BYU Law Review BYU Law Review

Volume 46 Issue 2 Article 10

Spring 3-11-2021

Compelling Suspects to Unlock Their Phones: Recommendations Compelling Suspects to Unlock Their Phones: Recommendations

for Prosecutors and Law Enforcement for Prosecutors and Law Enforcement

Carissa A. Uresk

Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/lawreview

Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Courts Commons, and the Law Enforcement and

Corrections Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Carissa A. Uresk,

Compelling Suspects to Unlock Their Phones: Recommendations for Prosecutors and

Law Enforcement

, 46 BYU L. Rev. 601 (2021).

Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/lawreview/vol46/iss2/10

This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Brigham Young University Law Review at BYU Law

Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Law Review by an authorized editor of BYU Law Digital

Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected].

6.URESK_FIN.NH (DO NOT DELETE) 3/11/2021 1:03 AM

601

Compelling Suspects to Unlock Their Phones:

Recommendations for Prosecutors and

Law Enforcement

Carissa A. Uresk

*

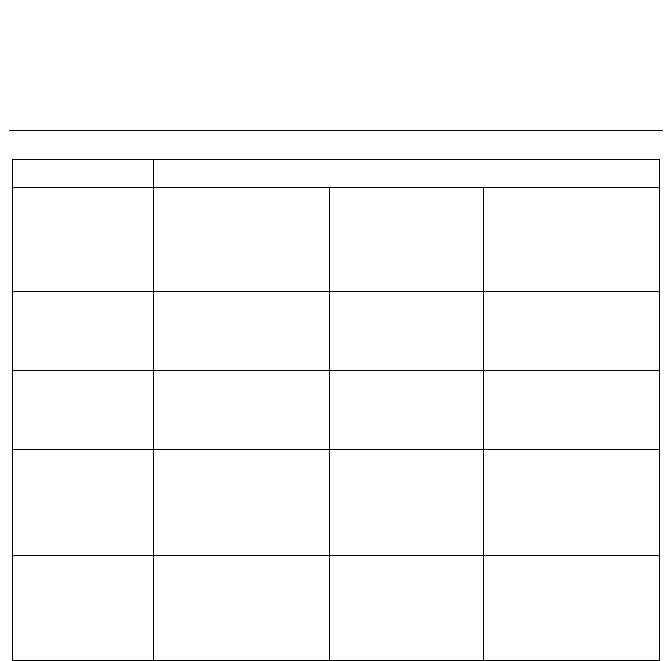

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. 602

I. TECHNOLOGY OVERVIEW............................................................................ 603

A. Phone Passcodes ........................................................................................ 603

B. Phone Encryption ...................................................................................... 604

C. Breaking into Locked Phones .................................................................. 605

1. Phones protected by PINs and alphanumeric passwords ........... 606

2. Phones protected by biometrics....................................................... 609

II. THE FIFTH AMENDMENT PRIVILEGE AGAINST SELF-INCRIMINATION ............ 612

A. Testimonial Communications.................................................................. 612

1. The act-of-production doctrine ........................................................ 613

2. The foregone-conclusion doctrine ................................................... 613

3. U.S. Supreme Court precedent ........................................................ 614

III. APPLYING THE FIFTH AMENDMENT TO COMPELLED PHONE UNLOCKS ........ 618

A. Phones Protected by PINs and Alphanumeric Passwords .................. 618

1. Is there a testimonial communication? ........................................... 618

2. Does the foregone-conclusion doctrine apply? ............................. 621

B. Phones Protected by Biometrics ............................................................... 637

1. Courts that have held biometrics are not testimonial ................... 638

2. Courts that have held biometrics are testimonial.......................... 640

3. Court that has not clearly chosen one approach ........................... 643

4. Is there a clear trend? ........................................................................ 644

C. Additional Factors That May Influence a Court’s Decision ................. 645

1. Is the prosecutor offering immunity? ............................................. 645

2. What was the suspect compelled to produce? ............................... 648

IV. RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PROSECUTORS AND LAW ENFORCEMENT ............. 650

CONCLUSION ................................................................................................ 655

*

J. Reuben Clark Law School, J.D. Candidate 2021. Westminster College in Salt Lake

City, Utah, B.A. 2017. My thanks to Kelsy Young, Utah County Attorney's Office, for telling

me about this issue; Professor Melinda Bowen, J. Reuben Clark Law School, for her feedback

and suggestions; and BYU Law Review members for their helpful comments.

6.URESK_FIN.NH (DO NOT DELETE) 3/11/2021 1:03 AM

BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW 46:2 (2021)

602

INTRODUCTION

In 2017, Katelin Seo told the Hamilton County Sheriff’s

Department that D.S. raped her.

1

With Seo’s consent, a detective

viewed and downloaded her iPhone’s contents.

2

Based on the phone’s contents, the detective decided not to file

charges against D.S. and instead began investigating Seo for

stalking and harassing D.S.

3

The detective spoke with D.S., who

said Seo called and texted him numerous times each day,

sometimes up to thirty times in one day.

4

Later that month, Seo was arrested for stalking and harassing

D.S.

5

When police arrested Seo, they seized her phone and asked

her for the password.

6

Although they had a warrant for the phone,

Seo refused to divulge her password.

7

So the State was in a bind:

it had legally seized a phone that it could not search because the

phone was locked and passcode protected.

8

This scenario is not unique to Hamilton County. Law

enforcement agencies across the country struggle with what to do

when they legally seize a phone and have court permission to

search that phone but are unable to because it is locked.

Ultimately, the solution is to compel the suspect to unlock

the phone. The suspect, however, can counter with a

Fifth Amendment claim: if the government compels the suspect to

unlock the phone, it may be unconstitutionally requiring the

suspect to self-incriminate.

In some jurisdictions, courts have addressed this issue and

established protocol for how to constitutionally compel a suspect

to unlock a phone.

9

In other jurisdictions, however, this issue

remains unresolved, leaving law enforcement and prosecutors

without clear guidance.

This paper offers recommendations for law enforcement and

prosecutors in jurisdictions where there is no binding caselaw on

1

. Eunjoo Seo v. State, 148 N.E.3d 952, 953 (Ind. 2020).

2

. Id.

3

. Id.

4

. Id.

5

. Id. at 953–54.

6

. Id. at 954.

7

. Id.

8

. Id.

9

. See infra notes 180, 221, 297, 313, and accompanying text.

6.URESK_FIN.NH (DO NOT DELETE) 3/11/2021 1:03 AM

603 Compelling Suspects to Unlock Phones

603

this issue. Part II is an overview of passcodes and how they protect

phone content. Part III is an explanation of relevant United States

Supreme Court precedent on the privilege against self-

incrimination. Part IV introduces the pertinent legal questions and

explains how some lower courts have addressed this issue. Part V

recommends how to successfully get court permission to compel

suspects to unlock their phones.

I. TECHNOLOGY OVERVIEW

Before delving into the legal issues, it is helpful to understand

the technology behind phone passcodes. Understanding how

passcodes work helps explain why this issue has developed, what

options law enforcement has, and the different legal issues lawyers

and courts must consider. This section will give an overview of

(A) the different types of phone passcodes, (B) what it means for a

device to be “encrypted,” and (C) the possibility of using

technology to forcibly unlock a passcode-protected phone.

A. Phone Passcodes

With smartphones, users can create passcodes that lock and

unlock their phones.

10

Passcodes are typically a personal

identification number (PIN), an alphanumeric password, or a

biometric feature.

11

A PIN is a four- or six-digit passcode.

12

If a phone is PIN

protected, users unlock the phone by entering a previously selected

string of digits.

13

An alphanumeric password is like a PIN

but allows users to create a passcode that includes both digits

and letters.

14

10

. Tahir Musa Ibrahim, Shafi’i Muhammad Abdulhamid, Ala Abdusalam Alarood,

Haruna Chiroma, Mohammed Ali Al-garadi, Nadim Rana, Amina Nuhu Muhammad,

Adamu Abubakar, Khalid Haruna & Lubna A. Gabralla, Recent Advances in Mobile

Touch Screen Security Authentication Methods: A Systematic Literature Review, 85 COMPUTS. &

SEC. 1, 2 (2019).

11

. Id. at 3–7.

12

. Id. at 4.

13

. Id.

14

. Lorenzo Franceschi-Bicchierai, Stop Using 6-Digit iPhone Passcodes, VICE:

MOTHERBOARD (Apr. 16, 2018, 11:56 AM), https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/59jq8a/

how-to-make-a-secure-iphone-passcode-6-digits.

6.URESK_FIN.NH (DO NOT DELETE) 3/11/2021 1:03 AM

BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW 46:2 (2021)

604

Biometrics are unique physical attributes used for identification

and authentication.

15

Common biometric authentication methods

for phones are fingerprint, facial, and iris.

16

For example, users can

scan their thumbprints into their phone.

17

When the phone is

locked, users scan their thumb again; if the new scan matches the

previously stored scan, the phone will unlock.

18

This process is

called “one-to-one matching” because the phone is comparing a

current sample to a previously made sample.

19

B. Phone Encryption

In addition to passcodes, smartphones increasingly use

encryption to protect data while the phone is locked.

20

When a

phone is encrypted, its contents

21

(plaintext) are converted to

unintelligible characters (ciphertext).

22

A decryption key is

necessary to change the contents from ciphertext to plaintext and

vice versa.

23

A decryption key is composed of “bits,” which are

strings of zeros and ones.

24

Decryption keys are typically 128- or

256-bits long and automatically generated by the phone’s

software.

25

While a 256-bit key has significantly more possible keys

than a 128-bit key, both have an “unimaginably large number[]” of

possible keys and are thus considered uncrackable.

26

Importantly, the phone’s passcode is not the decryption key.

27

Rather, the passcode is a way to release the more complex

15

. What Are Biometrics?, BIOMETRICS INST., https://www.biometricsinstitute.org/

what-is-biometrics/faqs/ (last visited Oct. 5, 2020).

16

. Robin Feldman, Considerations on the Emerging Implementation of Biometric

Technology, 25 HASTINGS COMMC’NS & ENT. L.J. 653, 655 (2003).

17

. Id. at 655–56.

18

. Id.

19

. Id.

20

. Orin S. Kerr & Bruce Schneier, Encryption Workarounds, 106 GEO. L.J. 989,

990 (2018).

21

. “Contents” includes text, images, videos, and programs. Id. at 993.

22

. Michael Price & Zach Simonetti, Defending Device Decryption Cases, CHAMPION,

July 2019, at 42.

23

. Id.

24

. Kerr & Schneier, supra note 20, at 993.

25

. Id. at 993–94.

26

. Id.

27

. Id. at 995.

6.URESK_FIN.NH (DO NOT DELETE) 3/11/2021 1:03 AM

605 Compelling Suspects to Unlock Phones

605

encryption key.

28

When a user enters the correct passcode,

the phone accesses the decryption key, which then decrypts the

device.

29

Thus, every time users lock their phones they also encrypt

their phones’ content.

30

When they unlock their phones, the content

is automatically decrypted.

31

This process is invisible to users.

32

The difference between locking and encrypting a device is

subtle but significant. Locking a phone is like locking a file room’s

door; if you can find another way into the room—through a

window, perhaps—the contents of the files are the same as if you

had unlocked and entered through the door.

33

However, imagine

that the door is locked and the files are shredded—that is an

encrypted device.

34

In practice, this means that law enforcement

can potentially access the contents of a locked, but not encrypted,

phone by removing and accessing the storage device with

laboratory equipment.

35

If the phone is encrypted, however, law

enforcement will only see unintelligible data.

36

For simplicity’s

sake, unless otherwise noted, when this Note refers to unlocking a

phone it also means decrypting an encrypted phone.

37

C. Breaking into Locked Phones

Of course, the simplest solution to this problem, in criminal

investigations, is for suspects to voluntarily unlock their phones.

38

28

. Laurent Sacharoff, Unlocking the Fifth Amendment: Passwords and Encrypted Devices,

87 FORDHAM L. REV. 203, 221 (2018).

29

. Id. at 222.

30

. See id. at 221.

31

. Id.

32

. Kerr & Schneier, supra note 20, at 994.

33

. See Price & Simonetti, supra note 22, at 43 (“For example, early iPhones could be

‘locked,’ but they did not encrypt the data inside, making it possible to read user contents by

bypassing the lock.”).

34

. See id.

35

. See Sacharoff, supra note 28, at 221.

36

. Id.

37

. Because nearly all smartphones now use encryption, the distinction is not often

necessary to point out. Id.

38

. Potentially, if a phone is protected by biometrics, law enforcement could attempt

to use the suspect’s biometrics without the suspect’s permission. For example, an officer

could hold a phone protected by facial identification up to a suspect’s face. This does,

however, raise a Fourth Amendment concern over whether the state has illegally seized the

suspect’s biometric features. This Note will not cover that issue, but for a discussion of the

topic see Opher Shweiki & Youli Lee, Compelled Use of Biometric Keys to Unlock a Digital Device:

Deciphering Recent Legal Developments, 67 DOJ J. FED. L. & PRAC. 23, 25–34 (2019).

6.URESK_FIN.NH (DO NOT DELETE) 3/11/2021 1:03 AM

BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW 46:2 (2021)

606

While some suspects may do so, it is unlikely that they will for a

variety of reasons—including a reluctance to self-incriminate and a

belief that the Constitution protects their noncompliance. Whatever

the reason, when users refuse to unlock their phones, law

enforcement can try to force the phone to unlock, so long as they

have legally seized the phone. The likely success of this approach

depends on the type of passcode protecting the phone.

1. Phones protected by PINs and alphanumeric passwords

PINs and alphanumeric passwords are designed in such a way

that the fastest way to break into the phone is through a brute-force

attack.

39

A brute-force attack entails attempting every possible

passcode until the phone unlocks.

40

The longer the code, the longer

a brute-force attack will take.

41

To prevent brute-force attacks,

many phone security systems have escalating time delays after a

user enters an invalid passcode.

42

These systems also let users

enable an option that erases the phone’s content after a certain

amount of incorrect entries.

43

For example, the current iPhone

operating system requires a user to wait one minute before entering

a passcode after five failed attempts.

44

That delay escalates to one

hour after nine failed attempts.

45

If the “Erase Data” function is

turned on, the device automatically erases all data after ten

consecutive failed attempts.

46

In the past, law enforcement has had difficulty breaking

four- and six-digit PINs. For example, in 2015, gunmen killed

fourteen people in San Bernardino, California.

47

The FBI believed

that one of the gunmen’s phones contained important evidence,

which the FBI could not access because the phone was protected by

39

. Kerr & Schneier, supra note 20, at 994.

40

. Id.

41

. Id. (“Adding a single bit to the encryption key only slightly increases the amount

of work necessary to encrypt, but doubles the amount of work necessary to brute-force attack

the algorithm.”).

42

. Id. at 1000.

43

. Id.

44

. Passcodes, APPLE INC., https://support.apple.com/guide/security/passcodes-

sec20230a10d/1/web/1 (last visited Oct. 5, 2020).

45

. Id.

46

. Id.

47

. Mike Isaac, Explaining Apple’s Fight with the F.B.I., N.Y. TIMES (Feb. 17, 2006),

https://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/18/technology/explaining-apples-fight-with-the-fbi.html.

6.URESK_FIN.NH (DO NOT DELETE) 3/11/2021 1:03 AM

607 Compelling Suspects to Unlock Phones

607

a four-digit passcode.

48

A legal battle between Apple and the FBI

ensued, and a federal court ordered Apple to unlock the iPhone.

49

Apple refused and, before scheduled court proceedings, a third

party found a way to unlock the phone for the FBI.

50

To Apple’s

chagrin, the FBI refused to divulge how the third party unlocked

the phone.

51

Since the Apple-FBI standoff, passcodes have become more

susceptible to brute-force attacks.

52

Law enforcement relies on two

companies to break into phones: Cellebrite and Grayshift.

53

Cellebrite is an Israeli-owned company that claims it can unlock

phones running up to Android 10 and iOS 13.3.x, as well as devices

manufactured by Motorola, LG, Sony, Nokia, and other

companies.

54

Cellebrite sells “on-premise” devices, meaning that

law enforcement officers can purchase Cellebrite technology

and use it themselves.

55

Because this technology is sold only to

law enforcement, it is hard to know the exact cost, but most

estimates show prices ranging from $2,499 to $15,999, depending

on the model.

56

Some agencies also use GrayKey, a device manufactured by

Grayshift. Grayshift has publicly advertised its ability to crack a

four-digit iPhone passcode in six-and-a-half to thirteen minutes.

57

If that number is accurate, it would take, on average, 22.2 hours to

crack a 6-digit passcode, 92.5 days to crack an 8-digit passcode, and

48

. Id.; Chris Fox & Dave Lee, Apple Rejects Order to Unlock Gunman’s Phone, BBC NEWS

(Feb. 17, 2016), https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-35594245.

49

. Id.

50

. Katie Benne, John Markoff & Nicole Perlroff, Apple’s New Challenge: Learning How

the U.S. Cracked Its iPhone, N.Y. TIMES (Mar. 29, 2016), https://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/

30/technology/apples-new-challenge-learning-how-the-us-cracked-its-iphone.html.

51

. Id.

52

. Franceschi-Bicchierai, supra note 14.

53

. Price & Simonetti, supra note 22, at 47.

54

. Cellebrite Premium, CELLEBRITE, https://www.cellebrite.com/en/ufed-premium/

(last visited Oct. 5, 2020).

55

. Unlock and Extract Critical Mobile Data in Your Agency with Cellebrite’s Premium,

CELLEBRITE, https://www.cellebrite.com/en/cellebrite-premium-2/ (last visited Oct. 5, 2020).

56

. Product Information: Cellebrite UFED Series, SC MEDIA (Oct. 1, 2015),

https://www.scmagazine.com/review/cellebrite-ufed-series/.

57

. Researcher Estimates GrayKey Can Unlock 6-Digit iPhone Passcode in 11 Hours, Here’s

How to Protect Yourself, APPLEINSIDER (Apr. 16, 2018), https://appleinsider.com/articles/18/

04/16/researcher-estimates-graykey-can-unlock-a-6-digit-iphone-passcode-in-11-hours-

heres-how-to-protect-yourself.

6.URESK_FIN.NH (DO NOT DELETE) 3/11/2021 1:03 AM

BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW 46:2 (2021)

608

25.4 years to crack a 10-digit passcode.

58

In comparison, it would

take five to six years to crack a six-character alphanumeric

password.

59

Like Cellebrite, GrayKey is sold only to law

enforcement and is an on-premise device that officers can use

themselves.

60

One GrayKey model permits 300 uses and costs

$15,000; another model allows unlimited uses and costs $30,000.

61

Unlike Cellebrite, GrayKey only works on Apple devices.

62

Further,

GrayKey can only unlock some versions of iOS 12 and lower.

63

In response to these technologies, phone manufacturers

develop better security systems.

64

For example, in 2018, Apple

announced a software update that automatically disables the

phone’s charging port an hour after the phone is locked.

65

Because

code-breaking devices plug into the charging port, this software

update thwarts those devices.

66

Apple claimed that the update was

not an attempt to “frustrate” law enforcement, but a way “to help

customers defend against hackers, identity thieves and intrusions

into their personal data.”

67

Since the update, Cellebrite, but

not Grayshift, has developed technology to work around that

58

. @matthew_d_green, TWITTER (Apr. 16, 2018, 8:17 AM), https://twitter.com/

matthew_d_green/status/985885001542782978?lang=en. Green is an associate professor

and cryptographer at the Johns Hopkins Information Security Institute. Matthew D. Green,

JOHNS HOPKINS UNIV. (Feb. 5, 2020), https://isi.jhu.edu/~mgreen/.

59

. Julia P. Eckart, The Department of Justice Versus Apple Inc.: The Great Encryption

Debate Between Privacy and National Security, 27 CATH. U.J.L. & TECH. 1, 10 (2019).

60

. GrayKey, GRAYSHIFT, https://graykey.grayshift.com/ (last visited Oct. 5, 2020).

61

. Thomas Brewster, Mysterious $15,000 ‘GrayKey’ Promises to Unlock iPhone X for the

Feds, FORBES (Mar. 5, 2018, 12:10 PM), https://www.forbes.com/sites/thomasbrewster/

2018/03/05/apple-iphone-x-graykey-hack/#6188c0fb2950.

62

. Andy Greenberg, Cellebrite Says It Can Unlock Any iPhone for Cops, WIRED

(June 14, 2019, 6:05 PM), https://www.wired.com/story/cellebrite-ufed-ios-12-iphone-

hack-android/.

63

. Id.

64

. Jack Nicas, Apple to Close iPhone Security Hole That Law Enforcement Uses to Crack

Devices, N.Y. TIMES (June 13, 2018), https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/13/technology/

apple-iphone-police.html.

65

. Id.

66

. Id.

67

. Roger Fingas, Apple Confirms iOS 12’s ‘USB Restricted Mode’ Will Thwart

Police, Criminal Access, APPLEINSIDER (June 13, 2018), https://appleinsider.com/articles/

18/06/13/apple-confirms-ios-12s-usb-restricted-mode-designed-to-thwart-spies-criminals-

police-seizures; Heather Kelly, Apple Closes Law Enforcement Loophole for the iPhone, CNN BUS.

(June 14, 2018, 5:35 AM), https://money.cnn.com/2018/06/13/technology/apple-iphone-

law-enforcement/index.html.

6.URESK_FIN.NH (DO NOT DELETE) 3/11/2021 1:03 AM

609 Compelling Suspects to Unlock Phones

609

software update.

68

This cycle resembles a cat-and-mouse game

where phone companies develop new software that seems

impermeable, a forensics company develops a workaround, the

phone manufacture creates a fix, and so on.

69

2. Phones protected by biometrics

In addition to passcodes, many phones are protected by

biometrics. The three most common types for phones are

fingerprint, facial, and iris identification.

Fingerprint identification, also called touch identification,

unlocks a phone when a “live” fingerprint placed on a sensor

matches a previously stored mathematical representation of that

fingerprint.

70

To create a stored mathematical representation, users

repeatedly place different sections of their fingerprint on the

phone’s sensor.

71

Because the sensor is smaller than the average

adult fingerprint, these repeated placements allow the phone to

gather a complete representation of the fingerprint.

72

However,

when users later unlock their phones, only a section of their

fingerprint is actually sensed.

73

This means that phones unlock by

comparing a smaller portion of a “live” fingerprint to a complete,

stored representation.

74

Similar to fingerprint identification, facial identification works

by comparing a “live” image of someone’s face to a previously

stored image.

75

The images are compared for mathematical, and not

just pictorial, likeness.

76

For example, Apple’s Face ID uses over

30,000 infrared dots to form a “depth map” that is a mathematical

representation of the face.

77

It also requires that the user’s attention

be directed at the device.

78

Apple claims that facial identification is

68

. Greenberg, supra note 62.

69

. Id.

70

. About Touch ID Advanced Security Technology, APPLE INC. (Sept. 11, 2017)

[hereinafter About Touch ID], https://support.apple.com/en-us/HT204587.

71

. Id.

72

. Id.

73

. Id.

74

. Id.

75

. About Face ID Advanced Technology, APPLE INC. (Feb. 26, 2020) [hereinafter About

Face ID], https://support.apple.com/en-us/HT208108.

76

. Id.

77

. Id.

78

. Id.

6.URESK_FIN.NH (DO NOT DELETE) 3/11/2021 1:03 AM

BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW 46:2 (2021)

610

more secure than fingerprint identification; it says the likelihood

of a random person looking at an iPhone protected by Face ID

and unlocking it are 1 in 1,000,000

79

(compared to 1 in 50,000

for Touch ID).

80

Iris identification is a less popular biometric-identification

method.

81

Iris identification uses an infrared light to take a high-

resolution image of an iris.

82

If the image matches a previously

stored image, the phone unlocks.

83

Samsung, which makes phones

with iris scanners, claims that “because virtually no two irises are

alike as well as being almost impossible to replicate, scanning your

irises is a fool-proof method of mobile security.”

84

Unlike PINs or alphanumeric passwords, biometrics cannot be

“guessed” through a brute-force attack. However, biometrics can

sometimes be replicated and the phone “tricked” into unlocking.

For example, a German hacking group claimed it unlocked an

iPhone 5s with a fake finger created from a photograph of the user’s

fingerprint on a glass surface.

85

Likewise, researchers at New York

University and Michigan State University claimed they made fake

fingerprints composed of common features that could unlock

phones up to sixty-five percent of the time.

86

However, these fake

fingerprints were not tested on actual phones, and other

79

. However, the “statistical probability is different for twins and siblings that look

like you and among children under the age of 13, because their distinct facial features may

not have fully developed.” Id.

80

. About Touch ID, supra note 70. But see JV Chamary, No, Apple’s Face ID Is Not a

‘Secure Password’, FORBES (Sept. 18, 2017, 11:00 AM), https://www.forbes.com/sites/

jvchamary/2017/09/18/security-apple-face-id-iphone-x/#30063e4d4c83 (claiming there is

“no real evidence to prove [Face ID] is more secure”).

81

. Many phones, like iPhones, do not have iris scanners, possibly because they do

not work well with screen protectors, contacts, and glasses. Comparison: iPhone X vs. Galaxy

Note 8 Biometrics, APPLEINSIDER (Dec. 11, 2017), https://appleinsider.com/articles/17/12/

11/comparison-iphone-x-vs-galaxy-note-8-biometrics.

82

. Iris Recognition, ELEC. FRONTIER FOUND. (Oct. 25, 2019), https://www.eff.org/

pages/iris-recognition.

83

. Id.

84

. How Does the Iris Scanner Work on Galaxy S9, Galaxy S9+, and Galaxy Note9?,

SAMSUNG, https://www.samsung.com/global/galaxy/what-is/iris-scanning/ (last visited

Oct. 5, 2020).

85

. Chaos Computer Club Breaks Apple TouchID, CHAOS COMPUT. CLUB (Sept. 21, 2013,

10:04 PM), https://www.ccc.de/en/updates/2013/ccc-breaks-apple-touchid.

86

. Aditi Roy, Nasir Memon & Arun Ross, MasterPrint: Exploring the Vulnerability of

Partial Fingerprint-Based Authentication Systems, 12 IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON INFO. FORENSICS

& SEC. 9, 2013–25 (Sept. 2017).

6.URESK_FIN.NH (DO NOT DELETE) 3/11/2021 1:03 AM

611 Compelling Suspects to Unlock Phones

611

researchers expect the unlock rate would be much lower in

real-world conditions.

87

These examples show that breaking into a

fingerprint-protected phone is possible, but victory is

unpredictable and expensive.

Groups have also had success with fake faces and eyes. For

example, Forbes used a three-dimensional, printed head to break

into four different phones running Android.

88

The fake head did

not work on iPhones.

89

A different researcher, however, was able to

fool an iPhone X’s Face ID using a three-dimensional printer,

silicone, and paper tape.

90

Similarly, a hacking group posted a

video of its members unlocking an iris-protected Samsung phone

by creating a “dummy eye” with a digital photograph, office

printer, and contact lens.

91

Importantly, there are often restrictions on when biometrics

will unlock a phone. For example, Motorola phones require users

to enter a PIN or password if the phone has been locked for

seventy-two hours, has restarted, or has unsuccessfully read a

fingerprint five times.

92

Likewise, iPhone Touch ID and Face ID will

not work if, among other reasons, there have been five unsuccessful

reading attempts, the phone has been locked for forty-eight hours,

or the phone has just turned on.

93

In sum, locked phones are not impenetrable. However,

breaking into a locked phone is impractical for three reasons:

(1) it is expensive, (2) it takes time, and (3) the technology is

87

. Vindu Goel, That Fingerprint Sensor on Your iPhone Is Not as Safe as You Think,

N.Y. TIMES (Apr. 10, 2017), https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/10/technology/

fingerprint-security-smartphones-apple-google-samsung.html.

88

. This process requires fifty cameras, which take pictures of the model’s head, and

software to compile all of the pictures. Thomas Brewster, We Broke Into a Bunch of Android

Phones With a 3D–Printed Head, FORBES (Dec. 13, 2018, 7:00 AM),

https://www.forbes.com/sites/thomasbrewster/2018/12/13/we-broke-into-a-bunch-of-

android-phones-with-a-3d-printed-head/#18bd796f1330.

89

. Id.

90

. Mai Nguyen, Vietnamese Researcher Shows iPhone X Face ID ‘Hack’,

REUTERS (Nov. 14, 2017, 6:46 AM), https://www.reuters.com/article/us-apple-vietnam-

hack/vietnamese-researcher-shows-iphone-x-face-id-hack-idUSKBN1DE1TH.

91

. Hacking the Samsung Galaxy S8 Irisscanner, CHAOS COMPUT. CLUB (May 23, 2017),

https://media.ccc.de/v/biometrie-s8-iris-en.

92

. Use Fingerprint Security—Moto G Plus 4th Generation, MOTOROLA,

https://support.motorola.com/us/en/solution/MS110999 (last visited Oct. 5, 2020).

93

. About Face ID, supra note 75; About Touch ID, supra note 70.

6.URESK_FIN.NH (DO NOT DELETE) 3/11/2021 1:03 AM

BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW 46:2 (2021)

612

constantly changing. For those reasons, law enforcement agencies

may choose to try compelling suspects to unlock their phones.

II. THE FIFTH AMENDMENT PRIVILEGE AGAINST

SELF-INCRIMINATION

The Fifth Amendment guarantees that “[n]o person . . . shall be

compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself.”

94

This privilege is triggered only when someone is “[1] compelled

[2] to make a testimonial communication [3] that is

incriminating.”

95

In compelled-phone-unlock cases, both parties

often agree that the passcode was compelled and is incriminating.

96

Thus, the issue in these cases is usually whether unlocking

a phone is a testimonial communication. The sections below

describe how the United States Supreme Court has defined

“testimonial communication.”

A. Testimonial Communications

In order to be testimonial, a communication must, “explicitly or

implicitly, relate a factual assertion or disclose information.”

97

Likewise, testimonial communications require individuals to

express the contents of their minds.

98

For that reason, the privilege

against self-incrimination is not implicated when suspects give a

blood sample,

99

stand in a lineup,

100

or wear certain clothing.

101

Although these actions may be compelled and incriminating,

94

. U.S. CONST. amend. V.

95

. Fisher v. United States, 425 U.S. 391, 408 (1976).

96

. In re Grand Jury Subpoena Duces Tecum Dated Mar. 25, 2011 (Grand Jury

Subpoena), 670 F.3d 1335, 1341 (11th Cir. 2012) (“Here, the Government appears to concede,

as it should, that the decryption and production are compelled and incriminatory.”).

Prosecutors are likely to concede that the act is incriminating because even non-inculpatory

communications are incriminating if they “furnish a link in the chain of evidence” needed to

prosecute. Hoffman v. United States, 341 U.S. 479, 486 (1951); see also United States v.

Hubbell, 530 U.S. 27, 37 (2000) (“It has, however, long been settled that [the Fifth

Amendment’s] protection encompasses compelled statements that lead to the discovery of

incriminating evidence even though the statements themselves are not incriminating and are

not introduced into evidence.”).

97

. Doe v. United States, 487 U.S. 201, 210 (1988).

98

. Curcio v. United States, 354 U.S. 118, 128 (1957).

99

. Schmerber v. California, 384 U.S. 757, 765 (1966).

100

. United States v. Wade, 388 U.S. 218, 221–22 (1967).

101

. Holt v. United States, 218 U.S. 245, 252–53 (1910).

6.URESK_FIN.NH (DO NOT DELETE) 3/11/2021 1:03 AM

613 Compelling Suspects to Unlock Phones

613

they are not testimonial communications because they do not

require individuals to reveal the contents of their minds.

102

While defining and clarifying the meaning of testimonial

communication, the Supreme Court has articulated two important

doctrines: the act-of-production doctrine and the foregone-

conclusion doctrine.

1. The act-of-production doctrine

When suspects hand over documents, they are making

a testimonial communication—wholly independent from

the documents’ contents—that they have possession, control,

and ownership over those documents.

103

This is the

act-of-production doctrine.

104

For example, the government may subpoena suspects’ diaries,

believing that those diaries contain evidence of a crime. The entries

in the diaries are most certainly testimonial communications.

Putting that aside, however, if the suspects surrender their diaries,

they would also be making testimonial communications—through

the act of production—that they own those diaries, have possession

of those diaries, and that those diaries are the ones the government

requested.

105

As the Supreme Court put it, “[t]he act of producing

evidence in response to a subpoena nevertheless has

communicative aspects of its own, wholly aside from the contents

of the papers produced.”

106

2. The foregone-conclusion doctrine

If the government already knows the information conveyed,

however, the act of production is not a testimonial

communication.

107

This is called the “foregone-conclusion

doctrine” because suspects add “little or nothing to the sum total of

the Government’s information” by producing the requested

information.

108

In other words, if the information that suspects

102

. Schmerber, 384 U.S. at 765; Wade, 388 U.S. at 221–22; Holt, 218 U.S. at 252–53.

103

. Fisher v. United States, 425 U.S. 391, 410 (1976).

104

. Id.

105

. See id.

106

. Id.

107

. Id. at 411.

108

. Id.

6.URESK_FIN.NH (DO NOT DELETE) 3/11/2021 1:03 AM

BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW 46:2 (2021)

614

communicate through the act of production is already known by

the government, the suspects are simply surrendering

information—not testifying.

109

Returning to the example from above, presume that the

government can independently prove that the suspects own and

have control over the requested diaries. In that case, any potential

testimonial communication is a foregone conclusion, and the

Fifth Amendment is not implicated.

110

3. U.S. Supreme Court precedent

The Supreme Court first articulated the act-of-production and

foregone-conclusion doctrines in United States v. Fisher. The Court

applied these doctrines again in United States v. Doe and United

States v. Hubbell. A description of the facts and holdings of each case

is helpful to understanding how the Supreme Court identifies

testimonial communications.

a. United States v. Fisher.

In Fisher, Internal Revenue agents interviewed taxpayers

suspected of violating federal income tax laws.

111

After the

interviews, the taxpayers collected tax documents from their

accountants and sent the documents to their lawyers.

112

When the

IRS served summonses on the lawyers for those documents, the

lawyers refused to comply, claiming, in part, that turning over

the documents would force the taxpayers to compulsorily

incriminate themselves.

113

The Court’s analysis focused on whether the documents were a

testimonial communication by the taxpayers. The Court

reiterated that “the privilege protects a person only against

being incriminated by his own compelled testimonial

communications.”

114

Although compelling taxpayers to produce an

accountant’s workpapers “without doubt involves substantial

compulsion,” the actual creation of the workpapers was not

compelled.

115

Further, the taxpayers were not being forced to reveal

109

. Id.

110

. See generally id. at 393–94.

111

. Id. at 394.

112

. Id.

113

. Id. at 394–95.

114

. Id. at 409.

115

. Id. at 409–10.

6.URESK_FIN.NH (DO NOT DELETE) 3/11/2021 1:03 AM

615 Compelling Suspects to Unlock Phones

615

the contents of their minds because they were not compelled to

“restate, repeat, or affirm the truth of the contents of the documents

sought.”

116

Since the tax documents were prepared by accountants,

and did not contain any testimonial declarations by the taxpayers,

the Court held that the taxpayers could not claim the documents

were their testimony.

117

Yet the Court recognized that compliance with the subpoena

“concedes the existence of the papers demanded and their

possession or control by the taxpayer.”

118

In other words,

by producing the documents, the taxpayers would be testifying

that the documents exist, are the documents requested, and are in

their possession.

119

Ultimately, however, the Court decided that producing the

documents would not be a testimonial communication.

120

This was

because the “existence and location of the papers are a foregone

conclusion and the taxpayer adds little or nothing to the sum total

of the Government’s information by conceding that he in fact has

the papers.”

121

By complying with the subpoena, the taxpayers

were not communicating any information to the government that

the government did not already know.

122

So the Fifth Amendment

did not protect the taxpayers from producing the documents.

123

b. United States v. Doe.

In Doe, a grand jury subpoenaed bank records from Doe,

its target.

124

Doe surrendered some records but invoked the

Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination for other

records.

125

When the government subpoenaed banks for those

records, the banks refused, citing bank-secrecy laws.

126

In response,

the government asked the district court to order Doe to sign consent

forms.

127

These forms applied to “any and all accounts over which

116

. Id. at 409.

117

. Id.

118

. Id. at 410.

119

. Id.

120

. Id. at 410–11.

121

. Id.

122

. Id.

123

. Id. at 414.

124

. Doe v. United States, 487 U.S. 201, 202 (1988).

125

. Id. at 202–03.

126

. Id. at 203.

127

. Id. at 203–04.

6.URESK_FIN.NH (DO NOT DELETE) 3/11/2021 1:03 AM

BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW 46:2 (2021)

616

Doe had a right of withdrawal, without acknowledging

the existence of any such account.”

128

The district court, after an

appeal to the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, ordered Doe

to sign the form.

129

When Doe refused to sign, he was held in

civil contempt; this sanction was stayed pending the Supreme

Court’s decision.

130

At the Supreme Court, Doe claimed that signing the forms

would be an incriminating, testimonial communication.

131

The

Court, however, held that by signing and executing the forms Doe

would not be communicating, explicitly or implicitly, any factual

assertions or conveying any information to the government.

132

This

was because the consent forms, by speaking in the hypothetical and

not referring to specific accounts, did not acknowledge that the

accounts actually existed or were controlled by Doe.

133

Ultimately,

by signing the forms, Doe would not be making any statement

about the existence of the bank accounts or his control over

those accounts.

134

Dissenting, Justice Stevens argued that a suspect “may in some

cases be forced to surrender a key to a strongbox containing

incriminating documents” but may not be forced to “reveal the

combination to his wall safe.”

135

The problem with the latter, he

argued, is that it requires a suspect to “use his mind to assist the

Government in developing its case.”

136

For Justice Stevens,

requiring Doe to execute the consent forms is akin to requiring him

to reveal a safe combination.

137

In a footnote, the majority said it did not “disagree with the

dissent that ‘[t]he expression of the contents of an individual’s

mind’ is testimonial communication for purposes of the

Fifth Amendment.”

138

It did, however, feel that what the

128

. Id. at 204.

129

. Id. at 205–06.

130

. Id.

131

. Id. at 207.

132

. Id. at 215.

133

. Id.

134

. Id. at 215–16.

135

. Id. at 219 (Stevens, J., dissenting).

136

. Id. at 220 (Stevens, J., dissenting).

137

. Id.

138

. Doe, 487 U.S. at 210 n.9.

6.URESK_FIN.NH (DO NOT DELETE) 3/11/2021 1:03 AM

617 Compelling Suspects to Unlock Phones

617

government requested was more like asking Doe for a key than a

safe combination.

139

Thus, signing the form was non-testimonial and the Fifth

Amendment did not protect Doe.

140

c. United States v. Hubbell.

In Hubbell, Webster Hubbell, a member of the Whitewater

Development Corporation, pled guilty to mail fraud and tax

evasion.

141

As part of that plea, Hubbell “promised to provide the

Independent Counsel with ‘full, complete, accurate, and truthful

information’ about matters relating to the Whitewater

investigation.”

142

To see if Hubbell was complying with that

promise, the Independent Counsel subpoenaed eleven different

categories of documents; Hubbell provided those documents,

which a grand jury used to charge Hubbell with other crimes.

143

The

district court, however, dismissed the indictment after determining

that the act-of-production doctrine protected Hubbell.

144

The case

made its way to the Supreme Court.

145

The Court decided that Hubbell was constitutionally protected

from complying with the subpoena.

146

It held that the government’s

request in this instance violated Hubbell’s privilege against

self-incrimination because the information it asked for was not a

“foregone conclusion.”

147

Unlike in Fisher, where the government

could independently prove the existence and authenticity of the

requested documents, the government here had no prior

knowledge of the documents that Hubbell produced in response to

the subpoena.

148

Indeed, the subpoena asked for such a breadth of

information that the prosecutor “needed [Hubbell’s] assistance

both to identify potential sources of information and to produce

those sources.”

149

This communicated facts not already known to

139

. Id.

140

. Id. at 217.

141

. United States v. Hubbell, 530 U.S. 27, 30 (2000).

142

. Id.

143

. Id. at 31.

144

. Id. at 31–32.

145

. Id. at 34.

146

. Id. at 45–46.

147

. Id. at 44.

148

. Id. at 44–45.

149

. Id. at 41.

6.URESK_FIN.NH (DO NOT DELETE) 3/11/2021 1:03 AM

BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW 46:2 (2021)

618

the government

150

and required Hubbell “to make extensive use of

the contents of his own mind.”

151

Accordingly, his act of production

was testimonial, and the Fifth Amendment protected him.

152

In sum, the government cannot compel individuals to make

self-incriminating, testimonial communications. While this

protection is limited to factual assertions that convey information,

it includes acts of production that reveal new information to

the government.

III. APPLYING THE FIFTH AMENDMENT TO COMPELLED

PHONE UNLOCKS

153

Given the reality of how difficult it is to unlock a phone, law

enforcement may try compelling suspects to unlock their phones.

Specifically, law enforcement may try to compel suspects to

(1) disclose their passcodes orally or in writing, (2) enter a

passcode without disclosing it, or (3) produce their phones in a

decrypted form.

154

While compulsion might be technologically simpler than trying

to break into a phone, it raises difficult legal questions regarding

the privilege against self-incrimination. Specifically, compelling

suspects to unlock their phones raises two questions: First, is there

a testimonial communication? Second, does the foregone-

conclusion doctrine apply? Because the analysis may vary

depending on the type of passcode, PINs and alphanumeric

passwords are addressed first and biometrics second.

A. Phones Protected by PINs and Alphanumeric Passwords

1. Is there a testimonial communication?

When law enforcement seeks to compel a suspect to unlock a

phone, the first question that courts address is whether the suspect

150

. Id. at 44–45.

151

. Id. at 43 (internal quotation marks omitted).

152

. Id. at 44–45.

153

. This Note only includes opinions and orders, accessible via Westlaw

and LexisNexis, from federal circuit courts, federal district courts, and state appellate

courts. State trial court decisions have been excluded based on their sheer volume

and inaccessibility.

154

. Kerr & Schneier, supra note 20, at 1001–02.

6.URESK_FIN.NH (DO NOT DELETE) 3/11/2021 1:03 AM

619 Compelling Suspects to Unlock Phones

619

is making a testimonial communication by unlocking the phone.

A phone passcode may be testimonial in two different ways.

First, a passcode may be testimonial if the actual passcode

explicitly relates a fact. For example, suspected heroin dealers

would be relating a fact if their passcodes were “ISELLHEROIN.”

Because this passcode relates a fact that is incriminating,

compelling it would likely implicate the Fifth Amendment.

155

However, this situation is not probable and has not yet been

addressed by a court.

Second, unlocking a phone is testimonial if the act of producing

the passcode communicates information independent from the

phone’s passcode. By unlocking a phone, users at the very least

communicate that they know the passcode to that phone.

156

Users

may also be communicating that they have possession, control, or

ownership over the phone.

157

But the act of unlocking a phone may not be testimonial if there

is no dispute that the suspect owns the phone and if the suspect is

not asked to reveal the password to law enforcement.

158

For

example, an FBI agent asked a suspect to unlock a phone and the

suspect did so, without telling or showing the agent the

password.

159

The Fourth Circuit said: “Certainly, [the suspect] has

not shown that her act communicated her cell phone’s unique

password.”

160

This was because the phone’s ownership was never

in dispute and the suspect “simply used the unexpressed contents

of her mind to type in the passcode herself.”

161

But the court

ultimately resolved this issue on other grounds, meaning it did not

155

. This type of passcode would not implicate the Fifth Amendment, however, if the

passcode were typed in by the user and not disclosed to the government. Orin S. Kerr,

Compelled Decryption and the Privilege Against Self-Incrimination, 97 TEX. L. REV. 767, 779 (2019).

156

. See, e.g., In re Grand Jury Subpoena Duces Tecum Dated Mar. 25, 2011 (Grand Jury

Subpoena), 670 F.3d 1335, 1346 (11th Cir. 2012); Commonwealth v. Gelfgatt, 11 N.E.3d 605,

614 (Mass. 2014).

157

. See, e.g., Grand Jury Subpoena, 670 F.3d at 1346; Gelfgatt, 11 N.E.3d at 614.

158

. United States v. Oloyede, 933 F.3d 302, 309 (4th Cir. 2019), cert. denied

sub nom. Popoola v. United States, 140 S. Ct. 1212 (2020), and cert. denied sub nom.

Ogundele v. United States, 140 S. Ct. 1213 (2020), and cert. denied sub nom. Popoola v. United

States, 140 S. Ct. 2554 (2020).

159

. Id. at 308.

160

. Id. at 309.

161

. Id.

6.URESK_FIN.NH (DO NOT DELETE) 3/11/2021 1:03 AM

BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW 46:2 (2021)

620

make a ruling on whether the suspect had made a testimonial

communication.

162

Contrary to the Fourth Circuit’s reasoning, most courts do find

that the act of unlocking phones is a testimonial communication.

163

To support this conclusion, some courts reference Justice Stevens’s

safe analogy from his Doe dissent.

164

Applying this analogy to

phones, some courts have stressed that passcodes are not like a key

because passcodes are not physical items.

165

Rather, passcodes are

contained within a person’s mind, like a safe combination.

166

Thus,

requiring suspects to reveal or use their passcodes also requires

them to reveal the contents of their minds.

167

One court, however, has questioned the relevance of this

analogy.

168

While the safe analogy may be useful for physical

documents, the court reasoned, it does not translate well to modern

phone technology.

169

Unfortunately, the Court did not provide

analysis on why it does not translate well.

Fortunately, others have analyzed why this analogy may no

longer be applicable. For example, two scholars argue that “[l]ike

many attempts to compare the digital and the physical worlds, the

safe analogy has some intuitive appeal, but it only tells part of the

story.”

170

The analogy “only tells part of the story” because phone

passcodes encrypt and decrypt the data they protect; safe

combinations do not.

171

For another scholar, the analogy is

unhelpful because it states a truism—obviously, revealing a safe

combination is testimonial because it “is a statement of a person’s

162

. Id. at 309–10.

163

. See infra notes 180, 221. In all of these cases, the courts determined that the act of

unlocking a phone was a testimonial communication.

164

. In re Grand Jury Subpoena Duces Tecum Dated Mar. 25, 2011 (Grand Jury

Subpoena), 670 F.3d 1335, 1346 (11th Cir. 2012); G.A.Q.L. v. State, 257 So. 3d 1058, 1061

(Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2018); Commonwealth v. Davis, 220 A.3d 534, 548 (Pa. 2019).

165

. E.g., Davis, 220 A.3d at 548 (“There is no physical manifestation of a password,

unlike a handwriting sample, blood draw, or a voice exemplar.”).

166

. Grand Jury Subpoena, 670 F.3d at 1346; G.A.Q.L., 257 So. 3d at 1061; Davis,

220 A.3d at 548.

167

. Grand Jury Subpoena, 670 F.3d at 1346; G.A.Q.L., 257 So. 3d at 1061; Davis,

220 A.3d at 548.

168

. State v. Stahl, 206 So. 3d 124, 135 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2016).

169

. Id.

170

. Price & Simonetti, supra note 22.

171

. Id.

6.URESK_FIN.NH (DO NOT DELETE) 3/11/2021 1:03 AM

621 Compelling Suspects to Unlock Phones

621

thoughts revealed to the government.”

172

A suspect can

decrypt a phone, however, without revealing the passcode to

the government.

173

Another consideration is the difference between unlocking and

decrypting a phone. As explained above, most phones today

encrypt when they are locked.

174

This means that a phone’s contents

are unreadable until a user enters the passcode, which releases

a more complex decryption key that makes the contents

readable again.

175

However, only two courts have addressed the

unlocking/decrypting distinction, and they found that it did not

impact the analysis. A federal district court in Washington, D.C.,

asserted that the distinction is not relevant because decryption “is

accomplished by the machine” and there is no evidence that it

“requires any mental effort by the [suspect].”

176

Likewise, a Florida

district court of appeal held that the distinction “is of no

consequence” because decryption “is simply an abbreviated means

of decrypting the phone’s contents.”

177

Neither court delved more

into the analysis.

178

Thus, this distinction does not seem like it will

be dispositive in most cases, but that could change as more courts

address this issue.

Regardless of whether a court finds the safe analogy or the

unlocking/decrypting distinction persuasive, it will undoubtedly

find that unlocking a phone is testimonial because when suspects

unlock a phone they communicate that they know the passcode.

179

2. Does the foregone-conclusion doctrine apply?

Next, courts must determine if the foregone-conclusion

doctrine applies, thus making the act of production

non-testimonial. This issue is where courts differ the most—not just

in how they answer the question but also in how they frame the

question. Specifically, courts are split on whether, for the exception

172

. Kerr, supra note 155, at 782.

173

. Id.

174

. See text accompanying supra notes 20–37.

175

. Id.

176

. In re Search of [Redacted] D.C., 317 F. Supp. 3d 523, 538 (D.D.C. 2018).

177

. G.A.Q.L. v. State, 257 So. 3d 1058, 1062 n.1 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2018)

178

. Id.; In re Search of [Redacted] D.C., 317 F. Supp. 3d at 538.

179

. See supra note 156 and accompanying text.

6.URESK_FIN.NH (DO NOT DELETE) 3/11/2021 1:03 AM

BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW 46:2 (2021)

622

to apply, the forgone conclusion must be the suspect’s knowledge

of the phone’s passcode or the suspect’s knowledge of the

phone’s contents.

a. Courts that apply the foregone-conclusion doctrine when the

government can independently prove that the suspect knows the

phone’s passcode.

Some courts have held that the foregone-conclusion doctrine

applies when the government can independently prove that the

suspect knows the phone’s passcode.

180

Arguably, when a suspect

unlocks a phone, that suspect is only communicating that they

180

. In re State’s Application to Compel M.S. to Provide Passcode, No. A–4509–18T2,

2020 WL 5498590, at *3–4 (N.J. Super. Ct. App. Div. Sept. 11, 2020) (holding that the foregone-

conclusion doctrine applies when the suspect’s ownership and control of phone is not

disputed); State v. Andrews, 234 A.3d 1254, 1274 (N.J. 2020) (holding that “although the act

of producing the passcodes is presumptively protected by the Fifth Amendment, its

testimonial value and constitutional protection may be overcome if the passcodes’ existence,

possession, and authentication are foregone conclusions”); State v. Pittman, 452 P.3d 1011,

1020 (Or. Ct. App. 2019) (holding that the “state did not need to establish, however, that the

contents of the iPhone were a foregone conclusion”), review allowed, 458 P.3d 1121 (Or. 2020);

Commonwealth v. Jones, 117 N.E.3d 702, 710 (Mass. 2019) (holding that “the only fact

conveyed by compelling a defendant to enter the password to an encrypted electronic device

is that the defendant knows the password . . . .”); State v. Johnson, 576 S.W.3d 205, 227 (Mo.

Ct. App.) (holding that foregone conclusion applied because the only “facts conveyed

through [the suspect’s] act of producing the passcode were the existence of the passcode, his

possession and control of the phone’s passcode, and the passcode’s authenticity”), transfer

denied (June 25, 2019), cert. denied, 140 S. Ct. 472 (2019); United States v. Spencer, No. 17-cr-

00259-CRB-1, 2018 WL 1964588, at *3 (N.D. Cal. Apr. 26, 2018) (holding that “the government

need only show it is a foregone conclusion that [the suspect] has the ability to decrypt the

devices”); In re Search of a Residence in Aptos, California 95003, No. 17-mj-70656-JSC-1, 2018

WL 1400401, at *6 (N.D. Cal. Mar. 20, 2018) (holding “that if the [suspect’s] knowledge of the

relevant encryption passwords is a foregone conclusion, then the Court may compel

decryption under the foregone conclusion doctrine”); In re Grand Jury Investigation, 88

N.E.3d 1178, 1182 (Mass. App. Ct. 2017) (holding that foregone conclusion applied because

“the Commonwealth knew that a PIN code was necessary to access the iPhone, that the

[suspect] possessed and controlled the iPhone, and that the petitioner knows the PIN code

and is able to enter it”); State v. Stahl, 206 So. 3d 124, 136–37 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2016) (holding

that the Fifth Amendment was not implicated because “the State established, with

reasonable particularity, its knowledge of the existence of the passcode, [the suspect’s]

control or possession of the passcode, and the self-authenticating nature of the passcode”);

Commonwealth v. Gelfgatt, 11 N.E.3d 605, 615 (Mass. 2014) (holding that the “facts that

would be conveyed by the [suspect] through his act of decryption—his ownership and

control of the computers and their contents, knowledge of the fact of encryption, and

knowledge of the encryption key—already are known to the government and, thus, are a

‘foregone conclusion’”); United States v. Gavegnano, 305 F. App’x 954, 956 (4th Cir. 2009)

(holding that any “self-incriminating testimony that [the suspect] may have provided by

revealing the password was already a ‘foregone conclusion’ because the Government

independently proved that [the suspect] was the sole user and possessor of the computer”).

6.URESK_FIN.NH (DO NOT DELETE) 3/11/2021 1:03 AM

623 Compelling Suspects to Unlock Phones

623

know the phone’s passcode.

181

So, the argument goes, the foregone-

conclusion doctrine applies if law enforcement can independently

prove that the suspect knows the phone’s passcode. If so, the

compulsion adds “little or nothing to the sum total of the

Government’s information,”

182

and the Fifth Amendment is

not implicated.

In one of the earlier cases applying this reasoning,

Commonwealth v. Gelfgatt, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial

Court held that the foregone-conclusion doctrine applied because

the Commonwealth could independently prove that the suspect

had ownership over the locked devices and knowledge of the

devices’ encryption keys.

183

Here, an attorney was arrested on

suspicion that he was carrying out a fraudulent mortgage

scheme.

184

When he was arrested, law enforcement seized several

computers

185

that were encrypted and password protected.

186

Law enforcement officers were not able to circumvent the

encryption, and the attorney would not unlock the devices,

although he did confirm his ability to decrypt them.

187

The

Commonwealth then moved to compel the attorney to decrypt the

devices, which the judge denied, citing the Fifth Amendment

privilege against self-incrimination.

188

On appeal, the court held that the Fifth Amendment did not

protect the attorney from entering the decryption keys because the

foregone-conclusion doctrine applied.

189

The court said, “The facts

that would be conveyed by the defendant through his act of

decryption—his ownership and control of the computers and their

contents, knowledge of the fact of encryption, and knowledge of

the encryption key—already are known to the government and,

181

. Although it may be probable that knowledge of a phone’s passcode and

knowledge of its contents are synonymous, it is not certain. For example, suspects could have

been told the passcode by someone else, or they could have not accessed the phone for

some time.

182

. Fisher v. United States, 425 U.S. 391, 411 (1976).

183

. Gelfgatt, 11 N.E.3d at 615.

184

. Id. at 609–10.

185

. Although this case is about computers, not phones, the Fifth Amendment analysis

is the same.

186

. Gelfgatt, 11 N.E.3d at 610.

187

. Id.

188

. Id. at 611.

189

. Id. at 615.

6.URESK_FIN.NH (DO NOT DELETE) 3/11/2021 1:03 AM

BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW 46:2 (2021)

624

thus, are a ‘foregone conclusion.’”

190

In other words, the

Commonwealth already knew the attorney could decrypt the

computers, so the attorney would not be communicating any new

information by entering the passcode. Here, the court is clear that

the focus of the analysis should be whether it is a foregone

conclusion that the suspect knows the passcode.

191

An important question at this stage is how the government can

prove it “knows” the suspect can unlock the phone. In some cases,

like Gelfgatt, suspects may confirm their ability to unlock a phone.

In other cases, however, the government may have to prove that

knowledge with supplemental evidence. For example, in State v.

Stahl, a Florida district court of appeal held that the foregone-

conclusion doctrine applied because the State proved, via the

suspect’s own admissions and phone records, that the suspect

knew the phone’s passcode.

192

In Stahl, police arrested a man they

believed was using his phone to take inappropriate pictures of

women.

193

The man denied taking the pictures and gave police

permission to search his iPhone, which was at his house.

194

When the suspect refused to unlock the iPhone, the State moved to

compel him to do so.

195

The trial court denied the motion on

Fifth Amendment grounds, and the State appealed.

196

On appeal, the court held that the State could compel the

suspect to unlock his phone. The court held that the State had

“established that it knows with reasonable particularity that the

passcode exists, is within the accused’s possession or control, and is

authentic.”

197

The State established the suspect knew the passcode

because he had earlier identified the phone as his, and the phone’s

190

. Id.

191

. Id.

192

. State v. Stahl, 206 So. 3d 124, 136 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2016).

193

. Id. at 127.

194

. Id. at 128.

195

. Id.

196

. Id.

197

. Id. at 136 (emphasis in original). The State established that a passcode exists simply

by stating that the phone could not be unlocked without a passcode. Id. Further, the court

held that, with locked phones, “we must recognize that the technology is self-

authenticating—no other means of authentication may exist.” Id. In other words, the

passcode is authenticated when the suspect enters it into the phone.

6.URESK_FIN.NH (DO NOT DELETE) 3/11/2021 1:03 AM

625 Compelling Suspects to Unlock Phones

625

number and service provider matched those listed on the suspect’s

cellphone-carrier records.

198

Similarly, in Commonwealth v. Jones, the Massachusetts Supreme

Judicial Court listed several pieces of information to support its

holding that the Commonwealth had independently proved the

suspect’s knowledge of the phone’s passcode.

199

In Jones, the

suspect was arrested for trafficking a person for sexual servitude.

200

When police arrested the suspect, they seized a locked LG phone

from his person.

201

When the suspect refused to unlock the phone,

the Commonwealth moved to compel the suspect to provide the

passcode; this was denied.

202

On appeal, the court held that the

suspect could be compelled to enter the passcode because his

knowledge of the passcode was a foregone conclusion.

203

The court relied on several pieces of evidence to find that the

suspect’s knowledge of the passcode was a foregone conclusion.

204

First, the woman who reported the suspect told police that the

suspect regularly used an LG phone to contact her.

205

She also

showed the police her phone, which had the LG’s number listed

under the suspect’s name in her contacts list.

206

The subscriber

information for the LG had a listed backup number; that backup

number belonged to the suspect.

207

Using cell-site location records,

the police were also able to show that the suspect and the LG were

in the same locations at various times.

208

Finally, the court found it

important that the LG was on the suspect’s person when he was

arrested.

209

The totality of the evidence was enough to convince the

court that the suspect had knowledge of the passcode.

210

To counteract this evidence, the suspect claimed that the

Commonwealth had to prove he had exclusive control over

198

. Id.

199

. Commonwealth v. Gelfgatt, 11 N.E.3d 605, 717 (Mass. 2014).

200

. Id. at 706.

201

. Id.

202

. Id.

203

. Id. at 707.

204

. Id. at 717.

205

. Id.

206

. Id.

207

. Id.

208

. Id.

209

. Id.

210

. Id.

6.URESK_FIN.NH (DO NOT DELETE) 3/11/2021 1:03 AM

BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW 46:2 (2021)

626

the phone.

211

The suspect pointed to evidence that others also used

the phone to show that he was not the LG’s sole owner.

212

The court,

however, held that the Commonwealth did not have to prove sole

or exclusive ownership.

213

Rather, it only had to prove the suspect’s

knowledge of the passcode.

214

Another important question is the burden of proof that the

government must meet. In Stahl, the court held that the government

has to know that the suspect can unlock the phone, but it does not

have to have “perfect knowledge.”

215

Specifically, the court

identified the standard as whether the government can know this

information with “reasonable particularity.”

216

The court did not

expressly define what level this standard is, nor have other courts

that have adopted this standard.

217

Alternatively, some courts have

set the standard at “clear and convincing evidence”

218

or “beyond

a reasonable doubt.”

219

However, “reasonable particularity” is the

more common standard.

220

211

. Id.

212

. Id.

213

. Id.

214

. Id.

215

. State v. Stahl, 206 So. 3d 124, 135 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2016) (quoting United States

v. Greenfield, 831 F.3d 106, 116 (2d Cir. 2016)).

216

. Id.

217

. In re Grand Jury Subpoena Duces Tecum Dated Mar. 25, 2011 (Grand Jury

Subpoena), 670 F.3d 1335, 1344 (11th Cir. 2012) (“Where the location, existence, and

authenticity of the purported evidence is known with reasonable particularity, the contents

of the individual’s mind are not used against him, and therefore no Fifth

Amendment protection is available.”); In re Search of a Residence in Aptos, California 95003,

No. 17-MJ-70656-JSC-1, 2018 WL 1400401, at *6 (N.D. Cal. Mar. 20, 2018) (“Finally, the

government’s showing of independent knowledge must be made to the standard of

‘reasonable particularity.’”); State v. Pittman, 452 P.3d 1011, 1019 (Or. Ct. App. 2019) (“That

is why it matters whether the government has identified the documents with ‘reasonable

particularity’ in the subpoena.”).

218

. United States v. Spencer, No. 17-cr-00259-CRB-1, 2018 WL 1964588, at *3

(N.D. Cal. Apr. 26, 2018) (“The question, accordingly, is whether the government has shown

by clear and convincing evidence that [the suspect’s] ability to decrypt the three devices is a

foregone conclusion.”).

219

. Commonwealth v. Jones, 117 N.E.3d 702, 714 (Mass. 2019) (“[F]or the foregone

conclusion to apply, the Commonwealth must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the

defendant knows the password.”).

220

. This is likely because there is United States Supreme Court and federal circuit

court precedent that uses the phrase “reasonable particularity.” United States v. Hubbell,

530 U.S. 27, 30 (2000); Grand Jury Subpoena, 670 F.3d at 1344; In re Grand Jury Subpoena,

Dated April 18, 2003, 383 F.3d 905, 910 (9th Cir. 2004).

6.URESK_FIN.NH (DO NOT DELETE) 3/11/2021 1:03 AM

627 Compelling Suspects to Unlock Phones

627

In short, some courts will compel suspects to unlock phones if

the government can independently prove that the suspect knows

the passcode. Usually, the government must prove this with

“reasonable particularity.” This independent knowledge can be

proved in a variety of ways. The easiest way is if suspects confirm

their ability to unlock a phone. Absent that confirmation, law

enforcement can rely on a variety of evidence to prove knowledge

of the passcode; for example, the phone was found on the suspect,

another person can connect the suspect to the phone,

cell-site location records connect the suspect to the phone, and

cellphone-carrier records also connect the suspect to the phone.

b. Courts that apply the foregone conclusion doctrine only when

the government has demonstrated independent knowledge of the

phone’s contents.

Some courts have held that the foregone-conclusion doctrine

only applies when the government has demonstrated independent

knowledge of the phone’s contents.

221

This requires law

221

. Varn v. State, No. 1D19–1967, 2020 WL 5244807, at *3 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. Sept. 3,

2020) (holding that the focus of the foregone-conclusion doctrine “is whether the State has

identified with reasonable particularity the evidence it seeks within the passcode-protected

cell phone”); Eunjoo Seo v. State, 148 N.E.3d 952, 958 (Ind. 2020) (holding that the foregone

conclusion doctrine did not apply because “the State has failed to demonstrate that any

particular files on the device exist or that [the suspect] possessed those files”);

Commonwealth v. Davis, 220 A.3d 534, 551 n.9 (Pa. 2019) (holding that even if the foregone

conclusion-doctrine could apply, the “Commonwealth must establish: (1) the existence of the

evidence demanded; (2) the possession or control of the evidence by the defendant; and (3)

the authenticity of the evidence”); Pollard v. State, 287 So. 3d 649, 657 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App.

2019) (holding that the foregone-conclusion doctrine only applies if “the state can describe

with reasonable particularity the information it seeks to access on a specific cellphone. . . .”),

reh’g denied (Dec. 23, 2019), review dismissed No. SC20–110, 2020 WL 1491793 (Fla. Mar. 25,

2020); People v. Spicer, 125 N.E.3d 1286, 1291 (Ill. App. Ct. 2019) (holding that “the proper

focus” of the foregone-conclusion doctrine “is not on the passcode but on the information

the passcode protects”); G.A.Q.L. v. State, 257 So. 3d 1058, 1063 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2018)

(holding that “the object of the foregone conclusion exception is not the password itself, but

the data the state seeks behind the passcode wall”); SEC v. Huang, No. CV 15–269, 2015 WL

5611644, at *3 (E.D. Pa. Sept. 23, 2015) (holding that the foregone-conclusion doctrine did not

apply because the SEC had no evidence that “any of the documents it alleges reside in the

passcode protected phones”); Commonwealth v. Baust, 89 Va. Cir. 267, 271 (Va. Cir. Ct. 2014)

(holding that a phone password was not a foregone conclusion because “it is not known

outside of [the suspect’s] mind” and that the Commonwealth could not compel decryption

because “the existence and location of the [phone’s contents are] not a foregone

conclusion.”); Grand Jury Subpoena, 670 F.3d at 1346 (holding that the foregone-conclusion

doctrine did not apply because “[n]othing in the record before us reveals that the

Government knows whether any files exist and are located on the hard drives . . . .”);

In re Boucher (Boucher II), No. 2:06–MJ–91, 2009 WL 424718, at *3 (D. Vt. Feb. 19, 2009)

6.URESK_FIN.NH (DO NOT DELETE) 3/11/2021 1:03 AM

BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW 46:2 (2021)

628

enforcement to describe what information it expects to find on the

locked phone. Because only two courts using this approach have

concluded that a suspect’s knowledge of a phone’s content was a

foregone conclusion, it is hard to know for certain how much detail

a court would require before granting a motion to compel.

The leading case on this approach—which requires law

enforcement to prove that the device’s contents are a foregone

conclusion—is Grand Jury Subpoena from the Eleventh Circuit.