February 2022

Humanitarian Access,

Great Power Conict, and

Large-Scale Combat Operations

A

Brittany Card

Rob Grace

Tarana Sable

Center for Human Rights and Humanitarian Studies

Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs

Brown University

About CHRHS

Established in 2019 at Brown University’s Watson Institute for International and Public Aairs,

the Center for Human Rights and Humanitarian Studies (CHRHS) is committed to tackling the

human rights and humanitarian challenges of the 21st century. Our mission is to promote a more

just, peaceful, and secure world by furthering a deeper understanding of global human rights and

humanitarian challenges, and encouraging collaboration between local communities, academics, and

practitioners to develop innovative solutions to these challenges.

About the Authors

e authors prepared this report in their capacities as researchers for CHRHS, Brittany Card as a

Visiting Scholar at CHRHS, Rob Grace as an Aliated Fellow at CHRHS, and Tarana Sable as a

Research Assistant at CHRHS.

Acknowledgments

e authors express gratitude to all research participants, including focus group participants and

interviewees, who played a role in this research process. Additionally, the authors received valuable

feedback on earlier dras of this report from Dave Polatty, Jonathan Robinson, Ziad Achkar, Adam

Levine, Alexandria Nylen, and Zach Shain. e authors also beneted from useful feedback and

edits from an additional external reviewer who wished to remain anonymous. In terms of outreach

to potential research participants, the authors are grateful to the chairs of various thematic working

groups based at CHRHS, in particular, Dave Polatty, Jonathan Robinson, and Hank Brightman.

e authors extend particular gratitude to Beth Eggelston for co-organizing and co-convening the

third focus group session, which focused on stakeholders based in Australia. A nal thank you to

Seth Stulen for serving as the graphic designer for the report. Any substantive errors are those of the

authors alone.

Disclaimer

The opinions and views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of any

organizations with which they are affiliated or for whom they work, including the US Government

or USAID.

Suggested Citation

Brittany Card, Rob Grace, Tarana Sable, “Humanitarian Access, Great Power Conict, and Large-

Scale Combat Operations,” Center for Human Rights and Humanitarian Studies, Watson Institute for

International and Public Aairs, Brown University, February 2022.

Table of Contents

Executive Summary i

Introduction 1

Part I: Denitions and Methodology 3

Part II: e Shiing Geopolitical and Security Landscape 6

Part III: Envisioning Possible Future Large-Scale Combat Operations 12

Part IV: Humanitarian Access Challenges During Large-Scale Combat Operations 15

Part V: Conclusion and Recommendations 27

Executive Summary

e geopolitical landscape of the world is shiing. Geopolitical dynamics are driving the re-emergence of great

power competition as the dominant paradigm through which major global powers view their relationships

with each other. For instance, the United States shied its focus from the ‘Global War on Terror’ framework

that dominated foreign policy planning for most of the 21st century to a focus on great power competition.

Within this new frame, China and Russia are identied as its greatest threats. Meanwhile, China and Russia

are pursuing global inuence as they view the US as a struggling hegemon. All three states appear braced for

long-term geopolitical contestation and are engaged in preparations for future potential conict, including in

the form of large-scale combat operations.

For humanitarian policymakers and practitioners, the state of thinking, analysis, and planning on these issues,

for the most part, remains nascent. e overall conclusion of this report is that it cannot remain nascent for

much longer. Conict between two or more states, especially in the form of large-scale combat operations,

should it occur, will lead to devastating impacts on civilian populations and signicant challenges for human-

itarian response.

e international humanitarian system as it exists today has never engaged in a response context of this nature.

Current ongoing complex emergencies that entail overlapping conicts between an array of non-state and

state actors—such as those in Ukraine, Syria, Yemen, and Iraq—and past great power military conicts, such

as World War I and World War II, oer some insight into the scale and scope of humanitarian needs, as well

as the response challenges, likely to arise during large-scale military conict between great powers. However,

the anticipated high-tempo and destructive nature of operations, scope of aected areas, and sheer number of

forces involved in operations across multiple domains—with a particular emphasis on the role of information

and cyber operations—is likely to have eects on civilian populations and militaries far beyond what one can

fully comprehend from current events.

To advance understanding of the humanitarian dimensions of large-scale combat operations between great

powers, or between other peer or near-peer states, this report analyzes humanitarian access challenges likely

to arise in such contexts. e analysis is based on focus group sessions and key informant interviews with

37 humanitarian, military, academic, and government stakeholders. is report examines these issues in ve

parts. Part I denes key terms and oers an overview of the methodology of this research project. Part II

provides a more in-depth examination of the current geopolitical environment. Part III discusses the likely

overall characteristics of future great power conict and large-scale combat operations. Part IV examines

three categories of anticipated humanitarian access challenges: political, operational, and tactical. Part V

articulates recommendations for humanitarian organizations, governments, and militaries to proactively

adopt to mitigate and prepare for the humanitarian access challenges identied in this research.

Humanitarian Access, Great Power Conict, and Large-Scale Combat Operations | i

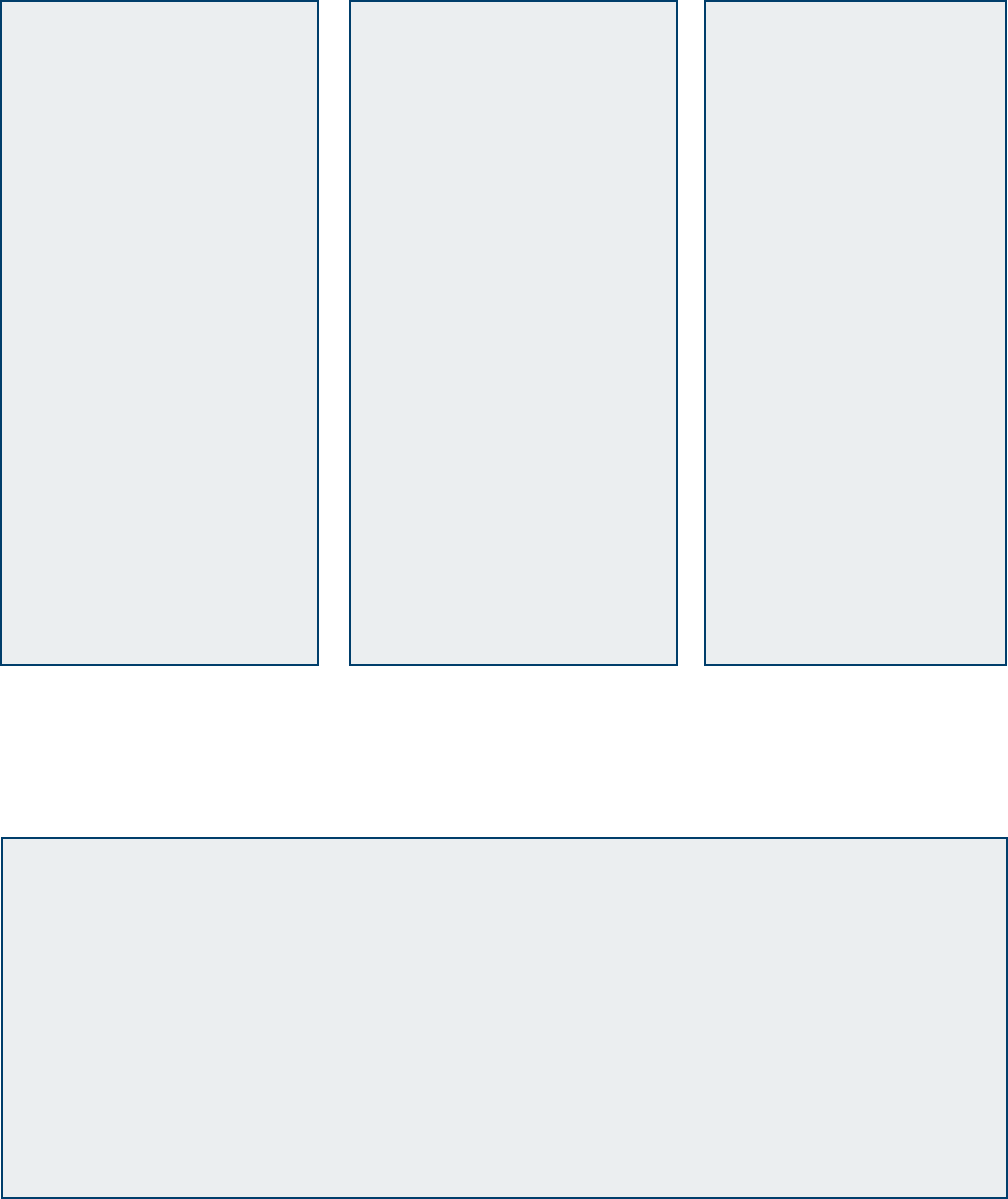

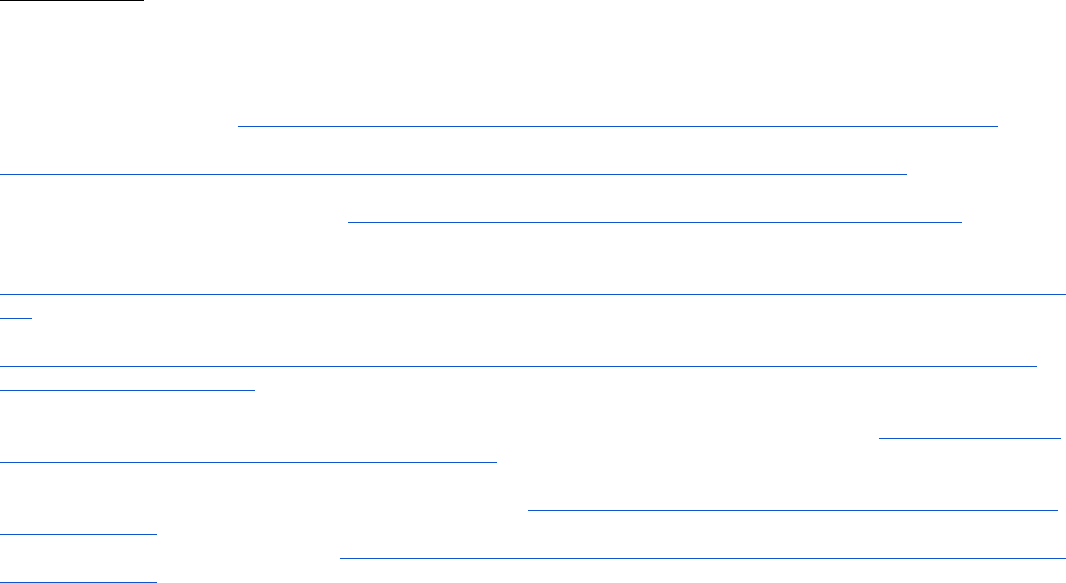

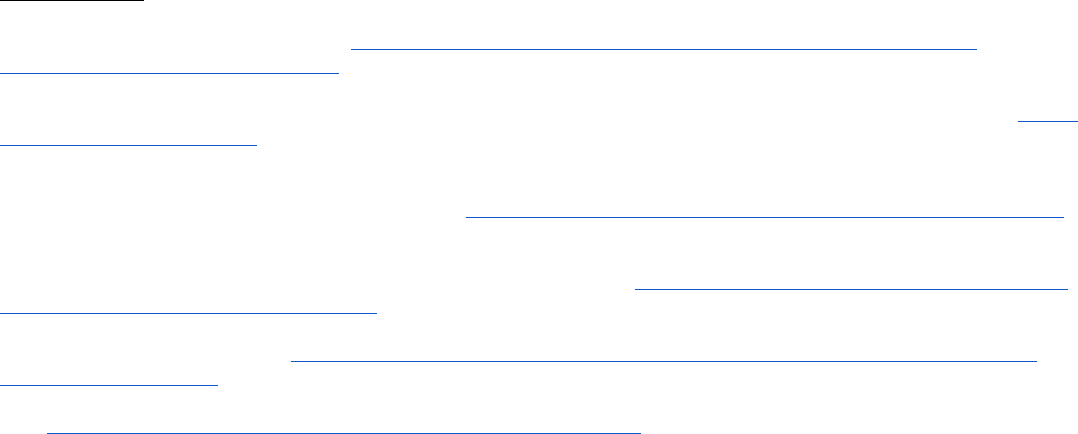

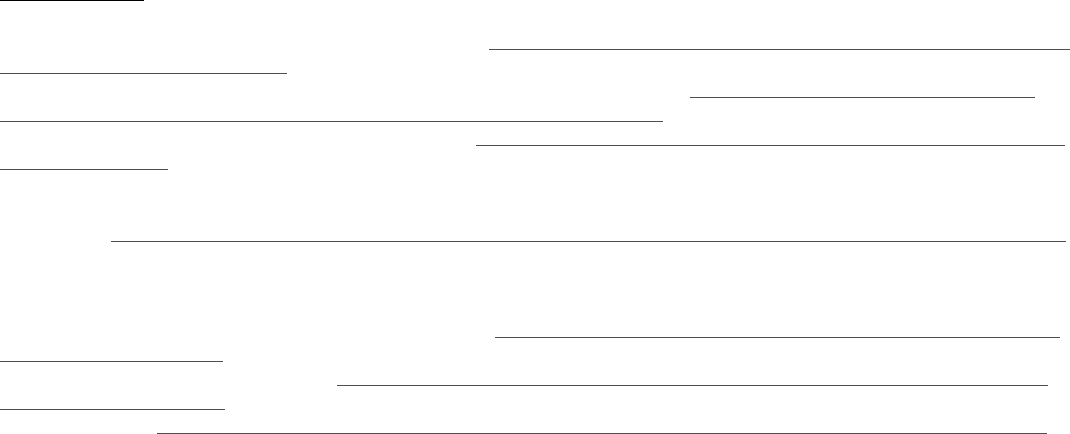

Humanitarian Access Challenges

During Large-Scale Combat Operations

Political Challenges

relating to high-level

political or strategic

engagements, oen inoling

issues relating to the norms

or values that undergird

humanitarian action

Limited impact of high-

level multilateral political

engagements

Politicized government

perceptions of the

international humanitarian

actors

Relationship decits with

potential state actors

Operational Challenges

relating to developing and

planning practical and

procedural methods for

activities or operations that

align with broader political

and strategic goals

Bureaucratic impediments

and donor restrictions

Limited operational role

of traditional international

humanitarian actors

Devising processes to

manage humanitarian

insecurity

Tactical Challenges

relating to implementing

operational arrangements

while also responding to

ground-level issues, which

can change rapidly

Managing access and

logistics across multiple

domains with limited

resources

Physical and digital threats

to aid worker security

Recommendations for Humanitarian

Organizations, Governments, and Militaries

Develop awareness in the humanitarian community about possible future scenarios, including

humanitarian implications and response requirements

Incorporate humanitarian and protection of civilian considerations into military planning

Build relationships with potential future parties to the conict

Conduct planning to ensure the continuity of humanitarian operations

Improve humanitarian-military relations through education and training

Humanitarian Access, Great Power Conict, and Large-Scale Combat Operations | ii

Humanitarian Access, Great Power Conict, and Large-Scale Combat Operations | 1

Introduction

“We are in great power competition today, and with competition, conict is

always a risk—this is not just a problem for tomorrow’s leaders.”

– Lt. Gen. Michael D. Lundy, US Army, October 2018

1

e geopolitical landscape of the world is shiing. e Interim National Security Strategic Guidance, issued

by United States (US) President Joe Biden in March 2021, warns against “strategic challenges from an

increasingly assertive China and destabilizing Russia.”

2

e publication dubs China “the only competitor

potentially capable of combining its economic, diplomatic, military, and technological power to mount a

sustained challenge to a stable and open international system,” whereas “Russia remains determined to enhance

its global inuence and play a disruptive role on the world stage.”

3

is vision of the security threats that the

US faces from abroad is very dierent from the ‘Global War on Terror’ framework that dominated US foreign

policy planning for most of the 21

st

century.

Meanwhile, the Chinese government has embraced the paradigm of a ‘New Type of Great Power Relationship’

to frame Sino-American relations and has undertaken a series of military modernization initiatives, aiming

to develop a ‘world-class’ military by 2049 that is equal or superior to the US.

4

Over the past decade, Russia’s

relationship with Western states has deteriorated, in part due to the conicts in Syria and Ukraine.

5

Whereas the

US sees China and Russia as rising threats, China and Russia see the US as a struggling hegemon prone toward

aggression to preserve its waning global inuence.

6

All three states appear braced for long-term geopolitical

contestation, with substantial military strategizing for future possible great power conict scenarios already

underway.

Lt. Gen. Michael D. Lundy, U.S. Army, “Meeting the Challenge of Large-Scale Combat Operations Today and Tomorrow,” Military Review,

September-October 2018, p. 112, https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Portals/7/military-review/Archives/English/SO-18/Lundy-LSCO.pdf.

Oce of the President, Interim National Security Strategic Guidance: e White House, March 2021, p. 14.

Ibid., p. 8.

Michael S. Chase, “China’s Search for a ‘New Type of Great Power Relationship,’” China Brief Vol. 12, Issue 17 (2012), https://jamestown.

org/program/chinas-search-for-a-new-type-of-great-power-relationship/; Department of Defense, Annual Report to Congress: Military and Se-

curity Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China (Washington, D.C.: Department of Defense, 2020), p. i, https://media.defense.

gov/2020/Sep/01/2002488689/-1/-1/1/2020-DOD-CHINA-MILITARY-POWER-REPORT-FINAL.PDF. For an analysis of the limita-

tions of Chinese strategic foresight, see Paul Charon, “Strategic Foresight in China: e Other Dimension Missing,” European Union Institute

for Security Studies, 2021, https://www.iss.europa.eu/sites/default/les/EUISSFiles/Brief_5_2021.pdf.

Dmitri Trenin, “Strategic, Mental Shi in Global Order,” Global Times, Carnegie Moscow Center, May 17, 2015, https://carnegiemoscow.

org/2015/05/17/ukraine-crisis-causes-strategic-mental-shi-in-global-order-pub-60122.

See “Wang Yi Meets with Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov,” Consulate General of the People’s Republic of China in New York, March

26, 2021, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/ce/cgny/eng/xw/t1864347.htm, which is a joint statement from China and Russia in which both coun-

tries call on the United States to “reect on the damage it has done to global peace and development in recent years, halt unilateral bullying, stop

meddling in other countries’ domestic aairs, and stop forming small circles to seek bloc confrontation.”

Humanitarian Access, Great Power Conict, and Large-Scale Combat Operations | 2

For humanitarian policymakers and practitioners, the state of thinking, analysis, and planning on these issues,

for the most part, remains nascent. e overall conclusion of this report is that it cannot remain nascent for

much longer. Conict between two or more states, especially in the form of large-scale combat operations,

should it occur, will lead to devastating impacts on civilian populations and pose signicant challenges

for humanitarian response.

7

Furthermore, large-scale combat operations will likely involve all ve of the

warghting domains: air, land, sea, space, and cyber.

e international humanitarian system as it exists today has never engaged in a response context of this nature.

Current ongoing complex emergencies that entail overlapping conicts between an array of non-state and

state actors—such as those in Ukraine, Syria, Yemen, and Iraq—and past great power military conicts, such

as World War I and World War II, oer some insight into the scale and scope of humanitarian needs, as well

as the response challenges, likely to arise during large-scale military conict between great powers. However,

the high tempo of operations, employment of conventional and advanced weapons, sheer number of military

forces involved, and scope of aected areas in future large-scale combat operations is likely to have eects on

civilian populations and militaries far beyond what one can fully comprehend from current events.

To advance understanding of the humanitarian dimensions of large-scale combat operations between great

powers, or between other peer or near-peer states, this report analyzes humanitarian access challenges likely

to arise in such contexts. Across the globe, and especially in the context of large-scale humanitarian crises,

populations already struggle to access essential services. Humanitarian organizations face a myriad of access

constraints, including issues related to entering a country (obtaining visas, importing equipment, goods, and

supplies); bureaucratic obstacles to operating within a country (obtaining permission from authorities to

implement programs or travel to certain areas); diversion of aid (including eorts to control humanitarian

programming in ways that serve security or political interests of states, non-state armed groups, or other actors);

security incidents (attacks against aid workers, goods, and equipment, as well as ongoing military operations);

and infrastructure constraints or weather-related hazards.

8

In armed conicts, additional challenges include

building simultaneous relationships with host states and non-state armed groups; navigating decisions on the

use of armed escorts; implementing humanitarian notication systems; and grappling with counter-terrorism

laws and policies that can complicate engagements with non-state armed groups designated as terrorists.

9

Adequate preparation for possible future great power conict scenarios must entail understanding how these

challenges are likely to manifest, in what ways the dynamics of large-scale combat operations might further

aggravate these challenges, what new challenges might arise, and what steps humanitarian and military actors

can take to better navigate these diculties. is report examines these issues in ve parts. Part I denes key

Daniel R. Mahanty and Annie Shiel, “Protecting Civilians Still Matters in Great-Power Conict,” Defense One, May 3, 2019, https://www.

defenseone.com/ideas/2019/05/protecting-civilians-still-matters-great-power-conict/156723/; and Daniel R. Mahanty, “Even a Short War

Over Taiwan or the Baltics Would Be Devastating,” Foreign Policy, July 29, 2021, https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/07/29/war-taiwan-chi-

na-united-states-russia-baltics-nato-military-civilians-deaths-losses-casualties/.

See “OCHA on Message: Humanitarian Access,” United Nations Oce for the Coordination of Humanitarian Aairs, April 2010, https://

www.unocha.org/sites/unocha/les/dms/Documents/OOM_HumAccess_English.pdf.

Rob Grace, “Surmounting Contemporary Challenges to Humanitarian-Military Relations,” Center for Human Rights and Humanitarian

Studies, Watson Institute for International and Public Aairs, Brown University, August 2020, p. 32-41, https://watson.brown.edu/chrhs/les/

chrhs/imce/research/Surmounting%20Contemporary%20Challenges%20to%20Humanitarian-Military%20Relations_Grace.pdf.

Humanitarian Access, Great Power Conict, and Large-Scale Combat Operations | 3

terms and oers an overview of the methodology of this research project. Part II provides a more in-depth

examination of the current geopolitical environment, including current military thinking and planning for

large-scale combat operations. Part III discusses the likely overall characteristics of future great power conict

and large-scale combat operations. Part IV examines anticipated humanitarian access challenges during large-

scale combat operations. Part V provides concluding remarks and recommendations.

Part I | Denitions and Methodology

A. Dening Key Terms

Great power conict refers to militarized incidents that involve great powers in the international system.

By “great powers,” this report means, “states whose interests and capabilities extend beyond their immediate

neighbors. More so than other states, they shape and respond to the structure of the international system.”

10

Conict can entail three dimensions. e rst is threats of the use of force, meaning “verbal indications of

hostile intent.”

11

e second is displays of force, which “involve military demonstrations but no combat

interaction.”

12

Displays of force may include public displays of naval or aerial force, an increase in military

readiness, and force mobilization.

13

e third dimension is the use of force, which encompasses a wide range

of conict types, including large-scale combat operations, proxy warfare, and the use of military force in

settings that fall short of the legal denition of armed conict.

14

Peer-to-peer or near-peer conict entails two or more states of relatively equal capabilities and political will

engaging in military confrontation with each other. A US-Army funded RAND report presents the following

denition of a peer competitor: “For a state to be a peer, it must have more than a strong military. Its power

must be multidimensional—economic, technological, intellectual, etc.—and it must be capable of harnessing

these capabilities to achieve a policy goal.”

15

e concept of peer-to-peer or near-peer conict encompasses

great power conict; however, this term can also apply to military confrontation between non-great powers

(for example, regional powers). As with great power conict, peer-to-peer or near-peer conict can entail

threats of the use of force, displays of force, and actual uses of force.

Bear F. Braumoeller, “Systemic Politics and the Origins of Great Power Conict,” American Political Science Review 102, no. 1 (2008): 77.

Daniel M. Jones, Stuart A. Bremer, and J. David Singer, “Militarized Interstate Disputes, 1812-1992: Rationale, Coding Rules, and Empirical

Patterns,” Conict Management and Peace Science 15, no. 2 (1996): 170.

Ibid.

Ibid., p. 172.

Ibid., p. 171-173.

omas S. Szayna, e Emergence of Peer Competitors: a Framework of Analysis (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2001), p. xii.

Humanitarian Access, Great Power Conict, and Large-Scale Combat Operations | 4

Large-scale combat operations are direct, extended major military confrontations between two or more

states. As the US Department of the Army Field Manual 3-0 (FM 3-0) denes the term, large-scale combat

operations “occur in the form of major operations and campaigns aimed at defeating an enemy’s armed

forces and military capabilities in support of national objectives.”

16

FM 3-0 also states, “Large-scale combat

operations are intense, lethal, and brutal. eir conditions include complexity, chaos, fear, violence, fatigue,

and uncertainty.”

17

Future large-scale combat operations, FM 3-0 articulates, are also likely to be multi-

domain in nature, entailing conict in “air, land, maritime, space, and the information environment (including

cyberspace).”

18

Proxy warfare is dened as a conict in which “a major power instigates or plays a major role in supporting

and directing a party to a conict but does only a small portion of the actual ghting itself.”

19

ere are

multiple ways for states to directly or indirectly engage in proxy conict, including through partnered military

operations; arms transfers; and nancial, logistical, or political support.

20

Humanitarian action refers to activities aiming to “assist people aected by disasters due to natural hazards

or armed conict, and seek to enhance the safeguarding of their rights.”

21

ese activities are guided by

humanitarian principles, the core four of which are humanity (alleviating suering wherever it is found),

impartiality (basing programming on needs and prioritizing the most vulnerable), neutrality (refraining from

taking sides in a conict), and independence (maintaining autonomy from other actors).

22

Humanitarian access refers to “both access by humanitarian actors to people in need of assistance and

protection and access by those in need to the goods and services essential for their survival and health, in

a manner consistent with core humanitarian principles.”

23

e dual-pronged denition of humanitarian

access places attention on two interrelated issues: 1) from the perspective of humanitarian organizations, the

extent to which the response environment enables their ability to implement programming; and 2) from the

perspective of people aected by large-scale emergencies, the extent to which their needs can be met, whether

by humanitarian organizations or through other means.

United States Department of the Army, Field Manual No. 3-0: Operations, October 6, 2017, p. 1-1.

17

Ibid., p. 1-4.

18

Ibid., p. 1-23.

19

Daniel L. Byman, “Why Engage in Proxy War? A State’s Perspective,” Brookings, May 21, 2018, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/or-

der-from-chaos/2018/05/21/why-engage-in-proxy-war-a-states-perspective/.

20

“Understanding Support Relationships,” International Committee of the Red Cross, https://sri.icrc.org/understanding-support.

21

“Humanitarian Action 101,” InterAction, https://www.interaction.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Humanitarian-Action-101.pdf. e

word ‘humanitarian’ has a certain degree of inherent ambiguity, and there are no denitive parameters to delineate organizations and activities

considered ‘humanitarian’ from those that are not. For an overview of the history of the term, ‘humanitarianism,’ see Craig Calhoun, “e Im-

perative to Reduce Suering: Charity, Progress, and Emergencies in the Field of Humanitarian Action,” in Humanitarianism in uestion, eds.

Michael Barnett and omas G. Weiss (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2008), 73-142.

22

See “OCHA on Message: Humanitarian Principles,” United Nations Oce for the Coordination of Humanitarian Aairs, June 2012,

https://www.unocha.org/sites/dms/Documents/OOM-humanitarianprinciples_eng_June12.pdf.

23

Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Aairs, Humanitarian Access in Situations of Armed Conict: Handbook on the International Nor-

mative Framework, Version 2, December 2014, p. 13, https://reliefweb.int/report/world/humanitarian-access-situations-armed-conict-hand-

book-international-normative.

Humanitarian Access, Great Power Conict, and Large-Scale Combat Operations | 5

B. Methodology

is report’s ndings are based on the authors’ analysis of relevant existing literature (including desk reviews

on humanitarian access, historical and contemporary concepts of great power competition and conict, and

the state of training and preparations for future conict), virtual focus group discussions that the authors

convened, and semi-structured interviews conducted with key informants. Between the focus group sessions

and key informant interviews, the research team captured perspectives from 37 humanitarian, military,

academic, and government stakeholders. Military stakeholders included active duty, reservist, and retired

service members. Academic stakeholders included individuals engaged in teaching and research. Additionally,

multiple research participants have previous relevant or dual-hatted professional experience, for example,

a former government stakeholder who now works with an academic institution or a current humanitarian

practitioner with prior military service.

e research team interviewed ve key informants and engaged 32 stakeholders across three focus group

sessions, each of which engaged a dierent set of stakeholders. Each focus group session lasted approximately

an hour and a half, and semi-structured interviews lasted between 25 and 45 minutes. e focus group sessions

and semi-structured interviews were conducted under Chatham House rules. Participants understood that

identiable information and organizational aliations would not be included in any publications resulting

from the research. e research team analyzed data from the focus groups and interviews using NVivo, a

qualitative data analysis soware. Two members of the research team coded all transcripts from focus groups

and interviews using inductive analysis to capture patterns in themes, topics, and concepts across the data.

e research team convened the rst two virtual focus group sessions in May 2021. e rst focus group session

had 11 participants and the second focus group session had 10 participants. Each focus group included a

combination of humanitarian, military, academic, and government stakeholders. Participants were identied

primarily through pre-existing networks, in particular drawing from members of the Protection of Civilians

Working Group, the Aid Worker Security Working Group, and the Humanitarian Access Working Group, all

of which are associated with the Civilian-Military Humanitarian Response Workshop convened annually by

the Center for Human Rights and Humanitarian Studies at Brown University and the US Naval War College

Civilian-Military Humanitarian Response Program. All members of these working groups have extensive

experience and/or expertise in humanitarian response. Additional selected experts on humanitarian access

and/or humanitarian civil-military coordination were also invited to participate in these sessions.

e third virtual focus group session, which had 12 participants, was convened in August 2021 in collaboration

with the Humanitarian Advisory Group, which co-hosted the session. e aim of this third session was to

capture the particular perspectives of experts knowledgeable about and/or working on relevant issues in

the Asia-Pacic region. is focus group was composed solely of humanitarian, military, academic, and

government stakeholders based in Australia.

Before each focus group session, the research team draed and disseminated a brieng document to

participants that oered an overview of key concepts and articulated a set of questions intended to frame

Humanitarian Access, Great Power Conict, and Large-Scale Combat Operations | 6

the discussion. e brieng document did not specify a particular scenario to orient participants’ comments.

Rather, participants were prompted to speak more generally about their perspectives on possible future great

power conict and large-scale combat scenarios. e geopolitical contest between the United States and

China/Russia framed much of the discussions, with a focus on imagining what future large-scale combat

operations would look like between these actors. However, participants also discussed other possible large-

scale combat operations scenarios, in particular, involving peer-to-peer or near-peer conict between regional

powers. Additionally, participants discussed proxy warfare, drawing connections to conicts already seen

today. e scope of this report reects this somewhat loose framing in terms of scenarios, while centering the

analysis on the intersection between great power conict and large-scale combat operations.

Finally, it is important to highlight that the focus group participants and semi-structured interview subjects do

not constitute a representative sample of a broader population of humanitarian, military, and/or governmental

actors. e sampling was purposive, aiming to collect perspectives from actors already working on or thinking

about these subjects or in a position to oer expert commentary. Two important limitations are that the

sample skews humanitarian (a limited set of military actors participated in the research) and Western (the

sample drew largely from people in the United States, the United Kingdom, various European countries,

and Australia). e research team hopes that this initial report will prompt future research to build on this

foundation (for example, by engaging more deeply with military actors, as well as non-Western policy actors,

practitioners, and experts, in particular, from China and Russia).

Part II

e Shiing Geopolitical and

Security Landscape

is section oers an overview of the shiing current geopolitical context and the potential implications for

possible future conict scenarios. e section proceeds in three parts. e rst part, as a point of departure,

examines how the US, over the past several years, has embraced a strategic shi toward great power competition.

e second part addresses perspectives and developments from China and Russia. e third part discusses

dierent perspectives on the likelihood of large-scale combat operations and how and why such conicts

might arise.

A. e United States’ Strategic Shi Toward Great Power Competition

Over the past several years, the US has formally reoriented its national security and foreign policy strategy

toward great power competition. e 2015 National Military Strategy indicated the resurgence of great power

Humanitarian Access, Great Power Conict, and Large-Scale Combat Operations | 7

competition,

24

and the 2017 National Security Strategy and 2018 National Defense Strategy cemented the

shi, identifying China and Russia as the main priorities for the US Department of Defense.

25

e 2021

Interim National Security Strategic Guidance—as noted in this report’s introduction—retained this focus on

great power competition, although the US has embraced ‘strategic competition’ as a framing device.

26

Further illustrating the shi toward great power competition, US Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin at his

conrmation hearing called China “the most signicant threat going forward” and noted that the US has

“seen [China] do a number of things that tend to make us believe that China wants to be the preeminent

power in the world in the not too-distant future.”

27

Austin asserted that China “is clearly a competitor that we

have to make sure that we begin to check their aggression.”

28

Moreover, in September 2021, US Department

of Defense Policy Chief Colin Kahl acknowledged the short-term threat that Russia poses to the US, stating,

“In the coming years, Russia may actually represent the primary security challenge that we face in the military

domain for the United States and certainly for Europe,” continuing, “Russia is an increasingly assertive

adversary that remains determined to enhance its global inuence and play a disruptive role on the global

stage, including through attempts to divide the West.”

29

US service-specic posture statements and command guidance documents reect this focus on great power

competition and conict.

30

For example, the 2021 budget submission for the US Department of the Air Force

seeks to align the Air Forces’ portfolios and develop operational concepts in accordance with the National

Defense Strategy, such as investing in logistics that can support rapid deployment of forces to forward

locations and the generation of combat power.

31

e US also seeks to limit the inuence of China and Russia

by repositioning its forces and upgrading military capabilities, especially in the Indo-Pacic region (to counter

China) and the North Atlantic (through the reestablishment of the US Navy’s Second Fleet, responsible for

the US east coast and the North Atlantic Ocean).

32

24

US Department of Defense, e National Military Strategy of the United States of America 2015, e United States Military’s Contribution

To National Security, June 2015, p. i, 1-4.

25

Oce of the President, National Security Strategy of the United States of America, December 2017, p. 55; US Department of Defense, Sum-

mary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy of the United States of America: Sharpening the American Military’s Competitive Edge, undated

but released January 2018, p. 1, https://dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/2018-National-Defense-Strategy-Summary.pdf,

26

Daniel Lipmann, Lara Seligman, Alexander Ward and uint Forgey, “Biden’s Era of ‘Strategic Competition,’” Politico, October 5, 2021,

https://www.politico.com/newsletters/national-security-daily/2021/10/05/bidens-era-of-strategic-competition-494588.

27

US Congress, Senate, Committee on Armed Services, Conrmation Hearing on the Expected Nomination of Lloyd J. Austin III to be Secre-

tary of Defense, 117th Cong., 1st. sess., 2021, https://www.armed-services.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/21-02_01-19-20211.pdf.

28

Ibid.

29

Jim Garamone, “DOD Policy Chief Kahl Discusses Strategic Competition With Baltic Allies,” Department of Defense, September 17, 2021,

https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/2780661/dod-policy-chief-kahl-discusses-strategic-competition-with-baltic-al-

lies/.

30

“CNO Gilday Releases Guidance to the Fleet; Focuses on Warghting, Warghters, and the Future Navy,” US Navy, December 4, 2019,

https://www.navy.mil/Press-Oce/Press-Releases/display-pressreleases/Article/2237608/cno-gilday-releases-guidance-to-the-eet-focus-

es-on-warghting-warghters-an/.

31

e Honorable Barbara Barrett and General David L. Goldfein, United States Air Force Posture Statement Fiscal Year 2021, United States

Air Force Presentation to the Armed Services Committee of the United States Senate, 116th Cong., 2nd Sess., 2021, https://www.armed-ser-

vices.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Barrett--Goldfein_03-03-20.pdf. e United States Air Force Posture Statement Fiscal Year 2021 reference to

the NDS refers to the 2018 NDS, as the 2021 Interim NDS had not been released yet.

32

Jerey Goldberg, “e Obama Doctrine,” e Atlantic, April 2016, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2016/04/the-obama-

doctrine/471525/#2; Marian Faa and Prianka Srinivasan, “Pentagon pushes for Pacic missile defence site to counter China’s threat to the US,”

Australian News Broadcast, March 18, 2021, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-03-19/united-states-pentagon-missile-defence-guam-count-

er-china/100015900. See Sam LaGrone, “Navy Reestablishes U.S. 2nd Fleet to Face Russian reat; Plan Calls for 250 Person Command in

Humanitarian Access, Great Power Conict, and Large-Scale Combat Operations | 8

US preparations for future conict, including in the form of large-scale combat operations, also involve

prioritizing investments in developing advanced technology for future warfare, such as autonomous weapons,

articial intelligence, and hypersonic weapons. According to a Congressional Research Report released in

October 2021, “e United States is the leader in developing many of these technologies. However, China and

Russia—key strategic competitors—are making steady progress in developing advanced military technologies.

As these technologies are integrated into foreign and domestic military forces and deployed, they could hold

signicant implications for the future of international security writ large…”

33

Furthermore, the need to prepare and train for large-scale combat operations is communicated across various

US Department of Defense documents—including doctrine and training initiatives—and war-gaming

exercises are already underway.

34

One has to look no further than to FM 3-0 (the aforementioned US Army

eld manual published in 2017) to understand how the US Army, and the US military more broadly, is

anticipating this possibility. FM 3-0 asserts, “While the U.S. Army must be manned, equipped, and trained to

operate across the range of military operations, large-scale ground combat against a peer threat represents the

most signicant readiness requirement.”

35

B. Perspectives and Developments from China and Russia

Chinese perspectives on the great power paradigm clash with those from the US. Chinese leaders and foreign

policy scholars generally reject the framework of great power conict to describe Sino-American relations.

For example, in commentary published by the China Institute of International Studies in 2020, Teng Jianqun

framed the notion of strategic competition between the US and China as a dishonest American rhetorical

device, writing that US air and naval activities in the Asia-Pacic region “are part of what the US calls ‘strategic

competition’ with China; equally, these could be seen as preparations for a possible future war close to the

Chinese mainland.”

36

Some Chinese scholars, such as Wang Jisi, believe that strategic competition between

China and the US is the “inevitable” outcome of a situation in which the US “cannot accept” the view that

Norfolk,” USNI News, May 4, 2018, https://news.usni.org/2018/05/04/navy-reestablishes-2nd-eet-plan-calls-for-250-person-command-in-

norfolk, which discusses the explicit link between the reestablishment of the Second Fleet and great power competition. In particular, Chief

of Naval Operations Admiral John Richardson has stated, “Our national defense strategy makes clear that we’re back in an era of great power

competition as the security environment continues to grow more challenging and complex...at’s why today, we’re standing up 2nd Fleet to

address these changes, particularly in the North Atlantic.”

33

US Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service, Emerging Military Technologies:

Background and Issues for Congress, by Kelley M. Sayler, R46458 (2021), https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R46458, p. i.

34

For an example of doctrine, see United States Department of the Army, U.S. Army in Multi-Domain Operations 2028, TRADOC 525-3-1

(Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 2018), https://permanent.fdlp.gov/gpo114669/TP525-3-1_30Nov2018.pdf. On training, in

October 2021, the US Army held its course for division and sta ocers to develop the “skills needed to plan successful large-scale combat oper-

ations in the major urban areas.” See John Spencer, “e US Army’s First Urban Warfare Planners Course,” Modern War Institute, https://mwi.

usma.edu/the-us-armys-rst-urban-warfare-planners-course/. For war games conducted as a component of US preparations for responding to a

possible Chinese seizure of Taiwan and/or surrounding islands, see Valerie Insinna, “A US Air Force War Game Shows What the Service Needs

to Hold O—or Win Against—China in 2030,” Defense News, April 12, 2021, https://www.defensenews.com/training-sim/2021/04/12/a-

us-air-force-war-game-shows-what-the-service-needs-to-hold-o-or-win-against-china-in-2030/; and Chris Dougherty, Jennie Matuschak and

Ripley Hunter, “e Poison Frog Strategy: Preventing a Chinese Fait Accompli Against Taiwanese Islands,” Center for a New American Securi-

ty, October 2021, https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/the-poison-frog-strategy.

35

United States Department of the Army, Field Manual No. 3-0: Operations, October 6, 2017, p. ix.

36

Teng Jianqun, “Regional Security Outlook 2021,” China Institute of International Studies, December 23, 2020, https://www.ciis.org.cn/

english/COMMENTARIES/202012/t20201223_7692.html.

Humanitarian Access, Great Power Conict, and Large-Scale Combat Operations | 9

American prestige on the world stage declined aer the 2008 nancial crisis and is “unwilling to acknowledge

its weakness vis-a-vis China.”

37

As noted earlier in this report, Chinese President Xi Jinping has promoted the

framework of a ‘New Type of Great Power Relationship’ between China and the US, a rubric that the US has

not embraced due to concern that it is tantamount to accepting China’s rise.

38

In the military realm, China now has the largest navy in the world and has land-based conventional ballistic

and cruise missiles that outnumber and outperform those of the US in terms of range.

39

e People’s

Liberation Army (PLA)—through equipment and systems modernization, historical analysis, information

collection, and training—is preparing for low and high intensity conicts.

40

e US Defense Intelligence

Agency “estimates the core strengths of the PLA to be long-range res, information warfare, and nuclear

capabilities. Furthermore, it acknowledges the PLA’s ever-improving power-projection capabilities and SOF

[special operations forces].”

41

China is also investing heavily in ‘anti-access’ or ‘area denial’ capabilities aimed

at blocking the United States’ naval access to the western Pacic, specically the waters that surround China’s

coastline.

42

Russia’s self-identication as a great power is well established. In fact, a RAND report notes, “Russia has

consistently described itself as a great power. At a minimum, this vision includes Russia’s desire to participate

in deciding global issues and to have a sphere of inuence in its region.”

43

However, Russian scholarship

conceptualizes Russia as a unique state that cannot be understood through the paradigms of Western

theories. Mariya Y. Omelicheva and Lidiya Zubytska write, “Kremlin authorities have tried to dene and

defend Russia’s great power identity by rejecting and downgrading what they view as alien to Russia. e anti-

Western and anti-American discourses and policies have been central to this approach.”

44

ese perspectives

inuence Russian foreign policy and academic discourse, which views a unipolar international system under

US dominance as “destabilizing,” particularly to Russian security.

45

Rather, Russian foreign policy promotes a

multipolar system, in which Russia retains special roles and rights based on its great power status.

46

Russia is also rapidly modernizing its military and building up its capacity for conict. According to Michael

Kofman and Andrea Kendall-Taylor, “Today, the Russian military is at its highest level of readiness, mobility,

37

Minghao Zhao, “Is a New Cold War Inevitable? Chinese Perspectives on US–China Strategic Competition,” e Chinese Journal of Interna-

tional Politics 12, no. 3 (2019): 371–394.

38

Cheng Li and Lucy Xu, “Chinese Enthusiasm and American Cynicism Over the ‘New Type of Great Power Relations,’” Brookings, December

4, 2014, https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/chinese-enthusiasm-and-american-cynicism-over-the-new-type-of-great-power-relations/.

39

US Department of Defense, Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China

(Washington, D.C.: Department of Defense, 2020), https://media.defense.gov/2020/Sep/01/2002488689/-1/-1/1/2020-DOD-CHINA-

MILITARY-POWER-REPORT-FINAL.PDF, p. ii and vi.

40

Paul Erickson, “Competition and Conict: Implications for Maneuver Brigades,” Modern War Institute, June 2021, p. 32, https://mwi.usma.

edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Competition-and-Conict-Implications-for-Maneuver-Brigades.pdf.

41

Ibid., p. 21.

42

Mike Yeo, “China’s Missile and Space Tech is Creating a Defensive Bubble Dicult to Penetrate,” Defense News, June 1, 2020, https://www.

defensenews.com/global/asia-pacic/2020/06/01/chinas-missile-and-space-tech-is-creating-a-defensive-bubble-dicult-to-penetrate/.

43

Andrew Radin and Clint Reach, Russian Views of the International Order (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2017), p. 15.

44

Mariya Y. Omelicheva and Lidiya Zubytska, “An Unending uest for Russia’s Place in the World: e Discursive Co-Evolution of the Study

and Practice of International Relations in Russia,” New Perspectives 24, no. 1 (2016): 20.

45

Ibid, p. 34.

46

Radin, Russian Views, p. 17.

Humanitarian Access, Great Power Conict, and Large-Scale Combat Operations | 10

and technical capability in decades.”

47

Over the last decade, Russia has upgraded its ground forces, which

include motorized, mechanized, and armored units with the missions of “forcible entry and holding and

seizing territory,” as a Modern War Institute report notes.

48

A Congressional Research Service report also

states that these forces “emphasize mobility and are increasingly capable of conducting short but complex,

high-tempo operations.”

49

However, the report continues, ground forces remain a relatively low funding

priority for Russia in comparison to “massed artillery, rocket re, and armored forces,” all of which have been

crucial to Russia’s engagement in Ukraine and Syria.

50

Russia has also deployed cyber and information operations in numerous contexts.

51

Indeed, Russia’s preferred

methods of warfare, encapsulated by the so-called Gerasimov Doctrine, are “nonmilitary means” of instigating

chaos and instability in foreign states (such as information warfare) supplemented by “military means of a

concealed character.”

52

Russia also remains a nuclear peer competitor with the US, and its proximity means

that its long-range conventional missile capabilities pose a unique and signicant threat to the US.

53

C. Where Will It All Lead? e Possibility of Large-Scale Combat Operations

Where will these developments lead? Future military confrontations could assume many forms, ranging

from grey zone conict (measures short of armed conict, including election interference or disinformation

campaigns) to head-to-head military combat.

54

In FM 3-0, the US Army puts forth: “e proliferation of

advanced technologies; adversary emphasis on force training, modernization, and professionalization; the

rise of revisionist, revanchist, and extremist ideologies; and the ever increasing speed of human interaction

makes large-scale ground combat more lethal, and more likely, than it has been in a generation.”

55

However,

analysts disagree about the likelihood of large-scale combat operations occurring. Some believe that great

power contestation will zzle out, predicting that one or more of these states (the US, China, and/or Russia)

47

Michael Kofman and Andrea Kendall-Taylor, “e Myth of Russian Decline: Why Moscow Will be a Persistent Power,” Foreign Af-

fairs, November/December, 2021, p. 142-152, https://www.proquest.com/magazines/myth-russian-decline-why-moscow-will-be/

docview/2584599186/se-2?accountid=9758.

48

Erickson, “Competition and Conict.”

49

US Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service, Russian Armed Forces: Capabilities, by Andrew S. Bowen, IFII589 (2020), https://

fas.org/sgp/crs/row/IF11589.pdf.

50

Ibid.

51

For an example of Russia using cyber and information operations, see Sarah P. White, “Understanding Cyberwarfare: Lessons from the

Russia-Georgia War,” Modern War Institute, March 20, 2018, https://mwi.usma.edu/understanding-cyberwarfare-lessons-russia-georgia-war/,

which notes that “overt cyberspace attacks...were relatively well synchronized with conventional military operations” by Russia against Georgia

in 2008.

52

Molly K. McKew, “e Gerasimov Doctrine,” Politico, September/October 2017, https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2017/09/05/

gerasimov-doctrine-russia-foreign-policy-215538/.

53

Eugene Rumer and Richard Sokolsky, “Grand Illusions: e Impact of Misperceptions About Russia on U.S. Policy,” Carnegie Endowment

for International Peace, June 30, 2021, https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/06/30/grand-illusions-impact-of-misperceptions-about-rus-

sia-on-u.s.-policy-pub-84845; and Kofman, “Myth of Russian Decline.” Additionally, for an analysis of strategic foresight within the Russian

government, see Andrew Monaghan, “How Russia Does Foresight: Where is the World Going?” European Union Institute for Security Studies,

2021, https://www.iss.europa.eu/sites/default/les/EUISSFiles/Brief_1_2021_0.pdf.

54

On grey zone conict, see “Competing in the Gray Zone: Countering Competition in the Space between War and Peace,” Center for Strate-

gic and International Studies, https://www.csis.org/features/competing-gray-zone.

55

U.S. Department of the Army, Field Manual No. 3-0: Operations, October 6, 2017; and “Analysis: Americans ink Conict with China is

Possible but Unlikely,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, https://chinasurvey.csis.org/analysis/china-conict-possible-but-unlike-

ly/.

Humanitarian Access, Great Power Conict, and Large-Scale Combat Operations | 11

will implode or lose their geopolitical standing.

56

Others believe the trend of geopolitical competition will

continue yet disagree on the likelihood of all-out warfare.

57

Few scholars assert that any great power is likely to purposefully initiate large-scale combat operations with

another near-peer competitor in the coming decades, especially given the high perceived risks of such a

conict. Yet, the probability of large-scale combat operations between great powers is certainly not negligible,

especially given the possibility of inadvertent escalations and miscalculations. In e Senkaku Paradox: Risking

Great Power Over Small Stakes, Michael E. O’Hanlon argues that the most plausible scenario in which large-

scale combat operations between the US, China, and Russia might occur would be an initially low-stakes

conict (what O’Hanlon refers to as a “localized crisis”) that escalates into full-edged war.

58

Similarly, in

the 2010 book, e China Dream: e Great Power inking and Strategic Positioning of China in the Post-

American Era, retired PLA ocer Liu Mingfu argues that China will ultimately surpass the US in geopolitical

power and that no matter how peacefully it seeks to do so, dramatic head-to-head conict between the US

and China in the coming decades is inevitable.

59

Indeed, tensions between the US and China exist in multiple geographic areas of the Asia-Pacic region

and beyond, including Taiwan, the South China Sea, and the West Pacic.

60

Each of these tension points

has the potential to escalate as a result of purposeful, inadvertent, or miscalculated actions. Although the

contemplation of possible confrontations between the US and China oen dominated discourse throughout

focus group sessions and key informant interviews conducted for this research, signicant US-Russian tensions

persist as well. Indeed, tensions have particularly escalated in the context of Russia’s large-scale invasion of

Ukraine in February 2022.

Regardless of debates among scholars and analysts about where exactly these developments will lead, the US,

China, and Russia are all bolstering their capabilities for future military combat in the context of great power

competition. e rest of this report examines the potential implications of possible future large-scale combat

operations on the humanitarian response environment, with a specic focus on humanitarian access.

56

For example, see George Friedman, e Next 100 Years: A Forecast for the 21st Century (New York: Anchor Books, 2009), which articulates a

prediction that neither China nor Russia will continue to rise and that both will implode during the 21st Century. Also see Alfred W. McCoy,

In the Shadows of the American Century: e Rise and Decline of U.S. Global Power (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2017), which examines the

possibility that US power will decline over the course of the 21st century.

57

For various perspectives, see, for example, John Mearsheimer, “e Inevitable Rivalry: America, China, and the Tragedy of Great-Power Poli-

tics,” Foreign Aairs, November/December 2021, https://www.foreignaairs.com/articles/china/2021-10-19/inevitable-rivalry-cold-war; and

Charles C. Krulak and Alex Friedman, “e US and China are not Destined for War,” Australian Strategic Policy Institute, August 24, 2021,

https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/the-us-and-china-are-not-destined-for-war/.

58

Michael E. O’Hanlon, “Introduction: Expanding the Competitive Space,” In e Senkaku Paradox: Risking Great Power War Over Small

Stakes, p. 1-18 (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2019), http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7864/j.ctv3znzxb.7.

59

Liu Mingfu, e China Dream: e Great Power inking and Strategic Positioning of China in the Post-American Era (Beijing: CN Times

Books, 2010). English translation published in 2015.

60

e US believes that China wishes to have the capability to seize Taiwan by 2027. See Sam LaGrone, “Milley: China Wants Capability to

Take Taiwan by 2027, Sees No Near-term Intent to Invade,” USNI News, June 23, 2021, https://news.usni.org/2021/06/23/milley-china-

wants-capability-to-take-taiwan-by-2027-sees-no-near-term-intent-to-invade.

Humanitarian Access, Great Power Conict, and Large-Scale Combat Operations | 12

Part III

Envisioning Possible Future Large-Scale

Combat Operations

is section presents potential characteristics of future large-scale combat operations, including conventional

military confrontation, as well as cyber and information operations, during great power conict.

61

e section

draws on perspectives from the focus group discussions and semi-structured interviews, as well as relevant

literature. In particular, this section discusses: 1) perceptions regarding key actors, geographic scope, and

duration; 2) the fast-paced, lethal, and destructive nature of future large-scale combat operations; and 3) the

role of information and cyber operations.

A. Key Actors, Geographic Scope, and Duration

Research participants strongly expressed the expectation that large-scale combat operations will entail a

combination of direct large-scale military confrontation and indirect confrontation through the use of

proxies, with great powers funding, arming, and working with and through other armed actors. ird-party

actors (state and non-state) are anticipated to play a signicant role.

62

Generally, research participants discussed the possibility of a global conict of an unbounded nature, vast in

geographic scope, playing out across multiple domains: air, land, sea, space, and cyberspace. Such a conict

would dier from current conicts due its metastatic nature, quickly expanding to secondary locations,

including to territories not necessarily in direct geographic proximity to the origin of ghting.

63

Some

participants contemplated the possibility of an attack on the US, Chinese, or Russian homelands, although

other research participants doubted the likelihood of this possibility, placing focus on tertiary locations.

Nevertheless, there is an expectation that great power conict would directly impact domestic populations,

given the likelihood of adversaries deploying cyber-attacks and information operations (discussed in greater

detail below). One research participant oered the following reection:

I personally think that the conict will look nothing like recent conicts of the last twenty,

thirty, forty years in terms of the scope and scale of violence… e unbounded nature of it is

something that governments, populations and militaries will nd dicult to stop. ere’s a lot

of planning going on at the moment, but in terms of how it compares: no comparison at all.

61

See Sandor Fabian, “Irregular versus Conventional Warfare: A Dichotomous Misconception,” Modern War Institute, 2021, https://mwi.

usma.edu/irregular-versus-conventional-warfare-a-dichotomous-misconception/.

62

As noted in the “Methodology” section of this report, discussions with research participants were loosely focused on the possibility of future

conict between the US versus China and/or Russia, but participants also raised the possibility of large-scale combat operations arising between

regional powers.

63

See David C. Gompert, Astrid Stuth Cevallos, and Cristina L. Garafola, War with China: inking rough the Unthinkable (Santa Monica,

CA: RAND, 2016), p. 27, https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR1100/RR1140/RAND_RR1140.pdf, which

notes, “In modern history, wars involving great and more or less evenly matched powers have sucked in numerous third parties (not just prewar

allies), lasted years, metastasized to other regions, and forced belligerents to shi their economies to a war footing and their societies to a war

psyche.”

Humanitarian Access, Great Power Conict, and Large-Scale Combat Operations | 13

is kind of warfare would engender a variety of challenges for conict de-escalation. First, as noted, the

destabilizing global consequences of great power conict could draw in other third-party actors, with the

metastatic nature of the conict causing military operations to expand and evolve in unpredictable ways.

Second, proxy forces, driven by their own sets of objectives, might continue to pursue these objectives even

aer tensions between great powers have been mitigated or resolved, further complicating eorts to contain

or end the military conict. ird, a lack of clarity about who is responsible for certain actions during military

operations that involve proxies could complicate diplomatic engagement eorts. is set of challenges,

combined with the peer or near-peer nature of states’ capabilities, could prevent a quick and decisive end to

military conict.

B. Fast-Paced, Lethal, and Destructive

Large-scale combat operations, should they occur, are likely to be intentionally chaotic, intense, lethal, and

destructive. Research participants likened the humanitarian consequences of such a conict to those of

World War II. Indeed, large-scale combat operations will cause extensive damage to civilian infrastructure,

particularly if armed actors target civilian infrastructure in their conduct of this ‘total war.’ e impacts on

civilians will amplify feelings of the conict being “more like an existential crisis rather than a discretionary

crisis,” as one research participant stated. In the words of another research participant, “If we move to total

war, it’s not a war of choice, it’s all in, and will involve everybody and go until someone wins.” e result will

be that the “population will be targeted from both sides to destroy the will of both countries,” a research

participant asserted. Furthermore, within this context, there is an expectation that states will pursue whole-

of-nation mobilization eorts to support their military operations.

64

Research participants expressed mixed views on the extent to which international humanitarian law (IHL)

would eectively limit the eects of such an armed conict. On the one hand, some research participants

argued that states will have an incentive to respect IHL for reasons that include promoting reciprocity and

claiming moral legitimacy. On the other hand, many participants envisioned peer-to-peer conict between

great powers as relatively unconstrained by IHL, with states viewing humanitarian considerations (including

civilian protection) to be secondary or tertiary concerns in the context of total warfare. ese research

participants expected great powers to violate IHL both unintentionally (resulting from a chaotic, fast-paced

conict environment) and intentionally (for example, targeting civilians and civilian objects protected by

IHL as part of a deliberate warghting strategy).

65

64

See Gompert, Cevallos, and Garafola, War with China, p. 27-28, which paints the following picture of possible war between the United

States and China: “Whole populations suspend normal life; large fractions of them are prepared or forced to throw their weight behind their

nation’s ght. Not just states but opposing ideologies, worldviews, and political systems might be pitted against each other. Whatever their

initial causes, such wars’ outcomes might determine which great powers and their blocs survive as such. Prewar international systems collapse or

are transformed to serve the victors’ interests. us, the costs of failing outweigh those of ghting.”

65

See Shane Reeves and Robert Lawless, “Reexamining the Law of War for Great Power Competition,” Articles of War, January 27, 2021,

https://lieber.westpoint.edu/reexamining-the-law-of-war-for-great-power-competition/; Lt. Col. John Cherry, Sqn. Ldr. Kieran Tinkler and

Michael Schmitt, “Avoiding Collateral Damage on the Battleeld,” Just Security, February 11, 2021, https://www.justsecurity.org/74619/avoid-

ing-collateral-damage-on-the-battleeld/; and Lt. Gen. Charles Pede and Col. Peter Hayden, “e Eighteenth Gap: Preserving the Command-

er’s Legal Maneuver Space on ‘Battleeld Next,’” Military Review: e Professional Journal of the U.S. Army, March–April 2021, https://www.

armyupress.army.mil/Journals/Military-Review/English-Edition-Archives/March-April-2021/Pede-e-18th-Gap/.

Humanitarian Access, Great Power Conict, and Large-Scale Combat Operations | 14

Within the context of large-scale combat operations, research participants discussed that armed actors may be

very unlikely to support implementing humanitarian pauses or humanitarian corridors, which if implemented

could oer an opportunity for militaries to re-position, re-supply, and potentially conduct other operations

during the pause.

66

is reluctance to support humanitarian pauses or corridors would be compounded by

states’ motivations to refrain from ceasing operations until the opposing side is completely defeated.

Research participants also predicted that the tempo and lethality of operations will require local governments

(spanning national to municipal levels) and civilian populations to remain constantly vigilant to threats to

their safety and will require civilians to take actions to protect themselves. In other words, fast-paced warfare

will place pressure on local governments,civilians themselves, and the humanitarian sector to ensure that

populations, even before the eruption of conict, are prepared to weather threats to civilian protection.

C. Cyber and Information Operations

States, militaries, and non-state actors in great power conict may pursue multiple types of operations

simultaneously, with conventional military operations conducted along with cyber and information

operations. Cyber-attacks cost little to carry out compared to conventional military operations, especially in

light of their ability to inict extensive damage on critical infrastructure, disrupt government and military

operations, and impact civilian populations in various ways, including by hindering access to basic services.

67

Determining who is responsible for such attacks (also known as cyber attribution) is a time and resource-

intensive process.

68

Further exacerbating the destruction and confusion inherent in fast-paced large-scale combat operations,

information operations could be widely used to limit access to necessary data, promote disinformation, and

control political and military narratives relevant to the conict. In the words of one research participant,

“Trying to control that narrative, to be seen as the provider of aid and the adversary as the uncaring,

illegitimate, discredited power will be more important.” ese operations may directly or indirectly aect

civilian populations, including by seeking to inuence public opinion on the conict and those involved.

All information platforms are vulnerable to this type of instrumentalization, but social media was of particular

interest to research participants. As one research participant underscored, reecting on the possibility of

a conict on the scale of World War II, but with contemporary cyber and information warfare elements

also mixed in, “If we’re looking on those kinds of scales, I think, one of the things that we’ve never faced

66

“Glossary of Terms: Pauses During Conict,” United Nations Oce for the Coordination of Humanitarian Aairs, June 2011, https://www.

unocha.org/sites/unocha/les/dms/Documents/AccessMechanisms.pdf.

67

For discussion and resources on the intersection between cyber operations and IHL, see Laurent Gisel, Tilman Rodenhäuser, and Knut

Dörmann, “Twenty Years On: International Humanitarian Law and the Protection of Civilians Against the Eects of Cyber Operations During

Armed Conicts,” International Review of the Red Cross 102, no. 913 (2020): 287-334; “Cyber Operations During Armed Conicts,” Inter-

national Committee of the Red Cross, https://www.icrc.org/en/war-and-law/conduct-hostilities/cyber-warfare; and “Cyber Warfare: Does

International Humanitarian Law Apply?” International Committee of the Red Cross, February 25, 2021, https://www.icrc.org/en/document/

cyber-warfare-and-international-humanitarian-law; and Michael N. Schmitt (ed), Tallinn Manual 2.0 on the International Law Applicable to

Cyber Operations (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2017).

68

United States, Oce of the Director of National Intelligence, A Guide to Cyber Attribution (Washington, D.C.: Oce of the Director of

National Intelligence, 2018), https://www.dni.gov/les/CTIIC/documents/ODNI_A_Guide_to_Cyber_Attribution.pdf.

Humanitarian Access, Great Power Conict, and Large-Scale Combat Operations | 15

before in those huge contexts is the impact of social media. e psychological operations and the scare

factor that dimension might bring to us would be a consideration from the outset.” ere are also possible

intersections in the information and space domains, in particular, relating to targeting satellites to interfere

with communication abilities.

Part IV

Humanitarian Access Challenges

During Large-Scale Combat Operations

Considering the conict characteristics presented in the previous section, this section discusses the

humanitarian access challenges likely to arise in future large-scale combat operations, in particular, during

crises arising from great power conict. is analysis draws primarily on the views articulated during focus

group discussions and key informant interviews. e section rst oers a broad overview of the challenging

nature of humanitarian access during large-scale combat operations. e section then delves more deeply into

particular access issues, categorized in terms of three types of challenges: 1) political, 2) operational, and 3)

tactical.

A. e Humanitarian Access Environment: An Overview

During future large-scale combat operations, the high tempo of operations, combatants’ employment of

conventional and advanced weapons, and the wide scope of aected areas spanning multiple domains—air,

land, sea, cyber, and space—are likely to aect civilian populations at a level unseen in recent humanitarian

crises. Indeed, the fast-paced, devastating, and continuous nature of the conict will directly impact civilians’

ability to survive, a view captured by one research participant, who stated:

e population will remain faced with the question of how they will survive such a scenario and

how they can make sure that, even if they’re physically safe—outside of the areas of conict,

shooting, and bombing—how can they be sure they will get the minimum goods and services

they need whilst in those locations?

Another research participant concurred, reecting, in particular, on the ‘total war’ approach that may be

adopted during large-scale combat operations:

is is going to be an ongoing conict. is is not going to be, like, you rest for the night. We

expect this to be an ongoing thing, 24/7 until it’s done. So it’s fast paced, very denite in terms

of what it needs to achieve, which is the neutralization of the other. And for the population,

this is going to be a dicult situation or scenario for them to be in.

Humanitarian Access, Great Power Conict, and Large-Scale Combat Operations | 16

One can certainly draw lessons from recent highly politicized access contexts in which global and/or regional

powers have had a signicant stake (e.g., Syria, Yemen, and Ukraine). However, challenges to humanitarian

access in great power conict, particularly large-scale combat operations, will far exceed the scale, scope,

and complexity of access obstacles encountered in current and recent contexts. e dynamics of large-scale

combat operations are likely to not only exacerbate existing challenges but also result in new, and at times

unprecedented, access challenges for humanitarian actors and civilian populations.

ere was a nearly universal perspective shared among research participants that military operations will

result in a scale and level of violence that yields a signicant number of civilian injuries and casualties, threats

to life and safety, and destruction of critical infrastructure. ese eects are especially important to consider,

as militaries and humanitarian organizations anticipate that future conicts are likely to occur in urban

environments, with disproportionate impacts on civilian populations, including their ability to access goods

and services.

69

e remainder of this section examines challenges that humanitarian organizations may encounter in trying

to access civilians in need. is analysis divides these challenges into the following three categories:

1. Political challenges relating to high-level political or strategic engagements, oen involving issues

relating to the norms or values that undergird humanitarian action.

2. Operational challenges relating to developing and planning practical and procedural methods for

activities or operations that align with broader political and strategic goals.

3. Tactical challenges relating to implementing operational arrangements while also responding to

ground-level issues, which can change rapidly.

ese three categories broadly align with analytical distinctions found in literature on humanitarian

negotiation, military planning, logistics, and organizational management.

70

ese categories are also

interrelated and potentially overlapping.

71

For example, politicized perceptions of international humanitarian

69

Margarita Konaev and John Spencer, “e Era of Urban Warfare is Already Here,” Foreign Policy Research Institute, March 21, 2018,

https://www.fpri.org/article/2018/03/the-era-of-urban-warfare-is-already-here/.

70

For relevant literature on humanitarian negotiation, see Field Manual on Frontline Negotiation (Geneva, Switzerland: Centre of Competence

on Humanitarian Negotiation, 2019), which presents three types of humanitarian negotiation: political, professional, and technical; and the

Humanitarian Negotiation Handbook (Geneva, Switzerland: Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue, 2004), which discusses three levels at which

humanitarian negotiations occur: high-level strategic, mid-level operational, ground-level frontline. For military perspectives on these three

levels (commonly labeled in military publications as strategic, operational, and tactical), as well as information about the historical development

of this framework, see Georgii Samoilovich Isserson, e Evolution of Operational Art (Fort Leavenworth, KS: Combat Studies Institute Press,

2013), https://permanent.fdlp.gov/gpo88396/OperationalArt.pdf; USAF College of Aerospace Doctrine, Research and Education (CADRE),

“ree Levels of War,” Air and Space Power Mentoring Guide, Vol. 1 (Maxwell AFB, AL: Air University Press, 1997), https://faculty.cc.gatech.

edu/~tpilsch/INTA4803TP/Articles/ree%20Levels%20of%20War=CADRE-excerpt.pdf; and John R. Deni, “Maintaining Transatlantic

Strategic, Operational and Tactical Interoperability in an Era of Austerity,” International Aairs 90, no. 3 (2014): 583–600. For examples in

which other elds have used a similar framework, see G. Schmidt & Wilbert E. Wilhelm, “Strategic, Tactical and Operational Decisions in

Multi-National Logistics Networks: A Review and Discussion of Modelling Issues,” International Journal of Production Research 38, no. 7

(2000): 1501–1523; and Roger Kaufman, Jerry Herman, and Kathi Watters, Educational Planning: Strategic, Tactical, Operational (Lanham,

MD: Scarecrow Press, 2002).

71

See CADRE, “ree Levels of War,” which notes, “e boundaries of the levels of war and conict tend to blur and do not necessarily corre-

spond to levels of command.”

Humanitarian Access, Great Power Conict, and Large-Scale Combat Operations | 17

actors can lead to tensions in high-level political engagements, spiraling into operational challenges (such

as governments instrumentalizing bureaucratic procedures to control humanitarian activities) and tactical

challenges (as frontline humanitarians grapple with ad hoc restrictions, for example, during checkpoint

negotiations). Conversely, ground-level tensions between humanitarian and military actors can escalate into

issues that operational-level and political-level actors seek to address.

In light of the inter-related and potentially overlapping nature of these categories, there are opportunities

for humanitarian actors, governments, militaries, other armed actors, and donors to work across and

transcend divides that oen exist between these categories. An implication is the importance of coordination

between actors engaged in high-level diplomatic interactions, mid-level operational planning, and frontline

implementation. Nevertheless, the analysis below situates particular access challenges within specic

categories, even if certain elements are relevant to other categories as well. Table 1 (below) lays out these

humanitarian access issues. e rest of this section oers details and analysis.

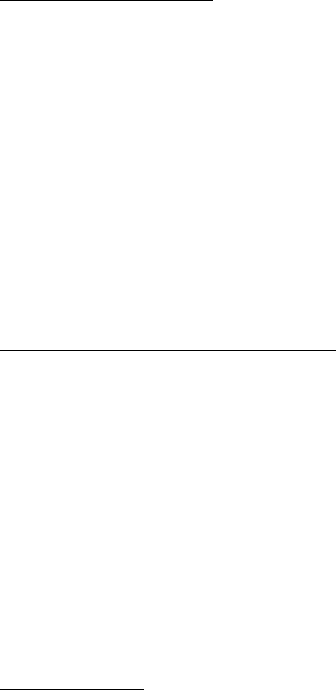

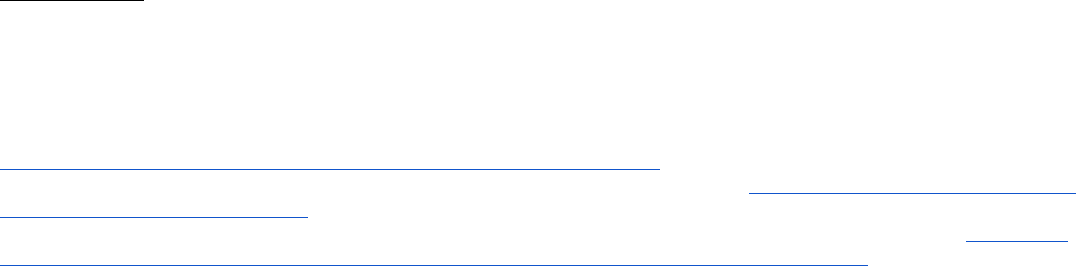

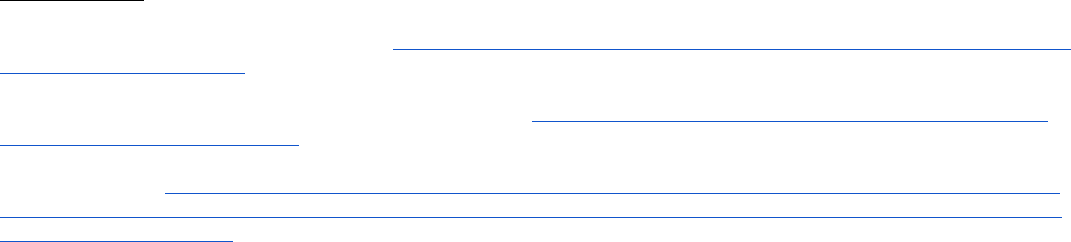

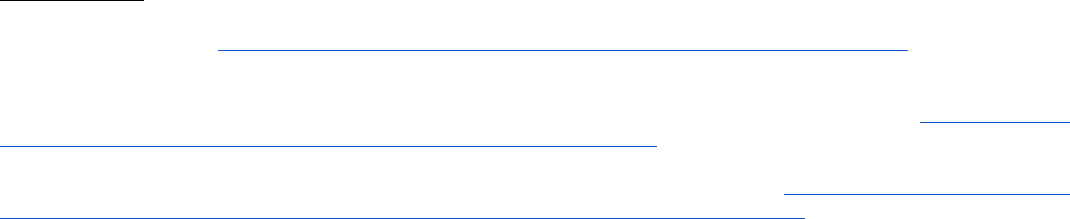

Table 1: Anticipated Humanitarian Access Challenges During Large-Scale Combat Operations

B. Political Humanitarian Access Challenges

Limited Impact of High-Level Multilateral Political Engagements

e geopolitically charged nature of peer-to-peer conict is expected to create signicant challenges for high-

level humanitarian advocacy eorts, including possibly curtailing their impact, especially in the context of the

United Nations (UN) Security Council. e reality is not new that political will, particularly that of state

actors, plays a powerfully disproportionate role in determining the extent to which humanitarian organizations

are able to operate. However, these dynamics are likely to be heightened and intensied, especially if one

envisions a World War II style conict. One research participant lamented this particular dynamic, describing

Political Challenges

Limited impact of high-

level multilateral political

engagements

Politicized government

perceptions of the international

humanitarian actors

Relationship decits with

potential state actors

Operational Challenges

Bureaucratic impediments and

donor restrictions

Limited operational role

of traditional international

humanitarian actors

Devising processes to manage

humanitarian insecurity

Tactical Challenges

Managing access and logistics

across multiple domains with

limited resources

Physical and digital threats to

aid worker security

Humanitarian Access, Great Power Conict, and Large-Scale Combat Operations | 18

how the already grave political conditionality on humanitarian access in certain contexts would turn even

graver during great power conict: