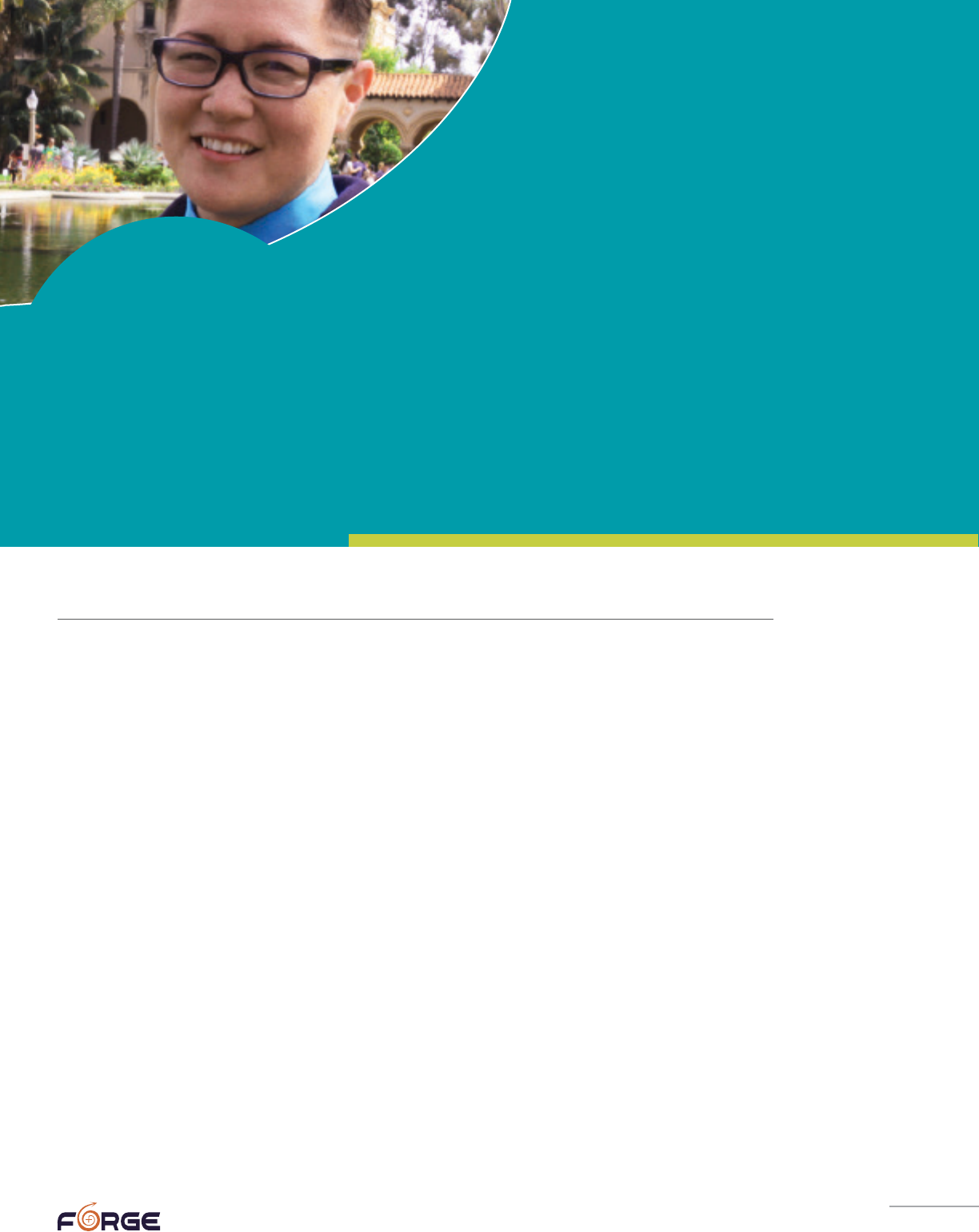

Michael Munson

Executive Director

Loree Cook-Daniels

Policy and Program Director

SEPTEMBER 2015

TRANSGENDER SEXUAL

VIOLENCE PROJECT

TRANSGENDER SEXUAL VIOLENCE SURVIVORS

A Self Help Guide

to Healing and

Understanding

PHOTO BY LEIGH HOUGHTALING

2

forge-forward.org

A SELF-HELP GUIDE TO HEALING AND UNDERSTANDING

Table of Contents

Thank You_____________________________________________________________________ 7

Introduction __________________________________________________________________ 8

Welcome _____________________________________________________________________ 8

Introduction to Self-Help Guide _________________________________________ 10

Guide Contents _____________________________________________________________ 11

Trauma and its Aftermaths __________________________________________ 13

The brain and trauma _____________________________________________________ 13

Additional readings on how trauma affects the brain _____________________________ 16

Aftereffects of sexual abuse or assault ________________________________ 16

Emotional regulation problems ________________________________________________ 18

Isolation / avoidance / denial __________________________________________________ 20

Shame, guilt, and self-blame __________________________________________________ 21

Depression / anxiety / self-harm / suicide ______________________________________ 22

Substance abuse ____________________________________________________________ 23

Physical health problems _____________________________________________________ 24

High need for control versus helplessness ______________________________________ 26

Anger _______________________________________________________________________ 26

Sleep disturbances / irritability ________________________________________________ 27

3

forge-forward.org

A SELF-HELP GUIDE TO HEALING AND UNDERSTANDING

Revictimization/ reenactment _________________________________________________ 27

Interpersonal problems _______________________________________________________ 28

Additional readings on the aftereffects of sexual assault and/or trauma ___________ 30

Transgender Survivors of Sexual Abuse _______________________ 32

Sexual violence statistics and myths ___________________________________ 32

Being too young and/or feeling responsible _____________________________________ 33

Not understanding that “sexual assault”

encompasses what happened to them _________________________________________ 34

Being male and/or having a female perpetrator _________________________________ 34

Experiencing additional complications due to gender identity or politics ___________ 35

Wanting to deny or avoid thinking about the trauma _____________________________ 35

Transgender sexual violence survivors data __________________________ 36

Most transgender survivors have experienced repeated sexual violence ___________ 36

Most transgender people were first assaulted as a child or youth _________________ 36

Most perpetrators were known to the victim ____________________________________ 37

More than a quarter of transgender survivors have been assaulted by females _____ 37

Gender is sometimes perceived to be the motivator of abuse ____________________ 38

Survivors rarely report the abuse ______________________________________________ 38

The abuse can leave physical scars ____________________________________________ 38

Emotional scars can last a very long time ______________________________________ 39

Relationships are heavily impacted ____________________________________________ 40

Survivors often partner with other sexual assault survivors _______________________ 41

Trans survivors access many types of help. _____________________________________ 42

Trans-specific aspects of sexual assault ______________________________ 43

Anti-trans abuse or sexual abuse? _____________________________________________ 43

Cause and effect _____________________________________________________________ 43

Trans bodies and body dysphoria ______________________________________________ 45

Not being believed or minimizing the assault(s) _________________________________ 45

Transgender perpetrators _____________________________________________________ 46

Service provider perpetrators _________________________________________________ 47

Meeting complex needs within a basic service system ___________________________ 48

4

forge-forward.org

A SELF-HELP GUIDE TO HEALING AND UNDERSTANDING

Complicated relationship with therapists _______________________________________ 49

Intersectionality ______________________________________________________________ 50

Options for Healing _____________________________________________________ 51

Talk therapy _________________________________________________________________ 51

Medication __________________________________________________________________ 52

Additional readings on medications ________________________________________ 52

Body-based therapies ________________________________________________________ 52

Additional readings on alternative therapies _________________________________ 53

Movement-based therapies ___________________________________________________ 54

Other “alternative” therapies __________________________________________________ 54

Faith-based support__________________________________________________________ 55

Peer-to-peer help ____________________________________________________________ 56

Mainstream and LGBT Services _________________________________________ 57

LGBT anti-violence programs (AVPs) ___________________________________________ 57

State sexual violence coalitions _______________________________________________ 57

National sexual assault hotline ________________________________________________ 58

Rape crisis hotlines or community rape treatment centers _______________________ 58

Sexual assault treatment centers, sexual assault

nurse examiners, and hospitals ________________________________________________ 58

Sexual assault response teams (SART) or

coordinated community response (CCR) _______________________________________ 59

Victim assistance programs ___________________________________________________ 59

Victim compensation _________________________________________________________ 59

LGBT community centers _____________________________________________________ 59

Support groups ______________________________________________________________ 60

Therapy _____________________________________________________________________ 60

Restraining orders ___________________________________________________________ 60

Law enforcement ____________________________________________________________ 60

Trans support groups _________________________________________________________ 61

12-step programs ____________________________________________________________ 61

Suicide hotlines and support __________________________________________________ 61

5

forge-forward.org

A SELF-HELP GUIDE TO HEALING AND UNDERSTANDING

FORGE Services____________________________________________________________ 62

For Survivors ________________________________________________________________ 62

For Providers ________________________________________________________________ 63

Self-Help Techniques and Concepts ____________________________ 65

Healing is hard work _________________________________________________________ 66

Techniques for coping with strong emotions ________________ 68

Getting out of the basement _____________________________________________ 68

Breathing ____________________________________________________________________ 69

90 seconds __________________________________________________________________ 69

Getting moving / getting physical _______________________________________ 70

Using your voice ___________________________________________________________ 70

Cross brain actions ________________________________________________________ 71

Checklists ___________________________________________________________________ 71

Use technology _____________________________________________________________ 71

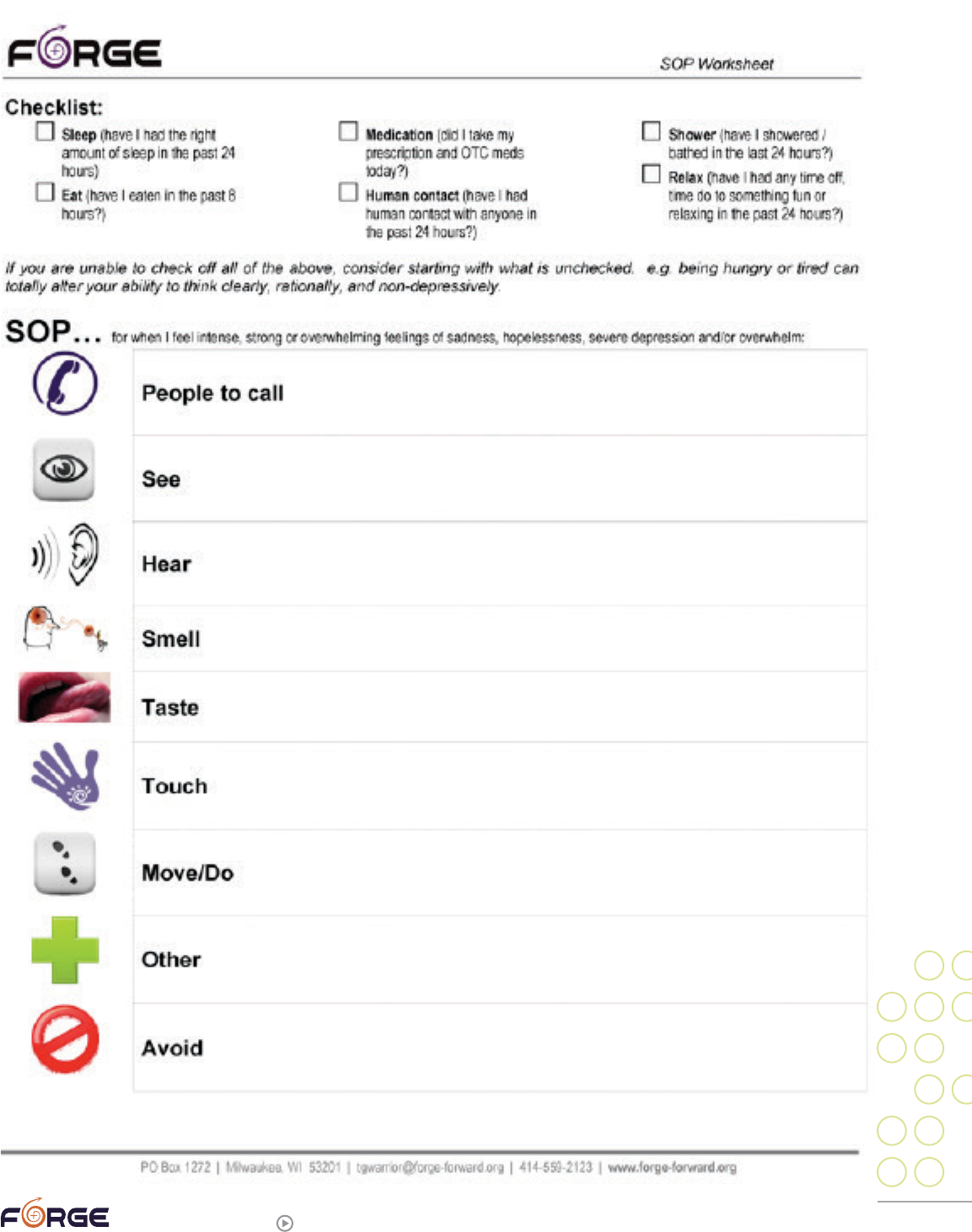

Emergency Standard Operating Procedures (SOP) __________________ 72

Techniques, exercises and concepts for healing __________ 76

Container exercise _________________________________________________________ 76

Coping with anniversary dates __________________________________________ 77

Coping with triggers _______________________________________________________ 80

Triggers: Dialogues _______________________________________________________ 80

Triggers: Coping via a “series of tasks” _____________________________________ 81

Additional readings on coping with triggers _________________________________ 83

Making meaning _____________________________________________________________ 83

Additional readings on making meaning ____________________________________ 84

Mindfulness and meditation ___________________________________________________ 84

Additional readings on mindfulness as a healing tool _________________________ 86

6

forge-forward.org

A SELF-HELP GUIDE TO HEALING AND UNDERSTANDING

Resourcing __________________________________________________________________ 87

Sexuality _____________________________________________________________________ 87

Additional readings on sexuality _______________________________________________ 89

Breath training ______________________________________________________________ 90

Emotions and healing _____________________________________________________ 91

The five stages of emotions ___________________________________________________ 91

Being witnessed in your emotions _____________________________________________ 93

Additional readings on emotional regulation _________________________________ 93

Challenging maladaptive or problematic beliefs ______________________ 94

Additional readings on coping with maladaptive beliefs ______________________ 96

Problem-solving and conflict resolution _______________________________ 96

Relationship attachment styles and issues __________________________ 100

Additional readings on attachment theory and couples ______________________ 103

Time perspective therapy ______________________________________________ 104

Additional resources on time perspective therapy __________________________ 105

Volunteering ______________________________________________________________ 117

Annotated bibliography of self-help books __________________________ 118

Appendices_______________________________________________________________ 109

Appendix A: If your assault just happened __________________________ 109

Appendix B: If your current relationship is abusive ________________ 111

Trans-specific power and control tactics ______________________________________ 114

Safety planning: A guide for transgender and

gender non-conforming individuals who are

experiencing intimate partner violence ________________________________________ 116

Appendix C: New non-discrimination

protections for trans people _________________________________ 130

7

forge-forward.org

A SELF-HELP GUIDE TO HEALING AND UNDERSTANDING

This publication was supported by Grant No. 2009-KS-

AX-K003 awarded by the Office on Violence Against

Women, U.S. Department of Justice. The opinions,

findings, conclusions, and recommendations expressed

in this publication are those of the author(s) and do

not necessarily reflect the views of the Department

of Justice, Office on Violence Against Women.

Some of the research data in this report came from

work supported by grant number 2009-SZ-B9-K003,

awarded by the Office for Victims of Crime, Office of

Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice.

Thank you

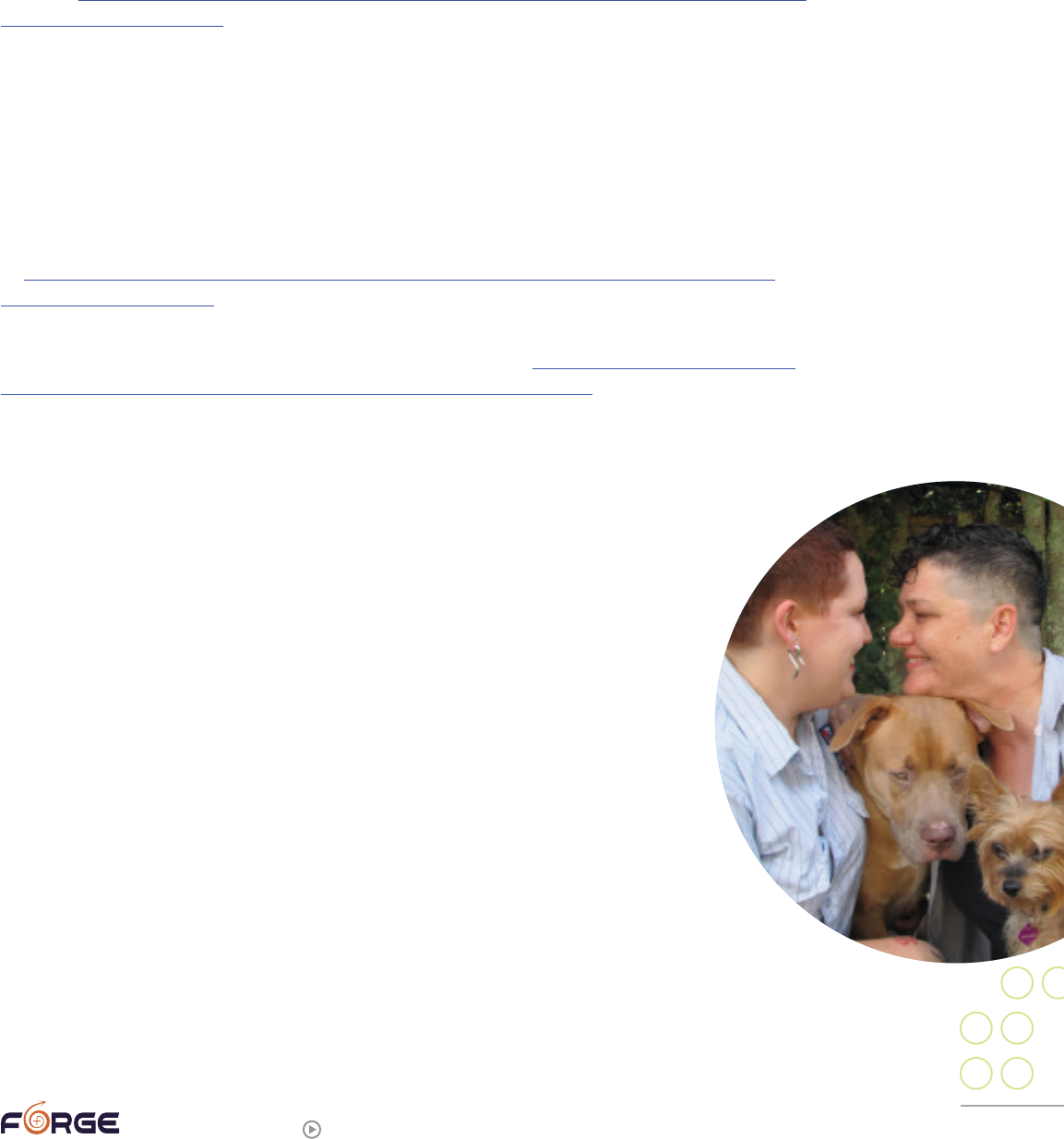

PHOTO BY MIA NAKANO

8

forge-forward.org

>

A SELF-HELP GUIDE TO HEALING AND UNDERSTANDING

Introduction

Welcome

Espavo. Thank you for taking your power and picking up

this publication.

Since some people never get beyond the first page of a book

or report, it is very important to us to make sure you—a

transgender

1

or gender non-conforming person who at some

point has experienced sexual assault, sexual coercion, sexual

threats, unwanted sexual or other physical touch, sexual

violence within a dating or intimate relationship, or sex with

an older person who should have known you were too young

to understand all the implications—hear the most important

things we would like you to know. So if you read nothing else,

please read this Welcome.

1. You are not alone.

Fifty percent (50%) or more of all transgender and gender

non-conforming people have experienced some form of

sexual abuse, sometimes from many different people over

1

Transgender: Throughout this document, we will use fluid language of “trans,” “transgender,” “gender non-conforming, and

“gender non-binary.” We honor and recognize the complexity and multiplicity of gender identities. We use these words in

their broadest meanings, inclusive of those whose identities lie outside of these terms often limiting terms.

TRANS* LANGUAGE

Throughout this document, we will use fluid

language of “trans,” “transgender,” “gender

non-conforming,” and “gender non-binary.”

We honor and recognize the complexity and

multiplicity of gender identities. We use these

words in their broadest meanings, inclusive

of those whose identities lie outside of these

terms often limiting terms.

ABUSE/ASSAULT/TRAUMA LANGUAGE

Throughout this publication, abuse, assault

and trauma will be used interchangeably.

Some people will resonate more with

“abuse,” others with “assault,” and others

still, will prefer “trauma.” You may have

additional words that feel more meaningful to

you. Please mentally substitute the language

you feel most comfortable with so you can

gain the most from this guide.

1

PHOTO BY MIA NAKANO

9

forge-forward.org

A SELF-HELP GUIDE TO HEALING AND UNDERSTANDING

many years.

2

So you are not alone in what you have experienced. Right

now there are people who care very much about you surviving, healing,

and thriving. Support and connection is available.

2. People can understand the complexities.

As a transgender or gender non-conforming sexual abuse survivor

3

,

you may feel like your experience is too complex for people—possibly

including you—to understand. Sexual assault already inextricably mixes

up issues of sex, gender, body image, power and self image without the

complication of gender identity issues; add that in, and it may seem like

people just cannot get it. And it may be true that you previously have not

found people capable of understanding. But that is changing. Not only has

FORGE’s staff been working on these issues for more than a decade (as

well as a growing number of trans and LGBTQ individuals and agencies),

but we have been training providers so they can better serve transgender

survivors. There are now people who are prepared and want to walk with

you as you sort through what happened and what you want to have happen next.

3. Healing is possible.

You may have been living with the aftermath of sexual abuse for decades now. You may

not know what parts of you have been shaped by your sexual abuse experiences. You may

think you are going to live the rest of your life carrying the scars of your experience. You

may think you were not affected at all. What we want you to know is that we understand

far more than we ever did before of what sexual assault does to people, and how to

heal that damage. There is no cure-all, no magic wand, but we know of more tools and

techniques than we ever did before.

We hope you join us in the following pages to find out more about how we can help you

help yourself.

2

Abuse/assault/trauma: Throughout this publication, these three words will be used interchangeably. Some people will reso-

nate more with “abuse,” others with “assault,” and others still, will prefer “trauma.” You may have additional words that feel

more meaningful to you. Please mentally substitute the language you feel most comfortable with so you can gain the most

from this guide.

3

Survivor/victim: Most of the time, this guide will use “survivor” language, since we know that many people who have

experienced abuse/assault feel more empowered by it than the word “victim.” There are many ways people classify what

happened to them, and who they are in response to what they experienced. If one word does not feel right for you, please

mentally substitute.

SURVIVOR/VICTIM LANGUAGE

Most of the time, this guide

will use “survivor” language,

since we know that many

people who have experienced

abuse/assault feel more em-

powered by it than the word

“victim.” There are many ways

people classify what hap-

pened to them, and who they

are in response to what they

experienced. If one word does

not feel right for you, please

mentally substitute.

10

forge-forward.org

A SELF-HELP GUIDE TO HEALING AND UNDERSTANDING

Introduction to this self-help guide

In 2003, Michael Munson and Loree Cook-Daniels, the facilitators of FORGE’s then-

10-year-old transgender and SOFFA (Significant Others, Friends, Family and Allies)

Milwaukee-based peer support group, realized that over half of the people who

attended monthly meetings had survived sexual assault.

We never asked the hundreds of people who attended meetings over those first 10 years,

but participants would often reference past (or current) abuse, and we began to mentally

track the high volume of people who had experienced sexual violence. 2003 was also

the year when a transgender sexual assault survivor attempted to access help from law

enforcement, sexual assault service providers, crime victim compensation, lawyers,

advocates, and therapists, and was repeatedly denied service or revictimized

by the system. We wondered: Is sexual violence against trans* people

this prevalent everywhere? Are services that are supposed to help

survivors this dysfunctional and damaging to trans people in other

parts of the country?

“Yes” was the answer we discovered from the national survey

FORGE conducted in 2004, with 265 trans respondents.

4

Not

only were sexual assault histories ubiquitous among trans

people, but so were negative experiences trying to get help.

In the years since, FORGE has continued to collect and

research the experiences of transgender sexual assault

survivors and their loved ones, as well as develop a

deeper understanding of trauma and the implications

for healing.

Beginning in 2009, we have been awarded several

groundbreaking federal grants to try to improve the

knowledge, skills and cultural competency of victim services

providers about the unique (and not-so-unique) needs of

transgender survivors; and grants to provide direct services to

trans survivors and loved ones.

Although it is critical to improve mainstream services’ ability to

appropriately and respectfully respond to the needs of transgender

sexual assault survivors and their loved ones, our 2004 study found that

many trans survivors turn to the internet and self-help materials rather than, or

in addition to, services from therapists or sexual assault programs. Unfortunately, many

self-help and internet-based materials are highly steeped in binary gender stereotypes,

making them painful reading for some transgender and gender non-binary survivors. In

addition, none of those materials addresses the specific complexities that face survivors

who are not only trying to find their way through the morass of feelings and memories

about the assault(s), but who are also trying to cope with how gender identity issues

interact with and complicate the picture.

4

FORGE. (2004). “Sexual Violence in the Transgender Community Survey,” (n=265) (data has not been formally published).

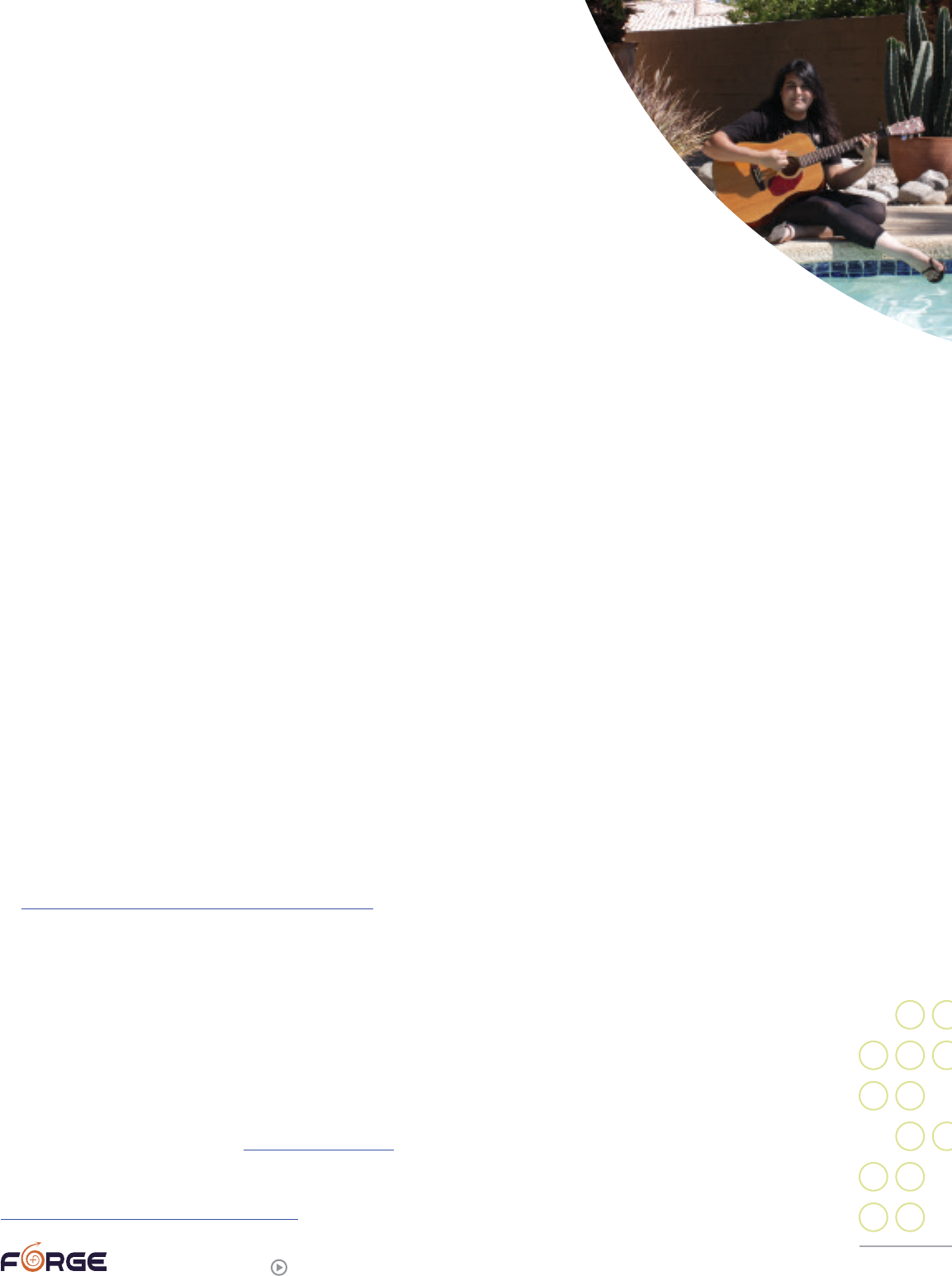

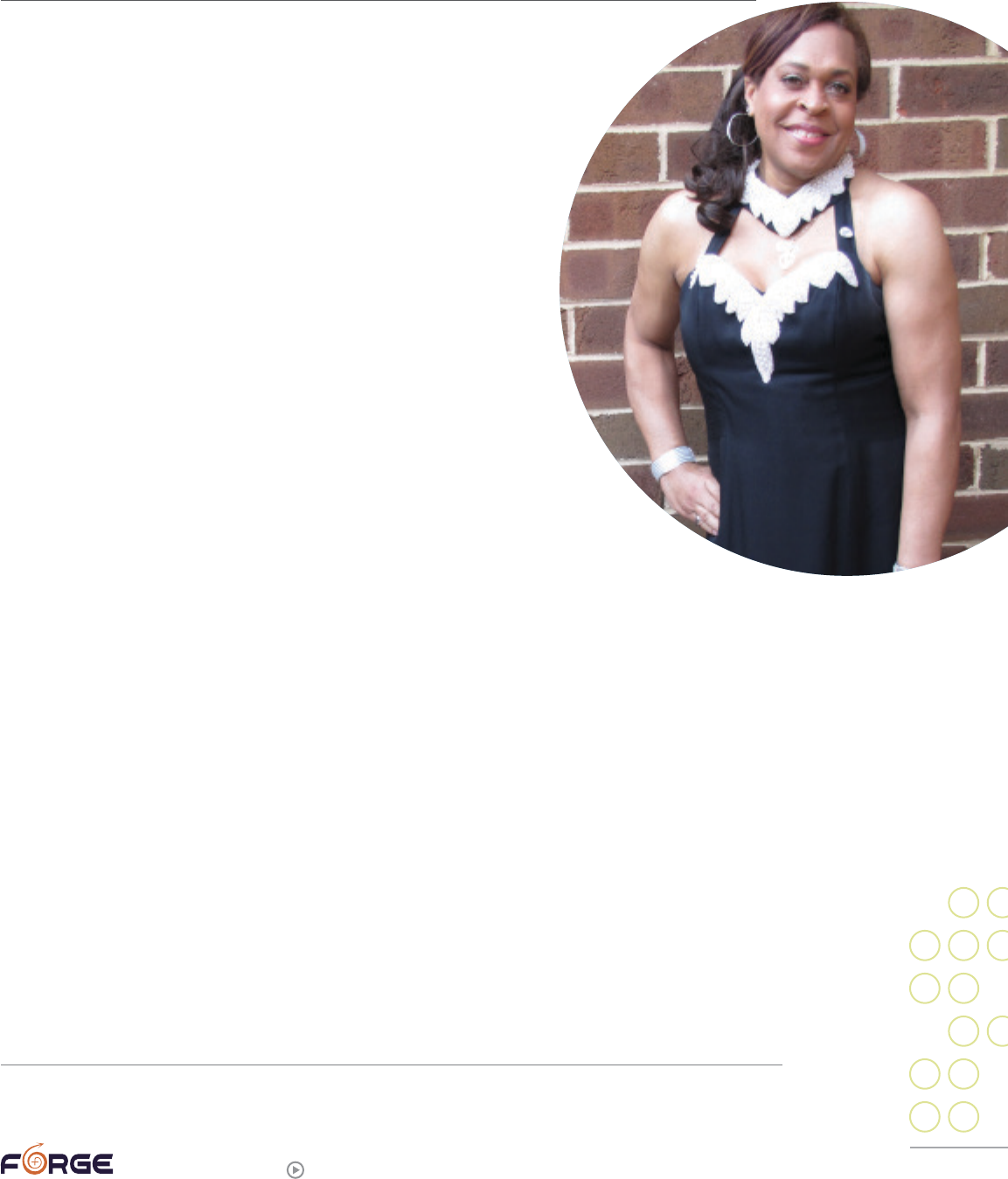

PHOTO BY KERRI CECIL

11

forge-forward.org

A SELF-HELP GUIDE TO HEALING AND UNDERSTANDING

This guide will help fill that void.

For example:

If you are a transgender sexual abuse survivor who is reading this manual as a

self-help tool, congratulations and good work! That action alone demonstrates

hope, a willingness to work on yourself, and self-awareness. Those are things

many survivors do not feel.

At the same time, you may be picking up a self-help manual because you have

learned that other people cannot be trusted to be helpful and supportive.

Particularly if the people who were supposed to care for you as a child failed to

do so consistently, you may have learned that the only person you can count on

is yourself. Those are things that many survivors feel and have experienced, too.

As you continue on your healing journey, you may learn enough skills, and

become confident enough to seek, find, and establish relationships with

people who are trustworthy, who can and will provide you with the support

and connection you probably crave deep down under your fear, anger,

disappointment and other protective emotions.

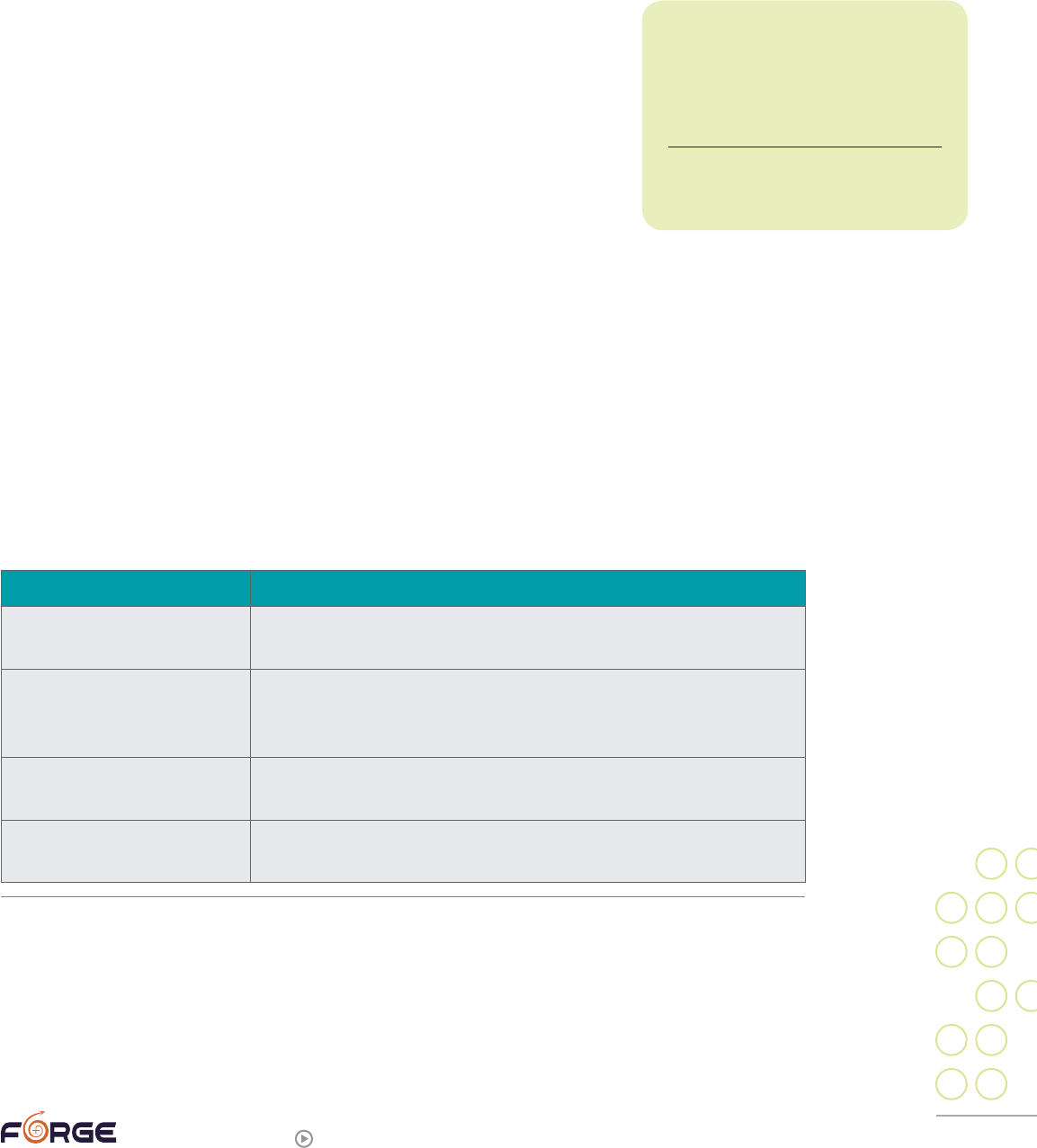

Guide Contents

There are six main sections to this guide.

1. The Introduction section talks about how the guide came about, what it contains, and

how to use it.

2. Trauma and its Aftermaths addresses what occurs in our brains at the moment

trauma happens, and why trauma memories and reactions are so different from the

rest of our experience. This section also describes many of the long-term effects of

trauma. Some readers will be surprised at what is here; many of us think we are

personally damaged and/or that being trans has caused certain personality traits and

reactions, when the actual cause often lies in the trauma(s) we have suffered.

3. The Transgender Survivors of Sexual Assault section reviews what FORGE and

others have learned about transgender sexual assault survivors over the past decade.

It reviews popular myths about sexual assault, including many that lead to trans

survivors not recognizing their experience as sexual assault or abuse. It reports what

FORGE has learned in its surveys of transgender sexual assault survivors about their

experiences, and includes many quotations from trans survivors. The last section

explores some of the unique and trans-specific issues trans survivors face, again

including many quotations. Although the primary purpose of this section is to show

you that you are not alone, please know that we necessarily had to leave out many

comments and issues due to space constraints. If one or more of your issues are not

reflected here, by no means draw the conclusion that you are the only one who is

grappling with them.

12

forge-forward.org

A SELF-HELP GUIDE TO HEALING AND UNDERSTANDING

4. Options for Healing briefly addresses talk therapy,

medications, body-based therapies, movement-based

therapies, other “alternative” therapies, faith-based

assistance, and peer-to-peer help. It then lists and describes

both mainstream and FORGE-sponsored services and resources

that may support your healing efforts.

5. Self-Help Techniques includes a selection of exercises and essays that you may

want to use to help promote your own well-being. The topics covered include: breath

training, challenging maladaptive or problematic beliefs, an emotional container

tool, coping with anniversary dates and triggers, emergency standard operating

procedures, emotions and healing, making meaning, mindfulness and meditation,

problem-solving and conflict resolution, relationship attachment styles and issues,

resourcing, sexuality, time perspective therapy, and volunteering. Some of the

exercises and essays include

additional readings; an annotated bibliography at the end should help guide

you to additional resources.

6. In the Appendices you will find some additional resources, including guidance on

what to do if your assault just happened, and an exciting new federal law that should

help improve the availability and quality of services offered to trans sexual assault

survivors. There is also an appendix with information for those who may currently be

in relationships that are unsafe, including a list of trans-related power and control

tactics and a trans-specific safety planning tool.

Each section has been designed to stand on its own, so feel free to go right to the topic or

topics you are most interested in, and put off or skip the others entirely. There is no 1-2-3

recipe for healing from trauma; in fact, one of the goals of recovery is learning how to

respect and take care of your own individuality. If something in this guide does not fit you

or does not make sense, let it go and move on to something else. It is your life; this guide

is but one of many tools that you might find useful.

PHOTO BY LEIGH HOUGHTALING

One of the goals of

recovery is learning

how to respect and

take care of your

own individuality.

13

forge-forward.org

>

A SELF-HELP GUIDE TO HEALING AND UNDERSTANDING

Trauma and

its Aftermaths

The brain and trauma

An intriguing and widely-accepted theory about human brains is that they evolved to

become more complex.

This theory says we have a “reptilian” brain that contains the basics for survival. It

processes input from the senses, keeps the system functioning, governs reproduction, and

is in charge of safety. We next developed a “mammalian” or “limbic brain,” found in all

mammals, that evolved around and on top of the central reptilian brain. The limbic brain

contains the circuits that handle emotion, memory, some social behavior, and learning.

The third, most recent and most complex layer is the neocortex. This is our thinking brain,

the part that allows us to think through what is happening and override the reactions of

the reptilian and limbic brains when, for instance, we realize that the person who just

jumped at us unexpectedly is a friend who is smiling and seeking to engage us in play.

2

Neocortex

(neomammalian)

Limbic System

(old mammalian)

Reptilian

Thinking

Emotional

Survival

PHOTO BY BRANDON TAYLOR

14

forge-forward.org

A SELF-HELP GUIDE TO HEALING AND UNDERSTANDING

There is a built-in hierarchy among these brain functions. The highest imperative of the

brain is to keep the organism alive, which is the reptilian’s brain first and most basic

function. Faced with a threat to life, the reptilian brain shuts down all “unnecessary”

functions—including not only digestion, muscle building, and reproductive

drive, but also higher-level thinking—in order to divert all available blood

and energy to the heart and muscles to power either “fighting” or “fleeing.”

Should these two options not seem viable, the reptilian brain will choose a

third, less well-known, option: “freezing,” “folding,” or “fainting.” All of these

options can be observed in animals that are faced with becoming someone’s

prey. While the advantages of fighting or fleeing are obvious, freezing or

folding can also be life-saving, if they cause the predator to lose interest

(many predators avoid dead prey in case it died of something that could kill

the animal who dines on it, as well). In addition, there are pain-deadening

aspects of freezing or folding that are merciful if the victim does not

succeed in eluding, defeating, or distracting the predator.

What many trauma survivors do not understand is that the thinking brain,

the neocortex, effectively shuts down when our lives are threatened. Many survivors

harshly criticize themselves later, wondering why they were so “cowardly” or “dumb” that

they could not come up with a way of avoiding or more quickly escaping the situation.

Trauma survivors need to understand that it is literally, biologically impossible for

people to access their thinking brain in life-and-death situations because the more

primitive brain is choosing among its three basic options (fight, flight, or freeze), and

creative problem-solving abilities are for the most part completely off-line. In fact, one

study found that sexual assault seems particularly likely to provoke a biological freeze

response: “88% of the victims of childhood sexual assault and 75% of the victims of adult

sexual assault reported moderate to high levels of paralysis during the assault.”

5

What happens to the brain after the

trauma is less clear, although there is

no shortage of theories. Many theories

focus on memories and why traumatic

memories are so prone to come back

as flashbacks (memories that feel like

they are present reality rather than a

memory), why they are so intrusive,

and why they can be forgotten for

many years and then recovered. Some

of these theories suggest that the

brain’s chemical bath is so different

from normal during a trauma that the

memories are encoded differently. Other

theories suggest that since certain parts

of the brain are off-line during trauma, memories are stored in atypical places. These

trauma theories in turn lead to trauma therapies. For example, one school believes that

it is critical to use your neocortex and language centers of the brain to link your trauma

memories into a story, because that process helps move memories into their more typical

storage mechanisms, in the process draining them of some of their potent emotions.

5

Levine, Peter A. (2010). In an Unspoken Voice: How the Body Releases Trauma and Restores Goodness, p. 59.

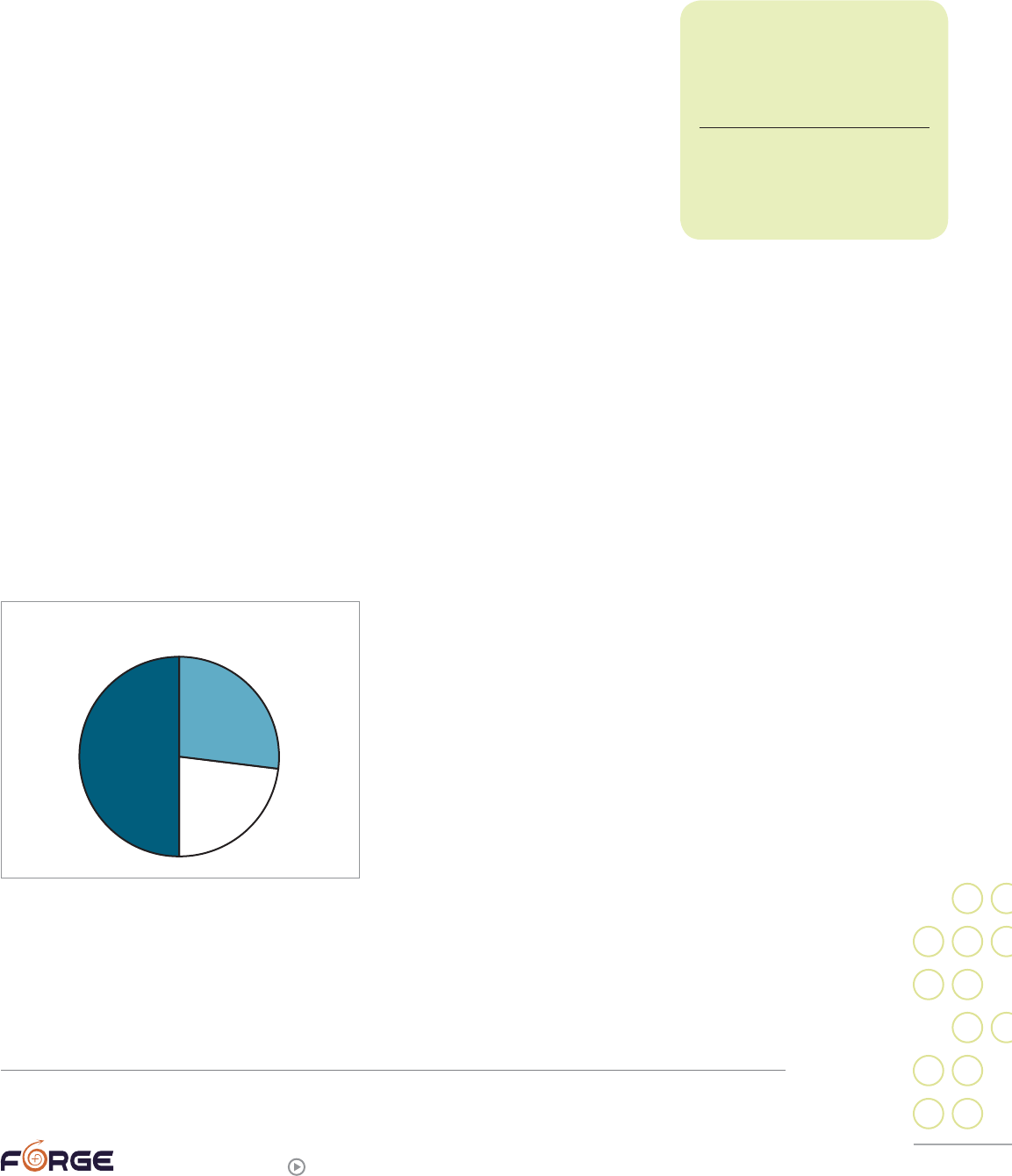

88% of the victims

of childhood sexual assault

and 75% of the victims of

adult sexual assault reported

moderate to high levels of

paralysis during the assault.

Levine, Peter A. (2010). In an

Unspoken Voice: How the Body

Releases Trauma and Restores

Goodness, p. 59.

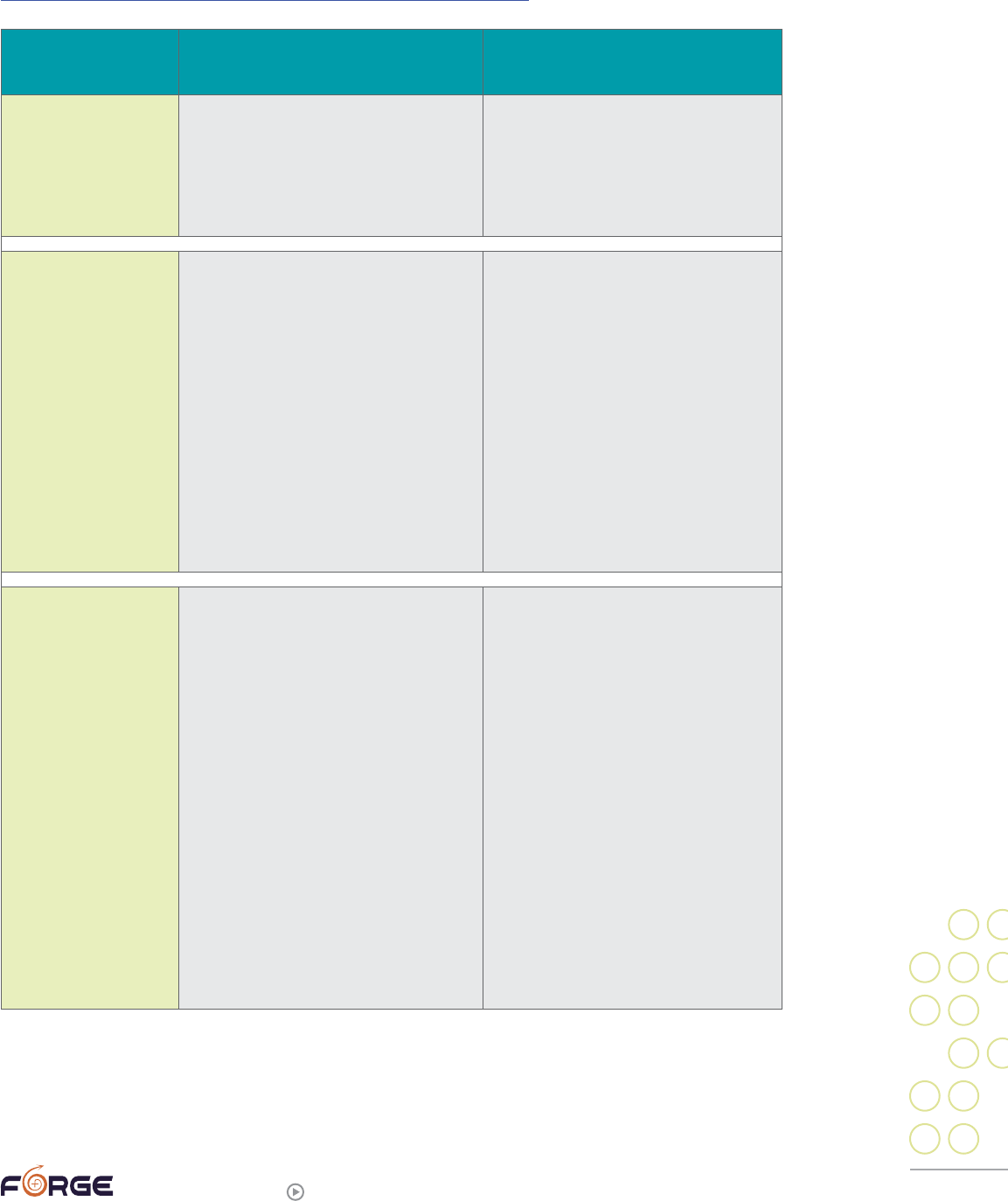

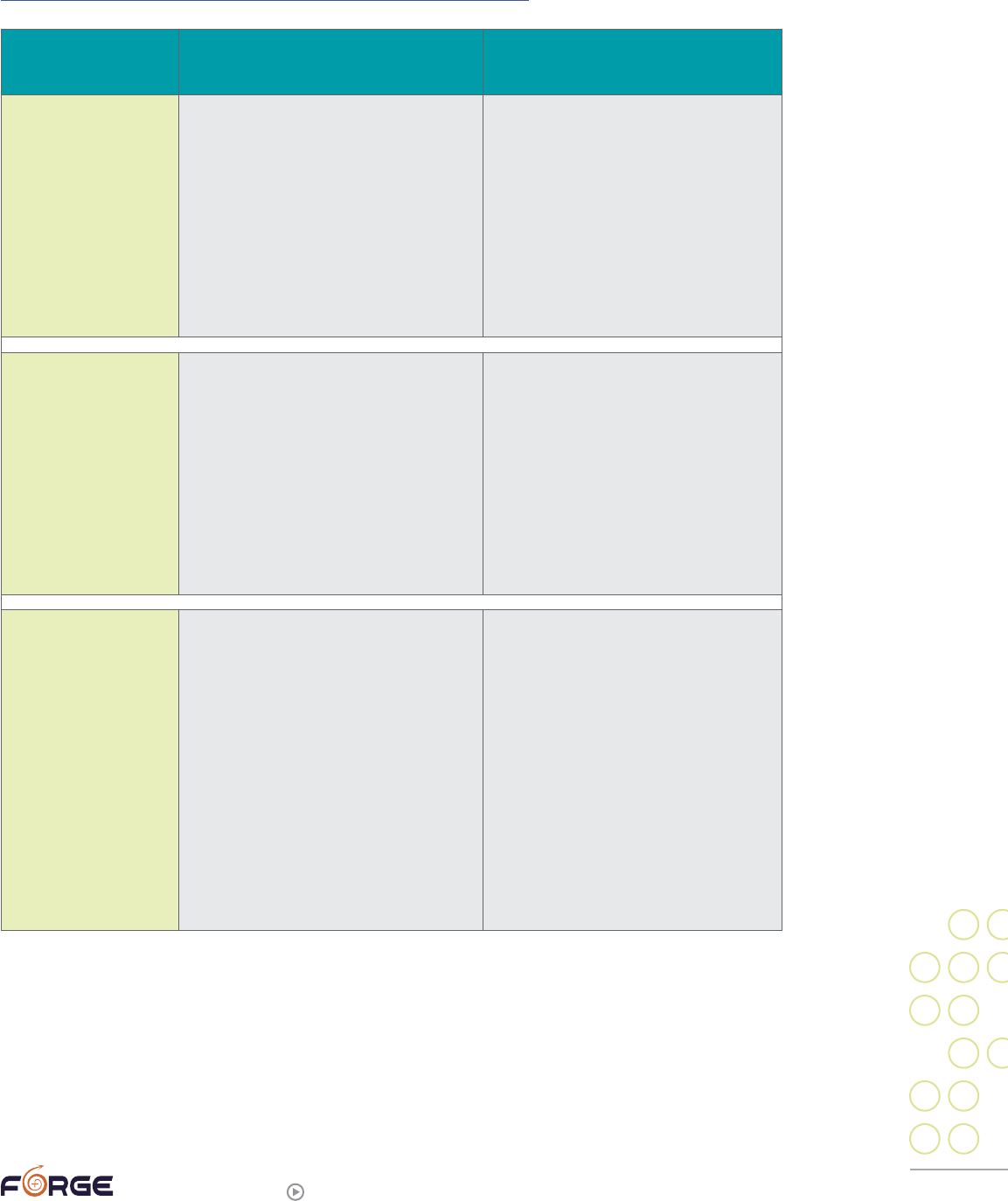

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

ADULTCHILDHOOD

88%

75%

PARALYSIS DURING SEXUAL ASSAULT

15

forge-forward.org

A SELF-HELP GUIDE TO HEALING AND UNDERSTANDING

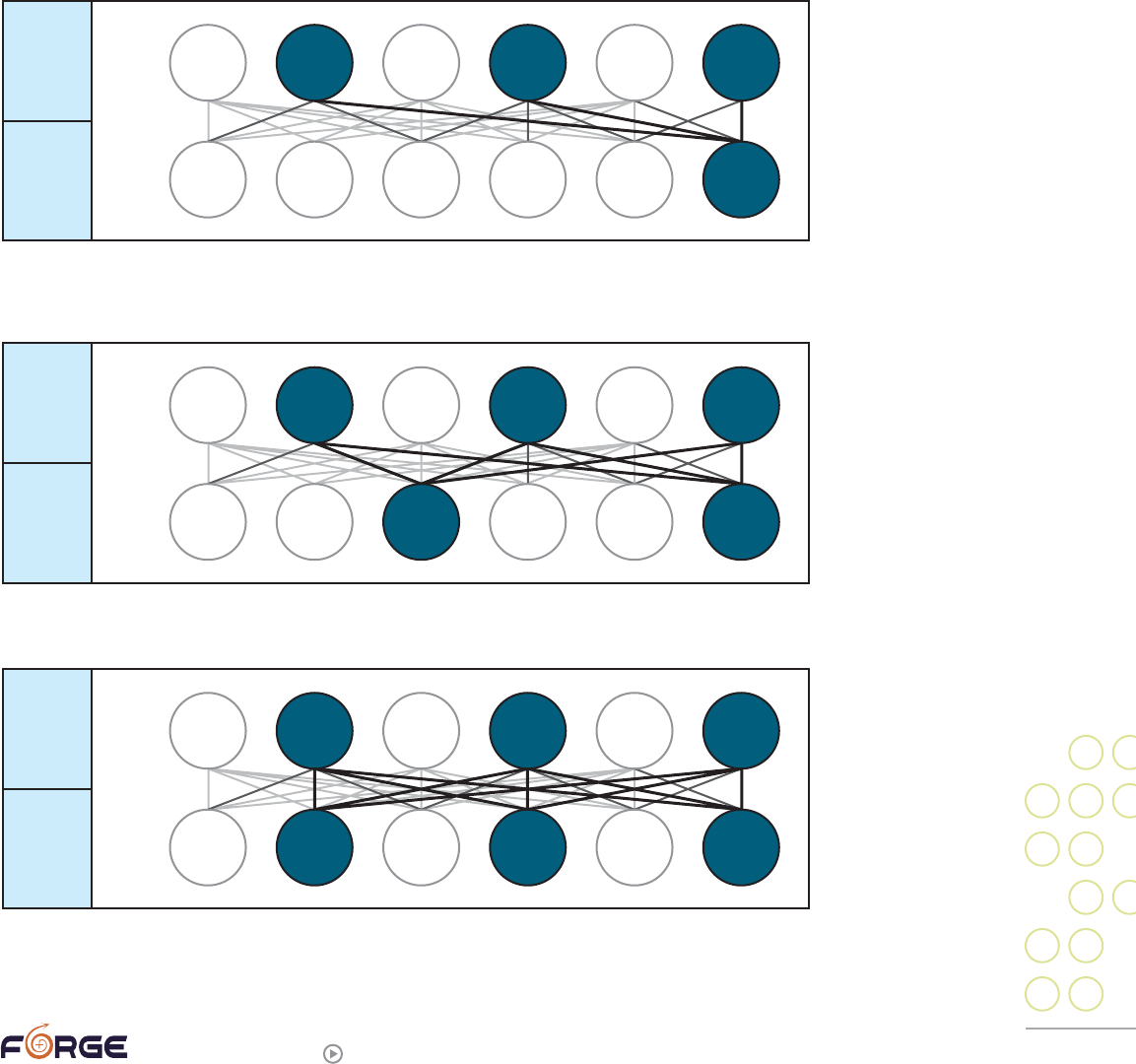

Some trauma therapies, like EMDR, involve rapidly and repeatedly shifting focus from

one side of the body to the other, in order to activate both hemispheres of the brain and

thereby “integrate” the memories.

Another popular trauma theory is that humans short-circuit the

biological trauma response because of judgments about it. Animals

recovering from a trauma often vigorously shake themselves or engage

in other physical behaviors that “re-set” their systems, whereas human

trauma survivors often repress or suppress such reactions. Trauma

therapies based on this view of trauma help trauma survivors gently

move their body into the last known position before the trauma, and then

carefully and slowly move through the “next actions” the body wants to

take (such as running, shaking, etc.).

Older therapies often focus on having the survivor continually re-live or

re-tell their story until it ceases to hold so much emotional power; newer

analyses indicate this method is only effective if the victim’s primary feeling is fear,

which can be reduced if it is re-lived enough in safe environments. (To learn more about

trauma therapy options, see FORGE’s companion guide, “Let’s talk about it! A Transgender

Survivor’s Guide to Accessing Therapy.”)

What is clear is that during a trauma in which someone feels their life is in danger, their

brain is not operating normally. What is also clear is that memories of what happened

during a trauma are qualitatively different from everyday memories. Although many

people do manage to recover from these traumatic events on their own over time, many

others carry psychological scars that can be debilitating. Some find that their lives begin

to be defined by the trauma, with new experiences and memories all filtered through and

into ways of thinking shaped by the trauma. It appears that sexual abuse is one of the

traumas most likely to lead to Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), the condition most

directly traceable to trauma, with between

50% and 77% of sexual assault survivors

suffering from PTSD at some point.

6

(We talk

more about PTSD in the following section,

“Aftereffects of Sexual Abuse or Assault.”)

Certain personal characteristics and

experiences seem to increase the likelihood

that a sexual assault survivor will develop

long-term symptoms. Experiencing previous

traumas, even if they were caused by natural

disasters rather than human actions, raises

the chances a survivor will develop PTSD. If a

person did not experience strong, supportive

relationships with their adult caretakers as a child, they will be more at-risk. If they

often dissociate (seem to psychologically move out of their bodies into another place

or time), they are at more risk of PTSD, especially if they dissociated at the time of the

trauma itself.

6

Cloitre, Marylene, Cohen, Lisa R., & Koenen, Karestan C. (2006). Treating survivors of childhood abuse: Psychotherapy for

the interrupted life, p. 11.

Between 50 and 77%

of sexual assault survivors

suffer from PTSD at some

point in their life.

Cloitre, Marylene, Cohen, Lisa R.,

& Koenen, Karestan C. (2006).

Treating survivors of childhood

abuse: Psychotherapy for the

interrupted life, p. 11.

PTSD IN SEXUAL ASSAULT SURVIVORS

50%-77%

16

forge-forward.org

A SELF-HELP GUIDE TO HEALING AND UNDERSTANDING

If you are a sexual assault survivor, it is critical that you not blame yourself for being

unable to prevent, more quickly end, forget, or just “get past” the experiences you may

now be struggling with. Certain biological processes in your brain and the rest of your

body took over when you were threatened or assaulted, making certain choices literally

impossible. These same chemical and physical processes made semi-permanent changes

in your brain. Although spontaneous healing is possible given enough time and the right

circumstances, it is more likely that you will need to engage in a long period of healing

and self-care, thoroughly grounded in compassion for yourself and the facts of biology.

In the next section we will talk about some of the possible long-term consequences

of trauma.

Aftereffects of sexual abuse or assault

After any sort of trauma, most people recover, either on their own or with the help of

community members or professionals.

However, sexual assault has widely been found to be the type of trauma most likely to

lead to long-term challenges. Studies of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), the type

of condition most directly traceable to trauma, show that between 50% and 77% of sexual

assault survivors end up meeting the criteria for PTSD.

7

According to the fifth edition

7

Cloitre, Marylene, Cohen, Lisa R., & Koenen, Karestan C. (2006). Treating survivors of childhood abuse: Psychotherapy for

the interrupted life, p. 11.

Additional readings on how trauma affects the brain

Cori, Jasmine Lee. (2008). Healing from trauma: A survivor’s guide to understanding

your symptoms and reclaiming your life. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania:

Da Capo Press.

See especially pages 16-18, “Caught in Lower Brain Centers.”

Levine, Peter A. (1997). Walking the tiger: Healing trauma. Berkeley, California:

North Atlantic Books.

This book is all about the biology of trauma, with a heavy emphasis on how animals

recover from trauma and what humans can learn from them.

Ogden, Pat, Minton, Kekuni, & Pain, Clare. (2006). Trauma and the body:

A sensorimotor approach to psychotherapy. New York, NY:

W.W. Norton & Company.

See especially pages 3-25, “Hierarchical Information Processing: Cognitive, Emotional,

and Sensorimotor Dimensions.”

17

forge-forward.org

A SELF-HELP GUIDE TO HEALING AND UNDERSTANDING

of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders of the American Psychiatric

Association (DSM-V), PTSD is defined as:

(A) The person was exposed to: death, threatened death, actual or threatened serious

injury, or actual or threatened sexual violence, as follows: (1 required)

(1) Direct exposure.

(2) Witnessing, in person.

(3) Indirectly, by learning that a close relative or close friend was exposed to

trauma. If the event involved actual or threatened death, it must have been

violent or accidental.

(4) Repeated or extreme indirect exposure to aversive details of the event(s),

usually in the course of professional duties (e.g., first responders, collecting

body parts; professionals repeatedly exposed to details of child abuse). This

does not include indirect non-professional exposure through electronic

media, television, movies, or pictures.

(B) The traumatic event is persistently re-experienced in the following way(s):

(1 required)

(1) Recurrent, involuntary, and intrusive memories. Note: Children older than 6

may express this symptom in repetitive play.

(2) Traumatic nightmares. Note: Children may have frightening dreams without

content related to the trauma(s).

(3) Dissociative responses (e.g., flashbacks) which may occur on a continuum

from brief episodes to complete loss of consciousness. Note: Children may

reenact the event in play.

(4) Intense or prolonged distress after exposure to traumatic reminders.

(5) Marked physiological reactivity after exposure to trauma-related stimuli.

(C) Persistent effortful avoidance of distressing trauma-related stimuli after the

event: (1 required)

(1) Trauma-related thoughts or feelings.

(2) Trauma-related external reminders (e.g., people, places, conversations,

activities, objects, or situations).

(D) Negative alterations in cognitions and mood that began or worsened after the

traumatic event: (2 required)

(1) Inability to recall key features of the traumatic event (usually dissociative

amnesia; not due to head injury, alcohol or drugs).

(2) Persistent (and often distorted) negative beliefs and expectations about

oneself or the world (e.g., “I am bad,” “the world is completely dangerous.”).

(3) Persistent distorted blame of self or others for causing the traumatic event

or for resulting consequences.

(4) Persistent negative trauma-related emotions (e.g., fear, horror, anger, guilt

or shame).

18

forge-forward.org

A SELF-HELP GUIDE TO HEALING AND UNDERSTANDING

(5) Markedly diminished interest in (pre-traumatic) significant activities.

(6) Feeling alienated from others (e.g., detachment or estrangement).

(7) Constricted affect: persistent inability to experience positive emotions.

(E) Trauma-related alterations in arousal and reactivity that began

or worsened after the traumatic event: (2 required)

(1) Irritable or aggressive behavior.

(2) Self-destructive or reckless behavior.

(3) Hypervigilance.

(4) Exaggerated startle response.

(5) Problems in concentration.

(6) Sleep disturbance.

(F) Persistence of symptoms (in Criteria B, C, D and E) for more

than one month.

(G) Significant symptom-related distress or functional impairment (e.g., social,

occupational).

(H) Disturbance is not due to medication, substance use, or other illness.

8

In simpler terms, trauma survivors are diagnosed with PTSD if they show signs of each of

the following for longer than a month:

Reexperiencing the trauma through flashbacks (memories that feel like they are

present reality rather than a memory), nightmares, remembering the trauma

when they don’t want to, or reacting strongly to things that remind them of

the trauma;

Avoiding normal parts of life that remind them of the trauma;

Altering their thoughts and feelings in a negative way, such as negative beliefs

about the self or the world;

Experiencing hyperarousal, or being overly physically and/or psychologically

reactive to every day events.

Of course, what we just described are the clinical requirements of a medical diagnosis.

In fact, the list of possible consequences of trauma is much, much longer. The following

sections are not exhaustive, but do cover many of the problems sexual assault survivors

may experience.

Emotional regulation problems

One of the most common aftereffects of trauma is having difficulty regulating one’s

emotions. Emotional regulation is the process of keeping your emotions at a level that

does not overwhelm you. Some of this is undoubtedly due to the brain/chemical changes

trauma induces, which lead to the classic PTSD symptoms of re-experiencing, avoiding,

8

Retrieved from http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/pages/dsm5_criteria_ptsd.asp, April 2, 2015.

“ the primary effect

of trauma is a chronic

inability to regulate one’s

emotional life.”

Johnson, Susan M. (2005). Emotionally-

focused couple therapy with trauma

survivors: Strengthening attachment

bonds, p. 17.

19

forge-forward.org

A SELF-HELP GUIDE TO HEALING AND UNDERSTANDING

and hyperarousal. It is hard to have control over your emotions if your body and mind are

constantly strongly reacting to threats or experiencing threats no one else experiences,

either because you are having flashbacks or have misinterpreted an innocent event like

someone suddenly coughing or laughing loudly.

If someone is traumatized as a child or youth, chances are good that they missed out on

some normal skill-building due to being “distracted” by coping with the trauma. This

may be especially true if the abuser was a parent, family member, teacher or caregiver

who would normally be teaching that child how to cope in the world, including how to

cope with their emotions. Not only will the child have a complicated, possibly fearful

relationship with their abuser/teacher, but the chances are good that the abuser will

themselves not have good emotional regulation skills, which helped lead them to abuse

in the first place. In any case, the young person simply does not acquire the strategies

for calming and self-soothing strong emotions. Asked what help they would like now, one

transgender sexual assault survivor stated they would like:

“ Therapy to help me develop the missing social skills that are a consequence of

my childhood abuse, and my years and years of cognitive dissociation.”

9

Finally, many psychologists and child development experts believe in “attachment theory,”

which holds that how the primary caregiver(s) interact with the infant and young child

not only sets lifelong patterns of relating in that child, but actually physically molds how

the child’s brain develops. This theory says that

even if a parent or caregiver is not an abuser, if

they do not respond adequately to the infant/

child’s needs, that child will develop a brain

that is less capable of handling strong emotions

and bouncing back from adversity (in other

words, resilience) than other peoples’ brains.

One possible aspect of emotional regulation

problems may be an inability to even identify

what emotions one is having. The person who

has this problem, also called alexithymia,

usually answers “I don’t know” or has only a very limited number of answers (“upset,”

9

Unless otherwise specified, all quotes were given to FORGE by transgender/SOFFA survivors in our 2004 study,

“Sexual Violence in the Transgender Community Survey,” (n=265) (data has not been formally published); our 2011 study,

“Transgender peoples’ access to sexual assault services,” a survey approved by the Morehouse School of Medicine’s

Institutional Review Board, (n=1005) (data has not been formally published); or through individual conversations via email,

phone, or in person. Wherever possible quotes are verbatim from the speaker/writer, with only light editing to improve

reader comprehension.

“ And suddenly it had come to her…that

the voice she was hearing was her own,

for the first time in her life.”

Anna Quindlen (1992, p. 393) as quoted in Cloitre, Marylene, Cohen,

Lisa R., & Koenen, Karestan C. (2006). Treating survivors of

childhood abuse: Psychotherapy for the interrupted life, p. 263.

Emotional regulation skills help make you less vulnerable to intense emotions.

Consider a broken thermostat in your apartment or home. When the thermostat is

not functioning at full capacity, it is difficult to regulate the temperature inside your

apartment/home. The inside state is more vulnerable to changes in the weather

outside. (For example, if it drops below freezing outside and the inside thermostat

isn’t able to maintain a steady temperature, it is more likely to get cold on the inside.)

Emotion regulation skills help the thermostat function better, help you realize sooner

when it’s not functioning effectively, and makes you less vulnerable to changes outside.

PHOTO BY MIA NAKANO

20

forge-forward.org

A SELF-HELP GUIDE TO HEALING AND UNDERSTANDING

“ok”) when asked how they are feeling. Not only may they not know the

words to put to what they are feeling, but they may even be unable to

distinguish one type of feeling from another. Obviously, if you cannot

even identify what you are feeling, it becomes much harder to learn

strategies for constructively dealing with that feeling. As a result,

many people end up using substances or behaviors (like chronically

working long hours, or playing endless video games) as a way to cope

with any strong feeling.

Isolation / avoidance / denial

Despite how many transgender people are sexual assault survivors,

you may not know many other survivors because trauma survivors

often isolate themselves and/or just do not talk about what happened to

them. Some of this isolation may come from fear of being re-victimized

or an awareness that one’s social skills are not as good as they could

be. Self-isolation can also be a way of simply trying to lower the

chances of being “triggered,” or having something happen that causes a flashback or

otherwise reminds the person of what they’ve experienced in the past. Avoidance is

a similar tactic; if the person can structure their days to avoid being reminded of the

trauma, they will have fewer painful memories and feelings. Denial can take many forms.

One is to claim that while the trauma happened, it had no effect or the person has long

since recovered and has no lingering effects. Another is to wonder if it even happened, or

to claim it was not nearly as bad an experience as others’.

Here are some examples of what trans survivors reported:

“It happened—I got over it.”

“It had nothing to do with who I am today, except for making me a lot stronger, and

a bit harder on the outside, and unable to fully enjoy sex.”

“Large groups are scary—large groups being more than 2 people who I don’t know

or more than 6 people that I do know.”

“[I] just wanted to forget about it.”

“I was hesitant to claim that my abuse was real abuse, and didn’t want to ‘take

away’ services or time from ‘real’ survivors who needed them more.”

“[I made a] deliberate effort to put events behind me and not think of them.”

“This survey is somewhat upsetting. I’d rather forget.”

Trigger:

An event, object, person, etc.

that sets a series of thoughts

in motion or reminds a person

of some aspect of his or her

traumatic past. The person may

be unaware of what is “triggering”

the memory (i.e., loud noises, a

particular color, piece of music,

odor, etc.).

Sidran Institute, downloaded October

27, 2013 from http://www.sidran.org/

sub.cfm?contentID=38§ionid=4

21

forge-forward.org

A SELF-HELP GUIDE TO HEALING AND UNDERSTANDING

Although it is still a controversial subject, many people forget they were ever sexually

assaulted or abused, sometimes for years or even decades. Various developments may

cause the memories to re-emerge:

“ It [sexual assault history] didn’t come up seriously until I started volunteering for

a group for ‘stopping abuse in the lesbian, bisexual women’s and transgendered

10

communities’—the training I went through kicked it ALL loose.

Other common triggers for the re-emergence of forgotten abuse memories include:

parenting a child who reaches the age when the abuse happened to the parent; revelation

of another family member’s abuse; and illness, loss of a partner, retirement, or some

other major life change. Some people believe they were in some way “protected” from their

memories until they became strong enough to handle them. This does not necessarily

mean the re-emergence process is easy:

I did not think I would have a nervous breakdown. I shattered like glass…

the emotions suddenly overwhelmed me…and I became dysfunctional.

It took over 10 years of psychotherapy, and 5 hospitalizations (mental health

wards) to heal from these events. All of this was at my own expense.

Shame, guilt, and self-blame

Shame is the feeling that you are damaged, unworthy, bad, dirty, wrong, unlovable,

unfixable, dangerous, not good enough, broken, and/or don’t deserve to live. Although

it should be what is felt by the perpetrator—the one who violated another person, used

someone to meet their own needs, or betrayed or manipulated someone’s innocence or

trust—instead, almost like a sexually transmitted infection, it ends up infecting the

victim. Unfortunately, it doesn’t feel like an outside infection to the victim; it just feels

like who they truly are: not good enough or not worthy of love and compassion.

Shame can lead to a whole range of negative outcomes. It may help explain the isolation

many survivors impose on themselves, and/or their avoidance of friendships or other

relationships. It may be part of the reason why survivors often do not feel like they

will live very long, and (perhaps consequently), why they may not bother planning for

the future. It can lead people into partnering with individuals who abuse them again,

because why should they deserve any better? People who feel shame often drown that

feeling in alcohol or drugs, or bury it under a mountain of busy-ness and overwork.

Guilt is related to shame. Shame is about who you think you are, whereas guilt is about

a behavior you may have done. Guilt is a feeling that you have done something wrong. A

sexual assault survivor who feels guilt may think they should have known better than to

have gone to someone’s house on a first date; the survivor who feels shame may think they

are so flawed they deserved to be assaulted. Although both can lead a survivor to blame

themselves for the assault, guilt implies one can learn to not do something again, while

the survivor with shame feels unfixable.

10

We acknowledge that some language in quotes may not align with current community usage of some terms.

22

forge-forward.org

A SELF-HELP GUIDE TO HEALING AND UNDERSTANDING

Why didn’t you access services?

“ I was ashamed of myself, my identity, my desires, my inner person. They cruci-

fy people like me. It would have been nice to know that I wasn’t a freak and that

there were others like me. But when they asked me what was my problem in

school they always assumed I was just a bad kid. Little did they realize I couldn’t

stand myself. And hated what I was. I felt I needed to be bad to be respected and

left alone.”

“ Shame has kept me silent all these years. This survey is one of the few times that

I have discussed these events. No wants to hear about this [sexual abuse by a

therapist], because therapists are supposed to be God and cannot do any wrong.”

“ In the beginning what stopped me [from getting help] was the belief that I some-

how caused the abuse.”

“Self-hatred.”

“Shame. Mainly shame.”

“I was too ashamed to tell anyone.”

It is important to recognize that the new (DSM-V) diagnostic criteria for PTSD has a new

emphasis on “negative alterations in cognitions and mood,” specifically calling out:

Persistent (and often distorted) negative beliefs and expectations about oneself

or the world (e.g., “I am bad,” “The world is completely dangerous”).

Persistent distorted blame of self or others for causing the traumatic event or

for resulting consequences.

Persistent negative trauma-related emotions (e.g., fear, horror, anger, guilt or

shame).

11

In other words, shame, guilt, and self-blame are hallmarks of having been traumatized;

they seem to come with the territory. That does not, however, mean that you have to

continue to live with them.

Depression / anxiety / self-harm / suicide

The finding that depression and anxiety both frequently accompany PTSD makes a great

deal of sense. If you are having unwanted memories, experiencing emotions that seem out

of control, are staying away from people and activities in order to lessen your chances

of being triggered, are not sleeping well, are reacting strongly to small things most

other people barely notice, blaming yourself for what happened, etc.—feeling depressed

and/or anxious seems pretty normal. It may also be important to note that depression

and anxiety are the most common mental health conditions affecting the general U.S.

population, as well.

Some people cope with depression and anxiety by going to the doctor, a therapist, and/or

obtaining prescriptions for psychotherapeutic drugs. Probably the majority, however,

11 Retrieved from http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/pages/dsm5_criteria_ptsd.asp, April 2, 2015.

23

forge-forward.org

A SELF-HELP GUIDE TO HEALING AND UNDERSTANDING

attempt to cope on their own by “self-medicating.” This can mean dampening down the

negative feelings through alcohol, prescription or non-prescription drugs, food (over- or

under-eating), becoming completely obsessive about exercise or work or some other

distracting activity, and self-harming behaviors such as cutting. In his doctoral

dissertation lore m. dickey, Ph.D. found that more than 40% of the transgender people he

surveyed had engaged in non-suicidal self-injury.

12

He suggests such self-harm has three

functions. One, which may seem ironic, is self-preservation: the “transgender person is

making an effort to address the pain and distress they are feeling in a manner that

recognizes the value that life has.” In other words, some people self-harm as a way of

avoiding a suicide attempt. The second reason is desperation, which he defines as

“causing pain so as not to feel numb or trying to feel something even though it is physical

pain.” The third reason is emotional abreaction. One source defines this as “reliving an

experience in order to purge it of its emotional excesses; a type of catharsis. Sometimes it

is a method of becoming conscious of repressed traumatic events.”

13

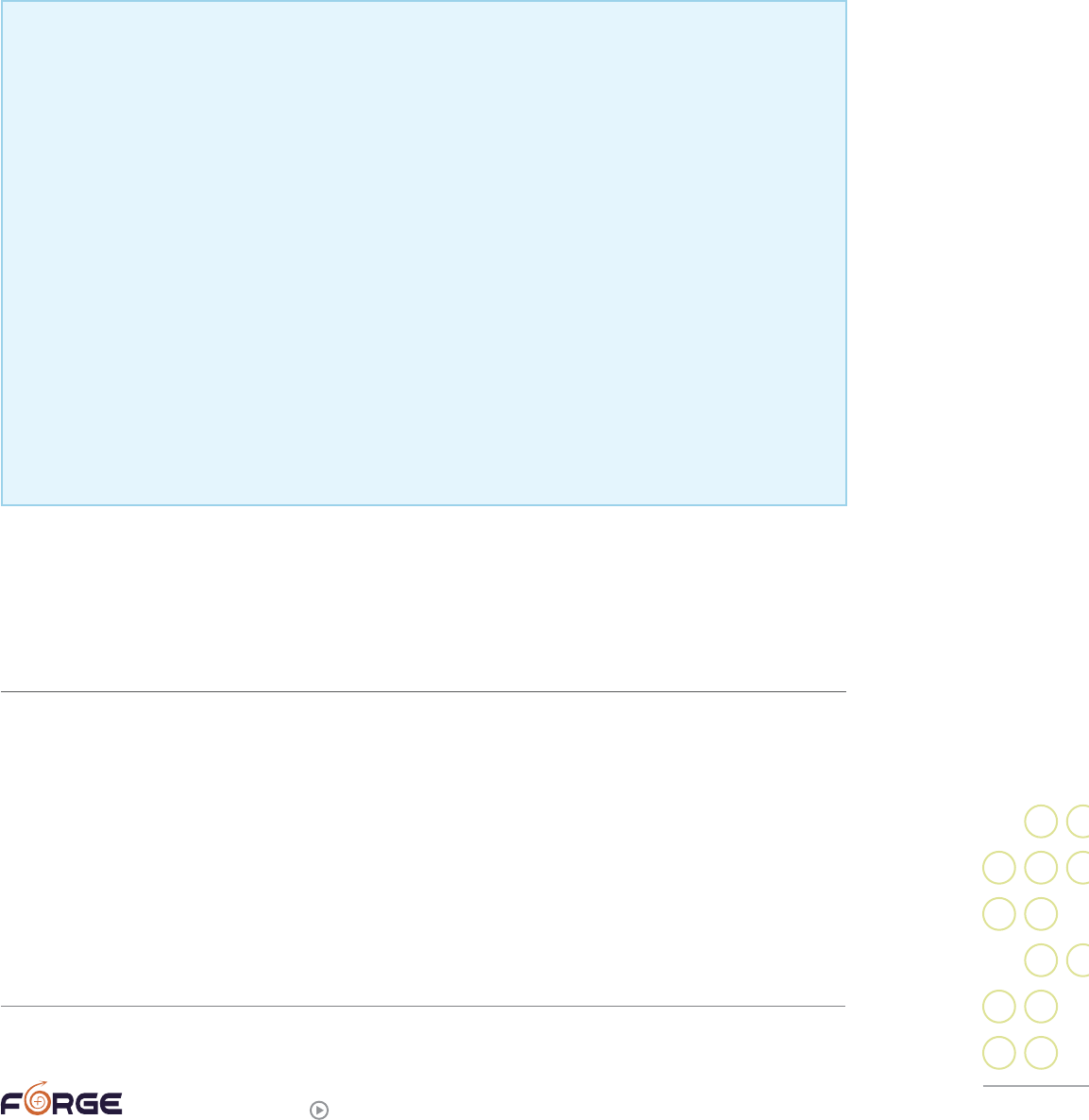

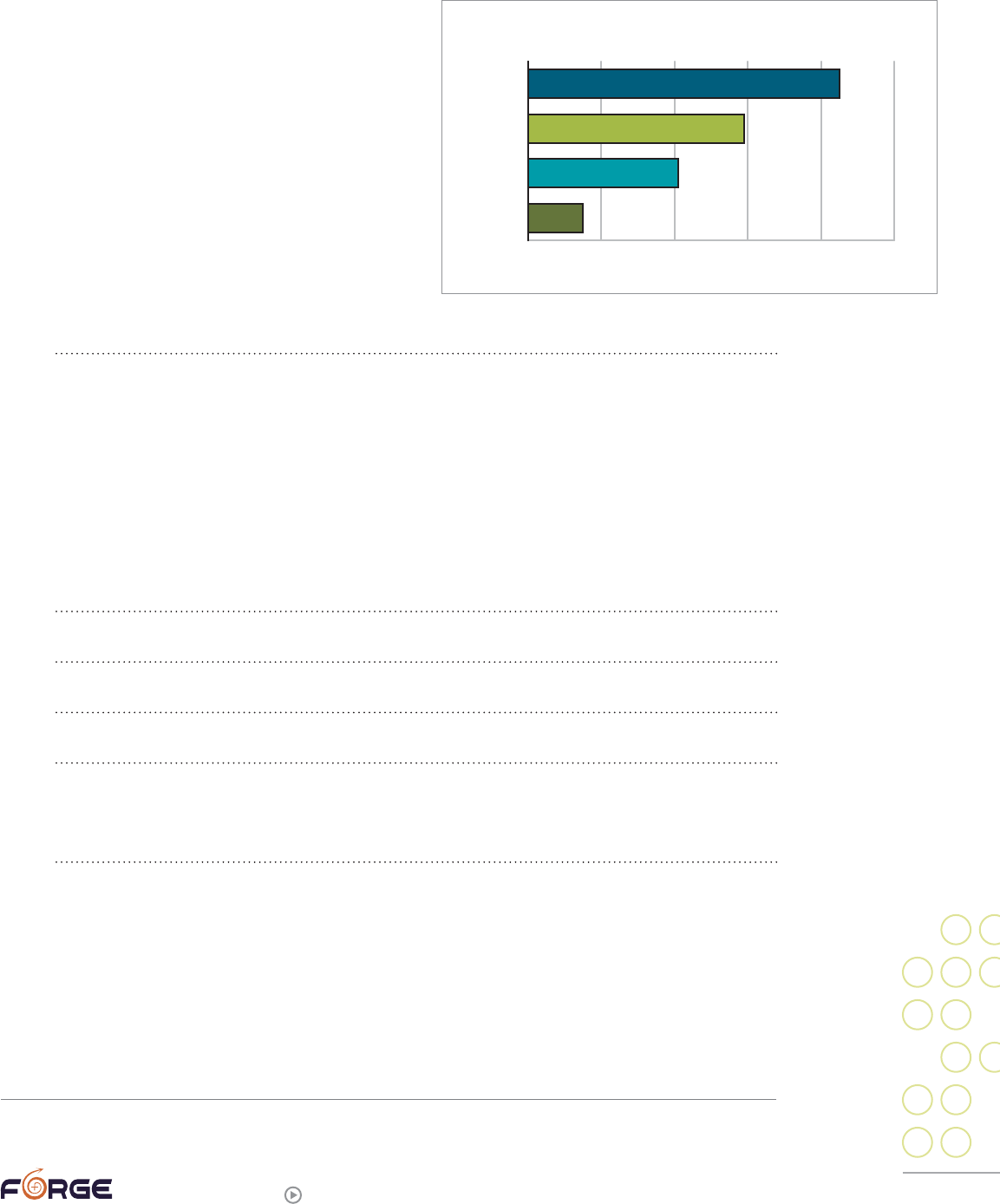

Other people do, in fact, become suicidal.

The National Transgender Discrimination

Study

14

found that overall, 41% of its

transgender and gender non-conforming

respondents had attempted suicide

at least once. For those who had been

sexually assaulted, the attempt rate went

up to 64%. These figures compare to 1.6%

for the general population. In other parts

of this guide you can find the numbers

for suicide hotlines and an “emergency

standard operating procedures” worksheet

that can help you plan how to better

handle suicidal feelings if you have them.

Substance abuse

As previously noted, many survivors

attempt to dampen or alter their difficult

symptoms or painful memories through self-medication, typically alcohol, drugs, or food.

Study after study finds high correlations between those who use substances to cope and

those suffering from PTSD. While substance use can sometimes temporarily diminish

symptoms such as nightmares, panic attacks, depression and numbing, substance use is

also associated with more trauma: violence and accidents are more likely when one or more

people are drunk or high. Although many trauma treatment programs will not accept people

who are actively abusing substances and many substance abuse treatment programs do not

address trauma issues, there is a growing consensus that because of the interrelationships

among trauma and substance use, simultaneous treatment is recommended. One such joint

treatment program has been described in a manual accessible to non-therapists: Seeking

12

dickey, lm, Reisner, SL, & Juntunen, CL. (2015). Non-suicidal self-injury in a large online sample of transgender adults.

Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. Vol. 46, No. 1, 3-11.

13

dickey, lm, Reisner, SL, & Juntunen, CL. (2015). Non-suicidal self-injury in a large online sample of transgender adults.

Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. Vol. 46, No. 1, 3-11.

14

Grant, Jaime M., et al (2011). Injustice at every turn: A report of the national transgender discrimination survey, National

Center on Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force.

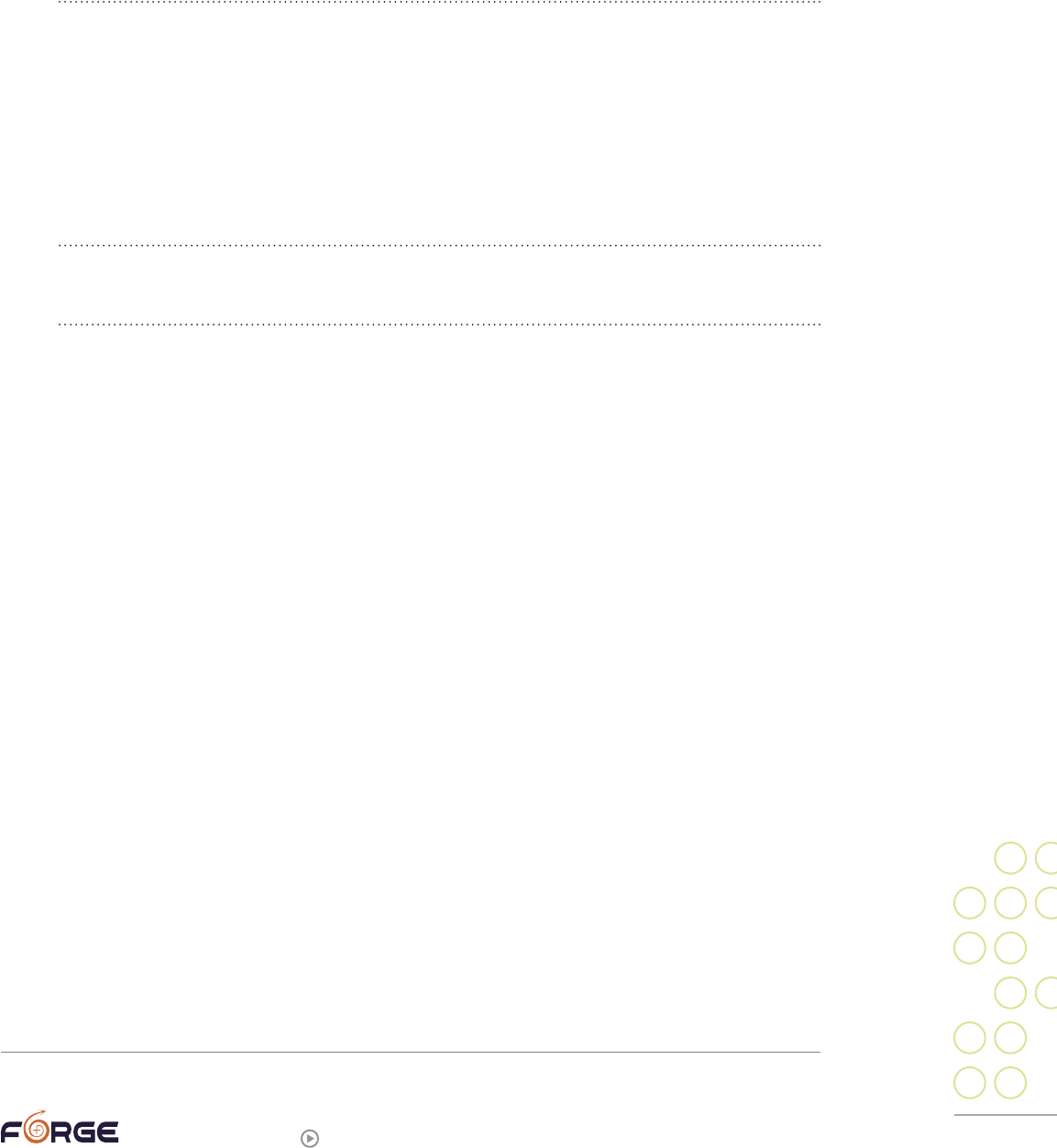

SUICIDE ATTEMPTS

0.0%

10.0%

20.0%

30.0%

40.0%

50.0%

60.0%

70.0%

80.0%

GENERAL

NON-TRANS

TRANS SA

SURVIVORS

TRANS

(ALL)

41.0%

64.0%

1.6%

24

forge-forward.org

A SELF-HELP GUIDE TO HEALING AND UNDERSTANDING

Safety: A Treatment Manual for PTSD and Substance

Abuse, by Lisa M. Najavits.

15

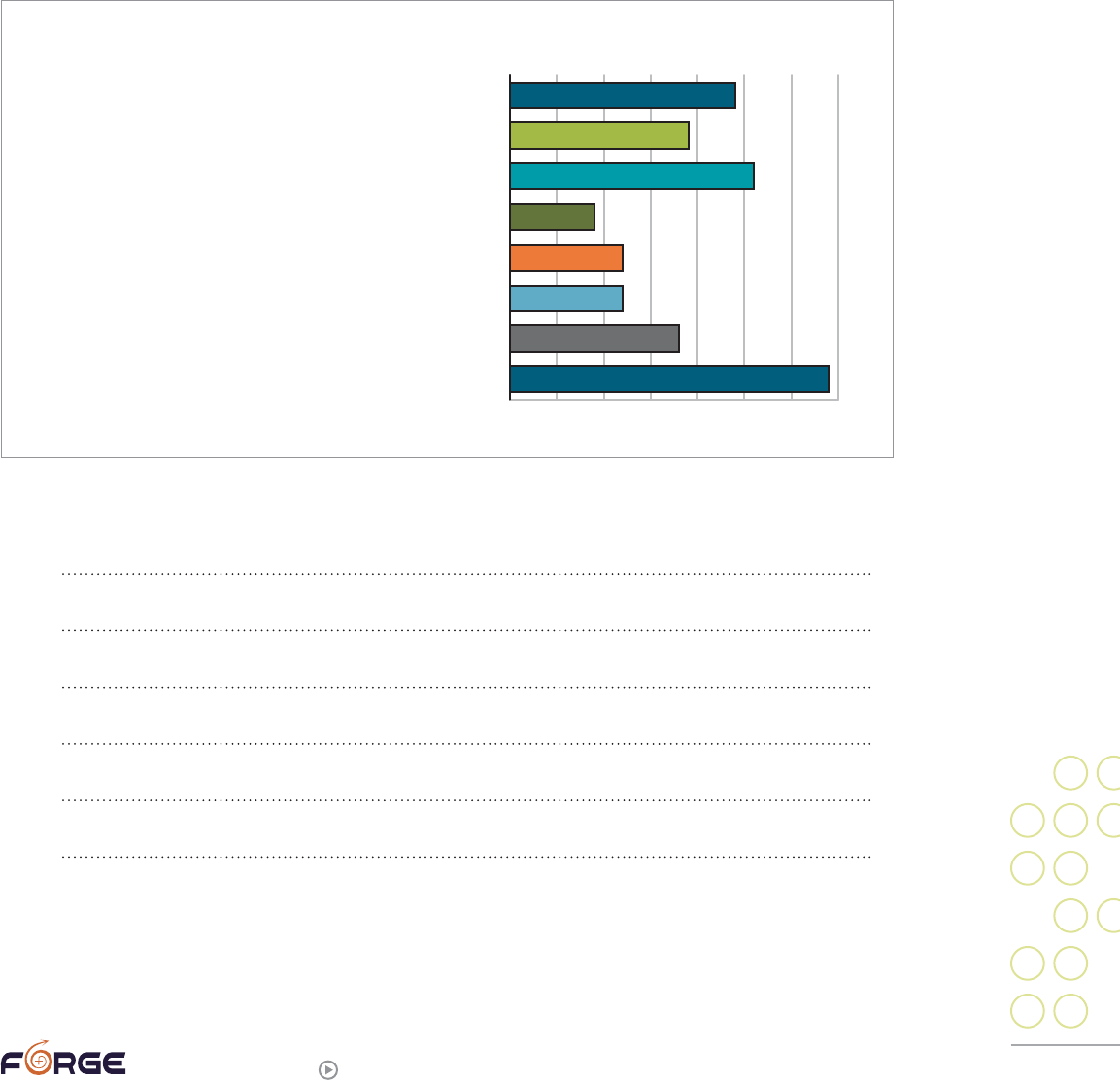

Physical health problems

While many researchers have linked abuse to

various psychological problems, awareness of

their linkage to physical medical conditions that

become apparent only decades later only began in

the mid-1980s. That is when physicians in Kaiser

Permanente’s Department of Preventative Medicine

in San Diego “discovered that patients successfully

losing weight in the Weight Program were the most

likely to drop out. This unexpected observation

led to our discovery that overeating and obesity

were often being used unconsciously as protective

solutions to unrecognized problems dating back

to childhood. Counterintuitively, obesity provided hidden benefits: it often was sexually,

physically, or emotionally protective.”

16

Curious about this linkage, Kaiser developed what

has become known as the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Initial reporting on

the ACE Study included findings from 17,000 patients, mostly middle-class, who asked for

comprehensive physical exams.

The ACE questionnaires asked people about their

childhood experiences as well as their current

health statuses. Later versions of the survey

asked about ten types of childhood experiences,

including child physical, emotional, and sexual

abuse. Rather than attempting to measure how

severe each type of maltreatment or “adverse

experience” was or how often it happened, the

researchers simply gave one “point” for each type

of adverse experience the patient had experienced.

Thus patients could have scores ranging from 0

(they had experienced none of the listed negative

childhood experiences) to 10 (they had experienced

them all). Only one-third of this middle-class

population had an ACE Score of 0; one in six had

an ACE Score of 4 or more. If any one category of abuse or adversity was experienced,

there was an 87% likelihood that the person would have also experienced at least one

more type.

17

The researchers then matched these patients’ ACE scores with their health records.

When it came to physical health, they looked at the basic causes underlying the 10 most

15

Najavits, Lisa M. (2002). Seeking safety: A treatment manual for PTSD and substance abuse.

16

Felitti, Vincent J. (2004). “The origins of addiction: Evidence from the Adverse Childhood Experiences study.” English

version of an article originally published in German. Available at http://www.nijc.org/pdfs/Subject%20Matter%20Articles/

Drugs%20and%20Alc/ACE%20Study%20-%20OriginsofAddiction.pdf, p. 2.

17

Felitti, Vincent J., & Anda, Robert F. (2010). “The relationship of adverse childhood experiences to adult medical disease,

psychiatric disorders, and sexual behavior: Implications for healthcare.” Chapter in Lanius, Ruth & Vermetten, Eric, (eds.)

The hidden epidemic: The impact of early life trauma on health and disease.

“Our findings indicate that the major

factor underlying addiction is adverse

childhood experiences that have not

healed with time and that are over-

whelmingly concealed from awareness

by shame, secrecy, and social taboo.”

Felitti, Vincent J. (2004). “The origins of addiction: Evidence from the

Adverse Childhood Experiences study.” English version of an article

originally published in German. Available at http://www.nijc.org/pdfs/

Subject%20Matter%20Articles/Drugs%20and%20Alc/ACE%20

Study%20-%20OriginsofAddiction.pdf, p. 8.

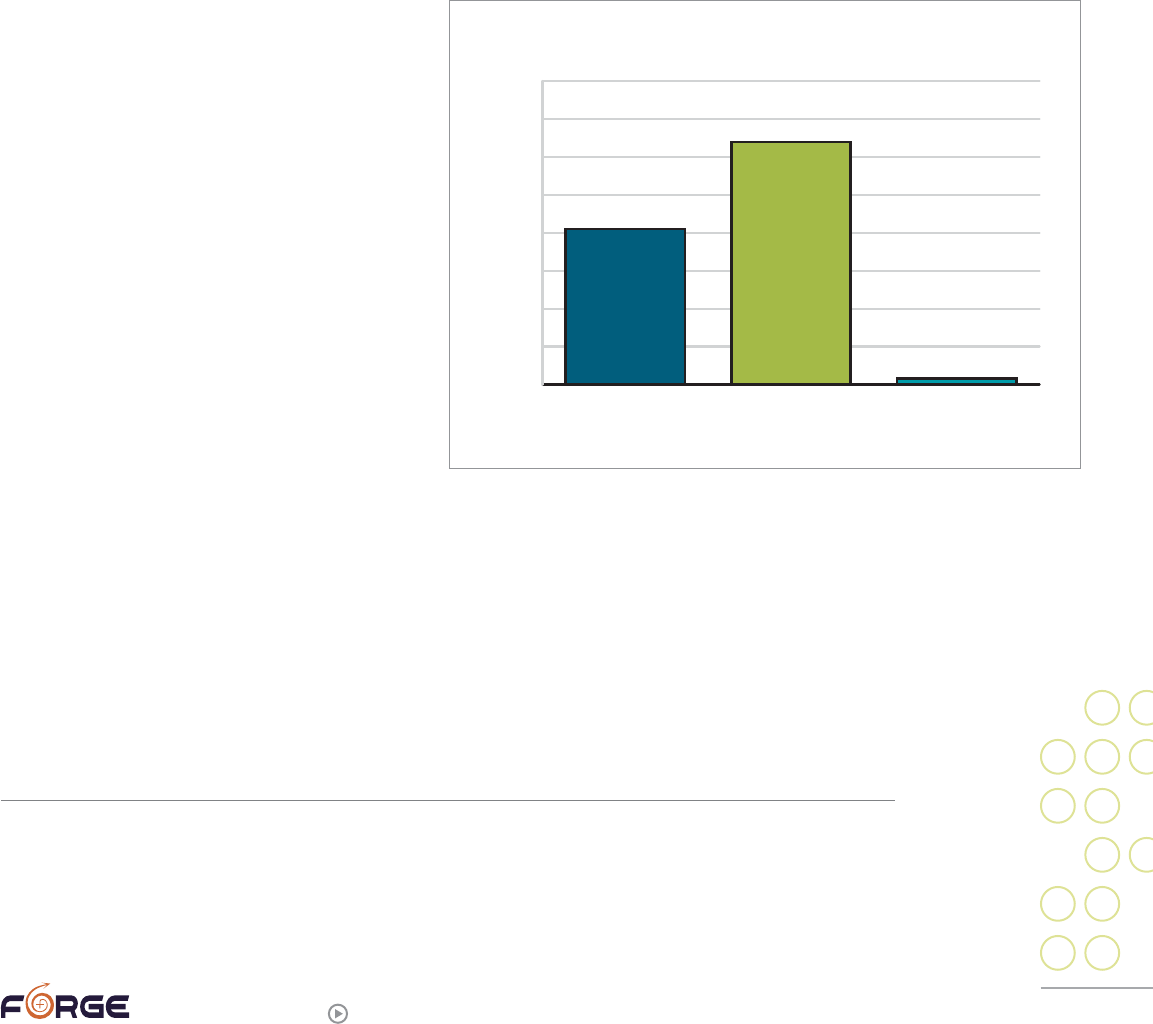

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

0

1

2

3

4+

CHILDHOOD EXPERIENCES VS. ADULT ALCOHOLISM

% ALCOHOLIC

ACE SCORE

25

forge-forward.org

A SELF-HELP GUIDE TO HEALING AND UNDERSTANDING

common causes of death in America. These include tobacco use (estimated 400,000 deaths

annually), diet and activity patterns (300,000 deaths), alcohol use (100,000 deaths), sexual

behavior (30,000 deaths) and drug use (20,000 deaths). Bar charts of the results could

not be more striking: for nearly every negative behavior that was measured, the bars

steadily rise from the lowest number of drinkers, smokers, etc. among those who had an

ACE score of 0 to, step by step, the highest reported ACE score (usually 4 or more or 6

or more). Perhaps most shocking was how much ACE scores were connected to medical

conditions such as liver disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), coronary

artery disease, and autoimmune disease(s). Even after removing all known risk factors

such as smoking and high cholesterol, there remained a step-wise increase in the risk of

these diseases by how high a patient’s ACE score was. In other words, it is not enough to

say that adults traumatized as children smoke, eat, and drink more, and therefore have

more chronic illnesses; there are additional factors. The researchers believe that not only

do trauma survivors attempt to self-medicate

through alcohol and cigarettes, but also that

there is wear-and-tear on the biological system

due to chronic stress. The precise biological

mechanisms by which this is taking place have

still not been determined, but that did not stop

the ACE Study researchers from flatly declaring:

“Adverse childhood experiences are the main

determinant of the health and social well-being

of the nation.”

18

The list of other physical health problems

that researchers have linked to a trauma

history is very long. Some of those that show up in the literature most often are: chronic

fatigue syndrome, chronic pain, fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, and multiple

chemical sensitivities. One researcher explains how trauma might be related to developing

“multiple idiopathic physical symptoms” (MIPS), or physical symptoms that are medically

unexplained. In the first step, a person experiences “symptoms.” What is interesting is that

many child abuse survivors never properly learn about emotions, due in part to having their

emotions ignored or twisted and used against them, such as being told some abuse does

not hurt or that a sexual act is “how parents show love.” As a result of the distortions their

abusers use, the victims may not be able to identify their own emotions and/or talk about

them with others. People with such “alexithymia” may confuse physical signs of emotion—

say, a rapidly beating heart when one is frightened—with medical illness. The second step

in development of a MIPS is the person’s assessment of their symptoms. Here, too, trauma

may play a role: “Psychosocial distress or mental disorders such as depression and anxiety

disorders, including PTSD, may also influence an individual’s appraisal of symptoms. For

example, an individual with depression may develop more pessimistic or catastrophic

symptom appraisals than someone who is not depressed.” In the third step, “the person

responds behaviorally on the basis of the symptom appraisal. For example, he or she may

seek health care, avoid activities or roles, or his or her functioning may be reduced.”

19

Part

18

Felitti, Vincent J., & Anda, Robert F. (2010). “The Relationship of Adverse Childhood Experiences to Adult Medical Disease,

Psychiatric Disorders and Sexual Behavior: Implications for Healthcare,” in Ruth A. Lanius, Eric Vermetten, and Clare Pain,

eds., The Impact of Early Life Trauma on Health and Disease: The Hidden Epidemic.

19

Engel, Charles C. Jr. (2004). ”Somatization and Multiple Idiopathic Physical Symptoms: Relationships to Traumatic Events

and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder,” in Paula P. Schnurr and Bonnie L. Green, eds., Trauma and Health: Physical Health

Consequences of Exposure to Extreme Stress, p. 193.

“ Adverse childhood experiences are the

main determinant of the health and social

well-being of the nation.”

Felitti, Vincent J., & Anda, Robert F. (2010). “The Relationship of Adverse

Childhood Experiences to Adult Medical Disease, Psychiatric Disorders and

Sexual Behavior: Implications for Healthcare,” in Ruth A. Lanius, Eric Ver-

metten, and Clare Pain, eds., The Impact of Early Life Trauma on Health and

Disease: The Hidden Epidemic.

26

forge-forward.org

A SELF-HELP GUIDE TO HEALING AND UNDERSTANDING

of the isolation and life constriction seen in some sexual assault survivors may grow out of

attempts to avoid interactions that might result in an increase of “symptoms.”

High need for control versus helplessness

Trauma survivors may be highly controlling, totally submissive, or careen wildly between

the two. Childhood sexual abuse expert Mike Lew explains:

“It is important to remember that all abuse involves lies. Children are being lied

to about themselves, about love, and about the nature of human caring. They are

being taught that there is no safety in the world, and they have no right to control

their own bodies. Loss of control of their bodies leads to control being a central

issue of their adult lives. They can become inflexible, controlling, and suspicious—

or helpless and indecisive.”

20

Other experts tie some survivors’ control needs more directly to the symptoms of

PTSD, pointing out that the only way to try to avoid being triggered is to control what’s

happening in your environment and do your best to limit surprises. This often translates

into trying to control others’ actions, and may be one of the mechanisms that underlie

the cycle of violence wherein some victims in turn become abusers. On a related point,

if a person has trouble regulating their emotional responses to another’s behavior, they

may instead try to control that person’s behavior. On the other hand, survivors may find

that it’s too hard to control others or their environment, and may simply give up trying,

instead becoming very passive, helpless, and submissive.

Anger

Anger plays a large role in many survivors’ lives. Some are afraid of anger, as their

abuser’s anger may have been what came before the abuse they experienced; these

survivors may not realize that it is even possible to feel anger without damaging someone.

Many were taught by their abusers that they were not allowed to be angry. Others learned

that anger equals power, and therefore may try to protect themselves by being the most

angry/powerful one in the room. Some anger, obviously, is righteous anger at their

perpetrator(s) and those who may have failed to protect them.

Because many survivors did not learn effective emotional regulation skills, anger is just one

of many emotions that may be problematic for survivors and those around them, simply

because it may feel out of control. In addition, strong emotions provoke chemical changes

in the brain, which tend to diminish the brain’s (more specifically, the neocortex’s) ability to

think things through and problem-solve. In the midst of strong emotions, people tend to act

and react far more easily and quickly than they are able to rationally consider and weigh

alternatives and possible consequences. This can result in less-than-optimal decisions that,

in turn, create more problems and strong negative emotions.

Psychiatrist and psychologist John Bowlby pointed out that anger can be despairing

(coming from a place of powerlessness) or it can be hopeful.

21

An anger that is hopeful

points a person to where changes can be made. This distinction may be helpful to

some survivors.

20

Lew, Mike. (2004). Victims no longer: The classic guide for men recovering from sexual child abuse (Second edition), p. 75.

21

Johnson, Susan M. (2005). Emotionally-focused couple therapy with trauma survivors: Strengthening attachment bonds, p. 39.

27

forge-forward.org

A SELF-HELP GUIDE TO HEALING AND UNDERSTANDING

Sleep disturbances / irritability

Many survivors have sleep problems. Nightmares, both specifically related to the abuse,

as well as other non-abuse-related nightmares, are common. Many people also find it

difficult to fall asleep or stay asleep through the night, frequently waking up. If the

survivor was traumatized at night, perhaps particularly in their own bed, they may

not feel safe enough to relax into sleep. Laura Davis notes that if a survivor is actively

recovering previously unknown memories of their abuse, sleeplessness may precede and/

or follow the emergence of new memories.

22

Lack of sleep can also contribute to increased mental health symptoms, such as

depression and anxiety, as well as create additional challenges concentrating or focusing

during the day. The lack of adequate and restful sleep can also directly impact physical

health—increasing headaches, impacting blood sugar regulation, increasing blood

pressure, and affecting metabolism.

Obviously, sleep disturbances can help lead to daytime irritability, which many survivors

experience for a variety of reasons.

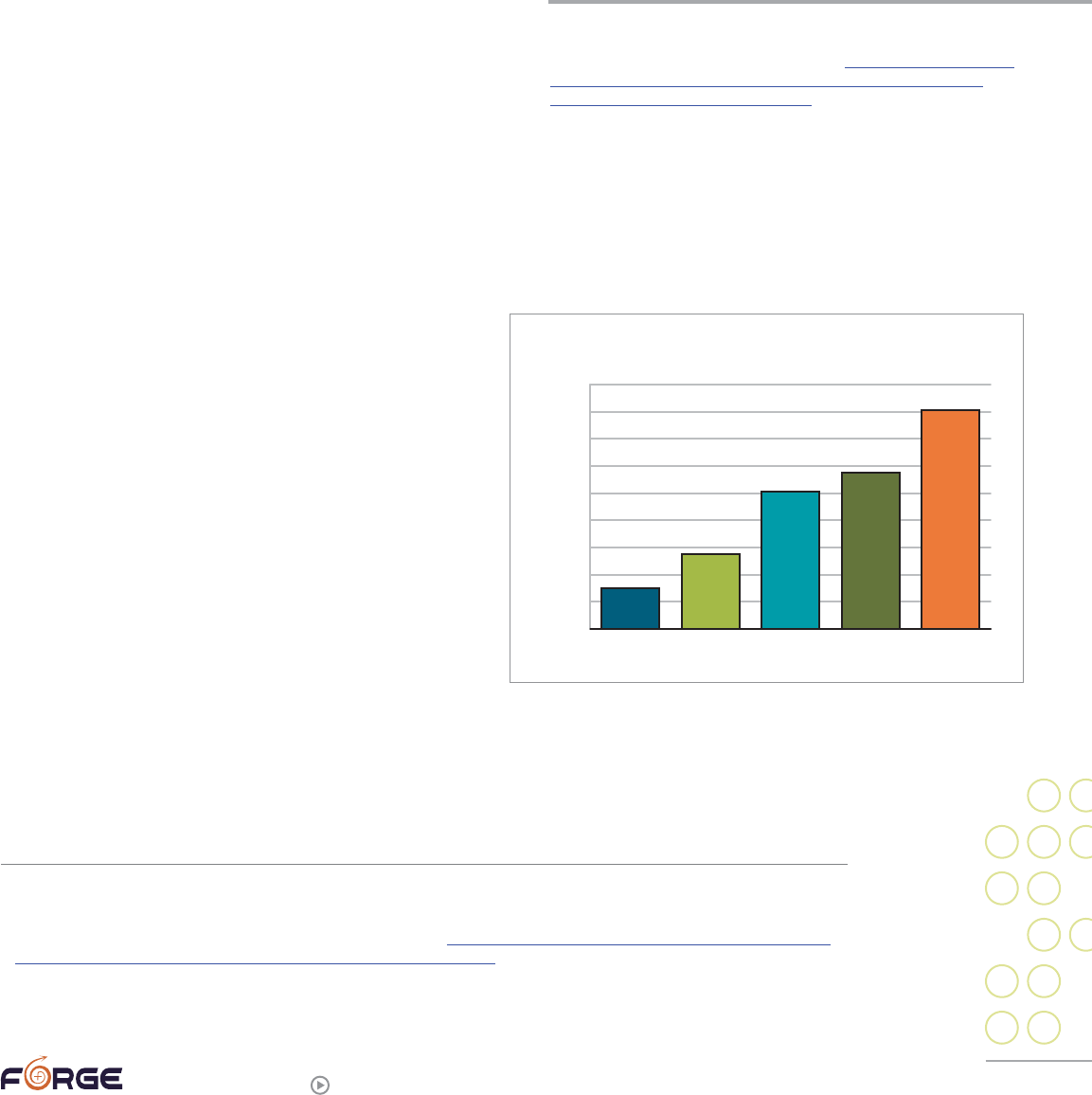

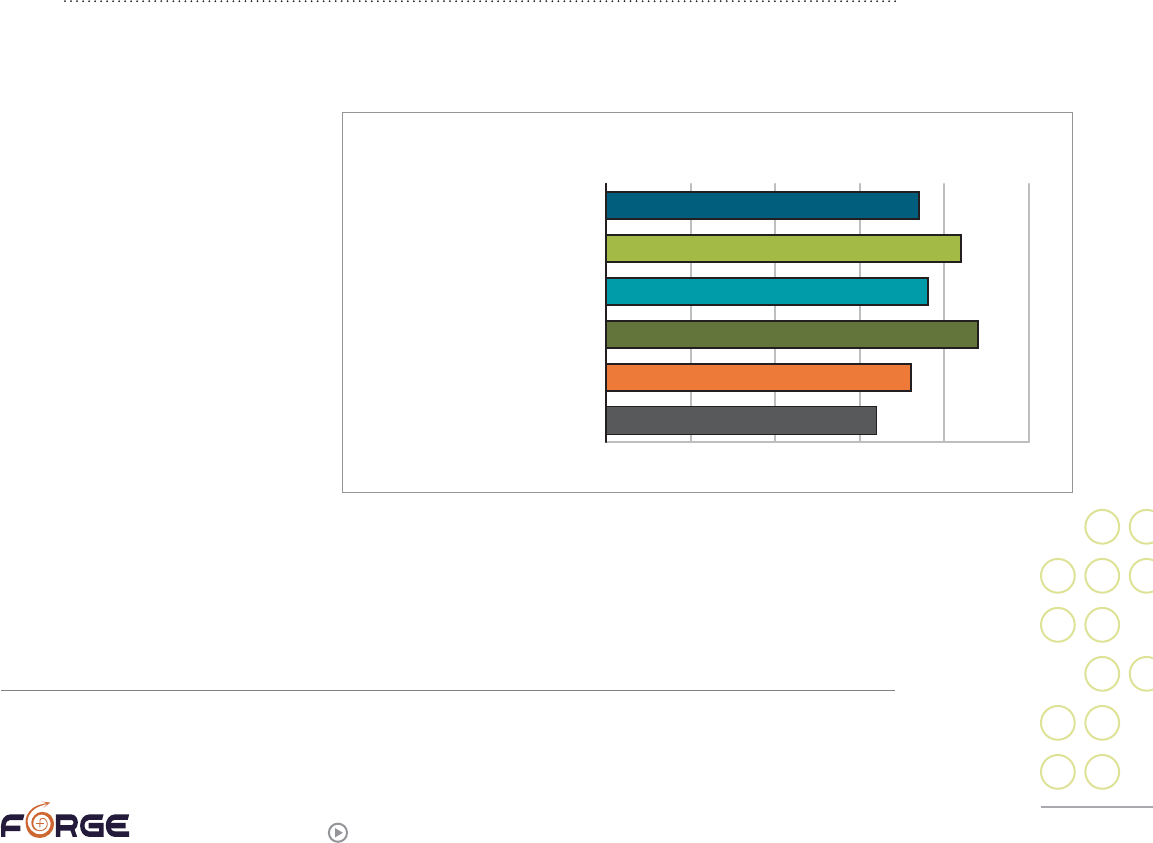

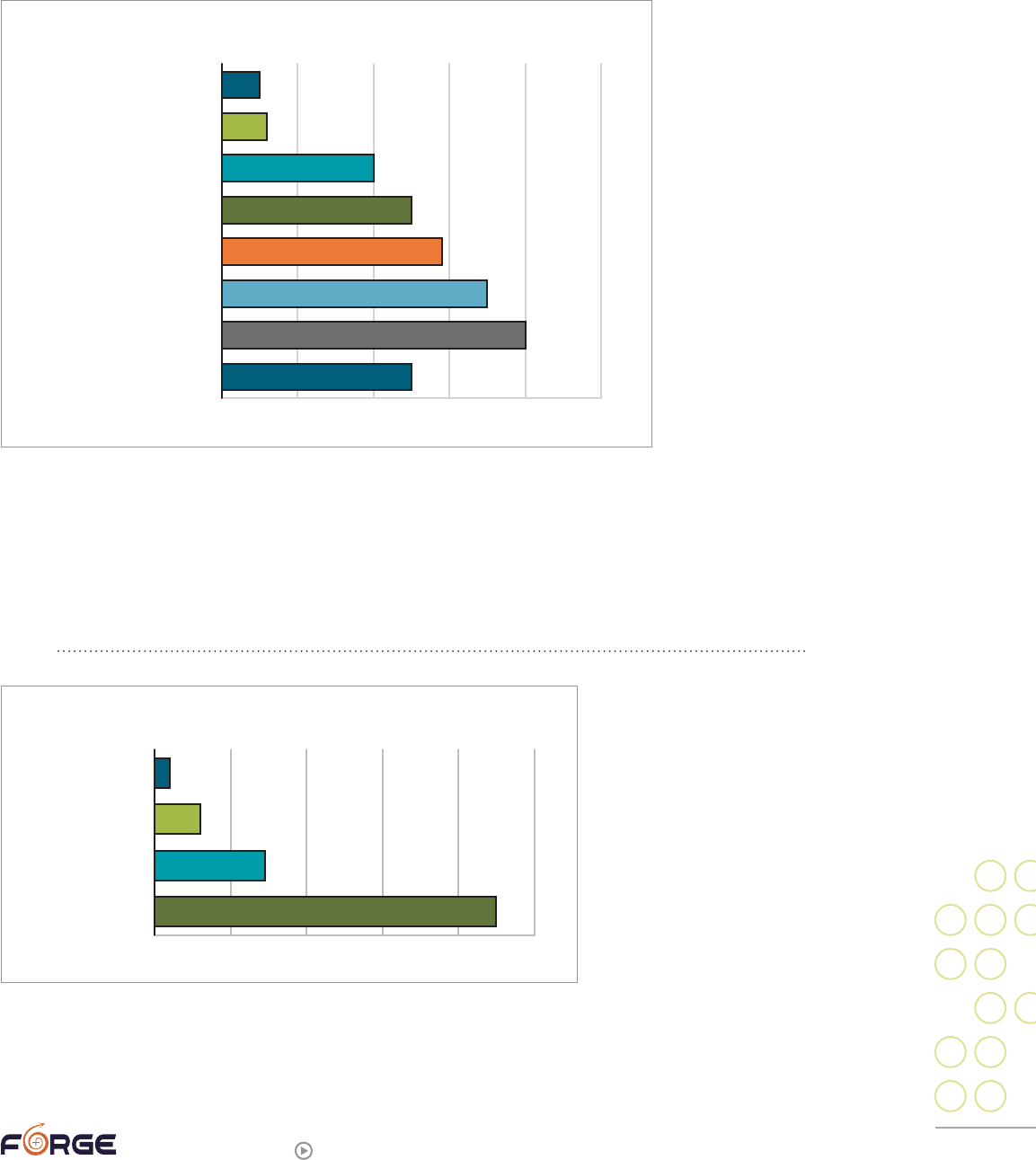

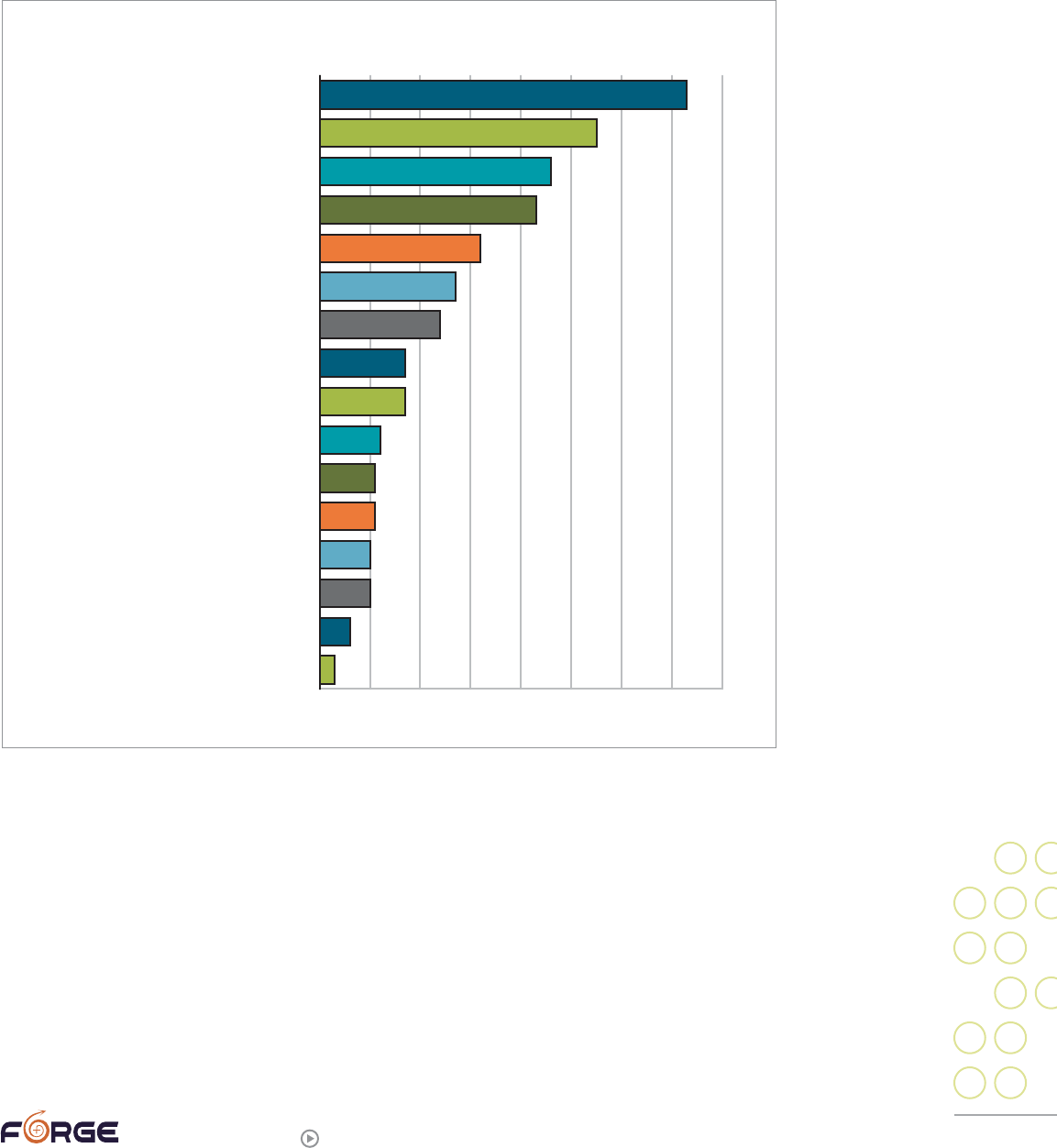

Revictimization / reenactment

“ I’ve been sexually assaulted, raped, molested, harassed many times throughout

my life….There have been way too many.”

Multiple studies have made clear that people who were abused in childhood have a far

greater likelihood of being abused again in adulthood, and/or in becoming abusers

themselves. “Polyvictimization”

is the current term for people

who have experienced multiple

types of abuse, and a 2011

FORGE study focused on sexual

assault showed how common

this is among trans people. We

asked trans respondents if they

had experienced any of these

types of abuse: child sexual

abuse, adult sexual abuse,

dating violence, domestic

violence, stalking, hate

violence, and other types

of violence. Those who

experienced any one type of

abuse were highly likely to experience other types, as well. For example, 64% of those who

had experienced child sexual abuse went on to experience at least one other type of

abuse, as well.

23

22

Davis, Laura. (1991). Allies in healing: When the person you love was sexually abused as a child, p. 107.

23

2011 study, “Transgender peoples’ access to sexual assault services,” a survey approved by the Morehouse School of

Medicine’s Institutional Review Board, (n=1005) (data has not been formally published).

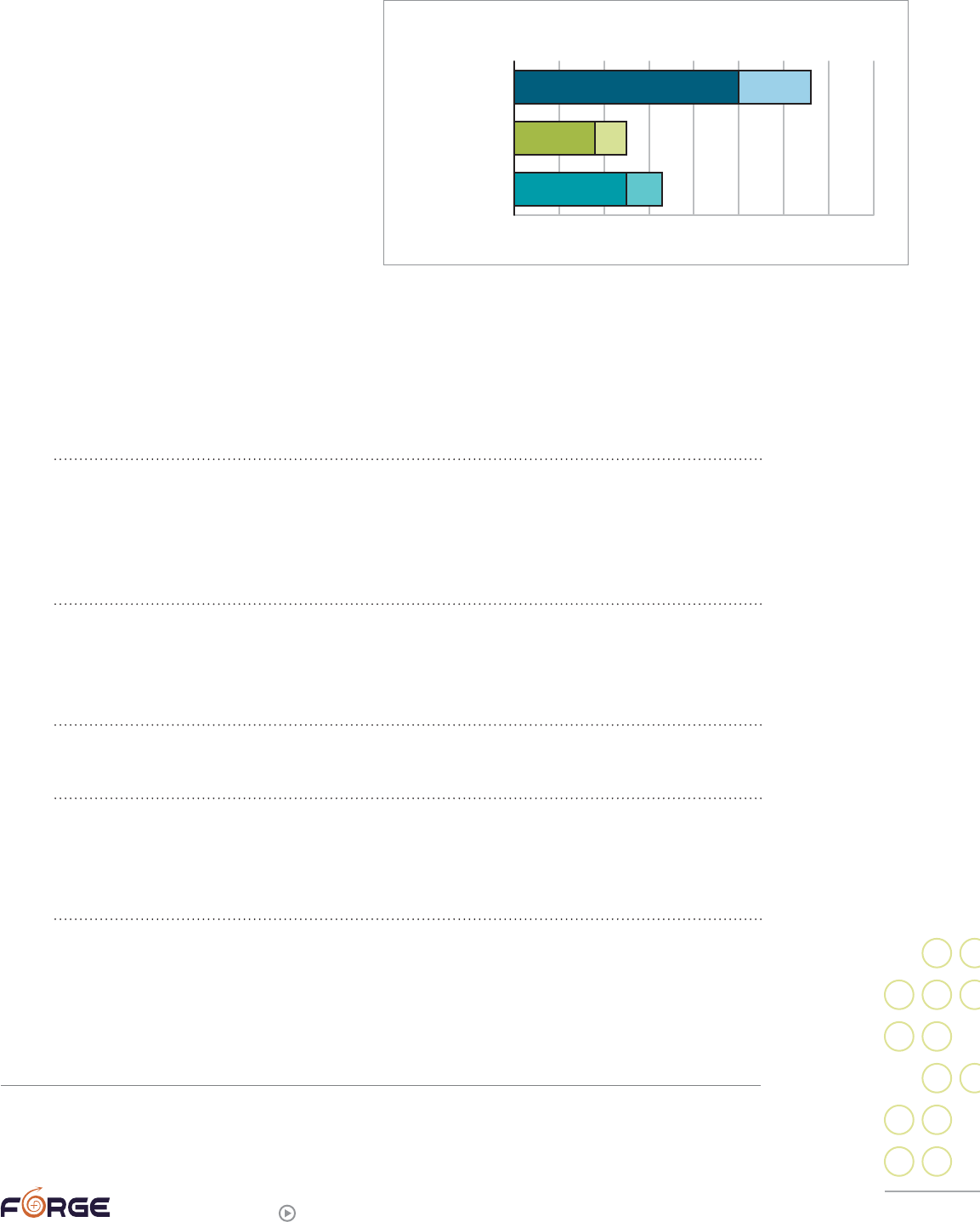

0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100%

74%

84%

76%

88%

72%

64%

POLYVICTIMIZATION

HATE MOTIVATED

STALKING

INTIMATE PARTNER VIOLENCE

DATING VIOLENCE

ADULT SEXUAL ASSAULT

CHILDHOOD SEXUAL ABUSE

28

forge-forward.org

A SELF-HELP GUIDE TO HEALING AND UNDERSTANDING

How often victims go on to become abusers themselves is less well-documented. A few

mainstream studies of the general public have indicated that men

24

(women abusers are

far less studied) who had been abused as children are twice as likely to abuse as adults

as are men who had not experienced child abuse.

Therapist Francine Shapiro suggests one theory for why this happens:

“ …until their childhood memories are processed the offenders

often have internalized responsibility for their own childhood

abuse. They are blaming themselves—blaming the recipient,

the victim. It is therefore no surprise that as an adult they

perceive the world in the same way and also blame their

own victims. Until they can place full responsibility on the

one that perpetrated against them, they will be unable to take

appropriate responsibility for their own abusive behaviors.”

25

A simpler theory is that people who grew up with adults who abused them may have

decided there are only two types of people: victims and abusers. To avoid being victimized

again, they may seek to gain and maintain the upper hand in all of their relationships.

It is critical to remember that not all victims become perpetrators.

Unfortunately, even some therapists inaccurately believe that past abuse will lead to

abusive behavior in adulthood. For example, FORGE worked with a survivor who was in

the process of transitioning from female to male and who was in therapy with his female

partner. The couple lived in a non-abusing, healthy relationship with each other and with

their children. The couple’s therapist counseled the female partner to leave him in order

to protect their children from abuse by him, a move that would have deprived the children

of a loving parent, destroyed a family, and deeply wounded the adults.

Interpersonal problems

“ As highly adaptive social organs, our brains are just as capable

of adjusting to unhealthy environments and pathological

caretakers as they are to good-enough parents.”

26

Not surprisingly, some sexual assault survivors experience a higher-than-usual number

of interpersonal problems. It may be hard for survivors to trust other people, especially

if the individual(s) who abused them were family members or people they were close to.

If they were abused in childhood, they may never have experienced respectful mutual

communication styles or problem-solving, instead learning that the person with more

24