Large Print Labels

From the street to the runway, the artist’s studio

to the museum gallery, and countless sites in

between, The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary

Art in the 21st Century explores hip hop’s profound

impact on contemporary art and culture. One of

the most vital movements of the 20th century, hip

hop is now a global industry and way of life. In the

21st century, hip hop practitioners have harnessed

digital technologies to gain unparalleled economic,

social, and cultural capital.

Hip hop emerged in the 1970s in the Bronx as a

form of celebration expressed by Black and Latinx

youth through emceeing (rapping), deejaying,

grafti-writing, and breakdancing. Over the past

50 years, these creative practices have produced

new forms of power as they critique, celebrate,

and refuse dominant ones.

Hip hop has deeply informed ‘’The Culture,” an

expression of Black Diasporic culture that has

largely dened itself against white dominance. In

the art museum, however, ‘’culture’’ has historically

meant a Europe-focused set of aesthetics, values,

and traditions sustained through gatekeeping.

The works in these galleries explore where

‘’culture’’ and ‘’The Culture’’ collide through six

themes: Language, Brand, Adornment, Tribute,

Pose, and Ascension. Language, whether in words,

music, or grafti, explores hip hop’s strategies of

subversion. Brand highlights the icons born from

hip hop and the seduction of success. Adornment

exuberantly challenges white ideas of taste with

alternate notions of beauty, while Tribute testies

to hip hop’s development of a visual canon. Pose

celebrates how hip hop speaks through the body

and its gestures. Ascension explores mortality,

spirituality, and the transcendent. Endlessly

inventive and multi-faceted, hip hop, and the art

it inspires, will continue to dazzle and empower.

Language

Hip hop is intrinsically an art form about language:

the visual language of grafti, a musical language

that includes scratching and sampling, and, of

course, the written and spoken word. An emcee

calls to the crowd with, “Let me hear you say...”

and orders language to a rhythm. Call-and-

response chants, followed by rap rhymes and lyrics

overlaid on tracks, form the foundations of hip hop

music. In addition to the poetry of music, one of

the most recognizable markers of hip hop is grafti.

Since the 1970s, grafti writers have colored city

trains, overpasses, and walls with vibrant hues of

spray paint. Many writers sign their works with

distinctive “tags.” Their exploration takes the

recognizable shapes of letters and numbers and

pushes their forms to—and beyond—the limit of

legibility.

Hip hop artists convey messages for anyone

to understand, while they code others in

references, technologies, or forms that require

insider knowledge, asserting the right not to be

universally understood.

How do you read the language of hip hop in

these works?

Front Image: Chinese grafti artist Chose tagging during a Puma event

celebrating the 50th anniversary of the classic Puma suede shoe, Guang-

zhou, China, 2017. Photo by Martha Cooper

Reverse Image: Lady Pink with her rst canvas, 1981.

Photo by Martha Cooper

Language Section Grafti

2024

WHEN in tribute to the artist RAPES

Curated by DSGN CLLCTV, Cincinnati, Ohio

Adam Pendleton

(American, b. 1984, Richmond, VA)

Untitled (WE ARE NOT)

2022

silkscreen ink on canvas

Courtesy of Carmel Barasch Family Collection

Black letters hover over dripping white letters, the

overwriting reminiscent of a tagged wall. The words

“we,” “are,” and “not” appear but are obscured by

further marks. Artist Adam Pendleton’s “Black Dada

Manifesto” guides much of his creative output. The

manifesto borrows both from Dadaism, an absurdist

artistic movement active during World War I (1914–

1918), and writer Amiri Baraka’s (1934–2014) poem

“Black Dada Nihilismus.” Both the Dadaists and

the Black Arts Movement, with which Baraka was

associated, operated within the framework of the

systemic violence of their respective political mo-

ments. Pendleton’s art refuses to be easily under-

stood as it explores the power and limits of what

language can address.

Jean-Michel Basquiat

(American, 1960–1988, New York City)

With Strings Two

1983

acrylic and oil stick on canvas

The Broad Art Foundation

Here, Jean-Michel Basquiat paid homage to jazz

musician Charlie “Bird” Parker (1920–1955), refer-

enced frequently throughout the artist’s

works. Basquiat included letters from Parker’s

name encased by a blue box, and below, the art-

ist wrote the title of Parker’s 1946 single “Orni-

thology,” struck through in red. An artist’s rever-

ence for iconic Black gures also occurs in hip hop:

name-dropping is a way for musicians to pay re-

spect to those who have come before and created

“the culture,” and to align themselves

with those creators.

Gordon Parks

(American, b. 1922 Fort Scott, KS;

d. 2006, New York City)

A Great Day in Hip Hop

1998

photograph

Courtesy of The Gordon Parks Foundation,

Pleasantville, NY

In 1998, 177 people gathered on the steps

of a brownstone in Harlem, New York, to

celebrate the impact and evolution of hip hop.

This photograph documents its exponential

growth and unprecedented movement into

mainstream culture.

Commissioned by the music publication XXL, A

Great Day in Hip Hop is an homage to Art Kane’s

(1925–1995) 1958 photograph, A Great Day in Har-

lem, which commemorates legendary jazz gures.

By referencing Kane’s popular image,

Parks’ work invites you to consider the evolution

of Black sound from jazz to hip hop.

Art Kane (American, 1925–1995), A Great Day in Harlem, August 12,1958;

© Art Kane Archive

Hip Hop in Cincinnati

Scribble Jam (1996 – 2009)

Born out of a magazine dedicated to grafti

writing culture, Scribble Jam became one of the

most prominent hip hop festivals in the Midwest

and the country. From its start in 1996, co-found-

ers “Fat” Nick Accurso, Jason Brunson, and DJ Mr.

Dibbs transformed this small backyard party into

a world-renowned hip hop festival through blood,

sweat, and tears.

Scribble Jam served as a hub of hip hop culture,

and its competitions became highlights of the festi-

val, incorporating the ve elements of hip hop: graf-

ti, DJ, emcee, B-Boy, and beatbox. Staying true

to these fundamentals and to its grass roots origins,

Scribble Jam did not accept corporate sponsorship.

Over the course of its 13 years (1996–2009),

national artists such as KRS-One, Atmosphere,

Living Legends, Eminem, Juice, MF Doom, and

Rhymefest graced the Scribble Jam stages. The

festival also did much for Cincinnati and Ohio hip

hop culture by giving these artists a national

platform. Prominent Ohio artists who enriched

the stages included Mood, Five Deez, Holmskillit,

Blueprint, Lone Catalysts, and Mhz.

The Scribble Jam years left a strong legacy of hip

hop culture in Cincinnati and represent the strong

relationships between both.

Gajin Fujita

(American, b. 1972, Los Angeles)

Ride or Die

2005

spray paint, paint marker, paint stick, gold and

whitegold leaf on wood panels

Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, Kansas City,

Missouri, Bebe and Crosby Kemper Collection, Mu-

seum purchase, Enid and Crosby Kemper and Wil-

liam T. Kemper Acquisition Fund

2005.39.01

A Japanese Edo-era (1603–1867) samurai rides in-

to battle on horseback, assailed by an onslaught of

piercing arrows. Emblazoned on his otherwise tradi-

tional helmet adorned with golden antlers is

a Los Angeles Dodgers logo. Perhaps referencing

the Edo-era printmaker’s mark, various grafti

tags engulf the rider.

Deeply informed by his years as an active member

of two grafti crews, Gajin Fujita often combines

historic Japanese art with the visual language of

street culture of Los Angeles,California. In works

like Ride or Die, conjoining the two serves as

a unique mode of activism and free-form

creative expression.

RAMM:ΣLL:ZΣΣ (Rammellzee)

(American, 1960–2010, Far Rockaway, NY)

Alphabet (pages 6, 8, and 10

from series of 11)

circa 1986

felt-tip pen and pencil on paper

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the

Gilbert B. and Lila Silverman Instruction Drawing

Collection, Detroit, 2018

The artist, performer, and philosopher RAM-

M:ΣLL:ZΣΣ retooled written language as a means

of exercising and circulating power. He sought to

obscure—and by doing so, repurpose—the Ro-

man alphabet through what he called the “arman-

amentation” of letters and a system he later called

IKONOKLAST PANZERISM.

His approach—or, in his words, “correction”—to

the inuential wild style form of grafti writing en-

ables each letter to perform a highly specic kind

of work. These intricate letterforms reference a phi-

losophy that commingles the street with the galac-

tic. RAMM:ΣLL:ZΣΣ wrote of the letter C, on view

nearby, “C Structure knowledge incomplete O, 60

(point-point+) missing from cipher=C, representing

third letter. Since O is broken, C cancels out itself

because its outline does not go around and come

around. In this formation XC equals nance.” Some

languages do not exist to be readily understood.

Julie Mehretu

(American, b. 1970, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia)

Six Bardos: Transmigration

2018

aquatint

Gemini G.E.L.

This print’s complex mapping of layered lines,

marks, and colors calls to mind a wall dense with

grafti. One of the original pillars or elements of

hip hop, grafti has challenged mainstream notions

of public space, private property, what is consid-

ered art, and what is considered a crime. In creating

these panels, which are part of a sweeping six-part

series, Mehretu drew inspiration from political graf-

ti and calligraphy and her upbringing, particularly

her father’s professional background in geography.

For the artist, making her mark to make space is

vital. “My work is an insistence on being here. I am

here, we are here, and we are in the building.”

Alvaro Barrington

(Venezuelan, b. 1983, Caracas, Venezuela)

They have They Can’t

2021

hessian (burlap) on aluminum frame, yarn, spray

paint, concrete on cardboard, and bandanas

Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami.

Gift of Private Collection, US

“They got money for wars, but can’t feed the

poor.” Sewn in yarn on burlap, the pointed lyrics

across They have They Can’t are from Tupac

Shakur’s (1971–1996) 1993 song “Keep Ya Head

Up,” which highlights Black persistence in the face

of racism, sexism, and marginalization. Another

reference to Shakur in this work is the large, embla-

zoned rose that nods to his autobiographical

poem “The Rose That Grew from Concrete.”

Of Grenadian and Haitian descent and raised in a

West Indian neighborhood in Brooklyn, New York,

Alvaro Barrington admires such rappers as Shakur

and DMX (1970–2021), who told “the story of the

[U.S.] war on drugs as a war against working-class

Black communities.”

Shirt

(American, b. 1983, New York City)

Don’t Talk To Me About No

Signicance Of Art

2021

inkjet on canvas

Courtesy of the artist

In this text-based work, 32 contemporary artists

and thinkers considered whether a rap song can

be called signicant art. The artist, Shirt, based

the concept and design on a 1922 issue of the

experimental art journal Manuscripts (MSS),

where contributors offered opinions on the

medium of photography.

The original prompt—“Can a photograph have

the signicance of art?”—largely elicited responses

from white, male artists and inuential cultural

theorists, most notably not photographers. Shirt

invites you to reevaluate the art world’s hierarchies

and consider who gets to be called an artist, what

is considered art, and who gets to decide.

Kahlil Robert Irving

(American, b. 1992, San Diego)

Arches & standards

(Stockley ain’t the only one)

Meissen Matter: STL and pedestal

2018

glazed and unglazed ceramic, luster, enamel, per-

sonally constructed and vintage decals

Courtesy of the artist

Caught within what looks like concrete, the artist

has nestled images of cigarette butts and corporate

logos among patterned ceramics. The wares ref-

erence Meissen, the famed German porcelain rst

produced in the 1700s. Look closer for images of

Jason Stockley (b. 1981), a St. Louis, Missouri, po-

lice ofcer acquitted in 2017 for the 2011 murder of

Anthony Lamar Smith (1987–2011), along with other

scenes of protests against police brutality. Here, the

artist collapsed contemporary acts of state violence

with porcelain, a material entangled with histories

of colonialism. The work sits on a pedestal wrapped

in ephemera reecting on Black life, death, remem-

brance, celebration, and survival.

Nicholas Galanin (Tlingit and Unangax̂ )

(American, b. 1979, Sitka, AK)

Tsu Héidei Shugaxtutaan 1

2006

single-channel video (black and white, sound)

duration: 4 minutes, 37 seconds, looped

Tsu Héidei Shugaxtutaan 2

2006

single-channel video (black and white, sound)

duration: 4 minutes, 7 seconds, looped

Both works courtesy of the artist and Peter Blum

Gallery, New York

In this pair of videos, Nicholas Galanin uses dance

and music to remix cultural references and bridge

the past and present. In the rst video, the u-

id movements of breakdancer David Elsewhere

(b. 1979) animate a white room and rhythmically

align with a song sung in Tlingit, the language of

the Indigenous people from the regions present-

ly known as Southeast Alaska and Western Can-

ada. In the second video, Tlingit dancer Dan Lit-

tleeld performs a Raven Dance to a pulsating

electro-dub soundscape.

Galanin wrote, “Culture cannot be contained as

it unfolds. My art enters this stream at many differ-

ent points, looking backwards, looking forwards,

generating its own sound and motion.” The Tlingit

titles, Tsu Héidei Shugaxtutaan 1 and 2, translate

to “We will again open this container of wisdom

that has been left in our care.” This phrase is also

sung in the video.

Troy Chew II

(American, b. 1992, Los Angeles)

As seen on TV

2021

oil on canvas with augmented reality

Courtesy of the artist and Altman Siegel,

San Francisco

LA II (Angel Ortiz)

(American, b. 1967, New York City)

Untitled (Large Multicolored

Teardrop Vase)

2009

acrylic, marker, and spray paint on ceramic vase

Courtesy of Woodward Gallery, New York

Shinique Smith

(American, b. 1971, Baltimore)

Shortysugarhoneybabydon’tbedistracted

2002

acrylic on vinyl

Collection of the artist, courtesy of the artist,

Shinique Smith

Dynamically owing across this sheet of vinyl are

swirls of red and white acrylic paint. Shinique

Smith’s work references the visually abundant and

gestural street art of the 1980s and 1990s and the

mid-20th-century Abstract Expressionist tradition

that pushed paint to the very edge canvas.

In her youth, Smith wrote grafti around her home-

town of Baltimore. She explains: “Grafti still inu-

ences my work, but in a nostalgic way, reminding

me of...the brash, fearless way you have as a teen-

ager. Creating art re-creates that energy for me.”

José Parlá

(American, b. 1973, Miami, FL)

Coral Way, Alive Five

2015

acrylic, oil, ink, collage, fabric, and plaster on wood

Collection of the artist

Paint and plaster cover wood to recreate a graf-

tied wall transplanted from the street. The sculp-

ture is part of a series referencing neighborhoods

in Miami, Florida—in this work, the neighborhood

of Coral Way. Here, the complex layers suggest

the many ways people make their mark on a city:

grafti writers paint on walls, posters get pasted

up or pulled down, nicks to concrete add texture

and dimension.

While this example draws on Parlá’s experienc-

es with grafti, one of hip hop’s ve pillars or el-

ements, its vertical, slab-like form also references

mid-20th-century minimalism and abstraction. Born

in Miami to Cuban parents, Parlá has spoken of his

practice as “erasing the hyphen” in the designa-

tion “Cuban-American” to bridge histories, spaces,

and politics.

Abbey Williams

(American, b. 1971, New York City)

Overture

2020

HD single-channel video (color, sound) duration: 4

minutes, 18 seconds, looped

Courtesy of the artist

In this video, Abbey Williams spliced together foot-

age of owers in bloom and the title credits from

the opening sequence of the 1964 lm musical My

Fair Lady. Williams superimposed black bars over

the text to suggest the redaction of language.

Sexually explicit lyrics by women hip hop artists

such as Khia (b. 1976), Nicki Minaj (b. 1982), and

Princess Nokia (b. 1992) oat over the bars in an

elaborate script. These bars expand, eventual-

ly blotting out the owers entirely to form a black

screen. By displacing the idealized femininity em-

bedded in the My Fair Lady narrative, Williams cri-

tiques white-centered denitions of what it means

to be “lady-like” and recenters certain kinds of

Black femininity instead.

Rozeal

(American, b. 1966, Washington, D.C.)

divine selektah…big up [after yoshitoshi’s

moon of the lial son]

2006

acrylic and gold leaf on panel

Collection of the University of Arizona Museum of

Art, Tucson; Museum Purchase with funds provided

by Robert J. Greenberg

Brand

“I’m not a businessman, I’m a business, man!”

exclaimed Jay-Z in 2005. Soon after, he became

the rst rapper to cross the billion-dollar net worth

threshold. The conceptof a brand is not limited to

differentiating and marketing commercial goods

but extends to how an individual uses available

communication technologies—including social

media—to position themself in the public sphere.

In previous decades, hip hop artists have functioned

as unofcial promoters of major brands that aligned

with their style and desired public persona. Today,

artists both partner directly with companies and

create their own independent brands to bolster

their personal business empires. Whether designing

fashion, recording music, or making art, artists blur

the boundaries between these art forms, between

being in business and being the business.

Is the artist a producer or is the artist a product?

Front Image: ARCHBOY, showing St. Louis rapper Smino in Los Angeles,

CA, November 8, 2018. Photo by Curtis Taylor Jr.

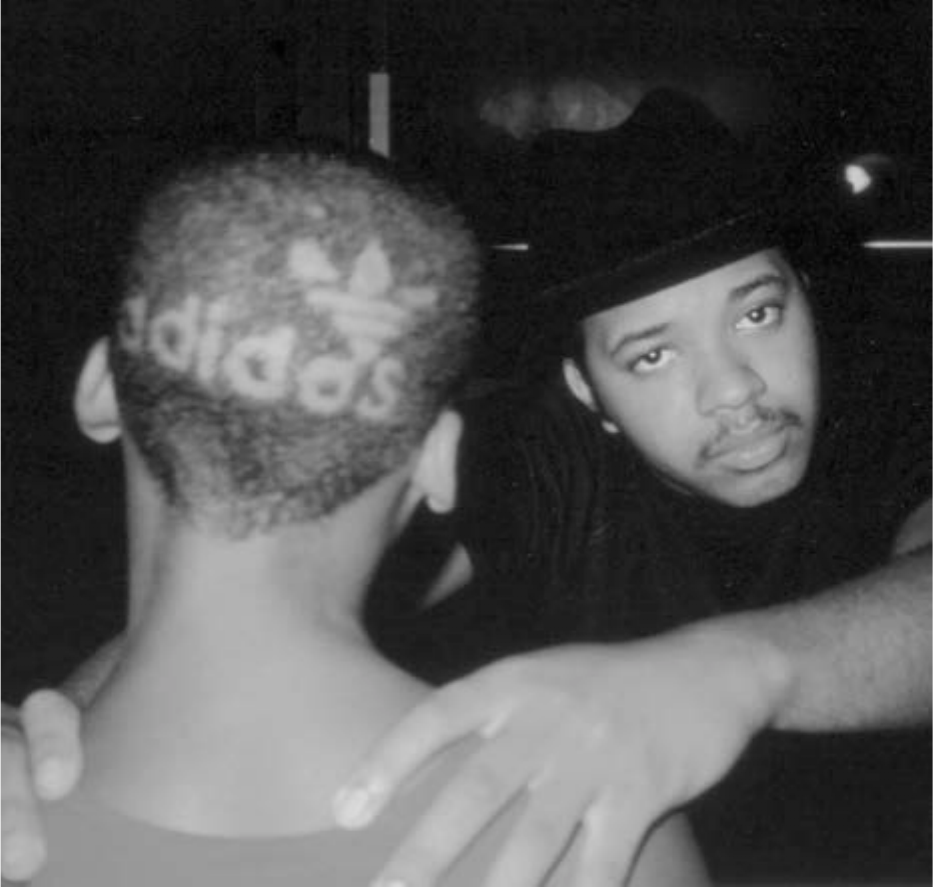

Reverse Image: Run backstage with fan in New Orleans, Raising Hell Tour,

1986 (printed 2003). Photo by Ricky Powell, Collection of the Smithsonian

National Museum of African American History and Culture © Ricky Powell

Brand Section Grafti

2024

2KEWL & AKTOE

Curated by DSGN CLLCTV, Cincinnati, Ohio

Larry W. Cook

(American, b. 1986, Landover, MD)

Picture Me Rollin’

2012

single-channel video (color, sound) duration: 1 min-

ute, 43 seconds, looped

Courtesy of the artist

A black Lamborghini spins in circles, cheered on by

men in white T-shirts and medallion necklaces. Larry

W. Cook reused a clip from the 2000 music video

“Get Your Roll On” by the rap group Big Tymers

(est. circa 1997), replacing the audio with a version

of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s (1929–1968) “I Have a

Dream” speech. The civil rights leader’s words have

been chopped and screwed, a hip hop turntable

technique that involves slowing down a track.

In the early 2000s, the rap music video aesthetic of

driving luxury cars as an assertion of hypermasculin-

ity emerged. Cook stated, “My video suggests that

the materialism gloried in hip hop music has be-

come the American Dream for many and is passed

down to younger generations.”

Jordan Casteel

(American, b. 1989, Denver)

Fendi

2018

oil on canvas

Private Collection, New York

An unidentied gure riding the subway holds bags

covered in Fendi logos in their lap. Despite the sym-

bols of the Italian fashion house, designed to catch

your eye, the artist sought to create a moment of

humanity in the otherwise unremarkable scene of a

subway ride. Through conspicuously branded luxury

items, a person aligns themselves with the lifestyle

and afuence the brand represents. Sometimes,

this image of wealth is at odds with reality.

In her gurative work, Casteel paints her sitters with

immediacy and individuality, hoping to “tell stories

of people who are often unseen, making someone

slow down and engage with them.”

Stan Douglas

(Canadian, b. 1960, Vancouver)

ISDN

2022

two-channel video (color, sound)

duration: 6 hours, 41 minutes, 28 seconds

(video variations), looped

duration: 82 hours, 2 minutes, 52 seconds

(musical variations), looped

Courtesy of the artist, Victoria Miro, and

David Zwirner

Two screens showcase a pair of performers, one in

London and another in Cairo. They take turns de-

livering freestyle rap verses in English and Arabic

transmitted through ISDN, a technology conceived

in the 1980s to send digital audio over a phone line.

According to the artist, this back-and-forth, call-

and-response reects global interconnectedness:

“The idea of having this endless music is to say that

when you do have this cross-fertilization between

cultures, the possibilities are endless.” Both pairs of

artists use the language of rap to explore systemic

social issues and ideas of race and class that con-

nect them across continents. This work underscores

that hip hop, transnational yet rooted in the African

Diaspora, is an undeniable global force and that,

despite its enormous commercial appeal, contin-

ues to adapt to the local conditions under which it

is made.

ISDN is one of Stan Douglas’ “recombinant” works

in which dialogue, soundtrack, and imagery recom-

bine and change, often over a prolonged period.

You are welcome to enter the work at any point.

Kudzanai Chiurai

(South African, b. 1981,

Harare, Zimbabwe)

The Minister of Enterprise

2009

Ultrachrome ink on photo bre paper

Courtesy of Kudzanai Chiurai and Goodman Gallery

Lighting his cigar with money, the Minister of En-

terprise stares deantly at you. He positions himself

in front of shining gold wallpaper, wearing tinted

sunglasses, and a gold watch and chain. In a theatri-

cal image, he embodies the conspicuous consump-

tion and desire for brandishing luxury goods seen

among many hip hop stars.

This work is part of a series of scathing mock por-

traits titled The Parliament. South Africa-based art-

ist and social activist Kudzanai Chiurai depicts mem-

bers of a ctitious government cabinet, inventing

characters representing the ministers of education,

nance, health, defense, home affairs, art, and cul-

ture. The series comments on political powers in

South Africa, corruption, and masculinity through

the aesthetics of hip hop culture.

Luis Gispert

(American, b. 1972, Jersey City)

Louis Uluru

2012

chromogenic print

Courtesy of Moran Moran Gallery

Jayson Musson

(American, b. 1977, New York City)

Knowledge of God

2015

mercerized cotton on stretched linen

Courtesy of the artist and Salon 94, New York

Rashaad Newsome

(American, b. 1979, New Orleans)

Power and Periphery (NOLA)

2012

collage in customized frame

Courtesy of Marlborough Gallery, New York

Daniel “Dapper Dan” Day for Gucci

(American, b. 1944, New York City)

Guccissima Leather Down Jacket

Spring/Summer 2018

lamb leather, polyamide, and goose down

Barrett Barrera Projects

Green dragons march around the sleeves of this

distinctive red leather jacket. The allover Gucci

logo in white leaves no doubt as to the identity

of the brand, but all is not as it appears.

The legendary designer known as Dapper Dan pro-

duced custom-made clothing out of existing luxu-

ry stock. In the 1980s and 1990s, he created iconic

looks for artists such as Eric B. & Rakim (est. 1986),

LL Cool J (b. 1968), and Salt-N-Pepa (est. 1985).

As his clients’ fortunes rose, so did his visibility—

high-end fashion houses led lawsuits, and his store

closed. When, in 2017, Gucci created a mink bomb-

er jacket suspiciously similar to one by Dapper Dan,

the public outcry was immediate. In a canny move,

Gucci invited Dapper Dan to design a fall 2018

capsule collection, of which this jacket is a part.

The borrowing from expensive brands to make

something unique questions the notion of the

“original” and underlines the uneasy relation-

ship between symbols of afuence and those they

deliberately exclude.

Sheila Rashid

(American, b.1988, Chicago)

Overalls

2016, recreated in 2023

gabardine, copper oxide buttons, and rivets

Courtesy of the artist

Chance the Rapper for New Era

(American, b. 1993, Chicago)

Chance 3 New Era Cap

2022

fabric, plastic, and stickers

The Baltimore Museum of Art: Museum Purchase

During the promotion of his 2016 Coloring Book al-

bum, Chance the Rapper (b. 1993) adopted overalls

and a baseball cap with the number three as his uni-

form and personal brand. The rapper commissioned

Chicago-based designer Sheila Rashid to create

the overalls, which he wore at many major public

events. The look visualized the joy and play in

Coloring Book’s sound.

For this exhibition, Rashid reproduced the overalls

from Chance the Rapper’s 2016 appearance on

the television show Saturday Night Live. The

ensemble also includes the baseball cap worn

for the performance.

Cross Colours by Carl Jones and

Thomas “TJ” Walker Jones

(American, b. 1953, Memphis; b. 1960,

Toomsuba, MS)

Denim Bucket Hat, worn by Cardi B

during 2018 Grammy’s Performance

1991

denim cotton

Cross Colours Archive

Travis Scott by Air Jordan

(American, b. 1992, Houston)

Cactus Jack Air Jordan 1

2019

leather, suede, rubber, and

cotton

Private Collection

In these retro high-top brown-and-pink suede

sneakers, the designer reverses the ever-recogniz-

able Nike swooshes—the tail faces the toe rather

than the heel. This feature is just one of the ways

that rapper Travis Scott’s partnership with Nike Air

Jordan breaks away from conventional Air Jordan

1 design. Tongue tags are stitched in red and sit

to the side of the tongue instead of the top, and

a stash pocket hides in the collar.

This collaboration has fueled record-breaking

engagement with Nike. It is a prime example of

how, by bringing their inuential cultural capital

to legacy brands, rappers have stepped into the

role previously held by elite athletes.

Hassan Hajjaj

(Moroccan, b. 1961, Larache, Morocco)

Cardi B Unity

2017 / 1438 (Gregorian / Hijri)

metallic Lambda print on 3 mm dibond in a

poplar sprayed-white frame with HH green

tea boxes with buttery

Courtesy of Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

Tariku Shiferaw

(Ethiopian, b. 1983, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia)

Money (Cardi B)

2018

spray paint, wood, price tags, and screws

Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Lelong & Co.,

New York

Tariku Shiferaw painted a large X and various

symbols on this box-like object. The open wood

slats suggest a shipping pallet used to move

goods and commodities and the straightforward

construction of minimalist sculpture.

The titles of Shiferaw’s works, such as Money

(Cardi B), reference artists known for music originat-

ing in Black communities, like hip hop, R&B,

reggae, Afrobeats, blues, and jazz. These genres

have historically been instruments of resistance

against societies that have repeatedly attempted

to erase—and prot from—Black labor. By invoking

one of the most bankable names in hip hop within

the context of the shipping crate, Shiferaw ques-

tions when a personal brand becomes a product.

Please do not touch.

Vivienne Westwood

(British, b. 1941, Cheshire, England;

d. 2022, London)

Buffalo Hat

1984

felt

Courtesy of Arby’s, Inspire Brands, Inc., Atlanta, GA

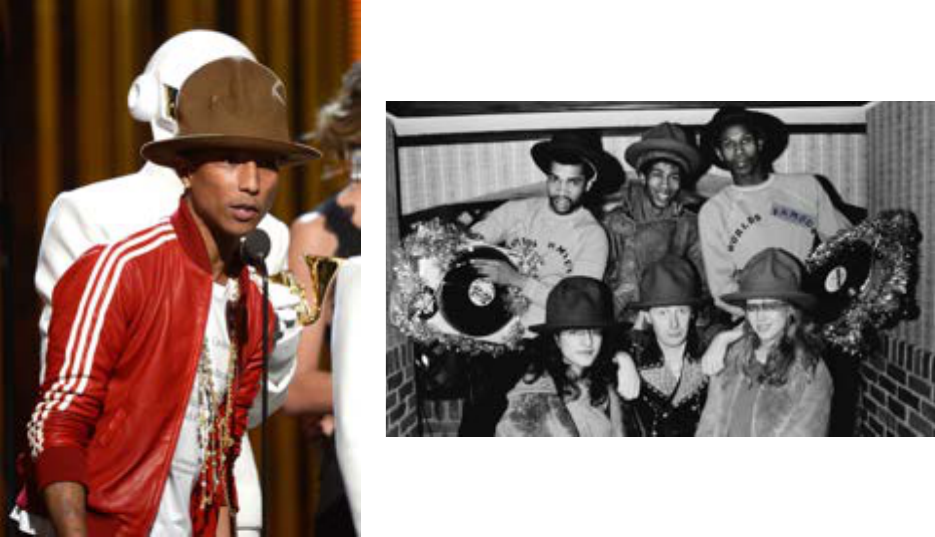

This wide-brimmed, oversized hat was famously

worn by musician Pharrell Williams (b. 1973) at

the 2014 Grammy Awards. It rst debuted in the

fall 1982 collection of legendary fashion designer

Vivienne Westwood. Her partner Malcolm McLaren

donned the hat alongside his hip hop group, The

World’s Famous Supreme Team. McLaren, best

known as the manager of the British punk band

the Sex Pistols, turned his attention to hip hop

in the 1980s. The hat became embedded in the

movement’s aesthetics through its appearance

in lms such as Wild Style (1982) and Beat

Street (1984).

Thirty-two years later, having circulated from

Westwood’s runway to movie sets and the streets of

New York City, Williams repopularized the buffalo

hat. His use of the accessory for his brand recalled

the era of classic hip hop and became a unique

signier of the artist.

Left: Pharrell Williams performs onstage during The Night That Changed

America: A Grammy Salute to the Beatles at the Los Angeles Convention

Center on January 27, 2014, in Los Angeles, California; Kevork Djansezian

/ Getty Images North America / Getty Images.

Above: Malcolm McLaren (front, center), rappers The World’s Famous

Supreme Team, and models wearing items from designer Vivienne

Westwood’s “Buffalo” collection, London, February 1983; Photo by

Dave Hogan / Hulton Archive / Getty Images

Malcolm McLaren

(British, b. 1946, London;

d. 2010, Bellinzona, Switzerland)

Duck Rock

1983

12-inch vinyl record and paper cover sleeve

The Baltimore Museum of Art: Museum Purchase

Zéh Palito

(Brazilian, b. 1991, Itaqui, Brazil)

It was all a dream

2022

acrylic on canvas

Courtesy of the artist, Simões de Assis and

Luce Gallery

This artwork has been generously supported by

Dr. & Mrs. Robert H Collins.

Adornment

“Now I like dollars/I like diamonds./I like stunting/I

like shining,” Cardi B raps at the top of “I Like It.”

Her words capture the recurrent identication of

self with adornment in the canon of hip hop. While

style often signies class and politics, almost no

culture dresses as self-referentially—or as

inuentially—as hip hop. From Lil’ Kim’s technicolor

wigs to the exuberant, excessive layering of gold

chains by Big Daddy Kane and Ra Kim, some of the

most important and unique styles have originated

in hip hop.

Jewelry ashes, grills glint in smiling mouths, and

iconic Air Force One sneakers are meant to be

seen. In her 2015 book Shine, art historian Krista

Thompson looks at how light is caught and styled

close to the body within the African Diaspora. She

explores the ways people today “use objects to

negotiate and represent their personhood,” in

contrast to how their ancestors were dened as

property. Adornment in hip hop culture can resist

Eurocentric ideals of beauty and challenge

concepts of taste and decorum.

What story does your style tell?

Front Image: LL Cool J, London. 1986 Photo by Richard Bellia

Reverse Image: Miss Kam, 2021. Photo by Philip Muriel

Adornment Section Grafti

2024

The K & KONQR (Front Grafti)

FRANK & UFOREK (Reverse Grafti)

Curated by DSGN CLLCTV, Cincinnati, Ohio

Wilmer Wilson IV

(American, b. 1989, Richmond, VA)

RID UM

2018

staples and pigment print on wood

Courtesy of the artist and Susan Inglett

Gallery, NYC

In this work, Wilmer Wilson IV rephotographed

and enlarged a party ier depicting three gures

dressed for a night out. Wilson’s laborious pro-

cess—afxing hundreds of staples to plywood—

is an effort “to cope with the impermanence of

things—like bodies, but also the fragments of ev-

eryday social life.”

RID UM recalls how party iers, typically used to

promote hip hop concerts, are stapled to wood-

en telephone poles across urban spaces. While

the staples offer a visually compelling surface, the

complete picture is somewhat difcult to decipher

due to the metallic glare, suggesting both invisibil-

ity and hypervisibility. Through this act of shielding,

Wilson has provided a means of protection to the

Black people depicted in the original photograph.

Derrick Adams

(American, b. 1970, Baltimore)

Style Grid 10

2019

acrylic paint and graphite on digital photograph

Courtesy of Derrick Adams Studio

Anthony Olubunmi Akinbola

(American, b. 1991, Columbia, MO)

CAMOUFLAGE #105 (Metropolis)

2020

durags and acrylic on wood panel

Keith Rivers Collection

Anthony Olubunmi Akinbola cut, stretched,

stitched, and collaged black durags (also spelled

“do-rags”) into a shimmering composition in this

four-panel work from his CAMOUFLAGE series.

Worn as fashion statements in their own right, these

exible headscarves also offer practical protection

for Black hair. The artist attened the durags to

transform these recognizable objects into patterns

that absorb and reect light. The allover movement

and solid black surface created by the artist brings

abstract monochrome painting into conversation

with the culture of Black adornment.

Lauren Halsey

(American, b. 1987, Los Angeles)

auntie fawn on tha 6

2021

synthetic hair on wood

Collection of Alyson & Gunner Winston

Bundles of brightly colored synthetic hair create a

cascade in rainbow hues. Often styled into wigs,

braids, and other hairstyles, candy-colored synthetic

hair has been popularized throughout the 21st cen-

tury by musicians such as Lil’ Kim (b. 1974), Lil’ Mo

(b. 1978), Blaque (est. 1999), and TLC (est. 1990).

Lauren Halsey creates works that celebrate the ev-

eryday world of her neighborhood of South Central

Los Angeles. This vibrant example celebrates syn-

thetic hair as a bold form of adornment within Black

communities and hair styling as an art form in its

own right.

Dionne Alexander

(American, b. 1967, Washington, DC)

Lil’ Kim Chanel Logo Wig

2001, recreated 2022

human hair wig

Courtesy of the artist

Lil’ Kim Versace Logo Wig

2001, recreated 2022

human hair wig

Courtesy of the artist

Lil’ Kim Purple Wig from MTV VMAs

1999, recreated 2022

synthetic hair wig

Courtesy of the artist

Lil’ Kim Zipper Wig from MTV VMAs

2001, recreated 2022

human hair wig, zipper

Courtesy of the artist

Lil’ Kim XXL Magazine

May 2000

paper

The Baltimore Museum of Art: Museum Purchase

Lil’ Kim Interview Magazine

November 1999

paper

The Baltimore Museum of Art: Museum Purchase

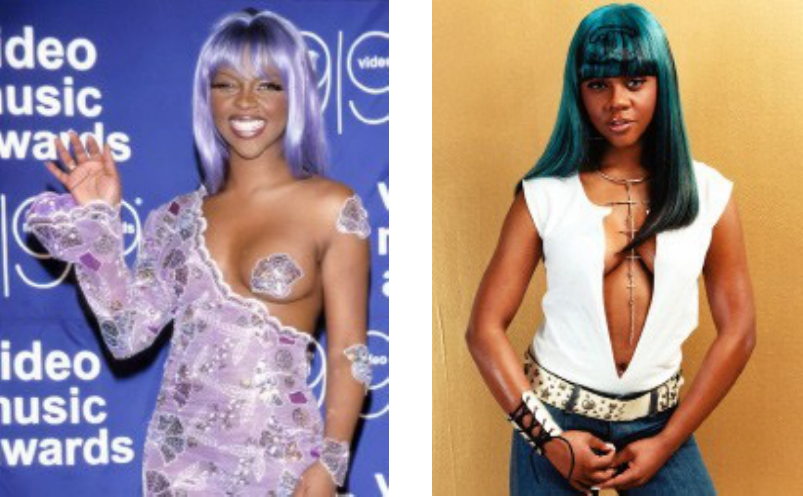

Left: Lil’ Kim at the MTV Video Music Awards, New York, 1999;

Kevin Mazur/Getty Images;

Right: Lil’ Kim, for Manhattan File magazine, 2001;

Photo by Danielle Levitt

Provocative lyrics, monochromatic outts, and vi-

brant wigs adorned with luxury brand logos dened

rapper Lil’ Kim’s (b. 1974) style in the early 2000s.

Her hairstylist during this period, Dionne Alexander,

dyed, imprinted, and stenciled some of the most

recognizable brand logos in mainstream fashion

onto these wigs, exemplifying hip hop’s popular-

ization of conspicuous consumption and branded

clothing and accessories. Alexander also created

iconic hairstyles for musical artists such as Mary J.

Blige (b. 1971), Lauryn Hill (b. 1975), and Missy

Elliott (b. 1971).

For this exhibition, Alexander reproduced some of

the most memorable wigs she created for Lil’ Kim,

which continue to reverberate in hip hop’s visual

culture today, inspiring a new generation of stylists

and music artists.

Murjoni Merriweather

(American, b. 1996, Temple Hills, MD)

Z E L L A

2022

ceramic and hand-braided synthetic hair

Courtesy of the artist ©mvrjoni

Please do not touch

Robert Pruitt

(American, b. 1975, Houston)

For Whom the Bell Curves

2004

gold chains

The Studio Museum in Harlem; Museum purchase

made possible by a gift from Rena Bransten, San

Francisco, and a gift from Burt Aaron, New York

2006.14

From a distance, these graceful arching lines recall

1960s minimalist wall sculpture. A closer look re-

veals layered references to Blackness in terms of

historical trauma and contemporary desire. Mascu-

linity in hip hop culture intertwines with gold chains,

a material associated with wealth and excess. Rob-

ert Pruitt used the form that typically graces a rap-

per’s neck to trace the routes of the transatlantic

slave trade from the western coast of Africa to

the eastern shores of the Americas, giving the

glittering links an ominous signicance.

Deana Lawson

(American, b. 1979, Rochester, NY)

Nation

2018

pigment-based inkjet print with

collaged photograph

Courtesy of the artist, David Kordansky Gallery,

and Gagosian

Two shirtless gures, dripping with gold, boldly

confront the camera. One wears a glistening cheek

retractor commonly used by dentists. A necklace

with an ankh, the ancient Egyptian symbol of life,

points toward the history of metalwork throughout

the African Diaspora. An inset image of George

Washington’s (1732–1799) dentures—made of ivory,

gold wire, and teeth from enslaved Black people—

obscures a standing gure.

By bringing Washington’s teeth into dialogue with

the mouthpiece worn by the sitter, Deana Lawson

drew a harrowing connection to the racial violence

that has shaped the United States. At the same

time, the work honors the culture of hip hop. Notes

the artist: “There is a nobility and majesty of a lot

of gold that’s worn, and how it’s appropriated in

hip hop, and how I think hip hop actually channels

ancient kingdoms.”

Megan Lewis

(American, b. 1989, Baltimore)

Fresh Squeezed Lemonade

2022

oil and acrylic on fabric

Courtesy of the artist

Hank Willis Thomas

(American, b. 1976, Plaineld, NJ)

Black Power

2006

chromogenic print, digital exposure

Barrett Barrera Projects

Bruno Baptistelli

(Brazilian, b. 1985, São Paulo, Brazil)

Memento

original cast 2020–2022; this cast 2023

gold grills

Courtesy of the artist

Using his own teeth as the mold for this gold-plated

grill, Brazilian-based artist Bruno Baptistelli placed

himself into the long history of cosmetic dentistry.

By mounting and covering the grill with a vitrine,

the artist treats gold teeth with reverence. The ti-

tle of this work reinforces this notion, evoking the

phrase memento mori (Latin for “remember that

you must die”).

Worn by hip hop originators such as Slick Rick

(b. 1965) and celebrated in songs like Nelly’s (b.

1974) 2005 single “Grillz,” gilded teeth are a

popular form of adornment in hip hop. The gold

signies an accumulation of wealth and refuses the

Eurocentric ideal of an unadorned white smile.

Miguel Luciano

(Puerto Rican, b. 1972,

San Juan, Puerto Rico)

Plátano Pride

2006

chromogenic photograph

Courtesy of the artist

Miguel Luciano

(Puerto Rican, b. 1972,

San Juan, Puerto Rico)

Pure Plantainum

2006

polyurethane encased in platinum with sterling

silver in plexiglass with synthetic ber

Smithsonian National Museum of African

American History and Culture, purchased with

funds provided by the Smithsonian Latino

Initiatives Pool, administered by the Smithsonian

Latino Center

Platinum encases a sculpted polyurethane plantain,

transforming a common food of the Caribbean in-

to jewelry. The humble fruit, rendered in a precious

metal, adorns a young person’s neck in the photo-

graph and rests against velvety black fabric in the

sculpture. Miguel Luciano describes the plantain

as “a stereotypical and yet iconic symbol.”

Plantain sap stains skin and clothing, an effect cap-

tured by the saying “la mancha de plátano,” the

mark of the plantain. This phrase originally refer-

enced the lingering brown stain left on rural farm-

workers harvesting the fruit and became an an-

ti-Black and classist euphemism. Now, it is a proud

assertion of Puerto Rican identity, especially for

the millions in the diaspora, and of connection to

heritage as lasting as the plantain stain.

Yvonne Osei

(German, b. 1990, Hamburg)

EXTENSIONS

2018

single-channel video (color, sound) duration:

6 minutes, 4 seconds, looped

Courtesy of the artist and Bruno David Gallery

Filming in Asafo in her home country of Ghana,

Yvonne Osei captured the performative quality

of the everyday cultural tradition of hair braiding.

Throughout the video, braids on the sitter’s head

grow longer and longer, and the camera pulls back

to capture their length. In the end, the braids are so

long that they drag behind the woman as she walks

through the city, her hair literally stopping trafc.

The title of this work nods to both the length of

the sitter’s braids and the impact of hair braiding

across the African Diaspora. Braided hair has his-

torically communicated group identity, status, and

geography. From Queen Latifah’s (b. 1970) 1990s

looks to A$AP Rocky’s (b. 1988) current style,

braided hair can serve as another political form

of self-presentation.

Tribute

From name-dropping in a song to wearing a por-

trait of a deceased rapper on a T-shirt, tributes,

respects, and shout-outs are fundamental to hip

hop culture. These references proclaim inuence

and who matters, honor legacies, and create

networks of artistic associations. Elevating artists

and styles contributes to hip hop’s canonization—

when certain artworks, songs, and rappers are

collectively recognized for their artistic excellence

and historical impact.

Hip hop as a global art form has become a

touchstone for artists of the 21st century. As visual

artists trace its conceptual and social lineage

through tribute, they engage the idea that the art

historical canon, previously homogenous, white,

and stable, is uid depending on your background

and preferences, questioning what is beautiful,

who is iconic, and whose histories are valued.

Who do you pay homage or respect to in

your life?

Front Image: “Wall Mural Tupac Shakur Live by the Gun” by Andre

Charles, New York, 1997. Photo by Al Pereira, Collection of the Smithso-

nian National Museum of African American History and Culture

© Al Pereira

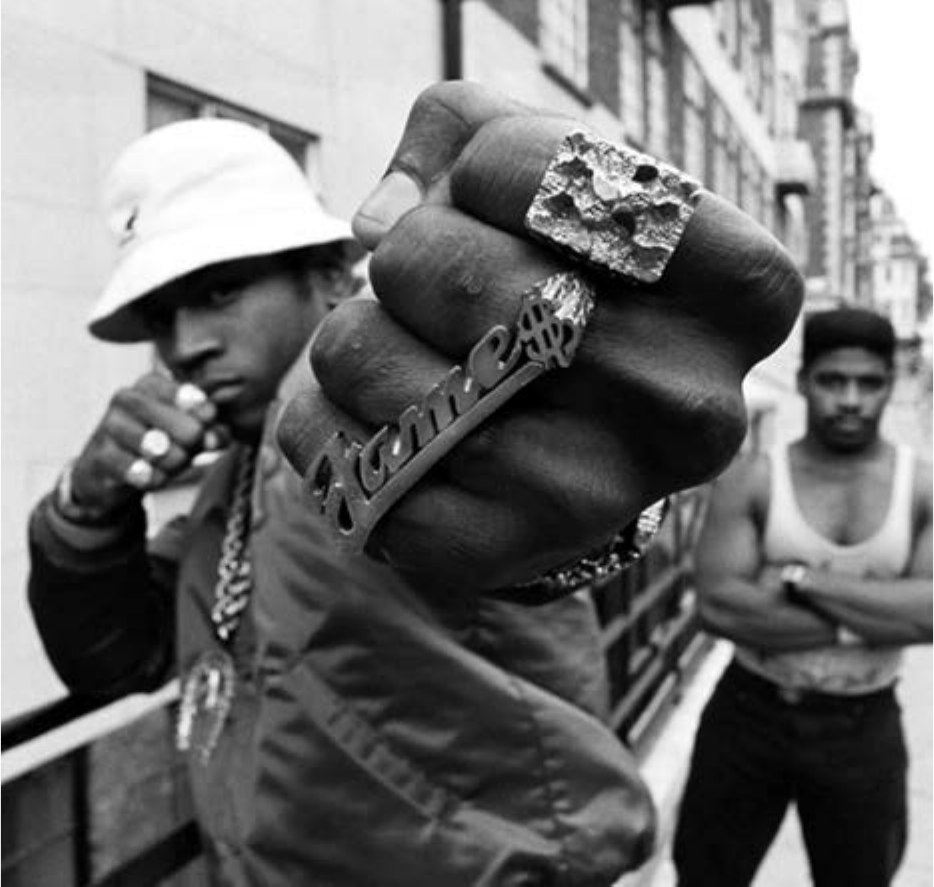

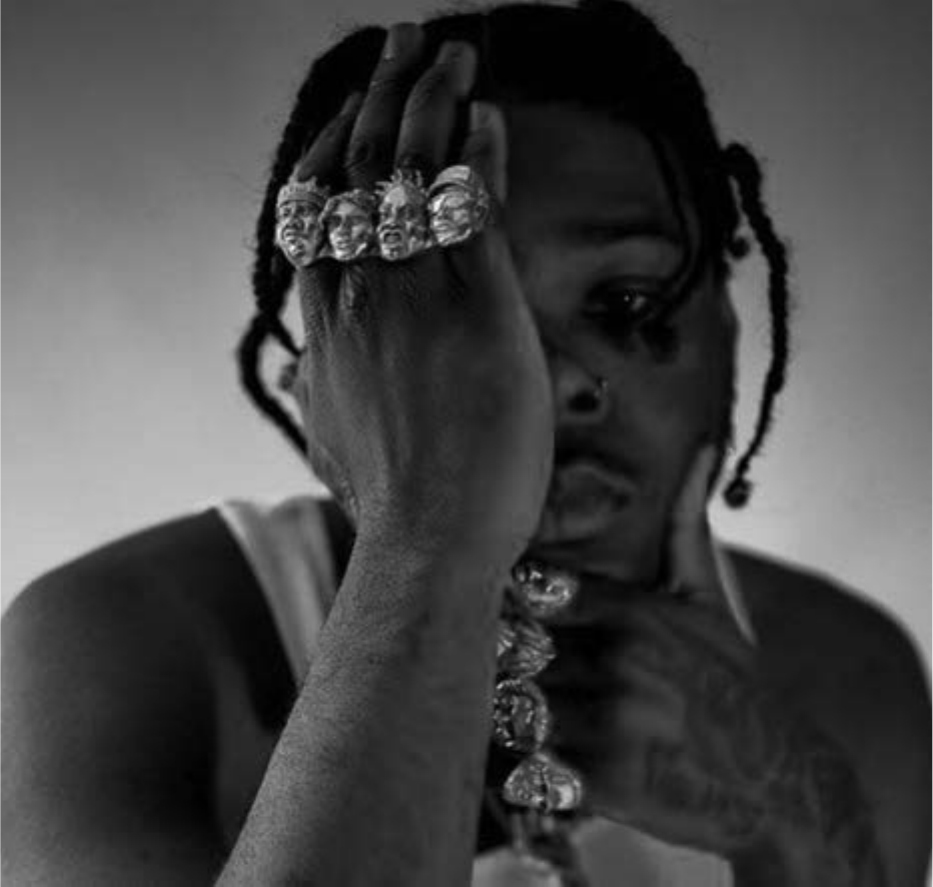

Reverse Image: “The Hip Hop Mount Rushmore”: Biggie, Tupac, Ol’ Dirty

Bastard, Eazy-E, Four Fingers of Def 4-nger ring by Johnny Nelson.

Photo by Danita Bethea on model Aurora Anthony, courtesy Johnny Nelson

Tribute Section Grafti

2024

The K & KONQR

Curated by DSGN CLLCTV, Cincinnati, Ohio

Jen Everett

(American, b. 1981, Detroit)

Unheard Sounds, Come Through:

Extended Mix

2022

wooden speakers, boom box, cassette tapes, vinyl

record sleeves, cassette player, vinyl photo sleeves,

and transistor radios

Courtesy of the artist

Cross Colours by Carl Jones and Thomas

“TJ” Walker

(American, b. 1953, Memphis;

b. 1960, Toomsuba, MS)

Color-Blocked Denim Ensemble with Hat

1990–1992

cotton, acrylic, and wool

Cross Colours Archive

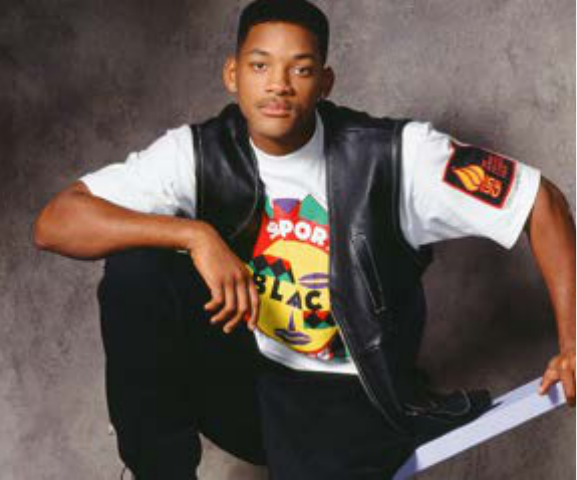

The boxy cut of the jacket and tapered pants of

this color-blocked denim ensemble is generous by

design. The stiff material affects how one moves,

stands, and walks—literally, the gure that one cuts.

Carl Jones and Thomas “TJ” Walker founded the

iconic streetwear brand Cross Colours in 1989 to

unify hip hop culture. After observing New York City

street style, the Los Angeles-based brand leaned

into the oversized look.

Cross Colours was among the rst streetwear

brands to understand their product as currency

and distributed it carefully, most notably to the

wardrobe department of the then-popular sitcom

The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air. The image of actor

Will Smith (b. 1968) wearing Cross Colours at the

height of his youthful charm circulated the style into

homes everywhere.

Will Smith in Cross Colours as the Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, 1994;

NBCU Photo Bank

Derrick Adams

(American, b. 1970, Baltimore)

Heir to the Throne

minted June 25, 2021

non-fungible token, HD

duration: 11 min., looped

Private Collection

Roberto Lugo

(American, b. 1981, Philadelphia)

Street Shrine 1:

A Notorious Story (Biggie)

2019

glazed ceramic

Collection of Peggy Scott and David Teplitzky

This artwork has been generously supported by

Dr. & Mrs. Robert H. Collins

Tschabalala Self

(American, b. 1990, New York City)

Setta’s Room 1996

2022

solvent transfer, paper, acrylic, thread, and collaged

painted canvas

Courtesy of the artist and Pilar Corrias, London

A young woman in a two-piece pink polka-dot outt

sits on the oor. She holds a landline phone in her

hand as her smiling gaze looks beyond the picture

frame. The artist, Tschabalala Self, based this work

on recollections of her sister Princetta, who self

acknowledges as an important early muse.

The pink walls and hardwood oor recall

Princetta’s teenage bedroom in the family’s

Harlem, New York, brownstone. A Lil’ Kim post-

er—a promotional image for her 1996 debut

album Hard Core—oats on a wall above the scene.

This poster was signicant to the artist, who

credits it as a formative touchstone for her interest

in how society situates the Black female body within

contemporary Black culture.

Shabez Jamal

(American, b. 1992, St. Louis)

Album Reconstruction No. 4

(After Kimberly)

Album Reconstruction No. 5 (After Inga)

Album Reconstruction No. 6

(After Katrina)

2022

mixed media (oak, acrylic sheets, Polaroid images,

chromogenic prints, and bronze photo corners)

Courtesy of the artist

Carrie Mae Weems

(American, b. 1953, Portland, OR)

Anointed

2017, printed 2023

archival pigment print

Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery

Mary J. Blige (b. 1971) receives a crown in this

red-tinged photograph, referencing the musician’s

nickname as the Queen of Hip Hop Soul. Carrie

Mae Weems honored the singer by placing her in

a lineage of other Black icons.

Commissioned for W Magazine’s 2017 art issue,

Weems’ regal portrayal stands at the intersection

of popular media, ne art, and music. According

to the artist, “I appropriated an image of Dinah

Washington, who was considered the queen of

blues, the queen of jazz. And of course, there’s

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s constant use of the crown

in relationship to jazz and music, and African

American cultural utterance.”

El Franco Lee II

(American, b. 1985, Houston)

DJ Screw in Heaven

2008

acrylic on canvas

Private Collection, Houston

Wearing a Fubu shirt and in the ow, DJ Screw

(1971–2000) presides over his turntables. Fans and

friends surround him in his home—an essential

part of the 1990s hip hop scene in Houston, Texas.

His hands appear to be in motion, scratching and

changing records. DJ Screw is a hip hop legend

who created the distorted “chopped and screwed”

sound; he would chop the lyrics, slow the tempo of

a song, and reduce the pitch. Additional lyrics, of-

ten freestyles by Houston-based rappers, were then

layered over his tracks.

DJ Screw tragically died of an overdose in 2000.

Houston-based artist El Franco Lee II drew on his

interest in comic books to create a detailed tribute

to the DJ in his element.

Alex de Mora

(British, b. 1982, Frimley, England)

West Coast Tattoos

2019, printed 2023

pigment-based inkjet print

Big Gee

2019, printed 2023

pigment-based inkjet print

East Coast Tattoos

2019, printed 2023

pigment-based inkjet print

All works courtesy of the artist and DMB

Two anking images depict a shirtless man with tat-

toos of notable American rappers. The left arm in-

cludes WestCoast stars Tupac Shakur (1971–1996),

Eazy-E (1964–1995), and Snoop Dogg (b. 1971),

while the right arm sports East Coast musicians The

Notorious B.I.G. (1972–1997), DMX (1970–2021),

and Nas (b. 1973). This tattooed tribute memorial-

izes their global inuence. The central photograph

features Mongolian hip hop celebrity Big Gee (b.

circa 1984) atop a camel in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia.

Hip hop reached Mongolia shortly after the fall of

communism in the mid-1990s, and Mongolian rap-

pers and fans were quick to emulate great hip hop

artists from the United States. In 2019, British pho-

tographer Alex de Mora traveled to Ulaanbaatar

to document the capital city’s prominent hip hop

scene and explore the specicities of its own hip

hop culture.

Maï Lucas

(French, b. 1968, Paris)

Sté Strausz

2002

archival pigment print

Oxmo Puccino

2000

archival pigment print

Both works courtesy of the artist

French hip hop luminary Sté Strausz (b. 1977)

confronts us with a bold and playful gaze. Oxmo

Puccino (b. 1974) poses deadpan against an urban

cityscape in a T-shirt that reads “Ghetto de France.”

Franco-Vietnamese artist Maï Lucas has been ob-

serving and photographing the hip hop and graf-

ti scene in Paris, France, and its suburbs since the

mid-1980s. As she says, it was a time when “no one

really thought that the culture was going to become

a major movement.”

Today, France is the world’s second-largest market

for hip hop, only behind the United States. Despite

being a global phenomenon, hip hop is constantly

adapting to express the specics of style anywhere

it ourishes.

Ernest Shaw Jr.

(American, b. 1969, Baltimore)

I Had A Dream I Could Buy My Way To

Heaven (Portrait of Ota Benga)

2022

pastel pencil, oil pastel, and grafti paint marker

on paper

Courtesy of the artist

Joyce J. Scott

(American, b. 1948, Baltimore)

Hip Hop Saints and Fallen Angels:

Da Brut

2014

monotype

Courtesy of Goya Contemporary Gallery, Baltimore

Fahamu Pecou

(American, b. 1975, New York City)

Real Negus Don’t Die: Thug

2013

graphite and acrylic on paper

Collection of Uri Vaknin and Tauq Adam

A gure looks down at the portrait of Tupac Shakur

(1971– 1996) on his T-shirt, paying homage to the

hip hop artist whose life and career were cut short.

This work is part of a series titled Real Negus

Don’t Die, in which Atlanta-based artist Fahamu

Pecou used the Rest in Peace T-shirt, a popular

mourning object in Black and Latinx working-class

communities, to center departed luminaries such

asShakur. Others include activist Fred Hampton

(1948–1969), record producer J Dilla (1974–2006),

and writer Lorraine Hansberry (1930–1965).

Wales Bonner

(British, b. 1990, London)

Adidas

(Herzogenaurach, Germany, est. 1949)

Lovers Tracktop

Fall/Winter 2020

recycled polyester, spandex,

acrylic, and wool

Wales Bonner Dub Tuxedo Trousers

Fall/Winter 2020

polyester and cotton

All works courtesy of Wales Bonner

adidas Originals by Pharrell Williams

(American, b. 1973, Virginia Beach, VA)

Track Jacket

2013

leather with zipper

Collection of Pharrell Williams

Daniel “Dapper Dan” Day for Gucci

(American, b. 1944, New York City)

Dapper Dan Tracksuit

2018

synthetic blend and wool

Barrett Barrera Projects

Baby Phat by Kimora Lee Simmons

(American, b. 1975, St. Louis)

Tracksuit

circa 2000

cotton, spandex, rhinestones, zipper

The Baltimore Museum of Art: Museum Purchase

NIA JUNE, Kirby Grifn,

and APoetNamedNate

(American, b. 1995, Baltimore; b. 1988,

Baltimore; b. 1994, Baltimore)

The Unveiling of God / a love letter

to my forefathers

2021

single-channel video (color, sound) duration:

20 minutes, 7 seconds, looped

Courtesy of the artists

In this short lm, Black men and boys swim, play,

embrace loved ones, and navigate various phys-

ical and emotional landscapes. The Unveiling of

God / a love letter to my forefathers is an operatic

visual poem that celebrates the Black men in the

artists’ lives.

Countering narrow and destructive ideas of mascu-

linity that are present—though not unchallenged—

in hip hop, NIA JUNE, Kirby Grifn, and APoetNam-

edNate created an arresting work that celebrates

male strength through tenderness.

As the artists note, “The Unveiling of God / a love

letter to my forefathers is a visual interpretation of

NIA JUNE’s imagination on the matter of her forefa-

thers and Black men prematurely removed from her

life. Through poetry, music, and moving portraits,

the lm asks its viewers: what could they have been,

unburdened by the gravity of an oppressive system

and known to the God in themselves?”

adidas Originals by Pharrell Williams

(American, b. 1973, Virginia Beach, VA)

Track Jacket

2013

leather with zipper

Collection of Pharrell Williams

Ascension

“Promise that you will sing about me/I said when

the lights shut off and it’s my turn,” Kendrick Lamar

gently asks in his 2012 song “Sing About Me, I’m

Dying of Thirst.” Death—or the specter of it—along

with notions of ascension and the afterlife freq-

uently appear in hip hop lyrics, from pouring one

out for a friend who has passed to the

precariousness of being Black in an urban

environment and never knowing which day is your

last to meditations on the kind of immortality

conferred by fame.

Inspired by themes of ascent in the culture, artists

create works that invite reection. Ordinary objects

transform into altars and monuments, and images

of Black bodies melt into heavenly clouds. Hip hop

is a cultural form artists use to process, grieve, and

remember those lost.

Pause and reect on the lives and experiences

amplied by the works on view.

Front Image: A man displays a T-shirt tribute to rapper Biggie Smalls,

a.k.a. The Notorious B.I.G., during the funeral procession route through

Brooklyn, March 18, 1997. Photo by Jon Levy/AFP via Getty Images

Reverse Image: YG with a picture Nipsey Hussle at a BLM protest in Los

Angeles, June 7, 2020. Photo by Tommy Oliver, Collection of the Smith-

sonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of

Tommy and Codie Oliver

Ascension Section Grafti

2024

FRANK & UFOREK

Curated by DSGN CLLCTV, Cincinnati, Ohio

Robert Hodge

(American, b. 1979, Houston)

Promise You Will Sing About Me

2019

mixed media collage constructed of canvas,

enamel, and acrylic paint, household items (shelves,

books, a vase, articial owers, a model ship,

a globe, fabric, reclaimed paper, newsprint, and

hemp thread)

Courtesy of the artist and David Shelton

Gallery, Houston

Devan Shimoyama

(American, b. 1989, Philadelphia)

Cloud Break

2022

Timberland boots, rhinestones, silk owers,

epoxy resin, and chain

Courtesy of the artist and Kavi Gupta Gallery

John Edmonds

(American, b. 1989, Washington, DC)

Ascent

2017

inkjet print on silk

Courtesy of the artist

This image of a gure seen from behind wearing

a white durag and fur coat is printed on a delicate

silk surface, which moves subtly with passing air cur-

rents. The ethereal work is part of John Edmonds’

DuRags series. The artist complicates dominant

views of Black masculinity by presenting sitters

adorned in durags in instances of vulnerability,

majesty, and delicacy.

Everything about Ascent is soft. The head and

shoulders of the individual seem to rise out of the

blurred coat, which suggests feathers or a cloud.

Here, the silky material of the durag transcends

its utilitarian function to become a headdress, a

helmet, a crown.

Damon Davis

(American, b. 1985, East St. Louis, IL)

Cracks XIX (EGO)

2022

concrete and homegrown crystals

Courtesy of the artist

The sharp edges of crystals shimmer and form a

protective layer over the concrete sculpture of

the artist’s face. A material that could be seen as

unremarkable as the sidewalk becomes precious

when covered with the icy ash of luxury. The

accumulation obscures the gure’s features and

references the desire to justify one’s worth for

social acceptance.

Born in East St. Louis, Illinois, Damon Davis has

characterized adornment as a form of ascension

or transcendence. “You come from poverty and

put things on to prove you are not poor.”

Texas Isaiah and Ms. Boogie

(American, Texas Isaiah and

Ms. Boogie, b. New York City)

Pelada: Chapter II

2021

pigment-based inkjet print

Courtesy of the artists

Texas Isaiah

(American, b. New York City)

Untitled

2023

mixed media

Courtesy of the artist

Ms. Boogie, an Afro-Latina transgender rapper,

proudly stands by an open gate in denim cut-offs

and a blue-and-purple top. Pelada means “naked”

or “peeled” in Spanish. The image bears witness

to Ms. Boogie during the conception of her debut

album, The Breakdown, which celebrates the trans-

formative and transcendent experience of the

evolution of her personhood.

In front of the image lies an altar with devotion-

al candles, photographs taken by the artist, his

baby pictures, pairs of Nikes, offerings for Balti-

more-based artists, a New York Yankees baseball

cap, and more. This altar is a small glimpse into the

practice that centers and grounds Texas Isaiah’s

life and career.

Both works explore how Isaiah has extended no-

tions of worship, prayer, remembrance, and the

importance of paying homage to the land and

fellow creatives.

Caution

The videos in this gallery contain sequences

of ashing lights and images. These occur for

several seconds within the rst minute and at

the 6- and 11-minute marks.

Kahlil Joseph

(American, b. 1981, Seattle)

m.A.A.d.

2014

two-channel video (color, sound) duration:

15 minutes, 26 seconds, looped

The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles,

Gift of the artist

m.A.A.d. is a lush, contemporary portrait of Comp-

ton, California. Located just outside Los Angeles,

the city is the hometown of Pulitzer-prize-winning

hip hop artist Kendrick Lamar (b. 1987). As the

camera glides through predominantly Black

neighborhoods, it pauses to capture everyday

moments—a car in motion, a marching band, a

barbershop—suffused with creativity, joy,

and sadness.

Set to songs from Lamar’s revered 2012 album

good kid, m.A.A.d narrates a young man’s redemp-

tion, the arrival of a new voice in emceeing, and

the rebirth of Los Angeles hip hop. Here, lmmak-

er Kahlil Joseph shifted attention from the album’s

main protagonist, allowing a range of characters

to paint a picture of daily life in Compton.

Pose

From the club to backyards and bedrooms, from

online to on the street and on stage, the works in

these galleries explore what someone’s gestures,

stance, and mode of presentation can communicate

to others. Here, artists explore and explode

stereotypes of gender and race, examine the line

between appreciation and appropriation, consider

the relationship between audience and performer,

and ask which bodies are deemed dangerous or

vulnerable and who decides.

For some, self-presentation is a means of survival;

for others, a way to claim space in a hostile world;

for still others, a tool in changing dominant

narratives about what the body can communicate.

As part of its total project of creating a new canon,

hip hop’s aesthetics of the body refuse to conform

to one standard and instead open up new ideas of

what the body can say.

How do you want to be seen?

Front Image: Salt-N-Pepa (left to right: Sandra “Pepa” Denton, Deirdre

“Spinderella” Roper, and Cheryl “Salt” James), New York, 1987.

Photo by Janette Beckman/Getty Images

Reverse Image: David Banner and Ludacris at “Diamond in the Back” vid-

eo shoot, Atlanta, 2004. Photo by Julia Beverly, Collection of the Smithso-

nian National Museum of African American History and Culture

© Julia Beverly/Ozone Magazine

Pose Section Grafti

2024

2KEWL & AKTOE (Front Grafti)

WHEN in tribute to the artist RAPES

(Reverse Grafti)

Curated by DSGN CLLCTV, Cincinnati, Ohio

Devin Allen

(American, b. 1988, Baltimore)

You Can’t Raid the Sun

2020

pigment-based inkjet print

Courtesy of the artist

Composed like a class picture yet exuberant as a

snapshot of friends, this portrait by Devin Allen

documents hip hop artists and activists from Bal-

timore. The image references Gordon Parks’ 1998

iconic photograph, A Great Day in Hip Hop, which

was an homage to the historic 1958 photograph, A

Great Day in Harlem, by Art Kane.

Nina Chanel Abney

(American, b. 1982, Harvey, IL)

Untitled

2022

collage on panel

Courtesy of the artist and Pace Prints

Amidst a cacophony of images and symbols, includ-

ing cars, a yacht, palm trees, and dollar signs, nude

women dance around a central male gure with a

single tear. The artist, Nina Chanel Abney, based

this collage on the work she created as cover art for

rapper Meek Mill’s (b. 1987) 2021 album Expensive

Pain. When the image appeared on buses and bill-

boards, it sparked a public debate: Does Abney’s

exaggerated abstraction of Black feminine sexuality

celebrate or critique the sexist stereotypes found in

many hip hop videos and lyrics?

Various Artists

Compilation of 16 CDs

1987–2022

Vinyl records from the collection of 70,000 records

of “DJ Fly Guy” Flynn

Before music streaming services dominated the

market, vinyl records, cassette tapes, and CD cov-

ers offered artists a way to communicate their vision

to their audiences before they heard a single note.

The crates of classic soul, funk, and R&B albums

that DJs sampled from provide the beginnings of a

hip hop aesthetic, and key samples from them form

the backbone of hip hop’s musical canon, from The

Isley Brothers’ Greatest Hits (sampled by Lil Wayne,

Salt-N-Pepa, and NWA) to Babe Ruth’s First Base

(sampled by Afrika Bambaataa, Doug E. Fresh, and

Cypress Hill).

As you encounter this snapshot of hip hop visu-

al representation, beginning with classic albums

used for iconic samples and ranging from the 1970s

through the present, consider what aspects of

self-presentation change and which remain consis-

tent over time.

Top row, left to right:

The Isley Brothers, Isleys’ Greatest Hits, 1973

Babe Ruth, First Base, 1972

Miquel Brown, Symphony of Love, 1978

James Brown, Revolution of the Mind:

Live at the Apollo, Volume III, 1971

Middle row, left to right:

J.J. Fad, Supersonic, 1988

Eric B. & Rakim, Paid in Full, 1987

Queen Latifah, Nature of a Sista’, 1991

Big Pun, Capital Punishment, 1998

Foxy Brown, Il Na Na, 1996

DMX, Flesh of My Flesh, Blood of My Blood, 1998

Missy Elliot, Supa Dupa Fly, 1997

Fugees, The Score, 1990

Bottom row, left to right:

Nelly, Country,Grammar, 2000

Nicki Minaj, Pink Friday, 2010

Lil Nas X, MONTERO, 2021

Megan Thee Stallion, Traumazine, 2022

Bad Bunny, YHLQMDLG, 2020

Miss Kam, Tew Be Continued, 2022

Lil Wayne, Tha Carter II, 2005

Rico Nasty, Nasty, 2018

Amani Lewis

(American, b. 1994, Baltimore)

Swamp Boy

2019

acrylic, oil pastel, glitter, embroidery, and

screen print

on canvas

Courtesy of the artist

As cameras ash and phone screens glow, West

Baltimore rapper Butch Dawson (b. 1993) grasps

a microphone during a concert for his 2018 EP

Swamp Boy. The audience crowds close to Dawson,

suggesting an intimate location. Over the last two

decades, Baltimore has been a hotbed for under-

ground music and art, with venues like the Copy-

Cat, Floristree, Bellfoundry, Annex, the Paradox,

and the Crown creating safe spaces for entertainers

and partygoers.

Amani Lewis built this collage from digitally edited

images and blurred and manipulated photographs

that were then screen printed onto canvas and n-

ished with painted details. The live performance

photography that is the source material for this

work gives the collage its sense of immediacy, as

though we too, are at the club.

Monica Ikegwu

(American, b. 1998, Baltimore)

Open/Closed

2021

oil on canvas

Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Myrtis

This artwork has been generously supported by

Erica Spitzig and Brent Patterson.

All Things Hip Hop,

A Scribble Jam Short

2024

Please enjoy this short video, a prelude to Scribble

Jam: A Documentary. The upcoming lm explores

the history of Cincinnati’s legendary hip hop festi-

val, Scribble Jam (1996–2009). Currently a

work in progress, the lm’s creators, listed below,

say this about their work:

“Our goal with this documentary is to tell the story

of Scribble Jam through the eyes of the people who

were most involved with its history. This includes

the lives and friendships of Scribble Jam’s founders,

its relationship with the city of Cincinnati, and its

monumental impact on hip hop history.”

To contribute to the completion of this video,

please visit: bit.ly/4aO8JN7 or scan the

video’s QR code.

Director

Tyler Brune

Producer

Jacob Lightner

Assistant Producer

Emma Tallent

Director of Photography

Zachary Schutte

Assistant Director/Production Assistant

Zoey Desmond

Sound Mixer/Audio Engineer

Abigail Spears

Story Editor/Production Assistant

William Iles

Social Media/BTS Photography

Abby Murphy

Production Assistant

Cameron Hollstegge

Assistant Audio Engineer

John Hensey

Production Assistant

Max Walsh

Gallery 104

Caution: The video in this gallery includes

references to violence, profanity, racial

stereotypes, and sexuality.

TNEG

4:44

2017

video (color, sound)

duration: 8 min., 30 sec.

Courtesy of Arthur Jafa and Gladstone Gallery

Telfar by Telfar Clemens

and Babak Radboy

(American, b. 1985, New York City;

Iranian, b. 1983, Tehran)

Azalea Tracksuit

2022

polyester jersey knit and rib knit collar

and cuffs with mesh lining

Medium Azalea Shopping Bag

2022

faux leather and twill

TELFAR, New York

Willy Chavarria

(American, b. 1976, Fresno, CA)

Buffalo Track Jacket and Kickback Pant

Spring/Summer 2022

nylon satin

Courtesy of the artist

Gallery 150

Aaron Fowler

(American, b. 1988, St. Louis)

Live Culture Force 1’s

2022

car parts and mixed media

Courtesy of the artist

Using recycled car parts and other media, Aaron

Fowler created a pair of oversized Nike Air Force

1 basketball shoes. The monumental scale empha-

sizes the resounding power of these sneakers as

a cultural icon exalted by hip hop performers.

In s2002 St. Louis hip hop artist Nelly (b. 1974),

featuring the St. Lunatics (est. 1993), released

the single “Air Force Ones,” making the shoe

a national fashion trend.

Fowler’s sculpture laces together this exhibition’s

co-organizing institutions, the Saint Louis Art Mu-

seum and the Baltimore Museum of Art. The Mis-

souri license plates reference the artist’s hometown

of St. Louis and the shoe’s signicance to the city.

Baltimore-area sneaker retailers, such as Downtown

Locker Room, successfully convinced Nike to resur-

rect the shoe in the late 1980s after the company’s

initial decision to discontinue production in 1984.

Gallery 212

William Cordova

(Peruvian, b. 1969, Lima, Peru)

Moby Dick (for Oscar Wilde,

Óscar Romero y Oscar Grant)

2003/2008/2022

mixed media on reclaimed police car

Courtesy of the artist and Sikkema Jenkins

& Co., New York

Artist William Cordova sawed a reclaimed police

cruiser in half, removed the wheels, and placed it

atop cinder blocks. The installation interweaves

various languages of urban life, crime-ghting,

social justice, and inspiration.

Cordova’s title refers to the stories of three

Oscars: author Oscar Wilde (1854–1900); activist

priest Óscar Romero (1917–1980); and father,

aspiring barber, and victim of police violence,

Oscar Grant (1986–2009). The bubble-style grafti

emblazons the names of such philosophers

and leaders as Frantz Fanon (1925–1961) and

Toussaint L’Ouverture (1743–1803).

Peek inside the windows for a curated selection of

books about racial equality and feel the vibrations

of the subwoofers and music, “Bass In Yo Face”

by André Leon Gray. Cordova wanted to create

a sanctuary and place of refuge for those in

vulnerable and underserved communities.

Gallery 214

Lauren Halsey

(American, b. 1987, Los Angeles)

Prototype Column For Tha Shaw (RIP

The Honorable Ermias Nipsey Hussle

Asghedom) I

2019

Prototype Column For Tha Shaw (RIP

The Honorable Ermias Nipsey Hussle

Asghedom) II

2019

hand-carved glass ber-reinforced gypsum

Rennie Collection, Vancouver

Cool white gypsum columns rise to the ceiling from

square bases, recalling the architecture of ancient

Egypt, Greece, or Rome. On their surfaces, Lauren

Halsey interspersed

contemporary gures and imagery among tradition-

al Egyptian motifs. Winged gures share space with

Los Angeles street scenes, grafti, lowriders, and a

prole of the city’s skyline.

Prototype Columns For Tha Shaw (RIP The Honor-

able Ermias Nipsey Hussle Asghedom) I and II

are a memorial and monument to the late rapper

Nipsey Hussle (1985–2019). Evoking both the

hieroglyphs and monumental tombs used by the

ancient Egyptians to commemorate the life and

death of their rulers, Halsey’s columns function

to honor the legacy of those lost too soon.

Please do not touch.