Copyright and Contracts:

Issues & Strategies

by Katherine Klosek

July 22, 2022

2

Copyrights and Contracts

Table of Contents

Introduction 3

Licenses for Digital Content Restrict Lawful Uses of Copyrighted Works 4

Contracts and Section 108 of US Copyright Act 6

Digital Millennium Copyright Act Report (2001) 6

Section 108 Study Group (2005–2008) 6

Copyright Oce Section 108 Study (2017) 6

Advocacy and Policy Strategies 7

Rights-Savings Clauses 8

Rights-Savings Clauses—Negotiation 8

Rights-Savings Clauses—Regulation 9

Statement Asserting Library Rights 10

Open Access 11

Open-Access Policies and Rights-Retention Strategies 12

State Strategies 12

Unenforceable Contracts 12

Public Funds 13

Federal Exemptions

14

Congressional Intervention 14

Next Steps 15

Test Case 15

ARL Strategies

16

3

Association of Research Libraries

Copyrights and Contracts

Introduction

Copyright and fair use have been cornerstones of the Association of

Research Libraries (ARL) public policy portfolio for many years. The

Association and its partners have influenced copyright and public-

access policies, advanced model licensing language to optimize

the terms of digital access for libraries, and educated stakeholders

across the research ecosystem about the importance of both user and

author rights. In tracking this work over decades, we have observed

a disturbing trend: when licensing digital content, publishers include

terms that prohibit certain uses that would otherwise be lawful under

the US Copyright Act and related regulations. Over time, a culture

and set of professional practices among both publishers and libraries

has normalized these restrictions; a prime example of this is the

outdated reliance on the Commission on New Technological Uses of

Copyrighted Works (CONTU) Guidelines for interlibrary loan.

In 2006, the American Library Association (ALA) framed this issue

as follows: “License agreements, rather than outright sales, have

become an accepted and prevalent means for publishers to provide

their products to libraries. And although licensing has proven to

be a convenient way to obtain journals, for example, license terms

can expand—or restrict—the uses of a work that would have been

allowed under the copyright law. Some people even ask, ‘Is copyright

dead?’ That is, does increased use of licensing of information make

copyright law irrelevant?” In 2019, ALA hosted a “Copyright Contract

Override Workshop” to continue this inquiry. The conversations

at that workshop led to a shift from discussing contract “override”

to contract “preemption,” a term that appears in the Copyright Act

itself. Participants of the ALA workshop also observed that issues and

strategies around contract preemption will vary at the state and federal

level. In 2020, ALA published “The Need for Change: A Position Paper

on E-lending by the Joint Digital Content Working Group;” the paper

acknowledged that some library vendors’ business practices mean that

libraries cannot access certain content, especially streaming.

4

Copyrights and Contracts

Association of Research Libraries

In 2020, ARL’s Advocacy and Public Policy Committee launched a

digital rights initiative focused on understanding and safeguarding

the full s

tack of research libraries’ rights: to acquire and lend digital

content to fulfill libraries’ functions in research, teaching, and learning;

to provide accessible works to people with print disabilities; and to

fulfill libraries’ collective preservation function for enduring access to

scholarly and cultural works. Our objective is to make sure that these

rights are well understood by research libraries, by Congress, by the

Copyright Office, and by the courts.

Licenses for Digital Content Restrict Lawful Uses of Copyrighted

Works

Since the inception of copyright law, libraries have enjoyed special

rights to promote the progress of science and the useful arts. Congress

and courts have reiterated that teaching and research—two functions

in which research libraries directly engage—are favored purposes of

fair use. In 2020, ARL libraries were spending a median of 80 percent

of their acquisitions budget to license electronic resources.

1

In such

a licensing arrangement, a copyright owner grants permission for

a licensee to use the work under certain terms and conditions; this

regime eectively extends the rights of the copyright owner to allow

their control of subsequent distributions of the work.

Unfortunately, in licenses for digital scholarly content—the majority

of content acquired by research libraries—publishers often include

terms that prohibit certain uses that would otherwise be allowable

under the Copyright Act. For instance, licenses may require libraries or

individual researchers to negotiate for otherwise lawful activities, such

as text and data mining, and to pay exorbitant fees on top of the cost of

the content itself. While new regulations allow researchers to

circumvent technological protection measures to access copyrighted

materials, licenses for that content may include terms that explicitly

prohibit this circumvention. In many cases, these activities might

actually increase the value of published material; for instance, if a

5

Association of Research Libraries

Copyrights and Contracts

data-mining project yields new knowledge about a topic covered in a

journal, it may very well spark new interest in that journal’s content.

Libraries and publishers have often assumed that license terms that

restrict copyright exceptions are enforceable under state contract law.

There is, however, surprisingly little case law on this point. Arguably,

contract terms that seek to limit exceptions under the Copyright Act

are preempted under a conflict-preemption theory. This is the theory

under which the district court in Association of American Publishers

(AAP) v. Brian E. Frosh found the Maryland e-book licensing statute to

be preempted by the federal Copyright Act. The judge in AAP v. Frosh

made clear that Congress established a uniform national system in the

Copyright Act, and a state could not adopt a law that conflicted with

that national system. Under that reasoning, an individual rightsholder

should not be able to rely on state contract law to override that national

uniformity.

To be sure, the Copyright Act’s exception for libraries and archives,

Section 108(f )(4), provides that “nothing in this section…in any way

aects…any contractual obligations assumed at any time by the library

or archives when it obtained a copy or phonorecord of a work in its

collections.” This suggests that Congress did not intend for Section

108 to preempt enforcement of contract terms under state contract

law. However, the language of Section 108(f )(4) does not apply to

other limitations relied upon by libraries, such as Sections 107, 121,

or 121A, so there is no reason to assume that Congress intended to

permit contracts to nullify these provisions. This particularly is the

case with respect to fair use, because it is an accommodation to the

First Amendment. Contract terms that would restrict fair use rights

inherently restrict the constitutional right to free speech.

To say the least, this is an extremely complex issue that has not yet

been fully considered by the courts. The few cases that have addressed

the issue are inconsistent and do not involve libraries.

2

6

Association of Research Libraries

Copyrights and Contracts

Contracts and Section 108 of US Copyright Act

In the context of discussions to update Section 108, libraries have

argued that the language of Section 108(f )(4), mentioned above, should

be amended. The Copyright Oce has not been receptive to this

suggestion.

Digital Millennium Copyright Act Report (2001)

In a 2001 report, the Copyright Oce acknowledged concerns that

library associations raised about licenses for digital information

displacing provisions of the Copyright Act. The report concluded,

“although market forces may well prevent right holders from

unreasonably limiting consumer privileges, it is possible that at some

point in the future a case could be made for statutory change.”

Section 108 Study Group (2005–2008)

In 2005, the US Copyright Oce and the National Digital Information

Infrastructure and Preservation Program of the Library of Congress

sponsored a study group to review how Section 108 of the US

Copyright Act could be updated to address digital works and digital

transmissions. In its final report in 2008, the study group agreed that

“the terms of any negotiated, enforceable contract should continue to

apply notwithstanding the section 108 exceptions,” pointing out that

“[f ]reedom to contract is a fundamental principle in American law.”

However, the group disagreed as to whether Section 108 exceptions—

such as those for preservation—should prevail over contrary terms in

non-negotiated contracts.

Copyright Oce Section 108 Study (2017)

In 2017, the Copyright Oce published a discussion document on

Section 108 with two proposed changes to Section 108(f )(4). The first

change would “clarify that the primacy of contract language applies

to license agreements as well as purchase agreements.” Here, the

Copyright Oce cited the study group’s analysis: although Section

7

Association of Research Libraries

Copyrights and Contracts

108 was enacted prior to the development of markets for licensing

electronic media, the provision covers non-negotiable licenses.

The second proposed change states that libraries, archives, and

museums would not be liable for copyright infringement “if they make

preservation or security copies of works covered by non-negotiable

contractual language prohibiting such activities.” In sum, under the

Copyright Oce’s proposal, a library that engaged in preservation

activities permitted by Section 108 but prohibited by a non-negotiated

license term would not infringe copyright but would breach the license.

Advocacy and Policy Strategies

Libraries and library consortia work to overcome problematic contract

terms by negotiating for favorable license terms that do not waive

rights like fair use, and that do not require a user to seek permission

from a rightsholder for otherwise lawful uses. Some larger, well-

resourced institutions have had success with rights-savings clauses,

a strategy that is described below. But voluntary, licensing-based

solutions may not be viable and sustainable for all institutions. Other

solutions, like changes to the Copyright Act, may present their own

challenges; any discussion about amending the Copyright Act would

certainly get the attention of rightsholders and their lobbyists, and may

result in unintended consequences that are worse than the status quo.

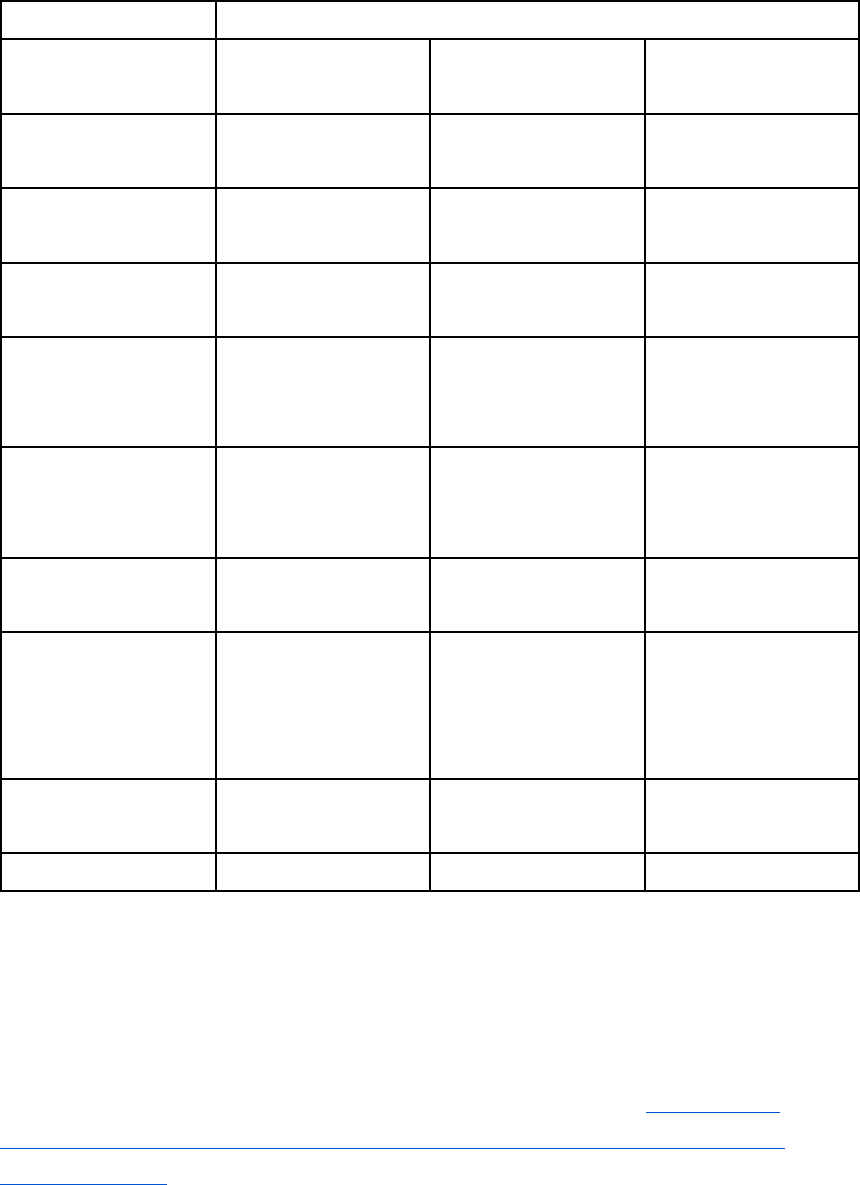

The remainder of this discussion paper explores strategies to allow

research libraries to advance the constitutional purpose of copyright.

The strategies are arranged in order of the scope of their potential

impact, which is also illustrated in the table below.

8

Association of Research Libraries

Copyrights and Contracts

Strategy Scope of Potential Impact

All Readers State by State Institution by

Institution

National open-

access policy

X

Campus open-

access policies

X

Rights-savings

clause

X

Statement

asserting

library rights

X

State

consumer-

protection law

X

State savings

clauses

X

State public

funds/

procurement

policy

X

Federal

exemptions

X

Test case X

Rights-Savings Clauses

Rights-Savings Clauses—Negotiation

When licensing digital materials, libraries may retain their fair-use

rights through fair-use savings clauses, as in this 2016 agreement

between the University of California and the American Chemical

Society (ACS):

9

Association of Research Libraries

Copyrights and Contracts

Fair Use: Nothing in this Agreement shall in any way exclude,

modify or aect anything the Grantee or an Authorized User is

allowed to do in respect of any of the ACS Products consistent with

the Fair Use Provisions of United States Copyright Law.

This strategy may be easiest and most eective for larger, wealthier

institutions that have more power when negotiating with vendors;

smaller, less-resourced institutions may not have the ability to walk

away from negotiations with vendors that are unwilling to meet the

terms of these clauses.

Libraries that do have the power to engage in meaningful negotiations

with publishers may consider broadening these savings clauses to

reflect that contract terms may not interfere with any rights granted

under copyright law, beyond fair use, to preserve exemptions like

breaking digital rights management (DRM) locks that the Copyright

Oce has granted under Section 1201 rulemaking. The Association of

Southeastern Research Libraries (ASERL) recommends that licenses

for content should forgo DRM restrictions in favor of usability:

Digital Rights Management (DRM) technology will not be used in

such a way as to limit the usage rights of a Licensee or any

Authorized User as specified in this Agreement or under applicable

law. In the event that Licensor utilizes or implements any type of

DRM technology to control the access to or usage of the licensed

content, Licensor will provide to Licensee a description of the

technical specifications of the DRM and how it impacts access to or

usage of the licensed content. If the use of DRM renders the

licensed content substantially less useful to the Licensee or its

Authorized Users, the Licensee has the right to terminate this

Agreement.

Rights-Savings Clauses—Regulation

The US Library of Congress (LC) receives copies of materials that

are distributed to the public electronically through the mandatory

10

Association of Research Libraries

Copyrights and Contracts

deposit; copyright deposit; and cataloging requests, mostly without

any licenses. But to address the problem of contractual restrictions on

digital materials, LC as part of the legislative branch issued a regulation

that preempts any license term that would limit LC’s rights under

copyright. The regulation includes a list of clauses that are deemed

to be inserted into each license agreement to which the LC is a party,

including the following:

Rights Under Copyright Law

The Library of Congress does not agree to any limitations on its

rights (e.g., fair use, reproduction, interlibrary loan, and archiving)

under the copyright laws of the United States (17 U.S.C. 101 et seq.),

and related intellectual property rights under foreign law,

international law, treaties, conventions, and other international

agreements.

The federal agencies that contain libraries—including Health and

Human Services, the Agricultural Research Service, the Departments

of Education and Transportation, and the Smithsonian Institution—

may discuss ways to emulate this regulation-based strategy

.

Statement Asserting Library Rights

As libraries dedicate increasing proportions of their budgets to

licensing digital works, negotiations for scholarly materials require

engagement with faculty and other campus stakeholders to be

successful; otherwise, faculty who need certain content may not be on

board with leaving negotiations. In instances when library agreements

with vendors do not save rights, researchers sometimes negotiate

individual agreements with data providers—independently of the

library—for access to content or for the right to conduct text- and data-

mining research on vendor-provided data sets. Vendors may charge

tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars for this type of access.

In order to build campuswide partnerships to support negotiations for

reasonable terms in licenses for scholarly materials, ARL may consider

developing a proactive rights statement based on the information

11

Copyrights and Contracts

Association of Research Libraries

compiled on KnowYourCopyrights.org. ARL has employed this strategy

of oering model language to support its members and the library

community in negotiating for fair terms. For instance, ARL developed

model license language in 2012 as a starting point for institutions to

consider as they draft local agreements. Similarly, ARL members and

other libraries may use a proactive library-rights statement to work

with faculty and others on campus to develop policies and practices to

preserve fair use and other rights granted by the Copyright Act.

Engaging faculty is critical to preserving rights during negotiations

for scholarly content, but this will not address the fundamental policy

problem: license terms supersede library rights in every situation

except for when a library refuses to agree to a license, or when a library

successfully negotiates to save certain rights. Rights-savings clauses

along with the strategies described below may strengthen libraries’

positions as arbiters of access to information.

Open Access

Strategies that do away with publication paywalls would moot this

problem; under an open-access strategy, information would be free

and available for use and reuse by the research community and the

rest of society. The ARL community, however, is well aware of the

challenges in broadening the adoption of open access. Because open

access is addressed in many other ARL documents, we do not discuss it

comprehensively here.

While the US does not currently have a national open-access law, many

universities and research institutions have adopted open-access

policies to reduce barriers to sharing research. Strong open-access

policies allow authors to retain all or part of their copyright, and/or

grant institutions limited and non-exclusive rights to its researchers’

work, which can enable dissemination of this work in open-access

repositories. For the past decade, US science agencies with more than

$100 million in research funding have been subject to the public-access

policies for both articles and data that resulted from federal funding.

Copyrights and Contracts

12

Association of Research Libraries

Copyrights and Contracts

Similar policies adopted by the Canadian Tri-Agency govern federally

funded Canadian research outputs. The strategies below address

journal articles; other strategies may be available for other publication

types (journals, monographs, conference proceedings, etc.)

Open-Access Policies and Rights-Retention Strategies

Global adoption of full open access would address many of the

problems described above, particularly for scholarly works that are

protected by copyright. According to the 2002 Budapest Open Access

Initiative (BOAI), “the only role for copyright…should be to give

authors control over the integrity of their work and the right to be

properly acknowledged and cited.” In other words, copyright should

not be a gatekeeper to providing public-access to scholarly materials;

open-access works are still protected by copyright. In describing how

to achieve open access to scholarly journal literature, the BOAI calls for

open-access journals that will use copyright to ensure permanent open

access to all articles they publish, rather than invoking copyright to

restrict access and use.

In a Rights Retention Strategy as envisioned by cOAlition S, authors

or their institutions retain copyright to their publications. When

submitting a manuscript, the author applies a Creative Commons CC-

BY license or another type of acceptable reuse license to the author-

accepted manuscript (AAM), and then deposits the AAM in an open-

access repository at the time of publication, without an embargo,

making the manuscript open and available for users to access, read, and

disseminate.

State Strategies

Unenforceable Contracts

State legislatures could adopt a provision stating that no contract term

inconsistent with copyright exceptions and limitations is enforceable

under the contract law of that state. In contrast to the Maryland

13

Association of Research Libraries

Copyrights and Contracts

e-book licensing law, this approach likely would not be preempted

by the Copyright Act because it is not inconsistent with the exclusive

rights provided to copyright owners under the Copyright Act; after

all, the Copyright Act includes those exceptions. There are some court

decisions finding such provisions not to be preempted (see Vault v.

Quaid, 847 F.2d 255 (5th Cir. 1988)). Indeed, the decision principally

relied upon by the district court in AAP v. Frosh—Orson v. Miramax, 189

F.3d 377, 386 (3d Cir. 1999)—stated:

a state regulation falling within the federally established exceptions

to those rights, such as fair use, see 17 U.S.C. § 107, may obligate a

copyright holder to change its practices to accommodate such uses,

see, e.g., Association of Am. Med. Colleges v. Cuomo 928 F.2d 519,

525-26 (2d Cir.1991) (remanding to district court to make factual

findings on whether existing state law constitutes fair use)

A state legislature could narrow such a contractual “override” provision

to apply only to licenses entered into by libraries.

Public Funds

State legislatures may consider establishing criteria for public

institutions to meet when spending public funding; examples may

include laws nullifying any terms that limit fair use in a license entered

into by a library that receives state funding, or restricting libraries that

receive state funding from entering into a license that limits fair use

and other rights aorded by the Copyright Act.

Legislation governing the use of public funds would not implicate

copyright law, and is therefore unlikely to be preempted. This strategy

has the potential to strengthen the negotiating power of public

institutions of higher education; regardless of their size and wealth,

they are the market for digital academic content. However, while

publishers are unlikely to walk away from transactions in states with

such laws, this strategy is narrower in scope and would only apply to

state-funded institutions.

14

Association of Research Libraries

Copyrights and Contracts

Federal Exemptions

Congressional Intervention

Congressional intervention to amend or clarify the Copyright Act

seems like an obvious strategy to address the problem of publishers

imposing license terms restricting lawful use of copyrighted works.

Indeed, the European Union recognizes that copyright exceptions

are useless if private parties could simply override them by contract,

and has included contract-preemption clauses in its directives for the

past three decades. For instance, the EU’s Copyright in the Digital

Single Market Directive provides that “Any contractual provision

contrary to the exceptions provided for in Articles 3, 5 and 6 shall be

unenforceable,” referencing articles that govern text mining and data

mining, digital cross-border teaching, and preservation by cultural

heritage organizations, respectively.

Singapore’s Copyright Bill combines exceptions for certain functions,

such as text mining and data mining, with language prohibiting

contracts from excluding these functions. For instance, Singapore’s

Copyright Act includes a specific exception for “computational data

analysis,” on top of its fair-use exception for research; in addition to

these protections, Singapore’s Copyright Act includes strong language

voiding contracts that would exclude or restrict this lawful use. For

instance, Part 5, “Permitted Uses of Copyright Works and Protected

Performances” includes the following section, listing computational

data analysis as a permitted use that may not be restricted by contract

Permitted uses that may not be excluded or restricted

187.–(1) Any contract term is void to the extent that it purports,

directly or indirectly, to exclude or restrict any permitted use

under any provision in —

(a) Division 6 (public collections), but not section 234 (supplying

copies of published literary, dramatic or musical works or articles

15

Association of Research Libraries

Copyrights and Contracts

between libraries and archives);

(b) Division 7 (computer programs);

(c) Division 8 (computational data analysis); or

(d) Division 17 (judicial proceedings and legal advice).

The Right to Research initiative found a more robust research

environment in countries that have open, general research exceptions,

such as fair use, as well as exceptions for specific activities, such as text

mining and data mining.

However, legislative proposals to adopt federal contract preemption

would face serious opposition from publishers. Any conversation about

amending the Copyright Act would open the door to rightsholders and

other copyright maximalists to assert their influence. Even a push to

enact general copyright misuse provision, so that victims of copyright

misuse would be entitled to actual and statutory damages, may not be

feasible.

Next Steps

ARL will continue to track and understand the legal, political, and

market-based barriers that libraries face.

Test Case

Given the legal uncertainty surrounding contract preemption, libraries

may consider a test-case strategy to see what is permitted under

current law. This would involve a library taking an action consistent

with fair use that is in contravention to a license term, then filing a

declaratory judgment action when the publisher sends a cease-and-

desist letter. A potential downside to the test case strategy is that a

publisher could just turn o access to the content. Unless the library

has downloaded the content and feels some limited sharing of it is

permitted by fair use, the library may be worse o than before.

16

Copyrights and Contracts

Association of Research Libraries

ARL Strategies

The issues presented above are complex and technical, and the best

path forward is unclear. Pursuing any of the strategies described

above will involve working in partnership with members of the

Library Copyright Alliance (LCA) and others in the library

community who advocate for balanced copyright and access to

information. As ARL members discuss these strategies, they may

wish to consider the following:

• How can we best socialize these strategies as an association? As

member institutions?

• Is the library community poised to take on any of these strategies

amongst ourselves? Are there partners we may wish to work with

to develop a best practice or strategy document?

• Is it useful to advance any of these strategies by influencing

public sentiment—for instance, by holding public conversations

or programs, commissioning articles and reports, or presenting at

conferences?

• If so, who might we partner with? What are some upcoming

opportunities?

• Which strategies might be best pursued quietly, without drawing

the attention of those who might push back?

• What context and additional information can ARL members

share about the strategies and examples discussed above?

Copyrights and Contracts

17

Endnotes

1

ARL Statistics 2020 data set, Association of Research Libraries.

2

Compare Vault v. Quaid, 847 F.2d 255 (5th Cir. 1988) with Bowers v. Baystate,

320 F.3d 1317 (2003). There are other arguments a library could raise against

the enforceability of non-negotiated licenses, such as that the library never

manifested assent to the license terms.