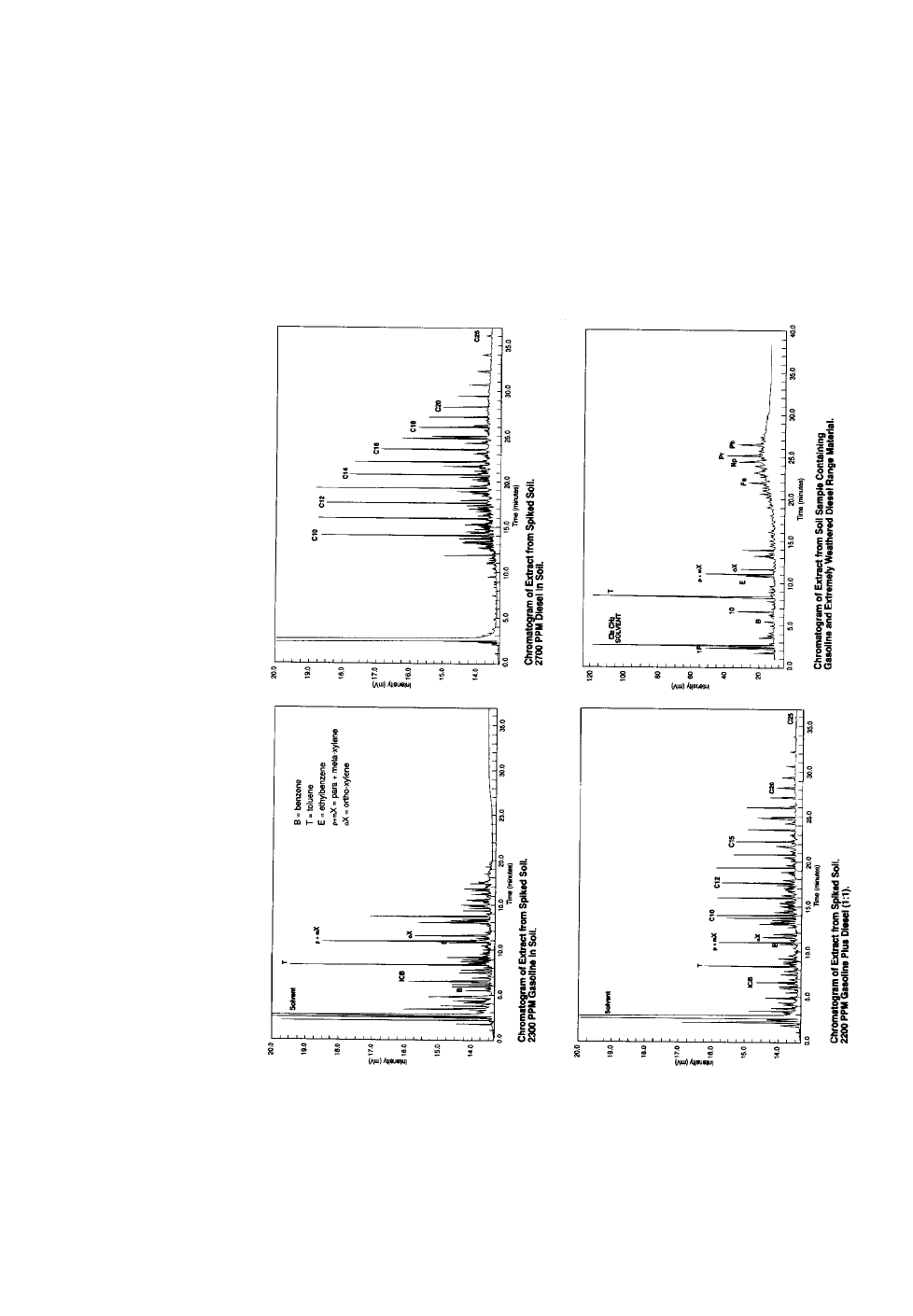

If the type of contaminant is unknown, a “fingerprint” analysis can help identify

it. A “fingerprint”, or pattern recognition, analysis is a direct injection GC/FID

analysis where the chromatogram is compared to chromatograms of reference

materials. Certain fuels can be identified by characteristic, reproducible chro-

matographic patterns. For example, chromatograms of gasoline and diesel differ

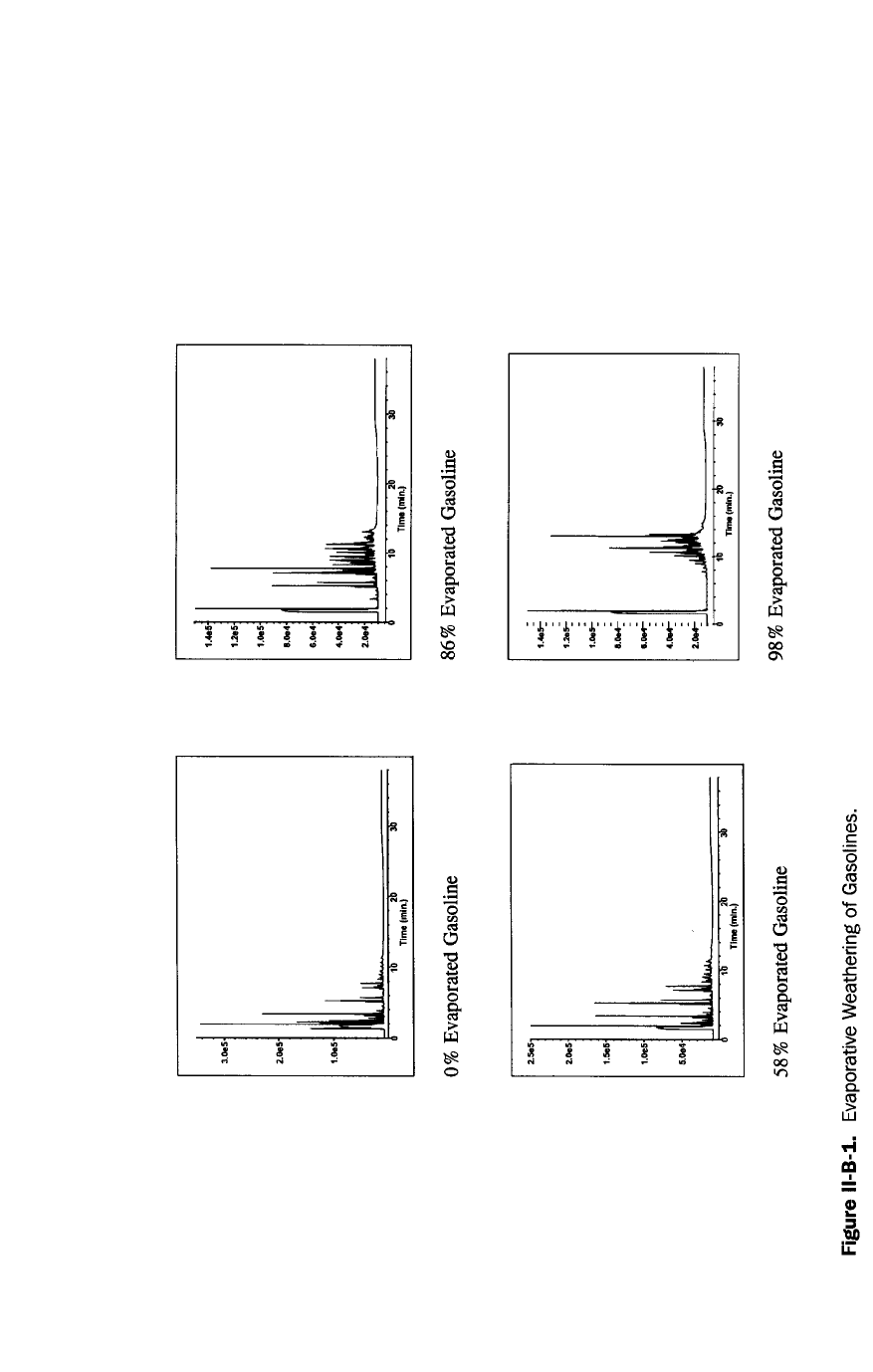

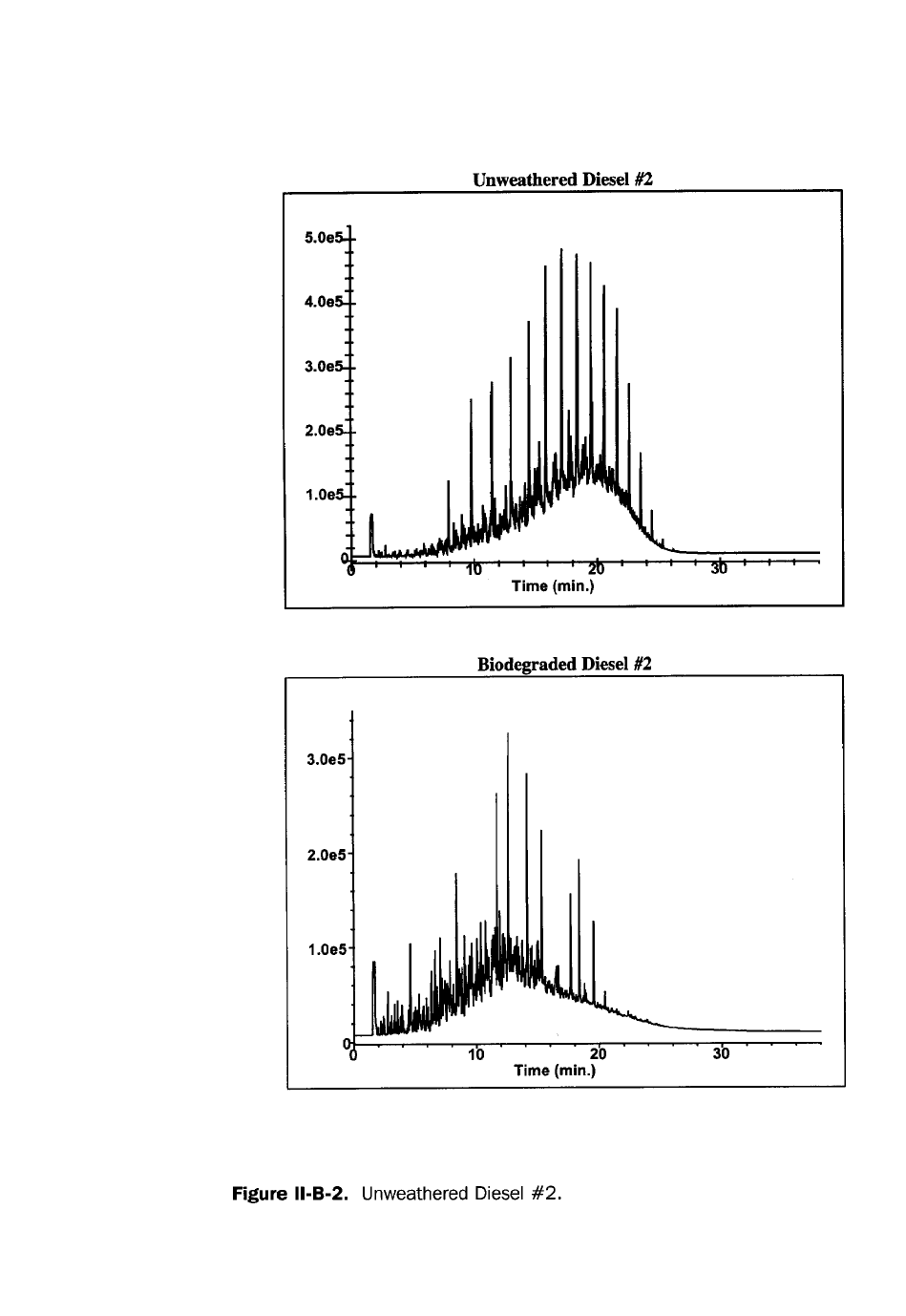

considerably, as shown in Figures 3 and 4. There are complicating factors, however.

Many hydrocarbon streams may have similar fingerprints. Diesel #2 and #2 fuel oil

both have the same boiling point range and chromatographic fingerprint. A fin-

gerprint can be used to conclusively identify a mixture when a known sample of

that mixture or samples of the mixture’s source materials are available as refer-

ences. As a fuel evaporates or biodegrades, its pattern can change so radically that

identification becomes difficult. Consequently, a GC “fingerprint” is not a conclu-

sive diagnostic tool. These chromatograms must be interpreted by experienced

analysts. While GC-based TPH and pattern recognition methods are very similar,

TPH methods stress calibration and quality control, while pattern recognition

methods stress detail and comparability.

Interferences/Limitations

The GC-based methods usually cannot quantitatively detect compounds below C

6

because these compounds are highly volatile and interference can occur from the

solvent peak. As much as 25% of fresh gasoline can be below C

6

. This is not a

problem for the analyst with weathered gasoline range and/or diesel range conta-

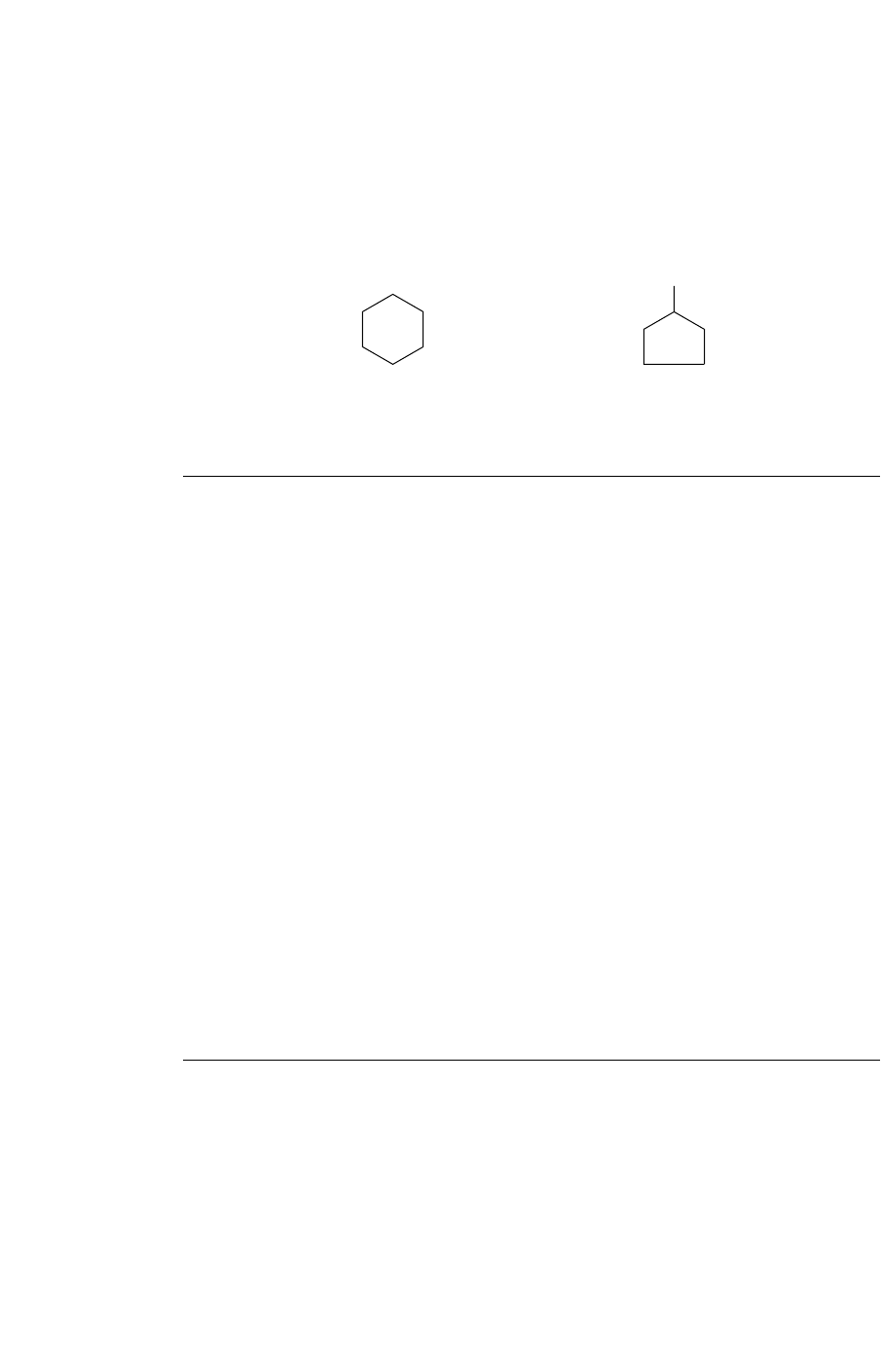

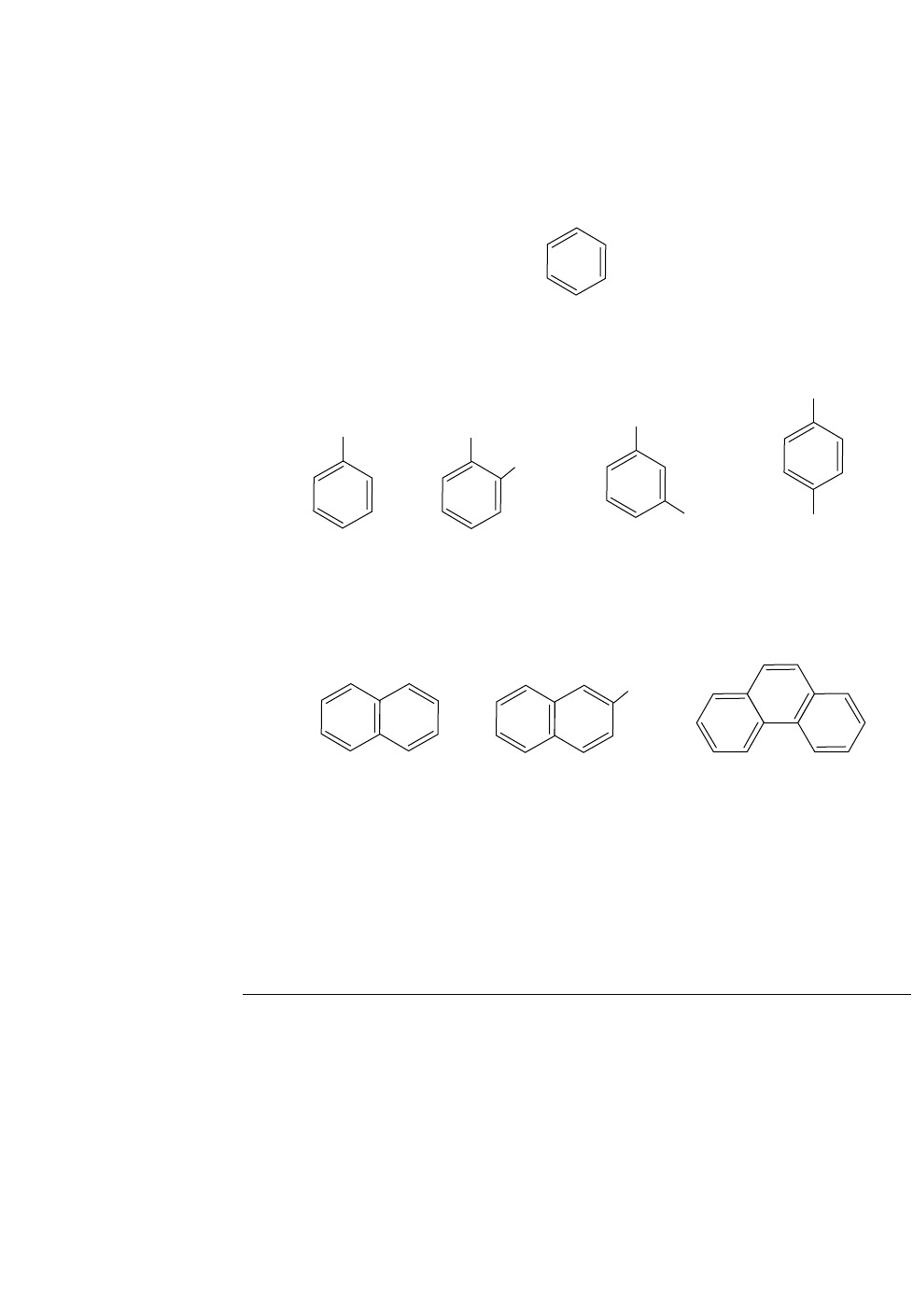

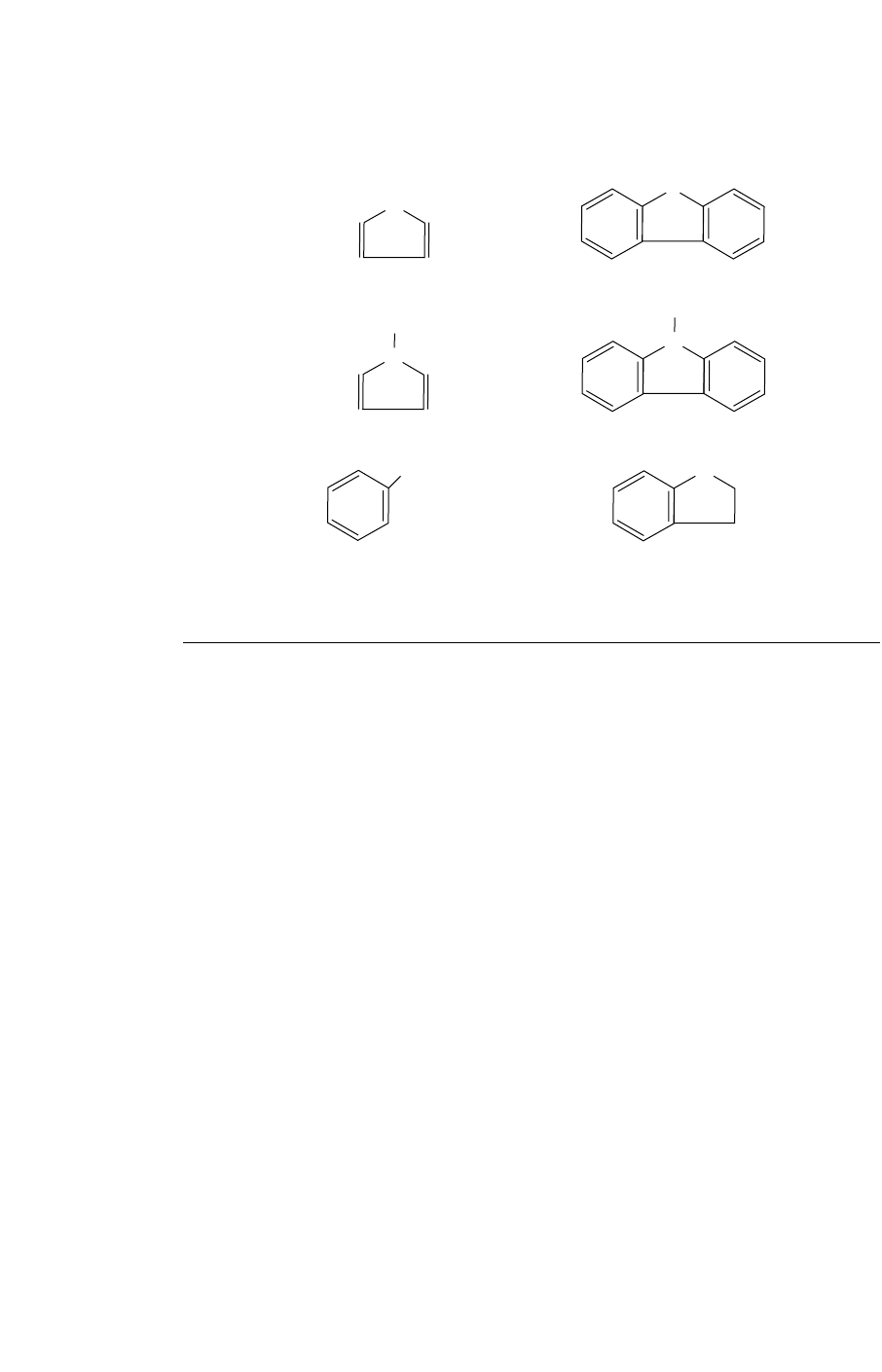

mination because most of the very volatile hydrocarbons (<C

6

) may no longer be

present in the sample.

GC-based TPH methods may also have problems quantifying polar hydrocarbon

constituents (nitrogen, oxygen, and sulfur containing molecules). Some polar

hydrocarbon constituents are too reactive to pass through a gas chromatograph

and thus will not reach the detector for measurement.

24

25

Figure 3. Gas Chromatograms of Fuels.

26

Figure 4. GC “Fingerprint” Chromatograms of Soil Contamination.

Oxygenated gasolines are sometimes analyzed by GC-based methods. Efficiency

of purge methods is lower for oxygenates such as ethers and alcohols. GC detector

response to oxygenates is lower relative to hydrocarbons. Therefore TPH results

will tend to be biased slightly low for ether-containing fuels compared to equivalent

amounts of traditional gasolines. Methanol and ethanol elute before C

6

; conse-

quently, they are not quantified and may not even be detected due to coelution

with the solvent. TPH results for fuels containing these alcohols also will have a

negative bias.

GC-based methods may overestimate TPH concentrations due to the detection

of non-petroleum compounds. Chlorinated compounds may be detected by GC-

based methods and reported as TPH. While leaded gasolines contain a few parts