Zeenab Aneez, Taberez Ahmed Neyazi,

Antonis Kalogeropoulos, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen

Reuters Institute

India Digital News Report

Zeenab Aneez, Taberez Ahmed Neyazi,

Antonis Kalogeropoulos, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen

Supported by

Surveyed by

Published by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism

DOI: 110.60625/risj-qqd1-y198

Reuters Institute

India Digital News Report

Contents

Foreword 5

Methodology 6

About the Authors 7

Acknowledgements 7

Executive Summary 8

1. Digital News in India 9

1.1 The Move to Digital Media 9

1.2 A Mobile-First Market 9

1.3 Distributed Discovery Dominated by Platforms 10

1.4 Social Media as Gateways to News 10

1.5 Navigating News on Social Media 12

1.6 WhatsApp Widely Used for News 12

2. News and Participation 13

2.1 Online and Oine Sources of News 13

2.2 Inequalities in How People Access News 13

2.3 Engaging with Online News 14

2.4 High Levels of Participation, Caution around 15

Political Expression

3. Brands and Trust 16

3.1 Legacy Brands Popular with Online News Consumers 16

3.2 Alternative and Partisan News Sites Embraced by Some 17

3.3 Trust in News – Media versus Platforms 17

3.4 Brand Level Trust 18

4. Disinformation 20

4.1 Disinformation: Perceptions, Concerns, and Exposure 20

4.2 Who is Responsible for Fixing Disinformation Issues? 20

5. Future Trends 21

5.1 Mobile Applications and Alerts 21

5.2 Appetite for Online News Video 21

5.3 Video Viewing Moving Osite 21

5.4 Ad-Blocking a Threat to the Business 22

5.5 Opportunities around Voice-Activated Speakers and Audio 22

5.6 Will Indians Pay for Online News? 22

5.7 Will More People Donate to News? 23

6. Conclusion 24

References 25

Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / India Digital News Report 4

5

Given how important and interesting it is, India has always been

conspicuously absent from the Reuters Institute annual Digital

News Report. I am therefore very glad that support from a wide

range of dierent Indian sponsors has now enabled us to produce

this, the rst stand-alone pilot India Digital News Report, in time

to inform discussions of news and media in India in advance of

the 2019 elections.

We publish this study at a time of dramatic change in the Indian

media, some of it promising, some of it troubling. The past few

years have seen explosive growth in especially mobile internet

access, and even though broadcast media and printed newspapers

are still doing better in India than in many other markets, the rapid

move to digital media will have profound implications for the

practice of journalism, the business of news, media institutions,

and thus by extension political and public life in India. We have

seen rapid growth in online audiences across websites, social

media, and more, but also mounting challenges to the business

of news as advertising moves to digital media. This shi coincides

with a changing political environment where activists, parties, and

politicians are enthusiastically embracing digital media, sometimes

circumventing editorial gatekeepers, sometimes attacking them

directly, attacks that contribute to wider concerns over media

freedom in India.

We are glad to be able to oer this report as a snapshot of this

development and how the rise of mobile media, social media

platforms, and messaging applications is in the process of

changing how Indians access news and engage with it, including

low trust in much news and rising concerns about various kinds

of disinformation. We hope our analysis will help inform decision-

making among Indian journalists and publishers, as well as

among policy makers and among the large US-based technology

companies that play an increasingly important role in the Indian

media environment.

The report is a pilot study in the sense that it deals exclusively

with a small (but important) subset of the Indian media market,

namely English-language news users with internet access. We

hope to be able to do more work in the future to shed more

empirical light on news and media habits among Hindi and

vernacular language users across the country, perhaps with time

including a more comprehensive study to cover the hundreds

of millions of Indians who still do not have internet access. For

the time being, it is important to stress that the results reported

here and our wider analysis is exclusively focused on English-

language Indian internet users, and should not be taken to be

representative of India more widely.

Our work here builds on the ongoing, annual Reuters Institute

Digital News Report, which in 2018 covered 37 markets across

the globe, and in 2019 will for the rst time include Africa too,

with the addition of South Africa. We are hugely grateful to our

sponsors who have now enabled us to do similar work in India,

namely, the Hindu Media Group, The Quint, the Indian Express,

and the Press Trust of India. We are also grateful to our polling

company YouGov, who did everything possible to help us expand

our research into India for the rst time and helped our research

team to analyse and contextualise the data.

Foreword

Professor Rasmus Kleis Nielsen

Director of the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ)

/ 5 4

Methodology

This study has been commissioned by the Reuters Institute

for the Study of Journalism as our first step towards a better

understanding of how digital news is being used in India. Research

was conducted by YouGov using an online questionnaire in early

January 2019. The methodology is similar to the Reuters Institute

2018 Digital News Report survey with some important limitations.

The sample is reective of the English-speaking population in

India that has access to the internet. As a result, it is skewed

towards male, auent, and educated respondents. As an online

survey, the results will further under-represent the consumption

habits of people who are not online (typically older, less auent,

and with limited formal education). Where relevant, we have tried

to make these two limitations (around language and internet

access) clear within the text.

• The data were weighted to targets based on the online

population of India on age and region. The targets are set by

YouGov and are based on data from the Internet and Mobile

Association of India.

• As this survey deals with news consumption, we ltered out

anyone who said that they had not consumed any news in

the past month, in order to ensure that irrelevant responses

didn’t adversely aect data quality. This category was lower

than 2.9% in India, similar to the average of the 37 countries

examined at the 2018 Digital News Report. Overall, we surveyed

1013 individuals.

• A comprehensive online English-language questionnaire

based on the 2018 Digital News Report was designed to capture

dierent aspects of news consumption.

1

http://www.digitalnewsreport.org/survey/2018/survey-methodology-2018/

The survey was conducted using the established English-speaking

online panels run by our polling company YouGov. The main

purpose is to track activities and changes within the digital space

– as well as gaining understanding about how oine media and

online media are used together.

In a few instances within the text we compare the results for India

with the results of other large and complex markets like Brazil,

Turkey, or the United States. These numbers are taken from the

2018 Reuters Institute Digital News Report survey undertaken

in early 2018. More information about the methodology and the

samples for these countries can be found on the Digital News

Report website.

1

Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / India Digital News Report 6

About the Authors

Zeenab Aneez is an independent researcher in the eld of digital

media and culture. She has a background in journalism and was

previously a reporter for The Hindu. She has an undergraduate

degree in Economics from the University of Madras and an MA

in Digital Media and Culture at the Centre for Interdisciplinary

Methodologies, University of Warwick, United Kingdom.

Taberez Ahmed Neyazi is Assistant Professor of New Media and

Political Communication at the National University of Singapore.

His research focuses on political communication and public

opinion, computational social science, digital, mobile, and social

media. He serves as co-Principal Investigator of India Election

Studies (IES) and the country coordinator for this project on media,

campaigning, and inuence in India’s national and state-level

elections.

Antonis Kalogeropoulos is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at

the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at the University

of Oxford. He is a co-author of the Digital News Report, an annual

survey of news consumption patterns across the world. He has

also published a range of academic articles more widely on

online and social media participation and online news video

consumption patterns in a comparative perspective.

Rasmus Kleis Nielsen is Director of the Reuters Institute for the

Study of Journalism and Professor of Political Communication

at the University of Oxford. His work focuses on changes in

the news media, on political communication, and the role of

digital technologies in both. He has done extensive research on

journalism, news media, campaign communication, and various

forms of activism across the world.

Acknowledgements

This report has been made possible by support from The Hindu Media Group, the Indian

Express, The Quint, and the Press Trust of India. We are very grateful for their support.

The data collection, analysis, and presentation has been conducted independently by

the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. Our work on this report has beneted

from the advice, experience, and input of the wider Reuters Institute research team,

in particular Nic Newman and Richard Fletcher, two of the authors of the main annual

Reuters Institute Digital News Report.

/ 7 6

In this report we show that English-language

Indian news users with internet access are

embracing a mobile-rst, platform-dominated

media environment with search engines, social

media, and messaging applications playing a

key role in how people access and use news in

a setting characterised by low trust in many

news media, high concerns over the possible

implications of expressing political views, and

widespread worries about dierent kinds of

disinformation.

KEY FINDINGS INCLUDE

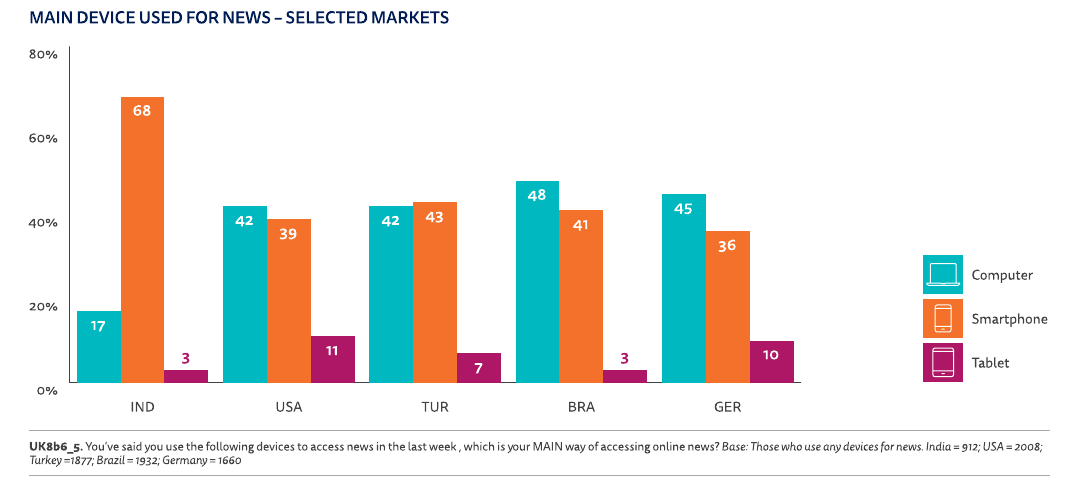

• A mobile-rst market: 68% of our respondents identify

smartphones as their main device for online news, 31% say

they only use mobile devices for accessing online news.

These gures are markedly higher than in other markets,

including developing markets like Brazil and Turkey.

• A platform-dominated market: an overwhelming majority

of respondents identify various forms of distributed discovery

as their main way of accessing news online. Search (32%)

and various kinds of social media (24%) are particularly

important. Only 18% consider direct access their main

way of getting news online.

• Facebook and WhatsApp are particularly widely used, with 75%

of respondents using Facebook (and 52% saying they get news

there), and 82% using WhatsApp (with 52% getting news there).

Other social media widely used for news include Instagram

(26%), Twitter (18%), and Facebook Messenger (16%).

• Online news generally (56%), and social media specically

(28%), have outpaced print (16%) as the main source of news

among respondents under 35, whereas respondents over 35

still mix online and oine media to a greater extent.

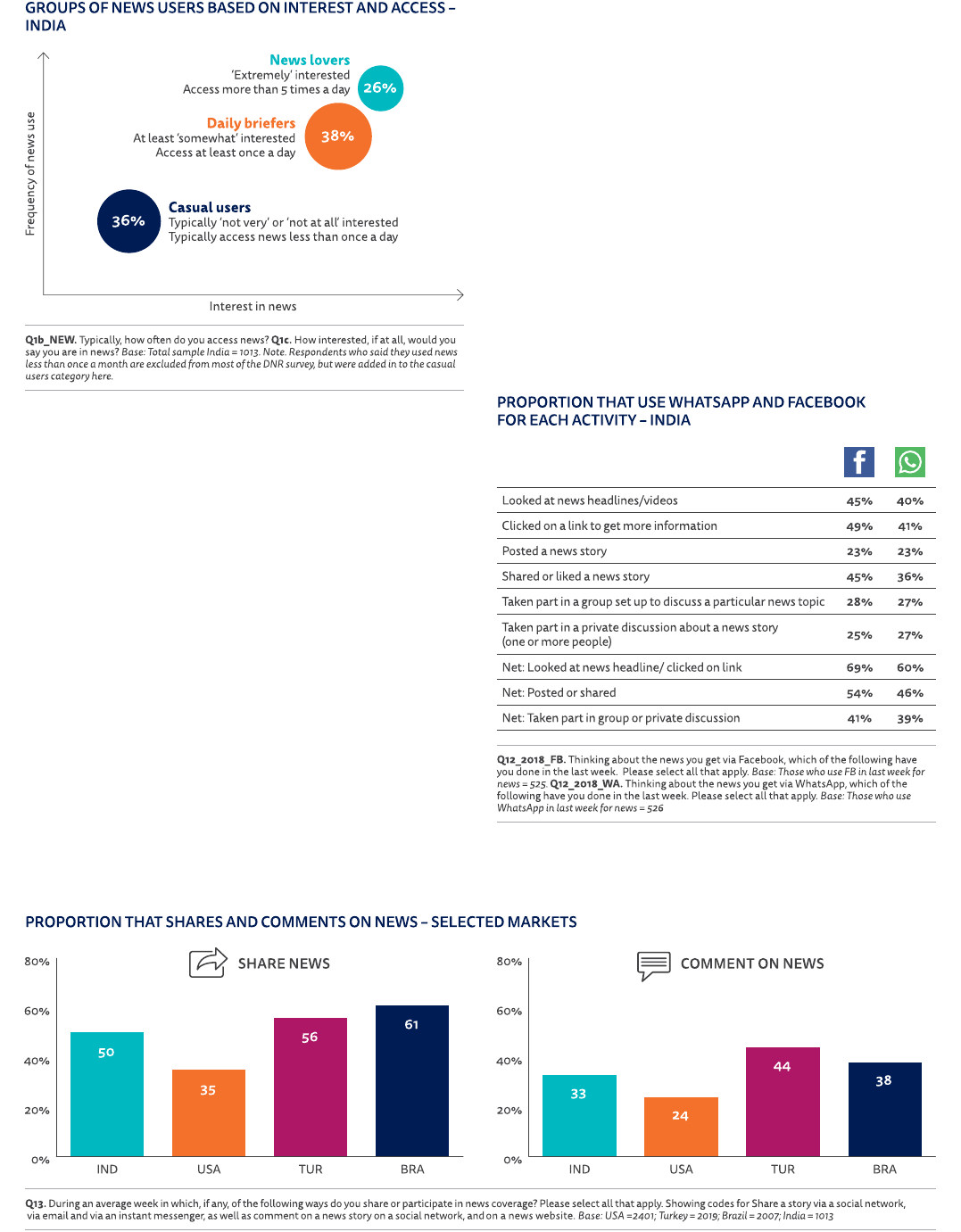

• Many of our respondents say that they share (50%) and/or

comment (33%) on online news, with particularly high levels

of engagement on Facebook and WhatsApp, but many also

express concerns that openly expressing their political views

online could make their friends of family think dierently of

them (49%), make work colleagues or other acquaintances

think dierently of them (50%) or, perhaps most worryingly,

fear it could get them into trouble with authorities (55%).

• The most widely used online news sources (beyond platforms)

are generally the websites of leading legacy media including

broadcasters and newspapers, but some digital-born news

media have signicant reach, including some alternative and

partisan sites who despite limited name recognition have built

relatively large audiences.

• Our respondents have low trust in news overall (36%) and even

the news they personally use (39%), but interestingly express

higher levels of trust in news in search (45%) and social media

(34%) than respondents in many other countries. Partisans at

both ends of the political spectrum have similar levels of trust

in the news, whereas non-partisans have lower levels.

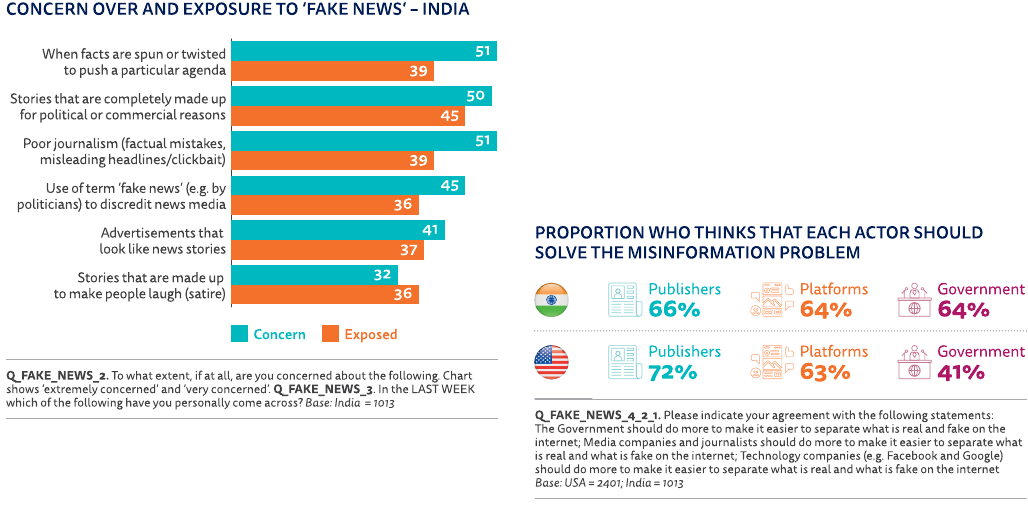

• 57% of our respondents are worried whether online news they

come across is real or fake, and when asked about dierent

kinds of potential disinformation, many of our respondents

express concern over hyperpartisan content (51%) and poor

journalism (51%) as well as false news (50%).

• Looking to the future, signicant numbers of respondents

express an appetite for more personalised mobile news

alerts, more online news video, for donating to support news

organisations, and to pay for news in the future, with 31% of

those who do not currently pay for online news saying they are

‘somewhat likely’ to pay, and 9% saying they are ‘very likely’ to.

The report is based on data from a survey of English-speaking, online

news users in India – a small (but important) subset of a larger, more

diverse, and very complex Indian media market. Our respondents are

generally more auent, have higher levels of formal education,

skews male, and are more likely to live in cities than the wider

Indian population and our ndings only concern our sample,

and thus cannot be taken to be more broadly representative.

Executive Summary

Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / India Digital News Report 8

. Digital News in India

. THE MOVE TO DIGITAL MEDIA

Indian publishers have oered online news and invested in their

websites since the 1990s, even though internet access initially

grew only slowly in India. In recent years, the explosive expansion

of especially mobile web access and signs of stagnation or even

decline in print readership and advertising have led to increased

investment in better websites, the recruitment of digital journalists

and developers, new social media and mobile strategies, the

creation and launch of apps, and experimentation with new and

emerging technologies.

2

Publishers are also diversifying their

content and building new brands and products to engage the needs

of their growing digital audience, and a number of digital-born news

media have been launched in one of the world’s most competitive

media markets.

3

This move is in response to rapidly evolving audience behaviour.

While it took 15 years from 1995 to 2010 before 100 million

Indians (8% of the population) had internet access, growth has

greatly accelerated since, surpassing an estimated 500 million

users by June 2018, more than 30% of the population, driven

primarily by tremendous growth in mobile internet access.

4

In this report we focus only on English news publishers which are

primarily read by higher socio-economic classes of urban people,

who use smartphones and have access to the internet.

5

By some

estimates, those who speak English as a primary language make up

only about 10% of India’s population.

6

The surveyed sample reects

this, and is hence not representative of the wider population of

Indian digital media users, especially given that current industry

trends are characterised by a surge in rural users and increasing

consumption of regional language content.

7

2

Aneez et al. 2016.

3

See e.g. Aneez et al. 2017; Sen and Nielsen 2016.

4

IAMAI-Kantar IMRB 2018.

5

EY-India 2018.

6

https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-20500312

7

Neyazi 2019.

We show that English-language Indian news users with internet

access are embracing a mobile-rst, platform-dominated media

environment with search engines, social media, and messaging

applications playing an absolutely key role in how people access

and use news in a setting characterised by low trust in many

news media, high concerns over the possible implications

of expressing political views, and widespread worries about

different kinds of disinformation.

. A MOBILEFIRST MARKET

India is emerging as an overwhelmingly mobile-rst, and for

many mobile-only, media market for internet use broadly, and

for online news use specically. Of our respondents, 68% identify

smartphones as their main device for online news. Preference for

smartphones for news access was signicantly higher than that

for desktop computers and tablets, preferred by 17% and 3%

respectively; 31% of our respondents say they only use mobile

devices for accessing online news. (A 2017 report by Omidyar

Network said Indian users spend about three hours a day

on their mobile phones, though only 2% of this time is spent

accessing news.)

This marks India as a much more mobile-rst online news

environment than even other developing markets like Brazil

and Turkey, let alone markets like the United States or those

found in Europe such as Germany.

/ 9 8

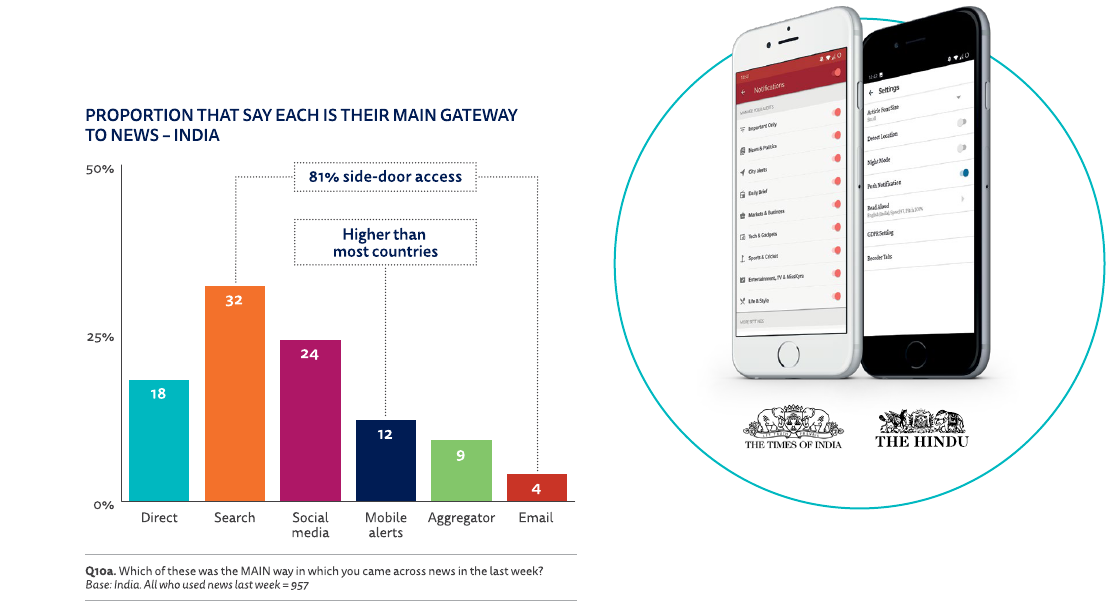

. DISTRIBUTED DISCOVERY DOMINATED

BY PLATFORMS

India has emerged as a large market for social media giants

like Facebook, LinkedIn, Instagram, and Twitter, and our survey

demonstrates how these digital intermediaries have become

absolutely central to online news distribution, providing

publishers with competition for attention and advertising, but

also new opportunities to reach wider online audiences.

Among our respondents, direct discovery of news (where users go

directly to a news organisation’s website or app) is seen as far less

important than various forms of distributed discovery (where users

discover and access news through a variety of digital platforms).

Search is an important gateway for many users, and as audiences

have embraced social media like Facebook and Twitter, publishers

have begun sharing breaking news and features on these platforms.

At the same time, messaging apps like WhatsApp are now being used

by millions to get online news, and by publishers sending news

directly to subscribers.

In our sample of English-speaking online news users, just 35% say

they go directly to news websites or apps, and only 18% consider

direct access their main way of accessing news online (compared

to 26% in the US and 35% in Brazil). An overwhelming majority

of the respondents identify various forms of distributed discovery

as their main way of accessing news online. Search (32%) and

various kinds of social media (24%) are particularly important.

Such side-door access through various intermediaries over which

news publishers themselves have limited control is far more

important among our Indian respondents than it is for online

news users in a market like the US. In fact, a higher proportion

of Indian respondents rely on distributed discovery as the main

gateway to news than is the case among respondents in other

developing markets like Brazil and Turkey.

The rise of distributed discovery presents new, convenient,

and oen engaging ways of accessing and using news, but also

means that the ow of information is increasingly inuenced by

algorithmic selection. Judging from our data, there is at this stage

limited awareness of this fact, with just 26% of our respondents

recognising that algorithms make decisions on what news stories to

show on Facebook (with 18% believing these decisions are made by

editors and journalists working for the social media company).

Faced with the rise of distributed discovery, many publishers are

investing in search engine optimisation, social media distribution,

and the like, and developing forms of side-door access over

which they have more control, like mobile alerts or notications

– identied by 12% of our respondents as their main source of

online news.

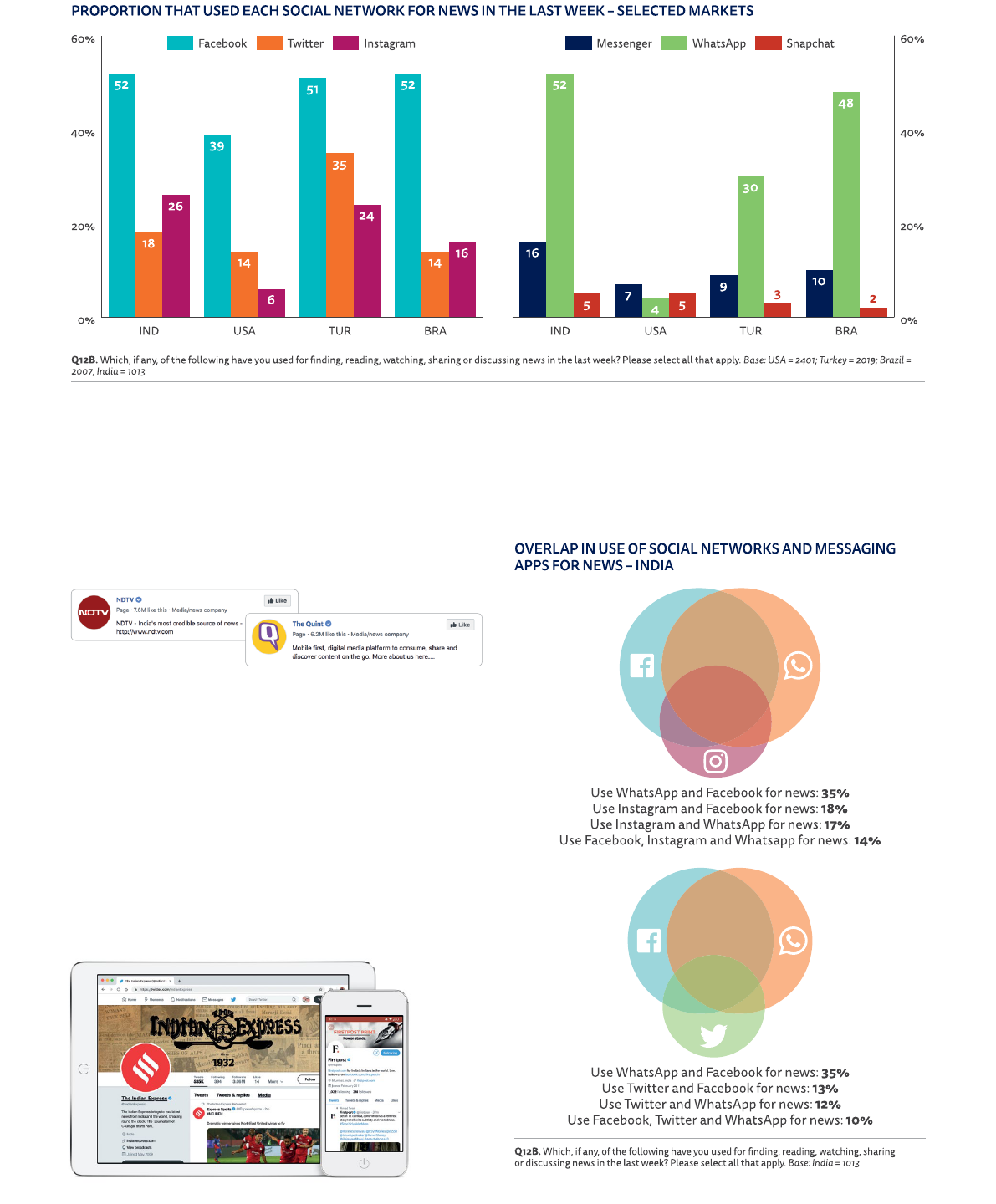

. SOCIAL MEDIA AS GATEWAYS TO NEWS

More than half of our Indian respondents report getting news

from social media, and a quarter identify social media as their

main source of online news.

Asked about individual platforms, Facebook’s main eponymous

social media platform (75%) and the company’s messaging

application WhatsApp (82%) are the most widely used in India

(90% of users surveyed use at least one Facebook product weekly,

for any purpose). Facebook and WhatsApp are also the most

widely used for news – 52% of our respondents say they get news

via Facebook, and 52% say they get news via WhatsApp, similar

gures to those seen in a market like Brazil.

Other social media widely used for news (or where users are

often exposed to news while using the platform for other

purposes) include Instagram (26%), Twitter (18%), and Facebook’s

Messenger (16%) – whereas, for example, Snapchat is much less

widely used (5%).

Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / India Digital News Report 10

Many Indian publishers are investing in social media teams to

reach online audiences through these intermediaries, which in

turn simultaneously helps them increase their reach but leaves

them exposed to sometimes dramatic changes to how ranking

algorithms or other platform infrastructures work. In many

online newsrooms journalists and editors try to ensure that their

news content performs well on Facebook even as the platform’s

algorithms and wider strategy constantly evolve.

8

Facebook is identied as a site used for news by almost three times

as many respondents as Twitter, but despite its much smaller

user base and the fact that it generates less website trac and

engagement, Twitter is still an important platform for breaking news

and a lively and oen unruly and uncomfortable part of online public

debate. In India, Twitter is seen by some as a toxic environment,

especially for women

9

and people belonging to the Dalit-Bahujan

and Adivasi community and other gender and sexual minorities.

10

However, Twitter has also served as an important platform for India’s

#MeToo movement, where a concerted eort by women journalists

to identify sexual predators and serial harassers in the news industry

began and gained momentum on Twitter. Several legacy and

digital-born publishers have built wide Twitter followings.

8

Aneez et al. 2017.

9

Bass 2018.

10

Soundararajan 2018.

Dierent forms of distributed discovery are not mutually

exclusive. For example, 35% of our respondents use Facebook

and WhatsApp for news, and a signicant subset of these in turn

also get news from social media like Instagram or Twitter.

/ 11 10

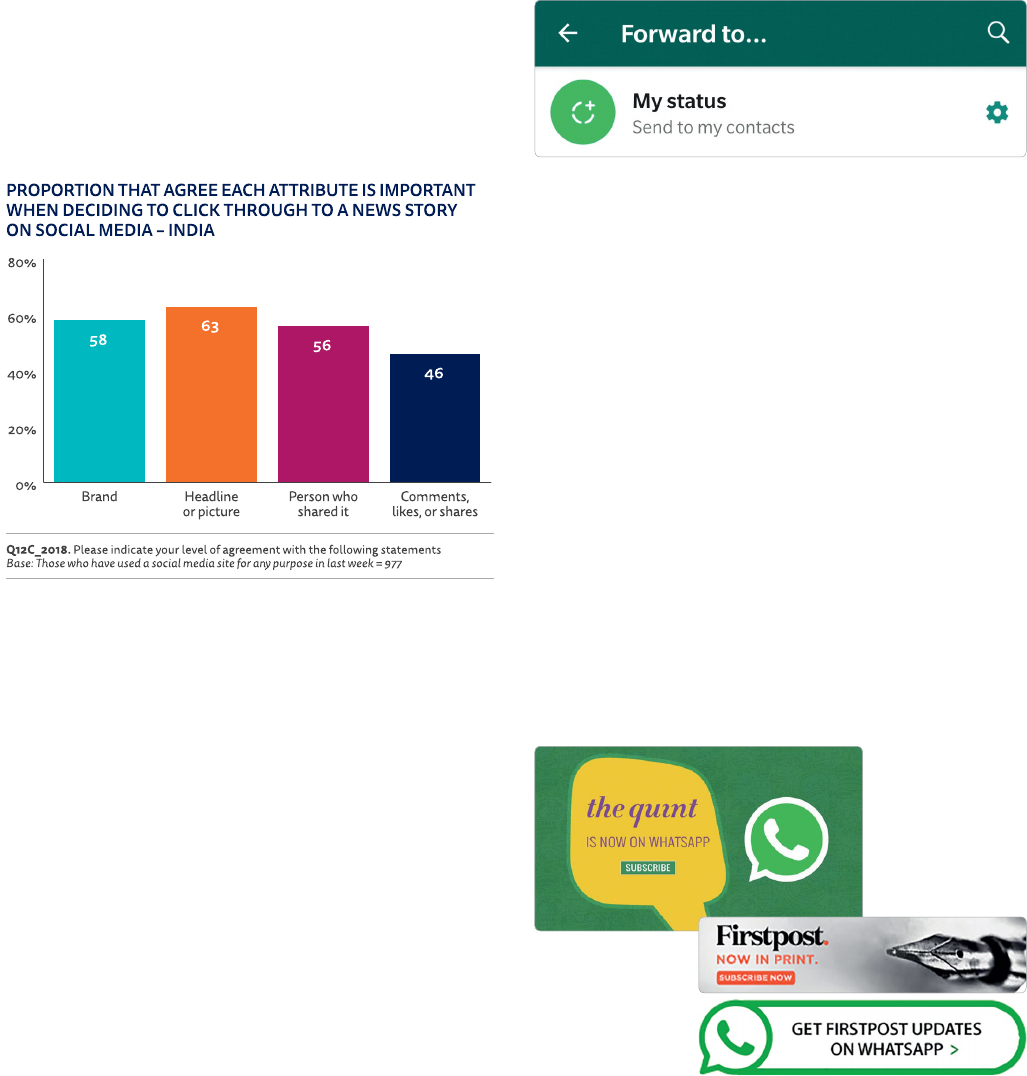

. NAVIGATING NEWS ON SOCIAL MEDIA

Given the massive ow of information from various sources on

these platforms, we asked respondents how they decide what

to click on when navigating news on social media: 56% say they

decide on the basis of who shared the post while for 63% the

headline is very important and for 58% the brand.

Oen these social cues and source cues are used in combination,

and one does not preclude the other – but our research documents

that the social cues (who shares a story) are more important in

India than in many other markets. This is in line with ndings in a

BBC report on disinformation in India that also found that rather

than questioning the source of the news, study participants relied

on alternative markers like number of comments, images, and the

sender of the messages.

11

. WHATSAPP WIDELY USED FOR NEWS

WhatsApp is not only very widely used in India, but also widely

used by our respondents for news. While search engines and

social media are increasingly important gateways to online

news across the world, the use of messaging applications like

WhatsApp and their role in the discovery of news vary widely from

country to country. Of our respondents, 82% use the messaging

application, and 52% reported getting news on WhatsApp, far

higher numbers than most markets in Europe and North America

but comparable, for example, to Brazil.

The number of WhatsApp users in India has reportedly doubled

from 2017 to 2018, and the ease of transferring multimedia

content to large private groups makes WhatsApp unique among

other social media platforms studied here.

12

The messaging

application is increasingly ubiquitous not only among general

users, but also in many India newsrooms where journalists

use it to enable quick transfer of multimedia content and

dissemination of content among editorial sta.

13

11

Chakrabarti et al. 2018.

12

Kumar and Kumar 2018.

13

Aneez et al. 2016.

14

Chakrabarti et al. 2018.

15

McLaughlin 2018.

Among our respondents, 40% of WhatsApp news users said

they have forwarded a news story during the past week. This is

certainly an important dynamic in the context of India, as news

consumed over WhatsApp is more likely to be shared by like-

minded individuals in a group. Large-scale group forwarding can

disseminate legitimate news to wide audiences, but has in some

instances also helped disinformation and rumours reach a very

large number of users.

14

As a result of its rising popularity as a way to share news, most

oen in closed groups, WhatsApp is thus increasingly seen as

part of India’s growing online disinformation problems.

The platform was among one of the channels used to spread

rumours that led to attacks on groups and individuals across the

country.

15

End-to-end encryption makes it dicult to identify

the source and track the spread of messages on it. It also makes

it dicult for news publishers (and others) to study reach and

engagement of their content through the platform.

In late 2018, the Indian government formally asked WhatsApp to

work towards altering features that allow the platform to be used

to disseminate disinformation at scale and the company has since

taken some measures to restrict the sharing of content on the

platform, including limiting the number of times messages can

be forwarded.

Disinformation problems and growing public scrutiny of

WhatsApp has clearly not deterred news publishers, who are

increasingly seeking to use the messaging application to reach

readers. Both legacy publishers like The Times of India and digital-

born publishers like Firstpost and The Quint, for example, now

provide WhatsApp subscriptions to their publications.

Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / India Digital News Report 12

16

EY-India 2018.

17

Media Research Users Council 2017.

18

Wang and Sparks 2019.

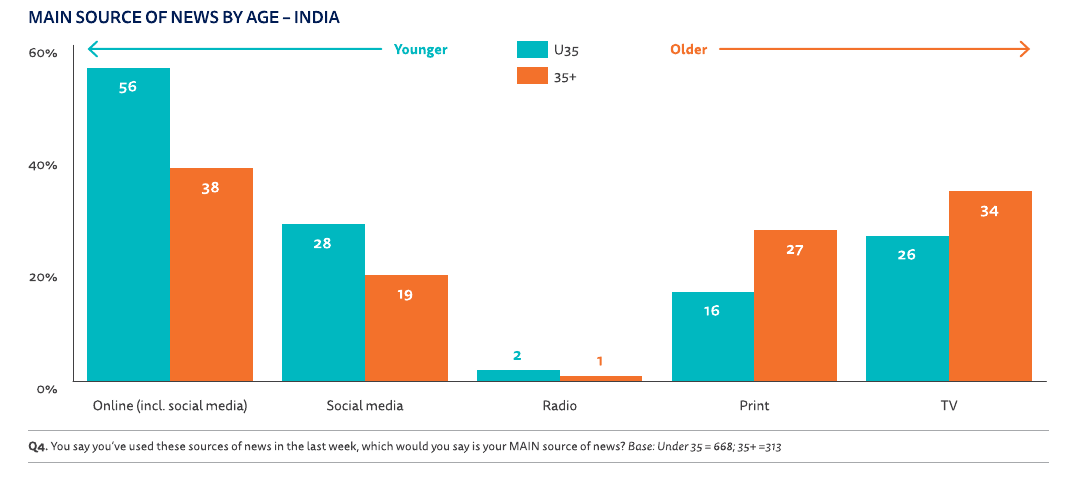

. ONLINE AND OFFLINE SOURCES OF NEWS

Even as the move to digital media has challenged newspapers and

broadcasters in much of the world, the print and television news

industry in India has continued to grow – though at a decreasing

rate.

16

With much of the population still oine, hundreds of

millions of Indians still turn to newspapers, television and radio

as their main sources of news.

17

(How resilient oine media will

be in the face of digital alternatives is an open question. In China,

newspaper circulation peaked as recently as 2012, but newspaper

advertising revenues declined by 75% from 2012 to 2016 as digital

media grew rapidly.

18

)

Among our respondents, English-speaking Indians with access

to the internet, oine sources remain important, but online

sources dominate, especially among younger people. The number

of internet users who identify online news as their main source

of news is directly comparable to the proportion in a country like

Brazil or the US. However, especially older Indian online news

users still supplement online news with television and print to

a higher extent than we see in other countries.

Among respondents over 35, online (38%) and television (34%)

are about equally widely named as the main source of news, and

print (27%) still more widely relied on than social media (19%).

But among respondents under 35, online generally (56%) and

social media specically (28%) are named as the main source of

news by many more than print (16%) and even television (26%).

. News and Participation

The fact that our survey covers only English speakers with

internet access is key here; the number of people accessing news

via print and television will be higher for regional language news

consumers and most obviously for those without internet access,

though as mobile web use spreads we expect to see this to change

in the years ahead.

. INEQUALITIES IN HOW PEOPLE ACCESS NEWS

English-language Indian internet users have access to a multitude

of legacy and digital-born news sources, but given this access,

how do their habits vary by interest and frequency of use?

Roughly six in ten of our respondents say they have a high interest

in news – about the same as in the United States but lower than

those in Turkey or Brazil. Nine out of ten report accessing news at

least once a day, showing how news routines can be regular even

when interest is moderate.

Accessing news is far from equally distributed, even among

internet users. By looking at level of interest and frequency of use,

we can segment our respondents into news lovers, daily briefers,

and casual users. News lovers (26%) have very high interest in

news and access news more than ve times a day. At the opposite

end of our segmentation are casual users (36%), who typically

show little or no interest in news and oen access news less oen

than once a day. Daily briefers (38%) occupy a middle ground with

at least some interest in news and access news at least daily.

/ 13 12

All three groups use high numbers of dierent sources compared

to their peers in other countries, perhaps indicative of a tradition

among many Indians to read several papers regularly (enabled

by low cover prices). News lovers on average say they’ve used

11.2 dierent sources in the past week, casual users 7.5, and daily

briefers 5.7. The distribution across the three groups is broadly

similar to what we have found in other countries, where news

lovers consistently make up a minority, greatly outnumbered

by daily briefers and casual users.

19

But among our sample of

English-language online news users, most respondents use

more sources of news than their peers in other countries.

. ENGAGING WITH ONLINE NEWS

Beyond consuming news, internet users have many other

opportunities to engage with news online by commenting, sharing,

and the like, whether via social media or older means like email.

Among our Indian respondents, the levels of participation are

higher than those seen, for example, in the United States and are

comparable to those seen in countries like Brazil and Turkey.

19

Newman et al. 2018.

Online news engagement among our English-language

respondents is primarily driven by sharing. Our data suggest

that Indian users share a little less on social media and email as

compared to users in Brazil or Turkey, but they still share much

more than users in the United States. Facebook, as the most

widely used social media platform, and WhatsApp, as the most

widely used messaging application, are central to how Indians

engage with online news.

Looking at Facebook, our respondents are particularly engaged,

with 69% saying they’ve looked at or clicked on news, 54% have

posted or shared news, and 41% have taken part in a group or

private discussion about news.

For WhatsApp, the numbers are similar, again, 60% have looked

at or clicked on news, 46% posted or shared, and 39% taken part

in group or private discussions. On both platforms, our Indian

respondents are more engaged in group and private discussions

than in most of the markets we compare them with here.

Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / India Digital News Report 14

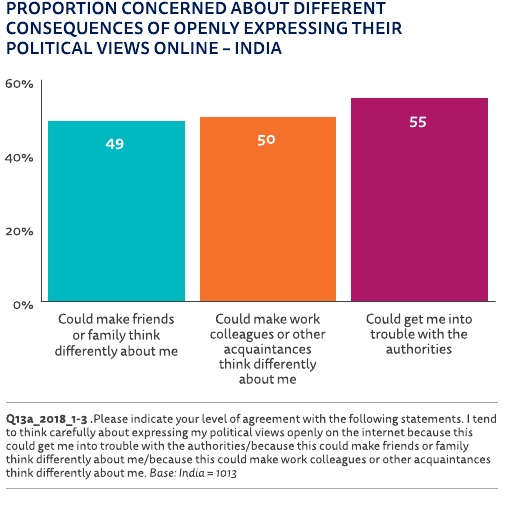

. HIGH LEVELS OF PARTICIPATION, CAUTION

AROUND POLITICAL EXPRESSION

The high levels of engagement with news on social media

documented above are accompanied by high levels of concern

about the possible consequences of expressing political views

on the internet. Asked to consider the statements ‘I tend to

think carefully about expressing my political views openly on

the internet because this could get me into trouble with the

authorities’, ‘I tend to think carefully about expressing my

political views openly on the internet because this could this

could make friends or family think dierently about me’ and

‘I tend to think carefully expressing my political views openly on

the internet because this could make work colleagues or other

acquaintances think dierently about me’, Indian respondents

express signicantly higher levels of concern in all three areas

than respondents in the United States. The levels of concern

are directly comparable to those found in Brazil and in Turkey.

These high levels of concern could be based in part on recent

events in India. Since 2012 at least 17 people have been

arrested for posting material that was considered oensive

or threatening to a politician. Arrests have included people

speaking out against Prime Minister Narendra Modi, former

Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, Bengal Chief Minister Mamata

Banerjee, and more recently, Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi

Adityanath. As recently as December 2018, a journalist was

jailed for criticising the BJP and Manipur Chief Minister.

To examine the possible link between political sympathies and

concern over expressing views online, we analysed the responses

by party preference. The only dierence we found is that that non-

partisans express less concern than do partisans of any persuasion.

/ 15 14

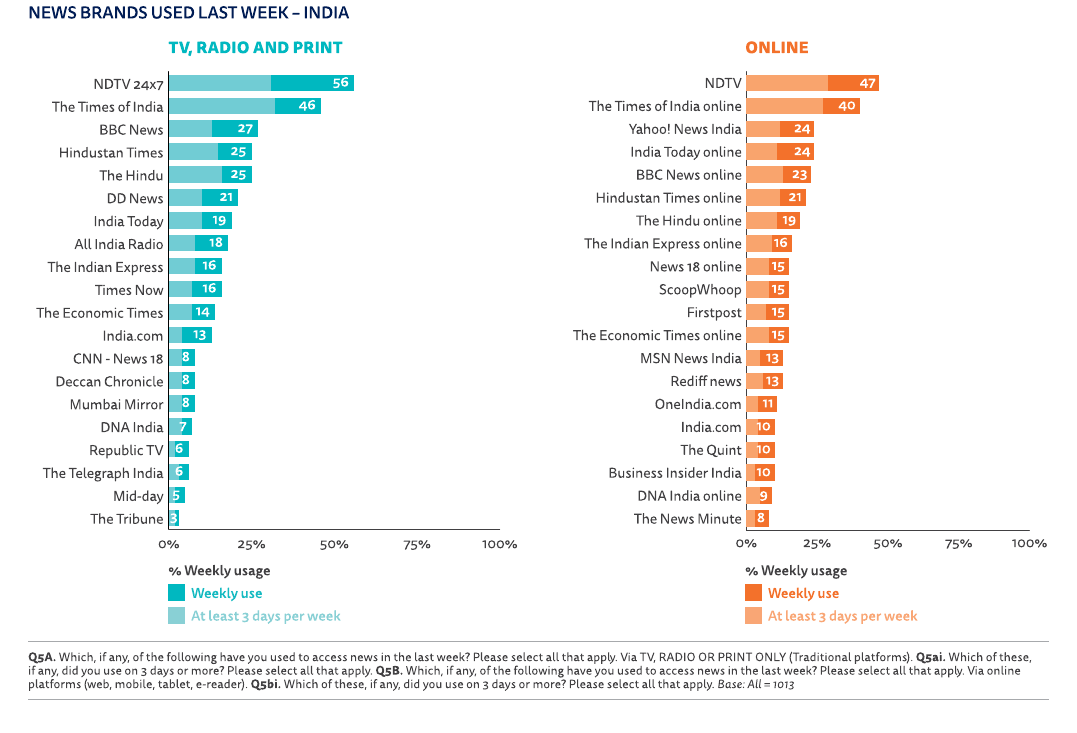

. LEGACY BRANDS POPULAR WITH ONLINE

NEWS CONSUMERS

As Indian internet users increasingly turn to online sources of

news, they oen opt for the digital oerings of legacy brands. NDTV

(56% oine, 47% online) and The Times of India (46% oine, 40%

online) are far more widely used among our respondents than

any other brands. The strong preference for just a couple of news

organisations has similarities with Brazil – where Rede Globo’s

television and digital oerings have very high reach – and is very

dierent from a market like the United States, where no brands

have comparable reach.

Beyond NDTV and The Times of India, other legacy brands like the

Hindustan Times, The Hindu, and the Indian Express are among the

top ten news websites by reach. Aggregators like Yahoo!, Redi

and MSN are also widely used, and the BBC has signicant reach

across broadcast (27%) and online (23%) among our English-

language respondents.

. Brands and Trust

Online, new digital-born media such as Firstpost and Scoopwhoop

are attracting a signicant percentage of weekly users. Other new

online entrants like the non-prot The Wire (7%) and the news site

Scroll (5%) have smaller weekly audiences than the major legacy

brands and the most widely used digital brands.

As a clear illustration of how digital and print still supplement

rather than supplant each other for many users in India, a

number of major English-language Indian newspapers have

wider oine reach than online reach – a very dierent scenario

from most other markets covered in the Digital News Report

research, where newspapers tend to have far smaller oine

reach than online reach.

Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / India Digital News Report 16

. ALTERNATIVE AND PARTISAN NEWS SITES

EMBRACED BY SOME

Like other countries, India has seen a growing number of new

alternative and partisan websites launched by entrepreneurs

leveraging the lower barriers of entry that digital media provide,

the potential for reaching a signicant audience especially on

social media, and the appetite in some parts of the public for

new and sometimes highly ideologically charged angles on news

and public aairs.

20

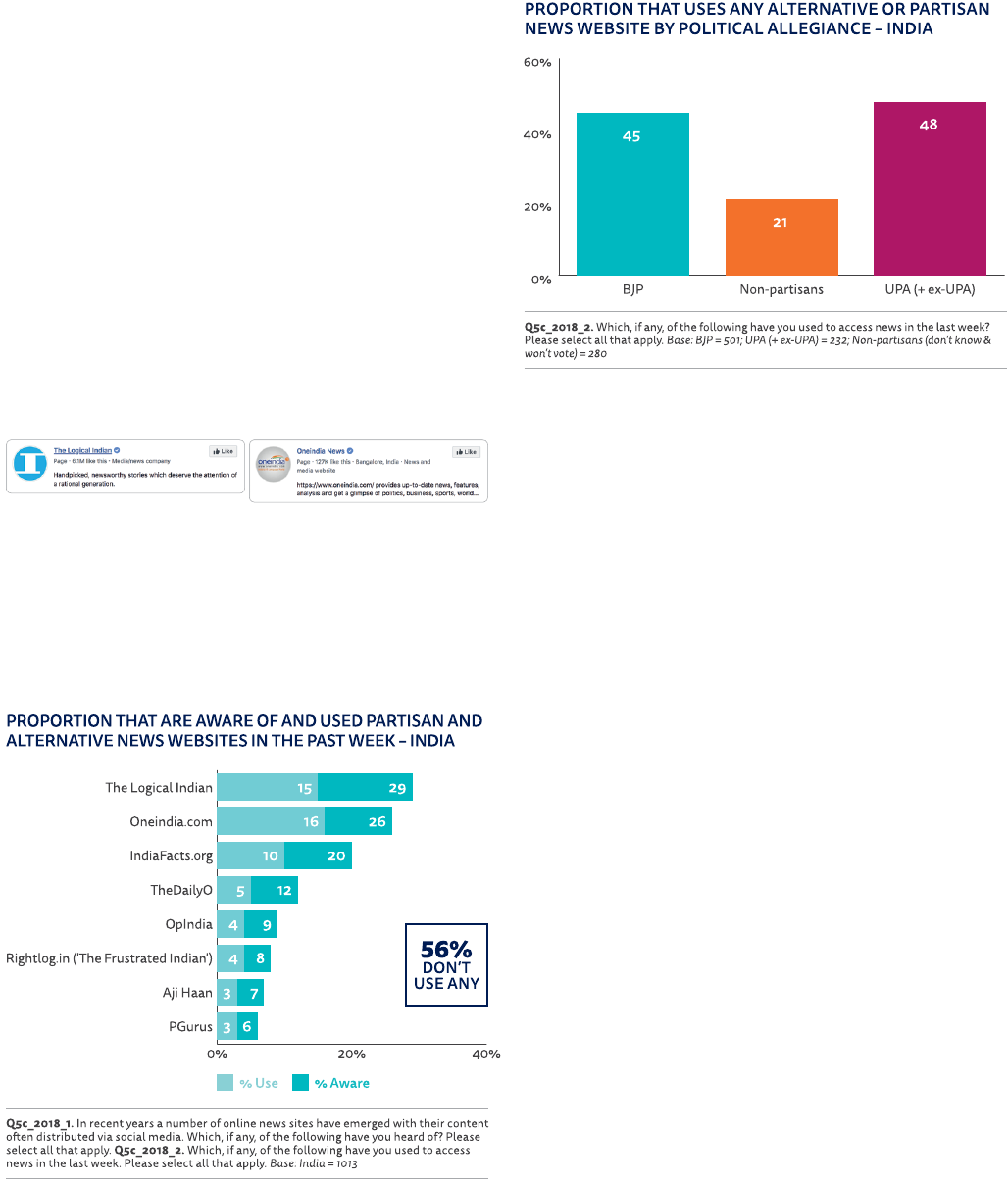

Our research shows that, despite their increased visibility and

sometimes highly motivated and vocal audiences, most of these

publishers have only a relatively limited and small audience. Few

of our respondents are even aware of most of these sites, and even

fewer say they have actually accessed them in the last week.

The main exceptions to the limited reach of most of these sites

are brands like The Logical Indian (15%), OneIndia (16%), and

IndiaFacts (10%), all of which are relatively widely known among

our respondents and have built signicant audiences – all have far

wider reach among our English-language Indian respondents than

major alternative and partisan news sites like Breitbart (7%) and

Occupy Democrats (5%) have in the United States. (Among these

three most accessed websites, The Logical Indian is seen by many

as close to the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), IndiaFacts is seen by many

as right-leaning and close to the Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP).)

Despite the evident success of some of these sites, it is worth

highlighting that 56% of our respondents have not used any of

these in the past week, and only IndiaFacts, OneIndia, and the

Logical Indian have name recognition among 20% or more of

our respondents. This is dierent from the United States, where

many alternative and partisan news sites have far higher name

recognition (though few loyal users).

20

We follow the denition in the Digital News Report (Newman et al. 2018) of alternative and partisan news sites as websites or blogs that oen have a political or ideological agenda and

a user base that tends to share these oen partisan views. Most were created relatively recently and are mainly distributed through social media. The motivation may not be purely

political as there may also be a strong business opportunity in focusing on these topics. The narrowness of their focus also separates them from some established news sites, which

may also have a reputation for partisan political coverage.

21

https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/our-research/news-brand-attribution-distributed-environments-do-people-know-where-they-get-their

To learn more about the perception that these websites are

aligned with one political party or other, we compared users

of these websites with their preferred website with reported

political aliation but found no signicant trends – though it was

evident that users who aligned with any political party were more

likely to use these sites in their daily news consumption.

An open-ended survey question about what draws users to

these websites generated some interesting responses. Some

repondents say they feel mainstream media do not represent

them and want news outlets that represent their views. Users nd

news on these sites to be ‘genuine’, ‘to-the-point’, and ‘accessible’.

“I use them because they give the accurate picture of

what is going on in our society in a clear and short way.”

(Male, 35, user of Oneindia.com and The Logical Indian)

“It’s not like that I am a permanent visitor of this

news website but sometimes, especially when I am

fact checking about some fake news, then I do use

this website.”

(Male, 29, user of Oneindia.com)

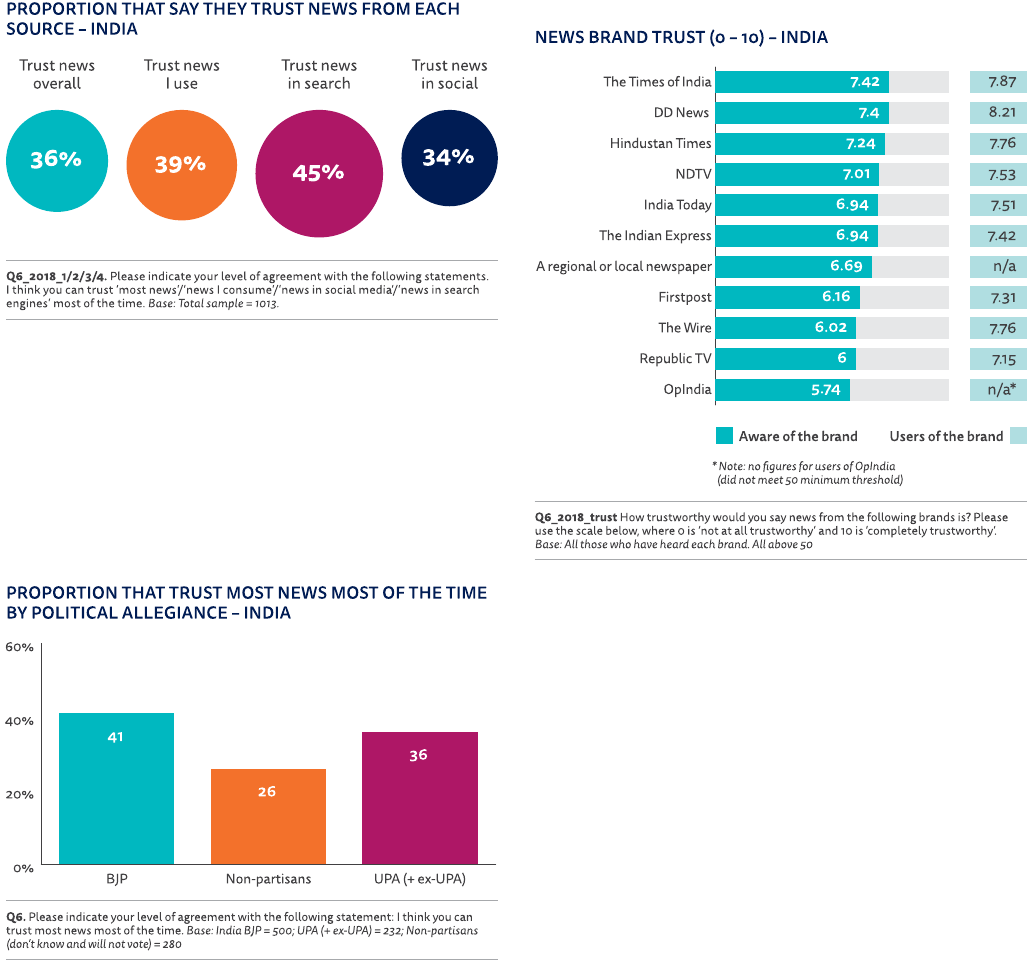

. TRUST IN NEWS MEDIA VERSUS PLATFORMS

As Indians increasingly use digital media to access and engage

with news, their trust in various forms of news will evolve. Reuters

Institute research in other countries has already documented how

trust plays out dierently as direct discovery of news via websites

and apps is increasingly supplemented with distributed discovery

via search engines and social media, and how social changes such

as political polarisation can inuence trust in news.

21

Our survey of English-language internet users in India captures

a very particular trust landscape characterised by low trust

in news in general, combined with higher levels of trust in

distributed channels like search and social.

/ 17 16

Only 39% of our respondents say they trust the ‘news they

use’ most of the time, and just 36% say they trust the ‘news in

general’ most of the time. The low overall level of trust in news

in general here is comparable to what we have found in both

Turkey and the United States (but significantly lower than, for

example, Brazil). Where India stands out is in the very small

difference – just three percentage points – between trust in the

news people actually use versus their trust in news in general.

(In the United States, for comparison, the difference is 16

percentage points, and in Turkey five.)

Given these low levels of trust, it is striking that our respondents

express greater condence in the news they access via search

engines (45%) and similar levels of trust in the news they access via

social media (34%). In many other countries, trust in news accessed

via distributed means of discovery is signicantly lower than trust

in news in general and especially the news people routinely use,

but in India, respondents seem to nd that algorithmic forms of

selection enhance – or at least do not erode – trustworthiness.

Trust in news is deeply tied up with wider social and political

issues, and in many countries, political partisanship is strongly

correlated with trust in the news. India displays a dierent pattern,

where trust among both those respondents who identify with

the BJP and those who identify with parties currently or recently

aligned with the UPA generally trust the news more than those

respondents who do not identify as partisans, perhaps suggesting

some discontent with the perceived relations between much of the

political establishment and the news media covering it.

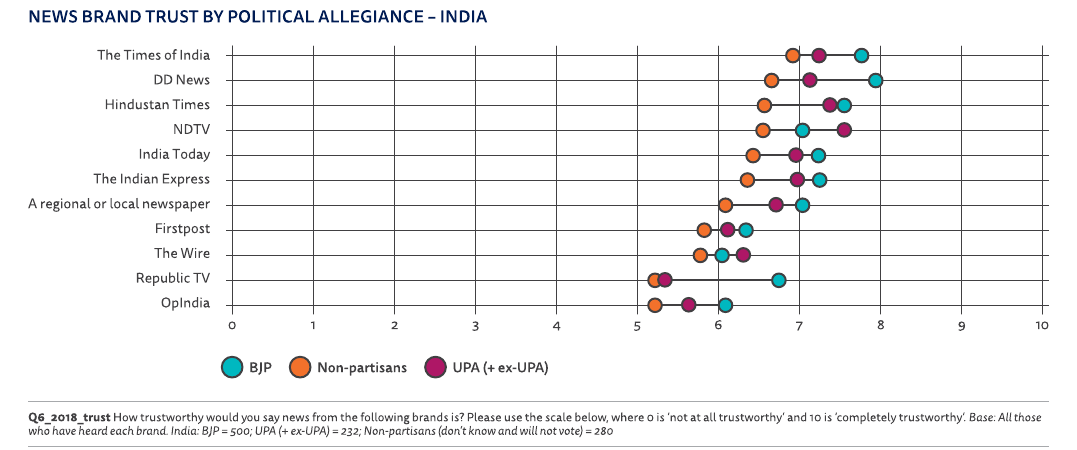

. BRAND LEVEL TRUST

While levels of trust in the news are generally low among our

respondents, at the level of individual brands there is signicant

variation. Asked to score a wide selection of dierent types of news

brands (TV, print, digital-born) on a scale from 0 to 10 where 0 is ‘not

at all trustworthy’ and 10 is ‘completely trustworthy’, some brands

are scored highly both by those who use the brand and those who

are aware of it but have not used it in the past week, whereas other

brands are only scored highly by their users and far less highly by

those who know the brand in question but do not use it.

In a powerful illustration of how familiarity and a long record

can help build trust, the most broadly trusted brands are all

legacy brands, including both newspapers like The Times of

India, Hindustan Times, and Indian Express as well as television

channels like DD News and NDTV. By contrast, newer entrants,

whether television stations like Republic TV or digital-born sites

like FirstPost, The Wire, and OpIndia, while highly rated by their

own users, are signicantly less trusted more broadly.

To examine the intersection between partisanship and trust, we

have analysed variation in trust at the brand level by political

orientation. The overall pattern reects our more general ndings

regarding trust – that non-partisans tend to trust individual brands

less than partisans, just as they trust the news in general less

than partisans. In most cases, respondents who identify with the

BJP trust individual news brands more than other respondents,

especially Republic TV. The only exceptions to this pattern are

NDTV and The Wire, both of these are more highly trusted by

respondents who identify with parties currently or recently aligned

with the UPA. It is important to stress, however, that most of these

dierences are small, and partisanship is far less correlated with

trust in news in India than it is in, for example, the United States.

Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / India Digital News Report 18

/ 19 18

. Disinformation

. DISINFORMATION PERCEPTIONS, CONCERNS,

AND EXPOSURE

In a highly politicised context, a country with a history of communal

violence and characterised by explosively growing access to new

digital media and low trust in news, disinformation has emerged

as a pressing issue in India. Of our respondents, 57% say they are

concerned about what is real and what is fake on the internet,

a number comparable to levels of concern in Turkey and the

United States.

Growing use of social media and messaging applications has been

accompanied by a series of troubling incidents, including a wave

of violence spurred in part by messages shared on WhatsApp and

Facebook. A BBC article from August 2018 suggests that at least 25

people have been lynched by mobs aer reading false news spread

on WhatsApp.

22

(It is worth noting that respondents who say they use

Facebook and/or WhatsApp for news do not report higher levels of

concern over whether the news they come across is real or fake.)

To better understand disinformation problems in India, we

asked our sample of English-language internet users about

their exposure to and concern over dierent types of potentially

problematic content that previous research for the Reuters

Institute identied as examples of what the public associate with

‘fake news’ and disinformation.

23

The categories include false

news narrowly dened (‘Stories that are completely made up for

political or commercial reasons’) but also hyperpartisan political

content, whether from politicians, pundits, or publishers (‘Stories

where facts are spun or twisted to push a particular agenda’),

‘poor journalism’ (stories that respondents consider marred

by factual mistakes, inaccuracies, etc.), and more.

Levels of concern over all these categories are high in India, with

the majority of our respondents expressing concern over hyper-

partisan content (51%), false news (50%), and poor journalism

(51%) – the percentage of respondents who in addition say that

they themselves have come across such problematic content in

the last week is generally lower, but still comparatively high, with

around four in ten reporting exposure. (We should stress here again

our sample are English speakers and that results might dier

considerably among users who consume and share news and

information in their local languages.)

Given the high levels of concern over hyperpartisan content, the

political context of disinformation, and evidence that some political

groups have actively disseminated disinformation, we examined

levels of concern and exposure by political leaning.

24

There are,

however, no partisan dierences. Concern over disinformation

and false news are similar across all our respondents regardless

of which party they support.

. WHO IS RESPONSIBLE FOR FIXING

DISINFORMATION ISSUES?

Given that many respondents agreed that India is plagued by a

range of disinformation issues, it is important to understand

who, if anyone, they believe should act to address these issues.

We asked respondents whether they felt publishers, platform

companies, and/or the government should do more to make it

easier to separate what is real and what is fake on the internet,

and reminded them that any action to decrease/reduce the

amount of misinformation (in the media or in social media) is

likely to have the consequence of reducing, to some extent,

the range of real or legitimate news or opinion available.

We nd considerable appetite for action against disinformation

and action from all dierent actors. Regardless of political

aliation, about two-thirds of our respondents felt that

publishers, platforms, and/or the government should all do

more to address disinformation problems. Compared to the

United States, our India respondents express similar levels of

appetite for action from publishers and platforms, and

signicantly greater appetite for government action.

22

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-india-45140158

23

Nielsen and Graves 2017.

24

A BBC report released in Dec. 2018 states that a signicant portion of the news being shared was political, and that right-wing networks were much more organised than the le when

it came to spreading fake nationalistic stories, including ones about the personality and prowess of Prime Minister Narendra Modi – see Chakrabarti et al. 2018.

Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / India Digital News Report 20

. Future Trends

. MOBILE APPLICATIONS AND ALERTS

As noted, 68% of our respondents name their smartphone as

their main device for accessing online news. The move to mobile

phones has clearly gone hand-in-hand with the move to distributed

discovery, where social media and other platform intermediaries

are becoming more important than conventional forms of direct

access. But publishers who have invested in mobile strategies are

seeing a return as smartphones also oer new ways of serving their

users. The fact that 12% of our respondents identied mobile alerts

as their main way of accessing online news suggests publishers

with eective mobile strategies have future opportunities to retain

a direct connection with their readers. While 50% of respondents

say they get the right number of news notications, 34% say they

get too many. For publishers interested in expanding their reach

and serving their audiences via mobile alerts, it is important to

understand what might convince people to sign up. We asked

those who do not currently receive news alerts what might

convince them to sign up, and while 17% say ‘nothing’ could,

more express an appetite for controlled, personalised alerts.

. APPETITE FOR ONLINE NEWS VIDEO

Online news video is another area with potential for growth,

and one in which many Indian publishers are already investing.

25

While a challenging area where substantial investments have

oen failed to meet high expectations elsewhere, as users who

increasingly embrace both high-end on-demand premium video

and short, sharable, social forms of video still seem to have a

modest appetite for online news video, the Indian market seems

to have potential for growth. And though English-language Indian

internet users currently consume more text over video, there is

an appetite for more video in the future – 35% of our respondents

say they would like to see more online video news. Despite many

still reading text stories, there seems to be an appetite for more

videos among internet users of all ages.

25

https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/our-research/indian-news-media-and-production-news-age-social-discovery

26

KPMG 2018.

. VIDEO VIEWING MOVING OFFSITE

From publishers’ point of view, the appetite for more online news

video is an opportunity, but the majority of online news video

viewing is taking place osite. Just 35% of our respondents say

they have watched online video news on a publisher’s website or

app, compared to 73% who have watched online video news on

osite platforms like YouTube and Facebook. (The numbers add

up to more than 100 because a signicant minority watch online

news video both on- and osite.) This is broadly in line with other

industry research suggesting YouTube and Facebook account for

60–70% of total online video consumption in India.

26

/ 21 20

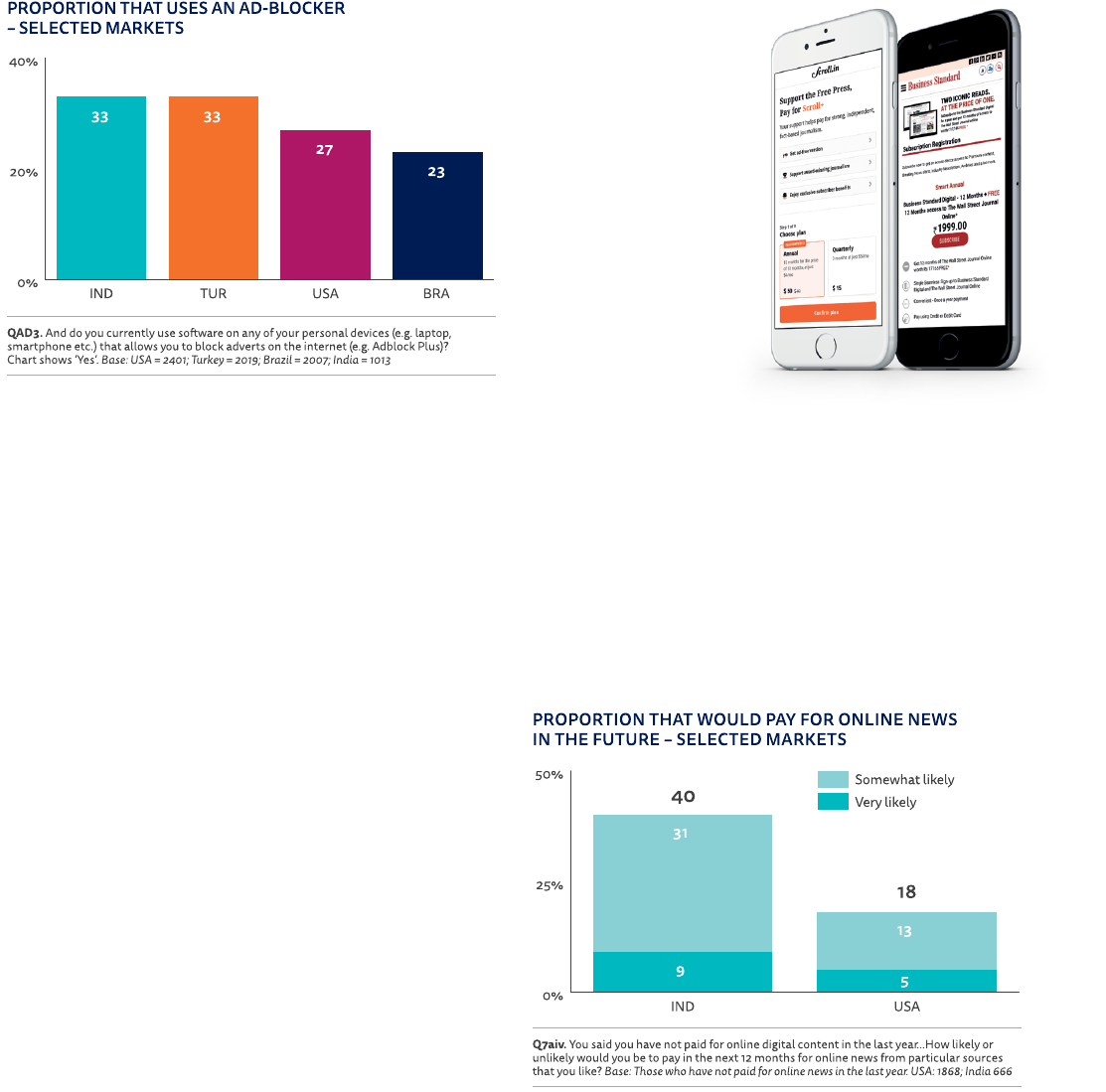

. ADBLOCKING ESPECIALLY AMONG YOUNGER

USERS A THREAT TO THE BUSINESS

Given Indian publishers’ reliance on advertising revenues,

widespread ad-blocking is a challenge for the business of online

news. Even though many publishers have taken steps to tackle

ad-blocking, a third of our respondents continue to use ad-blockers.

This is in line with other industry research which has suggested

at least 122 million Indians use ad-blockers, and that ad-blocking

is prevalent on both mobile and desktop.

27

. OPPORTUNITIES AROUND VOICEACTIVATED

SPEAKERS AND AUDIO

Another growing segment (though from a very low base in India) is

voice-activated speakers like Alexa and Google Home: 9% of our

English-language internet user respondents say they currently

use a voice-activated system, and more than half of these (5%)

use them to access news. Like publishers elsewhere, Indian news

media need to think about their strategy for this rapidly evolving

segment. Audio more broadly also oers opportunities, with

growing popularity among Indian internet users as well. Among

our respondents, the most popular podcasts are from traditional

Indian news brands like The Times of India, NDTV and Aaj Tak, but

international brands like TED, Oprah, and YouTube personality

Logan Paul are also popular.

. WILL INDIANS PAY FOR ONLINE NEWS?

In an increasingly competitive market for online advertising,

where audiences are embracing ad-blocking, and where

advertisers oen opt for the cheap, targeted options provided

by large platform companies, Indian publishers’ reliance on

advertising puts them at risk. Some are reconsidering their

strategy and business models and have been experimenting

with new pay models, some of them subscription based.

27

Punit 2016.

Widely used legacy brands like NDTV and The Times of India do not

have a paywall on their website, but they do oer subscription-

based mobile apps: NDTV app users can pay INR 550 (US$ 7.73)

annually for an ad-free experience and The Times of India’s ET

Prime recently launched a morning brieng app with a yearly

subscription for INR 2499 (US$ 35.11). The nancial newspaper

the Business Standard has operated a subscription model for

some time, the digital-born news site Scroll has introduced

Scroll+ oering exclusive subscriber benets, and the online-only

The Ken launched in 2017 with a subscription-based model. Other

publications are experimenting with subscription-based podcasts,

micropayments, and experiences.

The audience reaction to

growing experimentation

with pay models in Indian

journalism is still unclear.

A quarter of our English-

language, internet using

respondents say that they

have paid in some form for

some kind of digital news

in the last year, a gure that

will include many dierent

kinds of payments, many

not primarily for online

news (for example, print

subscriptions that come with

digital benets), is based

on recall which can lead to

overstatements, and is in any

case not representative of the

wider Indian media market.

More signicantly, our survey documents a considerable willingness

to pay for online news in the future. Of our respondents who do not

currently pay, 39% said they are at least ‘somewhat likely’ to pay for

news in the next year (much more than users in the United States),

and 9% said they were ‘very likely’ to pay for online news in the

future. This suggests that Indian publishers who can put together

a convincing content oering around great journalism, and deliver

it in a compelling way, have an opportunity to reach a signicant

number of potential subscribers.

Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / India Digital News Report 22

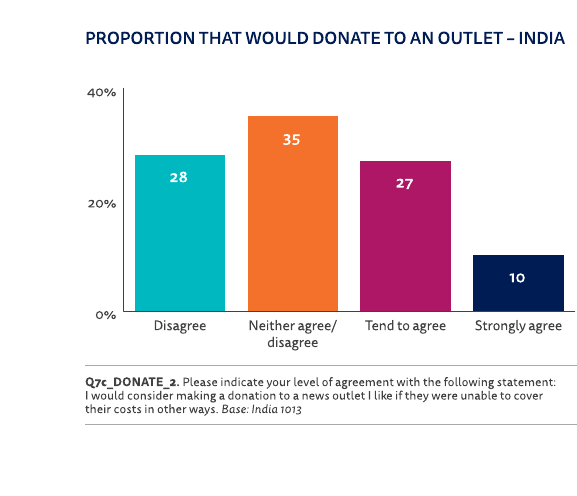

. WILL MORE PEOPLE DONATE TO NEWS?

With news organisations like Newslaundry and The Wire already

operating on a donations model, and non-prot news growing

around the world, it remains to be seen how many Indians

will donate to news. As in other markets, Indian internet users

displayed high levels of agreement with the idea that news

organisations should ask for donations from the public if they are

unable to cover their costs in other ways. Of our respondents, 10%

‘strongly agreed’ they would consider donating to a news outlet if

they were unable to cover their costs in other ways, suggesting

signicant potential for growing donation-based models.

When asked in open-ended survey questions why they might

donate to support news, respondents gave a range of dierent

reasons, from a desire to maintain standards, to concerns over

media freedom, to a desire to support entrepreneurialism.

“Because in the age of fake news it is very hard to

get the original content. But there are some media

websites and persons who are trying to maintain

the dignity of journalism and that’s why I support

them by donating. ”

(Male, 29)

“The digital news service is necessary for freedom

of media.”

(Male, 27)

“It will encourage more start-ups. ”

(Female, 21)

/ 23 22

Conclusion

In this report we have presented a snapshot of how

English-language internet users in India engage

with news and media, and shown that they are

embracing a mobile-rst, platform-dominated

media environment where search engines, social

media, and messaging applications play a key

role in how people access and use news. We also

nd that our respondents have low trust in many

news media, high concerns over the possible

implications of expressing political views, and are

worried about dierent kinds of disinformation.

We have studied only the news and media habits and opinions

of English-language internet users and our results should thus

not be taken as representative of the wider Indian media scene,

but the results presented here provide useful evidence on how

a signicant subset of the Indian public engages with news, and

provide publishers and others interested in serving this part of

the Indian public with important information about current and

future trends.

It is clear that we should expect to see the rapid move to digital,

mobile, and platform media continue, both due to growing internet

access across India, and due to generational replacement.

This move presents Indian publishers with a range of important

opportunities including developing their mobile oerings, their

news alerts, and their email newsletters to better serve domestic

and overseas audiences, as well as the opportunity to leverage

distributed discovery to reach people who do not come direct

to publishers (the majority of our respondents). It also presents

them with clear challenges, as digital media become a more

and more important part of the overall Indian media landscape,

competition for attention and advertising will intensify, and

legacy publishers used to dominating their home market will face

intensied competition from smaller digital-born new entrants

and, most importantly, from large platform companies.

The evolving relationship between publishers and platforms will

shape the wider evolution of Indian journalism and the Indian news

media industry, with hundreds of millions of new users coming

online in the years ahead, and opportunities around mobile, video,

and voice, but also challenges as digital advertising may not go

to publishers, who will have to consider other sources of revenue

to fund their journalism, including, for some, advertising beyond

display, donations, or pay models.

Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / India Digital News Report 24

References

Aneez, Z., Chattapadhyay, S. Parthasarathi, V., and Nielsen, R. K.

2016. Indian Newspapers’ Digital Transition: Dainik Jagran,

Hindustan Times, and Malayala Manorama. Oxford: Reuters

Institute for the Study of Journalism.

https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/

les/2017-04/Indian%20Newspapers%27%20Digital%20

Transition.pdf

Aneez, Z., Chattapadhyay, S., Parthasarathi, V., and Nielsen, R. K. 2017.

Indian News Media and the Production of News in the Age of Social

Discovery. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/

les/2017-12/Indian%20news%20media%20and%20the%20

production%20of%20news%20in%20the%20age%20of%20

social%20discovery_0.pdf

Bass, D. 2018. ‘Twitter is “Toxic Place for Women,” Says Amnesty

International’, Hindustan Times. 2018.

https://www.hindustantimes.com/world-news/twitter-is-toxic-

place-for-women-says-amnesty-international/story-

7yzTcN1zAMJy4OnoOR8VIP.html

Chakrabarti, S., Stengel, L., and Solanki, S. 2018. Duty, Identity,

Credibility: Fake News and the Ordinary Citizen in India. London:

BBC News.

http://downloads.bbc.co.uk/mediacentre/duty-identity-

credibility.pdf

EY-India 2018. Re-imagining India’s M&E Sector.

https://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/ey-re-imagining-

indias-me-sector-march-2018/%24File/ey-re-imagining-indias-

me-sector-march-2018.pdf

IAMAI-Kantar IMRB. 2018. Internet in India 2017.

https://cms.iamai.in/Content/ResearchPapers/15c3c84c-128a-

4ea9-9cf2-a50a6d18f21c.pdf

KPMG. 2018. Media Ecosystems: The Walls Fall Down. [Mumbai]:

KPMG in India. Media and Entertainment Report 2018.

https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/in/pdf/2018/09/

Media-ecosystems-The-walls-fall-down.pdf

Kumar, S., Kumar, P. 2018. ‘How Widespread is WhatsApp’s Usage

in India?, Live Mint.

https://www.livemint.com/Technology/O6DLmIibCCV5luEG9XuJWL/

How-widespread-is-WhatsApps-usage-in-India.html

Masani, Z. 2012. ‘English or Hinglish -which will India choose?’

BBC, 27 November.

https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-20500312

Media Research Users Council. 2017. Indian Readership Survey

2017. Mumbai.

http://mruc.net/uploads/posts/

a27e6e912eedeab9ef944cc3315a15.pdf

McLaughlin, T. 2018. ‘How WhatsApp Fuels Fake News and

Violence in India.’ Wired Magazine, 12 Dec.

https://www.wired.com/story/how-whatsapp-fuels-fake-news-

and-violence-in-india/

Nielsen, R. K., Graves, L. 2017. ‘News you don’t Believe’: Audience

Perspectives on Fake News. Fact Sheet. Oxford: Reuters Institute

for the Study of Journalism.

https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/

les/2017-10/Nielsen%26Graves_factsheet_1710v3_FINAL_

download.pdf

Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Kalogeropoulos, A., Levy, D. A. L.,

and Nielsen, R. K. 2018. Digital News Report 2018. Oxford:

Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

http://www.digitalnewsreport.org

Neyazi, T. A. 2019. ‘Internet Vernacularization, Mobilization and

Journalism’, in Shakuntala Rao (ed.), Indian Journalism in a New Era:

Changes, Challenges, and Perspectives. Delhi: Oxford University

Press, 95–114.

Omidyar Network 2017. Innovating for the Next Half Billion.

https://www.omidyar.com/sites/default/les/le_archive/

Next%20Half%20Billion/Innovating%20for%20Next%20

Half%20Billion.pdf

Punit, I. S. 2016. ‘Indian News Publishers are Cracking Down on

Ad-Blockers’, Quartz India, 1 July.

https://qz.com/india/721094/indian-news-publishers-are-

cracking-down-on-ad-blockers

Sen, A., Nielsen, R. K. 2016. Digital Journalism Start-Ups in India.

Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/les/2017-04/

Digital%20Journalism%20Start-ups%20in%20India_0.pdf

Soundararajan, T. 2018. ‘Twitter’s Caste Problem’, New York Times,

12 Mar. 2018.

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/03/opinion/twitter-india-

caste-trolls.html

Wang, H., Sparks, C. 2019. ‘Chinese Newspaper Groups in the

Digital Era: The Resurgence of the Party Press’, Journal of

Communication 69(1): 94–119.

https://academic.oup.com/joc/article-abstract/69/1/94/5253216

/ 25 24

BOOKS

NGOs as Newsmakers: The Changing Landscape of International

News

Matthew Powers (published with Columbia University Press)

Global Teamwork: The Rise of Collaboration in Investigative

Journalism

Richard Sambrook (ed)

Innovators in Digital News

Lucy Kueng (published with I.B.Tauris)

REPORTS

More Important, But Less Robust? Five Things Everybody Needs

to Know about the Future of Journalism

Rasmus Kleis Nielsen and Meera Selva

GLASNOST! Nine ways Facebook can make itself a better forum

for free speech and democracy

Timothy Garton Ash, Robert Gorwa, and Danaë Metaxa

Coming of Age: Developments in Digital-Born News Media in Europe

Tom Nicholls, Nabeelah Shabbir, Lucas Graves, and Rasmus

Kleis Nielsen

Time to Step Away From the ‘Bright, Shiny Things’? Towards A Sustainable

Model of Journalism Innovation in an Era of Perpetual Change

Julie Posetti

Indian News Media and the Production of News in the Age of

Social Discovery

Zeenab Aneez, Sumandro Chattapadhyay, Vibod Parthasarathi,

and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen

Going Digital: A Roadmap for Organisational Transformation

Lucy Kueng

‘I Saw the News on Facebook’: Brand Attribution when Accessing

News from Distributed Environments

Antonis Kalogeropoulos and Nic Newman

Virtual Reality and 360 Video for News

Zillah Watson

Indian Newspapers Digital Transition: Dainik Jagran, Hindustan

Times, and Malayala Manorama

Zeenab Aneez, Sumandro Chattapadhyay, Vibodh Parthasarathi,

and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen

Digital Journalism Start-Ups in India.

Arijit Sen and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen.

FACTSHEETS

An Industry-Led Debate: How UK Media Cover Articial Intelligence

J. Scott Brennen, Philip N. Howard, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen

‘News You Don’t Believe’: Audience Perspectives on ‘Fake News’

Rasmus Kleis Nielsen and Lucas Graves

Selected RISJ Publications

Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / India Digital News Report 26

/ 27 26