DEFINED

CONTRIBUTION

PLANS

403(b) Investment

Options, Fees, and

Other Characteristics

Varied

Report to the Chairman, Committee on

Education and Labor, House of

Representatives

March 2022

GAO-22-104439

United States Government Accountability Office

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-22-104439, a report to the

Chairman, Committee on Education and

Labor, House of Representatives

March 2022

DEFINED CONTRIBUTION PLANS

403(b) Investment Options, Fees, and Other

Characteristics Varied

What GAO Found

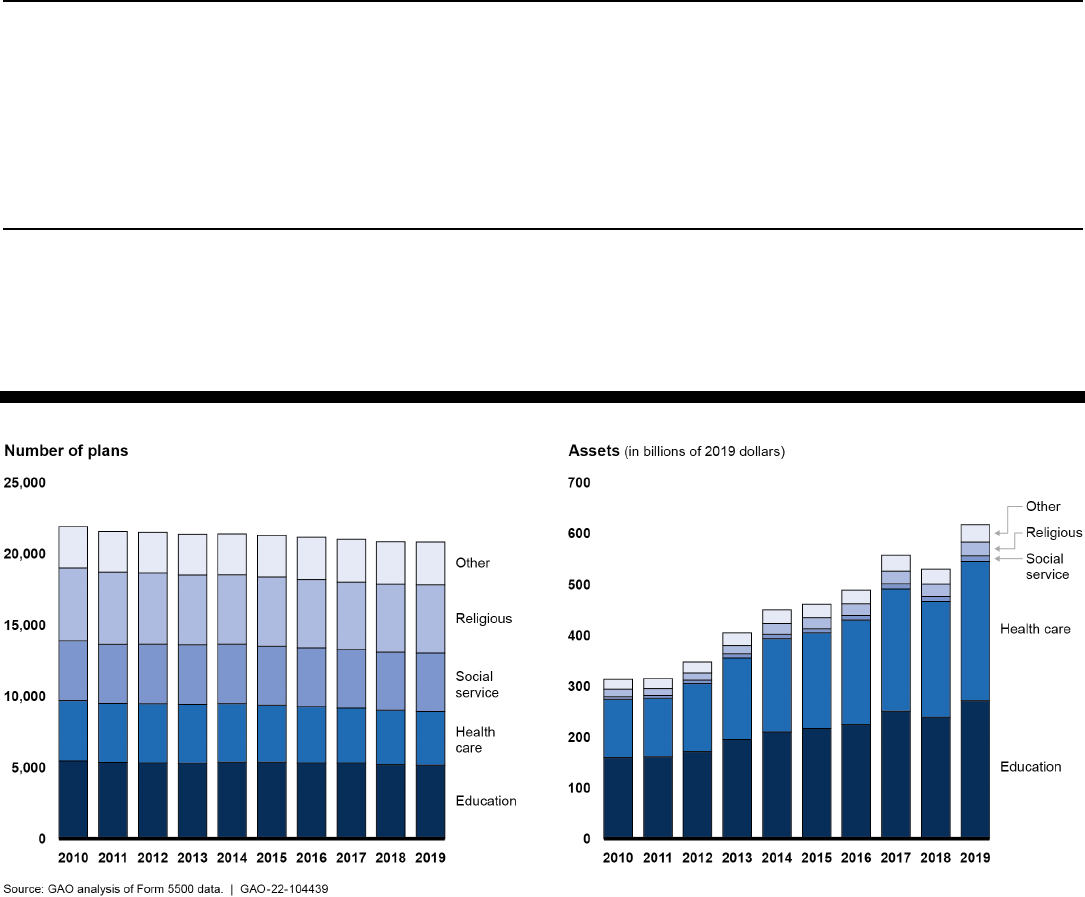

Total assets held by 403(b) plans—retirement savings plans for certain public

sector and tax-exempt sector employees—amounted to more than $1.1 trillion in

2020, according to industry data, and other characteristics varied. Industry data

show that about half of these assets were held in plans covered by the Employee

Retirement Income Security Act of 1974, as amended, (ERISA), which are

generally required to submit an annual filing known as the Form 5500. ERISA

403(b) assets grew from 2010 to 2019, the most recent year for which 5500 data

are available, while the number of plans declined, as shown in the figure.

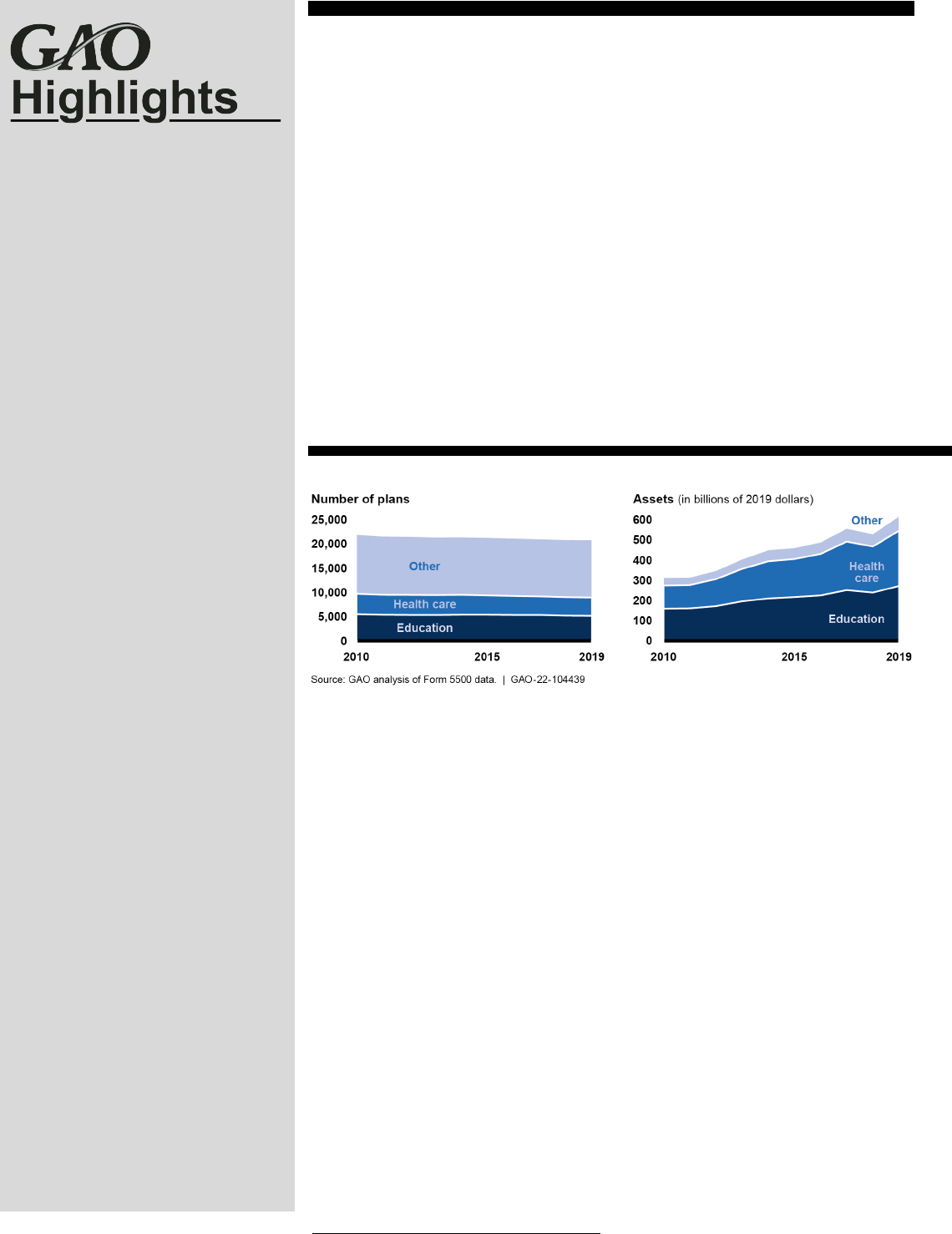

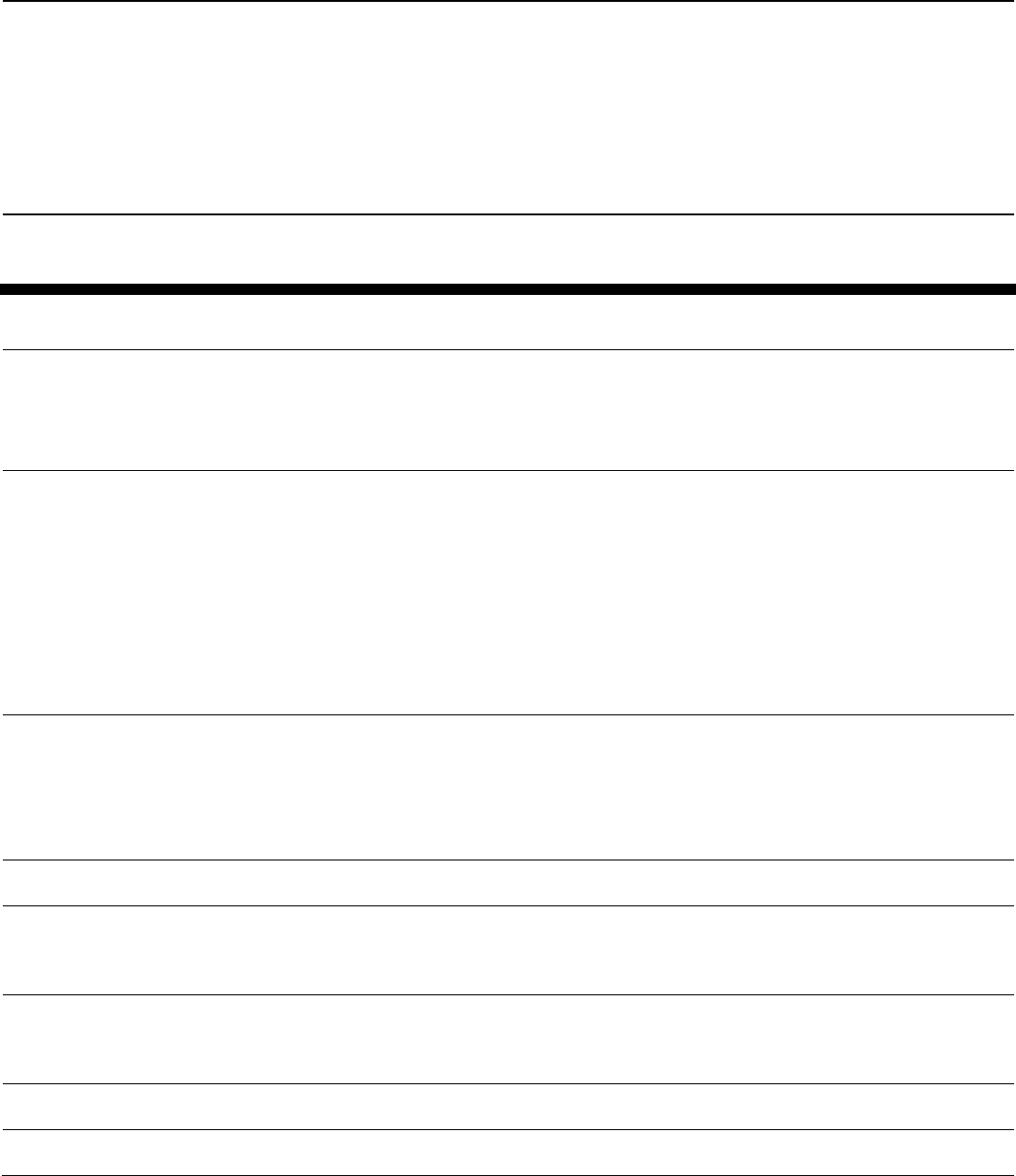

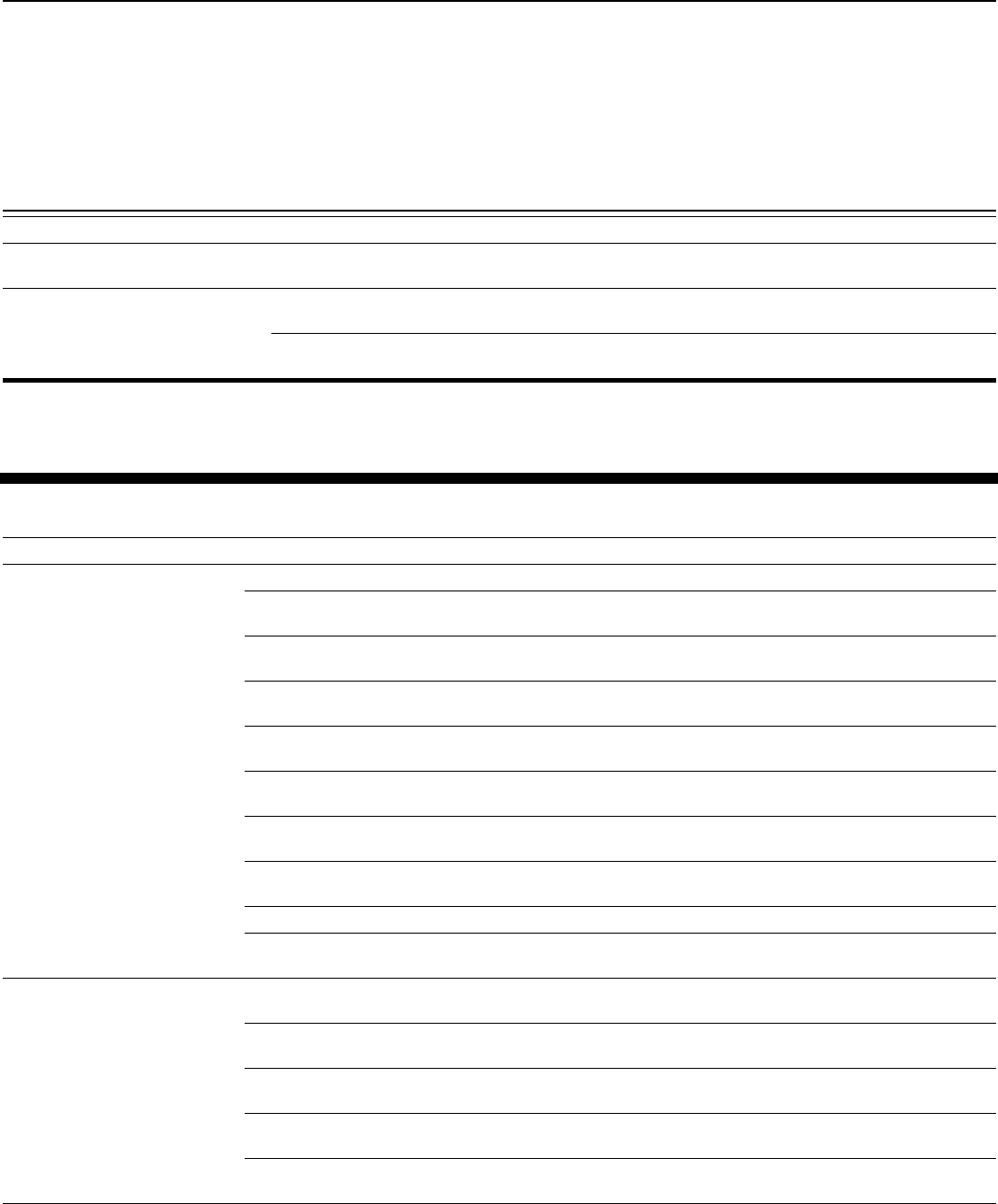

Number of 403(b) ERISA Plans and Value of Plans’ Assets, by Sector, 2010-2019

According to industry experts and 5500 data, these trends likely resulted from

consolidation of firms in the health care sector, which represents a large portion

of plan assets. The vast majority—93 percent—of ERISA 403(b) plans were the

employer’s sole or primary retirement plan. While less information is available for

403(b) plans not covered by ERISA (non-ERISA plans), which do not file a Form

5500, of the 21 plan sponsor respondents to GAO’s survey, most stated their

plans were supplemental to another retirement savings plan offered by the

employer. Available data also show that the number of investment options, which

may be annuities or mutual funds, offered by 403(b) plans varied but were

generally higher than the number offered by 401(k) plans in the private sector.

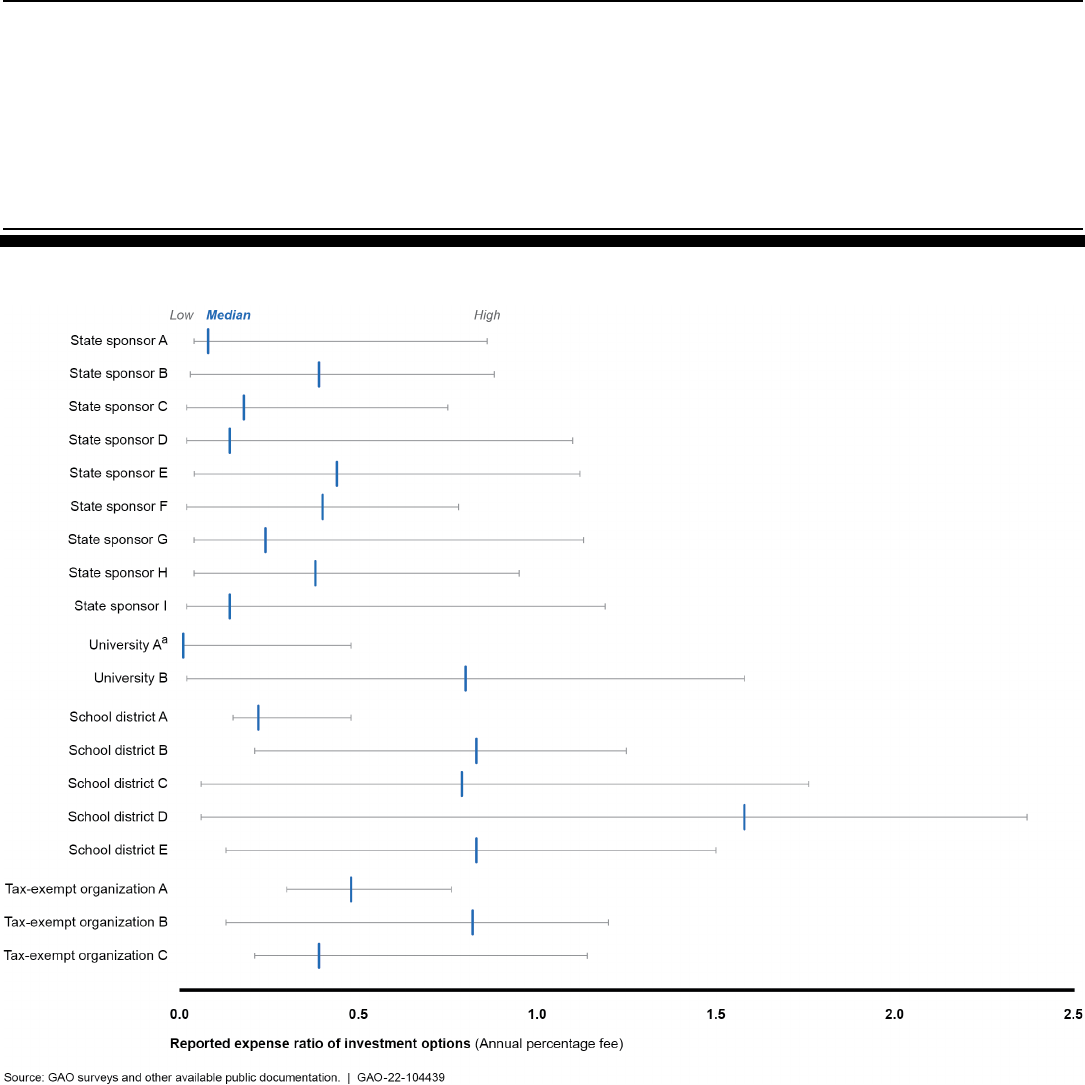

Fees for 403(b) plans varied widely according to GAO’s survey of ERISA and

non-ERISA plan sponsors and service providers, as well as Form 5500 data. For

example, plans that GAO surveyed reported record keeping and administrative

service fees ranging from 0.0008 percent of plan assets to 2.01 percent of plan

assets. In addition, fees for investment options offered by the plan ranged from

0.01 percent to 2.37 percent among plans GAO surveyed. Prior GAO work has

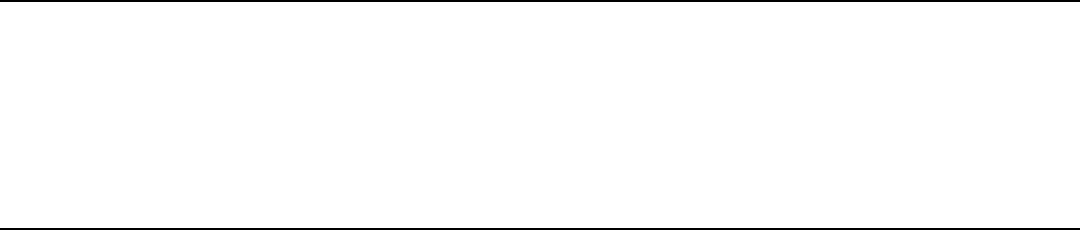

shown that even seemingly small fees can significantly reduce participants’

retirement savings over time. Available data also show that large 403(b) plans

had lower administrative fees than smaller ones. In GAO’s survey, university,

state-sponsored, and plan sponsors with $1 billion or more in assets reported

taking multiple steps to reduce fees, while other sponsors more often reported

not having information that would help them monitor fees. For example, five

public school district plan sponsors reported that they did not know expense

ratios, which are measures of how much of a fund's assets are used for

administrative and other operating expenses, for investment options offered by

their plan that would also allow them to monitor fees.

View GAO-22-104439. For more information,

contact Tranchau (Kris) T. Nguyen at

(202) 512

-7215 or nguyentt@gao.gov.

Why GAO Did This Study

Millions of teachers and other

employees of public schools,

universities, and

tax-exempt

organizations rely on savings they

accumulate in 403(b) plans to provide

income security in retirement. Like

401(k) plans, 403(b) plans are

account

-based defined contribution

plans sponsored by employers, and

individuals who participate in the plans

make investment decisions and bear

the investment risk. Private sector

employer

-sponsored retirement plans

are generally subject to ERISA

requirements intended to protect th

e

interests of plan participants. However,

some 403(b) plans are not covered by

ERISA. This report addresses

(1) the

number and characteristics of 403(b)

pl

ans; and (2) fees charged to 403(b)

plan participants.

For this report, GAO

analyzed plan-

level char

acteristics—including the

number of participants, the amount of

plan assets, and available information

on plan investment offerings from 2010

through 2019

—the most recent year

for which data are available

—from the

Department of Labor’s

(DOL) Form

5500 data

base as well as available

industry data. GAO analyzed

individual

-level data from the Health

and Retirement Study (HRS) of

respondents

over age

50 who reported

participating in 403(b) plans. GAO also

analyzed information on plan

characteristics and fees fro

m non-

generalizable surveys

GAO conducted

of 403(b) plan sponsors and 403(b)

service providers (a total of 45 survey

responses), and interviewed

DOL and

other U.S. agency officials,

industry

stakeholders

, and experts identified as

being knowledgeable about

403(b)

plans.

Page i GAO-22-104439 Defined Contribution Plans

Letter 1

Background 5

Available Data Show That Total 403(b) Plan Assets Have

Increased since 2010 and Other Characteristics, such as Plan

Participation, Varied Among Plans 13

Fees for 403(b) Plans Varied Widely, and Some Plans Reported

They Lacked Knowledge of Investment Fees 30

Agency Comments 51

Appendix I Objectives, Scope, and Methodology 53

Appendix II Detailed Findings from Analysis of Health and Retirement Study Data 63

Appendix III Detailed Data on Fees from Surveys of 403(b) Plan Sponsors and

Service Providers 70

Appendix IV Reported Surrender Fees and Short-Term Trading Fees by 403(b)

Plan Sponsors and Service Providers Surveyed 77

Appendix V GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgements 80

Tables

Table 1: Examples of Administrative and Investment Fees That

May Be Charged in 403(b) Plans 8

Table 2: Extent to Which Service Providers Surveyed by GAO

Reported 403(b) Plan Clients Offered Annuities and/or

Mutual Funds 28

Table 3: Investment Offerings and Knowledge of 403(b) Asset

Allocation Reported by the Eight Public School District

Plans That Responded to GAO’s Survey 29

Table 4: Percentage of ERISA 403(b) Plans Reporting Paying

Fees of $5,000 or More , by Fee Category 43

Contents

Page ii GAO-22-104439 Defined Contribution Plans

Table 5: Retirement Plan Participant Counts, Assets, Numbers of

Plan Investment Options, and Range of Fees and

Expenses for Plan Sponsors Surveyed by GAO 70

Table 6: 403(b) Retirement Plan Participant Counts, Total Assets,

and Range of Fees and Expenses for 403(b) Service

Providers Surveyed by GAO 74

Table 7: Summary of Surrender Fee Information Obtained From

Plan Sponsor Survey Respondents 77

Table 8: Summary of Surrender and Short-Term Trading Fee

Information Obtained From 403(b) Service Provider

Survey Respondents 78

Figures

Figure 1: The Type of Employer and Extent of the Employer’s

Involvement in the Plan Can Determine Whether a 403(b)

Plan Is Subject to ERISA 10

Figure 2: Number of 403(b) ERISA Plans and Value of ERISA

Plans’ Assets, by Sector, 2010-2019 15

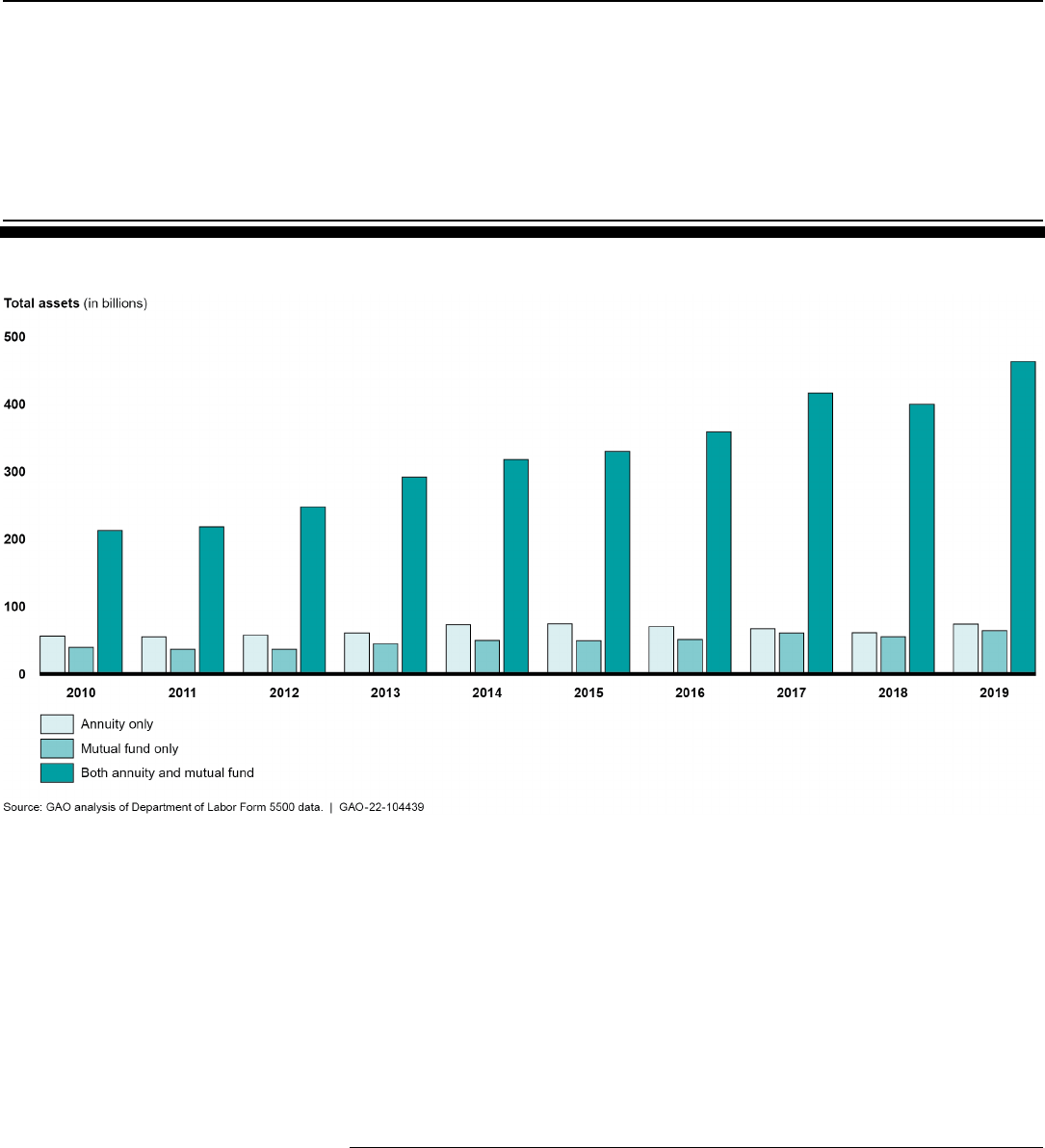

Figure 3: Reported Number of Investment Options Offered by

403(b) Plan Sponsors Surveyed by GAO 24

Figure 4: Trends in ERISA 403(b) Plans Offering Annuities Only,

Mutual Funds Only, or Both Annuities and Mutual Funds,

by Asset Value, 2010-2019 27

Figure 5: Reported Ranges and Calculated Medians of Expense

Ratios for Investment Options for Plan Sponsors

Surveyed by GAO 33

Figure 6: Illustrative Examples of Surrender Fees on a

Hypothetical Participant’s Account Balance, with an Initial

Account Balance of $10,000 39

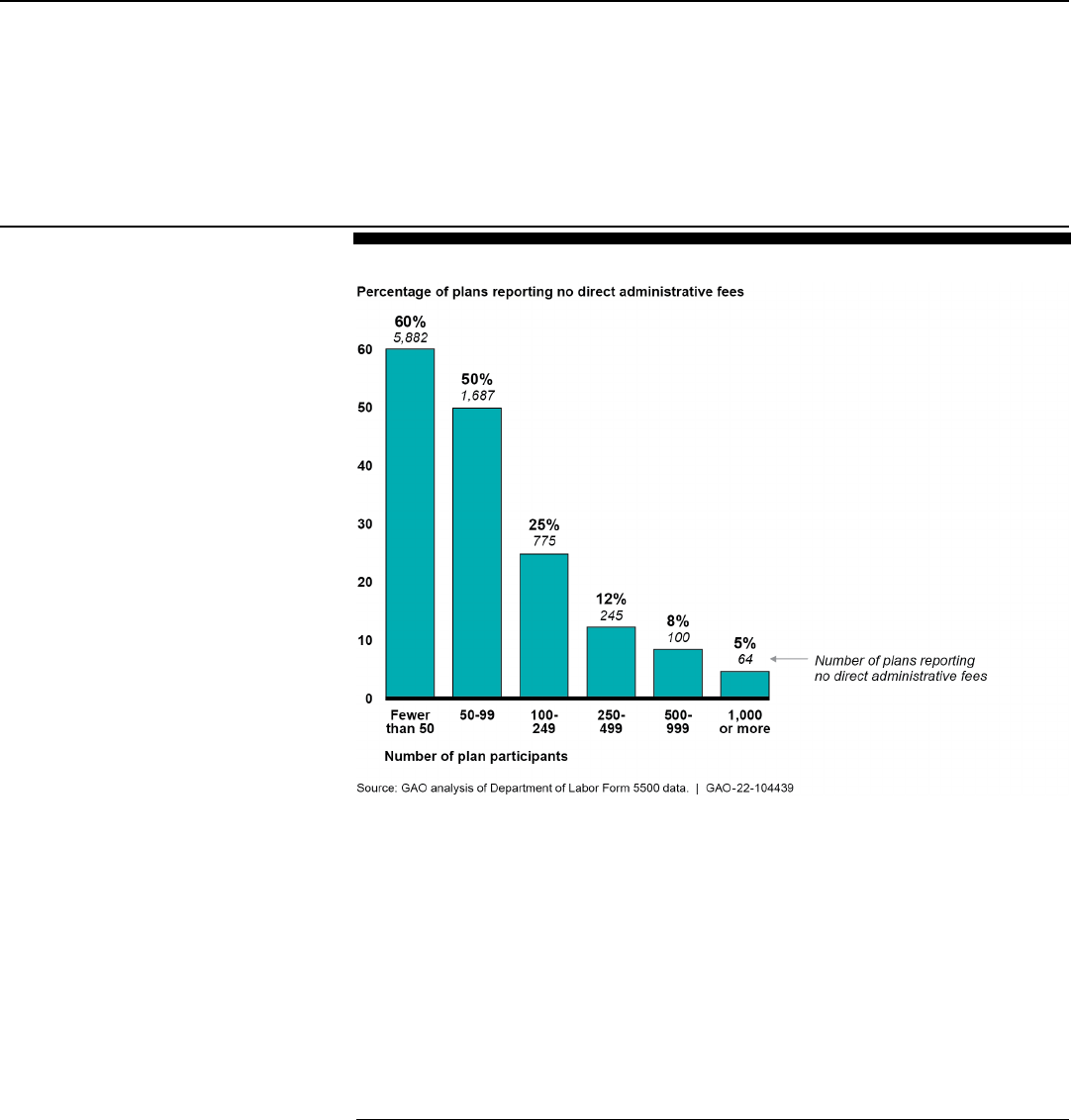

Figure 7: ERISA 403(b) Plans Reporting No Direct Administrative

Fees, 2019 42

Figure 8: Reported Average Direct Fee Amounts as a Percentage

of Assets Paid by 403(b) ERISA Plans for Administrative

Services, by Plan Size in Terms of Number of

Participants, 2019 45

Figure 9: Median Expense Ratios as a Percentage of Assets Paid

by 403(b) Plan Sponsors, by Plan Size in Terms of Total

Assets, from Example Plans Provided by 403(b) Service

Providers 47

Page iii GAO-22-104439 Defined Contribution Plans

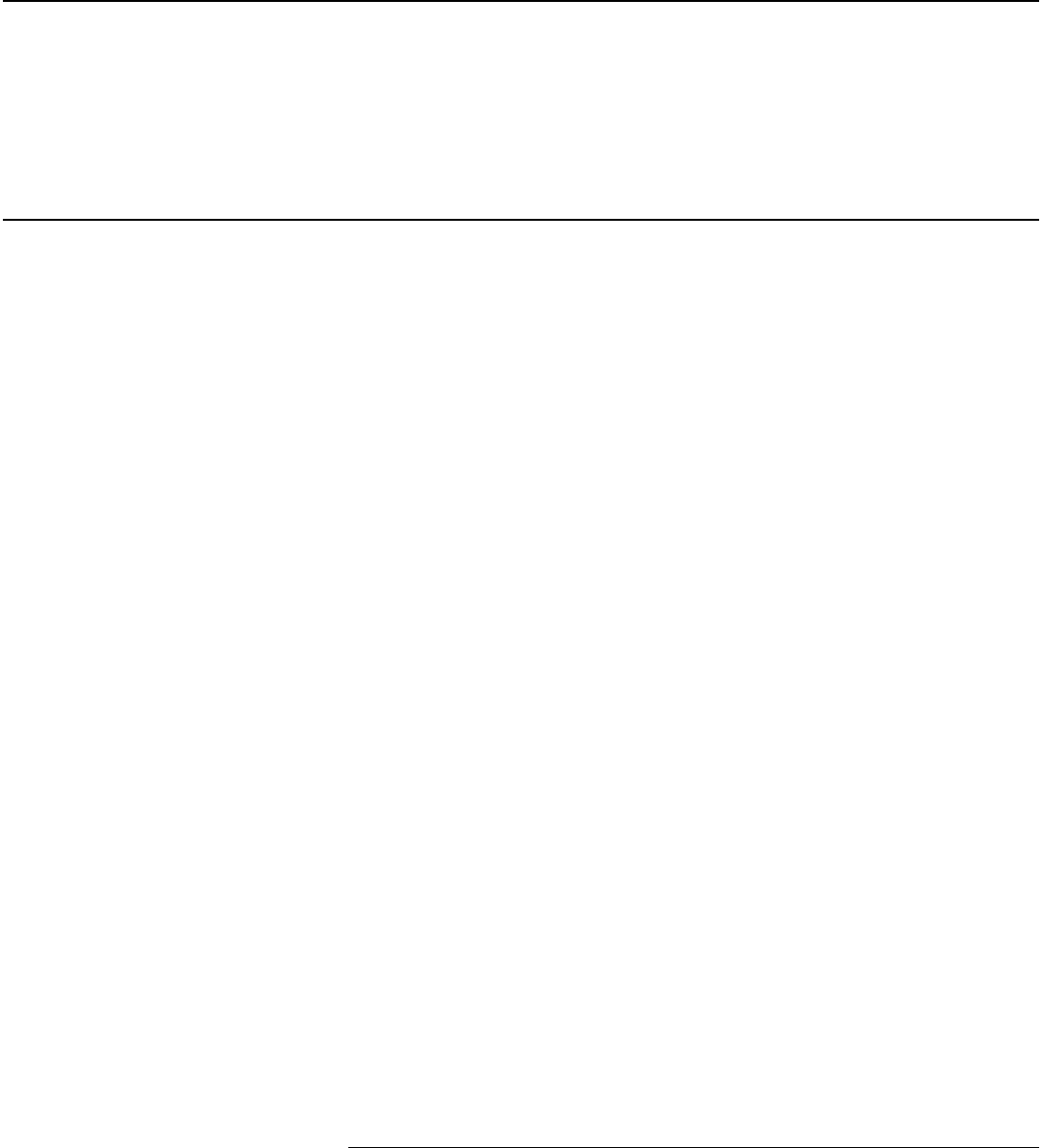

Figure 10: Estimated Percentage of Individuals Who Reported

Having a 403(b) or 401(k) Account as Their Only Plan,

Primary Plan, or Supplemental Plan, 2016 64

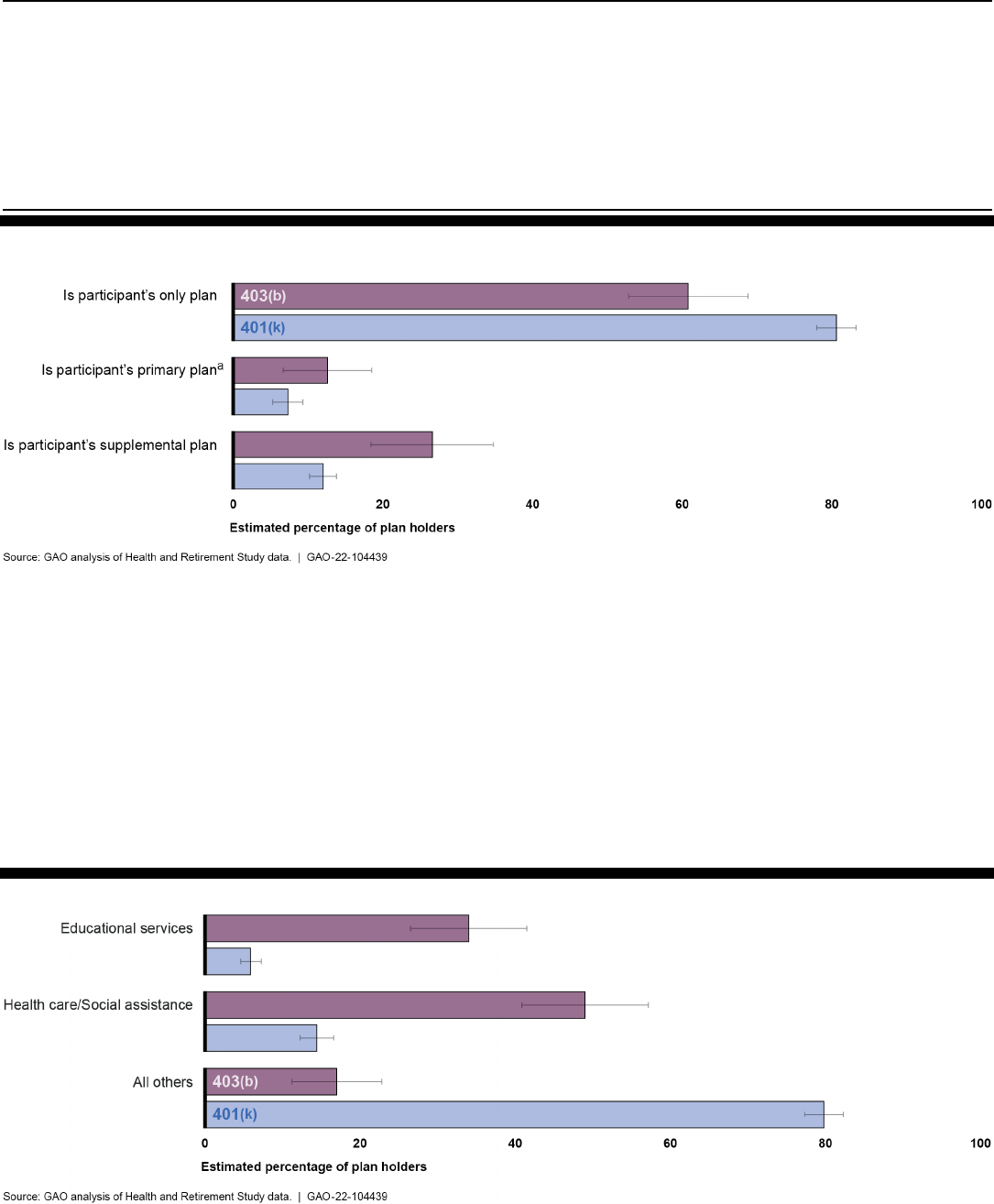

Figure 11: Estimated Percentage of Individuals Who Reported

Having a 403(b) or 401(k) Account, by Employer’s

Sector, 2016 64

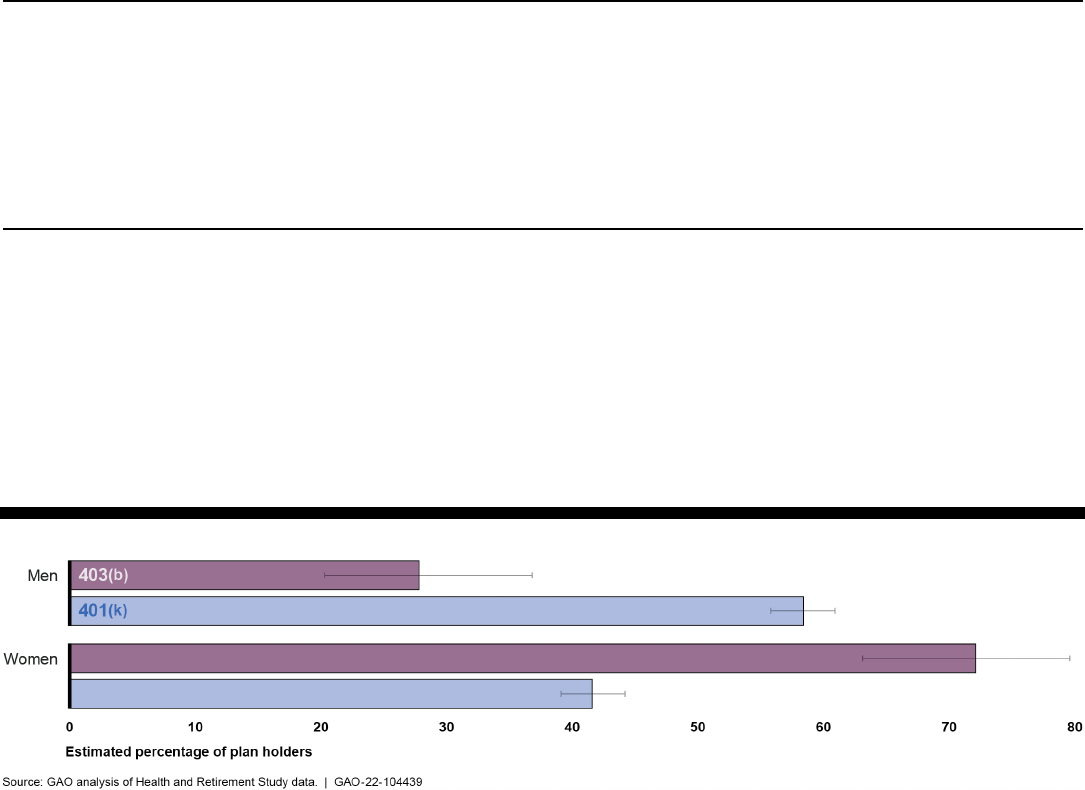

Figure 12: Estimated Percentage of Individuals Who Reported

Having a 403(b) or 401(k) Account, by Gender, 2016 65

Figure 13: Estimated Percentage of Individuals Who Reported

Having a 403(b) or 401(k) Account, by Race, 2016 66

Figure 14: Estimated Percentage of Individuals Who Reported

Having a 403(b) or 401(k) Account, by Age, 2016 66

Figure 15: Estimated Percentage of Individuals Who Reported

Having a 403(b) or 401(k) Account, by Education Level,

2016 67

Figure 16: Estimated Percentage of 403(b) Retirement Accounts’

Respondents Reported Household Assets, Compared to

401(k) Account Holders, 2016 68

Figure 17: Estimated Percentage of 403(b) Retirement Accounts’

Respondents Reported Earnings, Compared to 401(k)

Account Holders, 2016 68

Page iv GAO-22-104439 Defined Contribution Plans

Abbreviations

DOL Department of Labor

EBSA Employee Benefits Security Administration

ERISA Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974, as

amended

HRS Health and Retirement Study

ICI Investment Company Institute

IRC Internal Revenue Code

IRS Internal Revenue Service

NAICS North American Industry Classification System

NTSA National Tax-Deferred Savings Association

TPA third-party administrator

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety

without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain

copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be

necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Page 1 GAO-22-104439 Defined Contribution Plans

441 G St. N.W.

Washington, DC 20548

March 4, 2022

The Honorable Robert C. “Bobby” Scott

Chairman

Committee on Education and Labor

House of Representatives

Dear Chairman Scott:

Millions of teachers and other employees of public schools, universities,

and tax-exempt organizations rely on savings they accumulate in 403(b)

plans to provide income security in retirement. Like 401(k) plans offered

by many private sector employers, 403(b) plans are account-based

defined contribution plans sponsored by employers, and individuals who

participate in the plans make investment decisions and bear the

investment risk.

1

Currently, 403(b) plans are estimated to hold more than

$1 trillion in assets.

2

However, little is known about these plans’

investment options and fee structures—features that can affect how much

participants’ retirement savings will grow.

Certain aspects of 403(b) plans’ regulation differ from 401(k) and other

defined contribution plans in key ways. While 401(k) plans are covered by

the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974, as amended

(ERISA), only some 403(b) plans are covered by ERISA (ERISA plans).

For example, 403(b) plans offered by state or local governments, such as

public school districts or public universities are not covered by ERISA.

1

A defined contribution plan is an employer-sponsored account based retirement plan,

such as a 401(k) plan, that allows individuals to accumulate tax-advantaged retirement

savings in an individual account based on employee and/or employer contributions, and

the investment returns (gains and losses) earned on the account. While 401(k) plans can

be offered by private sector employers, 403(b) plans can be offered by private sector tax-

exempt employers or certain public school employers. A defined benefit plan is an

employer-sponsored retirement plan that typically provides a lifelong stream of payments

beginning at retirement, based on a formula specified in the plan that takes into account

factors such as the employee’s salary, years of service, and age at retirement. See GAO,

The Nation’s Retirement System: A Comprehensive Re-evaluation Is Needed to Better

Promote Future Retirement Security, GAO-18-111SP (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 18, 2017).

2

See Investment Company Institute, The U.S. Retirement Market, Third Quarter 2021. ICI

is an association representing regulated funds globally, including mutual funds, in the

United States, and similar funds offered to investors in jurisdictions worldwide. By

contrast, the Department of Labor has estimated that in 2019 there were 91 million

participants and $6.2 trillion in 401(k) plans. See the Department of Labor, Private

Pension Plan Bulletin: Abstract of 2019 Form 5500 Annual Reports (September 2021).

Letter

Page 2 GAO-22-104439 Defined Contribution Plans

ERISA establishes minimum standards and requirements intended to

protect plan participants and beneficiaries in most private sector

employer-sponsored retirement plans. 403(b) plans not covered by

ERISA (non-ERISA plans) are not subject to ERISA’s fiduciary

requirements, although these plans may be subject to state consumer

protection laws or other state-specific fiduciary laws.

This report addresses (1) the number and characteristics of ERISA and

non-ERISA 403(b) plans; and (2) fees charged to 403(b) plan

participants.

To describe the number and characteristics of 403(b) plans, we first

analyzed plan-level characteristics—including the number of participants,

the amount of plan assets, and available information on plan investment

offerings for ERISA 403(b) plans from 2010 through 2019, the most

recent year for which data are available—from the Department of Labor

(DOL)’s Form 5500 Private Pension Plan data. DOL’s Form 5500

Database captures information from ERISA-covered retirement plans—

including ERISA 403(b) plans—on the number of plan participants, assets

held by the plan, and fees paid by the plan, among other things. To

identify 403(b) plans, we used self-reported plan type information as well

as a string search on the name of the plan. For the purposes of this

report, we generally defined the largest plans as those with $1 billion or

more in assets, unless otherwise indicated. We defined small plans as

those with either 99 or fewer participants, $1 million or less in assets, or

as otherwise indicated. We also, where feasible, compared our results for

403(b) plans with those of 401(k) plans, which according to DOL data are

the largest type of defined contribution plan by assets and number of

participants. We reviewed documentation about how Form 5500 data are

collected and conducted electronic data tests for completeness and

accuracy, and contacted knowledgeable officials with specific questions

about the data. We determined that the data for the variables we used

were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of our reporting objectives.

Second, we analyzed individual-level data from the Health and

Retirement Study (HRS) of respondents over age 50 who reported having

a retirement benefit in ERISA or non-ERISA 403(b) plans from 2010

through 2016—the most recent year for which complete weighted data

are available—including their household assets, education, and the

Page 3 GAO-22-104439 Defined Contribution Plans

industry in which they are employed.

3

We reviewed technical

documentation, conducted electronic data tests for completeness and

accuracy, and contacted knowledgeable experts with specific questions

about HRS data. We determined that the data for the variables we used

were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of reporting on the estimated

number of individuals who reported participating in an ERISA or non-

ERISA 403(b) retirement plan,

4

the extent to which the 403(b) plan was

the participant’s primary retirement plan or supplemental retirement plan,

and the selected demographic characteristics of these individuals. In

addition, we examined available data on ERISA and non-ERISA 403(b)

plans from industry publications and third-party research. We also

included relevant information obtained by our surveys, as described

below.

To provide available information on what is known about fees charged to

403(b) plan participants, especially those in non-ERISA plans, we

surveyed five selected key populations: four sets of 403(b) plan sponsors,

as well as one set of 403(b) service providers.

5

We received 26 survey

responses from plan sponsors and 19 survey responses from service

providers, for a combined total of 45 survey responses overall. We

conducted the surveys from May to November 2021 and obtained the

following response rate from our populations:

3

Since HRS respondents are asked only about the retirement accounts at their current

job, the survey may not capture information regarding respondents’ retirement accounts

from previous jobs or from retirees.

4

This question is only asked of those individuals who are currently employed; therefore,

our results reflect the estimated population of current employees over age 50 and their

spouses who have a retirement benefit, and does not reflect the more general population

of currently employed or retired individuals aged 50 or older.

5

Our plan sponsor survey respondents comprised five ERISA and 21 non-ERISA plans.

For more information on how we identified 403(b) plans and service providers to survey

and our response rates, see appendix I.

Page 4 GAO-22-104439 Defined Contribution Plans

• Nine of 14 state-sponsored 403(b) plans identified and compiled in a

list published by the National Tax-Deferred Savings Association

(NTSA);

6

• Five of 11 of the largest 403(b) plan sponsors, as identified by

Pensions and Investments;

7

• Five of 15 small 403(b) plan sponsors, as identified by a random

sample of plans from DOL’s 5500 filings of 99 or fewer participants

and plans from the Form 5500 filings with $1 million or less in total

assets;

8

• Seven of 26 K-12 school districts, including five of the 10 largest

districts as measured by the number of students in the district and

selected by a certainty sample; as well as one of the 20 districts

randomly selected out of the remaining districts in 50 states plus the

District of Columbia, as measured by number of students in the district

by the National Center for Education Statistics; as well as one other

provider of services to a set of multiple school districts within one

certain county that we included and counted as a school district; and

• Twelve of 18 companies who serve as major vendors or record

keepers, or third-party administrators, as identified by Pensions and

Investments or as identified as key 403(b) plan vendors or record

keepers in our interviews with experts. We also included seven other

6

The National Tax-Deferred Savings Association is an industry group whose members

include 403(b) and 457 plan sponsors and service providers. Three states on NTSA’s list

have discontinued their plans in the last 3 years. One of the state’s that discontinued its

plan completed a survey, and we included this response in our analysis. We excluded the

other two states from our count of those surveyed. In addition, two additional ongoing

state-sponsored plans, which we included in our count of those surveyed, did not respond

to our survey.

7

Pensions and Investments is a news publication written for pension, portfolio, and

investment management executives in the institutional investment market. Each year it

publishes a list of the largest 403(b) plan sponsors. We examined its 2019, 2020, and

2021 lists; when combined, it totaled 11 distinct plan sponsors. We also excluded one

sponsor that appeared on the list of state sponsored plans to avoid double counting.

8

We initially randomly selected 20 small plans—10 with 99 or fewer participants and 10

with $1 million or less in total assets according to Form 5500 data—however, we excluded

six for various reasons (for example, plans that had apparently been terminated since the

2018 Form 5500 filing), as detailed in appendix I. We obtained responses from 5 of the 15

small plans we surveyed.

Page 5 GAO-22-104439 Defined Contribution Plans

respondents, who operate as record keepers, third-party

administrators, vendors, or consultants for 403(b) plans.

9

We received 26 survey responses from plan sponsors and 19 survey

responses from service providers, for a combined total of 45 survey

responses overall. In addition, we analyzed available information on fees

from DOL’s Form 5500 data and conducted semi-structured interviews of

stakeholders and experts. These stakeholders and experts included

representatives of industry associations, research organizations, and

service providers to 403(b) plans we identified as being knowledgeable

about 403(b) plans based on their published research or other

documentation or based on referrals from other organizations we

interviewed. For more detailed information on our scope and

methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from July 2020 through March 2022

in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards.

Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain

sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our

findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that

the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and

conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Retirement plans established under 26 U.S.C. § 403(b) are commonly

referred to as 403(b) plans.

10

These plans are often sponsored by public

schools and certain tax-exempt organizations. A 403(b) plan allows

participants—including employees of tax-exempt organizations;

11

employees of public schools, including K-12 schools, public colleges, and

universities; and certain ministers—to defer a portion of their salaries to

be held in the participants’ individual account within the plan. Employers

may also contribute to the plan for employees. After regulations became

9

For the purposes of this report, we refer to all such record keepers, third-party

administrators, vendors, and others who provide administrative services to a plan as

403(b) service providers.

10

For purposes of this report, references to 403(b) plans include annuity arrangements

under Internal Revenue Code (IRC) section 403(b)(1) and custodial account

arrangements under IRC section 403(b)(7). 403(b) plans also include retirement income

accounts maintained for employees of certain church-affiliated organizations under IRC

403(b)(9).

11

See 26 U.S.C. § 403(b)(1)(A)(i) referencing “an employer described in section 501(c)(3)

which is exempt from tax under section 501(a).” References in this report to “tax-exempt

organizations” are to these organizations described in 26 U.S.C. § 501(c)(3).

Background

Page 6 GAO-22-104439 Defined Contribution Plans

effective in 2009, 403(b) plans generally transitioned from primarily

individual employee-controlled accounts to more formally developed

plans.

12

Some 403(b) plans are a participant’s primary retirement

account, in that the 403(b) account is the participant’s sole retirement

savings account or has the highest balance among the individual’s other

defined contribution retirement accounts and the individual did not have a

defined benefit plan.

13

Other plans are supplemental, in that the 403(b)

account is not the participant’s primary source of retirement savings.

Sponsors of 403(b) plans may hire a variety of service providers to handle

one or more aspects of managing the plan, including the following:

• Plan administrators: Plan administrators run the 403(b) plan on a day-

to-day basis, assuring that the plans comply with relevant

requirements concerning eligibility and participation, and conducting

periodic reviews of the plan and its assets, among other things. Plan

sponsors can perform some or even all of these functions themselves,

but may hire a third-party administrator for some or all of the above

functions. Administrators may also hire investment advisors to assist

them with selecting investment options.

• Vendors: Vendors are entities that provide investment options—

generally either annuity contracts or mutual funds.

• Record keepers: Record keepers are generally in charge of

processing participants’ enrollments in plans, tracking contribution

types and participants’ investments, providing plan sponsors and

participants with account statements and other information to help

participants manage their accounts.

12

See BrightScope and Investment Company Institute (ICI), The BrightScope/ICI Defined

Contribution Plan Profile: A Close Look at ERISA 403(b) Plans, 2017 (January 2021).

Specifically, as of 2009, 403(b) plans are required to have a written program that

describes eligibility, benefits, and investments, among other things. 26 CFR Parts 1, 31,

54 and 602. These regulations became effective Jan. 1, 2009.

13

For the purposes of our report, we defined sole, primary, and supplemental based on

the reported balances of a participant’s various defined contribution plans in the HRS

analysis and based off the number of participants in any other defined contribution plans

in the Form 5500 analysis. If a plan sponsor offered or a survey respondent had a defined

benefit plan, we defined the 403(b) plan as supplemental in accordance with DOL’s

general practice.

403(b) Plan Sponsors

Contract with Service

Providers

Page 7 GAO-22-104439 Defined Contribution Plans

Investment options are generally more limited for 403(b) plans than they

are for other qualified retirement plans.

14

Amounts contributed into 403(b)

accounts may only be invested in annuity contracts or custodial accounts

that hold mutual funds.

15

Thus, investments in individual stocks and

bonds, bank savings accounts, individual treasury notes or bills, or similar

types of investments traditionally available under employer-sponsored

retirement plans are not permitted for 403(b) accounts.

16

Further, 403(b)

plan assets invested in annuity contracts may be invested in fixed or

variable annuities.

17

With a fixed annuity, participants are guaranteed a

specified rate of return on their contributions.

18

With a variable annuity,

participants can direct their plan contributions to different investment

14

A qualified retirement plan is a retirement plan that meets certain IRC requirements.

Generally, under a qualified plan, employers are able to take an income tax deduction for

their contributions to the plan and participants are able to defer income taxation on their

contributions to the plan, including any investment gains attributable to those

contributions, until distribution.

15

See 26 U.S.C. § 403(b)(1) & (7). Retirement income accounts provided by churches are

able to include investment options other than annuity contracts and mutual funds. See 26

U.S.C. § 403(b)(9). These accounts are typically referred to as church plans. Church plans

are plans that (1) have as their principal purpose or function the administration or funding

of retirement or welfare benefits for employees of a church or convention or association of

churches and (2) are controlled by or associated with a church or convention or

association of churches. See 29 U.S.C. § 1002(33)(A)-(C). However, church plans can

also elect to be subject to ERISA and its heightened requirements.

16

In contrast, 401(k) plans can offer a wider range of investment products. In addition,

401(k) plans are allowed to offer investment options through a collective investment trust.

26 U.S.C. § 401(k).

17

Owners of tax-deferred annuities pay taxes only when they make withdrawals, take a

lump sum, or begin receiving income from the account. At that point, the money received

is generally taxed at the participant’s ordinary income tax rate unless there is an

unpermitted early withdrawal (which would subject the amount to additional taxation).

18

There are also annuities that specify the amount of guaranteed monthly lifetime income

(income annuities) rather than a rate of return.

Permitted Investments in

403(b) Plans

Page 8 GAO-22-104439 Defined Contribution Plans

options, usually mutual funds, to be held in their annuity account.

19

For

fixed and variable annuities, the amount of money participants receive in

retirement will vary depending on various factors, which can include how

much participants contribute, the type of investment options offered by

the plan and the options selected by participants, the rate of return on the

investments, and plan fees and expenses.

20

Plan service providers charge various types of fees for different services.

Administrative fees can cover services such as record keeping for the

plan and communications with participants; as well as services incurred

on an individual participant basis, such as fees for processing a

participant loan or distribution. Investment-related fees are associated

with buying, selling, and managing investments, but they can also include

embedded costs of plan administration. Asset-based investment fees, a

type of investment-related fee, are typically the largest fees a participant

will pay. Often called the expense ratio, this fee expresses the percentage

of assets under management that is deducted each year for fund

expenses. For the purposes of this report, we surveyed plan sponsors

and 403(b) service providers regarding the several types of fees that

could be charged to 403(b) plan sponsors or participants, as described in

table 1.

Table 1: Examples of Administrative and Investment Fees That May Be Charged in 403(b) Plans

Fee type

Description

Record keeping and administrative services

Tracking individual contributions and reporting returns

Consulting and investment advice

Helping the plan sponsor select funds for the plan and monitor investments

Other administrative services

Trustee, legal, and audit services

19

A variable annuity has two phases: an accumulation phase and a payout phase. During

the accumulation phase, individuals can typically transfer their money from one

investment option to another without paying tax on their investment income and gains,

although they may be charged by the insurance company for transfers. At the beginning of

the payout phase, they may receive their purchase payments plus investment income and

gains (if any) as a lump-sum payment, or they may choose to receive them as a stream of

payments at regular intervals (generally monthly) for the remainder of their life (or the life

of their spouse or other beneficiary); there can be other withdrawal options as well.

Indexed annuities are a particular type of annuity that combines features of securities and

insurance products. In this type of annuity, an insurance company promises that

participants’ contributions will grow at a rate of return based on a market index, such as

the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index. For more information see Securities and Exchange

Commission, Variable Annuities: What You Should Know, SEC Pub. 011 (September

2007).

20

Annuities are regulated by state insurance commissions.

Types of Fees That 403(b)

Plan Services Providers

Charge

Page 9 GAO-22-104439 Defined Contribution Plans

Fee type

Description

Investment management

Managing investment fund assets (fees are generally stated as a percentage of the

amount of assets involved)

Marketing and distribution

a

Commissions to brokers and other salespersons, for expenses such as advertising

and other costs of promoting the fund to investors

Trading/transaction costs

Commissions and other fees associated with an investment manager’s buying and

selling of securities within a particular investment vehicle

Wrap fees

Aggregate fees that encompass multiple components, such as investment

management fees, surrender fees,

b

and administrative expense fees.

Source: GAO review of documentation. I GAO-22-104439

a

Also known as 12(b)(1) fees, named for the Securities and Exchange Commission rule that

authorizes a mutual fund to charge them. See 17 C.F.R. § 270.12b-1.

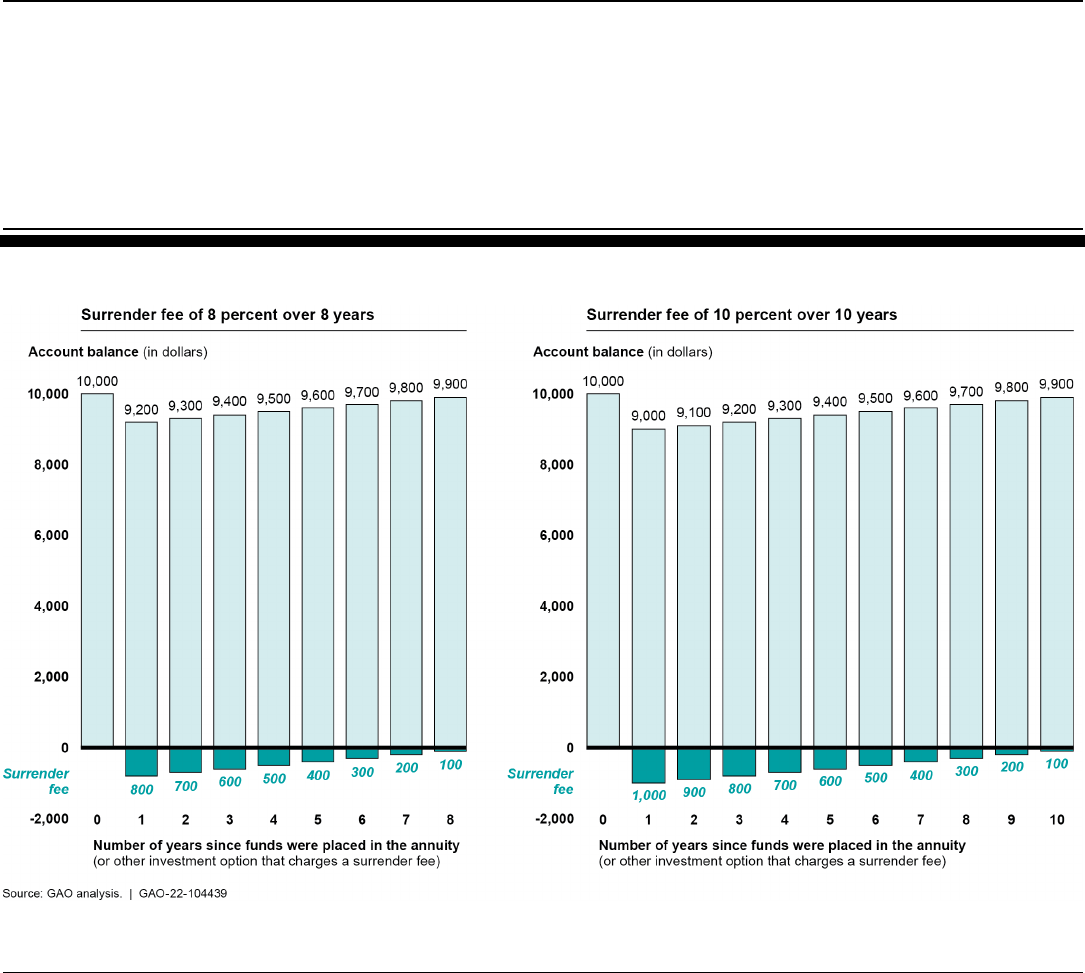

b

Surrender fees are fees for selling or withdrawing money from an investment before a set period of

time has passed. Surrender fees are often phased out over a period of years, and vary by specific

investment options, but generally involve a reduction of 1 to 2 percent per year until the surrender fee

is no longer charged. For example, an annuity with a 10-year, 10 percent surrender fee would charge

10 percent the first year to move money out of the annuity, 9 percent the second year, and so on,

until there is no surrender fee after the 10-year period.

Most private sector employer-sponsored retirement plans are subject to

ERISA requirements intended to protect the interests of plan participants.

Specifically, among other things,

• plan fiduciaries are required to discharge their duties solely in the

interest of participants and beneficiaries for the exclusive purpose of

providing benefits and defraying reasonable expenses of plan

administration and with the care, skill, prudence, and diligence under

the circumstances then prevailing of a prudent person acting in a like

capacity and familiar with such matters;

• plan fiduciaries are generally prohibited from entering into certain

transactions with the plan, such as by dealing with plan assets in the

fiduciary’s own interest;

• plan administrators are required to provide participants with a

summary plan description outlining their benefits, rights, and

responsibilities under the plan, and notify participants of any material

changes; and

• plan administrators are required to file annual reports including the

Form 5500 and applicable schedules and attachments that collect

information on particular plan aspects. This includes information on

plan investments, fees paid to service providers, the plan’s financial

condition, annual participant contributions, and the number of

participants.

DOL’s Employee Benefits Security Administration’s (EBSA) role includes

overseeing the administration of 403(b) retirement plans and the fiduciary

Regulation and Oversight

of 403(b) Plans

Page 10 GAO-22-104439 Defined Contribution Plans

protections of such plans subject to ERISA. EBSA’s mission is ensuring

the security of retirement, health, and other workplace-related benefits of

American workers and their families.

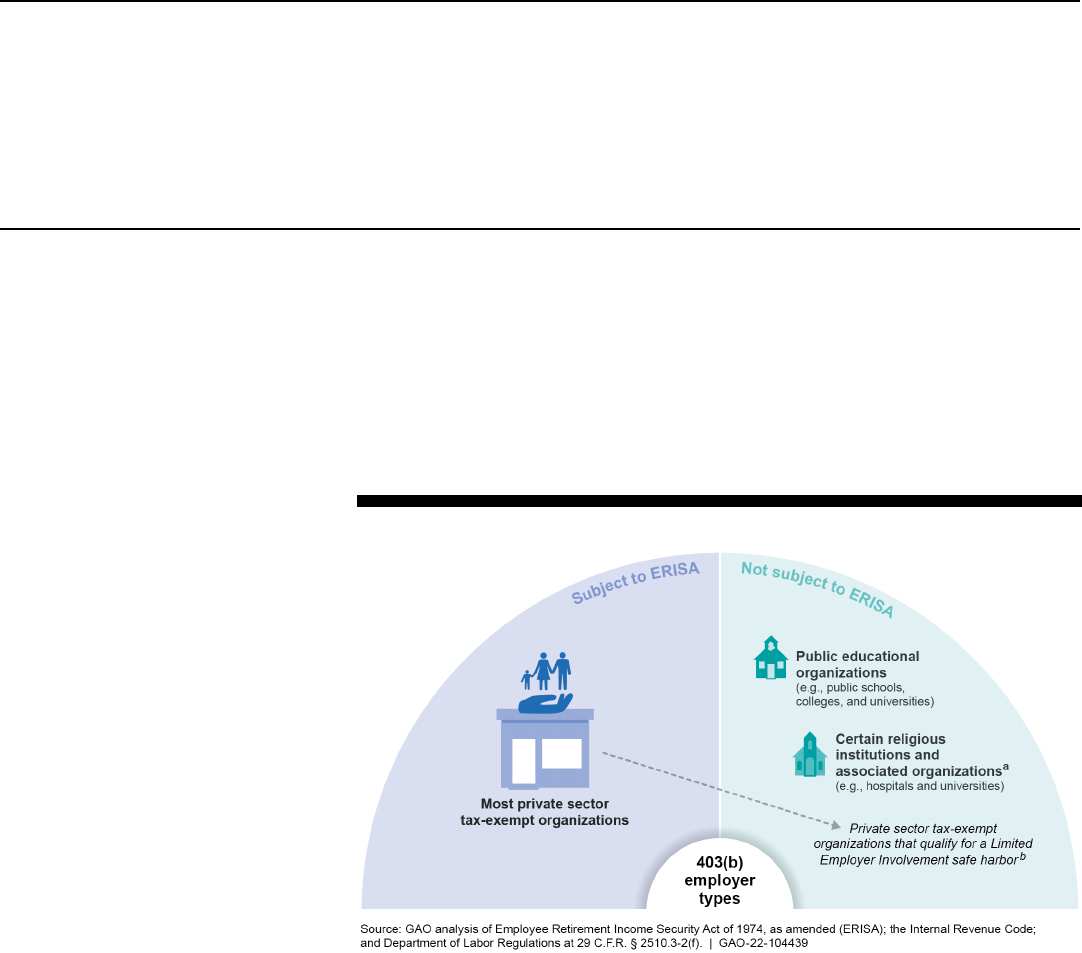

Not all 403(b) plans are subject to ERISA. The type of employer and, in

certain cases, the extent to which the employer is involved in the plan can

determine whether the plan is subject to ERISA. For example, plans

sponsored by public schools are generally exempt from ERISA, as shown

in figure 1.

Figure 1: The Type of Employer and Extent of the Employer’s Involvement in the

Plan Can Determine Whether a 403(b) Plan Is Subject to ERISA

a

Retirement plans offered by religious organizations are referred to as church plans. Church plans are

plans that (1) have as their principal purpose or function the administration or funding of retirement or

welfare benefits for employees of a church or convention or association of churches and (2) are

controlled by or associated with a church or convention or association of churches. See 29 U.S.C.

§ 1002(33)(A)-(C).

b

In certain circumstances, a 403(b) plan that meets certain criteria may qualify for a safe harbor

exemption and as such not be subject to ERISA. In order to fall under what we will refer to in this

report as the “Limited Employer Involvement” safe harbor, employer involvement in the plan must be

limited. See 29 C.F.R. § 2510.3-2(f); see also Department of Labor (DOL) Field Assistance Bulletin

2007-02 (July 24, 2007).

More specifically, in certain circumstances, a 403(b) plan that meets

certain criteria may qualify for a safe harbor exemption and as such not

be subject to ERISA. In order to fall under what we refer to in this report

as the “Limited Employer Involvement safe harbor,” employer involvement

Page 11 GAO-22-104439 Defined Contribution Plans

in the plan must be limited as described in DOL regulations.

21

For

example, to qualify for the safe harbor, employers are not allowed to

contribute to the plan or make discretionary determinations in

administering the plan, such as processing distributions, authorizing plan-

to-plan transfers, or making determinations of eligibility for loans or

hardship distributions; and participant involvement in the plan must be

voluntary (i.e., participants elect to participate in the plan, instead of being

automatically enrolled by the employer).

In addition to DOL’s EBSA, a number of federal and state agencies have

a role in regulating and overseeing 403(b) plans or investment options

provided to participants. Specifically:

• Internal Revenue Service (IRS) administers the Internal Revenue

Code (IRC), including provisions related to 403(b) retirement plans.

Among its responsibilities, IRS ensures that taxpayers comply with the

tax law and develops monitoring mechanisms to enforce retirement

plans’ compliance with IRC requirements for tax qualification.

• The Securities and Exchange Commission administers and enforces

federal securities laws and regulations that govern the sales and

marketing of variable annuities, mutual funds, and certain other

investment products in part through Regulation Best Interest.

22

This

regulation establishes a standard of conduct for brokers or dealers

who provide recommendations regarding securities, investment

strategies for securities, and other investment products used to fund

403(b) plans.

• State Insurance Commissioners administer and enforce state

regulations regarding fixed, variable, and indexed annuities that may

be offered in 403(b) plans. In addition, State Insurance

Commissioners may be in charge of administering and enforcing

individual state laws for 403(b) plans sponsored by a state,

subdivision, or instrumentality thereof covering employees of public-

supported schools.

The Form 5500 and a series of supplemental forms known as “schedules”

are the primary source for the federal government to collect information

regarding most private sector employer-sponsored retirement plans, and

21

See 29 C.F.R. § 2510.3-2(f); see also Department of Labor Field Assistance Bulletin

2007-02 (July 24, 2007).

22

17 C.F.R. § 240.15l-1.

Reporting Requirements

for ERISA 403(b) Plans

Page 12 GAO-22-104439 Defined Contribution Plans

were jointly developed by DOL, IRS, and the Pension Benefit Guaranty

Corporation.

23

The Form 5500 collects information from each retirement

plan on the number of plan participants, assets held and benefits paid by

the plan, and administrative fees paid by the plan, among other things.

The Form 5500 is part of ERISA’s overall reporting and disclosure

framework, which is intended to ensure that retirement plans, including

those 403(b) plans subject to ERISA, are operated and managed

according to certain prescribed standards and that participants,

beneficiaries, and federal agencies are provided or have access to

sufficient information to protect the rights and benefits of participants and

beneficiaries. EBSA uses the Form 5500 to monitor and enforce the

requirements of title I of ERISA. IRS uses the form to monitor and enforce

standards of compliance with the tax code, which relate to, among other

things, how employees become eligible to participate in benefit plans, and

how they become eligible to earn rights to benefits.

All 403(b) plans that are subject to ERISA are required to file a Form

5500. Plans with 100 or more participants at the start of a calendar year

are generally required to file a Form 5500, and have their financial

statements audited by an independent qualified public accountant and

submitted to DOL when filing Form 5500. Plans with fewer than 100

participants may generally file a shorter form called the Form 5500-SF

and are generally exempt from the independent qualified public

accountant audit requirement.

Form 5500 Data Do Not Represent All 403(b) Plans

Form 5500 data do not represent all 403(b) plans because not all plans are subject to

the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974, as amended (ERISA), including

its reporting requirements. ERISA does not cover governmental plans, certain church

plans, and 403(b) annuities and custodial accounts that meet the conditions of the safe

harbor under 29 CFR 2510.3-2(f), which is based on limited employer involvement.

Source: GAO analysis of 29 C.F.R. 2510.3-2(f). l GAO-22-104439

DOL and other federal agencies collect information on fees in several

different supplemental schedules attached to Form 5500 for retirement

plans covered by ERISA, including 403(b) plans. These include Schedule

C, in which sponsors of large retirement plans (including 403(b) plans)

are required to disclose both direct and indirect compensation paid to

service providers in connection with their services to the plan that

23

The Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation serves as trustee for certain terminated

pension plans that are underfunded and unable to pay guaranteed benefits.

Page 13 GAO-22-104439 Defined Contribution Plans

exceeds a $5,000 threshold; and include Schedule H, in which sponsors

provide financial information, including a series of line items for

administrative expenses paid directly by the plan to service providers.

Total assets in both ERISA and non-ERISA plans increased from 2010 to

2020, and the majority of participants were in the education and health

care sectors, as described below.

Assets in plan. The amount of assets held by participants in 403(b)

plans has grown considerably since 2010, according to available data.

Data from the Investment Company Institute (ICI) quarterly reports shows

total (ERISA and non-ERISA) 403(b) plan assets grew from $851 billion in

2010 to more than $1.1 trillion in 2020, driven by an increase in ERISA

plans.

24

According to our analysis of available data, the ERISA plan share

of total assets increased from 37 percent to 57 percent from 2010 to

2019.

25

According to our analysis of DOL’s Form 5500 data, the value of

ERISA 403(b) plan assets increased from $313 billion in 2010 to $617

billion in 2019, the most recent year for which these data are available.

26

Although no comprehensive data exist on non-ERISA 403(b) plans, which

are not subject to federal reporting requirements, using ICI total 403(b)

24

We applied an inflation adjustment to present ICI’s nominal dollar estimates in 2019 real

dollars. See Investment Company Institute, The U.S. Retirement Market, Third Quarter

2021.

25

These data represent our analysis of ICI’s estimates of the total (ERISA and non-

ERISA) 403(b) market as detailed in its quarterly retirement total market reports, and our

analysis of Form 5500 data, and calculating the annual ERISA percentage of assets.

26

All analyses of Form 5500 data are presented in 2019 adjusted dollars.

Available Data Show

That Total 403(b) Plan

Assets Have

Increased since 2010

and Other

Characteristics, such

as Plan Participation,

Varied Among Plans

Total 403(b) Plan Assets

Increased from 2010 to

2020, Driven by an

Increase in ERISA Plan

Assets, Which Are

Concentrated in the

Education and Health

Care Sectors

Page 14 GAO-22-104439 Defined Contribution Plans

plan asset estimates and GAO’s analysis of ERISA plan assets, we

estimated that the amount of non-ERISA plan assets decreased from

$538 billion in 2010 to $469 billion in 2019.

27

This represented a decrease

in the share of non-ERISA assets from 63 percent to 43 percent during

the time period.

Sector. Participants in ERISA 403(b) plans were concentrated in the

education or health care sectors, but the number of plans was similar

across sectors. Specifically, our analysis of Form 5500 data found that 56

percent of ERISA plan participants were in health care and another 27

percent of participants were in education in 2019.

28

On a plan basis, our

analysis of DOL’s Form 5500 data for 2019 found a fairly even distribution

across the number of ERISA plans in the education, health care, social

assistance, and religious sectors.

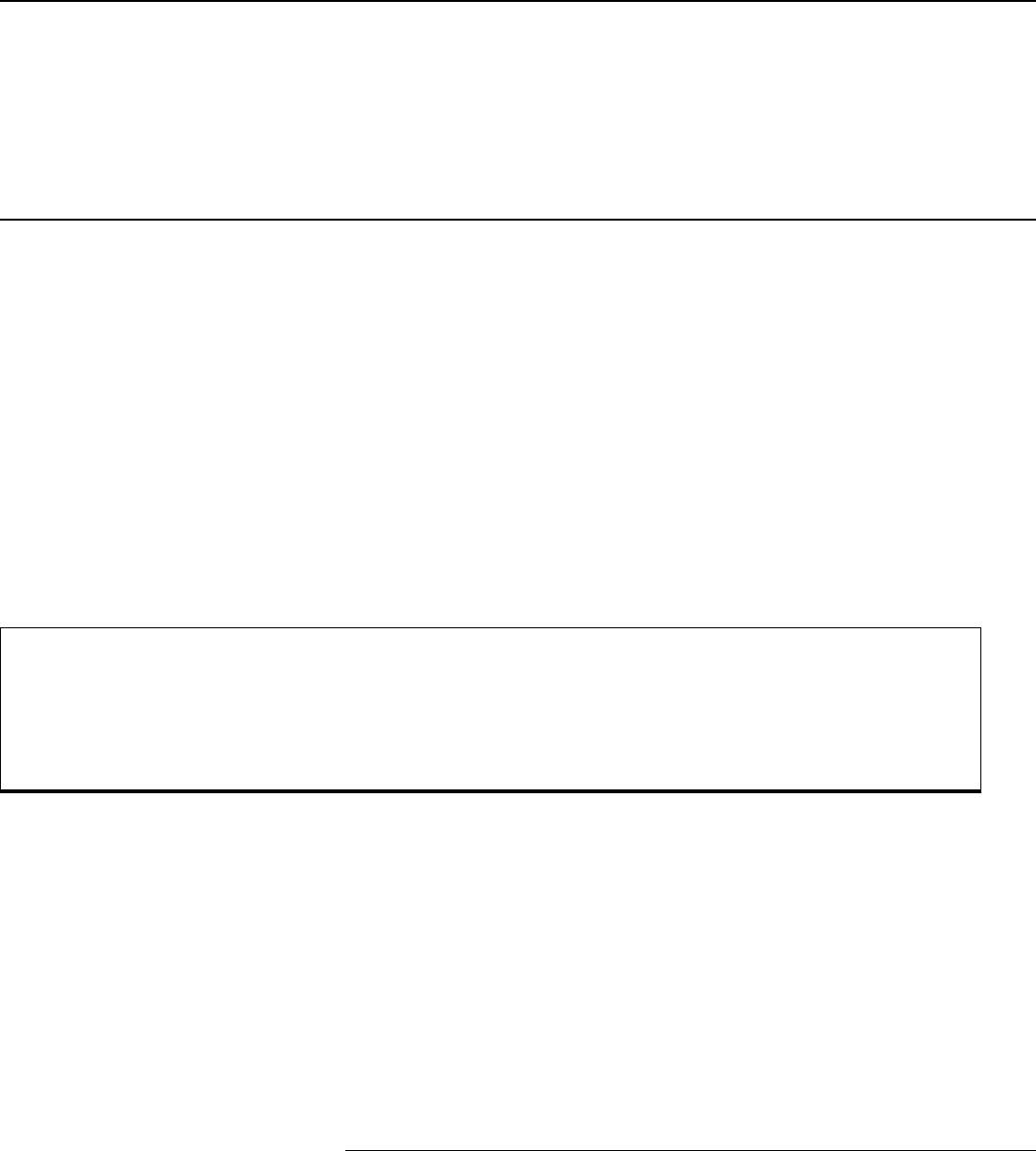

Number of plans. The number of ERISA 403(b) plans has declined since

2010, while the trend in the number of non-ERISA plans is unknown.

According to our analysis of DOL’s Form 5500 data, the number of ERISA

403(b) plans declined from 21,900 in 2010 to 20,900 in 2019, a decrease

of 5 percent.

29

Experts from a large nonpartisan retirement research

entity, as well as a retirement plan sponsor association, told us that the

health care sector has seen significant merger and acquisition activity,

which may, in part, be driving the decline in the number of ERISA plans,

given that many ERISA 403(b) plans are health care-related companies

and hospitals. Similarly, our analysis of Form 5500 data found that the

health care sector experienced the largest decline in the number of

27

Non-ERISA asset estimates are based on ICI’s estimates of annual (ERISA and non-

ERISA) total 403(b) market assets, less our ERISA asset values as determined through

our analysis of Form 5500 data. We applied an inflation adjustment to ICI’s nominal dollar

estimates to present in 2019 real dollars.

28

Plan sponsors report the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) code

corresponding to their principal business activity on the form 5500. We categorized as

follows: educational services including schools, colleges, & universities, business code

611000; health care, business codes from 621111 to 623000; social assistance, business

codes from 624100 to 624410; religious and similar (includes religions, grant making,

civic, professional, and similar organizations), business code 8130000; all other – all other

NAICS codes. In addition, our analysis of HRS data—which covers ERISA and non-

ERISA 403(b) plans—found similar results, and also found that a higher percentage of

403(b) participants were employed in the education or healthcare and social assistance

sectors, compared to 401(k) retirement account holders. See appendix II for detailed

results of our HRS analysis.

29

BrightScope/ICI’s annual reports on 403(b)s published from 2016 to 2021 and covering

2012 to 2017 show a similar trend in terms of decreasing number of ERISA plans from

2012 to 2017, and increasing number of participants and plan assets.

Page 15 GAO-22-104439 Defined Contribution Plans

ERISA 403(b) plans, with a 10.4 percent decrease from 2010 to 2019,

and had the largest increase in inflation-adjusted total 403(b) assets, an

increase of 140 percent between 2010 and 2019. Figure 2 shows the

decline in number of plans, by sector, and the increase in plan assets, by

sector.

Figure 2: Number of 403(b) ERISA Plans and Value of ERISA Plans’ Assets, by Sector, 2010-2019

Note: ERISA refers to the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974, as amended. Plan

sponsors report the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) code corresponding to

their principal business activity on the form 5500. We categorized as follows: education, including

schools, colleges, and universities, business code 611000; health care, business codes from 621111

to 623000; social service, business codes from 624100 to 624410; religious and similar (includes

religions, grant making, civic, professional, and similar organizations), business code 8130000; other–

all other NAICS codes.

Information on the total number of non-ERISA plans, which may be

sponsored by states, localities, school districts, or religious organizations,

among others, was not available. At the state-level, an industry group

reported that, as of August 2020, 16 states sponsored non-ERISA 403(b)

state-wide plans for certain public school workers. However, three states

from this list told us they had discontinued their state-sponsored 403(b)

plans.

Number of participants. Although the number of 403(b) ERISA plans

decreased from 2010 to 2019, our analysis of Form 5500 data found that

the number of participants in these plans grew from about 7.1 million to

Page 16 GAO-22-104439 Defined Contribution Plans

9.9 million over the same time period, an increase of 39 percent.

30

In

addition, our analysis of data from the Health and Retirement Study

(HRS), a nationally representative survey of respondents who are over

age 50, indicates that the number of individuals who reported having an

ERISA or non-ERISA 403(b) retirement account was statistically

unchanged between 2010 and 2016, the most recent year for which

complete data are available. Specifically, the estimated number of

individuals over age 50 who reported they had a 403(b) account was 1.9

million in 2010 and 2.0 million in 2016. This change is not statistically

significant at the 95 percent confidence level.

31

No comprehensive data

exist regarding the number of non-ERISA 403(b) participants.

32

Coverage rate. Other available data indicate that the share of older

Americans who were employed and participating in 403(b) plans (both

ERISA and non-ERISA) was statistically unchanged between 2010 and

2016. Our analysis of HRS data shows that an estimated 4.3 percent of

Americans over age 50 reported having a 403(b) plan in 2010, and 3.9

percent had a 403(b) plan in 2016, although this change is not statistically

significant at the 95 percent confidence level.

33

By contrast, available data indicate 401(k) plans and participation have

increased across all measures. Our analysis of Form 5500 data shows

that the number of plans, number of participants, and plan assets for

401(k) plans all increased during this period. More specifically, the

number of 401(k) plans and participants increased by 17 percent and 27

percent, respectively.

34

In addition, the amount of 401(k) plan assets

30

As noted earlier, an expert told us there has been significant merger and acquisition

activity in the healthcare market, which may, in part, be the driver of the decline in the

number of ERISA plan, given that many ERISA 403(b) plans are healthcare related

companies and hospitals. This may also account for the increase in the number of

participants in each plan.

31

The associated lower and upper bound confidence intervals with these estimates are +/-

290,000, and +/-360,000, respectively.

32

We reviewed the Current Population Survey and the Survey of Income and Program

Participation datasets but did not identify any data fields relating to 403(b) retirement

accounts.

33

The associated confidence intervals at the 95 percent level are +/-0.6 percent for 2010

and +/-0.6 percent for 2016 403(b) account participants.

34

Specifically, from 2010 to 2019 the number of 401(k) plans increased from 510,000 to

595,000 and the number of participants in such plans increased from 71 million to 90

million.

Page 17 GAO-22-104439 Defined Contribution Plans

increased by 72 percent.

35

However, our analysis of HRS data shows that

the share of Americans over age 50 with a 401(k) plan was statistically

unchanged between 2010 and 2016.

36

Specifically, the estimated percent

of individuals over age 50 with a 401(k) plan through their current job was

28.4 percent in 2010 and 30.0 percent in 2016, although this change was

not statistically significant at the 95 percent confidence level.

37

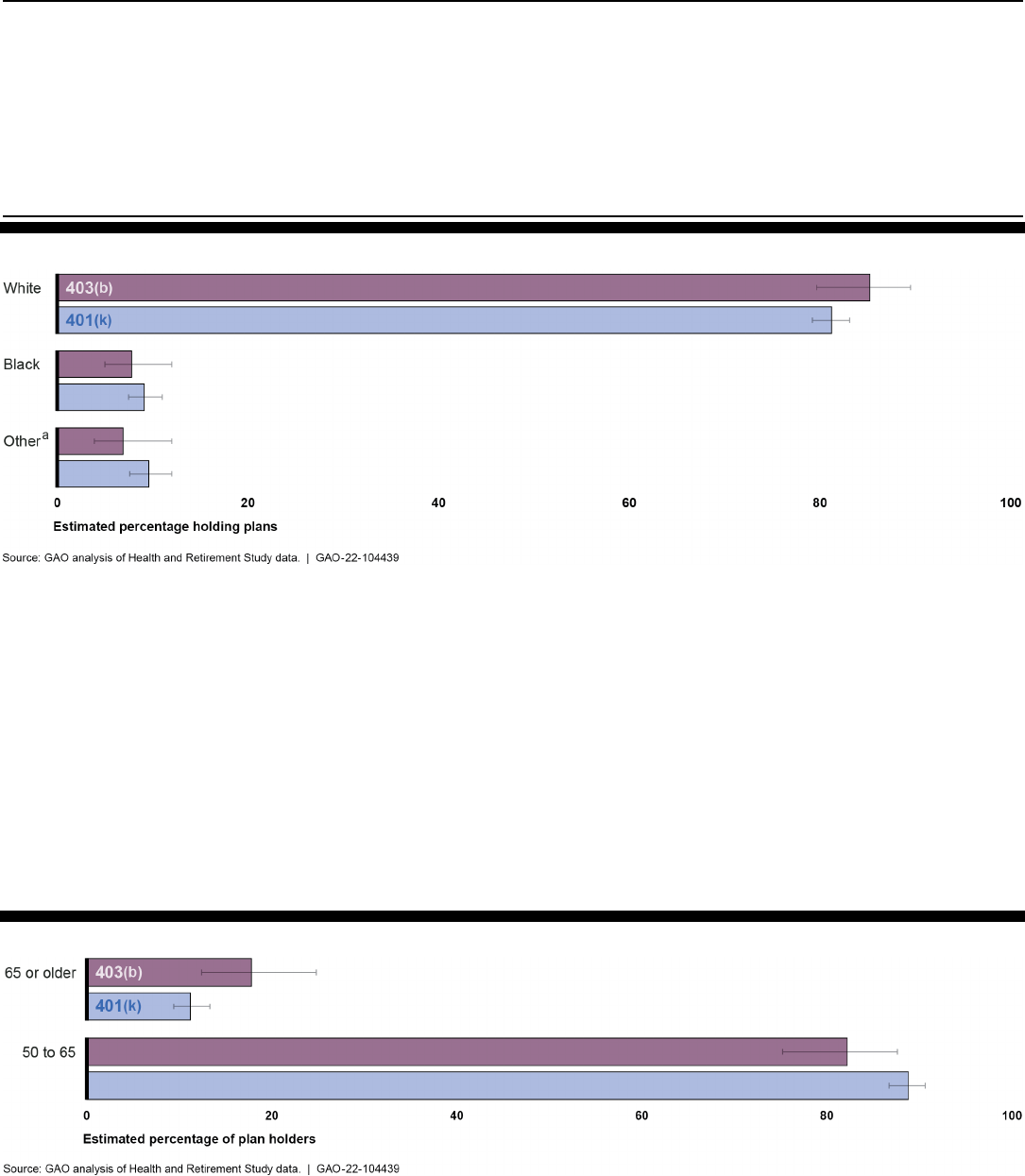

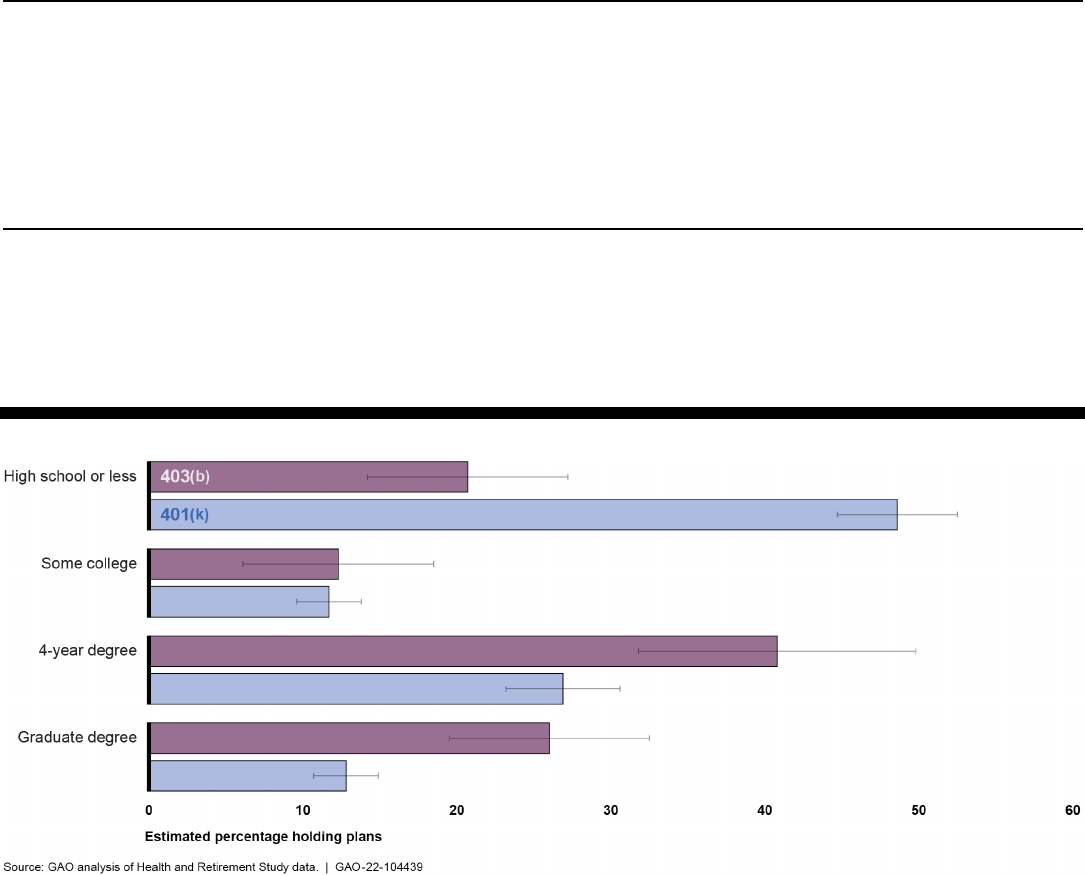

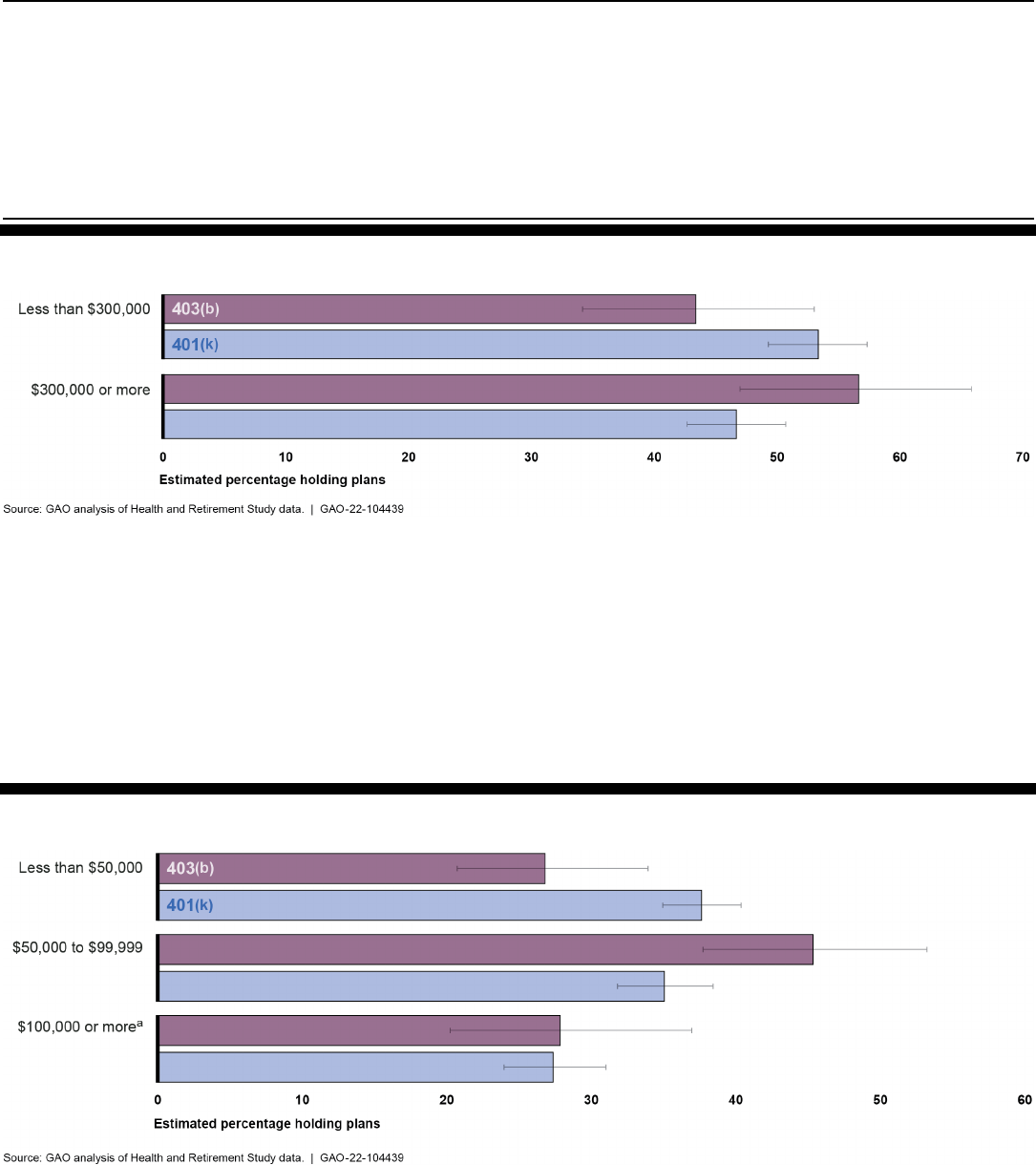

Demographic characteristics of 403(b) participants over age 50. Our

analysis of data indicate some differences in the demographic

characteristics of 403(b) and 401(k) participants over age 50.

38

Specifically, HRS data show that a greater estimated percentage of

403(b) participants—in either an ERISA or non-ERISA plan—were

female; were in the education or health care and social assistance

sectors; and had $300,000 or more in household assets, compared to

401(k) participants. In addition, a greater percentage of 403(b)

participants earned $50,000 or more annually. Some of our results did not

show statistically different results—for example, our estimates regarding

the extent to which 403(b) account holders are 65 years of age or older,

and by race. See appendix II for more detailed additional results of our

analyses of HRS data.

35

The amount of 401(k) plan assets increased from $3.6 trillion to $6.2 trillion from 2010 to

2019.

36

The HRS contains a data field to identify those respondents in its representative sample

of people in the United States who are 50 years of age or older that report having a 403(b)

retirement account. An analysis of HRS data yielded 279 403(b) plans identified by 270

HRS respondents for the 2016 wave, the most recent year for which complete data are

available. We selected 401(k) account holders as a comparison group here and elsewhere

in the report because, according to DOL data and reporting, 401(k) accounts comprise the

largest share of defined contribution retirement accounts on a plan basis.

37

The associated confidence intervals for these estimates at the 95 percent level are +/-

1.8 percent for 2010, and +/-1.7 percent for 2016 for 401(k) account participants.

38

The Form 5500 does not capture demographic information on ERISA 403(b) plan

participants, such as race, gender, income, and education. Our surveys of plan sponsors

and service providers were not designed to capture this information.

Page 18 GAO-22-104439 Defined Contribution Plans

Certain characteristics of ERISA and non-ERISA 403(b) plans varied; for

example, based on the results of our non-generalizable survey, non-

ERISA plans were more likely than ERISA plans to be supplemental to

other forms of retirement savings.

39

Primary versus supplemental plan status. The best available data

sources, while not directly comparable, seem to indicate that ERISA

403(b) plans tend to be the sole or primary plan offered by an employer,

while non-ERISA plans are mostly supplemental to another retirement

savings plan offered by an employer. According to HRS data—which do

not differentiate between ERISA and non-ERISA plans—an estimated 61

percent of individuals over age 50 with a 403(b) plan reported that the

403(b) plan was their only retirement plan, and another 13 percent

reported it was their primary plan. With respect to ERISA plans, our

analysis of Form 5500 data found that 93 percent of ERISA 403(b) plans

are the employer’s sole or primary retirement plan. By contrast, most (18

of 21) of the non-ERISA plan sponsors who responded to our survey said

that the 403(b) plan was a supplemental plan.

40

With respect to ERISA

plans, our analysis of Form 5500 data found that 93 percent of ERISA

403(b) plans are the employer’s sole or primary retirement plan.

41

By

contrast, most (18 of 21) of the non-ERISA plan sponsors who responded

39

Our analysis was based on available data, including the Form 5500, industry reports,

and our surveys of 403(b) plan sponsors. More information is available about ERISA

403(b) plans, which are subject to federal reporting requirements, than for non-ERISA

403(b) plans. We relied exclusively on the results of our surveys of non-ERISA plans to

provide some information regarding the non-ERISA 403(b) market; however, this

information must be considered non-generalizable due to the small numbers of

respondents to our survey. For the purposes of this report, we refer to 403(b) record

keepers, third-party administrators, vendors, and others who provide administrative

services to a plan as 403(b) service providers.

40

For the HRS analysis, we considered a plan to be primary if the respondent reported

having multiple defined contribution plan types and the 401(k) or 403(b) plan had the

largest reported balance. We considered a plan supplemental if the respondent did not

have the largest reported balance in that plan account among multiple defined contribution

plan types or if the respondent also reported a defined benefit plan (the defined benefit

plan was assumed to be primary).

41

For our analysis of Form 5500 data for ERISA plans, we considered a plan to be a

primary plan if there was no other defined benefit plan sponsored by employer and no

other defined contribution plan type (e.g. money purchase) that covered a larger group of

participants. We also analyzed Form 5500 data to determine the extent to which

employers made contributions to 403(b) and 401(k) plans, and found that 74 percent of

403(b) plan employers reported they made a contribution to participants’ accounts, while a

higher percentage of 401(k) plans (80 percent) reported they made contributions to

participants’ accounts.

Available Data Show That

Non-ERISA Plans Are

Often Supplemental to

Other Forms of Retirement

Savings and That Other

Characteristics, such as

Contribution Rates and

Participation, Vary among

403(b) Plans

Page 19 GAO-22-104439 Defined Contribution Plans

to our survey said that the 403(b) plan was a supplemental plan, meaning

that it was not the retirement plan holding the greatest share of assets for

most participants.

42

Experts told us that many public plans—such as

those offered by a university or state—usually have a defined benefit plan

and the 403(b) plan is typically a supplemental plan. The National Tax-

Deferred Savings Association noted that supplemental savings in 403(b)

plans have become increasingly important with widespread reductions in

benefits of state retirement system plans.

43

Contribution rates. While no comprehensive data exist on contribution

rates—the percentage of earnings participants or employers contribute to

a 403(b) plan—available data seem to indicate 403(b) employers

contribute less than 403(b) plan participants to 403(b) accounts.

Specifically, industry survey data from 2021 indicates that 403(b) plan

sponsors in 2020 on average contributed 4.6 percent of annual payroll,

and 403(b) participants on average contributed 6.2 percent of annual

earnings; those numbers represent a decrease from, respectively, 6.3

percent and 7.2 percent from 2019.

44

In a separate report regarding K-12

school plan sponsors, the National Tax-Deferred Savings Association

(NTSA) estimated in 2018 that only 6 percent of these non-ERISA 403(b)

K-12 school plan sponsors offered matching contributions. According to

NTSA, contribution rates in 403(b) plans are lower than rates in 401(k)

plans, in part, because many of these plans are supplemental to other

forms of retirement savings and very few employers offer matching

42

For our surveys, by primary, we mean that the respondent’s 403(b) plan had the largest

balance of all the respondent’s two or more reported defined contribution plans and there

was no defined benefit plan. By supplemental, we mean that the 403(b) or 401(k) plan

does not have the largest reported balance of multiple defined contribution plan types or if

the respondent also reported a defined benefit plan (e.g., the defined benefit plan is

assumed to be primary).

43

See National Tax-Deferred Savings Association, Improving Retirement Savings for

America’s Public Educators: A Comprehensive Survey of Public Education 403(b)

Retirement Plans (2018).

44

Tax-exempt associations, foundations and universities had the highest average

employer contribution rates as a percentage of gross annual payroll at 8.8 percent and 7

percent, respectively. The “research, science, and environmental organizations” and

“associations/foundations” sectors had the highest average participant elective deferral

contribution rates at 9.1 percent and 8.3 percent, respectively. This survey was of both

ERISA and non-ERISA plan sponsors. For more information, see Plan Sponsor Council of

America, 2021 403(b) Survey, Reflecting 2020 Plan Experience (2021) and 2020 403(b)

Survey, Reflecting 2019 Plan Experience (2020).

Page 20 GAO-22-104439 Defined Contribution Plans

contributions.

45

NTSA’s report also found that contribution rates in these

non-ERISA 403(b) K-12 school plans nationally roughly averaged 6.9

percent of the average teacher’s salary of about $56,000.

We also analyzed HRS data from 2016 to determine the extent to which

employers and employees made contributions to 403(b) or 401(k)

accounts. The text box below describes the extent to which employers or

participants made contributions to 403(b) accounts, compared to 401(k)

accounts, in 2016.

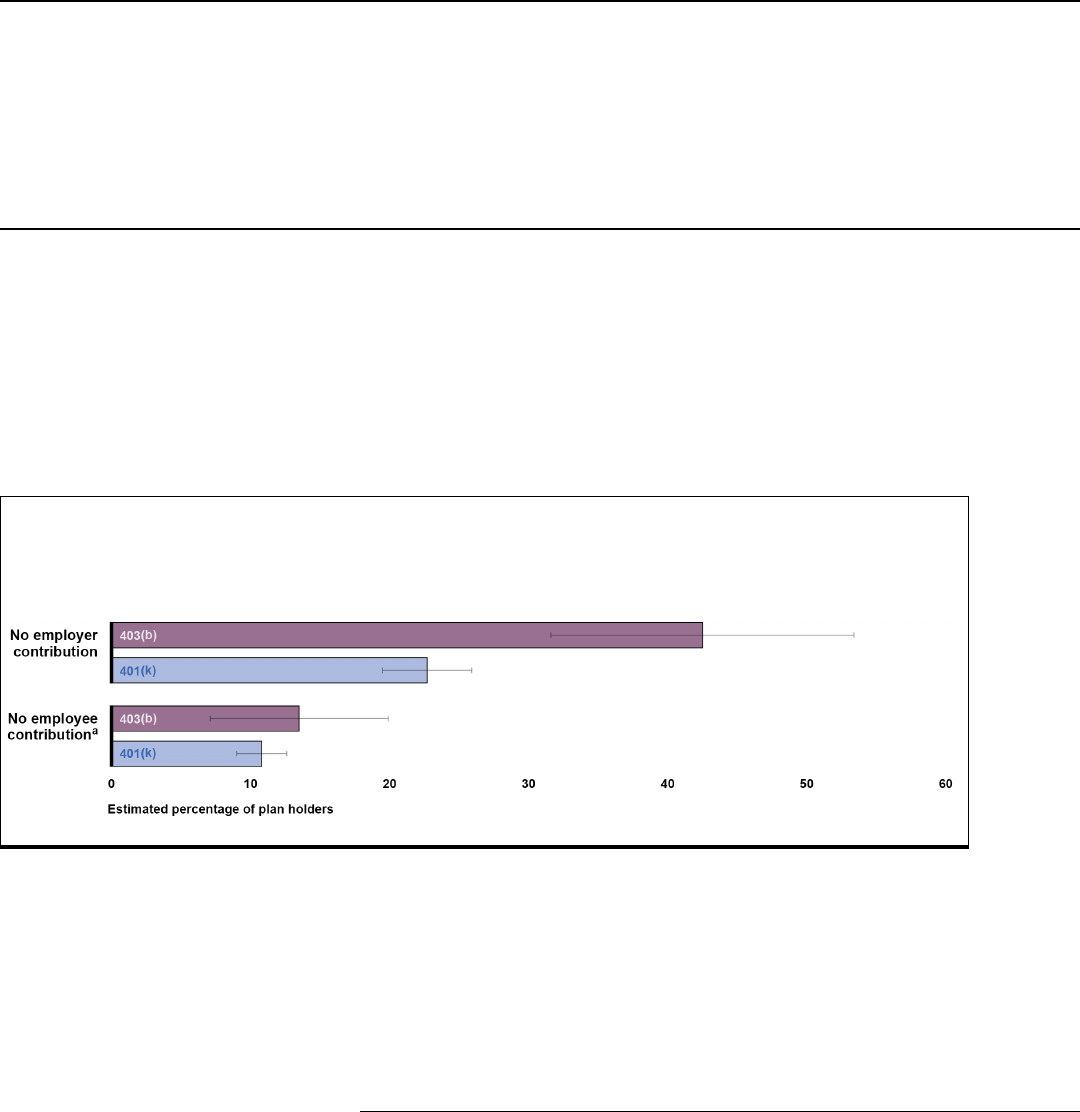

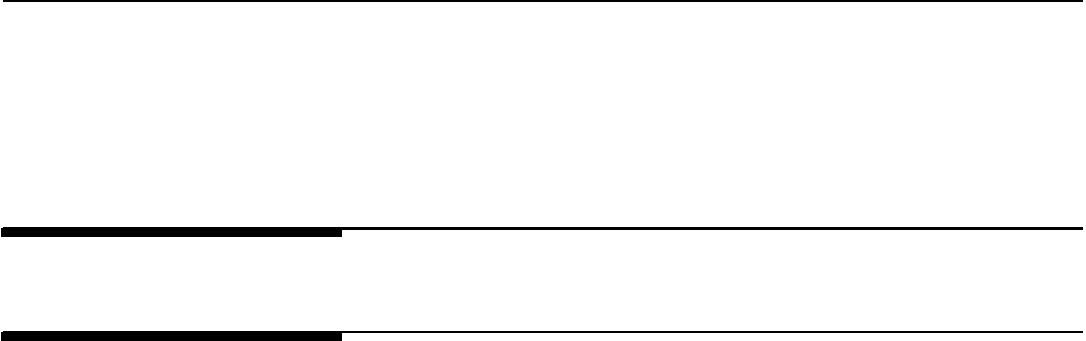

Extent to Which Employers or Employees Opted to Not Contribute to Their 403(b) or 401(k) Accounts

We found that a higher percentage of individuals over age 50 who had a 403(b) account reported there was no

employer contribution to their 403(b) account, compared to individuals over age 50 who reported they had a 401(k)

retirement account. There was no statistically significant difference in the percentage of 403(b) and 401(k) participants

over age 50 who reported they made no employee contribution. Our results are shown in the figure below.

Source: GAO analysis of Health and Retirement Study data l GAO-22-104439

Note: Results are generalizable to individuals over age 50 in the United States. With respect to

employer contribution, the estimated percentages and associated margins of error at the 95 percent

confidence level are as follows: 403(b) no employer contribution, 42.5 percent, +/-10.9 percent;

401(k) no employer contribution, 22.7 percent, +/-3.2 percent. With respect to employee contribution,

the estimated percentages and associated margins of error at the 95 percent confidence level are as

follows: 403(b) no employee contribution, 13.5 percent, +/-6.4 percent; 401(k) no employee

contribution, 10.8 percent, +/-1.8 percent. 2016 is the most recent year for which complete weighted

Health and Retirement Study data are available.

a

The estimated difference for no employee contribution was not statistically significant at the 95

percent confidence level.

45

In its report, NTSA stated 403(b) savings rates are generally lower than 401(k) savings

rates because: (1) in the corporate market, 401(k) plans are the primary retirement

savings plan and usually with no accompanying defined benefit savings program; (2) few

school districts match participant contributions whereas about half of corporate 401(k)

plans have such a match; (3) very few school districts auto-enroll employees into 403(b)

programs; and (4) two-thirds (66 percent) of school districts also offer employees a 457(b)

savings plan alternative. (A 457(b) plan is a tax-advantaged, compensation-deferred

savings plan similar in nature to a 401(k) plan, except they are mainly for state and local

public workers, together with highly paid executives at certain tax-exempt organizations.)

See NTSA, Improving Retirement Savings for America’s Public Educators: A

Comprehensive Survey of Public Education 403(b) Retirement Plans (2018).

Page 21 GAO-22-104439 Defined Contribution Plans

In addition, our plan survey results indicate that non-ERISA 403(b) plans

included an employer contribution to the plan less frequently than ERISA

403(b) plans. More specifically, our survey results show the following:

• Employer basic or minimum contribution: Three of five ERISA plans

provided a minimum contribution to a participant’s account, compared

to four of 21 non-ERISA plans.

• ERISA plans’ employer matching contribution: Four of five ERISA

plans matched a percentage of a participant’s contributions to an

account, compared to four of 21 non-ERISA plans.

Participation rates. Participation rates in 403(b) plans have steadily

increased over time, according to one industry survey, and plan sponsors

that responded to our survey reported wide ranges in plan participation

rates. Specifically:

• A 2021 study of 403(b) plan sponsors reported that, among those

who were eligible, the percentage of employees with a 403(b)

account balance increased from 77.4 percent in 2012 to 82.6

percent in 2020. The percentage of employees that contributed to

the plan increased from 66.2 to 77.2 percent during the same time

period.

46

• An industry study of public school employees found a wide range

of participation rates within plans offered by school districts. The

study found that the participation rates for the 4,473 school

districts in the survey ranged from less than 7.6 percent to more

than 99 percent. The study noted that the choices that each

school district makes available to employees and the resources

that they provide to help employees understand the benefits of

participation are key differences in driving participation rates.

47

• Respondents to our plan sponsor survey reported a wide range in

employee participation, from 2.5 percent to 100 percent. About

half of survey respondents (11 of 21) reported a participation rate

46

See Plan Sponsor Council of America, 2021 403(b) Survey, Reflecting 2020 Plan

Experience.

47

See National Tax-Deferred Savings Association, Improving Retirement Savings for

America’s Public Educators: A Comprehensive Survey of Public Education 403(b)

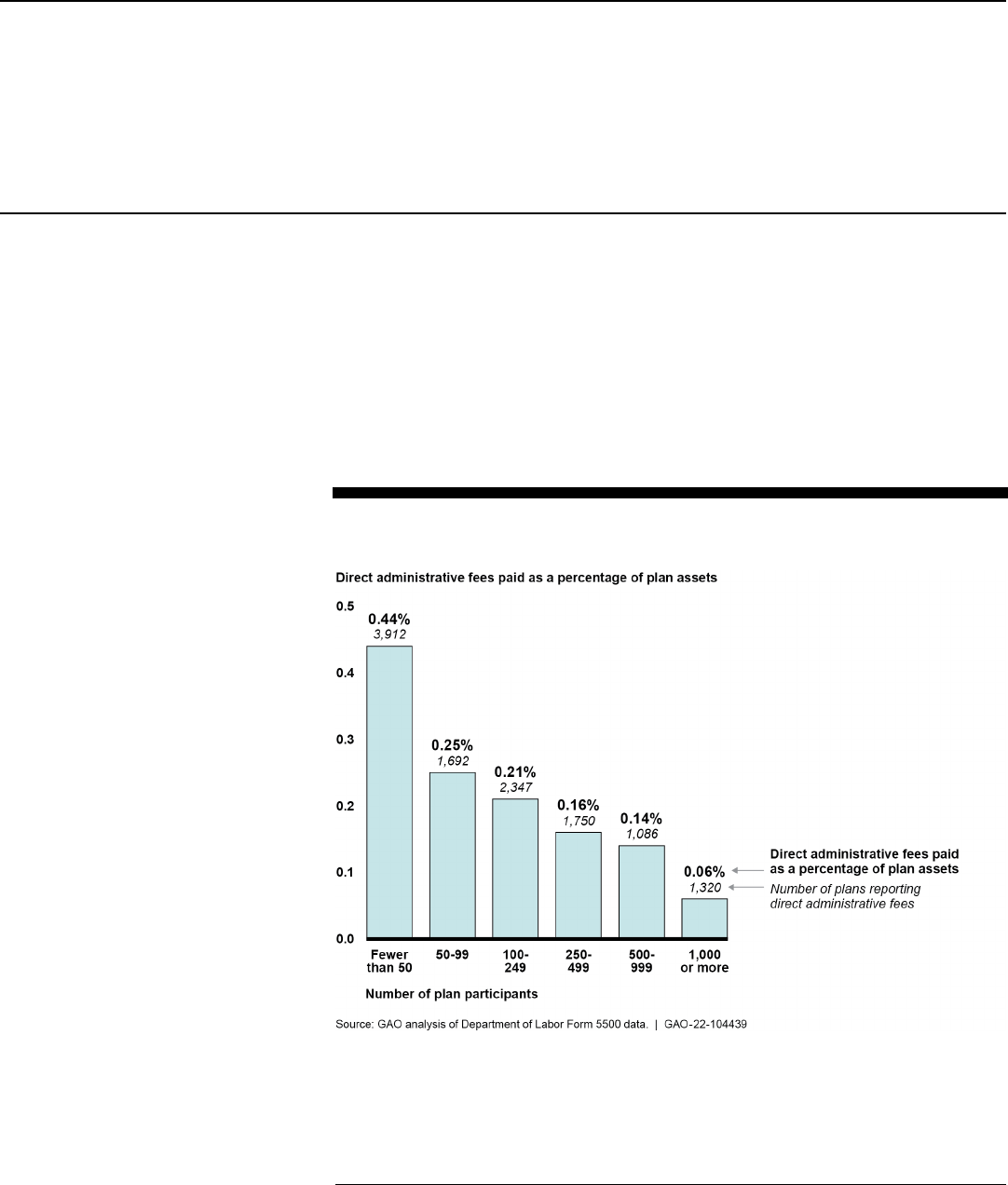

Retirement Plans (2018).

Page 22 GAO-22-104439 Defined Contribution Plans

of 50 percent or higher.

48

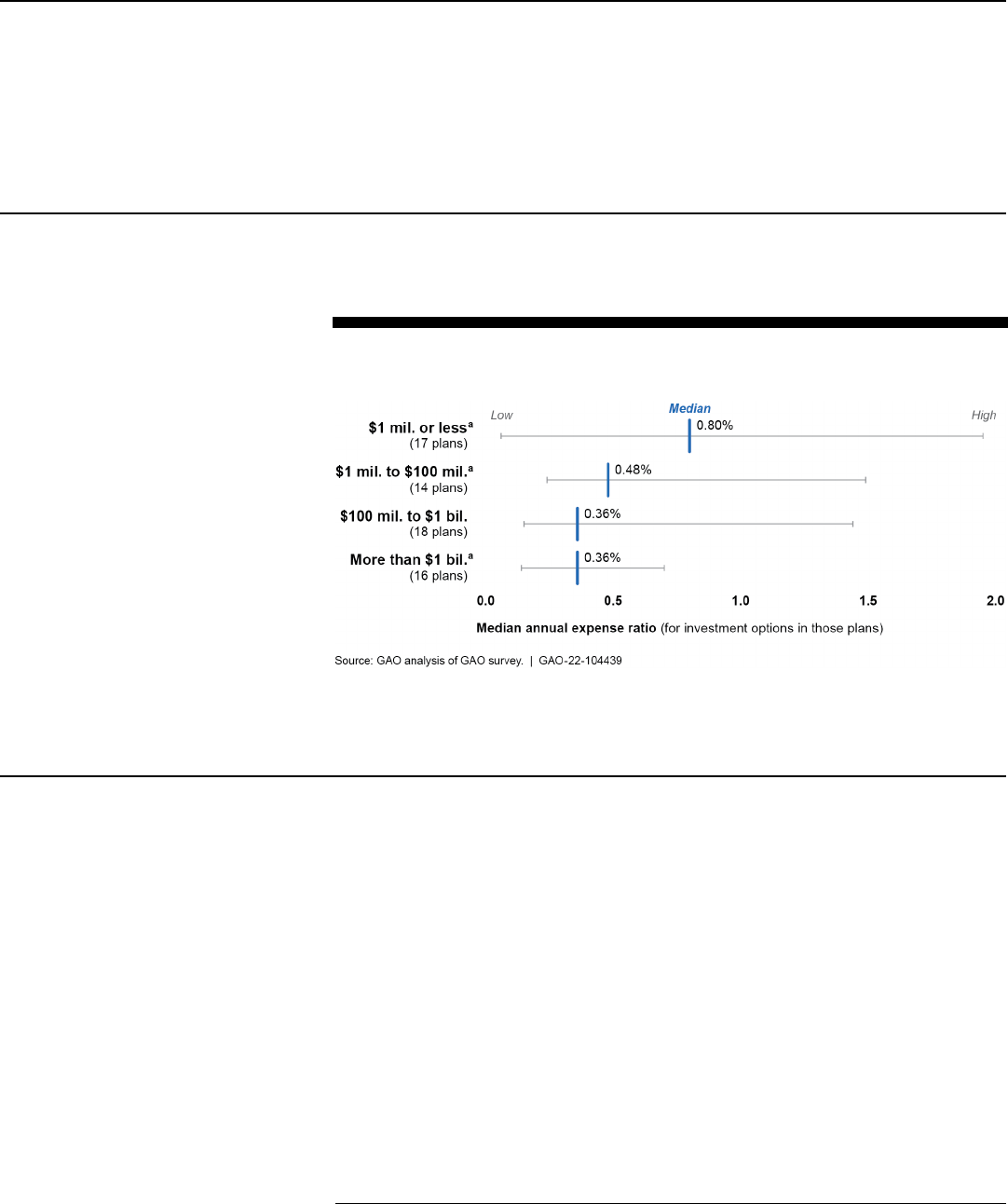

This participation rate for those plan

sponsors that responded to our survey did not appear to vary by

plan size, as measured by the number of participants.

49

Our survey results also identified some impacts due to the COVID-19

pandemic on 403(b) participant activities, as noted in the text box.

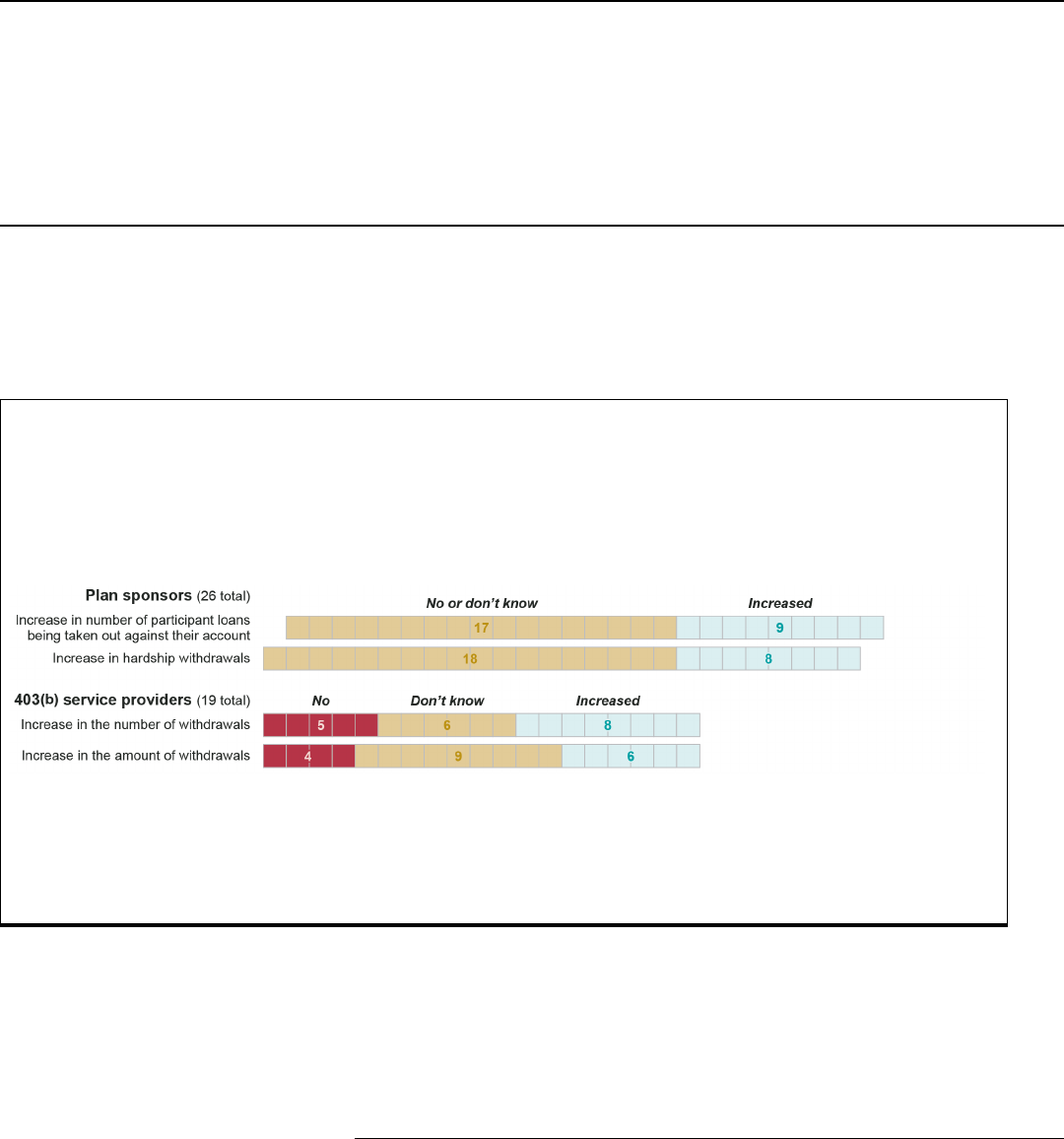

Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on 403(b) Participant Activity

Our survey data of ERISA and non-ERISA 403(b) plan sponsors found some reported an increase in participant loans and

hardship withdrawals due to the COVID-19 pandemic, while most reported there was no increase or they did not know. Our

plan sponsor survey asked plan sponsors to identify observed effects due to the pandemic by checking yes on a certain

option. Alternatively, respondents could check “do not know” to all options. As such, we are not able to discern the extent to

which plan sponsors would report “no” to a certain potential effect. Our survey of service providers found that eight of 19

service providers reported an increase in the number of withdrawals due to the pandemic, while five of 19 reported no such

increase, as shown in the graphic below

In addition, six service providers reported an increase in the amount of withdrawals, while four service providers reported no

such increase. Some plan sponsors reported that 403(b) plan participation rates or contributions decreased (in both cases,

four of 26); a few service providers also reported decreases in participation rates (three of 19). Respondents to our surveys

reported minimal other potential impacts of the pandemic on 403(b) participant activity. For example, two plan sponsors

reported decreases in participation due to layoffs, while four service providers reported decreases in employers’ matching

contributions. Seven service providers reported no such decrease in employer matching programs, and eight reported they did

not know. We did not ask service providers about plan sponsors’ reported participation impacts due to layoffs.

Source: GAO analysis of GAO survey results. l GAO-22-104439

Note: Our plan sponsor survey asked plan sponsors to identify observed effects due to the pandemic

by checking yes on a certain option. Alternatively, respondents could check “do not know” to all

options. As such, we are not able to discern the extent to which plan sponsors would report “no” to a

certain potential effect or “do not know” for all potential effects. We refer to all record keepers, third-

party administrators, vendors, and others who provide administrative services to a plan as 403(b)

service providers.

48

We excluded five survey respondents who provided participation data that did not allow

us to calculate a participation rate.

49

More specifically, the six smallest plans, with 2,000 or fewer participants, reported a

similarly large range of participation from 2.5 to 100 percent, and the six largest plans in

terms of participants—those with more than 20,000 participants each—reported a large

range of participation, from 9.9 to 78 percent. We note that one plan had a lower reported

participation rate of 0.13 percent; however, that plan is a recently discontinued state

sponsored plan, so we chose to not report that result as the lowest.

Page 23 GAO-22-104439 Defined Contribution Plans

Number of participants within plan. The majority of ERISA 403(b)

plans are small plans with 99 or fewer participants. Specifically, our

analysis of Form 5500 data found that 63 percent of ERISA 403(b) plans

have 99 or fewer participants. This is a smaller share than for 401(k)

plans, as 88 percent of 401(k) plans have 99 or fewer participants. No

comprehensive data exist regarding plan size in terms of participants in

non-ERISA 403(b) plans, and accordingly we cannot quantify the

percentage of non-ERISA 403(b) plans that may have fewer than 99

participants. The non-ERISA plan sponsors who responded to our survey

reported a range of plan sizes measured as the number of participants

within the plan, from two to 315,000 participants.

50

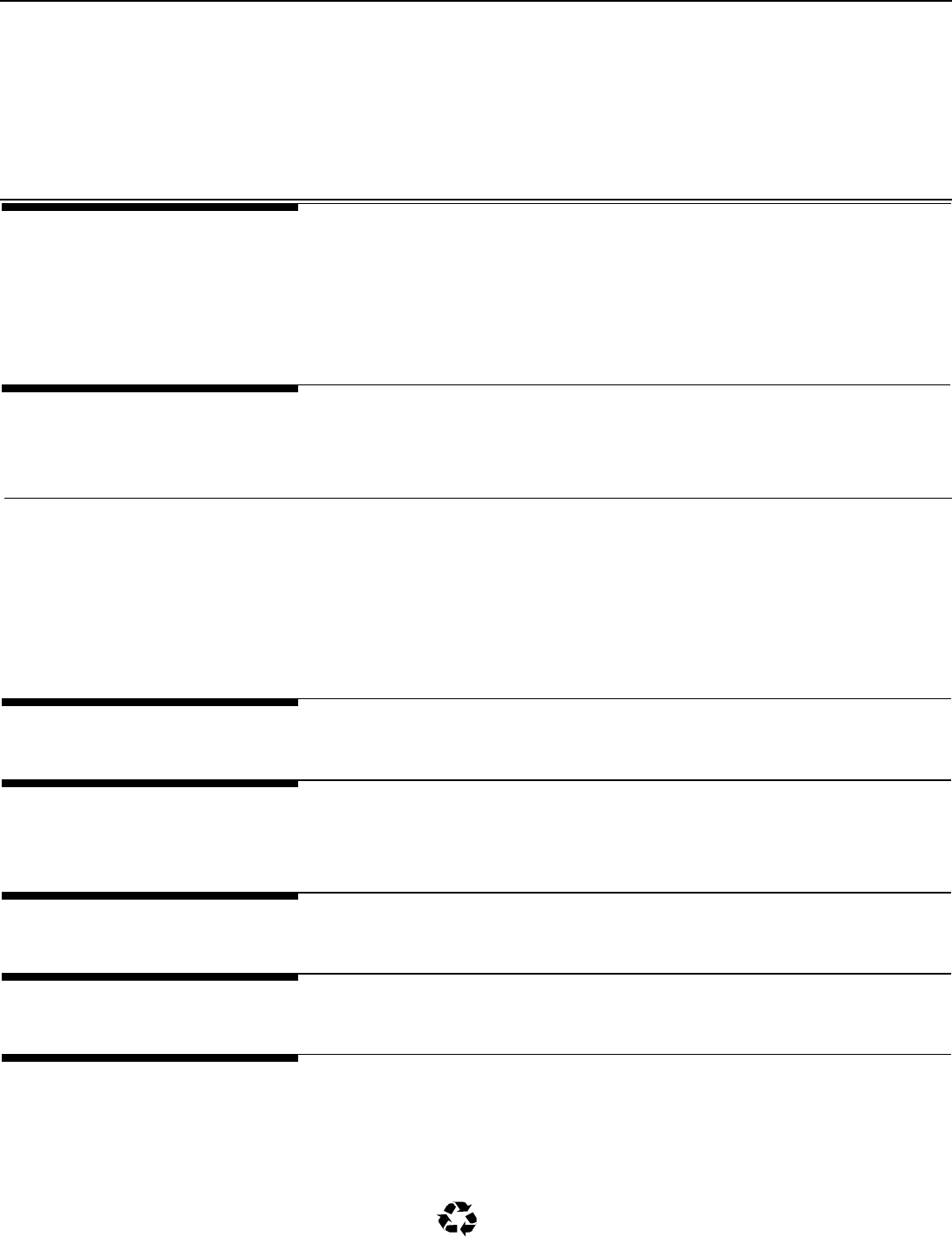

Available data indicate that ERISA and non-ERISA 403(b) plans had a

larger number of investment options compared to 401(k) plans. According

to reports published by BrightScope and the Investment Company

Institute, the ERISA 403(b) plans in its sample had an average of 32

investment options in 2017, compared to an average of 21 investment

options for its sample of 401(k) plans.

51

A 2021 survey from the Plan

Sponsor Council of America, which surveyed both ERISA and non-ERISA

plans, found that 403(b) plans consistently averaged having between 23

and 31 investment options available to 403(b) plan participants between

2011 and 2020.

52

In comparison, the Plan Sponsor Council of America

2020 survey of 401(k) plans found that 401(k) plans consistently

50

These numbers may include some inactive participants who are no longer contributing

to the plan.

51

For the purposes of this analysis and our report, a suite of target-date funds is counted

as a single investment option. Target-date funds are pooled investment products that

invest in a mix of assets and shift from higher-risk to lower-risk investments as a

participant approaches their target retirement date. BrightScope/ICI relies, according to ICI

representatives, on a manual review of the attachments provided by a firm in its audited

Form 5500 submission since the Form 5500 data do not include information regarding the

number of investment options; we did not conduct a similar analysis of Form 5500 audited

files. BrightScope/ICI’s audited sample is generally of plans with 100 or more participants.

See BrightScope and Investment Company Institute, The BrightScope/ICI Defined

Contribution Plan Profile: A Close Look at ERISA 403(b) Plans, 2017 (Washington, D.C.:

January 2021) and The BrightScope/ICI Defined Contribution Plan Profile: A Close Look

at 401(k) Plans, 2017 (Washington, D.C.: August 2020).

52

The Plan Sponsor Council of America received responses from 379 non-profit (tax-

exempt) entities that sponsor a 403(b) plan. It is not generalizable. See Plan Sponsor

Council of America, 2021 403(b) Survey Report, Reflecting 2020 Plan Experience (2021).

403(b) Plans Generally

Have a Greater Number of

Investment Options than

Do 401(k) Plans, but

Some 403(b) Plan

Sponsors Reported They

Did Not Know the

Numbers and Details of

Investment Options

Offered by Their Plans

Page 24 GAO-22-104439 Defined Contribution Plans

averaged having between 18 and 20 investment options available to

401(k) participants.

53

Among the plan sponsors we surveyed, the number of investment options

they made available varied widely, as shown in figure 3.

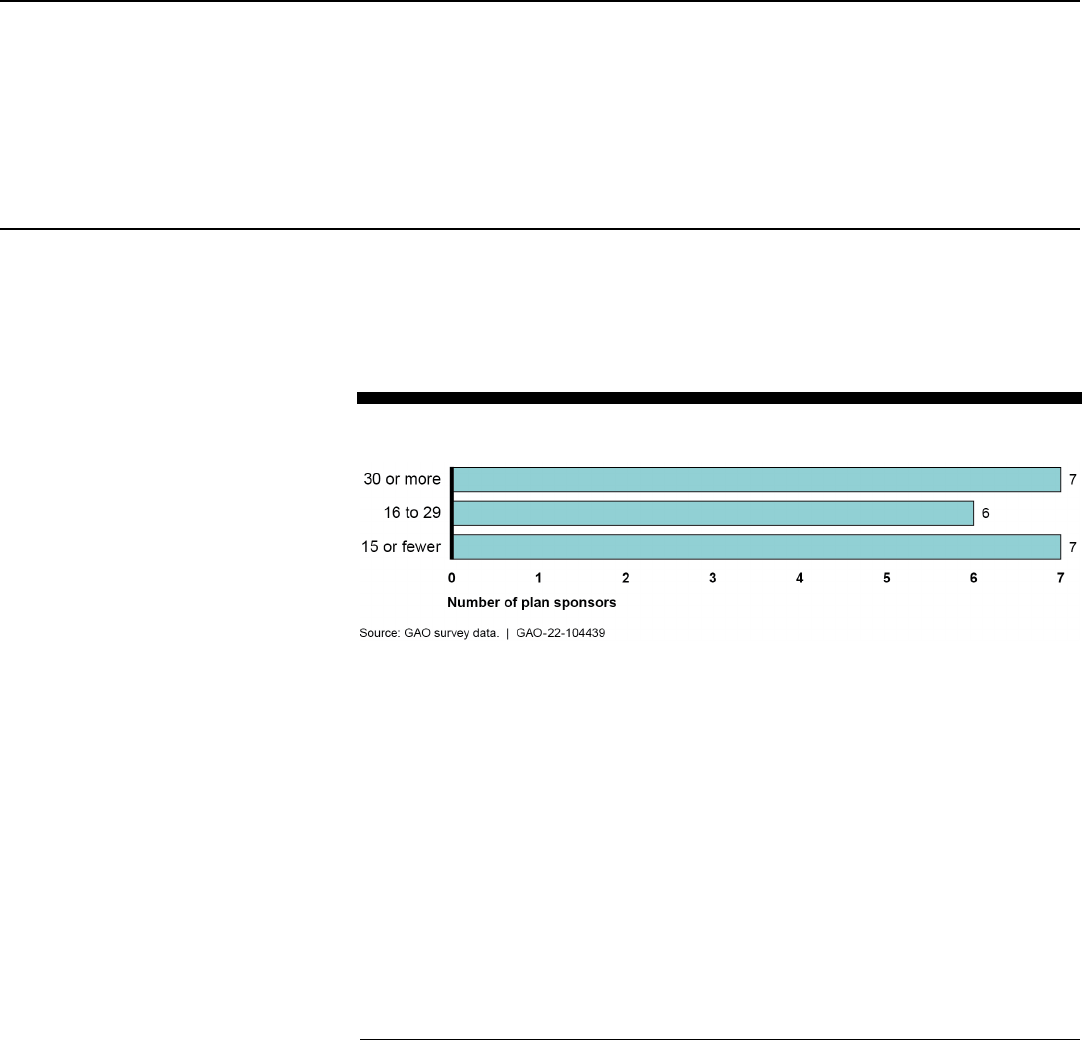

Figure 3: Reported Number of Investment Options Offered by 403(b) Plan Sponsors

Surveyed by GAO

Some plan sponsors offer a large number of investment options. For

example, one respondent representing a large state university system

reported that its non-ERISA plan offers on average 42 investment options

to participants,

54

while one respondent of a smaller plan reported that its

ERISA plan currently offers 48 options. Our survey results, however, did

not indicate a strong correlation between plan size measured in terms of

assets held and the number of available investment options. Specifically,

the largest eight plan sponsors in terms of assets reported offering a

median of 30 investment options, while the smallest seven plans reported

offering a median of 28 investment options.

55

53