Luca Castellazzi

Paolo

Bertoldi

Marina Economidou

Unlocking the energy

efficiency potential in the

rental & multifamily sectors

Overcoming the split incentive

barrier in the building sector

2017

EUR 28058 EN

This publication is a Technical report by the Joint Research Centre (JRC), the European Commission’s science

and knowledge service. It aims to provide evidence-based scientific support to the European policymaking

process. The scientific output expressed does not imply a policy position of the European Commission. Neither

the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the use that

might be made of this publication.

Contact information

Name: Luca Castellazzi

Address: European Commission, Joint Research Centre, Via E. Fermi 2749, 21027 Ispra, Italy

Email: luca.castellazzi@ec.europa.eu

Tel.: +39 0332 78 9977

JRC Science Hub

https://ec.europa.eu/jrc

JRC101251

EUR 28058 EN

PDF ISBN 978-92-79-58837-2 ISSN 1831-9424 doi:10.2790/912494

Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2017

© European Union, 2017

Reuse is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. The reuse policy of European Commission documents

is regulated by Decision 2011/833/EU (OJ L 330, 14.12.2011, p. 39).

For any use or reproduction of photos or other material that is not under the EU copyright, permission must be

sought directly from the copyright holders.

How to cite this report: Castellazzi, L., Bertoldi, P., Economidou, M. Overcoming the split incentive barrier in

the building sectors: unlocking the energy efficiency potential in the rental & multifamily sectors, EUR 28058

EN, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2017, ISBN 978-92-79-58837-2,

doi:10.2790/912494, JRC101251

All images © European Union 2017, except in the front page, originating from:

http://maxpixel.freegreatpicture.com/Apartment-For-Sale-Condominium-Home-Condo-Modern-1689853

(distributed with a Creative Commons Zero - CC0).

Contents

Abstract ............................................................................................................... 1

1. Introduction ...................................................................................................... 2

2. Problem definition ............................................................................................. 3

3. Possible solutions to overcome incentive misalignments ......................................... 5

3.1 Regulatory solutions......................................................................................... 5

3.2 Information tools ............................................................................................. 5

3.3 Financial incentives & models ............................................................................ 7

3.4 Voluntary approaches ....................................................................................... 8

4. Workshop presentation summaries ...................................................................... 9

4.1 Session 1: The role of rent structures in scaling-up energy renovations .................. 9

4.2 Session 2: Engaging commercial tenants in energy efficiency .............................. 12

4.3 Session 3: Legislations as an energy efficiency driver ......................................... 18

4.4 Session 4: Aligning multi-actor incentives through innovative financial instruments 26

5. Conclusions .................................................................................................... 31

References ......................................................................................................... 33

List of abbreviations and definitions ....................................................................... 34

List of figures ...................................................................................................... 35

List of tables ....................................................................................................... 36

i

Abstract

While the rental and multifamily sectors are associated with a significant energy

efficiency potential, it is widely recognised that these are difficult sectors to tap into.

Asymmetric information and split incentives are typically regarded as major barriers to

fostering energy efficiency upgrades in rented and multi-unit properties both in the

private and public as well as residential and commercial sectors. As Article 19 of the

Directive 2012/27/EU on energy efficiency calls for Member States to take appropriate

measures addressing this barrier, increased interest is drawn on how to design policies

and measures that unlock the energy efficiency potential in these difficult-to-access

sectors. Current solutions vary in nature, ranging from revised rent acts, green leases,

on-bill finance mechanisms, minimum energy performance standards, use of inclusive

rents and others.

In this context, the European Commission's Joint Research Centre, on behalf of DG

Energy, organised a workshop in Brussels on 20/1/2016 on unlocking the energy

efficiency potential in the rental & multifamily sectors with the aim to exchange

information about the extent at which split incentives act as a barrier to energy

efficiency investments in the building sector as well as investigate current solutions, their

effectiveness and ways forward. This report provides an overview of the split incentive

issue with some recommendation on how to address it and the workshop presentation

summaries.

1

1. Introduction

Improving energy efficiency is often seen as the most cost-effective means of achieving

the EU greenhouse gas emission targets. In particular, the energy efficiency potential of

the building sector has enjoyed increasing attention in recent years. Modernising the

building sector, however, is associated with a number of barriers. Split incentives are

common barriers between building owners and tenants that, in practice, hinder the

uptake of energy efficiency investments.

The presence of split incentives, in particular, inhibits the deployment of energy

efficiency upgrades in various segments in the building sector such as privately rented

homes, multi-apartment buildings, social housing units and leased commercial or public

premises. It stems from the misplacement of incentives between different actors (e.g.

landlords and tenants), which discourage energy efficiency improvements to come into

effect in reality. Despite this long-lasting barrier, little attention has been drawn on how

to resolve it and current public policy interventions have made relatively little progress

towards providing effective solutions that align incentives between concerned actors.

In order to help overcome this issue, the Energy Efficiency Directive (Directive

2012/27/EU) includes a provision in its Article 19(1)(a), of the Energy Efficiency

Directive (Directive 2012/27/EU), that recognises the importance of addressing the

barrier of split incentives in the building sector. It states:

Member States shall evaluate and if necessary take appropriate measures to

remove regulatory and non-regulatory barriers to energy efficiency, without

prejudice to the basic principles of the property and tenancy law of the

Member States, in particular as regards:

(a) the split of incentives between the owner and the tenant of a building or

among owners, with a view to ensuring that these parties are not deterred

from making efficiency- improving investments that they would otherwise

have made by the fact that they will not individually obtain the full benefits or

by the absence of rules for dividing the costs and benefits between them,

including national rules and measures regulating decision- making processes

in multi- owner properties

In this context, the European Commission's Joint Research Centre, on behalf of DG

Energy, organised a workshop on unlocking the energy efficiency potential in the rental

& multifamily sectors with the aim to exchange information about the extent at which

split incentives act as a barrier to energy efficiency investments in the building sector as

well as investigate current solutions, their effectiveness and ways forward. This report

provides an overview of the split incentive issue with some recommendation on how to

address it and the workshop presentation summaries.

The workshop agenda and all presentation material can be downloaded here

1

.

1

https://e3p.jrc.ec.europa.eu/events/unlocking-energy-efficiency-potential-rental-multifamily-sectors

2

2. Problem definition

Split incentives refer to any situation where the benefits of a transaction do not accrue

to the actor who pays for the transaction. In the context of energy efficiency in

buildings, split incentives are linked with cost recovery issues related to energy efficiency

upgrade investments due to the failure of distributing effectively financial obligations and

rewards of these investments between concerned actors. This can ultimately result in

inaction from either actor’s side, despite the fact that many of these upgrades are of

positive net present values. Investment costs of energy efficiency upgrades are part of

the capital expenses, while its financial benefits, in the simplest form, are seen as

reduced energy bills in the operational expenses side. If the actor who invests in energy

efficiency measures (i.e. actor in charge of capital expenses) is not the same as the

actor who reaps the subsequent financial benefits (i.e. actor in charge of operational

expenses), split incentives can arise. They simply refer to the misplacement of incentives

between the actor selecting the equipment or technologies of the upgrade and the actor

who pays the energy costs.

There are several types of split incentives that affect the building sector. These, together

with examples, are discussed hereunder.

Efficiency-related split incentives (ESI): These refer to situations where the end user is

in charge of the energy bills but cannot choose the technology needed to improve the

energy efficiency of their property and thereby has limited power in reducing their

energy bills or negotiating an energy efficiency upgrade. The landlord-tenant dilemma in

rental housing and commercial leasing cases based on ‘net’ or ‘cold’ type of lease is the

most typical example. In these cases, the landlords lack incentives for investing in

energy efficiency upgrades as they do not directly reap the benefit and often cannot

capitalise these upgrades into higher rents due to the uncertainty over the impact of the

upgrade on the property value and lack of experience on rent premiums. Efficiency-

related split incentives are also a concern in new properties, often sold to new owners

after the design and construction has been completed. In this case, the new owner is not

involved in the decision making process and the selection of energy-related features,

while the property developer’s main concern is to reduce the construction costs. The

issue of asymmetric information and premium charges exacerbates the problem.

Usage-related split incentives (USI): These have also been referred to as the “reverse”

split incentives in the literature (Bird & Hernandez, 2012). They occur when occupants

are not responsible for paying their utility bills and thereby have little or no interest to

conserve energy. In other words, the occupants do not face the marginal cost of their

own energy use and are not given any incentives in using energy efficiently. They occur

under “warm rent”

2

and gross rent structures where utility costs for heating, other

operating and capital expenses are all borne by the landlord. Evidence exist that

tenants,

under such rent structures, tend to consume more energy, e.g. several studies have

provided empirical evidence showing higher indoor temperatures during winter periods in

the case of heat inclusion in the rent (e.g. Levinson & Niemann, 2004). This type of

incentives is also present in the hotel industry.

Multi-tenant, multi-owner split incentives (MSI): Multi-tenant and multi-owner buildings

face an additional challenge associated with collective decision making between various

actors. Energy efficiency projects in these buildings can only be realised if consensus is

reached by all decision-making parties. Current decision structures act as a barrier in

collective agreements between owner-occupants of many existing buildings such as

condominiums (Matschoss, et al., 2013). In both multi-tenant and multi-owner buildings,

2

The term “warm rent” is a term typically used in some Western or Northern European countries

(e.g. Germany and Sweden) to refer to rent structures which include heating costs. .Cold rent, on

the contrary, refers to rent structures which do not include heating costs (Bullier & Milin, 2013

Blom & Sandquist, 2014).

3

the benefits and costs of an energy efficiency upgrade may vary from apartment to

apartment, which further complicates the situation.

Temporal split incentives (TSI): This refers to situations where the energy efficiency

investment does not pay off before the property gets transferred to its next

occupant/owner. In this situation, the occupant (tenant or owner-occupier) does not

have a clear idea of how long they will live in their property or simply plan to move

relatively soon. An energy efficiency upgrade attached to a high upfront capital cost will

not be an appealing investment in this situation and may be perceived as risky (Bird &

Hernandez, 2012).

4

3. Possible solutions to overcome incentive misalignments

In this section current solutions to split incentives practiced in the EU and beyond are

presented. A discussion of each solution together with a description of their applicability

for each segment of the building sector is presented below.

3.1 Regulatory solutions

Minimum performance levels in rented units

Mandating minimum standards for rented properties is a powerful measure which can

ensure that very inefficient buildings undergo energy efficiency upgrades or are simply

removed from the rental market. This can primarily protect social tenants or tenants

facing efficiency-related split incentives, who would otherwise have no power to

negotiate an energy efficiency upgrade in their rented properties. Under such regulation,

the responsibility rests with the owners, who are called to ensure a reasonable level of

energy efficiency in rental units, thereby sending a clear signal to the market. Based on

the same motivation behind minimum standards for equipment set by the Eco-design

directive (Directive 2009/125/EC), this can apply to both residential and commercial

properties, and can target both private and social landlords. The measure can

complement existing requirements set in the building codes for minimum energy

performance levels which currently apply only for new and major renovated buildings

3

.

To ease the burden of compliance by landlords, the availability of financial incentives or

the use of models that overcome the barrier of the upfront costs can be considered

alongside this regulation (see the following section on Financial incentives & models).

Revisions in rent acts and condominium acts

Improving the rent and condominium acts is essential for encouraging investments in

energy efficiency in rented properties or multi-unit buildings. Revisions to lift barriers in

regulations that inhibit the adoption of energy efficiency in these segments of the

building sector need to be considered in order to support the dialogue between involved

parties and introduce flexibility that would facilitate voluntary agreements between the

tenant and landlord (e.g. green leases). These should lay out legal framework and

specific conditions for the redistribution of investment cost and energy cost savings of an

energy efficiency upgrade between the landlord and the tenant or between multiple

owners. This should be accompanied with guidelines on cost- and benefit-sharing

practices. For example, when an energy efficiency upgrade is undertaken by a landlord,

a contribution from the saved energy costs can be asked from the tenant, provided that

both the landlord and tenant directly benefit from the undertaken work. Additional issues

that need to be addressed include extent to which the rent can be increased and

conditions under which the tenants can reject rent rises. Condominium laws should also

better define the democratic rules with respect to changes and maintenance work

undertaken in the building and the roles of all actors involved including the owners. A

single owner should not be allowed to stand in the way of the improvements, and

majority-based rules should be adopted.

3.2 Information tools

Energy labelling

Building energy labelling is a powerful disclosure tool which provides potential buyers,

tenants, financiers and other real estate actors with information on a property’s energy

performance. It offers the possibility to make more informed decisions during sale and

lease transactions and overcome, to a certain extent, information asymmetry issues,

which typically exacerbate the split incentive barrier. Through this information, the actor

3

As required by Directives 2002/31/EC and 2010/91/EU on the energy performance of buildings.

5

can make comparisons with other similar properties of interest, gain a better

understanding of the holistic costs associated with a property, and identify where and

how to invest in energy efficiency upgrades.

In the EU, the main policy framework through which this information tool has been

introduced is the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD, Directive

2002/31/EC). Under this Directive, all Member States were required to set up the

mechanisms and establish systems of certification of the energy performance of

buildings which make it possible for owners and tenants to identify the energy class of

their building together with recommended improvement measures on how to further

increase its energy performance. These mandatory Energy Performance Certificate

(EPCs) schemes set up by the Member States were further strengthened with additional

requirements, introduced with the recast of the EPBD (Directive 2010/91/EU). EPCs are

currently among the most important sources of information on the energy performance

of buildings, which, historically, has been very hard to obtain

4

. Available at the point of

lease or purchase, they can guide a potential owner or tenant during their decision

making process, can be used as a tool for calculating the pre and post-performance of a

renovated building and predict energy cost savings as a result of an energy efficiency

upgrade.

Individual metering, sub-metering and direct feedback

Individual metering is a prerequisite for the development of innovative rental structures

which can encourage energy efficiency upgrades in rented properties. Measurement of

individual energy consumption provides consumption feedback and increases awareness

on the usage patterns, which can ultimately change the behaviour of the tenant. It also

allows for detailed monitoring of energy efficiency upgrades based on actual, rather

predicted energy savings. The measured energy consumption can be a more useful

indicator when the redistribution calculation of costs and benefits are made. They are

particularly important for overcoming the usage-related split incentives. For example, a

gross warm rent model with direct feedback can allow landlord and tenant to agree on a

set of comfort conditions (e.g. indoor temperature during winter time). All costs

including heating are covered in the rent but direct feedback means that tenants can get

compensation if they consume less. Individual metering therefore encourages tenants to

adopt a more energy efficiency behaviour. Conversely, if tenants exceed the pre-set

consumption levels, the additional energy costs are borne by the tenants. The

functionality of real-time information on consumption for the users offered by smart

meters can further strengthen this feature and indeed align incentives between landlords

and tenants. Sub-metering can ensure detailed energy monitoring of apartments in

multi-family buildings and allow apartment tenants and owners to become more aware

of the monetary implications of energy consumption and savings.

The Energy Efficiency Directive includes a set of articles (namely Articles 9, 10 and 11)

on metering and billing which intend to have a profound impact in cases where individual

and sub- metering is not available. In particular, Articles 9 (1) & (3) of the Directive

impose metering requirements on district heating, district cooling and communal

heating/hot water systems. Article 9 (2) sets requirements for the roll-out of smart

meters. Article 9 (3) calls for individual metering in multi-unit buildings and also states

that Member States may consider the introduction of transparent rules on the allocation

of the costs of heat consumption in multi-apartment buildings. The impact of these

articles on metering practices, together how they can assist in energy efficiency

investments should be further examined.

4

A small number of countries (Netherlands, Denmark and some regions of Austria) had an energy

rating system before the adoption of EPBD in 2002 (Arcipowska, et al., 2014).

6

3.3 Financial incentives & models

Financial and fiscal incentives

Energy-efficiency incentives from governments, energy suppliers and other sources are

intended to overcome upfront costs barriers. They are however not designed to meet the

unique challenges faced by multi-unit buildings or rented properties. A survey carried

out by the JRC in 2013 showed that a large share of financial instruments targeted

homeowners, while many schemes whose eligible recipient list included multi-apartment

or rented units, did not use financing options that were carefully designed to meet the

specific needs of these segments of the building sector (Economidou & Bertoldi, 2014).

Various financial and fiscal incentive schemes can be designed to support specific

segments of the building sector in which involved parties would refrain from improving

the energy efficiency of the building under normal circumstances. In the UK, a tax break

scheme (with a dedicated budget of £35 million) has been designed to support

residential landlords in the period 2014 to March 2017. In the Netherlands, the state

plans to make available a €400 million subsidy for landlords in the rental social housing

sector for investments in energy efficiency for the period 2014–2017 with the aim of

contributing to the objectives of the Energy Saving Agreement for the Rental Sector.

Financial incentive programmes specifically designed to provide grants to multi-

apartment buildings include the National Renovation Programme for Residential Buildings

in Bulgaria and Latvian Improvement of Heat Insulation Programme. In the Flanders

region of Belgium, the procedures for energy grants were reformed in 2011 to simplify

applications from multi-owner apartments.

On-bill finance

On-bill financing is a mechanism of obtaining access to capital to fund building energy

efficiency upgrades, where repayments are made through the energy bill. On-bill

financing allocates the financing responsibility to the utility and maintains the loan

attached to the property, thereby offering an appropriate solution to overcome temporal

split incentives. It can also avoid the need to obtain upfront capital to cover the cost of

buying energy efficient equipment, which can be beneficial to the landlord. The energy

utility will typically aim to make the monthly payments equal to or less than the energy

savings achieved through the upgrade, which means that the tenant will be no worse off

financially.

While an on-bill finance scheme can address both owner-occupied and rented properties,

Bird & Hernandez (2012) stressed the need for a careful design of such schemes specifi-

cally targeting rented properties. A successful on-bill finance programme should create

incentives for all stakeholders: tenants (savings), landlords (savings/investment),

utilities (protection/decoupling) and by extension, banks. As high transaction costs

linked to the realisation of investments deter landlords from upgrading their rented

property, the authors proposed a small incentive to be considered for landlords of rented

properties in the private and/or social housing sectors. If landlords are allowed to get an

incentive in the form of a small share of savings, covering the transaction costs attached

to the upgrade, this could trigger participation in on-bill programmes on behalf of

landlords.

Property Assessment Clean Energy (PACE)

Property Assessed Clean Energy (PACE) is a means of financing energy efficiency

upgrade through the use of specific bonds offered by municipal governments to

investors. As in the case of on-bill finance, they can provide a solution to the temporal

split incentive problem. With PACE, the difference is that governments use the funds

raised by these bonds to loan money towards energy efficiency upgrades in residential

and commercial buildings. The loans are repaid over the assigned term – typically 15 or

20 years – via an annual assessment on their property tax bill. The long repayment term

attached to PACE programmes allows for investments with long payback times to be

7

considered in the upgrade. This additional tax assessment is placed on the property

rather than the property owner, which means that PACE assessments are also

transferable and can help overcome the split incentives between tenants and owners in

commercial and multi-tenant residential buildings. PACE programmes are secured by a

senior lien on the owner’s property, which avoids repayment security to be attached to

the borrower’s creditworthiness and is therefore more attractive to financiers and

borrowers alike.

3.4 Voluntary approaches

Green leases

As discussed previously, traditional forms of lease create asymmetries in the relationship

between landlords and tenants and therefore do not set the ground for energy efficiency

investments. Green leases can bridge these differences by splitting costs and benefits

between the parties in such a way that both parties can benefit from an energy

efficiency upgrade. Given that the necessary legislative foundations exist (see section on

rent and condominium acts), they can bridge the differences between landlords and

tenants in a way that both parties can gain from an energy efficiency upgrade.

Through a green lease, a clause or separate agreement is made between the concerned

actors that allows a property owner to raise the rent to finance energy efficiency

improvements to a property. As in the case of on-bill financing model, green leases

assume that energy cost savings should exceed finance charges, and should be set at a

percentage of monthly energy cost savings to the tenant. The cost recovery, typically

done by amortisation, can be based on the actual or predicted energy savings. In New

York City, recovering the cost based on predicted energy savings is considered risky by

tenants in case energy upgrades underperform. For this reason, the owners’ capital

expense that can pass through can be up to 80% of predicted savings in a given year.

This is based on industry’s experience which showed that actual savings are generally

within ±20 % of predicted savings. Tenants are therefore protected from

underperformance by a 20 % “performance buffer” (performance corrector factor).

This type of leases has gained increasing popularity in the past few years in the U.S. and

Australia. They are appropriate for large, commercial buildings rather than small units

such as houses. Despite their potential, green leases are not currently widely used in

Europe. A survey carried out by European Property Federation highlighted that there are

still various regulatory and non-regulatory hurdles that inhibit a wider use of green

leases in Europe. Sharing standard green lease guidelines can increase awareness

among key interest groups. The public rental sector can also lead by example by

adopting green leases for their rented premises.

8

4. Workshop presentation summaries

In this section the summaries of the presentations of the workshop on “Unlocking the

energy efficiency potential in the rental & multifamily sectors Workshop taken place in

Brussels on 20 January 2016, are presented.

4.1 Session 1: The role of rent structures in scaling-up energy

renovations

The economics of capitalising efficiency investments

Erdal Aydin, Maastricht University, Netherlands

According to EUROSTAT, in 2010, the residential sector accounted for nearly 27% of the

total energy consumption in the EU-27 countries. In order to achieve the 2020 energy

and climate targets, EU member states have been introducing a variety of policy

measures that aim to promote energy efficiency within the residential sector, considering

its high potential for energy conservation. As one of these policy measures, member

states were required to implement energy performance certification (EPC) schemes for

residential properties by 2009. By providing information to market participants about

buildings’ energy performance, policy makers expect an increase in the demand for

energy-efficient buildings, which in return, will lead to higher investment in energy

efficiency. However, the effectiveness of this policy depends on how much buyers are

willing to pay for increased EE. Furthermore, as upgrading a dwelling to improve its

energy efficiency could involve a significant financial investment, the uncertainty

regarding its financial return may be a reason for households not to undertake profitable

investments in energy efficiency. These market failures could cause what is termed as

“Energy Efficiency Gap”– the difference between the optimal level of energy efficiency

and the level actually realized. Therefore, from both the policy maker’s and investor’s

perspective, it is important to identify the market value of energy efficiency in the

housing sector.

In the presented study, using a large representative dataset from the Netherlands, it is

proposed an instrumental variable approach in order to correctly identify the

capitalization of energy efficiency in the housing market. The authors benefit from a

continuous energy efficiency measure provided by EPCs, which enabled them to estimate

the elasticity of house price with respect to its energy efficiency. As well as including

detailed dwelling characteristics in the hedonic model, an instrumental variable approach

was used to deal with the potential omitted variable bias. The 1973-74 oil crisis, which

created an exogenous discontinuity in the energy efficiency levels of the dwellings

constructed before and after this date, and the evolution of building codes are used as

instruments for energy efficiency. The results indicate as the energy efficiency level

increases by 50% for an average dwelling, the value of the dwelling increases by around

10%.

In order to examine whether the value of energy efficiency increases by the disclosure of

EPC, a common energy efficiency measure, this is based on actual energy consumption,

for certified and non-certified dwellings has been created. It has been found that the

market value of a percentage change in actual gas consumption is close to the value of

the energy efficiency change that is estimated based on EPC energy efficiency indicator.

The study findings do not provide any evidence suggesting a larger capitalization rate for

the dwellings that are transacted with EPCs. Regression discontinuity approach was also

used to test whether the label (classification), itself, has a market value. The results do

not indicate a significant change in transaction price at the threshold energy efficiency

level that is used to assign the dwellings into different label classes. Finally, in order to

examine the over-time variation in the capitalization of energy efficiency, the hedonic

model for each year separately from 2003 to 2011 was estimated. It was found that the

value of energy efficiency has doubled from 2003 to 2011, which might be partly

explained by the increase of energy prices, the relative decrease in house prices after

2008 and the general impact of policies and campaigns indicating the importance of EE.

9

Monetary value of energy efficiency and its impact on aligning incentives

Dr. Risto Kosonen, Aalto University, Finland

Energy efficient indoor environment is a common goal for all building project

stakeholders. Excellent indoor environment quality increases wellbeing and performance

of workers. Together with reducing of operation cost, high quality environment increase

value for investor and building owner. At the moment, there is a lack of understanding

on how good indoor environment can improve business based on earning logics of

owners, investors and tenants. Currently a good indoor environment is often fostered by

regulations not business interests. Thus, only few investor and owners have realized the

potential of sustainable indoor environments for their business.

Building owners and investors can financially benefit from sustainability and improved

indoor environmental quality. These improvements can result in increased property

value such as:

− Reduced life-cycle costs;

− Extended building and equipment life span;

− Longer tenant occupancy and lease renewals;

− Reduced churn costs;

− Reduced insurance costs;

− Reduced liability risks;

− Brand value.

In the facility management, the main concern of the net operation income is to reduce

running costs. Beside the improved occupancy and asset value, excellent indoor

environment affects rental yield. According the research results, better building rent

ability and lower maintenance costs can be achieved through good and energy efficient

indoor environment. Good indoor environment and energy efficiency attract tenants.

In fact, based on the findings it could be estimated that asset value of buildings with

excellent indoor environment is 10% higher that with the standard buildings and the

price premium is likely to significantly increase in the next 5 years. Moreover, in

buildings with high quality indoor environment the occupancy rate is approximately 10%

higher and the rent is 5% higher that with standard building.

Willingness to Pay for Energy Efficiency in the rental sector

Adan L. Martinez-Cruz, ETH Zurich, Switzerland

The results of two empirical studies performed at the Centre for Energy Policy (CEPE),

ETH Zurich, on the preferences and willingness to pay of tenants and landlords foe

energy saving renovation of buildings have been presented and discussed.

The results of the first study show that tenants are willing to pay more for the rent

(between 3 and 13%) if an energy-saving renovation is carried out (3% for an enhanced

insulated façade and 13% for a general insulation of the buildings, including natural

ventilation). The second study shows that owners of multi-family buildings consider

energy-saving renovations as risky and uncertain. These results have straightforward

public policy implications: if tenants are willing to pay for energy-saving renovations, but

owners perceive this type of investment as risky, then policies can be directed to

subsidize landlords to invest in energy-saving measures.

Finally, the first ideas of a new project on home buyers’ willingness to pay for green

homes have been presented. ETH aims to implement a field experiment with the help of

construction companies and it identified that architects, construction consultants, and

building companies are the most important source of information to perform

renovations. This finding justifies ETH attempt to include credible providers of

information for the experiment.

10

How to avoid the poverty trap for tenants and prevent “renovictions”

Pasquale Davide Lanzillotti, International Union of Tenants

In the EU there is an Energy poverty issue:

− 52 million people cannot keep their home adequately warm;

− 161 million are facing disproportionate housing expenditure;

− 87 million are living in poor quality dwellings;

− 41 million face arrears on their utility bills.

There is an "housing deprivation" issue as well: 15.7% EU population living in dwellings

with a leaking roof, damp walls, floors or foundations, or rot in window frames of floor

(SILC, 2014).

According to EUROSTAT there is also a worrying housing overburden rate for tenants in

private market, with significant share of tenants living in households where total housing

costs (including energy) represent more than 40% of their disposable income;

On average, 27.1% of tenants renting at market price have a housing cost overburden in

the EU 28

5

.

Being a tenant is per se a driver of energy poverty, because tenants live generally in

more inefficient dwellings ad don’t have same resources as landlords to invest in EE

measures nor the legal possibilities to require them.

In 21 European countries, renovation costs may be passed on to tenants through rent

increase - leading often to welfare losses or «renoviction» (displacement) and

gentrification.

Energy-efficient renovation should be at least cost neutral for tenants, i.e. balance

between rent increase and energy savings

At present, the Energy Efficiency Directive does not protect tenants against potential

losses resulting from EE improvements. It rather ask MS to «remove barriers» (Art. 19),

without taking social considerations into account.

Art. 7 par. 7(a) is deemed too weak and should be revised as follow:

«Within the energy efficiency obligation scheme, Member States have to:

(a) include requirements with a social aim in the saving obligations they impose,

including by requiring a share of energy efficiency measures to be implemented as a

priority in households affected by energy poverty or in social housing»

Moreover, “private rental housing” should be explicitly mentioned. IUT claims for a

review of the EED to ensure that tenants are not financially penalized by energy-efficient

renovation the “new deal for energy consumers” should be balanced as they are “at the

core of the Energy Union”.

Energy performance generally is not considered when setting the rent price in the

residential sector and it should be part of rent levels (as in the Dutch “points system”

and in a few German Mietspiegel) in order to stimulate investment in EE improvements

especially in the private rented sector.

For more market transparency ensure MS enforcement and compliance with Art. 12 -

energy performance certificates to be handed over to tenants/buyers, together with

training/ information campaigns for residents. When revising EPBD the mandatory

display of energy certificates in common parts of all buildings should be introduced.

5

Belgium, Denmark, Italy, Lithuania, Portugal, Romania, UK (>30%); • Bulgaria, Croatia, Hungary

and Spain (>40%); Greece (>50%); Source: Eurostat, 2014

11

In order to achieve socially balanced energy renovations some member states

introduced some innovative schemes:

− The Netherlands “points system” including energy label, plus a covenant on

energy savings in the rental housing sector providing for a total housing costs

guarantee: savings made in energy costs are greater than the increase in rent

due to the energy-savings

− The Swedish system of “gross rent” i.e. rent includes heating and hot water

charges and thus it is an incentive for landlord to make investments.

The shortage of decent and affordable housing, in combination with the inability of

residents/tenants to afford energy costs, maintenance & renovation can cause poverty

and social exclusion (e.g. displacement of tenants and gentrification of quarters). It is

thus crucial to put social/affordable rental housing and rent stabilisation mechanisms at

the centre of EE policies. A good example is the German rent law, which stated that

costs of EE measures financed through public loans may not be passed on the rents.

IUT welcomes new policy line of the European Commission (prioritize energy efficiency

investment in rental housing e.g. through EIB loans and EFSI)

Some actions are needed at different levels of governance to overcome the split

incentive issue. At EU level, financial instruments to support energy improvements in

rental housing have to be put in place.

At National level, binding energy-efficiency objective agreements together with schemes

to ensure that total housing costs are not higher after energy improvements (e.g. Dutch

covenant on energy savings) shall be set up, together with rent stabilisation

mechanisms. Finally, at local level energy performance shall be considered as a

component of rent to stimulate investment in both private and social sector, awareness

raising campaigns shall be developed and the display of EPCs should be mandatory in all

buildings.

4.2 Session 2: Engaging commercial tenants in energy efficiency

Tenancy ratings under the Australian Built Environment Rating System

Dr Paul Bannister, Exergy Australia

Australia launched the NABERS (National Australian Built Environment Rating System)

energy rating program for office buildings in 1999, with ratings for other commodities

(water, waste, indoor environment), and additional building types (shopping centres,

hotels, data centres) introduced over subsequent years. NABERS is a performance

based building greenhouse rating tool, where an existing building is compared against

the building stock based upon its actual energy consumption and its productive outputs

(occupied m

2

, hours per week, climate etc). Ratings are valid for 12 months, requiring

the ongoing maintenance of building performance. The rating is on a zero to 6 star scale,

in half star increments. In 1999, 2.5 stars was set to the median building performance

in the market, with 6 stars representing emissions approximately 75% lower than

median. Ratings are separately assessed on base buildings (land lord energy use) and

tenancies (tenant light and power).

NABERS policy has generally been market based, as opposed to compliance focused. For

example, there is no mandatory requirement for buildings to achieve a particular star

level. However, there are numerous policies to encourage market value of high NABERS

ratings, such as incentives through green lease requirements for government tenancies

(government being a significant tenant of Australian office buildings), and mandatory

public disclosure of existing building performance. This has been reflected in a significant

building valuation premium in the Australian office market for high NABERS rating office

buildings. Based on 2014 data, market wide total returns for buildings of 4 stars and

above was 10%p.a. vs 8.8%p.a for buildings of less than 4 stars. This was reflected in

both income and capital return. The value of NABERS ratings to owners was supported

12

by over 70% of the floor area in the market paying voluntarily to have an independent

assessment of their building by 2011, prior to the program becoming mandatory.

This alignment of energy performance with building valuations has had a profound

impact on the energy efficiency of landlords in the Australian office market, with the

majority of institutional property owners pledging to achieve ratings above 4.5 stars, or

emissions approximately 50% below the median emissions of the 1999 baseline. By

2015, the majority of these portfolios have achieved this, and has been reflected in the

performance across the whole building stock, with the median rating improving from 2.5

stars in 1999 to 4.2 stars in 2014, and capture of approximately 90% of the Australian

office building stock.

The adoption by building tenants has been considerably lower than that for landlords.

Anecdotal feedback indicates that this is due to less tangible alignment with core

business (property valuations are tangible for landlords) and energy representing a

smaller portion of business costs – of the order of 10% of rental for landlords, but under

1% of square meter equivalent wage costs for tenants. Further, adoption in building

classes with a poorer split between owner and user energy consumption has been poor,

a reflection of reluctance to report on consumption outside of the operational control of

the reporting entity.

The Australian experience has shown strong effect of measurement based rating tools in

driving market emissions, provided the market structure is supportive of utilising

performance ratings to inform purchasing decisions, and that complementary policy is

provided to assist the market valuation of high performing buildings.

From Energy Star to Tenant Star: the US experience

Adam Sledd, Institute for Market Transformation US

In fall 2015, US Congress passed the Energy Efficiency Improvement Act of 2015, a

small but important bipartisan bill focused on improving efficiency in U.S. buildings. For

many in the real estate industry, the most notable portion of the bill directed the U.S.

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) to

create a tenant-focused version of EPA’s very successful Energy Star for buildings

program. The new initiative, which the bill gives EPA the option of calling Tenant Star, is

being hailed by a wide range of industry stakeholders as the next great tool for driving

energy savings in commercial buildings. It’s not hard to see the allure of Tenant Star.

Energy Star’s Portfolio Manager is already successfully helping more than 400,000

commercial buildings measure, track, assess and report their energy and water use. And

last year Energy Star expanded its reach to multifamily housing with the help of Fannie

Mae. To test the program’s effectiveness, in 2012 EPA conducted a study of 35,000

buildings. The results showed that organizations benchmarking whole building energy

data (PDF) consistently in Portfolio Manager achieved average energy savings of 7

percent over three years. The key words there, however, are "whole building." As

property owners have become more sophisticated about managing energy use in their

buildings, the composition of that usage has changed. Plug and process loads, which

include tenant space items such as refrigerators, computers and printers, are widely

considered the fastest-growing category of energy use in office buildings. So while base

building systems such as boilers and chillers are getting more efficient, tenant spaces

may offset savings by ignoring efficiency in their space design and occupant behavior.

Owners who invest millions of dollars to have high-performing buildings are rightfully

worried that inefficient tenant spaces are, to some extent, undoing their good work.

Tenant Star could help secure investments in high-performing buildings by providing

owners with a federally funded engagement platform to present to prospective tenants.

The program’s savings potential is staggering when considering only the roughly 6 billion

square feet of existing leased office space in the U.S., and estimating about $1.10 per

square foot for lights and plug and process loads, just 15 percent savings in tenant

spaces would be worth almost a billion dollars in avoided energy costs — and that’s not

counting potential savings for retail, education and other types of tenants. Despite the

13

large potential, there is still a long road ahead to reach a world full of Tenant Star-

certified spaces.

From bill to real building efficiency

The bill didn’t actually provide funding for the program, which was a particular problem

because the EPA and DOE will have to build the program from scratch, and ENERGY

STAR already runs on a shoestring budget. ENERGY STAR uses data from the Energy

Information Administration’s (EIA) Commercial Building Energy Consumption Survey

(CBECS) as its baseline for whole building consumption, and there is no comparable

study for tenant spaces. Even in a best case scenario that Congress immediately funds

EIA to develop a tenant version of CBECS, results will not been seen before 2018. The

agencies have about six months to lay out a plan to capture enough data to build a

baseline for Tenant Star, and they’ll run into a considerable roadblock: the vast majority

of leased office spaces are not sub- or separately metered, meaning there isn’t an

obvious way to obtain detailed energy usage information. This is a really significant

problem. There are only a handful of markets around the country (New York, Chicago,

San Diego, and Cleveland, for example) where many office tenants receive utility bills

from either the landlord or utility that reflect real energy consumption, rather than a

per-square-foot estimation. So Tenant Star either will have to be built with a limited data

set, reflecting relatively few markets or types of buildings, or there will have to be a

major data collection process that could involve sub-metering tenant spaces around the

country. While we’re on the topic of office buildings, the same problem applies to a large

portion of the enclosed retail spaces not currently covered by Energy Star/CBECS: most

malls charge retailers for utility costs on a per-square-foot basis rather than actual

meter readings.

Information overload

One way to establish the program could be to focus on the space design rather than

operational data. However, LEED Commercial Interiors already has a well-established

market for certifying the design and projected performance of a tenant space — and

Energy Star is known for rewarding buildings’ energy performance, rather than projected

numbers. To change that now would likely only further confuse a marketplace already

bogged down by information overload. A better solution likely will involve EPA and DOE

working with as many owners and tenants from as many markets as possible to get

confidential access to sub- and separately metered data. The EPA then could base the

Tenant Star scoring system on this data in the same way it bases Energy Star on CBECS

data. The agency already did something very similar in creating Energy Star for data

centers. If we’re thinking about long-term impacts of Tenant Star, it’s a good bet that

the first widely felt one will be a potential surge in sub-metered tenant spaces, likely

accompanied by billing tenants for lights and plug load usage separate from other

operating expenses. Landlords mostly have avoided this structure until now, but it’s hard

to imagine that tenants will want to pursue Tenant Star certification without accruing the

benefits of a more-efficient space. A new Energy Star program won’t magically provoke

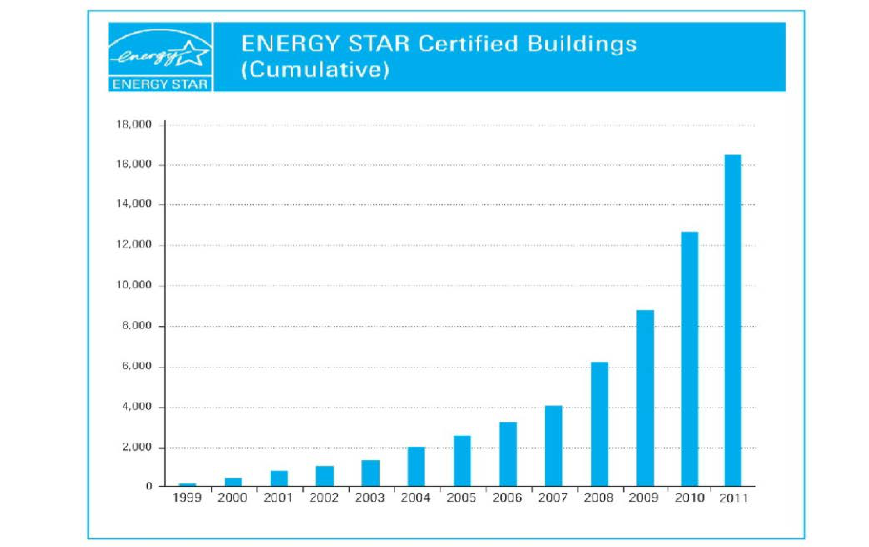

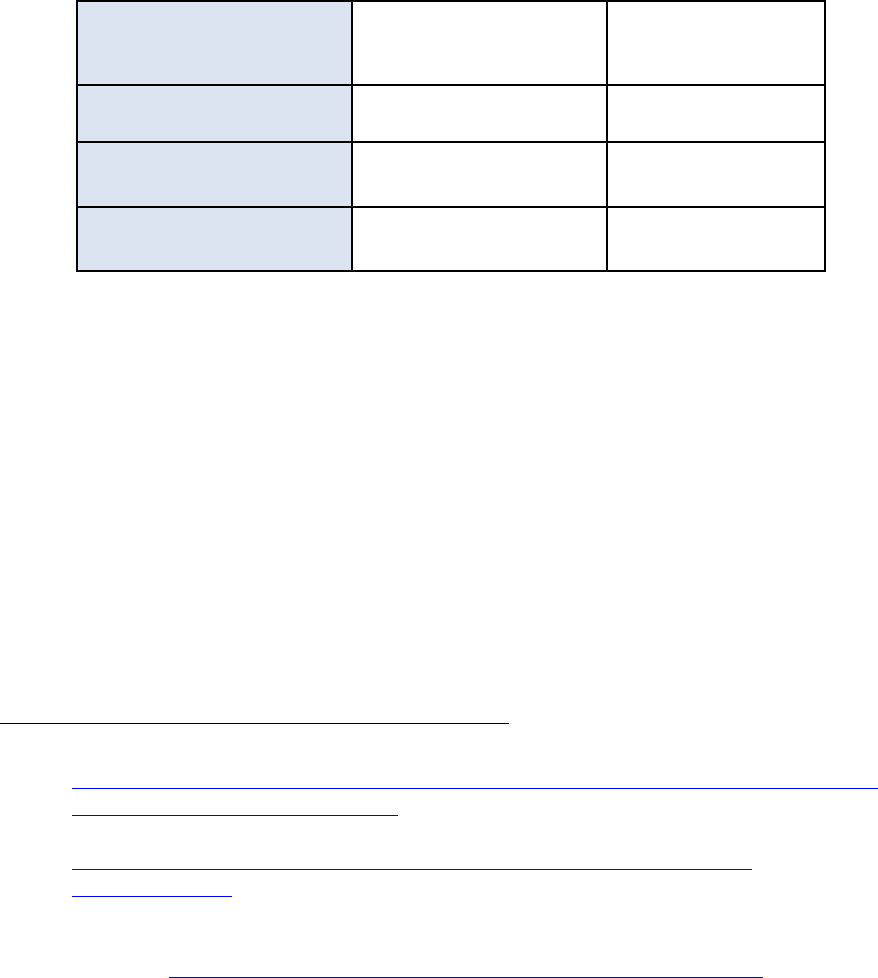

tenants to think or act differently about how they occupy their space, either. Figure 1

shows the adoption curve for the original buildings program.

14

Figure 1. Energy STAR Certified buildings (1999-2011)

Matching the same track record will require time and effort on the part of building

owners, and likely some changes to the way they currently interact with tenants and

structure their leases. Some leading owners and managers already understand this and

have solid tenant engagement programs in place. If you’re wondering which companies

have done so, the list of the 2014 and 2015 Green Lease Leaders is a great starting

point. For many owners and managers, the establishment of Tenant Star could provide

greater motivation for many owners and managers to develop a tenant engagement plan

that tackles reducing energy use. The potential is extraordinary, but realizing it will

require sustained effort to nail each step along the way

Latest developments on the use of green leases in Europe

Bruno Duquesne, Lawyer at the Brussels Bar Partner CMS DeBacker Belgium

As a pan-European legal organization present in 59 cities, CMS has taken on the task of

developing a uniform European standard on Green Lease.

In a first phase, legal position in 21 European countries were compared. A questionnaire

was set up and answers were provided by each jurisdiction. This study makes

recommendations on how to draft a green lease. Hereunder are provided the main

conclusion of the study.

The green lease should regulate the recording and calculation of operating costs based

on consumption (especially heating, refrigeration, electricity, water, etc.); in some

countries this has already been prescribed by law. Tenant should be obliged by contract

to accept the measures undertaken by the landlord (in particular refurbishment) to

improve energy efficiency in the building and to promote environmental protection.

Lease should grant landlord the right to pass an appropriate amount of the costs of

improving energy efficiency and observing environmental principles onto tenant or to

increase the rent by a reasonable amount. If a building has been certified as “green”,

tenant should undertake to observe the certification conditions and act accordingly, e.g.

only install elements in the building which are made of energy-efficient and eco-friendly

materials. The parties should agree to act in such a way as to save energy and promote

environmental protection (e.g. correct conduct as regards heating or refrigeration, water

15

consumption or recycling waste). Landlord should inform tenant about possible ways to

save energy and be environmentally responsible.

The following definition (proposed regulation) describes the content and the target of a

green lease:

A green lease is a lease agreement which is intended to ensure that a leased property is

used and managed in a manner which fosters sustainability. The tenant and the landlord

thus mutually undertake to conserve natural resources and energy with regard to the

leased property. The parties may also document the sustainability of the leased property

by acquiring or receiving certification and creating the conditions for the environmentally

friendly use of resources.

Across Europe there is a largely uniform understanding of the term “green leases”. The

content and the aim is to comply with aspects of sustainability when engaging in a lease

relationship. As a rule green leases are not regulated under statute.

Only in France is there a duty to attach an environmental appendix to certain leases.

This is for leased properties with an area greater than 2,000 m² and leased properties

which are used as offices or for commercial purposes.

The IBGE’s initiative on Green Leases in the Brussels Region (an example)

The Brussels Environment Agency (BIM/IBGE) has launched a project aiming at setting

up a new technique for the financing of energy saving renovation works. CMS is involved

in this project. The project is articulated in two phases:

− First phase: technical, financial and legal analyses relating to possible actions in

this field.

− Second phase : preparing a lease template aimed at organizing the landlord/

tenant relationship in the framework of a live test.

Selected lease relationship is the residential lease entered into in respect of a property

that does not make part of a co-ownership. Bottom line of proposed system is that both

landlord and tenant must benefit from the system. Landlord carries out the energy

saving works at own costs, but can recharge a part of those costs to tenant through a

monthly energy service charge. Tenant will however benefit from a part of the energy

saving. Landlord to recover 75% of his net investment. Remaining 25% will be regarded

as a capital gain for the property. The Net cost of the investment shall be equal to the

cost of the investment less any subsidies, grants, tax reductions, etc., and less any

deduction that should in any event have been borne by landlord (for ex. in order to

comply with certain statutory requirements).

IBGE prepared a list of authorized/qualifying investments and has created a calculator

enabling to calculate the energy savings for a given investment, taking the lifetime of

the investment into account.

Overcoming barriers to energy upgrades in multi-owned properties: lessons

from the WICKED retail project and residential issues

Susan Bright, Oxford University, UK

The retail sector is diverse, and about half the space is rented. Because of complex

interdependencies between stakeholders, energy management in the retail sector can be

defined as a 'wicked' problem (Rittel and Weber, 1973). The "Working with

Infrastructure, Creation of Knowledge and Energy strategy Development - WICKED"

initiative is an Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) funded

research project, exploring energy management issues and opportunities in the UK retail

sector. The WICKED academic research team combines expertise in energy use, maths,

computing, engineering, physics, law and organisational behaviour, and uses a multi-

level, interdisciplinary research approach. Alongside 'big data' analysis and the

development of new smart meters, WICKED carries out qualitative analysis of

16

organisational issues, focusing on energy management, the landlord-tenant relationship

and the role of green leases.

A number of findings emerged, based on interviews and document analysis. The 'split

incentive' manifests itself in complex and diverse ways, typically where a landlord wishes

to pass on costs of energy efficiency improvements to the tenant through the service

charge, but the tenant resists. This is only part of the picture and related issues and

barriers include capital and rental valuation, trade disruption, retailer focus on sales, lack

of access to upfront funding, long pay-backs, lack of data, distrust. The lease typically

reinforces these barriers on paper, e.g. by not allowing access and/ or cost recovery for

upgrades; but in practice is less relevant than other barriers.

There are examples of landlords and tenants cooperating to overcome these barriers;

generally 'outside the lease', and recovering costs through the service charge or other,

voluntary financial arrangements for cost sharing. These collaborations are driven by

trust, common interest and mutual benefit, and require commitment and resources.

'Green' lease clauses are typically used by large landlords in the prime market and tend

to be general, non-binding and aspirational; or to prevent the worsening of

environmental performance. Some leases allow landlord access to carry out energy

efficiency upgrades, but very few provide for cost recovery. Many retailers are resisting

green lease clauses due to lack of awareness, cost considerations, other pressures and

priorities, general distrust and/ or a reluctance to relinquish control and flexibility.

Views about the role of green leases are mixed and presented below.

To many they are irrelevant and seen as being 'in the cupboard'; conversely, what

matters is what is 'on the ground'. Some view green lease clauses as unhelpful,

reinforcing the traditional adversarial relationship between landlord and tenant.

On the other hand, for some green clauses can provide a framework for dialogue and

cooperation (possibly simply reflecting existing drivers).

The expected introduction of minimum energy efficiency standards (in 2018) is high on

the agenda for landlords and their advisers, and some retailers. Companies are

reviewing their property portfolios and their leases to manage risks. Responses to MEES

remain uncertain and could include energy efficiency improvements, but also offloading

of sub-standard properties, issues around enforcement and increased tension between

landlords and tenants over the cost of improvements.

A second project on the spilt incentive issue in the residential sector, "Future proofing flats:

Overcoming barriers to energy upgrades in private flats (apartments)" has then been

presented. This project, a research partnership with "Future Climate" NGO, the City of

Westminster, TLT solicitors, and the University of Oxford, is concerned with investigating the

legal and governance barriers to upgrades in apartments in the United Kingdom. In UK one in

five homes are apartments, and apartments are less likely than houses to have key energy

efficiency measures. Older flats in converted houses perform worst. In the City of

Westminster, 90% of homes are flats and the council is very concerned about the legal and

governance barriers to upgrading apartments.

A number of findings emerged:

− In England, apartments are sold on a leasehold basis. Leases present serious barriers to

energy upgrades: leaseholders commonly own only the unit that is their home and have

no power to make decisions in relation to the management of the common/shared parts

of the building, there is no standard wording in leases, and they are often poorly

drafted;

− The major problem in the context of energy upgrades is that leases — and the legal

rights in many European countries — give no power to improve the buildings.

17

− There is often 'title complexity' in apartment buildings: so any action taken needs to be

consistent with the rights of rental tenants, apartment owners, those with security

rights (mortgagees) and any commercial and retail leases.;

− In so far as action can be taken with consent, in England this will usually be 100%. Even in

countries with lower consent requirements, the barriers to obtaining consent make action

difficult. The barriers include difficulties in identifying and contacting owners, and reaching

consensus.

The research project has proposed a number of legal reforms: (a) a duty on the building owner

to undertake an energy efficiency survey of the whole building; (b) a right for unit owners to

improve the energy efficiency of the building; (c) changing the meaning of leases to permit

energy efficiency; and (d) a right for individual apartment owners to make energy

upgrades that are internal to the apartment.

4.3 Session 3: Legislations as an energy efficiency driver

An European comparison of tenancy regulation and energy efficient

refurbishment

Christoph U. Schmid, Universität Bremen, Germany

With a view to furthering climate protection and a sustainable reform of energy supply,

the European Union has committed itself to ambitious objectives in energy policy.

Directive 2012/27/EU, which had to be implemented into national law until June 2014,

specifically aims at increasing energy efficiency in the existing building stock. Indeed, a

huge potential for energy savings may be supposed to exist in this sector. Rental

dwellings therefore play a significant role in this context.

The presented study starts off from a socio-economic and comparative description of

tenancy law and markets in 12 EU Member States respectively 13 countries (as within

the UK, England and Scotland have been analysed separately) and Switzerland. The

comparative analysis of tenancy law provisions relevant to energy renovation in the

rental stock is based on this description, which extends to both the European and the

national level. On the basis of this analysis, the countries under review were divided into

several groups. This categorization aims at locating national tenancy law provisions

within the overall energy policy context and explaining under which conditions progress

in energy efficiency in buildings may be reached.

Beyond that, the study examines which approaches the various countries have chosen to

implement European provisions into national tenancy and housing law (in Switzerland in

the framework of autonomous alignment to European legal standards). To this end, the

study first needs to identify those fields of law and policy which have a strong bearing on

energy efficiency. The central legal basis in European primary law is Art. 194 TFEU,

which explicitly focuses on the promotion of energy efficiency and energy savings as

objectives of European energy policy.

Starting in January 2014, the research project underlying the present study analysed the

situation of the housing market with a particular focus on energy performance and its

interconnections with private tenancy law and public law regulations aiming at increasing

energy efficiency in the rental stock. This analysis was carried out in 14 selected

European legal orders: DK, DE, FI, EE, FR, IT, LV, NL, AT, PL, SE, England, Scotland and

Swiss. This selection encompasses both countries which are very different from Germany

and countries exhibiting similar legislative provisions as well as court and administrative

practice. This approach enables the identification of different regulatory models and

elements of best practice. In a methodological perspective, the project is based on a

synthesis of different approaches. First, secondary literature and own sources of

information were used. In this respect, the broad preliminary work undertaken by the

project team in the framework of the Tenlaw project (implemented by the Centre of

18

European Law and Politics at Bremen University (ZERP) under the 7

th

Framework

Programme of the EU could be relied upon.

6

As the central source of information, a detailed questionnaire was answered by

specialized national reporters for each of the countries under review. Its contents and

structure had a qualitative focus. This knowledge base of the project was reflected and

broadened in various workshops, which were organized together with the contracting

authority and to which representatives of other federal ministries and external experts

(from Spain, the Netherlands and Austria) were invited. In the final phase of the project,

the national reporters were consulted again to control its key results.

Scientific approach and intermediary results

Step 1: Country profiles

For each country, a profile was drafted which is based on multiple sources of information

and data including the expert answers to the questionnaire. The uniform structure of the

profiles may be summarized as follows:

− Basic features of the national housing system;

− Typology of rental buildings;

− Trends in housing policy and supply;

− Rental markets;

− Excursus on national tenancy law;

− Networks of actors active in rental housing;

− Energetic efficiency: basic features and trends.

These profiles contain a structured and coordinated information base on all covered

areas of research and for each of the countries under review.

Step 2: Influence of EU legislation on national tenancy law

In this step, stock is taken of the relevant EU legislation on energy efficiency. This

analysis shows that a large number of European directives and regulations considerably

influence housing markets and tenancy laws. These range from public procurement law

to technical standards and consumer law. These legislative instruments are structured

and evaluated according to whether they exercise direct or indirect influence on national

tenancy law.

Step 3: Comparative analysis of national tenancy law provision relevant to energy

renovation of buildings

The comparative analysis of national tenancy laws including the regulation of energy

renovation makes a distinction between (a) general tenancy law, (b) legal prescriptions

on the distribution of additional costs and utilities and (c) tenancy law provisions on

energy efficiency.

An evaluation of general tenancy law provisions shows that three types of countries may

be distinguished with respect to the duration of tenancy relationships:

− Countries in which fixed-term and open-ended tenancy contracts are lawful (e.g.

Austria);

− Countries in which only fixed-term tenancy contracts (normally covering longer

periods) are lawful (e.g. France, Italy);

− Countries in which fixed-term tenancy contracts are lawful only exceptionally

(e.g. Germany).

6

Vgl. www.tenlaw.uni-bremen.de

19

As regards termination of open-ended tenancy contracts, the countries under review

may be divided into three categories:

− Countries where open-ended contracts may be terminated without restrictions

(e.g. Switzerland);

− Countries where open-ended contracts may be terminated only for important,

legally pre-defined reasons (e.g. Denmark, Germany);

− Countries where open-ended contracts cannot, factually, be terminated (e.g.

Sweden).

The following further issues, which are relevant to a comparative law analysis and an

overall categorization of countries, are analysed:

− Rent regulation (in the case of the conclusion of new contracts and rent increases

in existing contracts);

− Obligations of the tenant to tolerate refurbishment works;

− The distribution in fact and in law of running costs and additional charges

between landlord and tenant;

− Information duties relating to the energetic state of rental dwellings and the

remedies available in case of their violation;

− Obligations to carry out energy refurbishment measures, e.g. in the case of

certain measures or of violation of certain technical or environmental standards;

− Special regulations on the division of costs of measures of energy renovation

between landlord and tenant (in countries allowing rent increases in existing

contracts);

− State aid for measures of energy renovation (tax incentives and direct subsidies).

Step 4: Categorisation and path developments in the countries under review

A further step, already completed, is devoted to the comparative description of different

framework conditions and implementation strategies. According to this analysis, the

countries under review may be subdivided into three main types:

− Type 1: “High share of non-profit rental dwellings with a comparatively high

degree of regulation of energy renovation”: Denmark, Sweden, Netherlands. The

countries pertaining to this group are characterised by a comparatively high

degree of regulation aimed at implementing measures of energy renovation and

shifting costs on tenants. The requests for public subsidies are low until medium

in this group. Non-profit housing associations and cooperatives have mostly high

relevance in these countries and security of tenure is likewise high;

− Type 2: "Medium degree of regulation on energy renovation combined with high

degree of security of tenure”: France, Germany, Austria. This group displays a

medium degree of regulation on energy renovation (normally, this regulation has

a procedural focus, except in Austria). The allocation of costs on tenants is legally

possible to different degrees (no uniform regulation in Austria). The requests for

subsidies are medium until high. Security of tenure is generally high in these

countries (in Austria, it depends on the type of rental buildings);

− Type 3: "Low degree of regulation on energy renovation combined with a rather

low degree of security of tenure“: Switzerland, England, Scotland, Italy and

Estonia. This group is made up of countries in which energy renovation measures

are comparatively little regulated. Thus, in England, Scotland and Switzerland,

only the procedure to be observed for energy renovation works is regulated. In

Estonia and Italy, the consent of the tenant is required; alternatively, the landlord

may terminate a rental contract in a medium term perspective. The allocation of

renovation costs on the tenant is not legally regulated but market-based. Security

of tenure in the private rental sector is generally low in this group.

20

Finland, Poland and Latvia display individual features in central issues, for which reason

they cannot be accommodated plausibly in this categorisation. For this reason, they

could not be integrated into final analysis either.

Moreover, the project has shown that, despite the close resemblance of central

parameters (e.g., the share of rental dwellings in the overall stock), the national

framework conditions and therefore also the national strategies to adapt the housing

stock to the objectives of energetic renovation may be very different. The following

factors are relevant in this respect: Stability of tenancy relationships

− High degree of regulation of energetic renovations

− Obligation of the tenant to tolerate energy refurbishment works

− Share of non-profit housing in the overall stock

Key results and conclusions

To promote energetic renovation of buildings, the European Commission primarily relies

on existing measures and strategies in the countries under review. These measures and

strategies have been shaped during the last decades against the background of different

national framework conditions (including the structure of the building stock, climatic

conditions and legal provisos) and constitute the basis of European energy policy.

At European level, EU Member States are subject to notification and reporting

requirements and obliged to elaborate national action plans for energetic efficiency and

strategies for the refurbishment of the existing housing stock.

An assessment of the impact of energy renovation measures on landlord and tenant

depends primarily on general tenancy law at national level. National provisions also

determine whether an adequate division of the benefits of such measures may be

achieved, as prescribed by Art. 19 Directive 2012/17/EU.

In most countries under review, the amount of the rent may be agreed upon freely by

the parties at the conclusion of the contract. Conversely, rent increases in existing

contracts are limited by regulatory provisions in most countries; in addition, their

interaction with the rules on termination of the tenancy relationship is relevant as

termination may constitute an obvious alternative for the landlord if legally possible.

As regards duration of tenancy contracts, open-ended contracts are predominant in

practice in most countries under review. Countries with fixed-term contracts do not

normally allow termination to achieve rent increases whereas termination to enable core

refurbishment works to enhance the energy performance of the building is generally

possible. At least in theory, short term contracts seem to offer the possibility of

implementing energy renovation measures at the end of each term. However, the data

show that in countries characterized by short term contracts such as the UK the volume

of energy renovation measures carried out up until now is rather low. This may be

explained by the fact that landlords may refrain from investments into old buildings in