K12EDUCATION

Departmentof

EducationShould

ProvideInformation

onEquityandSafety

inSchoolDress

Codes

Accessible Version

ReporttoCongressionalAddressees

October 2022

GAO-23-105348

United States Government Accountability Office

United States Government Accountability Office

GAOHighlights

Highlights of GAO-23-105348, a report to

congressional addressees

October 2022

K-12 EDUCATION

Department of Education Should Provide Information

on Equity and Safety in School Dress Codes

What GAO Found

While school districts often cite safety as the reason for having a dress code,

many dress codes include elements that may make the school environment less

equitable and safe for students. For example, an estimated 60 percent of dress

codes have rules involving measuring students’ bodies and clothing—which may

involve adults touching students. Consequently, students, particularly girls, may

feel less safe at school, according to a range of stakeholders GAO interviewed.

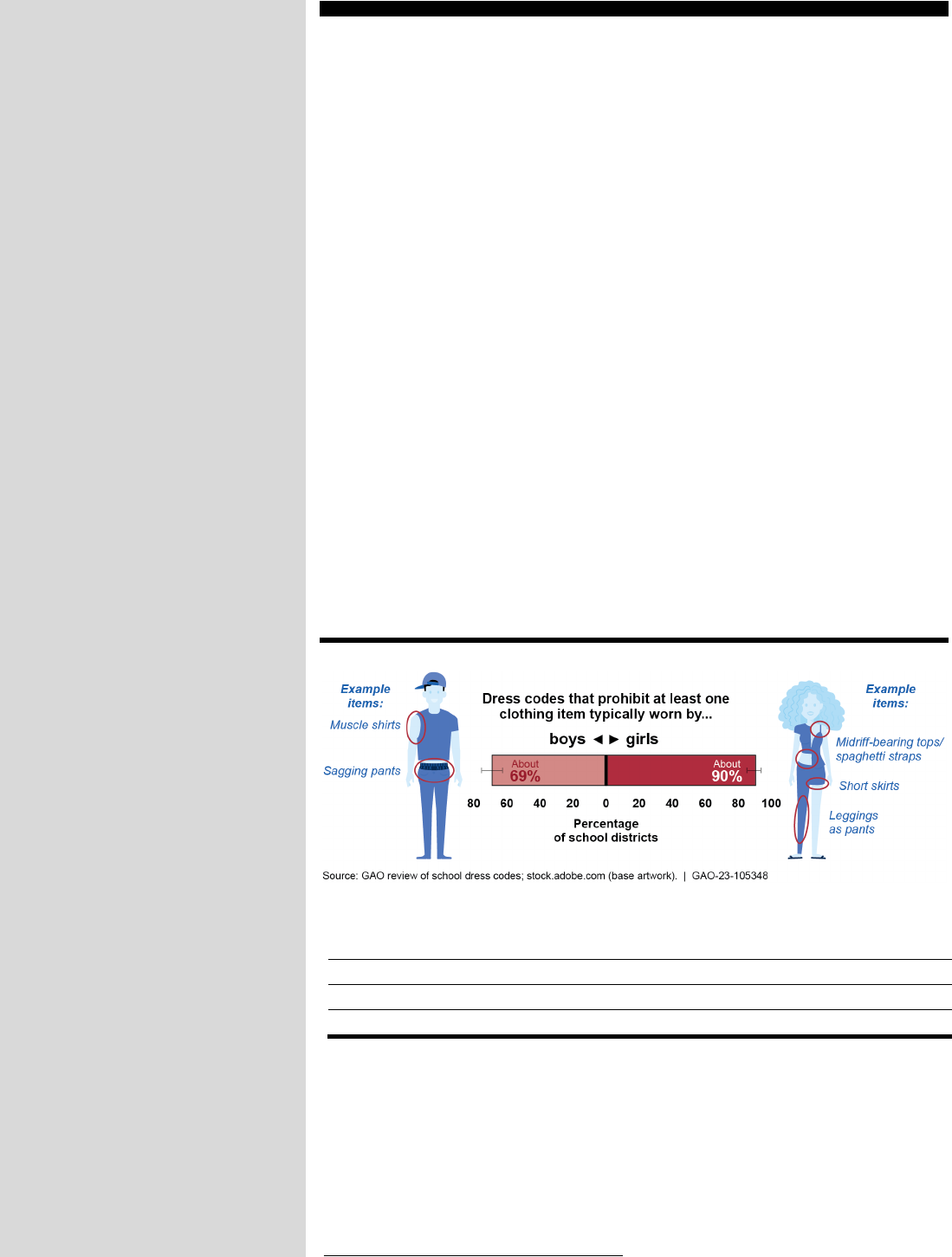

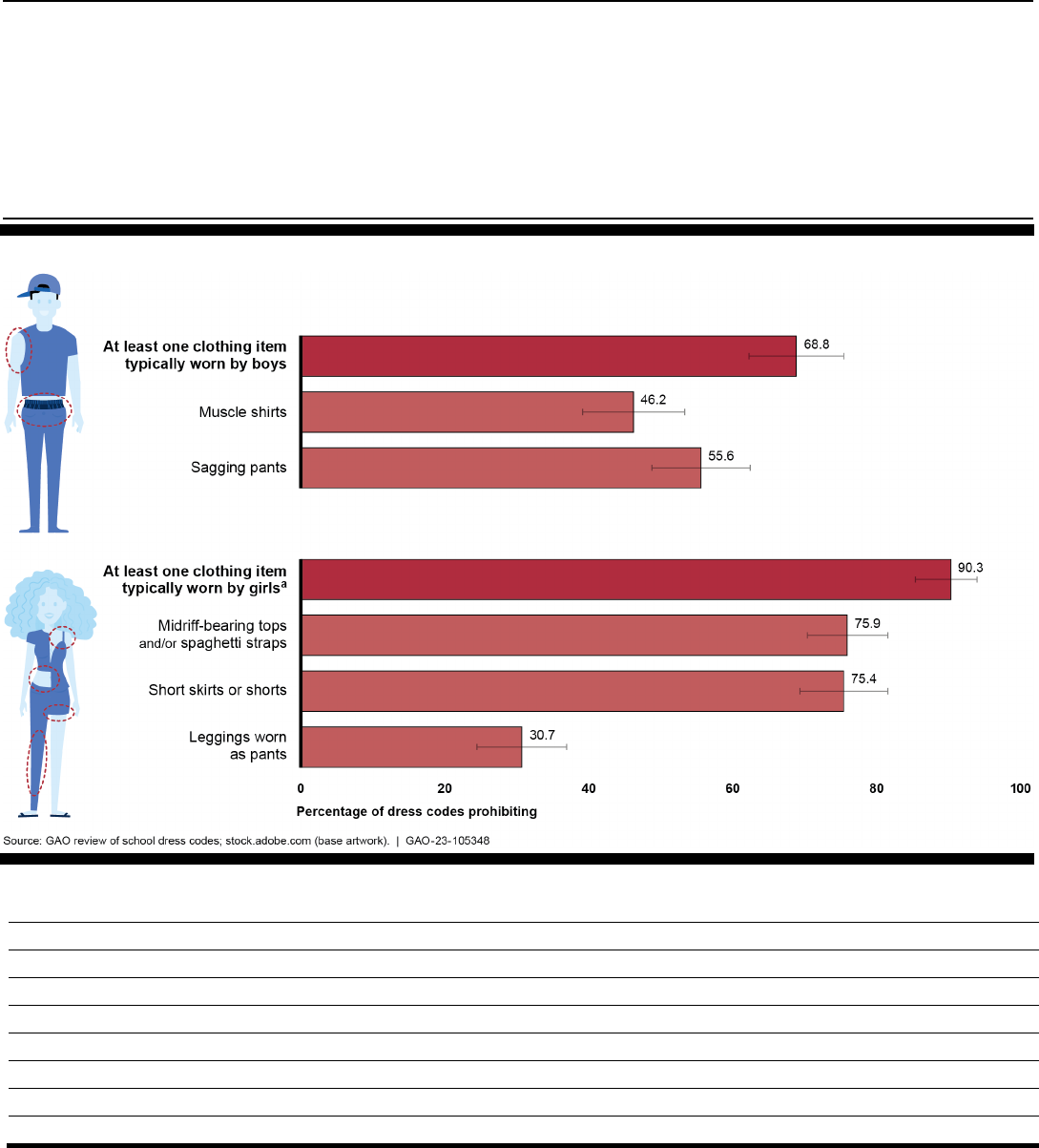

According to GAO’s nationally generalizable review of public school dress codes,

districts more frequently restrict items typically worn by girls—such as skirts, tank

tops, and leggings—than those typically worn by boys—such as muscle shirts.

Most dress codes also contain rules about students’ hair, hair styles, and head

coverings, which may disproportionately impact Black students and those of

certain religions and cultures, according to researchers and district officials.

Department of Education (Education) officials told GAO they are considering

options to provide helpful resources to stakeholders and the public, but as of

September 2022, Education had not provided information on dress codes.

Providing such information would align with the agency’s goal to enhance equity

and safety in schools.

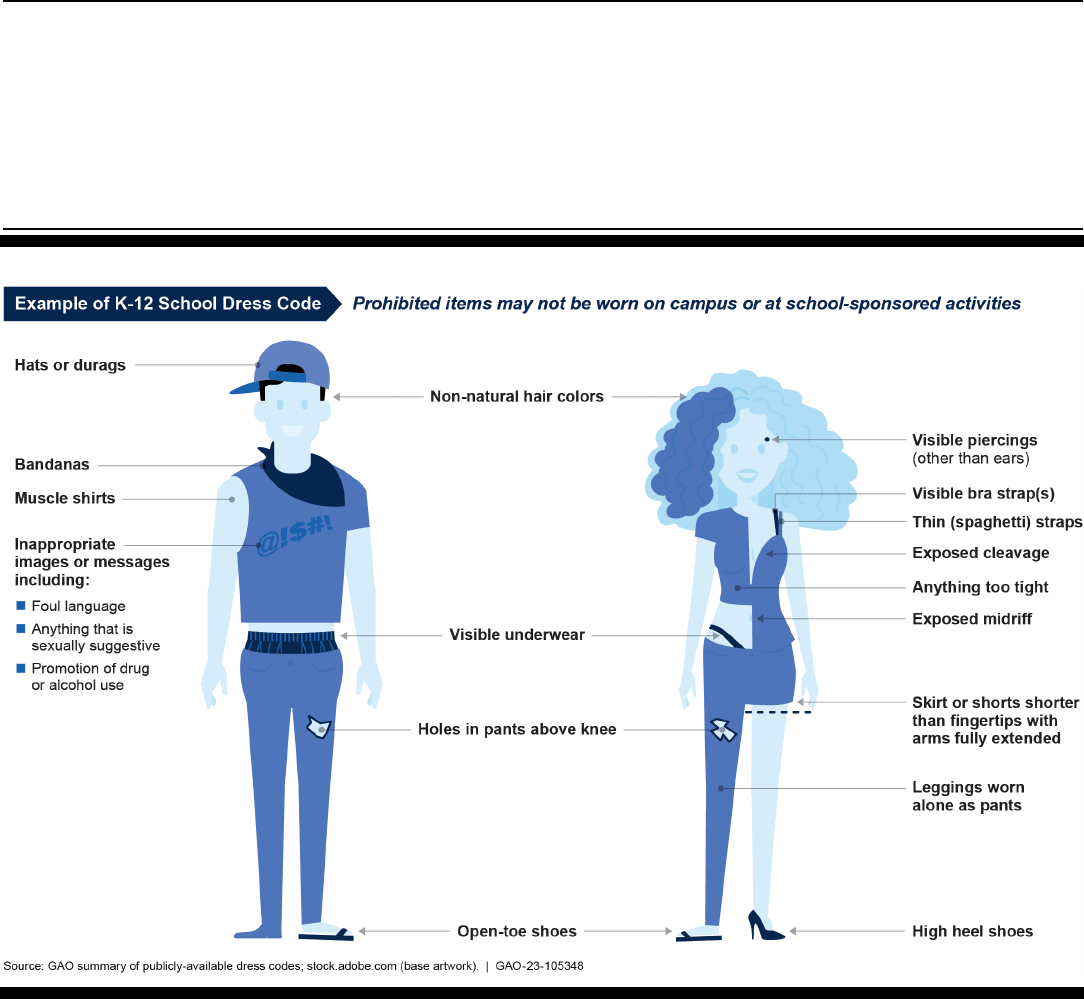

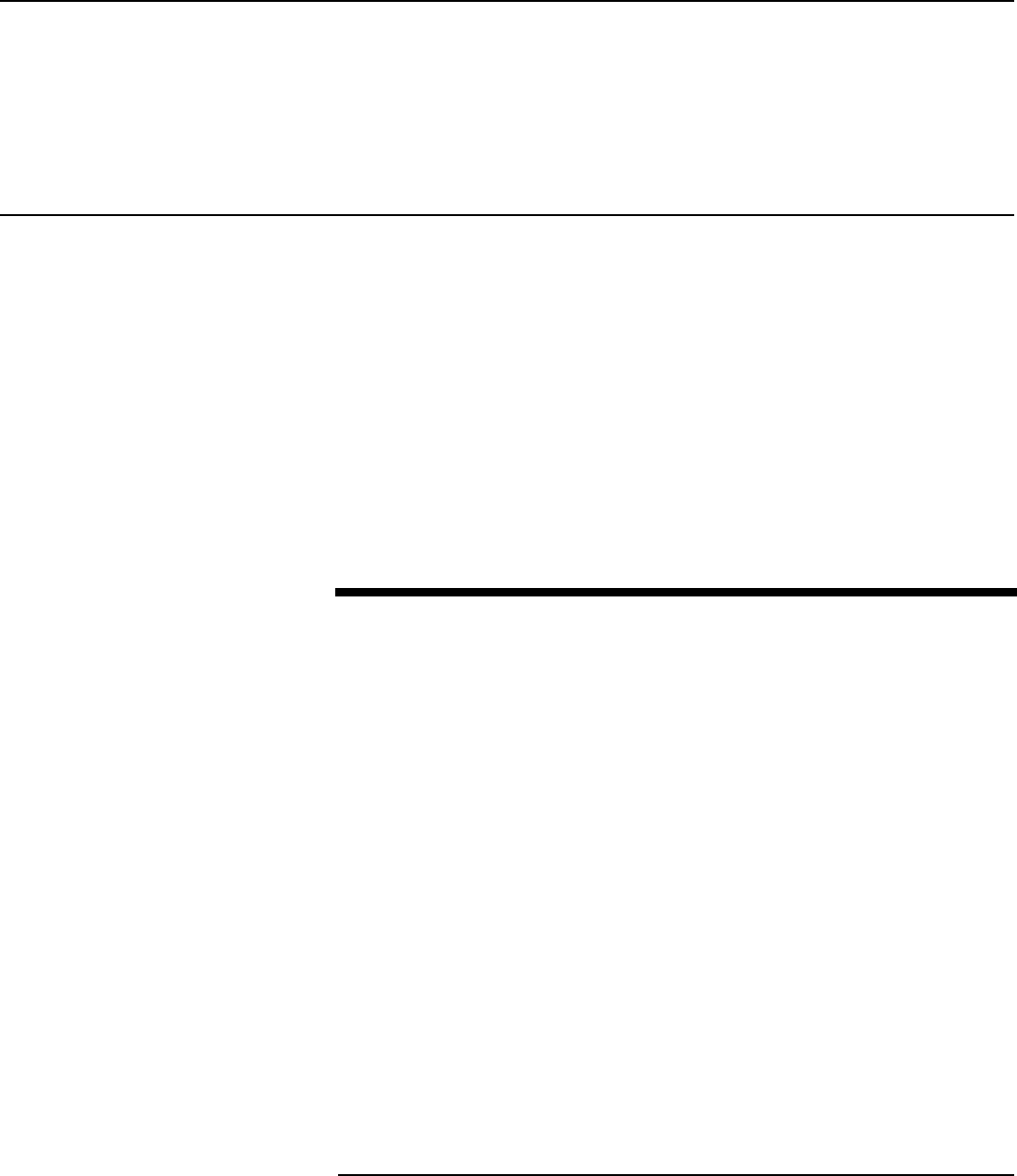

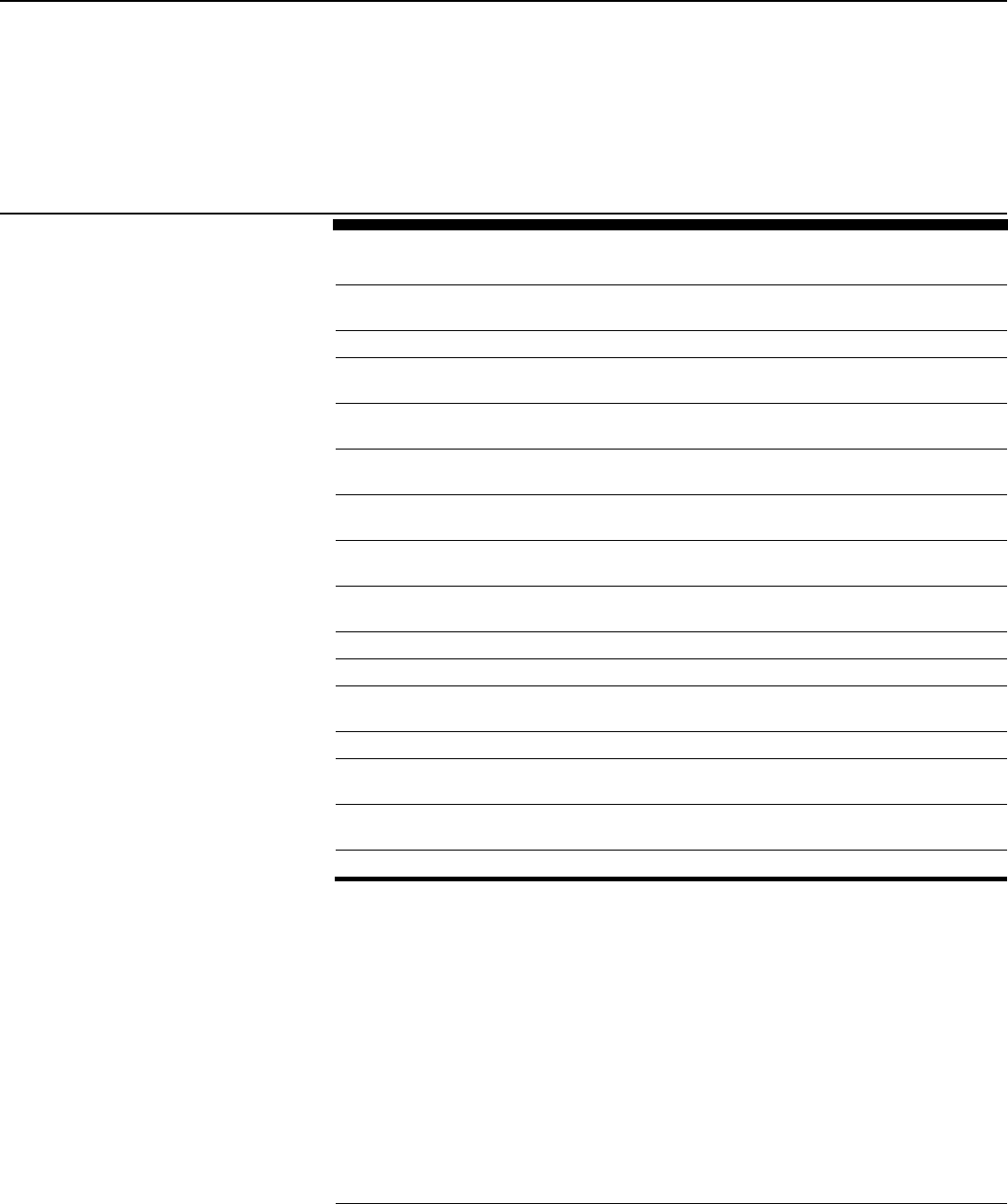

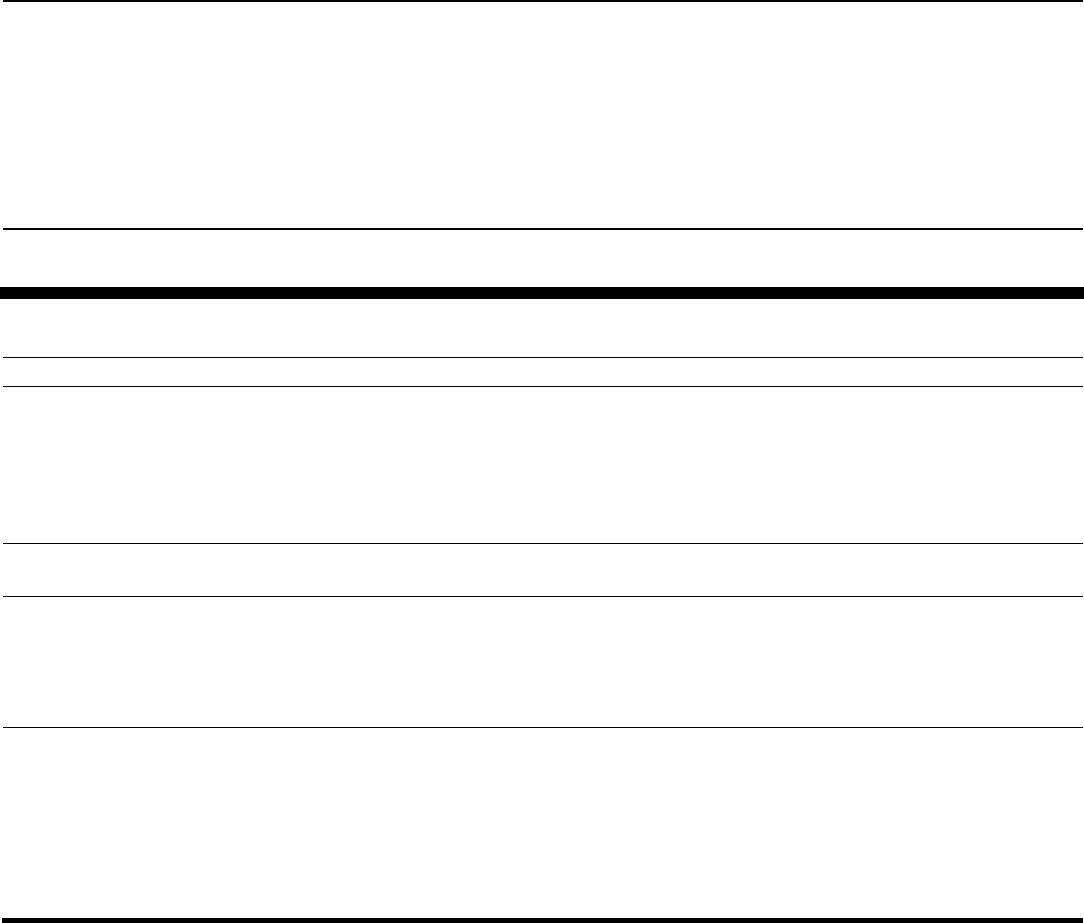

Items Commonly Prohibited by School Dress Codes

Accessible Data for Items Commonly Prohibited by School Dress Codes

Percentage of school districts with dress codes that prohibit at least one clothing

item typically worn by...

Category

Lower bound

Estimate

Upper bound

Boys

62.2

68.8

75.5

Girls

85.3

90.3

94

Example boy items: Muscle shirts; Sagging pants

Example girl items: Midriff-bearing tops/spaghetti straps; Short skirts; Leggings

as pants

Source: GAO review of school dress codes; stock.adobe.com (base artwork). | GAO-23-105348

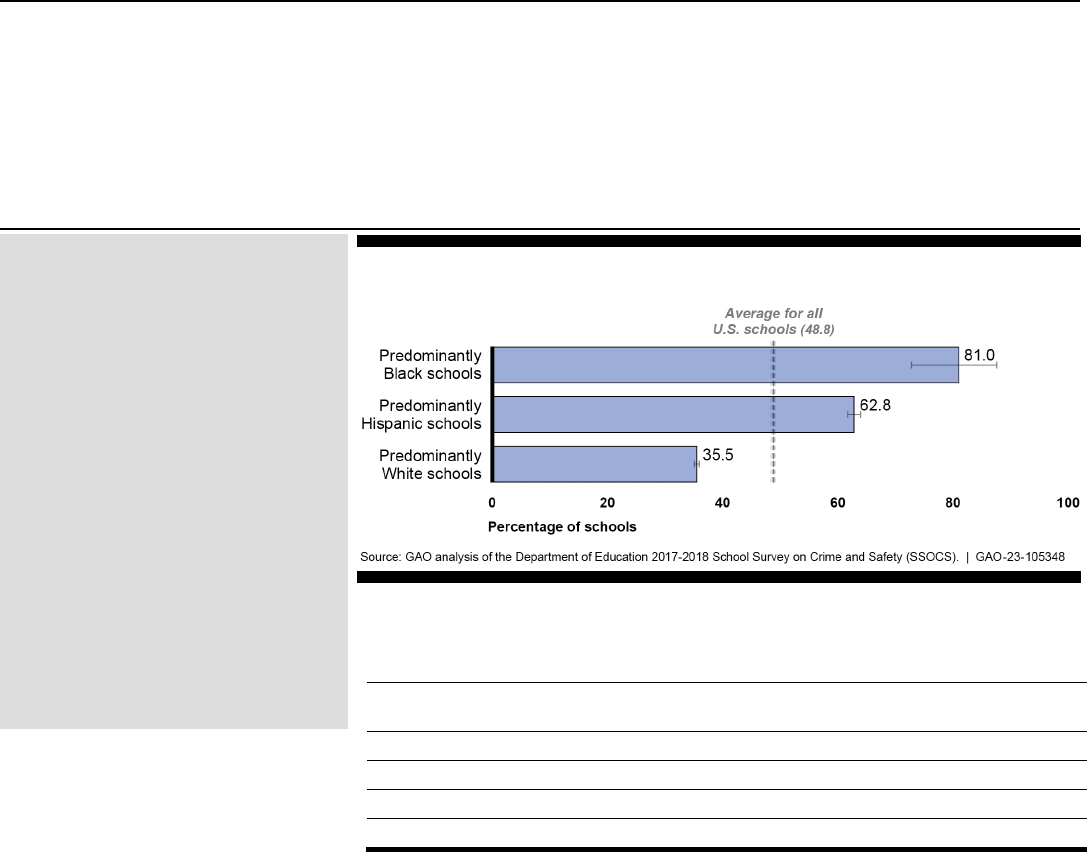

Schools that report enforcing strict dress codes predominantly enroll Black and

Hispanic students and are more likely to remove students from class. GAO’s

analysis of national data found that more than four in five predominantly Black

schools and nearly two-thirds of predominantly Hispanic schools enforce a strict

dress code, compared to about one-third of predominantly White schools. In

View GAO-23-105348. For more information,

contact Jacqueline M. Nowicki at (617) 788-

0580 or nowickij@gao.gov.

Why GAO Did This Study

In recent years, researchers,

advocates, parents, and students have

raised concerns about equity in school

dress codes. Concerns have included

the detrimental effects of removing

students from the classroom for dress

code violations.

A committee report accompanying

H.R. 7614 included a provision for

GAO to study dress code discipline.

This report also addresses a request to

study informal removals. This report

examines (1) the characteristics of K-

12 dress codes across school districts

nationwide, and how Education

supports the design of equitable and

safe dress codes; (2) the enforcement

of dress codes, and how Education

supports equitable dress code

enforcement.

To examine characteristics of dress

codes, GAO analyzed a nationally

representative sample of public school

district dress codes. To assess the

enforcement of dress codes and how

Education supports school districts,

GAO analyzed Education data;

reviewed relevant studies on dress

code discipline; and interviewed

academic researchers and officials

from national organizations, school

districts, and Education.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making four recommendations,

including that Education provide

resources to help districts design

equitable dress codes and collect and

disseminate information on the

prevalence and effects of informal

removals and non-exclusionary

discipline. Education described steps

to implement all four

recommendations.

addition, schools that enforce strict dress codes are associated with statistically

significant higher rates of discipline that removes students from the classroom

(e.g., suspensions). Further, an estimated 44 percent of dress codes outlined

“informal” removal policies, such as removing a student from class without

documenting it as a suspension. Education has recently noted challenges related

to informal removals in guidance documents but has no information on the

prevalence or impact of this emerging issue. Without information on the full range

of ways children are disciplined—including informal removals and non-

exclusionary discipline—Education’s efforts to provide resources on the equitable

enforcement of discipline will have critical gaps.

Page i GAO-23-105348 K-12 Education

Contents

GAO Highlights ii

Why GAO Did This Study ii

What GAO Recommends ii

What GAO Found ii

Letter 1

Background 4

Dress Codes Often Restrict Girls’ Clothing and Students’ Hair and

Head Coverings, and Education Does Not Have Resources on

Designing Equitable and Safe Dress Codes 10

Schools That Enforce Strict Dress Codes Suspend and Expel

More Students, and May Also Informally Remove Students for

Dress Code Violations 23

Conclusions 39

Recommendations for Executive Action 40

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation 41

Appendix I: Objectives, Scope, and Methodology 44

Appendix II: Technical Appendix for Regression Analyses 53

Appendix III: Snapshot of Selected School Districts That Revised Dress Codes 60

Appendix IV: Comments from the U.S. Department of Education 61

Accessible Text for Appendix IV: Comments from the U.S. Department of Education 64

Appendix V: GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments 67

Tables

Table 1: Population, Sample, and Completed Review Counts for

Our In Scope School Districts 46

Table 2: Created Variables Used in the Regression Analysis of

Department of Education’s School Survey on Crime and

Safety and Civil Rights Data Collection, School Years

2015-2016, and 2017-2018 57

Table 3: Variables Included in Our Regression Models Using the

Department of Education’s School Survey on Crime and

Safety and Civil Rights Data Collection, School Years

2015-2016, and 2017-2018 58

Page ii GAO-23-105348 K-12 Education

Table 4: Variables Included in Our Regression Model Using the

Department of Education’s School Survey on Crime and

Safety and Civil Rights Data Collection, 2017-2018 59

Table 5: Snapshot of Selected School Districts That Revised

Dress Codes 60

Figures

Figure 1: Examples of Items Prohibited by School Dress Code

Policies 5

Accessible Data for Figure 1: Examples of Items Prohibited by

School Dress Code Policies 5

Figure 2: Estimated Percentage of Schools Nationwide That

Report Enforcing a Strict Dress Code or Requiring

Uniforms, 1999-2020 8

Accessible Data for Figure 2: Estimated Percentage of Schools

Nationwide That Report Enforcing a Strict Dress Code or

Requiring Uniforms, 1999-2020 8

Figure 3: Estimated Percentage of Districts that Prohibit Clothing

Items Typically Worn by Girls or Boys 12

Accessible Data for Figure 3: Estimated Percentage of Districts

that Prohibit Clothing Items Typically Worn by Girls or

Boys 12

Figure 4: Estimated Percentage of Districts Prohibiting the

Exposure of Specific Body Parts 13

Accessible Data for Figure 4: Estimated Percentage of Districts

Prohibiting the Exposure of Specific Body Parts 13

Figure 5: Dress Code Excerpts: Examples of Rules Containing

Measurements 14

Accessible Data for Figure 5: Dress Code Excerpts: Examples of

Rules Containing Measurements 14

Figure 6: Dress Code Excerpts: Examples of Rules with

Subjective Language 15

Accessible Data for Figure 6: Dress Code Excerpts: Examples of

Rules with Subjective Language 15

Figure 7: Examples of religious and culturally significant head

coverings 16

Accessible Text for Figure 7: Examples of religious and culturally

significant head coverings 16

Figure 8: Culturally significant hairstyles and hair coverings 17

Accessible Data for Figure 8: Culturally significant hairstyles and

hair coverings 18

Page iii GAO-23-105348 K-12 Education

Figure 9: Estimated Percentage of School Districts Citing a

Particular Purpose for Their Dress Code, among the

Estimated 92 Percent of Districts That Stated a Purpose 19

Accessible Data for Figure 9: Estimated Percentage of School

Districts Citing a Particular Purpose for Their Dress

Code, among the Estimated 92 Percent of Districts That

Stated a Purpose 19

Figure 10: Estimated Percentage of Schools in Each Racial/Ethnic

Category That Report Enforcing a Strict Dress Code,

School Year 2017-18 25

Accessible Data for Figure 10: Estimated Percentage of Schools

in Each Racial/Ethnic Category That Report Enforcing a

Strict Dress Code, School Year 2017-18 25

Figure 11: Estimated Percentage of Public Schools That Report

Enforcing a Strict Dress Code, by Census Division,

School Year 2017-18 26

Accessible Data for Figure 11: Estimated Percentage of Public

Schools That Report Enforcing a Strict Dress Code, by

Census Division, School Year 2017-18 26

Figure 12: Estimated Percentage of Students Experiencing

Exclusionary Discipline in Schools That Enforce Strict

Dress Codes, School Year 2017-18 30

Accessible Data for Figure 12: Estimated Percentage of Students

Experiencing Exclusionary Discipline in Schools That

Enforce Strict Dress Codes, School Year 2017-18 30

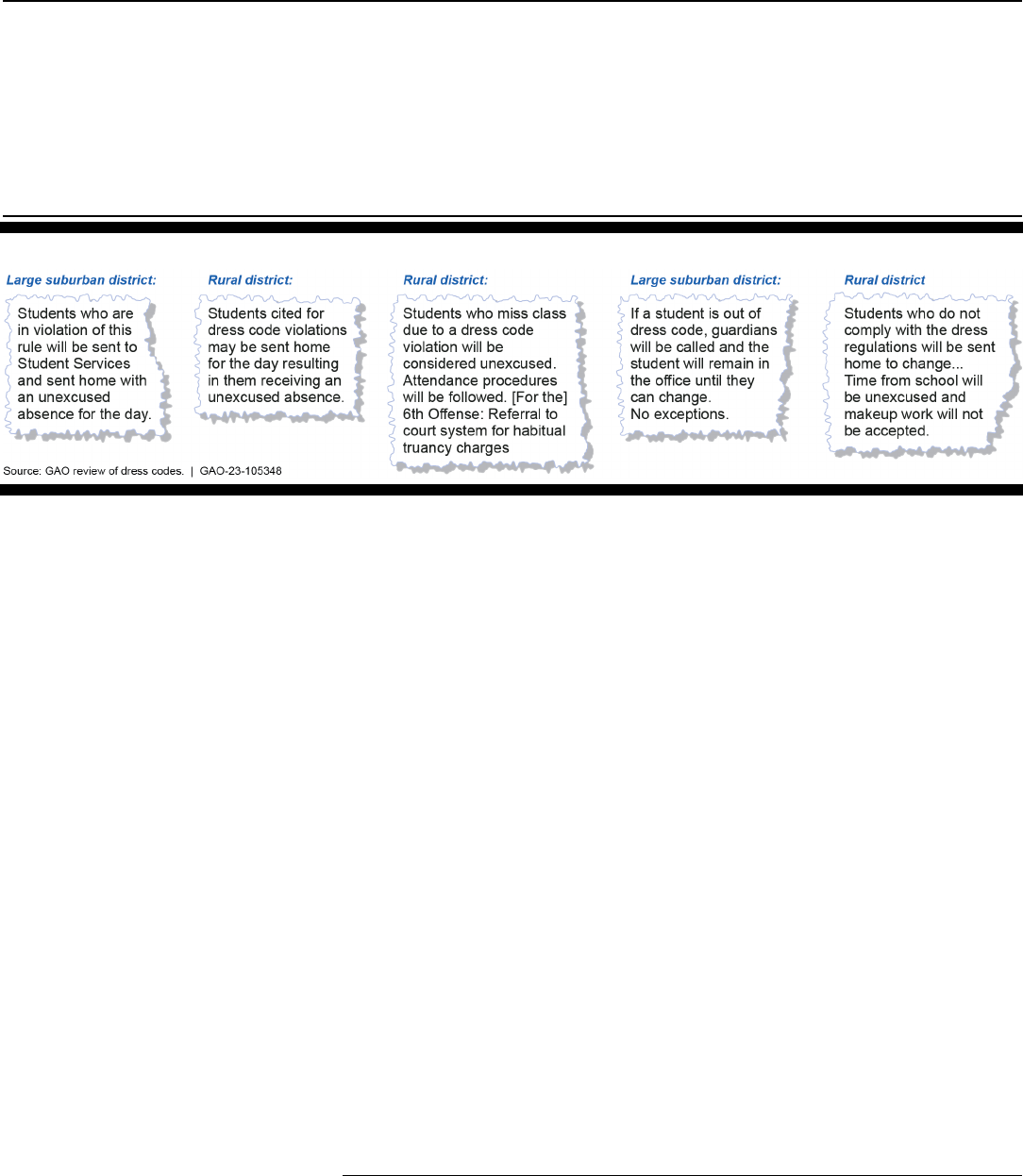

Figure 13: Dress Code Excerpts: Examples of Removing Students

from Class 35

Accessible Data for Figure 13: Dress Code Excerpts: Examples of

Removing Students from Class 35

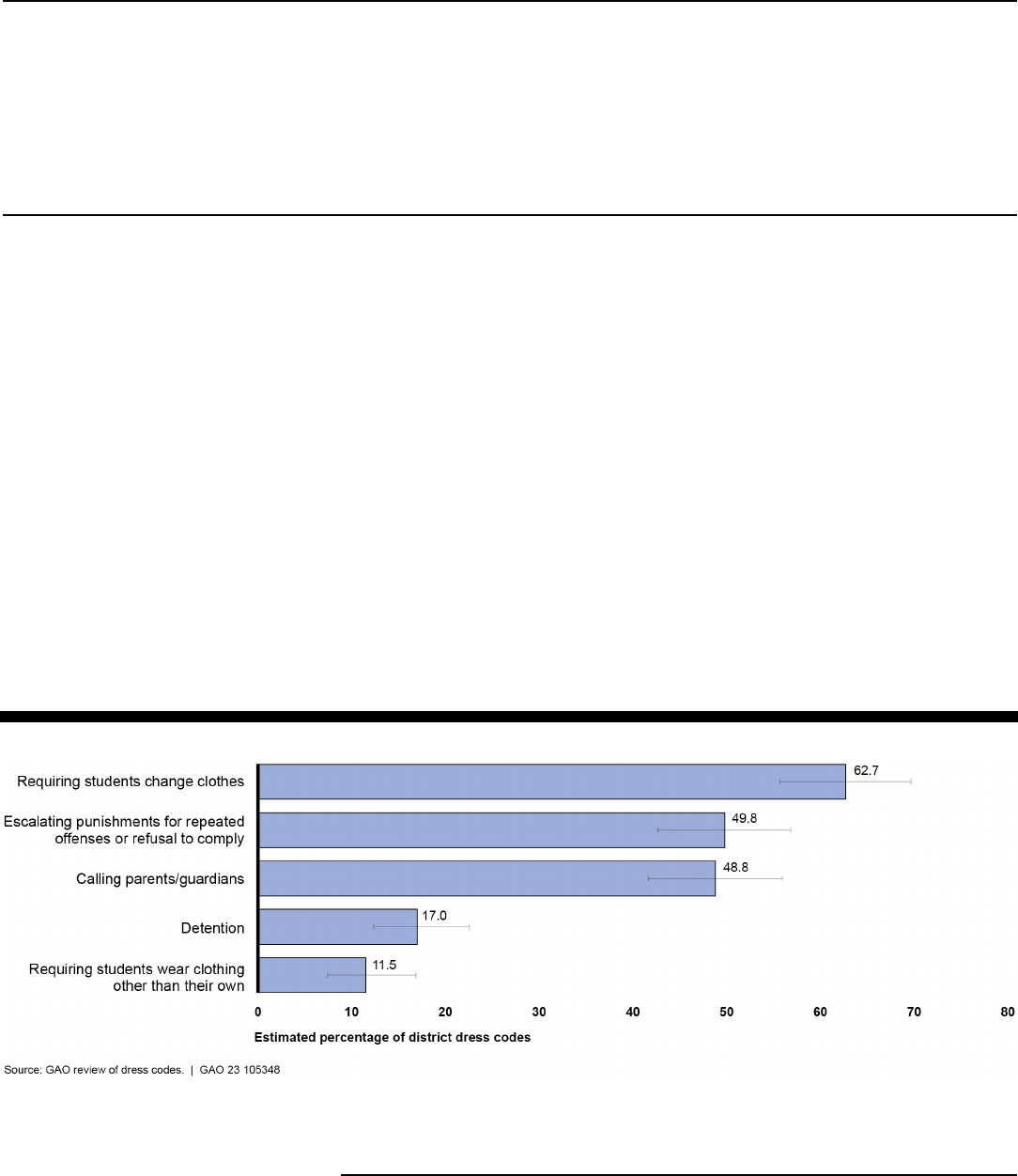

Figure 14: Non-Exclusionary Discipline Cited in Dress Codes

Violations, by Estimated Percent of Districts 37

Accessible Data for Figure 14: Non-Exclusionary Discipline Cited

in Dress Codes Violations, by Estimated Percent of

Districts 38

Abbreviations

APA American Psychological Association

CCD Common Core of Data

CRDC Civil Rights Data Collection

LEA local educational agency

NCES National Center for Education Statistics

Page iv GAO-23-105348 K-12 Education

NCSSLE National Center on Safe and Supportive Learning

Environments

OCR Office for Civil Rights

OSSS Office of Safe and Supportive Schools

REL Regional Educational Laboratory

SSOCS School Survey on Crime and Safety

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety

without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain

copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be

necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Page 1 GAO-23-105348 K-12 Education

441 G St. N.W.

Washington, DC 20548

Letter

October 25, 2022

Congressional Addressees

Nearly every public school district in the nation requires students to

adhere to a dress code. School dress codes provide overall guidelines for

how students are expected to dress for school; establish rules about

clothes, hair, and accessories; and lay out disciplinary consequences for

violating the dress code. For example, students who violate a school’s

dress code may be asked to change clothes, be sent home, or be

suspended from school.

In recent years, researchers, advocates, parents, and students have

raised concerns that dress codes disproportionately focus on girls’

clothing and bodies and that exclusionary discipline—the practice of

removing students from the classroom—for dress code violations may

disproportionately harm Black and Hispanic students, among other

students.

1

Recent reports and research studies have garnered national

attention and have shed light on concerns with certain elements of dress

codes, including those that are unclear or overly strict, require expensive

purchases, or prohibit items associated with cultural or racial identity,

such as banning head coverings or traditionally Black hairstyles.

2

In

addition, some of these studies have noted that having different dress

codes for girls and boys can present obstacles for transgender and

nonbinary students. Some school districts have responded to dress code

controversies by revising their dress codes—sometimes citing a

commitment to equity and inclusion when doing so—or by switching to

uniforms.

A committee report accompanying the House bill for the Departments of

Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education, and Related

1

The federal data sources we cite in this report use the term “Hispanic or Latino” in their

data collection, which refers to a person of Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, South or

Central American, or other Spanish culture or origin regardless of race. We use the term

Hispanic for the purposes of our reporting objectives.

2

National Women’s Law Center, Dress Coded: Black girls, bodies, and bias in D.C.

schools (2018), available at https://nwlc.org/resources/dresscoded; Dignity in Schools, A

Model Code on Education and Dignity: Presenting a human rights framework for schools

(2019), available at https://dignityinschools.org/modelcoded.

Letter

Page 2 GAO-23-105348 K-12 Education

Agencies Appropriations Act, 2021, included a provision for GAO to study

how school dress code and discipline policies are formulated and

executed across the country, ways in which dress codes may infringe

upon students’ civil rights, and promising practices related to dress code

discipline policies.

3

GAO was also asked to look at the topic of informal

removals by House Committee on Education and Labor Chairman Bobby

Scott and Representative A. Donald McEachin.

This report examines (1) the characteristics of K-12 dress codes across

school districts nationwide, and how the Department of Education

supports the design of equitable and safe dress codes; and (2) the

enforcement of dress codes, and how Education supports equitable dress

code enforcement.

To estimate the prevalence of dress code characteristics nationwide, we

analyzed publicly available dress code information from a nationally

generalizable, stratified random sample of school districts.

4

Using

Education’s Common Core of Data for school year 2020-21, we selected

a nationally representative sample of 236 public school districts and

systematically reviewed each district’s dress code using a structured data

collection instrument. We used a sampling strategy that accounted for

district demographics, size, and other variables to ensure certain

subpopulations of students were appropriately represented.

To obtain information on the enforcement of dress code discipline, we

analyzed data on dress codes and uniforms from Education’s School

Survey on Crime and Safety (school survey) for school years 2015-16

and 2017-18, the most recent available at the time of our review. We

matched the school survey with the 2015-16 and 2017-18 Civil Rights

Data Collection and Common Core of Data, and conducted generalized

linear regressions to explore associations between school-level

characteristics and policies. Such associations included enforcing a

“strict” dress code and rates of incidents of exclusionary discipline, such

as the percentage of students suspended, while controlling for other

factors such as school type and student demographics. Similarly, using

the 2017-18 data, we conducted generalized linear regressions to explore

associations between school-level characteristics and whether a school

3

H.R. Rep. No. 116-450, at 288 (2020).

4

Specifically, we stratified the sample into mutually exclusive strata that accounted for

districts’ number of students enrolled, urban classification (urban, suburban, or town/rural),

charter/non-charter status, and racial demographics. See appendix I for additional details.

Letter

Page 3 GAO-23-105348 K-12 Education

enforces a strict dress code, while controlling for other factors. We

conducted electronic data testing and obtained information from data

officials at Education, among other steps, to determine that these

datasets were reliable for these purposes.

Our models did not allow us to address causality, so we conducted a

targeted literature review to provide context for our findings. We identified

and reviewed relevant studies on discipline resulting from dress code

violations in K-12 public schools for the last 10 years (August 2011-

August 2021) that met our criteria.

5

We interviewed officials from three school districts that recently revised

their dress codes. We selected these districts for varying size, geographic

location, student demographics, and strategies used to revise their dress

codes (e.g., how data were collected, whether stakeholders were

consulted). Our interviews with school district officials are not

generalizable to all districts nationwide, but provide illustrative examples

of strategies districts may use when designing and revising dress code

policies. We also interviewed researchers and officials from national

organizations that conduct work on dress code discipline. Using social

media and outreach with a national organization, we also invited families

to participate in a brief questionnaire to obtain anecdotal perspectives

about their children’s dress codes/uniforms.

Finally, to obtain information on Education’s resources related to dress

code discipline, we reviewed relevant federal laws, regulations, guidance,

and documents, and interviewed agency officials. We compared

Education’s efforts with the agency’s strategic goals and objectives.

We conducted this performance audit from August 2021 to October 2022

in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards.

Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain

sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our

findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that

the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and

conclusions based on our audit objectives.

5

To be included in our review, studies must use empirical student level data, relate to

student outcomes associated with dress code disciplinary actions, use rigorous statistical

methods, and be documented in a peer-reviewed journal.

Letter

Page 4 GAO-23-105348 K-12 Education

Background

According to the Education Commission of the States, as of December

2021, 24 states and the District of Columbia explicitly grant local districts

the power to establish dress codes.

6

Some states and localities have also

enacted rules about the content of K-12 dress codes, such as those that

prohibit race-based hair discrimination in educational settings. For

example, California’s Educational Code prohibits, among other things,

discrimination on the basis of race and ethnicity, and defines race

“inclusive of traits historically associated with race, including, but not

limited to, hair texture and protective hairstyles.”

Dress codes may be embedded in larger discipline documents or student

codes of conduct. They may prohibit specific articles of clothing,

accessories, hair styles, or makeup. In addition, dress codes may contain

subjective language about clothing, such as that clothing be “appropriate,”

or not be “excessively tight,” “distracting,” “revealing,” or “sexually

suggestive.” Dress code policies also sometimes differ based on

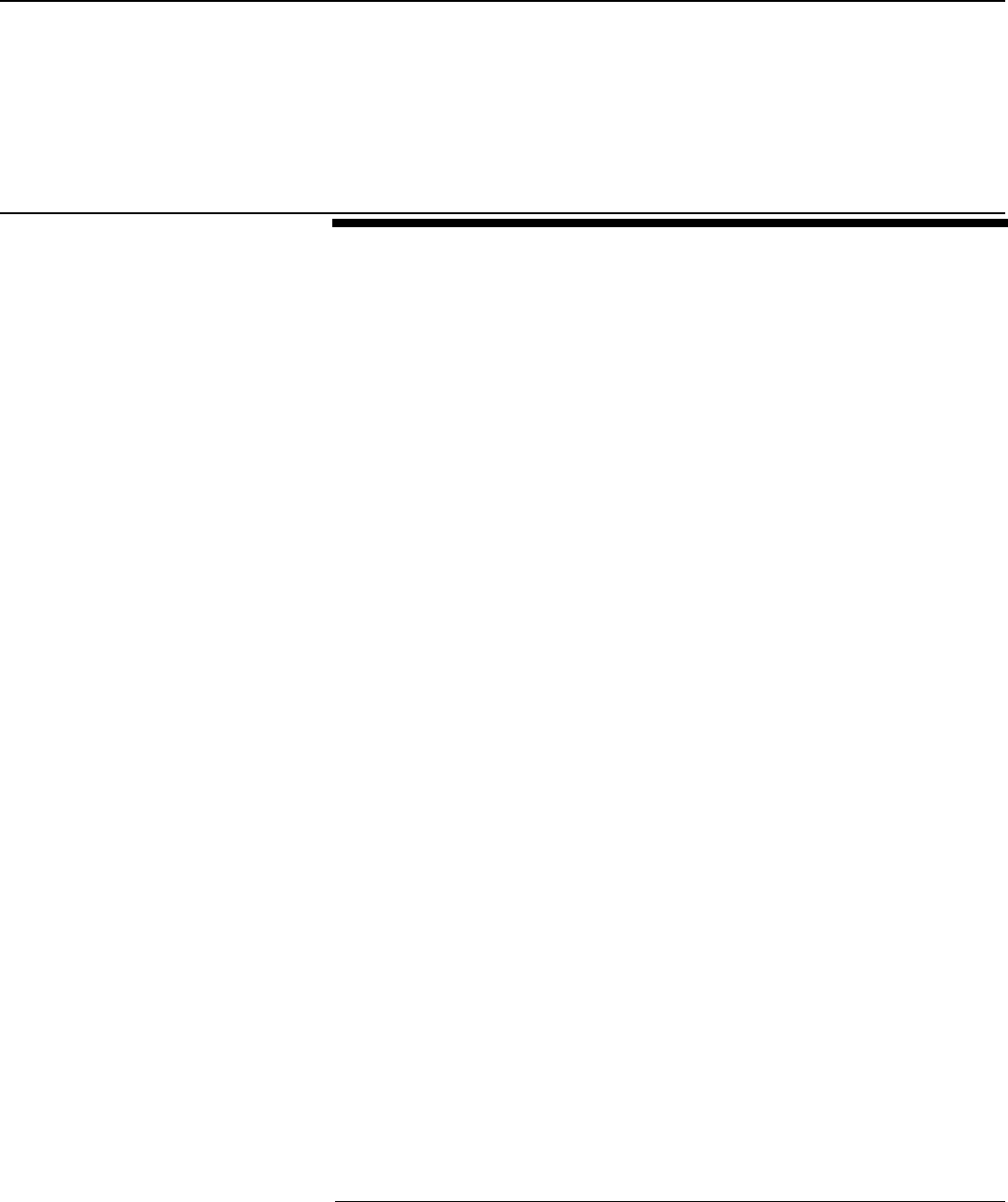

students’ sex or gender (see fig. 1).

6

We did not conduct a comprehensive review or analysis of state laws or policies as part

of this work.

Letter

Page 5 GAO-23-105348 K-12 Education

Figure 1: Examples of Items Prohibited by School Dress Code Policies

Accessible Data for Figure 1: Examples of Items Prohibited by School Dress Code Policies

Example of K-12 School Dress Code: Prohibited items may not be worn on campus or at school-sponsored

activities

Boys: Hats or durags; Bandanas; Muscle shirts; Inappropriate images or messages including: Foul language,

Anything that is sexually suggestive, or Promotion of drug or alcohol use

Girls: Visible piercings (other than ears); Visible bra strap(s); Thin (spaghetti) straps; Exposed cleavage;

Anything too tight; Exposed midriff; Skirt or shorts shorter than fingertips with arms fully extended; Leggings

worn alone as pants; High heel shoes

Both: Non-natural hair colors; Visible underwear; Holes in pants above knee; Open-toe shoes

Source: GAO summary of publicly-available dress codes; stock.adobe.com (base artwork). | GAO-23-105348

There are a variety of consequences for dress code violations. The

enforcement of dress codes can include requiring students to change

Letter

Page 6 GAO-23-105348 K-12 Education

clothes, in-school suspension, out-of-school suspension, and even

expulsion. Some examples of dress code enforcement have drawn

attention from the media. For a variety of examples of recent media

reports on dress code enforcement, see the text box below.

Letter

Page 7 GAO-23-105348 K-12 Education

Examples of dress code enforcement reported in the media from

April 2018 to June 2022

· A high school girl was told to “move around” for the school dean to

determine if her nipples were visible through her shirt. The student

was then instructed to put band aids on her chest.

· School staff drew on a Black boy’s head in permanent marker to

cover shaved designs in his hair.

· A female transgender student was told not to return to school until

she was following the school’s dress code guidelines for males.

· A high school girl was suspended for 10 days and prohibited from

attending her graduation ceremony for wearing a top that showed

her shoulders and back.

· Middle school girls were gathered at an assembly on dress code

and told they should not report inappropriate touching if they were

not following the dress code.

· A Black student was told he needed to remove his hair covering

(also called a durag) because an administrator said it was gang-

related.

· Two Asian American and Pacific Islander students were banned

from wearing leis and tupenus (cloth skirts)—cultural symbols of

celebration and pride—to their high school graduation.

Source: GAO review of selected news reports. | GAO 23 105348

RoleoftheDepartmentofEducationinSchoolDress

CodeEnforcement

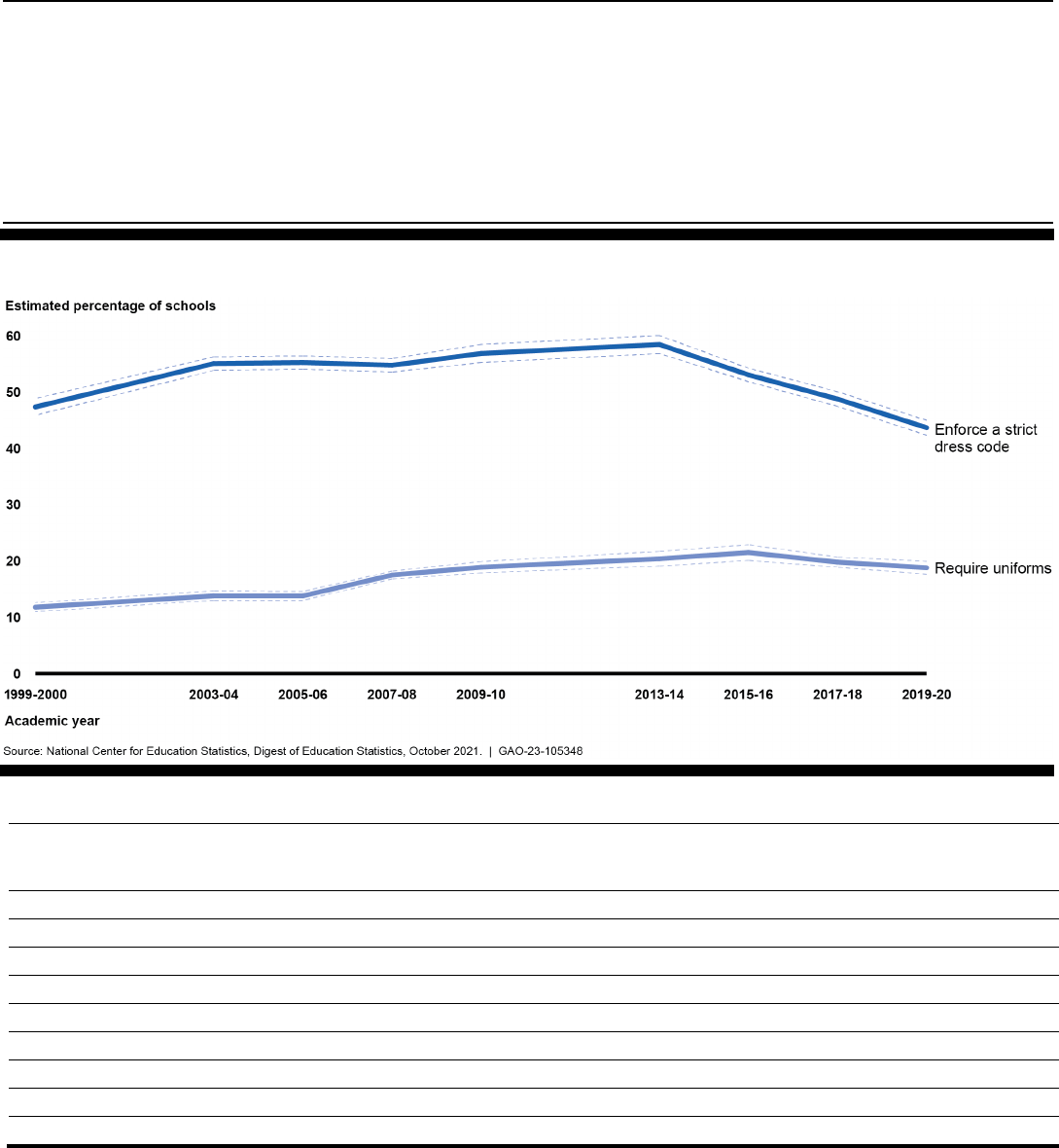

Education collects school-reported data on whether public schools

enforce a strict dress code or require uniforms through its School Survey

on Crime and Safety (school survey). The school survey is designed to

provide estimates of school crime, discipline, disorder, programs, and

policies, including dress code and uniform policies. In its 2021 Digest of

Education Statistics, Education estimates that, for school year 2019-20,

nearly half of schools nationwide reported they enforce a strict dress code

and nearly one in five require uniforms. These practices have remained

relatively stable over time (see fig. 2).

Letter

Page 8 GAO-23-105348 K-12 Education

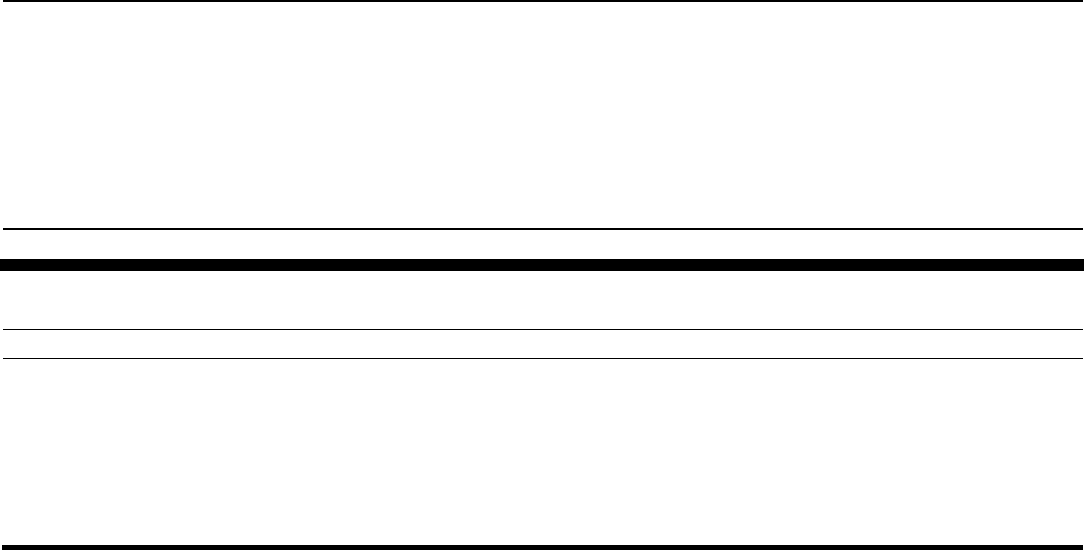

Figure 2: Estimated Percentage of Schools Nationwide That Report Enforcing a Strict Dress Code or Requiring Uniforms,

1999-2020

Accessible Data for Figure 2: Estimated Percentage of Schools Nationwide That Report Enforcing a Strict Dress Code or

Requiring Uniforms, 1999-2020

Academic year

Enforce a strict

dress code

(Lower bound)

Enforce a strict

dress code

(Estimate)

Enforce a strict

dress code

(Upper bound)

Require

uniforms

(Lower bound)

Require uniforms

(Estimate)

Require

uniforms

(Upper bound)

1999-2000

45.9

47.4

48.9

11

11.8

12.6

2003-04

53.9

55.1

56.3

13

13.8

14.7

2005-06

54.1

55.3

56.5

13

13.8

14.6

2007-08

53.6

54.8

56

16.8

17.5

18.2

2009-10

55.3

56.9

58.5

17.9

18.9

19.9

2013-14

56.9

58.5

60.1

19.1

20.4

21.7

2015-16

51.9

53.1

54.3

20.1

21.5

22.9

2017-18

47.5

48.8

50.1

18.9

19.8

20.7

2019-20

42.38

43.7

45.02

17.66

18.8

19.94

Source: National Center for Education Statistics, Digest of Education Statistics, October 2021. | GAO-23-105348

Education’s Office of Elementary and Secondary Education has an Office

of Safe and Supportive Schools (OSSS) that addresses the health and

well-being of students and school safety, security, and emergency

management and preparedness. OSSS administers, coordinates, and

recommends policy in addition to managing grant programs and technical

Letter

Page 9 GAO-23-105348 K-12 Education

assistance centers that address the overall safety and health of school

communities. One of its technical assistance centers, the National Center

on Safe and Supportive Learning Environments (NCSSLE) focuses on

improving student supports and academic enrichment by providing

technical assistance and support to states, districts, schools, and the

public on school climate and related topics. NCSSLE has developed

resources on school discipline and creating positive school climates, and

also offers related resources from external parties, including some

resources related to dress code discipline.

7

Education’s Office for Civil Rights (OCR) is responsible for enforcing

certain federal civil rights laws that prohibit discrimination in schools and

other programs or activities that receive federal assistance from

Education, such as

· Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Title VI), which prohibits

discrimination on the basis of race, color, or national origin by

recipients of federal funding;

8

· Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 (Title IX), which

prohibits sex discrimination in education programs that receive federal

funding;

9

and

· Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (Section 504) which

prohibits discrimination on the basis of disability by recipients of

federal funding.

10

Additionally, OCR has responsibilities under Title II of the Americans with

Disabilities Act of 1990 (Title II), which prohibits discrimination on the

basis of disability by public entities (such as public school districts, public

7

Information about NCSSLE’s resources are available on its website:

https://safesupportivelearning.ed.gov/.

8

42 U.S.C. §§ 2000d – 2000d-7. Although Title VI does not prohibit discrimination on the

basis of religion, according to Education, Title VI protects students of any religion from

discrimination, including harassment, based on a student’s actual or perceived shared

ancestry or ethnic characteristics, or citizenship or residency in a country with a dominant

religion or distinct religious identity.

9

20 U.S.C. §§ 1681 – 1689

10

29 U.S.C. § 794.

Letter

Page 10 GAO-23-105348 K-12 Education

colleges and universities, and public libraries), whether or not they

receive federal financial assistance.

11

DressCodesOftenRestrictGirls’Clothingand

Students’HairandHeadCoverings,and

EducationDoesNotHaveResourceson

DesigningEquitableandSafeDressCodes

DressCodesOftenRestrictGirls’ClothingandInclude

RulesThatNecessitateMeasuringStudents’Bodiesand

Clothes

Rules related to girls’ clothing and bodies. Nearly all K-12 public

school districts (an estimated 93 percent) have a policy on student dress,

according to our nationally generalizable review of district policies.

12

These dress codes more frequently restrict items typically worn by girls—

such as short skirts, spaghetti strap tank tops, and leggings—than those

typically worn by boys—such as muscle shirts (see fig. 3). An estimated

90 percent of dress codes prohibit clothing items typically associated with

girls compared to 69 percent that prohibit items typically associated with

boys.

13

Dress codes we reviewed include statements such as “halter or

strapless tops, and skirts or shorts shorter than mid-thigh are also

prohibited” and “yoga pants or any type of skin tight attire may not be

worn by itself. It may be worn underneath [other clothing] that is long

enough to ensure modesty.” Some parents who responded to our online

questionnaire expressed appreciation for aspects of their children’s dress

11

42 U.S.C. §§ 12131 – 12134.

12

Unless otherwise noted, all estimates from our review of publicly available district dress

codes have a margin of error of plus or minus 7 percentage points or less, at the 95

percent confidence level. The percentage estimates of school districts are based on

district information that was publicly available on school district websites from April-May

2022.

13

We identified clothing that is typically associated with girls or boys through a review of

prior research related to school dress codes, gendered language in our sample of dress

codes, and a review of “girls” and “boys” sections of the websites of national children’s

clothing retailers.

Letter

Page 11 GAO-23-105348 K-12 Education

Q&A: What do families think about school

dress codes and uniforms?

We asked families to respond to a

questionnaire about the dress code and

uniform policies in their children’s school.

Below are selected responses that represent

a range of views expressed:

· “My girls definitely feel anger towards the

school for not educating the boys and

making [the girls] aware every day what

they wear can be a distraction to the

boys.”

· “They love the dress code/uniform policy.

It is one less thing they have to think

about when they wake up in the morning

and they don’t have to worry about not

fitting in.”

· “They don’t like the ‘boys wear pants and

girls wear skirts’ type [of] language used

in the dress code. They want to be able

to wear anything they choose.”

· “It’s helped reinforce our own family

opinions that our 12 year old doesn’t

need to go to school with her stomach

showing.”

Source: GAO questionnaire. | GAO-23-105348

codes; others had concerns about dress code rules focused on clothing

typically worn by girls (see sidebar).

14

14

Using social media and outreach with a national organization, we invited families to

participate in a brief questionnaire to obtain anecdotal perspectives about their children’s

dress codes/uniforms. We received 47 responses in March and April 2022.

Letter

Page 12 GAO-23-105348 K-12 Education

Figure 3: Estimated Percentage of Districts that Prohibit Clothing Items Typically Worn by Girls or Boys

Accessible Data for Figure 3: Estimated Percentage of Districts that Prohibit Clothing Items Typically Worn by Girls or Boys

Percentage of dress codes prohibiting

Category

Lower bound

Estimate

Upper bound

At least one clothing item typically worn by boys

62.2

68.8

75.5

Muscle shirts

39.1

46.2

53.4

Sagging pants

48.7

55.6

62.5

At least one clothing item typically worn by girls

a

85.3

90.3

94

Midriff-bearing tops and/or spaghetti straps

70.3

75.9

81.6

Short skirts or shorts

69.3

75.4

81.6

Leggings worn as pants

24.4

30.7

37

Source: GAO review of school dress codes; stock.adobe.com (base artwork). | GAO-23-105348

a

Prohibited items typically worn by girls also include the following items not shown: tops with low cut

necklines, shoes with heels of a certain height, nylon and spandex, and clothing that is sheer or

transparent/translucent.

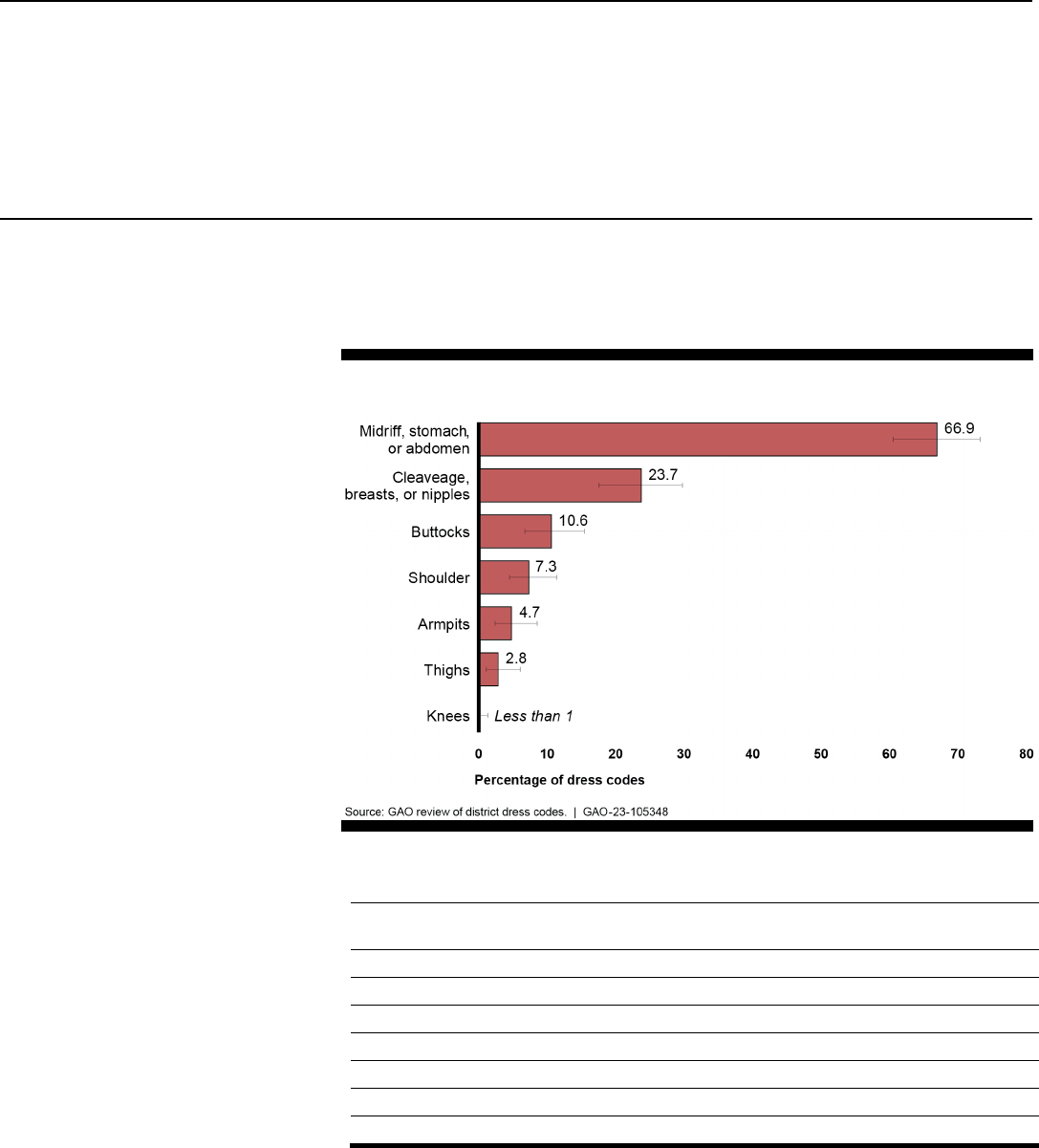

Most dress codes stipulate that students’ clothing must cover specific

body parts; these restrictions more frequently apply to clothing typically

Letter

Page 13 GAO-23-105348 K-12 Education

worn by girls, such as halter or crop tops. For example, most dress codes

(67 percent) prohibit clothing that exposes a student’s midriff. We also

estimate about a quarter of district dress codes specifically prohibit the

exposure of “cleavage,” “breasts,” or “nipples” (see fig. 4).

Figure 4: Estimated Percentage of Districts Prohibiting the Exposure of Specific

Body Parts

Accessible Data for Figure 4: Estimated Percentage of Districts Prohibiting the

Exposure of Specific Body Parts

Percentage of dress codes

Category

Lower

bound

Estimate

Upper

bound

Midriff, stomach, or abdomen

60.5

66.9

73.3

Cleaveage, breasts, or nipples

17.5

23.7

29.8

Buttocks

6.7

10.6

15.5

Shoulder

4.4

7.3

11.4

Armpits

2.3

4.7

8.6

Thighs

1

2.8

6.1

Knees

0

0

1.4

Source: GAO review of district dress codes. | GAO-23-105348

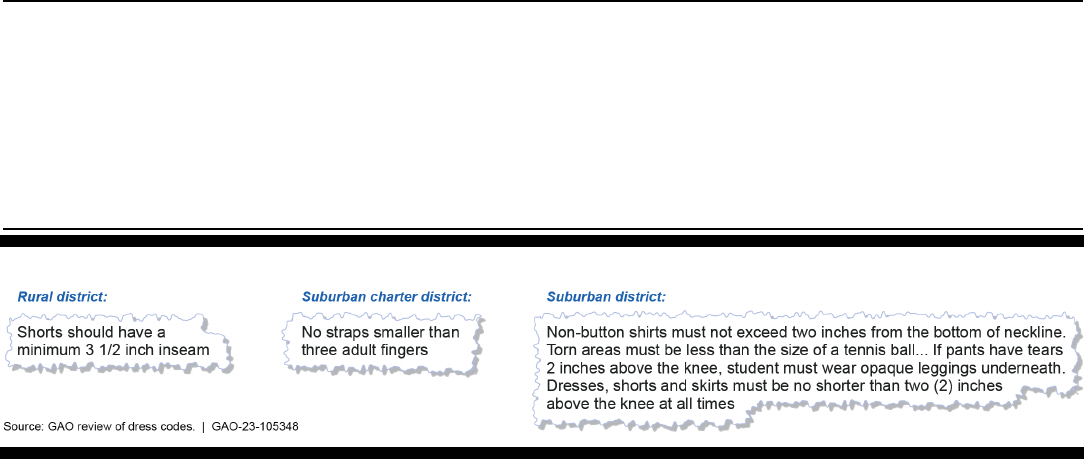

Rules requiring measurements and subjective interpretation. An

estimated 60 percent of districts use measurements to determine if

student clothing is permitted, based on our generalizable sample of

districts (see fig. 5).

Letter

Page 14 GAO-23-105348 K-12 Education

Figure 5: Dress Code Excerpts: Examples of Rules Containing Measurements

Accessible Data for Figure 5: Dress Code Excerpts: Examples of Rules Containing Measurements

· Rural district: Shorts should have a minimum 3 1/2 inch inseam

· Suburban charter district: No straps smaller than three adult fingers

· Suburban district: Non-button shirts must not exceed two inches from the bottom of neckline. Torn

areas must be less than the size of a tennis ball... If pants have tears 2 inches above the knee, student

must wear opaque leggings underneath. Dresses, shorts and skirts must be no shorter than two (2)

inches above the knee at all times

Source: GAO review of dress codes. | GAO-23-105348

Officials we spoke with from national organizations raised concerns that

measurement provisions in dress codes may lead to adults touching

students’ bodies to measure clothes. Officials at national organizations

and district officials noted that having staff determine if students’ shorts or

skirts met the required length was embarrassing to students, particularly if

this was done in front of their peers. In our review, we found examples of

dress codes that required students to move or stand in a specific way for

staff to check if their clothing conforms to the stated measurement rule.

For example, one dress code stated, “The test: No bare midsection or

back is revealed when arms are stretched over head.” Officials from

national organizations also raised concerns that aspects of dress codes

may have implications for student privacy. For example, we found

examples of dress codes that require students to wear undergarments,

such as “for females: bras must be worn.”

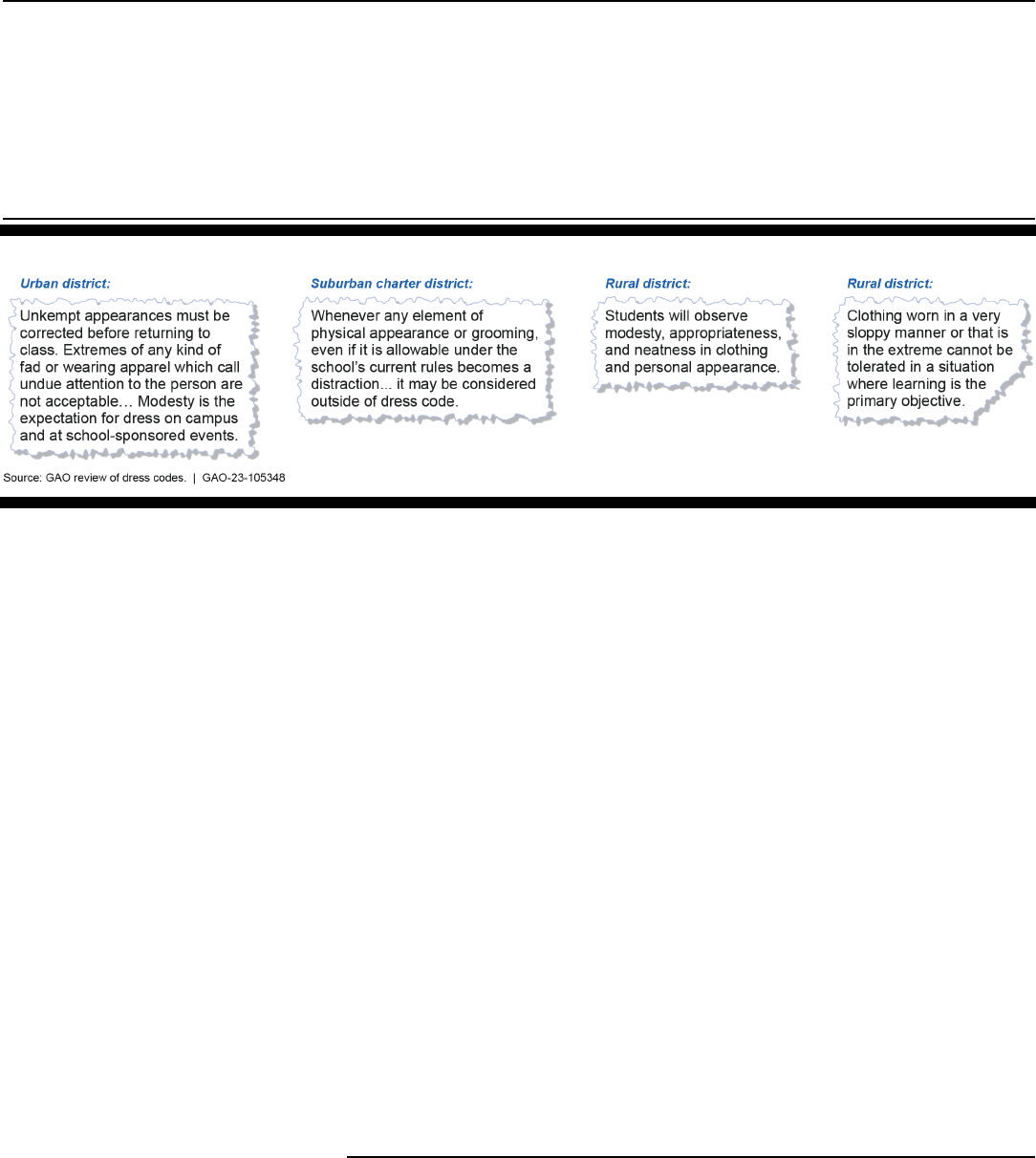

Moreover, almost all district dress code policies (an estimated 93 percent)

contain rules with subjective language that leave decisions about dress

code compliance open to interpretation. Commonly used subjective

phrases, such as “revealing” or “immodest” clothing, often apply to

standards of appearance typically associated with girls and women (see

fig. 6).

Letter

Page 15 GAO-23-105348 K-12 Education

Figure 6: Dress Code Excerpts: Examples of Rules with Subjective Language

Accessible Data for Figure 6: Dress Code Excerpts: Examples of Rules with Subjective Language

· Urban district: Unkempt appearances must be corrected before returning to class. Extremes of any kind

of fad or wearing apparel which call undue attention to the person are not acceptable… Modesty is the

expectation for dress on campus and at school-sponsored events.

· Suburban charter district: Whenever any element of physical appearance or grooming, even if it is

allowable under the school’s current rules becomes a distraction... it may be considered outside of

dress code.

· Rural district: Students will observe modesty, appropriateness, and neatness in clothing and personal

appearance.

· Rural district: Clothing worn in a very sloppy manner or that is in the extreme cannot be tolerated in a

situation where learning is the primary objective.

Source: GAO review of dress

According to researchers and officials at national organizations, rules that

are open to interpretation may also be disproportionately applied to

vulnerable student groups including LGBTQI+ students, Black students,

and students with disabilities.

15

About half of dress codes (an estimated

46 percent) have rules about the way clothing fits students, prohibiting

clothing that is “too tight” or “too loose.” Researchers have raised

concerns that this type of language may be enforced unequally based on

students’ body type or body maturity and risks causing embarrassment

and body shame for students.

15

While a number of variations on this acronym are currently in use to describe individuals

with diverse sexual orientations and gender identities, in this report, we define LGBTQI+

as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, questioning, or intersex. The “plus” is meant

to be inclusive of identities that may not be covered by the acronym LGBTQI+, including

asexual, nonbinary, and individuals who identify their sexual orientation or gender identity

in other ways.

Letter

Page 16 GAO-23-105348 K-12 Education

MostDistrictsHaveRulesaboutHeadCoveringsand

Students’Hair,andFewSpecifyReligious,Cultural,or

MedicalExemptions

Our generalizable analysis of dress codes found that over 80 percent of

districts prohibit head coverings such as hats, hoodies, bandanas, and

scarves; only one-third of these dress codes specify that they allow

religious exemptions; and few specify cultural or disability/medical

exemptions.

16

However, some head coverings have religious or cultural

significance for students (see fig. 7).

Figure 7: Examples of religious and culturally significant head coverings

Accessible Text for Figure 7: Examples of religious and culturally significant head coverings

Students may wear head coverings as a form of religious observance or a way to express cultural identity.

Here are three examples:

· picture of two women wearing a hijab

· picture of children wearing a kippah

· picture of child wearing a kufi cap

Source: GAO summary of interviews with national organizations; stock.adobe.com (photos). | GAO-23-105348

16

An estimated 5 percent of district dress codes specified exemptions for cultural items.

An estimated 30 percent of dress codes specify exemptions for medical or disability-

related items, such as allowing students with certain medical conditions to wear a baseball

cap. We reviewed publicly available dress code information from school districts; we did

not ask school district officials about religious, cultural, or disability-related exemptions.

The fact that a dress code did not specify an exemption does not necessarily mean that

the district does not allow for an exemption.

Letter

Page 17 GAO-23-105348 K-12 Education

In addition, most dress codes (an estimated 59 percent) contain rules

about students’ hair, hairstyles, and hair coverings, and these rules may

disproportionately impact Black students, according to researchers and

district officials we interviewed. For example, many districts (an estimated

44 percent) ban hair wraps, with some specifically naming durags or other

styles of hair wraps. In addition, one in five dress codes (an estimated 21

percent) include rules on student hair with subjective language such as,

“hair must look natural, clean, and well-groomed” or say students’ hair

must not be “distracting” or “extreme.”

We found a small number of dress codes with restrictions on hair length

(an estimated 2 percent) or dress codes that prohibited shaved lines in

hair (4 percent). Finally, we found examples of dress codes with rules

specific to natural, textured hair, which researchers have noted

disproportionately affect Black students. For example, one district

prohibited hair with “excessive curls” and another stated that “hair may be

no deeper than two inches when measured from the scalp.” (see fig. 8).

Figure 8: Culturally significant hairstyles and hair coverings

Education Case: Investigation of Alleged

Racial Discrimination in an Arizona School

In 2017, Education’s Office for Civil Rights

(OCR) investigated whether a student was

discriminated against on the basis of race

when it was reported that he was repeatedly

told by a teacher, then later the school

director, to cut or change his hair after

wearing an afro. According to OCR

documents, the school director said the afro

violated the school’s policy against “trendy

hairstyles” and school officials also cited

reasons not written in an official policy.

OCR found that the reasons given were

pretexts for discrimination, as the school

allowed “long hair that grows down (the

natural hair growth direction for most White

people), but not long hair that grows out/up

(the natural hair growth direction for most

African American people).” As a result, the

school voluntarily agreed to enter into a

resolution agreement to resolve the matter.

Source: GAO review of Department of Education documents.

| GAO-23-105348

Letter

Page 18 GAO-23-105348 K-12 Education

Accessible Data for Figure 8: Culturally significant hairstyles and hair coverings

Hairstyles, such as cornrows, locks, twists, afros, bantu knots, are an

expression of Black identity, culture, religion, and history.

In addition, the elasticity and texture of Black hair can make it more

susceptible to breaking. Black students may want to wear “protective

hairstyles” like braids and twists to maintain healthy hair. These

hairstyles, and hair coverings such as a durag, can be worn without

manipulating or damaging hair.

Source: GAO summary of NAACP fact sheet; stock.adobe.com (photos). | GAO 23-105348

SchoolDressCodesAreCommonlyAimedatPromoting

SafetyofStudents

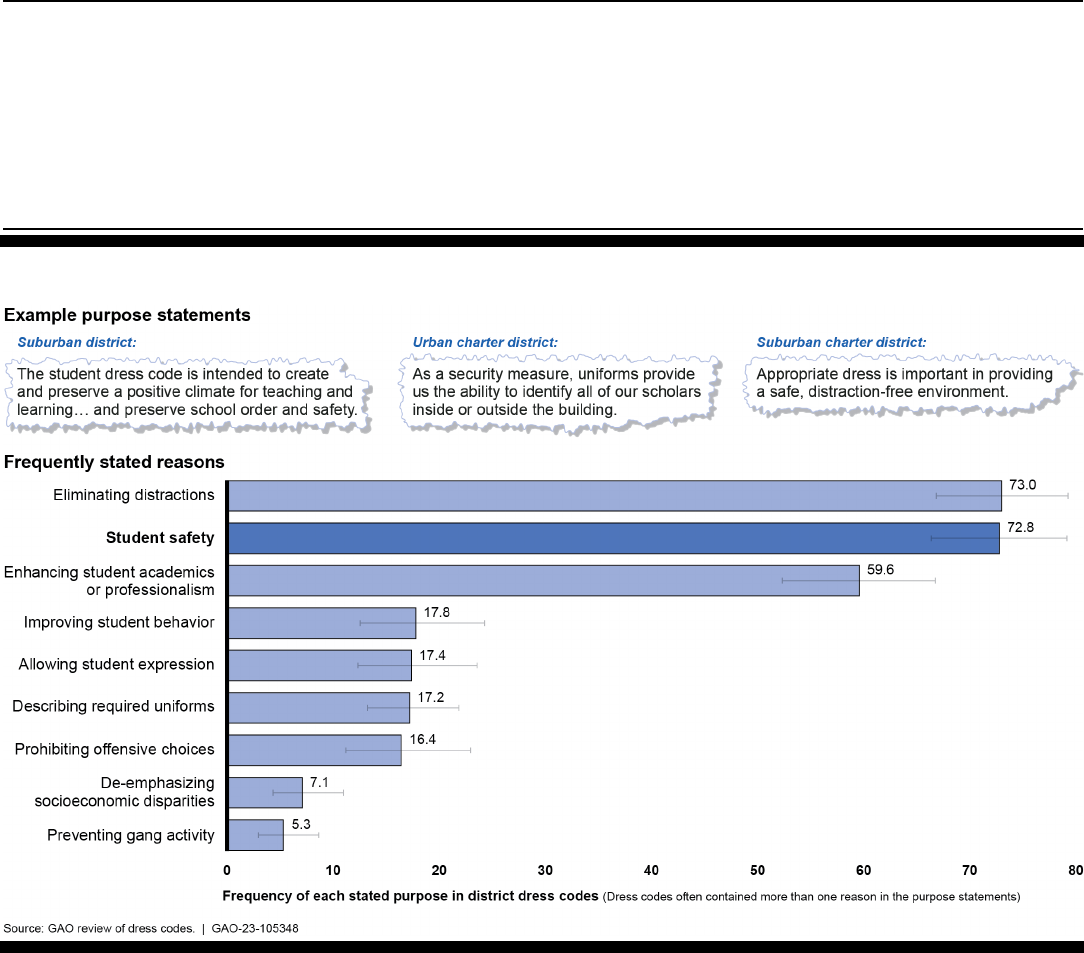

A commonly stated purpose of school dress codes is student safety and

security, with an estimated 73 percent of dress codes citing this as a goal

for the design of their dress codes (see fig. 9). Education officials noted

that schools can use dress codes to address safety and security, and

district officials stated that aspects of their dress codes were aimed at

promoting student safety. For example, officials in two of the districts we

interviewed said that in their districts, prohibiting hats and head coverings

is a safety measure to ensure administrators can readily identify students.

Letter

Page 19 GAO-23-105348 K-12 Education

Figure 9: Estimated Percentage of School Districts Citing a Particular Purpose for Their Dress Code, among the Estimated 92

Percent of Districts That Stated a Purpose

Accessible Data for Figure 9: Estimated Percentage of School Districts Citing a Particular Purpose for Their Dress Code,

among the Estimated 92 Percent of Districts That Stated a Purpose

· Suburban district: The student dress code is intended to create and preserve a positive climate for

teaching and learning… and preserve school order and safety.

· Urban charter district: As a security measure, uniforms provide us the ability to identify all of our

scholars inside or outside the building

· Suburban charter district: Appropriate dress is important in providing a safe, distraction-free

environment.

Frequency of each stated purpose in district dress codes

(Dress codes often contained more than one reason in the purpose statements)

Letter

Page 20 GAO-23-105348 K-12 Education

Frequently stated reasons

Lower bound

Estimate

Upper bound

Eliminating distractions

66.8

73

79.3

Student safety

66.3

72.8

79.2

Enhancing student academics or professionalism

52.3

59.6

66.8

Improving student behavior

12.5

17.8

24.3

Allowing student expression

12.3

17.4

23.6

Describing required uniforms

13.2

17.2

21.9

Prohibiting offensive choices

11.1

16.4

23

De-emphasizing socioeconomic disparities

4.3

7.1

11

Preventing gang activity

2.9

5.3

8.7

Source: GAO review of district dress codes. | GAO-23-105348

However, a range of stakeholders we interviewed—from school districts,

national organizations, and researchers—noted that aspects of dress

codes may inadvertently contribute to a less safe and secure environment

for students, particularly girls, for several reasons:

· The focus on clothing typically associated with girls reinforces the

harmful view that girls are responsible for distracting boys.

17

Researchers have pointed out that this unfairly burdens girls.

· Dress codes that focus on girls’ clothing and bodies contribute to

shifting the burden of being harassed from the perpetrator to the

victim, thus potentially creating an environment that is less safe for

girls.

18

· Dress codes that involve measurements or that may necessitate

adults touching students, leave students, often girls, more vulnerable

to inappropriate touching and sexual harassment.

17

In its 2021 primer on “Students Experiencing Inattention and Distractibility,” the

American Psychological Association (APA) notes that educators should not make

assumptions or claims about what is causing students’ inattention. On the topic of

sexualization of girls, the APA states that “parents can teach boys to value girls as friends,

sisters and girlfriends, rather than as sexual objects.”

18

The APA reports that sexualizing clothing may be a factor in harassment of girls. The

APA report underscores that girls do not “cause” harassment or abusive behavior by

wearing “sexy” clothes; and that no matter what girls wear, they have the right to be free of

sexual harassment and boys and men can and should control their behavior. American

Psychological Association, Task Force on the Sexualization of Girls, Report of the APA

Task Force on the Sexualization of Girls (2007), retrieved from

http://www.apa.org/pi/women/programs/girls/report-full.pdf.

Letter

Page 21 GAO-23-105348 K-12 Education

EducationDoesNotProvideInformationonHowto

DesignEquitableandSafeDressCodes

Education does not make resources available on creating equitable dress

code policies; however, researchers and officials from national

stakeholder organizations and school district officials we spoke with said

such information would be helpful. For example, officials from national

organizations and researchers said that districts and schools could

benefit from examples of more equitable dress codes that have gender-

neutral and gender-inclusive language. Officials in our three selected

school districts—all of which recently revised their dress codes to

promote equity—noted challenges during the revision process (see

appendix III for more information on these selected districts).

19

Specifically, they noted that districts can have difficulty finding guidance

or best practices on designing equitable dress codes. They all said that a

key reason for revising their dress codes was that girls felt unfairly

burdened by the previous policies. In addition, they and officials from

national stakeholder organizations told us they are concerned about

language in dress codes that is not inclusive of all gender identities.

20

Research on dress code policies bear out these concerns. According to a

2019 national school climate survey, 18 percent of LGBTQI+ youth

reported that their school prevented them from wearing specific clothing

because it did not fit with the school’s perception of clothing appropriate

for their gender.

21

In our review of dress codes, we found that an

estimated 15 percent of districts’ dress codes specify different rules for

clothing, accessories, or hairstyles based on students’ sex, such as “no

fingernail polish or makeup is allowed on male students.” None of the

dress codes we reviewed with sex-based rules explicitly protect

19

One district aimed to increase socioeconomic equity by implementing uniforms; the

other two districts included changes such as eliminating gender-based language, limiting

subjective language, and increasing awareness of cultural identities.

20

Gender identity can be defined as a person’s innate, deeply felt psychological sense of

gender, which may or may not correspond to the person’s sex assigned at birth. Gender

identity is distinct and separate from sexual orientation.

21

Responding to the survey were 16,713 youth who identify as LGBTQI+ between the

ages of 13 and 21. The survey was administered between April and August 2019. J.G.

Kosciw, C.M. Clark, N.L. Truong, and A.D. Zongrone, The 2019 National School Climate

Survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer youth in our

nation’s schools (New York: GLSEN, 2020).

Letter

Page 22 GAO-23-105348 K-12 Education

transgender or nonbinary students’ ability to dress according to their

gender identity.

Education has guidance on ways schools can support racial, cultural, and

gender equity, but this guidance does not explicitly address dress codes.

When we asked Education officials about providing districts or schools

with information to help them design equitable dress code policies, the

officials responded that the agency is committed to working on a range of

important topics and continues to consider a range of options to provide

helpful resources to stakeholders and the public. However, as of

September 2022, Education officials had not provided any additional

information on this topic. Resources to help districts and schools design

more equitable dress codes would align with Education’s goals to support

and build schools’ capacity to promote positive, inclusive, safe, and

supportive school climates in a nondiscriminatory manner.

Education also has a range of resources available on safety, security, and

school climate, but these publications contain limited information about

dress codes.

22

For example, Education’s National Center on Safe and

Supportive Learning Environments (NCSSLE) states that a positive

school climate “reflects attention to fostering social and physical safety,

providing support that enables students and staff to realize high

behavioral and academic standards as well as encouraging and

maintaining respectful, trusting, and caring relationships throughout the

school community.”

23

However, NCSSLE’s resources related to school

22

U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights, Fact Sheet: Supporting Intersex

Students (October 2021),

https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/ocr-factsheet-intersex-202110.pdf; U.S.

Department of Education Office for Civil Rights and Department of Justice Civil Rights

Division, Fact Sheet: Confronting Discrimination Based on National Origin and

Immigration Status (August 2021),

https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/confronting-discrimination-national-origin-i

mmigration-status; U.S. Department of Education, Supporting Transgender Youth in

School (June 2021),

https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/ed-factsheet-transgender-202106.pdf.

23

U.S. Department of Education, Office of Safe and Healthy Students, Quick guide on

making school climate improvements (Washington, D.C.: 2018),

http://safesupportivelearning.ed.gov/SCIRP/Quick-Guide.

Letter

Page 23 GAO-23-105348 K-12 Education

safety or school climate improvement do not have information on the

design or implementation of dress codes.

24

Because many districts view dress codes as facets of larger safety,

security, and school climate policies, incorporating dress code information

and examples into existing safety and security resources could better

enable Education to efficiently provide information to districts and schools

that enhances social and physical safety for all students, a key agency

goal. Education officials stated that OCR and NCSSLE would work

together to support, among other things, the possible development of

additional discipline resources that Education would make available.

However, as of September 2022, Education had not provided dress code

information in agency resources on safe and secure schools.

By providing resources to districts and schools on the design of dress

codes that includes information on equity and safety, Education could

further support its mission to provide equal access to educational

opportunity. In the absence of this information, Education may miss an

opportunity to help districts create or revise dress codes to promote a

safe, supportive learning environment that embraces all students.

SchoolsThatEnforceStrictDressCodes

SuspendandExpelMoreStudents,andMay

24

Education officials noted that the NCSSLE has some resources available on its website

that were not developed by Education, and two of these resources mention dress codes.

For example, a 2014 report on school discipline provides dress code violation examples

and recommendations. See E. Morgan, N. Salomon, M. Plotkin, and R. Cohen, The

School Discipline Consensus Report: Strategies from the Field to Keep Students Engaged

in School and Out of the Juvenile Justice System (New York: The Council of State

Governments Justice Center, 2014). However, these resources do not represent

Education’s official positions.

Letter

Page 24 GAO-23-105348 K-12 Education

AlsoInformallyRemoveStudentsforDress

CodeViolations

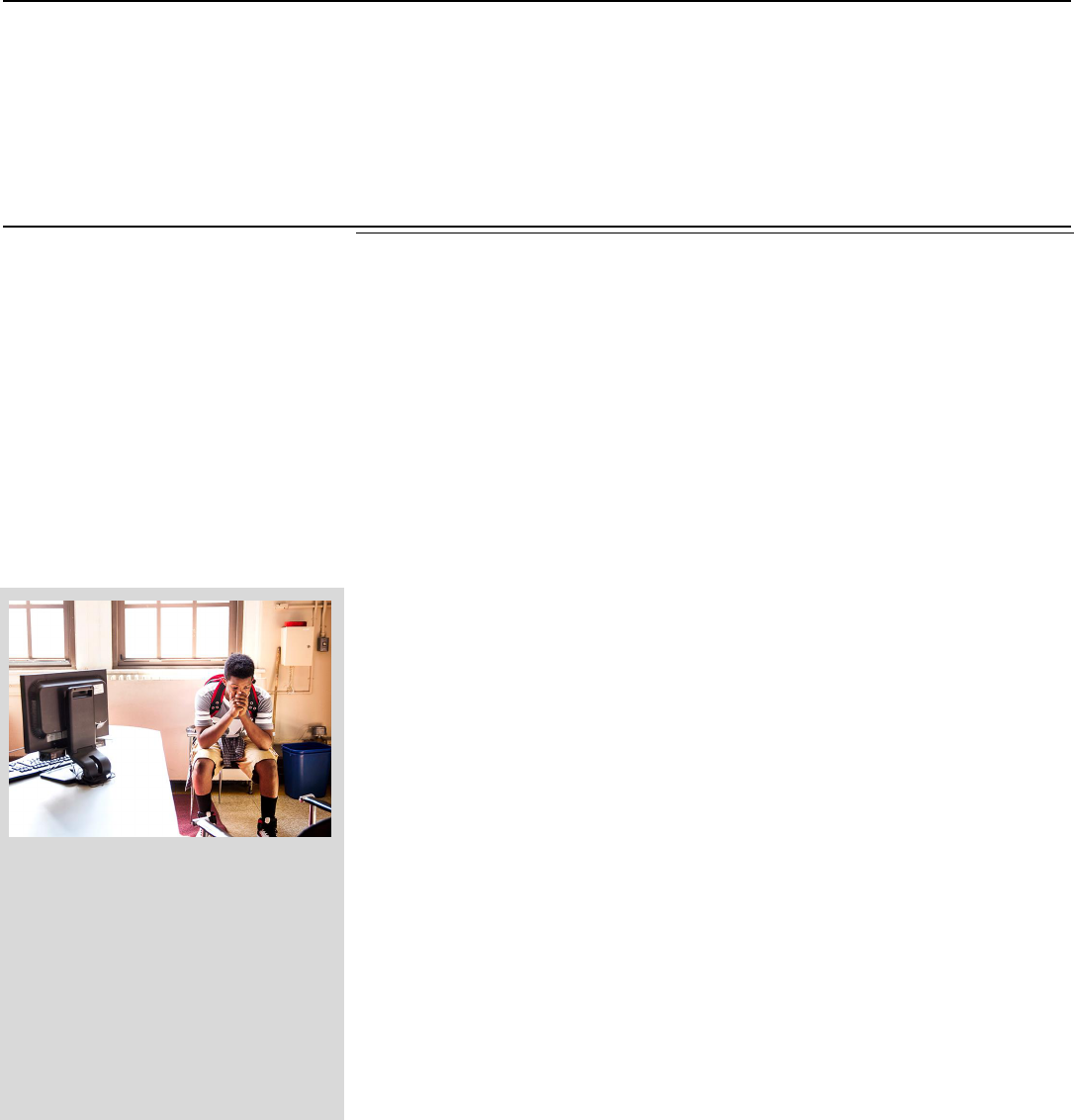

SchoolswithLargerProportionsofBlackandHispanic

StudentsandSchoolsintheSouthAreMoreLikelyto

EnforceaStrictDressCode

According to our analysis of Education’s 2017-18 School Survey on

Crime and Safety (school survey) data, schools with higher percentages

of Black and Hispanic students are more likely to enforce strict dress

codes, holding other school characteristics constant.

25

This analysis

shows that the likelihood of a school enforcing a strict dress code

increases as the percentage of Black and Hispanic students increases.

As shown in figure 10, more than four in five predominantly Black schools

(schools where Black students comprise at least 75 percent of the student

body) and nearly two-thirds of predominantly Hispanic schools enforce a

strict dress code.

25

We performed a logistic regression analysis to hold other school characteristics—such

as geographic region, grade level, and school type—constant. Our analysis was limited by

the collinearity of race and poverty, as race and poverty are closely linked. In our analysis,

it was not possible to identify how much a school’s likelihood of enforcing a strict dress

code is attributable to race versus poverty.

Letter

Page 25 GAO-23-105348 K-12 Education

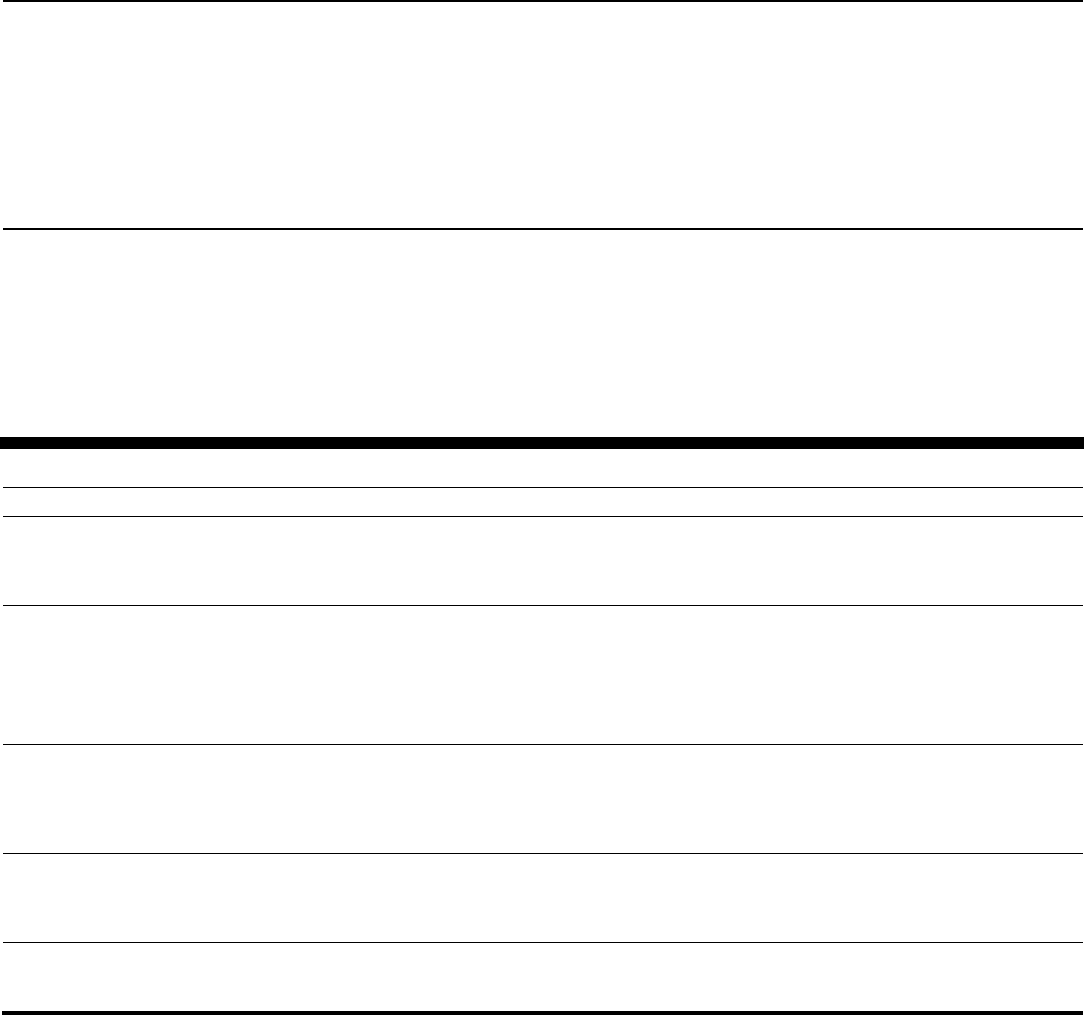

Figure 10: Estimated Percentage of Schools in Each Racial/Ethnic Category That

Report Enforcing a Strict Dress Code, School Year 2017-18

Accessible Data for Figure 10: Estimated Percentage of Schools in Each

Racial/Ethnic Category That Report Enforcing a Strict Dress Code, School Year

2017-18

Percentage of schools

Category

Lower

bound

Estimate

Upper

bound

Average for all U.S. schools

n/a

48.8

n/a

Predominantly Black schools

72.7

81

87.7

Predominantly Hispanic schools

61.6

62.8

64.0

Predominantly White schools

35.0

35.5

36.0

Source: GAO analysis of the Department of Education 2017-2018 School Survey on Crime and

Safety (SSOCS). | GAO-23-105348

Notes: Schools “predominantly” of a certain race/ethnicity are those where students of that particular

race/ethnicity make up 75 percent or more of the student population. We could not report on schools

predominantly enrolling Asian/Pacific Islander, Native American/Alaskan Native, or Multirace students

due to insufficient data. In addition, Hispanic students can be any race, but in Education’s data,

Hispanic is considered an ethnicity exclusive of race. Using a 95 percent confidence interval, the

margin of error for each school group is within +/- 8 percentage points.

A higher percentage of schools in the South enforce a strict dress code

with just over 70 percent of schools in the West South Central states

enforcing a strict dress code (see fig. 11). In contrast, less than 30

percent of schools in the West North Central states and in New England

enforced a strict dress code.

Q&A: What does “enforce a strict dress

code” mean?

In this report, schools that “enforce a strict

dress code” are identified and reported using

Education’s School Survey on Crime and

Safety, which asks school administrators,

“During the 2017-18 school year, was it a

practice of your school to enforce a strict

dress code?” The survey does not define “a

strict dress code” so school administrators

could interpret this question differently.

Enforcing a strict dress code and requiring

uniforms are addressed separately in the

survey. Regarding uniforms, the survey asks

“Was it a practice of your school to require

students to wear uniforms?” The data show

that, of schools that require a uniform, an

estimated 88 percent (95 percent confidence

interval 82.6-91.9) also report enforcing a

strict dress code. Of schools with strict dress

codes, only about 36 percent (95 percent

confidence interval 32.5-39.0) also report

requiring a uniform.

Source: GAO analysis of Education’s School Survey on

Crime and Safety. | GAO-23-105348

Letter

Page 26 GAO-23-105348 K-12 Education

Figure 11: Estimated Percentage of Public Schools That Report Enforcing a Strict Dress Code, by Census Division, School

Year 2017-18

Accessible Data for Figure 11: Estimated Percentage of Public Schools That Report Enforcing a Strict Dress Code, by Census

Division, School Year 2017-18

Census Division

Percentage of schools

enforcing a strict dress

code

Pacific (Alaska, Hawaii, Wash., Ore., Calif.)

44

Mountain (Mont., Idaho, Wyo., Nev., Utah, Colo., Ariz., New Mex.)

47

West North Central (N. Dak., S. Dak., Minn., Neb., Iowa., Kan., Mo.)

29

East North Central (Mich., Wisc., Ill., Ind., Ohio)

43

Mid Atlantic (N.Y., Penn., N.J.)

41

New England (Maine, N.H., Vt., Mass., Conn., R.I.)

28

West South Central (Texas, Okla., Ark., La.)

71

East South Central (Ken., Tenn., Miss., Ala.)

65

South Atlantic (Md., Del., W. Va., Va., N.C., S.C., Ga., Fla.)

57

Source: GAO analysis of the 2017-2018 School Survey on Crime and Safety (SSOCS) administered by the Department of Education; U.S. Census

Bureau (base map). | GAO-23-105348

Note: Using a 95 percent confidence interval, the margin of error for each Census division is within +/-

2 percentage points.

Similarly, when considering the four primary regions of the country (West,

Midwest, Northeast, and South), our regression analysis found that

Letter

Page 27 GAO-23-105348 K-12 Education

schools located in the South are estimated to be more than twice as likely

to enforce strict dress codes than schools in the Northeast.

26

In addition, national data show that schools that enforce strict dress

codes have other characteristics that differ from schools that do not

enforce strict dress codes. According to our regression analysis, schools

that are more likely to enforce a strict dress code have older students

(grades six and above). A higher percentage of large schools—schools

with more than 1,000 students—enforce a strict dress code.

27

An

estimated 71 percent of charter schools enforce strict dress codes

compared to 47 percent of non-charter schools. In addition, schools that

enforce strict dress codes also enroll higher percentages of students

eligible for free or reduced-price lunch—a proxy for students living in

poverty.

28

Officials from national organizations and districts we

interviewed noted that strict dress codes (and uniform requirements)

could pose challenges for low-income families who may struggle to buy

specific clothing items or afford certain hairstyles.

29

We analyzed schools

that require uniforms separately; see text box below.

26

Our odds ratio models estimate the likelihood that schools located in one region of the

country report enforcing a strict dress code, compared to schools located in the Northeast.

There are four Census regions and nine divisions. The West Census region is comprised

of the Pacific and Mountain divisions; the South region is comprised of the West South

Central, East South Central, and South Atlantic divisions; the Northeast region is

comprised of the Middle Atlantic and New England Regions; the Midwest region is

comprised of the West North Central and East North Central divisions. We estimated that

the odds of a school in the South having a strict dress code is 2.7 times the odds of a

school in the Northeast, and the 95 percent confidence interval of this estimate is 1.8-4.1.

27

An estimated 33 percent of small schools (1 to 200 students) report enforcing a strict

dress code compared to 50 percent of medium schools (201 to 1,000 students) and 56

percent of large schools (1,001 or more students). Using a 95 percent confidence interval,

the margin of errors for these estimates is within +/- 2 percentage points.

28

Using a 95 percent confidence interval, the margin of errors for these estimates on

charter schools is within +/- 2 percentage points.

29

Proponents of uniforms in public schools note that these policies can be a cost-savings

for families. However, officials we interviewed from national organizations stated that

uniforms can cause added expenses. For example, uniforms can be expensive and some

schools allow “dress down days or events” so families feel the need to purchase two sets

of clothing for students.

Letter

Page 28 GAO-23-105348 K-12 Education

Characteristics of Schools That Require Uniforms

A higher percentage of schools with the following characteristics require uniforms:

· More Black or Hispanic students: An estimated 72 percent of predominantly

Black and 52 percent of predominantly Hispanic schools require uniforms, as

compared to 2 percent of predominantly White schools. Schools “predominantly” of

a certain race/ethnicity are those where students of that particular race/ethnicity

make up 75 percent or more of the student population.

· Urban: An estimated 40 percent of schools in urban areas require students to wear

uniforms, as compared to 18 percent of schools in suburban areas and 7 percent in

rural areas.

· Elementary schools: An estimated 23 percent of elementary, 18 percent middle,

and 10 percent of high schools require students to wear uniforms.

· Charter schools: An estimated 64 percent of charter schools require students to

wear uniforms compared to 17 percent of non-charter schools.

Source: GAO analysis of the Department of Education’s School Survey on Crime and Safety for school year 2017-18; Rawpixel.com/stock.adobe.com. | GAO-23-105348

Note: Using a 95 percent confidence interval, the margin of errors for these estimates on uniforms is

within +/- 2 percentage points.

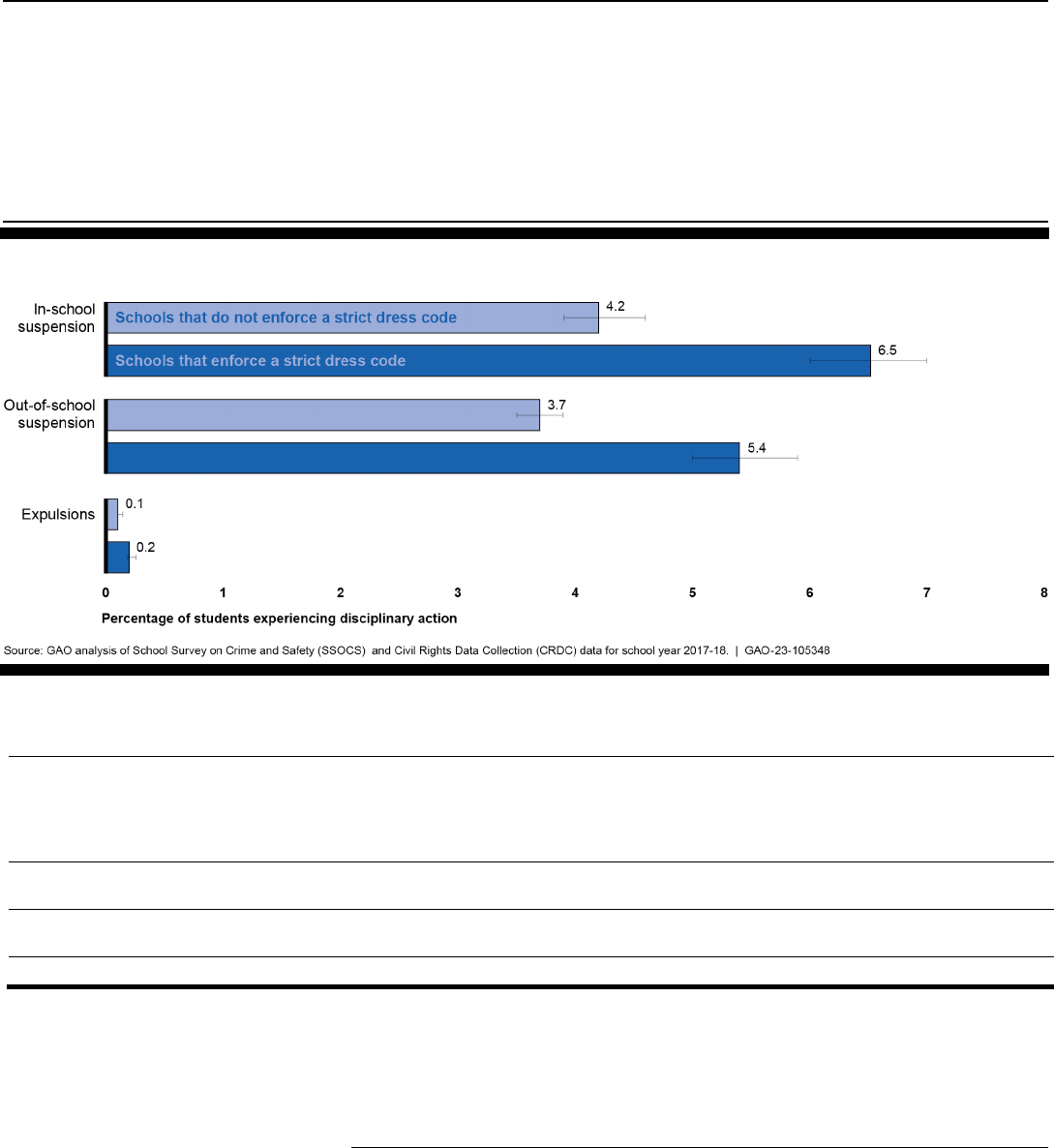

SchoolsThatEnforceStrictDressCodesAreAssociated

withHigherRatesofExclusionaryDiscipline,and

EducationDoesNotHaveGuidanceThatAddresses

DisparitiesinDisciplineEnforcement

Schools that enforce strict dress codes are associated with statistically

significant higher rates of exclusionary discipline—that is, practices that

remove students from the classroom, such as in-school suspensions, out-

of-school suspensions, and expulsions (see fig. 12).

30

This is true even

after controlling for student demographics, school type, size, geography,

and measures of school climate, such as levels of disorder and the

presence of security personnel (see appendix II for more information on

our regressions).

30

“Exclusionary discipline,” or any action that removes students from the learning

environment, includes more severe disciplinary measures such as suspensions and

expulsions, but it can also include sending students to the principal’s office or any other

action that takes a student out of the learning environment.

Exclusionary Discipline in Dress Codes

“Students who violate the [dress code] will not

be admitted to class and may be suspended

from school.”

Letter

Page 29 GAO-23-105348 K-12 Education

In our review of districts’ dress codes, we

found that an estimated 61 percent of dress

codes allow for the removal of students from

class for violations. Dress codes listed both

formal removal from the learning environment

(i.e., in-school and out-of-school suspensions)

and informal removal policies (i.e., students

sent home).

Source: GAO review of school district dress codes. |

GAO-23-105348

Letter

Page 30 GAO-23-105348 K-12 Education

Figure 12: Estimated Percentage of Students Experiencing Exclusionary Discipline in Schools That Enforce Strict Dress

Codes, School Year 2017-18

Accessible Data for Figure 12: Estimated Percentage of Students Experiencing Exclusionary Discipline in Schools That

Enforce Strict Dress Codes, School Year 2017-18

Percentage of students experiencing disciplinary action

Category

Schools that

do not enforce

a strict dress

code (lower

bound)

Schools that do

not enforce a

strict dress code

(estimate)

Schools that

do not enforce

a strict dress

code (upper

bound)

Schools that

enforce a strict

dress code

(lower bound)

Schools that

enforce a strict

dress code

(estimate)

Schools that

enforce a strict

dress code

(upper bound)

In-school

suspension

3.9

4.2

4.6

6

6.52

7

Out-of-school

suspension

3.5

3.7

3.9

5

5.4

5.9

Expulsions

0.1

0.1

0.15

0.18

0.2

0.26

Source: GAO analysis of School Survey on Crime and Safety (SSOCS) and Civil Rights Data Collection (CRDC) data for school year 2017-18. | GAO-

23-105348

Research shows exclusionary discipline is associated with short and long-

term negative outcomes for students, including increased risk for failing

standardized tests and increased rates of drop outs and incarceration.

31

31

One study showed that a single in-school suspension is predictive of significant risk for

academic failure (greater than 25 percent chance of failure) on a state-wide standardized

test, while controlling for individual and school level characteristics. See Danielle Smith,

Nickolaus A. Ortiz, Jamilia J. Blake, Miner Marchbanks III, Asha Unni, and Anthony A.

Peguero. “Tipping Point: Effect of the Number of In-school Suspensions on Academic

Failure,” California Contemporary School Psychology, 25 (May 2020): 466-475.

Letter

Page 31 GAO-23-105348 K-12 Education

For example, students who have been suspended are more likely to drop

out of school and become involved in the juvenile justice system than

their peers.

32

Studies, including our prior work, have shown disparities in who typically

gets disciplined (see sidebar on disparate consequences for dress code

violations). For example, our prior work showed that boys, Black students,

and students with disabilities are disproportionately disciplined across

discipline types, including exclusionary discipline. Other studies also

show Black and Hispanic students are more likely to receive harsher

32

See GAO, K-12 Education: Discipline Disparities for Black Students, Boys, and Students

with Disabilities, GAO-18-258 (Washington, D.C.: Mar 22, 2018).

Letter

Page 32 GAO-23-105348 K-12 Education

school discipline than their counterparts for the same violation.

33

One

study found that Black students were seven times more likely to receive

exclusionary discipline than their White peers.

34

District officials and

national organizations we spoke with echoed these findings and raised

concerns that, overall, dress codes can exacerbate disparities in school

discipline for Black students.

33

For examples of studies on the disproportionate impact for Black and Hispanic students,

see Matthew C. Fadus, Emilio A. Valdez, Brittany E. Bryant, Alexis M. Garcia, Brian

Neelon, Rachel L. Tomko, and Lindsay Squeglia, “Racial Disparities in Elementary School

Disciplinary Actions: Findings From the ABCD Study,” Journal of the American Academy

of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 60, no. 8. (August 2021): 998-1009 and Russell J.

Skiba, Robert H. Horner, Choong-Geun Chung, M. Karega Rausch, Seth L. May, and Tary

Tobin, “Race is Not Neutral: A National Investigation of African American and Latino

Disproportionality in School Discipline,” School Psychology Review, 40, no. 1 (2011): 85-

107.

34

See Aydin Bal, Jennifer Betters-Bubon, and Rachel E. Fish, “A Multilevel Analysis of

Statewide Disproportionality in Exclusionary Discipline and the Identification of Emotional

Disturbance,” Education and Urban Society, 51, no. 2 (2017): 247-268.

Education Case:

Disparate Consequences for Dress Code

and Other Discipline in a California District

In 2022, Education’s Office for Civil Rights

(OCR) found evidence that a California school

district engaged in disparate treatment based

on race in violation of Title VI by disciplining

Black students more frequently and more

harshly than similarly situated White students.

For example, an eighth-grade Black student

was referred for creating a hostile education

environment for wearing his pants low

(sagging) and refusing to pull his pants up

after repeated warnings. It was his first

discipline incident of the school year and he

received a one-day out-of-school suspension.

By contrast, a White eighth-grade student at

the same school was referred for obscenity for

sagging his pants in class after prior warnings.

In student interviews, Black students at one

district school reported to OCR that an

Assistant Principal followed them and treated

them differently from students of other racial

groups, including with respect to dress code

violations. Similarly, at least three students at

another school mentioned concerns about

how the school disproportionately applies the

dress code to Black girls.

To address the violations OCR found and to

ensure non-discrimination in student

discipline, the district entered into a resolution

agreement and committed to conduct a root

cause analysis to examine the causes of

racial disparities in its student discipline and

develop and implement a corresponding

Corrective Action Plan, among other

measures.

Source: GAO summary of Department of Education

document. | GAO-23-105348

Letter

Page 33 GAO-23-105348 K-12 Education

Further, officials from national organizations and districts we spoke with

raised concerns that Black girls may be particularly vulnerable to harm

from dress code enforcement. For example, they noted that dress codes

prohibiting hair coverings and hairstyles could be enforced more often

against Black girls. One study showed that Black girls are disciplined

primarily for less serious and more subjective offenses, such as disruptive

behavior, dress code violations, disobedience, and aggressive behavior.

35

This study also showed that Black girls are three times more likely than

White girls to be referred to the school office. Officials we interviewed at

national organizations also noted that Black girls may be perceived as

wearing more “revealing” or “distracting” clothing because research

shows that Black girls are mistakenly perceived to be older or more

mature.

Although Education does not have guidance that addresses disparities in

discipline enforcement, the agency recently signaled interest in issuing

resources to assist K-12 schools with improving school climate and safety

in the context of discipline. OCR has a goal, consistent with the civil rights

laws the agency enforces, to ensure equal access to education programs

and activities. In June 2021, Education requested information from the

public on discipline issues, including issues related to dress codes by July

23, 2021.

36

However, as of September 2022, it had not issued resources

on these topics. Federal information on how dress codes and other

discipline policies can be enforced in an equitable manner, and address

potential disproportionality, could help support and build schools’ capacity

to promote positive, inclusive, safe, and supportive school climates for

everyone.

35