HAL Id: halshs-02990281

https://shs.hal.science/halshs-02990281

Submitted on 5 Nov 2020

HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access

archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci-

entic research documents, whether they are pub-

lished or not. The documents may come from

teaching and research institutions in France or

abroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est

destinée au dépôt et à la diusion de documents

scientiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non,

émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de

recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires

publics ou privés.

MUTUAL ORGANIZATIONS, MUTUAL SOCIETIES

Edith Archambault

To cite this version:

Edith Archambault. MUTUAL ORGANIZATIONS, MUTUAL SOCIETIES. Regina A. List, Helmut

K. Anheier and Stefan Toepler. International Encyclopedia of Civil Society, 2nd edition, Springer,

inPress. �halshs-02990281�

1

MUTUAL ORGANIZATIONS, MUTUAL SOCIETIES

By Edith Archambault,

Centre d’économie de la Sorbonne

Université Paris1 Panthéon-Sorbonne

SYNONYM

Mutuals

KEY WORDS

Mutual Benefit Societies

Mutual Insurance Companies

Social economy

Demutualization

Welfare state

Democratic governance

Solidarity between members

Limited profit sharing

DEFINITION

According to a very large definition of the European Commission (mutual

organizations/societies “are voluntary groups of persons (natural or legal) whose purpose is

primarily to meet the needs of their members rather than achieve a return on investment”.

This large definition includes self-help groups, friendly societies, cooperatives, mutual

insurance companies, mutual benefit societies, credit unions, building societies, savings and

loans associations, micro-credit, burial associations, Freemasons… (European Commission,

20 Hereafter, it is a more restricted definition that is used, relying on principles shared by

most mutuals in Europe, the region where they are the most widespread. However some

international examples put European mutual societies in perspective.

The core organizations examined here will be mutual insurance companies and mutual benefit

societies. In that sense mutual societies are insurance companies run by their members for

protecting them against property, personal and social risks on a voluntary and non-

compulsory basis. Mutual insurance companies deal with property and life risks while mutual

benefit societies protect their members against social risks: illness, disability and old age

mainly.

INTRODUCTION

Mutual organizations or mutual societies, often designated as mutuals, exist everywhere in the

world, in developing as well as in industrialized countries, on a more or less institutionalized

form. In a developing country, some mutual organizations appear as voluntary associations

for gathering and pooling money to fund marriages, funerals or a business start-up for one or

several members (tontines or roscas). Other mutuals pool voluntary work to afford water

supplies or build roads in rural areas (development self-help associations). mutual aid is a

voluntary reciprocal exchange of resources and services for mutual benefit. Mutual aid, as

opposed to charity, does not connote moral superiority of the giver over the receiver.

In a developed country mutual societies are more and more businesses; they operate in the

same markets as corporations and compete with them. They are formed on a voluntary basis

2

to provide aid, benefits, insurance, credit or other services either to their members or to a

larger population. In many countries mutual organizations have a very remote historical

background as said hereafter.

As operating on the same markets as corporations, mutual societies are facing a global

competition challenging their historical values. As forerunners or complements to the social

security schemes, they have to find innovating responses to new social needs and to the crisis

of the welfare state. These key issues and new challenges are at the roots of the dynamics of

mutual organizations

If mutual societies are insurance companies run by their members for protecting them against

property, personal and social risks, this definition has to be specified by a set of principles

shared by the bulk of mutual organizations and inherited of historical experience. The major

part of these principles is also adopted by other social economy organizations:

Absence of shares: mutuals are a grouping of persons (physical or legal), the

members, and not a pooling of funds as in the case of corporations. Unlike

cooperatives, whose capital is represented by shares, the funds of mutuals are owned

and managed jointly and indivisibly. A mutual has no external shareholders to pay by

dividends, and does not usually seek to maximize profits. Mutual organizations exist

for the members to benefit from the services they provide; their main resource are the

fees or premiums paid by their members/owners

Free membership that means free entry and free exit for everyone who fulfills the

conditions laid down in the by-laws and abides by mutualism principles. According to

these conditions the mutual can be “open” to the population at large, such as health

mutuals in Belgium or “closed”, reserved to a geographical area, an industry or an

occupation. In the case of compulsory insurance, health insurance or car insurance for

example, the choice of the insurer has to be free.

Solidarity among members, a historical principle rooted in the 19

th

century worker’s

movement and the ideology of the solidarism current. To day, that means a joint

liability, a cross subsidization between good risks and bad risks in mutual benefit

society. and no discrimination among members according to their age or risk .

Democratic governance, conveyed by the principle “one person, one vote” in

opposition with the rule “one share, one vote” which is symbolic of corporate

governance. Board’s members are volunteers, in opposition with the practice of

director fees in corporations.

Independence: mutuals are private and independent organizations, neither controlled

by government representatives nor funded by public subsidies. In the absence of

shares, a mutual cannot be subject to a takeover bid by a standard business.

Limited profit sharing: the profit of a mutual can be partly shared among the owners/

members, usually as discounted premiums or rebates. The main part of the profit is

reinvested in order to improve the services proposed to members, to finance the

development of the business or to increase their own funds. Profit sharing has to be

limited because it is not the aim of the organization. The organization purpose is to

meet the interests of its members and sometimes of the community at large and also

to empower the members. The fact that profit sharing is authorized in mutual societies

prevents most of them to be included in the nonprofit sector, strictly non profit

distributing (Salamon and Anheier, 1997). However they belong to the larger social

economy (UN, 2018)

3

These principles often referred to as mutualism values are inherited of a deeply rooted

historical background.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Mutual benefit societies date back to the most ancient times while mutual insurance

companies are more recent. Some precursory mutual organizations could be found in Ancient

Egypt (mutual assistance among stone cutters) or in the Roman Empire (the same among

bricklayers). However mutual benefit societies are mainly descendants of the oldest part of the

European non-profit sector: they appeared in the Middle Ages as charitable brotherhoods

(continental Europe) or friendly societies (United Kingdom). Brotherhoods were fraternal

societies in urban areas linked to the guilds and therefore reserved to the same craft, business

or trade, they helped the needy members of the guild in the case of illness of their families or

the widow and the orphan in the case of death of the breadwinner. Friendly societies fulfilled

the same purposes but they were independent of the guilds and therefore more open than

brotherhoods. The corporatist system, on which the guilds and brotherhoods relied, became

weaker but survived with the rise of the free market and modern industry in most European

countries. In France, the 1789 Revolution suppressed both guilds and their social subsidiaries,

the brotherhoods (Archambault 1996; Dreyfus,1993).

Nevertheless mutual benefit societies flourished during the 19th Century in Europe, when

industrial revolution and rural depopulation pauperized the working class and broke the

traditional solidarity of the family or the village. They were inspired by ideological currents

such as utopist socialism (Owen, Proudhon), the Fabian movement or solidarism (Bourgeois,

Durkheim). Some of these mutuals were linked with the emerging labor-unions and other

were more middle-class oriented. Depending on the countries, the period and the degree of

recognition of the labor movement, they were either repressed or encouraged by the state.

(Toucas-Truyen, 1998)

Whatever their form, mutual benefit societies were the forerunner of the welfare states.

Mutual societies detected first the main social risks, sickness, disability and old age, that were

covered later by a public social insurance scheme in Continental European countries and by a

National Health service and pension funds in Anglo-saxon and Nordic countries. During the

20

th

century, modern welfare states challenged mutual benefit societies, forced to become

either complements or agents of the compulsory social security schemes. However most of

them keep their vanguard function (Esping-Andersen, 1999).

The forerunners of mutual insurance companies are more recent. They can be found in the

second part of 19

th

century when the progress of probabilistic mathematics transformed

insurance in a modern industry. Farmers pooled their savings to protect themselves against the

risks of their property, bad weather and fires mainly, on a mutual basis. Other mutual

insurance companies for retailers and craftsmen followed, in competition with insurance

corporations, but the dissemination of mutual insurance among the salaried population is more

recent; it was in many countries a by-product of the post WWII consumption society,

especially with the compulsory insurance of car accidents and other damage to real estate

property (Toucas-Truyen, 1998).

4

The second part of 19

th

century and the beginning of 20

th

century is also the time when mutual

forms of banking appeared in Europe either as mutual societies or cooperatives to pool the

savings and afford credit to the part of the population who had no access to commercial banks

because of their lack of guarantee. The Raiffeisen banks in Germany are the most

emblematical, the savings and loans associations or the savings banks the most widespread.

KEY ISSUES

Competition

Mutual insurance companies compete with investor-driven businesses. In this competition

they have advantages and disadvantages. Some features can be put on the asset side:

The mutuals rely on trust, a winning card in an industry with high information

asymmetry as Hansmann shows it: the insurer knows more than the client on the

probability of the risk but the client knows more on the quality of the car or dwelling

insured. Trust in mutual insurance companies is manifested by a lower discrimination

among members than in the competing businesses and by the education of their

members to prevent the risks and not to cheat in their accident claims.

They have a better quality/price ratio than their competitors due to their nearly

nonprofit status, to their policy of rebates, to the fact that they have no or few brokers

and also to the homogeneity of their members in the case of professional mutuals

They have a high financial solidity, because their investments are less risky and more

often ethical than those of their competitors and also because they are not subject to

take-over bids. In the periods of stock exchange crisis, they act as stabilizing agents

and shock absorbers. This financial stability incite mutual insurance companies to

have long term objectives (Boned,2008)

But the shortcomings of the mutual status exist also:

The mutual insurance companies have a limited access to external capital from the

financial markets while the restricted voting rights may also discourage external

investors. This limited access to capital markets is an obstacle to life insurance, an

activity that cannot be run with a pay as you go system as the property insurance. In

the latter the premiums are devoted to the members who had a loss on an annual basis

The size of some of the large mutual insurance societies is likely to distance

members from the decision-making centre. In the smaller ones, the application of

democratic governance may lead to delays in the decision-making process. Recently,

the application to mutual insurance companies of the European directives on insurance

incited them to merge to attain a critical size on the insurance market.

These disadvantages facing competition lead recently many Anglo-Saxon countries to a

demutualization trend

Demutualization

In the United Kingdom, the demutualization of the Building Societies was the beginning of a

wave of demutualization as part of the Thatcher’s government deregulation trend. The

building societies first arose in the 19th century from working men's mutual savings groups:

by pooling their savings, members could buy or build their own homes. With the development

of financial services, building societies offered mortgage loans as standard banks. In order to

diversify their services to keep up with banks and other financial institutions in the

commercial world the old societies needed to expand. To do that, they have to raise capital, a

difficult operation with a mutual form because they have no access to equity markets. In

5

1986, the building societies became joint stock societies, the British form of corporations, and

therefore they floated on the stock exchange. The capital and reserve funds were distributed

among members who became shareholders. Of course sharing the collective property of these

mutual organizations accumulated by many generations was a windfall gain for the present

members who received each about $1000. But the rising of costs and prices which followed

the demutualization was an unexpected consequence for consumers and the bankrupt of

Northern Rock, a former building society, during the subprime crisis was also a disillusion.

Despite the demutualisation, there are still more than 10,000 mutual societies in the UK today.

A major demutualization wave took place in the USA in the 1980s and again in the late 1990s

according to the same line and a smaller one in Australia. This demutualization trend affected

savings and loans association in the USA and building societies in Australia. Demutualization

was less pronounced in continental Europe and it is forbidden by law in some countries such

as France, Luxemburg or Ireland. In those countries who insist on the intergenerational nature

of solidarity, the registered capital and the reserve funds cannot be shared among the

members/owners if the organization disappears. In this case, the property of the organization

has to be transferred to another mutual or social economy organization or to the state.

Mutual benefit societies in changing welfare states

Mutual benefit societies compete with health complementary insurance provided by standard

insurance companies. In this competition to money transfers or reimbursements, they keep or

extend their market shares in most countries as they have a better quality/cost ratio. Health

mutuals rely on principles which are different of commercial insurance companies: fees are

often paid according to the member's income and not according to its personal risk or its age.

Bad risks are never rejected, there is no rate and benefit discrimination among members and

therefore a cross-subsidization between bad and good risks and rich and poor occurs

However mutual benefit societies are much more challenged by the retrenchment or change

of the public welfare states when the demand for social services increases. Two long-term

trends, the ageing of the population and the reduction of care self-service inside households

due to the growth of female employment, rise the demand of day care, homecare and nursing

homes. Facing what Esping-Andersen called the “family failure” of care services, during the

last decades, mutual benefit societies in some European countries provided social services or

facilities to the children, the disabled and the frail elderly, with high quality standards. In the

social homecare service provision, they compete with standard businesses and also with

nonprofit organizations. These personal services are financed partly by the household itself,

partly by the central and local governments or social security, partly by the employers.

Nordic and Anglo-saxon countries are the forerunners in this new welfare mix spreading

rapidly elsewhere.

INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVES

Europe

Rooted in this long and diverse historical background, the European mutual organizations/

societies are to-day important providers of insurance and health services. Mutual insurance

companies hold a very significant share of the insurance market: 50% of car and real estate

insurance in France, 22% of the whole insurance industry in Germany but they are rare in

Italy or Greece. Their market share in life insurance and pension funds is smaller but it is

growing. Recently some cooperative banks began to deliver insurance products as well and it

is why recent statistics include them with mutuals (Table1)

6

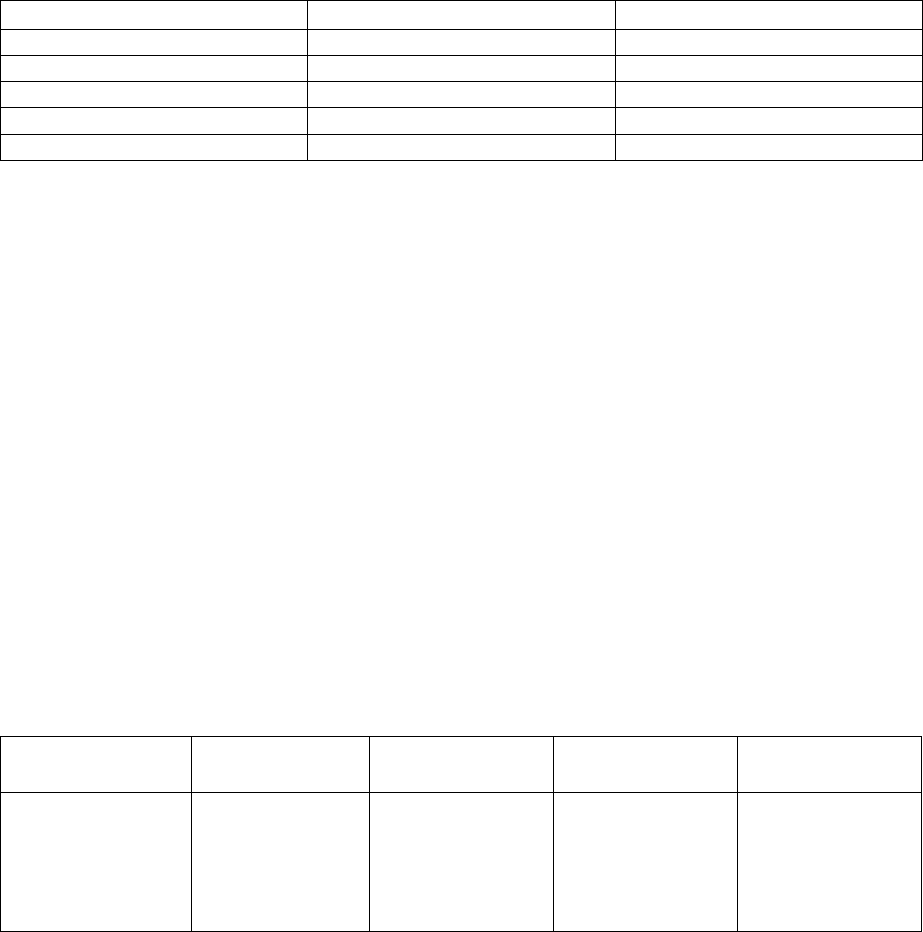

Table 1 Mutual and cooperative insurance sector in Europe and EU, 2016

Europe (36 countries)

EU (28 memberstates)

Premium income (€ billion)

429

410

Insurance market share

31.5%

32.6%

Total Assets (€ billion)

3.020

-

People employed

461.000

439.000

Members/policy holders

425.000.000

417.000.000

AMICE, 2020

France (EUR 878 billion) and Germany (EUR 718 billion) are the largest markets in terms of

assets held by mutual insurers, but smaller countries have also large assets in 2016, especially

Denmark (EUR 258 billion) and Sweden (EUR 238 billion)

There are mutual benefit societies in every European country and all of them provide health

insurance and other services. They are for historical reasons tightly linked to the social

security schemes but their role differ according to the form of the health protection: social

insurance, funded by employers and employees contributions, in most continental and oriental

countries (Bismarckian scheme) or National Health services financed by tax in Anglo-saxon,

Nordic and some Mediterranean countries (Beveridgian scheme) (Esping-Andersen, 1999)..

According to these various social protection schemes, mutual benefit societies either run the

compulsory health insurance (Germany, Belgium, Netherlands, Czech Republic, Slovaquia)

or provide a complementary sickness or old age insurance (France, Switzerland, Luxemburg

Spain, Portugal) or alternatives to the National Health System, such as quicker health care or

higher pensions (UK and Nordic countries). Mutual benefit societies cover a larger part of the

population in the Bismarckian than in the Beveridgian countries, as showed in Table2.

Table 2. Distribution of the population covered by a mutual benefit society in Europe

Less than 20% of

total population

20% to 4O% of

total population

40% to 60% of

total population

60% to 80% of

total population

80% to 100% of

total population

Italy

Greece

Spain

United Kingdom

Portugal

Hungary

Denmark

Sweden

Finland

Slovakia

Slovenia

Ireland

France

Czech Republic

Luxemburg

Germany

Netherlands

Belgium

Switzerland

Source: AIM, 2008

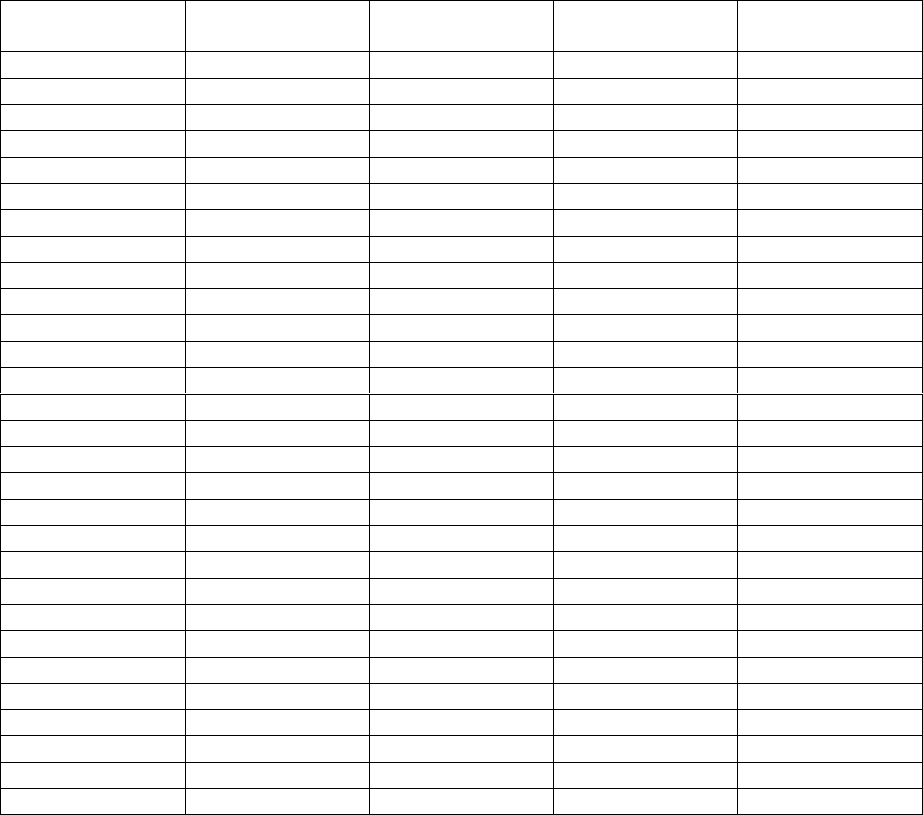

However in Europe, mutual organizations do not extend to other industries than their

historical ones: property, personal and social insurance or credit. That is why they are the

smaller part of social economy organizations. Table 3 gives an order of magnitude of the

respective part of cooperatives, mutuals and nonprofit organizations in social economy. Even

if these data are not strictly comparable because they are not based on a common

methodology, employment in mutual organizations is only 3.0 per cent of the total

employment in social economy organizations, compared to 30,8 per cent in cooperatives and

66.2 per cent in nonprofit organizations.

7

Table 3 Employment in mutual societies and other social economy organisations, EU 28

Country

Cooperatives

Mutual societies

Associations and

Foundations

Total

Social economy

Austria

70,474

1,576

236,000

308,050

Belgium

23,904

17,211

362,806

403,921

Bulgaria

53,841

1,169

27,040

82,050

Croatia

2,744

2,133

10,981

15,848

Cyprus

3,078

n.a

3,906

6,984

Czech Républic

50,210

5,368

107,243

162,921

Denmark

49,552

4,328

105,081

158,961

Estonia

9,850

186

28,000

38,036

Finland

93,511

6,594

82,000

38,036

France

208,532

136,723

1,927,557

2,372,812

Germany

860,000

102,119

1,673,861

2,635,980

Greece

14,983

1,533

101,000

117,516

Hungary

85,682

6,948

142,117

234,747

Ireland

39,935

455

54,757

95,147

Italy

1,267,603

20,531

635,611

1,923,745

Latvia

440

373

18,528

19,341

Lithuania

7,000

332

n.a

7,332

Luxemburg

2,941

400

21,998

25,345

Malta

768

209

1,427

2,404

Netherlands

126,797

2,860

669,121

798,778

Poland

235,200

1,900

128,000

365,000

Portugal

24,316

4,896

186,751

215,963

Romania

31;573

5,038

99,774

136,385

Slovakia

23,799

2,212

25,000

51,611

Slovénia

3,059

319

7,332

10,710

Spain

528,000

2,360

828,041

1,358,401

Sweden

57,516

13,908

124,408

195,832

United Kingdom

222,785

65,925

1,406,000

1,694,710

TOTAL EU-28

4,198,193

407,602

9,015,740

13,621,535

Chaves and Monzon (2019)

Belgium, Croatia, Czech Republic, Finland, France, Germany, Slovakia , Sweden and UK are

over this 3.0 per cent average, mainly corporatist and post-communist countries.

Other international perspectives

In the United States many insurance companies were initially mutual insurance; more some

corporations mutualized, their ownership passing to their policy holders. But as said further,

the reverse trend of demutualization occurred in the 1980s. Nowadays, even if their name

includes the term mutual, all insurance companies are joint stock owned. Many savings and

loan associations were also mutual companies, owned by their depositors, but most of them

are now under stock ownership. In the same way, some health insurance companies, formerly

created as nonprofit organizations, such as Blue Cross and Blue Shield, became under the

pressure of competition more standard businesses.

Nowadays, in many developing countries where public social insurance does not exist or is at

the very beginning, mutual organizations play the same role than the mutual benefit societies

in the European countries in 19

th

century, especially in Latin America, Asia or Africa. As in

Europe formerly, these mutuals are created by and for the most organized and educated part

8

of the population. The risks covered are illness, death and accident and also mutual help in

case of social events such as marriages and funerals, proportionally much more expensive

than in developed countries. Most of these mutual organizations were created during the last

three decades and they are a source of empowerment for the population. For example the

Fandene mutuals in Senegal are controlled by elected countrymen of the same village; in

Bolivia, Projecto de Salud provides free health care in exchange of volunteer work to build

the health facilities; in Philippines, Mother and Child Care relies on members fees but acts

also as a lobby to obtain low prices from the multinational drugs companies. When public

health insurance or health service is created, mutual organizations shift to other risks such as

old age. Mutual organizations such as the tontines are also widespread in developing

countries. Tontines pool the savings among a small group of members or a village; a random

winner every year takes all the money to realize a small business; the tontine’s life ends when

every member has got once the pooled savings. These financial mutuals look like the building

societies of the earliest times (Defourny et alii, 1999)

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

European mutual societies at the cross-road

Mutual societies are driven by two logics, insurance and solidarity, the former dominates in

insurance mutual companies and the later in mutual benefit societies. This frail equilibrium is

nowadays challenged by the European Commission ambiguous guidelines. In one hand the

European Commission acknowledges the public benefit role of mutual societies and other

social economy organizations. In the other hand, the insurance directives and the Solvency 2

guidelines consider them as insurance corporations and incite them to a kind of

standardization.

Another challenge is due to the merging trend in mutuals, partly a consequence of European

guidelines and implementation of Solvency 2 in 2016. In France for instance, mutuals were

5,800 in 1990 and only 400 in 2018. This horizontal integration increases the size of mutual

societies with the result of more difficult democratic governance with elected representatives

of the owners/members and less direct relationship with the members and the territory. The

difference made by mutuals has been reduced by the competition with standard businesses

that skim their good risks and.use personal big data to discriminate their policy holders. Many

mutuals created also corporate subsidiaries, another way of trivialization or institutional

isomorphism (Boned, 2008).

Mutual societies are fitted with post-industrial societies

Mutual societies are prototypes of social enterprises, an emerging form of enterprise. In post-

industrial societies personal services are difficult to standardize and offer a wide range of

quality and asymmetric information. These personal services are able to be provided by

mutual benefit societirs as well as nonprofit organizations with a better quality per cost ratio

than their shareholder driven counterparts. They can help to give an equitable access to health

care and an solidarity based health coverage Mutual insurance companies have a long-term

orientation that provides stability to the financial sector.

A democratic management fits the well educated youth who dislikes the authoritarianism of

standard firms and advocates the social responsibility of enterprise. A mutual form fits also

high technology services at least at their very beginning, when partners are supposed equal:

the wiki movement for example shows it. A mutual could also run pension funds and

retirement savings with a better financial solidity and a more ethical choice of investments

9

than for-profit pension funds. So in the future, pre-industrial forms of mutual organizations in

developing countries could coexist with post-industrial forms, well adapted to the knowledge

economy. In addition, the large assets of mutual insurance societies could be used partly to

invest in ecological transition.while banking and insurance industries are getting closer.

Mutuals are no doubt important partners to build a more inclusive economy (Noya, 2007)

CROSS REFERENCES

Cooperatives

Cross-subsidization

Empowerment

Information asymmetry

Solidarity

Social economy

Volunteer management

Durkheim

Hansmann

Proudhon

REFERENCES

Archambault E (1997). The Nonprofit sector in France. Manchester, Manchester University

Press

AIM (International Association of Mutual Benefit Societies)

http://www.aim-mutual.org,, consulted on 15/03/2008 and on 15/01/2020

AMICE (Association of the mutual and cooperative insurance sector in Europe)

https://www.amice-eu.org/?lang=fr, consulted on 13/01/2020

Boned O., (2008) « Les mutuelles en Europe. Le défi de l’identité, Vie Sociale, 2008/4, 131-

148

Chaves R. and Monzon Campos J-L (2019), Evolution récente de l’économie sociale en

Europe, CIRIEC , Working paper 2019/01

Defourny J., Develtere P. and Fonteneau B. (1999), L’économie sociale au Nord et au Sud,

Brussels, De Boeck

Dreyfus M. (1993), “The labour movement and mutual benefit societies. Towards an

international approach”. International Social Security Review. 46:3, 19-27

European Commission, Enterprise Directorate General (2003), Mutual Societies in an

Enlarged Europe, Consultation Document, 03/10/2003

Esping-Andersen G.(1999), Welfare states in Transition: National Adaptations in Global

Economies, London: Sage publications.

10

Noya A. and Clarence E. (2007), The social economy. Building inclusive economies, Paris:

OECD publishing

Salamon L. and Anheier H. (1997), Defining the Nonprofit Sector: A Cross-national Analysis,

Manchester: Manchester University Press

Toucas-Truyen P.(1995) Histoire de la mutualité et des assurances. L’actualité d’un choix,

Paris, Syros.

United Nations , Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Statistics Division (2018)

Satellite Account on Non-profit and Related Institutions and Volunteer Work

FURTHER VIEWING: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UZcdtHjhSJs

3,802 words + 210 definition + 217 References