members. Birth, marriage

and death records are al-

ways considered vital rec-

ords—but records of divorce

are also frequently classed

with them. They may be

kept on the state, county or

municipal levels. The

amount of detail varies and

one must not expect to find

them in quantity before the

last one hundred years for

most locations.

Family historians al-

ways want to discover the

dates and places of birth,

marriage, and death for

each of their ancestors. It is

not that these facts are so

interesting in and of them-

selves. A list of names,

dates and places can seem

pretty dry, actually. They

are only a means to an end,

in that they help us build a

structure upon which to

layer further details about

the lives and personalities

of our forebears.

For instance, if we did

not know when and where

our ancestors lived, we

wouldn’t know what major

historical events affected

them or where to look for

the records that might flesh

out their lives. We’d also

have little hope of being

able to connect them to

their parents and grandpar-

ents.

Public vital records are

among the easiest sources

to obtain and use when

one needs to establish

these crucial facts. They

usually contain detailed

and precise information

taken directly from family

Vital records often contain

very sensitive information,

like an individual’s cause of

death, the circumstances

leading up to a divorce, or

allusions to the illegitimacy

of a child. While individuals

may feel uncomfortable

about the public nature of

these documents, the state

sometimes has even more

compelling reasons for re-

stricting access to them.

Birth certificates, in par-

ticular, can enable criminals

to assume false identities

and obtain credit or other

privileges on false premis-

es. In recent years, there

has been a strong move-

ment by legislatures to limit

just who can see and ob-

tain copies of this material.

Death certificates and even

indexes to vital records are

also sometimes restricted.

Before you begin your

research, make sure that

you know what the privacy

law is for the location in-

volved. You will find that

some records are restricted

for a certain period of time

(often 50 to 100 years) after

they are created. Only the

individual listed on the rec-

ord or his or her immediate

family member may obtain a

copy, after proving their iden-

tity. Official (or certified) cop-

ies may be restricted while

unofficial (or uncertified) cop-

ies might not be.

Also, older records may

have been placed in the cus-

tody of a state level archive,

while the newer ones could

remain in a county office.

V i t a l S i g n s : D o c u m e n t i n g T h r e e

C r u c i a l L i f e E v e n t s

W H A T

Y O U ’ L L

F I N D

W I T H I N :

Overview

Access issues

Birth certifi-

cates in brief

Marriage bonds

Marriage licens-

es

Divorces

Death certifi-

cates

Substitutes for

vital records

L o c a l L a w a n d A c c e s s I s s u e s

C O U R T E S Y O F T H E H I G H P O I N T P U B L I C L I B R A R Y

Vital Records

A Beginner’s Guide from the Heritage Research Center

H E R I T A G E

R E S E A R C H

C E N T E R

High Point Public Library

901 N. Main Street

P. O. Box 2530

High Point, N.C. 27261

(336) 883-3637

HOURS:

MON: 9:00—6:00

TUE-THU: 9:00—8:00

FRI: 9:00—6:00

SAT: 9:00-1:00 2:00-6:00

SUN: CLOSED

Birth certificates have been

required in North Carolina only

since 1913. Some larger cities

may have kept some records a

few years prior to this date. In

this regard, North Carolina is

relatively typical of the United

States as a whole. Because of

this, birth certificates are gen-

erally not much help for 19th

century questions. There are

some jurisdictions that kept

earlier records of birth, mar-

riage and death, but these are

relatively rare and compliance

can be spotty. Examples are

the birth, death and marriage

registers of late 19th century

Virginia and Kentucky and the

township vital statistics books

kept throughout New England

from the 17th century.

The older the birth certifi-

cate, the less information it is

likely to give. But eventually,

certificates may include the

name, race, and age of each

parent and of the child, the

residence of the family, the

occupation and educational

level of the parents, length and

weight of the child at birth,

date and time of birth, whether

born dead or alive, whether

the child was premature or full

term, the name and place of

residence of the person who

gave the information, etc.

There may even be a footprint

or handprint for the child and a

thumb print for the mother.

Older registers of births

contain far less detail but mini-

mally give the date of birth,

name of the child and of the

parents (though perhaps not

the mother’s maiden name)

and the race of the child.

Birth certificates are often

the most protected form of vital

record. And remember that

many people failed to comply

with the law in the early days,

particularly when a child was

born at home without a doctor.

In those cases, look for a

delayed birth certificate.

curity (called a bondsman) to

the governor, swearing that

there was no impediment to the

marriage. If an impediment

later arose (such as bigamy),

the groom would be required to

pay the penal sum to the state.

The number of marriage bonds

varies widely from county to

county. Many have been lost or

destroyed over time and some

were stolen from courthouses

before they could be brought in

to the Archives. Some re-

mained among the papers of

various justices of the peace

and were never filed with the

clerk or registrar.

In other cases (perhaps a

majority), couples never filed a

bond at all, because of the fees

involved. Instead, couples often

elected to declare their inten-

tion to marry in their local

church on three successive

Sundays. This gave anyone

knowing of an impediment time

to object (called “declaring the

banns.”) Such marriages were

equally valid. Others, like the

Quakers, avoided bonds be-

cause of religious beliefs. The

bond itself is no guarantee that

a marriage took place, only that

one was intended. And the

date of the bond is not the date

the marriage. However, the

bride’s maiden name and the

groom’s name are given. The

bondsman is often a relative of

one or the other. It is rare to

find a marriage bond before the

1780s. The last bonds were

executed in the mid 1860’s.

Questions of property

ownership and inheritance

have always been concerns of

the state. Marriage rights play

an important role in these legal

realms. But records of marriage

have not always been carefully

kept. In some places, such as

Pennsylvania or South Caroli-

na, no civil registration of mar-

riage was required before the

20th century. In New England,

on the hand, marriage records

extend back to the earliest

days of settlement. For slaves,

marriage was illegal until free-

dom came. Only then were

couples allowed to register

their prior relationships as mar-

riages in cohabitation docu-

ments.

When it comes to North

Carolina records, the earliest

marriage documents are called

“marriage bonds.” They were

made by the groom and a se-

B i r t h C e r t i f i c a t e s :

A B r i e f O v e r v i e w

P a g e 2

T y i n g t h e K n o t 1 :

T h e M a r r i a g e B o n d

Myth busters:

In the earliest

days, many

marriages ,

perhaps a

majority,

went

unrecorded in

North

Carolina. The

fees involved

dissuaded

many couples

from going to

the

courthouse.

Marriages did

not have to be

recorded to

be legal until

1868.

V i t a l R e c o r d s

These are filed and indexed

separately and were obtained by

an adult (sometimes born even

before birth certificates were

required) in order to prove his/

her citizenship or date of birth for

social security eligibility, pass-

ports, or other legal purposes.

In North Carolina, vital sta-

tistics of all kinds are housed in

the county register of deeds

office and a copy is filed with the

Vital Records Section of the NC

Department of Health and Hu-

man Services. It is usually easier

to obtain copies through the

county. In the case of a birth,

one may find a certificate in

more than one place, if the birth

occurred in one county and the

parents resided in another.

bound volume), which acted as a

kind of index. The most complete

information about the marriage,

however, is to be found on the loose

sheet of paper called the license, not

in the register. Most counties, since

the 1950’s, have allowed the State

Archives to accession or copy their

licenses and marriage registers to

microfilm. But, unfortunately, some

counties have disposed of their older

licenses or lost them, leaving only

the marriage register as a reference.

Licenses are a great resource

for family research because they

include the race, name, residence,

and age of each party to the mar-

riage, the name and signature of the

person applying for the license, the names

of the parents of the bride and groom and

their residence, also whether they were

living or dead. The bottom portion of the

license, completed at the wedding, con-

tains the date and place of the wedding

and the signatures of the minister or JP

and witnesses. The register on the other

hand, includes only a summary.

Licenses and marriage registers are

often indexed by bride and/or groom and

can be viewed in the local courthouse in

the Register of Deeds office or at the

State Archives. Marriages of people of

color were kept separate from white mar-

riages. Some licenses have been ab-

stracted in book form by genealogy socie-

ties and have been acquired by the HRC.

ed and voted on in both hous-

es. Most petitions never made

it out of committee. Even few-

er managed to obtain the con-

sent of one or both houses.

When divorce was granted, it

was often only a sanctioned

separation allowing legal and

financial autonomy for the

wife, not absolute divorce.

The records are preserved

among the legislative papers

in the state of interest. They

most often include the petition

of the injured partner, the an-

swer of the offending party,

and affidavits and petitions by

witnesses for each.

In North Carolina, no di-

vorces are known to have

been granted in the colonial

period. Those considered in

the early stages of independ-

ence are located in the Gen-

eral Assembly session rec-

In days gone by, divorce

was a very difficult and desper-

ate proposition. Not only were

people considering divorce

shamed by their community, but

they found that the laws were

set up to impede their efforts.

A woman was particularly dis-

advantaged —even when she

produced evidence that her

husband had cheated on her,

did not support her, was wast-

ing the family’s wherewithal or

was physically abusing her.

After all, it was in the hands of

other men to decide whether or

not a divorce should be grant-

ed, and few had imagination

enough to sympathize with the

plight of women.

The earliest divorce re-

quests were usually considered

by state legislatures. They had

to be presented as a petition or

bill by the injured party (whether

husband or wife) and deliberat-

ords, separated by session of

the legislature in the files for

private bills or petitions. All of

the surviving legislative pa-

pers relating to divorce have

been abstracted and indexed

in the North Carolina Genea-

logical Society Journal.

From 1814 to 1835, the

legislature gradually passed

responsibility for divorce to

the Superior Courts in each

county. These papers

are classed under each

county’s divorce series

at the State Archives

and are filed together by

case (designated by

surname and date),

usually up through the

early 20th century.

More recent divorce

records may remain in

the Superior Court’s

archive.

T y i n g t h e K n o t 2 : L i c e n s e s

B r e a k i n g U p i s H a r d t o D o

P a g e 3

V i t a l R e c o r d s

“Not only were

people considering

divorce shamed by

their community,

but they found that

the laws were set up

to impede their

efforts.”

Beginning in 1868, North Carolina

moved to a system of issuing li-

censes for all marriages. No legal

marriage could take place without

one. This system continues to the

present day.

The groom or his representative

came to the clerk, paid a license fee,

and obtained a written permission

that any minister or justice of the

peace could use to validate a cere-

mony. The minister filled out the

bottom portion of the license with the

details of the marriage and then

returned it to the clerk who filed it.

The clerk also recorded summary

information from the license in the

county’s marriage register (a

is no civil record of marriage.

(2) Church records: Christenings,

baptisms, confirmations, mar-

riage, death and burial records

were kept by churches long be-

fore the state required it. Howev-

er, Quakers, Anglicans and Cath-

olics are far more likely to track

these than any of the other sects.

(3) Newspapers: These often con-

tain notices of marriage and

death in the 19th century, but only

more prominent people usually

figure in them and the notices are

often very brief.

Before the twentieth century, records

of birth, marriage, and death are

spotty, if they are available at all.

What can you do to find approximate

or exact dates for these key life

events in that era? There are many

resources available. The following

are only a few, select examples:

(1) Probate records: Wills and es-

tate files can give at least ap-

proximate dates of death and

sometimes, in the case of es-

tates, exact dates. Inheritance

records can reveal the maiden

names of wives for whom there

(4) Cemetery records: Readings of

cemeteries provide dates of birth

and death. They are usually only

widely available for people who

died in the mid to late 1800’s

and after.

(5) Census records: They give

easy access to a rough estimate

of the years of birth and mar-

riage for many people. Death

dates can be deduced to a ten

year time window.

(6) Family Bible records: No ex-

planation needed.

S u b s t i t u t e s n e e d e d . . .

The Last Station

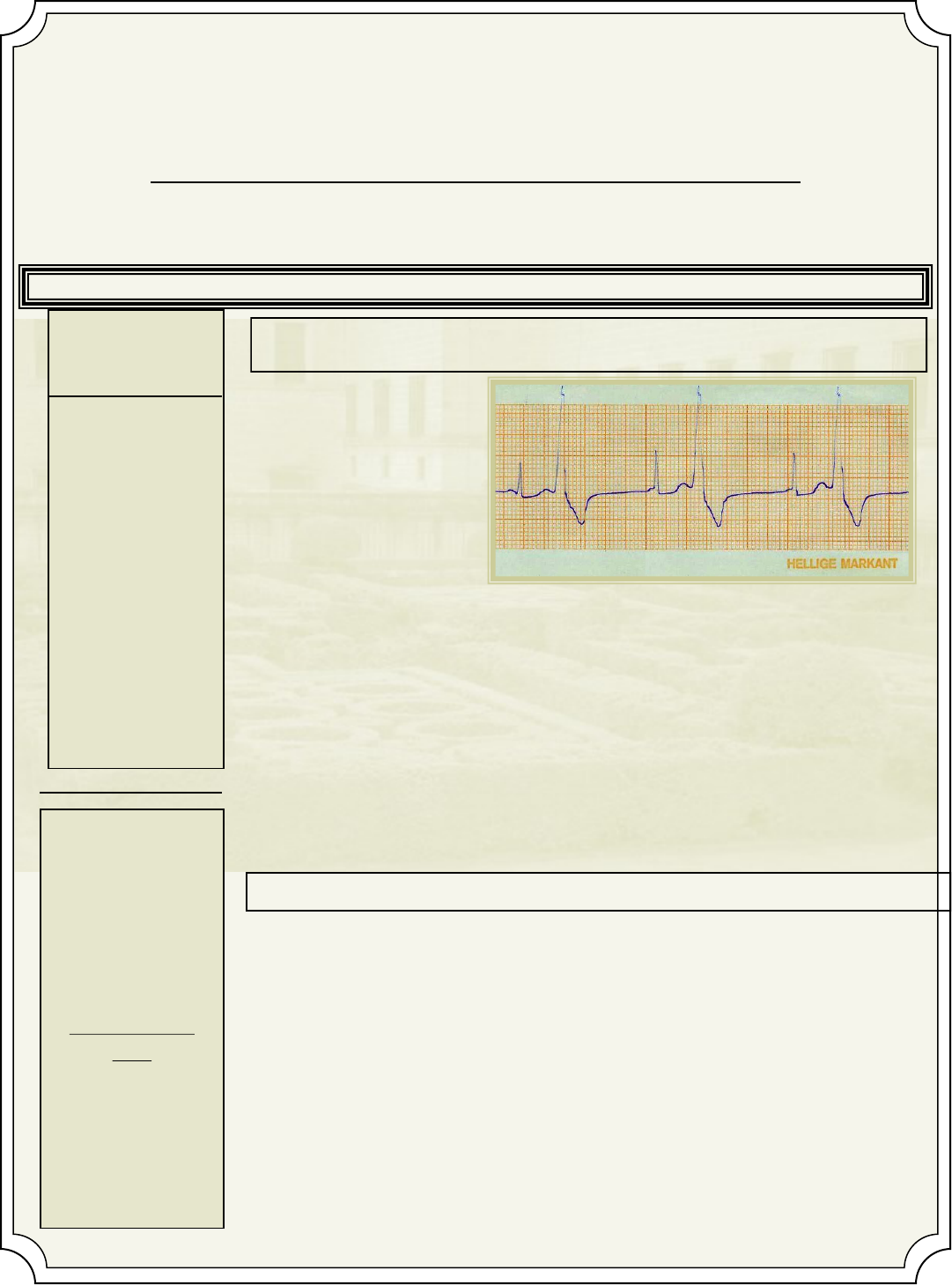

Death certificates, like birth certificates, begin in most locations, only in the

early twentieth century. In North Carolina, they start in 1913, but compliance, once

again, was not widespread until after World War II. For those who died at home or

without a doctor present, it was very common that no certificate would ever be filed.

However, when they are located, they can be of enormous benefit to the researcher.

Death certificates provide information about the deceased person’s date of

birth or age at death, marital status, date of death, cause of death, attending physi-

cian, if any, length of illness, place of birth, names of parents (including the maiden

name of the mother) and their places of birth, place of burial, and informant’s name

(the name of the person who provided the information.) Although they don’t begin

until the early 20th century, they can still be informative about persons who were

born as early as the 1830’s or 1840’s. They can tell us about where a person is bur-

ied even if that person’s grave marker never existed or has since disappeared. They can give us the maiden name of his moth-

er, even if his parents did not have a surviving marriage record. They can also inform us about family medical history or alert us

to crimes or catastrophes. It is important, however, to realize that they may be inaccurate if the person giving the information

was poorly informed or was in a deep state of grief or shock. Many of the bits of information they contain may be garbled by

faulty memory or incomplete knowledge. So it is best to cross-check them against other records.

In North Carolina, the Register of Deeds in each county maintains the death certificates. Copies were filed with the

Department of Health and Human Services in Raleigh, but it usually easier to work through the county. Ancestry.com currently

provides searchable access to images of original North Carolina death certificates through 1975 and an index only through

2004. Ancestry and FamilySearch.org, among other on-line sources, provide access to indexes of deaths or images of death

records for many localities including Chicago, Philadelphia, Alabama, South Carolina, Florida, Louisiana, Texas, Arizona, Geor-

gia, Michigan, West Virginia, Ohio and many others.

V i t a l R e c o r d s

P a g e 4