The State Senate

Senate Research Office

Bill Littlefield

Managing Director

Martha Wigton

Director

204 Legislative Office Building

18 Capitol Square

Atlanta, Georgia 30334

Telephone

404/ 656 0015

Fax

404/ 657 0929

The State Flag of Georgia:

The 1956 Change In Its Historical Context

Prepared by:

Alexander J. Azarian and Eden Fesshazion

Senate Research Office

August 2000

Table

of

Contents

Preface.....................................................................................i

I. Introduction: National Flags of the

Confederacy and the

Evolution of the State Flag of Georgia.................................1

II. The Confederate Battle Flag.................................................6

III. The 1956 Legislative Session:

Preserving segregation...........................................................9

IV. The 1956 Flag Change.........................................................18

V. John Sammons Bell.............................................................23

VI. Conclusion............................................................................27

Works Consulted..................................................................29

i

Preface

This paper is a study of the redesigning of Georgia’s present state flag during the 1956 session of

the General Assembly as well as a general review of the evolution of the pre-1956 state flag. No attempt

will be made in this paper to argue that the state flag is controversial simply because it incorporates the

Confederate battle flag or that it represents the Confederacy itself. Rather, this paper will focus on the flag

as it has become associated, since the 1956 session, with preserving segregation, resisting the 1954 U.S.

Supreme Court decision of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, and maintaining white supremacy

in Georgia. A careful examination of the history of Georgia’s state flag, the 1956 session of the General

Assembly, the designer of the present state flag – John Sammons Bell, the legislation redesigning the 1956

flag, and the status of segregation at that time, will all be addressed in this study.

j j j

1

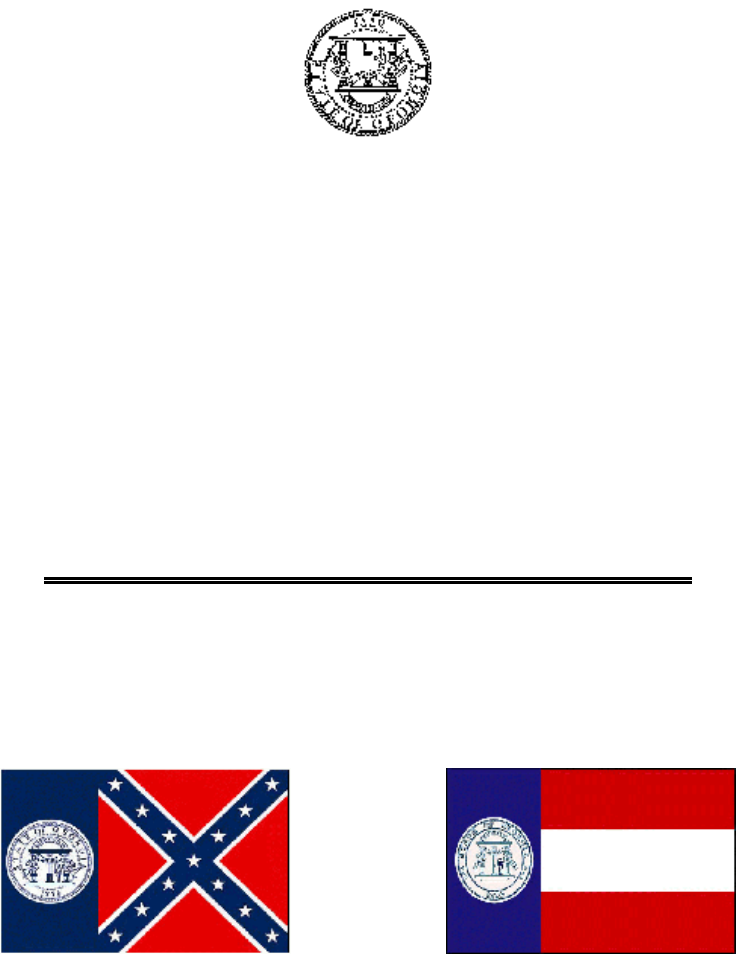

The “Stars and Bars”

The First Confederate

National Flag (1861 – 1863)

The Confederate Battle Flag

(1861-1865)

VII. Introduction: National Flags of the Confederacy

and the Evolution of the State Flag of Georgia

Soon after the formation of the Confederate States of America, delegates from the seceded states

met as a provisional government in Montgomery, Alabama. Among the early actions was appointment of

a committee to propose a new flag and seal for the Confederacy. The proposal adopted by the committee

called for a flag consisting of a red field divided by a white band one-third the width of the field, thus

producing three bars of equal width. The flag had a square blue union the height of two bars, on which was

placed a circle of white stars corresponding in number to the states of the Confederacy – South Carolina,

Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas.

The First National Flag of the Confederacy soon came to be known as the “Stars and Bars.” With

seven stars at first, the number of stars varied during 1861. The number of stars on most national flags

jumped to eleven with the secession of Virginia, Arkansas, North Carolina, and

Tennessee, and finally to thirteen in recognition of the symbolic admission of

Kentucky and Missouri to the Confederacy.

2

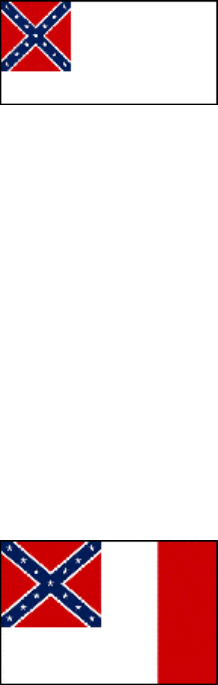

Second National Flag of

the Confederacy (1863-1865)

Third National Flag of the

Confederacy (1865)

The similarity of the Stars and Bars to the Stars and Stripes was not an accident. As the war

progressed, however, sentiment for keeping a reminder of the American flag diminished in the South. More

importantly, during the first major battle of the Civil War at Bull Run near Manassas Junction, Virginia, it

was hard to distinguish the Stars and Strips from the Stars and Bars at a distance. Consequently,

Confederate generals P.G.T. Beauregard and Joseph Johnston urged that a new Confederate flag be

designed for battle. The result was the square flag sometimes known as the “Southern Cross.” The

Confederate Battle Flag consisted of a blue saltire reminiscent of the St. Andrew's Cross, on which were

situated 13 stars, with the saltire edged in white, all on a red background.

Not more than a year after the adoption of the Stars and Bars, the issue of designing a new national

flag for the Confederate States was raised with the intention to create a flag that was in no way similar to

the Union's Stars and Stripes. On May 1, the last day of the session, both houses agreed to a flag

consisting of a white field, with a length twice as long as its width, and a square Confederate battle flag

two-thirds the width of the field to be used as a canton (or union) in the upper left. Despite the official

dimensions provided in the Flag Act of 1863, many copies were made shorter to achieve a more traditional

appearance and to prevent the white flag from being mistaken for a flag of truce. The Second National

Flag was widely known as the “Stainless Banner.” Because the first issue of this flag draped the coffin of

General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, it was also known as the “Jackson Flag.”

3

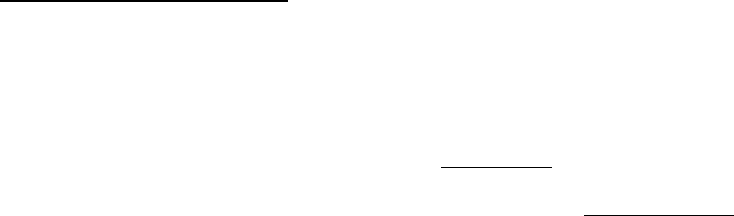

Unofficial Georgia State Flag

(? - 1879)

The First Official State Flag

1879 – 1902

Because it could be mistaken for a flag of truce, the “Stainless Banner” was modified, for the last

several months of the war, to include a red bar on the flying end. It was to be 1/4 of the area of the flag

beyond the now rectangular canton. The width was to be 2/3 of length. The canton was to be 3/5 of width

and 1/3 of length. This was signed into law on March 4, 1865. Authorized in the final months of the war,

relatively few copies of the Third National Flag were made, and even fewer survived.

State Flags of Georgia

History does not record who made the first Georgia state flag, when it was made, what it looked

like, or who authorized its creation. The banner most likely originated in one of the numerous militia units

that existed in antebellum Georgia. In 1861, a new provision was added to Georgia's code requiring the

governor to supply regimental flags to Georgia militia units assigned to fight outside the state. These flags

were to depict the "arms of the State" and the name of the regiment, but the code gave no indication as to

the color to be used on the arms or the flag's background. The above flag is a reconstruction of the

pre-1879 unofficial Georgia state flag as it would have appeared using a color version of the coat of arms

from the 1799 state seal.

In 1879, State Senator Herman H. Perry introduced legislation giving Georgia its first official state

flag. Senator Perry was a former colonel in the Confederate army, a fact that probably influenced his

proposal to take the Stars and Bars, remove the stars, extend the blue canton to the bottom of the flag, and

4

As Changed in 1902

c.1902 – c.1920

narrow its width slightly. Georgia finally adopted an official state flag because on the previous day, the

1879 General Assembly passed a law recodifying state law regulating volunteer troops. Included in the

revision was a provision that: "Every battalion of volunteers shall carry the flag of the State, when one is

adopted by Act of the General Assembly, as its battalion colors." Governor Colquitt approved Georgia's

first official state flag on October 17, 1879.

In 1902, as part of a major reorganization of state militia laws, Georgia's General Assembly

changed the state flag adopted in 1879. Where that flag had a plain blue field, the 1902 amendment

provided that the blue field contain the coat of arms of the State. The above flag is a reconstruction of how

Georgia's state flag would have appeared if the coat of arms from the actual state seal then in use had been

applied to the blue field of the 1879 flag. However, no known copies of the 1902 flag as depicted above

survive. By 1904, the coat of arms was being portrayed on a white shield, and it may be that technically

accurate versions of the 1902 flag were never produced.

Although the General Assembly enacted legislation in 1902 stipulating that Georgia’s coat of arms

be incorporated on the vertical blue band of the state flag, another version of the state flag existed with

Georgia’s coat of arms being placed on the blue band, and shown on a gold-outlined white shield, with the

date “1799" printed below the arms. Additionally, without any statutory authorization, a red ribbon with

“Georgia” was added below the shield on the blue background. Exactly who was responsible for these

departures from the 1902 statute – and when – is not known, but clearly by 1904, this was accepted as

5

c.1920 – 1956

Current Georgia State Flag

(1956-present)

Georgia's state flag. Several copies of this flag survive today attesting to its use. Interestingly, despite the

addition of the shield, date, and red ribbon, the flag clearly demonstrates that Georgia’s coat of arms was

not synonymous with the state seal. In 1914, the General Assembly changed the date on Georgia’s state

seal from 1799 (the year the seal was adopted) to 1776 (the year of independence).

By the late 1910s or early 1920s, a new, unofficial version of Georgia's state flag – one

incorporating the entire state seal – began appearing. There is no record of who ordered the change or

when it took place. The new flag may have resulted from the 1914 law changing the date on Georgia's

state seal from 1799 (the date the seal was adopted) to 1776 (the year of independence). Because some

flag makers had been including "1799" beneath the coat of arms, it became necessary to change the date

on new flags. At that point, possibly the Secretary of State or a flag manufacturer may have decided that

the entire state seal created a more uniform flag. The first state publication to show Georgia's flag with a

seal was the Georgia Official Register for 1927, which showed the above flag – but with a color seal. Also,

until the mid-1950s (when a new seal was drawn), various versions of the Georgia seal were used on state

flags.

1

The Confederate Battle Flag is regularly and mistakenly referred to as the “Stars and Bars.” However, the “Stars and

Bars” is actually the first National Flag of the Confederacy – composed of a blue canton in the upper left hand corner of seven

white stars, representing the seven original Confederate States, with three alternating horizontal bars of red and white (hence the

name). The number of stars on most national flags jumped to eleven with the secession of Virginia, Arkansas, North Carolina,

and Tennessee, and finally to thirteen (in recognition of the symbolic admission of Kentucky and Missouri to the Confederacy).

6

In early 1955, John Sammons Bell, chairman of the State Democratic Party and attorney for the

Association County Commissioners of Georgia (ACCG) suggested a new state flag for Georgia that would

incorporate the Confederate Battle Flag. At the 1956 session of the General Assembly, state senators

Jefferson Lee Davis and Willis Harden introduced Senate Bill 98 to change the state flag. Signed into law

on February 13, 1956, the bill became effective the following July 1.

j j j

VIII. The Confederate Battle Flag

Before an in-depth examination of the 1956 state flag can be carried out, it should be noted that

there is nothing inherently controversial or racist about the actual design of the Confederate battle flag.

1

The St. Andrew’s Cross – the flag’s distinctive feature – had its origin in the flag of Scotland, which King

James I of England combined with St. George’s Cross to form the Union Flag of Great Britain. It is

believed that St. Andrew, the patron saint of Scotland since A.D. 750. and brother of the apostle Peter,

was crucified by his persecutors upon a cross in the shape of an "X" in A.D. 60. White southerners, many

of whom traced their ancestry to Scotland, very easily related to this Christian symbol.

The first Confederate national flag, known as the Stars and Bars, was raised over Montgomery in

March 1861 and carried into the Battle of Bull Run in July of that year. During that battle, however, the

Confederate field commanders, while maneuvering their forces, had difficulty distinguishing the Stars and

Bars from the Stars and Stripes through the dust and smoke of the battlefield. In some cases the Stars and

Bars so resembled the U.S. flag that troops fired on friendly units killing and wounding fellow soldiers. As

a result, Confederate army and corps level officers all over the South began thinking about creating

2

George Schedler’s Racist Symbols and Reparations: Philosophical Reflections on Vestiges of the American Civil War

(Lahnam, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 1998), p. 24.

3

Despite some current misconceptions, the battle flag was never officially adopted by the original Ku Klux Klan. The

original founders of the Klan, however, preferred meaningless occult symbols – spangles, stars, half-moons. Only later, at some

point in the twentieth century during the Klan’s revival, did the battle flag become an unofficial but regular feature at Klan rallies.

7

distinctive unit battle flags that were completely different from those of the Union Army and which would

help make unit identification a lot easier. The commanding Confederate officer at the Battle of Bull Run,

General P.T.G. Beauregard, determined that a single distinct battle flag was needed for the entire

Confederate army. Confederate Congressman William Porcher Miles recommended a design

incorporating St. Andrew’s Cross. This flag was agreed upon but it was recommended that it would be

more convenient and lighter as well as less likely to be torn by bayonets or tree branches if made square.

This flag was issued in different sizes; 48 inches square for the infantry, 36 inches for the artillery, and 30

inches for the cavalry. Other flags such as State regimental colors were used by the Confederacy on the

battlefield, but the battle flag, although it was never officially recognized by the Confederate government,

came to represent the Confederate army. For practical military reasons, and not for racist reasons, the

Confederate army adopted the battle flag.

2

However, the focus of this paper is not the adoption of the

battle flag by the Confederate army; its focus is on the incorporation of the battle flag within Georgia’s

current state flag. In order to accomplish that, a closer examination must first be conducted on how the

Confederate battle flag was transformed from a purposeful, practical, and prideful military banner into what

some consider a symbol of intolerance, controversy, racism, and hatred.

Since the incorporation of the battle flag into Georgia’s state flag occurred long after the Civil War

ended, the central question arises as to how that adoption refers to any racist connotations that the battle

flag may have acquired since then. It must be understood how the meaning of the battle flag has changed

since the Civil War and explore what it meant at the time Georgia and other states adopted it or paid

homage to it. From the end of the Civil War until the late 1940s, display of the battle flag was mostly

limited to Confederate commemorations, Civil War re-enactments, and veterans’ parades. The flag had

simply become a tribute to Confederate veterans. It was during that time period, only thirty years after the

end of the war and fifty years before the modern civil rights movement, that Mississippi incorporated the

battle flag into its own state flag – well before the battle flag took on a different and more politically charged

meaning.

In 1948, the battle flag began to take on a different meaning when it appeared at the Dixiecrat

convention in Birmingham as a symbol of southern protest and resistance to the federal government –

displaying the flag then acquired a more political significance after this convention.

3

Georgia of course,

changed its flag in 1956, two years after Brown v. Board of Education was decided. In 1961, George

Wallace, the governor of Alabama, raised the Confederate battle flag over the capitol dome in Montgomery

4

Like the Confederate battle flag, the swastika was transformed into a racist symbol. Since ancient times, the swastika

has symbolized prosperity and good fortune and originally represented the revolving sun, fire, or life. As late as the first two

decades of the 20th Century, the swastika was still a harmless, ancient sign of good luck without any political connotations.

Only later, when the Nazis adopted it as their emblem, did it acquire its political significance.

5

Mike Edwards, “State Flag ‘Disappoints’ UDC,” Atlanta Journal, February 10, 1956, p. 4.

6

Tom Opdyke, “1956 Flag Change Rationalization Not Documented,” Atlanta Constitution, August 2, 1992, p. F1.

8

to commemorate the hundredth anniversary of the Civil War. The next year, South Carolina raised the

battle flag over its capitol. In 1963, as part of his continued opposition to integration, Governor Wallace

again raised the flag over the capitol dome. Despite the hundredth anniversary of the Civil War, the likely

meaning of the battle flag by that time was not the representation of the Confederacy, because the flag had

already been used by Dixiecrats and had become recognized as a symbol of protest and resistance. Based

on its association with the Dixiecrats, it was at least in part, if not entirely, a symbol of resistance to federally

enforced integration. Undoubtedly, too, it acquired a racist aspect from its use by the Ku Klux Klan,

whose violent activities increased during this period. However, it is important to remember that in spite of

these other uses, there remained displays of the battle flag as homage to the Confederate dead, with no

racist overtones.

It must also be remembered that despite the controversy over Georgia’s and Mississippi’s flags,

the two were created under very different circumstances. One determining factor of whether a symbol is

racist is if it is adopted at a time when the symbol had racist significance.

4

Therefore, it is doubtful that the

state flag of Mississippi – adopted in the nineteenth century – has the racist connotations of the 1940s and

beyond. Mississippi’s flag was simply adopted too early to have the racist connections that would come

later. Georgia’s 1956 flag and South Carolina’s and Alabama’s respective raising of the battle flag in 1962

and 1963, however, have a different meaning when placed in their historical context. Despite some

nonracist uses, the Dixiecrat, segregationist, and Klan uses of the flag by that time had distorted the flag’s

connection with the Confederate nation and its soldiers. The raising of the battle flag over the capitols is

clear – intimidation of those who would enforce integration and a statement of firm resolve to resist

integration. Likewise, when the battle flag was incorporated into the Georgia state flag, the state was in

a desperate situation to preserve segregation. Resisting, avoiding, undermining, and circumventing

integration was the 1956 General Assembly’s primary objective. The adoption of the battle flag was an

integral, albeit small, part of this resistance. The 1956 state flag, as Representative Denmark Groover so

clearly stated, “...will serve notice that we intend to uphold what we stood for, will stand for, and will fight

for.”

5

Nearly four decades later, former Representative James Mackay, who voted against changing the

flag in 1956, explained that “there was only one reason for putting that flag on there. Like the gun rack in

the back of a pickup truck, it telegraphs a message.”

6

j j j

9

IX.

The 1956 Legislative Session: Preserving Segregation

There will be no mixing of the races in the public schools and college classrooms of Georgia anywhere

or at any time as long as I am governor....All attempts to mix the races, whether they be in the

classrooms, on the playgrounds, in public conveyances or in any other area of close personal contact

on terms of equity, peril the mores of the South....the tragic decision of the United States Supreme

Court on May 17, 1954, poses a threat to the unparalleled harmony and growth that we have attained

here in the South for both races under the framework of established customs. Day by day, Georgia

moves nearer a showdown with this Federal Supreme Court – a tyrannical court ruthlessly seeking to

usurp control of state-created, state-developed, and state-financed schools and colleges....The next

portent looming on the horizon is a further declaration that a State’s power to prohibit mixed marriages

is unconstitutional.

Governor Marvin S. Griffin

State of the State Address

January 10, 1956

To better understand the state flag change in 1956, it must first be placed in its proper historical

context. As the 1950s unfolded, the nation’s schools soon became the primary target for civil rights

advocates over desegregation. The NAACP concentrated first on universities, successfully waging an

7

The Equal Protection clause of the 14

th

Amendment states that “No State shall make or enforce any law which shall

abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or

property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

8

BROWN v. BOARD OF EDUCATION, 347 U.S. (1954).

9

In the 1954 Brown case, the Court held that racial discrimination in public schools is unconstitutional. Having

announced the constitutional principle, the Court had to issue instructions on the means used to implement the principle. The

1955 Brown case, sometimes referred to as Brown II, has been heavily criticized for deferring too much to local school districts

and thus delaying the implementation of the 1954 Brown decision.

10

intensive legal battle to win admission for qualified blacks to graduate and professional schools. Led by

Thurgood Marshall, NAACP lawyers then took on the broader issue of segregation in the country’s public

schools. Challenging the 1896 Supreme Court decision, Plessy v. Ferguson, which upheld the

constitutionality of separate but equal public facilities, Marshall argued that even substantially equal but

separate schools did profound psychological damage to black children and thus violated the Fourteenth

Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

The continuing struggle over segregation between the federal courts and southern politicians

reached a crescendo in 1954. After chipping away at the foundations of segregation, a unanimous U.S.

Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka determined that the “separate but equal”

doctrine had no place in the field of education. In its decision, the Court concluded that the use of race to

segregate white and black children in the public schools is a denial to black children of the equal protection

of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.

7

Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote the landmark

opinion which flatly declared that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” To divide grade-

school children “solely because of their race,” Warren argued, “generates a feeling of inferiority as to their

status in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone.”

8

Despite the decision’s sweeping language, the Supreme Court ruled that integration should proceed “with

all deliberate speed” and left the details

to the lower federal courts.

9

However, the process of desegregating the schools proved to be agonizingly

slow. Officials in the border states quickly complied with the Court’s ruling, but states deeper in the south

resisted.

Governors Herman Talmadge and Marvin S. Griffin reacted to the Brown decision by threatening

to close the public schools rather than integrate them. In 1954, during Governor Talmadge’s last year in

office, Georgia voters ratified a constitutional amendment which authorized “educational grants” to children

for attending private (segregated) schools in lieu of public school education. The Georgia legislature

reacted to the 1954 Brown decision with a wide-ranging collection of legislation to deny its implementation.

Much of the major legislation introduced during the 1956 legislative session was directed toward setting

the 1954 private school plan into motion and preserving the institution of segregation throughout the state.

A series of laws codified the private school plan, including provisions that terminated state and local funding

11

for desegregated schools, authorized the governor to close such schools, provided for the payment of

tuition grants, permitted closed schools and facilities to be leased for private school use, extended teacher

retirement benefits to instructors in private schools, and allowed the governor to suspend compulsory

attendance laws. Other legislative proposals were introduced to maintain segregated parks, playgrounds,

restrooms, and punished law enforcement officials who failed to enforce segregation laws.

A. Governor Griffin’s Private School Plan

12

Senate Bill 1 – Closing of Public School Systems

This legislation empowers the governor to close individual schools or school systems whenever he determines that the public

schools“are not entitled under the laws of this state to state funds for their maintenance and operation...” When the public

schools of any county, city, or independent school district are ordered to be closed by the governor, each child of school age will

be entitled each year to receive an educational grant from both state and local funds for the cost of attending a private school.

The sole purpose of this bill was to circumvent court-ordered integration by abolishing the state’s public schools and reestablish

them as private segregated schools.

Senate Bill 3 – Lease of Public School Property

Authorizes county and local school boards to lease school buildings and other school property for private school purposes. If

the provisions in Senate Bill 1 were ever enacted, this bill was intended to provide for a smooth changeover from public to private

schools by allowing private schools to utilize existing public facilities.

Senate Bill 4 – State School Building Authority – Leases

Permits county and local school boards to sublease any facilities they are presently leasing from the School Building Authority.

Senate Bill 6 – Teachers’ Retirement System – Amendment

Enables teachers in private nonsectarian schools to come under the state teacher retirement system and continue in the teacher

retirement system.

Senate Bill 7 – Power of the Attorney General to Prosecute Any Action or Threatened Action That Would Violate

Segregation Laws (Measure Failed)

Empowers the Attorney General of Georgia to enjoin any violation or threatened violation of the 1955 segregation laws

prohibiting the expenditure of state funds for mixed schools. Empowers the Attorney General to prosecute any action or

threatened action that would violate the segregation law or which may tend to bring about or require or encourage a violation.

Senate Bill 8 – Private Schools – Certificates of Safety (Fire Hazards)

Requires all schools to meet fire safety regulations. This was a provision to ensure that newly created private segregated schools

do not relax on safety standards.

Throughout the 1950s, Georgia’s political leaders, continually reiterating that the state would never

accept desegregated schools, took steps to evade school integration. The 1951 legislature wrote into the

general appropriation bill a provision prohibiting the expenditure of public funds on desegregated

educational facilities and debated a constitutional amendment permitting the state to abolish the public

school system in favor of private segregated schools. Two years later, the 1953 General Assembly

approved a “private school” state constitutional amendment which would, in the event of court-ordered

integration, shut down public school systems, privatize the public schools, and authorize the state to provide

tuition grants directly to the parents of pupils to spend in the newly privatized segregated schools of their

choice. It is constitutionally doubtful if this plan would ever have been allowed to be implemented.

Georgia’s leaders, fearing the federal courts would find that enforced segregation in public schools did deny

equal protection, simply sought to remove the schools from state control. If public schools could not be

segregated, then Georgia’s leaders believed that private schools would be allowed to discriminate. By a

relatively narrow margin, Georgia voters approved the new amendment to the state Constitution in

November 1954.

10

Charles Pou, “Griffin to ‘Go Slow’ On Nullification Idea,” Atlanta Journal, January 9, 1956, p. 1 and 2.

11

Charles Pou, “Private Schools as Standby Needs Only Griffin Signature,” Atlanta Journal, January 26, 1956, p.12.

12

Ibid.

13

The continued outside pressure to force integration in the South apparently stiffened Georgia’s

political leaders’ resistance and determination to maintain segregation. This quickly became evident as the

1956 General Assembly convened on January 9. The lawmakers came to Atlanta clearly with the intention

of giving swift and overwhelming approval to a series of segregation bills designed to prevent race-mixing

in classrooms, public parks, golf courses, playgrounds, and swimming pools. Indeed, Speaker of the

House Marvin Moate made it clear that segregation would be the top issue of the 1956 session. In his

opening address to the House, the speaker affirmed that:

...certain problems exist that are peculiar to our section [of the nation] and with which the other parts

of our country have little knowledge and a complete lack of understanding....Not since the days of the

carpetbagger and the days of Reconstruction have problems more vital to the welfare of all our people

confronted the General Assembly – problems that cannot be ignored....You know the nature of the

problem, and it is not my purpose here to spell it out....The Southland has become the whipping boy

for other sections of the nation. Our very fault is being played up for all it is worth; our every virtue

has been played down....[There are those], within our own gates ... those who decry our traditions and

way of life, and who thereby become as a vulture that befouls its own nest.

10

Less than three weeks into the 1956 legislative session, the General Assembly passed Governor

Griffin’s private school plan. The key bill of the plan, Senate Bill One, gave the governor exclusive power

to close down any or all of the state’s school systems in the event a court ordered integration. The

governor then could authorize “educational grants” for students to attend segregated private schools.

Accompanying measures to the key bill permitted the leasing and subleasing of school facilities, and allowed

teachers in private schools to come under the teacher retirement system. Representative Denmark

Groover, Governor Griffin’s floor leader, called Senate Bill One “the most important piece of legislation

that will be presented this session.”

11

Although there was some opposition to the private school plan in the House, most of it involved

the constitutionality of the plan and the reluctance to abolish the public school system. Two Hall County

representatives, W.M. Williams and Bill Gunter, who voted against the legislation, introduced a failed

substitute bill which would have allowed only local school boards to close schools – taking the authority

away from the governor.

12

Although there was an unquestionable determination on the part of the

legislature to circumvent the U.S. Supreme Court desegregation ruling, several legislators struggled over

the private school versus public school issue. Eight House members from four counties signed a declaration

which criticized Griffin’s private school plan. The signers of the declaration felt that they could not support

legislation which would destroy the state’s public school systems; provide the governor the unlimited power

to shut down public schools; provide for lease, sale, transfer, or any disposition of public school properties

without statutory safeguards to protect the public interest; substitute present accredited public schools with

13

Charles Pou, “Small Group in House Opposes Private School Bill,” Atlanta Journal, January 20, 1956, p. 1.

14

“House Sends Proposals to Governor,” Macon Telegraph, January 26, 1956, p. 1.

15

Thomas B. Ross, “House Okays School Closing Bill Despite Increasing Opposition,” Atlanta Daily World, p. 1.

14

a grant of money to be applied toward an education of unknown quality at unspecified locations for an

uncertain school year with no required academic standards; and deny the right of peaceful assembly,

petition, or open discussion relative to the school problem.

13

Representative Hamilton Lokey of Atlanta

asserted that Senate Bill One was not constitutional, was only a skeleton bill, and could be considered

nothing more than a “subterfuge, a futile protest.... I am for segregation [but] I want to preserve our

schools.”

14

“I consider this bill unconstitutional,” he continued, “both under the laws of Georgia and the

United States, because there is no equal protection under this law.” He argued that its adoption would

result in the “destruction of our school system in return for a meager protest against the U.S. Supreme

Court.”

15

Though most Georgians favored continued segregation, not all were ready to abolish the public

schools. Opposition to the Governor’s plan, was not based on any desire to end segregation, but simply

on contentions that Griffin’s proposals would destroy the public school system and place too much power

in the hands of one man.

B. The Interposition Approach

House Resolution 185 – Interposition Resolution

This resolution declares the U.S. Supreme Court Decisions of May 17, 1954 (Brown v. Board of Education) and May 31, 1955

in the school segregation cases, and all similar decisions, by the Supreme Court “relating to separation of the races in the public

institutions of a state ... are null, void, and of no force or effect.

The state government’s continued and direct opposition to the federal courts gave substance to the

concept of interposition. Although rarely used, the practice of interposition occurs when a state feels that

the Supreme Court has overstepped its constitutional authority in rendering a decision and the state

legislature declares the decision void. Thus, the legislature interposes, or comes between, the Court and

the people to protect the people from an injustice. In 1956, interposition was proposed as a legal and

constitutional means to nullify the Supreme Court’s Brown decision. Proponents of the interposition move

interpreted this ruling to be not a ruling at all, but an actual amendment to the federal constitution. They

maintained that the U.S. Supreme Court exceeded its constituted authority and usurped the legislative

powers of both the U.S. Congress and the individual states because there is nothing in the U.S. Constitution

that prohibits segregation and the Court had no authority to outlaw it. Moreover, there are no provisions

in the Constitution dealing with education or public schools, so the Court, segregationists believed, was out

of bounds with the Brown decision. Therefore, it was believed that until the Constitution is amended

properly, the states would not be bound by the Court’s decision. The General Assembly made its position

explicit by adopting an interposition resolution. The Brown decision, the Georgia legislature declared, was

16

Georgia Laws 1956, Volume One, p. 642.

17

“Interposition Plan Passes House, 178-1,”Atlanta Journal, February 8, 1956, p.1, 7.

18

Thomas B. Ross, “Georgia House Oks ‘Null’ Proposal,” Atlanta Daily World, February 9, 1956, p.1.

19

Margaret Shannon, “Senate Unanimous for Interposition,” Atlanta Journal, February 13, 1956, p.1.

15

in the state of Georgia “null, void, and of no force or effect.”

16

The interposition resolution, House Resolution 185, was passed by the House 178-1 on February

8, 1956. Denmark Groover declared that the adoption of the resolution would be an historic action. “[It]

would be notice to the people of the nation interested in maintaining segregation and states’ rights that we

will stand between the Supreme Court and our citizens in their efforts to stand on their constitutional rights.”

Groover maintained that the resolution was based on sound legal ground and precedent and urged its

adoption “to show the nation we will not stand idly by and let states’ rights be swept from the Constitution

by a creature of the Constitution.”

17

The only vote against the resolution was cast by Representative

Hamilton Lokey because he believed that resolution was incomplete without a request to Congress to offer

an amendment to the Constitution specifically declaring that states have surrendered their authority to

operate their own schools.

18

Without a vote against it or even a fiery speech for it, the Georgia Senate adopted Governor

Griffin’s interposition resolution 39-0. Senator Howard Overby of Gainesville, Griffin’s Senate floor

leader, who had requested before the vote that the Senate not waste any precious time debating the merits

or legality of the resolution, explained that “we are merely stating our position that we deeply resent the

decision of the Supreme Court that we would have to do away with our way of life.”

19

16

C. Other Segregation Legislation

17

Senate Bill 2 – Trespass on Public Property

Prohibits any person from entering any state-owned or operated property that has been closed to the public by executive order of

the Governor or by order of the department head having supervision over such property. This legislation’s purpose was to prevent

any former public school from operating after the governor ordered its closing.

Senate Bill 5 – Disposal of Public Recreation Facilities

Authorizes the state or any county or municipality to sell, lease, grant, exchange or otherwise dispose of any property or interest

comprising parks, playgrounds, golf courses, swimming pools, or other property which has been dedicated to a public use for

recreational or park purposes, or which has been dedicated to such a use by any private person or corporation and later acquired

by the state or any county or municipality.

Senate Bill 152 – Department of Public Safety – Enforcement of Public Safety

Empowers the Georgia State Patrol and the Georgia Bureau of Investigation to enter any county or municipality, upon any official

thereof, to make arrests and otherwise enforce any laws of Georgia requiring segregation or separation of the white and colored races

in any manner or activity.

Senate Bill 153 – Peace Officers’ Retirement System

Provides that any peace officer who fails or refuses to enforce any law of this state requiring segregation of the white and colored

races in any manner or activity, shall forfeit all retirement benefits.

House Bill 108 – Atlanta Recreation Facilities

Empowers the mayor and board of aldermen to sell, exchange, farm out, lease, or rent any property and facilities dedicated to and

used as parks, playgrounds, golf courses, recreational facilities, together with all property connected therewith. All such property

may also be devoted to any other public use in the discretion of the mayor and board of aldermen.

House Bill 110 – School Systems – Eminent Domain

Empowers county boards of education and certain independent and public school systems to condemn private property for public

school purposes.

House Bill 267 – Waiting Rooms and Facilities for Passengers

Provides that all common carriers of passengers for hire in intrastate travel providing waiting room and reception room facilities,

shall provide separate accommodations for white and colored passengers traveling in intrastate travel. A violation will result in a

misdemeanor punishment.

House Bill 268 – Waiting Rooms for Passengers in Intrastate Travel

Requires that all persons traveling in intrastate travel occupy or use only the waiting rooms marked and provided for such persons.

A violation will result in a misdemeanor punishment.

House Bill 433 – County Superintendents of Schools – Suspension

Provides for a process of notice and hearing in cases of suspension of county school superintendents. HB 433 and its companion

bill, HB 434, makes it easier to suspend or remove county school superintendents who do not enforce segregation.

House Bill 434 – County Superintendents of Schools – Removal

Provides for a process of notice and hearing in cases of removal of county school superintendents.

House Resolution 51 – Censure of the Attorney General of the U.S. and the F.B.I.

Censures the Attorney General of the U.S. and the F.B.I. for the investigation of the Amos Reece trial’s jury. Mr. Reece, a black

man, was convicted of rape by an all white jury in Cobb County. The U.S. Attorney General maintained that Cobb County failed

to ensure that Mr. Reece be tried by a jury of his peers.

20

Margaret Shannon, “2 Segregation Bills Passed,” Atlanta Journal, February 10, 1956, p.1.

21

“Park Desegregation Target in House Bill,” Atlanta Journal, January 18, 1956, p.1.

22

Georgia Laws 1956, Volume One, p. 315.

18

Although the interposition legislation and Governor Griffin’s private school plan gained most of the

attention during the 1956 session, the General Assembly was also determined to pass a wide array of pro-

segregation legislation. It was the legislature’s every intention to see that nearly every aspect of public life

remained segregated.

The Georgia Senate, on February 10, 1956 passed two bills aimed at segregation in public

intrastate travel in waiting rooms. The segregation bills, House Bills 267 and 268, were intended as a

means of circumventing an Interstate Commerce Commission regulation which outlawed separate race

facilities for interstate passengers. The bills required all common carriers of passengers for hire to provide

separate and clearly marked waiting rooms for intrastate passengers of both races. Passengers of both

races would be required, under penalty of prosecution for a misdemeanor, to use the separate intrastate

rooms. All common carriers that provided toilets, drinking fountains, and rest rooms in the waiting rooms

would be required to provide separate facilities for white and colored intrastate passengers.

20

A failed bill, which would have revoked the charter of any Georgia city allowing desegregation of

public facilities, was introduced on January 18, 1956. The bill was introduced in reaction to the City of

Atlanta’s decision to desegregate its municipal golf courses in December 1955. The measure provided that

“in the event that segregation of the white and colored races is not maintained in any facilities of any

municipality in this state ... the charter of such municipality shall stand revoked.” The facilities listed were

parks, golf courses, tennis courts, swimming pools, playgrounds, auditoriums, gathering halls, libraries, and

athletic fields.

21

In an effort to convince law enforcement personnel that it was their duty to enforce segregation

laws, the General Assembly passed Senate Bill 153. This legislation punished any law enforcement officer

who “knowingly refuses or fails to attempt to enforce any law of this state requiring segregation or

separation of the white and colored races....” The punishment for failing to maintain segregation laws was

the forfeiture of “all retirement benefits ... all disability payments, and all death benefits ...” to which the law

enforcement officer would have otherwise been entitled.

22

In addition, the General Assembly passed House Resolution 51 censuring the U.S. Attorney

General and the F.B.I. for their investigation of the jury in the Amos Reece trial. Mr. Reece, a black man,

was convicted of rape by an all white jury in Cobb County. The U.S. Supreme Court later concluded that

because Mr. Reece was tried by an all white jury, Cobb County failed to provide a fair trial by his peers.

The Resolution declared that the FBI’s investigation was “a direct and vicious invasion into the power and

authority of the State of Georgia” by U.S. Attorney General Herbert Brownell for “purely political

23

Ibid., p. 126-27.

24

As quoted in the Atlanta Sunday Journal-Constitution, February 26, 1956, p. 10F.

19

reasons.”

23

It was in this environment that Georgia’s present state flag was born. Aside from the token

resistance, every legislator publicly supported preserving segregation in Georgia. The legislators of 1956

were so determined and desperate to maintain segregation that they were willing to abandon Georgia’s

public schools to avoid integration. They also supported a vast array of legislation which maintained

segregated state parks, golf courses, swimming pools, and recreation facilities as well as intrastate

transportation facilities. And in case any police officer became “confused” about enforcing segregation

laws, the General Assembly passed a law revoking the retirement benefits of any law enforcement officer

who failed or refused to enforce any segregation law. These legislators, who supported the self-destructive

segregation plans in defiance of the U.S. Supreme Court’s Brown decision, also gave their support to

changing the state flag to incorporate the Confederate battle flag. Their vehement segregation-at-all-cost

stance compelled the North Georgia Tribune to comment that “we dislike the spirit which hatched out the

new flag, and we don’t believe Robert E. Lee ... would like it either.”

24

j j j

25

“Ga. Legislature OK’s Bill Giving State New Flag,” North Georgia Tribune, February 15, 1956 p. 1.

20

X. The 1956 Flag Change

A. A Brief History of the State Flag of Georgia

As noted earlier, Senator Herman H. Perry of Waynesboro, a prominent lawyer and former

colonel of the Confederate Army, introduced a bill to establish the first official flag of Georgia during the

1879 session of the Georgia General Assembly. His design was based on the first national flag of the

Confederate States of America – commonly known as the “Stars and Bars.” It consisted of vertical stripe

of blue with three alternating horizontal bands of red, white and red. The flag was adopted as a memorial

to the Confederate men and women who had given their lives in the American Civil War. Upon the

signature of Governor Alfred H. Colquitt on October 17, 1879, Georgia received its first official flag. In

1902, the State Seal or the State Coat of Arms was added in the middle of the blue bar, and in 1905, the

legislature officially added the State Coat of Arms to the flag. In 1916, the entire bill was re-enacted to

legitimize the past changes. By the early 1920s, a new version of Georgia’s state flag – one incorporating

the entire state seal – began appearing. There is no record of who ordered the change or when it took

place. This flag represented Georgia during our nation’s greatest conflicts – the First and Second World

Wars as well as during the Korean War.

B. The 1956 Legislative Change

During the 1956 session – hailed by Governor Marvin Griffin as one of the best in history –

Senators Willis Neal Hardin of Commerce, and Jefferson Lee Davis of Cartersville, “steeped in the lore

of the war between the States,”

25

introduced Senate Bill 98 (drafted by John Sammons Bell) to change

the state flag. The bill would amend the Georgia Military Forces Reorganization Act of 1955 by

incorporating the Confederate Battle flag into the Georgia state flag. As the legislative session began, the

first sample batch of flags were already made up.

The flag change was first proposed at the closing session of the 41

st

annual convention of the

ACCG on April 26, 1955 in Augusta when segregationist John Sammons Bell, the Association’s attorney

and Georgia’s Democratic party chairman, introduced a resolution to change Georgia’s flag. He would

later design and create the present state flag. Although, the 1879 flag was adopted to commemorate the

fallen Confederate soldiers, the notion claimed by Mr. Bell and others was that Georgia’s pre-1956 flag

26

“Ask State Flag With Stars, Bars,” The Atlanta Constitution, April 25, 1955, p. 4.

27

“Policy of the Association for the Coming Year,” County Commissioners Comments, May 1955, p. 7.

28

Although the ACCG resolution declared that the 13 stars represent the 13 former colonies, O.C.G.A. 50-3-10

explains that the 13 stars correspond to the number of Confederate states recognized by the Confederate States Congress (the

eleven official Confederate states plus Tennessee and Missouri).

29

Reg Murphy, “Confederate Type State Flag Voted by Assembly,” Macon Telegraph, February 10, 1956, p. 1.

30

There is no definitive explanation for the unusual number of abstentions.

31

Georgia Laws 1956, Volume One, p. 39.

21

had no particular historical significance.

26

The resolution proposed by John Sammons Bell called for a

“new more colorful, and more attractive flag which will have meaning for Georgians,” in contrast to the old

flag which the resolution dismissed as “one which very few Georgians recognize.”

27

The new flag would

keep the state seal with the blue background which constituted one third of the flag, and the remainder of

the flag would have the Confederate battle flag, with crossed blue areas containing 13 white stars on a red

background, replacing the three horizontal bands of red, white and red. The ACCG resolution stated that

the proposed flag would preserve the colors of our country – red, white, and blue – and that the 13 stars

on the battle flag would serve as a reminder of the original 13 colonies and the prominent role Georgia

played in those early days.

28

Representative Groover would later note that counting from any direction,

the middle star on the new flag is the fourth one, and serves as a constant reminder that Georgia was the

fourth state to adopt the federal constitution.

29

On February 1, 1956, Senate bill 98, assigned to the Committee on Defense and Veterans Affairs,

passed the Senate with a 41-3 vote. In the House, Senate Bill 98, referred to the Committee on Historical

Research, passed on February 9

th

by a vote of 107 to 32 with 66 abstentions.

30

Incorporating the

Confederate Battle Flag as part of the state flag, Senate Bill 98 was signed into law by Governor Marvin

Griffin on February 13.

C. Supporters of The Flag Change

Little information exists as to why the flag was changed, there is no written record of what was said

on the Senate and House floors or in committee and Georgia does not include a statement of legislative

intent when a bill is introduced – SB 98 simply makes reference to the “Battle Flag of the Confederacy.”

31

Support for the 1956 flag change can be broken down into two basic arguments: the change was made in

preparation for the Civil War centennial, which was five years away; or that the change was made to

commemorate and pay tribute to the Confederate veterans of the Civil War.

Many defenders of the flag, including former governor Ernest Vandiver, who served as the

Lieutenant Governor in 1956, have attempted to refute the belief that the battle flag was added in defiance

of the Supreme Court rulings. Vandiver, in a letter to the Atlanta Constitution, insisted that the discussion

32

“State Flag Change had nothing to do with Segregation,” The Atlanta Constitution, July 21, 1992, p. 13.

33

“Ga. Legislature OK’s Bill Giving State New Flag,” North Georgia Tribune, February 15, 1956, p. 1.

34

Ibid.

35

“New Flag Urged by Jeff David,” Waycross Journal- Herald, February 3, 1956 p. 3.

36

William Henry Gilbert in a Letter to the Editors, Macon Telegraph, February 11, 1956, p.4.

22

on the bill centered around the coming centennial of the Civil War and that the flag was meant to be a

memorial to the bravery, fortitude and courage of the men who fought and died on the battlefield for the

Confederacy.

32

Governor Griffin’s floor leader, Representative Denmark Groover, who supported the flag

change, argued at the time that the old flag never had enough meaning for him when he was a boy and that

the new flag “would replace those meaningless stripes with something that has deep meaning in the hearts

of all true Southerners.”

33

Furthermore, “the move,” Groover contended, “would leave no doubt in

anyone’s mind that Georgia will not forget the teachings of Lee and Stonewall Jackson, and that this will

show that we in Georgia intend to uphold what we stood for, will stand for, and will fight for...anything we

in Georgia can do to preserve the memory of the Confederacy is a step forward.”

34

Senator Jefferson

Davis of Cartersville also argued that the state should be entitled to adopt the new flag, because “Georgia

suffered more than any other state in the Civil War and endured a scorched earth policy from the mountains

of Tennessee to the sea.”

35

The argument that the flag was changed in 1956 in preparation for the approaching Civil War

centennial appears to be a retrospective or after-the-fact argument. In other words, no one in 1956,

including the flag’s sponsors, claimed that the change was in anticipation of the coming anniversary. Those

who subscribe to this argument have adopted it long after the flag had been changed.

However, at least one citizen in 1956 viewed the change in a different light. William Henry Gilbert

of Swainsboro, wrote a letter to the editors of the Macon Telegraph approving the flag change but

explaining that it would be even better if the Georgia adopted the entire Confederate battle flag as the

state’s flag as the best “way of telling the government and the world that we will never surrender our

sovereignty and principles to any Supreme Court.”

36

Clearly, this individual believed that the change was

indeed in reaction to the Brown decision and in defiance of desegregation.

D. Opposition to the Change

Although many legislators who supported the flag change maintained that the new flag was meant

to honor the Confederate soldiers, former U.S. Congressman James Mackay, one of the 32 House

members who opposed the change, remembers otherwise. “There was only one reason for putting the flag

37

“History Unfurled’ 56 Flag Change Rationalization not Documented,” The Atlanta Constitution, August 2, 1992,

p. F1.

38

Ibid.

39

As quoted in the Atlanta Sunday Journal-Constitution, February 26, 1956, p. 10F.

40

“Flag-Waving,” Macon News, February 8, 1956, p.8.

41

“Why Such Haste in the Legislature to Adopt a New Flag for Georgia,” The Macon Telegraph, February 6, 1956,

p. 4.

42

“Flag Change is Unnecessary,” The Atlanta Constitution, February 9, 1956, p. 34.

23

on there, like the gun rack in the back of a pickup truck, it telegraphs a message”

37

A freshman legislator

at that time, retired Fulton County Superior Court Judge Jack Etheridge, maintained that although he did

not recall much debate over the issue, he did oppose the change because it at least appeared to be in

reaction to the Brown decision and that honoring the Confederacy could not be perceived as the reason

for changing the flag.

38

There was also some opposition to the change from the state’s many newspapers. The North

Georgia Tribune argued that:

...we can’t help but believe that [the new flag] will carry the state back a little nearer the Civil

War....There is little wisdom in a state taking an official action which would incite its people to lose

patriotism in the U.S.A. or cast a doubt on that part of the Pledge of Allegiance which says ‘one

nation, unto God, indivisible...’ So far as we are concerned, the old flag is good enough. We dislike

the spirit which hatched out the new flag, and we don’t believe Robert E. Lee...would like it either”

39

The Macon News argued that, “our [pre-1956] flag is a proud one and had served nobly for many years.

The men who served under it and the citizens who honored it thought it was good enough for them and

there is no point in changing it now.”

40

The Macon Telegraph stated that in the absence of any public

demand for a change, the legislature’s reasons for making the change were simply not sufficient.

41

The

Atlanta Constitution also thought that the flag change was unnecessary for the simple fact that “there has

been no recorded dissatisfaction with the present flag.”

42

Georgia’s leading black newspaper, the Atlanta

Daily World, asserted that “these must be sad days of retaliation against the insistence of the activation of

a real democracy on our home front....coming so soon upon the declaration that there should be no

43

“On Changing the Flag,” The Atlanta Daily World, February 14, 1956, p. 5.

44

“State Flag Change ‘Disappoints’ UDC,” The Atlanta Journal, February 10, 1956, p. 4.

45

Ibid.

46

John Walker Davis, “An Air of Defiance: Georgia’s State Flag Change of 1956.” The Georgia Historical Quarterly,

vol. LXXXII, no. 2 (Summer 1998): 305-330.

47

“Senate Okays New Flag for Georgia,” Elberton Star, February 3, 1956 p. 1.

48

Resolution passed by the Ladies Memorial Association, archived at the Atlanta History Center.

49

“Opposes Georgia Emblems Using Stars and Bars.” The Atlanta Constitution, June 9, 1955, p. 7.

24

discrimination of citizens in the public schools, there is an air of defiance in such revival of something the

country and the world have longed to see forgotten.”

43

When the flag change was first proposed, it received resistance from groups that one would think

would have highly favored the change – various Confederate organizations including the United Daughters

of the Confederacy (UDC). “They made the change strictly against the wishes of UDC chapters from all

the states that form our organization,” said Ms. Forrest E. Kibler, legislative chairwoman of the Georgia

UDC.

44

Ms. Kibler also pointed out that “eighteen different patriotic organizations in Georgia had asked

the legislature not to make the change.”

45

If the proponents of the flag change had been inspired to add

the battle flag to the state flag as a tribute to Confederate soldiers, why would the numerous Confederate

veteran organizations be opposed to such a move?

46

The Executive Board of the Georgia Division of UDC

had passed a resolution on January 11, 1956 opposing the proposed changes to the flag, citing that the

Confederate battle flag belonged to all the Confederate States – not merely to Georgia – and placing it on

the Georgia flag would cause strife.

47

Another group opposed to the flag change, the Ladies Memorial

Association, read deeper into the flag change and pointed out that the nation was becoming more unified,

sectionalism and prejudice were disappearing, and a movement of this kind would be a backward step.

Also opposing the new flag was the John B. Gordon Camp of the Sons of Confederate Veterans.

48

This

group protested against all uses of the battle flag except in commemoration of the Confederacy, or by the

official use of the Daughters of the Confederacy, the Sons of the Confederacy, and the Children of the

Confederacy.

49

Given the role that these organizations play in memorializing and paying tribute to the

Confederacy, they clearly would have lent their support to the sponsors of the new flag if they believed that

it truly paid tribute to Confederate veterans.

While many questioned the political and philosophical motives of the flag change, there were others

who considered the change to be an unnecessary expense that would burden taxpayers, since Georgia law

required every public school, and all public institutions to fly the state flag. In voting “no,” Representative

Mackay said that the present flag was “a symbol of sacred memory” and that “the change puts every flag

50

“‘Bald-Faced Lie,’ Bell Tags Flag Bill Charge,” The Atlanta Constitution, February 10, 1956, p. 1.

51

“Griffin-Hailed ‘Best’ Assembly Closes Books to Go Home,” Atlanta Journal, February 18, 1956 p. 11.

25

owner in Georgia to unnecessary expense.”

50

Alleviating the financial concerns of many, sponsors of the

bill pointed out that those institutions required to fly the new flag will replace the old flag with the new one

only as present flags wear out. Questions were also raised on whether anyone had a copyright on the flag

design which would entitle them to royalties – a charge denied by John Sammons Bell and Representative

Groover.

On the last day of the session, as the strains of “Dixie” echoed through the Senate chamber,

Senator Jefferson Davis paraded to the front of the chamber carrying the new Georgia state flag which bore

the Confederate battle flag.

51

Despite opposition from prominent groups such as the UDC, the flag bill was

signed into law by Governor Griffin.

j j j

XI. John Sammons Bell: Designer of the Present Flag

Born on January 26, 1914 to the Reverend Howell Phillip Bell Sr. and Ms. Kathrone (Sammons)

Bell, John Sammons Bell is the designer of the current Georgia state flag. A close examination of his career

and impressive curriculum vitae give some critical insight into his political and philosophical beliefs and

sheds some light on why the flag was redesigned in 1956.

A decorated World War II combat veteran and self-described “unreconstructed Confederate,”

Bell received his L.L.B. in 1946 and L.L.D. in 1960 from John Marshall Law School, and received his

J.D. from Emory University Law School in 1948. After being admitted to the Bar, he became director of

the Atlanta-Fulton County Veterans Service Center, and in 1947 became Assistant Attorney General of

the State of Georgia. In 1955 he became Deputy Assistant Attorney General for the University System’s

Board of Regents. Upon the death of Judge Lee B. Wyatt, Bell was appointed Judge to the Court of

Appeals of Georgia by Governor Ernest Vandiver on February 8, 1960 – a position that he held until his

resignation on February 1, 1979. In addition, he served as chief counsel for the Association County

Commissioners of Georgia (ACCG) throughout the 1950s. However, it was as Chairman of the State’s

Democratic Party from 1954 to 1960 that John Sammons Bell was most controversial and influential. As

the Party’s leader, he was an outspoken advocate for states’ rights, preserving segregation and the county-

52

Pat Watters, “1946 ‘Obedience’ Plea Hurled at Bell in Debate,” Atlanta Journal, October 28, 1954, p.42.

53

“Policy of the Association for Coming Year,” County Commissioners Comments, May 1955, p.7; and “Policy of the

Association for Coming Year,” County Commissioners Comments, May 1956, p.12.

54

Editorial, “Mr. Bell Talked Too Fast,” Atlanta Journal, August 8, 1956, p.22.

55

Clarke W. Duncan, “Echoes from the National Democratic Convention,” County Commissioners Comments,

September 1956, p.10.

26

unit system, while repeatedly criticizing the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court Decision,

integration, the national Democratic Party, and the federal government.

Bell, a one-time supporter of Governor Ellis Arnall, once had the reputation of being a “liberal” on

race issues. But since the early 1950s, he worked diligently to preserve segregation in Georgia.

Repeatedly critical of the Brown decision, Bell declared as early as October 1954, while campaigning for

the adoption of the private school amendment that would have circumvented the integration of public

schools, that “tyranny in any form ought to be opposed” and the Brown decision, he contended, “amounts

to nothing more than tyranny.”

52

In 1955, and again in 1956, the ACCG, extremely pro-segregationist at

that time and an organization in which Bell served as chief legal counsel, publicly declared that the Brown

decision “threatens to attempt to destroy the peaceful relationships existing between the white and black

races in the south and nation....and [t]hat the Association and the members thereof both jointly and severally

pledge to the Governor and all public officials of the State, full support in each and every way or means

required ... to protect and maintain the segregation of the races in our schools.” The ACCG also promised

that “regardless of what the Federal government or any division thereof says or does, that there will not be

mixing of the races in our schools and we positively and unequivocally so pledge ourselves.”

53

By 1956, Bell had become well-known as one of the nation’s staunchest pro-segregationist public

officials. In August of that year, while serving on the National Democratic Party’s Platform Committee in

Chicago, Bell indicated that he would not support Adlai Stevenson the party’s presidential nominee

because of Stevenson’s advocacy for a stronger civil right’s plank in the party platform. Stevenson, the

eventual Democratic nominee for president, maintained that the party plank should express the “unequivocal

approval” of the Supreme Court’s decision outlawing racial segregation in public schools. Bell declared

Stevenson’s position a “stupid blunder” and promised that he would not vote for him.

54

The ACCG

supported Bell in his position against the civil rights plank explaining that the “South could not go as far as

accepting the Supreme Court decision or anything in the nature of implementing that decision.”

55

When

questioned why other southern delegations did not join the Georgia delegation in voting down the

Democratic Platform, Bell bitterly explained that “there were too many pussy-footers heading southern

delegations. By far the most effective, courageous, and statesmanlike of them all was Governor Marvin

Griffin...who performed exemplary work for the party but never yielded an inch in his determination to

56

Ibid., p.10.

57

“Bell Assails Demo Unit for Faubus Blast,” Atlanta Journal, September 16, 1957, p.38.

58

Charles Pou, “Bell Bares Text of Vow by Butler on Mix Issue,” Atlanta Journal, July 17, 1959, p.1.

59

“Butler Says Mixing Pact ‘Old’ Issue,” Atlanta Journal, July 13, 1959, p.15.

27

preserve our southern traditions.”

56

The southern traditions Bell was referring to were segregation and

white rural domination of Georgia politics.

Following the 1956 Democratic Convention, Bell grew increasingly estranged from Democratic

National Chairman Paul Butler over the segregation issue. The emerging split became apparent in

September 1957 after the National Democratic Advisory Council, in a public statement, criticized Arkansas

Governor Orval Faubus for mobilizing the state National Guard to prevent Black students from attending

a public high school in Little Rock. Bell publicly condemned the Advisory Council and dismissed its

members as a “handpicked group composed largely...of the most racial left-wingers of our time....My only

fear,” Bell continued, “is that Governor Faubus will yield to dictatorial federal pressure and hysteria.”

57

One week later, Bell accused Butler of reversing an earlier assurance to him that he would never raise the

integration issue in party matters. Bell claimed that prior to Butler’s election to the Democratic National

Chairmanship in 1954, he made a “solemn pledge” to Bell that if he were elected national chairman he

would not raise the segregation issue as a subject of national political debate. But throughout 1957 and

1958, Bell grew increasingly concerned that Butler was taking the party too far to the left on the integration

issue and continued to demand, without success, Butler’s resignation as the Democratic National Chairman.

Their running feud reached a juncture in July 1959 when the issue of the “no-segregation-talk”

pledge suddenly reemerged. That month, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution released a copy of the actual

written pledge in which Butler promised to Bell back in 1954 that he would never inject the segregation

issue into party matters in exchange for Bell’s support of his candidacy for the

Democratic National Chairman at a national committee meeting. In the written pledge, Butler promised

to Bell that:

I do not consider the question of segregation a political issue. I see no reason for any chairman of our

party at any level to project segregation into our political discussions. As a lawyer, and if I were to

be party chairman, I would consider it not to be a matter subject to political debate or political

decision.

58

Butler explained that the pledge suggested that desegregation was a legal matter and did not see, at the

time, any reason to make it a political issue at the national level. But by 1959, Butler had argued,

integration had become the major social issue and that “any problem that affects any segment of the

population must become the concern of a political party.”

59

Bell indicated that he would not have voted

60

Charles Pou, “Bell Bares Text of Vow by Butler on Mix Issue,” Atlanta Journal, July 17, 1959, p.1.

61

Vivian Price, DeKalb News/Sun, p. 2F, July 13, 1988.

62

Ibid.

63

Charles Pou, “Bell Praises Plan to Spike Negro Votes,” Atlanta Journal, October 25, 1957, p.8.

28

for Butler had he not gotten the signed statement from him. He grew dissatisfied with the party’s national

chairman as the national Democratic party was visibly raising the segregation question while Butler did

nothing to stop it. “I do not see how the most liberal Democrats,” Bell lamented, “could approve of a man

remaining as the party’s top representative when he publicly admits that his word does not bind him and

that a political promise made is not important to keep.”

60

In spite of Bell’s public protests, Butler

maintained his seat as the Democratic National Chairman.

Bell has recently defended his motive for the 1956 flag design. He has maintained that the current

design was created because the old Confederate design had become “meaningless.” He wanted to forever

perpetuate the memory of the Confederate soldier who fought and died for his state and that the purpose

of the change was “to honor our ancestors who fought and died and who have been so much maligned.”

61

He has also argued that the flag was not redesigned in reaction to and in defiance of the 1954 Brown

decision. “Absolutely nothing could be further from the truth ... every bit of it is untrue....Anybody who

says anything to the contrary is wrong or perpetuating a willful lie.”

62

If history occurred in a vacuum, then

it would be very easy to accept Bell’s explanation. However, when a close study of the flag change is

placed in its historical context, his explanation for the 1956 change becomes problematic. Clearly, Bell was

a hard-line segregationist who showed nothing but contempt for the Brown decision, integration, and the

U.S. Supreme Court – even referring to a proposal, in 1957, designed to keep the Black population from

voting an initiative “certainly worthy of the most careful consideration.”

63

Likewise, the 1956 General

Assembly, was entirely devoted to passing legislation that would preserve segregation and white supremacy

in Georgia. Finally, the pre-1956 flag, which had originally been designed in 1879, was created and

designed by Colonel Herman Perry, a Confederate veteran who modeled the flag after the first national

Confederate flag, and who wanted that flag to serve as a memorial for Confederate veterans.

j j j

64

Mike Edwards, “State Flag ‘Disappoints’ UDC,” Atlanta Journal, February 10, 1956, p. 4.

65

Gary Pomerantz, “A Generational Perspective,” Atlanta Constitution, March 8, 1992.

66

It must be remembered that the 1956 flag legislation was not a Griffin Administration proposal nor was it sponsored

by Denmark Groover. Of course, Groover did vote for the change in 1956.

29

XII.

Conclusion

In 1956, Denmark Groover, in a fiery speech before the House of Representatives, declared that

the then-proposed state flag “...will serve notice that we intend to uphold what we stood for, will stand for,

and will fight for.”

64

Groover has since dismissed that statement as simply “rhetoric at a time of turmoil.

Those were the times. We had a bill to pass.”

65

On March 9, 1993, Groover moved many Georgians

when he stood in the House well to address his colleagues on the subject of the state flag.

66

In an emotional

67

Mark Sherman, “Mills Calls Halt to Efforts for a new Flag, Groover makes Emotional Appeal for Eventual

Compromise on Issue,” Atlanta Constitution, March 10, 1993, p.1.

68

Ibid.

69

Reg Murphy, “Confederate Type State Flag Voted By Assembly,” Macon Telegraph, February 10, 1956, p.1.

70

Mike Edwards, “State Flag Change ‘Disappoints’ UDC,” Atlanta Journal, February 10, 1956, p. 4.

30

speech, he acknowledged that the flag is offensive to some and conceded that, “I cannot say to you that

I personally was in no way motivated by a desire to defy. I can say in all honesty that my willingness was

in large part because ... that flag symbolized a willingness of a people to sacrifice their all for their beliefs.”

Appealing to his fellow-legislators to “come together on this which has become the most divisive issue that

has faced the people of Georgia in many, many a day,”

67

Groover unveiled his own compromise design

which still incorporated a portion of the Confederate battle flag. Although black legislators quickly rejected

his compromise design, Representative Billy McKinney remarked that “the fact that he made a positive

statement for compromise will lead some of the people in here to compromise.”

68

The 1956 General Assembly was devoted to maintaining the status of segregation in Georgia.

Laws were passed during that session that empowered the governor to close down integrated public

schools and reopen them as “private” segregated schools. Legislators approved bills that authorized the

state or any county or municipality to sell, lease, grant, exchange or otherwise dispose of parks,

playgrounds, golf courses, and swimming pools, in a move to “privatize” them so that they could remain