THE REPORT OF THE

About the National Center for Transgender Equality

The National Center for Transgender Equality (NCTE) is the nation’s leading social justice policy advocacy

organization devoted to ending discrimination and violence against transgender people. NCTE was founded

in 2003 by transgender activists who recognized the urgent need for policy change to advance transgender

equality. NCTE now has an extensive record winning life-saving changes for transgender people. NCTE works

by educating the public and by influencing local, state, and federal policymakers to change policies and laws

to improve the lives of transgender people. By empowering transgender people and our allies, NCTE creates a

strong and clear voice for transgender equality in our nation’s capital and around the country.

© 2016 The National Center for Transgender Equality. We encourage and grant permission for the reproduction

and distribution of this publication in whole or in part, provided that it is done with attribution to the National

Center for Transgender Equality. Further written permission is not required.

RECOMMENDED CITATION

James, S. E., Herman, J. L., Rankin, S., Keisling, M., Mottet, L., & Anafi, M. (2016). The Report of the 2015 U.S.

Transgender Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality.

The Report of the

2015 U.S. Transgender Survey

by:

Sandy E. James

Jody L. Herman

Susan Rankin

Mara Keisling

Lisa Mottet

Ma’ayan Anafi

December 2016

Acknowledgements ...............................................................................................................1

Executive Summary ............................................................................................................... 3

Chapter 1: Introduction ....................................................................................................... 18

Chapter 2: Methodology ..................................................................................................... 21

Chapter 3: Guide to Report and Terminology ...................................................................39

Chapter 4: Portrait of USTS Respondents ......................................................................... 43

Chapter 5: Family Life and Faith Communities ................................................................. 64

Chapter 6: Identity Documents .......................................................................................... 81

Chapter 7: Health ...............................................................................................................92

Chapter 8: Experiences at School .................................................................................... 130

Chapter 9: Income and Employment Status .................................................................... 139

Chapter 10: Employment and the Workplace .................................................................. 147

Chapter 11: Sex Work and Other Underground Economy Work ..................................... 157

Chapter 12: Military Service ............................................................................................. 166

Chapter 13: Housing, Homelessness, and Shelter Access ............................................. 175

Chapter 14: Police, Prisons, and Immigration Detention ................................................ 184

Chapter 15: Harassment and Violence ........................................................................... 197

Chapter 16: Places of Public Accommodation and Airport Security .............................. 212

Chapter 17: Experiences in Restrooms ............................................................................224

Chapter 18: Civic Participation and Policy Priorities ...................................................... 231

About the Authors ............................................................................................................. 241

Appendix A: Characteristics of the Sample .....................................................................243

Appendix B: Survey Instrument (Questionnaire) ........................................................... 250

Appendix C: Detailed Methodology ................................................................................ 291

Table of Contents

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

1

T

he report authors extend our gratitude to all the members of the transgender community who participated

in the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey and the hundreds of individuals and organizations that made this

survey report possible.

The following individuals in particular are recognized for their contributions during one or more stages of the

process, including survey development, implementation, distribution, data preparation and analysis, and reporting:

Osman Ahmed

M. V. Lee Badgett

Kellan Baker

Genny Beemyn

Aaron Belkin

Walter Bockting

Kyler Broadus

David Chae

Cecilia Chung

Loree Cook Daniels

Kerith Conron

Ruby Corado

Andrew Cray

Kate D’Adamo

Laura Durso

Jake Eleazer

Gary J. Gates

Jaime Grant

Emily Greytak

Ann Haas

Jack Harrison-Quintana

Mark Hatzenbuehler

Darby Hickey

Lourdes Ashley Hunter

Chai Jindasurat

JoAnne Keatley

Elliot Kennedy

Paul Lillig

Emilia Lombardi

Jenifer McGuire

Ilan Meyer

Shannon Price Minter

Aaron Morris

Asaf Orr

Dylan Orr

Sari Reisner

Gabriel Rodenborn

Shelby Rowe

Brad Sears

Jama Shelton

Jillian Shipherd

Sharon Stapel

Michael Steinberger

Catalina Velasquez

Bianca Wilson

The authors extend special gratitude to the following individuals for their contributions

to the project:

Ignacio Rivera, Survey Outreach Coordinator, for leading the survey outreach eorts and building a network of

individuals and organizations that led to the unprecedented levels of participation in this survey.

Andrew Flores for assistance with questionnaire development and the weighting procedures to prepare the data

for analysis.

Daniel Merson for continued work in cleaning the data set, re-coding the data, and providing population numbers

for comparative purposes in the final report.

Michael Rauch for programming and implementation of the complex survey.

Appreciation is also extended to NCTE interns, law fellows, sta, and volunteers who assisted

with the project, including outreach across the country, development of outreach materials, and

translation:

Bre Kidman

Cyres Gibson

Mati Gonzalez Gil

Romeo Jackson

Kory Masen

Imari Moon

Cullen O’Keefe

Nowmee Shehab

Acknowledgements

2015 U.S. TRANSGENDER SURVEY

2

A special thanks is also extended to USTS Interns, Fellows, and Assistants for their

work at various stages of the project:

Rodrigo Aguayo-Romero

Willem Miller

Shabab Mirza

Davida Schier

Jeymee Semiti

Danielle Stevens

Venus Selenite

The authors also thank the USTS Advisory Committee (UAC) members, who

devoted their time to the project by giving valuable recommendations around project

development and community outreach:

Danni Askini

Cherno Biko

Thomas Coughlin

Brooke Cerda Guzman

Trudie Jackson

Andrea Jenkins

Angelica Ross

Nowmee Shehab

Stephanie Skora

Brynn Tannehill

Additional acknowledgement goes to the more than 300 transgender, LGBT, and allied organizations

that promoted and distributed the survey to its members throughout the country for completion.

The authors also acknowledge current and former NCTE sta for their work

on the project, particularly:

Theo George and Vincent Villano for their pivotal work in survey project development and distribution

through their respective roles in digital media and communication strategy.

Arli Christian, Joanna Cifredo, K’ai Smith, and Harper Jean Tobin for their contributions as report co-writers,

including lending their subject-matter expertise and analysis to the findings included in this report.

Various individuals and firms assisted in spreading the word about the survey, both prior

to and during the data collection phase, and they also assisted with survey translation,

design, and reporting. Thanks goes to:

Sean Carlson

Leah Furumo

Molly Haigh

Anna Zuccaro

Design Action Collective

Dewey Square Group

ThoughtWorks

TransTech Social Enterprises

ZERN

Additionally, NCTE would like to express special appreciation to an anonymous donor for providing the

largest share of the funds needed to conduct and report on the U.S. Transgender Survey. Other important

funders were the Arcus Foundation, the Gill Foundation, the Human Rights Campaign Foundation, and

the David Bohnett Foundation. NCTE is also grateful to its other funders, many of which supported this

project through general operating support, including the Ford Foundation, the Evelyn & Walter Haas, Jr.

Fund, and the Tides Foundation.

Finally, NCTE would like to give special thanks to the National LGBTQ Task Force, for its previous

partnership in conducting the National Transgender Discrimination Survey as a joint project from 2008 to

2011, as well as for its support of NCTE’s re-development of it as the U.S. Transgender Survey.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

3

2015 U.S. TRANSGENDER SURVEY

4

USTS Executive Summary

T

he 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey (USTS) is the largest survey examining the

experiences of transgender people in the United States, with 27,715 respondents

from all fifty states, the District of Columbia, American Samoa, Guam, Puerto Rico,

and U.S. military bases overseas. Conducted in the summer of 2015 by the National Center

for Transgender Equality, the USTS was an anonymous, online survey for transgender

adults (18 and older) in the United States, available in English and Spanish. The USTS

serves as a follow-up to the groundbreaking 2008–09 National Transgender Discrimination

Survey (NTDS), which helped to shift how the public and policymakers view the lives of

transgender people and the challenges they face. The report of the 2015 USTS provides a

detailed look at the experiences of transgender people across a wide range of categories,

such as education, employment, family life, health, housing, and interactions with the

criminal justice system.

The findings reveal disturbing patterns of mistreatment and discrimination and startling

disparities between transgender people in the survey and the U.S. population when it

comes to the most basic elements of life, such as finding a job, having a place to live,

accessing medical care, and enjoying the support of family and community. Survey

respondents also experienced harassment and violence at alarmingly high rates. Several

themes emerge from the thousands of data points presented in the full survey report.

Pervasive Mistreatment and Violence

Respondents reported high levels of mistreatment, harassment, and violence in every

aspect of life. One in ten (10%) of those who were out to their immediate family reported

that a family member was violent towards them because they were transgender, and 8%

were kicked out of the house because they were transgender.

The majority of respondents who were out or perceived as transgender while in school

(K–12) experienced some form of mistreatment, including being verbally harassed (54%),

physically attacked (24%), and sexually assaulted (13%) because they were transgender.

Further, 17% experienced such severe mistreatment that they left a school as a result.

In the year prior to completing the survey, 30% of respondents who had a job reported

being fired, denied a promotion, or experiencing some other form of mistreatment in the

workplace due to their gender identity or expression, such as being verbally harassed or

physically or sexually assaulted at work.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

5

In the year prior to completing the survey, 46% of respondents were verbally harassed and

9% were physically attacked because of being transgender. During that same time period,

10% of respondents were sexually assaulted, and nearly half (47%) were sexually assaulted

at some point in their lifetime.

Severe Economic Hardship

and Instability

The findings show large economic disparities between transgender people in the survey

and the U.S. population. Nearly one-third (29%) of respondents were living in poverty,

compared to 12% in the U.S. population. A major contributor to the high rate of poverty is

likely respondents’ 15% unemployment rate—three times higher than the unemployment

rate in the U.S. population at the time of the survey (5%).

Respondents were also far less likely to own a home, with only 16% of respondents

reporting homeownership, compared to 63% of the U.S. population. Even more concerning,

nearly one-third (30%) of respondents have experienced homelessness at some point in

their lifetime, and 12% reported experiencing homelessness in the year prior to completing

the survey because they were transgender.

Harmful Eects on Physical

and Mental Health

The findings paint a troubling picture of the impact of stigma and discrimination on the

health of many transgender people. A staggering 39% of respondents experienced serious

psychological distress in the month prior to completing the survey, compared with only

5% of the U.S. population. Among the starkest findings is that 40% of respondents have

attempted suicide in their lifetime—nearly nine times the attempted suicide rate in the U.S.

population (4.6%).

Respondents also encountered high levels of mistreatment when seeking health care. In

the year prior to completing the survey, one-third (33%) of those who saw a health care

provider had at least one negative experience related to being transgender, such as being

verbally harassed or refused treatment because of their gender identity. Additionally,

nearly one-quarter (23%) of respondents reported that they did not seek the health care

they needed in the year prior to completing the survey due to fear of being mistreated as a

transgender person, and 33% did not go to a health care provider when needed because

they could not aord it.

2015 U.S. TRANSGENDER SURVEY

6

The Compounding Impact of Other

Forms of Discrimination

When respondents’ experiences are examined by race and ethnicity, a clear and disturbing

pattern is revealed: transgender people of color experience deeper and broader patterns

of discrimination than white respondents and the U.S. population. While respondents in the

USTS sample overall were more than twice as likely as the U.S. population to be living in

poverty, people of color

, including Latino/a (43%), American Indian (41%), multiracial (40%),

and Black (38%) respondents, were more than three times as likely as the U.S. population

(12%) to be living in poverty. The unemployment rate among transgender people of color

(20%) was four times higher than the U.S. unemployment rate (5%). People of color also

experienced greater health disparities. While 1.4% of all respondents were living with HIV—

nearly five times the rate in the U.S. population (0.3%)—the rate among Black respondents

(6.7%) was substantially higher, and the rate for Black transgender women was a staggering

19%.

Undocumented respondents were also more likely to face severe economic hardship and

violence than other respondents. In the year prior to completing the survey, nearly one-

quarter (24%) of undocumented respondents were physically attacked. Additionally, one-

half (50%) of undocumented respondents have experienced homelessness in their lifetime,

and 68% have faced intimate partner violence.

Respondents with disabilities also faced higher rates of economic instability and

mistreatment. Nearly one-quarter (24%) were unemployed, and 45% were living in poverty.

Transgender people with disabilities were more likely to be currently experiencing serious

psychological distress (59%) and more likely to have attempted suicide in their lifetime

(54%). They also reported higher rates of mistreatment by health care providers (42%).

Increased Visibility and Growing

Acceptance

Despite the undeniable hardships faced by transgender people, respondents’ experiences

also show some of the positive impacts of growing visibility and acceptance of transgender

people in the United States.

One such indication is that an unprecedented number of transgender people—nearly

28,000—completed the survey, more than four times the number of respondents in the

2008–09 NTDS. This number of transgender people who elevated their voices reflects the

historic growth in visibility that the transgender community has seen in recent years.

Additionally, this growing visibility has lifted up not only the voices of transgender men and

women, but also people who are non-binary, which is a term that is often used to describe

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

7

people whose gender identity is not exclusively male or female, including those who

identify as having no gender, a gender other than male or female, or more than one gender.

With non-binary people making up over one-third of the sample, the need for advocacy that

is inclusive of all identities in the transgender community is clearer than ever.

Respondents’ experiences also suggest growing acceptance by family members,

colleagues, classmates, and other people in their lives. More than half (60%) of respondents

who were out to their immediate family reported that their family was supportive of them

as a transgender person. More than two-thirds (68%) of those who were out to their

coworkers reported that their coworkers were supportive. Of students who were out to

their classmates, more than half (56%) reported that their classmates supported them as a

transgender person.

O

verall, the report provides evidence of hardships and barriers faced by

transgender people on a day-to-day basis. It portrays the challenges that

transgender people must overcome and the complex systems that they are

often forced to navigate in multiple areas of their lives in order to survive and thrive. Given

this evidence, governmental and private institutions throughout the United States should

address these disparities and ensure that transgender people are able to live fulfilling

lives in an inclusive society. This includes eliminating barriers to quality, aordable health

care, putting an end to discrimination in schools, the workplace, and other areas of public

life, and creating systems of support at the municipal, state, and federal levels that meet

the needs of transgender people and reduce the hardships they face. As the national

conversation about transgender people continues to evolve, public education eorts to

improve understanding and acceptance of transgender people are crucial. The rates of

suicide attempts, poverty, unemployment, and violence must serve as an immediate call

to action, and their reduction must be a priority. Despite policy improvements over the

last several years, it is clear that there is still much work ahead to ensure that transgender

people can live without fear of discrimination and violence.

2015 U.S. TRANSGENDER SURVEY

8

Overview of Key Findings

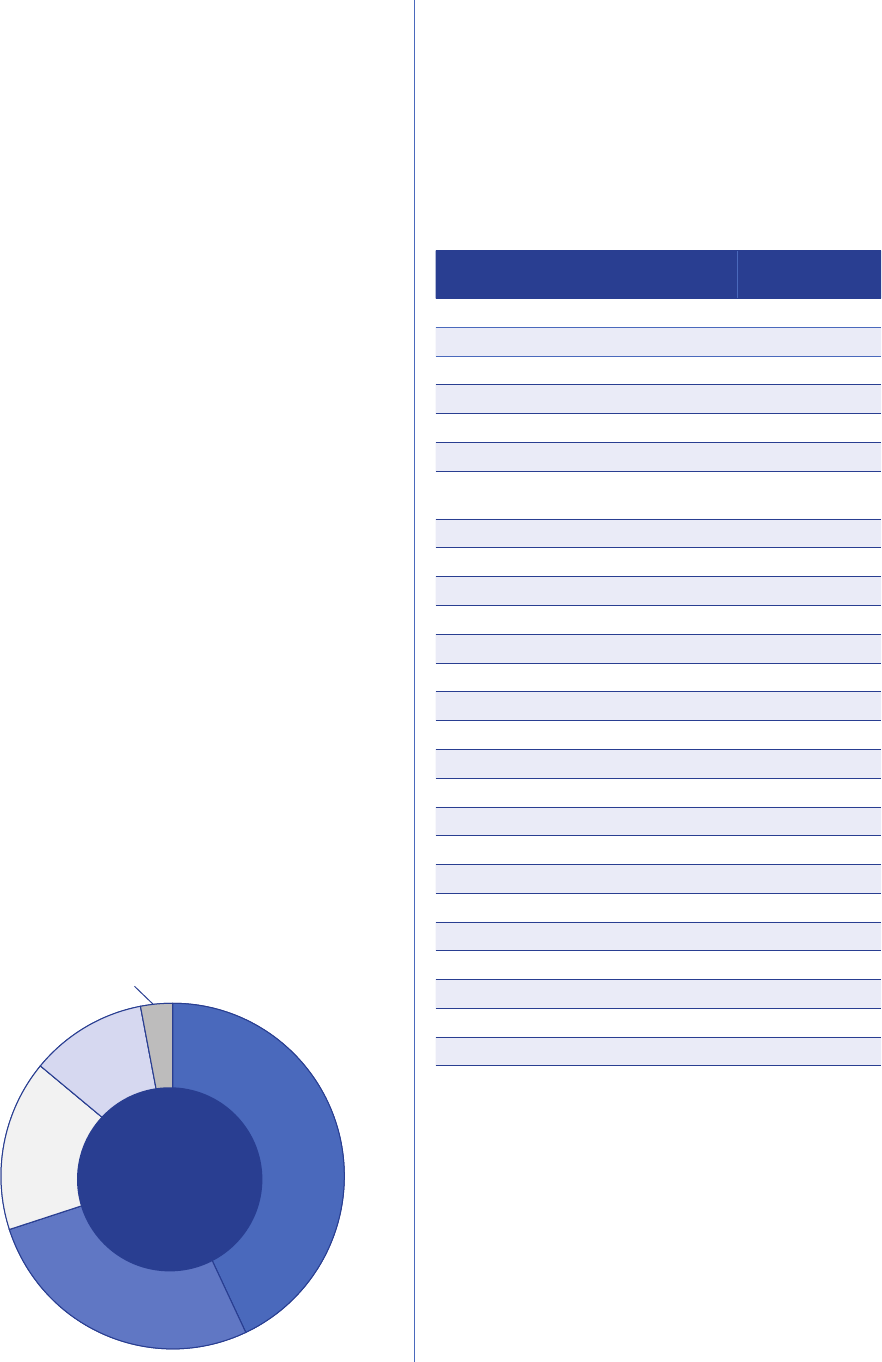

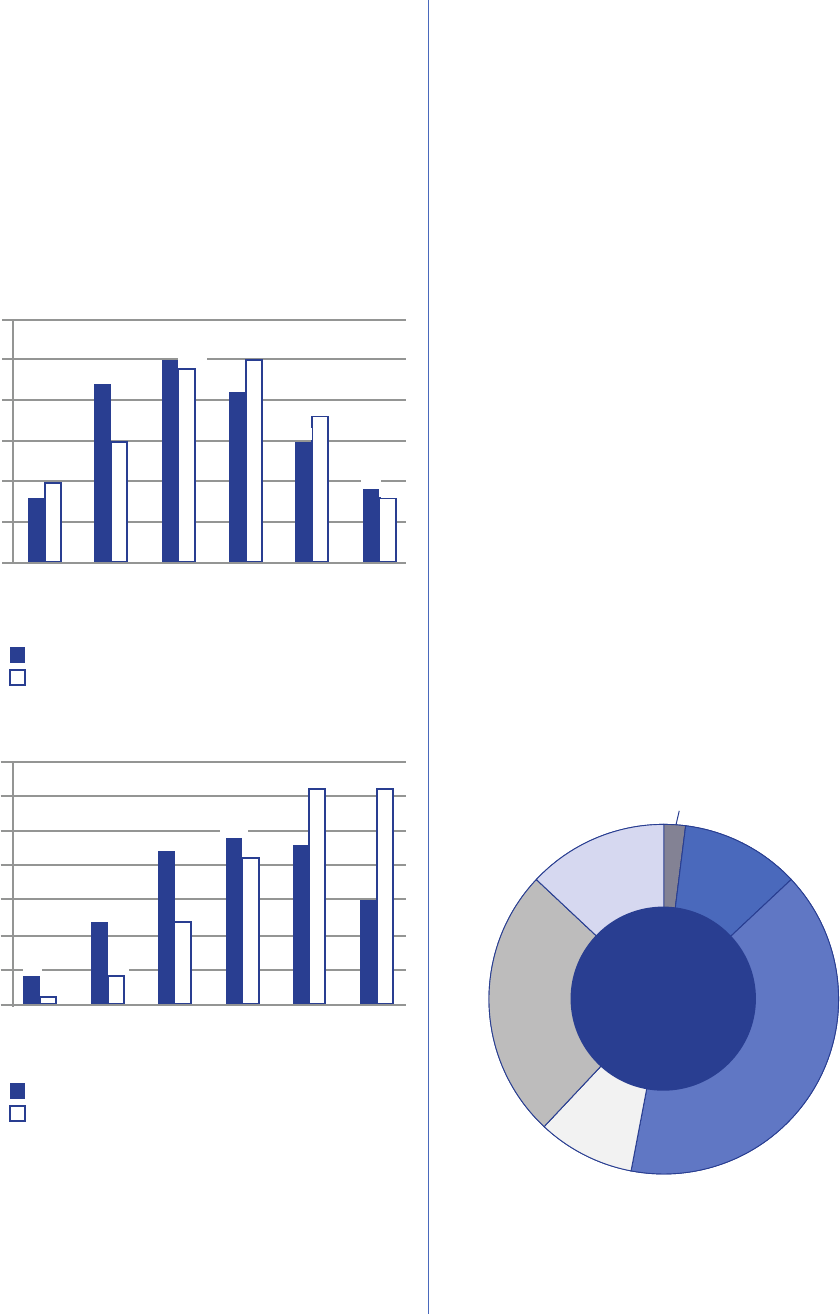

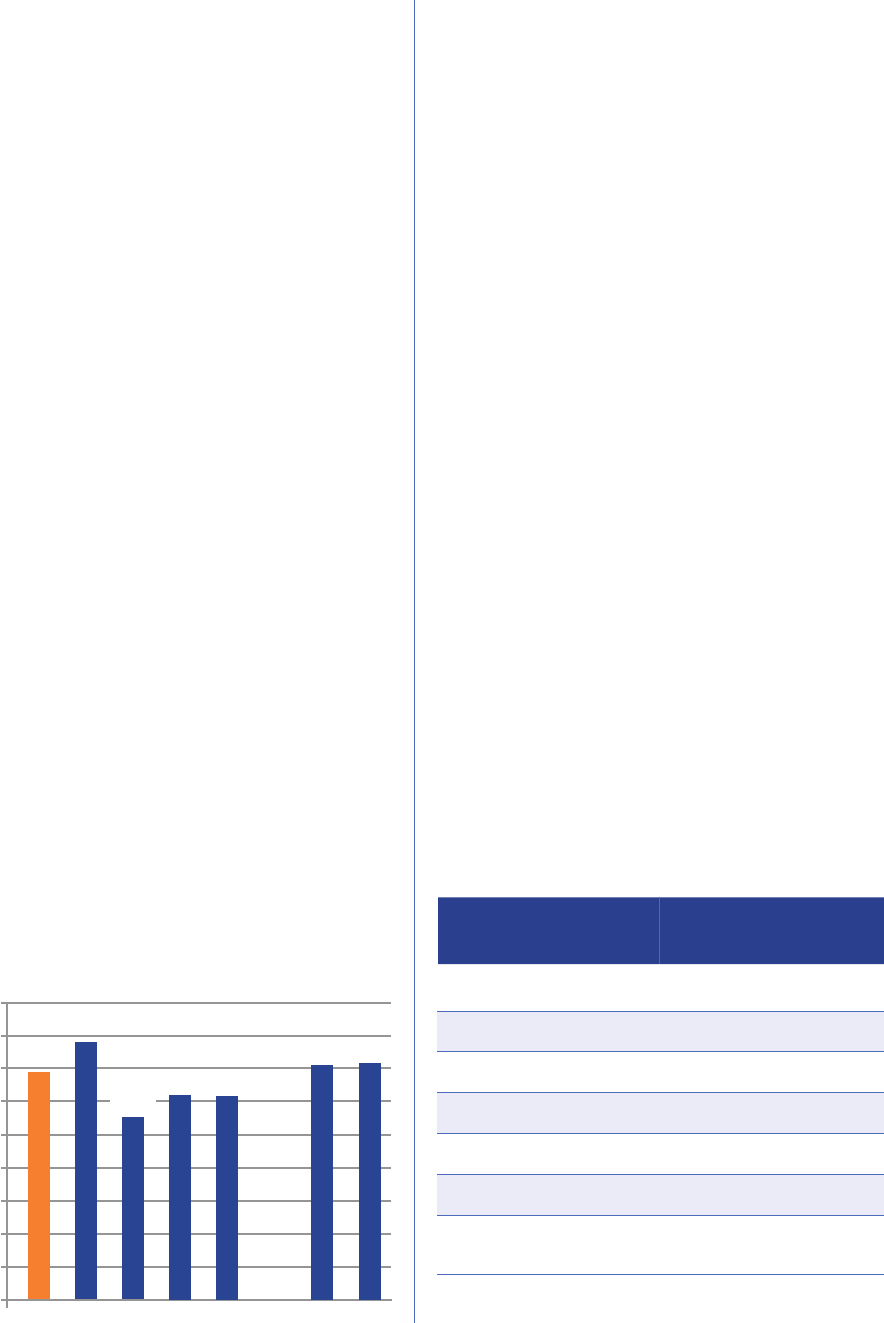

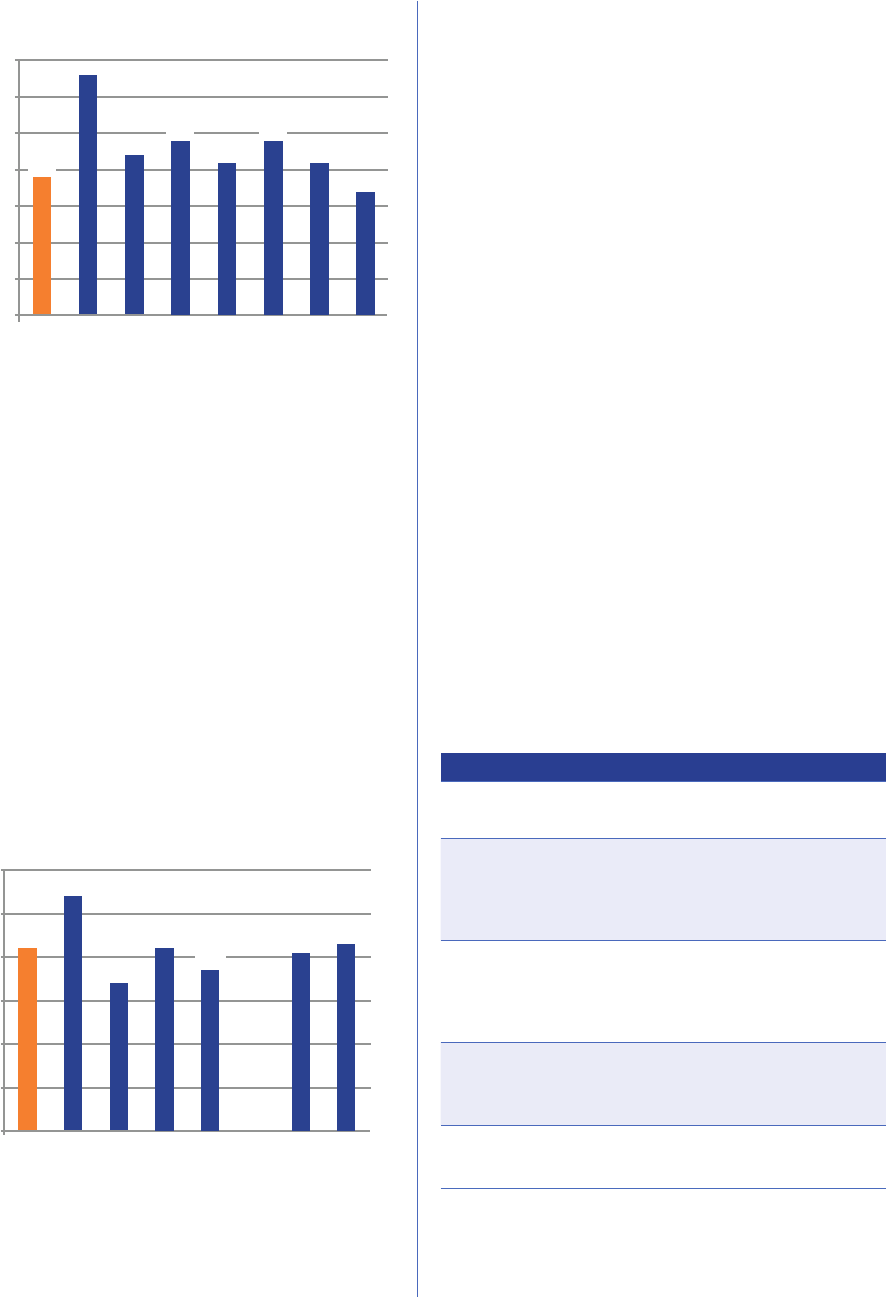

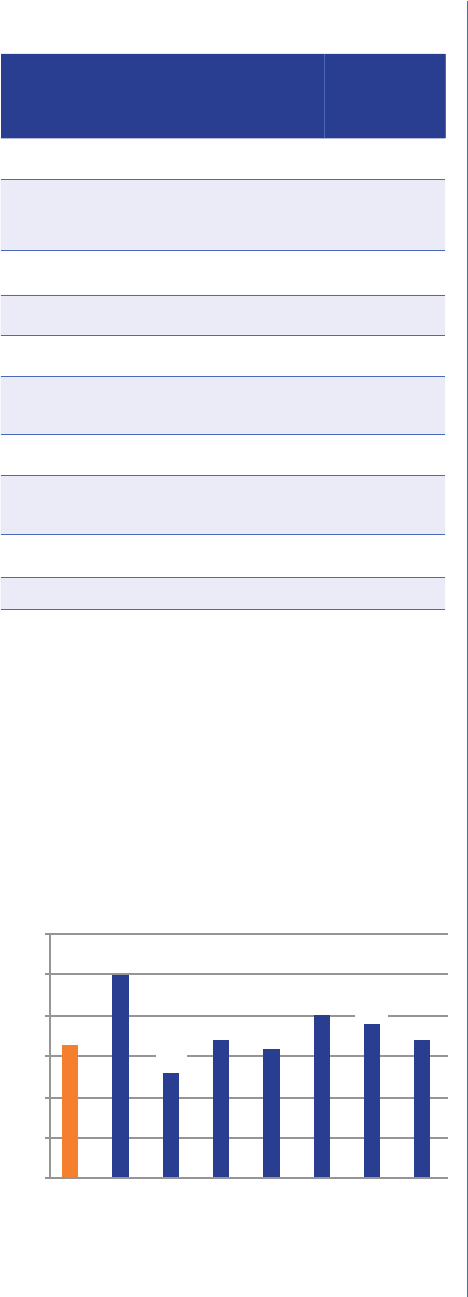

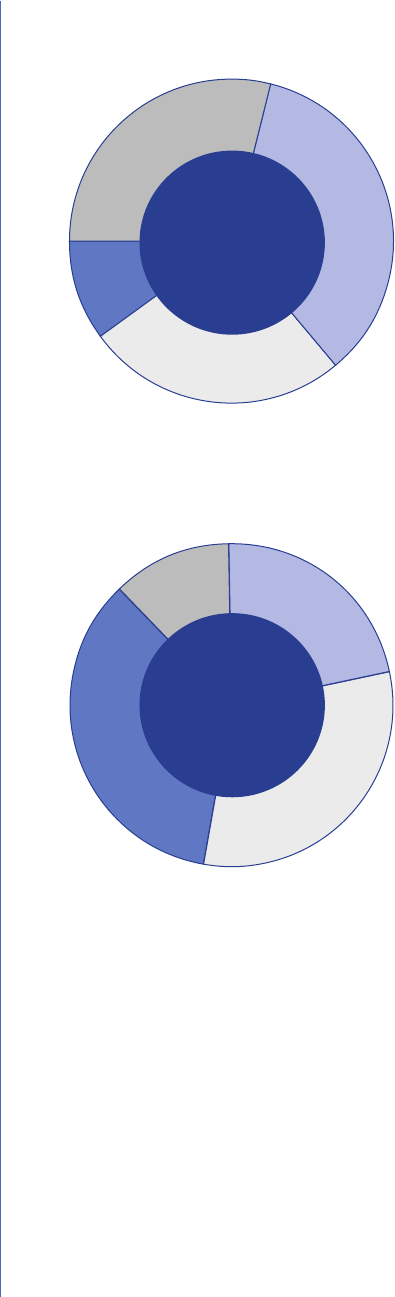

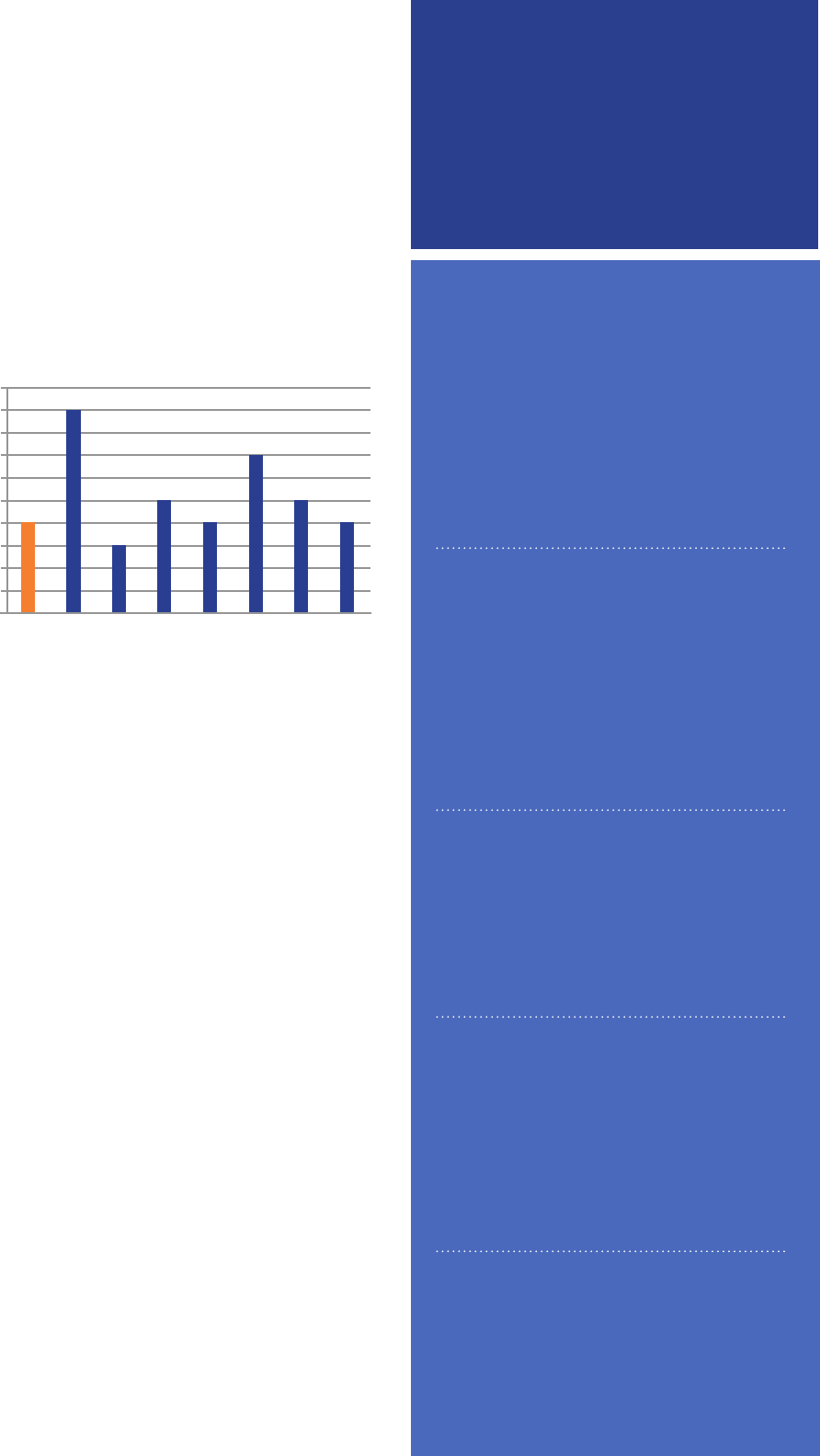

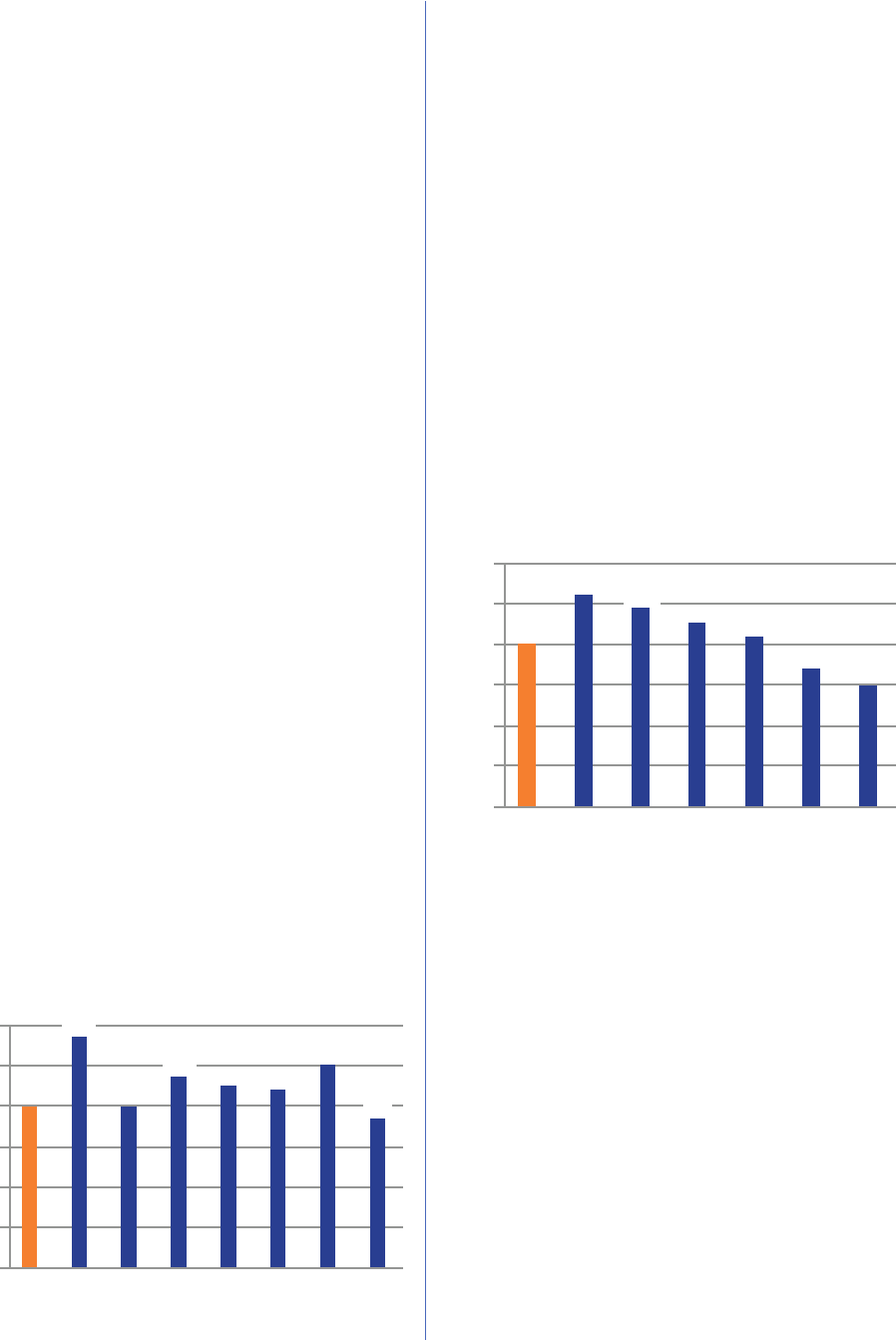

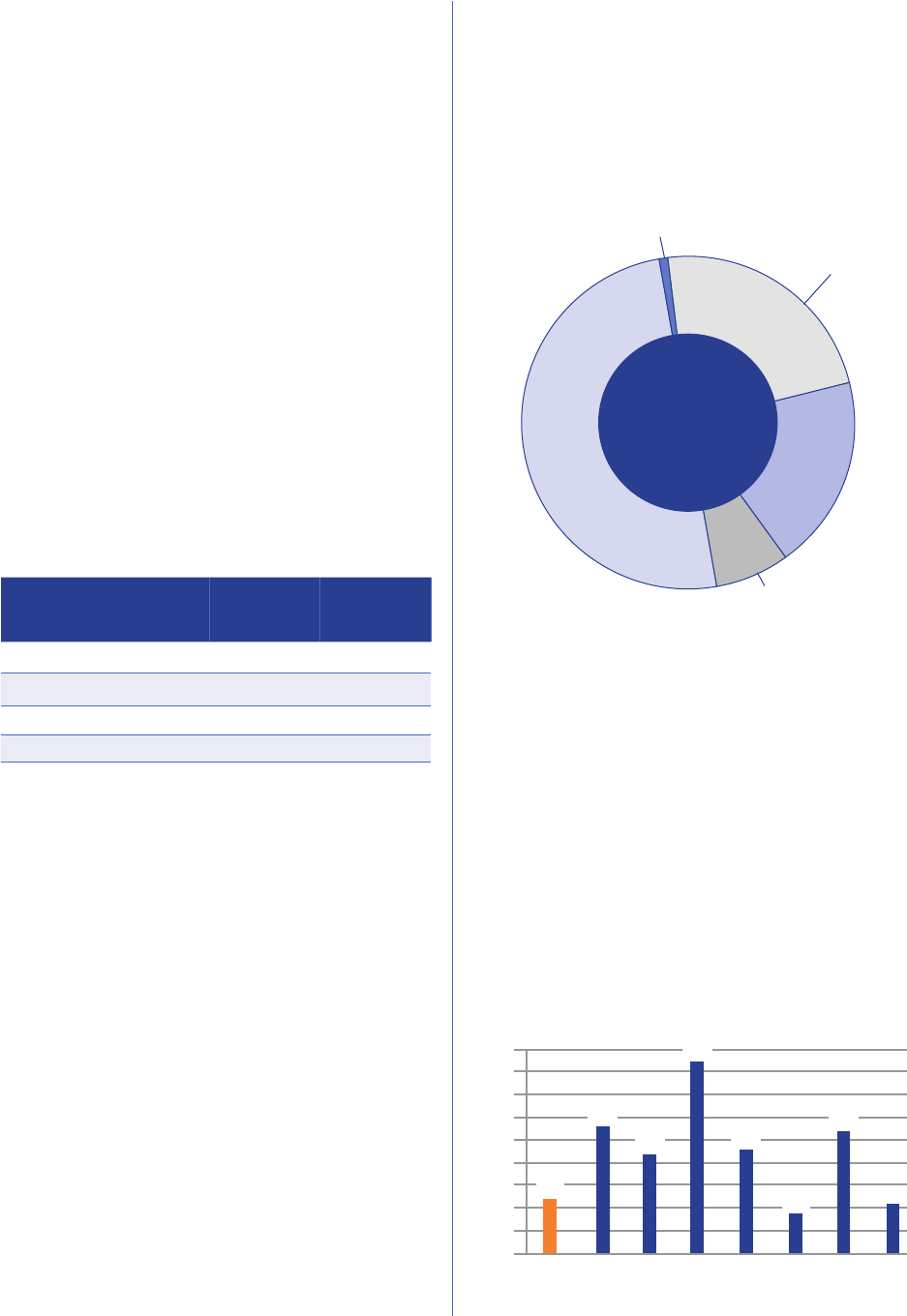

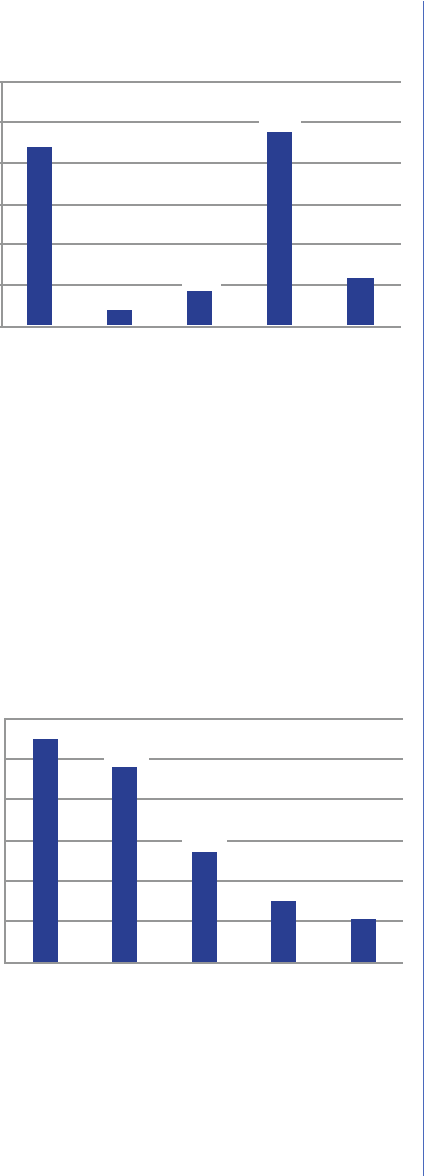

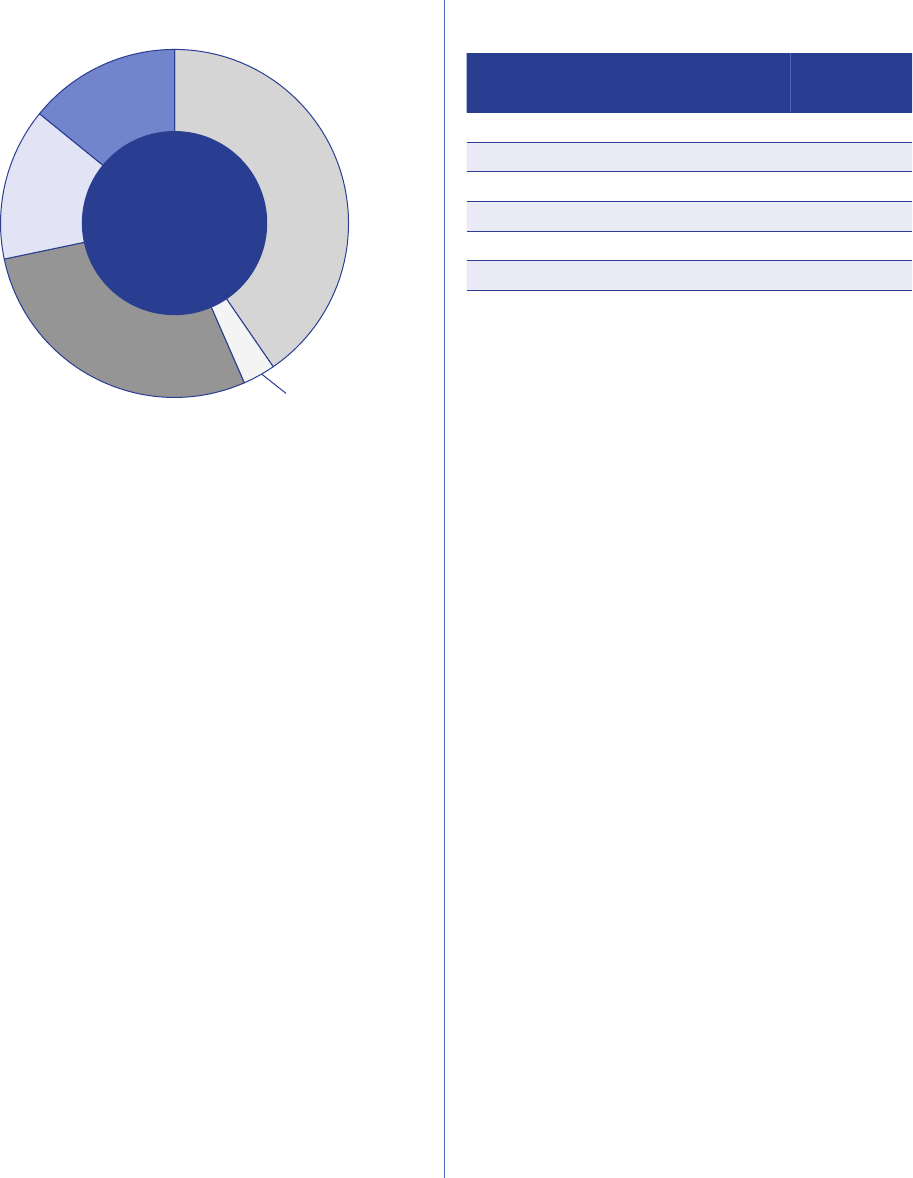

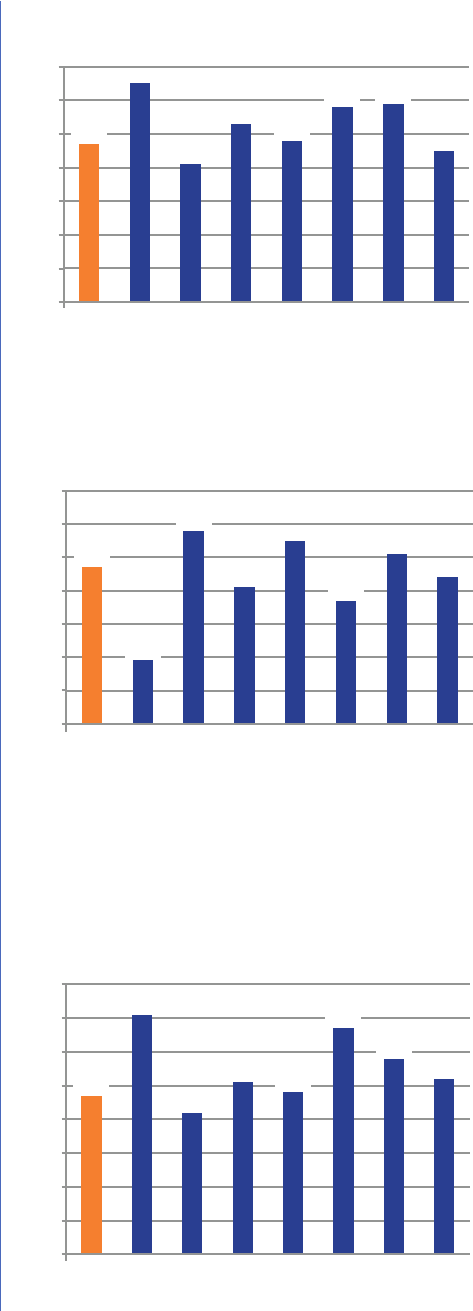

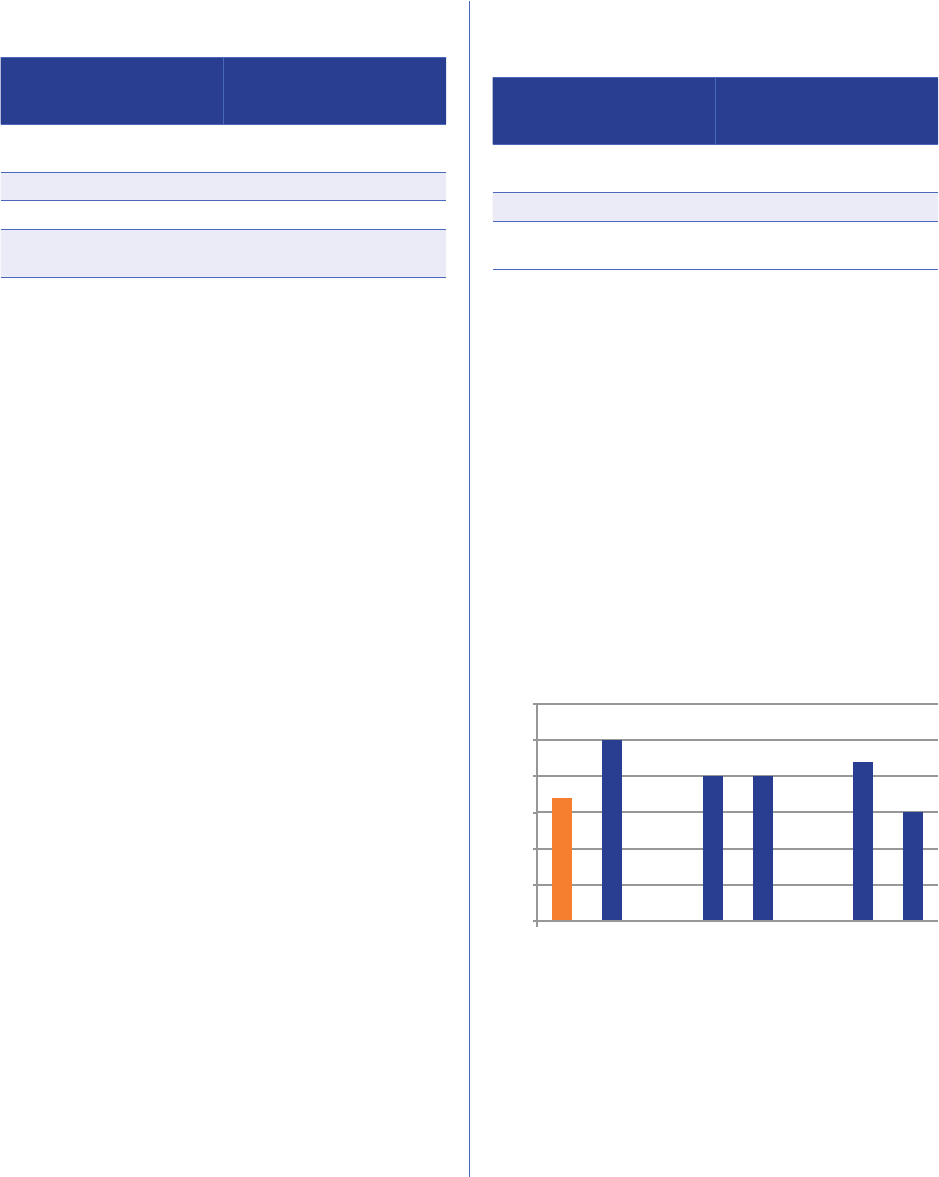

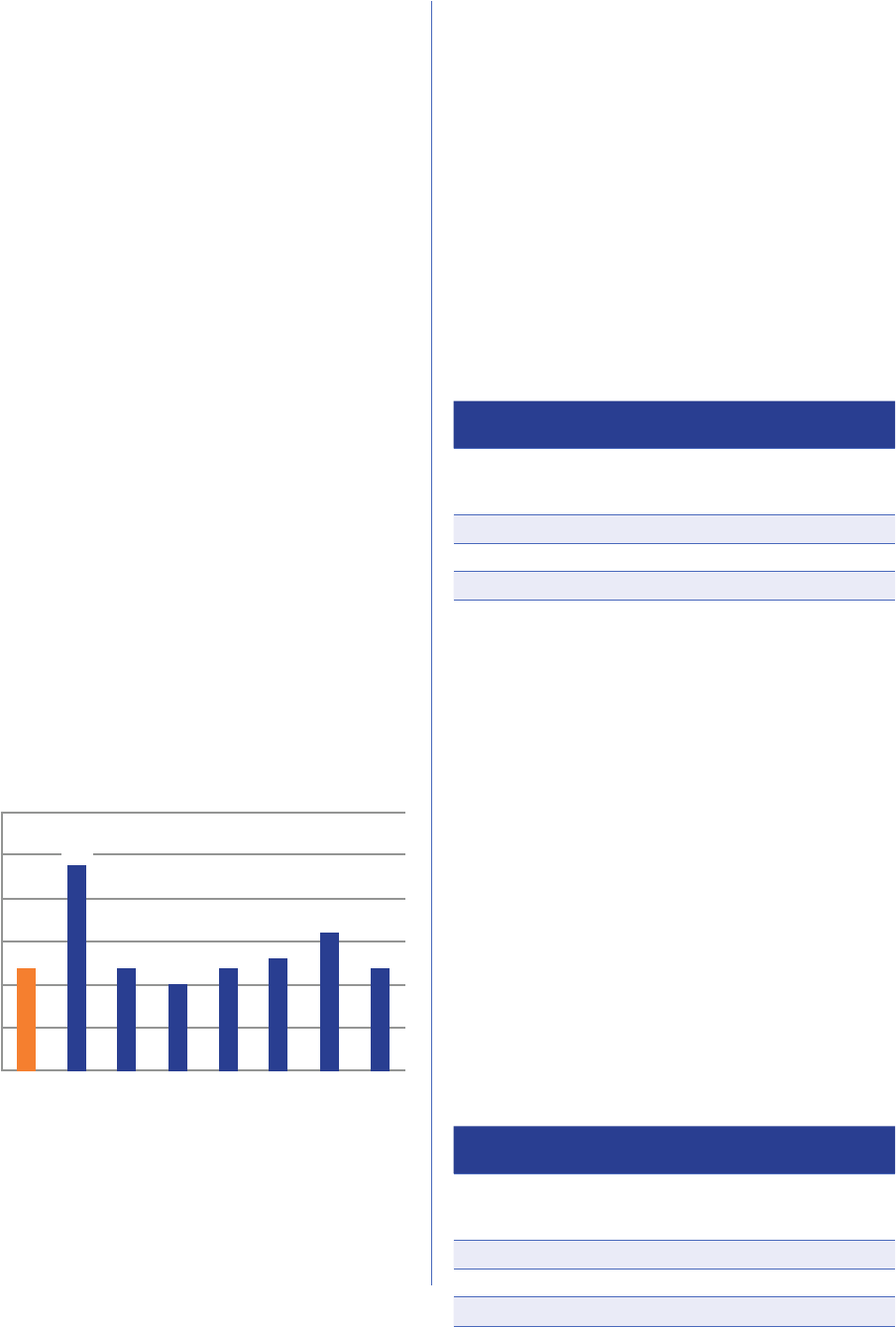

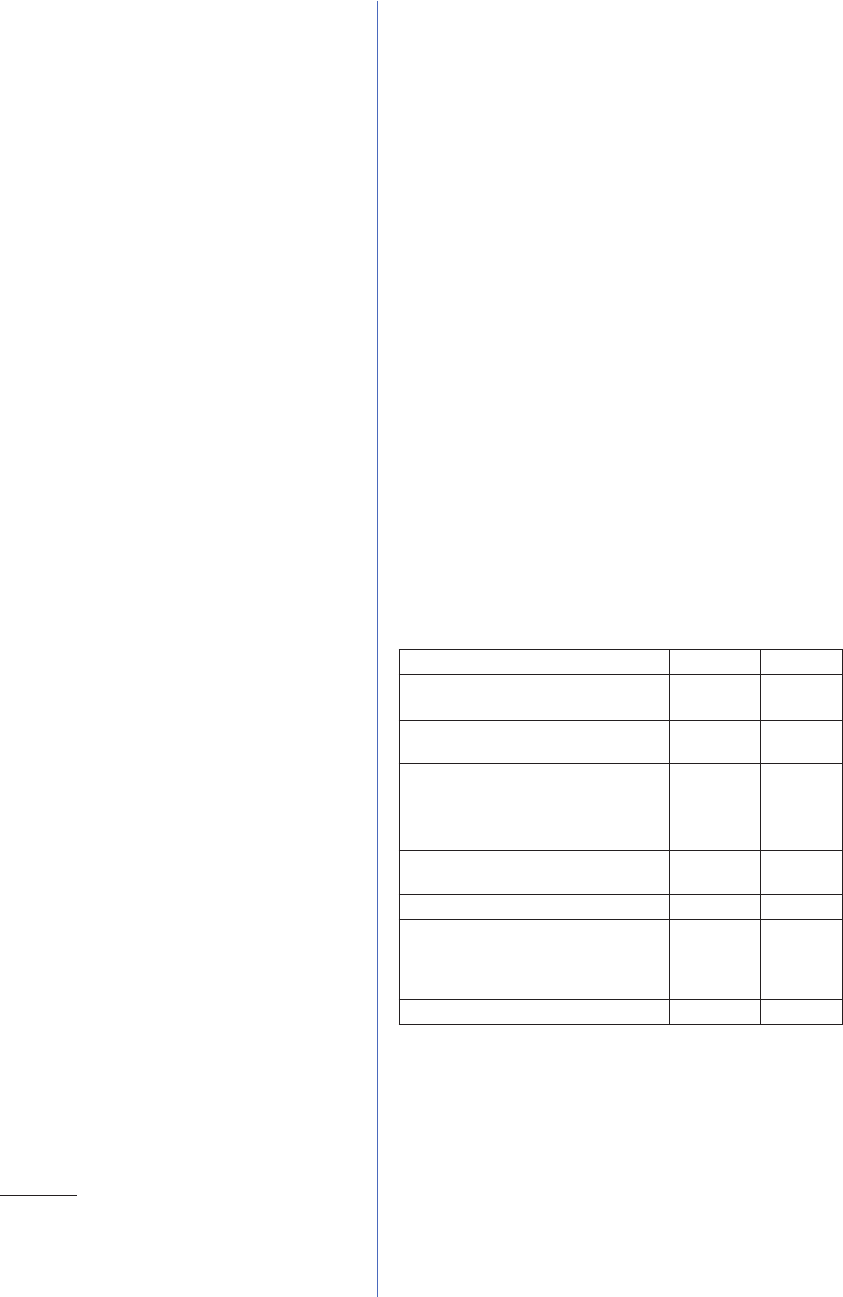

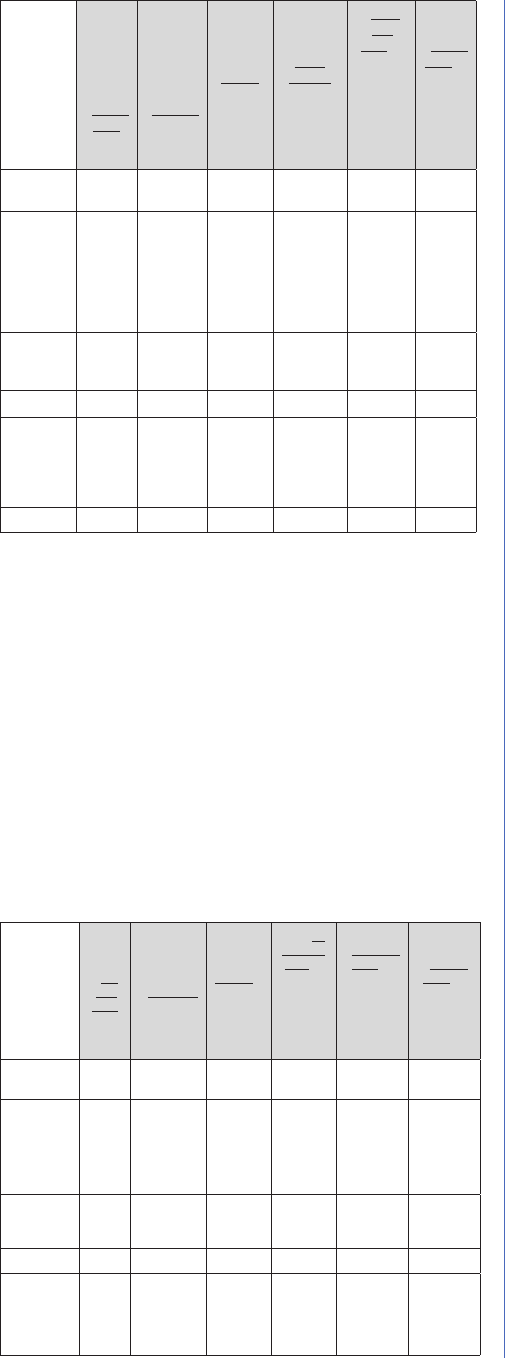

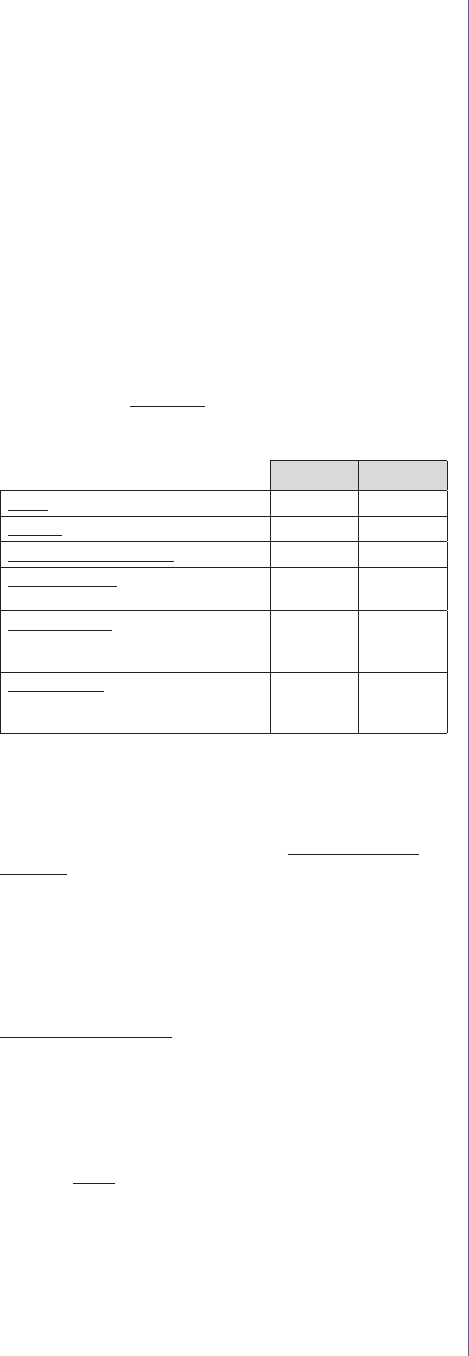

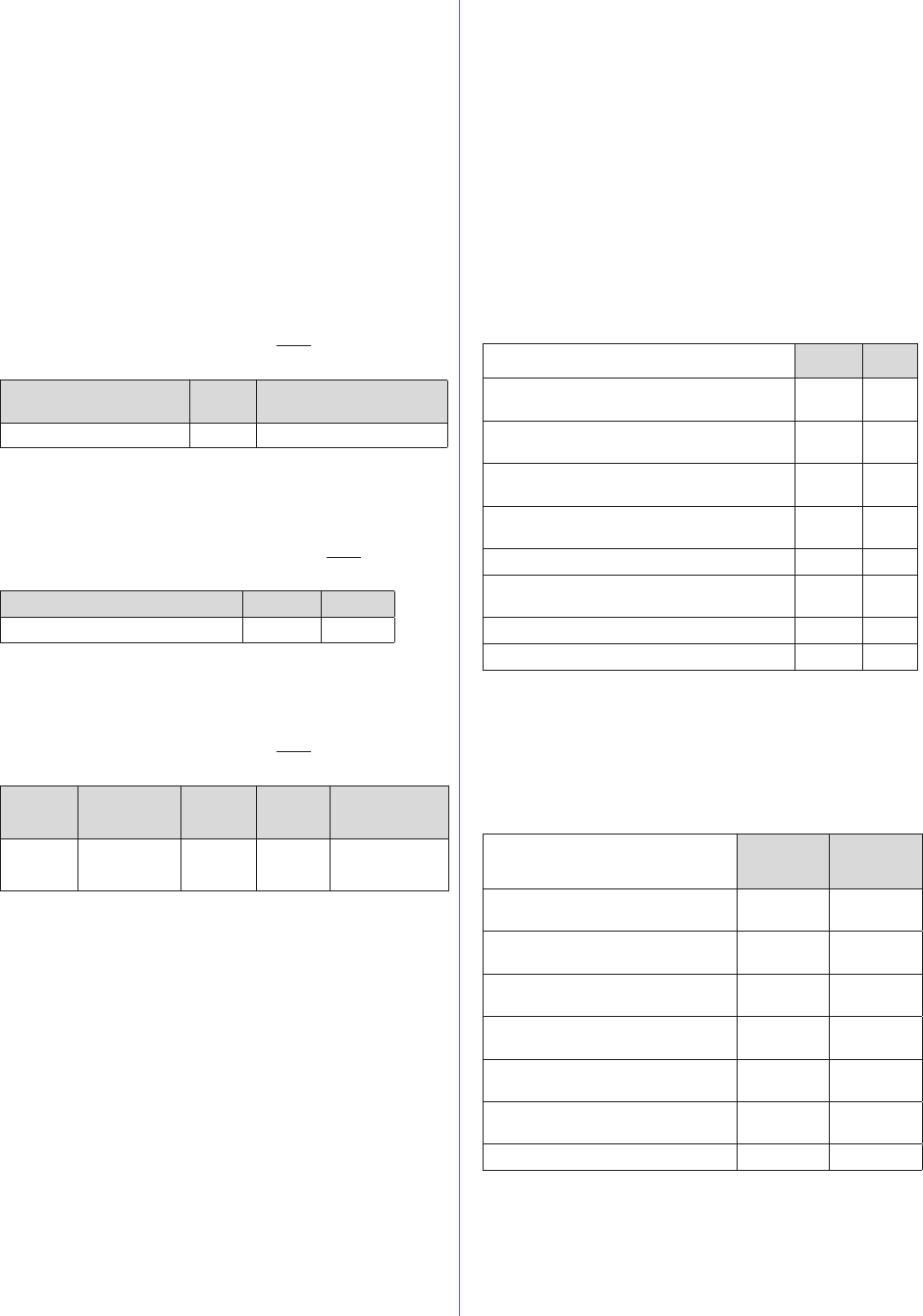

Family Life and Faith Communities

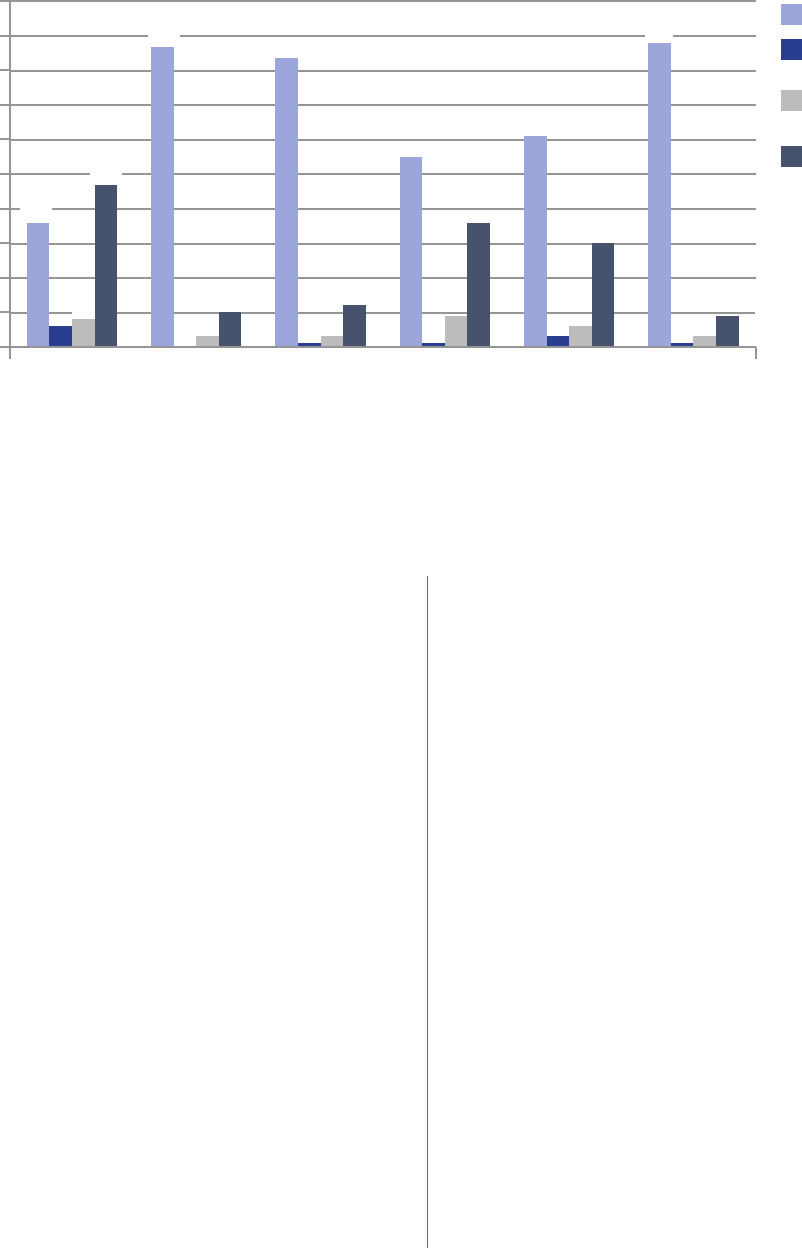

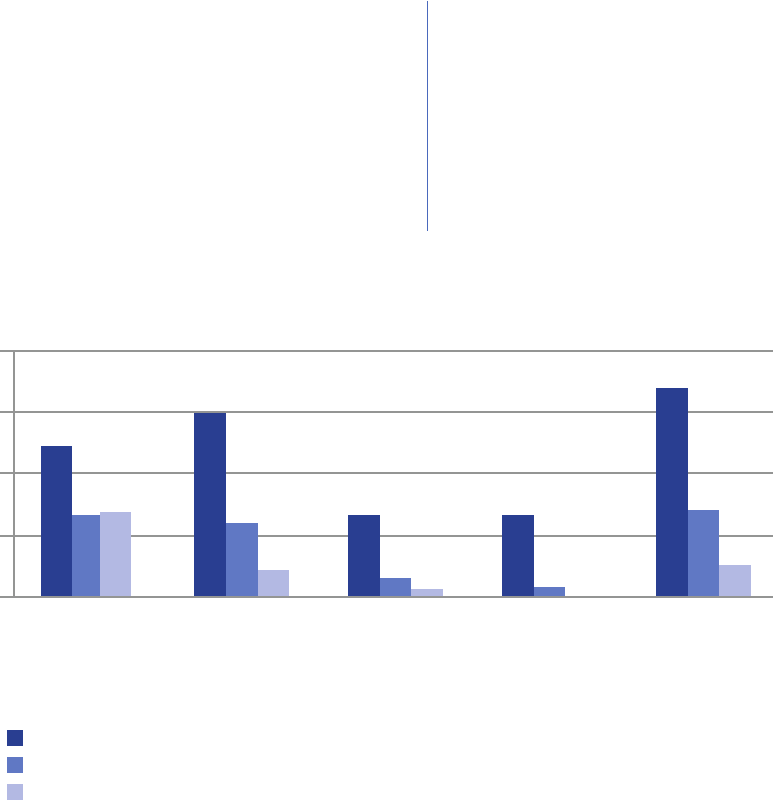

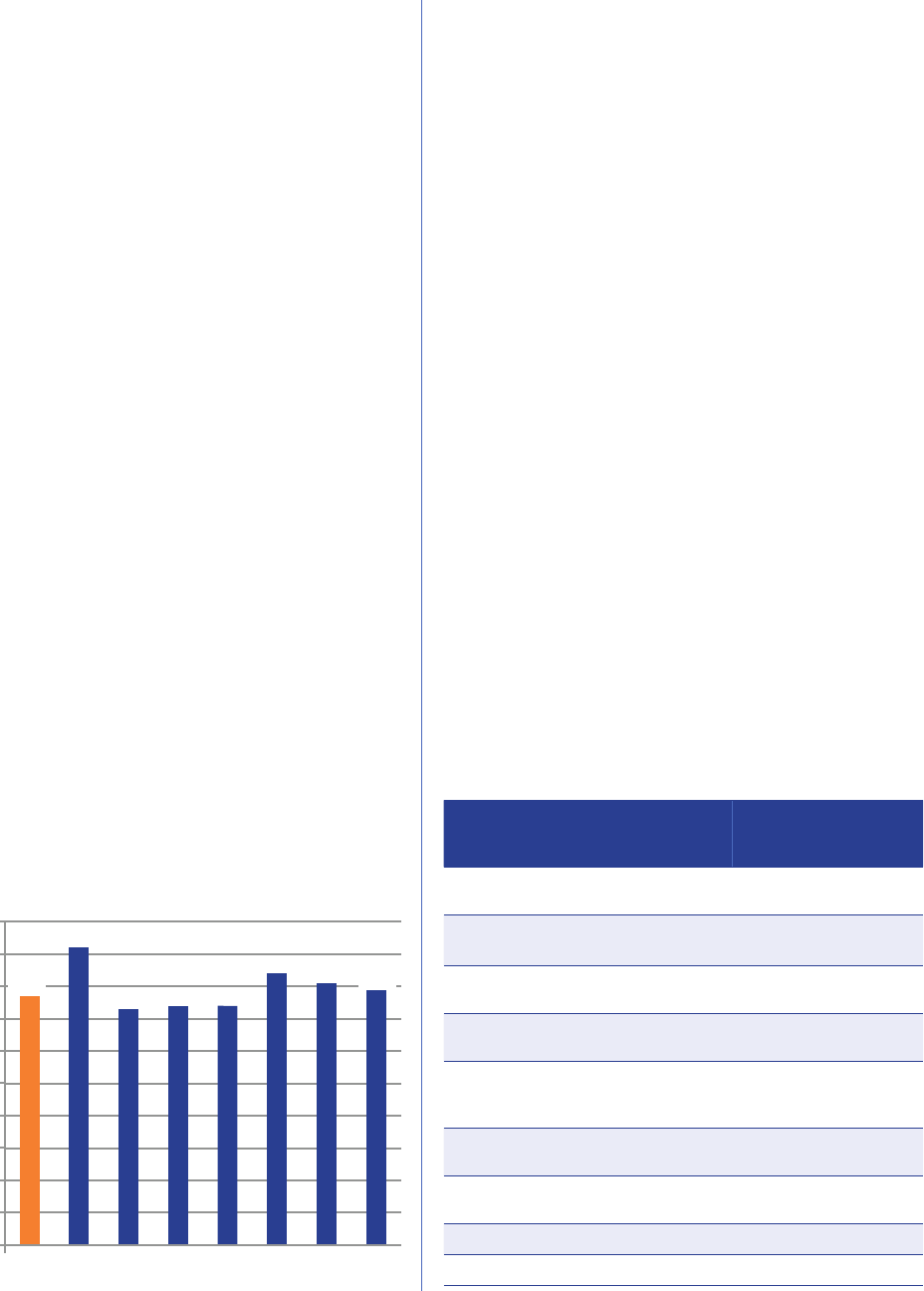

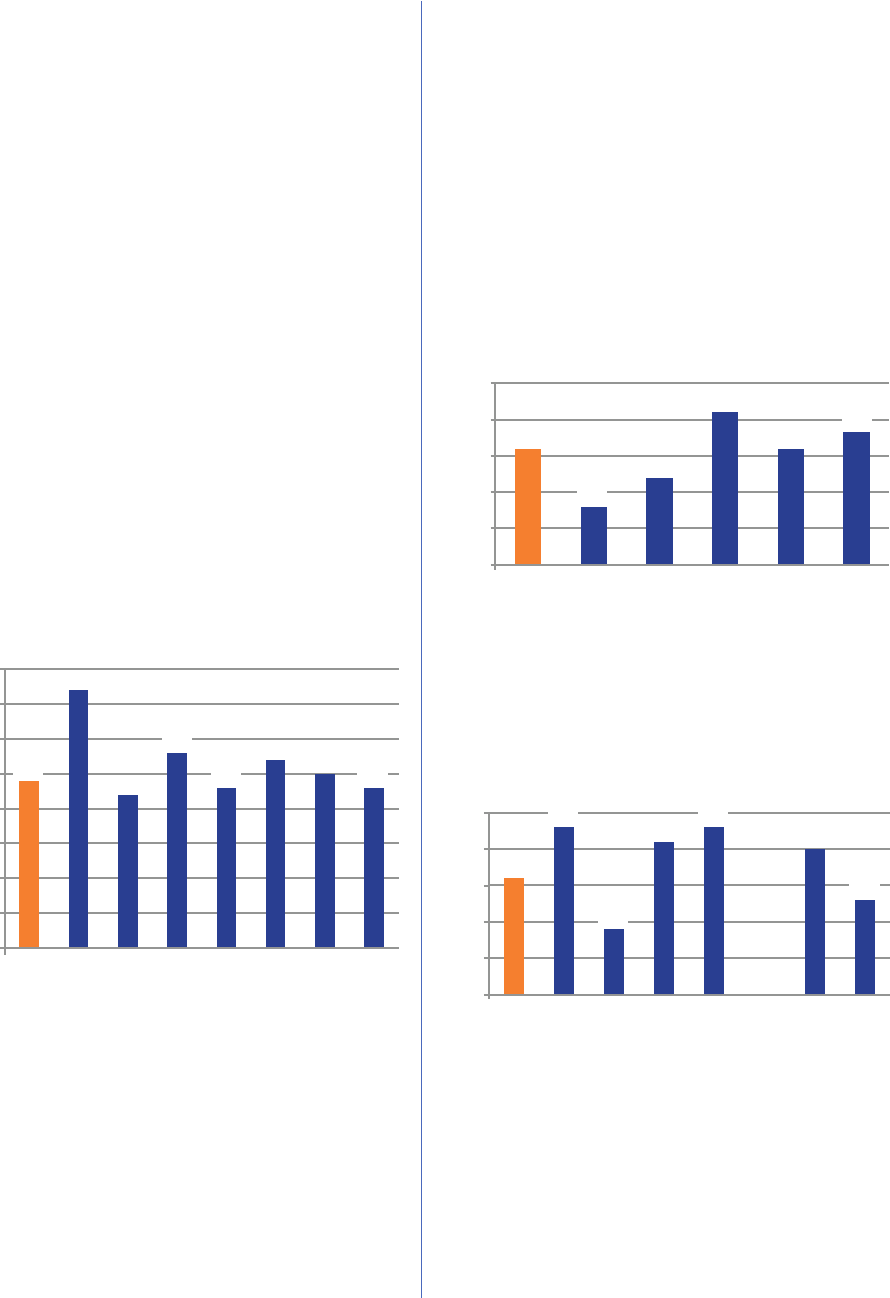

up with said that their family was generally supportive of their transgender identity,

while 18% said that their family was unsupportive, and 22% said that their family was

neither supportive nor unsupportive.

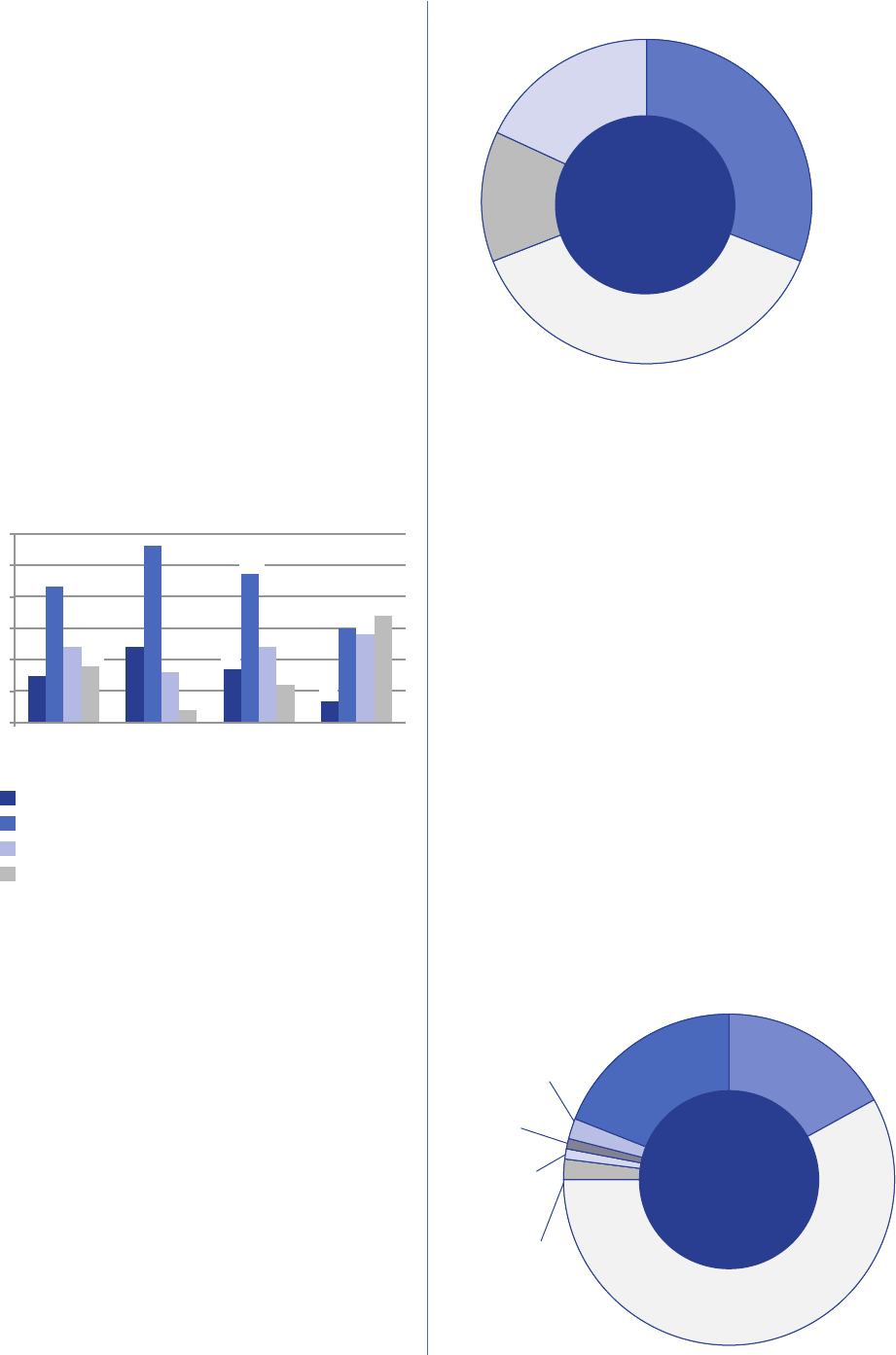

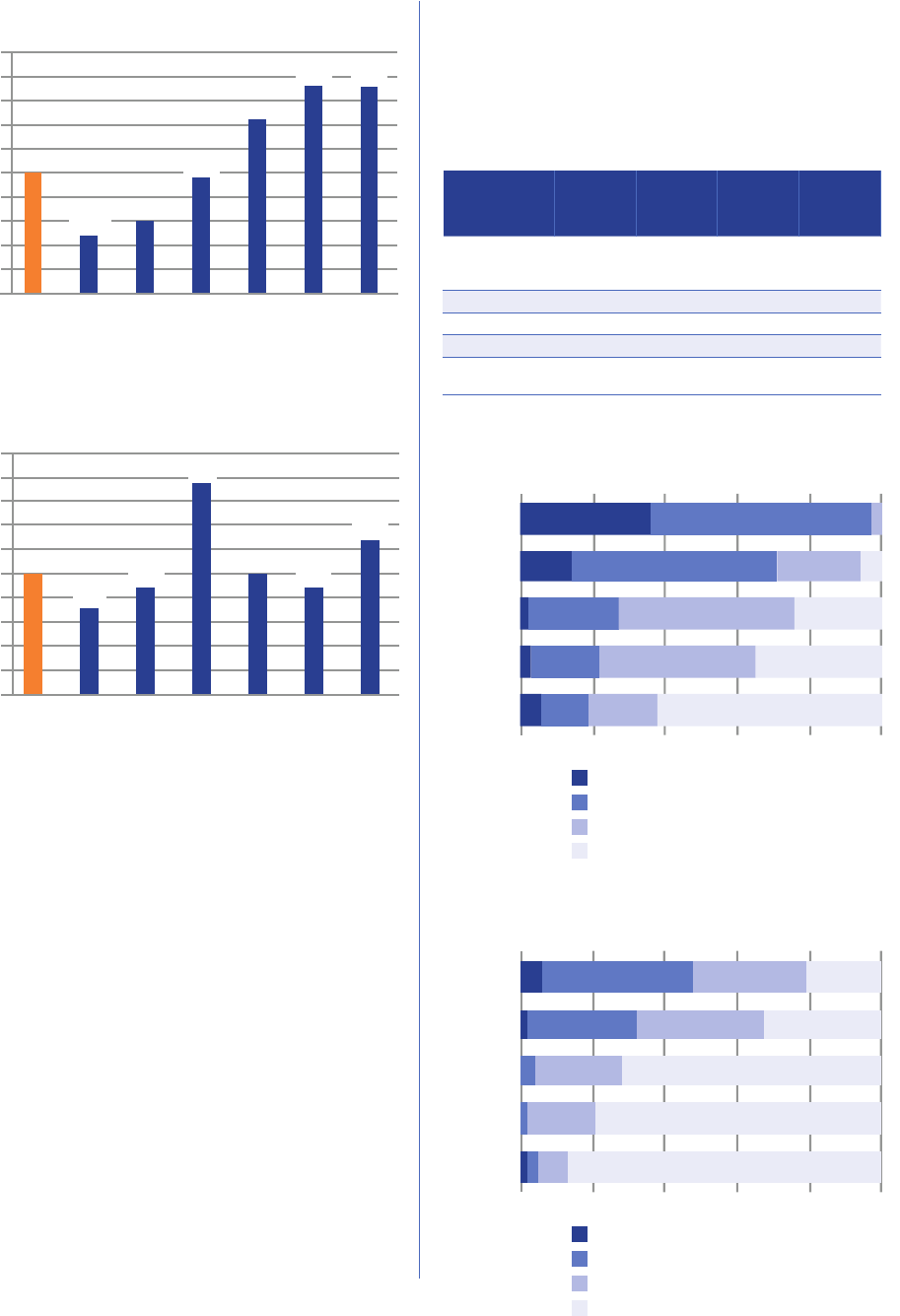

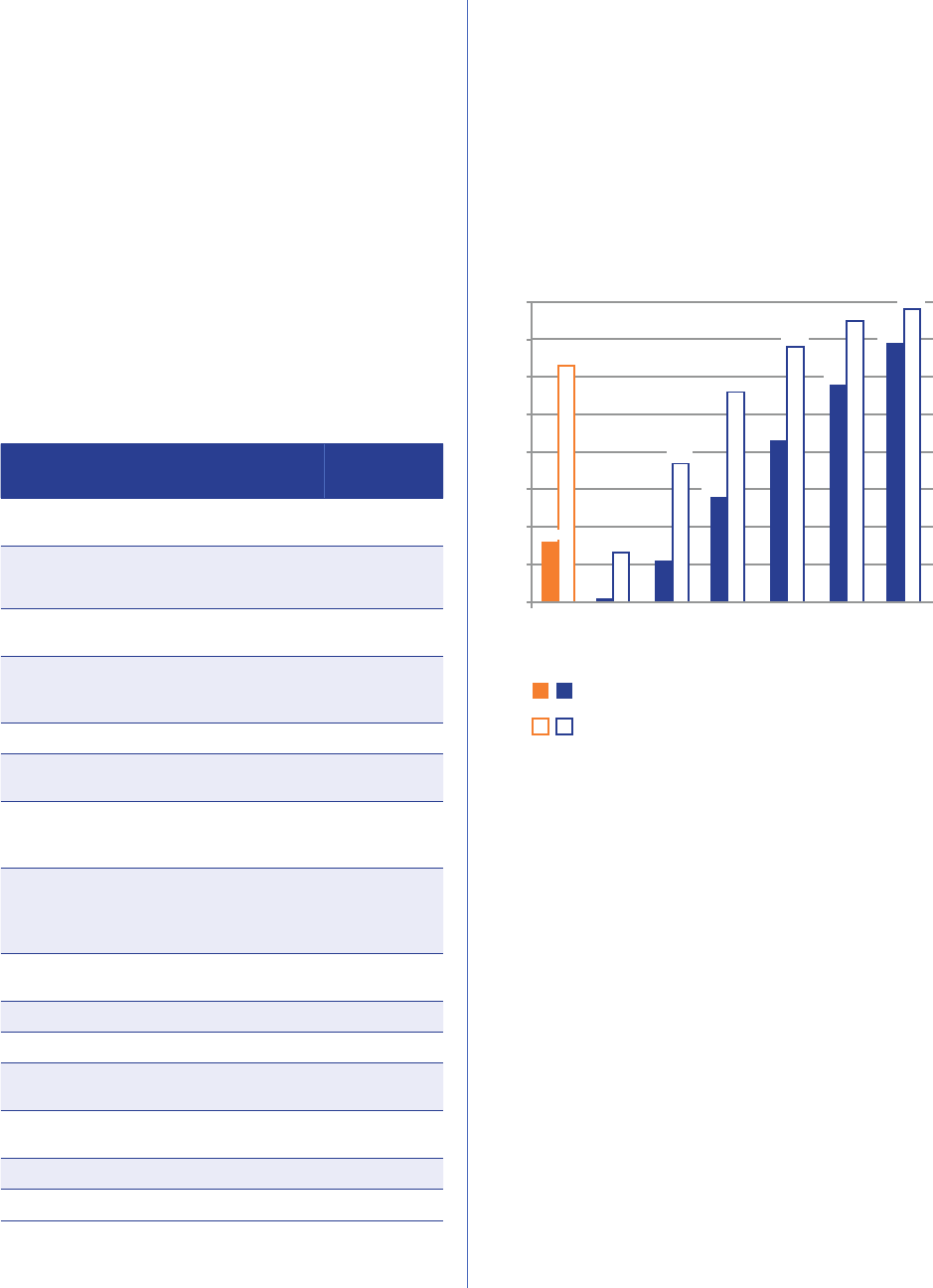

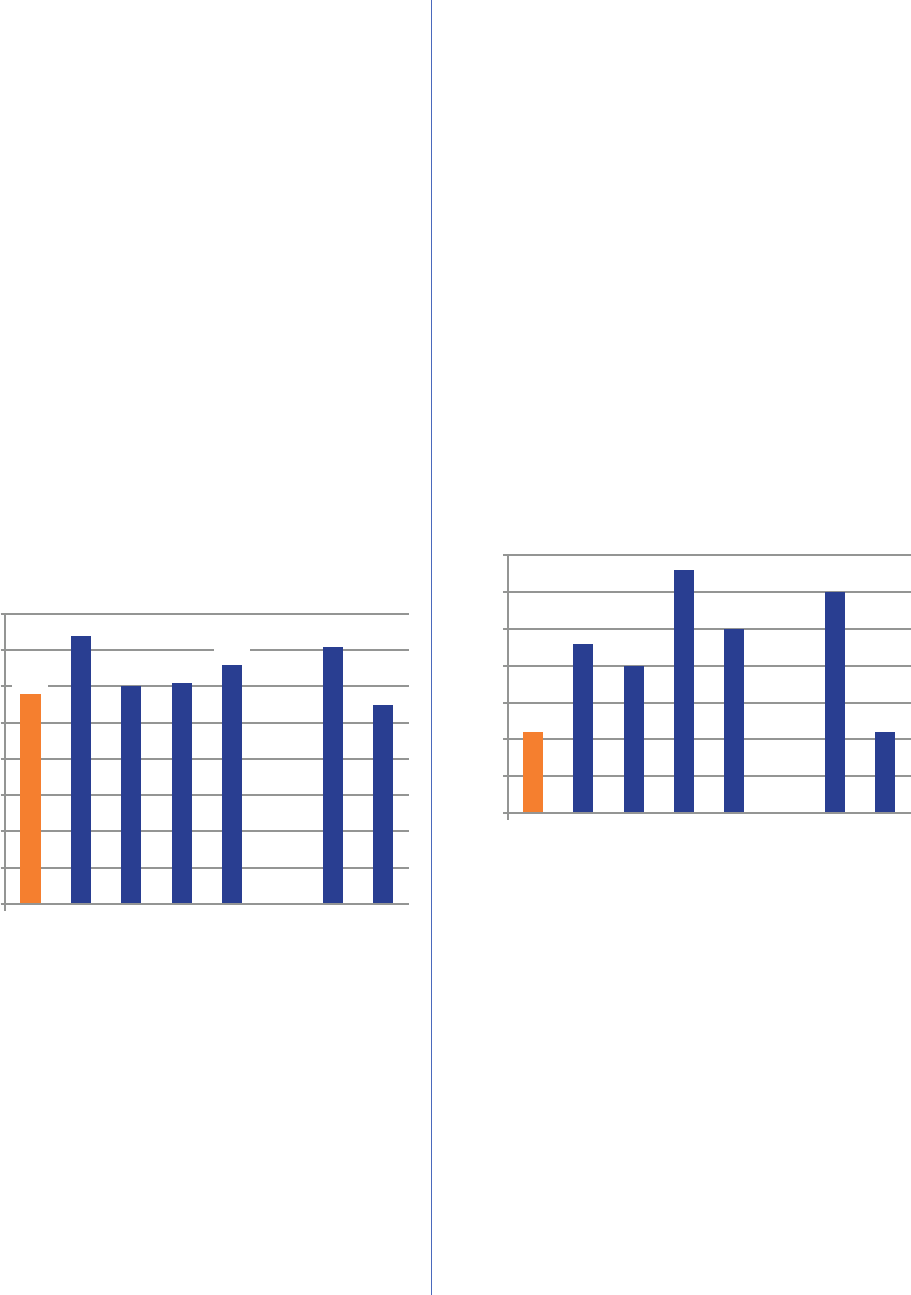

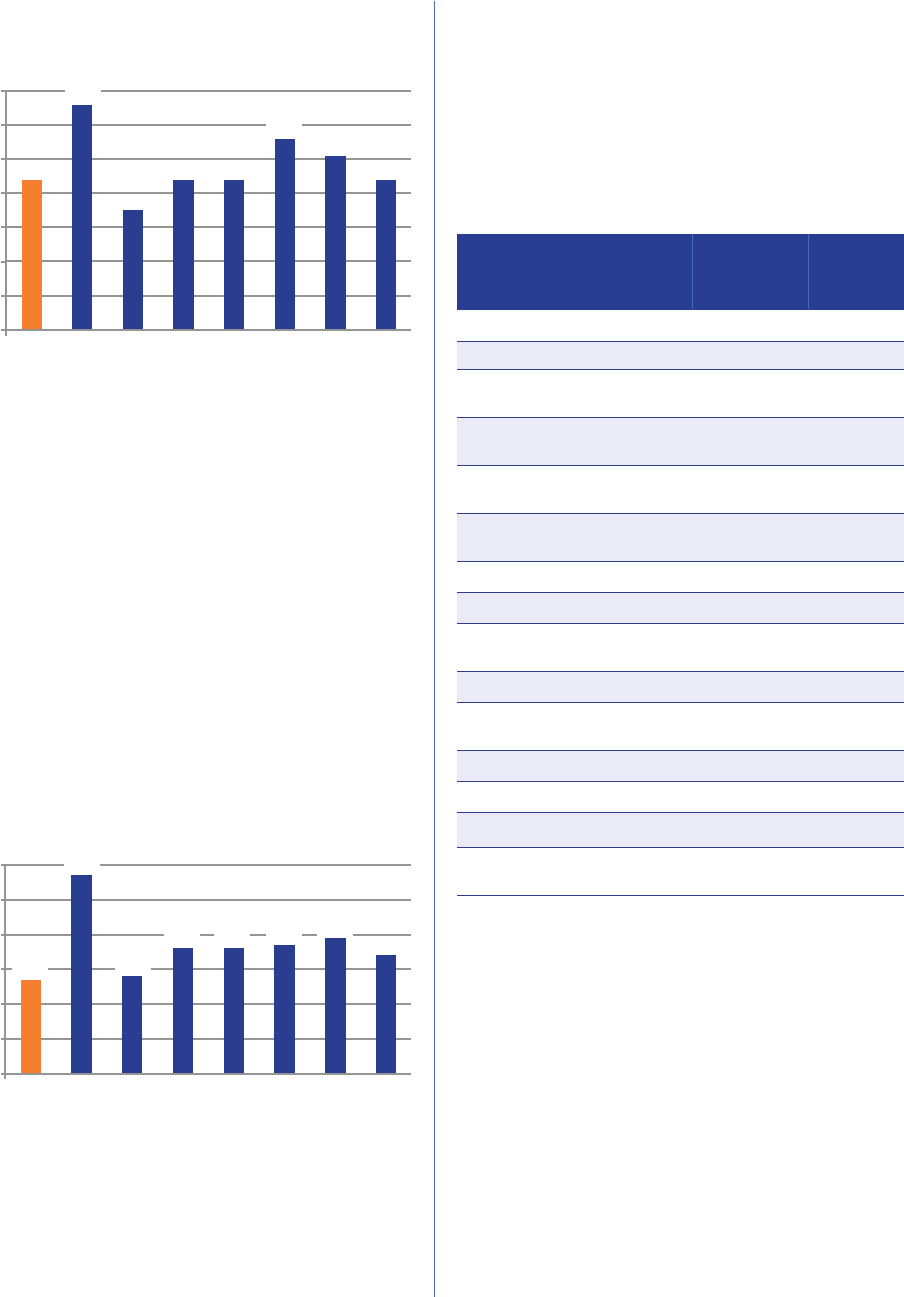

report a variety of negative experiences related to economic stability and health,

such as experiencing homelessness, attempting suicide, or experiencing serious

psychological distress.

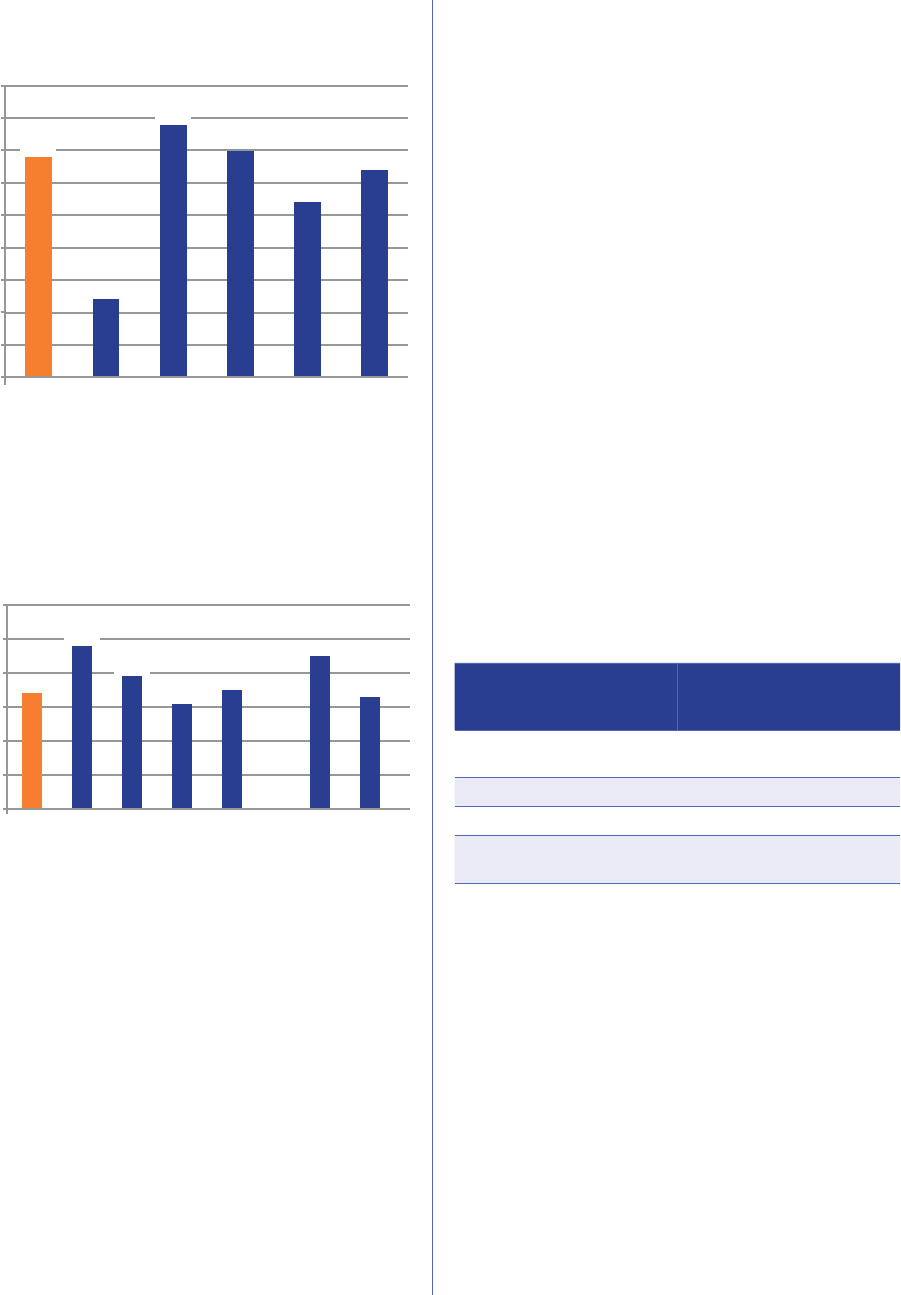

Experienced homelessness

Attempted suicide

Currently experiencing serious

psychological distress

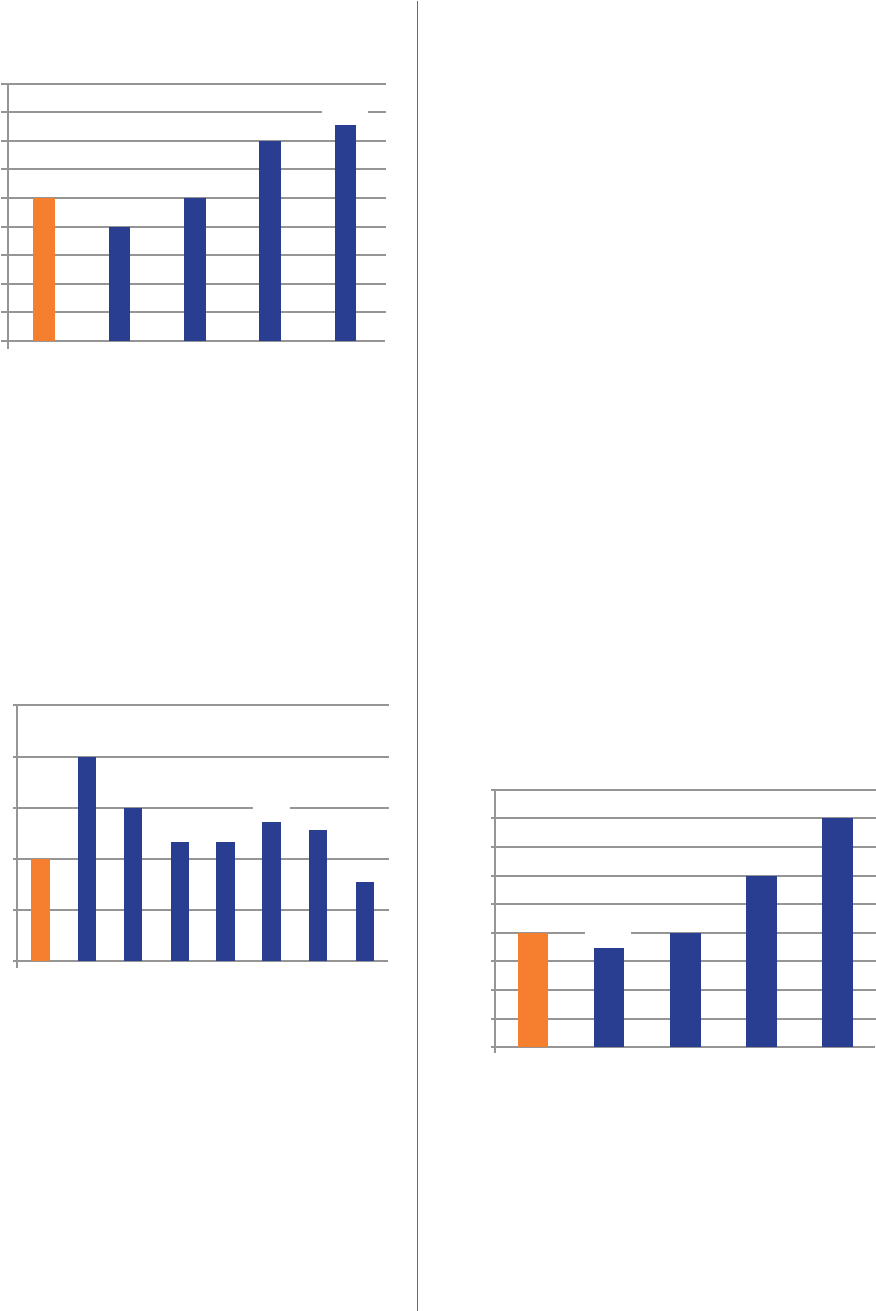

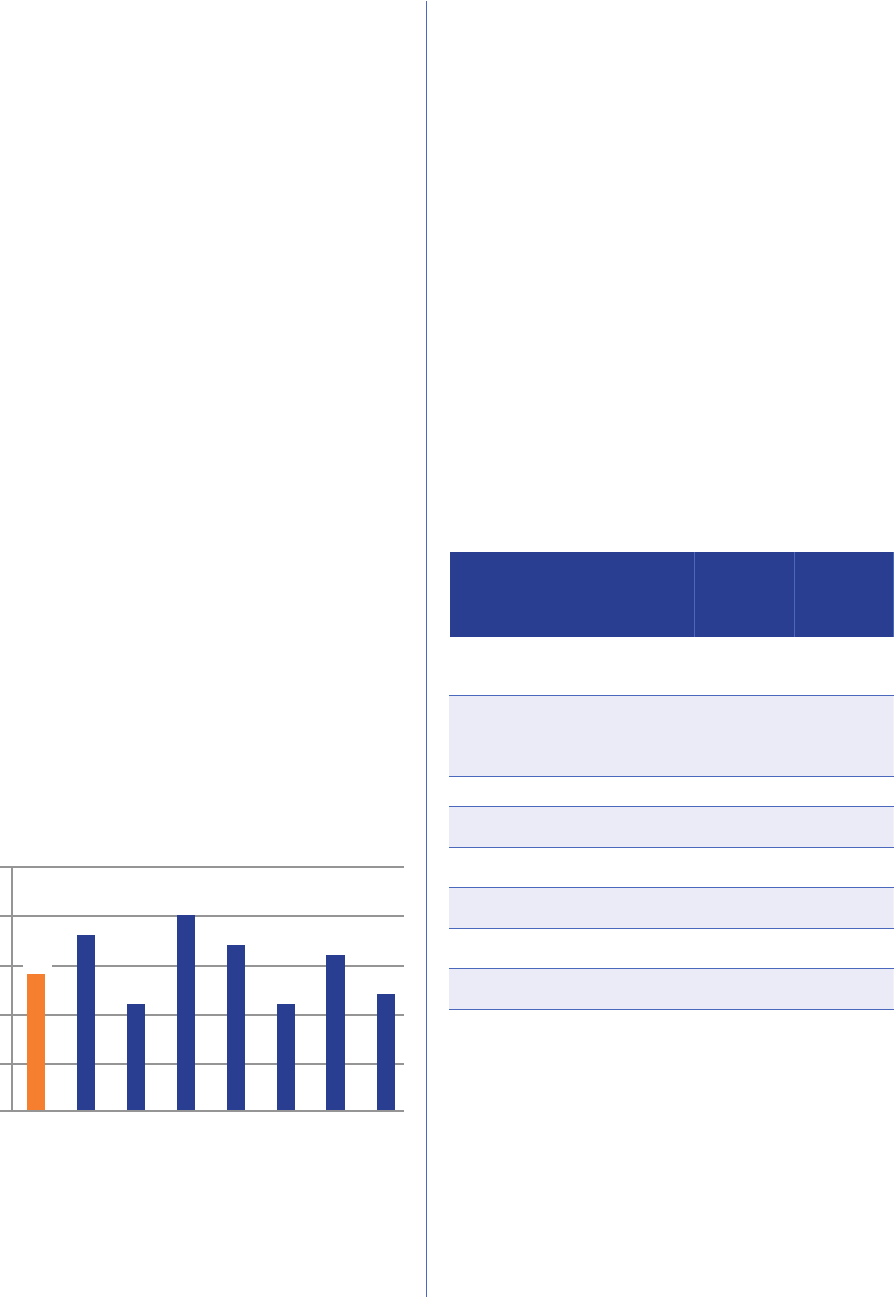

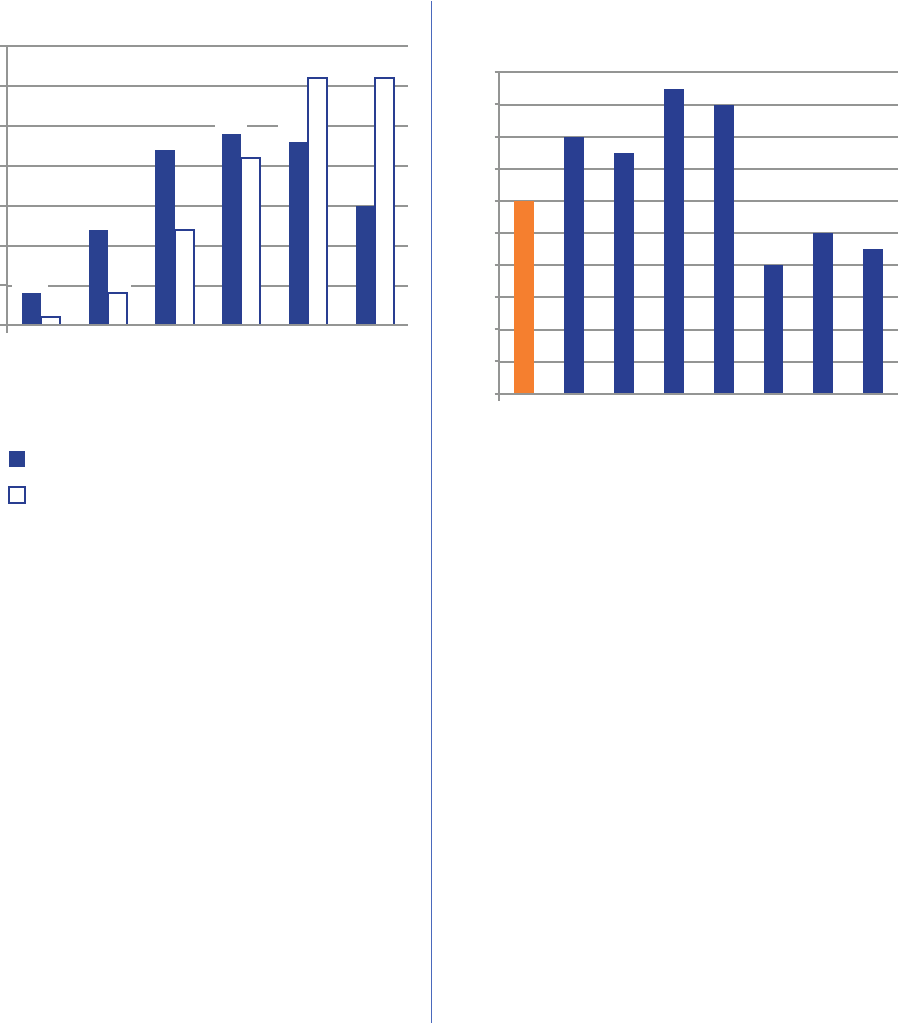

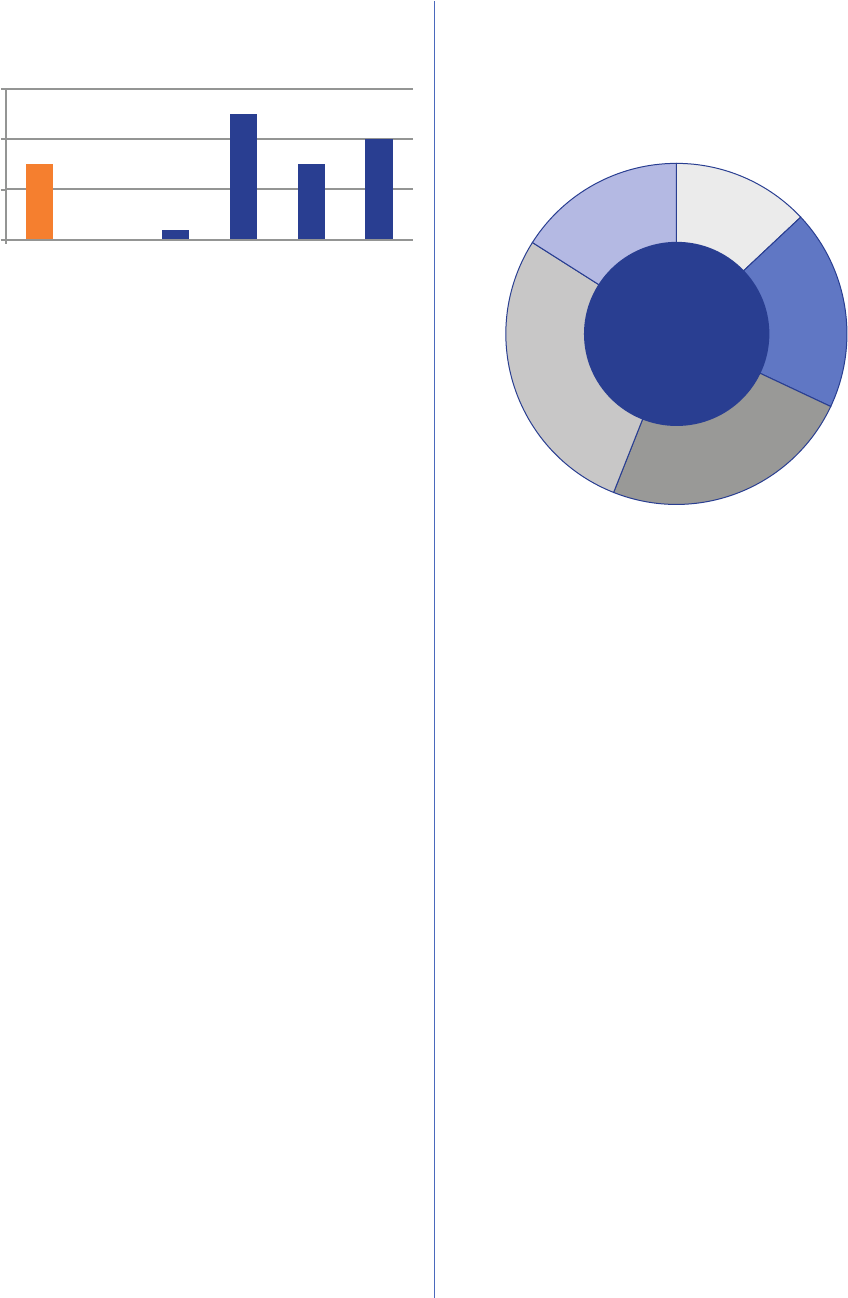

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60%

Negative experiences among those with

supportive and unsupportive families

% of respondents whose families were supportive

% of respondents whose families were unsupportive

respondents who were out to their immediate family reported that a

family member was violent towards them because they were transgender.

respondents who were out to their immediate family were kicked

out of the house, and one in ten (10%) ran away from home.

. Forty-two percent (42%) of those who left

later found a welcoming spiritual or religious community.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

9

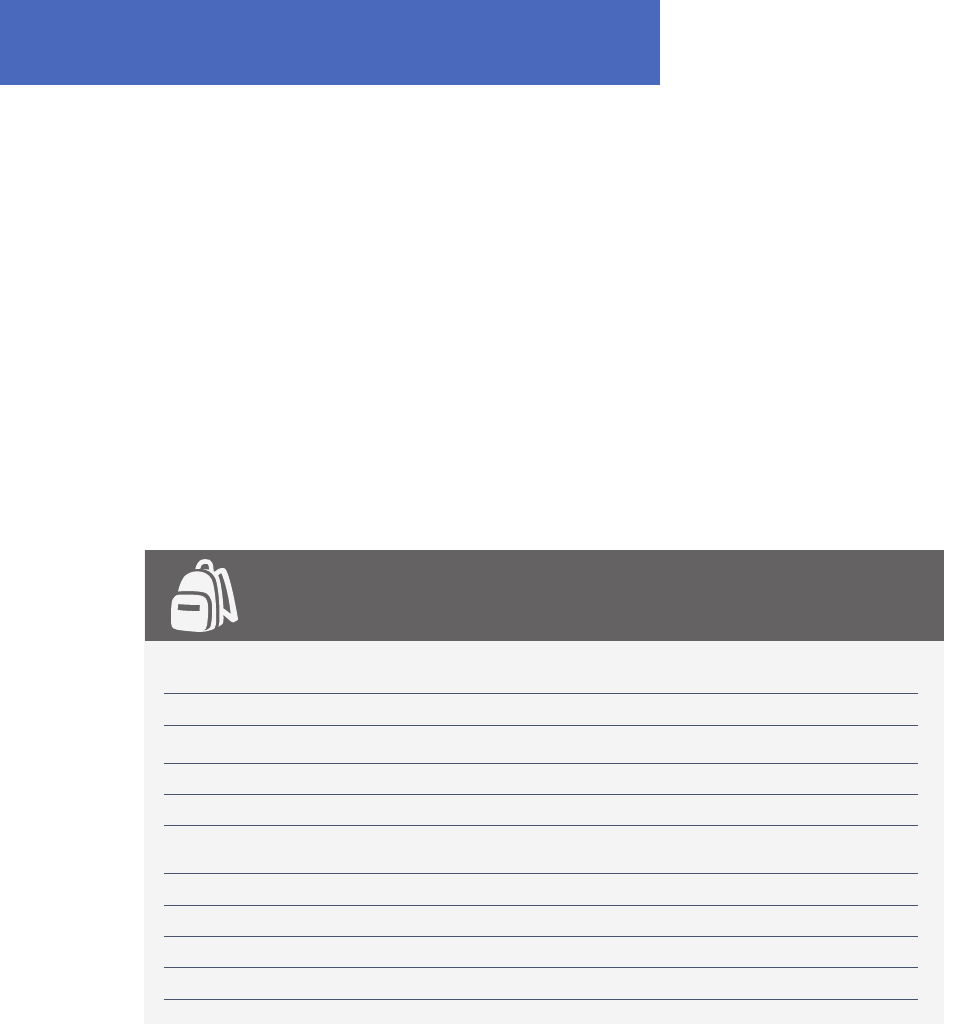

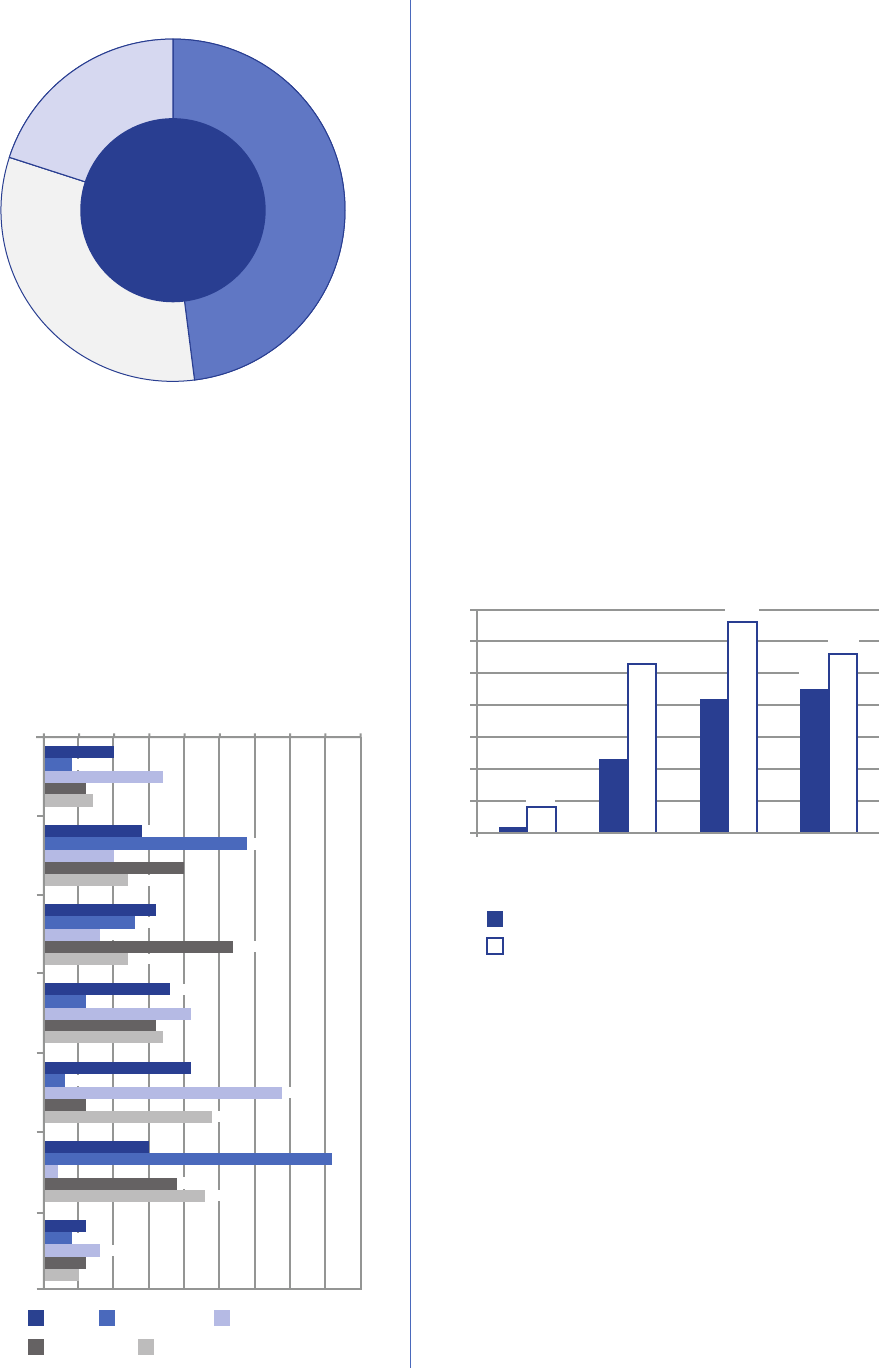

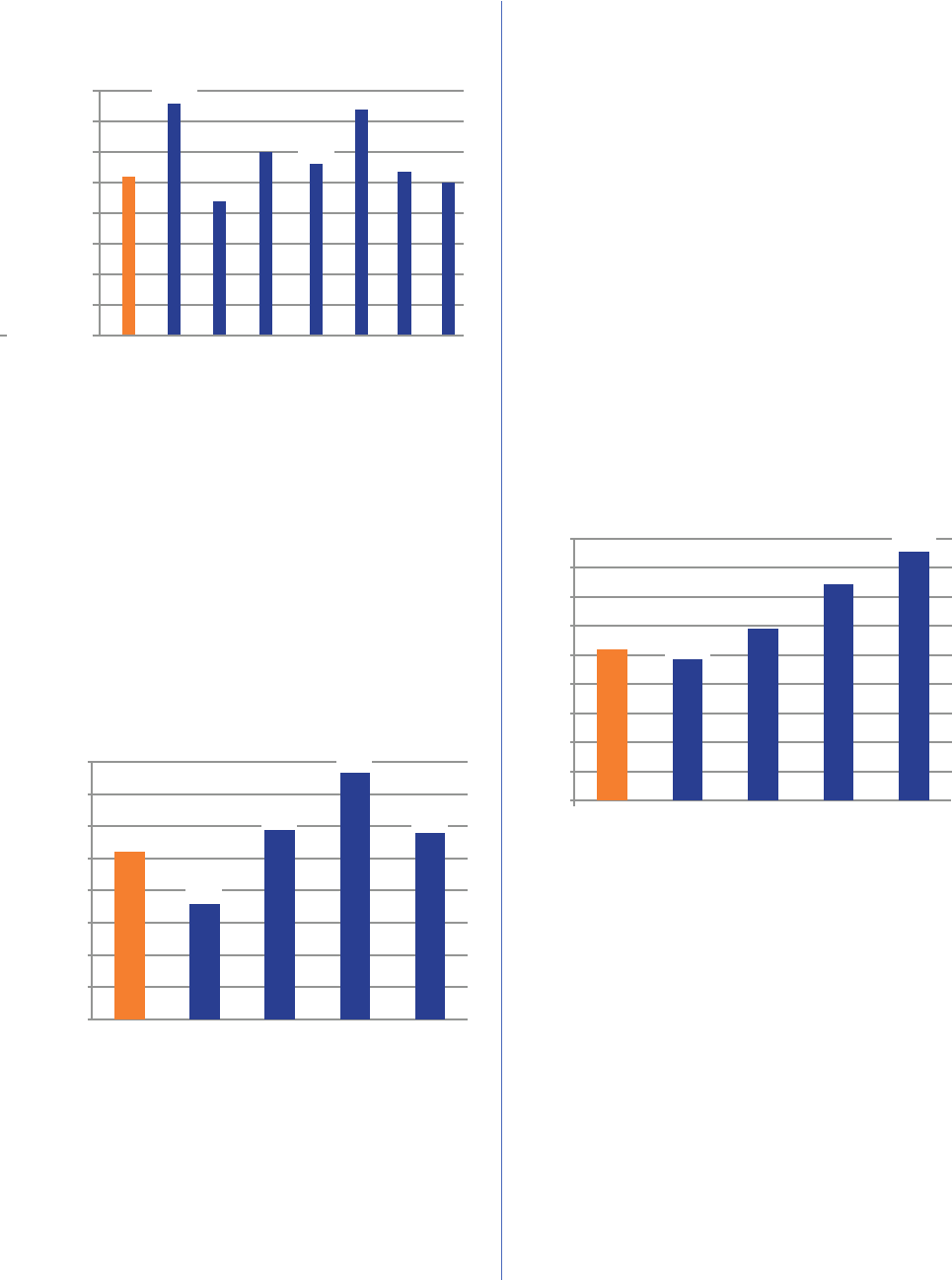

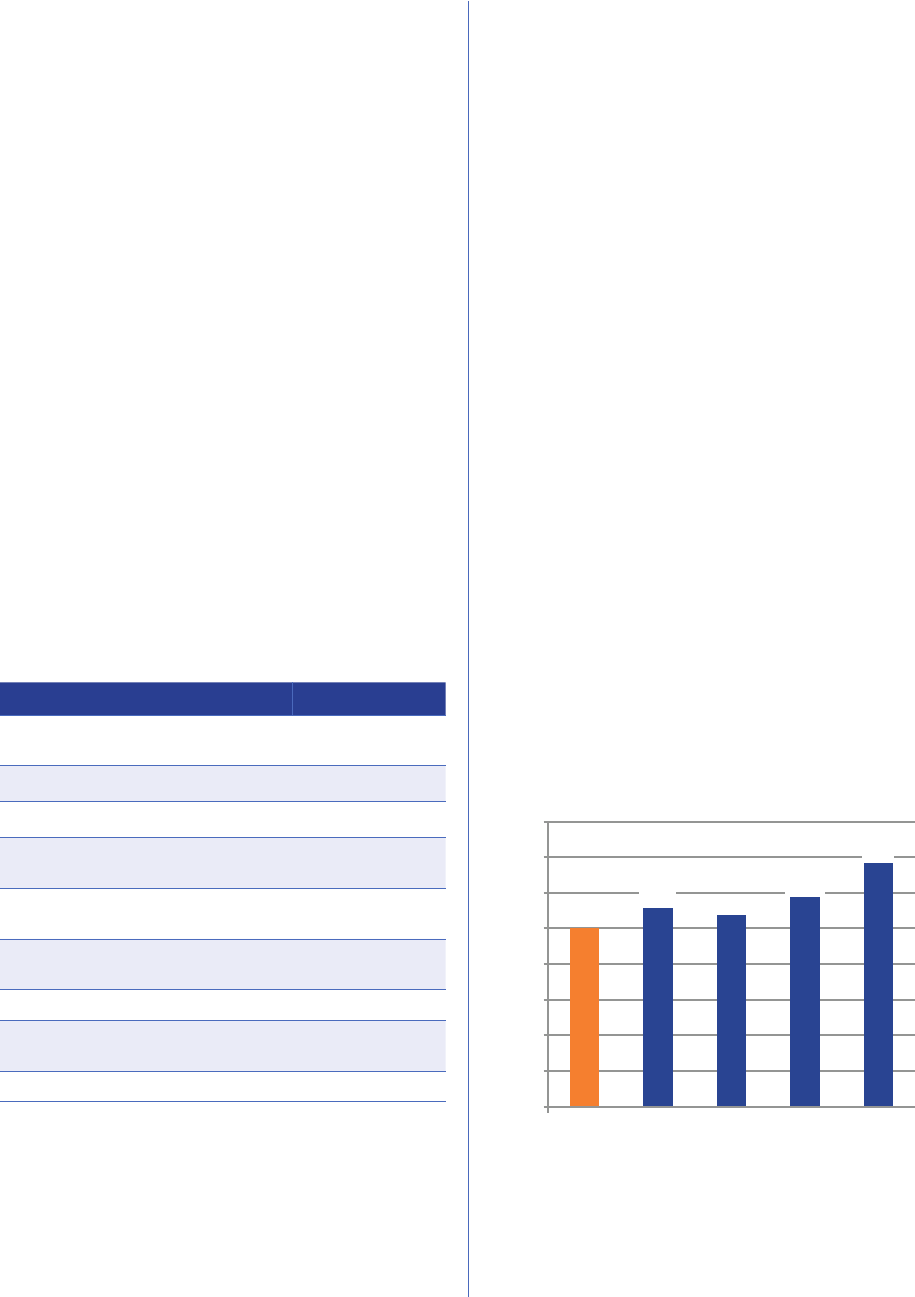

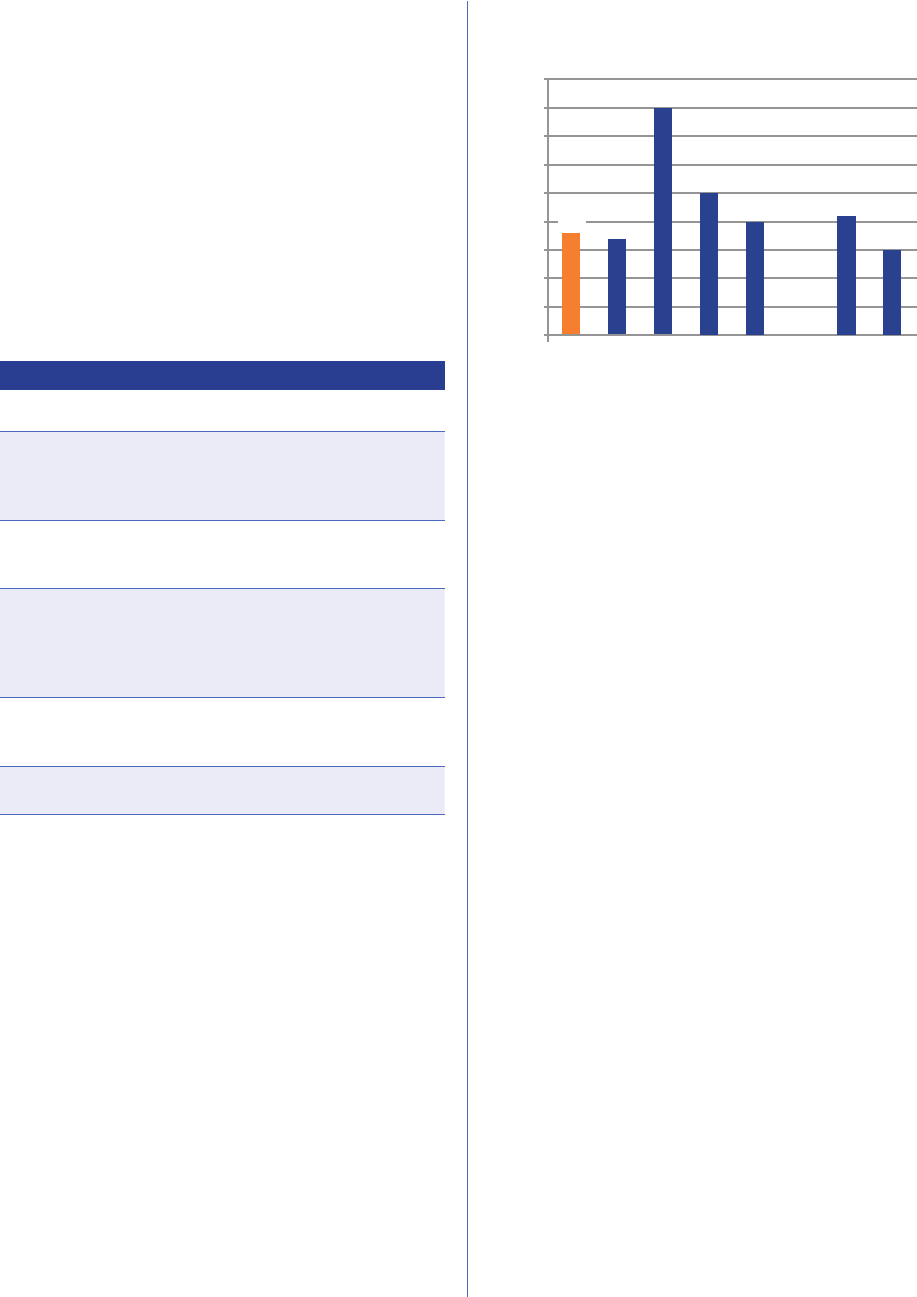

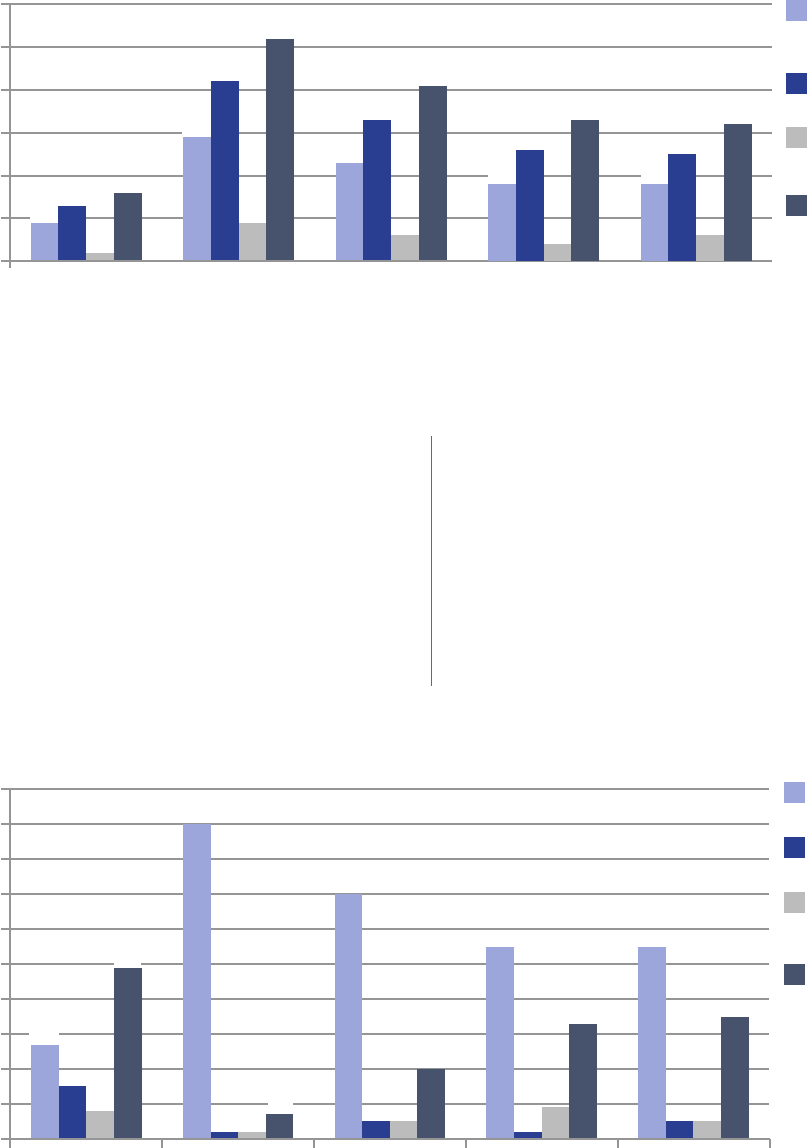

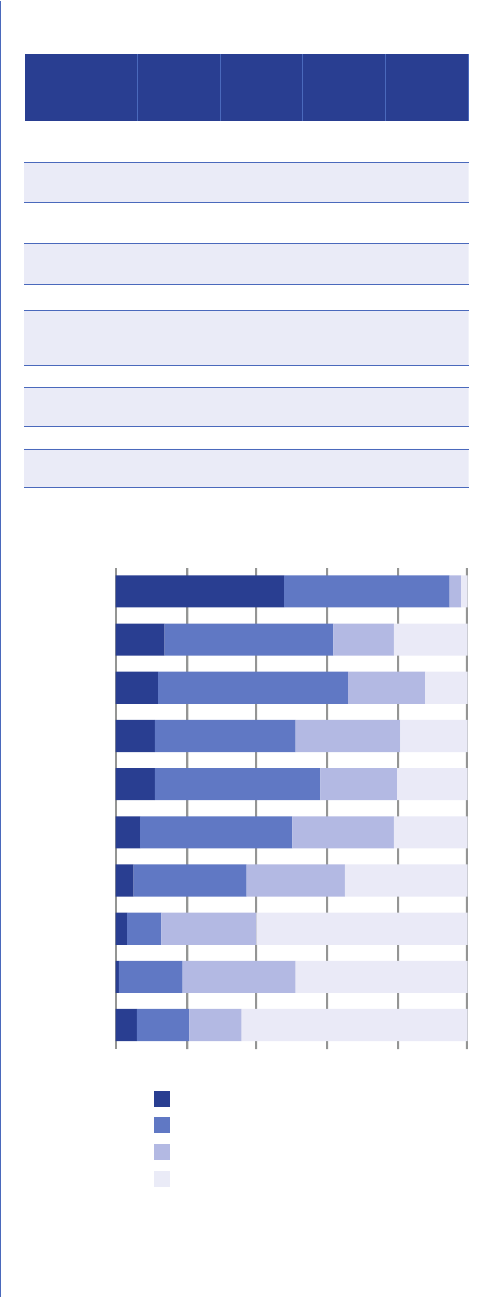

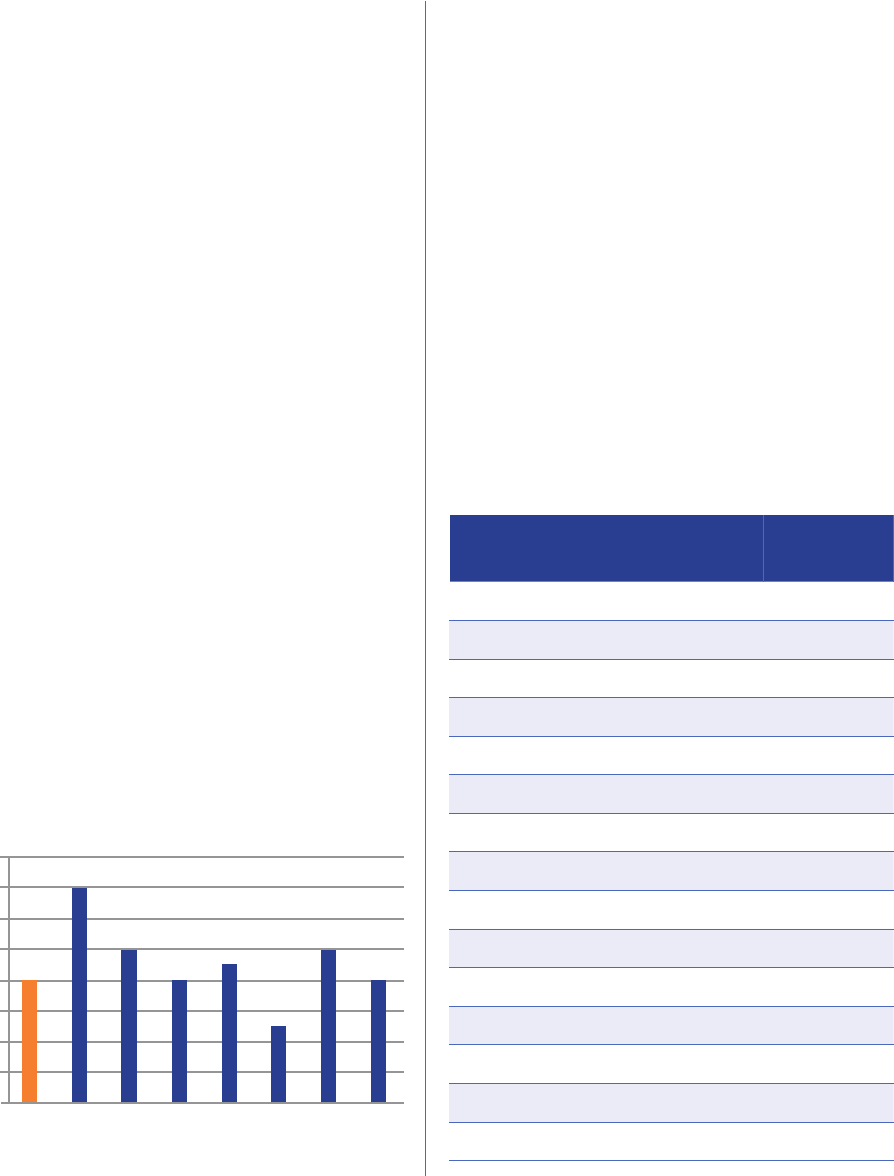

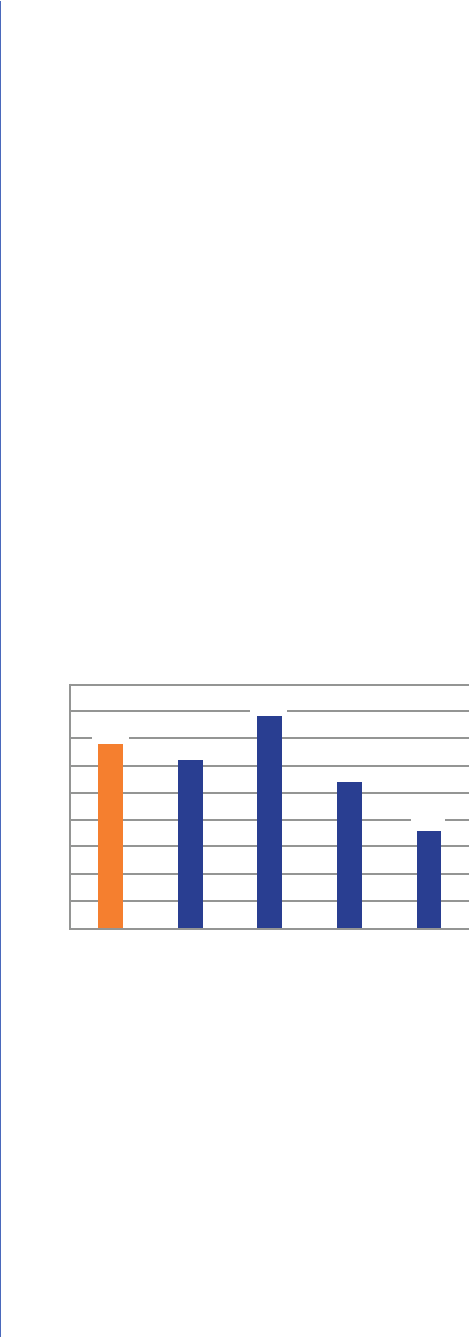

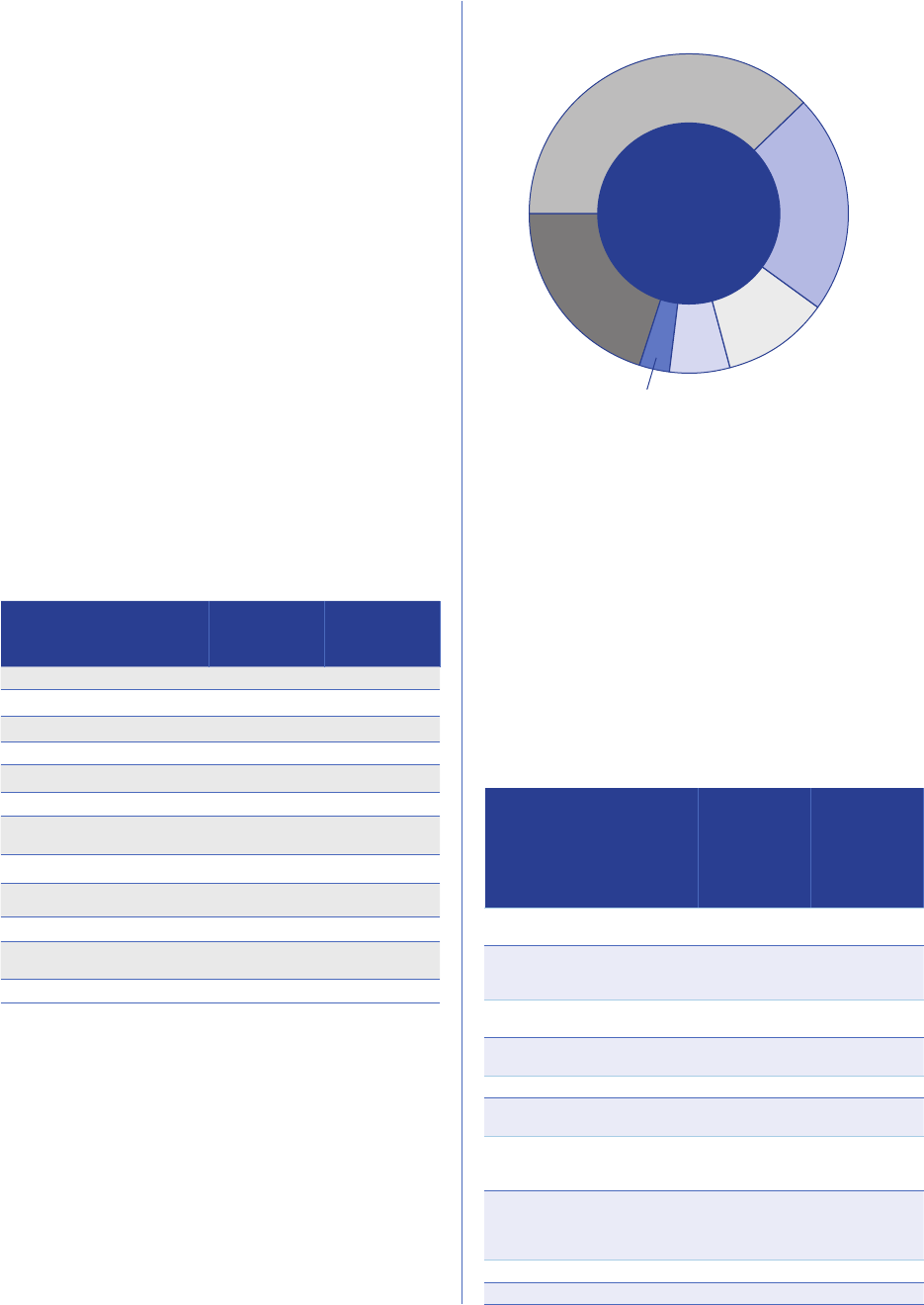

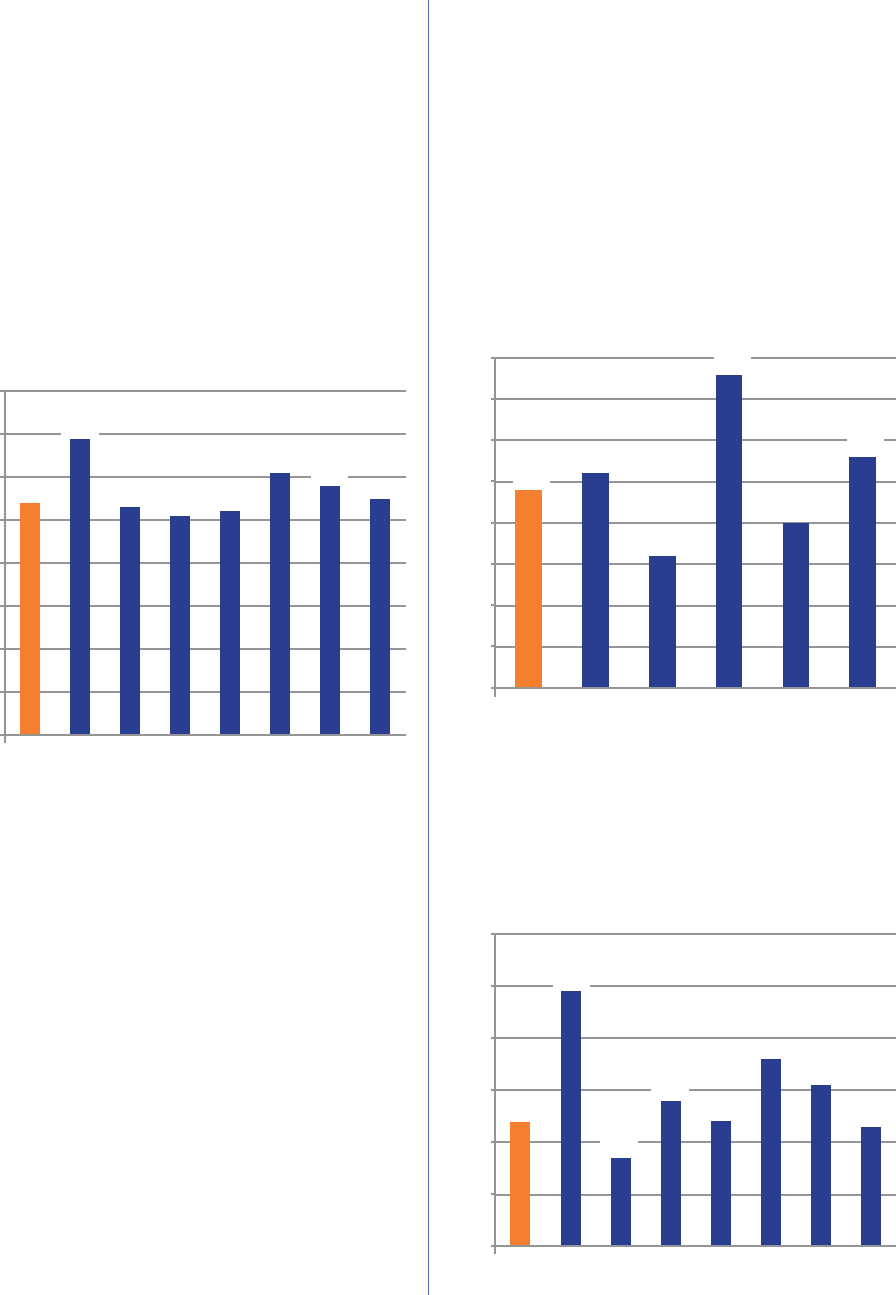

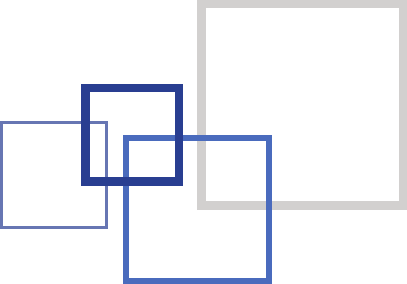

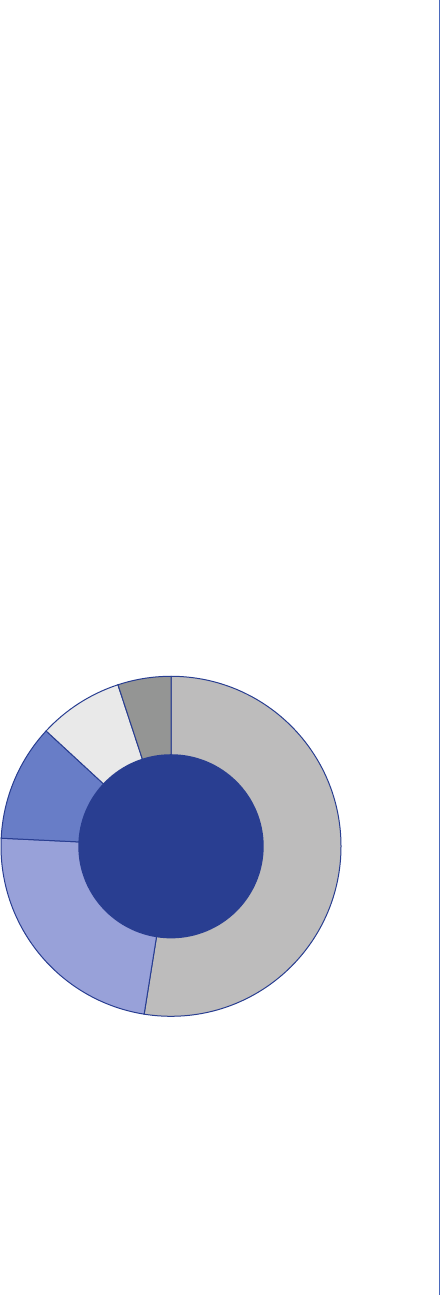

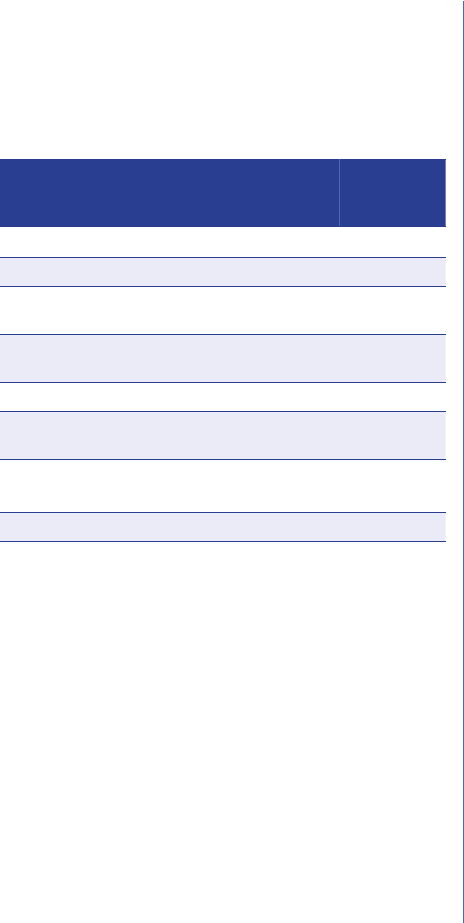

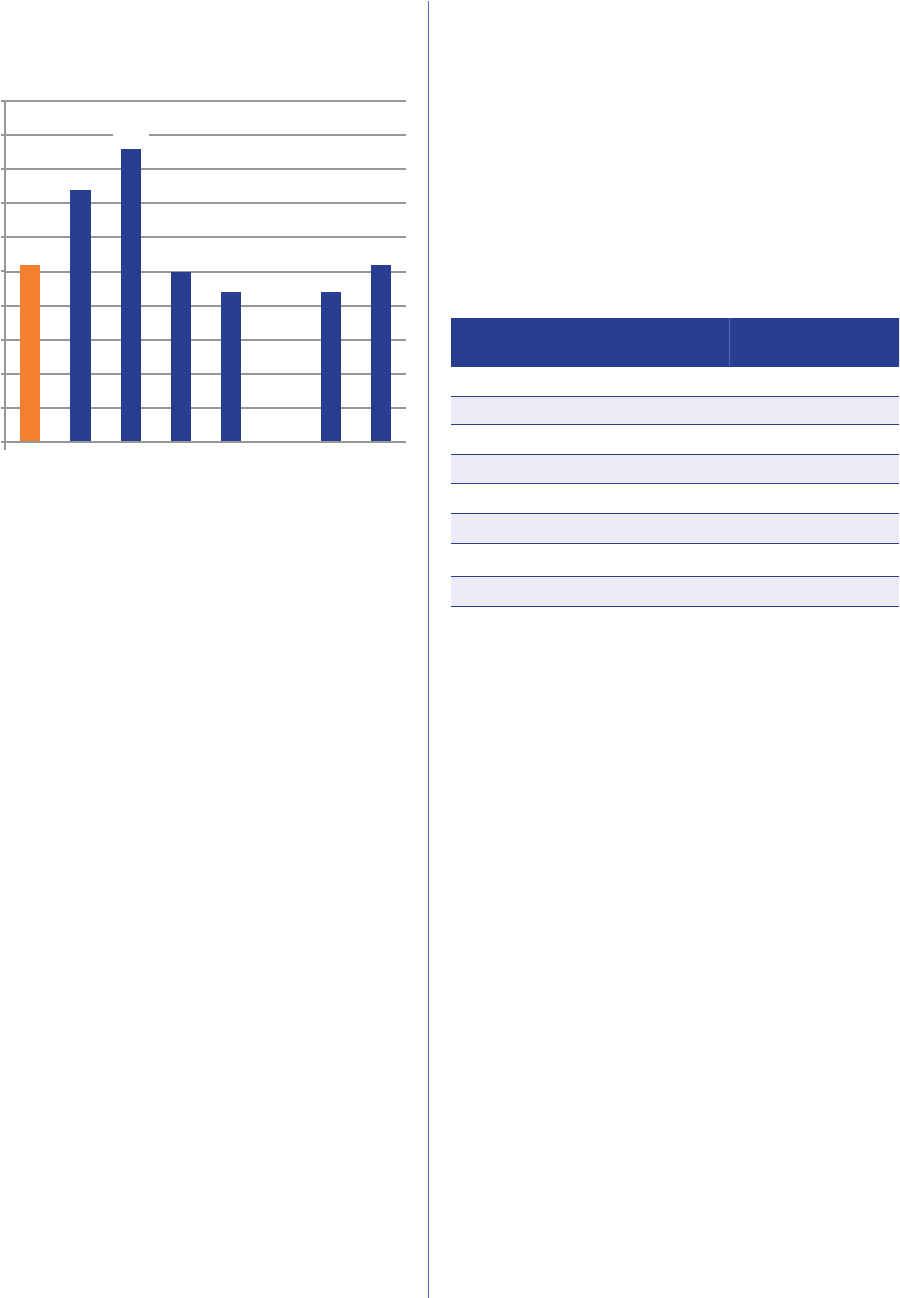

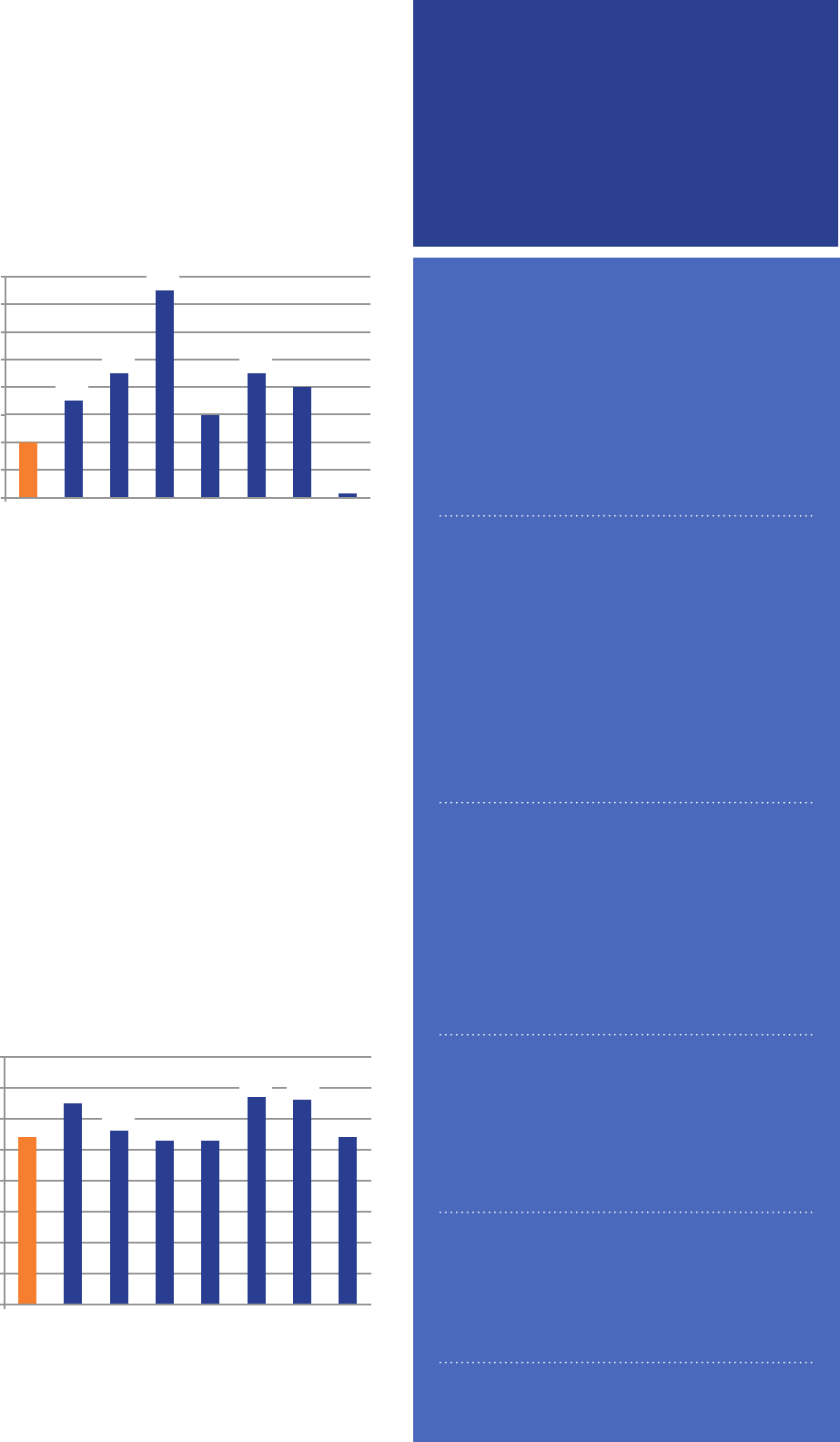

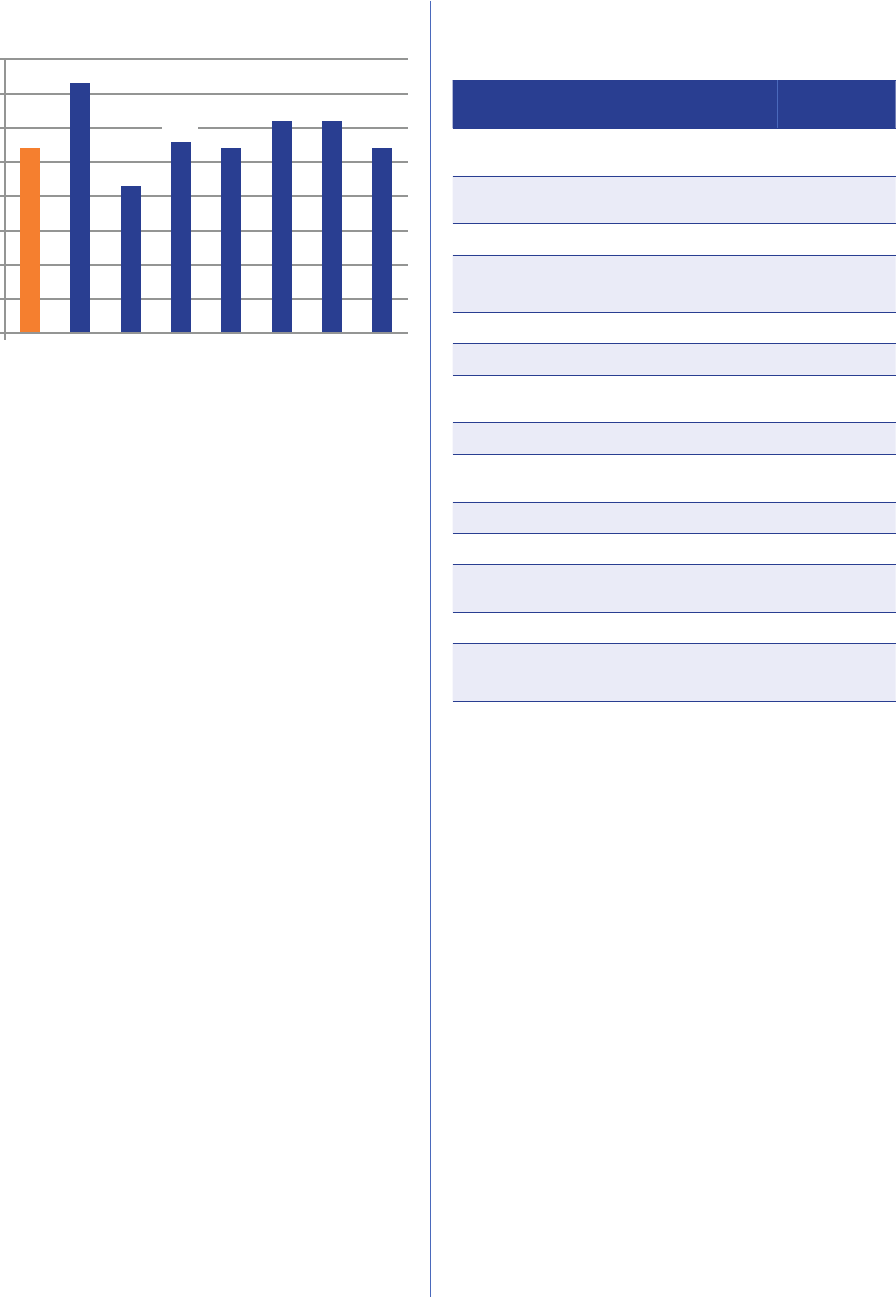

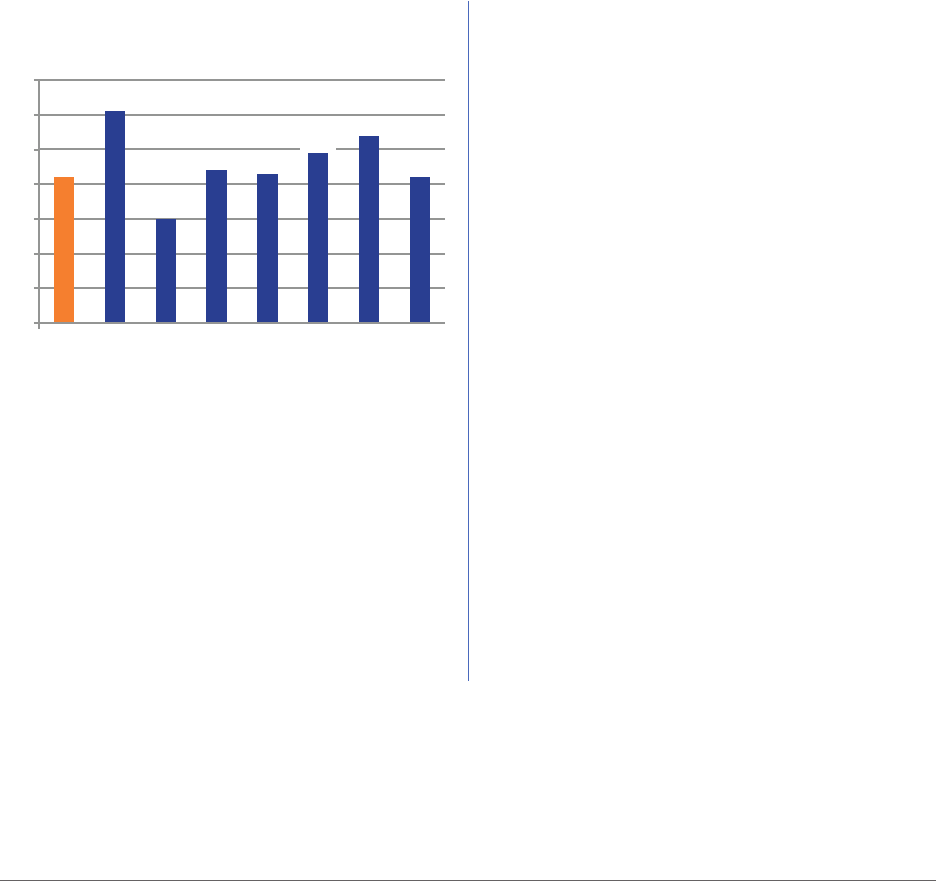

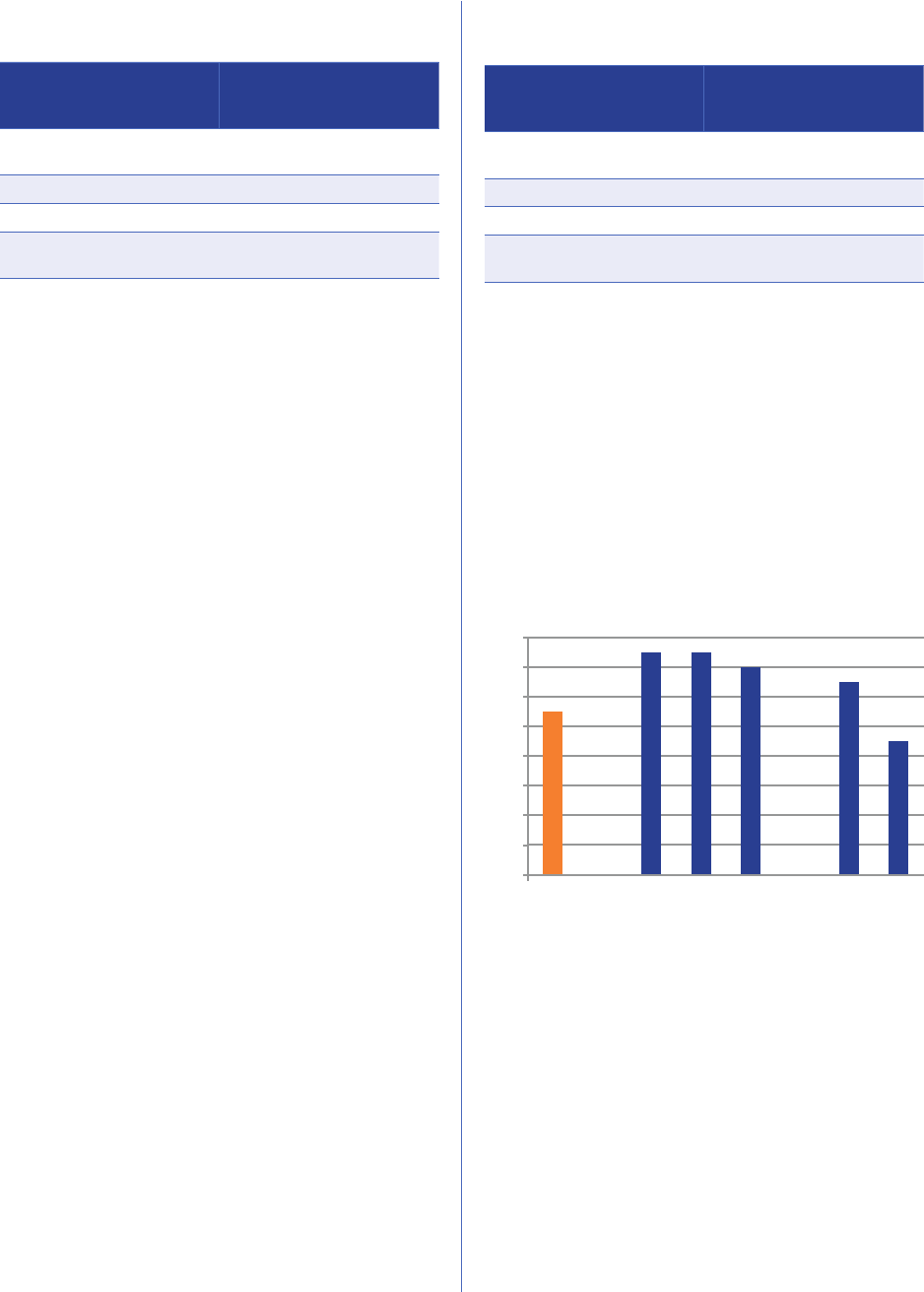

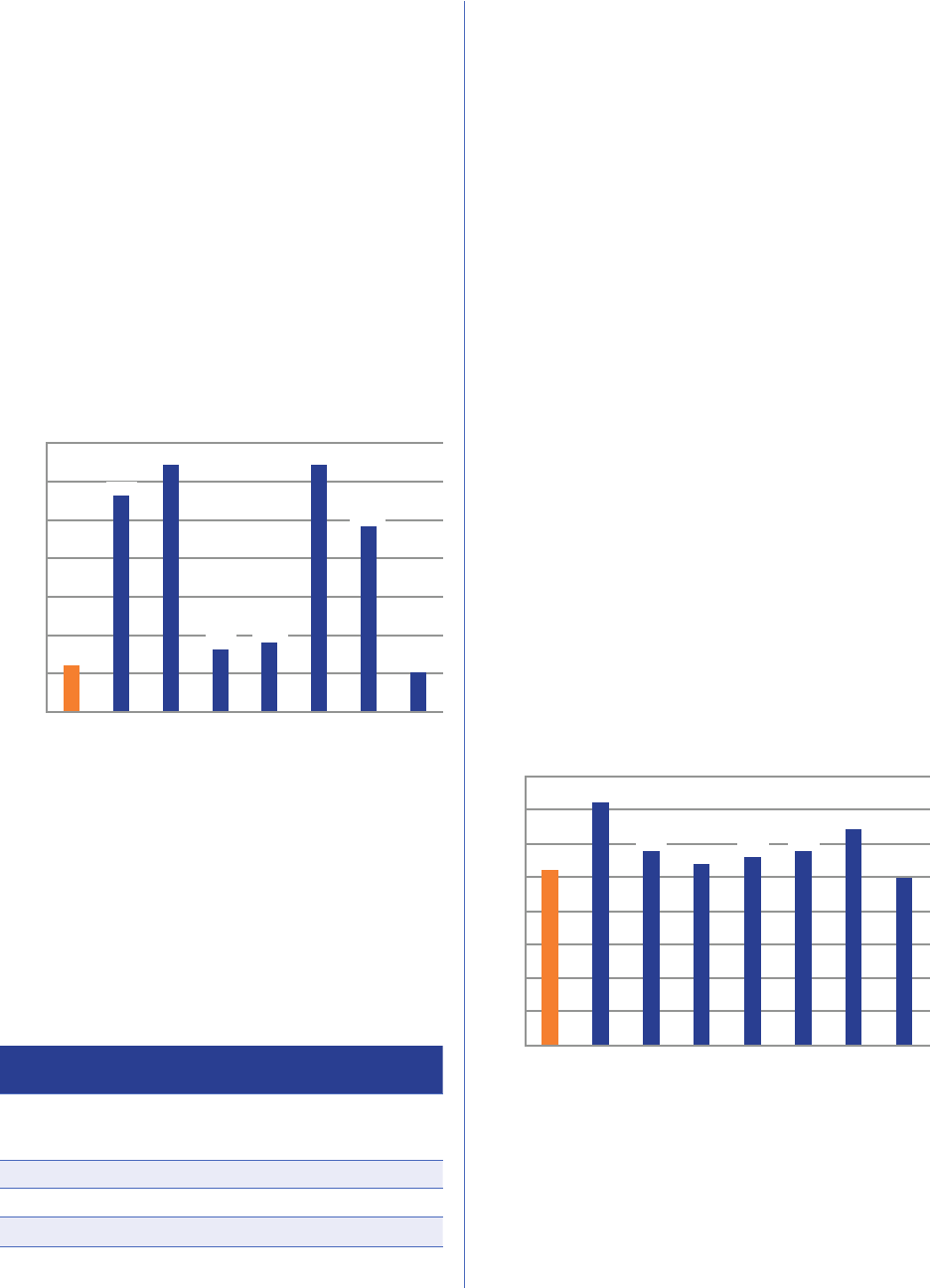

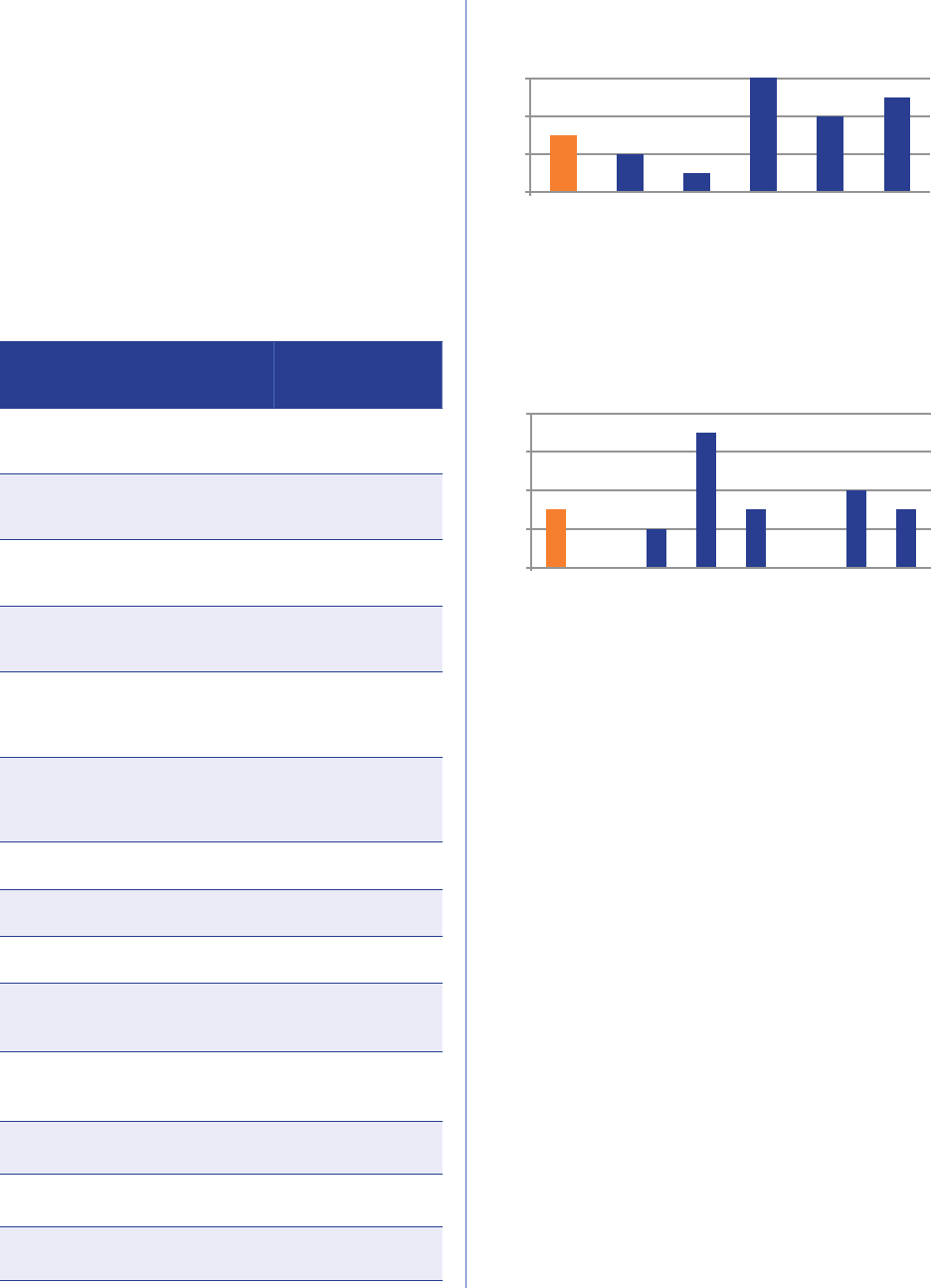

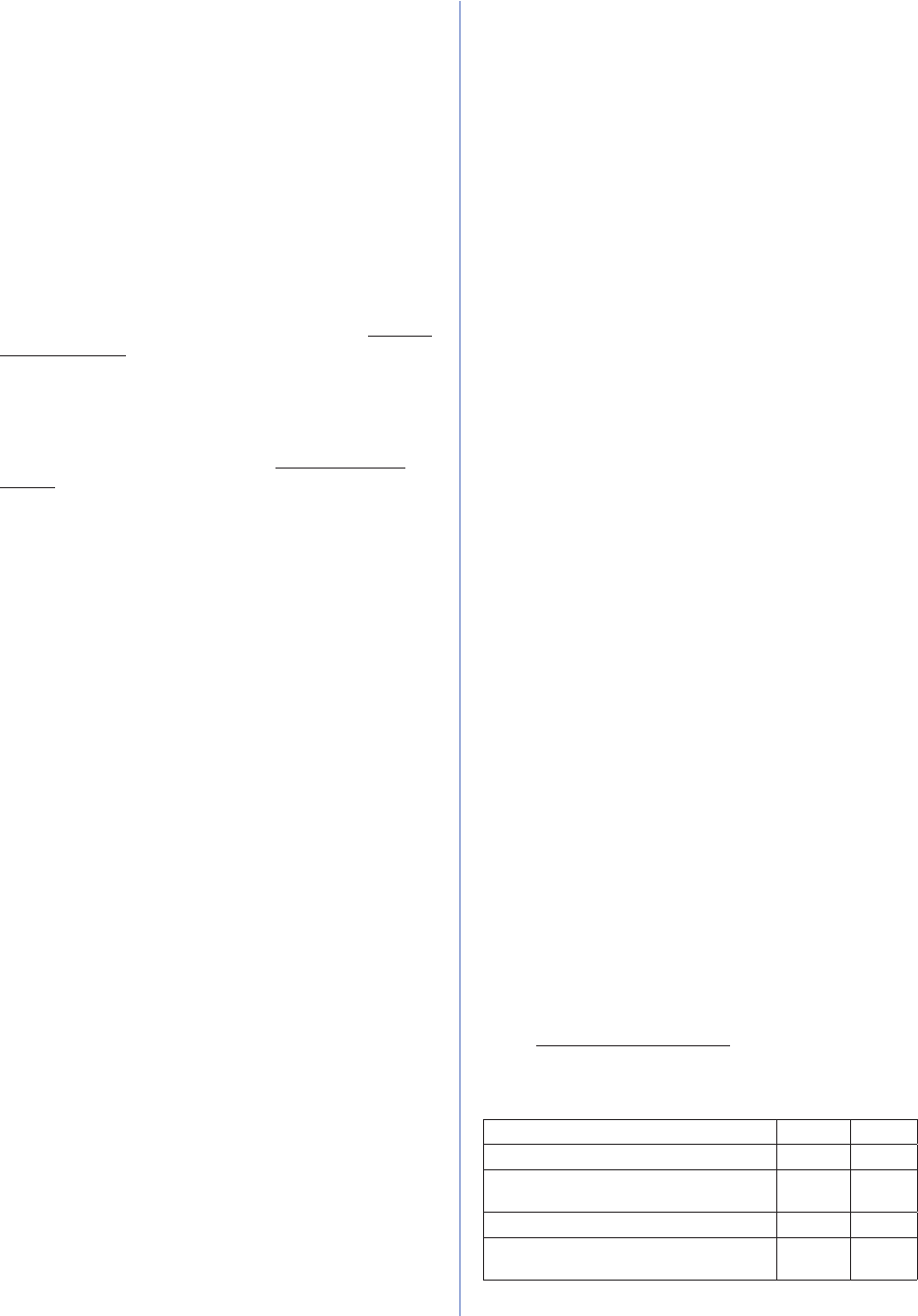

Identity Documents

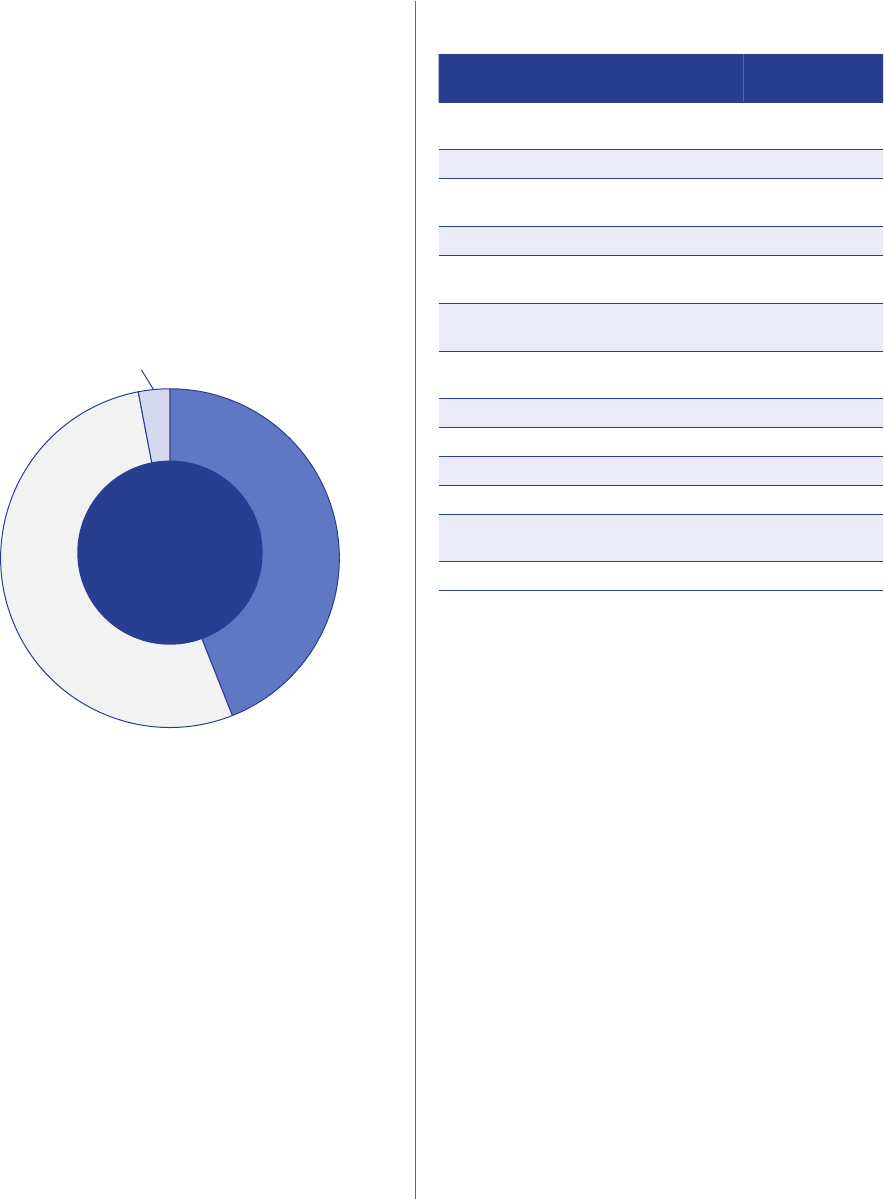

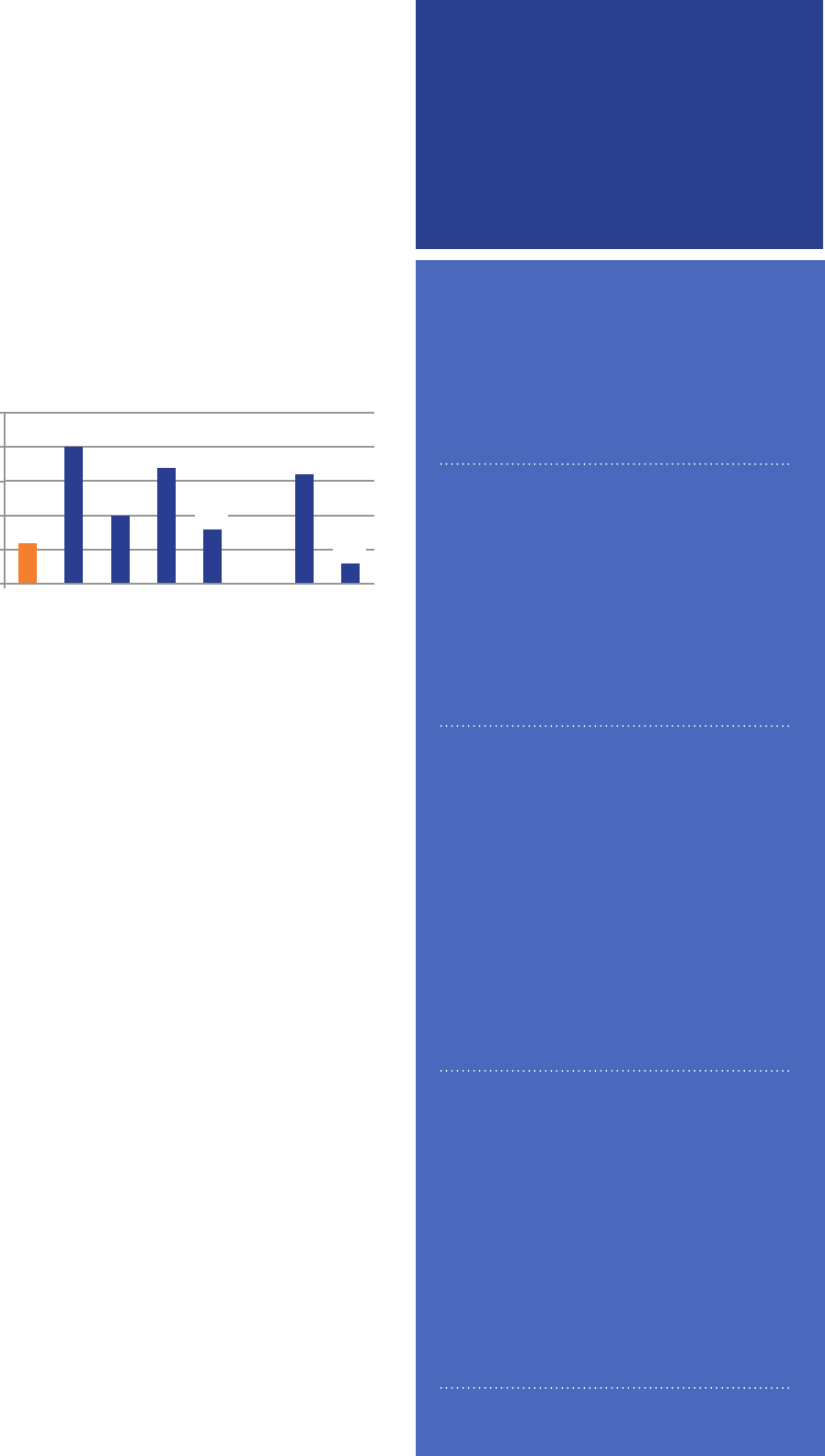

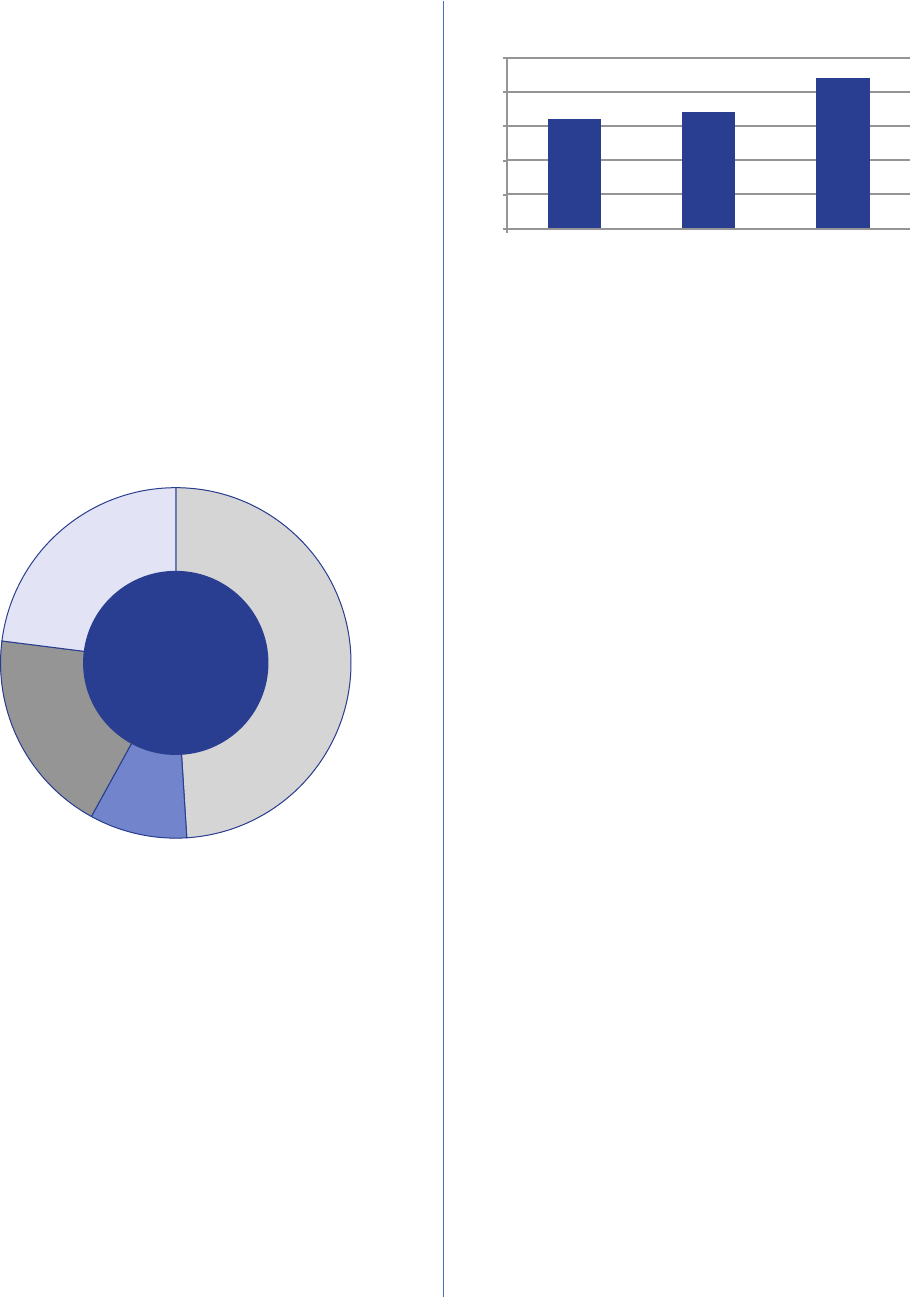

all of their IDs had the name and gender they

none of their IDs had the

name and gender they preferred.

Driver’s license/

state-issued ID

Social Security records

Student records (current

or last school attended)

Passport

Birth certificate

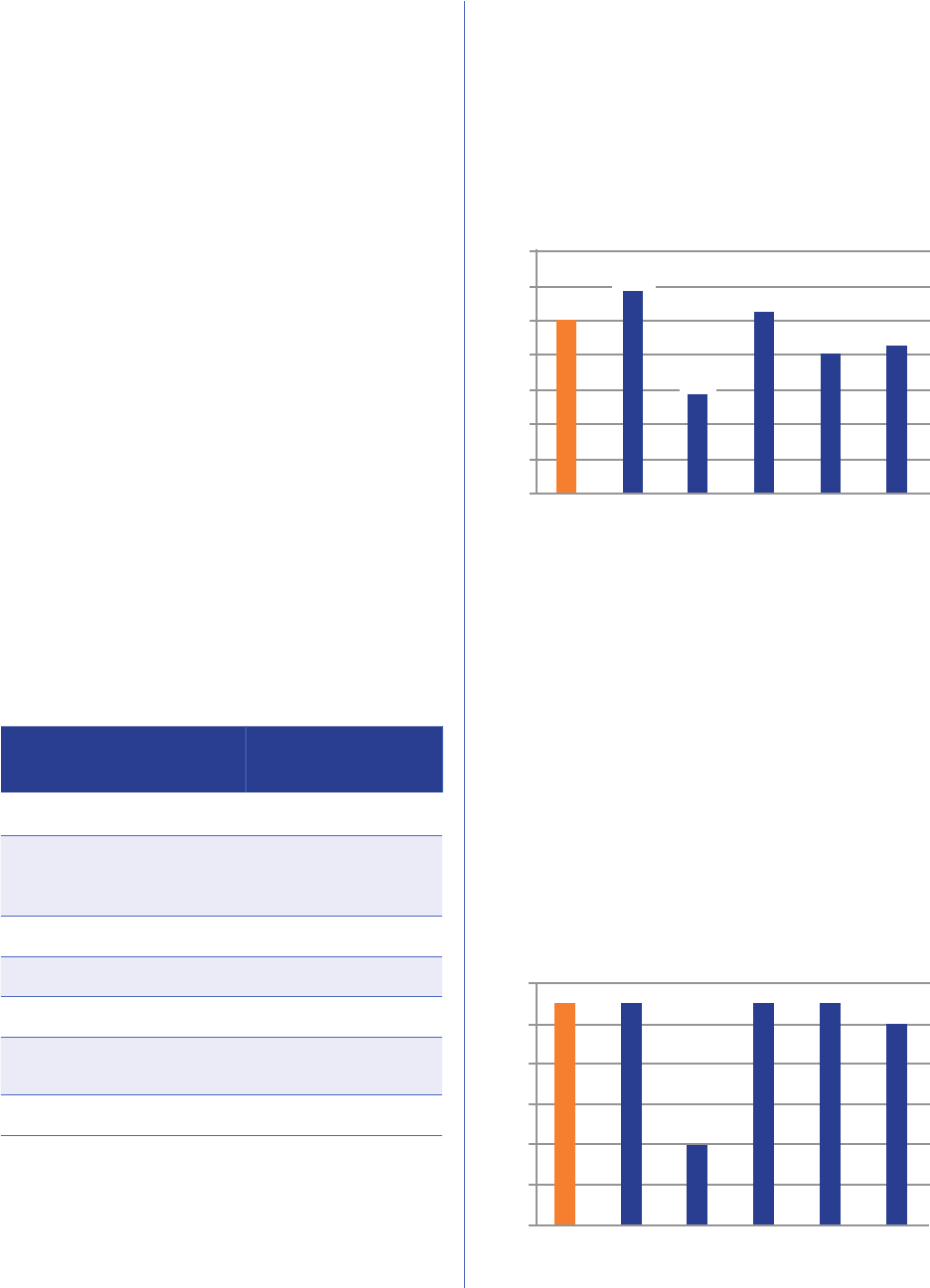

Updated name or gender on ID

Updated name Updated gender

0% 5% 10% 15% 20% 25% 30% 35% 40% 45% 50%

,

with 35% of those who have not changed their legal name and 32% of those who have not

updated the gender on their IDs reporting that it was because they could not aord it.

• Nearly of respondents who have shown an ID with a name or gender

that did not match their gender presentation were verbally harassed, denied benefits

or service, asked to leave, or assaulted.

10

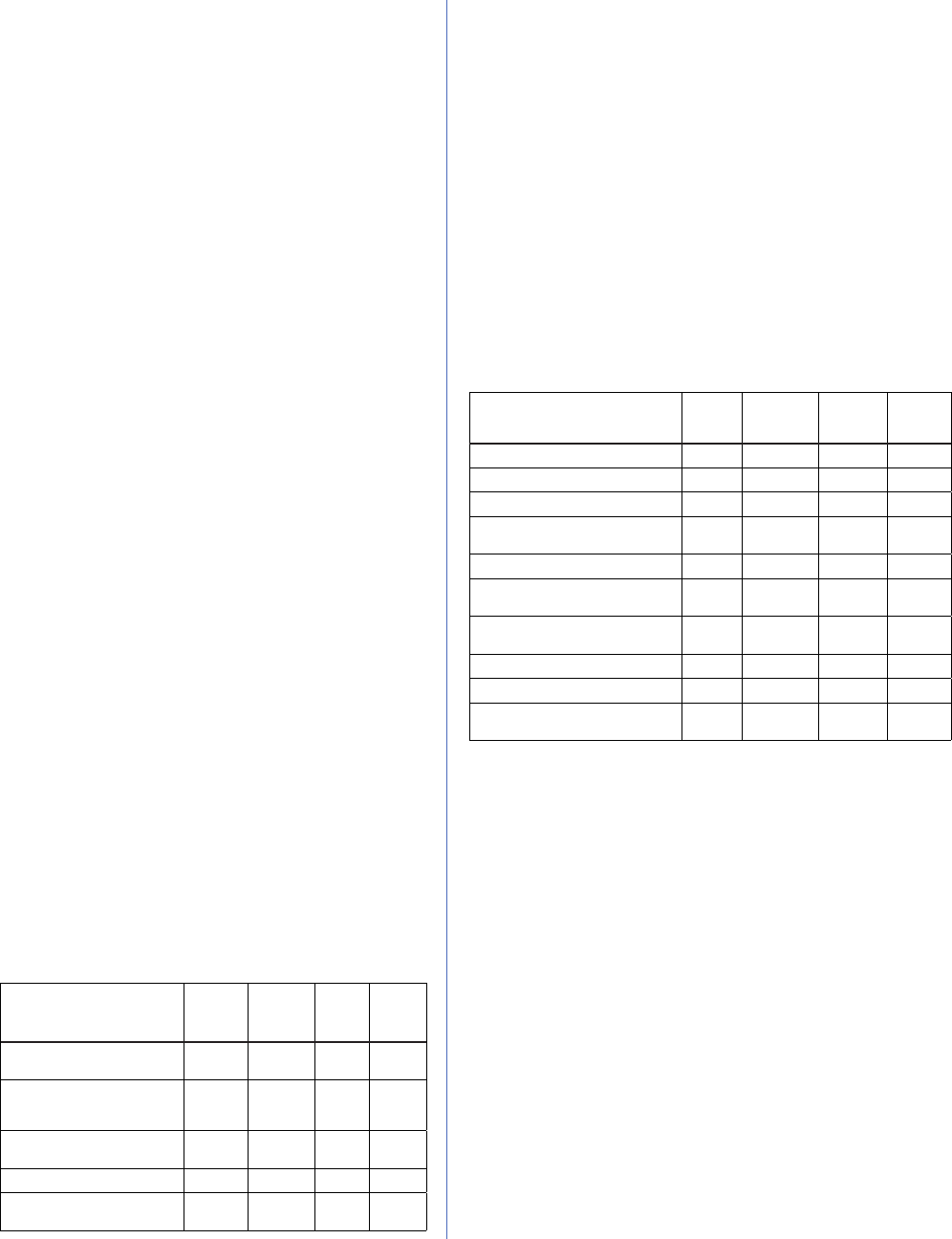

Health Insurance and Health Care

insurance related to being transgender, such as being denied coverage for care related to

gender transition or being denied coverage for routine care because they were transgender.

past year were denied, and 25% of those who sought coverage for hormones in the past

year were denied.

at least one negative experience related to being transgender, with higher rates for

people of color and people with disabilities. This included being refused treatment, verbally

harassed, or physically or sexually assaulted, or having to teach the provider about

transgender people in order to get appropriate care.

Inthepastyear,

of fear of being mistreated as a transgender person, and 33% did not see a doctor when

needed because they could not afford it.

Psychological Distress and

Attempted Suicide

in the

month before completing the survey (based on the Kessler 6 Psychological Distress Scale),

compared with only 5% of the U.S. population.

in their lifetime, nearly nine times the rate in

in the past year—nearly twelve times the rate in the

HIV

• Respondentswere

, especially transgender women

of color. , and

American Indian (4.6%) and Latina (4.4%) women also reported higher rates.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

11

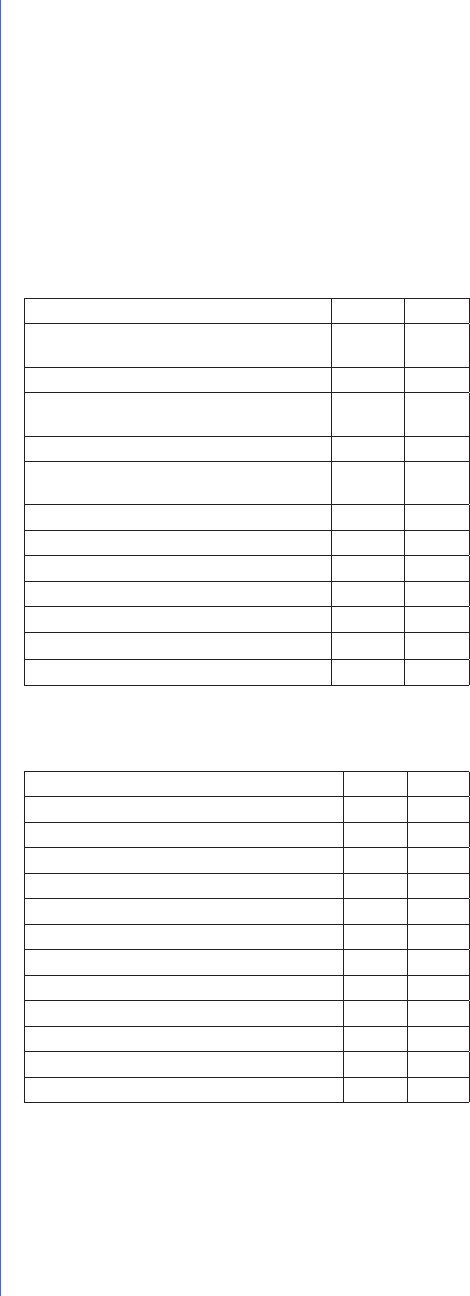

Experiences in Schools

of those who were out or perceived as transgender

at some point between Kindergarten and Grade 12 (K–12) experienced some form of

mistreatment, such as being verbally harassed, prohibited from dressing according

to their gender identity, disciplined more harshly, or physically or sexually assaulted

because people thought they were transgender.

of those who were out or perceived as transgender in K–12

were sexually assaulted in K–12 because of being transgender.

that they left a K–12 school.

of people who were out or perceived as transgender in

college or vocational school were verbally, physically, or sexually harassed.

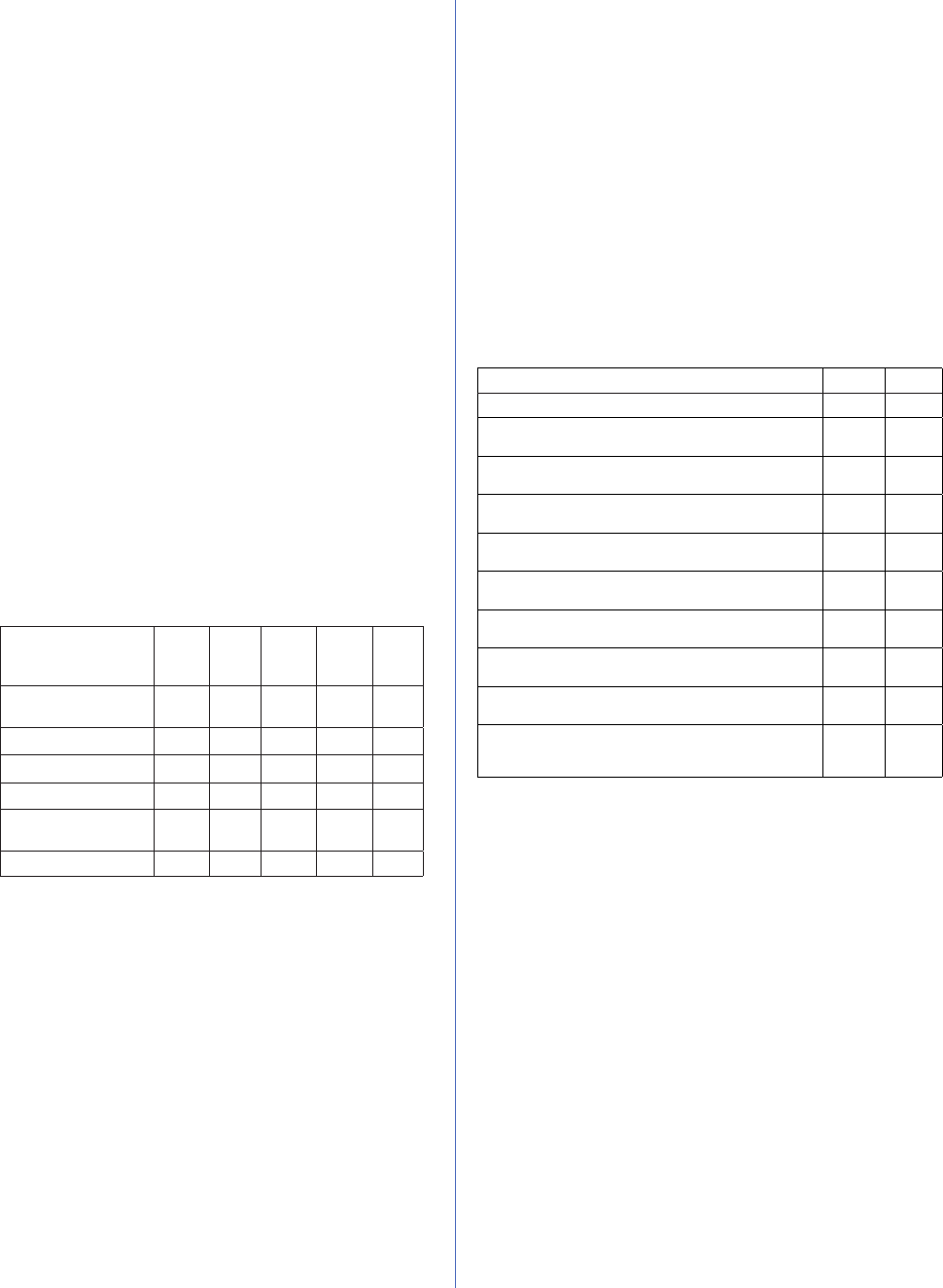

Experiences of people who were out as transgender in K–12 or believed

classmates, teachers, or school sta thought they were transgender

EXPERIENCES

PERCEIVED AS TRANSGENDER

Verbally harassed because people thought they were transgender 54%

Not allowed to dress in a way that fit their gender identity or expression 52%

Disciplined for fighting back against bullies 36%

Physically attacked because people thought they were transgender 24%

Believe they were disciplined more harshly because teachers or sta thought

they were transgender

20%

Left a school because the mistreatment was so bad 17%

Sexually assaulted because people thought they were transgender 13%

Expelled from school 6%

One or more experiences listed

2015 U.S. TRANSGENDER SURVEY

12

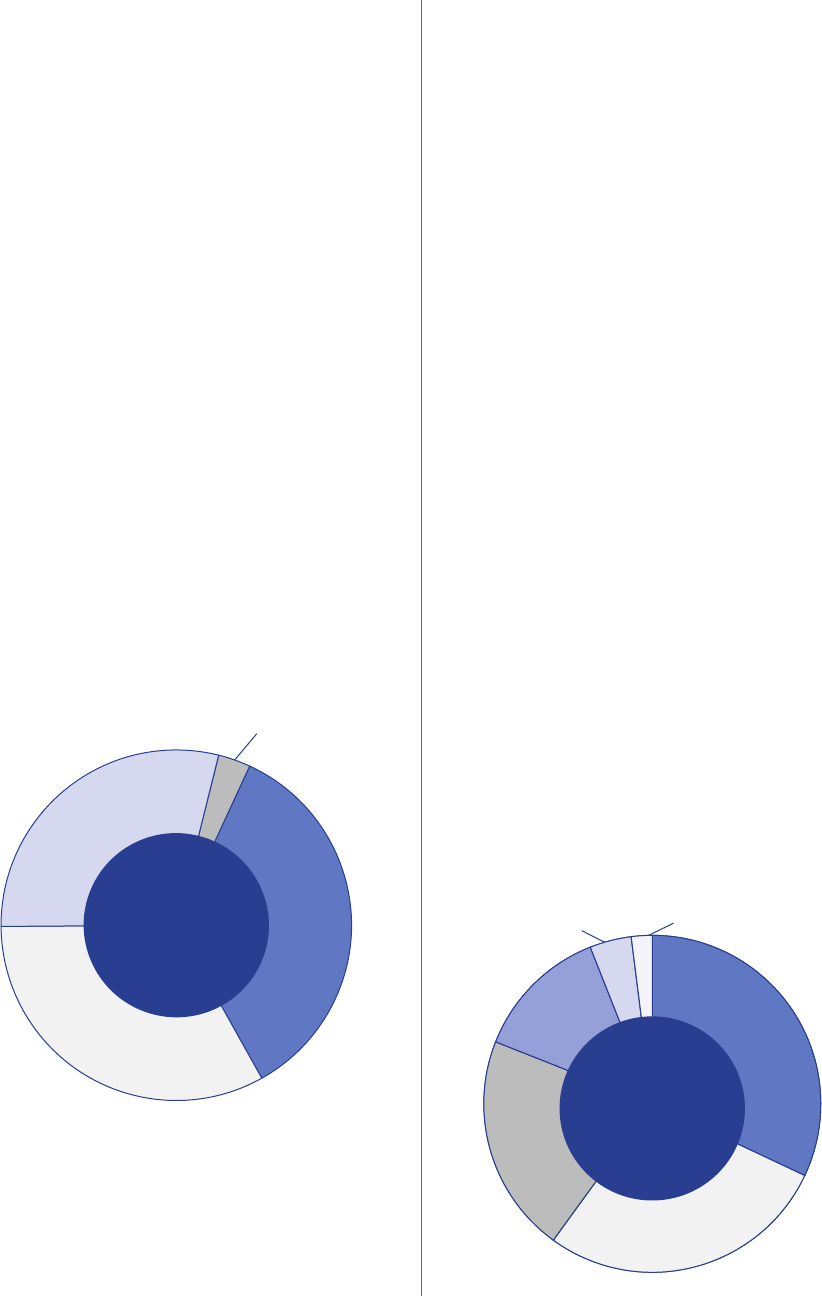

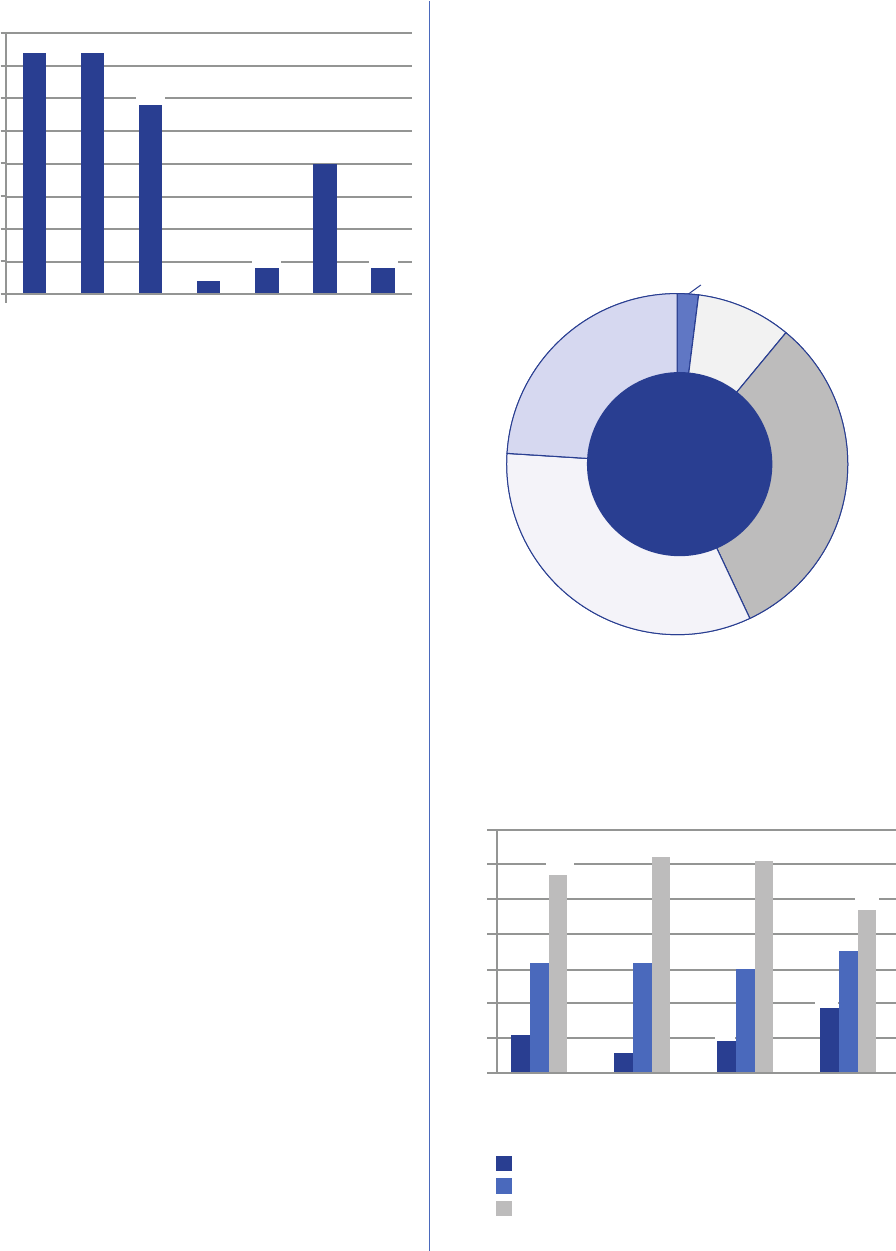

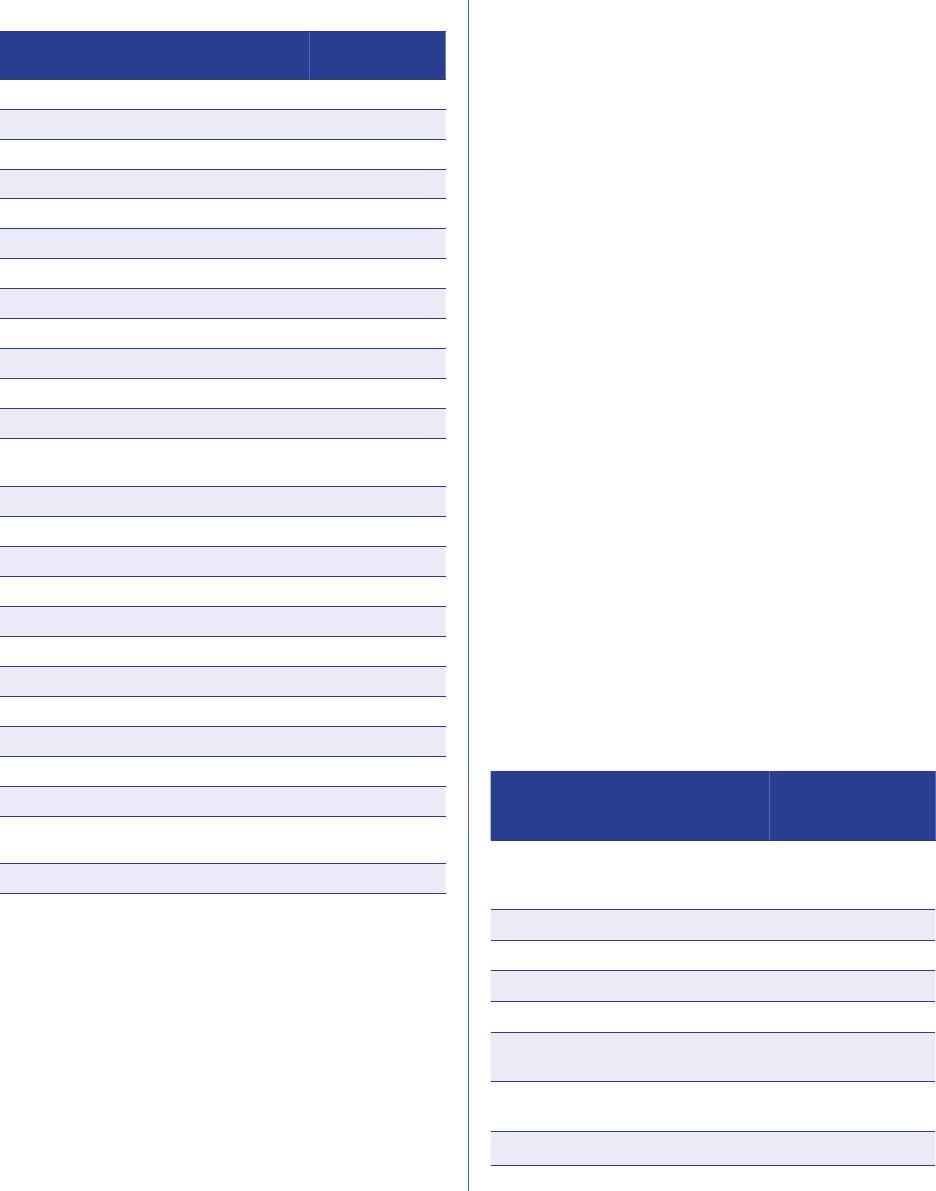

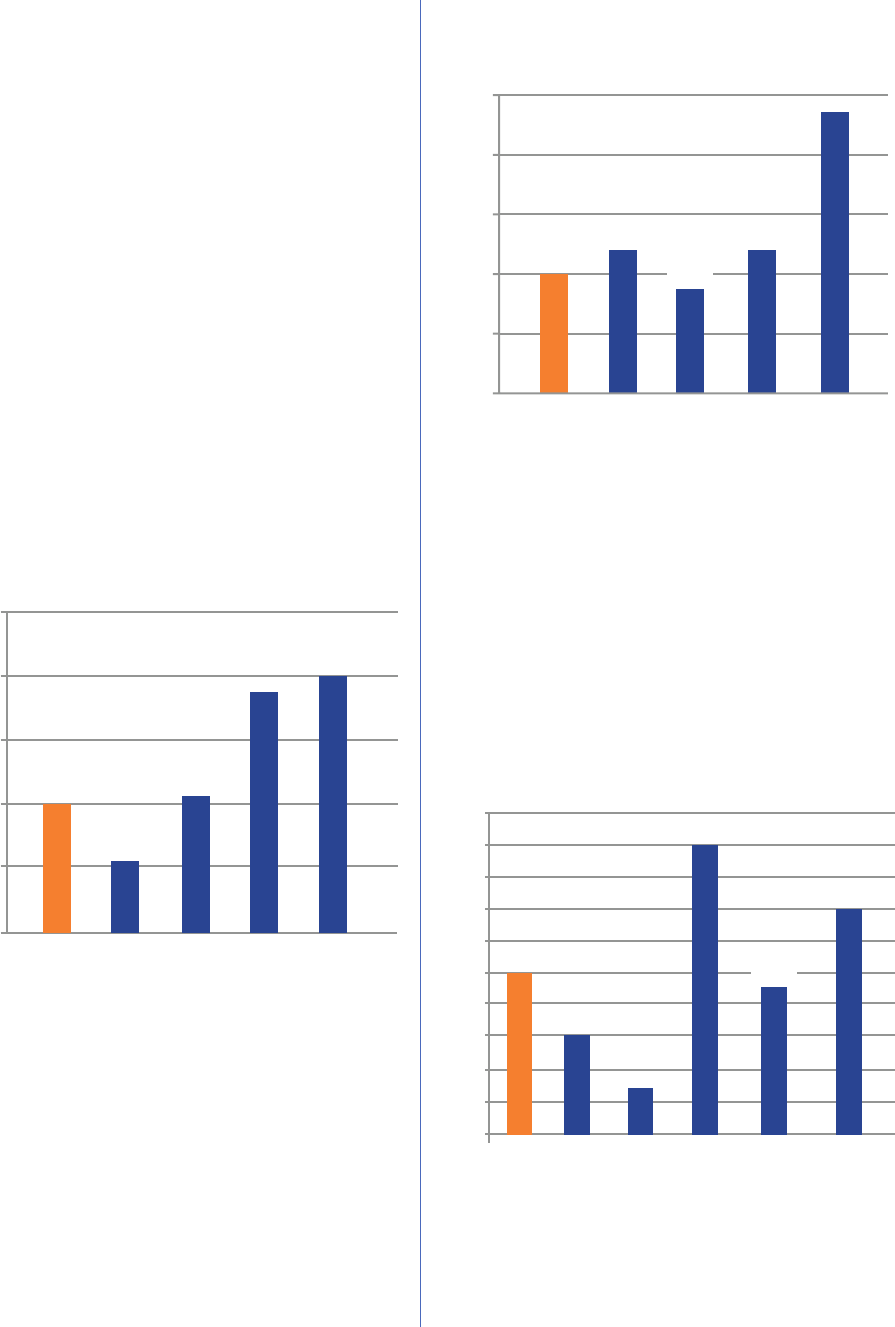

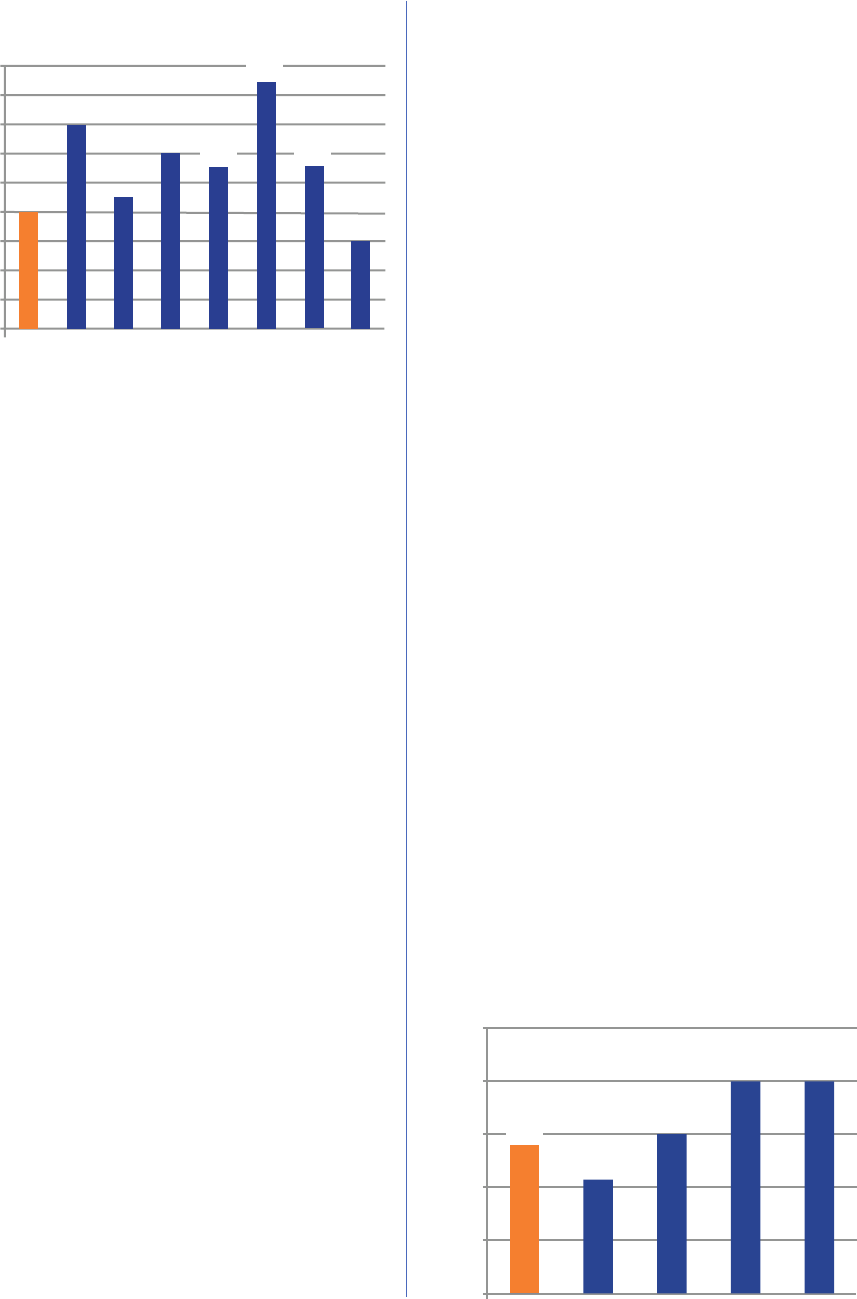

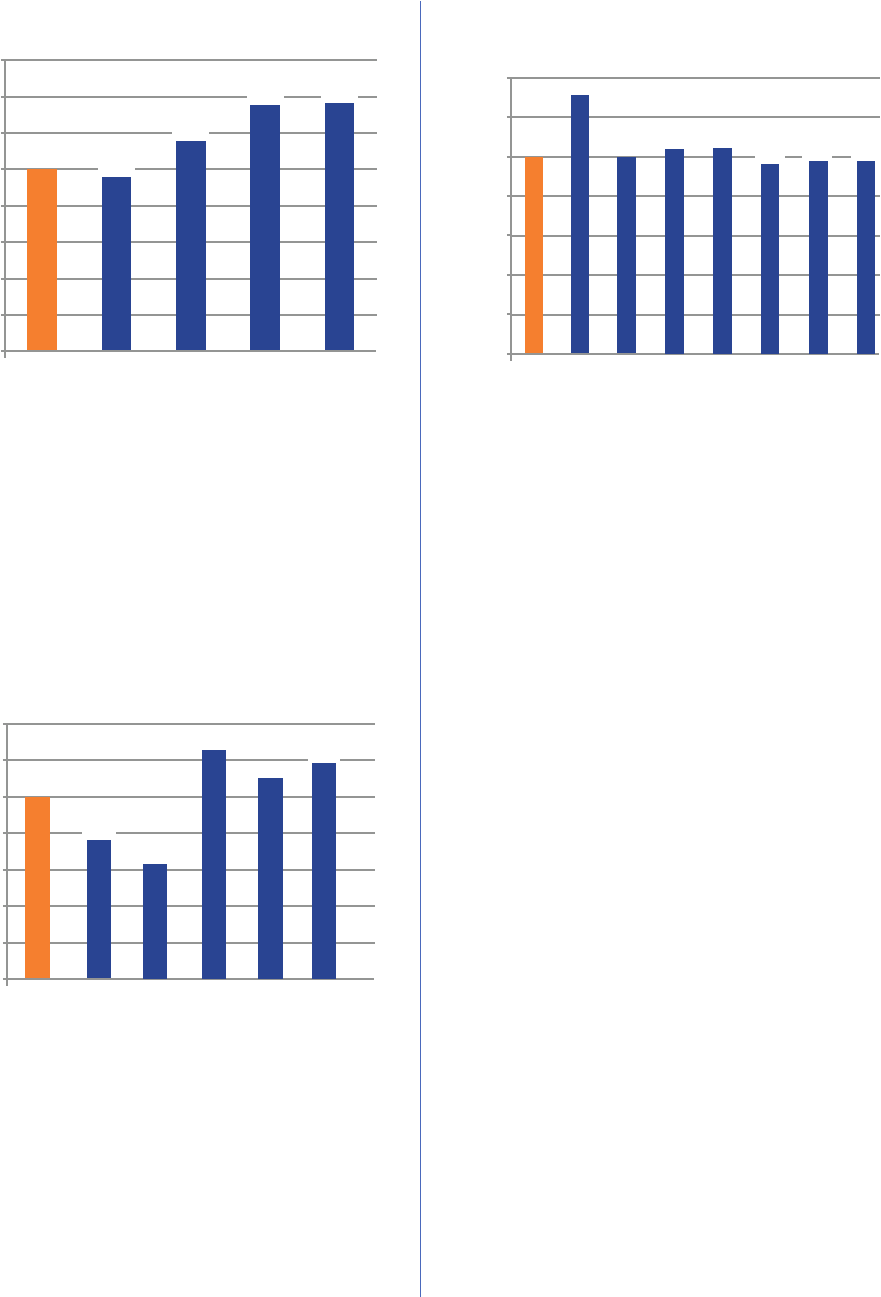

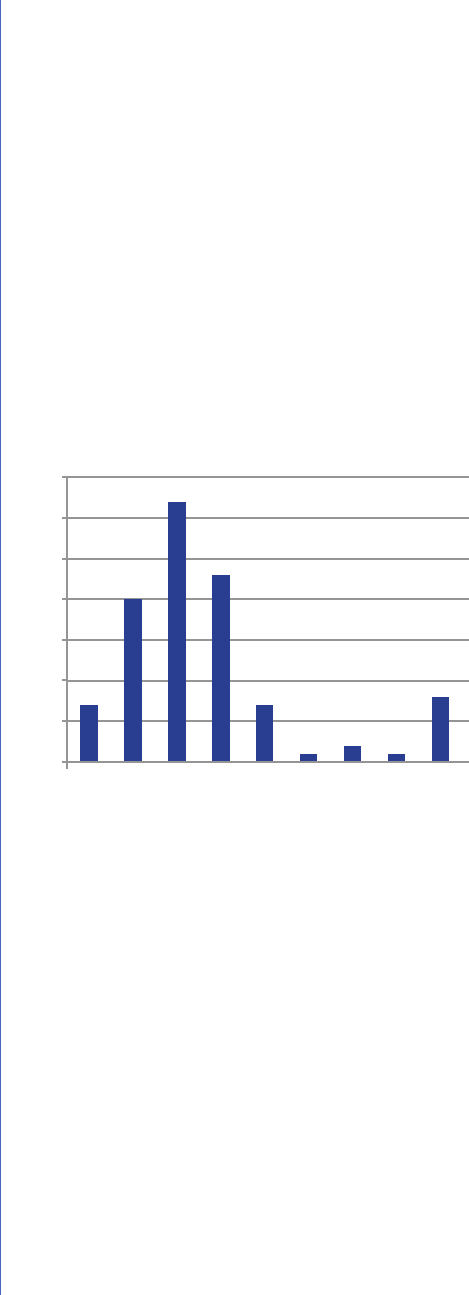

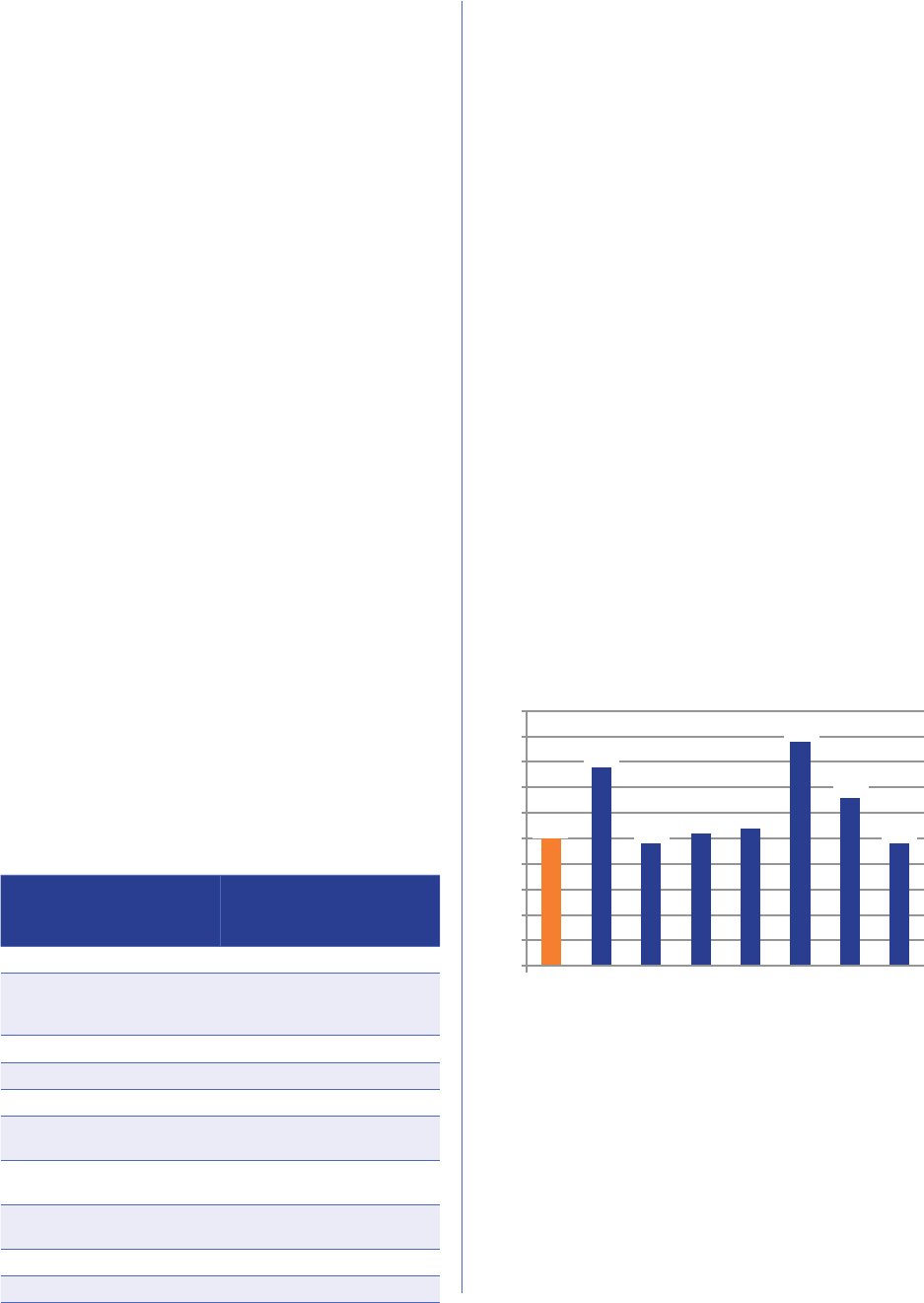

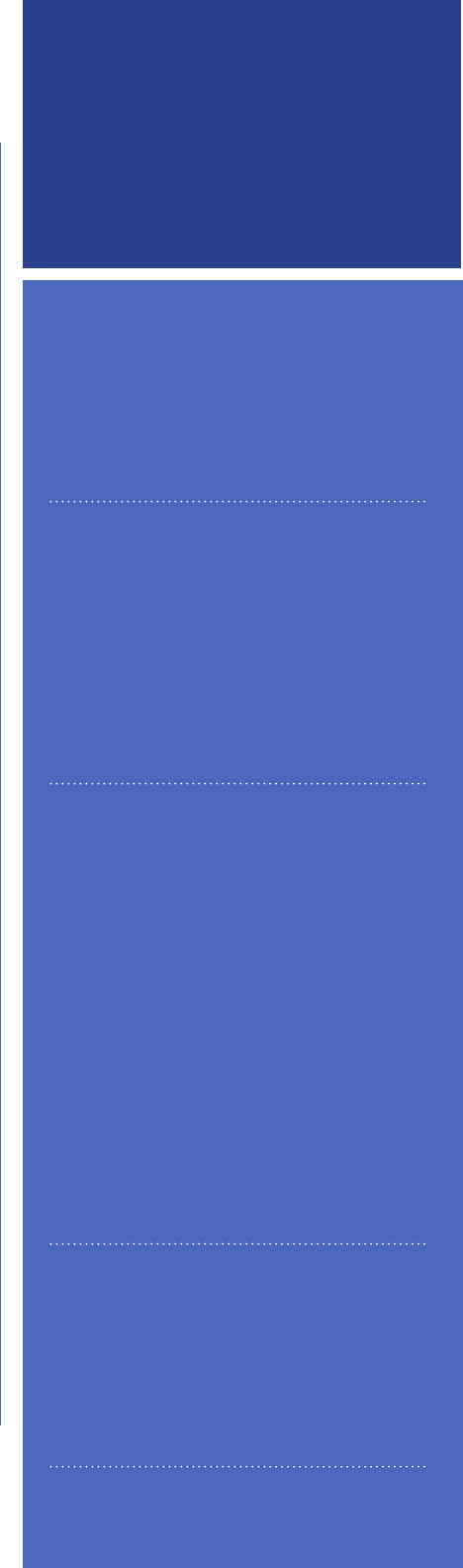

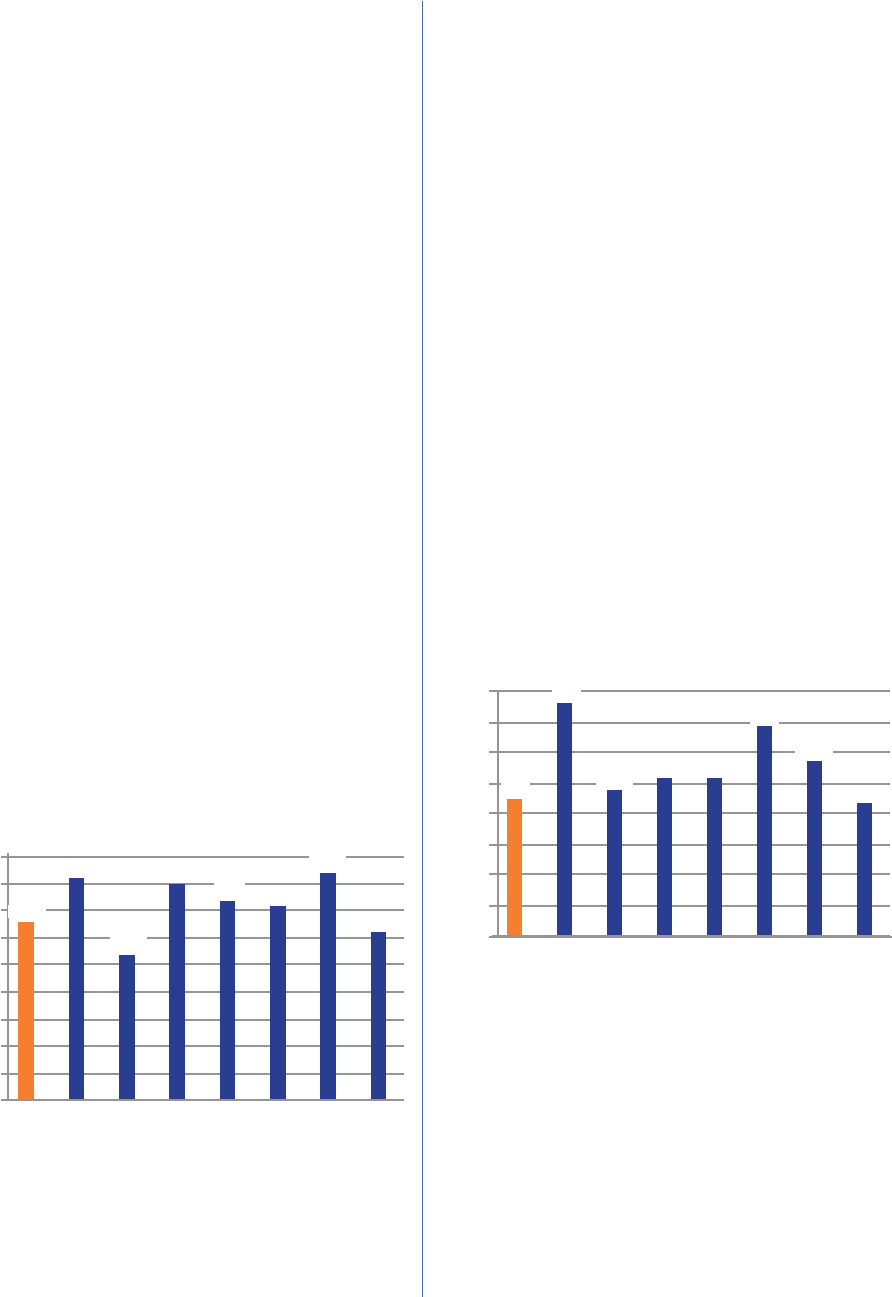

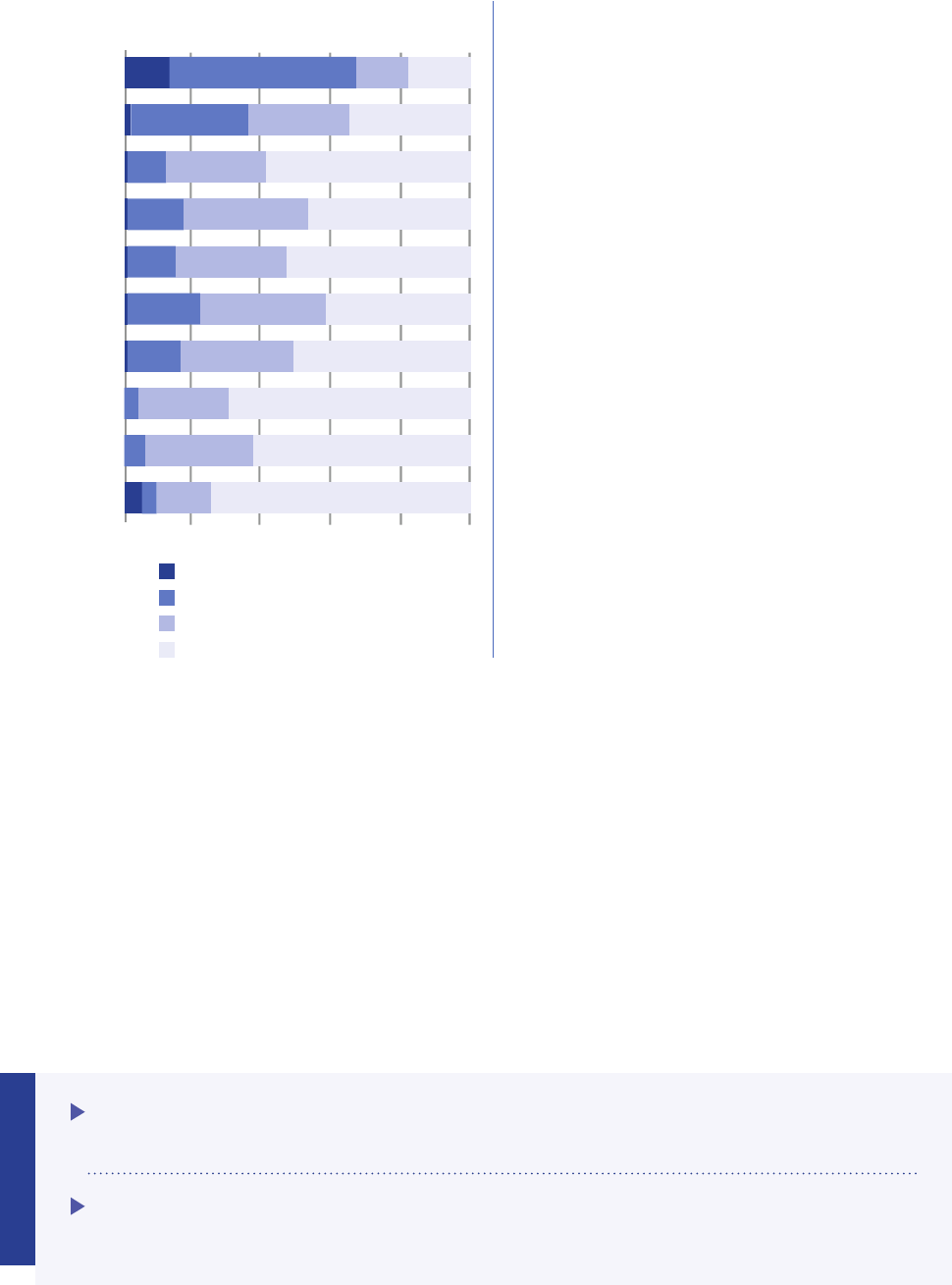

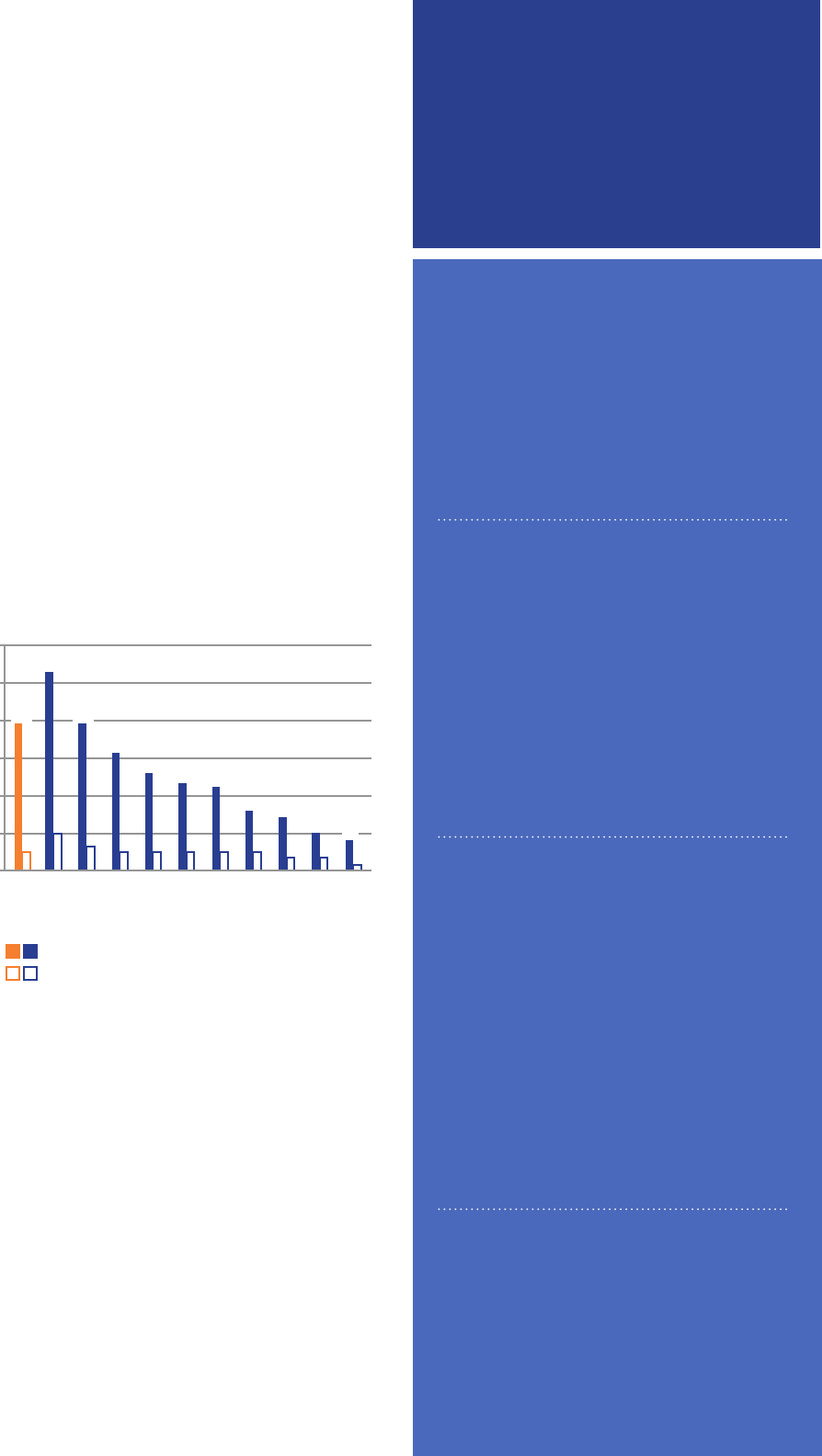

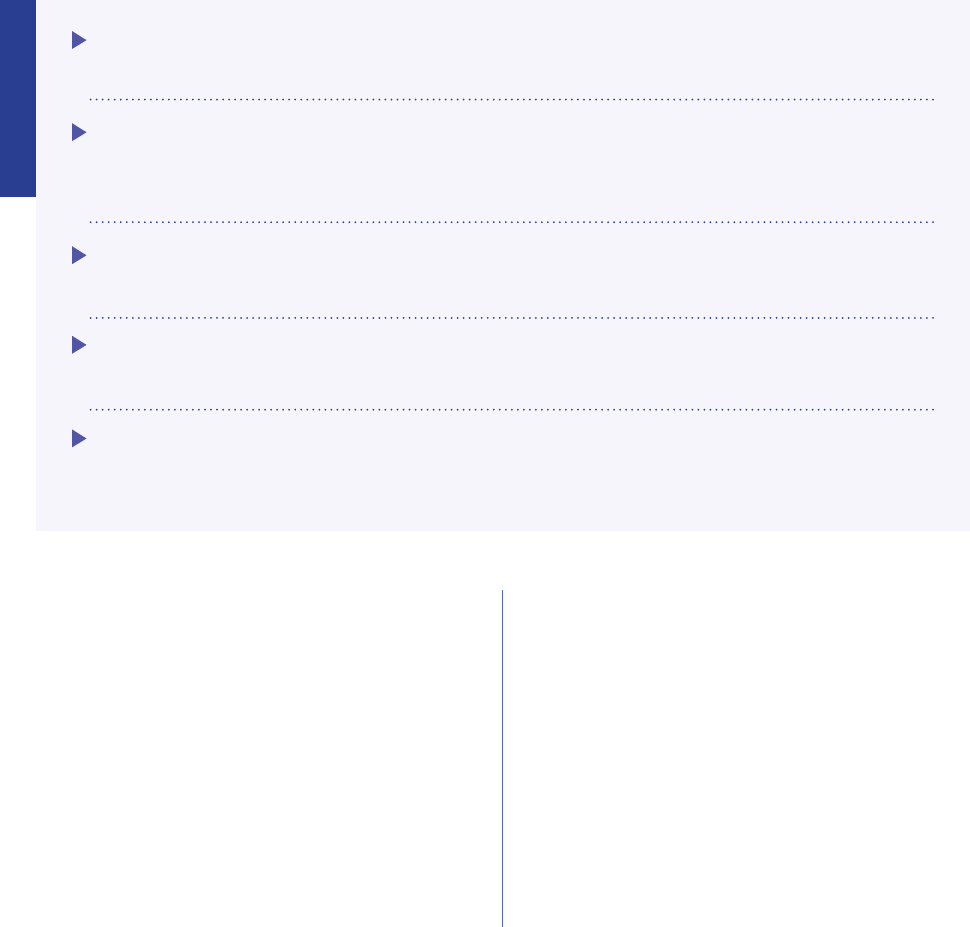

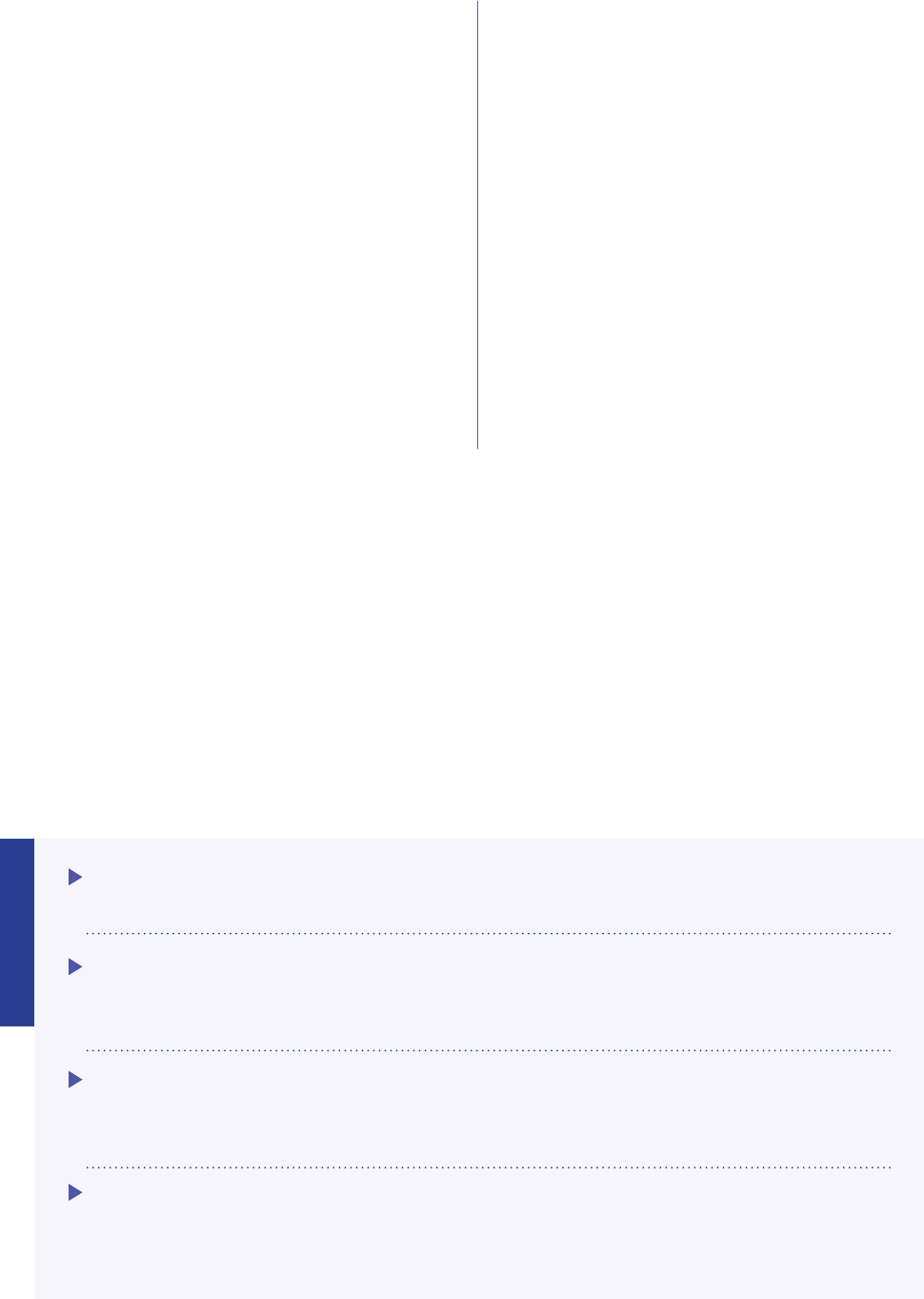

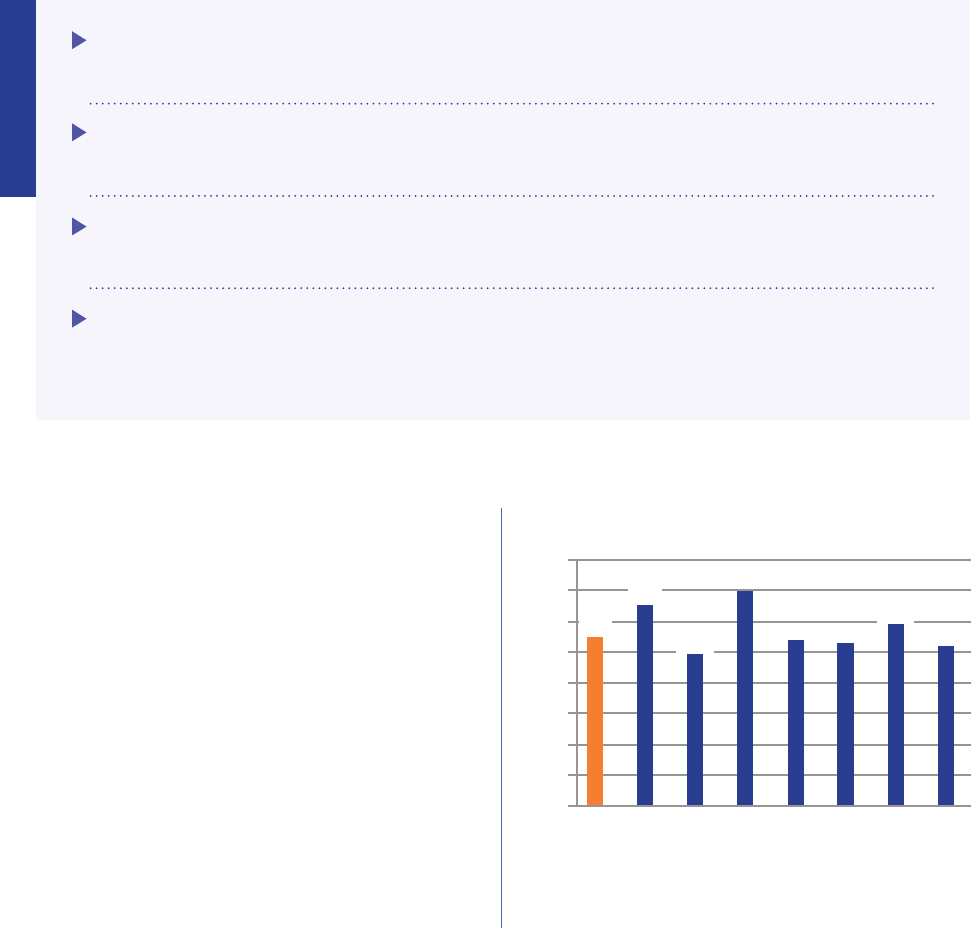

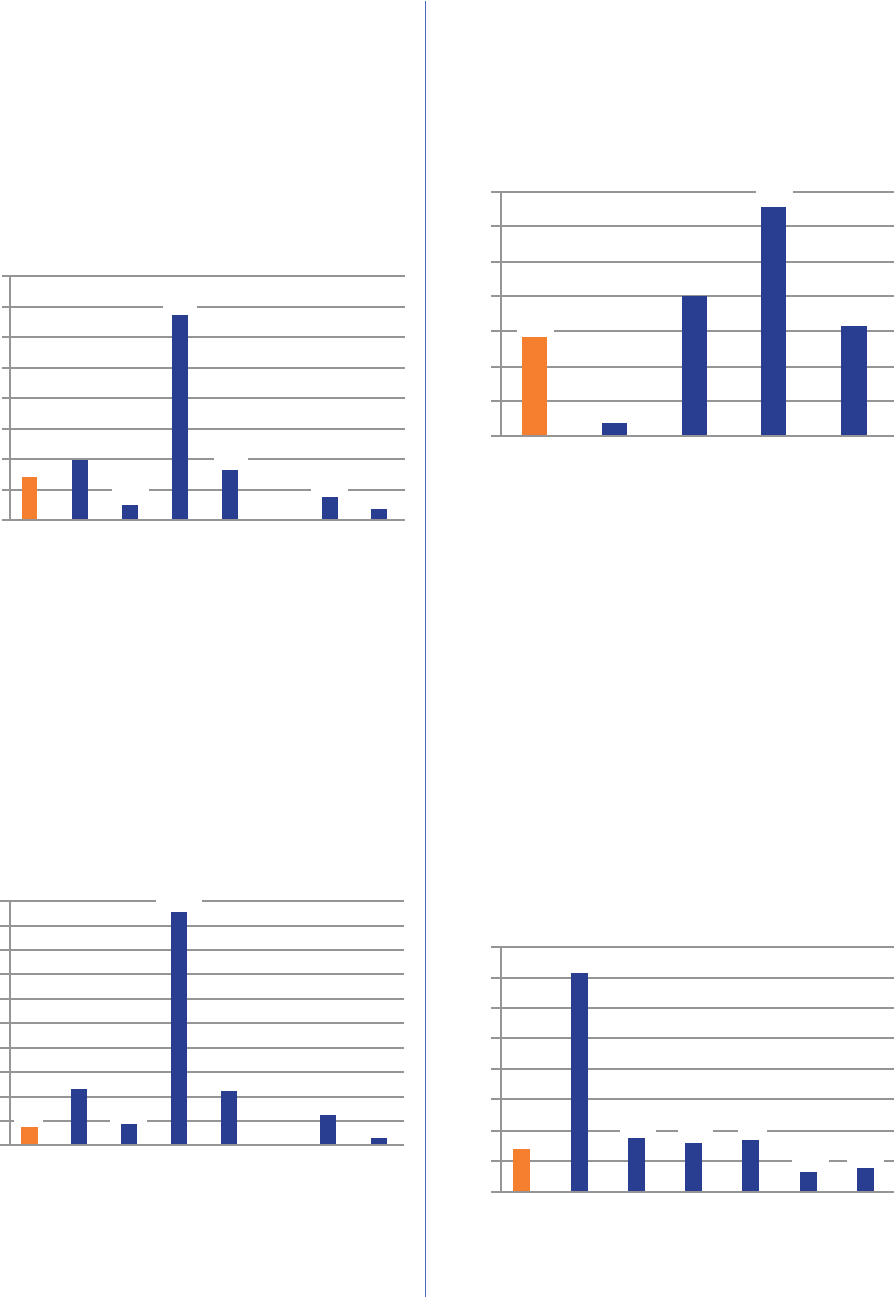

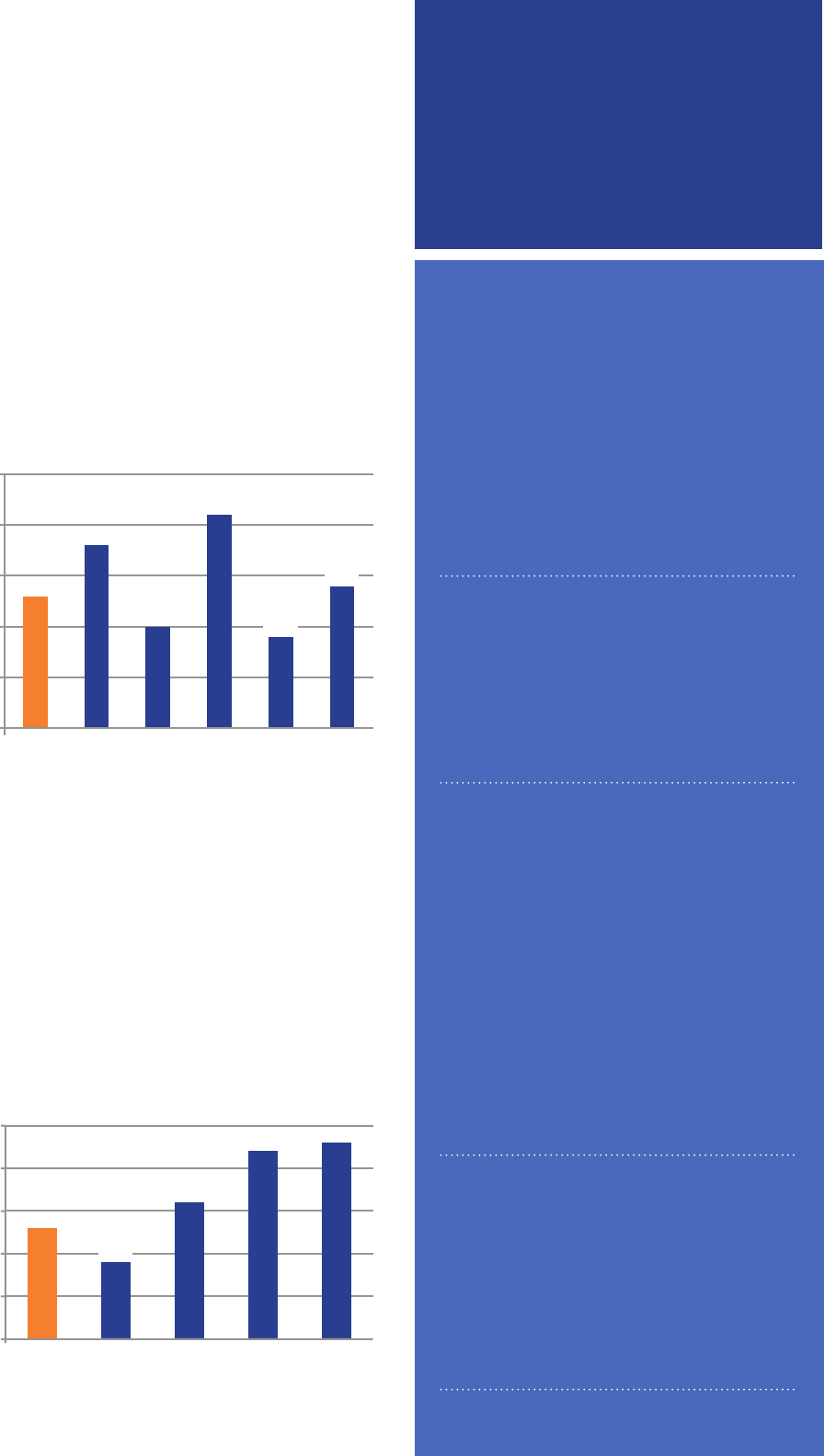

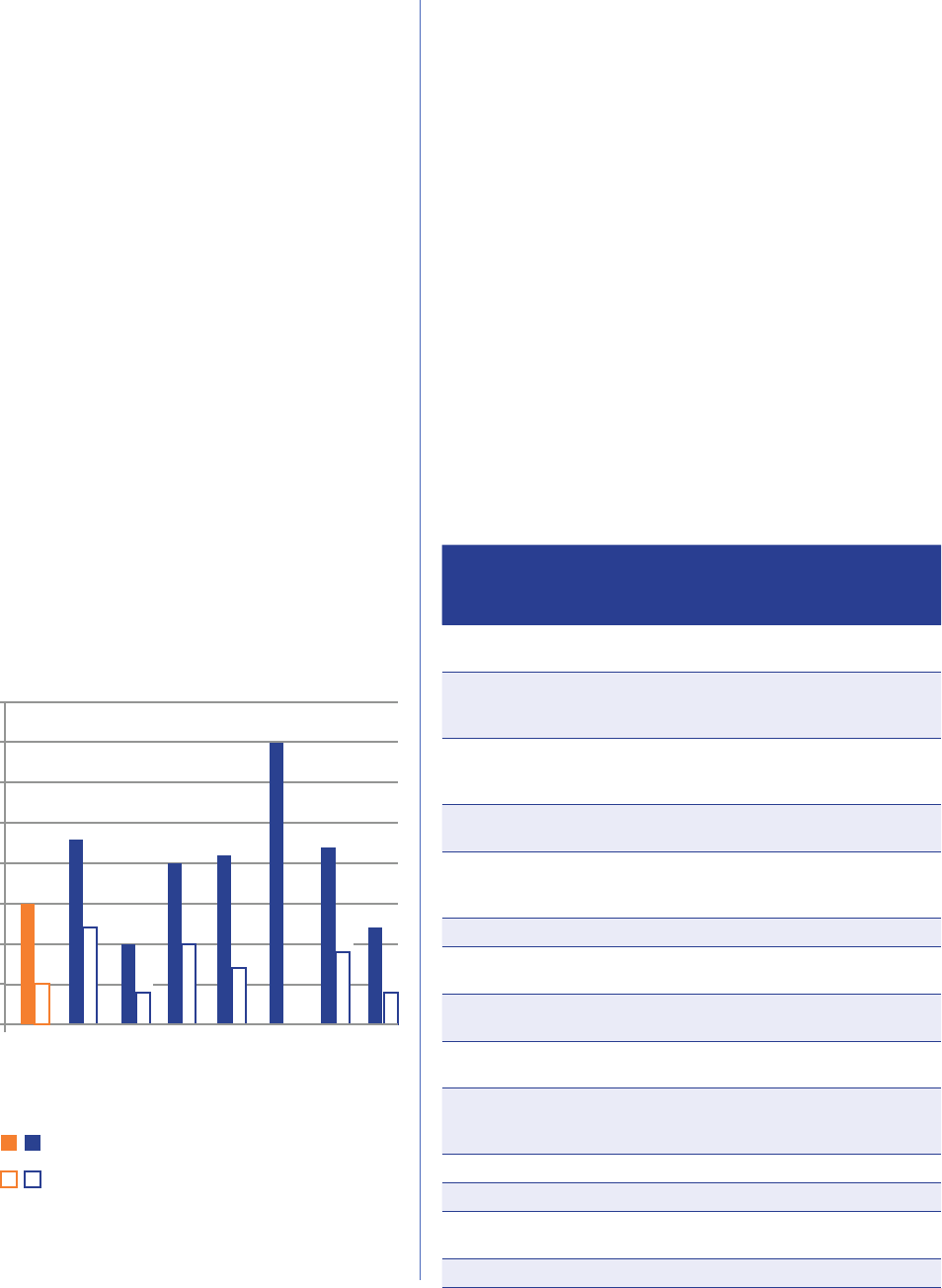

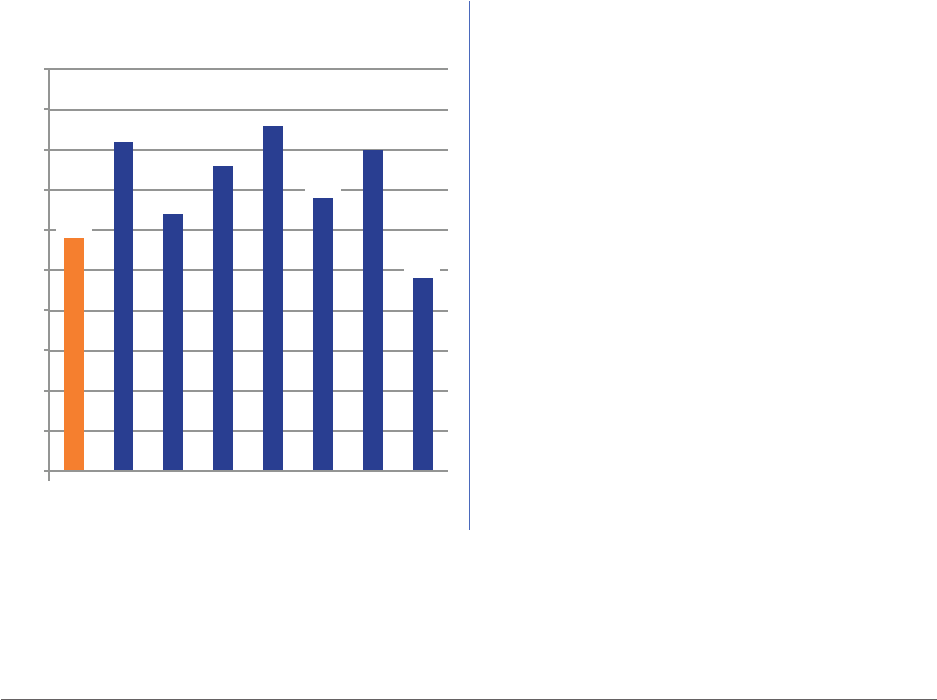

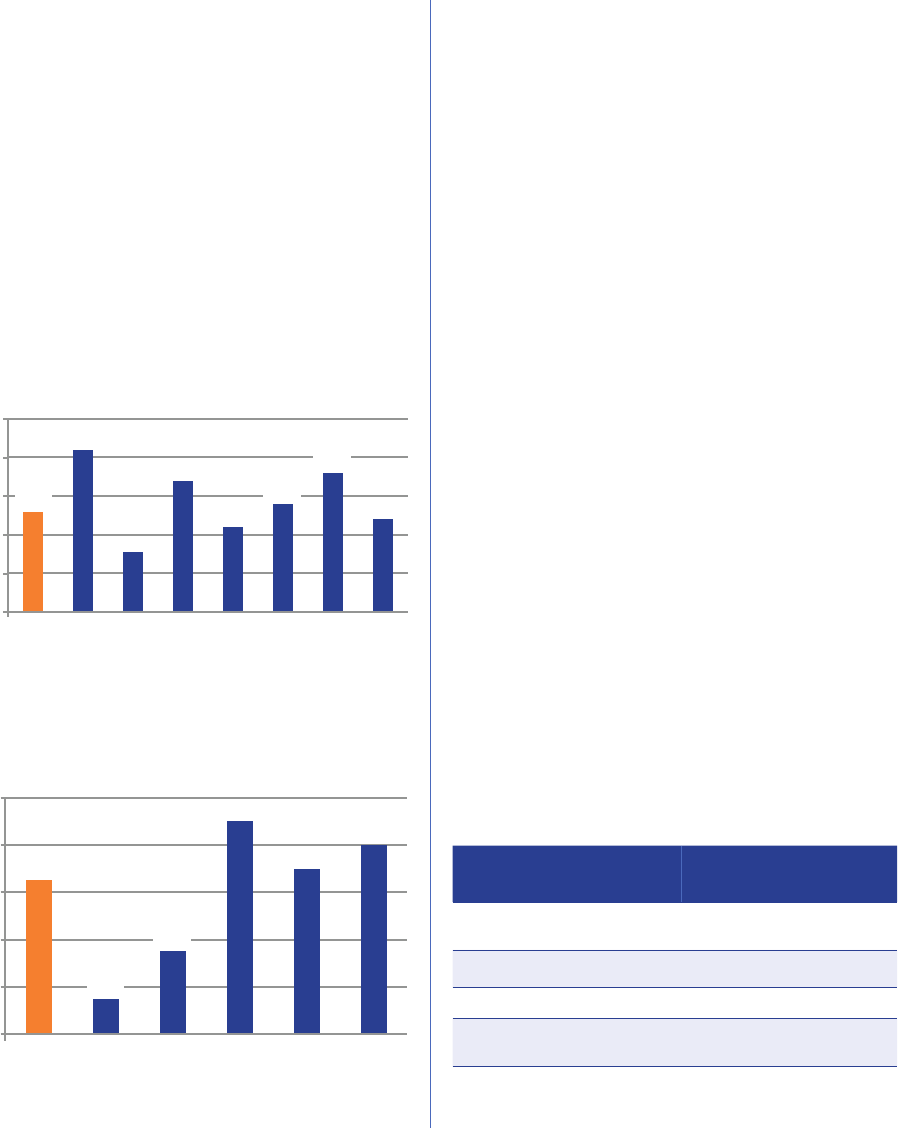

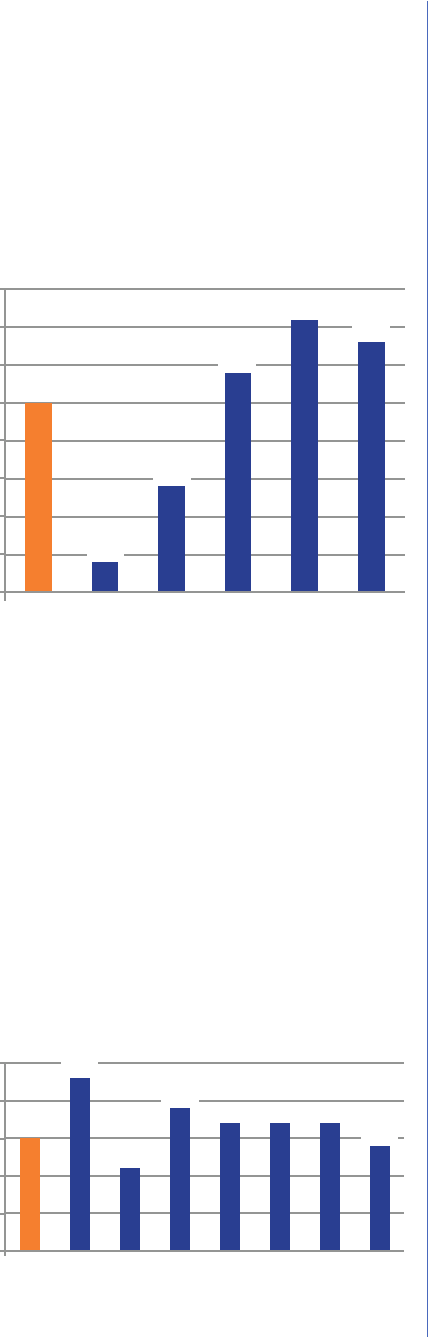

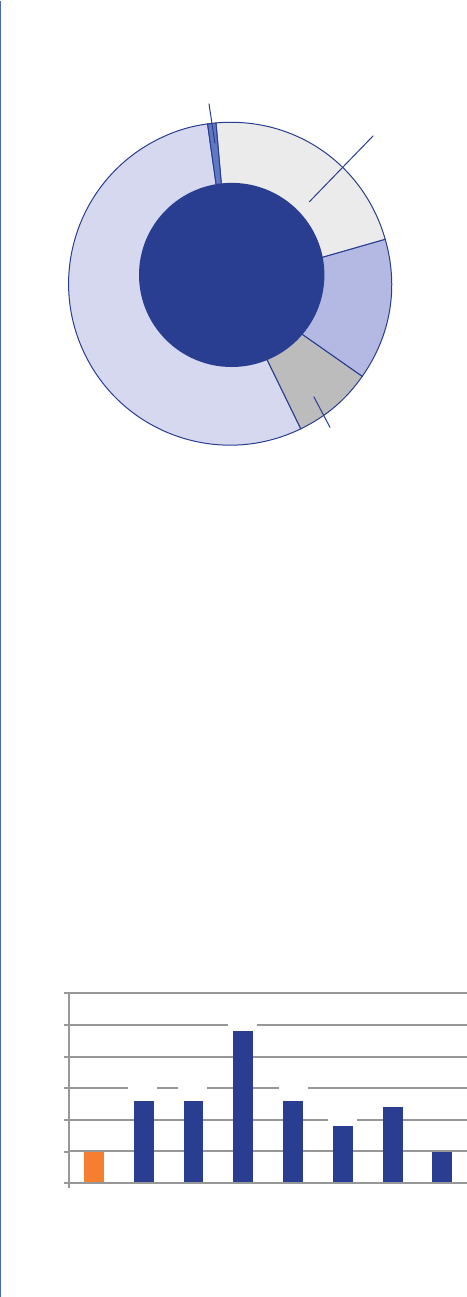

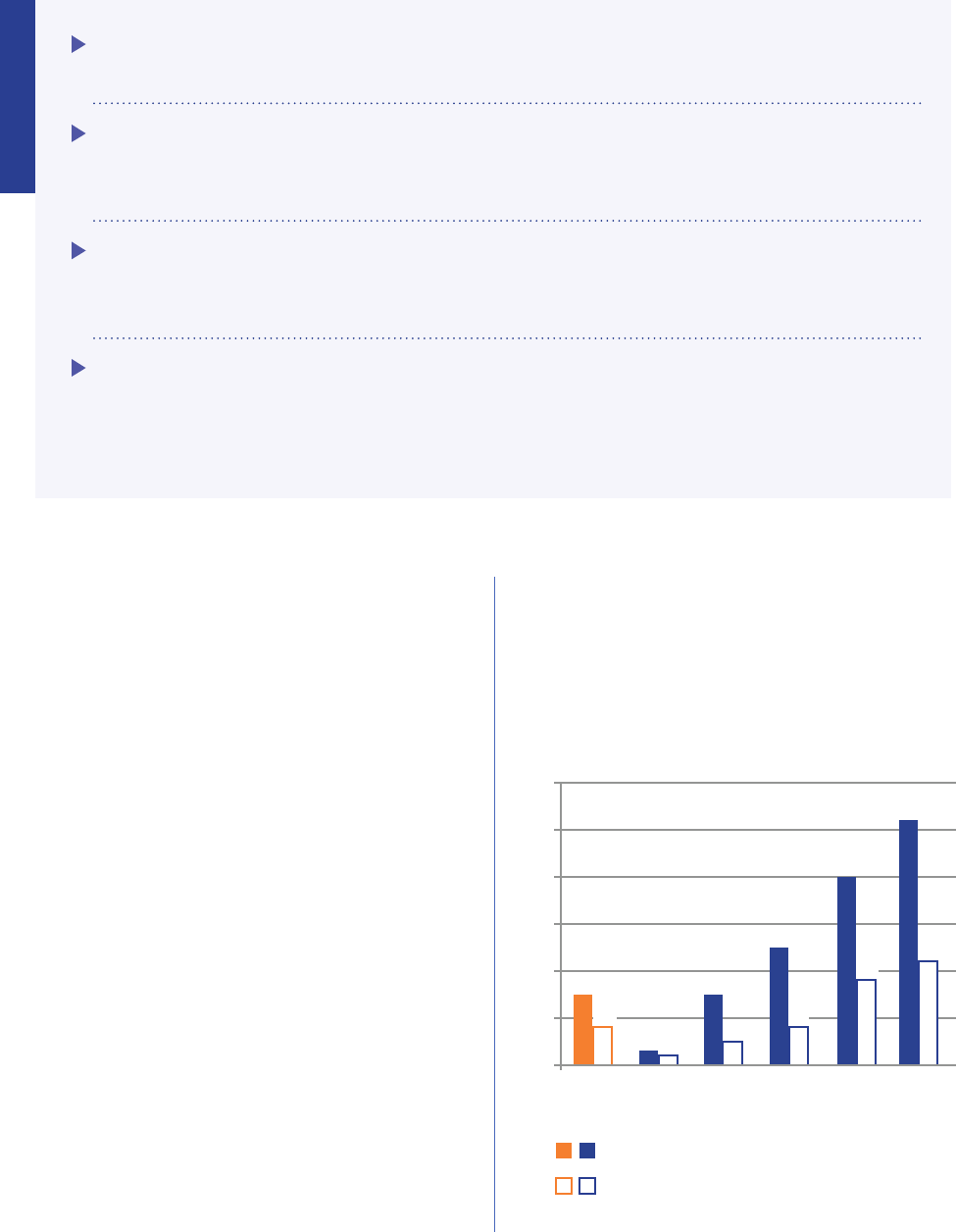

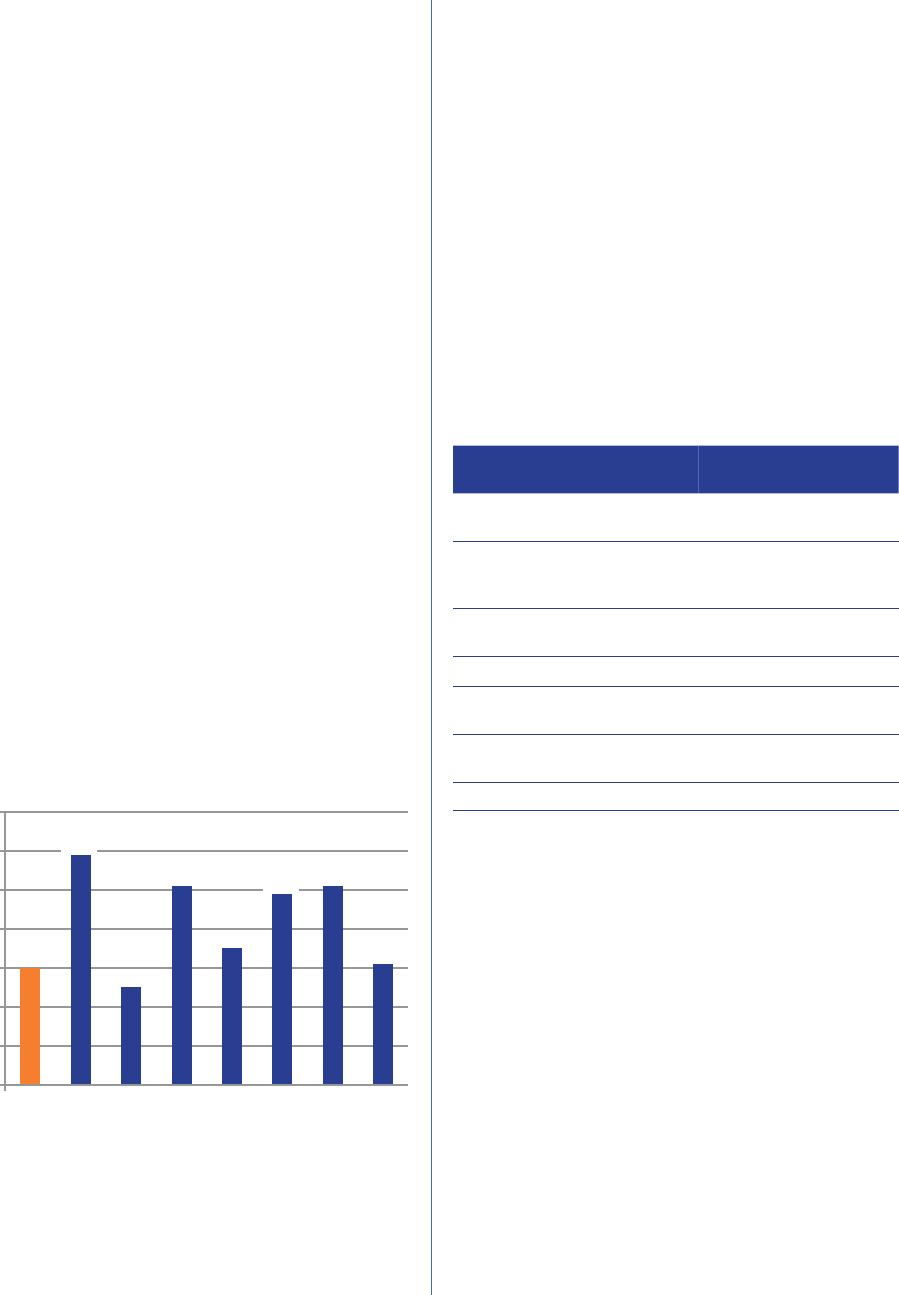

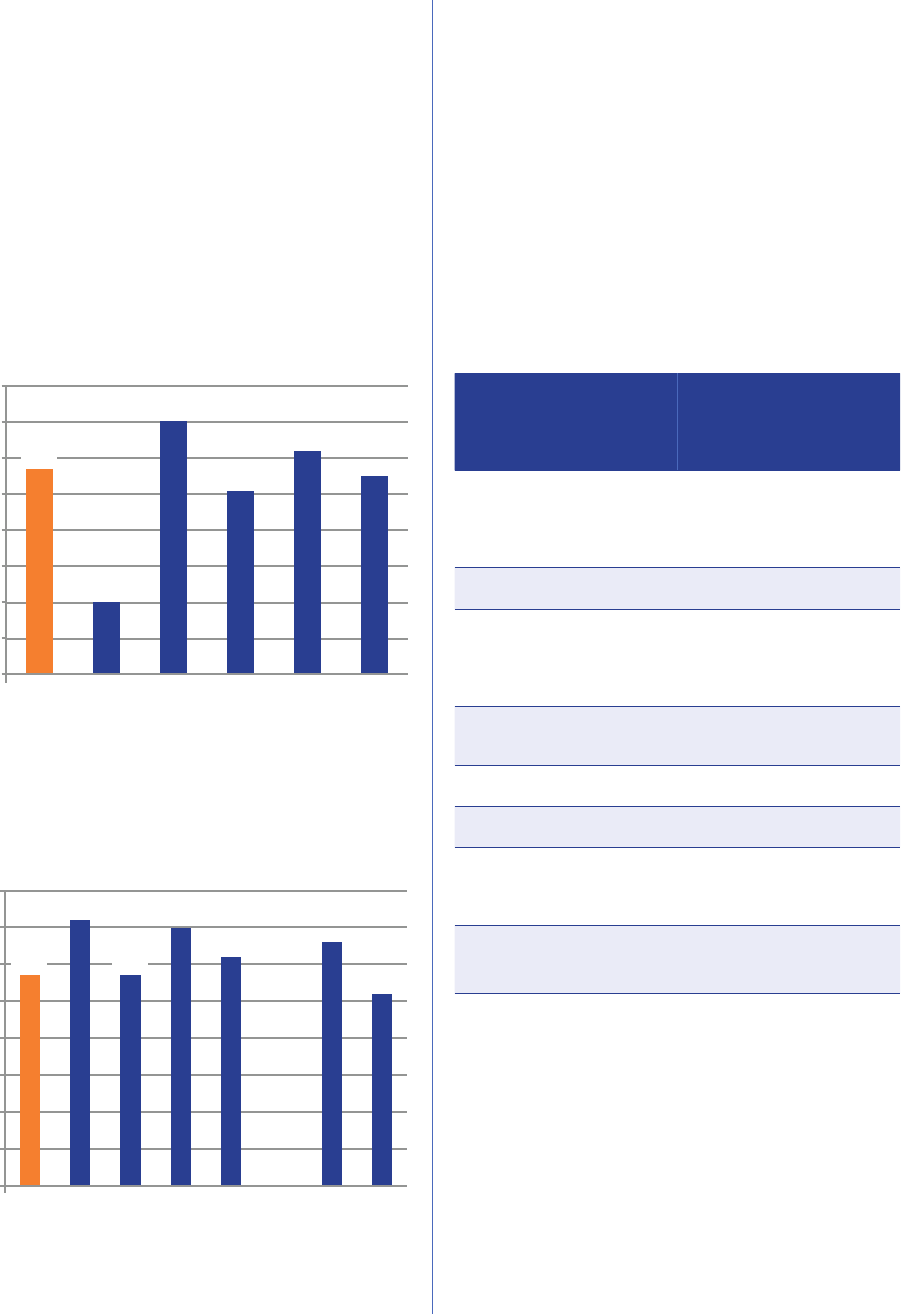

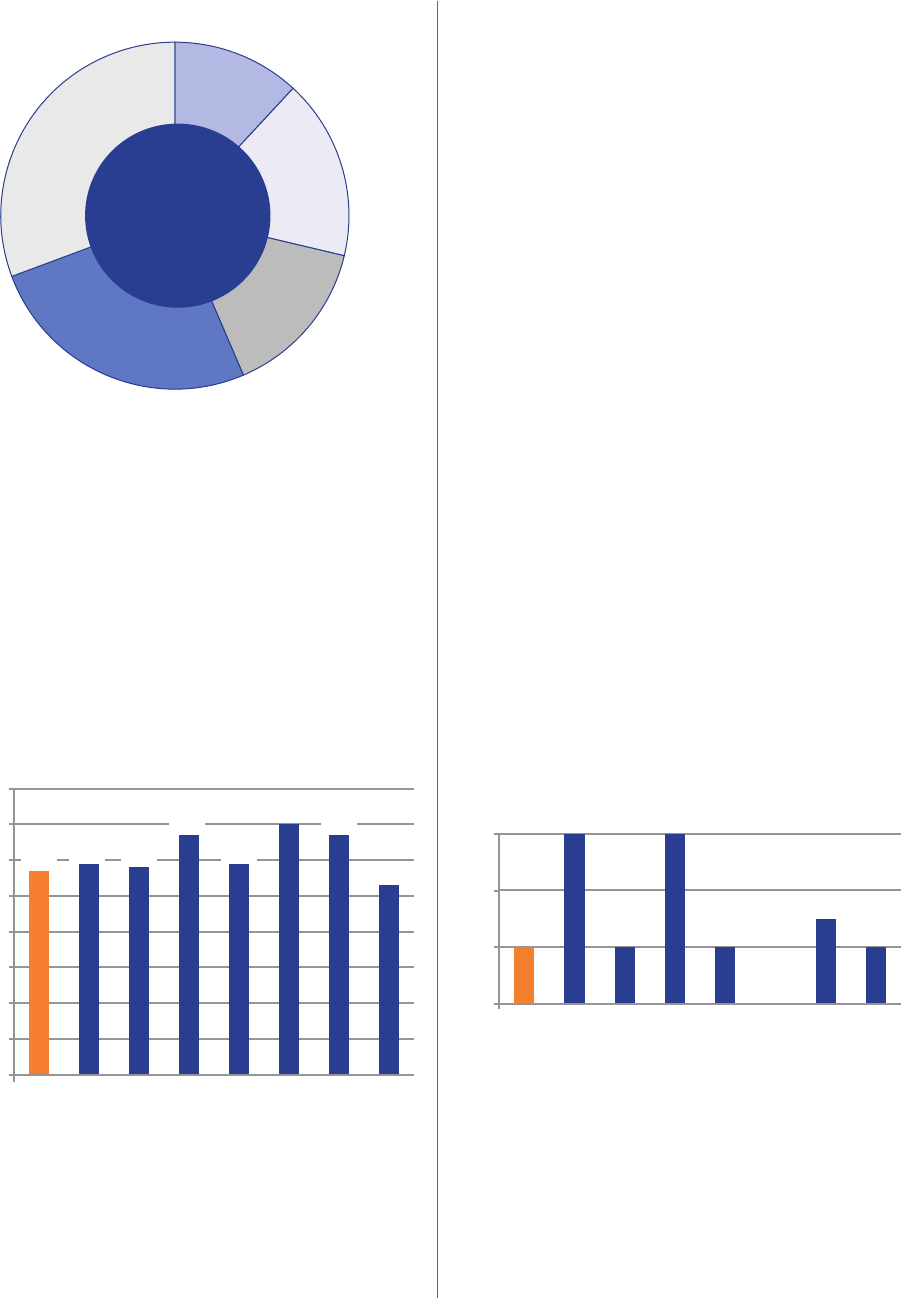

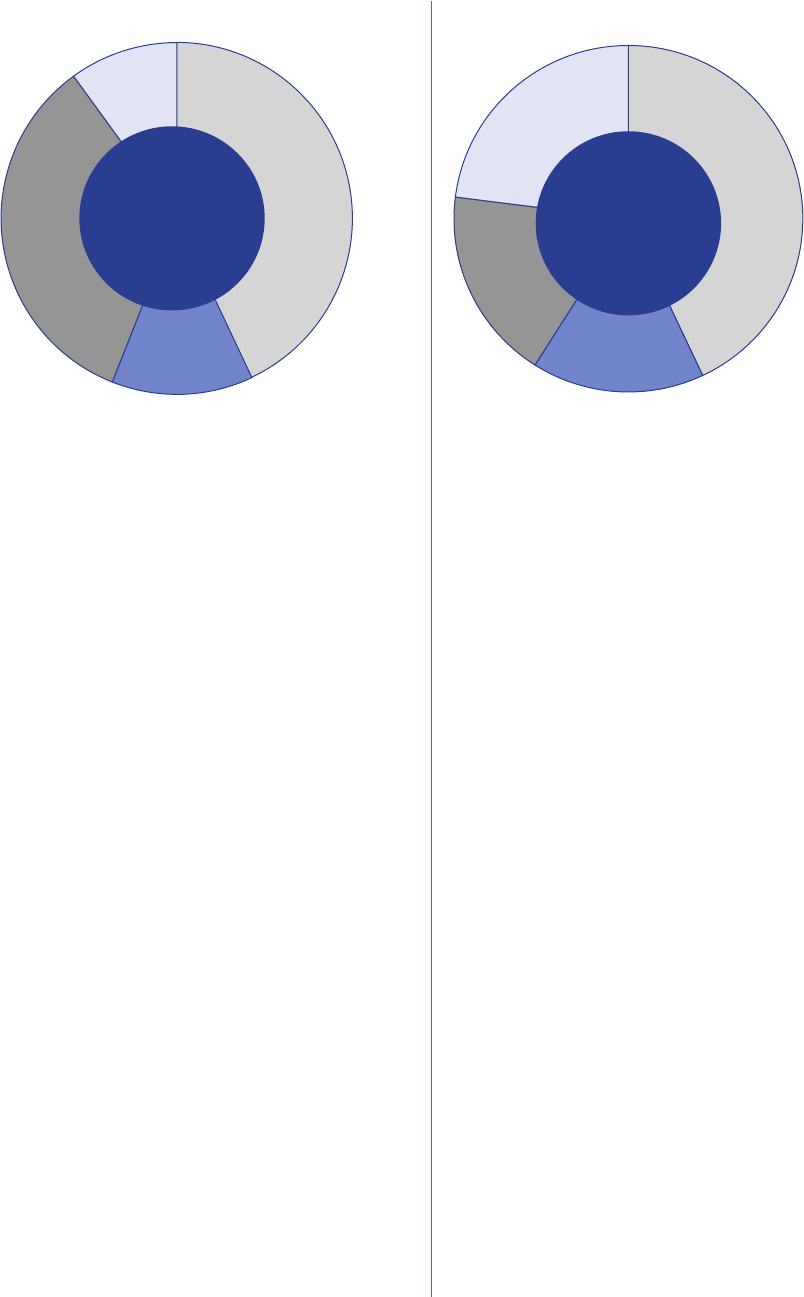

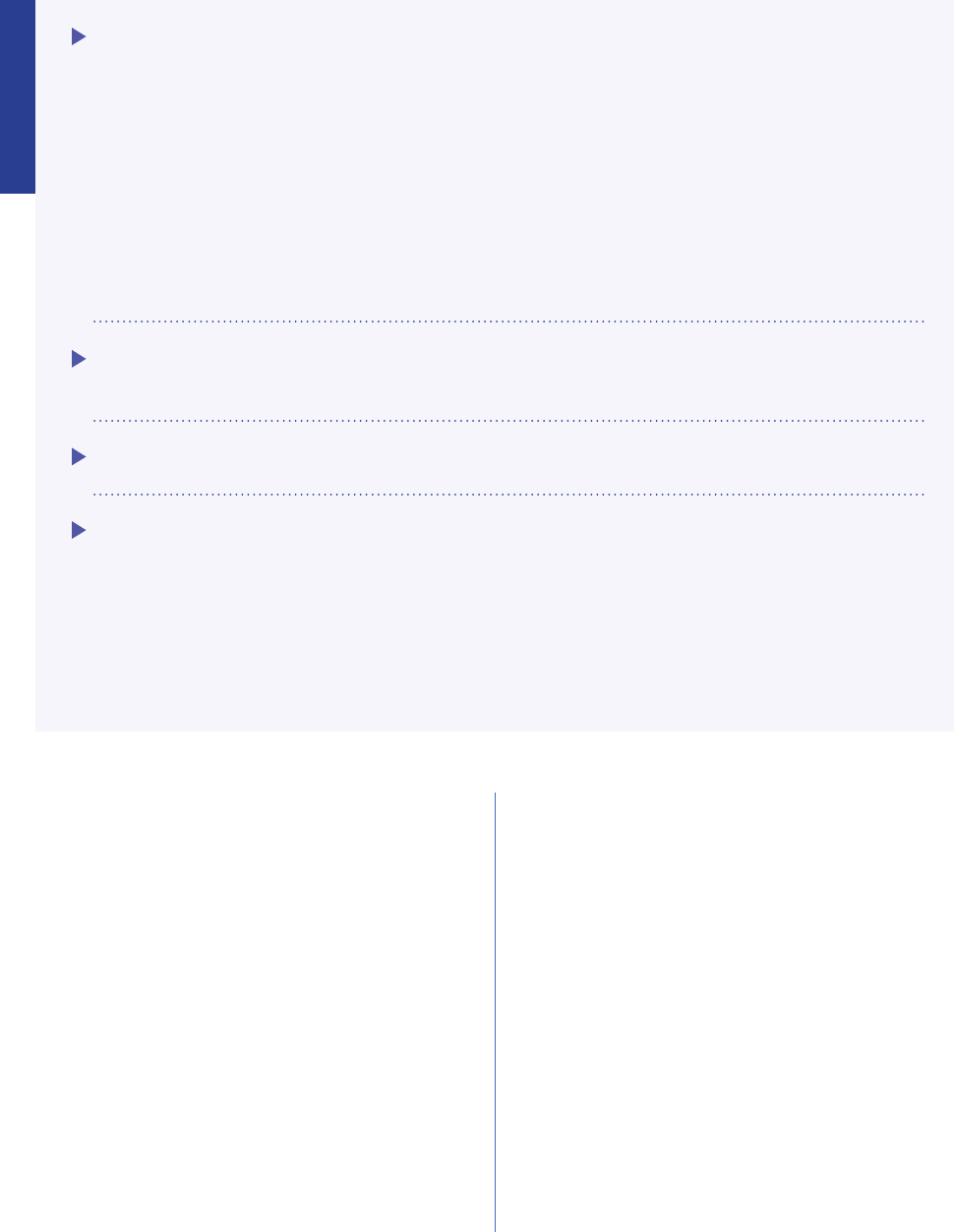

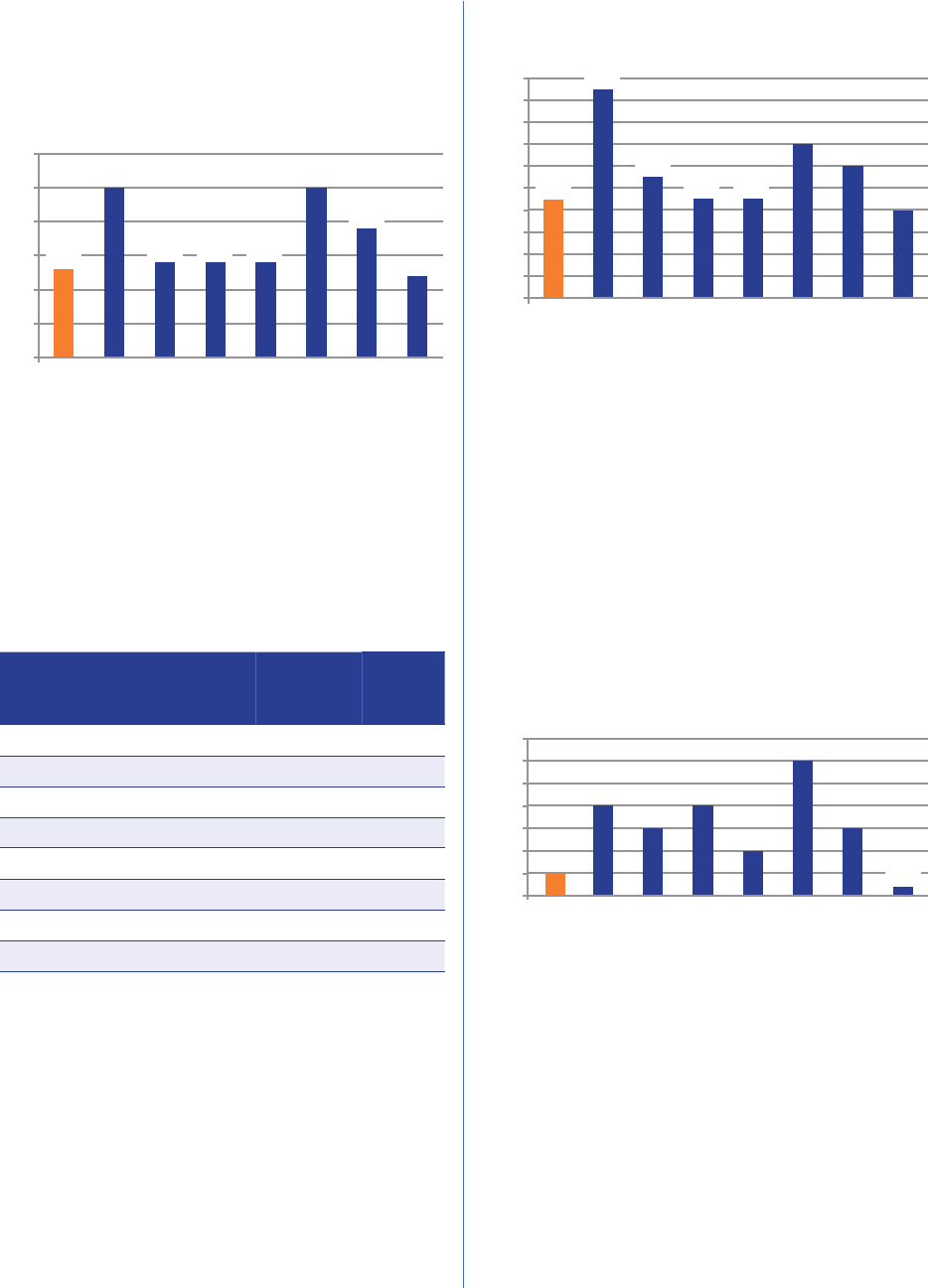

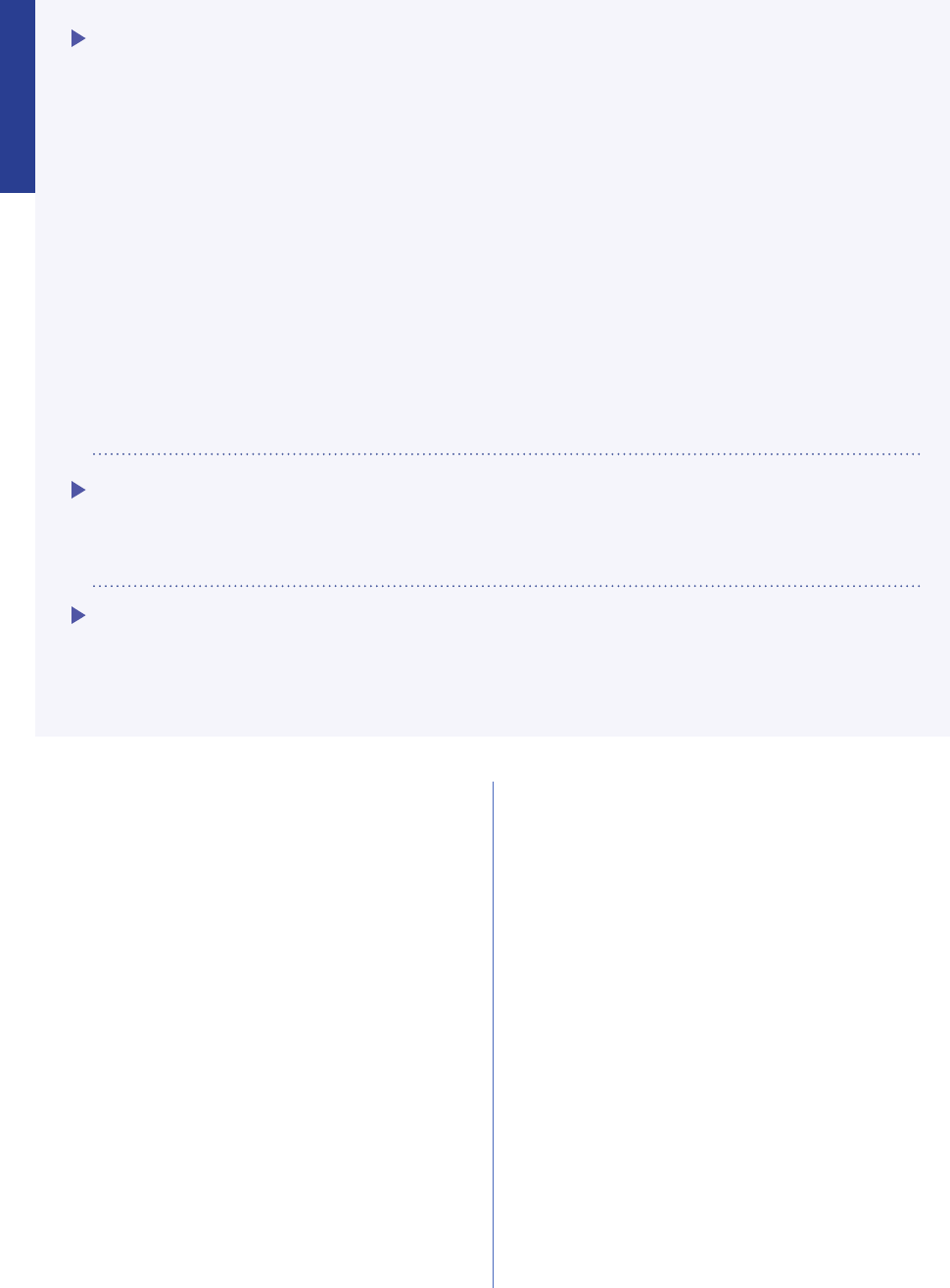

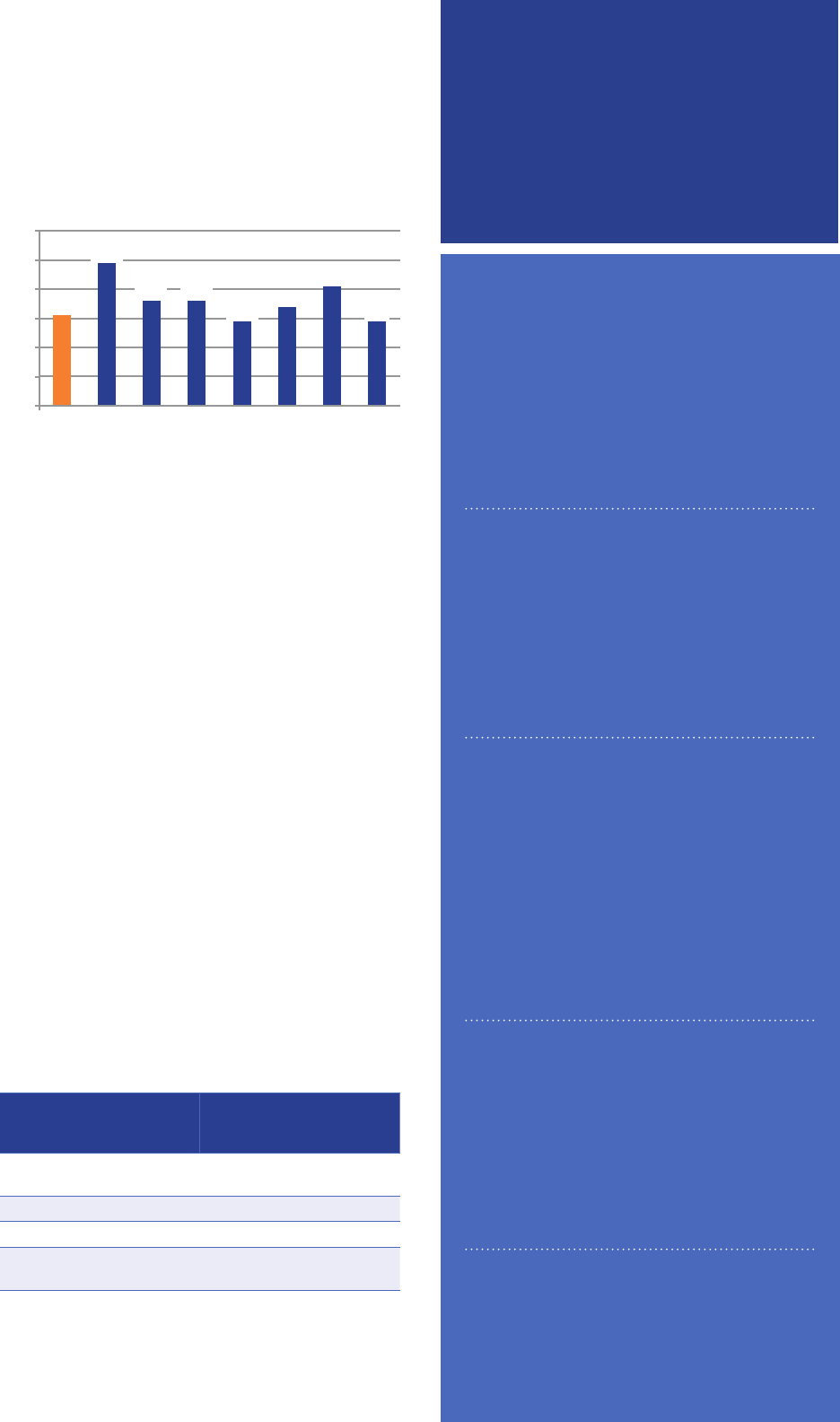

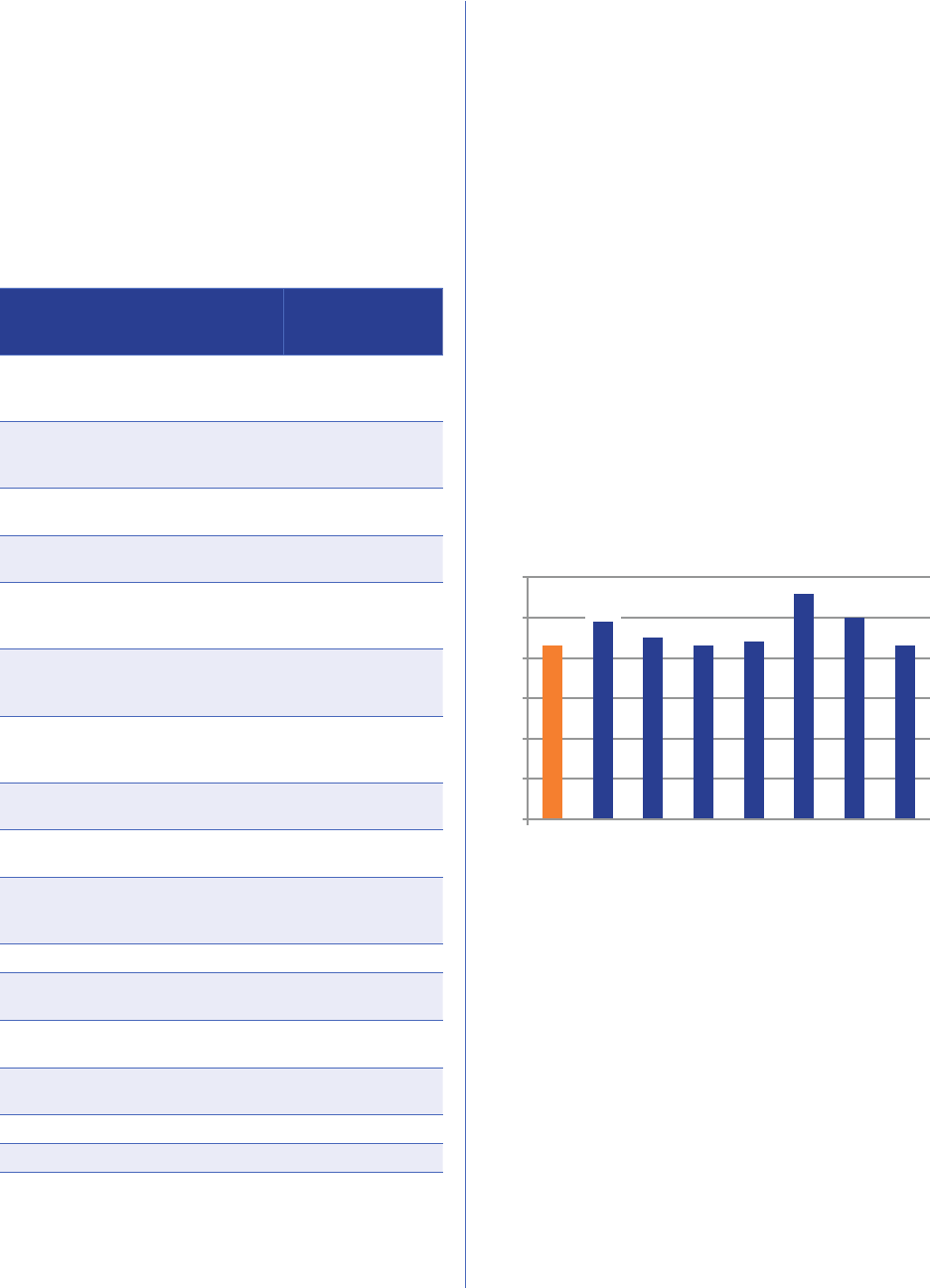

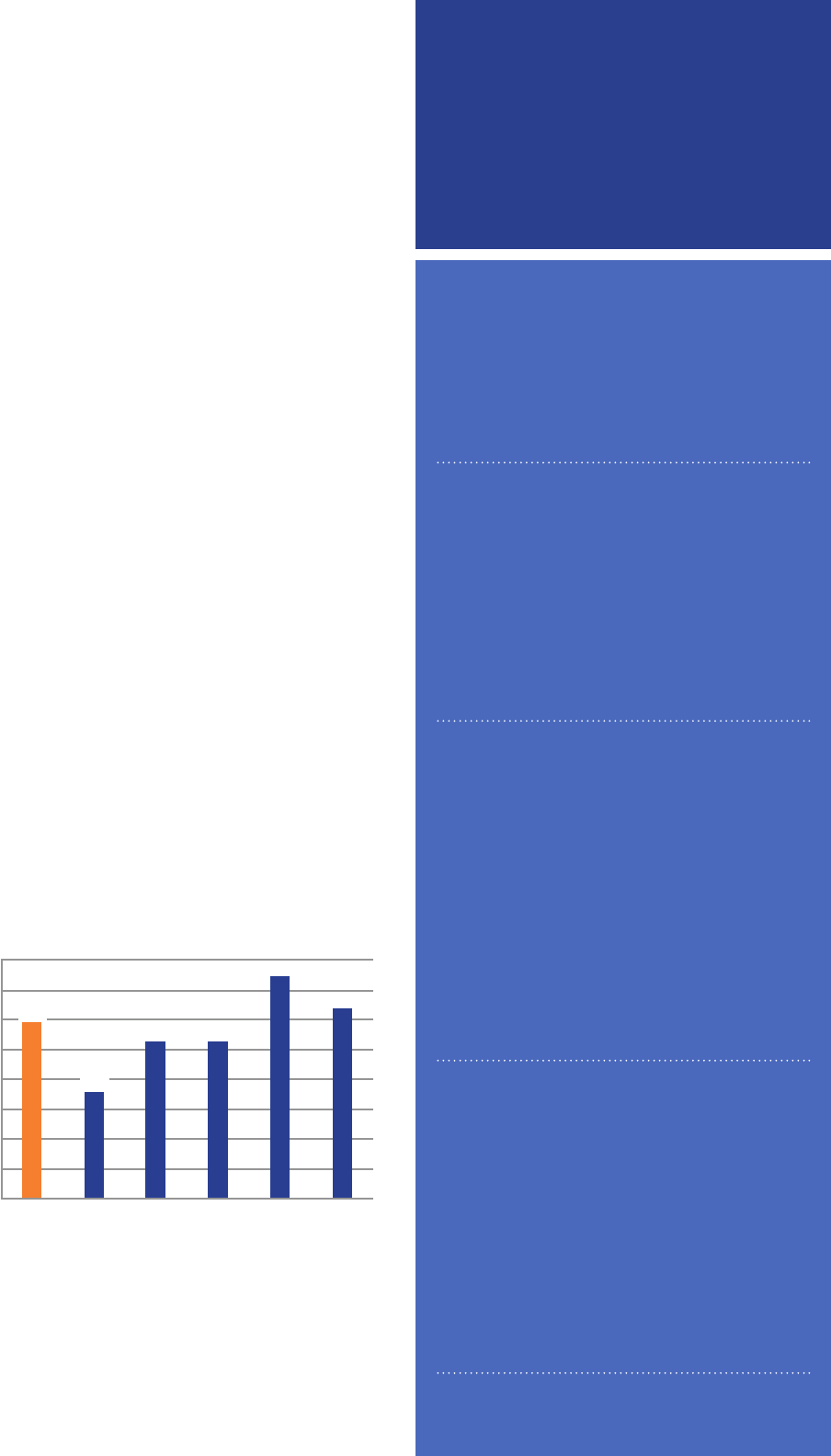

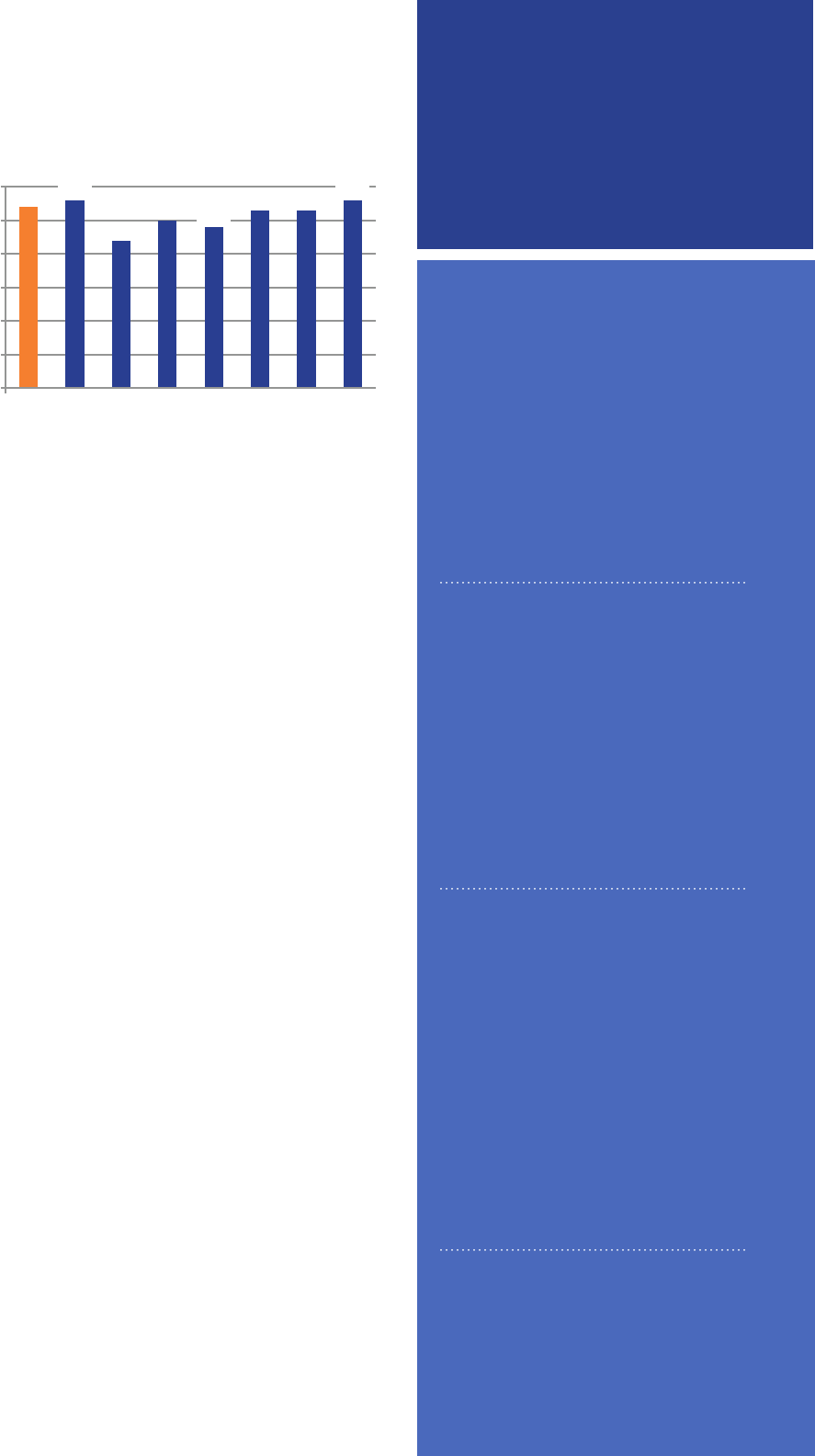

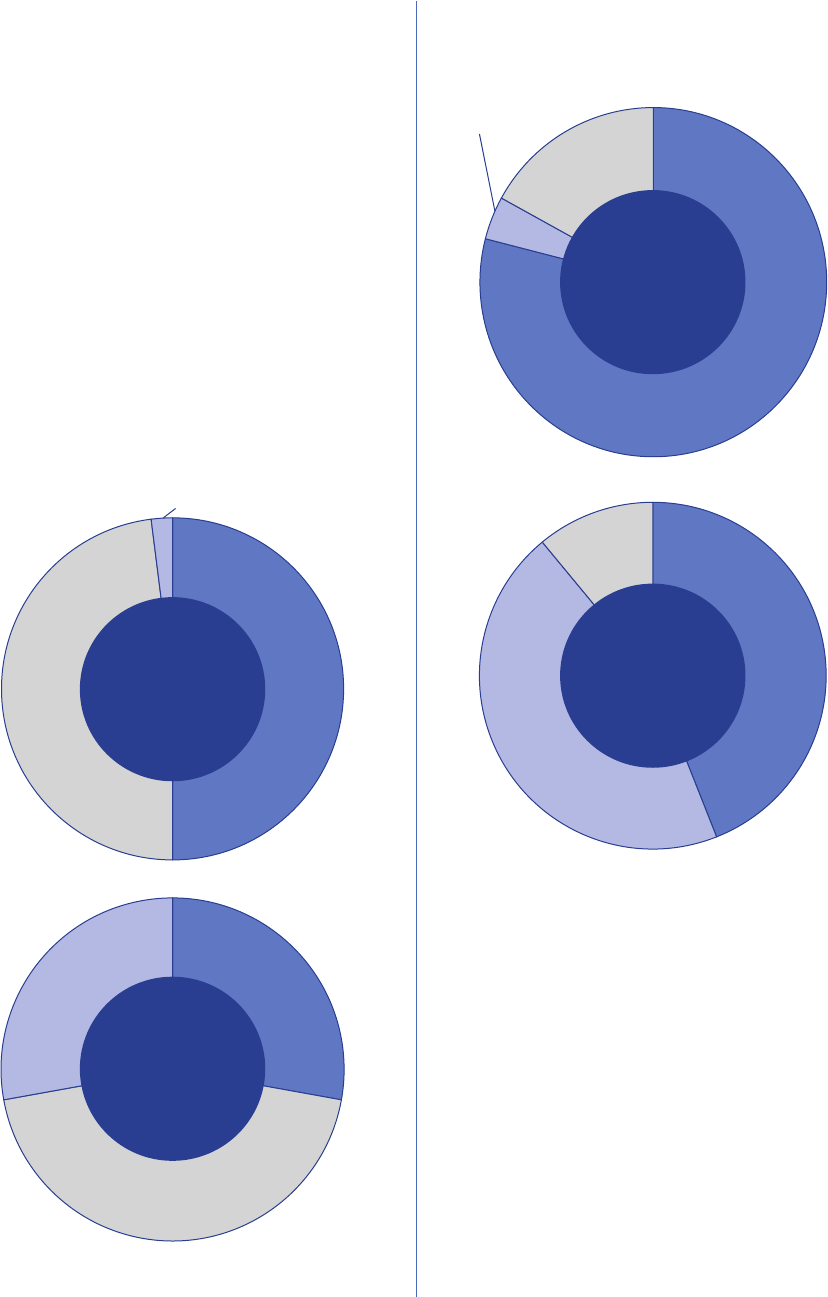

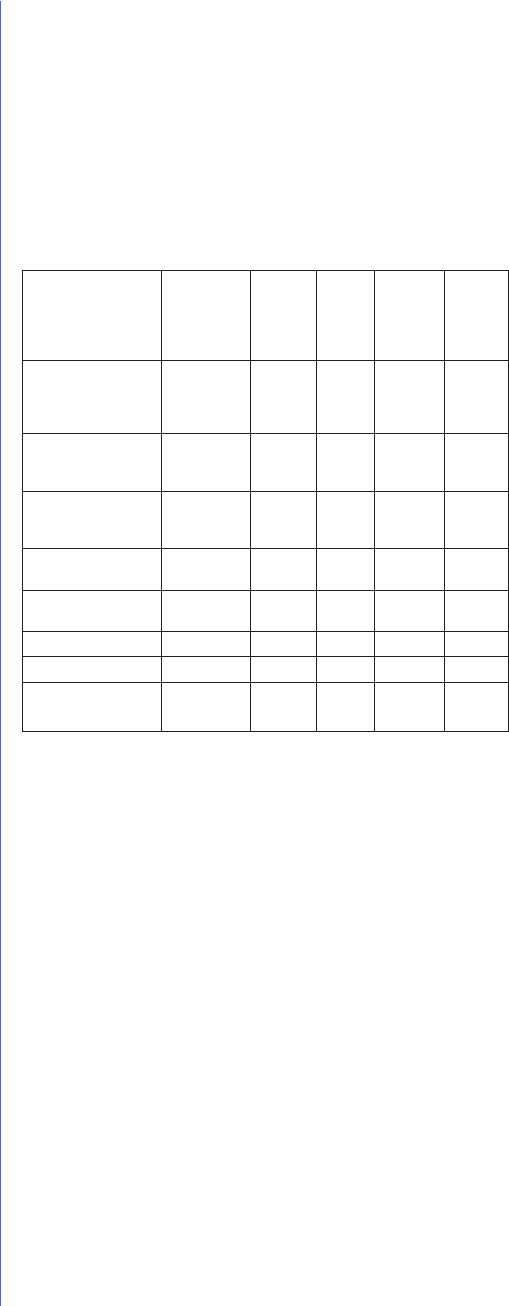

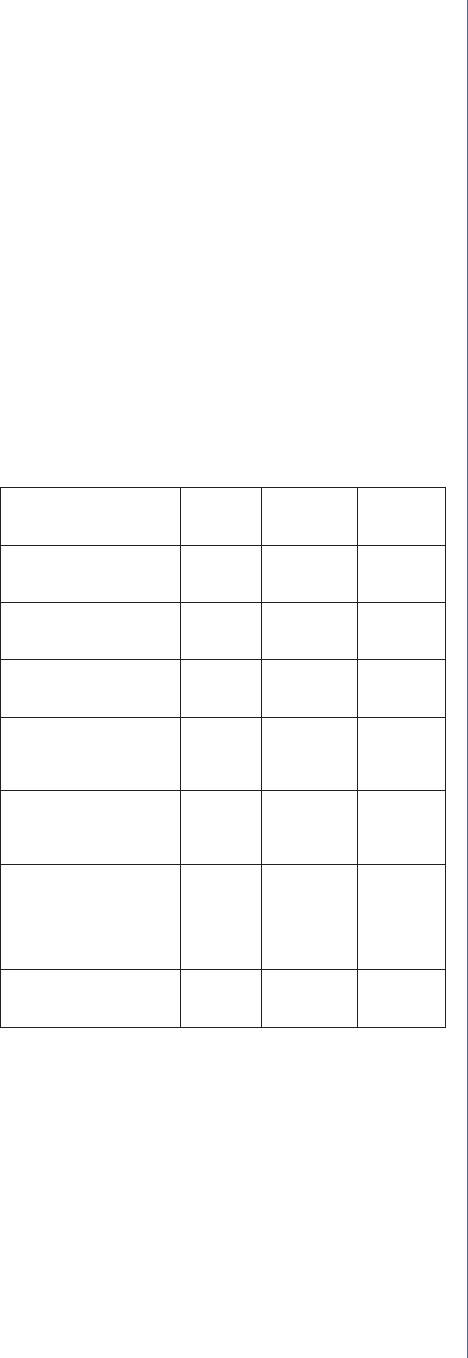

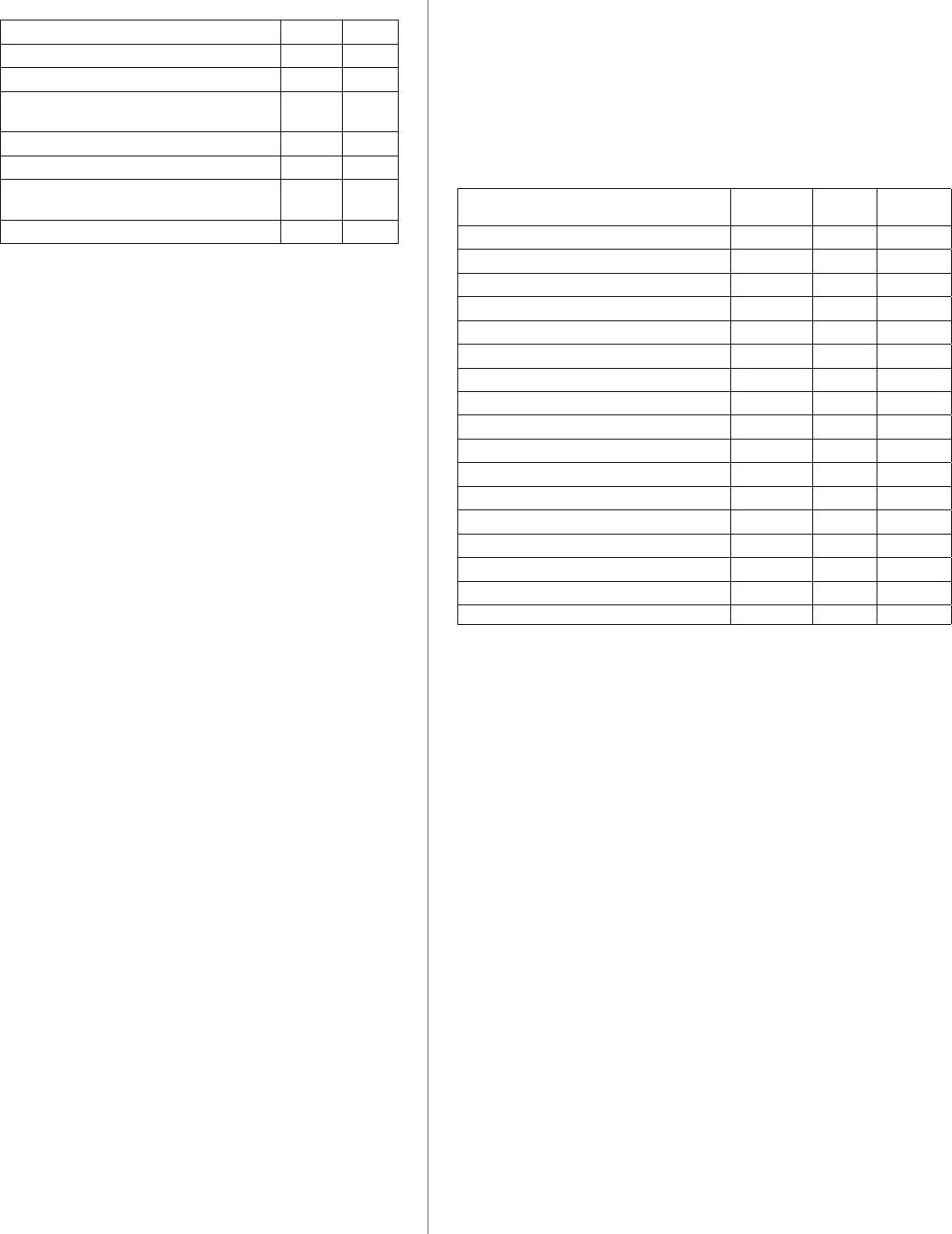

Unemployment rate

Income and Employment Status

with Middle Eastern, American Indian,

multiracial, Latino/a, and Black respondents experiencing higher rates of unemployment.

Overall

American Indian

Asian

Black

Latino/a

Middle Eastern*

Multiracial

White

0%

5% 10% 15% 20% 25% 30% 35%

% in USTS (supplemental survey weight applied) % in U.S. population (CPS)

* U.S. population data for Middle Eastern people alone is unavailable in the CPS.

Employment and the Workplace

respondents who have ever been employed—or 13% of all respondents

in the sample— in

their lifetime.

of those who held or applied for a job during that year—19% of all

respondents—

they applied for because of their gender identity or expression.

harassed, physically attacked, and/or sexually assaulted at work because of their

gender identity or expression.

forms of mistreatment based on their gender identity or expression during that year,

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

13

such as being forced to use a restroom that did not match their gender identity, being

told to present in the wrong gender in order to keep their job, or having a boss or

coworker share private information about their transgender status without their

permission.

denied a promotion, or experiencing some other form of mistreatment related to their

gender identity or expression.

of respondents who had a job in the past year took

steps to avoid mistreatment in the workplace, such as hiding or delaying their gender

transition or quitting their job.

discrimination in the past year, such as being evicted from their home or denied a

home or apartment because of being transgender.

in their lives.

because

of being transgender.

past year avoided staying in a shelter because they feared being mistreated

as a transgender person. Those who did stay in a shelter reported high levels of

mistreatment: respondents who stayed in a shelter in the

past year reported some form of mistreatment, including being harassed, sexually or

physically assaulted, or kicked out because of being transgender.

Seven out of ten respondents who

stayed in a shelter in the past year

reported being mistreated because

of being transgender.

• Respondentswerenearly

.

Housing, Homelessness,

and Shelter Access

2015 U.S. TRANSGENDER SURVEY

14

Sex Work and Other Underground

Economy Work

• Respondentsreportedhighratesofexperienceintheundergroundeconomy,including

sex work, drug sales, and other work that is currently criminalized.

have participated in the underground economy for income at some point in their lives—

including 12% who have done sex work in exchange for income—and 9% did so in the past

year, with higher rates among women of color.

• Respondentswhointeractedwiththepoliceeitherwhiledoingsexworkorwhilethe

police mistakenly thought they were doing sex work reported high rates of police

harassment, abuse, or mistreatment, with nearly reporting being

harassed, attacked, sexually assaulted, or mistreated in some other way by police.

experienced violence. More than three-quarters (77%) have experienced intimate partner

violence and 72% have been sexually assaulted, a substantially higher rate than the

overall sample. Out of those who were working in the underground economy at the time

they took the survey, nearly half (41%) were physically attacked in the past year and over

one-third (36%) were sexually assaulted during that year.

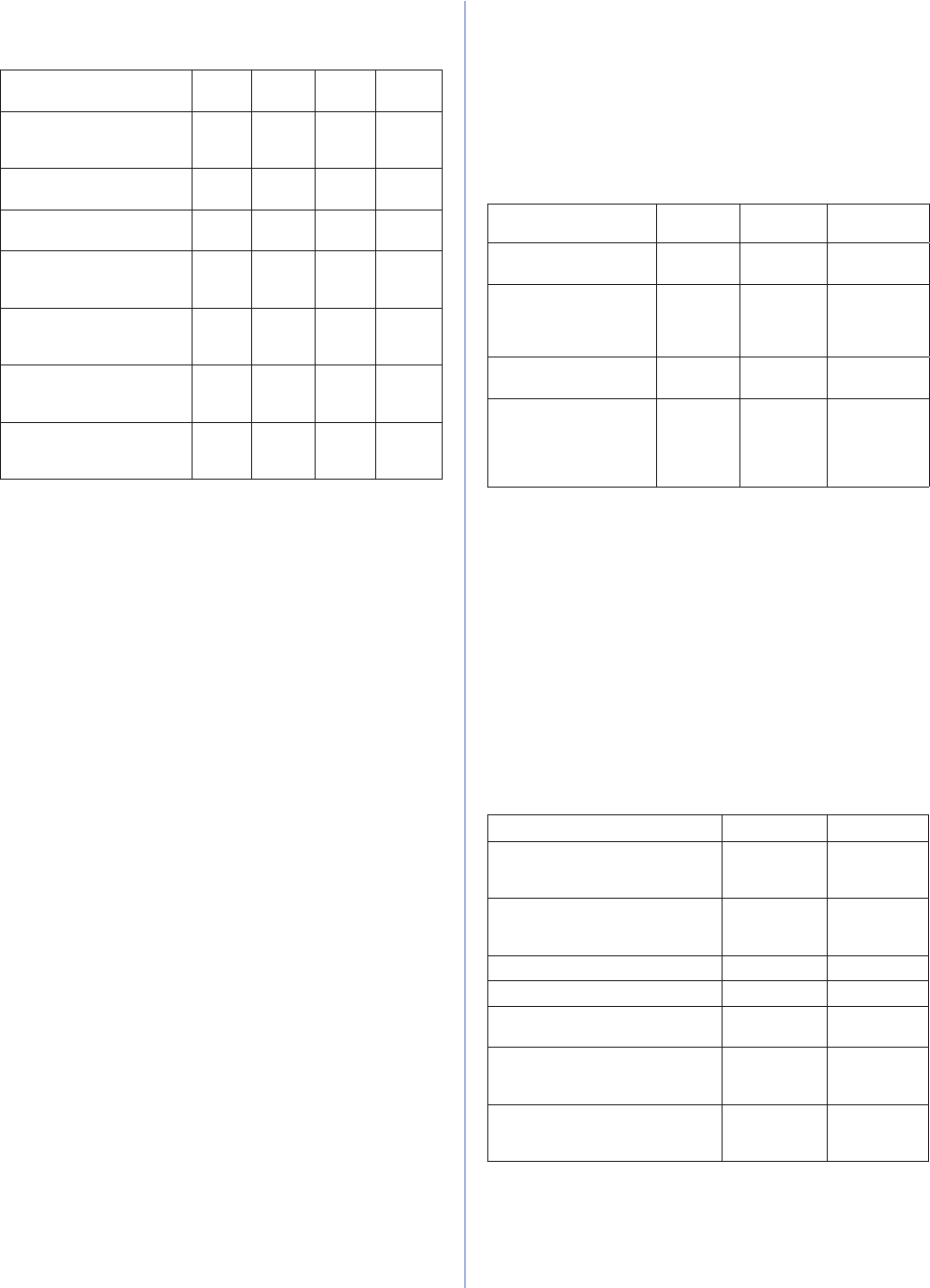

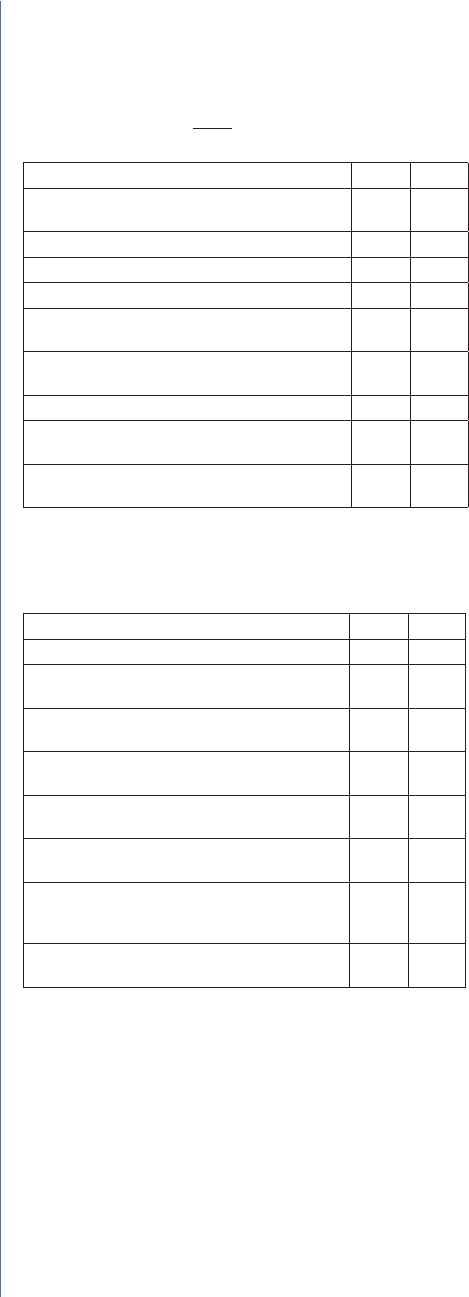

Police Interactions and Prisons

In

the past year, of respondents who interacted with police or law enforcement ocers who

thought or knew they were transgender,

mistreatment. This included being verbally harassed, repeatedly referred to as the wrong

gender, physically assaulted, or sexually assaulted, including being forced by ocers to

engage in sexual activity to avoid arrest.

were sex workers. In the past year, of those who interacted with law enforcement ocers

who thought or knew they were transgender, one-third (33%) of Black transgender women

and 30% of multiracial women said that an ocer assumed they were sex workers.

of respondents said they would feel uncomfortable asking the

police for help if they needed it.

• Ofthosewhowerearrestedinthepastyear(2%),

were arrested because they were transgender.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

15

• Respondentswhowereheldinjail,prison,orjuveniledetentioninthepastyearfacedhigh

rates of physical and sexual assault by facility sta and other inmates. In the past year,

nearly one-quarter (23%) were physically assaulted by sta or other inmates, and one in five

(20%) were sexually assaulted. Respondents were over five times more likely to be sexually

assaulted by facility sta than the U.S. population in jails and prisons, and over nine times

more likely to be sexually assaulted by other inmates.

Harassment and Violence

verbally harassed in the past year because of being

transgender.

physically attacked in the past year because of

being transgender.

at some point in their lifetime and

one in ten Respondents who have done sex

work (72%), those who have experienced homelessness (65%), and people with disabilities

(61%) were more likely to have been sexually assaulted in their lifetime.

, including acts

involving coercive control and physical harm.

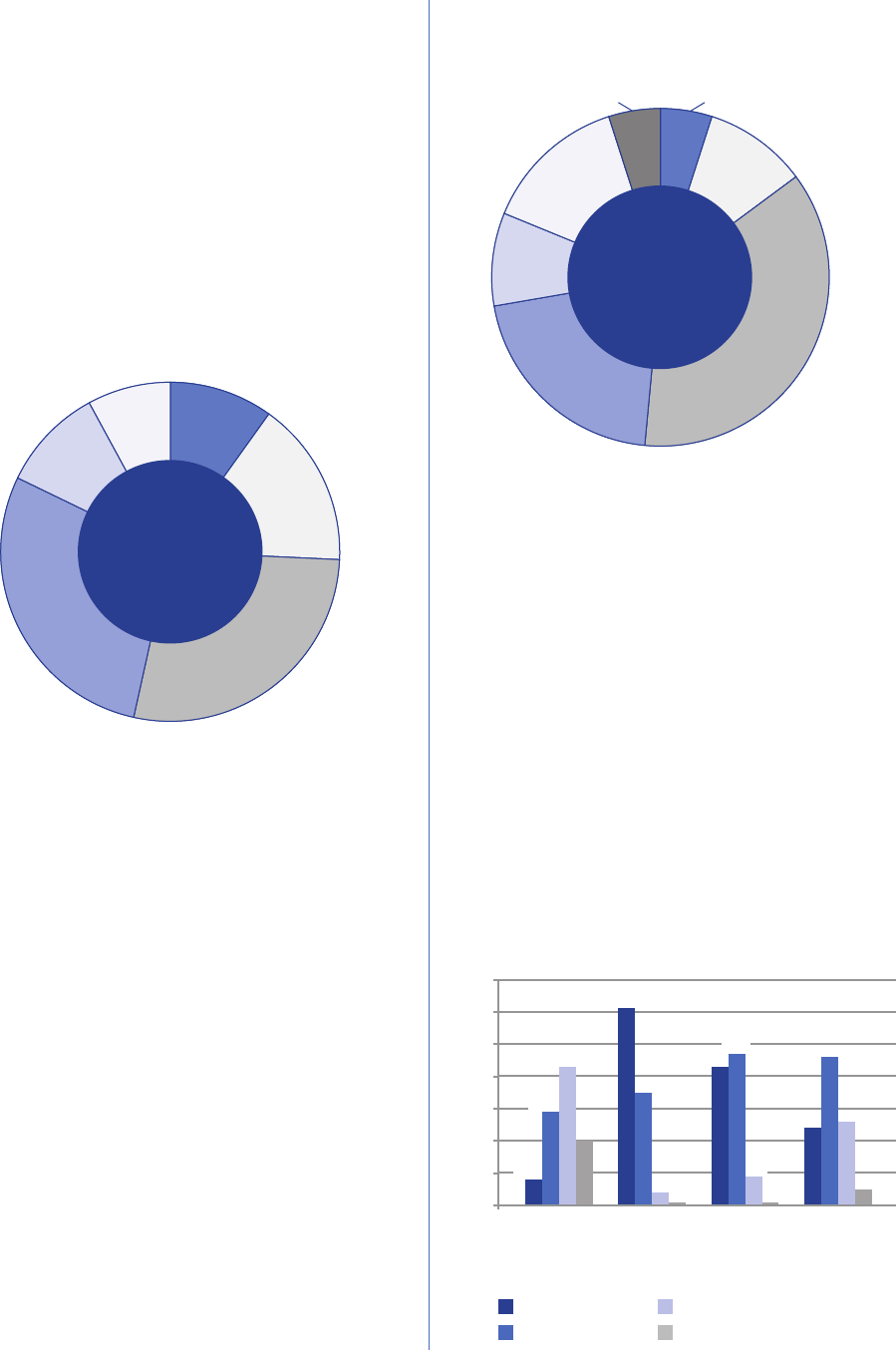

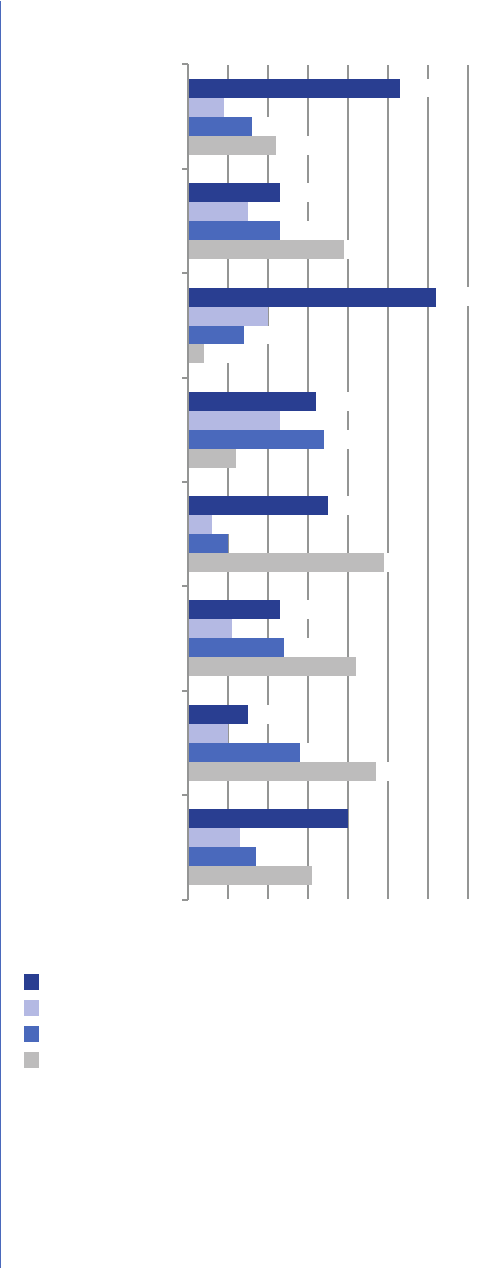

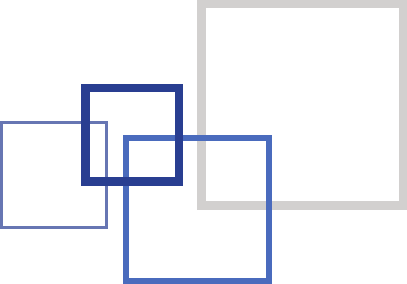

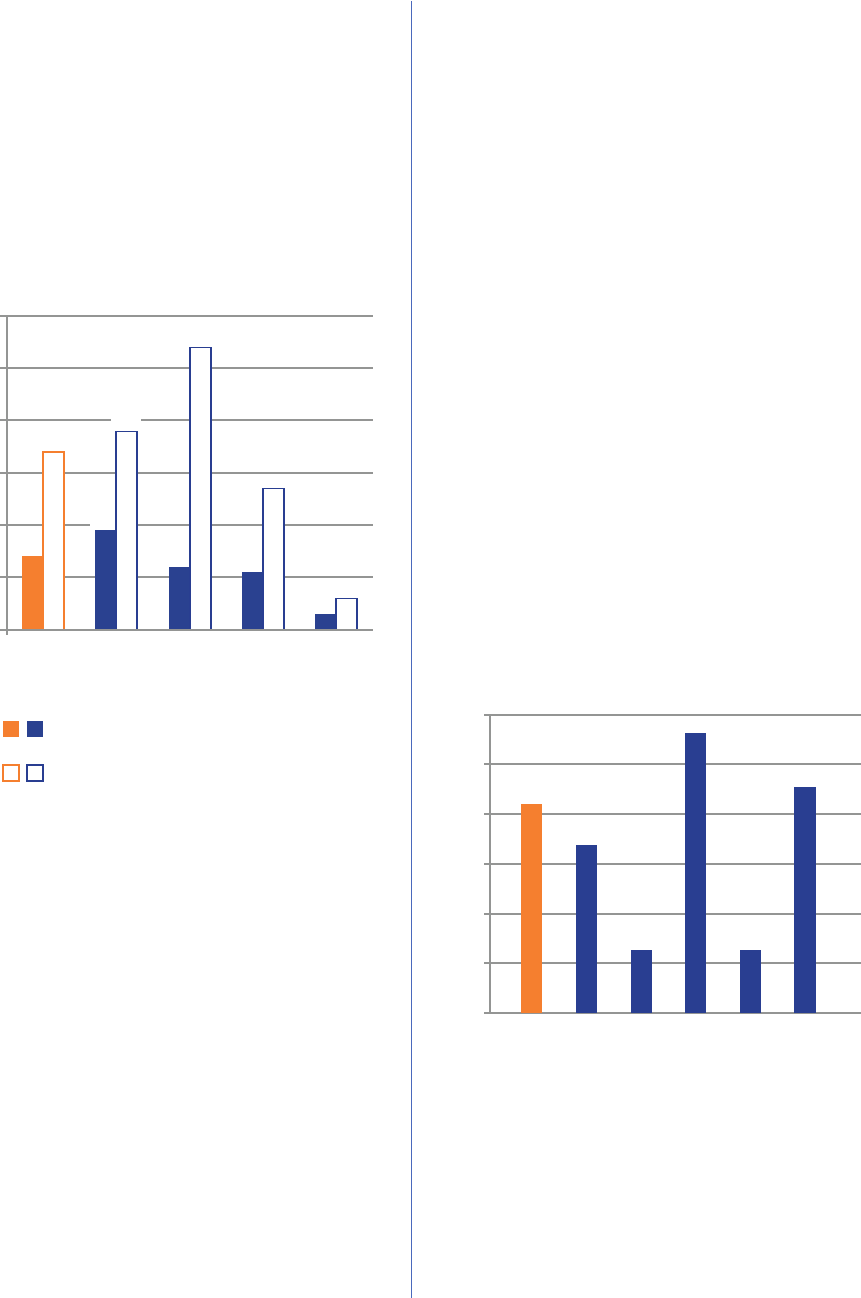

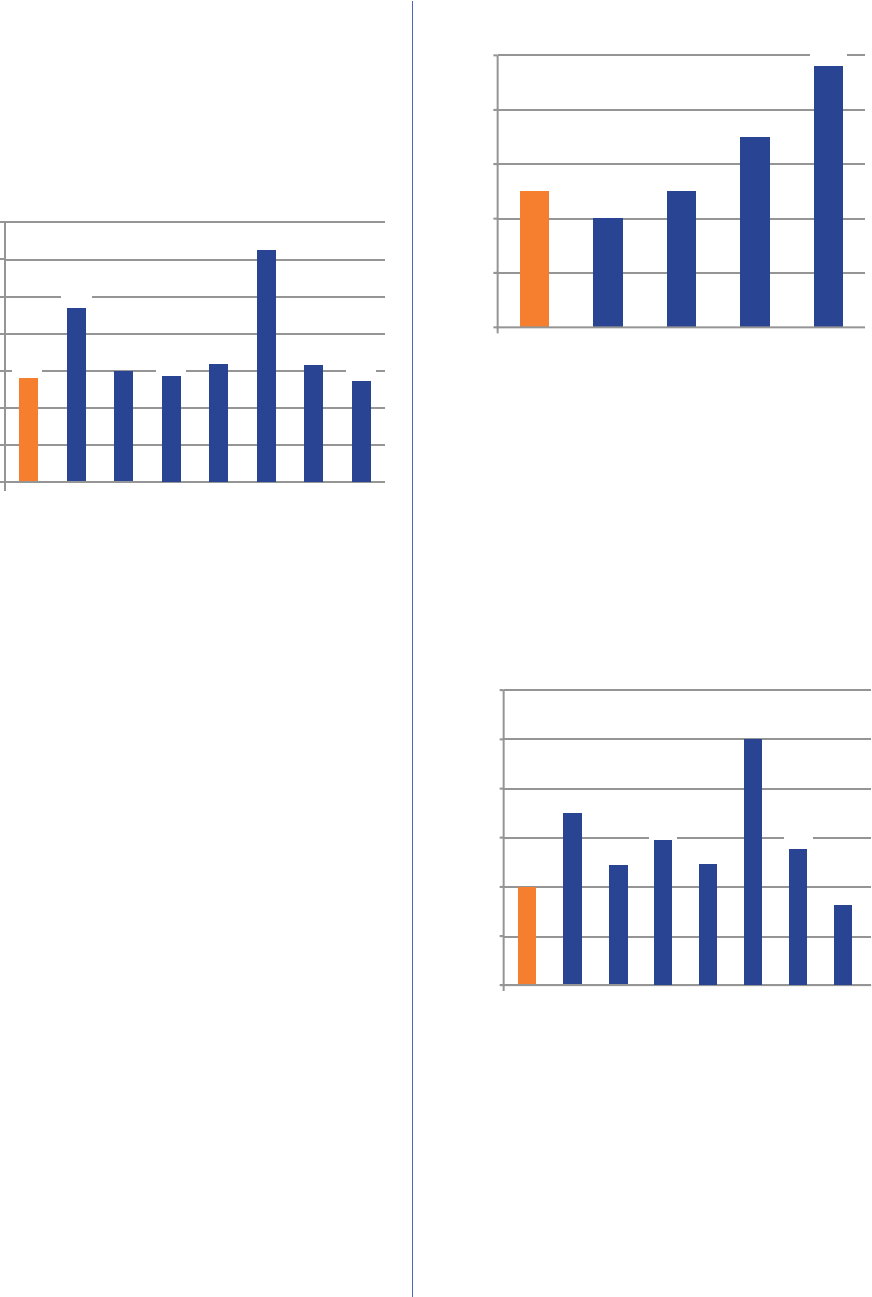

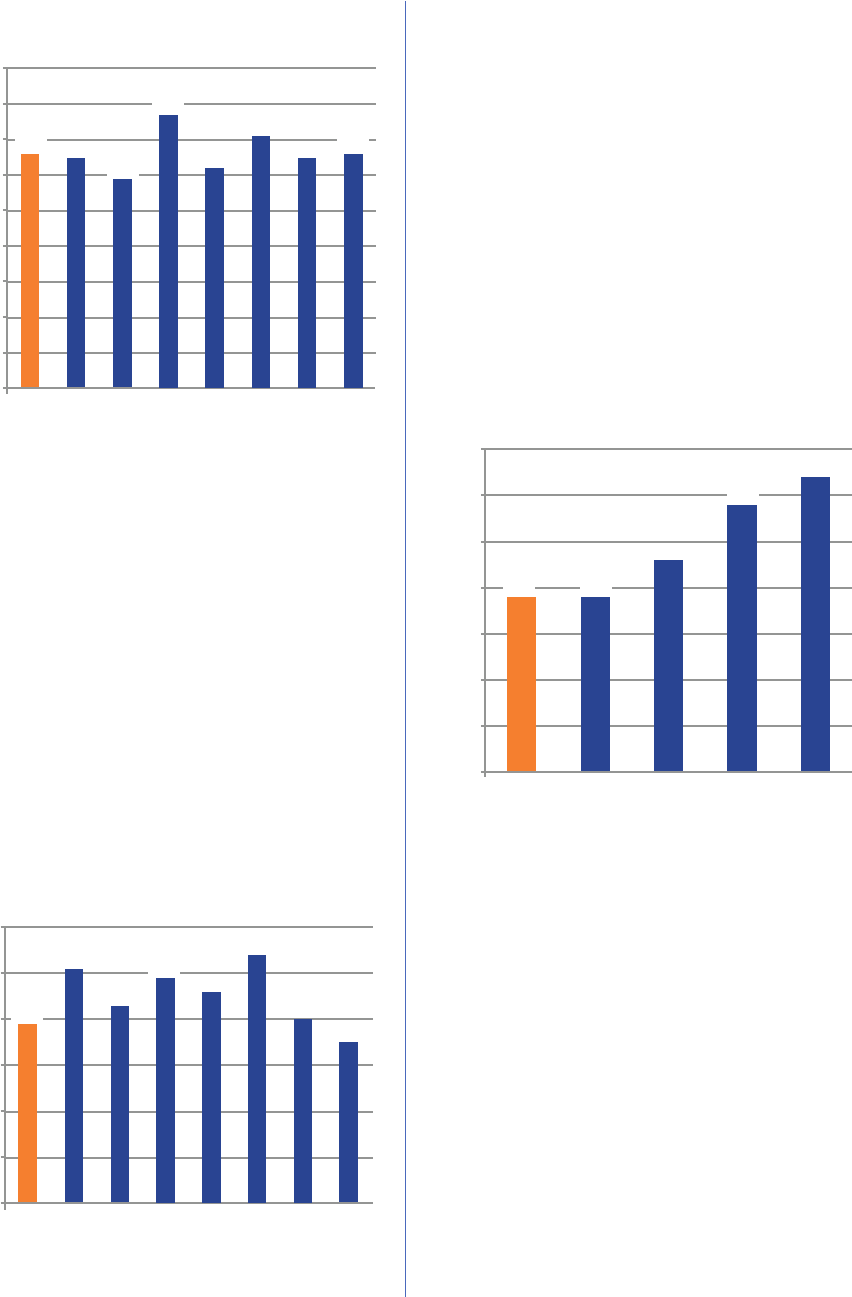

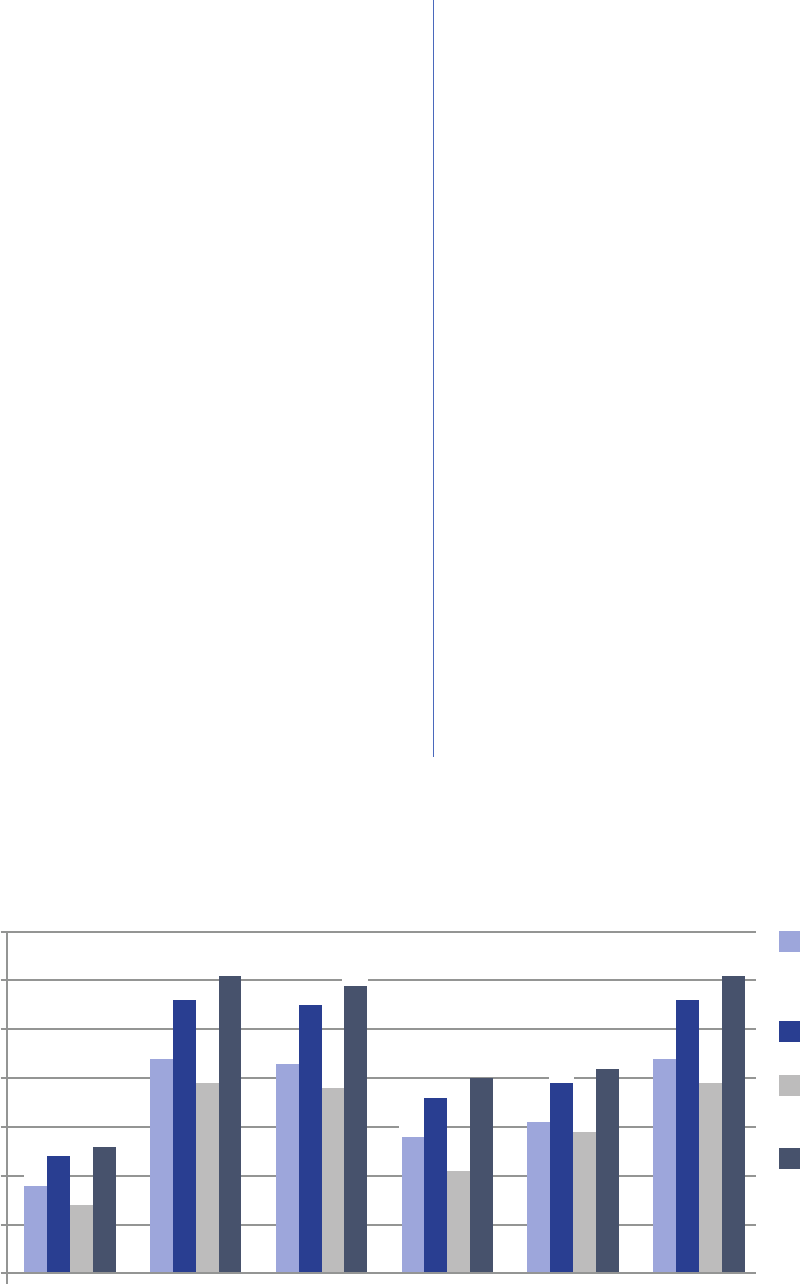

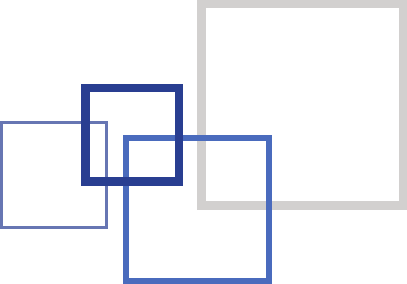

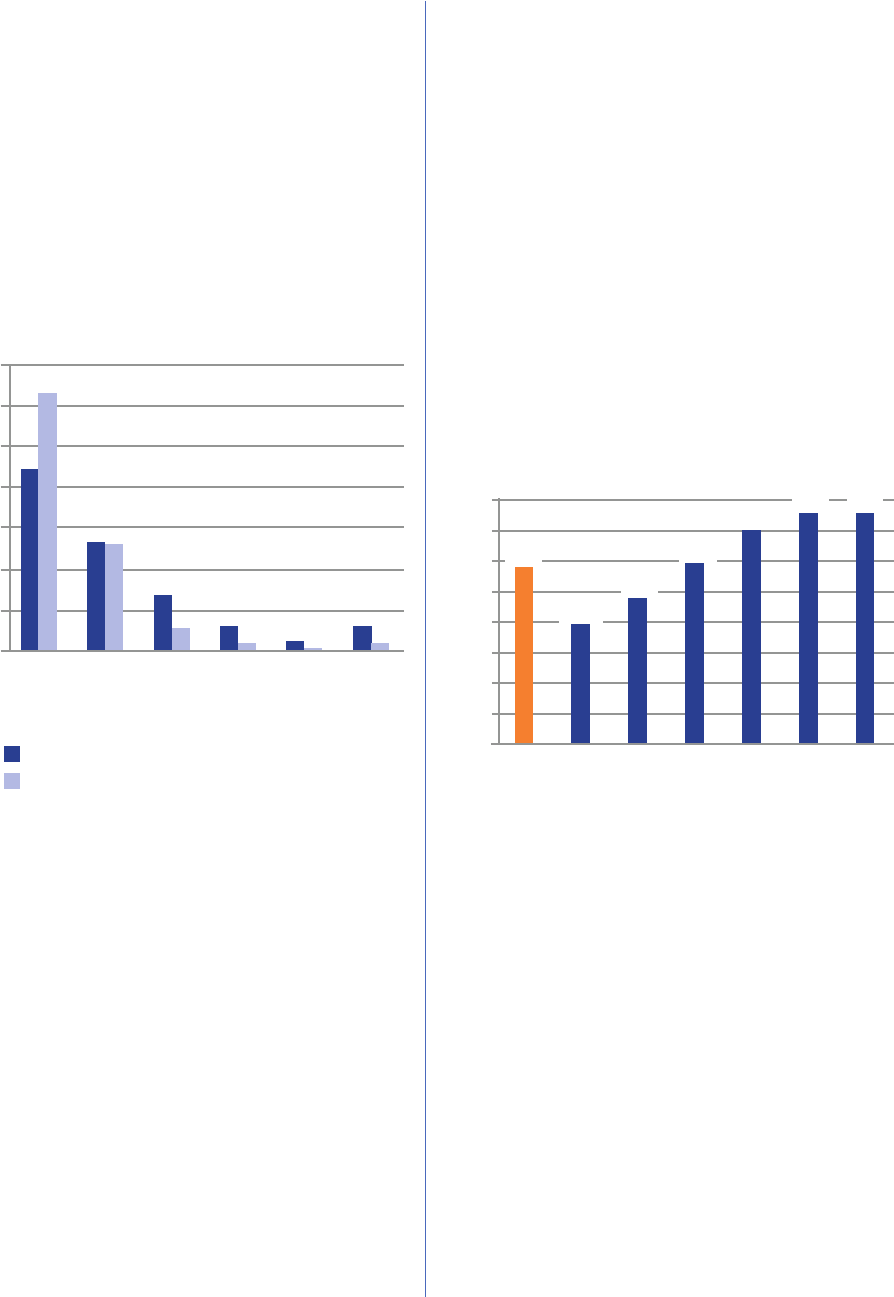

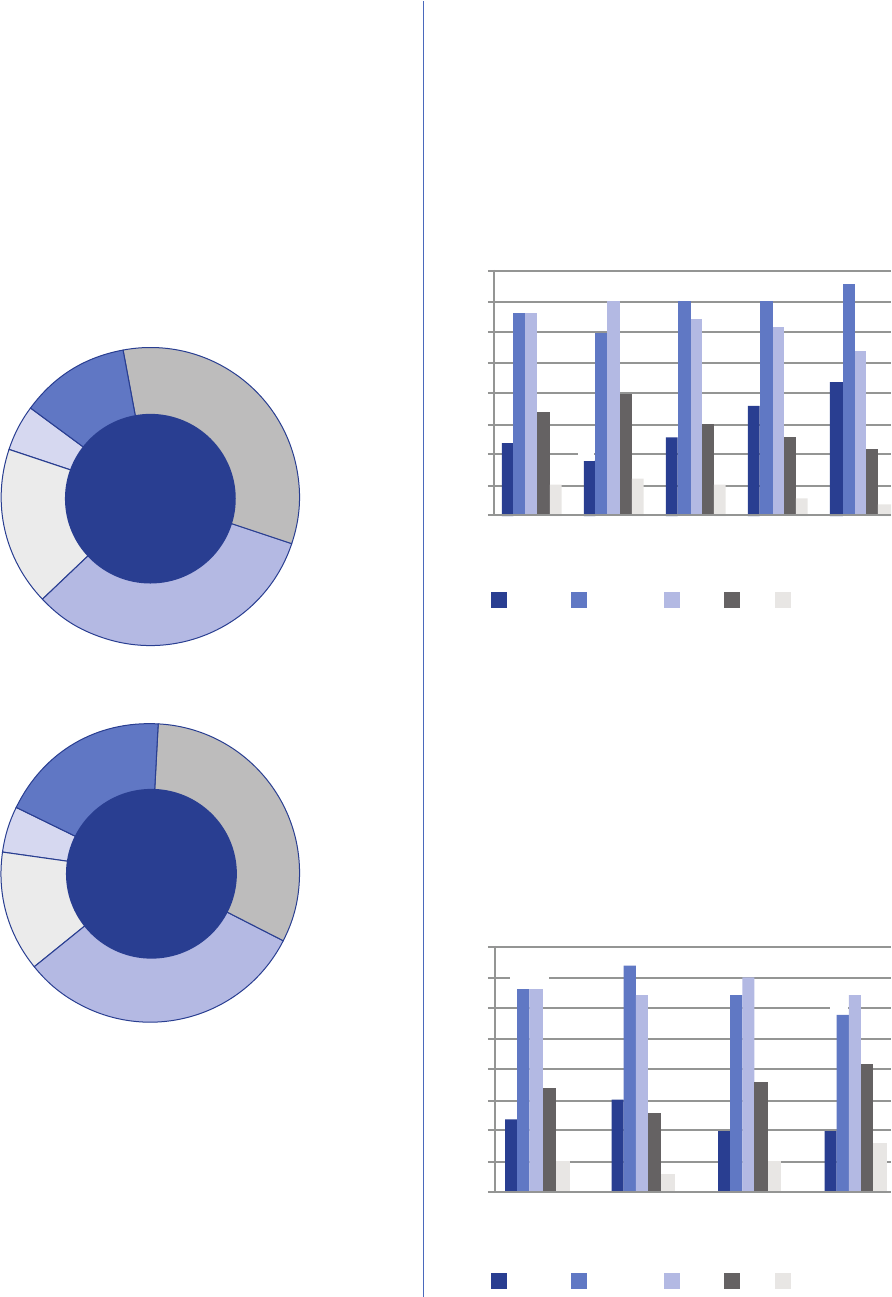

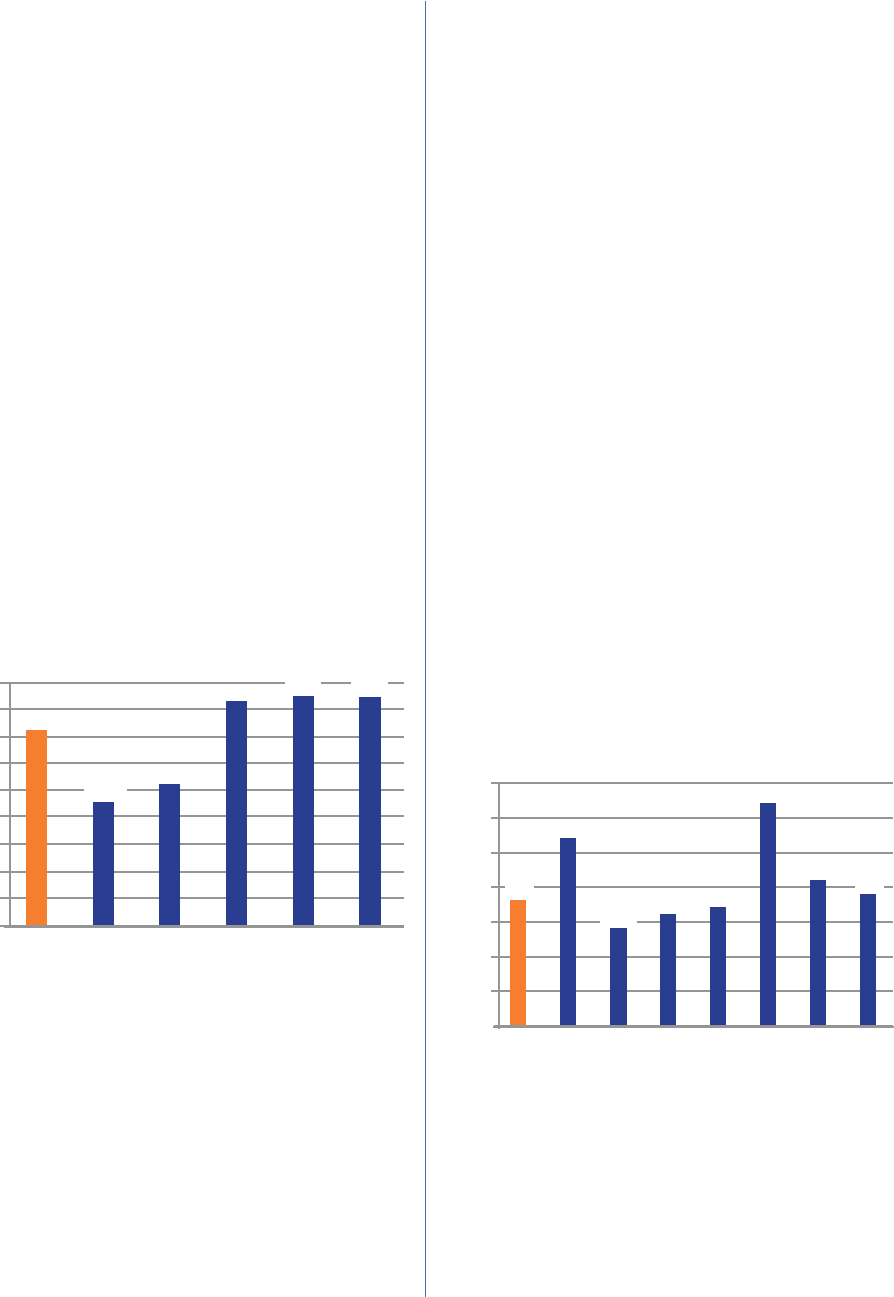

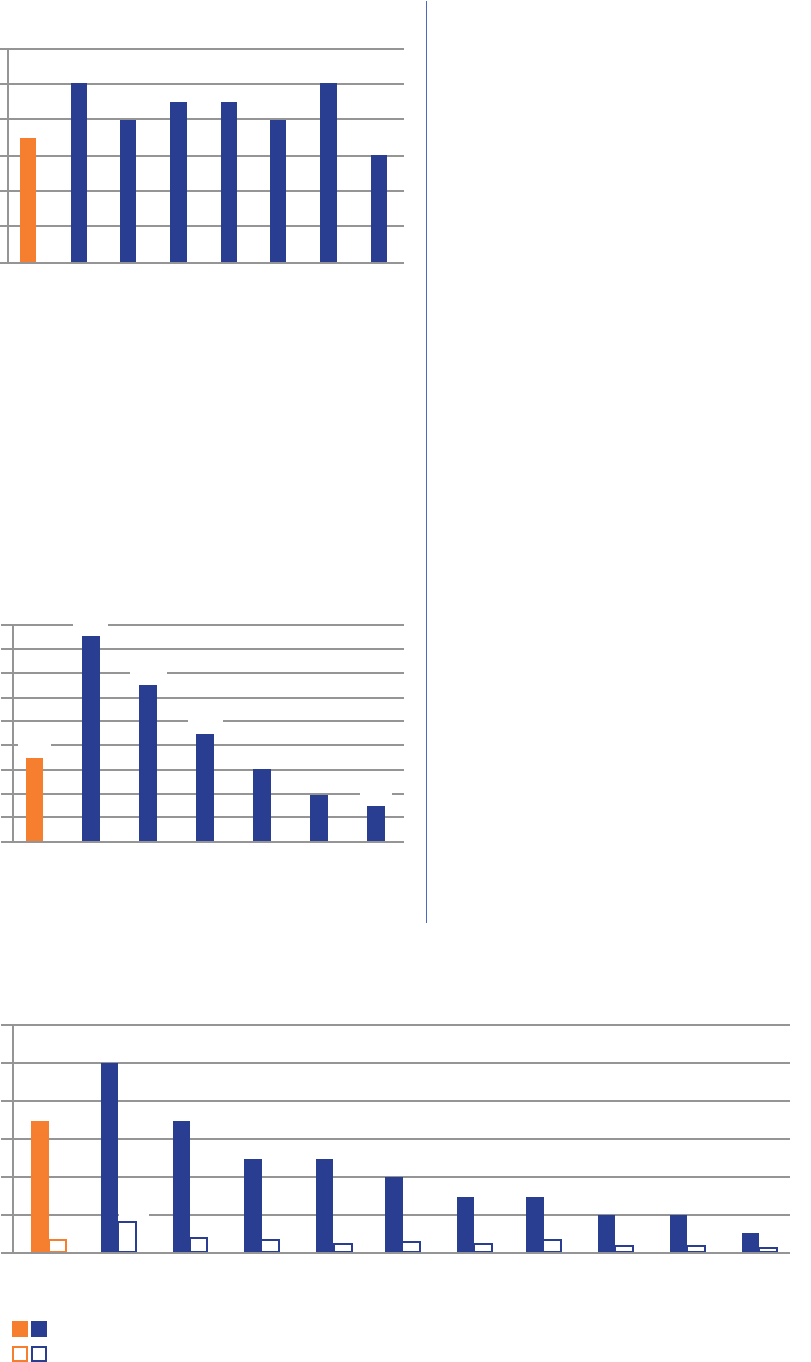

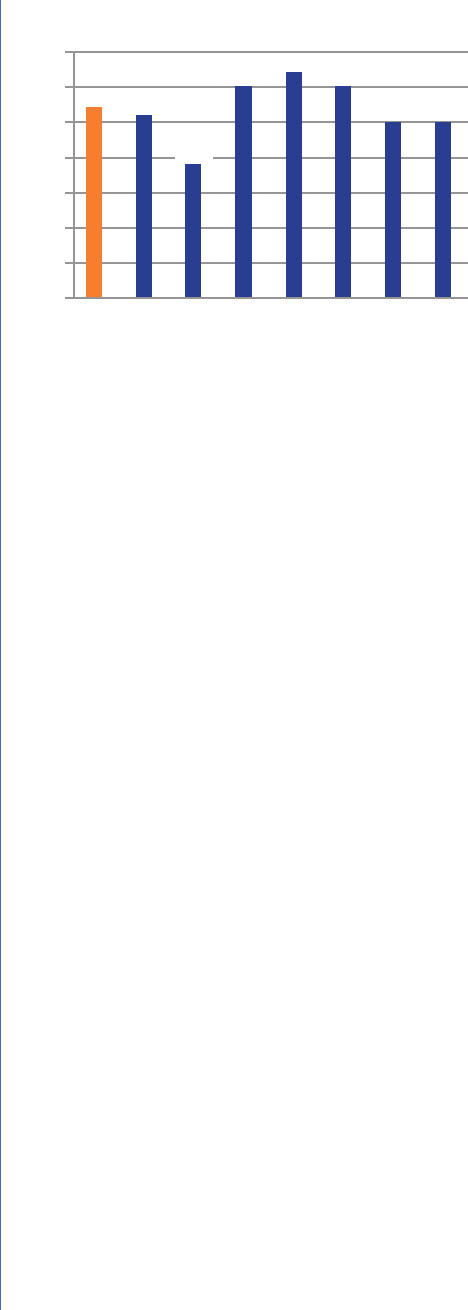

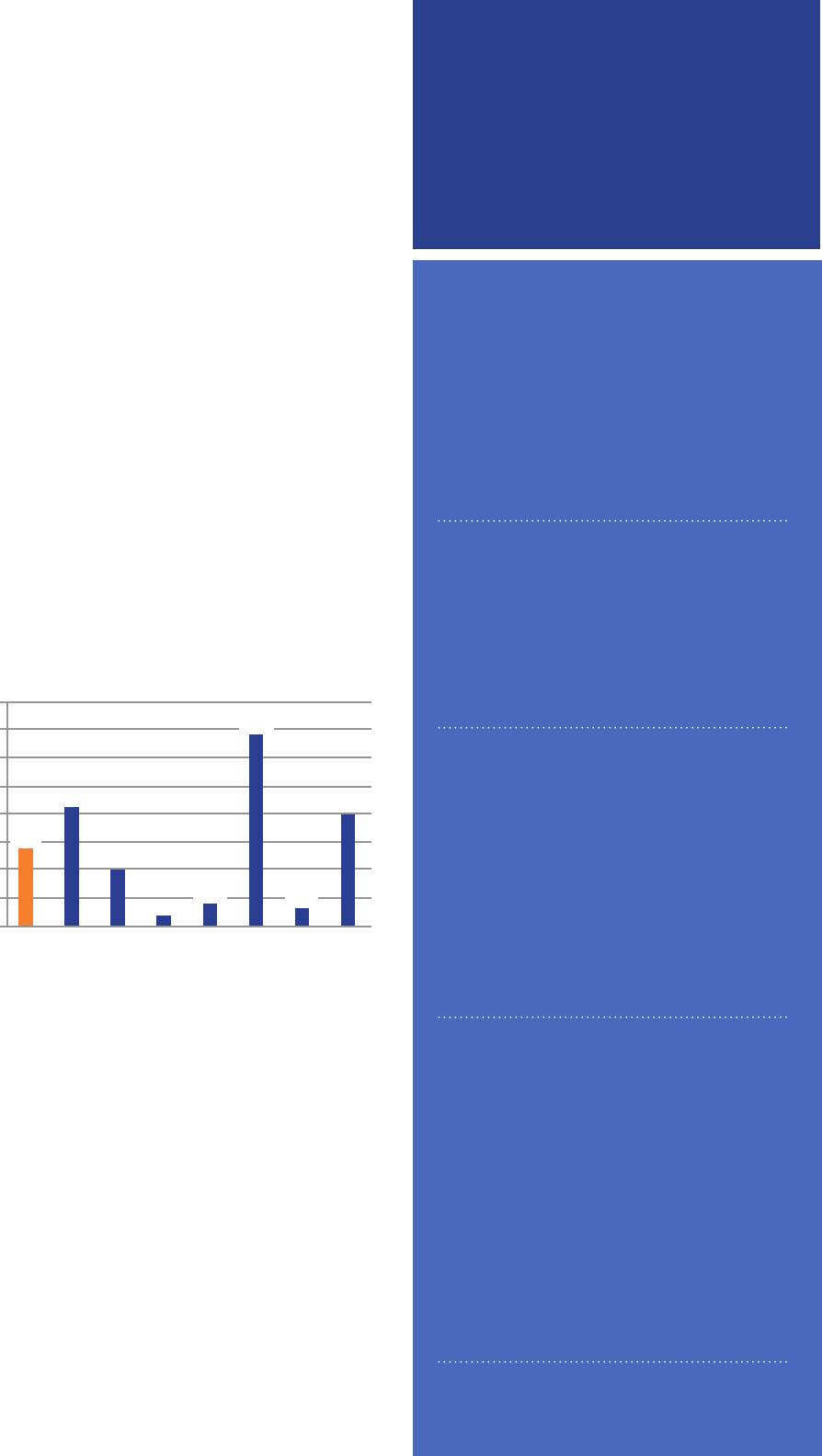

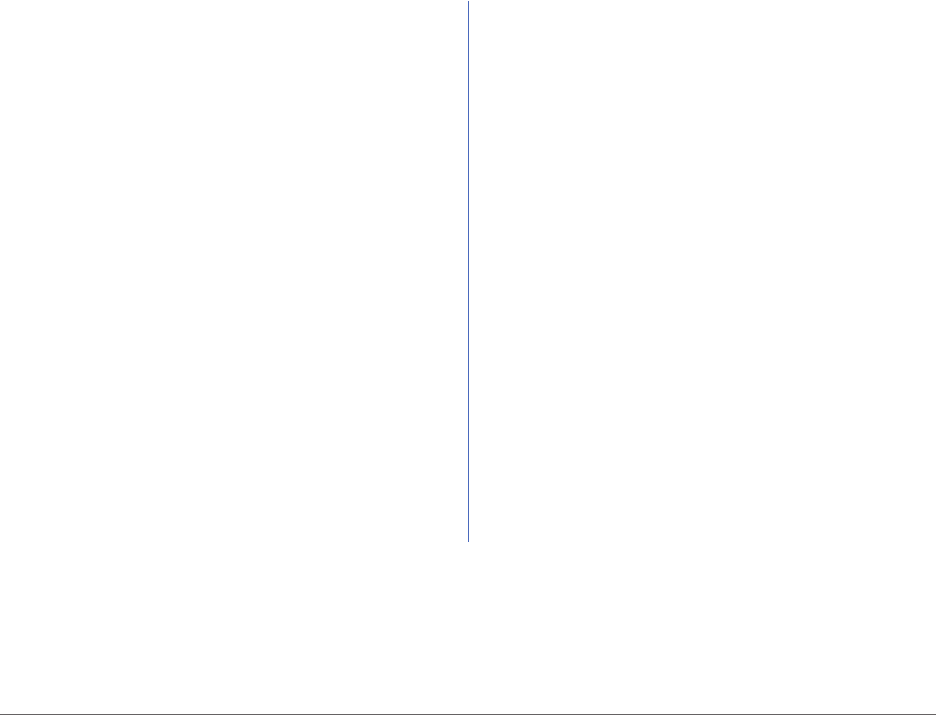

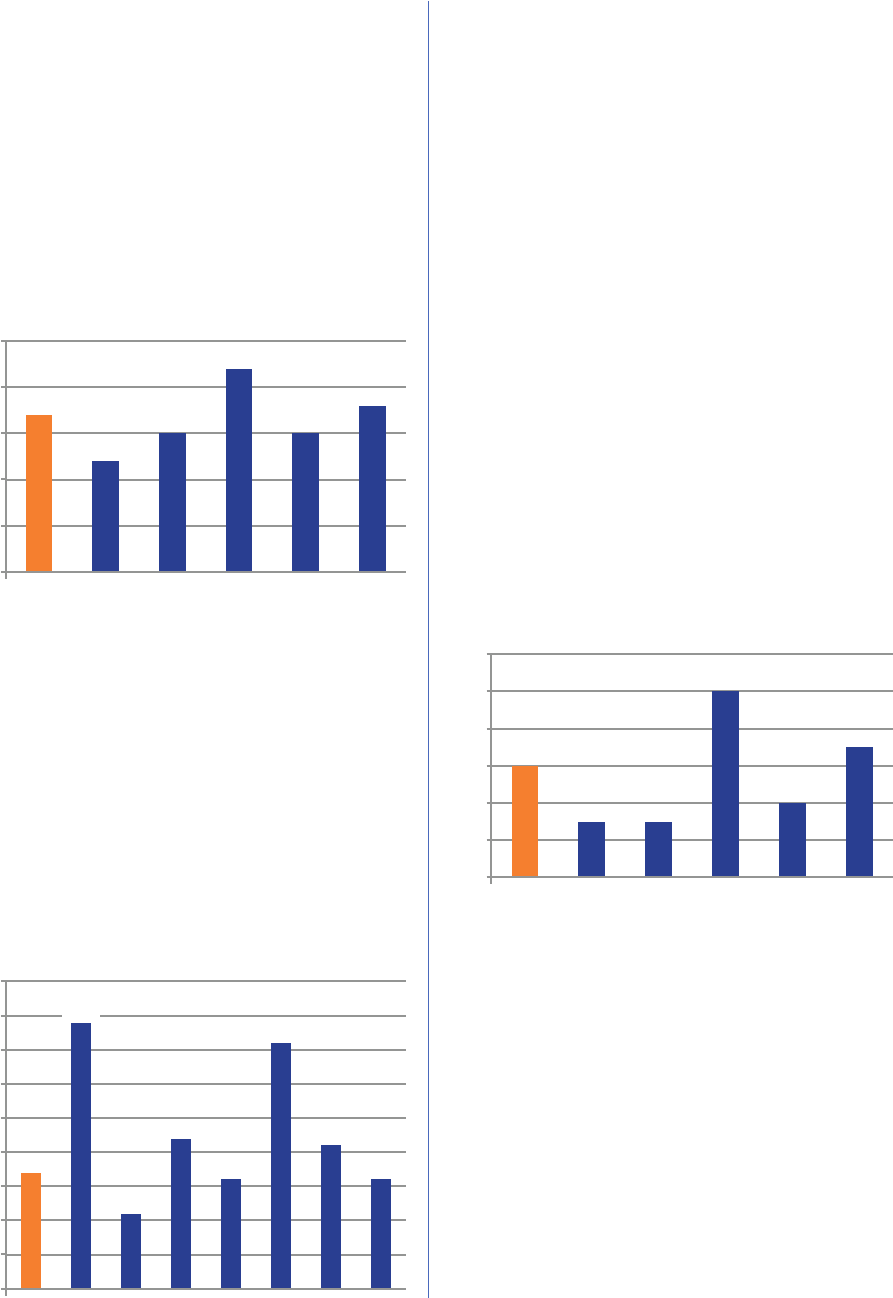

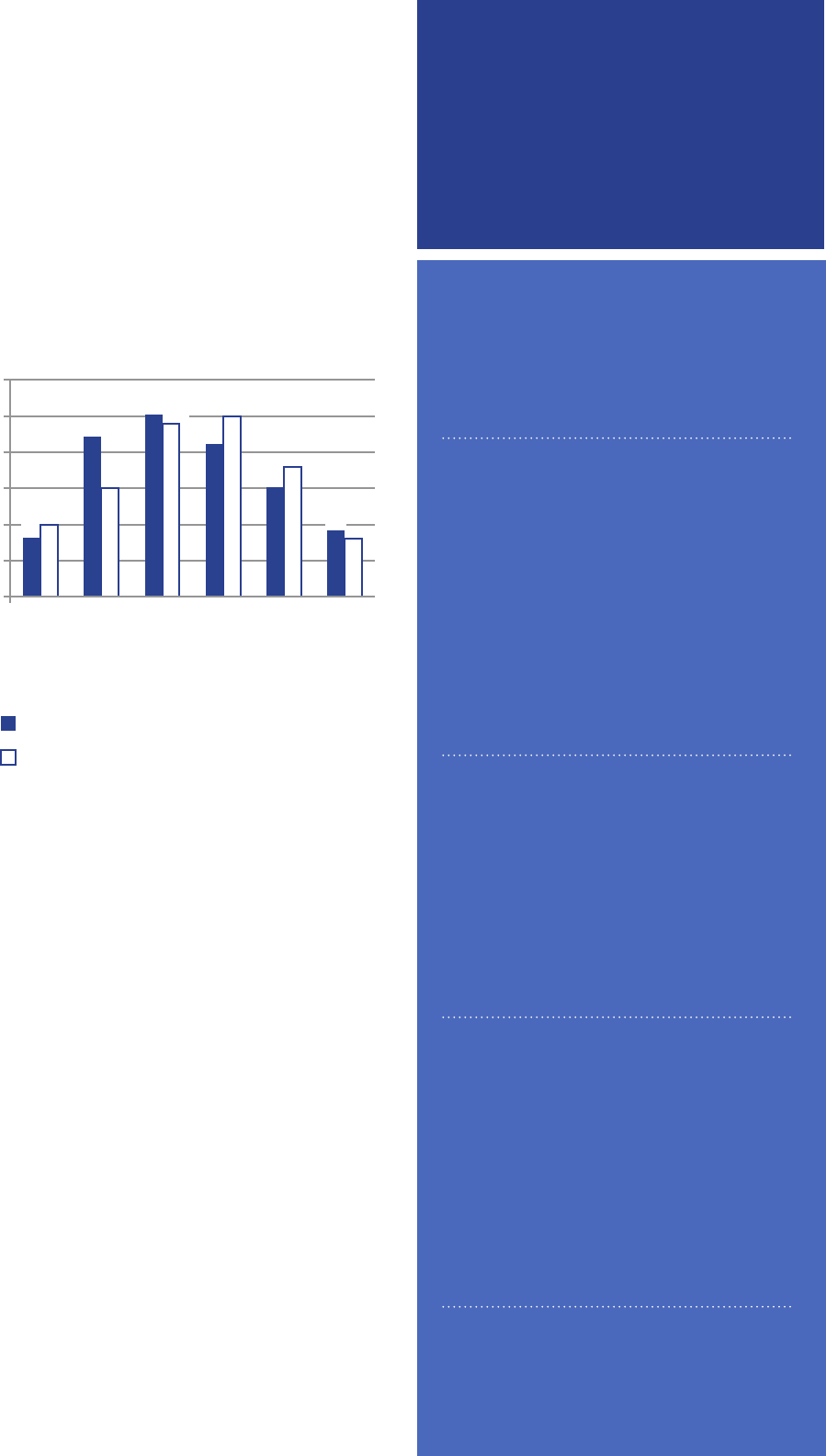

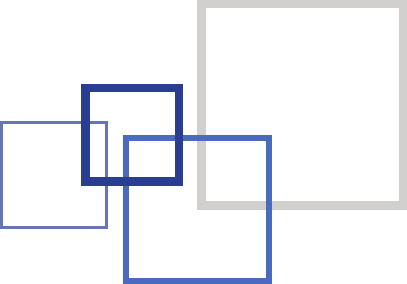

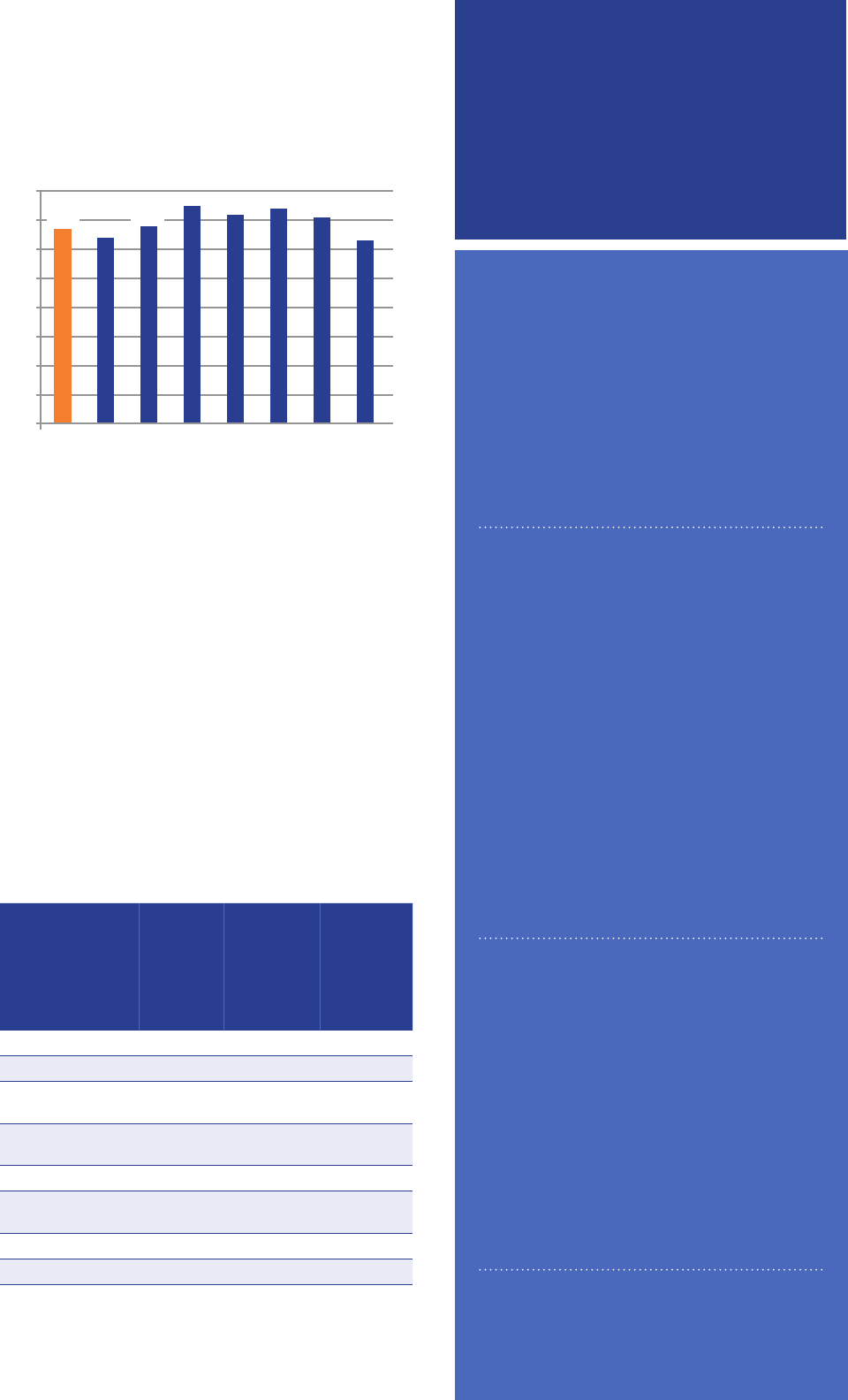

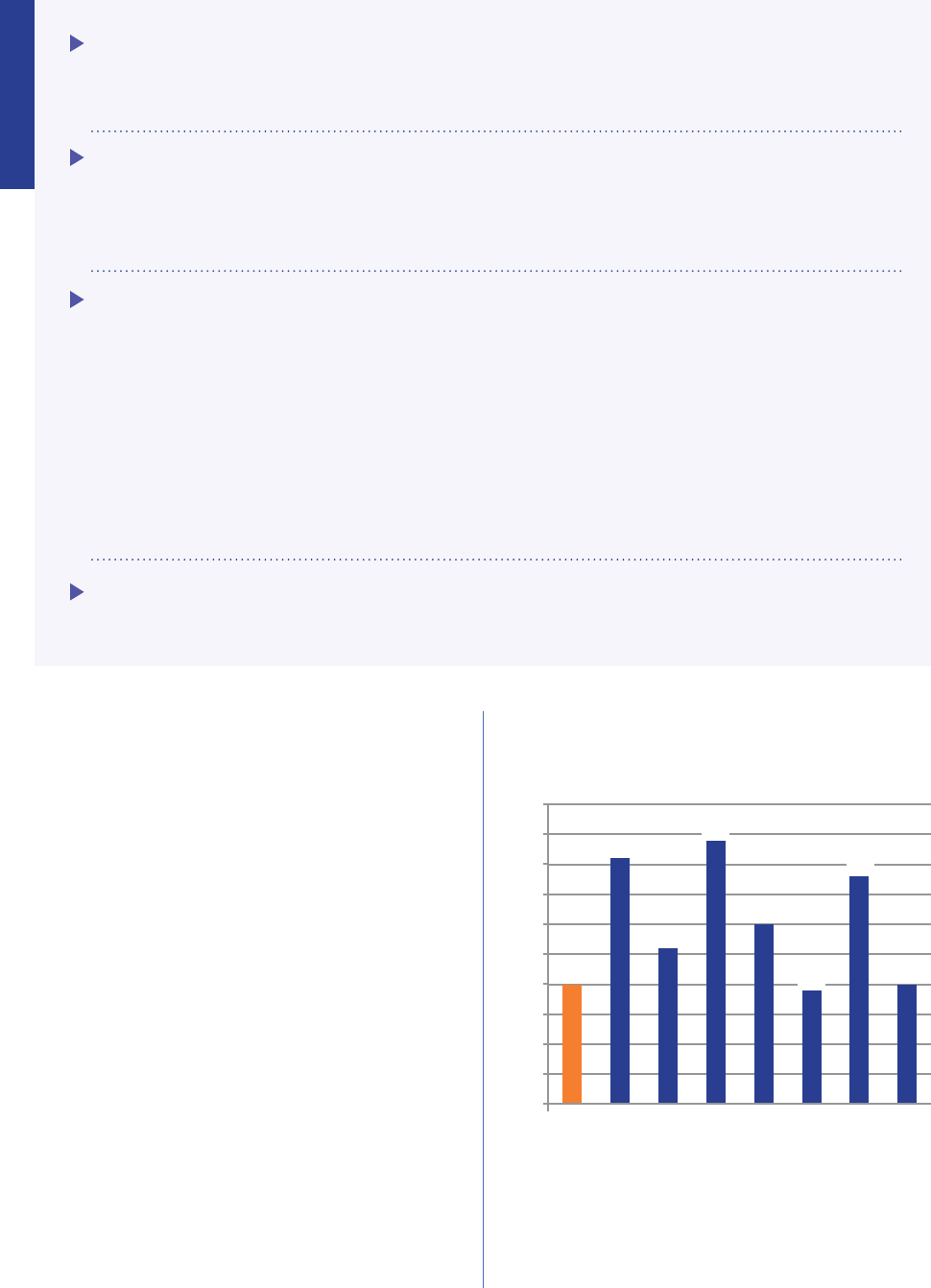

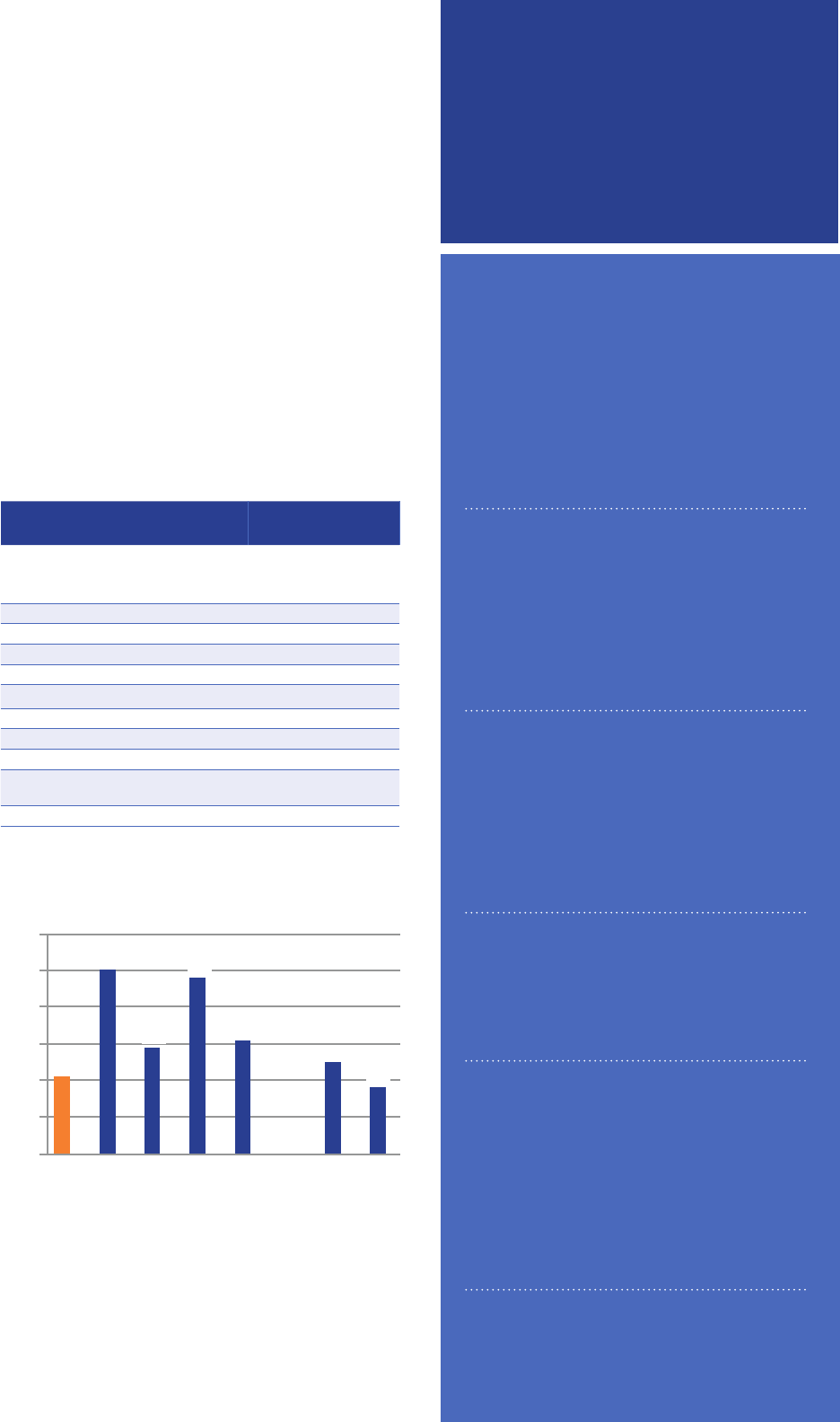

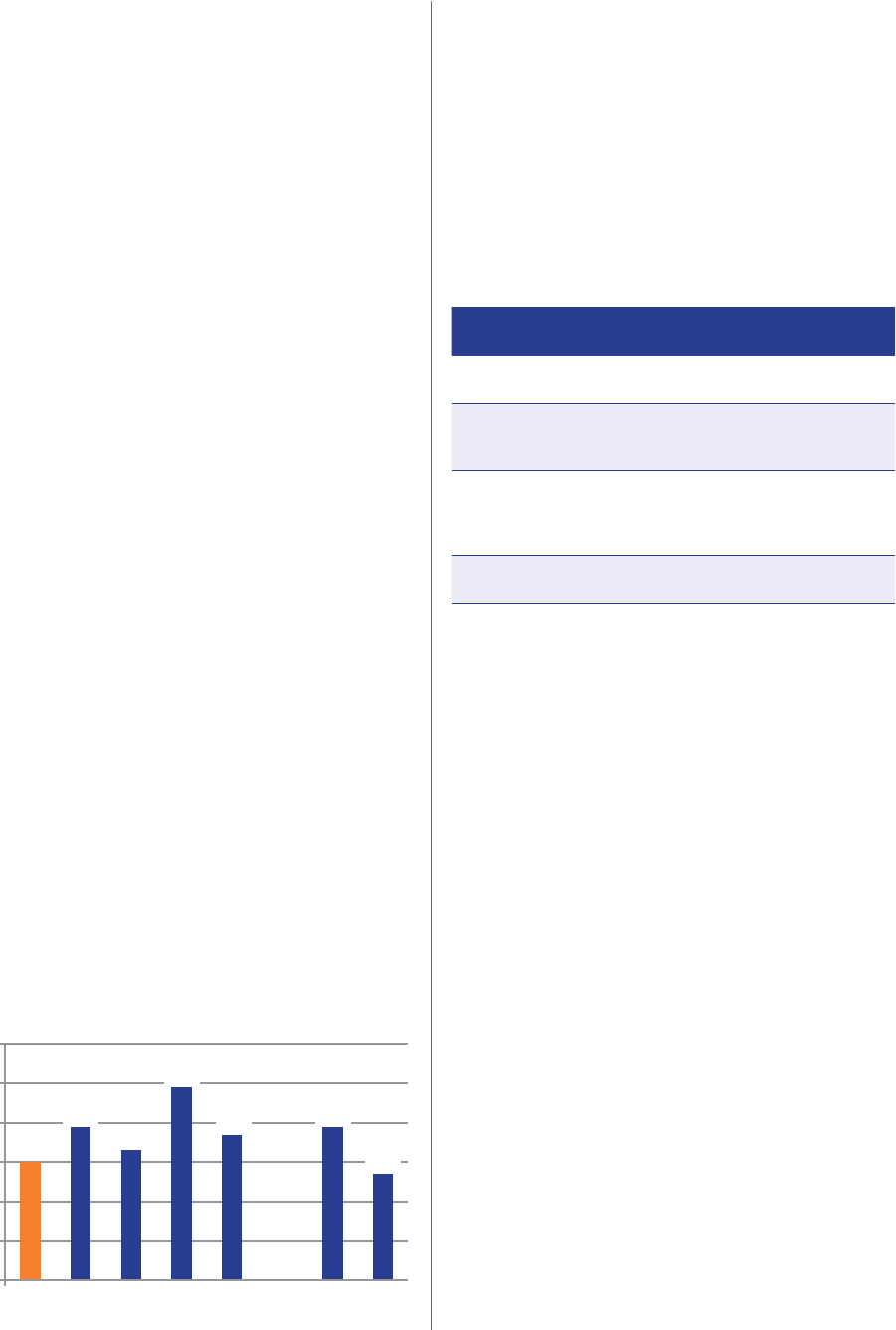

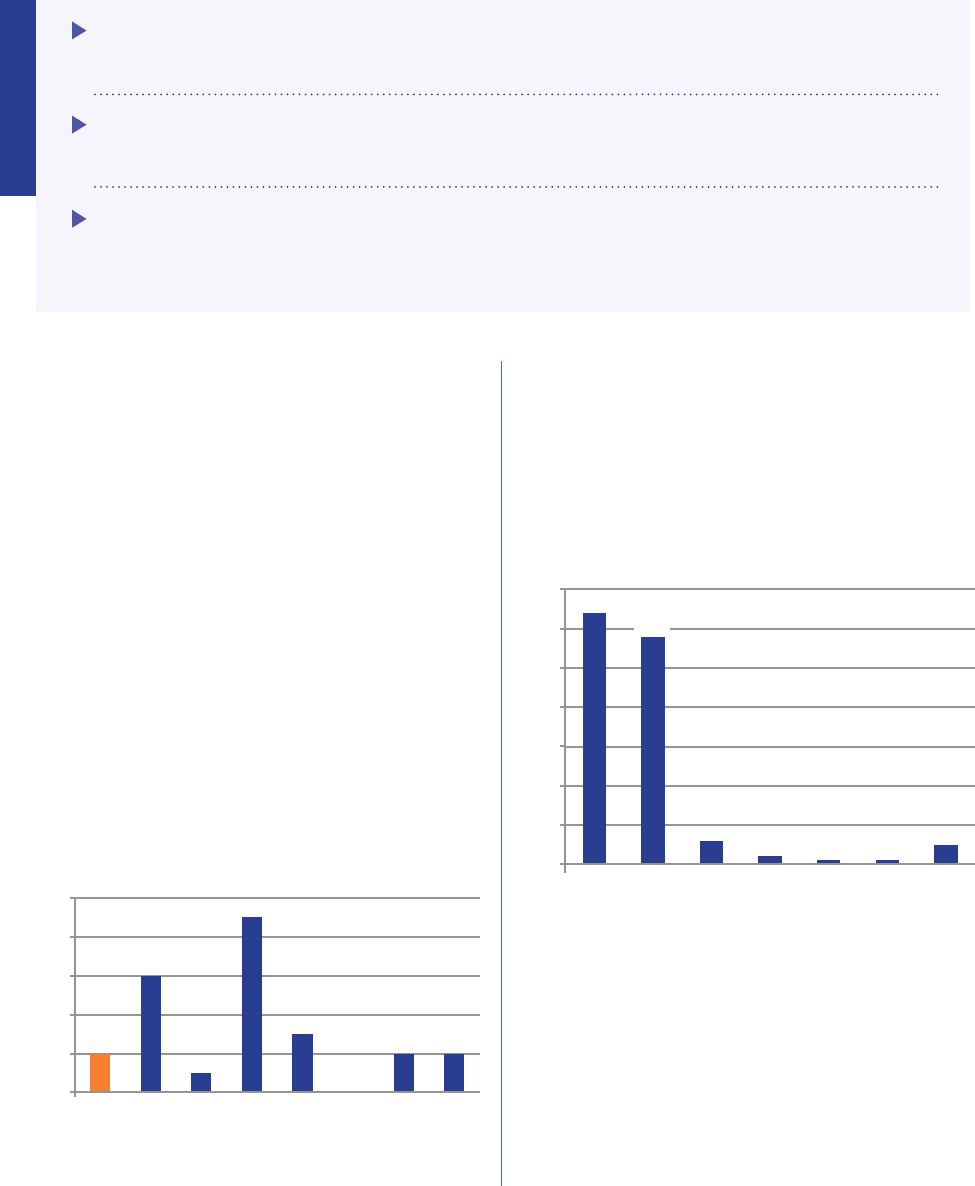

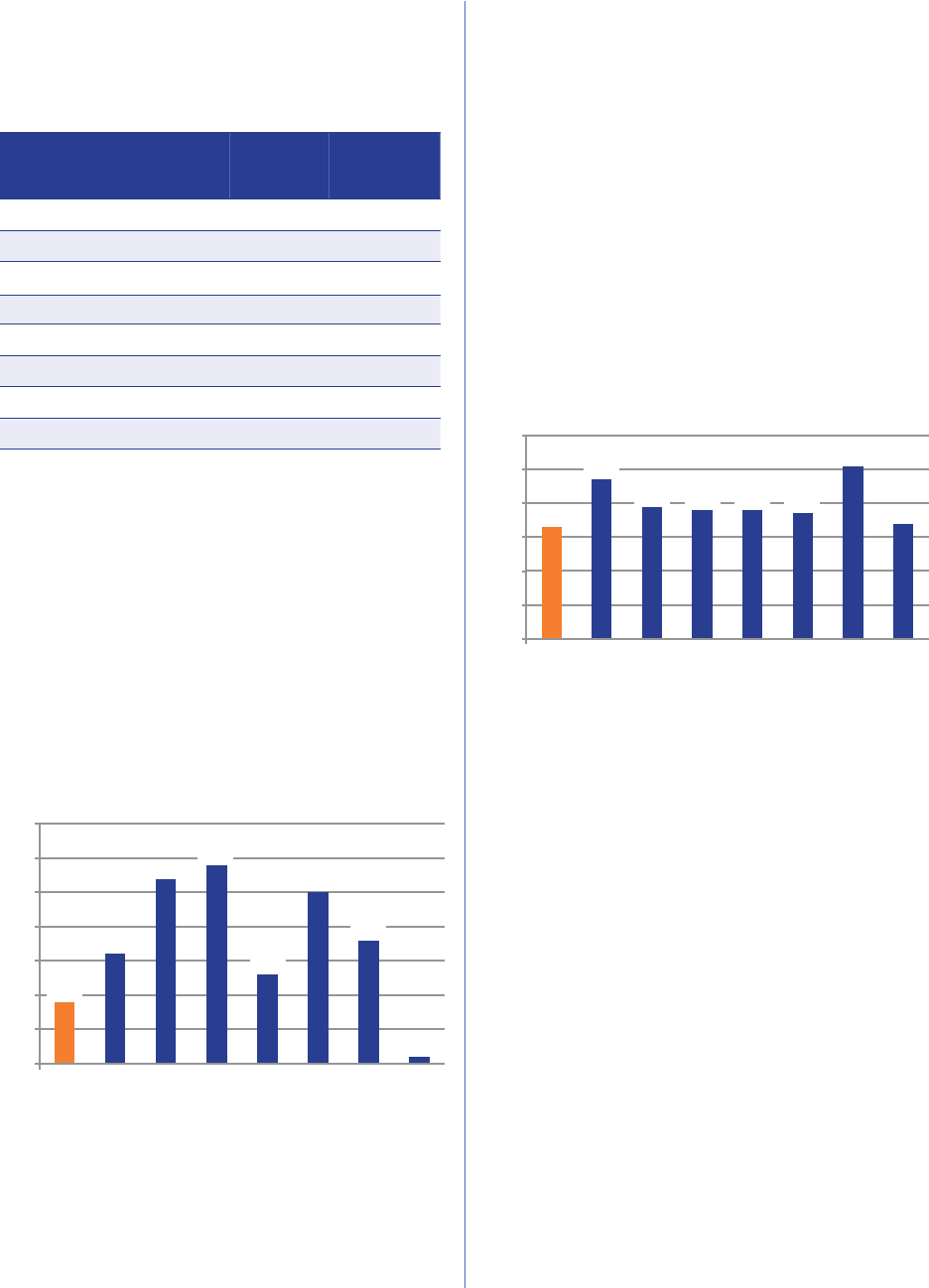

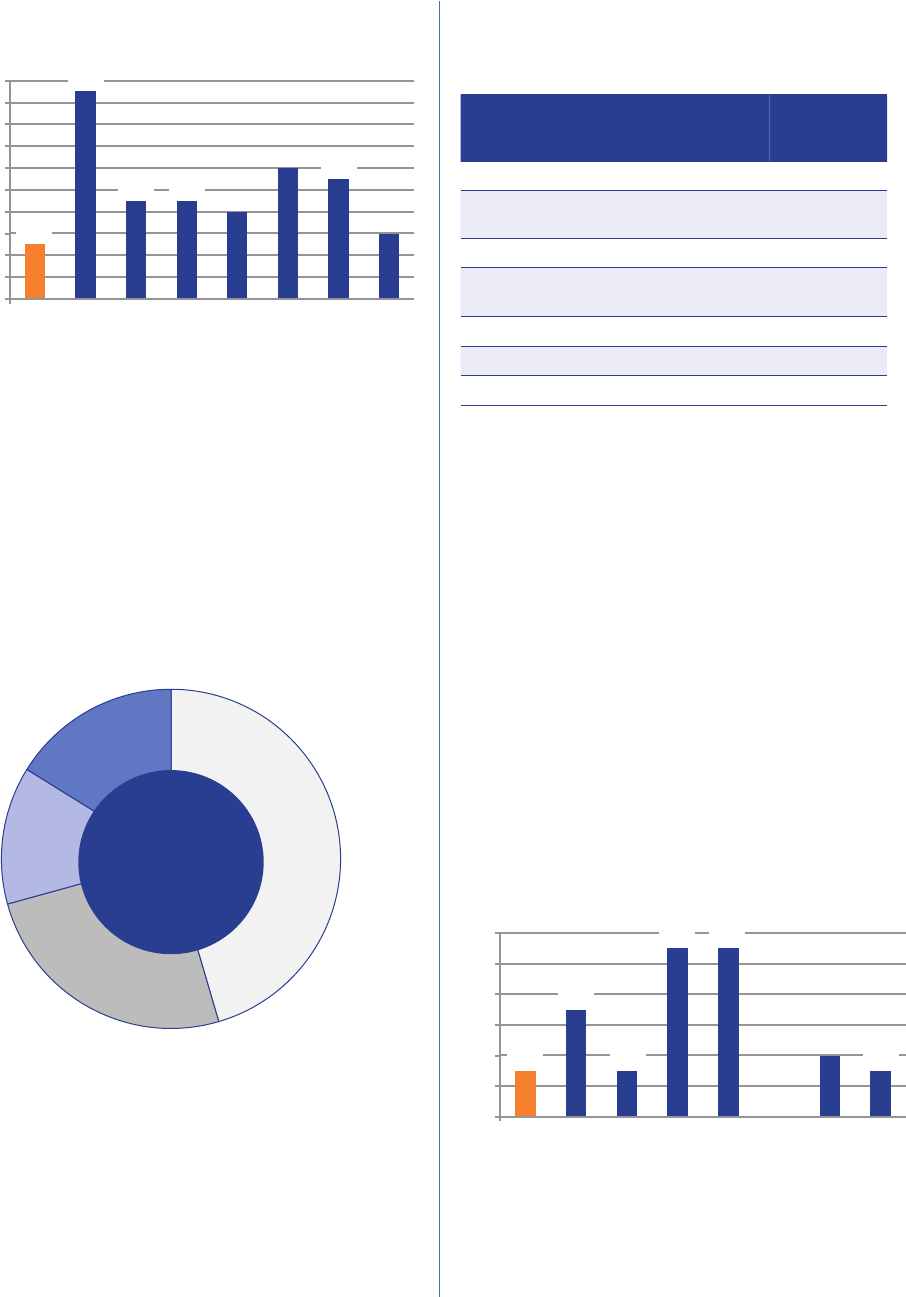

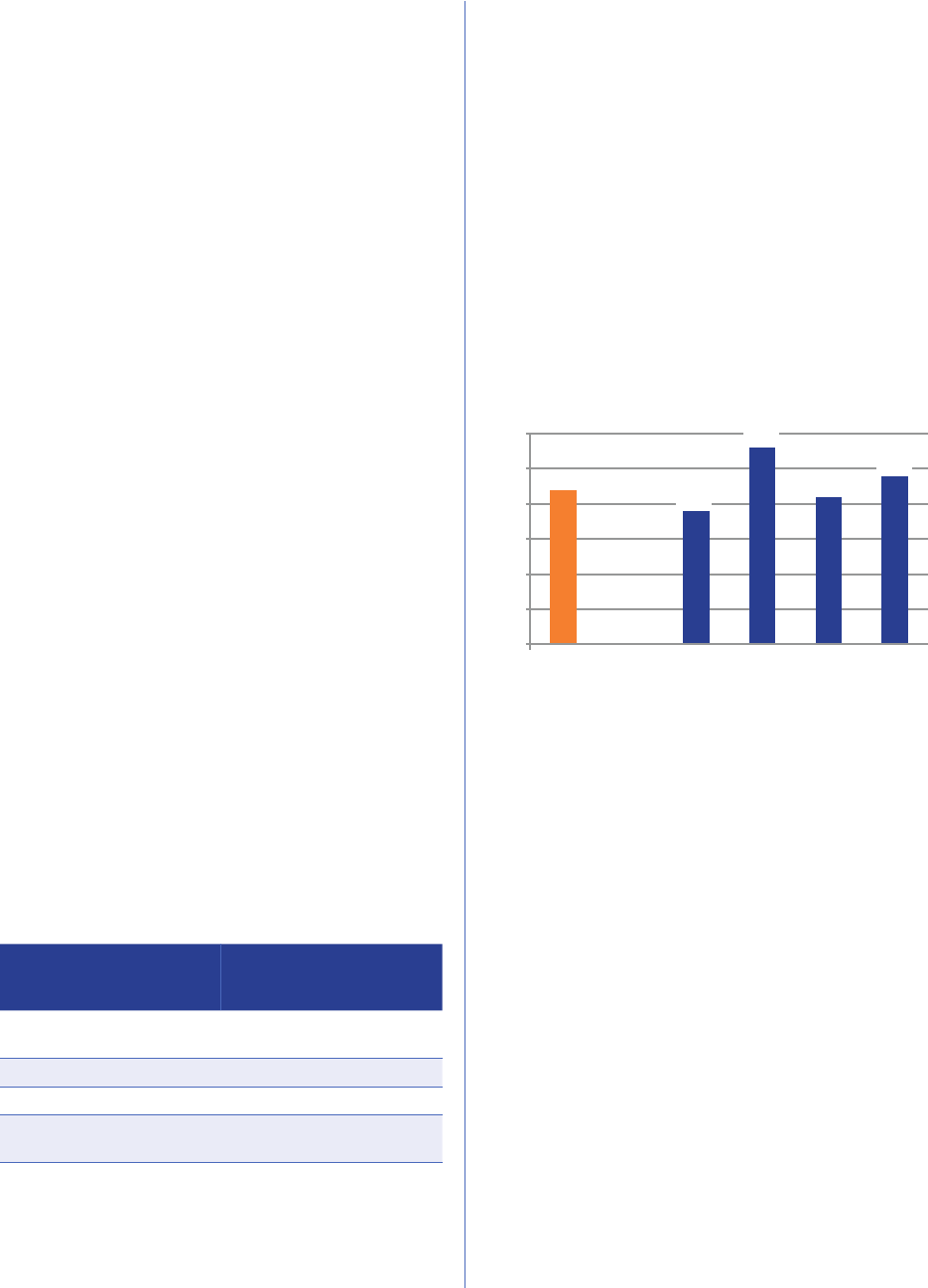

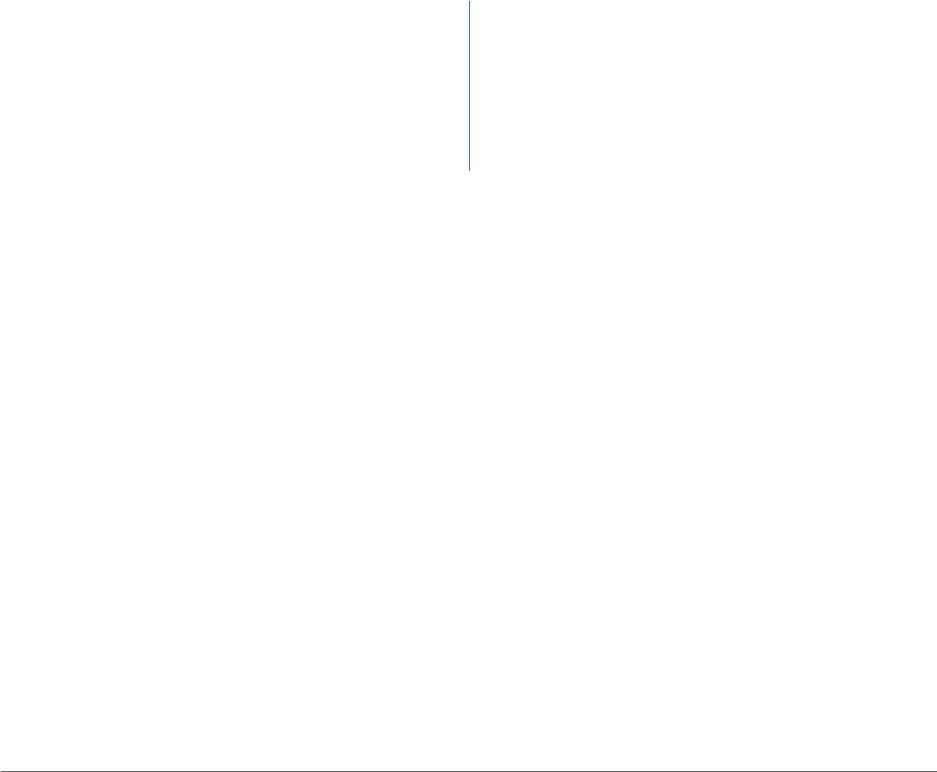

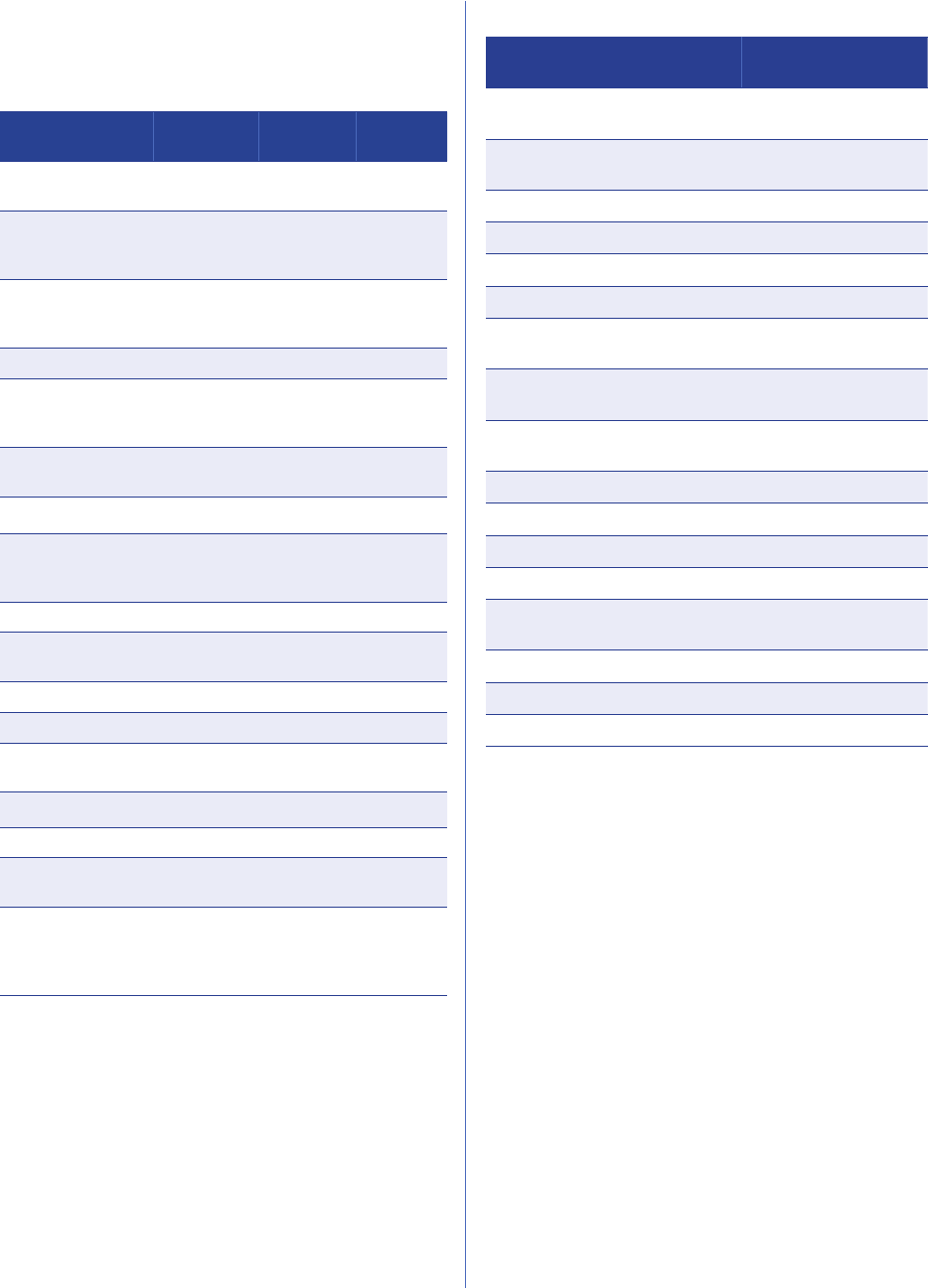

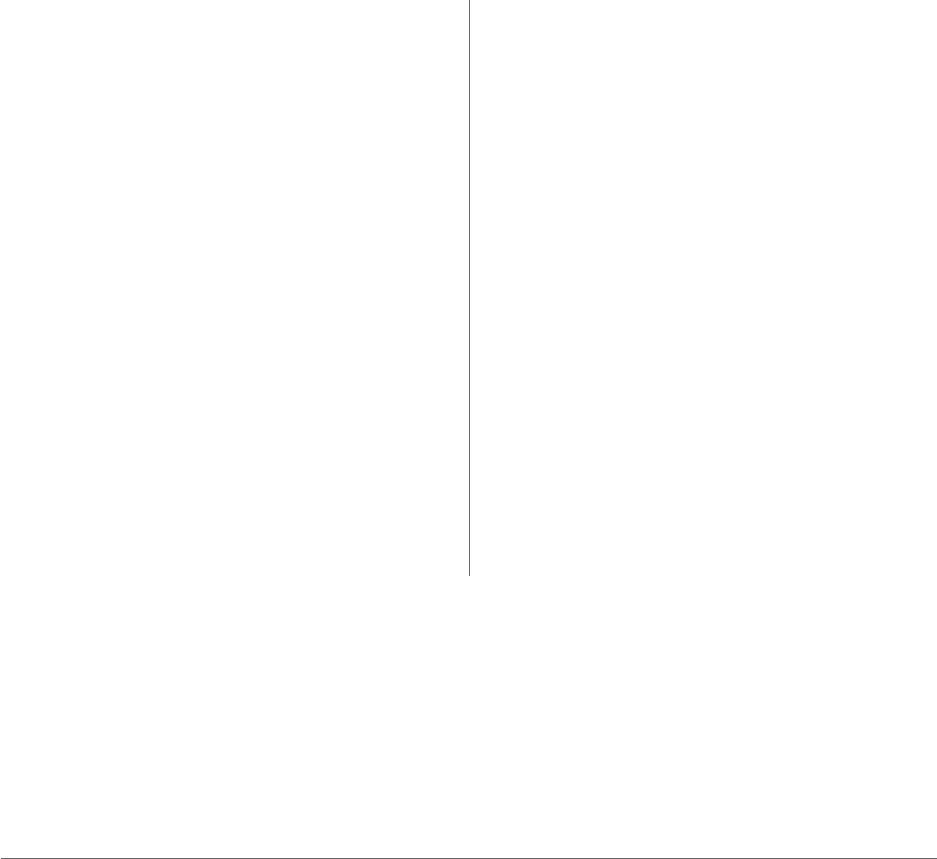

Transgender women reporting that police assumed they were sex workers in the past year

(out of those who interacted with ocers who thought they were transgender)

Overall*

American Indian

women

Asian women

Middle Eastern

women**

Multiracial women

Black women

Latina women

White women

*Represents respondents of all genders who interacted with ocers who thought they were transgender

**Sample size too low to report

0%

5% 10% 15% 20% 25% 30% 35%

2015 U.S. TRANSGENDER SURVEY

16

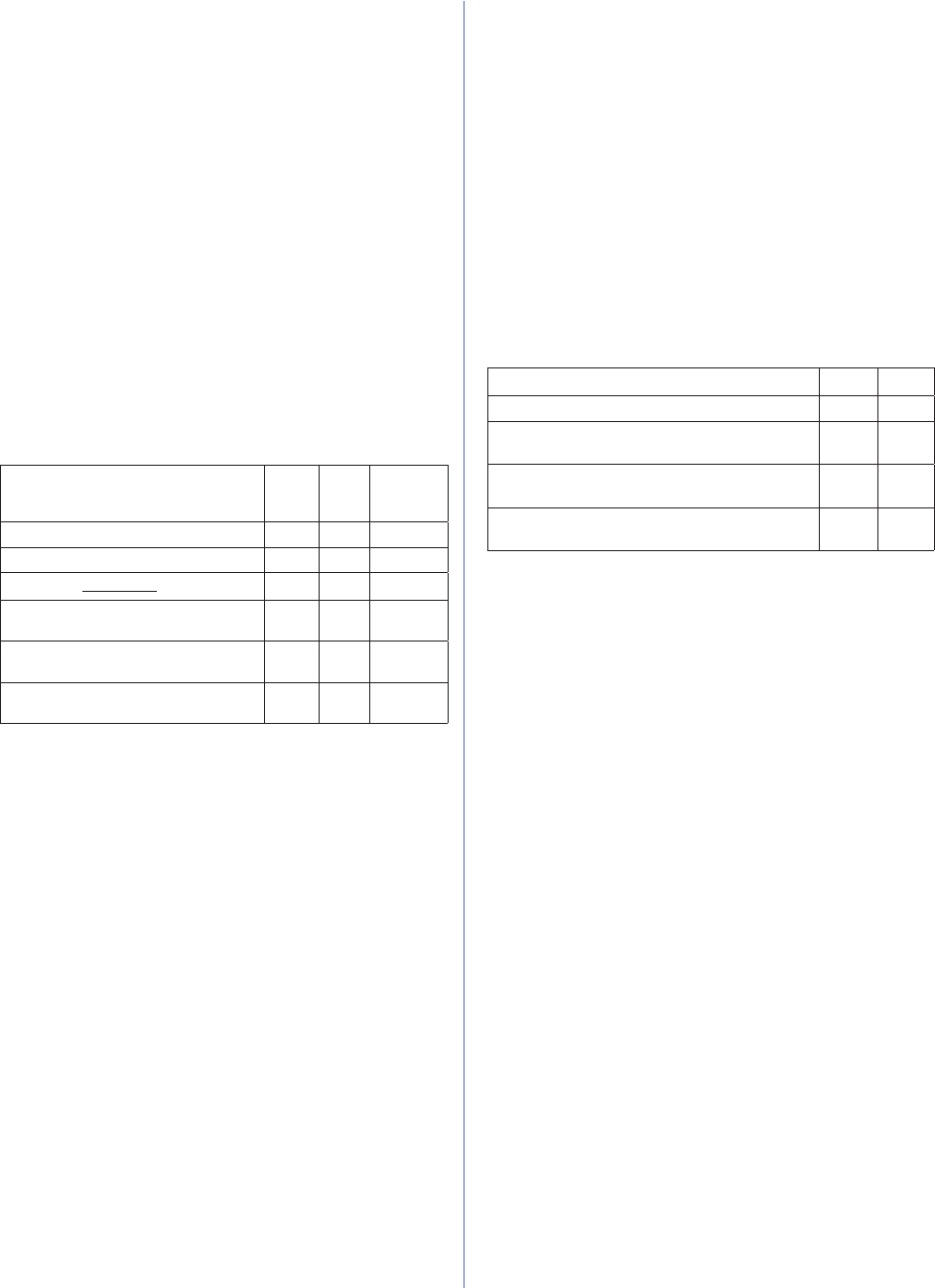

LOCATION VISITED

STAFF KNEW OR THOUGHT

THEY WERE TRANSGENDER

Public transportation 34%

Retail store, restaurant, hotel, or theater 31%

Drug or alcohol treatment program 22%

Domestic violence shelter or program or rape crisis center 22%

Gym or health club 18%

Public assistance or government benefit oce 17%

Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) 14%

Nursing home or extended care facility 14%

Court or courthouse 13%

Social Security oce 11%

Legal services from an attorney, clinic, or legal professional 6%

Denied equal treatment or service, verbally harassed, or physically attacked in public

accommodations in the past year because of being transgender

Places of Public Accommodation

• Respondentsreportedbeingdeniedequaltreatmentorservice,verballyharassed,

or physically attacked at many places of public accommodation—places that provide

services to the public, like retail stores, hotels, and government oces. Out of

respondents who visited a place of public accommodation where sta or employees

thought or knew they were transgender,

one type of mistreatment in the past year in a place of public accommodation. This

included 14% who were denied equal treatment or service, 24% who were verbally

harassed, and 2% who were physically attacked because of being transgender.

•

in the past year because they feared they would be mistreated as a transgender person.

Experiences in Restrooms

The survey data was collected before transgender people’s restroom use became the

subject of increasingly intense and often harmful public scrutiny in the national media

and legislatures around the country in 2016. Yet respondents reported facing frequent

harassment and barriers when using restrooms at school, work, or in public places.

restroom in the past year.

• Inthepastyear,

when accessing a restroom.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

17

of respondents avoided using

a public restroom in the past year because they were

afraid of confrontations or other problems they might

experience.

of respondents limited the

amount that they ate and drank to avoid using the

restroom in the past year.

reported having a urinary tract

infection, kidney infection, or another kidney-related

problem in the past year as a result of avoiding

restrooms.

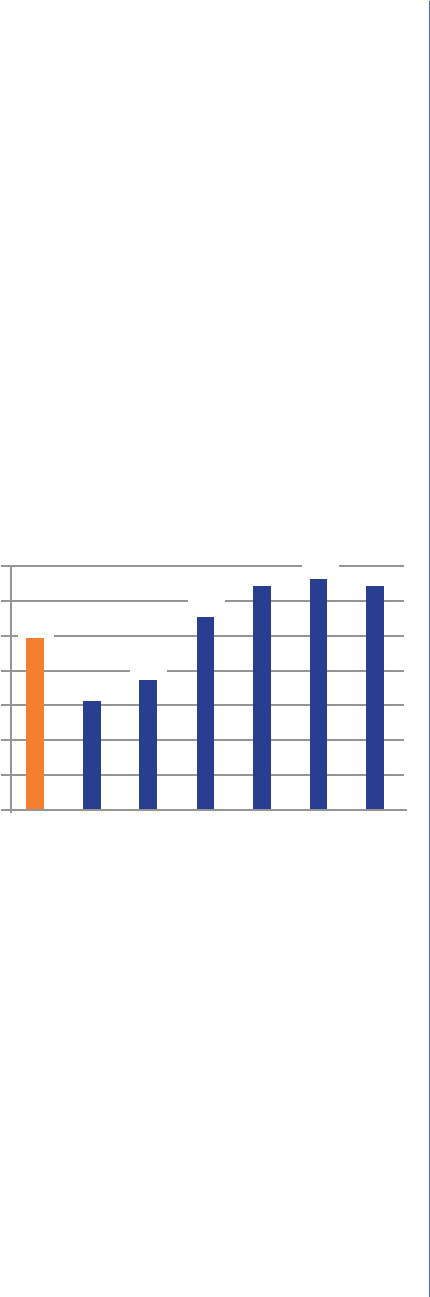

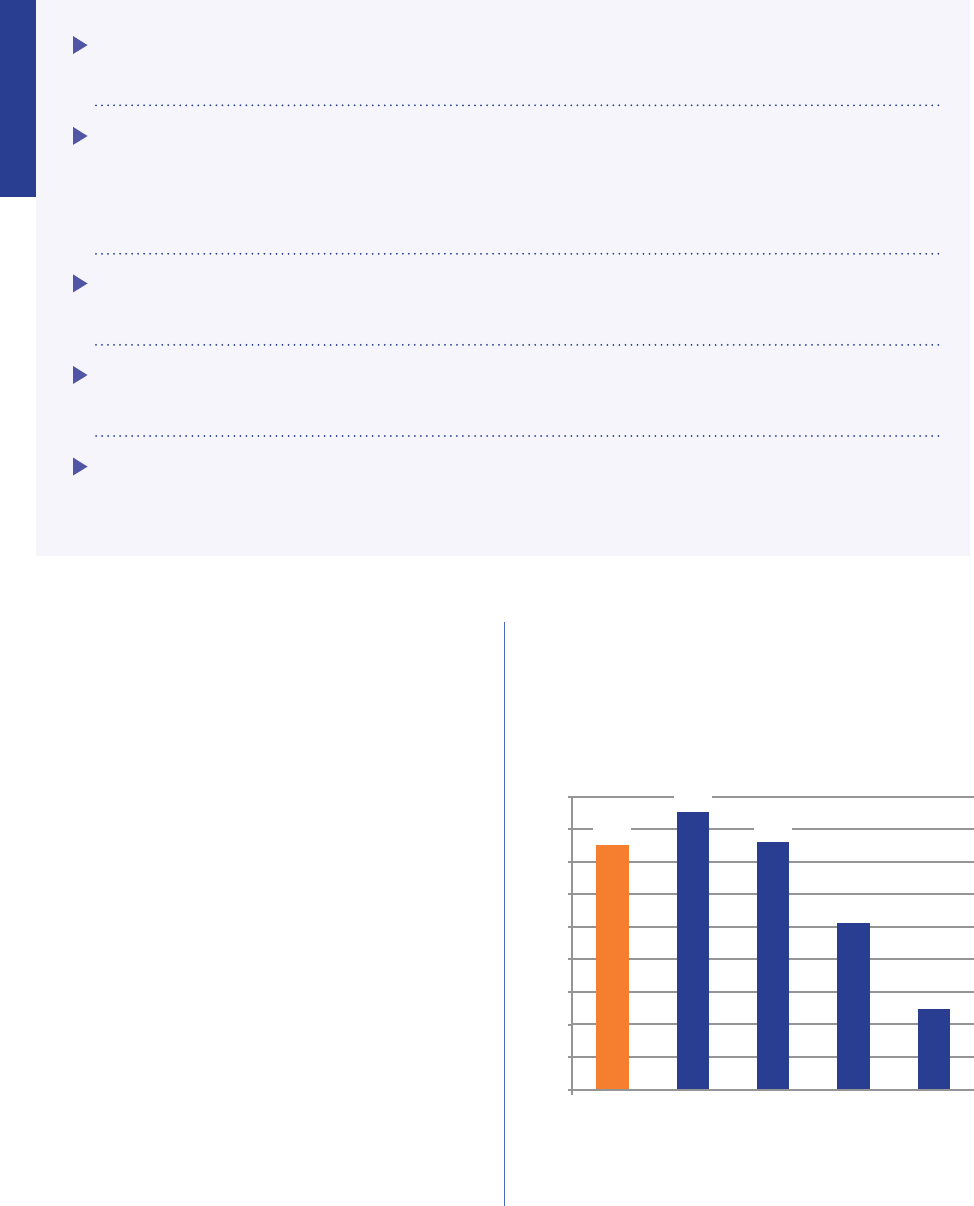

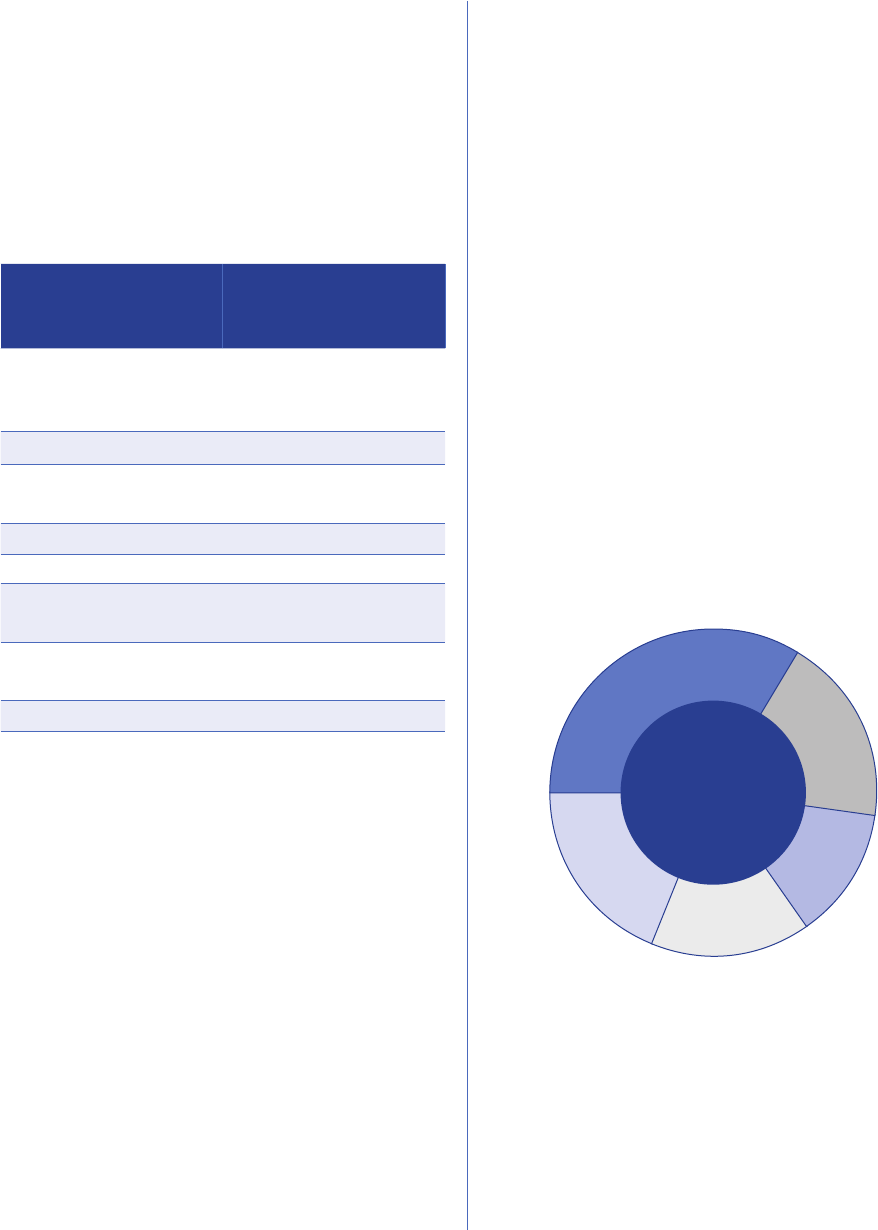

Civic Participation and Party Aliation

that they were registered to vote in the November 2014 midterm election, compared

to 65% in the U.S. population.

of U.S. citizens of voting age reported that they had voted in the

midterm election, compared to 42% in the U.S. population.

, compared to 27%, 43%, and 27% in the U.S.

population, respectively.

Political party aliation

POLITICAL PARTY

Democrat 50% 27%

Independent 48% 43%

Republican 2% 27%

of

respondents avoided using a

public restroom in the past year

because they were afraid

of confrontations

or other problems

they might

experience.

2015 U.S. TRANSGENDER SURVEY

18

T

his report presents the findings of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey (USTS), a study conducted

by the National Center for Transgender Equality (NCTE). With 27,715 respondents, it is the largest-

ever survey examining the lives of transgender people in the United States. The USTS provides a

detailed portrait of the experiences of transgender people across many areas, including health, family life,

employment, and interactions with the criminal justice system.

The USTS serves as a follow-up to the National Transgender Discrimination Survey (NTDS), which was

developed by NCTE and the National LGBTQ Task Force and conducted in 2008–09. The NTDS was the

first comprehensive survey examining the lives and experiences of transgender and gender nonconforming

people in the United States. With 6,456 respondents reporting on a range of experiences throughout their

lives, the NTDS was a groundbreaking study. The results were published in the 2011 report, Injustice at

Every Turn, and showed that discrimination against transgender people was pervasive in many areas of

life, including education, employment, health care, and housing. The report also highlighted the resilience

of transgender people in the face of such discrimination and found that family and peer support could

have a substantially positive impact on a transgender person’s quality of life. The report quickly became a

vital source of information about transgender people and continues to serve as an important resource for

advocates, policymakers, educators, service providers, media, and the general public.

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

INTRODUCTION

19

This report demonstrates that transgender people

continue to face discrimination in numerous areas

that significantly impact quality of life, financial

stability, and emotional wellbeing, including

employment, education, housing, and health care.

Furthermore, many respondents experienced

discrimination in multiple areas of their lives,

the cumulative eect of which leads to severe

economic and emotional hardship and can in turn

have devastating eects on other outcome areas,

such as health and safety.

Although issues impacting transgender people

have become more visible in the years since the

NTDS was published, the data overwhelmingly

demonstrates that there is still a long way to

go towards eliminating harmful discrimination

and providing sustainable systems of support

for transgender people throughout their lives.

These findings are presented with the recognition

that advocates, researchers, and transgender

communities will greatly benefit from additional

research conducted using this extensive data

source. The authors encourage subsequent

analyses to delve into areas of the data that this

report is unable to address, and as before, will

strive to make the dataset available for such

analyses.

Much has changed since the NTDS was conducted

in 2008–09 and results were published in 2011,

including increased visibility of transgender people

in the media and in society in general. Despite

making significant strides in the five years since

the report was published, there is still a substantial

amount of work to be done to address critical needs

in transgender communities throughout the United

States. Transgender people continue to experience

discrimination and anti-transgender bias in virtually

all areas of life.

The 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey was developed

by the National Center for Transgender Equality to

provide updated and more detailed data to inform

a wide range of audiences about the experiences

of transgender people, how things are changing,

and what can be done to improve the lives of

transgender individuals in the United States.

It is the largest survey of transgender people

conducted to date, far surpassing the previous

survey, with 27,715 respondents. This study

explores a wider range of topics than the previous

survey and more deeply examines specific issue

areas where transgender people are disparately

impacted, such as health care, HIV/AIDS, housing,

workplace discrimination, immigration, sex work,

and police interactions. Additionally, by closely

mirroring questions from federal and other existing

surveys, this study seeks to fill in the gaps left

by the lack of data collected about transgender

people in national surveys. Since federal survey

data is often used by government agencies to

make key determinations about policies and

programs that aect individuals in many areas of

life, such as employment and health, it is important

to provide specific data on the potential impact

of such policies on transgender people. This

report on the U.S. Transgender Survey data draws

comparisons between transgender people and the

U.S. population and examines disparities across

multiple issue areas.

2015 U.S. TRANSGENDER SURVEY

20

Report Roadmap

The next chapter of the report will give an

overview of the study’s methodology, which will

be followed by a guide to this report, including

information about terminology used throughout.

These will be followed by chapters discussing

respondents’ experiences across a range of areas

that impact transgender people’s lives:

• PortraitofUSTSRespondents

• FamilyLifeandFaithCommunities

• IdentityDocuments

• Health

• ExperiencesatSchool

• IncomeandEmploymentStatus

• EmploymentandtheWorkplace

• SexWorkandOtherUndergroundEconomy

Work

• MilitaryService

• Housing,Homelessness,andShelterAccess

• Police,Prisons,andImmigrationDetention

• HarassmentandViolence

• PlacesofPublicAccommodationandAirport

Security

• ExperiencesinRestrooms

• CivicParticipationandPolicyPriorities

The report also contains three appendices,

which oer more detailed information related to

the study:

Appendix A: Characteristics of the Sample

Appendix B: Survey Instrument (Questionnaire)

Appendix C: Detailed Methodology

METHODOLOGY

21

CHAPTER 2

Methodology

T

he U.S. Transgender Survey is the largest survey ever conducted to examine the experiences

of transgender people in the United States. The survey instrument was comprised of thirty-two

sections reflecting 1,140 distinct variables that covered a broad array of topics, such as health and

health care access, and experiences around employment, education, housing, law enforcement, and public

accommodation.

1

The survey was developed by a team of researchers and advocates and administered

online to transgender adults residing in the United States.

2

The survey was accessible via any web-enabled

device (e.g., computer, tablet, netbook, smart phone), accessible for respondents with disabilities (e.g.,

through screen readers), and made available in English and Spanish. Rankin & Associates Consulting

hosted the survey on several secure servers. The survey was accessed exclusively through a website

created specifically for the promotion and distribution of the survey.

3

Data was collected over a 34-day

period in the summer of 2015,

4

and the final sample included 27,715 respondents from all fifty states, the

District of Columbia, American Samoa, Guam, Puerto Rico, and U.S. military bases overseas. The survey

contained mainly closed-ended questions, but respondents were also oered the opportunity to provide

write-in responses in fifty-three of the survey questions. Over 80,000 write-in responses were provided by

respondents.

2015 U.S. TRANSGENDER SURVEY

22

I. About the U.S.

Transgender Survey

The U.S. Transgender Survey (USTS) was

developed as the follow-up to the groundbreaking

National Transgender Discrimination

Survey (NTDS), which was the first study to

comprehensively measure experiences and life

outcomes of transgender people in the United

States. Fielded in late 2008 to early 2009 by the

National Center for Transgender Equality (NCTE)

and the National LGBTQ Task Force (“the Task

Force”), the NTDS provided data that has informed

policymakers, advocates, and educators since

its publication in 2011. However, the NTDS report

acknowledged that the study had “just scratched

the surface of this extensive data source” and

encouraged advocates and researchers to

conduct additional research to continue collecting

data aimed at identifying and addressing the

needs of transgender people.

5

The NTDS

authors also examined the survey instrument

and concluded that there were “imperfections”

in the manner in which several questions had

been posed.

6

The authors addressed areas

for potential improvement with respect to both

survey question design and substantive content

in an “issues and analysis” section of the report.

7

These recommendations were considered in the

development of the U.S. Transgender Survey.

In subsequent years, researchers have

performed additional analyses using the NTDS

public use dataset provided by NCTE and the

Task Force. These analyses provided further

insight into the experiences of transgender

people, but also increased awareness of the

questions that remained unanswered after the

NTDS report was published. In some instances,

there was insucient information to draw

nuanced comparisons between life outcomes

of transgender people collected in the NTDS

and the U.S. general population. In other cases,

the ability to form additional conclusions was

limited due to a lack of follow-up questions. For

example, the NTDS asked a single question about

suicide attempts, which did not allow for a clear

examination of suicidal thoughts and behaviors.

8

Additionally, given the deficiency of longitudinal

data on outcomes specific to transgender people,

there remained a need to collect data that could

speak to the experiences of transgender people

over time and how outcomes may have changed

in the years since the NTDS was published. In

these respects, the NTDS provided an important

platform upon which to build the USTS to address

identified areas for improvement and collect data

that would enable new insights to be drawn about

transgender people in the United States.

The study was renamed the U.S. Transgender

Survey for several reasons. One was to clarify

the geographical location of the intended study

sample both during the data collection period

and following report publication. The use of “U.S.”

signaled that this study was developed with the

unique needs of transgender people in the United

States and U.S. territories in mind, considering

relevant policies, procedures, and practices

applicable to residents of the United States at the

time of the study in areas such as health care and

insurance, income, employment, housing, and

education. Recognizing the contextual dierences

between the experiences of transgender people

in the U.S. and in other parts of the world, the

research team sought to dispel any confusion

arising from the use of “national” in the title. The

new name was also intended to reflect the depth

and breadth of the experiences of transgender

people in the U.S. and elevate a variety of

narratives beyond discrimination, including the

resilience and resourcefulness of the transgender

community in the face of hardship, as well as

experiences of acceptance and armation.

“Discrimination” was removed from the title to

clarify that the survey was designed to capture all

such experiences. Additionally, removing the word

METHODOLOGY

23

reduced potential bias in respondents’ answers or

resulting from primarily attracting respondents who

felt they had experienced discrimination.

II. USTS Respondents

The study population included individuals who

identified as transgender, trans, genderqueer,

non-binary, and other identities on the transgender

identity spectrum, in order to encompass a wide

range of transgender identities, regardless of

terminology used by the respondent. Although

“transgender” was defined broadly for the

purposes of this study as being inclusive of a

wide range of identities—such as genderqueer,

non-binary, and crossdresser—the research

team recognized that many individuals for

whom the study was intended may have used

dierent terminology or definitions and might

have assumed that the term “transgender” did

not include them. To address this, promotional

materials armed that the survey was inclusive

of all transgender, trans, genderqueer, and non-

binary people. Additionally, materials specified that

the survey was for adults at any stage of their lives,

journey, or transition to encourage participation

among individuals with diverse experiences

regarding their transgender identity. An in-depth

description of survey respondents is available in

the Portrait of USTS Respondents chapter.

The study included individuals aged 18 and older

at the time of survey completion, as did the NTDS.

The study was not oered to individuals under

the age of 18 due to limitations created by specific

risk factors and recommendations associated with

research involving minors. These considerations,

including requirements for parental/guardian

consent, would have impacted the survey’s scope

and content and also reduced the literacy level at

which the survey could be oered.

9

Furthermore,

the current experiences and needs of transgender

youth often dier from those of adults in a number

of key areas, including experiences related to

education, employment, accessing health care,

and updating identity documents, and many

of these experiences or needs could not be

adequately captured in a survey that was not

specifically tailored to transgender people under

the age of 18.

The sample was limited to individuals currently

residing in a U.S. state or territory, or on a U.S.

military base overseas, since the study focused on

the experiences of people who were subject to

U.S. laws and policies at the time they completed

the survey. Individuals residing outside of the U.S.

may have vastly dierent experiences across a

number of outcome measures based on each

respective country’s laws, policies, and culture,

particularly in the areas of education, employment,

housing, and health care. Additionally, many

survey questions were taken from U.S. federal

government surveys that also limit their sample

population to individuals in the U.S., and the

research team sought to examine a similar

population with regard to geographical location

to allow for comparisons to the U.S. general

population.

III. Developing the

Survey Instrument

The USTS survey instrument was developed over

the course of a year by a core team of researchers

and advocates in collaboration with dozens of

individuals with lived experience, advocacy and

research experience, and subject-matter expertise.

When developing the survey instrument, the

research team focused on creating a questionnaire

that could provide data to address both current

and emerging needs of transgender people

while gathering information about disparities

2015 U.S. TRANSGENDER SURVEY

24

that often exist between transgender people

and non-transgender people throughout the U.S.

To achieve this, questions were included that

would allow comparisons between the USTS

sample and known benchmarks for the U.S.

population as a whole or populations within the

U.S. Consequently, questions were selected to

best match those previously asked in federal

government or other national surveys on a number

of measures, such as measures related to income

and health.

10

Changes were made to the language

of comparable questions whenever it was required

to more appropriately reflect issues pertaining to

transgender people and language in common use

in the transgender community while maintaining

comparability to the best extent possible. However,

in many cases, language was preserved to ensure

that responses to a USTS question would maintain

maximum comparability with surveys such as the

U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey

and Current Population Survey.

Several questions were also included in an

attempt to provide comparability between the

NTDS, where possible, to determine how certain

outcomes may have changed since the NTDS

data was collected in 2008–09. While the USTS

provides crucial updated data, it is important to

note that many of the questions asked in the NTDS

were either not included in the USTS, or they were

asked in a manner that reduced comparability with

the NTDS. For example, many USTS questions

asked about whether certain experiences

occurred within the past year instead of asking

whether those experiences occurred at any point

during an individual’s lifetime. These questions

were included for both comparability with federal

government or other national surveys and also

to yield improved data regarding changing

experiences in future iterations of the USTS. In

such instances, the NTDS continues to provide

the best available data regarding experiences

that occurred over respondents’ lifetime. The

authors suggest referring to both the USTS and

the NTDS to gain a full picture of issues impacting

transgender people.

The survey instrument was reviewed by

researchers, members of the transgender

community, and transgender advocates at multiple

intervals throughout the development process.

This included thorough reviews of sections that

addressed specific subject matter and the entire

questionnaire. The questionnaire was revised

based on feedback from dozens of reviewers.

a. Pilot Study

Prior to finalizing the survey instrument and

launching the survey in field, a pilot study

was conducted to evaluate the questionnaire.

The pilot study was conducted among a small

group of individuals with characteristics that

were representative of the sample the study

was intended to survey. The pilot study was

administered through an online test site using

the same platform and format in which the final

survey later appeared. The purpose of the pilot

study was to provide both a substantive and

technical evaluation of the survey. Approximately

100 individuals were invited to complete and

evaluate the survey online during a specified

period of time. In order to receive access to the

pilot study test site, invitees were required to

confirm their participation by indicating that they

met the following pilot study criteria: they were

(1) 18 years or older, (2) transgender, (3) willing to

provide feedback that would be used to make

improvements to the survey, (4) available to take

the survey online during specified dates, and

(5) agreeing to not share the questions in the

pilot study with anyone so as to not compromise

the study. Forty (40) individuals confirmed their

participation and received access to the pilot

study test site. Thirty-two (32) people completed

the study and submitted feedback on the

questionnaire, including participants in fifteen

states ranging in age from 19 to 78. Participants

METHODOLOGY

25

reported identifying with a range of gender

identities

11

and racial and ethnic identities,

including 34% who identified as people of color.

12

In addition to providing general feedback on

individual questions and the entire questionnaire,

pilot study participants were asked to address

specific questions as part of their evaluation,

including: (1) how long it took to complete the

survey, (2) what they thought about the length

of the survey, (3) whether any existing questions

were confusing or dicult to answer, (4) whether

they found any questions oensive or thought

they should be removed or fixed, (5) whether they

experienced technical or computer issues while

taking the survey, and (6) what they thought about

the statement explaining why the term “trans”

was used throughout the survey.

13

All participant

feedback was compiled, discussed, and used to

further develop the questionnaire, such as through

the revision of language and the addition of

questions to more thoroughly examine an issue.

b. Length

The final survey questionnaire contained a total

of 324 possible questions in thirty-two discrete

sections addressing a variety of subjects, such

as experiences related to health and health

care access, employment, education, housing,

interactions with law enforcement, and places

of public accommodation. The online survey

platform allowed respondents to move seamlessly

through the questionnaire and ensured they only

received questions that were appropriate based

on previous answers. This was accomplished

using skip logic, which created unique pathways

through the questionnaire, with each next step

in a pathway being dependent on an individual

respondent’s answer choices. For example,

respondents who reported that they had served

in the U.S. Armed Forces, Reserves, or National

Guard received a series of questions about their

military service, but those who had not served

did not receive those questions. Due to the

customized nature of the survey, the length varied

greatly between respondents, and no respondent

received all possible questions. Prior to the pilot

study, estimates indicated a survey-completion

time of 30–45 minutes. The completion-time

estimate was extended to 60 minutes based on

feedback from pilot study participants, and it was

consistent with many reports during the fielding

period.

14

Despite observations about survey length

discussed in the NTDS,

15

evolving data needs

relating to issues aecting transgender people

required an in-depth treatment of multiple issue

areas. This often required multiple questions to

thoroughly assess an issue—including in areas

where the NTDS asked only one question—and

resulted in a lengthier survey. Survey instrument

length was assessed throughout its development

to ensure it would be manageable for as many

participants as possible. Furthermore, through

multiple reviews and evaluations of the survey

instrument—including the pilot study—survey

takers reported that the length was appropriate for

a survey addressing such a wide range of issues

and the need for data outweighed concerns about

the overall length of the survey.

IV. Survey

Distribution and

Sample Limitations

The survey was produced and distributed in an

online-only format after a determination that it

would not be feasible to oer it in paper format

due to the length and the complexity of the skip

logic required to move through the questionnaire.

With so many unique possibilities for a customized

survey experience for each respondent, the

intricate level of navigation through the survey

2015 U.S. TRANSGENDER SURVEY

26

would have created an undue burden and

confusion for many respondents. This could have

led to questions being answered unnecessarily

or being skipped completely, which could have

increased the potential for missing data in the final

dataset.

16

This made online programming the best

option for ensuring that respondents received all

of the questions that were appropriate based on

their prior answers, decreasing the probability of

missing data. However, the potential impact of

internet survey bias on obtaining a diverse sample

has been well documented in survey research,

17

with findings that online and paper surveys may

reach transgender respondents with “vastly

dierent health and life experiences.”

18

With those

considerations in mind, outreach eorts were

focused on addressing potential demographic

disparities in our final sample that could result from

online bias and other issues relating to limited

access. Although the intention was to recruit a

sample that was as representative as possible

of transgender people in the U.S., it is important

to note that respondents in this study were not

randomly sampled and the actual population

characteristics of transgender people in the U.S.

are not known. Therefore, it is not appropriate

to generalize the findings in this study to all

transgender people.

V. Outreach

The main outreach objective was to provide

opportunities to access the survey for as many

transgender individuals as possible in dierent

communities across the U.S. and its territories.

Additionally, outreach eorts focused on reaching

people who may have had limited access to the

online platform and who were at increased risk of

being underrepresented in such survey research.

This included, but was not limited to, people of

color, seniors, people residing in rural areas, and

low-income individuals. The outreach strategy was

a multi-pronged approach to reach transgender

people through various connections and points-of-

access, including transgender- or LGBTQ-specific

organizations, support groups, health centers, and

online communities.

Outreach eorts began approximately six

months prior to the launch of the data-collection

period with a variety of tactics designed to raise

awareness of the survey, inform people when it

would be available, and generate opportunities

for community engagement, participation,

and support. A full-time Outreach Coordinator

worked for a period of six months to develop and

implement the outreach strategy along with a team

of paid and volunteer interns and fellows.

19

An initial phase of outreach involved developing

lists of active transgender, LGBTQ, and allied

organizations who served transgender people and

would eventually support the survey by spreading

the word through multiple communication platforms

and in some cases providing direct access to the

survey at their oces or facilities. Establishing

this network of “supporting organizations” was an

essential component of reaching a wide, diverse

sample of transgender people.

Over 800 organizations were contacted by email,

phone, and social media, and they were asked

if they would support the survey by sharing

information about it with their members and

contacts. Specifically, supporting organizations

were asked to share information through email

blasts and social media channels, and the

research team provided language and graphics

for organizations to use in an eort to recruit

appropriate respondents into the study. Of the

organizations contacted, approximately half

responded to requests for support, resulting in

direct recruitment correspondence with nearly

400 organizations at regular intervals during

the pre-data-collection period and while the

survey was in the field.

20,21

These organizations

METHODOLOGY

27

performed outreach that contributed to the

far reach of the survey and unprecedented

number of respondents.

22

The organizations

were also featured on the survey website so

potential respondents could determine whether

organizations they knew and trusted had pledged

support for the survey.

Nearly 400 organizations responded to outreach

and confirmed their support for the survey. The

remaining organizations did not respond directly

to invitations to learn more about the survey

and become supporters. Consequently, these

organizations did not receive correspondence

aimed at directly recruiting respondents prior to

the survey launch or during the data-collection

period. It is possible, however, that survey

respondents were still made aware of the survey

through those organizations. Since there is no

information regarding whether these organizations

shared information about the survey through their

channels, it is dicult to assess the full scope of

the outreach eorts.

a. Advisory Committee

A significant element of outreach involved

convening a USTS Advisory Committee (UAC).

The UAC was created to increase community

engagement in the survey project and raise

awareness by connecting with transgender people

in communities across the country through a

variety of networks. The UAC was comprised

of eleven individuals with advocacy, research,

and lived experience from a wide range of

geographical locations.

23

Members were invited

to join the committee as advisors on survey

outreach to facilitate the collection of survey data

that would best reflect the range of narratives and

experiences of transgender people in the U.S.

Each member brought unique skills and expertise

to contribute to the committee’s objectives. UAC

members participated in five monthly calls with

members of the USTS outreach team from May

to September 2015. UAC monthly calls focused

on providing project updates and identifying

pathways by which outreach could be conducted

to increase the survey’s reach and promote

participation from a diverse sample. Members

suggested organizations, individuals, and other

avenues through which to conduct outreach,

shared ideas and strategies for improving outreach

to specific populations of transgender people, and

spread the word about the survey through their

professional and personal networks.

b. Survey-Taking Events

In an eort to increase accessibility of the survey,

the outreach team worked with organizations

across the country to organize events or venues

where people could complete the survey. Survey-

Taking Events,

24

or “survey events,” were spaces in

which organizations oered resources to provide

access to the survey, such as computers or

other web-enabled devices. These organizations

provided a location in which to take the survey at

one particular time or over an extended period

of time, such as during specified hours over

the course of several days.

25

The events were

created with the intention of providing access to

individuals with limited or no computer or internet

access, those who may have needed assistance

when completing the survey, or those who needed

a safe place to take the survey. Additionally, the

population that had previously been identified as

being more likely to take a paper survey than an

online survey were considered,

26

and the events

were developed to target those individuals.

Given the potential variety of these survey

events—including the types of available resources

and times at which they were conducted—

guidelines were needed to maintain consistency

across the events and preserve the integrity of the

data-collection process. A protocol was developed

outlining the rules for hosting a survey event

to advise hosts on best practices for ensuring

2015 U.S. TRANSGENDER SURVEY

28

a successful data-collection process, including

guidelines to prevent the introduction of bias into

survey responses. The protocols described the

steps for becoming a survey-event host and tips

for how to conduct outreach about the event. The

protocol also specified that hosts should inform

NCTE of their event prior to hosting and report on

how many people attended the event and how

many people completed and submitted the survey.

This was helpful information for evaluating the

relative success and benefits of these events. All

confirmed supporting organizations were invited

to become survey event hosts, and those who

accepted the invitation were sent the protocol.

Seventy-one (71) organizations accepted the

invitation and confirmed the date(s) and time(s) of

their events.

27

Survey events were promoted on the survey

website and given a specific designation on the

supporting organization map (described further

in the “Survey Website” section), including

information about where and when people could

attend. Hosts were encouraged to promote their

event through multiple channels and consider

outreach methods beyond online avenues,

such as direct mail or flyers, to better reach

transgender people with limited or no internet

access. Additionally, hosts were provided with

flyer templates so they could promote the events

in their facilities or through communications

with their members or constituents. Of the

organizations who confirmed their survey events,

46 reported information about attendance at

the event. The hosts reported that 341 people

attended their events, including transgender and

non-transgender friends, family, and volunteers.

Approximately 199 respondents completed

the survey at these events.

28

However, survey

responses indicate that additional unreported

survey events or similar gatherings may have been

held where participants had an opportunity to

complete the survey.

29

Event-related information

submitted by organizations following the fielding

period was not comprehensive enough to make a

thorough determination as to whether the events

had achieved their previously stated objectives.

30

c. Incentives

As an incentive for completing the survey,

participants were oered a cash-prize drawing.

Incentives, such as cash prizes are widely

accepted as a means by which to encourage and

increase participation in survey research.

31

Studies

have shown that such incentives may have a

positive eect on survey response rate, which is

the proportion of individuals in the population of

interest that participates in the survey.

32

Research

has also found that lottery-style cash drawings

may be beneficial in online surveys,

33

since they

oer a practical method for providing incentives

in surveys with a large number of respondents by

eliminating the potential high cost of both the cash

incentive and prize distribution.

34

USTS respondents were oered the opportunity

to enter into a drawing for one of three cash

prizes upon completion of the survey, including

one $500 cash prize and two $250 cash prizes.

35

After completing and submitting their anonymous

survey responses, USTS respondents were re-

directed away from the survey hosting site

36

to a

web page on the NCTE-hosted USTS website. In

addition to being thanked for their participation

on this page, respondents received a message

confirming that their survey had been submitted

and any further information they gave would not

be connected to their survey responses. Only

individuals who completed and submitted the

survey were eligible for one of the cash prizes.

To enter into the prize drawing, respondents

were required to check a box giving their consent

to be entered.

37

Respondents were also asked

to provide their contact information in order to

be notified if selected in the drawing. The final

drawing contained 17,683 entrants. Each entrant

was assigned a number, and six numbers were

randomly chosen by a non-NCTE party: three

METHODOLOGY

29

numbers for the prize winners and three for

alternates if necessary. The three prize winners

were contacted and awarded their prizes upon

acceptance.

VI. Communications

Communications for the survey required a

multifaceted approach and a coordinated eort

with the outreach strategy to most eectively

reach a wide range of transgender people and

ensure a robust sample size. The goals of survey

communications were to: (1) inform people that

NCTE would be conducting a survey to further the

understanding of the experiences of transgender

people in the U.S initially gleaned through the

NTDS, (2) communicate when the survey would

be available to complete and how it could be

accessed, and (3) find creative ways of reaching

diverse populations of potential respondents. This

involved raising awareness of the survey through

several communication methods, including email,

social media, and print media, as well as through

additional unique campaigns. Many survey

promotional materials were produced in English

and Spanish to increase the accessibility of the

survey.

38

a. Survey Website

A website was created and designed specifically

for the promotion and distribution of the survey.

39

This website served as a platform for providing

information about the survey starting several

months prior to its release in the field, such as a

description of the survey, information about the

team working on the survey, frequently asked

questions, and sample language and graphics for

individuals and organizations to use for email and

social media communications, including sample

Facebook and Twitter postings. The website

also featured an interactive map, which included

information about organizations that had pledged

to support the survey. Additionally, the map

distinctly indicated information about organizations

that were hosting survey-taking events, including

the date, time, and location of such events. The

website later served as the only platform through

which the survey could be accessed and provided

English and Spanish links to enter the survey, since

there was no direct link available to the o-site

hosting platform.

b. Survey Pledge

The survey pledge campaign was developed to

raise awareness about the survey and generate

investment in the project. The campaign engaged

potential participants and allies by inviting them

to pledge to take the survey and/or spread the

word about the survey. The survey pledge was

a critical method of both informing people that

the survey would be launching and sustaining

engagement with potential respondents in the

months leading up to the fielding period. Pledges

received reminders about the survey launch date

and availability through email communications.

Beginning in January 2015, pledge palm cards

were distributed at a variety of events across

the country, including conferences and speaking

engagements. The cards contained information

about the upcoming survey and asked people to

sign up to help by committing to: (1) spread the

word about the survey; and/or (2) take the survey.

Transgender and non-transgender individuals were

asked to complete the pledge information, either

through a palm card or directly online through the

survey website. Individuals who completed pledge

information received email communications

throughout the pre-data-collection phase. Pledge

information was collected continuously for several

months, and by the time of the survey launch, over

14,000 people had pledged to take the survey.

Additionally, more than 500 people pledged to

promote the survey among their transgender

friends and family.

40

The pledge proved to be

2015 U.S. TRANSGENDER SURVEY

30

an eective method of assessing how many

people had learned about the survey and were

interested in completing it, where potential survey

respondents were distributed geographically,

and how more potential respondents could be

eectively engaged.

c. Photo Booth Campaign

In January 2015, a photo booth campaign was

launched as another method for engaging

people and raising awareness about the survey.

Individuals and groups were asked to take

photos holding one of two signs with messages

expressing support for the survey.

41

USTS photo

booths were conducted at several conferences

and events across the country. More than 300

photos were collected and shared directly through

NCTE’s Facebook page. Photos were also sent to

most participants so they could conduct their own

promotion using their photos.

d. Social Media

With the increased use of social media in the

years since the previous survey (the NTDS), it

was important to engage via these outlets to

further the reach of the survey. Facebook and

Twitter

42

became the primary social media outlets

used throughout the survey project, and their

use significantly amplified awareness, increasing

the number of people who were exposed to the

survey. A series of postings provided the ability

to rapidly and succinctly communicate with

individuals and groups who had an interest in

contributing to the survey’s success by completing