1

2

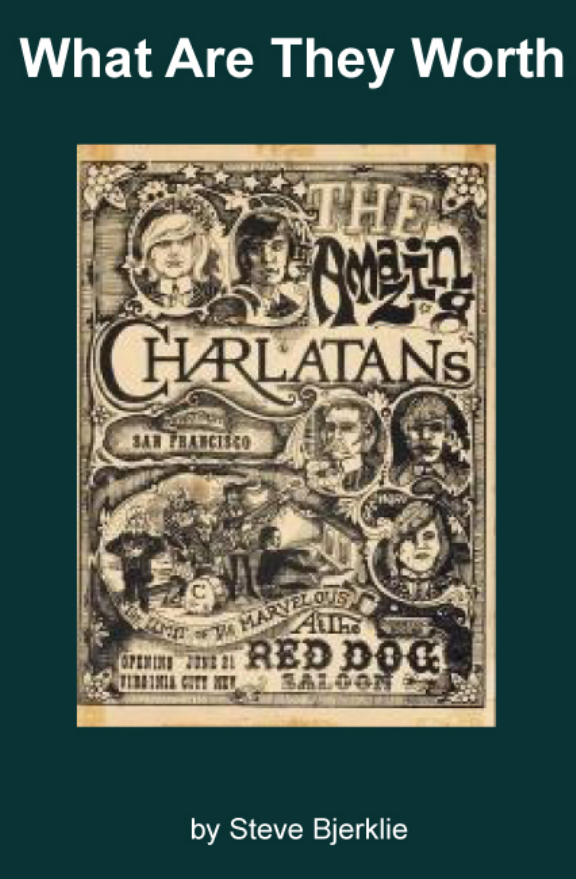

What Are They

Worth

by

Steve Bjeklie

3

INTRODUCTION

This is not intended to be a finely produced book, but rather a

readable document for those who are interested in in this series

on concert poster artists and graphic design. Some of these

articles still need work.

Here are some other links to more books, articles, and videos on

these topics:

Main Browsing Site:

http://SpiritGrooves

.net/

Organized Article Archive:

http://MichaelErlewine

.com/

YouTube Videos

https://www.youtube.com/user/merlewine

Spirit Grooves / Dharma Grooves

Copyright © Michael Erlewine

You are free to share these blogs

provided no money is charged

4

What Are They Worth?

By Steve Bjerklie

In the portentous, fog-bleary summer of 1980, just before the

presidential election of a man whose mug once graced movie

posters (a time when the nation agreed: greed is good), dance-

hall keeper Bill Graham made plans to commemorate two

upcoming concert runs he was producing for his favorite band,

the Grateful Dead, with two special-edition posters. These

posters weren't for advertising purposes but would be sold to

show-goers -- "vanity" posters, as they're called in the collecting

trade. Graham assigned Peter Barsotti, who worked for the

impresario (and who still works for Bill Graham Presents, or

BGP), and artist Dennis Larkins to design the new posters,

which trumpeted a three-week series of shows across late

September and early October by the Grateful Dead at the gaping

old Warfield Theater on Market Street and a following similar

series at New York's venerable Radio City Music Hall.

Both posters feature the Dead's essential iconography. In the

Warfield version, a 12-story "Skeleton Sam" wears a stars-and-

stripes Uncle Sam top hat and leans casually on the left side of

the theater building as another 12-story skeleton crowned with a

wreath of roses leans on the right. The Radio City version has

the same two skeletons in the same configuration leaning against

the music hall. Near the bottom of the posters, long lines of

Deadheads -- Barsotti and Larkins drew some of them as

caricatures of BGP employees -- clog the sidewalks in front of

the theaters. Scrawled across the marquee in the Warfield poster

is Bill Graham's famous elliptical quote about the Dead: "They're

not the best at what they do, they're the only ones that do what

they do."

The press run for each poster was limited to several thousand

copies. Neither poster was ever reprinted by BGP -- in fact, the

Radio City version became an instant collector's item when the

management of the theater balked at the image of skeletons

leaning on their landmark building and requested that BGP

destroy its stocks. The Warfield version also became a collector's

item eventually, much to my delight. A friend had given me and

my bride tickets to one of the Warfield shows as a wedding

present, and we bought a souvenir copy of the poster from a

5

booth in the theater's lobby, just as Bill Graham wanted us to.

Our new poster got added to the small collection of San

Francisco rock posters I had started years ago, when I was a kid

following the Avalon Ballroom and Fillmore West poster reps

into record stores to pick up fresh handbills.

San Francisco rock & roll posters are more than colorful graphic

images. They are visual, tactile representations of an age, of a

style, of a way of living in the world that once compelled legions

of kids to head West. They swirl, they startle, they stun. Thumb

through a pile of posters and dozens of legendary nights jump to

the eye: the Grateful Dead sharing the Fillmore West stage with

the Miles Davis Quintet; Big Brother and the Holding Company

with Janis Joplin opening for Howlin' Wolf; a Jefferson Airplane,

Grateful Dead and Quicksilver Messenger Service bill on New

Year's Eve. History doesn't still just live in the old posters, it still

dances. Wildly.

By 1994, with the Grateful Dead more popular than ever in the

band's 30-year history, Artrock, a storefront poster shop on

Mission Street in San Francisco, offered the Warfield

Barsotti/Larkins poster for sale for $400, which at the time was

an extraordinarily high price for a rock & roll poster of barely

teenage vintage. But when Jerry Garcia died in August 1995 and

the Grateful Dead's psychedelic circus finally shut down for

good, the price for any piece of paper bearing the words

"Grateful Dead" went crazy.

By last November when Artrock, now expanded at its Mission

Street location into a full-scale gallery and catalog-sales outlet,

hosted the opening of "The Art of the Dead," an exhibit of poster

art featuring the Grateful Dead that will cross the country over

the next two years, the price of the Warfield poster had climbed

to $950 in the Artrock catalog. My bride and I had bought it at

the show for $20. Its value, alas, has had better luck than the

marriage. But what is the real value of this poster? It is, after all, a

print, and thousands of copies were originally made. Even in the

early days of the San Francisco rock & roll ballroom scene, which

fostered psychedelic posters as advertising display art, print runs

were relatively high. On the original artwork for BG-32,

displayed in "The Art of the Dead," artist Wes Wilson penciled

"2500m" in the margin to remind the pressman to run 2,500

6

copies of the black-and-white poster, featuring a photo of Garcia

surrounded by Wilson's bulbous lettering, to advertise a Dead

show at the Fillmore in October 1966.

(Poster collectors, with the help of the original show producers,

have established a helpful poster numbering system. Posters for

Bill Graham-produced shows at the Fillmore Auditorium,

Winterland arena, Fillmore West and other San Francisco and

Bay Area venues from 1966 to 1971 are numbered in order and

prefixed "BG." Posters for 1966-68 shows produced by the

Family Dog collective, first at the Fillmore and then at the

Avalon Ballroom, are also numbered in order, prefixed "FD."

The Dog also booked a ballroom in Denver in 1968; these posters

are signified "FD D.")

Later posters were printed in greater quantities, to the point

where stacks of them were kept in storage by Graham and the

Dog's nominal chief executive, Chet Helms. Moreover, most of

the posters were reprinted by BGP and the Family Dog, the

reprint editions often numbering in the tens of thousands.

Reprints bring a lower price, of course, than first editions, but

only when a reprint is distinguishable from an original (both

BGP and the Family Dog clearly designated their authorized

reprints as such). BGP still owns the print negatives for most of

the posters for shows the company has produced since 1966,

which is to say that if it chose to, BGP could reprint again,

though the company's executive in charge of posters and

archives, Jerry Pompili, says he won't.

But since most of the stashes of original editions were discovered

and sold years ago, and since BGP will not, says Pompili, sell off

its remaining stocks of originals, the temptation to reprint is

huge, especially with prices soaring. After Jerry Garcia's death,

the thousand-dollar line was quickly broached by "Blue Rose," a

vanity poster drawn by Stanley Mouse and Alton Kelley for the

closing of Winterland in 1978 (a BGP show), and the brilliant,

disturbing "Trip or Freak" graphic from 1967, a collaborative

effort by Mouse, Kelley and Rick Griffin featuring a leering

image of Lon Chaney in full Phantom of the Opera makeup.

Prices for nearly all Grateful Dead poster collectibles -- the

Philip Garris owl-and-skull tombstone tableau for a 1976 BGP

Grateful Dead/Who show at the Oakland Coliseum; the striking

7

wing-and-pyramid Mouse/Kelley poster for the Dead's series of

1978 shows in Egypt; and of course FD-26, the poster Mouse and

Kelley prepared for the Avalon Ballroom in 1966 that associated

the skull and roses icon with the Grateful Dead for the first time

-- are in the stratosphere. Other rarities also rocketed in value.

An original copy of a handbill advertising one of the San

Francisco Mime Troupe benefits that Bill Graham organized, the

parties that introduced Graham to rock & roll, sold recently for

$5,000.

Unsurprisingly, not only have the choicest posters been

reprinted, they've been bootlegged as well, often by extremely

good counterfeiters. "What it all comes down to is that you have

nothing but someone's word that a poster is original and not a

reprint or a fake," patiently explains Jorn Weigelt, a San Mateo

dealer in fine-art posters. Last November, Weigelt's firm, The

Poster Connection, hosted the first auction in San Francisco of

collectible poster art. Inside the Chinatown Holiday Inn,

collectors, decorators and the curious bid on hundreds of rare

prints drawn by the likes of Abbot, Steinlen, and Troxler --

classic fin de siecle and early 20th-century display art. The

auction was a huge success: 85 percent of the lots sold, with a top

price of $4,600 bid for a seductive red-hued Bitter Campari

poster from 1900.

"You are dependent on the dealer," continues Weigelt, whose

father is a fine-art poster dealer in Germany. "I mean, how

would you know? Why would you know? And the dealers -- just

because someone's a dealer doesn't mean they know either."

Weigelt says that fakes have been a problem on occasion in the

fine-art market. "There are a lot of Lautrecs hanging in people's

living rooms that they paid $10,000 for. They look real, but

aren't." A new organization, the International Vintage Poster

Dealers Association, was incorporated this year; one of its

central purposes is to deal with fakes. "The knowledge of fakes is

limited," Weigelt comments. "The organization will provide

dealers with an opportunity to share information."

Does he think San Francisco rock posters will develop into a

fine-art market for collectors? "Perhaps. But the market has to be

clean. If there's a lot of uncertainty about what's real and what

isn't, and if collectors are unsure about certain dealers, the

8

market may not develop but remain a hobby for enthusiasts.

Long-lasting markets get that way when everyone's sure of what

they're buying."

But, as Weigelt points out, there's no way to be sure. There's

nothing, in the end, but someone's word, as insubstantial as a

ghost. Thirty years after the golden era of the psychedelic rock

poster in San Francisco, the posters still available for sale to

collectors and souvenir buyers comprise a wispy, tangled web of

originals, reprints, bootlegs and out-and-out fakes. And in the

middle of that web is the owner of the negatives for nearly all the

classic Family Dog posters, the largest rock & roll poster dealer

in the world: Artrock.

"Artrock's cornered the market and they set the prices," says

John Goddard, proprietor of Village Music in Mill Valley, one of

the best rock & roll record stores in the world, which has been

selling posters since the 1960s. "That's not necessarily good, but

that's the way it is." Artrock has, among other market

developments, established $35 as the base price for a copy of

most of the Family Dog posters -- that is, $35 for a reprint of

early numbers and $35 for an original copy of later numbers,

which are less sought after. Artrock's creation of a floor price is a

curious echo, by the way, of an innovation in another market.

Chet Helms, before he got into the rock & roll business at the

Avalon Ballroom, is the man in the mid-1960s who set $10 as the

basic price for a lid of grass.) Goddard himself has no quarrel

with Artrock, but points out that a lot of rumors regarding the

dealer might be the result of people coming in to Artrock with a

poster to sell, seeing another copy of the poster on Artrock's wall

for a fat price, but then being offered only a few bucks by the

store. "They think they should get half the sticker price, but what

they don't know is that Artrock may have 50 more copies of that

poster in the back. This happens to me with used records all the

time."

But could Artrock or other dealers be selling reprints or even

bootlegs as originals? "There's no good way to tell an original

from a really good reprint," Goddard says, "if the reprint doesn't

indicate that it's a reprint. Personally, I don't trust old posters

that are in mint condition. That's not to say a mint-condition

9

poster is a reprint or bootleg, but I like my old stuff with holes

and scratches and tears."

He continues: "But what's a reprint, anyway? A few years ago I

was down in New Orleans and got to know the printer who had

printed some of the posters for the great R&B shows in the

1950s. He still had the original printing plates for the posters,

and one day he uncovered a pile of 40-year-old paper in his back

room. So he printed the old posters on the old paper using the

original plates. Now: Are those reprints or not?" With negatives

for nearly all the classic psychede

lic-era posters still in existence

and still owned by companies that profit by the sale of posters ...

well, people have wondered.

"The major dealers don't sell bootlegs or reprints as originals,"

comments Grant McKinnon, general manager at S.F. Rock

Posters & Collectibles on Powell in North Beach, a rock-art

boutique. "They'll always come back to haunt you. But fakes are

out there. A few years ago I saw copies of BG-105" -- Rick

Griffin's famous "Flying Eyeball" poster for an amazing 1968 BGP

show featuring Albert King, John Mayall and Jimi Hendrix -- "for

sale on Haight Street for $5 to $10. Now, I knew those had to be

fakes. It's a very valuable poster. But they were really good fakes;

they looked just like the second printing. The only way you could

tell was from two tiny thumb prints on the edges -- something

only an expert or real dealer would look for. The people who

thought they were getting a deal on that poster just got burned."

McKinnon adds that it would be very difficult to get a reprint

past an expert as an original. "There's still a lot of knowledge

around from people who have been part of the poster scene or

collectors since the beginning. The information about color

variations in press runs and when the posters were actually

printed is still available." He goes on to point out that the inks

used to print the original posters 30 years ago differ from today's

inks in their mixture of elements and in how they decay and fade.

Papers, too, have changed.

McKinnon mentions the first volume of The Collector's Guide to

Psychedelic Rock Concert Posters, Postcards and Handbills:

1965-1973 by Eric King, which focuses on BGP and Family Dog

posters as well as on the famed "Neon Rose" series drawn by

10

Victor Moscoso for the Matrix. The King book meticulously

describes poster issues and editions, sizes, inks, paper quality and

what to look for in reprints and bootlegs. Another book, the

massive tome The Art of Rock: Posters from Presley to Punk,

compiled by Paul Grushkin and published in 1987, is the

standard reference for images. The two books together create the

basic reference material in the world of rock-poster collecting.

BGP's Jerry Pompili says that he's seen "Flying Eyeball" fakes

sold out of the trunks of cars "by sleazy East Coast guys." "If we

see it, we're on those people like gorillas. We've been very careful

with the posters over the years; they're an extremely valuable

asset to BGP. No asshole is going to get a fake by us." He claims

the only poster reprints BGP ever authorized were those

published in the 1970s by Winterland Productions, which at the

time was still a BGP subsidiary. These were sold with other rock

& roll bric-a-brac in the short-lived "Bill Graham's Rock Shop"

on Columbus Avenue. BGP itself owns only two complete sets of

the classic series, Nos. 1 through 287, according to Pompili. A

complete series is on display upstairs in the Fillmore

Auditorium, though "some of the rarer" posters at the Fillmore,

Pompili says, are actually photographs of originals.

Graham, in the beginning, did not see the value of the posters he

was commissioning for his shows at the Fillmore. Ben Friedman,

a legendary San Francisco entrepreneur (and storied crank) who

had started, managed or closed dozens of businesses, convinced

Graham to sell him a batch of posters for $1,000, which

Friedman then told Graham he was going to turn around and

sell for $2,000. Thus began a long relationship of mutual

admiration and frustration, which Friedman also extended to

the Family Dog.

By the time the ballrooms closed (the Avalon in 1968, Fillmore

West in 1971), Friedman owned the biggest inventory of rock

posters in the world. Some he bought for only ten cents each and

sold in his Postermat shop on Columbus for several dollars.

Some, including FD-14 (known as "Zig Zag Man") and FD-26,

he is reputed to have reprinted on his own -- bootlegged, in a

word. By the time he wanted to get out of the business because

of failing health, Friedman owned hundreds of thousands of

11

posters; he had posters in storage by the pallet-load. Facing

hefty medical bills, he sold the bulk of his inventory to another

businessman, Philip Cushway, who made the purchase on

behalf of the store Cushway owns, Artrock.

[Selections from an article by free-lance writer Steve Bjerklie,

used with the permission of the author. Copyright by Steve

Bjerklie, [email protected]]