Virginia Commonwealth University Virginia Commonwealth University

VCU Scholars Compass VCU Scholars Compass

Theses and Dissertations Graduate School

2007

The Art of Collaboration in the Classroom: Team Teaching The Art of Collaboration in the Classroom: Team Teaching

Performance Performance

Jenna M. Neilsen

Virginia Commonwealth University

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd

Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons

© The Author

Downloaded from Downloaded from

https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/912

This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has

been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass.

For more information, please contact [email protected].

© Jenna Neilsen and Julie Phillips 2007

All Rights Reserved

THE ART OF COLLABORATION IN THE CLASSROOM:

TEAM TEACHING PERFORMANCE

A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of

Fine Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University.

by

JENNA M. NEILSEN

B.A. Theatre, Ohio Northern University, 2001

B.A. Psychology, Ohio Northern University, 2001

and

JULIE K. PHILLIPS

B.A. Christian Studies: Drama and Youth Ministry,

North Central University, 2000

Director: Dr. Noreen C. Barnes

DIRECTOR OF GRADUATE STUDIES, THEATRE

Virginia Commonwealth University

Richmond, Virginia

May, 2007

ii

Acknowledgements

Just as this project reflects, we both fully acknowledge that this work could not have been

completed alone. Deserving thanks are our thesis committee, Dr. Noreen Barnes, Dr.

Tawnya Pettiford-Wates, and Professor Barry Bell.

We would also like to thank our students, who went on this journey with us, who shared

their lives with us and entrusted their education into our keeping.

Additionally:

Jenna would like to thank her husband, Reid, who reminds her on a daily basis of her

worth and purpose. And a thank you to her family, her friends and all those who have

shaped her personal and professional views of theatre.

Julie would like to thank her husband Michael, whose ability to put up with the bizarre

hours and stressed wife truly helped make this possible. She also would like to thank her

parents, Stephanie Dean, the staff in the Office of Graduate Admissions, the Guild of

Graduate Students, and everyone else who helped along the way.

So many people have contributed to the shaping of our views of theatre and collaboration

they are too numerous to mention, but we are deeply grateful.

Jenna would like to thank Julie for working with her, even when disagreements and

apparent impasses arose, and Julie would like to tell Jenna what a privilege it has been to

work side by side for so long. Thank you for making this journey together with me.

iii

Table of Contents

Page

Acknowledgements............................................................................................................. ii

Abstract ............................................................................................................................... v

Chapter

1 Definitions and Models..................................................................................... 1

Definition of Terms ...................................................................................... 1

Collaborative Models and Structures ........................................................... 6

2 Advantages and Disadvantages of Co-Teaching............................................. 22

Advantages ................................................................................................. 23

Disadvantages............................................................................................. 34

3 Collaborative Teaching Here and Now........................................................... 43

University Level ......................................................................................... 43

In the Arts ................................................................................................... 46

Why Acting?............................................................................................... 48

For Today ................................................................................................... 51

4 Collaboration in Action................................................................................... 55

Beginning Collaboration............................................................................. 56

Complications............................................................................................. 57

Class Sessions............................................................................................. 61

Results ........................................................................................................ 63

The Adaptation ........................................................................................... 64

iv

5 Team Teaching: A Guide............................................................................... 69

Putting Together the Right Team ............................................................... 69

Initial Planning ........................................................................................... 73

Top Ten Things to Remember.................................................................... 81

6 Conclusion ..................................................................................................... 83

Literature Cited ................................................................................................................. 84

Appendices........................................................................................................................ 87

A Introduction to Stage Performance Syllabus................................................... 87

B Acting I Syllabi ............................................................................................... 92

C Email Correspondence .................................................................................. 107

D Sample Grading Rubrics ............................................................................... 111

v

Abstract

THE ART OF COLLABORATION IN THE CLASSROOM:

TEAM TEACHING PERFORMANCE

By Jenna Neilsen, MFA and Julie Phillips, MFA

A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of

Fine Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University.

Virginia Commonwealth University, 2007

Major Director: Dr. Noreen Barnes

Head of Graduate Studies, Department of Theatre

The Art of Collaboration in the Classroom: Team Teaching Performance is a co-

written master’s thesis which records our research in the field of team teaching as it relates

to theatre education at the university level. It is our intent that this text be used as a tool

for helping universities and teachers decide if a collaborative teaching model is right for

their courses.

vi

A portion of the text is research-based, examining the scholarly writings which

have preceded our work. In Chapter 1, we compiled a set of definitions, in the hopes of

codifying the language used within this document as well as that used within the field. We

establish a hierarchy of terms associated with teaching in collaborative forms. We then

describe the various models associated with collaborative teaching, specifically the model

which we have employed: team teaching.

Chapter 2 explores the reasons for and against implementing collaborative teaching

structures in higher education. Chapter 3 discusses team teaching specifically, and

explores reasons for implementing it at the university level, and in artistic disciplines,

specifically acting. We also discuss the practical appropriateness for this model in today’s

classrooms.

The second section of the text is practical in nature. Chapter 4 includes a

description of our actual experiences working together in the classroom, including

discoveries, failures and successes. Finally, Chapter 5 is a guide for implementing team

teaching which covers the basic essentials of starting a team teaching program. This

section of the document can be used as a training tool for future co-teachers in the VCU

theatre graduate program.

This document was created in Microsoft Word 1997.

Definition of Terms

In order to discuss a topic with clarity and ease, a common set of definitions must

first be established. After examining the literature currently written on team teaching, it

can be concluded that no consistent set of definitions has been decided upon by the

education community as a whole. The term “team teaching” is not even consistently

defined among the works we have consulted. As a result, we have created a compilation of

the terms and definitions we have embraced and listed them in the section below which

give a context for the rest of the thesis.

Authority-Directed Team- A team structure in which all decisions are made by one lead

instructor and then carried out by the remaining team members. (Buckley 42)

Block teaching – Two or more instructors working together to teach multiple subjects back

to back to the same students, usually in an attempt to link the subject matter of

multiple disciplines.

1

2

Co-teaching – All teaching that involves two or more teachers serving as instructors for a

specific course or class session and sharing responsibility for that class. (Fishbaugh

103)

Coaching Model- One teacher instructs the class while the other observes, later offering

constructive criticism on pedagogical practices. This behavior is often

reciprocated, but each instructor is primarily responsible for their own class.

(Fishbaugh 5)

Complementary Teaching- A second teacher works to enhance the instruction provided by

the teacher with the primary responsibility for instruction, often in a different

methodology. Both teachers are responsible for the instruction of the class session.

(Villa 40)

Consulting Model- A novice instructor utilizes an experienced instructor for guidance and

instruction. The experienced instructor may or may not be present during the class

sessions, but does not participate in the delivery of information to students.

(Fishbaugh 64)

Coordinated Teams- A team structure which is a combination of both Authority-Directed

teams, and Self-Directed Teams, wherein members of the team are appointed by the

3

administration but teams appoint their own leaders and often rotate leadership

responsibilities. (Buckley 43)

Cross-Disciplinary- An attempt at examining one area of discipline from the viewpoint of

another discipline. For example: “the physics of music” (Davis 4)

Interdisciplinary- An attempt at bringing together the expertise of two or more disciplines

to create a new perspective. (Davis 4-5)

Multidisciplinary - An examination of a variety of perspectives with no necessity to create

a new perspective that fuses them together. (Davis 4)

Parallel Teaching - Teachers instruct different groups of students within one classroom

simultaneously. (Villa 28)

Self-Directed Teams- A team structure spontaneously formed by interested instructors

wherein all team members are given equal decision making power. (Buckley 42)

Supportive Teaching - One teacher is primarily responsible for the delivery of the lesson,

but another member of the team complements or enhances that lesson. For

example, a primary teacher might have a special education teacher who supports

their efforts as needed in the classroom. In a theatre setting, this could involve a

4

specialized unit on vocal safety taught by a guest lecturer which would enhance the

acting course taught by the primary instructor. (Villa 20).

Team – A number of persons associated together in work or activity (Merriam-Webster’s

1282).

Team Teaching – An arrangement which involves two or more instructors delivering the

same instruction to the same students at the same time. (Fishbaugh 103) (Villa 49)

Transdisciplinary - Ideas that transcend multiple disciplines (Davis 4).

Hierarchy of Terms

For our purposes, we will be following the hierarchy of definitions as follows. It is

a combination of the ideas of multiple authors but lends itself to being easily applied.

These are drawn from Martin Fishbaugh’s Models of Collaboration

and Richard Villa’s A

Guide to Co-Teaching: Practical Tips for Facilitating Student Learning.

All three of these

categories of teaching fit under the term collaborative teaching. All of these terms are

explained in detail in the next section, Collaborative Models.

1. Consulting

2. Coaching

3. Co-Teaching

A. Supportive Teaching

5

B. Parallel Teaching

C. Team Observing

D. Complementary Teaching

E. Block Teaching

F. Team Teaching

6

Collaborative Models and Structures

Since collaborative teaching encompasses a wide variety of methods and styles, the

most common types are broken up here into two different categories: Instruction Models

and Planning Structures. The instruction models address the teaming combinations often

used in carrying out instruction to students for courses taught collaboratively. Planning

structures address how the team is created and who has the planning and supervisory

power for the team.

Instruction Models

Teamed instruction is not as uncommon as it may seem. Most institutions of higher

education are already employing at least one of these instruction models in the college

classroom, either for teacher training purposes or to cope with large class sizes. The

purpose of this section is to expand the awareness of other models that may be able to meet

the needs of the University in a different way.

The three basic teaming models are consulting, coaching, and co-teaching. This

structure is based on the models of classroom collaboration described by Mary Fishbaugh,

in her book Models of Collaboration

, and Richard Villa’s A Guide to Co-Teaching:

Practical Tips for Facilitating Student Learning.

7

Consulting

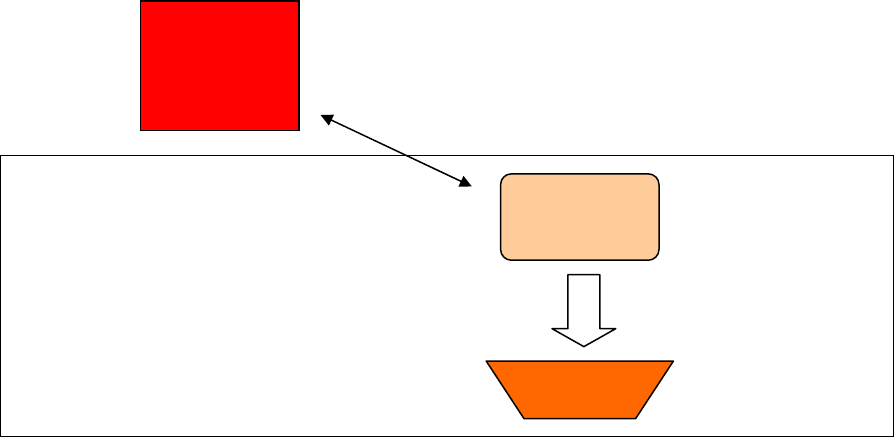

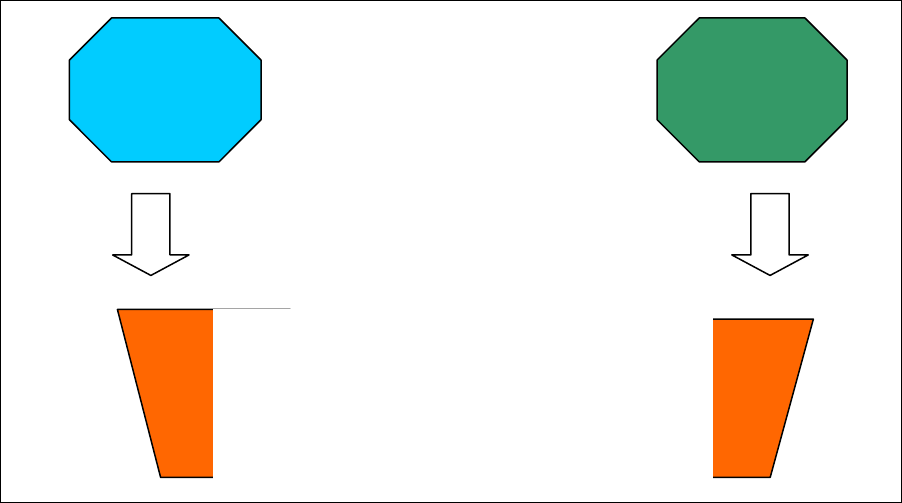

Figure 1: Consulting

Master

Teacher

Classroom

Novice

Teacher

Students

Consulting teams (see Figure 1) create a union of an experienced teacher educating

a novice teacher. This type of teaming can happen either in the classroom or, more often at

the college level, the master teacher is not directly involved with the students, but acts as

trainer and guide to the novice teacher. The master teacher’s influence diminishes as the

novice gains experience. Master teachers also benefit from the team since they are forced

to re-examine their own pedagogical practices as they share them with others.

This model is an excellent way to ease professors directly from their degree

programs into the world of college teaching. Primary and Secondary education employs

this model in the student teaching scenario, using the opportunity to work with an

8

experienced teacher to train prospective educators. It is also frequently used with graduate

student teaching assistants and informally in departments with new faculty members.

To some extent, this model is already common in theatre instruction. An acting

teacher may consult with a professor who has a specialty in vocal instruction in order to

help her students focus in on a particular skill. The voice teacher serves as master teacher

in the consulting model, imparting wisdom to the acting teacher.

Coaching

The coaching model is one where professors of equal level alternate coaching and

being coached as they assist each other. This type of collaboration allows teachers with

different strengths to coach each other in their classes. It is extremely useful for improving

pedagogical approaches to the material. Typically, each professor is responsible for the

instruction of one course, and then acts as observer during another course. Professors are

observed by the coach and then they discuss the problems and benefits of the teaching

methods being employed. This model does not directly affect the students since

instruction to students is still only carried out by one instructor, though it should improve

the education received by future students as a result of the instructor’s improved

pedagogical practice. Acting professors may be hesitant to employ this model in their

courses, as the entrance of an observer may change the performances of the students. It

would be most beneficial if the observing could take place over several class periods in

order for the observing instructor to have a firm grasp on the class dynamic and the

observed instructor’s style.

9

This model is sometimes paired with co-teaching to create a kind of “tag team”

alternative to the coaching model. This is the type of collaboration that might happen if an

Asian studies professor and a theatre history professor partnered to offer a course on Asian

theatre. One’s strength would lie in the cultures of Asia addressed in the course, the other

might have an expertise in historical world theatre. By both alternating teaching the same

course, students would be offered a well-rounded view of both the theatre and culture of

Asia. In this hybrid model, both professors are responsible for separate sections of the

same course, and take turns teaching in their areas of expertise. When one is not teaching,

she is observing the other and providing consultation on teaching practice and shared

content. [See Figure 2.1, 2.2].

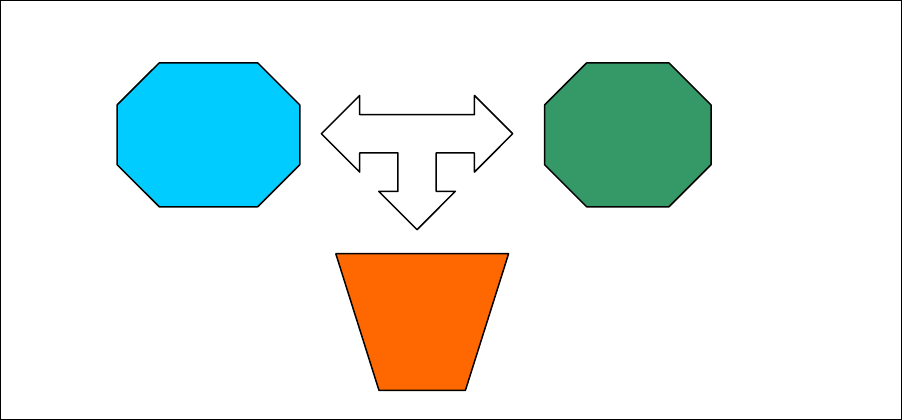

Figure 2.1: The Coaching Model Option 1

Professor

A

Instructs

Professor

B

Coaches

Students

Learn

10

Figure 2.2: The Coaching Model Option 2

Professor

A

Observes

Professor

B

Instructs

Students

Learn

Co-Teaching

In this model, both teachers work collaboratively to instruct the students. This can

take on various forms, but always involves the sharing, equal or unequal, between

members of instruction responsibilities. Supportive Teaching, Parallel Teaching, Team

Observing, Complementary Teaching, Block Teaching, and Team Teaching are all types of

this model of collaboration in classroom instruction.

Supportive Teaching

In supportive teaming, “one teacher is assigned primary responsibility for designing

and delivering a lesson, and the other member(s) of the team does something that

11

complements, supplements, or enhances the lesson” (Villa 20). This is the type of model

that often employs a TA as the supportive teacher, who assists the primary professor, but is

not responsible for creating the main lesson plan or presenting the bulk of the information.

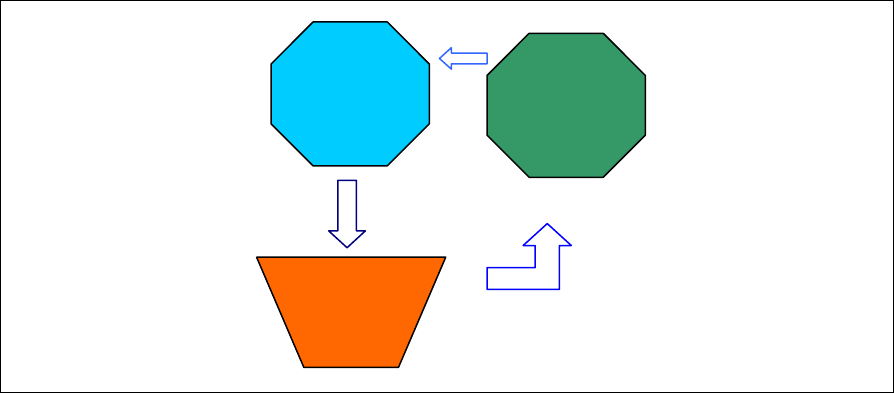

Parallel Teaching

Parallel Teaching is when teamed teachers “instruct different groups of students at

the same time in the classroom” (Villa 28). [See figure 3.1 Parallel Teaching].

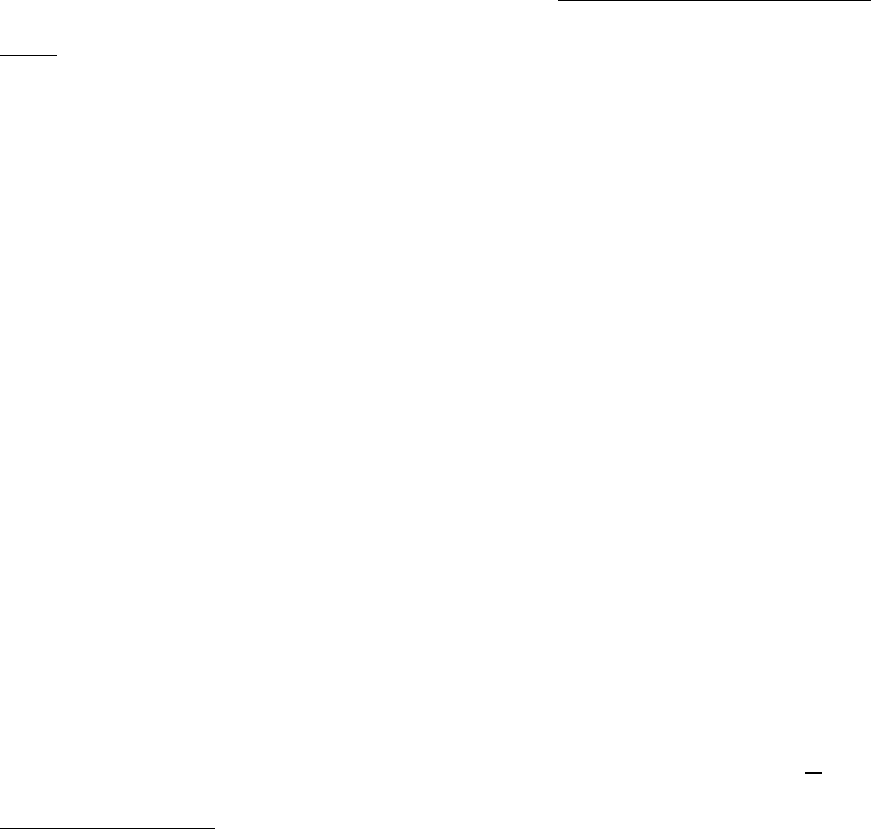

Figure 3.1 Parallel Teaching

Professor A Professor B

½ of the

Stud-

ents

½ of

Stud-

ents

This method is valuable if the goal is to lower the teacher-student ratio, and

involves slightly less group planning. Both teachers would provide the same instruction,

but to a smaller section of the whole class. This means that the lesson plans must be

12

agreed upon by both instructors prior to the class, but that each teacher can have individual

discretion as to the delivery of the information.

Station teaching is a specific type of parallel teaching, where students rotate to a

variety of physical locations in order to receive a different type of instruction in each area.

This is useful if the members of the team have expertise in different areas. Each member

of the teaching team could provide instruction on their area of expertise, repeating that

instruction until the entire class had received that information. It is also beneficial if the

content to be covered is best learned in a small group setting.

Team Observing

Team observing is the methodology by which one teacher is responsible for

instruction and the other for observing both the teacher and the students during instruction.

This is very similar to the coaching model, [see Figure 2.1, 2.2] but presupposes that both

instructors are equally responsible for the content of a single course. This method requires

little group planning for day to day instruction, as each teacher is responsible for his or her

own lesson plan.

Complementary Teaching

Complementary Teaching is when a second instructor “does something to enhance

the instruction provided by the other co-teacher(s)… one teacher often takes primary

responsibility for designing the lesson. Both teachers share in the delivery of the

information, sometimes with a varied delivery method” (Villa 40). In this model, both

13

instructors are present and participating in the delivery of information, but the primary

instructor carries overall responsibility. This method is most effective if the secondary

teacher attempts to use varied instruction styles to meet the needs of more learners. For

example, if the primary instructor is responsible for a lecture, which meets the needs of

auditory learners, the secondary instructor could attempt to convey that information

through visual or kinesthetic means, reinforcing the ideas set forth by the primary

instructor.

Block Teaching

In Block Teaching, two or more instructors work toward creating a connection

between multiple subjects. The classes are offered back to back in one block of time, and

instructors contribute the whole time, though they are primarily responsible for only one

section of the class. Usually this is implemented in an attempt to link the subject matter of

multiple disciplines. For example, an American Literature course would be paired with an

American History course and would follow the two subjects in a parallel manner, so that

when a subject such as the Civil War is being taught in history a book dealing with that

subject or written during that time is also being taught.

Team Teaching

Team Teaching is the most collaborative model, requiring the largest amount of group

planning. In this model, all instructors teach the same material to all the students,

simultaneously. Ann Austin refers to this model as ‘the interactive team’. “Team

14

members collaborate in all aspects of planning the course, preparing exams, and grading,

and they meet regularly to discuss the course, the students, and their teaching. Some

interactive teams, especially when just two faculty members make up the team, literally co-

teach by jointly discussing with each other and the students the day’s topic.” (Austin 37).

[See Figure 3.2].

3.2 Team Teaching

Professor A

Professor

B

Students

While the team teaching method requires the most group planning, in our pre-

planning stage we found this method to be the most satisfying. With this methodology, we

would both have a maximum amount of teaching time. This met our personal goals of

honing our individual pedagogical skills. With this method, we would also be forced to

work together in identifying our goals and praxis. The pre-planning allowed us to try out

15

new methods and discuss questions we had about each other’s ideas. By being physically

present during each class session, we were both able to interact with the students on a

regular basis. We were also able to use each other as examples, especially when

discussing scene work. As professors, we found this method to be most satisfying, despite

the longer planning it required.

It is also important to note that teams can easily shift from one model to the next in

order to fit their unique needs. For example, team teaching does not preclude the use of

complementary teachers. Nor does it exclude also employing parallel teaching or coaching

models at certain points in the course. Rather, the models are listed to help identify a basic

approach to teaching collaboratively that can be altered and expanded to suit the needs of

the particular course.

Planning Structures

Planning Structures allow the university to identify the hierarchical system that will

suit the needs of the department and professors involved. The structures are typically more

useful at the administrative or departmental level to coordinate teams effectively. Basic

coordination of teaching teams will come from the perceived experience level of the

instructors involved. There are three basic planning structures: Authority-Directed Teams,

Self-Directed Teams, and Coordinated Teams.

16

Authority-Directed Structure

The Authority-Directed Team is a team structure in which all decisions are made

by one lead instructor and then carried out by the remaining team members. “The

hierarchical structure [authority directed structure] has several advantages. Decisions can

be made fairly rapidly, without endless debate. Direction can be provided, duties clearly

specified, responsibilities assumed. But some members may resent not having decision-

making power” (Buckley 42). This type of structure can be especially useful if there is a

large gap in the experience level of the instructors, or the department wants to have the

final word in the decisions made by the teaching team.

Employed in conjunction with a Consulting model, the master teacher would be

responsible for making decisions that will aid the novice in learning to take on professorial

duties. In this instance, the duties of the novice would grow until a teaming model was no

longer necessary.

Self-Directed Teams

More hands-off programs will appreciate the Self-Directed Team structure. “Self-

directed, autonomous, or synergetic teams are spontaneously formed by faculty and/or

students. All the teachers are considered equal. Decisions are usually made by consensus

or by majority vote. Control is not a major issue. But endless discussions can be

frustrating” (Buckley 42). As Buckley illustrates, the self directed team can be a problem

for those who are not able, willing, or interested in engaging in long discussions. In our

classroom, we have employed the self-directed team approach. We were allowed to be

17

autonomous in choosing the model that worked best for us. This particular structure

worked because we are at an equal level of experience and both have a large interest in

exploring this type of work.

Coordinated Teams

Coordinated teams combine elements of the two preceding types {Authority-

Directed and Self-Directed}. Members are appointed by administrators after

consultation with the faculty on their interests and preferences. Team members

typically are drawn from several departments that share a core curriculum. Teams

may select and often rotate their own coordinators or leaders. Such decisions are

best based on the coordinator’s experience, leadership qualities, and enthusiasm for

team teaching.” (Buckley 43)

The coordinated team structure allows the administration to be involved in supervising the

work of the team, while still permitting the team to work autonomously.

Our Experiences in Classroom Collaboration

Jenna and Julie have both worked in collaborative classrooms under a variety of

models. Most of those have been extremely positive, and a few were not. Below are

highlights from our most memorable collaborative efforts in the theatre classroom.

Jenna

THEA307: Theatre History

18

Theatre History is generally taught by one instructor, with four graduate student

teaching assistants. The instructor does most lecturing, with each of the TAs doing one

lecture a semester and leading group break-out discussions and is therefore generally

structured in the supportive teaching model. However, the semester in which Jenna

assisted in this class was taught by two graduate students, with two additional graduate

Teaching Assistants. This course created an Observing Team Model. While both were

responsible for the same course, they would take turns lecturing. Both instructors were in

the classroom, and they would discuss after lectures what worked or did not work and why.

One taught the sections Greek Theatre and Renaissance Drama, the other on Roman

Theatre and Medieval Drama. Observing this style, it was apparent that the students

enjoyed the lectures of one of the two instructors more than the other. This set up a

negative environment in the room on certain days. It is possible that had they chosen a

more interactive method of delivery (rather than relying predominantly on lecture) and if

they had integrated their teaching with one another, perhaps the atmosphere of the

classroom would have been more conducive to learning.

South Eastern Theatre Conference 2006- “Yes-And” Improvisation Workshop

In this two-part workshop series (one aimed at educators and the other at students), one

presenter acted as lead and the rest of the team (five of us in all) demonstrated and added in

comments when needed. This sort of team teaching could be called supportive teaching.

This worked well because the lead teacher took charge from the beginning but was

receptive to the other instructors’ comments, suggestions and feedback.

19

Julie

Fox Theatrix

Julie was granted the opportunity to work collaboratively with other teachers and

create a team teaching model for an elementary school age after school program. She and

one other teacher were responsible for over 80 children in second through fifth grades,

although a third teacher was added to the team early in the process. For this team, due to

schedule restraints, they chose to utilize a combination of team teaching models. After

large group instructions and warm ups which most closely follow the team teaching model,

most class sessions consisted of parallel teaching, where the students were broken up into

small groups and taught the same topic simultaneously. With a group that large and

students so young, it was necessary to lower the teacher to student ratio in order to

communicate effectively. This class has continued to meet during the research period of

this project. It continues to function under a Self-Directed Structure.

Richmond Shakespeare Theatre: School Shakespeare Workshops

These workshops travel to various high school and junior high English classrooms,

educating the students about Shakespeare. The workshop is team taught by at least 2

instructors, and follows a Complementary Teaching model. One teacher is responsible for

the bulk of the material and the other complements with performances of Shakespearean

20

monologues, demonstrations of ideas, and humor to keep the students engaged and

focused.

Both Jenna and Julie:

THEA 212 Introduction to Drama

Though we never taught at the same time, both Julie and Jenna have experience

teaching this class. The course involves a large team of graduate students and one full time

professor. Each graduate student is assigned twenty to twenty-five undergraduate students.

In this model, the master teacher creates the syllabus, exams, quizzes, and paper topics. He

introduces the students to the small discussion group structure and schedules periodic guest

artist appearances. The bulk of the class is discussion based. This model, most closely

aligned with the Consulting Team model, was beneficial in many ways, but frustrating in

others. It was an excellent immersion into teaching small discussion groups.

Both Jenna and Julie found the experience extremely frustrating as someone who

had already taught her own class. The Authority-Directed structure left the instructors very

little power over where the discussion group went with the students' ideas, what paper

topics to choose, when items were due. Because the structure was not team generated, but

passed down from a master teacher, it was frustrating to be so removed from the master

teacher’s mindset.

This model was certainly not all bad. The small group discussion leaders met

occasionally to converse about grading criteria and attempt to make a guide to grading that

would be fair for all the students involved. Elements like that are extremely useful for

21

beginning teachers. Therefore there is some support and communal experience in terms of

teaching this class.

If not all of our teaching experience in teams was fulfilling, why would we

continue on to research this method? We believe that some models will work better for us

than others, and the key to successful teaming is to find the right model and structure to fit

the instructors involved. It is our goal that universities will examine the use of teaming so

they can utilize the benefits collaborative teaching has to offer. Looking at the advantages

and disadvantages of teaching in teams should help clarify which of these pedagogical

approaches are worth embracing.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Co-Teaching

Teaching in collaborative models can be both beneficial and detrimental to all

involved, and a thorough investigation of the pros and cons is necessary in order to

determine whether the advantages might outweigh the disadvantages. In the following

section we have examined the advantages of implementing a team teaching model, and

how it effects the students, teachers, department, and the university. While we have not

limited our discussion to just the co-teaching model, most of our arguments directly affect

that mode of teaching. The pros are followed by the potential disadvantages of team

teaching, which are also discussed in terms of the above mentioned categories. While we

have very strong personal feelings about ways to augment the advantages and reduce the

disadvantages, we will not be addressing those within this section. For more specific

details on ways to deal with pros and cons listed below, see the last chapter of the thesis,

Team Teaching: A Guide.

22

23

Advantages

The benefits of team-teaching are numerous for all involved. Each participant can

benefit from this structure of teaching. We will focus on the benefits for the teachers,

students and administration.

THE TEACHER

The old adage, "two minds are better than one," certainly applies when teaching.

According to Ann Austin and Roger G. Baldwin in the introduction to their book Faculty

Collaboration: Enhancing the Quality of Scholarship and Teaching,

It is a universally accepted principle in business and industry that the more

minds working on a problem, the greater the chance of finding a solution.

Researchers of high achievers from Napoleon Hill to Stephen Covey

identify the characteristic of working in teams as a major trait of people

who repeatedly effect [sic] successful outcomes. The success of the space

program in the 1960s would never have occurred without the collaborative

efforts of many different intellectual areas. (Austin xv)

Since teaming has proved so valuable in other fields, it behooves us to explore how

we can use teams more effectively in higher education. Although learning should be

centered on what is most advantageous for the students, professors certainly benefit from a

team teaching approach. Team-teaching allows professors an opportunity to share ideas

and gain new perspective on their subject matter. When teaching with someone of the

same discipline, the educator is exposed to different ways of teaching the same material

24

and challenged to question her own teaching style. Frequently, successful team-teaching

pairs new faculty with seasoned faculty members. This allows the seasoned faculty the

ability to observe fresh ways of teaching, and newer faculty members benefit from the

experience of the seasoned educator. Lecture was the most common modality in the sixties

and seventies when most of today’s seasoned faculty members were obtaining their post-

graduate degrees. Over the last thirty years, experiential learning has been increasingly

stressed in education. Often younger faculty members place more of an emphasis on this

type of learning. Pairing seasoned faculty with newer faculty allows the seasoned faculty

to be exposed to more types of teaching, in a non-threatening way.

As today’s senior faculty are joined, or prepare to be joined over the next

decade, by a substantial new cohort of junior colleagues, the prospect of

finding the colleagueship they have long sought in intergenerational

relationships with a new academic generation remains a tantalizing

possibility. While a number of junior-senior ‘mentoring’ initiatives are

indeed already underway, first impressions suggest that to date senior

faculty have not seen in their junior colleagues such an opportunity (nor

have their junior colleagues seen it in them). (Finkelstein 15)

The seasoned faculty is by no means the only part of the pairing who is enriched, as

that teacher can mentor the newer member, and will have found ways to deal with

problems that have not even been encountered by the new faculty member. There is a

great deal that a new faculty member can learn by being paired with a more experienced

25

professor, both in regard to the subject matter which is being taught and the inner workings

of the academic environment.

When teaching with someone from a different discipline, team-teaching exposes

how others view one's specialty:

As faculty members team teach or observe in courses outside their specialty, they

may gain an enhanced appreciation of the contributions that other disciplines and

perspectives can make to the students and to their own work. This appreciation

among colleagues is useful if the institution intends to undertake any curricular

innovation or reform. (Austin 44)

The way a film professor views acting can enlighten how a theatre professor approaches

the subject. An architect will see set design in a different way than a designer. Being

aware of how others perceive our discipline can make it easier for us as professionals and

professors to discuss our discipline outside the confines of our department. It will also

meet our pedagogical needs if students’ ability to work interdisciplinarily is enhanced.

“Another way in which team teaching can affect the curriculum is by opening an avenue

for the establishment of new courses that have no obvious departmental or disciplinary

home. Courses in ethnic studies and women’s studies have been initiated and ultimately

established firmly at some institutions through this route.” (Austin 44).

When teaching with someone of the same level and discipline, a great deal can be

learned. All the team-teaching models require that each teaching participant examine their

pedagogical practices, in order to articulate better the reasons behind them to the partner.

It is not humanly possible to avoid questioning the pedagogical practices of the partner

26

teacher when they differ from your own. By necessity, the two teachers must combine

their varied techniques to form a new pedagogical practice, which will most likely

influence their future solo teaching experiences. Thus, the team teaching model has the

potential to benefit future individual courses from the improved pedagogical practice of

both instructors. As Francis J. Buckley states in the book Team Teaching: What, Why and

How? when discussing single disciplinary teams,

Team teaching within a department is a relatively simple way to get experience

with the dynamics of a team, for many department members already know and trust

one another and may be curious about how others approach the material. There is

less fear of public humiliation when the limits of their knowledge are revealed. In

fact, they can rely on one another to keep the pace of class lively and to supplement

data with stories. Just the variety of voices and personalities stimulates interest.

(46)

It is clear, therefore, that teaching with someone of the same discipline, even the same area

of expertise, can prove beneficial to professors.

Another benefit of team-teaching for the professors involved is that of mutual

support. Teachers in team-teaching situations report a greater sense of belonging and less

isolation than teachers who teach alone. There is a sense of camaraderie and mutual

respect which can be lost in the traditional structure of solo teaching. According to A

Guide to Co-Teaching, “In co-teaching, teachers experience a sense of belonging and

freedom from isolation by having others with whom to share the responsibility for

accomplishing the challenging tasks of teaching in classrooms of diverse students” (xiv).

27

Two additional benefits of team-teaching for the professor are intertwined, that of

culpability and logistical support. Procrastination is a common problem for all people, and

those in the profession of teaching are no different. However, when one professor is

accountable to another the urgency of completing each task on schedule is stronger. As

long as there is mutual respect between those teaching together, there is incentive to

uphold one's portion of the workload. Those who are often guilty of procrastination can

find being accountable to another helpful in productively accomplishing tasks on time.

One faculty member was quoted in Handbook of College Teaching: Theory and

Applications as saying, “Teaching in front of other instructors helped me look at myself

the way the students look at me. It made me think much more clearly about what I wanted

to accomplish in terms of learning outcomes” (Prichard 128).

Logistical support is the flip side of culpability. As professors are also people,

events happen which take them away from the classroom and/or duties relating to teaching.

If illness or work takes one team member out of the classroom, there is someone to fill that

gap. Again, as long as there is mutual respect, these sorts of interruptions can be worked

with and the quality of classroom instruction can remain strong. This can be especially

beneficial in a research university that expects the professors to be continuing their

professional work alongside their teaching responsibilities. In a team teaching model,

especially that of co-teaching, instructors would feel free to pursue endeavors that may

take them out of the classroom temporarily, knowing they will not hinder the learning of

their students by canceling much needed class time.

28

THE STUDENT

Teaching should be focused on that which will allow the students to best

understand and apply knowledge. Team-teaching helps us in this pursuit in a number of

ways. They can be classified into two categories, those which are specific to the subject

and class, and those which are larger life lessons.

In terms of specificity to the subject matter at hand, having multiple instructors in

the classroom at the same time allows for smaller faculty-to-student ratios which allows for

more one-on-one time with faculty members. Groups can be divided to allow more

individual response time. The students are also hearing multiple perspectives each time

they, or their classmates, receive feedback. This allows them to have a broader range of

areas of improvement than if they were exposed to only one professor’s feedback or

opinion. Especially in the acting classroom, two sets of eyes on a performance can

illuminate two different ways to solve a single problem. For example, if a student is

having trouble establishing an environment for their character, both professors may

identify a way to help establish the environment, and the student can begin to see that there

is a myriad of choices they can make to achieve their goals. Students are empowered to

find their own solutions instead of relying on the single professorial perspective.

With multiple instructors, the likelihood of personality conflict from student to

professor, also diminishes. Some students and some instructors simply do not get along.

However, with two instructors there is a greater chance that the students will connect with

at least one of them. In fact, they may feel a greater connection to one instructor over the

other, and thus have an easier time expressing themselves to that individual.

29

Perhaps one of the best parts of team-teaching lies in its broader application in the

context of life lessons for students. In a classroom with multiple teachers, the students are

exposed to multiple viewpoints. For many college students, they have spent their

formative educational years with a single teacher who has given them one perspective.

William Perry was among the first to study the intellectual development of college

students, and he identified nine positions on the developmental sequence. Students in the

position of dualism, which describes many first year college students, “view knowledge as

truth – as factual information, correct theories, right answers. They view the professor as

an authority who know these truths and believe that teaching constitutes explaining them to

students” (Erickson 22). An exposure to multiple truths allows the students to see that

there are multiple answers to most questions, not just one. This encourages them to take

an active part in their own education, to examine multiple sides of an equation and to come

to their own conclusions as to the answer. While students at this level of intellectual

development will have the hardest time in a team taught classroom, they might benefit the

most from the interaction.

Team-teaching, especially across disciplines, can foster a greater sense of

community within the academics and curriculum of the students. It is difficult to relate

theater and history to one another if they are taught in different buildings, at different times

and by different professors who do not communicate. However, if one is exposed to both

of them in the same class, it is easy to see how closely they follow one another. Once a

person is exposed to this duplicity of thinking and the idea of interconnectivity between

30

disciplines is established, students will continue to make these sorts of connections

throughout their lives.

Our world is becoming more and more interconnected and dependent on

collaboration and teamwork. Team-teaching allows such collaboration to be modeled for

students, thereby encouraging it. Also, team-teaching lends itself to the ability to teach

with more interactive learning, which generally encourages team-building. Since teaching

methods such as lecturing and note taking require less time to prepare, more active

learning approaches are often heralded and seldom used. With two professors

brainstorming more active approaches to learning, the teaming model is more likely to

produce active learning experiences for students. While lecturing and note taking is

quantifiably as effective in terms of testing, studies have now proven that experiential

models of learning have long term learning benefits that far surpass those of traditional

educational models.

Lecture is about as effective as other teaching methods when recall of

information is tested. The lecture, however, turns out to be less effective

than other methods when instructional goals include retention of

information beyond the end of the course, application of information,

development of thinking skills, modification of attitude, or motivation for

further learning. In short, there is more to effective teaching than lecturing.

(Erickson 87).

31

Learning that lasts beyond the final exam is more likely to be achieved in classrooms that

use interactive approaches. Team teaching is a model that promotes interactive methods of

teaching and learning.

And lastly, dependent on the make-up of the teams, team-teaching can model

healthy diversity. If a man and woman are paired together, and are mutually respectful of

one another's place in the classroom, their mutual respect will be noticed by students. If

teachers from different religious, ethnic or racial backgrounds are paired and respectful of

one another's differences, this will also be noticed by the student.

THE ADMINISTRATION

The logistical aspects of team-teaching, particularly in regards to the administrative

strain, are often why such projects fail. However, there are certain benefits for a program

that implements team-teaching models.

The first benefit has been mentioned above in the teaching section of benefits:

improved job satisfaction for employees. When employees are satisfied with their job,

productivity and morale improve. Everyone wants to enjoy being at work. As teachers

who teach together are happier overall, it can be concluded that the workplace is more

conducive to a productive work environment.

Finkelstein reports “in the normal course of business as usual, they [senior faculty]

typically find little opportunity – formally or informally – to focus on teaching. Teaching

is isolated, and poorer for that isolation. Without periodic opportunities to revitalize their

professional lives generally and their teaching lives in particular, faculty members report

32

that their ‘teaching vitality’ tends to slip.” (25). These are not the words an administration

wants to hear about their most experienced faculty members. The data examined was the

result of an eleven campus study on senior faculty. Team teaching will allow faculty

members to examine their pedagogical skills and prevent teacher burn out from lowering

the quality of education for the students.

The second and third benefits, less disruption and larger class-size, are more

administrative and quantifiable. If there are two or more teachers responsible for a single

class, there is a smaller chance that the class will be canceled or suffer negative effects

from teacher illness or inability to travel. This results in more in class instruction and

therefore a better education for students. The ability to travel or take time off class for

research and creative projects without undermining the quality of students’ education, will

be attractive for new and current employees. It will also allow those employees to move

into higher ranks which seem to be linked to higher job satisfaction and employee

retention. As of 1989, according to the Carnegie Foundation, “77 percent of faculty at 4

year colleges agreed that it is difficult for a professor to achieve tenure if they do not

publish. (Tack 11) Additionally, at least 33 percent of full time faculty viewed

opportunities for research and creative projects as “quite a problem” or a “major problem”.

(Tack 11). By providing team teaching experiences, faculty in theatre departments could

experience a renewed freedom to participate in creative projects that call them out of town

during the course of a semester, thus allowing faculty to continue to be relevant theatre

practitioners as well as educators.

33

The second is that classes which are team taught can accommodate more students

than a class that has an individual instructor. This is a huge benefit if space is a problem,

since more students can be put into the spaces currently in existence, rather than having to

create more buildings to house them.

There is also the potential positive effect of student retention. According Prichard

in The Handbook of College Teaching

, “an argument can be made that “frontloading” the

curriculum with smaller classes in the freshman year would be more cost effective as far as

student retention is concerned since so many students are lost in the first year of college”

(132). Indeed, according to the VCU theatre website,

Our retention rate is much like other programs. About 35% of entering students

will graduate. Only the most dedicated, talented and serious individuals will

complete this program and have a successful career. However, the rewards are

worth the extra effort. Theatre is not a career for those who are not willing to

continually step up to the plate and prove themselves. (Twenty-Eight FAQ’s)

The first year of college is a decisive year for many students. According to the VCU 2020

Plan, retention is of top concern (Strategic Plan). In essence, putting two teachers into the

classroom for first-year students might be worth the added expense if it means more

students are retained for future years.

Another major benefit of team teaching for the department is the fusing of

pedagogical approaches into one practice. Professors who have created common

pedagogical practice in a team teaching model will now be able to create a cohesive vision

for the department. Instead of courses being compartmentalized into each teacher’s area of

34

expertise, the professors would begin to work as a unit in creating a 4 year curriculum that

is cohesive and dependent on the skills of all the faculty members. The theatre program

will become a unique training institution that offers a system of training different than any

other program. This could lead to increased student interest in the program, which again

leads to more funding and higher quality students.

Disadvantages

Of course, all pedagogical structures have their faults and team-teaching is no

exception. In the next section we will highlight some of the potential pitfalls to team-

teaching, as well as some ways to minimize these drawbacks. Again, we will examine this

area from the perspectives of teachers, students and administration.

THE TEACHERS

For teachers, the greatest drawback is the increase in work that is necessary to

effectively team-teach. Team-teaching often requires complete revision of lesson plans

and curriculum for a given class. It requires increased work in terms of team planning.

Decisions must be made in tandem, which means that regular meeting times must be

scheduled and attended. This is extra work, especially the first time the class is taught with

a teaming model. Evaluation of class content and student performance must also be done

in consultation. Teachers, who generally are already over-scheduled and taxed for time,

may experience an increase in stress with this added work. The most effective way for this

35

problem to be overcome is for the administration to acknowledge the extra work and

compensate for it by reducing workload in other areas. Of course, that is not always a

feasible solution. Team teaching has an adjustment period, which requires careful

planning so the experience will be positive rather than negative.

Personality conflict can also be a problem in team-teaching. Not everyone should,

or can, team-teach and certainly personality should be taken into consideration when

forming teams. Professors with very strong opinions about how their subject should be

taught might actually produce negative results if required to teach in certain teaming

models. The selection of participants for team teaching should be done very carefully, and

participants should be honest and informed about which types of models they would be

comfortable participating in.

In order to avoid this pitfall, professors and administrators should keep a few of the

following ideas in mind. First, all individuals participating in team-teaching should be

doing so voluntarily. A lot of friction can be avoided if the faculty is on the ground floor

of designing such classes. As affirmed in Team Teaching; What, Why and How

, “Poll the

faculty to determine their interest and willingness to try it. If forced, most will resist. If

invited, many will want to try it out” (20). If team-teaching is to be implemented across a

program, it should be done slowly and those hiring in should agree to work in such a

program. Teams should generally choose themselves and carefully discuss how they will

approach the work of the team prior to entering into the classroom.

Another potential problem with team-teaching, for faculty, is the need for

commonality. When working as a team it may be necessary, at times, to agree to disagree.

36

It may also be necessary to come to a consensus with the other individuals teaching so as

to present a united front in terms of teaching a particular subject. This means that those

teaching must willingly agree upon what should be covered in order to present the most

cohesive and organized lesson plan possible. At times this will mean letting go of personal

interests and compromising on content. This does not, however, mean that the teachers

should not, at times, give differing opinions or viewpoints as this is one of the strengths of

team-teaching. “Disagreements among their teachers about a topic illustrate for the

students that interpretations vary, and faculty members’ willingness to reveal the limits of

their knowledge may show students how intellectual growth occurs.” (Austin 43).

Each opinion must be conveyed in a way which respects the other and which does not

confuse the students. Teachers will need to be especially sensitive to those students still in

a dualism level of intellectual development, who will struggle with absorbing opposing

truths.

Though no one likes to admit, apathy and laziness can also be a problem in any

communal group. Apathy generally sets in for professors after teaching a course many

times in succession. Their interest of the subject or structure wanes. Though this can

happen with individual instructors, it is especially disruptive and difficult when only one of

a team feels this way. The only real solution to the problem is for that professor to take a

leave from the course (Davis 89). Laziness in group settings can also be a problem. As

concluded in Interdisciplinary Courses and Team-Teaching, “Research has shown that

individuals, in general, tend not to work as hard in groups as they do as individuals” (90).

37

There is no way to deal with this situation besides acknowledging it head-on and using one

another to motivate more work, rather than less.

Finally, teachers may have difficulty dealing with professional jealousy. Professors

may feel their methods are what make them valuable as an employee. To share those

methods with someone else is to potentially risk their own job security. There is also great

risk of accidental or intentional professional theft. If a teacher has developed a system that

is implemented in a team teaching scenario, the teaming teacher may begin to use this in

their work and receive credit if that work is published. This may be a reason newer

teachers are interested in this model and more experienced teachers would be wary of

teaming with someone who will not bring the same level of scholarship to the table.

This issue will have to be addressed sensitively and all parties involved need to be

aware of the risks involved in this sort of work.

THE STUDENTS

The biggest potential downfall for students is the confusion mentioned above. If

the professors do not organize a cohesive and well-structured lesson plan in which

differences of opinion are not the main focus, students can receive mixed messages. When

differences of opinions are presented well, it gives students a wider range of possibilities

and allows them to discover what their opinions are. If it is done poorly, it leaves the

students confused about the necessary content of the course and undermines their opinions

of the professors themselves.

38

Team-teaching does not fit the model in which most students have been educated.

It can be disconcerting for students to have to switch their understanding of how one is

taught. With team-teaching, which stresses experiential learning, it is more difficult for

students to memorize and regurgitate. Some students do not respond positively to the

added responsibility of active engagement. This is especially a concern when teaching first

year students. (see the section on teacher pros about levels of intellectual development).

The team-teaching classroom might be viewed as a threat for students still in a dualism

level of intellectual development. When we asked the students in our freshman Acting I

course, most indicated that they would prefer a course with two instructors over a course

with only one, but not all of the students felt that way. A small minority said they would

prefer to have only one instructor. It may be assumed this is because the team teaching

model violates their model of teacher-student interaction. This can be adequately

addressed through the way team-teaching is introduced to the class and showing respect for

students.

THE ADMINISTRATION

The administrative responsibilities for any university program are vast, and team

teaching can place additional strains on the administration. It is the opinion of the writers,

and several others, that ultimately the pros outweigh these cons. However, for each

program they will have to be considered.

The first is the financial factor. “What is all too frequently overlooked, however, is

the crucial corollary: senior faculty members’ success as teachers depends on the support

39

of their institutions” (LaCelle-Peterson 21). Faculty need the full, financial and practical

support of the administration. Because of the additional work placed on the teachers, they

should be compensated or their other workloads should be reduced. This would mean

either paying them more or hiring other individuals to take on the additional work. The

Handbook of College Teaching suggests the following in terms of the financial feasibility

of team-teaching:

A four-credit class with twenty students will never support two faculty

members at most colleges; as a result, each teacher is often given only a

half-course credit for team teaching such a course. This solution does not

respect the fact that two instructors are, in fact, teaching the class. Team

teaching is thereby penalized and the long-run viability of the enterprise

depends on faculty voluntarism. If, on the other hand, a team-taught class is

offered for eight credits with forty students, it will more adequately support

two faculty members. Many colleges are finding that large numbers of

team-taught, linked courses can be offered through this approach. (Prichard

132)

The second factor is the logistics of space and time. Because there are generally

more students in a team-taught class, the space that they will need is larger. Also, because

Coaching and Teaming models of team teaching require all of the instructors present for all

of the meetings, they can not have other classes scheduled at the same time. This is not

insurmountable, nor is it necessarily more inconvenient than scheduling classes for

individual classes, but should be considered.

40

The third factor is the allocation of administrative time. Many departmental

administrators are not currently spending much time working toward creating a learning

environment for faculty. A re-allocation of funds and time will have to be made in order to

change the prioritized goals for the department. “Senior faculty especially, need

multifaceted organizational structures that will encourage them to broaden their horizons,

approach their work in different and imaginative ways, and find new opportunities to grow

and change” (Finkelstein 17). The administration will need to decide that this is a priority

and allocate the amount of planning and time necessary to implement a team teaching

program.

The last is the decision of who to pair with whom. This decision often falls to the

head of the department. He or she must decide if it would be better to put professors of the

same status together to avoid potential clashes in seniority, or if the benefit of potential

learning from a professor of a different status would be more appropriate. He or she must

also decide if people of the same gender, race, etc. should be paired together because it will

create more homogeneity in the teaching or if the diversity of views often gained by

pairing people of different backgrounds is important in the team-teaching scenario. In the

final chapter of this thesis, we will address ways to help in the formulating of teams.

Attempts to encourage women and minorities to apply for open teaching positions

are customary, but university administration needs to do more to meet the needs of these

employees in order to retain them. “A common problem many women and minority faculty

report is the feeling of isolation and separation upon affiliation with an institution,

particularly, for minority individuals, a predominantly white one. Consequently,

41

institutional officials must work diligently to create opportunities, both on and off campus,

where women and minority faculty can interact with their peers both formally and

informally “ (Tack 84). Isolation, separateness, and pressure to continue professional

performance and research without funding or time to do so, all contribute to job

dissatisfaction for professors, especially for women and minorities, according to Tack.

Team teaching stands as a model for conquering all three of those battles. Working in

teams allows professors to invest in each other and strengthen the faculty as a whole.

Teaming can help the department achieve a cohesive curriculum that flows from one

instructor to the next. It can also provide that necessary time for faculty to continue their

own research and professional development, key to achieving tenure status. According to

their interpretation of a compilation of studies, Tack and Patitu, argue that women faculty

express much higher job dissatisfaction than men, but that this level of dissatisfaction

begins to even between the sexes as tenure, salary, and rank increase. They also indicate

that women faculty members are expected to have a much more active role in their

personal home lives than their male partners, despite the fact that “Women typically teach

more hours than men… and women faculty ‘bear a disproportionate share of undergraduate

instruction, have less contact with graduate students, and are less likely to be given

teaching assistants’ than their male colleagues.” (tack 36).

“In 1980-81, 49.7 percent of the full-time women faculty were tenured, compared

to 70 percent of the men faculty members. Today while the percentage of male faculty

members is the same, the percentage for women has dropped to 45.9 percent [according to

a study by the American Association of University in 1992].” (Tack 39). The expectation

42

that a rise in women junior faculty in the 1970’s would lead to a rise in female senior

faculty in the 1990’s has not proven to be the case. This could be addressed through

administrative programs that help to eliminate isolation and disproportionate workloads,

both of which would be examined or eliminated through the establishment of a team

teaching structure.

Collaborative Teaching Here and Now

University Level

Is there a place for collaborative teaching at the university level? Several

works are devoted to the study of teaming in the K-12 arena, but teaming models are not as

frequently utilized in higher education. In most universities, the first year student is

usually enrolled in the largest courses they will encounter in their academic career. In

order to support the smaller class sizes of upper level courses, introductory courses are

often large, and lecture based. This can be extremely daunting for students who have just

left the high school structure, with a maximum class size of between thirty and thirty five

students, and ample opportunity for one-on-one attention from the instructor.

Symbolically, the university, represented by huge lecture halls and a daunting campus,

creates a large and impersonal view of the university. According to Teaching First Year

College Students, when first year college students were interviewed about their past

relationships with high school teachers, “more than 40 percent report talking with teachers

outside of class [in high school] between one and five hours a week, and a quarter of them

indicated they spent time in a teacher’s home” (9). The successful high school student

enters college accustomed to high school teachers who remind them of due dates for

43

44

assignments and allow them to turn in late assignments for partial credit. For first year

students, the larger impersonal class sizes can hinder both learning and satisfaction with

college life. A team taught course can help a larger university seem more friendly and

personal to incoming students.

However, one-on-one attention for incoming students is not the only benefit for

team taught courses at the university level. A university can also benefit from team

teaching through interdisciplinary courses. Interdisciplinary learning offers a great number

of positives for the students who are taught in this fashion. According to James R. Davis’

Interdisciplinary Courses and Team Teaching

, there are five compelling reasons why

interdisciplinary learning is more important now than ever before. They are:

1. Education should now be focused on teaching students how to “locate,

retrieve, understand, and use information”, not simply to transmit

information from professors to student (38).

2. The world we live in is increasingly complex. Students today are going to

be asked to solve problems that are going to require the use of multiple

disciplines and a wide view of issues (39).

3. “Today students increasingly need exposure to cultural diversity, both in

its historical roots and in its contemporary expressions” (40).

4. There is an increasing need to prepare students for the practical work

world, including offering courses which “develop training settings that

more nearly correspond to the context of professional practice” (41).

45

5. “Interdisciplinary courses better serve the students themselves in their

quest for personal growth and the development of a clearer identity” (41).

As undergraduates, we both found ourselves torn between departments. Julie

worked with her school to create an interdisciplinary program combining adolescent

studies with theatre, and Jenna chose to double major in psychology and theatre. Both

attended smaller schools as undergraduates that encouraged interdisciplinary work and

more teacher/student interaction. Students who might normally be drawn to smaller

universities for such flexibility may find a larger university with cross-over classes

appealing.

The reverse would be true in a smaller college or university setting as well. A

school which does not have a specialist in “psychology and the theatre” (as few do), could

offer a team taught course on the psychology of acting, utilizing a professor of psychology

and a professor of acting. By using both professors, psychology students could have a

practical outlet for exploring the subconscious and acting students could have a theoretical

basis for exploring characters. By cross listing the course, a smaller university can offer a

course to students in both majors, which could be an elective for both, and offer a course

they could not have otherwise.

Team teaching in today’s university provides benefits for more than the students.

According to Katzenbach and Smith, in The Wisdom of Teams

:

Teams will play an increasingly essential part in first creating and then sustaining

high performance organizations. In fact, most models of the “organization of the

46

future” that we have heard about- “networked,” “clustered,” “nonhierarchical,”

“horizontal,” and so forth- are premised on teams surpassing individuals as the

primary performance unit in the company. (qtd. in Davis 77)

The faculties of universities need to work collectively, in order to produce the most

cohesive education possible, resulting in the best trained students. Team teaching helps

individuals hone their communication and conflict resolution skills, as well as improve

their team work and interpersonal abilities.

Based upon data collected by the New Jersey institute for Collegiate Teaching and

Learning in an action research project involving eleven campuses, LaCelle-Peterson and

Martin Finkelstein discovered that “senior faculty members care a great deal about

teaching and experience it as fulfilling.”(Finkelstein 25). Conversely, faculty members

found teaching isolating and felt they were given little opportunity to work on their

teaching. As a result of these findings they identified two ways for universities to support

faculty development: “creating structural alterations in the teaching situation to eliminate

the isolation of teaching, and brokering individual opportunities to revitalize individual

professors. “ (Finkelstein 25). Team teaching, when used for pedagogical enhancement, is

a methodology that meets both of those qualifications.

In the Arts

If team teaching is so desirable at universities, what makes it particularly

compelling in artistic fields? Traditionally, arts education was taught through an

apprentice/master teacher relationship. Students studied individually with a master of the

47

craft in the studio or workplace and were taught to copy the teacher. Now students in the

arts are taught at universities in classes full of other students. Art education has moved

away from emulation of the teacher and toward encouraging individual expression.

Students are asked to create something new and unique to them. It logically follows that

having a team taught course in an artistic field requires that they receive at least two artistic

perspectives, making sure that the outcome of their art is not merely an attempt to replicate

what that professor likes or knows. Students at the college level, especially first year

students, are prone to producing what they think their professor wants, instead of

producing art that is aesthetically pleasing to them. Along the same lines, most professors

in the arts have a specialty, an area of intense study and concentration. Either consciously

or not, professors teach to their areas of interest. Their students’ art often reflects this, as

we create based on what we are taught. The double instructor scenario can help to

eliminate the possibility of gearing work toward pleasing the professor or recreating the

one genre or method taught, and move students toward working for their own personal

feeling of achievement. This should eventually raise the level of achievement of students

as they become responsible for their own aesthetic. For an artistic field, it is necessary that

the pedagogical methods work toward this end in order to create a generation of artists who

are able to think “outside of the box.”

The arts, on many college campuses including Virginia Commonwealth University,