NFS

Form

10-900

EAMES

HOUSE

United

States

Department

of

the

Interior,

National

Park

Service

NATIONAL

HISTORIC

LANDMARK

NOMINATION

USDI/NPS

NRHP

Registration

Form

(Rev.

8-86)

OMB

No.

1024-0018

Page

1

National

Register

of

Historic

Places

Registration

Form

1.

NAME

OF

PROPERTY

Historic

Name:

Eames

House

Other

Name/Site

Number:

Case

Study

House

#8

2.

LOCATION

Street

&

Number:

203

N

Chautauqua

Boulevard

City/Town:

Pacific

Palisades

State:

California

County:

Los

Angeles

Code:

037

Not

for

publication:

N/A

Vicinity:

N/A

Zip

Code:

90272

3.

CLASSIFICATION

Ownership

of

Property

Private:

x

Public-Local:

_

Public-State:

_

Public-Federal:

Number

of

Resources

within

Property

Contributing:

2

Category

of

Property

Building(s):

District:

Site:

Structure:

Object:

Noncontributing:

buildings

sites

structures

objects

Total

x

Number

of

Contributing

Resources

Previously

Listed

in

the

National

Register:

None

Name

of

Related Multiple Property

Listing:

N/A

NATIONAL

HISTORIC

LANDMARK

NOMINATION

NFS

Form

10-900

USDI/NPS

NRHP

Registration

Form

(Rev.

8-86)

OMB

No.

1024-0018

EAMES

HOUSE Page

2

United

States

Department

of

the

Interior,

National

Park

Service

National

Register

of

Historic

Places

Registration

Form

4.

STATE/FEDERAL

AGENCY

CERTIFICATION

As

the

designated

authority

under

the

National

Historic

Preservation

Act

of

1966,

as

amended,

I

hereby

certify

that

this

__

nomination

__

request

for

determination

of

eligibility

meets

the

documentation

standards

for

registering

properties

in

the

National

Register

of

Historic

Places

and

meets

the

procedural

and

professional

requirements

set

forth

in

36

CFR

Part

60.

In

my

opinion,

the

property

__

meets

__

does

not

meet

the

National

Register

Criteria.

Signature

of

Certifying

Official

Date

State

or

Federal

Agency

and

Bureau

In

my

opinion,

the

property

__

meets

__

does

not

meet

the

National

Register

criteria.

Signature

of

Commenting

or

Other

Official

Date

State

or

Federal

Agency

and

Bureau

5.

NATIONAL

PARK

SERVICE

CERTIFICATION

I

hereby

certify

that

this

property

is:

Entered

in

the

National

Register

Determined

eligible

for

the

National

Register

Determined

not

eligible

for

the

National

Register

Removed

from

the

National

Register

Other

(explain):

Signature

of

Keeper

Date

of

Action

NFS

Form

10-900

EAMES

HOUSE

United

States

Department

of

the

Interior,

National

Park

Service

NATIONAL

HISTORIC

LANDMARK

NOMINATION

USDI/NPS

NRHP

Registration

Form

(Rev.

8-86)

OMB

No.

1024-0018

Page

3

National

Register

of

Historic

Places

Registration

Form

6.

FUNCTION

OR

USE

Historic:

Domestic

Current:

Domestic

Sub:

Single

dwelling

Sub:

Single

dwelling

7.

DESCRIPTION

Architectural

Classification:

Modern

Movement

Materials:

Foundation:

Concrete

Walls:

Glass,

stucco,

wood,

asbestos,

metal,

synthetics

Roof:

Asphalt

Other:

Metal

(steel

frame)

NATIONAL

HISTORIC

LANDMARK

NOMINATION

NFS

Form

10-900

USDI/NPS

MRHP

Registration

Form

(Rev.

8-86)

OMB

No.

1024-0018

EAMES

HOUSE Page

4

United

States

Department

of

the

Interior,

National

Park

Service

National

Register

of

Historic

Places

Registration

Form

Describe Present

and

Historic

Physical

Appearance

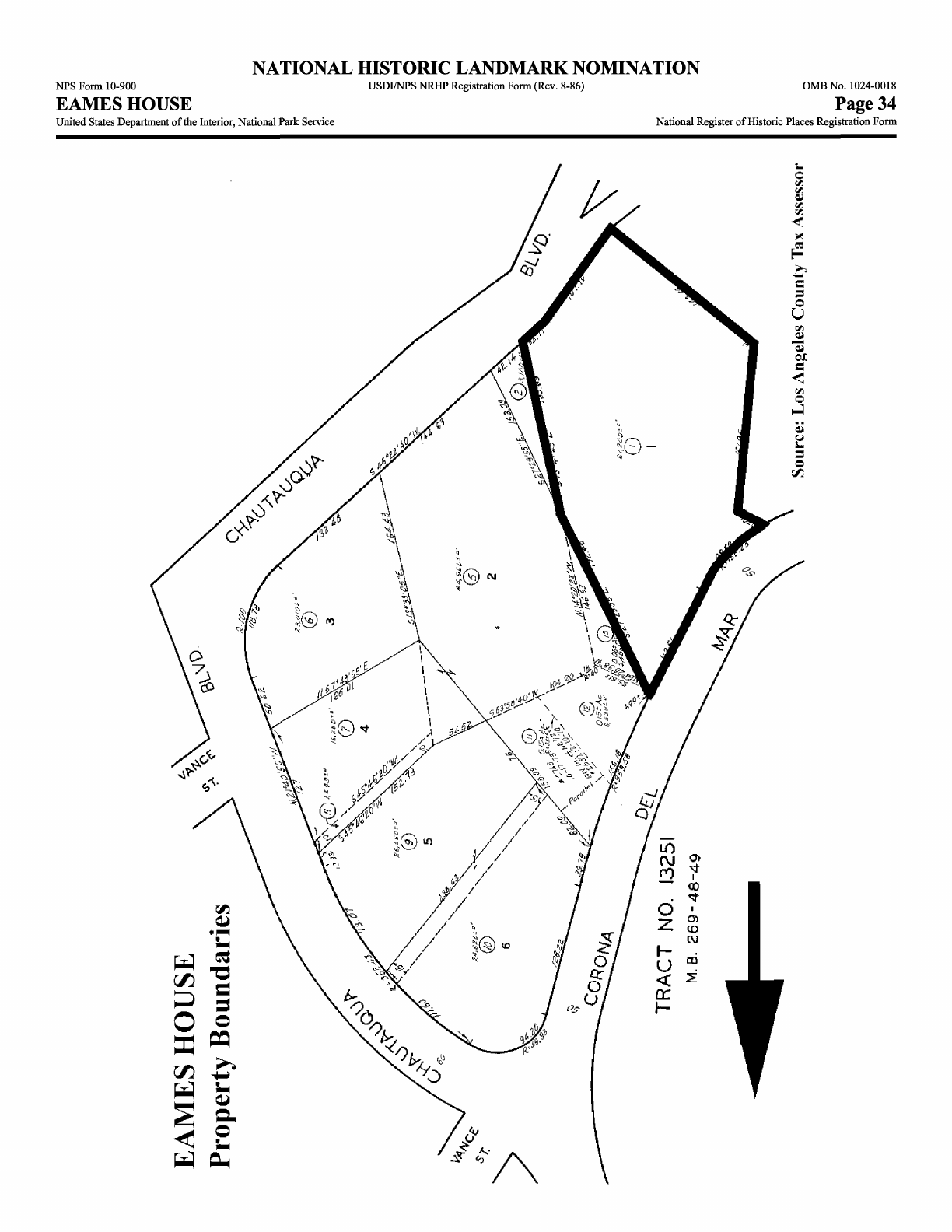

Location

The

Eames

House

is

located

in

the

Pacific

Palisades

area

of

Los

Angeles,

California.

The

property

is

composed

of

a

residence

and

studio

situated

on

a

bluff

overlooking

the

Pacific

Ocean.

The

residence and

studio

occupy

level

ground

at

the

base

of

a

steep

slope

along

the

western

edge

of

the

property.

The

community

of

Pacific

Palisades

sits

on

the

high

bluffs

along

the

Pacific Coast

between

the

cities

of

Santa

Monica and

Malibu.

Atop

the

bluffs,

flat

plateaus,

or

mesas,

are

defined

by

canyons

that

run inland

from

the

shoreline

cliffs.

The

broad

Santa

Monica

Canyon

divides

Pacific

Palisades from

the

City

of

Santa

Monica.

The

subject

property

occupies

a

lower

yet

distinct

plateau

on

the

northern

edge

of

Santa

Monica

Canyon,

overlooking

the

ocean

immediately

to

the

south.

The

mouth

of

the

canyon

is

located

on

marine

shales,

as

described

by

UCLA

geologist

Dr.

Richard

F.

Logan:

The

ever

threatening

cliff

that

overhangs

the Coast

Highway

at

Chautauqua

...

is

composed

entirely

of

slightly

consolidated

alluvium;

the

other

three

sides

all

involve

marine

shales,

which

become extremely

heavy

in

wet

years

through

absorption

of

rain

water,

and

simultaneously

become

greasy,

thus

lubricating

a

potential

massive

earth

movement.

The

major

part

of

Pacific

Palisades

is

free

of

all

danger

from

slides,

but

the

canyon

borders

and

sea-cliff

edge

present

some

serious

stabilization

problems.

l

The

Eames

House

is

located

within

a

cluster

of

four

single

family residences,

all

designed

as

part

of

the

Case

f\

Study

House

program.

The

property

is

not

visible

from

the

street,

and

is

accessed

via

a

private

drive

that

leads

from

Chautauqua

Boulevard.

A

sign

indicating

the

addresses

201

and

203

Chautauqua

is

posted

at

the

drive's

entrance.

The

asphalt

paved

drive

leads

first

to

the

property

at

201

Chautauqua

(The

Entenza

House,

Case

Study

House

#9),

and

terminates

at

the

Eames

property.

To

the

north,

the

drive

is

edged

by

a

serpentine

brick

wall

with

weeping

mortar.

The

wall

is

part

of

Richard

Neutra's

landscape

design

for

the

property

at

219

Chautauqua

(The

Bailey

House,

Case

Study

House

#20).

The

drive's

southern

edge

is

lined

with

a

wood

fence,

and

is

shaded

by

mature

trees

that

overhang

it.

The

Eames

House occupies an

irregularly-shaped

1.4-acre

site.

The

site

is

predominately

flat

with

a

steep

upward

slope

at

its

western

edge.

The

house

is

situated

parallel

to

the

slope

and

is

oriented

toward

a

grassy

area

to

the

east

known

as

"the

meadow."

The

property

is

densely

landscaped,

creating

a

sense

of

private

enclosure

and

separating

it

from

its

neighbors.

An earthen

mound,

or

berm,

is

situated

at

the

far

edge

of

the

property.

It

features

a

metal

fence

obscured

by

mature

shrubs,

providing

a

visual

screen

from

the

adjacent

Entenza

House.

Eucalyptus

trees

planted

along

the

eastern

elevations

of

the

house

provide added

privacy

and

shade.

A

wood

plank

pathway

leads

from

the

drive

and

runs

along

the

full

extent

of

the

house's

eastern

facade.

*Dr.

Richard

F.

Logan,

"Pacific

Palisades,

the

Natural

Setting,"

Pacific

Palisades,

Where

the

Mountains

Meet

the

Sea, ed.

Betty

Lou

Young.

(Pacific

Palisades,

CA:

Pacific

Palisades

Historical

Society

Press,

1983),

2.

2

Other

houses

within

this

cluster

include

Case

Study

House

#18

(199

Chautauqua

Boulevard);

Case

Study

#9

(201

Chautauqua

Boulevard);

and

Case

Study

House

#20 (219

Chautauqua

Boulevard).

NATIONAL

HISTORIC

LANDMARK

NOMINATION

NFS

Form

10-900

USDI/NPS

NRHP

Registration

Form

(Rev.

8-86)

OMB

No.

1024-0018

EAMES

HOUSE Page

5

United

States

Department

of

the

Interior,

National

Park

Service

National

Register

of

Historic

Places

Registration

Form

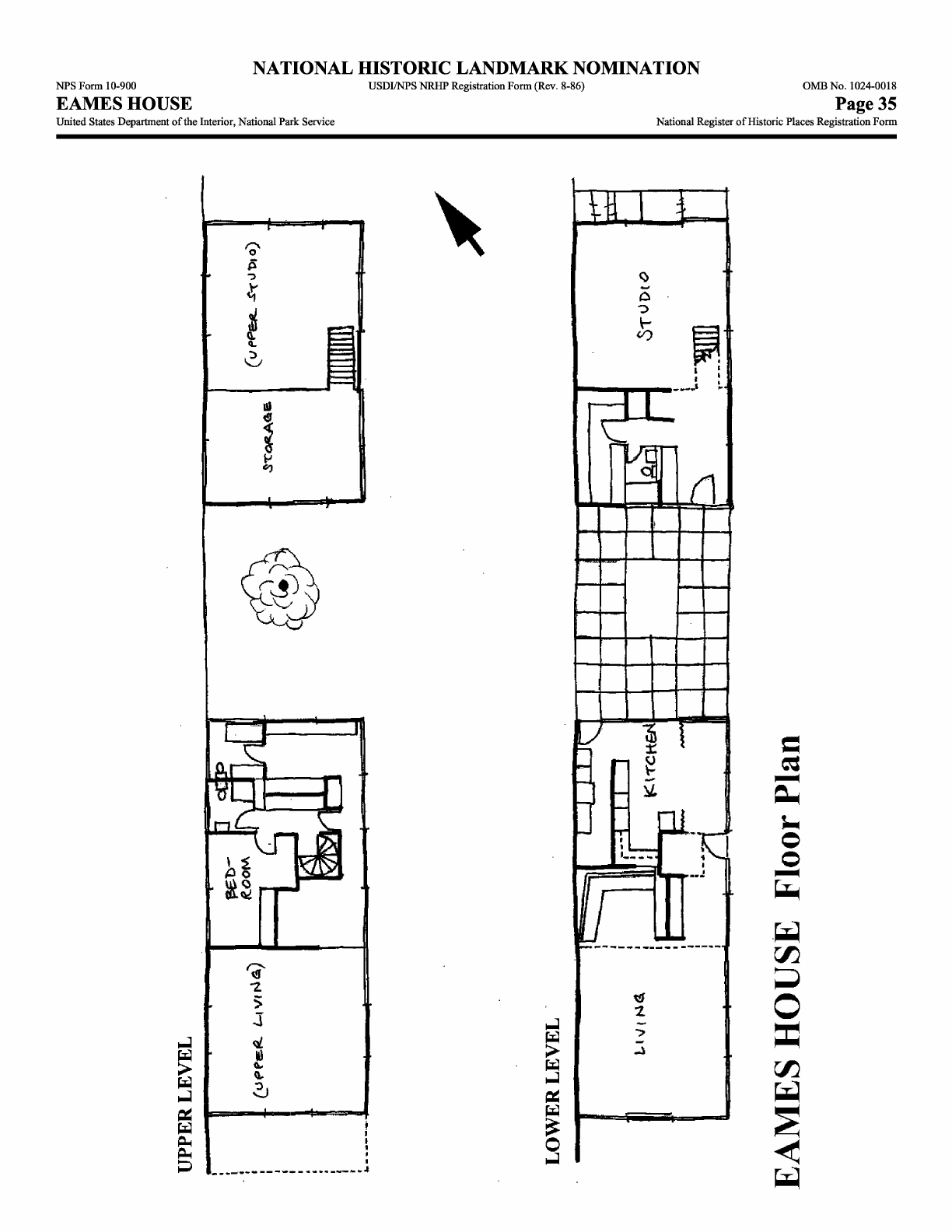

Design

and

Construction

The

Eames

House

is

composed

of

two

distinct

volumes,

a

living

component

(or

residence)

and

a

working

component

(or

studio).

The

two

volumes

are

arranged

in

a

linear

configuration

and

separated

by

an

open

court.

Both

volumes

are

rectangular

in

plan

with

horizontal

massing,

and

are

situated along

the

western

edge

of

the

property.

The

residence

is

1,500

square

feet,

with

the

studio

containing

an

additional

1,000

square

feet.

The

Eames

House

is

modular

in

its

design,

composed

of

20'

x

7'

4"

bays

that

rise

to

a

height

of

17

feet.

Each

bay

is

defined

by

a

steel

frame

consisting

of

two

rows

of

4-inch H-columns

set

20

feet

apart,

with

a

12-inch

open-web

joist

forming

the

top

member.

On

the

rear

(west)

elevation,

the

vertical

member

of

each

frame

is

partially

embedded

in

an

8-foot

high

poured

concrete

retaining

wall

at

the

base

of

the

slope

that

forms

the

lower

part

of

the

west

elevation

in

both

components.

Steel

decking

running

perpendicular

to

the

frames

forms

the

o

underside

of

the

flat

roof.

The

roof

is

a

gravel

surfaced,

built-up

assembly.

The

20-foot

wide

dimension

of

the

frames

define

the

width

of

both

the

residence

and

studio.

The

residence

consists

of

eight

bays, and

the

studio

is

five

bays

wide.

The

open

court

that

separates

the

two structures

is

the

equivalent

of

four

bays

in

width.

The

exposed

steel

frames

are

painted

black,

which

visually

delineates

each

bay

and

the

shared

structural

rhythm

of

the

two

components.

Diagonal cross-bracing,

composed

of

metal

cables

visible

on

the

exterior,

provides

structural

stability

for

the

frames.

Each

bay

is

in-filled with

one

of

several

materials,

including

panels

of

plaster, plywood,

asbestos,

glass,

and

"pylon"

(a

translucent

laminate

similar

to

fiberglass).

4

Some

bays

contain

one

type

of

infill

material,

such

as

a

single

plaster

panel.

Other

bays

are

divided

into

multiple

smaller

panels

of

uniform

dimension,

with

up

to

twelve

in

the

lower

story

(two

rows

of

six),

and

as

many

as

fourteen

in

the

upper

story

(two

rows

of

seven).

Like the

frames,

the

steel

sashes

and

sub-dividers

are

also

painted

black,

creating

a

horizontal

grid

pattern.

Plaster

panels

are

painted

black,

white,

beige,

red,

or

blue.

The

main

entrance

to

the

residence

is

located

on

the

primary

(east)

fagade.

The

hinged

door

is

off-set

right

of

center

in

elevation

and

consists

of

five

translucent

glazed

panels

that

echo

the

size

and appearance

of

the

panels

that

flank

the

door

to

the

right

and

directly

above.

Two

small

panels

located

above

and

spanning

the entire

width

of

the

entry

bay

frame

are

highlighted

in

gold.

A

rotating

black-glazed

ceramic

bell,

attributed

to

Mexican

potter,

Maria

Martinez,

flanks

the

main

entrance

to

the

right.

The

inner

portion

of

the

two

rectangular

volumes

(i.e.

the

northern

portion

of

the

residence,

and

southern

portion

of

the

studio),

are

each

divided

into

an

upper

and

lower

story,

with

additional

open-web

joists

at

a

height

of

8

feet.

The

outer portions

(i.e.

the

southern

portion

of

the

residence,

and

northern

portion

of

the

studio),

are

open

to

form

double-height interior

spaces.

A

deep

overhang

and

the

rear

wall

extend

beyond

the

south

faQade

of

the

residence, creating

another

outdoor

space.

5

Windows

include

both

fixed

and

operable

awning

casements

divided

into

two

horizontal

lights.

Windows

and

doors

are

glazed

with

a

combination

of

transparent

and translucent

glass.

Wire-reinforced

glass

is

used

in

some

bays

of

the

studio.

The

north,

east,

and

south

elevations

of

both

the

residence

and

studio

contain

large

areas

of

3

According

to

staff

at

the

Eames

Foundation,

gravel

surface

tar

paper

covers

one-half

inch insulation

on

the

roof

of

both

components.

4

James

Steele,

Eames

House,

Charles

and

Ray

Eames

(London:

Phaidon

Press

Limited,

1994),

10.

5

"Case

Study

House

for

1949:

The

Steel

Frame,"

Arts

&

Architecture

(March

1949),

30-31.

NATIONAL

HISTORIC

LANDMARK

NOMINATION

NFS

Form

10-900

USDI/NPS

NRHP

Registration

Form

(Rev.

8-86)

OMB

No.

1024-0018

EAMES

HOUSE Page

6

United

States

Department

of

the

Interior,

National

Park

Service

National

Register

of

Historic

Places

Registration

Form

glazed

panels,

forming

glass

walls.

The

northern

and

southern

elevations

of

both

the

residence

and

studio

feature

sliding

glass

doors.

Awning

casements

occur

on

the

rear

(west)

elevations

where

there

are

upper

story

interior

spaces

(bedrooms

and

bathrooms

in

the

residence,

and

an

office

in

the

studio).

Double-height

spaces

(the

living

room

in

the

residence,

and

the

main

work

space

in

the

studio)

have

solid

rear

(west)

walls.

There

are

two

outdoor

patios.

One

functions

as

an

open

court

or

outdoor

room

between

the

residence

and

studio.

The

other

is

situated

beneath

the

overhang

at

the

southern

end

of

the

residence.

Continuation

of

the

metal

roof

deck

and

the

rear

wood

paneled

wall

from

interior

to

exterior

creates

both

spatial

and

material

continuity

between

exterior

and

interior.

Both

outdoor

spaces feature

brick, wood,

and

marble

paving

configured

in

a

grid

pattern,

and

are

landscaped

with

planted

and

potted

vegetation.

Interior

Plan

The

interior

of

the

residence

features

an

open

plan,

with

one

space

flowing

easily

into

the

next.

As

noted

above,

the

northern

portion

of

the

residence

is

divided

into

two

stories. The

lower

story

contains

the

utilitarian

spaces

(kitchen

and

dining

areas),

with

private

spaces

(bedrooms

and

baths)

above

in

the

upper

story

or

loft.

The

loft

overlooks

the

double-height

living

space

in

the

southern

portion

of

the

residence.

Upon

entering

the

residence

through

the

main door

on

the

eastern

facade,

a

spiral

staircase

leading

to

the loft

is

directly

ahead.

The

staircase

is

constructed

of

steel

tread

brackets;

each

welded

to

a

short

section

of

metal

pipe

or

sleeve

that

are

threaded together

by

a

central

metal

post.

Plywood

treads

are

bolted

to

the

brackets

and

the

risers

are open.

The

skylight

located

directly

above

the

stairway

filters

natural

light

down

the

rectangular

opening

to

the

lower

level.

To

the

right

of

the

entrance,

a

dining area

along

the

front

of

the

residence

leads

to

the

kitchen,

which

can

be

closed

off

by

a

folding

partition.

The

kitchen

features

original

enameled

metal

cabinets

with

stainless

steel

and

marble

countertops.

The

dining and

kitchen

areas

open

onto

the

court

to

the

north.

Behind

the

kitchen,

a

narrow

utility

room

separated

by

a

corrugated

fiberglass

panel

runs

along

the

rear

elevation.

To

the

left

of

the

main

entrance,

a

short

single-story

hallway

with built-in

storage

cabinets,

opens

onto

the

double-height

volume

of

the

living

room,

which

occupies

the

entire

southern

portion

of

the

residence.

This

is

the

most

photographed

and

celebrated

space

in

the

Eames

House. The

floor

is

finished

with

white linoleum

tile,

and

the

ceiling

is

exposed

metal

roof

decking.

The

solid

rear

wall

is

finished

with

vertical

wood

paneling.

An

upper

and

lower

row

of

beige

pleated

curtains

cover

the

expansive

double-height

windows.

The

general

openness

of

the

living

room

is

countered

by

a

more

intimate

seating area

set

into

a

single-height

alcove

located

under

the

outer

edge

of

the

loft.

The

seating

area

features

a

built-in

L-shaped

sofa

and

a

wood

shelf

and

upper

storage

cabinets.

The

floor

in

this

area

is

carpeted.

The

upper

floor

contains

two

bedrooms,

two

bathrooms,

and

a

dressing

alcove.

The

two

bedrooms

occupy

the

loft

overlooking

the

living

room

and

can

be

closed

off

with

three

sliding

canvas-covered

wood

partitions.

A

similar

sliding

partition

separates the

two

bedrooms.

Original

goose-neck

light

fixtures

are

mounted

on

the

walls

in

the

bedroom

areas,

two

in

the

larger

bedroom,

and

one

in

the

smaller

bedroom.

A

bathroom

opens

off

of

the

rear

bedroom

and

features

an

original

sink,

toilet,

and

shower

stall.

The

dressing

alcove,

located

at

the

rear

of

the

loft,

leads

to

a

second,

larger

bathroom.

This

bathroom

contains

a

bathtub

and

features

black

and

white linoleum

floor

tiles

laid

out

in

a

checkerboard

pattern.

A

narrow

hallway

with built-in

cabinetry

occupies

the

center

of

the loft

at

the

top

of

the

staircase.

Additional

light

comes

into

the

upper

story

via

the

skylight

above

the

staircase.

The

upper

story

flooring

is

linoleum

tile

throughout,

with

square

wood

NATIONAL

HISTORIC

LANDMARK

NOMINATION

NFS

Form

10-900

USDI/NPS

NRHP

Registration

Form

(Rev.

8-86)

OMB

No.

1024-0018

EAMES

HOUSE Page

7

United

States

Department

of

the

Interior,

National

Park

Service

National

Register

of

Historic

Places

Registration

Form

panels

finishing

the

interior

walls.

Upstairs

windows

feature

horizontal

sliding

shades

composed

of

fiberglass

panels

in

wood

frames.

The

studio

building

also

features

an

open

plan.

As

in

the

residence,

a

portion

of

the

studio

is

divided

into

two

stories,

with

an

upper

loft overlooking

a

double-height

space.

Here,

the

southern

portion

of

the

studio

has two

levels.

The

ground

level

contains

a

kitchen

along

the

east

elevation,

with

a

powder

room

and

hallway

beyond.

An

enclosed

room

situated

to

the

rear

is

used

for

storage.

The

kitchen

looks

onto

the

open

court

to

the

south.

The

loft

contains

a

single

work

space

and

overlooks

a

double-height

studio

area

to

the

north.

The

upper

story

is

accessed via

an

open

steel

staircase

with

wood

treads,

open risers,

and

simple

pipe

handrails.

The

floors

are

wood

parquet

on

the

first

story

with

linoleum

tile upstairs.

The

ceiling

is

exposed

metal

roof

decking.

Additional

fiberglass

horizontal

sliding

shades

cover

the

multiple

windows

throughout.

Material

Integrity

The

Eames

House

retains

an

extraordinarily

high

degree

of

material

integrity,

and

ably

conveys

its

association

with

the

Case

Study

House

program

and

with

Charles

and

Ray

Eames.

In

all

seven

aspects

of

integrity,

the

property

is

remarkably

intact

and

true to

its

historic

design.

The

house

itself

is

situated

in

its

original

location

on

the

property.

Its

setting

is

generally

unchanged

from

its

original

appearance

with

the

exception

of

the

maturation

of

foliage.

All

major

elements

of

the

original landscape

design

are

extant,

including

the

grassy

ground

cover,

stands

of

eucalyptus

trees,

constructed

berm,

and

pedestrian

and

vehicular

pathways.

All

of

these

features

contribute

to

the

setting

of

the

Eames

House.

The

integrity

of

the

residence

and

studio

buildings

themselves

is

exceptionally

high.

The

workmanship

and

materials

are

intact.

The

house

has

been

well-maintained

with

little

need

for

substantial

repairs

or

replacements.

The

interior

spaces

appear

much

as

they

did

when

the

Eameses

lived

and

worked

in

them.

The

furnishings,

objects,

and

decoration

in

the

house

are

seen

today

just

as

they

were

in

the

many

photographs

through

which

the owners

exhaustively

interpreted

and

documented

the

property

during

their

years

of

residence.

Few

historic

properties

have

maintained

the

integrity

of

feeling

and

association evident

at

the

Eames

House.

This

is

largely

due

to

the

dedicated

and

ongoing

stewardship

of

the

family

that originally

designed

and

built

it.

The

association

of

the

property

with

Charles

and

Ray

Eames,

with

the

Case

Study

House

program,

and

with

its

own role in

Modern

domestic

architecture

in

the

United

States

is

very

strong.

NATIONAL

HISTORIC

LANDMARK

NOMINATION

NFS

Form

10-900

USDI/NPS

NRHP

Registration

Form

(Rev.

8-86)

OMB

No.

1024-0018

EAMES

HOUSE Page

8

United

States

Department

of

the

Interior,

National

Park

Service

National

Register

of

Historic

Places

Registration

Form

8.

STATEMENT

OF

SIGNIFICANCE

Certifying

official

has

considered

the

significance

of

this

property

in

relation

to

other

properties:

Nationally:

x

Statewide:

_

Locally:

Applicable

National

Register

Criteria:

A

_

B

_

C

_

D_

Criteria

Considerations

(Exceptions):

A

_

B

_

C

_

D

_

E

_

F_

G

NHL

Criteria:

1,2,4

NHL

Theme(s):

III.

Expressing

cultural values

5.

Architecture,

landscape

architecture, and

urban design

NHL

Exceptions:

8

Areas

of

Significance:

Architecture

Art

Invention

Period(s)

of

Significance:

1949

-1988

Significant

Dates:

1949, 1978,

1988

Significant

Person(s):

Eames, Charles

Eames,

Ray

Cultural

Affiliation:

N/A

Architect/Builder:

Eames,

Charles

and

Ray

(revised

as-built)

Eames,

Charles

and

Saarinen,

Eero

(original

design)

Historic

Contexts:

XVI.

Architecture

Z.

Modern

Modern

Architecture

Theme Study

(draft)

NATIONAL

HISTORIC

LANDMARK

NOMINATION

NFS

Form

10-900

USDI/NPS

MRHP

Registration

Form

(Rev.

8-86)

OMB

No.

1024-0018

EAMES

HOUSE Page

9

United

States

Department

of

the

Interior,

National

Park

Service

National

Register

of

Historic

Places

Registration

Form

State

Significance

of

Property,

and

Justify

Criteria,

Criteria

Considerations,

and

Areas

and

Periods

of

Significance

Noted

Above.

Summary

The

Eames

House

is

eligible

for

designation

as

a

National

Historic

Landmark

under

Criterion

#1

for

its

association

with

the

Case

Study

House

program

and

the

Modern

architecture

movement

in

the

United

States;

under

Criterion

#2

for

its

association

with

influential

designers

Charles

and Ray

Eames;

and

under

Criterion

#4

as

an

exceptionally

important

work

of

postwar

Modern

residential

design

and

construction.

The

Eames House,

Case

Study

House

#8,

is

the

most recognizable

and

most widely

published

of

all

the

residences

completed within

the

Case

Study

House program.

The

program

was

unique

in

the

nation

for

its

concerted

efforts

to

introduce

Modern

domestic

architecture

to

the

broader

public

in

the

period

after

World

War

II.

The

Eames

House

best

represents

the

goals

and

ideals

of

the

Case

Study

House program.

The

Eames

House

is

the

property

most

closely

associated

with

nationally-significant

designers

Charles

and

Ray

Eames.

The

property

served

as

their

private residence

and

working

studio

throughout

their

prolific

careers

as

furniture

designers,

filmmakers,

photographers,

exhibition

designers,

and

graphic

artists.

Charles

and Ray

occupied

the

house

from

the

completion

of

its

construction

in

1949

until

their

deaths

in

1978

and

1988,

respectively.

The

Eames

House

is

one

of

the

few

architectural

works

attributed

to

Charles

Eames,

and

embodies

many

of

the

distinguishing

characteristics

and

ideals

of

postwar

Modernism

in

the

United

States.

Since

the time

of

its

construction,

the

Eames

House

has

been

regarded

as

one

of

the

most

significant

experiments

in

American

domestic architecture.

The

period

of

significance

for

the

Eames

House

coincides

with

the

residency

of

its

designers,

extending

from

1949

until

1988.

John

Entenza

and

Arts

&

Architecture

Magazine

The

lineage

of

Arts

&

Architecture

magazine

dates

back

to

1911

and

a

publication entitled

Pacific

Builder.

Later renamed

California

Arts

&

Architecture,

the

magazine

was

regional

in

its

focus.

Not

considered

culturally

or

artistically

progressive,

the

magazine

emphasized

traditional

arts,

interior

design,

domestic

architecture,

and

gardening.

In

1938,

John

Entenza

purchased

California

Arts

&

Architecture.

Though

he

did

not

have

a

background

in

publishing,

Entenza

had

long

cultivated

an

interest

in

architecture.

6

Two

years

later,

he

would

become

the

magazine's

editor and

shift

its

focus

from

regional

art

to

internationally-recognized

movements

in

modernist

art

and

architecture.

To

communicate

this

new

direction,

Entenza

commissioned

graphic

artists

Herbert Matter

and

Alvin

Lustig

to

redesign

the

magazine's

graphics,

and

format.

The

newly

revamped

California

Arts

&

Architecture

debuted

in

February

of

1942,

with

the

word "California"

graphically

de-emphasized

on

the

cover

and

later

dropped

entirely

in

1944.

6

The

previous

year,

Entenza

had

commissioned

Los

Angeles

architect

Harwell

Hamilton

Harris

to

design

his

private

residence.

NATIONAL

HISTORIC

LANDMARK

NOMINATION

NFS

Form

10-900

USDI/NPS

MRHP

Registration

Form

(Rev.

8-86)

OMB

No.

1024-0018

EAMES

HOUSE

Page

10

United

States

Department

of

the

Interior,

National

Park

Service

National

Register

of

Historic

Places

Registration

Form

Entenza

used

a

significant

family

inheritance

to

purchase

and

sustain the magazine.

He

was

born

in

1903

in

Michigan

to

a

"Scottish

oil

heiress

and

a

Spanish

attorney involved

in

migrant

workers'

issues."

7

Because

the

magazine

was

not

financially

dependent

upon

advertising

revenues,

Entenza

was

able

to

be

highly

selective

in

his choice

of

advertisers.

According

to

architectural

historian

Esther

McCoy,

Entenza

would

accept

only those

he

considered

to

be

complementary

to

the

magazine's

progressive

editorial

content.

His

carefully

chosen

editorial

board

contained

some

of

the

most

active

and

knowledgeable

people

in

Southern

California's

art

and

architecture

communities.

Entenza's

tenure

at

Arts

&

Architecture

lasted

until

1962,

when

he

moved

from

Los

Angeles

to

Chicago

to

direct

the

Graham

Foundation, furthering

his

interest

and

influence

in

American

architectural

circles.

Esther

McCoy

states

that

"[n]o

single

event

raised

the

level

of

taste

in

Los

Angeles

as

did

the

magazine;

certainly

nothing

could have

put

the

city

on

the

international

scene

as

quickly."

8

At

the

time

Entenza

bought

the

magazine,

many

talented

architects

were

producing

experimental

designs

in

Los

Angeles.

Architects

Frank

Lloyd

Wright,

Lloyd

Wright,

R.

M.

Schindler,

Richard

Neutra,

and

J.

R.

Davidson

had

been

practicing

in

Los

Angeles

since

the

1920s.

Harwell Hamilton

Harris,

Gregory

Ain,

and

Raphael

Soriano

arrived

in

the

city

during the

1930s.

The

presence

of

these

architects

and

their

combined

body

of

work

comprised

a

recognizable

modernist

architectural

movement

in

Southern

California.

However,

opportunities

to

introduce

their

work

to

a

larger

audience

through

publication

was

limited.

McCoy

describes

how

a

1939

publication

of

local

residential

architecture

released

by

the

Southern

California

Chapter

of

the

American

Institute

of

Architects

did

include

modernist

architects

(Schindler,

Neutra,

and

Harris),

but

placed

their

work

at

the

back

of

the

book

behind

residences

designed

in

the

favored

revival

and

eclectic

styles.

With

the

editorial

changes

at

Arts

&

Architecture

in

the

1940s,

Entenza

provided

a

regional

forum

with

national

distribution

that

modernist

architects

in

Los

Angeles

had

previously

lacked.

The

content

of

the

magazine

under

the

editorial

leadership

of

John

Entenza included

reviews

and

features

on

a

wide

range

of

artistic

fields,

including

painting,

sculpture,

graphic

art,

art

theory,

photography,

film,

ceramics,

architecture, landscape

architecture, furniture

design,

structural engineering,

prefabrication,

and

industrial

design.

While the

architectural

projects

highlighted

were

mostly

by

Southern

California

architects,

the

publication

also

featured

works

in

Chicago, Florida,

Australia,

and

Mexico.

The

magazine

also

reported

on

art

and

architecture

exhibitions

at

museums

nationwide.

Nationally

known

contributors

to

the

magazine

included

Alvin

Lustig, Sidney Janus,

George

Nelson,

Peter

Yates,

Alfred

Auerbach,

Sibyl

Moholy-Nagy,

Edward

Steichen,

Bernard

Rudofsky,

Dore

Ashton,

and

Charles

Eames.

More

than

a

magazine

of

architecture

and

the

visual

arts,

the

magazine

also

included

highly-regarded

criticism

of

contemporary

music,

housing,

urban

issues, social

and

political

issues,

and technology.

Author

Elizabeth

A.

T.

Smith

noted

that

the

magazine

resisted

"differentiat[ing]

between

high

and

low

art

forms"

but

instead

demonstrated

its

belief

that "[c]ritical

emphasis

on

principals

of

form,

structure,

and

color

as

content

of

universal

significance

pervaded

treatment

of

all

the

arts,

obviating

hierarchical

distinctions

between

functional

and

nonfunctional

object-making."

9

Smith

further

concluded

from

an

analysis

of

the

magazine's

stated

goals

and

consistent

content

that

"the

urge

to

push

forward

in

the

creative,

social,

and

political

arenas..

.was

Arts

&

7

Goldstein,

Barbara,

Arts

&

Architecture,

the

Entenza

Years

(Cambridge,

Mass,

and

London:

the

MIT

Press,

1990),

8.

8

Esther

McCoy,

"Arts

&

Architecture

Case

Study

Houses,"

Blueprints

for

Modern

Living:

History

and

Legacy

of

the Case

Study

Houses,

ed.

Elizabeth

A.

T.

Smith (Los

Angeles:

Museum

of

Contemporary

Art;

and Cambridge,

MA

and

London:

The

MIT

Press,

1989),

16.

9

Elizabeth

A.

T.

Smith,

"Arts

&

Architecture and

the

Los

Angeles

Vanguard,"

Blueprints

for

Modern

Living,

History

and

Legacy

of

the

Case

Study

Houses,

ed.

Elizabeth

A.

T.

Smith (Los

Angeles:

Museum

of

Contemporary

Art;

and Cambridge,

MA

and

London:

The

MIT

Press,

1989),

53.

NATIONAL

HISTORIC

LANDMARK

NOMINATION

NFS

Form

10-900

USDI/NPS

NRHP

Registration

Form

(Rev.

8-86)

OMB

No.

1024-0018

EAMES

HOUSE

Page

11

United

States

Department

of

the

Interior,

National

Park

Service

National

Register

of

Historic

Places

Registration

Form

Architecture's

overriding

objective.

In

fulfilling

this

objective,

it

became

the

leading

periodical

of

its

kind

in

America, and

arguably

in

the

world, during

its

heyday."

10

The

Case

Study

House

Program

The

Case

Study

House

program

was

a

product

of

the

many

concerns

about

housing

and

architecture

voiced

in

the

magazine,

a

discussion

that

began

well

before

the

1945

announcement

of

the

program.

In

particular,

Arts

&

Architecture

sponsored

a

domestic

architecture

competition

in

1943

called

"Designs

for

Postwar Living."

This

competition

was

conceived

to

document

the

general

direction

in

which

domestic

architecture

was

heading,

as

well

as

to

generate

new

ideas

about

the

future

of

housing

after

the

war.

The

competition

was

held

during

a

period

in

which

private

housing

construction

had

essentially

ceased

due

to

the

nation's

involvement

in

World

War

II.

However,

it

was

already

apparent

that

the

demand

for

housing

following

the

war

would

be

profound.

When

the

top

designs

were

announced

in

the

magazine's

August

1943

issue,

the

nationwide

response

to

the

competition

was

emphasized

by

superimposing

the

names

and

home

cities

of

the

winners

over

a

map

of

the

United

States.

Winning

entries

originated

in

Los

Angeles,

San

Francisco,

Seattle,

Chicago,

Boston,

and

Washington,

D.C.

The

magazine

also

indicated

a

future

interest

in

similar

experiments:

"It

is

our

hope

that

we

will

soon

be

able

to

announce

a

series

of

such

competitions."

11

Rather than

continuing

with

a

series

of

competitions,

however,

Entenza

settled

upon

a

more

concentrated

program

of

commissioning

houses

by

a

select

group

of

architects.

In

January

1945,

Arts

&

Architecture

published

a

two-page

feature

about

the

Case

Study

House program.

The

parameters

of

the

program

were

outlined,

and

the

selection

of

architects

was

announced.

According

to

the

original

announcement

of

the

program:

Because

most

opinion,

both profound

and

light-headed,

in

terms

of

post

war

housing

is

nothing

but

speculation

in

the

form

of

talk

and

reams

of

paper,

it

occurs

to

us

that

it

might

be

a

good

idea

to

get

down

to

cases

and

at

least

make

a

beginning

in

the

gathering

of

that

mass

of

material

that

must

eventually

result

in

what

we

know

as

"house

~

post

war."

We

are,

within

the

limits

of

uncontrollable

feats,

proposing

to

begin

immediately

the

study,

planning,

and

actual

specifications

of

a

special

living

problem

in

the

Southern

California

area.

Eight

nationally

known

architects,

chosen

not

only

for

their

obvious

talents,

but

for

their

ability

to

evaluate

realistically

housing

in

terms

of

need

have

been

commissioned

to

take

a

plot

of

God's

green

earth

and

create

"good"

living

conditions

for

eight

American

families.

Briefly,

then,

we

will

begin

on

the

problem

as

posed

to

the

architect,

with

the

analysis

of

land

in

relation

to

work,

schools,

neighborhood

conditions

and

individual

family

need.

Each

house

will

be

designed

within

a

specified

budget,

subject,

of

course,

to

the

dictates

of

price

fluctuation.

Beginning

with

the

February

issue

of

the

magazine

and

for

eight months

or

longer

thereafter,

each

house will

make

its

appearance

with

the

comments

of

the

architect

~

his

reasons

for his

solution

and

his choice

of

specific

materials

to

be

used.

All

this

predicated

on

the

basis

of

a

house

that

he

knows

can

be

built

when

restrictions

are

lifted

or

as

soon

as

practicable

thereafter.

10

Ibid,

163.

n

Goldstein,

19.

NATIONAL

HISTORIC

LANDMARK

NOMINATION

NFS

Form

10-900

USDI/NPS

NRHP

Registration

Form

(Rev.

8-86)

OMB

No.

1024-0018

EAMES

HOUSE

Page

12

United

States

Department

of

the

Interior,

National

Park

Service

National

Register

of

Historic

Places

Registration

Form

Architects

will

be

responsible

to no one

but

the magazine,

which...

will

pose

as

"client".

It

is

to

be

clearly

understood that

every

consideration

will

be

given

to

new

materials

and

new

techniques

in house

construction.

And

we

must

repeat

again

that

these

materials

will

be

selected

on a

purely

merit

basis

by

the

architects

themselves

...

No

attempt

will

be

made

to

use

a

material

merely

because

it

is

new or

tricky.

On the

other

hand,

neither

will

there be

any

hesitation

in

discarding

old

materials

and techniques

if

their

only

value

is

that

they

have

been

generally

regarded

as

"safe".

All

eight

houses

will

be

opened

to

the

public

for

a

period

of

from

six

to

eight

weeks,

and

thereafter

an

attempt

will

be

made

to secure

and report

upon

tenancy

studies

to

see

how

successfully

the

job

has

been

done.

Each

house

will

be

completely

furnished...

to

the

architects'

specifications

or

under

his

supervision.

...

We

hope

(this

program)

will

be

understood

and

accepted

as

a

sincere

attempt

not

merely

to

preview,

but

to

assist

in

giving

some

direction

to

the

creative

thinking

on

housing

being

done

by

good

architects

and

good

manufacturers

whose

joint

objective

is

good

housing.

12

The

primary

goal

of

the

Case

Study

House

program

was

to

provide

an

opportunity

for

innovative

architects

to

imagine,

design,

and

construct

the

ideal

home

for

a

postwar

American

family.

Within

this

framework,

the

program

outlined

several

specific objectives:

experimentation

with

new

materials,

whether

newly

available

or

not

typically

used

in

residential

construction;

application

of

mass-production

techniques

to

the

process

of

home-

building;

creation

of

a

unique

design

with prefabricated,

standardized,

and

off-the-shelf

parts;

and

promotion

of

the

ideals

of

Modernism,

including

simplicity

of

form,

integration

of

indoor

and

outdoor

living

spaces,

and

the

avoidance

of

reference

to

historical

styles.

Coming

from

an

ideological

rather

than

an aesthetic

viewpoint,

the

program's

announcement

made

no

specific

comment

on

style,

and did

not

elaborate

on

the

particular

characteristics

of

the

"old

materials"

referred

to

as

objectionable,

nor

to

any

particular

aspects

of

pre-war

housing

that

had

become

obsolete.

Rather than

campaigning

directly

against

familiar,

traditional

houses,

the

program

sought

to

provide

a

positive

alternative

in

the

hope

that

with

exposure

to

Modern

houses,

people

would

be

seduced

not

only

by

their beauty

but

by

their

practicality,

affordability,

and

livability

as

well.

Despite

the

absence

of

overt

stylistic

dogma

in

the

announcement,

the

aesthetic

biases

of

the

program

were

clear.

The

first

publication

of

the

Entenza

House

betrayed

this

feeling

when

the

house's

just-erected

steel

frame

was

pictured

with

a

caption

stating

that

"as

is

often

the

case

it

has

in

this

state

an aesthetic

quality

one

would

1

"^

like

to

preserve."

Historian

Reyner

Banham

in

1971

recognized

the

character

of

the

Case

Study

Houses

as

a

stylistic

movement

by

stating

that

"(t)he

program,

the

magazine, Entenza,

and

a

handful

of

architects

really

made

it

appear

that

Los

Angeles

was

about

to

contribute

to

the

world

not

merely

odd

works

of

architectural

genius

but

a

whole

consistent

style."

14

Modernists

practicing

in

the

United

States

saw

that

there was

a

great

deal

at

stake

in

getting

their

message

out

to

the

general

public.

The

success

or

failure

of

the

Modernist

design

philosophy depended

to

a

great

extent

on

whether

the

American

public

felt

that

a

Modern

house

could

meet

their

actual

or

perceived

needs.

Architectural

historian

Thomas

Hines suggests

there was

a

need

to

"evangelize"

in

the

cause

of

spreading

the

acceptance

of

Modernism:

12

"Announcement:

the

Case

Study

House

Program,"

Arts

&

Architecture.

(January

1945),

54-55.

13

"Case

Study

House

No.

9

Under

Construction,"

Arts

&

Architecture. (January

1949),

32.

14

Reyner

Banham,

Los

Angeles:

The

Architecture

of

Four

Ecologies

(Alien

Lane,

The

Penguin

Press,

1971;

New

York:

Pelican

Books,

1973),

225.

NATIONAL

HISTORIC

LANDMARK

NOMINATION

NFS

Form

10-900

USDI/NPS

MRHP

Registration

Form

(Rev.

8-86)

OMB

No.

1024-0018

EAMES

HOUSE

Page

13

United

States

Department

of

the

Interior,

National

Park

Service

National

Register

of

Historic

Places

Registration

Form

Much

of

the

point

of

Entenza's

crusade

was

to

provide

a

cluster

of

models

for

a

postwar

housing

market

that,

if

not

guided,

-was

certain

to

explode

-with

potentially

damaging

and

insidious

architectural

effects. Simple,

sensitive,

minimalist,

prototypical,

prefabricated,

housing

was

clearly

to

be

the

ideal

instrument

for

meeting

the

needs

of

thousands

upon

thousands

of

families

in

the

new

postwar boom

[emphasis

added].

15

Opening

the

residences

to

the

public

was

an

important

part

of

the

Case

Study

House

concept.

The

opportunity

to

see

the

houses

in

their

pristine

state

was

offered

to

all

readers

of

the

magazine

and

publicized

in

the

Los

Angeles

Times.

At

a

time

when

the

population

of

Los

Angeles

was

just

approaching

two million,

nearly

370,000

people

would

visit

the

houses

in

the

first

three

years

of

the

program.

16

John

Entenza and

his

editorial

board

at

Arts

&

Architecture

selected

a

number

of

architects

to

participate

in

the

Case

Study

House program.

Alongside

the

announcement

of

the

program

in

his

magazine,

Entenza

revealed

the

first

seven

architects

to

accept

commissions

in

cooperation

with

the

program:

J.

R.

Davidson,

Sumner

Spaulding,

Richard

J.

Neutra,

William

Wilson

Wurster,

Ralph

Rapson,

Eero

Saarinen,

and

Charles

Eames.

17

The

Case

Study

House

program

spanned

a

considerable

period

of

time

and

generated

a

significant

body

of

work

that

was

actually

constructed

for

the

habitation

of

families.

Over

the

course

of

eighteen

years,

the

program

produced

designs

for

some

34

houses,

23

of

which

were

completed

during

Entenza's

tenure

with

the

magazine.

The

program

continued

under

the

editorship

of

David

Travers

until

1967.

Since

that

time,

the

Case

Study

houses

have

sustained

international

interest

for

nearly

a

half-century.

The

Case

Study

houses

enjoyed

a

revival

of

scholarly

and

popular

attention

beginning

in

1989

when

the

Museum

of

Contemporary

Art

in

Los

Angeles

mounted

a

major

exhibition

analyzing

and

showcasing

the

Case

Study

House

program.

Architectural

historians

Dolores

Hayden,

Reyner

Banham,

and

Thomas

Hines

were

among

those

who

contributed

essays

to

the

exhibition

catalogue.

This

catalogue

was

the

first

publication

since

Esther

McCoy's

1962

book

Modern

California

Houses

to

publish

all

of

the

houses

and

information

about

the

program

together

in

a

single

volume,

as

well

as

the

first

book

ever

to

provide

substantial

scholarly

and

critical

analysis

of

the

program.

18

Experimental

and

Demonstration

Houses

While

the

Case

Study

House

program

was

among

the

most significant

American

experiments

in

Modern

residential

architecture,

it

was

part

of

a

tradition

of

experimental

and

demonstration

houses

in

both

America

and

Europe

dating

back

to

the

mid-nineteenth

century.

Helen

Searing's

essay

in

the

catalogue for

the

1989

exhibition

"Blueprints

for

Modern

Living"

is

useful

in

placing

the

Case

Study

House

program

within

this

broader

context.

15

Thomas

Hines,

Case

Study

Trouve:

Sources

and

Precedents:

Southern

California

1920-1942,

Blueprints

for

Modern

Living,

History

and

Legacy

of

the

Case

Study

Houses,

ed.

Elizabeth

A.

T.

Smith (Los

Angeles:

Museum

of

Contemporary

Art;

and

Cambridge,

MA

and

London:

The

MIT

Press,

1989),

84.

16

The

population

of

the

City

of

Los

Angeles

was

slightly

less

than

two

million

in

1950.

17

By the

end

of

the

program, additional

architects

to

participate

in

the

program

included

Thorton

M.

Abell;

Buff,

Straub

&

Hensman

(Conrad

Buff

III,

Calvin

C.

Straub,

Donald

C.

Hensman);

A.

Quincy

Jones;

Frederick

E.

Emmons;

Don

R.

Knorr;

Killingsworth,

Brady

and

Smith

(Edward

Killingsworth,

Jules

Brady,

and

Waugh

Smith);

Pierre

Koenig;

Kemper

Nomland;

Kemper

Nomland,

Jr.;

Raphael

Soriano;

Whitney

R.

Smith;

Spaulding

and

Rex

(Sumner

Spaulding

and

John

Rex);

Rodney

Walker;

Wurster

and

Bernardi (William

W.

Wurster

and

Theodore

C.

Bernardi);

and

Craig

Ellwood.

18

A

second edition

of

McCoy's

1962

book,

retitled

Case

Study

Houses,

1945-1962,

was

published

in

1977.

NATIONAL

HISTORIC

LANDMARK

NOMINATION

NFS

Form

10-900

USDI/NPS

MRHP

Registration

Form

(Rev.

8-86)

OMB

No.

1024-0018

EAMES

HOUSE

Page

14

United

States

Department

of

the

Interior,

National

Park

Service

National

Register

of

Historic

Places

Registration

Form

According

to

Searing,

the

tradition

of

demonstration

houses

was

a

product

of

two influences.

First,

the

great

expositions

of

the

late

nineteenth