DEMOGRAPHIC RESEARCH

VOLUME 40, ARTICLE 14, PAGES 359-394

PUBLISHED 22 FEBRUARY 2019

https://www.demographic-research.org/Volumes/Vol40/14/

DOI: 10.4054/DemRes.2019.40.14

Research Article

‘Will the one who keeps the children keep the

house?’ Residential mobility after divorce by

parenthood status and custody arrangements in

France

Giulia Ferrari

Carole Bonnet

Anne Solaz

This publication is part of the Special Collection on “Separation, Divorce, and

Residential Mobility in a Comparative Perspective,” organized by Guest

Editors Júlia Mikolai, Hill Kulu, and Clara Mulder.

© 2019 Giulia Ferrari, Carole Bonnet & Anne Solaz.

This open-access work is published under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution 3.0 Germany (CC BY 3.0 DE), which permits use, reproduction,

and distribution in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source

are given credit.

See https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/de/legalcode.

Contents

1 Introduction 360

2 Background 361

2.1 Residential mobility and parental status 361

2.2 Residential mobility and custodial status 362

2.3 Consequences of the move 364

2.3.1 The distance of the move 364

2.3.2 Housing conditions 365

3 The French context 365

4 Data, methods, and variables 367

4.1 Data and sample 367

4.2 Methods 368

4.3 Variables 369

4.3.1 Outcomes 369

4.3.2 Variables of interest 369

4.3.3 Controls 370

5 Results 371

5.1 Descriptive statistics 371

5.2 Multivariate analysis 373

5.2.1 Moving after divorce 373

5.2.2 Moving distance 377

5.2.3 Housing conditions 378

5.3 Endogeneity issues 381

6 Discussion and conclusions 381

7 Acknowledgements 384

References 385

Appendix 389

Demographic Research: Volume 40, Article 14

Research Article

http://www.demographic-research.org 359

‘Will the one who keeps the children keep the house?’

Residential mobility after divorce by parenthood status and

custody arrangements in France

Giulia Ferrari

1

Carole Bonnet

2

Anne Solaz

2

Abstract

BACKGROUND

After divorce, at least one of the partners usually relocates and, according to past

research, it is more often the woman. Women’s housing conditions are likely to worsen.

Divorces where children are involved are frequent and shared custody arrangements are

becoming more common in Europe.

OBJECTIVE

This paper analyses the extent to which residential mobility after divorce is linked to

parental status and child custody arrangements in France, a topic that remains largely

unstudied. We assess not only the probability of moving but also the distance of the

move and changes in housing conditions.

METHODS

We apply logistic and linear regressions to different indicators from a recent

administrative database, the French Permanent Demographic Sample, 2010–2013,

which makes it possible to track divorced people and their households over time.

RESULTS

One year after divorce, women are more likely to move than men, although the gender

gap is narrower for parents. While sole custody is associated with fewer moves than

noncustody for both sexes, shared custody arrangements imply many more moves for

mothers than for fathers. Parents more often move near their previous joint home than

nonparents, especially those with shared custody. Housing conditions do not necessarily

deteriorate after separation, but women are often disadvantaged compared with men.

1

Institut National d’Études Démographiques (INED), Paris, France. Email: giulia.ferrari@ined.fr.

2

Institut National d’Études Démographiques (INED), Paris, France.

Ferrari, Bonnet & Solaz: Residential mobility after divorce by parenthood status and custody arrangements

360 http://www.demographic-research.org

CONTRIBUTION

This paper expands on the current literature in that it addresses changes in residency

after separation by including the effects of parental status and child custody

arrangements.

1. Introduction

Divorce has become a common life event that affects an ever-increasing share of the

population in most developed countries. The stigma previously associated with divorce

is less pronounced (Wolfinger 1999; Lyngstad and Jalovaara 2010) and the negative

consequences of separation on well-being are more limited or of shorter duration than

previously, for both adults (Hetherington 2003; Andreß and Bröckel 2007) and children

(Amato 2001). However, the period around divorce remains a time of considerable

difficulty and stress for most individuals (Amato 2010). Part of this stress is linked to

the residential relocation that divorce entails. At the time of separation, partners must

either look for a new home and agree on who will move or decide whether the joint

home is to be sold. The new housing may be worse because of financial, parental, or

professional constraints. Relocation may also involve a possible loss of social contacts

with friends and neighbours.

Divorce frequently involves children, in which case parents must also make

custody arrangements. A growing trend towards shared custody has been observed in

many countries (Cancian et al. 2014), supported by new laws encouraging an equal

division of parental responsibilities. This has certainly been the case in France, where

more than one in five divorces that involve children result in shared custody

arrangements, while the most common arrangement, in which the mother has sole

custody, is on the decrease (Bonnet, Garbinti, and Solaz 2015). These trends may shape

the residential mobility of divorced parents in the future, because shared custody

implies that both parents must provide housing for their children on a regular basis.

This means that they need to have enough space in their home and also live close to

each other, especially when the children are young. Child custody arrangements,

decided by the parents and submitted for the approval of a family court judge in France,

may also be guided by the postdivorce housing conditions of each parent. Child custody

arrangements and mobility choices are thus closely linked (Thomas, Mulder, and Cooke

2017).

In most cases, divorce involves the relocation of at least one partner. According to

Durier (2017), only 20% of divorces involve simultaneous moves by both partners

within the year following separation, meaning that one parent typically leaves the joint

Demographic Research: Volume 40, Article 14

http://www.demographic-research.org 361

home before the other. Parents may have reasons for staying in the same

accommodation or area that do not apply to childless partners, such as wanting to limit

the changes associated with separation, whether for their children or because they have

other financial constraints. Several questions therefore arise. Do divorcing parents and

childless couples have different patterns of behaviour as regards moving? Is the father

or the mother more likely to move out of the joint home? Is the move due to gender or

custodial status? What are the characteristics of these moves: for example, distance

from previous home, housing tenure, house size?

Using an extensive administrative database, we consider the factors that determine

residential moves and the conditions of the new housing (if any) for married couples

and civil unions (or PACS

3

) that have recently been dissolved in France. The current

study investigates only the dissolutions of formal unions.

4

It makes two primary

contributions. First, it documents short-term mobility following divorce in France for

parents relative to nonparents, which is novel because, apart from Villaume (2016),

most of the available evidence is limited and outdated (Festy 1988; Bonvalet 1993).

Second, in the context of an increasing trend in Europe towards shared custody, the

originality of our work lies in expanding on the current literature, specifically regarding

the determining factors and the types of moves that occur after separation. We do this

by studying the specific role played by child custody arrangements following divorce.

2. Background

2.1 Residential mobility and parental status

The literature has studied what happens when divorce triggers a change in residence for

at least one of the partners in the relationship (Sullivan 1986; Symon 1990; Feijten and

van Ham 2007), emphasizing that divorce-related residential mobility has specific

characteristics that differ from mobility linked to other family reasons (e.g., union

formation or childbirth). First, the moves are often made in haste (Feijten and van Ham

2007), as a sense of urgency may affect the way the house is sold or induce some

3

The French Civil Code Act of 15 November 1999, which has since been amended several times, provides

the opportunity for unmarried couples to organize their lives together, with some social and tax advantages to

both partners. A civil union or PACS (pacte civil de solidarité) may be established by a private or notarial act.

It is registered at the district court where the partners jointly reside.

4

The only way to identify cohabiting unions is by linking tax data to census data (which includes a question

about unregistered partnership). However, due to the rotating nature of the French census, this is not possible

on a yearly basis. Throughout the text, we will use the terms ‘divorce’ and ‘separation’ interchangeably,

because we are considering official dissolutions of the two types of formal unions that are available in France,

namely marriages and PACS.

Ferrari, Bonnet & Solaz: Residential mobility after divorce by parenthood status and custody arrangements

362 http://www.demographic-research.org

suboptimal choice of new accommodation. Second, the moves may be financially

constrained, since separation brings an end to the household’s economies of scale and,

in many cases, may also lead to a decrease in living standards, especially for women

(see Bonnet, Garbinti, and Solaz 2016 for France).

Moreover, the move may be spatially constrained because of the presence of

children, who can affect both the occurrence of a move and the geographical destination

(Mulder and Wagner 2010). Due to the parents’ desire not to unsettle the children even

more, they may attempt to ensure that their daily lives are as similar as possible to

before the divorce by keeping them in the same home – or at least in the same school.

Of course, the financial constraints (possibly faced by one parent more than the other)

can be particularly significant after divorce and may force one or both parents to leave

the joint home. Whatever their custodial status, parents are likely to stay closer to each

other if they want to maintain the parent–child relationship.

Hypothesis 1: We expect parents either to remain in the joint home or to move

closer to it more often than is the case for nonparents.

2.2 Residential mobility and custodial status

The literature, both theoretical and empirical, has paid much attention to which of the

two partners moves out, a topic which – even when children are not involved – clearly

has a gender dimension. Among parents, it is closely related to custodial status, because

women are much more likely to be the custodial parent. In this article, we go further by

trying to establish whether gender disparity in residential mobility is linked to custodial

status.

Building on a theoretical cost-benefit approach, Mulder and Wagner (2010) study

which parent moves out of the joint home following separation. The ‘mover’ is the one

for whom the cost (monetary and nonmonetary) of moving is lower than the cost of

staying. We expect the custodial parent to bear a higher cost – both monetary and

nonmonetary – of moving from the joint home than the noncustodial parent. Mulder

and Wagner identify three types of nonmonetary costs: housing disruption, which is

associated with the risk of a decline in housing conditions; the effort of finding new

accommodation and getting used to a new environment; and emotional distress. These

costs may be higher for custodial parents compared with noncustodial parents, because

relocation may affect the child(ren), who may lose some friends and, if the move

involves changing schools, have to adjust to new schoolmates or changes in

extracurricular activities. These developments could have some short-term negative

Demographic Research: Volume 40, Article 14

http://www.demographic-research.org 363

effects on educational performance, although not necessarily in the long term (Hango

2006).

Hypothesis 2: The cost-benefit approach predicts that the custodial parent is more

likely to stay in the joint home than the noncustodial parent following separation.

Remaining in the joint home requires sufficient resources to pay all the housing

costs after divorce, whereas, in the case of moving, it is possible to choose somewhere

smaller and therefore cheaper because of the reduced family size. So we may expect the

parent with more financial resources to remain in the house, which would be in line

with their greater bargaining power (Mulder et al. 2012).

Because custodial parents bear the largest share of child-related costs, which are

only partly balanced by the child support payment given by the noncustodial parent,

their relative resources compared with the noncustodial parent are diminished. Thus,

custodial parents are less likely to remain in the joint home. On the other hand, if we

include the bargaining power on certain nonfinancial aspects, such as the ability to

make decisions regarding the daily lives of the children, the custodial parent may be

considered to have more bargaining power than the noncustodial one. He or, in most

cases, she may advocate for “the best interests of the child,” which primarily means

remaining in the joint home. A family court judge may support these “best interests” by

deciding to keep the child in the joint home. These nonfinancial aspects may play a

greater role than financial ones, thus reducing the influence of relative financial

resources in sole custody arrangements. In shared custody arrangements, however,

where these nonfinancial aspects are split equally, the parents’ relative financial

resources may play a larger role.

These considerations help us understand the interrelationships of gender, custodial

status, and mobility, while possibly allowing us to disentangle the influence of gender

from that of custodial status. On the one hand, because women are on average

financially less well-off following divorce, they may be more likely to move out of the

joint home. On the other hand, women may be less likely to move because they are

often the primary caregivers of their children, and sole custodial parents are expected to

move less often. Cooke, Mulder, and Thomas (2016) observe that, among parents, those

with resident children are less likely to migrate than those without, while the latter are

just as likely to migrate as nonparents. Recent research indicates that women move out

of the joint home more often than men but not if they have children (Mulder and

Wagner 2010; Dewilde 2008; Gram-Hanssen and Bech-Danielsen 2008; Thomas,

Mulder, and Cooke 2017). These results are also found in France (Villaume 2016).

Ferrari, Bonnet & Solaz: Residential mobility after divorce by parenthood status and custody arrangements

364 http://www.demographic-research.org

Hypothesis 3: We expect the gender gap in observed changes in residence

following divorce to be moderated by sole custodial status, but not by shared or no

custody arrangements.

2.3 Consequences of the move

Beyond changes in residence, the question of spatial trajectories has also gained

importance in the literature (Feijten and van Ham 2007). Researchers are interested not

only in who moves but also in where people move to (in terms of distance and the type

of environment), as well as in the type of housing adjustments made.

2.3.1 The distance of the move

When parents want to maintain a constant relationship with their children, they may

wish to move close to where the children live. Moving far from the preseparation joint

home is generally associated with higher costs, both monetary (e.g., it is more

expensive to see the children after moving further away) and nonmonetary (e.g., there is

an increased risk of losing contact with children and friends). Parents will move closer

to the preseparation home than nonparents will (Mulder and Malmberg 2011; Cooke,

Mulder, and Thomas 2016). Gram-Hanssen and Bech-Danielsen (2008) show that

separated parents live closer to each other than childless people do. Cooke, Mulder, and

Thomas (2016) observe that parents’ postseparation migration decisions are highly

correlated, unlike those of childless ex-couples.

With regard to custodial status, a recent study by Thomas, Mulder, and Cooke

shows that “the distance between separated parents is almost three times shorter when

both have a child(ren) resident as compared to when only the mother has the shared

child(ren)” (2017: 11). Along the same lines, Stjernström and Strömgren (2012)

observe that distances between children and their absent parents have decreased over

time in Sweden. They link this trend to the increasingly common practice of shared

custody arrangements following separation, which reflects changing norms and values

concerning parenthood.

Thus, we expect that the more equally time with the children is shared, the closer

the parents will live to each other, because their child custody arrangements will

involve frequent visits and journeys to school.

Hypothesis 4: Parents with shared custody are expected to move less far away after

separation than parents with sole custody.

Demographic Research: Volume 40, Article 14

http://www.demographic-research.org 365

2.3.2 Housing conditions

As the literature has demonstrated, divorce often leads to a “downward move on the

housing ladder,” especially for women (Mikolai and Kulu 2018b). This downward

move is exemplified by an exit from homeownership (Dewilde 2008), which in Britain

is twice as likely for separated men and women as for couples (Mikolai and Kulu

2018b). However, the same study also shows gender differences. After separation,

women are more likely than men to move out of the joint home and more likely to

apply for social housing, especially when they are mothers, whereas men are more

likely to become homeowners. Further, the general worsening of the housing situation

on separation is also marked by a move to a smaller residence (Mikolai and Kulu

2018a). Since men are more likely to continue living in the joint home, they are less

likely to suffer from a decline in housing conditions. However, moving out strongly

depends on the presence of children and on child custody arrangements. Previous

studies (Mikolai and Kulu 2018a) in the British context found that parents are less

likely than childless people to move to smaller homes.

A larger property is necessary for the custodial parent because the child(ren) will

live with them, but a smaller one may be sufficient for the noncustodial parent. In cases

of shared custody, two properties of a similar size may be needed, though this will

mean giving up other expenses for parents with a limited budget.

Hypothesis 5: We expect the decline in housing quality to be less pronounced in

cases of both sole and shared custody than in cases of noncustody.

3. The French context

Marriage rates in France have halved since the beginning of the 1970s, while

cohabitation has become common. The civil union called PACS was introduced in 1999

and is now widespread as a form of legal union (Mazuy et al. 2014). Compared with

marriage, a PACS is simpler to enter into and to dissolve. It has also become similar in

terms of taxation,

5

although it offers less protection in matters such as inheritance

6

and

survivor’s pensions (in the case of a partner’s death). The legal framework for

cohabiting couples is less protective.

7

5

As of 2005, all PACS partners are required to file joint tax returns, as married couples do. Because income

taxation is progressive, filing jointly rather than separately leads to paying less tax in almost all cases where

one partner earns substantially more than the other.

6

Partners do not inherit from each other unless it is stipulated in a will.

7

Joint taxation is not possible and cohabiting partners are not eligible for a survivor’s pension.

Ferrari, Bonnet & Solaz: Residential mobility after divorce by parenthood status and custody arrangements

366 http://www.demographic-research.org

Separation and divorce are widespread in France. In 2014, 44 divorces were

recorded for every 100 marriages, and PACS dissolutions increased over the period

2010–2013. In 2012, 52% of divorces involved a child who was a minor (HCF 2014).

Until recently, divorce required the intervention of a family court judge. The

average duration of divorce proceedings depends on agreement between the divorcees

on all the legal and economic aspects of dissolution (home, alimony, child custody

arrangements, etc.). Uncontested divorce is rapid and takes 3.6 months

8

on average,

while more acrimonious divorces last longer, on average 27.8 months (French Ministry

of Justice 2016).

Court decisions mandate parental custody arrangements, child support payments,

and the distribution of property and goods. The decision about child custody might be

exactly what is proposed by the parents, who are often advised by their lawyers. In most

cases, they come to an agreement before the judgement. Agreement about the property

depends on occupancy arrangements. If renting, the partner who leaves the joint home

is obliged to keep paying his or her part of the rent until the divorce is finalized. If both

parents have equal ownership, the partner who stays in the joint home normally has to

buy the other partner’s share. If both partners leave and sell the property, they are in

general both entitled to half of the sale price. Special cases are ruled on specifically by

the judge.

With a few exceptions, legal custody, which gives parents the right to decide about

the well-being of their child (e.g., health and education), is shared, but physical custody

is granted exclusively to the mother in the majority of cases (70% of divorces in 2012)

(Carrasco and Dufour 2015). Shared custody is granted in about one-fifth of cases

(21%), while sole custody to fathers accounts for 6%. In the French context, shared

custody means roughly that the child’s time is divided equally between each parent.

Parents are also expected to share child-related costs equally. In cases of sole custody,

the visiting rights of the noncustodial partner and the amount of child support to be paid

are decided by the judge.

With regard to housing tenure, 58% of households were owner-occupiers of their

main residence in 2013 (Laferrère, Pouliquen, and Rougerie 2017), while the remainder

rented in either the private or the public (social) housing sectors. Social housing in

France provides accommodation at moderate rents to low-income households. Since the

early 2000s, the public administration’s objective has been to reach a 20% share of

social housing in the total housing provision of each municipality. Due to their low

income, single-parent families are overrepresented in social housing (Trevien 2014).

8

Since January 2017, the duration of an uncontested divorce has been further reduced and, as long as all

parties meet the deadline, couples can now divorce in less than a month.

Demographic Research: Volume 40, Article 14

http://www.demographic-research.org 367

4. Data, methods, and variables

4.1 Data and sample

To answer our research questions, we use the French Permanent Demographic Sample

(Echantillon démographique permanent or EDP), an administrative database linking

censuses, vital events registration, and salaries for individuals born in the first four days

of January, April, July, and October of each year (“EDP-individuals”). Since 2010, this

database has also been linked to the entire tax-declaring French population. The

strength of this data relative to panel or retrospective surveys is the large sample size,

the lack of attrition even in cases of moving, and the available information on shared

custody arrangements.

The analytical sample consists of 21,290 heterosexual divorced people or people

who have dissolved their civil unions (about 2.3% of unions) in 2011 or 2012 and were

tracked over at least three consecutive fiscal years. Because of missing values for some

of the control variables (especially on income), the empirical analyses were performed

on 20,099 observations (9,968 men and 10,131 women). The observation window

begins in the year before separation, when people are still married or in a civil union

and have filed a joint income tax return. The data provides information on their income

and current accommodation, as well as on several individual and household

characteristics. In the year of union dissolution (t), they declare themselves as either

“divorced” or “living single” (the latter applies to the PACS) or state that separation

was their last conjugal event. Finally, one year after separation (t + 1) and for half of the

sample at two years (t + 2), we study information on their current situation (Table 1).

9

The data allows tracking of EDP-individuals.

10

We gather information on other family

members, should there be any, if they are coresident. However, after a divorce or a

PACS dissolution, we can no longer identify the partners of EDP-individuals

11

(if they

are not EDP-individuals themselves) because they have left the household.

9

In cases of multiple tax returns for the same individual (frequent in cases of separation), we prioritized the

one with the earliest change in residence.

10

These people are unique because we can link their information from censuses, vital events registrations, and

tax returns, while being able to follow them over time.

11

This would be feasible for a very small portion of the sample (about 0.2%): in other words, couples

comprising two EDP-individuals who were both born on the selected dates of the panel inclusion criteria.

Ferrari, Bonnet & Solaz: Residential mobility after divorce by parenthood status and custody arrangements

368 http://www.demographic-research.org

Table 1: Dataset description

T – 1 (in couple, shared housing)

T (year of divorce or

civil union dissolution)

T + 1 (housing change,

location, conditions)

Sample size

2010 2011 2012 10,608

2011 2012 2013 10,682

Source: French Permanent Demographic Sample (INSEE), 2010–2013

4.2 Methods

Because the previous literature has shown that moves after divorce are likely to be

gendered (see Section 2.2), we estimate models for the entire sample and separately by

sex. Control variables for child custody arrangements are observed for parents only.

Therefore, for each sex (and outcome category) we estimate two models: for the whole

sample and for parents only.

Different models are estimated according to the nature of the outcome variable.

Logistic regressions are used to model both the probability of moving (Y = 1 when

people change accommodation the year after divorce, Y = 0 otherwise) and the

probability of experiencing worse housing conditions (Y = 1 if moving from owner-

occupier to renter, Y = 0 otherwise; Y = 1 if moving to fewer bedrooms per person,

Y = 0 otherwise; and Y = 1 if moving to a smaller property per person, Y = 0 otherwise).

To analyse the distance of the move, we estimate a multinomial logistic regression

on whether they move short (Y = 1 if same municipality), medium (Y = 2 if same

county), or long (Y = 3 if outside county) distances. We then use linear regressions on

the distance of the move measured in kilometres. This alternative indicator of

continuous distance is more accurate. Indeed, there might be cases in which two

municipalities are very close but belong to two different counties.

We are fully aware that child custody arrangements and mobility choices are

decided simultaneously and are interrelated. Therefore, we use an instrumental variable

to correct for this possible endogeneity due to possible reverse causality or unobserved

characteristics (the results are provided in Appendix Table A-5). We expect

endogeneity to be particularly significant as regards the distance moved following

divorce, but we have made this correction on the other outcomes considered (decision

to move and housing conditions). In our instrumental variable approach, we take

advantage of the huge territorial discrepancies in shared custody arrangements at the

regional level in France (Bonnet, Garbinti, and Solaz 2015). We thus use shared

custody at the county level (France is comprised of around 100 county-like

administrative divisions called départements) as an instrument for individual shared

custody arrangements. The share of child custody ranges from 7% to 21% depending on

the place of residence. Reasons for this may include the effect of the decisions of a

Demographic Research: Volume 40, Article 14

http://www.demographic-research.org 369

divorce court (or a family court judge) at the local level. We checked for other possible

explanations linked to local variations, such as socioeconomic situation or religiosity,

but no obvious external causes explain this rate, confirming that it is a reliable

instrument because it is randomly defined from the individual’s point of view. The high

value of the F-statistics in the first-stage regression guards against the risk of a weak

instrument.

4.3 Variables

4.3.1 Outcomes

We studied three dimensions of mobility: the probability of the move itself, its distance,

and the housing conditions following the move. First, we calculate the probability of

moving: that is, whether in the year following the divorce the EDP-individual lives in

the same accommodation as before the divorce. Then, for movers, we studied the

location of residence after divorce: whether the ex-partners live in the same

municipality as before, not in the same municipality but in the same county, or beyond,

that is to say outside the county of residence before divorce.

We also took into account the distance in kilometres between the two locations.

For this we used a software application called Metric, developed by INSEE (Bigard,

Timotéo, and Levy 2014), which calculates the direct-route distance between two

municipalities.

12

To measure housing conditions after divorce, we used several indicators: the type

of housing tenure (homeownership, private or public renting), the number of bedrooms

per person, and the size of the home per person in square metres. Exit from ownership

is another indicator of worse living conditions. The literature considers ownership to be

a desirable goal, and the well-being of a household is assumed to be greater when one is

an owner (Spilerman and Wolff 2012). Homeownership is also usually associated with

a wide range of beneficial outcomes (Dewilde 2008).

4.3.2 Variables of interest

Our variables of interest are parenthood status (parents or childless) at the moment of

divorce and, for the subsample of divorced parents, the child custody arrangements after

12

For overseas territories, we decided to take the maximum distance of the move, imputed differently by sex

and parenthood status. For people in Corsica, we took the distance between Marseille and the Corsican town

plus the distance between the town in metropolitan France and Marseille.

Ferrari, Bonnet & Solaz: Residential mobility after divorce by parenthood status and custody arrangements

370 http://www.demographic-research.org

divorce.

13

Thus, we distinguish between parents with sole, shared, or no child custody.

Type of child custody is associated with different income tax deductions and is thus

reported on tax returns.

14

The custody arrangement is self-declared, and the proportion

of shared custody declared by fathers is greater than that of mothers, who have more tax

incentives to declare sole custody.

15

Beyond tax optimization reasons, parents are more

likely to declare their children even if they do not live with them full-time, as shown by

Toulemon, Durier, and Marteau (2017).

4.3.3 Controls

We controlled for a set of sociodemographic variables (see Appendix Table A-1): sex;

age at divorce (20‒29, 30‒39, 40‒49, 50‒59, 60 and over); age gap between partners

(whether the man is older, both are the same age, or the woman is older); age of the

youngest child (less than 3 years, 4–14 years, 15 years or more); duration of marriage

(less than 4 years, 4–6 years, 7–10 years, more than 10 years or unknown duration

16

);

number of children; and nationality (native or foreign-born). With respect to

socioeconomic covariates, we considered two dimensions, education (divided into four

groups: lower than secondary, secondary, higher than secondary, or missing

17

) and

adjusted household income (grouped by quintiles). This is the sum of all employment-

related incomes (including unemployment or retirement benefits) received by the two

partners, divided by the number of consumption units, using the OECD-modified

equivalence scale that gives 1 for adults, 0.3 for children under 14, and 0.5 for children

14 and over or for other adults in the household. We also considered, as an additional

indicator of poverty, whether any household member received unemployment benefits

during the year before divorce. Such a situation could exacerbate housing difficulties in

a high-demand housing market and therefore hinder residential mobility. However, the

13

Again we use the term ‘divorce,’ but we consider both marriage and PACS dissolutions. Duties and rights

of parents do not change, regardless of their conjugal status.

14

Tax deductions are higher for parents with sole custody than for those with shared custody, where tax

deductions are shared.

15

Parents with no custody also include parents whose child moves elsewhere to another fiscal household: e.g.,

if he or she becomes a student and files a separate tax return.

16

Dates of marriages and civil unions are available from those that took place after 2000, so we assume that

unknown dates refer those that occurred before. We could not exclude the possibility that a few dates are

missing for other reasons.

17

Educational level is retrieved from the census, which is conducted on a rotating subsample of the French

resident population every five years. As the level of education is assumed to be quite stable over time, we

consider information on education each time the individual identified from fiscal data is found in the census.

However, the linkage was possible on only 63% of the total sample; the remainder was assumed to be

missing.

Demographic Research: Volume 40, Article 14

http://www.demographic-research.org 371

unemployed might also be less constrained than the employed in their choices about

place of residence, thus making them more spatially mobile.

We further controlled for housing tenure before divorce by distinguishing between

owner-occupiers, those with public and private rented accommodation, and, as a proxy

for location-specific capital, time spent in the predivorce home: fewer than 5 years, 5–9

years, and 10 years or more. Furthermore, we separated rural areas from cities

categorized as small (up to 20,000 inhabitants), medium (up to 200,000), and large (up

to 2 million inhabitants), and the Paris area. Finally, we took into account whether the

individual was married or in a civil union.

5. Results

5.1 Descriptive statistics

Divorce involves a change of residence for at least one partner and sometimes for both.

We omit the special cases of so-called LTA (living together apart) couples, who

continue to cohabit after divorce or separation for, say, financial reasons. This has been

shown to be uncommon (Martin, Cherlin, and Cross-Barnet 2011) and would concern

only 5% of divorced couples in the year immediately following divorce (Durier 2017).

Table 2 shows the distribution of the outcome variables for the entire sample and

the subsample of parents by sex. We find that fewer men move after divorce – 59% of

men compared with 67% of women – which is consistent with the literature.

For parents, this gender gap is narrower, with 61% of men and 66% of women

moving, while it is larger for the childless, with 56% of men and 71% of women. This

means that parental status (and probably the custodial status, as women are much more

likely to be given custody) moderates the gender gap in the likelihood of moving, as

predicted by Hypothesis 3.

When divorcees move, they relocate within the same municipality (29%) or even

outside it but within the same county (47%). The mean distance is around 79

kilometres, but the median remains low (18 kilometres). Therefore, consistent with

Hypothesis 1, parents do not move as far away from the preseparation home as

nonparents, and are more likely to move within the municipality. Moving outside the

county relates to one in five parents and more than 30% of childless ex-partners, who

have fewer reasons than parents to remain close to the joint home.

Ferrari, Bonnet & Solaz: Residential mobility after divorce by parenthood status and custody arrangements

372 http://www.demographic-research.org

Table 2: Observed outcome frequency distributions and descriptive statistics,

by sex and parenthood status (column percentages)

All Childless Parent

A year after divorce Total Men Women Men Women Men Women

Do they move?

No 37 41 33 44 29 39 34

Yes 63 59 67 56 71 61 66

Total 100 100 100 100 100 100 100

N 21,290 10,512 10,778 3,298 3,344 7,214 7,434

For movers only

Where do they move?

Same municipality 29 28 30 23 27 29 32

Same county 47 48 47 44 43 50 49

Different county 24 24 23 33 30 21 19

Total 100 100 100 100 100 100 100

Mean distance (kilometres)

Total

79 80 78 113 106 66 64

Median distance (kilometres)

Total

18 19 17 26 23 17 15

N 13,491 6,241 7,250 1,845 2,363 4,396 4,887

What changes in housing

conditions?

Fewer bedrooms 52 54 50 46 52 57 49

Same number of bedrooms 25 24 27 25 23 23 29

Fewer bedrooms per person

31 29 32 36 33 26 32

Same number of bedrooms

per person

15 13 16 18 19 11 15

Smaller size 67 67 67 59 66 70 68

Smaller size per person 34 30 38 39 36 27 39

N 13,491 6,241 7,250 1,845 2,363 4,397 4,889

For movers and owner-occupiers only

Owner-occupier to owner 31 35 29 41 34 33 26

Owner-occupier to private

renter

55 55 55 50 52 57 57

Owner-occupier to public

renter

14 10 16 9 14 10 17

Total 100 100 100 100 100 100 100

N 7,719 3,444 4,275 889 1,189 2,555 3,086

Source: French Permanent Demographic Sample (INSEE), 2010–2013.

The new home does not necessarily have fewer bedrooms: around half do, while a

quarter have a similar number and the remaining quarter have even more bedrooms than

the previous property. Fathers who move are the most likely to live in a new home with

fewer bedrooms (57%). One reason might be that they have custody of the child less

often. Though in most cases the property is smaller, it is not necessarily smaller relative

to the new household configuration after divorce. In other words, the reduction in

property size might be in line with the new household size. Among parents, mothers are

more affected by a reduction in their living area per person: 39% have less space per

Demographic Research: Volume 40, Article 14

http://www.demographic-research.org 373

person after divorce than before, compared with 27% of fathers. In contrast, among

childless divorcees, 39% of men and 36% of women have less space per person in their

new home. For childless people, particularly women, the housing is often smaller and

with fewer bedrooms, but it does not always involve a reduction per person, as they

benefit from the whole space if they live alone.

Among spouses who were owner-occupiers of their housing (59%), a substantial

proportion (69%) became tenants in either the private or the public sector within the

year following divorce.

18

Parents, and particularly women, are more likely to ‘lose’

their status of owner-occupier than childless divorcees. In most cases, they become

private tenants. Parents and women become public tenants more frequently than

childless people and men. In 17% of cases, mothers who were previously owners move

into public housing. Having fewer financial resources after separation is the main

reason for this. Given the difficulties and the time required to obtain social housing in

France, these rates are remarkable as they are observed right after the transition. They

suggest that there is a real desire to help divorced mothers and their children (Trevien

2014).

5.2 Multivariate analysis

5.2.1 Moving after divorce

Table 3 shows the results of the logistic regressions separately for the full sample and

for parents only, by sex.

In the full model, women are more likely to move than men. This result is in line

with the relative resources argument: because men are on average older than women

and earn higher wages in the labour market, their economic resources are also higher on

average, and they are more likely than women to have accumulated wealth at the

moment of divorce. Their higher income may allow them to keep a home that is family-

sized, whereas women have fewer resources, especially if they took time off from their

jobs to have children.

18

Our data does not show whether the joint house or flat belongs to both spouses or to only one. In most

cases, however, married couples are joint owners of their main residence. According to Bonnet, Keogh, and

Rapoport (2014), 84% of homes are equally and jointly owned by married spouses.

Ferrari, Bonnet & Solaz: Residential mobility after divorce by parenthood status and custody arrangements

374 http://www.demographic-research.org

Table 3: Logit models of moving out of the joint home one year after divorce,

by sex (odds ratios)

All

Men Women

All Parents All Parents

Parenthood (Ref: childless)

Parent 1.27*** 1.42*** 0.70***

Sex (Ref: man)

Woman 1.90***

Woman*Parent

0.60***

Child custody arrangement

Sole custody 0.41*** Ref.

Shared custody 0.39*** 2.90***

No custody

Ref. 2.55***

Number of children (Ref: 1 child)

2 children 1.30*** 0.86**

3 or more children 1.25*** 0.69***

Age of the youngest child (Ref: 0–3)

4–14 0.83** 0.91

15+

0.79** 0.67***

Age at divorce (Ref: 30–39)

20–29 1.40*** 1.32*** 1.20 1.35*** 1.14

40–49 0.72*** 0.81*** 0.83** 0.73*** 0.74***

50–59 0.59*** 0.77*** 0.74*** 0.57*** 0.56***

60+ 0.58*** 0.85* 0.62** 0.50*** 0.38**

Age difference between the partners (Ref: same age +/– 4years)

Man older 0.91*** 0.64*** 0.67*** 1.25*** 1.26***

Woman older 0.91 1.49*** 1.73*** 0.61*** 0.58***

Level of education (Ref: lower than secondary)

Secondary 0.95 0.95 0.93 0.88* 0.89

Higher than secondary 0.91** 1.00 1.09 0.79*** 0.74***

Not available 1.25*** 1.34*** 1.47*** 1.08 1.08

Adjusted household income quintiles (Ref: Q3: €18,347–22,665)

Q1: Up to €13,951 0.83* 0.79*** 0.70*** 0.87** 1.06

Q2: €13,952–18,346 0.91*** 0.88* 0.79*** 0.93 1.03

Q4: €22,666–29,653 1.14** 1.10 1.04 1.18** 1.07

Q5: More than €29,654 1.11*** 1.08 0.93 1.11 1.03

House occupancy status (Ref: owner-occupier)

Private renting 1.48*** 1.75*** 1.81*** 1.23*** 1.08

Public renting 0.74*** 1.16** 1.33*** 0.49*** 0.39***

Household member receiving unemployment benefits (Ref: no)

Yes 1.06 1.09* 1.13* 1.05 1.06

Union duration (Ref: less than 4 years)

4–6 years 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.01 0.92

7–10 years 1.04 1.00 0.96 1.06 0.95

Longer duration/unknown 1.17*** 1.17** 1.19* 1.07 0.97

Nationality (Ref: native)

Foreign-born 0.90** 0.89* 0.89 0.83*** 0.82**

Demographic Research: Volume 40, Article 14

http://www.demographic-research.org 375

Table 3: (Continued)

All

Men Women

All Parents All Parents

Town size (Ref: 200,000–1,999,999 inhabitants)

Rural 1.04 0.80*** 0.79*** 1.37*** 1.51***

2,000–19,999 inhabitants 1.13** 0.97 1.04 1.33*** 1.46***

20,000–199,999 inhabitants 1.05 1.06 1.03 1.05 1.16*

Paris area 0.78*** 0.86** 0.92 0.75*** 0.79***

Time spent in the accommodation (Ref: more than 10 years)

<5 years 1.32*** 1.51*** 1.58*** 1.27*** 1.26***

5–9 years 1.13*** 1.25*** 1.42*** 1.09 1.00

Type of union (Ref: marriage)

Civil union 0.89** 0.84** 0.89 1.00 1.00

Constant 1.17* 0.90 1.78*** 2.72*** 2.13***

Observations 20,099 9,968 6,503 10,131 6,638

Note: *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1.

Source: French Permanent Demographic Sample (INSEE), 2010–2013

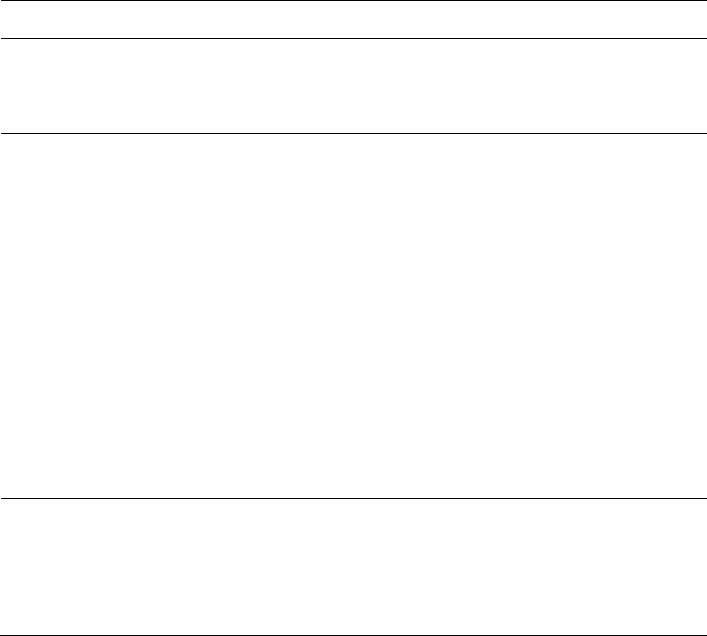

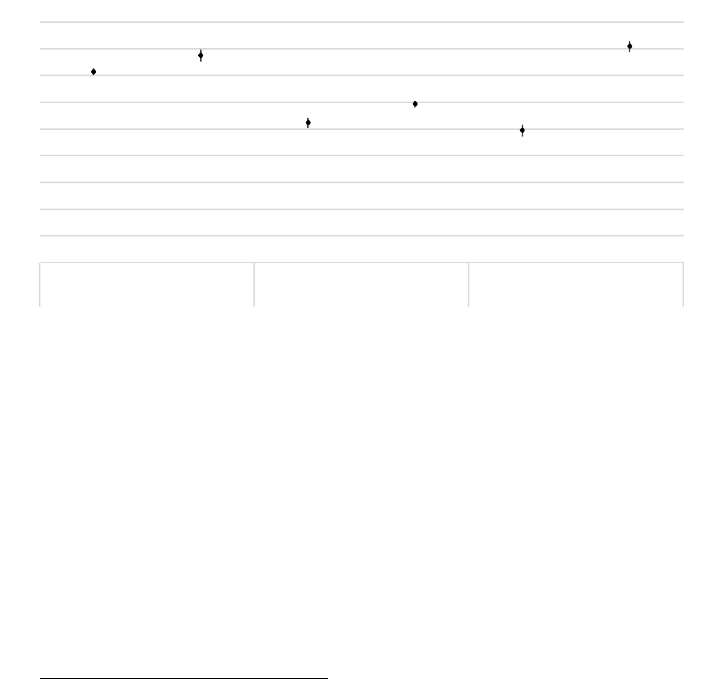

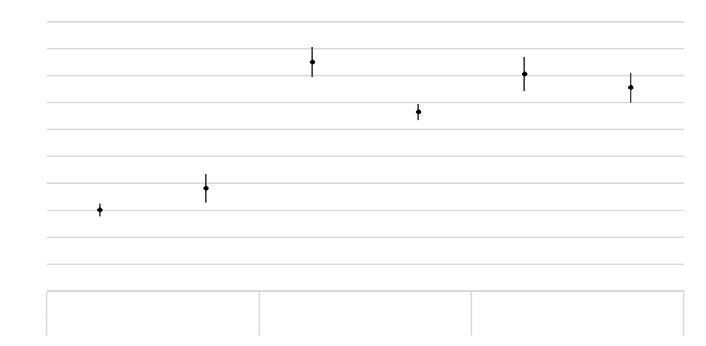

Parenthood positively affects residential mobility (first column of Table 3).

However, an interesting opposite effect of parenthood is observed by sex: fathers are

more likely than childless men to move out of the joint home, whereas mothers are less

likely than childless women to do so. These results are probably linked to both the

parental desire not to change the child’s environment (Mulder and Wagner 2010) and

the custody arrangements. This suggests that the mother, who is more likely to be the

custodial parent, will stay with the children in the original joint home whenever

possible, which is in line with Hypothesis 2. As shown by the regression on only

parents, which controls for the custody arrangements (third and fifth columns),

regardless of sex, the parent who has sole custody is indeed less likely to move than a

noncustodial parent.

19

The predicted probabilities of custody arrangements (computed

on the full model that accounts for the interaction between sex and custody

arrangements) clearly confirm that sole custodial parents are less likely to move (50%

for men, 60% for women) than noncustodial parents (70% or more). This is emphasized

by the increasing probability of moving for fathers with more than one child, but shows

a decreasing probability for mothers with several children. The joint home is kept for

the children and the sole custodial parent, probably to avoid relocating the children.

This may be reinforced by the family court judge, who may more often decide to grant

custody to the parent who keeps the house in “the best interests of the child.” The story

differs in shared custody arrangements. Here, fathers are much less likely to move

19

Note that the reference category differs for the male and female regressions because we prefer to refer to

the most frequent situation by sex: no custody for the fathers and sole custody for the mothers. However,

predicted probabilities for the three types of custody are also computed (Figure 1).

Ferrari, Bonnet & Solaz: Residential mobility after divorce by parenthood status and custody arrangements

376 http://www.demographic-research.org

(under 50%) than mothers (over 80%).

20

Because the children in shared custody may

remain (even if only part of the time) with either the father or the mother in the original

joint home, this is in line with our third hypothesis, since the issue of not moving the

children no longer plays a role in deciding who keeps the joint home. The greater

relative resources of fathers compared with mothers may therefore lead to their being

more likely to keep the joint home.

Figure 1: Predicted probabilities of moving one year after divorce, by sex and

child’s custody arrangements

Note: Whiskers represent 95% confidence intervals.

Source: French Permanent Demographic Sample (INSEE), 2010–2013

Regarding the other covariates, we find that the probability of moving after

divorce decreases with age. The age gap plays a role too, with the older spouse less

likely to move, while the younger one is more likely. This difference may be due to the

negotiation process between the couple or to wealth accumulation. The older spouse

may be the one who was already living in the joint home when the couple got together

or the one who has accumulated more wealth. The probability of moving also decreases

with the age of the youngest child, because moving is easier before children are

enrolled in school. The educational gradient is small: that is, not significant for men’s

moves and negative for women’s. However, we observe an income gradient. Men and

women belonging to low adjusted income quintiles are less likely to move than those

20

Our data does not allow for analysis of some atypical arrangements, such as when the children stay in the

joint home and the parents move in and out.

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

Men Women Men Women Men Women

No custody Sole custody Shared custody

Demographic Research: Volume 40, Article 14

http://www.demographic-research.org 377

belonging to the median quintile. It might be that, for financial reasons, disadvantaged

families move less or take longer to move.

Ownership status reduces mobility for men, while residing in the public and

private rental sector increases it. In contrast, renting in the public sector reduces the

chances of moving for women, especially for mothers who might keep the joint home.

In the same vein, when a family member has received unemployment benefits, it

increases the likelihood of moving for men. We also find that marriage duration has no

effect and that foreign-born status has a small negative effect on mobility for women.

People living in the Paris area are less likely to move, probably because of the high cost

of housing, which may prolong the search for a suitable place. We observe a gendered

result for living in a rural area. While men are less likely to move out of the joint home,

we find the opposite for women. This could be related to the fact that men more often

choose the couple’s place of residence or are likely to have initially owned it for

professional reasons, such as farming, or other reasons related to wealth. In these cases,

women would be the ones to leave the premises.

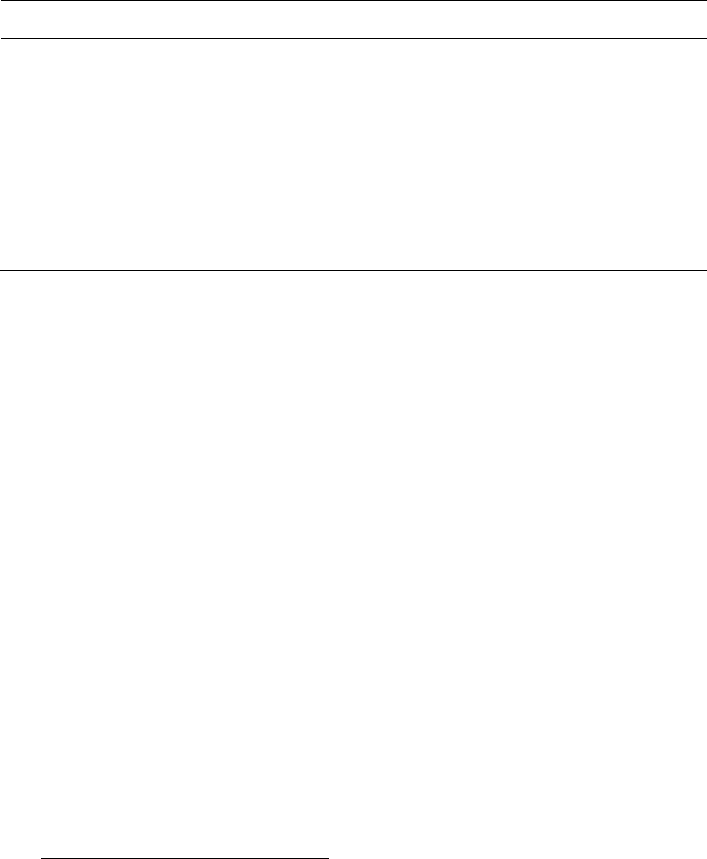

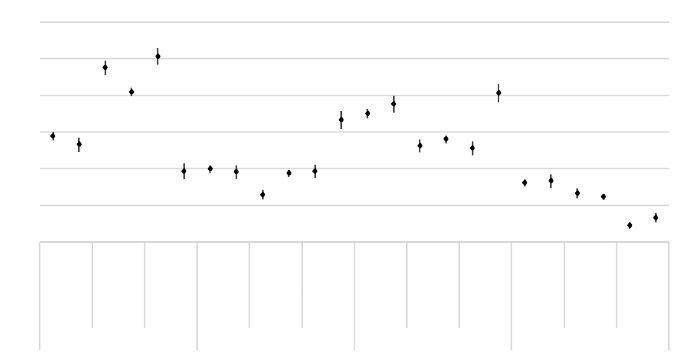

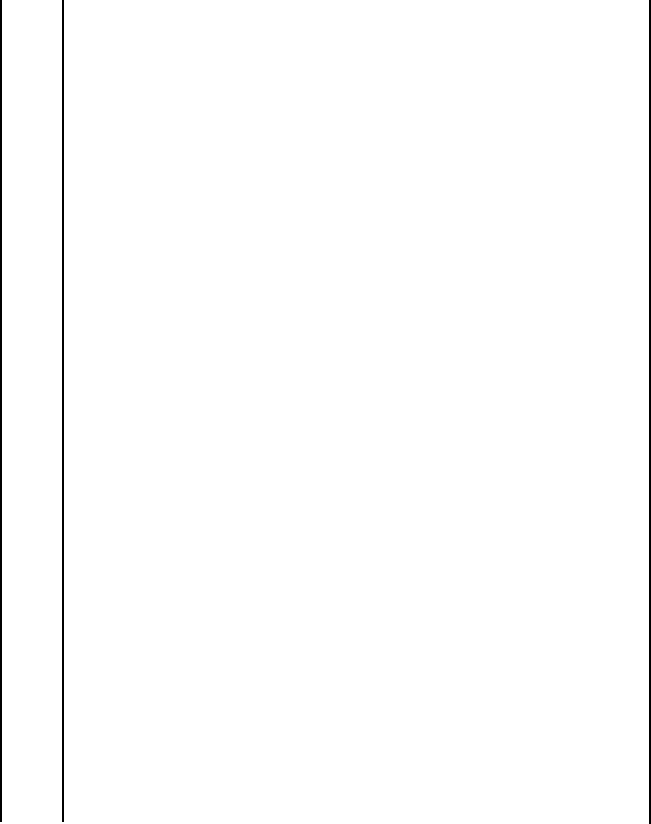

5.2.2 Moving distance

Shorter moving distances are observed for parents. Fathers and mothers are more likely

to move nearby in the same municipality than childless men and women (see Appendix

Table A-2

21

) and less likely to move far. When fathers move, they live 32 kilometres

closer to their former homes than childless divorced men, while mothers live 22

kilometres closer than childless divorced women (see Appendix Table A-3). These

results are in line with Hypothesis 1, probably in order to maintain contact with the

children. If parents have sole custody, they often keep the original joint home (Figure

2). Figure 2 also shows that shared custody arrangements limit parents’ relocation. The

predicted probability of fathers with shared custody living in the original joint home

reaches 50%, and 20% move into a new home while remaining in the same predivorce

municipality. While mothers in shared custody are more likely to move than lone

mothers or fathers in sole custody, they generally move closer to the joint home. Family

court judges probably take into account the distance between parents (among other

reasons) when deciding to accept or reject a shared custody arrangement. The

probability of parents with shared custody moving beyond the county borders is low

(less than 5% for fathers and less than 10% for mothers), while this may happen more

frequently with the sole custodial parent. Parents with sole custody have a 12%

probability of living outside the predivorce county in the year following divorce,

whereas the probability of leaving the original municipality while remaining in the

21

Because multinomial logistic coefficients are not easy to interpret we show average marginal effects.

Ferrari, Bonnet & Solaz: Residential mobility after divorce by parenthood status and custody arrangements

378 http://www.demographic-research.org

same county exceeds 25% for both fathers and mothers. Shared custody involves

moving a 37-kilometre shorter distance for men and a 78-kilometre shorter distance for

women, relative to non-custodial parents. For women, shared custody involves moving

a 55-kilometre shorter distance relative to those who have sole custody. This is in line

with our fourth hypothesis: that is, shared custody arrangements are associated with

shorter moves than other types of custody following divorce.

Figure 2: Predicted probabilities of not moving, moving within the same

municipality, moving within the same county, or beyond one year

after divorce, by sex and child custody arrangements

Note: Whiskers represent 95% confidence intervals.

Source: French Permanent Demographic Sample (INSEE), 2010–2013

5.2.3 Housing conditions

Finally, we looked at the decline in housing quality. To study whether conditions

deteriorate following separation, we combined different indicators of housing quality.

First, we examined the risk of stopping being a homeowner one year after divorce

(Table 4). Parental status is not associated with a higher probability of stopping

homeownership during the first year after separation. For fathers, having sole custodial

status is associated with a greater chance of remaining a homeowner. There is no

difference by custodial status for women. Women are more likely to lose their owner-

occupier status after divorce. This may be related to their comparatively worse financial

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

Men

Women

Men

Women

Men

Women

Men

Women

Men

Women

Men

Women

Men

Women

Men

Women

Men

Women

Men

Women

Men

Women

Men

Women

No

custody

Sole

custody

Shared

custody

No

custody

Sole

custody

Shared

custody

No

custody

Sole

custody

Shared

custody

No

custody

Sole

custody

Shared

custody

Not moving Same municipality Same county Greater distance

Demographic Research: Volume 40, Article 14

http://www.demographic-research.org 379

situation, which limits their ability to move and keep their ownership status. The

decision whether to sell the joint home is not particularly associated with custodial

status.

Table 4: Logit models of moving out of homeownership for the subsample of

movers one year after divorce, by sex (odds ratios)

All

Men Women

All Parents All Parents

Parenthood (Ref: childless)

Parent 1.15 1.17 1.14

Sex (Ref: man)

Woman 1.26**

Woman*Parent

1.02

Child custody arrangement (Ref: no custody)

Sole custody

0.76** Ref.

Shared custody 1.07 0.97

No custody

Ref. 0.93

Number of children (Ref: 1 child)

2 children 1.00 0.95

3 or more children

1.14* 0.97***

Age of the youngest child (Ref: 0–3)

4–14 0.85 0.83

15+

0.72* 0.51***

Age at divorce (Ref: 30–39)

20–29 0.93 1.22 0.92 0.79 0.88

40–49 0.78*** 0.79** 0.81 0.77*** 0.87

50–59 0.65*** 0.71*** 0.74 0.59*** 0.72

60+ 0.47*** 0.49*** 0.68 0.46*** 1.55

Age difference between the partners (Ref: same age +/– 4years)

Man older 1.04 0.96 0.97 1.12 1.02

Woman older 1.09 1.06 1.11 1.13 1.07

Level of education (Ref: lower than secondary)

Secondary 0.80** 0.89 0.99 0.73*** 0.68**

Higher than secondary 0.67*** 0.77** 0.82 0.59*** 0.52***

Not available 0.77*** 0.79** 0.81 0.75*** 0.69***

Adjusted household income quintiles (Ref: Q3: €18,347–22,665)

Q1: Up to €13,951 1.25** 1.09 1.19 1.40** 1.30

Q2: €13,952–18,346 1.27*** 1.19 1.09 1.32** 1.33*

Q4: €22,666–29,653 0.84** 0.98 1.01 0.72*** 0.67***

Q5: More than €29,654 0.73*** 0.76** 0.72** 0.69*** 0.64***

Household member receiving unemployment benefits (Ref: no)

Yes 1.03 1.00 1.03 1.07 1.05

Ferrari, Bonnet & Solaz: Residential mobility after divorce by parenthood status and custody arrangements

380 http://www.demographic-research.org

Table 4: (Continued)

All

Men Women

All Parents All Parents

Union duration (Ref: less than 4 years)

4–6 years 1.05 1.21 1.27 0.94 0.96

7–10 years 1.00 1.13 1.05 0.92 0.98

Longer duration/unknown 1.04 1.15 1.12 0.97 1.20

Nationality (Ref: native)

Foreign-born 1.25** 1.33** 1.40* 1.17 1.20

Town size (Ref: 200,000–1,999,999 inhabitants)

Rural 0.99 0.96 1.05 1.02 0.88

2,000–19,999 inhabitants 1.00 1.00 1.19 1.02 0.83

20,000–199,999 inhabitants 0.91 0.90 0.91 0.94 0.84

Paris area 0.83** 0.95 1.00 0.72** 0.54***

Time spent in the accommodation (Ref: more than 10 years)

<5 years 1.17** 1.20* 1.19 1.19* 1.30**

5–9 years 1.04 1.12 1.12 1.00 1.09

Type of union (Ref: marriage)

Civil union 0.89 0.81 0.77 0.96 0.99

Constant 2.68*** 2.13*** 2.66*** 4.12*** 6.42***

Observations 7,381 3,321 2,274 4,060 2,763

Note: *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1.

Source: French Permanent Demographic Sample (INSEE), 2010–2013

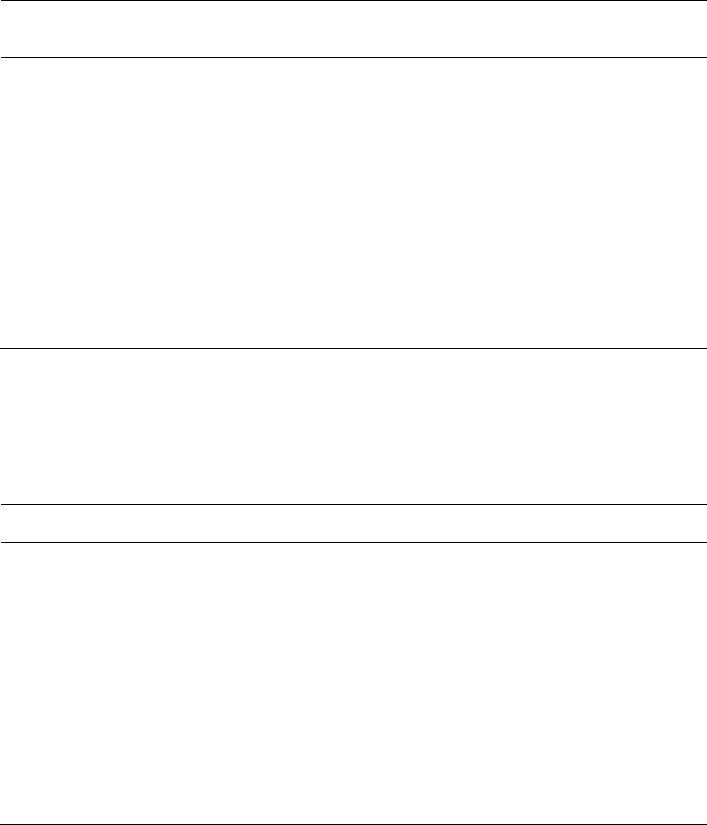

Second, we analysed the probability of living in a smaller property after divorce

(see Appendix Table A-4). We define a smaller property as a reduction in the number of

bedrooms or the space per person. Family size is thus taken into account.

Fathers do not seem to experience a greater reduction in the number of bedrooms

or the space per person than childless divorcees do after their separation. On the

contrary, mothers are more likely to have a smaller property than childless divorcees, in

terms of both number of bedrooms and space per person. Hence, fathers are less likely

to suffer a decline in their living standards after divorce than mothers. However, the

results of the model on parents (that only controls for child custody arrangements)

mitigate the relative advantage of fathers, since fathers who have custody are also

penalized. After divorce, they are more likely to live in housing that is smaller per

person. Figure 3 shows that parents who have custody, either sole or shared, are more

likely to have fewer bedrooms per person than parents whose children live elsewhere.

Thus, the decline in housing conditions after divorce is more pronounced for mothers

and for custodial parents in general. Our fifth hypothesis, which suggests a less marked

decline in housing quality in custody versus noncustody cases, is therefore not fully

supported by the data.

Demographic Research: Volume 40, Article 14

http://www.demographic-research.org 381

Figure 3: Predicted probabilities of moving to accommodation with fewer

bedrooms per person one year after divorce, by sex and child custody

arrangements

Note: Whiskers represent 95% confidence intervals.

Source: French Permanent Demographic Sample (INSEE), 2010–2013

5.3 Endogeneity issues

Custody arrangements and housing may be decided simultaneously. To tackle this

endogeneity issue, we tested the robustness of our results using an instrumental variable

approach. We took the proportion of shared custody at the county level as an

instrument. Table A-5 presents the main results. The sign and the significance of the

coefficients are very similar when using the instrumented custody arrangements

regarding the probability of moving, distance of the move, and housing conditions. This

means that, once endogeneity issues are taken into account, our results hold.

6. Discussion and conclusions

Although the economic and psychological consequences of divorce for both adults and

children have been widely investigated, housing outcomes of divorced individuals have

been less well studied, mainly because of the scarcity of adequate data for observing

residential changes around the time of divorce. Using recently available administrative

0

0.05

0.1

0.15

0.2

0.25

0.3

0.35

0.4

0.45

0.5

Men Women Men Women Men Women

No custody Sole custody Shared custody

Ferrari, Bonnet & Solaz: Residential mobility after divorce by parenthood status and custody arrangements

382 http://www.demographic-research.org

data which allows French divorcees to be tracked, we observed their mobility and the

changes in their housing characteristics after divorce. We focused on parental status

and postdivorce child custody arrangements.

Consistent with previous research and the relative resources argument that

emphasizes the role of bargaining power between partners, our empirical findings show

that women are more likely to move than men after divorce. In most cases, men have

higher earnings than women, and this could explain why they are more likely to keep

the joint home. But parenthood status mitigates the gender gap, which is narrower for

parents. Mothers move less frequently than childless women, while fathers move more

than childless men. Furthermore, we show that moving behaviour is related to the type

of custody. For both sexes, sole custodial status is associated with less moving than is

the case with noncustodial status, which may reflect a preference for not moving the

child(ren) from the joint home, at least shortly after divorce. However, shared custody

arrangements imply many more moves for mothers than for fathers. Parents move

nearby in cases of shared custody. The willingness to maintain relationships with the

child and his or her environment certainly plays a role. Yet these additional spatial

constraints may have implications for other aspects of life, such as job market

opportunities, chances of repartnering, relationships with the family of origin, and,

more broadly, participation in the housing market. The increased demand for shared

custody can imply a greater number of moves for women and may affect housing prices

and demand for certain types of homes (e.g., houses and flats with two or three

bedrooms).

Housing characteristics are not necessarily worse after divorce, but women are

more often disadvantaged. They are more likely to lose their owner-occupier status and

to have less space in their new home. The alternative of remaining would not

necessarily be better if they are unable to afford the whole cost of the joint (and often

oversized) home. This result corroborates previous findings on the greater negative

consequences of divorce for women than for men. Gender inequality in the

consequences of divorce, in terms of mobility and housing characteristics, may also be

of interest for public policy. There is now a debate in France about whether housing

allowances could be shared in cases of shared custody. The current policy allows for

only one parent to receive a housing allowance; the recipient is usually the mother

because she received other benefits from social security before the divorce, such as

family allowances. Thus, in shared custody arrangements, generally only the mother

receives a housing allowance, even if the father faces additional housing costs to

accommodate the children. A solution would be to share housing allowances. The

objective of the policymaker is to make benefits available to both parents if a child

spends significant time with them (Meyer and Carlson 2014; HCF 2014). The sharing

of housing allowances may be in line with this policy, as it helps parents share

Demographic Research: Volume 40, Article 14

http://www.demographic-research.org 383

economic and childcare costs. It may be desirable to support families (perhaps fathers in

particular) in their efforts to maintain postseparation proximity (when desired), as this

will facilitate their postseparation well-being.

This work has some limitations. First, the fiscal data that we used allowed us to

study only married people and civil partners, as they are the ones who filed joint income

tax returns. People who left cohabiting unions are thus excluded from our analysis. We

might expect to have similar results for cohabitating parents because they have similar

characteristics in France and their rights are comparable to those of married (and

PACSed) parents in terms of the children (Prioux 2009). Although it is not compulsory

for unmarried and PACSed parents, in most cases they go to a family court judge, who

decides on child custody and alimony. However, they enjoy fewer protections than

married people when the union dissolves. In contrast to divorce, no spousal alimony is

provided in cases of unequal resources between partners. However, based on our

different indicators for moving and housing characteristics, our results show few

differences between PACSed and married parents, suggesting that the results are likely

to be similar for cohabitating parents. Further research is necessary to confirm this

expectation.

Second, we observed the housing situation only one year after divorce. Although

the literature indicates that mobility is greater just following divorce, there may be a

later adjustment in housing conditions, in particular if the relocation was to nonoptimal

accommodation. Nevertheless, Villaume (2016) used a larger observation window of up

to four years to observe mobility after separation and found similar results regarding

parenthood status for women, although they were slightly different for fathers. She

found no distinction in the probability of moving by fatherhood status, whereas we

show that fatherhood has a positive effect on the probability of moving. This could

mean that it takes more time for childless men to move than it does for fathers. Some of

the changes in status from owner to renter may be only temporary because buying a

new home takes longer. With the next round of data (available soon), we intend to

extend the observation window after divorce.

Third, we can observe the postdivorce location of only one of the partners and so

cannot link the postdivorce locations of both partners, which may be of interest,

particularly for parents.

Fourth, as previously mentioned, child custody arrangements are not completely

exogenous and stable over time; they might change in the years following divorce

(Cretin 2015).

Nevertheless, our analysis has shed light on a previously understudied

phenomenon and shown that postdivorce childcare arrangements and residential choices

are related. It opens opportunities for further research to analyse postdivorce mobility

over the long term within a context of changing coparenting norms and behaviours.

Ferrari, Bonnet & Solaz: Residential mobility after divorce by parenthood status and custody arrangements

384 http://www.demographic-research.org

7. Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the French National Research Agency (grant ANR-16-CE41-

0007-01). We are grateful to the two anonymous reviewers and the guest editors for

their invaluable suggestions that significantly improved the paper. We also thank

Christopher Leichtnam for his careful language editing. In addition, we thank

participants at the research and policy symposium at St Andrews (UK) in May 2017, as

well as those who attended the 15th Meeting of the European Network for the

Sociological and Demographic Study of Divorce in Antwerp (Belgium) in October

2017, particularly for their comments and remarks.

Demographic Research: Volume 40, Article 14

http://www.demographic-research.org 385

References

Amato, P.R. (2001). Children of divorce in the 1990s: An update of the Amato and

Keith (1991) meta-analysis. Journal of Family Psychology 15(3): 355–370.

doi:10.1037/0893-3200.15.3.355.

Amato, P.R. (2010). Research on divorce: Continuing trends and new developments.

Journal of Marriage and Family 72(3): 650–666. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.

2010.00723.x.

Andreß, H.-J. and Bröckel, M. (2007). Income and life satisfaction after marital

disruption in Germany. Journal of Marriage and Family 69(2): 500–512.

doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00379.x.

Bigard, M., Timotéo, J., and Levy, D. (2014). Guide d’utilisation du distancier

METRIC [electronic resource]. Paris: Archives de Données Issues de la

Statistique Publique. http://www.progedo-adisp.fr/documents/MEDIAS/Guide_

distancier.pdf.

Bonnet, C., Garbinti, B., and Solaz, A. (2015). Les conditions de vie des enfants après

le divorce. Paris: Insee (Insee Première 1536).

Bonnet, C., Garbinti, B., and Solaz, A. (2016). Gender inequality after divorce: The flip

side of marital specialization: Evidence from a French administrative database.

Paris: Insee (Document de travail G2016–03).

Bonnet, C., Keogh, A., and Rapoport, B. (2014). Quels facteurs pour expliquer les

écarts de patrimoine entre hommes et femmes en France? Economie et

Statistique 472–473: 101–123. doi:10.3406/estat.2014.10491.

Bonvalet, C. (1993). Le logement et l’habitat dans les trajectoires familiales. Revue des

Politiques Sociales et Familiales 31(1): 19–37.

Cancian, M., Meyer, D., Brown, P., and Cook, S. (2014). Who gets custody now?

Dramatic changes in children’s living arrangements after divorce. Demography

51(4): 1381–1396. doi:10.1007/s13524-014-0307-8.

Carrasco, V. and Dufour, C. (2015). Les décisions des juges concernant les enfants de

parents séparés ont fortement évolué dans les années 2000. Paris: French

Ministry of Justice (Infostat Justice 132).

Cooke, T.J., Mulder, C.H., and Thomas, M. (2016). Union dissolution and migration.

Demographic Research 34(26): 741–760. doi:10.4054/DemRes.2016.34.26.

Ferrari, Bonnet & Solaz: Residential mobility after divorce by parenthood status and custody arrangements

386 http://www.demographic-research.org

Cretin, L. (2015). Résidence et pension alimentaire des enfants de parents séparés:

Décisions initiales et évolutions. In: Insee (ed.). Insee références: Couples et

familles. Paris: Insee: 41–50.

Dewilde, C. (2008). Divorce and the housing movements of owner-occupiers: A

European comparison. Housing Studies 23(6): 809–832. doi:10.1080/026730308

02423151.

Durier, S. (2017). Après une rupture d’union, l’homme reste plus souvent dans le

logement conjugal. Paris: Insee (Insee Focus 91).

Feijten, P. and Van Ham, M. (2007). Residential mobility and migration of the divorced

and separated. Demographic Research 17(21): 623–653. doi:10.4054/DemRes.

2007.17.21.

Festy, P. (1988). Statut d’occupation du dernier domicile conjugal et mobilité

résidentielle à partir de la separation. In: Transformation de la famille et habitat.

Paris: INED: 95–106.

French Ministry of Justice (2016). Les affaires familiales [electronic resource]. Paris:

French Ministry of Justice. http://www.justice.gouv.fr/art_pix/Stat_Annuaire_

ministere-justice_2016_chapitre1.pdf.

Gram-Hanssen, K. and Bech-Danielsen, C. (2008). Home dissolution: What happens

after separation? Housing Studies 23(3): 507–522. doi:10.1080/0267303080

2020635.

Hango, D.W. (2006). The long-term effect of childhood residential mobility on

educational attainment. The Sociological Quarterly 47(4): 631–664.

doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.2006.00061.x.

Hetherington, E.M. (2003). Social support and the adjustment of children in divorced

and remarried families. Childhood 10(2): 217–236. doi:10.1177/0907568203

010002007.

HCF – Haut Conseil de la Famille (2014). Les ruptures familiales: Etats des lieux et

propositions [electronic resource]. Paris: HCF. http://www.hcfea.fr/IMG/pdf/

2014_04_LES_RUPTURES_FAMILIALES.pdf.

Laferrère, A., Pouliquen, E., and Rougerie, C. (2017). Les conditions de logement en

France. Paris: Insee.

Lyngstad, T.H. and Jalovaara, M. (2010). A review of the antecedents of union

dissolution. Demographic Research 23(10): 257–292. doi:10.4054/DemRes.

2010.23.10.

Demographic Research: Volume 40, Article 14

http://www.demographic-research.org 387

Martin, C., Cherlin, A., and Cross-Barnet, C. (2011). Living together apart: Vivre

ensemble séparés: Une comparaison France–États-Unis. Population 66(3): 647–

669. doi:10.3917/popu.1103.0647.

Mazuy, M., Barbieri, M., d’Albis, H., and Reeve, P. (2014). Recent demographic trends

in France: The number of marriages continues to decrease. Population 69(3):

273–321.

Meyer, D.R. and Carlson, M.J. (2014). Family complexity: Implications for policy and

research. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science

654(1): 259–276. doi:10.1177/0002716214531385.

Mikolai, J. and Kulu, H. (2018a). Divorce, separation, and housing changes: A

multiprocess analysis of longitudinal data from England and Wales.

Demography 55(1): 83–106. doi:10.1080/00324728.2017.1391955.

Mikolai, J. and Kulu, H. (2018b). Short- and long-term effects of divorce and separation

on housing tenure in England and Wales. Population Studies 72(1): 17–39.

doi:10.1080/00324728.2017.1391955.

Mulder, C.H. and Malmberg, G. (2011). Moving related to separation: Who moves and

to what distance. Environment and Planning A 43(11): 2589–2607. doi:10.1068/

a43609.

Mulder, C.H. and Wagner, M. (2010). Union dissolution and mobility: Who moves

from the family home after separation? Journal of Marriage and Family 72(5):

1263–1273. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00763.x.

Mulder, C.H., Ten Hengel, B., Latten, J., and Das, M. (2012). Relative resources and

moving from the joint home around divorce. Journal of Housing and the Built

Environment 27(2): 153–168. doi:10.1007/s10901-011-9250-9.

Prioux, F. (2009). Les couples non mariés en 2005: Quelles différences avec les couples

mariés? Politiques sociales et familiales 96: 87–95.

Spilerman, S. and Wolff, F.C. (2012). Parental wealth and resource transfers: How they

matter in France for home-ownership and living standards. Social Science

Research 41(2): 207–223. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2011.08.002.

Stjernström, O. and Strömgren, M. (2012). Geographical distance between children and

absent parents in separated families. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human

Geography 94(3): 239–253. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0467.2012.00412.x.

Sullivan, O. (1986). Housing movements of the divorced and separated. Housing