56 | Social Education | January/February 2023

Social Education 87 (1)

©2023 National Council for the Social Studies

Illinois Global Scholar:

A Story of Teacher Advocacy

for Student Transformation

Seth Brady and Randy Smith

This past September, not long after school started,

NPR’s Morning Edition aired an interview about a

groundbreaking media literacy education law in

Illinois. I (Seth) was listening in the car on my way

to school. This rst-in-the-nation policy requires

all high school students to receive instruction in

media literacy. Among other requirements, stu-

dents must learn to analyze and evaluate media

messages, distinguish fact from opinion, and

reect upon media consumption and production.

A couple of minutes into the piece, host Rachel

Martin asked the professor being interviewed “Are

high school students responsive to this? I mean,

do they get it?” The tone of the question seemed

to tilt Martin’s hand: she appeared skeptical.

Sitting alone in my school’s parking lot, I found

myself answering her question out loud: “I know

at least one high school student who gets it!”

The one high school student I know “gets it”

is Braden Hajer. Braden was a student in my

capstone class back in the days of lockdown and

Zoom school. Two years before the NPR interview

aired (almost to the day) Braden had posed a

question that would lead him to draft the legisla-

tion now being discussed by two adult profession-

als (see page 61). Braden’s work on the bill wasn’t

an accident or lucky happenstance. Braden’s story

was only possible because of another story of

activism. In that story, a broad coalition driven by

Illinois educators marshaled their time, resources,

and collective wisdom to create the Illinois Global

Scholar Certicate and the powerful model of

inquiry that led Braden and dozens of other stu-

dents to take informed action to effect change.

Telling stories of citizen changemakers high-

lights the impact of ordinary people and reminds

us of the power we hold as citizens in a democ-

racy. Such stories also provide valuable instruction

Seth Brady and Randy Smith, along with Kevin Angell (a

student), speak with Senate Leader and IGS sponsor Kimberly

Lightford aer giving testimony at the Illinois State Capitol.

www.socialstudies.org | 57

on how to wield power for the common good.

Given the numerous challenges teachers currently

face, it is critical to become familiar with stories of

teacher advocacy.

Background of the Illinois Global Scholar

Certicate

The Illinois Global Scholar Certicate awards a

seal of merit, on the state-sanctioned transcript, to

students who demonstrate global competency. To

earn this certicate, students must complete eight

globally-focused courses, participate in globally-

focused service learning, engage in global col-

laboration or dialogue, and complete a capstone

project following the Illinois Global Scholar Inquiry

to Action process. This model requires students to

develop actionable questions addressing a spe-

cic issue, conduct research, connect and receive

feedback from two on-the-ground experts, and

then integrate that feedback into an artifact that is

taken into action to effect change. School districts

opt in to offer the certicate and, with the support

of the Illinois State Board of Education, determine

which curricular and extracurricular activities will

meet the four requirements. Illinois is unique

among states offering global education creden-

tials as it is the only state with a certicate created

by, championed, and managed by volunteer

educators. The educators who drove the certi-

cate forward secured funding, assembled a broad

coalition of stakeholders, drafted legislation, and

mobilized statewide support for the certicate.

The story of Illinois Global Scholar (IGS)

began in 2013 when a handful of educators

(Seth Brady, Cindy Oberle-Dahm, Jon Pazol,

Hina Patel, and Mario Perez) completed

Teachers for Global Classrooms, a fellowship

offered by the U.S. Department of State. This

year-long program equips K-12 teachers with

the skills and knowledge they need to integrate

a global perspective into all subject areas. After

finishing the program and completing a field

experience in one of several partner countries,

teachers are given a mandate to infuse a global

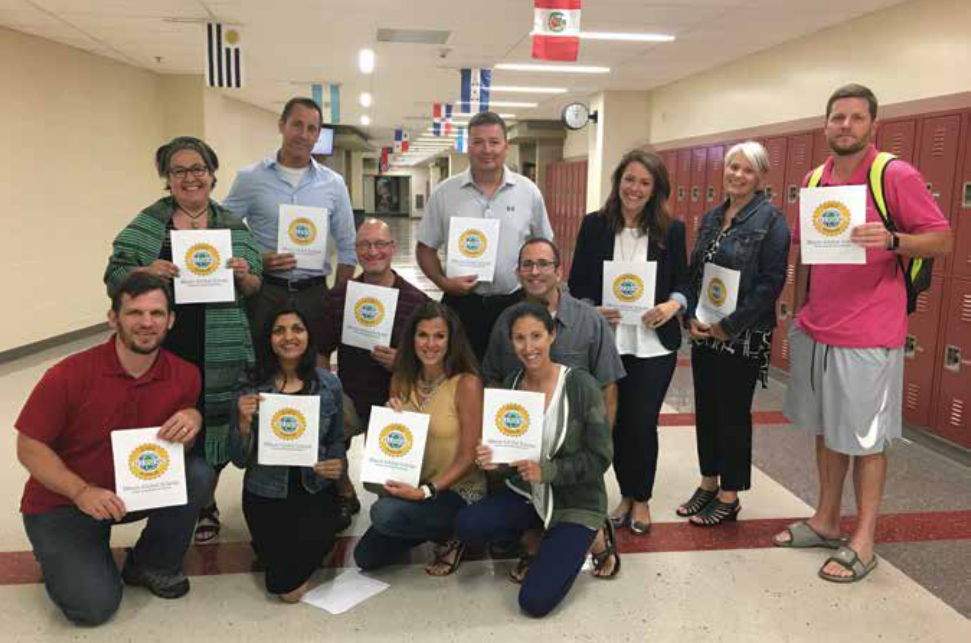

Members of the Illinois Global Scholar Coalition meet to nalize the Illinois Global Scholar Capstone Performance Assessment.

58 | Social Education | January/February 2023

perspective across the curriculum.

Successes and Obstacles

It was with this mandate that we (co-authors Seth

Brady and Randy Smith) began to brainstorm

about what a global education certicate might

look like in our own school district. As this

brainstorming expanded to include teachers in

other school departments, we soon discovered

widespread interest and support. Teachers in

these departments, along with our assistant

principal, formed a loose coalition, and soon we

shared our vision with faculty at the other high

school in our district. By the time we had created

a draft for a district-level certicate, we had easily

hosted more than two dozen meetings, including

several at the district level. With one nal meeting

to go, we expected the certicate to be approved

by the superintendent and then the school board.

Instead, we received a polite “no thank you.”

Though difcult to accept initially, the school

district’s answer made sense. Leadership liked the

idea of creating a certicate to recognize global

competence and the potential impact the initiative

might have for students, but had to weigh this

interest against limited time, resources, and fund-

ing. District leaders were already grappling with

several ongoing initiatives and didn’t want to take

up bandwidth by adding one more. Despite the

logic, the rejection was devastating and humbling.

We had gathered together a coalition of educa-

tors who saw value in the certicate and were will-

ing to expend their limited bandwidth to see the

program come to fruition. Why couldn’t district

leaders do the same?

Three weeks after our initial rejection from

our school district, we were awarded three

grants totaling over $30,000 to gather together

stakeholders to develop criteria for a state-level

global education certicate in Illinois. The grants

came from the U.S. Department of State/IREX; the

European Union Center at the University of Illinois

(a U.S. Department of Education Title VI Outreach

Center); and the Longview Foundation, a private

Members of the Illinois Global Scholar Coalition score student work to establish the interrater reliability of the Illinois Global

Scholar Capstone Performance Assessment.

www.socialstudies.org | 59

philanthropic organization committed to expand-

ing global education opportunities across the

country. These organizations provided much more

than funding. They served as partners connecting

us with people, answering our questions, and

providing information about and connections with

states that were developing programs similar to

the one we envisioned.

Building a Coalition

The support of these institutions helped us

build capacity and connected us to a national

network of global educators. With no state-level

global education network, we started with

someone we knew: Dr. Darlene Ruscitti, Regional

Superintendent of Schools for our county. While

we only expected a half-hour meeting, Dr. Ruscitti

enthusiastically embraced the idea and spent

two hours explaining the demographic and geo-

graphic diversity of our state and the importance

of gathering stakeholders that reected this

diversity. She insisted that the certicate should

be accessible to students and districts. She also

mentioned a handful of organizations she felt

would be interested in the certicate we were pro-

posing. After school and occasionally during lunch

hours, we began to contact these organizations

and share our vision. After making several calls,

we developed a specic approach. We began by

describing IGS with a two-minute elevator pitch

about the program, then requested advice, and

nally inquired about who else we should connect

with. We found that this approach honored the

wisdom each person had to offer. The approach

also invited people into our process as thought

partners and allowed us to expand our network

with very few cold calls.

After several months, we managed to engage

several dozen educators, most of the Title VI

Centers in our state, professors and others in

higher education, business leaders, and non-prot

organizations. These stakeholders helped us

see value in the certicate we hadn’t seen. Prior

to making these connections we had seen the

Members of the Illinois Global Scholar Coalition and Dr. Lydia Kyei-Blankson (far le) at a meeting to assess the Capstone

Performance Assessment for interrater reliability.

60 | Social Education | January/February 2023

certicate primarily as a means of forwarding cur-

ricular outcomes and providing rich experiences

for students. After speaking with stakeholders we

came to see the certicate as a means of prepar-

ing a global workforce, as a critical component

of STEM education, as a means to bolster Illinois

agriculture and agribusiness sectors, as a means

of attracting foreign investment to our state, as an

opportunity to build community and foster toler-

ance, and much more.

In addition to expanding the purpose and

appeal of the certicate, coalition building also

connected us with people such as Shawn Healy,

Donna McCaw, and Mary O’Brian who had the

expertise needed to help us with policy creation,

workshop organization, and assessment.

Reaching Consensus

The people we engaged to help with policy, work-

shops and assessment were critical to harnessing

the energy of the 50+ stakeholders who attended

Illinois Global Scholar workshops. The goal of

these workshops was to reach consensus on

certicate requirements and begin the process of

developing a robust assessment of global compe-

tency. Though these goals would be reached, the

process took time and effort as questions related

to equity, access, and rigor surfaced during work-

shop deliberations. Would the certicate require

a minimum grade point average? Would schools

that were less well-resourced be able to admin-

ister the certicate? Could four years of a world

language be required? What were the criteria by

which global courses would be determined?

As members of the coalition grappled with

these questions, a set of core values began to

emerge that came to inform decision making

about the certicate. This consensus building

didn’t mean everyone present got everything they

wanted. For example, prior to the workshops one

of our most important partners, the Illinois State

Board of Education (ISBE) indicated that it would

not support a certicate program that included a

four-year world language requirement because

less than half of the schools in Illinois offered a

fourth-year course. Members of the Illinois Council

of Teaching Foreign Languages strongly objected.

They had hoped that the certicate would expand

world language instruction in our state and were

disappointed with the state Board of Education’s

position.

On the assessment side, workshop attendees

labored to articulate a shared vision of what a

global scholar looks like, knows and can do. Once

this vision was established, the team developed

a set of tasks that would allow a student to

demonstrate these characteristics, and routed

state and national standards to these tasks. In the

end, the workshops resulted in a set of certicate

requirements as well as a draft of the capstone

performance assessment. Though this assessment

would be rened through several pilot studies,

expert validation, interrater reliability measures,

and the collective genius of several dozen more

educators, the assembled coalition had reached

consensus on certicate requirements and devel-

oped a shared vision of what students would need

to do to be declared an Illinois Global Scholar.

Navigating the Legislative Process

After developing the requirements for a future

certicate, a small team worked with the Illinois

State Board of Education to draft a two-page bill.

Though the legislative rules would eventually

total over 40 pages, limiting the initial bill to two

pages was strategic in that it narrowed the bill

to its essential elements, allowing legislators to

focus on the substance rather than the minutia of

implementation.

With a draft bill created, the team decided

to try to introduce the bill into both the Illinois

Senate and the House of Representatives,

allowing two opportunities for the bill to pass.

Many legislators responded to our sponsor-

ship requests with polite rejection. However,

our experience of coalition building left us

undeterred, and we quickly found legislators

to sponsor a bill in each chamber of the Illinois

General Assembly. With sponsors established, we

mobilized our coalition and began to systemati-

cally seek the support of all of the legislators

in our state. We made phone calls, sent emails,

solicited and wrote institutional letters of sup-

port, and even met many legislators in person.

To aid this effort, we created a well-designed

one-page fact sheet that explained the value the

certicate would have to different constituencies

and interests as well as an FAQ sheet to respond

www.socialstudies.org | 61

to legislator questions and pushback. Though we

would continue to receive a few polite rejections,

we slowly built up the number of sponsors and

succeeded in gaining support for the bill from

inuential legislators on both sides of the aisle,

including members of both party’s leadership.

In preparation for committee hearings, we asked

our coalition to create lists of stakeholders who

would be willing to le witness slips and found

students eager to give testimony. Once committee

hearings were scheduled, we sent out encourag-

ing emails with detailed instructions on how to le

witness slips. We took students to the state capitol

to testify and meet with legislators directly. When

the bill passed, we had a total of 39 sponsors

across both chambers and both political parties.

In the end, of the 165 votes cast, 160 legislators

voted for the bill, with only a handful of nays.

Implementation and Transformation

After the governor signed the bill, our school

district, which had originally passed on our

proposal, became the rst district in the state

to adopt the Illinois Global Scholar Certicate.

In the course of two years, we had overcome

several obstacles, built a broad coalition, reached

consensus on requirements, and managed

to move a bill through the Illinois Legislature.

And once this was achieved, we ended where

we began: with students. Students in our own

school, some of whom played a role in the bill’s

success, enrolled in a capstone course intent

on earning the certicate. Months before, the

assessment group had unanimously agreed that

the goal of the Illinois Global Scholar Capstone

Assessment should be “transformation.” I

remember privately thinking that this goal was

much too ambitious for a single course. However,

the collective genius of educators resulted in a

powerful new performance task now referred to

as the Inquiry to Action Process.

Students begin the Inquiry to Action Process by

developing an actionable question addressing a

global issue in a specic context. They then launch

an investigation and conduct research that seeks

to identify the wide range of factors that contrib-

ute to a given issue. Students then draft an artifact

and then rene the artifacts in light of feedback

from on-the-ground experts who students them-

selves must locate. Finally, students take these arti-

facts into action in domestic and global contexts

to effect measurable change.

In the very rst year the Illinois Global Scholar

Certicate was available, one student created an

inquiry question that sought to determine the

best way to end a future Ebola outbreak. This

question resulted in her coding a choose-your-

own-adventure game in which the player is a

Doctors Without Borders doctor experiencing an

Ebola outbreak. Rooted in the student’s research

on Ebola, the player of the game has to make

choices and experience the consequences of

their choices. Having had this game reviewed by

volunteers and Doctors Without Borders doctors

in Sierra Leone, the game was deployed in class-

rooms in Sierra Leone, with a pre-test and post-

test demonstrating that the playing of the game

deepened understanding of Ebola and positively

changed attitudes and risk behaviors related to

Ebola. Another student, who just wanted ”to do a

project on fashion” ended up becoming engaged

in the Bangladeshi labor movement and created

Braden’s story

Braden’s research into the history of misinformation resulted in his mission to do everything he could to help students

navigate the new media environment he (and we) nd ourselves in. Aer struggling with how to best eect change, he

draed a bill and then contacted Peter Adams from the News Literacy Project and Bill Adair, professor at Duke and

founder of Politifact, and requested their feedback. Using their input, he made adjustments to his dra bill, and then

contacted legislators who agreed to sponsor the bill. Next, Braden gave testimony to the Illinois General Assembly,

convinced more legislators to sponsor the bill, and launched a campaign to get ordinary citizens to complete witness

slips. In the end, the bill passed and Illinois became the rst state to pass mandatory media literacy education. ough

the NPR coverage made no mention of the eorts, the facts are clear: mandatory media literacy education would not

exist in Illinois without the civic activism of a high school student. He certainly “gets it.”

62 | Social Education | January/February 2023

a Public Service Announcement in the Bangla

language to help an NGO teach Bangladeshis

that joining a labor movement is legal. Future

students would go on to deploy disability edu-

cation modules for Afghan teachers, develop

an evaluative tool for international service

trips, and create a high-level graphic novel to

address suicide in Japan. In these examples

and many others, the powerful inquiry process

developed as part of Illinois Global Scholar

Certificate transformed students into globally-

engaged changemakers.

Lessons Learned

Though there are dozens more projects that

could be highlighted, what we realized over

time is that the process we were asking stu-

dents to go through was more or less the same

process we had gone through to create the cer-

tificate. We started with a question: How could

global education opportunities be improved for

Illinois students? We engaged in an investiga-

tive process to determine certificate require-

ments. We worked with a broad coalition of

expert professionals and revised the certificate

in light of their feedback. And we took action to

effect change. As is the case with students who

pursue the IGS certificate, our process came

with many lessons learned that are valuable to

educator-advocates:

1. Vision-Advice-Connection

When communicating with potential

stakeholders, be sure to clearly express

your vision, ask for their advice, and

never forget to ask with whom else you

might connect. This formula is a powerful

way to engage people with your idea

and coalition build. Asking for advice

honors the expertise and experience of

the person being asked and invites them

to add to the vision expressed. This in

turn helps build relationships and sets

the stage to inquire about other people

with similar interests.

2. Build a Broad Coalition

When considering advocacy, spend time

building a broad coalition. Though this

takes time, the process of coalition build-

ing around a particular idea or policy

can help vet and improve a proposed

policy or idea. This not only builds buy-in

within the coalition, it prepares coalition

members to address future pushback

or objections. Where legislation is

concerned, members of a coalition can

be called upon to contact legislators, le

witness slips, or garner support.

3. Consider the district or state as a

whole

How will a proposed piece of legislation

help all of the stakeholders involved

(students, educators, or schools) in your

district or state? What burdens might the

legislation place on citizens, students,

educators or students in your district or

state? To what extent does a policy lead

to shared prosperity for all stakeholders?

4. Consider situating yourself as a

peacebuilder

Social studies teachers often nd

themselves navigating a wide variety

of student perspectives and are well

aware of the fact that political labels

rarely encapsulate the complexity of any

individual person. Rather than assume

that a particular issue will be embraced

or rejected by one party or another, con-

sider seeing yourself as a peacebuilder

who seeks to understand the diverse

needs and interests of each individual

legislator and the constituents they serve.

5. Develop a communication strategy

Different stages of advocacy require

different methods of communication

and different media. Be ready with a

one-minute, three-minute, and ve-

minute “elevator speech” and prepare

a one-page information sheet that

presents the idea or policy, addresses

the most common concern or criticism,

and explains how the policy will benet

various groups of people.

www.socialstudies.org | 63

6. Access and equity are critical in

education

Equitable access to educational pro-

grams is critical to success. As such,

create policies and ideas that address

barriers to participation.

Conclusion

Educators occupy a unique position in their com-

munities. They stand at the intersection of local,

state, and federal policy and are entrusted to pre-

pare students to become active engaged citizens

in their communities. Though equipping teachers

with the skills and knowledge needed to advocate

may take teachers outside the traditional scope

of their duties, educators have a responsibility to

act for the common good and teach their students

to do the same. Given the challenges that face

our communities, nation, and world, becoming

advocates for students and schools is perhaps the

highest calling of both citizenship and the teach-

ing profession.

Seth Brady is an award-winning educator from

Naperville Central High School in Naperville,

Illinois, where he has taught for the past

years. In addition to organizing the coalition of

stakeholders to create a global education certicate

for Illinois high school students, Seth serves as

project director for Illinois Global Scholar. He

is an author of the C Framework for Religious

Studies and a strong advocate for religious literacy,

restorative practice, and inquiry.

Randy Smith has been an educator at Naperville

Central since . His primary courses are

AP Human Geography, AP US Government

and Politics, and American Government. He is

the Congressional Debate Team Head Coach

and serves during the summer as a reader or

table leader for the College Board in AP US

Government. He loves the way in which his

central role in creating the Illinois Global Scholar

certicate brought about a dynamic fusion of his

interests and passions, and yet more importantly,

has presented unique opportunities for dynamic

enrichment for students.

Interested in discussing advocacy or Illinois Global Scholar?

Email [email protected] or visit www.global-illinois.org

e Teachers’ Institute is FREE!!

Participants only pay their round-trip travel expenses to Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Learn in depth about Islamic faith, practice, history, and culture from university-level scholars.

Engage with curricular resources to teach about Islam in social studies, religion, or world history classes.

Utilize Institute materials, and collaborate on a final project that lends itself to immediate use in the classroom!

WWhile the focus of this Institute is on secondary education, we accept and consider applications from a diversity

of professionals.

Dar al Islam provides books, supplementary materials, access to our online knowledge base, on-site room and

board, and transportation between our campus in Abiquiu and the Albuquerque International Airport.

Apply Now! Applications are accepted on a rolling basis until May 15th with priority given to those submitted by

April 1st.

For more information visit www.daralislam.org.

F

For questions, contact us at [email protected].

Understanding Islam and Muslims

Dar al Islam is pleased to offer our 34th annual residential Teachers’ Institute

July 9 - July 22, 2023 in Abiquiu, New Mexico